User login

COVID-19 Screening and Testing Among Patients With Neurologic Dysfunction: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist

From the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, Division of Neuroscience Intensive Care, Jackson, MS.

Abstract

Objective: To test a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) screening tool to identify patients who qualify for testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction who are unable to answer the usual screening questions, which could help to prevent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers to COVID-19.

Methods: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) was implemented at our institution for 1 week as a quality improvement project to improve the pathway for COVID-19 screening and testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Results: A total of 14 new patients were admitted into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) service during the pilot period. The NCOT-PC was utilized on 9 (64%) patients with neurologic dysfunction; 7 of these patients were found to have a likelihood of requiring testing based on the NCOT-PC and were subsequently screened for COVID-19 testing by contacting the institution’s COVID-19 testing hotline (Med-Com). All these patients were subsequently transitioned into person-under-investigation status based on the determination from Med-Com. The NSICU staff involved were able to utilize NCOT-PC without issues. The NCOT-PC was immediately adopted into the NSICU process.

Conclusion: Use of the NCOT-PC tool was found to be feasible and improved the screening methodology of patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Keywords: coronavirus; health care planning; quality improvement; patient safety; medical decision-making; neuroscience intensive care unit.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has altered various standard emergent care pathways. Current recommendations regarding COVID-19 screening for testing involve asking patients about their symptoms, including fever, cough, chest pain, and dyspnea.1 This standard screening method poses a problem when caring for patients with neurologic dysfunction. COVID-19 patients may pre-sent with conditions that affect their ability to answer questions, such as stroke, encephalitis, neuromuscular disorders, or headache, and that may preclude the use of standard screening for testing.2 Patients with acute neurologic dysfunction who cannot undergo standard screening may leave the emergency department (ED) and transition into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) or any intensive care unit (ICU) without a reliable COVID-19 screening test.

The Protected Code Stroke pathway offers protection in the emergent setting for patients with stroke when their COVID-19 status is unknown.3 A similar process has been applied at our institution for emergent management of patients with cerebrovascular disease (stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage). However, the process from the ED after designating “difficult to screen” patients as persons under investigation (PUI) is unclear. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has delineated the priorities for testing, with not all declared PUIs requiring testing.4 This poses a great challenge, because patients designated as PUIs require the same management as a COVID-19-positive patient, with negative-pressure isolation rooms as well as use of protective personal equipment (PPE), which may not be readily available. It was also recognized that, because the ED staff can be overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients, there may not be enough time to perform detailed screening of patients with neurologic dysfunction and that “reverse masking” may not be done consistently for nonintubated patients. This may place patients and health care workers at risk of unprotected exposure.

Recognizing these challenges, we created a Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) as a quality improvement project. The aim of this project was to improve and standardize the current process of identifying patients with neurologic dysfunction who require COVID-19 testing to decrease the risk of unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

Methods

Patients and Definitions

This quality improvement project was undertaken at the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU. Because this was a quality improvement project, an Institutional Review Board exemption was granted.

The NCOT-PC was utilized in consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU during a period of 1 week. “Neurologic dysfunction” encompasses any neurologic illness affecting the mental status and/or level of alertness, subsequently precluding the ability to reliably screen the patient utilizing standard COVID-19 screening. “Med-Com” at our institution is the equivalent of the national COVID-19 testing hotline, where our institution’s infectious diseases experts screen calls for testing and determine whether testing is warranted. “Unprotected exposure” means exposure to COVID-19 without adequate and appropriate PPE.

