User login

FDA grants new indication to lumateperone (Caplyta) for bipolar depression

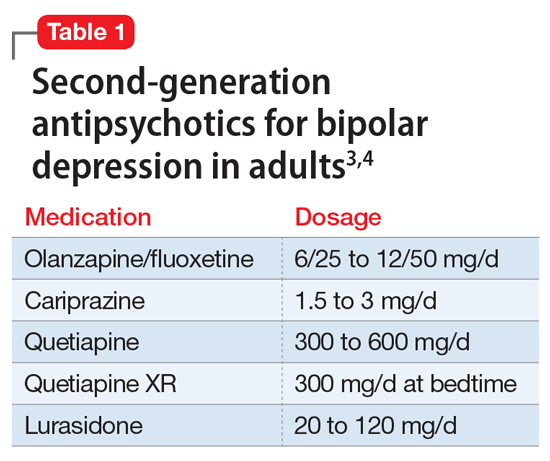

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded approval of lumateperone (Caplyta) to include treatment of adults with depressive episodes associated with bipolar I and II disorder, as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate.

This makes lumateperone the only FDA-approved drug for this indication.

“The efficacy, and favorable safety and tolerability profile, make Caplyta an important treatment option for the millions of patients living with bipolar I or II depression and represents a major development for these patients,” Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said in a company news release.

Lumateperone was first approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia.

‘Positioned to launch immediately’

that showed treatment with lumateperone, alone or with lithium or valproate, significantly improved depressive symptoms for patients with major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I and bipolar II disorders.

In these studies, treatment with a 42-mg once-daily dose was associated with significantly greater improvement from baseline in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score versus placebo.

Lumateperone also showed a statistically significant improvement in the key secondary endpoint relating to clinical global impression of bipolar disorder.

Somnolence/sedation, dizziness, nausea, and dry mouth were the most commonly reported adverse events associated with the medication. Minimal changes were observed in weight and vital signs and in results of metabolic or endocrine assessments. Incidence of extrapyramidal symptom–related events was low and was similar to those with placebo.

Sharon Mates, PhD, chairman and CEO of Intra-Cellular Therapies, noted in the same press release that the company is “positioned to launch immediately and are excited to offer Caplyta to the millions of patients living with bipolar depression.”

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded approval of lumateperone (Caplyta) to include treatment of adults with depressive episodes associated with bipolar I and II disorder, as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate.

This makes lumateperone the only FDA-approved drug for this indication.

“The efficacy, and favorable safety and tolerability profile, make Caplyta an important treatment option for the millions of patients living with bipolar I or II depression and represents a major development for these patients,” Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said in a company news release.

Lumateperone was first approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia.

‘Positioned to launch immediately’

that showed treatment with lumateperone, alone or with lithium or valproate, significantly improved depressive symptoms for patients with major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I and bipolar II disorders.

In these studies, treatment with a 42-mg once-daily dose was associated with significantly greater improvement from baseline in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score versus placebo.

Lumateperone also showed a statistically significant improvement in the key secondary endpoint relating to clinical global impression of bipolar disorder.

Somnolence/sedation, dizziness, nausea, and dry mouth were the most commonly reported adverse events associated with the medication. Minimal changes were observed in weight and vital signs and in results of metabolic or endocrine assessments. Incidence of extrapyramidal symptom–related events was low and was similar to those with placebo.

Sharon Mates, PhD, chairman and CEO of Intra-Cellular Therapies, noted in the same press release that the company is “positioned to launch immediately and are excited to offer Caplyta to the millions of patients living with bipolar depression.”

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded approval of lumateperone (Caplyta) to include treatment of adults with depressive episodes associated with bipolar I and II disorder, as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate.

This makes lumateperone the only FDA-approved drug for this indication.

“The efficacy, and favorable safety and tolerability profile, make Caplyta an important treatment option for the millions of patients living with bipolar I or II depression and represents a major development for these patients,” Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said in a company news release.

Lumateperone was first approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia.

‘Positioned to launch immediately’

that showed treatment with lumateperone, alone or with lithium or valproate, significantly improved depressive symptoms for patients with major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I and bipolar II disorders.

In these studies, treatment with a 42-mg once-daily dose was associated with significantly greater improvement from baseline in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score versus placebo.

Lumateperone also showed a statistically significant improvement in the key secondary endpoint relating to clinical global impression of bipolar disorder.

Somnolence/sedation, dizziness, nausea, and dry mouth were the most commonly reported adverse events associated with the medication. Minimal changes were observed in weight and vital signs and in results of metabolic or endocrine assessments. Incidence of extrapyramidal symptom–related events was low and was similar to those with placebo.

Sharon Mates, PhD, chairman and CEO of Intra-Cellular Therapies, noted in the same press release that the company is “positioned to launch immediately and are excited to offer Caplyta to the millions of patients living with bipolar depression.”

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More evidence ties some antipsychotics to increased breast cancer risk

New research provides more evidence that antipsychotics that raise prolactin levels are tied to a significantly increased risk for breast cancer.

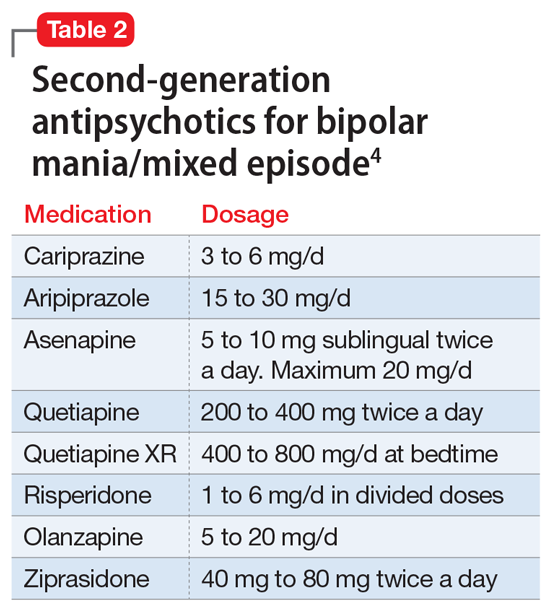

The relative risk for breast cancer was 62% higher in women who took category 1 antipsychotic medications associated with high prolactin levels. These include haloperidol (Haldol), paliperidone (Invega), and risperidone (Risperdal). Additionally, the risk was 54% higher in those taking category 2 antipsychotics that have mid-range effects on prolactin. These include iloperidone (Fanapt), lurasidone (Latuda), and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

In contrast, category 3 antipsychotics which have a lesser effect on prolactin levels were not associated with any increase in breast cancer risk. These drugs include aripiprazole (Abilify), asenapine (Saphris), brexpiprazole (Rexulti), cariprazine (Vraylar), clozapine (multiple brands), quetiapine (Seroquel), and ziprasidone (Geodon).

While the “absolute” breast cancer risk for these drugs is unclear, “we can make the case that high circulating prolactin levels are associated with breast cancer risk. This follows what is already known about prolactin from prior studies, notably the nurses’ health studies,” Tahir Rahman, MD, associate professor of psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, told this news organization.

“We don’t want to alarm patients taking antipsychotic drugs for life-threatening mental health problems, but we also think it is time for doctors to track prolactin levels and vigilantly monitor their patients who are being treated with antipsychotics,” Dr. Rahman added in a news release.

The study was published online Dec. 3 in the Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology.

Test prolactin levels

Using administrative claims data, the researchers evaluated breast cancer risk in women aged 18-64 exposed to antipsychotic medications compared with anticonvulsants and/or lithium.

They identified 914 cases of invasive breast cancer among 540,737 women.

Roughly 52% of the study population filled at least one prescription for a category 3 antipsychotic agent, whereas 15% filled at least one prescription for a category 1 agent; 49% of women filled at least one prescription for an anticonvulsant medication during the study period.

Exposure to all antipsychotics was independently associated with a 35% increased risk for breast cancer (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.14-1.61), the study team found.

Compared with anticonvulsants or lithium, the risk for breast cancer was significantly increased for high prolactin (category 1) antipsychotics (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.30-2.03) and for mid-prolactin (category 2) drugs (aHR 1.54; 95% CI, 1.19-1.99), with no increased risk for category 3 antipsychotics.

“Our research is obviously of interest for preventing breast cancer in antipsychotic-treated patients. Checking a blood prolactin level is cheap and easy [and a high level is] fairly simple to mitigate,” said Dr. Rahman.

A matter of debate

Reached for comment, Christoph Correll, MD, professor of psychiatry and molecular medicine, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, New York, said, “The potential elevation of breast cancer risk depending on the dose and time of treatment with antipsychotic medications with varying degrees of prolactin-raising properties has been a topic of research and matter of debate.”

This new study “adds another data point indicating that antipsychotics that are associated on average with a higher prolactin-raising effect than other antipsychotics may increase the risk of breast cancer in women to some degree,” said Dr. Correll, who was not involved with the study.

However, he cautioned that “naturalistic data are always vulnerable to residual confounding, for example, unmeasured effects that could also at least partially explain the results, and the follow-up time of only 4 years (maximum 6 years) in this study was relatively short.

“Nevertheless, given availability of many different antipsychotics with varying degrees of prolactin-raising potential, in women requiring antipsychotic treatment, less prolactin-raising antipsychotics may be preferable,” Dr. Correll said.

“In women receiving prolactin-raising antipsychotics for medium- and longer-term maintenance therapy, prolactin levels should be monitored,” he added.

When an elevated prolactin level is detected, this should be addressed “either via dose reduction, a switch to an alternative antipsychotic that does not raise prolactin levels significantly, or the addition of a partial or full D2 agonist when the prolactin-raising antipsychotic should be continued based on individualized risk assessment,” Dr. Correll advised.

This work was supported by an award from the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center; the National Cancer Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health; the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research; and the Center for Brain Research in Mood Disorders. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Correll has received royalties from UpToDate and is a stock option holder of LB Pharma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research provides more evidence that antipsychotics that raise prolactin levels are tied to a significantly increased risk for breast cancer.

The relative risk for breast cancer was 62% higher in women who took category 1 antipsychotic medications associated with high prolactin levels. These include haloperidol (Haldol), paliperidone (Invega), and risperidone (Risperdal). Additionally, the risk was 54% higher in those taking category 2 antipsychotics that have mid-range effects on prolactin. These include iloperidone (Fanapt), lurasidone (Latuda), and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

In contrast, category 3 antipsychotics which have a lesser effect on prolactin levels were not associated with any increase in breast cancer risk. These drugs include aripiprazole (Abilify), asenapine (Saphris), brexpiprazole (Rexulti), cariprazine (Vraylar), clozapine (multiple brands), quetiapine (Seroquel), and ziprasidone (Geodon).

While the “absolute” breast cancer risk for these drugs is unclear, “we can make the case that high circulating prolactin levels are associated with breast cancer risk. This follows what is already known about prolactin from prior studies, notably the nurses’ health studies,” Tahir Rahman, MD, associate professor of psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, told this news organization.

“We don’t want to alarm patients taking antipsychotic drugs for life-threatening mental health problems, but we also think it is time for doctors to track prolactin levels and vigilantly monitor their patients who are being treated with antipsychotics,” Dr. Rahman added in a news release.

The study was published online Dec. 3 in the Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology.

Test prolactin levels

Using administrative claims data, the researchers evaluated breast cancer risk in women aged 18-64 exposed to antipsychotic medications compared with anticonvulsants and/or lithium.

They identified 914 cases of invasive breast cancer among 540,737 women.

Roughly 52% of the study population filled at least one prescription for a category 3 antipsychotic agent, whereas 15% filled at least one prescription for a category 1 agent; 49% of women filled at least one prescription for an anticonvulsant medication during the study period.

Exposure to all antipsychotics was independently associated with a 35% increased risk for breast cancer (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.14-1.61), the study team found.

