User login

Use of Dupilumab in Severe, Multifactorial, Chronic Itch for Geriatric Patients

To the Editor:

Today’s geriatric population is the fastest growing in history. The National Institutes of Health predicts there will be over 1.5 billion individuals aged 65 years and older by the year 2050: 17% of the world’s population.1 Pruritus—either acute or chronic (>6 weeks)—is defined as a sensory perception that leads to an intense desire to scratch.2 Chronic pruritus is an increasing health concern that impacts quality of life within the geriatric population. Elderly patients have various risk factors for developing chronic itch, including aging skin, polypharmacy, and increased systemic comorbidities.3-7

Although the therapeutic armamentarium for chronic itch continues to grow, health care providers often are hesitant to prescribe medications for geriatric patients because of comorbidities and potential drug-drug interactions. Novel biologic therapies now provide alternatives for this complex population. Dupilumab is a fully humanized, monoclonal antibody approved for treatment-resistant atopic dermatitis. This biologic prevents helper T-cell (TH2) signaling, IL-4 and IL-13 release, and subsequent effector cell (eg, mast cell, eosinophil) activity.8-10 The combined efficacy and safety of this medication has changed the treatment landscape of resistant atopic dermatitis. We present the use of dupilumab in a geriatric patient with severe and recalcitrant itch resistant to numerous topical and oral medications.

An 81-year-old man presented to the clinic with a long history of generalized pruritic rash. His medical history was significant for insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension, and renal cancer following a right nephrectomy. Laboratory results approximately 14 months prior to the visit revealed a blood urea nitrogen level of 31 mg/dL (reference range, 7–20 mg/dL), creatinine level of 2.20 mg/dL (reference range, 0.7–1.3 mg/dL), and glomerular filtration rate of 29 mL/min (reference range, 90–120 mL/min). Physical examination revealed numerous pink excoriated papules on the face, neck, trunk, and extremities. Lichenified plaques were present on both arms and legs. The patient received the diagnosis of severe atopic dermatitis with greater than 10% body surface area involvement. The investigator global assessment score was 4/4, indicating severe disease burden, and biopsy results reported spongiotic dermatitis. He proceeded to trial various topical corticosteroids, including hydrocortisone ointment 2.5%, betamethasone valerate ointment 0.01%, fluocinonide ointment 0.05%, and mupirocin ointment without benefit. Three subsequent courses of oral steroids failed to provide durable relief. At this point, the peak pruritus numerical rating scale (NRS) score was 7/10, indicating severe pruritus, with a negative impact on the patient’s quality of life and sleep.

Therapy was switched to tacrolimus acetonide ointment 0.1%, betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05%, and triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1%. Eleven days later, the patient denied experiencing any response to the topical regimen and sought alternative therapy for the itch and associated poor sleep; the NRS score was 10/10, indicating very severe pruritus. Prednisone 20 mg and doxepin 10 mg were initiated for symptom management until the intended transition to dupilumab. The patient began dupilumab with a loading dose of 600 mg, then 300 mg every other week thereafter. At 2- and 4-month follow-up, the patient reported notable relief in symptoms. The rash had improved, and the NRS score decreased from 10/10 to 3/10. He endorsed improved sleep and quality of life.

Pruritus may arise from a series of age-related mechanisms such as structural and chemical changes within the epidermis, underlying neuropathy, medication side effects, infection, malignancy, thyroid dysregulation, liver disease, and chronic kidney disease (CKD).5,6,11 Identifying the underlying etiology often is difficult and involves a complete history and physical examination as well as an appropriate contextualized laboratory workup.

Our patient’s comorbid T2DM and renal disease may have contributed to the pruritus. Type 2 diabetes mellitus can cause diabetic neuropathy, a sequela known to lead to various complications, including pruritus. One study identified a 4-fold increase in pruritus in those with diabetic polyneuropathy compared with age-matched nondiabetics.12,13 An additional study found that pruritus was present in 70% of patients with small fiber neuropathy.14 We needed to consider the role of our patient’s insulin-dependent T2DM and potential underlying neuropathy when addressing the pruritic symptoms.

Furthermore, our patient’s stage IV CKD and elevated urea level also may factor into the pruritus. The pathophysiology of CKD-associated pruritus (also referred to as uremic pruritus) remains poorly understood. Suggested mechanisms include immune-mediated neural inflammation and erroneous nociceptive-receptor activity.15,16 Although uremic pruritus is appreciated primarily in late dialysis-dependent disease, research shows that a notable portion of those with lesser disease, similar to our patient, also experience a significant itch burden.17 Diminishing pruritus is difficult and often aided by management of the underlying renal disease.18

In addition to disease management, symptomatic treatment incorporates the use of emollients, corticosteroids, and antihistamines. Unfortunately, the clinical response in the elderly population to such regimens often is poor.19 Dupilumab is an optimistic therapeutic option for chronic pruritus. By inhibiting the IL-4α receptor found on helper T cells, this biologic inhibits TH2 differentiation and subsequent inflammatory activity. One report identified an optimistic response to dupilumab in the management of uremic pruritus.20 The remarkable improvement and absence of adverse effects in our patient confirmed the utility and safety of dupilumab in complex cases such as elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. Such relief may result from inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine activity as well as decreased afferent spinal cord itch stimuli.10 The positive results from this case cast a favorable outlook on the treatment of chronic itch in the complex geriatric population.

- World’s older population grows dramatically. News release. National Institute on Aging. Published March 28, 2016. Accessed December 23, 2022. http://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/worlds-older-population-grows-dramatically

- Grundmann S, Ständer S. Chronic pruritus: clinics and treatment. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:1-11.

- Berger TG, Shive M, Harper GM. Pruritus in the older patient: a clinical review. JAMA. 2013;310:2443-2450. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.282023

- Valdes-Rodriguez, R, Mollanazar NK, González-Muro J, et al. Itch prevalence and characteristics in a Hispanic geriatric population: a comprehensive study using a standardized itch questionnaire. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:417-421. doi:10.2340/00015555-1968

- Li J, Tang H, Hu X, et al. Aquaporin-3 gene and protein expression in sun-protected human skin decreases with skin ageing. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:106-112.

- Choi EH, Man MQ, Xu P, et al. Stratum corneum acidification is impaired in moderately aged human and murine skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2847-2856.

- Fenske NA, Lober CW. Structural and functional changes of normal aging skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(4 pt 1):571-585.

- Paller AS, Kabashima K, Bieber T. Therapeutic pipeline for atopic dermatitis: end of the drought? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:633-643. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.006

- Kabashima K. New concept of the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis: interplay among the barrier, allergy, and pruritus as a trinity. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;70:3-11.

- Feld M, Garcia R, Buddenkotte J, et al. The pruritus- and TH2-associated cytokine IL-31 promotes growth of sensory nerves. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:500-508.

- Valdes-Rodriguez R, Stull C, Yosipovitch G. Chronic pruritus in the elderly: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Drugs Aging. 2015;32:201-215. doi:10.1007/s40266-015-0246-0

- Misery L, Brenaut E, Le Garrec R, et al. Neuropathic pruritus. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:408-416.

- Yamaoka H, Sasaki H, Yamasaki H, et al. Truncal pruritus of unknown origin may be a symptom of diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:150-155.

- Brenaut E, Marcorelles P, Genestet S, et al. Pruritus: an underrecognized symptom of small-fiber neuropathies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:328-332.

- Adigun M, Badu LA, Berner NM, et al. Uremic pruritus review. US Pharm. 2015;40:HS12-HS15.

- Simonsen E, Komenda P, Lerner B, et al. Treatment of uremic pruritus: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70:638-655.

- Carstens E, Akiyama T, eds. Itch: Mechanisms and Treatment. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2014.

- Shirazian S, Aina O, Park Y, et al. Chronic kidney disease-associated pruritus: impact on quality of life and current management challenges. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2017;10:11-26.

- Brummer GC, Wang LT, Sontheimer RD. A possible role for dupilumab (Dupixent) in the management of idiopathic chronic eczematous eruption of aging. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt55z1f6xh.

- Silverberg JI, Brieva J. A successful case of dupilumab treatment for severe uremic pruritus. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:339-341.

To the Editor:

Today’s geriatric population is the fastest growing in history. The National Institutes of Health predicts there will be over 1.5 billion individuals aged 65 years and older by the year 2050: 17% of the world’s population.1 Pruritus—either acute or chronic (>6 weeks)—is defined as a sensory perception that leads to an intense desire to scratch.2 Chronic pruritus is an increasing health concern that impacts quality of life within the geriatric population. Elderly patients have various risk factors for developing chronic itch, including aging skin, polypharmacy, and increased systemic comorbidities.3-7

Although the therapeutic armamentarium for chronic itch continues to grow, health care providers often are hesitant to prescribe medications for geriatric patients because of comorbidities and potential drug-drug interactions. Novel biologic therapies now provide alternatives for this complex population. Dupilumab is a fully humanized, monoclonal antibody approved for treatment-resistant atopic dermatitis. This biologic prevents helper T-cell (TH2) signaling, IL-4 and IL-13 release, and subsequent effector cell (eg, mast cell, eosinophil) activity.8-10 The combined efficacy and safety of this medication has changed the treatment landscape of resistant atopic dermatitis. We present the use of dupilumab in a geriatric patient with severe and recalcitrant itch resistant to numerous topical and oral medications.

An 81-year-old man presented to the clinic with a long history of generalized pruritic rash. His medical history was significant for insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension, and renal cancer following a right nephrectomy. Laboratory results approximately 14 months prior to the visit revealed a blood urea nitrogen level of 31 mg/dL (reference range, 7–20 mg/dL), creatinine level of 2.20 mg/dL (reference range, 0.7–1.3 mg/dL), and glomerular filtration rate of 29 mL/min (reference range, 90–120 mL/min). Physical examination revealed numerous pink excoriated papules on the face, neck, trunk, and extremities. Lichenified plaques were present on both arms and legs. The patient received the diagnosis of severe atopic dermatitis with greater than 10% body surface area involvement. The investigator global assessment score was 4/4, indicating severe disease burden, and biopsy results reported spongiotic dermatitis. He proceeded to trial various topical corticosteroids, including hydrocortisone ointment 2.5%, betamethasone valerate ointment 0.01%, fluocinonide ointment 0.05%, and mupirocin ointment without benefit. Three subsequent courses of oral steroids failed to provide durable relief. At this point, the peak pruritus numerical rating scale (NRS) score was 7/10, indicating severe pruritus, with a negative impact on the patient’s quality of life and sleep.