Quality Improvement Process

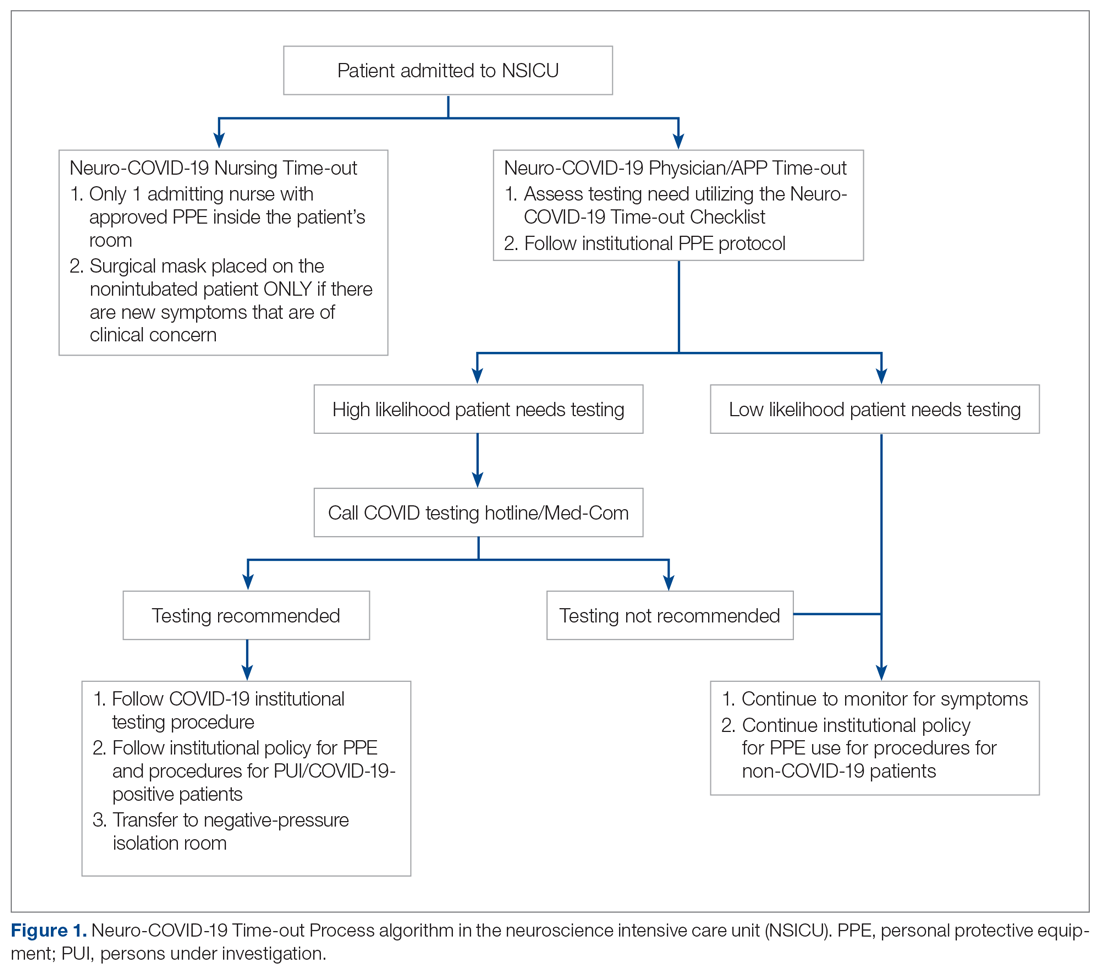

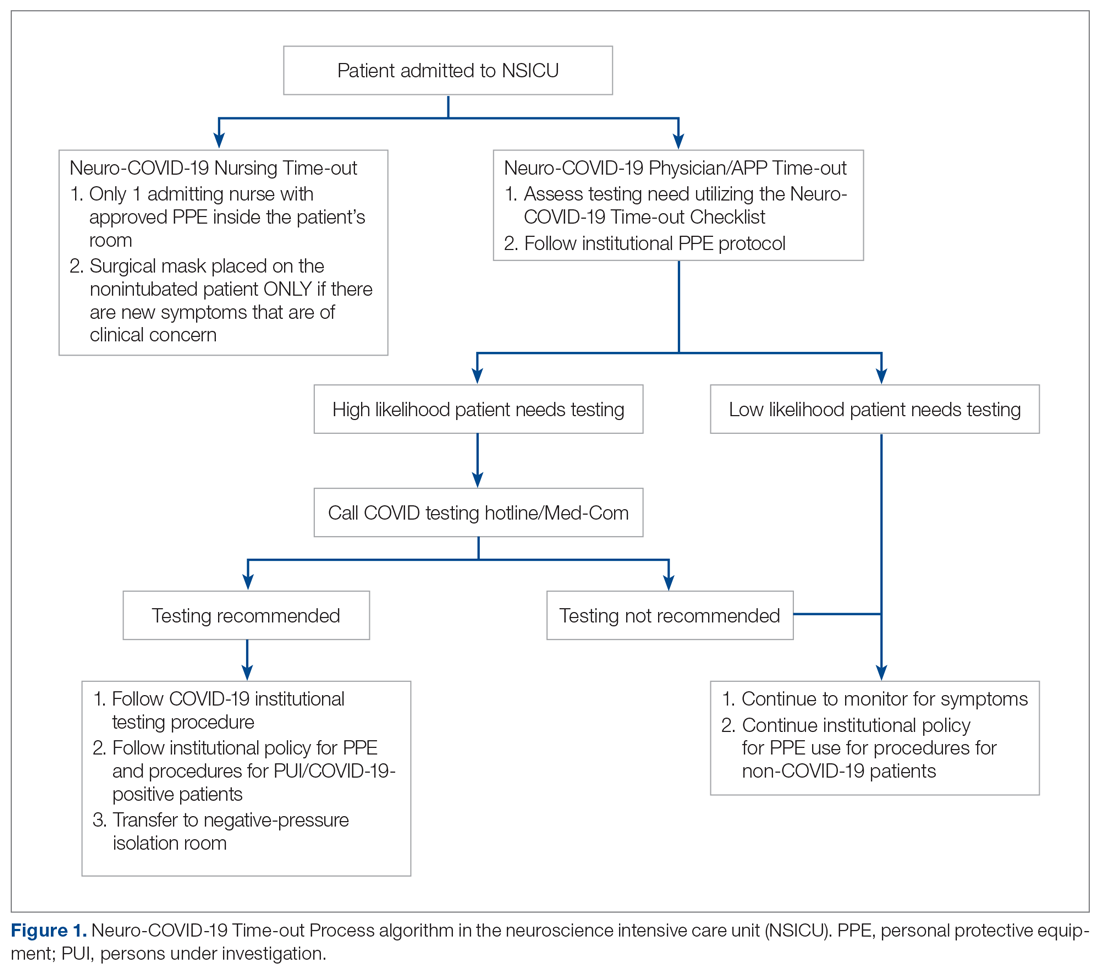

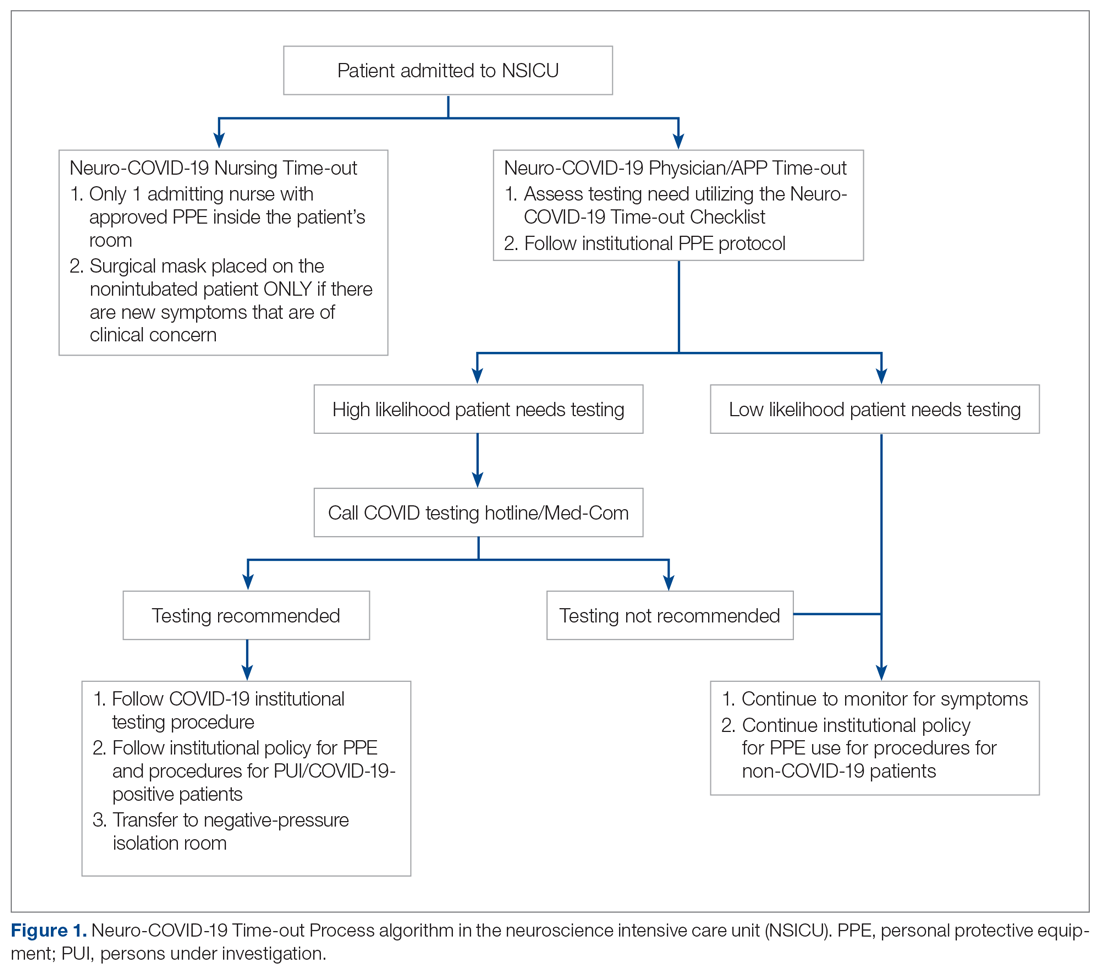

As more PUIs were being admitted to the institution, we used the Plan-Do-Study-Act method for process improvements in the NSICU.5 NSICU stakeholders, including attendings, the nurse manager, and nurse practitioners (NPs), developed an algorithm to facilitate the coordination of the NSICU staff in screening patients to identify those with a high likelihood of needing COVID-19 testing upon arrival in the NSICU (Figure 1). Once the NCOT-PC was finalized, NSICU stakeholders were educated regarding the use of this screening tool.

