User login

Time to prescribe sauna bathing for cardiovascular health?

Is it time to start recommending regular sauna bathing to improve heart health?

While a post-workout sauna can compound the benefits of exercise, the hormetic effects of heat therapy alone can produce significant gains for microvascular and endothelial function, no workout required.

“There’s enough evidence to say that regular sauna use improves cardiovascular health,” Matthew S. Ganio, PhD, a professor of exercise science at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, who studies thermoregulatory responses and cardiovascular health, said.

“The more they used it, the greater the reduction in cardiovascular events like heart attack. But you don’t need to be in there more than 20-30 minutes. That’s where it seemed to have the best effect,” Dr. Ganio said, adding that studies have shown a dose-response.

A prospective cohort study published in 2015 in JAMA Internal Medicine included 20 years of data on more than 2,300 Finnish men who regularly sauna bathed. The researchers found that among participants who sat in saunas more frequently, rates of death from heart disease and stroke were lower than among those who did so less often.

Cutaneous vasodilation

The body experiences several physiologic changes when exposed to heat therapy of any kind, including sauna, hot water submerging, shortwave diathermy, and heat wrapping. Many of these changes involve elements of the cardiovascular system, said Earric Lee, PhD, an exercise physiologist and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland, who has studied the effects of sauna on cardiovascular health.

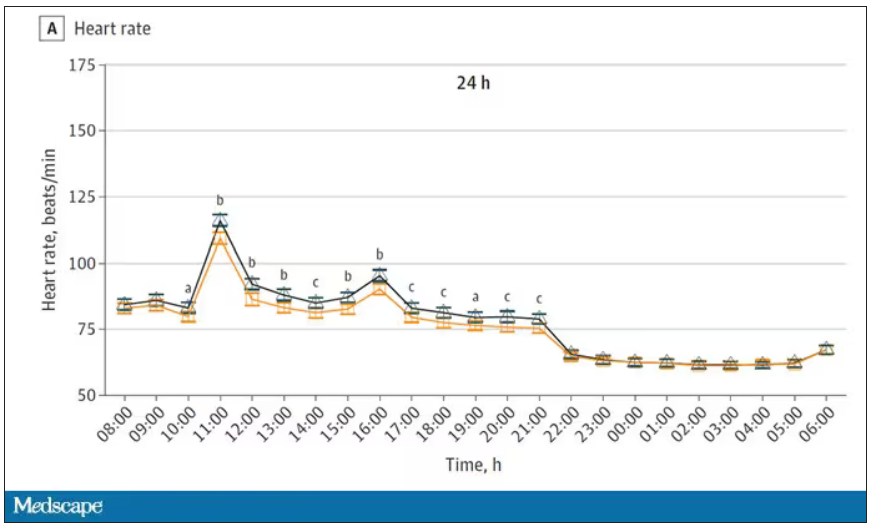

The mechanisms by which heat therapy improves cardiovascular fitness have not been determined, as few studies of sauna bathing have been conducted to this degree. One driver appears to be cutaneous vasodilation. To cool the body when exposed to extreme external heat, cutaneous vessels dilate and push blood to the skin, which lowers body temperature, increases heart rate, and delivers oxygen to muscles in the limbs in a way similar to aerobic exercise.

Sauna bathing has similar effects on heart rate and cardiac output. Studies have shown it can improve the circulation of blood through the body, as well as vascular endothelial function, which is closely tied to vascular tone.

“Increased cardiac output is one of the physiologic reasons sauna is good for heart health,” Dr. Ganio said.

During a sauna session, cardiac output can increase by as much as 70% in relation to elevated heart rate. And while heart rate and cardiac output rise, stroke volume remains stable. As stroke volume increases, the effort that muscle must exert increases. When heart rate rises, stroke volume often falls, which subjects the heart to less of a workout and reduces the amount of oxygen and blood circulating throughout the body.

Heat therapy also temporarily increases blood pressure, but in a way similar to exercise, which supports better long-term heart health, said Christopher Minson, PhD, the Kenneth M. and Kenda H. Singer Endowed Professor of Human Physiology at the University of Oregon in Eugene.

A small study of 19 healthy adults that was published in Complementary Therapies in Medicine in 2019 found that blood pressure and heart rate rose during a 25-minute sauna session as they might during moderate exercise, equivalent to an exercise load of about 60-100 watts. These parameters then steadily decreased for 30 minutes after the sauna. An earlier study found that in the long term, blood pressure was lower after a sauna than before a sauna.

Upregulated heat shock proteins

Both aerobic exercise and heat stress from sauna bathing increase the activity of heat shock proteins. A 2021 review published in Experimental Gerontology found that heat shock proteins become elevated in cells within 30 minutes of exposure to heat and remain elevated over time – an effect similar to exercise.

“Saunas increase heat shock proteins that break down old, dysfunctional proteins and then protect new proteins from becoming dysfunctional,” Hunter S. Waldman, PhD, an assistant professor of exercise science at the University of North Alabama in Florence, said. This effect is one way sauna bathing may quell systemic inflammation, Dr. Waldman said.

According to a 2018 review published in BioMed Research International, an abundance of heat shock proteins may increase exercise tolerance. The researchers concluded that the positive stress associated with elevated body temperature could help people be physically active for longer periods.

Added stress, especially heat-related strain, is not good for everyone, however. Dr. Waldman cautioned that heat exposure, be it through a sauna, hot tub, or other source, can be harmful for pregnant women and children and can be dangerous for people who have low blood pressure, since blood pressure often drops to rates that are lower than before taking a sauna. It also can impair semen quality for months after exposure, so people who are trying to conceive should avoid sauna bathing.

Anyone who has been diagnosed with a heart condition, including cardiac arrhythmia, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure, should always consult their physician prior to using sauna for the first time or before using it habitually, Dr. Lee said.

Effects compounded by exercise

Dr. Minson stressed that any type of heat therapy should be part of a lifestyle that includes mostly healthy habits overall, especially a regular exercise regime when possible.

“You have to have everything else working as well: finding time to relax, not being overly stressed, staying hydrated – all those things are critical with any exercise training and heat therapy program,” he said.

Dr. Lee said it’s easy to overhype the benefits of sauna bathing and agreed the practice should be used in tandem with other therapies, not as a replacement. So far, stacking research has shown it to be an effective extension of aerobic exercise.

A June 2023 review published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings found that while sauna bathing can produce benefits on its own, a post-workout sauna can extend the benefits of exercise. As a result, the researchers concluded, saunas likely provide the most benefit when combined with aerobic and strength training.

While some of the benefits of exercise overlap those associated with sauna bathing, “you’re going to get some benefits with exercise that you’re never going to get with sauna,” Dr. Ganio said.

For instance, strength training or aerobic exercise usually results in muscle contractions, which sauna bathing does not produce.

If a person is impaired in a way that makes exercise difficult, taking a sauna after aerobic activity can extend the cardiovascular benefits of the workout, even if muscle-building does not occur, Dr. Lee said.

“All other things considered, especially with aerobic exercise, it is very comparable, so we can look at adding sauna bathing post exercise as a way to lengthen the aerobic exercise workout,” he said. “It’s not to the same degree, but you can get many of the ranging benefits of exercising simply by going into the sauna.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Is it time to start recommending regular sauna bathing to improve heart health?

While a post-workout sauna can compound the benefits of exercise, the hormetic effects of heat therapy alone can produce significant gains for microvascular and endothelial function, no workout required.

“There’s enough evidence to say that regular sauna use improves cardiovascular health,” Matthew S. Ganio, PhD, a professor of exercise science at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, who studies thermoregulatory responses and cardiovascular health, said.

