User login

Novel drug ‘promising’ for concomitant depression, insomnia

In a randomized, placebo-controlled, adaptive dose–finding study conducted in more than 200 patients with MDD, those with more severe insomnia at baseline had a greater improvement in depressive symptoms versus those with less severe insomnia.

“As seltorexant is an orexin receptor antagonist, it is related to other medications that are marketed as sleeping pills, so it was important to show that its antidepressant efficacy was actually caused by improved sleep,” coinvestigator Michael E. Thase, MD, professor of psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“This novel antidepressant may well turn out to be a treatment of choice for depressed patients with insomnia,” said Dr. Thase, who is also a member of the medical and research staff of the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

The findings were presented at the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology annual meeting.

Clinically meaningful?

In an earlier exploratory study, seltorexant showed antidepressant and sleep-promoting effects in patients with MDD. In a phase 2b study, a 20-mg dose of the drug showed clinically meaningful improvement in the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score after 6 weeks of treatment.

In the current analysis, the investigators evaluated the effect of seltorexant in improving depressive symptoms beyond sleep-related improvement in patients with MDD, using the MADRS-WOSI (MADRS without the sleep item).

They also used the six-item core MADRS subscale, which excludes sleep, anxiety, and appetite items.

The 283 participants were randomly assigned 3:3:1 to receive seltorexant 10 mg or 20 mg or placebo once daily. They were also stratified into two groups according to the severity of their insomnia: those with a baseline Insomnia Severity Index [ISI] score of 15 or higher (58%) and those with a baseline ISI score of less than 15 (42%).

Results showed that the group receiving the 20-mg/day dose of seltorexant (n = 61 patients) obtained a statistically and clinically meaningful response, compared with the placebo group (n = 137 patients) after removing the insomnia and other “not core items” of the MADRS. The effect was clearest among those with high insomnia ratings.

Improvement in the MADRS-WOSI score was also observed in the seltorexant 20-mg group at week 3 and week 6, compared with the placebo group.

The LSM average distance

The least squares mean (LSM) average difference between the treatment and placebo groups in the MADRS-WOSI score at week 3 was −3.8 (90% confidence interval, −5.98 to −1.57; P = .005).

At week 6, the LSM between the groups in the MADRS-WOSI score was −2.5 (90% CI, −5.24 to 0.15; P = .12).

The results were consistent with improvement in the MADRS total score. At week 3, the LSM in the MADRS total score was -4.5 (90% CI, -6.96 to -2.07; P = .003) and, at week 6, it was -3.1 (90% CI, -6.13 to -0.16; P = .083).

Seltorexant 20 mg was especially effective in patients who had more severe insomnia.

Commenting on the study, Nagy Youssef, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said this was “a well-designed study examining a promising compound.”

“Especially if replicated, this study shows the promise of this molecule for this patient population,” said Dr. Youssef, who was not involved with the research.

The study was funded by Janssen Pharmaceutical of Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Thase reports financial relationships with numerous companies. Dr. Youssef reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a randomized, placebo-controlled, adaptive dose–finding study conducted in more than 200 patients with MDD, those with more severe insomnia at baseline had a greater improvement in depressive symptoms versus those with less severe insomnia.

“As seltorexant is an orexin receptor antagonist, it is related to other medications that are marketed as sleeping pills, so it was important to show that its antidepressant efficacy was actually caused by improved sleep,” coinvestigator Michael E. Thase, MD, professor of psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“This novel antidepressant may well turn out to be a treatment of choice for depressed patients with insomnia,” said Dr. Thase, who is also a member of the medical and research staff of the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

The findings were presented at the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology annual meeting.

Clinically meaningful?

In an earlier exploratory study, seltorexant showed antidepressant and sleep-promoting effects in patients with MDD. In a phase 2b study, a 20-mg dose of the drug showed clinically meaningful improvement in the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score after 6 weeks of treatment.

In the current analysis, the investigators evaluated the effect of seltorexant in improving depressive symptoms beyond sleep-related improvement in patients with MDD, using the MADRS-WOSI (MADRS without the sleep item).

They also used the six-item core MADRS subscale, which excludes sleep, anxiety, and appetite items.

The 283 participants were randomly assigned 3:3:1 to receive seltorexant 10 mg or 20 mg or placebo once daily. They were also stratified into two groups according to the severity of their insomnia: those with a baseline Insomnia Severity Index [ISI] score of 15 or higher (58%) and those with a baseline ISI score of less than 15 (42%).

Results showed that the group receiving the 20-mg/day dose of seltorexant (n = 61 patients) obtained a statistically and clinically meaningful response, compared with the placebo group (n = 137 patients) after removing the insomnia and other “not core items” of the MADRS. The effect was clearest among those with high insomnia ratings.

Improvement in the MADRS-WOSI score was also observed in the seltorexant 20-mg group at week 3 and week 6, compared with the placebo group.

The LSM average distance

The least squares mean (LSM) average difference between the treatment and placebo groups in the MADRS-WOSI score at week 3 was −3.8 (90% confidence interval, −5.98 to −1.57; P = .005).

At week 6, the LSM between the groups in the MADRS-WOSI score was −2.5 (90% CI, −5.24 to 0.15; P = .12).

The results were consistent with improvement in the MADRS total score. At week 3, the LSM in the MADRS total score was -4.5 (90% CI, -6.96 to -2.07; P = .003) and, at week 6, it was -3.1 (90% CI, -6.13 to -0.16; P = .083).

Seltorexant 20 mg was especially effective in patients who had more severe insomnia.

Commenting on the study, Nagy Youssef, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said this was “a well-designed study examining a promising compound.”

“Especially if replicated, this study shows the promise of this molecule for this patient population,” said Dr. Youssef, who was not involved with the research.

The study was funded by Janssen Pharmaceutical of Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Thase reports financial relationships with numerous companies. Dr. Youssef reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a randomized, placebo-controlled, adaptive dose–finding study conducted in more than 200 patients with MDD, those with more severe insomnia at baseline had a greater improvement in depressive symptoms versus those with less severe insomnia.

“As seltorexant is an orexin receptor antagonist, it is related to other medications that are marketed as sleeping pills, so it was important to show that its antidepressant efficacy was actually caused by improved sleep,” coinvestigator Michael E. Thase, MD, professor of psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“This novel antidepressant may well turn out to be a treatment of choice for depressed patients with insomnia,” said Dr. Thase, who is also a member of the medical and research staff of the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

The findings were presented at the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology annual meeting.

Clinically meaningful?

In an earlier exploratory study, seltorexant showed antidepressant and sleep-promoting effects in patients with MDD. In a phase 2b study, a 20-mg dose of the drug showed clinically meaningful improvement in the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score after 6 weeks of treatment.

In the current analysis, the investigators evaluated the effect of seltorexant in improving depressive symptoms beyond sleep-related improvement in patients with MDD, using the MADRS-WOSI (MADRS without the sleep item).

They also used the six-item core MADRS subscale, which excludes sleep, anxiety, and appetite items.

The 283 participants were randomly assigned 3:3:1 to receive seltorexant 10 mg or 20 mg or placebo once daily. They were also stratified into two groups according to the severity of their insomnia: those with a baseline Insomnia Severity Index [ISI] score of 15 or higher (58%) and those with a baseline ISI score of less than 15 (42%).

Results showed that the group receiving the 20-mg/day dose of seltorexant (n = 61 patients) obtained a statistically and clinically meaningful response, compared with the placebo group (n = 137 patients) after removing the insomnia and other “not core items” of the MADRS. The effect was clearest among those with high insomnia ratings.

Improvement in the MADRS-WOSI score was also observed in the seltorexant 20-mg group at week 3 and week 6, compared with the placebo group.

The LSM average distance

The least squares mean (LSM) average difference between the treatment and placebo groups in the MADRS-WOSI score at week 3 was −3.8 (90% confidence interval, −5.98 to −1.57; P = .005).

At week 6, the LSM between the groups in the MADRS-WOSI score was −2.5 (90% CI, −5.24 to 0.15; P = .12).

