User login

TAVR feasible, comparable with surgery in rheumatic heart disease

Patients with rheumatic heart disease (RHD) appear to have comparable outcomes, whether undergoing transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement (TAVR/SAVR), and when compared with TAVR in patients with nonrheumatic aortic stenosis, a new Medicare study finds.

An analysis of data from 1,159 Medicare beneficiaries with rheumatic aortic stenosis revealed that, over a median follow-up of 19 months, there was no difference in all-cause mortality with TAVR vs. SAVR (11.2 vs. 7.0 per 100 person-years; adjusted hazard ratio, 1.53; P = .2).

Mortality was also similar after a median follow-up of 17 months between TAVR in patients with rheumatic aortic stenosis and 88,554 additional beneficiaries with nonrheumatic aortic stenosis (15.2 vs. 17.7 deaths per 100 person-years; aHR, 0.87; P = .2).

“We need collaboration between industry and society leaders in developed countries to initiate a randomized, controlled trial to address the feasibility of TAVR in rheumatic heart disease in younger populations who aren’t surgical candidates or if there’s a lack of surgical capabilities in countries, but this is an encouraging first sign,” lead author Amgad Mentias, MD, MSc, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, said in an interview.

Although the prevalence of rheumatic heart disease (RHD) has fallen to less than 5% or so in the United States and Europe, it remains a significant problem in developing and low-income countries, with more than 1 million deaths per year, he noted. RHD patients typically present at younger ages, often with concomitant aortic regurgitation and mitral valve disease, but have less calcification than degenerative calcific aortic stenosis.

Commenting on the results, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, David F. Williams, PhD, said in an interview that “it is only now becoming possible to entertain the use of TAVR in such patients, and this paper demonstrates the feasibility of doing so.

“Although the study is based on geriatric patients of an industrialized country, it opens the door to the massive unmet clinical needs in poorer regions as well as emerging economies,” said Dr. Williams, a professor at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Winston-Salem, N.C., and coauthor of an accompanying editorial.

The study included Medicare beneficiaries treated from October 2015 to December 2017 for rheumatic aortic stenosis (TAVR, n = 605; SAVR, n = 55) or nonrheumatic aortic stenosis (n = 88,554).

Among those with rheumatic disease, SAVR patients were younger than TAVR patients (73.4 vs. 79.4 years), had a lower prevalence of most comorbidities, and were less frail (median frailty score, 5.3 vs. 11.3).

SAVR was associated with significantly higher weighted risk for in-hospital acute kidney injury (22.3% vs. 11.9%), blood transfusion (19.8% vs. 7.6%), cardiogenic shock (5.7% vs. 1.5%), new-onset atrial fibrillation (21.1% vs. 2.2%), and had longer hospital stays (median, 8 vs. 3 days), whereas new permanent pacemaker implantations trended higher with TAVR (12.5% vs 7.2%).

The TAVR and SAVR groups had comparable rates of adjusted in-hospital mortality (2.4% vs. 3.5%), 30-day mortality (3.6% vs. 3.2%), 30-day stroke (2.4% vs. 2.8%), and 1-year mortality (13.1% vs. 8.9%).

Among the two TAVR cohorts, patients with rheumatic disease were younger than those with nonrheumatic aortic stenosis (79.4 vs. 81.2 years); had a higher prevalence of heart failure, ischemic stroke, atrial fibrillation, and lung disease; and were more frail (median score, 11.3 vs. 6.9).

Still, there was no difference in weighted risk of in-hospital mortality (2.2% vs. 2.6%), 30-day mortality (3.6% vs. 3.7%), 30-day stroke (2.0% vs. 3.3%), or 1-year mortality (16.0% vs. 17.1%) between TAVR patients with and without rheumatic stenosis.

“We didn’t have specific information on echo[cardiography], so we don’t know how that affected our results, but one of the encouraging points is that after a median follow-up of almost 2 years, none of the patients who had TAVR in the rheumatic valve and who survived required redo aortic valve replacement,” Dr. Mentias said. “It’s still short term but it shows that for the short to mid term, the valve is durable.”

Data were not available on paravalvular regurgitation, an Achilles heel for TAVR, but Dr. Mentias said rates of this complication have come down significantly in the past 2 years with modifications to newer-generation TAVR valves.

Dr. Williams and colleagues say one main limitation of the study also highlights the major shortcoming of contemporary TAVRs when treating patients with RHD: “namely, their inadequate suitability for AR [aortic regurgitation], the predominant rheumatic lesion of the aortic valve” in low- to middle-income countries.

They pointed out that patients needing an aortic valve where RHD is rampant are at least 30 years younger than the 79-year-old TAVR recipients in the study.

In a comment, Dr. Williams said there are several unanswered questions about the full impact TAVR could have in the treatment of young RHD patients in underprivileged regions. “These mainly concern the durability of the valves in individuals who could expect greater longevity than the typical heart valve patient in the USA, and the adaptation of transcatheter techniques to provide cost-effective treatment in regions that lack the usual sophisticated clinical infrastructure.”

Dr. Mentias received support from a National Research Service Award institutional grant to the Abboud Cardiovascular Research Center. Dr. Williams and coauthors are directors of Strait Access Technologies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with rheumatic heart disease (RHD) appear to have comparable outcomes, whether undergoing transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement (TAVR/SAVR), and when compared with TAVR in patients with nonrheumatic aortic stenosis, a new Medicare study finds.

An analysis of data from 1,159 Medicare beneficiaries with rheumatic aortic stenosis revealed that, over a median follow-up of 19 months, there was no difference in all-cause mortality with TAVR vs. SAVR (11.2 vs. 7.0 per 100 person-years; adjusted hazard ratio, 1.53; P = .2).

Mortality was also similar after a median follow-up of 17 months between TAVR in patients with rheumatic aortic stenosis and 88,554 additional beneficiaries with nonrheumatic aortic stenosis (15.2 vs. 17.7 deaths per 100 person-years; aHR, 0.87; P = .2).

“We need collaboration between industry and society leaders in developed countries to initiate a randomized, controlled trial to address the feasibility of TAVR in rheumatic heart disease in younger populations who aren’t surgical candidates or if there’s a lack of surgical capabilities in countries, but this is an encouraging first sign,” lead author Amgad Mentias, MD, MSc, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, said in an interview.

Although the prevalence of rheumatic heart disease (RHD) has fallen to less than 5% or so in the United States and Europe, it remains a significant problem in developing and low-income countries, with more than 1 million deaths per year, he noted. RHD patients typically present at younger ages, often with concomitant aortic regurgitation and mitral valve disease, but have less calcification than degenerative calcific aortic stenosis.

Commenting on the results, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, David F. Williams, PhD, said in an interview that “it is only now becoming possible to entertain the use of TAVR in such patients, and this paper demonstrates the feasibility of doing so.

“Although the study is based on geriatric patients of an industrialized country, it opens the door to the massive unmet clinical needs in poorer regions as well as emerging economies,” said Dr. Williams, a professor at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Winston-Salem, N.C., and coauthor of an accompanying editorial.

The study included Medicare beneficiaries treated from October 2015 to December 2017 for rheumatic aortic stenosis (TAVR, n = 605; SAVR, n = 55) or nonrheumatic aortic stenosis (n = 88,554).

Among those with rheumatic disease, SAVR patients were younger than TAVR patients (73.4 vs. 79.4 years), had a lower prevalence of most comorbidities, and were less frail (median frailty score, 5.3 vs. 11.3).

SAVR was associated with significantly higher weighted risk for in-hospital acute kidney injury (22.3% vs. 11.9%), blood transfusion (19.8% vs. 7.6%), cardiogenic shock (5.7% vs. 1.5%), new-onset atrial fibrillation (21.1% vs. 2.2%), and had longer hospital stays (median, 8 vs. 3 days), whereas new permanent pacemaker implantations trended higher with TAVR (12.5% vs 7.2%).

The TAVR and SAVR groups had comparable rates of adjusted in-hospital mortality (2.4% vs. 3.5%), 30-day mortality (3.6% vs. 3.2%), 30-day stroke (2.4% vs. 2.8%), and 1-year mortality (13.1% vs. 8.9%).

Among the two TAVR cohorts, patients with rheumatic disease were younger than those with nonrheumatic aortic stenosis (79.4 vs. 81.2 years); had a higher prevalence of heart failure, ischemic stroke, atrial fibrillation, and lung disease; and were more frail (median score, 11.3 vs. 6.9).

