User login

FDA OKs first condom for anal sex

specifically designed for use during anal sex has gained Food and Drug Administration approval.

Anal intercourse is considered to be much riskier than vaginal sex for the transmission of infections such as HIV and HPV, a risk factor for anal cancer, agency officials said in a statement Feb. 23 announcing the decision. And though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has long encouraged the use of a condom during anal intercourse, the FDA had not until now deemed this practice safe.

The latex ONE Male Condom, from prophylactic maker Global Protection Corp. of Boston, has already been available for vaginal sex. The FDA action now allows the company to market the product for anal intercourse.

“This authorization helps us accomplish our priority to advance health equity through the development of safe and effective products that meet the needs of diverse populations,” Courtney Lias, PhD, the director of the FDA’s Office of GastroRenal, ObGyn, General Hospital, and Urology Devices, said in a statement.

The FDA said it relied on an Emory University clinical study of condom safety of more than 500 men. Those who took part in the study were evenly divided between men who have sex with men and men who have sex with women. The condom failure rate, meaning that a condom either broke or slipped, was less than 1% during anal sex. The failure rate was 3 times higher during vaginal intercourse.

The Emory researchers also found that roughly 70% of men who have sex with men would be more likely to use condoms marked as safe for anal sex, according to a survey of 10,000 people.

ONE Male Condoms sell for between $3.48 for a three-pack and $14.48 for a 24-pack, according to Milla Impola, Global Protection’s director of marketing and communications. The FDA said the condom should be used with a condom-compatible lubricant when used during anal sex.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

specifically designed for use during anal sex has gained Food and Drug Administration approval.

Anal intercourse is considered to be much riskier than vaginal sex for the transmission of infections such as HIV and HPV, a risk factor for anal cancer, agency officials said in a statement Feb. 23 announcing the decision. And though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has long encouraged the use of a condom during anal intercourse, the FDA had not until now deemed this practice safe.

The latex ONE Male Condom, from prophylactic maker Global Protection Corp. of Boston, has already been available for vaginal sex. The FDA action now allows the company to market the product for anal intercourse.

“This authorization helps us accomplish our priority to advance health equity through the development of safe and effective products that meet the needs of diverse populations,” Courtney Lias, PhD, the director of the FDA’s Office of GastroRenal, ObGyn, General Hospital, and Urology Devices, said in a statement.

The FDA said it relied on an Emory University clinical study of condom safety of more than 500 men. Those who took part in the study were evenly divided between men who have sex with men and men who have sex with women. The condom failure rate, meaning that a condom either broke or slipped, was less than 1% during anal sex. The failure rate was 3 times higher during vaginal intercourse.

The Emory researchers also found that roughly 70% of men who have sex with men would be more likely to use condoms marked as safe for anal sex, according to a survey of 10,000 people.

ONE Male Condoms sell for between $3.48 for a three-pack and $14.48 for a 24-pack, according to Milla Impola, Global Protection’s director of marketing and communications. The FDA said the condom should be used with a condom-compatible lubricant when used during anal sex.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

specifically designed for use during anal sex has gained Food and Drug Administration approval.

Anal intercourse is considered to be much riskier than vaginal sex for the transmission of infections such as HIV and HPV, a risk factor for anal cancer, agency officials said in a statement Feb. 23 announcing the decision. And though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has long encouraged the use of a condom during anal intercourse, the FDA had not until now deemed this practice safe.

The latex ONE Male Condom, from prophylactic maker Global Protection Corp. of Boston, has already been available for vaginal sex. The FDA action now allows the company to market the product for anal intercourse.

“This authorization helps us accomplish our priority to advance health equity through the development of safe and effective products that meet the needs of diverse populations,” Courtney Lias, PhD, the director of the FDA’s Office of GastroRenal, ObGyn, General Hospital, and Urology Devices, said in a statement.

The FDA said it relied on an Emory University clinical study of condom safety of more than 500 men. Those who took part in the study were evenly divided between men who have sex with men and men who have sex with women. The condom failure rate, meaning that a condom either broke or slipped, was less than 1% during anal sex. The failure rate was 3 times higher during vaginal intercourse.

The Emory researchers also found that roughly 70% of men who have sex with men would be more likely to use condoms marked as safe for anal sex, according to a survey of 10,000 people.

ONE Male Condoms sell for between $3.48 for a three-pack and $14.48 for a 24-pack, according to Milla Impola, Global Protection’s director of marketing and communications. The FDA said the condom should be used with a condom-compatible lubricant when used during anal sex.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Federal sex education programs linked to decrease in teen pregnancy

The birth rate for U.S. teenagers dropped 3% in counties where a federally funded sex education program was introduced, a recently published paper says.

Researchers concentrated on the effects of the Teen Pregnancy Prevention program (TPP), which was introduced during the Obama administration and administered on the county level. TPP programs provide more information on sex, contraception, and reproductive health than abstinence-only programs, the paper said.

“Sex education in the United States has been hotly debated among researchers, policy makers, and the public,” Nicholas Mark, a doctoral candidate in New York University’s department of sociology and the lead author of the paper, said in a news release. “Our analysis provides evidence that funding for more comprehensive sex education led to an overall reduction in the teen birth rate at the county level of more than 3%.”

Researchers examined teen birth rates in 55 counties from 1996 to 2009, before TTP, and from 2010 to 2016, after TTP. Next, they compared teen birth rates in the 55 counties with teen birth rates in 2,800 counties that didn’t have the funding in the years before and after TPP was introduced.

In the 55 counties, teen birth rates fell 1.5% in the first year of TTP funding and fell about 7% by the fifth year of funding, for an average drop of 3%, the news release said.

“We’ve known for some time that abstinence-only programs are ineffective at reducing teen birth rates,” said Lawrence Wu, a professor in NYU’s department of sociology and the paper’s senior author. “This work shows that more wide-reaching sex education programs – those not limited to abstinence – are successful in lowering rates of teen births.”

The paper was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

The paper said the findings probably understate the true effect of more comprehensive sex education at the individual level.

The authors said the findings are important because U.S. women are more likely to become mothers in their teens than women in other developed nations, with many teen pregnancies reported as unintended, the authors said.

As of 2020, teen birth rates and the number of births to teen mothers had dropped steadily since 1990. Teen birth rates fell by 70% over 3 decades.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The birth rate for U.S. teenagers dropped 3% in counties where a federally funded sex education program was introduced, a recently published paper says.

Researchers concentrated on the effects of the Teen Pregnancy Prevention program (TPP), which was introduced during the Obama administration and administered on the county level. TPP programs provide more information on sex, contraception, and reproductive health than abstinence-only programs, the paper said.

“Sex education in the United States has been hotly debated among researchers, policy makers, and the public,” Nicholas Mark, a doctoral candidate in New York University’s department of sociology and the lead author of the paper, said in a news release. “Our analysis provides evidence that funding for more comprehensive sex education led to an overall reduction in the teen birth rate at the county level of more than 3%.”

Researchers examined teen birth rates in 55 counties from 1996 to 2009, before TTP, and from 2010 to 2016, after TTP. Next, they compared teen birth rates in the 55 counties with teen birth rates in 2,800 counties that didn’t have the funding in the years before and after TPP was introduced.

In the 55 counties, teen birth rates fell 1.5% in the first year of TTP funding and fell about 7% by the fifth year of funding, for an average drop of 3%, the news release said.

“We’ve known for some time that abstinence-only programs are ineffective at reducing teen birth rates,” said Lawrence Wu, a professor in NYU’s department of sociology and the paper’s senior author. “This work shows that more wide-reaching sex education programs – those not limited to abstinence – are successful in lowering rates of teen births.”

The paper was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

The paper said the findings probably understate the true effect of more comprehensive sex education at the individual level.

The authors said the findings are important because U.S. women are more likely to become mothers in their teens than women in other developed nations, with many teen pregnancies reported as unintended, the authors said.

As of 2020, teen birth rates and the number of births to teen mothers had dropped steadily since 1990. Teen birth rates fell by 70% over 3 decades.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The birth rate for U.S. teenagers dropped 3% in counties where a federally funded sex education program was introduced, a recently published paper says.

