User login

Optimizing Narrowband UVB Phototherapy: Is It More Challenging for Your Older Patients?

Even with recent pharmacologic treatment advances, narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy remains a versatile, safe, and efficacious adjunctive or exclusive treatment for multiple dermatologic conditions, including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

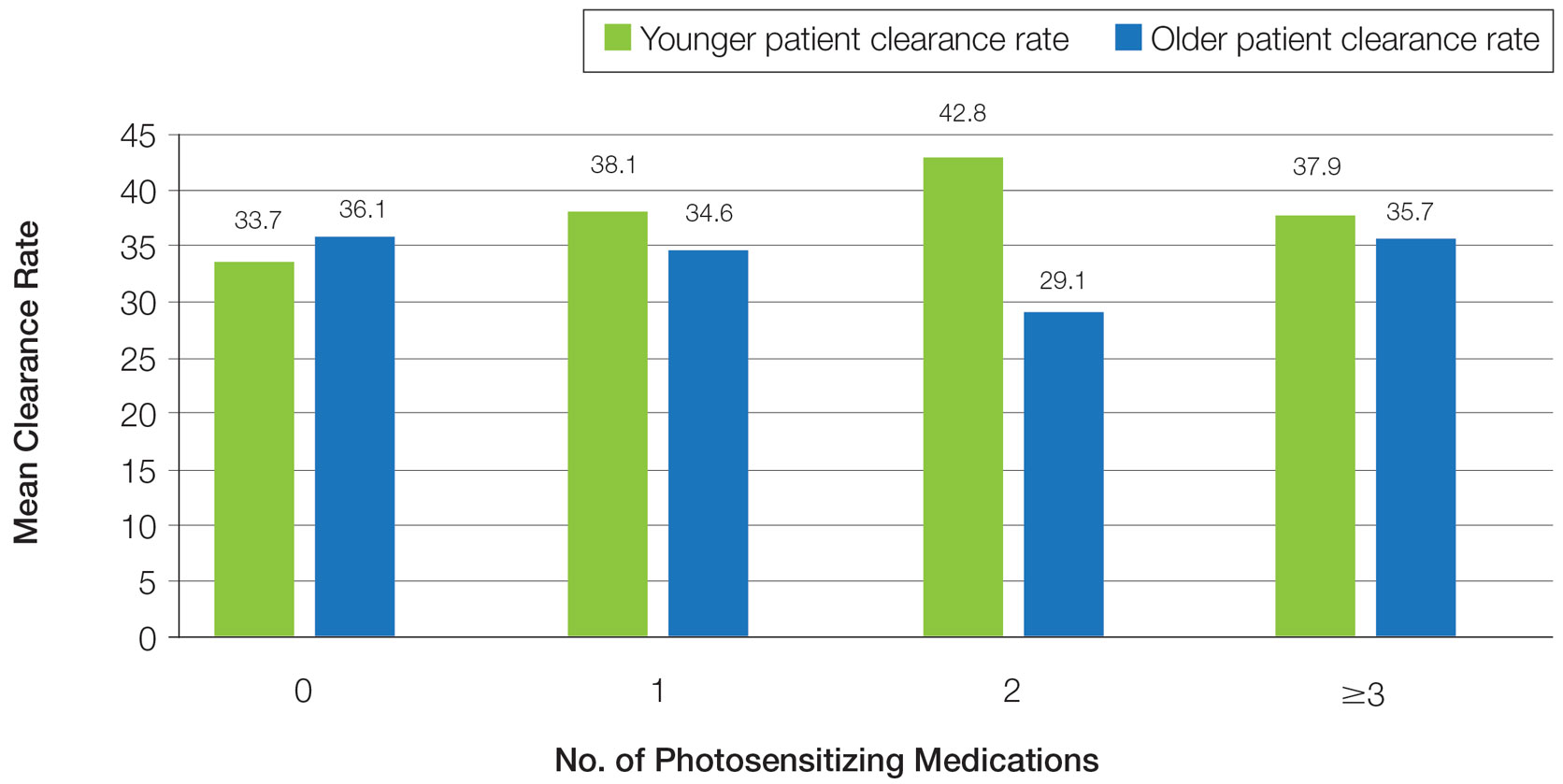

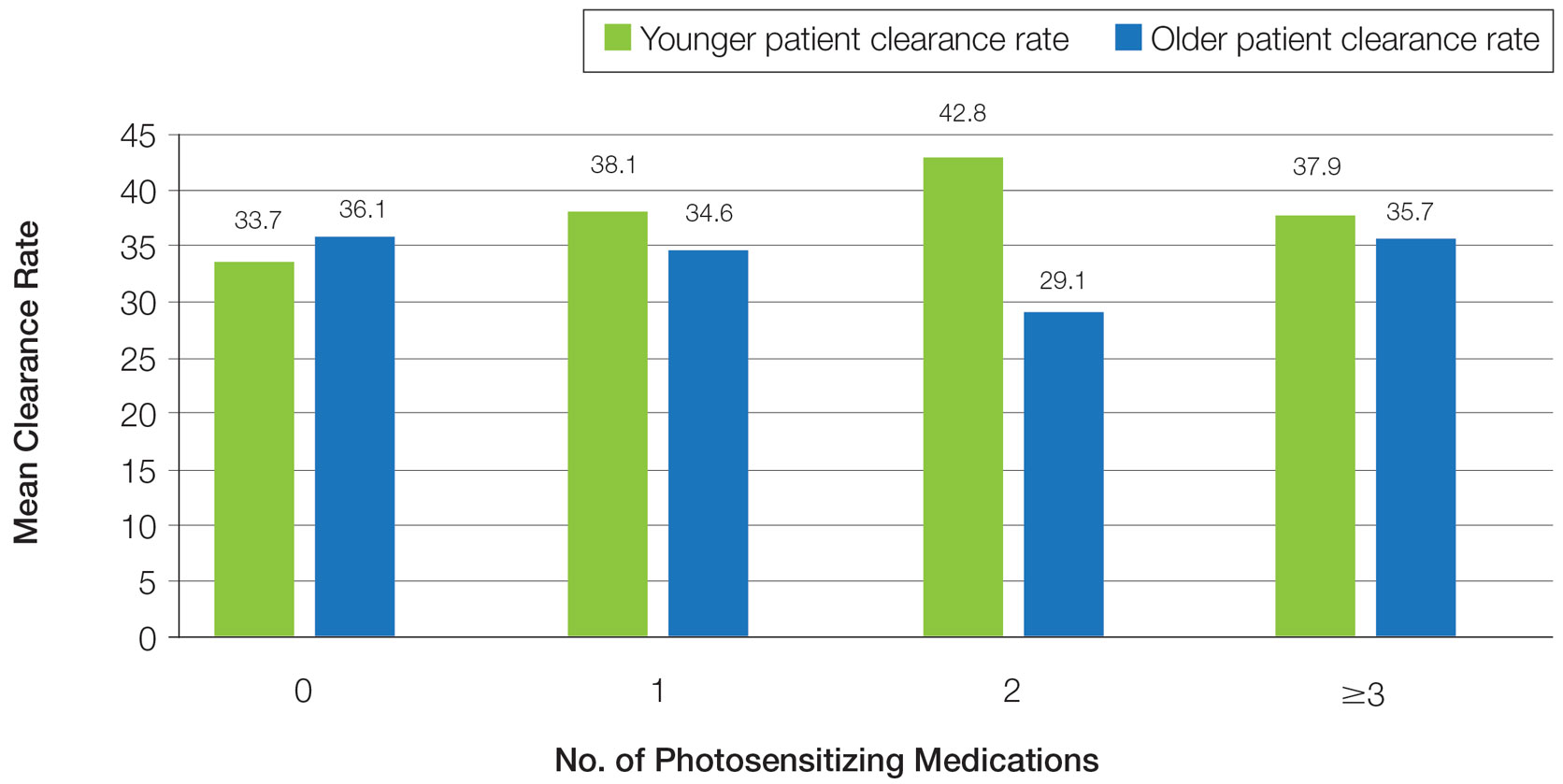

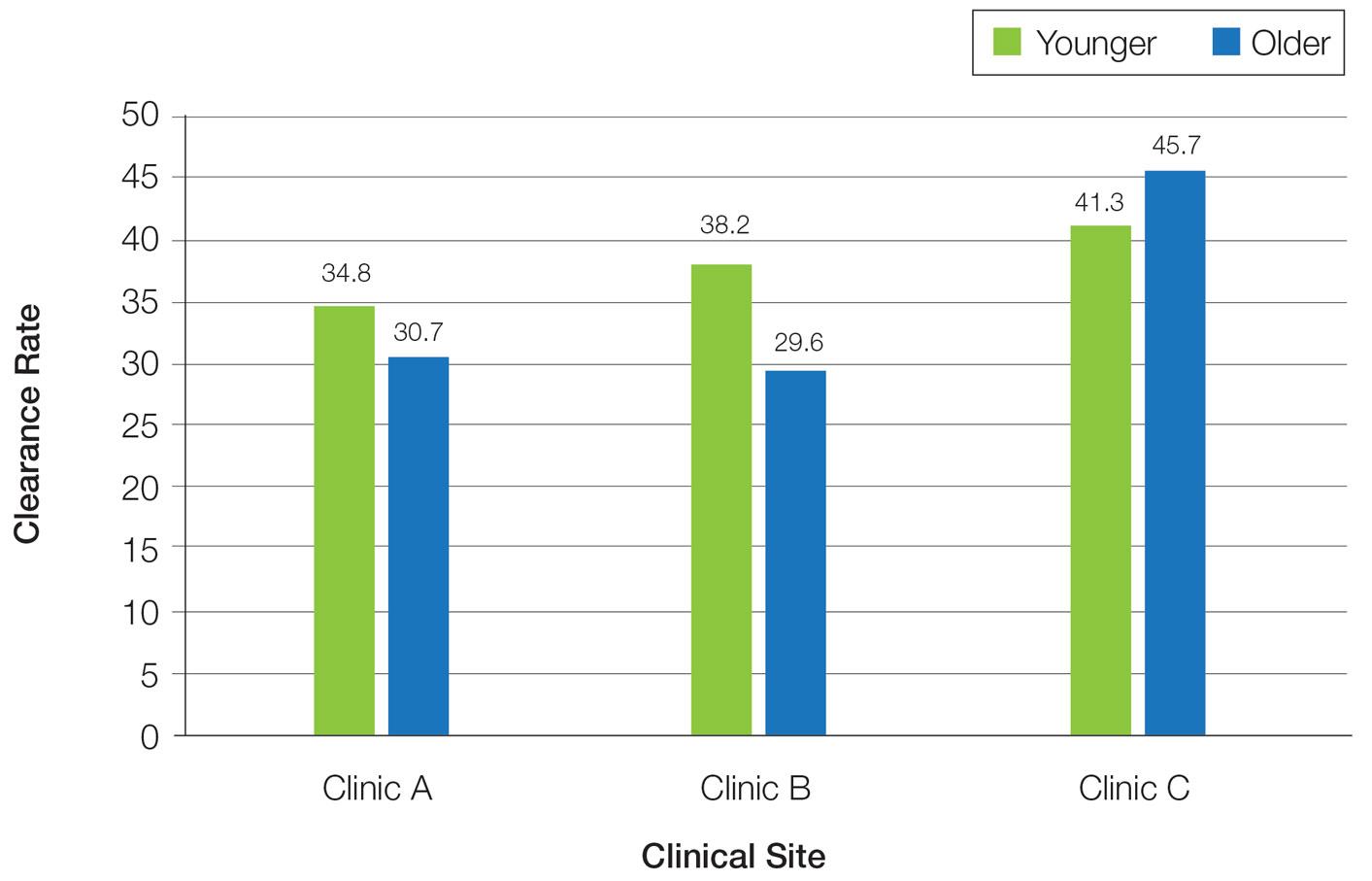

In a prior study, Matthews et al13 reported that 96% (50/52) of patients older than 65 years achieved medium to high levels of clearance with NB-UVB phototherapy. Nonetheless, 2 other findings in this study related to the number of treatments required to achieve clearance (ie, clearance rates) and erythema rates prompted further investigation. The first finding was higher-than-expected clearance rates. Older adults had a clearance rate with a mean of 33 treatments compared to prior studies featuring mean clearance rates of 20 to 28 treatments.7,8,14-16 This finding resembled a study in the United Kingdom17 with a median clearance rate in older adults of 30 treatments. In contrast, the median clearance rate from a study in Turkey18 was 42 treatments in older adults. We hypothesized that more photosensitizing medications used in older vs younger adults prompted more dose adjustments with NB-UVB phototherapy to avoid burning (ie, erythema) at baseline and throughout the treatment course. These dose adjustments may have increased the overall clearance rates. If true, we predicted that younger adults treated with the same protocol would have cleared more quickly, either because of age-related differences or because they likely had fewer comorbidities and therefore fewer medications.

The second finding from Matthews et al13 that warranted further investigation was a higher erythema rate compared to the older adult study from the United Kingdom.17 We hypothesized that potentially greater use of photosensitizing medications in the United States could explain the higher erythema rates. Although medication-induced photosensitivity is less likely with NB-UVB phototherapy than with UVA, certain medications can cause UVB photosensitivity, including thiazides, quinidine, calcium channel antagonists, phenothiazines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.8,19,20 Therefore, photosensitizing medication use either at baseline or during a course of NB-UVB phototherapy could increase the risk for erythema. Age-related skin changes also have been considered as a

This retrospective study aimed to determine if NB-UVB phototherapy is equally effective in both older and younger adults treated with the same protocol; to examine the association between the use of photosensitizing medications and clearance rates in both older and younger adults; and to examine the association between the use of photosensitizing medications and erythema rates in older vs younger adults.

Methods

Study Design and Patients—This retrospective cohort study used billing records to identify patients who received NB-UVB phototherapy at 3 different clinical sites within a large US health care system in Washington (Group Health Cooperative, now Kaiser Permanente Washington), serving more than 600,000 patients between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2016. The institutional review board of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute approved this study (IRB 1498087-4). Younger adults were classified as those 64 years or younger and older adults as those 65 years and older at the start of their phototherapy regimen. A power analysis determined that the optimal sample size for this study was 250 patients.

Individuals were excluded if they had fewer than 6 phototherapy treatments; a diagnosis of vitiligo, photosensitivity dermatitis, morphea, or pityriasis rubra pilaris; and/or treatment of the hands or feet only.

Phototherapy Protocol—Using a 48-lamp NB-UVB unit, trained phototherapy nurses provided all treatments following standardized treatment protocols13 based on previously published phototherapy guidelines.24 Nurses determined each patient’s disease clearance level using a 3-point clearance scale (high, medium, low).13 Each patient’s starting dose was determined based on the estimated MED for their skin phototype.

Statistical Analysis—Data were analyzed using Stata statistical software (StataCorp LLC). Univariate analyses were used to examine the data and identify outliers, bad values, and missing data, as well as to calculate descriptive statistics. Pearson χ2 and Fisher exact statistics were used to calculate differences in categorical variables. Linear multivariate regression models and logistic multivariate models were used to examine statistical relationships between variables. Statistical significance was defined as P≤.05.