The results were consistent with improvement in the MADRS total score. At week 3, the LSM in the MADRS total score was -4.5 (90% CI, -6.96 to -2.07; P = .003) and, at week 6, it was -3.1 (90% CI, -6.13 to -0.16; P = .083).

Seltorexant 20 mg was especially effective in patients who had more severe insomnia.

Commenting on the study, Nagy Youssef, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said this was “a well-designed study examining a promising compound.”

“Especially if replicated, this study shows the promise of this molecule for this patient population,” said Dr. Youssef, who was not involved with the research.

The study was funded by Janssen Pharmaceutical of Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Thase reports financial relationships with numerous companies. Dr. Youssef reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASCP 2022

Antipsychotic tied to dose-related weight gain, higher cholesterol

new research suggests.

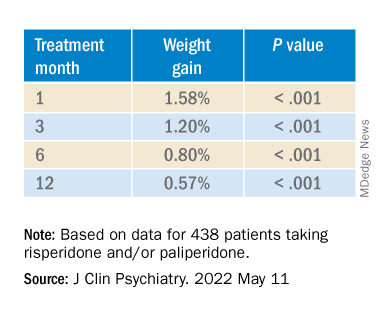

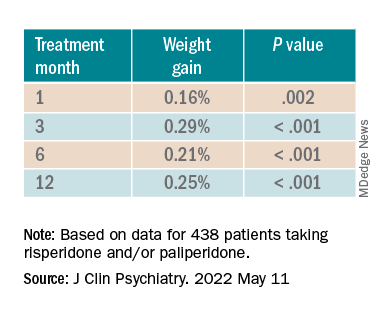

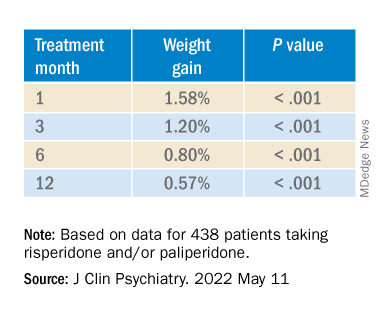

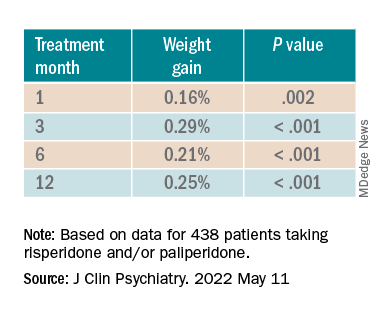

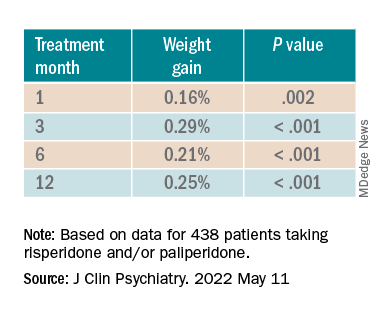

Investigators analyzed 1-year data for more than 400 patients who were taking risperidone and/or its metabolite paliperidone (Invega). Results showed increments of 1 mg of risperidone-equivalent doses were associated with an increase of 0.25% of weight within a year of follow-up.

“Although our findings report a positive and statistically significant dose-dependence of weight gain and cholesterol, both total and LDL [cholesterol], the size of the predicted changes of metabolic effects is clinically nonrelevant,” lead author Marianna Piras, PharmD, Centre for Psychiatric Neuroscience, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“Therefore, dose lowering would not have a beneficial effect on attenuating weight gain or cholesterol increases and could lead to psychiatric decompensation,” said Ms. Piras, who is also a PhD candidate in the unit of pharmacogenetics and clinical psychopharmacology at the University of Lausanne.

However, she added that because dose increments could increase risk for significant weight gain in the first month of treatment – the dose can be increased typically in a range of 1-10 grams – and strong dose increments could contribute to metabolic worsening over time, “risperidone minimum effective doses should be preferred.”

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Serious public health issue’

Compared with the general population, patients with mental illness present with a greater prevalence of metabolic disorders. In addition, several psychotropic medications, including antipsychotics, can induce metabolic alterations such as weight gain, the investigators noted.

Antipsychotic-induced metabolic adverse effects “constitute a serious public health issue” because they are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as obesity and/or dyslipidemia, “which have been associated with a 10-year reduced life expectancy in the psychiatric population,” Ms. Piras said.

“The dose-dependence of metabolic adverse effects is a debated subject that needs to be assessed for each psychotropic drug known to induce weight gain,” she added.

Several previous studies have examined whether there is a dose-related effect of antipsychotics on metabolic parameters, “with some results suggesting that [weight gain] seems to develop even when low off-label doses are prescribed,” Ms. Piras noted.

She and her colleagues had already studied dose-related metabolic effects of quetiapine (Seroquel) and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

Risperidone is an antipsychotic with a “medium to high metabolic risk profile,” the researchers note, and few studies have examined the impact of risperidone on metabolic parameters other than weight gain.

For the current analysis, they analyzed data from a longitudinal study that included 438 patients (mean age, 40.7 years; 50.7% men) who started treatment with risperidone and/or paliperidone between 2007 and 2018.

The participants had diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, “other,” or “unknown.”

Clinical follow-up periods were up to a year, but were no shorter than 3 weeks. The investigators also assessed the data at different time intervals at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months “to appreciate the evolution of the metabolic parameters.”

In addition, they collected demographic and clinical information, such as comorbidities, and measured patients’ weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure, plasma glucose, and lipids at baseline and at 1, 3, and 12 months and then annually. Weight, waist circumference, and BP were also assessed at 2 and 6 months.

Doses of paliperidone were converted into risperidone-equivalent doses.

Significant weight gain over time

The mean duration of follow-up for the participants, of whom 374 were being treated with risperidone and 64 with paliperidone, was 153 days. Close to half (48.2%) were taking other psychotropic medications known to be associated with some degree of metabolic risk.

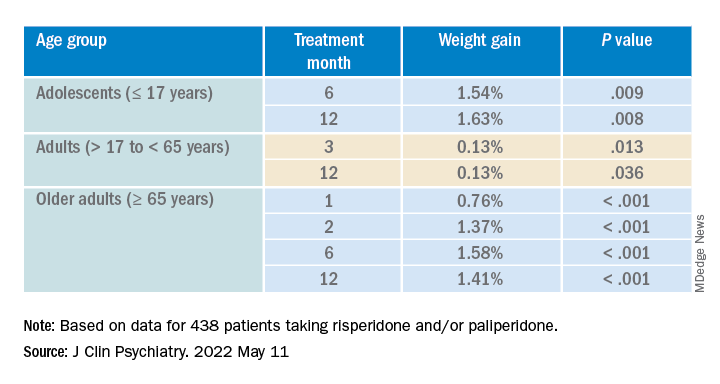

Patients were divided into two cohorts based on their daily dose intake (DDI): less than 3 mg/day (n = 201) and at least 3 mg/day (n = 237).

In the overall cohort, a “significant effect of time on weight change was found for each time point,” the investigators reported.

When the researchers looked at the changes according to DDI, they found that each 1-mg dose increase was associated with incremental weight gain at each time point.

Patients who had 5% or greater weight gain in the first month continued to gain weight more than patients who did not reach that threshold, leading the researchers to call that early threshold a “strong predictor of important weight gain in the long term.” There was a weight gain of 6.68% at 3 months, of 7.36% at 6 months, and of 7.7% at 12 months.