Compared with anticonvulsants or lithium, the risk for breast cancer was significantly increased for high prolactin (category 1) antipsychotics (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.30-2.03) and for mid-prolactin (category 2) drugs (aHR 1.54; 95% CI, 1.19-1.99), with no increased risk for category 3 antipsychotics.

“Our research is obviously of interest for preventing breast cancer in antipsychotic-treated patients. Checking a blood prolactin level is cheap and easy [and a high level is] fairly simple to mitigate,” said Dr. Rahman.

A matter of debate

Reached for comment, Christoph Correll, MD, professor of psychiatry and molecular medicine, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, New York, said, “The potential elevation of breast cancer risk depending on the dose and time of treatment with antipsychotic medications with varying degrees of prolactin-raising properties has been a topic of research and matter of debate.”

This new study “adds another data point indicating that antipsychotics that are associated on average with a higher prolactin-raising effect than other antipsychotics may increase the risk of breast cancer in women to some degree,” said Dr. Correll, who was not involved with the study.

However, he cautioned that “naturalistic data are always vulnerable to residual confounding, for example, unmeasured effects that could also at least partially explain the results, and the follow-up time of only 4 years (maximum 6 years) in this study was relatively short.

“Nevertheless, given availability of many different antipsychotics with varying degrees of prolactin-raising potential, in women requiring antipsychotic treatment, less prolactin-raising antipsychotics may be preferable,” Dr. Correll said.

“In women receiving prolactin-raising antipsychotics for medium- and longer-term maintenance therapy, prolactin levels should be monitored,” he added.

When an elevated prolactin level is detected, this should be addressed “either via dose reduction, a switch to an alternative antipsychotic that does not raise prolactin levels significantly, or the addition of a partial or full D2 agonist when the prolactin-raising antipsychotic should be continued based on individualized risk assessment,” Dr. Correll advised.

This work was supported by an award from the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center; the National Cancer Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health; the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research; and the Center for Brain Research in Mood Disorders. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Correll has received royalties from UpToDate and is a stock option holder of LB Pharma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research provides more evidence that antipsychotics that raise prolactin levels are tied to a significantly increased risk for breast cancer.

The relative risk for breast cancer was 62% higher in women who took category 1 antipsychotic medications associated with high prolactin levels. These include haloperidol (Haldol), paliperidone (Invega), and risperidone (Risperdal). Additionally, the risk was 54% higher in those taking category 2 antipsychotics that have mid-range effects on prolactin. These include iloperidone (Fanapt), lurasidone (Latuda), and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

In contrast, category 3 antipsychotics which have a lesser effect on prolactin levels were not associated with any increase in breast cancer risk. These drugs include aripiprazole (Abilify), asenapine (Saphris), brexpiprazole (Rexulti), cariprazine (Vraylar), clozapine (multiple brands), quetiapine (Seroquel), and ziprasidone (Geodon).

While the “absolute” breast cancer risk for these drugs is unclear, “we can make the case that high circulating prolactin levels are associated with breast cancer risk. This follows what is already known about prolactin from prior studies, notably the nurses’ health studies,” Tahir Rahman, MD, associate professor of psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, told this news organization.

“We don’t want to alarm patients taking antipsychotic drugs for life-threatening mental health problems, but we also think it is time for doctors to track prolactin levels and vigilantly monitor their patients who are being treated with antipsychotics,” Dr. Rahman added in a news release.

The study was published online Dec. 3 in the Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology.

Test prolactin levels

Using administrative claims data, the researchers evaluated breast cancer risk in women aged 18-64 exposed to antipsychotic medications compared with anticonvulsants and/or lithium.

They identified 914 cases of invasive breast cancer among 540,737 women.

Roughly 52% of the study population filled at least one prescription for a category 3 antipsychotic agent, whereas 15% filled at least one prescription for a category 1 agent; 49% of women filled at least one prescription for an anticonvulsant medication during the study period.

Exposure to all antipsychotics was independently associated with a 35% increased risk for breast cancer (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.14-1.61), the study team found.

Compared with anticonvulsants or lithium, the risk for breast cancer was significantly increased for high prolactin (category 1) antipsychotics (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.30-2.03) and for mid-prolactin (category 2) drugs (aHR 1.54; 95% CI, 1.19-1.99), with no increased risk for category 3 antipsychotics.

“Our research is obviously of interest for preventing breast cancer in antipsychotic-treated patients. Checking a blood prolactin level is cheap and easy [and a high level is] fairly simple to mitigate,” said Dr. Rahman.

A matter of debate

Reached for comment, Christoph Correll, MD, professor of psychiatry and molecular medicine, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, New York, said, “The potential elevation of breast cancer risk depending on the dose and time of treatment with antipsychotic medications with varying degrees of prolactin-raising properties has been a topic of research and matter of debate.”

This new study “adds another data point indicating that antipsychotics that are associated on average with a higher prolactin-raising effect than other antipsychotics may increase the risk of breast cancer in women to some degree,” said Dr. Correll, who was not involved with the study.

However, he cautioned that “naturalistic data are always vulnerable to residual confounding, for example, unmeasured effects that could also at least partially explain the results, and the follow-up time of only 4 years (maximum 6 years) in this study was relatively short.

“Nevertheless, given availability of many different antipsychotics with varying degrees of prolactin-raising potential, in women requiring antipsychotic treatment, less prolactin-raising antipsychotics may be preferable,” Dr. Correll said.

“In women receiving prolactin-raising antipsychotics for medium- and longer-term maintenance therapy, prolactin levels should be monitored,” he added.

When an elevated prolactin level is detected, this should be addressed “either via dose reduction, a switch to an alternative antipsychotic that does not raise prolactin levels significantly, or the addition of a partial or full D2 agonist when the prolactin-raising antipsychotic should be continued based on individualized risk assessment,” Dr. Correll advised.

This work was supported by an award from the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center; the National Cancer Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health; the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research; and the Center for Brain Research in Mood Disorders. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Correll has received royalties from UpToDate and is a stock option holder of LB Pharma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY

Case report: ECT for delirious mania

Delirious mania is a diagnostic term used in variety of settings, including the emergency department and inpatient psychiatry, but it does not have formal criteria established in the DSM-5. Delirious mania was first described in the 1800s and was referred to as “Bell’s Mania.”

As the late Max Fink, MD, wrote in the journal Bipolar Disorders (2002 Feb 23. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-561.1999.10112.x), delirious mania is considered to be a syndrome of the acute onset of the excitement, grandiosity, emotional lability, delusions, and insomnia characteristic of mania, and the disorientation and altered consciousness characteristic of delirium.

Such patients can be considered as having a component of bipolar I disorder, comprising mania with psychotic features. Delirious mania is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality, and demonstrates limited response to conventional treatment guidelines. Therefore, early detection and decisive treatment are imperative. The concurrence of delirium and mania is not unusual, yet currently there are no universal accepted treatment guidelines for delirious mania (BMC Psychiatry. 2012 Jun 21. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-65). The purpose of this case report is to inspire and support community psychiatric clinicians in managing such complex cases and to improve behavioral health care outcomes. To protect our patient’s identity, we changed several key identifiers.

The treatment plan emerges

This case is of a middle-aged man with an established diagnosis of bipolar disorder. He was referred to the ED because of worsening manic symptoms marked by mood lability, pressured speech, grandiose delusions, tangential thought processes, poor insight, and impaired sleep.

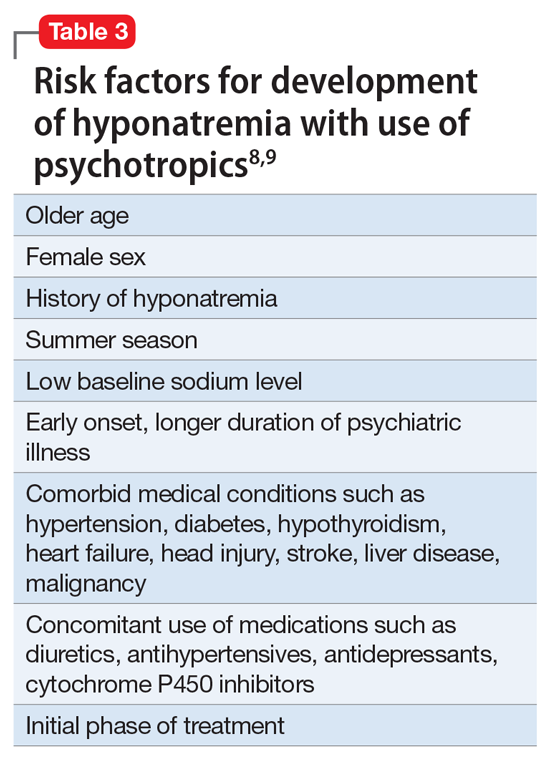

Laboratory studies in the ED revealed hyponatremia and serum sodium of 126meq/l (ref. range: 135-146). The patient’s toxicology screen was positive for benzodiazepines. He was stabilized on the medical floor and then transitioned to inpatient psychiatry.

Before his admission to psychiatry, the patient’s medications were alprazolam 1 mg at bed time, bupropion 100 mg twice daily, loxapine 25 mg morning and 50 mg at bed time, olanzapine 20 mg at bedtime and 5 mg twice daily, risperidone 2 mg twice daily and oxcarbazepine 900 mg twice daily.

The bupropion was discontinued because of manic behavior, and the patient’s dose of oxcarbazepine was lowered from 900 mg twice daily to 450 mg twice daily because of hyponatremia. Our team continued to administer risperidone, olanzapine, loxapine, and alprazolam to the patient. However, he was agitated and disorganized on the psychiatry floor. In addition, we noticed that the patient exhibited confusion, disorientation, an inability to connect with reality, and periods of profound agitation.

The patient was frequently restrained physically, and medications were administered to him for safety and containment. The use of benzodiazepines and anticholinergics was minimized. However, we noticed that the patient acted paranoid, disinhibited, and combative, and he became difficult to restrain. He seemed to have a high pain tolerance, responded to internal stimuli, and began hallucinating and displaying aggressive behavior toward staff persons.

It became apparent that the patient’s circadian rhythm had been altered. He slept for only a couple of hours during the day. During the course of treatment, in one incidence, the patient became agitated and charged at a nurse. Subsequently, the patient hit his head on a wall and fell – suffering a head strike and lacerations.

The team conducted investigations, including labs and neuroimaging, to make sure that the patient was OK. His CT head scan proved unremarkable. Liver function tests revealed mild transaminitis. His TSH, folate, B12, and B1 levels were normal.

We then placed the patient in a single room with continuous behavior monitoring. His recovery seemed to take a long time with trials of different antipsychotic medications, including olanzapine, loxapine, risperidone, and paliperidone. Because of his poor response to medications, the team considered using electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

However, the patient was unable to give informed consent for ECT because of his impaired mental status. At this point, our team submitted a substitute treatment plan that included ECT to the court for approval, and the court approved our plan.

After receiving approximately four bilateral ECT procedures three times a week, the patient’s condition started to improve gradually. He received total of 11 procedures.

Our patient became alert to time, place, and person, and his circadian rhythm normalized. Soon, his delirium cleared, and he demonstrated marked improvement in both insight into his illness and behavioral control. His grandiose delusions were still present, but he was easily redirectable. In addition, our patient demonstrated improved reality testing. He was able to be discharged home following medication adjustments and with community supports within a few short weeks of receiving ECT.

As Bo-Shyan Lee, MD, and associates reported (BMC Psychiatry. 2012 Jun 21;12:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-65), delirious mania is closely related to catatonia. Although there are different definitions for delirium and catatonia, even the most lethal form of catatonia meets the criteria for delirium. ECT is a well established first-line treatment for catatonia. This tool has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of delirious mania. Delirious mania can be life-threatening and should be managed aggressively. The most common causes of death are heart failure from arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, and respiratory failure. ECT is a safe treatment, and, as Dr. Fink argued, the mortality rate is even less than that associated with normal pregnancies (World J Biol Psychiatry. 2001 Jan;2[1]:1-8). In light of the safety and effectiveness of ECT, we think the tool should be considered not only in university hospital settings but as an early intervention in community settings. This case warrants further research in exploring hyperactive delirium and delirious mania.

