User login

Oral lichen planus prevalence estimates go global

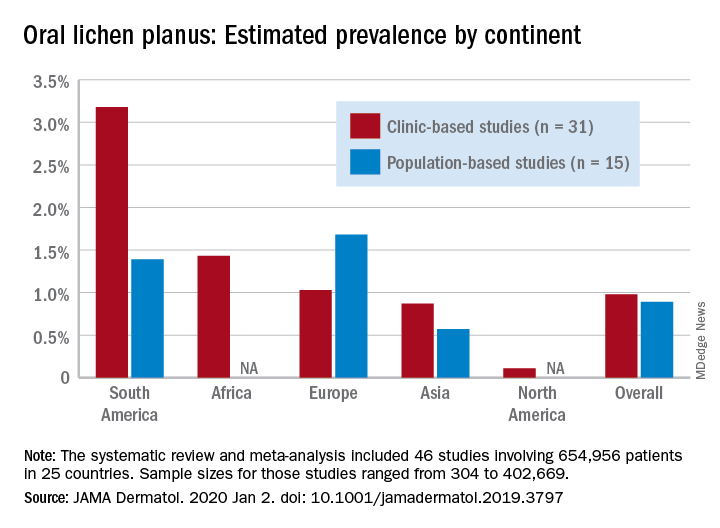

for the general population and 0.98% among clinical patients.

Globally, oral lichen planus (OLP) appears to be more prevalent in women than men (1.55% vs. 1.11% in population-based studies; 1.69% vs. 1.09% in clinic-based), in those aged 40 years and older (1.90% vs. 0.62% in clinic-based studies), and in non-Asian countries (see graph), Changchang Li, MD, and associates reported in JAMA Dermatology.

Of the 25 countries represented among the 46 included studies, Brazil had the highest OLP prevalence at 6.04% and India had the lowest at 0.02%. “Smokers and patients who abuse alcohol have a higher prevalence of OLP. This factor may explain why the highest prevalence … was found in Brazil, where 18.18% of residents report being smokers and 29.09% report consumption of alcoholic beverages,” wrote Dr. Li of the department of dermatology at Zhejiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Wenzhou, China, and associates.

The difference in OLP prevalence by sex may be related to fluctuating female hormone levels, “especially during menstruation or menopause, and that different social roles may lead to the body being in a state of stress,” the investigators suggested.

The age-related difference in OLP could be the result of “longstanding oral habits” or changes to the oral mucosa over time, such as mucosal thinning, decreased elasticity, less saliva secretion, and greater tissue permeability. The higher prevalence among those aged 40 years and older also may be “associated with metabolic changes during aging or with decreased immunity, nutritional deficiencies, medication use, or denture wear,” they wrote.

The review and meta-analysis involved 15 studies (n = 462,993) that included general population data and 31 (n = 191,963) that used information from clinical patients. Sample sizes for those studies ranged from 308 to 402,669.

Statistically significant publication bias was seen among the clinic-based studies but not those that were population based, Dr. Li and associates wrote, adding that “our findings should be considered with caution because of the high heterogeneity of the included studies.”

The study was funded by the First-Class Discipline Construction Foundation of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, the Young Top Talent Project of Scientific and Technological Innovation in Special Support Plan for Training High-level Talents, and the Youth Research and Cultivation Project of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: C Li et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3797.

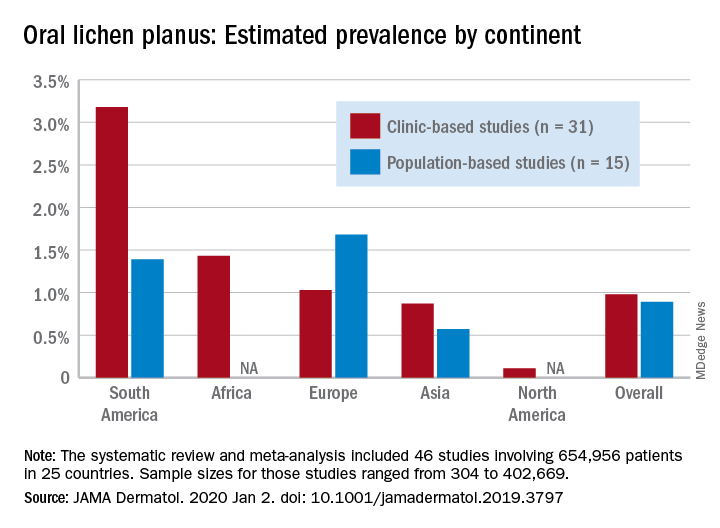

for the general population and 0.98% among clinical patients.

Globally, oral lichen planus (OLP) appears to be more prevalent in women than men (1.55% vs. 1.11% in population-based studies; 1.69% vs. 1.09% in clinic-based), in those aged 40 years and older (1.90% vs. 0.62% in clinic-based studies), and in non-Asian countries (see graph), Changchang Li, MD, and associates reported in JAMA Dermatology.

Of the 25 countries represented among the 46 included studies, Brazil had the highest OLP prevalence at 6.04% and India had the lowest at 0.02%. “Smokers and patients who abuse alcohol have a higher prevalence of OLP. This factor may explain why the highest prevalence … was found in Brazil, where 18.18% of residents report being smokers and 29.09% report consumption of alcoholic beverages,” wrote Dr. Li of the department of dermatology at Zhejiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Wenzhou, China, and associates.

The difference in OLP prevalence by sex may be related to fluctuating female hormone levels, “especially during menstruation or menopause, and that different social roles may lead to the body being in a state of stress,” the investigators suggested.

The age-related difference in OLP could be the result of “longstanding oral habits” or changes to the oral mucosa over time, such as mucosal thinning, decreased elasticity, less saliva secretion, and greater tissue permeability. The higher prevalence among those aged 40 years and older also may be “associated with metabolic changes during aging or with decreased immunity, nutritional deficiencies, medication use, or denture wear,” they wrote.

The review and meta-analysis involved 15 studies (n = 462,993) that included general population data and 31 (n = 191,963) that used information from clinical patients. Sample sizes for those studies ranged from 308 to 402,669.

Statistically significant publication bias was seen among the clinic-based studies but not those that were population based, Dr. Li and associates wrote, adding that “our findings should be considered with caution because of the high heterogeneity of the included studies.”

The study was funded by the First-Class Discipline Construction Foundation of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, the Young Top Talent Project of Scientific and Technological Innovation in Special Support Plan for Training High-level Talents, and the Youth Research and Cultivation Project of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: C Li et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3797.

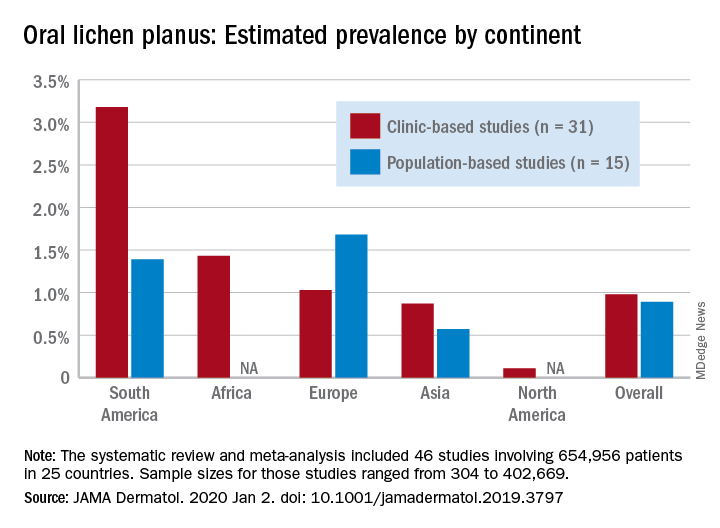

for the general population and 0.98% among clinical patients.

Globally, oral lichen planus (OLP) appears to be more prevalent in women than men (1.55% vs. 1.11% in population-based studies; 1.69% vs. 1.09% in clinic-based), in those aged 40 years and older (1.90% vs. 0.62% in clinic-based studies), and in non-Asian countries (see graph), Changchang Li, MD, and associates reported in JAMA Dermatology.