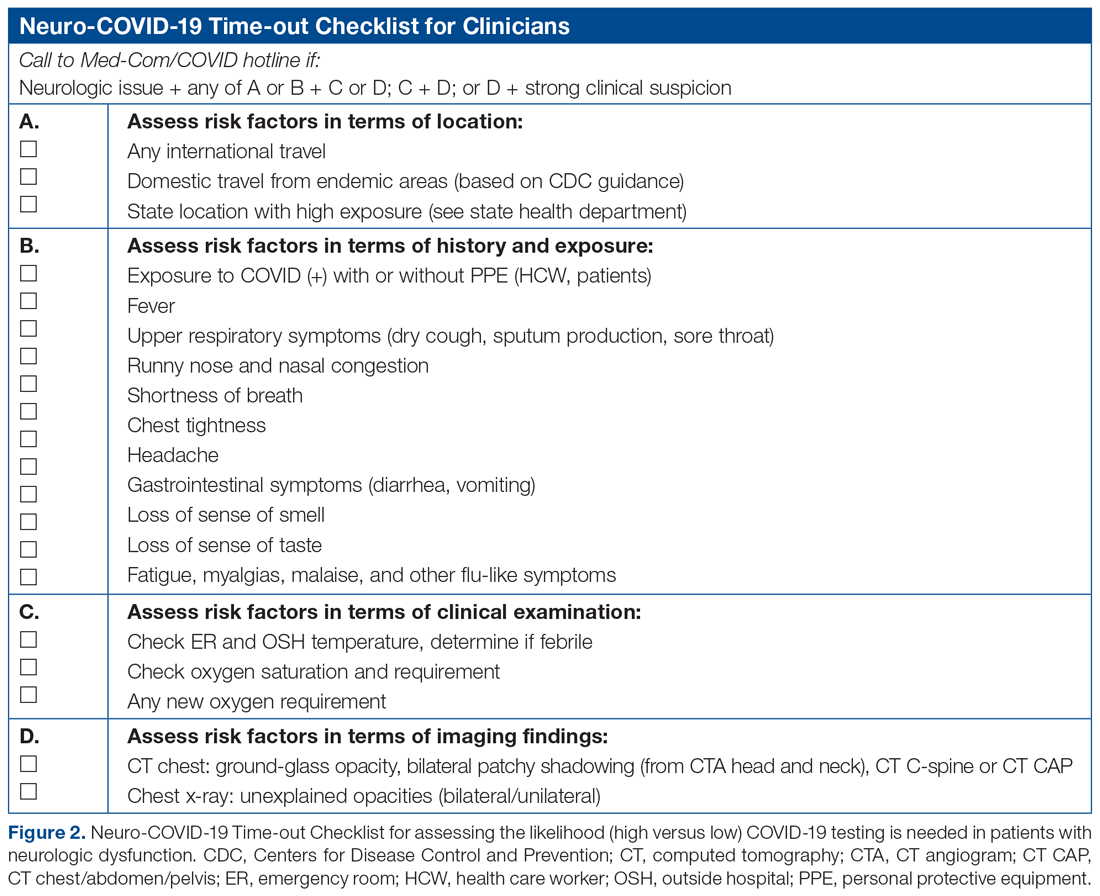

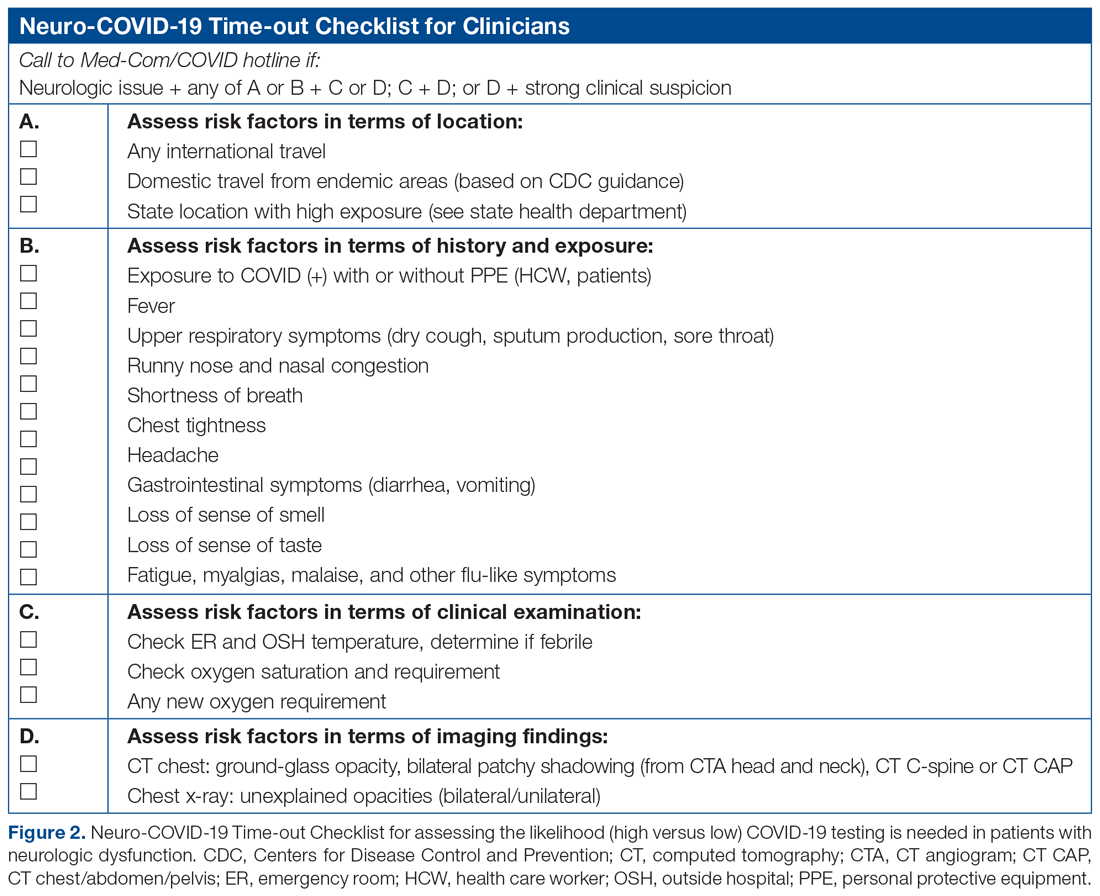

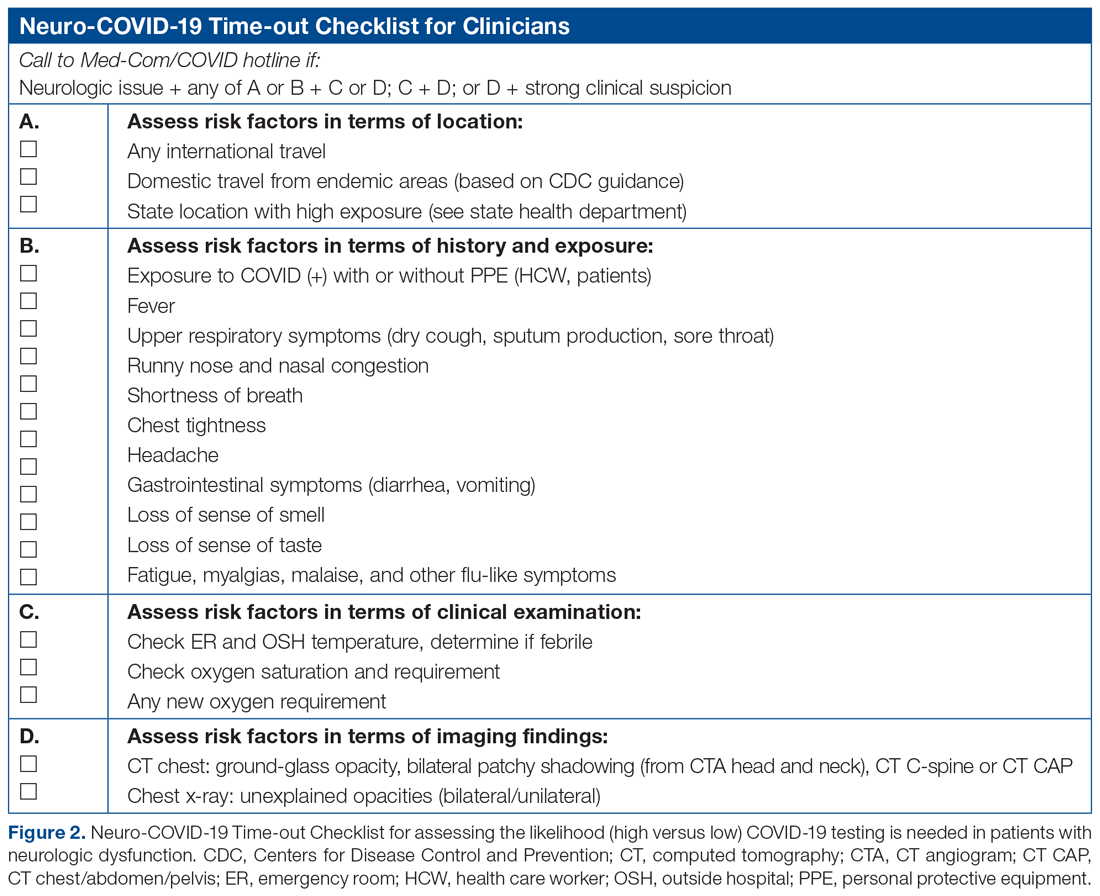

The checklist clinicians review when screening patients is shown in Figure 2. The risk factors comprising the checklist include patient history and clinical and radiographic characteristics that have been shown to be relevant for identifying patients with COVID-19.6,7 The imaging criteria utilize imaging that is part of the standard of care for NSICU patients. For example, computed tomography angiogram of the head and neck performed as part of the acute stroke protocol captures the upper part of the chest. These images are utilized for their incidental findings, such as apical ground-glass opacities and tree-in-bud formation. The risk factors applicable to the patient determine whether the clinician will call Med-Com for testing approval. Institutional COVID-19 processes were then followed accordingly.8 The decision from Med-Com was considered final, and no deviation from institutional policies was allowed.

NCOT-PC was utilized for consecutive days for 1 week before re-evaluation of its feasibility and adaptability.

Data Collection and Analysis

Consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted into the NSICU were assigned nonlinkable patient numbers. No identifiers were collected for the purpose of this project. The primary diagnosis for admission, the neurologic dysfunction that precluded standard screening, and checklist components that the patient fulfilled were collected.

To assess the tool’s feasibility, feedback regarding the ease of use of the NCOT-PC was gathered from the nurses, NPs, charge nurses, fellows, and other attendings. To assess the utility of the NCOT-PC in identifying patients who will be approved for COVID-19 testing, we calculated the proportion of patients who were deemed to have a high likelihood of testing and the proportion of patients who were approved for testing. Descriptive statistics were used, as applicable for the project, to summarize the utility of the NCOT-PC.

Results

We found that the NCOT-PC can be easily used by clinicians. The NSICU staff did not communicate any implementation issues, and since the NCOT-PC was implemented, no problems have been identified.

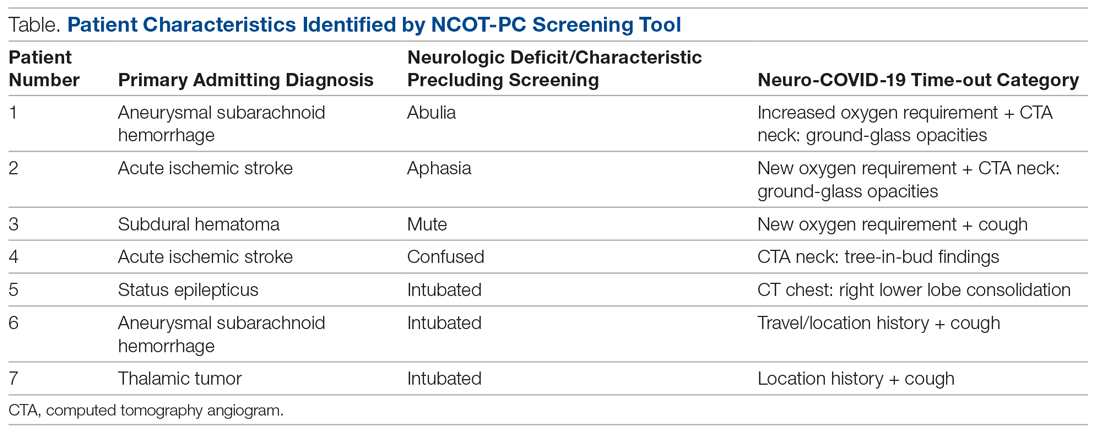

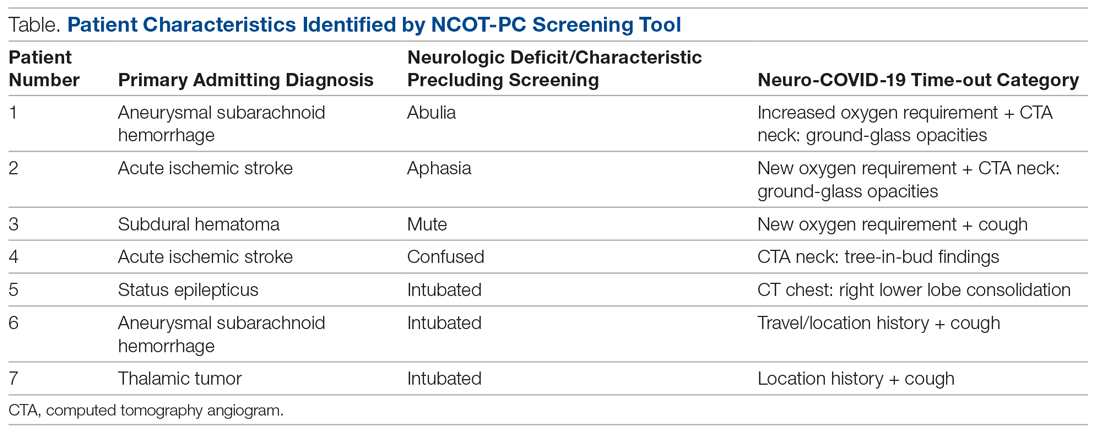

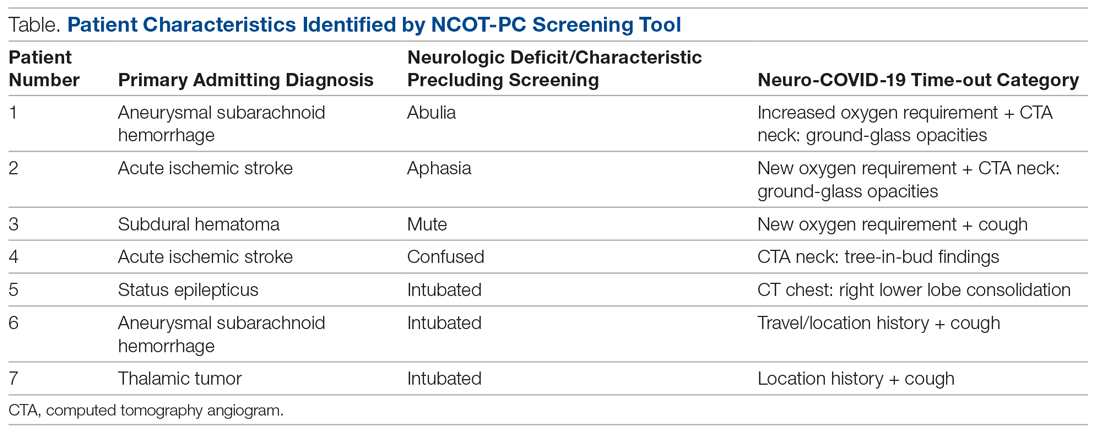

During the pilot period of the NCOT-PC, 14 new patients were admitted to the NSICU service. Nine (64%) of these had neurologic dysfunction, and the NCOT-PC was used to determine whether Med-Com should be called based on the patients’ likelihood (high vs low) of needing a COVID-19 test. Of those patients with neurologic dysfunction, 7 (78%) were deemed to have a high likelihood of needing a COVID-19 test based on the NCOT-PC. Med-Com was contacted regarding these patients, and all were deemed to require the COVID-19 test by Med-Com and were transitioned into PUI status per institutional policy (Table).