Researchers concentrated on the effects of the Teen Pregnancy Prevention program (TPP), which was introduced during the Obama administration and administered on the county level. TPP programs provide more information on sex, contraception, and reproductive health than abstinence-only programs, the paper said.

“Sex education in the United States has been hotly debated among researchers, policy makers, and the public,” Nicholas Mark, a doctoral candidate in New York University’s department of sociology and the lead author of the paper, said in a news release. “Our analysis provides evidence that funding for more comprehensive sex education led to an overall reduction in the teen birth rate at the county level of more than 3%.”

Researchers examined teen birth rates in 55 counties from 1996 to 2009, before TTP, and from 2010 to 2016, after TTP. Next, they compared teen birth rates in the 55 counties with teen birth rates in 2,800 counties that didn’t have the funding in the years before and after TPP was introduced.

In the 55 counties, teen birth rates fell 1.5% in the first year of TTP funding and fell about 7% by the fifth year of funding, for an average drop of 3%, the news release said.

“We’ve known for some time that abstinence-only programs are ineffective at reducing teen birth rates,” said Lawrence Wu, a professor in NYU’s department of sociology and the paper’s senior author. “This work shows that more wide-reaching sex education programs – those not limited to abstinence – are successful in lowering rates of teen births.”

The paper was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

The paper said the findings probably understate the true effect of more comprehensive sex education at the individual level.

The authors said the findings are important because U.S. women are more likely to become mothers in their teens than women in other developed nations, with many teen pregnancies reported as unintended, the authors said.

As of 2020, teen birth rates and the number of births to teen mothers had dropped steadily since 1990. Teen birth rates fell by 70% over 3 decades.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Drospirenone vs norethindrone progestin-only pills. Is there a clear winner?

Contraception and family planning have improved the health of all people by reducing maternal mortality, improving maternal and child health through birth spacing, supporting full education attainment, and advancing workforce participation.1 Contraception is cost-effective and should be supported by all health insurers. One economic study reported that depending on the contraceptive method utilized, up to $7 of health care costs were saved for each dollar spent on contraceptive services and supplies.2

Progestin-only pills (POPs) are an important contraceptive option for people in the following situations who3:

- have a contraindication to estrogen-containing contraceptives

- are actively breastfeeding

- are less than 21 days since birth

- have a preference to avoid estrogen.

POPs are contraindicated for women who have breast cancer, abnormal uterine bleeding, or active liver disease and for women who are pregnant. A history of bariatric surgery with a malabsorption procedure (Roux-en-Y and biliopancreatic diversion) and the use of antiepileptic medications that are strong enzyme inducers are additional situations where the risk of POP may outweigh the benefit.3 Alternative progestin-only options include the subdermal etonogestrel implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices. These 3 options provide superior contraceptive efficacy to POP.

As a contraceptive, norethindrone at a dose of 0.35 mg daily has two major flaws:

- it does not reliably inhibit ovulation

- it has a short half-life.

In clinical studies, norethindrone inhibits ovulation in approximately 50% of cycles.4,5 Because norethindrone at a dose of 0.35 mg does not reliably inhibit ovulation it relies on additional mechanisms for contraceptive efficacy, including thickening of the cervical mucus to block sperm entry into the upper reproductive tract, reduced fallopian tube motility, and thinning of the endometrium.6

Norethindrone POP is formulated in packs of 28 pills containing 0.35 mg intended for daily continuous administration and no medication-free intervals. One rationale for the low dose of 0.35 mg in norethindrone POP is that it approximates the lowest dose with contraceptive efficacy for breastfeeding women, which has the benefit of minimizing exposure of the baby to the medication. Estrogen-progestin birth control pills containing norethindrone as the progestin reliably inhibit ovulation and have a minimum of 1 mg of norethindrone in each hormone pill. A POP with 1 mg of norethindrone per pill would likely have greater contraceptive efficacy. When taken daily, norethindrone acetate 5 mg (Aygestin) suppresses ovarian estrogen production, ovulation, and often causes cessation of uterine bleeding.7 The short half-life of norethindrone (7.7 hours) further exacerbates the problem of an insufficient daily dose.6 The standard guidance is that norethindrone must be taken at the same time every day, a goal that is nearly impossible to achieve. If a dose of norethindrone is taken >3 hours late, backup contraception is recommended for 48 hours.6

Drospirenone is a chemical analogue of spironolactone. Drospirenone is a progestin that suppresses LH and FSH and has anti-androgenic and partial anti-mineralocorticoid effects.8 Drospirenone POP contains 4 mg of a nonmicronized formulation that is believed to provide a pharmacologically similar area under the curve in drug metabolism studies to the 3 mg of micronized drospirenone, present in drospirenone-containing estrogen-progestin contraceptives.8 It is provided in a pack of 28 pills with 24 drospirenone pills and 4 pills without hormone. Drospirenone has a long half-life of 30 to 34 hours.8 If ≥2 drospirenone pills are missed, backup contraception is recommended for 7 days.9 The contraceptive effectiveness of drospirenone POP is thought to be similar to estrogen-progestin pills.8 Theoretically, drospirenone, acting as an anti-mineralocorticoid, can cause hyperkalemia. People with renal and adrenal insufficiency are most vulnerable to this adverse effect and should not be prescribed drospirenone. Women taking drospirenone and a medication that strongly inhibits CYP3A4, an enzyme involved in drospirenone degradation—including ketoconazole, indinavir, boceprevir, and clarithromycin—may have increased circulating levels of drospirenone and be at an increased risk of hyperkalemia. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suggests that clinicians consider monitoring potassium concentration in women taking drospirenone who are also prescribed a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.9 In people with normal renal and adrenal function, drospirenone-induced hyperkalemia is not commonly observed.9

Drospirenone 4 mg has been reported to not affect the natural balance of pro- and anti-coagulation factors in women.10 Drospirenone 4 mg daily has been reported to cause a modest decrease in systolic (-8 mm Hg) and diastolic (-5 mm Hg) blood pressure for women with a baseline blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg. Drospirenone 4 mg daily did not change blood pressure measurement in women with a baseline systolic blood pressure <130 mm Hg.11 For women using drospirenone POP, circulating estradiol concentration is usually >30 pg/mL, with a mean concentration of 51 pg/mL.12,13 Drospirenone POP does not result in a significant change in body weight.14 Preliminary studies suggest that drospirenone is an effective contraceptive in women with a BMI >30 kg/m2.14,15 Drospirenone enters breast milk and the relative infant dose is reported to be 1.5%.9 In general, breastfeeding is considered reasonably safe when the relative infant dose of a medication is <10%.16

