User login

VTE, sepsis risk increased among COVID-19 patients with cancer

, according to data from a registry study.

Researchers analyzed data on 5,556 patients with COVID-19 who had an inpatient or emergency encounter at Mount Sinai Health System (MSHS) in New York between March 1 and May 27, 2020. Patients were included in an anonymous MSHS COVID-19 registry.

There were 421 patients who had cancer: 96 with a hematologic malignancy and 325 with solid tumors.

After adjustment for age, gender, and number of comorbidities, the odds ratios for acute VTE and sepsis for patients with cancer (versus those without cancer) were 1.77 and 1.34, respectively. The adjusted odds ratio for mortality in cancer patients was 1.02.

The results remained “relatively consistent” after stratification by solid and nonsolid cancer types, with no significant difference in outcomes between those two groups, and results remained consistent in a propensity-matched model, according to Naomi Alpert, a biostatistician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Ms. Alpert reported these findings at the AACR virtual meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer.

She noted that the cancer patients were older than the noncancer patients (mean age, 69.2 years vs. 63.8 years), and cancer patients were more likely to have two or more comorbid conditions (48.2% vs. 30.4%). Cancer patients also had significantly lower hemoglobin levels and red blood cell, platelet, and white blood cell counts (P < .01 for all).

“Low white blood cell count may be one of the reasons for higher risk of sepsis in cancer patients, as it may lead to a higher risk of infection,” Ms. Alpert said. “However, it’s not clear what role cancer therapies play in the risks of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, so there is still quite a bit to learn.”

In fact, the findings are limited by a lack of information about cancer treatment, as the registry was not designed for that purpose, she noted.

Another study limitation is the short follow-up of a month or less in most patients, due, in part, to the novelty of COVID-19, but also to the lack of information on patients after they left the hospital.

“However, we had a very large sample size, with more than 400 cancer patients included, and, to our knowledge, this is the largest analysis of its kind to be done so far,” Ms. Alpert said. “In the future, it’s going to be very important to assess the effect of cancer therapies on COVID-19 complications and to see if prior therapies had any effect on outcomes.”

Longer follow-up would also be helpful for assessing the chronic effects of COVID-19 on cancer patients over time, she said. “It would be important to see whether some of these elevated risks of venous thromboembolism and sepsis are associated with longer-term mortality risks than what we were able to measure here,” she added.

Asked about the discrepancy between mortality in this study and those of larger registries, such as the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) and TERAVOLT, Ms. Alpert noted that the current study included only patients who required hospitalization or emergency care.

“Our mortality rate was actually a bit higher than what was reported in some of the other studies,” she said. “We had about a 30% mortality rate in the cancer patients and about 25% for the noncancer patients, so ... we’re sort of looking at a subset of patients who we know are the sickest of the sick, which may explain some of the higher mortality that we’re seeing.”

Ms. Alpert reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Alpert N et al. AACR COVID-19 and Cancer, Abstract S12-02.

, according to data from a registry study.

Researchers analyzed data on 5,556 patients with COVID-19 who had an inpatient or emergency encounter at Mount Sinai Health System (MSHS) in New York between March 1 and May 27, 2020. Patients were included in an anonymous MSHS COVID-19 registry.

There were 421 patients who had cancer: 96 with a hematologic malignancy and 325 with solid tumors.

After adjustment for age, gender, and number of comorbidities, the odds ratios for acute VTE and sepsis for patients with cancer (versus those without cancer) were 1.77 and 1.34, respectively. The adjusted odds ratio for mortality in cancer patients was 1.02.

The results remained “relatively consistent” after stratification by solid and nonsolid cancer types, with no significant difference in outcomes between those two groups, and results remained consistent in a propensity-matched model, according to Naomi Alpert, a biostatistician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Ms. Alpert reported these findings at the AACR virtual meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer.

She noted that the cancer patients were older than the noncancer patients (mean age, 69.2 years vs. 63.8 years), and cancer patients were more likely to have two or more comorbid conditions (48.2% vs. 30.4%). Cancer patients also had significantly lower hemoglobin levels and red blood cell, platelet, and white blood cell counts (P < .01 for all).

“Low white blood cell count may be one of the reasons for higher risk of sepsis in cancer patients, as it may lead to a higher risk of infection,” Ms. Alpert said. “However, it’s not clear what role cancer therapies play in the risks of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, so there is still quite a bit to learn.”

In fact, the findings are limited by a lack of information about cancer treatment, as the registry was not designed for that purpose, she noted.

Another study limitation is the short follow-up of a month or less in most patients, due, in part, to the novelty of COVID-19, but also to the lack of information on patients after they left the hospital.

“However, we had a very large sample size, with more than 400 cancer patients included, and, to our knowledge, this is the largest analysis of its kind to be done so far,” Ms. Alpert said. “In the future, it’s going to be very important to assess the effect of cancer therapies on COVID-19 complications and to see if prior therapies had any effect on outcomes.”

Longer follow-up would also be helpful for assessing the chronic effects of COVID-19 on cancer patients over time, she said. “It would be important to see whether some of these elevated risks of venous thromboembolism and sepsis are associated with longer-term mortality risks than what we were able to measure here,” she added.

Asked about the discrepancy between mortality in this study and those of larger registries, such as the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) and TERAVOLT, Ms. Alpert noted that the current study included only patients who required hospitalization or emergency care.

“Our mortality rate was actually a bit higher than what was reported in some of the other studies,” she said. “We had about a 30% mortality rate in the cancer patients and about 25% for the noncancer patients, so ... we’re sort of looking at a subset of patients who we know are the sickest of the sick, which may explain some of the higher mortality that we’re seeing.”

Ms. Alpert reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Alpert N et al. AACR COVID-19 and Cancer, Abstract S12-02.

, according to data from a registry study.

Researchers analyzed data on 5,556 patients with COVID-19 who had an inpatient or emergency encounter at Mount Sinai Health System (MSHS) in New York between March 1 and May 27, 2020. Patients were included in an anonymous MSHS COVID-19 registry.

There were 421 patients who had cancer: 96 with a hematologic malignancy and 325 with solid tumors.

After adjustment for age, gender, and number of comorbidities, the odds ratios for acute VTE and sepsis for patients with cancer (versus those without cancer) were 1.77 and 1.34, respectively. The adjusted odds ratio for mortality in cancer patients was 1.02.

The results remained “relatively consistent” after stratification by solid and nonsolid cancer types, with no significant difference in outcomes between those two groups, and results remained consistent in a propensity-matched model, according to Naomi Alpert, a biostatistician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Ms. Alpert reported these findings at the AACR virtual meeting: COVID-19 and Cancer.

She noted that the cancer patients were older than the noncancer patients (mean age, 69.2 years vs. 63.8 years), and cancer patients were more likely to have two or more comorbid conditions (48.2% vs. 30.4%). Cancer patients also had significantly lower hemoglobin levels and red blood cell, platelet, and white blood cell counts (P < .01 for all).

“Low white blood cell count may be one of the reasons for higher risk of sepsis in cancer patients, as it may lead to a higher risk of infection,” Ms. Alpert said. “However, it’s not clear what role cancer therapies play in the risks of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, so there is still quite a bit to learn.”

In fact, the findings are limited by a lack of information about cancer treatment, as the registry was not designed for that purpose, she noted.