Results

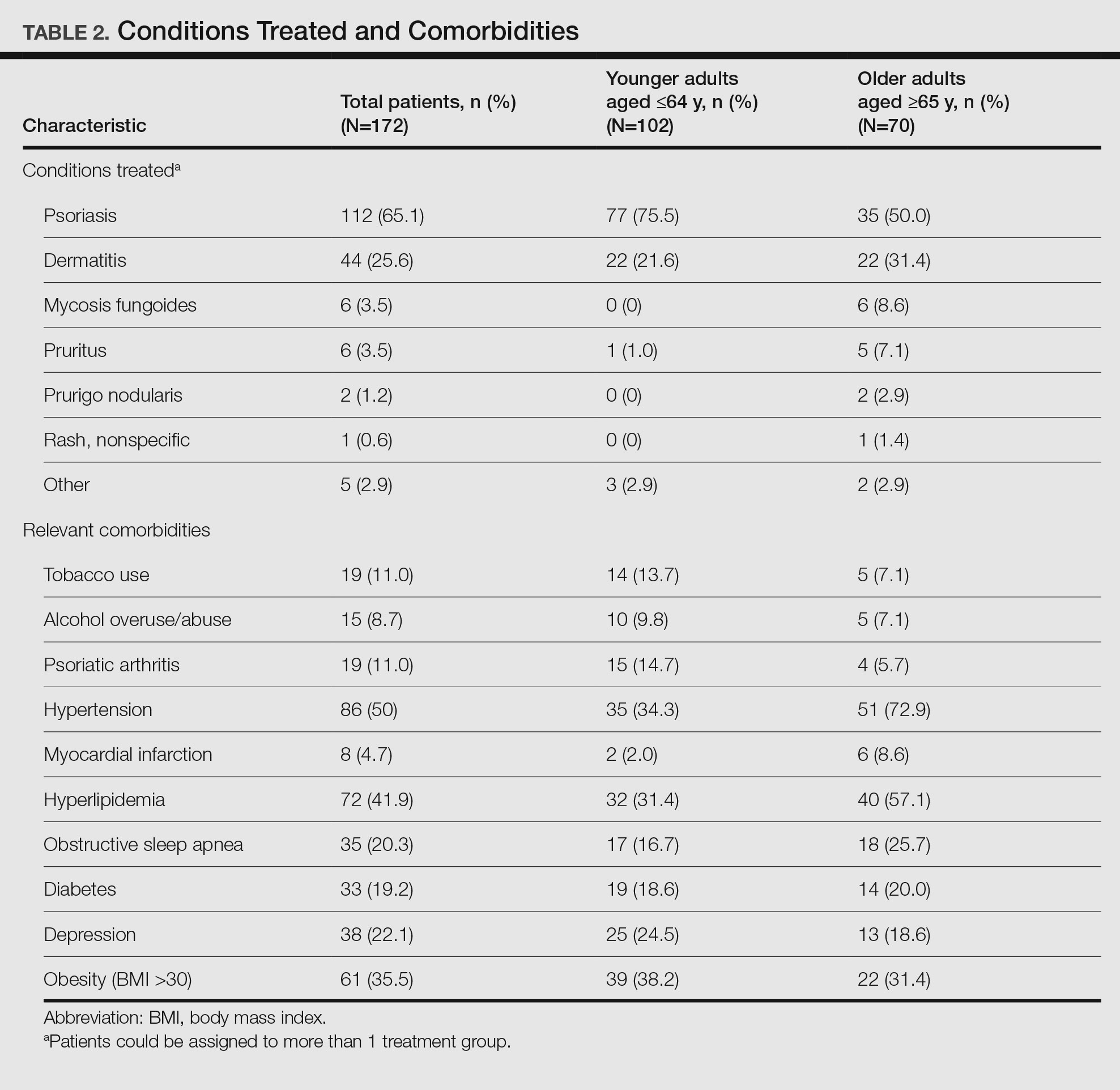

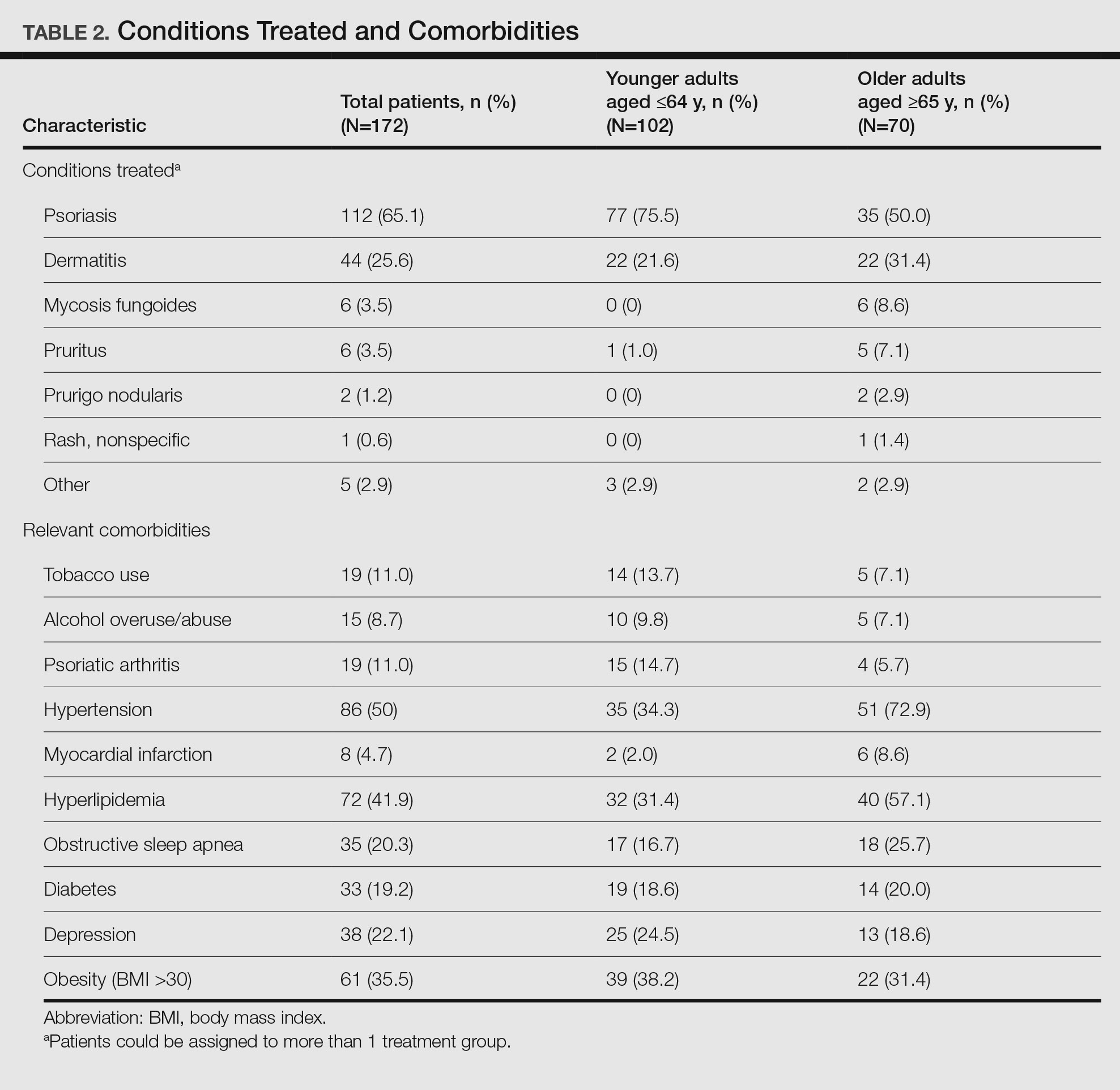

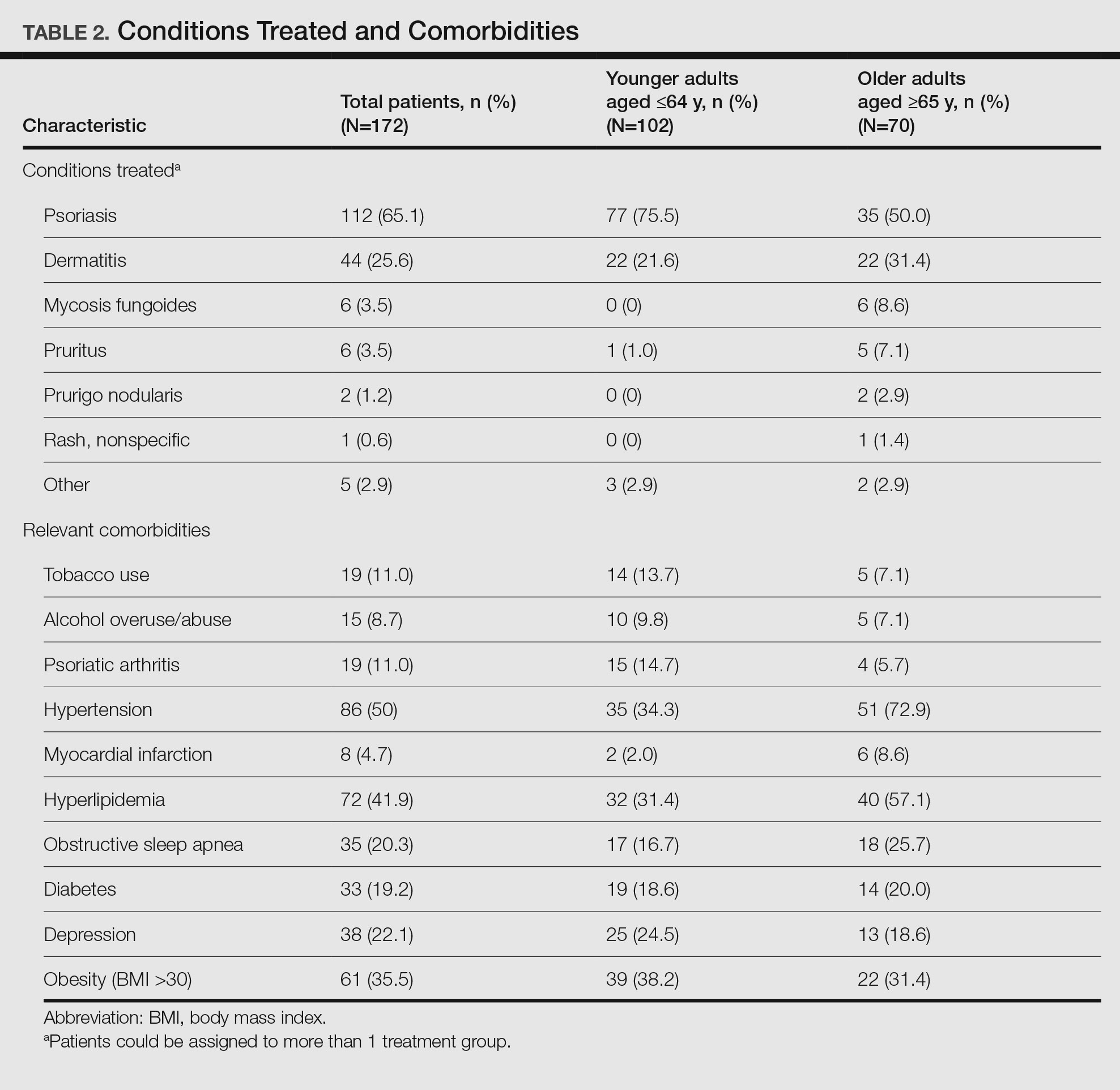

Patient Characteristics—Medical records were reviewed for 172 patients who received phototherapy between 2012 and 2016. Patients ranged in age from 23 to 91 years, with 102 patients 64 years and younger and 70 patients 65 years and older. Tables 1 and 2 outline the patient characteristics and conditions treated.

