User login

Is primary care relevant?

You probably still remember your pediatrician. Your relationship with her may have influenced your decision to become a physician. She was your parents’ go-to source for pretty much anything to do with your health. You had a primary care physician in large part because your parents felt that children were particularly vulnerable to disease and wanted to avoid any missteps on your road to maturity. On the other hand, while you were growing up your parents probably were much less concerned about their own health. Their peers and friends seemed healthy enough; why would they need annual checkups? Your folks made sure they had life insurance because accidental death and injury felt like more pressing concerns. If they had a primary physician, they may have visited him infrequently. They may have been more likely to visit their dentist, in part because the office put a strong emphasis on the value of preventive care.

A recent survey from Harvard Medical School, Boston, determined that, in 2015, 75% of adult Americans had an established source of primary care. (“Fewer Americans are getting primary care,” Jake Miller, the Harvard Gazette, Dec. 16, 2019). This number sounds pretty good and not unexpected until you learn that in 2002 that number was 77%. While 2% seems like a drop in the bucket, remember we live in a very populous bucket, and that 2% translates to millions fewer Americans who are not receiving primary care than did more than a decade ago.

While the researchers don’t have data to explain the decline in primary care, they suggest raising the pay of primary care physicians, incentivizing rural practice, and making health insurance more available and affordable as solutions. Of course these recommendations are not surprising. We’ve heard them before. More supply might translate into more usage. But could some of the decline in primary care be because it no longer feels relevant to a population that has become accustomed to instant gratification? One click and the thing you didn’t feel like waiting for in line today is on your doorstep tomorrow, or even sooner.

If we want to create meaningful change, we need to learn a thing or two about marketing from the competition and from the successful businesses who are shaping consumer behavior. It’s not surprising that, when people feel healthy (whether they are or not), they will devalue primary care. But if they sprain an ankle or have a cough that is keeping them up at night, they would like some medical attention ... now. And that will drive them away from primary care toward sources of fragmented care – the doc-in-the-box, the walk-in clinic, or even more unfortunately to the local emergency department.

If we want more people to establish relationships with primary care providers, we need to welcome them in the door ... when they feel a need. Once in the door we can establish rapport and show them there is a value to primary care while they are feeling grateful for the prompt attention we gave them. But too many primary care practices are shunting potential patients into fragmented care by appearing unwelcome to minor emergencies and by creating customer-unfriendly communication networks. Most people I know would be happy to go back to the old days of “take two aspirin and call me in the morning” primary care. At least you had talked to a doctor in real time, and you knew that he or she would see you the next day if you still had a problem.

You may think I’ve suddenly gone utopian. But there are ways to run a practice that welcomes patients with minor complaints on short notice. It requires some flexibility, some willingness to work longer on some days, and being more efficient.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

You probably still remember your pediatrician. Your relationship with her may have influenced your decision to become a physician. She was your parents’ go-to source for pretty much anything to do with your health. You had a primary care physician in large part because your parents felt that children were particularly vulnerable to disease and wanted to avoid any missteps on your road to maturity. On the other hand, while you were growing up your parents probably were much less concerned about their own health. Their peers and friends seemed healthy enough; why would they need annual checkups? Your folks made sure they had life insurance because accidental death and injury felt like more pressing concerns. If they had a primary physician, they may have visited him infrequently. They may have been more likely to visit their dentist, in part because the office put a strong emphasis on the value of preventive care.

A recent survey from Harvard Medical School, Boston, determined that, in 2015, 75% of adult Americans had an established source of primary care. (“Fewer Americans are getting primary care,” Jake Miller, the Harvard Gazette, Dec. 16, 2019). This number sounds pretty good and not unexpected until you learn that in 2002 that number was 77%. While 2% seems like a drop in the bucket, remember we live in a very populous bucket, and that 2% translates to millions fewer Americans who are not receiving primary care than did more than a decade ago.

While the researchers don’t have data to explain the decline in primary care, they suggest raising the pay of primary care physicians, incentivizing rural practice, and making health insurance more available and affordable as solutions. Of course these recommendations are not surprising. We’ve heard them before. More supply might translate into more usage. But could some of the decline in primary care be because it no longer feels relevant to a population that has become accustomed to instant gratification? One click and the thing you didn’t feel like waiting for in line today is on your doorstep tomorrow, or even sooner.

If we want to create meaningful change, we need to learn a thing or two about marketing from the competition and from the successful businesses who are shaping consumer behavior. It’s not surprising that, when people feel healthy (whether they are or not), they will devalue primary care. But if they sprain an ankle or have a cough that is keeping them up at night, they would like some medical attention ... now. And that will drive them away from primary care toward sources of fragmented care – the doc-in-the-box, the walk-in clinic, or even more unfortunately to the local emergency department.

If we want more people to establish relationships with primary care providers, we need to welcome them in the door ... when they feel a need. Once in the door we can establish rapport and show them there is a value to primary care while they are feeling grateful for the prompt attention we gave them. But too many primary care practices are shunting potential patients into fragmented care by appearing unwelcome to minor emergencies and by creating customer-unfriendly communication networks. Most people I know would be happy to go back to the old days of “take two aspirin and call me in the morning” primary care. At least you had talked to a doctor in real time, and you knew that he or she would see you the next day if you still had a problem.

You may think I’ve suddenly gone utopian. But there are ways to run a practice that welcomes patients with minor complaints on short notice. It requires some flexibility, some willingness to work longer on some days, and being more efficient.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

You probably still remember your pediatrician. Your relationship with her may have influenced your decision to become a physician. She was your parents’ go-to source for pretty much anything to do with your health. You had a primary care physician in large part because your parents felt that children were particularly vulnerable to disease and wanted to avoid any missteps on your road to maturity. On the other hand, while you were growing up your parents probably were much less concerned about their own health. Their peers and friends seemed healthy enough; why would they need annual checkups? Your folks made sure they had life insurance because accidental death and injury felt like more pressing concerns. If they had a primary physician, they may have visited him infrequently. They may have been more likely to visit their dentist, in part because the office put a strong emphasis on the value of preventive care.

A recent survey from Harvard Medical School, Boston, determined that, in 2015, 75% of adult Americans had an established source of primary care. (“Fewer Americans are getting primary care,” Jake Miller, the Harvard Gazette, Dec. 16, 2019). This number sounds pretty good and not unexpected until you learn that in 2002 that number was 77%. While 2% seems like a drop in the bucket, remember we live in a very populous bucket, and that 2% translates to millions fewer Americans who are not receiving primary care than did more than a decade ago.

While the researchers don’t have data to explain the decline in primary care, they suggest raising the pay of primary care physicians, incentivizing rural practice, and making health insurance more available and affordable as solutions. Of course these recommendations are not surprising. We’ve heard them before. More supply might translate into more usage. But could some of the decline in primary care be because it no longer feels relevant to a population that has become accustomed to instant gratification? One click and the thing you didn’t feel like waiting for in line today is on your doorstep tomorrow, or even sooner.

If we want to create meaningful change, we need to learn a thing or two about marketing from the competition and from the successful businesses who are shaping consumer behavior. It’s not surprising that, when people feel healthy (whether they are or not), they will devalue primary care. But if they sprain an ankle or have a cough that is keeping them up at night, they would like some medical attention ... now. And that will drive them away from primary care toward sources of fragmented care – the doc-in-the-box, the walk-in clinic, or even more unfortunately to the local emergency department.

If we want more people to establish relationships with primary care providers, we need to welcome them in the door ... when they feel a need. Once in the door we can establish rapport and show them there is a value to primary care while they are feeling grateful for the prompt attention we gave them. But too many primary care practices are shunting potential patients into fragmented care by appearing unwelcome to minor emergencies and by creating customer-unfriendly communication networks. Most people I know would be happy to go back to the old days of “take two aspirin and call me in the morning” primary care. At least you had talked to a doctor in real time, and you knew that he or she would see you the next day if you still had a problem.

You may think I’ve suddenly gone utopian. But there are ways to run a practice that welcomes patients with minor complaints on short notice. It requires some flexibility, some willingness to work longer on some days, and being more efficient.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Trump takes on multiple health topics in State of the Union

President Donald J. Trump took on multiple health care issues in his State of the Union address, imploring Congress to avoid the “socialism” of Medicare-for-all, to pass legislation banning late-term abortions, and to protect insurance coverage for preexisting conditions while joining together to reduce rising drug prices.

Mr. Trump said his administration has already been “taking on the big pharmaceutical companies,” claiming that, in 2019, “for the first time in 51 years, the cost of prescription drugs actually went down.”

That statement was called “misleading” by the New York Times because such efforts have excluded some high-cost drugs, and prices had risen by the end of the year, the publication noted in a fact-check of the president’s speech.

A survey issued in December 2019 found that the United States pays the highest prices in the world for pharmaceuticals, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

But the president did throw down a gauntlet for Congress. “Working together, the Congress can reduce drug prices substantially from current levels,” he said, stating that he had been “speaking to Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa and others in the Congress in order to get something on drug pricing done, and done properly.

“Get a bill to my desk, and I will sign it into law without delay,” Mr. Trump said.

A group of House Democrats then stood up in the chamber and loudly chanted, “HR3, HR3,” referring to the Lower Drug Costs Now Act, which the House passed in December 2019.

The bill would give the Department of Health & Human Services the power to negotiate directly with drug companies on up to 250 drugs per year, in particular, the highest-costing and most-utilized drugs.

The Senate has not taken up the legislation, but Sen. Grassley (R) and Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) introduced a similar bill, the Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act. It has been approved by the Senate Finance Committee but has not been moved to the Senate floor.

“I appreciate President Trump recognizing the work we’re doing to lower prescription drug prices,” Sen. Grassley said in a statement after the State of the Union. “Iowans and Americans across the country are demanding reforms that lower sky-high drug costs. A recent poll showed 70% of Americans want Congress to make lowering drug prices its top priority.”

Rep. Greg Walden (R-Ore.), the ranking Republican on the House Energy and Commerce Committee, said he believed Trump was committed to lowering drug costs. “I’ve never seen a president lean in further than President Donald Trump on lowering health care costs,” said Rep. Walden in a statement after the speech.

Trump touted his price transparency rule, which he said would go into effect next January, as a key way to cut health care costs.

Preexisting conditions

The president said that since he’d taken office, insurance had become more affordable and that the quality of health care had improved. He also said that he was making what he called an “iron-clad pledge” to American families.

“We will always protect patients with preexisting conditions – that is a guarantee,” Mr. Trump said.

In a press conference before the speech, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) took issue with that pledge. “The president swears that he supports protections for people with preexisting conditions, but right now, he is fighting in federal court to eliminate these lifesaving protections and every last protection and benefit of the Affordable Care Act,” she said.

During the speech, Rep. G. K. Butterfield (D-N.C.) tweeted “#FactCheck: Claiming to protect Americans with preexisting conditions, Trump and his administration have repeatedly sought to undermine protections offered by the ACA through executive orders and the courts. He is seeking to strike down the law and its protections entirely.”

Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, pointed out in a tweet that insurance plans that Trump touted as “affordable alternatives” are in fact missing those protections.

“Ironically, the cheaper health insurance plans that President Trump has expanded are short-term plans that don’t cover preexisting conditions,” Mr. Levitt said.

Socialist takeover

Mr. Trump condemned the Medicare-for-all proposals that have been introduced in Congress and that are being backed in whole or in part by all of the Democratic candidates for president.

