User login

<p>For MD-IQ and ClinicalEdge use only</p>

Closing the Loop: Optimizing Oncology Care Coordination for Veterans

Purpose/Rationale: In order to improve cancer care coordination (CCC) a quality improvement pilot study was performed using a novel tracking tool for Veterans at the VA North Texas Health Care System (VANTHCS) located in Dallas, Texas.

Background: The VANTHCS is the second largest VA health care system in the country, serving over 113,000 Veterans and delivering one million outpatient episodes of care each year. Cancer is one of the leading causes of these episodes of care. This specific population faces unique needs due to the complexity of cancer care. Particularly, newly diagnosed cancer patients are at risk for being lost to follow up, receiving timeliness of care as well as having interruptions in communication among providers and Veterans. Cancer care coordination has been shown to augment the quality of cancer care. Prior to the initiation of this study, there was no cancer care tracking tool in place and no comprehensive CCC across the continuum at VANTHCS.

Methods: In April 2017, discussion was initiated among the key cancer care providing stakeholders to formulate a plan to identify all Veteran patients newly diagnosed with cancer at VANTHCS. Utilizing histopathology and cytology reports from VistA, we developed an interface that displayed Veterans with new cancer diagnoses. This system was put in place to capture initial date of diagnosis and

monitor scheduled patient appointments through the date of initial treatments. A plan-do-study-act (PDSA) was conducted to assess for any changes.

Results: From May 2017 through May 2018, data were collected and analyzed in the Cancer Care Tracking Tool by a designated registered nurse (RN); approximately 1,400 newly diagnosed cancer cases were tracked. Fifty-three cases were identified requiring an intervention. This tracking prompted discussion with key cancer stakeholders for the need of a cancer program clinical coordinator (CPCC). A full-time CPCC was appointed in February 2018.

Conclusions/Implications: This innovative study presented an original approach to improve the quality of cancer care for Veterans. Through the Cancer Care Tracking Tool the RN and CPCC actively identified and addressed barriers to cancer care. This may have numerous implications for future studies including, patient satisfaction and enhanced patient outcomes.

Purpose/Rationale: In order to improve cancer care coordination (CCC) a quality improvement pilot study was performed using a novel tracking tool for Veterans at the VA North Texas Health Care System (VANTHCS) located in Dallas, Texas.

Background: The VANTHCS is the second largest VA health care system in the country, serving over 113,000 Veterans and delivering one million outpatient episodes of care each year. Cancer is one of the leading causes of these episodes of care. This specific population faces unique needs due to the complexity of cancer care. Particularly, newly diagnosed cancer patients are at risk for being lost to follow up, receiving timeliness of care as well as having interruptions in communication among providers and Veterans. Cancer care coordination has been shown to augment the quality of cancer care. Prior to the initiation of this study, there was no cancer care tracking tool in place and no comprehensive CCC across the continuum at VANTHCS.

Methods: In April 2017, discussion was initiated among the key cancer care providing stakeholders to formulate a plan to identify all Veteran patients newly diagnosed with cancer at VANTHCS. Utilizing histopathology and cytology reports from VistA, we developed an interface that displayed Veterans with new cancer diagnoses. This system was put in place to capture initial date of diagnosis and

monitor scheduled patient appointments through the date of initial treatments. A plan-do-study-act (PDSA) was conducted to assess for any changes.

Results: From May 2017 through May 2018, data were collected and analyzed in the Cancer Care Tracking Tool by a designated registered nurse (RN); approximately 1,400 newly diagnosed cancer cases were tracked. Fifty-three cases were identified requiring an intervention. This tracking prompted discussion with key cancer stakeholders for the need of a cancer program clinical coordinator (CPCC). A full-time CPCC was appointed in February 2018.

Conclusions/Implications: This innovative study presented an original approach to improve the quality of cancer care for Veterans. Through the Cancer Care Tracking Tool the RN and CPCC actively identified and addressed barriers to cancer care. This may have numerous implications for future studies including, patient satisfaction and enhanced patient outcomes.

Purpose/Rationale: In order to improve cancer care coordination (CCC) a quality improvement pilot study was performed using a novel tracking tool for Veterans at the VA North Texas Health Care System (VANTHCS) located in Dallas, Texas.

Background: The VANTHCS is the second largest VA health care system in the country, serving over 113,000 Veterans and delivering one million outpatient episodes of care each year. Cancer is one of the leading causes of these episodes of care. This specific population faces unique needs due to the complexity of cancer care. Particularly, newly diagnosed cancer patients are at risk for being lost to follow up, receiving timeliness of care as well as having interruptions in communication among providers and Veterans. Cancer care coordination has been shown to augment the quality of cancer care. Prior to the initiation of this study, there was no cancer care tracking tool in place and no comprehensive CCC across the continuum at VANTHCS.

Methods: In April 2017, discussion was initiated among the key cancer care providing stakeholders to formulate a plan to identify all Veteran patients newly diagnosed with cancer at VANTHCS. Utilizing histopathology and cytology reports from VistA, we developed an interface that displayed Veterans with new cancer diagnoses. This system was put in place to capture initial date of diagnosis and

monitor scheduled patient appointments through the date of initial treatments. A plan-do-study-act (PDSA) was conducted to assess for any changes.

Results: From May 2017 through May 2018, data were collected and analyzed in the Cancer Care Tracking Tool by a designated registered nurse (RN); approximately 1,400 newly diagnosed cancer cases were tracked. Fifty-three cases were identified requiring an intervention. This tracking prompted discussion with key cancer stakeholders for the need of a cancer program clinical coordinator (CPCC). A full-time CPCC was appointed in February 2018.

Conclusions/Implications: This innovative study presented an original approach to improve the quality of cancer care for Veterans. Through the Cancer Care Tracking Tool the RN and CPCC actively identified and addressed barriers to cancer care. This may have numerous implications for future studies including, patient satisfaction and enhanced patient outcomes.

First EDition: ED Visits by Older Patients Increase in the Weeks After a Disaster

ED Visits by Older Patients Increase in the Weeks After a Disaster

BY KELLIE DESANTIS

Visits to an ED by adults ages 65 years and older increase significantly in the weeks following a disaster, according to a study published in Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness.1

Older adults are vulnerable to the effects of disasters because of their diminished ability to adequately prepare for and respond to the effects of a disaster. Older adults suffering from visual, auditory, proprioceptive, and cognitive impairments are especially vulnerable and have the most difficulty complying with evacuation and preparatory warnings. Individuals with multiple chronic diseases, living in long-term care facilities or suffering from cognitive impairments are among the most vulnerable.

To better understand the impact of natural disasters on this vulnerable population, researchers examined the effects of the 2012 disaster, Hurricane Sandy, on older adults living in New York City (NYC) during the disaster. Researchers turned to the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) for data. The NYSDOH compiles a comprehensive database of claims from all ED visits in the Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS), which is the most complete source for ED utilization in New York state, and includes primary and secondary diagnosis codes and patient addresses.

Researchers evaluated ED utilization by adults 65 years and older in the weeks immediately before and after the Hurricane Sandy landfall. They excluded patients who lived in a nursing home, were incarcerated, or visited an ED associated with a specialty hospital (surgical subspecialty, oncological, or Veterans Administration). By using geographic distribution information available from SPARCS and the NYC Office of Emergency Management evacuation zones, researchers were able to compare the ED utilization for older adults living in the evacuation zones before the landfall of Hurricane Sandy and in the weeks shortly after the storm.

The analysis revealed a significant increase in ED utilization for older adults living in the evacuation zones in the 3 weeks after the storm compared to ED use before the storm. The number of weekly ED visits by older adults from all evacuation zones was 9,852 in the weeks before Hurricane Sandy and increased in the first week after the storm to 10,073. Among the most severely impacted were older adults in evacuation zone one, where ED utilization increased from 552 visits to 1,111 visits. The number of ED visits remained elevated for 3 weeks after the storm but returned to normal by the fourth week.

