User login

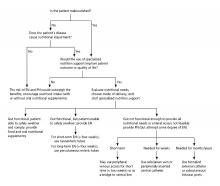

Which tube placement is best for a patient requiring enteral nutrition?

Comparative advantages of EN tubes

Case

A 68-year-old diabetic nonverbal female presents to the ED because of “seizure” 1 hour ago. On exam, her blood glucose is 200. She is unable to speak and has dysphagia because of a stroke she sustained last month. The patient’s husband adds that she hasn’t been eating and drinking sufficiently in the past couple of days. Imaging was negative for any acute intracranial bleeds or lesions. Labs showed a serum sodium level of 150 milliequivalents/L. D5W is started, and the following day, the patient has a sodium level of 154 milliequivalents/L.

Brief overview

Many hospitalized patients are unable to maintain hydration and/or nutritional status by mouth and will need enteral nutrition. Variables such as past medical history, swallowing ability, history of aspiration, prognosis, and functional capacity of each gastrointestinal segment will determine the best option for enteral nutrition for each patient. Each type of enteral tube feeding has advantages, disadvantages, and complications.

Overview of the data

Enteral nutrition should be started within 24-48 hours in a critically ill patient who is unable to maintain intake according to the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.1 This can be provided through a nasogastric (NG) tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, PEG tube with jejunal extension (PEG-J), or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunal (PEJ) tube.1

NG tubes are often the first method deployed because of their low cost and convenience. They are also suitable for the patient who requires this type of feeding for less than 4 weeks. However, NG tubes do require some patient cooperation (to place and maintain)and are contraindicated in some patients with orofacial trauma, upper GI tumors, inadequate lower esophageal sphincter tone, and gastroparesis.2

Another option is a PEG tube, which is a good alternative for patients who are sedated; ventilated; or have neurodegenerative processes, stroke with dysphagia, or head and neck cancers. These are typically recommended when enteral nutrition will be needed for more than 4 weeks. Disadvantages of PEG tubes include tube obstruction or displacement, gastroesophageal reflux, and leakage of gastric content around the percutaneous site or into the peritoneum.

PEG-J tubes, PEJ tubes, or jejunostomy tubes are best suited for patients with GI dysmotility, patients who have unsuccessfully undergone the aforementioned methods, patients with histories of partial gastrectomies, or patients with gastric or pancreatic cancers/multiple traumas. The PEG-J tube extends into the distal duodenum; because it is longer and more narrow, it is more likely to coil and occlude the flow of nutrients during feedings.2,3 Jejunal feeding methods incorporate a continuous pump controlled infusion; if set too rapidly, this could cause dumping syndrome. A benefit of jejunal nutrition is a lower risk of aspiration, compared with other enteral tubes.4

It is best to appraise the selected method for its efficacy and patient preference. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends starting with orogastric or nasogastric feeds, and switching to postpyloric or jejunal feeds for those intolerant to or at high risk for aspiration.5 The most important aspect is early enteral nutrition in hospitalized patients unable to maintain oral nutrition.

Application of the data to the original case

This is a severely hypernatremic diabetic patient unable to swallow. On day 2 of her hospitalization, the clinical team provided the patient with an NG tube for increased free-water intake to gradually decrease her serum sodium. By hospital day 4, the patient’s sodium had normalized. Considering the patient’s long-term prognosis and dysphagia, discussions were held with the patient and husband for PEG tube placement. The patient received a PEG tube and was subsequently discharged 2 days later.

Bottom line

Enteral nutrition is a common need among hospitalized patients. Modality of enteral nutrition will depend on the patient’s past medical history, anticipated duration, and preferences.

Dr. Basnet is the hospitalist program director for Apogee Physicians Group at Eastern New Mexico Medical Center in Roswell. Ms. Tayes is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine in Las Cruces, N.M., with interests in surgery, internal medicine, and emergency medicine. Ms. Gallivan is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine, with interests in cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, and internal medicine.

References

1. Boullata JI et al. ASPEN Safe Practices for Enteral Nutrition Therapy. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;1-89.

2. Kirby DF et al. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1282.

3. Lazarus BA et al. Aspiration associated with long-term gastric versus jejunal feeding: A critical analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:46.

4. Alkhawaja S et al. Postpyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 4;(8):CD008875.

5. McCalve SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition therapy in the hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:315-34. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.28.

Additional reading

Bellini LM. Nutrition Support in Advanced Lung Disease. UptoDate. https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.ad.bcomnm.org/contents/nutritional-support-in-advanced-lung-disease?. Published April 20, 2018.

Commercial Formulas for the Feeding Tube. The Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/nutrition/commercial-formulas-feeding-tube/. Published June 5, 2018.

Marik Z. Immunonutrition in critically ill patients: A systematic review and analysis of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11). doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1213-6.

Wischmeyer PE. Enteral nutrition can be given to patients on vasopressors. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(1):122-5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003965.

Comparative advantages of EN tubes

Comparative advantages of EN tubes

Case

A 68-year-old diabetic nonverbal female presents to the ED because of “seizure” 1 hour ago. On exam, her blood glucose is 200. She is unable to speak and has dysphagia because of a stroke she sustained last month. The patient’s husband adds that she hasn’t been eating and drinking sufficiently in the past couple of days. Imaging was negative for any acute intracranial bleeds or lesions. Labs showed a serum sodium level of 150 milliequivalents/L. D5W is started, and the following day, the patient has a sodium level of 154 milliequivalents/L.

Brief overview

Many hospitalized patients are unable to maintain hydration and/or nutritional status by mouth and will need enteral nutrition. Variables such as past medical history, swallowing ability, history of aspiration, prognosis, and functional capacity of each gastrointestinal segment will determine the best option for enteral nutrition for each patient. Each type of enteral tube feeding has advantages, disadvantages, and complications.

Overview of the data

Enteral nutrition should be started within 24-48 hours in a critically ill patient who is unable to maintain intake according to the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.1 This can be provided through a nasogastric (NG) tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, PEG tube with jejunal extension (PEG-J), or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunal (PEJ) tube.1

NG tubes are often the first method deployed because of their low cost and convenience. They are also suitable for the patient who requires this type of feeding for less than 4 weeks. However, NG tubes do require some patient cooperation (to place and maintain)and are contraindicated in some patients with orofacial trauma, upper GI tumors, inadequate lower esophageal sphincter tone, and gastroparesis.2

Another option is a PEG tube, which is a good alternative for patients who are sedated; ventilated; or have neurodegenerative processes, stroke with dysphagia, or head and neck cancers. These are typically recommended when enteral nutrition will be needed for more than 4 weeks. Disadvantages of PEG tubes include tube obstruction or displacement, gastroesophageal reflux, and leakage of gastric content around the percutaneous site or into the peritoneum.

PEG-J tubes, PEJ tubes, or jejunostomy tubes are best suited for patients with GI dysmotility, patients who have unsuccessfully undergone the aforementioned methods, patients with histories of partial gastrectomies, or patients with gastric or pancreatic cancers/multiple traumas. The PEG-J tube extends into the distal duodenum; because it is longer and more narrow, it is more likely to coil and occlude the flow of nutrients during feedings.2,3 Jejunal feeding methods incorporate a continuous pump controlled infusion; if set too rapidly, this could cause dumping syndrome. A benefit of jejunal nutrition is a lower risk of aspiration, compared with other enteral tubes.4

It is best to appraise the selected method for its efficacy and patient preference. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends starting with orogastric or nasogastric feeds, and switching to postpyloric or jejunal feeds for those intolerant to or at high risk for aspiration.5 The most important aspect is early enteral nutrition in hospitalized patients unable to maintain oral nutrition.

Application of the data to the original case

This is a severely hypernatremic diabetic patient unable to swallow. On day 2 of her hospitalization, the clinical team provided the patient with an NG tube for increased free-water intake to gradually decrease her serum sodium. By hospital day 4, the patient’s sodium had normalized. Considering the patient’s long-term prognosis and dysphagia, discussions were held with the patient and husband for PEG tube placement. The patient received a PEG tube and was subsequently discharged 2 days later.

Bottom line

Enteral nutrition is a common need among hospitalized patients. Modality of enteral nutrition will depend on the patient’s past medical history, anticipated duration, and preferences.

Dr. Basnet is the hospitalist program director for Apogee Physicians Group at Eastern New Mexico Medical Center in Roswell. Ms. Tayes is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine in Las Cruces, N.M., with interests in surgery, internal medicine, and emergency medicine. Ms. Gallivan is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine, with interests in cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, and internal medicine.

References

1. Boullata JI et al. ASPEN Safe Practices for Enteral Nutrition Therapy. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;1-89.

2. Kirby DF et al. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1282.

3. Lazarus BA et al. Aspiration associated with long-term gastric versus jejunal feeding: A critical analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:46.

4. Alkhawaja S et al. Postpyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 4;(8):CD008875.

5. McCalve SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition therapy in the hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:315-34. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.28.

Additional reading

Bellini LM. Nutrition Support in Advanced Lung Disease. UptoDate. https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.ad.bcomnm.org/contents/nutritional-support-in-advanced-lung-disease?. Published April 20, 2018.

Commercial Formulas for the Feeding Tube. The Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/nutrition/commercial-formulas-feeding-tube/. Published June 5, 2018.

