User login

Abortion debate may affect Rx decisions for pregnant women

Obstetrician Beverly Gray, MD, is already seeing the effects of the Roe v. Wade abortion debate in her North Carolina practice.

The state allows abortion but requires that women get counseling with a qualified health professional 72 hours before the procedure. “Aside from that, we still have patients asking for more efficacious contraceptive methods just in case,” said Dr. Gray, residency director and division director for women’s community and population health and associate professor for obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Patients and staff in her clinic have also been approaching her about tubal ligation. “They’re asking about additional birth control methods because they’re concerned about what’s going to happen” with the challenge to the historic Roe v. Wade decision in the Supreme Court and subsequent actions in the states to restrict or ban abortion, she said.

This has implications not just for abortion but for medications known to affect pregnancy. “What I’m really worried about is physicians will be withholding medicine because they’re concerned about teratogenic effects,” said Dr. Gray.

With more states issuing restrictions on abortion, doctors are worried that patients needing certain drugs to maintain their lupus flares, cancer, or other diseases may decide not to take them in the event they accidentally become pregnant. If the drug is known to affect the fetus, the fear is a patient who lives in a state with abortion restrictions will no longer have the option to terminate a pregnancy.

Instead, a scenario may arise in which the patient – and their physician – may opt not to treat at all with an otherwise lifesaving medication, experts told this news organization.

The U.S. landscape on abortion restrictions

A leaked draft of a U.S. Supreme Court opinion on Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban has sent the medical community into a tailspin. The case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, challenges the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that affirms the constitutional right to abortion. It’s anticipated the high court will decide on the case in June.

Although the upcoming decision is subject to change, the draft indicated the high court would uphold the Mississippi ban. This would essentially overturn the 1973 ruling. An earlier Supreme Court decision allowing a Texas law banning abortion at 6 weeks suggests the court may already be heading in this direction. At the state level, legislatures have been moving on divergent paths – some taking steps to preserve abortion rights, others initiating restrictions.

More than 100 abortion restrictions in 19 states took effect in 2021, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which tracks such metrics. In 2022, “two key themes are anti-abortion policymakers’ continued pursuit of various types of abortion bans and restrictions on medication abortion,” the institute reported.

Forty-six states and the District of Columbia have introduced 2,025 restrictions or proactive measures on sexual and reproductive health and rights so far this year. The latest tally from Guttmacher, updated in late May, revealed that 11 states so far have enacted 42 abortion restrictions. A total of 6 states (Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Wyoming) have issued nine bans on abortion.

Comparatively, 11 states have enacted 19 protective abortion measures.

Twenty-two states have introduced 117 restrictions on medication abortions, which account for 54% of U.S. abortions. This includes seven measures that would ban medication abortion outright, according to Guttmacher. Kentucky and South Dakota collectively have enacted 14 restrictions on medication abortion, as well as provisions that ban mailing of abortion pills.

Chilling effect on prescribing

Some physicians anticipate that drugs such as the “morning-after” pill (levonorgestrel) will become less available as restrictions go into effect, since these are medications designed to prevent pregnancy.*

However, the ongoing effort to put a lid on abortion measures has prompted concerns about a trickle-down effect on other medications that are otherwise life-changing or lifesaving to patients but pose a risk to the fetus.

Several drugs are well documented to affect fetal growth and development of the fetus, ranging from mild, transitory effects to severe, permanent birth defects, said Ronald G. Grifka, MD, chief medical officer of University of Michigan Health-West and clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor. “As new medications are developed, we will need heightened attention to make sure they are safe for the fetus,” he added.

Certain teratogenic medications are associated with a high risk of abortion even though this isn’t their primary use, noted Christina Chambers, PhD, MPH, co-director of the Center for Better Beginnings and associate director with the Altman Clinical & Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego.

“I don’t think anyone would intentionally take these drugs to induce spontaneous abortion. But if the drugs pose a risk for it, I can see how the laws might be stretched” to include them, said Dr. Chambers.

Methotrexate, a medication for autoimmune disorders, has a high risk of spontaneous abortion. So do acne medications such as isotretinoin.

Patients are usually told they’re not supposed to get pregnant on these drugs because there’s a high risk of pregnancy loss and risk of malformations and potential learning problems in the fetus. But many pregnancies aren’t planned, said Dr. Chambers. “Patients may forget about the side effects or think their birth control will protect them. And the next time they refill the medication, they may not hear about the warnings again.”

With a restrictive abortion law or ban in effect, a woman might think: “I won’t take this drug because if there’s any potential that I might get pregnant, I won’t have the option to abort an at-risk pregnancy.” Women and their doctors, for that matter, don’t want to put themselves in this position, said Dr. Chambers.

Rheumatologist Megan Clowse, MD, who prescribes several medications that potentially cause major birth defects and pregnancy loss, worries about the ramifications of these accumulating bans.

“Methotrexate has been a leading drug for us for decades for rheumatoid arthritis. Mycophenolate is a vital drug for lupus,” said Dr. Clowse, associate professor of medicine at Duke University’s division of rheumatology and immunology.

Both methotrexate and mycophenolate pose about a 40% risk of pregnancy loss and significantly increase the risk for birth defects. “I’m definitely concerned that there might be doctors or women who elect not to use those medications in women of reproductive age because of the potential risk for pregnancy and absence of abortion rights,” said Dr. Clowse.

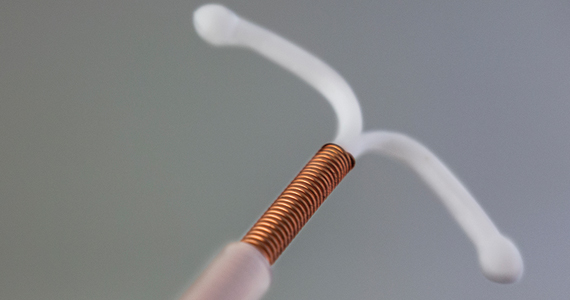

These situations might force women to use contraceptives they don’t want to use, such as hormonal implants or intrauterine devices, she added. Another side effect is that women and their partners may decide to abstain from sex.

The iPLEDGE factor

Some rheumatology drugs like lenalidomide (Revlimid) require a valid negative pregnancy test in a lab every month. Similarly, the iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy seeks to reduce the teratogenicity of isotretinoin by requiring two types of birth control and regular pregnancy tests by users.

For isotretinoin specifically, abortion restrictions “could lead to increased adherence to pregnancy prevention measures which are already stringent in iPLEDGE. But on the other hand, it could lead to reduced willingness of physicians to prescribe or patients to take the medication,” said Dr. Chambers.

With programs like iPLEDGE in effect, the rate of pregnancies and abortions that occur in dermatology are relatively low, said Jenny Murase, MD, associate clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco.

Nevertheless, as a physician who regularly prescribes medications like isotretinoin in women of childbearing age, “it’s terrifying to me that a woman wouldn’t have the option to terminate the pregnancy if a teratogenic effect from the medication caused a severe birth defect,” said Dr. Murase.

Dermatologists use other teratogenic medications such as thalidomide, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate for chronic dermatologic disease like psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

The situation is especially tricky for dermatologists since most patients – about 80% – never discuss their pregnancy with their specialist prior to pregnancy initiation. Dr. Murase recalls when a patient with chronic plaque psoriasis on methotrexate in her late 40s became pregnant and had an abortion even before Dr. Murase became aware of the pregnancy.