Researchers suggested several reasons for this increase in ED visits, including seeking refuge in the ED as a result of homelessness due to the disaster, the interruption of ongoing care for chronic illness, environmental exposure, and the lack of preparation for the lasting effect of the disaster.

To improve the response to such a disaster in the future, a NYC Hurricane Sandy Assessment report2 recommended developing a door-to-door service task force for older adults to improve preparedness for this vulnerable population. The task force would be responsible for implementing an action plan to ensure that healthcare services, communication, and provisions for this population continue without interruption in the weeks following a disaster. Legal and regulatory changes would allow for Medicare recipients to be eligible for "early medication refill" and pre-storm "early dialysis" programs to improve the continuity of care of the chronically ill.

1. Malik S, Lee DC, Doran KM, et al. Vulnerability of older adults in disasters: emergency department utilization by geriatric patients after hurricane sandy. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2017:1-10. doi:10.1017/dmp.2017.44

2. The City of New York, Office of the Mayor. Hurricane Sandy After Action Report. Published May 2013. http://www.nyc.gov/html/recovery/downlaods/pdf/sandy_aar_5.2.13.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2017.

Digital Rectal Examination of ED Patients with Acute GI Bleeding Cuts Rates of Admissions, Pharmacotherapy, and Endoscopy

BY JEFF BAUER

Patients presenting to the ED with acute gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding who receive a digital rectal examination have significantly lower rates of admissions, pharmacotherapy, and endoscopies, according to a retrospective study published in The American Journal of Medicine. Digital rectal examinations are an established part of the physical examination of a patient with GI bleeding, but physicians often are reluctant to conduct such examinations. Previous studies have found that 10% to 35% of patients with acute GI bleeding do not receive digital rectal examinations.

In the current study, researchers analyzed data from the electronic health records (EHRs) of patients ages 18 years and older who presented to the ED of a single institution with acute GI bleeding, as identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition codes. They collected patients’ medical histories, demographic information, and clinical and laboratory data. ED clinician notes were used to determine which patients received a digital rectal examination. The outcomes researchers assessed were hospital admission, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, initiation of medical therapy (a proton pump inhibitor or octreotide), inpatient endoscopy (upper endoscopy or colonoscopy), and packed red blood cell (RBC) transfusion.

Overall, 1237 patients presented with acute GI bleeding. Most patients were Caucasian (49.2%) or Hispanic (38.4%), 44.9% were female, and the median age was 53 years.

Slightly more than one-half of patients (55.6%) received a digital rectal examination. In total, 736 patients were admitted—including 222 admissions to the ICU; 751 were started on a proton pump inhibitor or octreotide, 274 underwent endoscopy, and 321 received an RBC transfusion.

Patients were more likely to receive a digital rectal examination if they were older, Hispanic, or receiving an anticoagulant. Patients were less likely to undergo such examinations if they presented with altered mental status or hematemesis. Compared to patients who did not receive a digital rectal examination, those who did were significantly less likely to be admitted to the hospital (P = .004), to be starting on medical therapy (P = .04), or to undergo endoscopy (P = .02). There were no significant differences between these two groups in terms of ICU admissions, gastroenterology consultations, or transfusions.

Researchers suggested that the 44% rate of patients with acute GI bleeding who did not receive digital rectal examinations was higher than had been reported in previous studies. The difference had been the result of relying solely on ED clinician notes for this data, without including notes from admitting or consulting clinicians. The authors also were unable to determine the reasons these examinations were not conducted.

Shrestha MP, Borgstrom M, Trowers E. Digital rectal examination reduces hospital admissions, endoscopies, and medical therapy in patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Med. 2017;130(7):819-825. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.01.036.

ED Visits by Older Patients Increase in the Weeks After a Disaster

BY KELLIE DESANTIS

Visits to an ED by adults ages 65 years and older increase significantly in the weeks following a disaster, according to a study published in Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness.1

Older adults are vulnerable to the effects of disasters because of their diminished ability to adequately prepare for and respond to the effects of a disaster. Older adults suffering from visual, auditory, proprioceptive, and cognitive impairments are especially vulnerable and have the most difficulty complying with evacuation and preparatory warnings. Individuals with multiple chronic diseases, living in long-term care facilities or suffering from cognitive impairments are among the most vulnerable.

To better understand the impact of natural disasters on this vulnerable population, researchers examined the effects of the 2012 disaster, Hurricane Sandy, on older adults living in New York City (NYC) during the disaster. Researchers turned to the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) for data. The NYSDOH compiles a comprehensive database of claims from all ED visits in the Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS), which is the most complete source for ED utilization in New York state, and includes primary and secondary diagnosis codes and patient addresses.

Researchers evaluated ED utilization by adults 65 years and older in the weeks immediately before and after the Hurricane Sandy landfall. They excluded patients who lived in a nursing home, were incarcerated, or visited an ED associated with a specialty hospital (surgical subspecialty, oncological, or Veterans Administration). By using geographic distribution information available from SPARCS and the NYC Office of Emergency Management evacuation zones, researchers were able to compare the ED utilization for older adults living in the evacuation zones before the landfall of Hurricane Sandy and in the weeks shortly after the storm.

The analysis revealed a significant increase in ED utilization for older adults living in the evacuation zones in the 3 weeks after the storm compared to ED use before the storm. The number of weekly ED visits by older adults from all evacuation zones was 9,852 in the weeks before Hurricane Sandy and increased in the first week after the storm to 10,073. Among the most severely impacted were older adults in evacuation zone one, where ED utilization increased from 552 visits to 1,111 visits. The number of ED visits remained elevated for 3 weeks after the storm but returned to normal by the fourth week.

Researchers suggested several reasons for this increase in ED visits, including seeking refuge in the ED as a result of homelessness due to the disaster, the interruption of ongoing care for chronic illness, environmental exposure, and the lack of preparation for the lasting effect of the disaster.

To improve the response to such a disaster in the future, a NYC Hurricane Sandy Assessment report2 recommended developing a door-to-door service task force for older adults to improve preparedness for this vulnerable population. The task force would be responsible for implementing an action plan to ensure that healthcare services, communication, and provisions for this population continue without interruption in the weeks following a disaster. Legal and regulatory changes would allow for Medicare recipients to be eligible for "early medication refill" and pre-storm "early dialysis" programs to improve the continuity of care of the chronically ill.

1. Malik S, Lee DC, Doran KM, et al. Vulnerability of older adults in disasters: emergency department utilization by geriatric patients after hurricane sandy. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2017:1-10. doi:10.1017/dmp.2017.44

2. The City of New York, Office of the Mayor. Hurricane Sandy After Action Report. Published May 2013. http://www.nyc.gov/html/recovery/downlaods/pdf/sandy_aar_5.2.13.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2017.

Digital Rectal Examination of ED Patients with Acute GI Bleeding Cuts Rates of Admissions, Pharmacotherapy, and Endoscopy

BY JEFF BAUER

Patients presenting to the ED with acute gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding who receive a digital rectal examination have significantly lower rates of admissions, pharmacotherapy, and endoscopies, according to a retrospective study published in The American Journal of Medicine. Digital rectal examinations are an established part of the physical examination of a patient with GI bleeding, but physicians often are reluctant to conduct such examinations. Previous studies have found that 10% to 35% of patients with acute GI bleeding do not receive digital rectal examinations.

In the current study, researchers analyzed data from the electronic health records (EHRs) of patients ages 18 years and older who presented to the ED of a single institution with acute GI bleeding, as identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition codes. They collected patients’ medical histories, demographic information, and clinical and laboratory data. ED clinician notes were used to determine which patients received a digital rectal examination. The outcomes researchers assessed were hospital admission, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, initiation of medical therapy (a proton pump inhibitor or octreotide), inpatient endoscopy (upper endoscopy or colonoscopy), and packed red blood cell (RBC) transfusion.

Overall, 1237 patients presented with acute GI bleeding. Most patients were Caucasian (49.2%) or Hispanic (38.4%), 44.9% were female, and the median age was 53 years.

