User login

Poverty-related stress linked to aggressive head and neck cancer

A humanized mouse model suggests that head and neck cancer growth may stem from chronic stress. The study found that animals had immunophenotypic changes and a greater propensity towards tumor growth and metastasis.

Other studies have shown this may be caused by the lack of access to health care services or poor quality care. but the difference remains even after adjusting for these factors, according to researchers writing in Head and Neck.

Led by Heather A. Himburg, PhD, associate professor of radiation oncology with the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, researchers conducted a study of head and neck cancer models in which tumor cells were implanted into a mouse with a humanized immune system.

Their theory was that psychosocial stress may contribute to the growth of head and neck tumors. The stress of poverty, social deprivation and social isolation can lead to the up-regulation of proinflammatory markers in circulating blood leukocytes, and this has been tied to worse outcomes in hematologic malignancies and breast cancer. Many such studies examined social adversity and found an association with greater tumor growth rates and treatment resistance.

Other researchers have used mouse models to study the phenomenon, but the results have been inconclusive. For example, some research linked the beta-adrenergic pathway to head and neck cancer, but clinical trials of beta-blockers showed no benefit, and even potential harm, for patients with head and neck cancers. Those results imply that this pathway does not drive tumor growth and metastasis in the presence of chronic stress.

Previous research used immunocompromised or nonhumanized mice. However, neither type of model reproduces the human tumor microenvironment, which may contribute to ensuing clinical failures. In the new study, researchers describe results from a preclinical model created using a human head and neck cancer xenograft in a mouse with a humanized immune system.

How the study was conducted

The animals were randomly assigned to normal housing of two or three animals from the same litter to a cage, or social isolation from littermates. There were five male and five female animals in each arm, and the animals were housed in their separate conditions for 4 weeks before tumor implantation.

The isolated animals experienced increased growth and metastasis of the xenografts, compared with controls. The results are consistent with findings in immunodeficient or syngeneic mice, but the humanized nature of the new model could lead to better translation of findings into clinical studies. “The humanized model system in this study demonstrated the presence of both human myeloid and lymphoid lineages as well as expression of at least 40 human cytokines. These data indicate that our model is likely to well-represent the human condition and better predict human clinical responses as compared to both immunodeficient and syngeneic models,” the authors wrote.

The researchers also found that chronic stress may act through an immunoregulatory effect, since there was greater human immune infiltrate into the tumors of stressed animals. Increased presence of regulatory components like myeloid-derived suppressor cells or regulatory T cells, or eroded function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, might explain this finding. The researchers also identified a proinflammatory change in peripheral blood monocular cells in the stressed group. When they analyzed samples from patients who were low income earners of less than $45,000 in annual household income, they found a similar pattern. “This suggests that chronic socioeconomic stress may induce a similar proinflammatory immune state as our chronic stress model system,” the authors wrote.

Tumors were also different between the two groups of mice. Tumors in stressed animals had a higher percentage of cancer stem cells, which is associated with more aggressive tumors and worse disease-free survival. The researchers suggested that up-regulated levels of the chemokine SDF-1 seen in the stressed animals may be driving the higher proportion of stem cells through its effects on the CXCR4 receptor, which is expressed by stem cells in various organs and may cause migration, proliferation, and cell survival.

The study was funded by an endowment from Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin and a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A humanized mouse model suggests that head and neck cancer growth may stem from chronic stress. The study found that animals had immunophenotypic changes and a greater propensity towards tumor growth and metastasis.

Other studies have shown this may be caused by the lack of access to health care services or poor quality care. but the difference remains even after adjusting for these factors, according to researchers writing in Head and Neck.

Led by Heather A. Himburg, PhD, associate professor of radiation oncology with the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, researchers conducted a study of head and neck cancer models in which tumor cells were implanted into a mouse with a humanized immune system.

Their theory was that psychosocial stress may contribute to the growth of head and neck tumors. The stress of poverty, social deprivation and social isolation can lead to the up-regulation of proinflammatory markers in circulating blood leukocytes, and this has been tied to worse outcomes in hematologic malignancies and breast cancer. Many such studies examined social adversity and found an association with greater tumor growth rates and treatment resistance.

Other researchers have used mouse models to study the phenomenon, but the results have been inconclusive. For example, some research linked the beta-adrenergic pathway to head and neck cancer, but clinical trials of beta-blockers showed no benefit, and even potential harm, for patients with head and neck cancers. Those results imply that this pathway does not drive tumor growth and metastasis in the presence of chronic stress.

Previous research used immunocompromised or nonhumanized mice. However, neither type of model reproduces the human tumor microenvironment, which may contribute to ensuing clinical failures. In the new study, researchers describe results from a preclinical model created using a human head and neck cancer xenograft in a mouse with a humanized immune system.

How the study was conducted

The animals were randomly assigned to normal housing of two or three animals from the same litter to a cage, or social isolation from littermates. There were five male and five female animals in each arm, and the animals were housed in their separate conditions for 4 weeks before tumor implantation.

The isolated animals experienced increased growth and metastasis of the xenografts, compared with controls. The results are consistent with findings in immunodeficient or syngeneic mice, but the humanized nature of the new model could lead to better translation of findings into clinical studies. “The humanized model system in this study demonstrated the presence of both human myeloid and lymphoid lineages as well as expression of at least 40 human cytokines. These data indicate that our model is likely to well-represent the human condition and better predict human clinical responses as compared to both immunodeficient and syngeneic models,” the authors wrote.

The researchers also found that chronic stress may act through an immunoregulatory effect, since there was greater human immune infiltrate into the tumors of stressed animals. Increased presence of regulatory components like myeloid-derived suppressor cells or regulatory T cells, or eroded function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, might explain this finding. The researchers also identified a proinflammatory change in peripheral blood monocular cells in the stressed group. When they analyzed samples from patients who were low income earners of less than $45,000 in annual household income, they found a similar pattern. “This suggests that chronic socioeconomic stress may induce a similar proinflammatory immune state as our chronic stress model system,” the authors wrote.

Tumors were also different between the two groups of mice. Tumors in stressed animals had a higher percentage of cancer stem cells, which is associated with more aggressive tumors and worse disease-free survival. The researchers suggested that up-regulated levels of the chemokine SDF-1 seen in the stressed animals may be driving the higher proportion of stem cells through its effects on the CXCR4 receptor, which is expressed by stem cells in various organs and may cause migration, proliferation, and cell survival.

The study was funded by an endowment from Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin and a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A humanized mouse model suggests that head and neck cancer growth may stem from chronic stress. The study found that animals had immunophenotypic changes and a greater propensity towards tumor growth and metastasis.

Other studies have shown this may be caused by the lack of access to health care services or poor quality care. but the difference remains even after adjusting for these factors, according to researchers writing in Head and Neck.

Led by Heather A. Himburg, PhD, associate professor of radiation oncology with the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, researchers conducted a study of head and neck cancer models in which tumor cells were implanted into a mouse with a humanized immune system.

Their theory was that psychosocial stress may contribute to the growth of head and neck tumors. The stress of poverty, social deprivation and social isolation can lead to the up-regulation of proinflammatory markers in circulating blood leukocytes, and this has been tied to worse outcomes in hematologic malignancies and breast cancer. Many such studies examined social adversity and found an association with greater tumor growth rates and treatment resistance.

Other researchers have used mouse models to study the phenomenon, but the results have been inconclusive. For example, some research linked the beta-adrenergic pathway to head and neck cancer, but clinical trials of beta-blockers showed no benefit, and even potential harm, for patients with head and neck cancers. Those results imply that this pathway does not drive tumor growth and metastasis in the presence of chronic stress.

Previous research used immunocompromised or nonhumanized mice. However, neither type of model reproduces the human tumor microenvironment, which may contribute to ensuing clinical failures. In the new study, researchers describe results from a preclinical model created using a human head and neck cancer xenograft in a mouse with a humanized immune system.

How the study was conducted

The animals were randomly assigned to normal housing of two or three animals from the same litter to a cage, or social isolation from littermates. There were five male and five female animals in each arm, and the animals were housed in their separate conditions for 4 weeks before tumor implantation.

The isolated animals experienced increased growth and metastasis of the xenografts, compared with controls. The results are consistent with findings in immunodeficient or syngeneic mice, but the humanized nature of the new model could lead to better translation of findings into clinical studies. “The humanized model system in this study demonstrated the presence of both human myeloid and lymphoid lineages as well as expression of at least 40 human cytokines. These data indicate that our model is likely to well-represent the human condition and better predict human clinical responses as compared to both immunodeficient and syngeneic models,” the authors wrote.

The researchers also found that chronic stress may act through an immunoregulatory effect, since there was greater human immune infiltrate into the tumors of stressed animals. Increased presence of regulatory components like myeloid-derived suppressor cells or regulatory T cells, or eroded function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, might explain this finding. The researchers also identified a proinflammatory change in peripheral blood monocular cells in the stressed group. When they analyzed samples from patients who were low income earners of less than $45,000 in annual household income, they found a similar pattern. “This suggests that chronic socioeconomic stress may induce a similar proinflammatory immune state as our chronic stress model system,” the authors wrote.

