User login

HER2-Positive Breast Cancer: Current Management

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths among women in the United States, according to the SEER database. It is estimated that 1 in 8 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some point during their lifetime (12.4% lifetime risk).1,2 Because breast tumors are clinically and histopathologically heterogeneous, different diagnostic and therapeutic approaches are required for each subtype. Among the subtypes, tumors that are positive for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) account for approximately 15% to 20% of all newly diagnosed localized and metastatic invasive breast tumors.3,4 Historically, this subset of tumors has been considered the most aggressive due to a higher propensity to relapse and metastasize, translating into poorer prognosis compared with other subtypes.5–7 However, with the advent of HER2-targeted therapy in the late 1990s, prognosis has significantly improved for both early- and late-stage HER2-positive tumors.8

Pathogenesis

The HER2 proto-oncogene belongs to a family of human epidermal growth factor receptors that includes 4 transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors: HER1 (also commonly known as epidermal growth factor receptor, EGFR), HER2, HER3, and HER4. Another commonly used nomenclature for this family of receptors is ERBB1 to ERBB4. Each of the receptors has a similar structure consisting of a growth factor–binding extracellular domain, a single transmembrane segment, an intracellular protein-tyrosine kinase catalytic domain, and a tyrosine-containing cytoplasmic tail. Activation of the extracellular domain leads to conformational changes that initiate a cascade of reactions resulting in protein kinase activation. ERBB tyrosine receptor kinases subsequently activate several intracellular pathways that are critical for cellular function and survival, including the PI3K-AKT, RAS-MAPK, and mTOR pathways. Hyperactivation or overexpression of these receptors leads to uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation, and eventually cancerogenesis.9,10

HER2 gene amplification can cause activation of the receptor’s extramembranous domain by way of either dimerization of two HER2 receptors or heterodimerization with other ERBB family receptors, leading to ligand-independent activation of cell signaling (ie, activation in the absence of external growth factors). Besides breast cancer, HER2 protein is overexpressed in several other tumor types, including esophageal and gastric adenocarcinomas, colon and gynecological malignancies, and to a lesser extent in other malignancies.

Biomarker Testing

All patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer should have their tumor tissue submitted for biomarker testing for estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), and HER2 overexpression, as the result this testing dictates therapy choices. The purpose of HER2 testing is to investigate whether the HER2 gene, located on chromosome 17, is overexpressed or amplified. HER2 status provides the basis for treatment selection, which impacts long-term outcome measures such as recurrence and survival. Routine testing of carcinoma in situ for HER2 expression/amplification is not recommended and has no implication on choice of therapy at this time.

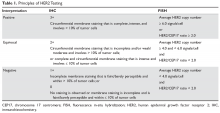

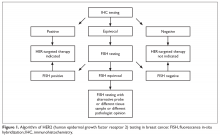

In 2013, the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) updated their clinical guideline recommendations for HER2 testing in breast cancer to improve its accuracy and its utility as a predictive marker.11 There are currently 2 approved modalities for HER2 testing: detection of HER2 protein overexpression by i

Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) testing assesses for HER2 amplification by determining the number of HER2 signals and

Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Therapy for Locoregional Disease

Case Patient 1

A 56-year-old woman undergoes ultrasound-guided biopsy of a self-palpated breast lump. Pathology shows invasive ductal carcinoma that is ER-positive, PR-negative, and HER2 equivocal by IHC (2+ staining). Follow-up FISH testing shows a HER2/CEP17 ratio of 2.5. The tumor is estimated to be 2 cm in diameter by imaging and exam with no clinically palpable axillary lymphadenopathy. The patient exhibits no constitutional or localized symptoms concerning for metastases.

- What is the recommended management approach for this patient?

According to the ASCO/CAP guidelines, this patient’s tumor qualifies as HER2-positive based upon testing results showing amplification of the gene. This result has important implications for management since nearly all patients with macroscopically invasive HER2-positive tumors should be considered for adjuvant chemotherapy in combination with anti-HER2 therapy. The patient should proceed with upfront tumor resection and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Systemic staging imaging (ie, computed tomography [CT] or bone scan) is not indicated in early stage breast cancer.12,13 Systemic staging scans are indicated when (1) any anatomical stage III disease is suspected (eg, with involvement of the skin or chest wall, the presence of enlarged matted or fixed axillary lymph nodes, and involvement of nodal stations other than in the axilla), and (2) when symptoms or abnormal laboratory values raise suspicion for distant metastases (eg, unexplained bone pain, unintentional weight loss, elevated serum alkaline phosphatase, and transaminitis).

Case 1 Continued

The patient presents to discuss treatment options after undergoing a lumpectomy and sentinel node biopsy procedure. The pathology report notes a single focus of carcinoma measuring 2 cm with negative sentinel lymph nodes.

- What agents are used for adjuvant therapy in HER2-postive breast cancer?

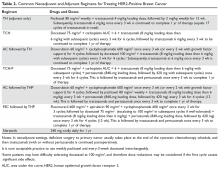

Nearly all patients with macroscopically invasive (> 1 mm) breast carcinoma should be considered for adjuvant therapy using a regimen that contains a taxane and trastuzumab. However, the benefit may be small for patients with tumors ≤ 5 mm (T1a, N0), so it is important to carefully weigh the risk against the benefit. Among the agents that targeting HER2, only trastuzumab has been shown to improve overall survival (OS) in the adjuvant setting; long-term follow-up data are awaited for other agents.8 A trastuzumab biosimilar, trastuzumab-dkst, was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the same indications as trastuzumab.14 The regimens most commonly used in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings for nonmetastatic breast cancer are summarized in Table 2.

Patients with small (≤ 3 cm), node-negative tumors can generally be considered for a reduced-intensity regimen that includes weekly paclitaxel plus trastuzumab. This combination proved efficacious in a single-group, multicenter study that enrolled 406 patients.15 Paclitaxel and trastuzumab were given once weekly for 12 weeks, followed by trastuzumab, either weekly or every 3 weeks, to complete 1 year of therapy.After a median follow-up of more than 6 years, the rates of distant and locoregional recurrence were 1% and 1.2%, respectively.16

A combination of docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab is a nonanthracycline regimen that is also appropriate in this setting, based on the results of the Breast Cancer International Research Group 006 (BCIRG-006) trial.17 This phase 3 randomized trial enrolled 3222 women with HER2-positive, invasive, high-risk adenocarcinoma. Eligible patients had a T1–3 tumor and either lymph node–negative or –positive disease and were randomly assigned to receive 1 of 3 regimens: group 1 received doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide every 3 weeks for 4 cycles followed by docetaxel every 3 weeks for 4 cycles (AC-T); group 2 received the AC-T regimen in combination with trastuzumab; and group 3 received docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab once every 3 weeks for 6 cycles (TCH). Groups 2 and 3 also received trastuzumab for an additional 34 weeks to complete 1 year of therapy. Trastuzumab-containing regimens were found to offer superior disease-free survival (DFS) and OS. When comparing the 2 trastuzumab arms after more than 10 years of follow-up, no statistically significant advantage of an anthracycline regimen over a nonanthracycline regimen was found.18 Furthermore, the anthracycline arm had a fivefold higher incidence of symptomatic congestive heart failure (grades 3 and 4), and the nonanthracycline regimen was associated with a lower incidence of treatment-related leukemia, a clinically significant finding despite not reaching statistical significance due to low overall numbers.

BCIRG-006, NSABP B-31, NCCTG N9831, and HERA are all large randomized trials with consistent results confirming trastuzumab’s role in reducing recurrence and improving survival in HER2-positive breast cancer in the adjuvant settings. The estimated overall benefit from addition of this agent was a 34% to 41% improvement in survival and a 33% to 52% improvement in DFS.8,17–20

Dual anti-HER2 therapy containing both trastuzumab and pertuzumab should be strongly considered for patients with macroscopic lymph node involvement based on the results of the APHINITY trial.21 In this study, the addition of pertuzumab to standard trastuzumab-based therapy led to a significant improvement in invasive-disease-free survival at 3 years. In subgroup analysis, the benefit was restricted to the node-positive group (3-year invasive-disease-free survival rates of 92% in the pertuzumab group versus 90.2% in the placebo group, P = 0.02). Patients with hormone receptor–negative disease derived greater benefit from the addition of pertuzumab. Regimens used in the APHINITY trial included the anti-HER2 agents trastuzumab and pertuzumab in combination with 1 of the following chemotherapy regimens: sequential cyclophosphamide plus either doxorubicin or epirubicin, followed by either 4 cycles of docetaxel or 12 weekly doses of paclitaxel; sequential fluorouracil plus either epirubicin or doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide (3 or 4 cycles), followed by 3 or 4 cycles of docetaxel or 12 weekly cycles of paclitaxel; or 6 cycles of concurrent docetaxel plus carboplatin.