Slightly more than one-half of patients (55.6%) received a digital rectal examination. In total, 736 patients were admitted—including 222 admissions to the ICU; 751 were started on a proton pump inhibitor or octreotide, 274 underwent endoscopy, and 321 received an RBC transfusion.

Patients were more likely to receive a digital rectal examination if they were older, Hispanic, or receiving an anticoagulant. Patients were less likely to undergo such examinations if they presented with altered mental status or hematemesis. Compared to patients who did not receive a digital rectal examination, those who did were significantly less likely to be admitted to the hospital (P = .004), to be starting on medical therapy (P = .04), or to undergo endoscopy (P = .02). There were no significant differences between these two groups in terms of ICU admissions, gastroenterology consultations, or transfusions.

Researchers suggested that the 44% rate of patients with acute GI bleeding who did not receive digital rectal examinations was higher than had been reported in previous studies. The difference had been the result of relying solely on ED clinician notes for this data, without including notes from admitting or consulting clinicians. The authors also were unable to determine the reasons these examinations were not conducted.

Shrestha MP, Borgstrom M, Trowers E. Digital rectal examination reduces hospital admissions, endoscopies, and medical therapy in patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Med. 2017;130(7):819-825. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.01.036.

ED Visits by Older Patients Increase in the Weeks After a Disaster

BY KELLIE DESANTIS

Visits to an ED by adults ages 65 years and older increase significantly in the weeks following a disaster, according to a study published in Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness.1

Older adults are vulnerable to the effects of disasters because of their diminished ability to adequately prepare for and respond to the effects of a disaster. Older adults suffering from visual, auditory, proprioceptive, and cognitive impairments are especially vulnerable and have the most difficulty complying with evacuation and preparatory warnings. Individuals with multiple chronic diseases, living in long-term care facilities or suffering from cognitive impairments are among the most vulnerable.

To better understand the impact of natural disasters on this vulnerable population, researchers examined the effects of the 2012 disaster, Hurricane Sandy, on older adults living in New York City (NYC) during the disaster. Researchers turned to the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) for data. The NYSDOH compiles a comprehensive database of claims from all ED visits in the Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS), which is the most complete source for ED utilization in New York state, and includes primary and secondary diagnosis codes and patient addresses.

Researchers evaluated ED utilization by adults 65 years and older in the weeks immediately before and after the Hurricane Sandy landfall. They excluded patients who lived in a nursing home, were incarcerated, or visited an ED associated with a specialty hospital (surgical subspecialty, oncological, or Veterans Administration). By using geographic distribution information available from SPARCS and the NYC Office of Emergency Management evacuation zones, researchers were able to compare the ED utilization for older adults living in the evacuation zones before the landfall of Hurricane Sandy and in the weeks shortly after the storm.

The analysis revealed a significant increase in ED utilization for older adults living in the evacuation zones in the 3 weeks after the storm compared to ED use before the storm. The number of weekly ED visits by older adults from all evacuation zones was 9,852 in the weeks before Hurricane Sandy and increased in the first week after the storm to 10,073. Among the most severely impacted were older adults in evacuation zone one, where ED utilization increased from 552 visits to 1,111 visits. The number of ED visits remained elevated for 3 weeks after the storm but returned to normal by the fourth week.

Researchers suggested several reasons for this increase in ED visits, including seeking refuge in the ED as a result of homelessness due to the disaster, the interruption of ongoing care for chronic illness, environmental exposure, and the lack of preparation for the lasting effect of the disaster.

To improve the response to such a disaster in the future, a NYC Hurricane Sandy Assessment report2 recommended developing a door-to-door service task force for older adults to improve preparedness for this vulnerable population. The task force would be responsible for implementing an action plan to ensure that healthcare services, communication, and provisions for this population continue without interruption in the weeks following a disaster. Legal and regulatory changes would allow for Medicare recipients to be eligible for "early medication refill" and pre-storm "early dialysis" programs to improve the continuity of care of the chronically ill.

1. Malik S, Lee DC, Doran KM, et al. Vulnerability of older adults in disasters: emergency department utilization by geriatric patients after hurricane sandy. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2017:1-10. doi:10.1017/dmp.2017.44

2. The City of New York, Office of the Mayor. Hurricane Sandy After Action Report. Published May 2013. http://www.nyc.gov/html/recovery/downlaods/pdf/sandy_aar_5.2.13.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2017.

Digital Rectal Examination of ED Patients with Acute GI Bleeding Cuts Rates of Admissions, Pharmacotherapy, and Endoscopy

BY JEFF BAUER

Patients presenting to the ED with acute gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding who receive a digital rectal examination have significantly lower rates of admissions, pharmacotherapy, and endoscopies, according to a retrospective study published in The American Journal of Medicine. Digital rectal examinations are an established part of the physical examination of a patient with GI bleeding, but physicians often are reluctant to conduct such examinations. Previous studies have found that 10% to 35% of patients with acute GI bleeding do not receive digital rectal examinations.

In the current study, researchers analyzed data from the electronic health records (EHRs) of patients ages 18 years and older who presented to the ED of a single institution with acute GI bleeding, as identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition codes. They collected patients’ medical histories, demographic information, and clinical and laboratory data. ED clinician notes were used to determine which patients received a digital rectal examination. The outcomes researchers assessed were hospital admission, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, initiation of medical therapy (a proton pump inhibitor or octreotide), inpatient endoscopy (upper endoscopy or colonoscopy), and packed red blood cell (RBC) transfusion.

Overall, 1237 patients presented with acute GI bleeding. Most patients were Caucasian (49.2%) or Hispanic (38.4%), 44.9% were female, and the median age was 53 years.

Slightly more than one-half of patients (55.6%) received a digital rectal examination. In total, 736 patients were admitted—including 222 admissions to the ICU; 751 were started on a proton pump inhibitor or octreotide, 274 underwent endoscopy, and 321 received an RBC transfusion.

Patients were more likely to receive a digital rectal examination if they were older, Hispanic, or receiving an anticoagulant. Patients were less likely to undergo such examinations if they presented with altered mental status or hematemesis. Compared to patients who did not receive a digital rectal examination, those who did were significantly less likely to be admitted to the hospital (P = .004), to be starting on medical therapy (P = .04), or to undergo endoscopy (P = .02). There were no significant differences between these two groups in terms of ICU admissions, gastroenterology consultations, or transfusions.

Researchers suggested that the 44% rate of patients with acute GI bleeding who did not receive digital rectal examinations was higher than had been reported in previous studies. The difference had been the result of relying solely on ED clinician notes for this data, without including notes from admitting or consulting clinicians. The authors also were unable to determine the reasons these examinations were not conducted.

Shrestha MP, Borgstrom M, Trowers E. Digital rectal examination reduces hospital admissions, endoscopies, and medical therapy in patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Med. 2017;130(7):819-825. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.01.036.

Reusing Syringes: Not Safe, Not Cost-Effective

In 2015, the Texas Department of State Health Services was notified that a hospital telemetry unit nurse had been reusing saline flush prefilled syringes in patients’ IV lines. Mistakenly believing that it was safe and that she was saving the hospital money, she had been reusing syringes for 6 months. This was not the hospital’s practice.

Because she had been putting patients at risk for bloodborne pathogens, the state, regional, and local health departments with consultation from the CDC worked with the hospital to investigate. The hospital notified 392 patients, advising them of potential exposure and offering them free testing for hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), and HIV. A year after the exposure, 262 had completed initial screening and 182 had completed all recommended testing.

Two patients had newly diagnosed HBV and 2 had HCV. A patient with known preexisting chronic HCV infection had been hospitalized on the telemetry unit on the same day as one of the patients with newly diagnosed HCV. That second patient did not share overlapping days with any patient with known HCV infection, nor did the 2 with newly diagnosed HBV infection share with each other or any other patient with a known HBV infection. No epidemiologic evidence linked the patients with newly diagnosed infections to a potential source patient. But when specimens were tested, the results indicated transmission linkage between the patient with chronic HCV infection and one of the patients with newly diagnosed HCV infection.