Therapy was switched to tacrolimus acetonide ointment 0.1%, betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05%, and triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1%. Eleven days later, the patient denied experiencing any response to the topical regimen and sought alternative therapy for the itch and associated poor sleep; the NRS score was 10/10, indicating very severe pruritus. Prednisone 20 mg and doxepin 10 mg were initiated for symptom management until the intended transition to dupilumab. The patient began dupilumab with a loading dose of 600 mg, then 300 mg every other week thereafter. At 2- and 4-month follow-up, the patient reported notable relief in symptoms. The rash had improved, and the NRS score decreased from 10/10 to 3/10. He endorsed improved sleep and quality of life.

Pruritus may arise from a series of age-related mechanisms such as structural and chemical changes within the epidermis, underlying neuropathy, medication side effects, infection, malignancy, thyroid dysregulation, liver disease, and chronic kidney disease (CKD).5,6,11 Identifying the underlying etiology often is difficult and involves a complete history and physical examination as well as an appropriate contextualized laboratory workup.

Our patient’s comorbid T2DM and renal disease may have contributed to the pruritus. Type 2 diabetes mellitus can cause diabetic neuropathy, a sequela known to lead to various complications, including pruritus. One study identified a 4-fold increase in pruritus in those with diabetic polyneuropathy compared with age-matched nondiabetics.12,13 An additional study found that pruritus was present in 70% of patients with small fiber neuropathy.14 We needed to consider the role of our patient’s insulin-dependent T2DM and potential underlying neuropathy when addressing the pruritic symptoms.

Furthermore, our patient’s stage IV CKD and elevated urea level also may factor into the pruritus. The pathophysiology of CKD-associated pruritus (also referred to as uremic pruritus) remains poorly understood. Suggested mechanisms include immune-mediated neural inflammation and erroneous nociceptive-receptor activity.15,16 Although uremic pruritus is appreciated primarily in late dialysis-dependent disease, research shows that a notable portion of those with lesser disease, similar to our patient, also experience a significant itch burden.17 Diminishing pruritus is difficult and often aided by management of the underlying renal disease.18

In addition to disease management, symptomatic treatment incorporates the use of emollients, corticosteroids, and antihistamines. Unfortunately, the clinical response in the elderly population to such regimens often is poor.19 Dupilumab is an optimistic therapeutic option for chronic pruritus. By inhibiting the IL-4α receptor found on helper T cells, this biologic inhibits TH2 differentiation and subsequent inflammatory activity. One report identified an optimistic response to dupilumab in the management of uremic pruritus.20 The remarkable improvement and absence of adverse effects in our patient confirmed the utility and safety of dupilumab in complex cases such as elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. Such relief may result from inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine activity as well as decreased afferent spinal cord itch stimuli.10 The positive results from this case cast a favorable outlook on the treatment of chronic itch in the complex geriatric population.

To the Editor:

Today’s geriatric population is the fastest growing in history. The National Institutes of Health predicts there will be over 1.5 billion individuals aged 65 years and older by the year 2050: 17% of the world’s population.1 Pruritus—either acute or chronic (>6 weeks)—is defined as a sensory perception that leads to an intense desire to scratch.2 Chronic pruritus is an increasing health concern that impacts quality of life within the geriatric population. Elderly patients have various risk factors for developing chronic itch, including aging skin, polypharmacy, and increased systemic comorbidities.3-7

Although the therapeutic armamentarium for chronic itch continues to grow, health care providers often are hesitant to prescribe medications for geriatric patients because of comorbidities and potential drug-drug interactions. Novel biologic therapies now provide alternatives for this complex population. Dupilumab is a fully humanized, monoclonal antibody approved for treatment-resistant atopic dermatitis. This biologic prevents helper T-cell (TH2) signaling, IL-4 and IL-13 release, and subsequent effector cell (eg, mast cell, eosinophil) activity.8-10 The combined efficacy and safety of this medication has changed the treatment landscape of resistant atopic dermatitis. We present the use of dupilumab in a geriatric patient with severe and recalcitrant itch resistant to numerous topical and oral medications.

An 81-year-old man presented to the clinic with a long history of generalized pruritic rash. His medical history was significant for insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension, and renal cancer following a right nephrectomy. Laboratory results approximately 14 months prior to the visit revealed a blood urea nitrogen level of 31 mg/dL (reference range, 7–20 mg/dL), creatinine level of 2.20 mg/dL (reference range, 0.7–1.3 mg/dL), and glomerular filtration rate of 29 mL/min (reference range, 90–120 mL/min). Physical examination revealed numerous pink excoriated papules on the face, neck, trunk, and extremities. Lichenified plaques were present on both arms and legs. The patient received the diagnosis of severe atopic dermatitis with greater than 10% body surface area involvement. The investigator global assessment score was 4/4, indicating severe disease burden, and biopsy results reported spongiotic dermatitis. He proceeded to trial various topical corticosteroids, including hydrocortisone ointment 2.5%, betamethasone valerate ointment 0.01%, fluocinonide ointment 0.05%, and mupirocin ointment without benefit. Three subsequent courses of oral steroids failed to provide durable relief. At this point, the peak pruritus numerical rating scale (NRS) score was 7/10, indicating severe pruritus, with a negative impact on the patient’s quality of life and sleep.

Therapy was switched to tacrolimus acetonide ointment 0.1%, betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05%, and triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1%. Eleven days later, the patient denied experiencing any response to the topical regimen and sought alternative therapy for the itch and associated poor sleep; the NRS score was 10/10, indicating very severe pruritus. Prednisone 20 mg and doxepin 10 mg were initiated for symptom management until the intended transition to dupilumab. The patient began dupilumab with a loading dose of 600 mg, then 300 mg every other week thereafter. At 2- and 4-month follow-up, the patient reported notable relief in symptoms. The rash had improved, and the NRS score decreased from 10/10 to 3/10. He endorsed improved sleep and quality of life.

Pruritus may arise from a series of age-related mechanisms such as structural and chemical changes within the epidermis, underlying neuropathy, medication side effects, infection, malignancy, thyroid dysregulation, liver disease, and chronic kidney disease (CKD).5,6,11 Identifying the underlying etiology often is difficult and involves a complete history and physical examination as well as an appropriate contextualized laboratory workup.

Our patient’s comorbid T2DM and renal disease may have contributed to the pruritus. Type 2 diabetes mellitus can cause diabetic neuropathy, a sequela known to lead to various complications, including pruritus. One study identified a 4-fold increase in pruritus in those with diabetic polyneuropathy compared with age-matched nondiabetics.12,13 An additional study found that pruritus was present in 70% of patients with small fiber neuropathy.14 We needed to consider the role of our patient’s insulin-dependent T2DM and potential underlying neuropathy when addressing the pruritic symptoms.

Furthermore, our patient’s stage IV CKD and elevated urea level also may factor into the pruritus. The pathophysiology of CKD-associated pruritus (also referred to as uremic pruritus) remains poorly understood. Suggested mechanisms include immune-mediated neural inflammation and erroneous nociceptive-receptor activity.15,16 Although uremic pruritus is appreciated primarily in late dialysis-dependent disease, research shows that a notable portion of those with lesser disease, similar to our patient, also experience a significant itch burden.17 Diminishing pruritus is difficult and often aided by management of the underlying renal disease.18

In addition to disease management, symptomatic treatment incorporates the use of emollients, corticosteroids, and antihistamines. Unfortunately, the clinical response in the elderly population to such regimens often is poor.19 Dupilumab is an optimistic therapeutic option for chronic pruritus. By inhibiting the IL-4α receptor found on helper T cells, this biologic inhibits TH2 differentiation and subsequent inflammatory activity. One report identified an optimistic response to dupilumab in the management of uremic pruritus.20 The remarkable improvement and absence of adverse effects in our patient confirmed the utility and safety of dupilumab in complex cases such as elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. Such relief may result from inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine activity as well as decreased afferent spinal cord itch stimuli.10 The positive results from this case cast a favorable outlook on the treatment of chronic itch in the complex geriatric population.

- World’s older population grows dramatically. News release. National Institute on Aging. Published March 28, 2016. Accessed December 23, 2022. http://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/worlds-older-population-grows-dramatically

- Grundmann S, Ständer S. Chronic pruritus: clinics and treatment. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:1-11.

- Berger TG, Shive M, Harper GM. Pruritus in the older patient: a clinical review. JAMA. 2013;310:2443-2450. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.282023

- Valdes-Rodriguez, R, Mollanazar NK, González-Muro J, et al. Itch prevalence and characteristics in a Hispanic geriatric population: a comprehensive study using a standardized itch questionnaire. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:417-421. doi:10.2340/00015555-1968

- Li J, Tang H, Hu X, et al. Aquaporin-3 gene and protein expression in sun-protected human skin decreases with skin ageing. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:106-112.

- Choi EH, Man MQ, Xu P, et al. Stratum corneum acidification is impaired in moderately aged human and murine skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2847-2856.

- Fenske NA, Lober CW. Structural and functional changes of normal aging skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(4 pt 1):571-585.

- Paller AS, Kabashima K, Bieber T. Therapeutic pipeline for atopic dermatitis: end of the drought? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:633-643. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.006

- Kabashima K. New concept of the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis: interplay among the barrier, allergy, and pruritus as a trinity. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;70:3-11.

- Feld M, Garcia R, Buddenkotte J, et al. The pruritus- and TH2-associated cytokine IL-31 promotes growth of sensory nerves. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:500-508.

- Valdes-Rodriguez R, Stull C, Yosipovitch G. Chronic pruritus in the elderly: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Drugs Aging. 2015;32:201-215. doi:10.1007/s40266-015-0246-0

- Misery L, Brenaut E, Le Garrec R, et al. Neuropathic pruritus. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:408-416.

- Yamaoka H, Sasaki H, Yamasaki H, et al. Truncal pruritus of unknown origin may be a symptom of diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:150-155.

- Brenaut E, Marcorelles P, Genestet S, et al. Pruritus: an underrecognized symptom of small-fiber neuropathies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:328-332.

- Adigun M, Badu LA, Berner NM, et al. Uremic pruritus review. US Pharm. 2015;40:HS12-HS15.

- Simonsen E, Komenda P, Lerner B, et al. Treatment of uremic pruritus: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70:638-655.

- Carstens E, Akiyama T, eds. Itch: Mechanisms and Treatment. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2014.

- Shirazian S, Aina O, Park Y, et al. Chronic kidney disease-associated pruritus: impact on quality of life and current management challenges. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2017;10:11-26.

- Brummer GC, Wang LT, Sontheimer RD. A possible role for dupilumab (Dupixent) in the management of idiopathic chronic eczematous eruption of aging. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt55z1f6xh.

- Silverberg JI, Brieva J. A successful case of dupilumab treatment for severe uremic pruritus. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:339-341.

