User login

The Surfside tragedy: A call for healing the healers

The mental health toll from the Surfside, Fla., Champlain Tower collapse will be felt by our patients for years to come. As mental health professionals in Miami-Dade County, it has been difficult to deal with the catastrophe layered on the escalating COVID-19 crisis.

With each passing day after the June 24 incident, we all learned who the 98 victims were. In session after session, the enormous impact of this unfathomable tragedy unfolded. Some mental health care professionals were directly affected with the loss of family members; some lost patients, and a large number of our patients lost someone or knew someone who lost someone. It was reminiscent of our work during the COVID-19 crisis when we found that we were dealing with the same stressors as those of our patients. As it was said then, we were all in the same storm – just in very different boats.

It was heartening to see how many colleagues rushed to the site of the building where family waiting areas were established. So many professionals wanted to assist that some had to be turned away.

The days right after the collapse were agonizing for all as we waited and hoped for survivors to be found. Search teams from across the United States and from Mexico and Israel – specifically, Israeli Defense Forces personnel with experience conducting operations in the wake of earthquakes in both Haiti and Nepal, took on the dangerous work. When no one was recovered after the first day, hope faded, and after 10 days, the search and rescue efforts turned to search and recovery. We were indeed a county and community in mourning.

According to Lina Haji, PsyD, GIA Miami, in addition to the direct impact of loss, clinicians who engaged in crisis response and bereavement counseling with those affected by the Surfside tragedy were subjected to vicarious trauma. Mental health care providers in the Miami area not only experienced the direct effect of this tragedy but have been hearing details and harrowing stories about the unimaginable experiences their patients endured over those critical weeks. Vicarious trauma can result in our own symptoms, compassion fatigue, or burnout as clinicians. This resulted in a call for mental health providers to come to the aid of their fellow colleagues.

So, on the 1-month anniversary of the initial collapse, at the urging of Patricia Stauber, RN, LCSW, a clinician with more than 30 years’ experience in providing grief counseling in hospital and private practice settings; Antonello Bonci, MD, the founder of GIA Miami; Charlotte Tomic, director of public relations for the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism; and I cohosted what we hope will be several Mental Health Appreciation retreats. Our goal was to create a space to focus on healing the healers. We had hoped to hold an in-person event, but at the last moment we opted for a Zoom-based event because COVID-19 cases were rising rapidly again.

Working on the front lines

Cassie Feldman, PsyD, a licensed clinical psychologist with extensive experience working with grief, loss, end of life, and responding to trauma-related consults, reflected on her experience responding to the collapse in the earliest days – first independently at the request of community religious leaders and then as part of CADENA Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rescue, humanitarian aid, and disaster response and prevention worldwide.

Dr. Feldman worked alongside other mental health professionals, local Miami-Dade police and fire officials, and the domestic and international rescue teams (CADENA’s Go Team from Mexico and the Israeli Defense Force’s Search and Rescue Delegation), providing Psychological First Aid, crisis intervention, and disaster response to the victims’ families and survivors.

This initially was a 24-hour coverage effort, requiring Dr. Feldman and her colleagues to clear their schedules, and at times to work 18-hour shifts in the early days of the crisis to address the need for consistency and continuity. Their commitment was to show up for the victims’ families and survivors, fully embracing the chaos and the demands of the situation. She noted that the disaster brought out the best of her and her colleagues.

They divided and conquered the work, alongside clinicians from Jewish Community Services and Project Chai intervening acutely where possible, and coordinating long-term care plans for those survivors and members of the victims’ support networks in need of consistent care.

Dr. Feldman reflected on the notion that we have all been processing losses prior to this – loss of normalcy because of the pandemic, loss of people we loved as a result, other personal losses – and that this community tragedy is yet another loss to disentangle. It didn’t feel good or natural for her to passively absorb the news knowing she had both the skill set and capacity to take on an active supportive role. The first days at the community center were disorganized; it was hard to know who was who and what was what. She described parents crying out for their children and children longing for their parents. Individuals were so overcome with emotion that they grew faint. Friends and families flooded in but were unaware of how to be fully supportive. The level of trauma was so high that the only interventions that were absorbed were those that were nonverbal or that fully addressed practical needs. People were frightened and in a state of shock.

Day by day, more order ensued and the efforts became more coordinated, but it became apparent to her that the “family reunification center” was devoid of reunification. She and her colleagues’ primary role became aiding the police department in making death notifications to the families and being supportive of the victims’ families and their loved ones during and in between the formal briefings, where so many concerned family members and friends gathered and waited.

“As the days went on, things became more structured and predictable,” Dr. Feldman noted. “We continued to connect with the victims’ families and survivors, [listened to] their stories, shared meals with them, spent downtime with them, began to intimately know their loved ones, and all the barriers they were now facing. We became invested in them, their unique intricacies, and to care deeply for them like our own families and loved ones. Small talk and conversation morphed into silent embraces where spoken words weren’t necessary.”

Dr. Feldman said some of her earliest memories were visiting ICU patients alongside her father, a critical care and ICU physician. Her father taught her that nonverbal communication and connection can be offered to patients in the most poignant moments of suffering.

Her “nascent experiences in the ICU,” she said, taught her that “the most useful of interventions was just being with people in their pain and bearing witness at times when there were just no words.”

Dr. Feldman said that when many of her colleagues learned about the switch from rescue to recovery, the pull was to jump in their cars and drive to the hotel where the families were based to offer support.

The unity she witnessed – from the disparate clinicians who were virtual strangers before the incident but a team afterward, from the families and the community, and from the first responders and rescue teams – was inspiring, Dr. Feldman said.

“We were all forced to think beyond ourselves, push ourselves past our limits, and unify in a way that remedied this period in history of deep fragmentation,” she said.

Understanding the role of psychoneuroimmunology

In another presentation during the Zoom event, Ms. Stauber offered her insights about the importance of support among mental health clinicians.

She cited research on women with HIV showing that those who are part of a support group had a stronger immune response than those who were not.

Ms. Stauber said the impact of COVID-19 and its ramifications – including fear, grief over losing loved ones, isolation from friends and family, and interference/cessation of normal routines – has put an enormous strain on clinicians and clients. One of her clients had to take her mother to the emergency room – never to see her again. She continues to ask: “If I’d been there, could I have saved her?”

Another client whose husband died of COVID-19–related illness agonizes over not being able to be at her husband’s side, not being able to hold his hand, not being able to say goodbye.

She said other cultures are more accepting of suffering as a condition of life and the acknowledgment that our time on earth is limited.

The “quick fix for everything” society carries over to people’s grief, said Ms. Stauber. As a result, many find it difficult to appreciate how much time it takes to heal.

Normal uncomplicated grief can take approximately 2-3 years, she said. By then, the shock has been wearing off, the emotional roller coaster of loss is calming down, coping skills are strengthened, and life can once again be more fulfilling or meaningful. Complicated grief or grief with trauma takes much longer, said Ms. Stauber, who is a consultant with a national crisis and debriefing company providing trauma and bereavement support to Fortune 500 companies.

Trauma adds another complexity to loss. To begin to appreciate the rough road ahead, Ms. Stauber said, it is important to understand the basic challenges facing grieving people.