Dr. Lamba is BR-2 unit medical director at BayRidge Hospital in Lynn, Mass. Ms. Kennedy is an attending clinician at BayRidge. Dr. Vu is medical director at BayRidge. He also serves as associate chief of psychiatry at Beverly (Mass.) Hospital and at Addison Gilbert Hospital in Gloucester, Mass. Dr. Lamba, Ms. Kennedy, and Dr. Vu have no disclosures.

Delirious mania is a diagnostic term used in variety of settings, including the emergency department and inpatient psychiatry, but it does not have formal criteria established in the DSM-5. Delirious mania was first described in the 1800s and was referred to as “Bell’s Mania.”

As the late Max Fink, MD, wrote in the journal Bipolar Disorders (2002 Feb 23. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-561.1999.10112.x), delirious mania is considered to be a syndrome of the acute onset of the excitement, grandiosity, emotional lability, delusions, and insomnia characteristic of mania, and the disorientation and altered consciousness characteristic of delirium.

Such patients can be considered as having a component of bipolar I disorder, comprising mania with psychotic features. Delirious mania is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality, and demonstrates limited response to conventional treatment guidelines. Therefore, early detection and decisive treatment are imperative. The concurrence of delirium and mania is not unusual, yet currently there are no universal accepted treatment guidelines for delirious mania (BMC Psychiatry. 2012 Jun 21. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-65). The purpose of this case report is to inspire and support community psychiatric clinicians in managing such complex cases and to improve behavioral health care outcomes. To protect our patient’s identity, we changed several key identifiers.

The treatment plan emerges

This case is of a middle-aged man with an established diagnosis of bipolar disorder. He was referred to the ED because of worsening manic symptoms marked by mood lability, pressured speech, grandiose delusions, tangential thought processes, poor insight, and impaired sleep.

Laboratory studies in the ED revealed hyponatremia and serum sodium of 126meq/l (ref. range: 135-146). The patient’s toxicology screen was positive for benzodiazepines. He was stabilized on the medical floor and then transitioned to inpatient psychiatry.

Before his admission to psychiatry, the patient’s medications were alprazolam 1 mg at bed time, bupropion 100 mg twice daily, loxapine 25 mg morning and 50 mg at bed time, olanzapine 20 mg at bedtime and 5 mg twice daily, risperidone 2 mg twice daily and oxcarbazepine 900 mg twice daily.

The bupropion was discontinued because of manic behavior, and the patient’s dose of oxcarbazepine was lowered from 900 mg twice daily to 450 mg twice daily because of hyponatremia. Our team continued to administer risperidone, olanzapine, loxapine, and alprazolam to the patient. However, he was agitated and disorganized on the psychiatry floor. In addition, we noticed that the patient exhibited confusion, disorientation, an inability to connect with reality, and periods of profound agitation.

The patient was frequently restrained physically, and medications were administered to him for safety and containment. The use of benzodiazepines and anticholinergics was minimized. However, we noticed that the patient acted paranoid, disinhibited, and combative, and he became difficult to restrain. He seemed to have a high pain tolerance, responded to internal stimuli, and began hallucinating and displaying aggressive behavior toward staff persons.

It became apparent that the patient’s circadian rhythm had been altered. He slept for only a couple of hours during the day. During the course of treatment, in one incidence, the patient became agitated and charged at a nurse. Subsequently, the patient hit his head on a wall and fell – suffering a head strike and lacerations.

The team conducted investigations, including labs and neuroimaging, to make sure that the patient was OK. His CT head scan proved unremarkable. Liver function tests revealed mild transaminitis. His TSH, folate, B12, and B1 levels were normal.

We then placed the patient in a single room with continuous behavior monitoring. His recovery seemed to take a long time with trials of different antipsychotic medications, including olanzapine, loxapine, risperidone, and paliperidone. Because of his poor response to medications, the team considered using electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

However, the patient was unable to give informed consent for ECT because of his impaired mental status. At this point, our team submitted a substitute treatment plan that included ECT to the court for approval, and the court approved our plan.

After receiving approximately four bilateral ECT procedures three times a week, the patient’s condition started to improve gradually. He received total of 11 procedures.

Our patient became alert to time, place, and person, and his circadian rhythm normalized. Soon, his delirium cleared, and he demonstrated marked improvement in both insight into his illness and behavioral control. His grandiose delusions were still present, but he was easily redirectable. In addition, our patient demonstrated improved reality testing. He was able to be discharged home following medication adjustments and with community supports within a few short weeks of receiving ECT.

As Bo-Shyan Lee, MD, and associates reported (BMC Psychiatry. 2012 Jun 21;12:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-65), delirious mania is closely related to catatonia. Although there are different definitions for delirium and catatonia, even the most lethal form of catatonia meets the criteria for delirium. ECT is a well established first-line treatment for catatonia. This tool has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of delirious mania. Delirious mania can be life-threatening and should be managed aggressively. The most common causes of death are heart failure from arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, and respiratory failure. ECT is a safe treatment, and, as Dr. Fink argued, the mortality rate is even less than that associated with normal pregnancies (World J Biol Psychiatry. 2001 Jan;2[1]:1-8). In light of the safety and effectiveness of ECT, we think the tool should be considered not only in university hospital settings but as an early intervention in community settings. This case warrants further research in exploring hyperactive delirium and delirious mania.

Dr. Lamba is BR-2 unit medical director at BayRidge Hospital in Lynn, Mass. Ms. Kennedy is an attending clinician at BayRidge. Dr. Vu is medical director at BayRidge. He also serves as associate chief of psychiatry at Beverly (Mass.) Hospital and at Addison Gilbert Hospital in Gloucester, Mass. Dr. Lamba, Ms. Kennedy, and Dr. Vu have no disclosures.

Delirious mania is a diagnostic term used in variety of settings, including the emergency department and inpatient psychiatry, but it does not have formal criteria established in the DSM-5. Delirious mania was first described in the 1800s and was referred to as “Bell’s Mania.”

As the late Max Fink, MD, wrote in the journal Bipolar Disorders (2002 Feb 23. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-561.1999.10112.x), delirious mania is considered to be a syndrome of the acute onset of the excitement, grandiosity, emotional lability, delusions, and insomnia characteristic of mania, and the disorientation and altered consciousness characteristic of delirium.

Such patients can be considered as having a component of bipolar I disorder, comprising mania with psychotic features. Delirious mania is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality, and demonstrates limited response to conventional treatment guidelines. Therefore, early detection and decisive treatment are imperative. The concurrence of delirium and mania is not unusual, yet currently there are no universal accepted treatment guidelines for delirious mania (BMC Psychiatry. 2012 Jun 21. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-65). The purpose of this case report is to inspire and support community psychiatric clinicians in managing such complex cases and to improve behavioral health care outcomes. To protect our patient’s identity, we changed several key identifiers.

The treatment plan emerges

This case is of a middle-aged man with an established diagnosis of bipolar disorder. He was referred to the ED because of worsening manic symptoms marked by mood lability, pressured speech, grandiose delusions, tangential thought processes, poor insight, and impaired sleep.

Laboratory studies in the ED revealed hyponatremia and serum sodium of 126meq/l (ref. range: 135-146). The patient’s toxicology screen was positive for benzodiazepines. He was stabilized on the medical floor and then transitioned to inpatient psychiatry.

Before his admission to psychiatry, the patient’s medications were alprazolam 1 mg at bed time, bupropion 100 mg twice daily, loxapine 25 mg morning and 50 mg at bed time, olanzapine 20 mg at bedtime and 5 mg twice daily, risperidone 2 mg twice daily and oxcarbazepine 900 mg twice daily.

The bupropion was discontinued because of manic behavior, and the patient’s dose of oxcarbazepine was lowered from 900 mg twice daily to 450 mg twice daily because of hyponatremia. Our team continued to administer risperidone, olanzapine, loxapine, and alprazolam to the patient. However, he was agitated and disorganized on the psychiatry floor. In addition, we noticed that the patient exhibited confusion, disorientation, an inability to connect with reality, and periods of profound agitation.

The patient was frequently restrained physically, and medications were administered to him for safety and containment. The use of benzodiazepines and anticholinergics was minimized. However, we noticed that the patient acted paranoid, disinhibited, and combative, and he became difficult to restrain. He seemed to have a high pain tolerance, responded to internal stimuli, and began hallucinating and displaying aggressive behavior toward staff persons.

It became apparent that the patient’s circadian rhythm had been altered. He slept for only a couple of hours during the day. During the course of treatment, in one incidence, the patient became agitated and charged at a nurse. Subsequently, the patient hit his head on a wall and fell – suffering a head strike and lacerations.

The team conducted investigations, including labs and neuroimaging, to make sure that the patient was OK. His CT head scan proved unremarkable. Liver function tests revealed mild transaminitis. His TSH, folate, B12, and B1 levels were normal.

We then placed the patient in a single room with continuous behavior monitoring. His recovery seemed to take a long time with trials of different antipsychotic medications, including olanzapine, loxapine, risperidone, and paliperidone. Because of his poor response to medications, the team considered using electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

However, the patient was unable to give informed consent for ECT because of his impaired mental status. At this point, our team submitted a substitute treatment plan that included ECT to the court for approval, and the court approved our plan.

After receiving approximately four bilateral ECT procedures three times a week, the patient’s condition started to improve gradually. He received total of 11 procedures.

Our patient became alert to time, place, and person, and his circadian rhythm normalized. Soon, his delirium cleared, and he demonstrated marked improvement in both insight into his illness and behavioral control. His grandiose delusions were still present, but he was easily redirectable. In addition, our patient demonstrated improved reality testing. He was able to be discharged home following medication adjustments and with community supports within a few short weeks of receiving ECT.

As Bo-Shyan Lee, MD, and associates reported (BMC Psychiatry. 2012 Jun 21;12:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-65), delirious mania is closely related to catatonia. Although there are different definitions for delirium and catatonia, even the most lethal form of catatonia meets the criteria for delirium. ECT is a well established first-line treatment for catatonia. This tool has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of delirious mania. Delirious mania can be life-threatening and should be managed aggressively. The most common causes of death are heart failure from arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, and respiratory failure. ECT is a safe treatment, and, as Dr. Fink argued, the mortality rate is even less than that associated with normal pregnancies (World J Biol Psychiatry. 2001 Jan;2[1]:1-8). In light of the safety and effectiveness of ECT, we think the tool should be considered not only in university hospital settings but as an early intervention in community settings. This case warrants further research in exploring hyperactive delirium and delirious mania.

Dr. Lamba is BR-2 unit medical director at BayRidge Hospital in Lynn, Mass. Ms. Kennedy is an attending clinician at BayRidge. Dr. Vu is medical director at BayRidge. He also serves as associate chief of psychiatry at Beverly (Mass.) Hospital and at Addison Gilbert Hospital in Gloucester, Mass. Dr. Lamba, Ms. Kennedy, and Dr. Vu have no disclosures.

Is it bipolar disorder, or a complex form of PTSD?

CASE A long history of suicidality

Mr. X, age 26, who has a history of bipolar II disorder and multiple inpatient admissions, presents to a state hospital after a suicide attempt by gunshot. He reports that throughout his lifetime, he has had >20 suicide attempts, often by overdose.

Mr. X is admitted to the hospital under a temporary detention order. He is initially adherent and cooperative with his psychiatric evaluations.

HISTORY Chronic physical and emotional pain

Mr. X is single, unemployed, and lives with his mother and nephew. He was diagnosed with bipolar II disorder during adolescence and receives sertraline, 50 mg twice a day, and lamotrigine, 100 mg twice a day, to which he reports adherence. He also was taking clonazepam and zolpidem, dosages unknown.