One-year therapy with neratinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor of HER2, is now approved by the FDA after completion of trastuzumab in the adjuvant setting, based on the results of the ExteNET trial.22 In this study, patients who had completed trastuzumab within the preceding 12 months, without evidence of recurrence, were randomly assigned to receive either oral neratinib or placebo daily for 1 year. The 2-year DFS rate was 93.9% and 91.6% for the neratinib and placebo groups, respectively. The most common adverse effect of neratinib was diarrhea, with approximately 40% of patients experiencing grade 3 diarrhea. In subgroup analyses, hormone receptor–positive patients derived the most benefit, while hormone receptor–negative patients derived no or marginal benefit.22 OS benefit has not yet been established.23

Trastuzumab therapy (with pertuzumab if indicated) should be offered for an optimal duration of 12 months (17 cycles, including those given with chemotherapy backbone). A shorter duration of therapy, 6 months, has been shown to be inferior,24 while a longer duration, 24 months, has been shown to provide no additional benefit.25

Finally, sequential addition of anti-estrogen endocrine therapy is indicated for hormone-positive tumors. Endocrine therapy is usually added after completion of the chemotherapy backbone of the regimen, but may be given concurrently with anti-HER2 therapy. If radiation is being administered, endocrine therapy can be given concurrently or started after radiation therapy is completed.

Case 1 Conclusion

The patient can be offered 1 of 2 adjuvant treatment regimens, either TH or TCH (Table 2). Since the patient had lumpectomy, she is an appropriate candidate for adjuvant radiation, which would be started after completion of the chemotherapy backbone (taxane/platinum). Endocrine therapy for at least 5 years should be offered sequentially or concurrently with radiation. Her long-term prognosis is very favorable.

Case Patient 2

A 43-year-old woman presents with a 4-cm breast mass, a separate skin nodule, and palpable matted axillary lymphadenopathy. Biopsies of the breast mass and subcutaneous nodule reveal invasive ductal carcinoma that is ER-negative, PR-negative, and HER2-positive by IHC (3+ staining). Based on clinical findings, the patient is staged as T4b (separate tumor nodule), N2 (matted axillary lymph nodes). Systemic staging with CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis shows no evidence of distant metastases.

- What is the recommended approach to management for this patient?

Recommendations for neoadjuvant therapy, given before definitive surgery, follow the same path as with other subtypes of breast cancer. Patients with suspected anatomical stage III disease are strongly encouraged to undergo upfront (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy in combination with HER2-targeted agents. In addition, all HER2-positive patients with clinically node-positive disease can be offered neoadjuvant therapy using chemotherapy plus dual anti-HER2 therapy (trastuzumab and pertuzumab), with complete pathological response expected in more than 60% of patients.26,27 Because this patient has locally advanced disease, especially skin involvement and matted axillary nodes, she should undergo neoadjuvant therapy. Preferred regimens contain both trastuzumab and pertuzumab in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy. The latter may be given concurrently (nonanthracycline regimens, such as docetaxel plus carboplatin) or sequentially (anthracycline-based regimens), as outlined in Table 2. Administration of anthracyclines and trastuzumab simultaneously is contraindicated due to increased risk of cardiomyopathy.28

Endocrine therapy is not indicated for this patient per the current standard of care because the tumor was ER- and PR-negative. Had the tumor been hormone receptor–positive, endocrine therapy for a minimum of 5 years would have been indicated. Likewise, in the case of hormone receptor–positive disease, 12 months of neratinib therapy after completion of trastuzumab may add further benefit, as shown in the ExteNET trial.22,23 Neratinib seems to have a propensity to prevent or delay trastuzumab-induced overexpression of estrogen receptors. This is mainly due to hormone receptor/HER2 crosstalk, a potential mechanism of resistance to trastuzumab.29,30

In addition to the medical therapy options discussed here, this patient would be expected to benefit from adjuvant radiation to the breast and regional lymph nodes, given the presence of T4 disease and bulky adenopathy in the axilla.31

Case 2 Conclusion

The patient undergoes neoadjuvant treatment (docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab every 21 days for a total of 6 cycles), followed by surgical resection (modified radical mastectomy) that reveals complete pathological response (no residual invasive carcinoma). Subsequently, she receives radiation therapy to the primary tumor site and regional lymph nodes while continuing trastuzumab and pertuzumab for 11 more cycles (17 total). Despite presenting with locally advanced disease, the patient has a favorable overall prognosis due to an excellent pathological response.

- What is the approach to follow-up after completion of primary therapy?

Patients may follow up every 3 to 6 months for clinical evaluation in the first 5 years after completing primary adjuvant therapy. An annual screening mammogram is recommended as well. Body imaging can be done if dictated by symptoms. However, routine CT, positron emission tomography, or bone scans are not recommended as part of follow-up in the absence of symptoms, mainly because of a lack of evidence that such surveillance improves survival.32

Metastatic HER2-Positive Breast Cancer

Metastatic breast cancer most commonly presents as a distant recurrence of previously treated local disease. However, 6% to 18% of patients have no prior history of breast cancer and present with de novo metastatic disease.33,34 The most commonly involved distant organs are the skeletal bones, liver, lung, distant lymph node stations, and brain. Compared to other subtypes, HER2-positive tumors have an increased tendency to involve the central nervous system.35–38 Although metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer is not considered curable, significant improvement in survival has been achieved, and patients with metastatic disease have median survival approaching 5 years.39

Case Presentation 3

A 69-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer 4 years ago presents with new-onset back pain and unintentional weight loss. On exam, she is found to have palpable axillary adenopathy on the same side as her previous cancer. Her initial disease was stage IIB ER-positive and HER2-positive and was treated with chemotherapy, mastectomy, and anastrozole, which the patient is still taking. She undergoes CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and radionucleotide bone scan, which show multiple liver and bony lesions suspicious for metastatic disease. Axillary lymph node biopsy confirms recurrent invasive carcinoma that is ER-positive and HER2-positive by IHC (3+).

- What is the approach to management of a patient who presents with symptoms of recurrent HER2-positive disease?

This patient likely has metastatic breast cancer based on the imaging findings. In such cases, a biopsy of the recurrent disease should always be considered, if feasible, to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other etiologies such as different malignances and benign conditions. Hormone-receptor and HER2 testing should also be performed on recurrent disease, since a change in HER2 status can be seen in 15% to 33% of cases.40–42

Based on data from the phase 3 CLEOPATRA trial, first-line systemic regimens for patients with metastatic breast cancer that is positive for HER2 should consist of a combination of docetaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab. Compared to placebo, adding pertuzumab yielded superior progression-free survival of 18.4 months (versus 12.4 months for placebo) and an unprecedented OS of 56.5 months (versus 40.8 for placebo).39 Weekly paclitaxel can replace docetaxel with comparable efficacy (Table 3).43

Patients can develop significant neuropathy as well as skin and nail changes after multiple cycles of taxane-based chemotherapy. Therefore, the taxane backbone may be dropped after 6 to 8 cycles, while patients continue the trastuzumab and pertuzumab combination until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Some patients may enjoy remarkable long-term survival on “maintenance” anti-HER2 therapy.44 Despite lack of high-level evidence, such as from large randomized trials, some experts recommend the addition of a hormone blocker after discontinuation of the taxane in ER-positive tumors.45

Premenopausal and perimenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive metastatic disease should be considered for simultaneous ovarian suppression. Ovarian suppression can be accomplished medically using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (goserelin) or surgically via salpingo-oophorectomy.46–48

Case 3 Conclusion

The patient receives 6 cycles of docetaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab, after which the docetaxel is discontinued due to neuropathy while she continues the other 2 agents. After 26 months of disease control, the patient is found to have new liver metastatic lesions, indicating progression of disease.

