User login

Internist reports from COVID-19 front lines near Seattle

KENT, WASHINGTON – The first thing I learned in this outbreak is that my sense of alarm has been deadened by years of medical practice. As a primary care doctor working south of Seattle, in the University of Washington’s Kent neighborhood clinic, I have dealt with long hours, the sometimes-insurmountable problems of the patients I care for, and the constant, gnawing fear of missing something and doing harm. To get through my day, I’ve done my best to rationalize that fear, to explain it away.

I can’t explain how, when I heard the news of the coronavirus epidemic in China, I didn’t think it would affect me. I can’t explain how news of the first patient presenting to an urgent care north of Seattle didn’t cause me, or all health care providers, to think about how we would respond. I can’t explain why so many doctors were dismissive of the very real threat that was about to explode. I can’t explain why it took 6 weeks for the COVID-19 outbreak to seem real to me.

If you work in a doctor’s office, emergency department, hospital, or urgent care center and have not seen a coronavirus case yet, you may have time to think through what is likely to happen in your community. We did not activate a chain of command or decide how information was going to be communicated to the front line and back to leadership. Few of us ran worst-case scenarios.

By March 12, we had 376 confirmed cases, and likely more than a thousand are undetected. The moment of realization of the severity of the outbreak didn’t come to me until Saturday, Feb. 29. In the week prior, several patients had come into the clinic with symptoms and potential exposures, but not meeting the narrow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention testing criteria. They were all advised by the Washington Department of Health to go home. At the time, it seemed like decent advice. Frontline providers didn’t know that there had been two cases of community transmission weeks before, or that one was about to become the first death in Washington state. I still advised patients to quarantine themselves. In the absence of testing, we had to assume everyone was positive and should stay home until 72 hours after their symptoms resolved. Studying the state’s FMLA [Family and Medical Leave Act] intently, I wrote insistent letters to inflexible bosses, explaining that their employees needed to stay home.

I worked that Saturday. Half of my patients had coughs. Our team insisted that they wear masks. One woman refused, and I refused to see her until she did. In a customer service–oriented health care system, I had been schooled to accommodate almost any patient request. But I was not about to put my staff and other patients at risk. Reluctantly, she complied.

On my lunch break, my partner called me to tell me he was at the grocery store. “Why?” I asked, since we usually went together. It became clear he was worried about an outbreak. He had been following the news closely and tried to tell me how deadly this could get and how quickly the disease could spread. I brushed his fears aside, as more evidence of his sweet and overly cautious nature. “It’ll be fine,” I said with misplaced confidence.

Later that day, I heard about the first death and the outbreak at Life Care, a nursing home north of Seattle. I learned that firefighters who had responded to distress calls were under quarantine. I learned through an epidemiologist that there were likely hundreds of undetected cases throughout Washington.

On Monday, our clinic decided to convert all cases with symptoms into telemedicine visits. Luckily, we had been building the capacity to see and treat patients virtually for a while. We have ramped up quickly, but there have been bumps along the way. It’s difficult to convince those who are anxious about their symptoms to allow us to use telemedicine for everyone’s safety. It is unclear how much liability we are taking on as individual providers with this approach or who will speak up for us if something goes wrong.

Patients don’t seem to know where to get their information, and they have been turning to increasingly bizarre sources. For the poorest, who have had so much trouble accessing care, I cannot blame them for not knowing whom to trust. I post what I know on Twitter and Facebook, but I know I’m no match for cynical social media algorithms.

Testing was still not available at my clinic the first week of March, and it remains largely unavailable throughout much of the country. We have lost weeks of opportunity to contain this. Luckily, on March 4, the University of Washington was finally allowed to use their homegrown test and bypass the limited supply from the CDC. But our capacity at UW is still limited, and the test remained unavailable to the majority of those potentially showing symptoms until March 9.

I am used to being less worried than my patients. I am used to reassuring them. But over the first week of March, I had an eerie sense that my alarm far outstripped theirs. I got relatively few questions about coronavirus, even as the number of cases continued to rise. It wasn’t until the end of the week that I noticed a few were truly fearful. Patients started stealing the gloves and the hand sanitizer, and we had to zealously guard them. My hands are raw from washing.

Throughout this time, I have been grateful for a centralized drive with clear protocols. I am grateful for clear messages at the beginning and end of the day from our CEO. I hope that other clinics model this and have daily in-person meetings, because too much cannot be conveyed in an email when the situation changes hourly.

But our health system nationally was already stretched thin before, and providers have sacrificed a lot, especially in the most critical settings, to provide decent patient care. Now we are asked to risk our health and safety, and our family’s, and I worry about the erosion of trust and work conditions for those on the front lines. I also worry our patients won’t believe us when we have allowed the costs of care to continue to rise and ruin their lives. I worry about the millions of people without doctors to call because they have no insurance, and because so many primary care physicians have left unsustainable jobs.

I am grateful that few of my colleagues have been sick and that those that were called out. I am grateful for the new nurse practitioners in our clinic who took the lion’s share of possibly affected patients and triaged hundreds of phone calls, creating note and message templates that we all use. I am grateful that my clinic manager insisted on doing a drill with all the staff members.

I am grateful that we were reminded that we are a team and that if the call center and cleaning crews and front desk are excluded, then our protocols are useless. I am grateful that our registered nurses quickly shifted to triage. I am grateful that I have testing available.

This week, for the first time since I started working, multiple patients asked how I am doing and expressed their thanks. I am most grateful for them.

I can’t tell you what to do or what is going to happen, but I can tell you that you need to prepare now. You need to run drills and catch the holes in your plans before the pandemic reaches you. You need to be creative and honest about the flaws in your organization that this pandemic will inevitably expose. You need to meet with your team every day and remember that we are all going to be stretched even thinner than before.

Most of us will get through this, but many of us won’t. And for those who do, we need to be honest about our successes and failures. We need to build a system that can do better next time. Because this is not the last pandemic we will face.

Dr. Elisabeth Poorman is a general internist at a University of Washington neighborhood clinic in Kent. She completed her residency at Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance and specializes in addiction medicine. She also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

KENT, WASHINGTON – The first thing I learned in this outbreak is that my sense of alarm has been deadened by years of medical practice. As a primary care doctor working south of Seattle, in the University of Washington’s Kent neighborhood clinic, I have dealt with long hours, the sometimes-insurmountable problems of the patients I care for, and the constant, gnawing fear of missing something and doing harm. To get through my day, I’ve done my best to rationalize that fear, to explain it away.

I can’t explain how, when I heard the news of the coronavirus epidemic in China, I didn’t think it would affect me. I can’t explain how news of the first patient presenting to an urgent care north of Seattle didn’t cause me, or all health care providers, to think about how we would respond. I can’t explain why so many doctors were dismissive of the very real threat that was about to explode. I can’t explain why it took 6 weeks for the COVID-19 outbreak to seem real to me.