His medical history is significant for severe childhood liver disease and inflammatory bowel disease. He dropped out of school during high school due to his multiple medical conditions, which resulted in a significantly diminished overall childhood experience, interrupted developmental trajectory, and chronic physical and emotional pain. He has never been employed and receives financial support through disability benefits. He spends his days on the internet or watching television. He reports daily cigarette and marijuana use and occasional alcohol use, but no other substance use. His mother helps manage his medical conditions and is his main support. His biological father was abusive towards his mother and absent for most of Mr. X’s life. Beyond his mother and therapist, Mr. X has minimal other interpersonal interactions, and reports feeling isolated, lonely, and frustrated.

EVALUATION Agitated and aggressive while hospitalized

Upon learning that he is being involuntarily committed, Mr. X becomes physically aggressive, makes verbal threats, and throws objects across his room. He is given diphenhydramine, 50 mg, haloperidol, 5 mg, and lorazepam, 2 mg, all of which are ordered on an as-needed basis. Mr. X is placed in an emergency restraint chair and put in seclusion. The episode resolves within an hour with reassurance and attention from the treatment team; the rapid escalation from and return to a calmer state is indicative of situational, stress-induced mood lability and impulsivity. Mr. X is counseled on maintaining safety and appropriate behavior, and is advised to ask for medication if he feels agitated or unable to control his behaviors. To maintain safe and appropriate behavior, he requires daily counseling and expectation management regarding his treatment timeline. No further aggressive incidents are noted throughout his hospitalization, and he requires only minimal use of the as-needed medications.

[polldaddy:10983392]

The authors’ observations

The least appropriate therapy for Mr. X would be exposure and response prevention, which allows patients to face their fears without the need to soothe or relieve related feelings with a compulsive act. It is designed to improve specific behavioral deficits most often associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder, a diagnosis inconsistent with Mr. X’s history and presentation. Trauma-focused CBT could facilitate healing from Mr. X’s childhood trauma/adverse childhood experiences, and DBT might help with his anger, maladaptive coping strategies, and chronic suicidality. Motivational interviewing might help with his substance use and his apparent lack of motivation for other forms of social engagement, including seeking employment.

Based on Mr. X’s history of trauma and chronic physical and emotional pain, the treatment team reevaluated him and reconsidered his original diagnosis.

Continue to: EVALUATION A closer look at the diagnosis...

EVALUATION A closer look at the diagnosis

After meeting with Mr. X, the treatment team begins to piece together a more robust picture of him. They review his childhood trauma involving his biological father, his chronic and limiting medical illnesses, and his restricted and somewhat regressive level of functioning. Further, they consider his >20 suicide attempts, numerous psychiatric hospitalizations, and mood and behavioral lability and reactivity. Based on its review, the treatment team concludes that a diagnosis of bipolar disorder II or major depressive disorder is not fully adequate to describe Mr. X’s clinical picture.