Phototherapy Effectiveness—

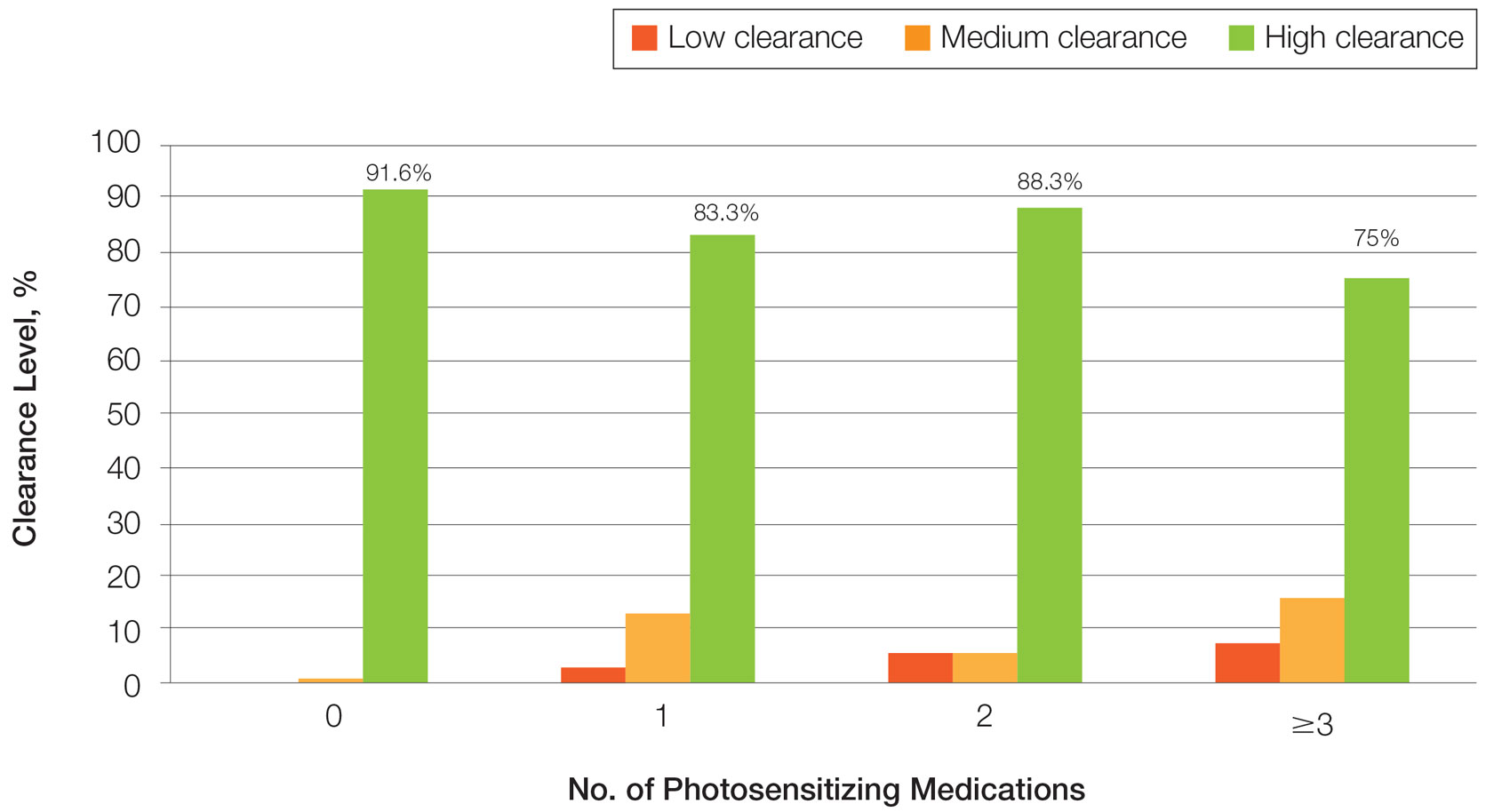

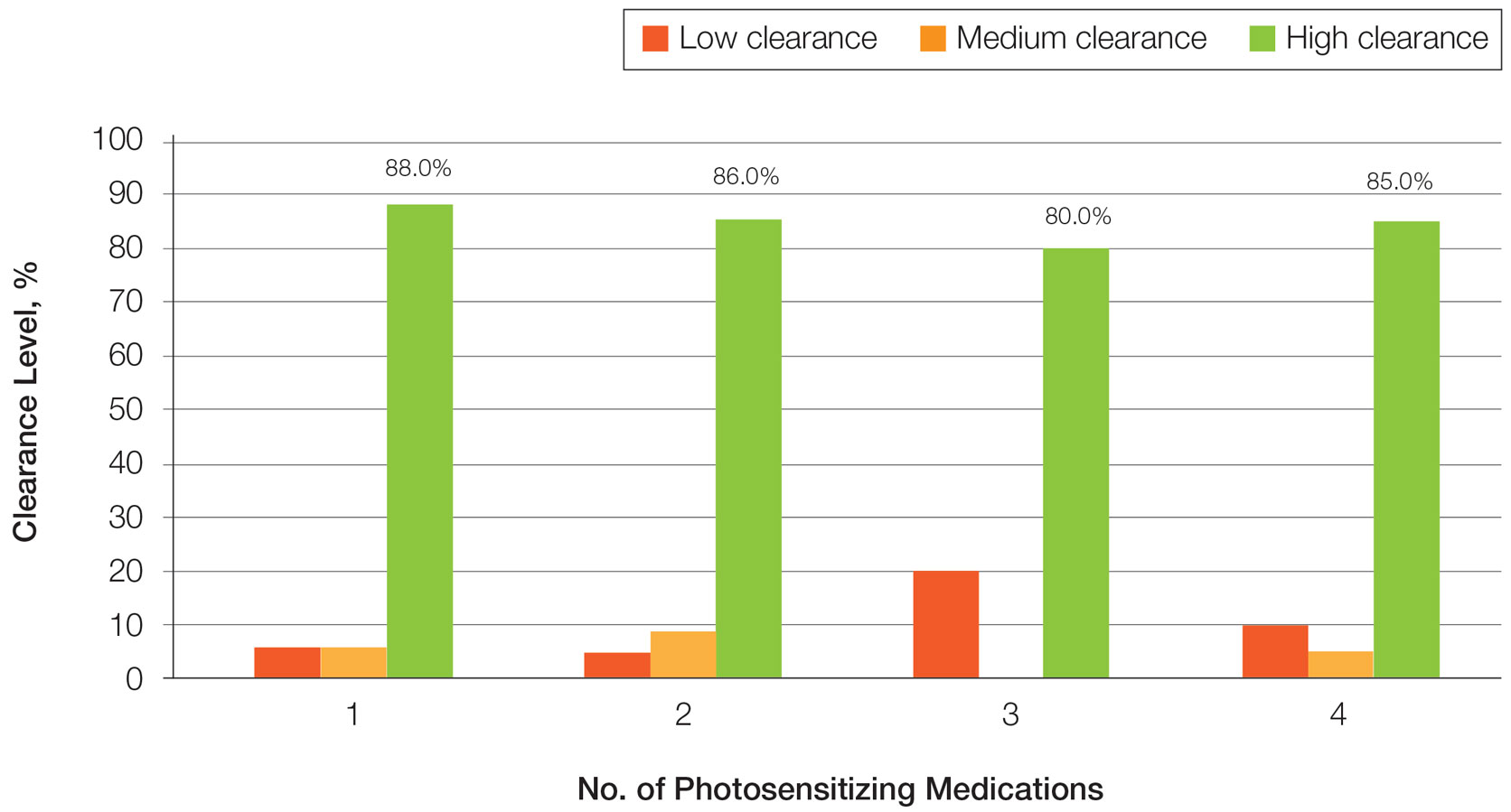

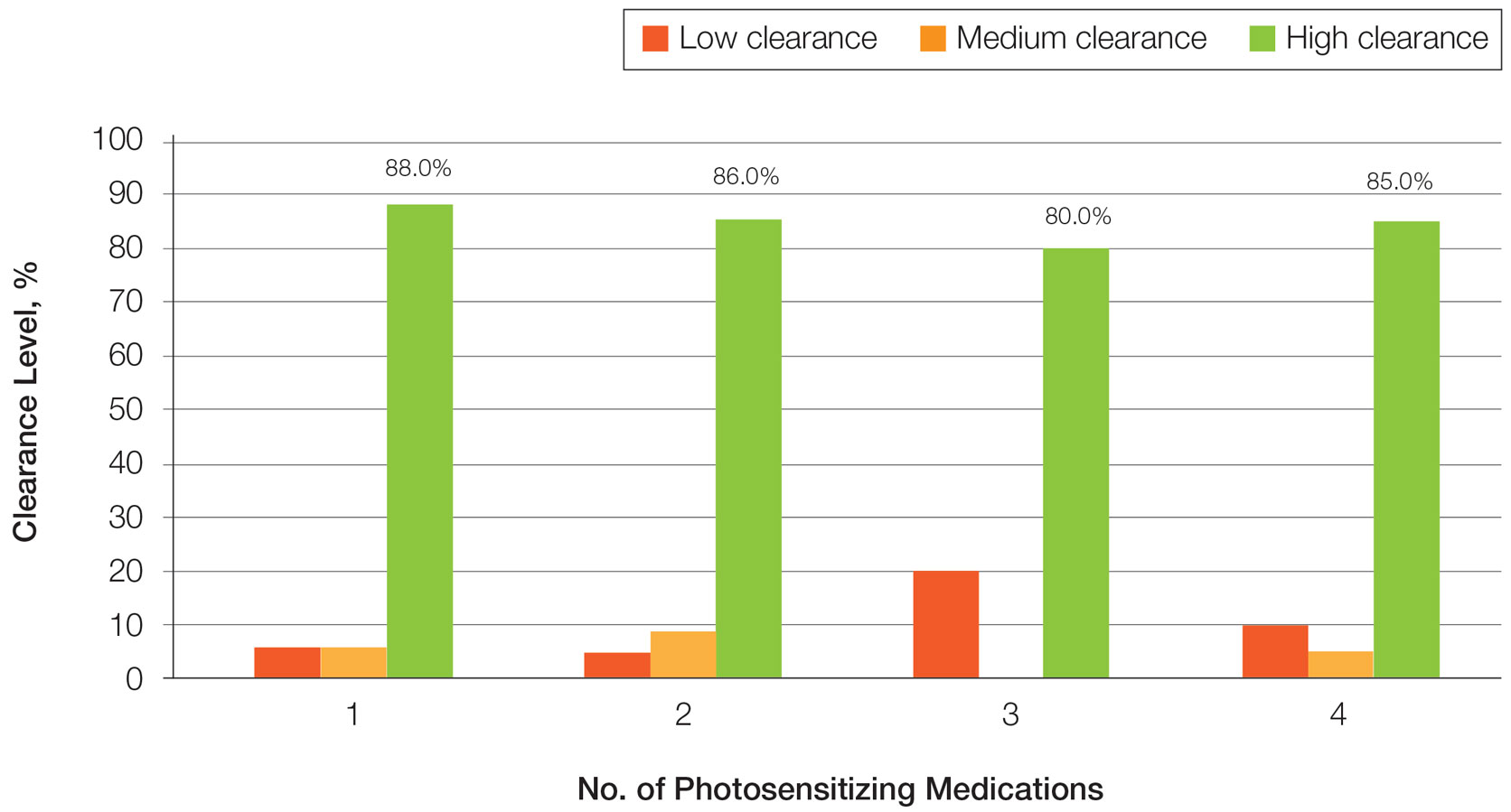

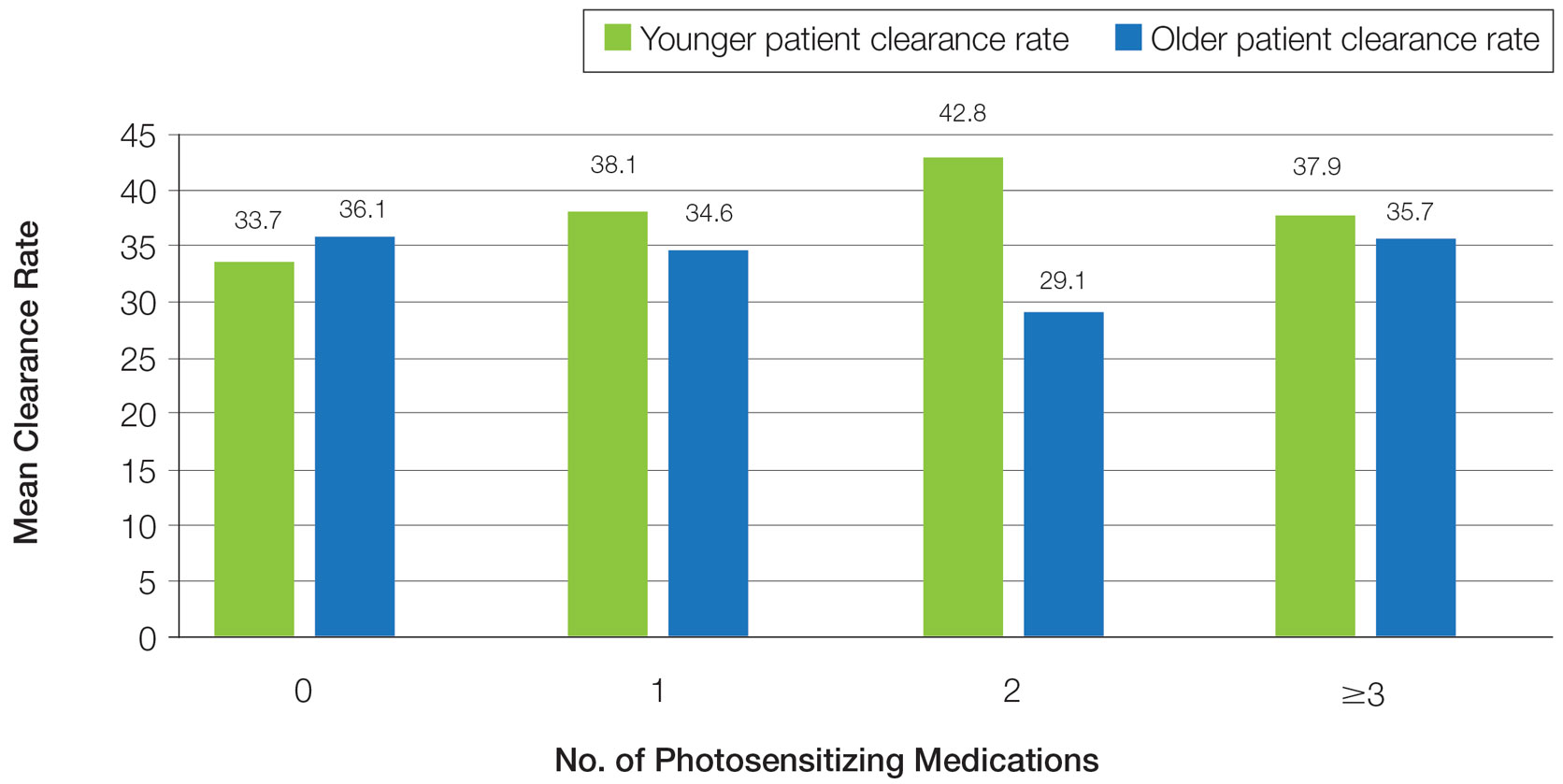

Photosensitizing Medications, Clearance Levels, and Clearance Rates—

Frequency of Treatments and Clearance Rates—Older adults more consistently completed the recommended frequency of treatments—3 times weekly—compared to younger adults (74.3% vs 58.5%). However, all patients who completed 3 treatments per week required a similar number of treatments to clear (older adults, mean [SD]: 35.7 [21.6]; younger adults, mean [SD]: 34.7 [19.0]; P=.85). Among patients completing 2 or fewer treatments per week, older adults required a mean (SD) of only 31 (9.0) treatments to clear vs 41.5 (21.3) treatments to clear for younger adults, but the difference was not statistically significant (P=.08). However, even those with suboptimal frequency ultimately achieved similar clearance levels.