If you work in a doctor’s office, emergency department, hospital, or urgent care center and have not seen a coronavirus case yet, you may have time to think through what is likely to happen in your community. We did not activate a chain of command or decide how information was going to be communicated to the front line and back to leadership. Few of us ran worst-case scenarios.

By March 12, we had 376 confirmed cases, and likely more than a thousand are undetected. The moment of realization of the severity of the outbreak didn’t come to me until Saturday, Feb. 29. In the week prior, several patients had come into the clinic with symptoms and potential exposures, but not meeting the narrow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention testing criteria. They were all advised by the Washington Department of Health to go home. At the time, it seemed like decent advice. Frontline providers didn’t know that there had been two cases of community transmission weeks before, or that one was about to become the first death in Washington state. I still advised patients to quarantine themselves. In the absence of testing, we had to assume everyone was positive and should stay home until 72 hours after their symptoms resolved. Studying the state’s FMLA [Family and Medical Leave Act] intently, I wrote insistent letters to inflexible bosses, explaining that their employees needed to stay home.

I worked that Saturday. Half of my patients had coughs. Our team insisted that they wear masks. One woman refused, and I refused to see her until she did. In a customer service–oriented health care system, I had been schooled to accommodate almost any patient request. But I was not about to put my staff and other patients at risk. Reluctantly, she complied.

On my lunch break, my partner called me to tell me he was at the grocery store. “Why?” I asked, since we usually went together. It became clear he was worried about an outbreak. He had been following the news closely and tried to tell me how deadly this could get and how quickly the disease could spread. I brushed his fears aside, as more evidence of his sweet and overly cautious nature. “It’ll be fine,” I said with misplaced confidence.

Later that day, I heard about the first death and the outbreak at Life Care, a nursing home north of Seattle. I learned that firefighters who had responded to distress calls were under quarantine. I learned through an epidemiologist that there were likely hundreds of undetected cases throughout Washington.

On Monday, our clinic decided to convert all cases with symptoms into telemedicine visits. Luckily, we had been building the capacity to see and treat patients virtually for a while. We have ramped up quickly, but there have been bumps along the way. It’s difficult to convince those who are anxious about their symptoms to allow us to use telemedicine for everyone’s safety. It is unclear how much liability we are taking on as individual providers with this approach or who will speak up for us if something goes wrong.

Patients don’t seem to know where to get their information, and they have been turning to increasingly bizarre sources. For the poorest, who have had so much trouble accessing care, I cannot blame them for not knowing whom to trust. I post what I know on Twitter and Facebook, but I know I’m no match for cynical social media algorithms.

Testing was still not available at my clinic the first week of March, and it remains largely unavailable throughout much of the country. We have lost weeks of opportunity to contain this. Luckily, on March 4, the University of Washington was finally allowed to use their homegrown test and bypass the limited supply from the CDC. But our capacity at UW is still limited, and the test remained unavailable to the majority of those potentially showing symptoms until March 9.

I am used to being less worried than my patients. I am used to reassuring them. But over the first week of March, I had an eerie sense that my alarm far outstripped theirs. I got relatively few questions about coronavirus, even as the number of cases continued to rise. It wasn’t until the end of the week that I noticed a few were truly fearful. Patients started stealing the gloves and the hand sanitizer, and we had to zealously guard them. My hands are raw from washing.

Throughout this time, I have been grateful for a centralized drive with clear protocols. I am grateful for clear messages at the beginning and end of the day from our CEO. I hope that other clinics model this and have daily in-person meetings, because too much cannot be conveyed in an email when the situation changes hourly.

But our health system nationally was already stretched thin before, and providers have sacrificed a lot, especially in the most critical settings, to provide decent patient care. Now we are asked to risk our health and safety, and our family’s, and I worry about the erosion of trust and work conditions for those on the front lines. I also worry our patients won’t believe us when we have allowed the costs of care to continue to rise and ruin their lives. I worry about the millions of people without doctors to call because they have no insurance, and because so many primary care physicians have left unsustainable jobs.

I am grateful that few of my colleagues have been sick and that those that were called out. I am grateful for the new nurse practitioners in our clinic who took the lion’s share of possibly affected patients and triaged hundreds of phone calls, creating note and message templates that we all use. I am grateful that my clinic manager insisted on doing a drill with all the staff members.

I am grateful that we were reminded that we are a team and that if the call center and cleaning crews and front desk are excluded, then our protocols are useless. I am grateful that our registered nurses quickly shifted to triage. I am grateful that I have testing available.

This week, for the first time since I started working, multiple patients asked how I am doing and expressed their thanks. I am most grateful for them.

I can’t tell you what to do or what is going to happen, but I can tell you that you need to prepare now. You need to run drills and catch the holes in your plans before the pandemic reaches you. You need to be creative and honest about the flaws in your organization that this pandemic will inevitably expose. You need to meet with your team every day and remember that we are all going to be stretched even thinner than before.

Most of us will get through this, but many of us won’t. And for those who do, we need to be honest about our successes and failures. We need to build a system that can do better next time. Because this is not the last pandemic we will face.

Dr. Elisabeth Poorman is a general internist at a University of Washington neighborhood clinic in Kent. She completed her residency at Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance and specializes in addiction medicine. She also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

KENT, WASHINGTON – The first thing I learned in this outbreak is that my sense of alarm has been deadened by years of medical practice. As a primary care doctor working south of Seattle, in the University of Washington’s Kent neighborhood clinic, I have dealt with long hours, the sometimes-insurmountable problems of the patients I care for, and the constant, gnawing fear of missing something and doing harm. To get through my day, I’ve done my best to rationalize that fear, to explain it away.

I can’t explain how, when I heard the news of the coronavirus epidemic in China, I didn’t think it would affect me. I can’t explain how news of the first patient presenting to an urgent care north of Seattle didn’t cause me, or all health care providers, to think about how we would respond. I can’t explain why so many doctors were dismissive of the very real threat that was about to explode. I can’t explain why it took 6 weeks for the COVID-19 outbreak to seem real to me.

If you work in a doctor’s office, emergency department, hospital, or urgent care center and have not seen a coronavirus case yet, you may have time to think through what is likely to happen in your community. We did not activate a chain of command or decide how information was going to be communicated to the front line and back to leadership. Few of us ran worst-case scenarios.

By March 12, we had 376 confirmed cases, and likely more than a thousand are undetected. The moment of realization of the severity of the outbreak didn’t come to me until Saturday, Feb. 29. In the week prior, several patients had come into the clinic with symptoms and potential exposures, but not meeting the narrow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention testing criteria. They were all advised by the Washington Department of Health to go home. At the time, it seemed like decent advice. Frontline providers didn’t know that there had been two cases of community transmission weeks before, or that one was about to become the first death in Washington state. I still advised patients to quarantine themselves. In the absence of testing, we had to assume everyone was positive and should stay home until 72 hours after their symptoms resolved. Studying the state’s FMLA [Family and Medical Leave Act] intently, I wrote insistent letters to inflexible bosses, explaining that their employees needed to stay home.