Tumors were also different between the two groups of mice. Tumors in stressed animals had a higher percentage of cancer stem cells, which is associated with more aggressive tumors and worse disease-free survival. The researchers suggested that up-regulated levels of the chemokine SDF-1 seen in the stressed animals may be driving the higher proportion of stem cells through its effects on the CXCR4 receptor, which is expressed by stem cells in various organs and may cause migration, proliferation, and cell survival.

The study was funded by an endowment from Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin and a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM HEAD & NECK

Global melanoma incidence high and on the rise

Even by cautious calculations,

An estimated 325,000 people worldwide received a new diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma in 2020, and if present trends continue, the incidence of new cases is predicted to increase by about 50% in 2040, with melanoma deaths expected to rise by almost 70%, Melina Arnold, PhD, from the Cancer Surveillance Branch of the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, and colleagues reported.

“Melanoma is the most lethal form of skin cancer; this epidemiological assessment found a heavy public health and economic burden, and our projections suggest that it will remain so in the coming decades,” they wrote in a study published online in JAMA Dermatology.

In an accompanying editorial, Mavis Obeng-Kusi, MPharm and Ivo Abraham, PhD from the Center for Health Outcomes and PharmacoEconomic Research at the University of Arizona, Tucson, commented that the findings are “sobering,” but may substantially underestimate the gravity of the problem in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).

“The study by Arnold et al. brings to the fore a public health concern that requires global attention and initiates conversations particularly related to LMIC settings, where the incidence and mortality of melanoma is thought to be minimal and for which preventive measures may be insufficient,” they wrote.

Down Under nations lead

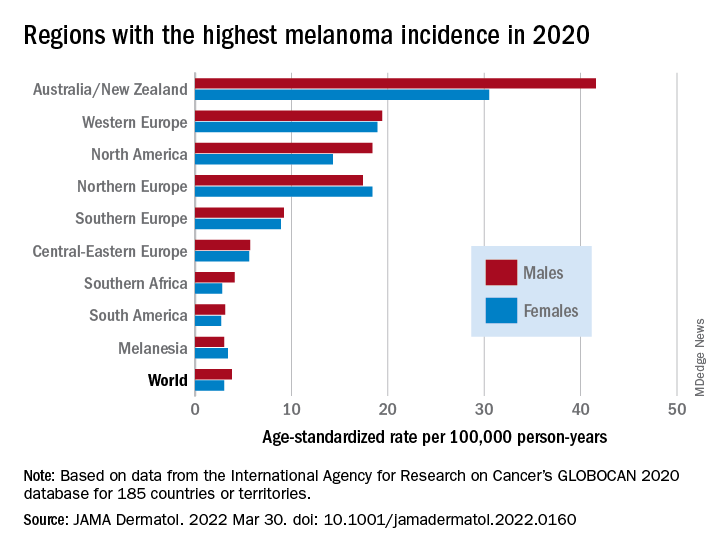

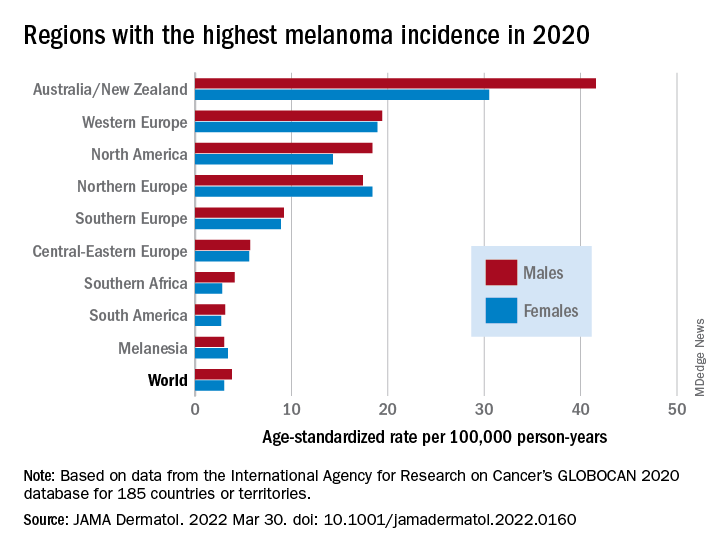

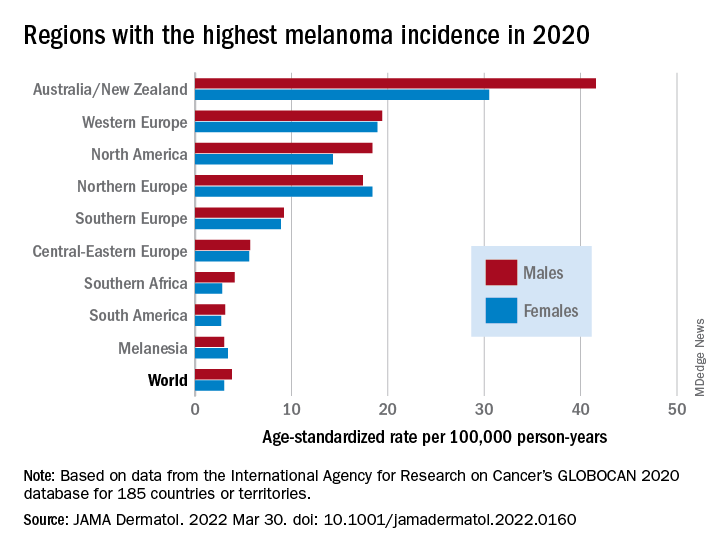

Dr. Arnold and colleagues looked at data on age-standardized melanoma incidence and mortality rates per 100,000 person-years (PY) by country, each of 20 world regions as defined by the United Nations, and according to the UN’s four-tier Human Development Index, which stratifies countries into low-, medium-, high-, and very high–income categories.

As noted previously, the researchers estimated that there were 325,000 new melanoma cases worldwide in 2020 (174,000 cases in males and 151,000 in females). There were 57,000 estimated melanoma deaths the same year (32,000 in males and 25,000 in females.

The highest incidence rates were seen in Australia and New Zealand, at 42 per 100,000 PY among males and 31 per 100,000 PY in females, followed by Western Europe with 19 per 100,000 PY in both males and females, North America with 18 and 14 cases per 100,000 PY in males and females respectively, and Northern Europe, with 17 per 100,000 PY in males, and 18 per 100,000 PY in females.

In contrast, in most African and Asian countries melanoma was rare, with rates commonly less than 1 per 100,000 PY, the investigators noted.

The melanoma mortality rate was highest in New Zealand, at 5 per 100,000 PY. Mortality rates worldwide varied less widely than incidence rates. In most other regions of the world, mortality rates were “much lower,” ranging between 0.2-1.0 per 100,000 PY, they wrote.

The authors estimated that, if 2020 rates remain stable, the global burden from melanoma in 2040 will increase to approximately 510,000 new cases and 96,000 deaths.

Public health efforts needed

In their editorial, Ms. Obeng-Kusi and Dr. Abraham pointed out that the study was hampered by the limited availability of cancer data from LMICs, leading the authors to estimate incidence and mortality rates based on proxy data, such as statistical modeling or averaged rates from neighboring countries.

They emphasized the need for going beyond the statistics: “Specific to cutaneous melanoma data, what is most important globally, knowing the exact numbers of cases and deaths or understanding the order of magnitude of the present and future epidemiology? No doubt the latter. Melanoma can be treated more easily if caught at earlier stages.”

Projections such as those provided by Dr. Arnold and colleagues could help to raise awareness of the importance of decreasing exposure to UV radiation, which accounts for three-fourths of all incident melanomas, the editorialists said.

The study was funded in part by a grant to coauthor Anna E. Cust, PhD, MPH. Dr. Cust reported receiving a fellowship from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council outside the submitted work. Dr. Arnold had no conflicts of interested to disclose. Dr. Abraham reported financial relationships with various entities. Ms. Obeng-Kusi had no disclosures.

Even by cautious calculations,

An estimated 325,000 people worldwide received a new diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma in 2020, and if present trends continue, the incidence of new cases is predicted to increase by about 50% in 2040, with melanoma deaths expected to rise by almost 70%, Melina Arnold, PhD, from the Cancer Surveillance Branch of the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, and colleagues reported.

“Melanoma is the most lethal form of skin cancer; this epidemiological assessment found a heavy public health and economic burden, and our projections suggest that it will remain so in the coming decades,” they wrote in a study published online in JAMA Dermatology.

In an accompanying editorial, Mavis Obeng-Kusi, MPharm and Ivo Abraham, PhD from the Center for Health Outcomes and PharmacoEconomic Research at the University of Arizona, Tucson, commented that the findings are “sobering,” but may substantially underestimate the gravity of the problem in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).