Discussion

The NCOT-PC project improved and standardized the process of identifying and screening patients with neurologic dysfunction for COVID-19 testing. The screening tool is feasible to use, and it decreased inadvertent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

The NCOT-PC was easy to administer. Educating the staff regarding the new process took only a few minutes and involved a meeting with the nurse manager, NPs, fellows, residents, and attendings. We found that this process works well in tandem with the standard institutional processes in place in terms of Protected Code Stroke pathway, PUI isolation, PPE use, and Med-Com screening for COVID-19 testing. Med-Com was called only if the patient fulfilled the checklist criteria. In addition, no extra cost was attributed to implementing the NCOT-PC, since we utilized imaging that was already done as part of the standard of care for patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The standardization of the process of screening for COVID-19 testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction improved patient selection. Before the NCOT-PC, there was no consistency in terms of who should get tested and the reason for testing patients with neurologic dysfunction. Patients can pass through the ED and arrive in the NSICU with an unclear screening status, which may cause inadvertent patient and health care worker exposure to COVID-19. With the NCOT-PC, we have avoided instances of inadvertent staff or patient exposure in the NSICU.

The NCOT-PC was adopted into the NSICU process after the first week it was piloted. Beyond the NSICU, the application of the NCOT-PC can be extended to any patient presentation that precludes standard screening, such as ED and interhospital transfers for stroke codes, trauma codes, code blue, or myocardial infarction codes. In our department, as we started the process of PCS for stroke codes, we included NCOT-PC for stroke patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The results of our initiative are largely limited by the decision-making process of Med-Com when patients are called in for testing. At the time of our project, there were no specific criteria used for patients with altered mental status, except for the standard screening methods, and it was through clinician-to-clinician discussion that testing decisions were made. Another limitation is the short period of time that the NCOT-PC was applied before adoption.

In summary, the NCOT-PC tool improved the screening process for COVID-19 testing in patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU. It was feasible and prevented unprotected staff and patient exposure to COVID-19. The NCOT-PC functionality was compatible with institutional COVID-19 policies in place, which contributed to its overall sustainability.

The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) were utilized in preparing this manuscript.9

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU staff for their input with implementation of the NCOT-PC.

Corresponding author: Prashant A. Natteru, MD, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 2500 North State St., Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Symptoms. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

2. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1-9.

3. Khosravani H, Rajendram P, Notario L, et al. Protected code stroke: hyperacute stroke management during the coronavirus disease 2019. (COVID-19) pandemic. Stroke. 2020;51:1891-1895.

4. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) evaluation and testing. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

5. Plan-Do-Study-Act Worksheet. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/PlanDoStudyActWorksheet.aspx. Accessed March 31,2020.

6. Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;10.1002/jmv.25728.

7. Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;101623.

8. UMMC’s COVID-19 Clinical Processes. www.umc.edu/CoronaVirus/Mississippi-Health-Care-Professionals/Clinical-Resources/Clinical-Resources.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

9. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised Publication Guidelines from a Detailed Consensus Process. The EQUATOR Network. www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/squire/. Accessed May 12, 2020.

From the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, Division of Neuroscience Intensive Care, Jackson, MS.

Abstract

Objective: To test a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) screening tool to identify patients who qualify for testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction who are unable to answer the usual screening questions, which could help to prevent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers to COVID-19.

Methods: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) was implemented at our institution for 1 week as a quality improvement project to improve the pathway for COVID-19 screening and testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Results: A total of 14 new patients were admitted into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) service during the pilot period. The NCOT-PC was utilized on 9 (64%) patients with neurologic dysfunction; 7 of these patients were found to have a likelihood of requiring testing based on the NCOT-PC and were subsequently screened for COVID-19 testing by contacting the institution’s COVID-19 testing hotline (Med-Com). All these patients were subsequently transitioned into person-under-investigation status based on the determination from Med-Com. The NSICU staff involved were able to utilize NCOT-PC without issues. The NCOT-PC was immediately adopted into the NSICU process.

Conclusion: Use of the NCOT-PC tool was found to be feasible and improved the screening methodology of patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Keywords: coronavirus; health care planning; quality improvement; patient safety; medical decision-making; neuroscience intensive care unit.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has altered various standard emergent care pathways. Current recommendations regarding COVID-19 screening for testing involve asking patients about their symptoms, including fever, cough, chest pain, and dyspnea.1 This standard screening method poses a problem when caring for patients with neurologic dysfunction. COVID-19 patients may pre-sent with conditions that affect their ability to answer questions, such as stroke, encephalitis, neuromuscular disorders, or headache, and that may preclude the use of standard screening for testing.2 Patients with acute neurologic dysfunction who cannot undergo standard screening may leave the emergency department (ED) and transition into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) or any intensive care unit (ICU) without a reliable COVID-19 screening test.

The Protected Code Stroke pathway offers protection in the emergent setting for patients with stroke when their COVID-19 status is unknown.3 A similar process has been applied at our institution for emergent management of patients with cerebrovascular disease (stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage). However, the process from the ED after designating “difficult to screen” patients as persons under investigation (PUI) is unclear. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has delineated the priorities for testing, with not all declared PUIs requiring testing.4 This poses a great challenge, because patients designated as PUIs require the same management as a COVID-19-positive patient, with negative-pressure isolation rooms as well as use of protective personal equipment (PPE), which may not be readily available. It was also recognized that, because the ED staff can be overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients, there may not be enough time to perform detailed screening of patients with neurologic dysfunction and that “reverse masking” may not be done consistently for nonintubated patients. This may place patients and health care workers at risk of unprotected exposure.

Recognizing these challenges, we created a Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) as a quality improvement project. The aim of this project was to improve and standardize the current process of identifying patients with neurologic dysfunction who require COVID-19 testing to decrease the risk of unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

Methods

Patients and Definitions

This quality improvement project was undertaken at the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU. Because this was a quality improvement project, an Institutional Review Board exemption was granted.

The NCOT-PC was utilized in consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU during a period of 1 week. “Neurologic dysfunction” encompasses any neurologic illness affecting the mental status and/or level of alertness, subsequently precluding the ability to reliably screen the patient utilizing standard COVID-19 screening. “Med-Com” at our institution is the equivalent of the national COVID-19 testing hotline, where our institution’s infectious diseases experts screen calls for testing and determine whether testing is warranted. “Unprotected exposure” means exposure to COVID-19 without adequate and appropriate PPE.

Quality Improvement Process

As more PUIs were being admitted to the institution, we used the Plan-Do-Study-Act method for process improvements in the NSICU.5 NSICU stakeholders, including attendings, the nurse manager, and nurse practitioners (NPs), developed an algorithm to facilitate the coordination of the NSICU staff in screening patients to identify those with a high likelihood of needing COVID-19 testing upon arrival in the NSICU (Figure 1). Once the NCOT-PC was finalized, NSICU stakeholders were educated regarding the use of this screening tool.

The checklist clinicians review when screening patients is shown in Figure 2. The risk factors comprising the checklist include patient history and clinical and radiographic characteristics that have been shown to be relevant for identifying patients with COVID-19.6,7 The imaging criteria utilize imaging that is part of the standard of care for NSICU patients. For example, computed tomography angiogram of the head and neck performed as part of the acute stroke protocol captures the upper part of the chest. These images are utilized for their incidental findings, such as apical ground-glass opacities and tree-in-bud formation. The risk factors applicable to the patient determine whether the clinician will call Med-Com for testing approval. Institutional COVID-19 processes were then followed accordingly.8 The decision from Med-Com was considered final, and no deviation from institutional policies was allowed.

NCOT-PC was utilized for consecutive days for 1 week before re-evaluation of its feasibility and adaptability.

Data Collection and Analysis

Consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted into the NSICU were assigned nonlinkable patient numbers. No identifiers were collected for the purpose of this project. The primary diagnosis for admission, the neurologic dysfunction that precluded standard screening, and checklist components that the patient fulfilled were collected.

To assess the tool’s feasibility, feedback regarding the ease of use of the NCOT-PC was gathered from the nurses, NPs, charge nurses, fellows, and other attendings. To assess the utility of the NCOT-PC in identifying patients who will be approved for COVID-19 testing, we calculated the proportion of patients who were deemed to have a high likelihood of testing and the proportion of patients who were approved for testing. Descriptive statistics were used, as applicable for the project, to summarize the utility of the NCOT-PC.

Results

We found that the NCOT-PC can be easily used by clinicians. The NSICU staff did not communicate any implementation issues, and since the NCOT-PC was implemented, no problems have been identified.

During the pilot period of the NCOT-PC, 14 new patients were admitted to the NSICU service. Nine (64%) of these had neurologic dysfunction, and the NCOT-PC was used to determine whether Med-Com should be called based on the patients’ likelihood (high vs low) of needing a COVID-19 test. Of those patients with neurologic dysfunction, 7 (78%) were deemed to have a high likelihood of needing a COVID-19 test based on the NCOT-PC. Med-Com was contacted regarding these patients, and all were deemed to require the COVID-19 test by Med-Com and were transitioned into PUI status per institutional policy (Table).

Discussion

The NCOT-PC project improved and standardized the process of identifying and screening patients with neurologic dysfunction for COVID-19 testing. The screening tool is feasible to use, and it decreased inadvertent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

The NCOT-PC was easy to administer. Educating the staff regarding the new process took only a few minutes and involved a meeting with the nurse manager, NPs, fellows, residents, and attendings. We found that this process works well in tandem with the standard institutional processes in place in terms of Protected Code Stroke pathway, PUI isolation, PPE use, and Med-Com screening for COVID-19 testing. Med-Com was called only if the patient fulfilled the checklist criteria. In addition, no extra cost was attributed to implementing the NCOT-PC, since we utilized imaging that was already done as part of the standard of care for patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The standardization of the process of screening for COVID-19 testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction improved patient selection. Before the NCOT-PC, there was no consistency in terms of who should get tested and the reason for testing patients with neurologic dysfunction. Patients can pass through the ED and arrive in the NSICU with an unclear screening status, which may cause inadvertent patient and health care worker exposure to COVID-19. With the NCOT-PC, we have avoided instances of inadvertent staff or patient exposure in the NSICU.

