User login

Adherence to ADHD meds may lower unemployment risk

Investigators analyzed data for almost 13,000 working-age adults with ADHD and found ADHD medication use during the previous 2 years was associated with a 10% lower risk for long-term unemployment in the following year.

In addition, among the female participants, longer treatment duration was associated with a lower risk for subsequent long-term unemployment. In both genders, within-individual comparisons showed long-term unemployment was lower during periods of ADHD medication treatment, compared with nontreatment periods.

“This evidence should be considered together with the existing knowledge of risks and benefits of ADHD medications when developing treatment plans for working-aged adults,” lead author Lin Li, MSc, a doctoral candidate at the School of Medical Science, Örebro University, Sweden, told this news organization.

“However, the effect size is relatively small in magnitude, indicating that other treatment programs, such as psychotherapy, are also needed to help individuals with ADHD in work-related settings,” Ms. Li said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Evidence gap

Adults with ADHD “have occupational impairments, such as poor work performance, less job stability, financial problems, and increased risk for unemployment,” the investigators write.

However, “less is known about the extent to which pharmacological treatment of ADHD is associated with reductions in unemployment rates,” they add.

“People with ADHD have been reported to have problems in work-related performance,” Ms. Li noted. “ADHD medications could reduce ADHD symptoms and also help with academic achievement, but there is limited evidence on the association between ADHD medication and occupational outcomes.”

To address this gap in evidence, the researchers turned to several major Swedish registries to identify 25,358 individuals with ADHD born between 1958 and 1978 who were aged 30 to 55 years during the study period of Jan. 1, 2008, through Dec. 31, 2013).

Of these, 12,875 (41.5% women; mean age, 37.9 years) were included in the analysis. Most participants (81.19%) had more than 9 years of education.

The registers provided information not only about diagnosis, but also about prescription medications these individuals took for ADHD, including methylphenidate, amphetamine, dexamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, and atomoxetine.

Administrative records provided data about yearly accumulated unemployment days, with long-term unemployment defined as having at least 90 days of unemployment in a calendar year.

Covariates included age at baseline, sex, country of birth, highest educational level, crime records, and psychiatric comorbidities.

Most patients (69.34%) had at least one psychiatric comorbidity, with depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders being the most common (in 40.28%, 35.27%, and 28.77%, respectively).

Symptom reduction

The mean length of medication use was 49 days (range, 0-366 days) per year. Of participants in whom these data were available, 31.29% of women and 31.03% of men never used ADHD medications. Among participants treated with ADHD medication (68.71%), only 3.23% of the women and 3.46% of the men had persistent use during the follow-up period.

Among women and men in whom these data were available, (38.85% of the total sample), 35.70% and 41.08%, respectively, were recorded as having one or more long-term unemployment stretches across the study period. In addition, 0.15% and 0.4%, respectively, had long-term unemployment during each of those years.

Use of ADHD medications during the previous 2 years was associated with a 10% lower risk for long-term unemployment in the following year (adjusted relative risk, 0.90; 95% confidence interval, 0.87-0.95).

The researchers also found an association between use of ADHD medications and long-term unemployment among women (RR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.76-0.89) but not among men (RR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.91-1.01).

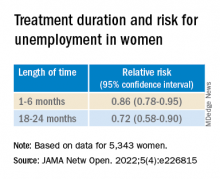

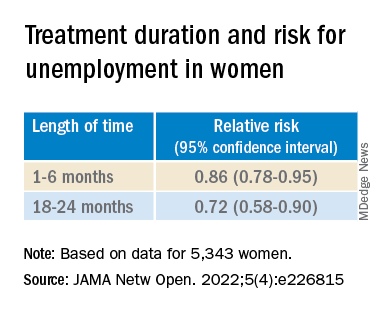

Among women in particular, longer treatment duration was associated with a lower risk of subsequent long-term unemployment (P < .001 for trend).

Within-individual comparisons showed the long-term unemployment rate was lower during periods when individuals were being treated with ADHD medication vs. periods of nontreatment (RR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.85-0.94).

“Among 12,875 working-aged adults with ADHD in Sweden, we found the use of ADHD medication is associated with a lower risk of long-term unemployment, especially for women,” Ms. Li said.

“The hypothesis of this study is that ADHD medications are effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, which may in turn help to improve work performance among individuals with ADHD,” she added.

However, Ms. Li cautioned, “the information on ADHD symptoms is not available in Swedish National Registers, so more research is needed to test the hypothesis.”

The investigators also suggest that future research “should further explore the effectiveness of stimulant and nonstimulant ADHD medications” and replicate their findings in other settings.

Findings ‘make sense’

Commenting on the study, Ari Tuckman PsyD, expert spokesman for Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, said, there is “a lot to like about this study, specifically the large sample size and within-individual comparisons that the Scandinavians’ databases allow.”

“We know that ADHD can impact both finding and keeping a job, so it absolutely makes sense that medication use would reduce duration of unemployment,” said Dr. Tuckman, who is in private practice in West Chester, Pa., and was not involved with the research.

However, “I would venture that the results would have been more robust if the authors had been able to only look at those on optimized medication regimens, which is far too few,” he added. “This lack of optimization would have been even more true 10 years ago, which is when the data was from.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Swedish Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare, an award from the Swedish Research Council, and a grant from Shire International GmbH, a member of the Takeda group of companies. Ms. Li and Dr. Tuckman have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original paper.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed data for almost 13,000 working-age adults with ADHD and found ADHD medication use during the previous 2 years was associated with a 10% lower risk for long-term unemployment in the following year.

In addition, among the female participants, longer treatment duration was associated with a lower risk for subsequent long-term unemployment. In both genders, within-individual comparisons showed long-term unemployment was lower during periods of ADHD medication treatment, compared with nontreatment periods.

“This evidence should be considered together with the existing knowledge of risks and benefits of ADHD medications when developing treatment plans for working-aged adults,” lead author Lin Li, MSc, a doctoral candidate at the School of Medical Science, Örebro University, Sweden, told this news organization.

“However, the effect size is relatively small in magnitude, indicating that other treatment programs, such as psychotherapy, are also needed to help individuals with ADHD in work-related settings,” Ms. Li said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Evidence gap

Adults with ADHD “have occupational impairments, such as poor work performance, less job stability, financial problems, and increased risk for unemployment,” the investigators write.

However, “less is known about the extent to which pharmacological treatment of ADHD is associated with reductions in unemployment rates,” they add.

“People with ADHD have been reported to have problems in work-related performance,” Ms. Li noted. “ADHD medications could reduce ADHD symptoms and also help with academic achievement, but there is limited evidence on the association between ADHD medication and occupational outcomes.”

To address this gap in evidence, the researchers turned to several major Swedish registries to identify 25,358 individuals with ADHD born between 1958 and 1978 who were aged 30 to 55 years during the study period of Jan. 1, 2008, through Dec. 31, 2013).

Of these, 12,875 (41.5% women; mean age, 37.9 years) were included in the analysis. Most participants (81.19%) had more than 9 years of education.

The registers provided information not only about diagnosis, but also about prescription medications these individuals took for ADHD, including methylphenidate, amphetamine, dexamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, and atomoxetine.

Administrative records provided data about yearly accumulated unemployment days, with long-term unemployment defined as having at least 90 days of unemployment in a calendar year.

Covariates included age at baseline, sex, country of birth, highest educational level, crime records, and psychiatric comorbidities.

Most patients (69.34%) had at least one psychiatric comorbidity, with depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders being the most common (in 40.28%, 35.27%, and 28.77%, respectively).

Symptom reduction

The mean length of medication use was 49 days (range, 0-366 days) per year. Of participants in whom these data were available, 31.29% of women and 31.03% of men never used ADHD medications. Among participants treated with ADHD medication (68.71%), only 3.23% of the women and 3.46% of the men had persistent use during the follow-up period.

Among women and men in whom these data were available, (38.85% of the total sample), 35.70% and 41.08%, respectively, were recorded as having one or more long-term unemployment stretches across the study period. In addition, 0.15% and 0.4%, respectively, had long-term unemployment during each of those years.

Use of ADHD medications during the previous 2 years was associated with a 10% lower risk for long-term unemployment in the following year (adjusted relative risk, 0.90; 95% confidence interval, 0.87-0.95).

The researchers also found an association between use of ADHD medications and long-term unemployment among women (RR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.76-0.89) but not among men (RR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.91-1.01).

Among women in particular, longer treatment duration was associated with a lower risk of subsequent long-term unemployment (P < .001 for trend).