“This is where our profession may be needed; we are providing support for those suffering the immense pain of loss in a world that often has difficulty being present or patient with loss,” she said. “We are indeed providing an emotional life raft.”

Ultimately, self-care is critical, Ms. Stauber said. “Consider self-care a job requirement” to be successful. She also offered the following tips for self-care:

1. Share your own loss experience with a caring and nonjudgmental person.

2. Consider ongoing supervision and consultation with colleagues who understand the nature of your work.

3. Be willing to ask for help.

4. Be aware of risks and countertransference in our work.

5. Attend workshops.

6. Remember that you do not have to and cannot do it all by yourself – we absolutely need more grief and trauma trained therapists.

7. Involve yourself in activities outside of work that feed your soul and nourish your spirit.

8. Schedule play.

9. Develop a healthy self-care regimen to remain present doing this work.

10. Consider the benefits of exercise.

11. Enjoy the beauty and wonder of nature.

12. Consider yoga, meditation, spa retreats – such as Kripalu, Miraval, and Canyon Ranch.

13. Spend time with loving family and friends.

14. Adopt a pet.

15. Eat healthy foods; get plenty of rest.

16. Walk in the rain.

17. Listen to music.

18. Enjoy a relaxing bubble bath.

19. Sing, dance, and enjoy the blessings of this life.

20. Love yourself; you truly can be your own best friend.

To advocate on behalf of mental health for patients, we must do the same for mental health professionals. The retreat was well received, and we learned a lot from our speakers. After the program, we offered a 45-minute yoga class and then 30-minute sound bowl meditation. We plan to repeat the event in September to help our community deal with the ongoing stress of such overwhelming loss.

While our community will never be the same, we hope that, by coming together, we can all find a way to support one another and strive to help ourselves and others manage as we navigate yet another unprecedented crisis.

Dr. Ritvo, who has more than 30 years’ experience in psychiatry, practices telemedicine. She is author of “BeKindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018). Dr. Ritvo has no disclosures.

The mental health toll from the Surfside, Fla., Champlain Tower collapse will be felt by our patients for years to come. As mental health professionals in Miami-Dade County, it has been difficult to deal with the catastrophe layered on the escalating COVID-19 crisis.

With each passing day after the June 24 incident, we all learned who the 98 victims were. In session after session, the enormous impact of this unfathomable tragedy unfolded. Some mental health care professionals were directly affected with the loss of family members; some lost patients, and a large number of our patients lost someone or knew someone who lost someone. It was reminiscent of our work during the COVID-19 crisis when we found that we were dealing with the same stressors as those of our patients. As it was said then, we were all in the same storm – just in very different boats.

It was heartening to see how many colleagues rushed to the site of the building where family waiting areas were established. So many professionals wanted to assist that some had to be turned away.

The days right after the collapse were agonizing for all as we waited and hoped for survivors to be found. Search teams from across the United States and from Mexico and Israel – specifically, Israeli Defense Forces personnel with experience conducting operations in the wake of earthquakes in both Haiti and Nepal, took on the dangerous work. When no one was recovered after the first day, hope faded, and after 10 days, the search and rescue efforts turned to search and recovery. We were indeed a county and community in mourning.

According to Lina Haji, PsyD, GIA Miami, in addition to the direct impact of loss, clinicians who engaged in crisis response and bereavement counseling with those affected by the Surfside tragedy were subjected to vicarious trauma. Mental health care providers in the Miami area not only experienced the direct effect of this tragedy but have been hearing details and harrowing stories about the unimaginable experiences their patients endured over those critical weeks. Vicarious trauma can result in our own symptoms, compassion fatigue, or burnout as clinicians. This resulted in a call for mental health providers to come to the aid of their fellow colleagues.

So, on the 1-month anniversary of the initial collapse, at the urging of Patricia Stauber, RN, LCSW, a clinician with more than 30 years’ experience in providing grief counseling in hospital and private practice settings; Antonello Bonci, MD, the founder of GIA Miami; Charlotte Tomic, director of public relations for the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism; and I cohosted what we hope will be several Mental Health Appreciation retreats. Our goal was to create a space to focus on healing the healers. We had hoped to hold an in-person event, but at the last moment we opted for a Zoom-based event because COVID-19 cases were rising rapidly again.

Working on the front lines

Cassie Feldman, PsyD, a licensed clinical psychologist with extensive experience working with grief, loss, end of life, and responding to trauma-related consults, reflected on her experience responding to the collapse in the earliest days – first independently at the request of community religious leaders and then as part of CADENA Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rescue, humanitarian aid, and disaster response and prevention worldwide.

Dr. Feldman worked alongside other mental health professionals, local Miami-Dade police and fire officials, and the domestic and international rescue teams (CADENA’s Go Team from Mexico and the Israeli Defense Force’s Search and Rescue Delegation), providing Psychological First Aid, crisis intervention, and disaster response to the victims’ families and survivors.

This initially was a 24-hour coverage effort, requiring Dr. Feldman and her colleagues to clear their schedules, and at times to work 18-hour shifts in the early days of the crisis to address the need for consistency and continuity. Their commitment was to show up for the victims’ families and survivors, fully embracing the chaos and the demands of the situation. She noted that the disaster brought out the best of her and her colleagues.

They divided and conquered the work, alongside clinicians from Jewish Community Services and Project Chai intervening acutely where possible, and coordinating long-term care plans for those survivors and members of the victims’ support networks in need of consistent care.

Dr. Feldman reflected on the notion that we have all been processing losses prior to this – loss of normalcy because of the pandemic, loss of people we loved as a result, other personal losses – and that this community tragedy is yet another loss to disentangle. It didn’t feel good or natural for her to passively absorb the news knowing she had both the skill set and capacity to take on an active supportive role. The first days at the community center were disorganized; it was hard to know who was who and what was what. She described parents crying out for their children and children longing for their parents. Individuals were so overcome with emotion that they grew faint. Friends and families flooded in but were unaware of how to be fully supportive. The level of trauma was so high that the only interventions that were absorbed were those that were nonverbal or that fully addressed practical needs. People were frightened and in a state of shock.

Day by day, more order ensued and the efforts became more coordinated, but it became apparent to her that the “family reunification center” was devoid of reunification. She and her colleagues’ primary role became aiding the police department in making death notifications to the families and being supportive of the victims’ families and their loved ones during and in between the formal briefings, where so many concerned family members and friends gathered and waited.

“As the days went on, things became more structured and predictable,” Dr. Feldman noted. “We continued to connect with the victims’ families and survivors, [listened to] their stories, shared meals with them, spent downtime with them, began to intimately know their loved ones, and all the barriers they were now facing. We became invested in them, their unique intricacies, and to care deeply for them like our own families and loved ones. Small talk and conversation morphed into silent embraces where spoken words weren’t necessary.”

Dr. Feldman said some of her earliest memories were visiting ICU patients alongside her father, a critical care and ICU physician. Her father taught her that nonverbal communication and connection can be offered to patients in the most poignant moments of suffering.

Her “nascent experiences in the ICU,” she said, taught her that “the most useful of interventions was just being with people in their pain and bearing witness at times when there were just no words.”

Dr. Feldman said that when many of her colleagues learned about the switch from rescue to recovery, the pull was to jump in their cars and drive to the hotel where the families were based to offer support.