- World’s older population grows dramatically. News release. National Institute on Aging. Published March 28, 2016. Accessed December 23, 2022. http://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/worlds-older-population-grows-dramatically

- Grundmann S, Ständer S. Chronic pruritus: clinics and treatment. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:1-11.

- Berger TG, Shive M, Harper GM. Pruritus in the older patient: a clinical review. JAMA. 2013;310:2443-2450. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.282023

- Valdes-Rodriguez, R, Mollanazar NK, González-Muro J, et al. Itch prevalence and characteristics in a Hispanic geriatric population: a comprehensive study using a standardized itch questionnaire. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:417-421. doi:10.2340/00015555-1968

- Li J, Tang H, Hu X, et al. Aquaporin-3 gene and protein expression in sun-protected human skin decreases with skin ageing. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:106-112.

- Choi EH, Man MQ, Xu P, et al. Stratum corneum acidification is impaired in moderately aged human and murine skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2847-2856.

- Fenske NA, Lober CW. Structural and functional changes of normal aging skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(4 pt 1):571-585.

- Paller AS, Kabashima K, Bieber T. Therapeutic pipeline for atopic dermatitis: end of the drought? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:633-643. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.006

- Kabashima K. New concept of the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis: interplay among the barrier, allergy, and pruritus as a trinity. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;70:3-11.

- Feld M, Garcia R, Buddenkotte J, et al. The pruritus- and TH2-associated cytokine IL-31 promotes growth of sensory nerves. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:500-508.

- Valdes-Rodriguez R, Stull C, Yosipovitch G. Chronic pruritus in the elderly: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Drugs Aging. 2015;32:201-215. doi:10.1007/s40266-015-0246-0

- Misery L, Brenaut E, Le Garrec R, et al. Neuropathic pruritus. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:408-416.

- Yamaoka H, Sasaki H, Yamasaki H, et al. Truncal pruritus of unknown origin may be a symptom of diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:150-155.

- Brenaut E, Marcorelles P, Genestet S, et al. Pruritus: an underrecognized symptom of small-fiber neuropathies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:328-332.

- Adigun M, Badu LA, Berner NM, et al. Uremic pruritus review. US Pharm. 2015;40:HS12-HS15.

- Simonsen E, Komenda P, Lerner B, et al. Treatment of uremic pruritus: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70:638-655.

- Carstens E, Akiyama T, eds. Itch: Mechanisms and Treatment. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2014.

- Shirazian S, Aina O, Park Y, et al. Chronic kidney disease-associated pruritus: impact on quality of life and current management challenges. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2017;10:11-26.

- Brummer GC, Wang LT, Sontheimer RD. A possible role for dupilumab (Dupixent) in the management of idiopathic chronic eczematous eruption of aging. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt55z1f6xh.

- Silverberg JI, Brieva J. A successful case of dupilumab treatment for severe uremic pruritus. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:339-341.

PRACTICE POINTS

- A series of age-related mechanisms within the epidermis, underlying neuropathy, medication side effects, infection, malignancy, thyroid dysregulation, liver disease, and chronic kidney disease may contribute to pruritus in elderly patients.

- Patients with mild kidney disease may still experience a recalcitrant and notable itch burden.

- Dupilumab is efficacious and safe in the management of chronic pruritus, even in complex cases such as elderly patients with multiple comorbidities.

Cutaneous Manifestations in Hereditary Alpha Tryptasemia

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia (HaT), an autosomal-dominant disorder of tryptase overproduction, was first described in 2014 by Lyons et al.1 It has been associated with multiple dermatologic, allergic, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities. These multisystem concerns may include cutaneous flushing, chronic pruritus, urticaria, GI tract symptoms, arthralgia, and autonomic dysfunction.2 The diverse symptoms and the recent discovery of HaT make recognition of this disorder challenging. Currently, it also is believed that HaT is associated with an elevated risk for anaphylaxis and is a biomarker for severe symptoms in disorders with increased mast cell burden such as mastocytosis.3-5

Given the potential cutaneous manifestations and the fact that dermatologic symptoms may be the initial presentation of HaT, awareness and recognition of this condition by dermatologists are essential for diagnosis and treatment. This review summarizes the cutaneous presentations consistent with HaT and discusses various conditions that share overlapping dermatologic symptoms with HaT.

Background on HaT

Mast cells are known to secrete several vasoactive mediators including tryptase and histamine when activated by foreign substances, similar to IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions. In their baseline state, mast cells continuously secrete immature forms of tryptases called protryptases.6 These protryptases come in 2 forms: α and β. Although mature tryptase is acutely elevatedin anaphylaxis, persistently elevated total serum tryptase levels frequently are regarded as indicative of a systemic mast cell disorder such as systemic mastocytosis (SM).3 Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals with the disorder have an elevated basal serum tryptase level (>8 ng/mL). Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been identified as another possible cause of persistently elevated levels.2,6

Genetics and Epidemiology of HaT—The humantryptase locus at chromosome 16p13.3 is composed of 4 paralog genes: TPSG1, TPSB2, TPSAB1, and TPSD1.4 Only TPSAB1 encodes for α-tryptase, while both TPSB2 and TPSAB1 encode for β-tryptase.4 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia is an autosomal-dominant disorder resulting from a copy number increase in the α-tryptase encoding sequence within the TPSAB1 gene. Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals identified with the disorder have a basal serum tryptase level greater than 8 ng/mL, with mean (SD) levels of 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL with gene duplication and triplication, respectively (reference range, 0–11.4 ng/mL).2,6 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia likely is common and largely undiagnosed, with a recently estimated prevalence of 5% in the United Kingdom7 and 5.6% in a cohort of 125 individuals from Italy, Slovenia, and the United States.5

Implications of Increased α-tryptase Levels—After an inciting stimulus, the active portions of α-protryptase and β-protryptase are secreted as tetramers by activated mast cells via degranulation. In vitro, β-tryptase homotetramers have been found to play a role in anaphylaxis, while α-homotetramers are nearly inactive.8,9 Recently, however, it has been discovered that α2β2 tetramers also can form and do so in a higher ratio in individuals with increased α-tryptase–encoding gene copies, such as those with HaT.8 These heterotetramers exhibit unique properties compared with the homotetramers and may stimulate epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 and protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2). Epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 activation likely contributes to vibratory urticaria in patients, while activation of PAR2 may have a range of clinical effects, including worsening asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, pruritus, and the exacerbation of dermal inflammation and hyperalgesia.8,10 Thus, α- and β-tryptase tetramers can be considered mediators that may influence the severity of disorders in which mast cells are naturally prevalent and likely contribute to the phenotype of those with HaT.7 Furthermore, these characteristics have been shown to potentially increase in severity with increasing tryptase levels and with increased TPSAB1 duplications.1,2 In contrast, more than 25% of the population is deficient in α-tryptase without known deleterious effects.5

Cutaneous Manifestations of HaT

A case series reported by Lyons et al1 in 2014 detailed persistent elevated basal serum tryptase levels in 9 families with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance. In this cohort, 31 of 33 (94%) affected individuals had a history of atopic dermatitis (AD), and 26 of 33 (79%) affected individuals reported symptoms consistent with mast cell degranulation, including urticaria; flushing; and/or crampy abdominal pain unprovoked or triggered by heat, exercise, vibration, stress, certain foods, or minor physical stimulation.1 A later report by Lyons et al2 in 2016 identified the TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequence copy number increase as the causative entity for HaT by examining a group of 96 patients from 35 families with frequent recurrent cutaneous flushing and pruritus, sometimes associated with urticaria and sleep disruption. Flushing and pruritus were found in 45% (33/73) of those with a TPSAB1 duplication and 80% (12/15) of those with a triplication (P=.022), suggesting a gene dose effect regarding α-tryptase encoding sequence copy number and these symptoms.2

A 2019 study further explored the clinical finding of urticaria in patients with HaT by specifically examining if vibration-induced urticaria was affected by TPSAB1 gene dosage.8 A cohort of 56 volunteers—35 healthy and 21 with HaT—underwent tryptase genotyping and cutaneous vibratory challenge. The presence of TPSAB1 was significantly correlated with induction of vibration-induced urticaria (P<.01), as the severity and prevalence of the urticarial response increased along with α- and β-tryptase gene ratios.8

Urticaria and angioedema also were seen in 51% (36/70) of patients in a cohort of HaT patients in the United Kingdom, in which 41% (29/70) also had skin flushing. In contrast to prior studies, these manifestations were not more common in patients with gene triplications or quintuplications than those with duplications.7 In another recent retrospective evaluation conducted at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts)(N=101), 80% of patients aged 4 to 85 years with confirmed diagnoses of HaT had skin manifestations such as urticaria, flushing, and pruritus.4