The NCOT-PC was adopted into the NSICU process after the first week it was piloted. Beyond the NSICU, the application of the NCOT-PC can be extended to any patient presentation that precludes standard screening, such as ED and interhospital transfers for stroke codes, trauma codes, code blue, or myocardial infarction codes. In our department, as we started the process of PCS for stroke codes, we included NCOT-PC for stroke patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The results of our initiative are largely limited by the decision-making process of Med-Com when patients are called in for testing. At the time of our project, there were no specific criteria used for patients with altered mental status, except for the standard screening methods, and it was through clinician-to-clinician discussion that testing decisions were made. Another limitation is the short period of time that the NCOT-PC was applied before adoption.

In summary, the NCOT-PC tool improved the screening process for COVID-19 testing in patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU. It was feasible and prevented unprotected staff and patient exposure to COVID-19. The NCOT-PC functionality was compatible with institutional COVID-19 policies in place, which contributed to its overall sustainability.

The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) were utilized in preparing this manuscript.9

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU staff for their input with implementation of the NCOT-PC.

Corresponding author: Prashant A. Natteru, MD, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 2500 North State St., Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, Division of Neuroscience Intensive Care, Jackson, MS.

Abstract

Objective: To test a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) screening tool to identify patients who qualify for testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction who are unable to answer the usual screening questions, which could help to prevent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers to COVID-19.

Methods: The Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) was implemented at our institution for 1 week as a quality improvement project to improve the pathway for COVID-19 screening and testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Results: A total of 14 new patients were admitted into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) service during the pilot period. The NCOT-PC was utilized on 9 (64%) patients with neurologic dysfunction; 7 of these patients were found to have a likelihood of requiring testing based on the NCOT-PC and were subsequently screened for COVID-19 testing by contacting the institution’s COVID-19 testing hotline (Med-Com). All these patients were subsequently transitioned into person-under-investigation status based on the determination from Med-Com. The NSICU staff involved were able to utilize NCOT-PC without issues. The NCOT-PC was immediately adopted into the NSICU process.

Conclusion: Use of the NCOT-PC tool was found to be feasible and improved the screening methodology of patients with neurologic dysfunction.

Keywords: coronavirus; health care planning; quality improvement; patient safety; medical decision-making; neuroscience intensive care unit.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has altered various standard emergent care pathways. Current recommendations regarding COVID-19 screening for testing involve asking patients about their symptoms, including fever, cough, chest pain, and dyspnea.1 This standard screening method poses a problem when caring for patients with neurologic dysfunction. COVID-19 patients may pre-sent with conditions that affect their ability to answer questions, such as stroke, encephalitis, neuromuscular disorders, or headache, and that may preclude the use of standard screening for testing.2 Patients with acute neurologic dysfunction who cannot undergo standard screening may leave the emergency department (ED) and transition into the neuroscience intensive care unit (NSICU) or any intensive care unit (ICU) without a reliable COVID-19 screening test.

The Protected Code Stroke pathway offers protection in the emergent setting for patients with stroke when their COVID-19 status is unknown.3 A similar process has been applied at our institution for emergent management of patients with cerebrovascular disease (stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage). However, the process from the ED after designating “difficult to screen” patients as persons under investigation (PUI) is unclear. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has delineated the priorities for testing, with not all declared PUIs requiring testing.4 This poses a great challenge, because patients designated as PUIs require the same management as a COVID-19-positive patient, with negative-pressure isolation rooms as well as use of protective personal equipment (PPE), which may not be readily available. It was also recognized that, because the ED staff can be overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients, there may not be enough time to perform detailed screening of patients with neurologic dysfunction and that “reverse masking” may not be done consistently for nonintubated patients. This may place patients and health care workers at risk of unprotected exposure.

Recognizing these challenges, we created a Neuro-COVID-19 Time-out Process and Checklist (NCOT-PC) as a quality improvement project. The aim of this project was to improve and standardize the current process of identifying patients with neurologic dysfunction who require COVID-19 testing to decrease the risk of unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

Methods

Patients and Definitions

This quality improvement project was undertaken at the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU. Because this was a quality improvement project, an Institutional Review Board exemption was granted.

The NCOT-PC was utilized in consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU during a period of 1 week. “Neurologic dysfunction” encompasses any neurologic illness affecting the mental status and/or level of alertness, subsequently precluding the ability to reliably screen the patient utilizing standard COVID-19 screening. “Med-Com” at our institution is the equivalent of the national COVID-19 testing hotline, where our institution’s infectious diseases experts screen calls for testing and determine whether testing is warranted. “Unprotected exposure” means exposure to COVID-19 without adequate and appropriate PPE.

Quality Improvement Process

As more PUIs were being admitted to the institution, we used the Plan-Do-Study-Act method for process improvements in the NSICU.5 NSICU stakeholders, including attendings, the nurse manager, and nurse practitioners (NPs), developed an algorithm to facilitate the coordination of the NSICU staff in screening patients to identify those with a high likelihood of needing COVID-19 testing upon arrival in the NSICU (Figure 1). Once the NCOT-PC was finalized, NSICU stakeholders were educated regarding the use of this screening tool.

The checklist clinicians review when screening patients is shown in Figure 2. The risk factors comprising the checklist include patient history and clinical and radiographic characteristics that have been shown to be relevant for identifying patients with COVID-19.6,7 The imaging criteria utilize imaging that is part of the standard of care for NSICU patients. For example, computed tomography angiogram of the head and neck performed as part of the acute stroke protocol captures the upper part of the chest. These images are utilized for their incidental findings, such as apical ground-glass opacities and tree-in-bud formation. The risk factors applicable to the patient determine whether the clinician will call Med-Com for testing approval. Institutional COVID-19 processes were then followed accordingly.8 The decision from Med-Com was considered final, and no deviation from institutional policies was allowed.

NCOT-PC was utilized for consecutive days for 1 week before re-evaluation of its feasibility and adaptability.

Data Collection and Analysis

Consecutive patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted into the NSICU were assigned nonlinkable patient numbers. No identifiers were collected for the purpose of this project. The primary diagnosis for admission, the neurologic dysfunction that precluded standard screening, and checklist components that the patient fulfilled were collected.

To assess the tool’s feasibility, feedback regarding the ease of use of the NCOT-PC was gathered from the nurses, NPs, charge nurses, fellows, and other attendings. To assess the utility of the NCOT-PC in identifying patients who will be approved for COVID-19 testing, we calculated the proportion of patients who were deemed to have a high likelihood of testing and the proportion of patients who were approved for testing. Descriptive statistics were used, as applicable for the project, to summarize the utility of the NCOT-PC.

Results

We found that the NCOT-PC can be easily used by clinicians. The NSICU staff did not communicate any implementation issues, and since the NCOT-PC was implemented, no problems have been identified.

During the pilot period of the NCOT-PC, 14 new patients were admitted to the NSICU service. Nine (64%) of these had neurologic dysfunction, and the NCOT-PC was used to determine whether Med-Com should be called based on the patients’ likelihood (high vs low) of needing a COVID-19 test. Of those patients with neurologic dysfunction, 7 (78%) were deemed to have a high likelihood of needing a COVID-19 test based on the NCOT-PC. Med-Com was contacted regarding these patients, and all were deemed to require the COVID-19 test by Med-Com and were transitioned into PUI status per institutional policy (Table).

Discussion

The NCOT-PC project improved and standardized the process of identifying and screening patients with neurologic dysfunction for COVID-19 testing. The screening tool is feasible to use, and it decreased inadvertent unprotected exposure of patients and health care workers.

The NCOT-PC was easy to administer. Educating the staff regarding the new process took only a few minutes and involved a meeting with the nurse manager, NPs, fellows, residents, and attendings. We found that this process works well in tandem with the standard institutional processes in place in terms of Protected Code Stroke pathway, PUI isolation, PPE use, and Med-Com screening for COVID-19 testing. Med-Com was called only if the patient fulfilled the checklist criteria. In addition, no extra cost was attributed to implementing the NCOT-PC, since we utilized imaging that was already done as part of the standard of care for patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The standardization of the process of screening for COVID-19 testing among patients with neurologic dysfunction improved patient selection. Before the NCOT-PC, there was no consistency in terms of who should get tested and the reason for testing patients with neurologic dysfunction. Patients can pass through the ED and arrive in the NSICU with an unclear screening status, which may cause inadvertent patient and health care worker exposure to COVID-19. With the NCOT-PC, we have avoided instances of inadvertent staff or patient exposure in the NSICU.

The NCOT-PC was adopted into the NSICU process after the first week it was piloted. Beyond the NSICU, the application of the NCOT-PC can be extended to any patient presentation that precludes standard screening, such as ED and interhospital transfers for stroke codes, trauma codes, code blue, or myocardial infarction codes. In our department, as we started the process of PCS for stroke codes, we included NCOT-PC for stroke patients with neurologic dysfunction.

The results of our initiative are largely limited by the decision-making process of Med-Com when patients are called in for testing. At the time of our project, there were no specific criteria used for patients with altered mental status, except for the standard screening methods, and it was through clinician-to-clinician discussion that testing decisions were made. Another limitation is the short period of time that the NCOT-PC was applied before adoption.

In summary, the NCOT-PC tool improved the screening process for COVID-19 testing in patients with neurologic dysfunction admitted to the NSICU. It was feasible and prevented unprotected staff and patient exposure to COVID-19. The NCOT-PC functionality was compatible with institutional COVID-19 policies in place, which contributed to its overall sustainability.

The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) were utilized in preparing this manuscript.9

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the University of Mississippi Medical Center NSICU staff for their input with implementation of the NCOT-PC.

Corresponding author: Prashant A. Natteru, MD, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 2500 North State St., Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Symptoms. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

2. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1-9.

3. Khosravani H, Rajendram P, Notario L, et al. Protected code stroke: hyperacute stroke management during the coronavirus disease 2019. (COVID-19) pandemic. Stroke. 2020;51:1891-1895.

4. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) evaluation and testing. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

5. Plan-Do-Study-Act Worksheet. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/PlanDoStudyActWorksheet.aspx. Accessed March 31,2020.

6. Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;10.1002/jmv.25728.

7. Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;101623.

8. UMMC’s COVID-19 Clinical Processes. www.umc.edu/CoronaVirus/Mississippi-Health-Care-Professionals/Clinical-Resources/Clinical-Resources.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

9. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised Publication Guidelines from a Detailed Consensus Process. The EQUATOR Network. www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/squire/. Accessed May 12, 2020.

1. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Symptoms. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

2. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1-9.

3. Khosravani H, Rajendram P, Notario L, et al. Protected code stroke: hyperacute stroke management during the coronavirus disease 2019. (COVID-19) pandemic. Stroke. 2020;51:1891-1895.

4. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) evaluation and testing. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

5. Plan-Do-Study-Act Worksheet. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/PlanDoStudyActWorksheet.aspx. Accessed March 31,2020.

6. Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;10.1002/jmv.25728.

7. Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;101623.

8. UMMC’s COVID-19 Clinical Processes. www.umc.edu/CoronaVirus/Mississippi-Health-Care-Professionals/Clinical-Resources/Clinical-Resources.html. Accessed April 9, 2020.

9. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised Publication Guidelines from a Detailed Consensus Process. The EQUATOR Network. www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/squire/. Accessed May 12, 2020.

Systemic Corticosteroids in Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19

Study Overview

Objective. To assess the association between administration of systemic corticosteroids, compared with usual care or placebo, and 28-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Design. Prospective meta-analysis with data from 7 randomized clinical trials conducted in 12 countries.

Setting and participants. This prospective meta-analysis included randomized clinical trials conducted between February 26, 2020, and June 9, 2020, that examined the clinical efficacy of administration of corticosteroids in hospitalized COVID-19 patients who were critically ill. Trials were systematically identified from ClinicalTrials.gov, the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, and the EU Clinical Trials Register, using the search terms COVID-19, corticosteroids, and steroids. Additional trials were identified by experts from the WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group. Senior investigators of these identified trials were asked to participate in weekly calls to develop a protocol for the prospective meta-analysis.1 Subsequently, trials that had randomly assigned critically ill patients to receive corticosteroids versus usual care or placebo were invited to participate in this meta-analysis. Data were pooled from patients recruited to the participating trials through June 9, 2020, and aggregated in overall and in predefined subgroups.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality up to 30 days after randomization. Because 5 of the included trials reported mortality at 28 days after randomization, the primary outcome was reported as 28-day all-cause mortality. The secondary outcome was serious adverse events (SAEs). The authors also gathered data on the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients, the number of patients lost to follow-up, and outcomes according to intervention group, overall, and in subgroups (ie, patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or vasoactive medication; age ≤ 60 years or > 60 years [the median across trials]; sex [male or female]; and the duration patients were symptomatic [≤ 7 days or > 7 days]). For each trial, the risk of bias was assessed independently by 4 investigators using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for the overall effects of corticosteroids on mortality and SAEs and the effect of assignment and allocated interventions. Inconsistency between trial results was evaluated using the I2 statistic. The trials were classified according to the corticosteroids used in the intervention group and the dose administered using a priori-defined cutoffs (15 mg/day of dexamethasone, 400 mg/day of hydrocortisone, and 1 mg/kg/day of methylprednisolone). The primary analysis utilized was an inverse variance-weighted fixed-effect meta-analysis of odds ratios (ORs) for overall mortality. Random-effects meta-analyses with Paule-Mandel estimate of heterogeneity were also performed.

Main results. Seven trials (DEXA-COVID 19, CoDEX, RECOVERY, CAPE COVID, COVID STEROID, REMAP-CAP, and Steroids-SARI) were included in the final meta-analysis. The enrolled patients were from Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Denmark, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The date of final follow-up was July 6, 2020. The corticosteroids groups included dexamethasone at low (6 mg/day orally or intravenously [IV]) and high (20 mg/day IV) doses; low-dose hydrocortisone (200 mg/day IV or 50 mg every 6 hr IV); and high-dose methylprednisolone (40 mg every 12 hr IV). In total, 1703 patients were randomized, with 678 assigned to the corticosteroids group and 1025 to the usual-care or placebo group. The median age of patients was 60 years (interquartile range, 52-68 years), and 29% were women. The larger number of patients in the usual-care/placebo group was a result of the 1:2 randomization (corticosteroids versus usual care or placebo) in the RECOVERY trial, which contributed 59.1% of patients included in this prospective meta-analysis. The majority of patients were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization (1559 patients). The administration of adjunctive treatments, such as azithromycin or antiviral agents, varied among the trials. The risk of bias was determined as low for 6 of the 7 mortality results.

A total of 222 of 678 patients in the corticosteroids group died, and 425 of 1025 patients in the usual care or placebo group died. The summary OR was 0.66 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.53-0.82; P < 0.001) based on a fixed-effect meta-analysis, and 0.70 (95% CI, 0.48-1.01; P = 0.053) based on the random-effects meta-analysis, for 28-day all-cause mortality comparing all corticosteroids with usual care or placebo. There was little inconsistency between trial results (I2 = 15.6%; P = 0.31). The fixed-effect summary OR for the association with 28-day all-cause mortality was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.50-0.82; P < 0.001) for dexamethasone compared with usual care or placebo (3 trials, 1282 patients, and 527 deaths); the OR was 0.69 (95% CI, 0.43-1.12; P = 0.13) for hydrocortisone (3 trials, 374 patients, and 94 deaths); and the OR was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.29-2.87; P = 0.87) for methylprednisolone (1 trial, 47 patients, and 26 deaths). Moreover, in trials that administered low-dose corticosteroids, the overall fixed-effect OR for 28-day all-cause mortality was 0.61 (95% CI, 0.48-0.78; P < 0.001). In the subgroup analysis, the overall fixed-effect OR was 0.69 (95% CI, 0.55-0.86) in patients who were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization, and the OR was 0.41 (95% CI, 0.19-0.88) in patients who were not receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization.

Six trials (all except the RECOVERY trial) reported SAEs, with 64 events occurring among 354 patients assigned to the corticosteroids group and 80 SAEs occurring among 342 patients assigned to the usual-care or placebo group. There was no suggestion that the risk of SAEs was higher in patients who were administered corticosteroids.

Conclusion. The administration of systemic corticosteroids was associated with a lower 28-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19 compared to those who received usual care or placebo.

Commentary

Corticosteroids are anti-inflammatory and vasoconstrictive medications that have long been used in intensive care units for the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock. However, the therapeutic role of corticosteroids for treating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection was uncertain at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic due to concerns that this class of medications may cause an impaired immune response in the setting of a life-threatening SARS-CoV-2 infection. Evidence supporting this notion included prior studies showing that corticosteroid therapy was associated with delayed viral clearance of Middle East respiratory syndrome or a higher viral load of SARS-CoV.2,3 The uncertainty surrounding the therapeutic use of corticosteroids in treating COVID-19 led to a simultaneous global effort to conduct randomized controlled trials to urgently examine this important clinical question. The open-label Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, conducted in the UK, was the first large-scale randomized clinical trial that reported the clinical benefit of corticosteroids in treating patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Specifically, it showed that low-dose dexamethasone (6 mg/day) administered orally or IV for up to 10 days resulted in a 2.8% absolute reduction in 28-day mortality, with the greatest benefit, an absolute risk reduction of 12.1%, conferred to patients who were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at the time of randomization.4 In response to these findings, the National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel recommended the use of dexamethasone in patients with COVID-19 who are on mechanical ventilation or who require supplemental oxygen, and recommended against the use of dexamethasone for those not requiring supplemental oxygen.5

The meta-analysis discussed in this commentary, conducted by the WHO REACT Working Group, has replicated initial findings from the RECOVERY trial. This prospective meta-analysis pooled data from 7 randomized controlled trials of corticosteroid therapy in 1703 critically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Similar to findings from the RECOVERY trial, corticosteroids were associated with lower all-cause mortality at 28 days after randomization, and this benefit was observed both in critically ill patients who were receiving mechanical ventilation or supplemental oxygen without mechanical ventilation. Interestingly, while the OR estimates were imprecise, the reduction in mortality rates was similar between patients who were administered dexamethasone and hydrocortisone, which may suggest a general drug class effect. In addition, the mortality benefit of corticosteroids appeared similar for those aged ≤ 60 years and those aged > 60 years, between female and male patients, and those who were symptomatic for ≤ 7 days or > 7 days before randomization. Moreover, the administration of corticosteroids did not appear to increase the risk of SAEs. While more data are needed, results from the RECOVERY trial and this prospective meta-analysis indicate that corticosteroids should be an essential pharmacologic treatment for COVID-19, and suggest its potential role as a standard of care for critically ill patients with COVID-19.

This study has several limitations. First, not all trials systematically identified participated in the meta-analysis. Second, long-term outcomes after hospital discharge were not captured, and thus the effect of corticosteroids on long-term mortality and other adverse outcomes, such as hospital readmission, remain unknown. Third, because children were excluded from study participation, the effect of corticosteroids on pediatric COVID-19 patients is unknown. Fourth, the RECOVERY trial contributed more than 50% of patients in the current analysis, although there was little inconsistency in the effects of corticosteroids on mortality between individual trials. Last, the meta-analysis was unable to establish the optimal dose or duration of corticosteroid intervention in critically ill COVID-19 patients, or determine its efficacy in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, all of which are key clinical questions that will need to be addressed with further clinical investigations.

The development of effective treatments for COVID-19 is critical to mitigating the devastating consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Several recent COVID-19 clinical trials have shown promise in this endeavor. For instance, the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACCT-1) found that intravenous remdesivir, as compared to placebo, significantly shortened time to recovery in adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who had evidence of lower respiratory tract infection.6 Moreover, there is some evidence to suggest that convalescent plasma and aerosol inhalation of IFN-κ may have beneficial effects in treating COVID-19.7,8 Thus, clinical trials designed to investigate combination therapy approaches including corticosteroids, remdesivir, convalescent plasma, and others are urgently needed to help identify interventions that most effectively treat COVID-19.

Applications for Clinical Practice

The use of corticosteroids in critically ill patients with COVID-19 reduces overall mortality. This treatment is inexpensive and available in most care settings, including low-resource regions, and provides hope for better outcomes in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Katerina Oikonomou, MD, PhD

General Hospital of Larissa, Larissa, Greece

Fred Ko, MD, MS

1. Sterne JAC, Diaz J, Villar J, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with COVID-19: A structured summary of a study protocol for a prospective meta-analysis of randomized trials. Trials. 2020;21:734.