Another study limitation is the short follow-up of a month or less in most patients, due, in part, to the novelty of COVID-19, but also to the lack of information on patients after they left the hospital.

“However, we had a very large sample size, with more than 400 cancer patients included, and, to our knowledge, this is the largest analysis of its kind to be done so far,” Ms. Alpert said. “In the future, it’s going to be very important to assess the effect of cancer therapies on COVID-19 complications and to see if prior therapies had any effect on outcomes.”

Longer follow-up would also be helpful for assessing the chronic effects of COVID-19 on cancer patients over time, she said. “It would be important to see whether some of these elevated risks of venous thromboembolism and sepsis are associated with longer-term mortality risks than what we were able to measure here,” she added.

Asked about the discrepancy between mortality in this study and those of larger registries, such as the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) and TERAVOLT, Ms. Alpert noted that the current study included only patients who required hospitalization or emergency care.

“Our mortality rate was actually a bit higher than what was reported in some of the other studies,” she said. “We had about a 30% mortality rate in the cancer patients and about 25% for the noncancer patients, so ... we’re sort of looking at a subset of patients who we know are the sickest of the sick, which may explain some of the higher mortality that we’re seeing.”

Ms. Alpert reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Alpert N et al. AACR COVID-19 and Cancer, Abstract S12-02.

FROM AACR: COVID-19 AND CANCER

First guideline on NGS testing in cancer, from ESMO

Recommendations on the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) tests for patients with metastatic cancer have been issued by the European Society for Medical Oncology, the first recommendations of their kind to be published by any medical society.

“Until now, there were no recommendations from scientific societies on how to use this technique in daily clinical practice to profile metastatic cancers,” Fernanda Mosele, MD, medical oncologist, Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France, said in a statement.

NGS testing is already used extensively in oncology, particularly in metastatic cancer, she noted. The technology is used to assess the sequence of DNA in genes from a tumor tissue sample. Numerous genes can be quickly sequenced at the same time at relatively low cost. The results provide information on mutations that are present, which, in turn, helps with deciding which treatments to use, including drugs targeting the identified mutations.

“Our intent is that they [the guidelines] will unify decision-making about how NGS should be used for patients with metastatic cancer,” Dr. Mosele said.

The recommendations were published online August 25 in Annals of Oncology.

Overall, ESMO recommends the use of tumor multigene NGS for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, and cholangiocarcinoma.

For other cancers, the authors said that NGS is not recommended in clinical practice but could be used for research purposes.

However, patients should be informed that it is unlikely that test results would benefit them much personally.

Physicians and patients may decide together to subject the tumor to mutational testing using a large panel of genes, provided testing doesn’t burden the health care system with additional costs.

“This recommendation acknowledges that a small number of patients could benefit from a drug because they have a rare mutation,” Joaquin Mateo, MD, chair of the ESMO working group, said in a statement.

“So beyond the cancers in which everyone should receive NGS, there is room for physicians and patients to discuss the pros and cons of ordering these tests,” he added.

ESMO also does not recommend the use of off-label drugs matched to any genomic alteration detected by NGS unless an access program and a decisional procedure have been developed, either regionally or nationally.

No need for NGS testing of other cancers

In contrast to NSCLC, “there is currently no need to perform tumor multigene NGS for patients with mBC [metastatic breast cancer] in the context of daily practice,” ESMO stated.

This is largely because somatic sequencing cannot fully substitute for germline testing for BRCA status, and other mutations, such as HER2, can be detected using immunohistochemistry (IHC).

The same can be said for patients with metastatic gastric cancer, inasmuch as detection of alterations can and should be done using cheaper testing methods, ESMO pointed out.

However, ESMO members still emphasized that it’s important to include patients with metastatic breast cancer in molecular screening programs as well as in clinical trials testing targeted agents.

Similarly, there is no need to test metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) using multigene NGS in daily practice, inasmuch as most level 1 alterations in mCRC can be determined by IHC or PCR.

However, NGS can be considered as an alternative to PCR-based tests in mCRC, provided NGS is not associated with additional cost.

ESMO again recommended that research centers include mCRC patients in molecular screening programs in order for them to have access to innovative clinical trial agents.

As for advanced prostate cancer, ESMO does recommend that clinicians perform NGS on tissue samples to assess the tumor’s mutational status, at least for the presence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, when patients have access to the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors for treatment.

The authors cautioned, however, that this strategy is unlikely to be cost-effective, so larger panels should be used only when there are specific agreements with payers.

Multigene NGS is also not recommended for patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), although ESMO points out that it is the role of research centers to propose multigene sequencing for these patients in the context of molecular screening programs.

This is again to facilitate access to innovative drugs for these patients.

Similar to recommendations for patients with advanced PDAC, patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) do not need to have tumor multigene NGS either.

Considering the high unmet needs of HCC patients, ESMO feels that research centers should propose multigene sequencing to patients with advanced HCC in the context of molecular screening programs.

In contrast, ESMO recommended that tumor multigene NGS be used to detect actionable alterations in patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma.

Again, they predict that this strategy is unlikely to be cost-effective, so larger panels should only be used if a specific agreement is in place with payers.

ESMO also assessed the frequency of level 1 alterations in less frequent tumor types, including ovarian cancers. Because BRCA1 and BRCA2 somatic mutations in ovarian tumors have been associated with increased response to the PARP inhibitors, the use of multigene NGS is justified with this malignancy, ESMO states.

The authors also recommend that tumor mutational burden be determined in cervical cancer, moderately differentiated neuroendocrine tumors, salivary cancers, vulvar cancer, and thyroid cancers.

Dr. Mosele has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Many coauthors have relationships with the pharmaceutical industry, as listed in the article.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Recommendations on the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) tests for patients with metastatic cancer have been issued by the European Society for Medical Oncology, the first recommendations of their kind to be published by any medical society.

“Until now, there were no recommendations from scientific societies on how to use this technique in daily clinical practice to profile metastatic cancers,” Fernanda Mosele, MD, medical oncologist, Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France, said in a statement.

NGS testing is already used extensively in oncology, particularly in metastatic cancer, she noted. The technology is used to assess the sequence of DNA in genes from a tumor tissue sample. Numerous genes can be quickly sequenced at the same time at relatively low cost. The results provide information on mutations that are present, which, in turn, helps with deciding which treatments to use, including drugs targeting the identified mutations.

“Our intent is that they [the guidelines] will unify decision-making about how NGS should be used for patients with metastatic cancer,” Dr. Mosele said.

The recommendations were published online August 25 in Annals of Oncology.

Overall, ESMO recommends the use of tumor multigene NGS for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, and cholangiocarcinoma.

For other cancers, the authors said that NGS is not recommended in clinical practice but could be used for research purposes.

However, patients should be informed that it is unlikely that test results would benefit them much personally.

Physicians and patients may decide together to subject the tumor to mutational testing using a large panel of genes, provided testing doesn’t burden the health care system with additional costs.

“This recommendation acknowledges that a small number of patients could benefit from a drug because they have a rare mutation,” Joaquin Mateo, MD, chair of the ESMO working group, said in a statement.

“So beyond the cancers in which everyone should receive NGS, there is room for physicians and patients to discuss the pros and cons of ordering these tests,” he added.