Because dermatologists routinely prescribe long-term medications for chronic diseases like acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis, it is important to have a conversation regarding the risks and benefits of long-term medication should a pregnancy occur in any woman of childbearing age, she said.

Fewer women in clinical trials?

Abortion restrictions could possibly discourage women of reproductive age to participate in a clinical trial for a new medication, said Dr. Chambers.

A female patient with a chronic disease who’s randomized to receive a new medication may be required to use certain types of birth control because of unknown potential adverse effects the drug may have on the fetus. But in some cases, accidental pregnancies happen.

The participant in the trial may say, “I don’t know enough about the safety of this drug in pregnancy, and I’ve already taken it. I want to terminate the pregnancy,” said Dr. Chambers. Thinking ahead, a woman may decide not to do the trial to avoid the risk of getting pregnant and not having the option to terminate the pregnancy.

This could apply to new drugs such as antiviral treatments, or medications for severe chronic disease that typically have no clinical trial data in pregnancy prior to initial release into the market.

Women may start taking the drug without thinking about getting pregnant, then realize there are no safety data and become concerned about its effects on a future pregnancy.

The question is: Will abortion restrictions have a chilling effect on these new drugs as well? Patients and their doctors may decide not to try it until more data are available. “I can see where abortion restrictions would change the risk or benefit calculation in thinking about what you do or don’t prescribe or take during reproductive age,” said Dr. Chambers.

The upside of restrictions?

If there’s a positive side to these developments with abortion bans, it may encourage women taking new medications or joining clinical trials to think even more carefully about adherence to effective contraception, said Dr. Chambers.

Some methods are more effective than others, she emphasized. “When you have an unplanned pregnancy, it could mean that the method you used wasn’t optimal or you weren’t using it as recommended.” A goal moving forward is to encourage more thoughtful use of highly effective contraceptives, thus reducing the number of unplanned pregnancies, she added.

If patients are taking methotrexate, “the time to think about pregnancy is before getting pregnant so you can switch to a drug that’s compatible with pregnancy,” she said.

This whole thought process regarding pregnancy planning could work toward useful health goals, said Dr. Chambers. “Nobody thinks termination is the preferred method, but planning ahead should involve a discussion of what works best for the patient.”

Patients do have other choices, said Dr. Grifka. “Fortunately, there are many commonly prescribed medications which cross the placenta and have no ill effects on the fetus.”

Talking to patients about choices

Dr. Clowse, who spends a lot of time training rheumatologists, encourages them to have conversations with patients about pregnancy planning. It’s a lot to manage, getting the right drug to a female patient with chronic illness, especially in this current climate of abortion upheaval, she noted.

Her approach is to have an open and honest conversation with patients about their concerns and fears, what the realities are, and what the potential future options are for certain rheumatology drugs in the United States.

Some women who see what’s happening across the country may become so risk averse that they may choose to die rather than take a lifesaving drug that poses certain risks under new restrictions.

“I think that’s tragic,” said Dr. Clowse.

To help their patients, Dr. Gray believes physicians across specialties should better educate themselves about physiology in pregnancy and how to counsel patients on the impact of not taking medications in pregnancy.

In her view, it’s almost coercive to say to a patient, “You really need to have effective contraception if I’m going to give you this lifesaving or quality-of-life-improving medication.”

When confronting such scenarios, Dr. Gray doesn’t think physicians need to change how they counsel patients about contraception. “I don’t think we should be putting pressure on patients to consider other permanent methods just because there’s a lack of abortion options.”

Patients will eventually make those decisions for themselves, she said. “They’re going to want a more efficacious method because they’re worried about not having access to abortion if they get pregnant.”

Dr. Gray reports being a site principal investigator for a phase 3 trial for VeraCept IUD, funded by Sebela Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Clowse reports receiving research funding and doing consulting for GlaxoSmithKline.

*Correction, 6/2/2022: A previous version of this article misstated the intended use of drugs such as the “morning-after” pill (levonorgestrel). They are taken to prevent unintended pregnancy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Obstetrician Beverly Gray, MD, is already seeing the effects of the Roe v. Wade abortion debate in her North Carolina practice.

The state allows abortion but requires that women get counseling with a qualified health professional 72 hours before the procedure. “Aside from that, we still have patients asking for more efficacious contraceptive methods just in case,” said Dr. Gray, residency director and division director for women’s community and population health and associate professor for obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Patients and staff in her clinic have also been approaching her about tubal ligation. “They’re asking about additional birth control methods because they’re concerned about what’s going to happen” with the challenge to the historic Roe v. Wade decision in the Supreme Court and subsequent actions in the states to restrict or ban abortion, she said.

This has implications not just for abortion but for medications known to affect pregnancy. “What I’m really worried about is physicians will be withholding medicine because they’re concerned about teratogenic effects,” said Dr. Gray.

With more states issuing restrictions on abortion, doctors are worried that patients needing certain drugs to maintain their lupus flares, cancer, or other diseases may decide not to take them in the event they accidentally become pregnant. If the drug is known to affect the fetus, the fear is a patient who lives in a state with abortion restrictions will no longer have the option to terminate a pregnancy.

Instead, a scenario may arise in which the patient – and their physician – may opt not to treat at all with an otherwise lifesaving medication, experts told this news organization.

The U.S. landscape on abortion restrictions

A leaked draft of a U.S. Supreme Court opinion on Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban has sent the medical community into a tailspin. The case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, challenges the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that affirms the constitutional right to abortion. It’s anticipated the high court will decide on the case in June.

Although the upcoming decision is subject to change, the draft indicated the high court would uphold the Mississippi ban. This would essentially overturn the 1973 ruling. An earlier Supreme Court decision allowing a Texas law banning abortion at 6 weeks suggests the court may already be heading in this direction. At the state level, legislatures have been moving on divergent paths – some taking steps to preserve abortion rights, others initiating restrictions.

More than 100 abortion restrictions in 19 states took effect in 2021, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which tracks such metrics. In 2022, “two key themes are anti-abortion policymakers’ continued pursuit of various types of abortion bans and restrictions on medication abortion,” the institute reported.

Forty-six states and the District of Columbia have introduced 2,025 restrictions or proactive measures on sexual and reproductive health and rights so far this year. The latest tally from Guttmacher, updated in late May, revealed that 11 states so far have enacted 42 abortion restrictions. A total of 6 states (Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Wyoming) have issued nine bans on abortion.

Comparatively, 11 states have enacted 19 protective abortion measures.

Twenty-two states have introduced 117 restrictions on medication abortions, which account for 54% of U.S. abortions. This includes seven measures that would ban medication abortion outright, according to Guttmacher. Kentucky and South Dakota collectively have enacted 14 restrictions on medication abortion, as well as provisions that ban mailing of abortion pills.

Chilling effect on prescribing

Some physicians anticipate that drugs such as the “morning-after” pill (levonorgestrel) will become less available as restrictions go into effect, since these are medications designed to prevent pregnancy.*

However, the ongoing effort to put a lid on abortion measures has prompted concerns about a trickle-down effect on other medications that are otherwise life-changing or lifesaving to patients but pose a risk to the fetus.

Several drugs are well documented to affect fetal growth and development of the fetus, ranging from mild, transitory effects to severe, permanent birth defects, said Ronald G. Grifka, MD, chief medical officer of University of Michigan Health-West and clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor. “As new medications are developed, we will need heightened attention to make sure they are safe for the fetus,” he added.