Taken together, the CDC concluded, the findings indicated that at least 1 HCV infection was “likely transmitted” in the telemetry unit as a result of the inappropriate reuse and sharing of syringes. The investigation, the CDC adds, illustrates a need for ongoing education and oversight of health care providers regarding safe injection practices.

In 2015, the Texas Department of State Health Services was notified that a hospital telemetry unit nurse had been reusing saline flush prefilled syringes in patients’ IV lines. Mistakenly believing that it was safe and that she was saving the hospital money, she had been reusing syringes for 6 months. This was not the hospital’s practice.

Because she had been putting patients at risk for bloodborne pathogens, the state, regional, and local health departments with consultation from the CDC worked with the hospital to investigate. The hospital notified 392 patients, advising them of potential exposure and offering them free testing for hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), and HIV. A year after the exposure, 262 had completed initial screening and 182 had completed all recommended testing.

Two patients had newly diagnosed HBV and 2 had HCV. A patient with known preexisting chronic HCV infection had been hospitalized on the telemetry unit on the same day as one of the patients with newly diagnosed HCV. That second patient did not share overlapping days with any patient with known HCV infection, nor did the 2 with newly diagnosed HBV infection share with each other or any other patient with a known HBV infection. No epidemiologic evidence linked the patients with newly diagnosed infections to a potential source patient. But when specimens were tested, the results indicated transmission linkage between the patient with chronic HCV infection and one of the patients with newly diagnosed HCV infection.

Taken together, the CDC concluded, the findings indicated that at least 1 HCV infection was “likely transmitted” in the telemetry unit as a result of the inappropriate reuse and sharing of syringes. The investigation, the CDC adds, illustrates a need for ongoing education and oversight of health care providers regarding safe injection practices.

In 2015, the Texas Department of State Health Services was notified that a hospital telemetry unit nurse had been reusing saline flush prefilled syringes in patients’ IV lines. Mistakenly believing that it was safe and that she was saving the hospital money, she had been reusing syringes for 6 months. This was not the hospital’s practice.

Because she had been putting patients at risk for bloodborne pathogens, the state, regional, and local health departments with consultation from the CDC worked with the hospital to investigate. The hospital notified 392 patients, advising them of potential exposure and offering them free testing for hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), and HIV. A year after the exposure, 262 had completed initial screening and 182 had completed all recommended testing.

Two patients had newly diagnosed HBV and 2 had HCV. A patient with known preexisting chronic HCV infection had been hospitalized on the telemetry unit on the same day as one of the patients with newly diagnosed HCV. That second patient did not share overlapping days with any patient with known HCV infection, nor did the 2 with newly diagnosed HBV infection share with each other or any other patient with a known HBV infection. No epidemiologic evidence linked the patients with newly diagnosed infections to a potential source patient. But when specimens were tested, the results indicated transmission linkage between the patient with chronic HCV infection and one of the patients with newly diagnosed HCV infection.

Taken together, the CDC concluded, the findings indicated that at least 1 HCV infection was “likely transmitted” in the telemetry unit as a result of the inappropriate reuse and sharing of syringes. The investigation, the CDC adds, illustrates a need for ongoing education and oversight of health care providers regarding safe injection practices.

Local Data on Cancer Mortality Reveal Valuable ‘Patterns’ in Changes

Cancer death rates in the U.S. declined by 20% between 1980 and 2014, but not everywhere: In 160 counties, mortality rose substantially during the same time, according to University of Washington researchers. And those weren’t the only striking variations they found.

The researchers analyzed data on deaths from 29 cancer types. Deaths dropped from about 240 per 100,000 people in 1980 to 192 per 100,000 in 2014. But the researchers say they found “stark” disparities. In 2014, the county with the highest overall cancer mortality had about 7 times as many cancer deaths per 100,000 residents as the county with the lowest overall cancer mortality. For many cancers there were distinct clusters of counties in different regions with especially high mortality, such as in Kentucky, West Virginia, and Alabama.

Related: Major Cancer Death Rates Are Down

The pattern of changes across counties also varied tremendously by type, the researchers say. For instance, breast, cervical, prostate, testicular, and other cancers, mortality rates declined in nearly all counties, whereas liver cancer and mesothelioma increased in nearly all counties.

Previous reports on geographic differences in cancer mortality have focused on variation by state, the researchers say. But the local patterns they found would have been masked by a national or state number. Their innovative approach to aggregating and analyzing the data at the county level has value, they note, because “public health programs and policies are mainly designed and implemented at the local level.”

The policy response from the public health and medical care communities, the researchers add, depends on “parsing these trends into component factors”: trends driven by known risk factors, unexplained trends in incidence, cancers for which screening and early detection can make a major difference, and cancers for which high-quality treatment can make a major difference. Local information, the researchers point out, can be useful for health care practitioners to understand community needs for care and aid in identifying “cancer hot spots” that need more investigation.

In an article for the National Cancer Institute’s newsletter, Eric Durbin, DPh, director of cancer informatics for the Kentucky Cancer Registry at the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center, cautioned against basing too many assumptions on local data, especially in rural, sparsely populated areas where small number changes can translate into giant percentages. “We really have no other way to guide cancer prevention and control activities other than using [that] data. Otherwise, you’re just throwing money or resources at a problem without any way to measure the impact,” added Durbin.

Sources:

- National Cancer Institute. U.S. cancer mortality rates falling, but some regions left behind, study finds. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2017/cancer-death-disparities. Published February 21, 2017. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- Mokdad AH, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Fitzmaurice C, et al. JAMA. 2017;317(4):388-406.

doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20324.

Cancer death rates in the U.S. declined by 20% between 1980 and 2014, but not everywhere: In 160 counties, mortality rose substantially during the same time, according to University of Washington researchers. And those weren’t the only striking variations they found.

The researchers analyzed data on deaths from 29 cancer types. Deaths dropped from about 240 per 100,000 people in 1980 to 192 per 100,000 in 2014. But the researchers say they found “stark” disparities. In 2014, the county with the highest overall cancer mortality had about 7 times as many cancer deaths per 100,000 residents as the county with the lowest overall cancer mortality. For many cancers there were distinct clusters of counties in different regions with especially high mortality, such as in Kentucky, West Virginia, and Alabama.

Related: Major Cancer Death Rates Are Down

The pattern of changes across counties also varied tremendously by type, the researchers say. For instance, breast, cervical, prostate, testicular, and other cancers, mortality rates declined in nearly all counties, whereas liver cancer and mesothelioma increased in nearly all counties.

Previous reports on geographic differences in cancer mortality have focused on variation by state, the researchers say. But the local patterns they found would have been masked by a national or state number. Their innovative approach to aggregating and analyzing the data at the county level has value, they note, because “public health programs and policies are mainly designed and implemented at the local level.”

The policy response from the public health and medical care communities, the researchers add, depends on “parsing these trends into component factors”: trends driven by known risk factors, unexplained trends in incidence, cancers for which screening and early detection can make a major difference, and cancers for which high-quality treatment can make a major difference. Local information, the researchers point out, can be useful for health care practitioners to understand community needs for care and aid in identifying “cancer hot spots” that need more investigation.

In an article for the National Cancer Institute’s newsletter, Eric Durbin, DPh, director of cancer informatics for the Kentucky Cancer Registry at the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center, cautioned against basing too many assumptions on local data, especially in rural, sparsely populated areas where small number changes can translate into giant percentages. “We really have no other way to guide cancer prevention and control activities other than using [that] data. Otherwise, you’re just throwing money or resources at a problem without any way to measure the impact,” added Durbin.

Sources:

- National Cancer Institute. U.S. cancer mortality rates falling, but some regions left behind, study finds. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2017/cancer-death-disparities. Published February 21, 2017. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- Mokdad AH, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Fitzmaurice C, et al. JAMA. 2017;317(4):388-406.

doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20324.

Cancer death rates in the U.S. declined by 20% between 1980 and 2014, but not everywhere: In 160 counties, mortality rose substantially during the same time, according to University of Washington researchers. And those weren’t the only striking variations they found.