ESMO also does not recommend the use of off-label drugs matched to any genomic alteration detected by NGS unless an access program and a decisional procedure have been developed, either regionally or nationally.

No need for NGS testing of other cancers

In contrast to NSCLC, “there is currently no need to perform tumor multigene NGS for patients with mBC [metastatic breast cancer] in the context of daily practice,” ESMO stated.

This is largely because somatic sequencing cannot fully substitute for germline testing for BRCA status, and other mutations, such as HER2, can be detected using immunohistochemistry (IHC).

The same can be said for patients with metastatic gastric cancer, inasmuch as detection of alterations can and should be done using cheaper testing methods, ESMO pointed out.

However, ESMO members still emphasized that it’s important to include patients with metastatic breast cancer in molecular screening programs as well as in clinical trials testing targeted agents.

Similarly, there is no need to test metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) using multigene NGS in daily practice, inasmuch as most level 1 alterations in mCRC can be determined by IHC or PCR.

However, NGS can be considered as an alternative to PCR-based tests in mCRC, provided NGS is not associated with additional cost.

ESMO again recommended that research centers include mCRC patients in molecular screening programs in order for them to have access to innovative clinical trial agents.

As for advanced prostate cancer, ESMO does recommend that clinicians perform NGS on tissue samples to assess the tumor’s mutational status, at least for the presence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, when patients have access to the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors for treatment.

The authors cautioned, however, that this strategy is unlikely to be cost-effective, so larger panels should be used only when there are specific agreements with payers.

Multigene NGS is also not recommended for patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), although ESMO points out that it is the role of research centers to propose multigene sequencing for these patients in the context of molecular screening programs.

This is again to facilitate access to innovative drugs for these patients.

Similar to recommendations for patients with advanced PDAC, patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) do not need to have tumor multigene NGS either.

Considering the high unmet needs of HCC patients, ESMO feels that research centers should propose multigene sequencing to patients with advanced HCC in the context of molecular screening programs.

In contrast, ESMO recommended that tumor multigene NGS be used to detect actionable alterations in patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma.

Again, they predict that this strategy is unlikely to be cost-effective, so larger panels should only be used if a specific agreement is in place with payers.

ESMO also assessed the frequency of level 1 alterations in less frequent tumor types, including ovarian cancers. Because BRCA1 and BRCA2 somatic mutations in ovarian tumors have been associated with increased response to the PARP inhibitors, the use of multigene NGS is justified with this malignancy, ESMO states.

The authors also recommend that tumor mutational burden be determined in cervical cancer, moderately differentiated neuroendocrine tumors, salivary cancers, vulvar cancer, and thyroid cancers.

Dr. Mosele has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Many coauthors have relationships with the pharmaceutical industry, as listed in the article.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Recommendations on the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) tests for patients with metastatic cancer have been issued by the European Society for Medical Oncology, the first recommendations of their kind to be published by any medical society.

“Until now, there were no recommendations from scientific societies on how to use this technique in daily clinical practice to profile metastatic cancers,” Fernanda Mosele, MD, medical oncologist, Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France, said in a statement.

NGS testing is already used extensively in oncology, particularly in metastatic cancer, she noted. The technology is used to assess the sequence of DNA in genes from a tumor tissue sample. Numerous genes can be quickly sequenced at the same time at relatively low cost. The results provide information on mutations that are present, which, in turn, helps with deciding which treatments to use, including drugs targeting the identified mutations.

“Our intent is that they [the guidelines] will unify decision-making about how NGS should be used for patients with metastatic cancer,” Dr. Mosele said.

The recommendations were published online August 25 in Annals of Oncology.

Overall, ESMO recommends the use of tumor multigene NGS for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, and cholangiocarcinoma.

For other cancers, the authors said that NGS is not recommended in clinical practice but could be used for research purposes.

However, patients should be informed that it is unlikely that test results would benefit them much personally.

Physicians and patients may decide together to subject the tumor to mutational testing using a large panel of genes, provided testing doesn’t burden the health care system with additional costs.

“This recommendation acknowledges that a small number of patients could benefit from a drug because they have a rare mutation,” Joaquin Mateo, MD, chair of the ESMO working group, said in a statement.

“So beyond the cancers in which everyone should receive NGS, there is room for physicians and patients to discuss the pros and cons of ordering these tests,” he added.

ESMO also does not recommend the use of off-label drugs matched to any genomic alteration detected by NGS unless an access program and a decisional procedure have been developed, either regionally or nationally.

No need for NGS testing of other cancers

In contrast to NSCLC, “there is currently no need to perform tumor multigene NGS for patients with mBC [metastatic breast cancer] in the context of daily practice,” ESMO stated.

This is largely because somatic sequencing cannot fully substitute for germline testing for BRCA status, and other mutations, such as HER2, can be detected using immunohistochemistry (IHC).

The same can be said for patients with metastatic gastric cancer, inasmuch as detection of alterations can and should be done using cheaper testing methods, ESMO pointed out.

However, ESMO members still emphasized that it’s important to include patients with metastatic breast cancer in molecular screening programs as well as in clinical trials testing targeted agents.

Similarly, there is no need to test metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) using multigene NGS in daily practice, inasmuch as most level 1 alterations in mCRC can be determined by IHC or PCR.

However, NGS can be considered as an alternative to PCR-based tests in mCRC, provided NGS is not associated with additional cost.

ESMO again recommended that research centers include mCRC patients in molecular screening programs in order for them to have access to innovative clinical trial agents.

As for advanced prostate cancer, ESMO does recommend that clinicians perform NGS on tissue samples to assess the tumor’s mutational status, at least for the presence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, when patients have access to the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors for treatment.

The authors cautioned, however, that this strategy is unlikely to be cost-effective, so larger panels should be used only when there are specific agreements with payers.

Multigene NGS is also not recommended for patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), although ESMO points out that it is the role of research centers to propose multigene sequencing for these patients in the context of molecular screening programs.

This is again to facilitate access to innovative drugs for these patients.

Similar to recommendations for patients with advanced PDAC, patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) do not need to have tumor multigene NGS either.

Considering the high unmet needs of HCC patients, ESMO feels that research centers should propose multigene sequencing to patients with advanced HCC in the context of molecular screening programs.

In contrast, ESMO recommended that tumor multigene NGS be used to detect actionable alterations in patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma.

Again, they predict that this strategy is unlikely to be cost-effective, so larger panels should only be used if a specific agreement is in place with payers.

ESMO also assessed the frequency of level 1 alterations in less frequent tumor types, including ovarian cancers. Because BRCA1 and BRCA2 somatic mutations in ovarian tumors have been associated with increased response to the PARP inhibitors, the use of multigene NGS is justified with this malignancy, ESMO states.

The authors also recommend that tumor mutational burden be determined in cervical cancer, moderately differentiated neuroendocrine tumors, salivary cancers, vulvar cancer, and thyroid cancers.