I worked that Saturday. Half of my patients had coughs. Our team insisted that they wear masks. One woman refused, and I refused to see her until she did. In a customer service–oriented health care system, I had been schooled to accommodate almost any patient request. But I was not about to put my staff and other patients at risk. Reluctantly, she complied.

On my lunch break, my partner called me to tell me he was at the grocery store. “Why?” I asked, since we usually went together. It became clear he was worried about an outbreak. He had been following the news closely and tried to tell me how deadly this could get and how quickly the disease could spread. I brushed his fears aside, as more evidence of his sweet and overly cautious nature. “It’ll be fine,” I said with misplaced confidence.

Later that day, I heard about the first death and the outbreak at Life Care, a nursing home north of Seattle. I learned that firefighters who had responded to distress calls were under quarantine. I learned through an epidemiologist that there were likely hundreds of undetected cases throughout Washington.

On Monday, our clinic decided to convert all cases with symptoms into telemedicine visits. Luckily, we had been building the capacity to see and treat patients virtually for a while. We have ramped up quickly, but there have been bumps along the way. It’s difficult to convince those who are anxious about their symptoms to allow us to use telemedicine for everyone’s safety. It is unclear how much liability we are taking on as individual providers with this approach or who will speak up for us if something goes wrong.

Patients don’t seem to know where to get their information, and they have been turning to increasingly bizarre sources. For the poorest, who have had so much trouble accessing care, I cannot blame them for not knowing whom to trust. I post what I know on Twitter and Facebook, but I know I’m no match for cynical social media algorithms.

Testing was still not available at my clinic the first week of March, and it remains largely unavailable throughout much of the country. We have lost weeks of opportunity to contain this. Luckily, on March 4, the University of Washington was finally allowed to use their homegrown test and bypass the limited supply from the CDC. But our capacity at UW is still limited, and the test remained unavailable to the majority of those potentially showing symptoms until March 9.

I am used to being less worried than my patients. I am used to reassuring them. But over the first week of March, I had an eerie sense that my alarm far outstripped theirs. I got relatively few questions about coronavirus, even as the number of cases continued to rise. It wasn’t until the end of the week that I noticed a few were truly fearful. Patients started stealing the gloves and the hand sanitizer, and we had to zealously guard them. My hands are raw from washing.

Throughout this time, I have been grateful for a centralized drive with clear protocols. I am grateful for clear messages at the beginning and end of the day from our CEO. I hope that other clinics model this and have daily in-person meetings, because too much cannot be conveyed in an email when the situation changes hourly.

But our health system nationally was already stretched thin before, and providers have sacrificed a lot, especially in the most critical settings, to provide decent patient care. Now we are asked to risk our health and safety, and our family’s, and I worry about the erosion of trust and work conditions for those on the front lines. I also worry our patients won’t believe us when we have allowed the costs of care to continue to rise and ruin their lives. I worry about the millions of people without doctors to call because they have no insurance, and because so many primary care physicians have left unsustainable jobs.

I am grateful that few of my colleagues have been sick and that those that were called out. I am grateful for the new nurse practitioners in our clinic who took the lion’s share of possibly affected patients and triaged hundreds of phone calls, creating note and message templates that we all use. I am grateful that my clinic manager insisted on doing a drill with all the staff members.

I am grateful that we were reminded that we are a team and that if the call center and cleaning crews and front desk are excluded, then our protocols are useless. I am grateful that our registered nurses quickly shifted to triage. I am grateful that I have testing available.

This week, for the first time since I started working, multiple patients asked how I am doing and expressed their thanks. I am most grateful for them.

I can’t tell you what to do or what is going to happen, but I can tell you that you need to prepare now. You need to run drills and catch the holes in your plans before the pandemic reaches you. You need to be creative and honest about the flaws in your organization that this pandemic will inevitably expose. You need to meet with your team every day and remember that we are all going to be stretched even thinner than before.

Most of us will get through this, but many of us won’t. And for those who do, we need to be honest about our successes and failures. We need to build a system that can do better next time. Because this is not the last pandemic we will face.

Dr. Elisabeth Poorman is a general internist at a University of Washington neighborhood clinic in Kent. She completed her residency at Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance and specializes in addiction medicine. She also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

No sedation fails to improve mortality in mechanically ventilated patients

ORLANDO – For critically ill, according to results of a multicenter, randomized trial.

The lack of sedation did significantly improve certain secondary endpoints, including a reduced number of thromboembolic events and preservation of physical function, according to Palle Toft, PhD, DMSc, of Odense (Denmark) University Hospital.

However, the 90-day mortality rate was 42.4% in the no-sedation group versus 37.0% in the sedation group in the NONSEDA study, which was intended to test the hypothesis that mortality would be lower in the no-sedation group.

That 5.4 percentage point difference between arms in NONSEDA was not statistically significant (P = .65) in results of the study, presented at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine and concurrently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Yet that mortality trend is in the “opposite direction” of an earlier, single-center trial by Dr. Toft and colleagues, noted Claude Guérin, MD, PhD, in a related editorial that also appeared in the journal. In that earlier study, the reported hospital mortality rates were 36% for no sedation and 47% for sedation with daily interruption.

“The results from this trial [NONSEDA] are important because they arouse concern about omitting sedation in mechanically ventilated patients and reinforce the need to monitor sedation clinically, with the aim of discontinuing it as early as possible or at least interrupting it daily,” Dr. Guérin wrote in his editorial.

That said, the earlier, single-center trial was not statistically powered to show between-group differences in mortality, Dr. Toft and coauthors wrote in their journal article.

In his presentation, Dr. Toft emphasized that light sedation with a wake-up trial was “comparable” with no sedation with regard to mortality.

“I think my main message is that we have to individualize patient treatment,” Dr. Toft told attendees at a late-breaking literature session. “Many patients would benefit from nonsedation, and some would benefit by light sedation with a daily wake-up trial. We have to respect patient autonomy, and try to establish a two-way communication with patients in 2020.”

Sandra L. Kane-Gill, PharmD, treasurer of SCCM and assistant professor of pharmacy and therapeutics at the University of Pittsburgh, said that current SCCM guidelines recommend using light sedation in critically ill, mechanically ventilated adults.

“I think we should stay consistent with what the guidelines are saying,” Dr. Kane-Gill said in an interview. “How you do that may vary, but targeting light sedation is consistent with what the evidence is suggesting in those guidelines.”

The depth of sedation between the no-sedation group in the light sedation group in the present study was not as great as the investigators had anticipated, which may explain the lack of statistically significant difference in mortality, according to Dr. Kane-Gill.

According to the report, 38.4% of patients in the no-sedation group received medication for sedation during their ICU stay, while Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scores increased in both groups, indicating a more alert state in both groups.

The multicenter NONSEDA trial included 700 mechanically ventilated ICU patients randomized either to no sedation or to light sedation, such that the patient was arousable, with daily interruption.

Previous studies have shown that daily interruption of sedation reduced mechanical ventilation duration, ICU stay length, and mortality in comparison with no interruption, the investigators noted.