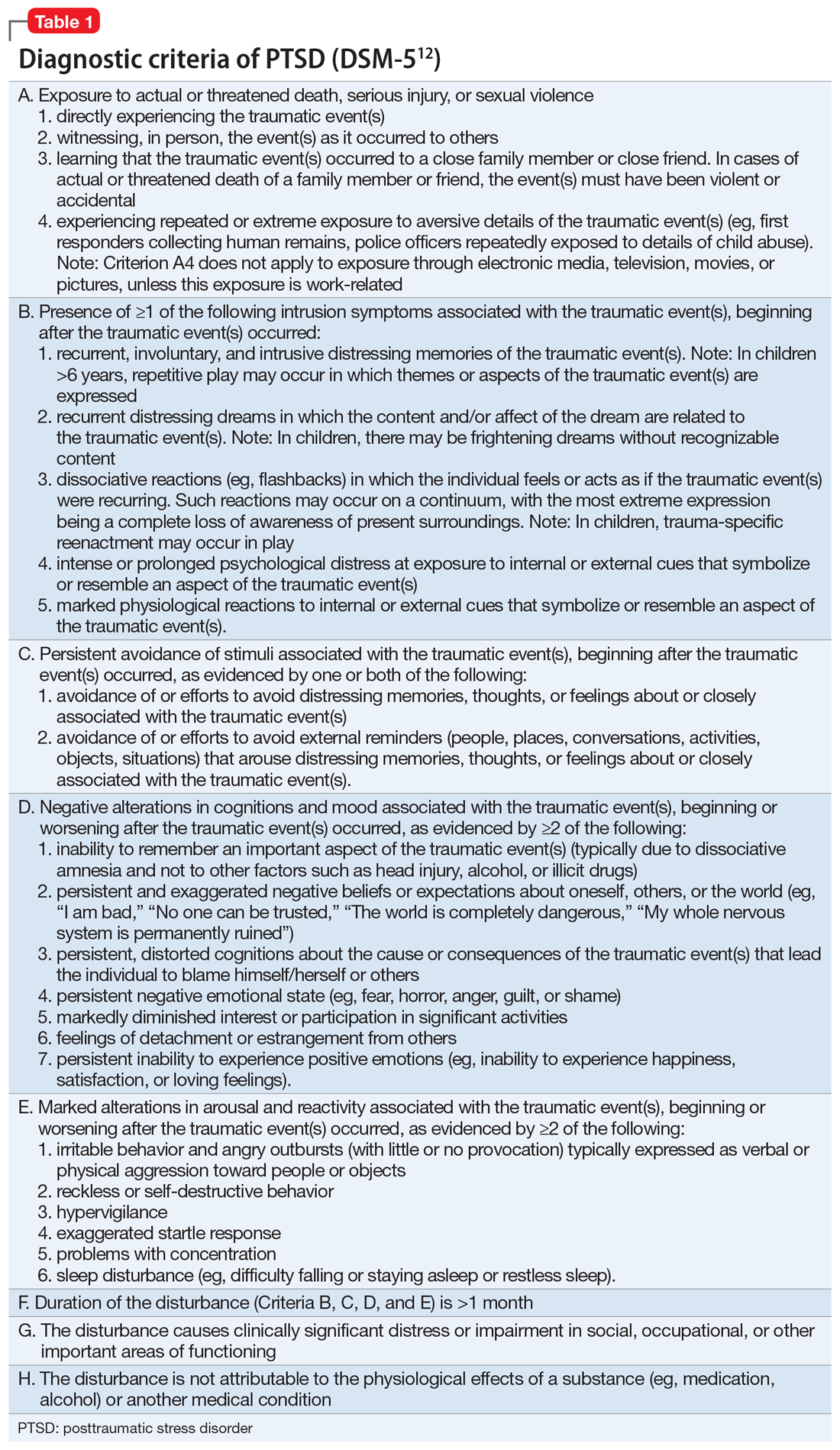

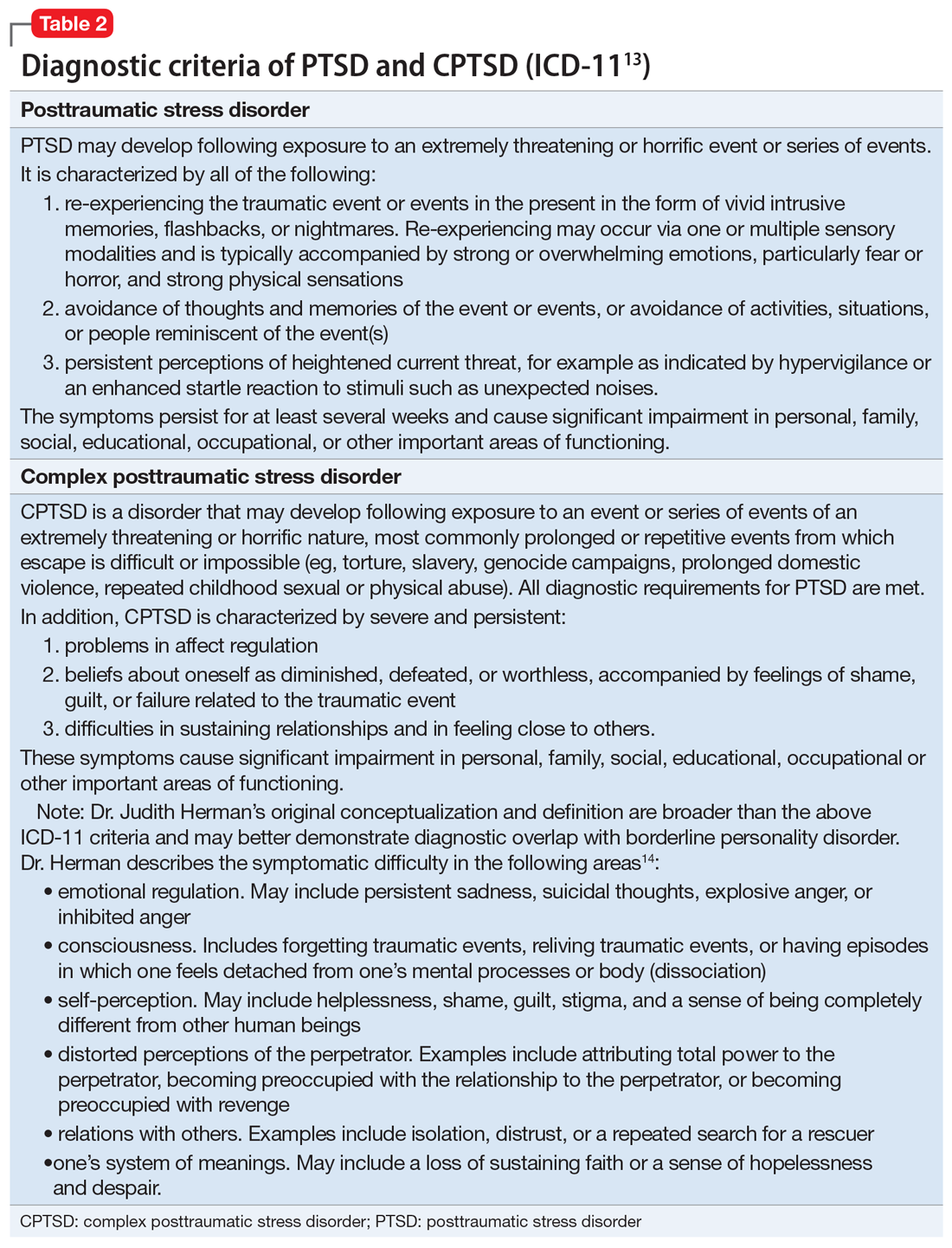

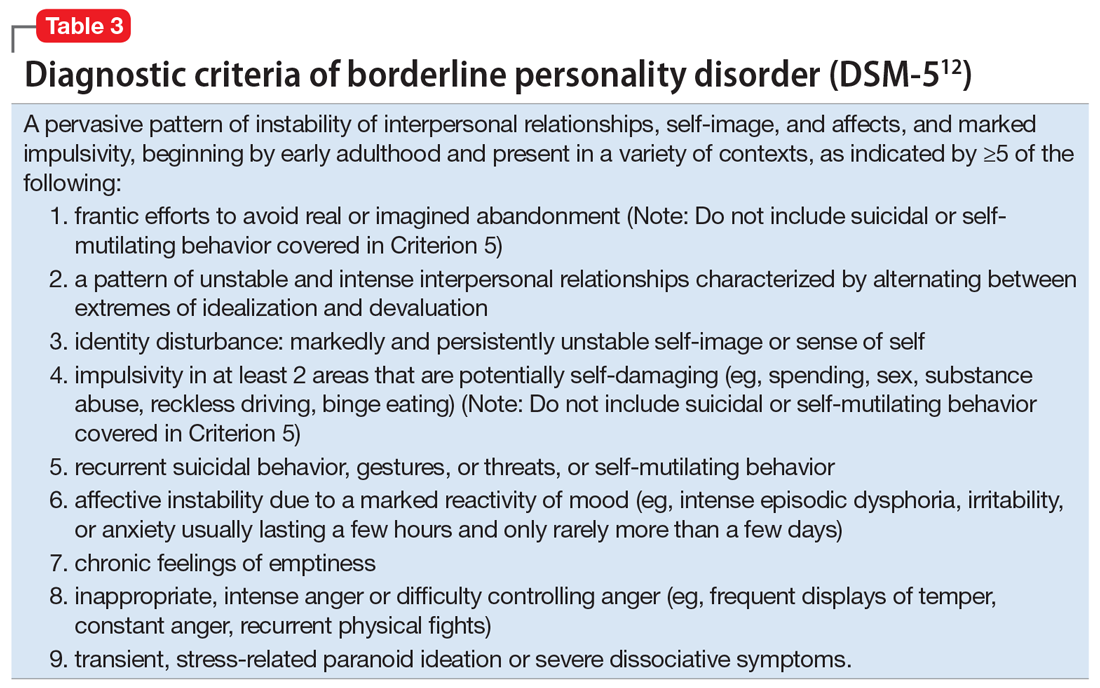

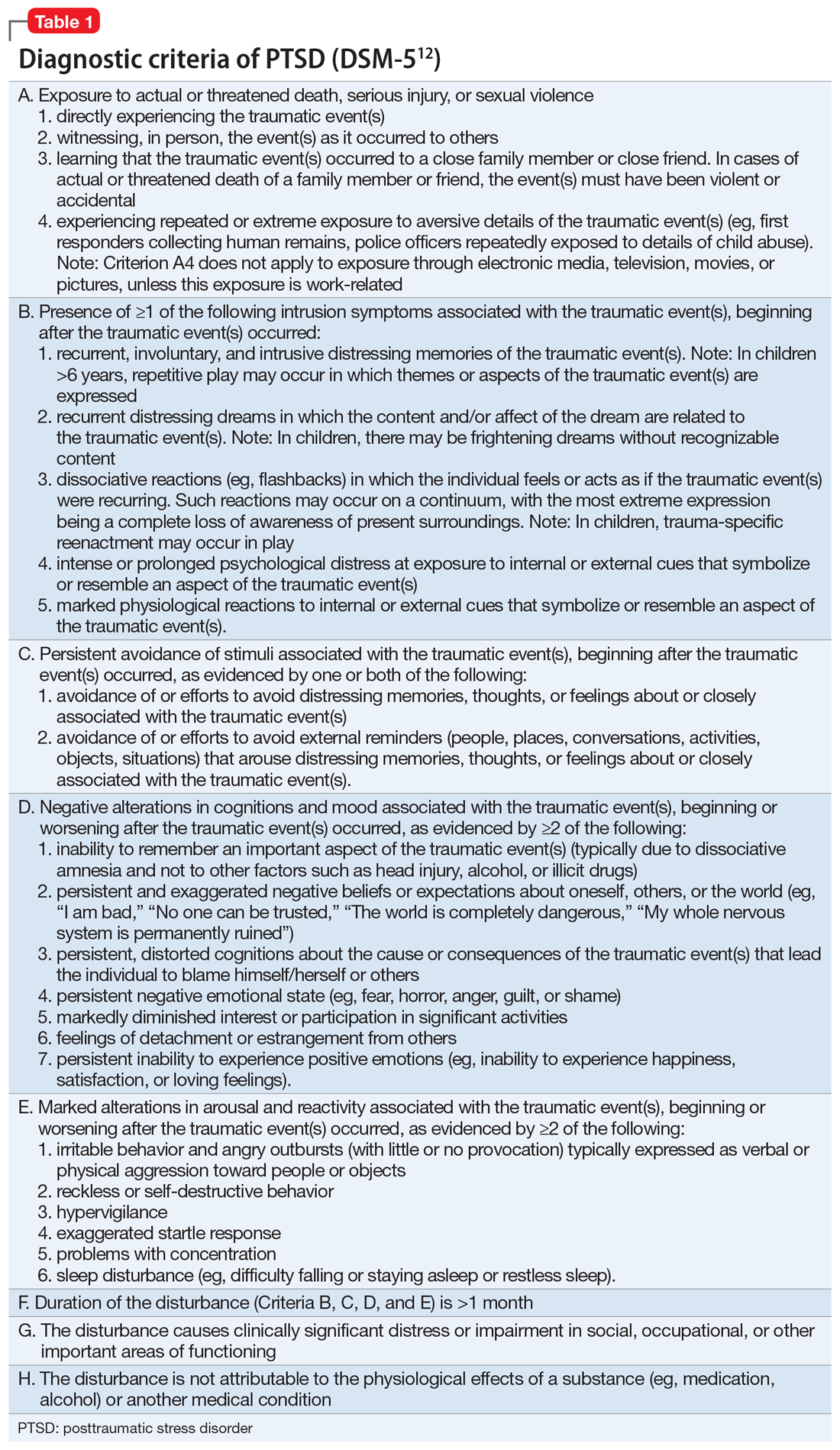

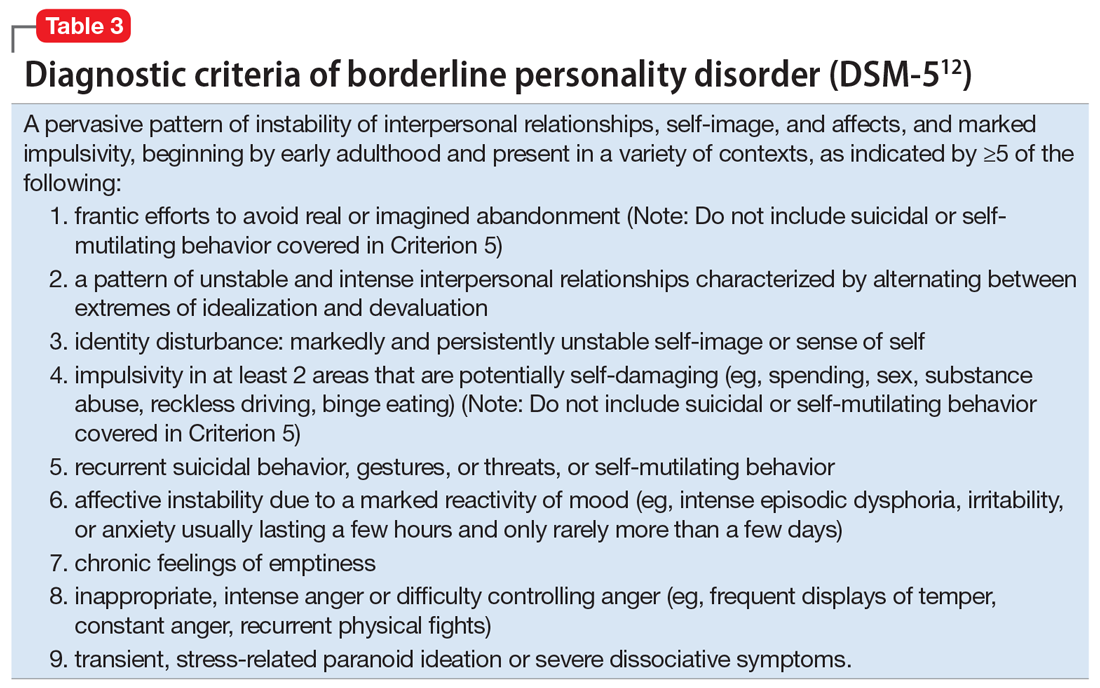

At no point during his hospitalization does Mr. X meet full criteria for a major depressive episode or display mania or hypomania. The treatment team considers posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the setting of chronic, repetitive trauma given Mr. X’s nightmares, dissociative behavior, anger, negative cognitions, and intrusive symptoms. However, not all his symptoms fall within the diagnostic criteria of PTSD. There are also elements of borderline personality disorder in Mr. X’s history, most notably his multiple suicide attempts, emotional lability, and disrupted interpersonal attachments. In this context, a diagnosis of complex PTSD (CPTSD) seems most appropriate in capturing the array of trauma-related symptoms with which he presents.

Complex PTSD

Since at least the early to mid-1990s, there has been recognition of a qualitatively distinct clinical picture that can emerge when an individual’s exposure to trauma or adversity is chronic or repetitive, causing not only familiar PTSD symptomatology but also alterations in self-perception, interpersonal functioning, and affective instability. Complex PTSD was first described by Judith Herman, MD, in 1992 as a distinct entity from PTSD.1 She theorized that PTSD derives primarily from singular traumatic events, while a distinct clinical syndrome might arise after prolonged, repeated trauma.1 A diagnosis of CPTSD might arise in situations with more chronicity than a classic single circumscribed traumatic event, such as being held in captivity, under the control of perpetrators for extended periods of time, imprisoned, or subject to prolonged sexual abuse. Herman’s description of CPTSD identifies 3 areas of psychopathology that extend beyond PTSD1:

- symptomatic refers to the complex, diffuse, and tenacious symptom presentation

- characterological focuses on the personality changes in terms of dissociation, ego-fragmentation, and identity complications

- vulnerability describes characteristic repeated harm with respect to self-mutilation or other self-injurious behaviors, and suicidality.

Taxometrics, official recognition, and controversy

Complex PTSD was proposed for inclusion in DSM-IV as “Disorders of Extreme Stress Not Otherwise Specified,” or DESNOS. Reportedly, it was interpreted as a severe presentation of PTSD, and therefore not included in the manual as a separate diagnosis.2 In contrast, ICD-10 included a CPTSD-like entity of “Enduring Personality Change After Catastrophic Event” (EPCACE). Although the existence of CPTSD as a categorically distinct diagnosis in the psychiatric mainstream has been debated and discussed for years, with many arguably unaware of its existence, clinicians and researchers specializing in trauma are well-versed in its clinical utility. As such, CPTSD was again discussed during the development of DSM-5. In an apparent attempt to balance this clinical utility with ongoing concerns about its validity as a diagnostically distinct syndrome, DSM-5 did not officially recognize CPTSD, but added several criteria to PTSD referencing changes in self-perception, affective instability, and dysphoria, as well as a dissociative subtype, effectively expanding the scope of a PTSD diagnosis to also include CPTSD symptoms when applicable. ICD-11 has taken a different direction, and officially recognizes CPTSD as a distinct diagnosis.

ICD-11 presents CPTSD as a “sibling” disorder, which it distinguishes from PTSD with high levels of dissociation, depression, and borderline personality disorder traits.3 Within this framework, the diagnosis of CPTSD requires that the PTSD criteria be met in addition to symptoms that fall into a “disturbances of self-organization” category. When parsing the symptoms of the “disturbances of self-organization” category, the overlap with borderline personality disorder symptoms is apparent.4 This overlap has given rise to yet another controversy regarding CPTSD’s categorical validity; in addition to its distinctness from PTSD, its distinctness from borderline personality disorder has also been debated. In a study examining the similarity between CPTSD and borderline personality disorder, Jowett et al5 concluded that CPTSD was associated with greater exposure to multiple traumas earlier in life and resulted in higher functional impairment than borderline personality disorder, ultimately supporting CPTSD as a separate entity with features that overlap borderline personality disorder.5 According to Ford and Courtois6 “the evidence ... suggests that a sub-group of BPD patients—who often but not always have comorbid PTSD—may be best understood and treated if CPTSD is explicitly addressed as well—and in some cases, in lieu of—BPD.”

