User login

The hateful patient

A 64-year-old White woman with very few medical problems complains of bug bites. She had seen no bugs and had no visible bites. There is no rash. “So what bit me?” she asked, pulling her mask down for emphasis. How should I know? I thought, but didn’t say. She and I have been through this many times.

Before I could respond, she filled the pause with her usual complaints including how hard it is to get an appointment with me and how every appointment with me is a waste of her time. Ignoring the contradistinction of her charges, I took some satisfaction realizing she has just given me a topic to write about: The hateful patient.

They are frustrating, troublesome, rude, sometimes racist, misogynistic, depressing, hopeless, and disheartening. They call you, email you, and come to see you just to annoy you (so it seems). And they’re everywhere. According to one study, nearly one in six are “difficult patients.” It feels like more lately because the vaccine has brought haters back into clinic, just to get us.

But hateful patients aren’t new. In 1978, James E. Groves, MD, a Harvard psychiatrist, wrote a now-classic New England Journal of Medicine article about them called: Taking Care of the Hateful Patient. Even Osler, back in 1889, covered these patients in his lecture to University of Pennsylvania students, advising us to “deal gently with this deliciously credulous old human nature in which we work ... restrain your indignation.” But like much of Osler’s advice, it is easier said than done.

Dr. Groves is more helpful, and presents a model to understand them. Difficult patients, as we’d now call them, fall into four stereotypes: dependent clingers, entitled demanders, manipulative help-rejectors, and self-destructive deniers. It’s Dr. Groves’s bottom line I found insightful. He says that, when patients create negative feelings in us, we’re more likely to make errors. He then gives sound advice: Set firm boundaries and learn to counter the countertransference these patients provoke. Don’t disavow or discharge, Dr. Groves advises, redirect these emotions to motivate you to dig deeper. There you’ll find clinical data that will facilitate understanding and enable better patient management. Yes, easier said.

In addition to Dr. Groves’s analysis of how we harm these patients, I’d add that these disagreeable, malingering patients also harm us doctors. The hangover from a difficult patient encounter can linger for several appointments later or, worse, carryover to home. And now with patient emails proliferating, demanding patients behave as if we have an inexhaustible ability to engage them. We don’t. Many physicians are struggling to care at all; their low empathy battery warnings are blinking red, less than 1% remaining.

What is toxic to us doctors is the maelstrom of cognitive dissonance these patients create in us. Have you ever felt relief to learn a difficult patient has “finally” died? How could we think such a thing?! Didn’t we choose medicine instead of Wall Street because we care about people? But manipulative patients can make us care less. We even use secret language with each other to protect ourselves from them, those GOMERs (get out of my emergency room), bouncebacks, patients with status dramaticus, and those ornery FTDs (failure to die). Save yourself, we say to each other, this patient will kill you.

Caring for my somatizing 64-year-old patient has been difficult, but writing this has helped me reframe our interaction. Unsurprisingly, at the end of her failed visit she asked when she could see me again. “I need to schedule now because I have to find a neighbor to watch my dogs. It takes two buses to come here and I can’t take them with me.” Ah, there’s the clinical data Dr. Groves said I’d find – she’s not here to hurt me, she’s here because I’m all she’s got. At least for this difficult patient, I have a plan. At the bottom of my note I type “RTC 3 mo.”

Dr. Benabio is director of healthcare transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

A 64-year-old White woman with very few medical problems complains of bug bites. She had seen no bugs and had no visible bites. There is no rash. “So what bit me?” she asked, pulling her mask down for emphasis. How should I know? I thought, but didn’t say. She and I have been through this many times.

Before I could respond, she filled the pause with her usual complaints including how hard it is to get an appointment with me and how every appointment with me is a waste of her time. Ignoring the contradistinction of her charges, I took some satisfaction realizing she has just given me a topic to write about: The hateful patient.

They are frustrating, troublesome, rude, sometimes racist, misogynistic, depressing, hopeless, and disheartening. They call you, email you, and come to see you just to annoy you (so it seems). And they’re everywhere. According to one study, nearly one in six are “difficult patients.” It feels like more lately because the vaccine has brought haters back into clinic, just to get us.

But hateful patients aren’t new. In 1978, James E. Groves, MD, a Harvard psychiatrist, wrote a now-classic New England Journal of Medicine article about them called: Taking Care of the Hateful Patient. Even Osler, back in 1889, covered these patients in his lecture to University of Pennsylvania students, advising us to “deal gently with this deliciously credulous old human nature in which we work ... restrain your indignation.” But like much of Osler’s advice, it is easier said than done.

Dr. Groves is more helpful, and presents a model to understand them. Difficult patients, as we’d now call them, fall into four stereotypes: dependent clingers, entitled demanders, manipulative help-rejectors, and self-destructive deniers. It’s Dr. Groves’s bottom line I found insightful. He says that, when patients create negative feelings in us, we’re more likely to make errors. He then gives sound advice: Set firm boundaries and learn to counter the countertransference these patients provoke. Don’t disavow or discharge, Dr. Groves advises, redirect these emotions to motivate you to dig deeper. There you’ll find clinical data that will facilitate understanding and enable better patient management. Yes, easier said.

In addition to Dr. Groves’s analysis of how we harm these patients, I’d add that these disagreeable, malingering patients also harm us doctors. The hangover from a difficult patient encounter can linger for several appointments later or, worse, carryover to home. And now with patient emails proliferating, demanding patients behave as if we have an inexhaustible ability to engage them. We don’t. Many physicians are struggling to care at all; their low empathy battery warnings are blinking red, less than 1% remaining.

What is toxic to us doctors is the maelstrom of cognitive dissonance these patients create in us. Have you ever felt relief to learn a difficult patient has “finally” died? How could we think such a thing?! Didn’t we choose medicine instead of Wall Street because we care about people? But manipulative patients can make us care less. We even use secret language with each other to protect ourselves from them, those GOMERs (get out of my emergency room), bouncebacks, patients with status dramaticus, and those ornery FTDs (failure to die). Save yourself, we say to each other, this patient will kill you.

Caring for my somatizing 64-year-old patient has been difficult, but writing this has helped me reframe our interaction. Unsurprisingly, at the end of her failed visit she asked when she could see me again. “I need to schedule now because I have to find a neighbor to watch my dogs. It takes two buses to come here and I can’t take them with me.” Ah, there’s the clinical data Dr. Groves said I’d find – she’s not here to hurt me, she’s here because I’m all she’s got. At least for this difficult patient, I have a plan. At the bottom of my note I type “RTC 3 mo.”

Dr. Benabio is director of healthcare transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

A 64-year-old White woman with very few medical problems complains of bug bites. She had seen no bugs and had no visible bites. There is no rash. “So what bit me?” she asked, pulling her mask down for emphasis. How should I know? I thought, but didn’t say. She and I have been through this many times.

Before I could respond, she filled the pause with her usual complaints including how hard it is to get an appointment with me and how every appointment with me is a waste of her time. Ignoring the contradistinction of her charges, I took some satisfaction realizing she has just given me a topic to write about: The hateful patient.

They are frustrating, troublesome, rude, sometimes racist, misogynistic, depressing, hopeless, and disheartening. They call you, email you, and come to see you just to annoy you (so it seems). And they’re everywhere. According to one study, nearly one in six are “difficult patients.” It feels like more lately because the vaccine has brought haters back into clinic, just to get us.

But hateful patients aren’t new. In 1978, James E. Groves, MD, a Harvard psychiatrist, wrote a now-classic New England Journal of Medicine article about them called: Taking Care of the Hateful Patient. Even Osler, back in 1889, covered these patients in his lecture to University of Pennsylvania students, advising us to “deal gently with this deliciously credulous old human nature in which we work ... restrain your indignation.” But like much of Osler’s advice, it is easier said than done.

Dr. Groves is more helpful, and presents a model to understand them. Difficult patients, as we’d now call them, fall into four stereotypes: dependent clingers, entitled demanders, manipulative help-rejectors, and self-destructive deniers. It’s Dr. Groves’s bottom line I found insightful. He says that, when patients create negative feelings in us, we’re more likely to make errors. He then gives sound advice: Set firm boundaries and learn to counter the countertransference these patients provoke. Don’t disavow or discharge, Dr. Groves advises, redirect these emotions to motivate you to dig deeper. There you’ll find clinical data that will facilitate understanding and enable better patient management. Yes, easier said.