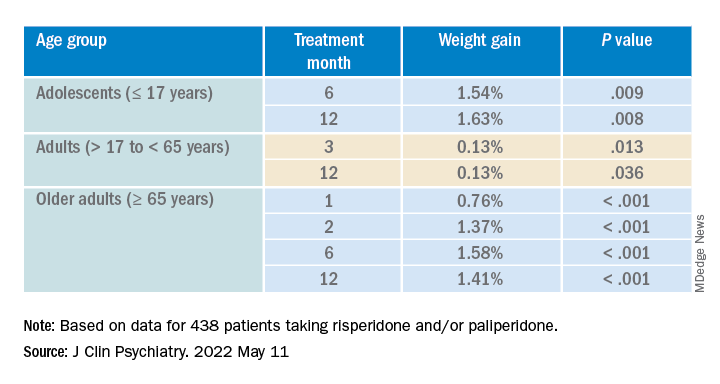

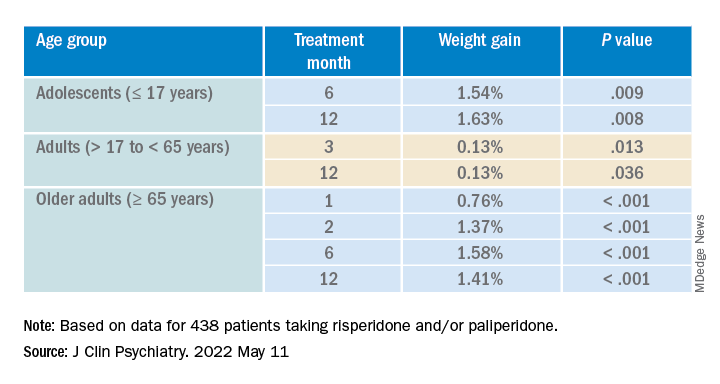

After the patients were stratified by age, there were differences in the effect of DDI on various age groups at different time points.

Dose was shown to have a significant effect on weight gain for women at all four time points (P ≥ .001), but for men only at 3 months (P = .003).

For each additional 1-mg dose, there was a 0.05 mmol/L (1.93 mg/dL) increase in total cholesterol (P = .018) after 1 year and a 0.04 mmol/L (1.54 mg/dL) increase in LDL cholesterol (P = .011).

There were no significant effects of time or DDI on triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, glucose levels, and systolic BP, and there was a negative effect of DDI on diastolic BP (P = .001).

The findings “provide evidence for a small dose effect of risperidone” on weight gain and total and LDL cholesterol levels, the investigators note.

Ms. Piras added that because each antipsychotic differs in its metabolic risk profile, “further analyses on other antipsychotics are ongoing in our laboratory, so far confirming our findings.”

Small increases, big changes

Commenting on the study, Erika Nurmi, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience, University of California, Los Angeles, said the study is “unique in the field.”

It “leverages real-world data from a large patient registry to ask a long-unanswered question: Are weight and metabolic adverse effects proportional to dose? Big data approaches like these are very powerful, given the large number of participants that can be included,” said Dr. Nurmi, who was not involved with the research.

However, she cautioned, the “biggest drawback [is that] these data are by nature much more complex and prone to confounding effects.”

In this case, a “critical confounder” for the study was that the majority of individuals taking higher risperidone doses were also taking other drugs known to cause weight gain, whereas the majority of those on lower risperidone doses were not. “This difference may explain the dose relationship observed,” she said.

Because real-world, big data are “valuable but also messy, conclusions drawn from them must be interpreted with caution,” Dr. Nurmi said.

She added that it is generally wise to use the lowest effective dose possible.

“Clinicians should appreciate that even small doses of antipsychotics can cause big changes in weight. Risks and benefits of medications must be carefully considered in clinical practice,” Dr. Nurmi said.

The research was funded in part by the Swiss National Research Foundation. Piras reports no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Nurmi reported no relevant financial relationships, but she is an unpaid member of the Tourette Association of America’s medical advisory board and of the Myriad Genetics scientific advisory board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Investigators analyzed 1-year data for more than 400 patients who were taking risperidone and/or its metabolite paliperidone (Invega). Results showed increments of 1 mg of risperidone-equivalent doses were associated with an increase of 0.25% of weight within a year of follow-up.

“Although our findings report a positive and statistically significant dose-dependence of weight gain and cholesterol, both total and LDL [cholesterol], the size of the predicted changes of metabolic effects is clinically nonrelevant,” lead author Marianna Piras, PharmD, Centre for Psychiatric Neuroscience, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“Therefore, dose lowering would not have a beneficial effect on attenuating weight gain or cholesterol increases and could lead to psychiatric decompensation,” said Ms. Piras, who is also a PhD candidate in the unit of pharmacogenetics and clinical psychopharmacology at the University of Lausanne.

However, she added that because dose increments could increase risk for significant weight gain in the first month of treatment – the dose can be increased typically in a range of 1-10 grams – and strong dose increments could contribute to metabolic worsening over time, “risperidone minimum effective doses should be preferred.”

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Serious public health issue’

Compared with the general population, patients with mental illness present with a greater prevalence of metabolic disorders. In addition, several psychotropic medications, including antipsychotics, can induce metabolic alterations such as weight gain, the investigators noted.

Antipsychotic-induced metabolic adverse effects “constitute a serious public health issue” because they are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as obesity and/or dyslipidemia, “which have been associated with a 10-year reduced life expectancy in the psychiatric population,” Ms. Piras said.

“The dose-dependence of metabolic adverse effects is a debated subject that needs to be assessed for each psychotropic drug known to induce weight gain,” she added.

Several previous studies have examined whether there is a dose-related effect of antipsychotics on metabolic parameters, “with some results suggesting that [weight gain] seems to develop even when low off-label doses are prescribed,” Ms. Piras noted.

She and her colleagues had already studied dose-related metabolic effects of quetiapine (Seroquel) and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

Risperidone is an antipsychotic with a “medium to high metabolic risk profile,” the researchers note, and few studies have examined the impact of risperidone on metabolic parameters other than weight gain.

For the current analysis, they analyzed data from a longitudinal study that included 438 patients (mean age, 40.7 years; 50.7% men) who started treatment with risperidone and/or paliperidone between 2007 and 2018.

The participants had diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, “other,” or “unknown.”

Clinical follow-up periods were up to a year, but were no shorter than 3 weeks. The investigators also assessed the data at different time intervals at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months “to appreciate the evolution of the metabolic parameters.”

In addition, they collected demographic and clinical information, such as comorbidities, and measured patients’ weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure, plasma glucose, and lipids at baseline and at 1, 3, and 12 months and then annually. Weight, waist circumference, and BP were also assessed at 2 and 6 months.

Doses of paliperidone were converted into risperidone-equivalent doses.

Significant weight gain over time

The mean duration of follow-up for the participants, of whom 374 were being treated with risperidone and 64 with paliperidone, was 153 days. Close to half (48.2%) were taking other psychotropic medications known to be associated with some degree of metabolic risk.

Patients were divided into two cohorts based on their daily dose intake (DDI): less than 3 mg/day (n = 201) and at least 3 mg/day (n = 237).

In the overall cohort, a “significant effect of time on weight change was found for each time point,” the investigators reported.

When the researchers looked at the changes according to DDI, they found that each 1-mg dose increase was associated with incremental weight gain at each time point.

Patients who had 5% or greater weight gain in the first month continued to gain weight more than patients who did not reach that threshold, leading the researchers to call that early threshold a “strong predictor of important weight gain in the long term.” There was a weight gain of 6.68% at 3 months, of 7.36% at 6 months, and of 7.7% at 12 months.

After the patients were stratified by age, there were differences in the effect of DDI on various age groups at different time points.

Dose was shown to have a significant effect on weight gain for women at all four time points (P ≥ .001), but for men only at 3 months (P = .003).

For each additional 1-mg dose, there was a 0.05 mmol/L (1.93 mg/dL) increase in total cholesterol (P = .018) after 1 year and a 0.04 mmol/L (1.54 mg/dL) increase in LDL cholesterol (P = .011).

There were no significant effects of time or DDI on triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, glucose levels, and systolic BP, and there was a negative effect of DDI on diastolic BP (P = .001).

The findings “provide evidence for a small dose effect of risperidone” on weight gain and total and LDL cholesterol levels, the investigators note.

Ms. Piras added that because each antipsychotic differs in its metabolic risk profile, “further analyses on other antipsychotics are ongoing in our laboratory, so far confirming our findings.”

Small increases, big changes

Commenting on the study, Erika Nurmi, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience, University of California, Los Angeles, said the study is “unique in the field.”

