User login

Some physicians still lack access to COVID-19 vaccines

It would be overused and trite to say that the pandemic has drastically altered all of our lives and will cause lasting impact on how we function in society and medicine for years to come. While it seems that the current trend of the latest Omicron variant is on the downslope, the path to get to this point has been fraught with challenges that have struck at the very core of our society. As a primary care physician on the front lines seeing COVID patients, I have had to deal with not only the disease but the politics around it. I practice in Florida, and I still cannot give COVID vaccines in my office.

I am a firm believer in the ability for physicians to be able to give all the necessary adult vaccines and provide them for their patients. The COVID vaccine exacerbated a majorly flawed system that further increased the health care disparities in the country. The current vaccine system for the majority of adult vaccines involves the physician’s being able to directly purchase supplies from the vaccine manufacturer, administer them to the patients, and be reimbursed.

Third parties can purchase vaccines at lower rates than those for physicians

The Affordable Care Act mandates that all vaccines approved by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention must be covered. This allows for better access to care as physicians will be able to purchase, store, and deliver vaccines to their patients. The fallacy in this system is that third parties get involved and rebates or incentives are given to these groups to purchase vaccines at a rate lower than those for physicians.

In addition, many organizations can get access to vaccines before physicians and at a lower cost. That system was flawed to begin with and created a deterrent for access to care and physician involvement in the vaccination process. This was worsened by different states being given the ability to decide how vaccines would be distributed for COVID.

Many pharmacies were able to give out COVID vaccines while many physician offices still have not received access to any of the vaccines. One of the major safety issues with this is that no physicians were involved in the administration of the vaccine, and it is unclear what training was given to the individuals injecting that vaccine. Finally, different places were interpreting the recommendations from ACIP on their own and not necessarily following the appropriate guidelines. All of these factors have further widened the health care disparity gap and made it difficult to provide the COVID vaccines in doctors’ offices.

Recommended next steps, solutions to problem

The question is what to do about this. The most important thing is to get the vaccines in arms so they can save lives. In addition, doctors need to be able to get the vaccines in their offices.

Many patients trust their physicians to advise them on what to do regarding health care. The majority of patients want to know if they should get the vaccine and ask for counseling. Physicians answering patients’ questions about vaccines is an important step in overcoming vaccine hesitancy.

Also, doctors need to be informed and supportive of the vaccine process.

The next step is the governmental aspect with those in power making sure that vaccines are accessible to all. Even if the vaccine cannot be given in the office, doctors should still be recommending that patients receive them. Plus, doctors should take every opportunity to ask about what vaccines their patients have received and encourage their patients to get vaccinated.

The COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective and have been monitored for safety more than any other vaccine. There are multiple systems in place to look for any signals that could indicate an issue was caused by a COVID-19 vaccine. These vaccines can be administered with other vaccines, and there is a great opportunity for physicians to encourage patients to receive these life-saving vaccines.

While it may seem that the COVID-19 case counts are on the downslope, the importance of continuing to vaccinate is predicated on the very real concern that the disease is still circulating and the unvaccinated are still at risk for severe infection.

Dr. Goldman is immediate past governor of the Florida chapter of the American College of Physicians, a regent for the American College of Physicians, vice-president of the Florida Medical Association, and president of the Florida Medical Association Political Action Committee. You can reach Dr. Goldman at [email protected].

It would be overused and trite to say that the pandemic has drastically altered all of our lives and will cause lasting impact on how we function in society and medicine for years to come. While it seems that the current trend of the latest Omicron variant is on the downslope, the path to get to this point has been fraught with challenges that have struck at the very core of our society. As a primary care physician on the front lines seeing COVID patients, I have had to deal with not only the disease but the politics around it. I practice in Florida, and I still cannot give COVID vaccines in my office.

I am a firm believer in the ability for physicians to be able to give all the necessary adult vaccines and provide them for their patients. The COVID vaccine exacerbated a majorly flawed system that further increased the health care disparities in the country. The current vaccine system for the majority of adult vaccines involves the physician’s being able to directly purchase supplies from the vaccine manufacturer, administer them to the patients, and be reimbursed.

Third parties can purchase vaccines at lower rates than those for physicians

The Affordable Care Act mandates that all vaccines approved by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention must be covered. This allows for better access to care as physicians will be able to purchase, store, and deliver vaccines to their patients. The fallacy in this system is that third parties get involved and rebates or incentives are given to these groups to purchase vaccines at a rate lower than those for physicians.

In addition, many organizations can get access to vaccines before physicians and at a lower cost. That system was flawed to begin with and created a deterrent for access to care and physician involvement in the vaccination process. This was worsened by different states being given the ability to decide how vaccines would be distributed for COVID.

Many pharmacies were able to give out COVID vaccines while many physician offices still have not received access to any of the vaccines. One of the major safety issues with this is that no physicians were involved in the administration of the vaccine, and it is unclear what training was given to the individuals injecting that vaccine. Finally, different places were interpreting the recommendations from ACIP on their own and not necessarily following the appropriate guidelines. All of these factors have further widened the health care disparity gap and made it difficult to provide the COVID vaccines in doctors’ offices.

Recommended next steps, solutions to problem

The question is what to do about this. The most important thing is to get the vaccines in arms so they can save lives. In addition, doctors need to be able to get the vaccines in their offices.

Many patients trust their physicians to advise them on what to do regarding health care. The majority of patients want to know if they should get the vaccine and ask for counseling. Physicians answering patients’ questions about vaccines is an important step in overcoming vaccine hesitancy.

Also, doctors need to be informed and supportive of the vaccine process.

The next step is the governmental aspect with those in power making sure that vaccines are accessible to all. Even if the vaccine cannot be given in the office, doctors should still be recommending that patients receive them. Plus, doctors should take every opportunity to ask about what vaccines their patients have received and encourage their patients to get vaccinated.

The COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective and have been monitored for safety more than any other vaccine. There are multiple systems in place to look for any signals that could indicate an issue was caused by a COVID-19 vaccine. These vaccines can be administered with other vaccines, and there is a great opportunity for physicians to encourage patients to receive these life-saving vaccines.

While it may seem that the COVID-19 case counts are on the downslope, the importance of continuing to vaccinate is predicated on the very real concern that the disease is still circulating and the unvaccinated are still at risk for severe infection.

Dr. Goldman is immediate past governor of the Florida chapter of the American College of Physicians, a regent for the American College of Physicians, vice-president of the Florida Medical Association, and president of the Florida Medical Association Political Action Committee. You can reach Dr. Goldman at [email protected].

It would be overused and trite to say that the pandemic has drastically altered all of our lives and will cause lasting impact on how we function in society and medicine for years to come. While it seems that the current trend of the latest Omicron variant is on the downslope, the path to get to this point has been fraught with challenges that have struck at the very core of our society. As a primary care physician on the front lines seeing COVID patients, I have had to deal with not only the disease but the politics around it. I practice in Florida, and I still cannot give COVID vaccines in my office.

I am a firm believer in the ability for physicians to be able to give all the necessary adult vaccines and provide them for their patients. The COVID vaccine exacerbated a majorly flawed system that further increased the health care disparities in the country. The current vaccine system for the majority of adult vaccines involves the physician’s being able to directly purchase supplies from the vaccine manufacturer, administer them to the patients, and be reimbursed.

Third parties can purchase vaccines at lower rates than those for physicians

The Affordable Care Act mandates that all vaccines approved by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention must be covered. This allows for better access to care as physicians will be able to purchase, store, and deliver vaccines to their patients. The fallacy in this system is that third parties get involved and rebates or incentives are given to these groups to purchase vaccines at a rate lower than those for physicians.