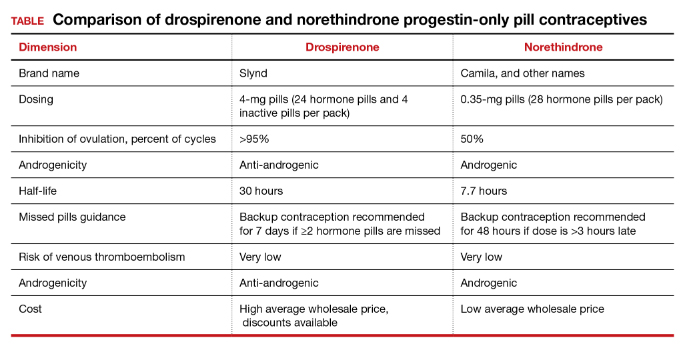

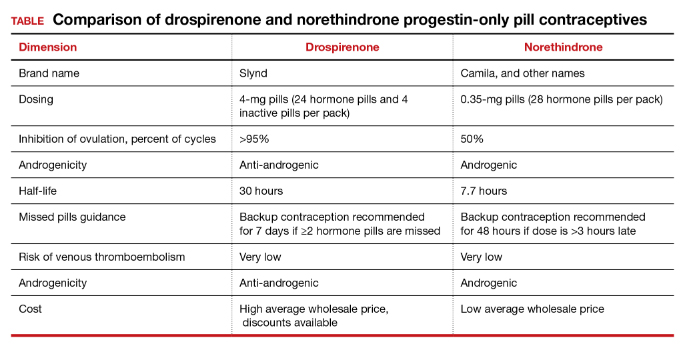

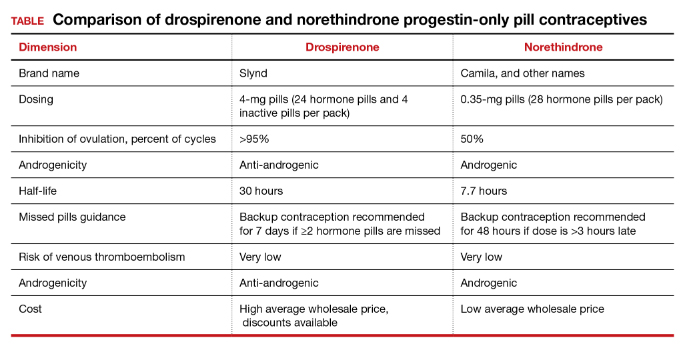

The most common adverse effect reported with both norethindrone and drospirenone POP is unscheduled uterine bleeding. With norethindrone POP about 50% of users have a relatively preserved monthly bleeding pattern and approximately 50% have bleeding between periods, spotting and/or prolonged bleeding.17,18 A similar frequency of unscheduled uterine bleeding has been reported with drospirenone POP.14,19 Unscheduled and bothersome uterine bleeding is a common reason people discontinue POP. For drospirenone POP, the FDA reports a Pearl Index of 4.9 Other studies report a Pearl Index of 0.73 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31 to 1.43) for drospirenone POP.14 For norethindrone POP, the FDA reports that in typical use about 5% of people using the contraceptive method would become pregnant.6 The TABLE provides a comparison of the key features of the two available POP contraceptives. My assessment is that drospirenone has superior contraceptive properties over norethindrone POP. However, a head-to-head clinical trial would be necessary to determine the relative contraceptive effectiveness of drospirenone versus norethindrone POP.

Maintaining contraception access

Access to contraception without a copayment is an important component of a comprehensive and equitable insurance program.20 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advocates that all people “should have unhindered and affordable access to all U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptives.”21 ACOG also calls for the “full implementation of the Affordable Care Act requirement that new and revised private health insurance plans cover all U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved contraceptives without cost sharing, including nonequivalent options within one method category.” The National Women’s Law Center22 provides helpful resources to ensure access to legislated contraceptive benefits, including a phone script for speaking with an insurance benefits agent23 and a toolkit for advocating for your contraceptive choice.24 We need to ensure that people have unfettered access to all FDA-approved contraceptives because access to contraception is an important component of public health. Although drospirenone is more costly than norethindrone POP, drospirenone contraception should be available to all patients seeking POP contraception. ●

- Kavanaugh ML, Andreson RM. Contraception and beyond: the health benefits of services provided at family planning centers, NY. Guttmacher Institute. 2013. www.gutmacher.org/pubs/helth-benefits.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Foster DG, Rostovtseva DP, Brindis CD, et al. Cost savings from the provision of specific methods of contraception in a publicly funded program. Am J Pub Health. 2009;99:446-451.

- Curtis M, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Rice CF, Killick SR, Dieben T, et al. A comparison of the inhibition of ovulation achieved by desogestrel 75 µg and levonorgestrel 30 µg daily. Human Reprod. 1999;14:982-985.

- Milsom I, Korver T. Ovulation incidence with oral contraceptives: a literature review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2008;34:237-246.

- OrthoMicronor [package insert]. OrthoMcNeil: Raritan, New Jersey. June 2008.

- Brown JB, Fotherby K, Loraine JA. The effect of norethisterone and its acetate on ovarian and pituitary function during the menstrual cycle. J Endocrinol. 1962;25:331-341.

- Romer T, Bitzer J, Egarter C, et al. Oral progestins in hormonal contraception: importance and future perspectives of a new progestin only-pill containing 4 mg drospirenone. Geburtsch Frauenheilk. 2021;81:1021-1030.

- Slynd [package insert]. Exeltis: Florham Park, New Jersey. May 2019.

- Regidor PA, Colli E, Schindlre AE. Drospirenone as estrogen-free pill and hemostasis: coagulatory study results comparing a novel 4 mg formulation in a 24+4 cycle with desogestrel 75 µg per day. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32:749-751.

- Palacios S, Colli E, Regidor PA. Efficacy and cardiovascular safety of the new estrogen-free contraceptive pill containing 4 mg drospirenone alone in a 24/4 regime. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20:218.

- Hadji P, Colli E, Regidor PA. Bone health in estrogen-free contraception. Osteoporosis Int. 2019;30:2391-2400.

- Mitchell VE, Welling LM. Not all progestins are created equally: considering unique progestins individually in psychobehavioral research. Adapt Human Behav Physiol. 2020;6:381-412.

- Palacios S, Colli E, Regidor PA. Multicenter, phase III trials on the contraceptive efficacy, tolerability and safety of a new drospirenone-only pill. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:1549-1557.

- Archer DF, Ahrendt HJ, Drouin D. Drospirenone-only oral contraceptive: results from a multicenter noncomparative trial of efficacy, safety and tolerability. Contraception. 2015;92:439-444.

- Anderson PO, Sauberan JB. Modeling drug passage into human milk. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;100:42-52. doi: 10.1002/cpt.377.

- Belsey EM. Vaginal bleeding patterns among women using one natural and eight hormonal methods of contraception. Contraception. 1988;38:181-206.

- Broome M, Fotherby K. Clinical experience with the progestin-only pill. Contraception. 1990;42:489-495.

- Apter D, Colli E, Gemzell-Danielsson K, et al. Multicenter, open-label trial to assess the safety and tolerability of drospirenone 4.0 mg over 6 cycles in female adolescents with a 7-cycle extension phase. Contraception. 2020;101:412.

- Birth control benefits. Healthcare.gov website. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/birth-control-benefits/. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Access to contraception. Committee Opinion No. 615. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:250-256.

- Health care and reproductive rights. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/issue/health-care. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- How to find out if your health plan covers birth control at no cost to you. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/072014-insuranceflowchart_vupdated.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Toolkit: Getting the coverage you deserve. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/final_nwlclogo_preventive servicestoolkit_9-25-13.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

Contraception and family planning have improved the health of all people by reducing maternal mortality, improving maternal and child health through birth spacing, supporting full education attainment, and advancing workforce participation.1 Contraception is cost-effective and should be supported by all health insurers. One economic study reported that depending on the contraceptive method utilized, up to $7 of health care costs were saved for each dollar spent on contraceptive services and supplies.2

Progestin-only pills (POPs) are an important contraceptive option for people in the following situations who3:

- have a contraindication to estrogen-containing contraceptives

- are actively breastfeeding

- are less than 21 days since birth

- have a preference to avoid estrogen.

POPs are contraindicated for women who have breast cancer, abnormal uterine bleeding, or active liver disease and for women who are pregnant. A history of bariatric surgery with a malabsorption procedure (Roux-en-Y and biliopancreatic diversion) and the use of antiepileptic medications that are strong enzyme inducers are additional situations where the risk of POP may outweigh the benefit.3 Alternative progestin-only options include the subdermal etonogestrel implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices. These 3 options provide superior contraceptive efficacy to POP.

As a contraceptive, norethindrone at a dose of 0.35 mg daily has two major flaws:

- it does not reliably inhibit ovulation

- it has a short half-life.