While mortality at 90 days did not differ significantly between the no-sedation and light-sedation approaches, no sedation reduced thromboembolic events, Dr. Toft said at the meeting. The number of thrombolic events within 90 days was 10 (5%) in the sedation group and 1 (0.5%) in the no-sedation group (P less than .05), according to the reported data.

Likewise, several measures of physical function significantly improved in an a prior defined subgroup of 200 patients, he said. Those measures included hand grip at extubation and ICU discharge, as well as scores on the Barthel Index for Activities of Daily Living.

Nonsedation might improve kidney function, based on other reported outcomes of the study, Dr. Toft said. The number of coma- and delirium-free days was 3.0 in the no-sedation group versus 1.0 in the sedation group (P less than .01), he added.

The benefits of no sedation may extend beyond objective changes in health outcomes, according to Dr. Toft. “The patients are able to communicate with the staff, they might be able to enjoy food, in the evening they can look at the television instead of being sedated – and they can be mobilized and they can write their opinion about the treatments to the doctor, and in this way, you have two-way communication,” he explained in his presentation.

Dr. Toft reported that he had no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Toft P et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1906759.

ORLANDO – For critically ill, according to results of a multicenter, randomized trial.

The lack of sedation did significantly improve certain secondary endpoints, including a reduced number of thromboembolic events and preservation of physical function, according to Palle Toft, PhD, DMSc, of Odense (Denmark) University Hospital.

However, the 90-day mortality rate was 42.4% in the no-sedation group versus 37.0% in the sedation group in the NONSEDA study, which was intended to test the hypothesis that mortality would be lower in the no-sedation group.

That 5.4 percentage point difference between arms in NONSEDA was not statistically significant (P = .65) in results of the study, presented at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine and concurrently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Yet that mortality trend is in the “opposite direction” of an earlier, single-center trial by Dr. Toft and colleagues, noted Claude Guérin, MD, PhD, in a related editorial that also appeared in the journal. In that earlier study, the reported hospital mortality rates were 36% for no sedation and 47% for sedation with daily interruption.

“The results from this trial [NONSEDA] are important because they arouse concern about omitting sedation in mechanically ventilated patients and reinforce the need to monitor sedation clinically, with the aim of discontinuing it as early as possible or at least interrupting it daily,” Dr. Guérin wrote in his editorial.

That said, the earlier, single-center trial was not statistically powered to show between-group differences in mortality, Dr. Toft and coauthors wrote in their journal article.

In his presentation, Dr. Toft emphasized that light sedation with a wake-up trial was “comparable” with no sedation with regard to mortality.

“I think my main message is that we have to individualize patient treatment,” Dr. Toft told attendees at a late-breaking literature session. “Many patients would benefit from nonsedation, and some would benefit by light sedation with a daily wake-up trial. We have to respect patient autonomy, and try to establish a two-way communication with patients in 2020.”

Sandra L. Kane-Gill, PharmD, treasurer of SCCM and assistant professor of pharmacy and therapeutics at the University of Pittsburgh, said that current SCCM guidelines recommend using light sedation in critically ill, mechanically ventilated adults.

“I think we should stay consistent with what the guidelines are saying,” Dr. Kane-Gill said in an interview. “How you do that may vary, but targeting light sedation is consistent with what the evidence is suggesting in those guidelines.”

The depth of sedation between the no-sedation group in the light sedation group in the present study was not as great as the investigators had anticipated, which may explain the lack of statistically significant difference in mortality, according to Dr. Kane-Gill.

According to the report, 38.4% of patients in the no-sedation group received medication for sedation during their ICU stay, while Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scores increased in both groups, indicating a more alert state in both groups.

The multicenter NONSEDA trial included 700 mechanically ventilated ICU patients randomized either to no sedation or to light sedation, such that the patient was arousable, with daily interruption.

Previous studies have shown that daily interruption of sedation reduced mechanical ventilation duration, ICU stay length, and mortality in comparison with no interruption, the investigators noted.

While mortality at 90 days did not differ significantly between the no-sedation and light-sedation approaches, no sedation reduced thromboembolic events, Dr. Toft said at the meeting. The number of thrombolic events within 90 days was 10 (5%) in the sedation group and 1 (0.5%) in the no-sedation group (P less than .05), according to the reported data.

Likewise, several measures of physical function significantly improved in an a prior defined subgroup of 200 patients, he said. Those measures included hand grip at extubation and ICU discharge, as well as scores on the Barthel Index for Activities of Daily Living.

Nonsedation might improve kidney function, based on other reported outcomes of the study, Dr. Toft said. The number of coma- and delirium-free days was 3.0 in the no-sedation group versus 1.0 in the sedation group (P less than .01), he added.

The benefits of no sedation may extend beyond objective changes in health outcomes, according to Dr. Toft. “The patients are able to communicate with the staff, they might be able to enjoy food, in the evening they can look at the television instead of being sedated – and they can be mobilized and they can write their opinion about the treatments to the doctor, and in this way, you have two-way communication,” he explained in his presentation.

Dr. Toft reported that he had no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Toft P et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1906759.

ORLANDO – For critically ill, according to results of a multicenter, randomized trial.

The lack of sedation did significantly improve certain secondary endpoints, including a reduced number of thromboembolic events and preservation of physical function, according to Palle Toft, PhD, DMSc, of Odense (Denmark) University Hospital.

However, the 90-day mortality rate was 42.4% in the no-sedation group versus 37.0% in the sedation group in the NONSEDA study, which was intended to test the hypothesis that mortality would be lower in the no-sedation group.

That 5.4 percentage point difference between arms in NONSEDA was not statistically significant (P = .65) in results of the study, presented at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine and concurrently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Yet that mortality trend is in the “opposite direction” of an earlier, single-center trial by Dr. Toft and colleagues, noted Claude Guérin, MD, PhD, in a related editorial that also appeared in the journal. In that earlier study, the reported hospital mortality rates were 36% for no sedation and 47% for sedation with daily interruption.

“The results from this trial [NONSEDA] are important because they arouse concern about omitting sedation in mechanically ventilated patients and reinforce the need to monitor sedation clinically, with the aim of discontinuing it as early as possible or at least interrupting it daily,” Dr. Guérin wrote in his editorial.

That said, the earlier, single-center trial was not statistically powered to show between-group differences in mortality, Dr. Toft and coauthors wrote in their journal article.

In his presentation, Dr. Toft emphasized that light sedation with a wake-up trial was “comparable” with no sedation with regard to mortality.

“I think my main message is that we have to individualize patient treatment,” Dr. Toft told attendees at a late-breaking literature session. “Many patients would benefit from nonsedation, and some would benefit by light sedation with a daily wake-up trial. We have to respect patient autonomy, and try to establish a two-way communication with patients in 2020.”

Sandra L. Kane-Gill, PharmD, treasurer of SCCM and assistant professor of pharmacy and therapeutics at the University of Pittsburgh, said that current SCCM guidelines recommend using light sedation in critically ill, mechanically ventilated adults.

