User login

Cuffless blood pressure monitors: Still a numbers game

Medscape’s Editor-in-Chief Eric Topol, MD, referred to continual noninvasive, cuffless, accurate blood pressure devices as “a holy grail in sensor technology.”

He personally tested a cuff-calibrated, over-the-counter device available in Europe that claims to monitor daily blood pressure changes and produce data that can help physicians titrate medications.

Dr. Topol does not believe that it is ready for prime time. Yes, cuffless devices are easy to use, and generate lots of data. But are those data accurate?

Many experts say not yet, even as the market continues to grow and more devices are introduced and highlighted at high-profile consumer events.

Burned before

Limitations of cuffed devices are well known, including errors related to cuff size, patient positioning, patient habits or behaviors (for example, caffeine/nicotine use, acute meal digestion, full bladder, very recent physical activity) and clinicians’ failure to take accurate measurements.

Like many clinicians, Timothy B. Plante, MD, MHS, assistant professor at the University of Vermont Medical Center thrombosis & hemostasis program in Burlington, is very excited about cuffless technology. However, “we’ve been burned by it before,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Plante’s 2016 validation study of an instant blood pressure smartphone app found that its measurements were “highly inaccurate,” with such low sensitivity that more than three-quarters of individuals with hypertensive blood levels would be falsely reassured that their blood pressure was in the normal range.

His team’s 2023 review of the current landscape, which includes more sophisticated devices, concluded that accuracy remains an issue: “Unfortunately, the pace of regulation of these devices has failed to match the speed of innovation and direct availability to patient consumers. There is an urgent need to develop a consensus on standards by which cuffless BP devices can be tested for accuracy.”

Devices, indications differ

Cuffless devices estimate blood pressure indirectly. Most operate based on pulse wave analysis and pulse arrival time (PWA-PAT), explained Ramakrishna Mukkamala, PhD, in a commentary. Dr. Mukkamala is a professor in the departments of bioengineering and anesthesiology and perioperative medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

PWA involves measuring a peripheral arterial waveform using an optical sensor such as the green lights on the back of a wrist-worn device, or a ‘force sensor’ such as a finger cuff or pressing on a smartphone. Certain features are extracted from the waveform using machine learning and calibrated to blood pressure values.

PAT techniques work together with PWA; they record the ECG and extract features from that signal as well as the arterial waveform for calibration to blood pressure values.

The algorithm used to generate the BP numbers comprises a proprietary baseline model that may include demographics and other patient characteristics. A cuff measurement is often part of the baseline model because most cuffless devices require periodic (typically weekly or monthly) calibration using a cuffed device.

Cuffless devices that require cuff calibration compare the estimate they get to the cuff-calibrated number. In this scenario, the cuffless device may come up with the same blood pressure numbers simply because the baseline model – which is made up of thousands of data points relevant to the patient – has not changed.

This has led some experts to question whether PWA-PAT cuffless device readings actually add anything to the baseline model.

They don’t, according to Microsoft Research in what Dr. Mukkamala and coauthors referred to (in a review published in Hypertension) as “a complex article describing perhaps the most important and highest resource project to date (Aurora Project) on assessing the accuracy of PWA and PWA devices.”

The Microsoft article was written for bioengineers. The review in Hypertension explains the project for clinicians, and concludes that, “Cuffless BP devices based on PWA and PWA-PAT, which are similar to some regulatory-cleared devices, were of no additional value in measuring auscultatory or 24-hour ambulatory cuff BP when compared with a baseline model in which BP was predicted without an actual measurement.”

IEEE and FDA validation

Despite these concerns, several cuffless devices using PWA and PAT have been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration.

Validating cuffless devices is no simple matter. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers published a validation protocol for cuffless blood pressure devices in 2014 that was amended in 2019 to include a requirement to evaluate performance in different positions and in the presence of motion with varying degrees of noise artifact.

However, Daichi Shimbo, MD, codirector of the Columbia Hypertension Center in New York and vice chair of the American Heart Association Statement on blood pressure monitoring, and colleagues point out limitations, even in the updated standard. These include not requiring evaluation for drift over time; lack of specific dynamic testing protocols for stressors such as exercise or environmental temperatures; and an unsuitable reference standard (oscillometric cuff-based devices) during movement.

Dr. Shimbo said in an interview that, although he is excited about them, “these cuffless devices are not aligned with regulatory bodies. If a device gives someone a wrong blood pressure, they might be diagnosed with hypertension when they don’t have it or might miss the fact that they’re hypertensive because they get a normal blood pressure reading. If there’s no yardstick by which you say these devices are good, what are we really doing – helping, or causing a problem?”

“The specifics of how a device estimates blood pressure can determine what testing is needed to ensure that it is providing accurate performance in the intended conditions of use,” Jeremy Kahn, an FDA press officer, said in an interview. “For example, for cuffless devices that are calibrated initially with a cuff-based blood pressure device, the cuffless device needs to specify the period over which it can provide accurate readings and have testing to demonstrate that it provides accurate results over that period of use.”

The FDA said its testing is different from what the Microsoft Aurora Project used in their study.

“The intent of that testing, as the agency understands it, is to evaluate whether the device is providing useful input based on the current physiology of the patient rather than relying on predetermined values based on calibration or patient attributes. We evaluate this clinically in two separate tests: an induced change in blood pressure test and tracking of natural blood pressure changes with longer term device use,” Mr. Kahn explained.

Analyzing a device’s performance on individuals who have had natural changes in blood pressure as compared to a calibration value or initial reading “can also help discern if the device is using physiological data from the patient to determine their blood pressure accurately,” he said.

Experts interviewed for this article who remain skeptical about cuffless BP monitoring question whether the numbers that appear during the induced blood pressure change, and with the natural blood pressure changes that may occur over time, accurately reflect a patient’s blood pressure.

“The FDA doesn’t approve these devices; they clear them,” Dr. Shimbo pointed out. “Clearing them means they can be sold to the general public in the U.S. It’s not a strong statement that they’re accurate.”

Moving toward validation, standards

Ultimately, cuffless BP monitors may require more than one validation protocol and standard, depending on their technology, how and where they will be used, and by whom.

And as Dr. Plante and colleagues write, “Importantly, validation should be performed in diverse and special populations, including pregnant women and individuals across a range of heart rates, skin tones, wrist sizes, common arrhythmias, and beta-blocker use.”

Organizations that might be expected to help move validation and standards forward have mostly remained silent. The American Medical Association’s US Blood Pressure Validated Device Listing website includes only cuffed devices, as does the website of the international scientific nonprofit STRIDE BP.

The European Society of Hypertension 2022 consensus statement on cuffless devices concluded that, until there is an internationally accepted accuracy standard and the devices have been tested in healthy people and those with suspected or diagnosed hypertension, “cuffless BP devices should not be used for the evaluation or management of hypertension in clinical practice.”

This month, ESH published recommendations for “specific, clinically meaningful, and pragmatic validation procedures for different types of intermittent cuffless devices” that will be presented at their upcoming annual meeting June 26.

Updated protocols from IEEE “are coming out soon,” according to Dr. Shimbo. The FDA says currently cleared devices won’t need to revalidate according to new standards unless the sponsor makes significant modifications in software algorithms, device hardware, or targeted patient populations.

Device makers take the initiative

In the face of conflicting reports on accuracy and lack of a robust standard, some device makers are publishing their own tests or encouraging validation by potential customers.

For example, institutions that are considering using the Biobeat cuffless blood pressure monitor watch “usually start with small pilots with our devices to do internal validation,” Lior Ben Shettrit, the company’s vice president of business development, said in an interview. “Only after they complete the internal validation are they willing to move forward to full implementation.”

Cardiologist Dean Nachman, MD, is leading validation studies of the Biobeat device at the Hadassah Ein Kerem Medical Center in Jerusalem. For the first validation, the team recruited 1,057 volunteers who did a single blood pressure measurement with the cuffless device and with a cuffed device.

“We found 96.3% agreement in identifying hypertension and an interclass correlation coefficient of 0.99 and 0.97 for systolic and diastolic measurements, respectively,” he said. “Then we took it to the next level and compared the device to ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure monitoring and found comparable measurements.”

The investigators are not done yet. “We need data from thousands of patients, with subgroups, to not have any concerns,” he says. “Right now, we are using the device as a general monitor – as an EKG plus heart rate plus oxygen saturation level monitor – and as a blood pressure monitor for 24-hour blood pressure monitoring.”

The developers of the Aktiia device, which is the one Dr. Topol tested, take a different perspective. “When somebody introduces a new technology that is disrupting something that has been in place for over 100 years, there will always be some grumblings, ruffling of feathers, people saying it’s not ready, it’s not ready, it’s not ready,” Aktiia’s chief medical officer Jay Shah, MD, noted.

“But a lot of those comments are coming from the isolation of an ivory tower,” he said.

Aktiia cofounder and chief technology officer Josep Solà said that “no device is probably as accurate as if you have an invasive catheter,” adding that “we engage patients to look at their blood pressure day by day. … If each individual measurement of each of those patient is slightly less accurate than a cuff, who cares? We have 40 measurements per day on each patient. The accuracy and precision of each of those is good.”

Researchers from the George Institute for Global Health recently compared the Aktiia device to conventional ambulatory monitoring in 41 patients and found that “it did not accurately track night-time BP decline and results suggested it was unable to track medication-induced BP changes.”

“In the context of 24/7 monitoring of hypertensive patients,” Mr. Solà said, “whatever you do, if it’s better than a sham device or a baseline model and you track the blood pressure changes, it’s a hundred times much better than doing nothing.”

Dr. Nachman and Dr. Plante reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Shimbo reported that he received funding from NIH and has consulted for Abbott Vascular, Edward Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Tryton Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medscape’s Editor-in-Chief Eric Topol, MD, referred to continual noninvasive, cuffless, accurate blood pressure devices as “a holy grail in sensor technology.”

He personally tested a cuff-calibrated, over-the-counter device available in Europe that claims to monitor daily blood pressure changes and produce data that can help physicians titrate medications.

Dr. Topol does not believe that it is ready for prime time. Yes, cuffless devices are easy to use, and generate lots of data. But are those data accurate?

Many experts say not yet, even as the market continues to grow and more devices are introduced and highlighted at high-profile consumer events.

Burned before

Limitations of cuffed devices are well known, including errors related to cuff size, patient positioning, patient habits or behaviors (for example, caffeine/nicotine use, acute meal digestion, full bladder, very recent physical activity) and clinicians’ failure to take accurate measurements.

Like many clinicians, Timothy B. Plante, MD, MHS, assistant professor at the University of Vermont Medical Center thrombosis & hemostasis program in Burlington, is very excited about cuffless technology. However, “we’ve been burned by it before,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Plante’s 2016 validation study of an instant blood pressure smartphone app found that its measurements were “highly inaccurate,” with such low sensitivity that more than three-quarters of individuals with hypertensive blood levels would be falsely reassured that their blood pressure was in the normal range.

His team’s 2023 review of the current landscape, which includes more sophisticated devices, concluded that accuracy remains an issue: “Unfortunately, the pace of regulation of these devices has failed to match the speed of innovation and direct availability to patient consumers. There is an urgent need to develop a consensus on standards by which cuffless BP devices can be tested for accuracy.”