Certain teratogenic medications are associated with a high risk of abortion even though this isn’t their primary use, noted Christina Chambers, PhD, MPH, co-director of the Center for Better Beginnings and associate director with the Altman Clinical & Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego.

“I don’t think anyone would intentionally take these drugs to induce spontaneous abortion. But if the drugs pose a risk for it, I can see how the laws might be stretched” to include them, said Dr. Chambers.

Methotrexate, a medication for autoimmune disorders, has a high risk of spontaneous abortion. So do acne medications such as isotretinoin.

Patients are usually told they’re not supposed to get pregnant on these drugs because there’s a high risk of pregnancy loss and risk of malformations and potential learning problems in the fetus. But many pregnancies aren’t planned, said Dr. Chambers. “Patients may forget about the side effects or think their birth control will protect them. And the next time they refill the medication, they may not hear about the warnings again.”

With a restrictive abortion law or ban in effect, a woman might think: “I won’t take this drug because if there’s any potential that I might get pregnant, I won’t have the option to abort an at-risk pregnancy.” Women and their doctors, for that matter, don’t want to put themselves in this position, said Dr. Chambers.

Rheumatologist Megan Clowse, MD, who prescribes several medications that potentially cause major birth defects and pregnancy loss, worries about the ramifications of these accumulating bans.

“Methotrexate has been a leading drug for us for decades for rheumatoid arthritis. Mycophenolate is a vital drug for lupus,” said Dr. Clowse, associate professor of medicine at Duke University’s division of rheumatology and immunology.

Both methotrexate and mycophenolate pose about a 40% risk of pregnancy loss and significantly increase the risk for birth defects. “I’m definitely concerned that there might be doctors or women who elect not to use those medications in women of reproductive age because of the potential risk for pregnancy and absence of abortion rights,” said Dr. Clowse.

These situations might force women to use contraceptives they don’t want to use, such as hormonal implants or intrauterine devices, she added. Another side effect is that women and their partners may decide to abstain from sex.

The iPLEDGE factor

Some rheumatology drugs like lenalidomide (Revlimid) require a valid negative pregnancy test in a lab every month. Similarly, the iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy seeks to reduce the teratogenicity of isotretinoin by requiring two types of birth control and regular pregnancy tests by users.

For isotretinoin specifically, abortion restrictions “could lead to increased adherence to pregnancy prevention measures which are already stringent in iPLEDGE. But on the other hand, it could lead to reduced willingness of physicians to prescribe or patients to take the medication,” said Dr. Chambers.

With programs like iPLEDGE in effect, the rate of pregnancies and abortions that occur in dermatology are relatively low, said Jenny Murase, MD, associate clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco.

Nevertheless, as a physician who regularly prescribes medications like isotretinoin in women of childbearing age, “it’s terrifying to me that a woman wouldn’t have the option to terminate the pregnancy if a teratogenic effect from the medication caused a severe birth defect,” said Dr. Murase.

Dermatologists use other teratogenic medications such as thalidomide, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate for chronic dermatologic disease like psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

The situation is especially tricky for dermatologists since most patients – about 80% – never discuss their pregnancy with their specialist prior to pregnancy initiation. Dr. Murase recalls when a patient with chronic plaque psoriasis on methotrexate in her late 40s became pregnant and had an abortion even before Dr. Murase became aware of the pregnancy.

Because dermatologists routinely prescribe long-term medications for chronic diseases like acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis, it is important to have a conversation regarding the risks and benefits of long-term medication should a pregnancy occur in any woman of childbearing age, she said.

Fewer women in clinical trials?

Abortion restrictions could possibly discourage women of reproductive age to participate in a clinical trial for a new medication, said Dr. Chambers.

A female patient with a chronic disease who’s randomized to receive a new medication may be required to use certain types of birth control because of unknown potential adverse effects the drug may have on the fetus. But in some cases, accidental pregnancies happen.

The participant in the trial may say, “I don’t know enough about the safety of this drug in pregnancy, and I’ve already taken it. I want to terminate the pregnancy,” said Dr. Chambers. Thinking ahead, a woman may decide not to do the trial to avoid the risk of getting pregnant and not having the option to terminate the pregnancy.

This could apply to new drugs such as antiviral treatments, or medications for severe chronic disease that typically have no clinical trial data in pregnancy prior to initial release into the market.

Women may start taking the drug without thinking about getting pregnant, then realize there are no safety data and become concerned about its effects on a future pregnancy.

The question is: Will abortion restrictions have a chilling effect on these new drugs as well? Patients and their doctors may decide not to try it until more data are available. “I can see where abortion restrictions would change the risk or benefit calculation in thinking about what you do or don’t prescribe or take during reproductive age,” said Dr. Chambers.

The upside of restrictions?

If there’s a positive side to these developments with abortion bans, it may encourage women taking new medications or joining clinical trials to think even more carefully about adherence to effective contraception, said Dr. Chambers.

Some methods are more effective than others, she emphasized. “When you have an unplanned pregnancy, it could mean that the method you used wasn’t optimal or you weren’t using it as recommended.” A goal moving forward is to encourage more thoughtful use of highly effective contraceptives, thus reducing the number of unplanned pregnancies, she added.

If patients are taking methotrexate, “the time to think about pregnancy is before getting pregnant so you can switch to a drug that’s compatible with pregnancy,” she said.

This whole thought process regarding pregnancy planning could work toward useful health goals, said Dr. Chambers. “Nobody thinks termination is the preferred method, but planning ahead should involve a discussion of what works best for the patient.”

Patients do have other choices, said Dr. Grifka. “Fortunately, there are many commonly prescribed medications which cross the placenta and have no ill effects on the fetus.”

Talking to patients about choices

Dr. Clowse, who spends a lot of time training rheumatologists, encourages them to have conversations with patients about pregnancy planning. It’s a lot to manage, getting the right drug to a female patient with chronic illness, especially in this current climate of abortion upheaval, she noted.

Her approach is to have an open and honest conversation with patients about their concerns and fears, what the realities are, and what the potential future options are for certain rheumatology drugs in the United States.

Some women who see what’s happening across the country may become so risk averse that they may choose to die rather than take a lifesaving drug that poses certain risks under new restrictions.

“I think that’s tragic,” said Dr. Clowse.

To help their patients, Dr. Gray believes physicians across specialties should better educate themselves about physiology in pregnancy and how to counsel patients on the impact of not taking medications in pregnancy.

In her view, it’s almost coercive to say to a patient, “You really need to have effective contraception if I’m going to give you this lifesaving or quality-of-life-improving medication.”

When confronting such scenarios, Dr. Gray doesn’t think physicians need to change how they counsel patients about contraception. “I don’t think we should be putting pressure on patients to consider other permanent methods just because there’s a lack of abortion options.”

Patients will eventually make those decisions for themselves, she said. “They’re going to want a more efficacious method because they’re worried about not having access to abortion if they get pregnant.”

Dr. Gray reports being a site principal investigator for a phase 3 trial for VeraCept IUD, funded by Sebela Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Clowse reports receiving research funding and doing consulting for GlaxoSmithKline.

*Correction, 6/2/2022: A previous version of this article misstated the intended use of drugs such as the “morning-after” pill (levonorgestrel). They are taken to prevent unintended pregnancy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Obstetrician Beverly Gray, MD, is already seeing the effects of the Roe v. Wade abortion debate in her North Carolina practice.

