User login

Parabens: The 2019 Nonallergen of the Year

Each year, the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) names an allergen of the year with the purpose of promoting greater awareness of a key allergen and its impact on patients. Often, the allergen of the year is an emerging allergen that may represent an underrecognized or novel cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). In 2019, the ACDS chose parabens as the “nonallergen” of the year to draw attention to their low rate of associated ACD despite high public interest in limiting exposure to parabens.1

What types of products contain parabens?

Parabens are preservatives commonly found in many different categories of personal care products. Preservatives inhibit microbial growth and are necessary ingredients in water-based products. The 4 most common parabens used in personal care products are methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben.1 Parabens are metabolized to 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and are excreted in urine. When parabens are applied topically, there is minimal penetration through intact human skin.2 In the United States, parabens are allowed as preservatives in cosmetics at concentrations up to 0.4% when used alone or up to 0.8% when used in combination with other parabens.3

Consumers are exposed to parabens in a wide variety of personal care products. The Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) is a system owned and managed by the ACDS that typically is used to generate lists of safe personal care products for patients and also can be queried for the presence of individual chemicals in products. According to a 2018 query of the CAMP, parabens were found in 19% of all products.1 A more recent query of CAMP (http://www.contactderm.org/resources/acds-camp) in March 2019 showed parabens were present in 39.3% of makeup products, especially in eye products, foundations, and concealers; parabens also were found in 34% of moisturizers, 11.5% of soaps, and 19% of sunscreens. Notably, 14.8% of prescription topical steroids listed in the CAMP contained a paraben. Another method for evaluating chemical contents of personal care products is a review of the Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program, a US Food and Drug Administration–based registry for cosmetic products. Survey data from the Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program in 2018 documented methylparaben in 11,626 formulations.4 Other parabens included propylparaben (8885 products), butylparaben (3915 products), and ethylparaben (3860 products). Parabens were reported more frequently in leave-on rather than rinse-off products.4

In medications, parabens are recommended at concentrations of no more than 0.1%.1 Fransway et al1 compiled a list of medications that contain parabens, including commonly prescribed dermatologic topical medications such as corticosteroids, several acne preparations, eflornithine, fluorouracil, hydroquinone, imiquimod, urea, and sertaconazole. Oral and parenteral medications including local anesthetics and corticosteroids also may contain parabens.

Consumers also may be exposed to parabens through foodstuffs. Methylparaben and propylparaben have been classified as generally recognized as safe in foods by the US Food and Drug Administration.5 The acceptable daily intake of parabens in food is 0 to 10 mg/kg of body weight,1 and the estimated dietary intake for a typical adult is 307 mg/kg of body weight daily.6 Several studies on paraben content in foodstuffs have confirmed their presence in both natural and processed foods.1,6 Systemic contact dermatitis caused by ingestion of parabens is rare. In general, individuals with positive patch test reactions to parabens should not routinely avoid them in foods or oral medications,1 but they should, of course, be avoided in topical medications.

What is the rate of ACD with parabens?

One of the main reasons that parabens were designated as the ACDS nonallergen of the year is the very low rate of ACD associated with parabens. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group, a research group with members in the United States and Canada, reported a 0.6% positive reaction rate when patch testing with paraben mix 12%,7 which closely compares with a 0.8% positive reaction rate when patch testing with paraben mix 16% using the Mayo Clinic standard series.8 From the standpoint of ACD, this very low patch test reaction rate makes parabens one of the safest preservative options for use in cosmetic products.

Are there health risks associated with parabens?

The paraben controversy in the scientific literature and in the lay press centers around potential health risks and endocrine disruption. We will focus on the conversation regarding parabens and the risk for endocrine disruption and association with breast cancer.

Parabens have been reported to have estrogenic effects; however, the bulk of the data is limited to in vitro and animal studies, with less evidence of endocrine disruption in humans.2 In vitro studies have demonstrated that the estrogenic potency of parabens is much less than that of estrogen. In one study, parabens were shown to be 10,000-fold less potent than 17β-estradiol9; in a separate study, they had a maximum potency of only 1/4000 that of estrogen.10 Additionally, an in vitro study showed varying ability for parabens to bind estrogen receptors, with a greater ability to bind with longer alkyl side chains.11 The result is decreased or increased estrogen activity, dependent on side chain length and type of receptor.2 Finally, some studies add conflicting results that parabens may actually create an antiestrogenic effect in human breast cancer cells.12 From the standpoint of estrogen mimicry, there are no known studies in humans confirming harmful effects associated with paraben exposure.

The reported association between parabens and breast cancer is closely related to their theoretical estrogenic effects. The conversation regarding parabens and breast cancer has been fueled by the identification of parabens in human breast tumors and their presence in concentrations similar to what is needed to stimulate in vitro breast cancer cells.2 The existing data do not confirm causation. An association with parabens in topical axillary personal care products has been theorized but not confirmed; for example, it was shown that paraben levels were highest in the axillary region of breast cancer tissue, including women who had never used deodorant. It was concluded that the presence of axillary parabens was due to sources other than topical axillary personal care products.13 Another study confirmed there was not an increased risk for breast cancer in patients who applied personal care products to the axillary area within an hour of shaving.14 The existing data do not support topical paraben exposure as a risk for breast cancer.

Final Thoughts

Parabens are preservatives frequently found in personal care products and exhibit a very low rate of associated ACD. Consumers may be exposed to parabens through foods, cosmetics, and medications. Although there have been consumer concerns regarding endocrine disruption or carcinogenicity associated with parabens, definite evidence of their harm is lacking in the scientific literature, and many studies confirm their safety.2 With their high prevalence in personal care products and low rates of associated contact allergy, parabens remain ideal preservative agents.

Ultimately, contact dermatitis is a common yet often underrecognized dermatologic condition. To address this knowledge gap in clinical practice, we are proud to launch Final Interpretation, a new column in Cutis covering emerging trends in contact dermatitis. We will address pearls, pitfalls, and updates in contact dermatitis. Although our primary focus will be ACD, other important causes of contact dermatitis will be highlighted. Look for the inaugural column in the June 2019 issue of Cutis.

- Fransway AF, Fransway PJ, Belsito DV, et al. Parabens: contact (non)allergen of the year. Dermatitis. 2019;30:3-31.

- Fransway AF, Fransway PJ, Belsito DV, et al. Paraben toxicology. Dermatitis. 2019;30:32-45.

- Final amended report on the safety assessment of methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, isopropylparaben, butylparaben, isobutylparaben, and benzylparaben as used in cosmetic products. Int J Toxicol. 2008;27(suppl 4):1-82.

- Cosmetic Ingredient Review. Amended safety assessment of parabens as used in cosmetics. https://www.cir-safety.org/sites/default/files/Parabens.pdf. Published August 29, 2018. Accessed March 12, 2019.

- Methylparaben. Fed Regist. 2018;21(3):1490. To be codified at 21 CFR §184.

- Liao C, Liu F, Kannan K. Occurrence of and dietary exposure to parabens in foodstuffs from the United States. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:3918-3925.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Zug KA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch Test Results: 2015-2016. Dermatitis. 2018;29:297-309.

- Veverka KK, Hall MR, Yiannias JA, et al. Trends in patch testing with the Mayo Clinic standard series, 2011-2015. Dermatitis. 2018;29:310-315.

- Routledge EJ, Parker J, Odum J, et al. Some alkyl hydroxy benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;153:12-19.

- Miller D, Brian B, Wheals BB, et al. Estrogenic activity of phenolic additives determined by an in vitro yeast bioassay. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:133-138.

- Blair RM, Fang H, Branham WS. The estrogen receptor relative binding affinities of 188 natural and xenochemicals: structural diversity of ligands. Toxicol Sci. 2000;54:138-153.

- van Meeuwen JA, van Son O, Piersma AH, et al. Aromatase inhibiting and combined estrogenic effects of parabens and estrogenic effects of other additives in cosmetics. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;230:372-382.

- Barr L, Metaxas G, Harbach CA, et al. Measurement of paraben concentrations in human breast tissue at serial locations across the breast from axilla to sternum. J Appl Toxicol. 2012;32:219-232.

- Mirick DK, Davis S, Thomas DB. Antiperspirant use and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1578-1580

.

Each year, the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) names an allergen of the year with the purpose of promoting greater awareness of a key allergen and its impact on patients. Often, the allergen of the year is an emerging allergen that may represent an underrecognized or novel cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). In 2019, the ACDS chose parabens as the “nonallergen” of the year to draw attention to their low rate of associated ACD despite high public interest in limiting exposure to parabens.1

What types of products contain parabens?

Parabens are preservatives commonly found in many different categories of personal care products. Preservatives inhibit microbial growth and are necessary ingredients in water-based products. The 4 most common parabens used in personal care products are methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben.1 Parabens are metabolized to 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and are excreted in urine. When parabens are applied topically, there is minimal penetration through intact human skin.2 In the United States, parabens are allowed as preservatives in cosmetics at concentrations up to 0.4% when used alone or up to 0.8% when used in combination with other parabens.3

Consumers are exposed to parabens in a wide variety of personal care products. The Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) is a system owned and managed by the ACDS that typically is used to generate lists of safe personal care products for patients and also can be queried for the presence of individual chemicals in products. According to a 2018 query of the CAMP, parabens were found in 19% of all products.1 A more recent query of CAMP (http://www.contactderm.org/resources/acds-camp) in March 2019 showed parabens were present in 39.3% of makeup products, especially in eye products, foundations, and concealers; parabens also were found in 34% of moisturizers, 11.5% of soaps, and 19% of sunscreens. Notably, 14.8% of prescription topical steroids listed in the CAMP contained a paraben. Another method for evaluating chemical contents of personal care products is a review of the Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program, a US Food and Drug Administration–based registry for cosmetic products. Survey data from the Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program in 2018 documented methylparaben in 11,626 formulations.4 Other parabens included propylparaben (8885 products), butylparaben (3915 products), and ethylparaben (3860 products). Parabens were reported more frequently in leave-on rather than rinse-off products.4

In medications, parabens are recommended at concentrations of no more than 0.1%.1 Fransway et al1 compiled a list of medications that contain parabens, including commonly prescribed dermatologic topical medications such as corticosteroids, several acne preparations, eflornithine, fluorouracil, hydroquinone, imiquimod, urea, and sertaconazole. Oral and parenteral medications including local anesthetics and corticosteroids also may contain parabens.

Consumers also may be exposed to parabens through foodstuffs. Methylparaben and propylparaben have been classified as generally recognized as safe in foods by the US Food and Drug Administration.5 The acceptable daily intake of parabens in food is 0 to 10 mg/kg of body weight,1 and the estimated dietary intake for a typical adult is 307 mg/kg of body weight daily.6 Several studies on paraben content in foodstuffs have confirmed their presence in both natural and processed foods.1,6 Systemic contact dermatitis caused by ingestion of parabens is rare. In general, individuals with positive patch test reactions to parabens should not routinely avoid them in foods or oral medications,1 but they should, of course, be avoided in topical medications.

What is the rate of ACD with parabens?

One of the main reasons that parabens were designated as the ACDS nonallergen of the year is the very low rate of ACD associated with parabens. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group, a research group with members in the United States and Canada, reported a 0.6% positive reaction rate when patch testing with paraben mix 12%,7 which closely compares with a 0.8% positive reaction rate when patch testing with paraben mix 16% using the Mayo Clinic standard series.8 From the standpoint of ACD, this very low patch test reaction rate makes parabens one of the safest preservative options for use in cosmetic products.

Are there health risks associated with parabens?

The paraben controversy in the scientific literature and in the lay press centers around potential health risks and endocrine disruption. We will focus on the conversation regarding parabens and the risk for endocrine disruption and association with breast cancer.

Parabens have been reported to have estrogenic effects; however, the bulk of the data is limited to in vitro and animal studies, with less evidence of endocrine disruption in humans.2 In vitro studies have demonstrated that the estrogenic potency of parabens is much less than that of estrogen. In one study, parabens were shown to be 10,000-fold less potent than 17β-estradiol9; in a separate study, they had a maximum potency of only 1/4000 that of estrogen.10 Additionally, an in vitro study showed varying ability for parabens to bind estrogen receptors, with a greater ability to bind with longer alkyl side chains.11 The result is decreased or increased estrogen activity, dependent on side chain length and type of receptor.2 Finally, some studies add conflicting results that parabens may actually create an antiestrogenic effect in human breast cancer cells.12 From the standpoint of estrogen mimicry, there are no known studies in humans confirming harmful effects associated with paraben exposure.

The reported association between parabens and breast cancer is closely related to their theoretical estrogenic effects. The conversation regarding parabens and breast cancer has been fueled by the identification of parabens in human breast tumors and their presence in concentrations similar to what is needed to stimulate in vitro breast cancer cells.2 The existing data do not confirm causation. An association with parabens in topical axillary personal care products has been theorized but not confirmed; for example, it was shown that paraben levels were highest in the axillary region of breast cancer tissue, including women who had never used deodorant. It was concluded that the presence of axillary parabens was due to sources other than topical axillary personal care products.13 Another study confirmed there was not an increased risk for breast cancer in patients who applied personal care products to the axillary area within an hour of shaving.14 The existing data do not support topical paraben exposure as a risk for breast cancer.

Final Thoughts

Parabens are preservatives frequently found in personal care products and exhibit a very low rate of associated ACD. Consumers may be exposed to parabens through foods, cosmetics, and medications. Although there have been consumer concerns regarding endocrine disruption or carcinogenicity associated with parabens, definite evidence of their harm is lacking in the scientific literature, and many studies confirm their safety.2 With their high prevalence in personal care products and low rates of associated contact allergy, parabens remain ideal preservative agents.

Ultimately, contact dermatitis is a common yet often underrecognized dermatologic condition. To address this knowledge gap in clinical practice, we are proud to launch Final Interpretation, a new column in Cutis covering emerging trends in contact dermatitis. We will address pearls, pitfalls, and updates in contact dermatitis. Although our primary focus will be ACD, other important causes of contact dermatitis will be highlighted. Look for the inaugural column in the June 2019 issue of Cutis.