“The study by Arnold et al. brings to the fore a public health concern that requires global attention and initiates conversations particularly related to LMIC settings, where the incidence and mortality of melanoma is thought to be minimal and for which preventive measures may be insufficient,” they wrote.

Down Under nations lead

Dr. Arnold and colleagues looked at data on age-standardized melanoma incidence and mortality rates per 100,000 person-years (PY) by country, each of 20 world regions as defined by the United Nations, and according to the UN’s four-tier Human Development Index, which stratifies countries into low-, medium-, high-, and very high–income categories.

As noted previously, the researchers estimated that there were 325,000 new melanoma cases worldwide in 2020 (174,000 cases in males and 151,000 in females). There were 57,000 estimated melanoma deaths the same year (32,000 in males and 25,000 in females.

The highest incidence rates were seen in Australia and New Zealand, at 42 per 100,000 PY among males and 31 per 100,000 PY in females, followed by Western Europe with 19 per 100,000 PY in both males and females, North America with 18 and 14 cases per 100,000 PY in males and females respectively, and Northern Europe, with 17 per 100,000 PY in males, and 18 per 100,000 PY in females.

In contrast, in most African and Asian countries melanoma was rare, with rates commonly less than 1 per 100,000 PY, the investigators noted.

The melanoma mortality rate was highest in New Zealand, at 5 per 100,000 PY. Mortality rates worldwide varied less widely than incidence rates. In most other regions of the world, mortality rates were “much lower,” ranging between 0.2-1.0 per 100,000 PY, they wrote.

The authors estimated that, if 2020 rates remain stable, the global burden from melanoma in 2040 will increase to approximately 510,000 new cases and 96,000 deaths.

Public health efforts needed

In their editorial, Ms. Obeng-Kusi and Dr. Abraham pointed out that the study was hampered by the limited availability of cancer data from LMICs, leading the authors to estimate incidence and mortality rates based on proxy data, such as statistical modeling or averaged rates from neighboring countries.

They emphasized the need for going beyond the statistics: “Specific to cutaneous melanoma data, what is most important globally, knowing the exact numbers of cases and deaths or understanding the order of magnitude of the present and future epidemiology? No doubt the latter. Melanoma can be treated more easily if caught at earlier stages.”

Projections such as those provided by Dr. Arnold and colleagues could help to raise awareness of the importance of decreasing exposure to UV radiation, which accounts for three-fourths of all incident melanomas, the editorialists said.

The study was funded in part by a grant to coauthor Anna E. Cust, PhD, MPH. Dr. Cust reported receiving a fellowship from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council outside the submitted work. Dr. Arnold had no conflicts of interested to disclose. Dr. Abraham reported financial relationships with various entities. Ms. Obeng-Kusi had no disclosures.

Even by cautious calculations,

An estimated 325,000 people worldwide received a new diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma in 2020, and if present trends continue, the incidence of new cases is predicted to increase by about 50% in 2040, with melanoma deaths expected to rise by almost 70%, Melina Arnold, PhD, from the Cancer Surveillance Branch of the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, and colleagues reported.

“Melanoma is the most lethal form of skin cancer; this epidemiological assessment found a heavy public health and economic burden, and our projections suggest that it will remain so in the coming decades,” they wrote in a study published online in JAMA Dermatology.

In an accompanying editorial, Mavis Obeng-Kusi, MPharm and Ivo Abraham, PhD from the Center for Health Outcomes and PharmacoEconomic Research at the University of Arizona, Tucson, commented that the findings are “sobering,” but may substantially underestimate the gravity of the problem in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).

“The study by Arnold et al. brings to the fore a public health concern that requires global attention and initiates conversations particularly related to LMIC settings, where the incidence and mortality of melanoma is thought to be minimal and for which preventive measures may be insufficient,” they wrote.

Down Under nations lead

Dr. Arnold and colleagues looked at data on age-standardized melanoma incidence and mortality rates per 100,000 person-years (PY) by country, each of 20 world regions as defined by the United Nations, and according to the UN’s four-tier Human Development Index, which stratifies countries into low-, medium-, high-, and very high–income categories.

As noted previously, the researchers estimated that there were 325,000 new melanoma cases worldwide in 2020 (174,000 cases in males and 151,000 in females). There were 57,000 estimated melanoma deaths the same year (32,000 in males and 25,000 in females.

The highest incidence rates were seen in Australia and New Zealand, at 42 per 100,000 PY among males and 31 per 100,000 PY in females, followed by Western Europe with 19 per 100,000 PY in both males and females, North America with 18 and 14 cases per 100,000 PY in males and females respectively, and Northern Europe, with 17 per 100,000 PY in males, and 18 per 100,000 PY in females.

In contrast, in most African and Asian countries melanoma was rare, with rates commonly less than 1 per 100,000 PY, the investigators noted.

The melanoma mortality rate was highest in New Zealand, at 5 per 100,000 PY. Mortality rates worldwide varied less widely than incidence rates. In most other regions of the world, mortality rates were “much lower,” ranging between 0.2-1.0 per 100,000 PY, they wrote.

The authors estimated that, if 2020 rates remain stable, the global burden from melanoma in 2040 will increase to approximately 510,000 new cases and 96,000 deaths.

Public health efforts needed

In their editorial, Ms. Obeng-Kusi and Dr. Abraham pointed out that the study was hampered by the limited availability of cancer data from LMICs, leading the authors to estimate incidence and mortality rates based on proxy data, such as statistical modeling or averaged rates from neighboring countries.

They emphasized the need for going beyond the statistics: “Specific to cutaneous melanoma data, what is most important globally, knowing the exact numbers of cases and deaths or understanding the order of magnitude of the present and future epidemiology? No doubt the latter. Melanoma can be treated more easily if caught at earlier stages.”

Projections such as those provided by Dr. Arnold and colleagues could help to raise awareness of the importance of decreasing exposure to UV radiation, which accounts for three-fourths of all incident melanomas, the editorialists said.

The study was funded in part by a grant to coauthor Anna E. Cust, PhD, MPH. Dr. Cust reported receiving a fellowship from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council outside the submitted work. Dr. Arnold had no conflicts of interested to disclose. Dr. Abraham reported financial relationships with various entities. Ms. Obeng-Kusi had no disclosures.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

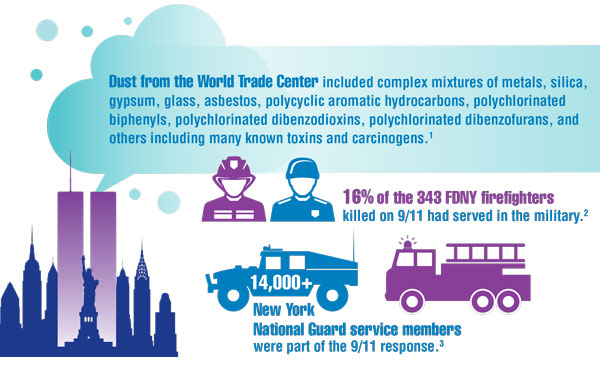

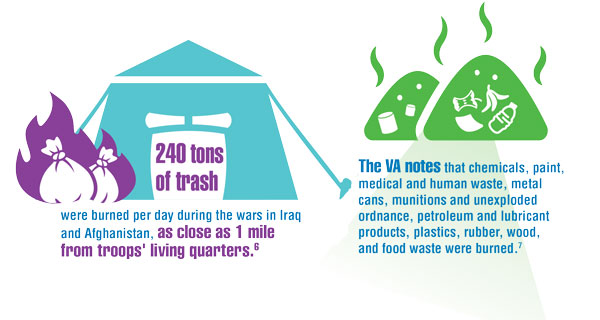

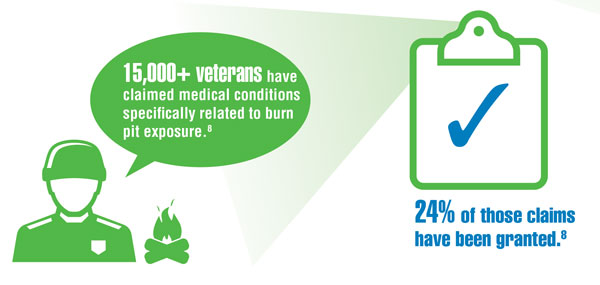

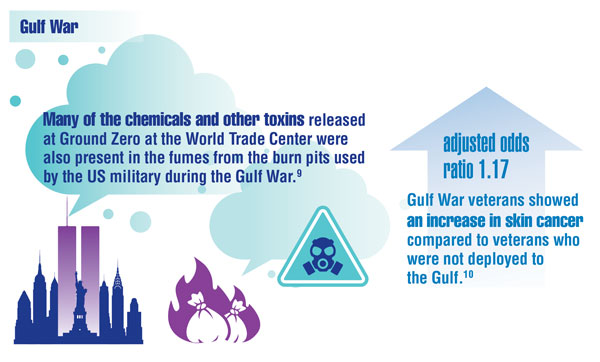

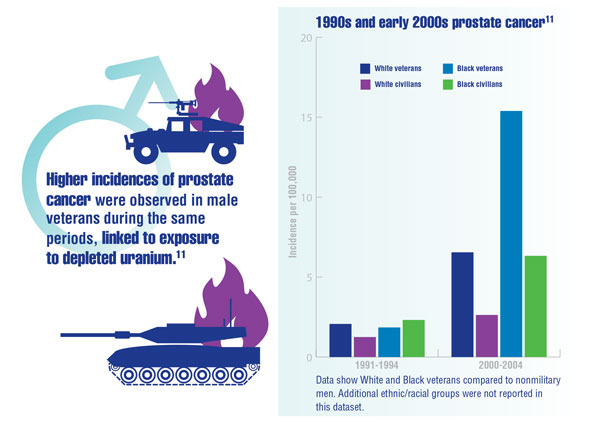

Cancer Data Trends 2022: Exposure-Related Cancers

- Santiago-Colón A, Daniels R, Reissman D, et al. World Trade Center Health Program: first decade of research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19):7290. doi:10.3390/ijerph17197290

- Frank Dwyer, FDNY Deputy Commissioner. Personal communication (email, December 20, 2021).