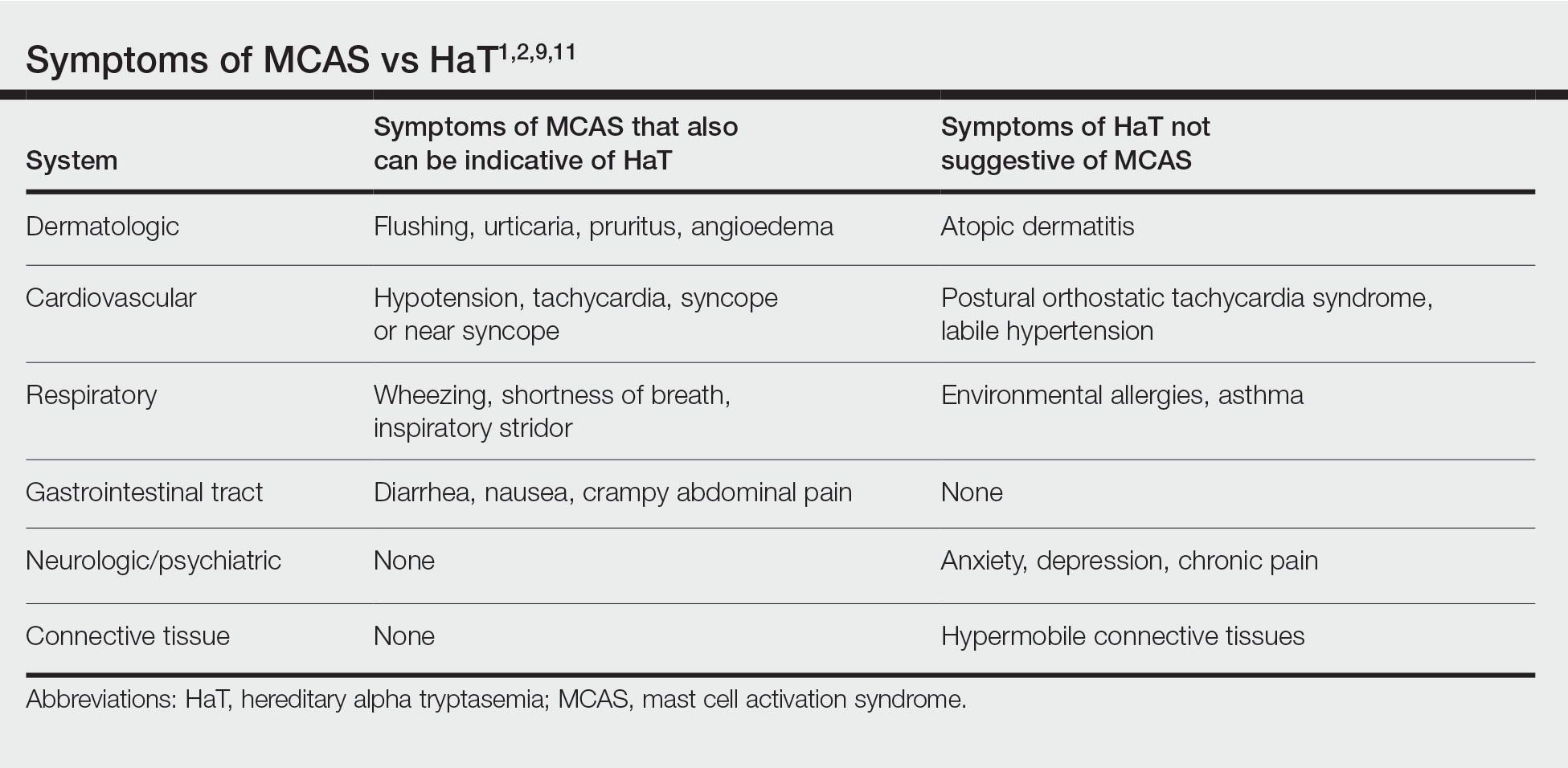

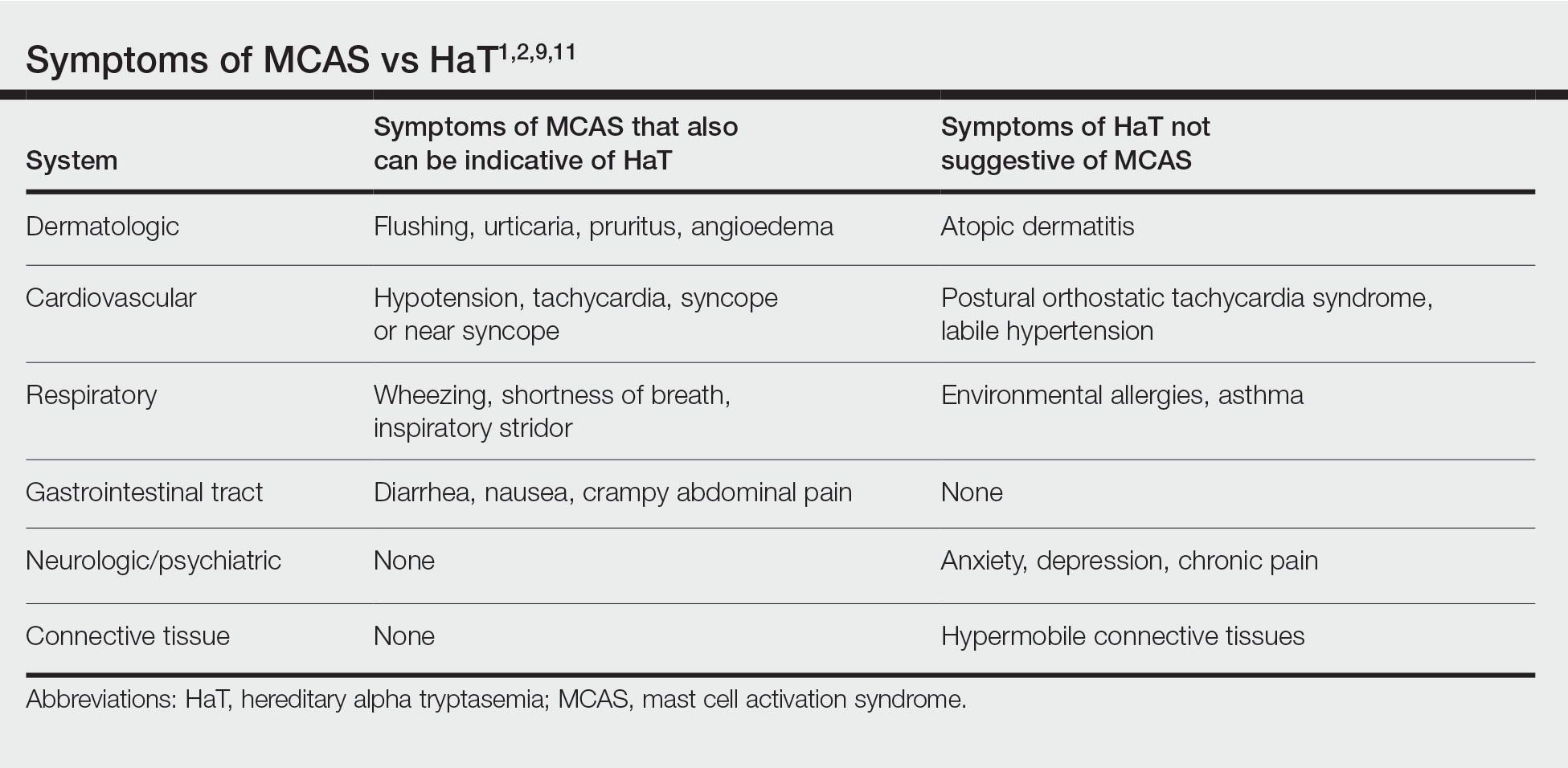

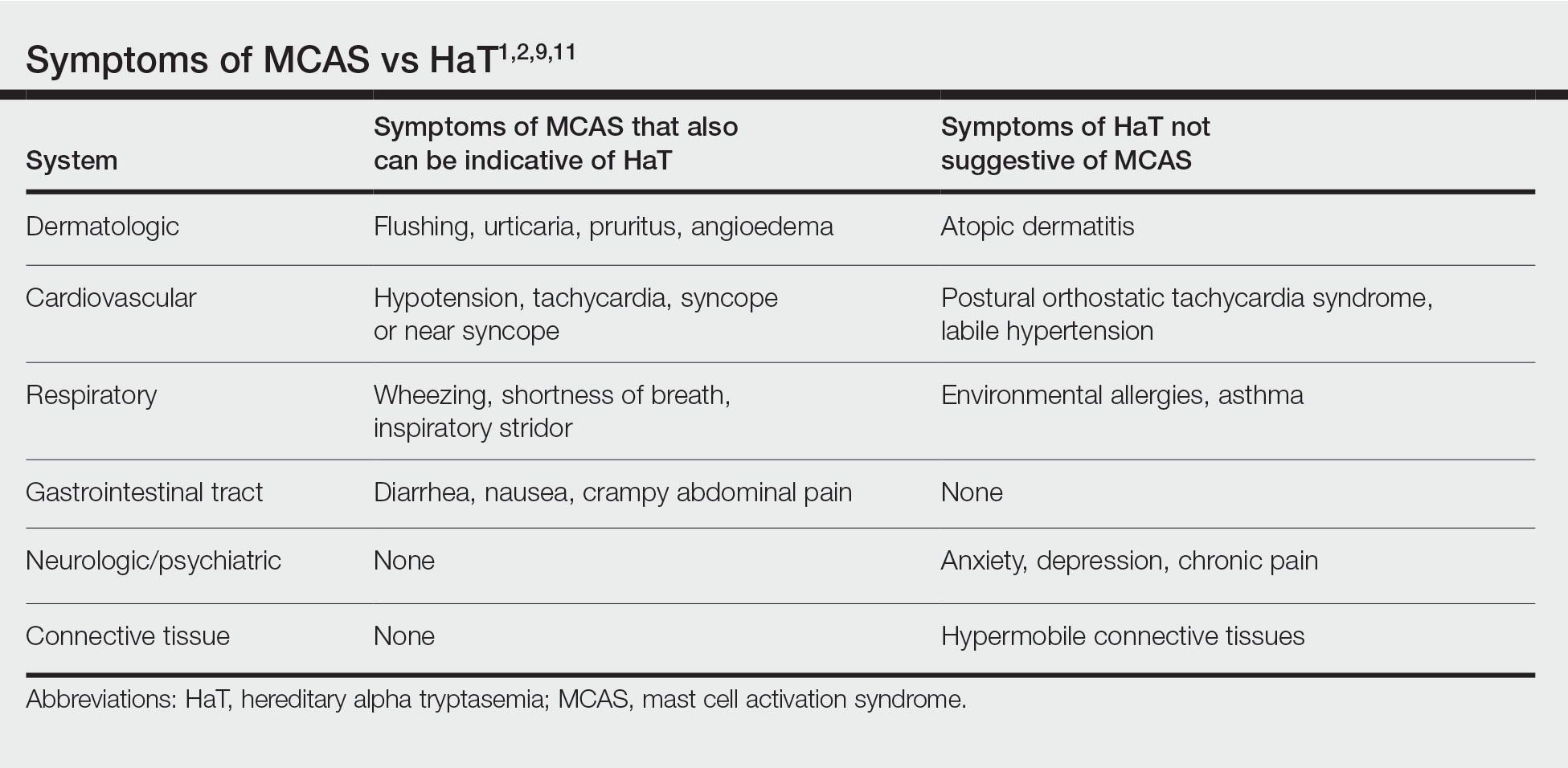

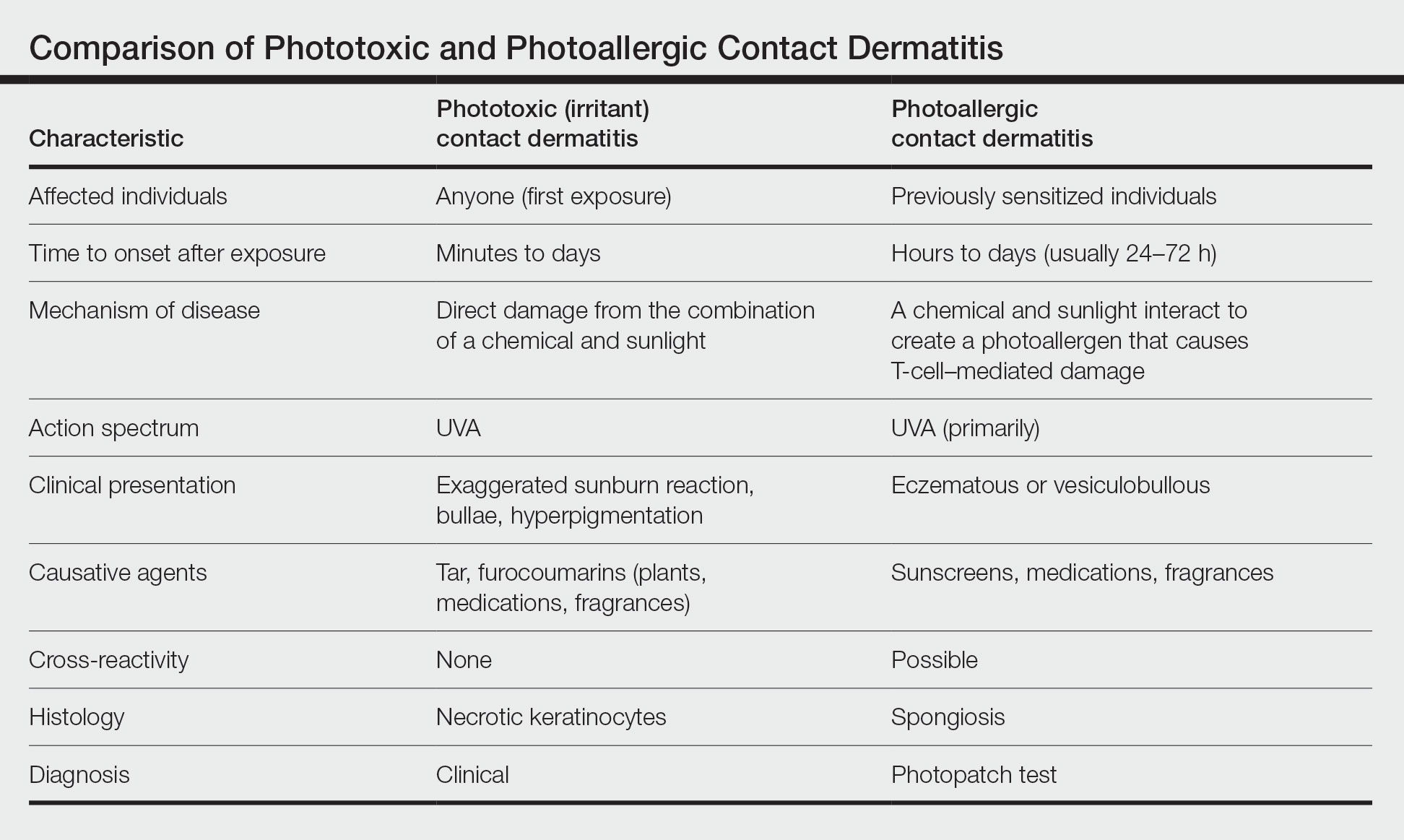

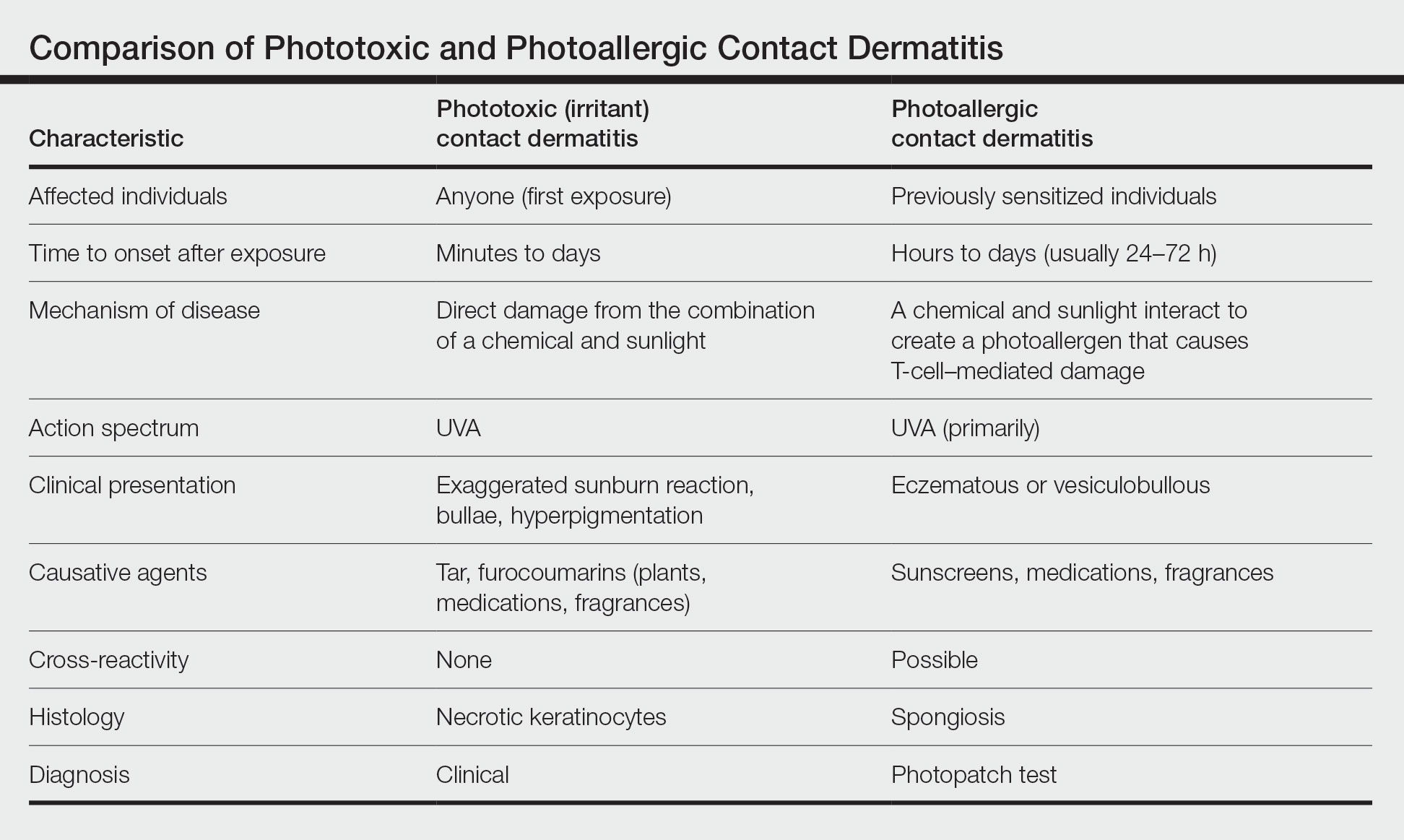

HaT and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome—In 2019, a Mast Cell Disorders Committee Work Group Report outlined recommendations for diagnosing and treating primary mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), a disorder in which mast cells seem to be more easily activated. Mast cell activation syndrome is defined as a primary clinical condition in which there are episodic signs and symptoms of systemic anaphylaxis (Table) concurrently affecting at least 2 organ systems, resulting from secreted mast cell mediators.9,11 The 2019 report also touched on clinical criteria that lack precision for diagnosing MCAS yet are in use, including dermographism and several types of rashes.9 Episode triggers frequent in MCAS include hot water, alcohol, stress, exercise, infection, hormonal changes, and physical stimuli.

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been suggested to be a risk factor for MCAS, which also can be associated with SM and clonal MCAS.9 Patients with MCAS should be tested for increased α-tryptase gene copy number given the overlap in symptoms, the likely predisposition of those with HaT to develop MCAS, and the fact that these patients could be at an increased risk for anaphylaxis.4,7,9,11 However, the clinical phenotype for HaT includes allergic disorders affecting the skin as well as neuropsychiatric and connective tissue abnormalities that are distinctive from MCAS. Although HaT may be considered a heritable risk factor for MCAS, MCAS is only 1 potential phenotype associated with HaT.9

Implications of HaT

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia should be considered in all patients with basal tryptase levels greater than 8 ng/mL. Cutaneous symptoms are among the most common presentations for individuals with HaT and can include AD, chronic or episodic urticaria, pruritus, flushing, and angioedema. However, HaT is unique because of the coupling of these common dermatologic findings with other abnormalities, including abdominal pain and diarrhea, hypermobile joints, and autonomic dysfunction. Patients with HaT also may manifest psychiatric concerns of anxiety, depression, and chronic pain, all of which have been linked to this disorder.