Still, there was no difference in weighted risk of in-hospital mortality (2.2% vs. 2.6%), 30-day mortality (3.6% vs. 3.7%), 30-day stroke (2.0% vs. 3.3%), or 1-year mortality (16.0% vs. 17.1%) between TAVR patients with and without rheumatic stenosis.

“We didn’t have specific information on echo[cardiography], so we don’t know how that affected our results, but one of the encouraging points is that after a median follow-up of almost 2 years, none of the patients who had TAVR in the rheumatic valve and who survived required redo aortic valve replacement,” Dr. Mentias said. “It’s still short term but it shows that for the short to mid term, the valve is durable.”

Data were not available on paravalvular regurgitation, an Achilles heel for TAVR, but Dr. Mentias said rates of this complication have come down significantly in the past 2 years with modifications to newer-generation TAVR valves.

Dr. Williams and colleagues say one main limitation of the study also highlights the major shortcoming of contemporary TAVRs when treating patients with RHD: “namely, their inadequate suitability for AR [aortic regurgitation], the predominant rheumatic lesion of the aortic valve” in low- to middle-income countries.

They pointed out that patients needing an aortic valve where RHD is rampant are at least 30 years younger than the 79-year-old TAVR recipients in the study.

In a comment, Dr. Williams said there are several unanswered questions about the full impact TAVR could have in the treatment of young RHD patients in underprivileged regions. “These mainly concern the durability of the valves in individuals who could expect greater longevity than the typical heart valve patient in the USA, and the adaptation of transcatheter techniques to provide cost-effective treatment in regions that lack the usual sophisticated clinical infrastructure.”

Dr. Mentias received support from a National Research Service Award institutional grant to the Abboud Cardiovascular Research Center. Dr. Williams and coauthors are directors of Strait Access Technologies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with rheumatic heart disease (RHD) appear to have comparable outcomes, whether undergoing transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement (TAVR/SAVR), and when compared with TAVR in patients with nonrheumatic aortic stenosis, a new Medicare study finds.

An analysis of data from 1,159 Medicare beneficiaries with rheumatic aortic stenosis revealed that, over a median follow-up of 19 months, there was no difference in all-cause mortality with TAVR vs. SAVR (11.2 vs. 7.0 per 100 person-years; adjusted hazard ratio, 1.53; P = .2).

Mortality was also similar after a median follow-up of 17 months between TAVR in patients with rheumatic aortic stenosis and 88,554 additional beneficiaries with nonrheumatic aortic stenosis (15.2 vs. 17.7 deaths per 100 person-years; aHR, 0.87; P = .2).

“We need collaboration between industry and society leaders in developed countries to initiate a randomized, controlled trial to address the feasibility of TAVR in rheumatic heart disease in younger populations who aren’t surgical candidates or if there’s a lack of surgical capabilities in countries, but this is an encouraging first sign,” lead author Amgad Mentias, MD, MSc, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, said in an interview.

Although the prevalence of rheumatic heart disease (RHD) has fallen to less than 5% or so in the United States and Europe, it remains a significant problem in developing and low-income countries, with more than 1 million deaths per year, he noted. RHD patients typically present at younger ages, often with concomitant aortic regurgitation and mitral valve disease, but have less calcification than degenerative calcific aortic stenosis.

Commenting on the results, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, David F. Williams, PhD, said in an interview that “it is only now becoming possible to entertain the use of TAVR in such patients, and this paper demonstrates the feasibility of doing so.

“Although the study is based on geriatric patients of an industrialized country, it opens the door to the massive unmet clinical needs in poorer regions as well as emerging economies,” said Dr. Williams, a professor at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Winston-Salem, N.C., and coauthor of an accompanying editorial.

The study included Medicare beneficiaries treated from October 2015 to December 2017 for rheumatic aortic stenosis (TAVR, n = 605; SAVR, n = 55) or nonrheumatic aortic stenosis (n = 88,554).

Among those with rheumatic disease, SAVR patients were younger than TAVR patients (73.4 vs. 79.4 years), had a lower prevalence of most comorbidities, and were less frail (median frailty score, 5.3 vs. 11.3).

SAVR was associated with significantly higher weighted risk for in-hospital acute kidney injury (22.3% vs. 11.9%), blood transfusion (19.8% vs. 7.6%), cardiogenic shock (5.7% vs. 1.5%), new-onset atrial fibrillation (21.1% vs. 2.2%), and had longer hospital stays (median, 8 vs. 3 days), whereas new permanent pacemaker implantations trended higher with TAVR (12.5% vs 7.2%).

The TAVR and SAVR groups had comparable rates of adjusted in-hospital mortality (2.4% vs. 3.5%), 30-day mortality (3.6% vs. 3.2%), 30-day stroke (2.4% vs. 2.8%), and 1-year mortality (13.1% vs. 8.9%).

Among the two TAVR cohorts, patients with rheumatic disease were younger than those with nonrheumatic aortic stenosis (79.4 vs. 81.2 years); had a higher prevalence of heart failure, ischemic stroke, atrial fibrillation, and lung disease; and were more frail (median score, 11.3 vs. 6.9).

Still, there was no difference in weighted risk of in-hospital mortality (2.2% vs. 2.6%), 30-day mortality (3.6% vs. 3.7%), 30-day stroke (2.0% vs. 3.3%), or 1-year mortality (16.0% vs. 17.1%) between TAVR patients with and without rheumatic stenosis.

“We didn’t have specific information on echo[cardiography], so we don’t know how that affected our results, but one of the encouraging points is that after a median follow-up of almost 2 years, none of the patients who had TAVR in the rheumatic valve and who survived required redo aortic valve replacement,” Dr. Mentias said. “It’s still short term but it shows that for the short to mid term, the valve is durable.”

Data were not available on paravalvular regurgitation, an Achilles heel for TAVR, but Dr. Mentias said rates of this complication have come down significantly in the past 2 years with modifications to newer-generation TAVR valves.

Dr. Williams and colleagues say one main limitation of the study also highlights the major shortcoming of contemporary TAVRs when treating patients with RHD: “namely, their inadequate suitability for AR [aortic regurgitation], the predominant rheumatic lesion of the aortic valve” in low- to middle-income countries.

They pointed out that patients needing an aortic valve where RHD is rampant are at least 30 years younger than the 79-year-old TAVR recipients in the study.

In a comment, Dr. Williams said there are several unanswered questions about the full impact TAVR could have in the treatment of young RHD patients in underprivileged regions. “These mainly concern the durability of the valves in individuals who could expect greater longevity than the typical heart valve patient in the USA, and the adaptation of transcatheter techniques to provide cost-effective treatment in regions that lack the usual sophisticated clinical infrastructure.”

Dr. Mentias received support from a National Research Service Award institutional grant to the Abboud Cardiovascular Research Center. Dr. Williams and coauthors are directors of Strait Access Technologies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA okays transcatheter pulmonary valve for congenital heart disease

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Medtronic’s Harmony Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve (TPV) System to treat severe pulmonary regurgitation in pediatric and adult patients who have a native or surgically repaired right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT).

The Harmony TPV is the first nonsurgical heart valve to treat severe pulmonary valve regurgitation, which is common in patients with congenital heart disease, the agency said in a news release. Its use can delay the time before a patient needs open-heart surgery and potentially reduce the number of these surgeries required over a lifetime.

“The Harmony TPV provides a new treatment option for adult and pediatric patients with certain types of congenital heart disease,” Bram Zuckerman, MD, director of the Office of Cardiovascular Devices in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

“It offers a less-invasive treatment alternative to open-heart surgery to patients with a leaky native or surgically repaired RVOT and may help patients improve their quality of life and return to their normal activities more quickly, thus fulfilling an unmet clinical need of many patients with congenital heart disease,” he said.

The Harmony valve, which was granted breakthrough device designation, is a 22-mm or 25-mm porcine pericardium valve, sewn to a nitinol frame. It is implanted with a 25-French delivery system using a coil-loading catheter.

The FDA approval was based on the 70-patient prospective, nonrandomized, multicenter Harmony TPV Clinical study, in which 100% of patients achieved the primary safety endpoint of no procedure or device-related deaths 30 days after implantation.

Among 65 patients with evaluable echocardiographic data, 89.2% met the primary effectiveness endpoint of no additional surgical or interventional device-related procedures and acceptable heart blood flow at 6 months.