“The more they used it, the greater the reduction in cardiovascular events like heart attack. But you don’t need to be in there more than 20-30 minutes. That’s where it seemed to have the best effect,” Dr. Ganio said, adding that studies have shown a dose-response.

A prospective cohort study published in 2015 in JAMA Internal Medicine included 20 years of data on more than 2,300 Finnish men who regularly sauna bathed. The researchers found that among participants who sat in saunas more frequently, rates of death from heart disease and stroke were lower than among those who did so less often.

Cutaneous vasodilation

The body experiences several physiologic changes when exposed to heat therapy of any kind, including sauna, hot water submerging, shortwave diathermy, and heat wrapping. Many of these changes involve elements of the cardiovascular system, said Earric Lee, PhD, an exercise physiologist and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland, who has studied the effects of sauna on cardiovascular health.

The mechanisms by which heat therapy improves cardiovascular fitness have not been determined, as few studies of sauna bathing have been conducted to this degree. One driver appears to be cutaneous vasodilation. To cool the body when exposed to extreme external heat, cutaneous vessels dilate and push blood to the skin, which lowers body temperature, increases heart rate, and delivers oxygen to muscles in the limbs in a way similar to aerobic exercise.

Sauna bathing has similar effects on heart rate and cardiac output. Studies have shown it can improve the circulation of blood through the body, as well as vascular endothelial function, which is closely tied to vascular tone.

“Increased cardiac output is one of the physiologic reasons sauna is good for heart health,” Dr. Ganio said.

During a sauna session, cardiac output can increase by as much as 70% in relation to elevated heart rate. And while heart rate and cardiac output rise, stroke volume remains stable. As stroke volume increases, the effort that muscle must exert increases. When heart rate rises, stroke volume often falls, which subjects the heart to less of a workout and reduces the amount of oxygen and blood circulating throughout the body.

Heat therapy also temporarily increases blood pressure, but in a way similar to exercise, which supports better long-term heart health, said Christopher Minson, PhD, the Kenneth M. and Kenda H. Singer Endowed Professor of Human Physiology at the University of Oregon in Eugene.

A small study of 19 healthy adults that was published in Complementary Therapies in Medicine in 2019 found that blood pressure and heart rate rose during a 25-minute sauna session as they might during moderate exercise, equivalent to an exercise load of about 60-100 watts. These parameters then steadily decreased for 30 minutes after the sauna. An earlier study found that in the long term, blood pressure was lower after a sauna than before a sauna.

Upregulated heat shock proteins

Both aerobic exercise and heat stress from sauna bathing increase the activity of heat shock proteins. A 2021 review published in Experimental Gerontology found that heat shock proteins become elevated in cells within 30 minutes of exposure to heat and remain elevated over time – an effect similar to exercise.

“Saunas increase heat shock proteins that break down old, dysfunctional proteins and then protect new proteins from becoming dysfunctional,” Hunter S. Waldman, PhD, an assistant professor of exercise science at the University of North Alabama in Florence, said. This effect is one way sauna bathing may quell systemic inflammation, Dr. Waldman said.

According to a 2018 review published in BioMed Research International, an abundance of heat shock proteins may increase exercise tolerance. The researchers concluded that the positive stress associated with elevated body temperature could help people be physically active for longer periods.

Added stress, especially heat-related strain, is not good for everyone, however. Dr. Waldman cautioned that heat exposure, be it through a sauna, hot tub, or other source, can be harmful for pregnant women and children and can be dangerous for people who have low blood pressure, since blood pressure often drops to rates that are lower than before taking a sauna. It also can impair semen quality for months after exposure, so people who are trying to conceive should avoid sauna bathing.

Anyone who has been diagnosed with a heart condition, including cardiac arrhythmia, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure, should always consult their physician prior to using sauna for the first time or before using it habitually, Dr. Lee said.

Effects compounded by exercise

Dr. Minson stressed that any type of heat therapy should be part of a lifestyle that includes mostly healthy habits overall, especially a regular exercise regime when possible.

“You have to have everything else working as well: finding time to relax, not being overly stressed, staying hydrated – all those things are critical with any exercise training and heat therapy program,” he said.

Dr. Lee said it’s easy to overhype the benefits of sauna bathing and agreed the practice should be used in tandem with other therapies, not as a replacement. So far, stacking research has shown it to be an effective extension of aerobic exercise.

A June 2023 review published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings found that while sauna bathing can produce benefits on its own, a post-workout sauna can extend the benefits of exercise. As a result, the researchers concluded, saunas likely provide the most benefit when combined with aerobic and strength training.

While some of the benefits of exercise overlap those associated with sauna bathing, “you’re going to get some benefits with exercise that you’re never going to get with sauna,” Dr. Ganio said.

For instance, strength training or aerobic exercise usually results in muscle contractions, which sauna bathing does not produce.

If a person is impaired in a way that makes exercise difficult, taking a sauna after aerobic activity can extend the cardiovascular benefits of the workout, even if muscle-building does not occur, Dr. Lee said.

“All other things considered, especially with aerobic exercise, it is very comparable, so we can look at adding sauna bathing post exercise as a way to lengthen the aerobic exercise workout,” he said. “It’s not to the same degree, but you can get many of the ranging benefits of exercising simply by going into the sauna.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Is it time to start recommending regular sauna bathing to improve heart health?

While a post-workout sauna can compound the benefits of exercise, the hormetic effects of heat therapy alone can produce significant gains for microvascular and endothelial function, no workout required.

“There’s enough evidence to say that regular sauna use improves cardiovascular health,” Matthew S. Ganio, PhD, a professor of exercise science at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, who studies thermoregulatory responses and cardiovascular health, said.

“The more they used it, the greater the reduction in cardiovascular events like heart attack. But you don’t need to be in there more than 20-30 minutes. That’s where it seemed to have the best effect,” Dr. Ganio said, adding that studies have shown a dose-response.

A prospective cohort study published in 2015 in JAMA Internal Medicine included 20 years of data on more than 2,300 Finnish men who regularly sauna bathed. The researchers found that among participants who sat in saunas more frequently, rates of death from heart disease and stroke were lower than among those who did so less often.

Cutaneous vasodilation

The body experiences several physiologic changes when exposed to heat therapy of any kind, including sauna, hot water submerging, shortwave diathermy, and heat wrapping. Many of these changes involve elements of the cardiovascular system, said Earric Lee, PhD, an exercise physiologist and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland, who has studied the effects of sauna on cardiovascular health.

The mechanisms by which heat therapy improves cardiovascular fitness have not been determined, as few studies of sauna bathing have been conducted to this degree. One driver appears to be cutaneous vasodilation. To cool the body when exposed to extreme external heat, cutaneous vessels dilate and push blood to the skin, which lowers body temperature, increases heart rate, and delivers oxygen to muscles in the limbs in a way similar to aerobic exercise.

Sauna bathing has similar effects on heart rate and cardiac output. Studies have shown it can improve the circulation of blood through the body, as well as vascular endothelial function, which is closely tied to vascular tone.

“Increased cardiac output is one of the physiologic reasons sauna is good for heart health,” Dr. Ganio said.

During a sauna session, cardiac output can increase by as much as 70% in relation to elevated heart rate. And while heart rate and cardiac output rise, stroke volume remains stable. As stroke volume increases, the effort that muscle must exert increases. When heart rate rises, stroke volume often falls, which subjects the heart to less of a workout and reduces the amount of oxygen and blood circulating throughout the body.

Heat therapy also temporarily increases blood pressure, but in a way similar to exercise, which supports better long-term heart health, said Christopher Minson, PhD, the Kenneth M. and Kenda H. Singer Endowed Professor of Human Physiology at the University of Oregon in Eugene.