Within-individual comparisons showed the long-term unemployment rate was lower during periods when individuals were being treated with ADHD medication vs. periods of nontreatment (RR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.85-0.94).

“Among 12,875 working-aged adults with ADHD in Sweden, we found the use of ADHD medication is associated with a lower risk of long-term unemployment, especially for women,” Ms. Li said.

“The hypothesis of this study is that ADHD medications are effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, which may in turn help to improve work performance among individuals with ADHD,” she added.

However, Ms. Li cautioned, “the information on ADHD symptoms is not available in Swedish National Registers, so more research is needed to test the hypothesis.”

The investigators also suggest that future research “should further explore the effectiveness of stimulant and nonstimulant ADHD medications” and replicate their findings in other settings.

Findings ‘make sense’

Commenting on the study, Ari Tuckman PsyD, expert spokesman for Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, said, there is “a lot to like about this study, specifically the large sample size and within-individual comparisons that the Scandinavians’ databases allow.”

“We know that ADHD can impact both finding and keeping a job, so it absolutely makes sense that medication use would reduce duration of unemployment,” said Dr. Tuckman, who is in private practice in West Chester, Pa., and was not involved with the research.

However, “I would venture that the results would have been more robust if the authors had been able to only look at those on optimized medication regimens, which is far too few,” he added. “This lack of optimization would have been even more true 10 years ago, which is when the data was from.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Swedish Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare, an award from the Swedish Research Council, and a grant from Shire International GmbH, a member of the Takeda group of companies. Ms. Li and Dr. Tuckman have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original paper.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed data for almost 13,000 working-age adults with ADHD and found ADHD medication use during the previous 2 years was associated with a 10% lower risk for long-term unemployment in the following year.

In addition, among the female participants, longer treatment duration was associated with a lower risk for subsequent long-term unemployment. In both genders, within-individual comparisons showed long-term unemployment was lower during periods of ADHD medication treatment, compared with nontreatment periods.

“This evidence should be considered together with the existing knowledge of risks and benefits of ADHD medications when developing treatment plans for working-aged adults,” lead author Lin Li, MSc, a doctoral candidate at the School of Medical Science, Örebro University, Sweden, told this news organization.

“However, the effect size is relatively small in magnitude, indicating that other treatment programs, such as psychotherapy, are also needed to help individuals with ADHD in work-related settings,” Ms. Li said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Evidence gap

Adults with ADHD “have occupational impairments, such as poor work performance, less job stability, financial problems, and increased risk for unemployment,” the investigators write.

However, “less is known about the extent to which pharmacological treatment of ADHD is associated with reductions in unemployment rates,” they add.

“People with ADHD have been reported to have problems in work-related performance,” Ms. Li noted. “ADHD medications could reduce ADHD symptoms and also help with academic achievement, but there is limited evidence on the association between ADHD medication and occupational outcomes.”

To address this gap in evidence, the researchers turned to several major Swedish registries to identify 25,358 individuals with ADHD born between 1958 and 1978 who were aged 30 to 55 years during the study period of Jan. 1, 2008, through Dec. 31, 2013).

Of these, 12,875 (41.5% women; mean age, 37.9 years) were included in the analysis. Most participants (81.19%) had more than 9 years of education.

The registers provided information not only about diagnosis, but also about prescription medications these individuals took for ADHD, including methylphenidate, amphetamine, dexamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, and atomoxetine.

Administrative records provided data about yearly accumulated unemployment days, with long-term unemployment defined as having at least 90 days of unemployment in a calendar year.

Covariates included age at baseline, sex, country of birth, highest educational level, crime records, and psychiatric comorbidities.

Most patients (69.34%) had at least one psychiatric comorbidity, with depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders being the most common (in 40.28%, 35.27%, and 28.77%, respectively).

Symptom reduction

The mean length of medication use was 49 days (range, 0-366 days) per year. Of participants in whom these data were available, 31.29% of women and 31.03% of men never used ADHD medications. Among participants treated with ADHD medication (68.71%), only 3.23% of the women and 3.46% of the men had persistent use during the follow-up period.

Among women and men in whom these data were available, (38.85% of the total sample), 35.70% and 41.08%, respectively, were recorded as having one or more long-term unemployment stretches across the study period. In addition, 0.15% and 0.4%, respectively, had long-term unemployment during each of those years.

Use of ADHD medications during the previous 2 years was associated with a 10% lower risk for long-term unemployment in the following year (adjusted relative risk, 0.90; 95% confidence interval, 0.87-0.95).

The researchers also found an association between use of ADHD medications and long-term unemployment among women (RR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.76-0.89) but not among men (RR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.91-1.01).

Among women in particular, longer treatment duration was associated with a lower risk of subsequent long-term unemployment (P < .001 for trend).

Within-individual comparisons showed the long-term unemployment rate was lower during periods when individuals were being treated with ADHD medication vs. periods of nontreatment (RR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.85-0.94).

“Among 12,875 working-aged adults with ADHD in Sweden, we found the use of ADHD medication is associated with a lower risk of long-term unemployment, especially for women,” Ms. Li said.

“The hypothesis of this study is that ADHD medications are effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, which may in turn help to improve work performance among individuals with ADHD,” she added.

However, Ms. Li cautioned, “the information on ADHD symptoms is not available in Swedish National Registers, so more research is needed to test the hypothesis.”

The investigators also suggest that future research “should further explore the effectiveness of stimulant and nonstimulant ADHD medications” and replicate their findings in other settings.

Findings ‘make sense’

Commenting on the study, Ari Tuckman PsyD, expert spokesman for Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, said, there is “a lot to like about this study, specifically the large sample size and within-individual comparisons that the Scandinavians’ databases allow.”

“We know that ADHD can impact both finding and keeping a job, so it absolutely makes sense that medication use would reduce duration of unemployment,” said Dr. Tuckman, who is in private practice in West Chester, Pa., and was not involved with the research.

However, “I would venture that the results would have been more robust if the authors had been able to only look at those on optimized medication regimens, which is far too few,” he added. “This lack of optimization would have been even more true 10 years ago, which is when the data was from.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Swedish Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare, an award from the Swedish Research Council, and a grant from Shire International GmbH, a member of the Takeda group of companies. Ms. Li and Dr. Tuckman have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original paper.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Metacognitive training an effective, durable treatment for schizophrenia

Metacognitive training (MCT) is effective in reducing positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, new research suggests.

MCT for psychosis is a brief intervention that “combines psychoeducation, cognitive bias modification, and strategy teaching but does not directly target psychosis symptoms.”

Additionally, MCT led to improvement in self-esteem and functioning, and all benefits were maintained up to 1 year post intervention.

“Our study demonstrates the effectiveness and durability of a brief, nonconfrontational intervention in the reduction of serious and debilitating symptoms of schizophrenia,” study investigator Danielle Penney, a doctoral candidate at the University of Montreal, told this news organization.

“Our results were observed in several treatment contexts and suggest that MCT can be successfully delivered by a variety of mental health practitioners [and] provide solid evidence to consider MCT in international treatment guidelines for schizophrenia spectrum disorders,” Ms. Penney said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Novel contribution’

MCT is a brief intervention consisting of eight to 16 modules that can be delivered in a group setting or on an individual basis. Instead of directly targeting psychotic symptoms, it uses an “indirect approach by promoting awareness of cognitive biases,” the investigators note.

Such biases include maladaptive thinking styles common to psychosis, such as jumping to conclusions, belief inflexibility, and overconfidence in judgments.

It is hypothesized that these biases “contribute to the formation and maintenance of positive symptoms, particularly delusions,” the researchers write.

MCT “aims to plant doubt in delusional beliefs through raising awareness of cognitive biases and aims to raise service engagement by proposing work on this less-confrontational objective first, which is likely to facilitate the therapeutic alliance and more direct work on psychotic symptoms,” they add.

Previous studies of MCT for psychosis yielded inconsistent results. Of the eight previous meta-analyses that analyzed MCT for psychosis, “none investigated the long-term effects of the intervention on directly targeted treatment outcomes,” such as delusions and cognitive biases, Ms. Penney said.

She added that “to our knowledge, no meta-analysis has examined the effectiveness of important indirectly targeted outcomes,” including self-esteem and functioning.

“These important gaps in the literature,” along with a large increase in recently conducted MCT efficacy trials, “provided the motivation for the current study,” said Ms. Penney.