Adverse events included irregular or abnormal heart rhythms in 23.9% of patients, including 14.1% ventricular tachycardia; leakage around the valve in 8.5%, including 1.4% major leakage; minor bleeding in 7.0%, narrowing of the pulmonary valve in 4.2%, and movement of the implant in 4.2%.

Follow-up was scheduled annually through 5 years and has been extended to 10 years as part of the postapproval study, the FDA noted.

The Harmony TPV device is contraindicated for patients with an infection in the heart or elsewhere, for patients who cannot tolerate blood-thinning medicines, and for those with a sensitivity to nitinol (titanium or nickel).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Medtronic’s Harmony Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve (TPV) System to treat severe pulmonary regurgitation in pediatric and adult patients who have a native or surgically repaired right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT).

The Harmony TPV is the first nonsurgical heart valve to treat severe pulmonary valve regurgitation, which is common in patients with congenital heart disease, the agency said in a news release. Its use can delay the time before a patient needs open-heart surgery and potentially reduce the number of these surgeries required over a lifetime.

“The Harmony TPV provides a new treatment option for adult and pediatric patients with certain types of congenital heart disease,” Bram Zuckerman, MD, director of the Office of Cardiovascular Devices in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

“It offers a less-invasive treatment alternative to open-heart surgery to patients with a leaky native or surgically repaired RVOT and may help patients improve their quality of life and return to their normal activities more quickly, thus fulfilling an unmet clinical need of many patients with congenital heart disease,” he said.

The Harmony valve, which was granted breakthrough device designation, is a 22-mm or 25-mm porcine pericardium valve, sewn to a nitinol frame. It is implanted with a 25-French delivery system using a coil-loading catheter.

The FDA approval was based on the 70-patient prospective, nonrandomized, multicenter Harmony TPV Clinical study, in which 100% of patients achieved the primary safety endpoint of no procedure or device-related deaths 30 days after implantation.

Among 65 patients with evaluable echocardiographic data, 89.2% met the primary effectiveness endpoint of no additional surgical or interventional device-related procedures and acceptable heart blood flow at 6 months.

Adverse events included irregular or abnormal heart rhythms in 23.9% of patients, including 14.1% ventricular tachycardia; leakage around the valve in 8.5%, including 1.4% major leakage; minor bleeding in 7.0%, narrowing of the pulmonary valve in 4.2%, and movement of the implant in 4.2%.

Follow-up was scheduled annually through 5 years and has been extended to 10 years as part of the postapproval study, the FDA noted.

The Harmony TPV device is contraindicated for patients with an infection in the heart or elsewhere, for patients who cannot tolerate blood-thinning medicines, and for those with a sensitivity to nitinol (titanium or nickel).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Medtronic’s Harmony Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve (TPV) System to treat severe pulmonary regurgitation in pediatric and adult patients who have a native or surgically repaired right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT).

The Harmony TPV is the first nonsurgical heart valve to treat severe pulmonary valve regurgitation, which is common in patients with congenital heart disease, the agency said in a news release. Its use can delay the time before a patient needs open-heart surgery and potentially reduce the number of these surgeries required over a lifetime.

“The Harmony TPV provides a new treatment option for adult and pediatric patients with certain types of congenital heart disease,” Bram Zuckerman, MD, director of the Office of Cardiovascular Devices in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

“It offers a less-invasive treatment alternative to open-heart surgery to patients with a leaky native or surgically repaired RVOT and may help patients improve their quality of life and return to their normal activities more quickly, thus fulfilling an unmet clinical need of many patients with congenital heart disease,” he said.

The Harmony valve, which was granted breakthrough device designation, is a 22-mm or 25-mm porcine pericardium valve, sewn to a nitinol frame. It is implanted with a 25-French delivery system using a coil-loading catheter.

The FDA approval was based on the 70-patient prospective, nonrandomized, multicenter Harmony TPV Clinical study, in which 100% of patients achieved the primary safety endpoint of no procedure or device-related deaths 30 days after implantation.

Among 65 patients with evaluable echocardiographic data, 89.2% met the primary effectiveness endpoint of no additional surgical or interventional device-related procedures and acceptable heart blood flow at 6 months.

Adverse events included irregular or abnormal heart rhythms in 23.9% of patients, including 14.1% ventricular tachycardia; leakage around the valve in 8.5%, including 1.4% major leakage; minor bleeding in 7.0%, narrowing of the pulmonary valve in 4.2%, and movement of the implant in 4.2%.

Follow-up was scheduled annually through 5 years and has been extended to 10 years as part of the postapproval study, the FDA noted.

The Harmony TPV device is contraindicated for patients with an infection in the heart or elsewhere, for patients who cannot tolerate blood-thinning medicines, and for those with a sensitivity to nitinol (titanium or nickel).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BASILICA technique prevents TAVR-related coronary obstruction in registry study

For patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), the intentional laceration technique of diseased valve leaflets called BASILICA is effective and reasonably safe for preventing coronary artery obstruction, according to a late-breaking study presented at CRT 2021 sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

In a series of 214 patients entered into a registry over a recent 30-month period, leaflets posing risk were effectively traversed with the technique in 95% of cases, and complication rates were reasonably low with 30-day stroke and death rate of 3.4%, reported Jaffar M. Khan, BMBCH, PhD, cardiovascular branch of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The rate of complications is acceptable given the large potential risk, according to Dr. Khan. If coronary obstruction occurs, reported mortality rates have been as high as 50%. The 1-year survival rate in the registry following BASILICA was 84%.

Results should ‘push people toward BASILICA’

The acronym BASILICA stands for bioprosthetic or native aortic scallop intentional laceration to prevent iatrogenic coronary artery obstruction. In the procedure, performed immediately before TAVR, guidewires are introduced to first traverse and then lacerate aortic leaflets threatening obstruction of a coronary artery.

In cases where diseased valve leaflets pose a risk of coronary obstruction, most interventionalists “are comfortable with surgery when patients are at low or intermediate risk, but the choices for high-risk patients are a snorkel stent or BASILICA. Given the limits of snorkel stenting, these data should be reassuring and push people toward BASILICA,” Dr. Khan said.

The 214 patients were entered into the registry from June 2015 to December 2020. The mean age was 74.9 years. Of valves treated, 73% were failed bioprosthetic devices. The remaining were native aortic valves. Solo BASILICA was performed in most patients, but 21.5% underwent a doppio procedure, meaning the laceration of two leaflets.

Despite BASILICA, 10 patients (4.7%) had some degree of coronary obstruction, including 5 with partial obstruction of the main coronary artery and 1 with partial obstruction of the right coronary artery. All of these partial obstructions were successfully treated with orthotopic stents.

An obstruction of the right coronary artery was successfully treated with balloon angioplasty. Another patient with significant left main coronary artery obstruction required cardiopulmonary bypass but was successfully treated with snorkel stenting. Of two patients with complete obstruction of the left main coronary artery caused by the skirt of the TAVR device, one died in hospital despite several maneuvers to restore perfusion.

Procedural complications included a mitral chord laceration, which subsequently led to valve replacement, and three guidewire transversals into surrounding tissue that did not result in serious sequelae. Hypotension requiring pressors occurred in 8.5%.

There was a “slight trend” for worse outcomes in those undergoing doppio rather than solo BASILICA, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. Cerebral embolic protection was offered to a minority of patients in this series. The trend for a lower risk of stroke in this group did not reach significance, Dr. Khan reported.

Best for high-volume centers, for now

Although these data support the conclusion that BASILICA “is feasible in a real-world setting,” Dr. Khan acknowledged that BASILICA might not be appropriate at low-volume centers. Dr. Khan cited data that indicates obstruction of a coronary artery by a diseased leaflet occurs in less than 1% of TAVR cases.

“Not every site doing a handful of TAVRs is going to want to tackle these cases, but those working in a high-volume center will from time to time encounter patients with coronary obstruction or who are at increased risk,” Dr. Khan said.

In North America, there has been a proctoring program to disseminate the skills required to perform BASILICA, according to Dr. Khan, who explained that proctors typically participate in two or three cases before these are performed without supervision.

So far, the uptake of BASILICA has been limited.

“BASILICA has not been catching on in EUROPE,” said Didier F. Loulmet, MD, chief of cardiac surgery at Tisch Hospital, New York University Langone Health. There might be several reasons, but Dr. Loulmet said that lack of a comparable proctoring program is one factor.”