A small study of 19 healthy adults that was published in Complementary Therapies in Medicine in 2019 found that blood pressure and heart rate rose during a 25-minute sauna session as they might during moderate exercise, equivalent to an exercise load of about 60-100 watts. These parameters then steadily decreased for 30 minutes after the sauna. An earlier study found that in the long term, blood pressure was lower after a sauna than before a sauna.

Upregulated heat shock proteins

Both aerobic exercise and heat stress from sauna bathing increase the activity of heat shock proteins. A 2021 review published in Experimental Gerontology found that heat shock proteins become elevated in cells within 30 minutes of exposure to heat and remain elevated over time – an effect similar to exercise.

“Saunas increase heat shock proteins that break down old, dysfunctional proteins and then protect new proteins from becoming dysfunctional,” Hunter S. Waldman, PhD, an assistant professor of exercise science at the University of North Alabama in Florence, said. This effect is one way sauna bathing may quell systemic inflammation, Dr. Waldman said.

According to a 2018 review published in BioMed Research International, an abundance of heat shock proteins may increase exercise tolerance. The researchers concluded that the positive stress associated with elevated body temperature could help people be physically active for longer periods.

Added stress, especially heat-related strain, is not good for everyone, however. Dr. Waldman cautioned that heat exposure, be it through a sauna, hot tub, or other source, can be harmful for pregnant women and children and can be dangerous for people who have low blood pressure, since blood pressure often drops to rates that are lower than before taking a sauna. It also can impair semen quality for months after exposure, so people who are trying to conceive should avoid sauna bathing.

Anyone who has been diagnosed with a heart condition, including cardiac arrhythmia, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure, should always consult their physician prior to using sauna for the first time or before using it habitually, Dr. Lee said.

Effects compounded by exercise

Dr. Minson stressed that any type of heat therapy should be part of a lifestyle that includes mostly healthy habits overall, especially a regular exercise regime when possible.

“You have to have everything else working as well: finding time to relax, not being overly stressed, staying hydrated – all those things are critical with any exercise training and heat therapy program,” he said.

Dr. Lee said it’s easy to overhype the benefits of sauna bathing and agreed the practice should be used in tandem with other therapies, not as a replacement. So far, stacking research has shown it to be an effective extension of aerobic exercise.

A June 2023 review published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings found that while sauna bathing can produce benefits on its own, a post-workout sauna can extend the benefits of exercise. As a result, the researchers concluded, saunas likely provide the most benefit when combined with aerobic and strength training.

While some of the benefits of exercise overlap those associated with sauna bathing, “you’re going to get some benefits with exercise that you’re never going to get with sauna,” Dr. Ganio said.

For instance, strength training or aerobic exercise usually results in muscle contractions, which sauna bathing does not produce.

If a person is impaired in a way that makes exercise difficult, taking a sauna after aerobic activity can extend the cardiovascular benefits of the workout, even if muscle-building does not occur, Dr. Lee said.

“All other things considered, especially with aerobic exercise, it is very comparable, so we can look at adding sauna bathing post exercise as a way to lengthen the aerobic exercise workout,” he said. “It’s not to the same degree, but you can get many of the ranging benefits of exercising simply by going into the sauna.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA OKs low-dose colchicine for broad CV indication

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the anti-inflammatory drug colchicine 0.5 mg tablets (Lodoco) as the first specific anti-inflammatory drug demonstrated to reduce the risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary revascularization, and cardiovascular death in adult patients with established atherosclerotic disease or with multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

The drug, which targets residual inflammation as an underlying cause of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, has a dosage of 0.5 mg once daily, and can be used alone or in combination with cholesterol-lowering medications.

The drug’s manufacturer, Agepha Pharma, said it anticipates that Lodoco will be available for prescription in the second half of 2023.

Colchicine has been available for many years and used at higher doses for the acute treatment of gout and pericarditis, but the current formulation is a much lower dose for long-term use in patients with atherosclerotic heart disease.

Data supporting the approval has come from two major randomized trials, LoDoCo-2 and COLCOT.

In the LoDoCo-2 trial, the anti-inflammatory drug cut the risk of cardiovascular events by one third when added to standard prevention therapies in patients with chronic coronary disease. And in the COLCOT study, use of colchicine reduced cardiovascular events by 23% compared with placebo in patients with a recent MI.

Paul Ridker, MD, director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who has been a pioneer in establishing inflammation as an underlying cause of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, welcomed the Lodoco approval.

‘A very big day for cardiology’

“This is a very big day for cardiology,” Dr. Ridker said in an interview.

“The FDA approval of colchicine for patients with atherosclerotic disease is a huge signal that physicians need to be aware of inflammation as a key player in cardiovascular disease,” he said.

Dr. Ridker was the lead author of a recent study showing that among patients receiving contemporary statins, inflammation assessed by high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) was a stronger predictor for risk of future cardiovascular events and death than LDL cholesterol.

He pointed out that

“That is virtually identical to the indication approved for statin therapy. That shows just how important the FDA thinks this is,” he commented.

But Dr. Ridker added that, while the label does not specify that Lodoco has to be used in addition to statin therapy, he believes that it will be used as additional therapy to statins in the vast majority of patients.

“This is not an alternative to statin therapy. In the randomized trials, the benefits were seen on top of statins,” he stressed.

Dr. Ridker believes that physicians will need time to feel comfortable with this new approach.

“Initially, I think, it will be used mainly by cardiologists who know about inflammation, but I believe over time it will be widely prescribed by internists, in much the same way as statins are used today,” he commented.

Dr. Ridker said he already uses low dose colchicine in his high-risk patients who have high levels of inflammation as seen on hsCRP testing. He believes this is where the drug will mostly be used initially, as this is where it is likely to be most effective.

The prescribing information states that Lodoco is contraindicated in patients who are taking strong CYP3A4 inhibitors or P-glycoprotein inhibitors, such as ketoconazole, fluconazole, and clarithromycin, and in patients with preexisting blood dyscrasias, renal failure, and severe hepatic impairment.

Common side effects reported in published clinical studies and literature with the use of colchicine are gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal cramping) and myalgia.

More serious adverse effects are listed as blood dyscrasias such as myelosuppression, leukopenia, granulocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia, and aplastic anemia; and neuromuscular toxicity in the form of myotoxicity including rhabdomyolysis, which may occur, especially in combination with other drugs known to cause this effect. If these adverse effects occur, it is recommended that the drug be stopped.

The prescribing information also notes that Lodoco may rarely and transiently impair fertility in males; and that patients with renal or hepatic impairment should be monitored closely for adverse effects of colchicine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the anti-inflammatory drug colchicine 0.5 mg tablets (Lodoco) as the first specific anti-inflammatory drug demonstrated to reduce the risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary revascularization, and cardiovascular death in adult patients with established atherosclerotic disease or with multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

The drug, which targets residual inflammation as an underlying cause of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, has a dosage of 0.5 mg once daily, and can be used alone or in combination with cholesterol-lowering medications.

The drug’s manufacturer, Agepha Pharma, said it anticipates that Lodoco will be available for prescription in the second half of 2023.

Colchicine has been available for many years and used at higher doses for the acute treatment of gout and pericarditis, but the current formulation is a much lower dose for long-term use in patients with atherosclerotic heart disease.

Data supporting the approval has come from two major randomized trials, LoDoCo-2 and COLCOT.

In the LoDoCo-2 trial, the anti-inflammatory drug cut the risk of cardiovascular events by one third when added to standard prevention therapies in patients with chronic coronary disease. And in the COLCOT study, use of colchicine reduced cardiovascular events by 23% compared with placebo in patients with a recent MI.

