User login

Overweight in heterozygous FH tied to even higher CAD risk

MANNHEIM, GERMANY – – rates that appear to have a substantial impact on these patients’ already increased risk of coronary artery disease, a registry analysis suggests.

Data on almost 36,000 individuals with FH were collated from an international registry, revealing that 55% of adults and 25% of children and adolescents with the homozygous form of FH had overweight or obesity. The figures for heterozygous FH were 52% and 27%, respectively.

Crucially, overweight or obesity was associated with substantially increased rates of coronary artery disease, particularly in persons with heterozygous FH, among whom adults with obesity faced a twofold increased risk, rising to more than sixfold in children and adolescents.

Moreover, “obesity is associated with a worse lipid profile, even from childhood, regardless of whether a patient is on medication,” said study presenter Amany Elshorbagy, DPhil, Cardiovascular Epidemiologist, department of primary care and public health, Imperial College London.

She added that, with the increased risk of coronary artery disease associated with heterozygous FH, the results showed that “together with lipid-lowering medication, weight management is needed.”

The research was presented at the annual meeting of the European Atherosclerosis Society.

Tended to be thin

Alberico L. Catapano, MD, PhD, director of cardiovascular research and of the Lipoproteins and Atherosclerosis Laboratory of IRCCS Multimedica, Milan, and past president of the EAS, said in an interview that, historically, few FH patients were overweight or obese; rather, they tended to be thin.

However, there is now “a trend for people with FH to show more diabetes and obesity,” with the “bottom line” being that, as they are already at increased risk of coronary artery disease, it pushes their risk up even further.

In other words, if a risk factor such as obesity is added “on top of the strongest risk factor, that is LDL cholesterol, it is not one plus one makes two, it is one plus one makes three,” he said.

As such, Dr. Catapano believes that the study is “very interesting,” because it further underlines the importance of weight management for individuals with increased LDL cholesterol, “especially when you have genetic forms, like FH.”

Dr. Catapano’s comments were echoed by session co-chair Ulrike Schatz, MD, leader of the lipidology specialty department at the University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, Technical University of Dresden (Germany).

Indeed, she told Dr. Elshorbagy before her presentation that she finds “a lot of my FH patients have a tendency towards anorexia.”

In an interview, Dr. Elshorbagy said that that reaction was typical of “most of the clinicians” she had spoken to. Upon seeing her data, especially for homozygous FH patients, they say, “They are on the lean side.”

Consequently, the research team went into the study “with the expectation that they might have a lower prevalence of obesity and overweight than the general population,” but “that’s not what we’re seeing.”

Dr. Elshorbagy noted that it would be helpful to have longitudinal data to determine whether, 50 years ago, patients with HF “were leaner, along with the rest of the population.”

The registry data are cross-sectional, and the team is now reaching out to the respective national lead investigators to submit follow-up data on their patients, with the aim of looking at changes in body weight and the impact on outcomes over time.

Another key question for the researchers is in regard to fat distribution, as body mass index “is not the best predictor of heart disease,” Dr. Elshorbagy said, but is rather central obesity.

Although they have also asked investigators to share waist circumference data, she conceded that it is a measurement that “is a lot harder to standardize across centers and countries; it’s not like putting patients on a scale.”

Overall, Dr. Elshorbagy believes that her findings indicate that clinicians should take a broader, more holistic approach toward their patients – in other words, an approach in which lipid lowering medication is “key but is just one of several things we need to do to make sure the coronary event rate goes down.”

More with than without

Dr. Elshorbagy began her presentation by highlighting that the prevalence of overweight and obesity ranges from 50% to 70% and that it is “the only health condition where you’ve got more people worldwide with the condition than without.”

Crucially, overweight increases the risk of coronary artery disease by approximately 20%. Among patients with obesity, the risk rises to 50%.

Given that FH patients “already have a very high risk of cardiovascular disease from their high cholesterol levels,” the team set out to determine rates of obesity and overweight in this population and their impact on coronary artery disease risk.

They used cross-sectional data from the EAS FH Studies Collaboration Global Registry, which involves 29,262 adults aged greater than or equal to 18 years and 6,275 children and adolescents aged 5 to 17 years with heterozygous FH, and 325 adults and 57 children with homozygous FH.

Dividing the adults into standard BMI categories, they found that 16% of heterozygous and 23% of homozygous FH patients had obesity, while 52% and 55%, respectively, had overweight or obesity.

For children, the team used World Health Organization z score cutoffs, which indicated that 9% of patients with heterozygous FH and 7% of patients with homozygous FH had obesity. Rates of overweight or obesity were 27% and 25%, respectively.

Among patients with heterozygous FH, rates of overweight or obesity among adults were 50% in high-income countries and 63% in other countries; among children, the rates were and 27% and 29%, respectively.

Stratified by region, the team found that the lowest rate of overweight or obesity among adult patients with heterozygous FH was in Eastern Asia, at 27%, while the highest was in Northern Africa/Western Asia (the Middle East), at 82%.

In North America, 56% of adult patients had overweight or obesity. The prevalence of coronary artery disease rose with increasing BMI.

Among adult patients with heterozygous FH, 11.3% of those with normal weight had coronary artery disease; the percentage rose to 22.9% among those with overweight, and 30.9% among those with obesity. Among children, the corresponding figures were 0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.7%.

Putting adults and children with homozygous FH together, the researchers found that 29.0% of patients with normal weight had coronary artery disease, compared with 31.3% of those with overweight and 49.3% of those with obesity.

Moreover, the results showed that levels of LDL and remnant cholesterol were significantly associated with BMI in adults and children with heterozygous FH, even after adjusting for age, sex, and lipid-lowering medication (P < .001 for all).

Multivariate analysis that took into account age, sex, lipid-lowering medication, and LDL cholesterol revealed that having obesity, compared with not having obesity, was associated with a substantial increase in the risk of coronary artery disease among patients with heterozygous FH.

Among adults with the condition, the odds ratio was 2.16 (95% confidence interval, 1.97-2.36), while among children and adolescents, it was 6.87 (95% CI, 1.55-30.46).

The results remained similar after further adjustment for the presence of diabetes and when considering peripheral artery disease and stroke.

No funding for the study was declared. Dr. Elshorbagy has relationships with Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, and Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MANNHEIM, GERMANY – – rates that appear to have a substantial impact on these patients’ already increased risk of coronary artery disease, a registry analysis suggests.

Data on almost 36,000 individuals with FH were collated from an international registry, revealing that 55% of adults and 25% of children and adolescents with the homozygous form of FH had overweight or obesity. The figures for heterozygous FH were 52% and 27%, respectively.

Crucially, overweight or obesity was associated with substantially increased rates of coronary artery disease, particularly in persons with heterozygous FH, among whom adults with obesity faced a twofold increased risk, rising to more than sixfold in children and adolescents.

Moreover, “obesity is associated with a worse lipid profile, even from childhood, regardless of whether a patient is on medication,” said study presenter Amany Elshorbagy, DPhil, Cardiovascular Epidemiologist, department of primary care and public health, Imperial College London.

She added that, with the increased risk of coronary artery disease associated with heterozygous FH, the results showed that “together with lipid-lowering medication, weight management is needed.”

The research was presented at the annual meeting of the European Atherosclerosis Society.

Tended to be thin

Alberico L. Catapano, MD, PhD, director of cardiovascular research and of the Lipoproteins and Atherosclerosis Laboratory of IRCCS Multimedica, Milan, and past president of the EAS, said in an interview that, historically, few FH patients were overweight or obese; rather, they tended to be thin.

However, there is now “a trend for people with FH to show more diabetes and obesity,” with the “bottom line” being that, as they are already at increased risk of coronary artery disease, it pushes their risk up even further.

In other words, if a risk factor such as obesity is added “on top of the strongest risk factor, that is LDL cholesterol, it is not one plus one makes two, it is one plus one makes three,” he said.

As such, Dr. Catapano believes that the study is “very interesting,” because it further underlines the importance of weight management for individuals with increased LDL cholesterol, “especially when you have genetic forms, like FH.”