Devices, indications differ

Cuffless devices estimate blood pressure indirectly. Most operate based on pulse wave analysis and pulse arrival time (PWA-PAT), explained Ramakrishna Mukkamala, PhD, in a commentary. Dr. Mukkamala is a professor in the departments of bioengineering and anesthesiology and perioperative medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

PWA involves measuring a peripheral arterial waveform using an optical sensor such as the green lights on the back of a wrist-worn device, or a ‘force sensor’ such as a finger cuff or pressing on a smartphone. Certain features are extracted from the waveform using machine learning and calibrated to blood pressure values.

PAT techniques work together with PWA; they record the ECG and extract features from that signal as well as the arterial waveform for calibration to blood pressure values.

The algorithm used to generate the BP numbers comprises a proprietary baseline model that may include demographics and other patient characteristics. A cuff measurement is often part of the baseline model because most cuffless devices require periodic (typically weekly or monthly) calibration using a cuffed device.

Cuffless devices that require cuff calibration compare the estimate they get to the cuff-calibrated number. In this scenario, the cuffless device may come up with the same blood pressure numbers simply because the baseline model – which is made up of thousands of data points relevant to the patient – has not changed.

This has led some experts to question whether PWA-PAT cuffless device readings actually add anything to the baseline model.

They don’t, according to Microsoft Research in what Dr. Mukkamala and coauthors referred to (in a review published in Hypertension) as “a complex article describing perhaps the most important and highest resource project to date (Aurora Project) on assessing the accuracy of PWA and PWA devices.”

The Microsoft article was written for bioengineers. The review in Hypertension explains the project for clinicians, and concludes that, “Cuffless BP devices based on PWA and PWA-PAT, which are similar to some regulatory-cleared devices, were of no additional value in measuring auscultatory or 24-hour ambulatory cuff BP when compared with a baseline model in which BP was predicted without an actual measurement.”

IEEE and FDA validation

Despite these concerns, several cuffless devices using PWA and PAT have been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration.

Validating cuffless devices is no simple matter. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers published a validation protocol for cuffless blood pressure devices in 2014 that was amended in 2019 to include a requirement to evaluate performance in different positions and in the presence of motion with varying degrees of noise artifact.

However, Daichi Shimbo, MD, codirector of the Columbia Hypertension Center in New York and vice chair of the American Heart Association Statement on blood pressure monitoring, and colleagues point out limitations, even in the updated standard. These include not requiring evaluation for drift over time; lack of specific dynamic testing protocols for stressors such as exercise or environmental temperatures; and an unsuitable reference standard (oscillometric cuff-based devices) during movement.

Dr. Shimbo said in an interview that, although he is excited about them, “these cuffless devices are not aligned with regulatory bodies. If a device gives someone a wrong blood pressure, they might be diagnosed with hypertension when they don’t have it or might miss the fact that they’re hypertensive because they get a normal blood pressure reading. If there’s no yardstick by which you say these devices are good, what are we really doing – helping, or causing a problem?”

“The specifics of how a device estimates blood pressure can determine what testing is needed to ensure that it is providing accurate performance in the intended conditions of use,” Jeremy Kahn, an FDA press officer, said in an interview. “For example, for cuffless devices that are calibrated initially with a cuff-based blood pressure device, the cuffless device needs to specify the period over which it can provide accurate readings and have testing to demonstrate that it provides accurate results over that period of use.”

The FDA said its testing is different from what the Microsoft Aurora Project used in their study.

“The intent of that testing, as the agency understands it, is to evaluate whether the device is providing useful input based on the current physiology of the patient rather than relying on predetermined values based on calibration or patient attributes. We evaluate this clinically in two separate tests: an induced change in blood pressure test and tracking of natural blood pressure changes with longer term device use,” Mr. Kahn explained.

Analyzing a device’s performance on individuals who have had natural changes in blood pressure as compared to a calibration value or initial reading “can also help discern if the device is using physiological data from the patient to determine their blood pressure accurately,” he said.

Experts interviewed for this article who remain skeptical about cuffless BP monitoring question whether the numbers that appear during the induced blood pressure change, and with the natural blood pressure changes that may occur over time, accurately reflect a patient’s blood pressure.

“The FDA doesn’t approve these devices; they clear them,” Dr. Shimbo pointed out. “Clearing them means they can be sold to the general public in the U.S. It’s not a strong statement that they’re accurate.”

Moving toward validation, standards

Ultimately, cuffless BP monitors may require more than one validation protocol and standard, depending on their technology, how and where they will be used, and by whom.

And as Dr. Plante and colleagues write, “Importantly, validation should be performed in diverse and special populations, including pregnant women and individuals across a range of heart rates, skin tones, wrist sizes, common arrhythmias, and beta-blocker use.”

Organizations that might be expected to help move validation and standards forward have mostly remained silent. The American Medical Association’s US Blood Pressure Validated Device Listing website includes only cuffed devices, as does the website of the international scientific nonprofit STRIDE BP.

The European Society of Hypertension 2022 consensus statement on cuffless devices concluded that, until there is an internationally accepted accuracy standard and the devices have been tested in healthy people and those with suspected or diagnosed hypertension, “cuffless BP devices should not be used for the evaluation or management of hypertension in clinical practice.”

This month, ESH published recommendations for “specific, clinically meaningful, and pragmatic validation procedures for different types of intermittent cuffless devices” that will be presented at their upcoming annual meeting June 26.

Updated protocols from IEEE “are coming out soon,” according to Dr. Shimbo. The FDA says currently cleared devices won’t need to revalidate according to new standards unless the sponsor makes significant modifications in software algorithms, device hardware, or targeted patient populations.

Device makers take the initiative

In the face of conflicting reports on accuracy and lack of a robust standard, some device makers are publishing their own tests or encouraging validation by potential customers.

For example, institutions that are considering using the Biobeat cuffless blood pressure monitor watch “usually start with small pilots with our devices to do internal validation,” Lior Ben Shettrit, the company’s vice president of business development, said in an interview. “Only after they complete the internal validation are they willing to move forward to full implementation.”

Cardiologist Dean Nachman, MD, is leading validation studies of the Biobeat device at the Hadassah Ein Kerem Medical Center in Jerusalem. For the first validation, the team recruited 1,057 volunteers who did a single blood pressure measurement with the cuffless device and with a cuffed device.

“We found 96.3% agreement in identifying hypertension and an interclass correlation coefficient of 0.99 and 0.97 for systolic and diastolic measurements, respectively,” he said. “Then we took it to the next level and compared the device to ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure monitoring and found comparable measurements.”

The investigators are not done yet. “We need data from thousands of patients, with subgroups, to not have any concerns,” he says. “Right now, we are using the device as a general monitor – as an EKG plus heart rate plus oxygen saturation level monitor – and as a blood pressure monitor for 24-hour blood pressure monitoring.”

The developers of the Aktiia device, which is the one Dr. Topol tested, take a different perspective. “When somebody introduces a new technology that is disrupting something that has been in place for over 100 years, there will always be some grumblings, ruffling of feathers, people saying it’s not ready, it’s not ready, it’s not ready,” Aktiia’s chief medical officer Jay Shah, MD, noted.

“But a lot of those comments are coming from the isolation of an ivory tower,” he said.

Aktiia cofounder and chief technology officer Josep Solà said that “no device is probably as accurate as if you have an invasive catheter,” adding that “we engage patients to look at their blood pressure day by day. … If each individual measurement of each of those patient is slightly less accurate than a cuff, who cares? We have 40 measurements per day on each patient. The accuracy and precision of each of those is good.”

Researchers from the George Institute for Global Health recently compared the Aktiia device to conventional ambulatory monitoring in 41 patients and found that “it did not accurately track night-time BP decline and results suggested it was unable to track medication-induced BP changes.”

“In the context of 24/7 monitoring of hypertensive patients,” Mr. Solà said, “whatever you do, if it’s better than a sham device or a baseline model and you track the blood pressure changes, it’s a hundred times much better than doing nothing.”

Dr. Nachman and Dr. Plante reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Shimbo reported that he received funding from NIH and has consulted for Abbott Vascular, Edward Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Tryton Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medscape’s Editor-in-Chief Eric Topol, MD, referred to continual noninvasive, cuffless, accurate blood pressure devices as “a holy grail in sensor technology.”

He personally tested a cuff-calibrated, over-the-counter device available in Europe that claims to monitor daily blood pressure changes and produce data that can help physicians titrate medications.

Dr. Topol does not believe that it is ready for prime time. Yes, cuffless devices are easy to use, and generate lots of data. But are those data accurate?

Many experts say not yet, even as the market continues to grow and more devices are introduced and highlighted at high-profile consumer events.

Burned before

Limitations of cuffed devices are well known, including errors related to cuff size, patient positioning, patient habits or behaviors (for example, caffeine/nicotine use, acute meal digestion, full bladder, very recent physical activity) and clinicians’ failure to take accurate measurements.

Like many clinicians, Timothy B. Plante, MD, MHS, assistant professor at the University of Vermont Medical Center thrombosis & hemostasis program in Burlington, is very excited about cuffless technology. However, “we’ve been burned by it before,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Plante’s 2016 validation study of an instant blood pressure smartphone app found that its measurements were “highly inaccurate,” with such low sensitivity that more than three-quarters of individuals with hypertensive blood levels would be falsely reassured that their blood pressure was in the normal range.

His team’s 2023 review of the current landscape, which includes more sophisticated devices, concluded that accuracy remains an issue: “Unfortunately, the pace of regulation of these devices has failed to match the speed of innovation and direct availability to patient consumers. There is an urgent need to develop a consensus on standards by which cuffless BP devices can be tested for accuracy.”

Devices, indications differ

Cuffless devices estimate blood pressure indirectly. Most operate based on pulse wave analysis and pulse arrival time (PWA-PAT), explained Ramakrishna Mukkamala, PhD, in a commentary. Dr. Mukkamala is a professor in the departments of bioengineering and anesthesiology and perioperative medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

PWA involves measuring a peripheral arterial waveform using an optical sensor such as the green lights on the back of a wrist-worn device, or a ‘force sensor’ such as a finger cuff or pressing on a smartphone. Certain features are extracted from the waveform using machine learning and calibrated to blood pressure values.

PAT techniques work together with PWA; they record the ECG and extract features from that signal as well as the arterial waveform for calibration to blood pressure values.

The algorithm used to generate the BP numbers comprises a proprietary baseline model that may include demographics and other patient characteristics. A cuff measurement is often part of the baseline model because most cuffless devices require periodic (typically weekly or monthly) calibration using a cuffed device.

Cuffless devices that require cuff calibration compare the estimate they get to the cuff-calibrated number. In this scenario, the cuffless device may come up with the same blood pressure numbers simply because the baseline model – which is made up of thousands of data points relevant to the patient – has not changed.

This has led some experts to question whether PWA-PAT cuffless device readings actually add anything to the baseline model.

They don’t, according to Microsoft Research in what Dr. Mukkamala and coauthors referred to (in a review published in Hypertension) as “a complex article describing perhaps the most important and highest resource project to date (Aurora Project) on assessing the accuracy of PWA and PWA devices.”