“This is a relatively complex procedure performed in a small number of patients, so building up expertise is quite a challenge, particularly in small centers,” he added. He encouraged proctoring as “the way that it has to be propagated.”

The results presented by Dr. Khan on March 6 at CRT 2021 were simultaneously published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Dr. Khan has patents on several devices, including catheters to lacerate valve leaflet. Dr. Loulmet reported no potential conflicts of interest.

For patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), the intentional laceration technique of diseased valve leaflets called BASILICA is effective and reasonably safe for preventing coronary artery obstruction, according to a late-breaking study presented at CRT 2021 sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

In a series of 214 patients entered into a registry over a recent 30-month period, leaflets posing risk were effectively traversed with the technique in 95% of cases, and complication rates were reasonably low with 30-day stroke and death rate of 3.4%, reported Jaffar M. Khan, BMBCH, PhD, cardiovascular branch of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The rate of complications is acceptable given the large potential risk, according to Dr. Khan. If coronary obstruction occurs, reported mortality rates have been as high as 50%. The 1-year survival rate in the registry following BASILICA was 84%.

Results should ‘push people toward BASILICA’

The acronym BASILICA stands for bioprosthetic or native aortic scallop intentional laceration to prevent iatrogenic coronary artery obstruction. In the procedure, performed immediately before TAVR, guidewires are introduced to first traverse and then lacerate aortic leaflets threatening obstruction of a coronary artery.

In cases where diseased valve leaflets pose a risk of coronary obstruction, most interventionalists “are comfortable with surgery when patients are at low or intermediate risk, but the choices for high-risk patients are a snorkel stent or BASILICA. Given the limits of snorkel stenting, these data should be reassuring and push people toward BASILICA,” Dr. Khan said.

The 214 patients were entered into the registry from June 2015 to December 2020. The mean age was 74.9 years. Of valves treated, 73% were failed bioprosthetic devices. The remaining were native aortic valves. Solo BASILICA was performed in most patients, but 21.5% underwent a doppio procedure, meaning the laceration of two leaflets.

Despite BASILICA, 10 patients (4.7%) had some degree of coronary obstruction, including 5 with partial obstruction of the main coronary artery and 1 with partial obstruction of the right coronary artery. All of these partial obstructions were successfully treated with orthotopic stents.

An obstruction of the right coronary artery was successfully treated with balloon angioplasty. Another patient with significant left main coronary artery obstruction required cardiopulmonary bypass but was successfully treated with snorkel stenting. Of two patients with complete obstruction of the left main coronary artery caused by the skirt of the TAVR device, one died in hospital despite several maneuvers to restore perfusion.

Procedural complications included a mitral chord laceration, which subsequently led to valve replacement, and three guidewire transversals into surrounding tissue that did not result in serious sequelae. Hypotension requiring pressors occurred in 8.5%.

There was a “slight trend” for worse outcomes in those undergoing doppio rather than solo BASILICA, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. Cerebral embolic protection was offered to a minority of patients in this series. The trend for a lower risk of stroke in this group did not reach significance, Dr. Khan reported.

Best for high-volume centers, for now

Although these data support the conclusion that BASILICA “is feasible in a real-world setting,” Dr. Khan acknowledged that BASILICA might not be appropriate at low-volume centers. Dr. Khan cited data that indicates obstruction of a coronary artery by a diseased leaflet occurs in less than 1% of TAVR cases.

“Not every site doing a handful of TAVRs is going to want to tackle these cases, but those working in a high-volume center will from time to time encounter patients with coronary obstruction or who are at increased risk,” Dr. Khan said.

In North America, there has been a proctoring program to disseminate the skills required to perform BASILICA, according to Dr. Khan, who explained that proctors typically participate in two or three cases before these are performed without supervision.

So far, the uptake of BASILICA has been limited.

“BASILICA has not been catching on in EUROPE,” said Didier F. Loulmet, MD, chief of cardiac surgery at Tisch Hospital, New York University Langone Health. There might be several reasons, but Dr. Loulmet said that lack of a comparable proctoring program is one factor.”

“This is a relatively complex procedure performed in a small number of patients, so building up expertise is quite a challenge, particularly in small centers,” he added. He encouraged proctoring as “the way that it has to be propagated.”

The results presented by Dr. Khan on March 6 at CRT 2021 were simultaneously published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Dr. Khan has patents on several devices, including catheters to lacerate valve leaflet. Dr. Loulmet reported no potential conflicts of interest.

For patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), the intentional laceration technique of diseased valve leaflets called BASILICA is effective and reasonably safe for preventing coronary artery obstruction, according to a late-breaking study presented at CRT 2021 sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

In a series of 214 patients entered into a registry over a recent 30-month period, leaflets posing risk were effectively traversed with the technique in 95% of cases, and complication rates were reasonably low with 30-day stroke and death rate of 3.4%, reported Jaffar M. Khan, BMBCH, PhD, cardiovascular branch of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The rate of complications is acceptable given the large potential risk, according to Dr. Khan. If coronary obstruction occurs, reported mortality rates have been as high as 50%. The 1-year survival rate in the registry following BASILICA was 84%.

Results should ‘push people toward BASILICA’

The acronym BASILICA stands for bioprosthetic or native aortic scallop intentional laceration to prevent iatrogenic coronary artery obstruction. In the procedure, performed immediately before TAVR, guidewires are introduced to first traverse and then lacerate aortic leaflets threatening obstruction of a coronary artery.

In cases where diseased valve leaflets pose a risk of coronary obstruction, most interventionalists “are comfortable with surgery when patients are at low or intermediate risk, but the choices for high-risk patients are a snorkel stent or BASILICA. Given the limits of snorkel stenting, these data should be reassuring and push people toward BASILICA,” Dr. Khan said.

The 214 patients were entered into the registry from June 2015 to December 2020. The mean age was 74.9 years. Of valves treated, 73% were failed bioprosthetic devices. The remaining were native aortic valves. Solo BASILICA was performed in most patients, but 21.5% underwent a doppio procedure, meaning the laceration of two leaflets.

Despite BASILICA, 10 patients (4.7%) had some degree of coronary obstruction, including 5 with partial obstruction of the main coronary artery and 1 with partial obstruction of the right coronary artery. All of these partial obstructions were successfully treated with orthotopic stents.

An obstruction of the right coronary artery was successfully treated with balloon angioplasty. Another patient with significant left main coronary artery obstruction required cardiopulmonary bypass but was successfully treated with snorkel stenting. Of two patients with complete obstruction of the left main coronary artery caused by the skirt of the TAVR device, one died in hospital despite several maneuvers to restore perfusion.

Procedural complications included a mitral chord laceration, which subsequently led to valve replacement, and three guidewire transversals into surrounding tissue that did not result in serious sequelae. Hypotension requiring pressors occurred in 8.5%.

There was a “slight trend” for worse outcomes in those undergoing doppio rather than solo BASILICA, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. Cerebral embolic protection was offered to a minority of patients in this series. The trend for a lower risk of stroke in this group did not reach significance, Dr. Khan reported.

Best for high-volume centers, for now

Although these data support the conclusion that BASILICA “is feasible in a real-world setting,” Dr. Khan acknowledged that BASILICA might not be appropriate at low-volume centers. Dr. Khan cited data that indicates obstruction of a coronary artery by a diseased leaflet occurs in less than 1% of TAVR cases.

“Not every site doing a handful of TAVRs is going to want to tackle these cases, but those working in a high-volume center will from time to time encounter patients with coronary obstruction or who are at increased risk,” Dr. Khan said.

In North America, there has been a proctoring program to disseminate the skills required to perform BASILICA, according to Dr. Khan, who explained that proctors typically participate in two or three cases before these are performed without supervision.

So far, the uptake of BASILICA has been limited.

“BASILICA has not been catching on in EUROPE,” said Didier F. Loulmet, MD, chief of cardiac surgery at Tisch Hospital, New York University Langone Health. There might be several reasons, but Dr. Loulmet said that lack of a comparable proctoring program is one factor.”

“This is a relatively complex procedure performed in a small number of patients, so building up expertise is quite a challenge, particularly in small centers,” he added. He encouraged proctoring as “the way that it has to be propagated.”