Dr. Catapano’s comments were echoed by session co-chair Ulrike Schatz, MD, leader of the lipidology specialty department at the University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, Technical University of Dresden (Germany).

Indeed, she told Dr. Elshorbagy before her presentation that she finds “a lot of my FH patients have a tendency towards anorexia.”

In an interview, Dr. Elshorbagy said that that reaction was typical of “most of the clinicians” she had spoken to. Upon seeing her data, especially for homozygous FH patients, they say, “They are on the lean side.”

Consequently, the research team went into the study “with the expectation that they might have a lower prevalence of obesity and overweight than the general population,” but “that’s not what we’re seeing.”

Dr. Elshorbagy noted that it would be helpful to have longitudinal data to determine whether, 50 years ago, patients with HF “were leaner, along with the rest of the population.”

The registry data are cross-sectional, and the team is now reaching out to the respective national lead investigators to submit follow-up data on their patients, with the aim of looking at changes in body weight and the impact on outcomes over time.

Another key question for the researchers is in regard to fat distribution, as body mass index “is not the best predictor of heart disease,” Dr. Elshorbagy said, but is rather central obesity.

Although they have also asked investigators to share waist circumference data, she conceded that it is a measurement that “is a lot harder to standardize across centers and countries; it’s not like putting patients on a scale.”

Overall, Dr. Elshorbagy believes that her findings indicate that clinicians should take a broader, more holistic approach toward their patients – in other words, an approach in which lipid lowering medication is “key but is just one of several things we need to do to make sure the coronary event rate goes down.”

More with than without

Dr. Elshorbagy began her presentation by highlighting that the prevalence of overweight and obesity ranges from 50% to 70% and that it is “the only health condition where you’ve got more people worldwide with the condition than without.”

Crucially, overweight increases the risk of coronary artery disease by approximately 20%. Among patients with obesity, the risk rises to 50%.

Given that FH patients “already have a very high risk of cardiovascular disease from their high cholesterol levels,” the team set out to determine rates of obesity and overweight in this population and their impact on coronary artery disease risk.

They used cross-sectional data from the EAS FH Studies Collaboration Global Registry, which involves 29,262 adults aged greater than or equal to 18 years and 6,275 children and adolescents aged 5 to 17 years with heterozygous FH, and 325 adults and 57 children with homozygous FH.

Dividing the adults into standard BMI categories, they found that 16% of heterozygous and 23% of homozygous FH patients had obesity, while 52% and 55%, respectively, had overweight or obesity.

For children, the team used World Health Organization z score cutoffs, which indicated that 9% of patients with heterozygous FH and 7% of patients with homozygous FH had obesity. Rates of overweight or obesity were 27% and 25%, respectively.

Among patients with heterozygous FH, rates of overweight or obesity among adults were 50% in high-income countries and 63% in other countries; among children, the rates were and 27% and 29%, respectively.

Stratified by region, the team found that the lowest rate of overweight or obesity among adult patients with heterozygous FH was in Eastern Asia, at 27%, while the highest was in Northern Africa/Western Asia (the Middle East), at 82%.

In North America, 56% of adult patients had overweight or obesity. The prevalence of coronary artery disease rose with increasing BMI.

Among adult patients with heterozygous FH, 11.3% of those with normal weight had coronary artery disease; the percentage rose to 22.9% among those with overweight, and 30.9% among those with obesity. Among children, the corresponding figures were 0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.7%.

Putting adults and children with homozygous FH together, the researchers found that 29.0% of patients with normal weight had coronary artery disease, compared with 31.3% of those with overweight and 49.3% of those with obesity.

Moreover, the results showed that levels of LDL and remnant cholesterol were significantly associated with BMI in adults and children with heterozygous FH, even after adjusting for age, sex, and lipid-lowering medication (P < .001 for all).

Multivariate analysis that took into account age, sex, lipid-lowering medication, and LDL cholesterol revealed that having obesity, compared with not having obesity, was associated with a substantial increase in the risk of coronary artery disease among patients with heterozygous FH.

Among adults with the condition, the odds ratio was 2.16 (95% confidence interval, 1.97-2.36), while among children and adolescents, it was 6.87 (95% CI, 1.55-30.46).

The results remained similar after further adjustment for the presence of diabetes and when considering peripheral artery disease and stroke.

No funding for the study was declared. Dr. Elshorbagy has relationships with Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, and Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MANNHEIM, GERMANY – – rates that appear to have a substantial impact on these patients’ already increased risk of coronary artery disease, a registry analysis suggests.

Data on almost 36,000 individuals with FH were collated from an international registry, revealing that 55% of adults and 25% of children and adolescents with the homozygous form of FH had overweight or obesity. The figures for heterozygous FH were 52% and 27%, respectively.

Crucially, overweight or obesity was associated with substantially increased rates of coronary artery disease, particularly in persons with heterozygous FH, among whom adults with obesity faced a twofold increased risk, rising to more than sixfold in children and adolescents.

Moreover, “obesity is associated with a worse lipid profile, even from childhood, regardless of whether a patient is on medication,” said study presenter Amany Elshorbagy, DPhil, Cardiovascular Epidemiologist, department of primary care and public health, Imperial College London.

She added that, with the increased risk of coronary artery disease associated with heterozygous FH, the results showed that “together with lipid-lowering medication, weight management is needed.”

The research was presented at the annual meeting of the European Atherosclerosis Society.

Tended to be thin

Alberico L. Catapano, MD, PhD, director of cardiovascular research and of the Lipoproteins and Atherosclerosis Laboratory of IRCCS Multimedica, Milan, and past president of the EAS, said in an interview that, historically, few FH patients were overweight or obese; rather, they tended to be thin.

However, there is now “a trend for people with FH to show more diabetes and obesity,” with the “bottom line” being that, as they are already at increased risk of coronary artery disease, it pushes their risk up even further.

In other words, if a risk factor such as obesity is added “on top of the strongest risk factor, that is LDL cholesterol, it is not one plus one makes two, it is one plus one makes three,” he said.

As such, Dr. Catapano believes that the study is “very interesting,” because it further underlines the importance of weight management for individuals with increased LDL cholesterol, “especially when you have genetic forms, like FH.”

Dr. Catapano’s comments were echoed by session co-chair Ulrike Schatz, MD, leader of the lipidology specialty department at the University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, Technical University of Dresden (Germany).

Indeed, she told Dr. Elshorbagy before her presentation that she finds “a lot of my FH patients have a tendency towards anorexia.”

In an interview, Dr. Elshorbagy said that that reaction was typical of “most of the clinicians” she had spoken to. Upon seeing her data, especially for homozygous FH patients, they say, “They are on the lean side.”

Consequently, the research team went into the study “with the expectation that they might have a lower prevalence of obesity and overweight than the general population,” but “that’s not what we’re seeing.”

Dr. Elshorbagy noted that it would be helpful to have longitudinal data to determine whether, 50 years ago, patients with HF “were leaner, along with the rest of the population.”

The registry data are cross-sectional, and the team is now reaching out to the respective national lead investigators to submit follow-up data on their patients, with the aim of looking at changes in body weight and the impact on outcomes over time.

Another key question for the researchers is in regard to fat distribution, as body mass index “is not the best predictor of heart disease,” Dr. Elshorbagy said, but is rather central obesity.

Although they have also asked investigators to share waist circumference data, she conceded that it is a measurement that “is a lot harder to standardize across centers and countries; it’s not like putting patients on a scale.”

Overall, Dr. Elshorbagy believes that her findings indicate that clinicians should take a broader, more holistic approach toward their patients – in other words, an approach in which lipid lowering medication is “key but is just one of several things we need to do to make sure the coronary event rate goes down.”

More with than without

Dr. Elshorbagy began her presentation by highlighting that the prevalence of overweight and obesity ranges from 50% to 70% and that it is “the only health condition where you’ve got more people worldwide with the condition than without.”

Crucially, overweight increases the risk of coronary artery disease by approximately 20%. Among patients with obesity, the risk rises to 50%.