Of the 25 countries represented among the 46 included studies, Brazil had the highest OLP prevalence at 6.04% and India had the lowest at 0.02%. “Smokers and patients who abuse alcohol have a higher prevalence of OLP. This factor may explain why the highest prevalence … was found in Brazil, where 18.18% of residents report being smokers and 29.09% report consumption of alcoholic beverages,” wrote Dr. Li of the department of dermatology at Zhejiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Wenzhou, China, and associates.

The difference in OLP prevalence by sex may be related to fluctuating female hormone levels, “especially during menstruation or menopause, and that different social roles may lead to the body being in a state of stress,” the investigators suggested.

The age-related difference in OLP could be the result of “longstanding oral habits” or changes to the oral mucosa over time, such as mucosal thinning, decreased elasticity, less saliva secretion, and greater tissue permeability. The higher prevalence among those aged 40 years and older also may be “associated with metabolic changes during aging or with decreased immunity, nutritional deficiencies, medication use, or denture wear,” they wrote.

The review and meta-analysis involved 15 studies (n = 462,993) that included general population data and 31 (n = 191,963) that used information from clinical patients. Sample sizes for those studies ranged from 308 to 402,669.

Statistically significant publication bias was seen among the clinic-based studies but not those that were population based, Dr. Li and associates wrote, adding that “our findings should be considered with caution because of the high heterogeneity of the included studies.”

The study was funded by the First-Class Discipline Construction Foundation of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, the Young Top Talent Project of Scientific and Technological Innovation in Special Support Plan for Training High-level Talents, and the Youth Research and Cultivation Project of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: C Li et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3797.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Experts in Europe issue guidance on atopic dermatitis in pregnancy

MADRID – European atopic dermatitis experts have issued formal guidance on a seriously neglected topic: treatment of the disease during pregnancy, breastfeeding, and in men planning to father children.

The impetus for the project was clear: “,” Christian Vestergaard, MD, PhD, declared at a meeting of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

He presented highlights of the task force’s position paper on the topic, for which he served as first author. The group’s recommendations are based on expert opinion, since randomized clinical trial literature in this area is nonexistent because of ethical concerns. But the task force, comprising a who’s who in European dermatology, drew on a wealth of collective clinical experience in this area.

“We have all of Europe involved in doing this position statement. It’s meant as what we think is proper treatment and what we can say about the different drugs,” explained Dr. Vestergaard, a dermatologist at the University of Aarhus (Denmark).

Most nonobstetricians are intimidated by atopic dermatitis (AD) in pregnancy, and are concerned about the potential for treatment-related harm to the fetus. As a consequence, they are reluctant to recommend anything beyond weak class I topical corticosteroids and emollients. That’s clearly insufficient in light of the vast scope of need, he asserted. After all, AD affects 15%-20% of all children and persists or reappears in adulthood in one out of five of them. Half of those adults are women, many of whom will at some point wish to become pregnant. And many men with AD will eventually want to father children.

A key message from the task force is that untreated AD in pregnancy potentially places the mother and fetus at risk of serious complications, including Staphylococcus aureus infection and eczema herpeticum.

“If you take one thing away from our position paper, it’s that you can use class II or III topical corticosteroids in pregnant women as first-line therapy,” Dr. Vestergaard said.

This stance contradicts a longstanding widely held concern that topical steroids in pregnancy might increase the risk of facial cleft in the offspring, a worry that has been convincingly debunked in a Cochrane systematic review of 14 studies including more than 1.6 million pregnancies. The report concluded there was no association between topical corticosteroids of any potency with preterm delivery, birth defects, or low Apgar scores (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Oct 26. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007346.pub3).

The task force recommends that if class II or III topical corticosteroid use in pregnancy exceeds 200 g/month, it’s worth considering add-on UV therapy, with narrow band UVB-311 nm as the regimen of choice; it can be used liberally. UV therapy with psoralens is not advised because of a theoretical risk of mutagenicity.

Product labeling for the topical calcineurin inhibitors declares that the agents should not be used during pregnancy. However, the European task force position paper takes issue with that and declares that topical tacrolimus (Protopic) can be considered an off-label first-line therapy in pregnant women with an insufficient response to liberal use of emollients. The same holds true for breastfeeding patients with AD. Just as when topical corticosteroids are used in the nipple area, topical tacrolimus should be applied after nursing, and the nipple area should be gently cleaned before nursing.

The rationale behind recommending topical tacrolimus as a first-line treatment is that systemic absorption of the drug is trivial. Plus, observational studies of oral tacrolimus in pregnant women who have received a solid organ transplant have shown no increase in congenital malformations.

The task force recommends against the use of topical pimecrolimus (Elidel) or crisaborole (Eucrisa) in pregnancy or lactation due to lack of clinical experience in these settings, Dr. Vestergaard continued.

The task force position is that chlorhexidine and other topical antiseptics – with the notable exception of triclosan – can be used in pregnancy to prevent recurrent skin infections. Aminoglycosides should be avoided, but topical fusidic acid is a reasonable antibiotic for treatment of small areas of clinically infected atopic dermatitis in pregnancy.

Systemic therapies

If disease control is insufficient with topical therapy, it’s appropriate to engage in shared decision-making with the patient regarding systemic treatment. She needs to understand up front that the worldwide overall background stillbirth rate in the general population is about 3%, and that severe congenital malformations are present in up to 6% of all live births.

“You need to inform them that they can have systemic therapy and give birth to a child with congenital defects which have nothing to do with the medication,” noted Dr. Vestergaard.

That said, the task force recommends cyclosporine as the off-label, first-line systemic therapy in pregnancy and lactation when long-term treatment is required. This guidance is based largely upon reassuring evidence in solid organ transplant recipients.

The recommended second-line therapy is systemic corticosteroids, but it’s a qualified recommendation. Dr. Vestergaard and colleagues find that systemic corticosteroid therapy is only rarely needed in pregnant AD patients, and the task force recommendation is to limit the use to less than 2-3 weeks and no more than 0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone. Dexamethasone is not recommended.

Azathioprine should not be started in pregnancy, according to the task force, but when no other options are available, it may be continued in women already on the drug, albeit at half of the prepregnancy dose.

Dupilumab (Dupixent) is to be avoided in pregnant women with AD until more clinical experience becomes available.

Treatment of prospective fathers with AD

The European task force recommends that topical therapies can be prescribed in prospective fathers without any special concerns. The same is true for systemic corticosteroids. Methotrexate should be halted 3 months before planned pregnancy, as is the case for mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept). Azathioprine is recommended when other options have failed. Cyclosporine is deemed a reasonable option in the treatment of men with severe AD at the time of conception if other treatments have failed; of note, neither the Food and Drug Administration nor the European regulatory agency have issued contraindications for the use of the drug in men who wish to become fathers.

Mycophenolate mofetil carries a theoretical risk of teratogenicity. The European task force recommends that men should use condoms while on the drug and for at least 90 days afterward.

Unplanned pregnancy in women on systemic therapy

The recommended course of action is to immediately stop systemic therapy, intensify appropriate topical therapy in anticipation of worsening AD, and refer the patient to an obstetrician and a teratology information center for an individualized risk assessment. Methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil are known teratogens.

The full 16-page task force position paper was published shortly before EADV 2019 (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Sep;33[9]:1644-59).

The report was developed without commercial sponsorship. Dr. Vestergaard indicated he has received research grants from and/or serves as a consultant to eight pharmaceutical companies.

Jenny Murase, MD, is with the department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, and is the director of medical consultative dermatology at the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group, Mountain View, Calif. She has served on advisory boards for Dermira, Sanofi, and UCB; performed dermatologic consulting for UpToDate and Ferndale, and given nonbranded lectures for disease state management awareness for Regeneron and UCB.

Jenny Murase, MD, is with the department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, and is the director of medical consultative dermatology at the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group, Mountain View, Calif. She has served on advisory boards for Dermira, Sanofi, and UCB; performed dermatologic consulting for UpToDate and Ferndale, and given nonbranded lectures for disease state management awareness for Regeneron and UCB.