- What therapeutic options are available for this patient?

Patients whose disease progresses after receiving taxane- and trastuzumab-containing regimens are candidates to receive the novel antibody-drug conjugate ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1). Early progressors (ie, patients with early stage disease who have progression of disease while receiving adjuvant trastuzumab or within 6 months of completion of adjuvant trastuzumab) are also candidates for T-DM1. Treatment usually fits in the second line or beyond based on data from the EMILIA trial, which randomly assigned patients to receive either capecitabine plus lapatinib or T-DM1.49,50 Progression-free survival in the T-DM1 group was 9.6 months versus 6.4 months for the comparator. Improvement of 4 months in OS persisted with longer follow-up despite a crossover rate of 27%. Furthermore, a significantly higher objective response rate and fewer adverse effects were reported in the T-DM1 patients. Most patients included in the EMILIA trial were pertuzumab-naive. However, the benefit of T-DM1 appears to persist, albeit to a lesser extent, for pertuzumab-pretreated patients.51,52

Patients in whom treatment fails with 2 or more lines of therapy containing taxane-trastuzumab (with or without pertuzumab) and T-DM1 are candidates to receive a combination of capecitabine and lapatinib, a TKI, in the third line and beyond. Similarly, the combination of capecitabine with trastuzumab in the same settings appears to have equal efficacy.53,54 Trastuzumab may be continued beyond progression while changing the single-agent chemotherapy drug for subsequent lines of therapy, per ASCO guidelines,55 although improvement in OS has not been demonstrated beyond the third line in a large randomized trial (Table 3).

Approved HER2-Targeted Drugs

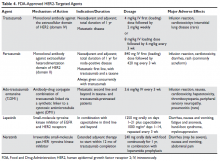

HER2-directed therapy is implemented in the management of nearly all stages of HER2-positive invasive breast cancer, including early and late stages (Table 4).

Trastuzumab

Trastuzumab was the first anti-HER2 agent to be approved by the FDA in 1998. It is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against the extracellular domain of the HER2 receptor (domain IV). Trastuzumab functions by interrupting HER2 signal transduction and by flagging tumor cells for immune destruction.56 Cardiotoxicity, usually manifested as left ventricular systolic dysfunction, is the most noteworthy adverse effect of trastuzumab. The most prominent risk factors for cardiomyopathy in patients receiving trastuzumab are low baseline ejection fraction (< 55%), age > 50 years, co-administration and higher cumulative dose of anthracyclines, and increased body mass index and obesity.57–59 Whether patients receive therapy in the neoadjuvant, adjuvant, or metastatic settings, baseline cardiac function assessment with echocardiogram or multiple-gated acquisition scan is required. While well-designed randomized trials validating the value and frequency of monitoring are lacking, repeated cardiac testing every 3 months is generally recommended for patients undergoing adjuvant therapy. Patients with metastatic disease who are receiving treatment with palliative intent may be monitored less frequently.60,61

An asymptomatic drop in ejection fraction is the most common manifestation of cardiac toxicity. Other cardiac manifestations have also been reported with much less frequency, including arrhythmias, severe congestive heart failure, ventricular thrombus formation, and even cardiac death. Until monitoring and dose-adjustment guidelines are issued, the guidance provided in the FDA-approved prescribing information should be followed, which recommends holding trastuzumab when there is ≥ 16% absolute reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) from the baseline value; or if the LVEF value is below the institutional lower limit of normal and the drop is ≥ 10%. After holding the drug, cardiac function can be re-evaluated every 4 weeks. In most patients, trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity can be reversed by withholding trastuzumab and initiating cardioprotective therapy, although the latter remains controversial. Re-challenging after recovery of ejection fraction is possible and toxicity does not appear to be proportional to cumulative dose. Cardiomyopathy due to trastuzumab therapy is potentially reversible within 6 months in more than 80% of cases.28,57,60–63

Other notable adverse effects of trastuzumab include pulmonary toxicity (such as interstitial lung disease) and infusion reactions (usually during or within 24 hours of first dose).

Pertuzumab

Pertuzumab is another humanized monoclonal antibody directed to a different extracellular domain of the HER2 receptor, the dimerization domain (domain II), which is responsible for heterodimerization of HER2 with other HER receptors, especially HER3. This agent should always be co-administered with trastuzumab as the 2 drugs produce synergistic anti-tumor effect, without competition for the receptor. Activation of HER3, via dimerization with HER2, produces an alternative mechanism of downstream signaling, even in the presence of trastuzumab and in the absence of growth factors (Figure 2).

Ado-Trastuzumab Emtansine

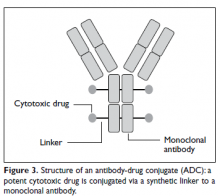

Ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) is an antibody-drug conjugate that combines the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab with the cytotoxic agent DM1 (emtansine), a potent microtubule inhibitor and a derivative of maytansine, in a single structure (Figure 3).

Lapatinib

Lapatinib is an oral small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor of EGFR (HER1) and HER2 receptors. It is approved in combination with capecitabine for patients with HER2-expressing metastatic breast cancer who previously received trastuzumab, an anthracycline, and a taxane chemotherapy or T-DM1. Lapatinib is also approved in combination with letrozole in postmenopausal women with HER2-positive, hormone receptor–positive metastatic disease, although it is unclear where this regimen would fit in the current schema. It may be considered for patients with hormone receptor–positive disease who are not candidates for therapy with taxane-trastuzumab and T-DM1 or who decline this therapy. Diarrhea is seen in most patients treated with lapatinib and may be severe in 20% of cases when lapatinib is combined with capecitabine. Decreases in LVEF have been reported and cardiac function monitoring at baseline and periodically may be considered.69,70 Lapatinib is not approved for use in adjuvant settings.

Neratinib

Neratinib is an oral small-molecule irreversible tyrosine kinase inhibitor of HER1, HER2, and HER4. It is currently approved only for extended adjuvant therapy after completion of 1 year of standard trastuzumab therapy. It is given orally every day for 1 year. The main side effect, expected in nearly all patients, is diarrhea, which can be severe in up to 40% of patients and may lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Diarrhea usually starts early in the course of therapy and can be most intense during the first cycle. Therefore, prophylactic antidiarrheal therapy is recommended to reduce the intensity of diarrhea. Loperamide prophylaxis may be initiated simultaneously for all patients using a tapering schedule. Drug interruption or dose reduction may be required if diarrhea is severe or refractory.21,71 Neratinib is not FDA-approved in the metastatic settings.

Conclusion

HER2-positive tumors represent a distinct subset(s) of breast tumors with unique pathological and clinical characteristics. Treatment with a combination of cytotoxic chemotherapy and HER2-targeted agents has led to a dramatic improvement in survival for patients with locoregional and advanced disease. Trastuzumab is an integral part of adjuvant therapy for HER2-positive invasive disease. Pertuzumab should be added to trastuzumab in node-positive disease. Neratinib may be considered after completion of trastuzumab therapy in patients with hormone receptor–positive disease. For metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer, a regimen consisting of docetaxel plus trastuzumab and pertuzumab is the standard first-line therapy. Ado-trastuzumab is an ideal next line option for patients whose disease progresses on trastuzumab and taxanes.

1. Yedjou CG, Tchounwou PB, Payton M, et al. Assessing the racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer mortality in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14(5).

2. Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:271–89.

3. Huang HJ, Neven P, Drijkoningen M, et al. Association between tumour characteristics and HER-2/neu by immunohistochemistry in 1362 women with primary operable breast cancer. J Clin Pathol 2005;58:611–6.

4. Noone AM, Cronin KA, Altekruse SF, et al. Cancer incidence and survival trends by subtype using data from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program, 1992-2013. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:632–41.

5. Cronin KA, Harlan LC, Dodd KW, et al. Population-based estimate of the prevalence of HER-2 positive breast cancer tumors for early stage patients in the US. Cancer Invest 2010;28:963–-8.

6. Huang HJ, Neven P, Drijkoningen M, et al. Hormone receptors do not predict the HER2/neu status in all age groups of women with an operable breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2005;16:1755–61.

7. Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA 2006;295:2492–502.

8. Perez EA, Romond EH, Suman VJ, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: planned joint analysis of overall survival from NSABP B-31 and NCCTG N9831. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3744–52.

9. Brennan PJ, Kumagai T, Berezov A, et al. HER2/neu: mechanisms of dimerization/oligomerization. Oncogene 2000;19:6093–101.

10. Roskoski R Jr. The ErbB/HER receptor protein-tyrosine kinases and cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;319:1–11.

11. Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3997–4013.

12. Ravaioli A, Pasini G, Polselli A, et al. Staging of breast cancer: new recommended standard procedure. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2002;72:53–60.

13. Puglisi F, Follador A, Minisini AM, et al. Baseline staging tests after a new diagnosis of breast cancer: further evidence of their limited indications. Ann Oncol 2005;16:263–6.

14. FDA approves trastuzumab biosimilar. Cancer Discov 2018;8:130.

15. Tolaney SM, Barry WT, Dang CT, et al. Adjuvant paclitaxel and trastuzumab for node-negative, HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:134–41.

16. Tolaney SM, Barry WT, Guo H, Dillon D, et al. Seven-year (yr) follow-up of adjuvant paclitaxel (T) and trastuzumab (H) (APT trial) for node-negative, HER2-positive breast cancer (BC) [ASCO abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(suppl):511.

17. Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N, et al. Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1273–83.

18. Slamon DJ, Eiermann W, Robert NJ, et al. Ten year follow-up of BCIRG-006 comparing doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel (AC -> T) with doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel and trastuzumab (AC -> TH) with docetaxel, carboplatin and trastuzumab (TCH) in HER2+early breast cancer [SABC abstract]. Cancer Res 2016;76(4 supplement):S5-04.

19. Jahanzeb M. Adjuvant trastuzumab therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer 2008;8:324–33.

20. Cameron D, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Gelber RD, et al. 11 years’ follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive early breast cancer: final analysis of the HERceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial. Lancet 2017;389:1195–205.

21. von Minckwitz G, Procter M, de Azambuja E, et al. Adjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:122–31.

22. Chan A, Delaloge S, Holmes FA, et al. Neratinib after trastuzumab-based adjuvant therapy in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer (ExteNET): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:367–77.

23. Martin M, Holmes FA, Ejlertsen B, et al. Neratinib after trastuzumab-based adjuvant therapy in HER2-positive breast cancer (ExteNET): 5-year analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1688–700.

24. Pivot X, Romieu G, Debled M, et al. 6 months versus 12 months of adjuvant trastuzumab for patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer (PHARE): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:741–8.

25. Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, et al. 2 years versus 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer (HERA): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;382:1021–8.

26. Schneeweiss A, Chia S, Hickish T, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab in combination with standard neoadjuvant anthracycline-containing and anthracycline-free chemotherapy regimens in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer: a randomized phase II cardiac safety study (TRYPHAENA). Ann Oncol 2013;24:2278–84.

27. Schneeweiss A, Chia S, Hickish T, et al. Long-term efficacy analysis of the randomised, phase II TRYPHAENA cardiac safety study: Evaluating pertuzumab and trastuzumab plus standard neoadjuvant anthracycline-containing and anthracycline-free chemotherapy regimens in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2018;89:27–35

28. de Azambuja E, Procter MJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Trastuzumab-associated cardiac events at 8 years of median follow-up in the Herceptin Adjuvant trial (BIG 1-01). J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2159–65.

29. Dowsett M, Harper-Wynne C, Boeddinghaus I, et al. HER-2 amplification impedes the antiproliferative effects of hormone therapy in estrogen receptor-positive primary breast cancer. Cancer Res 2001;61:8452–8.

30. Nahta R, O’Regan RM. Therapeutic implications of estrogen receptor signaling in HER2-positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;135:39–48.

31. Recht A, Comen EA, Fine RE, et al. Postmastectomy radiotherapy: An American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Surgical Oncology focused guideline update. Pract Radiat Oncol 2016;6:e219-e34.

32. Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology breast cancer survivorship care guideline. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:611–35.

33. Zeichner SB, Herna S, Mani A, et al. Survival of patients with de-novo metastatic breast cancer: analysis of data from a large breast cancer-specific private practice, a university-based cancer center and review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;153:617–24.

34. Dawood S, Broglio K, Ensor J, et al. Survival differences among women with de novo stage IV and relapsed breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2010;21:2169–74.

35. Savci-Heijink CD, Halfwerk H, Hooijer GK, et al. Retrospective analysis of metastatic behaviour of breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;150:547–57.

36. Kimbung S, Loman N, Hedenfalk I. Clinical and molecular complexity of breast cancer metastases. Semin Cancer Biol 2015;35:85–95.

37. Bendell JC, Domchek SM, Burstein HJ, et al. Central nervous system metastases in women who receive trastuzumab-based therapy for metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer 2003;97:2972–7.

38. Burstein HJ, Lieberman G, Slamon DJ, et al. Isolated central nervous system metastases in patients with HER2-overexpressing advanced breast cancer treated with first-line trastuzumab-based therapy. Ann Oncol 2005;16:1772–7.

39. Swain SM, Baselga J, Kim SB, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:724–34.

40. Lindstrom LS, Karlsson E, Wilking UM, et al. Clinically used breast cancer markers such as estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 are unstable throughout tumor progression. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2601–8.

41. Guarneri V, Giovannelli S, Ficarra G, et al. Comparison of HER-2 and hormone receptor expression in primary breast cancers and asynchronous paired metastases: impact on patient management. Oncologist 2008;13:838–44.

42. Salkeni MA, Hall SJ. Metastatic breast cancer: Endocrine therapy landscape reshaped. Avicenna J Med 2017;7:144–52.

43. Dang C, Iyengar N, Datko F, et al. Phase II study of paclitaxel given once per week along with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:442–7.

44. Cantini L, Pistelli M, Savini A, et al. Long-responders to anti-HER2 therapies: A case report and review of the literature. Mol Clin Oncol 2018;8:147–52.

45. Sutherland S, Miles D, Makris A. Use of maintenance endocrine therapy after chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2016;69:216–22.

46. Falkson G, Holcroft C, Gelman RS, et al. Ten-year follow-up study of premenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:1453–8.

47. Boccardo F, Rubagotti A, Perrotta A, et al. Ovarian ablation versus goserelin with or without tamoxifen in pre-perimenopausal patients with advanced breast cancer: results of a multicentric Italian study. Ann Oncol 1994;5:337–42.

48 Taylor CW, Green S, Dalton WS, et al. Multicenter randomized clinical trial of goserelin versus surgical ovariectomy in premenopausal patients with receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: an intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:994–9.

49. Verma S, Miles D, Gianni L, et al. Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1783–91.

50. Dieras V, Miles D, Verma S, et al. Trastuzumab emtansine versus capecitabine plus lapatinib in patients with previously treated HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (EMILIA): a descriptive analysis of final overall survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:732–42.

51. Dzimitrowicz H, Berger M, Vargo C, et al. T-DM1 Activity in metastatic human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancers that received prior therapy with trastuzumab and pertuzumab. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3511–7.

52. Fabi A, Giannarelli D, Moscetti L, et al. Ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in HER2+ advanced breast cancer patients: does pretreatment with pertuzumab matter? Future Oncol 2017;13:2791–7.

53. Madden R, Kosari S, Peterson GM, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: A systematic review. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2018;56:72–80.

54. Pivot X, Manikhas A, Zurawski B, et al. CEREBEL (EGF111438): A phase III, randomized, open-label study of lapatinib plus capecitabine versus trastuzumab plus capecitabine in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1564–73.

55. Giordano SH, Temin S, Kirshner JJ, et al. Systemic therapy for patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2078–99.

56. Hudis CA. Trastuzumab--mechanism of action and use in clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2007;357:39–51.

57. Russell SD, Blackwell KL, Lawrence J, et al. Independent adjudication of symptomatic heart failure with the use of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by trastuzumab adjuvant therapy: a combined review of cardiac data from the National Surgical Adjuvant breast and Bowel Project B-31 and the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3416–21.