Paul Ridker, MD, director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who has been a pioneer in establishing inflammation as an underlying cause of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, welcomed the Lodoco approval.

‘A very big day for cardiology’

“This is a very big day for cardiology,” Dr. Ridker said in an interview.

“The FDA approval of colchicine for patients with atherosclerotic disease is a huge signal that physicians need to be aware of inflammation as a key player in cardiovascular disease,” he said.

Dr. Ridker was the lead author of a recent study showing that among patients receiving contemporary statins, inflammation assessed by high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) was a stronger predictor for risk of future cardiovascular events and death than LDL cholesterol.

He pointed out that

“That is virtually identical to the indication approved for statin therapy. That shows just how important the FDA thinks this is,” he commented.

But Dr. Ridker added that, while the label does not specify that Lodoco has to be used in addition to statin therapy, he believes that it will be used as additional therapy to statins in the vast majority of patients.

“This is not an alternative to statin therapy. In the randomized trials, the benefits were seen on top of statins,” he stressed.

Dr. Ridker believes that physicians will need time to feel comfortable with this new approach.

“Initially, I think, it will be used mainly by cardiologists who know about inflammation, but I believe over time it will be widely prescribed by internists, in much the same way as statins are used today,” he commented.

Dr. Ridker said he already uses low dose colchicine in his high-risk patients who have high levels of inflammation as seen on hsCRP testing. He believes this is where the drug will mostly be used initially, as this is where it is likely to be most effective.

The prescribing information states that Lodoco is contraindicated in patients who are taking strong CYP3A4 inhibitors or P-glycoprotein inhibitors, such as ketoconazole, fluconazole, and clarithromycin, and in patients with preexisting blood dyscrasias, renal failure, and severe hepatic impairment.

Common side effects reported in published clinical studies and literature with the use of colchicine are gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal cramping) and myalgia.

More serious adverse effects are listed as blood dyscrasias such as myelosuppression, leukopenia, granulocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia, and aplastic anemia; and neuromuscular toxicity in the form of myotoxicity including rhabdomyolysis, which may occur, especially in combination with other drugs known to cause this effect. If these adverse effects occur, it is recommended that the drug be stopped.

The prescribing information also notes that Lodoco may rarely and transiently impair fertility in males; and that patients with renal or hepatic impairment should be monitored closely for adverse effects of colchicine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the anti-inflammatory drug colchicine 0.5 mg tablets (Lodoco) as the first specific anti-inflammatory drug demonstrated to reduce the risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary revascularization, and cardiovascular death in adult patients with established atherosclerotic disease or with multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

The drug, which targets residual inflammation as an underlying cause of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, has a dosage of 0.5 mg once daily, and can be used alone or in combination with cholesterol-lowering medications.

The drug’s manufacturer, Agepha Pharma, said it anticipates that Lodoco will be available for prescription in the second half of 2023.

Colchicine has been available for many years and used at higher doses for the acute treatment of gout and pericarditis, but the current formulation is a much lower dose for long-term use in patients with atherosclerotic heart disease.

Data supporting the approval has come from two major randomized trials, LoDoCo-2 and COLCOT.

In the LoDoCo-2 trial, the anti-inflammatory drug cut the risk of cardiovascular events by one third when added to standard prevention therapies in patients with chronic coronary disease. And in the COLCOT study, use of colchicine reduced cardiovascular events by 23% compared with placebo in patients with a recent MI.

Paul Ridker, MD, director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who has been a pioneer in establishing inflammation as an underlying cause of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, welcomed the Lodoco approval.

‘A very big day for cardiology’

“This is a very big day for cardiology,” Dr. Ridker said in an interview.

“The FDA approval of colchicine for patients with atherosclerotic disease is a huge signal that physicians need to be aware of inflammation as a key player in cardiovascular disease,” he said.

Dr. Ridker was the lead author of a recent study showing that among patients receiving contemporary statins, inflammation assessed by high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) was a stronger predictor for risk of future cardiovascular events and death than LDL cholesterol.

He pointed out that

“That is virtually identical to the indication approved for statin therapy. That shows just how important the FDA thinks this is,” he commented.

But Dr. Ridker added that, while the label does not specify that Lodoco has to be used in addition to statin therapy, he believes that it will be used as additional therapy to statins in the vast majority of patients.

“This is not an alternative to statin therapy. In the randomized trials, the benefits were seen on top of statins,” he stressed.

Dr. Ridker believes that physicians will need time to feel comfortable with this new approach.

“Initially, I think, it will be used mainly by cardiologists who know about inflammation, but I believe over time it will be widely prescribed by internists, in much the same way as statins are used today,” he commented.

Dr. Ridker said he already uses low dose colchicine in his high-risk patients who have high levels of inflammation as seen on hsCRP testing. He believes this is where the drug will mostly be used initially, as this is where it is likely to be most effective.

The prescribing information states that Lodoco is contraindicated in patients who are taking strong CYP3A4 inhibitors or P-glycoprotein inhibitors, such as ketoconazole, fluconazole, and clarithromycin, and in patients with preexisting blood dyscrasias, renal failure, and severe hepatic impairment.

Common side effects reported in published clinical studies and literature with the use of colchicine are gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal cramping) and myalgia.

More serious adverse effects are listed as blood dyscrasias such as myelosuppression, leukopenia, granulocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia, and aplastic anemia; and neuromuscular toxicity in the form of myotoxicity including rhabdomyolysis, which may occur, especially in combination with other drugs known to cause this effect. If these adverse effects occur, it is recommended that the drug be stopped.

The prescribing information also notes that Lodoco may rarely and transiently impair fertility in males; and that patients with renal or hepatic impairment should be monitored closely for adverse effects of colchicine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Aspirin warning: Anemia may increase with daily use

, according to results from a new randomized controlled trial.

In the study, which was published in Annals of Internal Medicine, investigators analyzed data from the Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial and examined hemoglobin concentrations among 19,114 healthy, community-dwelling older patients.

“We knew from large clinical trials, including our ASPREE trial, that daily low-dose aspirin increased the risk of clinically significant bleeding,” said Zoe McQuilten, MBBS, PhD, a hematologist at Monash University in Australia and the study’s lead author. “From our study, we found that low-dose aspirin also increased the risk of anemia during the trial, and this was most likely due to bleeding that was not clinically apparent.”

Anemia is common among elderly patients. It can cause fatigue, fast or irregular heartbeat, headache, chest pain, and pounding or whooshing sounds in the ear, according to the Cleveland Clinic. It can also worsen conditions such as heart failure, cognitive impairment, and depression in people aged 65 and older.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force changed its recommendation on aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in 2022, recommending against initiating low-dose aspirin for adults aged 60 years or older. For adults aged 40-59 who have a 10% or greater 10-year risk for cardiovascular disease, the agency recommends that patients and clinicians make the decision to initiate low-dose aspirin use on a case-by-case basis, as the net benefit is small.

Dr. McQuilten said she spent the last 5 years designing substages of anemia and conditions such as blood cancer. In many cases of anemia, doctors are unable to determine the underlying cause, she said. One study published in the Journal of American Geriatrics Society in 2021 found that in about one-third of anemia cases, the etiology was not clear.

About 50% of people older than 60 who were involved in the latest study took aspirin for prevention from 2011 to 2018. That number likely dropped after changes were made to the guidelines in 2022, according to Dr. McQuilten, but long-term use may have continued among older patients. The researchers also examined ferritin levels, which serve as a proxy for iron levels, at baseline and after 3 years.