Jenny Murase, MD, is with the department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, and is the director of medical consultative dermatology at the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group, Mountain View, Calif. She has served on advisory boards for Dermira, Sanofi, and UCB; performed dermatologic consulting for UpToDate and Ferndale, and given nonbranded lectures for disease state management awareness for Regeneron and UCB.

MADRID – European atopic dermatitis experts have issued formal guidance on a seriously neglected topic: treatment of the disease during pregnancy, breastfeeding, and in men planning to father children.

The impetus for the project was clear: “,” Christian Vestergaard, MD, PhD, declared at a meeting of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

He presented highlights of the task force’s position paper on the topic, for which he served as first author. The group’s recommendations are based on expert opinion, since randomized clinical trial literature in this area is nonexistent because of ethical concerns. But the task force, comprising a who’s who in European dermatology, drew on a wealth of collective clinical experience in this area.

“We have all of Europe involved in doing this position statement. It’s meant as what we think is proper treatment and what we can say about the different drugs,” explained Dr. Vestergaard, a dermatologist at the University of Aarhus (Denmark).

Most nonobstetricians are intimidated by atopic dermatitis (AD) in pregnancy, and are concerned about the potential for treatment-related harm to the fetus. As a consequence, they are reluctant to recommend anything beyond weak class I topical corticosteroids and emollients. That’s clearly insufficient in light of the vast scope of need, he asserted. After all, AD affects 15%-20% of all children and persists or reappears in adulthood in one out of five of them. Half of those adults are women, many of whom will at some point wish to become pregnant. And many men with AD will eventually want to father children.

A key message from the task force is that untreated AD in pregnancy potentially places the mother and fetus at risk of serious complications, including Staphylococcus aureus infection and eczema herpeticum.

“If you take one thing away from our position paper, it’s that you can use class II or III topical corticosteroids in pregnant women as first-line therapy,” Dr. Vestergaard said.

This stance contradicts a longstanding widely held concern that topical steroids in pregnancy might increase the risk of facial cleft in the offspring, a worry that has been convincingly debunked in a Cochrane systematic review of 14 studies including more than 1.6 million pregnancies. The report concluded there was no association between topical corticosteroids of any potency with preterm delivery, birth defects, or low Apgar scores (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Oct 26. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007346.pub3).

The task force recommends that if class II or III topical corticosteroid use in pregnancy exceeds 200 g/month, it’s worth considering add-on UV therapy, with narrow band UVB-311 nm as the regimen of choice; it can be used liberally. UV therapy with psoralens is not advised because of a theoretical risk of mutagenicity.

Product labeling for the topical calcineurin inhibitors declares that the agents should not be used during pregnancy. However, the European task force position paper takes issue with that and declares that topical tacrolimus (Protopic) can be considered an off-label first-line therapy in pregnant women with an insufficient response to liberal use of emollients. The same holds true for breastfeeding patients with AD. Just as when topical corticosteroids are used in the nipple area, topical tacrolimus should be applied after nursing, and the nipple area should be gently cleaned before nursing.

The rationale behind recommending topical tacrolimus as a first-line treatment is that systemic absorption of the drug is trivial. Plus, observational studies of oral tacrolimus in pregnant women who have received a solid organ transplant have shown no increase in congenital malformations.

The task force recommends against the use of topical pimecrolimus (Elidel) or crisaborole (Eucrisa) in pregnancy or lactation due to lack of clinical experience in these settings, Dr. Vestergaard continued.

The task force position is that chlorhexidine and other topical antiseptics – with the notable exception of triclosan – can be used in pregnancy to prevent recurrent skin infections. Aminoglycosides should be avoided, but topical fusidic acid is a reasonable antibiotic for treatment of small areas of clinically infected atopic dermatitis in pregnancy.

Systemic therapies

If disease control is insufficient with topical therapy, it’s appropriate to engage in shared decision-making with the patient regarding systemic treatment. She needs to understand up front that the worldwide overall background stillbirth rate in the general population is about 3%, and that severe congenital malformations are present in up to 6% of all live births.

“You need to inform them that they can have systemic therapy and give birth to a child with congenital defects which have nothing to do with the medication,” noted Dr. Vestergaard.

That said, the task force recommends cyclosporine as the off-label, first-line systemic therapy in pregnancy and lactation when long-term treatment is required. This guidance is based largely upon reassuring evidence in solid organ transplant recipients.

The recommended second-line therapy is systemic corticosteroids, but it’s a qualified recommendation. Dr. Vestergaard and colleagues find that systemic corticosteroid therapy is only rarely needed in pregnant AD patients, and the task force recommendation is to limit the use to less than 2-3 weeks and no more than 0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone. Dexamethasone is not recommended.

Azathioprine should not be started in pregnancy, according to the task force, but when no other options are available, it may be continued in women already on the drug, albeit at half of the prepregnancy dose.

Dupilumab (Dupixent) is to be avoided in pregnant women with AD until more clinical experience becomes available.

Treatment of prospective fathers with AD

The European task force recommends that topical therapies can be prescribed in prospective fathers without any special concerns. The same is true for systemic corticosteroids. Methotrexate should be halted 3 months before planned pregnancy, as is the case for mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept). Azathioprine is recommended when other options have failed. Cyclosporine is deemed a reasonable option in the treatment of men with severe AD at the time of conception if other treatments have failed; of note, neither the Food and Drug Administration nor the European regulatory agency have issued contraindications for the use of the drug in men who wish to become fathers.

Mycophenolate mofetil carries a theoretical risk of teratogenicity. The European task force recommends that men should use condoms while on the drug and for at least 90 days afterward.

Unplanned pregnancy in women on systemic therapy

The recommended course of action is to immediately stop systemic therapy, intensify appropriate topical therapy in anticipation of worsening AD, and refer the patient to an obstetrician and a teratology information center for an individualized risk assessment. Methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil are known teratogens.

The full 16-page task force position paper was published shortly before EADV 2019 (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Sep;33[9]:1644-59).

The report was developed without commercial sponsorship. Dr. Vestergaard indicated he has received research grants from and/or serves as a consultant to eight pharmaceutical companies.

MADRID – European atopic dermatitis experts have issued formal guidance on a seriously neglected topic: treatment of the disease during pregnancy, breastfeeding, and in men planning to father children.

The impetus for the project was clear: “,” Christian Vestergaard, MD, PhD, declared at a meeting of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

He presented highlights of the task force’s position paper on the topic, for which he served as first author. The group’s recommendations are based on expert opinion, since randomized clinical trial literature in this area is nonexistent because of ethical concerns. But the task force, comprising a who’s who in European dermatology, drew on a wealth of collective clinical experience in this area.

“We have all of Europe involved in doing this position statement. It’s meant as what we think is proper treatment and what we can say about the different drugs,” explained Dr. Vestergaard, a dermatologist at the University of Aarhus (Denmark).

Most nonobstetricians are intimidated by atopic dermatitis (AD) in pregnancy, and are concerned about the potential for treatment-related harm to the fetus. As a consequence, they are reluctant to recommend anything beyond weak class I topical corticosteroids and emollients. That’s clearly insufficient in light of the vast scope of need, he asserted. After all, AD affects 15%-20% of all children and persists or reappears in adulthood in one out of five of them. Half of those adults are women, many of whom will at some point wish to become pregnant. And many men with AD will eventually want to father children.

A key message from the task force is that untreated AD in pregnancy potentially places the mother and fetus at risk of serious complications, including Staphylococcus aureus infection and eczema herpeticum.

“If you take one thing away from our position paper, it’s that you can use class II or III topical corticosteroids in pregnant women as first-line therapy,” Dr. Vestergaard said.

This stance contradicts a longstanding widely held concern that topical steroids in pregnancy might increase the risk of facial cleft in the offspring, a worry that has been convincingly debunked in a Cochrane systematic review of 14 studies including more than 1.6 million pregnancies. The report concluded there was no association between topical corticosteroids of any potency with preterm delivery, birth defects, or low Apgar scores (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Oct 26. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007346.pub3).

The task force recommends that if class II or III topical corticosteroid use in pregnancy exceeds 200 g/month, it’s worth considering add-on UV therapy, with narrow band UVB-311 nm as the regimen of choice; it can be used liberally. UV therapy with psoralens is not advised because of a theoretical risk of mutagenicity.