Each year, the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) names an allergen of the year with the purpose of promoting greater awareness of a key allergen and its impact on patients. Often, the allergen of the year is an emerging allergen that may represent an underrecognized or novel cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). In 2019, the ACDS chose parabens as the “nonallergen” of the year to draw attention to their low rate of associated ACD despite high public interest in limiting exposure to parabens.1

What types of products contain parabens?

Parabens are preservatives commonly found in many different categories of personal care products. Preservatives inhibit microbial growth and are necessary ingredients in water-based products. The 4 most common parabens used in personal care products are methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben.1 Parabens are metabolized to 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and are excreted in urine. When parabens are applied topically, there is minimal penetration through intact human skin.2 In the United States, parabens are allowed as preservatives in cosmetics at concentrations up to 0.4% when used alone or up to 0.8% when used in combination with other parabens.3

Consumers are exposed to parabens in a wide variety of personal care products. The Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) is a system owned and managed by the ACDS that typically is used to generate lists of safe personal care products for patients and also can be queried for the presence of individual chemicals in products. According to a 2018 query of the CAMP, parabens were found in 19% of all products.1 A more recent query of CAMP (http://www.contactderm.org/resources/acds-camp) in March 2019 showed parabens were present in 39.3% of makeup products, especially in eye products, foundations, and concealers; parabens also were found in 34% of moisturizers, 11.5% of soaps, and 19% of sunscreens. Notably, 14.8% of prescription topical steroids listed in the CAMP contained a paraben. Another method for evaluating chemical contents of personal care products is a review of the Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program, a US Food and Drug Administration–based registry for cosmetic products. Survey data from the Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program in 2018 documented methylparaben in 11,626 formulations.4 Other parabens included propylparaben (8885 products), butylparaben (3915 products), and ethylparaben (3860 products). Parabens were reported more frequently in leave-on rather than rinse-off products.4

In medications, parabens are recommended at concentrations of no more than 0.1%.1 Fransway et al1 compiled a list of medications that contain parabens, including commonly prescribed dermatologic topical medications such as corticosteroids, several acne preparations, eflornithine, fluorouracil, hydroquinone, imiquimod, urea, and sertaconazole. Oral and parenteral medications including local anesthetics and corticosteroids also may contain parabens.

Consumers also may be exposed to parabens through foodstuffs. Methylparaben and propylparaben have been classified as generally recognized as safe in foods by the US Food and Drug Administration.5 The acceptable daily intake of parabens in food is 0 to 10 mg/kg of body weight,1 and the estimated dietary intake for a typical adult is 307 mg/kg of body weight daily.6 Several studies on paraben content in foodstuffs have confirmed their presence in both natural and processed foods.1,6 Systemic contact dermatitis caused by ingestion of parabens is rare. In general, individuals with positive patch test reactions to parabens should not routinely avoid them in foods or oral medications,1 but they should, of course, be avoided in topical medications.

What is the rate of ACD with parabens?

One of the main reasons that parabens were designated as the ACDS nonallergen of the year is the very low rate of ACD associated with parabens. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group, a research group with members in the United States and Canada, reported a 0.6% positive reaction rate when patch testing with paraben mix 12%,7 which closely compares with a 0.8% positive reaction rate when patch testing with paraben mix 16% using the Mayo Clinic standard series.8 From the standpoint of ACD, this very low patch test reaction rate makes parabens one of the safest preservative options for use in cosmetic products.

Are there health risks associated with parabens?

The paraben controversy in the scientific literature and in the lay press centers around potential health risks and endocrine disruption. We will focus on the conversation regarding parabens and the risk for endocrine disruption and association with breast cancer.

Parabens have been reported to have estrogenic effects; however, the bulk of the data is limited to in vitro and animal studies, with less evidence of endocrine disruption in humans.2 In vitro studies have demonstrated that the estrogenic potency of parabens is much less than that of estrogen. In one study, parabens were shown to be 10,000-fold less potent than 17β-estradiol9; in a separate study, they had a maximum potency of only 1/4000 that of estrogen.10 Additionally, an in vitro study showed varying ability for parabens to bind estrogen receptors, with a greater ability to bind with longer alkyl side chains.11 The result is decreased or increased estrogen activity, dependent on side chain length and type of receptor.2 Finally, some studies add conflicting results that parabens may actually create an antiestrogenic effect in human breast cancer cells.12 From the standpoint of estrogen mimicry, there are no known studies in humans confirming harmful effects associated with paraben exposure.

The reported association between parabens and breast cancer is closely related to their theoretical estrogenic effects. The conversation regarding parabens and breast cancer has been fueled by the identification of parabens in human breast tumors and their presence in concentrations similar to what is needed to stimulate in vitro breast cancer cells.2 The existing data do not confirm causation. An association with parabens in topical axillary personal care products has been theorized but not confirmed; for example, it was shown that paraben levels were highest in the axillary region of breast cancer tissue, including women who had never used deodorant. It was concluded that the presence of axillary parabens was due to sources other than topical axillary personal care products.13 Another study confirmed there was not an increased risk for breast cancer in patients who applied personal care products to the axillary area within an hour of shaving.14 The existing data do not support topical paraben exposure as a risk for breast cancer.

Final Thoughts

Parabens are preservatives frequently found in personal care products and exhibit a very low rate of associated ACD. Consumers may be exposed to parabens through foods, cosmetics, and medications. Although there have been consumer concerns regarding endocrine disruption or carcinogenicity associated with parabens, definite evidence of their harm is lacking in the scientific literature, and many studies confirm their safety.2 With their high prevalence in personal care products and low rates of associated contact allergy, parabens remain ideal preservative agents.

Ultimately, contact dermatitis is a common yet often underrecognized dermatologic condition. To address this knowledge gap in clinical practice, we are proud to launch Final Interpretation, a new column in Cutis covering emerging trends in contact dermatitis. We will address pearls, pitfalls, and updates in contact dermatitis. Although our primary focus will be ACD, other important causes of contact dermatitis will be highlighted. Look for the inaugural column in the June 2019 issue of Cutis.

- Fransway AF, Fransway PJ, Belsito DV, et al. Parabens: contact (non)allergen of the year. Dermatitis. 2019;30:3-31.

- Fransway AF, Fransway PJ, Belsito DV, et al. Paraben toxicology. Dermatitis. 2019;30:32-45.

- Final amended report on the safety assessment of methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, isopropylparaben, butylparaben, isobutylparaben, and benzylparaben as used in cosmetic products. Int J Toxicol. 2008;27(suppl 4):1-82.

- Cosmetic Ingredient Review. Amended safety assessment of parabens as used in cosmetics. https://www.cir-safety.org/sites/default/files/Parabens.pdf. Published August 29, 2018. Accessed March 12, 2019.

- Methylparaben. Fed Regist. 2018;21(3):1490. To be codified at 21 CFR §184.

- Liao C, Liu F, Kannan K. Occurrence of and dietary exposure to parabens in foodstuffs from the United States. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:3918-3925.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Zug KA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch Test Results: 2015-2016. Dermatitis. 2018;29:297-309.

- Veverka KK, Hall MR, Yiannias JA, et al. Trends in patch testing with the Mayo Clinic standard series, 2011-2015. Dermatitis. 2018;29:310-315.

- Routledge EJ, Parker J, Odum J, et al. Some alkyl hydroxy benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;153:12-19.

- Miller D, Brian B, Wheals BB, et al. Estrogenic activity of phenolic additives determined by an in vitro yeast bioassay. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:133-138.

- Blair RM, Fang H, Branham WS. The estrogen receptor relative binding affinities of 188 natural and xenochemicals: structural diversity of ligands. Toxicol Sci. 2000;54:138-153.

- van Meeuwen JA, van Son O, Piersma AH, et al. Aromatase inhibiting and combined estrogenic effects of parabens and estrogenic effects of other additives in cosmetics. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;230:372-382.

- Barr L, Metaxas G, Harbach CA, et al. Measurement of paraben concentrations in human breast tissue at serial locations across the breast from axilla to sternum. J Appl Toxicol. 2012;32:219-232.

- Mirick DK, Davis S, Thomas DB. Antiperspirant use and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1578-1580

.

- Fransway AF, Fransway PJ, Belsito DV, et al. Parabens: contact (non)allergen of the year. Dermatitis. 2019;30:3-31.

- Fransway AF, Fransway PJ, Belsito DV, et al. Paraben toxicology. Dermatitis. 2019;30:32-45.

- Final amended report on the safety assessment of methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, isopropylparaben, butylparaben, isobutylparaben, and benzylparaben as used in cosmetic products. Int J Toxicol. 2008;27(suppl 4):1-82.

- Cosmetic Ingredient Review. Amended safety assessment of parabens as used in cosmetics. https://www.cir-safety.org/sites/default/files/Parabens.pdf. Published August 29, 2018. Accessed March 12, 2019.

- Methylparaben. Fed Regist. 2018;21(3):1490. To be codified at 21 CFR §184.

- Liao C, Liu F, Kannan K. Occurrence of and dietary exposure to parabens in foodstuffs from the United States. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:3918-3925.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Zug KA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch Test Results: 2015-2016. Dermatitis. 2018;29:297-309.

- Veverka KK, Hall MR, Yiannias JA, et al. Trends in patch testing with the Mayo Clinic standard series, 2011-2015. Dermatitis. 2018;29:310-315.

- Routledge EJ, Parker J, Odum J, et al. Some alkyl hydroxy benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;153:12-19.

- Miller D, Brian B, Wheals BB, et al. Estrogenic activity of phenolic additives determined by an in vitro yeast bioassay. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:133-138.

- Blair RM, Fang H, Branham WS. The estrogen receptor relative binding affinities of 188 natural and xenochemicals: structural diversity of ligands. Toxicol Sci. 2000;54:138-153.

- van Meeuwen JA, van Son O, Piersma AH, et al. Aromatase inhibiting and combined estrogenic effects of parabens and estrogenic effects of other additives in cosmetics. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;230:372-382.

- Barr L, Metaxas G, Harbach CA, et al. Measurement of paraben concentrations in human breast tissue at serial locations across the breast from axilla to sternum. J Appl Toxicol. 2012;32:219-232.

- Mirick DK, Davis S, Thomas DB. Antiperspirant use and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1578-1580

.

Dermatologists name isobornyl acrylate contact allergen of the year

WASHINGTON – The American Contact Dermatitis Society has selected isobornyl acrylate the contact allergen of the year. It is an acrylic monomer used as an adhesive.

Among other applications, isobornyl acrylate is often used in medical devices. The selection was made based in part on multiple case reports of diabetes patients developing contact allergies to their diabetes devices, such as insulin pumps, explained Golara Honari, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, who presented the selection at the ACDS annual meeting.

The significance of this allergen is that testing through routine panels does not identify it, so clinician awareness is especially important, Dr. Honari noted in a video interview at the meeting.

Most of the reported contact allergen cases have been in patients with diabetes, but clinicians should think about other possible sources, such as acrylic nails, she said. As for treatment, clinicians and patients can consider alternative diabetes devices without isobornyl acrylate, she said.

In the future, close collaboration between clinicians and the medical device industry to develop appropriate labeling can help increase awareness of the potential for allergic reactions, she added.

Dr. Honari had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – The American Contact Dermatitis Society has selected isobornyl acrylate the contact allergen of the year. It is an acrylic monomer used as an adhesive.

Among other applications, isobornyl acrylate is often used in medical devices. The selection was made based in part on multiple case reports of diabetes patients developing contact allergies to their diabetes devices, such as insulin pumps, explained Golara Honari, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, who presented the selection at the ACDS annual meeting.

The significance of this allergen is that testing through routine panels does not identify it, so clinician awareness is especially important, Dr. Honari noted in a video interview at the meeting.

Most of the reported contact allergen cases have been in patients with diabetes, but clinicians should think about other possible sources, such as acrylic nails, she said. As for treatment, clinicians and patients can consider alternative diabetes devices without isobornyl acrylate, she said.

In the future, close collaboration between clinicians and the medical device industry to develop appropriate labeling can help increase awareness of the potential for allergic reactions, she added.

Dr. Honari had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – The American Contact Dermatitis Society has selected isobornyl acrylate the contact allergen of the year. It is an acrylic monomer used as an adhesive.

Among other applications, isobornyl acrylate is often used in medical devices. The selection was made based in part on multiple case reports of diabetes patients developing contact allergies to their diabetes devices, such as insulin pumps, explained Golara Honari, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, who presented the selection at the ACDS annual meeting.

The significance of this allergen is that testing through routine panels does not identify it, so clinician awareness is especially important, Dr. Honari noted in a video interview at the meeting.

Most of the reported contact allergen cases have been in patients with diabetes, but clinicians should think about other possible sources, such as acrylic nails, she said. As for treatment, clinicians and patients can consider alternative diabetes devices without isobornyl acrylate, she said.

In the future, close collaboration between clinicians and the medical device industry to develop appropriate labeling can help increase awareness of the potential for allergic reactions, she added.

Dr. Honari had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

AT ACDS 2019

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Infiltrates Seen During Excision of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer

To the Editor:

Specific characteristics of a lymphocytic infiltrate noted on frozen section histologic examination during Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) tumor excision should raise suspicion of an underlying chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). This infiltrate may be the presenting sign of the underlying leukemia and has variable presentation that may mimic aggressive features. The following 3 cases highlight this phenomenon.

A 74-year-old man (patient 1) with a medical history of multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) presented for definitive treatment of a biopsy-proven infiltrative basal cell carcinoma involving the right infra-auricular region. Mohs section histologic evaluation revealed patches of lymphocytic infiltrates so dense they obscured the tumor margins. The lymphocytic infiltrates persisted even after 3 MMS stages, though they were moderately less dense compared to the initial MMS stage. Clinical interpretation determined no relationship between the lymphocytic infiltrates and residual tumor. Due to concerns that this lymphocytic infiltrate may indicate an underlying leukemic process, preoperative laboratory tests were ordered prior to closure of the surgical wound, which demonstrated an elevated white blood cell count of 65,000/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL) with 93% lymphocytes. A follow-up complete blood cell count (CBC) and blood smear confirmed the diagnosis of CLL. The patient was referred to a hematologist/oncologist.