It is unclear in HaT if the presence of extra-allelic copies of tryptase in an individual is directly pathogenic. The effects of increased basal tryptase and α2β2 tetramers have been shown to likely be responsible for some of the clinical features in these individuals but also may magnify other individual underlying disease(s) or diathesis in which mast cells are naturally abundant.8 In the skin, this increased mast cell activation and subsequent histamine release frequently are visible as dermatographia and urticaria. However, mast cell numbers also are known to be increased in both psoriatic and AD skin lesions,12 thus severe presentation of these diseases in conjunction with the other symptoms associated with mast cell activation should prompt suspicion for HaT.

Effects of HaT on Other Cutaneous Disease—Given the increase of mast cells in AD skin lesions and fact that 94% of patients in the 2014 Lyons et al1 study cited a history of AD, HaT may be a risk factor in the development of AD. Interestingly, in addition to the increased mast cells in AD lesions, PAR2+ nerve fibers also are increased in AD lesions and have been implicated in the nonhistaminergic pruritus experienced by patients with AD.12 Thus, given the proposed propensity for α2β2 tetramers to activate PAR2, it is possible this mechanism may contribute to severe pruritus in individuals with AD and concurrent HaT, as those with HaT express increased α2β2 tetramers. However, no study to date has directly compared AD symptoms in patients with concurrent HaT vs patients without it. Further research is needed on how HaT impacts other allergic and inflammatory skin diseases such as AD and psoriasis, but one may reasonably consider HaT when treating chronic inflammatory skin diseases refractory to typical interventions and/or severe presentations. Although HaT is an autosomal-dominant disorder, it is not detected by standard whole exome sequencing or microarrays. A commercial test is available, utilizing a buccal swab to test for TPSAB1 copy number.

HaT and Mast Cell Disorders—When evaluating someone with suspected HaT, it is important to screen for other symptoms of mast cell activation. For instance, in the GI tract increased mast cell activation results in activation of motor neurons and nociceptors and increases secretion and peristalsis with consequent bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.10 Likewise, tryptase also has neuromodulatory effects that amplify the perception of pain and are likely responsible for the feelings of hyperalgesia reported in patients with HaT.13

There is substantial overlap in the clinical pictures of HaT and MCAS, and HaT is considered a heritable risk factor for MCAS. Consequently, any patient undergoing workup for MCAS also should be tested for HaT. Although HaT is associated with consistently elevated tryptase, MCAS is episodic in nature, and an increase in tryptase levels of at least 20% plus 2 ng/mL from baseline only in the presence of other symptoms reflective of mast cell activation (Table) is a prerequisite for diagnosis.9 Chronic signs and symptoms of atopy, chronic urticaria, and severe asthma are not indicative of MCAS but are frequently seen in HaT.