Photosensitizing Medications and Erythema Rates—

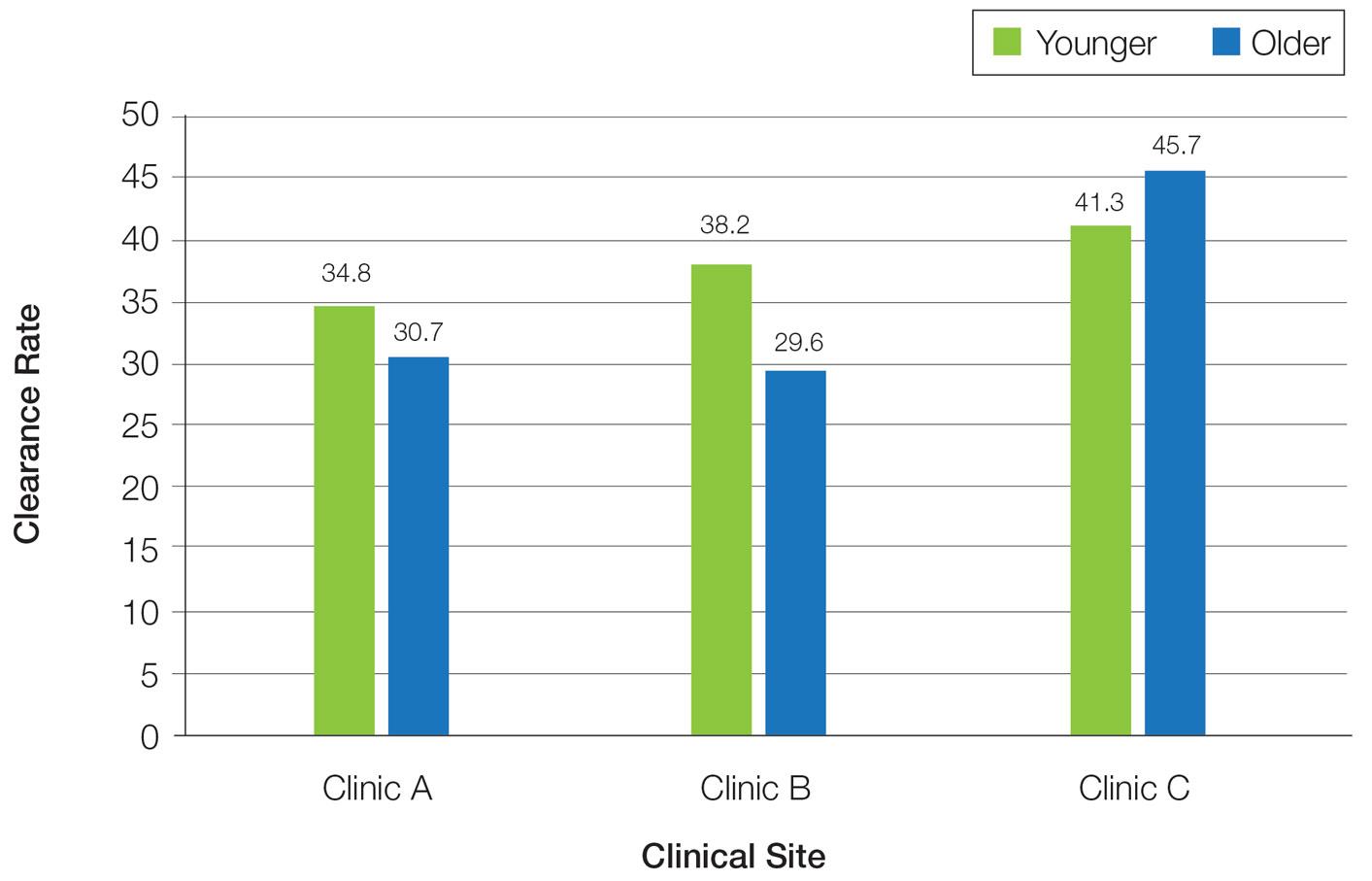

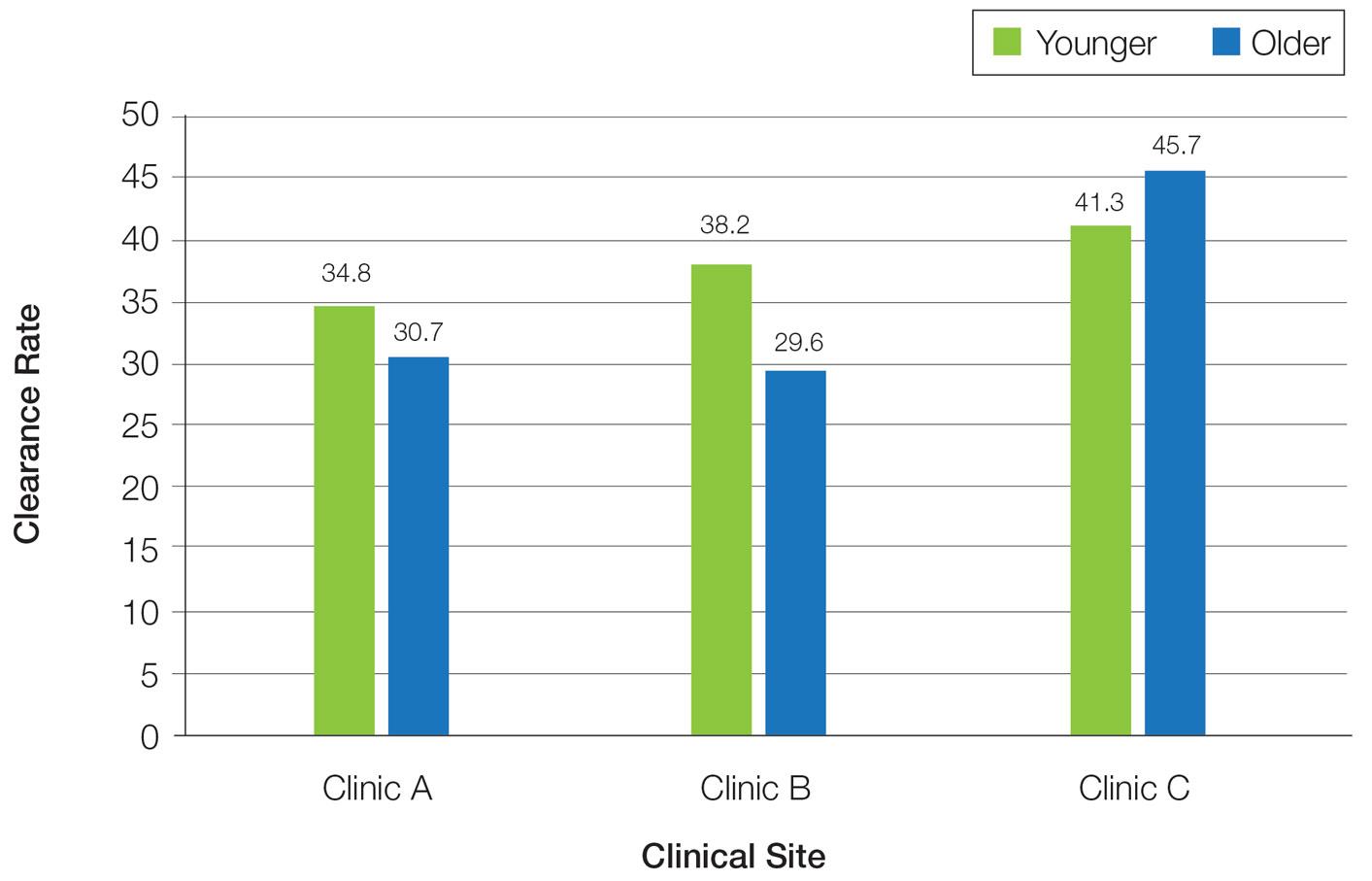

Overall, phototherapy nurses adjusted the starting dose according to the phototype-based protocol an average of 69% of the time for patients on medications with photosensitivity listed as a potential side effect. However, the frequency depended significantly on the clinic (clinic A, 24%; clinic B, 92%; clinic C, 87%)(P≤.001). Nurses across all clinics consistently decreased the treatment dose when patients reported starting new photosensitizing medications. Patients with adjusted starting doses had slightly but not significantly higher clearance rates compared to those without (mean, 37.8 vs 35.5; t(104)=0.58; P=.56).