Given that FH patients “already have a very high risk of cardiovascular disease from their high cholesterol levels,” the team set out to determine rates of obesity and overweight in this population and their impact on coronary artery disease risk.

They used cross-sectional data from the EAS FH Studies Collaboration Global Registry, which involves 29,262 adults aged greater than or equal to 18 years and 6,275 children and adolescents aged 5 to 17 years with heterozygous FH, and 325 adults and 57 children with homozygous FH.

Dividing the adults into standard BMI categories, they found that 16% of heterozygous and 23% of homozygous FH patients had obesity, while 52% and 55%, respectively, had overweight or obesity.

For children, the team used World Health Organization z score cutoffs, which indicated that 9% of patients with heterozygous FH and 7% of patients with homozygous FH had obesity. Rates of overweight or obesity were 27% and 25%, respectively.

Among patients with heterozygous FH, rates of overweight or obesity among adults were 50% in high-income countries and 63% in other countries; among children, the rates were and 27% and 29%, respectively.

Stratified by region, the team found that the lowest rate of overweight or obesity among adult patients with heterozygous FH was in Eastern Asia, at 27%, while the highest was in Northern Africa/Western Asia (the Middle East), at 82%.

In North America, 56% of adult patients had overweight or obesity. The prevalence of coronary artery disease rose with increasing BMI.

Among adult patients with heterozygous FH, 11.3% of those with normal weight had coronary artery disease; the percentage rose to 22.9% among those with overweight, and 30.9% among those with obesity. Among children, the corresponding figures were 0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.7%.

Putting adults and children with homozygous FH together, the researchers found that 29.0% of patients with normal weight had coronary artery disease, compared with 31.3% of those with overweight and 49.3% of those with obesity.

Moreover, the results showed that levels of LDL and remnant cholesterol were significantly associated with BMI in adults and children with heterozygous FH, even after adjusting for age, sex, and lipid-lowering medication (P < .001 for all).

Multivariate analysis that took into account age, sex, lipid-lowering medication, and LDL cholesterol revealed that having obesity, compared with not having obesity, was associated with a substantial increase in the risk of coronary artery disease among patients with heterozygous FH.

Among adults with the condition, the odds ratio was 2.16 (95% confidence interval, 1.97-2.36), while among children and adolescents, it was 6.87 (95% CI, 1.55-30.46).

The results remained similar after further adjustment for the presence of diabetes and when considering peripheral artery disease and stroke.

No funding for the study was declared. Dr. Elshorbagy has relationships with Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, and Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT EAS 2023

PTSD, anxiety linked to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

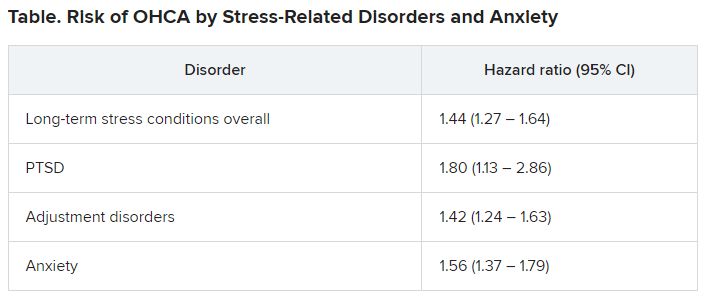

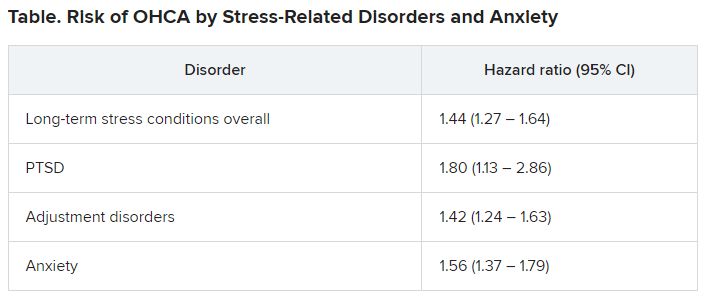

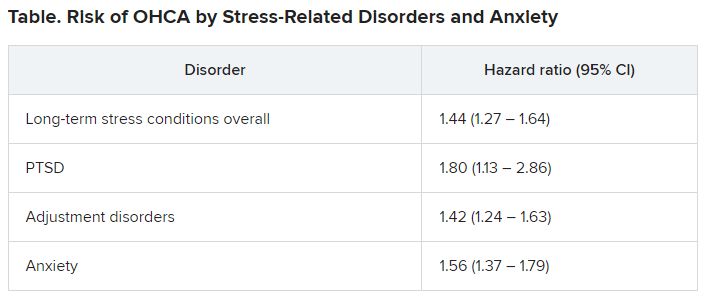

Investigators compared more than 35,000 OHCA case patients with a similar number of matched control persons and found an almost 1.5 times higher hazard of long-term stress conditions among OHCA case patients, compared with control persons, with a similar hazard for anxiety. Posttraumatic stress disorder was associated with an almost twofold higher risk of OHCA.

The findings applied equally to men and women and were independent of the presence of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

“This study raises awareness of the higher risks of OHCA and early risk monitoring to prevent OHCA in patients with stress-related disorders and anxiety,” write Talip Eroglu, of the department of cardiology, Copenhagen University Hospital, and colleagues.

The study was published online in BMJ Open Heart.

Stress disorders and anxiety overrepresented

OHCA “predominantly arises from lethal cardiac arrhythmias ... that occur most frequently in the setting of coronary heart disease,” the authors write. However, increasing evidence suggests that rates of OHCA may also be increased in association with noncardiac diseases.

Individuals with stress-related disorders and anxiety are “overrepresented” among victims of cardiac arrest as well as those with multiple CVDs. But previous studies of OHCA have been limited by small numbers of cardiac arrests. In addition, those studies involved only data from selected populations or used in-hospital diagnosis to identify cardiac arrest, thereby potentially omitting OHCA patients who died prior to hospital admission.

The researchers therefore turned to data from Danish health registries that include a large, unselected cohort of patients with OHCA to investigate whether long-term stress conditions (that is, PTSD and adjustment disorder) or anxiety disorder were associated with OHCA.

They stratified the cohort according to sex, age, and CVD to identify which risk factor confers the highest risk of OHCA in patients with long-term stress conditions or anxiety, and they conducted sensitivity analyses of potential confounders, such as depression.

The design was a nested-case control model in which records at an individual patient level across registries were cross-linked to data from other national registries and were compared to matched control persons from the general population (35,195 OHCAs and 351,950 matched control persons; median IQR age, 72 [62-81] years; 66.82% men).

The prevalence of comorbidities and use of cardiovascular drugs were higher among OHCA case patients than among non-OHCA control persons.

Keep aware of stress and anxiety as risk factors

Among OHCA and non-OHCA participants, long-term stress conditions were diagnosed in 0.92% and 0.45%, respectively. Anxiety was diagnosed in 0.85% of OHCA case patients and in 0.37% of non-OHCA control persons.

These conditions were associated with a higher rate of OHCA after adjustment for common OHCA risk factors.

There were no significant differences in results when the researchers adjusted for the use of anxiolytics and antidepressants.

When they examined the prevalence of concomitant medication use or comorbidities, they found that depression was more frequent among patients with long-term stress and anxiety, compared with individuals with neither of those diagnoses. Additionally, patients with long-term stress and anxiety more often used anxiolytics, antidepressants, and QT-prolonging drugs.

Stratification of the analyses according to sex revealed that the OHCA rate was increased in both women and men with long-term stress and anxiety. There were no significant differences between the sexes. There were also no significant differences between the association among different age groups, nor between patients with and those without CVD, ischemic heart disease, or heart failure.

Previous research has shown associations of stress-related disorders or anxiety with cardiovascular outcomes, including myocardial infarction, heart failure, and cerebrovascular disease. These disorders might be “biological mediators in the causal pathway of OHCA” and contribute to the increased OHCA rate associated with stress-related disorders and anxiety, the authors suggest.

Nevertheless, they note, stress-related disorders and anxiety remained significantly associated with OHCA after controlling for these variables, “suggesting that it is unlikely that traditional risk factors of OHCA alone explain this relationship.”