Another cause of persistently elevated tryptase levels is SM. Systemic mastocytosis is defined by aberrant clonal mast cell expansion and systemic involvement11 and can cause persistent symptoms, unlike MCAS alone. However, SM also can be associated with MCAS.9 Notably, a baseline serum tryptase level greater than 20 ng/mL—much higher than the threshold of greater than 8 ng/mL for suspicion of HaT—is seen in 75% of SM cases and is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for the disease.9,11 However, the 2016 study identifying increased TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequences as the causative entity for HaT by Lyons et al2 found the average (SD) basal serum tryptase level in individuals with α-tryptase–encoding sequence duplications to be 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL in those with triplications. Thus, there likely is no threshold for elevated baseline tryptase levels that would indicate SM over HaT as a more likely diagnosis. However, SM will present with new persistently elevated tryptase levels, whereas the elevation in HaT is believed to be lifelong.5 Also in contrast to HaT, SM can present with liver, spleen, and lymph node involvement; bone sclerosis; and cytopenia.11,14

Mastocytosis is much rarer than HaT, with an estimated prevalence of 9 cases per 100,000 individuals in the United States.11 Although HaT diagnostic testing is noninvasive, SM requires a bone marrow biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Given the likely much higher prevalence of HaT than SM and the patient burden of a bone marrow biopsy, HaT should be considered before proceeding with a bone marrow biopsy to evaluate for SM when a patient presents with persistent systemic symptoms of mast cell activation and elevated baseline tryptase levels. Furthermore, it also would be prudent to test for HaT in patients with known SM, as a cohort study by Lyons et al5 indicated that HaT is likely more common in those with SM (12.2% [10/82] of cohort with known SM vs 5.3% of 398 controls), and patients with concurrent SM and HaT were at a higher risk for severe anaphylaxis (RR=9.5; P=.007).

Studies thus far surrounding HaT have not evaluated timing of initial symptom onset or age of initial presentation for HaT. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that those with increased TPSAB1 copy number will be symptomatic, as there have been reports of asymptomatic individuals with HaT who had basal serum levels greater than 8 ng/mL.7 As research into HaT continues and larger cohorts are evaluated, questions surrounding timing of symptom onset and various factors that may make someone more likely to display a particular phenotype will be answered.

Treatment—Long-term prognosis for individuals with HaT is largely unknown. Unfortunately, there are limited data to support a single effective treatment strategy for managing HaT, and treatment has varied based on predominant symptoms. For cutaneous and GI tract symptoms, trials of maximal H1 and H2 antihistamines twice daily have been recommended.4 Omalizumab was reported to improve chronic urticaria in 3 of 3 patients, showing potential promise as a treatment.4 Mast cell stabilizers, such as oral cromolyn, have been used for severe GI symptoms, while some patients also have reported improvement with oral ketotifen.6 Other medications, such as tricyclic antidepressants, clemastine fumarate, and gabapentin, have been beneficial anecdotally.6 Given the lack of harmful effects seen in individuals who are α-tryptase deficient, α-tryptase inhibition is an intriguing target for future therapies.

Conclusion

Patients who present with a constellation of dermatologic, allergic, GI tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities consistent with HaT may receive a prompt diagnosis if the association is recognized. The full relationship between HaT and other chronic dermatologic disorders is still unknown. Ultimately, heightened interest and research into HaT will lead to more treatment options available for affected patients.

1. Lyons JJ, Sun G, Stone KD, et al. Mendelian inheritance of elevated serum tryptase associated with atopy and connective tissue abnormalities. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1471-1474.

2. Lyons JJ, Yu X, Hughes JD, et al. Elevated basal serum tryptase identifies a multisystem disorder associated with increased TPSAB1 copy number. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1564-1569.

3. Schwartz L. Diagnostic value of tryptase in anaphylaxis and mastocytosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;6:451-463.

4. Giannetti MP, Weller E, Bormans C, et al. Hereditary alpha-tryptasemia in 101 patients with mast cell activation–related symptomatology including anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126:655-660.

5. Lyons JJ, Chovanec J, O’Connell MP, et al. Heritable risk for severe anaphylaxis associated with increased α-tryptase–encoding germline copy number at TPSAB1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;147:622-632.

6. Lyons JJ. Hereditary alpha tryptasemia: genotyping and associated clinical features. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2018;38:483-495.

7. Robey RC, Wilcock A, Bonin H, et al. Hereditary alpha-tryptasemia: UK prevalence and variability in disease expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:3549-3556.

8. Le QT, Lyons JJ, Naranjo AN, et al. Impact of naturally forming human α/β-tryptase heterotetramers in the pathogenesis of hereditary α-tryptasemia. J Exp Med. 2019;216:2348-2361.

9. Weiler CR, Austen KF, Akin C, et al. AAAAI Mast Cell Disorders Committee Work Group Report: mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) diagnosis and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:883-896.

10. Ramsay DB, Stephen S, Borum M, et al. Mast cells in gastrointestinal disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6:772-777.

11. Giannetti A, Filice E, Caffarelli C, et al. Mast cell activation disorders. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:124.

12. Siiskonen H, Harvima I. Mast cells and sensory nerves contribute to neurogenic inflammation and pruritus in chronic skin inflammation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:422.

13. Varrassi G, Fusco M, Skaper SD, et al. A pharmacological rationale to reduce the incidence of opioid induced tolerance and hyperalgesia: a review. Pain Ther. 2018;7:59-75.

14. Núñez E, Moreno-Borque R, García-Montero A, et al. Serum tryptase monitoring in indolent systemic mastocytosis: association with disease features and patient outcome. PLoS One. 2013;8:E76116.

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia (HaT), an autosomal-dominant disorder of tryptase overproduction, was first described in 2014 by Lyons et al.1 It has been associated with multiple dermatologic, allergic, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities. These multisystem concerns may include cutaneous flushing, chronic pruritus, urticaria, GI tract symptoms, arthralgia, and autonomic dysfunction.2 The diverse symptoms and the recent discovery of HaT make recognition of this disorder challenging. Currently, it also is believed that HaT is associated with an elevated risk for anaphylaxis and is a biomarker for severe symptoms in disorders with increased mast cell burden such as mastocytosis.3-5

Given the potential cutaneous manifestations and the fact that dermatologic symptoms may be the initial presentation of HaT, awareness and recognition of this condition by dermatologists are essential for diagnosis and treatment. This review summarizes the cutaneous presentations consistent with HaT and discusses various conditions that share overlapping dermatologic symptoms with HaT.

Background on HaT

Mast cells are known to secrete several vasoactive mediators including tryptase and histamine when activated by foreign substances, similar to IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions. In their baseline state, mast cells continuously secrete immature forms of tryptases called protryptases.6 These protryptases come in 2 forms: α and β. Although mature tryptase is acutely elevatedin anaphylaxis, persistently elevated total serum tryptase levels frequently are regarded as indicative of a systemic mast cell disorder such as systemic mastocytosis (SM).3 Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals with the disorder have an elevated basal serum tryptase level (>8 ng/mL). Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been identified as another possible cause of persistently elevated levels.2,6

Genetics and Epidemiology of HaT—The humantryptase locus at chromosome 16p13.3 is composed of 4 paralog genes: TPSG1, TPSB2, TPSAB1, and TPSD1.4 Only TPSAB1 encodes for α-tryptase, while both TPSB2 and TPSAB1 encode for β-tryptase.4 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia is an autosomal-dominant disorder resulting from a copy number increase in the α-tryptase encoding sequence within the TPSAB1 gene. Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals identified with the disorder have a basal serum tryptase level greater than 8 ng/mL, with mean (SD) levels of 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL with gene duplication and triplication, respectively (reference range, 0–11.4 ng/mL).2,6 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia likely is common and largely undiagnosed, with a recently estimated prevalence of 5% in the United Kingdom7 and 5.6% in a cohort of 125 individuals from Italy, Slovenia, and the United States.5

Implications of Increased α-tryptase Levels—After an inciting stimulus, the active portions of α-protryptase and β-protryptase are secreted as tetramers by activated mast cells via degranulation. In vitro, β-tryptase homotetramers have been found to play a role in anaphylaxis, while α-homotetramers are nearly inactive.8,9 Recently, however, it has been discovered that α2β2 tetramers also can form and do so in a higher ratio in individuals with increased α-tryptase–encoding gene copies, such as those with HaT.8 These heterotetramers exhibit unique properties compared with the homotetramers and may stimulate epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 and protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2). Epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 activation likely contributes to vibratory urticaria in patients, while activation of PAR2 may have a range of clinical effects, including worsening asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, pruritus, and the exacerbation of dermal inflammation and hyperalgesia.8,10 Thus, α- and β-tryptase tetramers can be considered mediators that may influence the severity of disorders in which mast cells are naturally prevalent and likely contribute to the phenotype of those with HaT.7 Furthermore, these characteristics have been shown to potentially increase in severity with increasing tryptase levels and with increased TPSAB1 duplications.1,2 In contrast, more than 25% of the population is deficient in α-tryptase without known deleterious effects.5

Cutaneous Manifestations of HaT

A case series reported by Lyons et al1 in 2014 detailed persistent elevated basal serum tryptase levels in 9 families with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance. In this cohort, 31 of 33 (94%) affected individuals had a history of atopic dermatitis (AD), and 26 of 33 (79%) affected individuals reported symptoms consistent with mast cell degranulation, including urticaria; flushing; and/or crampy abdominal pain unprovoked or triggered by heat, exercise, vibration, stress, certain foods, or minor physical stimulation.1 A later report by Lyons et al2 in 2016 identified the TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequence copy number increase as the causative entity for HaT by examining a group of 96 patients from 35 families with frequent recurrent cutaneous flushing and pruritus, sometimes associated with urticaria and sleep disruption. Flushing and pruritus were found in 45% (33/73) of those with a TPSAB1 duplication and 80% (12/15) of those with a triplication (P=.022), suggesting a gene dose effect regarding α-tryptase encoding sequence copy number and these symptoms.2

A 2019 study further explored the clinical finding of urticaria in patients with HaT by specifically examining if vibration-induced urticaria was affected by TPSAB1 gene dosage.8 A cohort of 56 volunteers—35 healthy and 21 with HaT—underwent tryptase genotyping and cutaneous vibratory challenge. The presence of TPSAB1 was significantly correlated with induction of vibration-induced urticaria (P<.01), as the severity and prevalence of the urticarial response increased along with α- and β-tryptase gene ratios.8

Urticaria and angioedema also were seen in 51% (36/70) of patients in a cohort of HaT patients in the United Kingdom, in which 41% (29/70) also had skin flushing. In contrast to prior studies, these manifestations were not more common in patients with gene triplications or quintuplications than those with duplications.7 In another recent retrospective evaluation conducted at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts)(N=101), 80% of patients aged 4 to 85 years with confirmed diagnoses of HaT had skin manifestations such as urticaria, flushing, and pruritus.4

HaT and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome—In 2019, a Mast Cell Disorders Committee Work Group Report outlined recommendations for diagnosing and treating primary mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), a disorder in which mast cells seem to be more easily activated. Mast cell activation syndrome is defined as a primary clinical condition in which there are episodic signs and symptoms of systemic anaphylaxis (Table) concurrently affecting at least 2 organ systems, resulting from secreted mast cell mediators.9,11 The 2019 report also touched on clinical criteria that lack precision for diagnosing MCAS yet are in use, including dermographism and several types of rashes.9 Episode triggers frequent in MCAS include hot water, alcohol, stress, exercise, infection, hormonal changes, and physical stimuli.