- Campbell R. New York Guard members reflect on 9/11 response. US Army News. Published September 8, 2021. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://www.army.mil/article/250057/new_york_guard_members_reflect_on_911_response

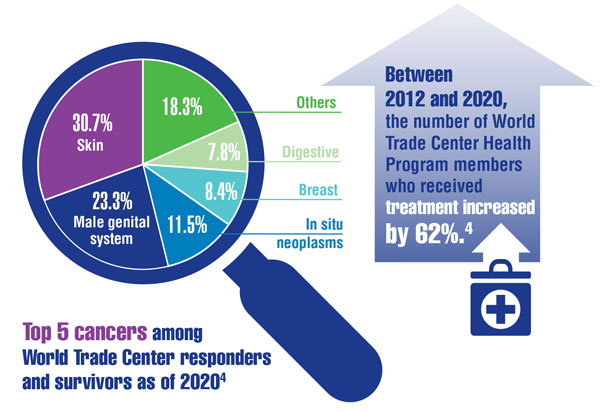

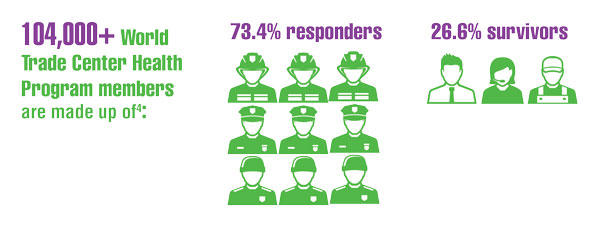

- Azofeifa A, Martin GR, Satiago-Colón A, et al. World Trade Center Health Program — United States, 2012−2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021;70(4):1-21. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss7004a1

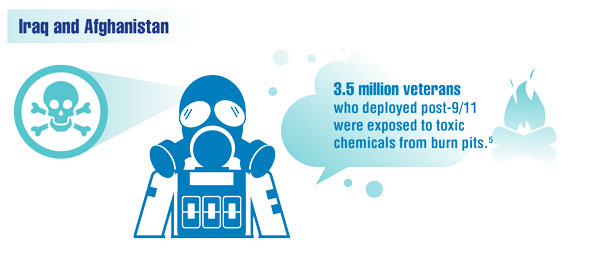

- Lantry L, Meneses I. Expanded benefits for vets exposed to burn pits coming, but for some it's too late. ABC News. Published November 23, 2021. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/expanded-benefits-vets-exposed-burn-pits-coming-late/story?id=81261917

- Kennedy K. “The enemy is lurking in our bodies”—Women veterans say toxic exposure caused breast cancer. The War Horse. Published October 14, 2021. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://thewarhorse.org/military-women-face-higher-breast-cancer-rates-from-exposure/

- US Department of Veteran Affairs. Airborne hazards and burn pit exposure. Updated August 5, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/burnpits/

- VA spokesperson, US Department of Veterans Affairs. Personal communication (e-mail, December 20, 2021).

- Burn Pits 360. Toxic exposure table (in reference to VA 10-03). Published 2020. Accessed December 20, 2021. https://burnpits360.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Toxic-Exposure-Table-2020_V2.pdf

- Dursa EK, Cao G, Porter B, et al. The health of Gulf War and Gulf era veterans over time: US Department of Veterans Affairs’ Gulf War longitudinal study. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(10):889-894. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002331

- Zhu K, Devesa SS, Wu H, et al. Cancer incidence in the US military population: comparison with rates from the SEER program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1740-1745. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0041

- Santiago-Colón A, Daniels R, Reissman D, et al. World Trade Center Health Program: first decade of research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19):7290. doi:10.3390/ijerph17197290

- Frank Dwyer, FDNY Deputy Commissioner. Personal communication (email, December 20, 2021).

- Campbell R. New York Guard members reflect on 9/11 response. US Army News. Published September 8, 2021. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://www.army.mil/article/250057/new_york_guard_members_reflect_on_911_response

- Azofeifa A, Martin GR, Satiago-Colón A, et al. World Trade Center Health Program — United States, 2012−2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021;70(4):1-21. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss7004a1

- Lantry L, Meneses I. Expanded benefits for vets exposed to burn pits coming, but for some it's too late. ABC News. Published November 23, 2021. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/expanded-benefits-vets-exposed-burn-pits-coming-late/story?id=81261917

- Kennedy K. “The enemy is lurking in our bodies”—Women veterans say toxic exposure caused breast cancer. The War Horse. Published October 14, 2021. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://thewarhorse.org/military-women-face-higher-breast-cancer-rates-from-exposure/

- US Department of Veteran Affairs. Airborne hazards and burn pit exposure. Updated August 5, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/burnpits/

- VA spokesperson, US Department of Veterans Affairs. Personal communication (e-mail, December 20, 2021).

- Burn Pits 360. Toxic exposure table (in reference to VA 10-03). Published 2020. Accessed December 20, 2021. https://burnpits360.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Toxic-Exposure-Table-2020_V2.pdf

- Dursa EK, Cao G, Porter B, et al. The health of Gulf War and Gulf era veterans over time: US Department of Veterans Affairs’ Gulf War longitudinal study. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(10):889-894. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002331

- Zhu K, Devesa SS, Wu H, et al. Cancer incidence in the US military population: comparison with rates from the SEER program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1740-1745. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0041

- Santiago-Colón A, Daniels R, Reissman D, et al. World Trade Center Health Program: first decade of research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19):7290. doi:10.3390/ijerph17197290

- Frank Dwyer, FDNY Deputy Commissioner. Personal communication (email, December 20, 2021).

- Campbell R. New York Guard members reflect on 9/11 response. US Army News. Published September 8, 2021. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://www.army.mil/article/250057/new_york_guard_members_reflect_on_911_response

- Azofeifa A, Martin GR, Satiago-Colón A, et al. World Trade Center Health Program — United States, 2012−2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021;70(4):1-21. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss7004a1

- Lantry L, Meneses I. Expanded benefits for vets exposed to burn pits coming, but for some it's too late. ABC News. Published November 23, 2021. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/expanded-benefits-vets-exposed-burn-pits-coming-late/story?id=81261917

- Kennedy K. “The enemy is lurking in our bodies”—Women veterans say toxic exposure caused breast cancer. The War Horse. Published October 14, 2021. Accessed December 17, 2021. https://thewarhorse.org/military-women-face-higher-breast-cancer-rates-from-exposure/

- US Department of Veteran Affairs. Airborne hazards and burn pit exposure. Updated August 5, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/burnpits/

- VA spokesperson, US Department of Veterans Affairs. Personal communication (e-mail, December 20, 2021).

- Burn Pits 360. Toxic exposure table (in reference to VA 10-03). Published 2020. Accessed December 20, 2021. https://burnpits360.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Toxic-Exposure-Table-2020_V2.pdf

- Dursa EK, Cao G, Porter B, et al. The health of Gulf War and Gulf era veterans over time: US Department of Veterans Affairs’ Gulf War longitudinal study. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(10):889-894. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002331

- Zhu K, Devesa SS, Wu H, et al. Cancer incidence in the US military population: comparison with rates from the SEER program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1740-1745. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0041

Cancer Data Trends 2022

Federal Practitioner, in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), present the 2022 edition of Cancer Data Trends (click to view the digital edition). This special issue provides updates on some of the top cancers and related concerns affecting veterans through original infographics and visual storytelling.

In this issue:

- Exposure-Related Cancers

- Cancer in Women

- Genitourinary Cancers

- Gastrointestinal Cancers

- Telehealth in Oncology

- Precision Oncology

- Palliative and Hospice Care

- Alcohol and Cancer

- Lung Cancer

- Oropharyngeal Cancer

- Hematologic Cancers

Federal Practitioner and AVAHO would like to thank the following experts for their contributions to this issue:

Anita Aggarwal, DO, PhD; Sara Ahmed, PhD; Katherine Faricy-Anderson, MD; Apar Kishor Ganti, MD, MS; Solomon A Graf, MD; Kate Hendricks Thomas, PhD; Michael Kelley, MD; Mark Klein, MD, Gina McWhirter, MSN, MBA, RN; Bruce Montgomery, MD; Vida Almario Passero, MD, MBA; Thomas D Rodgers, MD; Vlad C Sandulache, MD, PhD; David H Wang, MD, PhD.