They suggest several potential mechanisms. One is that the relationship is likely mediated by the activity of the sympathetic autonomic nervous system, which “leads to an increase in heart rate, release of neurotransmitters into the circulation, and local release of neurotransmitters in the heart.”

Each of these factors “may potentially influence cardiac electrophysiology and facilitate ventricular arrhythmias and OHCA.”

In addition to a biological mechanism, behavioral and psychosocial factors may also contribute to OHCA risk, since stress-related disorders and anxiety “often lead to unhealthy lifestyle, such as smoking and lower physical activity, which in turn may increase the risk of OHCA.” Given the absence of data on these features in the registries the investigators used, they were unable to account for them.

However, “it is unlikely that knowledge of these factors would have altered our conclusions considering that we have adjusted for all the relevant cardiovascular comorbidities.”

Similarly, other psychiatric disorders, such as depression, can contribute to OHCA risk, but they adjusted for depression in their multivariable analyses.

“Awareness of the higher risks of OHCA in patients with stress-related disorders and anxiety is important when treating these patients,” they conclude.

Detrimental to the heart, not just the psyche

Glenn Levine, MD, master clinician and professor of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, called it an “important study in that it is a large, nationwide cohort study and thus provides important information to complement much smaller, focused studies.”

Like those other studies, “it finds that negative psychological health, specifically, long-term stress (as well as anxiety), is associated with a significantly increased risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,” continued Dr. Levine, who is the chief of the cardiology section at Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, and was not involved with the study.

Dr. Levine thinks the study “does a good job, as best one can for such a study, in trying to control for other factors, and zeroing in specifically on stress (and anxiety), trying to assess their independent contributions to the risk of developing cardiac arrest.”

The take-home message for clinicians and patients “is that negative psychological stress factors, such as stress and anxiety, are not only detrimental to one’s psychological health but likely increase one’s risk for adverse cardiac events, such as cardiac arrest,” he stated.

No specific funding for the study was disclosed. Mr. Eroglu has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Levine reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators compared more than 35,000 OHCA case patients with a similar number of matched control persons and found an almost 1.5 times higher hazard of long-term stress conditions among OHCA case patients, compared with control persons, with a similar hazard for anxiety. Posttraumatic stress disorder was associated with an almost twofold higher risk of OHCA.

The findings applied equally to men and women and were independent of the presence of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

“This study raises awareness of the higher risks of OHCA and early risk monitoring to prevent OHCA in patients with stress-related disorders and anxiety,” write Talip Eroglu, of the department of cardiology, Copenhagen University Hospital, and colleagues.

The study was published online in BMJ Open Heart.

Stress disorders and anxiety overrepresented

OHCA “predominantly arises from lethal cardiac arrhythmias ... that occur most frequently in the setting of coronary heart disease,” the authors write. However, increasing evidence suggests that rates of OHCA may also be increased in association with noncardiac diseases.

Individuals with stress-related disorders and anxiety are “overrepresented” among victims of cardiac arrest as well as those with multiple CVDs. But previous studies of OHCA have been limited by small numbers of cardiac arrests. In addition, those studies involved only data from selected populations or used in-hospital diagnosis to identify cardiac arrest, thereby potentially omitting OHCA patients who died prior to hospital admission.

The researchers therefore turned to data from Danish health registries that include a large, unselected cohort of patients with OHCA to investigate whether long-term stress conditions (that is, PTSD and adjustment disorder) or anxiety disorder were associated with OHCA.

They stratified the cohort according to sex, age, and CVD to identify which risk factor confers the highest risk of OHCA in patients with long-term stress conditions or anxiety, and they conducted sensitivity analyses of potential confounders, such as depression.

The design was a nested-case control model in which records at an individual patient level across registries were cross-linked to data from other national registries and were compared to matched control persons from the general population (35,195 OHCAs and 351,950 matched control persons; median IQR age, 72 [62-81] years; 66.82% men).

The prevalence of comorbidities and use of cardiovascular drugs were higher among OHCA case patients than among non-OHCA control persons.

Keep aware of stress and anxiety as risk factors

Among OHCA and non-OHCA participants, long-term stress conditions were diagnosed in 0.92% and 0.45%, respectively. Anxiety was diagnosed in 0.85% of OHCA case patients and in 0.37% of non-OHCA control persons.

These conditions were associated with a higher rate of OHCA after adjustment for common OHCA risk factors.

There were no significant differences in results when the researchers adjusted for the use of anxiolytics and antidepressants.

When they examined the prevalence of concomitant medication use or comorbidities, they found that depression was more frequent among patients with long-term stress and anxiety, compared with individuals with neither of those diagnoses. Additionally, patients with long-term stress and anxiety more often used anxiolytics, antidepressants, and QT-prolonging drugs.

Stratification of the analyses according to sex revealed that the OHCA rate was increased in both women and men with long-term stress and anxiety. There were no significant differences between the sexes. There were also no significant differences between the association among different age groups, nor between patients with and those without CVD, ischemic heart disease, or heart failure.

Previous research has shown associations of stress-related disorders or anxiety with cardiovascular outcomes, including myocardial infarction, heart failure, and cerebrovascular disease. These disorders might be “biological mediators in the causal pathway of OHCA” and contribute to the increased OHCA rate associated with stress-related disorders and anxiety, the authors suggest.

Nevertheless, they note, stress-related disorders and anxiety remained significantly associated with OHCA after controlling for these variables, “suggesting that it is unlikely that traditional risk factors of OHCA alone explain this relationship.”

They suggest several potential mechanisms. One is that the relationship is likely mediated by the activity of the sympathetic autonomic nervous system, which “leads to an increase in heart rate, release of neurotransmitters into the circulation, and local release of neurotransmitters in the heart.”

Each of these factors “may potentially influence cardiac electrophysiology and facilitate ventricular arrhythmias and OHCA.”

In addition to a biological mechanism, behavioral and psychosocial factors may also contribute to OHCA risk, since stress-related disorders and anxiety “often lead to unhealthy lifestyle, such as smoking and lower physical activity, which in turn may increase the risk of OHCA.” Given the absence of data on these features in the registries the investigators used, they were unable to account for them.

However, “it is unlikely that knowledge of these factors would have altered our conclusions considering that we have adjusted for all the relevant cardiovascular comorbidities.”

Similarly, other psychiatric disorders, such as depression, can contribute to OHCA risk, but they adjusted for depression in their multivariable analyses.

“Awareness of the higher risks of OHCA in patients with stress-related disorders and anxiety is important when treating these patients,” they conclude.

Detrimental to the heart, not just the psyche

Glenn Levine, MD, master clinician and professor of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, called it an “important study in that it is a large, nationwide cohort study and thus provides important information to complement much smaller, focused studies.”

Like those other studies, “it finds that negative psychological health, specifically, long-term stress (as well as anxiety), is associated with a significantly increased risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,” continued Dr. Levine, who is the chief of the cardiology section at Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, and was not involved with the study.

Dr. Levine thinks the study “does a good job, as best one can for such a study, in trying to control for other factors, and zeroing in specifically on stress (and anxiety), trying to assess their independent contributions to the risk of developing cardiac arrest.”

The take-home message for clinicians and patients “is that negative psychological stress factors, such as stress and anxiety, are not only detrimental to one’s psychological health but likely increase one’s risk for adverse cardiac events, such as cardiac arrest,” he stated.

No specific funding for the study was disclosed. Mr. Eroglu has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Levine reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators compared more than 35,000 OHCA case patients with a similar number of matched control persons and found an almost 1.5 times higher hazard of long-term stress conditions among OHCA case patients, compared with control persons, with a similar hazard for anxiety. Posttraumatic stress disorder was associated with an almost twofold higher risk of OHCA.

The findings applied equally to men and women and were independent of the presence of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

“This study raises awareness of the higher risks of OHCA and early risk monitoring to prevent OHCA in patients with stress-related disorders and anxiety,” write Talip Eroglu, of the department of cardiology, Copenhagen University Hospital, and colleagues.