Comment

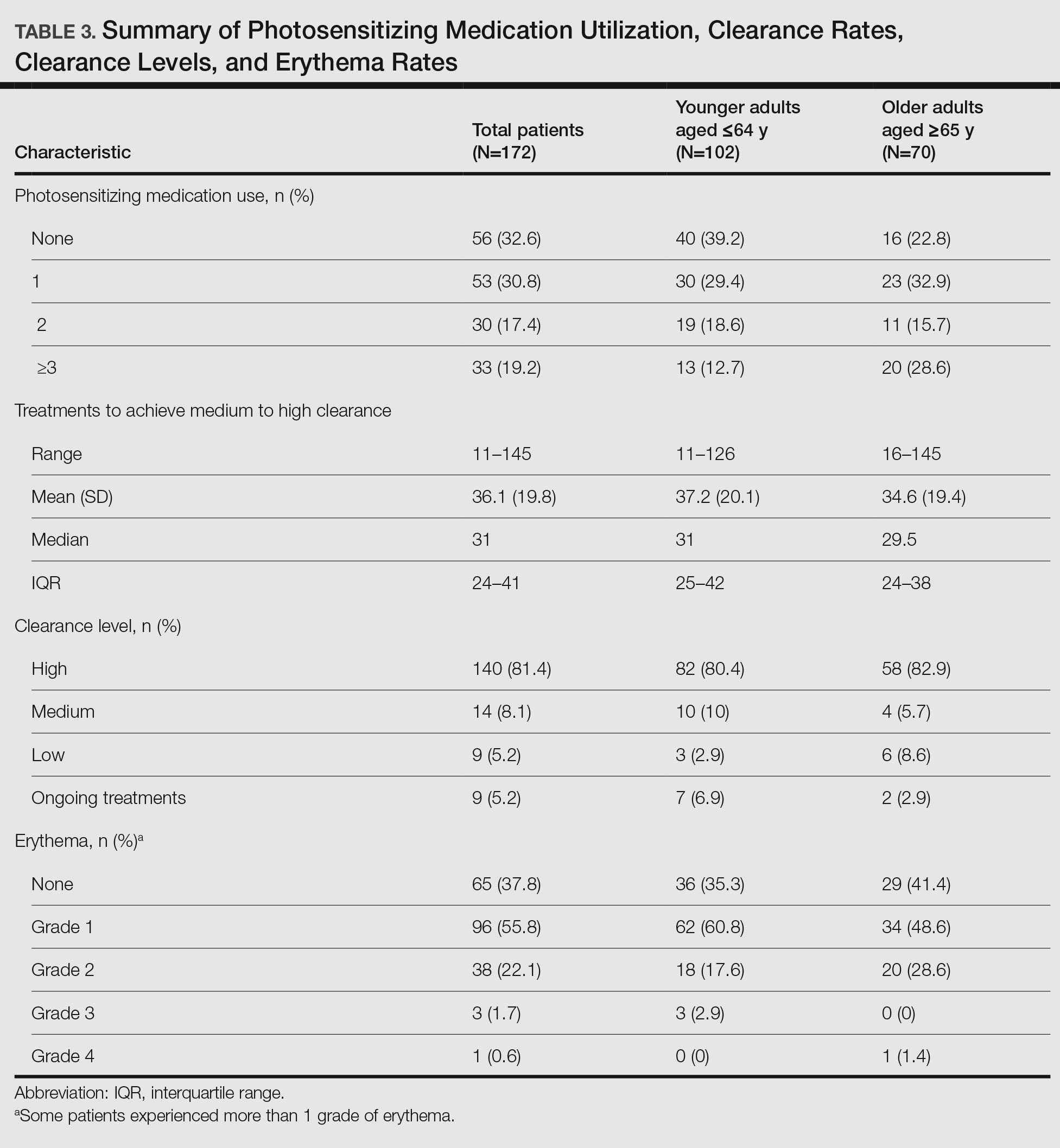

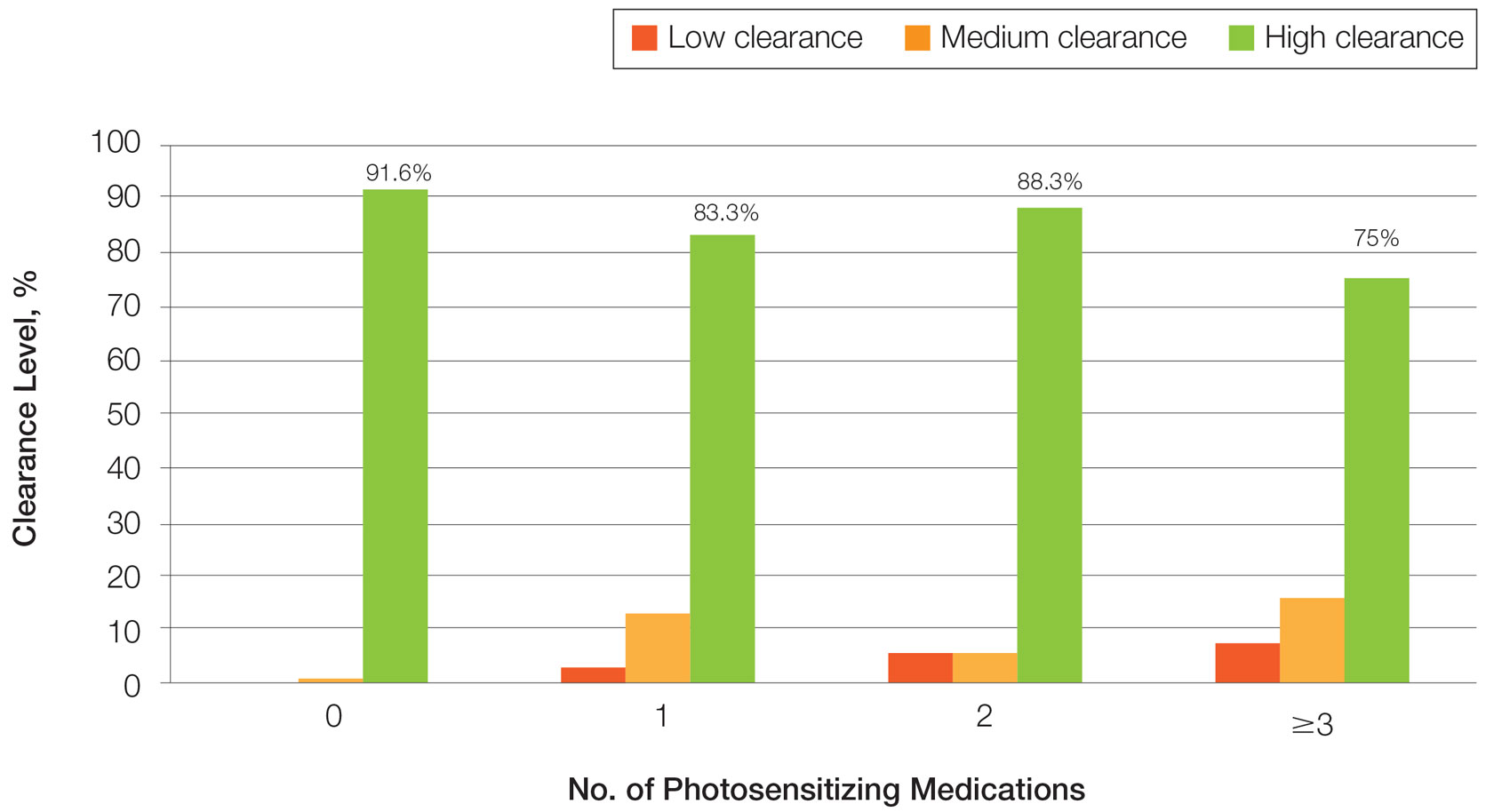

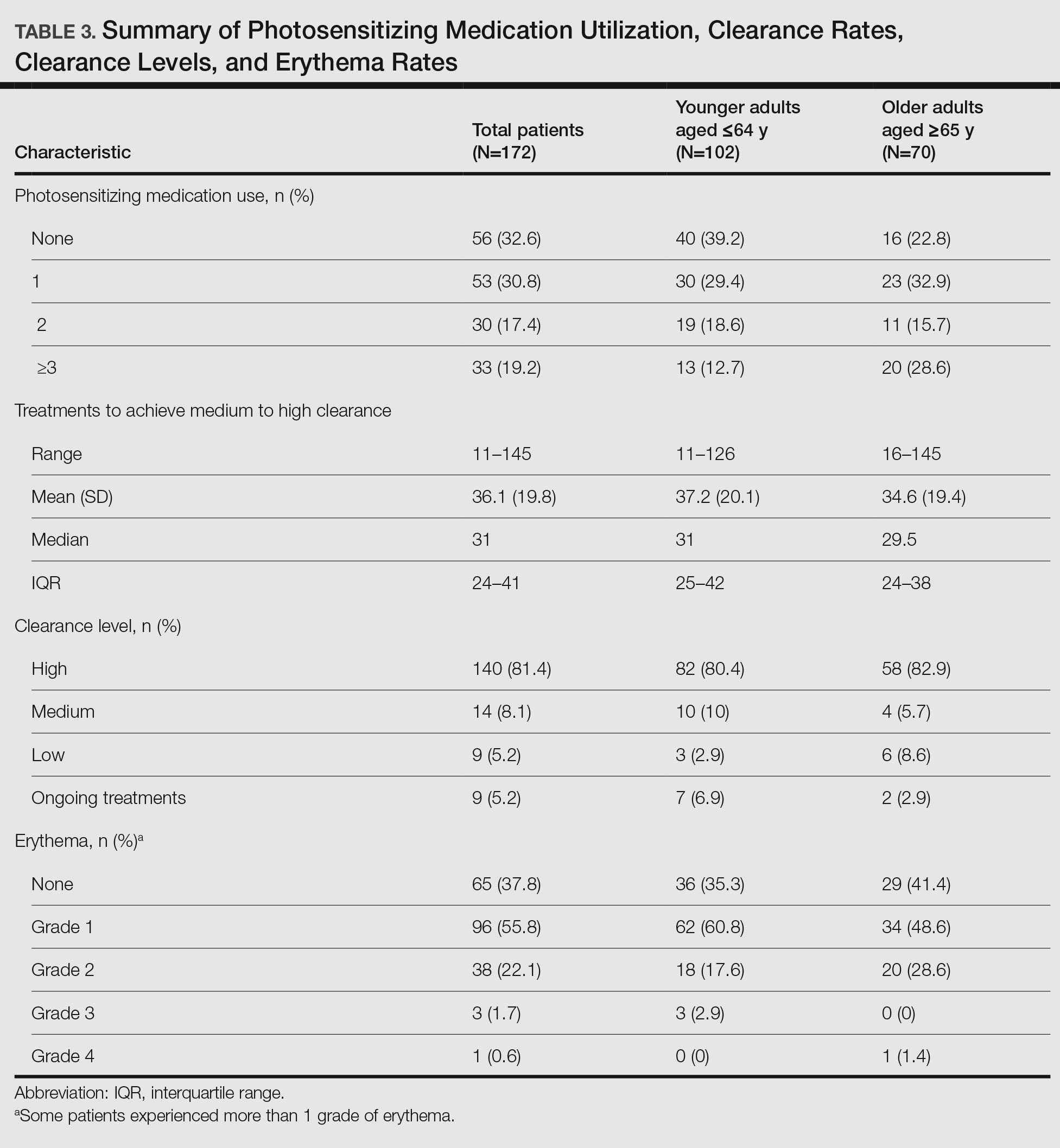

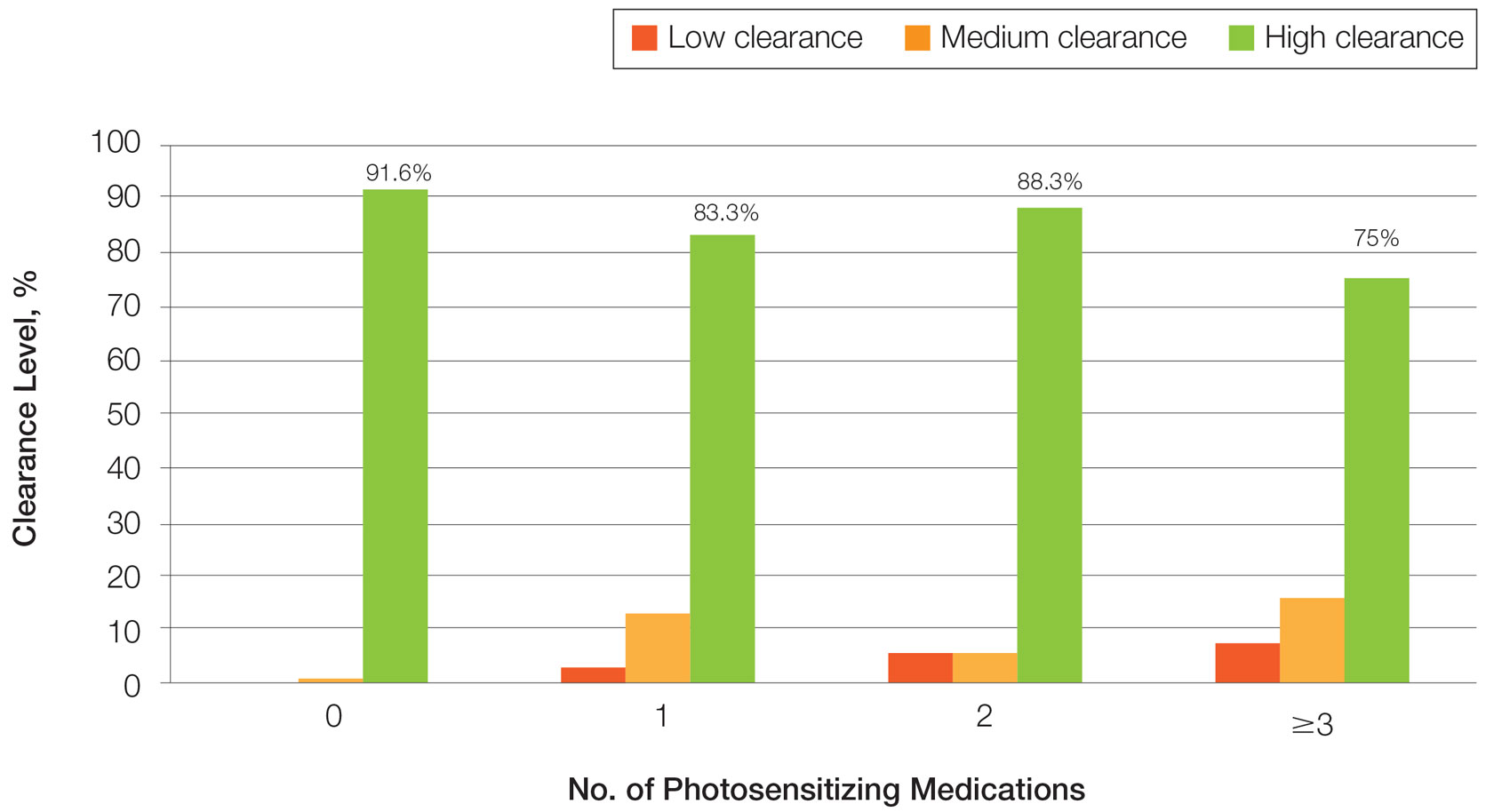

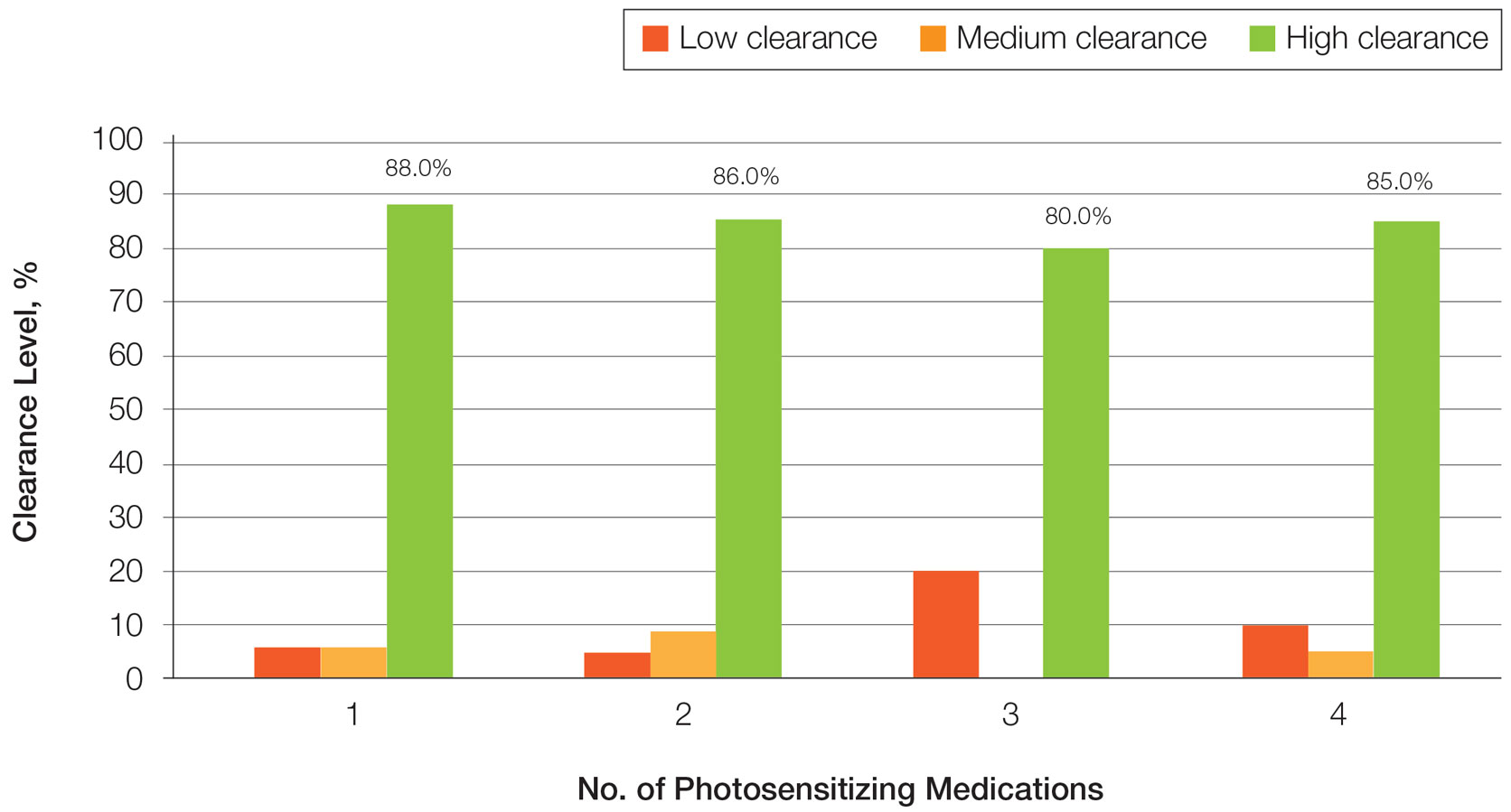

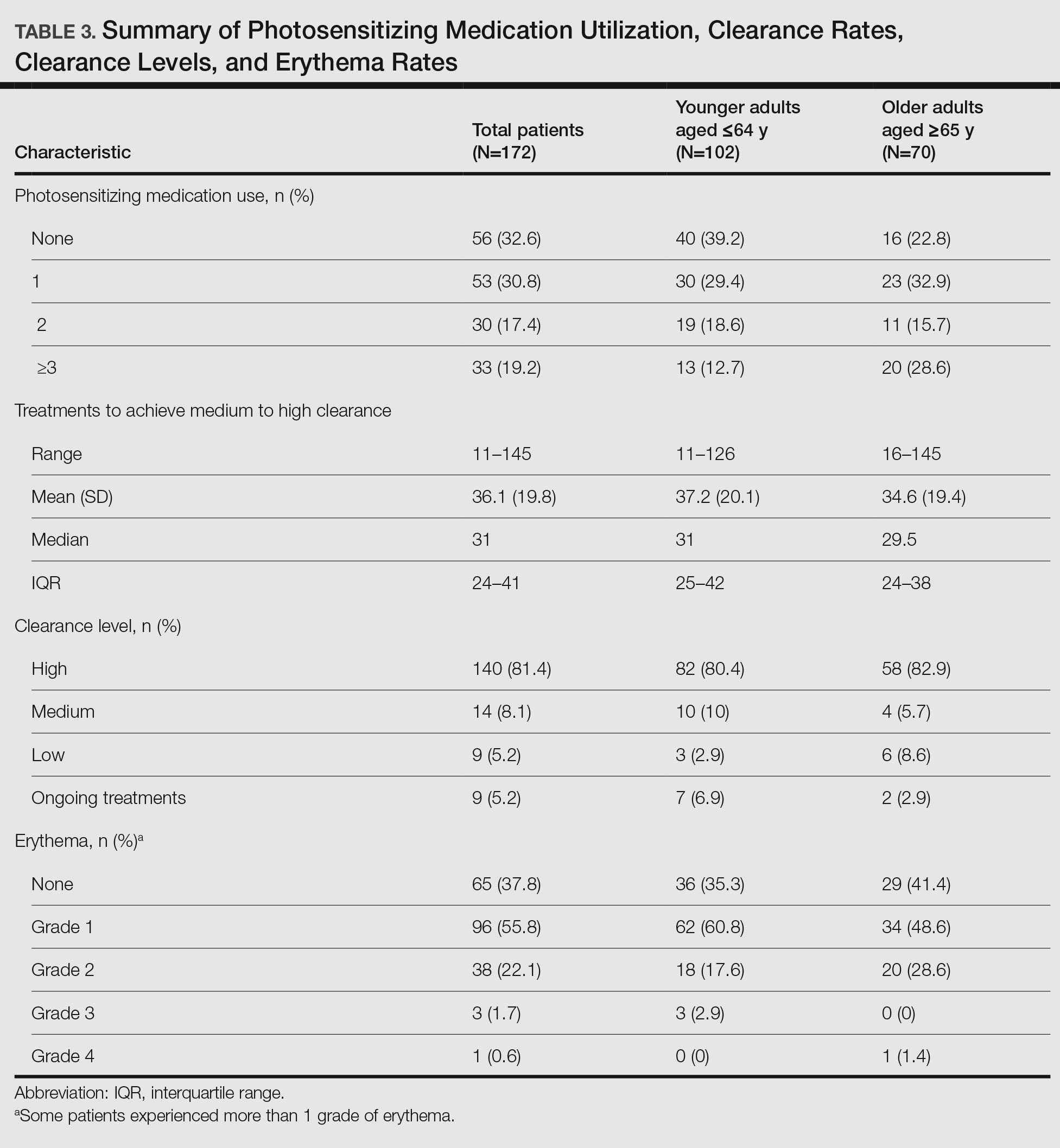

Impact of Photosensitizing Medications on Clearance—Photosensitizing medications and treatment frequency were 2 factors that might explain the slower clearance rates in younger adults. In this study, both groups of patients used similar numbers of photosensitizing medications, but more older adults were taking 3 or more medications (Table 3). We found no statistically significant relationship between taking photosensitizing medications and either the clearance rates or the level of clearance achieved in either age group.

Impact of Treatment Frequency—Weekly treatment frequency also was examined. One prior study demonstrated that treatments 3 times weekly led to a faster clearance time and higher clearance levels compared with twice-weekly treatment.7 When patients completed treatments twice weekly, it took an average of 1.5 times more days to clear, which impacted cost and clinical resource availability. The patients ranged in age from 17 to 80 years, but outcomes in older patients were not described separately.7 Interestingly, our study seemed to find a difference between age groups when the impact of treatment frequency was examined. Older adults completed nearly 4 fewer mean treatments to clear when treating less often, with more than 80% achieving high levels of clearance, whereas the younger adults required almost 7 more treatments to clear when they came in less frequently, with approximately 80% achieving a high level of clearance. As a result, our study found that in both age groups, slowing the treatment frequency extended the treatment time to clearance—more for the younger adults than the older adults—but did not significantly change the percentage of individuals reaching full clearance in either group.

Erythema Rates—There was no association between photosensitizing medications and erythema rates except when patients were taking at least 3 medications. Most medications that listed photosensitivity as a possible side effect did not specify their relevant range of UV radiation; therefore, all such medications were examined during this analysis. Prior research has shown UVB range photosensitizing medications include thiazides, quinidine, calcium channel antagonists, phenothiazines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.19 A sensitivity analysis that focused only on these medications found no association between them and any particular grade of erythema. However, patients taking 3 or more of any medications listing photosensitivity as a side effect had an increased risk for grade 2 erythema.

Erythema rates in this study were consistent with a 2013 systematic review that reported 57% of patients with asymptomatic grade 1 erythema.25 In the 2 other comparative older adult studies, erythema rates varied widely: 35% in a study from Turkey18compared to only1.89% in a study from the United Kingdom.17

The starting dose for NB-UVB may drive erythema rates. The current study’s protocols were based on an estimated MED that is subjectively determined by the dermatology provider’s assessment of the patient’s skin sensitivity via examination and questions to the patient about their response to environmental sun exposure (ie, burning and tanning)26 and is frequently used to determine the starting dose and subsequent dose escalation. Certain medications have been found to increase photosensitivity and erythema,20 which can change an individual’s MED. If photosensitizing medications are started prior to or during a course of NB-UVB without a pretreatment MED, they might increase the risk for erythema. This study did not identify specific erythema-inducing medications but did find that taking 3 or more photosensitizing medications was associated with increased episodes of grade 2 erythema. Similarly, Harrop et al8 found that patients who were taking photosensitizing medications were more likely to have grade 2 or higher erythema, despite baseline MED testing, which is an established safety mechanism to reduce the risk and severity of erythema.14,20,27 The authors of a recent study of older adults in Taiwan specifically recommended MED testing due to the unpredictable influence of polypharmacy on MED calculations in this population.28 Therefore, this study’s use of an estimated MED in older adults may have influenced the starting dose as well as the incidence and severity of erythemic events. Age-related skin changes likely are ruled out as a consideration for mild erythema by the similarity of grade 1 erythema rates in both older and younger adults. Other studies have identified differences between the age groups, where older patients experienced more intense erythema in the late phase of UVB treatments.22,23 This phenomenon could increase the risk for a grade 2 erythema, which may correspond with this study’s findings.

Other potential causes of erythema were ruled out during our study, including erythema related to missed treatments and shielding mishaps. Other factors, however, may impact the level of sensitivity each patient has to phototherapy, including genetics, epigenetics, and cumulative sun damage. With NB-UVB, near-erythemogenic doses are optimal to achieve effective treatments but require a delicate balance to achieve, which may be more problematic for older adults, especially those taking several medications.

Study Limitations—Our study design made it difficult to draw conclusions about rarer dermatologic conditions. Some patients received treatments over years that were not included in the study period. Finally, power calculations suggested that our actual sample size was too small, with approximately one-third of the required sample missing.

Practical Implications—The goals of phototherapy are to achieve a high level of disease clearance with the fewest number of treatments possible and minimal side effects.

The extra staff training and patient monitoring required for MED testing likely is to add value and preserve resources if faster clearance rates could be achieved and may warrant further investigation. Phototherapy centers require standardized treatment protocols, diligent well-trained staff, and program monitoring to ensure consistent care to all patients. This study highlighted the ongoing opportunity for health care organizations to conduct evidence-based practice inquiries to continually optimize care for their patients.

- Fernández-Guarino M, Aboin-Gonzalez S, Barchino L, et al. Treatment of moderate and severe adult chronic atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB and the combination of narrow-band UVB/UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:19-23.

- Foerster J, Boswell K, West J, et al. Narrowband UVB treatment is highly effective and causes a strong reduction in the use of steroid and other creams in psoriasis patients in clinical practice. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181813.

- Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, Boms S, et al. Narrowband UVB phototherapy in skin conditions beyond psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:660-670.

- Ryu HH, Choe YS, Jo S, et al. Remission period in psoriasis after multiple cycles of narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. J Dermatol. 2014;41:622-627.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

- Tintle S, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. Reversal of atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB phototherapy and biomarkers for therapeutic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:583-593.e581-584.

- Cameron H, Dawe RS, Yule S, et al. A randomized, observer-blinded trial of twice vs. three times weekly narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy for chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:973-978.

- Harrop G, Dawe RS, Ibbotson S. Are photosensitizing medications associated with increased risk of important erythemal reactions during ultraviolet B phototherapy? Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:1184-1185.

- Torres AE, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH, et al. Role of phototherapy in the era of biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:479-485.

- Bukvic´ć Mokos Z, Jovic´ A, Cˇeovic´ R, et al. Therapeutic challenges in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:128-139.

- Di Lernia V, Goldust M. An overview of the efficacy and safety of systemic treatments for psoriasis in the elderly. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18:897-903.

- Oliveira C, Torres T. More than skin deep: the systemic nature of atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:250-258.