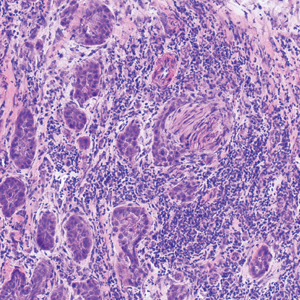

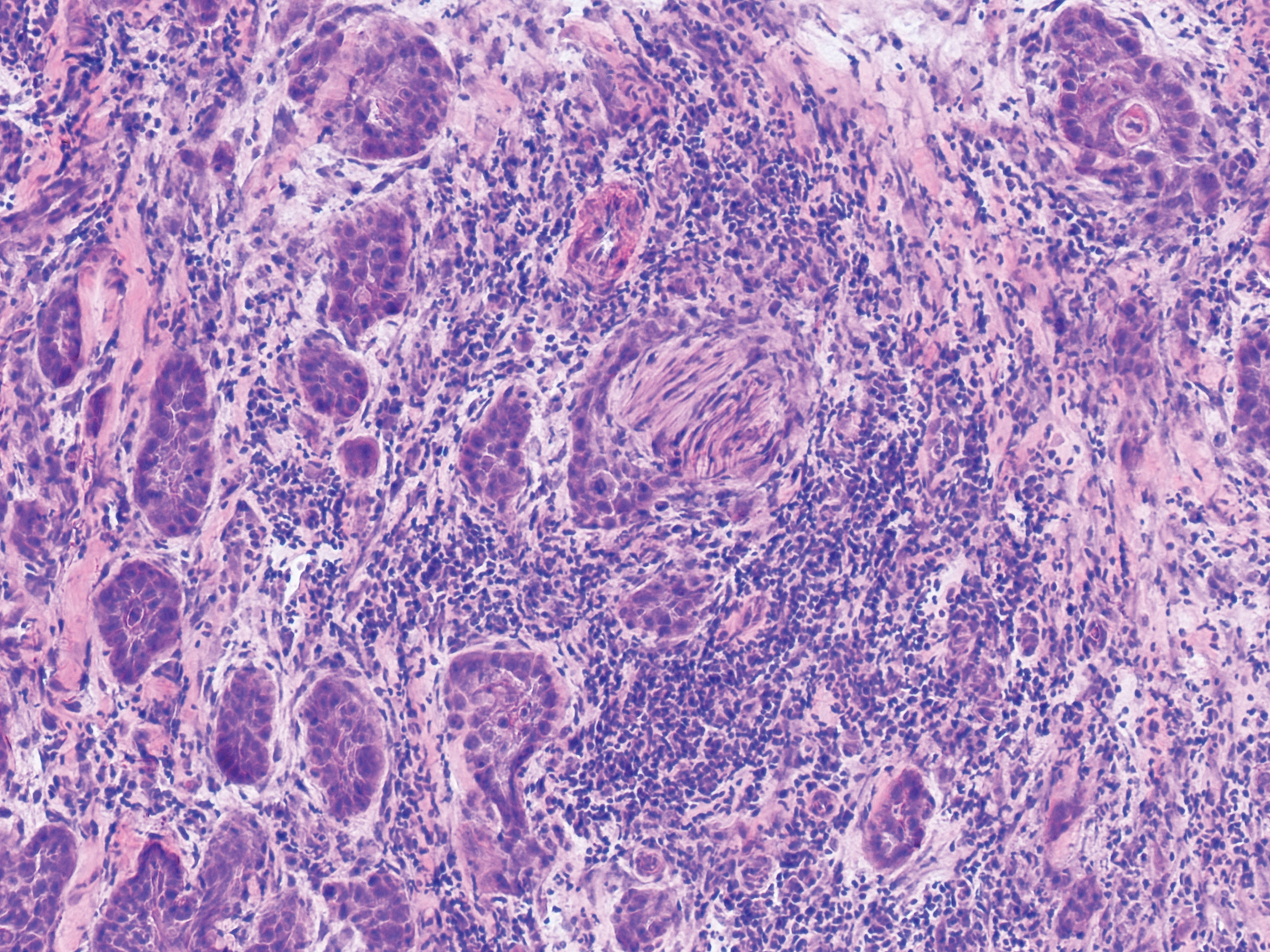

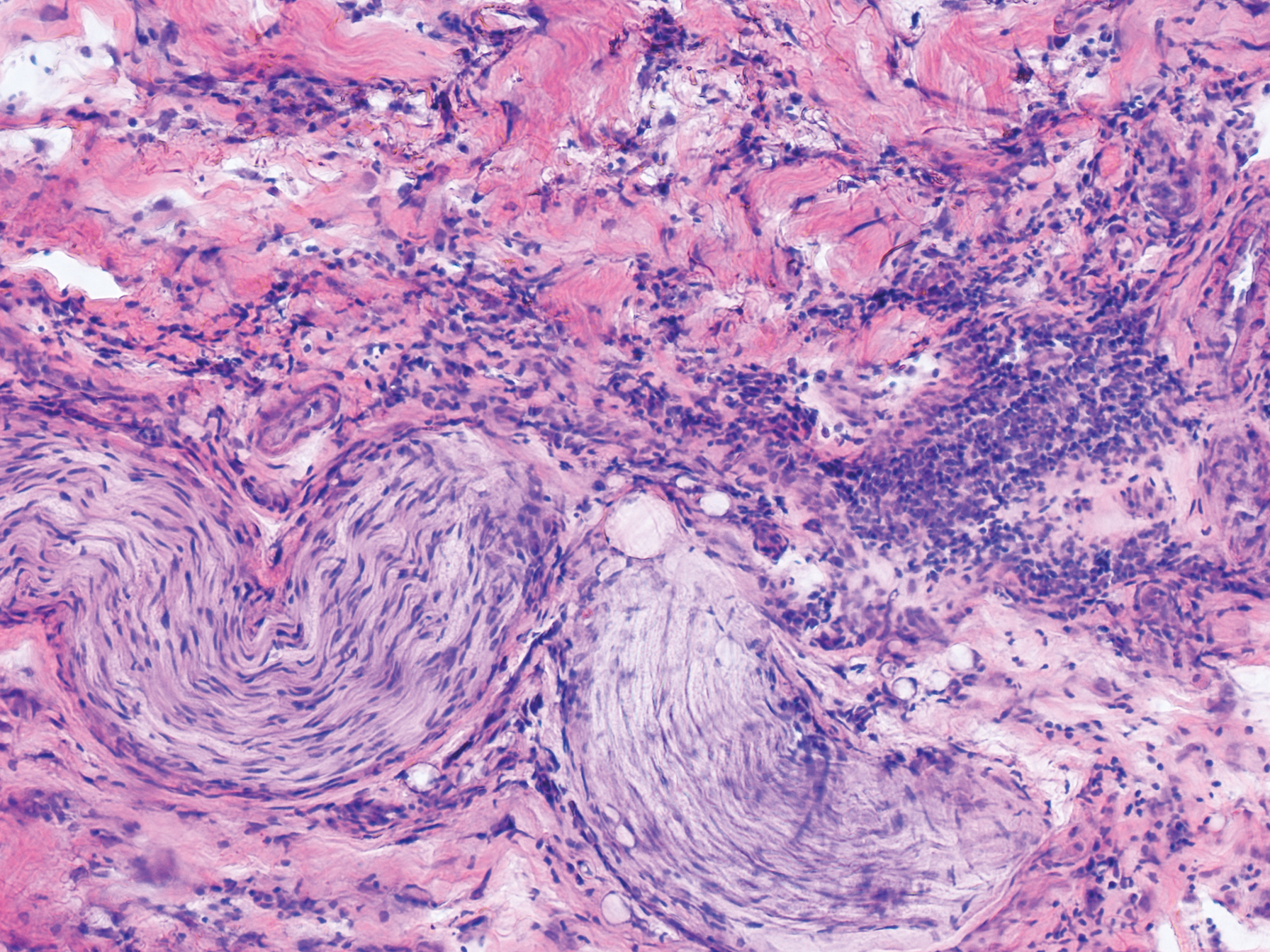

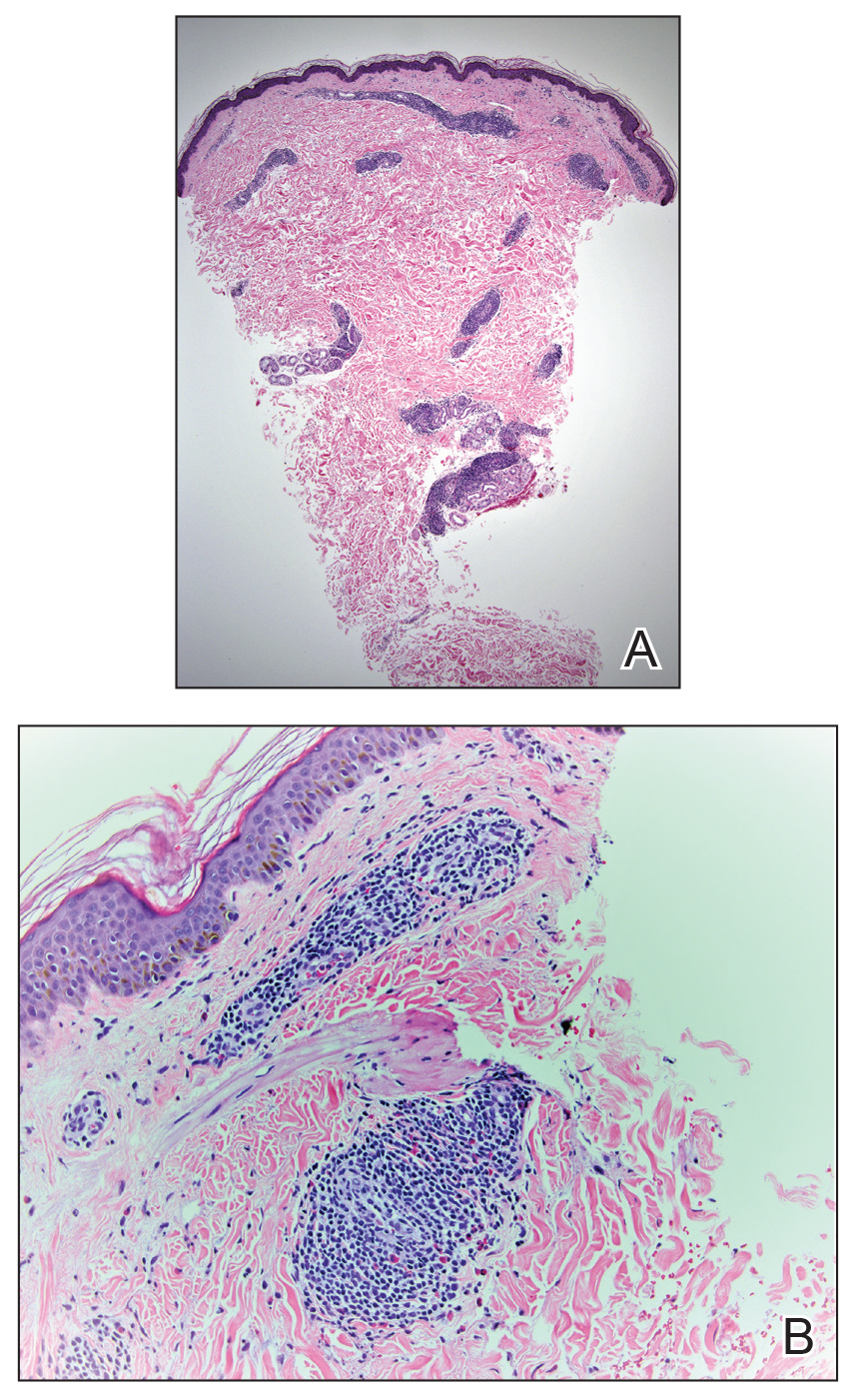

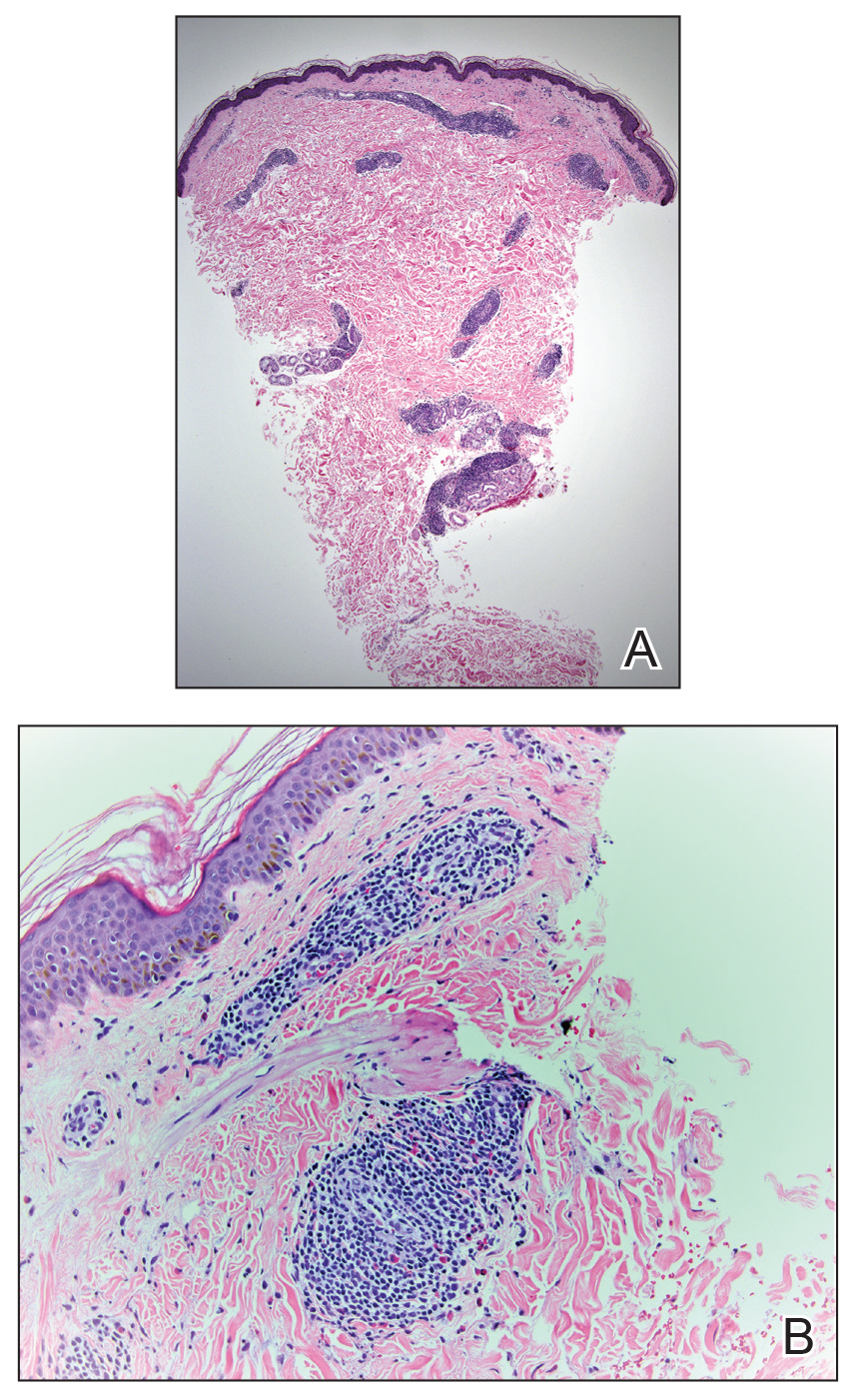

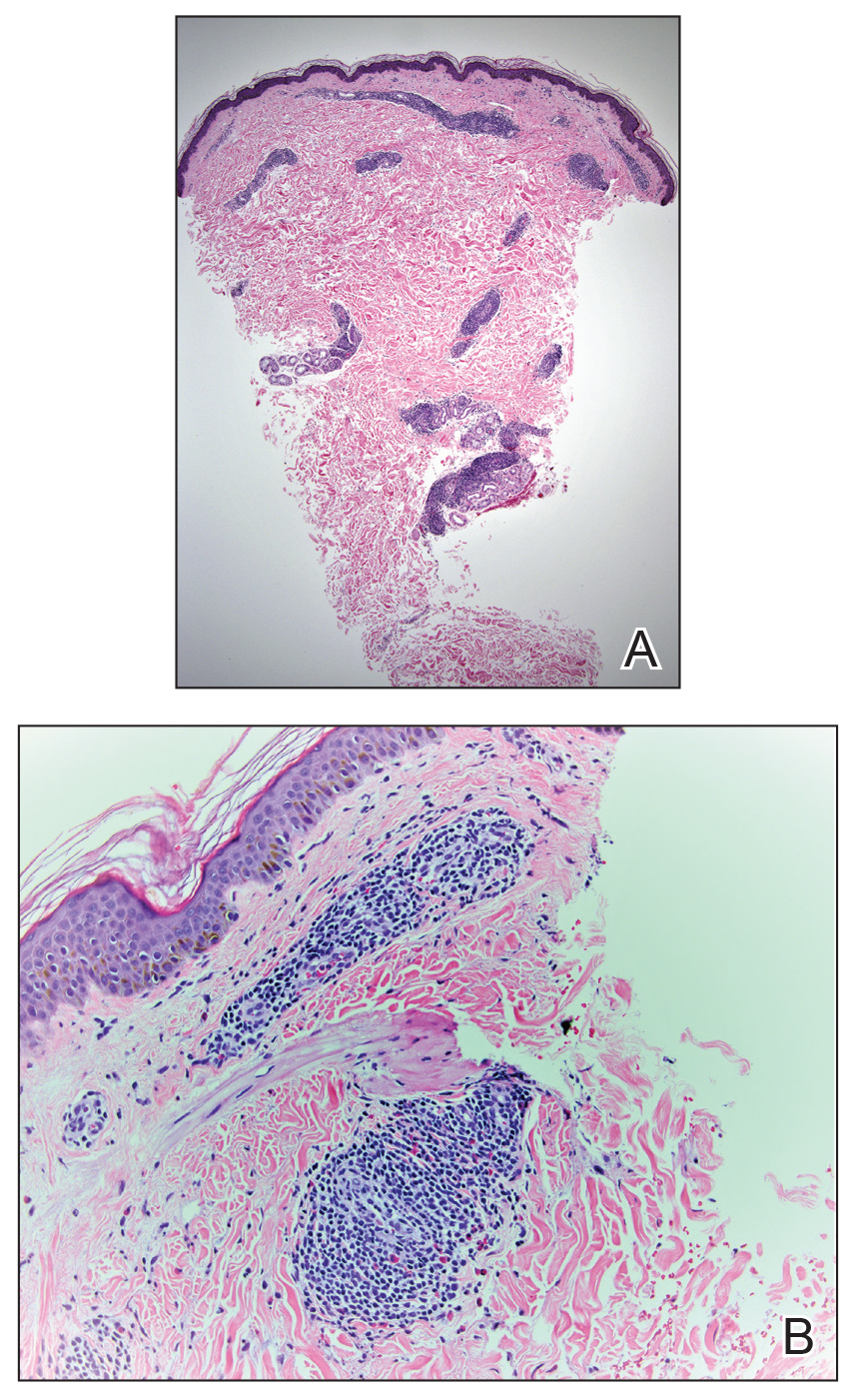

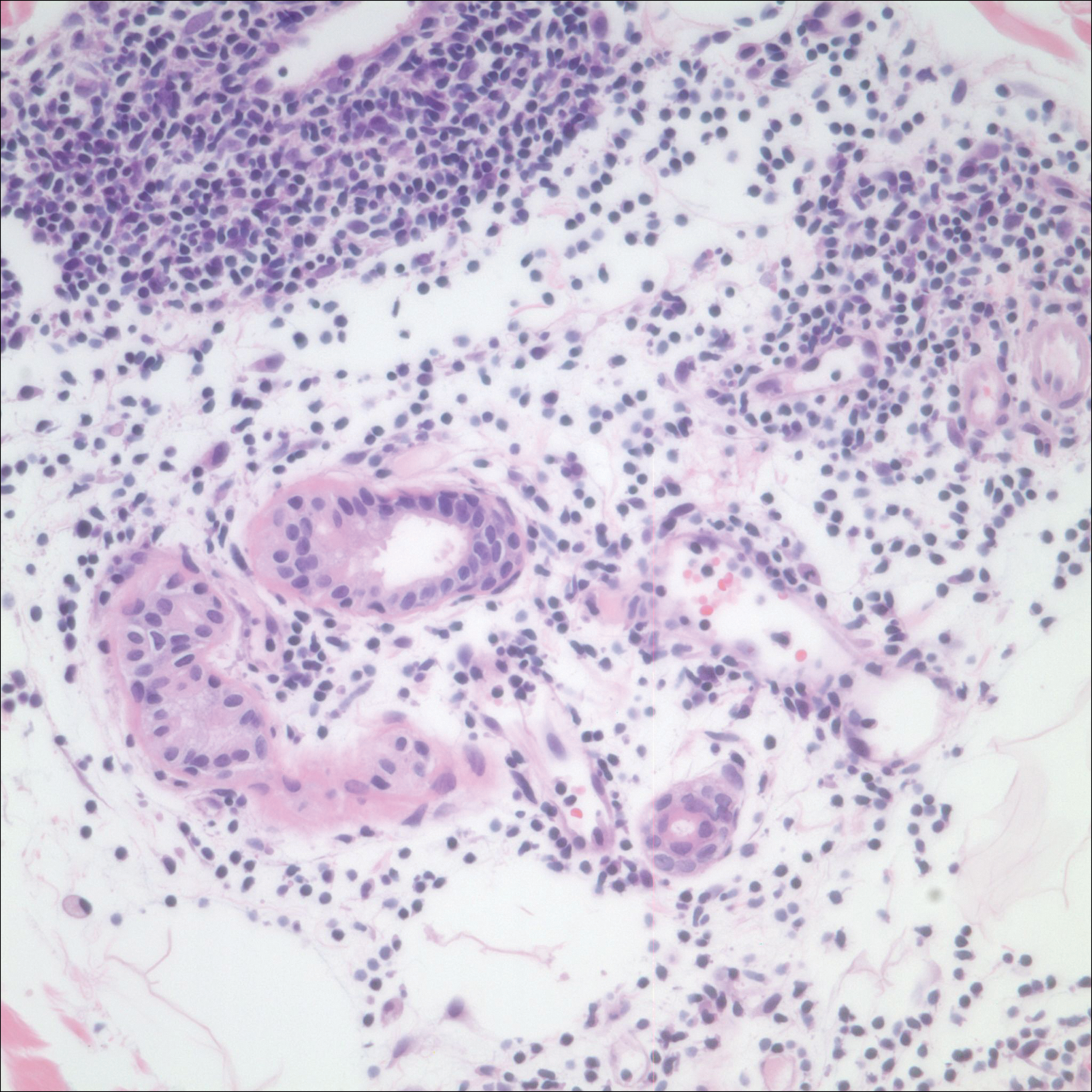

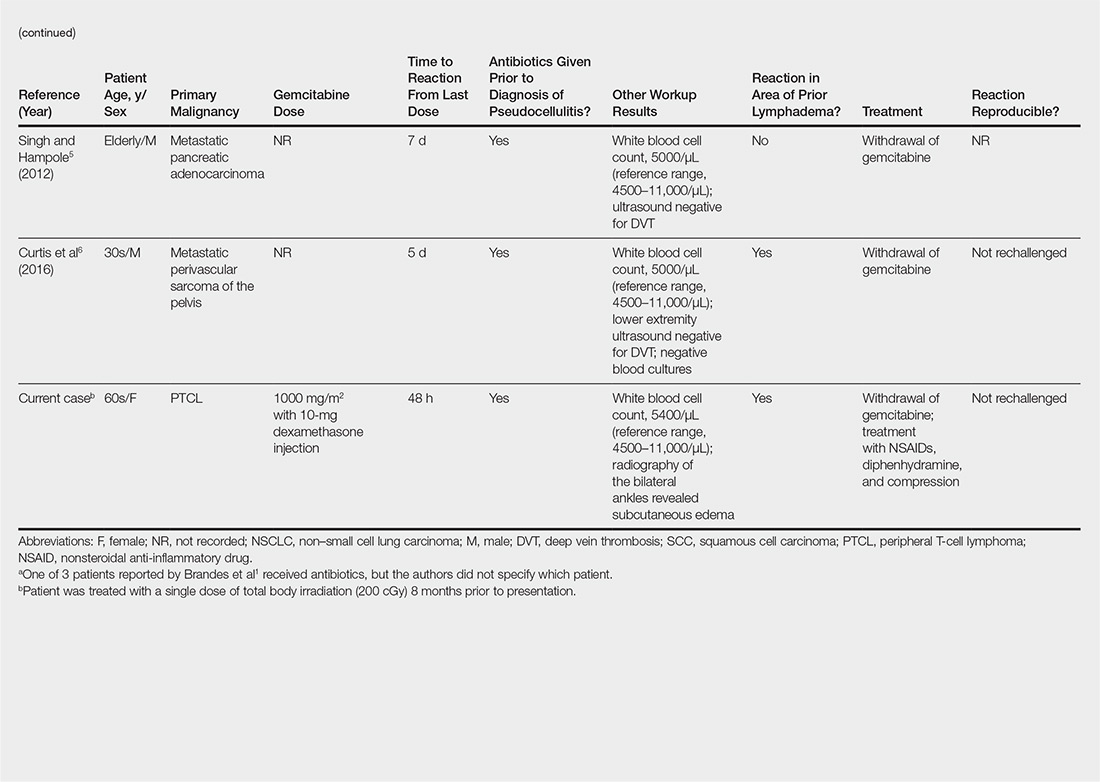

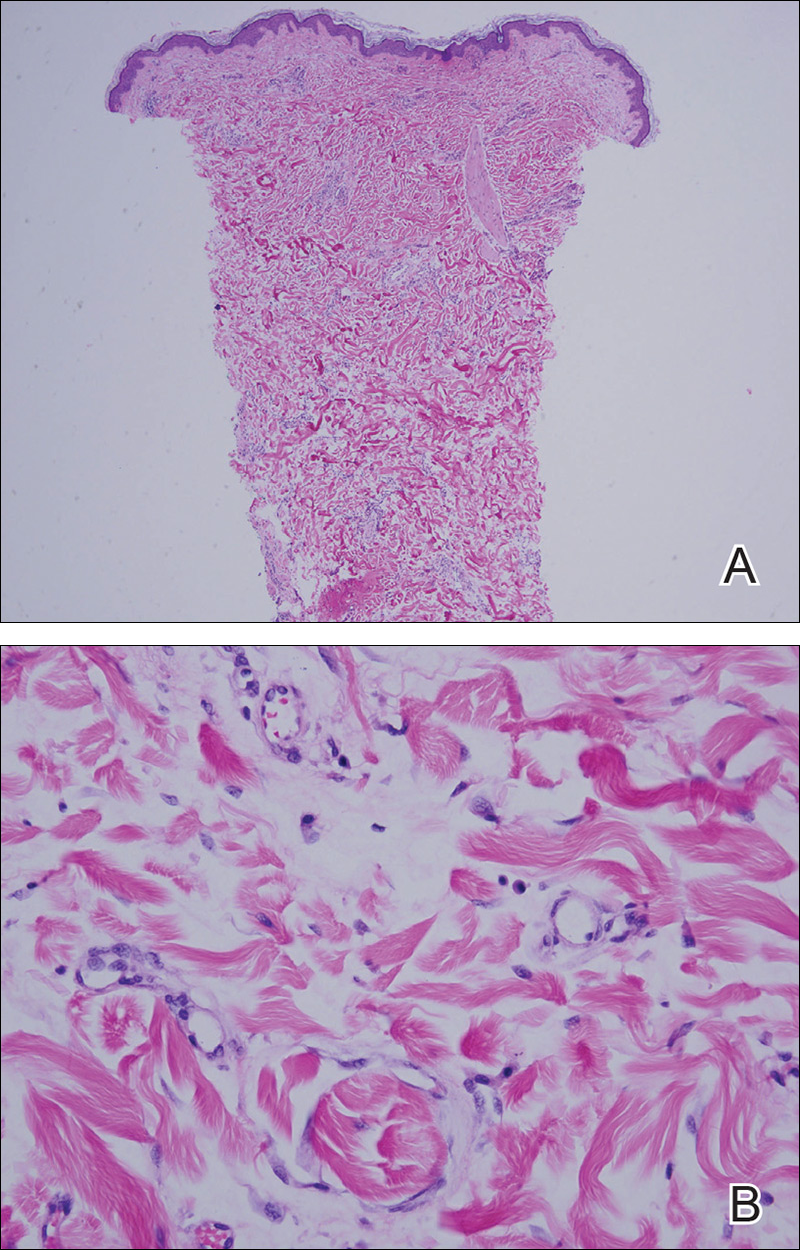

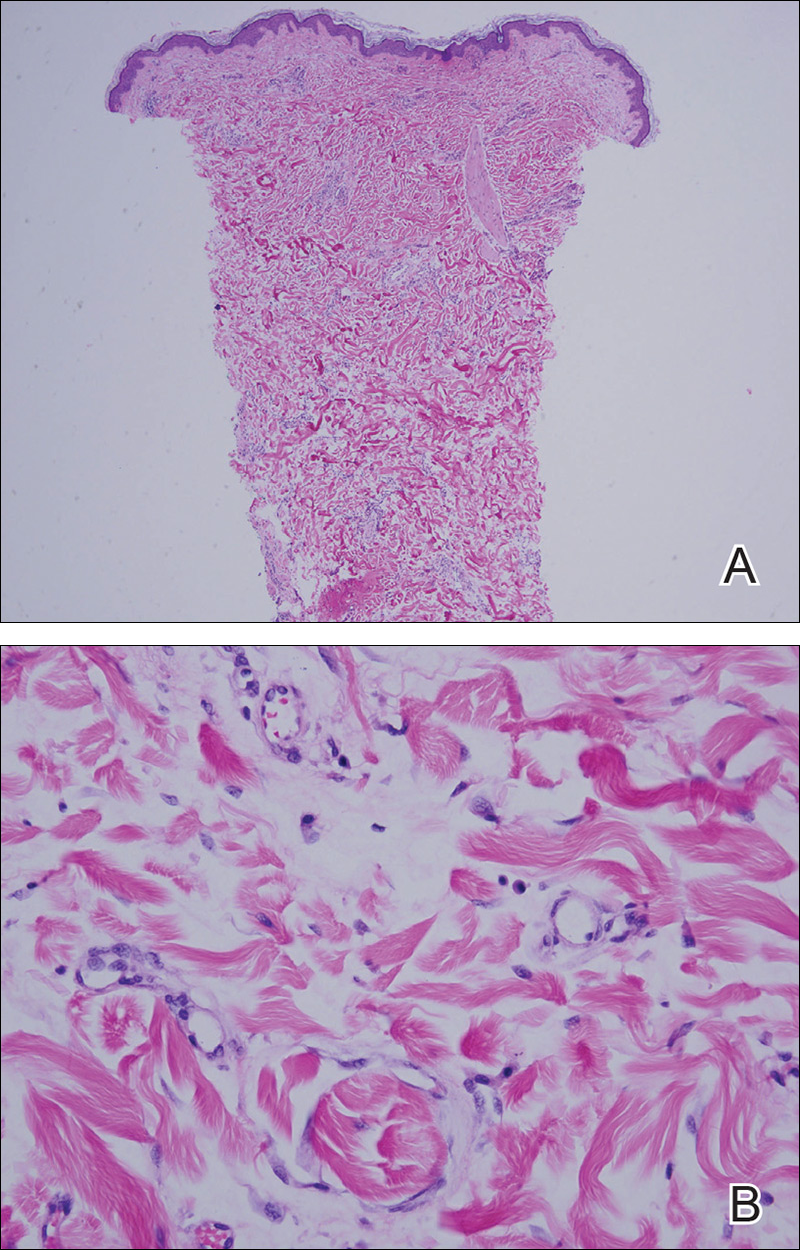

An 84-year old man (patient 2) with a medical history of numerous precancerous lesions and 1 squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) presented for a biopsy, which determined moderately differentiated SCC. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed. The initial stage of MMS histologic examination demonstrated basosquamous carcinoma in the specimen margins, including perineural growth, with an extensive lymphoid infiltrate surrounding the tumor (Figure 1). A second stage of MMS was performed, and although margins appeared to be clear of the basosquamous histology, complete assessment was difficult due to areas of dense inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2), including perineural infiltration that remained and appeared to extend deeper into the tissues. Pathology was consulted and it was determined that the perineural infiltration was unlikely related to tumor spread but rather secondary to an unknown cause. Further investigation of the patient’s medical history revealed previously diagnosed CLL, which had been omitted by the patient, as he had forgotten this diagnosis and denied a history of cancer, lymphoma, and even leukemia. A query to the patient’s primary care physician found the most recent CBC demonstrated an elevated white blood cell count of 37,600/µL with 78% lymphocytes.

