User login

Ultrasound improves specificity of psoriatic arthritis referrals

The use of ultrasound in screening for psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis could reduce the number of unnecessary referrals to rheumatologists, according to a research letter published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Up to one-third of patients with psoriasis have underlying psoriatic arthritis (PsA), but half of all patients with psoriasis experience nonspecific musculoskeletal complaints.

“Different screening tools have been developed for the dermatology practice to distinguish patients with a higher likelihood of having PsA; however, the low specificities of these tools limit their use in clinical practice,” wrote Dilek Solmaz, MD, and colleagues at the University of Ottawa.

In this prospective study, 51 patients with psoriasis were screened for referral to a rheumatologist using the Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients and Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool questionnaires. They also underwent a limited ultrasound scanning of wrists, hands, feet, and the most painful joint, which was reviewed by experienced rheumatologists.

A dermatologist was asked to make a decision on referral based on the questionnaire data alone, then invited to revisit that decision after viewing the ultrasound results. When basing their decision on the questionnaires only, the dermatologist decided to refer 92% of patients to a rheumatologist. Of these patients, 40% were subsequently diagnosed with PsA, which represented a sensitivity of 95% but specificity of just 9%.

After reviewing the ultrasound data, the dermatologist revised their recommendations and only referred 43% of patients. Of these, 68% were later diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis. Among the patients who were not referred after the ultrasound review, five were diagnosed with PsA, but two had isolated axial involvement with no peripheral joint disease. Excluding these two cases, the sensitivity decreased to 88% but specificity increased to 77%.

“Screening tools in psoriasis that have high sensitivities usually have low specificities, which means a higher number of patients to be referred to rheumatology than needed,” the authors wrote. “Our study demonstrated that a musculoskeletal [ultrasound] based on a predefined protocol improves the referrals made to rheumatology.”

The authors did note that the ultrasounds were reviewed by experienced rheumatologists, so the results might not be generalizable to less-experienced sonographers without experience in musculoskeletal disorders.

The study was funded by AbbVie. One author declared receiving funding for a fellowship from UCB. Two authors declared honoraria and advisory consultancies with the pharmaceutical sector, including AbbVie.

SOURCE: Solmaz D et al. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Nov 28. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18515.

The use of ultrasound in screening for psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis could reduce the number of unnecessary referrals to rheumatologists, according to a research letter published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Up to one-third of patients with psoriasis have underlying psoriatic arthritis (PsA), but half of all patients with psoriasis experience nonspecific musculoskeletal complaints.

“Different screening tools have been developed for the dermatology practice to distinguish patients with a higher likelihood of having PsA; however, the low specificities of these tools limit their use in clinical practice,” wrote Dilek Solmaz, MD, and colleagues at the University of Ottawa.

In this prospective study, 51 patients with psoriasis were screened for referral to a rheumatologist using the Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients and Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool questionnaires. They also underwent a limited ultrasound scanning of wrists, hands, feet, and the most painful joint, which was reviewed by experienced rheumatologists.

A dermatologist was asked to make a decision on referral based on the questionnaire data alone, then invited to revisit that decision after viewing the ultrasound results. When basing their decision on the questionnaires only, the dermatologist decided to refer 92% of patients to a rheumatologist. Of these patients, 40% were subsequently diagnosed with PsA, which represented a sensitivity of 95% but specificity of just 9%.

After reviewing the ultrasound data, the dermatologist revised their recommendations and only referred 43% of patients. Of these, 68% were later diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis. Among the patients who were not referred after the ultrasound review, five were diagnosed with PsA, but two had isolated axial involvement with no peripheral joint disease. Excluding these two cases, the sensitivity decreased to 88% but specificity increased to 77%.

“Screening tools in psoriasis that have high sensitivities usually have low specificities, which means a higher number of patients to be referred to rheumatology than needed,” the authors wrote. “Our study demonstrated that a musculoskeletal [ultrasound] based on a predefined protocol improves the referrals made to rheumatology.”

The authors did note that the ultrasounds were reviewed by experienced rheumatologists, so the results might not be generalizable to less-experienced sonographers without experience in musculoskeletal disorders.

The study was funded by AbbVie. One author declared receiving funding for a fellowship from UCB. Two authors declared honoraria and advisory consultancies with the pharmaceutical sector, including AbbVie.

SOURCE: Solmaz D et al. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Nov 28. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18515.

The use of ultrasound in screening for psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis could reduce the number of unnecessary referrals to rheumatologists, according to a research letter published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Up to one-third of patients with psoriasis have underlying psoriatic arthritis (PsA), but half of all patients with psoriasis experience nonspecific musculoskeletal complaints.

“Different screening tools have been developed for the dermatology practice to distinguish patients with a higher likelihood of having PsA; however, the low specificities of these tools limit their use in clinical practice,” wrote Dilek Solmaz, MD, and colleagues at the University of Ottawa.

In this prospective study, 51 patients with psoriasis were screened for referral to a rheumatologist using the Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients and Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool questionnaires. They also underwent a limited ultrasound scanning of wrists, hands, feet, and the most painful joint, which was reviewed by experienced rheumatologists.

A dermatologist was asked to make a decision on referral based on the questionnaire data alone, then invited to revisit that decision after viewing the ultrasound results. When basing their decision on the questionnaires only, the dermatologist decided to refer 92% of patients to a rheumatologist. Of these patients, 40% were subsequently diagnosed with PsA, which represented a sensitivity of 95% but specificity of just 9%.

After reviewing the ultrasound data, the dermatologist revised their recommendations and only referred 43% of patients. Of these, 68% were later diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis. Among the patients who were not referred after the ultrasound review, five were diagnosed with PsA, but two had isolated axial involvement with no peripheral joint disease. Excluding these two cases, the sensitivity decreased to 88% but specificity increased to 77%.

“Screening tools in psoriasis that have high sensitivities usually have low specificities, which means a higher number of patients to be referred to rheumatology than needed,” the authors wrote. “Our study demonstrated that a musculoskeletal [ultrasound] based on a predefined protocol improves the referrals made to rheumatology.”