The incidence of anemia was 51 events per 1,000 person-years in the aspirin group compared with 43 events per 1,000 person-years in the placebo group, according to the researchers. The estimated probability of experiencing anemia within 5 years was 23.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 22.4%-24.6%) in the aspirin group and 20.3% (95% CI: 19.3% to 21.4%) in the placebo group. Aspirin therapy resulted in a 20% increase in the risk for anemia (95% CI, 1.12-1.29).

People who took aspirin were more likely to have lower serum levels of ferritin at the 3-year mark than were those who received placebo. The average decrease in ferritin among participants who took aspirin was 11.5% greater (95% CI, 9.3%-13.7%) than among those who took placebo.

Basil Eldadah, MD, PhD, supervisory medical officer at the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health, said the findings should encourage clinicians to pay closer attention to hemoglobin levels and have conversations with patients to discuss their need for taking aspirin.

“If somebody is already taking aspirin for any reason, keep an eye on hemoglobin,” said Dr. Eldadah, who was not involved in the study. “For somebody who’s taking aspirin and who’s older, and it’s not for an indication like cardiovascular disease, consider seriously whether that’s the best treatment option.”

The study did not examine the functional consequences of anemia on participants, which Dr. Eldadah said could be fodder for future research. The researchers said one limitation was that it was not clear whether anemia was sufficient to cause symptoms that affected participants’ quality of life or whether occult bleeding caused the anemia. The researchers also did not document whether patients saw their regular physicians and received treatment for anemia over the course of the trial.

The study was funded through grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The authors reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and stock options, and have participated on data monitoring boards not related to the study for Vifor Pharma, ITL Biomedical, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare, AbbVie, and Abbott Diagnostics.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to results from a new randomized controlled trial.

In the study, which was published in Annals of Internal Medicine, investigators analyzed data from the Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial and examined hemoglobin concentrations among 19,114 healthy, community-dwelling older patients.

“We knew from large clinical trials, including our ASPREE trial, that daily low-dose aspirin increased the risk of clinically significant bleeding,” said Zoe McQuilten, MBBS, PhD, a hematologist at Monash University in Australia and the study’s lead author. “From our study, we found that low-dose aspirin also increased the risk of anemia during the trial, and this was most likely due to bleeding that was not clinically apparent.”

Anemia is common among elderly patients. It can cause fatigue, fast or irregular heartbeat, headache, chest pain, and pounding or whooshing sounds in the ear, according to the Cleveland Clinic. It can also worsen conditions such as heart failure, cognitive impairment, and depression in people aged 65 and older.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force changed its recommendation on aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in 2022, recommending against initiating low-dose aspirin for adults aged 60 years or older. For adults aged 40-59 who have a 10% or greater 10-year risk for cardiovascular disease, the agency recommends that patients and clinicians make the decision to initiate low-dose aspirin use on a case-by-case basis, as the net benefit is small.

Dr. McQuilten said she spent the last 5 years designing substages of anemia and conditions such as blood cancer. In many cases of anemia, doctors are unable to determine the underlying cause, she said. One study published in the Journal of American Geriatrics Society in 2021 found that in about one-third of anemia cases, the etiology was not clear.

About 50% of people older than 60 who were involved in the latest study took aspirin for prevention from 2011 to 2018. That number likely dropped after changes were made to the guidelines in 2022, according to Dr. McQuilten, but long-term use may have continued among older patients. The researchers also examined ferritin levels, which serve as a proxy for iron levels, at baseline and after 3 years.

The incidence of anemia was 51 events per 1,000 person-years in the aspirin group compared with 43 events per 1,000 person-years in the placebo group, according to the researchers. The estimated probability of experiencing anemia within 5 years was 23.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 22.4%-24.6%) in the aspirin group and 20.3% (95% CI: 19.3% to 21.4%) in the placebo group. Aspirin therapy resulted in a 20% increase in the risk for anemia (95% CI, 1.12-1.29).

People who took aspirin were more likely to have lower serum levels of ferritin at the 3-year mark than were those who received placebo. The average decrease in ferritin among participants who took aspirin was 11.5% greater (95% CI, 9.3%-13.7%) than among those who took placebo.

Basil Eldadah, MD, PhD, supervisory medical officer at the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health, said the findings should encourage clinicians to pay closer attention to hemoglobin levels and have conversations with patients to discuss their need for taking aspirin.

“If somebody is already taking aspirin for any reason, keep an eye on hemoglobin,” said Dr. Eldadah, who was not involved in the study. “For somebody who’s taking aspirin and who’s older, and it’s not for an indication like cardiovascular disease, consider seriously whether that’s the best treatment option.”

The study did not examine the functional consequences of anemia on participants, which Dr. Eldadah said could be fodder for future research. The researchers said one limitation was that it was not clear whether anemia was sufficient to cause symptoms that affected participants’ quality of life or whether occult bleeding caused the anemia. The researchers also did not document whether patients saw their regular physicians and received treatment for anemia over the course of the trial.

The study was funded through grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The authors reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and stock options, and have participated on data monitoring boards not related to the study for Vifor Pharma, ITL Biomedical, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare, AbbVie, and Abbott Diagnostics.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to results from a new randomized controlled trial.

In the study, which was published in Annals of Internal Medicine, investigators analyzed data from the Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial and examined hemoglobin concentrations among 19,114 healthy, community-dwelling older patients.

“We knew from large clinical trials, including our ASPREE trial, that daily low-dose aspirin increased the risk of clinically significant bleeding,” said Zoe McQuilten, MBBS, PhD, a hematologist at Monash University in Australia and the study’s lead author. “From our study, we found that low-dose aspirin also increased the risk of anemia during the trial, and this was most likely due to bleeding that was not clinically apparent.”

Anemia is common among elderly patients. It can cause fatigue, fast or irregular heartbeat, headache, chest pain, and pounding or whooshing sounds in the ear, according to the Cleveland Clinic. It can also worsen conditions such as heart failure, cognitive impairment, and depression in people aged 65 and older.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force changed its recommendation on aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in 2022, recommending against initiating low-dose aspirin for adults aged 60 years or older. For adults aged 40-59 who have a 10% or greater 10-year risk for cardiovascular disease, the agency recommends that patients and clinicians make the decision to initiate low-dose aspirin use on a case-by-case basis, as the net benefit is small.

Dr. McQuilten said she spent the last 5 years designing substages of anemia and conditions such as blood cancer. In many cases of anemia, doctors are unable to determine the underlying cause, she said. One study published in the Journal of American Geriatrics Society in 2021 found that in about one-third of anemia cases, the etiology was not clear.

About 50% of people older than 60 who were involved in the latest study took aspirin for prevention from 2011 to 2018. That number likely dropped after changes were made to the guidelines in 2022, according to Dr. McQuilten, but long-term use may have continued among older patients. The researchers also examined ferritin levels, which serve as a proxy for iron levels, at baseline and after 3 years.

The incidence of anemia was 51 events per 1,000 person-years in the aspirin group compared with 43 events per 1,000 person-years in the placebo group, according to the researchers. The estimated probability of experiencing anemia within 5 years was 23.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 22.4%-24.6%) in the aspirin group and 20.3% (95% CI: 19.3% to 21.4%) in the placebo group. Aspirin therapy resulted in a 20% increase in the risk for anemia (95% CI, 1.12-1.29).

People who took aspirin were more likely to have lower serum levels of ferritin at the 3-year mark than were those who received placebo. The average decrease in ferritin among participants who took aspirin was 11.5% greater (95% CI, 9.3%-13.7%) than among those who took placebo.

Basil Eldadah, MD, PhD, supervisory medical officer at the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health, said the findings should encourage clinicians to pay closer attention to hemoglobin levels and have conversations with patients to discuss their need for taking aspirin.