Dr. Mosele has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Many coauthors have relationships with the pharmaceutical industry, as listed in the article.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

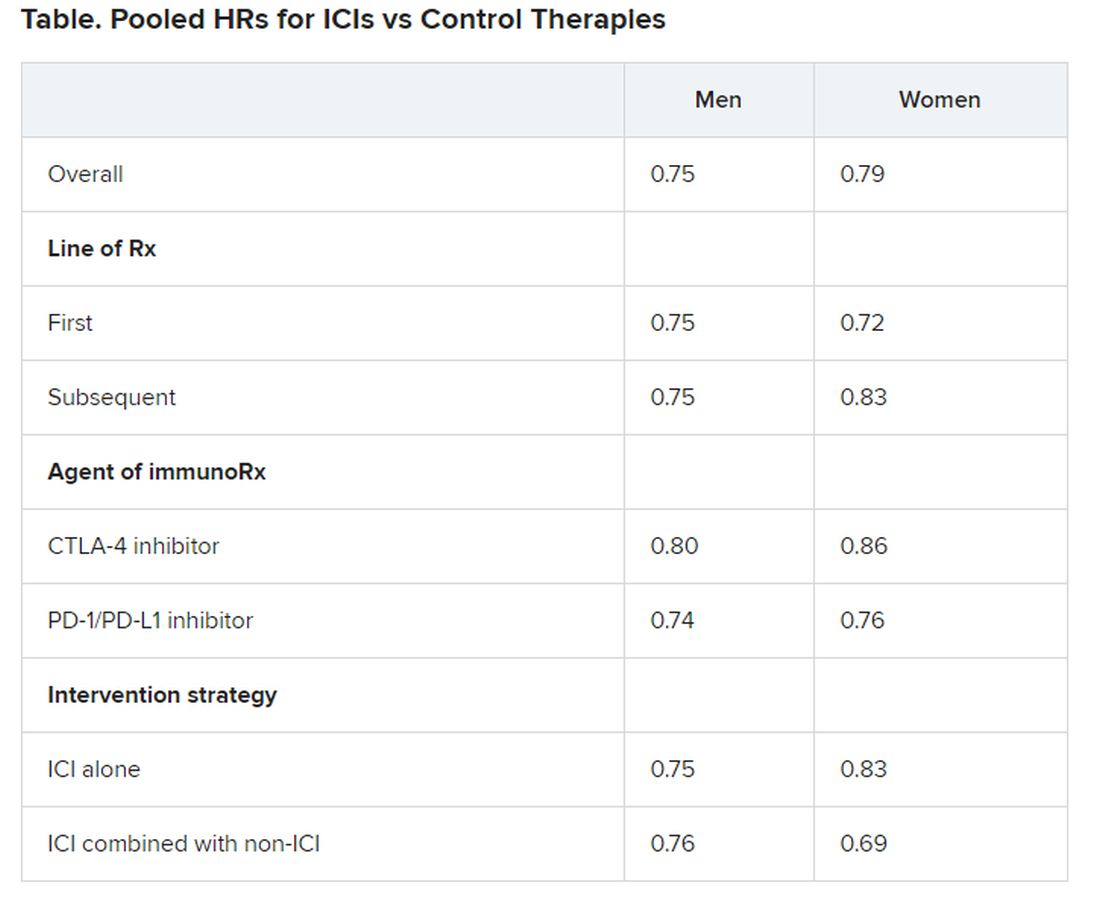

Immunotherapy should not be withheld because of sex, age, or PS

The improvement in survival in many cancer types that is seen with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), when compared to control therapies, is not affected by the patient’s sex, age, or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), according to a new meta-analysis.

Therefore, treatment with these immunotherapies should not be withheld on the basis of these factors, the authors concluded.

Asked whether there have been such instances of withholding ICIs, lead author Yucai Wang, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told Medscape Medical News: “We did this study solely based on scientific questions we had and not because we were seeing any bias at the moment in the use of ICIs.

“And we saw that the survival benefits were very similar across all of the categories [we analyzed], with a survival benefit of about 20% from immunotherapy across the board, which is clinically meaningful,” he added.

The study was published online August 7 in JAMA Network Open.

“The comparable survival advantage between patients of different sex, age, and ECOG PS may encourage more patients to receive ICI treatment regardless of cancer types, lines of therapy, agents of immunotherapy, and intervention therapies,” the authors commented.

Wang noted that there have been conflicting reports in the literature suggesting that male patients may benefit more from immunotherapy than female patients and that older patients may benefit more from the same treatment than younger patients.

However, there are also suggestions in the literature that women experience a stronger immune response than men and that, with aging, the immune system generally undergoes immunosenescence.

In addition, the PS of oncology patients has been implicated in how well patients respond to immunotherapy.

Wang noted that the findings of past studies have contradicted each other.

Findings of the Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included 37 randomized clinical trials that involved a total of 23,760 patients with a variety of advanced cancers. “Most of the trials were phase 3 (n = 34) and conduced for subsequent lines of therapy (n = 22),” the authors explained.

The most common cancers treated with an ICI were non–small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

Pooled overall survival (OS) hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated on the basis of sex, age (younger than 65 years and 65 years and older), and an ECOG PS of 0 and 1 or higher.

Responses were stratified on the basis of cancer type, line of therapy, the ICI used, and the immunotherapy strategy used in the ICI arm.

Most of the drugs evaluated were PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The specific drugs assessed included ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.

A total of 32 trials that involved more than 20,000 patients reported HRs for death according to the patients’ sex. Thirty-four trials that involved more than 21,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ age, and 30 trials that involved more than 19,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ ECOG PS.

No significant differences in OS benefit were seen by cancer type, line of therapy, agent of immunotherapy, or intervention strategy, the investigators pointed out.

There were also no differences in survival benefit associated with immunotherapy vs control therapies for patients with an ECOG PS of 0 and an ECOG PS of 1 or greater. The OS benefit was 0.81 for those with an ECOG PS of 0 and 0.79 for those with an ECOG PS of 1 or greater.

Wang has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The improvement in survival in many cancer types that is seen with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), when compared to control therapies, is not affected by the patient’s sex, age, or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), according to a new meta-analysis.

Therefore, treatment with these immunotherapies should not be withheld on the basis of these factors, the authors concluded.

Asked whether there have been such instances of withholding ICIs, lead author Yucai Wang, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told Medscape Medical News: “We did this study solely based on scientific questions we had and not because we were seeing any bias at the moment in the use of ICIs.

“And we saw that the survival benefits were very similar across all of the categories [we analyzed], with a survival benefit of about 20% from immunotherapy across the board, which is clinically meaningful,” he added.

The study was published online August 7 in JAMA Network Open.

“The comparable survival advantage between patients of different sex, age, and ECOG PS may encourage more patients to receive ICI treatment regardless of cancer types, lines of therapy, agents of immunotherapy, and intervention therapies,” the authors commented.

Wang noted that there have been conflicting reports in the literature suggesting that male patients may benefit more from immunotherapy than female patients and that older patients may benefit more from the same treatment than younger patients.

However, there are also suggestions in the literature that women experience a stronger immune response than men and that, with aging, the immune system generally undergoes immunosenescence.

In addition, the PS of oncology patients has been implicated in how well patients respond to immunotherapy.

Wang noted that the findings of past studies have contradicted each other.

Findings of the Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included 37 randomized clinical trials that involved a total of 23,760 patients with a variety of advanced cancers. “Most of the trials were phase 3 (n = 34) and conduced for subsequent lines of therapy (n = 22),” the authors explained.