PTSD and CPTSD may therefore both be understood to fall within a spectrum of trauma diagnoses; this paradigm postulates that there exists a wide variety of posttraumatic patient presentations, perhaps on a continuum. On the less severe side of the trauma spectrum, the symptoms traditionally seen and characterized as PTSD (such as hypervigilance, nightmares, and flashbacks) may be found, while, with increasingly severe or prolonged trauma, there may be a tendency to see more complex elements (such as dissociation, personality changes mimicking borderline personality disorder, depression, anxiety, self-injurious behavior, and suicidality).7 Nevertheless, controversy about discriminant validity still exists. A review article by Resnick et al8 argued that the existing evidence is not strong enough to support CPTSD as a standalone entity. However, Resnick et al8 agreed that a singular PTSD diagnosis has limitations, and that there is a need for more research in the field of trauma psychiatry.

Continue to: Utility of the diagnostic conceptualization...

Utility of the diagnostic conceptualization

Although the controversy surrounding the distinction of CPTSD demands categorical clarity with respect to PTSD and borderline personality disorder as a means of resolution, the diagnosis has practical applications that should not limit its use in clinical formulation or treatment planning. Comorbid diagnoses do not prevent clinicians from diagnosing and treating patients who present with complicated manifestations of trauma.9 In fact, having overlapping diagnoses would highlight the array of patient presentations that can be seen in the posttraumatic condition. Furthermore, in the pursuit of individualized care approaches, the addition of CPTSD as a diagnostic conception would allow for more integrated treatment options using a multi-modular approach.10

The addition of CPTSD as a diagnosis is helpful in determining the etiology of a patient’s presentation and therefore formulating the most appropriate treatment plan. While the 2-pronged approach of psychopharmacology and therapy is the central dogma of psychiatric care, there are many specific options to consider for each. By viewing such patients through the lens of trauma as opposed to depression and anxiety, there is a clear shift in treatment that has the potential to make more lasting impacts and progress.11

CPTSD may coexist with PTSD, but it extends beyond it to include a pleomorphic symptom picture encompassing personality changes and a high risk for repeated harm. Failure to correctly classify a patient’s presentation as a response to repetitive, prolonged trauma may result in discrimination and inappropriate or ineffective treatment recommendations.