The results presented by Dr. Khan on March 6 at CRT 2021 were simultaneously published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Dr. Khan has patents on several devices, including catheters to lacerate valve leaflet. Dr. Loulmet reported no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM CRT 2021

DOACs offered after heart valve surgery despite absence of data

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are used in about 1% of patients undergoing surgical mechanical aortic and mitral valve replacement, but in up to 6% of surgical bioprosthetic valve replacements, according to registry data presented at CRT 2021.

In an analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) registry during 2014-2017, DOAC use increased steadily among those undergoing surgical bioprosthetic valve replacement, reaching a number that is potentially clinically significant, according to Ankur Kalra, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Akron General Hospital who has an academic appointment at the Cleveland Clinic.

There was no increase in the use of DOACs observed among patients undergoing mechanical valve replacement, “but even if the number is 1%, they should probably not be used at all until we accrue more data,” Dr. Kalra said.

DOACs discouraged in patients with mechanical or bioprosthetic valves

In Food and Drug Administration labeling, DOACs are contraindicated or not recommended. This can be traced to the randomized RE-ALIGN trial, which was stopped prematurely due to evidence of harm from a DOAC, according to Dr. Kalra.

In RE-ALIGN, which enrolled patients undergoing mechanical aortic or mitral valve replacement, dabigatran was associated not only with more bleeding events than warfarin, but also more thromboembolic events.

There are no randomized data comparing the factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban or apixaban to warfarin in heart valve surgery, but Dr. Kalra noted cautionary language is found in the labeling of both, “perhaps due to the RE-ALIGN data.”

Registry shows trends in prescribing

In the STS registry data, 193 (1.1%) of the 18,142 patients undergoing mechanical aortic valve surgery, 139 (1.0%) of the 13,942 patients undergoing mechanical mitral valve surgery, 5,625 (4.7%) of the 116,203 patients undergoing aortic bioprosthetic aortic valve surgery, and 2,180 (5.9%) of the 39,243 patients undergoing bioprosthetic mitral valve surgery were on a DOAC at discharge.

Among those receiving a mechanical value and placed on a DOAC, about two-thirds were on a factor Xa inhibitor rather than dabigatran. For those receiving a bioprosthetic value, the proportion was greater than 80%. Dr. Kalra speculated that the RE-ALIGN trial might be the reason factor Xa inhibitors were favored.

In both types of valves, whether mechanical or bioprosthetic, more comorbidities predicted a greater likelihood of receiving a DOAC rather than warfarin. For those receiving mechanical values, the comorbidities with a significant association with greater DOAC use included hypertension (P = .003), dyslipidemia (P = .02), arrhythmia (P < .001), and peripheral arterial disease (P < 0.001).

The same factors were significant for predicting increased likelihood of a DOAC following bioprosthetic valve replacement, but there were additional factors, including atrial fibrillation independent of other types of arrhythmias (P < .001), a factor not significant for mechanical valves, as well as diabetes (P < .001), cerebrovascular disease (P < .001), dialysis (P < .001), and endocarditis (P < .001).

“This is probably intuitive, but patients who were on a factor Xa inhibitor before their valve replacement were also more likely to be discharged on a factor Xa inhibitor,” Dr. Kalra said at the virtual meeting, sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

The year-to-year increase in DOAC use among those undergoing bioprosthetic valve replacement over the study period, which was a significant trend, was not observed among those undergoing mechanical valve replacement. Rather, the 1% proportion remained stable over the study period.

“We wanted to look at outcomes, but we found that the STS database, which only includes data out to 30 days, is not structured for this type of analysis,” Dr. Kalra said. He was also concerned about the limitations of a comparison in which 1% of the sample was being compared to 99%.

Expert: One percent is ‘very small number’

David J. Cohen, MD, commented on the 1% figure, which was so low that a moderator questioned whether it could be due mostly to coding errors.

“This is a very, very small number so at some level it is reassuring that it is so low in the mechanical valves,” Dr. Cohen said. However, he was more circumspect about the larger number in bioprosthetic valves.

“I have always thought it was a bit strange there was a warning against using them in bioprosthetic valves, especially in the aortic position,” he said.

“The trials that established the benefits of DOACs were all in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, but this did not mean non–aortic stenosis; it meant non–mitral valvular. There have been articles written about how that has been misinterpreted,” said Dr. Cohen, director of clinical and outcomes research at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation and director of academic affairs at St. Francis Hospital, Roslyn, N.Y.

For his part, Dr. Kalra reported that he does not consider DOACs in patients who have undergone a surgical mechanical valve replacement. For bioprosthetic valves, he “prefers” warfarin over DOACs.

Overall, the evidence from the registry led Dr. Kalra to suggest that physicians should continue to “exercise caution” in using DOACs instead of warfarin after any surgical valve replacement “until randomized clinical trials provide sufficient evidence” to make a judgment about relative efficacy and safety.

Results of the study were published online as a research letter in Jama Network Open after Dr. Kalra’s presentation. Dr. Kalra and Dr. Cohen report no potential conflicts of interest.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are used in about 1% of patients undergoing surgical mechanical aortic and mitral valve replacement, but in up to 6% of surgical bioprosthetic valve replacements, according to registry data presented at CRT 2021.

In an analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) registry during 2014-2017, DOAC use increased steadily among those undergoing surgical bioprosthetic valve replacement, reaching a number that is potentially clinically significant, according to Ankur Kalra, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Akron General Hospital who has an academic appointment at the Cleveland Clinic.

There was no increase in the use of DOACs observed among patients undergoing mechanical valve replacement, “but even if the number is 1%, they should probably not be used at all until we accrue more data,” Dr. Kalra said.

DOACs discouraged in patients with mechanical or bioprosthetic valves

In Food and Drug Administration labeling, DOACs are contraindicated or not recommended. This can be traced to the randomized RE-ALIGN trial, which was stopped prematurely due to evidence of harm from a DOAC, according to Dr. Kalra.

In RE-ALIGN, which enrolled patients undergoing mechanical aortic or mitral valve replacement, dabigatran was associated not only with more bleeding events than warfarin, but also more thromboembolic events.

There are no randomized data comparing the factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban or apixaban to warfarin in heart valve surgery, but Dr. Kalra noted cautionary language is found in the labeling of both, “perhaps due to the RE-ALIGN data.”

Registry shows trends in prescribing

In the STS registry data, 193 (1.1%) of the 18,142 patients undergoing mechanical aortic valve surgery, 139 (1.0%) of the 13,942 patients undergoing mechanical mitral valve surgery, 5,625 (4.7%) of the 116,203 patients undergoing aortic bioprosthetic aortic valve surgery, and 2,180 (5.9%) of the 39,243 patients undergoing bioprosthetic mitral valve surgery were on a DOAC at discharge.

Among those receiving a mechanical value and placed on a DOAC, about two-thirds were on a factor Xa inhibitor rather than dabigatran. For those receiving a bioprosthetic value, the proportion was greater than 80%. Dr. Kalra speculated that the RE-ALIGN trial might be the reason factor Xa inhibitors were favored.

In both types of valves, whether mechanical or bioprosthetic, more comorbidities predicted a greater likelihood of receiving a DOAC rather than warfarin. For those receiving mechanical values, the comorbidities with a significant association with greater DOAC use included hypertension (P = .003), dyslipidemia (P = .02), arrhythmia (P < .001), and peripheral arterial disease (P < 0.001).

The same factors were significant for predicting increased likelihood of a DOAC following bioprosthetic valve replacement, but there were additional factors, including atrial fibrillation independent of other types of arrhythmias (P < .001), a factor not significant for mechanical valves, as well as diabetes (P < .001), cerebrovascular disease (P < .001), dialysis (P < .001), and endocarditis (P < .001).

“This is probably intuitive, but patients who were on a factor Xa inhibitor before their valve replacement were also more likely to be discharged on a factor Xa inhibitor,” Dr. Kalra said at the virtual meeting, sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

The year-to-year increase in DOAC use among those undergoing bioprosthetic valve replacement over the study period, which was a significant trend, was not observed among those undergoing mechanical valve replacement. Rather, the 1% proportion remained stable over the study period.

“We wanted to look at outcomes, but we found that the STS database, which only includes data out to 30 days, is not structured for this type of analysis,” Dr. Kalra said. He was also concerned about the limitations of a comparison in which 1% of the sample was being compared to 99%.