“I think we should stay consistent with what the guidelines are saying,” Dr. Kane-Gill said in an interview. “How you do that may vary, but targeting light sedation is consistent with what the evidence is suggesting in those guidelines.”

The depth of sedation between the no-sedation group in the light sedation group in the present study was not as great as the investigators had anticipated, which may explain the lack of statistically significant difference in mortality, according to Dr. Kane-Gill.

According to the report, 38.4% of patients in the no-sedation group received medication for sedation during their ICU stay, while Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scores increased in both groups, indicating a more alert state in both groups.

The multicenter NONSEDA trial included 700 mechanically ventilated ICU patients randomized either to no sedation or to light sedation, such that the patient was arousable, with daily interruption.

Previous studies have shown that daily interruption of sedation reduced mechanical ventilation duration, ICU stay length, and mortality in comparison with no interruption, the investigators noted.

While mortality at 90 days did not differ significantly between the no-sedation and light-sedation approaches, no sedation reduced thromboembolic events, Dr. Toft said at the meeting. The number of thrombolic events within 90 days was 10 (5%) in the sedation group and 1 (0.5%) in the no-sedation group (P less than .05), according to the reported data.

Likewise, several measures of physical function significantly improved in an a prior defined subgroup of 200 patients, he said. Those measures included hand grip at extubation and ICU discharge, as well as scores on the Barthel Index for Activities of Daily Living.

Nonsedation might improve kidney function, based on other reported outcomes of the study, Dr. Toft said. The number of coma- and delirium-free days was 3.0 in the no-sedation group versus 1.0 in the sedation group (P less than .01), he added.

The benefits of no sedation may extend beyond objective changes in health outcomes, according to Dr. Toft. “The patients are able to communicate with the staff, they might be able to enjoy food, in the evening they can look at the television instead of being sedated – and they can be mobilized and they can write their opinion about the treatments to the doctor, and in this way, you have two-way communication,” he explained in his presentation.

Dr. Toft reported that he had no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Toft P et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1906759.

REPORTING FROM CCC49

What hospitalists need to know about COVID-19

This article last updated 4/8/20. (Disclaimer: The information in this article may not be updated regularly. For more COVID-19 coverage, bookmark our COVID-19 updates page. The editors of The Hospitalist encourage clinicians to also review information on the CDC website and on the AHA website.)

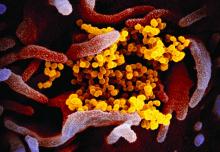

An infectious disease outbreak that began in December 2019 in Wuhan (Hubei Province), China, was found to be caused by the seventh strain of coronavirus, initially called the novel (new) coronavirus. The virus was later labeled as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named COVID-19. Until 2019, only six strains of human coronaviruses had previously been identified.

As of April 8, 2020, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 has been detected in at least 209 countries and has spread to every contintent except Antarctica. More than 1,469,245 people have become infected globally, and at least 86,278 have died. Based on the cases detected and tested in the United States through the U.S. public health surveillance systems, we have had 406,693 confirmed cases and 13,089 deaths.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic.

As the number of cases increases in the United States, we hope to provide answers about some common questions regarding COVID-19. The information summarized in this article is obtained and modified from the CDC.

What are the clinical features of COVID-19?

Ranges from asymptomatic infection, a mild disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms of acute respiratory illness, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and septic shock.

Who is at risk for COVID-19?

Persons who have had prolonged, unprotected close contact with a patient with symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19, and those with recent travel to China, especially Hubei Province.

Who is at risk for severe disease from COVID-19?

Older adults and persons who have underlying chronic medical conditions, such as immunocompromising conditions.

How is COVID-19 spread?

Person-to-person, mainly through respiratory droplets. SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated from upper respiratory tract specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

When is someone infectious?

Incubation period may range from 2 to 14 days. Detection of viral RNA does not necessarily mean that infectious virus is present, as it may be detectable in the upper or lower respiratory tract for weeks after illness onset.

Can someone who has been quarantined for COVID-19 spread the illness to others?

For COVID-19, the period of quarantine is 14 days from the last date of exposure, because 14 days is the longest incubation period seen for similar coronaviruses. Someone who has been released from COVID-19 quarantine is not considered a risk for spreading the virus to others because they have not developed illness during the incubation period.

Can a person test negative and later test positive for COVID-19?

Yes. In the early stages of infection, it is possible the virus will not be detected.

Do patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 need to be admitted to the hospital?

Not all patients with COVID-19 require hospital admission. Patients whose clinical presentation warrants inpatient clinical management for supportive medical care should be admitted to the hospital under appropriate isolation precautions. The decision to monitor these patients in the inpatient or outpatient setting should be made on a case-by-case basis.

What should you do if you suspect a patient for COVID-19?

Immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department. State health departments that have identified a person under investigation (PUI) should immediately contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 and complete a COVID-19 PUI case investigation form.

CDC’s EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during after-hours or on weekends/holidays.

What type of isolation is needed for COVID-19?

Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) using Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions with eye protection.

How should health care personnel protect themselves when evaluating a patient who may have COVID-19?

Standard Precautions, Contact Precautions, Airborne Precautions, and use eye protection (e.g., goggles or a face shield).

What face mask do health care workers wear for respiratory protection?

A fit-tested NIOSH-certified disposable N95 filtering facepiece respirator should be worn before entry into the patient room or care area. Disposable respirators should be removed and discarded after exiting the patient’s room or care area and closing the door. Perform hand hygiene after discarding the respirator.

If reusable respirators (e.g., powered air purifying respirator/PAPR) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use.

What should you tell the patient if COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed?

Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be asked to wear a surgical mask as soon as they are identified, to prevent spread to others.

Should any diagnostic or therapeutic interventions be withheld because of concerns about the transmission of COVID-19?

No.

How do you test a patient for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

At this time, diagnostic testing for COVID-19 can be conducted only at CDC.

The CDC recommends collecting and testing multiple clinical specimens from different sites, including two specimen types – lower respiratory and upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal aspirates or washes, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, bronchioalveolar lavage, tracheal aspirates, sputum, and serum) using a real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified regardless of the time of symptom onset. Turnaround time for the PCR assay testing is about 24-48 hours.

Testing for other respiratory pathogens should not delay specimen shipping to CDC. If a PUI tests positive for another respiratory pathogen, after clinical evaluation and consultation with public health authorities, they may no longer be considered a PUI.

Will existing respiratory virus panels detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

No.

How is COVID-19 treated?

Symptomatic management. Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for viral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome and should be avoided unless they are indicated for another reason (e.g., COPD exacerbation, refractory septic shock following Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines). There are currently no antiviral drugs licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19.

What is considered ‘close contact’ for health care exposures?

Being within approximately 6 feet (2 meters), of a person with COVID-19 for a prolonged period of time (such as caring for or visiting the patient, or sitting within 6 feet of the patient in a health care waiting area or room); or having unprotected direct contact with infectious secretions or excretions of the patient (e.g., being coughed on, touching used tissues with a bare hand). However, until more is known about transmission risks, it would be reasonable to consider anything longer than a brief (e.g., less than 1-2 minutes) exposure as prolonged.