In addition to Dr. Groves’s analysis of how we harm these patients, I’d add that these disagreeable, malingering patients also harm us doctors. The hangover from a difficult patient encounter can linger for several appointments later or, worse, carryover to home. And now with patient emails proliferating, demanding patients behave as if we have an inexhaustible ability to engage them. We don’t. Many physicians are struggling to care at all; their low empathy battery warnings are blinking red, less than 1% remaining.

What is toxic to us doctors is the maelstrom of cognitive dissonance these patients create in us. Have you ever felt relief to learn a difficult patient has “finally” died? How could we think such a thing?! Didn’t we choose medicine instead of Wall Street because we care about people? But manipulative patients can make us care less. We even use secret language with each other to protect ourselves from them, those GOMERs (get out of my emergency room), bouncebacks, patients with status dramaticus, and those ornery FTDs (failure to die). Save yourself, we say to each other, this patient will kill you.

Caring for my somatizing 64-year-old patient has been difficult, but writing this has helped me reframe our interaction. Unsurprisingly, at the end of her failed visit she asked when she could see me again. “I need to schedule now because I have to find a neighbor to watch my dogs. It takes two buses to come here and I can’t take them with me.” Ah, there’s the clinical data Dr. Groves said I’d find – she’s not here to hurt me, she’s here because I’m all she’s got. At least for this difficult patient, I have a plan. At the bottom of my note I type “RTC 3 mo.”

Dr. Benabio is director of healthcare transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

FDA OKs stimulation device for anxiety in depression

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for the noninvasive BrainsWay Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (Deep TMS) System to include treatment of comorbid anxiety symptoms in adult patients with depression, the company has announced.

As reported by this news organization, the neurostimulation system has previously received FDA approval for treatment-resistant major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and smoking addiction.

In the August 18 announcement, BrainsWay reported that it has also received 510(k) clearance from the FDA to market its TMS system for the reduction of anxious depression symptoms.

“This clearance is confirmation of what many have believed anecdotally for years – that Deep TMS is a unique form of therapy that can address comorbid anxiety symptoms using the same depression treatment protocol,” Aron Tendler, MD, chief medical officer at BrainsWay, said in a press release.

‘Consistent, robust’ effect

, which included both randomized controlled trials and open-label studies.

“The data demonstrated a treatment effect that was consistent, robust, and clinically meaningful for decreasing anxiety symptoms in adult patients suffering from major depressive disorder [MDD],” the company said in its release.

Data from three of the randomized trials showed an effect size of 0.3 when compared with a sham device and an effect size of 0.9 when compared with medication. The overall, weighted, pooled effect size was 0.55.

The company noted that in more than 70 published studies with about 16,000 total participants, effect sizes have ranged from 0.2-0.37 for drug-based anxiety treatments.

“The expanded FDA labeling now allows BrainsWay to market its Deep TMS System for the treatment of depressive episodes and for decreasing anxiety symptoms for those who may exhibit comorbid anxiety symptoms in adult patients suffering from [MDD] and who failed to achieve satisfactory improvement from previous antidepressant medication treatment in the current episode,” the company said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for the noninvasive BrainsWay Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (Deep TMS) System to include treatment of comorbid anxiety symptoms in adult patients with depression, the company has announced.

As reported by this news organization, the neurostimulation system has previously received FDA approval for treatment-resistant major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and smoking addiction.

In the August 18 announcement, BrainsWay reported that it has also received 510(k) clearance from the FDA to market its TMS system for the reduction of anxious depression symptoms.

“This clearance is confirmation of what many have believed anecdotally for years – that Deep TMS is a unique form of therapy that can address comorbid anxiety symptoms using the same depression treatment protocol,” Aron Tendler, MD, chief medical officer at BrainsWay, said in a press release.

‘Consistent, robust’ effect

, which included both randomized controlled trials and open-label studies.

“The data demonstrated a treatment effect that was consistent, robust, and clinically meaningful for decreasing anxiety symptoms in adult patients suffering from major depressive disorder [MDD],” the company said in its release.

Data from three of the randomized trials showed an effect size of 0.3 when compared with a sham device and an effect size of 0.9 when compared with medication. The overall, weighted, pooled effect size was 0.55.

The company noted that in more than 70 published studies with about 16,000 total participants, effect sizes have ranged from 0.2-0.37 for drug-based anxiety treatments.

“The expanded FDA labeling now allows BrainsWay to market its Deep TMS System for the treatment of depressive episodes and for decreasing anxiety symptoms for those who may exhibit comorbid anxiety symptoms in adult patients suffering from [MDD] and who failed to achieve satisfactory improvement from previous antidepressant medication treatment in the current episode,” the company said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for the noninvasive BrainsWay Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (Deep TMS) System to include treatment of comorbid anxiety symptoms in adult patients with depression, the company has announced.

As reported by this news organization, the neurostimulation system has previously received FDA approval for treatment-resistant major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and smoking addiction.

In the August 18 announcement, BrainsWay reported that it has also received 510(k) clearance from the FDA to market its TMS system for the reduction of anxious depression symptoms.

“This clearance is confirmation of what many have believed anecdotally for years – that Deep TMS is a unique form of therapy that can address comorbid anxiety symptoms using the same depression treatment protocol,” Aron Tendler, MD, chief medical officer at BrainsWay, said in a press release.

‘Consistent, robust’ effect

, which included both randomized controlled trials and open-label studies.

“The data demonstrated a treatment effect that was consistent, robust, and clinically meaningful for decreasing anxiety symptoms in adult patients suffering from major depressive disorder [MDD],” the company said in its release.

Data from three of the randomized trials showed an effect size of 0.3 when compared with a sham device and an effect size of 0.9 when compared with medication. The overall, weighted, pooled effect size was 0.55.

The company noted that in more than 70 published studies with about 16,000 total participants, effect sizes have ranged from 0.2-0.37 for drug-based anxiety treatments.

“The expanded FDA labeling now allows BrainsWay to market its Deep TMS System for the treatment of depressive episodes and for decreasing anxiety symptoms for those who may exhibit comorbid anxiety symptoms in adult patients suffering from [MDD] and who failed to achieve satisfactory improvement from previous antidepressant medication treatment in the current episode,” the company said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Reassuring’ findings for second-generation antipsychotics during pregnancy

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) taken by pregnant women are linked to a low rate of adverse effects in their children, new research suggests.

Data from a large registry study of almost 2,000 women showed that 2.5% of the live births in a group that had been exposed to antipsychotics had confirmed major malformations compared with 2% of the live births in a non-exposed group. This translated into an estimated odds ratio of 1.5 for major malformations.

“The 2.5% absolute risk for major malformations is consistent with the estimates of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national baseline rate of major malformations in the general population,” lead author Adele Viguera, MD, MPH, director of research for women’s mental health, Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute, told this news organization.

“Our results are reassuring and suggest that second-generation antipsychotics, as a class, do not substantially increase the risk of major malformations,” Dr. Viguera said.

The findings were published online August 3 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Safety data scarce

Despite the increasing use of SGAs to treat a “spectrum of psychiatric disorders,” relatively little data are available on the reproductive safety of these agents, Dr. Viguera said.

The National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics (NPRAA) was established in 2008 to determine risk for major malformation among infants exposed to these medications during the first trimester, relative to a comparison group of unexposed infants of mothers with histories of psychiatric morbidity.

The NPRAA follows pregnant women (aged 18 to 45 years) with psychiatric illness who are exposed or unexposed to SGAs during pregnancy. Participants are recruited through nationwide provider referral, self-referral, and advertisement through the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health website.