In clinical studies, norethindrone inhibits ovulation in approximately 50% of cycles.4,5 Because norethindrone at a dose of 0.35 mg does not reliably inhibit ovulation it relies on additional mechanisms for contraceptive efficacy, including thickening of the cervical mucus to block sperm entry into the upper reproductive tract, reduced fallopian tube motility, and thinning of the endometrium.6

Norethindrone POP is formulated in packs of 28 pills containing 0.35 mg intended for daily continuous administration and no medication-free intervals. One rationale for the low dose of 0.35 mg in norethindrone POP is that it approximates the lowest dose with contraceptive efficacy for breastfeeding women, which has the benefit of minimizing exposure of the baby to the medication. Estrogen-progestin birth control pills containing norethindrone as the progestin reliably inhibit ovulation and have a minimum of 1 mg of norethindrone in each hormone pill. A POP with 1 mg of norethindrone per pill would likely have greater contraceptive efficacy. When taken daily, norethindrone acetate 5 mg (Aygestin) suppresses ovarian estrogen production, ovulation, and often causes cessation of uterine bleeding.7 The short half-life of norethindrone (7.7 hours) further exacerbates the problem of an insufficient daily dose.6 The standard guidance is that norethindrone must be taken at the same time every day, a goal that is nearly impossible to achieve. If a dose of norethindrone is taken >3 hours late, backup contraception is recommended for 48 hours.6

Drospirenone is a chemical analogue of spironolactone. Drospirenone is a progestin that suppresses LH and FSH and has anti-androgenic and partial anti-mineralocorticoid effects.8 Drospirenone POP contains 4 mg of a nonmicronized formulation that is believed to provide a pharmacologically similar area under the curve in drug metabolism studies to the 3 mg of micronized drospirenone, present in drospirenone-containing estrogen-progestin contraceptives.8 It is provided in a pack of 28 pills with 24 drospirenone pills and 4 pills without hormone. Drospirenone has a long half-life of 30 to 34 hours.8 If ≥2 drospirenone pills are missed, backup contraception is recommended for 7 days.9 The contraceptive effectiveness of drospirenone POP is thought to be similar to estrogen-progestin pills.8 Theoretically, drospirenone, acting as an anti-mineralocorticoid, can cause hyperkalemia. People with renal and adrenal insufficiency are most vulnerable to this adverse effect and should not be prescribed drospirenone. Women taking drospirenone and a medication that strongly inhibits CYP3A4, an enzyme involved in drospirenone degradation—including ketoconazole, indinavir, boceprevir, and clarithromycin—may have increased circulating levels of drospirenone and be at an increased risk of hyperkalemia. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suggests that clinicians consider monitoring potassium concentration in women taking drospirenone who are also prescribed a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.9 In people with normal renal and adrenal function, drospirenone-induced hyperkalemia is not commonly observed.9

Drospirenone 4 mg has been reported to not affect the natural balance of pro- and anti-coagulation factors in women.10 Drospirenone 4 mg daily has been reported to cause a modest decrease in systolic (-8 mm Hg) and diastolic (-5 mm Hg) blood pressure for women with a baseline blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg. Drospirenone 4 mg daily did not change blood pressure measurement in women with a baseline systolic blood pressure <130 mm Hg.11 For women using drospirenone POP, circulating estradiol concentration is usually >30 pg/mL, with a mean concentration of 51 pg/mL.12,13 Drospirenone POP does not result in a significant change in body weight.14 Preliminary studies suggest that drospirenone is an effective contraceptive in women with a BMI >30 kg/m2.14,15 Drospirenone enters breast milk and the relative infant dose is reported to be 1.5%.9 In general, breastfeeding is considered reasonably safe when the relative infant dose of a medication is <10%.16

The most common adverse effect reported with both norethindrone and drospirenone POP is unscheduled uterine bleeding. With norethindrone POP about 50% of users have a relatively preserved monthly bleeding pattern and approximately 50% have bleeding between periods, spotting and/or prolonged bleeding.17,18 A similar frequency of unscheduled uterine bleeding has been reported with drospirenone POP.14,19 Unscheduled and bothersome uterine bleeding is a common reason people discontinue POP. For drospirenone POP, the FDA reports a Pearl Index of 4.9 Other studies report a Pearl Index of 0.73 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31 to 1.43) for drospirenone POP.14 For norethindrone POP, the FDA reports that in typical use about 5% of people using the contraceptive method would become pregnant.6 The TABLE provides a comparison of the key features of the two available POP contraceptives. My assessment is that drospirenone has superior contraceptive properties over norethindrone POP. However, a head-to-head clinical trial would be necessary to determine the relative contraceptive effectiveness of drospirenone versus norethindrone POP.

Maintaining contraception access

Access to contraception without a copayment is an important component of a comprehensive and equitable insurance program.20 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advocates that all people “should have unhindered and affordable access to all U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptives.”21 ACOG also calls for the “full implementation of the Affordable Care Act requirement that new and revised private health insurance plans cover all U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved contraceptives without cost sharing, including nonequivalent options within one method category.” The National Women’s Law Center22 provides helpful resources to ensure access to legislated contraceptive benefits, including a phone script for speaking with an insurance benefits agent23 and a toolkit for advocating for your contraceptive choice.24 We need to ensure that people have unfettered access to all FDA-approved contraceptives because access to contraception is an important component of public health. Although drospirenone is more costly than norethindrone POP, drospirenone contraception should be available to all patients seeking POP contraception. ●

Contraception and family planning have improved the health of all people by reducing maternal mortality, improving maternal and child health through birth spacing, supporting full education attainment, and advancing workforce participation.1 Contraception is cost-effective and should be supported by all health insurers. One economic study reported that depending on the contraceptive method utilized, up to $7 of health care costs were saved for each dollar spent on contraceptive services and supplies.2

Progestin-only pills (POPs) are an important contraceptive option for people in the following situations who3:

- have a contraindication to estrogen-containing contraceptives

- are actively breastfeeding

- are less than 21 days since birth

- have a preference to avoid estrogen.

POPs are contraindicated for women who have breast cancer, abnormal uterine bleeding, or active liver disease and for women who are pregnant. A history of bariatric surgery with a malabsorption procedure (Roux-en-Y and biliopancreatic diversion) and the use of antiepileptic medications that are strong enzyme inducers are additional situations where the risk of POP may outweigh the benefit.3 Alternative progestin-only options include the subdermal etonogestrel implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices. These 3 options provide superior contraceptive efficacy to POP.

As a contraceptive, norethindrone at a dose of 0.35 mg daily has two major flaws:

- it does not reliably inhibit ovulation

- it has a short half-life.

In clinical studies, norethindrone inhibits ovulation in approximately 50% of cycles.4,5 Because norethindrone at a dose of 0.35 mg does not reliably inhibit ovulation it relies on additional mechanisms for contraceptive efficacy, including thickening of the cervical mucus to block sperm entry into the upper reproductive tract, reduced fallopian tube motility, and thinning of the endometrium.6

Norethindrone POP is formulated in packs of 28 pills containing 0.35 mg intended for daily continuous administration and no medication-free intervals. One rationale for the low dose of 0.35 mg in norethindrone POP is that it approximates the lowest dose with contraceptive efficacy for breastfeeding women, which has the benefit of minimizing exposure of the baby to the medication. Estrogen-progestin birth control pills containing norethindrone as the progestin reliably inhibit ovulation and have a minimum of 1 mg of norethindrone in each hormone pill. A POP with 1 mg of norethindrone per pill would likely have greater contraceptive efficacy. When taken daily, norethindrone acetate 5 mg (Aygestin) suppresses ovarian estrogen production, ovulation, and often causes cessation of uterine bleeding.7 The short half-life of norethindrone (7.7 hours) further exacerbates the problem of an insufficient daily dose.6 The standard guidance is that norethindrone must be taken at the same time every day, a goal that is nearly impossible to achieve. If a dose of norethindrone is taken >3 hours late, backup contraception is recommended for 48 hours.6

Drospirenone is a chemical analogue of spironolactone. Drospirenone is a progestin that suppresses LH and FSH and has anti-androgenic and partial anti-mineralocorticoid effects.8 Drospirenone POP contains 4 mg of a nonmicronized formulation that is believed to provide a pharmacologically similar area under the curve in drug metabolism studies to the 3 mg of micronized drospirenone, present in drospirenone-containing estrogen-progestin contraceptives.8 It is provided in a pack of 28 pills with 24 drospirenone pills and 4 pills without hormone. Drospirenone has a long half-life of 30 to 34 hours.8 If ≥2 drospirenone pills are missed, backup contraception is recommended for 7 days.9 The contraceptive effectiveness of drospirenone POP is thought to be similar to estrogen-progestin pills.8 Theoretically, drospirenone, acting as an anti-mineralocorticoid, can cause hyperkalemia. People with renal and adrenal insufficiency are most vulnerable to this adverse effect and should not be prescribed drospirenone. Women taking drospirenone and a medication that strongly inhibits CYP3A4, an enzyme involved in drospirenone degradation—including ketoconazole, indinavir, boceprevir, and clarithromycin—may have increased circulating levels of drospirenone and be at an increased risk of hyperkalemia. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suggests that clinicians consider monitoring potassium concentration in women taking drospirenone who are also prescribed a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.9 In people with normal renal and adrenal function, drospirenone-induced hyperkalemia is not commonly observed.9