“As we work to improve Americans’ health care, there are those who want to take away your health care, take away your doctor, and abolish private insurance entirely,” said Mr. Trump.

He said that 132 members of Congress “have endorsed legislation to impose a socialist takeover of our health care system, wiping out the private health insurance plans of 180 million Americans.”

Added Mr. Trump: “We will never let socialism destroy American health care!”

Medicare-for-all has waxed and waned in popularity among voters, with generally more Democrats than Republicans favoring a single-payer system, with or without a public option.

Preliminary exit polls in Iowa that were conducted during Monday’s caucus found that 57% of Iowa Democratic caucus-goers supported a single-payer plan; 38% opposed such a plan, according to the Washington Post.

Opioids, the coronavirus, and abortion

In some of his final remarks on health care, Mr. Trump cited progress in the opioid crisis, noting that, in 2019, drug overdose deaths declined for the first time in 30 years.

He said that his administration was coordinating with the Chinese government regarding the coronavirus outbreak and noted the launch of initiatives to improve care for people with kidney disease, Alzheimer’s, and mental health problems.

Mr. Trump repeated his 2019 State of the Union claim that the government would help end AIDS in America by the end of the decade.

The president also announced that he was asking Congress for “an additional $50 million” to fund neonatal research. He followed that up with a plea about abortion.

“I am calling upon the members of Congress here tonight to pass legislation finally banning the late-term abortion of babies,” he said.

Insulin costs?

In the days before the speech, some news outlets had reported that Mr. Trump and the HHS were working on a plan to lower insulin prices for Medicare beneficiaries, and there were suggestions it would come up in the speech.

At least 13 members of Congress invited people advocating for lower insulin costs as their guests for the State of the Union, Stat reported. Rep. Pelosi invited twins from San Francisco with type 1 diabetes as her guests.

But Mr. Trump never mentioned insulin in his speech.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

President Donald J. Trump took on multiple health care issues in his State of the Union address, imploring Congress to avoid the “socialism” of Medicare-for-all, to pass legislation banning late-term abortions, and to protect insurance coverage for preexisting conditions while joining together to reduce rising drug prices.

Mr. Trump said his administration has already been “taking on the big pharmaceutical companies,” claiming that, in 2019, “for the first time in 51 years, the cost of prescription drugs actually went down.”

That statement was called “misleading” by the New York Times because such efforts have excluded some high-cost drugs, and prices had risen by the end of the year, the publication noted in a fact-check of the president’s speech.

A survey issued in December 2019 found that the United States pays the highest prices in the world for pharmaceuticals, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

But the president did throw down a gauntlet for Congress. “Working together, the Congress can reduce drug prices substantially from current levels,” he said, stating that he had been “speaking to Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa and others in the Congress in order to get something on drug pricing done, and done properly.

“Get a bill to my desk, and I will sign it into law without delay,” Mr. Trump said.

A group of House Democrats then stood up in the chamber and loudly chanted, “HR3, HR3,” referring to the Lower Drug Costs Now Act, which the House passed in December 2019.

The bill would give the Department of Health & Human Services the power to negotiate directly with drug companies on up to 250 drugs per year, in particular, the highest-costing and most-utilized drugs.

The Senate has not taken up the legislation, but Sen. Grassley (R) and Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) introduced a similar bill, the Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act. It has been approved by the Senate Finance Committee but has not been moved to the Senate floor.

“I appreciate President Trump recognizing the work we’re doing to lower prescription drug prices,” Sen. Grassley said in a statement after the State of the Union. “Iowans and Americans across the country are demanding reforms that lower sky-high drug costs. A recent poll showed 70% of Americans want Congress to make lowering drug prices its top priority.”

Rep. Greg Walden (R-Ore.), the ranking Republican on the House Energy and Commerce Committee, said he believed Trump was committed to lowering drug costs. “I’ve never seen a president lean in further than President Donald Trump on lowering health care costs,” said Rep. Walden in a statement after the speech.

Trump touted his price transparency rule, which he said would go into effect next January, as a key way to cut health care costs.

Preexisting conditions

The president said that since he’d taken office, insurance had become more affordable and that the quality of health care had improved. He also said that he was making what he called an “iron-clad pledge” to American families.

“We will always protect patients with preexisting conditions – that is a guarantee,” Mr. Trump said.

In a press conference before the speech, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) took issue with that pledge. “The president swears that he supports protections for people with preexisting conditions, but right now, he is fighting in federal court to eliminate these lifesaving protections and every last protection and benefit of the Affordable Care Act,” she said.

During the speech, Rep. G. K. Butterfield (D-N.C.) tweeted “#FactCheck: Claiming to protect Americans with preexisting conditions, Trump and his administration have repeatedly sought to undermine protections offered by the ACA through executive orders and the courts. He is seeking to strike down the law and its protections entirely.”

Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, pointed out in a tweet that insurance plans that Trump touted as “affordable alternatives” are in fact missing those protections.

“Ironically, the cheaper health insurance plans that President Trump has expanded are short-term plans that don’t cover preexisting conditions,” Mr. Levitt said.

Socialist takeover

Mr. Trump condemned the Medicare-for-all proposals that have been introduced in Congress and that are being backed in whole or in part by all of the Democratic candidates for president.

“As we work to improve Americans’ health care, there are those who want to take away your health care, take away your doctor, and abolish private insurance entirely,” said Mr. Trump.

He said that 132 members of Congress “have endorsed legislation to impose a socialist takeover of our health care system, wiping out the private health insurance plans of 180 million Americans.”

Added Mr. Trump: “We will never let socialism destroy American health care!”

Medicare-for-all has waxed and waned in popularity among voters, with generally more Democrats than Republicans favoring a single-payer system, with or without a public option.

Preliminary exit polls in Iowa that were conducted during Monday’s caucus found that 57% of Iowa Democratic caucus-goers supported a single-payer plan; 38% opposed such a plan, according to the Washington Post.

Opioids, the coronavirus, and abortion

In some of his final remarks on health care, Mr. Trump cited progress in the opioid crisis, noting that, in 2019, drug overdose deaths declined for the first time in 30 years.

He said that his administration was coordinating with the Chinese government regarding the coronavirus outbreak and noted the launch of initiatives to improve care for people with kidney disease, Alzheimer’s, and mental health problems.

Mr. Trump repeated his 2019 State of the Union claim that the government would help end AIDS in America by the end of the decade.

The president also announced that he was asking Congress for “an additional $50 million” to fund neonatal research. He followed that up with a plea about abortion.

“I am calling upon the members of Congress here tonight to pass legislation finally banning the late-term abortion of babies,” he said.

Insulin costs?

In the days before the speech, some news outlets had reported that Mr. Trump and the HHS were working on a plan to lower insulin prices for Medicare beneficiaries, and there were suggestions it would come up in the speech.

At least 13 members of Congress invited people advocating for lower insulin costs as their guests for the State of the Union, Stat reported. Rep. Pelosi invited twins from San Francisco with type 1 diabetes as her guests.

But Mr. Trump never mentioned insulin in his speech.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

President Donald J. Trump took on multiple health care issues in his State of the Union address, imploring Congress to avoid the “socialism” of Medicare-for-all, to pass legislation banning late-term abortions, and to protect insurance coverage for preexisting conditions while joining together to reduce rising drug prices.

Mr. Trump said his administration has already been “taking on the big pharmaceutical companies,” claiming that, in 2019, “for the first time in 51 years, the cost of prescription drugs actually went down.”

That statement was called “misleading” by the New York Times because such efforts have excluded some high-cost drugs, and prices had risen by the end of the year, the publication noted in a fact-check of the president’s speech.

A survey issued in December 2019 found that the United States pays the highest prices in the world for pharmaceuticals, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

But the president did throw down a gauntlet for Congress. “Working together, the Congress can reduce drug prices substantially from current levels,” he said, stating that he had been “speaking to Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa and others in the Congress in order to get something on drug pricing done, and done properly.

“Get a bill to my desk, and I will sign it into law without delay,” Mr. Trump said.

A group of House Democrats then stood up in the chamber and loudly chanted, “HR3, HR3,” referring to the Lower Drug Costs Now Act, which the House passed in December 2019.

The bill would give the Department of Health & Human Services the power to negotiate directly with drug companies on up to 250 drugs per year, in particular, the highest-costing and most-utilized drugs.

The Senate has not taken up the legislation, but Sen. Grassley (R) and Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) introduced a similar bill, the Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act. It has been approved by the Senate Finance Committee but has not been moved to the Senate floor.

“I appreciate President Trump recognizing the work we’re doing to lower prescription drug prices,” Sen. Grassley said in a statement after the State of the Union. “Iowans and Americans across the country are demanding reforms that lower sky-high drug costs. A recent poll showed 70% of Americans want Congress to make lowering drug prices its top priority.”

Rep. Greg Walden (R-Ore.), the ranking Republican on the House Energy and Commerce Committee, said he believed Trump was committed to lowering drug costs. “I’ve never seen a president lean in further than President Donald Trump on lowering health care costs,” said Rep. Walden in a statement after the speech.

Trump touted his price transparency rule, which he said would go into effect next January, as a key way to cut health care costs.

Preexisting conditions

The president said that since he’d taken office, insurance had become more affordable and that the quality of health care had improved. He also said that he was making what he called an “iron-clad pledge” to American families.

“We will always protect patients with preexisting conditions – that is a guarantee,” Mr. Trump said.

In a press conference before the speech, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) took issue with that pledge. “The president swears that he supports protections for people with preexisting conditions, but right now, he is fighting in federal court to eliminate these lifesaving protections and every last protection and benefit of the Affordable Care Act,” she said.

During the speech, Rep. G. K. Butterfield (D-N.C.) tweeted “#FactCheck: Claiming to protect Americans with preexisting conditions, Trump and his administration have repeatedly sought to undermine protections offered by the ACA through executive orders and the courts. He is seeking to strike down the law and its protections entirely.”

Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, pointed out in a tweet that insurance plans that Trump touted as “affordable alternatives” are in fact missing those protections.

“Ironically, the cheaper health insurance plans that President Trump has expanded are short-term plans that don’t cover preexisting conditions,” Mr. Levitt said.

Socialist takeover

Mr. Trump condemned the Medicare-for-all proposals that have been introduced in Congress and that are being backed in whole or in part by all of the Democratic candidates for president.

“As we work to improve Americans’ health care, there are those who want to take away your health care, take away your doctor, and abolish private insurance entirely,” said Mr. Trump.

He said that 132 members of Congress “have endorsed legislation to impose a socialist takeover of our health care system, wiping out the private health insurance plans of 180 million Americans.”

Added Mr. Trump: “We will never let socialism destroy American health care!”

Medicare-for-all has waxed and waned in popularity among voters, with generally more Democrats than Republicans favoring a single-payer system, with or without a public option.

Preliminary exit polls in Iowa that were conducted during Monday’s caucus found that 57% of Iowa Democratic caucus-goers supported a single-payer plan; 38% opposed such a plan, according to the Washington Post.

Opioids, the coronavirus, and abortion

In some of his final remarks on health care, Mr. Trump cited progress in the opioid crisis, noting that, in 2019, drug overdose deaths declined for the first time in 30 years.

He said that his administration was coordinating with the Chinese government regarding the coronavirus outbreak and noted the launch of initiatives to improve care for people with kidney disease, Alzheimer’s, and mental health problems.

Mr. Trump repeated his 2019 State of the Union claim that the government would help end AIDS in America by the end of the decade.