58. Ewer SM, Ewer MS. Cardiotoxicity profile of trastuzumab. Drug Saf 2008;31:459–67.

59. Guenancia C, Lefebvre A, Cardinale D, et al. Obesity as a risk factor for anthracyclines and trastuzumab cardiotoxicity in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3157–65.

60. Dang CT, Yu AF, Jones LW, et al. Cardiac surveillance guidelines for trastuzumab-containing therapy in early-stage breast cancer: getting to the heart of the matter. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1030–3.

61. Brann AM, Cobleigh MA, Okwuosa TM. Cardiovascular monitoring with trastuzumab therapy: how frequent is too frequent? JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1123–4.

62. Suter TM, Procter M, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Trastuzumab-associated cardiac adverse effects in the herceptin adjuvant trial. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3859–65.

63. Procter M, Suter TM, de Azambuja E, et al. Longer-term assessment of trastuzumab-related cardiac adverse events in the Herceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3422–8.

64. Yamashita-Kashima Y, Shu S, Yorozu K, et al. Mode of action of pertuzumab in combination with trastuzumab plus docetaxel therapy in a HER2-positive breast cancer xenograft model. Oncol Lett 2017;14:4197–205.

65. Staudacher AH, Brown MP. Antibody drug conjugates and bystander killing: is antigen-dependent internalisation required? Br J Cancer 2017;117:1736–42.

66. Girish S, Gupta M, Wang B, et al. Clinical pharmacology of trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1): an antibody-drug conjugate in development for the treatment of HER2-positive cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2012;69:1229–40.

67. Uppal H, Doudement E, Mahapatra K, et al. Potential mechanisms for thrombocytopenia development with trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1). Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:123–33.

68. Yan H, Endo Y, Shen Y, et al. Ado-trastuzumab emtansine targets hepatocytes via human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 to induce hepatotoxicity. Mol Cancer Ther 2016;15:480–90.

69. Spector NL, Xia W, Burris H 3rd, et al. Study of the biologic effects of lapatinib, a reversible inhibitor of ErbB1 and ErbB2 tyrosine kinases, on tumor growth and survival pathways in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2502–12.

70. Johnston S, Pippen J Jr, Pivot X, et al. Lapatinib combined with letrozole versus letrozole and placebo as first-line therapy for postmenopausal hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5538–46.

71. Neratinib (Nerlynx) for HER2-positive breast cancer. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2018;60(1539):23.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths among women in the United States, according to the SEER database. It is estimated that 1 in 8 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some point during their lifetime (12.4% lifetime risk).1,2 Because breast tumors are clinically and histopathologically heterogeneous, different diagnostic and therapeutic approaches are required for each subtype. Among the subtypes, tumors that are positive for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) account for approximately 15% to 20% of all newly diagnosed localized and metastatic invasive breast tumors.3,4 Historically, this subset of tumors has been considered the most aggressive due to a higher propensity to relapse and metastasize, translating into poorer prognosis compared with other subtypes.5–7 However, with the advent of HER2-targeted therapy in the late 1990s, prognosis has significantly improved for both early- and late-stage HER2-positive tumors.8

Pathogenesis

The HER2 proto-oncogene belongs to a family of human epidermal growth factor receptors that includes 4 transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors: HER1 (also commonly known as epidermal growth factor receptor, EGFR), HER2, HER3, and HER4. Another commonly used nomenclature for this family of receptors is ERBB1 to ERBB4. Each of the receptors has a similar structure consisting of a growth factor–binding extracellular domain, a single transmembrane segment, an intracellular protein-tyrosine kinase catalytic domain, and a tyrosine-containing cytoplasmic tail. Activation of the extracellular domain leads to conformational changes that initiate a cascade of reactions resulting in protein kinase activation. ERBB tyrosine receptor kinases subsequently activate several intracellular pathways that are critical for cellular function and survival, including the PI3K-AKT, RAS-MAPK, and mTOR pathways. Hyperactivation or overexpression of these receptors leads to uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation, and eventually cancerogenesis.9,10

HER2 gene amplification can cause activation of the receptor’s extramembranous domain by way of either dimerization of two HER2 receptors or heterodimerization with other ERBB family receptors, leading to ligand-independent activation of cell signaling (ie, activation in the absence of external growth factors). Besides breast cancer, HER2 protein is overexpressed in several other tumor types, including esophageal and gastric adenocarcinomas, colon and gynecological malignancies, and to a lesser extent in other malignancies.

Biomarker Testing

All patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer should have their tumor tissue submitted for biomarker testing for estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), and HER2 overexpression, as the result this testing dictates therapy choices. The purpose of HER2 testing is to investigate whether the HER2 gene, located on chromosome 17, is overexpressed or amplified. HER2 status provides the basis for treatment selection, which impacts long-term outcome measures such as recurrence and survival. Routine testing of carcinoma in situ for HER2 expression/amplification is not recommended and has no implication on choice of therapy at this time.

In 2013, the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) updated their clinical guideline recommendations for HER2 testing in breast cancer to improve its accuracy and its utility as a predictive marker.11 There are currently 2 approved modalities for HER2 testing: detection of HER2 protein overexpression by i

Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) testing assesses for HER2 amplification by determining the number of HER2 signals and

Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Therapy for Locoregional Disease

Case Patient 1

A 56-year-old woman undergoes ultrasound-guided biopsy of a self-palpated breast lump. Pathology shows invasive ductal carcinoma that is ER-positive, PR-negative, and HER2 equivocal by IHC (2+ staining). Follow-up FISH testing shows a HER2/CEP17 ratio of 2.5. The tumor is estimated to be 2 cm in diameter by imaging and exam with no clinically palpable axillary lymphadenopathy. The patient exhibits no constitutional or localized symptoms concerning for metastases.

- What is the recommended management approach for this patient?

According to the ASCO/CAP guidelines, this patient’s tumor qualifies as HER2-positive based upon testing results showing amplification of the gene. This result has important implications for management since nearly all patients with macroscopically invasive HER2-positive tumors should be considered for adjuvant chemotherapy in combination with anti-HER2 therapy. The patient should proceed with upfront tumor resection and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Systemic staging imaging (ie, computed tomography [CT] or bone scan) is not indicated in early stage breast cancer.12,13 Systemic staging scans are indicated when (1) any anatomical stage III disease is suspected (eg, with involvement of the skin or chest wall, the presence of enlarged matted or fixed axillary lymph nodes, and involvement of nodal stations other than in the axilla), and (2) when symptoms or abnormal laboratory values raise suspicion for distant metastases (eg, unexplained bone pain, unintentional weight loss, elevated serum alkaline phosphatase, and transaminitis).

Case 1 Continued

The patient presents to discuss treatment options after undergoing a lumpectomy and sentinel node biopsy procedure. The pathology report notes a single focus of carcinoma measuring 2 cm with negative sentinel lymph nodes.

- What agents are used for adjuvant therapy in HER2-postive breast cancer?

Nearly all patients with macroscopically invasive (> 1 mm) breast carcinoma should be considered for adjuvant therapy using a regimen that contains a taxane and trastuzumab. However, the benefit may be small for patients with tumors ≤ 5 mm (T1a, N0), so it is important to carefully weigh the risk against the benefit. Among the agents that targeting HER2, only trastuzumab has been shown to improve overall survival (OS) in the adjuvant setting; long-term follow-up data are awaited for other agents.8 A trastuzumab biosimilar, trastuzumab-dkst, was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the same indications as trastuzumab.14 The regimens most commonly used in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings for nonmetastatic breast cancer are summarized in Table 2.