An 84-year-old man (patient 3) with a known history of CLL was referred for MMS excision of a 3.5×4.0-cm SCC on the right anterior temple extending onto the lateral upper and lower eyelids. Mohs frozen section histologic examination of excised tissue revealed patches of heavy lymphocytic infiltrates not found exclusively around the residual tumor but additionally around superficial and deep neurovascular bundles. The second stage of MMS appeared to be clear of tumor cells, but lymphocytic infiltrates remained. Because this patient had a clear history of CLL, the decision was made in conjunction with a dermatopathologist to conclude the surgery at this point. However, secondary to the aggressive, deeply invasive growth of this SCC, the patient was referred for adjunctive radiation therapy to the surgical site after wound reconstruction.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is the most common leukemia in the Western world1 and is estimated to account for 27% of all new cases of leukemia. An individual’s lifetime risk is 0.5%. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is predominantly a disease of the elderly, with an average age at diagnosis of 71 years. It is more common among males, North American and European populations, and those with a positive family history. Although epidemiologic factors including farming, prolonged pesticide exposure, and contact with Agent Orange have tentative links to CLL, the relationships are poorly established.2

Symptoms associated with acute leukemia only rarely manifest in patients with CLL.3 If present, symptoms are vague and include weakness, fatigue, weight loss, fever, night sweats, and a feeling of abdominal fullness.2,3 On clinical examination, patients also may have lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, or hepatomegaly. Increasing severity of symptoms at time of presentation directly correlates with the severity and staging at the time of diagnosis.4 Not only do patients with CLL have a greater incidence of NMSCs with more notable subclinical tumor extension than the average person, but these individuals also have a greatly increased risk for skin cancer recurrence posttreatment.5,6

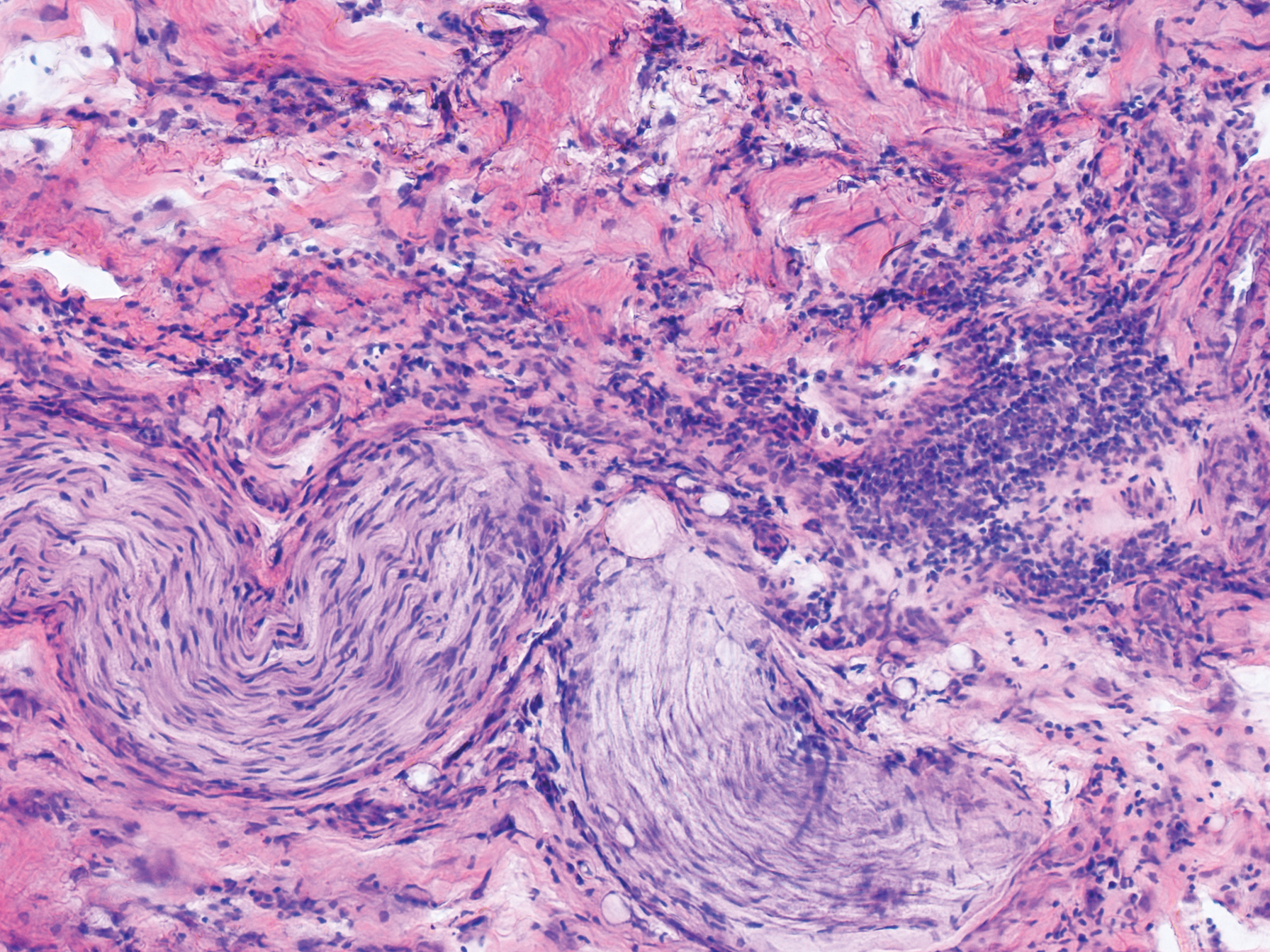

Although tissue pathology is not routinely part of the diagnosis of patients with CLL, findings can add to clinical suspicion. Smudge cells, which are cell debris, are characteristic morphologic features found in CLL. Most CLL cells are characteristically small mature lymphocytes with a dense nucleus.3 The presence of aggregates of these cells may obscure tumor margins during resection of NMSCs.7 This infiltrate is present in more than one-third of patients with CLL, as described in one retrospective cohort. This study simultaneously demonstrated the relationship between CLL and a 2-fold increase in postoperative defect size, which was attributed to either subclinical tumor spread or extra tissue removal to ensure clearance due to the leukemic infiltrates themselves.8 The presence of perineural tumor growth, which can occur with aggressive SCC and basal cell carcinoma, may be mimicked by perineural involvement of CLL cells rather than the reactive inflammation associated with continued tumor margins.7