“If somebody is already taking aspirin for any reason, keep an eye on hemoglobin,” said Dr. Eldadah, who was not involved in the study. “For somebody who’s taking aspirin and who’s older, and it’s not for an indication like cardiovascular disease, consider seriously whether that’s the best treatment option.”

The study did not examine the functional consequences of anemia on participants, which Dr. Eldadah said could be fodder for future research. The researchers said one limitation was that it was not clear whether anemia was sufficient to cause symptoms that affected participants’ quality of life or whether occult bleeding caused the anemia. The researchers also did not document whether patients saw their regular physicians and received treatment for anemia over the course of the trial.

The study was funded through grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The authors reported receiving consulting fees, honoraria, and stock options, and have participated on data monitoring boards not related to the study for Vifor Pharma, ITL Biomedical, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare, AbbVie, and Abbott Diagnostics.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Upping CO2 does not benefit OHCA patients: TAME

The Targeted Therapeutic Mild Hypercapnia After Resuscitated Cardiac Arrest (TAME) study showed that the intervention failed to improve neurologic or functional outcomes or quality of life at 6 months. However, the researchers also found that slightly elevated CO2 levels were not associated with worse outcomes.

“I think these results show that our hypothesis – that raising CO2 levels as applied in this trial may be beneficial for these patients – was not effective, even though previous work suggested that it would be,” co–lead investigator Alistair Nichol, MD, said in an interview.

“This was a rigorous trial; the intervention was well delivered, and the results are pretty clear. Unfortunately, we have proved a null hypothesis – that this approach doesn’t seem to work,” Dr. Nichol, who is professor of critical care medicine at University College Dublin, said.

“However, we did find that hypercapnia was safe. This is an important finding, as sometimes in very sick patients such as those who develop pneumonia, we have to drive the ventilator less hard to minimize injury to the lungs, and this can lead to higher CO2 levels,” he added. “Our results show that this practice should not be harmful, which is reassuring.”

The TAME study was presented at the Critical Care Reviews 2023 Meeting (CCR23) held in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

It was simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The researchers explain that after the return of spontaneous circulation, brain hypoperfusion may contribute to cerebral hypoxia, exacerbate brain damage, and lead to poor neurologic outcomes. The partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) is the major physiologic regulator of cerebrovascular tone, and increasing CO2 levels increases cerebral blood flow.

Two previous observational studies showed that exposure to hypercapnia was associated with an increase in the likelihood of being discharged home and better neurologic outcomes at 12 months, compared with hypocapnia or normocapnia.

In addition, a physiologic study showed that deliberate increases in PaCO2 induced higher cerebral oxygen saturations, compared with normocapnia. A phase 2 randomized trial showed that hypercapnia significantly attenuated the release of neuron-specific enolase, a biomarker of brain injury, and also suggested better 6-month neurologic recovery with hypercapnia compared with normocapnia.

The current TAME trial was conducted to try to confirm these results in a larger, more definitive study.

For the trial, 1,700 adults with coma who had been resuscitated after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest were randomly assigned to receive either 24 hours of mild hypercapnia (target PaCO2, 50-55 mm Hg) or normocapnia (target PaCO2, 35-45 mm Hg).

The primary outcome – a favorable neurologic outcome, defined as a score of 5 or higher on the Glasgow Outcome Scale–Extended at 6 months – occurred in 43.5% in the mild hypercapnia group and in 44.6% in the normocapnia group (relative risk, 0.98; P = .76).

By 6 months, 48.2% of those in the mild hypercapnia group and 45.9% in the normocapnia group had died (relative risk with mild hypercapnia, 1.05; 95% confidence interval, 0.94-1.16). In the mild hypercapnia group, 53.4% had a poor functional outcome, defined as a Modified Rankin Scale score of 4-6, compared with 51.3% in the normocapnia group.

Health-related quality of life, as assessed by the EQ Visual Analogue Scale component of the EuroQol-5D-5L, was similar in the two groups.

In terms of safety, results showed that mild hypercapnia did not increase the incidence of prespecified adverse events.

The authors note that there is concern that mild hypercapnia may worsen cerebral edema and elevate intracranial pressure; however, elevated intracranial pressure is uncommon in the first 72 hours after the return of spontaneous circulation.

In the TAME trial, there was one case of cerebral edema in the hypercapnia group. “This is a very low rate and would be expected in a group this size, so this does not indicate a safety concern,” Dr. Nichol commented.

The researchers are planning further analyses of biological samples to look for possible prognostic markers.

“These out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients are a very diverse group, and it may be possible that some patients could have benefited from hypercapnia while others may have been harmed,” Dr. Nichol noted.

“Raising CO2 levels does improve overall delivery of oxygen to the brain, but this might not have occurred in the right areas. It may be possible that some patients benefited, and analysis of biological samples will help us look more closely at this.”

He added that other ongoing trials are investigating hypercapnia in patients with traumatic brain injury.

“These patients are managed differently and often have probes in their brain to measure the response to CO2, so more of a precision medicine approach is possible,” he explained.

He also noted that the TAME study, which was conducted in conjunction with the TTM-2 study investigating hypothermia in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients, has established a network of ICU teams around the world, providing an infrastructure for further trials to be performed in this patient population in the future.

The TAME trial was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Health Research Board of Ireland, and the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Targeted Therapeutic Mild Hypercapnia After Resuscitated Cardiac Arrest (TAME) study showed that the intervention failed to improve neurologic or functional outcomes or quality of life at 6 months. However, the researchers also found that slightly elevated CO2 levels were not associated with worse outcomes.

“I think these results show that our hypothesis – that raising CO2 levels as applied in this trial may be beneficial for these patients – was not effective, even though previous work suggested that it would be,” co–lead investigator Alistair Nichol, MD, said in an interview.

“This was a rigorous trial; the intervention was well delivered, and the results are pretty clear. Unfortunately, we have proved a null hypothesis – that this approach doesn’t seem to work,” Dr. Nichol, who is professor of critical care medicine at University College Dublin, said.

“However, we did find that hypercapnia was safe. This is an important finding, as sometimes in very sick patients such as those who develop pneumonia, we have to drive the ventilator less hard to minimize injury to the lungs, and this can lead to higher CO2 levels,” he added. “Our results show that this practice should not be harmful, which is reassuring.”

The TAME study was presented at the Critical Care Reviews 2023 Meeting (CCR23) held in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

It was simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The researchers explain that after the return of spontaneous circulation, brain hypoperfusion may contribute to cerebral hypoxia, exacerbate brain damage, and lead to poor neurologic outcomes. The partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) is the major physiologic regulator of cerebrovascular tone, and increasing CO2 levels increases cerebral blood flow.

Two previous observational studies showed that exposure to hypercapnia was associated with an increase in the likelihood of being discharged home and better neurologic outcomes at 12 months, compared with hypocapnia or normocapnia.

In addition, a physiologic study showed that deliberate increases in PaCO2 induced higher cerebral oxygen saturations, compared with normocapnia. A phase 2 randomized trial showed that hypercapnia significantly attenuated the release of neuron-specific enolase, a biomarker of brain injury, and also suggested better 6-month neurologic recovery with hypercapnia compared with normocapnia.

The current TAME trial was conducted to try to confirm these results in a larger, more definitive study.

For the trial, 1,700 adults with coma who had been resuscitated after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest were randomly assigned to receive either 24 hours of mild hypercapnia (target PaCO2, 50-55 mm Hg) or normocapnia (target PaCO2, 35-45 mm Hg).

The primary outcome – a favorable neurologic outcome, defined as a score of 5 or higher on the Glasgow Outcome Scale–Extended at 6 months – occurred in 43.5% in the mild hypercapnia group and in 44.6% in the normocapnia group (relative risk, 0.98; P = .76).