Patients with small (≤ 3 cm), node-negative tumors can generally be considered for a reduced-intensity regimen that includes weekly paclitaxel plus trastuzumab. This combination proved efficacious in a single-group, multicenter study that enrolled 406 patients.15 Paclitaxel and trastuzumab were given once weekly for 12 weeks, followed by trastuzumab, either weekly or every 3 weeks, to complete 1 year of therapy.After a median follow-up of more than 6 years, the rates of distant and locoregional recurrence were 1% and 1.2%, respectively.16

A combination of docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab is a nonanthracycline regimen that is also appropriate in this setting, based on the results of the Breast Cancer International Research Group 006 (BCIRG-006) trial.17 This phase 3 randomized trial enrolled 3222 women with HER2-positive, invasive, high-risk adenocarcinoma. Eligible patients had a T1–3 tumor and either lymph node–negative or –positive disease and were randomly assigned to receive 1 of 3 regimens: group 1 received doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide every 3 weeks for 4 cycles followed by docetaxel every 3 weeks for 4 cycles (AC-T); group 2 received the AC-T regimen in combination with trastuzumab; and group 3 received docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab once every 3 weeks for 6 cycles (TCH). Groups 2 and 3 also received trastuzumab for an additional 34 weeks to complete 1 year of therapy. Trastuzumab-containing regimens were found to offer superior disease-free survival (DFS) and OS. When comparing the 2 trastuzumab arms after more than 10 years of follow-up, no statistically significant advantage of an anthracycline regimen over a nonanthracycline regimen was found.18 Furthermore, the anthracycline arm had a fivefold higher incidence of symptomatic congestive heart failure (grades 3 and 4), and the nonanthracycline regimen was associated with a lower incidence of treatment-related leukemia, a clinically significant finding despite not reaching statistical significance due to low overall numbers.

BCIRG-006, NSABP B-31, NCCTG N9831, and HERA are all large randomized trials with consistent results confirming trastuzumab’s role in reducing recurrence and improving survival in HER2-positive breast cancer in the adjuvant settings. The estimated overall benefit from addition of this agent was a 34% to 41% improvement in survival and a 33% to 52% improvement in DFS.8,17–20

Dual anti-HER2 therapy containing both trastuzumab and pertuzumab should be strongly considered for patients with macroscopic lymph node involvement based on the results of the APHINITY trial.21 In this study, the addition of pertuzumab to standard trastuzumab-based therapy led to a significant improvement in invasive-disease-free survival at 3 years. In subgroup analysis, the benefit was restricted to the node-positive group (3-year invasive-disease-free survival rates of 92% in the pertuzumab group versus 90.2% in the placebo group, P = 0.02). Patients with hormone receptor–negative disease derived greater benefit from the addition of pertuzumab. Regimens used in the APHINITY trial included the anti-HER2 agents trastuzumab and pertuzumab in combination with 1 of the following chemotherapy regimens: sequential cyclophosphamide plus either doxorubicin or epirubicin, followed by either 4 cycles of docetaxel or 12 weekly doses of paclitaxel; sequential fluorouracil plus either epirubicin or doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide (3 or 4 cycles), followed by 3 or 4 cycles of docetaxel or 12 weekly cycles of paclitaxel; or 6 cycles of concurrent docetaxel plus carboplatin.

One-year therapy with neratinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor of HER2, is now approved by the FDA after completion of trastuzumab in the adjuvant setting, based on the results of the ExteNET trial.22 In this study, patients who had completed trastuzumab within the preceding 12 months, without evidence of recurrence, were randomly assigned to receive either oral neratinib or placebo daily for 1 year. The 2-year DFS rate was 93.9% and 91.6% for the neratinib and placebo groups, respectively. The most common adverse effect of neratinib was diarrhea, with approximately 40% of patients experiencing grade 3 diarrhea. In subgroup analyses, hormone receptor–positive patients derived the most benefit, while hormone receptor–negative patients derived no or marginal benefit.22 OS benefit has not yet been established.23

Trastuzumab therapy (with pertuzumab if indicated) should be offered for an optimal duration of 12 months (17 cycles, including those given with chemotherapy backbone). A shorter duration of therapy, 6 months, has been shown to be inferior,24 while a longer duration, 24 months, has been shown to provide no additional benefit.25

Finally, sequential addition of anti-estrogen endocrine therapy is indicated for hormone-positive tumors. Endocrine therapy is usually added after completion of the chemotherapy backbone of the regimen, but may be given concurrently with anti-HER2 therapy. If radiation is being administered, endocrine therapy can be given concurrently or started after radiation therapy is completed.

Case 1 Conclusion

The patient can be offered 1 of 2 adjuvant treatment regimens, either TH or TCH (Table 2). Since the patient had lumpectomy, she is an appropriate candidate for adjuvant radiation, which would be started after completion of the chemotherapy backbone (taxane/platinum). Endocrine therapy for at least 5 years should be offered sequentially or concurrently with radiation. Her long-term prognosis is very favorable.

Case Patient 2

A 43-year-old woman presents with a 4-cm breast mass, a separate skin nodule, and palpable matted axillary lymphadenopathy. Biopsies of the breast mass and subcutaneous nodule reveal invasive ductal carcinoma that is ER-negative, PR-negative, and HER2-positive by IHC (3+ staining). Based on clinical findings, the patient is staged as T4b (separate tumor nodule), N2 (matted axillary lymph nodes). Systemic staging with CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis shows no evidence of distant metastases.

- What is the recommended approach to management for this patient?

Recommendations for neoadjuvant therapy, given before definitive surgery, follow the same path as with other subtypes of breast cancer. Patients with suspected anatomical stage III disease are strongly encouraged to undergo upfront (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy in combination with HER2-targeted agents. In addition, all HER2-positive patients with clinically node-positive disease can be offered neoadjuvant therapy using chemotherapy plus dual anti-HER2 therapy (trastuzumab and pertuzumab), with complete pathological response expected in more than 60% of patients.26,27 Because this patient has locally advanced disease, especially skin involvement and matted axillary nodes, she should undergo neoadjuvant therapy. Preferred regimens contain both trastuzumab and pertuzumab in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy. The latter may be given concurrently (nonanthracycline regimens, such as docetaxel plus carboplatin) or sequentially (anthracycline-based regimens), as outlined in Table 2. Administration of anthracyclines and trastuzumab simultaneously is contraindicated due to increased risk of cardiomyopathy.28

Endocrine therapy is not indicated for this patient per the current standard of care because the tumor was ER- and PR-negative. Had the tumor been hormone receptor–positive, endocrine therapy for a minimum of 5 years would have been indicated. Likewise, in the case of hormone receptor–positive disease, 12 months of neratinib therapy after completion of trastuzumab may add further benefit, as shown in the ExteNET trial.22,23 Neratinib seems to have a propensity to prevent or delay trastuzumab-induced overexpression of estrogen receptors. This is mainly due to hormone receptor/HER2 crosstalk, a potential mechanism of resistance to trastuzumab.29,30

In addition to the medical therapy options discussed here, this patient would be expected to benefit from adjuvant radiation to the breast and regional lymph nodes, given the presence of T4 disease and bulky adenopathy in the axilla.31

Case 2 Conclusion

The patient undergoes neoadjuvant treatment (docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab every 21 days for a total of 6 cycles), followed by surgical resection (modified radical mastectomy) that reveals complete pathological response (no residual invasive carcinoma). Subsequently, she receives radiation therapy to the primary tumor site and regional lymph nodes while continuing trastuzumab and pertuzumab for 11 more cycles (17 total). Despite presenting with locally advanced disease, the patient has a favorable overall prognosis due to an excellent pathological response.

- What is the approach to follow-up after completion of primary therapy?

Patients may follow up every 3 to 6 months for clinical evaluation in the first 5 years after completing primary adjuvant therapy. An annual screening mammogram is recommended as well. Body imaging can be done if dictated by symptoms. However, routine CT, positron emission tomography, or bone scans are not recommended as part of follow-up in the absence of symptoms, mainly because of a lack of evidence that such surveillance improves survival.32

Metastatic HER2-Positive Breast Cancer

Metastatic breast cancer most commonly presents as a distant recurrence of previously treated local disease. However, 6% to 18% of patients have no prior history of breast cancer and present with de novo metastatic disease.33,34 The most commonly involved distant organs are the skeletal bones, liver, lung, distant lymph node stations, and brain. Compared to other subtypes, HER2-positive tumors have an increased tendency to involve the central nervous system.35–38 Although metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer is not considered curable, significant improvement in survival has been achieved, and patients with metastatic disease have median survival approaching 5 years.39

Case Presentation 3

A 69-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer 4 years ago presents with new-onset back pain and unintentional weight loss. On exam, she is found to have palpable axillary adenopathy on the same side as her previous cancer. Her initial disease was stage IIB ER-positive and HER2-positive and was treated with chemotherapy, mastectomy, and anastrozole, which the patient is still taking. She undergoes CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and radionucleotide bone scan, which show multiple liver and bony lesions suspicious for metastatic disease. Axillary lymph node biopsy confirms recurrent invasive carcinoma that is ER-positive and HER2-positive by IHC (3+).