2. Lee N, Allen Chan KC, Hui DS, et al. Effects of early corticosteroid treatment on plasma SARS-associated Coronavirus RNA concentrations in adult patients. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:304-309.

3. Arabi YM, Mandourah Y, Al-Hameed F, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for citically Ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:757-767.

4. RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 - preliminary report [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 17]. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMoa2021436.

5. NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/immune-based-therapy/immunomodulators/corticosteroids/. Accessed September 11, 2020.

6. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19--preliminary report [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 22]. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMoa2007764.

7. Casadevall A, Joyner MJ, Pirofski LA. A randomized trial of convalescent plasma for covid-19-potentially hopeful signals. JAMA. 2020;324:455-457.

8. Fu W, Liu Y, Xia L, et al. A clinical pilot study on the safety and efficacy of aerosol inhalation treatment of IFN-κ plus TFF2 in patients with moderate COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:100478.

Study Overview

Objective. To assess the association between administration of systemic corticosteroids, compared with usual care or placebo, and 28-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Design. Prospective meta-analysis with data from 7 randomized clinical trials conducted in 12 countries.

Setting and participants. This prospective meta-analysis included randomized clinical trials conducted between February 26, 2020, and June 9, 2020, that examined the clinical efficacy of administration of corticosteroids in hospitalized COVID-19 patients who were critically ill. Trials were systematically identified from ClinicalTrials.gov, the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, and the EU Clinical Trials Register, using the search terms COVID-19, corticosteroids, and steroids. Additional trials were identified by experts from the WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group. Senior investigators of these identified trials were asked to participate in weekly calls to develop a protocol for the prospective meta-analysis.1 Subsequently, trials that had randomly assigned critically ill patients to receive corticosteroids versus usual care or placebo were invited to participate in this meta-analysis. Data were pooled from patients recruited to the participating trials through June 9, 2020, and aggregated in overall and in predefined subgroups.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality up to 30 days after randomization. Because 5 of the included trials reported mortality at 28 days after randomization, the primary outcome was reported as 28-day all-cause mortality. The secondary outcome was serious adverse events (SAEs). The authors also gathered data on the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients, the number of patients lost to follow-up, and outcomes according to intervention group, overall, and in subgroups (ie, patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or vasoactive medication; age ≤ 60 years or > 60 years [the median across trials]; sex [male or female]; and the duration patients were symptomatic [≤ 7 days or > 7 days]). For each trial, the risk of bias was assessed independently by 4 investigators using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for the overall effects of corticosteroids on mortality and SAEs and the effect of assignment and allocated interventions. Inconsistency between trial results was evaluated using the I2 statistic. The trials were classified according to the corticosteroids used in the intervention group and the dose administered using a priori-defined cutoffs (15 mg/day of dexamethasone, 400 mg/day of hydrocortisone, and 1 mg/kg/day of methylprednisolone). The primary analysis utilized was an inverse variance-weighted fixed-effect meta-analysis of odds ratios (ORs) for overall mortality. Random-effects meta-analyses with Paule-Mandel estimate of heterogeneity were also performed.

Main results. Seven trials (DEXA-COVID 19, CoDEX, RECOVERY, CAPE COVID, COVID STEROID, REMAP-CAP, and Steroids-SARI) were included in the final meta-analysis. The enrolled patients were from Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Denmark, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The date of final follow-up was July 6, 2020. The corticosteroids groups included dexamethasone at low (6 mg/day orally or intravenously [IV]) and high (20 mg/day IV) doses; low-dose hydrocortisone (200 mg/day IV or 50 mg every 6 hr IV); and high-dose methylprednisolone (40 mg every 12 hr IV). In total, 1703 patients were randomized, with 678 assigned to the corticosteroids group and 1025 to the usual-care or placebo group. The median age of patients was 60 years (interquartile range, 52-68 years), and 29% were women. The larger number of patients in the usual-care/placebo group was a result of the 1:2 randomization (corticosteroids versus usual care or placebo) in the RECOVERY trial, which contributed 59.1% of patients included in this prospective meta-analysis. The majority of patients were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization (1559 patients). The administration of adjunctive treatments, such as azithromycin or antiviral agents, varied among the trials. The risk of bias was determined as low for 6 of the 7 mortality results.

A total of 222 of 678 patients in the corticosteroids group died, and 425 of 1025 patients in the usual care or placebo group died. The summary OR was 0.66 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.53-0.82; P < 0.001) based on a fixed-effect meta-analysis, and 0.70 (95% CI, 0.48-1.01; P = 0.053) based on the random-effects meta-analysis, for 28-day all-cause mortality comparing all corticosteroids with usual care or placebo. There was little inconsistency between trial results (I2 = 15.6%; P = 0.31). The fixed-effect summary OR for the association with 28-day all-cause mortality was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.50-0.82; P < 0.001) for dexamethasone compared with usual care or placebo (3 trials, 1282 patients, and 527 deaths); the OR was 0.69 (95% CI, 0.43-1.12; P = 0.13) for hydrocortisone (3 trials, 374 patients, and 94 deaths); and the OR was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.29-2.87; P = 0.87) for methylprednisolone (1 trial, 47 patients, and 26 deaths). Moreover, in trials that administered low-dose corticosteroids, the overall fixed-effect OR for 28-day all-cause mortality was 0.61 (95% CI, 0.48-0.78; P < 0.001). In the subgroup analysis, the overall fixed-effect OR was 0.69 (95% CI, 0.55-0.86) in patients who were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization, and the OR was 0.41 (95% CI, 0.19-0.88) in patients who were not receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization.

Six trials (all except the RECOVERY trial) reported SAEs, with 64 events occurring among 354 patients assigned to the corticosteroids group and 80 SAEs occurring among 342 patients assigned to the usual-care or placebo group. There was no suggestion that the risk of SAEs was higher in patients who were administered corticosteroids.

Conclusion. The administration of systemic corticosteroids was associated with a lower 28-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19 compared to those who received usual care or placebo.

Commentary

Corticosteroids are anti-inflammatory and vasoconstrictive medications that have long been used in intensive care units for the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock. However, the therapeutic role of corticosteroids for treating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection was uncertain at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic due to concerns that this class of medications may cause an impaired immune response in the setting of a life-threatening SARS-CoV-2 infection. Evidence supporting this notion included prior studies showing that corticosteroid therapy was associated with delayed viral clearance of Middle East respiratory syndrome or a higher viral load of SARS-CoV.2,3 The uncertainty surrounding the therapeutic use of corticosteroids in treating COVID-19 led to a simultaneous global effort to conduct randomized controlled trials to urgently examine this important clinical question. The open-label Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, conducted in the UK, was the first large-scale randomized clinical trial that reported the clinical benefit of corticosteroids in treating patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Specifically, it showed that low-dose dexamethasone (6 mg/day) administered orally or IV for up to 10 days resulted in a 2.8% absolute reduction in 28-day mortality, with the greatest benefit, an absolute risk reduction of 12.1%, conferred to patients who were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at the time of randomization.4 In response to these findings, the National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel recommended the use of dexamethasone in patients with COVID-19 who are on mechanical ventilation or who require supplemental oxygen, and recommended against the use of dexamethasone for those not requiring supplemental oxygen.5

The meta-analysis discussed in this commentary, conducted by the WHO REACT Working Group, has replicated initial findings from the RECOVERY trial. This prospective meta-analysis pooled data from 7 randomized controlled trials of corticosteroid therapy in 1703 critically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Similar to findings from the RECOVERY trial, corticosteroids were associated with lower all-cause mortality at 28 days after randomization, and this benefit was observed both in critically ill patients who were receiving mechanical ventilation or supplemental oxygen without mechanical ventilation. Interestingly, while the OR estimates were imprecise, the reduction in mortality rates was similar between patients who were administered dexamethasone and hydrocortisone, which may suggest a general drug class effect. In addition, the mortality benefit of corticosteroids appeared similar for those aged ≤ 60 years and those aged > 60 years, between female and male patients, and those who were symptomatic for ≤ 7 days or > 7 days before randomization. Moreover, the administration of corticosteroids did not appear to increase the risk of SAEs. While more data are needed, results from the RECOVERY trial and this prospective meta-analysis indicate that corticosteroids should be an essential pharmacologic treatment for COVID-19, and suggest its potential role as a standard of care for critically ill patients with COVID-19.

This study has several limitations. First, not all trials systematically identified participated in the meta-analysis. Second, long-term outcomes after hospital discharge were not captured, and thus the effect of corticosteroids on long-term mortality and other adverse outcomes, such as hospital readmission, remain unknown. Third, because children were excluded from study participation, the effect of corticosteroids on pediatric COVID-19 patients is unknown. Fourth, the RECOVERY trial contributed more than 50% of patients in the current analysis, although there was little inconsistency in the effects of corticosteroids on mortality between individual trials. Last, the meta-analysis was unable to establish the optimal dose or duration of corticosteroid intervention in critically ill COVID-19 patients, or determine its efficacy in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, all of which are key clinical questions that will need to be addressed with further clinical investigations.

The development of effective treatments for COVID-19 is critical to mitigating the devastating consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Several recent COVID-19 clinical trials have shown promise in this endeavor. For instance, the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACCT-1) found that intravenous remdesivir, as compared to placebo, significantly shortened time to recovery in adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who had evidence of lower respiratory tract infection.6 Moreover, there is some evidence to suggest that convalescent plasma and aerosol inhalation of IFN-κ may have beneficial effects in treating COVID-19.7,8 Thus, clinical trials designed to investigate combination therapy approaches including corticosteroids, remdesivir, convalescent plasma, and others are urgently needed to help identify interventions that most effectively treat COVID-19.

Applications for Clinical Practice

The use of corticosteroids in critically ill patients with COVID-19 reduces overall mortality. This treatment is inexpensive and available in most care settings, including low-resource regions, and provides hope for better outcomes in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Katerina Oikonomou, MD, PhD

General Hospital of Larissa, Larissa, Greece

Fred Ko, MD, MS

Study Overview

Objective. To assess the association between administration of systemic corticosteroids, compared with usual care or placebo, and 28-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Design. Prospective meta-analysis with data from 7 randomized clinical trials conducted in 12 countries.