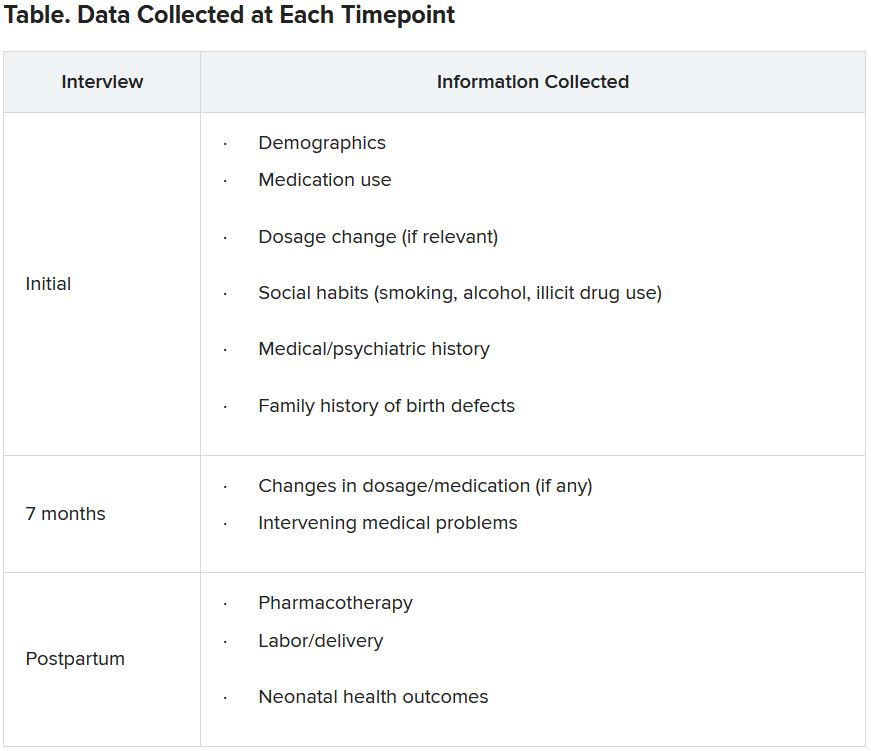

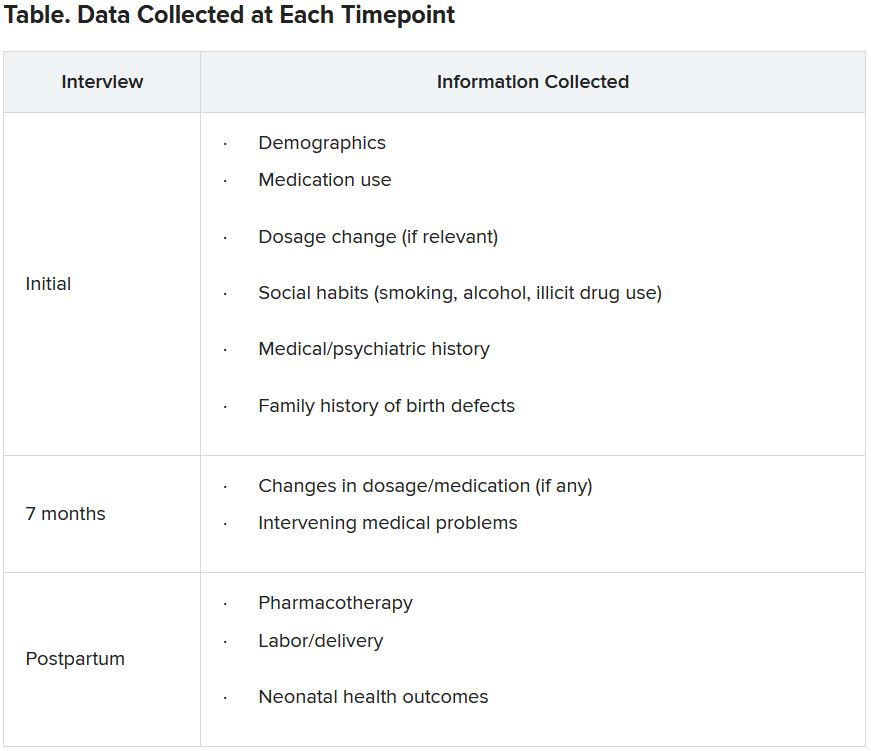

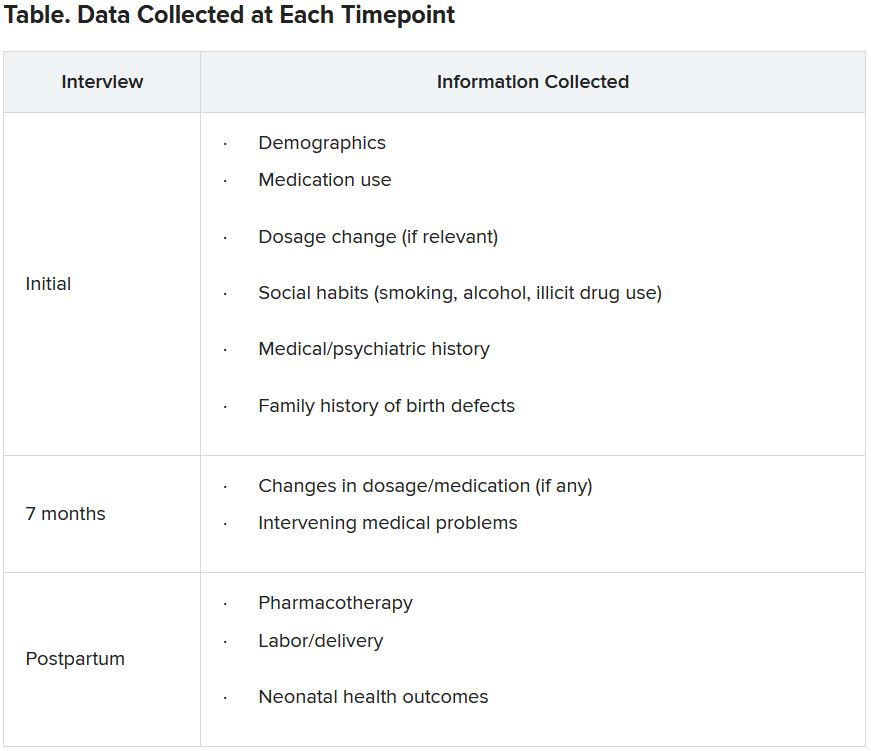

Specific data collected are shown in the following table.

Since publication of the first results in 2015, the sample size for the trial has increased – and the absolute and relative risk for major malformations observed in the study population are “more precise,” the investigators note. The current study presented updated previous findings.

Demographic differences

Of the 1,906 women who enrolled as of April 2020, 1,311 (mean age, 32.6 years; 81.3% White) completed the study and were eligible for inclusion in the analysis.

Although the groups had a virtually identical mean age, fewer women in the exposure group were married compared with those in the non-exposure group (77% vs. 90%, respectively) and fewer had a college education (71.2% vs. 87.8%). There was also a higher percentage of first-trimester cigarette smokers in the exposure group (18.4% vs. 5.1%).

On the other hand, more women in the non-exposure group used alcohol than in the exposure group (28.6% vs. 21.4%, respectively).

The most frequent psychiatric disorder in the exposure group was bipolar disorder (63.9%), followed by major depression (12.9%), anxiety (5.8%), and schizophrenia (4.5%). Only 11.4% of women in the non-exposure group were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, whereas 34.1% were diagnosed with major depression, 31.3% with anxiety, and none with schizophrenia.

Notably, a large percentage of women in both groups had a history of postpartum depression and/or psychosis (41.4% and 35.5%, respectively).

The most frequently used SGAs in the exposure group were quetiapine (Seroquel), aripiprazole (Abilify), and lurasidone (Latuda).

Participants in the exposure group had a higher age at initial onset of primary psychiatric diagnosis and a lower proportion of lifetime illness compared with those in the non-exposure group.

Major clinical implication?

Among 640 live births in the exposure group, which included 17 twin pregnancies and 1 triplet pregnancy, 2.5% reported major malformations. Among 704 live births in the control group, which included 14 twin pregnancies, 1.99% reported major malformations.

The estimated OR for major malformations comparing exposed and unexposed infants was 1.48 (95% confidence interval, 0.625-3.517).

The authors note that their findings were consistent with one of the largest studies to date, which included a nationwide sample of more than 1 million women. Its results showed that, among infants exposed to SGAs versus those who were not exposed, the estimated risk ratio after adjusting for psychiatric conditions was 1.05 (95% CI, 0.96-1.16).

Additionally, “a hallmark of a teratogen is that it tends to cause a specific type or pattern of malformations, and we found no preponderance of one single type of major malformation or specific pattern of malformations among the exposed and unexposed groups,” Dr. Viguera said

“A major clinical implication of these findings is that for women with major mood and/or psychotic disorders, treatment with an atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy may be the most prudent clinical decision, much as continued treatment is recommended for pregnant women with other serious and chronic medical conditions, such as epilepsy,” she added.