Drospirenone 4 mg has been reported to not affect the natural balance of pro- and anti-coagulation factors in women.10 Drospirenone 4 mg daily has been reported to cause a modest decrease in systolic (-8 mm Hg) and diastolic (-5 mm Hg) blood pressure for women with a baseline blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg. Drospirenone 4 mg daily did not change blood pressure measurement in women with a baseline systolic blood pressure <130 mm Hg.11 For women using drospirenone POP, circulating estradiol concentration is usually >30 pg/mL, with a mean concentration of 51 pg/mL.12,13 Drospirenone POP does not result in a significant change in body weight.14 Preliminary studies suggest that drospirenone is an effective contraceptive in women with a BMI >30 kg/m2.14,15 Drospirenone enters breast milk and the relative infant dose is reported to be 1.5%.9 In general, breastfeeding is considered reasonably safe when the relative infant dose of a medication is <10%.16

The most common adverse effect reported with both norethindrone and drospirenone POP is unscheduled uterine bleeding. With norethindrone POP about 50% of users have a relatively preserved monthly bleeding pattern and approximately 50% have bleeding between periods, spotting and/or prolonged bleeding.17,18 A similar frequency of unscheduled uterine bleeding has been reported with drospirenone POP.14,19 Unscheduled and bothersome uterine bleeding is a common reason people discontinue POP. For drospirenone POP, the FDA reports a Pearl Index of 4.9 Other studies report a Pearl Index of 0.73 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31 to 1.43) for drospirenone POP.14 For norethindrone POP, the FDA reports that in typical use about 5% of people using the contraceptive method would become pregnant.6 The TABLE provides a comparison of the key features of the two available POP contraceptives. My assessment is that drospirenone has superior contraceptive properties over norethindrone POP. However, a head-to-head clinical trial would be necessary to determine the relative contraceptive effectiveness of drospirenone versus norethindrone POP.

Maintaining contraception access

Access to contraception without a copayment is an important component of a comprehensive and equitable insurance program.20 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advocates that all people “should have unhindered and affordable access to all U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptives.”21 ACOG also calls for the “full implementation of the Affordable Care Act requirement that new and revised private health insurance plans cover all U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved contraceptives without cost sharing, including nonequivalent options within one method category.” The National Women’s Law Center22 provides helpful resources to ensure access to legislated contraceptive benefits, including a phone script for speaking with an insurance benefits agent23 and a toolkit for advocating for your contraceptive choice.24 We need to ensure that people have unfettered access to all FDA-approved contraceptives because access to contraception is an important component of public health. Although drospirenone is more costly than norethindrone POP, drospirenone contraception should be available to all patients seeking POP contraception. ●

- Kavanaugh ML, Andreson RM. Contraception and beyond: the health benefits of services provided at family planning centers, NY. Guttmacher Institute. 2013. www.gutmacher.org/pubs/helth-benefits.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Foster DG, Rostovtseva DP, Brindis CD, et al. Cost savings from the provision of specific methods of contraception in a publicly funded program. Am J Pub Health. 2009;99:446-451.

- Curtis M, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Rice CF, Killick SR, Dieben T, et al. A comparison of the inhibition of ovulation achieved by desogestrel 75 µg and levonorgestrel 30 µg daily. Human Reprod. 1999;14:982-985.

- Milsom I, Korver T. Ovulation incidence with oral contraceptives: a literature review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2008;34:237-246.

- OrthoMicronor [package insert]. OrthoMcNeil: Raritan, New Jersey. June 2008.

- Brown JB, Fotherby K, Loraine JA. The effect of norethisterone and its acetate on ovarian and pituitary function during the menstrual cycle. J Endocrinol. 1962;25:331-341.

- Romer T, Bitzer J, Egarter C, et al. Oral progestins in hormonal contraception: importance and future perspectives of a new progestin only-pill containing 4 mg drospirenone. Geburtsch Frauenheilk. 2021;81:1021-1030.

- Slynd [package insert]. Exeltis: Florham Park, New Jersey. May 2019.

- Regidor PA, Colli E, Schindlre AE. Drospirenone as estrogen-free pill and hemostasis: coagulatory study results comparing a novel 4 mg formulation in a 24+4 cycle with desogestrel 75 µg per day. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32:749-751.

- Palacios S, Colli E, Regidor PA. Efficacy and cardiovascular safety of the new estrogen-free contraceptive pill containing 4 mg drospirenone alone in a 24/4 regime. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20:218.

- Hadji P, Colli E, Regidor PA. Bone health in estrogen-free contraception. Osteoporosis Int. 2019;30:2391-2400.

- Mitchell VE, Welling LM. Not all progestins are created equally: considering unique progestins individually in psychobehavioral research. Adapt Human Behav Physiol. 2020;6:381-412.

- Palacios S, Colli E, Regidor PA. Multicenter, phase III trials on the contraceptive efficacy, tolerability and safety of a new drospirenone-only pill. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:1549-1557.

- Archer DF, Ahrendt HJ, Drouin D. Drospirenone-only oral contraceptive: results from a multicenter noncomparative trial of efficacy, safety and tolerability. Contraception. 2015;92:439-444.

- Anderson PO, Sauberan JB. Modeling drug passage into human milk. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;100:42-52. doi: 10.1002/cpt.377.

- Belsey EM. Vaginal bleeding patterns among women using one natural and eight hormonal methods of contraception. Contraception. 1988;38:181-206.

- Broome M, Fotherby K. Clinical experience with the progestin-only pill. Contraception. 1990;42:489-495.

- Apter D, Colli E, Gemzell-Danielsson K, et al. Multicenter, open-label trial to assess the safety and tolerability of drospirenone 4.0 mg over 6 cycles in female adolescents with a 7-cycle extension phase. Contraception. 2020;101:412.

- Birth control benefits. Healthcare.gov website. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/birth-control-benefits/. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Access to contraception. Committee Opinion No. 615. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:250-256.

- Health care and reproductive rights. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/issue/health-care. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- How to find out if your health plan covers birth control at no cost to you. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/072014-insuranceflowchart_vupdated.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Toolkit: Getting the coverage you deserve. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/final_nwlclogo_preventive servicestoolkit_9-25-13.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Kavanaugh ML, Andreson RM. Contraception and beyond: the health benefits of services provided at family planning centers, NY. Guttmacher Institute. 2013. www.gutmacher.org/pubs/helth-benefits.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Foster DG, Rostovtseva DP, Brindis CD, et al. Cost savings from the provision of specific methods of contraception in a publicly funded program. Am J Pub Health. 2009;99:446-451.

- Curtis M, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Rice CF, Killick SR, Dieben T, et al. A comparison of the inhibition of ovulation achieved by desogestrel 75 µg and levonorgestrel 30 µg daily. Human Reprod. 1999;14:982-985.

- Milsom I, Korver T. Ovulation incidence with oral contraceptives: a literature review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2008;34:237-246.

- OrthoMicronor [package insert]. OrthoMcNeil: Raritan, New Jersey. June 2008.

- Brown JB, Fotherby K, Loraine JA. The effect of norethisterone and its acetate on ovarian and pituitary function during the menstrual cycle. J Endocrinol. 1962;25:331-341.

- Romer T, Bitzer J, Egarter C, et al. Oral progestins in hormonal contraception: importance and future perspectives of a new progestin only-pill containing 4 mg drospirenone. Geburtsch Frauenheilk. 2021;81:1021-1030.

- Slynd [package insert]. Exeltis: Florham Park, New Jersey. May 2019.