In addition, many organizations can get access to vaccines before physicians and at a lower cost. That system was flawed to begin with and created a deterrent for access to care and physician involvement in the vaccination process. This was worsened by different states being given the ability to decide how vaccines would be distributed for COVID.

Many pharmacies were able to give out COVID vaccines while many physician offices still have not received access to any of the vaccines. One of the major safety issues with this is that no physicians were involved in the administration of the vaccine, and it is unclear what training was given to the individuals injecting that vaccine. Finally, different places were interpreting the recommendations from ACIP on their own and not necessarily following the appropriate guidelines. All of these factors have further widened the health care disparity gap and made it difficult to provide the COVID vaccines in doctors’ offices.

Recommended next steps, solutions to problem

The question is what to do about this. The most important thing is to get the vaccines in arms so they can save lives. In addition, doctors need to be able to get the vaccines in their offices.

Many patients trust their physicians to advise them on what to do regarding health care. The majority of patients want to know if they should get the vaccine and ask for counseling. Physicians answering patients’ questions about vaccines is an important step in overcoming vaccine hesitancy.

Also, doctors need to be informed and supportive of the vaccine process.

The next step is the governmental aspect with those in power making sure that vaccines are accessible to all. Even if the vaccine cannot be given in the office, doctors should still be recommending that patients receive them. Plus, doctors should take every opportunity to ask about what vaccines their patients have received and encourage their patients to get vaccinated.

The COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective and have been monitored for safety more than any other vaccine. There are multiple systems in place to look for any signals that could indicate an issue was caused by a COVID-19 vaccine. These vaccines can be administered with other vaccines, and there is a great opportunity for physicians to encourage patients to receive these life-saving vaccines.

While it may seem that the COVID-19 case counts are on the downslope, the importance of continuing to vaccinate is predicated on the very real concern that the disease is still circulating and the unvaccinated are still at risk for severe infection.

Dr. Goldman is immediate past governor of the Florida chapter of the American College of Physicians, a regent for the American College of Physicians, vice-president of the Florida Medical Association, and president of the Florida Medical Association Political Action Committee. You can reach Dr. Goldman at [email protected].

Columbia names interim chair of psychiatry after Twitter controversy

Helen Blair Simpson, MD, PhD, will take over for Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, who was suspended over a tweet he sent that was widely condemned as both racist and sexist.

She will also serve as interim director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and interim psychiatrist-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, the email stated.

All appointments were effective on Feb. 28.

Latest response

Dr. Simpson, who joined the faculty at Columbia in 1999, previously served as a professor and vice chair of research for the psychiatry department, director of Columbia’s Center for Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, and director of psychiatry research at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Dr. Simpson is associate editor of JAMA Psychiatry and is president-elect of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Her research has been continuously funded by the National Institute of Mental Health since 1999, and she has advised both the World Health Organization and the American Psychiatric Association on the diagnosis and treatment of OCD.

Dr. Simpson has a bachelor’s degree in biology from Yale University and completed an MD-PhD program at The Rockefeller University and Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. She did her residency in psychiatry at New York–Presbyterian.

The announcement is Columbia’s latest response to the furor that erupted on social media following Dr. Lieberman’s tweet about Sudanese model Nyakim Gatwech, in which he wrote, “Whether a work of art or a freak of nature she’s a beautiful sight to behold.”

Twitter reacted immediately and negatively to the tweet, which even Dr. Lieberman later acknowledged was “racist and sexist” in an email apology he sent Feb. 22 to faculty and staff in the department of psychiatry.

As reported by this news organization, Columbia suspended Dr. Lieberman from his chair position on Feb. 23 and permanently removed him from the post of psychiatrist-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Lieberman also resigned as executive director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

The email announcing Simpson’s appointment was signed by Katrina Armstrong, MD, incoming CEO, Columbia University Irving Medical Center and dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons; Anil K. Rustgi, MD, interim executive vice president and dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and Medicine; Steven J. Corwin, MD; president and CEO, New York–Presbyterian; and Ann Marie Sullivan, MD, commissioner of the New York State Office of Mental Health.

This is a developing story.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Helen Blair Simpson, MD, PhD, will take over for Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, who was suspended over a tweet he sent that was widely condemned as both racist and sexist.

She will also serve as interim director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and interim psychiatrist-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, the email stated.

All appointments were effective on Feb. 28.

Latest response

Dr. Simpson, who joined the faculty at Columbia in 1999, previously served as a professor and vice chair of research for the psychiatry department, director of Columbia’s Center for Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, and director of psychiatry research at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Dr. Simpson is associate editor of JAMA Psychiatry and is president-elect of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Her research has been continuously funded by the National Institute of Mental Health since 1999, and she has advised both the World Health Organization and the American Psychiatric Association on the diagnosis and treatment of OCD.

Dr. Simpson has a bachelor’s degree in biology from Yale University and completed an MD-PhD program at The Rockefeller University and Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. She did her residency in psychiatry at New York–Presbyterian.

The announcement is Columbia’s latest response to the furor that erupted on social media following Dr. Lieberman’s tweet about Sudanese model Nyakim Gatwech, in which he wrote, “Whether a work of art or a freak of nature she’s a beautiful sight to behold.”

Twitter reacted immediately and negatively to the tweet, which even Dr. Lieberman later acknowledged was “racist and sexist” in an email apology he sent Feb. 22 to faculty and staff in the department of psychiatry.

As reported by this news organization, Columbia suspended Dr. Lieberman from his chair position on Feb. 23 and permanently removed him from the post of psychiatrist-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Lieberman also resigned as executive director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

The email announcing Simpson’s appointment was signed by Katrina Armstrong, MD, incoming CEO, Columbia University Irving Medical Center and dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons; Anil K. Rustgi, MD, interim executive vice president and dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and Medicine; Steven J. Corwin, MD; president and CEO, New York–Presbyterian; and Ann Marie Sullivan, MD, commissioner of the New York State Office of Mental Health.

This is a developing story.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Helen Blair Simpson, MD, PhD, will take over for Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, who was suspended over a tweet he sent that was widely condemned as both racist and sexist.

She will also serve as interim director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and interim psychiatrist-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, the email stated.

All appointments were effective on Feb. 28.

Latest response

Dr. Simpson, who joined the faculty at Columbia in 1999, previously served as a professor and vice chair of research for the psychiatry department, director of Columbia’s Center for Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, and director of psychiatry research at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Dr. Simpson is associate editor of JAMA Psychiatry and is president-elect of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Her research has been continuously funded by the National Institute of Mental Health since 1999, and she has advised both the World Health Organization and the American Psychiatric Association on the diagnosis and treatment of OCD.

Dr. Simpson has a bachelor’s degree in biology from Yale University and completed an MD-PhD program at The Rockefeller University and Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. She did her residency in psychiatry at New York–Presbyterian.

The announcement is Columbia’s latest response to the furor that erupted on social media following Dr. Lieberman’s tweet about Sudanese model Nyakim Gatwech, in which he wrote, “Whether a work of art or a freak of nature she’s a beautiful sight to behold.”

Twitter reacted immediately and negatively to the tweet, which even Dr. Lieberman later acknowledged was “racist and sexist” in an email apology he sent Feb. 22 to faculty and staff in the department of psychiatry.

As reported by this news organization, Columbia suspended Dr. Lieberman from his chair position on Feb. 23 and permanently removed him from the post of psychiatrist-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Lieberman also resigned as executive director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

The email announcing Simpson’s appointment was signed by Katrina Armstrong, MD, incoming CEO, Columbia University Irving Medical Center and dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons; Anil K. Rustgi, MD, interim executive vice president and dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and Medicine; Steven J. Corwin, MD; president and CEO, New York–Presbyterian; and Ann Marie Sullivan, MD, commissioner of the New York State Office of Mental Health.