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been suggested to be a risk factor for MCAS, which also can be associated with SM and clonal MCAS.9 Patients with MCAS should be tested for increased α-tryptase gene copy number given the overlap in symptoms, the likely predisposition of those with HaT to develop MCAS, and the fact that these patients could be at an increased risk for anaphylaxis.4,7,9,11 However, the clinical phenotype for HaT includes allergic disorders affecting the skin as well as neuropsychiatric and connective tissue abnormalities that are distinctive from MCAS. Although HaT may be considered a heritable risk factor for MCAS, MCAS is only 1 potential phenotype associated with HaT.9

Implications of HaT

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia should be considered in all patients with basal tryptase levels greater than 8 ng/mL. Cutaneous symptoms are among the most common presentations for individuals with HaT and can include AD, chronic or episodic urticaria, pruritus, flushing, and angioedema. However, HaT is unique because of the coupling of these common dermatologic findings with other abnormalities, including abdominal pain and diarrhea, hypermobile joints, and autonomic dysfunction. Patients with HaT also may manifest psychiatric concerns of anxiety, depression, and chronic pain, all of which have been linked to this disorder.

It is unclear in HaT if the presence of extra-allelic copies of tryptase in an individual is directly pathogenic. The effects of increased basal tryptase and α2β2 tetramers have been shown to likely be responsible for some of the clinical features in these individuals but also may magnify other individual underlying disease(s) or diathesis in which mast cells are naturally abundant.8 In the skin, this increased mast cell activation and subsequent histamine release frequently are visible as dermatographia and urticaria. However, mast cell numbers also are known to be increased in both psoriatic and AD skin lesions,12 thus severe presentation of these diseases in conjunction with the other symptoms associated with mast cell activation should prompt suspicion for HaT.

Effects of HaT on Other Cutaneous Disease—Given the increase of mast cells in AD skin lesions and fact that 94% of patients in the 2014 Lyons et al1 study cited a history of AD, HaT may be a risk factor in the development of AD. Interestingly, in addition to the increased mast cells in AD lesions, PAR2+ nerve fibers also are increased in AD lesions and have been implicated in the nonhistaminergic pruritus experienced by patients with AD.12 Thus, given the proposed propensity for α2β2 tetramers to activate PAR2, it is possible this mechanism may contribute to severe pruritus in individuals with AD and concurrent HaT, as those with HaT express increased α2β2 tetramers. However, no study to date has directly compared AD symptoms in patients with concurrent HaT vs patients without it. Further research is needed on how HaT impacts other allergic and inflammatory skin diseases such as AD and psoriasis, but one may reasonably consider HaT when treating chronic inflammatory skin diseases refractory to typical interventions and/or severe presentations. Although HaT is an autosomal-dominant disorder, it is not detected by standard whole exome sequencing or microarrays. A commercial test is available, utilizing a buccal swab to test for TPSAB1 copy number.

HaT and Mast Cell Disorders—When evaluating someone with suspected HaT, it is important to screen for other symptoms of mast cell activation. For instance, in the GI tract increased mast cell activation results in activation of motor neurons and nociceptors and increases secretion and peristalsis with consequent bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.10 Likewise, tryptase also has neuromodulatory effects that amplify the perception of pain and are likely responsible for the feelings of hyperalgesia reported in patients with HaT.13

There is substantial overlap in the clinical pictures of HaT and MCAS, and HaT is considered a heritable risk factor for MCAS. Consequently, any patient undergoing workup for MCAS also should be tested for HaT. Although HaT is associated with consistently elevated tryptase, MCAS is episodic in nature, and an increase in tryptase levels of at least 20% plus 2 ng/mL from baseline only in the presence of other symptoms reflective of mast cell activation (Table) is a prerequisite for diagnosis.9 Chronic signs and symptoms of atopy, chronic urticaria, and severe asthma are not indicative of MCAS but are frequently seen in HaT.

Another cause of persistently elevated tryptase levels is SM. Systemic mastocytosis is defined by aberrant clonal mast cell expansion and systemic involvement11 and can cause persistent symptoms, unlike MCAS alone. However, SM also can be associated with MCAS.9 Notably, a baseline serum tryptase level greater than 20 ng/mL—much higher than the threshold of greater than 8 ng/mL for suspicion of HaT—is seen in 75% of SM cases and is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for the disease.9,11 However, the 2016 study identifying increased TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequences as the causative entity for HaT by Lyons et al2 found the average (SD) basal serum tryptase level in individuals with α-tryptase–encoding sequence duplications to be 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL in those with triplications. Thus, there likely is no threshold for elevated baseline tryptase levels that would indicate SM over HaT as a more likely diagnosis. However, SM will present with new persistently elevated tryptase levels, whereas the elevation in HaT is believed to be lifelong.5 Also in contrast to HaT, SM can present with liver, spleen, and lymph node involvement; bone sclerosis; and cytopenia.11,14

Mastocytosis is much rarer than HaT, with an estimated prevalence of 9 cases per 100,000 individuals in the United States.11 Although HaT diagnostic testing is noninvasive, SM requires a bone marrow biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Given the likely much higher prevalence of HaT than SM and the patient burden of a bone marrow biopsy, HaT should be considered before proceeding with a bone marrow biopsy to evaluate for SM when a patient presents with persistent systemic symptoms of mast cell activation and elevated baseline tryptase levels. Furthermore, it also would be prudent to test for HaT in patients with known SM, as a cohort study by Lyons et al5 indicated that HaT is likely more common in those with SM (12.2% [10/82] of cohort with known SM vs 5.3% of 398 controls), and patients with concurrent SM and HaT were at a higher risk for severe anaphylaxis (RR=9.5; P=.007).

Studies thus far surrounding HaT have not evaluated timing of initial symptom onset or age of initial presentation for HaT. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that those with increased TPSAB1 copy number will be symptomatic, as there have been reports of asymptomatic individuals with HaT who had basal serum levels greater than 8 ng/mL.7 As research into HaT continues and larger cohorts are evaluated, questions surrounding timing of symptom onset and various factors that may make someone more likely to display a particular phenotype will be answered.

Treatment—Long-term prognosis for individuals with HaT is largely unknown. Unfortunately, there are limited data to support a single effective treatment strategy for managing HaT, and treatment has varied based on predominant symptoms. For cutaneous and GI tract symptoms, trials of maximal H1 and H2 antihistamines twice daily have been recommended.4 Omalizumab was reported to improve chronic urticaria in 3 of 3 patients, showing potential promise as a treatment.4 Mast cell stabilizers, such as oral cromolyn, have been used for severe GI symptoms, while some patients also have reported improvement with oral ketotifen.6 Other medications, such as tricyclic antidepressants, clemastine fumarate, and gabapentin, have been beneficial anecdotally.6 Given the lack of harmful effects seen in individuals who are α-tryptase deficient, α-tryptase inhibition is an intriguing target for future therapies.

Conclusion

Patients who present with a constellation of dermatologic, allergic, GI tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities consistent with HaT may receive a prompt diagnosis if the association is recognized. The full relationship between HaT and other chronic dermatologic disorders is still unknown. Ultimately, heightened interest and research into HaT will lead to more treatment options available for affected patients.

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia (HaT), an autosomal-dominant disorder of tryptase overproduction, was first described in 2014 by Lyons et al.1 It has been associated with multiple dermatologic, allergic, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities. These multisystem concerns may include cutaneous flushing, chronic pruritus, urticaria, GI tract symptoms, arthralgia, and autonomic dysfunction.2 The diverse symptoms and the recent discovery of HaT make recognition of this disorder challenging. Currently, it also is believed that HaT is associated with an elevated risk for anaphylaxis and is a biomarker for severe symptoms in disorders with increased mast cell burden such as mastocytosis.3-5

Given the potential cutaneous manifestations and the fact that dermatologic symptoms may be the initial presentation of HaT, awareness and recognition of this condition by dermatologists are essential for diagnosis and treatment. This review summarizes the cutaneous presentations consistent with HaT and discusses various conditions that share overlapping dermatologic symptoms with HaT.