Product labeling for the topical calcineurin inhibitors declares that the agents should not be used during pregnancy. However, the European task force position paper takes issue with that and declares that topical tacrolimus (Protopic) can be considered an off-label first-line therapy in pregnant women with an insufficient response to liberal use of emollients. The same holds true for breastfeeding patients with AD. Just as when topical corticosteroids are used in the nipple area, topical tacrolimus should be applied after nursing, and the nipple area should be gently cleaned before nursing.

The rationale behind recommending topical tacrolimus as a first-line treatment is that systemic absorption of the drug is trivial. Plus, observational studies of oral tacrolimus in pregnant women who have received a solid organ transplant have shown no increase in congenital malformations.

The task force recommends against the use of topical pimecrolimus (Elidel) or crisaborole (Eucrisa) in pregnancy or lactation due to lack of clinical experience in these settings, Dr. Vestergaard continued.

The task force position is that chlorhexidine and other topical antiseptics – with the notable exception of triclosan – can be used in pregnancy to prevent recurrent skin infections. Aminoglycosides should be avoided, but topical fusidic acid is a reasonable antibiotic for treatment of small areas of clinically infected atopic dermatitis in pregnancy.

Systemic therapies

If disease control is insufficient with topical therapy, it’s appropriate to engage in shared decision-making with the patient regarding systemic treatment. She needs to understand up front that the worldwide overall background stillbirth rate in the general population is about 3%, and that severe congenital malformations are present in up to 6% of all live births.

“You need to inform them that they can have systemic therapy and give birth to a child with congenital defects which have nothing to do with the medication,” noted Dr. Vestergaard.

That said, the task force recommends cyclosporine as the off-label, first-line systemic therapy in pregnancy and lactation when long-term treatment is required. This guidance is based largely upon reassuring evidence in solid organ transplant recipients.

The recommended second-line therapy is systemic corticosteroids, but it’s a qualified recommendation. Dr. Vestergaard and colleagues find that systemic corticosteroid therapy is only rarely needed in pregnant AD patients, and the task force recommendation is to limit the use to less than 2-3 weeks and no more than 0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone. Dexamethasone is not recommended.

Azathioprine should not be started in pregnancy, according to the task force, but when no other options are available, it may be continued in women already on the drug, albeit at half of the prepregnancy dose.

Dupilumab (Dupixent) is to be avoided in pregnant women with AD until more clinical experience becomes available.

Treatment of prospective fathers with AD

The European task force recommends that topical therapies can be prescribed in prospective fathers without any special concerns. The same is true for systemic corticosteroids. Methotrexate should be halted 3 months before planned pregnancy, as is the case for mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept). Azathioprine is recommended when other options have failed. Cyclosporine is deemed a reasonable option in the treatment of men with severe AD at the time of conception if other treatments have failed; of note, neither the Food and Drug Administration nor the European regulatory agency have issued contraindications for the use of the drug in men who wish to become fathers.

Mycophenolate mofetil carries a theoretical risk of teratogenicity. The European task force recommends that men should use condoms while on the drug and for at least 90 days afterward.

Unplanned pregnancy in women on systemic therapy

The recommended course of action is to immediately stop systemic therapy, intensify appropriate topical therapy in anticipation of worsening AD, and refer the patient to an obstetrician and a teratology information center for an individualized risk assessment. Methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil are known teratogens.

The full 16-page task force position paper was published shortly before EADV 2019 (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Sep;33[9]:1644-59).

The report was developed without commercial sponsorship. Dr. Vestergaard indicated he has received research grants from and/or serves as a consultant to eight pharmaceutical companies.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Papules on hands and soles

Although these lesions were consistent with actinic keratosis, the location on the palms and the patient’s history of growing up on a ranch in northern Mexico (where he said he was exposed to high arsenic levels in the water and soil), suggested that this was a case of arsenical keratosis. A biopsy excluded frank squamous cell carcinoma; further testing was not needed to make the diagnosis.

While both actinic and arsenical keratoses are precancerous growths with delayed presentations of 20 to 30 years, arsenical keratoses do not typically appear in sun-exposed areas. Rather, these lesions appear on a patient’s palms or soles. They also may present as plate-like hyperpigmentation of the palms and soles or corn-like keratotic papules.

Arsenic occurs naturally in soil and groundwater worldwide and acts as a toxin and carcinogen. It accumulates in the skin, hair, nails, and teeth—making these sites markers of chronic disease. Chronic exposure leads to skin and lung cancer. Cancer of other organs also is possible. Peripheral neuropathy and pancytopenia are hallmarks of chronic exposure.

If arsenical keratosis is suspected, testing for arsenic levels in water or in the work environment is recommended. That said, arsenic exposure is often remote (given the time that has elapsed) and hard to prove.

A blood count and renal and liver function tests should be considered to assess for organ damage. In this case, these tests were normal and the patient was treated with cryotherapy and monitored for recurrence with annual skin exams. Oral retinoids, such as acitretin, have had success in suppressing the frequency and severity of episodes of new lesions in small case reports.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

US Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Arsenic Toxicity. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=1&po=0. Updated January 15, 2010. Accessed January 2, 2020.

Although these lesions were consistent with actinic keratosis, the location on the palms and the patient’s history of growing up on a ranch in northern Mexico (where he said he was exposed to high arsenic levels in the water and soil), suggested that this was a case of arsenical keratosis. A biopsy excluded frank squamous cell carcinoma; further testing was not needed to make the diagnosis.

While both actinic and arsenical keratoses are precancerous growths with delayed presentations of 20 to 30 years, arsenical keratoses do not typically appear in sun-exposed areas. Rather, these lesions appear on a patient’s palms or soles. They also may present as plate-like hyperpigmentation of the palms and soles or corn-like keratotic papules.

Arsenic occurs naturally in soil and groundwater worldwide and acts as a toxin and carcinogen. It accumulates in the skin, hair, nails, and teeth—making these sites markers of chronic disease. Chronic exposure leads to skin and lung cancer. Cancer of other organs also is possible. Peripheral neuropathy and pancytopenia are hallmarks of chronic exposure.

If arsenical keratosis is suspected, testing for arsenic levels in water or in the work environment is recommended. That said, arsenic exposure is often remote (given the time that has elapsed) and hard to prove.

A blood count and renal and liver function tests should be considered to assess for organ damage. In this case, these tests were normal and the patient was treated with cryotherapy and monitored for recurrence with annual skin exams. Oral retinoids, such as acitretin, have had success in suppressing the frequency and severity of episodes of new lesions in small case reports.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Although these lesions were consistent with actinic keratosis, the location on the palms and the patient’s history of growing up on a ranch in northern Mexico (where he said he was exposed to high arsenic levels in the water and soil), suggested that this was a case of arsenical keratosis. A biopsy excluded frank squamous cell carcinoma; further testing was not needed to make the diagnosis.

While both actinic and arsenical keratoses are precancerous growths with delayed presentations of 20 to 30 years, arsenical keratoses do not typically appear in sun-exposed areas. Rather, these lesions appear on a patient’s palms or soles. They also may present as plate-like hyperpigmentation of the palms and soles or corn-like keratotic papules.

Arsenic occurs naturally in soil and groundwater worldwide and acts as a toxin and carcinogen. It accumulates in the skin, hair, nails, and teeth—making these sites markers of chronic disease. Chronic exposure leads to skin and lung cancer. Cancer of other organs also is possible. Peripheral neuropathy and pancytopenia are hallmarks of chronic exposure.

If arsenical keratosis is suspected, testing for arsenic levels in water or in the work environment is recommended. That said, arsenic exposure is often remote (given the time that has elapsed) and hard to prove.

A blood count and renal and liver function tests should be considered to assess for organ damage. In this case, these tests were normal and the patient was treated with cryotherapy and monitored for recurrence with annual skin exams. Oral retinoids, such as acitretin, have had success in suppressing the frequency and severity of episodes of new lesions in small case reports.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

US Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Arsenic Toxicity. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=1&po=0. Updated January 15, 2010. Accessed January 2, 2020.

US Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Arsenic Toxicity. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=1&po=0. Updated January 15, 2010. Accessed January 2, 2020.