It “leverages real-world data from a large patient registry to ask a long-unanswered question: Are weight and metabolic adverse effects proportional to dose? Big data approaches like these are very powerful, given the large number of participants that can be included,” said Dr. Nurmi, who was not involved with the research.

However, she cautioned, the “biggest drawback [is that] these data are by nature much more complex and prone to confounding effects.”

In this case, a “critical confounder” for the study was that the majority of individuals taking higher risperidone doses were also taking other drugs known to cause weight gain, whereas the majority of those on lower risperidone doses were not. “This difference may explain the dose relationship observed,” she said.

Because real-world, big data are “valuable but also messy, conclusions drawn from them must be interpreted with caution,” Dr. Nurmi said.

She added that it is generally wise to use the lowest effective dose possible.

“Clinicians should appreciate that even small doses of antipsychotics can cause big changes in weight. Risks and benefits of medications must be carefully considered in clinical practice,” Dr. Nurmi said.

The research was funded in part by the Swiss National Research Foundation. Piras reports no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Nurmi reported no relevant financial relationships, but she is an unpaid member of the Tourette Association of America’s medical advisory board and of the Myriad Genetics scientific advisory board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Investigators analyzed 1-year data for more than 400 patients who were taking risperidone and/or its metabolite paliperidone (Invega). Results showed increments of 1 mg of risperidone-equivalent doses were associated with an increase of 0.25% of weight within a year of follow-up.

“Although our findings report a positive and statistically significant dose-dependence of weight gain and cholesterol, both total and LDL [cholesterol], the size of the predicted changes of metabolic effects is clinically nonrelevant,” lead author Marianna Piras, PharmD, Centre for Psychiatric Neuroscience, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“Therefore, dose lowering would not have a beneficial effect on attenuating weight gain or cholesterol increases and could lead to psychiatric decompensation,” said Ms. Piras, who is also a PhD candidate in the unit of pharmacogenetics and clinical psychopharmacology at the University of Lausanne.

However, she added that because dose increments could increase risk for significant weight gain in the first month of treatment – the dose can be increased typically in a range of 1-10 grams – and strong dose increments could contribute to metabolic worsening over time, “risperidone minimum effective doses should be preferred.”

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Serious public health issue’

Compared with the general population, patients with mental illness present with a greater prevalence of metabolic disorders. In addition, several psychotropic medications, including antipsychotics, can induce metabolic alterations such as weight gain, the investigators noted.

Antipsychotic-induced metabolic adverse effects “constitute a serious public health issue” because they are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as obesity and/or dyslipidemia, “which have been associated with a 10-year reduced life expectancy in the psychiatric population,” Ms. Piras said.

“The dose-dependence of metabolic adverse effects is a debated subject that needs to be assessed for each psychotropic drug known to induce weight gain,” she added.

Several previous studies have examined whether there is a dose-related effect of antipsychotics on metabolic parameters, “with some results suggesting that [weight gain] seems to develop even when low off-label doses are prescribed,” Ms. Piras noted.

She and her colleagues had already studied dose-related metabolic effects of quetiapine (Seroquel) and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

Risperidone is an antipsychotic with a “medium to high metabolic risk profile,” the researchers note, and few studies have examined the impact of risperidone on metabolic parameters other than weight gain.

For the current analysis, they analyzed data from a longitudinal study that included 438 patients (mean age, 40.7 years; 50.7% men) who started treatment with risperidone and/or paliperidone between 2007 and 2018.

The participants had diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, “other,” or “unknown.”

Clinical follow-up periods were up to a year, but were no shorter than 3 weeks. The investigators also assessed the data at different time intervals at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months “to appreciate the evolution of the metabolic parameters.”

In addition, they collected demographic and clinical information, such as comorbidities, and measured patients’ weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure, plasma glucose, and lipids at baseline and at 1, 3, and 12 months and then annually. Weight, waist circumference, and BP were also assessed at 2 and 6 months.

Doses of paliperidone were converted into risperidone-equivalent doses.

Significant weight gain over time

The mean duration of follow-up for the participants, of whom 374 were being treated with risperidone and 64 with paliperidone, was 153 days. Close to half (48.2%) were taking other psychotropic medications known to be associated with some degree of metabolic risk.

Patients were divided into two cohorts based on their daily dose intake (DDI): less than 3 mg/day (n = 201) and at least 3 mg/day (n = 237).

In the overall cohort, a “significant effect of time on weight change was found for each time point,” the investigators reported.

When the researchers looked at the changes according to DDI, they found that each 1-mg dose increase was associated with incremental weight gain at each time point.

Patients who had 5% or greater weight gain in the first month continued to gain weight more than patients who did not reach that threshold, leading the researchers to call that early threshold a “strong predictor of important weight gain in the long term.” There was a weight gain of 6.68% at 3 months, of 7.36% at 6 months, and of 7.7% at 12 months.

After the patients were stratified by age, there were differences in the effect of DDI on various age groups at different time points.

Dose was shown to have a significant effect on weight gain for women at all four time points (P ≥ .001), but for men only at 3 months (P = .003).

For each additional 1-mg dose, there was a 0.05 mmol/L (1.93 mg/dL) increase in total cholesterol (P = .018) after 1 year and a 0.04 mmol/L (1.54 mg/dL) increase in LDL cholesterol (P = .011).

There were no significant effects of time or DDI on triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, glucose levels, and systolic BP, and there was a negative effect of DDI on diastolic BP (P = .001).

The findings “provide evidence for a small dose effect of risperidone” on weight gain and total and LDL cholesterol levels, the investigators note.

Ms. Piras added that because each antipsychotic differs in its metabolic risk profile, “further analyses on other antipsychotics are ongoing in our laboratory, so far confirming our findings.”

Small increases, big changes

Commenting on the study, Erika Nurmi, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience, University of California, Los Angeles, said the study is “unique in the field.”

It “leverages real-world data from a large patient registry to ask a long-unanswered question: Are weight and metabolic adverse effects proportional to dose? Big data approaches like these are very powerful, given the large number of participants that can be included,” said Dr. Nurmi, who was not involved with the research.

However, she cautioned, the “biggest drawback [is that] these data are by nature much more complex and prone to confounding effects.”

In this case, a “critical confounder” for the study was that the majority of individuals taking higher risperidone doses were also taking other drugs known to cause weight gain, whereas the majority of those on lower risperidone doses were not. “This difference may explain the dose relationship observed,” she said.

Because real-world, big data are “valuable but also messy, conclusions drawn from them must be interpreted with caution,” Dr. Nurmi said.

She added that it is generally wise to use the lowest effective dose possible.

“Clinicians should appreciate that even small doses of antipsychotics can cause big changes in weight. Risks and benefits of medications must be carefully considered in clinical practice,” Dr. Nurmi said.

The research was funded in part by the Swiss National Research Foundation. Piras reports no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Nurmi reported no relevant financial relationships, but she is an unpaid member of the Tourette Association of America’s medical advisory board and of the Myriad Genetics scientific advisory board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

The mental health of health care professionals takes center stage

Mental illness has been waiting in the wings for years; ignored, ridiculed, minimized, and stigmatized. Those who succumbed to it tried to lend testimonials, but to no avail. Those who were spared its effects remained in disbelief. So, it stayed on the sidelines, growing in intensity and breadth, yet stifled by the masses, until 2 years ago.

In March 2020, when COVID-19 became a pandemic, the importance of mental health finally became undeniable. As the pandemic’s effects progressed and wreaked havoc on our nation, our mental illness rates simultaneously surged. This surge paralleled that of the COVID-19 pandemic’s and in fact, contributed to a secondary crisis, allowing mental health to finally be addressed and gain center stage status.

But “mental health” is not easily defined, as it takes on many forms and is expressed in a variety of ways and via a myriad of symptoms. It does not discriminate by gender, race, age, socioeconomic status, educational level, profession, religion, or geography. At times, mental health status is consistent but at other times it can fluctuate in intensity, duration, and expression. It can be difficult to manage, yet there are various treatment modalities that can be implemented to lessen the impact of mental illness. Stressful events seem to potentiate its manifestation and yet, there are times it seems to appear spontaneously, much as an uninvited guest.