Federal Practitioner, in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), present the 2022 edition of Cancer Data Trends (click to view the digital edition). This special issue provides updates on some of the top cancers and related concerns affecting veterans through original infographics and visual storytelling.

In this issue:

- Exposure-Related Cancers

- Cancer in Women

- Genitourinary Cancers

- Gastrointestinal Cancers

- Telehealth in Oncology

- Precision Oncology

- Palliative and Hospice Care

- Alcohol and Cancer

- Lung Cancer

- Oropharyngeal Cancer

- Hematologic Cancers

Federal Practitioner and AVAHO would like to thank the following experts for their contributions to this issue:

Anita Aggarwal, DO, PhD; Sara Ahmed, PhD; Katherine Faricy-Anderson, MD; Apar Kishor Ganti, MD, MS; Solomon A Graf, MD; Kate Hendricks Thomas, PhD; Michael Kelley, MD; Mark Klein, MD, Gina McWhirter, MSN, MBA, RN; Bruce Montgomery, MD; Vida Almario Passero, MD, MBA; Thomas D Rodgers, MD; Vlad C Sandulache, MD, PhD; David H Wang, MD, PhD.

Federal Practitioner, in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), present the 2022 edition of Cancer Data Trends (click to view the digital edition). This special issue provides updates on some of the top cancers and related concerns affecting veterans through original infographics and visual storytelling.

In this issue:

- Exposure-Related Cancers

- Cancer in Women

- Genitourinary Cancers

- Gastrointestinal Cancers

- Telehealth in Oncology

- Precision Oncology

- Palliative and Hospice Care

- Alcohol and Cancer

- Lung Cancer

- Oropharyngeal Cancer

- Hematologic Cancers

Federal Practitioner and AVAHO would like to thank the following experts for their contributions to this issue:

Anita Aggarwal, DO, PhD; Sara Ahmed, PhD; Katherine Faricy-Anderson, MD; Apar Kishor Ganti, MD, MS; Solomon A Graf, MD; Kate Hendricks Thomas, PhD; Michael Kelley, MD; Mark Klein, MD, Gina McWhirter, MSN, MBA, RN; Bruce Montgomery, MD; Vida Almario Passero, MD, MBA; Thomas D Rodgers, MD; Vlad C Sandulache, MD, PhD; David H Wang, MD, PhD.

Cancer survivors: Move more, sit less for a longer life, study says

Being physically active, on the other hand, lowers the risk of early death, new research shows.

What’s “alarming” is that so many cancer survivors have a sedentary lifestyle, Chao Cao and Lin Yang, PhD, with Alberta Health Services in Calgary, who worked on the study, said in an interview.

The American Cancer Society recommends that cancer survivors follow the same physical activity guidance as the general population. The target is 150-300 minutes of moderate activity or 75-150 minutes of vigorous activity each week (or a combination of these).

“Getting to or exceeding the upper limit of 300 minutes is ideal,” Mr. Cao and Dr. Yang say.

Yet in their study of more than 1,500 cancer survivors, more than half (57%) were inactive, reporting no weekly leisure-time physical activity in the past week.

About 16% were “insufficiently” active, or getting less than 150 minutes per week. Meanwhile, 28% were active, achieving more than 150 minutes of weekly physical activity.

Digging deeper, the researchers found that more than one-third of cancer survivors reported sitting for 6-8 hours each day, and one-quarter reported sitting for more than 8 hours per day.

Over the course of up to 9 years, 293 of the cancer survivors died – 114 from cancer, 41 from heart diseases, and 138 from other causes.

After accounting for things that might influence the results, the risk of dying from any cause or cancer was about 65% lower in cancer survivors who were physically active, relative to their inactive peers.

Sitting for long periods was especially risky, according to the study in JAMA Oncology.

Compared with cancer survivors who sat for less than 4 hours each day, cancer survivors who reported sitting for more than 8 hours a day had nearly twice the risk of dying from any cause and more than twice the risk of dying from cancer.

Cancer survivors who sat for more than 8 hours a day, and were inactive or not active enough, had as much as five times the risk of death from any cause or cancer.

“Be active and sit less, move more, and move frequently,” advise Mr. Cao and Dr. Yang. “Avoiding prolonged sitting is essential for most cancer survivors to reduce excess mortality risks.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Being physically active, on the other hand, lowers the risk of early death, new research shows.

What’s “alarming” is that so many cancer survivors have a sedentary lifestyle, Chao Cao and Lin Yang, PhD, with Alberta Health Services in Calgary, who worked on the study, said in an interview.

The American Cancer Society recommends that cancer survivors follow the same physical activity guidance as the general population. The target is 150-300 minutes of moderate activity or 75-150 minutes of vigorous activity each week (or a combination of these).

“Getting to or exceeding the upper limit of 300 minutes is ideal,” Mr. Cao and Dr. Yang say.

Yet in their study of more than 1,500 cancer survivors, more than half (57%) were inactive, reporting no weekly leisure-time physical activity in the past week.

About 16% were “insufficiently” active, or getting less than 150 minutes per week. Meanwhile, 28% were active, achieving more than 150 minutes of weekly physical activity.

Digging deeper, the researchers found that more than one-third of cancer survivors reported sitting for 6-8 hours each day, and one-quarter reported sitting for more than 8 hours per day.

Over the course of up to 9 years, 293 of the cancer survivors died – 114 from cancer, 41 from heart diseases, and 138 from other causes.

After accounting for things that might influence the results, the risk of dying from any cause or cancer was about 65% lower in cancer survivors who were physically active, relative to their inactive peers.

Sitting for long periods was especially risky, according to the study in JAMA Oncology.

Compared with cancer survivors who sat for less than 4 hours each day, cancer survivors who reported sitting for more than 8 hours a day had nearly twice the risk of dying from any cause and more than twice the risk of dying from cancer.

Cancer survivors who sat for more than 8 hours a day, and were inactive or not active enough, had as much as five times the risk of death from any cause or cancer.

“Be active and sit less, move more, and move frequently,” advise Mr. Cao and Dr. Yang. “Avoiding prolonged sitting is essential for most cancer survivors to reduce excess mortality risks.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Being physically active, on the other hand, lowers the risk of early death, new research shows.

What’s “alarming” is that so many cancer survivors have a sedentary lifestyle, Chao Cao and Lin Yang, PhD, with Alberta Health Services in Calgary, who worked on the study, said in an interview.

The American Cancer Society recommends that cancer survivors follow the same physical activity guidance as the general population. The target is 150-300 minutes of moderate activity or 75-150 minutes of vigorous activity each week (or a combination of these).

“Getting to or exceeding the upper limit of 300 minutes is ideal,” Mr. Cao and Dr. Yang say.

Yet in their study of more than 1,500 cancer survivors, more than half (57%) were inactive, reporting no weekly leisure-time physical activity in the past week.

About 16% were “insufficiently” active, or getting less than 150 minutes per week. Meanwhile, 28% were active, achieving more than 150 minutes of weekly physical activity.

Digging deeper, the researchers found that more than one-third of cancer survivors reported sitting for 6-8 hours each day, and one-quarter reported sitting for more than 8 hours per day.

Over the course of up to 9 years, 293 of the cancer survivors died – 114 from cancer, 41 from heart diseases, and 138 from other causes.

After accounting for things that might influence the results, the risk of dying from any cause or cancer was about 65% lower in cancer survivors who were physically active, relative to their inactive peers.

Sitting for long periods was especially risky, according to the study in JAMA Oncology.

Compared with cancer survivors who sat for less than 4 hours each day, cancer survivors who reported sitting for more than 8 hours a day had nearly twice the risk of dying from any cause and more than twice the risk of dying from cancer.

Cancer survivors who sat for more than 8 hours a day, and were inactive or not active enough, had as much as five times the risk of death from any cause or cancer.

“Be active and sit less, move more, and move frequently,” advise Mr. Cao and Dr. Yang. “Avoiding prolonged sitting is essential for most cancer survivors to reduce excess mortality risks.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Two leading oral cancer treatment guidelines differ on recurrence and survival predictions

(OCSCC), according to a retrospective study.

Treatment of OCSCC involves resection of the primary tumor, followed by neck dissection or postoperative radiotherapy when needed, but choice of treatment requires an accurate assessment of resection margins. Previous studies have failed to consistently show a correlation between margin status and clinical outcomes. Tumor size, depth of invasion, and other factors may explain inconsistent findings, but another possibility is the variability in how margin status is defined.