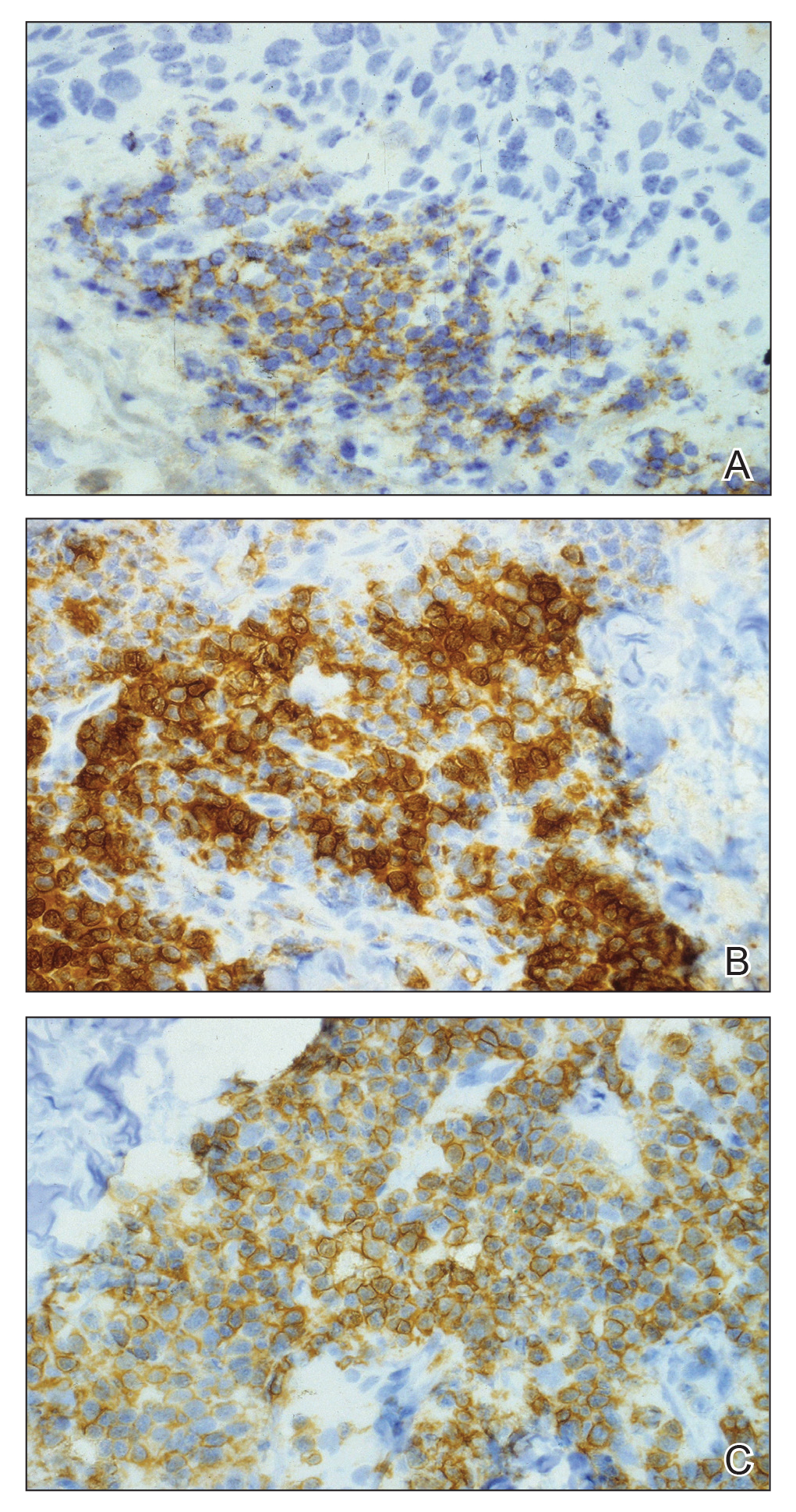

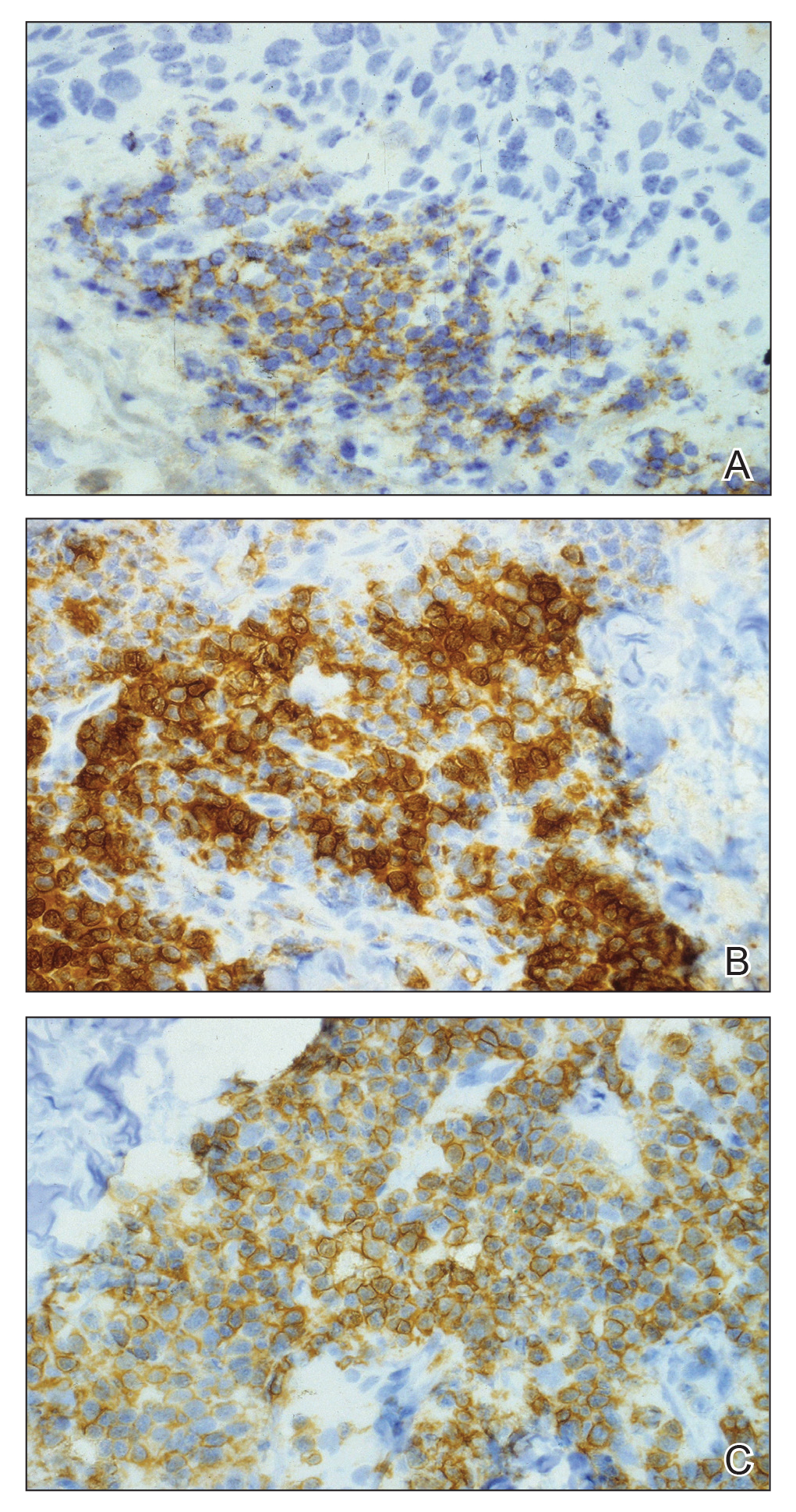

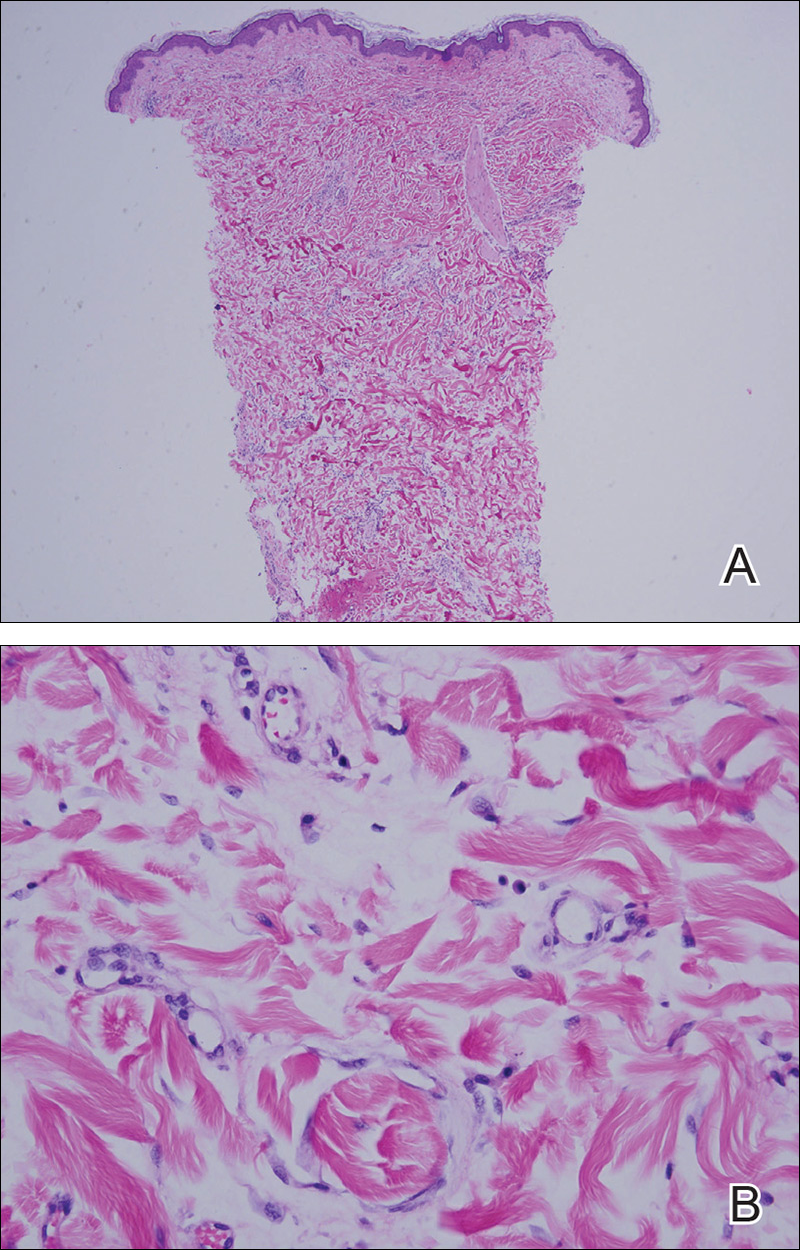

When evaluating a patient with suspected CLL, laboratory tests should include a CBC with differential and examination of the peripheral smear. If abnormal, immunophenotyping of lymphocytes by flow cytometry will rule out other lymphoproliferative diseases and verify CLL as the diagnosis.3 Diagnosis of CLL requires the presence of monoclonal B lymphocytes (≥5×109/L) in the peripheral blood as confirmed by flow cytometry.3 Clonality of circulating B lymphocytes must be confirmed, and immunophenotyping will establish a diagnosis with leukemic cells having positive expression of CD20 (Figure 3A) and CD23 (Figure 3B)(characteristic of B-cell lineage) with coexpression of CD43 and CD5 (Figure 3C)(characteristic of T-cell lineage).7,9 This pattern of immunohistochemical markers can be differentiated from the normal immune response to cutaneous malignancies, which have the pattern of being CD3+, CD5+, and CD43+ with absence of B-cell markers (ie, CD20, CD23)(Table).7

The pathogenesis of this peritumoral infiltrate is unknown, though multiple theories exist. One theory is that the neoplastic lymphocytes are responding as a dysfunctional arm of the immune system to tumor-specific antigens. In patients with CLL, leukemic lymphocytes comprise a large portion of the circulating leukocyte population and this peritumoral infiltrate may simply be a reflection of the circulating leukocytic population. Another theory contends that neoplastic lymphocytes are simply nonspecific aggregations secondary to tumor neovascularization and increased vascular permeability.10

This neoplastic infiltrate seen incidentally during MMS excision of NMSCs not only provides a unique opportunity to diagnose and intervene in those with unknown CLL but also to be aware of complicating features that can spare the patient from unnecessary tissue removal, thereby maximizing the benefit of MMS. This infiltrate can obscure tumor margins; is unusually dense and patchy, with or without infiltrating perineural or perivascular components; and persists beyond what would seem to be an adequate margin to clear a tumor. These cases show these findings, which exemplify the peritumoral infiltrate of CLL and should prompt further workup.

- Rozman C, Monserrat E. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1052-1057.

- What are the risk factors for chronic lymphocytic leukemia? American Cancer Society website. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html. Revised May 10, 2018. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111:5446-5456.

- Rai KR, Wasil T, Iqbal U, et al. Clinical staging and prognostic markers in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2004;18:795-805, vii.

- Mehrany K, Weenig RH, Pittelkow MR, et al. High recurrence rates of squamous cell carcinoma after Mohs’ surgery in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:38-42.

- Brewer JD, Shanafelt TD, Khezri F, et al. Increased incidence and recurrence rates of nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a Rochester epidemiology project population-based study in Minnesota. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:302-309.

- Wilson ML, Elston DM, Tyler WB, et al. Dense lymphocytic infiltrates associated with non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:4.

- Mehrany K, Byrd DR, Roenigk RK, et al. Lymphocytic infiltrates and subclinical epithelial tumor extension in patients with chronic leukemia and solid-organ transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:129-134.

- Khandelwal A, Seilstad KH, Magro CM. Subclinical chronic lymphocytic leukaemia associated with a 13q deletion presenting initially in the skin: apropos of a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:256-259.

- Padgett JK, Parlette HL, English JC. A diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia prompted by cutaneous lymphocytic infiltrates present in mohs micrographic surgery frozen sections. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:769-771.

To the Editor:

Specific characteristics of a lymphocytic infiltrate noted on frozen section histologic examination during Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) tumor excision should raise suspicion of an underlying chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). This infiltrate may be the presenting sign of the underlying leukemia and has variable presentation that may mimic aggressive features. The following 3 cases highlight this phenomenon.

A 74-year-old man (patient 1) with a medical history of multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) presented for definitive treatment of a biopsy-proven infiltrative basal cell carcinoma involving the right infra-auricular region. Mohs section histologic evaluation revealed patches of lymphocytic infiltrates so dense they obscured the tumor margins. The lymphocytic infiltrates persisted even after 3 MMS stages, though they were moderately less dense compared to the initial MMS stage. Clinical interpretation determined no relationship between the lymphocytic infiltrates and residual tumor. Due to concerns that this lymphocytic infiltrate may indicate an underlying leukemic process, preoperative laboratory tests were ordered prior to closure of the surgical wound, which demonstrated an elevated white blood cell count of 65,000/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL) with 93% lymphocytes. A follow-up complete blood cell count (CBC) and blood smear confirmed the diagnosis of CLL. The patient was referred to a hematologist/oncologist.

An 84-year old man (patient 2) with a medical history of numerous precancerous lesions and 1 squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) presented for a biopsy, which determined moderately differentiated SCC. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed. The initial stage of MMS histologic examination demonstrated basosquamous carcinoma in the specimen margins, including perineural growth, with an extensive lymphoid infiltrate surrounding the tumor (Figure 1). A second stage of MMS was performed, and although margins appeared to be clear of the basosquamous histology, complete assessment was difficult due to areas of dense inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2), including perineural infiltration that remained and appeared to extend deeper into the tissues. Pathology was consulted and it was determined that the perineural infiltration was unlikely related to tumor spread but rather secondary to an unknown cause. Further investigation of the patient’s medical history revealed previously diagnosed CLL, which had been omitted by the patient, as he had forgotten this diagnosis and denied a history of cancer, lymphoma, and even leukemia. A query to the patient’s primary care physician found the most recent CBC demonstrated an elevated white blood cell count of 37,600/µL with 78% lymphocytes.