Marik Z. Immunonutrition in critically ill patients: A systematic review and analysis of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11). doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1213-6.

Wischmeyer PE. Enteral nutrition can be given to patients on vasopressors. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(1):122-5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003965.

Case

A 68-year-old diabetic nonverbal female presents to the ED because of “seizure” 1 hour ago. On exam, her blood glucose is 200. She is unable to speak and has dysphagia because of a stroke she sustained last month. The patient’s husband adds that she hasn’t been eating and drinking sufficiently in the past couple of days. Imaging was negative for any acute intracranial bleeds or lesions. Labs showed a serum sodium level of 150 milliequivalents/L. D5W is started, and the following day, the patient has a sodium level of 154 milliequivalents/L.

Brief overview

Many hospitalized patients are unable to maintain hydration and/or nutritional status by mouth and will need enteral nutrition. Variables such as past medical history, swallowing ability, history of aspiration, prognosis, and functional capacity of each gastrointestinal segment will determine the best option for enteral nutrition for each patient. Each type of enteral tube feeding has advantages, disadvantages, and complications.

Overview of the data

Enteral nutrition should be started within 24-48 hours in a critically ill patient who is unable to maintain intake according to the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.1 This can be provided through a nasogastric (NG) tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, PEG tube with jejunal extension (PEG-J), or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunal (PEJ) tube.1

NG tubes are often the first method deployed because of their low cost and convenience. They are also suitable for the patient who requires this type of feeding for less than 4 weeks. However, NG tubes do require some patient cooperation (to place and maintain)and are contraindicated in some patients with orofacial trauma, upper GI tumors, inadequate lower esophageal sphincter tone, and gastroparesis.2

Another option is a PEG tube, which is a good alternative for patients who are sedated; ventilated; or have neurodegenerative processes, stroke with dysphagia, or head and neck cancers. These are typically recommended when enteral nutrition will be needed for more than 4 weeks. Disadvantages of PEG tubes include tube obstruction or displacement, gastroesophageal reflux, and leakage of gastric content around the percutaneous site or into the peritoneum.

PEG-J tubes, PEJ tubes, or jejunostomy tubes are best suited for patients with GI dysmotility, patients who have unsuccessfully undergone the aforementioned methods, patients with histories of partial gastrectomies, or patients with gastric or pancreatic cancers/multiple traumas. The PEG-J tube extends into the distal duodenum; because it is longer and more narrow, it is more likely to coil and occlude the flow of nutrients during feedings.2,3 Jejunal feeding methods incorporate a continuous pump controlled infusion; if set too rapidly, this could cause dumping syndrome. A benefit of jejunal nutrition is a lower risk of aspiration, compared with other enteral tubes.4

It is best to appraise the selected method for its efficacy and patient preference. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends starting with orogastric or nasogastric feeds, and switching to postpyloric or jejunal feeds for those intolerant to or at high risk for aspiration.5 The most important aspect is early enteral nutrition in hospitalized patients unable to maintain oral nutrition.

Application of the data to the original case

This is a severely hypernatremic diabetic patient unable to swallow. On day 2 of her hospitalization, the clinical team provided the patient with an NG tube for increased free-water intake to gradually decrease her serum sodium. By hospital day 4, the patient’s sodium had normalized. Considering the patient’s long-term prognosis and dysphagia, discussions were held with the patient and husband for PEG tube placement. The patient received a PEG tube and was subsequently discharged 2 days later.

Bottom line

Enteral nutrition is a common need among hospitalized patients. Modality of enteral nutrition will depend on the patient’s past medical history, anticipated duration, and preferences.

Dr. Basnet is the hospitalist program director for Apogee Physicians Group at Eastern New Mexico Medical Center in Roswell. Ms. Tayes is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine in Las Cruces, N.M., with interests in surgery, internal medicine, and emergency medicine. Ms. Gallivan is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine, with interests in cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, and internal medicine.

References

1. Boullata JI et al. ASPEN Safe Practices for Enteral Nutrition Therapy. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;1-89.

2. Kirby DF et al. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1282.

3. Lazarus BA et al. Aspiration associated with long-term gastric versus jejunal feeding: A critical analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:46.

4. Alkhawaja S et al. Postpyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 4;(8):CD008875.

5. McCalve SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition therapy in the hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:315-34. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.28.

Additional reading

Bellini LM. Nutrition Support in Advanced Lung Disease. UptoDate. https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.ad.bcomnm.org/contents/nutritional-support-in-advanced-lung-disease?. Published April 20, 2018.

Commercial Formulas for the Feeding Tube. The Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/nutrition/commercial-formulas-feeding-tube/. Published June 5, 2018.

Marik Z. Immunonutrition in critically ill patients: A systematic review and analysis of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11). doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1213-6.

Wischmeyer PE. Enteral nutrition can be given to patients on vasopressors. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(1):122-5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003965.

COVID-19: More hydroxychloroquine data from France, more questions

A controversial study led by Didier Raoult, MD, PhD, on the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with COVID-19 was published March 20. The latest results from the same Marseille team, which involve 80 patients, were reported on March 27.

The investigators report a significant reduction in the viral load (83% patients had negative results on quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing at day 7, and 93% had negative results on day 8). There was a “clinical improvement compared to the natural progression.” One death occurred, and three patients were transferred to intensive care units.

If the data seem encouraging, the lack of a control arm in the study leaves clinicians perplexed, however.

Benjamin Davido, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Raymond-Poincaré Hospital in Garches, Paris, spoke in an interview about the implications of these new results.

What do you think about the new results presented by Prof. Raoult’s team? Do they confirm the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine?

These results are complementary [to the original results] but don’t offer any new information or new statistical evidence. They are absolutely superimposable and say overall that, between 5 and 7 days [of treatment], very few patients shed the virus. But that is not the question that everyone is asking.

Even if we don’t necessarily have to conduct a randomized study, we should at least compare the treatment, either against another therapy – which could be hydroxychloroquine monotherapy, or just standard of care. It needed an authentic control arm.

To recruit 80 patients so quickly, the researchers probably took people with essentially ambulatory forms of the disease (there was a call for screening in the south of France) – therefore, by definition, less severe cases.

But to describe such a population of patients as going home and saying, “There were very few hospitalizations and it is going well,” does not in any way prove that the treatment reduces hospitalizations.

The argument for not having a control arm in this study was that it would be unethical. What do you think?

I agree with this argument when it comes to patients presenting with risk factors or who are starting to develop pneumonia.

But I don’t think this is the case at the beginning of the illness. Of course, you don’t want to wait to have severe disease or for the patient to be in intensive care to start treatment. In these cases, it is indeed very difficult to find a control arm.

In the ongoing Discovery trial, which involves more than 3,000 patients in Europe, including 800 in France, the patients have severe disease, and there are five treatment arms. Moreover, hydroxychloroquine is given without azithromycin. What do you think of this?

I think it’s a mistake. It will not answer the question of the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19, especially as they’re not studying azithromycin in a situation where the compound seems necessary for the effectiveness of the treatment.

In addition, Discovery reinforces the notion of studying Kaletra [lopinavir/ritonavir, AbbVie] again, while Chinese researchers have shown that it does not work, the argument being that Kaletra was given too late (N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282). Therefore, if we make the same mistakes from a methodological point of view, we will end up with negative results.

What should have been done in the Marseille study?

The question is: Are there more or fewer hospitalizations when we treat a homogeneous population straight away?

The answer could be very clear, as a control already exists! They are the patients that flow into our hospitals every day – ironically, these 80 patients [in the latest results, presented March 27] could be among the 80% who had a form similar to nasopharyngitis and resolved.

In this illness, we know that there are 80% spontaneous recoveries and 20% so-called severe forms. Therefore, with 80 patients, we are very underpowered. The cohort is too small for a disease in which 80% of the evolution is benign.

It would take 1,000 patients, and then, even without a control arm, we would have an answer.

On March 26, Didier Raoult’s team also announced having already treated 700 patients with hydroxychloroquine, with only one death. Therefore, if this cohort increases significantly in Marseille and we see that, on the map, there are fewer issues with patient flow and saturation in Marseille and that there are fewer patients in intensive care, you will have to wonder about the effect of hydroxychloroquine.

We will find out very quickly. If it really works, and they treat all the patients presenting at Timone Hospital, we will soon have the answer. It will be a real-life study.

What are the other studies on hydroxychloroquine that could give us answers?

There was a Chinese study that did not show a difference in effectiveness between hydroxychloroquine and placebo, but that was, again, conducted in only around 20 patients (J Zhejiang Univ (Med Sci). 2020. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.03). This cohort is too small and tells us nothing; it cannot show anything. We must wait for the results of larger trials being conducted in China.

It surprises me that, today, we still do not have Italian data on the use of chloroquine-type drugs ... perhaps because they have a care pathway that means there is no outpatient treatment and that they arrive already with severe disease. The Italian recommendations nevertheless indicate the use of hydroxychloroquine.

I also wonder about the lack of studies of cohorts where, in retrospect, we could have followed people previously treated with hydroxychloroquine for chronic diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, etc.). Or we could identify all those patients on the health insurance system who had prescriptions.

That is how we discovered the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco: There was an increase in the number of prescriptions for trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) that corresponded to a population subtype (homosexual), and we realized that it was for a disease that resembled pneumocystosis. We discovered that via the drug!