The study was published online in BMJ Open Heart.

Stress disorders and anxiety overrepresented

OHCA “predominantly arises from lethal cardiac arrhythmias ... that occur most frequently in the setting of coronary heart disease,” the authors write. However, increasing evidence suggests that rates of OHCA may also be increased in association with noncardiac diseases.

Individuals with stress-related disorders and anxiety are “overrepresented” among victims of cardiac arrest as well as those with multiple CVDs. But previous studies of OHCA have been limited by small numbers of cardiac arrests. In addition, those studies involved only data from selected populations or used in-hospital diagnosis to identify cardiac arrest, thereby potentially omitting OHCA patients who died prior to hospital admission.

The researchers therefore turned to data from Danish health registries that include a large, unselected cohort of patients with OHCA to investigate whether long-term stress conditions (that is, PTSD and adjustment disorder) or anxiety disorder were associated with OHCA.

They stratified the cohort according to sex, age, and CVD to identify which risk factor confers the highest risk of OHCA in patients with long-term stress conditions or anxiety, and they conducted sensitivity analyses of potential confounders, such as depression.

The design was a nested-case control model in which records at an individual patient level across registries were cross-linked to data from other national registries and were compared to matched control persons from the general population (35,195 OHCAs and 351,950 matched control persons; median IQR age, 72 [62-81] years; 66.82% men).

The prevalence of comorbidities and use of cardiovascular drugs were higher among OHCA case patients than among non-OHCA control persons.

Keep aware of stress and anxiety as risk factors

Among OHCA and non-OHCA participants, long-term stress conditions were diagnosed in 0.92% and 0.45%, respectively. Anxiety was diagnosed in 0.85% of OHCA case patients and in 0.37% of non-OHCA control persons.

These conditions were associated with a higher rate of OHCA after adjustment for common OHCA risk factors.

There were no significant differences in results when the researchers adjusted for the use of anxiolytics and antidepressants.

When they examined the prevalence of concomitant medication use or comorbidities, they found that depression was more frequent among patients with long-term stress and anxiety, compared with individuals with neither of those diagnoses. Additionally, patients with long-term stress and anxiety more often used anxiolytics, antidepressants, and QT-prolonging drugs.

Stratification of the analyses according to sex revealed that the OHCA rate was increased in both women and men with long-term stress and anxiety. There were no significant differences between the sexes. There were also no significant differences between the association among different age groups, nor between patients with and those without CVD, ischemic heart disease, or heart failure.

Previous research has shown associations of stress-related disorders or anxiety with cardiovascular outcomes, including myocardial infarction, heart failure, and cerebrovascular disease. These disorders might be “biological mediators in the causal pathway of OHCA” and contribute to the increased OHCA rate associated with stress-related disorders and anxiety, the authors suggest.

Nevertheless, they note, stress-related disorders and anxiety remained significantly associated with OHCA after controlling for these variables, “suggesting that it is unlikely that traditional risk factors of OHCA alone explain this relationship.”

They suggest several potential mechanisms. One is that the relationship is likely mediated by the activity of the sympathetic autonomic nervous system, which “leads to an increase in heart rate, release of neurotransmitters into the circulation, and local release of neurotransmitters in the heart.”

Each of these factors “may potentially influence cardiac electrophysiology and facilitate ventricular arrhythmias and OHCA.”

In addition to a biological mechanism, behavioral and psychosocial factors may also contribute to OHCA risk, since stress-related disorders and anxiety “often lead to unhealthy lifestyle, such as smoking and lower physical activity, which in turn may increase the risk of OHCA.” Given the absence of data on these features in the registries the investigators used, they were unable to account for them.

However, “it is unlikely that knowledge of these factors would have altered our conclusions considering that we have adjusted for all the relevant cardiovascular comorbidities.”

Similarly, other psychiatric disorders, such as depression, can contribute to OHCA risk, but they adjusted for depression in their multivariable analyses.

“Awareness of the higher risks of OHCA in patients with stress-related disorders and anxiety is important when treating these patients,” they conclude.

Detrimental to the heart, not just the psyche

Glenn Levine, MD, master clinician and professor of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, called it an “important study in that it is a large, nationwide cohort study and thus provides important information to complement much smaller, focused studies.”

Like those other studies, “it finds that negative psychological health, specifically, long-term stress (as well as anxiety), is associated with a significantly increased risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,” continued Dr. Levine, who is the chief of the cardiology section at Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, and was not involved with the study.

Dr. Levine thinks the study “does a good job, as best one can for such a study, in trying to control for other factors, and zeroing in specifically on stress (and anxiety), trying to assess their independent contributions to the risk of developing cardiac arrest.”

The take-home message for clinicians and patients “is that negative psychological stress factors, such as stress and anxiety, are not only detrimental to one’s psychological health but likely increase one’s risk for adverse cardiac events, such as cardiac arrest,” he stated.

No specific funding for the study was disclosed. Mr. Eroglu has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Levine reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ OPEN HEART

Plant-based diet tied to healthier blood lipid levels

, in a new meta-analysis of 30 trials.

The findings suggest that “plant-based diets have the potential to lessen the atherosclerotic burden from atherogenic lipoproteins and thereby reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease,” write Caroline Amelie Koch, a medical student at the University of Copenhagen, and colleagues. Their findings were published online in the European Heart Journal (2023 May 24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad211).

“Vegetarian and vegan diets were associated with a 14% reduction in all artery-clogging lipoproteins as indicated by apoB,” senior author Ruth Frikke-Schmidt, DMSc, PhD, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, and professor, University of Copenhagen, said in a press release from her university.

“This corresponds to a third of the effect of taking cholesterol-lowering medications such as statins,” she added, “and would result in a 7% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease in someone who maintained a plant-based diet for 5 years.”

“Importantly, we found similar results, across continents, ages, different ranges of body mass index, and among people in different states of health,” Dr. Frikke-Schmidt stressed.

And combining statins with plant-based diets would likely produce a synergistic effect, she speculated.

“If people start eating vegetarian or vegan diets from an early age,” she said, “the potential for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease caused by blocked arteries is substantial.”

In addition, the researchers conclude: “Shifting to plant-based diets at a populational level will reduce emissions of greenhouse gases considerably – together making these diets efficient means [moving] towards a more sustainable development, while at the same time reducing the growing burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.”

More support for vegan, vegetarian diets

These new findings “add to the body of evidence supporting favorable effects of healthy vegan and vegetarian dietary patterns on circulating levels of LDL-C and atherogenic lipoproteins, which would be expected to reduce ASCVD risk,” Kevin C. Maki, PhD, and Carol Kirkpatrick, PhD, MPH, write in an accompanying editorial.

“While it is not necessary to entirely omit foods such as meat, poultry, and fish/seafood to follow a recommended dietary pattern, reducing consumption of such foods is a reasonable option for those who prefer to do so,” note Dr. Maki, of Indiana University School of Public Health, Bloomington, and Kirkpatrick, of Idaho State University, Pocatello.

Plant-based diet needs to be ‘well-planned’

Several experts who were not involved in this meta-analysis shed light on the study and its implications in comments to the U.K. Science Media Center.

“Although a vegetarian and vegan diet can be very healthy and beneficial with respect to cardiovascular risk, it is important that it is well planned so that nutrients it can be low in are included, including iron, iodine, vitamin B12, and vitamin D,” said Duane Mellor, PhD, a registered dietitian and senior lecturer, Aston Medical School, Aston University, Birmingham, England.

Some people “may find it easier to follow a Mediterranean-style diet that features plenty of fruit, vegetables, pulses, wholegrains, fish, eggs and low-fat dairy, with only small amounts of meat,” Tracy Parker, senior dietitian at the British Heart Foundation, London, suggested.

“There is considerable evidence that this type of diet can help lower your risk of developing heart and circulatory diseases by improving cholesterol and blood pressure levels, reducing inflammation, and controlling blood glucose levels,” she added.