- Regidor PA, Colli E, Schindlre AE. Drospirenone as estrogen-free pill and hemostasis: coagulatory study results comparing a novel 4 mg formulation in a 24+4 cycle with desogestrel 75 µg per day. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32:749-751.

- Palacios S, Colli E, Regidor PA. Efficacy and cardiovascular safety of the new estrogen-free contraceptive pill containing 4 mg drospirenone alone in a 24/4 regime. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20:218.

- Hadji P, Colli E, Regidor PA. Bone health in estrogen-free contraception. Osteoporosis Int. 2019;30:2391-2400.

- Mitchell VE, Welling LM. Not all progestins are created equally: considering unique progestins individually in psychobehavioral research. Adapt Human Behav Physiol. 2020;6:381-412.

- Palacios S, Colli E, Regidor PA. Multicenter, phase III trials on the contraceptive efficacy, tolerability and safety of a new drospirenone-only pill. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:1549-1557.

- Archer DF, Ahrendt HJ, Drouin D. Drospirenone-only oral contraceptive: results from a multicenter noncomparative trial of efficacy, safety and tolerability. Contraception. 2015;92:439-444.

- Anderson PO, Sauberan JB. Modeling drug passage into human milk. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;100:42-52. doi: 10.1002/cpt.377.

- Belsey EM. Vaginal bleeding patterns among women using one natural and eight hormonal methods of contraception. Contraception. 1988;38:181-206.

- Broome M, Fotherby K. Clinical experience with the progestin-only pill. Contraception. 1990;42:489-495.

- Apter D, Colli E, Gemzell-Danielsson K, et al. Multicenter, open-label trial to assess the safety and tolerability of drospirenone 4.0 mg over 6 cycles in female adolescents with a 7-cycle extension phase. Contraception. 2020;101:412.

- Birth control benefits. Healthcare.gov website. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/birth-control-benefits/. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Access to contraception. Committee Opinion No. 615. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:250-256.

- Health care and reproductive rights. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/issue/health-care. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- How to find out if your health plan covers birth control at no cost to you. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/072014-insuranceflowchart_vupdated.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Toolkit: Getting the coverage you deserve. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/final_nwlclogo_preventive servicestoolkit_9-25-13.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

More than a month after launch, iPLEDGE glitches persist

which mandates the program to prevent fetal exposure to the teratogenic effects of isotretinoin, and by the American Academy of Dermatology Association, whose members have repeatedly asked the FDA for meetings to discuss solutions. The AADA is the legislative and advocacy arm of AAD.

When the new program launched Dec. 13, 2021, the website crashed repeatedly, with physicians and patients complaining they got locked out or bounced off the platform when they tried to follow instructions to enter information. Hold times to talk to a live person stretched to hours.

The latest improvement attempt, announced Jan. 14 by the FDA, is a tool created by the Isotretinoin Products Manufacturers Group, the manufacturers responsible for the FDA-mandated REMS program. It is meant to allow prescribers and designees to send log-in links directly to patients’ email accounts through the iPLEDGE REMS portal, bypassing the troublesome call center.

And it’s not the answer, dermatologists said.

“The new tool does not solve issues such as prescribers or pharmacies not being able to access the site, unacceptably long call center wait times, inefficiencies caused by frequent attestation requirements for those who cannot become pregnant, patients becoming ‘locked out’ because they missed a window period through no fault of their own, among others,” said John Barbieri, MD, MBA, director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and instructor in dermatology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

The day after the FDA update about the new tool, Klint Peebles, MD, a dermatologist at Kaiser Permanente in Washington, D.C., tweeted: “Lip service and empty words.” He noted that the situation has been “disastrous from the start” as the new platform launched.

Under the iPLEDGE program in place for the acne drug, physicians, patients, and pharmacies prescribing, using, or dispensing the drug must all be registered, with requirements that include the use of two forms of an effective contraceptive and regular pregnancy testing for patients who can become pregnant.

The aim of the new gender-neutral approach to the risk mitigation program is to make the experience more inclusive for transgender patients. The previous three risk categories (females of reproductive potential, females not of reproductive potential, and males) are now reduced to just two (those capable of getting pregnant and those not capable of getting pregnant).

The problem is the execution of the new platform. The transition from the old website to the new was done quickly. By most accounts, the Dec. 13 rollout was chaotic, a failure, and disastrous, triggering numerous expressions of frustration on Twitter and other social media, with some calling for the program to be halted until the bugs could be worked out.

“While the new gender-neutral categories are a welcome improvement to the system, the new categorization approach was not the underlying reason for the new platform and its failed rollout, which was instead due to a change in vendor,” Dr. Barbieri told this news organization.

AADA: More recent efforts to improve the system

“We have a letter to the FDA asking for a stakeholders meeting to include us, the IPMG, and pharmacists because there are ongoing problems, though there have been some improvement in terms of certain elements,” Ilona Frieden, MD, chair of the AADA’s iPLEDGE Workgroup and professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview shortly after the FDA posted the update on the new tool. “That said, there are many patients who have not gotten isotretinoin during the 1 month since the roll-out of the new platform.”

What still needs to be fixed? “We have ongoing concerns about the lack of transparency of the IPMG, about call center wait times, actual number of prescriptions on the hands of patients compared to the previous month, and those patients who can get pregnant who – despite complying with all of the REMS requirements – are being locked out because of the lack of timely attestation to their negative pregnancy status due to the website, not the patients themselves,” Dr. Frieden told this news organization.

“We are continuing to advocate to have decreased attestation requirements for individuals who cannot become pregnant – because this will improve the efficiency of the system for those patients for whom the REMS program goals are truly intended – those who can become pregnant, since the primary aim of the REMS program is to minimize fetal exposure.”

An AADA spokesperson said that the IPMG has invited the AADA to a joint stakeholders meeting on Jan. 26, along with representatives from the FDA and pharmacy industry.

Spotty progress

“The iPLEDGE situation is as frustrating as ever,” said Neil S. Goldberg, MD, a dermatologist in Westchester County, New York, after the FDA’s Jan. 14 update was released. “It’s like they never tested the new website before deploying it.”

Among the issues he has experienced in his practice, he said, is an instance in which iPLEDGE swapped the first names of a mother and daughter, so it was impossible to fill the prescription. “It happened twice in the same day,” Dr. Goldberg said. The patient had to call iPLEDGE to fix this, but the call center wasn’t taking calls.

In today’s technology environment, he said, it’s hard to believe that “we have to put up with this.”

Some have seen success. ‘’The tool is working fine on our end,” said Mitesh Patel, PharmD, pharmacy manager at Sunshine Pharmacy in White Plains, N.Y. However, he added that some doctors and patients are still having issues. He encourages dermatologists still having issues with the system to reach out to independent pharmacies that have processed iPLEDGE prescriptions and ‘’lean on them to assist.”

This news organization contacted CVS and Walgreens about how the system is working at their locations, but has not yet received a response.

Dr. Goldberg, Dr. Frieden, Dr. Barbieri, and Dr. Peebles have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This story was updated on 1/24/22.

which mandates the program to prevent fetal exposure to the teratogenic effects of isotretinoin, and by the American Academy of Dermatology Association, whose members have repeatedly asked the FDA for meetings to discuss solutions. The AADA is the legislative and advocacy arm of AAD.

When the new program launched Dec. 13, 2021, the website crashed repeatedly, with physicians and patients complaining they got locked out or bounced off the platform when they tried to follow instructions to enter information. Hold times to talk to a live person stretched to hours.

The latest improvement attempt, announced Jan. 14 by the FDA, is a tool created by the Isotretinoin Products Manufacturers Group, the manufacturers responsible for the FDA-mandated REMS program. It is meant to allow prescribers and designees to send log-in links directly to patients’ email accounts through the iPLEDGE REMS portal, bypassing the troublesome call center.

And it’s not the answer, dermatologists said.

“The new tool does not solve issues such as prescribers or pharmacies not being able to access the site, unacceptably long call center wait times, inefficiencies caused by frequent attestation requirements for those who cannot become pregnant, patients becoming ‘locked out’ because they missed a window period through no fault of their own, among others,” said John Barbieri, MD, MBA, director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and instructor in dermatology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

The day after the FDA update about the new tool, Klint Peebles, MD, a dermatologist at Kaiser Permanente in Washington, D.C., tweeted: “Lip service and empty words.” He noted that the situation has been “disastrous from the start” as the new platform launched.