If hydroxychloroquine is effective, it is enough to look at people who took it before the epidemic and see how they fared. And there, we do not need a control arm. This could give us some direction. The March 26 decree of the new Véran Law states that community pharmacies can dispense to patients with a previous prescription, so we can find these individuals.

Do you think that the lack of, or difficulty in setting up, studies on hydroxychloroquine in France is linked to decisions that are more political than scientific?

Perhaps the contaminated blood scandal still casts a shadow in France, and there is a great deal of anxiety over the fact that we are already in a crisis, and we do not want a second one. I can understand that.

However, just a week ago, access to this drug (and others with market approval that have been on the market for several years) was blocked in hospital central pharmacies, while we are the medical specialists with the authorization! It was unacceptable.

It was sorted out 48 hours ago: hydroxychloroquine is now available in the hospital, and to my knowledge, we no longer have a problem obtaining it.

It took time to alleviate doubts over the major health risks with this drug. [Officials] seemed almost like amateurs in their hesitation; I think they lacked foresight. We have forgotten that the treatment advocated by Prof. Didier Raoult is not chloroquine but rather hydroxychloroquine, and we know that the adverse effects are less [with hydroxychloroquine] than with chloroquine.

You yourself have treated patients with chloroquine, despite the risk for toxicity highlighted by some.

Initially, when we first started treating patients, we thought of chloroquine because we did not have data on hydroxychloroquine, only Chinese data with chloroquine. We therefore prescribed chloroquine several days before prescribing hydroxychloroquine.

The question of the toxicity of chloroquine was not unjustified, but I think we took far too much time to decide on the toxicity of hydroxychloroquine. Is [the latter] political? I don’t know. It was widely publicized, which amazes me for a drug that is already available.

On the other hand, everyone was talking at the same time about the toxicity of NSAIDs. ... One has the impression it was to create a diversion. I think there were double standards at play and a scapegoat was needed to gain some time and ask questions.

What is sure is that it is probably not for financial reasons, as hydroxychloroquine costs nothing. That’s to say there were probably pharmaceutical issues at stake for possible competitors of hydroxychloroquine; I do not want to get into this debate, and it doesn’t matter, as long as we have an answer.

Today, the only thing we have advanced on is the “safety” of hydroxychloroquine, the low risk to the general population. ... On the other hand, we have still not made any progress on the evidence of efficacy, compared with other treatments.

Personally, I really believe in hydroxychloroquine. It would nevertheless be a shame to think we had found the fountain of youth and realize, in 4 weeks, that we have the same number of deaths. That is the problem. I hope that we will soon have solid data so we do not waste time focusing solely on hydroxychloroquine.

What are the other avenues of research that grab your attention?

The Discovery trial will probably give an answer on remdesivir [GS-5734, Gilead], which is a direct antiviral and could be interesting. But there are other studies being conducted currently in China.

There is also favipiravir [T-705, Avigan, Toyama Chemical], which is an anti-influenza drug used in Japan, which could explain, in part, the control of the epidemic in that country. There are effects in vitro on coronavirus. But it is not at all studied in France at the moment. Therefore, we should not focus exclusively on hydroxychloroquine; we must keep a close eye on other molecules, in particular the “old” drugs, like this antiviral.

The study was supported by the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire (IHU) Méditerranée Infection, the National Research Agency, under the Investissements d’avenir program, Région Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur, and European funding FEDER PRIMI. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A controversial study led by Didier Raoult, MD, PhD, on the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with COVID-19 was published March 20. The latest results from the same Marseille team, which involve 80 patients, were reported on March 27.

The investigators report a significant reduction in the viral load (83% patients had negative results on quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing at day 7, and 93% had negative results on day 8). There was a “clinical improvement compared to the natural progression.” One death occurred, and three patients were transferred to intensive care units.

If the data seem encouraging, the lack of a control arm in the study leaves clinicians perplexed, however.

Benjamin Davido, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Raymond-Poincaré Hospital in Garches, Paris, spoke in an interview about the implications of these new results.

What do you think about the new results presented by Prof. Raoult’s team? Do they confirm the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine?

These results are complementary [to the original results] but don’t offer any new information or new statistical evidence. They are absolutely superimposable and say overall that, between 5 and 7 days [of treatment], very few patients shed the virus. But that is not the question that everyone is asking.

Even if we don’t necessarily have to conduct a randomized study, we should at least compare the treatment, either against another therapy – which could be hydroxychloroquine monotherapy, or just standard of care. It needed an authentic control arm.

To recruit 80 patients so quickly, the researchers probably took people with essentially ambulatory forms of the disease (there was a call for screening in the south of France) – therefore, by definition, less severe cases.

But to describe such a population of patients as going home and saying, “There were very few hospitalizations and it is going well,” does not in any way prove that the treatment reduces hospitalizations.

The argument for not having a control arm in this study was that it would be unethical. What do you think?

I agree with this argument when it comes to patients presenting with risk factors or who are starting to develop pneumonia.

But I don’t think this is the case at the beginning of the illness. Of course, you don’t want to wait to have severe disease or for the patient to be in intensive care to start treatment. In these cases, it is indeed very difficult to find a control arm.

In the ongoing Discovery trial, which involves more than 3,000 patients in Europe, including 800 in France, the patients have severe disease, and there are five treatment arms. Moreover, hydroxychloroquine is given without azithromycin. What do you think of this?

I think it’s a mistake. It will not answer the question of the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19, especially as they’re not studying azithromycin in a situation where the compound seems necessary for the effectiveness of the treatment.

In addition, Discovery reinforces the notion of studying Kaletra [lopinavir/ritonavir, AbbVie] again, while Chinese researchers have shown that it does not work, the argument being that Kaletra was given too late (N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282). Therefore, if we make the same mistakes from a methodological point of view, we will end up with negative results.

What should have been done in the Marseille study?

The question is: Are there more or fewer hospitalizations when we treat a homogeneous population straight away?

The answer could be very clear, as a control already exists! They are the patients that flow into our hospitals every day – ironically, these 80 patients [in the latest results, presented March 27] could be among the 80% who had a form similar to nasopharyngitis and resolved.

In this illness, we know that there are 80% spontaneous recoveries and 20% so-called severe forms. Therefore, with 80 patients, we are very underpowered. The cohort is too small for a disease in which 80% of the evolution is benign.

It would take 1,000 patients, and then, even without a control arm, we would have an answer.

On March 26, Didier Raoult’s team also announced having already treated 700 patients with hydroxychloroquine, with only one death. Therefore, if this cohort increases significantly in Marseille and we see that, on the map, there are fewer issues with patient flow and saturation in Marseille and that there are fewer patients in intensive care, you will have to wonder about the effect of hydroxychloroquine.

We will find out very quickly. If it really works, and they treat all the patients presenting at Timone Hospital, we will soon have the answer. It will be a real-life study.

What are the other studies on hydroxychloroquine that could give us answers?

There was a Chinese study that did not show a difference in effectiveness between hydroxychloroquine and placebo, but that was, again, conducted in only around 20 patients (J Zhejiang Univ (Med Sci). 2020. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.03). This cohort is too small and tells us nothing; it cannot show anything. We must wait for the results of larger trials being conducted in China.

It surprises me that, today, we still do not have Italian data on the use of chloroquine-type drugs ... perhaps because they have a care pathway that means there is no outpatient treatment and that they arrive already with severe disease. The Italian recommendations nevertheless indicate the use of hydroxychloroquine.

I also wonder about the lack of studies of cohorts where, in retrospect, we could have followed people previously treated with hydroxychloroquine for chronic diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, etc.). Or we could identify all those patients on the health insurance system who had prescriptions.

That is how we discovered the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco: There was an increase in the number of prescriptions for trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) that corresponded to a population subtype (homosexual), and we realized that it was for a disease that resembled pneumocystosis. We discovered that via the drug!

If hydroxychloroquine is effective, it is enough to look at people who took it before the epidemic and see how they fared. And there, we do not need a control arm. This could give us some direction. The March 26 decree of the new Véran Law states that community pharmacies can dispense to patients with a previous prescription, so we can find these individuals.

Do you think that the lack of, or difficulty in setting up, studies on hydroxychloroquine in France is linked to decisions that are more political than scientific?

Perhaps the contaminated blood scandal still casts a shadow in France, and there is a great deal of anxiety over the fact that we are already in a crisis, and we do not want a second one. I can understand that.

However, just a week ago, access to this drug (and others with market approval that have been on the market for several years) was blocked in hospital central pharmacies, while we are the medical specialists with the authorization! It was unacceptable.

It was sorted out 48 hours ago: hydroxychloroquine is now available in the hospital, and to my knowledge, we no longer have a problem obtaining it.

It took time to alleviate doubts over the major health risks with this drug. [Officials] seemed almost like amateurs in their hesitation; I think they lacked foresight. We have forgotten that the treatment advocated by Prof. Didier Raoult is not chloroquine but rather hydroxychloroquine, and we know that the adverse effects are less [with hydroxychloroquine] than with chloroquine.

You yourself have treated patients with chloroquine, despite the risk for toxicity highlighted by some.

Initially, when we first started treating patients, we thought of chloroquine because we did not have data on hydroxychloroquine, only Chinese data with chloroquine. We therefore prescribed chloroquine several days before prescribing hydroxychloroquine.