Expert: One percent is ‘very small number’

David J. Cohen, MD, commented on the 1% figure, which was so low that a moderator questioned whether it could be due mostly to coding errors.

“This is a very, very small number so at some level it is reassuring that it is so low in the mechanical valves,” Dr. Cohen said. However, he was more circumspect about the larger number in bioprosthetic valves.

“I have always thought it was a bit strange there was a warning against using them in bioprosthetic valves, especially in the aortic position,” he said.

“The trials that established the benefits of DOACs were all in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, but this did not mean non–aortic stenosis; it meant non–mitral valvular. There have been articles written about how that has been misinterpreted,” said Dr. Cohen, director of clinical and outcomes research at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation and director of academic affairs at St. Francis Hospital, Roslyn, N.Y.

For his part, Dr. Kalra reported that he does not consider DOACs in patients who have undergone a surgical mechanical valve replacement. For bioprosthetic valves, he “prefers” warfarin over DOACs.

Overall, the evidence from the registry led Dr. Kalra to suggest that physicians should continue to “exercise caution” in using DOACs instead of warfarin after any surgical valve replacement “until randomized clinical trials provide sufficient evidence” to make a judgment about relative efficacy and safety.

Results of the study were published online as a research letter in Jama Network Open after Dr. Kalra’s presentation. Dr. Kalra and Dr. Cohen report no potential conflicts of interest.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are used in about 1% of patients undergoing surgical mechanical aortic and mitral valve replacement, but in up to 6% of surgical bioprosthetic valve replacements, according to registry data presented at CRT 2021.

In an analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) registry during 2014-2017, DOAC use increased steadily among those undergoing surgical bioprosthetic valve replacement, reaching a number that is potentially clinically significant, according to Ankur Kalra, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Akron General Hospital who has an academic appointment at the Cleveland Clinic.

There was no increase in the use of DOACs observed among patients undergoing mechanical valve replacement, “but even if the number is 1%, they should probably not be used at all until we accrue more data,” Dr. Kalra said.

DOACs discouraged in patients with mechanical or bioprosthetic valves

In Food and Drug Administration labeling, DOACs are contraindicated or not recommended. This can be traced to the randomized RE-ALIGN trial, which was stopped prematurely due to evidence of harm from a DOAC, according to Dr. Kalra.

In RE-ALIGN, which enrolled patients undergoing mechanical aortic or mitral valve replacement, dabigatran was associated not only with more bleeding events than warfarin, but also more thromboembolic events.

There are no randomized data comparing the factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban or apixaban to warfarin in heart valve surgery, but Dr. Kalra noted cautionary language is found in the labeling of both, “perhaps due to the RE-ALIGN data.”

Registry shows trends in prescribing

In the STS registry data, 193 (1.1%) of the 18,142 patients undergoing mechanical aortic valve surgery, 139 (1.0%) of the 13,942 patients undergoing mechanical mitral valve surgery, 5,625 (4.7%) of the 116,203 patients undergoing aortic bioprosthetic aortic valve surgery, and 2,180 (5.9%) of the 39,243 patients undergoing bioprosthetic mitral valve surgery were on a DOAC at discharge.

Among those receiving a mechanical value and placed on a DOAC, about two-thirds were on a factor Xa inhibitor rather than dabigatran. For those receiving a bioprosthetic value, the proportion was greater than 80%. Dr. Kalra speculated that the RE-ALIGN trial might be the reason factor Xa inhibitors were favored.

In both types of valves, whether mechanical or bioprosthetic, more comorbidities predicted a greater likelihood of receiving a DOAC rather than warfarin. For those receiving mechanical values, the comorbidities with a significant association with greater DOAC use included hypertension (P = .003), dyslipidemia (P = .02), arrhythmia (P < .001), and peripheral arterial disease (P < 0.001).

The same factors were significant for predicting increased likelihood of a DOAC following bioprosthetic valve replacement, but there were additional factors, including atrial fibrillation independent of other types of arrhythmias (P < .001), a factor not significant for mechanical valves, as well as diabetes (P < .001), cerebrovascular disease (P < .001), dialysis (P < .001), and endocarditis (P < .001).

“This is probably intuitive, but patients who were on a factor Xa inhibitor before their valve replacement were also more likely to be discharged on a factor Xa inhibitor,” Dr. Kalra said at the virtual meeting, sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

The year-to-year increase in DOAC use among those undergoing bioprosthetic valve replacement over the study period, which was a significant trend, was not observed among those undergoing mechanical valve replacement. Rather, the 1% proportion remained stable over the study period.

“We wanted to look at outcomes, but we found that the STS database, which only includes data out to 30 days, is not structured for this type of analysis,” Dr. Kalra said. He was also concerned about the limitations of a comparison in which 1% of the sample was being compared to 99%.

Expert: One percent is ‘very small number’

David J. Cohen, MD, commented on the 1% figure, which was so low that a moderator questioned whether it could be due mostly to coding errors.

“This is a very, very small number so at some level it is reassuring that it is so low in the mechanical valves,” Dr. Cohen said. However, he was more circumspect about the larger number in bioprosthetic valves.

“I have always thought it was a bit strange there was a warning against using them in bioprosthetic valves, especially in the aortic position,” he said.

“The trials that established the benefits of DOACs were all in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, but this did not mean non–aortic stenosis; it meant non–mitral valvular. There have been articles written about how that has been misinterpreted,” said Dr. Cohen, director of clinical and outcomes research at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation and director of academic affairs at St. Francis Hospital, Roslyn, N.Y.

For his part, Dr. Kalra reported that he does not consider DOACs in patients who have undergone a surgical mechanical valve replacement. For bioprosthetic valves, he “prefers” warfarin over DOACs.

Overall, the evidence from the registry led Dr. Kalra to suggest that physicians should continue to “exercise caution” in using DOACs instead of warfarin after any surgical valve replacement “until randomized clinical trials provide sufficient evidence” to make a judgment about relative efficacy and safety.

Results of the study were published online as a research letter in Jama Network Open after Dr. Kalra’s presentation. Dr. Kalra and Dr. Cohen report no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM CRT 2021

Is the tide turning on the ‘grubby’ affair of EXCEL and the European guidelines?

“I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” The choice of the secretary general of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery to open with this quote was the first hint that the next presentation at the 2019 annual meeting would be anything but dull. The session chair followed with a reminder to keep the discussion polite and civil.

Presenter David Taggart, MD, PhD, did not disappoint. The professor of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Oxford (England) began with the announcement that he had withdrawn his name from a recent paper in the New England Journal of Medicine. He then proceeded to accuse his coinvestigators of misrepresenting the findings of a major clinical trial.

Dr. Taggart was chair of the surgical committee for the Abbott-sponsored EXCEL trial, which compared two procedures for patients who had blockages in their left main coronary artery: percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using coronary stents, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG). The investigators designed the trial to compare outcomes for the two treatments using a composite endpoint of death, stroke, and MI. The 3-year follow-up data had been published in NEJM without controversy – or, at least, without public controversy.

But when it came time to publish the 5-year follow-up, there was a significantly higher rate of death in the stent group, and both Dr. Taggart and the journal editors were concerned that this finding was being downplayed in the manuscript.

In their comments to the authors, the journal editors had recommended including the mortality difference (unless clearly trivial) ‘”in the concluding statement in the final paragraph.” Yet, the concluding statement of the published paper read that there “was no significant difference between PCI and CABG.”

In Dr. Taggart’s view, that claim was dangerous for patients, and so he was left with no choice but to remove himself as an author, a first for the academic with over 300 scientific papers to his name.

Earlier publications from the EXCEL trial had influenced European treatment guidelines. But subsequent allegations of misconduct and hidden data spurred the EACTS to repudiate those guidelines out of concern “that some results in the EXCEL trial appear to have been concealed and that some patients may therefore have received the wrong clinical advice.”

The controversy pitted cardiothoracic surgeons against interventional cardiologists, who were seen as increasingly encroaching on the surgeons’ turf. Dr. Taggart was a long-time critic of the subspecialty.

Surgeons demanded an independent analysis of the EXCEL trial data – a demand that the investigators have yet to satisfy. Dr. Taggart was the first to speak publicly, but others had major reservations about the trial reporting and conduct years earlier.

Mortality data held back

One such person was Lars Wallentin, MD, a professor of cardiology at Uppsala (Sweden) University Hospital, who chaired the independent committee that monitored the safety and scientific validity of the EXCEL trial.