Dupilumab-induced head and neck erythema described in atopic dermatitis patients

MADRID – A growing recognition that from their background skin disease emerged as a hot topic of discussion at a meeting of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“During treatment with dupilumab, we saw something that is really different from the classic eczema that patients experienced prior to dupilumab, with no or minimal scaling, itch, or burning sensation. We do not believe this is a delayed effect of dupilumab on that specific region. We think this is a dupilumab-induced entity that we’re looking at. You should take home, in my opinion, that this is a common side effect that’s underreported in daily practice at this moment, and it’s not reported in clinical trials at all,” said Linde de Wijs, MD, of the department of dermatology, Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

She presented a detailed case series of seven affected patients which included histologic examination of lesional skin biopsies. The biopsies were characterized by a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, an increase in ectatic capillaries in the papillary dermis, and a notable dearth of spongiosis, eosinophils, and neutrophils. Four patients had bulbous elongated rete ridges evocative of a psoriasiform dermatitis. The overall histologic picture was suggestive of a drug-induced skin reaction.

A striking finding was that, even though AD patients typically place high importance on achieving total clearing of disease on the head and neck, these seven closely studied patients nonetheless rated their treatment satisfaction as 9 out of a possible 10 points. Dr. de Wijs interpreted this as testimony to dupilumab’s potent efficacy and comparatively acceptable safety profile, especially the apparent side effect’s absence of scaling and itch.

“Remember, these are patients with really severe atopic dermatitis who’ve been treated with a lot of immunosuppressants prior to dupilumab,” she said.

Once the investigators began to suspect the existence of a novel dupilumab-induced skin reaction, they conducted a retrospective chart review of more than 150 patients treated with dupilumab (Dupixent) and determined that roughly 30% had developed this distinctive sharply demarcated patchy erythema on the head and neck characterized by absence of itch. The sequence involved clearance of the AD in response to dupilumab, followed by gradual development of the head and neck erythema 10-39 weeks after the start of treatment.

The erythema proved treatment refractory. Dr. de Wijs and her colleagues tried topical corticosteroids, including potent ones, as well as topical tacrolimus, antifungals, antibiotics, emollients, oral steroids, and antihistamines, to no avail. Patch testing to investigate allergic contact dermatitis as a possible etiology was unremarkable.

She hypothesized that, since dupilumab blocks the key signaling pathways for Th2 T-cell differentiation by targeting the interleukin-4 receptor alpha, it’s possible that the biologic promotes a shift towards activation of the Th17 pathway, which might explain the observed histologic findings.

The fact that this erythema wasn’t reported in the major randomized clinical trials of dupilumab underscores the enormous value of clinical practice registries, she said.

“We are not the only ones observing this phenomenon,” noted Dr. de Wijs, citing recently published reports by other investigators (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82[1]:230-2; JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Jul 1;155[7]:850-2).

Indeed, her talk was immediately followed by a presentation by Sebastien Barbarot, MD, PhD, who reported on a French national retrospective study of head and neck dermatitis arising in patients on dupilumab that was conducted by the French Atopic Dermatitis Network using the organization’s GREAT database. Among 1,000 adult patients with AD treated with the biologic at 29 French centers, 10 developed a de novo head and neck dermatitis, and 32 others experienced more than 50% worsening of eczema signs on the head and neck from baseline beginning about 2 months after starting on dupilumab.

This 4.2% incidence is probably an underestimate, since dermatologists weren’t aware of the phenomenon and didn’t specifically ask patients about it, observed Dr. Barbarot, a dermatologist at the University of Nantes (France).

Among the key findings: No differences in clinical characteristics were found between the de novo and exacerbation groups, nearly half of affected patients had concomitant conjunctivitis, and seven patients discontinued dupilumab because of an intolerable burning sensation on the head/neck.

“I think this condition is quite different from rosacea,” Dr. Barbarot emphasized.

French dermatologists generally turned to topical corticosteroids or topical tacrolimus to treat the face and neck dermatitis, with mixed results; 22 of the 42 patients showed improvement and 8 worsened.

Marjolein de Bruin-Weller, MD, PhD, a dermatologist at Utrecht (the Netherlands) University and head of the Dutch National Eczema Expertise Center, said she and her colleagues have also encountered this dupilumab-related head and neck erythema and are convinced that a subset of affected patients have Malassezia-induced dermatitis with neutrophils present on lesional biopsies. “It responds very well to treatment. I think it’s very important to try itraconazole because sometimes it works,” she said.

Dr. de Wijs replied that she and her coworkers tried 2 weeks of itraconazole in several patients, with no effect. And none of their seven biopsied patients had an increase in neutrophils.

“It might be a very heterogenous polyform entity that we’re now observing,” she commented. Dr. de Bruin-Weller concurred.

Dr. Barbarot said he’d be interested in a formal study of antifungal therapy in patients with dupilumab-related head and neck dermatitis. Mechanistically, it seems plausible that dupilumab-induced activation of the TH17 pathway might lead to proliferation of Malassezia fungus.

Dr. de Wijs and Dr. Barbarot reported having no financial conflicts regarding their respective studies, which were conducted free of commercial sponsorship.

MADRID – A growing recognition that from their background skin disease emerged as a hot topic of discussion at a meeting of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“During treatment with dupilumab, we saw something that is really different from the classic eczema that patients experienced prior to dupilumab, with no or minimal scaling, itch, or burning sensation. We do not believe this is a delayed effect of dupilumab on that specific region. We think this is a dupilumab-induced entity that we’re looking at. You should take home, in my opinion, that this is a common side effect that’s underreported in daily practice at this moment, and it’s not reported in clinical trials at all,” said Linde de Wijs, MD, of the department of dermatology, Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

She presented a detailed case series of seven affected patients which included histologic examination of lesional skin biopsies. The biopsies were characterized by a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, an increase in ectatic capillaries in the papillary dermis, and a notable dearth of spongiosis, eosinophils, and neutrophils. Four patients had bulbous elongated rete ridges evocative of a psoriasiform dermatitis. The overall histologic picture was suggestive of a drug-induced skin reaction.

A striking finding was that, even though AD patients typically place high importance on achieving total clearing of disease on the head and neck, these seven closely studied patients nonetheless rated their treatment satisfaction as 9 out of a possible 10 points. Dr. de Wijs interpreted this as testimony to dupilumab’s potent efficacy and comparatively acceptable safety profile, especially the apparent side effect’s absence of scaling and itch.

“Remember, these are patients with really severe atopic dermatitis who’ve been treated with a lot of immunosuppressants prior to dupilumab,” she said.

Once the investigators began to suspect the existence of a novel dupilumab-induced skin reaction, they conducted a retrospective chart review of more than 150 patients treated with dupilumab (Dupixent) and determined that roughly 30% had developed this distinctive sharply demarcated patchy erythema on the head and neck characterized by absence of itch. The sequence involved clearance of the AD in response to dupilumab, followed by gradual development of the head and neck erythema 10-39 weeks after the start of treatment.

The erythema proved treatment refractory. Dr. de Wijs and her colleagues tried topical corticosteroids, including potent ones, as well as topical tacrolimus, antifungals, antibiotics, emollients, oral steroids, and antihistamines, to no avail. Patch testing to investigate allergic contact dermatitis as a possible etiology was unremarkable.

She hypothesized that, since dupilumab blocks the key signaling pathways for Th2 T-cell differentiation by targeting the interleukin-4 receptor alpha, it’s possible that the biologic promotes a shift towards activation of the Th17 pathway, which might explain the observed histologic findings.

The fact that this erythema wasn’t reported in the major randomized clinical trials of dupilumab underscores the enormous value of clinical practice registries, she said.

“We are not the only ones observing this phenomenon,” noted Dr. de Wijs, citing recently published reports by other investigators (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82[1]:230-2; JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Jul 1;155[7]:850-2).

Indeed, her talk was immediately followed by a presentation by Sebastien Barbarot, MD, PhD, who reported on a French national retrospective study of head and neck dermatitis arising in patients on dupilumab that was conducted by the French Atopic Dermatitis Network using the organization’s GREAT database. Among 1,000 adult patients with AD treated with the biologic at 29 French centers, 10 developed a de novo head and neck dermatitis, and 32 others experienced more than 50% worsening of eczema signs on the head and neck from baseline beginning about 2 months after starting on dupilumab.