The unity she witnessed – from the disparate clinicians who were virtual strangers before the incident but a team afterward, from the families and the community, and from the first responders and rescue teams – was inspiring, Dr. Feldman said.

“We were all forced to think beyond ourselves, push ourselves past our limits, and unify in a way that remedied this period in history of deep fragmentation,” she said.

Understanding the role of psychoneuroimmunology

In another presentation during the Zoom event, Ms. Stauber offered her insights about the importance of support among mental health clinicians.

She cited research on women with HIV showing that those who are part of a support group had a stronger immune response than those who were not.

Ms. Stauber said the impact of COVID-19 and its ramifications – including fear, grief over losing loved ones, isolation from friends and family, and interference/cessation of normal routines – has put an enormous strain on clinicians and clients. One of her clients had to take her mother to the emergency room – never to see her again. She continues to ask: “If I’d been there, could I have saved her?”

Another client whose husband died of COVID-19–related illness agonizes over not being able to be at her husband’s side, not being able to hold his hand, not being able to say goodbye.

She said other cultures are more accepting of suffering as a condition of life and the acknowledgment that our time on earth is limited.

The “quick fix for everything” society carries over to people’s grief, said Ms. Stauber. As a result, many find it difficult to appreciate how much time it takes to heal.

Normal uncomplicated grief can take approximately 2-3 years, she said. By then, the shock has been wearing off, the emotional roller coaster of loss is calming down, coping skills are strengthened, and life can once again be more fulfilling or meaningful. Complicated grief or grief with trauma takes much longer, said Ms. Stauber, who is a consultant with a national crisis and debriefing company providing trauma and bereavement support to Fortune 500 companies.

Trauma adds another complexity to loss. To begin to appreciate the rough road ahead, Ms. Stauber said, it is important to understand the basic challenges facing grieving people.

“This is where our profession may be needed; we are providing support for those suffering the immense pain of loss in a world that often has difficulty being present or patient with loss,” she said. “We are indeed providing an emotional life raft.”

Ultimately, self-care is critical, Ms. Stauber said. “Consider self-care a job requirement” to be successful. She also offered the following tips for self-care:

1. Share your own loss experience with a caring and nonjudgmental person.

2. Consider ongoing supervision and consultation with colleagues who understand the nature of your work.

3. Be willing to ask for help.

4. Be aware of risks and countertransference in our work.

5. Attend workshops.

6. Remember that you do not have to and cannot do it all by yourself – we absolutely need more grief and trauma trained therapists.

7. Involve yourself in activities outside of work that feed your soul and nourish your spirit.

8. Schedule play.

9. Develop a healthy self-care regimen to remain present doing this work.

10. Consider the benefits of exercise.

11. Enjoy the beauty and wonder of nature.

12. Consider yoga, meditation, spa retreats – such as Kripalu, Miraval, and Canyon Ranch.

13. Spend time with loving family and friends.

14. Adopt a pet.

15. Eat healthy foods; get plenty of rest.

16. Walk in the rain.

17. Listen to music.

18. Enjoy a relaxing bubble bath.

19. Sing, dance, and enjoy the blessings of this life.

20. Love yourself; you truly can be your own best friend.

To advocate on behalf of mental health for patients, we must do the same for mental health professionals. The retreat was well received, and we learned a lot from our speakers. After the program, we offered a 45-minute yoga class and then 30-minute sound bowl meditation. We plan to repeat the event in September to help our community deal with the ongoing stress of such overwhelming loss.

While our community will never be the same, we hope that, by coming together, we can all find a way to support one another and strive to help ourselves and others manage as we navigate yet another unprecedented crisis.

Dr. Ritvo, who has more than 30 years’ experience in psychiatry, practices telemedicine. She is author of “BeKindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018). Dr. Ritvo has no disclosures.

The mental health toll from the Surfside, Fla., Champlain Tower collapse will be felt by our patients for years to come. As mental health professionals in Miami-Dade County, it has been difficult to deal with the catastrophe layered on the escalating COVID-19 crisis.

With each passing day after the June 24 incident, we all learned who the 98 victims were. In session after session, the enormous impact of this unfathomable tragedy unfolded. Some mental health care professionals were directly affected with the loss of family members; some lost patients, and a large number of our patients lost someone or knew someone who lost someone. It was reminiscent of our work during the COVID-19 crisis when we found that we were dealing with the same stressors as those of our patients. As it was said then, we were all in the same storm – just in very different boats.

It was heartening to see how many colleagues rushed to the site of the building where family waiting areas were established. So many professionals wanted to assist that some had to be turned away.

The days right after the collapse were agonizing for all as we waited and hoped for survivors to be found. Search teams from across the United States and from Mexico and Israel – specifically, Israeli Defense Forces personnel with experience conducting operations in the wake of earthquakes in both Haiti and Nepal, took on the dangerous work. When no one was recovered after the first day, hope faded, and after 10 days, the search and rescue efforts turned to search and recovery. We were indeed a county and community in mourning.

According to Lina Haji, PsyD, GIA Miami, in addition to the direct impact of loss, clinicians who engaged in crisis response and bereavement counseling with those affected by the Surfside tragedy were subjected to vicarious trauma. Mental health care providers in the Miami area not only experienced the direct effect of this tragedy but have been hearing details and harrowing stories about the unimaginable experiences their patients endured over those critical weeks. Vicarious trauma can result in our own symptoms, compassion fatigue, or burnout as clinicians. This resulted in a call for mental health providers to come to the aid of their fellow colleagues.

So, on the 1-month anniversary of the initial collapse, at the urging of Patricia Stauber, RN, LCSW, a clinician with more than 30 years’ experience in providing grief counseling in hospital and private practice settings; Antonello Bonci, MD, the founder of GIA Miami; Charlotte Tomic, director of public relations for the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism; and I cohosted what we hope will be several Mental Health Appreciation retreats. Our goal was to create a space to focus on healing the healers. We had hoped to hold an in-person event, but at the last moment we opted for a Zoom-based event because COVID-19 cases were rising rapidly again.

Working on the front lines

Cassie Feldman, PsyD, a licensed clinical psychologist with extensive experience working with grief, loss, end of life, and responding to trauma-related consults, reflected on her experience responding to the collapse in the earliest days – first independently at the request of community religious leaders and then as part of CADENA Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rescue, humanitarian aid, and disaster response and prevention worldwide.

Dr. Feldman worked alongside other mental health professionals, local Miami-Dade police and fire officials, and the domestic and international rescue teams (CADENA’s Go Team from Mexico and the Israeli Defense Force’s Search and Rescue Delegation), providing Psychological First Aid, crisis intervention, and disaster response to the victims’ families and survivors.

This initially was a 24-hour coverage effort, requiring Dr. Feldman and her colleagues to clear their schedules, and at times to work 18-hour shifts in the early days of the crisis to address the need for consistency and continuity. Their commitment was to show up for the victims’ families and survivors, fully embracing the chaos and the demands of the situation. She noted that the disaster brought out the best of her and her colleagues.

They divided and conquered the work, alongside clinicians from Jewish Community Services and Project Chai intervening acutely where possible, and coordinating long-term care plans for those survivors and members of the victims’ support networks in need of consistent care.