The authors did note that the ultrasounds were reviewed by experienced rheumatologists, so the results might not be generalizable to less-experienced sonographers without experience in musculoskeletal disorders.

The study was funded by AbbVie. One author declared receiving funding for a fellowship from UCB. Two authors declared honoraria and advisory consultancies with the pharmaceutical sector, including AbbVie.

SOURCE: Solmaz D et al. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Nov 28. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18515.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Make the Diagnosis

A skin biopsy of one of the lesions showed granulomatous inflammation composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and giant cells around hair follicles with negative mycobacterium stains and fungal stains, consistent with granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Tissue cultures from a skin biopsy for aerobic bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungus all were negative.

The patient initially was treated with erythromycin, but after 2 weeks, he reported abdominal pain and nausea and was unable to tolerate the medication. He was switched to clarithromycin, which he took for 6 weeks with clearance of the lesions.

A year later, some of the lesions recurred. He was treated again with clarithromycin and the lesions resolved.

Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (CGPD) is a benign skin eruption that occurs in prepubertal children. It also has been called facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption (FACE), and it tends to occur most commonly in children of darker skin types.1 but there are some cases reported of extra facial involvement.2 The lesions usually are not symptomatic, and they are more common in boys. The cause of this condition is not known, but possible triggers could include prior exposure to topical and systemic corticosteroids, as well as exposure to certain allergens such as formaldehyde.1

In histopathology, the lesions are characterized by granulomatous infiltrates around the hair follicles and the upper dermis. The granulomas are formed of macrophages, lymphocytes, and giant cell, as were seen in our patient.3

Several conditions can look very similar to CGPD; these include sarcoidosis, lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF), and granulomatous rosacea.

Sarcoidosis is a rare condition in children, and the lesions can be similar to the ones seen in our patient. Patients with sarcoidosis usually present with other systemic symptoms including fever, weight loss, respiratory symptoms, and fatigue; none of these were seen in our patient. Under the microscope, the lesions are characterized by “naked granulomas” instead of the inflammatory granulomas seen on our patient.

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is a rare inflammatory skin condition commonly seen in young adults and is thought to be a variant of rosacea. It is characterized by skin-color to pink to yellow dome-shaped papules on the central face. Histologically, the lesions present as dermal epithelioid cell granulomas with central necrosis and surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate with multinucleate giant cells.4

Granulomatous rosacea and CGPD are considered two separate entities. Granulomatous rosacea tends to have a more chronic course, is not that common in children, and clinically presents with pustules, papules, and cysts around the eyes and cheeks.

Infectious processes like tuberculosis and fungal infections were ruled out in our patient with cultures and histopathology. Allergic contact dermatitis on the face can present with skin-color to pink papules, but they usually are very pruritic and improve with topical corticosteroids, while these medications can worsen CGPD.

CGPD can be a self-limiting condition. When mild, it can be treated with topical metronidazole, topical erythromycin, topical clindamycin solution, or pimecrolimus. Our patient failed treatment with pimecrolimus. For severe presentations, oral tetracyclines, erythromycin, and other macrolides, metronidazole, and oral isotretinoin can help clear the lesions.5

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Ann Dermatol. 2011 Aug;23(3):386-8.

2. Int J Dermatol. 2007 Feb;46(2):143-5.

3. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009 Feb 28;13(2):115-8.

4. An Bras Dermatol. 2017 Nov-Dec;92(6):851-3.

5. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jan-Feb; 9(1):68-70.

A skin biopsy of one of the lesions showed granulomatous inflammation composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and giant cells around hair follicles with negative mycobacterium stains and fungal stains, consistent with granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Tissue cultures from a skin biopsy for aerobic bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungus all were negative.

The patient initially was treated with erythromycin, but after 2 weeks, he reported abdominal pain and nausea and was unable to tolerate the medication. He was switched to clarithromycin, which he took for 6 weeks with clearance of the lesions.

A year later, some of the lesions recurred. He was treated again with clarithromycin and the lesions resolved.

Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (CGPD) is a benign skin eruption that occurs in prepubertal children. It also has been called facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption (FACE), and it tends to occur most commonly in children of darker skin types.1 but there are some cases reported of extra facial involvement.2 The lesions usually are not symptomatic, and they are more common in boys. The cause of this condition is not known, but possible triggers could include prior exposure to topical and systemic corticosteroids, as well as exposure to certain allergens such as formaldehyde.1

In histopathology, the lesions are characterized by granulomatous infiltrates around the hair follicles and the upper dermis. The granulomas are formed of macrophages, lymphocytes, and giant cell, as were seen in our patient.3

Several conditions can look very similar to CGPD; these include sarcoidosis, lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF), and granulomatous rosacea.

Sarcoidosis is a rare condition in children, and the lesions can be similar to the ones seen in our patient. Patients with sarcoidosis usually present with other systemic symptoms including fever, weight loss, respiratory symptoms, and fatigue; none of these were seen in our patient. Under the microscope, the lesions are characterized by “naked granulomas” instead of the inflammatory granulomas seen on our patient.

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is a rare inflammatory skin condition commonly seen in young adults and is thought to be a variant of rosacea. It is characterized by skin-color to pink to yellow dome-shaped papules on the central face. Histologically, the lesions present as dermal epithelioid cell granulomas with central necrosis and surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate with multinucleate giant cells.4

Granulomatous rosacea and CGPD are considered two separate entities. Granulomatous rosacea tends to have a more chronic course, is not that common in children, and clinically presents with pustules, papules, and cysts around the eyes and cheeks.

Infectious processes like tuberculosis and fungal infections were ruled out in our patient with cultures and histopathology. Allergic contact dermatitis on the face can present with skin-color to pink papules, but they usually are very pruritic and improve with topical corticosteroids, while these medications can worsen CGPD.