The most common cancers treated with an ICI were non–small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

Pooled overall survival (OS) hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated on the basis of sex, age (younger than 65 years and 65 years and older), and an ECOG PS of 0 and 1 or higher.

Responses were stratified on the basis of cancer type, line of therapy, the ICI used, and the immunotherapy strategy used in the ICI arm.

Most of the drugs evaluated were PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The specific drugs assessed included ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.

A total of 32 trials that involved more than 20,000 patients reported HRs for death according to the patients’ sex. Thirty-four trials that involved more than 21,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ age, and 30 trials that involved more than 19,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ ECOG PS.

No significant differences in OS benefit were seen by cancer type, line of therapy, agent of immunotherapy, or intervention strategy, the investigators pointed out.

There were also no differences in survival benefit associated with immunotherapy vs control therapies for patients with an ECOG PS of 0 and an ECOG PS of 1 or greater. The OS benefit was 0.81 for those with an ECOG PS of 0 and 0.79 for those with an ECOG PS of 1 or greater.

Wang has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The improvement in survival in many cancer types that is seen with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), when compared to control therapies, is not affected by the patient’s sex, age, or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), according to a new meta-analysis.

Therefore, treatment with these immunotherapies should not be withheld on the basis of these factors, the authors concluded.

Asked whether there have been such instances of withholding ICIs, lead author Yucai Wang, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told Medscape Medical News: “We did this study solely based on scientific questions we had and not because we were seeing any bias at the moment in the use of ICIs.

“And we saw that the survival benefits were very similar across all of the categories [we analyzed], with a survival benefit of about 20% from immunotherapy across the board, which is clinically meaningful,” he added.

The study was published online August 7 in JAMA Network Open.

“The comparable survival advantage between patients of different sex, age, and ECOG PS may encourage more patients to receive ICI treatment regardless of cancer types, lines of therapy, agents of immunotherapy, and intervention therapies,” the authors commented.

Wang noted that there have been conflicting reports in the literature suggesting that male patients may benefit more from immunotherapy than female patients and that older patients may benefit more from the same treatment than younger patients.

However, there are also suggestions in the literature that women experience a stronger immune response than men and that, with aging, the immune system generally undergoes immunosenescence.

In addition, the PS of oncology patients has been implicated in how well patients respond to immunotherapy.

Wang noted that the findings of past studies have contradicted each other.

Findings of the Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included 37 randomized clinical trials that involved a total of 23,760 patients with a variety of advanced cancers. “Most of the trials were phase 3 (n = 34) and conduced for subsequent lines of therapy (n = 22),” the authors explained.

The most common cancers treated with an ICI were non–small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

Pooled overall survival (OS) hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated on the basis of sex, age (younger than 65 years and 65 years and older), and an ECOG PS of 0 and 1 or higher.

Responses were stratified on the basis of cancer type, line of therapy, the ICI used, and the immunotherapy strategy used in the ICI arm.

Most of the drugs evaluated were PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The specific drugs assessed included ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.

A total of 32 trials that involved more than 20,000 patients reported HRs for death according to the patients’ sex. Thirty-four trials that involved more than 21,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ age, and 30 trials that involved more than 19,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ ECOG PS.

No significant differences in OS benefit were seen by cancer type, line of therapy, agent of immunotherapy, or intervention strategy, the investigators pointed out.

There were also no differences in survival benefit associated with immunotherapy vs control therapies for patients with an ECOG PS of 0 and an ECOG PS of 1 or greater. The OS benefit was 0.81 for those with an ECOG PS of 0 and 0.79 for those with an ECOG PS of 1 or greater.

Wang has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Aspirin may accelerate cancer progression in older adults

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.

Of the 1,933 patients with newly diagnosed cancer, 65.7% had a localized cancer, 18.8% had a new metastatic cancer, 5.8% had metastatic disease from an existing cancer, and 9.7% had a new hematologic or lymphatic cancer.

A quarter of cancer patients (n = 495) died as a result of their malignancy, with 52 dying from a cancer they already had at randomization.

Aspirin was not associated with the risk of first incident cancer diagnosis or incident localized cancer diagnosis. The hazard ratios were 1.04 for all incident cancers (95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.14) and 0.99 for incident localized cancers (95% CI, 0.89-1.11).

However, aspirin was associated with an increased risk of metastatic cancer and cancer presenting at stage 4. The HR for metastatic cancer was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.00-1.43), and the HR for newly diagnosed stage 4 cancer was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02-1.45).

Furthermore, “an increased progression to death was observed amongst those randomized to aspirin, regardless of whether the initial cancer presentation had been localized or metastatic,” the investigators wrote.

The HRs for death were 1.35 for all cancers (95% CI, 1.13-1.61), 1.47 for localized cancers (95% CI, 1.07-2.02), and 1.30 for metastatic cancers (95% CI, 1.03-1.63).

“Deaths were particularly high among those on aspirin who were diagnosed with advanced solid cancers,” study author Andrew Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a press statement.

Indeed, HRs for death in patients with solid tumors presenting at stage 3 and 4 were a respective 2.11 (95% CI, 1.03-4.33) and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.04-1.64). This suggests a possible adverse effect of aspirin on the growth of cancers once they have already developed in older adults, Dr. Chan said.

Where does that leave aspirin for cancer prevention?

“Although these results suggest that we should be cautious about starting aspirin therapy in otherwise healthy older adults, this does not mean that individuals who are already taking aspirin – particularly if they began taking it at a younger age – should stop their aspirin regimen,” Dr. Chan said.

There are decades of data supporting the use of daily aspirin to prevent multiple cancer types, particularly colorectal cancer, in individuals under the age of 70 years. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, regular aspirin use was linked to a 27% reduced risk for colorectal cancer, a 33% reduced risk for squamous cell esophageal cancer, a 39% decreased risk for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia, a 36% decreased risk for stomach cancer, a 38% decreased risk for hepatobiliary tract cancer, and a 22% decreased risk for pancreatic cancer.

While these figures are mostly based on observational and case-control studies, it “reaffirms the fact that, overall, when you look at all of the ages, that there is still a benefit of aspirin for cancer,” John Cuzick, PhD, of Queen Mary University of London (England), said in an interview.

In fact, the meta-analysis goes as far as suggesting that perhaps the dose of aspirin being used is too low, with the authors noting that there was a 35% risk reduction in colorectal cancer with a dose of 325 mg daily. That’s a new finding, Dr. Cuzick said.

He noted that the ASPREE study largely consists of patients 70 years of age or older, and the authors “draw some conclusions which we can’t ignore about potential safety.”

One of the safety concerns is the increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, which is why Dr. Cuzick and colleagues previously recommended caution in the use of aspirin to prevent cancer in elderly patients. The group published a study in 2015 that suggested a benefit of taking aspirin daily for 5-10 years in patients aged 50-65 years, but the risk/benefit ratio was unclear for patients 70 years and older.

The ASPREE data now add to those uncertainties and suggest “there may be some side effects that we do not understand,” Dr. Cuzick said.

“I’m still optimistic that aspirin is going to be important for cancer prevention, but probably focusing on ages 50-70,” he added. “[The ASPREE data] reinforce the caution that we have to take in terms of trying to understand what the side effects are and what’s going on at these older ages.”