Dr. Feldman reflected on the notion that we have all been processing losses prior to this – loss of normalcy because of the pandemic, loss of people we loved as a result, other personal losses – and that this community tragedy is yet another loss to disentangle. It didn’t feel good or natural for her to passively absorb the news knowing she had both the skill set and capacity to take on an active supportive role. The first days at the community center were disorganized; it was hard to know who was who and what was what. She described parents crying out for their children and children longing for their parents. Individuals were so overcome with emotion that they grew faint. Friends and families flooded in but were unaware of how to be fully supportive. The level of trauma was so high that the only interventions that were absorbed were those that were nonverbal or that fully addressed practical needs. People were frightened and in a state of shock.

Day by day, more order ensued and the efforts became more coordinated, but it became apparent to her that the “family reunification center” was devoid of reunification. She and her colleagues’ primary role became aiding the police department in making death notifications to the families and being supportive of the victims’ families and their loved ones during and in between the formal briefings, where so many concerned family members and friends gathered and waited.

“As the days went on, things became more structured and predictable,” Dr. Feldman noted. “We continued to connect with the victims’ families and survivors, [listened to] their stories, shared meals with them, spent downtime with them, began to intimately know their loved ones, and all the barriers they were now facing. We became invested in them, their unique intricacies, and to care deeply for them like our own families and loved ones. Small talk and conversation morphed into silent embraces where spoken words weren’t necessary.”

Dr. Feldman said some of her earliest memories were visiting ICU patients alongside her father, a critical care and ICU physician. Her father taught her that nonverbal communication and connection can be offered to patients in the most poignant moments of suffering.

Her “nascent experiences in the ICU,” she said, taught her that “the most useful of interventions was just being with people in their pain and bearing witness at times when there were just no words.”

Dr. Feldman said that when many of her colleagues learned about the switch from rescue to recovery, the pull was to jump in their cars and drive to the hotel where the families were based to offer support.

The unity she witnessed – from the disparate clinicians who were virtual strangers before the incident but a team afterward, from the families and the community, and from the first responders and rescue teams – was inspiring, Dr. Feldman said.

“We were all forced to think beyond ourselves, push ourselves past our limits, and unify in a way that remedied this period in history of deep fragmentation,” she said.

Understanding the role of psychoneuroimmunology

In another presentation during the Zoom event, Ms. Stauber offered her insights about the importance of support among mental health clinicians.

She cited research on women with HIV showing that those who are part of a support group had a stronger immune response than those who were not.

Ms. Stauber said the impact of COVID-19 and its ramifications – including fear, grief over losing loved ones, isolation from friends and family, and interference/cessation of normal routines – has put an enormous strain on clinicians and clients. One of her clients had to take her mother to the emergency room – never to see her again. She continues to ask: “If I’d been there, could I have saved her?”

Another client whose husband died of COVID-19–related illness agonizes over not being able to be at her husband’s side, not being able to hold his hand, not being able to say goodbye.

She said other cultures are more accepting of suffering as a condition of life and the acknowledgment that our time on earth is limited.

The “quick fix for everything” society carries over to people’s grief, said Ms. Stauber. As a result, many find it difficult to appreciate how much time it takes to heal.

Normal uncomplicated grief can take approximately 2-3 years, she said. By then, the shock has been wearing off, the emotional roller coaster of loss is calming down, coping skills are strengthened, and life can once again be more fulfilling or meaningful. Complicated grief or grief with trauma takes much longer, said Ms. Stauber, who is a consultant with a national crisis and debriefing company providing trauma and bereavement support to Fortune 500 companies.

Trauma adds another complexity to loss. To begin to appreciate the rough road ahead, Ms. Stauber said, it is important to understand the basic challenges facing grieving people.

“This is where our profession may be needed; we are providing support for those suffering the immense pain of loss in a world that often has difficulty being present or patient with loss,” she said. “We are indeed providing an emotional life raft.”

Ultimately, self-care is critical, Ms. Stauber said. “Consider self-care a job requirement” to be successful. She also offered the following tips for self-care:

1. Share your own loss experience with a caring and nonjudgmental person.

2. Consider ongoing supervision and consultation with colleagues who understand the nature of your work.

3. Be willing to ask for help.

4. Be aware of risks and countertransference in our work.

5. Attend workshops.

6. Remember that you do not have to and cannot do it all by yourself – we absolutely need more grief and trauma trained therapists.

7. Involve yourself in activities outside of work that feed your soul and nourish your spirit.

8. Schedule play.

9. Develop a healthy self-care regimen to remain present doing this work.

10. Consider the benefits of exercise.

11. Enjoy the beauty and wonder of nature.

12. Consider yoga, meditation, spa retreats – such as Kripalu, Miraval, and Canyon Ranch.

13. Spend time with loving family and friends.

14. Adopt a pet.

15. Eat healthy foods; get plenty of rest.

16. Walk in the rain.

17. Listen to music.

18. Enjoy a relaxing bubble bath.

19. Sing, dance, and enjoy the blessings of this life.

20. Love yourself; you truly can be your own best friend.

To advocate on behalf of mental health for patients, we must do the same for mental health professionals. The retreat was well received, and we learned a lot from our speakers. After the program, we offered a 45-minute yoga class and then 30-minute sound bowl meditation. We plan to repeat the event in September to help our community deal with the ongoing stress of such overwhelming loss.

While our community will never be the same, we hope that, by coming together, we can all find a way to support one another and strive to help ourselves and others manage as we navigate yet another unprecedented crisis.

Dr. Ritvo, who has more than 30 years’ experience in psychiatry, practices telemedicine. She is author of “BeKindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018). Dr. Ritvo has no disclosures.

Late-onset, treatment-resistant anxiety and depression

CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

[polldaddy:10891920]