The question of the toxicity of chloroquine was not unjustified, but I think we took far too much time to decide on the toxicity of hydroxychloroquine. Is [the latter] political? I don’t know. It was widely publicized, which amazes me for a drug that is already available.

On the other hand, everyone was talking at the same time about the toxicity of NSAIDs. ... One has the impression it was to create a diversion. I think there were double standards at play and a scapegoat was needed to gain some time and ask questions.

What is sure is that it is probably not for financial reasons, as hydroxychloroquine costs nothing. That’s to say there were probably pharmaceutical issues at stake for possible competitors of hydroxychloroquine; I do not want to get into this debate, and it doesn’t matter, as long as we have an answer.

Today, the only thing we have advanced on is the “safety” of hydroxychloroquine, the low risk to the general population. ... On the other hand, we have still not made any progress on the evidence of efficacy, compared with other treatments.

Personally, I really believe in hydroxychloroquine. It would nevertheless be a shame to think we had found the fountain of youth and realize, in 4 weeks, that we have the same number of deaths. That is the problem. I hope that we will soon have solid data so we do not waste time focusing solely on hydroxychloroquine.

What are the other avenues of research that grab your attention?

The Discovery trial will probably give an answer on remdesivir [GS-5734, Gilead], which is a direct antiviral and could be interesting. But there are other studies being conducted currently in China.

There is also favipiravir [T-705, Avigan, Toyama Chemical], which is an anti-influenza drug used in Japan, which could explain, in part, the control of the epidemic in that country. There are effects in vitro on coronavirus. But it is not at all studied in France at the moment. Therefore, we should not focus exclusively on hydroxychloroquine; we must keep a close eye on other molecules, in particular the “old” drugs, like this antiviral.

The study was supported by the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire (IHU) Méditerranée Infection, the National Research Agency, under the Investissements d’avenir program, Région Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur, and European funding FEDER PRIMI. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A controversial study led by Didier Raoult, MD, PhD, on the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with COVID-19 was published March 20. The latest results from the same Marseille team, which involve 80 patients, were reported on March 27.

The investigators report a significant reduction in the viral load (83% patients had negative results on quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing at day 7, and 93% had negative results on day 8). There was a “clinical improvement compared to the natural progression.” One death occurred, and three patients were transferred to intensive care units.

If the data seem encouraging, the lack of a control arm in the study leaves clinicians perplexed, however.

Benjamin Davido, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Raymond-Poincaré Hospital in Garches, Paris, spoke in an interview about the implications of these new results.

What do you think about the new results presented by Prof. Raoult’s team? Do they confirm the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine?

These results are complementary [to the original results] but don’t offer any new information or new statistical evidence. They are absolutely superimposable and say overall that, between 5 and 7 days [of treatment], very few patients shed the virus. But that is not the question that everyone is asking.

Even if we don’t necessarily have to conduct a randomized study, we should at least compare the treatment, either against another therapy – which could be hydroxychloroquine monotherapy, or just standard of care. It needed an authentic control arm.

To recruit 80 patients so quickly, the researchers probably took people with essentially ambulatory forms of the disease (there was a call for screening in the south of France) – therefore, by definition, less severe cases.

But to describe such a population of patients as going home and saying, “There were very few hospitalizations and it is going well,” does not in any way prove that the treatment reduces hospitalizations.

The argument for not having a control arm in this study was that it would be unethical. What do you think?

I agree with this argument when it comes to patients presenting with risk factors or who are starting to develop pneumonia.

But I don’t think this is the case at the beginning of the illness. Of course, you don’t want to wait to have severe disease or for the patient to be in intensive care to start treatment. In these cases, it is indeed very difficult to find a control arm.

In the ongoing Discovery trial, which involves more than 3,000 patients in Europe, including 800 in France, the patients have severe disease, and there are five treatment arms. Moreover, hydroxychloroquine is given without azithromycin. What do you think of this?

I think it’s a mistake. It will not answer the question of the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19, especially as they’re not studying azithromycin in a situation where the compound seems necessary for the effectiveness of the treatment.

In addition, Discovery reinforces the notion of studying Kaletra [lopinavir/ritonavir, AbbVie] again, while Chinese researchers have shown that it does not work, the argument being that Kaletra was given too late (N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282). Therefore, if we make the same mistakes from a methodological point of view, we will end up with negative results.

What should have been done in the Marseille study?

The question is: Are there more or fewer hospitalizations when we treat a homogeneous population straight away?

The answer could be very clear, as a control already exists! They are the patients that flow into our hospitals every day – ironically, these 80 patients [in the latest results, presented March 27] could be among the 80% who had a form similar to nasopharyngitis and resolved.

In this illness, we know that there are 80% spontaneous recoveries and 20% so-called severe forms. Therefore, with 80 patients, we are very underpowered. The cohort is too small for a disease in which 80% of the evolution is benign.

It would take 1,000 patients, and then, even without a control arm, we would have an answer.

On March 26, Didier Raoult’s team also announced having already treated 700 patients with hydroxychloroquine, with only one death. Therefore, if this cohort increases significantly in Marseille and we see that, on the map, there are fewer issues with patient flow and saturation in Marseille and that there are fewer patients in intensive care, you will have to wonder about the effect of hydroxychloroquine.

We will find out very quickly. If it really works, and they treat all the patients presenting at Timone Hospital, we will soon have the answer. It will be a real-life study.

What are the other studies on hydroxychloroquine that could give us answers?

There was a Chinese study that did not show a difference in effectiveness between hydroxychloroquine and placebo, but that was, again, conducted in only around 20 patients (J Zhejiang Univ (Med Sci). 2020. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.03). This cohort is too small and tells us nothing; it cannot show anything. We must wait for the results of larger trials being conducted in China.

It surprises me that, today, we still do not have Italian data on the use of chloroquine-type drugs ... perhaps because they have a care pathway that means there is no outpatient treatment and that they arrive already with severe disease. The Italian recommendations nevertheless indicate the use of hydroxychloroquine.

I also wonder about the lack of studies of cohorts where, in retrospect, we could have followed people previously treated with hydroxychloroquine for chronic diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, etc.). Or we could identify all those patients on the health insurance system who had prescriptions.

That is how we discovered the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco: There was an increase in the number of prescriptions for trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) that corresponded to a population subtype (homosexual), and we realized that it was for a disease that resembled pneumocystosis. We discovered that via the drug!

If hydroxychloroquine is effective, it is enough to look at people who took it before the epidemic and see how they fared. And there, we do not need a control arm. This could give us some direction. The March 26 decree of the new Véran Law states that community pharmacies can dispense to patients with a previous prescription, so we can find these individuals.

Do you think that the lack of, or difficulty in setting up, studies on hydroxychloroquine in France is linked to decisions that are more political than scientific?

Perhaps the contaminated blood scandal still casts a shadow in France, and there is a great deal of anxiety over the fact that we are already in a crisis, and we do not want a second one. I can understand that.

However, just a week ago, access to this drug (and others with market approval that have been on the market for several years) was blocked in hospital central pharmacies, while we are the medical specialists with the authorization! It was unacceptable.

It was sorted out 48 hours ago: hydroxychloroquine is now available in the hospital, and to my knowledge, we no longer have a problem obtaining it.

It took time to alleviate doubts over the major health risks with this drug. [Officials] seemed almost like amateurs in their hesitation; I think they lacked foresight. We have forgotten that the treatment advocated by Prof. Didier Raoult is not chloroquine but rather hydroxychloroquine, and we know that the adverse effects are less [with hydroxychloroquine] than with chloroquine.

You yourself have treated patients with chloroquine, despite the risk for toxicity highlighted by some.

Initially, when we first started treating patients, we thought of chloroquine because we did not have data on hydroxychloroquine, only Chinese data with chloroquine. We therefore prescribed chloroquine several days before prescribing hydroxychloroquine.

The question of the toxicity of chloroquine was not unjustified, but I think we took far too much time to decide on the toxicity of hydroxychloroquine. Is [the latter] political? I don’t know. It was widely publicized, which amazes me for a drug that is already available.

On the other hand, everyone was talking at the same time about the toxicity of NSAIDs. ... One has the impression it was to create a diversion. I think there were double standards at play and a scapegoat was needed to gain some time and ask questions.

What is sure is that it is probably not for financial reasons, as hydroxychloroquine costs nothing. That’s to say there were probably pharmaceutical issues at stake for possible competitors of hydroxychloroquine; I do not want to get into this debate, and it doesn’t matter, as long as we have an answer.

Today, the only thing we have advanced on is the “safety” of hydroxychloroquine, the low risk to the general population. ... On the other hand, we have still not made any progress on the evidence of efficacy, compared with other treatments.

Personally, I really believe in hydroxychloroquine. It would nevertheless be a shame to think we had found the fountain of youth and realize, in 4 weeks, that we have the same number of deaths. That is the problem. I hope that we will soon have solid data so we do not waste time focusing solely on hydroxychloroquine.

What are the other avenues of research that grab your attention?

The Discovery trial will probably give an answer on remdesivir [GS-5734, Gilead], which is a direct antiviral and could be interesting. But there are other studies being conducted currently in China.