This is a developing story.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health care on holidays

My office was open on Presidents Day this year. Granted, I’ve never closed for it.

We’re also open on Veteran’s Day, Columbus Day, and Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Occasionally (usually MLK or Veteran’s days) we get a call from someone unhappy we’re open that day. Banks, government offices, and schools are closed, and they feel that, by not following suit, I’m insulting the memory of veterans and those who fought for civil rights.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. In fact, I don’t know any doctors’ offices that AREN’T open on those days.

Part of this is patient centered. When people need to see a doctor, they don’t want to wait too long. The emergency room isn’t where the majority of things should be handled. Besides, they’re already swamped with nonemergent cases.

Most practices work 8-5 on weekdays, and are booked out. Every additional weekday you’re closed only adds to the wait. So I try to be there enough days to care for people, but not enough so that I lose my sanity or family.

In my area, a fair number of my patients are schoolteachers, who work the same hours I do. So many of them come in on those days, and appreciate that I’m open when they’re off.

Another part is practical. In a small practice, cash flow is critical, and there are just so many days in a given year you can be closed without hurting your financial picture. So most practices are closed for the Big 6 (Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years). Usually this also includes Black Friday and Christmas Eve. So a total of 8 days per year (in addition to vacations).

Unlike other businesses (such as stores and restaurants) most medical offices aren’t open on weekends and nights, so our entire revenue stream is dependent on weekdays from 8 to 5. In this day and age, with most practices running on razor-thin margins, every day off adds to the red line. I can’t take care of anyone if I can’t pay my rent and staff.

I mean no disrespect to anyone. Like other doctors I work hard to provide quality care to all. But So I try to be there for them as much as I can, without going overboard and at the same time keeping my small practice afloat.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

My office was open on Presidents Day this year. Granted, I’ve never closed for it.

We’re also open on Veteran’s Day, Columbus Day, and Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Occasionally (usually MLK or Veteran’s days) we get a call from someone unhappy we’re open that day. Banks, government offices, and schools are closed, and they feel that, by not following suit, I’m insulting the memory of veterans and those who fought for civil rights.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. In fact, I don’t know any doctors’ offices that AREN’T open on those days.

Part of this is patient centered. When people need to see a doctor, they don’t want to wait too long. The emergency room isn’t where the majority of things should be handled. Besides, they’re already swamped with nonemergent cases.

Most practices work 8-5 on weekdays, and are booked out. Every additional weekday you’re closed only adds to the wait. So I try to be there enough days to care for people, but not enough so that I lose my sanity or family.

In my area, a fair number of my patients are schoolteachers, who work the same hours I do. So many of them come in on those days, and appreciate that I’m open when they’re off.

Another part is practical. In a small practice, cash flow is critical, and there are just so many days in a given year you can be closed without hurting your financial picture. So most practices are closed for the Big 6 (Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years). Usually this also includes Black Friday and Christmas Eve. So a total of 8 days per year (in addition to vacations).

Unlike other businesses (such as stores and restaurants) most medical offices aren’t open on weekends and nights, so our entire revenue stream is dependent on weekdays from 8 to 5. In this day and age, with most practices running on razor-thin margins, every day off adds to the red line. I can’t take care of anyone if I can’t pay my rent and staff.

I mean no disrespect to anyone. Like other doctors I work hard to provide quality care to all. But So I try to be there for them as much as I can, without going overboard and at the same time keeping my small practice afloat.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

My office was open on Presidents Day this year. Granted, I’ve never closed for it.

We’re also open on Veteran’s Day, Columbus Day, and Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Occasionally (usually MLK or Veteran’s days) we get a call from someone unhappy we’re open that day. Banks, government offices, and schools are closed, and they feel that, by not following suit, I’m insulting the memory of veterans and those who fought for civil rights.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. In fact, I don’t know any doctors’ offices that AREN’T open on those days.

Part of this is patient centered. When people need to see a doctor, they don’t want to wait too long. The emergency room isn’t where the majority of things should be handled. Besides, they’re already swamped with nonemergent cases.

Most practices work 8-5 on weekdays, and are booked out. Every additional weekday you’re closed only adds to the wait. So I try to be there enough days to care for people, but not enough so that I lose my sanity or family.

In my area, a fair number of my patients are schoolteachers, who work the same hours I do. So many of them come in on those days, and appreciate that I’m open when they’re off.

Another part is practical. In a small practice, cash flow is critical, and there are just so many days in a given year you can be closed without hurting your financial picture. So most practices are closed for the Big 6 (Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years). Usually this also includes Black Friday and Christmas Eve. So a total of 8 days per year (in addition to vacations).

Unlike other businesses (such as stores and restaurants) most medical offices aren’t open on weekends and nights, so our entire revenue stream is dependent on weekdays from 8 to 5. In this day and age, with most practices running on razor-thin margins, every day off adds to the red line. I can’t take care of anyone if I can’t pay my rent and staff.

I mean no disrespect to anyone. Like other doctors I work hard to provide quality care to all. But So I try to be there for them as much as I can, without going overboard and at the same time keeping my small practice afloat.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

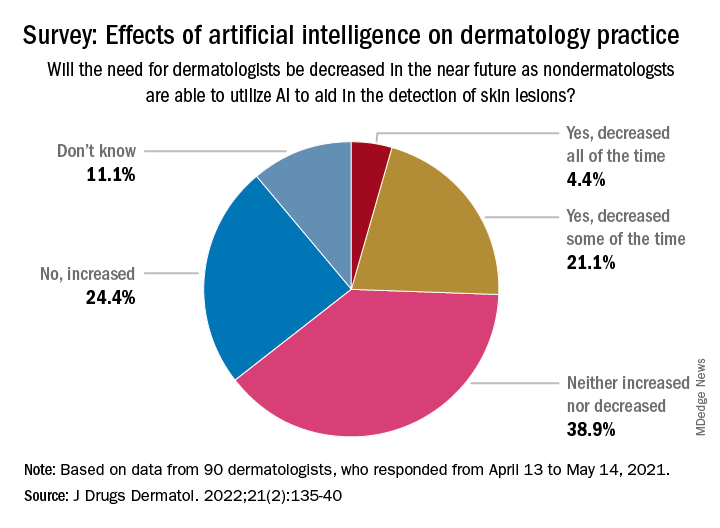

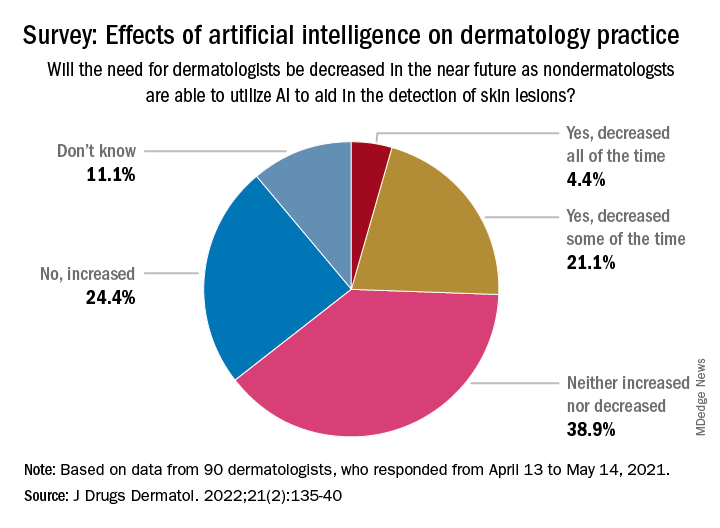

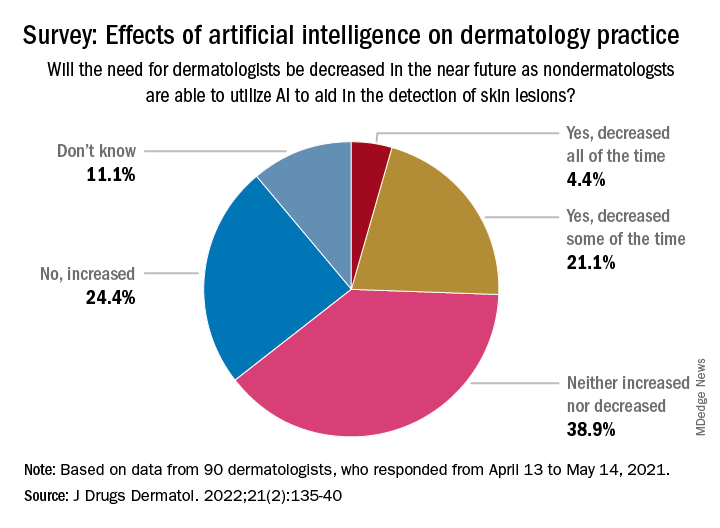

Survey: Artificial intelligence finds support among dermatologists

according to the results of a small survey.