The president also announced that he was asking Congress for “an additional $50 million” to fund neonatal research. He followed that up with a plea about abortion.

“I am calling upon the members of Congress here tonight to pass legislation finally banning the late-term abortion of babies,” he said.

Insulin costs?

In the days before the speech, some news outlets had reported that Mr. Trump and the HHS were working on a plan to lower insulin prices for Medicare beneficiaries, and there were suggestions it would come up in the speech.

At least 13 members of Congress invited people advocating for lower insulin costs as their guests for the State of the Union, Stat reported. Rep. Pelosi invited twins from San Francisco with type 1 diabetes as her guests.

But Mr. Trump never mentioned insulin in his speech.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. cancer centers embroiled in Chinese research thefts

Academic cancer centers around the United States continue to get caught up in an ever-evolving investigation into researchers – American and Chinese – who did not disclose payments from or the work they did for Chinese institutions while simultaneously accepting taxpayer money through U.S. government grants.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation has been ferreting out researchers it says have acted illegally.

On Jan. 28, the agency arrested Charles Lieber, a chemist from Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and also unveiled charges against Zheng Zaosong, a cancer researcher who is in the United States on a Harvard-sponsored visa.

The FBI said Mr. Zheng, who worked at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, tried to smuggle 21 vials of biological material and research to China. Mr. Zheng was arrested in December at Boston’s Logan Airport. He admitted he planned to conduct and publish research in China using the stolen samples, said the FBI.

“All of the individuals charged today were either directly or indirectly working for the Chinese government, at our country’s expense,” said the agent in charge of the FBI’s Boston office, Joseph R. Bonavolonta.

Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA), who has been pushing for more government action against foreign theft of U.S. research, said in a statement, “I’m glad the FBI appears to be taking foreign threats to taxpayer-funded research seriously, but I fear that this case is only the tip of the iceberg.”

The FBI said it is investigating China-related cases in all 50 states.

Ross McKinney, MD, the chief scientific officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), said he is aware of some 200 investigations, not all of which are cancer related, at 70-75 institutions.

“It’s a very ubiquitous problem,” Dr. McKinney said in an interview.

He also pointed out that some 6,000 National Institutes of Health–funded principal investigators are of Asian background. “So that 200 is a pretty small proportion,” said Dr. McKinney.

The NIH warned some 10,000 institutions in August 2018 that it had uncovered Chinese manipulation of peer review and a lack of disclosure of work for Chinese institutions. It urged the institutions to report irregularities.

For universities, “the trouble is sorting out who is the violator from who is not,” said Dr. McKinney. He noted that they are not set up to investigate whether someone has a laboratory in China.

“The fact that the Chinese government exploited the fact that universities are typically fairly trusting is extremely disappointing,” he said.

Moffitt story still unfolding

The most serious allegations have been leveled against six former employees of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, Florida.

In December 2019, Moffitt announced that the six – including President and CEO Alan List, MD, and the center director, Thomas Sellers, PhD – had left Moffitt as a result of “violations of conflict of interest rules through their work in China.”

New details have emerged, thanks to a new investigative report from a committee of the Florida House of Representatives.

The report said that Sheng Wei, a naturalized U.S. citizen who had worked at Moffitt since 2008 – when Moffitt began its affiliation with the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital – was instrumental in recruiting top executives into the Thousand Talents program, which Wei had joined in 2010, according to the report. These executives included Dr. List, Dr. Sellers, and also Daniel Sullivan, head of Moffitt’s clinical science program, and cancer biologist Pearlie Epling-Burnette, it noted.

Begun in 2008, China’s Thousand Talents Plan gave salaries, funding, laboratory space, and other incentives to researchers who promised to bring U.S.-gained knowledge and research to China.

All information about this program has been removed from the Internet, but the program may still be active, Dr. McKinney commented.

According to the report, Dr. List pledged to work for the Tianjin cancer center 9 months a year for $71,000 annually. He was appointed head of the hematology department ($85,300 a year) in 2016. He opened a bank account in China to receive that salary and other Thousand Talents payments, the report found. The report notes that the exact amount Dr. List was paid is still not known.

Initially, Dr. Sellers, who was the principal investigator for Moffitt’s National Cancer Institute core grant, said he had not been involved in the Thousand Talents program. He later admitted that he had pledged to work in China 2 months a year for the program and that he’d opened a Chinese bank account and had deposited at least $35,000 into the account, the report notes.

The others pledged to work for the Thousand Talents program and also opened bank accounts in China and received money in those accounts.

Another Moffitt employee, Howard McLeod, MD, had worked for Thousand Talents before he joined Moffitt but did not disclose his China work. Dr. McLeod also supervised and had a close relationship with another researcher, Yijing (Bob) He, MD, who was employed by Moffitt but who lived in China, unbeknownst to Moffitt. “Dr. He appears to have functioned as an agent of Dr. McLeod in China,” said the report.

The report concluded that “none of the Moffitt faculty who were Talents program participants properly or timely disclosed their Talents program involvement to Moffitt, and none disclosed the full extent of their Talents program activities prior to Moffitt’s internal investigation.”

No charges have been filed against any of the former Moffitt employees.

However, the Cancer Letter has reported that Dr. Sellers is claiming he was not involved in the program and that he is preparing to sue Moffitt.

AAMC’s Dr. McKinney notes that it is illegal for researchers to take U.S. government grant money and pledge a certain amount of time but not deliver on that commitment because they are working for someone else – in this case, China. They also lied about not having any other research support, which is also illegal, he said.

The researchers received Chinese money and deposited it in Chinese accounts, which was never reported to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

“One of the hallmarks of the Chinese recruitment program was that people were instructed to not tell their normal U.S. host institution and not tell any U.S. government agency about their relationship with China,” Dr. McKinney said. “It was creating a culture where dishonesty in this situation was norm,” he added.

The lack of honesty brings up bigger questions for the field, he said. “Once you start lying about one thing, do you lie about your science, too?”

Lack of oversight?

Dr. McKinney said the NIH, as well as universities and hospitals, had a long and trusting relationship with China and should not be blamed for falling prey to the Chinese government’s concerted effort to steal intellectual property.

But some government watchdog groups have chided the NIH for lax oversight. In February 2019, the federal Health & Human Services’ Office of Inspector General found that “NIH has not assessed the risks to national security when permitting data access to foreign [principal investigators].”

Federal investigators have said that Thousand Talents has been one of the biggest threats.

The U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations reported in November 2019 that “the federal government’s grant-making agencies did little to prevent this from happening, nor did the FBI and other federal agencies develop a coordinated response to mitigate the threat.”

The NIH invests $31 billion a year in medical research through 50,000 competitive grants to more than 300,000 researchers, according to that report. Even after uncovering grant fraud and peer-review manipulation that benefited China, “significant gaps in NIH’s grant integrity process remain,” the report states. Site visits by the NIH’s Division of Grants Compliance and Oversight dropped from 28 in 2012 to just 3 in 2018, the report noted.

Widening dragnet

In April 2019, Science reported that the NIH identified five researchers at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who had failed to disclose their ties to Chinese enterprises and who had failed to keep peer review confidential.

Two resigned before they could be fired, one was fired, another eventually left the institution, and the fifth was found to have not willfully engaged in subterfuge.

Just a month later, Emory University in Atlanta announced that it had fired a husband and wife research team. The neuroscientists were known for their studies of Huntington disease. Both were U.S. citizens and had worked at Emory for more than 2 decades, according to the Science report.

The Moffitt situation led to the Florida legislature’s investigation, and also prompted some soul searching. The Tampa Bay Times reported that U.S. Senator Rick Scott (R-FL) asked state universities to provide information on what they are doing to stop foreign influence. The University of Florida then acknowledged that four faculty members resigned or were terminated because of ties to a foreign recruitment program.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Academic cancer centers around the United States continue to get caught up in an ever-evolving investigation into researchers – American and Chinese – who did not disclose payments from or the work they did for Chinese institutions while simultaneously accepting taxpayer money through U.S. government grants.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation has been ferreting out researchers it says have acted illegally.

On Jan. 28, the agency arrested Charles Lieber, a chemist from Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and also unveiled charges against Zheng Zaosong, a cancer researcher who is in the United States on a Harvard-sponsored visa.

The FBI said Mr. Zheng, who worked at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, tried to smuggle 21 vials of biological material and research to China. Mr. Zheng was arrested in December at Boston’s Logan Airport. He admitted he planned to conduct and publish research in China using the stolen samples, said the FBI.

“All of the individuals charged today were either directly or indirectly working for the Chinese government, at our country’s expense,” said the agent in charge of the FBI’s Boston office, Joseph R. Bonavolonta.

Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA), who has been pushing for more government action against foreign theft of U.S. research, said in a statement, “I’m glad the FBI appears to be taking foreign threats to taxpayer-funded research seriously, but I fear that this case is only the tip of the iceberg.”

The FBI said it is investigating China-related cases in all 50 states.

Ross McKinney, MD, the chief scientific officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), said he is aware of some 200 investigations, not all of which are cancer related, at 70-75 institutions.

“It’s a very ubiquitous problem,” Dr. McKinney said in an interview.

He also pointed out that some 6,000 National Institutes of Health–funded principal investigators are of Asian background. “So that 200 is a pretty small proportion,” said Dr. McKinney.

The NIH warned some 10,000 institutions in August 2018 that it had uncovered Chinese manipulation of peer review and a lack of disclosure of work for Chinese institutions. It urged the institutions to report irregularities.

For universities, “the trouble is sorting out who is the violator from who is not,” said Dr. McKinney. He noted that they are not set up to investigate whether someone has a laboratory in China.

“The fact that the Chinese government exploited the fact that universities are typically fairly trusting is extremely disappointing,” he said.

Moffitt story still unfolding

The most serious allegations have been leveled against six former employees of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, Florida.

In December 2019, Moffitt announced that the six – including President and CEO Alan List, MD, and the center director, Thomas Sellers, PhD – had left Moffitt as a result of “violations of conflict of interest rules through their work in China.”

New details have emerged, thanks to a new investigative report from a committee of the Florida House of Representatives.

The report said that Sheng Wei, a naturalized U.S. citizen who had worked at Moffitt since 2008 – when Moffitt began its affiliation with the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital – was instrumental in recruiting top executives into the Thousand Talents program, which Wei had joined in 2010, according to the report. These executives included Dr. List, Dr. Sellers, and also Daniel Sullivan, head of Moffitt’s clinical science program, and cancer biologist Pearlie Epling-Burnette, it noted.

Begun in 2008, China’s Thousand Talents Plan gave salaries, funding, laboratory space, and other incentives to researchers who promised to bring U.S.-gained knowledge and research to China.

All information about this program has been removed from the Internet, but the program may still be active, Dr. McKinney commented.

According to the report, Dr. List pledged to work for the Tianjin cancer center 9 months a year for $71,000 annually. He was appointed head of the hematology department ($85,300 a year) in 2016. He opened a bank account in China to receive that salary and other Thousand Talents payments, the report found. The report notes that the exact amount Dr. List was paid is still not known.

Initially, Dr. Sellers, who was the principal investigator for Moffitt’s National Cancer Institute core grant, said he had not been involved in the Thousand Talents program. He later admitted that he had pledged to work in China 2 months a year for the program and that he’d opened a Chinese bank account and had deposited at least $35,000 into the account, the report notes.

The others pledged to work for the Thousand Talents program and also opened bank accounts in China and received money in those accounts.