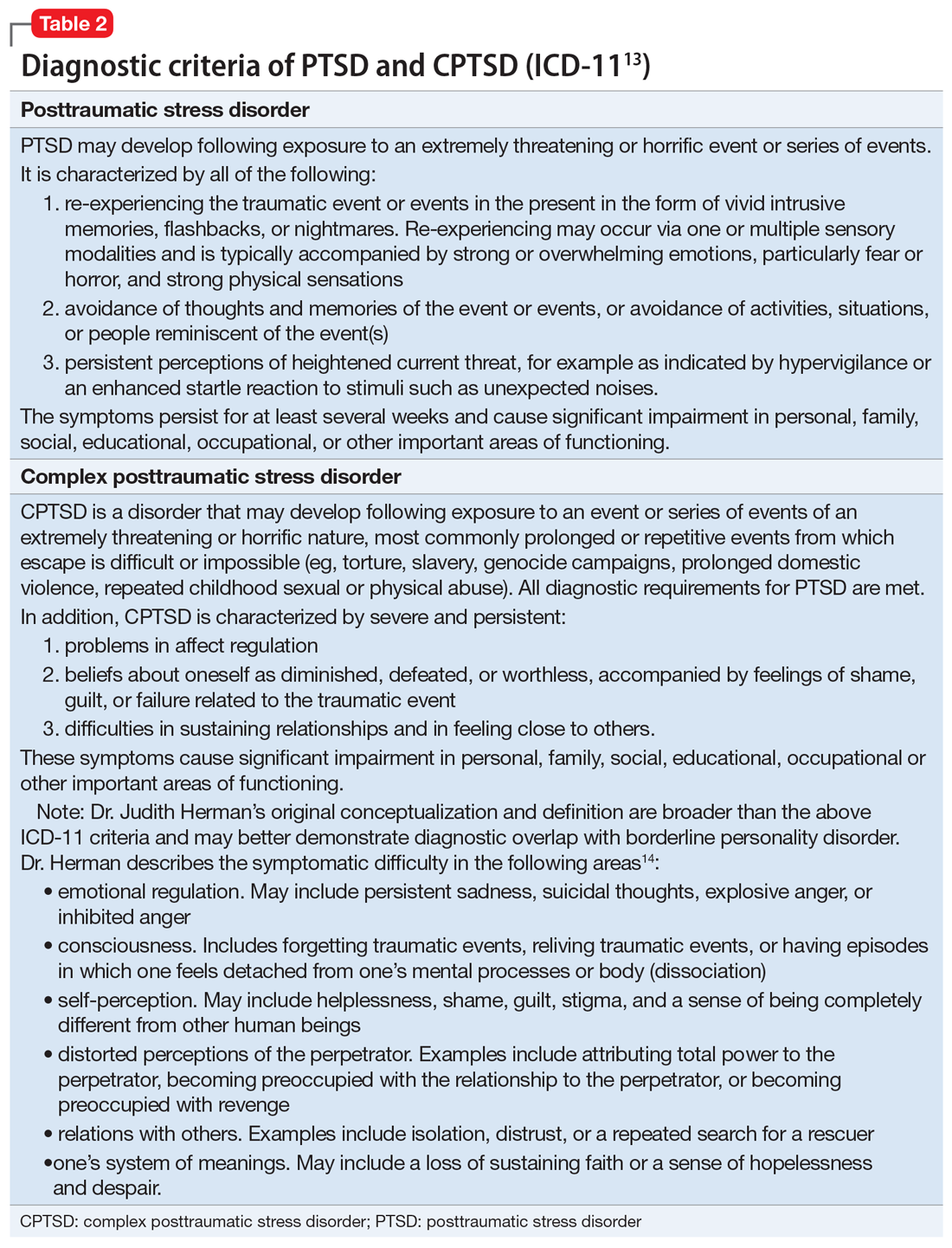

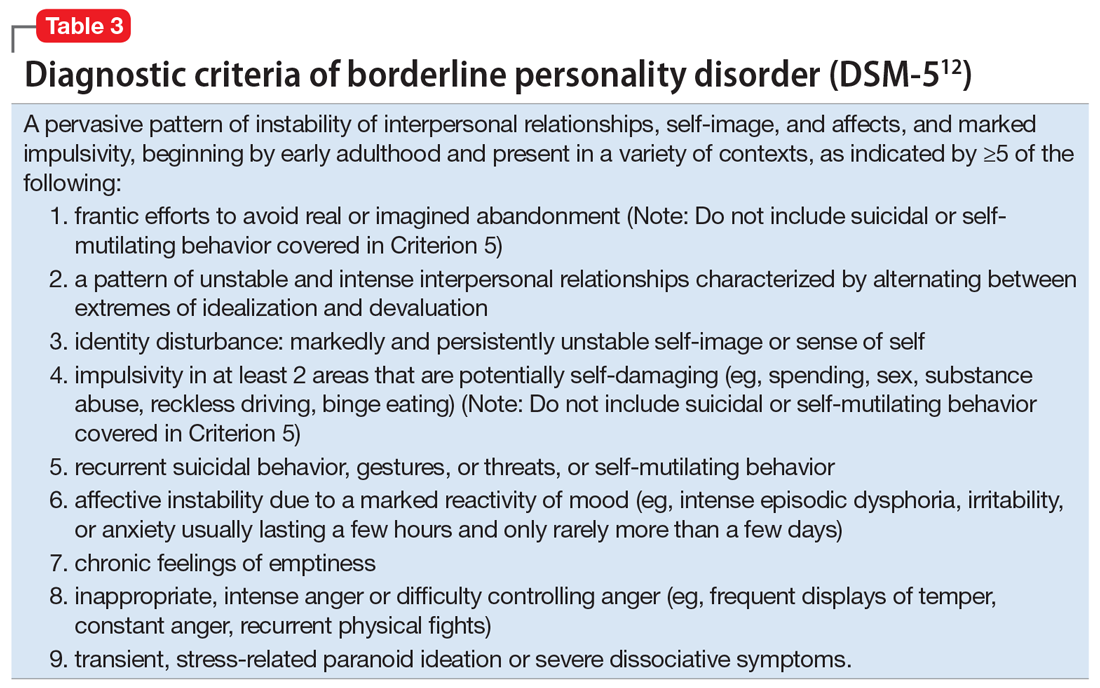

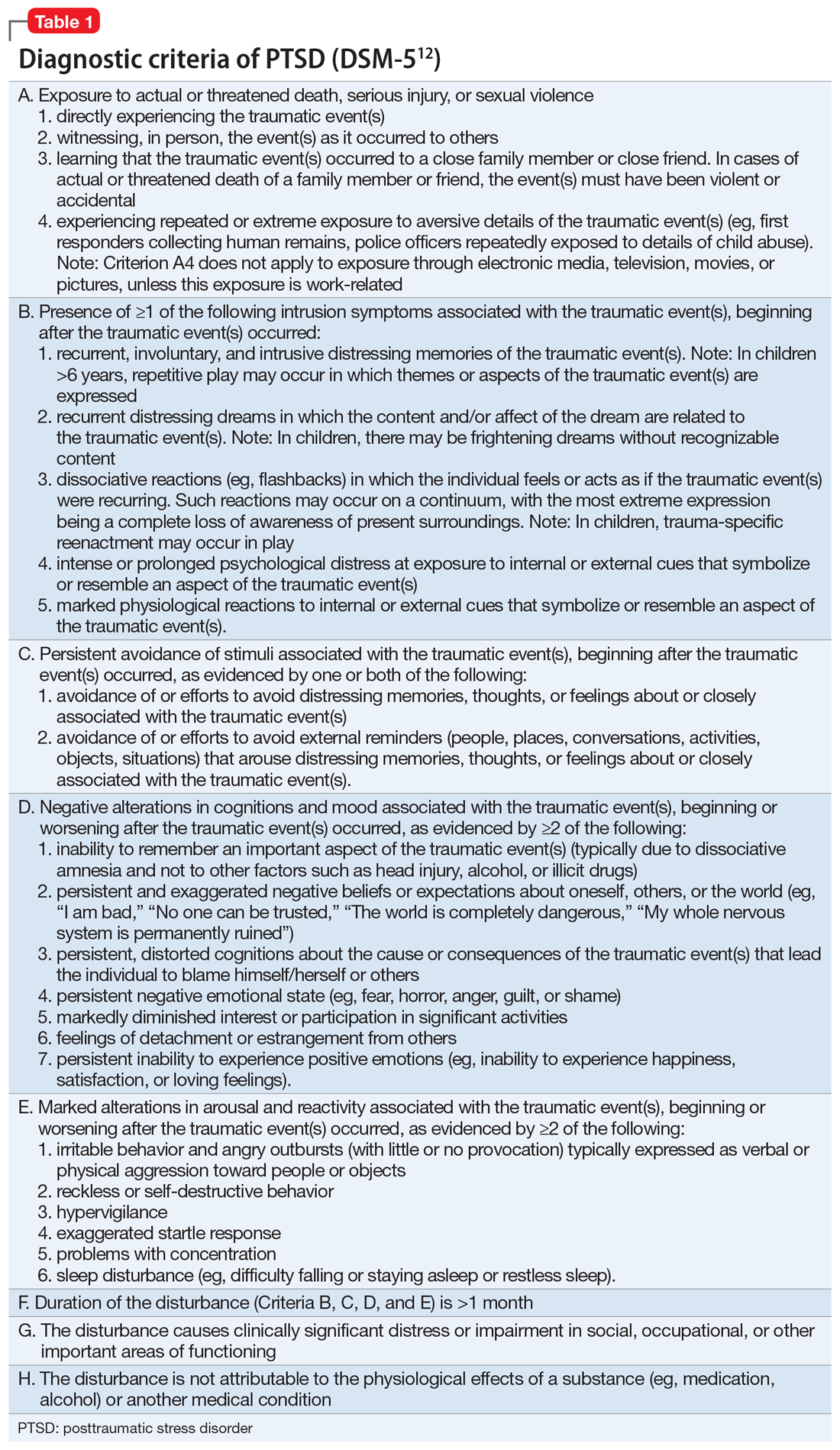

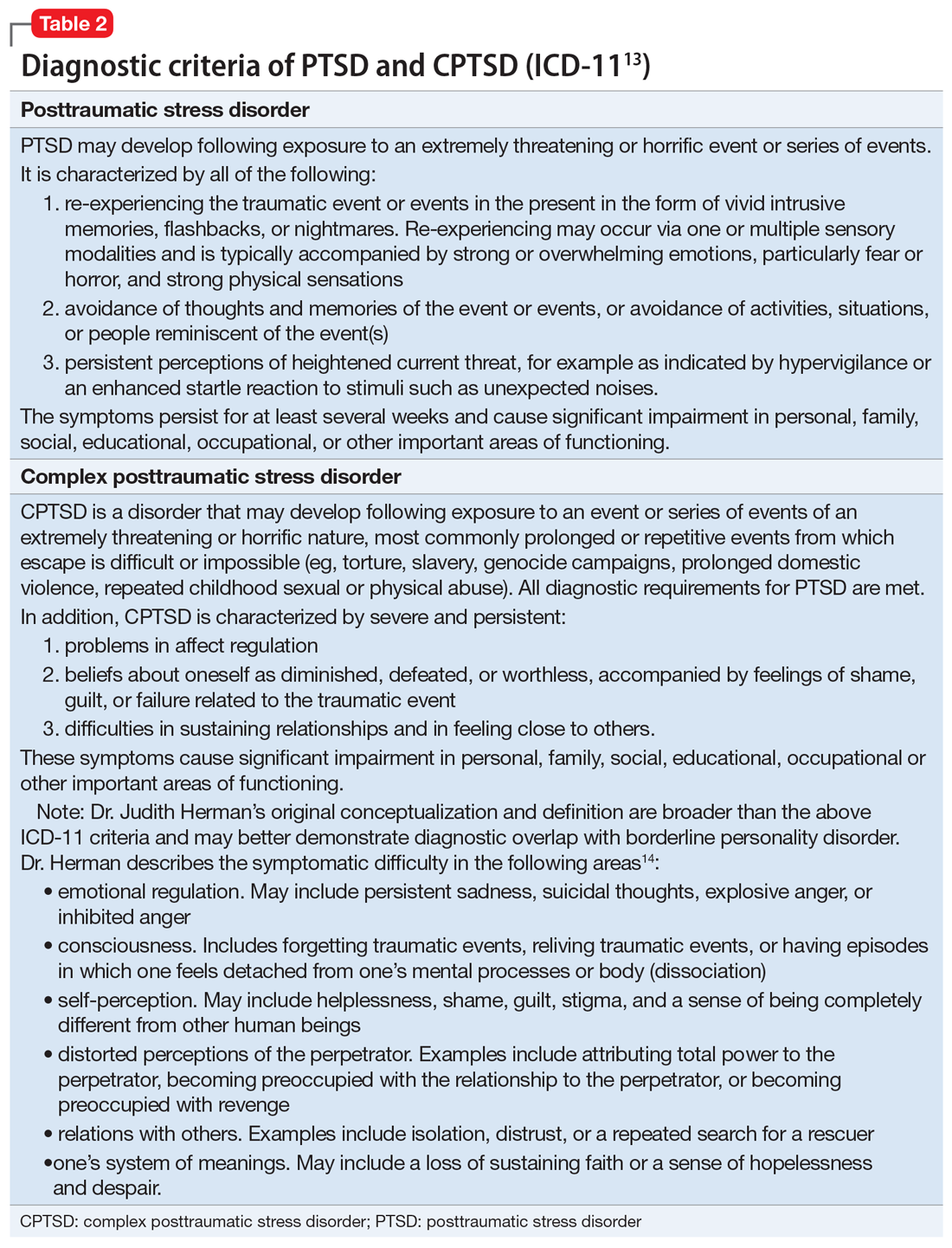

For a comparison of the diagnostic criteria of PTSD, CPTSD, and borderline personality disorder, see Table 112, Table 2,13,14, and Table 312.

Patients with CPTSD

One of the authors (NR) has cared for several similar individuals presenting for treatment with vague diagnoses of “chronic depression and anxiety” for years, sometimes with a speculative bipolar disorder diagnosis due to situational mood swings or reactivity, and a generally poor response to both medications and psychotherapy. These patients were frustrated because none of the diagnoses seemed to fully “fit” with their pattern of symptoms or subjective experience, and treatment seemed minimally helpful. Very often, their social history revealed a variety of adversities or traumatic events, such as childhood sexual or physical abuse, a home environment plagued by domestic violence, or being raised by one or both parents with their own history of trauma, or perhaps a personality or substance use disorder. Although many of these patients’ symptom profiles aligned only partially with “typical” PTSD, they were often better captured by CPTSD, with a focus on negative self-perception and impact on close relationships. Helping the patient “connect the dots” to create a more continuous narrative, and consequently reconceptualizing the diagnosis as a complex trauma disorder, has proven effective in a number of these cases, allowing the patient to make sense of their symptoms in the context of their personal history, reducing stigma, and allowing for different avenues with medication, therapy, and self-understanding. It can also help to validate the impact of a patient’s adverse experiences and encourage a patient to view their symptoms as an understandable or even once-adaptive response to traumatic stress, rather than a sign of personal weakness or defectiveness.

TREATMENT A trauma-focused approach

Once the treatment team considersMr. X’s significant childhood trauma and reconceptualizes his behaviors through this lens, treatment is adjusted accordingly. His significant reactivity, dissociative symptoms, social impairment, and repeated suicide attempts are better understood and have more significance through a trauma lens, which provides a better explanation than a primary mood disorder.

Therapeutic interventions in the hospital are tailored according to the treatment team’s new insight. Specific DBT skills are practiced, insight-oriented therapy and motivational interviewing are used, and Mr. X and his therapist begin to explore his trauma, both from his biological father and from his intense stressors experienced because of his medical issues.

Mr. X’s mother, who is very involved in his care, is provided with education on this conceptualization and given instruction on trauma-focused therapies in the outpatient setting. While Mr. X’s medication regimen is not changed significantly, for some patients, the reformulation from a primary mood or anxiety disorder to a trauma disorder might require a change in the pharmacotherapy regimen to address behavioral symptoms such as mood reactivity or issues with sleep.

OUTCOME Decreased intensity of suicidal thoughts

By the time of discharge, Mr. X has maintained safety, with no further outbursts, and subjectively reports feeling more understood and validated. Although chronic suicidal ideation can take months or years of treatment to resolve, at the time of discharge Mr. X reports a decreased intensity of these thoughts, and no acute suicidal ideation, plan, or intent. His discharge planning emphasizes ongoing work specifically related to coping with symptoms of traumatic stress, and the involvement of his main social support in facilitating this work.

The authors’ observations

As a caveat, it may be in some cases that chronic negative affect, dysphoria, and self-perception are better understood as a comorbid depressive disorder rather than subsumed into a PTSD/ CPTSD diagnosis. Also, because situational mood instability and impulsivity are often interpreted as bipolar disorder, a history of hypomania and mania should be ruled out. In Mr. X’s case, the diagnostic reformulation did not significantly impact pharmacotherapy because the target symptoms of mood instability, irritability, anxiety, and depression remained, despite the change in diagnosis.

Although the DSM-5 PTSD criteria effectively incorporate many CPTSD elements, we argue that this inclusivity comes at the expense of appreciating CPTSD as a qualitatively distinct condition, and we prefer ICD-11’s recognition of CPTSD as a separate diagnosis that incorporates PTSD criteria but extends the definition to include negative self-concept, affect dysregulation, and interpersonal difficulties.

Related Resources

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Published January 1, 2007. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/ professional/treat/essentials/complex_ptsd.asp

- Jowett S, Karatzias T, Shevlin M, et al. Differentiating symptom profiles of ICD-11 PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder: a latent class analysis in a multiply traumatized sample. Personality disorders: theory, research, and treatment. 2020;11(1):36.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lorazepam • Ativan

Sertraline • Zoloft

Zolpidem • Ambien

Bottom Line

Consider a diagnosis of complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) when providing care for patients with chronic depression and suicidality with a history of trauma or childhood adversity. This reformulation can allow clinicians to understand the contributing factors more holistically; align with the patient more effectively; appreciate past and present interpersonal, psychological, and psychosocial factors that may precipitate and perpetuate symptoms; and allow for treatment recommendations beyond those of mood and anxiety disorders.

1. Herman JL. Complex PTSD: a syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1992;5(3):377-391.

2. Friedman MJ. Finalizing PTSD in DSM-5: getting here from there and where to go next. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):548-556. doi: 10.1002/jts.21840 3. Hyland P, Shevlin M, Fyvie C, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder in DSM-5 and ICD-11: clinical and behavioral correlates. J Trauma Stress. 2018; 31(12):174-180.

4. Brand B, Loewenstein R. Dissociative disorders: an overview of assessment, phenomenology and treatment. Psychiatric Times. Published 2010. Accessed October 4, 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bethany-Brand/publication/231337464_Dissociative_Disorders_An_Overview_of_Assessment_Phenomonology_and_Treatment/links/09e415068c721ef9b5000000/Dissociative-Disorders-An-Overview-of-Assessment-Phenomonology-and-Treatment.pdf

5. Jowett S, Karatzias T, Shevlin M, et al. Differentiating symptom profiles of ICD-11 PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder: a latent class analysis in a multiply traumatized sample. Personality Disorders: theory, research, and treatment. 2020;11(1):36.

6. Ford JD, Courtois CA. Complex PTSD, affect dysregulation, and borderline personality disorder. Bord Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2014;1:9. doi.org/10.1186/2051-6673-1-9

7. van der Kolk BA. The trauma spectrum: the interaction of biological and social events in the genesis of the trauma response. J Trauma Stress. 1998;1(3):273-290.

8. Resnick PA, Bovin MJ, Calloway AL, et al. A critical evaluation of the complex PTSD literature: implications for DSM-5. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25(3);241-251.

9. Herman J. CPTSD is a distinct entity: comment on Resick et al. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25(3): 256-257.

10. Karatzias T, Cloitre M. Treating adults with complex posttraumatic stress disorder using a modular approach to treatment: rationale, evidence, and directions for future research. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32(6):870-876.

11. Perry S, Cooper AM, Michels R. The psychodynamic formulation: its purpose, structure, and clinical application. Am J Psych. 1987;144(5):543-550.

12. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

13. International Classification of Diseases, 11th revision. 2019; World Health Organization.

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Complex PTSD. Published January 1, 2007. Accessed October 4, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/essentials/complex_ptsd.asp

CASE A long history of suicidality

Mr. X, age 26, who has a history of bipolar II disorder and multiple inpatient admissions, presents to a state hospital after a suicide attempt by gunshot. He reports that throughout his lifetime, he has had >20 suicide attempts, often by overdose.

Mr. X is admitted to the hospital under a temporary detention order. He is initially adherent and cooperative with his psychiatric evaluations.

HISTORY Chronic physical and emotional pain

Mr. X is single, unemployed, and lives with his mother and nephew. He was diagnosed with bipolar II disorder during adolescence and receives sertraline, 50 mg twice a day, and lamotrigine, 100 mg twice a day, to which he reports adherence. He also was taking clonazepam and zolpidem, dosages unknown.

His medical history is significant for severe childhood liver disease and inflammatory bowel disease. He dropped out of school during high school due to his multiple medical conditions, which resulted in a significantly diminished overall childhood experience, interrupted developmental trajectory, and chronic physical and emotional pain. He has never been employed and receives financial support through disability benefits. He spends his days on the internet or watching television. He reports daily cigarette and marijuana use and occasional alcohol use, but no other substance use. His mother helps manage his medical conditions and is his main support. His biological father was abusive towards his mother and absent for most of Mr. X’s life. Beyond his mother and therapist, Mr. X has minimal other interpersonal interactions, and reports feeling isolated, lonely, and frustrated.