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

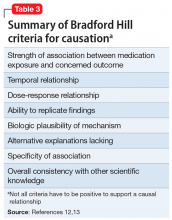

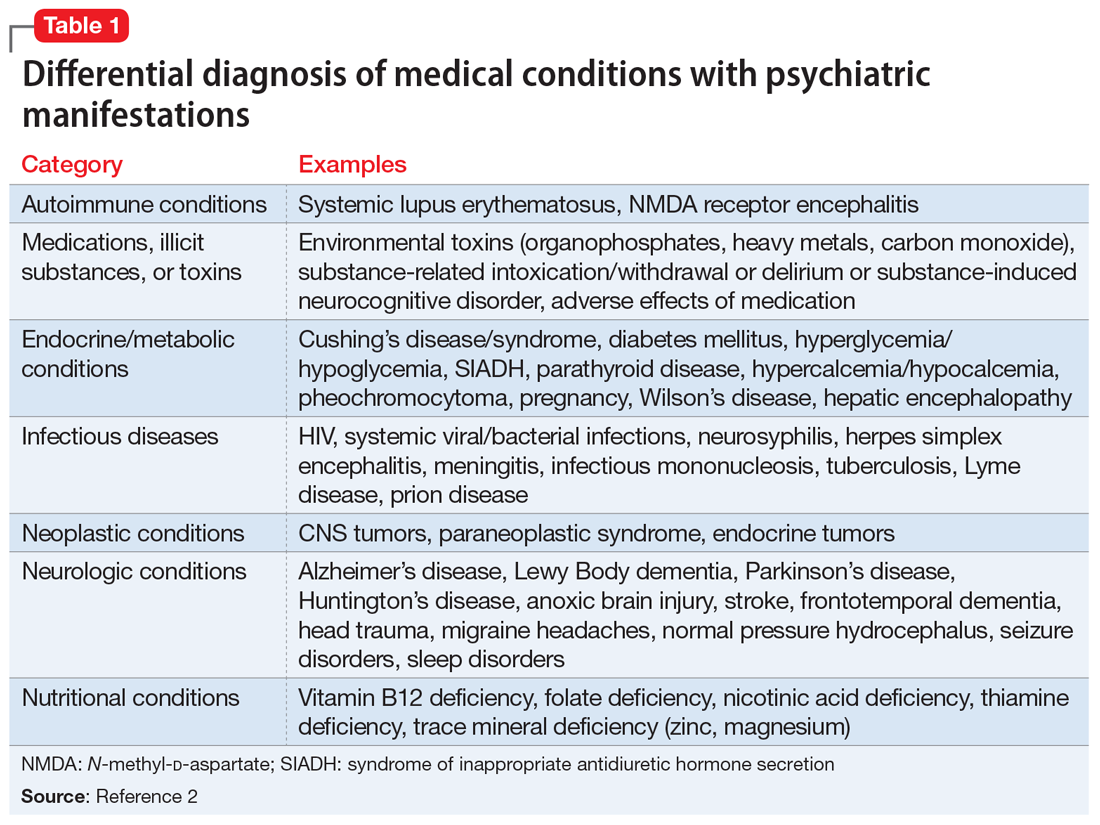

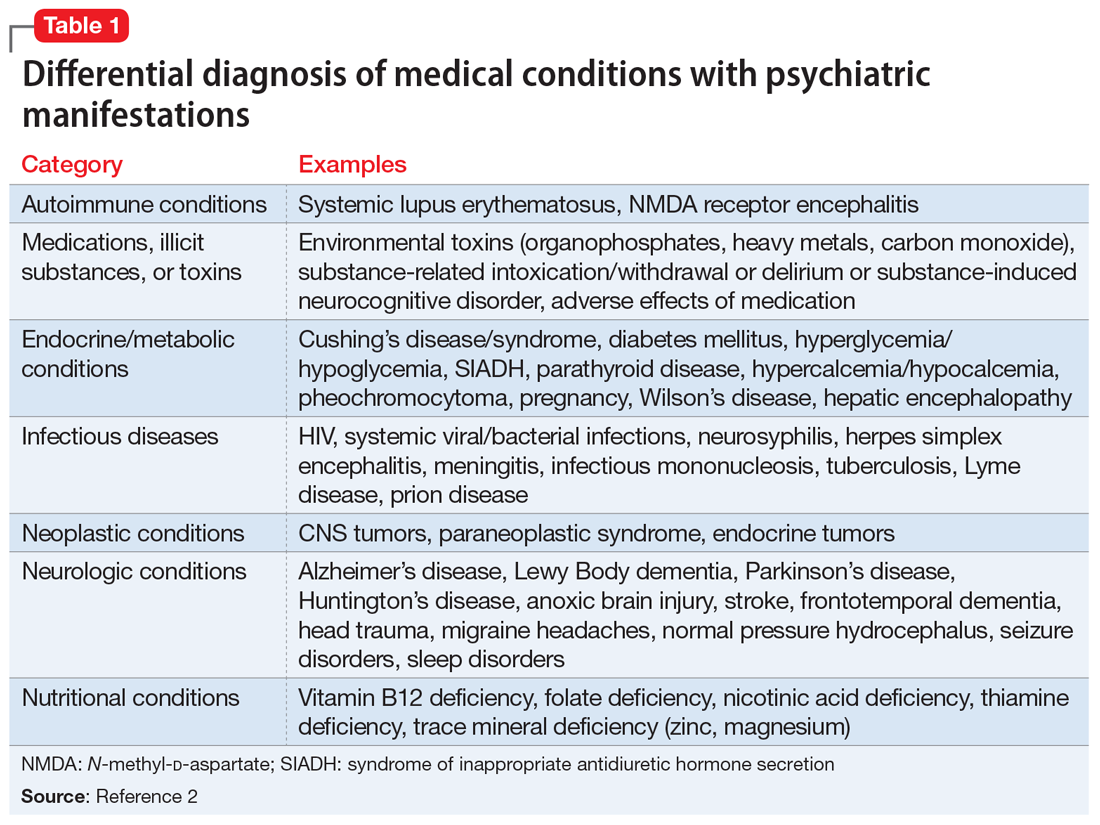

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...

Two months later, Mr. A undergoes a transsphenoidal tumor resection of the pituitary adenoma, and biopsy results confirm an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary macroadenoma, which is consistent with Cushing’s disease. Following surgery, steroid treatment with dexamethasone is discontinued due to a persistently elevated

[polldaddy:10891923]

The authors’ observations

Chronic excess glucocorticoid production is the underlying pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease, which is most commonly caused by an ACTH-producing adenoma.4,5 When these hormones become dysregulated, the result can be over- or underproduction of cortisol, which can lead to physical and psychiatric manifestations.6

Cushing’s disease most commonly manifests with the physical symptoms of centripetal fat deposition, abdominal striae, facial plethora, muscle atrophy, bone density loss, immunosuppression, and cardiovascular complications.5

Hypercortisolism can precipitate anxiety (12% to 79%), mood disorders (50% to 70%), and (less commonly) psychotic disorders; however, in a clinical setting, if a patient presented with one of these as a chief complaint, they would likely first be treated psychiatrically rather than worked up medically for a rare medical condition.5,7-13

Mr. A’s initial bloodwork was unremarkable, but cortisol levels were not obtained at that time because testing for cortisol levels to rule out an underlying medical condition is not routine in patients with depression and anxiety. In Mr. A’s case, a neuroendocrine workup was only ordered once his PCP’s niece coincidentally was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma.

Continue to: For Mr. A...

For Mr. A, Cushing’s disease presented as a psychiatric disorder with anxiety and insomnia that were resistant to numerous psychiatric medications during an 8-month period. If Mr. A’s PCP had not ordered a brain MRI, he may have continued to receive ineffective psychiatric treatment for some time. Many of Mr. A’s physical symptoms were consistent with Cushing’s disease and mental illness, including erectile dysfunction, fatigue, and muscle weakness; however, his 15-pound weight loss pointed more toward psychiatric illness and further disguised his underlying medical diagnosis, because sudden weight gain is commonly seen in Cushing’s disease (Table 24,5,7,9).

TREATMENT Persistent psychiatric symptoms, then finally relief

Four weeks after surgery, Mr. A’s psychiatric symptoms gradually intensify, which prompts him to see a psychiatrist. A mental status examination (MSE) shows that he is well-nourished, with normal activity, appropriate behavior, and coherent thought process, but depressed mood and flat affect. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. He reports that despite being advised to have realistic expectations, he had high hopes that the surgery would lead to remission of all his symptoms, and expresses disappointment that he does not feel “back to normal.”