The Microsoft article was written for bioengineers. The review in Hypertension explains the project for clinicians, and concludes that, “Cuffless BP devices based on PWA and PWA-PAT, which are similar to some regulatory-cleared devices, were of no additional value in measuring auscultatory or 24-hour ambulatory cuff BP when compared with a baseline model in which BP was predicted without an actual measurement.”

IEEE and FDA validation

Despite these concerns, several cuffless devices using PWA and PAT have been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration.

Validating cuffless devices is no simple matter. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers published a validation protocol for cuffless blood pressure devices in 2014 that was amended in 2019 to include a requirement to evaluate performance in different positions and in the presence of motion with varying degrees of noise artifact.

However, Daichi Shimbo, MD, codirector of the Columbia Hypertension Center in New York and vice chair of the American Heart Association Statement on blood pressure monitoring, and colleagues point out limitations, even in the updated standard. These include not requiring evaluation for drift over time; lack of specific dynamic testing protocols for stressors such as exercise or environmental temperatures; and an unsuitable reference standard (oscillometric cuff-based devices) during movement.

Dr. Shimbo said in an interview that, although he is excited about them, “these cuffless devices are not aligned with regulatory bodies. If a device gives someone a wrong blood pressure, they might be diagnosed with hypertension when they don’t have it or might miss the fact that they’re hypertensive because they get a normal blood pressure reading. If there’s no yardstick by which you say these devices are good, what are we really doing – helping, or causing a problem?”

“The specifics of how a device estimates blood pressure can determine what testing is needed to ensure that it is providing accurate performance in the intended conditions of use,” Jeremy Kahn, an FDA press officer, said in an interview. “For example, for cuffless devices that are calibrated initially with a cuff-based blood pressure device, the cuffless device needs to specify the period over which it can provide accurate readings and have testing to demonstrate that it provides accurate results over that period of use.”

The FDA said its testing is different from what the Microsoft Aurora Project used in their study.

“The intent of that testing, as the agency understands it, is to evaluate whether the device is providing useful input based on the current physiology of the patient rather than relying on predetermined values based on calibration or patient attributes. We evaluate this clinically in two separate tests: an induced change in blood pressure test and tracking of natural blood pressure changes with longer term device use,” Mr. Kahn explained.

Analyzing a device’s performance on individuals who have had natural changes in blood pressure as compared to a calibration value or initial reading “can also help discern if the device is using physiological data from the patient to determine their blood pressure accurately,” he said.

Experts interviewed for this article who remain skeptical about cuffless BP monitoring question whether the numbers that appear during the induced blood pressure change, and with the natural blood pressure changes that may occur over time, accurately reflect a patient’s blood pressure.

“The FDA doesn’t approve these devices; they clear them,” Dr. Shimbo pointed out. “Clearing them means they can be sold to the general public in the U.S. It’s not a strong statement that they’re accurate.”

Moving toward validation, standards

Ultimately, cuffless BP monitors may require more than one validation protocol and standard, depending on their technology, how and where they will be used, and by whom.

And as Dr. Plante and colleagues write, “Importantly, validation should be performed in diverse and special populations, including pregnant women and individuals across a range of heart rates, skin tones, wrist sizes, common arrhythmias, and beta-blocker use.”

Organizations that might be expected to help move validation and standards forward have mostly remained silent. The American Medical Association’s US Blood Pressure Validated Device Listing website includes only cuffed devices, as does the website of the international scientific nonprofit STRIDE BP.

The European Society of Hypertension 2022 consensus statement on cuffless devices concluded that, until there is an internationally accepted accuracy standard and the devices have been tested in healthy people and those with suspected or diagnosed hypertension, “cuffless BP devices should not be used for the evaluation or management of hypertension in clinical practice.”

This month, ESH published recommendations for “specific, clinically meaningful, and pragmatic validation procedures for different types of intermittent cuffless devices” that will be presented at their upcoming annual meeting June 26.

Updated protocols from IEEE “are coming out soon,” according to Dr. Shimbo. The FDA says currently cleared devices won’t need to revalidate according to new standards unless the sponsor makes significant modifications in software algorithms, device hardware, or targeted patient populations.

Device makers take the initiative

In the face of conflicting reports on accuracy and lack of a robust standard, some device makers are publishing their own tests or encouraging validation by potential customers.

For example, institutions that are considering using the Biobeat cuffless blood pressure monitor watch “usually start with small pilots with our devices to do internal validation,” Lior Ben Shettrit, the company’s vice president of business development, said in an interview. “Only after they complete the internal validation are they willing to move forward to full implementation.”

Cardiologist Dean Nachman, MD, is leading validation studies of the Biobeat device at the Hadassah Ein Kerem Medical Center in Jerusalem. For the first validation, the team recruited 1,057 volunteers who did a single blood pressure measurement with the cuffless device and with a cuffed device.

“We found 96.3% agreement in identifying hypertension and an interclass correlation coefficient of 0.99 and 0.97 for systolic and diastolic measurements, respectively,” he said. “Then we took it to the next level and compared the device to ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure monitoring and found comparable measurements.”

The investigators are not done yet. “We need data from thousands of patients, with subgroups, to not have any concerns,” he says. “Right now, we are using the device as a general monitor – as an EKG plus heart rate plus oxygen saturation level monitor – and as a blood pressure monitor for 24-hour blood pressure monitoring.”

The developers of the Aktiia device, which is the one Dr. Topol tested, take a different perspective. “When somebody introduces a new technology that is disrupting something that has been in place for over 100 years, there will always be some grumblings, ruffling of feathers, people saying it’s not ready, it’s not ready, it’s not ready,” Aktiia’s chief medical officer Jay Shah, MD, noted.

“But a lot of those comments are coming from the isolation of an ivory tower,” he said.

Aktiia cofounder and chief technology officer Josep Solà said that “no device is probably as accurate as if you have an invasive catheter,” adding that “we engage patients to look at their blood pressure day by day. … If each individual measurement of each of those patient is slightly less accurate than a cuff, who cares? We have 40 measurements per day on each patient. The accuracy and precision of each of those is good.”

Researchers from the George Institute for Global Health recently compared the Aktiia device to conventional ambulatory monitoring in 41 patients and found that “it did not accurately track night-time BP decline and results suggested it was unable to track medication-induced BP changes.”

“In the context of 24/7 monitoring of hypertensive patients,” Mr. Solà said, “whatever you do, if it’s better than a sham device or a baseline model and you track the blood pressure changes, it’s a hundred times much better than doing nothing.”

Dr. Nachman and Dr. Plante reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Shimbo reported that he received funding from NIH and has consulted for Abbott Vascular, Edward Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Tryton Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Early hysterectomy linked to higher CVD, stroke risk

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Risk of CVD rapidly increases after menopause, possibly owing to loss of protective effects of female sex hormones and hemorheologic changes.

- Results of previous studies of the association between hysterectomy and CVD were mixed.

- Using national health insurance data, this cohort study included 55,539 South Korean women (median age, 45 years) who underwent a hysterectomy and a propensity-matched group of women.

- The primary outcome was CVD, including myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery revascularization, and stroke.

TAKEAWAY:

- During follow-up of just under 8 years, the hysterectomy group had an increased risk of CVD compared with the non-hysterectomy group (hazard ratio [HR] 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09-1.44; P = .002)

- The incidence of MI and coronary revascularization was comparable between groups, but the risk of stroke was significantly higher among those who had had a hysterectomy (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.12-1.53; P < .001)

- This increase in risk was similar after excluding patients who also underwent adnexal surgery.

IN PRACTICE:

Early hysterectomy was linked to higher CVD risk, especially stroke, but since the CVD incidence wasn’t high, a change in clinical practice may not be needed, said the authors.

STUDY DETAILS:

The study was conducted by Jin-Sung Yuk, MD, PhD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, and colleagues. It was published online June 12 in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective and observational and used administrative databases that may be prone to inaccurate coding. The findings may not be generalizable outside Korea.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Risk of CVD rapidly increases after menopause, possibly owing to loss of protective effects of female sex hormones and hemorheologic changes.

- Results of previous studies of the association between hysterectomy and CVD were mixed.

- Using national health insurance data, this cohort study included 55,539 South Korean women (median age, 45 years) who underwent a hysterectomy and a propensity-matched group of women.

- The primary outcome was CVD, including myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery revascularization, and stroke.

TAKEAWAY:

- During follow-up of just under 8 years, the hysterectomy group had an increased risk of CVD compared with the non-hysterectomy group (hazard ratio [HR] 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09-1.44; P = .002)

- The incidence of MI and coronary revascularization was comparable between groups, but the risk of stroke was significantly higher among those who had had a hysterectomy (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.12-1.53; P < .001)

- This increase in risk was similar after excluding patients who also underwent adnexal surgery.

IN PRACTICE:

Early hysterectomy was linked to higher CVD risk, especially stroke, but since the CVD incidence wasn’t high, a change in clinical practice may not be needed, said the authors.

STUDY DETAILS:

The study was conducted by Jin-Sung Yuk, MD, PhD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, and colleagues. It was published online June 12 in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective and observational and used administrative databases that may be prone to inaccurate coding. The findings may not be generalizable outside Korea.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Risk of CVD rapidly increases after menopause, possibly owing to loss of protective effects of female sex hormones and hemorheologic changes.

- Results of previous studies of the association between hysterectomy and CVD were mixed.

- Using national health insurance data, this cohort study included 55,539 South Korean women (median age, 45 years) who underwent a hysterectomy and a propensity-matched group of women.

- The primary outcome was CVD, including myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery revascularization, and stroke.

TAKEAWAY:

- During follow-up of just under 8 years, the hysterectomy group had an increased risk of CVD compared with the non-hysterectomy group (hazard ratio [HR] 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09-1.44; P = .002)

- The incidence of MI and coronary revascularization was comparable between groups, but the risk of stroke was significantly higher among those who had had a hysterectomy (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.12-1.53; P < .001)

- This increase in risk was similar after excluding patients who also underwent adnexal surgery.

IN PRACTICE:

Early hysterectomy was linked to higher CVD risk, especially stroke, but since the CVD incidence wasn’t high, a change in clinical practice may not be needed, said the authors.

STUDY DETAILS:

The study was conducted by Jin-Sung Yuk, MD, PhD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, and colleagues. It was published online June 12 in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective and observational and used administrative databases that may be prone to inaccurate coding. The findings may not be generalizable outside Korea.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is there benefit to adding ezetimibe to a statin for the secondary prevention of CVD?