To investigate, the researchers searched 11 databases, beginning with data from 2007, which was when the first report of MCT was published. Studies included participants with schizophrenia spectrum and related psychotic disorders.

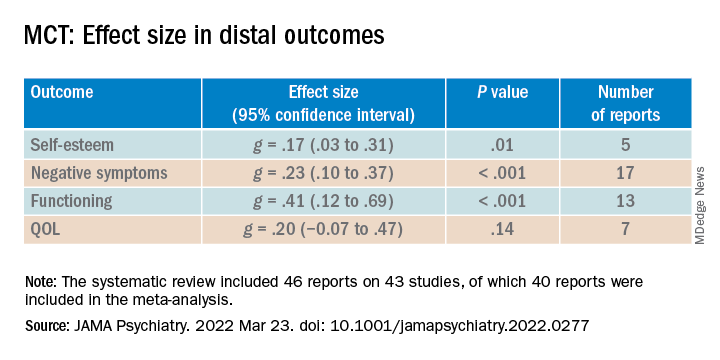

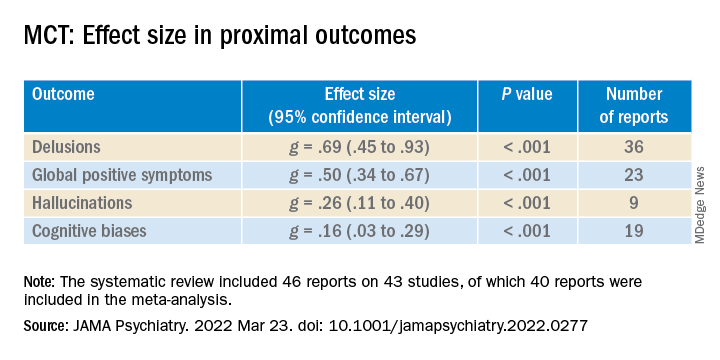

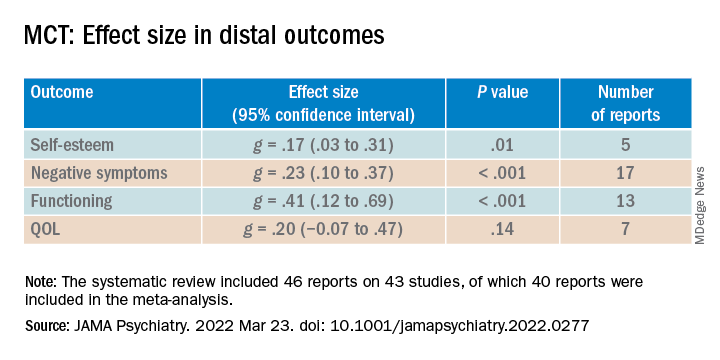

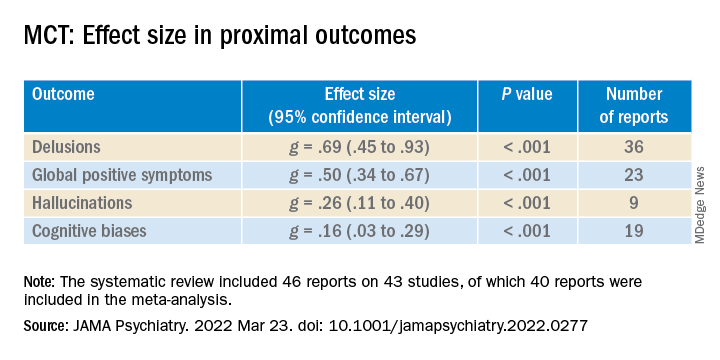

Outcomes for the current review and meta-analysis were organized according to a “proximal-distal framework.” Proximal outcomes were those directly targeted by MCT, while distal outcomes were those not directly targeted by MCT but that were associated with improvement in proximal outcomes, either directly or indirectly.

The investigators examined these outcomes quantitatively and qualitatively from preintervention to postintervention and follow-up, “which, to our knowledge, is a novel contribution,” they write.

The review included 43 studies, of which 30 (70%) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 11 (25%) were non-RCTs, and two (5%) were quantitative descriptive studies. Of these, 40 reports (n = 1,816 participants) were included in the meta-analysis, and six were included in the narrative review.

Transdiagnostic treatment?

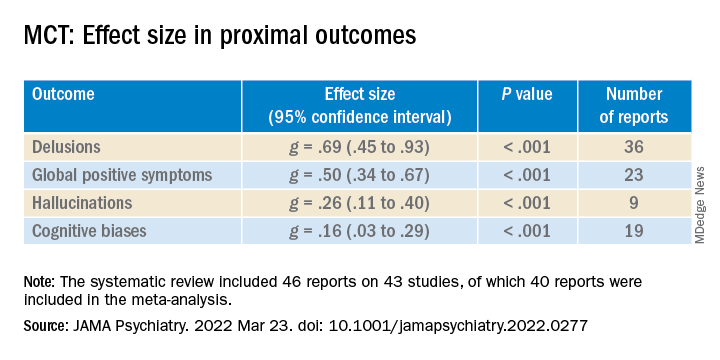

Results showed a “small to moderate” effect size (ES) in global proximal outcomes (g = .39; 95% confidence interval, .25-.53; P < .001; 38 reports).

When proximal outcomes were analyzed separately, the largest ES was found for delusions; smaller ES values were found for hallucinations and cognitive biases.

Newer studies reported higher ES values for hallucinations, compared with older studies (β = .04; 95% CI, .00-.07).

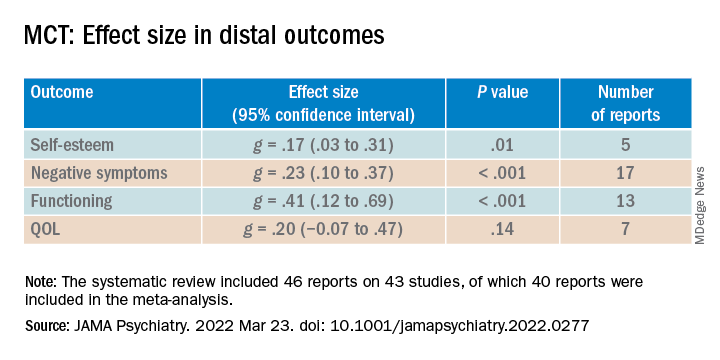

ES was small to moderate for distal outcomes (g = .31; 95% CI, .19-.44; P < .001; 26 reports). “Small but significant” ES values were shown for self-esteem and negative symptoms, small to moderate for functioning, and small but nonsignificant for quality of life (QOL).

The researchers also analyzed RCTs by comparing differences between the treatment and control groups in scores from follow-up to post-treatment. Although the therapeutic gains made by the experimental group were “steadily maintained, the ES values were “small” and nonsignificant.

When the difference in scores between follow-up and baseline were compared in both groups, small to moderate ES values were found for proximal as well as distal outcomes.

“These results further indicate that net therapeutic gains remain significant even 1 year following MCT,” the investigators note.

Lower-quality studies showed significantly lower ES values for distal (between-group comparison, P = .05) but not proximal outcomes.

Overall, the findings suggest that MCT is a “beneficial and durable low-threshold intervention that can be flexibly delivered at minimal cost in a variety of contexts to individuals with psychotic disorders,” the researchers write.

They note that MCT has also been associated with positive outcomes in other patient populations, including patients with borderline personality disorder, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Future research “might consider investigating MCT as a transdiagnostic treatment,” they add.

Consistent beneficial effects

Commenting on the study, Philip Harvey, PhD, Leonard M. Miller Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and director of the Division of Psychology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, noted that self-awareness and self-assessment are critically important features in patients with serious mental illness.

Impairments in these areas “can actually have a greater impact on everyday functioning than cognitive deficits,” said Dr. Harvey, who is also the editor-in-chief of Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. He was not involved with the current meta-analysis.

He noted that the current results show that “MCT has consistent beneficial effects.”

“This is an intervention that should be considered for most people with serious mental illness, with a specific focus on those with specific types of delusions and more global challenges in self-assessment,” Dr. Harvey concluded.

Funding was provided by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded through the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University. Ms. Penney reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other investigators are listed in the original article. Dr. Harvey reported being a reviewer of the article but that he was not involved in its authorship.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Metacognitive training (MCT) is effective in reducing positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, new research suggests.

MCT for psychosis is a brief intervention that “combines psychoeducation, cognitive bias modification, and strategy teaching but does not directly target psychosis symptoms.”