Mental health has a strong synergistic relationship with physical health, as they are very interdependent and allow us to function at our best only when they are both operating optimally. It should come as no surprise then, that the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to the exponential surge of mental illnesses. Capitalizing on its nondiscriminatory nature, mental illness impacted a large segment of the population – both those suffering from COVID-19 as well as those treating them.

As the nation starts to heal from the immediate and lingering physical and emotional consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, President Biden has chosen to address and try to meet the needs of the health care heroes, the healers. The signing of H.R. 1667, the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act into law on March 18, 2022, showed dedication to the health care community that has given tirelessly to our nation during the COVID-19 pandemic, and is itself recuperating from that effort.

Taking a top-down approach is essential to assuring the health of the nation. If our healers are not healthy, physically and mentally, they will not be able treat those whom they are dedicated to helping. Openly discussing and acknowledging the mental health problems of health care workers as a community makes it okay to not be okay. It normalizes the need for health care workers to prioritize their own mental health. It can also start to ease the fear of professional backlash or repercussions for practicing self-care.

I, for one, am very grateful for the prioritizing and promoting of the importance of mental health and wellness amongst health care workers. This helps to reduce the stigma of mental illness, helps us understand its impact, and allows us to formulate strategies and solutions to address its effects. The time has come.

Dr. Jarkon is a psychiatrist and director of the Center for Behavioral Health at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y.

Mental illness has been waiting in the wings for years; ignored, ridiculed, minimized, and stigmatized. Those who succumbed to it tried to lend testimonials, but to no avail. Those who were spared its effects remained in disbelief. So, it stayed on the sidelines, growing in intensity and breadth, yet stifled by the masses, until 2 years ago.

In March 2020, when COVID-19 became a pandemic, the importance of mental health finally became undeniable. As the pandemic’s effects progressed and wreaked havoc on our nation, our mental illness rates simultaneously surged. This surge paralleled that of the COVID-19 pandemic’s and in fact, contributed to a secondary crisis, allowing mental health to finally be addressed and gain center stage status.

But “mental health” is not easily defined, as it takes on many forms and is expressed in a variety of ways and via a myriad of symptoms. It does not discriminate by gender, race, age, socioeconomic status, educational level, profession, religion, or geography. At times, mental health status is consistent but at other times it can fluctuate in intensity, duration, and expression. It can be difficult to manage, yet there are various treatment modalities that can be implemented to lessen the impact of mental illness. Stressful events seem to potentiate its manifestation and yet, there are times it seems to appear spontaneously, much as an uninvited guest.

Mental health has a strong synergistic relationship with physical health, as they are very interdependent and allow us to function at our best only when they are both operating optimally. It should come as no surprise then, that the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to the exponential surge of mental illnesses. Capitalizing on its nondiscriminatory nature, mental illness impacted a large segment of the population – both those suffering from COVID-19 as well as those treating them.

As the nation starts to heal from the immediate and lingering physical and emotional consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, President Biden has chosen to address and try to meet the needs of the health care heroes, the healers. The signing of H.R. 1667, the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act into law on March 18, 2022, showed dedication to the health care community that has given tirelessly to our nation during the COVID-19 pandemic, and is itself recuperating from that effort.

Taking a top-down approach is essential to assuring the health of the nation. If our healers are not healthy, physically and mentally, they will not be able treat those whom they are dedicated to helping. Openly discussing and acknowledging the mental health problems of health care workers as a community makes it okay to not be okay. It normalizes the need for health care workers to prioritize their own mental health. It can also start to ease the fear of professional backlash or repercussions for practicing self-care.

I, for one, am very grateful for the prioritizing and promoting of the importance of mental health and wellness amongst health care workers. This helps to reduce the stigma of mental illness, helps us understand its impact, and allows us to formulate strategies and solutions to address its effects. The time has come.

Dr. Jarkon is a psychiatrist and director of the Center for Behavioral Health at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y.

Mental illness has been waiting in the wings for years; ignored, ridiculed, minimized, and stigmatized. Those who succumbed to it tried to lend testimonials, but to no avail. Those who were spared its effects remained in disbelief. So, it stayed on the sidelines, growing in intensity and breadth, yet stifled by the masses, until 2 years ago.

In March 2020, when COVID-19 became a pandemic, the importance of mental health finally became undeniable. As the pandemic’s effects progressed and wreaked havoc on our nation, our mental illness rates simultaneously surged. This surge paralleled that of the COVID-19 pandemic’s and in fact, contributed to a secondary crisis, allowing mental health to finally be addressed and gain center stage status.

But “mental health” is not easily defined, as it takes on many forms and is expressed in a variety of ways and via a myriad of symptoms. It does not discriminate by gender, race, age, socioeconomic status, educational level, profession, religion, or geography. At times, mental health status is consistent but at other times it can fluctuate in intensity, duration, and expression. It can be difficult to manage, yet there are various treatment modalities that can be implemented to lessen the impact of mental illness. Stressful events seem to potentiate its manifestation and yet, there are times it seems to appear spontaneously, much as an uninvited guest.

Mental health has a strong synergistic relationship with physical health, as they are very interdependent and allow us to function at our best only when they are both operating optimally. It should come as no surprise then, that the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to the exponential surge of mental illnesses. Capitalizing on its nondiscriminatory nature, mental illness impacted a large segment of the population – both those suffering from COVID-19 as well as those treating them.

As the nation starts to heal from the immediate and lingering physical and emotional consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, President Biden has chosen to address and try to meet the needs of the health care heroes, the healers. The signing of H.R. 1667, the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act into law on March 18, 2022, showed dedication to the health care community that has given tirelessly to our nation during the COVID-19 pandemic, and is itself recuperating from that effort.

Taking a top-down approach is essential to assuring the health of the nation. If our healers are not healthy, physically and mentally, they will not be able treat those whom they are dedicated to helping. Openly discussing and acknowledging the mental health problems of health care workers as a community makes it okay to not be okay. It normalizes the need for health care workers to prioritize their own mental health. It can also start to ease the fear of professional backlash or repercussions for practicing self-care.

I, for one, am very grateful for the prioritizing and promoting of the importance of mental health and wellness amongst health care workers. This helps to reduce the stigma of mental illness, helps us understand its impact, and allows us to formulate strategies and solutions to address its effects. The time has come.

Dr. Jarkon is a psychiatrist and director of the Center for Behavioral Health at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y.

High rates of med student burnout during COVID

NEW ORLEANS –

Researchers surveyed 613 medical students representing all years of a medical program during the last week of the Spring semester of 2021.

Based on the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS), more than half (54%) of the students had symptoms of burnout.

Eighty percent of students scored high on emotional exhaustion, 57% scored high on cynicism, and 36% scored low on academic effectiveness.

Compared with male medical students, female medical students were more apt to exhibit signs of burnout (60% vs. 44%), emotional exhaustion (80% vs. 73%), and cynicism (62% vs. 49%).

After adjusting for associated factors, female medical students were significantly more likely to suffer from burnout than male students (odds ratio, 1.90; 95% confidence interval, 1.34-2.70; P < .001).

Smoking was also linked to higher likelihood of burnout among medical students (OR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.18-3.81; P < .05). The death of a family member from COVID-19 also put medical students at heightened risk for burnout (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.08-2.36; P < .05).

The survey results were presented at the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Annual Meeting.

The findings point to the need to study burnout prevalence in universities and develop strategies to promote the mental health of future physicians, presenter Sofia Jezzini-Martínez, fourth-year medical student, Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon, Monterrey, Mexico, wrote in her conference abstract.

In related research presented at the APA meeting, researchers surveyed second-, third-, and fourth-year medical students from California during the pandemic.

Roughly 80% exhibited symptoms of anxiety and 68% exhibited depressive symptoms, of whom about 18% also reported having thoughts of suicide.

Yet only about half of the medical students exhibiting anxiety or depressive symptoms sought help from a mental health professional, and 20% reported using substances to cope with stress.

“Given that the pandemic is ongoing, we hope to draw attention to mental health needs of medical students and influence medical schools to direct appropriate and timely resources to this group,” presenter Sarthak Angal, MD, psychiatry resident, Kaiser Permanente San Jose Medical Center, California, wrote in his conference abstract.