And Aedin Cassidy, PhD, chair in nutrition & preventative medicine, Queen’s University Belfast (Ireland), noted that “not all plant-based diets are equal. Healthy plant-based diets, characterized by fruits, vegetables, and whole grains improve health, but other plant diets (for example, those including refined carbohydrates, processed foods high in fat/salt, etc.) do not.”

This new study shows that plant-based diets have the potential to improve health by improving blood lipids, “but this is one of many potential mechanisms, including impact on blood pressure, weight maintenance, and blood sugars,” she added.

“This work represents a well-conducted analysis of 30 clinical trials involving over two thousand participants and highlights the value of a vegetarian diet in reducing the risk of heart attack or stroke through reduction in blood cholesterol levels,” said Robert Storey, BM, DM, professor of cardiology, University of Sheffield, U.K.

However, it also demonstrates that the impact of diet on an individual’s cholesterol level is relatively limited, he added.

“This is because people inherit the tendency for their livers to produce too much cholesterol, meaning that high cholesterol is more strongly influenced by our genes than by our diet,” he explained.

This is “why statins are needed to block cholesterol production in people who are at higher risk of or have already suffered from a heart attack, stroke, or other illness related to cholesterol build-up in blood vessels.”

Beneficial effect on ApoB, LDL-C, and total cholesterol

ApoB is the main apolipoprotein in LDL-C (“bad” cholesterol), the researchers note. Previous studies have shown that LDL-C and apoB-containing particles are associated with increased risk of ASCVD.

They aimed to estimate the effect of vegetarian or vegan diets on blood levels of total cholesterol, LDL-C, triglycerides, and apoB in people randomized to a vegetarian or vegan diet versus an omnivorous diet (that is, including meat and dairy).

They identified 30 studies published between 1982 and 2022 and conducted in the United States (18 studies), Sweden (2), Finland (2), South Korea (2), Australia (1), Brazil (1), Czech Republic (1), Italy (1), Iran (1), and New Zealand (1).

The diet interventions lasted from 10 days to 5 years with a mean of 29 weeks (15 studies ≤ 3 months; 12 studies 3-12 months; and three studies > 1 year). Nine studies used a crossover design, and the rest used a parallel design whereby participants followed only one diet.

The studies had 11 to 291 participants (mean, 79 participants) with a mean BMI of 21.5-35.1 kg/m2 and a mean age of 20-67 years. Thirteen studies included participants treated with lipid-lowering therapy at baseline.

The dietary intervention was vegetarian in 15 trials (three lacto-vegetarian and 12 lacto-ovo-vegetarian) and vegan in the other 15 trials.

On average, compared with people eating an omnivore diet, people eating a plant-based diet had a 7% reduction in total cholesterol from baseline (–0.34 mmol/L), a 10% reduction in LDL-C from baseline (–0.30 mmol/L), and a 14% reduction in apoB from baseline (–12.9 mg/dL) (all P < .01).

The effects were similar across age, continent, study duration, health status, intervention diet, intervention program, and study design subgroups.

There was no significant difference in triglyceride levels in patients in the omnivore versus plant-based diet groups.

Such diets could considerably reduce greenhouse gases

Senior author Dr. Frikke-Schmidt noted: “Recent systematic reviews have shown that if the populations of high-income countries shift to plant-based diets, this can reduce net emissions of greenhouse gases by between 35% to 49%.”

“Plant-based diets are key instruments for changing food production to more environmentally sustainable forms, while at the same time reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease” in an aging population, she said.

“We should be eating a varied, plant-rich diet, not too much, and quenching our thirst with water,” she concluded.

The study was funded by the Lundbeck Foundation, the Danish Heart Foundation, and the Leducq Foundation. The authors, editorialists, Ms. Parker, Dr. Cassidy, and Dr. Storey have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mellor has disclosed that he is a vegetarian.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, in a new meta-analysis of 30 trials.

The findings suggest that “plant-based diets have the potential to lessen the atherosclerotic burden from atherogenic lipoproteins and thereby reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease,” write Caroline Amelie Koch, a medical student at the University of Copenhagen, and colleagues. Their findings were published online in the European Heart Journal (2023 May 24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad211).

“Vegetarian and vegan diets were associated with a 14% reduction in all artery-clogging lipoproteins as indicated by apoB,” senior author Ruth Frikke-Schmidt, DMSc, PhD, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, and professor, University of Copenhagen, said in a press release from her university.

“This corresponds to a third of the effect of taking cholesterol-lowering medications such as statins,” she added, “and would result in a 7% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease in someone who maintained a plant-based diet for 5 years.”

“Importantly, we found similar results, across continents, ages, different ranges of body mass index, and among people in different states of health,” Dr. Frikke-Schmidt stressed.

And combining statins with plant-based diets would likely produce a synergistic effect, she speculated.

“If people start eating vegetarian or vegan diets from an early age,” she said, “the potential for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease caused by blocked arteries is substantial.”

In addition, the researchers conclude: “Shifting to plant-based diets at a populational level will reduce emissions of greenhouse gases considerably – together making these diets efficient means [moving] towards a more sustainable development, while at the same time reducing the growing burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.”

More support for vegan, vegetarian diets

These new findings “add to the body of evidence supporting favorable effects of healthy vegan and vegetarian dietary patterns on circulating levels of LDL-C and atherogenic lipoproteins, which would be expected to reduce ASCVD risk,” Kevin C. Maki, PhD, and Carol Kirkpatrick, PhD, MPH, write in an accompanying editorial.

“While it is not necessary to entirely omit foods such as meat, poultry, and fish/seafood to follow a recommended dietary pattern, reducing consumption of such foods is a reasonable option for those who prefer to do so,” note Dr. Maki, of Indiana University School of Public Health, Bloomington, and Kirkpatrick, of Idaho State University, Pocatello.

Plant-based diet needs to be ‘well-planned’

Several experts who were not involved in this meta-analysis shed light on the study and its implications in comments to the U.K. Science Media Center.

“Although a vegetarian and vegan diet can be very healthy and beneficial with respect to cardiovascular risk, it is important that it is well planned so that nutrients it can be low in are included, including iron, iodine, vitamin B12, and vitamin D,” said Duane Mellor, PhD, a registered dietitian and senior lecturer, Aston Medical School, Aston University, Birmingham, England.

Some people “may find it easier to follow a Mediterranean-style diet that features plenty of fruit, vegetables, pulses, wholegrains, fish, eggs and low-fat dairy, with only small amounts of meat,” Tracy Parker, senior dietitian at the British Heart Foundation, London, suggested.

“There is considerable evidence that this type of diet can help lower your risk of developing heart and circulatory diseases by improving cholesterol and blood pressure levels, reducing inflammation, and controlling blood glucose levels,” she added.

And Aedin Cassidy, PhD, chair in nutrition & preventative medicine, Queen’s University Belfast (Ireland), noted that “not all plant-based diets are equal. Healthy plant-based diets, characterized by fruits, vegetables, and whole grains improve health, but other plant diets (for example, those including refined carbohydrates, processed foods high in fat/salt, etc.) do not.”

This new study shows that plant-based diets have the potential to improve health by improving blood lipids, “but this is one of many potential mechanisms, including impact on blood pressure, weight maintenance, and blood sugars,” she added.

“This work represents a well-conducted analysis of 30 clinical trials involving over two thousand participants and highlights the value of a vegetarian diet in reducing the risk of heart attack or stroke through reduction in blood cholesterol levels,” said Robert Storey, BM, DM, professor of cardiology, University of Sheffield, U.K.

However, it also demonstrates that the impact of diet on an individual’s cholesterol level is relatively limited, he added.

“This is because people inherit the tendency for their livers to produce too much cholesterol, meaning that high cholesterol is more strongly influenced by our genes than by our diet,” he explained.

This is “why statins are needed to block cholesterol production in people who are at higher risk of or have already suffered from a heart attack, stroke, or other illness related to cholesterol build-up in blood vessels.”

Beneficial effect on ApoB, LDL-C, and total cholesterol

ApoB is the main apolipoprotein in LDL-C (“bad” cholesterol), the researchers note. Previous studies have shown that LDL-C and apoB-containing particles are associated with increased risk of ASCVD.