There is also favipiravir [T-705, Avigan, Toyama Chemical], which is an anti-influenza drug used in Japan, which could explain, in part, the control of the epidemic in that country. There are effects in vitro on coronavirus. But it is not at all studied in France at the moment. Therefore, we should not focus exclusively on hydroxychloroquine; we must keep a close eye on other molecules, in particular the “old” drugs, like this antiviral.

The study was supported by the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire (IHU) Méditerranée Infection, the National Research Agency, under the Investissements d’avenir program, Région Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur, and European funding FEDER PRIMI. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

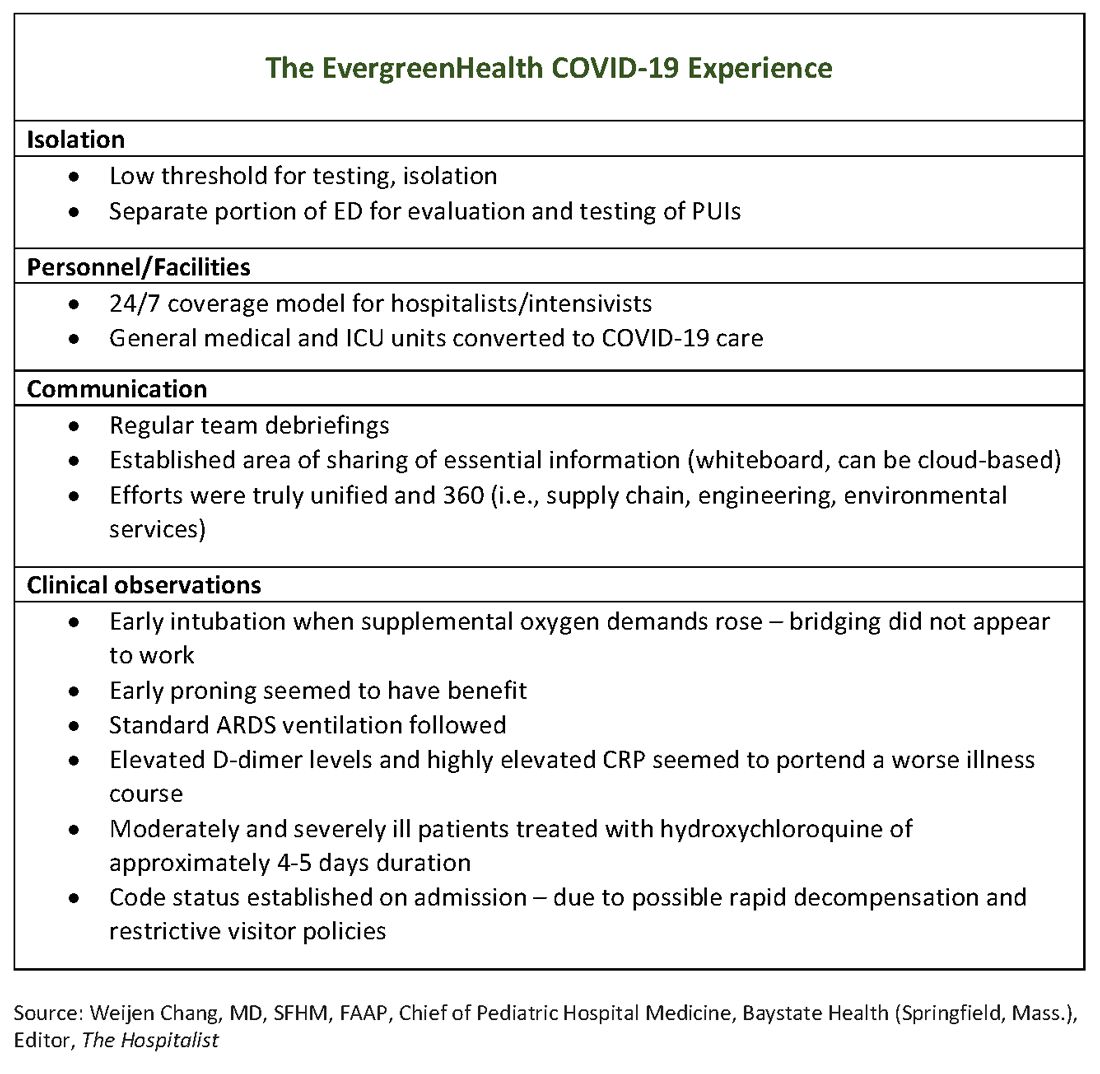

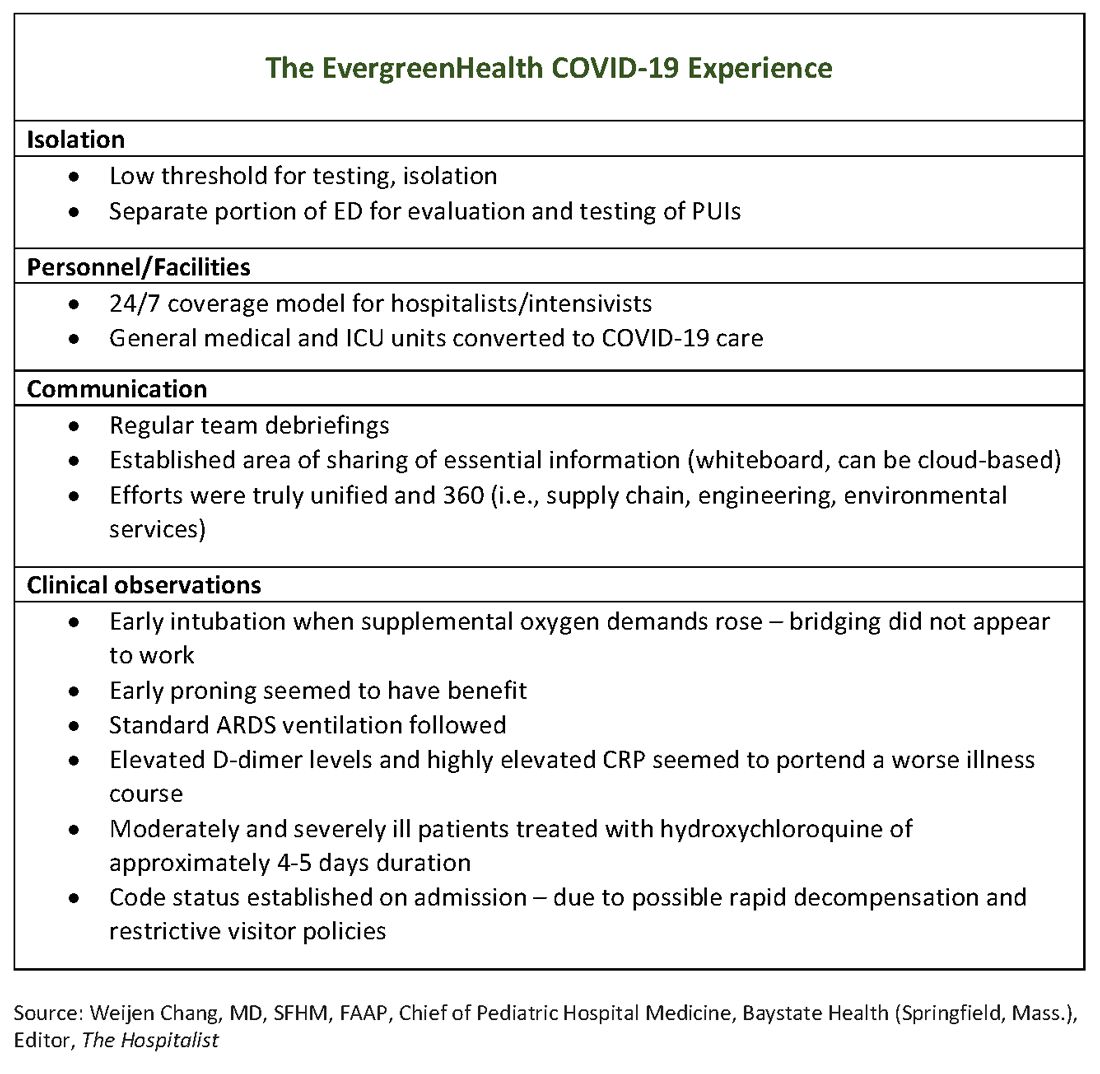

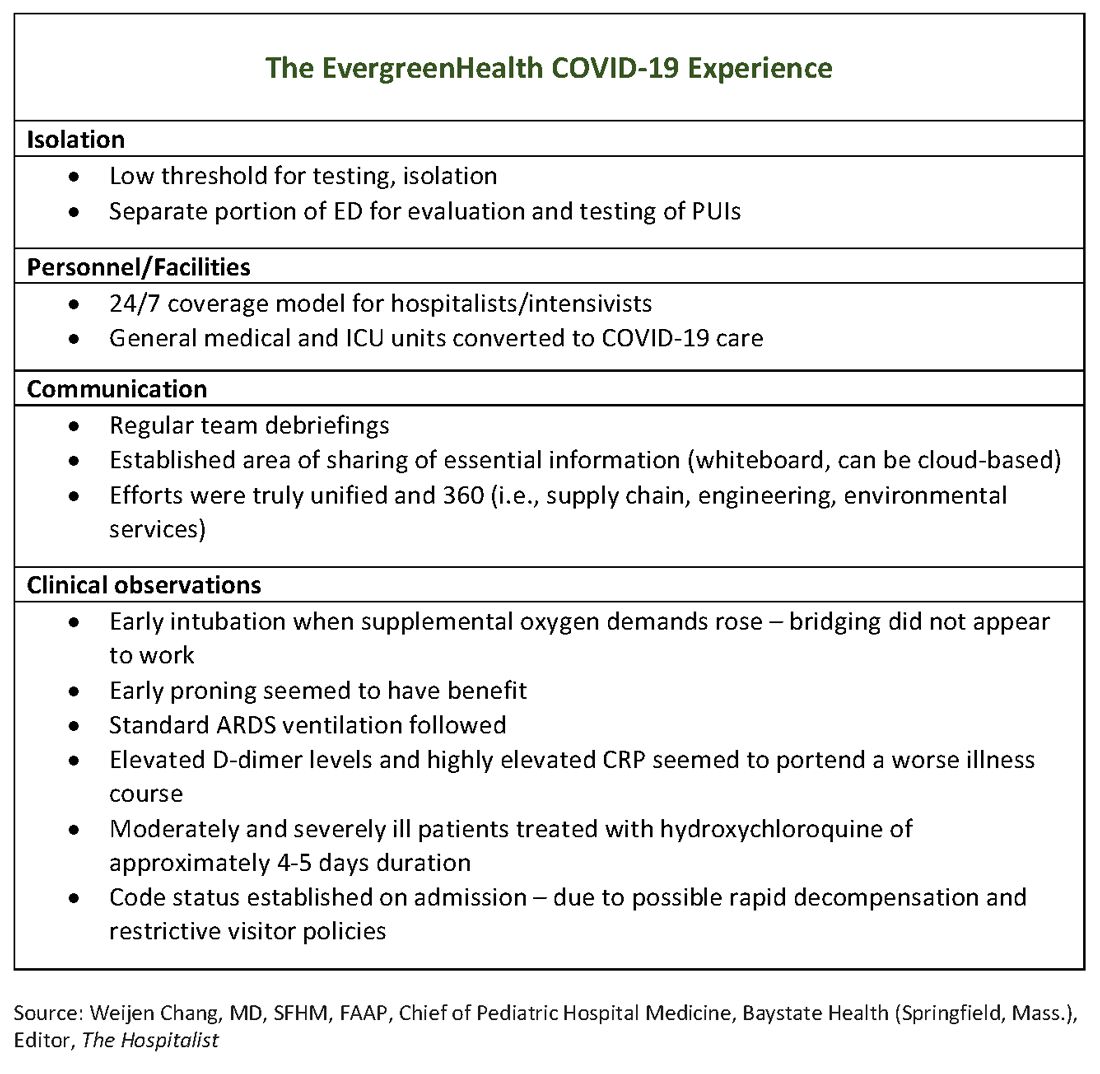

Top 10 must-dos in ICU in COVID-19 include prone ventilation

As the first international guidelines on the management of critically ill patients with COVID-19 are understandably comprehensive, one expert involved in their development highlights the essential recommendations and explains the rationale behind prone ventilation.

A panel of 39 experts from 12 countries from across the globe developed the 50 recommendations within four domains, under the auspices of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign. They are issued by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), and will subsequently be published in the journal Intensive Care Medicine.

A central aspect of the guidance is what works, and what does not, in treating critically ill patients with COVID-19 in intensive care.

Ten of the recommendations cover potential pharmacotherapies, most of which have only weak or no evidence of benefit, as discussed in a recent perspective on Medscape. All 50 recommendations, along with the associated level of evidence, are detailed in table 2 in the paper.

There is also an algorithm for the management of patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 (figure 2) and a summary of clinical practice recommendations (figure 3).

In an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association issued just days after these new guidelines, Francois Lamontagne, MD, MSc, and Derek C. Angus, MD, MPH, say they “represent an excellent first step toward optimal, evidence-informed care for patients with COVID-19.” Lamontagne is from Universitaire de Sherbrooke, Canada, and Angus is from University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pennsylvania, and is an associate editor with JAMA.

Dealing With Tide of COVID-19 Patients, Protecting Healthcare Workers