What happens if the health care personnel (HCP) are exposed to confirmed COVID-19 patients? What’s the protocol for HCP exposed to persons under investigation (PUI) if test results are delayed beyond 48-72 hours?

Management is similar in both these scenarios. CDC categorized exposures as high, medium, low, and no identifiable risk. High- and medium-risk exposures are managed similarly with active monitoring for COVID-19 until 14 days after last potential exposure and exclude from work for 14 days after last exposure. Active monitoring means that the state or local public health authority assumes responsibility for establishing regular communication with potentially exposed people to assess for the presence of fever or respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath, sore throat). For HCP with high- or medium-risk exposures, CDC recommends this communication occurs at least once each day. For full details, please see www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html.

Should postexposure prophylaxis be used for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19?

None available.

COVID-19 test results are negative in a symptomatic patient you suspected of COVID-19? What does it mean?

A negative test result for a sample collected while a person has symptoms likely means that the COVID-19 virus is not causing their current illness.

What if your hospital does not have an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Transfer the patient to a facility that has an available AIIR. If a transfer is impractical or not medically appropriate, the patient should be cared for in a single-person room and the door should be kept closed. The room should ideally not have an exhaust that is recirculated within the building without high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. Health care personnel should still use gloves, gown, respiratory and eye protection and follow all other recommended infection prevention and control practices when caring for these patients.

What if your hospital does not have enough Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Prioritize patients for AIIR who are symptomatic with severe illness (e.g., those requiring ventilator support).

When can patients with confirmed COVID-19 be discharged from the hospital?

Patients can be discharged from the health care facility whenever clinically indicated. Isolation should be maintained at home if the patient returns home before the time period recommended for discontinuation of hospital transmission-based precautions.

Considerations to discontinue transmission-based precautions include all of the following:

- Resolution of fever, without the use of antipyretic medication.

- Improvement in illness signs and symptoms.

- Negative rRT-PCR results from at least two consecutive sets of paired nasopharyngeal and throat swabs specimens collected at least 24 hours apart (total of four negative specimens – two nasopharyngeal and two throat) from a patient with COVID-19 are needed before discontinuing transmission-based precautions.

Should people be concerned about pets or other animals and COVID-19?

To date, CDC has not received any reports of pets or other animals becoming sick with COVID-19.

Should patients avoid contact with pets or other animals if they are sick with COVID-19?

Patients should restrict contact with pets and other animals while they are sick with COVID-19, just like they would around other people.

Does CDC recommend the use of face masks in the community to prevent COVID-19?

CDC does not recommend that people who are well wear a face mask to protect themselves from respiratory illnesses, including COVID-19. A face mask should be used by people who have COVID-19 and are showing symptoms to protect others from the risk of getting infected.

Should medical waste or general waste from health care facilities treating PUIs and patients with confirmed COVID-19 be handled any differently or need any additional disinfection?

No. CDC’s guidance states that management of laundry, food service utensils, and medical waste should be performed in accordance with routine procedures.

Can people who recover from COVID-19 be infected again?

Unknown. The immune response to COVID-19 is not yet understood.

What is the mortality rate of COVID-19, and how does it compare to the mortality rate of influenza (flu)?

The average 10-year mortality rate for flu, using CDC data, is found to be around 0.1%. Even though this percentage appears to be small, influenza is estimated to be responsible for 30,000 to 40,000 deaths annually in the U.S.

According to statistics released by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention on Feb. 17, the mortality rate of COVID-19 is estimated to be around 2.3%. This calculation was based on cases reported through Feb. 11, and calcuated by dividing the number of coronavirus-related deaths at the time (1,023) by the number of confirmed cases (44,672) of COVID-19 infection. However, this report has its limitations, since Chinese officials have a vague way of defining who has COVID-19 infection.

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently estimates the mortality rate for COVID-19 to be between 2% and 4%.

Dr. Sitammagari is a co-medical director for quality and assistant professor of internal medicine at Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. He is also a physician advisor. He currently serves as treasurer for the NC-Triangle Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine and as an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization. Dr. Skandhan was a cofounder of the Wiregrass chapter of SHM and currently serves on the Advisory board. He is also a member of the editorial board of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Dahlin is a second-year internal medicine resident at Southeast Health, Dothan, Ala. She serves as her class representative and is the cochair/resident liaison for the research committee at SEH. Dr. Dahlin also serves as a resident liaison for the Wiregrass chapter of SHM.

This article last updated 4/8/20. (Disclaimer: The information in this article may not be updated regularly. For more COVID-19 coverage, bookmark our COVID-19 updates page. The editors of The Hospitalist encourage clinicians to also review information on the CDC website and on the AHA website.)

An infectious disease outbreak that began in December 2019 in Wuhan (Hubei Province), China, was found to be caused by the seventh strain of coronavirus, initially called the novel (new) coronavirus. The virus was later labeled as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named COVID-19. Until 2019, only six strains of human coronaviruses had previously been identified.

As of April 8, 2020, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 has been detected in at least 209 countries and has spread to every contintent except Antarctica. More than 1,469,245 people have become infected globally, and at least 86,278 have died. Based on the cases detected and tested in the United States through the U.S. public health surveillance systems, we have had 406,693 confirmed cases and 13,089 deaths.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic.

As the number of cases increases in the United States, we hope to provide answers about some common questions regarding COVID-19. The information summarized in this article is obtained and modified from the CDC.

What are the clinical features of COVID-19?

Ranges from asymptomatic infection, a mild disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms of acute respiratory illness, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and septic shock.

Who is at risk for COVID-19?

Persons who have had prolonged, unprotected close contact with a patient with symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19, and those with recent travel to China, especially Hubei Province.

Who is at risk for severe disease from COVID-19?

Older adults and persons who have underlying chronic medical conditions, such as immunocompromising conditions.

How is COVID-19 spread?

Person-to-person, mainly through respiratory droplets. SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated from upper respiratory tract specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

When is someone infectious?

Incubation period may range from 2 to 14 days. Detection of viral RNA does not necessarily mean that infectious virus is present, as it may be detectable in the upper or lower respiratory tract for weeks after illness onset.

Can someone who has been quarantined for COVID-19 spread the illness to others?

For COVID-19, the period of quarantine is 14 days from the last date of exposure, because 14 days is the longest incubation period seen for similar coronaviruses. Someone who has been released from COVID-19 quarantine is not considered a risk for spreading the virus to others because they have not developed illness during the incubation period.

Can a person test negative and later test positive for COVID-19?

Yes. In the early stages of infection, it is possible the virus will not be detected.

Do patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 need to be admitted to the hospital?

Not all patients with COVID-19 require hospital admission. Patients whose clinical presentation warrants inpatient clinical management for supportive medical care should be admitted to the hospital under appropriate isolation precautions. The decision to monitor these patients in the inpatient or outpatient setting should be made on a case-by-case basis.

What should you do if you suspect a patient for COVID-19?

Immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department. State health departments that have identified a person under investigation (PUI) should immediately contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 and complete a COVID-19 PUI case investigation form.

CDC’s EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during after-hours or on weekends/holidays.

What type of isolation is needed for COVID-19?

Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) using Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions with eye protection.

How should health care personnel protect themselves when evaluating a patient who may have COVID-19?

Standard Precautions, Contact Precautions, Airborne Precautions, and use eye protection (e.g., goggles or a face shield).

What face mask do health care workers wear for respiratory protection?

A fit-tested NIOSH-certified disposable N95 filtering facepiece respirator should be worn before entry into the patient room or care area. Disposable respirators should be removed and discarded after exiting the patient’s room or care area and closing the door. Perform hand hygiene after discarding the respirator.

If reusable respirators (e.g., powered air purifying respirator/PAPR) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use.

What should you tell the patient if COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed?

Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be asked to wear a surgical mask as soon as they are identified, to prevent spread to others.

Should any diagnostic or therapeutic interventions be withheld because of concerns about the transmission of COVID-19?

No.

How do you test a patient for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

At this time, diagnostic testing for COVID-19 can be conducted only at CDC.

The CDC recommends collecting and testing multiple clinical specimens from different sites, including two specimen types – lower respiratory and upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal aspirates or washes, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, bronchioalveolar lavage, tracheal aspirates, sputum, and serum) using a real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified regardless of the time of symptom onset. Turnaround time for the PCR assay testing is about 24-48 hours.

Testing for other respiratory pathogens should not delay specimen shipping to CDC. If a PUI tests positive for another respiratory pathogen, after clinical evaluation and consultation with public health authorities, they may no longer be considered a PUI.

Will existing respiratory virus panels detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

No.

How is COVID-19 treated?

Symptomatic management. Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for viral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome and should be avoided unless they are indicated for another reason (e.g., COPD exacerbation, refractory septic shock following Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines). There are currently no antiviral drugs licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19.

What is considered ‘close contact’ for health care exposures?

Being within approximately 6 feet (2 meters), of a person with COVID-19 for a prolonged period of time (such as caring for or visiting the patient, or sitting within 6 feet of the patient in a health care waiting area or room); or having unprotected direct contact with infectious secretions or excretions of the patient (e.g., being coughed on, touching used tissues with a bare hand). However, until more is known about transmission risks, it would be reasonable to consider anything longer than a brief (e.g., less than 1-2 minutes) exposure as prolonged.

What happens if the health care personnel (HCP) are exposed to confirmed COVID-19 patients? What’s the protocol for HCP exposed to persons under investigation (PUI) if test results are delayed beyond 48-72 hours?

Management is similar in both these scenarios. CDC categorized exposures as high, medium, low, and no identifiable risk. High- and medium-risk exposures are managed similarly with active monitoring for COVID-19 until 14 days after last potential exposure and exclude from work for 14 days after last exposure. Active monitoring means that the state or local public health authority assumes responsibility for establishing regular communication with potentially exposed people to assess for the presence of fever or respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath, sore throat). For HCP with high- or medium-risk exposures, CDC recommends this communication occurs at least once each day. For full details, please see www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html.

Should postexposure prophylaxis be used for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19?

None available.

COVID-19 test results are negative in a symptomatic patient you suspected of COVID-19? What does it mean?

A negative test result for a sample collected while a person has symptoms likely means that the COVID-19 virus is not causing their current illness.

What if your hospital does not have an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Transfer the patient to a facility that has an available AIIR. If a transfer is impractical or not medically appropriate, the patient should be cared for in a single-person room and the door should be kept closed. The room should ideally not have an exhaust that is recirculated within the building without high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. Health care personnel should still use gloves, gown, respiratory and eye protection and follow all other recommended infection prevention and control practices when caring for these patients.

What if your hospital does not have enough Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Prioritize patients for AIIR who are symptomatic with severe illness (e.g., those requiring ventilator support).

When can patients with confirmed COVID-19 be discharged from the hospital?

Patients can be discharged from the health care facility whenever clinically indicated. Isolation should be maintained at home if the patient returns home before the time period recommended for discontinuation of hospital transmission-based precautions.

Considerations to discontinue transmission-based precautions include all of the following:

- Resolution of fever, without the use of antipyretic medication.

- Improvement in illness signs and symptoms.

- Negative rRT-PCR results from at least two consecutive sets of paired nasopharyngeal and throat swabs specimens collected at least 24 hours apart (total of four negative specimens – two nasopharyngeal and two throat) from a patient with COVID-19 are needed before discontinuing transmission-based precautions.

Should people be concerned about pets or other animals and COVID-19?

To date, CDC has not received any reports of pets or other animals becoming sick with COVID-19.

Should patients avoid contact with pets or other animals if they are sick with COVID-19?

Patients should restrict contact with pets and other animals while they are sick with COVID-19, just like they would around other people.

Does CDC recommend the use of face masks in the community to prevent COVID-19?

CDC does not recommend that people who are well wear a face mask to protect themselves from respiratory illnesses, including COVID-19. A face mask should be used by people who have COVID-19 and are showing symptoms to protect others from the risk of getting infected.

Should medical waste or general waste from health care facilities treating PUIs and patients with confirmed COVID-19 be handled any differently or need any additional disinfection?

No. CDC’s guidance states that management of laundry, food service utensils, and medical waste should be performed in accordance with routine procedures.

Can people who recover from COVID-19 be infected again?

Unknown. The immune response to COVID-19 is not yet understood.

What is the mortality rate of COVID-19, and how does it compare to the mortality rate of influenza (flu)?

The average 10-year mortality rate for flu, using CDC data, is found to be around 0.1%. Even though this percentage appears to be small, influenza is estimated to be responsible for 30,000 to 40,000 deaths annually in the U.S.

According to statistics released by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention on Feb. 17, the mortality rate of COVID-19 is estimated to be around 2.3%. This calculation was based on cases reported through Feb. 11, and calcuated by dividing the number of coronavirus-related deaths at the time (1,023) by the number of confirmed cases (44,672) of COVID-19 infection. However, this report has its limitations, since Chinese officials have a vague way of defining who has COVID-19 infection.

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently estimates the mortality rate for COVID-19 to be between 2% and 4%.

Dr. Sitammagari is a co-medical director for quality and assistant professor of internal medicine at Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. He is also a physician advisor. He currently serves as treasurer for the NC-Triangle Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine and as an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization. Dr. Skandhan was a cofounder of the Wiregrass chapter of SHM and currently serves on the Advisory board. He is also a member of the editorial board of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Dahlin is a second-year internal medicine resident at Southeast Health, Dothan, Ala. She serves as her class representative and is the cochair/resident liaison for the research committee at SEH. Dr. Dahlin also serves as a resident liaison for the Wiregrass chapter of SHM.

This article last updated 4/8/20. (Disclaimer: The information in this article may not be updated regularly. For more COVID-19 coverage, bookmark our COVID-19 updates page. The editors of The Hospitalist encourage clinicians to also review information on the CDC website and on the AHA website.)