They aimed to estimate the effect of vegetarian or vegan diets on blood levels of total cholesterol, LDL-C, triglycerides, and apoB in people randomized to a vegetarian or vegan diet versus an omnivorous diet (that is, including meat and dairy).

They identified 30 studies published between 1982 and 2022 and conducted in the United States (18 studies), Sweden (2), Finland (2), South Korea (2), Australia (1), Brazil (1), Czech Republic (1), Italy (1), Iran (1), and New Zealand (1).

The diet interventions lasted from 10 days to 5 years with a mean of 29 weeks (15 studies ≤ 3 months; 12 studies 3-12 months; and three studies > 1 year). Nine studies used a crossover design, and the rest used a parallel design whereby participants followed only one diet.

The studies had 11 to 291 participants (mean, 79 participants) with a mean BMI of 21.5-35.1 kg/m2 and a mean age of 20-67 years. Thirteen studies included participants treated with lipid-lowering therapy at baseline.

The dietary intervention was vegetarian in 15 trials (three lacto-vegetarian and 12 lacto-ovo-vegetarian) and vegan in the other 15 trials.

On average, compared with people eating an omnivore diet, people eating a plant-based diet had a 7% reduction in total cholesterol from baseline (–0.34 mmol/L), a 10% reduction in LDL-C from baseline (–0.30 mmol/L), and a 14% reduction in apoB from baseline (–12.9 mg/dL) (all P < .01).

The effects were similar across age, continent, study duration, health status, intervention diet, intervention program, and study design subgroups.

There was no significant difference in triglyceride levels in patients in the omnivore versus plant-based diet groups.

Such diets could considerably reduce greenhouse gases

Senior author Dr. Frikke-Schmidt noted: “Recent systematic reviews have shown that if the populations of high-income countries shift to plant-based diets, this can reduce net emissions of greenhouse gases by between 35% to 49%.”

“Plant-based diets are key instruments for changing food production to more environmentally sustainable forms, while at the same time reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease” in an aging population, she said.

“We should be eating a varied, plant-rich diet, not too much, and quenching our thirst with water,” she concluded.

The study was funded by the Lundbeck Foundation, the Danish Heart Foundation, and the Leducq Foundation. The authors, editorialists, Ms. Parker, Dr. Cassidy, and Dr. Storey have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mellor has disclosed that he is a vegetarian.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, in a new meta-analysis of 30 trials.

The findings suggest that “plant-based diets have the potential to lessen the atherosclerotic burden from atherogenic lipoproteins and thereby reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease,” write Caroline Amelie Koch, a medical student at the University of Copenhagen, and colleagues. Their findings were published online in the European Heart Journal (2023 May 24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad211).

“Vegetarian and vegan diets were associated with a 14% reduction in all artery-clogging lipoproteins as indicated by apoB,” senior author Ruth Frikke-Schmidt, DMSc, PhD, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, and professor, University of Copenhagen, said in a press release from her university.

“This corresponds to a third of the effect of taking cholesterol-lowering medications such as statins,” she added, “and would result in a 7% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease in someone who maintained a plant-based diet for 5 years.”

“Importantly, we found similar results, across continents, ages, different ranges of body mass index, and among people in different states of health,” Dr. Frikke-Schmidt stressed.

And combining statins with plant-based diets would likely produce a synergistic effect, she speculated.

“If people start eating vegetarian or vegan diets from an early age,” she said, “the potential for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease caused by blocked arteries is substantial.”

In addition, the researchers conclude: “Shifting to plant-based diets at a populational level will reduce emissions of greenhouse gases considerably – together making these diets efficient means [moving] towards a more sustainable development, while at the same time reducing the growing burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.”

More support for vegan, vegetarian diets

These new findings “add to the body of evidence supporting favorable effects of healthy vegan and vegetarian dietary patterns on circulating levels of LDL-C and atherogenic lipoproteins, which would be expected to reduce ASCVD risk,” Kevin C. Maki, PhD, and Carol Kirkpatrick, PhD, MPH, write in an accompanying editorial.

“While it is not necessary to entirely omit foods such as meat, poultry, and fish/seafood to follow a recommended dietary pattern, reducing consumption of such foods is a reasonable option for those who prefer to do so,” note Dr. Maki, of Indiana University School of Public Health, Bloomington, and Kirkpatrick, of Idaho State University, Pocatello.

Plant-based diet needs to be ‘well-planned’

Several experts who were not involved in this meta-analysis shed light on the study and its implications in comments to the U.K. Science Media Center.

“Although a vegetarian and vegan diet can be very healthy and beneficial with respect to cardiovascular risk, it is important that it is well planned so that nutrients it can be low in are included, including iron, iodine, vitamin B12, and vitamin D,” said Duane Mellor, PhD, a registered dietitian and senior lecturer, Aston Medical School, Aston University, Birmingham, England.

Some people “may find it easier to follow a Mediterranean-style diet that features plenty of fruit, vegetables, pulses, wholegrains, fish, eggs and low-fat dairy, with only small amounts of meat,” Tracy Parker, senior dietitian at the British Heart Foundation, London, suggested.

“There is considerable evidence that this type of diet can help lower your risk of developing heart and circulatory diseases by improving cholesterol and blood pressure levels, reducing inflammation, and controlling blood glucose levels,” she added.

And Aedin Cassidy, PhD, chair in nutrition & preventative medicine, Queen’s University Belfast (Ireland), noted that “not all plant-based diets are equal. Healthy plant-based diets, characterized by fruits, vegetables, and whole grains improve health, but other plant diets (for example, those including refined carbohydrates, processed foods high in fat/salt, etc.) do not.”

This new study shows that plant-based diets have the potential to improve health by improving blood lipids, “but this is one of many potential mechanisms, including impact on blood pressure, weight maintenance, and blood sugars,” she added.

“This work represents a well-conducted analysis of 30 clinical trials involving over two thousand participants and highlights the value of a vegetarian diet in reducing the risk of heart attack or stroke through reduction in blood cholesterol levels,” said Robert Storey, BM, DM, professor of cardiology, University of Sheffield, U.K.

However, it also demonstrates that the impact of diet on an individual’s cholesterol level is relatively limited, he added.

“This is because people inherit the tendency for their livers to produce too much cholesterol, meaning that high cholesterol is more strongly influenced by our genes than by our diet,” he explained.

This is “why statins are needed to block cholesterol production in people who are at higher risk of or have already suffered from a heart attack, stroke, or other illness related to cholesterol build-up in blood vessels.”

Beneficial effect on ApoB, LDL-C, and total cholesterol

ApoB is the main apolipoprotein in LDL-C (“bad” cholesterol), the researchers note. Previous studies have shown that LDL-C and apoB-containing particles are associated with increased risk of ASCVD.

They aimed to estimate the effect of vegetarian or vegan diets on blood levels of total cholesterol, LDL-C, triglycerides, and apoB in people randomized to a vegetarian or vegan diet versus an omnivorous diet (that is, including meat and dairy).

They identified 30 studies published between 1982 and 2022 and conducted in the United States (18 studies), Sweden (2), Finland (2), South Korea (2), Australia (1), Brazil (1), Czech Republic (1), Italy (1), Iran (1), and New Zealand (1).

The diet interventions lasted from 10 days to 5 years with a mean of 29 weeks (15 studies ≤ 3 months; 12 studies 3-12 months; and three studies > 1 year). Nine studies used a crossover design, and the rest used a parallel design whereby participants followed only one diet.

The studies had 11 to 291 participants (mean, 79 participants) with a mean BMI of 21.5-35.1 kg/m2 and a mean age of 20-67 years. Thirteen studies included participants treated with lipid-lowering therapy at baseline.

The dietary intervention was vegetarian in 15 trials (three lacto-vegetarian and 12 lacto-ovo-vegetarian) and vegan in the other 15 trials.

On average, compared with people eating an omnivore diet, people eating a plant-based diet had a 7% reduction in total cholesterol from baseline (–0.34 mmol/L), a 10% reduction in LDL-C from baseline (–0.30 mmol/L), and a 14% reduction in apoB from baseline (–12.9 mg/dL) (all P < .01).