The concept of ‘satisficing’

Commenting on the study, Vivien Burt, MD, PhD, founder and director/consultant of the Women’s Life Center at the Resnick University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Neuropsychiatric Hospital, called the findings “reassuring.”

The results “support the conclusion that in pregnant women with serious psychiatric illnesses, the use of SGAs is often a better option than avoiding these medications and exposing both the women and their offspring to the adverse consequences of maternal mental illness,” she said.

An accompanying editorial co-authored by Dr. Burt and colleague Sonya Rasminsky, MD, introduced the concept of “satisficing” – a term coined by Herbert Simon, a behavioral economist and Nobel Laureate. “Satisficing” is a “decision-making strategy that aims for a satisfactory (‘good enough’) outcome rather than a perfect one.”

The concept applies to decision-making beyond the field of economics “and is critical to how physicians help patients make decisions when they are faced with multiple treatment options,” said Dr. Burt, a professor emeritus of psychiatry at UCLA.

“The goal of ‘satisficing’ is to plan for the most satisfactory outcome, knowing that there are always unknowns, so in an uncertain world, clinicians should carefully help their patients make decisions that will allow them to achieve an outcome they can best live with,” she noted.

The investigators note that their findings may not be generalizable to the larger population of women taking SGAs, given that their participants were “overwhelmingly White, married, and well-educated women.”

They add that enrollment into the NPRAA registry is ongoing and larger sample sizes will “further narrow the confidence interval around the risk estimates and allow for adjustment of likely sources of confounding.”

The NPRAA is supported by Alkermes, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, SAGE Therapeutics, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Aurobindo Pharma. Past sponsors of the NPRAA are listed in the original paper. Dr. Viguera receives research support from the NPRAA, Alkermes Biopharmaceuticals, Aurobindo Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and SAGE Therapeutics and receives adviser/consulting fees from Up-to-Date. Dr. Burt has been a consultant/speaker for Sage Therapeutics. Dr. Rasminsky has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) taken by pregnant women are linked to a low rate of adverse effects in their children, new research suggests.

Data from a large registry study of almost 2,000 women showed that 2.5% of the live births in a group that had been exposed to antipsychotics had confirmed major malformations compared with 2% of the live births in a non-exposed group. This translated into an estimated odds ratio of 1.5 for major malformations.

“The 2.5% absolute risk for major malformations is consistent with the estimates of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national baseline rate of major malformations in the general population,” lead author Adele Viguera, MD, MPH, director of research for women’s mental health, Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute, told this news organization.

“Our results are reassuring and suggest that second-generation antipsychotics, as a class, do not substantially increase the risk of major malformations,” Dr. Viguera said.

The findings were published online August 3 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Safety data scarce

Despite the increasing use of SGAs to treat a “spectrum of psychiatric disorders,” relatively little data are available on the reproductive safety of these agents, Dr. Viguera said.

The National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics (NPRAA) was established in 2008 to determine risk for major malformation among infants exposed to these medications during the first trimester, relative to a comparison group of unexposed infants of mothers with histories of psychiatric morbidity.

The NPRAA follows pregnant women (aged 18 to 45 years) with psychiatric illness who are exposed or unexposed to SGAs during pregnancy. Participants are recruited through nationwide provider referral, self-referral, and advertisement through the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health website.

Specific data collected are shown in the following table.

Since publication of the first results in 2015, the sample size for the trial has increased – and the absolute and relative risk for major malformations observed in the study population are “more precise,” the investigators note. The current study presented updated previous findings.

Demographic differences

Of the 1,906 women who enrolled as of April 2020, 1,311 (mean age, 32.6 years; 81.3% White) completed the study and were eligible for inclusion in the analysis.

Although the groups had a virtually identical mean age, fewer women in the exposure group were married compared with those in the non-exposure group (77% vs. 90%, respectively) and fewer had a college education (71.2% vs. 87.8%). There was also a higher percentage of first-trimester cigarette smokers in the exposure group (18.4% vs. 5.1%).

On the other hand, more women in the non-exposure group used alcohol than in the exposure group (28.6% vs. 21.4%, respectively).

The most frequent psychiatric disorder in the exposure group was bipolar disorder (63.9%), followed by major depression (12.9%), anxiety (5.8%), and schizophrenia (4.5%). Only 11.4% of women in the non-exposure group were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, whereas 34.1% were diagnosed with major depression, 31.3% with anxiety, and none with schizophrenia.

Notably, a large percentage of women in both groups had a history of postpartum depression and/or psychosis (41.4% and 35.5%, respectively).

The most frequently used SGAs in the exposure group were quetiapine (Seroquel), aripiprazole (Abilify), and lurasidone (Latuda).

Participants in the exposure group had a higher age at initial onset of primary psychiatric diagnosis and a lower proportion of lifetime illness compared with those in the non-exposure group.

Major clinical implication?

Among 640 live births in the exposure group, which included 17 twin pregnancies and 1 triplet pregnancy, 2.5% reported major malformations. Among 704 live births in the control group, which included 14 twin pregnancies, 1.99% reported major malformations.

The estimated OR for major malformations comparing exposed and unexposed infants was 1.48 (95% confidence interval, 0.625-3.517).

The authors note that their findings were consistent with one of the largest studies to date, which included a nationwide sample of more than 1 million women. Its results showed that, among infants exposed to SGAs versus those who were not exposed, the estimated risk ratio after adjusting for psychiatric conditions was 1.05 (95% CI, 0.96-1.16).

Additionally, “a hallmark of a teratogen is that it tends to cause a specific type or pattern of malformations, and we found no preponderance of one single type of major malformation or specific pattern of malformations among the exposed and unexposed groups,” Dr. Viguera said

“A major clinical implication of these findings is that for women with major mood and/or psychotic disorders, treatment with an atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy may be the most prudent clinical decision, much as continued treatment is recommended for pregnant women with other serious and chronic medical conditions, such as epilepsy,” she added.

The concept of ‘satisficing’

Commenting on the study, Vivien Burt, MD, PhD, founder and director/consultant of the Women’s Life Center at the Resnick University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Neuropsychiatric Hospital, called the findings “reassuring.”

The results “support the conclusion that in pregnant women with serious psychiatric illnesses, the use of SGAs is often a better option than avoiding these medications and exposing both the women and their offspring to the adverse consequences of maternal mental illness,” she said.

An accompanying editorial co-authored by Dr. Burt and colleague Sonya Rasminsky, MD, introduced the concept of “satisficing” – a term coined by Herbert Simon, a behavioral economist and Nobel Laureate. “Satisficing” is a “decision-making strategy that aims for a satisfactory (‘good enough’) outcome rather than a perfect one.”

The concept applies to decision-making beyond the field of economics “and is critical to how physicians help patients make decisions when they are faced with multiple treatment options,” said Dr. Burt, a professor emeritus of psychiatry at UCLA.

“The goal of ‘satisficing’ is to plan for the most satisfactory outcome, knowing that there are always unknowns, so in an uncertain world, clinicians should carefully help their patients make decisions that will allow them to achieve an outcome they can best live with,” she noted.

The investigators note that their findings may not be generalizable to the larger population of women taking SGAs, given that their participants were “overwhelmingly White, married, and well-educated women.”

They add that enrollment into the NPRAA registry is ongoing and larger sample sizes will “further narrow the confidence interval around the risk estimates and allow for adjustment of likely sources of confounding.”

The NPRAA is supported by Alkermes, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, SAGE Therapeutics, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Aurobindo Pharma. Past sponsors of the NPRAA are listed in the original paper. Dr. Viguera receives research support from the NPRAA, Alkermes Biopharmaceuticals, Aurobindo Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and SAGE Therapeutics and receives adviser/consulting fees from Up-to-Date. Dr. Burt has been a consultant/speaker for Sage Therapeutics. Dr. Rasminsky has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) taken by pregnant women are linked to a low rate of adverse effects in their children, new research suggests.

Data from a large registry study of almost 2,000 women showed that 2.5% of the live births in a group that had been exposed to antipsychotics had confirmed major malformations compared with 2% of the live births in a non-exposed group. This translated into an estimated odds ratio of 1.5 for major malformations.