- Matthews S, Pike K, Chien A. Phototherapy: safe and effective for challenging skin conditions in older adults. Cutis. 2021;108:E15-E21.

- Rodríguez-Granados MT, Estany-Gestal A, Pousa-Martínez M, et al. Is it useful to calculate minimal erythema dose before narrowband UV-B phototherapy? Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:852-858.

- Parlak N, Kundakci N, Parlak A, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy starting and incremental dose in patients with psoriasis: comparison of percentage dose and fixed dose protocols. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2015;31:90-97.

- Kleinpenning MM, Smits T, Boezeman J, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B therapy in psoriasis: randomized double-blind comparison of high-dose and low-dose irradiation regimens. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1351-1356.

- Powell JB, Gach JE. Phototherapy in the elderly. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:605-610.

- Bulur I, Erdogan HK, Aksu AE, et al. The efficacy and safety of phototherapy in geriatric patients: a retrospective study. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:33-38.

- Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH. Drug-induced photosensitivity. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:363-368, ix.

- Cameron H, Dawe RS. Photosensitizing drugs may lower the narrow-band ultraviolet B (TL-01) minimal erythema dose. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:389-390.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Gloor M, Scherotzke A. Age dependence of ultraviolet light-induced erythema following narrow-band UVB exposure. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2002;18:121-126.

- Cox NH, Diffey BL, Farr PM. The relationship between chronological age and the erythemal response to ultraviolet B radiation. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:315-319.

- Morrison W. Phototherapy and Photochemotherapy for Skin Disease. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2005.

- Almutawa F, Alnomair N, Wang Y, et al. Systematic review of UV-based therapy for psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:87-109.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

- Kwon IH, Kwon HH, Na SJ, et al. Could colorimetric method replace the individual minimal erythemal dose (MED) measurements in determining the initial dose of narrow-band UVB treatment for psoriasis patients with skin phototype III-V? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:494-498.

- Chen WA, Chang CM. The minimal erythema dose of narrowband ultraviolet B in elderly Taiwanese [published online September 1, 2021]. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. doi:10.1111/phpp.12730

Even with recent pharmacologic treatment advances, narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy remains a versatile, safe, and efficacious adjunctive or exclusive treatment for multiple dermatologic conditions, including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

In a prior study, Matthews et al13 reported that 96% (50/52) of patients older than 65 years achieved medium to high levels of clearance with NB-UVB phototherapy. Nonetheless, 2 other findings in this study related to the number of treatments required to achieve clearance (ie, clearance rates) and erythema rates prompted further investigation. The first finding was higher-than-expected clearance rates. Older adults had a clearance rate with a mean of 33 treatments compared to prior studies featuring mean clearance rates of 20 to 28 treatments.7,8,14-16 This finding resembled a study in the United Kingdom17 with a median clearance rate in older adults of 30 treatments. In contrast, the median clearance rate from a study in Turkey18 was 42 treatments in older adults. We hypothesized that more photosensitizing medications used in older vs younger adults prompted more dose adjustments with NB-UVB phototherapy to avoid burning (ie, erythema) at baseline and throughout the treatment course. These dose adjustments may have increased the overall clearance rates. If true, we predicted that younger adults treated with the same protocol would have cleared more quickly, either because of age-related differences or because they likely had fewer comorbidities and therefore fewer medications.

The second finding from Matthews et al13 that warranted further investigation was a higher erythema rate compared to the older adult study from the United Kingdom.17 We hypothesized that potentially greater use of photosensitizing medications in the United States could explain the higher erythema rates. Although medication-induced photosensitivity is less likely with NB-UVB phototherapy than with UVA, certain medications can cause UVB photosensitivity, including thiazides, quinidine, calcium channel antagonists, phenothiazines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.8,19,20 Therefore, photosensitizing medication use either at baseline or during a course of NB-UVB phototherapy could increase the risk for erythema. Age-related skin changes also have been considered as a

This retrospective study aimed to determine if NB-UVB phototherapy is equally effective in both older and younger adults treated with the same protocol; to examine the association between the use of photosensitizing medications and clearance rates in both older and younger adults; and to examine the association between the use of photosensitizing medications and erythema rates in older vs younger adults.

Methods

Study Design and Patients—This retrospective cohort study used billing records to identify patients who received NB-UVB phototherapy at 3 different clinical sites within a large US health care system in Washington (Group Health Cooperative, now Kaiser Permanente Washington), serving more than 600,000 patients between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2016. The institutional review board of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute approved this study (IRB 1498087-4). Younger adults were classified as those 64 years or younger and older adults as those 65 years and older at the start of their phototherapy regimen. A power analysis determined that the optimal sample size for this study was 250 patients.

Individuals were excluded if they had fewer than 6 phototherapy treatments; a diagnosis of vitiligo, photosensitivity dermatitis, morphea, or pityriasis rubra pilaris; and/or treatment of the hands or feet only.

Phototherapy Protocol—Using a 48-lamp NB-UVB unit, trained phototherapy nurses provided all treatments following standardized treatment protocols13 based on previously published phototherapy guidelines.24 Nurses determined each patient’s disease clearance level using a 3-point clearance scale (high, medium, low).13 Each patient’s starting dose was determined based on the estimated MED for their skin phototype.

Statistical Analysis—Data were analyzed using Stata statistical software (StataCorp LLC). Univariate analyses were used to examine the data and identify outliers, bad values, and missing data, as well as to calculate descriptive statistics. Pearson χ2 and Fisher exact statistics were used to calculate differences in categorical variables. Linear multivariate regression models and logistic multivariate models were used to examine statistical relationships between variables. Statistical significance was defined as P≤.05.

Results

Patient Characteristics—Medical records were reviewed for 172 patients who received phototherapy between 2012 and 2016. Patients ranged in age from 23 to 91 years, with 102 patients 64 years and younger and 70 patients 65 years and older. Tables 1 and 2 outline the patient characteristics and conditions treated.

Phototherapy Effectiveness—

Photosensitizing Medications, Clearance Levels, and Clearance Rates—

Frequency of Treatments and Clearance Rates—Older adults more consistently completed the recommended frequency of treatments—3 times weekly—compared to younger adults (74.3% vs 58.5%). However, all patients who completed 3 treatments per week required a similar number of treatments to clear (older adults, mean [SD]: 35.7 [21.6]; younger adults, mean [SD]: 34.7 [19.0]; P=.85). Among patients completing 2 or fewer treatments per week, older adults required a mean (SD) of only 31 (9.0) treatments to clear vs 41.5 (21.3) treatments to clear for younger adults, but the difference was not statistically significant (P=.08). However, even those with suboptimal frequency ultimately achieved similar clearance levels.

Photosensitizing Medications and Erythema Rates—

Overall, phototherapy nurses adjusted the starting dose according to the phototype-based protocol an average of 69% of the time for patients on medications with photosensitivity listed as a potential side effect. However, the frequency depended significantly on the clinic (clinic A, 24%; clinic B, 92%; clinic C, 87%)(P≤.001). Nurses across all clinics consistently decreased the treatment dose when patients reported starting new photosensitizing medications. Patients with adjusted starting doses had slightly but not significantly higher clearance rates compared to those without (mean, 37.8 vs 35.5; t(104)=0.58; P=.56).

Comment

Impact of Photosensitizing Medications on Clearance—Photosensitizing medications and treatment frequency were 2 factors that might explain the slower clearance rates in younger adults. In this study, both groups of patients used similar numbers of photosensitizing medications, but more older adults were taking 3 or more medications (Table 3). We found no statistically significant relationship between taking photosensitizing medications and either the clearance rates or the level of clearance achieved in either age group.

Impact of Treatment Frequency—Weekly treatment frequency also was examined. One prior study demonstrated that treatments 3 times weekly led to a faster clearance time and higher clearance levels compared with twice-weekly treatment.7 When patients completed treatments twice weekly, it took an average of 1.5 times more days to clear, which impacted cost and clinical resource availability. The patients ranged in age from 17 to 80 years, but outcomes in older patients were not described separately.7 Interestingly, our study seemed to find a difference between age groups when the impact of treatment frequency was examined. Older adults completed nearly 4 fewer mean treatments to clear when treating less often, with more than 80% achieving high levels of clearance, whereas the younger adults required almost 7 more treatments to clear when they came in less frequently, with approximately 80% achieving a high level of clearance. As a result, our study found that in both age groups, slowing the treatment frequency extended the treatment time to clearance—more for the younger adults than the older adults—but did not significantly change the percentage of individuals reaching full clearance in either group.

Erythema Rates—There was no association between photosensitizing medications and erythema rates except when patients were taking at least 3 medications. Most medications that listed photosensitivity as a possible side effect did not specify their relevant range of UV radiation; therefore, all such medications were examined during this analysis. Prior research has shown UVB range photosensitizing medications include thiazides, quinidine, calcium channel antagonists, phenothiazines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.19 A sensitivity analysis that focused only on these medications found no association between them and any particular grade of erythema. However, patients taking 3 or more of any medications listing photosensitivity as a side effect had an increased risk for grade 2 erythema.

Erythema rates in this study were consistent with a 2013 systematic review that reported 57% of patients with asymptomatic grade 1 erythema.25 In the 2 other comparative older adult studies, erythema rates varied widely: 35% in a study from Turkey18compared to only1.89% in a study from the United Kingdom.17

The starting dose for NB-UVB may drive erythema rates. The current study’s protocols were based on an estimated MED that is subjectively determined by the dermatology provider’s assessment of the patient’s skin sensitivity via examination and questions to the patient about their response to environmental sun exposure (ie, burning and tanning)26 and is frequently used to determine the starting dose and subsequent dose escalation. Certain medications have been found to increase photosensitivity and erythema,20 which can change an individual’s MED. If photosensitizing medications are started prior to or during a course of NB-UVB without a pretreatment MED, they might increase the risk for erythema. This study did not identify specific erythema-inducing medications but did find that taking 3 or more photosensitizing medications was associated with increased episodes of grade 2 erythema. Similarly, Harrop et al8 found that patients who were taking photosensitizing medications were more likely to have grade 2 or higher erythema, despite baseline MED testing, which is an established safety mechanism to reduce the risk and severity of erythema.14,20,27 The authors of a recent study of older adults in Taiwan specifically recommended MED testing due to the unpredictable influence of polypharmacy on MED calculations in this population.28 Therefore, this study’s use of an estimated MED in older adults may have influenced the starting dose as well as the incidence and severity of erythemic events. Age-related skin changes likely are ruled out as a consideration for mild erythema by the similarity of grade 1 erythema rates in both older and younger adults. Other studies have identified differences between the age groups, where older patients experienced more intense erythema in the late phase of UVB treatments.22,23 This phenomenon could increase the risk for a grade 2 erythema, which may correspond with this study’s findings.

Other potential causes of erythema were ruled out during our study, including erythema related to missed treatments and shielding mishaps. Other factors, however, may impact the level of sensitivity each patient has to phototherapy, including genetics, epigenetics, and cumulative sun damage. With NB-UVB, near-erythemogenic doses are optimal to achieve effective treatments but require a delicate balance to achieve, which may be more problematic for older adults, especially those taking several medications.

Study Limitations—Our study design made it difficult to draw conclusions about rarer dermatologic conditions. Some patients received treatments over years that were not included in the study period. Finally, power calculations suggested that our actual sample size was too small, with approximately one-third of the required sample missing.

Practical Implications—The goals of phototherapy are to achieve a high level of disease clearance with the fewest number of treatments possible and minimal side effects.

The extra staff training and patient monitoring required for MED testing likely is to add value and preserve resources if faster clearance rates could be achieved and may warrant further investigation. Phototherapy centers require standardized treatment protocols, diligent well-trained staff, and program monitoring to ensure consistent care to all patients. This study highlighted the ongoing opportunity for health care organizations to conduct evidence-based practice inquiries to continually optimize care for their patients.

Even with recent pharmacologic treatment advances, narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy remains a versatile, safe, and efficacious adjunctive or exclusive treatment for multiple dermatologic conditions, including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

In a prior study, Matthews et al13 reported that 96% (50/52) of patients older than 65 years achieved medium to high levels of clearance with NB-UVB phototherapy. Nonetheless, 2 other findings in this study related to the number of treatments required to achieve clearance (ie, clearance rates) and erythema rates prompted further investigation. The first finding was higher-than-expected clearance rates. Older adults had a clearance rate with a mean of 33 treatments compared to prior studies featuring mean clearance rates of 20 to 28 treatments.7,8,14-16 This finding resembled a study in the United Kingdom17 with a median clearance rate in older adults of 30 treatments. In contrast, the median clearance rate from a study in Turkey18 was 42 treatments in older adults. We hypothesized that more photosensitizing medications used in older vs younger adults prompted more dose adjustments with NB-UVB phototherapy to avoid burning (ie, erythema) at baseline and throughout the treatment course. These dose adjustments may have increased the overall clearance rates. If true, we predicted that younger adults treated with the same protocol would have cleared more quickly, either because of age-related differences or because they likely had fewer comorbidities and therefore fewer medications.

The second finding from Matthews et al13 that warranted further investigation was a higher erythema rate compared to the older adult study from the United Kingdom.17 We hypothesized that potentially greater use of photosensitizing medications in the United States could explain the higher erythema rates. Although medication-induced photosensitivity is less likely with NB-UVB phototherapy than with UVA, certain medications can cause UVB photosensitivity, including thiazides, quinidine, calcium channel antagonists, phenothiazines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.8,19,20 Therefore, photosensitizing medication use either at baseline or during a course of NB-UVB phototherapy could increase the risk for erythema. Age-related skin changes also have been considered as a

This retrospective study aimed to determine if NB-UVB phototherapy is equally effective in both older and younger adults treated with the same protocol; to examine the association between the use of photosensitizing medications and clearance rates in both older and younger adults; and to examine the association between the use of photosensitizing medications and erythema rates in older vs younger adults.

Methods

Study Design and Patients—This retrospective cohort study used billing records to identify patients who received NB-UVB phototherapy at 3 different clinical sites within a large US health care system in Washington (Group Health Cooperative, now Kaiser Permanente Washington), serving more than 600,000 patients between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2016. The institutional review board of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute approved this study (IRB 1498087-4). Younger adults were classified as those 64 years or younger and older adults as those 65 years and older at the start of their phototherapy regimen. A power analysis determined that the optimal sample size for this study was 250 patients.

Individuals were excluded if they had fewer than 6 phototherapy treatments; a diagnosis of vitiligo, photosensitivity dermatitis, morphea, or pityriasis rubra pilaris; and/or treatment of the hands or feet only.

Phototherapy Protocol—Using a 48-lamp NB-UVB unit, trained phototherapy nurses provided all treatments following standardized treatment protocols13 based on previously published phototherapy guidelines.24 Nurses determined each patient’s disease clearance level using a 3-point clearance scale (high, medium, low).13 Each patient’s starting dose was determined based on the estimated MED for their skin phototype.

Statistical Analysis—Data were analyzed using Stata statistical software (StataCorp LLC). Univariate analyses were used to examine the data and identify outliers, bad values, and missing data, as well as to calculate descriptive statistics. Pearson χ2 and Fisher exact statistics were used to calculate differences in categorical variables. Linear multivariate regression models and logistic multivariate models were used to examine statistical relationships between variables. Statistical significance was defined as P≤.05.

Results

Patient Characteristics—Medical records were reviewed for 172 patients who received phototherapy between 2012 and 2016. Patients ranged in age from 23 to 91 years, with 102 patients 64 years and younger and 70 patients 65 years and older. Tables 1 and 2 outline the patient characteristics and conditions treated.

Phototherapy Effectiveness—

Photosensitizing Medications, Clearance Levels, and Clearance Rates—

Frequency of Treatments and Clearance Rates—Older adults more consistently completed the recommended frequency of treatments—3 times weekly—compared to younger adults (74.3% vs 58.5%). However, all patients who completed 3 treatments per week required a similar number of treatments to clear (older adults, mean [SD]: 35.7 [21.6]; younger adults, mean [SD]: 34.7 [19.0]; P=.85). Among patients completing 2 or fewer treatments per week, older adults required a mean (SD) of only 31 (9.0) treatments to clear vs 41.5 (21.3) treatments to clear for younger adults, but the difference was not statistically significant (P=.08). However, even those with suboptimal frequency ultimately achieved similar clearance levels.