Evidence summary

Adding ezetimibe reduces nonfatal events but does not improve mortality

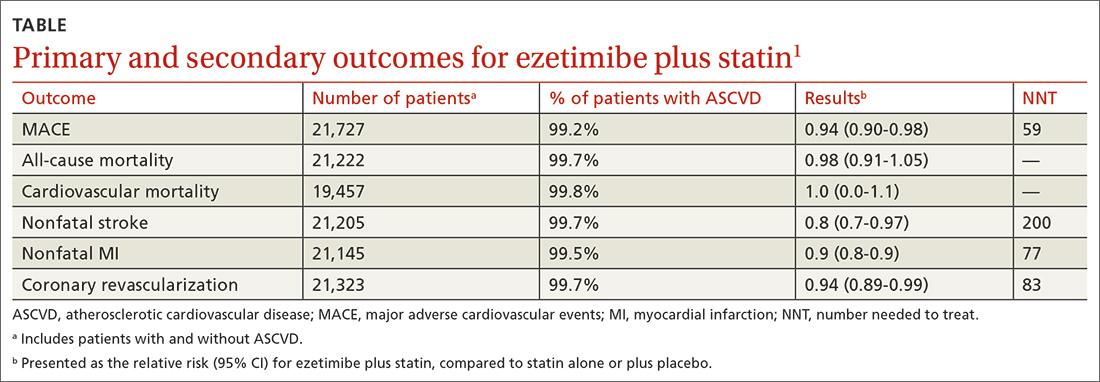

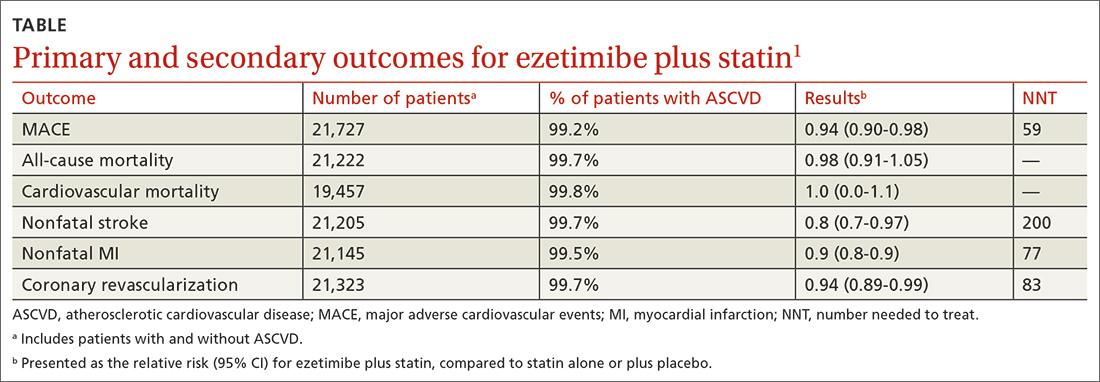

A 2018 Cochrane meta-analysis included 10 RCTs (N = 21,919 patients) that evaluated the efficacy and safety of ezetimibe plus a statin (dual therapy) vs a statin alone or plus placebo (monotherapy) for the secondary prevention of CVD. Mean age of patients ranged from 55 to 84 years. Almost all of the patients (> 99%) included in the analyses had existing ASCVD. The dose of ezetimibe was 10 mg; statins used included atorvastatin 10 to 80 mg, pitavastatin 2 to 4 mg, rosuvastatin 10 mg, and simvastatin 20 to 80 mg.1

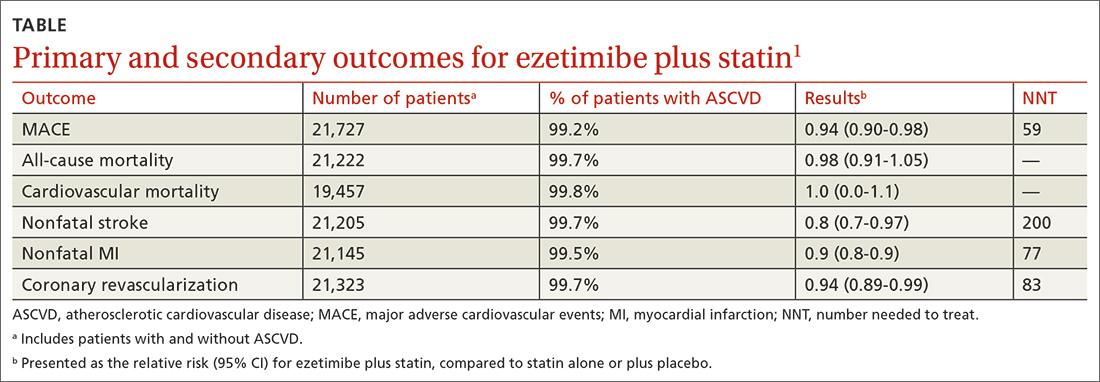

The primary outcomes were MACE and all-cause mortality. MACE is defined as a composite of CVD, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), nonfatal stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization procedures. The TABLE1 provides a detailed breakdown of each of the outcomes.

The dual-therapy group compared to the monotherapy group had a lower risk for MACE (26.6% vs 28.3%; 1.7% absolute risk reduction; 6% relative risk reduction; NNT = 59) and little or no difference in the reduction of all-cause mortality. For secondary outcomes, the dual-therapy group had a lower risk for nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and coronary revascularization. There was no difference in cardiovascular mortality or adverse events between the 2 groups. The quality of evidence was high for all-cause mortality and moderate for cardiovascular mortality, MACE, MI, and stroke.1

The 2015 IMPROVE-IT study, the largest included in the Cochrane review, was a double-blind RCT (N = 18,144) conducted at 1147 sites in 39 countries comparing simvastatin 40 mg/d plus ezetimibe 10 mg/d (dual therapy) vs simvastatin 40 mg/d plus placebo (monotherapy). Patients were at least 50 years old (average age, 64 years) and had been hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) within the previous 10 days; 76% were male and 84% were White. The average low-density lipoprotein (LDL) concentration at baseline was 94 mg/dL in both groups.2

The primary endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, a major coronary event (nonfatal MI, unstable angina requiring hospitalization, coronary revascularization at least 30 days after randomization), or nonfatal stroke, with a median follow-up of 6 years. The simvastatin plus ezetimibe group compared to the simvastatin-only group had a lower risk for the primary end point (HR = 0.94; 95% CI, 0.89-0.99; NNT = 50), but no differences in cardiovascular or all-cause mortality. Since the study only recruited patients with recent ACS, results are only applicable to that specific population.2

The 2022 RACING study was a multicenter, open-label, randomized, noninferiority trial that evaluated the combination of ezetimibe 10 mg and a moderate-intensity statin (rosuvastatin 10 mg) compared to a high-intensity statin alone (rosuvastatin 20 mg) in adults (N = 3780) with ASCVD. Included patients were ages 19 to 80 years (mean, 64 years) and had a baseline LDL concentration of 80 mg/dL (standard deviation, 64-100 mg/dL) with known ASCVD (defined by prior MI, ACS, history of coronary or other arterial revascularization, ischemic stroke, or peripheral artery disease); 75% were male.3

The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, major cardiovascular events, or nonfatal stroke. At 3 years, an intention-to-treat analysis found no significant difference between the combination and monotherapy groups (9% vs 9.9%; absolute difference, –0.78%; 95% CI, –2.39% to 0.83%). Dose reduction or discontinuation of the study drug(s) due to intolerance was lower in the combination group than in the monotherapy group (4.8% vs 8.2%; P < 0.0001). The study may be limited by the fact that it was nonblinded and all participants were South Korean, which limits generalizability.3

Recommendations from others

A 2022 evidence-based clinical practice guideline published in BMJ recommends adding ezetimibe to a statin to decrease all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, nonfatal stroke, and nonfatal MI in patients with known CVD, regardless of their LDL concentration (weak recommendation based on a systematic review and network meta-analysis).4

In 2019, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology recommended ezetimibe for patients with clinical ASCVD who are on maximally tolerated statin therapy and have an LDL concentration of 70 mg/dL or higher (Class 2b recommendation [meaning it can be considered] based on a meta-analysis of moderate-quality RCTs).5

Editor’s takeaway

The data on this important and well-studied question have inched closer to firm and clear answers. First, adding ezetimibe to a lower-intensity statin when a higher-intensity statin is not tolerated is an effective treatment. Second, adding ezetimibe to a statin improves nonfatal ASCVD outcomes but not fatal ones. What has not yet been made clear, because a noninferiority trial does not answer this question, is whether the highest intensity statin plus ezetimibe is superior to that high-intensity statin alone, regardless of LDL concentration.

1. Zhan S, Tang M, Liu F, et al. Ezetimibe for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and all‐cause mortality events. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2018;11:CD012502. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012502.pub2

2. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387-2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489 pmid:26039521

3. Kim BK, Hong SJ, Lee YJ, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe combination therapy versus high-intensity statin monotherapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (RACING): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2022;400:380-390. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00916-3

4. Hao Q, Aertgeerts B, Guyatt G, et al. PCSK9 inhibitors and ezetimibe for the reduction of cardiovascular events: a clinical practice guideline with risk-stratified recommendations. BMJ. 2022;377:e069066. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-069066

5. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:e285-e350. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003

Evidence summary

Adding ezetimibe reduces nonfatal events but does not improve mortality

A 2018 Cochrane meta-analysis included 10 RCTs (N = 21,919 patients) that evaluated the efficacy and safety of ezetimibe plus a statin (dual therapy) vs a statin alone or plus placebo (monotherapy) for the secondary prevention of CVD. Mean age of patients ranged from 55 to 84 years. Almost all of the patients (> 99%) included in the analyses had existing ASCVD. The dose of ezetimibe was 10 mg; statins used included atorvastatin 10 to 80 mg, pitavastatin 2 to 4 mg, rosuvastatin 10 mg, and simvastatin 20 to 80 mg.1

The primary outcomes were MACE and all-cause mortality. MACE is defined as a composite of CVD, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), nonfatal stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization procedures. The TABLE1 provides a detailed breakdown of each of the outcomes.