The researchers analyzed data on deaths from 29 cancer types. Deaths dropped from about 240 per 100,000 people in 1980 to 192 per 100,000 in 2014. But the researchers say they found “stark” disparities. In 2014, the county with the highest overall cancer mortality had about 7 times as many cancer deaths per 100,000 residents as the county with the lowest overall cancer mortality. For many cancers there were distinct clusters of counties in different regions with especially high mortality, such as in Kentucky, West Virginia, and Alabama.

Related: Major Cancer Death Rates Are Down

The pattern of changes across counties also varied tremendously by type, the researchers say. For instance, breast, cervical, prostate, testicular, and other cancers, mortality rates declined in nearly all counties, whereas liver cancer and mesothelioma increased in nearly all counties.

Previous reports on geographic differences in cancer mortality have focused on variation by state, the researchers say. But the local patterns they found would have been masked by a national or state number. Their innovative approach to aggregating and analyzing the data at the county level has value, they note, because “public health programs and policies are mainly designed and implemented at the local level.”

The policy response from the public health and medical care communities, the researchers add, depends on “parsing these trends into component factors”: trends driven by known risk factors, unexplained trends in incidence, cancers for which screening and early detection can make a major difference, and cancers for which high-quality treatment can make a major difference. Local information, the researchers point out, can be useful for health care practitioners to understand community needs for care and aid in identifying “cancer hot spots” that need more investigation.

In an article for the National Cancer Institute’s newsletter, Eric Durbin, DPh, director of cancer informatics for the Kentucky Cancer Registry at the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center, cautioned against basing too many assumptions on local data, especially in rural, sparsely populated areas where small number changes can translate into giant percentages. “We really have no other way to guide cancer prevention and control activities other than using [that] data. Otherwise, you’re just throwing money or resources at a problem without any way to measure the impact,” added Durbin.

Sources:

- National Cancer Institute. U.S. cancer mortality rates falling, but some regions left behind, study finds. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2017/cancer-death-disparities. Published February 21, 2017. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- Mokdad AH, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Fitzmaurice C, et al. JAMA. 2017;317(4):388-406.

doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20324.

Review of the Long-Term Effects of Proton Pump Inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are one of the most frequently used drug classes, given that they are readily accessible over-the-counter as well as via prescription. About 100 million PPI prescriptions dispensed an

The human stomach uses 3 primary neurotransmitters that regulate gastric acid secretion: acetylcholine (ACh), histamine (H), and gastrin (G). The interactions between these neurotransmitters promote and inhibit hydrogen ion (H+) generation. Stimulation of their corresponding receptors draws H+ into parietal cells that line the stomach. Once in the cell, a H+-K+-ATPase (more commonly known as the proton pump) actively transports H+ into the lumen of the stomach. The H+ bind with chlorine ions to form hydrochloric acid, which increases stomach acidity.5 Histamine receptors were thought to be responsible for the greatest degree of stimulation. Hence, histamine type 2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) became a novel means of therapy to reduce stomach acidity. While utilizing H2RAs was effective, it was theorized the downstream inhibition of the action of all 3 neurotransmitters would serve as a more successful therapy. Therefore, PPIs were developed to target the H+-K+-ATPase Over the past decade, many studies have evaluated the long-term PPI adverse effects (AEs). These include calcium and magnesium malabsorption, vitamin B12 deficiency, Clostridium difficile (C difficile) associated disease (CDAD), and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). Within the past year, data have become available linking PPI use to dementia and chronic kidney disease (CKD).3,4 The following article reviews literature on the safety of long-term PPI use and proposes recommendations for proper use for their most common indications.

Malabsorption

Calcium & Long-Term Fracture Risk

Calcium is an essential component in bone health and formation. In fact, 99% of all calcium found in the body is stored in bones.6 The primary source of calcium is through diet and oral supplements. After it is ingested, calcium is absorbed from the stomach into the blood in a pH dependent manner. If the pH of the stomach is too high (ie, too basic) calcium is not absorbed into blood and remains in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract for fecal excretion. Without sufficient calcium, the body’s osteoclasts and osteoblasts remain inactive, which hinders proper bone turnover.7

The decrease in acidity leads to calcium malabsorption and increases fracture risk long- term.8 Khalili and colleagues surveyed 80,000 postmenopausal women to measure the incidence of hip fracture in women taking PPIs. The study found that there was a 35% increase in risk of hip fracture among women who regularly used PPIs for at least 2 years (age-adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 1.35; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.13 -1.62). Adjusted HRs for 4-year and 6- to 8-year use of a PPI was 1.42 (95% CI, 1.05-1.93) and 1.55 (95% CI, 1.03-2.32), respectively, indicating that the longer women were on PPI therapy, the higher the risk of hip fracture. The study also evaluated the time since stopping PPI and the risk of hip fracture. Women who stopped PPI use more than 2 years prior had a similar risk to that of women who never used a PPI, indicating that the effect was reversible.9

Magnesium

Magnesium is an important intracellular ion that has a number of key functions in metabolism and ion transport in the human body. Once ingested, magnesium is absorbed into the bloodstream from the small and large intestines via passive and active transport. Transient receptor potential melastatin 6 (TRPM6) is one of the essential proteins that serve as a transporter for magnesium.10 The high affinity for magnesium of these transporters allows them to maintain adequate levels of magnesium in the blood. In states of low magnesium (hypomagnesemia), the body is at risk for many AEs including seizures, arrhythmias, tetany, and hypotension.11

Proton pump inhibitors have been linked to hypomagnesemia, and recent evaluation has clarified a potential mechanism.12 TRPM6 activity is increased in an acidic environment. When a PPI increases the pH of the stomach, TRPM6 and magnesium levels decrease.12 Luk and colleagues identified 66,102 subjects experiencing AEs while taking a PPI. Hypomagnesemia had a prevalence rate of 1% in these patients. According to the researchers, PPIs were associated with hypomagnesemia and that pantoprazole had the highest incidence among all other PPIs studied (OR, 4.3; 95% CI, 3.3 – 5.7; P < .001).13

Vitamin B12

In recent years, vitamin B12 has been the subject of many studies. An area of concern is vitamin B12’s neurologic effect, as it has been successfully demonstrated that vitamin B12 is essential for proper cognitive function.14 Some data suggest that degeneration is present in parts of the spinal column in patients with cognitive decline or neurologic problems. These lesions are due to improper myelin formation and are specific to vitamin B12 deficiency.15 In 2013 the CDC published the Healthy Brain Initiative, which stated cognitive impairment can be caused by vitamin B12 deficiency.16

Similar to calcium, vitamin B12 needs an acidic environment to be digested and absorbed.17 Vitamin B12 is released from food proteins via gastric acid and pepsin. Once free, the vitamin B12 pairs with R-binders secreted in the stomach. Pancreatic enzymes then degrade this complex into a form that can be absorbed into circulation by the intestine. Given that PPIs reduce the acidity of the stomach, they also reduce the body’s ability to release vitamin B12 from food proteins and be paired with the R-binders.18

In 2013, Lam and colleagues evaluated the association between vitamin B12 deficiency and the use of PPIs and H2RAs. An extensive evaluation was performed on 25,956 patients with a diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency and 184,199 patients without. About 12% of patients with vitamin B12 deficiency had received more than a 2-year supply of a PPI, whereas only 7.2% of the patients without vitamin B12 deficiency received a 2-year supply of a PPI. Four point 3 percent of patients with vitamin B12 deficiency received more than a 2-year supply of an H2RA. Only 3.2% of patients without vitamin B12 deficiency received more than a 2-year supply of H2RA. The study concluded that a 2-year or greater history of PPI (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.58-1.73) or H2RA (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.17-1.34) use was associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.19

PPIs and Infections

Clostridium difficile-associated disease

Nationwide CDAD has become a prevalent infection nationwide. In 2011, C difficile caused nearly 500,000 infections and was associated with 29,000 deaths in the U.S.20 One study stated that C difficile is the third most common cause of infectious diarrhea in people aged >75 years.21

C difficile is part of the body’s normal flora in the large intestine. It grows and colonizes in an environment of low acidity. Therefore, in the stomach, where the pH is relatively low, C difficile is unable to colonize.22 When a PPI is introduced, the increased gastric pH increases the risk for CDAD.