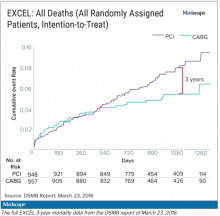

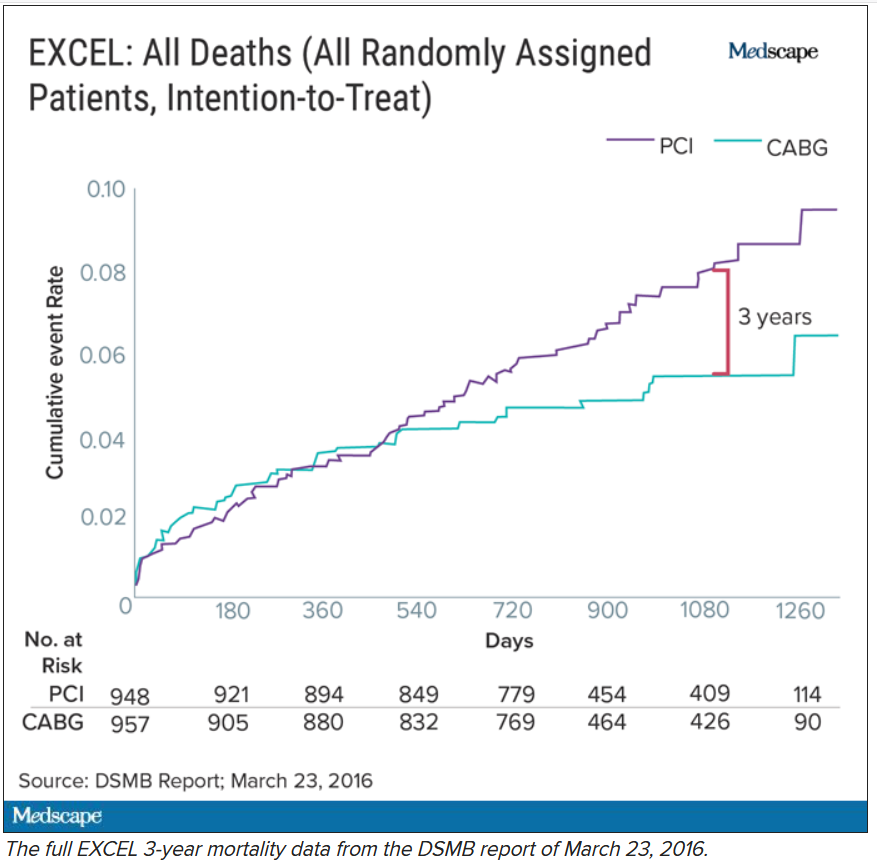

The committee, known as the data and safety monitoring board (DSMB), received a report on March 23, 2016, that showed that increasingly more patients who had received stents were dying, compared with the group of patients that had undergone CABG. A graph of the survival curves showed the gap between the two groups widening after 3 years (Figure 1).

By September of that year, Dr. Wallentin and other members of the DSMB were anxious to share the concerning mortality difference with the broader medical community.

They were aware that EACTS and the European Society of Cardiology had started the process of updating their guidelines on myocardial revascularization, and were keen for the guideline writing committee to see all of the data.

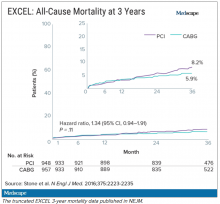

Meanwhile, the trial investigators, led by principal investigator Gregg Stone, MD, then at New York–Presbyterian Hospital and Columbia University Medical Center, were preparing to publish a report of the 3-year outcomes. Recruitment for EXCEL started in September 2010, so at the time of the 3-year analysis in 2016, some patients had been followed up for over 5 years. But the data, published in NEJM in October 2016, were capped at 3 years (Figure 2). It didn’t show the widening gap in late mortality that Dr. Wallentin and the rest of the DSMB had seen.

When asked about this, the investigators said they were transparent about their plans to cap the data at 3 years in an amendment to the study protocol. Stone’s coprincipal investigators were interventional cardiologist Patrick Serruys, MD, then of Imperial College London; and two surgeons: Joseph Sabik, MD, then of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, and A. Pieter Kappetein, MD, PhD, then at Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam. The four principal investigators all declared financial payments from stent manufacturers either to themselves or their institutions.

Study sponsor Abbott has distanced itself from the decisions made and has referred all questions about the trial to the EXCEL investigators. Charles Simonton, chief medical officer at Abbott (now at Abiomed) was a coauthor on both the 3- and 5-year papers. Dr. Wallentin believes that the sponsor must have been aware of the DSMB’s concerns.

Continuing DSMB concerns

A year later, the DSMB was still troubled. Dr. Wallentin emailed Dr. Stone in September 2017 asking for an updated analysis of the mortality data without any capping in time.

Dr. Wallentin added that he didn’t think that unblinding the mortality results would be an issue at that stage because these were late deaths in a trial where the interventions were long completed. But, he warned, “it might be very concerning if, in the future, suspicions were raised that already available information on mortality was withheld from the cardiology and thoracic surgery community.”

The investigators took a month to respond. They declined the request, saying that the trial was not statistically powered to measure mortality. In his email to Dr. Wallentin, Dr. Stone stressed that they were committed to complete disclosure of all of the EXCEL data and that the responsible time point to unblind was after 4 years. His coprincipal investigators (Dr. Serruys, Dr. Sabik, and Dr. Kappetein) as well as EXCEL statistical committee chair Stuart Pocock, PhD, and Mr. Simonton were all copied on the email.

Dr. Wallentin deferred to the principal investigators’ arguments.

Missing MI data

Death was not the only outcome of the EXCEL trial to draw scrutiny.

The EXCEL investigators used a unique definition of MI that was almost exclusively based on a rise in the cardiac biomarker CK-MB. This protocol definition of MI was later adapted into the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions definition in a paper coauthored by Dr. Stone. The investigators agreed to also measure MIs that met the more commonly used Third Universal Definition as a secondary endpoint. The Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction uses a change in biomarkers – preferably troponin or alternatively CK-MB – coupled with other clinical signs.

It is standard practice to report secondary endpoints in any analysis of the main findings of a study. Yet, the EXCEL investigators did not report the universal definition of MI in either the 3-year or 5-year publications.

This is critical because MI according to one definition may not count according to the other, and the final tally could tip the trial results positive, negative, or neutral for coronary stents.

In Dr. Taggart’s opinion, the protocol definition puts CABG at a disadvantage because it uses the same biomarker threshold for procedural-related MI for both PCI and CABG. Because surgery involves more manipulation of the heart, cardiac enzyme levels will naturally be higher after CABG than PCI. These procedure-related enzyme elevations are not “true clinical MIs,” according to Dr. Taggart and others.

Late last year, a dataset containing the 3-year follow-up of EXCEL, including the information on the universal definition of MI, was leaked to the BBC. Working with biostatisticians, the BBC confirmed that according to this definition, there were more MIs in the stent group.

Originally, the investigators disputed the finding, calling the BBC data “imaginary.” They claimed that they were unable to calculate a rate of MI according to the universal definition because they lacked routine collection of troponins, although the universal definition also allows use of CK-MB. They have since published an analysis of 5-year MI data according to the universal definition, which showed twice the rate of MI in the PCI group.

From the leaked data, the BBC calculated the main composite endpoint of death, stroke, and MI using the universal definition of MI. Now the results swung in favor of CABG.

Impact on guidelines

None of this was known at the time the European cardiology societies convened a committee to write their new guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The writing panel disagreed about whether PCI and CABG were equivalent for patients with left main coronary artery disease (CAD).

Besides EXCEL, another study, the NOBLE trial, compared PCI and CABG in left main CAD and came to opposite conclusions – conclusions that matched the leaked data. In that trial, European investigators chose a slightly different primary endpoint: a composite of death, MI, stroke, and the need for a repeat procedure. They used the universal definition of MI exclusively, and notably, they omitted procedural MI from their clinical event count. The results, published at the same time as the EXCEL 3-year findings, suggested that CABG was better.

Given the discrepant findings of two large trials, the guideline committee considered all of the available data comparing the two methods of revascularization for left main CAD. But even then, things weren’t clear-cut. One draft meta-analysis, supported by the National Institute for Health Research, suggested that results were worse for first- and second-generation drug-eluting coronary stents – including those used in EXCEL – compared with surgery.