Editor in chief of Intensive Care Medicine Giuseppe Citerio, MD, from University of Milano-Bicocca, Monza, Italy, said: “COVID-19 cases are rising rapidly worldwide, and so we are increasingly seeing that intensive care units [ICUs] have difficulty in dealing with the tide of patients.”

“We need more resource in ICUs, and quickly. This means more ventilators and more trained personnel. In the meantime, this guidance aims to rationalize our approach and to avoid unproven strategies,” he explains in a press release from ESICM.

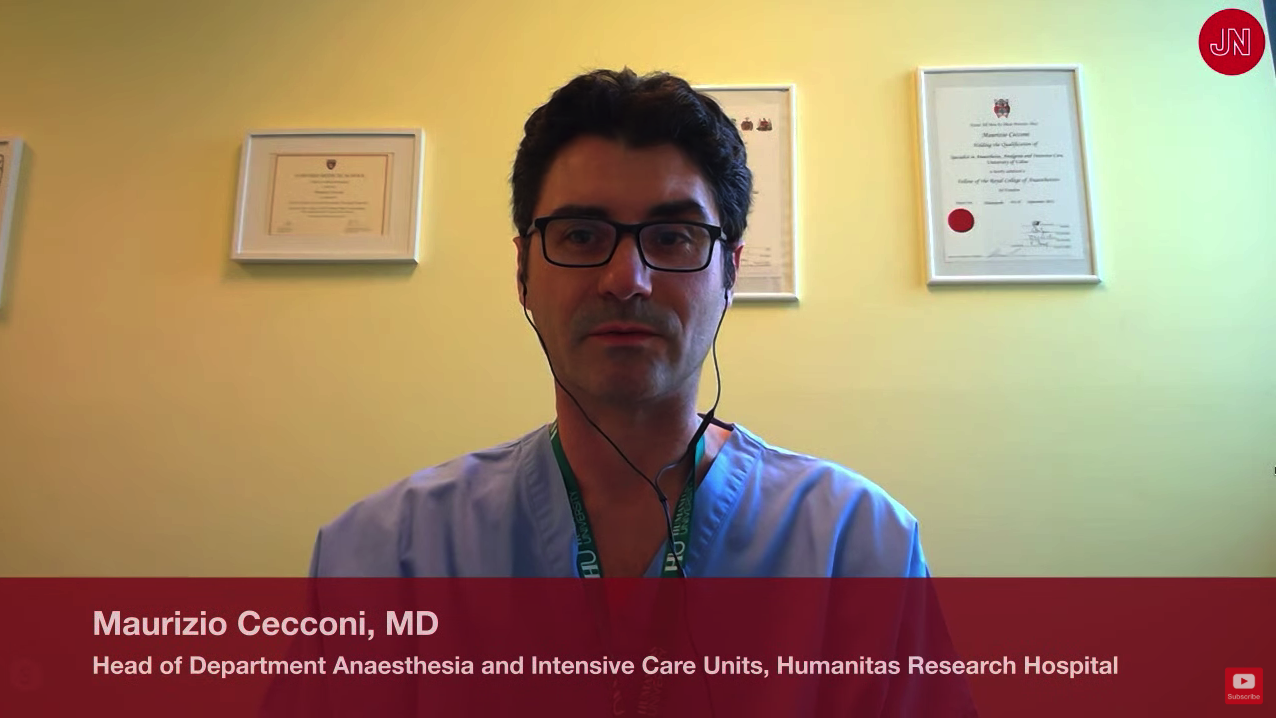

“This is the first guidance to lay out what works and what doesn’t in treating coronavirus-infected patients in intensive care. It’s based on decades of research on acute respiratory infection being applied to COVID-19 patients,” added ESICM President-Elect Maurizio Cecconi, MD, from Humanitas University, Milan, Italy.

“At the same time as caring for patients, we need to make sure that health workers are following procedures which will allow themselves to be protected against infection,” he stressed.

“We must protect them, they are in the frontline. We cannot allow our healthcare workers to be at risk. On top of that, if they get infected they could also spread the disease further.”

Top-10 Recommendations

While all 50 recommendations are key to the successful management of COVID-19 patients, busy clinicians on the frontline need to zone in on those indispensable practical recommendations that they should implement immediately.

Medscape Medical News therefore asked lead author Waleed Alhazzani, MD, MSc, from the Division of Critical Care, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada, to give his personal top 10, the first three of which are focused on limiting the spread of infection.

1. For healthcare workers performing aerosol-generating procedures1 on patients with COVID-19 in the ICU, we recommend using fitted respirator masks (N95 respirators, FFP2, or equivalent), as compared to surgical/medical masks, in addition to other personal protective equipment (eg, gloves, gown, and eye protection such as a face shield or safety goggles.

2. We recommend performing aerosol-generating procedures on ICU patients with COVID-19 in a negative-pressure room.

3. For healthcare workers providing usual care for nonventilated COVID-19 patients, we suggest using surgical/medical masks, as compared to respirator masks in addition to other personal protective equipment.

4. For healthcare workers performing endotracheal intubation on patients with COVID-19, we suggest using video guided laryngoscopy, over direct laryngoscopy, if available.

5. We recommend endotracheal intubation in patients with COVID-19, performed by healthcare workers experienced with airway management, to minimize the number of attempts and risk of transmission.