Dial and colleagues conducted a multicenter case control study to determine whether gastric acid suppression increases the risk of CDAD. Compared with patients who did not take a gastric acid suppressant, those taking a PPI had a 2.9-fold increase in developing CDAD (95% CI, 2.4-3.4). Comparatively, H2RAs had a 2.0-fold increase for CDAD (95% CI, 1.6 to 2.7). These results correlated with the fact that PPIs have a greater impact on gastric pH than do H2RAs.23

Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) has become a growing concern in the U.S. According to the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and American Thoracic clinical consensus guidelines, CAP remains one of the top reasons for hospitalizations in the U.S., and about 10% of patients admitted to the hospital for CAP end up in the intensive care unit (ICU).24 In the past, PPIs have been linked to patients’ predisposal for developingCAP.25 Although controversial, available evidence suggests a direct association. In 2008 Sarker and colleagues theorized a mechanism that the acid reduction of the gastric lumen allows for increased bacterial colonization in the upper part of the GI tract.26 Since the acidity of the stomach serves as a defense mechanism against many ingested bacteria, many pathogens will be able to survive in the more basic environment.25

Sarkar and colleagues went on to evaluate 80,000 cases over 15 years. The objective was to examine the association between PPI use and the date of diagnosis of the CAP infection, known as the index date. The study demonstrated that PPI use was not associated with increased CAP risk in the long-term (adjusted odds ratio (OR), 1.02; 95% CI, 0.97-1.08). The study did find a strong increase in the risk of CAP if a PPI was started within 2 days (adjusted OR, 6.53; 95% CI, 3.95-10.80), 7 days (adjusted OR, 3.79; 95% CI, 2.66-5.42), and 14 days (adjusted OR, 3.21; 95% CI, 2.46-4.18) of the index date.26

Four years later, de Jagar and colleagues examined the differences in microbial etiology in CAP patients with and without an active PPI. Over a 4-year study period, 463 individuals were selected with clinical suspicion of CAP. The microbial etiology could be determined in 70% of those patients. The remaining 30% were excluded due to an alternative diagnosis. One of the most likely pathogens to cause a CAP infection is Streptococcus pneumoniae (S pneumonia).27 Patients prescribed a PPI were significantly more likely to be infected with S pneumoniae than those not prescribed a PPI (28% vs 11%). The study concluded that the risk of S pneumoniae in patients taking a PPI was 2.23 times more likely (95% CI, 1.28-3.75).28

Dementia

In 2040, it is estimated that more than 80 million people will have from dementia.29 This is expected to become a large fiscal burden on the health care system. In 2010, about $604 billion was spent on therapy for dementia worldwide.30 Although no cure for dementia exists, it is more feasible than in previous years to prevent its occurrence. However, many medications, including PPIs, are associated with the development of dementia; therefore, it is important to minimize their use when possible.

As noted earlier vitamin B12 deficiency may lead to cognitive decline. Due to the malabsorption of vitamin B12 that results from PPI use, it is hypothesized that PPIs may be associated with incidence of dementia. Badiola and colleagues discovered that in the brains of mice given a PPI, levels of β-amyloid increased significantly affecting enzymes responsible for cognition.31 In a February 2016, JAMA article, researchers conducted a prospective cohort study evaluating 73,679 patients aged ≥75 years with no dementia at baseline. They went on to assess regular use of a PPI, defined as at least 1 PPI prescription every 3 months, and the incidence of dementia. Patients with regular use of a PPI (≥ 1 PPI prescription every 3 months) had a 44% increase risk of incident dementia (HR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.36-1.52; P < .001).3 Therefore, it is theorized that avoiding PPI use in the elderly may prevent the development of dementia.

Chronic Kidney Disease

The prevalence of CKD has drastically increased in recent decades. It is estimated that up to 13% of people in the U.S. are affected by CKD.32 Some studies suggest that dosing errors occur at much higher rates in patients with declined glomerular filtration rate (GFR).33 The correct utilization use of medications becomes especially pertinent to this population. Several studies have already linked PPI use to acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) and acute kidney injury (AKI).34-36

Lazarus and colleagues evaluated the association between PPI use and the incidence of CKD. Their analysis was performed in a long-term running population-based cohort and replicated in a separate health care system. In the running cohort, patients receiving a PPI had a 1.45-fold greater chance of developing CKD (95% CI, 1.11-1.90; P = .006). In that same cohort, patients on a PPI had a 1.72-fold increase risk of AKI (95% CI, 1.28-2.30; P < .001).4 Similar outcomes were seen in the replicated cohort. However, the replicated cohort did observe that twice daily dosing of a PPI (adjusted HR, 1.46; CI, 1.28-1.67; P < .001) had a stronger association with CKD than once- daily dosing (adjusted HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.09-1.21; P < .001). H2RAs exhibited no association with CKD in the running cohort (HR, 1.15; 97% CI, 0.98-1.36; P = .10) or the replication cohort (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.88-0.99; P = .03).4

Clinical PPI Recommendations

There are several FDA-approved and unapproved indications that warrant PPI therapy. Proton pump inhibitor indications include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), peptic ulcer disease (PUD), Helicobacter pylori, and ulcers associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

GERD Recommendations

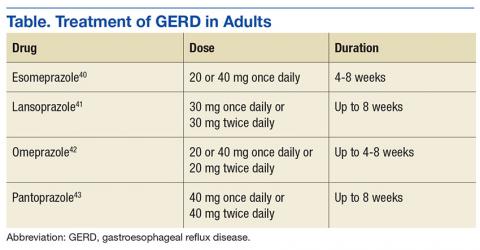

Optimal dosing and duration is important with all medications to maximize efficacy and minimize toxicity. In the case of PPIs, dosing and duration are of particularly concern due to the aforementioned AEs. Table illustrates manufacturer-recommended dosing and duration for the most commonly prescribed PPIs. Although these dosing regimens are based on clinical studies, PPIs are commonly prescribed at higher doses and for longer durations. By extending the duration of therapy, the risk of potential long-term AEs increases dramatically. If durations are limited to the recommended window, risk of AEs can be reduced.

Alternative Therapies

There are several strategies that exist to limit the use of PPIs, including lifestyle modifications to prevent GERD, supplementation of an alternative agent to prevent high doses of the PPI, or discontinuing PPI therapy all together. Lifestyle modifications provide additional benefit as monotherapy or to supplement a pharmacologic regimen.

The American Journal of Gastroenterology promoted lifestyle modifications that include:

- Weight loss for patients with GERD who are overweight and had a recent weight gain;

- Elevation of the head of the bed (if nighttime symptoms present);

- Elimination of dietary triggers;

- Fatty foods, caffeine, chocolate, spicy food, food with high fat content, carbonated beverages, and peppermint;

- Avoiding tight fitting garments to prevent increase in gastric pressure;

- Promote salivation through oral lozenges or chewing gum to neutralize refluxed acid;

- Avoidance of tobacco and alcohol; and

- Abdominal breathing exercise to strengthen the barrier of the lower esophageal sphincter.37

The above modifications may reduce the need for pharmacologic therapy, thereby reducing possible of long-term AEs.

If lifestyle modifications alone are not enough, it is reasonable to use a H2RA for acute symptom relief or reduce high doses and frequencies of a PPI. H2RAs are well studied and effective in the management of GERD. According to the American College of Gastroenterology 2013 clinical practice guidelines, H2RAs can serve as an effective maintenance medication to relieve heartburn in patients without erosive disease. The guideline also states that a bedtime H2RA can be used to supplement a once- daily daytime PPI if nighttime reflux exists. This can eliminate the need to exceed manufacturer-recommended doses.37

One of the final challenges to overcome is a patient that has been maintained on chronic PPI therapy. However, caution should be exercised if choosing to discontinue a PPI. In a study by Niklesson and colleagues, after a 4-week course of pantoprazole given to healthy volunteers, those patients with no preexisting symptoms developed dyspeptic symptoms of GERD, such as heartburn, indigestion, and stomach discomfort. This correlation suggests that a rebound hypersecretion occurs after prolonged suppression of the proton pump, and therefore a gradual taper should be used.38 Although no definitive national recommendations on how to taper a patient off of a PPI exist, one suggestion is a 2- to 3-week taper by using a half-dose once daily or full dose on alternate days.39 This strategy has exhibited moderate success rates when used. Oral and written education on symptom management and the administration of H2RAs for infrequent breakthrough symptoms supplemented the reduction of the PPI.