Just 9% of the 90 respondents acknowledged that they have used AI in their practices, while 81% said they had not, and 10% weren’t sure or didn’t know. Despite that lack of familiarity, however, “many embrace the potential positive benefits, such as reducing misdiagnoses” and a majority (94.5%) “would use it at least in certain scenarios,” Vishal A. Patel, MD, and associates said in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Dermatologists aged 40 years and under were more likely to have used AI previously: 15% reported previous experience, compared with 4% of those over age 40 – but the difference in “age did not have a significant effect on perception of AI,” the investigators noted, adding that most of the dermatologists over 40 believe “that AI would be most beneficial and used for detection of malignant skin lesions.”

The survey also asked about ways the respondents would use AI to help their patients. Almost two-thirds of respondents (66%) chose analysis and management of electronic health records “for research purposes to improve patient outcomes,” compared with 56% who chose identifying unknown/screening skin lesions “with a list of differential diagnoses,” 32% who chose telemedicine, and 26% who chose primary surveys of skin, said Dr. Patel, director of cutaneous oncology at the George Washington University Cancer Center in Washington, and coauthors.

The respondents were fairly evenly split when asked about the possible impact of nondermatologists using AI in the near future to detect skin lesions, such as melanomas, on the need for dermatologists. Just over a quarter said that the need for dermatologists will be decreased all (about 4.4%) or some (about 21.1%) of the time, and 24.4% said that the need will be increased, with the largest share (39.9%) of respondents choosing the middle ground: neither increased or decreased, the investigators reported.

The survey form was emailed to 850 members of the Orlando Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference listserv, with responses accepted from April 13 to May 14, 2021. The investigators noted that the response rate was low enough to be a limiting factor, making selection bias “by those with a particular interest in the topic” a possibility.

No funding sources for the study were disclosed. Dr. Patel disclosed that he is chief medical officer for Lazarus AI, the other authors had no disclosures listed.

according to the results of a small survey.

Just 9% of the 90 respondents acknowledged that they have used AI in their practices, while 81% said they had not, and 10% weren’t sure or didn’t know. Despite that lack of familiarity, however, “many embrace the potential positive benefits, such as reducing misdiagnoses” and a majority (94.5%) “would use it at least in certain scenarios,” Vishal A. Patel, MD, and associates said in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Dermatologists aged 40 years and under were more likely to have used AI previously: 15% reported previous experience, compared with 4% of those over age 40 – but the difference in “age did not have a significant effect on perception of AI,” the investigators noted, adding that most of the dermatologists over 40 believe “that AI would be most beneficial and used for detection of malignant skin lesions.”

The survey also asked about ways the respondents would use AI to help their patients. Almost two-thirds of respondents (66%) chose analysis and management of electronic health records “for research purposes to improve patient outcomes,” compared with 56% who chose identifying unknown/screening skin lesions “with a list of differential diagnoses,” 32% who chose telemedicine, and 26% who chose primary surveys of skin, said Dr. Patel, director of cutaneous oncology at the George Washington University Cancer Center in Washington, and coauthors.

The respondents were fairly evenly split when asked about the possible impact of nondermatologists using AI in the near future to detect skin lesions, such as melanomas, on the need for dermatologists. Just over a quarter said that the need for dermatologists will be decreased all (about 4.4%) or some (about 21.1%) of the time, and 24.4% said that the need will be increased, with the largest share (39.9%) of respondents choosing the middle ground: neither increased or decreased, the investigators reported.

The survey form was emailed to 850 members of the Orlando Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference listserv, with responses accepted from April 13 to May 14, 2021. The investigators noted that the response rate was low enough to be a limiting factor, making selection bias “by those with a particular interest in the topic” a possibility.

No funding sources for the study were disclosed. Dr. Patel disclosed that he is chief medical officer for Lazarus AI, the other authors had no disclosures listed.

according to the results of a small survey.

Just 9% of the 90 respondents acknowledged that they have used AI in their practices, while 81% said they had not, and 10% weren’t sure or didn’t know. Despite that lack of familiarity, however, “many embrace the potential positive benefits, such as reducing misdiagnoses” and a majority (94.5%) “would use it at least in certain scenarios,” Vishal A. Patel, MD, and associates said in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Dermatologists aged 40 years and under were more likely to have used AI previously: 15% reported previous experience, compared with 4% of those over age 40 – but the difference in “age did not have a significant effect on perception of AI,” the investigators noted, adding that most of the dermatologists over 40 believe “that AI would be most beneficial and used for detection of malignant skin lesions.”

The survey also asked about ways the respondents would use AI to help their patients. Almost two-thirds of respondents (66%) chose analysis and management of electronic health records “for research purposes to improve patient outcomes,” compared with 56% who chose identifying unknown/screening skin lesions “with a list of differential diagnoses,” 32% who chose telemedicine, and 26% who chose primary surveys of skin, said Dr. Patel, director of cutaneous oncology at the George Washington University Cancer Center in Washington, and coauthors.

The respondents were fairly evenly split when asked about the possible impact of nondermatologists using AI in the near future to detect skin lesions, such as melanomas, on the need for dermatologists. Just over a quarter said that the need for dermatologists will be decreased all (about 4.4%) or some (about 21.1%) of the time, and 24.4% said that the need will be increased, with the largest share (39.9%) of respondents choosing the middle ground: neither increased or decreased, the investigators reported.

The survey form was emailed to 850 members of the Orlando Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference listserv, with responses accepted from April 13 to May 14, 2021. The investigators noted that the response rate was low enough to be a limiting factor, making selection bias “by those with a particular interest in the topic” a possibility.

No funding sources for the study were disclosed. Dr. Patel disclosed that he is chief medical officer for Lazarus AI, the other authors had no disclosures listed.

FROM JOURNAL OF DRUGS IN DERMATOLOGY

Industry payments linked with rheumatologists’ prescribing

Payments to rheumatologists by pharmaceutical companies, whether through food and beverages or consulting fees, are linked with a higher likelihood of prescribing drugs and higher Medicare spending, according to a new study published Feb. 2 in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Alí Duarte-García, MD, of the division of rheumatology in the department of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., led the study.

Researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of Medicare Part B Public Use File, Medicare Part D Public Use File, and Open Payments data for 2013-2015. They included prescription drugs that accounted for 80% of the total Medicare pharmaceutical expenditures in rheumatology.

They then calculated annual average drug cost per beneficiary per year, the percentage of rheumatologists who received payments, and the average payment per physician per drug per year. Industry payments were categorized as either food/beverage or consulting/compensation.

Multivariable regression models were used to assess links between industry payments, prescribing patterns, and prescription drug spending.