Dr. Cuzick is currently leading the AsCaP Project, an international effort to better understand why aspirin might work in preventing some cancer types but not others. AsCaP is supported by Cancer Research UK and also includes Dr. Chan among the researchers attempting to find out which patients may benefit the most from aspirin and which may be at greater risk of adverse effects.

The ASPREE trial was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the National Cancer Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Several ASPREE investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bayer Pharma. The editorialists had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cuzick has been an advisory board member for Bayer in the past.

SOURCE: McNeil J et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114.

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.

Of the 1,933 patients with newly diagnosed cancer, 65.7% had a localized cancer, 18.8% had a new metastatic cancer, 5.8% had metastatic disease from an existing cancer, and 9.7% had a new hematologic or lymphatic cancer.

A quarter of cancer patients (n = 495) died as a result of their malignancy, with 52 dying from a cancer they already had at randomization.

Aspirin was not associated with the risk of first incident cancer diagnosis or incident localized cancer diagnosis. The hazard ratios were 1.04 for all incident cancers (95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.14) and 0.99 for incident localized cancers (95% CI, 0.89-1.11).

However, aspirin was associated with an increased risk of metastatic cancer and cancer presenting at stage 4. The HR for metastatic cancer was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.00-1.43), and the HR for newly diagnosed stage 4 cancer was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02-1.45).

Furthermore, “an increased progression to death was observed amongst those randomized to aspirin, regardless of whether the initial cancer presentation had been localized or metastatic,” the investigators wrote.

The HRs for death were 1.35 for all cancers (95% CI, 1.13-1.61), 1.47 for localized cancers (95% CI, 1.07-2.02), and 1.30 for metastatic cancers (95% CI, 1.03-1.63).

“Deaths were particularly high among those on aspirin who were diagnosed with advanced solid cancers,” study author Andrew Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a press statement.

Indeed, HRs for death in patients with solid tumors presenting at stage 3 and 4 were a respective 2.11 (95% CI, 1.03-4.33) and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.04-1.64). This suggests a possible adverse effect of aspirin on the growth of cancers once they have already developed in older adults, Dr. Chan said.

Where does that leave aspirin for cancer prevention?

“Although these results suggest that we should be cautious about starting aspirin therapy in otherwise healthy older adults, this does not mean that individuals who are already taking aspirin – particularly if they began taking it at a younger age – should stop their aspirin regimen,” Dr. Chan said.

There are decades of data supporting the use of daily aspirin to prevent multiple cancer types, particularly colorectal cancer, in individuals under the age of 70 years. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, regular aspirin use was linked to a 27% reduced risk for colorectal cancer, a 33% reduced risk for squamous cell esophageal cancer, a 39% decreased risk for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia, a 36% decreased risk for stomach cancer, a 38% decreased risk for hepatobiliary tract cancer, and a 22% decreased risk for pancreatic cancer.

While these figures are mostly based on observational and case-control studies, it “reaffirms the fact that, overall, when you look at all of the ages, that there is still a benefit of aspirin for cancer,” John Cuzick, PhD, of Queen Mary University of London (England), said in an interview.

In fact, the meta-analysis goes as far as suggesting that perhaps the dose of aspirin being used is too low, with the authors noting that there was a 35% risk reduction in colorectal cancer with a dose of 325 mg daily. That’s a new finding, Dr. Cuzick said.

He noted that the ASPREE study largely consists of patients 70 years of age or older, and the authors “draw some conclusions which we can’t ignore about potential safety.”

One of the safety concerns is the increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, which is why Dr. Cuzick and colleagues previously recommended caution in the use of aspirin to prevent cancer in elderly patients. The group published a study in 2015 that suggested a benefit of taking aspirin daily for 5-10 years in patients aged 50-65 years, but the risk/benefit ratio was unclear for patients 70 years and older.

The ASPREE data now add to those uncertainties and suggest “there may be some side effects that we do not understand,” Dr. Cuzick said.

“I’m still optimistic that aspirin is going to be important for cancer prevention, but probably focusing on ages 50-70,” he added. “[The ASPREE data] reinforce the caution that we have to take in terms of trying to understand what the side effects are and what’s going on at these older ages.”

Dr. Cuzick is currently leading the AsCaP Project, an international effort to better understand why aspirin might work in preventing some cancer types but not others. AsCaP is supported by Cancer Research UK and also includes Dr. Chan among the researchers attempting to find out which patients may benefit the most from aspirin and which may be at greater risk of adverse effects.

The ASPREE trial was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the National Cancer Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Several ASPREE investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bayer Pharma. The editorialists had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cuzick has been an advisory board member for Bayer in the past.

SOURCE: McNeil J et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114.

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.

Of the 1,933 patients with newly diagnosed cancer, 65.7% had a localized cancer, 18.8% had a new metastatic cancer, 5.8% had metastatic disease from an existing cancer, and 9.7% had a new hematologic or lymphatic cancer.

A quarter of cancer patients (n = 495) died as a result of their malignancy, with 52 dying from a cancer they already had at randomization.

Aspirin was not associated with the risk of first incident cancer diagnosis or incident localized cancer diagnosis. The hazard ratios were 1.04 for all incident cancers (95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.14) and 0.99 for incident localized cancers (95% CI, 0.89-1.11).

However, aspirin was associated with an increased risk of metastatic cancer and cancer presenting at stage 4. The HR for metastatic cancer was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.00-1.43), and the HR for newly diagnosed stage 4 cancer was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02-1.45).

Furthermore, “an increased progression to death was observed amongst those randomized to aspirin, regardless of whether the initial cancer presentation had been localized or metastatic,” the investigators wrote.

The HRs for death were 1.35 for all cancers (95% CI, 1.13-1.61), 1.47 for localized cancers (95% CI, 1.07-2.02), and 1.30 for metastatic cancers (95% CI, 1.03-1.63).

“Deaths were particularly high among those on aspirin who were diagnosed with advanced solid cancers,” study author Andrew Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a press statement.

Indeed, HRs for death in patients with solid tumors presenting at stage 3 and 4 were a respective 2.11 (95% CI, 1.03-4.33) and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.04-1.64). This suggests a possible adverse effect of aspirin on the growth of cancers once they have already developed in older adults, Dr. Chan said.

Where does that leave aspirin for cancer prevention?

“Although these results suggest that we should be cautious about starting aspirin therapy in otherwise healthy older adults, this does not mean that individuals who are already taking aspirin – particularly if they began taking it at a younger age – should stop their aspirin regimen,” Dr. Chan said.

There are decades of data supporting the use of daily aspirin to prevent multiple cancer types, particularly colorectal cancer, in individuals under the age of 70 years. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, regular aspirin use was linked to a 27% reduced risk for colorectal cancer, a 33% reduced risk for squamous cell esophageal cancer, a 39% decreased risk for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia, a 36% decreased risk for stomach cancer, a 38% decreased risk for hepatobiliary tract cancer, and a 22% decreased risk for pancreatic cancer.

While these figures are mostly based on observational and case-control studies, it “reaffirms the fact that, overall, when you look at all of the ages, that there is still a benefit of aspirin for cancer,” John Cuzick, PhD, of Queen Mary University of London (England), said in an interview.