Additionally, MCT led to improvement in self-esteem and functioning, and all benefits were maintained up to 1 year post intervention.

“Our study demonstrates the effectiveness and durability of a brief, nonconfrontational intervention in the reduction of serious and debilitating symptoms of schizophrenia,” study investigator Danielle Penney, a doctoral candidate at the University of Montreal, told this news organization.

“Our results were observed in several treatment contexts and suggest that MCT can be successfully delivered by a variety of mental health practitioners [and] provide solid evidence to consider MCT in international treatment guidelines for schizophrenia spectrum disorders,” Ms. Penney said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Novel contribution’

MCT is a brief intervention consisting of eight to 16 modules that can be delivered in a group setting or on an individual basis. Instead of directly targeting psychotic symptoms, it uses an “indirect approach by promoting awareness of cognitive biases,” the investigators note.

Such biases include maladaptive thinking styles common to psychosis, such as jumping to conclusions, belief inflexibility, and overconfidence in judgments.

It is hypothesized that these biases “contribute to the formation and maintenance of positive symptoms, particularly delusions,” the researchers write.

MCT “aims to plant doubt in delusional beliefs through raising awareness of cognitive biases and aims to raise service engagement by proposing work on this less-confrontational objective first, which is likely to facilitate the therapeutic alliance and more direct work on psychotic symptoms,” they add.

Previous studies of MCT for psychosis yielded inconsistent results. Of the eight previous meta-analyses that analyzed MCT for psychosis, “none investigated the long-term effects of the intervention on directly targeted treatment outcomes,” such as delusions and cognitive biases, Ms. Penney said.

She added that “to our knowledge, no meta-analysis has examined the effectiveness of important indirectly targeted outcomes,” including self-esteem and functioning.

“These important gaps in the literature,” along with a large increase in recently conducted MCT efficacy trials, “provided the motivation for the current study,” said Ms. Penney.

To investigate, the researchers searched 11 databases, beginning with data from 2007, which was when the first report of MCT was published. Studies included participants with schizophrenia spectrum and related psychotic disorders.

Outcomes for the current review and meta-analysis were organized according to a “proximal-distal framework.” Proximal outcomes were those directly targeted by MCT, while distal outcomes were those not directly targeted by MCT but that were associated with improvement in proximal outcomes, either directly or indirectly.

The investigators examined these outcomes quantitatively and qualitatively from preintervention to postintervention and follow-up, “which, to our knowledge, is a novel contribution,” they write.

The review included 43 studies, of which 30 (70%) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 11 (25%) were non-RCTs, and two (5%) were quantitative descriptive studies. Of these, 40 reports (n = 1,816 participants) were included in the meta-analysis, and six were included in the narrative review.

Transdiagnostic treatment?

Results showed a “small to moderate” effect size (ES) in global proximal outcomes (g = .39; 95% confidence interval, .25-.53; P < .001; 38 reports).

When proximal outcomes were analyzed separately, the largest ES was found for delusions; smaller ES values were found for hallucinations and cognitive biases.

Newer studies reported higher ES values for hallucinations, compared with older studies (β = .04; 95% CI, .00-.07).

ES was small to moderate for distal outcomes (g = .31; 95% CI, .19-.44; P < .001; 26 reports). “Small but significant” ES values were shown for self-esteem and negative symptoms, small to moderate for functioning, and small but nonsignificant for quality of life (QOL).

The researchers also analyzed RCTs by comparing differences between the treatment and control groups in scores from follow-up to post-treatment. Although the therapeutic gains made by the experimental group were “steadily maintained, the ES values were “small” and nonsignificant.

When the difference in scores between follow-up and baseline were compared in both groups, small to moderate ES values were found for proximal as well as distal outcomes.

“These results further indicate that net therapeutic gains remain significant even 1 year following MCT,” the investigators note.

Lower-quality studies showed significantly lower ES values for distal (between-group comparison, P = .05) but not proximal outcomes.

Overall, the findings suggest that MCT is a “beneficial and durable low-threshold intervention that can be flexibly delivered at minimal cost in a variety of contexts to individuals with psychotic disorders,” the researchers write.

They note that MCT has also been associated with positive outcomes in other patient populations, including patients with borderline personality disorder, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Future research “might consider investigating MCT as a transdiagnostic treatment,” they add.

Consistent beneficial effects

Commenting on the study, Philip Harvey, PhD, Leonard M. Miller Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and director of the Division of Psychology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, noted that self-awareness and self-assessment are critically important features in patients with serious mental illness.

Impairments in these areas “can actually have a greater impact on everyday functioning than cognitive deficits,” said Dr. Harvey, who is also the editor-in-chief of Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. He was not involved with the current meta-analysis.

He noted that the current results show that “MCT has consistent beneficial effects.”

“This is an intervention that should be considered for most people with serious mental illness, with a specific focus on those with specific types of delusions and more global challenges in self-assessment,” Dr. Harvey concluded.

Funding was provided by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded through the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University. Ms. Penney reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other investigators are listed in the original article. Dr. Harvey reported being a reviewer of the article but that he was not involved in its authorship.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Metacognitive training (MCT) is effective in reducing positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, new research suggests.

MCT for psychosis is a brief intervention that “combines psychoeducation, cognitive bias modification, and strategy teaching but does not directly target psychosis symptoms.”

Additionally, MCT led to improvement in self-esteem and functioning, and all benefits were maintained up to 1 year post intervention.

“Our study demonstrates the effectiveness and durability of a brief, nonconfrontational intervention in the reduction of serious and debilitating symptoms of schizophrenia,” study investigator Danielle Penney, a doctoral candidate at the University of Montreal, told this news organization.

“Our results were observed in several treatment contexts and suggest that MCT can be successfully delivered by a variety of mental health practitioners [and] provide solid evidence to consider MCT in international treatment guidelines for schizophrenia spectrum disorders,” Ms. Penney said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Novel contribution’

MCT is a brief intervention consisting of eight to 16 modules that can be delivered in a group setting or on an individual basis. Instead of directly targeting psychotic symptoms, it uses an “indirect approach by promoting awareness of cognitive biases,” the investigators note.

Such biases include maladaptive thinking styles common to psychosis, such as jumping to conclusions, belief inflexibility, and overconfidence in judgments.

It is hypothesized that these biases “contribute to the formation and maintenance of positive symptoms, particularly delusions,” the researchers write.

MCT “aims to plant doubt in delusional beliefs through raising awareness of cognitive biases and aims to raise service engagement by proposing work on this less-confrontational objective first, which is likely to facilitate the therapeutic alliance and more direct work on psychotic symptoms,” they add.

Previous studies of MCT for psychosis yielded inconsistent results. Of the eight previous meta-analyses that analyzed MCT for psychosis, “none investigated the long-term effects of the intervention on directly targeted treatment outcomes,” such as delusions and cognitive biases, Ms. Penney said.

She added that “to our knowledge, no meta-analysis has examined the effectiveness of important indirectly targeted outcomes,” including self-esteem and functioning.

“These important gaps in the literature,” along with a large increase in recently conducted MCT efficacy trials, “provided the motivation for the current study,” said Ms. Penney.

To investigate, the researchers searched 11 databases, beginning with data from 2007, which was when the first report of MCT was published. Studies included participants with schizophrenia spectrum and related psychotic disorders.

Outcomes for the current review and meta-analysis were organized according to a “proximal-distal framework.” Proximal outcomes were those directly targeted by MCT, while distal outcomes were those not directly targeted by MCT but that were associated with improvement in proximal outcomes, either directly or indirectly.

The investigators examined these outcomes quantitatively and qualitatively from preintervention to postintervention and follow-up, “which, to our knowledge, is a novel contribution,” they write.

The review included 43 studies, of which 30 (70%) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 11 (25%) were non-RCTs, and two (5%) were quantitative descriptive studies. Of these, 40 reports (n = 1,816 participants) were included in the meta-analysis, and six were included in the narrative review.

Transdiagnostic treatment?

Results showed a “small to moderate” effect size (ES) in global proximal outcomes (g = .39; 95% confidence interval, .25-.53; P < .001; 38 reports).

When proximal outcomes were analyzed separately, the largest ES was found for delusions; smaller ES values were found for hallucinations and cognitive biases.

Newer studies reported higher ES values for hallucinations, compared with older studies (β = .04; 95% CI, .00-.07).

ES was small to moderate for distal outcomes (g = .31; 95% CI, .19-.44; P < .001; 26 reports). “Small but significant” ES values were shown for self-esteem and negative symptoms, small to moderate for functioning, and small but nonsignificant for quality of life (QOL).