Under the iPLEDGE program in place for the acne drug, physicians, patients, and pharmacies prescribing, using, or dispensing the drug must all be registered, with requirements that include the use of two forms of an effective contraceptive and regular pregnancy testing for patients who can become pregnant.

The aim of the new gender-neutral approach to the risk mitigation program is to make the experience more inclusive for transgender patients. The previous three risk categories (females of reproductive potential, females not of reproductive potential, and males) are now reduced to just two (those capable of getting pregnant and those not capable of getting pregnant).

The problem is the execution of the new platform. The transition from the old website to the new was done quickly. By most accounts, the Dec. 13 rollout was chaotic, a failure, and disastrous, triggering numerous expressions of frustration on Twitter and other social media, with some calling for the program to be halted until the bugs could be worked out.

“While the new gender-neutral categories are a welcome improvement to the system, the new categorization approach was not the underlying reason for the new platform and its failed rollout, which was instead due to a change in vendor,” Dr. Barbieri told this news organization.

AADA: More recent efforts to improve the system

“We have a letter to the FDA asking for a stakeholders meeting to include us, the IPMG, and pharmacists because there are ongoing problems, though there have been some improvement in terms of certain elements,” Ilona Frieden, MD, chair of the AADA’s iPLEDGE Workgroup and professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview shortly after the FDA posted the update on the new tool. “That said, there are many patients who have not gotten isotretinoin during the 1 month since the roll-out of the new platform.”

What still needs to be fixed? “We have ongoing concerns about the lack of transparency of the IPMG, about call center wait times, actual number of prescriptions on the hands of patients compared to the previous month, and those patients who can get pregnant who – despite complying with all of the REMS requirements – are being locked out because of the lack of timely attestation to their negative pregnancy status due to the website, not the patients themselves,” Dr. Frieden told this news organization.

“We are continuing to advocate to have decreased attestation requirements for individuals who cannot become pregnant – because this will improve the efficiency of the system for those patients for whom the REMS program goals are truly intended – those who can become pregnant, since the primary aim of the REMS program is to minimize fetal exposure.”

An AADA spokesperson said that the IPMG has invited the AADA to a joint stakeholders meeting on Jan. 26, along with representatives from the FDA and pharmacy industry.

Spotty progress

“The iPLEDGE situation is as frustrating as ever,” said Neil S. Goldberg, MD, a dermatologist in Westchester County, New York, after the FDA’s Jan. 14 update was released. “It’s like they never tested the new website before deploying it.”

Among the issues he has experienced in his practice, he said, is an instance in which iPLEDGE swapped the first names of a mother and daughter, so it was impossible to fill the prescription. “It happened twice in the same day,” Dr. Goldberg said. The patient had to call iPLEDGE to fix this, but the call center wasn’t taking calls.

In today’s technology environment, he said, it’s hard to believe that “we have to put up with this.”

Some have seen success. ‘’The tool is working fine on our end,” said Mitesh Patel, PharmD, pharmacy manager at Sunshine Pharmacy in White Plains, N.Y. However, he added that some doctors and patients are still having issues. He encourages dermatologists still having issues with the system to reach out to independent pharmacies that have processed iPLEDGE prescriptions and ‘’lean on them to assist.”

This news organization contacted CVS and Walgreens about how the system is working at their locations, but has not yet received a response.

Dr. Goldberg, Dr. Frieden, Dr. Barbieri, and Dr. Peebles have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This story was updated on 1/24/22.

which mandates the program to prevent fetal exposure to the teratogenic effects of isotretinoin, and by the American Academy of Dermatology Association, whose members have repeatedly asked the FDA for meetings to discuss solutions. The AADA is the legislative and advocacy arm of AAD.

When the new program launched Dec. 13, 2021, the website crashed repeatedly, with physicians and patients complaining they got locked out or bounced off the platform when they tried to follow instructions to enter information. Hold times to talk to a live person stretched to hours.

The latest improvement attempt, announced Jan. 14 by the FDA, is a tool created by the Isotretinoin Products Manufacturers Group, the manufacturers responsible for the FDA-mandated REMS program. It is meant to allow prescribers and designees to send log-in links directly to patients’ email accounts through the iPLEDGE REMS portal, bypassing the troublesome call center.

And it’s not the answer, dermatologists said.

“The new tool does not solve issues such as prescribers or pharmacies not being able to access the site, unacceptably long call center wait times, inefficiencies caused by frequent attestation requirements for those who cannot become pregnant, patients becoming ‘locked out’ because they missed a window period through no fault of their own, among others,” said John Barbieri, MD, MBA, director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and instructor in dermatology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

The day after the FDA update about the new tool, Klint Peebles, MD, a dermatologist at Kaiser Permanente in Washington, D.C., tweeted: “Lip service and empty words.” He noted that the situation has been “disastrous from the start” as the new platform launched.

Under the iPLEDGE program in place for the acne drug, physicians, patients, and pharmacies prescribing, using, or dispensing the drug must all be registered, with requirements that include the use of two forms of an effective contraceptive and regular pregnancy testing for patients who can become pregnant.

The aim of the new gender-neutral approach to the risk mitigation program is to make the experience more inclusive for transgender patients. The previous three risk categories (females of reproductive potential, females not of reproductive potential, and males) are now reduced to just two (those capable of getting pregnant and those not capable of getting pregnant).

The problem is the execution of the new platform. The transition from the old website to the new was done quickly. By most accounts, the Dec. 13 rollout was chaotic, a failure, and disastrous, triggering numerous expressions of frustration on Twitter and other social media, with some calling for the program to be halted until the bugs could be worked out.

“While the new gender-neutral categories are a welcome improvement to the system, the new categorization approach was not the underlying reason for the new platform and its failed rollout, which was instead due to a change in vendor,” Dr. Barbieri told this news organization.

AADA: More recent efforts to improve the system

“We have a letter to the FDA asking for a stakeholders meeting to include us, the IPMG, and pharmacists because there are ongoing problems, though there have been some improvement in terms of certain elements,” Ilona Frieden, MD, chair of the AADA’s iPLEDGE Workgroup and professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview shortly after the FDA posted the update on the new tool. “That said, there are many patients who have not gotten isotretinoin during the 1 month since the roll-out of the new platform.”

What still needs to be fixed? “We have ongoing concerns about the lack of transparency of the IPMG, about call center wait times, actual number of prescriptions on the hands of patients compared to the previous month, and those patients who can get pregnant who – despite complying with all of the REMS requirements – are being locked out because of the lack of timely attestation to their negative pregnancy status due to the website, not the patients themselves,” Dr. Frieden told this news organization.

“We are continuing to advocate to have decreased attestation requirements for individuals who cannot become pregnant – because this will improve the efficiency of the system for those patients for whom the REMS program goals are truly intended – those who can become pregnant, since the primary aim of the REMS program is to minimize fetal exposure.”

An AADA spokesperson said that the IPMG has invited the AADA to a joint stakeholders meeting on Jan. 26, along with representatives from the FDA and pharmacy industry.

Spotty progress

“The iPLEDGE situation is as frustrating as ever,” said Neil S. Goldberg, MD, a dermatologist in Westchester County, New York, after the FDA’s Jan. 14 update was released. “It’s like they never tested the new website before deploying it.”

Among the issues he has experienced in his practice, he said, is an instance in which iPLEDGE swapped the first names of a mother and daughter, so it was impossible to fill the prescription. “It happened twice in the same day,” Dr. Goldberg said. The patient had to call iPLEDGE to fix this, but the call center wasn’t taking calls.

In today’s technology environment, he said, it’s hard to believe that “we have to put up with this.”

Some have seen success. ‘’The tool is working fine on our end,” said Mitesh Patel, PharmD, pharmacy manager at Sunshine Pharmacy in White Plains, N.Y. However, he added that some doctors and patients are still having issues. He encourages dermatologists still having issues with the system to reach out to independent pharmacies that have processed iPLEDGE prescriptions and ‘’lean on them to assist.”