The dual-therapy group compared to the monotherapy group had a lower risk for MACE (26.6% vs 28.3%; 1.7% absolute risk reduction; 6% relative risk reduction; NNT = 59) and little or no difference in the reduction of all-cause mortality. For secondary outcomes, the dual-therapy group had a lower risk for nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and coronary revascularization. There was no difference in cardiovascular mortality or adverse events between the 2 groups. The quality of evidence was high for all-cause mortality and moderate for cardiovascular mortality, MACE, MI, and stroke.1

The 2015 IMPROVE-IT study, the largest included in the Cochrane review, was a double-blind RCT (N = 18,144) conducted at 1147 sites in 39 countries comparing simvastatin 40 mg/d plus ezetimibe 10 mg/d (dual therapy) vs simvastatin 40 mg/d plus placebo (monotherapy). Patients were at least 50 years old (average age, 64 years) and had been hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) within the previous 10 days; 76% were male and 84% were White. The average low-density lipoprotein (LDL) concentration at baseline was 94 mg/dL in both groups.2

The primary endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, a major coronary event (nonfatal MI, unstable angina requiring hospitalization, coronary revascularization at least 30 days after randomization), or nonfatal stroke, with a median follow-up of 6 years. The simvastatin plus ezetimibe group compared to the simvastatin-only group had a lower risk for the primary end point (HR = 0.94; 95% CI, 0.89-0.99; NNT = 50), but no differences in cardiovascular or all-cause mortality. Since the study only recruited patients with recent ACS, results are only applicable to that specific population.2

The 2022 RACING study was a multicenter, open-label, randomized, noninferiority trial that evaluated the combination of ezetimibe 10 mg and a moderate-intensity statin (rosuvastatin 10 mg) compared to a high-intensity statin alone (rosuvastatin 20 mg) in adults (N = 3780) with ASCVD. Included patients were ages 19 to 80 years (mean, 64 years) and had a baseline LDL concentration of 80 mg/dL (standard deviation, 64-100 mg/dL) with known ASCVD (defined by prior MI, ACS, history of coronary or other arterial revascularization, ischemic stroke, or peripheral artery disease); 75% were male.3

The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, major cardiovascular events, or nonfatal stroke. At 3 years, an intention-to-treat analysis found no significant difference between the combination and monotherapy groups (9% vs 9.9%; absolute difference, –0.78%; 95% CI, –2.39% to 0.83%). Dose reduction or discontinuation of the study drug(s) due to intolerance was lower in the combination group than in the monotherapy group (4.8% vs 8.2%; P < 0.0001). The study may be limited by the fact that it was nonblinded and all participants were South Korean, which limits generalizability.3

Recommendations from others

A 2022 evidence-based clinical practice guideline published in BMJ recommends adding ezetimibe to a statin to decrease all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, nonfatal stroke, and nonfatal MI in patients with known CVD, regardless of their LDL concentration (weak recommendation based on a systematic review and network meta-analysis).4

In 2019, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology recommended ezetimibe for patients with clinical ASCVD who are on maximally tolerated statin therapy and have an LDL concentration of 70 mg/dL or higher (Class 2b recommendation [meaning it can be considered] based on a meta-analysis of moderate-quality RCTs).5

Editor’s takeaway

The data on this important and well-studied question have inched closer to firm and clear answers. First, adding ezetimibe to a lower-intensity statin when a higher-intensity statin is not tolerated is an effective treatment. Second, adding ezetimibe to a statin improves nonfatal ASCVD outcomes but not fatal ones. What has not yet been made clear, because a noninferiority trial does not answer this question, is whether the highest intensity statin plus ezetimibe is superior to that high-intensity statin alone, regardless of LDL concentration.

Evidence summary

Adding ezetimibe reduces nonfatal events but does not improve mortality

A 2018 Cochrane meta-analysis included 10 RCTs (N = 21,919 patients) that evaluated the efficacy and safety of ezetimibe plus a statin (dual therapy) vs a statin alone or plus placebo (monotherapy) for the secondary prevention of CVD. Mean age of patients ranged from 55 to 84 years. Almost all of the patients (> 99%) included in the analyses had existing ASCVD. The dose of ezetimibe was 10 mg; statins used included atorvastatin 10 to 80 mg, pitavastatin 2 to 4 mg, rosuvastatin 10 mg, and simvastatin 20 to 80 mg.1

The primary outcomes were MACE and all-cause mortality. MACE is defined as a composite of CVD, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), nonfatal stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization procedures. The TABLE1 provides a detailed breakdown of each of the outcomes.

The dual-therapy group compared to the monotherapy group had a lower risk for MACE (26.6% vs 28.3%; 1.7% absolute risk reduction; 6% relative risk reduction; NNT = 59) and little or no difference in the reduction of all-cause mortality. For secondary outcomes, the dual-therapy group had a lower risk for nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and coronary revascularization. There was no difference in cardiovascular mortality or adverse events between the 2 groups. The quality of evidence was high for all-cause mortality and moderate for cardiovascular mortality, MACE, MI, and stroke.1

The 2015 IMPROVE-IT study, the largest included in the Cochrane review, was a double-blind RCT (N = 18,144) conducted at 1147 sites in 39 countries comparing simvastatin 40 mg/d plus ezetimibe 10 mg/d (dual therapy) vs simvastatin 40 mg/d plus placebo (monotherapy). Patients were at least 50 years old (average age, 64 years) and had been hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) within the previous 10 days; 76% were male and 84% were White. The average low-density lipoprotein (LDL) concentration at baseline was 94 mg/dL in both groups.2

The primary endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, a major coronary event (nonfatal MI, unstable angina requiring hospitalization, coronary revascularization at least 30 days after randomization), or nonfatal stroke, with a median follow-up of 6 years. The simvastatin plus ezetimibe group compared to the simvastatin-only group had a lower risk for the primary end point (HR = 0.94; 95% CI, 0.89-0.99; NNT = 50), but no differences in cardiovascular or all-cause mortality. Since the study only recruited patients with recent ACS, results are only applicable to that specific population.2

The 2022 RACING study was a multicenter, open-label, randomized, noninferiority trial that evaluated the combination of ezetimibe 10 mg and a moderate-intensity statin (rosuvastatin 10 mg) compared to a high-intensity statin alone (rosuvastatin 20 mg) in adults (N = 3780) with ASCVD. Included patients were ages 19 to 80 years (mean, 64 years) and had a baseline LDL concentration of 80 mg/dL (standard deviation, 64-100 mg/dL) with known ASCVD (defined by prior MI, ACS, history of coronary or other arterial revascularization, ischemic stroke, or peripheral artery disease); 75% were male.3

The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, major cardiovascular events, or nonfatal stroke. At 3 years, an intention-to-treat analysis found no significant difference between the combination and monotherapy groups (9% vs 9.9%; absolute difference, –0.78%; 95% CI, –2.39% to 0.83%). Dose reduction or discontinuation of the study drug(s) due to intolerance was lower in the combination group than in the monotherapy group (4.8% vs 8.2%; P < 0.0001). The study may be limited by the fact that it was nonblinded and all participants were South Korean, which limits generalizability.3

Recommendations from others

A 2022 evidence-based clinical practice guideline published in BMJ recommends adding ezetimibe to a statin to decrease all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, nonfatal stroke, and nonfatal MI in patients with known CVD, regardless of their LDL concentration (weak recommendation based on a systematic review and network meta-analysis).4

In 2019, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology recommended ezetimibe for patients with clinical ASCVD who are on maximally tolerated statin therapy and have an LDL concentration of 70 mg/dL or higher (Class 2b recommendation [meaning it can be considered] based on a meta-analysis of moderate-quality RCTs).5

Editor’s takeaway

The data on this important and well-studied question have inched closer to firm and clear answers. First, adding ezetimibe to a lower-intensity statin when a higher-intensity statin is not tolerated is an effective treatment. Second, adding ezetimibe to a statin improves nonfatal ASCVD outcomes but not fatal ones. What has not yet been made clear, because a noninferiority trial does not answer this question, is whether the highest intensity statin plus ezetimibe is superior to that high-intensity statin alone, regardless of LDL concentration.

1. Zhan S, Tang M, Liu F, et al. Ezetimibe for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and all‐cause mortality events. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2018;11:CD012502. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012502.pub2

2. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387-2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489 pmid:26039521

3. Kim BK, Hong SJ, Lee YJ, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe combination therapy versus high-intensity statin monotherapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (RACING): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2022;400:380-390. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00916-3

4. Hao Q, Aertgeerts B, Guyatt G, et al. PCSK9 inhibitors and ezetimibe for the reduction of cardiovascular events: a clinical practice guideline with risk-stratified recommendations. BMJ. 2022;377:e069066. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-069066

5. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:e285-e350. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003

1. Zhan S, Tang M, Liu F, et al. Ezetimibe for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and all‐cause mortality events. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2018;11:CD012502. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012502.pub2

2. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387-2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489 pmid:26039521

3. Kim BK, Hong SJ, Lee YJ, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe combination therapy versus high-intensity statin monotherapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (RACING): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2022;400:380-390. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00916-3

4. Hao Q, Aertgeerts B, Guyatt G, et al. PCSK9 inhibitors and ezetimibe for the reduction of cardiovascular events: a clinical practice guideline with risk-stratified recommendations. BMJ. 2022;377:e069066. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-069066

5. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:e285-e350. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003

EVIDENCE-BASED REVIEW:

YES. In patients with known cardio- vascular disease (CVD), ezetimibe with a statin decreases

In adults with atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), the combination of ezetimibe and a moderate-intensity statin (rosuvastatin 10 mg) was noninferior at decreasing cardiovascular death, major cardiovascular events, and nonfatal stroke, but was more tolerable, compared to a high-intensity statin (rosuvastatin 20 mg) alone (SOR, B; 1 RCT).

64-year-old woman • hot flashes, facial flushing, excessive sweating, and palpitations • daily headaches • history of hypertension • Dx?

THE CASE

A 64-year-old woman sought care after having hot flashes, facial flushing, excessive sweating, palpitations, and daily headaches for 1 month. She had a history of hypertension that was well controlled with hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d but over the previous month, it had become more difficult to control. Her blood pressure remained elevated to 150/100 mm Hg despite the addition of lisinopril 40 mg/d and amlodipine 10 mg/d, indicating resistant hypertension. She had no family history of hypertension, diabetes, or obesity or any other pertinent medical or surgical history. Physical examination was negative for weight gain, stretch marks, or muscle weakness.