CGPD can be a self-limiting condition. When mild, it can be treated with topical metronidazole, topical erythromycin, topical clindamycin solution, or pimecrolimus. Our patient failed treatment with pimecrolimus. For severe presentations, oral tetracyclines, erythromycin, and other macrolides, metronidazole, and oral isotretinoin can help clear the lesions.5

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Ann Dermatol. 2011 Aug;23(3):386-8.

2. Int J Dermatol. 2007 Feb;46(2):143-5.

3. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009 Feb 28;13(2):115-8.

4. An Bras Dermatol. 2017 Nov-Dec;92(6):851-3.

5. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jan-Feb; 9(1):68-70.

A skin biopsy of one of the lesions showed granulomatous inflammation composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and giant cells around hair follicles with negative mycobacterium stains and fungal stains, consistent with granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Tissue cultures from a skin biopsy for aerobic bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungus all were negative.

The patient initially was treated with erythromycin, but after 2 weeks, he reported abdominal pain and nausea and was unable to tolerate the medication. He was switched to clarithromycin, which he took for 6 weeks with clearance of the lesions.

A year later, some of the lesions recurred. He was treated again with clarithromycin and the lesions resolved.

Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (CGPD) is a benign skin eruption that occurs in prepubertal children. It also has been called facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption (FACE), and it tends to occur most commonly in children of darker skin types.1 but there are some cases reported of extra facial involvement.2 The lesions usually are not symptomatic, and they are more common in boys. The cause of this condition is not known, but possible triggers could include prior exposure to topical and systemic corticosteroids, as well as exposure to certain allergens such as formaldehyde.1

In histopathology, the lesions are characterized by granulomatous infiltrates around the hair follicles and the upper dermis. The granulomas are formed of macrophages, lymphocytes, and giant cell, as were seen in our patient.3

Several conditions can look very similar to CGPD; these include sarcoidosis, lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF), and granulomatous rosacea.

Sarcoidosis is a rare condition in children, and the lesions can be similar to the ones seen in our patient. Patients with sarcoidosis usually present with other systemic symptoms including fever, weight loss, respiratory symptoms, and fatigue; none of these were seen in our patient. Under the microscope, the lesions are characterized by “naked granulomas” instead of the inflammatory granulomas seen on our patient.

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is a rare inflammatory skin condition commonly seen in young adults and is thought to be a variant of rosacea. It is characterized by skin-color to pink to yellow dome-shaped papules on the central face. Histologically, the lesions present as dermal epithelioid cell granulomas with central necrosis and surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate with multinucleate giant cells.4

Granulomatous rosacea and CGPD are considered two separate entities. Granulomatous rosacea tends to have a more chronic course, is not that common in children, and clinically presents with pustules, papules, and cysts around the eyes and cheeks.

Infectious processes like tuberculosis and fungal infections were ruled out in our patient with cultures and histopathology. Allergic contact dermatitis on the face can present with skin-color to pink papules, but they usually are very pruritic and improve with topical corticosteroids, while these medications can worsen CGPD.

CGPD can be a self-limiting condition. When mild, it can be treated with topical metronidazole, topical erythromycin, topical clindamycin solution, or pimecrolimus. Our patient failed treatment with pimecrolimus. For severe presentations, oral tetracyclines, erythromycin, and other macrolides, metronidazole, and oral isotretinoin can help clear the lesions.5

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Ann Dermatol. 2011 Aug;23(3):386-8.

2. Int J Dermatol. 2007 Feb;46(2):143-5.

3. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009 Feb 28;13(2):115-8.

4. An Bras Dermatol. 2017 Nov-Dec;92(6):851-3.

5. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jan-Feb; 9(1):68-70.

An 8-year-old African American male presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of a 3-month history of flesh-colored bumps on the face. According to the patient's mother, the lesions started with small pimple-like lesions around the nose and then spread to the whole face. Some lesions were crusty and somewhat itchy. He was treated with cephalexin and pimecrolimus with no improvement. The mother was very concerned because the lesions were close to the eyes and spreading.

He had no fevers, arthritis, or upper respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms. He recently came back from a trip to Africa to visit his family. No other family members were affected. He used some new soaps, sunscreens, and moisturizers while he was in Africa.

On physical examination, the boy was in no acute distress. He had multiple flesh-colored papules on the face, especially around the eyes, nose, and mouth, where some lesions appeared crusted. There were no other skin lesions elsewhere on his body. There was no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