In fact, the meta-analysis goes as far as suggesting that perhaps the dose of aspirin being used is too low, with the authors noting that there was a 35% risk reduction in colorectal cancer with a dose of 325 mg daily. That’s a new finding, Dr. Cuzick said.

He noted that the ASPREE study largely consists of patients 70 years of age or older, and the authors “draw some conclusions which we can’t ignore about potential safety.”

One of the safety concerns is the increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, which is why Dr. Cuzick and colleagues previously recommended caution in the use of aspirin to prevent cancer in elderly patients. The group published a study in 2015 that suggested a benefit of taking aspirin daily for 5-10 years in patients aged 50-65 years, but the risk/benefit ratio was unclear for patients 70 years and older.

The ASPREE data now add to those uncertainties and suggest “there may be some side effects that we do not understand,” Dr. Cuzick said.

“I’m still optimistic that aspirin is going to be important for cancer prevention, but probably focusing on ages 50-70,” he added. “[The ASPREE data] reinforce the caution that we have to take in terms of trying to understand what the side effects are and what’s going on at these older ages.”

Dr. Cuzick is currently leading the AsCaP Project, an international effort to better understand why aspirin might work in preventing some cancer types but not others. AsCaP is supported by Cancer Research UK and also includes Dr. Chan among the researchers attempting to find out which patients may benefit the most from aspirin and which may be at greater risk of adverse effects.

The ASPREE trial was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the National Cancer Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Several ASPREE investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bayer Pharma. The editorialists had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cuzick has been an advisory board member for Bayer in the past.

SOURCE: McNeil J et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE

One-off blast of RT, rather than weeks, for early breast cancer

Long-term outcomes now being reported confirm earlier reports from the same trial showing efficacy for the use of targeted intraoperative radiotherapy (TARGIT) in patients with early breast cancer.

This novel approach, which delivers a one-off blast of radiation directed at the tumor bed and is given during lumpectomy, has similar efficacy and lowers non–breast cancer mortality when compared with whole-breast external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), which is delivered in fractions over 3-6 weeks after surgery.

Giving the boost of radiation during surgery has numerous benefits, say the authors: it is more convenient for patients and saves on healthcare costs.

However, the controversy over local recurrence rates, sparked by the earlier results, still remains. The difference in the 5-year local recurrence rate between TARGIT and EBRT was within the 2.5% margin for non-inferiority: the rate was 2.11% in 1140 TARGIT recipients, compared with 0.95% in 1158 EBRT recipients, for a difference of 1.16% (13 recurrences).

The new longer-term results from the TARGIT-A trial were published August 20 in the BMJ, and confirm earlier results from this trial published in 2014. Meanwhile, other approaches to intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) have also been reported.

Nevertheless, whole-breast radiotherapy remains the standard of care today, note the authors.

“The biggest battle the TARGIT investigator family has faced is our challenge to the conventional dogma that radiotherapy has to be given in multiple daily doses, and moreover that whole-breast radiotherapy is always essential,” said lead author Jayant Vaidya, MD, professor of surgery and oncology at University College London, UK. He was one of the team of investigators that together developed the TARGIT approach in the 1990s, as he recalls in a related BMJ blog post.

It is unclear whether the TARGIT-A long-term outcomes will change practice, Rachel Jimenez, MD, associate program director of the Harvard Radiation Oncology Residency Program and assistant professor of radiation oncology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, told Medscape Medical News.

She noted there was controversy and debate over the earlier reports from TARGIT-A, and those findings “did little to change practice patterns over the past 6 years,” she said.

“With the publication of longer-term follow-up, my expectation would be that perceptions of IORT will remain unchanged in the radiation oncology community, and that those previously supportive of the TARGIT-A approach will continue to embrace it while those initially skeptical will be unlikely to change practice despite the longer-term results,” she said.

“However, despite the controversy surrounding TARGIT-A, it is heartening as a clinician who cares for breast cancer patients to see a trend within the early breast cancer clinical trials space toward the evaluation of increasingly targeted and abbreviated courses of radiation,” Jimenez commented.

Details of new long-term results

TARGIT-A is an open-label, 32-center multinational study conducted in 2298 women aged 45 years or older with early-stage invasive ductal carcinoma who were eligible for breast-conserving surgery. Between March 24, 2000, and June 25, 2012, participants were randomized 1:1 to risk-adapted TARGIT immediately after lumpectomy or to whole-breast EBRT delivered for the standard 3-6 week daily fractionated course.

At a median follow-up of 8.6 years — with some patients followed for nearly 19 years — no significant difference was seen between the treatment groups in local recurrence-free survival (167 vs 147 events; hazard ratio, 1.13); invasive local recurrence-free survival (154 vs 146 events; HR, 1.04); mastectomy-free survival (170 vs 175 events; HR, 0.96); distant disease-free survival (133 vs 148 events; HR, 0.88); overall survival (110 vs 131 events; HR, 0.82); or breast cancer mortality (6 vs 57 events; HR, 1.12).

“Mortality from other causes was significantly lower (45 vs 74 events; HR, 0.59),” the authors note.

Controversy of Earlier Results

Vaidya and colleagues comment that these new results confirm earlier findings from this trial. They were initially presented in 2012 by Vaidya at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium and subsequently published in The Lancet, as previously reported by Medscape Medical News. Those earlier results showed a trend toward lower overall mortality with TARGIT (absolute difference, -1.3%; P = .01) and significantly fewer deaths from causes other than breast cancer (absolute difference, -2.1%; P = .009).

However, TARGIT was associated with slightly more same-breast recurrences at that time (3.3% vs 1.3%; P = 0.42), even though this was still within the 2.5% margin for non-inferiority.

The new longer-term results show a similar pattern.

It was this risk of same-breast recurrences that sparked the heated debate over the findings, as some breast cancer experts argued that this needs to be weighed against various potential benefits of IORT for patients: greater convenience, potentially improved mortality, and lower costs.

The extent of that “vigorous debate” was highlighted in 2015 in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, (the Red Journal), in which editor-in-chief Anthony Zietman, MD, shared numerous letters to the editor, written in response to two editorials, that contained “passionately and articulately expressed” views from “senior investigators and breast cancer physicians from around the globe.”

At the same time, in 2015, another approach to IORT was reported at the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) annual meeting and simultaneously published online in The Lancet. This was accelerated partial-breast irradiation (APBI) delivered directly to the tumor bed using multicatheter brachytherapy at the time of lumpectomy in women with early breast cancer. The results showed outcomes that were comparable with whole-breast irradiation, but with fewer side effects.

Those findings prompted a 2016 update to the ASTRO consensus statement on APBI to note that APBI after lumpectomy may be suitable for more women with early-stage breast cancer, including younger patients and those with ductal carcinoma in situ.

In comments to Medscape Medical News, Jimenez noted that several recent studies have shown efficacy for various IORT approaches. There have been two phase 3 non-inferiority studies, namely the NSABP B-39 and the RAPID trial, that evaluate the use of APBI in lieu of whole-breast radiation. There have also been two trials as well as the evaluation of a 5-day ultrahypofractionated whole-breast radiation course per the UK Fast and Fast-Forward trials, compared with several weeks of whole-breast radiation.

“Collectively, these studies lend support for fewer and/or more targeted radiotherapy treatments for our patients and have the potential to reduce patient burden and limit healthcare costs,” Jimenez told Medscape Medical News.