Photosensitizing Medications and Erythema Rates—

Overall, phototherapy nurses adjusted the starting dose according to the phototype-based protocol an average of 69% of the time for patients on medications with photosensitivity listed as a potential side effect. However, the frequency depended significantly on the clinic (clinic A, 24%; clinic B, 92%; clinic C, 87%)(P≤.001). Nurses across all clinics consistently decreased the treatment dose when patients reported starting new photosensitizing medications. Patients with adjusted starting doses had slightly but not significantly higher clearance rates compared to those without (mean, 37.8 vs 35.5; t(104)=0.58; P=.56).

Comment

Impact of Photosensitizing Medications on Clearance—Photosensitizing medications and treatment frequency were 2 factors that might explain the slower clearance rates in younger adults. In this study, both groups of patients used similar numbers of photosensitizing medications, but more older adults were taking 3 or more medications (Table 3). We found no statistically significant relationship between taking photosensitizing medications and either the clearance rates or the level of clearance achieved in either age group.

Impact of Treatment Frequency—Weekly treatment frequency also was examined. One prior study demonstrated that treatments 3 times weekly led to a faster clearance time and higher clearance levels compared with twice-weekly treatment.7 When patients completed treatments twice weekly, it took an average of 1.5 times more days to clear, which impacted cost and clinical resource availability. The patients ranged in age from 17 to 80 years, but outcomes in older patients were not described separately.7 Interestingly, our study seemed to find a difference between age groups when the impact of treatment frequency was examined. Older adults completed nearly 4 fewer mean treatments to clear when treating less often, with more than 80% achieving high levels of clearance, whereas the younger adults required almost 7 more treatments to clear when they came in less frequently, with approximately 80% achieving a high level of clearance. As a result, our study found that in both age groups, slowing the treatment frequency extended the treatment time to clearance—more for the younger adults than the older adults—but did not significantly change the percentage of individuals reaching full clearance in either group.

Erythema Rates—There was no association between photosensitizing medications and erythema rates except when patients were taking at least 3 medications. Most medications that listed photosensitivity as a possible side effect did not specify their relevant range of UV radiation; therefore, all such medications were examined during this analysis. Prior research has shown UVB range photosensitizing medications include thiazides, quinidine, calcium channel antagonists, phenothiazines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.19 A sensitivity analysis that focused only on these medications found no association between them and any particular grade of erythema. However, patients taking 3 or more of any medications listing photosensitivity as a side effect had an increased risk for grade 2 erythema.

Erythema rates in this study were consistent with a 2013 systematic review that reported 57% of patients with asymptomatic grade 1 erythema.25 In the 2 other comparative older adult studies, erythema rates varied widely: 35% in a study from Turkey18compared to only1.89% in a study from the United Kingdom.17

The starting dose for NB-UVB may drive erythema rates. The current study’s protocols were based on an estimated MED that is subjectively determined by the dermatology provider’s assessment of the patient’s skin sensitivity via examination and questions to the patient about their response to environmental sun exposure (ie, burning and tanning)26 and is frequently used to determine the starting dose and subsequent dose escalation. Certain medications have been found to increase photosensitivity and erythema,20 which can change an individual’s MED. If photosensitizing medications are started prior to or during a course of NB-UVB without a pretreatment MED, they might increase the risk for erythema. This study did not identify specific erythema-inducing medications but did find that taking 3 or more photosensitizing medications was associated with increased episodes of grade 2 erythema. Similarly, Harrop et al8 found that patients who were taking photosensitizing medications were more likely to have grade 2 or higher erythema, despite baseline MED testing, which is an established safety mechanism to reduce the risk and severity of erythema.14,20,27 The authors of a recent study of older adults in Taiwan specifically recommended MED testing due to the unpredictable influence of polypharmacy on MED calculations in this population.28 Therefore, this study’s use of an estimated MED in older adults may have influenced the starting dose as well as the incidence and severity of erythemic events. Age-related skin changes likely are ruled out as a consideration for mild erythema by the similarity of grade 1 erythema rates in both older and younger adults. Other studies have identified differences between the age groups, where older patients experienced more intense erythema in the late phase of UVB treatments.22,23 This phenomenon could increase the risk for a grade 2 erythema, which may correspond with this study’s findings.

Other potential causes of erythema were ruled out during our study, including erythema related to missed treatments and shielding mishaps. Other factors, however, may impact the level of sensitivity each patient has to phototherapy, including genetics, epigenetics, and cumulative sun damage. With NB-UVB, near-erythemogenic doses are optimal to achieve effective treatments but require a delicate balance to achieve, which may be more problematic for older adults, especially those taking several medications.

Study Limitations—Our study design made it difficult to draw conclusions about rarer dermatologic conditions. Some patients received treatments over years that were not included in the study period. Finally, power calculations suggested that our actual sample size was too small, with approximately one-third of the required sample missing.

Practical Implications—The goals of phototherapy are to achieve a high level of disease clearance with the fewest number of treatments possible and minimal side effects.

The extra staff training and patient monitoring required for MED testing likely is to add value and preserve resources if faster clearance rates could be achieved and may warrant further investigation. Phototherapy centers require standardized treatment protocols, diligent well-trained staff, and program monitoring to ensure consistent care to all patients. This study highlighted the ongoing opportunity for health care organizations to conduct evidence-based practice inquiries to continually optimize care for their patients.

- Fernández-Guarino M, Aboin-Gonzalez S, Barchino L, et al. Treatment of moderate and severe adult chronic atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB and the combination of narrow-band UVB/UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:19-23.

- Foerster J, Boswell K, West J, et al. Narrowband UVB treatment is highly effective and causes a strong reduction in the use of steroid and other creams in psoriasis patients in clinical practice. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181813.

- Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, Boms S, et al. Narrowband UVB phototherapy in skin conditions beyond psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:660-670.

- Ryu HH, Choe YS, Jo S, et al. Remission period in psoriasis after multiple cycles of narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. J Dermatol. 2014;41:622-627.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

- Tintle S, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. Reversal of atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB phototherapy and biomarkers for therapeutic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:583-593.e581-584.

- Cameron H, Dawe RS, Yule S, et al. A randomized, observer-blinded trial of twice vs. three times weekly narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy for chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:973-978.

- Harrop G, Dawe RS, Ibbotson S. Are photosensitizing medications associated with increased risk of important erythemal reactions during ultraviolet B phototherapy? Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:1184-1185.

- Torres AE, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH, et al. Role of phototherapy in the era of biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:479-485.

- Bukvic´ć Mokos Z, Jovic´ A, Cˇeovic´ R, et al. Therapeutic challenges in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:128-139.

- Di Lernia V, Goldust M. An overview of the efficacy and safety of systemic treatments for psoriasis in the elderly. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18:897-903.

- Oliveira C, Torres T. More than skin deep: the systemic nature of atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:250-258.

- Matthews S, Pike K, Chien A. Phototherapy: safe and effective for challenging skin conditions in older adults. Cutis. 2021;108:E15-E21.

- Rodríguez-Granados MT, Estany-Gestal A, Pousa-Martínez M, et al. Is it useful to calculate minimal erythema dose before narrowband UV-B phototherapy? Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:852-858.

- Parlak N, Kundakci N, Parlak A, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy starting and incremental dose in patients with psoriasis: comparison of percentage dose and fixed dose protocols. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2015;31:90-97.

- Kleinpenning MM, Smits T, Boezeman J, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B therapy in psoriasis: randomized double-blind comparison of high-dose and low-dose irradiation regimens. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1351-1356.

- Powell JB, Gach JE. Phototherapy in the elderly. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:605-610.

- Bulur I, Erdogan HK, Aksu AE, et al. The efficacy and safety of phototherapy in geriatric patients: a retrospective study. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:33-38.

- Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH. Drug-induced photosensitivity. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:363-368, ix.

- Cameron H, Dawe RS. Photosensitizing drugs may lower the narrow-band ultraviolet B (TL-01) minimal erythema dose. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:389-390.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Gloor M, Scherotzke A. Age dependence of ultraviolet light-induced erythema following narrow-band UVB exposure. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2002;18:121-126.

- Cox NH, Diffey BL, Farr PM. The relationship between chronological age and the erythemal response to ultraviolet B radiation. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:315-319.

- Morrison W. Phototherapy and Photochemotherapy for Skin Disease. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2005.

- Almutawa F, Alnomair N, Wang Y, et al. Systematic review of UV-based therapy for psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:87-109.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

- Kwon IH, Kwon HH, Na SJ, et al. Could colorimetric method replace the individual minimal erythemal dose (MED) measurements in determining the initial dose of narrow-band UVB treatment for psoriasis patients with skin phototype III-V? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:494-498.

- Chen WA, Chang CM. The minimal erythema dose of narrowband ultraviolet B in elderly Taiwanese [published online September 1, 2021]. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. doi:10.1111/phpp.12730

- Fernández-Guarino M, Aboin-Gonzalez S, Barchino L, et al. Treatment of moderate and severe adult chronic atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB and the combination of narrow-band UVB/UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:19-23.

- Foerster J, Boswell K, West J, et al. Narrowband UVB treatment is highly effective and causes a strong reduction in the use of steroid and other creams in psoriasis patients in clinical practice. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181813.

- Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, Boms S, et al. Narrowband UVB phototherapy in skin conditions beyond psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:660-670.

- Ryu HH, Choe YS, Jo S, et al. Remission period in psoriasis after multiple cycles of narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. J Dermatol. 2014;41:622-627.

- Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:464-476.

- Tintle S, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. Reversal of atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB phototherapy and biomarkers for therapeutic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:583-593.e581-584.

- Cameron H, Dawe RS, Yule S, et al. A randomized, observer-blinded trial of twice vs. three times weekly narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy for chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:973-978.

- Harrop G, Dawe RS, Ibbotson S. Are photosensitizing medications associated with increased risk of important erythemal reactions during ultraviolet B phototherapy? Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:1184-1185.

- Torres AE, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH, et al. Role of phototherapy in the era of biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:479-485.

- Bukvic´ć Mokos Z, Jovic´ A, Cˇeovic´ R, et al. Therapeutic challenges in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:128-139.

- Di Lernia V, Goldust M. An overview of the efficacy and safety of systemic treatments for psoriasis in the elderly. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18:897-903.

- Oliveira C, Torres T. More than skin deep: the systemic nature of atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:250-258.

- Matthews S, Pike K, Chien A. Phototherapy: safe and effective for challenging skin conditions in older adults. Cutis. 2021;108:E15-E21.

- Rodríguez-Granados MT, Estany-Gestal A, Pousa-Martínez M, et al. Is it useful to calculate minimal erythema dose before narrowband UV-B phototherapy? Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:852-858.

- Parlak N, Kundakci N, Parlak A, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy starting and incremental dose in patients with psoriasis: comparison of percentage dose and fixed dose protocols. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2015;31:90-97.

- Kleinpenning MM, Smits T, Boezeman J, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B therapy in psoriasis: randomized double-blind comparison of high-dose and low-dose irradiation regimens. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1351-1356.

- Powell JB, Gach JE. Phototherapy in the elderly. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:605-610.

- Bulur I, Erdogan HK, Aksu AE, et al. The efficacy and safety of phototherapy in geriatric patients: a retrospective study. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:33-38.

- Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH. Drug-induced photosensitivity. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:363-368, ix.

- Cameron H, Dawe RS. Photosensitizing drugs may lower the narrow-band ultraviolet B (TL-01) minimal erythema dose. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:389-390.

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804.

- Gloor M, Scherotzke A. Age dependence of ultraviolet light-induced erythema following narrow-band UVB exposure. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2002;18:121-126.

- Cox NH, Diffey BL, Farr PM. The relationship between chronological age and the erythemal response to ultraviolet B radiation. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:315-319.

- Morrison W. Phototherapy and Photochemotherapy for Skin Disease. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2005.

- Almutawa F, Alnomair N, Wang Y, et al. Systematic review of UV-based therapy for psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:87-109.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

- Kwon IH, Kwon HH, Na SJ, et al. Could colorimetric method replace the individual minimal erythemal dose (MED) measurements in determining the initial dose of narrow-band UVB treatment for psoriasis patients with skin phototype III-V? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:494-498.

- Chen WA, Chang CM. The minimal erythema dose of narrowband ultraviolet B in elderly Taiwanese [published online September 1, 2021]. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. doi:10.1111/phpp.12730

Practice Points

- Narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy remains a safe and efficacious nonpharmacologic treatment for dermatologic conditions in older and younger adults.

- Compared to younger adults, older adults using the same protocols need similar or even fewer treatments to achieve high levels of clearance.

- Individuals taking 3 or more photosensitizing medications, regardless of age, may be at higher risk for substantial erythema with NB-UVB phototherapy.

- Phototherapy program monitoring is important to ensure quality care and investigate opportunities for care optimization.

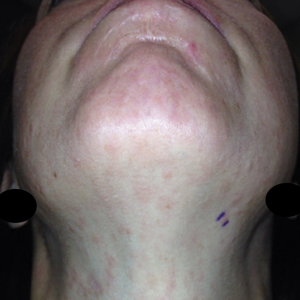

Dermatoses often occur in people who wear face masks

according to a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis.

“This report finds the most statistically significant risk factor for developing a facial dermatosis under a face mask is how long one wears the mask. Specifically, wearing a mask for more than 4 to 6 hours correlated most strongly with the development of a facial skin problem,” Jami L. Miller, MD, associate professor of dermatology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization. Dr. Miller was not involved in the study.

“The type of mask and the environment were of less significance,” she added.

Mask wearing for infection control has been common during the COVID-19 pandemic and will likely continue for some time, study coauthors Lim Yi Shen Justin, MBBS, and Yik Weng Yew*, MBBS, MPH, PhD, Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, write in Contact Dermatitis. And cross-sectional studies have suggested a link between mask wearing and various facial dermatoses.

To evaluate this link, as well as potential risk factors for facial dermatoses, the researchers reviewed 37 studies published between 2004 and 2022 involving 29,557 adult participants self-reporting regular use of any face mask type across 17 countries in Europe and Asia. The mask types commonly studied in the papers they analyzed included surgical masks and respirators.

Facial dermatoses were self-reported in 30 studies (81.1%) and were diagnosed by trained dermatologists in seven studies (18.9%).

Dr. Justin and Dr. Yew found that:

- The overall prevalence of facial dermatoses was 55%

- Individually, facial dermatitis, itch, acne, and pressure injuries were consistently reported as facial dermatoses, with pooled prevalence rates of 24%, 30%, 31%, and 31%, respectively

- The duration of mask wearing was the most significant risk factor for facial dermatoses (P < .001)

- Respirators, including N95 masks, were not more likely than surgical masks to be linked with facial dermatoses

“Understanding risk factors of mask wearing, including situation, duration, and type of mask, may allow for targeted interventions to mitigate problems,” Dr. Yew told this news organization.

He advised taking a break from mask wearing after 4 to 6 hours to improve outcomes.

Dr. Yew acknowledged limitations, including that most of the reviewed studies relied on self-reported symptoms.

“Patient factors were not investigated in most studies; therefore, we were not able to ascertain their contributory role in the development of facial dermatoses from mask wearing,” he said. “We were also unable to prove causation between risk factors and outcome.”

Four dermatologists welcome the findings

Dr. Miller called this an “interesting, and certainly relevant” study, now that mask wearing is common and facial skin problems are fairly common complaints in medical visits.

“As the authors say, irritants or contact allergens with longer exposures can be expected to cause a more severe dermatitis than short contact,” she said. “Longer duration also can cause occlusion of pores and hair follicles, which can be expected to worsen acne and folliculitis.”

“I was surprised that the type of mask did not seem to matter significantly,” she added. “Patients wearing N95 masks may be relieved to know N95s do not cause more skin problems than lighter masks.”

Still, Dr. Miller had several questions, including if the materials and chemical finishes that vary by manufacturer may affect skin conditions.

Olga Bunimovich, MD, assistant professor, department of dermatology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pennsylvania, called this study “an excellent step towards characterizing the role masks play in facial dermatoses.”