The state allows abortion but requires that women get counseling with a qualified health professional 72 hours before the procedure. “Aside from that, we still have patients asking for more efficacious contraceptive methods just in case,” said Dr. Gray, residency director and division director for women’s community and population health and associate professor for obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Patients and staff in her clinic have also been approaching her about tubal ligation. “They’re asking about additional birth control methods because they’re concerned about what’s going to happen” with the challenge to the historic Roe v. Wade decision in the Supreme Court and subsequent actions in the states to restrict or ban abortion, she said.

This has implications not just for abortion but for medications known to affect pregnancy. “What I’m really worried about is physicians will be withholding medicine because they’re concerned about teratogenic effects,” said Dr. Gray.

With more states issuing restrictions on abortion, doctors are worried that patients needing certain drugs to maintain their lupus flares, cancer, or other diseases may decide not to take them in the event they accidentally become pregnant. If the drug is known to affect the fetus, the fear is a patient who lives in a state with abortion restrictions will no longer have the option to terminate a pregnancy.

Instead, a scenario may arise in which the patient – and their physician – may opt not to treat at all with an otherwise lifesaving medication, experts told this news organization.

The U.S. landscape on abortion restrictions

A leaked draft of a U.S. Supreme Court opinion on Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban has sent the medical community into a tailspin. The case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, challenges the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that affirms the constitutional right to abortion. It’s anticipated the high court will decide on the case in June.

Although the upcoming decision is subject to change, the draft indicated the high court would uphold the Mississippi ban. This would essentially overturn the 1973 ruling. An earlier Supreme Court decision allowing a Texas law banning abortion at 6 weeks suggests the court may already be heading in this direction. At the state level, legislatures have been moving on divergent paths – some taking steps to preserve abortion rights, others initiating restrictions.

More than 100 abortion restrictions in 19 states took effect in 2021, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which tracks such metrics. In 2022, “two key themes are anti-abortion policymakers’ continued pursuit of various types of abortion bans and restrictions on medication abortion,” the institute reported.

Forty-six states and the District of Columbia have introduced 2,025 restrictions or proactive measures on sexual and reproductive health and rights so far this year. The latest tally from Guttmacher, updated in late May, revealed that 11 states so far have enacted 42 abortion restrictions. A total of 6 states (Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Wyoming) have issued nine bans on abortion.

Comparatively, 11 states have enacted 19 protective abortion measures.

Twenty-two states have introduced 117 restrictions on medication abortions, which account for 54% of U.S. abortions. This includes seven measures that would ban medication abortion outright, according to Guttmacher. Kentucky and South Dakota collectively have enacted 14 restrictions on medication abortion, as well as provisions that ban mailing of abortion pills.

Chilling effect on prescribing

Some physicians anticipate that drugs such as the “morning-after” pill (levonorgestrel) will become less available as restrictions go into effect, since these are medications designed to prevent pregnancy.*

However, the ongoing effort to put a lid on abortion measures has prompted concerns about a trickle-down effect on other medications that are otherwise life-changing or lifesaving to patients but pose a risk to the fetus.

Several drugs are well documented to affect fetal growth and development of the fetus, ranging from mild, transitory effects to severe, permanent birth defects, said Ronald G. Grifka, MD, chief medical officer of University of Michigan Health-West and clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor. “As new medications are developed, we will need heightened attention to make sure they are safe for the fetus,” he added.

Certain teratogenic medications are associated with a high risk of abortion even though this isn’t their primary use, noted Christina Chambers, PhD, MPH, co-director of the Center for Better Beginnings and associate director with the Altman Clinical & Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego.

“I don’t think anyone would intentionally take these drugs to induce spontaneous abortion. But if the drugs pose a risk for it, I can see how the laws might be stretched” to include them, said Dr. Chambers.

Methotrexate, a medication for autoimmune disorders, has a high risk of spontaneous abortion. So do acne medications such as isotretinoin.

Patients are usually told they’re not supposed to get pregnant on these drugs because there’s a high risk of pregnancy loss and risk of malformations and potential learning problems in the fetus. But many pregnancies aren’t planned, said Dr. Chambers. “Patients may forget about the side effects or think their birth control will protect them. And the next time they refill the medication, they may not hear about the warnings again.”

With a restrictive abortion law or ban in effect, a woman might think: “I won’t take this drug because if there’s any potential that I might get pregnant, I won’t have the option to abort an at-risk pregnancy.” Women and their doctors, for that matter, don’t want to put themselves in this position, said Dr. Chambers.

Rheumatologist Megan Clowse, MD, who prescribes several medications that potentially cause major birth defects and pregnancy loss, worries about the ramifications of these accumulating bans.

“Methotrexate has been a leading drug for us for decades for rheumatoid arthritis. Mycophenolate is a vital drug for lupus,” said Dr. Clowse, associate professor of medicine at Duke University’s division of rheumatology and immunology.

Both methotrexate and mycophenolate pose about a 40% risk of pregnancy loss and significantly increase the risk for birth defects. “I’m definitely concerned that there might be doctors or women who elect not to use those medications in women of reproductive age because of the potential risk for pregnancy and absence of abortion rights,” said Dr. Clowse.

These situations might force women to use contraceptives they don’t want to use, such as hormonal implants or intrauterine devices, she added. Another side effect is that women and their partners may decide to abstain from sex.

The iPLEDGE factor

Some rheumatology drugs like lenalidomide (Revlimid) require a valid negative pregnancy test in a lab every month. Similarly, the iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy seeks to reduce the teratogenicity of isotretinoin by requiring two types of birth control and regular pregnancy tests by users.

For isotretinoin specifically, abortion restrictions “could lead to increased adherence to pregnancy prevention measures which are already stringent in iPLEDGE. But on the other hand, it could lead to reduced willingness of physicians to prescribe or patients to take the medication,” said Dr. Chambers.

With programs like iPLEDGE in effect, the rate of pregnancies and abortions that occur in dermatology are relatively low, said Jenny Murase, MD, associate clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco.

Nevertheless, as a physician who regularly prescribes medications like isotretinoin in women of childbearing age, “it’s terrifying to me that a woman wouldn’t have the option to terminate the pregnancy if a teratogenic effect from the medication caused a severe birth defect,” said Dr. Murase.

Dermatologists use other teratogenic medications such as thalidomide, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate for chronic dermatologic disease like psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

The situation is especially tricky for dermatologists since most patients – about 80% – never discuss their pregnancy with their specialist prior to pregnancy initiation. Dr. Murase recalls when a patient with chronic plaque psoriasis on methotrexate in her late 40s became pregnant and had an abortion even before Dr. Murase became aware of the pregnancy.

Because dermatologists routinely prescribe long-term medications for chronic diseases like acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis, it is important to have a conversation regarding the risks and benefits of long-term medication should a pregnancy occur in any woman of childbearing age, she said.

Fewer women in clinical trials?

Abortion restrictions could possibly discourage women of reproductive age to participate in a clinical trial for a new medication, said Dr. Chambers.

A female patient with a chronic disease who’s randomized to receive a new medication may be required to use certain types of birth control because of unknown potential adverse effects the drug may have on the fetus. But in some cases, accidental pregnancies happen.

The participant in the trial may say, “I don’t know enough about the safety of this drug in pregnancy, and I’ve already taken it. I want to terminate the pregnancy,” said Dr. Chambers. Thinking ahead, a woman may decide not to do the trial to avoid the risk of getting pregnant and not having the option to terminate the pregnancy.