“The 2.5% absolute risk for major malformations is consistent with the estimates of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national baseline rate of major malformations in the general population,” lead author Adele Viguera, MD, MPH, director of research for women’s mental health, Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute, told this news organization.

“Our results are reassuring and suggest that second-generation antipsychotics, as a class, do not substantially increase the risk of major malformations,” Dr. Viguera said.

The findings were published online August 3 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Safety data scarce

Despite the increasing use of SGAs to treat a “spectrum of psychiatric disorders,” relatively little data are available on the reproductive safety of these agents, Dr. Viguera said.

The National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics (NPRAA) was established in 2008 to determine risk for major malformation among infants exposed to these medications during the first trimester, relative to a comparison group of unexposed infants of mothers with histories of psychiatric morbidity.

The NPRAA follows pregnant women (aged 18 to 45 years) with psychiatric illness who are exposed or unexposed to SGAs during pregnancy. Participants are recruited through nationwide provider referral, self-referral, and advertisement through the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health website.

Specific data collected are shown in the following table.

Since publication of the first results in 2015, the sample size for the trial has increased – and the absolute and relative risk for major malformations observed in the study population are “more precise,” the investigators note. The current study presented updated previous findings.

Demographic differences

Of the 1,906 women who enrolled as of April 2020, 1,311 (mean age, 32.6 years; 81.3% White) completed the study and were eligible for inclusion in the analysis.

Although the groups had a virtually identical mean age, fewer women in the exposure group were married compared with those in the non-exposure group (77% vs. 90%, respectively) and fewer had a college education (71.2% vs. 87.8%). There was also a higher percentage of first-trimester cigarette smokers in the exposure group (18.4% vs. 5.1%).

On the other hand, more women in the non-exposure group used alcohol than in the exposure group (28.6% vs. 21.4%, respectively).

The most frequent psychiatric disorder in the exposure group was bipolar disorder (63.9%), followed by major depression (12.9%), anxiety (5.8%), and schizophrenia (4.5%). Only 11.4% of women in the non-exposure group were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, whereas 34.1% were diagnosed with major depression, 31.3% with anxiety, and none with schizophrenia.

Notably, a large percentage of women in both groups had a history of postpartum depression and/or psychosis (41.4% and 35.5%, respectively).

The most frequently used SGAs in the exposure group were quetiapine (Seroquel), aripiprazole (Abilify), and lurasidone (Latuda).

Participants in the exposure group had a higher age at initial onset of primary psychiatric diagnosis and a lower proportion of lifetime illness compared with those in the non-exposure group.

Major clinical implication?

Among 640 live births in the exposure group, which included 17 twin pregnancies and 1 triplet pregnancy, 2.5% reported major malformations. Among 704 live births in the control group, which included 14 twin pregnancies, 1.99% reported major malformations.

The estimated OR for major malformations comparing exposed and unexposed infants was 1.48 (95% confidence interval, 0.625-3.517).

The authors note that their findings were consistent with one of the largest studies to date, which included a nationwide sample of more than 1 million women. Its results showed that, among infants exposed to SGAs versus those who were not exposed, the estimated risk ratio after adjusting for psychiatric conditions was 1.05 (95% CI, 0.96-1.16).

Additionally, “a hallmark of a teratogen is that it tends to cause a specific type or pattern of malformations, and we found no preponderance of one single type of major malformation or specific pattern of malformations among the exposed and unexposed groups,” Dr. Viguera said

“A major clinical implication of these findings is that for women with major mood and/or psychotic disorders, treatment with an atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy may be the most prudent clinical decision, much as continued treatment is recommended for pregnant women with other serious and chronic medical conditions, such as epilepsy,” she added.

The concept of ‘satisficing’

Commenting on the study, Vivien Burt, MD, PhD, founder and director/consultant of the Women’s Life Center at the Resnick University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Neuropsychiatric Hospital, called the findings “reassuring.”

The results “support the conclusion that in pregnant women with serious psychiatric illnesses, the use of SGAs is often a better option than avoiding these medications and exposing both the women and their offspring to the adverse consequences of maternal mental illness,” she said.

An accompanying editorial co-authored by Dr. Burt and colleague Sonya Rasminsky, MD, introduced the concept of “satisficing” – a term coined by Herbert Simon, a behavioral economist and Nobel Laureate. “Satisficing” is a “decision-making strategy that aims for a satisfactory (‘good enough’) outcome rather than a perfect one.”

The concept applies to decision-making beyond the field of economics “and is critical to how physicians help patients make decisions when they are faced with multiple treatment options,” said Dr. Burt, a professor emeritus of psychiatry at UCLA.

“The goal of ‘satisficing’ is to plan for the most satisfactory outcome, knowing that there are always unknowns, so in an uncertain world, clinicians should carefully help their patients make decisions that will allow them to achieve an outcome they can best live with,” she noted.

The investigators note that their findings may not be generalizable to the larger population of women taking SGAs, given that their participants were “overwhelmingly White, married, and well-educated women.”

They add that enrollment into the NPRAA registry is ongoing and larger sample sizes will “further narrow the confidence interval around the risk estimates and allow for adjustment of likely sources of confounding.”

The NPRAA is supported by Alkermes, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, SAGE Therapeutics, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Aurobindo Pharma. Past sponsors of the NPRAA are listed in the original paper. Dr. Viguera receives research support from the NPRAA, Alkermes Biopharmaceuticals, Aurobindo Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and SAGE Therapeutics and receives adviser/consulting fees from Up-to-Date. Dr. Burt has been a consultant/speaker for Sage Therapeutics. Dr. Rasminsky has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Shedding the super-doctor myth requires an honest look at systemic racism

An overwhelmingly loud and high-pitched screech rattles against your hip. You startle and groan into the pillow as your thoughts settle into conscious awareness. It is 3 a.m. You are a 2nd-year resident trudging through the night shift, alerted to the presence of a new patient awaiting an emergency assessment. You are the only in-house physician. Walking steadfastly toward the emergency unit, you enter and greet the patient. Immediately, you observe a look of surprise followed immediately by a scowl.

You extend a hand, but your greeting is abruptly cut short with: “I want to see a doctor!” You pace your breaths to quell annoyance and resume your introduction, asserting that you are a doctor and indeed the only doctor on duty. After moments of deep sighs and questions regarding your credentials, you persuade the patient to start the interview.

It is now 8 a.m. The frustration of the night starts to ease as you prepare to leave. While gathering your things, a visitor is overheard inquiring the whereabouts of a hospital unit. Volunteering as a guide, you walk the person toward the opposite end of the hospital. Bleary eyed, muscle laxed, and bone weary, you point out the entrance, then turn to leave. The steady rhythm of your steps suddenly halts as you hear from behind: “Thank you! You speak English really well!” Blankly, you stare. Your voice remains mute while your brain screams: “What is that supposed to mean?” But you do not utter a sound, because intuitively, you know the answer.

While reading this scenario, what did you feel? Pride in knowing that the physician was able to successfully navigate a busy night? Relief in the physician’s ability to maintain a professional demeanor despite belittling microaggressions? Are you angry? Would you replay those moments like reruns of a bad TV show? Can you imagine entering your home and collapsing onto the bed as your tears of fury pool over your rumpled sheets?

The emotional release of that morning is seared into my memory. Over the years, I questioned my reactions. Was I too passive? Should I have schooled them on their ignorance? Had I done so, would I have incurred reprimands? Would standing up for myself cause years of hard work to fall away? Moreover, had I defended myself, would I forever have been viewed as “The Angry Black Woman?”

This story is more than a vignette. For me, it is another reminder that, despite how far we have come, we have much further to go. As a Black woman in a professional sphere, I stand upon the shoulders of those who sacrificed for a dream, a greater purpose. My foremothers and forefathers fought bravely and tirelessly so that we could attain levels of success that were only once but a dream. Despite this progress, a grimace, carelessly spoken words, or a mindless gesture remind me that, no matter how much I toil and what levels of success I achieve, when I meet someone for the first time or encounter someone from my past, I find myself wondering whether I am remembered for me or because I am “The Black One.”

Honest look at medicine is imperative

It is important to consider multiple facets of the super-doctor myth. We are dedicated, fearless, authoritative, ambitious individuals. We do not yield to sickness, family obligations, or fatigue. Medicine is a calling, and the patient deserves the utmost respect and professional behavior. Impervious to ethnicity, race, nationality, or creed, we are unbiased and always in service of the greater good. Often, however, I wonder how the expectations of patient-focused, patient-centered care can prevail without an honest look at the vicissitudes facing medicine.