By 6 months, 48.2% of those in the mild hypercapnia group and 45.9% in the normocapnia group had died (relative risk with mild hypercapnia, 1.05; 95% confidence interval, 0.94-1.16). In the mild hypercapnia group, 53.4% had a poor functional outcome, defined as a Modified Rankin Scale score of 4-6, compared with 51.3% in the normocapnia group.

Health-related quality of life, as assessed by the EQ Visual Analogue Scale component of the EuroQol-5D-5L, was similar in the two groups.

In terms of safety, results showed that mild hypercapnia did not increase the incidence of prespecified adverse events.

The authors note that there is concern that mild hypercapnia may worsen cerebral edema and elevate intracranial pressure; however, elevated intracranial pressure is uncommon in the first 72 hours after the return of spontaneous circulation.

In the TAME trial, there was one case of cerebral edema in the hypercapnia group. “This is a very low rate and would be expected in a group this size, so this does not indicate a safety concern,” Dr. Nichol commented.

The researchers are planning further analyses of biological samples to look for possible prognostic markers.

“These out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients are a very diverse group, and it may be possible that some patients could have benefited from hypercapnia while others may have been harmed,” Dr. Nichol noted.

“Raising CO2 levels does improve overall delivery of oxygen to the brain, but this might not have occurred in the right areas. It may be possible that some patients benefited, and analysis of biological samples will help us look more closely at this.”

He added that other ongoing trials are investigating hypercapnia in patients with traumatic brain injury.

“These patients are managed differently and often have probes in their brain to measure the response to CO2, so more of a precision medicine approach is possible,” he explained.

He also noted that the TAME study, which was conducted in conjunction with the TTM-2 study investigating hypothermia in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients, has established a network of ICU teams around the world, providing an infrastructure for further trials to be performed in this patient population in the future.

The TAME trial was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Health Research Board of Ireland, and the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Targeted Therapeutic Mild Hypercapnia After Resuscitated Cardiac Arrest (TAME) study showed that the intervention failed to improve neurologic or functional outcomes or quality of life at 6 months. However, the researchers also found that slightly elevated CO2 levels were not associated with worse outcomes.

“I think these results show that our hypothesis – that raising CO2 levels as applied in this trial may be beneficial for these patients – was not effective, even though previous work suggested that it would be,” co–lead investigator Alistair Nichol, MD, said in an interview.

“This was a rigorous trial; the intervention was well delivered, and the results are pretty clear. Unfortunately, we have proved a null hypothesis – that this approach doesn’t seem to work,” Dr. Nichol, who is professor of critical care medicine at University College Dublin, said.

“However, we did find that hypercapnia was safe. This is an important finding, as sometimes in very sick patients such as those who develop pneumonia, we have to drive the ventilator less hard to minimize injury to the lungs, and this can lead to higher CO2 levels,” he added. “Our results show that this practice should not be harmful, which is reassuring.”

The TAME study was presented at the Critical Care Reviews 2023 Meeting (CCR23) held in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

It was simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The researchers explain that after the return of spontaneous circulation, brain hypoperfusion may contribute to cerebral hypoxia, exacerbate brain damage, and lead to poor neurologic outcomes. The partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) is the major physiologic regulator of cerebrovascular tone, and increasing CO2 levels increases cerebral blood flow.

Two previous observational studies showed that exposure to hypercapnia was associated with an increase in the likelihood of being discharged home and better neurologic outcomes at 12 months, compared with hypocapnia or normocapnia.

In addition, a physiologic study showed that deliberate increases in PaCO2 induced higher cerebral oxygen saturations, compared with normocapnia. A phase 2 randomized trial showed that hypercapnia significantly attenuated the release of neuron-specific enolase, a biomarker of brain injury, and also suggested better 6-month neurologic recovery with hypercapnia compared with normocapnia.

The current TAME trial was conducted to try to confirm these results in a larger, more definitive study.

For the trial, 1,700 adults with coma who had been resuscitated after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest were randomly assigned to receive either 24 hours of mild hypercapnia (target PaCO2, 50-55 mm Hg) or normocapnia (target PaCO2, 35-45 mm Hg).

The primary outcome – a favorable neurologic outcome, defined as a score of 5 or higher on the Glasgow Outcome Scale–Extended at 6 months – occurred in 43.5% in the mild hypercapnia group and in 44.6% in the normocapnia group (relative risk, 0.98; P = .76).

By 6 months, 48.2% of those in the mild hypercapnia group and 45.9% in the normocapnia group had died (relative risk with mild hypercapnia, 1.05; 95% confidence interval, 0.94-1.16). In the mild hypercapnia group, 53.4% had a poor functional outcome, defined as a Modified Rankin Scale score of 4-6, compared with 51.3% in the normocapnia group.

Health-related quality of life, as assessed by the EQ Visual Analogue Scale component of the EuroQol-5D-5L, was similar in the two groups.

In terms of safety, results showed that mild hypercapnia did not increase the incidence of prespecified adverse events.

The authors note that there is concern that mild hypercapnia may worsen cerebral edema and elevate intracranial pressure; however, elevated intracranial pressure is uncommon in the first 72 hours after the return of spontaneous circulation.

In the TAME trial, there was one case of cerebral edema in the hypercapnia group. “This is a very low rate and would be expected in a group this size, so this does not indicate a safety concern,” Dr. Nichol commented.

The researchers are planning further analyses of biological samples to look for possible prognostic markers.

“These out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients are a very diverse group, and it may be possible that some patients could have benefited from hypercapnia while others may have been harmed,” Dr. Nichol noted.

“Raising CO2 levels does improve overall delivery of oxygen to the brain, but this might not have occurred in the right areas. It may be possible that some patients benefited, and analysis of biological samples will help us look more closely at this.”

He added that other ongoing trials are investigating hypercapnia in patients with traumatic brain injury.

“These patients are managed differently and often have probes in their brain to measure the response to CO2, so more of a precision medicine approach is possible,” he explained.

He also noted that the TAME study, which was conducted in conjunction with the TTM-2 study investigating hypothermia in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients, has established a network of ICU teams around the world, providing an infrastructure for further trials to be performed in this patient population in the future.

The TAME trial was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Health Research Board of Ireland, and the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CCR23

Syncope not associated with increased risk for car crash

In a case-crossover study that examined health and driving data for about 3,000 drivers in British Columbia, researchers found similar rates of ED visits for syncope before the dates of car crashes (1.6%) and before control dates (1.2%).

“An emergency visit for syncope did not appear to increase the risk of subsequent traffic crash,” lead author John A. Staples, MD, MPH, clinical associate professor of general internal medicine at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

Case-crossover study

Syncope prompts more than 1 million visits to EDs in the United States each year. About 9% of patients with syncope have recurrence within 1 year.

Some jurisdictions legally require clinicians to advise patients at higher risk for syncope recurrence to stop driving temporarily. But guidelines about when and whom to restrict are not standardized, said Dr. Staples.

“I came to this topic because I work as a physician in a hospital and, a few years ago, I advised a young woman who suffered a serious injury after she passed out while driving and crashed her car,” he added. “She wanted to know if she could drive again and when. I found out that there wasn’t much evidence that could guide my advice to her. That is what planted the seed that eventually grew into this study.”

The researchers examined driving data from the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia and detailed ED visit data from regional health authorities. They included licensed drivers who were diagnosed with syncope and collapse at an ED between 2010 and 2015 in their study. The researchers focused on eligible participants who were involved in a motor vehicle collision between August 2011 and December 2015.