This could apply to new drugs such as antiviral treatments, or medications for severe chronic disease that typically have no clinical trial data in pregnancy prior to initial release into the market.

Women may start taking the drug without thinking about getting pregnant, then realize there are no safety data and become concerned about its effects on a future pregnancy.

The question is: Will abortion restrictions have a chilling effect on these new drugs as well? Patients and their doctors may decide not to try it until more data are available. “I can see where abortion restrictions would change the risk or benefit calculation in thinking about what you do or don’t prescribe or take during reproductive age,” said Dr. Chambers.

The upside of restrictions?

If there’s a positive side to these developments with abortion bans, it may encourage women taking new medications or joining clinical trials to think even more carefully about adherence to effective contraception, said Dr. Chambers.

Some methods are more effective than others, she emphasized. “When you have an unplanned pregnancy, it could mean that the method you used wasn’t optimal or you weren’t using it as recommended.” A goal moving forward is to encourage more thoughtful use of highly effective contraceptives, thus reducing the number of unplanned pregnancies, she added.

If patients are taking methotrexate, “the time to think about pregnancy is before getting pregnant so you can switch to a drug that’s compatible with pregnancy,” she said.

This whole thought process regarding pregnancy planning could work toward useful health goals, said Dr. Chambers. “Nobody thinks termination is the preferred method, but planning ahead should involve a discussion of what works best for the patient.”

Patients do have other choices, said Dr. Grifka. “Fortunately, there are many commonly prescribed medications which cross the placenta and have no ill effects on the fetus.”

Talking to patients about choices

Dr. Clowse, who spends a lot of time training rheumatologists, encourages them to have conversations with patients about pregnancy planning. It’s a lot to manage, getting the right drug to a female patient with chronic illness, especially in this current climate of abortion upheaval, she noted.

Her approach is to have an open and honest conversation with patients about their concerns and fears, what the realities are, and what the potential future options are for certain rheumatology drugs in the United States.

Some women who see what’s happening across the country may become so risk averse that they may choose to die rather than take a lifesaving drug that poses certain risks under new restrictions.

“I think that’s tragic,” said Dr. Clowse.

To help their patients, Dr. Gray believes physicians across specialties should better educate themselves about physiology in pregnancy and how to counsel patients on the impact of not taking medications in pregnancy.

In her view, it’s almost coercive to say to a patient, “You really need to have effective contraception if I’m going to give you this lifesaving or quality-of-life-improving medication.”

When confronting such scenarios, Dr. Gray doesn’t think physicians need to change how they counsel patients about contraception. “I don’t think we should be putting pressure on patients to consider other permanent methods just because there’s a lack of abortion options.”

Patients will eventually make those decisions for themselves, she said. “They’re going to want a more efficacious method because they’re worried about not having access to abortion if they get pregnant.”

Dr. Gray reports being a site principal investigator for a phase 3 trial for VeraCept IUD, funded by Sebela Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Clowse reports receiving research funding and doing consulting for GlaxoSmithKline.

*Correction, 6/2/2022: A previous version of this article misstated the intended use of drugs such as the “morning-after” pill (levonorgestrel). They are taken to prevent unintended pregnancy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Contraceptive use boosted by enhanced counseling

Contraceptive counseling and interventions beyond usual care significantly increased the use of contraceptives with no accompanying increase in sexually transmitted infections or reduction in condom use, based on data from a new meta-analysis.

“Although effective contraception is available in the United States and guidelines support contraceptive care in clinical practice, providing contraceptive care has not been widely adopted across medical specialties as a preventive health service that is routinely offered to eligible patients, such as mammography screening,” lead author Heidi D. Nelson, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, Calif., said in an interview.

“Access to and coverage of contraceptive care are frequently challenged by legislation and insurance policies, and influential preventive services guideline groups, such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, have not issued recommendations for contraceptive care,” Dr. Nelson said.

“The evidence to determine the benefits and harms of contraceptive care as a preventive health service has not been examined using methods similar to those used for other preventive services and clinicians may lack guidance on the effectiveness of contraception services relevant to their practices,” she added.

In a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine, Dr. Nelson and colleagues reviewed data from 38 randomized, controlled trials with a total of 25,472 participants. The trials evaluated the effectiveness of various types of contraceptive counseling and provision interventions beyond usual care on subsequent contraception use, compared with nonintervention comparison groups.

Overall, higher contraceptive use was associated with counseling interventions (risk ratio, 1.39), advance provision of emergency contraception (RR, 2.12), counseling or provision of emergency contraception postpartum (RR, 1.15), or counseling or provision of emergency contraception at the time of abortion (RR, 1.19), compared with usual care or active controls across studies.

Most of the included trials were not powered to distinguish intended versus unintended pregnancy rates, but pregnancy rates were lower among intervention groups, compared with controls.

Five of the selected studies assessed the potential negative effect of contraceptive counseling with regard to increased rates of STIs and two studies examined decreased condom use. However, neither STI rates nor condom use were significantly different between study participants who received various contraceptive counseling interventions (such as advanced provision of emergency contraception, clinician training, and individual counseling) and those who did not (RR, 1.05 and RR, 1.03, respectively).

“These results indicate that additional efforts to assist patients with their contraception decisions improve its subsequent use,” and are not surprising, said Dr. Nelson.

“All clinicians providing health care to women, not only clinicians providing reproductive health care specifically, need to recognize contraceptive care as an essential preventive health service and assume responsibility for delivering contraceptive counseling and provision services appropriate for each patient,” Dr. Nelson emphasized. “Clinicians lacking contraceptive care clinical skills may require additional training or refer their patients if needed to assure high quality care.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the variability of interventions across studies and the lack of data on unintended pregnancy outcomes, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that various contraceptive counseling and interventions beyond usual care increased contraceptive use with no reduction in condom use or increase in STIs, they wrote.

“Additional research should further evaluate approaches to contraceptive counseling and provision to determine best practices,” Dr. Nelson said in an interview. “This is particularly important for medically high-risk populations, those with limited access to care, and additional populations and settings that have not yet been studied, including transgender and nonbinary patients. Research is needed to refine measures of pregnancy intention and planning; and create uniform definitions of contraceptive care, interventions, measures of use, and outcomes.”.

Make easy, effective contraception accessible to all

The news of a potential overturn of the 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision that protects a pregnant person’s ability to choose abortion “shines a bright light on the importance of promoting the use of contraception,” and on the findings of the current review, Christine Laine, MD, editor-in-chief of Annals of Internal Medicine, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “Easy, effective, accessible, and affordable contraception becomes increasingly essential as ending unintended pregnancy becomes increasingly difficult, unsafe, inaccessible, and legally risky.”

The available evidence showed the benefits of enhanced counseling, providing emergency contraception in advance, and providing contraceptive interventions immediately after delivery or pregnancy termination, she wrote. The findings have strong clinical implications, especially with regard to the Healthy People 2030 goal of reducing unintended pregnancy from the current 43% to 36.5%.

Dr. Laine called on internal medicine physicians in particular to recognize the negative health consequences of unintended pregnancy, and to consider contraceptive counseling part of their responsibility to their patients.

“To expand the numbers of people who receive this essential preventive service, we must systematically incorporate contraceptive counseling into health care with the same fervor that we devote to other preventive services. The health of our patients – and their families – depends on it,” she concluded.