Another meta-analysis, later published in The Lancet, drew a different conclusion and found that PCI was just as good as surgery. The main author, Stuart Head, a cardiothoracic surgeon on the ESC/EACTS guideline committee, was a research fellow with EXCEL investigator Dr. Kappetein at Erasmus. EXCEL investigators Dr. Stone, Dr. Kappetein, and Dr. Serruys were coauthors of the Lancet meta-analysis.

There was heated discussion about the committee’s draft recommendations, which gave both CABG and PCI a Class IA recommendation in patients with left main CAD and low anatomical complexity. In October 2017, the ESC commissioned an anonymous external reviewer to weigh in. James Brophy, MD, PhD, a cardiologist and professor of medicine and epidemiology at McGill University, Montreal, confirmed that he was the reviewer after he published an updated version in June 2020.

Looking at all of the data available at the time comparing the procedures for left main CAD, Dr. Brophy’s analysis suggested a 73% chance that the excess in death, stroke, or MI represents at least two excess events per 100 patients treated with PCI rather than CABG.

Dr. Brophy thought that most patients would find these differences clinically meaningful and advised against giving both procedures the same class of recommendation. He was also concerned that many readers will skip to the summary recommendation table without reading the entire guideline document.

“I feel this is misleading in its present form,” he wrote in 2017.

Despite Dr. Brophy’s review, the guideline committee stuck with its original recommendations. The final 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization gave equal weight to both CABG and PCI in patients with left main CAD and low anatomical complexity. In contrast, US guidelines do not put PCI and CABG on the same footing for any group of patients with left main CAD.

The lead author of the ESC/EACTS guidelines section on left main disease, and around a third of those on the writing task force, all declared financial payments from stent manufacturers either to themselves or their institutions. The EXCEL principal investigator, Dr. Kappetein, was secretary general of EACTS and oversaw the guidelines process for the surgical organization. He left to work for Medtronic midway through the process and was later joined there by his former research fellow, Stuart Head.

Dr. Brophy said in an interview that given the final guideline recommendations, he assumed that the committee had other reviews and went with the majority opinion.

But not everyone involved in the guidelines saw Dr. Brophy’s review. Nick Freemantle, a statistical reviewer appointed by EACTS, expected to see it but didn’t. This omission calls into question the neutrality of the whole process, in his view.

Mr. Freemantle believes that the deck was stacked so that he only saw the pieces of evidence that supported the conclusions that were already decided and that he was not shown “the bits that don’t fit that neatly.”

“And without that narrative, it all feels a bit grubby, to be honest,” he said.

Professor Barbara Casadei, ESC president, disputed this, saying that the guidelines were approved by all surgical members, including the EACTS council.

Missing from Dr. Brophy’s review were the later data from EXCEL. As he had told the DSMB in 2017, Stone presented the 4-year data from EXCEL at the TCT conference in September 2018. At this point, the analysis showed that 10.3% of people had died after PCI and 7.4% after CABG.

But this presentation was not given much prominence at the conference, which Dr. Stone organized, and occurred during a didactic session in a small room rather than on one of the main stages where the 3-year data from EXCEL were announced with much fanfare. The presentation also took place 3 weeks after the European guidelines were published.

Surgeons withdraw support

After the BBC report last year that the universal definition of MI data had been collected but not published in the 3-year follow-up manuscript, and showed more MI in the PCI group than the protocol definition, the EACTS withdrew its support for the guidelines. The ESC continued to uphold the guidelines «until there is robust scientific evidence (as opposed to allegations) indicating we should do otherwise,” said Ms. Casadei.

A spokesperson for NEJM said the journal stood by the EXCEL papers because “there is no credible harm to patients from the publication of the paper and accurate reporting of trial results.” NEJM has since conducted a review and published a series of letters in response. The letters have reinvigorated rather than appeased the dissenters, as reported by Medscape.

A number of cardiologists and researchers started a petition on change.org to revise the EACTS/ESC left main CAD guidelines, and surgical societies across the globe have written to the editor of NEJM asking him to retract or amend the EXCEL papers.

This has not happened. The journal’s editor maintains that the letters containing the analyses are “sufficient information” to allow readers and guideline authors to “evaluate the trial findings.”

Dr. Taggart was dismissive of that response. “There is still no recognition or acknowledgment that failure to publish these data in 2016 ‘misled’ the guideline writers for the ESC/EACTS guidelines, and there is still no formal correction of the 2016 and 2019 NEJM manuscripts.”

Over a year after the BBC received the leaked data, the EXCEL investigators published an analysis of the primary outcome using the universal definition of MI data in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

It shows 141 events in the PCI arm, compared with 102 in the CABG arm. The investigators acknowledge that the rates of procedural MI differ depending on the definition used. According to their analysis, the protocol definition was predictive of mortality after both treatments, whereas the universal definition of procedural MI was predictive of mortality only after CABG. Not everyone agrees with this interpretation, and an accompanying editorial questioned these conclusions.

For Dr. Wallentin, it’s a relief that these data are in the public domain so that their interpretation and clinical consequences can be “openly discussed.” He hoped that the whole experience will result in something constructive and useful for the future.

As for the guidelines, the tide may be turning.

In a joint statement with EACTS on Oct. 6, 2020, the ESC agreed to review its guidelines for left main disease in the light of emerging, longer-term outcome data from the trials of CABG versus PCI.

Dr. Taggart has no regrets about speaking out despite this being “an exceedingly painful and bruising experience.”

The saga, he said, “reflects very badly on our specialty, the investigators, industry, and the world’s ‘leading’ medical journal.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” The choice of the secretary general of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery to open with this quote was the first hint that the next presentation at the 2019 annual meeting would be anything but dull. The session chair followed with a reminder to keep the discussion polite and civil.

Presenter David Taggart, MD, PhD, did not disappoint. The professor of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Oxford (England) began with the announcement that he had withdrawn his name from a recent paper in the New England Journal of Medicine. He then proceeded to accuse his coinvestigators of misrepresenting the findings of a major clinical trial.

Dr. Taggart was chair of the surgical committee for the Abbott-sponsored EXCEL trial, which compared two procedures for patients who had blockages in their left main coronary artery: percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using coronary stents, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG). The investigators designed the trial to compare outcomes for the two treatments using a composite endpoint of death, stroke, and MI. The 3-year follow-up data had been published in NEJM without controversy – or, at least, without public controversy.

But when it came time to publish the 5-year follow-up, there was a significantly higher rate of death in the stent group, and both Dr. Taggart and the journal editors were concerned that this finding was being downplayed in the manuscript.

In their comments to the authors, the journal editors had recommended including the mortality difference (unless clearly trivial) ‘”in the concluding statement in the final paragraph.” Yet, the concluding statement of the published paper read that there “was no significant difference between PCI and CABG.”

In Dr. Taggart’s view, that claim was dangerous for patients, and so he was left with no choice but to remove himself as an author, a first for the academic with over 300 scientific papers to his name.

Earlier publications from the EXCEL trial had influenced European treatment guidelines. But subsequent allegations of misconduct and hidden data spurred the EACTS to repudiate those guidelines out of concern “that some results in the EXCEL trial appear to have been concealed and that some patients may therefore have received the wrong clinical advice.”

The controversy pitted cardiothoracic surgeons against interventional cardiologists, who were seen as increasingly encroaching on the surgeons’ turf. Dr. Taggart was a long-time critic of the subspecialty.

Surgeons demanded an independent analysis of the EXCEL trial data – a demand that the investigators have yet to satisfy. Dr. Taggart was the first to speak publicly, but others had major reservations about the trial reporting and conduct years earlier.

Mortality data held back

One such person was Lars Wallentin, MD, a professor of cardiology at Uppsala (Sweden) University Hospital, who chaired the independent committee that monitored the safety and scientific validity of the EXCEL trial.

The committee, known as the data and safety monitoring board (DSMB), received a report on March 23, 2016, that showed that increasingly more patients who had received stents were dying, compared with the group of patients that had undergone CABG. A graph of the survival curves showed the gap between the two groups widening after 3 years (Figure 1).

By September of that year, Dr. Wallentin and other members of the DSMB were anxious to share the concerning mortality difference with the broader medical community.

They were aware that EACTS and the European Society of Cardiology had started the process of updating their guidelines on myocardial revascularization, and were keen for the guideline writing committee to see all of the data.