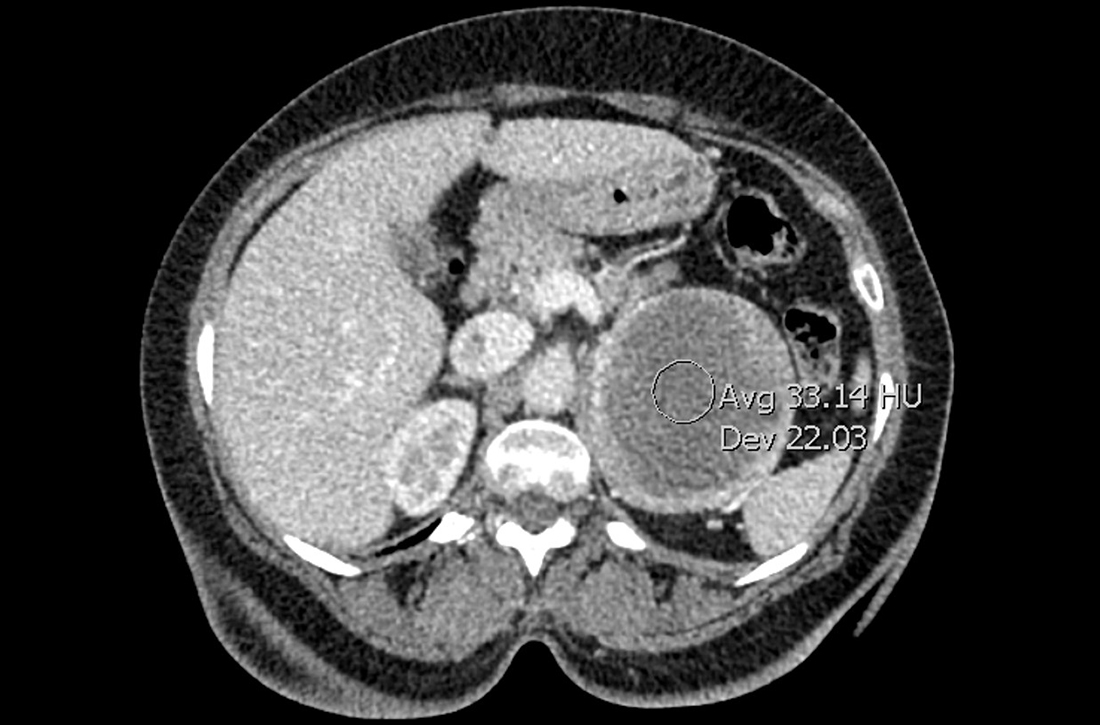

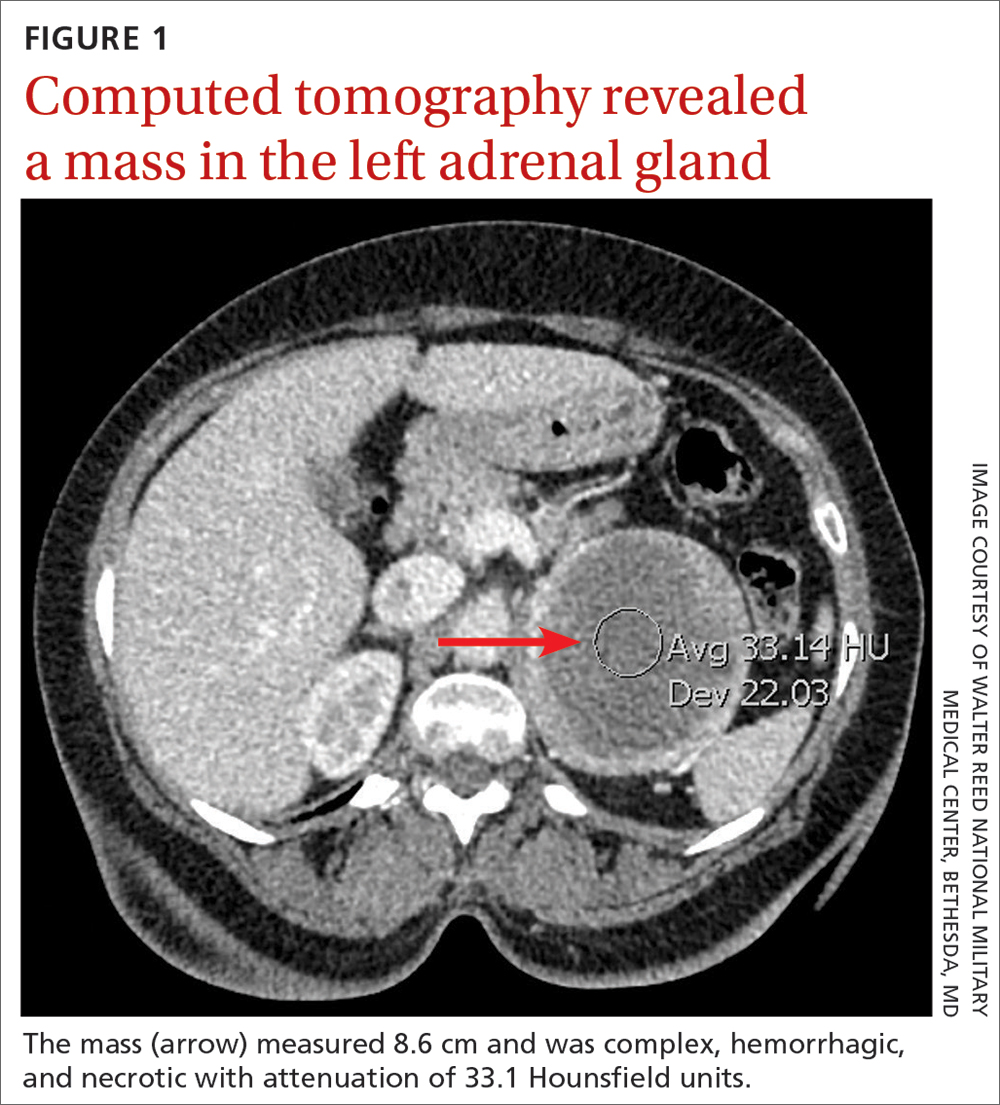

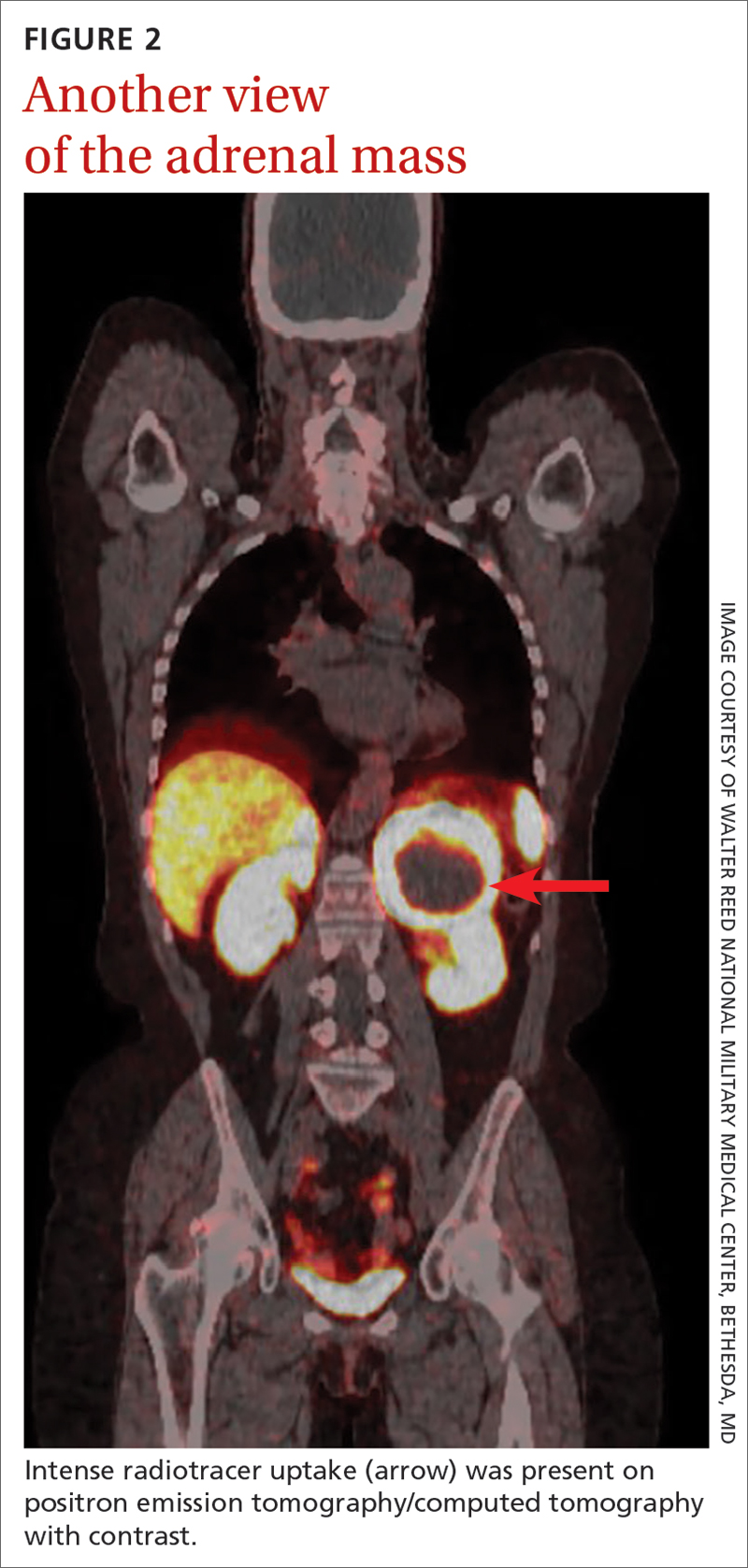

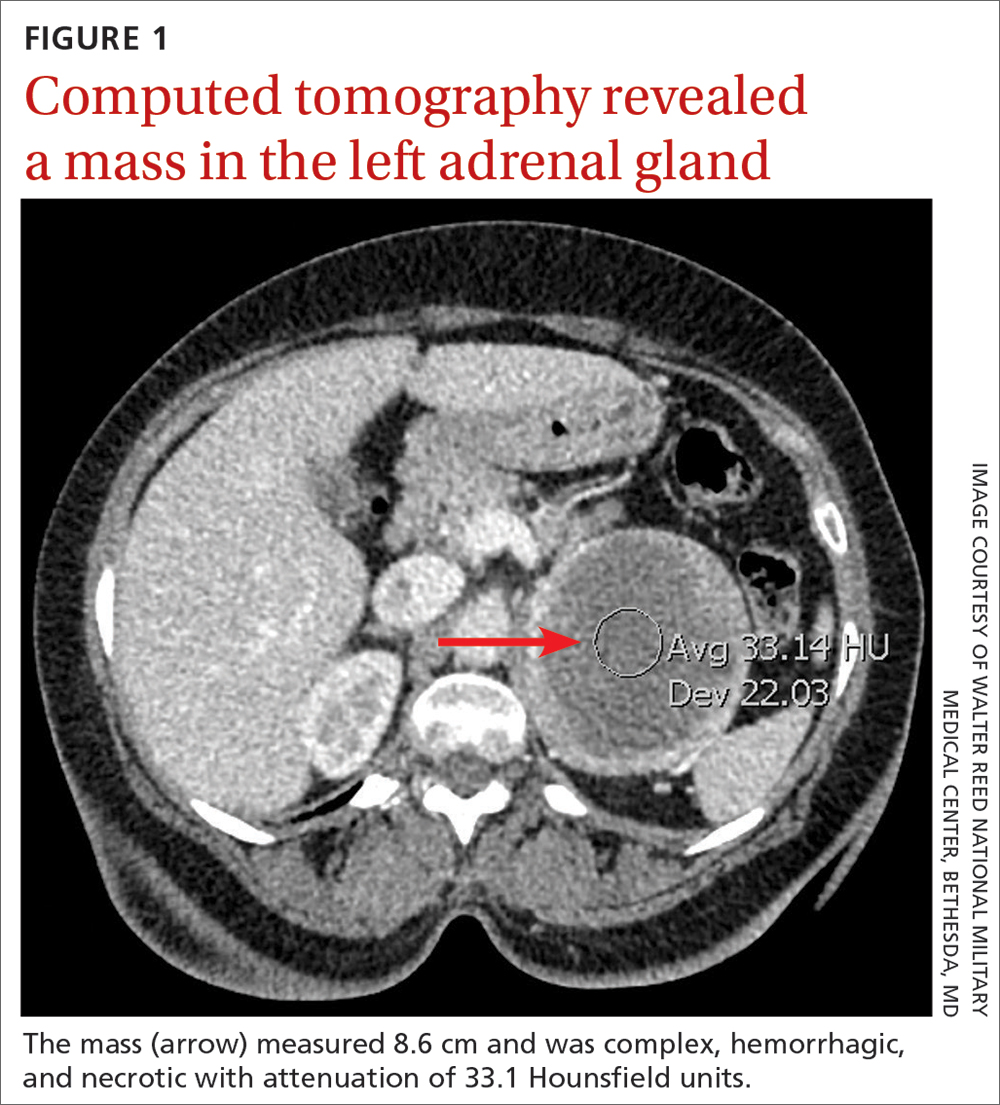

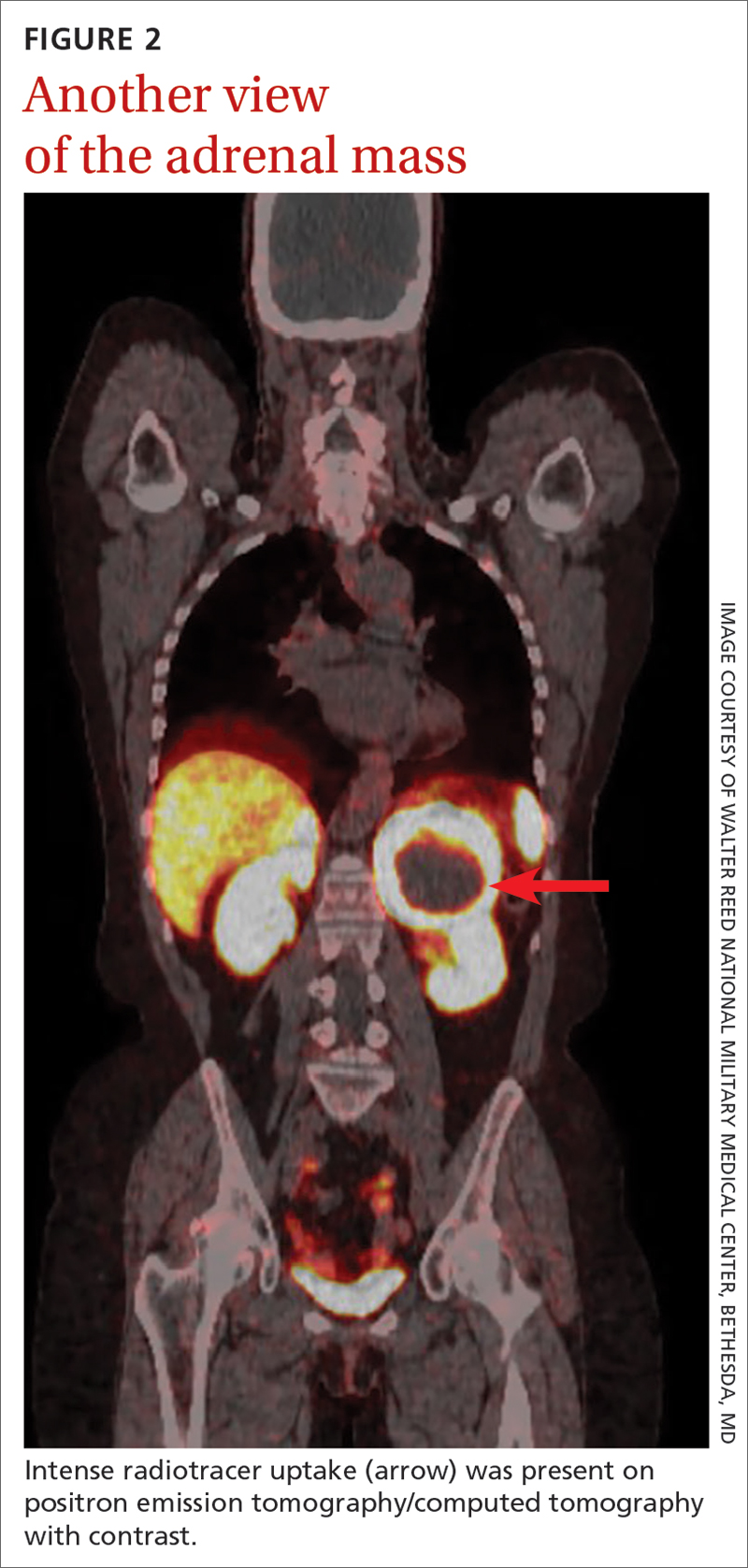

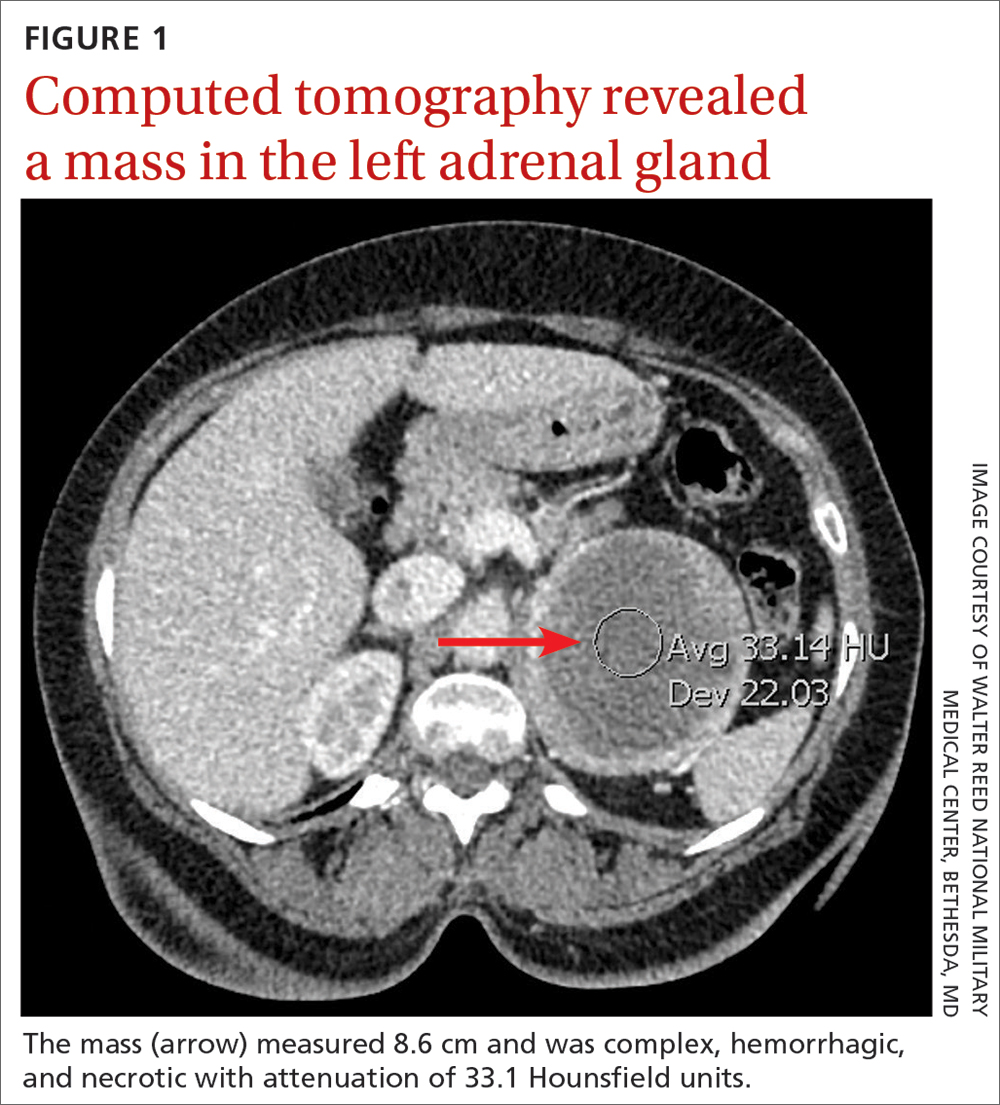

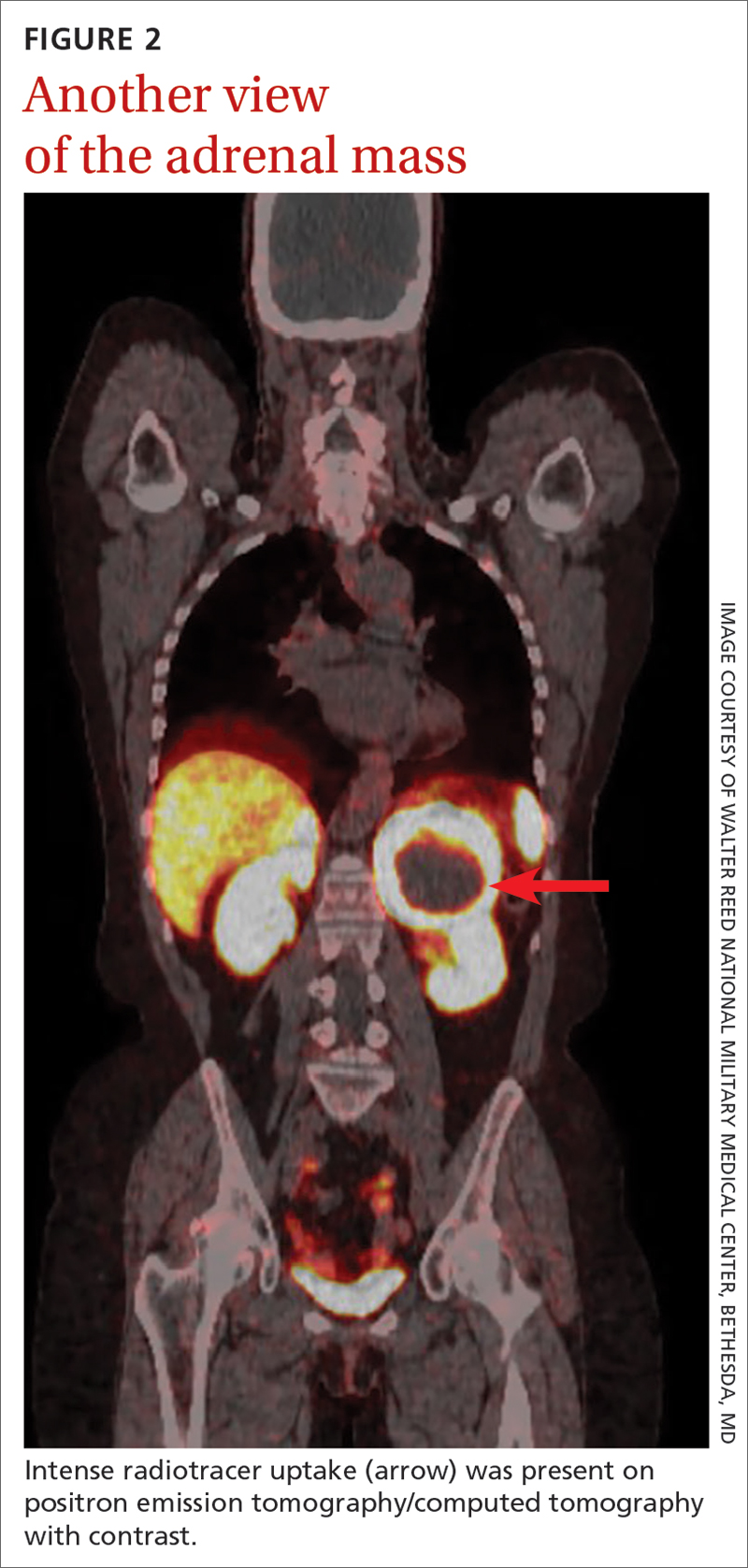

Laboratory tests revealed a normal serum aldosterone-renin ratio, renal function, and thyroid function; however, she had elevated levels of normetanephrine (2429 pg/mL; normal range, 0-145 pg/mL) and metanephrine (143 pg/mL; normal range, 0-62 pg/mL). Computed tomography (CT) revealed an 8.6-cm complex, hemorrhagic, necrotic left adrenal mass with attenuation of 33.1 Hounsfield units (HU) (FIGURE 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a T2 hyperintense left adrenal mass. An evaluation for Cushing syndrome was negative, and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT with gallium-68 dotatate was ordered. It showed intense radiotracer uptake in the left adrenal gland, with a maximum standardized uptake value of 70.1 (FIGURE 2).