The study was supported by the Resources Legacy Fund. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Laine had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Contraceptive counseling and interventions beyond usual care significantly increased the use of contraceptives with no accompanying increase in sexually transmitted infections or reduction in condom use, based on data from a new meta-analysis.

“Although effective contraception is available in the United States and guidelines support contraceptive care in clinical practice, providing contraceptive care has not been widely adopted across medical specialties as a preventive health service that is routinely offered to eligible patients, such as mammography screening,” lead author Heidi D. Nelson, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, Calif., said in an interview.

“Access to and coverage of contraceptive care are frequently challenged by legislation and insurance policies, and influential preventive services guideline groups, such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, have not issued recommendations for contraceptive care,” Dr. Nelson said.

“The evidence to determine the benefits and harms of contraceptive care as a preventive health service has not been examined using methods similar to those used for other preventive services and clinicians may lack guidance on the effectiveness of contraception services relevant to their practices,” she added.

In a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine, Dr. Nelson and colleagues reviewed data from 38 randomized, controlled trials with a total of 25,472 participants. The trials evaluated the effectiveness of various types of contraceptive counseling and provision interventions beyond usual care on subsequent contraception use, compared with nonintervention comparison groups.

Overall, higher contraceptive use was associated with counseling interventions (risk ratio, 1.39), advance provision of emergency contraception (RR, 2.12), counseling or provision of emergency contraception postpartum (RR, 1.15), or counseling or provision of emergency contraception at the time of abortion (RR, 1.19), compared with usual care or active controls across studies.

Most of the included trials were not powered to distinguish intended versus unintended pregnancy rates, but pregnancy rates were lower among intervention groups, compared with controls.

Five of the selected studies assessed the potential negative effect of contraceptive counseling with regard to increased rates of STIs and two studies examined decreased condom use. However, neither STI rates nor condom use were significantly different between study participants who received various contraceptive counseling interventions (such as advanced provision of emergency contraception, clinician training, and individual counseling) and those who did not (RR, 1.05 and RR, 1.03, respectively).

“These results indicate that additional efforts to assist patients with their contraception decisions improve its subsequent use,” and are not surprising, said Dr. Nelson.

“All clinicians providing health care to women, not only clinicians providing reproductive health care specifically, need to recognize contraceptive care as an essential preventive health service and assume responsibility for delivering contraceptive counseling and provision services appropriate for each patient,” Dr. Nelson emphasized. “Clinicians lacking contraceptive care clinical skills may require additional training or refer their patients if needed to assure high quality care.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the variability of interventions across studies and the lack of data on unintended pregnancy outcomes, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that various contraceptive counseling and interventions beyond usual care increased contraceptive use with no reduction in condom use or increase in STIs, they wrote.

“Additional research should further evaluate approaches to contraceptive counseling and provision to determine best practices,” Dr. Nelson said in an interview. “This is particularly important for medically high-risk populations, those with limited access to care, and additional populations and settings that have not yet been studied, including transgender and nonbinary patients. Research is needed to refine measures of pregnancy intention and planning; and create uniform definitions of contraceptive care, interventions, measures of use, and outcomes.”.

Make easy, effective contraception accessible to all

The news of a potential overturn of the 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision that protects a pregnant person’s ability to choose abortion “shines a bright light on the importance of promoting the use of contraception,” and on the findings of the current review, Christine Laine, MD, editor-in-chief of Annals of Internal Medicine, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “Easy, effective, accessible, and affordable contraception becomes increasingly essential as ending unintended pregnancy becomes increasingly difficult, unsafe, inaccessible, and legally risky.”

The available evidence showed the benefits of enhanced counseling, providing emergency contraception in advance, and providing contraceptive interventions immediately after delivery or pregnancy termination, she wrote. The findings have strong clinical implications, especially with regard to the Healthy People 2030 goal of reducing unintended pregnancy from the current 43% to 36.5%.

Dr. Laine called on internal medicine physicians in particular to recognize the negative health consequences of unintended pregnancy, and to consider contraceptive counseling part of their responsibility to their patients.

“To expand the numbers of people who receive this essential preventive service, we must systematically incorporate contraceptive counseling into health care with the same fervor that we devote to other preventive services. The health of our patients – and their families – depends on it,” she concluded.

The study was supported by the Resources Legacy Fund. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Laine had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Contraceptive counseling and interventions beyond usual care significantly increased the use of contraceptives with no accompanying increase in sexually transmitted infections or reduction in condom use, based on data from a new meta-analysis.

“Although effective contraception is available in the United States and guidelines support contraceptive care in clinical practice, providing contraceptive care has not been widely adopted across medical specialties as a preventive health service that is routinely offered to eligible patients, such as mammography screening,” lead author Heidi D. Nelson, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, Calif., said in an interview.

“Access to and coverage of contraceptive care are frequently challenged by legislation and insurance policies, and influential preventive services guideline groups, such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, have not issued recommendations for contraceptive care,” Dr. Nelson said.

“The evidence to determine the benefits and harms of contraceptive care as a preventive health service has not been examined using methods similar to those used for other preventive services and clinicians may lack guidance on the effectiveness of contraception services relevant to their practices,” she added.

In a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine, Dr. Nelson and colleagues reviewed data from 38 randomized, controlled trials with a total of 25,472 participants. The trials evaluated the effectiveness of various types of contraceptive counseling and provision interventions beyond usual care on subsequent contraception use, compared with nonintervention comparison groups.

Overall, higher contraceptive use was associated with counseling interventions (risk ratio, 1.39), advance provision of emergency contraception (RR, 2.12), counseling or provision of emergency contraception postpartum (RR, 1.15), or counseling or provision of emergency contraception at the time of abortion (RR, 1.19), compared with usual care or active controls across studies.

Most of the included trials were not powered to distinguish intended versus unintended pregnancy rates, but pregnancy rates were lower among intervention groups, compared with controls.

Five of the selected studies assessed the potential negative effect of contraceptive counseling with regard to increased rates of STIs and two studies examined decreased condom use. However, neither STI rates nor condom use were significantly different between study participants who received various contraceptive counseling interventions (such as advanced provision of emergency contraception, clinician training, and individual counseling) and those who did not (RR, 1.05 and RR, 1.03, respectively).

“These results indicate that additional efforts to assist patients with their contraception decisions improve its subsequent use,” and are not surprising, said Dr. Nelson.

“All clinicians providing health care to women, not only clinicians providing reproductive health care specifically, need to recognize contraceptive care as an essential preventive health service and assume responsibility for delivering contraceptive counseling and provision services appropriate for each patient,” Dr. Nelson emphasized. “Clinicians lacking contraceptive care clinical skills may require additional training or refer their patients if needed to assure high quality care.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the variability of interventions across studies and the lack of data on unintended pregnancy outcomes, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that various contraceptive counseling and interventions beyond usual care increased contraceptive use with no reduction in condom use or increase in STIs, they wrote.

“Additional research should further evaluate approaches to contraceptive counseling and provision to determine best practices,” Dr. Nelson said in an interview. “This is particularly important for medically high-risk populations, those with limited access to care, and additional populations and settings that have not yet been studied, including transgender and nonbinary patients. Research is needed to refine measures of pregnancy intention and planning; and create uniform definitions of contraceptive care, interventions, measures of use, and outcomes.”.