We find ourselves amid a tumultuous year overshadowed by a devastating pandemic that skews heavily toward Black and Brown communities, in addition to political turmoil and racial reckoning that sprang forth from fear, anger, and determination ignited by the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd – communities united in outrage lamenting the cries of Black Lives Matter.

I remember the tears briskly falling upon my blouse as I watched Mr. Floyd’s life violently ripped from this Earth. Shortly thereafter, I remember the phone calls, emails, and texts from close friends, acquaintances, and colleagues offering support, listening ears, pledging to learn and endeavoring to understand the struggle for recognition and the fight for human rights. Even so, the deafening support was clouded by the preternatural silence of some medical organizations. Within the Black physician community, outrage was palpable. We reflected upon years of sacrifice and perseverance despite the challenge of bigotry, ignorance, and racism – not only from patients and their families – but also colleagues and administrators. Yet, in our time of horror and need, in those moments of vulnerability ... silence. Eventually, lengthy proclamations of support were expressed through various media. However, it felt too safe, too corporate, and too generic and inauthentic. As a result, an exodus of Black physicians from leadership positions and academic medicine took hold as the blatant continuation of rhetoric – coupled with ineffective outreach and support – finally took its toll.

Frequently, I question how the obstacles of medical school, residency, and beyond are expected to be traversed while living in a world that consistently affords additional challenges to those who look, act, or speak in a manner that varies from the perceived standard. In a culture where the myth of the super doctor reigns, how do we reconcile attainment of a false and detrimental narrative while the overarching pressure acutely felt by Black physicians magnifies in the setting of stereotypes, sociopolitical turbulence, bigotry, and racism? How can one sacrifice for an entity that is unwilling to acknowledge the psychological implications of that sacrifice?

For instance, while in medical school, I transitioned my hair to its natural state but was counseled against doing so because of the risk of losing residency opportunities as a direct result of my “unprofessional” appearance. Throughout residency, multiple incidents come to mind, including frequent demands to see my hospital badge despite the same not being of asked of my White cohorts; denial of entry into physician entrance within the residency building because, despite my professional attire, I was presumed to be a member of the custodial staff; and patients being confused and asking for a doctor despite my long white coat and clear introductions.

Furthermore, the fluency of my speech and the absence of regional dialect or vernacular are quite often lauded by patients. Inquiries to touch my hair as well as hypotheses regarding my nationality or degree of “blackness” with respect to the shape of my nose, eyes, and lips are openly questioned. Unfortunately, those uncomfortable incidents have not been limited to patient encounters.

In one instance, while presenting a patient in the presence of my attending and a 3rd-year medical student, I was sternly admonished for disclosing the race of the patient. I sat still and resolute as this doctor spoke on increased risk of bias in diagnosis and treatment when race is identified. Outwardly, I projected patience but inside, I seethed. In that moment, I realized that I would never have the luxury of ignorance or denial. Although I desire to be valued for my prowess in medicine, the mythical status was not created with my skin color in mind. For is avoidance not but a reflection of denial?

In these chaotic and uncertain times, how can we continue to promote a pathological ideal when the roads traveled are so fundamentally skewed? If a White physician faces a belligerent and argumentative patient, there is opportunity for debriefing both individually and among a larger cohort via classes, conferences, and supervisions. Conversely, when a Black physician is derided with racist sentiment, will they have the same opportunity for reflection and support? Despite identical expectations of professionalism and growth, how can one be successful in a system that either directly or indirectly encourages the opposite?

As we try to shed the super-doctor myth, we must recognize that this unattainable and detrimental persona hinders progress. This myth undermines our ability to understand our fragility, the limitations of our capabilities, and the strength of our vulnerability. We must take an honest look at the manner in which our individual biases and the deeply ingrained (and potentially unconscious) systemic biases are counterintuitive to the success and support of physicians of color.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

An overwhelmingly loud and high-pitched screech rattles against your hip. You startle and groan into the pillow as your thoughts settle into conscious awareness. It is 3 a.m. You are a 2nd-year resident trudging through the night shift, alerted to the presence of a new patient awaiting an emergency assessment. You are the only in-house physician. Walking steadfastly toward the emergency unit, you enter and greet the patient. Immediately, you observe a look of surprise followed immediately by a scowl.

You extend a hand, but your greeting is abruptly cut short with: “I want to see a doctor!” You pace your breaths to quell annoyance and resume your introduction, asserting that you are a doctor and indeed the only doctor on duty. After moments of deep sighs and questions regarding your credentials, you persuade the patient to start the interview.

It is now 8 a.m. The frustration of the night starts to ease as you prepare to leave. While gathering your things, a visitor is overheard inquiring the whereabouts of a hospital unit. Volunteering as a guide, you walk the person toward the opposite end of the hospital. Bleary eyed, muscle laxed, and bone weary, you point out the entrance, then turn to leave. The steady rhythm of your steps suddenly halts as you hear from behind: “Thank you! You speak English really well!” Blankly, you stare. Your voice remains mute while your brain screams: “What is that supposed to mean?” But you do not utter a sound, because intuitively, you know the answer.

While reading this scenario, what did you feel? Pride in knowing that the physician was able to successfully navigate a busy night? Relief in the physician’s ability to maintain a professional demeanor despite belittling microaggressions? Are you angry? Would you replay those moments like reruns of a bad TV show? Can you imagine entering your home and collapsing onto the bed as your tears of fury pool over your rumpled sheets?

The emotional release of that morning is seared into my memory. Over the years, I questioned my reactions. Was I too passive? Should I have schooled them on their ignorance? Had I done so, would I have incurred reprimands? Would standing up for myself cause years of hard work to fall away? Moreover, had I defended myself, would I forever have been viewed as “The Angry Black Woman?”

This story is more than a vignette. For me, it is another reminder that, despite how far we have come, we have much further to go. As a Black woman in a professional sphere, I stand upon the shoulders of those who sacrificed for a dream, a greater purpose. My foremothers and forefathers fought bravely and tirelessly so that we could attain levels of success that were only once but a dream. Despite this progress, a grimace, carelessly spoken words, or a mindless gesture remind me that, no matter how much I toil and what levels of success I achieve, when I meet someone for the first time or encounter someone from my past, I find myself wondering whether I am remembered for me or because I am “The Black One.”

Honest look at medicine is imperative

It is important to consider multiple facets of the super-doctor myth. We are dedicated, fearless, authoritative, ambitious individuals. We do not yield to sickness, family obligations, or fatigue. Medicine is a calling, and the patient deserves the utmost respect and professional behavior. Impervious to ethnicity, race, nationality, or creed, we are unbiased and always in service of the greater good. Often, however, I wonder how the expectations of patient-focused, patient-centered care can prevail without an honest look at the vicissitudes facing medicine.

We find ourselves amid a tumultuous year overshadowed by a devastating pandemic that skews heavily toward Black and Brown communities, in addition to political turmoil and racial reckoning that sprang forth from fear, anger, and determination ignited by the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd – communities united in outrage lamenting the cries of Black Lives Matter.

I remember the tears briskly falling upon my blouse as I watched Mr. Floyd’s life violently ripped from this Earth. Shortly thereafter, I remember the phone calls, emails, and texts from close friends, acquaintances, and colleagues offering support, listening ears, pledging to learn and endeavoring to understand the struggle for recognition and the fight for human rights. Even so, the deafening support was clouded by the preternatural silence of some medical organizations. Within the Black physician community, outrage was palpable. We reflected upon years of sacrifice and perseverance despite the challenge of bigotry, ignorance, and racism – not only from patients and their families – but also colleagues and administrators. Yet, in our time of horror and need, in those moments of vulnerability ... silence. Eventually, lengthy proclamations of support were expressed through various media. However, it felt too safe, too corporate, and too generic and inauthentic. As a result, an exodus of Black physicians from leadership positions and academic medicine took hold as the blatant continuation of rhetoric – coupled with ineffective outreach and support – finally took its toll.