Another Moffitt employee, Howard McLeod, MD, had worked for Thousand Talents before he joined Moffitt but did not disclose his China work. Dr. McLeod also supervised and had a close relationship with another researcher, Yijing (Bob) He, MD, who was employed by Moffitt but who lived in China, unbeknownst to Moffitt. “Dr. He appears to have functioned as an agent of Dr. McLeod in China,” said the report.

The report concluded that “none of the Moffitt faculty who were Talents program participants properly or timely disclosed their Talents program involvement to Moffitt, and none disclosed the full extent of their Talents program activities prior to Moffitt’s internal investigation.”

No charges have been filed against any of the former Moffitt employees.

However, the Cancer Letter has reported that Dr. Sellers is claiming he was not involved in the program and that he is preparing to sue Moffitt.

AAMC’s Dr. McKinney notes that it is illegal for researchers to take U.S. government grant money and pledge a certain amount of time but not deliver on that commitment because they are working for someone else – in this case, China. They also lied about not having any other research support, which is also illegal, he said.

The researchers received Chinese money and deposited it in Chinese accounts, which was never reported to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

“One of the hallmarks of the Chinese recruitment program was that people were instructed to not tell their normal U.S. host institution and not tell any U.S. government agency about their relationship with China,” Dr. McKinney said. “It was creating a culture where dishonesty in this situation was norm,” he added.

The lack of honesty brings up bigger questions for the field, he said. “Once you start lying about one thing, do you lie about your science, too?”

Lack of oversight?

Dr. McKinney said the NIH, as well as universities and hospitals, had a long and trusting relationship with China and should not be blamed for falling prey to the Chinese government’s concerted effort to steal intellectual property.

But some government watchdog groups have chided the NIH for lax oversight. In February 2019, the federal Health & Human Services’ Office of Inspector General found that “NIH has not assessed the risks to national security when permitting data access to foreign [principal investigators].”

Federal investigators have said that Thousand Talents has been one of the biggest threats.

The U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations reported in November 2019 that “the federal government’s grant-making agencies did little to prevent this from happening, nor did the FBI and other federal agencies develop a coordinated response to mitigate the threat.”

The NIH invests $31 billion a year in medical research through 50,000 competitive grants to more than 300,000 researchers, according to that report. Even after uncovering grant fraud and peer-review manipulation that benefited China, “significant gaps in NIH’s grant integrity process remain,” the report states. Site visits by the NIH’s Division of Grants Compliance and Oversight dropped from 28 in 2012 to just 3 in 2018, the report noted.

Widening dragnet

In April 2019, Science reported that the NIH identified five researchers at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who had failed to disclose their ties to Chinese enterprises and who had failed to keep peer review confidential.

Two resigned before they could be fired, one was fired, another eventually left the institution, and the fifth was found to have not willfully engaged in subterfuge.

Just a month later, Emory University in Atlanta announced that it had fired a husband and wife research team. The neuroscientists were known for their studies of Huntington disease. Both were U.S. citizens and had worked at Emory for more than 2 decades, according to the Science report.

The Moffitt situation led to the Florida legislature’s investigation, and also prompted some soul searching. The Tampa Bay Times reported that U.S. Senator Rick Scott (R-FL) asked state universities to provide information on what they are doing to stop foreign influence. The University of Florida then acknowledged that four faculty members resigned or were terminated because of ties to a foreign recruitment program.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Academic cancer centers around the United States continue to get caught up in an ever-evolving investigation into researchers – American and Chinese – who did not disclose payments from or the work they did for Chinese institutions while simultaneously accepting taxpayer money through U.S. government grants.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation has been ferreting out researchers it says have acted illegally.

On Jan. 28, the agency arrested Charles Lieber, a chemist from Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and also unveiled charges against Zheng Zaosong, a cancer researcher who is in the United States on a Harvard-sponsored visa.

The FBI said Mr. Zheng, who worked at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, tried to smuggle 21 vials of biological material and research to China. Mr. Zheng was arrested in December at Boston’s Logan Airport. He admitted he planned to conduct and publish research in China using the stolen samples, said the FBI.

“All of the individuals charged today were either directly or indirectly working for the Chinese government, at our country’s expense,” said the agent in charge of the FBI’s Boston office, Joseph R. Bonavolonta.

Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA), who has been pushing for more government action against foreign theft of U.S. research, said in a statement, “I’m glad the FBI appears to be taking foreign threats to taxpayer-funded research seriously, but I fear that this case is only the tip of the iceberg.”

The FBI said it is investigating China-related cases in all 50 states.

Ross McKinney, MD, the chief scientific officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), said he is aware of some 200 investigations, not all of which are cancer related, at 70-75 institutions.

“It’s a very ubiquitous problem,” Dr. McKinney said in an interview.

He also pointed out that some 6,000 National Institutes of Health–funded principal investigators are of Asian background. “So that 200 is a pretty small proportion,” said Dr. McKinney.

The NIH warned some 10,000 institutions in August 2018 that it had uncovered Chinese manipulation of peer review and a lack of disclosure of work for Chinese institutions. It urged the institutions to report irregularities.

For universities, “the trouble is sorting out who is the violator from who is not,” said Dr. McKinney. He noted that they are not set up to investigate whether someone has a laboratory in China.

“The fact that the Chinese government exploited the fact that universities are typically fairly trusting is extremely disappointing,” he said.

Moffitt story still unfolding

The most serious allegations have been leveled against six former employees of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, Florida.

In December 2019, Moffitt announced that the six – including President and CEO Alan List, MD, and the center director, Thomas Sellers, PhD – had left Moffitt as a result of “violations of conflict of interest rules through their work in China.”

New details have emerged, thanks to a new investigative report from a committee of the Florida House of Representatives.

The report said that Sheng Wei, a naturalized U.S. citizen who had worked at Moffitt since 2008 – when Moffitt began its affiliation with the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital – was instrumental in recruiting top executives into the Thousand Talents program, which Wei had joined in 2010, according to the report. These executives included Dr. List, Dr. Sellers, and also Daniel Sullivan, head of Moffitt’s clinical science program, and cancer biologist Pearlie Epling-Burnette, it noted.

Begun in 2008, China’s Thousand Talents Plan gave salaries, funding, laboratory space, and other incentives to researchers who promised to bring U.S.-gained knowledge and research to China.

All information about this program has been removed from the Internet, but the program may still be active, Dr. McKinney commented.

According to the report, Dr. List pledged to work for the Tianjin cancer center 9 months a year for $71,000 annually. He was appointed head of the hematology department ($85,300 a year) in 2016. He opened a bank account in China to receive that salary and other Thousand Talents payments, the report found. The report notes that the exact amount Dr. List was paid is still not known.

Initially, Dr. Sellers, who was the principal investigator for Moffitt’s National Cancer Institute core grant, said he had not been involved in the Thousand Talents program. He later admitted that he had pledged to work in China 2 months a year for the program and that he’d opened a Chinese bank account and had deposited at least $35,000 into the account, the report notes.

The others pledged to work for the Thousand Talents program and also opened bank accounts in China and received money in those accounts.

Another Moffitt employee, Howard McLeod, MD, had worked for Thousand Talents before he joined Moffitt but did not disclose his China work. Dr. McLeod also supervised and had a close relationship with another researcher, Yijing (Bob) He, MD, who was employed by Moffitt but who lived in China, unbeknownst to Moffitt. “Dr. He appears to have functioned as an agent of Dr. McLeod in China,” said the report.

The report concluded that “none of the Moffitt faculty who were Talents program participants properly or timely disclosed their Talents program involvement to Moffitt, and none disclosed the full extent of their Talents program activities prior to Moffitt’s internal investigation.”

No charges have been filed against any of the former Moffitt employees.

However, the Cancer Letter has reported that Dr. Sellers is claiming he was not involved in the program and that he is preparing to sue Moffitt.

AAMC’s Dr. McKinney notes that it is illegal for researchers to take U.S. government grant money and pledge a certain amount of time but not deliver on that commitment because they are working for someone else – in this case, China. They also lied about not having any other research support, which is also illegal, he said.

The researchers received Chinese money and deposited it in Chinese accounts, which was never reported to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

“One of the hallmarks of the Chinese recruitment program was that people were instructed to not tell their normal U.S. host institution and not tell any U.S. government agency about their relationship with China,” Dr. McKinney said. “It was creating a culture where dishonesty in this situation was norm,” he added.

The lack of honesty brings up bigger questions for the field, he said. “Once you start lying about one thing, do you lie about your science, too?”

Lack of oversight?

Dr. McKinney said the NIH, as well as universities and hospitals, had a long and trusting relationship with China and should not be blamed for falling prey to the Chinese government’s concerted effort to steal intellectual property.

But some government watchdog groups have chided the NIH for lax oversight. In February 2019, the federal Health & Human Services’ Office of Inspector General found that “NIH has not assessed the risks to national security when permitting data access to foreign [principal investigators].”

Federal investigators have said that Thousand Talents has been one of the biggest threats.

The U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations reported in November 2019 that “the federal government’s grant-making agencies did little to prevent this from happening, nor did the FBI and other federal agencies develop a coordinated response to mitigate the threat.”

The NIH invests $31 billion a year in medical research through 50,000 competitive grants to more than 300,000 researchers, according to that report. Even after uncovering grant fraud and peer-review manipulation that benefited China, “significant gaps in NIH’s grant integrity process remain,” the report states. Site visits by the NIH’s Division of Grants Compliance and Oversight dropped from 28 in 2012 to just 3 in 2018, the report noted.

Widening dragnet

In April 2019, Science reported that the NIH identified five researchers at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who had failed to disclose their ties to Chinese enterprises and who had failed to keep peer review confidential.

Two resigned before they could be fired, one was fired, another eventually left the institution, and the fifth was found to have not willfully engaged in subterfuge.

Just a month later, Emory University in Atlanta announced that it had fired a husband and wife research team. The neuroscientists were known for their studies of Huntington disease. Both were U.S. citizens and had worked at Emory for more than 2 decades, according to the Science report.

The Moffitt situation led to the Florida legislature’s investigation, and also prompted some soul searching. The Tampa Bay Times reported that U.S. Senator Rick Scott (R-FL) asked state universities to provide information on what they are doing to stop foreign influence. The University of Florida then acknowledged that four faculty members resigned or were terminated because of ties to a foreign recruitment program.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physician groups push back on Medicaid block grant plan

It took less than a day for physician groups to start pushing back at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services over its new Medicaid block grant plan, which was introduced on Jan. 30.

Dubbed “Healthy Adult Opportunity,” the agency is offering all states the chance to participate in a block grant program through the 1115 waiver process.

According to a fact sheet issued by the agency, the program will focus on “adults under age 65 who are not eligible for Medicaid on the basis of disability or their need for long term care services and supports, and who are not eligible under a state plan. Other very low-income parents, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people eligible on the basis of a disability will not be directly affected – except from the improvement that results from states reinvesting savings into strengthening their overall programs.”

States will be operating within a defined budget when participating in the program and expenditures exceeding that defined budget will not be eligible for additional federal funding. Budgets will be based on a state’s historic costs, as well as national and regional trends, and will be tied to inflation with the potential to have adjustments made for extraordinary events. States can set their baseline using the prior year’s total spending or a per-enrollee spending model.

A Jan. 30 letter to state Medicaid directors notes that states participating in the program “will be granted extensive flexibility to test alternative approaches to implementing their Medicaid programs, including the ability to make many ongoing program adjustments without the need for demonstration or state plan amendments that require prior approval.”