This news organization contacted CVS and Walgreens about how the system is working at their locations, but has not yet received a response.

Dr. Goldberg, Dr. Frieden, Dr. Barbieri, and Dr. Peebles have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This story was updated on 1/24/22.

FDA updates status of iPLEDGE access problems

The, one month after a modified program was launched, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Jan. 14.

The IPMG has “created a new tool within the system to help resolve account access for some user groups without using the call center. This tool is intended to allow prescribers and designees to send login links directly to their patients’ desired email address through the Manage Patients page of the iPLEDGE REMS portal,” the FDA statement said.

“Prescribers can also send login links to their designees still having difficulty accessing their iPLEDGE account,” and users should check their emails for messages from iPLEDGE, including spam folders, the FDA advises. The iPLEDGE strategy is designed to prevent fetal exposure to isotretinoin, which is highly teratogenic.

Days after the new, gender-neutral approach to the isotretinoin risk mitigation program was launched on Dec. 13, the FDA convened an emergency meeting with representatives from the American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) to discuss the problematic rollout of the program, which was described as disastrous, chaotic, and a failure, with dermatologists on Twitter and elsewhere expressing anger and frustration over not being able to access the program or reach the call center.

A statement by the FDA on Dec. 23 followed, urging manufacturers to develop solutions for the website and to work with the AADA and pharmacy organizations to find solutions that would minimize treatment interruptions during the transition.

The modified REMS, launched on Dec. 13, is designed to make it more inclusive for transgender patients prescribed isotretinoin. Instead of three risk categories (females of reproductive potential, females not of reproductive potential, and males), patients who are prescribed isotretinoin for acne are assigned to one of two risk categories: those who can get pregnant and those who cannot get pregnant.

In the Jan. 14 statement, the FDA notes that the agency is continuing to work with the IPMG regarding the problems clinicians, pharmacists, and patients have had with accessing iPLEDGE over the last month.

“Although there has been progress, there is a significant amount of work still to be done,” the FDA acknowledged. “While we consider potential steps within the scope of FDA’s authorities, we will continue to meet with the IPMG for updates on the status of the problems with the iPLEDGE REMS and their progress towards having the system work as intended for all users.”

The, one month after a modified program was launched, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Jan. 14.

The IPMG has “created a new tool within the system to help resolve account access for some user groups without using the call center. This tool is intended to allow prescribers and designees to send login links directly to their patients’ desired email address through the Manage Patients page of the iPLEDGE REMS portal,” the FDA statement said.

“Prescribers can also send login links to their designees still having difficulty accessing their iPLEDGE account,” and users should check their emails for messages from iPLEDGE, including spam folders, the FDA advises. The iPLEDGE strategy is designed to prevent fetal exposure to isotretinoin, which is highly teratogenic.

Days after the new, gender-neutral approach to the isotretinoin risk mitigation program was launched on Dec. 13, the FDA convened an emergency meeting with representatives from the American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) to discuss the problematic rollout of the program, which was described as disastrous, chaotic, and a failure, with dermatologists on Twitter and elsewhere expressing anger and frustration over not being able to access the program or reach the call center.

A statement by the FDA on Dec. 23 followed, urging manufacturers to develop solutions for the website and to work with the AADA and pharmacy organizations to find solutions that would minimize treatment interruptions during the transition.

The modified REMS, launched on Dec. 13, is designed to make it more inclusive for transgender patients prescribed isotretinoin. Instead of three risk categories (females of reproductive potential, females not of reproductive potential, and males), patients who are prescribed isotretinoin for acne are assigned to one of two risk categories: those who can get pregnant and those who cannot get pregnant.

In the Jan. 14 statement, the FDA notes that the agency is continuing to work with the IPMG regarding the problems clinicians, pharmacists, and patients have had with accessing iPLEDGE over the last month.

“Although there has been progress, there is a significant amount of work still to be done,” the FDA acknowledged. “While we consider potential steps within the scope of FDA’s authorities, we will continue to meet with the IPMG for updates on the status of the problems with the iPLEDGE REMS and their progress towards having the system work as intended for all users.”

The, one month after a modified program was launched, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Jan. 14.

The IPMG has “created a new tool within the system to help resolve account access for some user groups without using the call center. This tool is intended to allow prescribers and designees to send login links directly to their patients’ desired email address through the Manage Patients page of the iPLEDGE REMS portal,” the FDA statement said.

“Prescribers can also send login links to their designees still having difficulty accessing their iPLEDGE account,” and users should check their emails for messages from iPLEDGE, including spam folders, the FDA advises. The iPLEDGE strategy is designed to prevent fetal exposure to isotretinoin, which is highly teratogenic.

Days after the new, gender-neutral approach to the isotretinoin risk mitigation program was launched on Dec. 13, the FDA convened an emergency meeting with representatives from the American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) to discuss the problematic rollout of the program, which was described as disastrous, chaotic, and a failure, with dermatologists on Twitter and elsewhere expressing anger and frustration over not being able to access the program or reach the call center.

A statement by the FDA on Dec. 23 followed, urging manufacturers to develop solutions for the website and to work with the AADA and pharmacy organizations to find solutions that would minimize treatment interruptions during the transition.

The modified REMS, launched on Dec. 13, is designed to make it more inclusive for transgender patients prescribed isotretinoin. Instead of three risk categories (females of reproductive potential, females not of reproductive potential, and males), patients who are prescribed isotretinoin for acne are assigned to one of two risk categories: those who can get pregnant and those who cannot get pregnant.

In the Jan. 14 statement, the FDA notes that the agency is continuing to work with the IPMG regarding the problems clinicians, pharmacists, and patients have had with accessing iPLEDGE over the last month.

“Although there has been progress, there is a significant amount of work still to be done,” the FDA acknowledged. “While we consider potential steps within the scope of FDA’s authorities, we will continue to meet with the IPMG for updates on the status of the problems with the iPLEDGE REMS and their progress towards having the system work as intended for all users.”

Medicaid expansion curbs disparities, increases immigrant access, in postpartum care

Expanding Medicaid coverage has proved beneficial to postpartum women and may even help reduce disparities, say two new papers.

In the first study, expansion of Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act was associated with higher rates of postpartum coverage and outpatient visits, according to results published in JAMA Health Forum.

Racial and ethnic disparities were also reduced in postpartum coverage, although these disparities remained between Black and White women for outpatient visits.

In the second study, published in JAMA Network Open, researchers found that when postpartum care is covered as part of Emergency Medicaid, women who have been denied access because of their citizenship status are able to use these services, which includes contraception.

Federal law currently prohibits undocumented and documented immigrants who have been in the United States for less than 5 years from receiving full-benefit Medicaid. Coverage is limited to Emergency Medicaid, which offers benefits only for life-threatening conditions, including hospital admission for childbirth. Coverage is not available for prenatal or postpartum care, including contraception.

For the first article, lead author Maria W. Steenland, SD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and colleagues point out that compared with other high-income countries, maternal mortality is higher in the United States and largely driven by persistent racial disparities. Compared with non-Hispanic White women, the rates of maternal death are more than twice as high among American Indian and Alaska Native women, and more than threefold greater in non-Hispanic Black women.

“To be clear, visits increased by around the same amount for Black and White individuals after Medicaid expansion, it is just that visits started off lower among Black women, and remained lower by a similar degree,” said Dr. Steenland.

One explanation is that Black women experience racial discrimination during pregnancy-related health care including childbirth hospitalizations and this may make them more reticent to seek postpartum care, she explained. “In addition, the ability to seek health care is determined by insurance as well as other social factors such as paid leave from work, childcare, and transportation, and these other factors may have remained a larger barrier for Black women after expansion.”

In this cohort study, they looked at the association of Medicaid expansion in Arkansas with continuous postpartum coverage, postpartum health care use, and change in racial disparities in the study outcomes. Using the Arkansas All-Payer Claims Database for persons with a childbirth between 2013 and 2015, the authors identified 60,990 childbirths. Of this group, 67% were White, 22% Black, and 7% Hispanic, and 72.3% were covered by Medicaid. The remaining 27.7% were paid for by a commercial payer.