Managing expectations

Weighing in on medical student burnout, Ihuoma Njoku, MD, department of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, noted that, “particularly for women in multiple fields, including medicine, there’s a lot of burden placed on them.”

“Women are pulled in a lot of different directions and have increased demands, which may help explain their higher rate of burnout,” Dr. Njoku commented.

She noted that these surveys were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, “a period when students’ education experience was a lot different than what they expected and maybe what they wanted.”

Dr. Njoku noted that the challenges of the pandemic are particularly hard on fourth-year medical students.

“A big part of fourth year is applying to residency, and many were doing virtual interviews for residency. That makes it hard to really get an appreciation of the place you will spend the next three to eight years of your life,” she told this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW ORLEANS –

Researchers surveyed 613 medical students representing all years of a medical program during the last week of the Spring semester of 2021.

Based on the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS), more than half (54%) of the students had symptoms of burnout.

Eighty percent of students scored high on emotional exhaustion, 57% scored high on cynicism, and 36% scored low on academic effectiveness.

Compared with male medical students, female medical students were more apt to exhibit signs of burnout (60% vs. 44%), emotional exhaustion (80% vs. 73%), and cynicism (62% vs. 49%).

After adjusting for associated factors, female medical students were significantly more likely to suffer from burnout than male students (odds ratio, 1.90; 95% confidence interval, 1.34-2.70; P < .001).

Smoking was also linked to higher likelihood of burnout among medical students (OR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.18-3.81; P < .05). The death of a family member from COVID-19 also put medical students at heightened risk for burnout (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.08-2.36; P < .05).

The survey results were presented at the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Annual Meeting.

The findings point to the need to study burnout prevalence in universities and develop strategies to promote the mental health of future physicians, presenter Sofia Jezzini-Martínez, fourth-year medical student, Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon, Monterrey, Mexico, wrote in her conference abstract.

In related research presented at the APA meeting, researchers surveyed second-, third-, and fourth-year medical students from California during the pandemic.

Roughly 80% exhibited symptoms of anxiety and 68% exhibited depressive symptoms, of whom about 18% also reported having thoughts of suicide.

Yet only about half of the medical students exhibiting anxiety or depressive symptoms sought help from a mental health professional, and 20% reported using substances to cope with stress.

“Given that the pandemic is ongoing, we hope to draw attention to mental health needs of medical students and influence medical schools to direct appropriate and timely resources to this group,” presenter Sarthak Angal, MD, psychiatry resident, Kaiser Permanente San Jose Medical Center, California, wrote in his conference abstract.

Managing expectations

Weighing in on medical student burnout, Ihuoma Njoku, MD, department of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, noted that, “particularly for women in multiple fields, including medicine, there’s a lot of burden placed on them.”

“Women are pulled in a lot of different directions and have increased demands, which may help explain their higher rate of burnout,” Dr. Njoku commented.

She noted that these surveys were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, “a period when students’ education experience was a lot different than what they expected and maybe what they wanted.”

Dr. Njoku noted that the challenges of the pandemic are particularly hard on fourth-year medical students.

“A big part of fourth year is applying to residency, and many were doing virtual interviews for residency. That makes it hard to really get an appreciation of the place you will spend the next three to eight years of your life,” she told this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW ORLEANS –

Researchers surveyed 613 medical students representing all years of a medical program during the last week of the Spring semester of 2021.

Based on the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS), more than half (54%) of the students had symptoms of burnout.

Eighty percent of students scored high on emotional exhaustion, 57% scored high on cynicism, and 36% scored low on academic effectiveness.

Compared with male medical students, female medical students were more apt to exhibit signs of burnout (60% vs. 44%), emotional exhaustion (80% vs. 73%), and cynicism (62% vs. 49%).

After adjusting for associated factors, female medical students were significantly more likely to suffer from burnout than male students (odds ratio, 1.90; 95% confidence interval, 1.34-2.70; P < .001).

Smoking was also linked to higher likelihood of burnout among medical students (OR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.18-3.81; P < .05). The death of a family member from COVID-19 also put medical students at heightened risk for burnout (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.08-2.36; P < .05).

The survey results were presented at the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Annual Meeting.

The findings point to the need to study burnout prevalence in universities and develop strategies to promote the mental health of future physicians, presenter Sofia Jezzini-Martínez, fourth-year medical student, Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon, Monterrey, Mexico, wrote in her conference abstract.

In related research presented at the APA meeting, researchers surveyed second-, third-, and fourth-year medical students from California during the pandemic.

Roughly 80% exhibited symptoms of anxiety and 68% exhibited depressive symptoms, of whom about 18% also reported having thoughts of suicide.

Yet only about half of the medical students exhibiting anxiety or depressive symptoms sought help from a mental health professional, and 20% reported using substances to cope with stress.

“Given that the pandemic is ongoing, we hope to draw attention to mental health needs of medical students and influence medical schools to direct appropriate and timely resources to this group,” presenter Sarthak Angal, MD, psychiatry resident, Kaiser Permanente San Jose Medical Center, California, wrote in his conference abstract.

Managing expectations

Weighing in on medical student burnout, Ihuoma Njoku, MD, department of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, noted that, “particularly for women in multiple fields, including medicine, there’s a lot of burden placed on them.”

“Women are pulled in a lot of different directions and have increased demands, which may help explain their higher rate of burnout,” Dr. Njoku commented.

She noted that these surveys were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, “a period when students’ education experience was a lot different than what they expected and maybe what they wanted.”

Dr. Njoku noted that the challenges of the pandemic are particularly hard on fourth-year medical students.

“A big part of fourth year is applying to residency, and many were doing virtual interviews for residency. That makes it hard to really get an appreciation of the place you will spend the next three to eight years of your life,” she told this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM APA 2022

At-home vagus nerve stimulation promising for postpartum depression

At-home, noninvasive auricular vagus nerve stimulation (aVNS) therapy is well-tolerated and associated with a significant reduction in postpartum depressive and anxiety symptoms, new research suggests.

In a small proof-of-concept pilot study of 25 women with postpartum depression receiving 6 weeks of daily aVNS treatment, results showed that 74% achieved response and 61% achieved remission, as shown in reduced scores on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D17).

Although invasive electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment-resistant depression in 2005, it involves risk for implantation, infection, and significant side effects, coinvestigator Kristina M. Deligiannidis, MD, director, Women’s Behavioral Health, Zucker Hillside Hospital, Northwell Health, Glen Oaks, New York, told this news organization.

“This newer approach, transcutaneous auricular VNS, is non-invasive, is well tolerated, and has shown initial efficacy in major depression in men and women,” she said.

The findings were presented at the virtual American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) Annual Meeting.

Potential alternative to meds

“Given that aVNS is a non-invasive treatment which can be administered at home, we wanted to test if this approach was safe, feasible, and could reduce depressive symptoms in women with postpartum depression, as many of these women have barriers to accessing current treatments,” Dr. Deligiannidis said.

Auricular VNS uses surface skin electrodes to stimulate nerve endings of a branch of the vagus nerve, located on the surface of the outer ear. Those nerve endings travel to the brain where they have been shown to modulate brain communication in areas important for mood and anxiety regulation, she said.

Dr. Deligiannidis noted that evidence-based treatments for postpartum depression include psychotherapies and antidepressants. However, some women have difficulty accessing weekly psychotherapy, and, when antidepressants are indicated, many are reluctant to take them if they are breastfeeding because of concerns about the medications getting into their breast milk, she said.

Although most antidepressants are safe in lactation, many women postpone antidepressant treatment until they have finished breastfeeding, which can postpone their postpartum depression treatment, Dr. Deligiannidis added.

“At home treatments reduce many barriers women have to current treatments, and this intervention [of aVNS] does not impact breastfeeding, as it is not a medication approach,” she said.

The researchers enrolled 25 women (mean age, 33.7 years) diagnosed with postpartum depression. Ten of the women (40%) were on a stable dose of antidepressant medication.