Among the activities states can engage in under this plan are adjusting cost-sharing requirements, adopting a closed formulary, and applying additional conditions of eligibility. Requests, if approved, will be approved for a 5-year initial period, with a renewal option of up to 10 years.

But physician groups are not seeing a benefit with this new block grant program.

“Moving to a block grant system will likely limit the ability of Medicaid patients to receive preventive and needed medical care from their family physicians, and it will only increase the health disparities that exist in these communities, worsen overall health outcomes, and ultimately increase costs,” Gary LeRoy, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in a statement.

The American Medical Association concurred.

“The AMA opposes caps on federal Medicaid funding, such as block grants, because they would increase the number of uninsured and undermine Medicaid’s role as an indispensable safety net,” Patrice Harris, MD, the AMA’s president, said in a statement. “The AMA supports flexibility in Medicaid and encourages CMS to work with states to develop and test new Medicaid models that best meet the needs and priorities of low-income patients. While encouraging flexibility, the AMA is mindful that expanding Medicaid has been a literal lifesaver for low-income patients. We need to find ways to build on this success. We look forward to reviewing the proposal in detail.”

Officials at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said the changes have the potential to harm women and children’s health, as well as negatively impact physician reimbursement and ultimately access to care.

“Limits on the federal contribution to the Medicaid program would negatively impact patients by forcing states to reduce the number of people who are eligible for Medicaid coverage, eliminate covered services, and increase beneficiary cost-sharing,” ACOG President Ted Anderson, MD, said in a statement. “ACOG is also concerned that this block grant opportunity could lower physician reimbursement for certain services, forcing providers out of the program and jeopardizing patients’ ability to access health care services. Given our nation’s stark rates of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity, we are alarmed by the Administration’s willingness to weaken physician payment in Medicaid.”

It took less than a day for physician groups to start pushing back at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services over its new Medicaid block grant plan, which was introduced on Jan. 30.

Dubbed “Healthy Adult Opportunity,” the agency is offering all states the chance to participate in a block grant program through the 1115 waiver process.

According to a fact sheet issued by the agency, the program will focus on “adults under age 65 who are not eligible for Medicaid on the basis of disability or their need for long term care services and supports, and who are not eligible under a state plan. Other very low-income parents, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people eligible on the basis of a disability will not be directly affected – except from the improvement that results from states reinvesting savings into strengthening their overall programs.”

States will be operating within a defined budget when participating in the program and expenditures exceeding that defined budget will not be eligible for additional federal funding. Budgets will be based on a state’s historic costs, as well as national and regional trends, and will be tied to inflation with the potential to have adjustments made for extraordinary events. States can set their baseline using the prior year’s total spending or a per-enrollee spending model.

A Jan. 30 letter to state Medicaid directors notes that states participating in the program “will be granted extensive flexibility to test alternative approaches to implementing their Medicaid programs, including the ability to make many ongoing program adjustments without the need for demonstration or state plan amendments that require prior approval.”

Among the activities states can engage in under this plan are adjusting cost-sharing requirements, adopting a closed formulary, and applying additional conditions of eligibility. Requests, if approved, will be approved for a 5-year initial period, with a renewal option of up to 10 years.

But physician groups are not seeing a benefit with this new block grant program.

“Moving to a block grant system will likely limit the ability of Medicaid patients to receive preventive and needed medical care from their family physicians, and it will only increase the health disparities that exist in these communities, worsen overall health outcomes, and ultimately increase costs,” Gary LeRoy, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in a statement.

The American Medical Association concurred.

“The AMA opposes caps on federal Medicaid funding, such as block grants, because they would increase the number of uninsured and undermine Medicaid’s role as an indispensable safety net,” Patrice Harris, MD, the AMA’s president, said in a statement. “The AMA supports flexibility in Medicaid and encourages CMS to work with states to develop and test new Medicaid models that best meet the needs and priorities of low-income patients. While encouraging flexibility, the AMA is mindful that expanding Medicaid has been a literal lifesaver for low-income patients. We need to find ways to build on this success. We look forward to reviewing the proposal in detail.”

Officials at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said the changes have the potential to harm women and children’s health, as well as negatively impact physician reimbursement and ultimately access to care.

“Limits on the federal contribution to the Medicaid program would negatively impact patients by forcing states to reduce the number of people who are eligible for Medicaid coverage, eliminate covered services, and increase beneficiary cost-sharing,” ACOG President Ted Anderson, MD, said in a statement. “ACOG is also concerned that this block grant opportunity could lower physician reimbursement for certain services, forcing providers out of the program and jeopardizing patients’ ability to access health care services. Given our nation’s stark rates of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity, we are alarmed by the Administration’s willingness to weaken physician payment in Medicaid.”

It took less than a day for physician groups to start pushing back at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services over its new Medicaid block grant plan, which was introduced on Jan. 30.

Dubbed “Healthy Adult Opportunity,” the agency is offering all states the chance to participate in a block grant program through the 1115 waiver process.

According to a fact sheet issued by the agency, the program will focus on “adults under age 65 who are not eligible for Medicaid on the basis of disability or their need for long term care services and supports, and who are not eligible under a state plan. Other very low-income parents, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people eligible on the basis of a disability will not be directly affected – except from the improvement that results from states reinvesting savings into strengthening their overall programs.”

States will be operating within a defined budget when participating in the program and expenditures exceeding that defined budget will not be eligible for additional federal funding. Budgets will be based on a state’s historic costs, as well as national and regional trends, and will be tied to inflation with the potential to have adjustments made for extraordinary events. States can set their baseline using the prior year’s total spending or a per-enrollee spending model.

A Jan. 30 letter to state Medicaid directors notes that states participating in the program “will be granted extensive flexibility to test alternative approaches to implementing their Medicaid programs, including the ability to make many ongoing program adjustments without the need for demonstration or state plan amendments that require prior approval.”

Among the activities states can engage in under this plan are adjusting cost-sharing requirements, adopting a closed formulary, and applying additional conditions of eligibility. Requests, if approved, will be approved for a 5-year initial period, with a renewal option of up to 10 years.

But physician groups are not seeing a benefit with this new block grant program.

“Moving to a block grant system will likely limit the ability of Medicaid patients to receive preventive and needed medical care from their family physicians, and it will only increase the health disparities that exist in these communities, worsen overall health outcomes, and ultimately increase costs,” Gary LeRoy, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in a statement.

The American Medical Association concurred.

“The AMA opposes caps on federal Medicaid funding, such as block grants, because they would increase the number of uninsured and undermine Medicaid’s role as an indispensable safety net,” Patrice Harris, MD, the AMA’s president, said in a statement. “The AMA supports flexibility in Medicaid and encourages CMS to work with states to develop and test new Medicaid models that best meet the needs and priorities of low-income patients. While encouraging flexibility, the AMA is mindful that expanding Medicaid has been a literal lifesaver for low-income patients. We need to find ways to build on this success. We look forward to reviewing the proposal in detail.”

Officials at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said the changes have the potential to harm women and children’s health, as well as negatively impact physician reimbursement and ultimately access to care.

“Limits on the federal contribution to the Medicaid program would negatively impact patients by forcing states to reduce the number of people who are eligible for Medicaid coverage, eliminate covered services, and increase beneficiary cost-sharing,” ACOG President Ted Anderson, MD, said in a statement. “ACOG is also concerned that this block grant opportunity could lower physician reimbursement for certain services, forcing providers out of the program and jeopardizing patients’ ability to access health care services. Given our nation’s stark rates of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity, we are alarmed by the Administration’s willingness to weaken physician payment in Medicaid.”

A Comparison of 4 Single-Question Measures of Patient Satisfaction

From Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Abstract

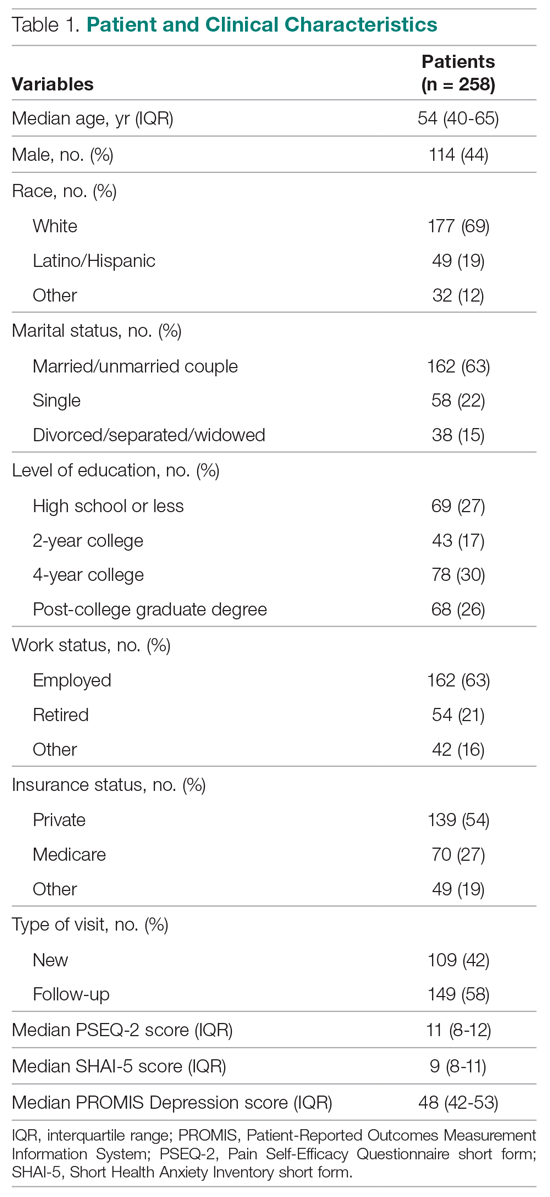

- Objective: Satisfaction measures often show substantial ceiling effects. This randomized controlled trial tested the null hypothesis that there is no difference in mean overall satisfaction, ceiling and floor effect, and data distribution between 4 different kinds of single-question scales assessing the helpfulness of a visit. We also hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared with the Net Promoter Scores (NPS).

- Design: Randomized controlled trial.