Six days later, Mr. A’s wife takes him to the hospital. His MSE shows that he has a tense appearance, fidgety activity, depressed and anxious mood, restricted affect, circumstantial thought process, and paranoid delusions that his wife was plotting against him. He says he still is experiencing insomnia. He also discloses having suicidal ideations with a plan and intent to overdose on medication, as well as homicidal ideations about killing his wife and children. Mr. A provides reasons for why he would want to hurt his family, and does not appear to be bothered by these thoughts.

Mr. A is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit and is prescribed quetiapine, 100 mg every night at bedtime. During the next 2 days, quetiapine is titrated to 300 mg every night at bedtime. On hospital Day 3, Mr. A says he is feeling worse than the previous days. He is still having vague suicidal thoughts and feels agitated, guilty, and depressed. To treat these persistent symptoms, quetiapine is further increased to 400 mg every night at bedtime, and he is initiated on bupropion XL, 150 mg, to treat persistent symptoms.

After 1 week of hospitalization, the treatment team meets with Mr. A and his wife, who has been supportive throughout her husband’s hospitalization. During the meeting, they both agree that Mr. A has experienced some improvement because he is no longer having suicidal or homicidal thoughts, but he is still feeling depressed and frustrated by his continued insomnia. Following the meeting, Mr. A’s quetiapine is further increased to 450 mg every night at bedtime to address continued insomnia, and bupropion XL is increased to 300 mg/d to address continued depressive symptoms. During the next few days, his affective symptoms improve; however, his initial insomnia continues, and quetiapine is further increased to 500 mg every night at bedtime.

Continue to: On hospital Day 20...

On hospital Day 20, Mr. A is discharged back to his outpatient psychiatrist and receives quetiapine, 500 mg every night at bedtime, and bupropion XL, 300 mg/d. Although Mr. A’s depression and anxiety continue to be well controlled, his insomnia persists. Sleep hygiene is addressed, and alprazolam, 0.5 mg every night at bedtime, is added to his regimen, which proves to be effective.

OUTCOME A slow remission

After a year of treatment, Mr. A is slowly tapered off of all medications. Two years later, he is in complete remission of all psychiatric symptoms and no longer requires any psychotropic medications.

The authors’ observations

Treatment for hypercortisolism in patients with psychiatric symptoms triggered by glucocorticoid imbalance has typically resulted in a decrease in the severity of their psychiatric symptoms.9,11 A prospective longitudinal study examining 33 patients found that correction of hypercortisolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome often led to resolution of their psychiatric symptoms, with 87.9% of patients back to baseline within 1 year.14 However, to our knowledge, few reports have described the management of patients whose symptoms are resistant to treatment of hypercortisolism.

In our case, after transsphenoidal resection of an adenoma, Mr. A became suicidal and paranoid, and his anxiety and insomnia also persisted. A possible explanation for the worsening of Mr. A’s symptoms after surgery could be the slow recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and therefore a temporary deficiency in glucocorticoid, which caused an increase in catecholamines, leading to an increase in stress.14 This concept of a “slow recovery” is supported by the fact that Mr. A was successfully weaned off all medication after 1 year of treatment, and achieved complete remission of psychiatric symptoms for >2 years. Furthermore, the severity of Mr. A’s symptoms appeared to correlate with his 24-hour urine cortisol and

Future research should evaluate the utility of screening all patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and/or insomnia for hypercortisolism. Even without other clues to endocrinopathies, serum cortisol levels can be used as a screening tool for diagnosing underlying medical causes in patients with anxiety and depression.2 A greater understanding of the relationship between medical and psychiatric manifestations will allow clinicians to better care for patients. Further research is needed to elucidate the quantitative relationship between cortisol levels and anxiety to evaluate severity, guide treatment planning, and follow treatment response for patients with anxiety. It may be useful to determine the threshold between elevated cortisol levels due to anxiety vs elevated cortisol due to an underlying medical pathology such as Cushing’s disease. Additionally, little research has been conducted to compare how psychiatric symptoms respond to pituitary macroadenoma resection alone, pharmaceutical intervention alone, or a combination of these approaches. It would be beneficial to evaluate these treatment strategies to elucidate the most effective method to reduce psychiatric symptoms in patients with hypercortisolism, and perhaps to reduce the incidence of post-resection worsening of psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: This case was challenging...

This case was challenging because Mr. A did not initially respond to psychiatric intervention, his psychiatric symptoms worsened after transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary adenoma, and his symptoms were alleviated only after psychiatric medications were re-initiated following surgery. This case highlights the importance of considering an underlying medically diagnosable and treatable cause of psychiatric illness, and illustrates the complex ongoing management that may be necessary to help a patient with this condition achieve their baseline. Further, Mr. A’s case shows that the absence of response to standard psychiatric therapies should warrant earlier laboratory and/or imaging evaluation prior to or in conjunction with psychiatric referral. Additionally, testing for cortisol levels is not typically done for a patient with treatment-resistant anxiety, and this case highlights the importance of considering hypercortisolism in such circumstances.

Bottom Line

Consider testing cortisol levels in patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and insomnia, because cortisol plays a role in Cushing’s disease and anxiety. The severity of psychiatric manifestations of Cushing’s disease may correlate with cortisol levels. Treatment should focus on symptomatic management and underlying etiology.

Related Resources

- Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

- Rotham J. Cushing’s syndrome: a tale of frequent misdiagnosis. National Center for Health Research. 2020. www.center4research.org/cushings-syndrome-frequent-misdiagnosis/

- Middleman D. Psychiatric issues of Cushing’s patients: coping with Cushing’s. Cushing’s Support and Research Foundation. www.csrf.net/coping-with-cushings/psychiatric-issues-of-cushings-patients/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Diazepam • Valium

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Zolpidem tartrate • Ambien CR

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Neural sciences. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, et al. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

3. Anfinson TJ, Kathol RG. Screening laboratory evaluation in psychiatric patients: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14(4):248-257.

4. Fehm HL, Voigt KH. Pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease. Pathobiol Annu. 1979;9:225-255.

5. Fujii Y, Mizoguchi Y, Masuoka J, et al. Cushing’s syndrome and psychosis: a case report and literature review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5):18.

6. Raff H, Sharma ST, Nieman LK. Physiological basis for the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of adrenal disorders: Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal insufficiency, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Compr Physiol. 2011;4(2):739-769.

7. Santos A, Resimini E, Pascual JC, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with Cushing’s syndrome: prevalence diagnosis, and management. Drugs. 2017;77(8):829-842.

8. Arnaldi G, Angeli A, Atkinson B, et al. Diagnosis and complications of Cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5593-5602.

9. Sonino N, Fava GA. Psychosomatic aspects of Cushing’s disease. Psychother Psychosom. 1998;67(3):140-146.

10. Loosen PT, Chambliss B, DeBold CR, et al. Psychiatric phenomenology in Cushing’s disease. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1992;25(4):192-198.

11. Kelly WF, Kelly MJ, Faragher B. A prospective study of psychiatric and psychological aspects of Cushing’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;45(6):715-720.

12. Katho RG, Delahunt JW, Hannah L. Transition from bipolar affective disorder to intermittent Cushing’s syndrome: case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46(5):194-196.

13. Hirsh D, Orr G, Kantarovich V, et al. Cushing’s syndrome presenting as a schizophrenia-like psychotic state. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2000;37(1):46-50.