An 84-year-old man (patient 3) with a known history of CLL was referred for MMS excision of a 3.5×4.0-cm SCC on the right anterior temple extending onto the lateral upper and lower eyelids. Mohs frozen section histologic examination of excised tissue revealed patches of heavy lymphocytic infiltrates not found exclusively around the residual tumor but additionally around superficial and deep neurovascular bundles. The second stage of MMS appeared to be clear of tumor cells, but lymphocytic infiltrates remained. Because this patient had a clear history of CLL, the decision was made in conjunction with a dermatopathologist to conclude the surgery at this point. However, secondary to the aggressive, deeply invasive growth of this SCC, the patient was referred for adjunctive radiation therapy to the surgical site after wound reconstruction.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is the most common leukemia in the Western world1 and is estimated to account for 27% of all new cases of leukemia. An individual’s lifetime risk is 0.5%. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is predominantly a disease of the elderly, with an average age at diagnosis of 71 years. It is more common among males, North American and European populations, and those with a positive family history. Although epidemiologic factors including farming, prolonged pesticide exposure, and contact with Agent Orange have tentative links to CLL, the relationships are poorly established.2

Symptoms associated with acute leukemia only rarely manifest in patients with CLL.3 If present, symptoms are vague and include weakness, fatigue, weight loss, fever, night sweats, and a feeling of abdominal fullness.2,3 On clinical examination, patients also may have lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, or hepatomegaly. Increasing severity of symptoms at time of presentation directly correlates with the severity and staging at the time of diagnosis.4 Not only do patients with CLL have a greater incidence of NMSCs with more notable subclinical tumor extension than the average person, but these individuals also have a greatly increased risk for skin cancer recurrence posttreatment.5,6

Although tissue pathology is not routinely part of the diagnosis of patients with CLL, findings can add to clinical suspicion. Smudge cells, which are cell debris, are characteristic morphologic features found in CLL. Most CLL cells are characteristically small mature lymphocytes with a dense nucleus.3 The presence of aggregates of these cells may obscure tumor margins during resection of NMSCs.7 This infiltrate is present in more than one-third of patients with CLL, as described in one retrospective cohort. This study simultaneously demonstrated the relationship between CLL and a 2-fold increase in postoperative defect size, which was attributed to either subclinical tumor spread or extra tissue removal to ensure clearance due to the leukemic infiltrates themselves.8 The presence of perineural tumor growth, which can occur with aggressive SCC and basal cell carcinoma, may be mimicked by perineural involvement of CLL cells rather than the reactive inflammation associated with continued tumor margins.7

When evaluating a patient with suspected CLL, laboratory tests should include a CBC with differential and examination of the peripheral smear. If abnormal, immunophenotyping of lymphocytes by flow cytometry will rule out other lymphoproliferative diseases and verify CLL as the diagnosis.3 Diagnosis of CLL requires the presence of monoclonal B lymphocytes (≥5×109/L) in the peripheral blood as confirmed by flow cytometry.3 Clonality of circulating B lymphocytes must be confirmed, and immunophenotyping will establish a diagnosis with leukemic cells having positive expression of CD20 (Figure 3A) and CD23 (Figure 3B)(characteristic of B-cell lineage) with coexpression of CD43 and CD5 (Figure 3C)(characteristic of T-cell lineage).7,9 This pattern of immunohistochemical markers can be differentiated from the normal immune response to cutaneous malignancies, which have the pattern of being CD3+, CD5+, and CD43+ with absence of B-cell markers (ie, CD20, CD23)(Table).7

The pathogenesis of this peritumoral infiltrate is unknown, though multiple theories exist. One theory is that the neoplastic lymphocytes are responding as a dysfunctional arm of the immune system to tumor-specific antigens. In patients with CLL, leukemic lymphocytes comprise a large portion of the circulating leukocyte population and this peritumoral infiltrate may simply be a reflection of the circulating leukocytic population. Another theory contends that neoplastic lymphocytes are simply nonspecific aggregations secondary to tumor neovascularization and increased vascular permeability.10

This neoplastic infiltrate seen incidentally during MMS excision of NMSCs not only provides a unique opportunity to diagnose and intervene in those with unknown CLL but also to be aware of complicating features that can spare the patient from unnecessary tissue removal, thereby maximizing the benefit of MMS. This infiltrate can obscure tumor margins; is unusually dense and patchy, with or without infiltrating perineural or perivascular components; and persists beyond what would seem to be an adequate margin to clear a tumor. These cases show these findings, which exemplify the peritumoral infiltrate of CLL and should prompt further workup.

To the Editor:

Specific characteristics of a lymphocytic infiltrate noted on frozen section histologic examination during Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) tumor excision should raise suspicion of an underlying chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). This infiltrate may be the presenting sign of the underlying leukemia and has variable presentation that may mimic aggressive features. The following 3 cases highlight this phenomenon.

A 74-year-old man (patient 1) with a medical history of multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) presented for definitive treatment of a biopsy-proven infiltrative basal cell carcinoma involving the right infra-auricular region. Mohs section histologic evaluation revealed patches of lymphocytic infiltrates so dense they obscured the tumor margins. The lymphocytic infiltrates persisted even after 3 MMS stages, though they were moderately less dense compared to the initial MMS stage. Clinical interpretation determined no relationship between the lymphocytic infiltrates and residual tumor. Due to concerns that this lymphocytic infiltrate may indicate an underlying leukemic process, preoperative laboratory tests were ordered prior to closure of the surgical wound, which demonstrated an elevated white blood cell count of 65,000/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL) with 93% lymphocytes. A follow-up complete blood cell count (CBC) and blood smear confirmed the diagnosis of CLL. The patient was referred to a hematologist/oncologist.

An 84-year old man (patient 2) with a medical history of numerous precancerous lesions and 1 squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) presented for a biopsy, which determined moderately differentiated SCC. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed. The initial stage of MMS histologic examination demonstrated basosquamous carcinoma in the specimen margins, including perineural growth, with an extensive lymphoid infiltrate surrounding the tumor (Figure 1). A second stage of MMS was performed, and although margins appeared to be clear of the basosquamous histology, complete assessment was difficult due to areas of dense inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2), including perineural infiltration that remained and appeared to extend deeper into the tissues. Pathology was consulted and it was determined that the perineural infiltration was unlikely related to tumor spread but rather secondary to an unknown cause. Further investigation of the patient’s medical history revealed previously diagnosed CLL, which had been omitted by the patient, as he had forgotten this diagnosis and denied a history of cancer, lymphoma, and even leukemia. A query to the patient’s primary care physician found the most recent CBC demonstrated an elevated white blood cell count of 37,600/µL with 78% lymphocytes.

An 84-year-old man (patient 3) with a known history of CLL was referred for MMS excision of a 3.5×4.0-cm SCC on the right anterior temple extending onto the lateral upper and lower eyelids. Mohs frozen section histologic examination of excised tissue revealed patches of heavy lymphocytic infiltrates not found exclusively around the residual tumor but additionally around superficial and deep neurovascular bundles. The second stage of MMS appeared to be clear of tumor cells, but lymphocytic infiltrates remained. Because this patient had a clear history of CLL, the decision was made in conjunction with a dermatopathologist to conclude the surgery at this point. However, secondary to the aggressive, deeply invasive growth of this SCC, the patient was referred for adjunctive radiation therapy to the surgical site after wound reconstruction.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is the most common leukemia in the Western world1 and is estimated to account for 27% of all new cases of leukemia. An individual’s lifetime risk is 0.5%. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is predominantly a disease of the elderly, with an average age at diagnosis of 71 years. It is more common among males, North American and European populations, and those with a positive family history. Although epidemiologic factors including farming, prolonged pesticide exposure, and contact with Agent Orange have tentative links to CLL, the relationships are poorly established.2

Symptoms associated with acute leukemia only rarely manifest in patients with CLL.3 If present, symptoms are vague and include weakness, fatigue, weight loss, fever, night sweats, and a feeling of abdominal fullness.2,3 On clinical examination, patients also may have lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, or hepatomegaly. Increasing severity of symptoms at time of presentation directly correlates with the severity and staging at the time of diagnosis.4 Not only do patients with CLL have a greater incidence of NMSCs with more notable subclinical tumor extension than the average person, but these individuals also have a greatly increased risk for skin cancer recurrence posttreatment.5,6

Although tissue pathology is not routinely part of the diagnosis of patients with CLL, findings can add to clinical suspicion. Smudge cells, which are cell debris, are characteristic morphologic features found in CLL. Most CLL cells are characteristically small mature lymphocytes with a dense nucleus.3 The presence of aggregates of these cells may obscure tumor margins during resection of NMSCs.7 This infiltrate is present in more than one-third of patients with CLL, as described in one retrospective cohort. This study simultaneously demonstrated the relationship between CLL and a 2-fold increase in postoperative defect size, which was attributed to either subclinical tumor spread or extra tissue removal to ensure clearance due to the leukemic infiltrates themselves.8 The presence of perineural tumor growth, which can occur with aggressive SCC and basal cell carcinoma, may be mimicked by perineural involvement of CLL cells rather than the reactive inflammation associated with continued tumor margins.7

When evaluating a patient with suspected CLL, laboratory tests should include a CBC with differential and examination of the peripheral smear. If abnormal, immunophenotyping of lymphocytes by flow cytometry will rule out other lymphoproliferative diseases and verify CLL as the diagnosis.3 Diagnosis of CLL requires the presence of monoclonal B lymphocytes (≥5×109/L) in the peripheral blood as confirmed by flow cytometry.3 Clonality of circulating B lymphocytes must be confirmed, and immunophenotyping will establish a diagnosis with leukemic cells having positive expression of CD20 (Figure 3A) and CD23 (Figure 3B)(characteristic of B-cell lineage) with coexpression of CD43 and CD5 (Figure 3C)(characteristic of T-cell lineage).7,9 This pattern of immunohistochemical markers can be differentiated from the normal immune response to cutaneous malignancies, which have the pattern of being CD3+, CD5+, and CD43+ with absence of B-cell markers (ie, CD20, CD23)(Table).7

The pathogenesis of this peritumoral infiltrate is unknown, though multiple theories exist. One theory is that the neoplastic lymphocytes are responding as a dysfunctional arm of the immune system to tumor-specific antigens. In patients with CLL, leukemic lymphocytes comprise a large portion of the circulating leukocyte population and this peritumoral infiltrate may simply be a reflection of the circulating leukocytic population. Another theory contends that neoplastic lymphocytes are simply nonspecific aggregations secondary to tumor neovascularization and increased vascular permeability.10

This neoplastic infiltrate seen incidentally during MMS excision of NMSCs not only provides a unique opportunity to diagnose and intervene in those with unknown CLL but also to be aware of complicating features that can spare the patient from unnecessary tissue removal, thereby maximizing the benefit of MMS. This infiltrate can obscure tumor margins; is unusually dense and patchy, with or without infiltrating perineural or perivascular components; and persists beyond what would seem to be an adequate margin to clear a tumor. These cases show these findings, which exemplify the peritumoral infiltrate of CLL and should prompt further workup.

- Rozman C, Monserrat E. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1052-1057.

- What are the risk factors for chronic lymphocytic leukemia? American Cancer Society website. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html. Revised May 10, 2018. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111:5446-5456.

- Rai KR, Wasil T, Iqbal U, et al. Clinical staging and prognostic markers in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2004;18:795-805, vii.

- Mehrany K, Weenig RH, Pittelkow MR, et al. High recurrence rates of squamous cell carcinoma after Mohs’ surgery in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:38-42.

- Brewer JD, Shanafelt TD, Khezri F, et al. Increased incidence and recurrence rates of nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a Rochester epidemiology project population-based study in Minnesota. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:302-309.

- Wilson ML, Elston DM, Tyler WB, et al. Dense lymphocytic infiltrates associated with non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:4.

- Mehrany K, Byrd DR, Roenigk RK, et al. Lymphocytic infiltrates and subclinical epithelial tumor extension in patients with chronic leukemia and solid-organ transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:129-134.

- Khandelwal A, Seilstad KH, Magro CM. Subclinical chronic lymphocytic leukaemia associated with a 13q deletion presenting initially in the skin: apropos of a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:256-259.

- Padgett JK, Parlette HL, English JC. A diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia prompted by cutaneous lymphocytic infiltrates present in mohs micrographic surgery frozen sections. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:769-771.

- Rozman C, Monserrat E. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1052-1057.

- What are the risk factors for chronic lymphocytic leukemia? American Cancer Society website. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html. Revised May 10, 2018. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111:5446-5456.

- Rai KR, Wasil T, Iqbal U, et al. Clinical staging and prognostic markers in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2004;18:795-805, vii.

- Mehrany K, Weenig RH, Pittelkow MR, et al. High recurrence rates of squamous cell carcinoma after Mohs’ surgery in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:38-42.

- Brewer JD, Shanafelt TD, Khezri F, et al. Increased incidence and recurrence rates of nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a Rochester epidemiology project population-based study in Minnesota. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:302-309.

- Wilson ML, Elston DM, Tyler WB, et al. Dense lymphocytic infiltrates associated with non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:4.

- Mehrany K, Byrd DR, Roenigk RK, et al. Lymphocytic infiltrates and subclinical epithelial tumor extension in patients with chronic leukemia and solid-organ transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:129-134.

- Khandelwal A, Seilstad KH, Magro CM. Subclinical chronic lymphocytic leukaemia associated with a 13q deletion presenting initially in the skin: apropos of a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:256-259.

- Padgett JK, Parlette HL, English JC. A diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia prompted by cutaneous lymphocytic infiltrates present in mohs micrographic surgery frozen sections. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:769-771.

Practice Points

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) may be seen during histologic examination of specimens during Mohs micrographic surgery as a monomorphic infiltrate of small mature lymphocytes with dense nuclei. Patients may be unaware of their diagnosis, which can be the presenting feature.

- An infiltrate of CLL may mimic aggressive behavior of nonmelanoma skin cancers including perineural invasion. A leukemic infiltrate may appear more dense and monomorphic. If needed, immunohistochemical staining of leukemic cells will show CD5 and CD23 positivity.

- Anecdotally, patients with CLL may not remember this pertinent medical history. Whether due to its asymptomatic nature or lack of treatment in early stages, direct questioning about CLL may be warranted if this characteristic infiltrate is encountered.