For each patient, the date of the crash was used to establish three control dates without crashes. The control dates were 26 weeks, 52 weeks, and 78 weeks before the crash. The investigators compared the rate of emergency visit for syncope in the 28 days before the crash with the rate of emergency visit for syncope in the 28 days before each control date.

An emergency visit for syncope occurred in 47 of 3,026 precrash intervals and 112 of 9,078 control intervals. This result indicated that syncope was not significantly associated with subsequent crash (adjusted odds ratio, 1.27; P = .18).

In addition, there was no significant association between syncope and crash in subgroups considered to be at higher risk for adverse outcomes after syncope, such as patients older than 65 years and patients with cardiovascular disease or cardiac syncope.

Gaps in data

“It’s a complicated study design but one that’s helpful to understand the temporal relationship between syncope and crash,” said Dr. Staples. “If we had found that the syncope visit was more likely to occur in the 4 weeks before the crash than in earlier matched 4-week control periods, we would have concluded that syncope transiently increases crash risk.”

Dr. Staples emphasized that this was a real-world study and that some patients with syncope at higher risk for a car crash likely stopped driving. “This study doesn’t say there’s no relationship between syncope and subsequent crash, just that our current practices, including current driving restrictions, seem to do an acceptable job of preventing some crashes.”

Limitations of the study influence the interpretation of the results. For example, the data sources did not indicate how patients modified their driving, said Dr. Staples.

Also lacking is information about how physicians identified which patients were at heightened risk for another syncope episode and advised those patients not to drive. “Now would be a good time to start to think about what other studies are needed to better tailor driving restrictions for the right patient,” said Dr. Staples.

‘A messy situation’

In a comment, Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, professor of cardiovascular medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, called the conclusions “well thought out.” He said the study addressed a common, often perplexing problem in a practical way. Dr. Bhatt was not involved in the research.

“This study is trying to address the issue of what to do with people who have had syncope or fainting and have had a car crash. In general, we don’t really know what to do with those people, but there’s a lot of concern for many reasons, for both the patient and the public. There are potential legal liabilities, and the whole thing, generally speaking, tends to be a messy situation. Usually, the default position physicians take is to be very cautious and conservative, and restrict driving,” said Dr. Bhatt.

The study is reassuring, he added. “The authors have contextualized this risk very nicely. Physicians worry a lot about patients who have had an episode of syncope while driving and restrict their patients’ driving, at least temporarily. But as a society, we are much more permissive about people who drive drunk or under the influence, or who drive without seat belts, or who speed, or text while driving. So, within that larger context, we are extremely worried about this one source of risk that is probably less than these other sources of risk.”

Most of the time, the cause of the syncope is benign, said Dr. Bhatt. “We rule out the bad things, like a heart attack or cardiac arrest, seizure, and arrhythmia. Afterwards, the risk from driving is relatively small.” The study results support current practices and suggest “that we probably don’t need to be excessive with our restrictions.

“There is going to be a wide variation in practice, with some physicians wanting to be more restrictive, but there is a lot of subjectivity in how these recommendations are acted on in real life. That’s why I think this study really should reassure physicians that it’s okay to use common sense and good medical judgment when giving advice on driving to their patients,” Dr. Bhatt concluded.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Heart and Stroke Foundation Canada. Dr. Staples and Dr. Bhatt reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a case-crossover study that examined health and driving data for about 3,000 drivers in British Columbia, researchers found similar rates of ED visits for syncope before the dates of car crashes (1.6%) and before control dates (1.2%).

“An emergency visit for syncope did not appear to increase the risk of subsequent traffic crash,” lead author John A. Staples, MD, MPH, clinical associate professor of general internal medicine at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

Case-crossover study

Syncope prompts more than 1 million visits to EDs in the United States each year. About 9% of patients with syncope have recurrence within 1 year.

Some jurisdictions legally require clinicians to advise patients at higher risk for syncope recurrence to stop driving temporarily. But guidelines about when and whom to restrict are not standardized, said Dr. Staples.

“I came to this topic because I work as a physician in a hospital and, a few years ago, I advised a young woman who suffered a serious injury after she passed out while driving and crashed her car,” he added. “She wanted to know if she could drive again and when. I found out that there wasn’t much evidence that could guide my advice to her. That is what planted the seed that eventually grew into this study.”

The researchers examined driving data from the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia and detailed ED visit data from regional health authorities. They included licensed drivers who were diagnosed with syncope and collapse at an ED between 2010 and 2015 in their study. The researchers focused on eligible participants who were involved in a motor vehicle collision between August 2011 and December 2015.

For each patient, the date of the crash was used to establish three control dates without crashes. The control dates were 26 weeks, 52 weeks, and 78 weeks before the crash. The investigators compared the rate of emergency visit for syncope in the 28 days before the crash with the rate of emergency visit for syncope in the 28 days before each control date.

An emergency visit for syncope occurred in 47 of 3,026 precrash intervals and 112 of 9,078 control intervals. This result indicated that syncope was not significantly associated with subsequent crash (adjusted odds ratio, 1.27; P = .18).

In addition, there was no significant association between syncope and crash in subgroups considered to be at higher risk for adverse outcomes after syncope, such as patients older than 65 years and patients with cardiovascular disease or cardiac syncope.

Gaps in data

“It’s a complicated study design but one that’s helpful to understand the temporal relationship between syncope and crash,” said Dr. Staples. “If we had found that the syncope visit was more likely to occur in the 4 weeks before the crash than in earlier matched 4-week control periods, we would have concluded that syncope transiently increases crash risk.”

Dr. Staples emphasized that this was a real-world study and that some patients with syncope at higher risk for a car crash likely stopped driving. “This study doesn’t say there’s no relationship between syncope and subsequent crash, just that our current practices, including current driving restrictions, seem to do an acceptable job of preventing some crashes.”

Limitations of the study influence the interpretation of the results. For example, the data sources did not indicate how patients modified their driving, said Dr. Staples.

Also lacking is information about how physicians identified which patients were at heightened risk for another syncope episode and advised those patients not to drive. “Now would be a good time to start to think about what other studies are needed to better tailor driving restrictions for the right patient,” said Dr. Staples.

‘A messy situation’

In a comment, Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, professor of cardiovascular medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, called the conclusions “well thought out.” He said the study addressed a common, often perplexing problem in a practical way. Dr. Bhatt was not involved in the research.

“This study is trying to address the issue of what to do with people who have had syncope or fainting and have had a car crash. In general, we don’t really know what to do with those people, but there’s a lot of concern for many reasons, for both the patient and the public. There are potential legal liabilities, and the whole thing, generally speaking, tends to be a messy situation. Usually, the default position physicians take is to be very cautious and conservative, and restrict driving,” said Dr. Bhatt.

The study is reassuring, he added. “The authors have contextualized this risk very nicely. Physicians worry a lot about patients who have had an episode of syncope while driving and restrict their patients’ driving, at least temporarily. But as a society, we are much more permissive about people who drive drunk or under the influence, or who drive without seat belts, or who speed, or text while driving. So, within that larger context, we are extremely worried about this one source of risk that is probably less than these other sources of risk.”

Most of the time, the cause of the syncope is benign, said Dr. Bhatt. “We rule out the bad things, like a heart attack or cardiac arrest, seizure, and arrhythmia. Afterwards, the risk from driving is relatively small.” The study results support current practices and suggest “that we probably don’t need to be excessive with our restrictions.

“There is going to be a wide variation in practice, with some physicians wanting to be more restrictive, but there is a lot of subjectivity in how these recommendations are acted on in real life. That’s why I think this study really should reassure physicians that it’s okay to use common sense and good medical judgment when giving advice on driving to their patients,” Dr. Bhatt concluded.