Make easy, effective contraception accessible to all

The news of a potential overturn of the 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision that protects a pregnant person’s ability to choose abortion “shines a bright light on the importance of promoting the use of contraception,” and on the findings of the current review, Christine Laine, MD, editor-in-chief of Annals of Internal Medicine, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “Easy, effective, accessible, and affordable contraception becomes increasingly essential as ending unintended pregnancy becomes increasingly difficult, unsafe, inaccessible, and legally risky.”

The available evidence showed the benefits of enhanced counseling, providing emergency contraception in advance, and providing contraceptive interventions immediately after delivery or pregnancy termination, she wrote. The findings have strong clinical implications, especially with regard to the Healthy People 2030 goal of reducing unintended pregnancy from the current 43% to 36.5%.

Dr. Laine called on internal medicine physicians in particular to recognize the negative health consequences of unintended pregnancy, and to consider contraceptive counseling part of their responsibility to their patients.

“To expand the numbers of people who receive this essential preventive service, we must systematically incorporate contraceptive counseling into health care with the same fervor that we devote to other preventive services. The health of our patients – and their families – depends on it,” she concluded.

The study was supported by the Resources Legacy Fund. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Laine had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

IUD cuts heavy menses in nulliparous patients with obesity

New phase 3 data support the use of the levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine device in nulliparous women with obesity and heavy menstrual bleeding. The findings, presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, showed a 97% reduction in blood loss 6 months after placement of the device, which is sold as the contraceptive Liletta by Medicines360 and AbbVie.

Experts say the results fill a gap in research because prior clinical trials of the IUD and a competitor, Mirena (Bayer), excluded significantly obese as well as nulliparous populations.

William Schlaff, MD, professor and chairman of the department of obstetrics & gynecology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, said the absence of confirmatory evidence in these women has meant that, although use of the IUD has been “pretty widespread,” clinicians have been uncertain about the efficacy of the approach.

“Now we have objective data from a well-designed study that supports a practice that many of us have felt is probably a good one,” Dr. Schlaff, who was not involved in the new study, said in an interview.

Lead researcher Mitchell Creinin, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, and colleagues at several centers across the country provided treatment with Liletta to 105 individuals with proven heavy menstrual bleeding. The patients’ median blood loss during two menses prior to placement of the device was 165 mL (range, 73-520 mL).

Participant demographics were: 65% White, 24% Black, 10% Hispanic, 4% Asian, and 7% who identified with other racial groups. Mean body mass index was 30.9 kg/m2, and 45% of individuals met the criteria for obesity (BMI > 30), including 13% who had a BMI of at least 40. Nearly 30% of participants in the study had never given birth and none had known medical, anatomic, infectious, or neoplastic causes of bleeding.

According to Dr. Creinin, 86 women were assessed 3 months after device placement, and their median blood loss at the time was 9.5 mL (interquartile range, 2.5-22.9 mL), representing a median 93% decrease from baseline. Median blood loss 6 months after placement of the IUD was 3.8 mL (IQR, 0-10.1 mL), a 97% reduction from baseline.

Regardless of parity or BMI, blood loss at 6 months was 97%-97.5% lower than baseline, Dr. Creinin reported.

Among the 23% of participants who did not complete the study, 4% experienced expulsions of the device, which Dr. Creinin said is a rate twice as high as that seen in women using hormone-releasing IUDs for contraception. However, he said it “is consistent with other studies among patients with quantitatively proven heavy menstrual bleeding.”

Another 6% of women who did not complete the study removed the device owing to bleeding and cramping complaints, 9% were lost to follow-up or withdrew consent, and 5% discontinued treatment for unspecified reasons, Dr. Creinin said.

“Etiologies for heavy menstrual bleeding may be different in the individuals we studied, so our findings provide assurance that these populations with heavy menstrual bleeding are equally well treated” with the IUD, Dr. Creinin said.

Dr. Creinin reported study funding from Medicines360. Dr. Schlaff reported no financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New phase 3 data support the use of the levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine device in nulliparous women with obesity and heavy menstrual bleeding. The findings, presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, showed a 97% reduction in blood loss 6 months after placement of the device, which is sold as the contraceptive Liletta by Medicines360 and AbbVie.

Experts say the results fill a gap in research because prior clinical trials of the IUD and a competitor, Mirena (Bayer), excluded significantly obese as well as nulliparous populations.

William Schlaff, MD, professor and chairman of the department of obstetrics & gynecology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, said the absence of confirmatory evidence in these women has meant that, although use of the IUD has been “pretty widespread,” clinicians have been uncertain about the efficacy of the approach.

“Now we have objective data from a well-designed study that supports a practice that many of us have felt is probably a good one,” Dr. Schlaff, who was not involved in the new study, said in an interview.

Lead researcher Mitchell Creinin, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, and colleagues at several centers across the country provided treatment with Liletta to 105 individuals with proven heavy menstrual bleeding. The patients’ median blood loss during two menses prior to placement of the device was 165 mL (range, 73-520 mL).

Participant demographics were: 65% White, 24% Black, 10% Hispanic, 4% Asian, and 7% who identified with other racial groups. Mean body mass index was 30.9 kg/m2, and 45% of individuals met the criteria for obesity (BMI > 30), including 13% who had a BMI of at least 40. Nearly 30% of participants in the study had never given birth and none had known medical, anatomic, infectious, or neoplastic causes of bleeding.

According to Dr. Creinin, 86 women were assessed 3 months after device placement, and their median blood loss at the time was 9.5 mL (interquartile range, 2.5-22.9 mL), representing a median 93% decrease from baseline. Median blood loss 6 months after placement of the IUD was 3.8 mL (IQR, 0-10.1 mL), a 97% reduction from baseline.

Regardless of parity or BMI, blood loss at 6 months was 97%-97.5% lower than baseline, Dr. Creinin reported.

Among the 23% of participants who did not complete the study, 4% experienced expulsions of the device, which Dr. Creinin said is a rate twice as high as that seen in women using hormone-releasing IUDs for contraception. However, he said it “is consistent with other studies among patients with quantitatively proven heavy menstrual bleeding.”

Another 6% of women who did not complete the study removed the device owing to bleeding and cramping complaints, 9% were lost to follow-up or withdrew consent, and 5% discontinued treatment for unspecified reasons, Dr. Creinin said.

“Etiologies for heavy menstrual bleeding may be different in the individuals we studied, so our findings provide assurance that these populations with heavy menstrual bleeding are equally well treated” with the IUD, Dr. Creinin said.

Dr. Creinin reported study funding from Medicines360. Dr. Schlaff reported no financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New phase 3 data support the use of the levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine device in nulliparous women with obesity and heavy menstrual bleeding. The findings, presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, showed a 97% reduction in blood loss 6 months after placement of the device, which is sold as the contraceptive Liletta by Medicines360 and AbbVie.

Experts say the results fill a gap in research because prior clinical trials of the IUD and a competitor, Mirena (Bayer), excluded significantly obese as well as nulliparous populations.

William Schlaff, MD, professor and chairman of the department of obstetrics & gynecology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, said the absence of confirmatory evidence in these women has meant that, although use of the IUD has been “pretty widespread,” clinicians have been uncertain about the efficacy of the approach.

“Now we have objective data from a well-designed study that supports a practice that many of us have felt is probably a good one,” Dr. Schlaff, who was not involved in the new study, said in an interview.