Conclusion

Proton pump inhibitors have become a popular and effective drug class for a multitude of indications. However, it is crucial to recognize the risk of long-term use. It is important to properly assess the need for a PPI and to use appropriate dosing and duration, since prolonged durations and doses above the manufacturer’s recommendations is a primary contributor to long-term consequences. Both package inserts and clinical guidelines serve as valuable resources to help balance the risks and benefits of this medication class and can help guide therapeutic decisions.

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Low magnesium levels can be associated with long-term use of Proton Pump Inhibitor drugs (PPIs). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm245011.htm. Updated April 7, 2016. Accessed January 12, 2017.

2. Forgacs I. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ. 2008;336(7634):2-3.

3. Gomm W, von Holt K, Thome F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(4):410-416.

4. Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):238-246.

5. Wolfe MM, Soll AH. The physiology of gastric acid secretion. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(26):1707-1715.

6. Flynn A. The role of dietary calcium in bone health. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62(4):851-858.

7. Mizunashi K, Furukawa Y, Katano K, Abe K. Effect of omeprazole, an inhibitor of H+, K(+)-ATPase, on bone resorption in humans. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;53(1):21-25.

8. O’Connell MB, Darren DM, Murray AM, Heaney RP, Kerzner LJ. Effects of proton pump inhibitors on calcium carbonate absorption in women: a randomized crossover trial. Am J Med. 2005;118(7):778-781.

9. Khalili H, Huang ES, Jacobson BC, Camargo CA Jr, Feskanich D, Chan AT. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of hip fracture in relation to dietary and lifestyle factors: a prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e372.

10. Schweigel M, Martens H. Magnesium transport in the gastrointestinal tract. Front Biosci. 2000;5:D666-D677.

11. Hess MW, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, Drenth JP. Systematic review: hypomagnesaemia induced by proton pump inhibition. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(5):405-413.

12. William JH, Danziger J. Proton-pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia: current research and proposed mechanisms. World J Nephrol. 2016;5(2):152-157.

13. Luk CP, Parsons R, Lee YP, Hughes JD. Proton pump inhibitor-associated hypomagnesemia: what do FDA data tell us? Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(6):773-780.

14. Health Quality Ontario. Vitamin B12 and cognitive function: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2013;13(23):1-45.

15. Green R, Kinsella LJ. Current concepts in the diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1435-1440.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Healthy Brain Initiative. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/2013-healthy-brain-initiative.pdf. Accessed January 17, 2017.

17. Toh BH, van Driel IR, Gleeson PA. Pernicious anemia. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(20):1441-1448.

18. Tefferi A, Pruthi RK. The biochemical basis of cobalamin deficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69(2):181-186.

19. Lam JR, Schneider JL, Zhao W, Corley DA. Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2435-2442.

20. Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):825-834.

21. National Clostridium difficile Standards Group. National Clostridium difficile Standards Group: report to the Department of Health. J Hosp Infect. 2004;56(suppl 1):1-38.

22. Thorens J, Frohlich F, Schwizer W, et al. Bacterial overgrowth during treatment with omeprazole compared with cimetidine. Gut. 1996;39(1):54-59.

23. Dial S, Delaney JAC, Barkun AN, et al. Use of gastric acid-suppressive agents and the risk of community-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated disease. JAMA. 2005;294(23):2989-2995

24. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America; and American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 2):S27-S72.

25. Laheij RJ, Sturkenboom MC, Hassing RJ, Dieleman J, Stricker BH, Jansen JB. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia and use of gastric acid-suppressive drugs. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1955-1960.

26. Sarkar M, Hennessy S, Yang Y. Proton-pump inhibitor use and the risk for community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(6):391-398.

27. Waterer GW, Wunderink RG. The influence of the severity of community-acquired pneumonia on the usefulness of blood cultures. Respir Med. 2001;95(1):78-82.

28. de Jagar CP, Wever PC, Gemen EF, et al. Proton pump inhibitor therapy predisposes to community-acquired Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(10):941-949.

29. Reitz C, Brayne C, Mayeux R. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(3):137-152.

30. Wimo A, Jönsson L, Bond J, Prince M, Winblad B; Alzheimer Disease International. The worldwide economic impact of dementia 2010. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):1-11.

31. Badiola N, Alcalde V, Pujol A, et al. The proton-pump inhibitor lansoprazole enhances amyloid beta production. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58537.

32. Stevens LA, Li S, Wang C, et al. Prevalence of CKD and comorbid illness in elderly patients in the United States: results from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3)(suppl 2):S23-S33.

33. Weir MR, Fink JC. Safety of medical therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2014;23(3):306-313.

34. Blank ML, Parkin L, Paul C, Herbison P. A nationwide nested case-control study indicates an increased risk of acute interstitial nephritis with proton pump inhibitor use. Kidney Int. 2014;86(4):837-844.

35. Antoniou T, Macdonald EM, Holland S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of acute kidney injury in older patients: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3(2):E166-E171.

36. Klepser DG, Collier DS, Cochran GL. Proton pump inhibitors and acute kidney injury: a nested case-control study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:150.

37. Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(3):308-328.

38. Niklasson A, Lindström L, Simrén M, Lindberg G, Björnsson E. Dyspeptic symptom development after discontinuation of a proton pump inhibitor: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(7):1531-1537.

39. Haastrup P, Paulsen MS, Begtrup LM, Hansen JM, Jarbøl DE. Strategies for discontinuation of proton pump inhibitors: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31(6):625-630.

40. Nexium [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals; 2012.

41. Prevacid [package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals; 2012.

42. Prilosec [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals; 2012.

43. Protonix [package insert]. Konstanz, Germany: Pfizer; 2012.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are one of the most frequently used drug classes, given that they are readily accessible over-the-counter as well as via prescription. About 100 million PPI prescriptions dispensed an

The human stomach uses 3 primary neurotransmitters that regulate gastric acid secretion: acetylcholine (ACh), histamine (H), and gastrin (G). The interactions between these neurotransmitters promote and inhibit hydrogen ion (H+) generation. Stimulation of their corresponding receptors draws H+ into parietal cells that line the stomach. Once in the cell, a H+-K+-ATPase (more commonly known as the proton pump) actively transports H+ into the lumen of the stomach. The H+ bind with chlorine ions to form hydrochloric acid, which increases stomach acidity.5 Histamine receptors were thought to be responsible for the greatest degree of stimulation. Hence, histamine type 2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) became a novel means of therapy to reduce stomach acidity. While utilizing H2RAs was effective, it was theorized the downstream inhibition of the action of all 3 neurotransmitters would serve as a more successful therapy. Therefore, PPIs were developed to target the H+-K+-ATPase Over the past decade, many studies have evaluated the long-term PPI adverse effects (AEs). These include calcium and magnesium malabsorption, vitamin B12 deficiency, Clostridium difficile (C difficile) associated disease (CDAD), and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). Within the past year, data have become available linking PPI use to dementia and chronic kidney disease (CKD).3,4 The following article reviews literature on the safety of long-term PPI use and proposes recommendations for proper use for their most common indications.