6. For intubated and mechanically ventilated adults with suspicion of COVID-19, we suggest obtaining endotracheal aspirates, over bronchial wash or bronchoalveolar lavage samples.

7. For adults with COVID-19 and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, we suggest using high-flow nasal cannula [HFNC] over noninvasive positive pressure ventilation [NIPPV].

8. For adults with COVID-19 receiving NIPPV or HFNC, we recommend close monitoring for worsening of respiratory status and early intubation in a controlled setting if worsening occurs.

9. For mechanically ventilated adults with COVID-19 and moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS], we suggest prone ventilation for 12 to 16 hours over no prone ventilation.

10. For mechanically ventilated adults with COVID-19 and respiratory failure (without ARDS), we don’t recommend routine use of systemic corticosteroids.

1 This includes endotracheal intubation, bronchoscopy, open suctioning, administration of nebulized treatment, manual ventilation before intubation, physical proning of the patient, disconnecting the patient from the ventilator, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, tracheostomy, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

These choices are in broad agreement with those selected by Jason T. Poston, MD, University of Chicago, Illinois, and colleagues in their synopsis of these guidelines, published online March 26 in JAMA, although they also highlight another recommendation on infection control:

- For healthcare workers who are performing non-aerosol-generating procedures on mechanically ventilated (closed circuit) patients with COVID-19, we suggest using surgical/medical masks, as opposed to respirator masks, in addition to other personal protective equipment.

Importance of Prone Ventilation, Perhaps for Many Days

One recommendation singled out by both Alhazzani and coauthors, and Poston and colleagues, relates to prone ventilation for 12 to 16 hours in adults with moderate to severe ARDS receiving mechanical ventilation.

Michelle N. Gong, MD, MS, chief of critical care medicine at Montefiore Medical Center, New York City, also highlighted this practice in a live-stream interview with JAMA editor in chief Howard Bauchner, MD.

She explained that, in her institution, they have been “very aggressive about proning these patients as early as possible, but unlike some of the past ARDS patients…they tend to require many, many days of proning in order to get a response”.

Gong added that patients “may improve very rapidly when they are proned, but when we supinate them, they lose [the improvement] and then they get proned for upwards of 10 days or more, if need be.”

Alhazzani told Medscape Medical News that prone ventilation “is a simple intervention that requires training of healthcare providers but can be applied in most contexts.”

He explained that the recommendation “is driven by indirect evidence from ARDS,” not specifically those in COVID-19, with recent studies having shown that COVID-19 “can affect lung bases and may cause significant atelectasis and reduced lung compliance in the context of ARDS.”

“Prone ventilation has been shown to reduce mortality in patients with moderate to severe ARDS. Therefore, we issued a suggestion for clinicians to consider prone ventilation in this population.”

‘Impressively Thorough’ Recommendations, With Some Caveats

In their JAMA editorial, Lamontagne and Angus describe the recommendations as “impressively thorough and expansive.”

They note that they address resource scarcity, which “is likely to be a critical issue in low- and middle-income countries experiencing any reasonably large number of cases and in high-income countries experiencing a surge in the demand for critical care.”

The authors say, however, that a “weakness” of the guidelines is that they make recommendations for interventions that “lack supporting evidence.”

Consequently, “when prioritizing scarce resources, clinicians and healthcare systems will have to choose among options that have limited evidence to support them.”

“In future iterations of the guidelines, there should be more detailed recommendations for how clinicians should prioritize scarce resources, or include more recommendations against the use of unproven therapies.”

“The tasks ahead for the dissemination and uptake of optimal critical care are herculean,” Lamontagne and Angus say.

They include “a need to generate more robust evidence, consider carefully the application of that evidence across a wide variety of clinical circumstances, and generate supporting materials to ensure effective implementation of the guideline recommendations,” they conclude.

ESICM recommendations coauthor Yaseen Arabi is the principal investigator on a clinical trial for lopinavir/ritonavir and interferon in Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and he was a nonpaid consultant on antiviral active for MERS- coronavirus (CoV) for Gilead Sciences and SAB Biotherapeutics. He is an investigator on REMAP-CAP trial and is a Board Members of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC). Coauthor Eddy Fan declared receiving consultancy fees from ALung Technologies and MC3 Cardiopulmonary. Coauthor Maurizio Cecconi declared consultancy work with Edwards Lifesciences, Directed Systems, and Cheetah Medical.

JAMA Clinical Guidelines Synopsis coauthor Poston declares receiving honoraria for the CHEST Critical Care Board Review Course.

Editorialist Lamontagne reported receiving grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé, and the Lotte & John Hecht Foundation, unrelated to this work. Editorialist Angus participated in the development of Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for sepsis, but had no role in the creation of the current COVID-19 guidelines, nor the decision to create these guidelines.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As the first international guidelines on the management of critically ill patients with COVID-19 are understandably comprehensive, one expert involved in their development highlights the essential recommendations and explains the rationale behind prone ventilation.

A panel of 39 experts from 12 countries from across the globe developed the 50 recommendations within four domains, under the auspices of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign. They are issued by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), and will subsequently be published in the journal Intensive Care Medicine.

A central aspect of the guidance is what works, and what does not, in treating critically ill patients with COVID-19 in intensive care.

Ten of the recommendations cover potential pharmacotherapies, most of which have only weak or no evidence of benefit, as discussed in a recent perspective on Medscape. All 50 recommendations, along with the associated level of evidence, are detailed in table 2 in the paper.

There is also an algorithm for the management of patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 (figure 2) and a summary of clinical practice recommendations (figure 3).

In an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association issued just days after these new guidelines, Francois Lamontagne, MD, MSc, and Derek C. Angus, MD, MPH, say they “represent an excellent first step toward optimal, evidence-informed care for patients with COVID-19.” Lamontagne is from Universitaire de Sherbrooke, Canada, and Angus is from University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pennsylvania, and is an associate editor with JAMA.

Dealing With Tide of COVID-19 Patients, Protecting Healthcare Workers

Editor in chief of Intensive Care Medicine Giuseppe Citerio, MD, from University of Milano-Bicocca, Monza, Italy, said: “COVID-19 cases are rising rapidly worldwide, and so we are increasingly seeing that intensive care units [ICUs] have difficulty in dealing with the tide of patients.”

“We need more resource in ICUs, and quickly. This means more ventilators and more trained personnel. In the meantime, this guidance aims to rationalize our approach and to avoid unproven strategies,” he explains in a press release from ESICM.

“This is the first guidance to lay out what works and what doesn’t in treating coronavirus-infected patients in intensive care. It’s based on decades of research on acute respiratory infection being applied to COVID-19 patients,” added ESICM President-Elect Maurizio Cecconi, MD, from Humanitas University, Milan, Italy.

“At the same time as caring for patients, we need to make sure that health workers are following procedures which will allow themselves to be protected against infection,” he stressed.

“We must protect them, they are in the frontline. We cannot allow our healthcare workers to be at risk. On top of that, if they get infected they could also spread the disease further.”

Top-10 Recommendations

While all 50 recommendations are key to the successful management of COVID-19 patients, busy clinicians on the frontline need to zone in on those indispensable practical recommendations that they should implement immediately.

Medscape Medical News therefore asked lead author Waleed Alhazzani, MD, MSc, from the Division of Critical Care, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada, to give his personal top 10, the first three of which are focused on limiting the spread of infection.

1. For healthcare workers performing aerosol-generating procedures1 on patients with COVID-19 in the ICU, we recommend using fitted respirator masks (N95 respirators, FFP2, or equivalent), as compared to surgical/medical masks, in addition to other personal protective equipment (eg, gloves, gown, and eye protection such as a face shield or safety goggles.

2. We recommend performing aerosol-generating procedures on ICU patients with COVID-19 in a negative-pressure room.

3. For healthcare workers providing usual care for nonventilated COVID-19 patients, we suggest using surgical/medical masks, as compared to respirator masks in addition to other personal protective equipment.

4. For healthcare workers performing endotracheal intubation on patients with COVID-19, we suggest using video guided laryngoscopy, over direct laryngoscopy, if available.

5. We recommend endotracheal intubation in patients with COVID-19, performed by healthcare workers experienced with airway management, to minimize the number of attempts and risk of transmission.

6. For intubated and mechanically ventilated adults with suspicion of COVID-19, we suggest obtaining endotracheal aspirates, over bronchial wash or bronchoalveolar lavage samples.

7. For adults with COVID-19 and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, we suggest using high-flow nasal cannula [HFNC] over noninvasive positive pressure ventilation [NIPPV].

8. For adults with COVID-19 receiving NIPPV or HFNC, we recommend close monitoring for worsening of respiratory status and early intubation in a controlled setting if worsening occurs.

9. For mechanically ventilated adults with COVID-19 and moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS], we suggest prone ventilation for 12 to 16 hours over no prone ventilation.

10. For mechanically ventilated adults with COVID-19 and respiratory failure (without ARDS), we don’t recommend routine use of systemic corticosteroids.

1 This includes endotracheal intubation, bronchoscopy, open suctioning, administration of nebulized treatment, manual ventilation before intubation, physical proning of the patient, disconnecting the patient from the ventilator, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, tracheostomy, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

These choices are in broad agreement with those selected by Jason T. Poston, MD, University of Chicago, Illinois, and colleagues in their synopsis of these guidelines, published online March 26 in JAMA, although they also highlight another recommendation on infection control:

- For healthcare workers who are performing non-aerosol-generating procedures on mechanically ventilated (closed circuit) patients with COVID-19, we suggest using surgical/medical masks, as opposed to respirator masks, in addition to other personal protective equipment.