The researchers also analyzed RCTs by comparing differences between the treatment and control groups in scores from follow-up to post-treatment. Although the therapeutic gains made by the experimental group were “steadily maintained, the ES values were “small” and nonsignificant.

When the difference in scores between follow-up and baseline were compared in both groups, small to moderate ES values were found for proximal as well as distal outcomes.

“These results further indicate that net therapeutic gains remain significant even 1 year following MCT,” the investigators note.

Lower-quality studies showed significantly lower ES values for distal (between-group comparison, P = .05) but not proximal outcomes.

Overall, the findings suggest that MCT is a “beneficial and durable low-threshold intervention that can be flexibly delivered at minimal cost in a variety of contexts to individuals with psychotic disorders,” the researchers write.

They note that MCT has also been associated with positive outcomes in other patient populations, including patients with borderline personality disorder, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Future research “might consider investigating MCT as a transdiagnostic treatment,” they add.

Consistent beneficial effects

Commenting on the study, Philip Harvey, PhD, Leonard M. Miller Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and director of the Division of Psychology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, noted that self-awareness and self-assessment are critically important features in patients with serious mental illness.

Impairments in these areas “can actually have a greater impact on everyday functioning than cognitive deficits,” said Dr. Harvey, who is also the editor-in-chief of Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. He was not involved with the current meta-analysis.

He noted that the current results show that “MCT has consistent beneficial effects.”

“This is an intervention that should be considered for most people with serious mental illness, with a specific focus on those with specific types of delusions and more global challenges in self-assessment,” Dr. Harvey concluded.

Funding was provided by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded through the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University. Ms. Penney reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other investigators are listed in the original article. Dr. Harvey reported being a reviewer of the article but that he was not involved in its authorship.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Even light physical activity linked to lower dementia risk

Older adults who participate in even light physical activity (LPA) may have a lower risk of developing dementia, new research suggests.

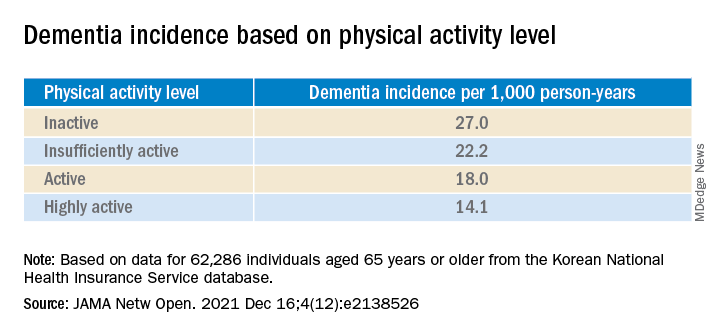

In a retrospective analysis of more than 62,000 individuals aged 65 or older without preexisting dementia, 6% developed dementia.

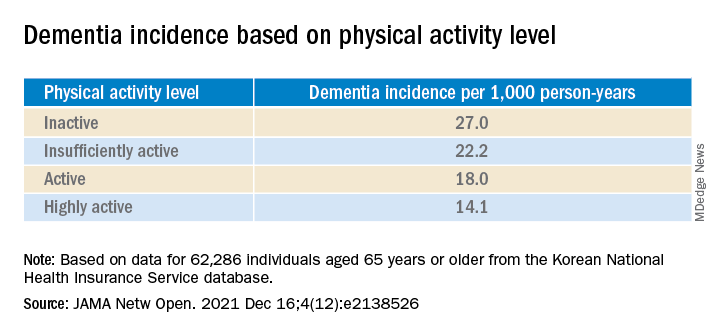

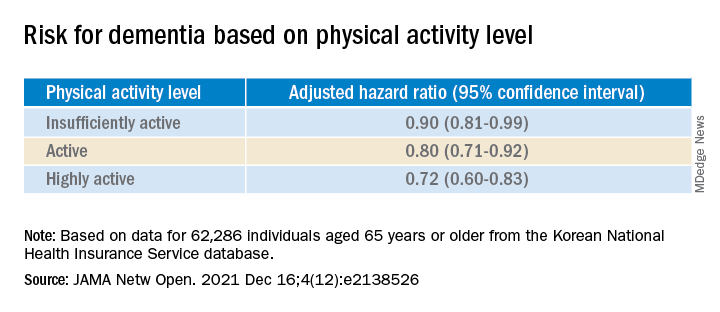

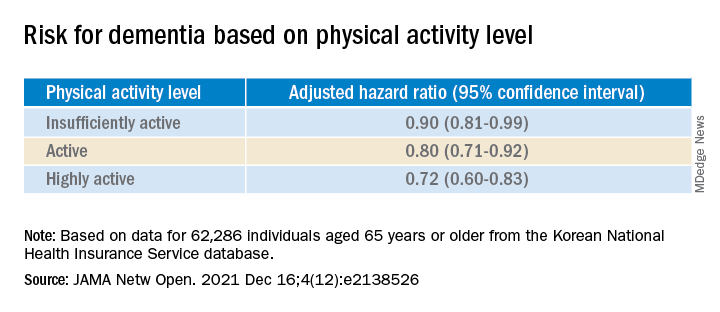

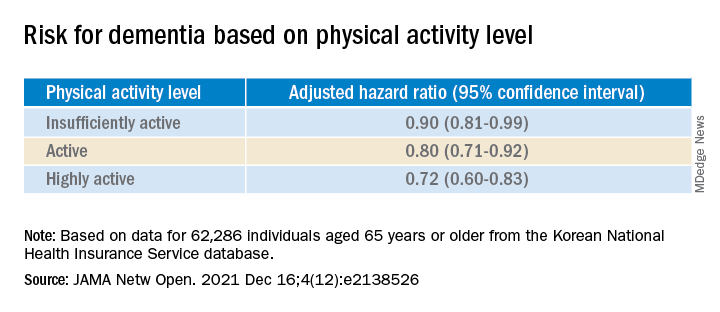

Compared with inactive individuals, “insufficiently active,” “active,” and “highly active” individuals all had a 10%, 20%, and 28% lower risk for dementia, respectively. And this association was consistent regardless of age, sex, other comorbidities, or after the researchers censored for stroke.

Even the lowest amount of LPA was associated with reduced dementia risk, investigators noted.

“In older adults, an increased physical activity level, including a low amount of LPA, was associated with a reduced risk of dementia,” Minjae Yoon, MD, division of cardiology, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues wrote.

“Promotion of LPA might reduce the risk of dementia in older adults,” they added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Reverse causation?

Physical activity has been shown previously to be associated with reduced dementia risk. Current World Health Organization guidelines recommend that adults with normal cognition should engage in PA to reduce their risk for cognitive decline.

However, some studies have not yielded this result, “suggesting that previous findings showing a lower risk of dementia in physically active people could be attributed to reverse causation,” the investigators noted. Additionally, previous research regarding exercise intensity has been “inconsistent” concerning the role of LPA in reducing dementia risk.

Many older adults with frailty and comorbidity cannot perform intense or even moderate PA, therefore “these adults would have to gain the benefits of physical activity from LPA,” the researchers noted.

To clarify the potential association between PA and new-onset dementia, they focused specifically on the “dose-response association” between PA and dementia – especially LPA.

Between 2009 and 2012, the investigators enrolled 62,286 older individuals (60.4% women; mean age, 73.2 years) with available health checkup data from the National Health Insurance Service–Senior Database of Korea. All had no history of dementia.

Leisure-time PA was assessed with self-report questionnaires that used a 7-day recall method and included three questions regarding usual frequency (in days per week):

- Vigorous PA (VPA) for at least 20 minutes

- Moderate-intensity PA (MPA) for at least 30 minutes

- LPA for at least 30 minutes

VPA was defined as “intense exercise that caused severe shortness of breath, MPA was defined as activity causing mild shortness of breath, and LPA was defined as “walking at a slow or leisurely pace.”

PA-related energy expenditure was also calculated in metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes per week by “summing the product of frequency, intensity, and duration,” the investigators noted.

Participants were stratified on the basis of their weekly total PA levels into the following groups:

- Inactive (no LPA beyond basic movements)

- Insufficiently active (less than the recommended target range of 1-499 MET-min/wk)

- Active (meeting the recommended target range of 500-999 MET-min/wk)

- Highly active (exceeding the recommended target range of at least 1,000 MET-min/wk)

Of all participants, 35% were categorized as inactive, 25% were insufficiently active, 24.4% were active, and 15.2% were highly active.