Malabsorption

Calcium & Long-Term Fracture Risk

Calcium is an essential component in bone health and formation. In fact, 99% of all calcium found in the body is stored in bones.6 The primary source of calcium is through diet and oral supplements. After it is ingested, calcium is absorbed from the stomach into the blood in a pH dependent manner. If the pH of the stomach is too high (ie, too basic) calcium is not absorbed into blood and remains in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract for fecal excretion. Without sufficient calcium, the body’s osteoclasts and osteoblasts remain inactive, which hinders proper bone turnover.7

The decrease in acidity leads to calcium malabsorption and increases fracture risk long- term.8 Khalili and colleagues surveyed 80,000 postmenopausal women to measure the incidence of hip fracture in women taking PPIs. The study found that there was a 35% increase in risk of hip fracture among women who regularly used PPIs for at least 2 years (age-adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 1.35; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.13 -1.62). Adjusted HRs for 4-year and 6- to 8-year use of a PPI was 1.42 (95% CI, 1.05-1.93) and 1.55 (95% CI, 1.03-2.32), respectively, indicating that the longer women were on PPI therapy, the higher the risk of hip fracture. The study also evaluated the time since stopping PPI and the risk of hip fracture. Women who stopped PPI use more than 2 years prior had a similar risk to that of women who never used a PPI, indicating that the effect was reversible.9

Magnesium

Magnesium is an important intracellular ion that has a number of key functions in metabolism and ion transport in the human body. Once ingested, magnesium is absorbed into the bloodstream from the small and large intestines via passive and active transport. Transient receptor potential melastatin 6 (TRPM6) is one of the essential proteins that serve as a transporter for magnesium.10 The high affinity for magnesium of these transporters allows them to maintain adequate levels of magnesium in the blood. In states of low magnesium (hypomagnesemia), the body is at risk for many AEs including seizures, arrhythmias, tetany, and hypotension.11

Proton pump inhibitors have been linked to hypomagnesemia, and recent evaluation has clarified a potential mechanism.12 TRPM6 activity is increased in an acidic environment. When a PPI increases the pH of the stomach, TRPM6 and magnesium levels decrease.12 Luk and colleagues identified 66,102 subjects experiencing AEs while taking a PPI. Hypomagnesemia had a prevalence rate of 1% in these patients. According to the researchers, PPIs were associated with hypomagnesemia and that pantoprazole had the highest incidence among all other PPIs studied (OR, 4.3; 95% CI, 3.3 – 5.7; P < .001).13

Vitamin B12

In recent years, vitamin B12 has been the subject of many studies. An area of concern is vitamin B12’s neurologic effect, as it has been successfully demonstrated that vitamin B12 is essential for proper cognitive function.14 Some data suggest that degeneration is present in parts of the spinal column in patients with cognitive decline or neurologic problems. These lesions are due to improper myelin formation and are specific to vitamin B12 deficiency.15 In 2013 the CDC published the Healthy Brain Initiative, which stated cognitive impairment can be caused by vitamin B12 deficiency.16

Similar to calcium, vitamin B12 needs an acidic environment to be digested and absorbed.17 Vitamin B12 is released from food proteins via gastric acid and pepsin. Once free, the vitamin B12 pairs with R-binders secreted in the stomach. Pancreatic enzymes then degrade this complex into a form that can be absorbed into circulation by the intestine. Given that PPIs reduce the acidity of the stomach, they also reduce the body’s ability to release vitamin B12 from food proteins and be paired with the R-binders.18

In 2013, Lam and colleagues evaluated the association between vitamin B12 deficiency and the use of PPIs and H2RAs. An extensive evaluation was performed on 25,956 patients with a diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency and 184,199 patients without. About 12% of patients with vitamin B12 deficiency had received more than a 2-year supply of a PPI, whereas only 7.2% of the patients without vitamin B12 deficiency received a 2-year supply of a PPI. Four point 3 percent of patients with vitamin B12 deficiency received more than a 2-year supply of an H2RA. Only 3.2% of patients without vitamin B12 deficiency received more than a 2-year supply of H2RA. The study concluded that a 2-year or greater history of PPI (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.58-1.73) or H2RA (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.17-1.34) use was associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.19

PPIs and Infections

Clostridium difficile-associated disease

Nationwide CDAD has become a prevalent infection nationwide. In 2011, C difficile caused nearly 500,000 infections and was associated with 29,000 deaths in the U.S.20 One study stated that C difficile is the third most common cause of infectious diarrhea in people aged >75 years.21

C difficile is part of the body’s normal flora in the large intestine. It grows and colonizes in an environment of low acidity. Therefore, in the stomach, where the pH is relatively low, C difficile is unable to colonize.22 When a PPI is introduced, the increased gastric pH increases the risk for CDAD.

Dial and colleagues conducted a multicenter case control study to determine whether gastric acid suppression increases the risk of CDAD. Compared with patients who did not take a gastric acid suppressant, those taking a PPI had a 2.9-fold increase in developing CDAD (95% CI, 2.4-3.4). Comparatively, H2RAs had a 2.0-fold increase for CDAD (95% CI, 1.6 to 2.7). These results correlated with the fact that PPIs have a greater impact on gastric pH than do H2RAs.23

Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) has become a growing concern in the U.S. According to the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and American Thoracic clinical consensus guidelines, CAP remains one of the top reasons for hospitalizations in the U.S., and about 10% of patients admitted to the hospital for CAP end up in the intensive care unit (ICU).24 In the past, PPIs have been linked to patients’ predisposal for developingCAP.25 Although controversial, available evidence suggests a direct association. In 2008 Sarker and colleagues theorized a mechanism that the acid reduction of the gastric lumen allows for increased bacterial colonization in the upper part of the GI tract.26 Since the acidity of the stomach serves as a defense mechanism against many ingested bacteria, many pathogens will be able to survive in the more basic environment.25

Sarkar and colleagues went on to evaluate 80,000 cases over 15 years. The objective was to examine the association between PPI use and the date of diagnosis of the CAP infection, known as the index date. The study demonstrated that PPI use was not associated with increased CAP risk in the long-term (adjusted odds ratio (OR), 1.02; 95% CI, 0.97-1.08). The study did find a strong increase in the risk of CAP if a PPI was started within 2 days (adjusted OR, 6.53; 95% CI, 3.95-10.80), 7 days (adjusted OR, 3.79; 95% CI, 2.66-5.42), and 14 days (adjusted OR, 3.21; 95% CI, 2.46-4.18) of the index date.26

Four years later, de Jagar and colleagues examined the differences in microbial etiology in CAP patients with and without an active PPI. Over a 4-year study period, 463 individuals were selected with clinical suspicion of CAP. The microbial etiology could be determined in 70% of those patients. The remaining 30% were excluded due to an alternative diagnosis. One of the most likely pathogens to cause a CAP infection is Streptococcus pneumoniae (S pneumonia).27 Patients prescribed a PPI were significantly more likely to be infected with S pneumoniae than those not prescribed a PPI (28% vs 11%). The study concluded that the risk of S pneumoniae in patients taking a PPI was 2.23 times more likely (95% CI, 1.28-3.75).28

Dementia

In 2040, it is estimated that more than 80 million people will have from dementia.29 This is expected to become a large fiscal burden on the health care system. In 2010, about $604 billion was spent on therapy for dementia worldwide.30 Although no cure for dementia exists, it is more feasible than in previous years to prevent its occurrence. However, many medications, including PPIs, are associated with the development of dementia; therefore, it is important to minimize their use when possible.

As noted earlier vitamin B12 deficiency may lead to cognitive decline. Due to the malabsorption of vitamin B12 that results from PPI use, it is hypothesized that PPIs may be associated with incidence of dementia. Badiola and colleagues discovered that in the brains of mice given a PPI, levels of β-amyloid increased significantly affecting enzymes responsible for cognition.31 In a February 2016, JAMA article, researchers conducted a prospective cohort study evaluating 73,679 patients aged ≥75 years with no dementia at baseline. They went on to assess regular use of a PPI, defined as at least 1 PPI prescription every 3 months, and the incidence of dementia. Patients with regular use of a PPI (≥ 1 PPI prescription every 3 months) had a 44% increase risk of incident dementia (HR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.36-1.52; P < .001).3 Therefore, it is theorized that avoiding PPI use in the elderly may prevent the development of dementia.