EVALUATION Agitated and aggressive while hospitalized

Upon learning that he is being involuntarily committed, Mr. X becomes physically aggressive, makes verbal threats, and throws objects across his room. He is given diphenhydramine, 50 mg, haloperidol, 5 mg, and lorazepam, 2 mg, all of which are ordered on an as-needed basis. Mr. X is placed in an emergency restraint chair and put in seclusion. The episode resolves within an hour with reassurance and attention from the treatment team; the rapid escalation from and return to a calmer state is indicative of situational, stress-induced mood lability and impulsivity. Mr. X is counseled on maintaining safety and appropriate behavior, and is advised to ask for medication if he feels agitated or unable to control his behaviors. To maintain safe and appropriate behavior, he requires daily counseling and expectation management regarding his treatment timeline. No further aggressive incidents are noted throughout his hospitalization, and he requires only minimal use of the as-needed medications.

[polldaddy:10983392]

The authors’ observations

The least appropriate therapy for Mr. X would be exposure and response prevention, which allows patients to face their fears without the need to soothe or relieve related feelings with a compulsive act. It is designed to improve specific behavioral deficits most often associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder, a diagnosis inconsistent with Mr. X’s history and presentation. Trauma-focused CBT could facilitate healing from Mr. X’s childhood trauma/adverse childhood experiences, and DBT might help with his anger, maladaptive coping strategies, and chronic suicidality. Motivational interviewing might help with his substance use and his apparent lack of motivation for other forms of social engagement, including seeking employment.

Based on Mr. X’s history of trauma and chronic physical and emotional pain, the treatment team reevaluated him and reconsidered his original diagnosis.

Continue to: EVALUATION A closer look at the diagnosis...

EVALUATION A closer look at the diagnosis

After meeting with Mr. X, the treatment team begins to piece together a more robust picture of him. They review his childhood trauma involving his biological father, his chronic and limiting medical illnesses, and his restricted and somewhat regressive level of functioning. Further, they consider his >20 suicide attempts, numerous psychiatric hospitalizations, and mood and behavioral lability and reactivity. Based on its review, the treatment team concludes that a diagnosis of bipolar disorder II or major depressive disorder is not fully adequate to describe Mr. X’s clinical picture.

At no point during his hospitalization does Mr. X meet full criteria for a major depressive episode or display mania or hypomania. The treatment team considers posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the setting of chronic, repetitive trauma given Mr. X’s nightmares, dissociative behavior, anger, negative cognitions, and intrusive symptoms. However, not all his symptoms fall within the diagnostic criteria of PTSD. There are also elements of borderline personality disorder in Mr. X’s history, most notably his multiple suicide attempts, emotional lability, and disrupted interpersonal attachments. In this context, a diagnosis of complex PTSD (CPTSD) seems most appropriate in capturing the array of trauma-related symptoms with which he presents.

Complex PTSD

Since at least the early to mid-1990s, there has been recognition of a qualitatively distinct clinical picture that can emerge when an individual’s exposure to trauma or adversity is chronic or repetitive, causing not only familiar PTSD symptomatology but also alterations in self-perception, interpersonal functioning, and affective instability. Complex PTSD was first described by Judith Herman, MD, in 1992 as a distinct entity from PTSD.1 She theorized that PTSD derives primarily from singular traumatic events, while a distinct clinical syndrome might arise after prolonged, repeated trauma.1 A diagnosis of CPTSD might arise in situations with more chronicity than a classic single circumscribed traumatic event, such as being held in captivity, under the control of perpetrators for extended periods of time, imprisoned, or subject to prolonged sexual abuse. Herman’s description of CPTSD identifies 3 areas of psychopathology that extend beyond PTSD1:

- symptomatic refers to the complex, diffuse, and tenacious symptom presentation

- characterological focuses on the personality changes in terms of dissociation, ego-fragmentation, and identity complications

- vulnerability describes characteristic repeated harm with respect to self-mutilation or other self-injurious behaviors, and suicidality.

Taxometrics, official recognition, and controversy

Complex PTSD was proposed for inclusion in DSM-IV as “Disorders of Extreme Stress Not Otherwise Specified,” or DESNOS. Reportedly, it was interpreted as a severe presentation of PTSD, and therefore not included in the manual as a separate diagnosis.2 In contrast, ICD-10 included a CPTSD-like entity of “Enduring Personality Change After Catastrophic Event” (EPCACE). Although the existence of CPTSD as a categorically distinct diagnosis in the psychiatric mainstream has been debated and discussed for years, with many arguably unaware of its existence, clinicians and researchers specializing in trauma are well-versed in its clinical utility. As such, CPTSD was again discussed during the development of DSM-5. In an apparent attempt to balance this clinical utility with ongoing concerns about its validity as a diagnostically distinct syndrome, DSM-5 did not officially recognize CPTSD, but added several criteria to PTSD referencing changes in self-perception, affective instability, and dysphoria, as well as a dissociative subtype, effectively expanding the scope of a PTSD diagnosis to also include CPTSD symptoms when applicable. ICD-11 has taken a different direction, and officially recognizes CPTSD as a distinct diagnosis.

ICD-11 presents CPTSD as a “sibling” disorder, which it distinguishes from PTSD with high levels of dissociation, depression, and borderline personality disorder traits.3 Within this framework, the diagnosis of CPTSD requires that the PTSD criteria be met in addition to symptoms that fall into a “disturbances of self-organization” category. When parsing the symptoms of the “disturbances of self-organization” category, the overlap with borderline personality disorder symptoms is apparent.4 This overlap has given rise to yet another controversy regarding CPTSD’s categorical validity; in addition to its distinctness from PTSD, its distinctness from borderline personality disorder has also been debated. In a study examining the similarity between CPTSD and borderline personality disorder, Jowett et al5 concluded that CPTSD was associated with greater exposure to multiple traumas earlier in life and resulted in higher functional impairment than borderline personality disorder, ultimately supporting CPTSD as a separate entity with features that overlap borderline personality disorder.5 According to Ford and Courtois6 “the evidence ... suggests that a sub-group of BPD patients—who often but not always have comorbid PTSD—may be best understood and treated if CPTSD is explicitly addressed as well—and in some cases, in lieu of—BPD.”

PTSD and CPTSD may therefore both be understood to fall within a spectrum of trauma diagnoses; this paradigm postulates that there exists a wide variety of posttraumatic patient presentations, perhaps on a continuum. On the less severe side of the trauma spectrum, the symptoms traditionally seen and characterized as PTSD (such as hypervigilance, nightmares, and flashbacks) may be found, while, with increasingly severe or prolonged trauma, there may be a tendency to see more complex elements (such as dissociation, personality changes mimicking borderline personality disorder, depression, anxiety, self-injurious behavior, and suicidality).7 Nevertheless, controversy about discriminant validity still exists. A review article by Resnick et al8 argued that the existing evidence is not strong enough to support CPTSD as a standalone entity. However, Resnick et al8 agreed that a singular PTSD diagnosis has limitations, and that there is a need for more research in the field of trauma psychiatry.

Continue to: Utility of the diagnostic conceptualization...

Utility of the diagnostic conceptualization

Although the controversy surrounding the distinction of CPTSD demands categorical clarity with respect to PTSD and borderline personality disorder as a means of resolution, the diagnosis has practical applications that should not limit its use in clinical formulation or treatment planning. Comorbid diagnoses do not prevent clinicians from diagnosing and treating patients who present with complicated manifestations of trauma.9 In fact, having overlapping diagnoses would highlight the array of patient presentations that can be seen in the posttraumatic condition. Furthermore, in the pursuit of individualized care approaches, the addition of CPTSD as a diagnostic conception would allow for more integrated treatment options using a multi-modular approach.10

The addition of CPTSD as a diagnosis is helpful in determining the etiology of a patient’s presentation and therefore formulating the most appropriate treatment plan. While the 2-pronged approach of psychopharmacology and therapy is the central dogma of psychiatric care, there are many specific options to consider for each. By viewing such patients through the lens of trauma as opposed to depression and anxiety, there is a clear shift in treatment that has the potential to make more lasting impacts and progress.11

CPTSD may coexist with PTSD, but it extends beyond it to include a pleomorphic symptom picture encompassing personality changes and a high risk for repeated harm. Failure to correctly classify a patient’s presentation as a response to repetitive, prolonged trauma may result in discrimination and inappropriate or ineffective treatment recommendations.

For a comparison of the diagnostic criteria of PTSD, CPTSD, and borderline personality disorder, see Table 112, Table 2,13,14, and Table 312.

Patients with CPTSD

One of the authors (NR) has cared for several similar individuals presenting for treatment with vague diagnoses of “chronic depression and anxiety” for years, sometimes with a speculative bipolar disorder diagnosis due to situational mood swings or reactivity, and a generally poor response to both medications and psychotherapy. These patients were frustrated because none of the diagnoses seemed to fully “fit” with their pattern of symptoms or subjective experience, and treatment seemed minimally helpful. Very often, their social history revealed a variety of adversities or traumatic events, such as childhood sexual or physical abuse, a home environment plagued by domestic violence, or being raised by one or both parents with their own history of trauma, or perhaps a personality or substance use disorder. Although many of these patients’ symptom profiles aligned only partially with “typical” PTSD, they were often better captured by CPTSD, with a focus on negative self-perception and impact on close relationships. Helping the patient “connect the dots” to create a more continuous narrative, and consequently reconceptualizing the diagnosis as a complex trauma disorder, has proven effective in a number of these cases, allowing the patient to make sense of their symptoms in the context of their personal history, reducing stigma, and allowing for different avenues with medication, therapy, and self-understanding. It can also help to validate the impact of a patient’s adverse experiences and encourage a patient to view their symptoms as an understandable or even once-adaptive response to traumatic stress, rather than a sign of personal weakness or defectiveness.

TREATMENT A trauma-focused approach

Once the treatment team considersMr. X’s significant childhood trauma and reconceptualizes his behaviors through this lens, treatment is adjusted accordingly. His significant reactivity, dissociative symptoms, social impairment, and repeated suicide attempts are better understood and have more significance through a trauma lens, which provides a better explanation than a primary mood disorder.

Therapeutic interventions in the hospital are tailored according to the treatment team’s new insight. Specific DBT skills are practiced, insight-oriented therapy and motivational interviewing are used, and Mr. X and his therapist begin to explore his trauma, both from his biological father and from his intense stressors experienced because of his medical issues.

Mr. X’s mother, who is very involved in his care, is provided with education on this conceptualization and given instruction on trauma-focused therapies in the outpatient setting. While Mr. X’s medication regimen is not changed significantly, for some patients, the reformulation from a primary mood or anxiety disorder to a trauma disorder might require a change in the pharmacotherapy regimen to address behavioral symptoms such as mood reactivity or issues with sleep.

OUTCOME Decreased intensity of suicidal thoughts

By the time of discharge, Mr. X has maintained safety, with no further outbursts, and subjectively reports feeling more understood and validated. Although chronic suicidal ideation can take months or years of treatment to resolve, at the time of discharge Mr. X reports a decreased intensity of these thoughts, and no acute suicidal ideation, plan, or intent. His discharge planning emphasizes ongoing work specifically related to coping with symptoms of traumatic stress, and the involvement of his main social support in facilitating this work.

The authors’ observations

As a caveat, it may be in some cases that chronic negative affect, dysphoria, and self-perception are better understood as a comorbid depressive disorder rather than subsumed into a PTSD/ CPTSD diagnosis. Also, because situational mood instability and impulsivity are often interpreted as bipolar disorder, a history of hypomania and mania should be ruled out. In Mr. X’s case, the diagnostic reformulation did not significantly impact pharmacotherapy because the target symptoms of mood instability, irritability, anxiety, and depression remained, despite the change in diagnosis.