‘Directly associated’ with prescribing probability

The authors concluded that “pharmaceutical company payments to rheumatologists were directly associated with the probability of the physician’s prescribing a drug marketed by that company, the proportion of prescriptions that are for that drug, and the resulting Medicare expenditures.”

The authors noted that food and beverage payments were associated with increased Medicare reimbursement amounts for all drugs except rituximab.

The article includes examples that help quantify the link between payments and prescribing.

The authors wrote that for each $100 in food/beverage payments, Medicare reimbursement increased 6% to 44%. The increases were particularly high for infliximab and rACTH (repository corticotropin injection), “whereby a payment of $100 to a prescriber of these drugs was associated with increases of approximately $72,000 and $30,000 in Medicare reimbursements, respectively. For most of the other drugs, for every $100 in payments, the Medicare reimbursement increased by $8,000 to $13,000.”

The associations were strongest for food and beverage payments even though those were for lower dollar amounts.

The researchers found that every $100 in food and beverage payments, which also include gifts, entertainment, or educational materials, was linked with more than twofold higher probability of prescribing and higher Medicare reimbursements than for every $1,000 paid in consulting fees and compensation.

That finding and findings from previous studies, they say, “suggest that the current approach to regulating industry influence, which focuses on disclosure of large payments, may be inadequate.”

Aaron P. Mitchell, MD, a medical oncologist and health services researcher with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, told this news organization that the findings regarding rACTH show the potential harm of industry payments that are linked with prescribing.

The drug is a naturally produced hormone used for both rheumatologic and neurologic conditions. “Since it is an unpatentable drug – really just a hormone – it’s kind of grandfathered in and never had to get [Food and Drug Administration] approval for its current indications,” Dr. Mitchell said.

The drug, which costs nearly $230,000 per Medicare beneficiary, hasn’t been tested head to head in large randomized trials against much cheaper rheumatology drugs, such as prednisone.

In the case of infliximab, he noted, for every $100 in food/beverage payments, there was an increase of $72,000 in Medicare spending.

Dr. Mitchell studies industry influence in a variety of specialties and said rheumatology follows the universal pattern, although the drugs used in the specialty are more expensive than in many specialties.

He agrees with the authors that focusing on disclosures to address the problem is probably not enough.

“We’ve been in this period of full and open disclosure for going on 10 years, and we haven’t really seen a decline in these payments,” he said.

Results won’t surprise rheumatologists

Karen Onel, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Ethics and Conflict of Interest Committee, who said she was speaking only for herself and not on behalf of the committee, told this news organization that the study will not be surprising to rheumatologists or to physicians in other specialties who are aware of the plethora of studies that concluded that industry payments influence prescribing.*

Physicians are well aware of the problem, but “they all think it’s not them,” she said.

She said a shortcoming of this study is that it is unclear what the payments were for, because many things are lumped together in the categories. In the case of food and beverage payments, she said that could include payments physicians don’t realize are going on their open payments profile.

Dr. Onel gives a personal example. When she goes to a medical conference, she says, “I don’t eat on pharma’s dime.” But because badge numbers are scanned, it appears she accepted the food provided by the pharmaceutical sponsor when she enters a room where food or coffee is being served.

She said that although there are outliers like rACTH that often get highlighted, “the numbers are very low of the physicians who had [industry] money, and the change in prescribing patterns actually was very low.”

She pointed to an important limitation that the authors list: The study was limited to patients with fee-for-service Medicare coverage and did not include those with private insurance.

“For example, Aetna, Cigna, and UnitedHealthcare have restricted reimbursement for rACTH in recent years, citing its lack of proven efficacy and the availability of more affordable options, and rACTH is not in the Veterans Affairs formulary,” the authors wrote.

Rapid development of specialty drugs

Still, the authors wrote, the associations described in this article are of high interest because even though rheumatologists make up a small proportion of the physician workforce, they have among the highest costs per prescription in Medicare drug claims.

“Rheumatology, second only to oncology, has entered an era of rapid development of specialty drugs, including biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs),” the authors wrote.

The complex drugs are expensive to produce and require expertise in handling. Most are under patent with no generic or approved biosimilar equivalent.

Nearly half of all U.S. rheumatologists received some payment from a pharmaceutical company in the study period, and most payments to rheumatologists were for low dollar amounts.

The highest per-year annual expenditures were attributed to etanercept ($741 million), adalimumab ($620 million), and infliximab ($539 million).

These drugs were expensive per beneficiary ($20,728 for etanercept, $21,492 for adalimumab, and $15,941 for infliximab) and were prescribed by a large number of rheumatologists (4,068, 3,872, and 1,349, respectively).

Addressing the problem

Dr. Mitchell says the leaders of individual societies need to fill the gaps that leave busy clinicians searching for easy ways to get up-to-date information on drugs.

He says in all specialties, “Industry should not be the most easily and readily available source of information.

“We’re in the age of Zoom now,” he said. “There’s no reason you have to be sitting for an hour at lunch with a sales rep and not a brown-bag lunch getting a 1-hour update from a society on a new drug indication.

“We will get higher-quality information if we’re doing the education ourselves, and we’d be removing the sense of obligation to pay back the industry gift givers,” Dr. Mitchell said.

Dr. Onel said among the most critical work is making sure that the leadership of ACR is free of conflicts of interest.

“They are making decisions for the entire organization. We need to feel safe and comfortable that they are acting in the best interest of the rheumatologists and patients versus corporate partners,” she said.

Guidelines must strictly follow the standards from the Institute of Medicine that fewer than 50% of the regular guideline committee members may have commercial conflicts, Dr. Onel said.

She added that training on real or apparent conflicts of interest must start in medical school, residency, and fellowship, before physicians start to think they know their own practice patterns and that the results don’t apply to them.

However, the reality is that the industry and physicians will always need each other, she said.

Dr. Onel describes a tension between rheumatologists needing industry’s help for research and education, especially when federal money for research can be difficult to get, and managing those relationships to avoid real or apparent conflicts.

“We want the public’s trust,” she said.

A study coauthor has served on advisory boards of Boehringer Ingelheim (> $10,000) and Gilead Sciences (> $10,000); has served on speakers bureaus for Simply Speaking (> $10,000) and Boehringer Ingelheim (< $10,000); and has received royalties from UpToDate (> $10,000). Dr. Mitchell and Dr. Onel reported no relevant financial relationships.

* Update, 2/25/22: This article, which originally attributed comments to Dr. Karen Onel personally, has been updated to further emphasize that these comments were not on behalf of the committee that she leads.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Payments to rheumatologists by pharmaceutical companies, whether through food and beverages or consulting fees, are linked with a higher likelihood of prescribing drugs and higher Medicare spending, according to a new study published Feb. 2 in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Alí Duarte-García, MD, of the division of rheumatology in the department of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., led the study.

Researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of Medicare Part B Public Use File, Medicare Part D Public Use File, and Open Payments data for 2013-2015. They included prescription drugs that accounted for 80% of the total Medicare pharmaceutical expenditures in rheumatology.

They then calculated annual average drug cost per beneficiary per year, the percentage of rheumatologists who received payments, and the average payment per physician per drug per year. Industry payments were categorized as either food/beverage or consulting/compensation.

Multivariable regression models were used to assess links between industry payments, prescribing patterns, and prescription drug spending.

‘Directly associated’ with prescribing probability

The authors concluded that “pharmaceutical company payments to rheumatologists were directly associated with the probability of the physician’s prescribing a drug marketed by that company, the proportion of prescriptions that are for that drug, and the resulting Medicare expenditures.”

The authors noted that food and beverage payments were associated with increased Medicare reimbursement amounts for all drugs except rituximab.

The article includes examples that help quantify the link between payments and prescribing.