This 4.2% incidence is probably an underestimate, since dermatologists weren’t aware of the phenomenon and didn’t specifically ask patients about it, observed Dr. Barbarot, a dermatologist at the University of Nantes (France).

Among the key findings: No differences in clinical characteristics were found between the de novo and exacerbation groups, nearly half of affected patients had concomitant conjunctivitis, and seven patients discontinued dupilumab because of an intolerable burning sensation on the head/neck.

“I think this condition is quite different from rosacea,” Dr. Barbarot emphasized.

French dermatologists generally turned to topical corticosteroids or topical tacrolimus to treat the face and neck dermatitis, with mixed results; 22 of the 42 patients showed improvement and 8 worsened.

Marjolein de Bruin-Weller, MD, PhD, a dermatologist at Utrecht (the Netherlands) University and head of the Dutch National Eczema Expertise Center, said she and her colleagues have also encountered this dupilumab-related head and neck erythema and are convinced that a subset of affected patients have Malassezia-induced dermatitis with neutrophils present on lesional biopsies. “It responds very well to treatment. I think it’s very important to try itraconazole because sometimes it works,” she said.

Dr. de Wijs replied that she and her coworkers tried 2 weeks of itraconazole in several patients, with no effect. And none of their seven biopsied patients had an increase in neutrophils.

“It might be a very heterogenous polyform entity that we’re now observing,” she commented. Dr. de Bruin-Weller concurred.

Dr. Barbarot said he’d be interested in a formal study of antifungal therapy in patients with dupilumab-related head and neck dermatitis. Mechanistically, it seems plausible that dupilumab-induced activation of the TH17 pathway might lead to proliferation of Malassezia fungus.

Dr. de Wijs and Dr. Barbarot reported having no financial conflicts regarding their respective studies, which were conducted free of commercial sponsorship.

MADRID – A growing recognition that from their background skin disease emerged as a hot topic of discussion at a meeting of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“During treatment with dupilumab, we saw something that is really different from the classic eczema that patients experienced prior to dupilumab, with no or minimal scaling, itch, or burning sensation. We do not believe this is a delayed effect of dupilumab on that specific region. We think this is a dupilumab-induced entity that we’re looking at. You should take home, in my opinion, that this is a common side effect that’s underreported in daily practice at this moment, and it’s not reported in clinical trials at all,” said Linde de Wijs, MD, of the department of dermatology, Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

She presented a detailed case series of seven affected patients which included histologic examination of lesional skin biopsies. The biopsies were characterized by a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, an increase in ectatic capillaries in the papillary dermis, and a notable dearth of spongiosis, eosinophils, and neutrophils. Four patients had bulbous elongated rete ridges evocative of a psoriasiform dermatitis. The overall histologic picture was suggestive of a drug-induced skin reaction.

A striking finding was that, even though AD patients typically place high importance on achieving total clearing of disease on the head and neck, these seven closely studied patients nonetheless rated their treatment satisfaction as 9 out of a possible 10 points. Dr. de Wijs interpreted this as testimony to dupilumab’s potent efficacy and comparatively acceptable safety profile, especially the apparent side effect’s absence of scaling and itch.

“Remember, these are patients with really severe atopic dermatitis who’ve been treated with a lot of immunosuppressants prior to dupilumab,” she said.

Once the investigators began to suspect the existence of a novel dupilumab-induced skin reaction, they conducted a retrospective chart review of more than 150 patients treated with dupilumab (Dupixent) and determined that roughly 30% had developed this distinctive sharply demarcated patchy erythema on the head and neck characterized by absence of itch. The sequence involved clearance of the AD in response to dupilumab, followed by gradual development of the head and neck erythema 10-39 weeks after the start of treatment.

The erythema proved treatment refractory. Dr. de Wijs and her colleagues tried topical corticosteroids, including potent ones, as well as topical tacrolimus, antifungals, antibiotics, emollients, oral steroids, and antihistamines, to no avail. Patch testing to investigate allergic contact dermatitis as a possible etiology was unremarkable.

She hypothesized that, since dupilumab blocks the key signaling pathways for Th2 T-cell differentiation by targeting the interleukin-4 receptor alpha, it’s possible that the biologic promotes a shift towards activation of the Th17 pathway, which might explain the observed histologic findings.

The fact that this erythema wasn’t reported in the major randomized clinical trials of dupilumab underscores the enormous value of clinical practice registries, she said.

“We are not the only ones observing this phenomenon,” noted Dr. de Wijs, citing recently published reports by other investigators (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82[1]:230-2; JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Jul 1;155[7]:850-2).

Indeed, her talk was immediately followed by a presentation by Sebastien Barbarot, MD, PhD, who reported on a French national retrospective study of head and neck dermatitis arising in patients on dupilumab that was conducted by the French Atopic Dermatitis Network using the organization’s GREAT database. Among 1,000 adult patients with AD treated with the biologic at 29 French centers, 10 developed a de novo head and neck dermatitis, and 32 others experienced more than 50% worsening of eczema signs on the head and neck from baseline beginning about 2 months after starting on dupilumab.

This 4.2% incidence is probably an underestimate, since dermatologists weren’t aware of the phenomenon and didn’t specifically ask patients about it, observed Dr. Barbarot, a dermatologist at the University of Nantes (France).

Among the key findings: No differences in clinical characteristics were found between the de novo and exacerbation groups, nearly half of affected patients had concomitant conjunctivitis, and seven patients discontinued dupilumab because of an intolerable burning sensation on the head/neck.

“I think this condition is quite different from rosacea,” Dr. Barbarot emphasized.

French dermatologists generally turned to topical corticosteroids or topical tacrolimus to treat the face and neck dermatitis, with mixed results; 22 of the 42 patients showed improvement and 8 worsened.

Marjolein de Bruin-Weller, MD, PhD, a dermatologist at Utrecht (the Netherlands) University and head of the Dutch National Eczema Expertise Center, said she and her colleagues have also encountered this dupilumab-related head and neck erythema and are convinced that a subset of affected patients have Malassezia-induced dermatitis with neutrophils present on lesional biopsies. “It responds very well to treatment. I think it’s very important to try itraconazole because sometimes it works,” she said.

Dr. de Wijs replied that she and her coworkers tried 2 weeks of itraconazole in several patients, with no effect. And none of their seven biopsied patients had an increase in neutrophils.

“It might be a very heterogenous polyform entity that we’re now observing,” she commented. Dr. de Bruin-Weller concurred.

Dr. Barbarot said he’d be interested in a formal study of antifungal therapy in patients with dupilumab-related head and neck dermatitis. Mechanistically, it seems plausible that dupilumab-induced activation of the TH17 pathway might lead to proliferation of Malassezia fungus.

Dr. de Wijs and Dr. Barbarot reported having no financial conflicts regarding their respective studies, which were conducted free of commercial sponsorship.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Efficacy and safety of lowering dupilumab frequency for AD

Patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis who responded well to the approved dupilumab regimen of 300 mg every 2 weeks in pivotal phase 3 monotherapy trials were more likely to have a continued response over the longer term if they maintained this regimen rather than switching to longer dosing intervals or discontinuing the medication.

This finding comes from a 36-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that enrolled 422 – SOLO 1 and SOLO 2.

The new international study – SOLO-CONTINUE – randomized these patients to continue the original regimen (weekly or every 2 weeks), to receive 300 mg of the biologic medication every 4 or 8 weeks, or to receive placebo.

Patients who continued the original regimen had the most consistent maintenance of treatment effect, while patients on longer dosage intervals or placebo had a dose-dependent reduction in response and no safety advantage. The incidence of treatment-emergent antidrug antibody was lowest with dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks, and slightly higher with less-frequent dosing intervals, reported Margitta Worm, MD, of the Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and coinvestigators.

“Because administration every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks did not provide an additional safety advantage and was numerically outperformed by administration weekly or every 2 weeks, we believe that it is prudent to adhere to the approved every 2 weeks regimen for adults and avoid less frequent treatment regimens (every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks) for long-term maintenance of efficacy,” they wrote in JAMA Dermatology.