The participants self-administered 6 weeks of open-label aVNS for 15 minutes daily at home. They were then observed without intervention for an additional 2 weeks. The women also completed medical, psychiatric, and safety interviews throughout the study period.

Promising findings

At baseline, the mean HAM-D17 was 18.4 and was similar for those on (17.8) and off (18.9) antidepressants.

By week 6, the mean HAM-D17 total score decreased by 9.7 points overall, compared with baseline score. For participants on antidepressants, the HAM-D17 decreased by 8.7 points; for women off antidepressants, it decreased by 10.3 points.

In addition, 74% of the women achieved a response to the therapy, and 61% achieved remission of their depressive symptoms.

The most common adverse effects were discomfort (n = 5 patients), headache (n = 3), and dizziness (n = 2). All resolved without intervention.

Commenting on the findings, Anita Clayton, MD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, said the study was “quite interesting.”

Dr. Clayton, who was not involved with the research, also noted the “pretty high” response and remission rates.

“So, I think this does have promise, and it would be worth doing a study where you look at placebo versus this treatment,” she said.

“Many women are fearful of taking medicines postpartum, even peripartum, unless they have had pre-existing severe depression. This is not a medicine, and it sounds like it could be useful even in people who are pregnant, although it’s harder to do studies in pregnant women,” Dr. Clayton added.

The study was funded by Nesos Corporation. Dr. Deligiannidis received contracted research funds from Nesos Corporation to conduct this study. She also serves as a consultant to Sage Therapeutics, Brii Biosciences, and GH Research. Dr. Clayton reports financial relationships with Dare Bioscience, Janssen, Praxis Precision Medicines, Relmada Therapeutics, Sage Therapeutics, AbbVie, Brii Biosciences, Fabre-Kramer, Field Trip Health, Mind Cure Health, Ovoca Bio, PureTech Health, S1 Biopharma, Takeda/Lundbeck, Vella Bioscience, WCG MedAvante-ProPhase, Ballantine Books/Random House, Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire, Guilford Publications, Euthymics Bioscience, and Mediflix.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

At-home, noninvasive auricular vagus nerve stimulation (aVNS) therapy is well-tolerated and associated with a significant reduction in postpartum depressive and anxiety symptoms, new research suggests.

In a small proof-of-concept pilot study of 25 women with postpartum depression receiving 6 weeks of daily aVNS treatment, results showed that 74% achieved response and 61% achieved remission, as shown in reduced scores on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D17).

Although invasive electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment-resistant depression in 2005, it involves risk for implantation, infection, and significant side effects, coinvestigator Kristina M. Deligiannidis, MD, director, Women’s Behavioral Health, Zucker Hillside Hospital, Northwell Health, Glen Oaks, New York, told this news organization.

“This newer approach, transcutaneous auricular VNS, is non-invasive, is well tolerated, and has shown initial efficacy in major depression in men and women,” she said.

The findings were presented at the virtual American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) Annual Meeting.

Potential alternative to meds

“Given that aVNS is a non-invasive treatment which can be administered at home, we wanted to test if this approach was safe, feasible, and could reduce depressive symptoms in women with postpartum depression, as many of these women have barriers to accessing current treatments,” Dr. Deligiannidis said.

Auricular VNS uses surface skin electrodes to stimulate nerve endings of a branch of the vagus nerve, located on the surface of the outer ear. Those nerve endings travel to the brain where they have been shown to modulate brain communication in areas important for mood and anxiety regulation, she said.

Dr. Deligiannidis noted that evidence-based treatments for postpartum depression include psychotherapies and antidepressants. However, some women have difficulty accessing weekly psychotherapy, and, when antidepressants are indicated, many are reluctant to take them if they are breastfeeding because of concerns about the medications getting into their breast milk, she said.

Although most antidepressants are safe in lactation, many women postpone antidepressant treatment until they have finished breastfeeding, which can postpone their postpartum depression treatment, Dr. Deligiannidis added.

“At home treatments reduce many barriers women have to current treatments, and this intervention [of aVNS] does not impact breastfeeding, as it is not a medication approach,” she said.

The researchers enrolled 25 women (mean age, 33.7 years) diagnosed with postpartum depression. Ten of the women (40%) were on a stable dose of antidepressant medication.

The participants self-administered 6 weeks of open-label aVNS for 15 minutes daily at home. They were then observed without intervention for an additional 2 weeks. The women also completed medical, psychiatric, and safety interviews throughout the study period.

Promising findings

At baseline, the mean HAM-D17 was 18.4 and was similar for those on (17.8) and off (18.9) antidepressants.

By week 6, the mean HAM-D17 total score decreased by 9.7 points overall, compared with baseline score. For participants on antidepressants, the HAM-D17 decreased by 8.7 points; for women off antidepressants, it decreased by 10.3 points.

In addition, 74% of the women achieved a response to the therapy, and 61% achieved remission of their depressive symptoms.

The most common adverse effects were discomfort (n = 5 patients), headache (n = 3), and dizziness (n = 2). All resolved without intervention.

Commenting on the findings, Anita Clayton, MD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, said the study was “quite interesting.”

Dr. Clayton, who was not involved with the research, also noted the “pretty high” response and remission rates.

“So, I think this does have promise, and it would be worth doing a study where you look at placebo versus this treatment,” she said.

“Many women are fearful of taking medicines postpartum, even peripartum, unless they have had pre-existing severe depression. This is not a medicine, and it sounds like it could be useful even in people who are pregnant, although it’s harder to do studies in pregnant women,” Dr. Clayton added.

The study was funded by Nesos Corporation. Dr. Deligiannidis received contracted research funds from Nesos Corporation to conduct this study. She also serves as a consultant to Sage Therapeutics, Brii Biosciences, and GH Research. Dr. Clayton reports financial relationships with Dare Bioscience, Janssen, Praxis Precision Medicines, Relmada Therapeutics, Sage Therapeutics, AbbVie, Brii Biosciences, Fabre-Kramer, Field Trip Health, Mind Cure Health, Ovoca Bio, PureTech Health, S1 Biopharma, Takeda/Lundbeck, Vella Bioscience, WCG MedAvante-ProPhase, Ballantine Books/Random House, Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire, Guilford Publications, Euthymics Bioscience, and Mediflix.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

At-home, noninvasive auricular vagus nerve stimulation (aVNS) therapy is well-tolerated and associated with a significant reduction in postpartum depressive and anxiety symptoms, new research suggests.

In a small proof-of-concept pilot study of 25 women with postpartum depression receiving 6 weeks of daily aVNS treatment, results showed that 74% achieved response and 61% achieved remission, as shown in reduced scores on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D17).

Although invasive electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment-resistant depression in 2005, it involves risk for implantation, infection, and significant side effects, coinvestigator Kristina M. Deligiannidis, MD, director, Women’s Behavioral Health, Zucker Hillside Hospital, Northwell Health, Glen Oaks, New York, told this news organization.

“This newer approach, transcutaneous auricular VNS, is non-invasive, is well tolerated, and has shown initial efficacy in major depression in men and women,” she said.

The findings were presented at the virtual American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) Annual Meeting.

Potential alternative to meds

“Given that aVNS is a non-invasive treatment which can be administered at home, we wanted to test if this approach was safe, feasible, and could reduce depressive symptoms in women with postpartum depression, as many of these women have barriers to accessing current treatments,” Dr. Deligiannidis said.

Auricular VNS uses surface skin electrodes to stimulate nerve endings of a branch of the vagus nerve, located on the surface of the outer ear. Those nerve endings travel to the brain where they have been shown to modulate brain communication in areas important for mood and anxiety regulation, she said.

Dr. Deligiannidis noted that evidence-based treatments for postpartum depression include psychotherapies and antidepressants. However, some women have difficulty accessing weekly psychotherapy, and, when antidepressants are indicated, many are reluctant to take them if they are breastfeeding because of concerns about the medications getting into their breast milk, she said.

Although most antidepressants are safe in lactation, many women postpone antidepressant treatment until they have finished breastfeeding, which can postpone their postpartum depression treatment, Dr. Deligiannidis added.