The authors wrote that for each $100 in food/beverage payments, Medicare reimbursement increased 6% to 44%. The increases were particularly high for infliximab and rACTH (repository corticotropin injection), “whereby a payment of $100 to a prescriber of these drugs was associated with increases of approximately $72,000 and $30,000 in Medicare reimbursements, respectively. For most of the other drugs, for every $100 in payments, the Medicare reimbursement increased by $8,000 to $13,000.”

The associations were strongest for food and beverage payments even though those were for lower dollar amounts.

The researchers found that every $100 in food and beverage payments, which also include gifts, entertainment, or educational materials, was linked with more than twofold higher probability of prescribing and higher Medicare reimbursements than for every $1,000 paid in consulting fees and compensation.

That finding and findings from previous studies, they say, “suggest that the current approach to regulating industry influence, which focuses on disclosure of large payments, may be inadequate.”

Aaron P. Mitchell, MD, a medical oncologist and health services researcher with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, told this news organization that the findings regarding rACTH show the potential harm of industry payments that are linked with prescribing.

The drug is a naturally produced hormone used for both rheumatologic and neurologic conditions. “Since it is an unpatentable drug – really just a hormone – it’s kind of grandfathered in and never had to get [Food and Drug Administration] approval for its current indications,” Dr. Mitchell said.

The drug, which costs nearly $230,000 per Medicare beneficiary, hasn’t been tested head to head in large randomized trials against much cheaper rheumatology drugs, such as prednisone.

In the case of infliximab, he noted, for every $100 in food/beverage payments, there was an increase of $72,000 in Medicare spending.

Dr. Mitchell studies industry influence in a variety of specialties and said rheumatology follows the universal pattern, although the drugs used in the specialty are more expensive than in many specialties.

He agrees with the authors that focusing on disclosures to address the problem is probably not enough.

“We’ve been in this period of full and open disclosure for going on 10 years, and we haven’t really seen a decline in these payments,” he said.

Results won’t surprise rheumatologists

Karen Onel, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Ethics and Conflict of Interest Committee, who said she was speaking only for herself and not on behalf of the committee, told this news organization that the study will not be surprising to rheumatologists or to physicians in other specialties who are aware of the plethora of studies that concluded that industry payments influence prescribing.*

Physicians are well aware of the problem, but “they all think it’s not them,” she said.

She said a shortcoming of this study is that it is unclear what the payments were for, because many things are lumped together in the categories. In the case of food and beverage payments, she said that could include payments physicians don’t realize are going on their open payments profile.

Dr. Onel gives a personal example. When she goes to a medical conference, she says, “I don’t eat on pharma’s dime.” But because badge numbers are scanned, it appears she accepted the food provided by the pharmaceutical sponsor when she enters a room where food or coffee is being served.

She said that although there are outliers like rACTH that often get highlighted, “the numbers are very low of the physicians who had [industry] money, and the change in prescribing patterns actually was very low.”

She pointed to an important limitation that the authors list: The study was limited to patients with fee-for-service Medicare coverage and did not include those with private insurance.

“For example, Aetna, Cigna, and UnitedHealthcare have restricted reimbursement for rACTH in recent years, citing its lack of proven efficacy and the availability of more affordable options, and rACTH is not in the Veterans Affairs formulary,” the authors wrote.

Rapid development of specialty drugs

Still, the authors wrote, the associations described in this article are of high interest because even though rheumatologists make up a small proportion of the physician workforce, they have among the highest costs per prescription in Medicare drug claims.

“Rheumatology, second only to oncology, has entered an era of rapid development of specialty drugs, including biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs),” the authors wrote.

The complex drugs are expensive to produce and require expertise in handling. Most are under patent with no generic or approved biosimilar equivalent.

Nearly half of all U.S. rheumatologists received some payment from a pharmaceutical company in the study period, and most payments to rheumatologists were for low dollar amounts.

The highest per-year annual expenditures were attributed to etanercept ($741 million), adalimumab ($620 million), and infliximab ($539 million).

These drugs were expensive per beneficiary ($20,728 for etanercept, $21,492 for adalimumab, and $15,941 for infliximab) and were prescribed by a large number of rheumatologists (4,068, 3,872, and 1,349, respectively).

Addressing the problem

Dr. Mitchell says the leaders of individual societies need to fill the gaps that leave busy clinicians searching for easy ways to get up-to-date information on drugs.

He says in all specialties, “Industry should not be the most easily and readily available source of information.

“We’re in the age of Zoom now,” he said. “There’s no reason you have to be sitting for an hour at lunch with a sales rep and not a brown-bag lunch getting a 1-hour update from a society on a new drug indication.

“We will get higher-quality information if we’re doing the education ourselves, and we’d be removing the sense of obligation to pay back the industry gift givers,” Dr. Mitchell said.

Dr. Onel said among the most critical work is making sure that the leadership of ACR is free of conflicts of interest.

“They are making decisions for the entire organization. We need to feel safe and comfortable that they are acting in the best interest of the rheumatologists and patients versus corporate partners,” she said.

Guidelines must strictly follow the standards from the Institute of Medicine that fewer than 50% of the regular guideline committee members may have commercial conflicts, Dr. Onel said.

She added that training on real or apparent conflicts of interest must start in medical school, residency, and fellowship, before physicians start to think they know their own practice patterns and that the results don’t apply to them.

However, the reality is that the industry and physicians will always need each other, she said.

Dr. Onel describes a tension between rheumatologists needing industry’s help for research and education, especially when federal money for research can be difficult to get, and managing those relationships to avoid real or apparent conflicts.

“We want the public’s trust,” she said.

A study coauthor has served on advisory boards of Boehringer Ingelheim (> $10,000) and Gilead Sciences (> $10,000); has served on speakers bureaus for Simply Speaking (> $10,000) and Boehringer Ingelheim (< $10,000); and has received royalties from UpToDate (> $10,000). Dr. Mitchell and Dr. Onel reported no relevant financial relationships.

* Update, 2/25/22: This article, which originally attributed comments to Dr. Karen Onel personally, has been updated to further emphasize that these comments were not on behalf of the committee that she leads.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Payments to rheumatologists by pharmaceutical companies, whether through food and beverages or consulting fees, are linked with a higher likelihood of prescribing drugs and higher Medicare spending, according to a new study published Feb. 2 in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Alí Duarte-García, MD, of the division of rheumatology in the department of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., led the study.

Researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of Medicare Part B Public Use File, Medicare Part D Public Use File, and Open Payments data for 2013-2015. They included prescription drugs that accounted for 80% of the total Medicare pharmaceutical expenditures in rheumatology.

They then calculated annual average drug cost per beneficiary per year, the percentage of rheumatologists who received payments, and the average payment per physician per drug per year. Industry payments were categorized as either food/beverage or consulting/compensation.

Multivariable regression models were used to assess links between industry payments, prescribing patterns, and prescription drug spending.

‘Directly associated’ with prescribing probability

The authors concluded that “pharmaceutical company payments to rheumatologists were directly associated with the probability of the physician’s prescribing a drug marketed by that company, the proportion of prescriptions that are for that drug, and the resulting Medicare expenditures.”

The authors noted that food and beverage payments were associated with increased Medicare reimbursement amounts for all drugs except rituximab.

The article includes examples that help quantify the link between payments and prescribing.

The authors wrote that for each $100 in food/beverage payments, Medicare reimbursement increased 6% to 44%. The increases were particularly high for infliximab and rACTH (repository corticotropin injection), “whereby a payment of $100 to a prescriber of these drugs was associated with increases of approximately $72,000 and $30,000 in Medicare reimbursements, respectively. For most of the other drugs, for every $100 in payments, the Medicare reimbursement increased by $8,000 to $13,000.”