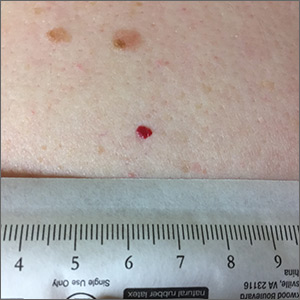

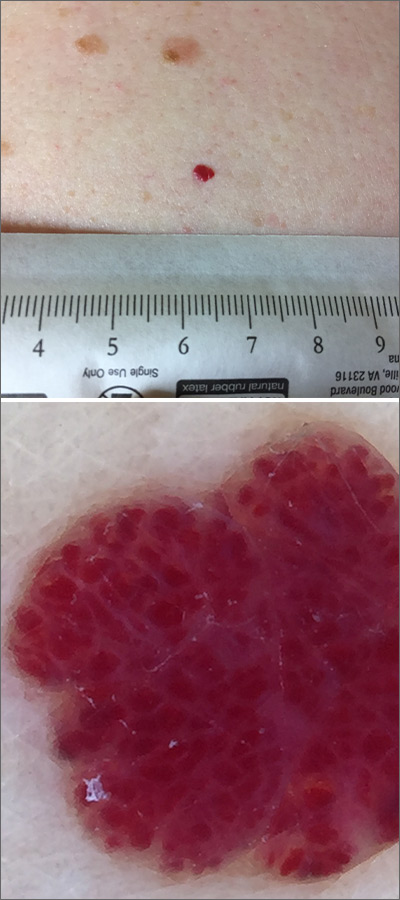

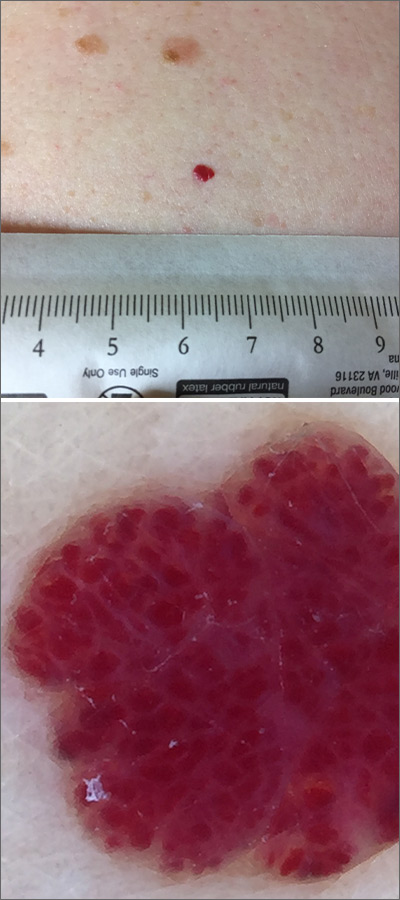

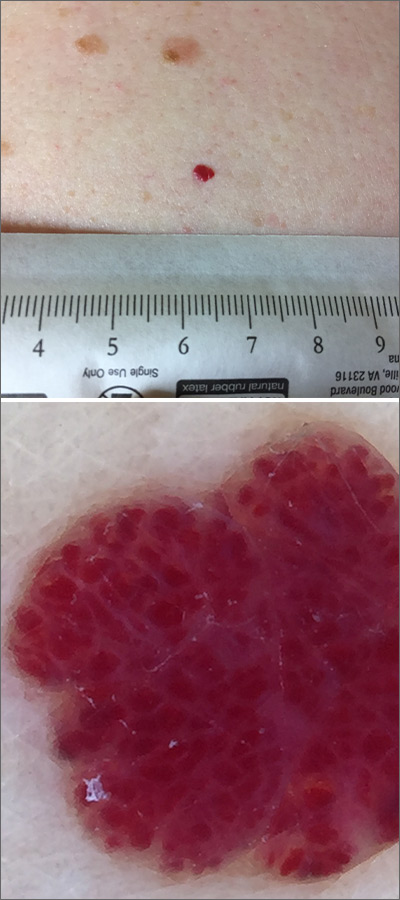

Red lesion on back

Dermoscopy was performed, which confirmed that this was a cherry angioma, also called a cherry hemangioma or Campbell de Morgan spot.

Cherry angiomas are benign proliferations that typically appear after age 30 as tiny bright erythematous macules that, over time, enlarge into papules. In their early, and smaller, stages they are typically maraschino cherry red, hence the name cherry angiomas. As they enlarge or become thrombosed, some lesions become darker red or even black in color. (The dermoscopy image shown here demonstrates the bright red globular red pattern that is classically seen with cherry angiomas.)

Cherry angiomas do not require treatment. If treatment is desired for cosmetic purposes, they can be treated with electrocautery, cryosurgery, or laser. The patient in this case was not worried about the appearance of the lesion and opted to leave it alone unless he developed symptoms.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Dermoscopy was performed, which confirmed that this was a cherry angioma, also called a cherry hemangioma or Campbell de Morgan spot.

Cherry angiomas are benign proliferations that typically appear after age 30 as tiny bright erythematous macules that, over time, enlarge into papules. In their early, and smaller, stages they are typically maraschino cherry red, hence the name cherry angiomas. As they enlarge or become thrombosed, some lesions become darker red or even black in color. (The dermoscopy image shown here demonstrates the bright red globular red pattern that is classically seen with cherry angiomas.)

Cherry angiomas do not require treatment. If treatment is desired for cosmetic purposes, they can be treated with electrocautery, cryosurgery, or laser. The patient in this case was not worried about the appearance of the lesion and opted to leave it alone unless he developed symptoms.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Dermoscopy was performed, which confirmed that this was a cherry angioma, also called a cherry hemangioma or Campbell de Morgan spot.

Cherry angiomas are benign proliferations that typically appear after age 30 as tiny bright erythematous macules that, over time, enlarge into papules. In their early, and smaller, stages they are typically maraschino cherry red, hence the name cherry angiomas. As they enlarge or become thrombosed, some lesions become darker red or even black in color. (The dermoscopy image shown here demonstrates the bright red globular red pattern that is classically seen with cherry angiomas.)

Cherry angiomas do not require treatment. If treatment is desired for cosmetic purposes, they can be treated with electrocautery, cryosurgery, or laser. The patient in this case was not worried about the appearance of the lesion and opted to leave it alone unless he developed symptoms.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

New guideline provides recommendations for radiation therapy of basal cell, squamous cell cancers

who are not candidates for surgery, according to a new guideline from an American Society for Radiation Oncology task force.

“We hope that the dermatology community will find this guideline helpful, especially when it comes to defining clinical and pathological characteristics that may necessitate a discussion about the merits of postoperative radiation therapy,” said lead author Anna Likhacheva, MD, of the Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento, Calif., in an email. The guideline was published in Practical Radiation Oncology.

To address five key questions in regard to radiation therapy (RT) for the two most common skin cancers, the American Society for Radiation Oncology convened a task force of radiation, medical, and surgical oncologists; dermatopathologists; a radiation oncology resident; a medical physicist; and a dermatologist. They reviewed studies of adults with nonmetastatic, invasive basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) that were published between May 1998 and June 2018, with the caveat that “there are limited, well-conducted modern randomized trials” in this area. As such, the majority of the recommendations have low to moderate quality of evidence designations.

“The conspicuous lack of prospective and randomized data should serve as a reminder to open clinical trials and collect outcomes data in a prospective fashion,” added Dr. Likhacheva, noting that “improving the quality of data on this topic will ultimately serve our common goal of improving patient outcomes.”

Their first recommendation was to strongly consider definitive RT as an alternative to surgery for BCC and cSCC, especially in areas where a surgical procedure would potentially compromise function or cosmesis. However, they did discourage its use in patients with genetic conditions associated with increased radiosensitivity.