Controversy remains

During the total median follow-up of 42 months, 6% of participants had all-cause dementia. After the researchers excluded the first 2 years, incidence of dementia was 21.6 per 1000 person-years during follow-up.

“The cumulative incidence of dementia was associated with a progressively decreasing trend with increasing physical activity” (P = .001 for trend), the investigators reported.

When using a competing-risk multivariable regression model, they found that higher levels of PA were associated with lower risk for dementia, compared with the inactive group.

Similar findings were obtained after censoring for stroke, and were consistent for all follow-up periods. In subgroup analysis, the association between PA level and dementia risk remained consistent, regardless of age, sex, and comorbidities.

Even a low amount of LPA (1-299 MET-min/wk) was linked to reduced risk for dementia versus total sedentary behavior (adjusted HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74-0.99).

The investigators noted that some “controversy” remains regarding the possibility of reverse causation and, because their study was observational in nature, “it cannot be used to establish causal relationship.”

Nevertheless, the study had important strengths, including the large number of older adults with available data, the assessment of dose-response association between PA and dementia, and the sensitivity analyses they performed, the researchers added.

Piece of important evidence

Commenting on the findings, Takashi Tarumi, PhD, senior research investigator, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Ibaraki, Japan, said previous studies have suggested “an inverse association between physical activity and dementia risk, such that older adults performing a higher dose of exercise may have a greater benefit for reducing the dementia risk.”

Dr. Tarumi, an associate editor at the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, added the current study “significantly extends our knowledge by showing that dementia risk can also be reduced by light physical activities when they are performed for longer hours.”

This provides “another piece of important evidence” to support clinicians recommending regular physical activity for the prevention of dementia in later life, said Dr. Tarumi, who was not involved with the research.

Also commenting, Martin Underwood, MD, Warwick Medical School, Coventry, England, described the association between reduced physical inactivity and dementia as well established – and noted the current study “appears to confirm earlier observational data showing this relationship.”

The current results have “still not been able to fully exclude the possibility of reverse causation,” said Dr. Underwood, who was also not associated with the study.

However, the finding that more physically active individuals are less likely to develop dementia “only becomes of real interest if we can show that increased physical activity prevents the onset, or slows the progression, of dementia,” he noted.

“To my knowledge this has not yet been established” in randomized clinical trials, Dr. Underwood added.

The study was supported by grants from the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea; and by a research grant from Yonsei University. One coauthor reported serving as a speaker for Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Medtronic, and Daiichi-Sankyo, and receiving research funds from Medtronic and Abbott. No other author disclosures were reported. Dr. Tarumi and Dr. Underwood have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Older adults who participate in even light physical activity (LPA) may have a lower risk of developing dementia, new research suggests.

In a retrospective analysis of more than 62,000 individuals aged 65 or older without preexisting dementia, 6% developed dementia.

Compared with inactive individuals, “insufficiently active,” “active,” and “highly active” individuals all had a 10%, 20%, and 28% lower risk for dementia, respectively. And this association was consistent regardless of age, sex, other comorbidities, or after the researchers censored for stroke.

Even the lowest amount of LPA was associated with reduced dementia risk, investigators noted.

“In older adults, an increased physical activity level, including a low amount of LPA, was associated with a reduced risk of dementia,” Minjae Yoon, MD, division of cardiology, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues wrote.

“Promotion of LPA might reduce the risk of dementia in older adults,” they added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Reverse causation?

Physical activity has been shown previously to be associated with reduced dementia risk. Current World Health Organization guidelines recommend that adults with normal cognition should engage in PA to reduce their risk for cognitive decline.

However, some studies have not yielded this result, “suggesting that previous findings showing a lower risk of dementia in physically active people could be attributed to reverse causation,” the investigators noted. Additionally, previous research regarding exercise intensity has been “inconsistent” concerning the role of LPA in reducing dementia risk.

Many older adults with frailty and comorbidity cannot perform intense or even moderate PA, therefore “these adults would have to gain the benefits of physical activity from LPA,” the researchers noted.

To clarify the potential association between PA and new-onset dementia, they focused specifically on the “dose-response association” between PA and dementia – especially LPA.

Between 2009 and 2012, the investigators enrolled 62,286 older individuals (60.4% women; mean age, 73.2 years) with available health checkup data from the National Health Insurance Service–Senior Database of Korea. All had no history of dementia.

Leisure-time PA was assessed with self-report questionnaires that used a 7-day recall method and included three questions regarding usual frequency (in days per week):

- Vigorous PA (VPA) for at least 20 minutes

- Moderate-intensity PA (MPA) for at least 30 minutes

- LPA for at least 30 minutes

VPA was defined as “intense exercise that caused severe shortness of breath, MPA was defined as activity causing mild shortness of breath, and LPA was defined as “walking at a slow or leisurely pace.”

PA-related energy expenditure was also calculated in metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes per week by “summing the product of frequency, intensity, and duration,” the investigators noted.

Participants were stratified on the basis of their weekly total PA levels into the following groups:

- Inactive (no LPA beyond basic movements)

- Insufficiently active (less than the recommended target range of 1-499 MET-min/wk)

- Active (meeting the recommended target range of 500-999 MET-min/wk)

- Highly active (exceeding the recommended target range of at least 1,000 MET-min/wk)

Of all participants, 35% were categorized as inactive, 25% were insufficiently active, 24.4% were active, and 15.2% were highly active.

Controversy remains

During the total median follow-up of 42 months, 6% of participants had all-cause dementia. After the researchers excluded the first 2 years, incidence of dementia was 21.6 per 1000 person-years during follow-up.

“The cumulative incidence of dementia was associated with a progressively decreasing trend with increasing physical activity” (P = .001 for trend), the investigators reported.

When using a competing-risk multivariable regression model, they found that higher levels of PA were associated with lower risk for dementia, compared with the inactive group.

Similar findings were obtained after censoring for stroke, and were consistent for all follow-up periods. In subgroup analysis, the association between PA level and dementia risk remained consistent, regardless of age, sex, and comorbidities.

Even a low amount of LPA (1-299 MET-min/wk) was linked to reduced risk for dementia versus total sedentary behavior (adjusted HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74-0.99).

The investigators noted that some “controversy” remains regarding the possibility of reverse causation and, because their study was observational in nature, “it cannot be used to establish causal relationship.”

Nevertheless, the study had important strengths, including the large number of older adults with available data, the assessment of dose-response association between PA and dementia, and the sensitivity analyses they performed, the researchers added.

Piece of important evidence

Commenting on the findings, Takashi Tarumi, PhD, senior research investigator, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Ibaraki, Japan, said previous studies have suggested “an inverse association between physical activity and dementia risk, such that older adults performing a higher dose of exercise may have a greater benefit for reducing the dementia risk.”

Dr. Tarumi, an associate editor at the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, added the current study “significantly extends our knowledge by showing that dementia risk can also be reduced by light physical activities when they are performed for longer hours.”

This provides “another piece of important evidence” to support clinicians recommending regular physical activity for the prevention of dementia in later life, said Dr. Tarumi, who was not involved with the research.

Also commenting, Martin Underwood, MD, Warwick Medical School, Coventry, England, described the association between reduced physical inactivity and dementia as well established – and noted the current study “appears to confirm earlier observational data showing this relationship.”

The current results have “still not been able to fully exclude the possibility of reverse causation,” said Dr. Underwood, who was also not associated with the study.

However, the finding that more physically active individuals are less likely to develop dementia “only becomes of real interest if we can show that increased physical activity prevents the onset, or slows the progression, of dementia,” he noted.

“To my knowledge this has not yet been established” in randomized clinical trials, Dr. Underwood added.

The study was supported by grants from the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea; and by a research grant from Yonsei University. One coauthor reported serving as a speaker for Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Medtronic, and Daiichi-Sankyo, and receiving research funds from Medtronic and Abbott. No other author disclosures were reported. Dr. Tarumi and Dr. Underwood have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Older adults who participate in even light physical activity (LPA) may have a lower risk of developing dementia, new research suggests.

In a retrospective analysis of more than 62,000 individuals aged 65 or older without preexisting dementia, 6% developed dementia.

Compared with inactive individuals, “insufficiently active,” “active,” and “highly active” individuals all had a 10%, 20%, and 28% lower risk for dementia, respectively. And this association was consistent regardless of age, sex, other comorbidities, or after the researchers censored for stroke.

Even the lowest amount of LPA was associated with reduced dementia risk, investigators noted.