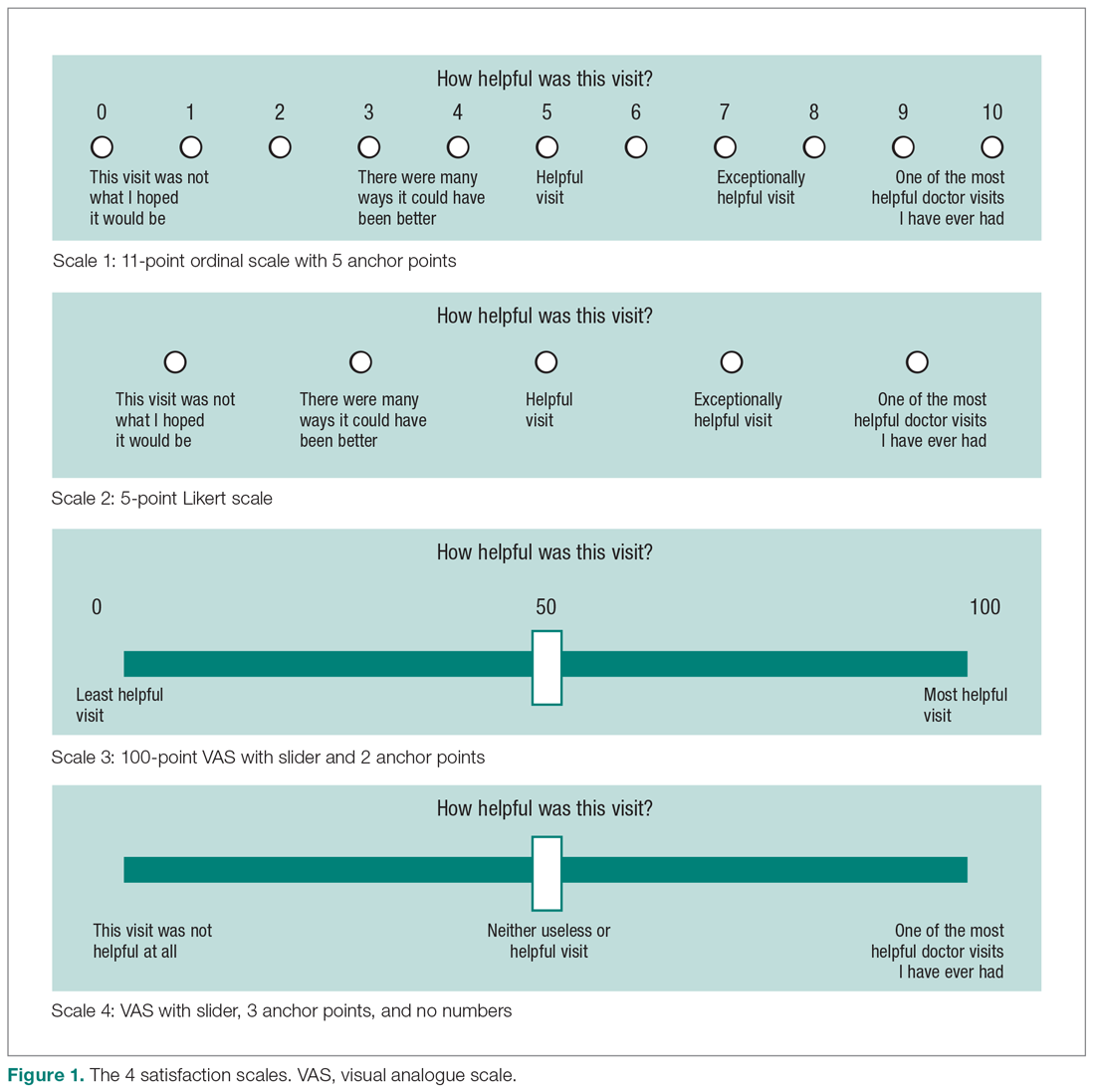

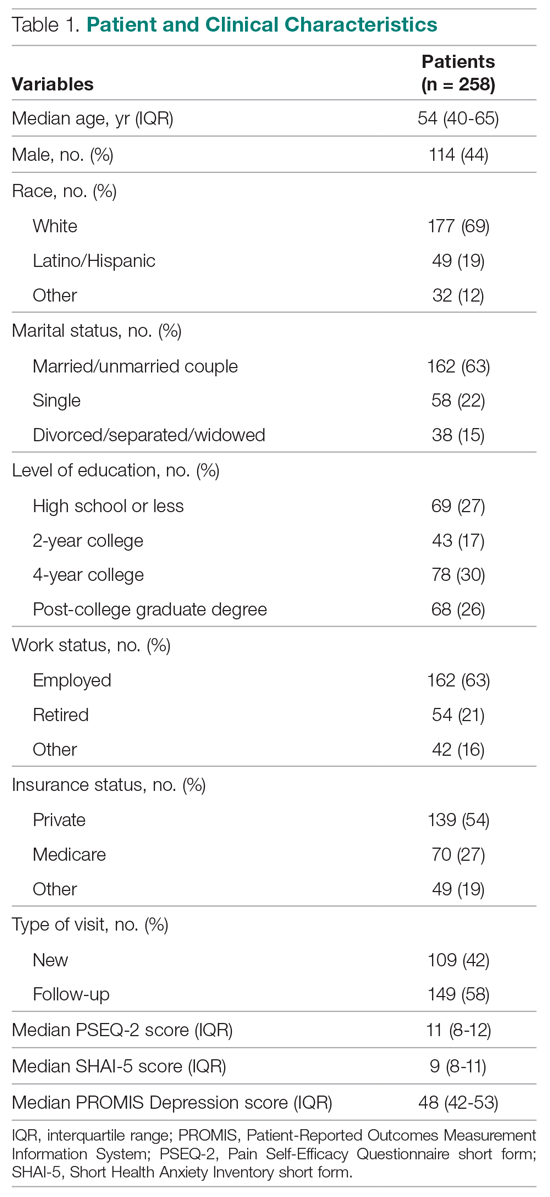

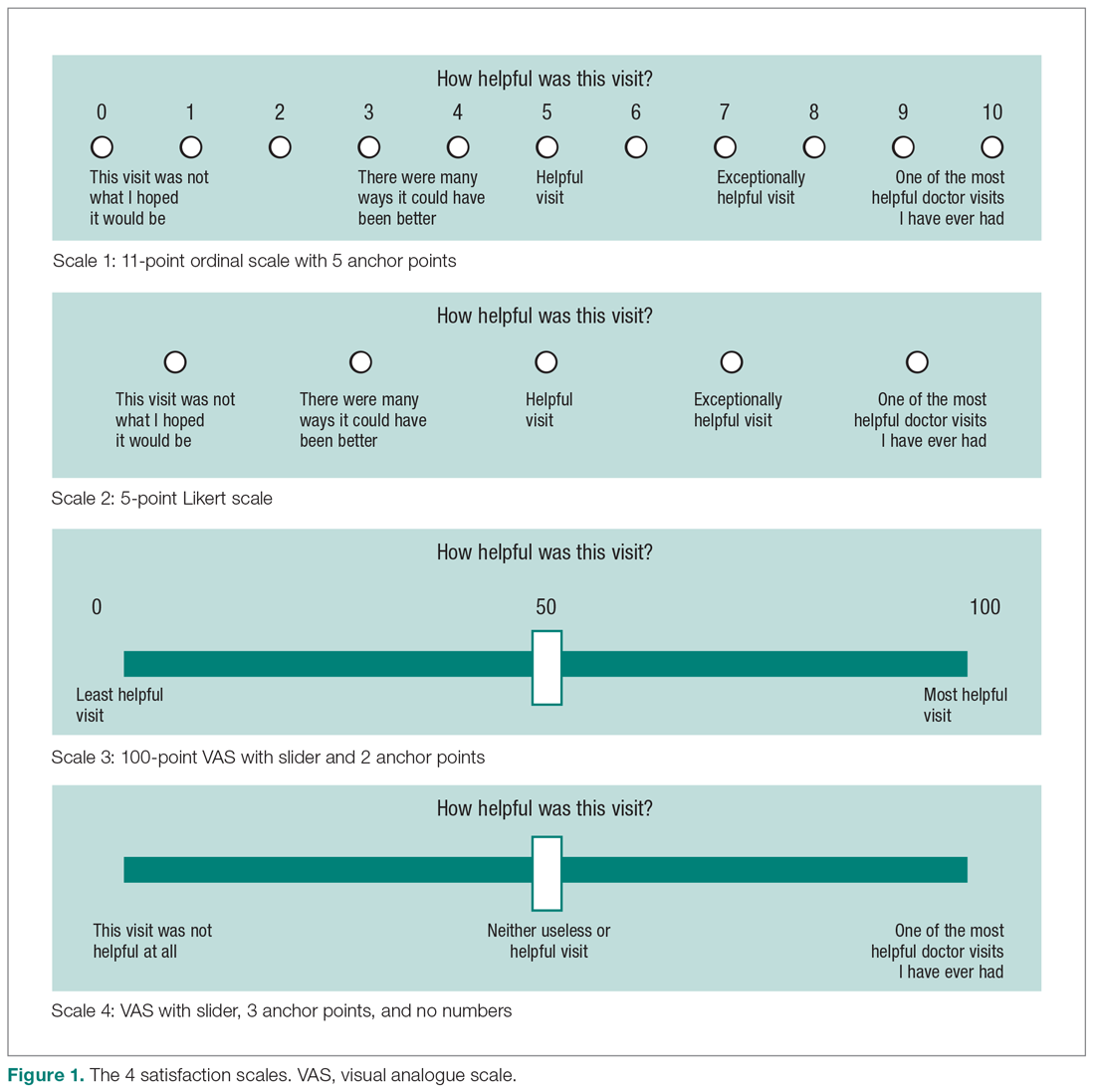

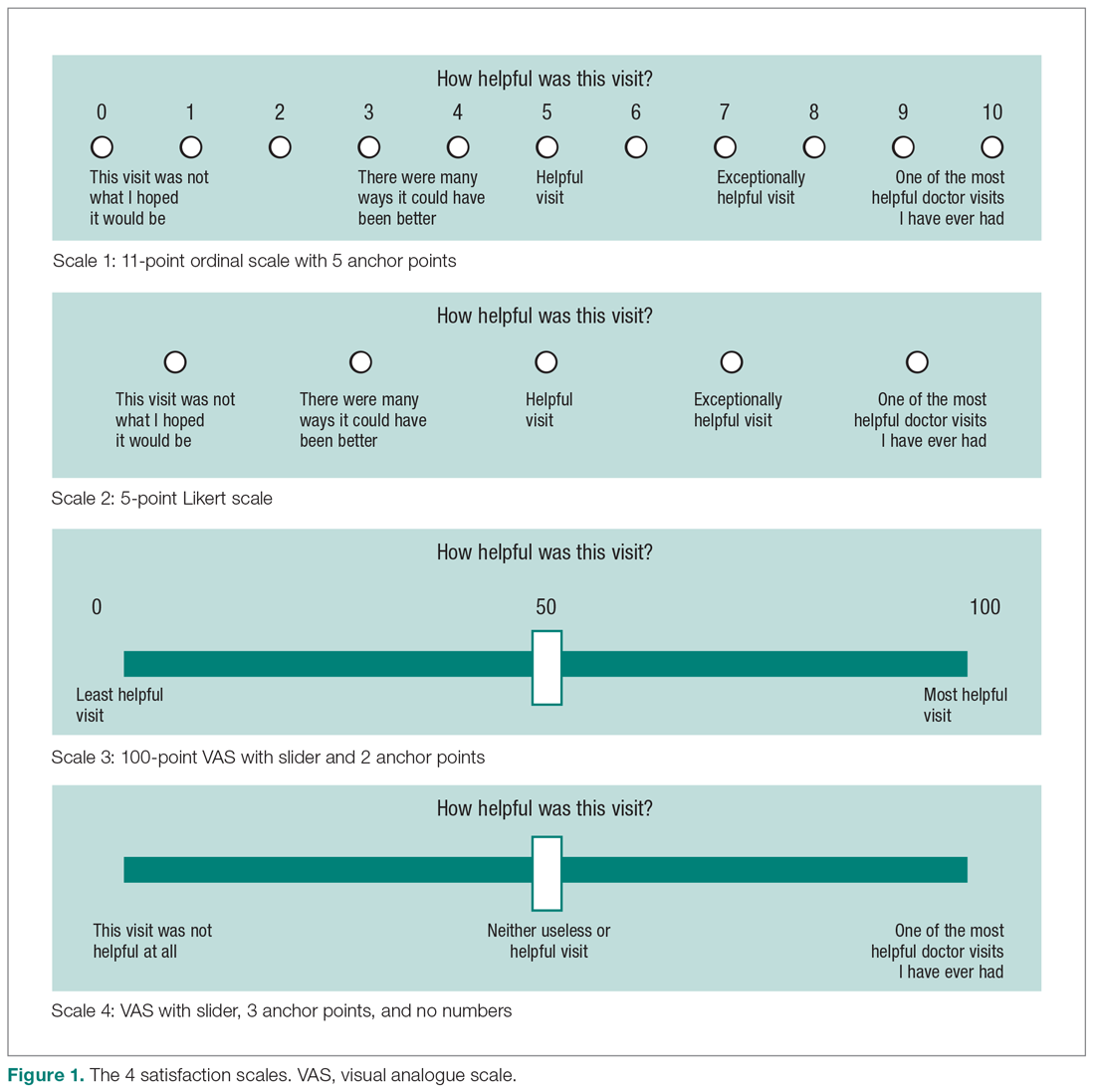

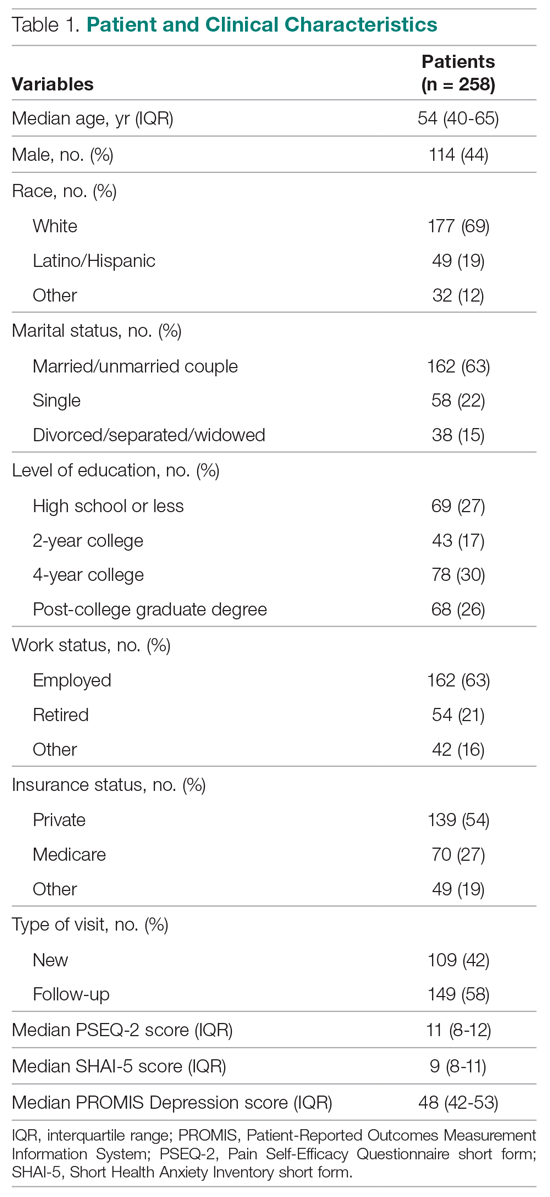

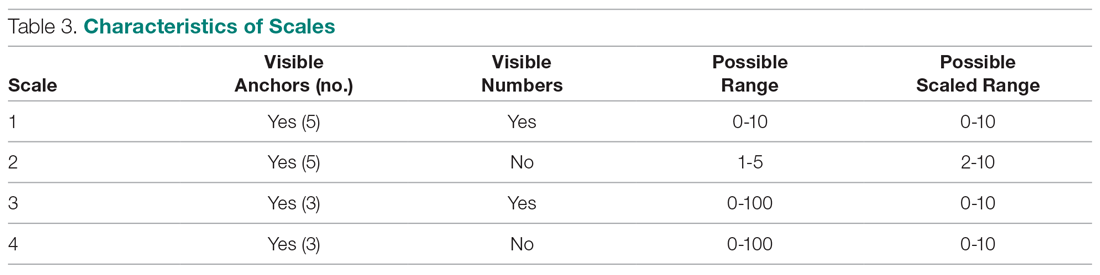

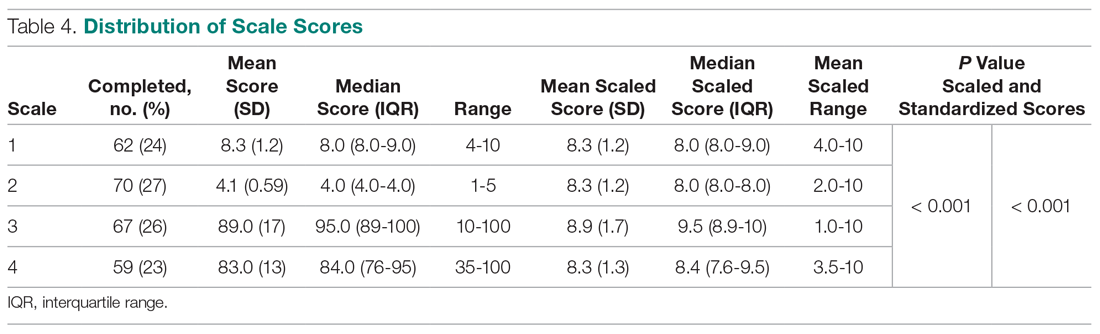

- Methods: We enrolled 258 adult, English-speaking new and returning patients. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 different scale types: (1) an 11-point ordinal scale with 5 anchor points; (2) a 5-point Likert scale; (3) a 0-100 visual analogue scale (VAS) electronic slider with 3 anchor points and visible numbers; and (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers. Additionally, patients completed the 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2), 5-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory scale (SHAI-5), and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression. We assessed mean and median score, floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis for each scale. Spearman correlation tests were used to test correlations between satisfaction and psychological status.