The effects were similar across age, continent, study duration, health status, intervention diet, intervention program, and study design subgroups.

There was no significant difference in triglyceride levels in patients in the omnivore versus plant-based diet groups.

Such diets could considerably reduce greenhouse gases

Senior author Dr. Frikke-Schmidt noted: “Recent systematic reviews have shown that if the populations of high-income countries shift to plant-based diets, this can reduce net emissions of greenhouse gases by between 35% to 49%.”

“Plant-based diets are key instruments for changing food production to more environmentally sustainable forms, while at the same time reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease” in an aging population, she said.

“We should be eating a varied, plant-rich diet, not too much, and quenching our thirst with water,” she concluded.

The study was funded by the Lundbeck Foundation, the Danish Heart Foundation, and the Leducq Foundation. The authors, editorialists, Ms. Parker, Dr. Cassidy, and Dr. Storey have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mellor has disclosed that he is a vegetarian.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL

Circulatory support for RV failure caused by pulmonary embolism

A new review article highlights approaches for mechanical circulatory support in patients with high-risk acute pulmonary embolism (PE).

Pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic significance is widely underdiagnosed, and the mortality rate can be as high as 30%, but new therapeutic developments offer promise. “Over the past few years, a renewed interest in mechanical circulatory support (MCS; both percutaneous and surgical) for acute RVF has emerged, increasing viable treatment options for high-risk acute PE,” wrote the authors of the review, which was published online in Interventional Cardiology Clinics.

Poor outcomes are often driven by RVF, which is tricky to diagnose and manage, and it stems from a sudden increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) following PE. “The mechanism for increased PVR in acute PE is multifactorial, including direct blood flow impedance, local hypoxia-induced vasoconstriction, and platelet/thrombin-induced release of vasoactive peptides. The cascade of events that then leads to RVF includes decreased RV stoke volume, increased RV wall tension, and RV dilation,” the authors wrote.

The authors noted that diuretics help to correct changes to RV geometry and can improve left ventricle filling, which improves hemodynamics. Diuretics can be used in patients who are hypotensive and volume overloaded, but vasopressors should be employed to support blood pressure.

When using mechanical ventilation, strategies such as low tidal volumes, minimization of positive end expiratory pressure, and prevention of hypoxemia and acidemia should be employed to prevent an increase of pulmonary vascular resistance, which can worsen RV failure.

Pulmonary vasodilators aren’t recommended for acute PE, but inhaled pulmonary vasodilators may be considered in hemodynamically unstable patients.

Surgically implanted right ventricle assistance device are generally not used for acute RV failure in high-risk PE, unless the patient has not improved after medical management.

Percutaneous devices

Percutaneous mechanical circulatory support devices can be used for patients experiencing refractory shock. The review highlighted three such devices, including the Impella RP, tandem-heart right ventricular assist devices (TH-RVAD) or Protek Duo, and venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO), but they are not without limitations. “Challenges to using these devices in patients with acute PE include clot dislodgement, vascular complications, infections, device migration, and fracture of individual elements,” the authors wrote.

The Impella RP is easy to deploy and bypasses the RV, but it can’t provide blood oxygenation and may cause bleeding or hemolysis. TH-RVAD oxygenates the blood and bypasses the RV, but suffers from a large sheath size. VA-ECMO oxygenates the blood but may cause bleeding.

There are important differences among the mechanical support devices, according to Jonathan Ludmir, MD, who was asked to comment. “In reality, if someone has a large pulmonary embolism burden, to put in the Impella RP or the Protek Duo would be a little bit risky, because you’d be sometimes putting the device right where the clot is. At least what we do in our institution, when someone is in extremis despite using [intravenous] medications like vasopressors or inotropes, VA-ECMO is kind of the go to. This is both the quickest and probably most effective way to support the patient. I say the quickest because this is a procedure you can do at the bedside.”

Benefits of PERT

One message that the review only briefly mentions, but Dr. Ludmir believes is key, is employing a pulmonary embolism response team. “That’s been looked at extensively, and it’s a really key part of any decision-making. If someone presents to the emergency room or someone inside the hospital has an acute pulmonary embolism, you have a team of people that can respond and help assess the next step. Typically, that involves a cardiologist or an interventional cardiologist, a hematologist, vascular surgeon, often a cardiac surgeon, so it’s a whole slew of people. Based on the patient assessment they can quickly decide, can this patient just be okay with a blood thinner like heparin? Does this patient need something more aggressive, like a thrombectomy? Or is this a serious case where you involve the shock team or the ECMO team, and you have to stabilize the patient on mechanical circulatory support, so you can accomplish what you need to do to get rid of the pulmonary embolism,” said Dr. Ludmir, who is an assistant professor of medicine at Corrigan Minehan Heart Center at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

“Every case is individualized, hence the importance of having a team of a variety of different backgrounds and thoughts to approach it. And I think that’s kind of like the key takeaway. Yes, you have to be familiar with all the therapies, but at the end of the day, not every patient is going to fit into the algorithm for how you approach pulmonary embolism,” said Dr. Ludmir.

Dr. Ludmir has no relevant conflicts of interest.

A new review article highlights approaches for mechanical circulatory support in patients with high-risk acute pulmonary embolism (PE).

Pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic significance is widely underdiagnosed, and the mortality rate can be as high as 30%, but new therapeutic developments offer promise. “Over the past few years, a renewed interest in mechanical circulatory support (MCS; both percutaneous and surgical) for acute RVF has emerged, increasing viable treatment options for high-risk acute PE,” wrote the authors of the review, which was published online in Interventional Cardiology Clinics.

Poor outcomes are often driven by RVF, which is tricky to diagnose and manage, and it stems from a sudden increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) following PE. “The mechanism for increased PVR in acute PE is multifactorial, including direct blood flow impedance, local hypoxia-induced vasoconstriction, and platelet/thrombin-induced release of vasoactive peptides. The cascade of events that then leads to RVF includes decreased RV stoke volume, increased RV wall tension, and RV dilation,” the authors wrote.

The authors noted that diuretics help to correct changes to RV geometry and can improve left ventricle filling, which improves hemodynamics. Diuretics can be used in patients who are hypotensive and volume overloaded, but vasopressors should be employed to support blood pressure.

When using mechanical ventilation, strategies such as low tidal volumes, minimization of positive end expiratory pressure, and prevention of hypoxemia and acidemia should be employed to prevent an increase of pulmonary vascular resistance, which can worsen RV failure.

Pulmonary vasodilators aren’t recommended for acute PE, but inhaled pulmonary vasodilators may be considered in hemodynamically unstable patients.

Surgically implanted right ventricle assistance device are generally not used for acute RV failure in high-risk PE, unless the patient has not improved after medical management.

Percutaneous devices

Percutaneous mechanical circulatory support devices can be used for patients experiencing refractory shock. The review highlighted three such devices, including the Impella RP, tandem-heart right ventricular assist devices (TH-RVAD) or Protek Duo, and venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO), but they are not without limitations. “Challenges to using these devices in patients with acute PE include clot dislodgement, vascular complications, infections, device migration, and fracture of individual elements,” the authors wrote.

The Impella RP is easy to deploy and bypasses the RV, but it can’t provide blood oxygenation and may cause bleeding or hemolysis. TH-RVAD oxygenates the blood and bypasses the RV, but suffers from a large sheath size. VA-ECMO oxygenates the blood but may cause bleeding.

There are important differences among the mechanical support devices, according to Jonathan Ludmir, MD, who was asked to comment. “In reality, if someone has a large pulmonary embolism burden, to put in the Impella RP or the Protek Duo would be a little bit risky, because you’d be sometimes putting the device right where the clot is. At least what we do in our institution, when someone is in extremis despite using [intravenous] medications like vasopressors or inotropes, VA-ECMO is kind of the go to. This is both the quickest and probably most effective way to support the patient. I say the quickest because this is a procedure you can do at the bedside.”

Benefits of PERT