RCPath and CAP are among the most commonly used definitions. RCPath defines a positive margin as invasive tumor within 1 mm of the surgical margin, while CAP defines a positive margin as the presence of primary tumor or high-grade dysplasia at the margin itself. CAP recommends determination of a “final margin status” that also considers separately submitted extra tumor bed margins. Nevertheless, multiple studies have shown that reliance on the main tumor specimen outperformed the combined approach in predicting recurrence and survival.

In a study published online March 7 in Oral Oncology, researchers examined records from 300 patients (33.7% of whom were female) at South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital in Ireland between 2007 and 2020. The researchers found that 28.7% had margins determined by the RCPath definition and 16.7% according to the CAP definition. Forty-nine percent underwent extra tumor bed resections.

The mean follow-up period was 49 months, 64 months for surviving patients. Multivariate analyses accounting for other established prognosticators found that local recurrence was associated with CAP margins (odds ratio [OR], 1.86; 955 confidence interval [CI], 1.02-3.48) and T3/T4 classification (OR, 2.80; 95% CI, 1.53-5.13). CAP margins predicted disease-specific survival (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.53-5.13) and narrowly missed significance in predicting overall survival (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 0.99-2.75). RCPath margins were not predictive.

The researchers found a significant association between RCPath definition and metastatic nodal disease and extranodal extension, but there was no such relationship between these negative predictors and CAP and final margin status. “This finding may explain the superior independent prognostic ability of CAP margin status over RCPath in our cohort and is consistent with that of previous studies, which concluded that other histological risk factors are more important than margin status in predicting outcome,” the authors wrote.

Studies suggest that margins fewer than 1 mm remain a high-risk group, with worse survival outcomes than those of patients with 1- to 5-mm margins, even if the risk is lower than tumor at margins. “The optimum cut-off between low-risk and high-risk margins in OCSCC remains unresolved,” the authors wrote.

The study was retrospective and relied on data from a single center, and the patients included in the study may not be directly comparable to other OCSCC patients. The study was funded by the Head and Neck Oncology Fund, South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital.

(OCSCC), according to a retrospective study.

Treatment of OCSCC involves resection of the primary tumor, followed by neck dissection or postoperative radiotherapy when needed, but choice of treatment requires an accurate assessment of resection margins. Previous studies have failed to consistently show a correlation between margin status and clinical outcomes. Tumor size, depth of invasion, and other factors may explain inconsistent findings, but another possibility is the variability in how margin status is defined.

RCPath and CAP are among the most commonly used definitions. RCPath defines a positive margin as invasive tumor within 1 mm of the surgical margin, while CAP defines a positive margin as the presence of primary tumor or high-grade dysplasia at the margin itself. CAP recommends determination of a “final margin status” that also considers separately submitted extra tumor bed margins. Nevertheless, multiple studies have shown that reliance on the main tumor specimen outperformed the combined approach in predicting recurrence and survival.

In a study published online March 7 in Oral Oncology, researchers examined records from 300 patients (33.7% of whom were female) at South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital in Ireland between 2007 and 2020. The researchers found that 28.7% had margins determined by the RCPath definition and 16.7% according to the CAP definition. Forty-nine percent underwent extra tumor bed resections.

The mean follow-up period was 49 months, 64 months for surviving patients. Multivariate analyses accounting for other established prognosticators found that local recurrence was associated with CAP margins (odds ratio [OR], 1.86; 955 confidence interval [CI], 1.02-3.48) and T3/T4 classification (OR, 2.80; 95% CI, 1.53-5.13). CAP margins predicted disease-specific survival (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.53-5.13) and narrowly missed significance in predicting overall survival (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 0.99-2.75). RCPath margins were not predictive.

The researchers found a significant association between RCPath definition and metastatic nodal disease and extranodal extension, but there was no such relationship between these negative predictors and CAP and final margin status. “This finding may explain the superior independent prognostic ability of CAP margin status over RCPath in our cohort and is consistent with that of previous studies, which concluded that other histological risk factors are more important than margin status in predicting outcome,” the authors wrote.

Studies suggest that margins fewer than 1 mm remain a high-risk group, with worse survival outcomes than those of patients with 1- to 5-mm margins, even if the risk is lower than tumor at margins. “The optimum cut-off between low-risk and high-risk margins in OCSCC remains unresolved,” the authors wrote.

The study was retrospective and relied on data from a single center, and the patients included in the study may not be directly comparable to other OCSCC patients. The study was funded by the Head and Neck Oncology Fund, South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital.

(OCSCC), according to a retrospective study.

Treatment of OCSCC involves resection of the primary tumor, followed by neck dissection or postoperative radiotherapy when needed, but choice of treatment requires an accurate assessment of resection margins. Previous studies have failed to consistently show a correlation between margin status and clinical outcomes. Tumor size, depth of invasion, and other factors may explain inconsistent findings, but another possibility is the variability in how margin status is defined.

RCPath and CAP are among the most commonly used definitions. RCPath defines a positive margin as invasive tumor within 1 mm of the surgical margin, while CAP defines a positive margin as the presence of primary tumor or high-grade dysplasia at the margin itself. CAP recommends determination of a “final margin status” that also considers separately submitted extra tumor bed margins. Nevertheless, multiple studies have shown that reliance on the main tumor specimen outperformed the combined approach in predicting recurrence and survival.

In a study published online March 7 in Oral Oncology, researchers examined records from 300 patients (33.7% of whom were female) at South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital in Ireland between 2007 and 2020. The researchers found that 28.7% had margins determined by the RCPath definition and 16.7% according to the CAP definition. Forty-nine percent underwent extra tumor bed resections.

The mean follow-up period was 49 months, 64 months for surviving patients. Multivariate analyses accounting for other established prognosticators found that local recurrence was associated with CAP margins (odds ratio [OR], 1.86; 955 confidence interval [CI], 1.02-3.48) and T3/T4 classification (OR, 2.80; 95% CI, 1.53-5.13). CAP margins predicted disease-specific survival (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.53-5.13) and narrowly missed significance in predicting overall survival (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 0.99-2.75). RCPath margins were not predictive.

The researchers found a significant association between RCPath definition and metastatic nodal disease and extranodal extension, but there was no such relationship between these negative predictors and CAP and final margin status. “This finding may explain the superior independent prognostic ability of CAP margin status over RCPath in our cohort and is consistent with that of previous studies, which concluded that other histological risk factors are more important than margin status in predicting outcome,” the authors wrote.

Studies suggest that margins fewer than 1 mm remain a high-risk group, with worse survival outcomes than those of patients with 1- to 5-mm margins, even if the risk is lower than tumor at margins. “The optimum cut-off between low-risk and high-risk margins in OCSCC remains unresolved,” the authors wrote.

The study was retrospective and relied on data from a single center, and the patients included in the study may not be directly comparable to other OCSCC patients. The study was funded by the Head and Neck Oncology Fund, South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital.

FROM ORAL ONCOLOGY

Immunotherapy treatment shows promise for resectable liver cancer

(HCC), according to findings from an open-label phase 2 clinical trial published in The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatolgy.

The study compared the anti-PD1 antibody nivolumab (Opdivo, Bristol Myers Squibb) alone and nivolumab plus the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab (Yervoy, Bristol Myers Squibb) among patients with resectable disease at a single center in Sweden. The treatments were found to be “safe and feasible in patients with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma,” wrote researchers who were led by Ahmed O. Kaseb, MD, a medical oncologist with MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

The rate of 5-year tumor recurrence following HCC resection can be as high as 70%, and there are no approved neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapies.

Immune checkpoint therapy has not been well studied in early-stage HCC, but it is used in advanced HCC.

The combination of PDL1 blockade with atezolizumab and VEGF blockade with bevacizumab, is currently a first-line treatment for advanced HCC. “Checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD1 and PDL1 and CTLA4 are active, tolerable, and clinically beneficial against advanced HCC,” according to researchers writing in a Nature Reviews article published in April 2021.

There are other promising immunotherapies under study for HCC, such as additional checkpoint inhibitors, adoptive cell transfer, vaccination, and virotherapy.

Small study of 27 patients

The Lancet study included 27 patients (64 years mean age, 19 patients were male). Twenty-three percent of patients on nivolumab alone had a partial pathological response at week 6, while none in the combination group had a response. Among 20 patients who underwent surgery, 3 of 9 (33%) and 3 of 11 (27%) in the combination group experienced a major pathological response. Two patients in the nivolumab and three patients in the combination group achieved a complete pathological response.

Disease progression occurred in 7 of 12 patients who were evaluated in the nivolumab group, and 4 of 13 patients in the combination group. Estimated median time to disease progression in the nivolumab group was 9.4 months (95% confidence interval, 1.47 to not estimable) and 19.53 months (95% CI, 2.33 to not estimable) in the combination group. Two-year progression-free survival was estimated to be 42% (95% CI, 21%-81%) in the nivolumab group and 26% (95% CI, 8%-78%, no significant difference) in the combination group.