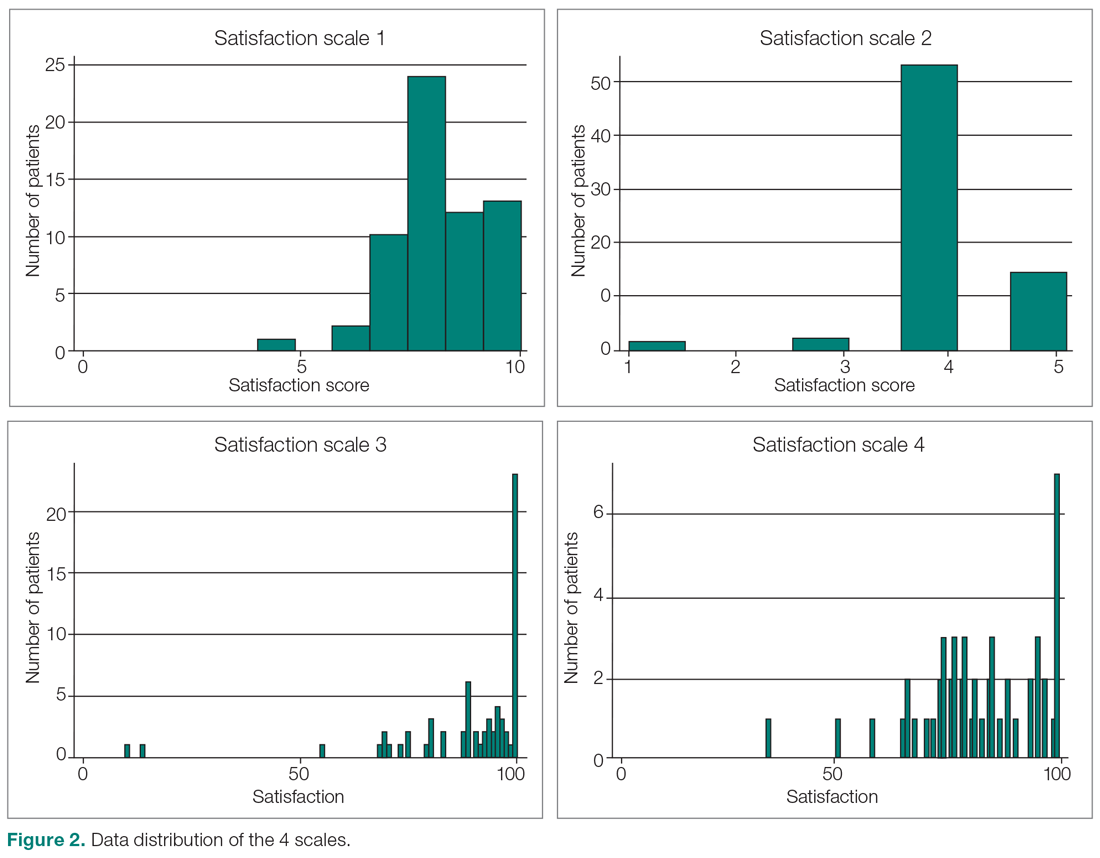

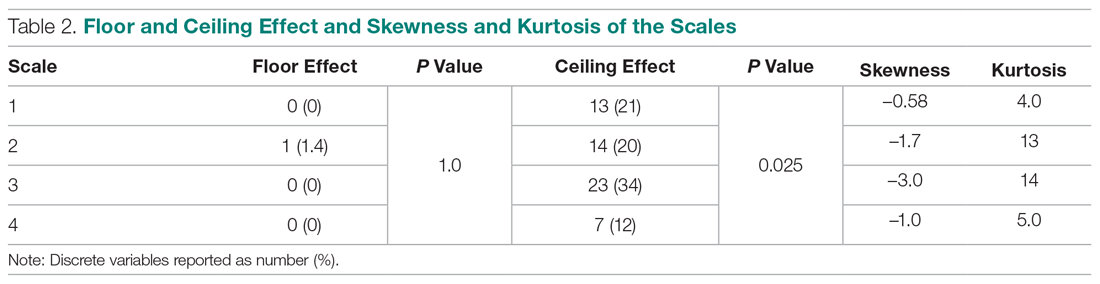

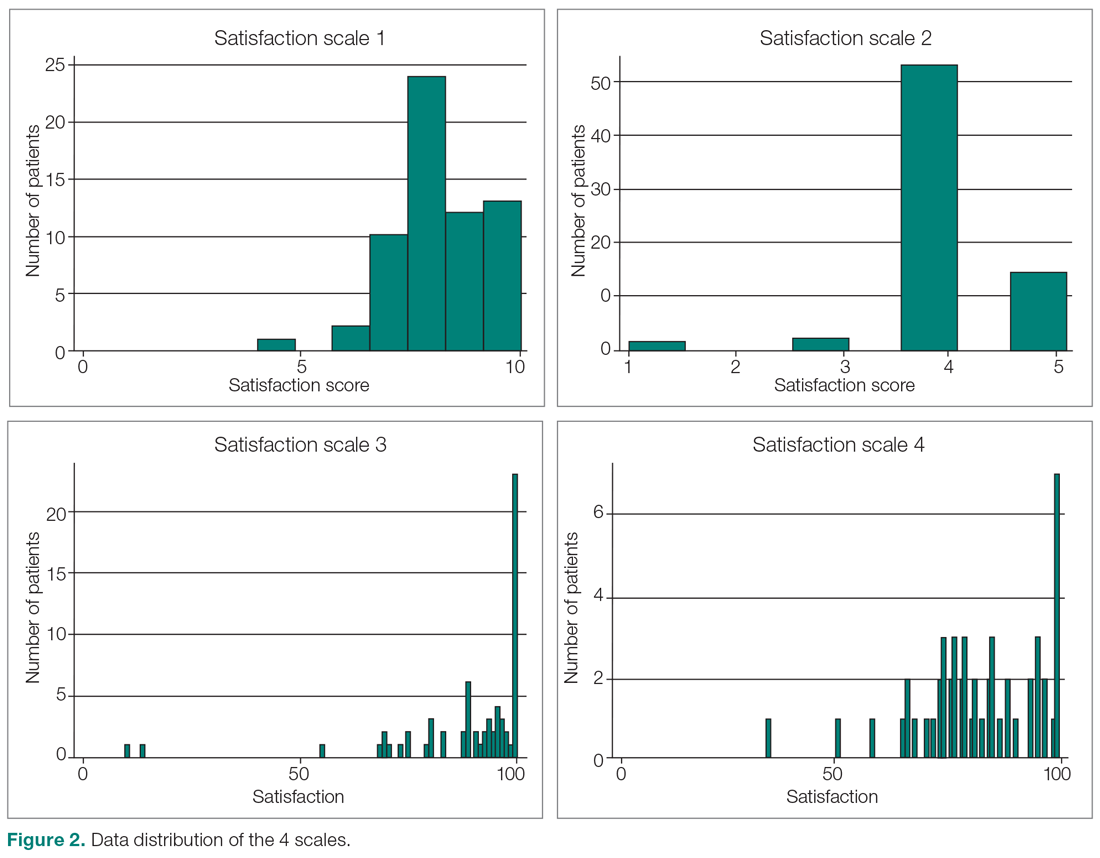

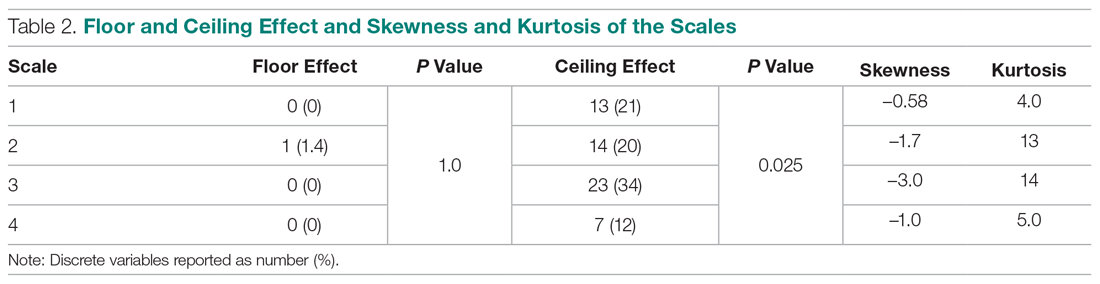

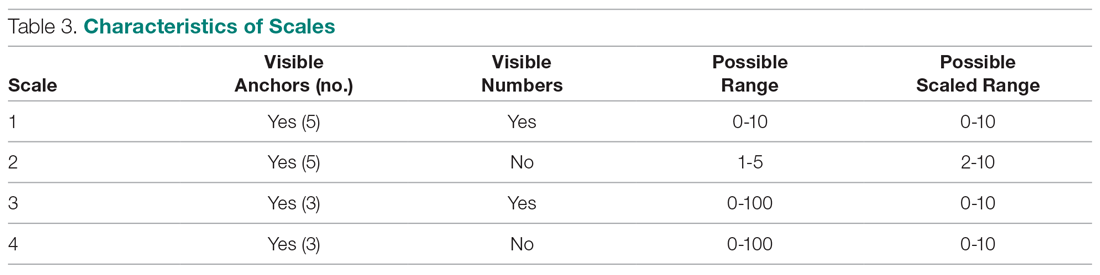

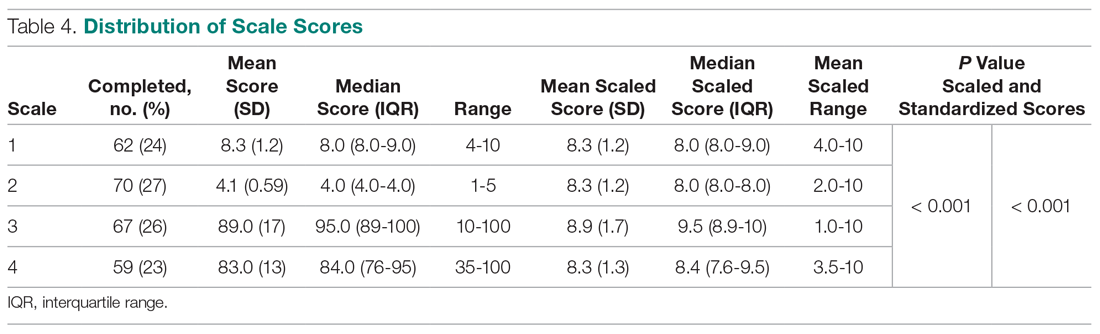

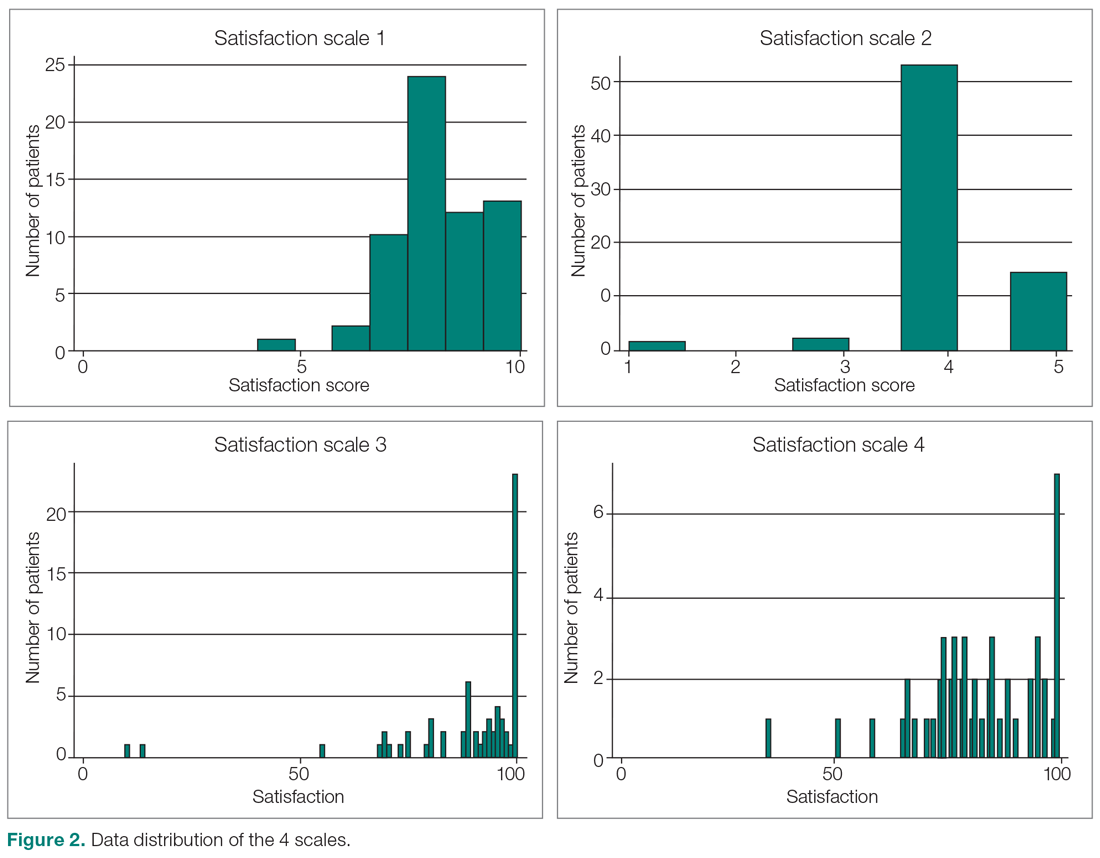

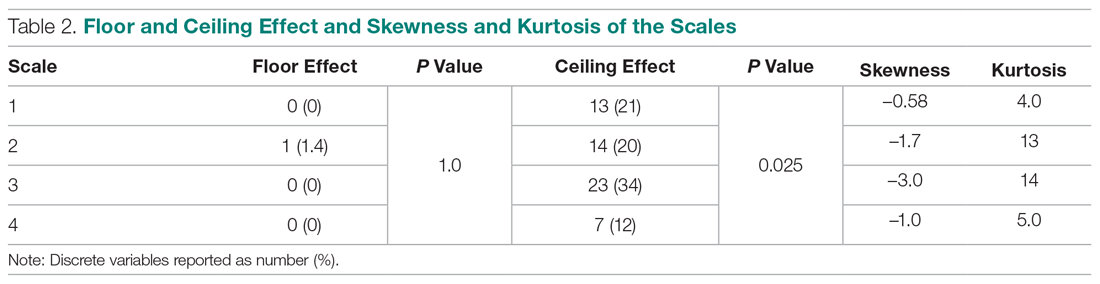

- Results: The nonnumerical 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and the 5-point Likert scale had the least ceiling effect (12% and 20%, respectively). The 11-point ordinal scale had skewness and kurtosis closest to a normal distribution (skew = –0.58 and kurtosis = 4.0). Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064). NPS were 35, 16, 67, and 20 for the scales, respectively.

- Conclusion: Single-question measures of satisfaction can be adjusted to limit the ceiling effect. Additional research in this area is warranted.

Keywords: patient satisfaction; floor and ceiling effect; skewness and kurtosis; quality improvement.

Patient satisfaction is an important quality metric that is increasingly being measured, reported, and incentivized. A qualitative study identified 7 themes influencing satisfaction among people visiting an orthopedic surgeon’s office: trust, relatedness, expectations, wait time, visit duration, communication, and empathy.1 However, another study found that satisfaction and perceived empathy are not associated with wait time or visit duration, but rather with the quality of the visit.2 Satisfaction measures that incorporate many of these features in relatively long questionnaires are associated with lower response rates3 and overlap with the factors whose influence on satisfaction one would like to study (eg, perceived empathy or communication effectiveness).4 Single- and multiple-question satisfaction scores are prone to a strong right skew, with a substantial ceiling effect.5 Ceiling effect occurs when a considerable proportion (about half) of participants select 1 of the top 2 scores (or the maximum score). An ideal scale would measure satisfaction independent from other factors, would use 1 or just a few questions, and would have little or no ceiling effect.

In this randomized controlled trial, we examined whether there were significant differences in mean and median satisfaction, floor and ceiling effect, and data distribution (by looking at skewness and kurtosis) between 4 different kinds of satisfaction scales asking about the helpfulness of a visit. Additionally, we hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared to the Net Promoter Scores (NPS). NPS are commonly used in the service industry to measure customer satisfaction; we are using these scores as a measure of patient satisfaction.

Methods

Study Design

All English-speaking new and return patients ages 18 to 89 years visiting an orthopedic surgeon in 1 of 7 clinics located in a large urban area were considered eligible for this study. Enrollment took place intermittently over a 5-month period. We were granted a waiver of written informed consent. Patients indicated their consent by completing the surveys. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of the 4 questionnaires containing different scale types using an Excel random-number generator. After the visit, patients were asked to complete the survey. All questionnaires were administered on an encrypted tablet via a HIPAA-compliant, secure web-based application for building and managing online surveys and databases (REDCap; Research Electronic Data Capture).6 This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board and is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03686735).7

Outcome Measures