Treatment success in the original SOLO trials was defined as having achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0-1, or 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index Scores (EASI-75). As primary endpoints, SOLO-CONTINUE looked at the mean percentage change in EASI score over the course of the trial, and the percentage of patients who maintained EASI-75 at week 36.

Patients in the SOLO-CONTINUE trial who were randomized to receive dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks had a mean percent change in EASI score of –0.06%. In contrast, patients assigned to the placebo group had a 21.7% decrease, and those taking the medication at 4- and 8-week intervals had mean changes of –3.84% and –6.84%, respectively. Post hoc analyses showed no apparent difference between dupilumab weekly and every 2 weeks in the maintenance of clinical response, the investigators reported.

Among patients with EASI-75 response at baseline, significantly more patients maintained this response at week 36 than patients receiving placebo, and there was again an apparent dose-dependent response. The percentage with EASI-75 at week 36 was 71.6% with the weekly or every-2-weeks regimen, 58.3% with the 4-week regimen, 54.9% with the 8-week regimen, and 30.4% in the placebo group.

Continuing treatment with 300 mg weekly or every 2 weeks resulted in greater maintenance of response across multiple other clinical endpoints and patient-reported outcomes as well (such as pruritus, atopic dermatitis symptoms, sleep, pain or discomfort, quality of life, and symptoms of anxiety and depression).

The more-frequent regimens also conferred no greater risk than less-frequent administration, and there were no new safety signals over the 36-week trial. Treatment-emergent adverse events (the most common were headache, nasopharyngitis, injection-site reactions, and herpes simplex virus infection) occurred in 70.7% of patients in the weekly or every-2-weeks group, 73.6% in the 4-week group, 75% in the 8-week group, and 81.7% in the placebo group.

Unlike earlier studies, the incidence of conjunctivitis was low (less than 6%) across all treatment groups, possibly because patients in the SOLO-CONTINUE trial were all high-level responders who tend to have conjunctivitis less frequently, the authors wrote.

Patients receiving less-frequent doses of dupilumab, particularly every 8 weeks, had greater rates of skin infections, flares, and rescue medication use than patients receiving doses weekly or every 2 weeks, the investigators reported. Treatment-emergent antidrug antibody incidence was slightly higher with less-frequent doses (11.7% and 6% in the 8-week and 4-week groups, respectively, compared with 4.3% and 1.2% in the every-2-weeks and weekly groups), which indicates a “higher incidence of immunogenicity with less-frequent dosage intervals” and is “consistent with other biologics,” they wrote.

Dupilumab is a human monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-4 receptor alpha that inhibits signaling of IL-4 and IL-13. The study was conducted at 185 sites in North America, Europe, Asia, and Japan. Patients had a mean age of 38.2 years; 53.8% were male.

While the trial suggests that the approved regimen of 300 mg every 2 weeks is best for long-term treatment, “therapeutic decisions are often influenced by cost-benefit considerations, in which case practitioners and other stakeholders involved in these decisions should carefully balance potential savings against suboptimal efficacy and long-term risks associated with discontinuous treatment regimens,” the investigators wrote.

The SOLO-CONTINUE trial was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron, the companies that market dupilumab. Dr. Worm reported receiving honoraria for consulting and lecture activity from Regeneron and Sanofi during and outside the conduct of the study, among other disclosures. The other authors had multiple disclosures related to these and multiple other pharmaceutical companies, or were employees of Sanofi or Regeneron.

SOURCE: Worm M et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Dec 26. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3617.

The desire to decrease or stop a therapy such as dupilumab may be motivated by cost, current and potential adverse effects, and individual needs. Because atopic dermatitis is a waxing-and-waning disease with a predilection for cycles of escalation, there is some thought a priori that reduced treatment schedules or discontinued use of a drug may be possible in a state of low disease activity.

The investigators of the SOLO-CONTINUE trial found, however, that continuous treatment with the dosage used in the original SOLO trials (300 mg weekly or every 2 weeks) resulted in a better maintenance of response than a less-frequent dosage and was significantly better than placebo for all endpoints. The less-frequent dosage regimens (every 4 weeks and every 8 weeks), on the other hand, produced some dose-dependent reduction in efficacy.

The development of antidrug antibodies was found in approximately 11% of individuals who received placebo or dupilumab every 8 weeks, 6% of the monthly treatment group, and only 1% in the weekly group, suggesting that less-frequent administration results in higher immunogenicity. However, most of the antidrug antibody levels were low and did not seem to have any clinical effect, making this finding of uncertain relevance to patient care.

The study is valuable because, as more patients are exposed to the drug, more will want or need to reduce the dosage or stop use over time – and although it seems optimal to continue an every-2-weeks treatment regimen, this may not always be feasible. As we integrate new therapies and learn more about atopic dermatitis, it is important that we understand the options and implications around decreasing the dosage of dupilumab. This newly concluded trial is helpful in this regard.

Peter A. Lio, MD, is with the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and the Chicago Integrative Eczema Center. He reported receiving grants and personal fees from Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, and other companies, as well as other disclosures. His comments appear in JAMA Dermatology (2019 Dec 26. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3331).

The desire to decrease or stop a therapy such as dupilumab may be motivated by cost, current and potential adverse effects, and individual needs. Because atopic dermatitis is a waxing-and-waning disease with a predilection for cycles of escalation, there is some thought a priori that reduced treatment schedules or discontinued use of a drug may be possible in a state of low disease activity.

The investigators of the SOLO-CONTINUE trial found, however, that continuous treatment with the dosage used in the original SOLO trials (300 mg weekly or every 2 weeks) resulted in a better maintenance of response than a less-frequent dosage and was significantly better than placebo for all endpoints. The less-frequent dosage regimens (every 4 weeks and every 8 weeks), on the other hand, produced some dose-dependent reduction in efficacy.

The development of antidrug antibodies was found in approximately 11% of individuals who received placebo or dupilumab every 8 weeks, 6% of the monthly treatment group, and only 1% in the weekly group, suggesting that less-frequent administration results in higher immunogenicity. However, most of the antidrug antibody levels were low and did not seem to have any clinical effect, making this finding of uncertain relevance to patient care.

The study is valuable because, as more patients are exposed to the drug, more will want or need to reduce the dosage or stop use over time – and although it seems optimal to continue an every-2-weeks treatment regimen, this may not always be feasible. As we integrate new therapies and learn more about atopic dermatitis, it is important that we understand the options and implications around decreasing the dosage of dupilumab. This newly concluded trial is helpful in this regard.

Peter A. Lio, MD, is with the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and the Chicago Integrative Eczema Center. He reported receiving grants and personal fees from Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, and other companies, as well as other disclosures. His comments appear in JAMA Dermatology (2019 Dec 26. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3331).

The desire to decrease or stop a therapy such as dupilumab may be motivated by cost, current and potential adverse effects, and individual needs. Because atopic dermatitis is a waxing-and-waning disease with a predilection for cycles of escalation, there is some thought a priori that reduced treatment schedules or discontinued use of a drug may be possible in a state of low disease activity.

The investigators of the SOLO-CONTINUE trial found, however, that continuous treatment with the dosage used in the original SOLO trials (300 mg weekly or every 2 weeks) resulted in a better maintenance of response than a less-frequent dosage and was significantly better than placebo for all endpoints. The less-frequent dosage regimens (every 4 weeks and every 8 weeks), on the other hand, produced some dose-dependent reduction in efficacy.

The development of antidrug antibodies was found in approximately 11% of individuals who received placebo or dupilumab every 8 weeks, 6% of the monthly treatment group, and only 1% in the weekly group, suggesting that less-frequent administration results in higher immunogenicity. However, most of the antidrug antibody levels were low and did not seem to have any clinical effect, making this finding of uncertain relevance to patient care.

The study is valuable because, as more patients are exposed to the drug, more will want or need to reduce the dosage or stop use over time – and although it seems optimal to continue an every-2-weeks treatment regimen, this may not always be feasible. As we integrate new therapies and learn more about atopic dermatitis, it is important that we understand the options and implications around decreasing the dosage of dupilumab. This newly concluded trial is helpful in this regard.