14. Dorn LD, Burgess ES, Friedman TC, et al. The longitudinal course of psychopathology in Cushing’s syndrome after correction of hypercortisolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(3):912-919.

15. Starkman MN, Schteingart DE, Schork MA. Cushing’s syndrome after treatment: changes in cortisol and ACTH levels, and amelioration of the depressive syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(3):177-178.

CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

[polldaddy:10891920]

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...

Two months later, Mr. A undergoes a transsphenoidal tumor resection of the pituitary adenoma, and biopsy results confirm an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary macroadenoma, which is consistent with Cushing’s disease. Following surgery, steroid treatment with dexamethasone is discontinued due to a persistently elevated

[polldaddy:10891923]

The authors’ observations

Chronic excess glucocorticoid production is the underlying pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease, which is most commonly caused by an ACTH-producing adenoma.4,5 When these hormones become dysregulated, the result can be over- or underproduction of cortisol, which can lead to physical and psychiatric manifestations.6

Cushing’s disease most commonly manifests with the physical symptoms of centripetal fat deposition, abdominal striae, facial plethora, muscle atrophy, bone density loss, immunosuppression, and cardiovascular complications.5

Hypercortisolism can precipitate anxiety (12% to 79%), mood disorders (50% to 70%), and (less commonly) psychotic disorders; however, in a clinical setting, if a patient presented with one of these as a chief complaint, they would likely first be treated psychiatrically rather than worked up medically for a rare medical condition.5,7-13

Mr. A’s initial bloodwork was unremarkable, but cortisol levels were not obtained at that time because testing for cortisol levels to rule out an underlying medical condition is not routine in patients with depression and anxiety. In Mr. A’s case, a neuroendocrine workup was only ordered once his PCP’s niece coincidentally was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma.

Continue to: For Mr. A...

For Mr. A, Cushing’s disease presented as a psychiatric disorder with anxiety and insomnia that were resistant to numerous psychiatric medications during an 8-month period. If Mr. A’s PCP had not ordered a brain MRI, he may have continued to receive ineffective psychiatric treatment for some time. Many of Mr. A’s physical symptoms were consistent with Cushing’s disease and mental illness, including erectile dysfunction, fatigue, and muscle weakness; however, his 15-pound weight loss pointed more toward psychiatric illness and further disguised his underlying medical diagnosis, because sudden weight gain is commonly seen in Cushing’s disease (Table 24,5,7,9).

TREATMENT Persistent psychiatric symptoms, then finally relief

Four weeks after surgery, Mr. A’s psychiatric symptoms gradually intensify, which prompts him to see a psychiatrist. A mental status examination (MSE) shows that he is well-nourished, with normal activity, appropriate behavior, and coherent thought process, but depressed mood and flat affect. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. He reports that despite being advised to have realistic expectations, he had high hopes that the surgery would lead to remission of all his symptoms, and expresses disappointment that he does not feel “back to normal.”

Six days later, Mr. A’s wife takes him to the hospital. His MSE shows that he has a tense appearance, fidgety activity, depressed and anxious mood, restricted affect, circumstantial thought process, and paranoid delusions that his wife was plotting against him. He says he still is experiencing insomnia. He also discloses having suicidal ideations with a plan and intent to overdose on medication, as well as homicidal ideations about killing his wife and children. Mr. A provides reasons for why he would want to hurt his family, and does not appear to be bothered by these thoughts.

Mr. A is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit and is prescribed quetiapine, 100 mg every night at bedtime. During the next 2 days, quetiapine is titrated to 300 mg every night at bedtime. On hospital Day 3, Mr. A says he is feeling worse than the previous days. He is still having vague suicidal thoughts and feels agitated, guilty, and depressed. To treat these persistent symptoms, quetiapine is further increased to 400 mg every night at bedtime, and he is initiated on bupropion XL, 150 mg, to treat persistent symptoms.

After 1 week of hospitalization, the treatment team meets with Mr. A and his wife, who has been supportive throughout her husband’s hospitalization. During the meeting, they both agree that Mr. A has experienced some improvement because he is no longer having suicidal or homicidal thoughts, but he is still feeling depressed and frustrated by his continued insomnia. Following the meeting, Mr. A’s quetiapine is further increased to 450 mg every night at bedtime to address continued insomnia, and bupropion XL is increased to 300 mg/d to address continued depressive symptoms. During the next few days, his affective symptoms improve; however, his initial insomnia continues, and quetiapine is further increased to 500 mg every night at bedtime.

Continue to: On hospital Day 20...

On hospital Day 20, Mr. A is discharged back to his outpatient psychiatrist and receives quetiapine, 500 mg every night at bedtime, and bupropion XL, 300 mg/d. Although Mr. A’s depression and anxiety continue to be well controlled, his insomnia persists. Sleep hygiene is addressed, and alprazolam, 0.5 mg every night at bedtime, is added to his regimen, which proves to be effective.

OUTCOME A slow remission

After a year of treatment, Mr. A is slowly tapered off of all medications. Two years later, he is in complete remission of all psychiatric symptoms and no longer requires any psychotropic medications.

The authors’ observations

Treatment for hypercortisolism in patients with psychiatric symptoms triggered by glucocorticoid imbalance has typically resulted in a decrease in the severity of their psychiatric symptoms.9,11 A prospective longitudinal study examining 33 patients found that correction of hypercortisolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome often led to resolution of their psychiatric symptoms, with 87.9% of patients back to baseline within 1 year.14 However, to our knowledge, few reports have described the management of patients whose symptoms are resistant to treatment of hypercortisolism.

In our case, after transsphenoidal resection of an adenoma, Mr. A became suicidal and paranoid, and his anxiety and insomnia also persisted. A possible explanation for the worsening of Mr. A’s symptoms after surgery could be the slow recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and therefore a temporary deficiency in glucocorticoid, which caused an increase in catecholamines, leading to an increase in stress.14 This concept of a “slow recovery” is supported by the fact that Mr. A was successfully weaned off all medication after 1 year of treatment, and achieved complete remission of psychiatric symptoms for >2 years. Furthermore, the severity of Mr. A’s symptoms appeared to correlate with his 24-hour urine cortisol and

Future research should evaluate the utility of screening all patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and/or insomnia for hypercortisolism. Even without other clues to endocrinopathies, serum cortisol levels can be used as a screening tool for diagnosing underlying medical causes in patients with anxiety and depression.2 A greater understanding of the relationship between medical and psychiatric manifestations will allow clinicians to better care for patients. Further research is needed to elucidate the quantitative relationship between cortisol levels and anxiety to evaluate severity, guide treatment planning, and follow treatment response for patients with anxiety. It may be useful to determine the threshold between elevated cortisol levels due to anxiety vs elevated cortisol due to an underlying medical pathology such as Cushing’s disease. Additionally, little research has been conducted to compare how psychiatric symptoms respond to pituitary macroadenoma resection alone, pharmaceutical intervention alone, or a combination of these approaches. It would be beneficial to evaluate these treatment strategies to elucidate the most effective method to reduce psychiatric symptoms in patients with hypercortisolism, and perhaps to reduce the incidence of post-resection worsening of psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: This case was challenging...