Frequently, I question how the obstacles of medical school, residency, and beyond are expected to be traversed while living in a world that consistently affords additional challenges to those who look, act, or speak in a manner that varies from the perceived standard. In a culture where the myth of the super doctor reigns, how do we reconcile attainment of a false and detrimental narrative while the overarching pressure acutely felt by Black physicians magnifies in the setting of stereotypes, sociopolitical turbulence, bigotry, and racism? How can one sacrifice for an entity that is unwilling to acknowledge the psychological implications of that sacrifice?

For instance, while in medical school, I transitioned my hair to its natural state but was counseled against doing so because of the risk of losing residency opportunities as a direct result of my “unprofessional” appearance. Throughout residency, multiple incidents come to mind, including frequent demands to see my hospital badge despite the same not being of asked of my White cohorts; denial of entry into physician entrance within the residency building because, despite my professional attire, I was presumed to be a member of the custodial staff; and patients being confused and asking for a doctor despite my long white coat and clear introductions.

Furthermore, the fluency of my speech and the absence of regional dialect or vernacular are quite often lauded by patients. Inquiries to touch my hair as well as hypotheses regarding my nationality or degree of “blackness” with respect to the shape of my nose, eyes, and lips are openly questioned. Unfortunately, those uncomfortable incidents have not been limited to patient encounters.

In one instance, while presenting a patient in the presence of my attending and a 3rd-year medical student, I was sternly admonished for disclosing the race of the patient. I sat still and resolute as this doctor spoke on increased risk of bias in diagnosis and treatment when race is identified. Outwardly, I projected patience but inside, I seethed. In that moment, I realized that I would never have the luxury of ignorance or denial. Although I desire to be valued for my prowess in medicine, the mythical status was not created with my skin color in mind. For is avoidance not but a reflection of denial?

In these chaotic and uncertain times, how can we continue to promote a pathological ideal when the roads traveled are so fundamentally skewed? If a White physician faces a belligerent and argumentative patient, there is opportunity for debriefing both individually and among a larger cohort via classes, conferences, and supervisions. Conversely, when a Black physician is derided with racist sentiment, will they have the same opportunity for reflection and support? Despite identical expectations of professionalism and growth, how can one be successful in a system that either directly or indirectly encourages the opposite?

As we try to shed the super-doctor myth, we must recognize that this unattainable and detrimental persona hinders progress. This myth undermines our ability to understand our fragility, the limitations of our capabilities, and the strength of our vulnerability. We must take an honest look at the manner in which our individual biases and the deeply ingrained (and potentially unconscious) systemic biases are counterintuitive to the success and support of physicians of color.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

An overwhelmingly loud and high-pitched screech rattles against your hip. You startle and groan into the pillow as your thoughts settle into conscious awareness. It is 3 a.m. You are a 2nd-year resident trudging through the night shift, alerted to the presence of a new patient awaiting an emergency assessment. You are the only in-house physician. Walking steadfastly toward the emergency unit, you enter and greet the patient. Immediately, you observe a look of surprise followed immediately by a scowl.

You extend a hand, but your greeting is abruptly cut short with: “I want to see a doctor!” You pace your breaths to quell annoyance and resume your introduction, asserting that you are a doctor and indeed the only doctor on duty. After moments of deep sighs and questions regarding your credentials, you persuade the patient to start the interview.

It is now 8 a.m. The frustration of the night starts to ease as you prepare to leave. While gathering your things, a visitor is overheard inquiring the whereabouts of a hospital unit. Volunteering as a guide, you walk the person toward the opposite end of the hospital. Bleary eyed, muscle laxed, and bone weary, you point out the entrance, then turn to leave. The steady rhythm of your steps suddenly halts as you hear from behind: “Thank you! You speak English really well!” Blankly, you stare. Your voice remains mute while your brain screams: “What is that supposed to mean?” But you do not utter a sound, because intuitively, you know the answer.

While reading this scenario, what did you feel? Pride in knowing that the physician was able to successfully navigate a busy night? Relief in the physician’s ability to maintain a professional demeanor despite belittling microaggressions? Are you angry? Would you replay those moments like reruns of a bad TV show? Can you imagine entering your home and collapsing onto the bed as your tears of fury pool over your rumpled sheets?

The emotional release of that morning is seared into my memory. Over the years, I questioned my reactions. Was I too passive? Should I have schooled them on their ignorance? Had I done so, would I have incurred reprimands? Would standing up for myself cause years of hard work to fall away? Moreover, had I defended myself, would I forever have been viewed as “The Angry Black Woman?”

This story is more than a vignette. For me, it is another reminder that, despite how far we have come, we have much further to go. As a Black woman in a professional sphere, I stand upon the shoulders of those who sacrificed for a dream, a greater purpose. My foremothers and forefathers fought bravely and tirelessly so that we could attain levels of success that were only once but a dream. Despite this progress, a grimace, carelessly spoken words, or a mindless gesture remind me that, no matter how much I toil and what levels of success I achieve, when I meet someone for the first time or encounter someone from my past, I find myself wondering whether I am remembered for me or because I am “The Black One.”

Honest look at medicine is imperative

It is important to consider multiple facets of the super-doctor myth. We are dedicated, fearless, authoritative, ambitious individuals. We do not yield to sickness, family obligations, or fatigue. Medicine is a calling, and the patient deserves the utmost respect and professional behavior. Impervious to ethnicity, race, nationality, or creed, we are unbiased and always in service of the greater good. Often, however, I wonder how the expectations of patient-focused, patient-centered care can prevail without an honest look at the vicissitudes facing medicine.

We find ourselves amid a tumultuous year overshadowed by a devastating pandemic that skews heavily toward Black and Brown communities, in addition to political turmoil and racial reckoning that sprang forth from fear, anger, and determination ignited by the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd – communities united in outrage lamenting the cries of Black Lives Matter.

I remember the tears briskly falling upon my blouse as I watched Mr. Floyd’s life violently ripped from this Earth. Shortly thereafter, I remember the phone calls, emails, and texts from close friends, acquaintances, and colleagues offering support, listening ears, pledging to learn and endeavoring to understand the struggle for recognition and the fight for human rights. Even so, the deafening support was clouded by the preternatural silence of some medical organizations. Within the Black physician community, outrage was palpable. We reflected upon years of sacrifice and perseverance despite the challenge of bigotry, ignorance, and racism – not only from patients and their families – but also colleagues and administrators. Yet, in our time of horror and need, in those moments of vulnerability ... silence. Eventually, lengthy proclamations of support were expressed through various media. However, it felt too safe, too corporate, and too generic and inauthentic. As a result, an exodus of Black physicians from leadership positions and academic medicine took hold as the blatant continuation of rhetoric – coupled with ineffective outreach and support – finally took its toll.

Frequently, I question how the obstacles of medical school, residency, and beyond are expected to be traversed while living in a world that consistently affords additional challenges to those who look, act, or speak in a manner that varies from the perceived standard. In a culture where the myth of the super doctor reigns, how do we reconcile attainment of a false and detrimental narrative while the overarching pressure acutely felt by Black physicians magnifies in the setting of stereotypes, sociopolitical turbulence, bigotry, and racism? How can one sacrifice for an entity that is unwilling to acknowledge the psychological implications of that sacrifice?

For instance, while in medical school, I transitioned my hair to its natural state but was counseled against doing so because of the risk of losing residency opportunities as a direct result of my “unprofessional” appearance. Throughout residency, multiple incidents come to mind, including frequent demands to see my hospital badge despite the same not being of asked of my White cohorts; denial of entry into physician entrance within the residency building because, despite my professional attire, I was presumed to be a member of the custodial staff; and patients being confused and asking for a doctor despite my long white coat and clear introductions.

Furthermore, the fluency of my speech and the absence of regional dialect or vernacular are quite often lauded by patients. Inquiries to touch my hair as well as hypotheses regarding my nationality or degree of “blackness” with respect to the shape of my nose, eyes, and lips are openly questioned. Unfortunately, those uncomfortable incidents have not been limited to patient encounters.

In one instance, while presenting a patient in the presence of my attending and a 3rd-year medical student, I was sternly admonished for disclosing the race of the patient. I sat still and resolute as this doctor spoke on increased risk of bias in diagnosis and treatment when race is identified. Outwardly, I projected patience but inside, I seethed. In that moment, I realized that I would never have the luxury of ignorance or denial. Although I desire to be valued for my prowess in medicine, the mythical status was not created with my skin color in mind. For is avoidance not but a reflection of denial?