“In older adults, an increased physical activity level, including a low amount of LPA, was associated with a reduced risk of dementia,” Minjae Yoon, MD, division of cardiology, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues wrote.

“Promotion of LPA might reduce the risk of dementia in older adults,” they added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Reverse causation?

Physical activity has been shown previously to be associated with reduced dementia risk. Current World Health Organization guidelines recommend that adults with normal cognition should engage in PA to reduce their risk for cognitive decline.

However, some studies have not yielded this result, “suggesting that previous findings showing a lower risk of dementia in physically active people could be attributed to reverse causation,” the investigators noted. Additionally, previous research regarding exercise intensity has been “inconsistent” concerning the role of LPA in reducing dementia risk.

Many older adults with frailty and comorbidity cannot perform intense or even moderate PA, therefore “these adults would have to gain the benefits of physical activity from LPA,” the researchers noted.

To clarify the potential association between PA and new-onset dementia, they focused specifically on the “dose-response association” between PA and dementia – especially LPA.

Between 2009 and 2012, the investigators enrolled 62,286 older individuals (60.4% women; mean age, 73.2 years) with available health checkup data from the National Health Insurance Service–Senior Database of Korea. All had no history of dementia.

Leisure-time PA was assessed with self-report questionnaires that used a 7-day recall method and included three questions regarding usual frequency (in days per week):

- Vigorous PA (VPA) for at least 20 minutes

- Moderate-intensity PA (MPA) for at least 30 minutes

- LPA for at least 30 minutes

VPA was defined as “intense exercise that caused severe shortness of breath, MPA was defined as activity causing mild shortness of breath, and LPA was defined as “walking at a slow or leisurely pace.”

PA-related energy expenditure was also calculated in metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes per week by “summing the product of frequency, intensity, and duration,” the investigators noted.

Participants were stratified on the basis of their weekly total PA levels into the following groups:

- Inactive (no LPA beyond basic movements)

- Insufficiently active (less than the recommended target range of 1-499 MET-min/wk)

- Active (meeting the recommended target range of 500-999 MET-min/wk)

- Highly active (exceeding the recommended target range of at least 1,000 MET-min/wk)

Of all participants, 35% were categorized as inactive, 25% were insufficiently active, 24.4% were active, and 15.2% were highly active.

Controversy remains

During the total median follow-up of 42 months, 6% of participants had all-cause dementia. After the researchers excluded the first 2 years, incidence of dementia was 21.6 per 1000 person-years during follow-up.

“The cumulative incidence of dementia was associated with a progressively decreasing trend with increasing physical activity” (P = .001 for trend), the investigators reported.

When using a competing-risk multivariable regression model, they found that higher levels of PA were associated with lower risk for dementia, compared with the inactive group.

Similar findings were obtained after censoring for stroke, and were consistent for all follow-up periods. In subgroup analysis, the association between PA level and dementia risk remained consistent, regardless of age, sex, and comorbidities.

Even a low amount of LPA (1-299 MET-min/wk) was linked to reduced risk for dementia versus total sedentary behavior (adjusted HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74-0.99).

The investigators noted that some “controversy” remains regarding the possibility of reverse causation and, because their study was observational in nature, “it cannot be used to establish causal relationship.”

Nevertheless, the study had important strengths, including the large number of older adults with available data, the assessment of dose-response association between PA and dementia, and the sensitivity analyses they performed, the researchers added.

Piece of important evidence

Commenting on the findings, Takashi Tarumi, PhD, senior research investigator, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Ibaraki, Japan, said previous studies have suggested “an inverse association between physical activity and dementia risk, such that older adults performing a higher dose of exercise may have a greater benefit for reducing the dementia risk.”

Dr. Tarumi, an associate editor at the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, added the current study “significantly extends our knowledge by showing that dementia risk can also be reduced by light physical activities when they are performed for longer hours.”

This provides “another piece of important evidence” to support clinicians recommending regular physical activity for the prevention of dementia in later life, said Dr. Tarumi, who was not involved with the research.

Also commenting, Martin Underwood, MD, Warwick Medical School, Coventry, England, described the association between reduced physical inactivity and dementia as well established – and noted the current study “appears to confirm earlier observational data showing this relationship.”

The current results have “still not been able to fully exclude the possibility of reverse causation,” said Dr. Underwood, who was also not associated with the study.

However, the finding that more physically active individuals are less likely to develop dementia “only becomes of real interest if we can show that increased physical activity prevents the onset, or slows the progression, of dementia,” he noted.

“To my knowledge this has not yet been established” in randomized clinical trials, Dr. Underwood added.

The study was supported by grants from the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea; and by a research grant from Yonsei University. One coauthor reported serving as a speaker for Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Medtronic, and Daiichi-Sankyo, and receiving research funds from Medtronic and Abbott. No other author disclosures were reported. Dr. Tarumi and Dr. Underwood have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More fatalities in heart transplant patients with COVID-19

COVID-19 infection is associated with a high risk for mortality in heart transplant (HT) recipients, a new case series suggests.

Investigators looked at data on 28 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 who received a HT between March 1, 2020, and April 24, 2020 and found a case-fatality rate of 25%.

“The high case fatality in our case series should alert physicians to the vulnerability of heart transplant recipients during the COVID-19 pandemic,” senior author Nir Uriel, MD, MSc, professor of medicine at Columbia University, New York, said in an interview.

“These patients require extra precautions to prevent the development of infection,” said Dr. Uriel, who is also a cardiologist at New York Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

The study was published online May 13 in JAMA Cardiology.

Similar presentation

HT recipients can have several comorbidities after the procedure, including hypertension, diabetes, cardiac allograft vasculopathy, and ongoing immunosuppression, all of which can place them at risk for infection and adverse outcomes with COVID-19 infection, the authors wrote.

The researchers therefore embarked on a case series looking at 28 HT recipients with COVID-19 infection (median age, 64.0 years; interquartile range, 53.5-70.5; 79% male) to “describe the outcomes of recipients of HT who are chronically immunosuppressed and develop COVID-19 and raise important questions about the role of the immune system in the process.”

The median time from HT to study period was 8.6 (IQR, 4.2-14.5) years. Most patients had numerous comorbidities.

“The presentation of COVID-19 was similar to nontransplant patients with fever, dyspnea, cough, and GI symptoms,” Dr. Uriel reported.

No protective effect

Twenty-two patients (79%) required admission to the hospital, seven of whom (25%) required admission to the ICU and mechanical ventilation.

Despite the presence of immunosuppressive therapy, all patients had significant elevation of inflammatory biomarkers (median peak high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hs-CRP], 11.83 mg/dL; IQR, 7.44-19.26; median peak interleukin [IL]-6, 105 pg/mL; IQR, 38-296).

Three-quarters had myocardial injury, with a median high-sensitivity troponin T of 0.055 (0.0205 - 0.1345) ng/mL.

Treatments of COVID-19 included hydroxychloroquine (18 patients; 78%), high-dose corticosteroids (eight patients; 47%), and IL-6 receptor antagonists (six patients; 26%).

Moreover, during hospitalization, mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued in most (70%) patients, and one-quarter had a reduction in their calcineurin inhibitor dose.

“Heart transplant recipients generally require more intense immunosuppressive therapy than most other solid organ transplant recipients, and this high baseline immunosuppression increases their propensity to develop infections and their likelihood of experiencing severe manifestations of infections,” Dr. Uriel commented.

“With COVID-19, in which the body’s inflammatory reaction appears to play a role in disease severity, there has been a question of whether immunosuppression may offer a protective effect,” he continued.

“This case series suggests that this is not the case, although this would need to be confirmed in larger studies,” he said.

Low threshold

Among the 22 patients who were admitted to the hospital, half were discharged home and four (18%) were still hospitalized at the end of the study.

Of the seven patients who died, two died at the study center, and five died in an outside institution.

“In the HT population, social distancing (or isolation), strict use of masks when in public, proper handwashing, and sanitization of surfaces are of paramount importance in the prevention of COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Uriel stated.

“In addition, we have restricted these patients’ contact with the hospital as much as possible during the pandemic,” he said.

However, “there should be a low threshold to hospitalize heart transplant patients who develop infection with COVID-19. Furthermore, in our series, outcomes were better for patients hospitalized at the transplant center; therefore, strong consideration should be given to transferring HT patients when hospitalized at another hospital,” he added.

The authors emphasized that COVID-19 patients “will require ongoing monitoring in the recovery phase, as an immunosuppression regimen is reintroduced and the consequences to the allograft itself become apparent.”