Importance of Prone Ventilation, Perhaps for Many Days

One recommendation singled out by both Alhazzani and coauthors, and Poston and colleagues, relates to prone ventilation for 12 to 16 hours in adults with moderate to severe ARDS receiving mechanical ventilation.

Michelle N. Gong, MD, MS, chief of critical care medicine at Montefiore Medical Center, New York City, also highlighted this practice in a live-stream interview with JAMA editor in chief Howard Bauchner, MD.

She explained that, in her institution, they have been “very aggressive about proning these patients as early as possible, but unlike some of the past ARDS patients…they tend to require many, many days of proning in order to get a response”.

Gong added that patients “may improve very rapidly when they are proned, but when we supinate them, they lose [the improvement] and then they get proned for upwards of 10 days or more, if need be.”

Alhazzani told Medscape Medical News that prone ventilation “is a simple intervention that requires training of healthcare providers but can be applied in most contexts.”

He explained that the recommendation “is driven by indirect evidence from ARDS,” not specifically those in COVID-19, with recent studies having shown that COVID-19 “can affect lung bases and may cause significant atelectasis and reduced lung compliance in the context of ARDS.”

“Prone ventilation has been shown to reduce mortality in patients with moderate to severe ARDS. Therefore, we issued a suggestion for clinicians to consider prone ventilation in this population.”

‘Impressively Thorough’ Recommendations, With Some Caveats

In their JAMA editorial, Lamontagne and Angus describe the recommendations as “impressively thorough and expansive.”

They note that they address resource scarcity, which “is likely to be a critical issue in low- and middle-income countries experiencing any reasonably large number of cases and in high-income countries experiencing a surge in the demand for critical care.”

The authors say, however, that a “weakness” of the guidelines is that they make recommendations for interventions that “lack supporting evidence.”

Consequently, “when prioritizing scarce resources, clinicians and healthcare systems will have to choose among options that have limited evidence to support them.”

“In future iterations of the guidelines, there should be more detailed recommendations for how clinicians should prioritize scarce resources, or include more recommendations against the use of unproven therapies.”

“The tasks ahead for the dissemination and uptake of optimal critical care are herculean,” Lamontagne and Angus say.

They include “a need to generate more robust evidence, consider carefully the application of that evidence across a wide variety of clinical circumstances, and generate supporting materials to ensure effective implementation of the guideline recommendations,” they conclude.

ESICM recommendations coauthor Yaseen Arabi is the principal investigator on a clinical trial for lopinavir/ritonavir and interferon in Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and he was a nonpaid consultant on antiviral active for MERS- coronavirus (CoV) for Gilead Sciences and SAB Biotherapeutics. He is an investigator on REMAP-CAP trial and is a Board Members of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC). Coauthor Eddy Fan declared receiving consultancy fees from ALung Technologies and MC3 Cardiopulmonary. Coauthor Maurizio Cecconi declared consultancy work with Edwards Lifesciences, Directed Systems, and Cheetah Medical.

JAMA Clinical Guidelines Synopsis coauthor Poston declares receiving honoraria for the CHEST Critical Care Board Review Course.

Editorialist Lamontagne reported receiving grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé, and the Lotte & John Hecht Foundation, unrelated to this work. Editorialist Angus participated in the development of Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for sepsis, but had no role in the creation of the current COVID-19 guidelines, nor the decision to create these guidelines.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As the first international guidelines on the management of critically ill patients with COVID-19 are understandably comprehensive, one expert involved in their development highlights the essential recommendations and explains the rationale behind prone ventilation.

A panel of 39 experts from 12 countries from across the globe developed the 50 recommendations within four domains, under the auspices of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign. They are issued by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), and will subsequently be published in the journal Intensive Care Medicine.

A central aspect of the guidance is what works, and what does not, in treating critically ill patients with COVID-19 in intensive care.

Ten of the recommendations cover potential pharmacotherapies, most of which have only weak or no evidence of benefit, as discussed in a recent perspective on Medscape. All 50 recommendations, along with the associated level of evidence, are detailed in table 2 in the paper.

There is also an algorithm for the management of patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 (figure 2) and a summary of clinical practice recommendations (figure 3).

In an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association issued just days after these new guidelines, Francois Lamontagne, MD, MSc, and Derek C. Angus, MD, MPH, say they “represent an excellent first step toward optimal, evidence-informed care for patients with COVID-19.” Lamontagne is from Universitaire de Sherbrooke, Canada, and Angus is from University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pennsylvania, and is an associate editor with JAMA.

Dealing With Tide of COVID-19 Patients, Protecting Healthcare Workers

Editor in chief of Intensive Care Medicine Giuseppe Citerio, MD, from University of Milano-Bicocca, Monza, Italy, said: “COVID-19 cases are rising rapidly worldwide, and so we are increasingly seeing that intensive care units [ICUs] have difficulty in dealing with the tide of patients.”

“We need more resource in ICUs, and quickly. This means more ventilators and more trained personnel. In the meantime, this guidance aims to rationalize our approach and to avoid unproven strategies,” he explains in a press release from ESICM.

“This is the first guidance to lay out what works and what doesn’t in treating coronavirus-infected patients in intensive care. It’s based on decades of research on acute respiratory infection being applied to COVID-19 patients,” added ESICM President-Elect Maurizio Cecconi, MD, from Humanitas University, Milan, Italy.

“At the same time as caring for patients, we need to make sure that health workers are following procedures which will allow themselves to be protected against infection,” he stressed.

“We must protect them, they are in the frontline. We cannot allow our healthcare workers to be at risk. On top of that, if they get infected they could also spread the disease further.”

Top-10 Recommendations

While all 50 recommendations are key to the successful management of COVID-19 patients, busy clinicians on the frontline need to zone in on those indispensable practical recommendations that they should implement immediately.

Medscape Medical News therefore asked lead author Waleed Alhazzani, MD, MSc, from the Division of Critical Care, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada, to give his personal top 10, the first three of which are focused on limiting the spread of infection.

1. For healthcare workers performing aerosol-generating procedures1 on patients with COVID-19 in the ICU, we recommend using fitted respirator masks (N95 respirators, FFP2, or equivalent), as compared to surgical/medical masks, in addition to other personal protective equipment (eg, gloves, gown, and eye protection such as a face shield or safety goggles.

2. We recommend performing aerosol-generating procedures on ICU patients with COVID-19 in a negative-pressure room.

3. For healthcare workers providing usual care for nonventilated COVID-19 patients, we suggest using surgical/medical masks, as compared to respirator masks in addition to other personal protective equipment.

4. For healthcare workers performing endotracheal intubation on patients with COVID-19, we suggest using video guided laryngoscopy, over direct laryngoscopy, if available.

5. We recommend endotracheal intubation in patients with COVID-19, performed by healthcare workers experienced with airway management, to minimize the number of attempts and risk of transmission.

6. For intubated and mechanically ventilated adults with suspicion of COVID-19, we suggest obtaining endotracheal aspirates, over bronchial wash or bronchoalveolar lavage samples.

7. For adults with COVID-19 and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, we suggest using high-flow nasal cannula [HFNC] over noninvasive positive pressure ventilation [NIPPV].

8. For adults with COVID-19 receiving NIPPV or HFNC, we recommend close monitoring for worsening of respiratory status and early intubation in a controlled setting if worsening occurs.

9. For mechanically ventilated adults with COVID-19 and moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS], we suggest prone ventilation for 12 to 16 hours over no prone ventilation.

10. For mechanically ventilated adults with COVID-19 and respiratory failure (without ARDS), we don’t recommend routine use of systemic corticosteroids.

1 This includes endotracheal intubation, bronchoscopy, open suctioning, administration of nebulized treatment, manual ventilation before intubation, physical proning of the patient, disconnecting the patient from the ventilator, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, tracheostomy, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

These choices are in broad agreement with those selected by Jason T. Poston, MD, University of Chicago, Illinois, and colleagues in their synopsis of these guidelines, published online March 26 in JAMA, although they also highlight another recommendation on infection control:

- For healthcare workers who are performing non-aerosol-generating procedures on mechanically ventilated (closed circuit) patients with COVID-19, we suggest using surgical/medical masks, as opposed to respirator masks, in addition to other personal protective equipment.

Importance of Prone Ventilation, Perhaps for Many Days

One recommendation singled out by both Alhazzani and coauthors, and Poston and colleagues, relates to prone ventilation for 12 to 16 hours in adults with moderate to severe ARDS receiving mechanical ventilation.

Michelle N. Gong, MD, MS, chief of critical care medicine at Montefiore Medical Center, New York City, also highlighted this practice in a live-stream interview with JAMA editor in chief Howard Bauchner, MD.

She explained that, in her institution, they have been “very aggressive about proning these patients as early as possible, but unlike some of the past ARDS patients…they tend to require many, many days of proning in order to get a response”.

Gong added that patients “may improve very rapidly when they are proned, but when we supinate them, they lose [the improvement] and then they get proned for upwards of 10 days or more, if need be.”