Bedbugs in the Workplace

What’s Eating You? Bedbugs

Bedbugs are common pests causing several health and economic consequences. With increased travel, pesticide resistance, and a lack of awareness about prevention, bedbugs have become even more difficult to control, especially within large population centers.1 The US Environmental Protection Agency considers bedbugs to be a considerable public health issue.2 Typically, they are found in private residences; however, there have been more reports of bedbugs discovered in the workplace within the last 20 years.3-5 Herein, we present a case of bedbugs presenting in this unusual environment.

Case Report

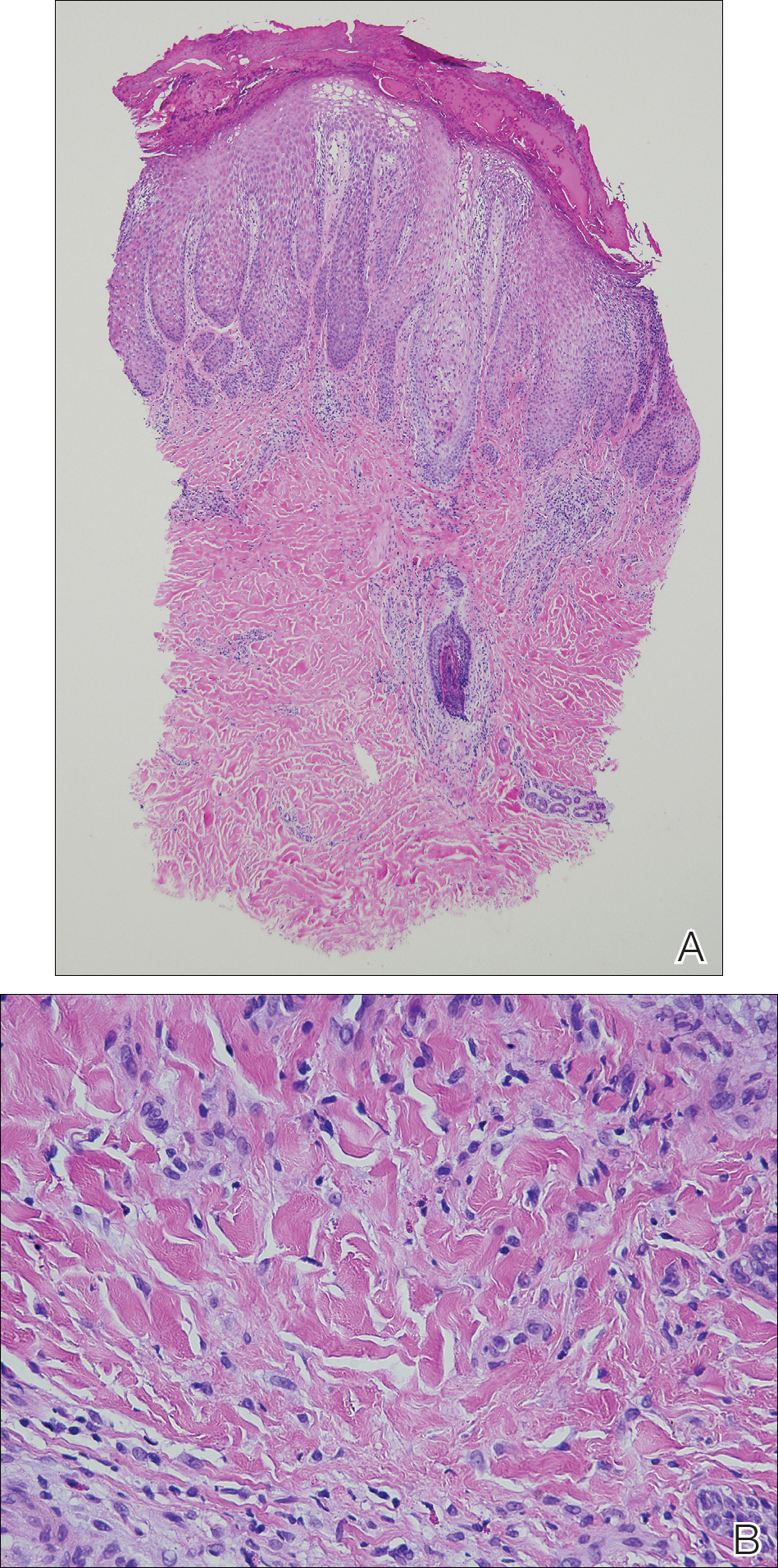

A 42-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with intensely itchy bumps over the bilateral posterior arms of 3 months’ duration. He had no other skin, hair, or nail concerns. Over the last 3 months prior to dermatologic evaluation, he was treated by an outside physician with topical steroids, systemic antibiotics, topical antifungals, and even systemic steroids with no improvement of the lesions or symptoms. On clinical examination at the current presentation, 8 to 10 pink dermal papules coalescing into 10-cm round patches were noted on the bilateral posterior arms (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the posterior right arm was performed, and histologic analysis showed a dense superficial and deep infiltrate and a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 2). No notable epidermal changes were observed.

At this time, the patient was counseled that the most likely cause was some unknown arthropod exposure. Given the chronicity of the patient’s disease course, bedbugs were favored; however, an extensive search of the patient’s home failed to uncover any arthropods, let alone bedbugs. A few weeks later, the patient discovered insects emanating from the mesh backing of his office chair while at work (Figure 3). The location of the intruders corresponded exactly with the lesions on the posterior arms. The occupational health office at his workplace collected samples of the arthropods and confirmed they were bedbugs. The patient’s lesions resolved with topical clobetasol once eradication of the workplace was complete.

Discussion

Morphology and Epidemiology

Bedbugs are wingless arthropods that have flat, oval-shaped, reddish brown bodies. They are approximately 4.5-mm long and 2.5-mm wide (Figure 4). The 2 most common species of bedbugs that infect humans are Cimex lectularius and Cimex hemipterus. Bedbugs are most commonly found in hotels, apartments, and residential households near sleep locations. They reside in crevices, cracks, mattresses, cushions, dressers, and other structures proximal to the bed. During the day they remain hidden, but at night they emerge for a blood meal. The average lifespan of a bedbug is 6 to 12 months.6 Females lay more than 200 eggs that hatch in approximately 6 to 10 days.7 Bedbugs progress through 5 nymph stages before becoming adults; several blood meals are required to advance each stage.6

Although commonly attributed to the home, bedbugs are being increasingly seen in the office setting.3-5 In a survey given to pest management professionals in 2015, more than 45% reported that they were contracted by corporations for bedbug infestations in office settings, an increase from 18% in 2010 and 36% in 2013.3 Bedbugs are brought into offices through clothing, luggage, books, and other personal items. Unable to find hosts at night, bedbugs adapt to daytime hours and spread to more unpredictable locations, including chairs, office equipment, desks, and computers.4 Additionally, they frequently move around to find a suitable host.5 As a result, the growth rate of bedbugs in an office setting is much slower than in the home, with fewer insects. Our patient did not have bedbugs at home, but it is possible that other employees transported them to the office over time.

Clinical Manifestations

Bedbugs cause pruritic and nonpruritic skin rashes, often of the arms, legs, neck, and face. A common reaction is an erythematous papule with a hemorrhagic punctum caused by one bite.8 Other presentations include purpuric macules, bullae, and papular urticaria.8-10 Although bedbugs are suspected to transmit infectious diseases, no reports have substantiated that claim.11

Our patient had several coalescing dermal papules on the arms indicating multiple bites around the same area. Due to the stationary aspect of his job—with the arms resting on his chair while typing at his desk—our patient was an easy target for consistent blood meals.

Detection

Due to an overall smaller population of insects in an office setting, detection of bedbugs in the workplace can be difficult. Infestations can be primarily identified on visual inspection by pest control.12 The mesh backing on our patient’s chair was one site where bedbugs resided. It is important to check areas where employees congregate, such as lounges, lunch areas, conference rooms, and printers.4 It also is essential to examine coatracks and locker rooms, as employees may leave personal items that can serve as a source of transmission of the bugs from home. Additional detection tools provided by pest management professionals include canines, as well as devices that emit pheromones, carbon dioxide, or heat to ensnare the insects.12

Treatment

Treatment of bedbug bites is quite variable. For some patients, lesions may resolve on their own. Pruritic maculopapular eruptions can be treated with topical pramoxine or doxepin.8 Patients who develop allergic urticaria can use oral antihistamines. Systemic reactions such as anaphylaxis can be treated with a combination of intramuscular epinephrine, antihistamines, and corticosteroids.8 The etiology of our patient’s condition initially was unknown, and thus he was given unnecessary systemic steroids and antifungals until the source of the rash was identified and eradicated. Topical clobetasol was subsequently administered and was sufficient to resolve his symptoms.

Final Thoughts

Bedbugs continue to remain a nuisance in the home. This case provides an example of bedbugs in the office, a location that is not commonly associated with bedbug infestations. Bedbugs pose numerous psychological, economic, and health consequences.2 Productivity can be reduced, as patients with symptomatic lesions will be unable to work effectively, and those who are unaffected may be unwilling to work knowing their office environment poses a health risk. In addition, employees may worry about bringing the bedbugs home. It is important that employees be educated on the signs of a bedbug infestation and take preventive measures to stop spreading or introducing them to the office space. Due to the scattered habitation of bedbugs in offices, pest control managers need to be vigilant to identify sources of infestation and eradicate accordingly. Clinical manifestations can be nonspecific, resembling autoimmune disorders, fungal infections, or bites from other various arthropods; thus, treatment is highly dependent on the patient’s history and occupational exposure.

Bedbugs have successfully adapted to a new environment in the office space. Dermatologists and other health care professionals can no longer exclusively associate bedbugs with the home. When the clinical and histological presentation suggests an arthropod assault, we must counsel our patients to surveil their homes and work settings alike. If necessary, they should seek the assistance of occupational health professionals.

1. Ralph N, Jones HE, Thorpe LE. Self-reported bed bug infestation among New York City residents: prevalence and risk factors. J Environ Health; 2013;76:38-45.

2. US Environmental Protection Agency. Bed Bugs are public health pests. EPA website. https://www.epa.gov/bedbugs/bed-bugs-are-public-health-pests. Accessed December 6, 2018.

3. Potter MF, Haynes KF, Fredericks J. Bed bugs across America: 2015 Bugs Without Borders survey. Pestworld. 2015:4-14. https://www.npmapestworld.org/default/assets/File/newsroom/magazine/2015/nov-dec_2015.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

4. Pinto LJ, Cooper R, Kraft SK. Bed bugs in office buildings: the ultimate challenge? MGK website. http://giecdn.blob.core.windows.net/fileuploads/file/bedbugs-office-buildings.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

5. Baumblatt JA, Dunn JR, Schaffner W, et al. An outbreak of bed bug infestation in an office building. J Environ Health. 2014;76:16-19.

6. Parasites: bed bugs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. www.cdc.gov/parasites/bedbugs/biology.html. Updated March 17, 2015. Accessed September 21, 2018.

7. Bed bugs. University of Minnesota Extension website. https://www.extension.umn.edu/garden/insects/find/bed-bugs-in-residences. Accessed September 21, 2018.

8. Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358-1366.

9. Scarupa, MD, Economides A. Bedbug bites masquerading as urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1508-1509.

10. Abdel-Naser MB, Lotfy RA, Al-Sherbiny MM, et al. Patients with papular urticaria have IgG antibodies to bedbug (Cimex lectularius) antigens. Parasitol Res. 2006;98:550-556.

11. Lai O, Ho D, Glick S, et al. Bed bugs and possible transmission of human pathogens: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:531-538.

12. Vaidyanathan R, Feldlaufer MF. Bed bug detection: current technologies and future directions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:619-625.

Bedbugs are common pests causing several health and economic consequences. With increased travel, pesticide resistance, and a lack of awareness about prevention, bedbugs have become even more difficult to control, especially within large population centers.1 The US Environmental Protection Agency considers bedbugs to be a considerable public health issue.2 Typically, they are found in private residences; however, there have been more reports of bedbugs discovered in the workplace within the last 20 years.3-5 Herein, we present a case of bedbugs presenting in this unusual environment.

Case Report

A 42-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with intensely itchy bumps over the bilateral posterior arms of 3 months’ duration. He had no other skin, hair, or nail concerns. Over the last 3 months prior to dermatologic evaluation, he was treated by an outside physician with topical steroids, systemic antibiotics, topical antifungals, and even systemic steroids with no improvement of the lesions or symptoms. On clinical examination at the current presentation, 8 to 10 pink dermal papules coalescing into 10-cm round patches were noted on the bilateral posterior arms (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the posterior right arm was performed, and histologic analysis showed a dense superficial and deep infiltrate and a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 2). No notable epidermal changes were observed.

At this time, the patient was counseled that the most likely cause was some unknown arthropod exposure. Given the chronicity of the patient’s disease course, bedbugs were favored; however, an extensive search of the patient’s home failed to uncover any arthropods, let alone bedbugs. A few weeks later, the patient discovered insects emanating from the mesh backing of his office chair while at work (Figure 3). The location of the intruders corresponded exactly with the lesions on the posterior arms. The occupational health office at his workplace collected samples of the arthropods and confirmed they were bedbugs. The patient’s lesions resolved with topical clobetasol once eradication of the workplace was complete.

Discussion

Morphology and Epidemiology

Bedbugs are wingless arthropods that have flat, oval-shaped, reddish brown bodies. They are approximately 4.5-mm long and 2.5-mm wide (Figure 4). The 2 most common species of bedbugs that infect humans are Cimex lectularius and Cimex hemipterus. Bedbugs are most commonly found in hotels, apartments, and residential households near sleep locations. They reside in crevices, cracks, mattresses, cushions, dressers, and other structures proximal to the bed. During the day they remain hidden, but at night they emerge for a blood meal. The average lifespan of a bedbug is 6 to 12 months.6 Females lay more than 200 eggs that hatch in approximately 6 to 10 days.7 Bedbugs progress through 5 nymph stages before becoming adults; several blood meals are required to advance each stage.6