The associations were strongest for food and beverage payments even though those were for lower dollar amounts.

The researchers found that every $100 in food and beverage payments, which also include gifts, entertainment, or educational materials, was linked with more than twofold higher probability of prescribing and higher Medicare reimbursements than for every $1,000 paid in consulting fees and compensation.

That finding and findings from previous studies, they say, “suggest that the current approach to regulating industry influence, which focuses on disclosure of large payments, may be inadequate.”

Aaron P. Mitchell, MD, a medical oncologist and health services researcher with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, told this news organization that the findings regarding rACTH show the potential harm of industry payments that are linked with prescribing.

The drug is a naturally produced hormone used for both rheumatologic and neurologic conditions. “Since it is an unpatentable drug – really just a hormone – it’s kind of grandfathered in and never had to get [Food and Drug Administration] approval for its current indications,” Dr. Mitchell said.

The drug, which costs nearly $230,000 per Medicare beneficiary, hasn’t been tested head to head in large randomized trials against much cheaper rheumatology drugs, such as prednisone.

In the case of infliximab, he noted, for every $100 in food/beverage payments, there was an increase of $72,000 in Medicare spending.

Dr. Mitchell studies industry influence in a variety of specialties and said rheumatology follows the universal pattern, although the drugs used in the specialty are more expensive than in many specialties.

He agrees with the authors that focusing on disclosures to address the problem is probably not enough.

“We’ve been in this period of full and open disclosure for going on 10 years, and we haven’t really seen a decline in these payments,” he said.

Results won’t surprise rheumatologists

Karen Onel, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Ethics and Conflict of Interest Committee, who said she was speaking only for herself and not on behalf of the committee, told this news organization that the study will not be surprising to rheumatologists or to physicians in other specialties who are aware of the plethora of studies that concluded that industry payments influence prescribing.*

Physicians are well aware of the problem, but “they all think it’s not them,” she said.

She said a shortcoming of this study is that it is unclear what the payments were for, because many things are lumped together in the categories. In the case of food and beverage payments, she said that could include payments physicians don’t realize are going on their open payments profile.

Dr. Onel gives a personal example. When she goes to a medical conference, she says, “I don’t eat on pharma’s dime.” But because badge numbers are scanned, it appears she accepted the food provided by the pharmaceutical sponsor when she enters a room where food or coffee is being served.

She said that although there are outliers like rACTH that often get highlighted, “the numbers are very low of the physicians who had [industry] money, and the change in prescribing patterns actually was very low.”

She pointed to an important limitation that the authors list: The study was limited to patients with fee-for-service Medicare coverage and did not include those with private insurance.

“For example, Aetna, Cigna, and UnitedHealthcare have restricted reimbursement for rACTH in recent years, citing its lack of proven efficacy and the availability of more affordable options, and rACTH is not in the Veterans Affairs formulary,” the authors wrote.

Rapid development of specialty drugs

Still, the authors wrote, the associations described in this article are of high interest because even though rheumatologists make up a small proportion of the physician workforce, they have among the highest costs per prescription in Medicare drug claims.

“Rheumatology, second only to oncology, has entered an era of rapid development of specialty drugs, including biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs),” the authors wrote.

The complex drugs are expensive to produce and require expertise in handling. Most are under patent with no generic or approved biosimilar equivalent.

Nearly half of all U.S. rheumatologists received some payment from a pharmaceutical company in the study period, and most payments to rheumatologists were for low dollar amounts.

The highest per-year annual expenditures were attributed to etanercept ($741 million), adalimumab ($620 million), and infliximab ($539 million).

These drugs were expensive per beneficiary ($20,728 for etanercept, $21,492 for adalimumab, and $15,941 for infliximab) and were prescribed by a large number of rheumatologists (4,068, 3,872, and 1,349, respectively).

Addressing the problem

Dr. Mitchell says the leaders of individual societies need to fill the gaps that leave busy clinicians searching for easy ways to get up-to-date information on drugs.

He says in all specialties, “Industry should not be the most easily and readily available source of information.

“We’re in the age of Zoom now,” he said. “There’s no reason you have to be sitting for an hour at lunch with a sales rep and not a brown-bag lunch getting a 1-hour update from a society on a new drug indication.

“We will get higher-quality information if we’re doing the education ourselves, and we’d be removing the sense of obligation to pay back the industry gift givers,” Dr. Mitchell said.

Dr. Onel said among the most critical work is making sure that the leadership of ACR is free of conflicts of interest.

“They are making decisions for the entire organization. We need to feel safe and comfortable that they are acting in the best interest of the rheumatologists and patients versus corporate partners,” she said.

Guidelines must strictly follow the standards from the Institute of Medicine that fewer than 50% of the regular guideline committee members may have commercial conflicts, Dr. Onel said.

She added that training on real or apparent conflicts of interest must start in medical school, residency, and fellowship, before physicians start to think they know their own practice patterns and that the results don’t apply to them.

However, the reality is that the industry and physicians will always need each other, she said.

Dr. Onel describes a tension between rheumatologists needing industry’s help for research and education, especially when federal money for research can be difficult to get, and managing those relationships to avoid real or apparent conflicts.

“We want the public’s trust,” she said.

A study coauthor has served on advisory boards of Boehringer Ingelheim (> $10,000) and Gilead Sciences (> $10,000); has served on speakers bureaus for Simply Speaking (> $10,000) and Boehringer Ingelheim (< $10,000); and has received royalties from UpToDate (> $10,000). Dr. Mitchell and Dr. Onel reported no relevant financial relationships.

* Update, 2/25/22: This article, which originally attributed comments to Dr. Karen Onel personally, has been updated to further emphasize that these comments were not on behalf of the committee that she leads.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When physicians are the plaintiffs

Have you experienced malpractice?

No, I’m not asking whether you have experienced litigation. I’m asking whether you, as a physician, have actually experienced substandard care from a colleague. I have heard many such experiences over the years, and mistreatment doesn’t seem to be getting any less frequent.

The first is that, unlike the Pope, who has a dedicated confessor trained to minister to his spiritual needs, no one formally trains physicians to treat physicians. As a result, most of us feel slightly uneasy at treating other physicians. We naturally wish to keep our colleagues well, but at the same time realize that our clinical skills are being very closely scrutinized. What if they are found to be wanting? This discomfiture can make a physician treating a physician overly compulsive, or worse, overtly dismissive.

Second, we physicians are famously poor patients. We pretend we don’t need the advice we give others, to monitor our health and promptly seek care when something feels amiss. And, for the period during which we delay a medical encounter, we often attempt to diagnose and treat ourselves.

Sometimes we are successful, which reinforces this approach. Other times, we fail at being our own caregiver and present to someone else either too late, or with avoidable complications. In the former instance, we congratulate ourselves and learn nothing from the experience. In the latter, we may heap shame upon ourselves for our folly, and we may learn; but it could be a lethal lesson. In the worst scenario, our colleague gives in to frustration (or angst), and heaps even more shame onto their late-presenting physician patient.

Third, when we do submit to being a patient, we often demand VIP treatment. This is probably in response to our anxiety that some of the worst things we have seen happen to patients might happen to us if we are not vigilant to ensure we receive a higher level of care. But of course, such hypervigilance can lead to excessive care and testing, with all the attendant hazards, or alternatively to dilution of care if our caregivers decide we are just too much trouble.

Fourth, as a fifth-generation physician myself, I am convinced that physicians and physician family members are either prone to unusual manifestations of common diseases or unusual diseases, or that rare disease entities and complications are actually more common than literature suggests, and they simply aren’t pursued or diagnosed in nonphysician families.

No matter how we may have arrived in a position to need medical care, how often is such care substandard? And how do we respond when we suspect, or know, this to be the case? Are physicians more, or less, likely to take legal action in the face of it?