Background on HaT

Mast cells are known to secrete several vasoactive mediators including tryptase and histamine when activated by foreign substances, similar to IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions. In their baseline state, mast cells continuously secrete immature forms of tryptases called protryptases.6 These protryptases come in 2 forms: α and β. Although mature tryptase is acutely elevatedin anaphylaxis, persistently elevated total serum tryptase levels frequently are regarded as indicative of a systemic mast cell disorder such as systemic mastocytosis (SM).3 Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals with the disorder have an elevated basal serum tryptase level (>8 ng/mL). Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been identified as another possible cause of persistently elevated levels.2,6

Genetics and Epidemiology of HaT—The humantryptase locus at chromosome 16p13.3 is composed of 4 paralog genes: TPSG1, TPSB2, TPSAB1, and TPSD1.4 Only TPSAB1 encodes for α-tryptase, while both TPSB2 and TPSAB1 encode for β-tryptase.4 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia is an autosomal-dominant disorder resulting from a copy number increase in the α-tryptase encoding sequence within the TPSAB1 gene. Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals identified with the disorder have a basal serum tryptase level greater than 8 ng/mL, with mean (SD) levels of 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL with gene duplication and triplication, respectively (reference range, 0–11.4 ng/mL).2,6 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia likely is common and largely undiagnosed, with a recently estimated prevalence of 5% in the United Kingdom7 and 5.6% in a cohort of 125 individuals from Italy, Slovenia, and the United States.5

Implications of Increased α-tryptase Levels—After an inciting stimulus, the active portions of α-protryptase and β-protryptase are secreted as tetramers by activated mast cells via degranulation. In vitro, β-tryptase homotetramers have been found to play a role in anaphylaxis, while α-homotetramers are nearly inactive.8,9 Recently, however, it has been discovered that α2β2 tetramers also can form and do so in a higher ratio in individuals with increased α-tryptase–encoding gene copies, such as those with HaT.8 These heterotetramers exhibit unique properties compared with the homotetramers and may stimulate epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 and protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2). Epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 activation likely contributes to vibratory urticaria in patients, while activation of PAR2 may have a range of clinical effects, including worsening asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, pruritus, and the exacerbation of dermal inflammation and hyperalgesia.8,10 Thus, α- and β-tryptase tetramers can be considered mediators that may influence the severity of disorders in which mast cells are naturally prevalent and likely contribute to the phenotype of those with HaT.7 Furthermore, these characteristics have been shown to potentially increase in severity with increasing tryptase levels and with increased TPSAB1 duplications.1,2 In contrast, more than 25% of the population is deficient in α-tryptase without known deleterious effects.5

Cutaneous Manifestations of HaT

A case series reported by Lyons et al1 in 2014 detailed persistent elevated basal serum tryptase levels in 9 families with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance. In this cohort, 31 of 33 (94%) affected individuals had a history of atopic dermatitis (AD), and 26 of 33 (79%) affected individuals reported symptoms consistent with mast cell degranulation, including urticaria; flushing; and/or crampy abdominal pain unprovoked or triggered by heat, exercise, vibration, stress, certain foods, or minor physical stimulation.1 A later report by Lyons et al2 in 2016 identified the TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequence copy number increase as the causative entity for HaT by examining a group of 96 patients from 35 families with frequent recurrent cutaneous flushing and pruritus, sometimes associated with urticaria and sleep disruption. Flushing and pruritus were found in 45% (33/73) of those with a TPSAB1 duplication and 80% (12/15) of those with a triplication (P=.022), suggesting a gene dose effect regarding α-tryptase encoding sequence copy number and these symptoms.2

A 2019 study further explored the clinical finding of urticaria in patients with HaT by specifically examining if vibration-induced urticaria was affected by TPSAB1 gene dosage.8 A cohort of 56 volunteers—35 healthy and 21 with HaT—underwent tryptase genotyping and cutaneous vibratory challenge. The presence of TPSAB1 was significantly correlated with induction of vibration-induced urticaria (P<.01), as the severity and prevalence of the urticarial response increased along with α- and β-tryptase gene ratios.8

Urticaria and angioedema also were seen in 51% (36/70) of patients in a cohort of HaT patients in the United Kingdom, in which 41% (29/70) also had skin flushing. In contrast to prior studies, these manifestations were not more common in patients with gene triplications or quintuplications than those with duplications.7 In another recent retrospective evaluation conducted at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts)(N=101), 80% of patients aged 4 to 85 years with confirmed diagnoses of HaT had skin manifestations such as urticaria, flushing, and pruritus.4

HaT and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome—In 2019, a Mast Cell Disorders Committee Work Group Report outlined recommendations for diagnosing and treating primary mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), a disorder in which mast cells seem to be more easily activated. Mast cell activation syndrome is defined as a primary clinical condition in which there are episodic signs and symptoms of systemic anaphylaxis (Table) concurrently affecting at least 2 organ systems, resulting from secreted mast cell mediators.9,11 The 2019 report also touched on clinical criteria that lack precision for diagnosing MCAS yet are in use, including dermographism and several types of rashes.9 Episode triggers frequent in MCAS include hot water, alcohol, stress, exercise, infection, hormonal changes, and physical stimuli.

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been suggested to be a risk factor for MCAS, which also can be associated with SM and clonal MCAS.9 Patients with MCAS should be tested for increased α-tryptase gene copy number given the overlap in symptoms, the likely predisposition of those with HaT to develop MCAS, and the fact that these patients could be at an increased risk for anaphylaxis.4,7,9,11 However, the clinical phenotype for HaT includes allergic disorders affecting the skin as well as neuropsychiatric and connective tissue abnormalities that are distinctive from MCAS. Although HaT may be considered a heritable risk factor for MCAS, MCAS is only 1 potential phenotype associated with HaT.9

Implications of HaT

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia should be considered in all patients with basal tryptase levels greater than 8 ng/mL. Cutaneous symptoms are among the most common presentations for individuals with HaT and can include AD, chronic or episodic urticaria, pruritus, flushing, and angioedema. However, HaT is unique because of the coupling of these common dermatologic findings with other abnormalities, including abdominal pain and diarrhea, hypermobile joints, and autonomic dysfunction. Patients with HaT also may manifest psychiatric concerns of anxiety, depression, and chronic pain, all of which have been linked to this disorder.

It is unclear in HaT if the presence of extra-allelic copies of tryptase in an individual is directly pathogenic. The effects of increased basal tryptase and α2β2 tetramers have been shown to likely be responsible for some of the clinical features in these individuals but also may magnify other individual underlying disease(s) or diathesis in which mast cells are naturally abundant.8 In the skin, this increased mast cell activation and subsequent histamine release frequently are visible as dermatographia and urticaria. However, mast cell numbers also are known to be increased in both psoriatic and AD skin lesions,12 thus severe presentation of these diseases in conjunction with the other symptoms associated with mast cell activation should prompt suspicion for HaT.

Effects of HaT on Other Cutaneous Disease—Given the increase of mast cells in AD skin lesions and fact that 94% of patients in the 2014 Lyons et al1 study cited a history of AD, HaT may be a risk factor in the development of AD. Interestingly, in addition to the increased mast cells in AD lesions, PAR2+ nerve fibers also are increased in AD lesions and have been implicated in the nonhistaminergic pruritus experienced by patients with AD.12 Thus, given the proposed propensity for α2β2 tetramers to activate PAR2, it is possible this mechanism may contribute to severe pruritus in individuals with AD and concurrent HaT, as those with HaT express increased α2β2 tetramers. However, no study to date has directly compared AD symptoms in patients with concurrent HaT vs patients without it. Further research is needed on how HaT impacts other allergic and inflammatory skin diseases such as AD and psoriasis, but one may reasonably consider HaT when treating chronic inflammatory skin diseases refractory to typical interventions and/or severe presentations. Although HaT is an autosomal-dominant disorder, it is not detected by standard whole exome sequencing or microarrays. A commercial test is available, utilizing a buccal swab to test for TPSAB1 copy number.

HaT and Mast Cell Disorders—When evaluating someone with suspected HaT, it is important to screen for other symptoms of mast cell activation. For instance, in the GI tract increased mast cell activation results in activation of motor neurons and nociceptors and increases secretion and peristalsis with consequent bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.10 Likewise, tryptase also has neuromodulatory effects that amplify the perception of pain and are likely responsible for the feelings of hyperalgesia reported in patients with HaT.13

There is substantial overlap in the clinical pictures of HaT and MCAS, and HaT is considered a heritable risk factor for MCAS. Consequently, any patient undergoing workup for MCAS also should be tested for HaT. Although HaT is associated with consistently elevated tryptase, MCAS is episodic in nature, and an increase in tryptase levels of at least 20% plus 2 ng/mL from baseline only in the presence of other symptoms reflective of mast cell activation (Table) is a prerequisite for diagnosis.9 Chronic signs and symptoms of atopy, chronic urticaria, and severe asthma are not indicative of MCAS but are frequently seen in HaT.

Another cause of persistently elevated tryptase levels is SM. Systemic mastocytosis is defined by aberrant clonal mast cell expansion and systemic involvement11 and can cause persistent symptoms, unlike MCAS alone. However, SM also can be associated with MCAS.9 Notably, a baseline serum tryptase level greater than 20 ng/mL—much higher than the threshold of greater than 8 ng/mL for suspicion of HaT—is seen in 75% of SM cases and is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for the disease.9,11 However, the 2016 study identifying increased TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequences as the causative entity for HaT by Lyons et al2 found the average (SD) basal serum tryptase level in individuals with α-tryptase–encoding sequence duplications to be 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL in those with triplications. Thus, there likely is no threshold for elevated baseline tryptase levels that would indicate SM over HaT as a more likely diagnosis. However, SM will present with new persistently elevated tryptase levels, whereas the elevation in HaT is believed to be lifelong.5 Also in contrast to HaT, SM can present with liver, spleen, and lymph node involvement; bone sclerosis; and cytopenia.11,14

Mastocytosis is much rarer than HaT, with an estimated prevalence of 9 cases per 100,000 individuals in the United States.11 Although HaT diagnostic testing is noninvasive, SM requires a bone marrow biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Given the likely much higher prevalence of HaT than SM and the patient burden of a bone marrow biopsy, HaT should be considered before proceeding with a bone marrow biopsy to evaluate for SM when a patient presents with persistent systemic symptoms of mast cell activation and elevated baseline tryptase levels. Furthermore, it also would be prudent to test for HaT in patients with known SM, as a cohort study by Lyons et al5 indicated that HaT is likely more common in those with SM (12.2% [10/82] of cohort with known SM vs 5.3% of 398 controls), and patients with concurrent SM and HaT were at a higher risk for severe anaphylaxis (RR=9.5; P=.007).

Studies thus far surrounding HaT have not evaluated timing of initial symptom onset or age of initial presentation for HaT. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that those with increased TPSAB1 copy number will be symptomatic, as there have been reports of asymptomatic individuals with HaT who had basal serum levels greater than 8 ng/mL.7 As research into HaT continues and larger cohorts are evaluated, questions surrounding timing of symptom onset and various factors that may make someone more likely to display a particular phenotype will be answered.

Treatment—Long-term prognosis for individuals with HaT is largely unknown. Unfortunately, there are limited data to support a single effective treatment strategy for managing HaT, and treatment has varied based on predominant symptoms. For cutaneous and GI tract symptoms, trials of maximal H1 and H2 antihistamines twice daily have been recommended.4 Omalizumab was reported to improve chronic urticaria in 3 of 3 patients, showing potential promise as a treatment.4 Mast cell stabilizers, such as oral cromolyn, have been used for severe GI symptoms, while some patients also have reported improvement with oral ketotifen.6 Other medications, such as tricyclic antidepressants, clemastine fumarate, and gabapentin, have been beneficial anecdotally.6 Given the lack of harmful effects seen in individuals who are α-tryptase deficient, α-tryptase inhibition is an intriguing target for future therapies.

Conclusion