Their second recommendation was to strongly consider postoperative radiation therapy for clinically or radiologically apparent gross perineural spread. They also strongly recommended PORT for cSCC patients with close or positive margins, with T3 or T4 tumors, or with desmoplastic or infiltrative tumors.

Their third recommendation was to strongly consider therapeutic lymphadenectomy followed by adjuvant RT in patients with cSCC or BCC that has metastasized to the regional lymph nodes. They also recommended definitive RT in medically inoperable patients with the same metastasized cSCC or BCC. In addition, patients with BCC or cSCC undergoing adjuvant RT after therapeutic lymphadenectomy were recommended a dose of 6,000-6,600 cGy, while patients with cSCC undergoing elective RT without a lymphadenectomy were recommended a dose of 5,000-5,400 cGy.

Their fourth recommendation focused on techniques and dose-fractionation schedules for RT in the definitive or postoperative setting. For patients with BCC and cSCC receiving definitive RT, the biologically effective dose (BED10) range for conventional fractionation – defined as 180-200 cGy/fraction – should be 70-93.5 and the BED10 range for hypofractionation – defined as 210-500 cGy/fraction – should be 56-88. For patients with BCC and cSCC receiving postoperative RT, the BED10 range for conventional fractionation should be 59.5-79.2 and the BED10 range for hypofractionation should be 56-70.2.

Finally, their fifth recommendation was to not add concurrent carboplatin to adjuvant RT in patients with resected, locally advanced cSCC. They also conditionally recommended adding concurrent drug therapies to definitive RT in patients with unresected, locally advanced cSCC.

Several of the authors reported receiving honoraria and travel expenses from medical and pharmaceutical companies, along with serving on their advisory boards. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Likhacheva A et al. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2019 Dec 9. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2019.10.014.

who are not candidates for surgery, according to a new guideline from an American Society for Radiation Oncology task force.

“We hope that the dermatology community will find this guideline helpful, especially when it comes to defining clinical and pathological characteristics that may necessitate a discussion about the merits of postoperative radiation therapy,” said lead author Anna Likhacheva, MD, of the Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento, Calif., in an email. The guideline was published in Practical Radiation Oncology.

To address five key questions in regard to radiation therapy (RT) for the two most common skin cancers, the American Society for Radiation Oncology convened a task force of radiation, medical, and surgical oncologists; dermatopathologists; a radiation oncology resident; a medical physicist; and a dermatologist. They reviewed studies of adults with nonmetastatic, invasive basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) that were published between May 1998 and June 2018, with the caveat that “there are limited, well-conducted modern randomized trials” in this area. As such, the majority of the recommendations have low to moderate quality of evidence designations.

“The conspicuous lack of prospective and randomized data should serve as a reminder to open clinical trials and collect outcomes data in a prospective fashion,” added Dr. Likhacheva, noting that “improving the quality of data on this topic will ultimately serve our common goal of improving patient outcomes.”

Their first recommendation was to strongly consider definitive RT as an alternative to surgery for BCC and cSCC, especially in areas where a surgical procedure would potentially compromise function or cosmesis. However, they did discourage its use in patients with genetic conditions associated with increased radiosensitivity.

Their second recommendation was to strongly consider postoperative radiation therapy for clinically or radiologically apparent gross perineural spread. They also strongly recommended PORT for cSCC patients with close or positive margins, with T3 or T4 tumors, or with desmoplastic or infiltrative tumors.

Their third recommendation was to strongly consider therapeutic lymphadenectomy followed by adjuvant RT in patients with cSCC or BCC that has metastasized to the regional lymph nodes. They also recommended definitive RT in medically inoperable patients with the same metastasized cSCC or BCC. In addition, patients with BCC or cSCC undergoing adjuvant RT after therapeutic lymphadenectomy were recommended a dose of 6,000-6,600 cGy, while patients with cSCC undergoing elective RT without a lymphadenectomy were recommended a dose of 5,000-5,400 cGy.

Their fourth recommendation focused on techniques and dose-fractionation schedules for RT in the definitive or postoperative setting. For patients with BCC and cSCC receiving definitive RT, the biologically effective dose (BED10) range for conventional fractionation – defined as 180-200 cGy/fraction – should be 70-93.5 and the BED10 range for hypofractionation – defined as 210-500 cGy/fraction – should be 56-88. For patients with BCC and cSCC receiving postoperative RT, the BED10 range for conventional fractionation should be 59.5-79.2 and the BED10 range for hypofractionation should be 56-70.2.

Finally, their fifth recommendation was to not add concurrent carboplatin to adjuvant RT in patients with resected, locally advanced cSCC. They also conditionally recommended adding concurrent drug therapies to definitive RT in patients with unresected, locally advanced cSCC.

Several of the authors reported receiving honoraria and travel expenses from medical and pharmaceutical companies, along with serving on their advisory boards. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Likhacheva A et al. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2019 Dec 9. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2019.10.014.

who are not candidates for surgery, according to a new guideline from an American Society for Radiation Oncology task force.

“We hope that the dermatology community will find this guideline helpful, especially when it comes to defining clinical and pathological characteristics that may necessitate a discussion about the merits of postoperative radiation therapy,” said lead author Anna Likhacheva, MD, of the Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento, Calif., in an email. The guideline was published in Practical Radiation Oncology.

To address five key questions in regard to radiation therapy (RT) for the two most common skin cancers, the American Society for Radiation Oncology convened a task force of radiation, medical, and surgical oncologists; dermatopathologists; a radiation oncology resident; a medical physicist; and a dermatologist. They reviewed studies of adults with nonmetastatic, invasive basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) that were published between May 1998 and June 2018, with the caveat that “there are limited, well-conducted modern randomized trials” in this area. As such, the majority of the recommendations have low to moderate quality of evidence designations.

“The conspicuous lack of prospective and randomized data should serve as a reminder to open clinical trials and collect outcomes data in a prospective fashion,” added Dr. Likhacheva, noting that “improving the quality of data on this topic will ultimately serve our common goal of improving patient outcomes.”