“The study provides a window into the prevalence of these conditions, as well as some understanding of the factors that may be contributing to it,” Dr. Bunimovich, who was not part of the study, added. But “we can also utilize this information to alter behavior in the work environment, allowing ‘mask-free’ breaks to decrease the risk of facial dermatoses.”

Elma Baron, MD, professor and director, Skin Study Center, department of dermatology, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, expected skin problems to be linked with mask wearing but didn’t expect the prevalence to be as high as 55%, which she called “very significant.”

“Mask wearing is an important means to prevent transmission of communicable infections, and the practice will most likely continue,” she said.

“Given the data, it is reasonable to advise patients who are already prone to these specific dermatoses to be proactive,” she added. “Early intervention with proper topical medications, preferably prescribed by a dermatologist or other health care provider, and changing masks frequently before they get soaked with moisture, will hopefully lessen the severity of skin rashes and minimize the negative impact on quality of life.”

Also commenting on the study, Susan Massick, MD, dermatologist and clinical associate professor of internal medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Westerville, said in an interview that she urges people to wear masks, despite these risks.

“The majority of concerns are straightforward, manageable, and overall benign,” she said. “We have a multitude of treatments that can help control, address, or improve symptoms.”

“Masks are an effective and easy way to protect yourself from infection, and they remain one of the most reliable preventions we have,” Dr. Massick noted. “The findings in this article should not preclude anyone from wearing a mask, nor should facial dermatoses be a cause for people to stop wearing their masks.”

The study received no funding. The authors, as well as Dr. Baron, Dr. Miller, Dr. Bunimovich, and Dr. Massick, who were not involved in the study, reported no relevant financial relationships. All experts commented by email.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Correction, 9/22/22: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Dr. Yik Weng Yew.

according to a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis.

“This report finds the most statistically significant risk factor for developing a facial dermatosis under a face mask is how long one wears the mask. Specifically, wearing a mask for more than 4 to 6 hours correlated most strongly with the development of a facial skin problem,” Jami L. Miller, MD, associate professor of dermatology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization. Dr. Miller was not involved in the study.

“The type of mask and the environment were of less significance,” she added.

Mask wearing for infection control has been common during the COVID-19 pandemic and will likely continue for some time, study coauthors Lim Yi Shen Justin, MBBS, and Yik Weng Yew*, MBBS, MPH, PhD, Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, write in Contact Dermatitis. And cross-sectional studies have suggested a link between mask wearing and various facial dermatoses.

To evaluate this link, as well as potential risk factors for facial dermatoses, the researchers reviewed 37 studies published between 2004 and 2022 involving 29,557 adult participants self-reporting regular use of any face mask type across 17 countries in Europe and Asia. The mask types commonly studied in the papers they analyzed included surgical masks and respirators.

Facial dermatoses were self-reported in 30 studies (81.1%) and were diagnosed by trained dermatologists in seven studies (18.9%).

Dr. Justin and Dr. Yew found that:

- The overall prevalence of facial dermatoses was 55%

- Individually, facial dermatitis, itch, acne, and pressure injuries were consistently reported as facial dermatoses, with pooled prevalence rates of 24%, 30%, 31%, and 31%, respectively

- The duration of mask wearing was the most significant risk factor for facial dermatoses (P < .001)

- Respirators, including N95 masks, were not more likely than surgical masks to be linked with facial dermatoses

“Understanding risk factors of mask wearing, including situation, duration, and type of mask, may allow for targeted interventions to mitigate problems,” Dr. Yew told this news organization.

He advised taking a break from mask wearing after 4 to 6 hours to improve outcomes.

Dr. Yew acknowledged limitations, including that most of the reviewed studies relied on self-reported symptoms.

“Patient factors were not investigated in most studies; therefore, we were not able to ascertain their contributory role in the development of facial dermatoses from mask wearing,” he said. “We were also unable to prove causation between risk factors and outcome.”

Four dermatologists welcome the findings

Dr. Miller called this an “interesting, and certainly relevant” study, now that mask wearing is common and facial skin problems are fairly common complaints in medical visits.

“As the authors say, irritants or contact allergens with longer exposures can be expected to cause a more severe dermatitis than short contact,” she said. “Longer duration also can cause occlusion of pores and hair follicles, which can be expected to worsen acne and folliculitis.”

“I was surprised that the type of mask did not seem to matter significantly,” she added. “Patients wearing N95 masks may be relieved to know N95s do not cause more skin problems than lighter masks.”

Still, Dr. Miller had several questions, including if the materials and chemical finishes that vary by manufacturer may affect skin conditions.

Olga Bunimovich, MD, assistant professor, department of dermatology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pennsylvania, called this study “an excellent step towards characterizing the role masks play in facial dermatoses.”

“The study provides a window into the prevalence of these conditions, as well as some understanding of the factors that may be contributing to it,” Dr. Bunimovich, who was not part of the study, added. But “we can also utilize this information to alter behavior in the work environment, allowing ‘mask-free’ breaks to decrease the risk of facial dermatoses.”

Elma Baron, MD, professor and director, Skin Study Center, department of dermatology, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, expected skin problems to be linked with mask wearing but didn’t expect the prevalence to be as high as 55%, which she called “very significant.”

“Mask wearing is an important means to prevent transmission of communicable infections, and the practice will most likely continue,” she said.

“Given the data, it is reasonable to advise patients who are already prone to these specific dermatoses to be proactive,” she added. “Early intervention with proper topical medications, preferably prescribed by a dermatologist or other health care provider, and changing masks frequently before they get soaked with moisture, will hopefully lessen the severity of skin rashes and minimize the negative impact on quality of life.”

Also commenting on the study, Susan Massick, MD, dermatologist and clinical associate professor of internal medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Westerville, said in an interview that she urges people to wear masks, despite these risks.

“The majority of concerns are straightforward, manageable, and overall benign,” she said. “We have a multitude of treatments that can help control, address, or improve symptoms.”

“Masks are an effective and easy way to protect yourself from infection, and they remain one of the most reliable preventions we have,” Dr. Massick noted. “The findings in this article should not preclude anyone from wearing a mask, nor should facial dermatoses be a cause for people to stop wearing their masks.”

The study received no funding. The authors, as well as Dr. Baron, Dr. Miller, Dr. Bunimovich, and Dr. Massick, who were not involved in the study, reported no relevant financial relationships. All experts commented by email.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Correction, 9/22/22: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Dr. Yik Weng Yew.

according to a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis.

“This report finds the most statistically significant risk factor for developing a facial dermatosis under a face mask is how long one wears the mask. Specifically, wearing a mask for more than 4 to 6 hours correlated most strongly with the development of a facial skin problem,” Jami L. Miller, MD, associate professor of dermatology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization. Dr. Miller was not involved in the study.

“The type of mask and the environment were of less significance,” she added.

Mask wearing for infection control has been common during the COVID-19 pandemic and will likely continue for some time, study coauthors Lim Yi Shen Justin, MBBS, and Yik Weng Yew*, MBBS, MPH, PhD, Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, write in Contact Dermatitis. And cross-sectional studies have suggested a link between mask wearing and various facial dermatoses.

To evaluate this link, as well as potential risk factors for facial dermatoses, the researchers reviewed 37 studies published between 2004 and 2022 involving 29,557 adult participants self-reporting regular use of any face mask type across 17 countries in Europe and Asia. The mask types commonly studied in the papers they analyzed included surgical masks and respirators.

Facial dermatoses were self-reported in 30 studies (81.1%) and were diagnosed by trained dermatologists in seven studies (18.9%).

Dr. Justin and Dr. Yew found that:

- The overall prevalence of facial dermatoses was 55%

- Individually, facial dermatitis, itch, acne, and pressure injuries were consistently reported as facial dermatoses, with pooled prevalence rates of 24%, 30%, 31%, and 31%, respectively

- The duration of mask wearing was the most significant risk factor for facial dermatoses (P < .001)

- Respirators, including N95 masks, were not more likely than surgical masks to be linked with facial dermatoses

“Understanding risk factors of mask wearing, including situation, duration, and type of mask, may allow for targeted interventions to mitigate problems,” Dr. Yew told this news organization.

He advised taking a break from mask wearing after 4 to 6 hours to improve outcomes.

Dr. Yew acknowledged limitations, including that most of the reviewed studies relied on self-reported symptoms.

“Patient factors were not investigated in most studies; therefore, we were not able to ascertain their contributory role in the development of facial dermatoses from mask wearing,” he said. “We were also unable to prove causation between risk factors and outcome.”

Four dermatologists welcome the findings

Dr. Miller called this an “interesting, and certainly relevant” study, now that mask wearing is common and facial skin problems are fairly common complaints in medical visits.

“As the authors say, irritants or contact allergens with longer exposures can be expected to cause a more severe dermatitis than short contact,” she said. “Longer duration also can cause occlusion of pores and hair follicles, which can be expected to worsen acne and folliculitis.”

“I was surprised that the type of mask did not seem to matter significantly,” she added. “Patients wearing N95 masks may be relieved to know N95s do not cause more skin problems than lighter masks.”

Still, Dr. Miller had several questions, including if the materials and chemical finishes that vary by manufacturer may affect skin conditions.

Olga Bunimovich, MD, assistant professor, department of dermatology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pennsylvania, called this study “an excellent step towards characterizing the role masks play in facial dermatoses.”

“The study provides a window into the prevalence of these conditions, as well as some understanding of the factors that may be contributing to it,” Dr. Bunimovich, who was not part of the study, added. But “we can also utilize this information to alter behavior in the work environment, allowing ‘mask-free’ breaks to decrease the risk of facial dermatoses.”

Elma Baron, MD, professor and director, Skin Study Center, department of dermatology, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, expected skin problems to be linked with mask wearing but didn’t expect the prevalence to be as high as 55%, which she called “very significant.”

“Mask wearing is an important means to prevent transmission of communicable infections, and the practice will most likely continue,” she said.

“Given the data, it is reasonable to advise patients who are already prone to these specific dermatoses to be proactive,” she added. “Early intervention with proper topical medications, preferably prescribed by a dermatologist or other health care provider, and changing masks frequently before they get soaked with moisture, will hopefully lessen the severity of skin rashes and minimize the negative impact on quality of life.”

Also commenting on the study, Susan Massick, MD, dermatologist and clinical associate professor of internal medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Westerville, said in an interview that she urges people to wear masks, despite these risks.

“The majority of concerns are straightforward, manageable, and overall benign,” she said. “We have a multitude of treatments that can help control, address, or improve symptoms.”

“Masks are an effective and easy way to protect yourself from infection, and they remain one of the most reliable preventions we have,” Dr. Massick noted. “The findings in this article should not preclude anyone from wearing a mask, nor should facial dermatoses be a cause for people to stop wearing their masks.”

The study received no funding. The authors, as well as Dr. Baron, Dr. Miller, Dr. Bunimovich, and Dr. Massick, who were not involved in the study, reported no relevant financial relationships. All experts commented by email.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Correction, 9/22/22: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Dr. Yik Weng Yew.

Can Atopic Dermatitis and Allergic Contact Dermatitis Coexist?

Atopic dermatitis (AD) and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) are 2 common inflammatory skin conditions that may have similar clinical presentations. Historically, it was thought that these conditions could not be diagnosed simultaneously due to their differing immune mechanisms; however, this belief has been challenged by recent evidence suggesting a more nuanced relationship between the 2 disease processes. In this review, we examine the complex interplay between AD and ACD and explain how shifts in conventional understanding of the 2 conditions shaped our evolving recognition of their ability to coexist.

Epidemiology of AD and ACD

Atopic dermatitis is the most common inflammatory skin disease in children and adolescents, with an estimated prevalence reaching 21%.1 In 60% of cases, onset of AD will occur within the first year of life, and 90% of cases begin within the first 5 years.2 Resolution may occur by adulthood; however, AD may continue to impact up to 8% to 9% of adults, with an increased prevalence in those older than 75 years.1 This may represent an underestimation of the burden of adult AD; one systematic review of 17 studies found that the pooled proportion of adult-onset AD was greater than 25%.3

In contrast, ACD previously was assumed to be a disease that more commonly impacted adults and only rarely children, primarily due to an early misconception that children were not frequently exposed to contact allergens and their immune systems were too immature to react to them even if exposed.4,5 However, it is now known that children do have risk factors for development of ACD, including a thinner stratum corneum and potentially a more absorbent skin surface.4 In addition, a 2022 study by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) found similar rates of ACD in children (n=1871) and adults (n=41,699) referred for patch testing (55.2% and 57.3%, respectively) as well as similar rates of having at least 1 relevant positive patch test (49.2% and 52.2%).6

In opposition to traditional beliefs, these findings highlight that AD and ACD can occur across age groups.

Immune Mechanism

The pathogenesis of AD represents a multifactorial process involving the immune system, cutaneous flora, genetic predisposition, and surrounding environment. Immunologically, acute AD is driven by a predominantly TH2 helper T-cell response with high levels of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-137; TH22, TH17, and TH1 also have been implicated.8 Notably, TH17 is found in high levels during the acute eczema phase, while TH1 and TH22are associated with the chronic phase.7

The pathophysiology of ACD is not completely understood. The classic paradigm involves 2 phases: sensitization and elicitation. Sensitization involves antigen-presenting cells that take up allergens absorbed by the skin to present them in regional lymph nodes where antigen-specific T lymphocytes are generated. Elicitation occurs upon re-exposure to the allergen, at which time the primed T lymphocytes are recruited to the skin, causing inflammation.9 Allergic contact dermatitis initially was thought to be driven by TH1 cytokines and IL-17 but now is understood to be more complex.10 Studies have revealed immune polarization of contact allergens, demonstrating that nickel primarily induces a TH1/TH17 response, whereas fragrance and rubber accelerators skew to TH2; TH9 and TH22 also may be involved depending on the causative allergen.11,12

Of note, the immunologic differences between AD and ACD led early investigators to believe that patients with AD were relatively protected from ACD.13 However, as previously described, there are several overlapping cytokines between AD and ACD. Furthermore, research has revealed that risk of contact sensitization might be increased in the chronic eczema phase due to the shared TH1 pathway.14 Barrier-disrupted skin (such as that in AD) also may increase the cytokine response and the density of antigen-presenting cells, leading to a proallergic state.15 This suggests that the immunologic pathways of AD and ACD are more intertwined than was previously understood.

Underlying Risk Factors

Skin barrier dysfunction is a key step in the pathogenesis of AD. Patients with AD commonly have loss-of-function mutations in the filaggrin gene, a protein that is key to the function of the stratum corneum. Loss of this protein may not only impact the immune response as previously noted but also may lead to increased transepidermal water loss and bacterial colonization.16 Interestingly, a 2014 review examined how this mutation could lead to an increased risk of sensitization to bivalent metal ions via an impaired chelating ability of the skin.17 Furthermore, a 2016 study conducted in Dutch construction workers revealed an increased risk for contact dermatitis (irritant and allergic) for those with a loss-of-function filaggrin mutation.18

Importantly, this same mutation may explain why patients with AD tend to have increased skin colonization by Staphylococcus aureus. The abundance of S aureus and the relative decrease in the diversity of other microorganisms on the skin may be associated with increased AD severity.19 Likewise, S aureus may play a role in the pathogenesis of ACD via production of its exotoxin directed at the T-cell receptor V beta 17 region. In particular, this receptor has been associated with nickel sensitization.17

Another risk factor to consider is increased exposure to contact sensitizers when treating AD. For instance, management often includes use of over-the-counter emollients, natural or botanical remedies with purported benefits for AD, cleansers, and detergents. However, these products can contain some of the most prevalent contact allergens seen in those with AD, including methyl-isothiazolinone, formaldehyde releasers, and fragrance.20 Topical corticosteroids also are frequently used, and ACD to steroid molecules can occur, particularly to tixocortol-21-pivalate (a marker for class A corticosteroids) and budesonide (a marker for class B corticosteroids).21 Other allergens (eg, benzyl alcohol, propylene glycol) also may be found as inactive ingredients of topical corticosteroids.22 These exposures may place AD patients at risk for ACD.

The Coexistence of AD and ACD