THE DIAGNOSIS

After appropriate preparation with alpha blockade (phenoxybenzamine 20 mg twice daily for 7 days) and fluid resuscitation (normal saline run over 12 hours preoperatively), the patient underwent successful open surgical resection of the adrenal mass, during which her blood pressure was controlled with a nitroprusside infusion and boluses of esmolol and labetalol. Pathology results showed cells in a nested pattern with round to oval nuclei in a vascular background. There was no necrosis, increased mitotic figures, capsular invasion, or increased cellularity. Chromogranin immunohistochemical staining was positive. Given her resistant hypertension, clinical symptoms, and pathology results, the patient was given a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma.

DISCUSSION

Resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure that is elevated above goal despite the use of 3 maximally titrated antihypertensive agents from different classes or that is well controlled with at least 4 antihypertensive medications.1 The prevalence of resistant hypertension is 12% to 18% in adults being treated for hypertension.1 Patients with resistant hypertension have a higher risk for cardiovascular events and death, are more likely to have a secondary cause of hypertension, and may benefit from special diagnostic testing or treatment approaches to control their blood pressure.1

There are many causes of resistant hypertension; primary aldosteronism is the most common cause (prevalence as high as 20%).2 Given the increased risk for cardiovascular/cerebrovascular disease, all patients with resistant hypertension should be screened for this condition.2 Other causes of resistant hypertension include renal parenchymal disease, renal artery stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, thyroid dysfunction, Cushing syndrome, paraganglioma, and as seen in our case, pheochromocytoma. Although pheochromocytoma is a rare cause of resistant hypertension (0.01%-4%),1 it is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality if left untreated and may be inherited, making it an essential diagnosis to consider in all patients with resistant hypertension.1,3

Common symptoms of pheochromocytoma are hypertension (paroxysmal or sustained), headaches, palpitations, pallor, and piloerection (or cold sweats).1 Patients with pheochromocytoma typically exhibit metanephrine levels that are more than 4 times the upper limit of normal.4 Therefore, measurement of plasma free metanephrines or urinary fractionated metanephrines is recommended.5 Elevated metanephrine levels also are caused by obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, and certain medications and should be ruled out.5

All pheochromocytomas are potentially malignant. Despite the existence of pathologic scoring systems6,7 and radiographic features that suggest malignancy,8,9 no single risk-stratification tool is recommended in the current literature.10 Ultimately, the only way to confirm malignancy is to see metastases where chromaffin tissue is not normally found on imaging.10

Continue to: Pathologic features to look for...

Pathologic features to look for include capsular/periadrenal adipose invasion, increased cellularity, necrosis, tumor cell spindling, increased/atypical mitotic figures, and nuclear pleomorphism. Radiographic features include larger size (≥ 4-6 cm),11 an irregular shape, necrosis, calcifications, attenuation of 10 HU or higher on noncontrast CT, absolute washout of 60% or lower, and relative washout of 40% or lower.8,12 On MRI, malignant lesions appear hypointense on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging.9 Fluorodeoxyglucose avidity on PET scan also is indicative of malignancy.8,9

Treatment for pheochromocytoma is surgical resection. An experienced surgical team and proper preoperative preparation are necessary because the induction of anesthesia, endotracheal intubation, and tumor manipulation can lead to a release of catecholamines, potentially resulting in an intraoperative hypertensive crisis, cardiac arrhythmias, and multiorgan failure.

Proper preoperative preparation includes taking an alpha-adrenergic blocker, such as phenoxybenzamine, prazosin, terazosin, or doxazosin, for at least 7 days to normalize the patient’s blood pressure. Patients should be counseled that they may experience nasal congestion, orthostasis, and fatigue while taking these medications. Volume expansion with intravenous fluids also should be performed and a high-salt diet considered. Beta-adrenergic blockade can be initiated once appropriate alpha-adrenergic blockade is achieved to control the patient’s heart rate; beta-blockers should never be started first because of the risk for severe hypertension. Careful hemodynamic monitoring is vital intraoperatively and postoperatively.5,13 Because metastatic lesions can occur decades after resection, long-term follow-up is critical.5,10

Following tumor resection, our patient’s blood pressure was supported with intravenous fluids and phenylephrine. She was able to discontinue all her antihypertensive medications postoperatively, and her plasma free and urinary fractionated metanephrine levels returned to within normal limits 8 weeks after surgery. Five years after surgery, she continues to have no signs of recurrence, as evidenced by annual negative plasma free metanephrines testing and abdominal/pelvic CT.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case highlights the importance of recognizing resistant hypertension and a potential secondary cause of this disease—pheochromocytoma. Although rare, pheochromocytomas confer increased risk for cardiovascular disease and death. Thus, swift recognition and proper preparation for surgical resection are necessary. Malignant lesions can be diagnosed only upon discovery of metastatic disease and can recur for decades after surgical resection, making diligent long-term follow-up imperative.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicole O. Vietor, MD, Division of Endocrinology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 8901 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda, MD 20889; [email protected]

1. Carey RM, Calhoun DA, Bakris GL, et al. Resistant hypertension: detection, evaluation, and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2018;72:e53-e90. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000084

2. Young WF Jr. Diagnosis and treatment of primary aldosteronism: practical clinical perspectives. J Intern Med. 2019;285:126-148. doi: 10.1111/joim.12831

3. Young WF Jr, Calhoun DA, Lenders JWM, et al. Screening for endocrine hypertension: an Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr Rev. 2017;38:103-122. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00054

4. Lenders JWM, Pacak K, Walther MM, et al. Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: which test is best? JAMA. 2002;287:1427-1434. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1427

5. Lenders JW, Duh Q-Y, Eisenhofer G, et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1915-1942. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1498

6. Kimura N, Takayanagi R, Takizawa N, et al. Pathological grading for predicting metastasis in phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:405-414. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0494

7. Thompson LDR. Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 100 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:551-566. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200205000-00002

8. Vaidya A, Hamrahian A, Bancos I, et al. The evaluation of incidentally discovered adrenal masses. Endocr Pract. 2019;25:178-192. doi: 10.4158/DSCR-2018-0565

9. Young WF Jr. Conventional imaging in adrenocortical carcinoma: update and perspectives. Horm Cancer. 2011;2:341-347. doi: 10.1007/s12672-011-0089-z

10. Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:552-565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1806651

11. Iñiguez-Ariza NM, Kohlenberg JD, Delivanis DA, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and radiological characteristics of a single-center retrospective cohort of 705 large adrenal tumors. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;2:30-39. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.11.002

12. Marty M, Gaye D, Perez P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography to identify adenomas among adrenal incidentalomas in an endocrinological population. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178:439-446. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-1056

13. Pacak K. Preoperative management of the pheochromocytoma patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4069-4079. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1720

THE CASE

A 64-year-old woman sought care after having hot flashes, facial flushing, excessive sweating, palpitations, and daily headaches for 1 month. She had a history of hypertension that was well controlled with hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d but over the previous month, it had become more difficult to control. Her blood pressure remained elevated to 150/100 mm Hg despite the addition of lisinopril 40 mg/d and amlodipine 10 mg/d, indicating resistant hypertension. She had no family history of hypertension, diabetes, or obesity or any other pertinent medical or surgical history. Physical examination was negative for weight gain, stretch marks, or muscle weakness.

Laboratory tests revealed a normal serum aldosterone-renin ratio, renal function, and thyroid function; however, she had elevated levels of normetanephrine (2429 pg/mL; normal range, 0-145 pg/mL) and metanephrine (143 pg/mL; normal range, 0-62 pg/mL). Computed tomography (CT) revealed an 8.6-cm complex, hemorrhagic, necrotic left adrenal mass with attenuation of 33.1 Hounsfield units (HU) (FIGURE 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a T2 hyperintense left adrenal mass. An evaluation for Cushing syndrome was negative, and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT with gallium-68 dotatate was ordered. It showed intense radiotracer uptake in the left adrenal gland, with a maximum standardized uptake value of 70.1 (FIGURE 2).

THE DIAGNOSIS

After appropriate preparation with alpha blockade (phenoxybenzamine 20 mg twice daily for 7 days) and fluid resuscitation (normal saline run over 12 hours preoperatively), the patient underwent successful open surgical resection of the adrenal mass, during which her blood pressure was controlled with a nitroprusside infusion and boluses of esmolol and labetalol. Pathology results showed cells in a nested pattern with round to oval nuclei in a vascular background. There was no necrosis, increased mitotic figures, capsular invasion, or increased cellularity. Chromogranin immunohistochemical staining was positive. Given her resistant hypertension, clinical symptoms, and pathology results, the patient was given a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma.

DISCUSSION

Resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure that is elevated above goal despite the use of 3 maximally titrated antihypertensive agents from different classes or that is well controlled with at least 4 antihypertensive medications.1 The prevalence of resistant hypertension is 12% to 18% in adults being treated for hypertension.1 Patients with resistant hypertension have a higher risk for cardiovascular events and death, are more likely to have a secondary cause of hypertension, and may benefit from special diagnostic testing or treatment approaches to control their blood pressure.1

There are many causes of resistant hypertension; primary aldosteronism is the most common cause (prevalence as high as 20%).2 Given the increased risk for cardiovascular/cerebrovascular disease, all patients with resistant hypertension should be screened for this condition.2 Other causes of resistant hypertension include renal parenchymal disease, renal artery stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, thyroid dysfunction, Cushing syndrome, paraganglioma, and as seen in our case, pheochromocytoma. Although pheochromocytoma is a rare cause of resistant hypertension (0.01%-4%),1 it is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality if left untreated and may be inherited, making it an essential diagnosis to consider in all patients with resistant hypertension.1,3

Common symptoms of pheochromocytoma are hypertension (paroxysmal or sustained), headaches, palpitations, pallor, and piloerection (or cold sweats).1 Patients with pheochromocytoma typically exhibit metanephrine levels that are more than 4 times the upper limit of normal.4 Therefore, measurement of plasma free metanephrines or urinary fractionated metanephrines is recommended.5 Elevated metanephrine levels also are caused by obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, and certain medications and should be ruled out.5

All pheochromocytomas are potentially malignant. Despite the existence of pathologic scoring systems6,7 and radiographic features that suggest malignancy,8,9 no single risk-stratification tool is recommended in the current literature.10 Ultimately, the only way to confirm malignancy is to see metastases where chromaffin tissue is not normally found on imaging.10

Continue to: Pathologic features to look for...