Their first recommendation was to strongly consider definitive RT as an alternative to surgery for BCC and cSCC, especially in areas where a surgical procedure would potentially compromise function or cosmesis. However, they did discourage its use in patients with genetic conditions associated with increased radiosensitivity.

Their second recommendation was to strongly consider postoperative radiation therapy for clinically or radiologically apparent gross perineural spread. They also strongly recommended PORT for cSCC patients with close or positive margins, with T3 or T4 tumors, or with desmoplastic or infiltrative tumors.

Their third recommendation was to strongly consider therapeutic lymphadenectomy followed by adjuvant RT in patients with cSCC or BCC that has metastasized to the regional lymph nodes. They also recommended definitive RT in medically inoperable patients with the same metastasized cSCC or BCC. In addition, patients with BCC or cSCC undergoing adjuvant RT after therapeutic lymphadenectomy were recommended a dose of 6,000-6,600 cGy, while patients with cSCC undergoing elective RT without a lymphadenectomy were recommended a dose of 5,000-5,400 cGy.

Their fourth recommendation focused on techniques and dose-fractionation schedules for RT in the definitive or postoperative setting. For patients with BCC and cSCC receiving definitive RT, the biologically effective dose (BED10) range for conventional fractionation – defined as 180-200 cGy/fraction – should be 70-93.5 and the BED10 range for hypofractionation – defined as 210-500 cGy/fraction – should be 56-88. For patients with BCC and cSCC receiving postoperative RT, the BED10 range for conventional fractionation should be 59.5-79.2 and the BED10 range for hypofractionation should be 56-70.2.

Finally, their fifth recommendation was to not add concurrent carboplatin to adjuvant RT in patients with resected, locally advanced cSCC. They also conditionally recommended adding concurrent drug therapies to definitive RT in patients with unresected, locally advanced cSCC.

Several of the authors reported receiving honoraria and travel expenses from medical and pharmaceutical companies, along with serving on their advisory boards. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Likhacheva A et al. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2019 Dec 9. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2019.10.014.

FROM PRACTICAL RADIATION ONCOLOGY

Identifying bacterial infections in setting of atopic dermatitis

While of infections in AD and features common to both can make it difficult to make a clinical diagnosis of infections.

Addressing this issue, the International Eczema Council Skin Infection Group reviewed the most current evidence on the clinical features of bacterial infections and the interaction between host and bacterial factors that affect severity and morbidity in people with atopic dermatitis (AD). Recurrent skin infections, especially from Staphylococcus aureus and occasionally from beta-hemolytic streptococci, are more common in people with AD than those who do not have AD for a variety of reasons, Helen Alexander, MD, from the unit for population-based dermatology research at St. John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London, and associates wrote in the review article published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

“The reduced skin barrier, cutaneous innate and adaptive immune abnormalities and trauma from scratching all contribute to the increased risk of skin infection,” they wrote. “However, the wide variability in clinical presentation of bacterial infection in AD and the inherent features of AD – cutaneous erythema and warmth, oozing associated with edema, and regional lymphadenopathy – overlap with those of infection, making clinical diagnosis challenging.”

The clinical appearance of AD may also mask signs of the bacterial infection, they added, and providers cannot rely on positive skin swab culture from the possibly infected area since S. aureus is so common in AD. An added challenge can occur in patients of different ethnicities, in whom both AD and bacterial infection may manifest differently. For example, perifollicular accentuation often occurs with AD in dark-skinned patients with violet-colored, often muted erythema.

An estimated 70% of lesional and 39% of nonlesional AD skin is colonized with S. aureus, the authors noted, but it’s not clear how best to recognize and manage asymptomatic S. aureus colonization. Among the factors that can increase susceptibility to S. aureus colonization and infection are impaired skin barriers, type 2 inflammation and lower levels of microbial diversity in the skin microbiome.

Specific clinical features of S. aureus in patients with AD include “weeping, honey-colored crusts and pustules, both interfollicular and follicular based,” and the pustules, though not common, can involve pain and itching. By comparison, signs of beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection may include “well-defined, bright red erythema, thick-walled pustules and heavy crusting,” the authors wrote.

Fever and lymphadenopathy may occur in severe cases, as well as abscesses, particularly with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infection. It’s unclear whether MRSA occurs more often in people with AD since its incidence varies so widely geographically, they noted.

In the differential diagnosis, providers should consider the possibility that a patient has a concomitant viral or fungal infection. Eczema herpeticum from herpes simplex virus is a common viral infection with risk factors that include “moderate to severe AD, filaggrin loss-of-function mutation, a history of S. aureus skin infection, greater allergen sensitization and type 2 immunity,” the authors wrote.

The yeast Malassezia is implicated in inflammation in patients with dermatitis that affects the head, neck, upper chest, back, and other areas high in sebaceous glands. Some patients have greater sensitivity to Malassezia, and “cross-reactivity between Malassezia-specific IgE and Candida albicans” has occurred as well, they wrote. Current evidence favors benefit from antifungal drugs, though not conclusively.

“Although we have some understanding of how S. aureus colonizes the skin and causes inflammation in AD, many questions related to this complex relationship remain unanswered,” the authors concluded. They added that better understanding the mechanisms of S. aureus and downstream host immune mediators of inflammatory pathways involving S. aureus could potentially lead to new therapeutic targets for infection in AD patients.

The statement was funded in part by the senior author’s fellowships from the National Institutes of Health Research, and the International Eczema Council received sponsorship from AbbVie, Amgen, Asana Biosciences, Celgene, Chugai, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Kyowa Kirin, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Sanofi Genzyme, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sienna and Valeant. Of the 16 authors, 13 disclosed financial ties to a wide range of pharmaceutical companies, including those listed above.

SOURCE: Alexander H et al. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1111/bjd.1864319.

While of infections in AD and features common to both can make it difficult to make a clinical diagnosis of infections.