Among 20 patients who underwent surgery, 6 patients had experienced a major pathological response. None of the 6 patients had a recurrence after a median follow-up of 26.8 months, versus 7 recurrences among 14 patients without a pathological response (log-rank P = .049).

Seventy-seven percent of patients in the nivolumab group experienced at least one adverse event (23% grade 3-4), as did 86% in the combination group (43% grade 3-4, difference nonsignificant). No patients delayed or canceled surgery because of adverse events.

Patients who had a major pathological response on the combination treatment had higher levels of immune infiltration versus baseline values. Those who had complete pathological responses in the nivolumab group had high infiltration at baseline. Those results imply some optimism for further study. “These data suggest that, with the immune-priming ability of anti–CTLA-4 treatment, nivolumab plus ipilimumab was able to generate a major pathological response even in tumours that had low immune infiltration at baseline,” the authors wrote.

The study was limited by its open-label nature and small sample size, and it was conducted at a single center.

The study was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kaseb reports consulting, advisory roles or stock ownership, or both with Bristol-Myers Squibb.

(HCC), according to findings from an open-label phase 2 clinical trial published in The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatolgy.

The study compared the anti-PD1 antibody nivolumab (Opdivo, Bristol Myers Squibb) alone and nivolumab plus the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab (Yervoy, Bristol Myers Squibb) among patients with resectable disease at a single center in Sweden. The treatments were found to be “safe and feasible in patients with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma,” wrote researchers who were led by Ahmed O. Kaseb, MD, a medical oncologist with MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

The rate of 5-year tumor recurrence following HCC resection can be as high as 70%, and there are no approved neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapies.

Immune checkpoint therapy has not been well studied in early-stage HCC, but it is used in advanced HCC.

The combination of PDL1 blockade with atezolizumab and VEGF blockade with bevacizumab, is currently a first-line treatment for advanced HCC. “Checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD1 and PDL1 and CTLA4 are active, tolerable, and clinically beneficial against advanced HCC,” according to researchers writing in a Nature Reviews article published in April 2021.

There are other promising immunotherapies under study for HCC, such as additional checkpoint inhibitors, adoptive cell transfer, vaccination, and virotherapy.

Small study of 27 patients

The Lancet study included 27 patients (64 years mean age, 19 patients were male). Twenty-three percent of patients on nivolumab alone had a partial pathological response at week 6, while none in the combination group had a response. Among 20 patients who underwent surgery, 3 of 9 (33%) and 3 of 11 (27%) in the combination group experienced a major pathological response. Two patients in the nivolumab and three patients in the combination group achieved a complete pathological response.

Disease progression occurred in 7 of 12 patients who were evaluated in the nivolumab group, and 4 of 13 patients in the combination group. Estimated median time to disease progression in the nivolumab group was 9.4 months (95% confidence interval, 1.47 to not estimable) and 19.53 months (95% CI, 2.33 to not estimable) in the combination group. Two-year progression-free survival was estimated to be 42% (95% CI, 21%-81%) in the nivolumab group and 26% (95% CI, 8%-78%, no significant difference) in the combination group.

Among 20 patients who underwent surgery, 6 patients had experienced a major pathological response. None of the 6 patients had a recurrence after a median follow-up of 26.8 months, versus 7 recurrences among 14 patients without a pathological response (log-rank P = .049).

Seventy-seven percent of patients in the nivolumab group experienced at least one adverse event (23% grade 3-4), as did 86% in the combination group (43% grade 3-4, difference nonsignificant). No patients delayed or canceled surgery because of adverse events.

Patients who had a major pathological response on the combination treatment had higher levels of immune infiltration versus baseline values. Those who had complete pathological responses in the nivolumab group had high infiltration at baseline. Those results imply some optimism for further study. “These data suggest that, with the immune-priming ability of anti–CTLA-4 treatment, nivolumab plus ipilimumab was able to generate a major pathological response even in tumours that had low immune infiltration at baseline,” the authors wrote.

The study was limited by its open-label nature and small sample size, and it was conducted at a single center.

The study was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kaseb reports consulting, advisory roles or stock ownership, or both with Bristol-Myers Squibb.

(HCC), according to findings from an open-label phase 2 clinical trial published in The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatolgy.

The study compared the anti-PD1 antibody nivolumab (Opdivo, Bristol Myers Squibb) alone and nivolumab plus the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab (Yervoy, Bristol Myers Squibb) among patients with resectable disease at a single center in Sweden. The treatments were found to be “safe and feasible in patients with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma,” wrote researchers who were led by Ahmed O. Kaseb, MD, a medical oncologist with MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

The rate of 5-year tumor recurrence following HCC resection can be as high as 70%, and there are no approved neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapies.

Immune checkpoint therapy has not been well studied in early-stage HCC, but it is used in advanced HCC.

The combination of PDL1 blockade with atezolizumab and VEGF blockade with bevacizumab, is currently a first-line treatment for advanced HCC. “Checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD1 and PDL1 and CTLA4 are active, tolerable, and clinically beneficial against advanced HCC,” according to researchers writing in a Nature Reviews article published in April 2021.

There are other promising immunotherapies under study for HCC, such as additional checkpoint inhibitors, adoptive cell transfer, vaccination, and virotherapy.

Small study of 27 patients

The Lancet study included 27 patients (64 years mean age, 19 patients were male). Twenty-three percent of patients on nivolumab alone had a partial pathological response at week 6, while none in the combination group had a response. Among 20 patients who underwent surgery, 3 of 9 (33%) and 3 of 11 (27%) in the combination group experienced a major pathological response. Two patients in the nivolumab and three patients in the combination group achieved a complete pathological response.

Disease progression occurred in 7 of 12 patients who were evaluated in the nivolumab group, and 4 of 13 patients in the combination group. Estimated median time to disease progression in the nivolumab group was 9.4 months (95% confidence interval, 1.47 to not estimable) and 19.53 months (95% CI, 2.33 to not estimable) in the combination group. Two-year progression-free survival was estimated to be 42% (95% CI, 21%-81%) in the nivolumab group and 26% (95% CI, 8%-78%, no significant difference) in the combination group.

Among 20 patients who underwent surgery, 6 patients had experienced a major pathological response. None of the 6 patients had a recurrence after a median follow-up of 26.8 months, versus 7 recurrences among 14 patients without a pathological response (log-rank P = .049).

Seventy-seven percent of patients in the nivolumab group experienced at least one adverse event (23% grade 3-4), as did 86% in the combination group (43% grade 3-4, difference nonsignificant). No patients delayed or canceled surgery because of adverse events.

Patients who had a major pathological response on the combination treatment had higher levels of immune infiltration versus baseline values. Those who had complete pathological responses in the nivolumab group had high infiltration at baseline. Those results imply some optimism for further study. “These data suggest that, with the immune-priming ability of anti–CTLA-4 treatment, nivolumab plus ipilimumab was able to generate a major pathological response even in tumours that had low immune infiltration at baseline,” the authors wrote.

The study was limited by its open-label nature and small sample size, and it was conducted at a single center.

The study was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kaseb reports consulting, advisory roles or stock ownership, or both with Bristol-Myers Squibb.

FROM THE LANCET GASTROENTEROLOGY & HEPATOLOGY

Rise in oral cancers among young nonsmokers points to immunodeficiency

, and the outcomes may be related to immune deficiencies. The finding comes from a database of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) patients treated between 1985 and 2015.

“Recent studies have shown an association between high neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a marker for poor outcome in several different cancers. This ratio is a surrogate marker for a patient’s immune function. A high ratio indicates an impaired immune function. This means that the ability for the immune system to identify and eradicate abnormal cells which have the potential to form cancer cells is impaired. We don’t know why this is occurring,” said Ian Ganly, MD, PhD, a head and neck surgeon with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Ganly is lead author of the new study, published online March 5 in Oral Oncology.

“Physicians should be aware these patients may have impaired immunity and may have a more aggressive presentation and clinical behavior. Such patients may require more comprehensive staging investigations for cancer and may require more comprehensive treatment. Following treatment these patients should also have a detailed and regular follow-up examination with appropriate imaging to detect early recurrence,” he said in an interview.

The research also suggests that immunotherapy may be effective in this group. “However, our findings are only preliminary and further research into this area is required before such therapy can be justified,” Dr. Ganly said.

The study comprised 2,073 patients overall (median age, 62; 43.5% female) and 100 younger nonsmoking patients (median age, 34; 56.0% female). After multivariate analysis, compared to young smokers, nonsmokers with OSCC had a greater risk of mortality (P = .0229), although they had a lower mortality risk than both smokers and nonsmokers over 40. After adjustments, young nonsmokers had a mortality resembling that of older patients, while mortality among young smokers was distinctly lower than that of older patients.

In a subset of 88 young nonsmoking patients, there was a higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (median, 2.456) than that of similarly aged patients with thyroid cancer (median, 2.000; P = .0093) or salivary gland benign pathologies (median, 2.158; P = .0343).