Peter A. Lio, MD, is with the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and the Chicago Integrative Eczema Center. He reported receiving grants and personal fees from Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, and other companies, as well as other disclosures. His comments appear in JAMA Dermatology (2019 Dec 26. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3331).

Patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis who responded well to the approved dupilumab regimen of 300 mg every 2 weeks in pivotal phase 3 monotherapy trials were more likely to have a continued response over the longer term if they maintained this regimen rather than switching to longer dosing intervals or discontinuing the medication.

This finding comes from a 36-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that enrolled 422 – SOLO 1 and SOLO 2.

The new international study – SOLO-CONTINUE – randomized these patients to continue the original regimen (weekly or every 2 weeks), to receive 300 mg of the biologic medication every 4 or 8 weeks, or to receive placebo.

Patients who continued the original regimen had the most consistent maintenance of treatment effect, while patients on longer dosage intervals or placebo had a dose-dependent reduction in response and no safety advantage. The incidence of treatment-emergent antidrug antibody was lowest with dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks, and slightly higher with less-frequent dosing intervals, reported Margitta Worm, MD, of the Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and coinvestigators.

“Because administration every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks did not provide an additional safety advantage and was numerically outperformed by administration weekly or every 2 weeks, we believe that it is prudent to adhere to the approved every 2 weeks regimen for adults and avoid less frequent treatment regimens (every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks) for long-term maintenance of efficacy,” they wrote in JAMA Dermatology.

Treatment success in the original SOLO trials was defined as having achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0-1, or 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index Scores (EASI-75). As primary endpoints, SOLO-CONTINUE looked at the mean percentage change in EASI score over the course of the trial, and the percentage of patients who maintained EASI-75 at week 36.

Patients in the SOLO-CONTINUE trial who were randomized to receive dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks had a mean percent change in EASI score of –0.06%. In contrast, patients assigned to the placebo group had a 21.7% decrease, and those taking the medication at 4- and 8-week intervals had mean changes of –3.84% and –6.84%, respectively. Post hoc analyses showed no apparent difference between dupilumab weekly and every 2 weeks in the maintenance of clinical response, the investigators reported.

Among patients with EASI-75 response at baseline, significantly more patients maintained this response at week 36 than patients receiving placebo, and there was again an apparent dose-dependent response. The percentage with EASI-75 at week 36 was 71.6% with the weekly or every-2-weeks regimen, 58.3% with the 4-week regimen, 54.9% with the 8-week regimen, and 30.4% in the placebo group.

Continuing treatment with 300 mg weekly or every 2 weeks resulted in greater maintenance of response across multiple other clinical endpoints and patient-reported outcomes as well (such as pruritus, atopic dermatitis symptoms, sleep, pain or discomfort, quality of life, and symptoms of anxiety and depression).

The more-frequent regimens also conferred no greater risk than less-frequent administration, and there were no new safety signals over the 36-week trial. Treatment-emergent adverse events (the most common were headache, nasopharyngitis, injection-site reactions, and herpes simplex virus infection) occurred in 70.7% of patients in the weekly or every-2-weeks group, 73.6% in the 4-week group, 75% in the 8-week group, and 81.7% in the placebo group.

Unlike earlier studies, the incidence of conjunctivitis was low (less than 6%) across all treatment groups, possibly because patients in the SOLO-CONTINUE trial were all high-level responders who tend to have conjunctivitis less frequently, the authors wrote.

Patients receiving less-frequent doses of dupilumab, particularly every 8 weeks, had greater rates of skin infections, flares, and rescue medication use than patients receiving doses weekly or every 2 weeks, the investigators reported. Treatment-emergent antidrug antibody incidence was slightly higher with less-frequent doses (11.7% and 6% in the 8-week and 4-week groups, respectively, compared with 4.3% and 1.2% in the every-2-weeks and weekly groups), which indicates a “higher incidence of immunogenicity with less-frequent dosage intervals” and is “consistent with other biologics,” they wrote.

Dupilumab is a human monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-4 receptor alpha that inhibits signaling of IL-4 and IL-13. The study was conducted at 185 sites in North America, Europe, Asia, and Japan. Patients had a mean age of 38.2 years; 53.8% were male.

While the trial suggests that the approved regimen of 300 mg every 2 weeks is best for long-term treatment, “therapeutic decisions are often influenced by cost-benefit considerations, in which case practitioners and other stakeholders involved in these decisions should carefully balance potential savings against suboptimal efficacy and long-term risks associated with discontinuous treatment regimens,” the investigators wrote.

The SOLO-CONTINUE trial was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron, the companies that market dupilumab. Dr. Worm reported receiving honoraria for consulting and lecture activity from Regeneron and Sanofi during and outside the conduct of the study, among other disclosures. The other authors had multiple disclosures related to these and multiple other pharmaceutical companies, or were employees of Sanofi or Regeneron.

SOURCE: Worm M et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Dec 26. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3617.

Patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis who responded well to the approved dupilumab regimen of 300 mg every 2 weeks in pivotal phase 3 monotherapy trials were more likely to have a continued response over the longer term if they maintained this regimen rather than switching to longer dosing intervals or discontinuing the medication.

This finding comes from a 36-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that enrolled 422 – SOLO 1 and SOLO 2.

The new international study – SOLO-CONTINUE – randomized these patients to continue the original regimen (weekly or every 2 weeks), to receive 300 mg of the biologic medication every 4 or 8 weeks, or to receive placebo.

Patients who continued the original regimen had the most consistent maintenance of treatment effect, while patients on longer dosage intervals or placebo had a dose-dependent reduction in response and no safety advantage. The incidence of treatment-emergent antidrug antibody was lowest with dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks, and slightly higher with less-frequent dosing intervals, reported Margitta Worm, MD, of the Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and coinvestigators.

“Because administration every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks did not provide an additional safety advantage and was numerically outperformed by administration weekly or every 2 weeks, we believe that it is prudent to adhere to the approved every 2 weeks regimen for adults and avoid less frequent treatment regimens (every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks) for long-term maintenance of efficacy,” they wrote in JAMA Dermatology.

Treatment success in the original SOLO trials was defined as having achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0-1, or 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index Scores (EASI-75). As primary endpoints, SOLO-CONTINUE looked at the mean percentage change in EASI score over the course of the trial, and the percentage of patients who maintained EASI-75 at week 36.

Patients in the SOLO-CONTINUE trial who were randomized to receive dupilumab weekly or every 2 weeks had a mean percent change in EASI score of –0.06%. In contrast, patients assigned to the placebo group had a 21.7% decrease, and those taking the medication at 4- and 8-week intervals had mean changes of –3.84% and –6.84%, respectively. Post hoc analyses showed no apparent difference between dupilumab weekly and every 2 weeks in the maintenance of clinical response, the investigators reported.

Among patients with EASI-75 response at baseline, significantly more patients maintained this response at week 36 than patients receiving placebo, and there was again an apparent dose-dependent response. The percentage with EASI-75 at week 36 was 71.6% with the weekly or every-2-weeks regimen, 58.3% with the 4-week regimen, 54.9% with the 8-week regimen, and 30.4% in the placebo group.

Continuing treatment with 300 mg weekly or every 2 weeks resulted in greater maintenance of response across multiple other clinical endpoints and patient-reported outcomes as well (such as pruritus, atopic dermatitis symptoms, sleep, pain or discomfort, quality of life, and symptoms of anxiety and depression).

The more-frequent regimens also conferred no greater risk than less-frequent administration, and there were no new safety signals over the 36-week trial. Treatment-emergent adverse events (the most common were headache, nasopharyngitis, injection-site reactions, and herpes simplex virus infection) occurred in 70.7% of patients in the weekly or every-2-weeks group, 73.6% in the 4-week group, 75% in the 8-week group, and 81.7% in the placebo group.

Unlike earlier studies, the incidence of conjunctivitis was low (less than 6%) across all treatment groups, possibly because patients in the SOLO-CONTINUE trial were all high-level responders who tend to have conjunctivitis less frequently, the authors wrote.