Indeed, the TARGIT-A researchers write that their long-term findings “have shown that risk-adapted single-dose TARGIT-IORT given during lumpectomy can effectively replace the mandatory use of several weeks of daily postoperative whole-breast radiotherapy in patients with breast cancer undergoing breast conservation.”

Given the numerous benefits to patients that this approach provides, the choice should ultimately rest with the patient, the authors conclude.

An extended follow-up of the trial (TARGIT-Ex) is ongoing, as is the TARGIT-B(oost) trial looking at TARGIT-IORT as a tumor bed boost with EBRT boost in younger women and those with higher-risk disease.

The TARGIT-A trial was sponsored by University College London Hospitals (UCLH) Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre and funded by UCLH Charities, the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment program, Ninewells Cancer Campaign, the National Health and Medical Research Council, and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. The authors reported numerous disclosures, as detailed in the publication.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term outcomes now being reported confirm earlier reports from the same trial showing efficacy for the use of targeted intraoperative radiotherapy (TARGIT) in patients with early breast cancer.

This novel approach, which delivers a one-off blast of radiation directed at the tumor bed and is given during lumpectomy, has similar efficacy and lowers non–breast cancer mortality when compared with whole-breast external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), which is delivered in fractions over 3-6 weeks after surgery.

Giving the boost of radiation during surgery has numerous benefits, say the authors: it is more convenient for patients and saves on healthcare costs.

However, the controversy over local recurrence rates, sparked by the earlier results, still remains. The difference in the 5-year local recurrence rate between TARGIT and EBRT was within the 2.5% margin for non-inferiority: the rate was 2.11% in 1140 TARGIT recipients, compared with 0.95% in 1158 EBRT recipients, for a difference of 1.16% (13 recurrences).

The new longer-term results from the TARGIT-A trial were published August 20 in the BMJ, and confirm earlier results from this trial published in 2014. Meanwhile, other approaches to intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) have also been reported.

Nevertheless, whole-breast radiotherapy remains the standard of care today, note the authors.

“The biggest battle the TARGIT investigator family has faced is our challenge to the conventional dogma that radiotherapy has to be given in multiple daily doses, and moreover that whole-breast radiotherapy is always essential,” said lead author Jayant Vaidya, MD, professor of surgery and oncology at University College London, UK. He was one of the team of investigators that together developed the TARGIT approach in the 1990s, as he recalls in a related BMJ blog post.

It is unclear whether the TARGIT-A long-term outcomes will change practice, Rachel Jimenez, MD, associate program director of the Harvard Radiation Oncology Residency Program and assistant professor of radiation oncology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, told Medscape Medical News.

She noted there was controversy and debate over the earlier reports from TARGIT-A, and those findings “did little to change practice patterns over the past 6 years,” she said.

“With the publication of longer-term follow-up, my expectation would be that perceptions of IORT will remain unchanged in the radiation oncology community, and that those previously supportive of the TARGIT-A approach will continue to embrace it while those initially skeptical will be unlikely to change practice despite the longer-term results,” she said.

“However, despite the controversy surrounding TARGIT-A, it is heartening as a clinician who cares for breast cancer patients to see a trend within the early breast cancer clinical trials space toward the evaluation of increasingly targeted and abbreviated courses of radiation,” Jimenez commented.

Details of new long-term results

TARGIT-A is an open-label, 32-center multinational study conducted in 2298 women aged 45 years or older with early-stage invasive ductal carcinoma who were eligible for breast-conserving surgery. Between March 24, 2000, and June 25, 2012, participants were randomized 1:1 to risk-adapted TARGIT immediately after lumpectomy or to whole-breast EBRT delivered for the standard 3-6 week daily fractionated course.

At a median follow-up of 8.6 years — with some patients followed for nearly 19 years — no significant difference was seen between the treatment groups in local recurrence-free survival (167 vs 147 events; hazard ratio, 1.13); invasive local recurrence-free survival (154 vs 146 events; HR, 1.04); mastectomy-free survival (170 vs 175 events; HR, 0.96); distant disease-free survival (133 vs 148 events; HR, 0.88); overall survival (110 vs 131 events; HR, 0.82); or breast cancer mortality (6 vs 57 events; HR, 1.12).

“Mortality from other causes was significantly lower (45 vs 74 events; HR, 0.59),” the authors note.

Controversy of Earlier Results

Vaidya and colleagues comment that these new results confirm earlier findings from this trial. They were initially presented in 2012 by Vaidya at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium and subsequently published in The Lancet, as previously reported by Medscape Medical News. Those earlier results showed a trend toward lower overall mortality with TARGIT (absolute difference, -1.3%; P = .01) and significantly fewer deaths from causes other than breast cancer (absolute difference, -2.1%; P = .009).

However, TARGIT was associated with slightly more same-breast recurrences at that time (3.3% vs 1.3%; P = 0.42), even though this was still within the 2.5% margin for non-inferiority.

The new longer-term results show a similar pattern.

It was this risk of same-breast recurrences that sparked the heated debate over the findings, as some breast cancer experts argued that this needs to be weighed against various potential benefits of IORT for patients: greater convenience, potentially improved mortality, and lower costs.

The extent of that “vigorous debate” was highlighted in 2015 in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, (the Red Journal), in which editor-in-chief Anthony Zietman, MD, shared numerous letters to the editor, written in response to two editorials, that contained “passionately and articulately expressed” views from “senior investigators and breast cancer physicians from around the globe.”

At the same time, in 2015, another approach to IORT was reported at the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) annual meeting and simultaneously published online in The Lancet. This was accelerated partial-breast irradiation (APBI) delivered directly to the tumor bed using multicatheter brachytherapy at the time of lumpectomy in women with early breast cancer. The results showed outcomes that were comparable with whole-breast irradiation, but with fewer side effects.

Those findings prompted a 2016 update to the ASTRO consensus statement on APBI to note that APBI after lumpectomy may be suitable for more women with early-stage breast cancer, including younger patients and those with ductal carcinoma in situ.

In comments to Medscape Medical News, Jimenez noted that several recent studies have shown efficacy for various IORT approaches. There have been two phase 3 non-inferiority studies, namely the NSABP B-39 and the RAPID trial, that evaluate the use of APBI in lieu of whole-breast radiation. There have also been two trials as well as the evaluation of a 5-day ultrahypofractionated whole-breast radiation course per the UK Fast and Fast-Forward trials, compared with several weeks of whole-breast radiation.

“Collectively, these studies lend support for fewer and/or more targeted radiotherapy treatments for our patients and have the potential to reduce patient burden and limit healthcare costs,” Jimenez told Medscape Medical News.

Indeed, the TARGIT-A researchers write that their long-term findings “have shown that risk-adapted single-dose TARGIT-IORT given during lumpectomy can effectively replace the mandatory use of several weeks of daily postoperative whole-breast radiotherapy in patients with breast cancer undergoing breast conservation.”

Given the numerous benefits to patients that this approach provides, the choice should ultimately rest with the patient, the authors conclude.

An extended follow-up of the trial (TARGIT-Ex) is ongoing, as is the TARGIT-B(oost) trial looking at TARGIT-IORT as a tumor bed boost with EBRT boost in younger women and those with higher-risk disease.