The researchers are now studying the genomics of tumors found in smokers and nonsmokers and comparing them to tumors in older smokers and nonsmokers with OSCCs. They are performing a similar comparison of the immune environment of the tumors and patients’ immune system function. “For the genomics aspect I am looking to see if there are any unique alterations in the young nonsmokers that may explain the biology of these cancers. If so, there may be some alterations that can be targeted with new drugs. For the immune aspect, our goal is to see if there are any specific alterations in immune function unique to this population. Then it may be possible to deliver specific types of immunotherapy that focus in on these deficiencies,” said Dr. Ganly.

The study was funded by Fundación Alfonso Martín Escudero and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Ganly has no relevant financial disclosures.

, and the outcomes may be related to immune deficiencies. The finding comes from a database of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) patients treated between 1985 and 2015.

“Recent studies have shown an association between high neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a marker for poor outcome in several different cancers. This ratio is a surrogate marker for a patient’s immune function. A high ratio indicates an impaired immune function. This means that the ability for the immune system to identify and eradicate abnormal cells which have the potential to form cancer cells is impaired. We don’t know why this is occurring,” said Ian Ganly, MD, PhD, a head and neck surgeon with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Ganly is lead author of the new study, published online March 5 in Oral Oncology.

“Physicians should be aware these patients may have impaired immunity and may have a more aggressive presentation and clinical behavior. Such patients may require more comprehensive staging investigations for cancer and may require more comprehensive treatment. Following treatment these patients should also have a detailed and regular follow-up examination with appropriate imaging to detect early recurrence,” he said in an interview.

The research also suggests that immunotherapy may be effective in this group. “However, our findings are only preliminary and further research into this area is required before such therapy can be justified,” Dr. Ganly said.

The study comprised 2,073 patients overall (median age, 62; 43.5% female) and 100 younger nonsmoking patients (median age, 34; 56.0% female). After multivariate analysis, compared to young smokers, nonsmokers with OSCC had a greater risk of mortality (P = .0229), although they had a lower mortality risk than both smokers and nonsmokers over 40. After adjustments, young nonsmokers had a mortality resembling that of older patients, while mortality among young smokers was distinctly lower than that of older patients.

In a subset of 88 young nonsmoking patients, there was a higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (median, 2.456) than that of similarly aged patients with thyroid cancer (median, 2.000; P = .0093) or salivary gland benign pathologies (median, 2.158; P = .0343).

The researchers are now studying the genomics of tumors found in smokers and nonsmokers and comparing them to tumors in older smokers and nonsmokers with OSCCs. They are performing a similar comparison of the immune environment of the tumors and patients’ immune system function. “For the genomics aspect I am looking to see if there are any unique alterations in the young nonsmokers that may explain the biology of these cancers. If so, there may be some alterations that can be targeted with new drugs. For the immune aspect, our goal is to see if there are any specific alterations in immune function unique to this population. Then it may be possible to deliver specific types of immunotherapy that focus in on these deficiencies,” said Dr. Ganly.

The study was funded by Fundación Alfonso Martín Escudero and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Ganly has no relevant financial disclosures.

, and the outcomes may be related to immune deficiencies. The finding comes from a database of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) patients treated between 1985 and 2015.

“Recent studies have shown an association between high neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a marker for poor outcome in several different cancers. This ratio is a surrogate marker for a patient’s immune function. A high ratio indicates an impaired immune function. This means that the ability for the immune system to identify and eradicate abnormal cells which have the potential to form cancer cells is impaired. We don’t know why this is occurring,” said Ian Ganly, MD, PhD, a head and neck surgeon with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Ganly is lead author of the new study, published online March 5 in Oral Oncology.

“Physicians should be aware these patients may have impaired immunity and may have a more aggressive presentation and clinical behavior. Such patients may require more comprehensive staging investigations for cancer and may require more comprehensive treatment. Following treatment these patients should also have a detailed and regular follow-up examination with appropriate imaging to detect early recurrence,” he said in an interview.

The research also suggests that immunotherapy may be effective in this group. “However, our findings are only preliminary and further research into this area is required before such therapy can be justified,” Dr. Ganly said.

The study comprised 2,073 patients overall (median age, 62; 43.5% female) and 100 younger nonsmoking patients (median age, 34; 56.0% female). After multivariate analysis, compared to young smokers, nonsmokers with OSCC had a greater risk of mortality (P = .0229), although they had a lower mortality risk than both smokers and nonsmokers over 40. After adjustments, young nonsmokers had a mortality resembling that of older patients, while mortality among young smokers was distinctly lower than that of older patients.

In a subset of 88 young nonsmoking patients, there was a higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (median, 2.456) than that of similarly aged patients with thyroid cancer (median, 2.000; P = .0093) or salivary gland benign pathologies (median, 2.158; P = .0343).

The researchers are now studying the genomics of tumors found in smokers and nonsmokers and comparing them to tumors in older smokers and nonsmokers with OSCCs. They are performing a similar comparison of the immune environment of the tumors and patients’ immune system function. “For the genomics aspect I am looking to see if there are any unique alterations in the young nonsmokers that may explain the biology of these cancers. If so, there may be some alterations that can be targeted with new drugs. For the immune aspect, our goal is to see if there are any specific alterations in immune function unique to this population. Then it may be possible to deliver specific types of immunotherapy that focus in on these deficiencies,” said Dr. Ganly.

The study was funded by Fundación Alfonso Martín Escudero and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Ganly has no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ORAL ONCOLOGY

Breast density linked to familial breast cancer risk

observed during mammography, according to a new study of two retrospective cohorts published online Feb. 17 in JAMA Network Open. The findings suggest that breast density measured during mammography may have a genetic component, and suggest the importance of initiating early mammography in premenopausal women with a family history of breast cancer.

“We know that mammographic breast density is a very strong risk factor for breast cancer, probably one of the strongest risk factors, and it’s also a surrogate marker for breast cancer development, especially in premenopausal women. We also know that family history of breast cancer is a strong risk factor for breast cancer as well. Surprisingly, we have very limited information on how these risk factors are related to each other. There have been only two studies that have been done in this field in premenopausal women, and the studies are conflicting. So, we felt that we need to really understand how these two factors are related to each other and whether that would have an impact on modifying or refining mammographic screening in high-risk women,” Adetunji T. Toriola, MD, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. Dr. Toriola is professor of surgery at Washington University, St. Louis.

Previous research identified risk factors for dense breast tissue. A genome-wide association study found 31 genetic loci associated with dense breast tissue, and 17 had a known association with breast cancer risk.

In the JAMA Network Open study, the researchers included data from women who were treated at Washington University’s Joanne Knight Breast Health Center and Siteman Cancer Center. The discovery group included 375 premenopausal women who received annual mammography screening in 2016 and had dense volume and non-dense volume measured during each screen. The validation set drew from 14,040 premenopausal women seen at the centers between 2010 and 2015.

In the discovery group, women with a family history of breast cancer had greater volumetric percent density (odds ratio [OR], 1.25; P < .001). The validation set produced a similar result (OR, 1.30; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.45). Subanalyses revealed similar associations in non-Hispanic White and Black or African American women.

The current study included a higher percentage of women with a family history of breast cancer than previous studies, and also controlled for more variables. This may have removed confounding variables that could have affected previous studies.

“It reinforces the need to start mammogram screening early in women who have a family history of breast cancer,” Dr. Toriola said.

The study had some limitations, including a higher percentage of women with a family history of breast cancer than the National Health Interview Survey (23.2% and 15.3%, versus 8.4%), explained by the fact that women with a family history of breast cancer are more likely to seek out screening. The average age of women was on average 47 years, making them closer to perimenopausal than premenopausal.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

observed during mammography, according to a new study of two retrospective cohorts published online Feb. 17 in JAMA Network Open. The findings suggest that breast density measured during mammography may have a genetic component, and suggest the importance of initiating early mammography in premenopausal women with a family history of breast cancer.

“We know that mammographic breast density is a very strong risk factor for breast cancer, probably one of the strongest risk factors, and it’s also a surrogate marker for breast cancer development, especially in premenopausal women. We also know that family history of breast cancer is a strong risk factor for breast cancer as well. Surprisingly, we have very limited information on how these risk factors are related to each other. There have been only two studies that have been done in this field in premenopausal women, and the studies are conflicting. So, we felt that we need to really understand how these two factors are related to each other and whether that would have an impact on modifying or refining mammographic screening in high-risk women,” Adetunji T. Toriola, MD, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. Dr. Toriola is professor of surgery at Washington University, St. Louis.

Previous research identified risk factors for dense breast tissue. A genome-wide association study found 31 genetic loci associated with dense breast tissue, and 17 had a known association with breast cancer risk.

In the JAMA Network Open study, the researchers included data from women who were treated at Washington University’s Joanne Knight Breast Health Center and Siteman Cancer Center. The discovery group included 375 premenopausal women who received annual mammography screening in 2016 and had dense volume and non-dense volume measured during each screen. The validation set drew from 14,040 premenopausal women seen at the centers between 2010 and 2015.