An infectious disease outbreak that began in December 2019 in Wuhan (Hubei Province), China, was found to be caused by the seventh strain of coronavirus, initially called the novel (new) coronavirus. The virus was later labeled as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named COVID-19. Until 2019, only six strains of human coronaviruses had previously been identified.

As of April 8, 2020, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 has been detected in at least 209 countries and has spread to every contintent except Antarctica. More than 1,469,245 people have become infected globally, and at least 86,278 have died. Based on the cases detected and tested in the United States through the U.S. public health surveillance systems, we have had 406,693 confirmed cases and 13,089 deaths.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic.

As the number of cases increases in the United States, we hope to provide answers about some common questions regarding COVID-19. The information summarized in this article is obtained and modified from the CDC.

What are the clinical features of COVID-19?

Ranges from asymptomatic infection, a mild disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms of acute respiratory illness, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and septic shock.

Who is at risk for COVID-19?

Persons who have had prolonged, unprotected close contact with a patient with symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19, and those with recent travel to China, especially Hubei Province.

Who is at risk for severe disease from COVID-19?

Older adults and persons who have underlying chronic medical conditions, such as immunocompromising conditions.

How is COVID-19 spread?

Person-to-person, mainly through respiratory droplets. SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated from upper respiratory tract specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

When is someone infectious?

Incubation period may range from 2 to 14 days. Detection of viral RNA does not necessarily mean that infectious virus is present, as it may be detectable in the upper or lower respiratory tract for weeks after illness onset.

Can someone who has been quarantined for COVID-19 spread the illness to others?

For COVID-19, the period of quarantine is 14 days from the last date of exposure, because 14 days is the longest incubation period seen for similar coronaviruses. Someone who has been released from COVID-19 quarantine is not considered a risk for spreading the virus to others because they have not developed illness during the incubation period.

Can a person test negative and later test positive for COVID-19?

Yes. In the early stages of infection, it is possible the virus will not be detected.

Do patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 need to be admitted to the hospital?

Not all patients with COVID-19 require hospital admission. Patients whose clinical presentation warrants inpatient clinical management for supportive medical care should be admitted to the hospital under appropriate isolation precautions. The decision to monitor these patients in the inpatient or outpatient setting should be made on a case-by-case basis.

What should you do if you suspect a patient for COVID-19?

Immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department. State health departments that have identified a person under investigation (PUI) should immediately contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 and complete a COVID-19 PUI case investigation form.

CDC’s EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during after-hours or on weekends/holidays.

What type of isolation is needed for COVID-19?

Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) using Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions with eye protection.

How should health care personnel protect themselves when evaluating a patient who may have COVID-19?

Standard Precautions, Contact Precautions, Airborne Precautions, and use eye protection (e.g., goggles or a face shield).

What face mask do health care workers wear for respiratory protection?

A fit-tested NIOSH-certified disposable N95 filtering facepiece respirator should be worn before entry into the patient room or care area. Disposable respirators should be removed and discarded after exiting the patient’s room or care area and closing the door. Perform hand hygiene after discarding the respirator.

If reusable respirators (e.g., powered air purifying respirator/PAPR) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use.

What should you tell the patient if COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed?

Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be asked to wear a surgical mask as soon as they are identified, to prevent spread to others.

Should any diagnostic or therapeutic interventions be withheld because of concerns about the transmission of COVID-19?

No.

How do you test a patient for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

At this time, diagnostic testing for COVID-19 can be conducted only at CDC.

The CDC recommends collecting and testing multiple clinical specimens from different sites, including two specimen types – lower respiratory and upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal aspirates or washes, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, bronchioalveolar lavage, tracheal aspirates, sputum, and serum) using a real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified regardless of the time of symptom onset. Turnaround time for the PCR assay testing is about 24-48 hours.

Testing for other respiratory pathogens should not delay specimen shipping to CDC. If a PUI tests positive for another respiratory pathogen, after clinical evaluation and consultation with public health authorities, they may no longer be considered a PUI.

Will existing respiratory virus panels detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

No.

How is COVID-19 treated?

Symptomatic management. Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for viral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome and should be avoided unless they are indicated for another reason (e.g., COPD exacerbation, refractory septic shock following Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines). There are currently no antiviral drugs licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19.

What is considered ‘close contact’ for health care exposures?

Being within approximately 6 feet (2 meters), of a person with COVID-19 for a prolonged period of time (such as caring for or visiting the patient, or sitting within 6 feet of the patient in a health care waiting area or room); or having unprotected direct contact with infectious secretions or excretions of the patient (e.g., being coughed on, touching used tissues with a bare hand). However, until more is known about transmission risks, it would be reasonable to consider anything longer than a brief (e.g., less than 1-2 minutes) exposure as prolonged.

What happens if the health care personnel (HCP) are exposed to confirmed COVID-19 patients? What’s the protocol for HCP exposed to persons under investigation (PUI) if test results are delayed beyond 48-72 hours?

Management is similar in both these scenarios. CDC categorized exposures as high, medium, low, and no identifiable risk. High- and medium-risk exposures are managed similarly with active monitoring for COVID-19 until 14 days after last potential exposure and exclude from work for 14 days after last exposure. Active monitoring means that the state or local public health authority assumes responsibility for establishing regular communication with potentially exposed people to assess for the presence of fever or respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath, sore throat). For HCP with high- or medium-risk exposures, CDC recommends this communication occurs at least once each day. For full details, please see www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html.

Should postexposure prophylaxis be used for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19?

None available.

COVID-19 test results are negative in a symptomatic patient you suspected of COVID-19? What does it mean?

A negative test result for a sample collected while a person has symptoms likely means that the COVID-19 virus is not causing their current illness.

What if your hospital does not have an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Transfer the patient to a facility that has an available AIIR. If a transfer is impractical or not medically appropriate, the patient should be cared for in a single-person room and the door should be kept closed. The room should ideally not have an exhaust that is recirculated within the building without high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. Health care personnel should still use gloves, gown, respiratory and eye protection and follow all other recommended infection prevention and control practices when caring for these patients.

What if your hospital does not have enough Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Prioritize patients for AIIR who are symptomatic with severe illness (e.g., those requiring ventilator support).

When can patients with confirmed COVID-19 be discharged from the hospital?

Patients can be discharged from the health care facility whenever clinically indicated. Isolation should be maintained at home if the patient returns home before the time period recommended for discontinuation of hospital transmission-based precautions.

Considerations to discontinue transmission-based precautions include all of the following:

- Resolution of fever, without the use of antipyretic medication.

- Improvement in illness signs and symptoms.

- Negative rRT-PCR results from at least two consecutive sets of paired nasopharyngeal and throat swabs specimens collected at least 24 hours apart (total of four negative specimens – two nasopharyngeal and two throat) from a patient with COVID-19 are needed before discontinuing transmission-based precautions.

Should people be concerned about pets or other animals and COVID-19?