This case was challenging because Mr. A did not initially respond to psychiatric intervention, his psychiatric symptoms worsened after transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary adenoma, and his symptoms were alleviated only after psychiatric medications were re-initiated following surgery. This case highlights the importance of considering an underlying medically diagnosable and treatable cause of psychiatric illness, and illustrates the complex ongoing management that may be necessary to help a patient with this condition achieve their baseline. Further, Mr. A’s case shows that the absence of response to standard psychiatric therapies should warrant earlier laboratory and/or imaging evaluation prior to or in conjunction with psychiatric referral. Additionally, testing for cortisol levels is not typically done for a patient with treatment-resistant anxiety, and this case highlights the importance of considering hypercortisolism in such circumstances.

Bottom Line

Consider testing cortisol levels in patients with treatment-resistant anxiety and insomnia, because cortisol plays a role in Cushing’s disease and anxiety. The severity of psychiatric manifestations of Cushing’s disease may correlate with cortisol levels. Treatment should focus on symptomatic management and underlying etiology.

Related Resources

- Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

- Rotham J. Cushing’s syndrome: a tale of frequent misdiagnosis. National Center for Health Research. 2020. www.center4research.org/cushings-syndrome-frequent-misdiagnosis/

- Middleman D. Psychiatric issues of Cushing’s patients: coping with Cushing’s. Cushing’s Support and Research Foundation. www.csrf.net/coping-with-cushings/psychiatric-issues-of-cushings-patients/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Dexamethasone • Decadron

Diazepam • Valium

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Zolpidem tartrate • Ambien CR

CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

[polldaddy:10891920]

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...

Two months later, Mr. A undergoes a transsphenoidal tumor resection of the pituitary adenoma, and biopsy results confirm an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary macroadenoma, which is consistent with Cushing’s disease. Following surgery, steroid treatment with dexamethasone is discontinued due to a persistently elevated

[polldaddy:10891923]

The authors’ observations

Chronic excess glucocorticoid production is the underlying pathophysiology of Cushing’s disease, which is most commonly caused by an ACTH-producing adenoma.4,5 When these hormones become dysregulated, the result can be over- or underproduction of cortisol, which can lead to physical and psychiatric manifestations.6

Cushing’s disease most commonly manifests with the physical symptoms of centripetal fat deposition, abdominal striae, facial plethora, muscle atrophy, bone density loss, immunosuppression, and cardiovascular complications.5

Hypercortisolism can precipitate anxiety (12% to 79%), mood disorders (50% to 70%), and (less commonly) psychotic disorders; however, in a clinical setting, if a patient presented with one of these as a chief complaint, they would likely first be treated psychiatrically rather than worked up medically for a rare medical condition.5,7-13

Mr. A’s initial bloodwork was unremarkable, but cortisol levels were not obtained at that time because testing for cortisol levels to rule out an underlying medical condition is not routine in patients with depression and anxiety. In Mr. A’s case, a neuroendocrine workup was only ordered once his PCP’s niece coincidentally was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma.

Continue to: For Mr. A...

For Mr. A, Cushing’s disease presented as a psychiatric disorder with anxiety and insomnia that were resistant to numerous psychiatric medications during an 8-month period. If Mr. A’s PCP had not ordered a brain MRI, he may have continued to receive ineffective psychiatric treatment for some time. Many of Mr. A’s physical symptoms were consistent with Cushing’s disease and mental illness, including erectile dysfunction, fatigue, and muscle weakness; however, his 15-pound weight loss pointed more toward psychiatric illness and further disguised his underlying medical diagnosis, because sudden weight gain is commonly seen in Cushing’s disease (Table 24,5,7,9).

TREATMENT Persistent psychiatric symptoms, then finally relief

Four weeks after surgery, Mr. A’s psychiatric symptoms gradually intensify, which prompts him to see a psychiatrist. A mental status examination (MSE) shows that he is well-nourished, with normal activity, appropriate behavior, and coherent thought process, but depressed mood and flat affect. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. He reports that despite being advised to have realistic expectations, he had high hopes that the surgery would lead to remission of all his symptoms, and expresses disappointment that he does not feel “back to normal.”

Six days later, Mr. A’s wife takes him to the hospital. His MSE shows that he has a tense appearance, fidgety activity, depressed and anxious mood, restricted affect, circumstantial thought process, and paranoid delusions that his wife was plotting against him. He says he still is experiencing insomnia. He also discloses having suicidal ideations with a plan and intent to overdose on medication, as well as homicidal ideations about killing his wife and children. Mr. A provides reasons for why he would want to hurt his family, and does not appear to be bothered by these thoughts.

Mr. A is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit and is prescribed quetiapine, 100 mg every night at bedtime. During the next 2 days, quetiapine is titrated to 300 mg every night at bedtime. On hospital Day 3, Mr. A says he is feeling worse than the previous days. He is still having vague suicidal thoughts and feels agitated, guilty, and depressed. To treat these persistent symptoms, quetiapine is further increased to 400 mg every night at bedtime, and he is initiated on bupropion XL, 150 mg, to treat persistent symptoms.

After 1 week of hospitalization, the treatment team meets with Mr. A and his wife, who has been supportive throughout her husband’s hospitalization. During the meeting, they both agree that Mr. A has experienced some improvement because he is no longer having suicidal or homicidal thoughts, but he is still feeling depressed and frustrated by his continued insomnia. Following the meeting, Mr. A’s quetiapine is further increased to 450 mg every night at bedtime to address continued insomnia, and bupropion XL is increased to 300 mg/d to address continued depressive symptoms. During the next few days, his affective symptoms improve; however, his initial insomnia continues, and quetiapine is further increased to 500 mg every night at bedtime.

Continue to: On hospital Day 20...

On hospital Day 20, Mr. A is discharged back to his outpatient psychiatrist and receives quetiapine, 500 mg every night at bedtime, and bupropion XL, 300 mg/d. Although Mr. A’s depression and anxiety continue to be well controlled, his insomnia persists. Sleep hygiene is addressed, and alprazolam, 0.5 mg every night at bedtime, is added to his regimen, which proves to be effective.

OUTCOME A slow remission

After a year of treatment, Mr. A is slowly tapered off of all medications. Two years later, he is in complete remission of all psychiatric symptoms and no longer requires any psychotropic medications.

The authors’ observations

Treatment for hypercortisolism in patients with psychiatric symptoms triggered by glucocorticoid imbalance has typically resulted in a decrease in the severity of their psychiatric symptoms.9,11 A prospective longitudinal study examining 33 patients found that correction of hypercortisolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome often led to resolution of their psychiatric symptoms, with 87.9% of patients back to baseline within 1 year.14 However, to our knowledge, few reports have described the management of patients whose symptoms are resistant to treatment of hypercortisolism.

In our case, after transsphenoidal resection of an adenoma, Mr. A became suicidal and paranoid, and his anxiety and insomnia also persisted. A possible explanation for the worsening of Mr. A’s symptoms after surgery could be the slow recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and therefore a temporary deficiency in glucocorticoid, which caused an increase in catecholamines, leading to an increase in stress.14 This concept of a “slow recovery” is supported by the fact that Mr. A was successfully weaned off all medication after 1 year of treatment, and achieved complete remission of psychiatric symptoms for >2 years. Furthermore, the severity of Mr. A’s symptoms appeared to correlate with his 24-hour urine cortisol and