I certainly don’t know any statistics. Physicians are in an excellent position to take such action, because judges and juries will likely believe that a doctor can recognize negligence when we fall victim to it. But we may also be reluctant to publicly admit the way (or ways) in which we may have contributed to substandard care or outcome.

Based on decades of working with physician clients who have been sued, and having been sued myself (thus witnessing and also experiencing the effects of litigation), I am probably more reluctant than normal patients or physicians to consider taking legal action. This, despite the fact that I am also a lawyer and (through organized medicine) know many colleagues in all specialties who might serve as expert witnesses.

I have experienced serial substandard care, which has left me highly conflicted about the efficacy of my chosen profession. As a resident, I had my first odd pain condition and consulted an “elder statesperson” from my institution, whom I assumed to be a “doctor’s doctor” because he was a superb teacher (wrong!)

He completely missed the diagnosis and further belittled (indeed, libeled) me in the medical record. (Some years later, I learned that, during that period, he was increasingly demented and tended to view all female patients as having “wandering uterus” equivalents.) Fortunately, I found a better diagnostician, or at least one more willing to lend credence to my complaints, who successfully removed the first of several “zebra” lesions I have experienced.

As a young faculty member, I had an odd presentation of a recurring gynecologic condition, which was treated surgically, successfully, except that my fertility was cut in half – a possibility about which I had not been informed when giving operative consent. Would I have sued this fellow faculty member for that? Never, because she invariably treated me with respect as a colleague.

Later in my career after leaving academia, the same condition recurred in a new location. My old-school gynecologist desired to do an extensive procedure, to which I demurred unless specific pathology was found intraoperatively. Affronted, he subjected me to laparoscopy, did nothing but look, and then left the hospital leaving me and the PACU nurse to try to decipher his instructions (which said, basically, “I didn’t find anything; don’t bother me again.”). Several years of pain later, a younger gynecologist performed the correct procedure to address my problem, which has never recurred. Would I have sued him? No, because I believe he had a disability.

At age 59, I developed a new mole. My beloved general practitioner, in the waning years of his practice, forgot to consult a colleague to remove it for several months. When I forced the issue, the mole was removed and turned out to be a rare pediatric condition considered a precursor to melanoma. The same general practitioner had told me I needn’t worry about my “mild hypercalcemia.”

Ten years later I diagnosed my own parathyroid adenoma, in the interim losing 10% of my bone density. Would I have sued him? No, for he always showed he cared. (Though maybe, if I had fractured my spine or hip.)

If you have been the victim of physician malpractice, how did you respond?

Do we serve our profession well by how we handle substandard care – upon ourselves (or our loved ones)?

Dr. Andrew is a former assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and founder and principal of MDMentor, Victoria, B.C.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Have you experienced malpractice?

No, I’m not asking whether you have experienced litigation. I’m asking whether you, as a physician, have actually experienced substandard care from a colleague. I have heard many such experiences over the years, and mistreatment doesn’t seem to be getting any less frequent.

The first is that, unlike the Pope, who has a dedicated confessor trained to minister to his spiritual needs, no one formally trains physicians to treat physicians. As a result, most of us feel slightly uneasy at treating other physicians. We naturally wish to keep our colleagues well, but at the same time realize that our clinical skills are being very closely scrutinized. What if they are found to be wanting? This discomfiture can make a physician treating a physician overly compulsive, or worse, overtly dismissive.

Second, we physicians are famously poor patients. We pretend we don’t need the advice we give others, to monitor our health and promptly seek care when something feels amiss. And, for the period during which we delay a medical encounter, we often attempt to diagnose and treat ourselves.

Sometimes we are successful, which reinforces this approach. Other times, we fail at being our own caregiver and present to someone else either too late, or with avoidable complications. In the former instance, we congratulate ourselves and learn nothing from the experience. In the latter, we may heap shame upon ourselves for our folly, and we may learn; but it could be a lethal lesson. In the worst scenario, our colleague gives in to frustration (or angst), and heaps even more shame onto their late-presenting physician patient.

Third, when we do submit to being a patient, we often demand VIP treatment. This is probably in response to our anxiety that some of the worst things we have seen happen to patients might happen to us if we are not vigilant to ensure we receive a higher level of care. But of course, such hypervigilance can lead to excessive care and testing, with all the attendant hazards, or alternatively to dilution of care if our caregivers decide we are just too much trouble.

Fourth, as a fifth-generation physician myself, I am convinced that physicians and physician family members are either prone to unusual manifestations of common diseases or unusual diseases, or that rare disease entities and complications are actually more common than literature suggests, and they simply aren’t pursued or diagnosed in nonphysician families.

No matter how we may have arrived in a position to need medical care, how often is such care substandard? And how do we respond when we suspect, or know, this to be the case? Are physicians more, or less, likely to take legal action in the face of it?

I certainly don’t know any statistics. Physicians are in an excellent position to take such action, because judges and juries will likely believe that a doctor can recognize negligence when we fall victim to it. But we may also be reluctant to publicly admit the way (or ways) in which we may have contributed to substandard care or outcome.

Based on decades of working with physician clients who have been sued, and having been sued myself (thus witnessing and also experiencing the effects of litigation), I am probably more reluctant than normal patients or physicians to consider taking legal action. This, despite the fact that I am also a lawyer and (through organized medicine) know many colleagues in all specialties who might serve as expert witnesses.

I have experienced serial substandard care, which has left me highly conflicted about the efficacy of my chosen profession. As a resident, I had my first odd pain condition and consulted an “elder statesperson” from my institution, whom I assumed to be a “doctor’s doctor” because he was a superb teacher (wrong!)

He completely missed the diagnosis and further belittled (indeed, libeled) me in the medical record. (Some years later, I learned that, during that period, he was increasingly demented and tended to view all female patients as having “wandering uterus” equivalents.) Fortunately, I found a better diagnostician, or at least one more willing to lend credence to my complaints, who successfully removed the first of several “zebra” lesions I have experienced.

As a young faculty member, I had an odd presentation of a recurring gynecologic condition, which was treated surgically, successfully, except that my fertility was cut in half – a possibility about which I had not been informed when giving operative consent. Would I have sued this fellow faculty member for that? Never, because she invariably treated me with respect as a colleague.

Later in my career after leaving academia, the same condition recurred in a new location. My old-school gynecologist desired to do an extensive procedure, to which I demurred unless specific pathology was found intraoperatively. Affronted, he subjected me to laparoscopy, did nothing but look, and then left the hospital leaving me and the PACU nurse to try to decipher his instructions (which said, basically, “I didn’t find anything; don’t bother me again.”). Several years of pain later, a younger gynecologist performed the correct procedure to address my problem, which has never recurred. Would I have sued him? No, because I believe he had a disability.

At age 59, I developed a new mole. My beloved general practitioner, in the waning years of his practice, forgot to consult a colleague to remove it for several months. When I forced the issue, the mole was removed and turned out to be a rare pediatric condition considered a precursor to melanoma. The same general practitioner had told me I needn’t worry about my “mild hypercalcemia.”

Ten years later I diagnosed my own parathyroid adenoma, in the interim losing 10% of my bone density. Would I have sued him? No, for he always showed he cared. (Though maybe, if I had fractured my spine or hip.)

If you have been the victim of physician malpractice, how did you respond?

Do we serve our profession well by how we handle substandard care – upon ourselves (or our loved ones)?

Dr. Andrew is a former assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and founder and principal of MDMentor, Victoria, B.C.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Have you experienced malpractice?

No, I’m not asking whether you have experienced litigation. I’m asking whether you, as a physician, have actually experienced substandard care from a colleague. I have heard many such experiences over the years, and mistreatment doesn’t seem to be getting any less frequent.