Vulnerable population

Commenting on the study, Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, MSc, William Harvey Distinguished Chair in Advanced Cardiovascular Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, suggested that “in epidemiological terms, [the findings] might not look as bad as the way they are reflected in the paper.”

Given that Columbia is “one of the larger heart transplant centers in the U.S., following probably 1,000 patients, having only 22 out of perhaps thousands whom they transplanted or are actively following would actually represent a low serious infection rate,” said Dr. Mehra, who is also the executive director of the Center for Advanced Heart Disease at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston.

“We must not forget to emphasize that, when assessing these case fatality rates, we must look at the entire population at risk, not only the handful that we were able to observe,” explained Dr. Mehra, who was not involved with the study.

Moreover, the patients were “older and had comorbidities, with poor underlying kidney function and other complications, and underlying coronary artery disease in the transplanted heart,” so “it would not surprise me that they had such a high fatality rate, since they had a high degree of vulnerability,” he said.

Dr. Mehra, who is also the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, said that the journal has received manuscripts still in the review process that suggest different fatality rates than those found in the current case series.

However, he acknowledged that, because these are patients with serious vulnerability due to underlying heart disease, “you can’t be lackadaisical and need to do everything to decrease this vulnerability.”

The authors noted that, although their study did not show a protective effect from immunosuppression against COVID-19, further studies are needed to assess each individual immunosuppressive agent and provide a definitive answer.

The study was supported by a grant to one of the investigators from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Uriel reports no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the publication. Dr. Mehra reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 infection is associated with a high risk for mortality in heart transplant (HT) recipients, a new case series suggests.

Investigators looked at data on 28 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 who received a HT between March 1, 2020, and April 24, 2020 and found a case-fatality rate of 25%.

“The high case fatality in our case series should alert physicians to the vulnerability of heart transplant recipients during the COVID-19 pandemic,” senior author Nir Uriel, MD, MSc, professor of medicine at Columbia University, New York, said in an interview.

“These patients require extra precautions to prevent the development of infection,” said Dr. Uriel, who is also a cardiologist at New York Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

The study was published online May 13 in JAMA Cardiology.

Similar presentation

HT recipients can have several comorbidities after the procedure, including hypertension, diabetes, cardiac allograft vasculopathy, and ongoing immunosuppression, all of which can place them at risk for infection and adverse outcomes with COVID-19 infection, the authors wrote.

The researchers therefore embarked on a case series looking at 28 HT recipients with COVID-19 infection (median age, 64.0 years; interquartile range, 53.5-70.5; 79% male) to “describe the outcomes of recipients of HT who are chronically immunosuppressed and develop COVID-19 and raise important questions about the role of the immune system in the process.”

The median time from HT to study period was 8.6 (IQR, 4.2-14.5) years. Most patients had numerous comorbidities.

“The presentation of COVID-19 was similar to nontransplant patients with fever, dyspnea, cough, and GI symptoms,” Dr. Uriel reported.

No protective effect

Twenty-two patients (79%) required admission to the hospital, seven of whom (25%) required admission to the ICU and mechanical ventilation.

Despite the presence of immunosuppressive therapy, all patients had significant elevation of inflammatory biomarkers (median peak high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hs-CRP], 11.83 mg/dL; IQR, 7.44-19.26; median peak interleukin [IL]-6, 105 pg/mL; IQR, 38-296).

Three-quarters had myocardial injury, with a median high-sensitivity troponin T of 0.055 (0.0205 - 0.1345) ng/mL.

Treatments of COVID-19 included hydroxychloroquine (18 patients; 78%), high-dose corticosteroids (eight patients; 47%), and IL-6 receptor antagonists (six patients; 26%).

Moreover, during hospitalization, mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued in most (70%) patients, and one-quarter had a reduction in their calcineurin inhibitor dose.

“Heart transplant recipients generally require more intense immunosuppressive therapy than most other solid organ transplant recipients, and this high baseline immunosuppression increases their propensity to develop infections and their likelihood of experiencing severe manifestations of infections,” Dr. Uriel commented.

“With COVID-19, in which the body’s inflammatory reaction appears to play a role in disease severity, there has been a question of whether immunosuppression may offer a protective effect,” he continued.

“This case series suggests that this is not the case, although this would need to be confirmed in larger studies,” he said.

Low threshold

Among the 22 patients who were admitted to the hospital, half were discharged home and four (18%) were still hospitalized at the end of the study.

Of the seven patients who died, two died at the study center, and five died in an outside institution.

“In the HT population, social distancing (or isolation), strict use of masks when in public, proper handwashing, and sanitization of surfaces are of paramount importance in the prevention of COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Uriel stated.

“In addition, we have restricted these patients’ contact with the hospital as much as possible during the pandemic,” he said.

However, “there should be a low threshold to hospitalize heart transplant patients who develop infection with COVID-19. Furthermore, in our series, outcomes were better for patients hospitalized at the transplant center; therefore, strong consideration should be given to transferring HT patients when hospitalized at another hospital,” he added.

The authors emphasized that COVID-19 patients “will require ongoing monitoring in the recovery phase, as an immunosuppression regimen is reintroduced and the consequences to the allograft itself become apparent.”

Vulnerable population

Commenting on the study, Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, MSc, William Harvey Distinguished Chair in Advanced Cardiovascular Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, suggested that “in epidemiological terms, [the findings] might not look as bad as the way they are reflected in the paper.”

Given that Columbia is “one of the larger heart transplant centers in the U.S., following probably 1,000 patients, having only 22 out of perhaps thousands whom they transplanted or are actively following would actually represent a low serious infection rate,” said Dr. Mehra, who is also the executive director of the Center for Advanced Heart Disease at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston.

“We must not forget to emphasize that, when assessing these case fatality rates, we must look at the entire population at risk, not only the handful that we were able to observe,” explained Dr. Mehra, who was not involved with the study.

Moreover, the patients were “older and had comorbidities, with poor underlying kidney function and other complications, and underlying coronary artery disease in the transplanted heart,” so “it would not surprise me that they had such a high fatality rate, since they had a high degree of vulnerability,” he said.

Dr. Mehra, who is also the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, said that the journal has received manuscripts still in the review process that suggest different fatality rates than those found in the current case series.

However, he acknowledged that, because these are patients with serious vulnerability due to underlying heart disease, “you can’t be lackadaisical and need to do everything to decrease this vulnerability.”

The authors noted that, although their study did not show a protective effect from immunosuppression against COVID-19, further studies are needed to assess each individual immunosuppressive agent and provide a definitive answer.

The study was supported by a grant to one of the investigators from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Uriel reports no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the publication. Dr. Mehra reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 infection is associated with a high risk for mortality in heart transplant (HT) recipients, a new case series suggests.

Investigators looked at data on 28 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 who received a HT between March 1, 2020, and April 24, 2020 and found a case-fatality rate of 25%.

“The high case fatality in our case series should alert physicians to the vulnerability of heart transplant recipients during the COVID-19 pandemic,” senior author Nir Uriel, MD, MSc, professor of medicine at Columbia University, New York, said in an interview.

“These patients require extra precautions to prevent the development of infection,” said Dr. Uriel, who is also a cardiologist at New York Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

The study was published online May 13 in JAMA Cardiology.

Similar presentation

HT recipients can have several comorbidities after the procedure, including hypertension, diabetes, cardiac allograft vasculopathy, and ongoing immunosuppression, all of which can place them at risk for infection and adverse outcomes with COVID-19 infection, the authors wrote.

The researchers therefore embarked on a case series looking at 28 HT recipients with COVID-19 infection (median age, 64.0 years; interquartile range, 53.5-70.5; 79% male) to “describe the outcomes of recipients of HT who are chronically immunosuppressed and develop COVID-19 and raise important questions about the role of the immune system in the process.”

The median time from HT to study period was 8.6 (IQR, 4.2-14.5) years. Most patients had numerous comorbidities.

“The presentation of COVID-19 was similar to nontransplant patients with fever, dyspnea, cough, and GI symptoms,” Dr. Uriel reported.

No protective effect

Twenty-two patients (79%) required admission to the hospital, seven of whom (25%) required admission to the ICU and mechanical ventilation.

Despite the presence of immunosuppressive therapy, all patients had significant elevation of inflammatory biomarkers (median peak high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hs-CRP], 11.83 mg/dL; IQR, 7.44-19.26; median peak interleukin [IL]-6, 105 pg/mL; IQR, 38-296).