In these chaotic and uncertain times, how can we continue to promote a pathological ideal when the roads traveled are so fundamentally skewed? If a White physician faces a belligerent and argumentative patient, there is opportunity for debriefing both individually and among a larger cohort via classes, conferences, and supervisions. Conversely, when a Black physician is derided with racist sentiment, will they have the same opportunity for reflection and support? Despite identical expectations of professionalism and growth, how can one be successful in a system that either directly or indirectly encourages the opposite?

As we try to shed the super-doctor myth, we must recognize that this unattainable and detrimental persona hinders progress. This myth undermines our ability to understand our fragility, the limitations of our capabilities, and the strength of our vulnerability. We must take an honest look at the manner in which our individual biases and the deeply ingrained (and potentially unconscious) systemic biases are counterintuitive to the success and support of physicians of color.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

Obesity leads to depression via social and metabolic factors

New research provides further evidence that a high body mass index (BMI) leads to depressed mood and poor well-being via social and physical factors.

Obesity and depression are “major global health challenges; our findings suggest that reducing obesity will lower depression and improve well-being,” co–lead author Jessica O’Loughlin, PhD student, University of Exeter Medical School, United Kingdom, told this news organization.

“Doctors should consider both the biological consequences of having a higher BMI as well as the social implications when treating patients with obesity in order to help reduce the odds of them developing depression,” Ms. O’Loughlin added.

The study was published online July 16 in Human Molecular Genetics.

Large body of evidence

A large body of evidence indicates that higher BMI leads to depression.

Ms. O’Loughlin and colleagues leveraged genetic data from more than 145,000 individuals in the UK Biobank and Mendelian randomization to determine whether the causal link between high BMI and depression is the result of psychosocial pathways, physical pathways, or both.

The analysis showed that a genetically determined 1 standard deviation higher BMI (4.6 kg/m2) was associated with higher likelihood of depression (odds ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.95) and lower well-being (beta, -0.15; 95% CI, -0.26 to -0.04).

Using genetics to distinguish metabolic and psychosocial effects, the results also indicate that, even in the absence of adverse metabolic effects, “higher adiposity remains causal to depression and lowers wellbeing,” the researchers report.

“ and when using genetic variants that make you fatter but metabolically healthier (favorable adiposity genetic variants),” said Ms. O’Loughlin.

“Although we can’t tell which factor plays a bigger role in the adiposity-depression relationship, our analysis suggests that both physical and social factors (e.g., social stigma) play a role in the relationship between higher BMI and higher odds of depression,” she added.

In contrast, there was little evidence that higher BMI in the presence or absence of adverse metabolic consequences causes generalized anxiety disorder.

“Finding ways to support people to lose weight could benefit their mental health as well as their physical health,” co–lead author Francesco Casanova, PhD, with the University of Exeter, said in a statement.

Unexpected finding

Reached for comment, Samoon Ahmad, MD, professor, department of psychiatry, New York University, said that “multiple studies have shown a correlation between stress, obesity, inflammation, overall well-being, and psychiatric disorders, particularly depressive and anxiety disorders.”

He said this new study is important for three reasons.

“The first is the cohort size. There were over 145,000 participants involved in the study, which is significant and serves to make its conclusions stronger,” Dr. Ahmad noted.

“The second point is that the authors found that the correlation between higher adiposity and depression and lower well-being scores occurred even in patients without adverse metabolic effects,” he said in an interview.

“Of note, obesity significantly increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and a host of other illnesses as well as inflammatory conditions, which can all have a negative impact on quality of life. Consequently, these can contribute to depression as well as anxiety,” Dr. Ahmad added.

“Interestingly, what this study suggests is that even people without these additional stressors are reporting higher rates of depression and lower scores of well-being, while higher adiposity is the common denominator,” he noted.

“Third, the paper found little to no correlation between higher adiposity and generalized anxiety disorder. This comes as a complete surprise because anxiety and depression are very common comorbidities,” Dr. Ahmad said.

“Moreover, numerous studies as well as clinical data suggest that obesity leads to chronic inflammation, which in turn is associated with less favorable metabolic profiles, and that anxiety and depressive disorders may in some way be psychiatric manifestations of inflammation. To see one but not the other was quite an unexpected finding,” Dr. Ahmad said.

The study was funded by the Academy of Medical Sciences. Ms. O’Loughlin, Dr. Casanova, and Dr. Ahmad have disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research provides further evidence that a high body mass index (BMI) leads to depressed mood and poor well-being via social and physical factors.

Obesity and depression are “major global health challenges; our findings suggest that reducing obesity will lower depression and improve well-being,” co–lead author Jessica O’Loughlin, PhD student, University of Exeter Medical School, United Kingdom, told this news organization.

“Doctors should consider both the biological consequences of having a higher BMI as well as the social implications when treating patients with obesity in order to help reduce the odds of them developing depression,” Ms. O’Loughlin added.

The study was published online July 16 in Human Molecular Genetics.

Large body of evidence

A large body of evidence indicates that higher BMI leads to depression.

Ms. O’Loughlin and colleagues leveraged genetic data from more than 145,000 individuals in the UK Biobank and Mendelian randomization to determine whether the causal link between high BMI and depression is the result of psychosocial pathways, physical pathways, or both.

The analysis showed that a genetically determined 1 standard deviation higher BMI (4.6 kg/m2) was associated with higher likelihood of depression (odds ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.95) and lower well-being (beta, -0.15; 95% CI, -0.26 to -0.04).

Using genetics to distinguish metabolic and psychosocial effects, the results also indicate that, even in the absence of adverse metabolic effects, “higher adiposity remains causal to depression and lowers wellbeing,” the researchers report.

“ and when using genetic variants that make you fatter but metabolically healthier (favorable adiposity genetic variants),” said Ms. O’Loughlin.

“Although we can’t tell which factor plays a bigger role in the adiposity-depression relationship, our analysis suggests that both physical and social factors (e.g., social stigma) play a role in the relationship between higher BMI and higher odds of depression,” she added.

In contrast, there was little evidence that higher BMI in the presence or absence of adverse metabolic consequences causes generalized anxiety disorder.

“Finding ways to support people to lose weight could benefit their mental health as well as their physical health,” co–lead author Francesco Casanova, PhD, with the University of Exeter, said in a statement.

Unexpected finding

Reached for comment, Samoon Ahmad, MD, professor, department of psychiatry, New York University, said that “multiple studies have shown a correlation between stress, obesity, inflammation, overall well-being, and psychiatric disorders, particularly depressive and anxiety disorders.”

He said this new study is important for three reasons.

“The first is the cohort size. There were over 145,000 participants involved in the study, which is significant and serves to make its conclusions stronger,” Dr. Ahmad noted.

“The second point is that the authors found that the correlation between higher adiposity and depression and lower well-being scores occurred even in patients without adverse metabolic effects,” he said in an interview.

“Of note, obesity significantly increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and a host of other illnesses as well as inflammatory conditions, which can all have a negative impact on quality of life. Consequently, these can contribute to depression as well as anxiety,” Dr. Ahmad added.

“Interestingly, what this study suggests is that even people without these additional stressors are reporting higher rates of depression and lower scores of well-being, while higher adiposity is the common denominator,” he noted.

“Third, the paper found little to no correlation between higher adiposity and generalized anxiety disorder. This comes as a complete surprise because anxiety and depression are very common comorbidities,” Dr. Ahmad said.

“Moreover, numerous studies as well as clinical data suggest that obesity leads to chronic inflammation, which in turn is associated with less favorable metabolic profiles, and that anxiety and depressive disorders may in some way be psychiatric manifestations of inflammation. To see one but not the other was quite an unexpected finding,” Dr. Ahmad said.

The study was funded by the Academy of Medical Sciences. Ms. O’Loughlin, Dr. Casanova, and Dr. Ahmad have disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research provides further evidence that a high body mass index (BMI) leads to depressed mood and poor well-being via social and physical factors.

Obesity and depression are “major global health challenges; our findings suggest that reducing obesity will lower depression and improve well-being,” co–lead author Jessica O’Loughlin, PhD student, University of Exeter Medical School, United Kingdom, told this news organization.

“Doctors should consider both the biological consequences of having a higher BMI as well as the social implications when treating patients with obesity in order to help reduce the odds of them developing depression,” Ms. O’Loughlin added.