- What is the approach to management of a patient who presents with symptoms of recurrent HER2-positive disease?

This patient likely has metastatic breast cancer based on the imaging findings. In such cases, a biopsy of the recurrent disease should always be considered, if feasible, to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other etiologies such as different malignances and benign conditions. Hormone-receptor and HER2 testing should also be performed on recurrent disease, since a change in HER2 status can be seen in 15% to 33% of cases.40–42

Based on data from the phase 3 CLEOPATRA trial, first-line systemic regimens for patients with metastatic breast cancer that is positive for HER2 should consist of a combination of docetaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab. Compared to placebo, adding pertuzumab yielded superior progression-free survival of 18.4 months (versus 12.4 months for placebo) and an unprecedented OS of 56.5 months (versus 40.8 for placebo).39 Weekly paclitaxel can replace docetaxel with comparable efficacy (Table 3).43

Patients can develop significant neuropathy as well as skin and nail changes after multiple cycles of taxane-based chemotherapy. Therefore, the taxane backbone may be dropped after 6 to 8 cycles, while patients continue the trastuzumab and pertuzumab combination until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Some patients may enjoy remarkable long-term survival on “maintenance” anti-HER2 therapy.44 Despite lack of high-level evidence, such as from large randomized trials, some experts recommend the addition of a hormone blocker after discontinuation of the taxane in ER-positive tumors.45

Premenopausal and perimenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive metastatic disease should be considered for simultaneous ovarian suppression. Ovarian suppression can be accomplished medically using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (goserelin) or surgically via salpingo-oophorectomy.46–48

Case 3 Conclusion

The patient receives 6 cycles of docetaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab, after which the docetaxel is discontinued due to neuropathy while she continues the other 2 agents. After 26 months of disease control, the patient is found to have new liver metastatic lesions, indicating progression of disease.

- What therapeutic options are available for this patient?

Patients whose disease progresses after receiving taxane- and trastuzumab-containing regimens are candidates to receive the novel antibody-drug conjugate ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1). Early progressors (ie, patients with early stage disease who have progression of disease while receiving adjuvant trastuzumab or within 6 months of completion of adjuvant trastuzumab) are also candidates for T-DM1. Treatment usually fits in the second line or beyond based on data from the EMILIA trial, which randomly assigned patients to receive either capecitabine plus lapatinib or T-DM1.49,50 Progression-free survival in the T-DM1 group was 9.6 months versus 6.4 months for the comparator. Improvement of 4 months in OS persisted with longer follow-up despite a crossover rate of 27%. Furthermore, a significantly higher objective response rate and fewer adverse effects were reported in the T-DM1 patients. Most patients included in the EMILIA trial were pertuzumab-naive. However, the benefit of T-DM1 appears to persist, albeit to a lesser extent, for pertuzumab-pretreated patients.51,52

Patients in whom treatment fails with 2 or more lines of therapy containing taxane-trastuzumab (with or without pertuzumab) and T-DM1 are candidates to receive a combination of capecitabine and lapatinib, a TKI, in the third line and beyond. Similarly, the combination of capecitabine with trastuzumab in the same settings appears to have equal efficacy.53,54 Trastuzumab may be continued beyond progression while changing the single-agent chemotherapy drug for subsequent lines of therapy, per ASCO guidelines,55 although improvement in OS has not been demonstrated beyond the third line in a large randomized trial (Table 3).

Approved HER2-Targeted Drugs

HER2-directed therapy is implemented in the management of nearly all stages of HER2-positive invasive breast cancer, including early and late stages (Table 4).

Trastuzumab

Trastuzumab was the first anti-HER2 agent to be approved by the FDA in 1998. It is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against the extracellular domain of the HER2 receptor (domain IV). Trastuzumab functions by interrupting HER2 signal transduction and by flagging tumor cells for immune destruction.56 Cardiotoxicity, usually manifested as left ventricular systolic dysfunction, is the most noteworthy adverse effect of trastuzumab. The most prominent risk factors for cardiomyopathy in patients receiving trastuzumab are low baseline ejection fraction (< 55%), age > 50 years, co-administration and higher cumulative dose of anthracyclines, and increased body mass index and obesity.57–59 Whether patients receive therapy in the neoadjuvant, adjuvant, or metastatic settings, baseline cardiac function assessment with echocardiogram or multiple-gated acquisition scan is required. While well-designed randomized trials validating the value and frequency of monitoring are lacking, repeated cardiac testing every 3 months is generally recommended for patients undergoing adjuvant therapy. Patients with metastatic disease who are receiving treatment with palliative intent may be monitored less frequently.60,61

An asymptomatic drop in ejection fraction is the most common manifestation of cardiac toxicity. Other cardiac manifestations have also been reported with much less frequency, including arrhythmias, severe congestive heart failure, ventricular thrombus formation, and even cardiac death. Until monitoring and dose-adjustment guidelines are issued, the guidance provided in the FDA-approved prescribing information should be followed, which recommends holding trastuzumab when there is ≥ 16% absolute reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) from the baseline value; or if the LVEF value is below the institutional lower limit of normal and the drop is ≥ 10%. After holding the drug, cardiac function can be re-evaluated every 4 weeks. In most patients, trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity can be reversed by withholding trastuzumab and initiating cardioprotective therapy, although the latter remains controversial. Re-challenging after recovery of ejection fraction is possible and toxicity does not appear to be proportional to cumulative dose. Cardiomyopathy due to trastuzumab therapy is potentially reversible within 6 months in more than 80% of cases.28,57,60–63

Other notable adverse effects of trastuzumab include pulmonary toxicity (such as interstitial lung disease) and infusion reactions (usually during or within 24 hours of first dose).

Pertuzumab

Pertuzumab is another humanized monoclonal antibody directed to a different extracellular domain of the HER2 receptor, the dimerization domain (domain II), which is responsible for heterodimerization of HER2 with other HER receptors, especially HER3. This agent should always be co-administered with trastuzumab as the 2 drugs produce synergistic anti-tumor effect, without competition for the receptor. Activation of HER3, via dimerization with HER2, produces an alternative mechanism of downstream signaling, even in the presence of trastuzumab and in the absence of growth factors (Figure 2).

Ado-Trastuzumab Emtansine

Ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) is an antibody-drug conjugate that combines the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab with the cytotoxic agent DM1 (emtansine), a potent microtubule inhibitor and a derivative of maytansine, in a single structure (Figure 3).

Lapatinib

Lapatinib is an oral small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor of EGFR (HER1) and HER2 receptors. It is approved in combination with capecitabine for patients with HER2-expressing metastatic breast cancer who previously received trastuzumab, an anthracycline, and a taxane chemotherapy or T-DM1. Lapatinib is also approved in combination with letrozole in postmenopausal women with HER2-positive, hormone receptor–positive metastatic disease, although it is unclear where this regimen would fit in the current schema. It may be considered for patients with hormone receptor–positive disease who are not candidates for therapy with taxane-trastuzumab and T-DM1 or who decline this therapy. Diarrhea is seen in most patients treated with lapatinib and may be severe in 20% of cases when lapatinib is combined with capecitabine. Decreases in LVEF have been reported and cardiac function monitoring at baseline and periodically may be considered.69,70 Lapatinib is not approved for use in adjuvant settings.

Neratinib

Neratinib is an oral small-molecule irreversible tyrosine kinase inhibitor of HER1, HER2, and HER4. It is currently approved only for extended adjuvant therapy after completion of 1 year of standard trastuzumab therapy. It is given orally every day for 1 year. The main side effect, expected in nearly all patients, is diarrhea, which can be severe in up to 40% of patients and may lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Diarrhea usually starts early in the course of therapy and can be most intense during the first cycle. Therefore, prophylactic antidiarrheal therapy is recommended to reduce the intensity of diarrhea. Loperamide prophylaxis may be initiated simultaneously for all patients using a tapering schedule. Drug interruption or dose reduction may be required if diarrhea is severe or refractory.21,71 Neratinib is not FDA-approved in the metastatic settings.