“At home treatments reduce many barriers women have to current treatments, and this intervention [of aVNS] does not impact breastfeeding, as it is not a medication approach,” she said.

The researchers enrolled 25 women (mean age, 33.7 years) diagnosed with postpartum depression. Ten of the women (40%) were on a stable dose of antidepressant medication.

The participants self-administered 6 weeks of open-label aVNS for 15 minutes daily at home. They were then observed without intervention for an additional 2 weeks. The women also completed medical, psychiatric, and safety interviews throughout the study period.

Promising findings

At baseline, the mean HAM-D17 was 18.4 and was similar for those on (17.8) and off (18.9) antidepressants.

By week 6, the mean HAM-D17 total score decreased by 9.7 points overall, compared with baseline score. For participants on antidepressants, the HAM-D17 decreased by 8.7 points; for women off antidepressants, it decreased by 10.3 points.

In addition, 74% of the women achieved a response to the therapy, and 61% achieved remission of their depressive symptoms.

The most common adverse effects were discomfort (n = 5 patients), headache (n = 3), and dizziness (n = 2). All resolved without intervention.

Commenting on the findings, Anita Clayton, MD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, said the study was “quite interesting.”

Dr. Clayton, who was not involved with the research, also noted the “pretty high” response and remission rates.

“So, I think this does have promise, and it would be worth doing a study where you look at placebo versus this treatment,” she said.

“Many women are fearful of taking medicines postpartum, even peripartum, unless they have had pre-existing severe depression. This is not a medicine, and it sounds like it could be useful even in people who are pregnant, although it’s harder to do studies in pregnant women,” Dr. Clayton added.

The study was funded by Nesos Corporation. Dr. Deligiannidis received contracted research funds from Nesos Corporation to conduct this study. She also serves as a consultant to Sage Therapeutics, Brii Biosciences, and GH Research. Dr. Clayton reports financial relationships with Dare Bioscience, Janssen, Praxis Precision Medicines, Relmada Therapeutics, Sage Therapeutics, AbbVie, Brii Biosciences, Fabre-Kramer, Field Trip Health, Mind Cure Health, Ovoca Bio, PureTech Health, S1 Biopharma, Takeda/Lundbeck, Vella Bioscience, WCG MedAvante-ProPhase, Ballantine Books/Random House, Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire, Guilford Publications, Euthymics Bioscience, and Mediflix.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Intensive outpatient PTSD treatment linked to fewer emergency encounters

NEW ORLEANS – , according to a new study released at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

In an analysis of 256 individuals, over the 12 months before they joined the IOP, 28.7% and 24.8% had inpatient and emergency department encounters, respectively, according to the researchers. Afterward, those numbers fell to 15.9% (P < .01) and 18.2% (P = .04), respectively.

“Engagement in IOP for patients with PTSD may help avoid the need for higher levels of care such as residential or inpatient treatment,” Nathan Lingafelter, MD, a psychiatrist and researcher at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., said in an interview.

Dr. Lingafelter described IOP programs as typically “offering patients a combination of individual therapy, group therapy, and medication management all at an increased frequency of about 3 half-days per week. IOPs are thought to be helpful in helping patients with severe symptoms while they are still in the community – i.e., living in their homes, with their families, occasionally still working at reduced time.”

While other studies have examined the effects of IOP, “the existing literature focuses on how IOP reduces symptoms, rather than looking at how IOP involvement might be associated with patients utilizing different acute care resources,” he said. “Prior studies have also been conducted mostly in veteran populations and in populations with less diversity than our population in Oakland.”

For the new study, researchers tracked 256 IOP participants (83% female; mean age = 39; 44% White, 27% Black, 14% Hispanic, and 7% Asian). The wide majority – 85% – had comorbid depressive disorders.

“Patients are assigned a case manager when they enter the program who they can meet with individually, and they spend time attending group therapy sessions. Patients are also able to meet with a psychiatrist to discuss medications,” Dr. Lingafelter said. “A major component in both the group and individual therapy is helping patients identify which kind of interventions work for them and what we can do now that will help. IOP can really help clarify for patients what their trauma responses are and how to start treatments that actually fit their symptoms.”

The subjects had a mean 0.3 psychiatric encounters in the year before joining the program and 0.2 in the year after (P < .01). Their mean emergency department visits related to mental health fell from 0.5 to 0.3 (P = .03).

The study has limitations. Participants took part in IOP therapy from 2017 to 2018, before the pandemic disrupted mental health treatment. It does not examine whether medication use changed after IOP treatment. It is retrospective and doesn’t confirm that IOP had any positive effect.

Multiple benefits of IOP

In an interview, Deborah C. Beidel, PhD, director of UCF RESTORES at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, said IOP has several advantages as a treatment for PTSD. Her clinic, which focuses on PTSD treatment for military veterans, has used the approach to treat hundreds of people.

“First, IOPs can address the stigma that surrounds mental health treatment. If you have a physical injury, you take time off from work to go to physical therapy, which is time-limited. If you have a stress injury, why not do the same? Take a few weeks, get it treated, and get back to work,” she said. “The second reason is that the most effective treatment for PTSD is exposure therapy, which is more effective when treatment sessions occur in a daily as opposed to a weekly or monthly time frame. Third, from a cost and feasibility perspective, an intensive program could reduce overall medical costs and get people back to work sooner.”

The new study is “definitely useful” since it examines the impact of IOP over a longer term, Dr. Beidel said. This kind of data “can influence policy, particularly with insurance companies. If we can build the evidence that short, intensive treatment produces better long-term outcomes, insurance companies will be more likely to pay for the IOP.”

The University of Central Florida program is funded by federal research grants and state funding, she said. “When we calculate the cost, it comes to about $10,000 in therapy time plus an average of about $3,000 in travel related costs – transportation, lodging, meals – for those who travel from out of state for our program.”

What’s next? “Further study is needed to characterize whether these findings are applicable to other practice settings, including virtual treatment programs; the long-term durability of these findings; and whether similar patterns of reduced resource use extend to non–mental health–specific care utilization,” said Dr. Lingafelter, the study’s lead author.

No study funding and no author disclosures were reported. Dr. Beidel disclosed IOP-related research support from the U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command–Military Operational Medicine Research Program.

NEW ORLEANS – , according to a new study released at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

In an analysis of 256 individuals, over the 12 months before they joined the IOP, 28.7% and 24.8% had inpatient and emergency department encounters, respectively, according to the researchers. Afterward, those numbers fell to 15.9% (P < .01) and 18.2% (P = .04), respectively.

“Engagement in IOP for patients with PTSD may help avoid the need for higher levels of care such as residential or inpatient treatment,” Nathan Lingafelter, MD, a psychiatrist and researcher at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., said in an interview.

Dr. Lingafelter described IOP programs as typically “offering patients a combination of individual therapy, group therapy, and medication management all at an increased frequency of about 3 half-days per week. IOPs are thought to be helpful in helping patients with severe symptoms while they are still in the community – i.e., living in their homes, with their families, occasionally still working at reduced time.”

While other studies have examined the effects of IOP, “the existing literature focuses on how IOP reduces symptoms, rather than looking at how IOP involvement might be associated with patients utilizing different acute care resources,” he said. “Prior studies have also been conducted mostly in veteran populations and in populations with less diversity than our population in Oakland.”

For the new study, researchers tracked 256 IOP participants (83% female; mean age = 39; 44% White, 27% Black, 14% Hispanic, and 7% Asian). The wide majority – 85% – had comorbid depressive disorders.

“Patients are assigned a case manager when they enter the program who they can meet with individually, and they spend time attending group therapy sessions. Patients are also able to meet with a psychiatrist to discuss medications,” Dr. Lingafelter said. “A major component in both the group and individual therapy is helping patients identify which kind of interventions work for them and what we can do now that will help. IOP can really help clarify for patients what their trauma responses are and how to start treatments that actually fit their symptoms.”

The subjects had a mean 0.3 psychiatric encounters in the year before joining the program and 0.2 in the year after (P < .01). Their mean emergency department visits related to mental health fell from 0.5 to 0.3 (P = .03).