Addressing this issue, the International Eczema Council Skin Infection Group reviewed the most current evidence on the clinical features of bacterial infections and the interaction between host and bacterial factors that affect severity and morbidity in people with atopic dermatitis (AD). Recurrent skin infections, especially from Staphylococcus aureus and occasionally from beta-hemolytic streptococci, are more common in people with AD than those who do not have AD for a variety of reasons, Helen Alexander, MD, from the unit for population-based dermatology research at St. John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London, and associates wrote in the review article published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

“The reduced skin barrier, cutaneous innate and adaptive immune abnormalities and trauma from scratching all contribute to the increased risk of skin infection,” they wrote. “However, the wide variability in clinical presentation of bacterial infection in AD and the inherent features of AD – cutaneous erythema and warmth, oozing associated with edema, and regional lymphadenopathy – overlap with those of infection, making clinical diagnosis challenging.”

The clinical appearance of AD may also mask signs of the bacterial infection, they added, and providers cannot rely on positive skin swab culture from the possibly infected area since S. aureus is so common in AD. An added challenge can occur in patients of different ethnicities, in whom both AD and bacterial infection may manifest differently. For example, perifollicular accentuation often occurs with AD in dark-skinned patients with violet-colored, often muted erythema.

An estimated 70% of lesional and 39% of nonlesional AD skin is colonized with S. aureus, the authors noted, but it’s not clear how best to recognize and manage asymptomatic S. aureus colonization. Among the factors that can increase susceptibility to S. aureus colonization and infection are impaired skin barriers, type 2 inflammation and lower levels of microbial diversity in the skin microbiome.

Specific clinical features of S. aureus in patients with AD include “weeping, honey-colored crusts and pustules, both interfollicular and follicular based,” and the pustules, though not common, can involve pain and itching. By comparison, signs of beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection may include “well-defined, bright red erythema, thick-walled pustules and heavy crusting,” the authors wrote.

Fever and lymphadenopathy may occur in severe cases, as well as abscesses, particularly with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infection. It’s unclear whether MRSA occurs more often in people with AD since its incidence varies so widely geographically, they noted.

In the differential diagnosis, providers should consider the possibility that a patient has a concomitant viral or fungal infection. Eczema herpeticum from herpes simplex virus is a common viral infection with risk factors that include “moderate to severe AD, filaggrin loss-of-function mutation, a history of S. aureus skin infection, greater allergen sensitization and type 2 immunity,” the authors wrote.

The yeast Malassezia is implicated in inflammation in patients with dermatitis that affects the head, neck, upper chest, back, and other areas high in sebaceous glands. Some patients have greater sensitivity to Malassezia, and “cross-reactivity between Malassezia-specific IgE and Candida albicans” has occurred as well, they wrote. Current evidence favors benefit from antifungal drugs, though not conclusively.

“Although we have some understanding of how S. aureus colonizes the skin and causes inflammation in AD, many questions related to this complex relationship remain unanswered,” the authors concluded. They added that better understanding the mechanisms of S. aureus and downstream host immune mediators of inflammatory pathways involving S. aureus could potentially lead to new therapeutic targets for infection in AD patients.

The statement was funded in part by the senior author’s fellowships from the National Institutes of Health Research, and the International Eczema Council received sponsorship from AbbVie, Amgen, Asana Biosciences, Celgene, Chugai, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Kyowa Kirin, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Sanofi Genzyme, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sienna and Valeant. Of the 16 authors, 13 disclosed financial ties to a wide range of pharmaceutical companies, including those listed above.

SOURCE: Alexander H et al. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1111/bjd.1864319.

While of infections in AD and features common to both can make it difficult to make a clinical diagnosis of infections.

Addressing this issue, the International Eczema Council Skin Infection Group reviewed the most current evidence on the clinical features of bacterial infections and the interaction between host and bacterial factors that affect severity and morbidity in people with atopic dermatitis (AD). Recurrent skin infections, especially from Staphylococcus aureus and occasionally from beta-hemolytic streptococci, are more common in people with AD than those who do not have AD for a variety of reasons, Helen Alexander, MD, from the unit for population-based dermatology research at St. John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London, and associates wrote in the review article published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

“The reduced skin barrier, cutaneous innate and adaptive immune abnormalities and trauma from scratching all contribute to the increased risk of skin infection,” they wrote. “However, the wide variability in clinical presentation of bacterial infection in AD and the inherent features of AD – cutaneous erythema and warmth, oozing associated with edema, and regional lymphadenopathy – overlap with those of infection, making clinical diagnosis challenging.”

The clinical appearance of AD may also mask signs of the bacterial infection, they added, and providers cannot rely on positive skin swab culture from the possibly infected area since S. aureus is so common in AD. An added challenge can occur in patients of different ethnicities, in whom both AD and bacterial infection may manifest differently. For example, perifollicular accentuation often occurs with AD in dark-skinned patients with violet-colored, often muted erythema.

An estimated 70% of lesional and 39% of nonlesional AD skin is colonized with S. aureus, the authors noted, but it’s not clear how best to recognize and manage asymptomatic S. aureus colonization. Among the factors that can increase susceptibility to S. aureus colonization and infection are impaired skin barriers, type 2 inflammation and lower levels of microbial diversity in the skin microbiome.

Specific clinical features of S. aureus in patients with AD include “weeping, honey-colored crusts and pustules, both interfollicular and follicular based,” and the pustules, though not common, can involve pain and itching. By comparison, signs of beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection may include “well-defined, bright red erythema, thick-walled pustules and heavy crusting,” the authors wrote.

Fever and lymphadenopathy may occur in severe cases, as well as abscesses, particularly with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infection. It’s unclear whether MRSA occurs more often in people with AD since its incidence varies so widely geographically, they noted.

In the differential diagnosis, providers should consider the possibility that a patient has a concomitant viral or fungal infection. Eczema herpeticum from herpes simplex virus is a common viral infection with risk factors that include “moderate to severe AD, filaggrin loss-of-function mutation, a history of S. aureus skin infection, greater allergen sensitization and type 2 immunity,” the authors wrote.