Lead researcher Mitchell Creinin, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, and colleagues at several centers across the country provided treatment with Liletta to 105 individuals with proven heavy menstrual bleeding. The patients’ median blood loss during two menses prior to placement of the device was 165 mL (range, 73-520 mL).

Participant demographics were: 65% White, 24% Black, 10% Hispanic, 4% Asian, and 7% who identified with other racial groups. Mean body mass index was 30.9 kg/m2, and 45% of individuals met the criteria for obesity (BMI > 30), including 13% who had a BMI of at least 40. Nearly 30% of participants in the study had never given birth and none had known medical, anatomic, infectious, or neoplastic causes of bleeding.

According to Dr. Creinin, 86 women were assessed 3 months after device placement, and their median blood loss at the time was 9.5 mL (interquartile range, 2.5-22.9 mL), representing a median 93% decrease from baseline. Median blood loss 6 months after placement of the IUD was 3.8 mL (IQR, 0-10.1 mL), a 97% reduction from baseline.

Regardless of parity or BMI, blood loss at 6 months was 97%-97.5% lower than baseline, Dr. Creinin reported.

Among the 23% of participants who did not complete the study, 4% experienced expulsions of the device, which Dr. Creinin said is a rate twice as high as that seen in women using hormone-releasing IUDs for contraception. However, he said it “is consistent with other studies among patients with quantitatively proven heavy menstrual bleeding.”

Another 6% of women who did not complete the study removed the device owing to bleeding and cramping complaints, 9% were lost to follow-up or withdrew consent, and 5% discontinued treatment for unspecified reasons, Dr. Creinin said.

“Etiologies for heavy menstrual bleeding may be different in the individuals we studied, so our findings provide assurance that these populations with heavy menstrual bleeding are equally well treated” with the IUD, Dr. Creinin said.

Dr. Creinin reported study funding from Medicines360. Dr. Schlaff reported no financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACOG 2022

Abortion politics lead to power struggles over family planning grants

BOZEMAN, Mont. – In a busy downtown coffee shop, a drawing of a ski lift with intrauterine devices for chairs draws the eyes of sleepy customers getting their morning underway with a caffeine jolt.

The flyer touts the services of Bridgercare, a nonprofit reproductive health clinic a few miles up the road. The clinic offers wellness exams, birth control, and LGBTQ+ services – and, starting in April, it oversees the state’s multimillion-dollar share of federal family planning program funding.

In March, Bridgercare beat out the state health department to become administrator of Montana’s $2.3 million Title X program, which helps pay for family planning and preventive health services. The organization applied for the grant because its leaders were concerned about a new state law that sought to restrict which local providers are funded.

What is happening in Montana is the latest example of an ongoing power struggle between nonprofits and conservative-leaning states over who receives federal family planning money. That has intensified in recent years as the Title X program has increasingly become entangled with the politics of abortion.

This year, the federal government set aside $257 million for family planning and preventive care. The providers that get that funding often serve families with low incomes, and Title X is one of the few federal programs in which people without legal permission to be in the United States can participate.

“The program permeates into communities that otherwise would be unreached by public health efforts,” said Rebecca Kreitzer, an associate professor of public policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services controlled the distribution of the state’s Title X funds for decades. Bridgercare sought the administrator role to circumvent a Republican-sponsored law passed last year that required the state to prioritize the money for local health departments and federally qualified health centers. That would have put the nonprofit – which doesn’t provide abortion procedures – and similar organizations at the bottom of the list. The law also banned clinics that perform abortions from receiving Title X funds from the state health department.

Bridgercare Executive Director Stephanie McDowell said the group applied for the grant to try to protect the program from decisions coming out of the state capitol. “Because of the politicization of Title X, we’re seeing how it’s run, swinging back and forth based on partisan leadership,” Ms. McDowell said.

A U.S. Department of Health & Human Services spokesperson, Tara Broido, didn’t answer a question about whether the agency intentionally awarded grants to nonprofits to avoid state politics. Instead, she said in a statement that applicants were evaluated in a competitive process by a panel of independent reviewers based on criteria to deliver high-quality, client-centered services.

Federal law prohibits the money from being used to perform abortions. But it can cover other services provided by groups that offer abortions – the largest and best-known by far is Planned Parenthood. In recent years, conservative politicians have tried to keep such providers from receiving Title X funding.

In some cases, contraception has entered the debate around which family planning services government should help fund. Some abortion opponents have raised concerns that long-lasting forms of birth control, such as IUDs, lead to abortions. Those claims are disputed by reproductive health experts.

In 2019, the Trump administration introduced several new rules for Title X, including disqualifying from receiving the funding family planning clinics that also offered abortion services or referrals. Many clinics across the nation left the program instead of conforming to the rules. Simultaneously, the spread of COVID-19 interrupted routine care. The number of patients served by Title X plummeted.

The Biden administration reversed most of those rules, including allowing providers with abortion services back into the Title X program. States also try to influence the funding’s reach, either through legislation or budget rules.

The current Title X funding cycle is 5 years, and the amount of money available each year could shift based on the state’s network of providers or federal budget changes. Jon Ebelt, a spokesperson for the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, didn’t answer when asked whether the state planned to reapply to administer the funding in 2027. He said the department was disappointed with the Biden administration’s “refusal” to renew the state’s funding.

“We recognize, however, that recent proabortion federal rule changes have distorted Title X and conflict with Montana law,” he said.

Conservative states have been tangling with nonprofits and the federal government over Title X funding for more than a decade. In 2011, during the Obama administration, Texas whittled down the state’s family planning spending and prioritized sending the federal money to general primary care providers over reproductive health clinics. As a result, 25% of family planning clinics in Texas closed. In 2013, a nonprofit now called Every Body Texas joined the competition to distribute the state’s Title X dollars and won.

“Filling and rebuilding those holes have taken this last decade, essentially,” said Berna Mason, director of service delivery improvement for Every Body Texas.

In 2019, the governor of Nebraska proposed a budget that would have prohibited the money from going to any organization that provided abortions or referred patients for abortions outside of an emergency. It also would have required that funding recipients be legally and financially separate from such clinics, a restriction that would have gone further than the Trump administration’s rules. Afterward, a family planning council won the right to administer Title X money.

In 2017, the nonprofit Arizona Family Health Partnership lost its status as that state’s only Title X administrator when the state health department was given 25% of the funding to deliver to providers. That came after Arizona lawmakers ordered the department to apply for the funds and distribute them first to state- or county-owned clinics, with the remaining money going to primary care facilities. The change was backed by groups that were opposed to abortion, and reproductive health care providers saw it as an attempt to weaken clinics that offer abortion services.

However, the state left nearly all the money it received untouched, and although it’s still required by law to apply for Title X funding, it hasn’t received a portion of the grant since.

Bré Thomas, CEO of Arizona Family Health Partnership, said that, even though the nonprofit is the sole administrator of the Title X funding again, the threat remains that some or all could be taken away because of politics. “We’re at the will of who’s in charge,” Ms. Thomas said.

Nonprofits say they have an advantage over state agencies in expanding services because they have more flexibility in fundraising and fewer administrative hurdles.

In April, Mississippi nonprofit Converge took over administration of Title X funds, a role the state had held for decades. The organization’s founders said they weren’t worried that conservative politicians would restrict access to services but simply believed they could do a better job. “Service quality was very low, and it was very hard to get appointments,” said cofounder Danielle Lampton.

A Mississippi State Department of Health spokesperson, Liz Sharlot, said the agency looks forward to working with Converge.