Setting and participants. This prospective meta-analysis included randomized clinical trials conducted between February 26, 2020, and June 9, 2020, that examined the clinical efficacy of administration of corticosteroids in hospitalized COVID-19 patients who were critically ill. Trials were systematically identified from ClinicalTrials.gov, the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, and the EU Clinical Trials Register, using the search terms COVID-19, corticosteroids, and steroids. Additional trials were identified by experts from the WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group. Senior investigators of these identified trials were asked to participate in weekly calls to develop a protocol for the prospective meta-analysis.1 Subsequently, trials that had randomly assigned critically ill patients to receive corticosteroids versus usual care or placebo were invited to participate in this meta-analysis. Data were pooled from patients recruited to the participating trials through June 9, 2020, and aggregated in overall and in predefined subgroups.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality up to 30 days after randomization. Because 5 of the included trials reported mortality at 28 days after randomization, the primary outcome was reported as 28-day all-cause mortality. The secondary outcome was serious adverse events (SAEs). The authors also gathered data on the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients, the number of patients lost to follow-up, and outcomes according to intervention group, overall, and in subgroups (ie, patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or vasoactive medication; age ≤ 60 years or > 60 years [the median across trials]; sex [male or female]; and the duration patients were symptomatic [≤ 7 days or > 7 days]). For each trial, the risk of bias was assessed independently by 4 investigators using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for the overall effects of corticosteroids on mortality and SAEs and the effect of assignment and allocated interventions. Inconsistency between trial results was evaluated using the I2 statistic. The trials were classified according to the corticosteroids used in the intervention group and the dose administered using a priori-defined cutoffs (15 mg/day of dexamethasone, 400 mg/day of hydrocortisone, and 1 mg/kg/day of methylprednisolone). The primary analysis utilized was an inverse variance-weighted fixed-effect meta-analysis of odds ratios (ORs) for overall mortality. Random-effects meta-analyses with Paule-Mandel estimate of heterogeneity were also performed.

Main results. Seven trials (DEXA-COVID 19, CoDEX, RECOVERY, CAPE COVID, COVID STEROID, REMAP-CAP, and Steroids-SARI) were included in the final meta-analysis. The enrolled patients were from Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Denmark, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The date of final follow-up was July 6, 2020. The corticosteroids groups included dexamethasone at low (6 mg/day orally or intravenously [IV]) and high (20 mg/day IV) doses; low-dose hydrocortisone (200 mg/day IV or 50 mg every 6 hr IV); and high-dose methylprednisolone (40 mg every 12 hr IV). In total, 1703 patients were randomized, with 678 assigned to the corticosteroids group and 1025 to the usual-care or placebo group. The median age of patients was 60 years (interquartile range, 52-68 years), and 29% were women. The larger number of patients in the usual-care/placebo group was a result of the 1:2 randomization (corticosteroids versus usual care or placebo) in the RECOVERY trial, which contributed 59.1% of patients included in this prospective meta-analysis. The majority of patients were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization (1559 patients). The administration of adjunctive treatments, such as azithromycin or antiviral agents, varied among the trials. The risk of bias was determined as low for 6 of the 7 mortality results.

A total of 222 of 678 patients in the corticosteroids group died, and 425 of 1025 patients in the usual care or placebo group died. The summary OR was 0.66 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.53-0.82; P < 0.001) based on a fixed-effect meta-analysis, and 0.70 (95% CI, 0.48-1.01; P = 0.053) based on the random-effects meta-analysis, for 28-day all-cause mortality comparing all corticosteroids with usual care or placebo. There was little inconsistency between trial results (I2 = 15.6%; P = 0.31). The fixed-effect summary OR for the association with 28-day all-cause mortality was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.50-0.82; P < 0.001) for dexamethasone compared with usual care or placebo (3 trials, 1282 patients, and 527 deaths); the OR was 0.69 (95% CI, 0.43-1.12; P = 0.13) for hydrocortisone (3 trials, 374 patients, and 94 deaths); and the OR was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.29-2.87; P = 0.87) for methylprednisolone (1 trial, 47 patients, and 26 deaths). Moreover, in trials that administered low-dose corticosteroids, the overall fixed-effect OR for 28-day all-cause mortality was 0.61 (95% CI, 0.48-0.78; P < 0.001). In the subgroup analysis, the overall fixed-effect OR was 0.69 (95% CI, 0.55-0.86) in patients who were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization, and the OR was 0.41 (95% CI, 0.19-0.88) in patients who were not receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization.

Six trials (all except the RECOVERY trial) reported SAEs, with 64 events occurring among 354 patients assigned to the corticosteroids group and 80 SAEs occurring among 342 patients assigned to the usual-care or placebo group. There was no suggestion that the risk of SAEs was higher in patients who were administered corticosteroids.

Conclusion. The administration of systemic corticosteroids was associated with a lower 28-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19 compared to those who received usual care or placebo.

Commentary

Corticosteroids are anti-inflammatory and vasoconstrictive medications that have long been used in intensive care units for the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock. However, the therapeutic role of corticosteroids for treating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection was uncertain at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic due to concerns that this class of medications may cause an impaired immune response in the setting of a life-threatening SARS-CoV-2 infection. Evidence supporting this notion included prior studies showing that corticosteroid therapy was associated with delayed viral clearance of Middle East respiratory syndrome or a higher viral load of SARS-CoV.2,3 The uncertainty surrounding the therapeutic use of corticosteroids in treating COVID-19 led to a simultaneous global effort to conduct randomized controlled trials to urgently examine this important clinical question. The open-label Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, conducted in the UK, was the first large-scale randomized clinical trial that reported the clinical benefit of corticosteroids in treating patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Specifically, it showed that low-dose dexamethasone (6 mg/day) administered orally or IV for up to 10 days resulted in a 2.8% absolute reduction in 28-day mortality, with the greatest benefit, an absolute risk reduction of 12.1%, conferred to patients who were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at the time of randomization.4 In response to these findings, the National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel recommended the use of dexamethasone in patients with COVID-19 who are on mechanical ventilation or who require supplemental oxygen, and recommended against the use of dexamethasone for those not requiring supplemental oxygen.5

The meta-analysis discussed in this commentary, conducted by the WHO REACT Working Group, has replicated initial findings from the RECOVERY trial. This prospective meta-analysis pooled data from 7 randomized controlled trials of corticosteroid therapy in 1703 critically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Similar to findings from the RECOVERY trial, corticosteroids were associated with lower all-cause mortality at 28 days after randomization, and this benefit was observed both in critically ill patients who were receiving mechanical ventilation or supplemental oxygen without mechanical ventilation. Interestingly, while the OR estimates were imprecise, the reduction in mortality rates was similar between patients who were administered dexamethasone and hydrocortisone, which may suggest a general drug class effect. In addition, the mortality benefit of corticosteroids appeared similar for those aged ≤ 60 years and those aged > 60 years, between female and male patients, and those who were symptomatic for ≤ 7 days or > 7 days before randomization. Moreover, the administration of corticosteroids did not appear to increase the risk of SAEs. While more data are needed, results from the RECOVERY trial and this prospective meta-analysis indicate that corticosteroids should be an essential pharmacologic treatment for COVID-19, and suggest its potential role as a standard of care for critically ill patients with COVID-19.

This study has several limitations. First, not all trials systematically identified participated in the meta-analysis. Second, long-term outcomes after hospital discharge were not captured, and thus the effect of corticosteroids on long-term mortality and other adverse outcomes, such as hospital readmission, remain unknown. Third, because children were excluded from study participation, the effect of corticosteroids on pediatric COVID-19 patients is unknown. Fourth, the RECOVERY trial contributed more than 50% of patients in the current analysis, although there was little inconsistency in the effects of corticosteroids on mortality between individual trials. Last, the meta-analysis was unable to establish the optimal dose or duration of corticosteroid intervention in critically ill COVID-19 patients, or determine its efficacy in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, all of which are key clinical questions that will need to be addressed with further clinical investigations.

The development of effective treatments for COVID-19 is critical to mitigating the devastating consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Several recent COVID-19 clinical trials have shown promise in this endeavor. For instance, the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACCT-1) found that intravenous remdesivir, as compared to placebo, significantly shortened time to recovery in adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who had evidence of lower respiratory tract infection.6 Moreover, there is some evidence to suggest that convalescent plasma and aerosol inhalation of IFN-κ may have beneficial effects in treating COVID-19.7,8 Thus, clinical trials designed to investigate combination therapy approaches including corticosteroids, remdesivir, convalescent plasma, and others are urgently needed to help identify interventions that most effectively treat COVID-19.

Applications for Clinical Practice

The use of corticosteroids in critically ill patients with COVID-19 reduces overall mortality. This treatment is inexpensive and available in most care settings, including low-resource regions, and provides hope for better outcomes in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Katerina Oikonomou, MD, PhD

General Hospital of Larissa, Larissa, Greece

Fred Ko, MD, MS

1. Sterne JAC, Diaz J, Villar J, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with COVID-19: A structured summary of a study protocol for a prospective meta-analysis of randomized trials. Trials. 2020;21:734.

2. Lee N, Allen Chan KC, Hui DS, et al. Effects of early corticosteroid treatment on plasma SARS-associated Coronavirus RNA concentrations in adult patients. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:304-309.

3. Arabi YM, Mandourah Y, Al-Hameed F, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for citically Ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:757-767.

4. RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 - preliminary report [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 17]. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMoa2021436.

5. NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/immune-based-therapy/immunomodulators/corticosteroids/. Accessed September 11, 2020.

6. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19--preliminary report [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 22]. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMoa2007764.

7. Casadevall A, Joyner MJ, Pirofski LA. A randomized trial of convalescent plasma for covid-19-potentially hopeful signals. JAMA. 2020;324:455-457.

8. Fu W, Liu Y, Xia L, et al. A clinical pilot study on the safety and efficacy of aerosol inhalation treatment of IFN-κ plus TFF2 in patients with moderate COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:100478.

1. Sterne JAC, Diaz J, Villar J, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with COVID-19: A structured summary of a study protocol for a prospective meta-analysis of randomized trials. Trials. 2020;21:734.

2. Lee N, Allen Chan KC, Hui DS, et al. Effects of early corticosteroid treatment on plasma SARS-associated Coronavirus RNA concentrations in adult patients. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:304-309.

3. Arabi YM, Mandourah Y, Al-Hameed F, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for citically Ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:757-767.