Conclusion

HER2-positive tumors represent a distinct subset(s) of breast tumors with unique pathological and clinical characteristics. Treatment with a combination of cytotoxic chemotherapy and HER2-targeted agents has led to a dramatic improvement in survival for patients with locoregional and advanced disease. Trastuzumab is an integral part of adjuvant therapy for HER2-positive invasive disease. Pertuzumab should be added to trastuzumab in node-positive disease. Neratinib may be considered after completion of trastuzumab therapy in patients with hormone receptor–positive disease. For metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer, a regimen consisting of docetaxel plus trastuzumab and pertuzumab is the standard first-line therapy. Ado-trastuzumab is an ideal next line option for patients whose disease progresses on trastuzumab and taxanes.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths among women in the United States, according to the SEER database. It is estimated that 1 in 8 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some point during their lifetime (12.4% lifetime risk).1,2 Because breast tumors are clinically and histopathologically heterogeneous, different diagnostic and therapeutic approaches are required for each subtype. Among the subtypes, tumors that are positive for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) account for approximately 15% to 20% of all newly diagnosed localized and metastatic invasive breast tumors.3,4 Historically, this subset of tumors has been considered the most aggressive due to a higher propensity to relapse and metastasize, translating into poorer prognosis compared with other subtypes.5–7 However, with the advent of HER2-targeted therapy in the late 1990s, prognosis has significantly improved for both early- and late-stage HER2-positive tumors.8

Pathogenesis

The HER2 proto-oncogene belongs to a family of human epidermal growth factor receptors that includes 4 transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors: HER1 (also commonly known as epidermal growth factor receptor, EGFR), HER2, HER3, and HER4. Another commonly used nomenclature for this family of receptors is ERBB1 to ERBB4. Each of the receptors has a similar structure consisting of a growth factor–binding extracellular domain, a single transmembrane segment, an intracellular protein-tyrosine kinase catalytic domain, and a tyrosine-containing cytoplasmic tail. Activation of the extracellular domain leads to conformational changes that initiate a cascade of reactions resulting in protein kinase activation. ERBB tyrosine receptor kinases subsequently activate several intracellular pathways that are critical for cellular function and survival, including the PI3K-AKT, RAS-MAPK, and mTOR pathways. Hyperactivation or overexpression of these receptors leads to uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation, and eventually cancerogenesis.9,10

HER2 gene amplification can cause activation of the receptor’s extramembranous domain by way of either dimerization of two HER2 receptors or heterodimerization with other ERBB family receptors, leading to ligand-independent activation of cell signaling (ie, activation in the absence of external growth factors). Besides breast cancer, HER2 protein is overexpressed in several other tumor types, including esophageal and gastric adenocarcinomas, colon and gynecological malignancies, and to a lesser extent in other malignancies.

Biomarker Testing

All patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer should have their tumor tissue submitted for biomarker testing for estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), and HER2 overexpression, as the result this testing dictates therapy choices. The purpose of HER2 testing is to investigate whether the HER2 gene, located on chromosome 17, is overexpressed or amplified. HER2 status provides the basis for treatment selection, which impacts long-term outcome measures such as recurrence and survival. Routine testing of carcinoma in situ for HER2 expression/amplification is not recommended and has no implication on choice of therapy at this time.

In 2013, the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) updated their clinical guideline recommendations for HER2 testing in breast cancer to improve its accuracy and its utility as a predictive marker.11 There are currently 2 approved modalities for HER2 testing: detection of HER2 protein overexpression by i

Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) testing assesses for HER2 amplification by determining the number of HER2 signals and

Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Therapy for Locoregional Disease

Case Patient 1

A 56-year-old woman undergoes ultrasound-guided biopsy of a self-palpated breast lump. Pathology shows invasive ductal carcinoma that is ER-positive, PR-negative, and HER2 equivocal by IHC (2+ staining). Follow-up FISH testing shows a HER2/CEP17 ratio of 2.5. The tumor is estimated to be 2 cm in diameter by imaging and exam with no clinically palpable axillary lymphadenopathy. The patient exhibits no constitutional or localized symptoms concerning for metastases.

- What is the recommended management approach for this patient?

According to the ASCO/CAP guidelines, this patient’s tumor qualifies as HER2-positive based upon testing results showing amplification of the gene. This result has important implications for management since nearly all patients with macroscopically invasive HER2-positive tumors should be considered for adjuvant chemotherapy in combination with anti-HER2 therapy. The patient should proceed with upfront tumor resection and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Systemic staging imaging (ie, computed tomography [CT] or bone scan) is not indicated in early stage breast cancer.12,13 Systemic staging scans are indicated when (1) any anatomical stage III disease is suspected (eg, with involvement of the skin or chest wall, the presence of enlarged matted or fixed axillary lymph nodes, and involvement of nodal stations other than in the axilla), and (2) when symptoms or abnormal laboratory values raise suspicion for distant metastases (eg, unexplained bone pain, unintentional weight loss, elevated serum alkaline phosphatase, and transaminitis).

Case 1 Continued

The patient presents to discuss treatment options after undergoing a lumpectomy and sentinel node biopsy procedure. The pathology report notes a single focus of carcinoma measuring 2 cm with negative sentinel lymph nodes.

- What agents are used for adjuvant therapy in HER2-postive breast cancer?

Nearly all patients with macroscopically invasive (> 1 mm) breast carcinoma should be considered for adjuvant therapy using a regimen that contains a taxane and trastuzumab. However, the benefit may be small for patients with tumors ≤ 5 mm (T1a, N0), so it is important to carefully weigh the risk against the benefit. Among the agents that targeting HER2, only trastuzumab has been shown to improve overall survival (OS) in the adjuvant setting; long-term follow-up data are awaited for other agents.8 A trastuzumab biosimilar, trastuzumab-dkst, was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the same indications as trastuzumab.14 The regimens most commonly used in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings for nonmetastatic breast cancer are summarized in Table 2.

Patients with small (≤ 3 cm), node-negative tumors can generally be considered for a reduced-intensity regimen that includes weekly paclitaxel plus trastuzumab. This combination proved efficacious in a single-group, multicenter study that enrolled 406 patients.15 Paclitaxel and trastuzumab were given once weekly for 12 weeks, followed by trastuzumab, either weekly or every 3 weeks, to complete 1 year of therapy.After a median follow-up of more than 6 years, the rates of distant and locoregional recurrence were 1% and 1.2%, respectively.16

A combination of docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab is a nonanthracycline regimen that is also appropriate in this setting, based on the results of the Breast Cancer International Research Group 006 (BCIRG-006) trial.17 This phase 3 randomized trial enrolled 3222 women with HER2-positive, invasive, high-risk adenocarcinoma. Eligible patients had a T1–3 tumor and either lymph node–negative or –positive disease and were randomly assigned to receive 1 of 3 regimens: group 1 received doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide every 3 weeks for 4 cycles followed by docetaxel every 3 weeks for 4 cycles (AC-T); group 2 received the AC-T regimen in combination with trastuzumab; and group 3 received docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab once every 3 weeks for 6 cycles (TCH). Groups 2 and 3 also received trastuzumab for an additional 34 weeks to complete 1 year of therapy. Trastuzumab-containing regimens were found to offer superior disease-free survival (DFS) and OS. When comparing the 2 trastuzumab arms after more than 10 years of follow-up, no statistically significant advantage of an anthracycline regimen over a nonanthracycline regimen was found.18 Furthermore, the anthracycline arm had a fivefold higher incidence of symptomatic congestive heart failure (grades 3 and 4), and the nonanthracycline regimen was associated with a lower incidence of treatment-related leukemia, a clinically significant finding despite not reaching statistical significance due to low overall numbers.

BCIRG-006, NSABP B-31, NCCTG N9831, and HERA are all large randomized trials with consistent results confirming trastuzumab’s role in reducing recurrence and improving survival in HER2-positive breast cancer in the adjuvant settings. The estimated overall benefit from addition of this agent was a 34% to 41% improvement in survival and a 33% to 52% improvement in DFS.8,17–20