The yeast Malassezia is implicated in inflammation in patients with dermatitis that affects the head, neck, upper chest, back, and other areas high in sebaceous glands. Some patients have greater sensitivity to Malassezia, and “cross-reactivity between Malassezia-specific IgE and Candida albicans” has occurred as well, they wrote. Current evidence favors benefit from antifungal drugs, though not conclusively.

“Although we have some understanding of how S. aureus colonizes the skin and causes inflammation in AD, many questions related to this complex relationship remain unanswered,” the authors concluded. They added that better understanding the mechanisms of S. aureus and downstream host immune mediators of inflammatory pathways involving S. aureus could potentially lead to new therapeutic targets for infection in AD patients.

The statement was funded in part by the senior author’s fellowships from the National Institutes of Health Research, and the International Eczema Council received sponsorship from AbbVie, Amgen, Asana Biosciences, Celgene, Chugai, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Kyowa Kirin, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Sanofi Genzyme, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sienna and Valeant. Of the 16 authors, 13 disclosed financial ties to a wide range of pharmaceutical companies, including those listed above.

SOURCE: Alexander H et al. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1111/bjd.1864319.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

iPLEDGE vexes dermatologists treating transgender patients

Physicians treating transgender patients – in particular, transgender men who were born female – are faced with a confusing process when prescribing isotretinoin for severe acne.

A research letter published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology reports that established to prevent female patients from starting isotretinoin therapy while pregnant or from becoming pregnant while exposed to the teratogenic medication.

Nearly 90% of respondents favored changing the current gender-specific categories in iPLEDGE to gender-neutral ones, classifying patients only by whether or not they have the ability to become pregnant.

For their research, Courtney Ensslin, MD, of the department of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues, distributed an 18-point questionnaire to 385 members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology that included questions assessing clinicians’ knowledge about the reproductive potential of transgender men and women. The recipients were asked to distribute it to faculty members and residents. The survey also described three clinical scenarios in which the physician needed to decide how to register a patient in iPLEDGE. The clinicians largely opted to class transgender men as women with childbearing potential, even if the category conflicted with the patient’s self-identified and legally recognized male gender.

Of the 136 clinicians who responded, 60% were women, almost half were aged 25-34 years. About 12% of respondents said the complexities of prescribing isotretinoin to a transgender patient led them to choose alternative therapies. And the survey revealed some gaps on providers’ general literacy on transgender patients and their reproductive potential. For example, fewer than a third of respondents answered correctly as to whether testosterone treatment decreases the quality and development of an immature ovum.

The researchers wrote that the survey results, while limited by a small sample of respondents that skewed toward younger women providers, suggest that “continued education on fertility in transgender patients is needed because prescribers must fully understand each patient’s reproductive potential to safely prescribe teratogenic medications.” Additionally, they pointed out, the results support ongoing efforts to reform iPLEDGE, as the current categories “do not offer an inclusive approach to care for transgender patients.”

Earlier this year the American Academy of Dermatology issued a position statement that described a number of ongoing initiatives aimed at improving treatment for patients who are members of gender and sexual minorities. These included the “revision of the AAD position statement on isotretinoin to support a gender-neutral categorization model for [iPLEDGE] … based on child-bearing potential rather than on gender identity,” the statement said.

Dr. Ensslin and colleagues reported conflicts of interest related to their research. The study was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Ensslin C et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Dec;81(6):1426-9.

Physicians treating transgender patients – in particular, transgender men who were born female – are faced with a confusing process when prescribing isotretinoin for severe acne.

A research letter published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology reports that established to prevent female patients from starting isotretinoin therapy while pregnant or from becoming pregnant while exposed to the teratogenic medication.

Nearly 90% of respondents favored changing the current gender-specific categories in iPLEDGE to gender-neutral ones, classifying patients only by whether or not they have the ability to become pregnant.

For their research, Courtney Ensslin, MD, of the department of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues, distributed an 18-point questionnaire to 385 members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology that included questions assessing clinicians’ knowledge about the reproductive potential of transgender men and women. The recipients were asked to distribute it to faculty members and residents. The survey also described three clinical scenarios in which the physician needed to decide how to register a patient in iPLEDGE. The clinicians largely opted to class transgender men as women with childbearing potential, even if the category conflicted with the patient’s self-identified and legally recognized male gender.

Of the 136 clinicians who responded, 60% were women, almost half were aged 25-34 years. About 12% of respondents said the complexities of prescribing isotretinoin to a transgender patient led them to choose alternative therapies. And the survey revealed some gaps on providers’ general literacy on transgender patients and their reproductive potential. For example, fewer than a third of respondents answered correctly as to whether testosterone treatment decreases the quality and development of an immature ovum.

The researchers wrote that the survey results, while limited by a small sample of respondents that skewed toward younger women providers, suggest that “continued education on fertility in transgender patients is needed because prescribers must fully understand each patient’s reproductive potential to safely prescribe teratogenic medications.” Additionally, they pointed out, the results support ongoing efforts to reform iPLEDGE, as the current categories “do not offer an inclusive approach to care for transgender patients.”

Earlier this year the American Academy of Dermatology issued a position statement that described a number of ongoing initiatives aimed at improving treatment for patients who are members of gender and sexual minorities. These included the “revision of the AAD position statement on isotretinoin to support a gender-neutral categorization model for [iPLEDGE] … based on child-bearing potential rather than on gender identity,” the statement said.

Dr. Ensslin and colleagues reported conflicts of interest related to their research. The study was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Ensslin C et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Dec;81(6):1426-9.

Physicians treating transgender patients – in particular, transgender men who were born female – are faced with a confusing process when prescribing isotretinoin for severe acne.

A research letter published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology reports that established to prevent female patients from starting isotretinoin therapy while pregnant or from becoming pregnant while exposed to the teratogenic medication.

Nearly 90% of respondents favored changing the current gender-specific categories in iPLEDGE to gender-neutral ones, classifying patients only by whether or not they have the ability to become pregnant.

For their research, Courtney Ensslin, MD, of the department of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues, distributed an 18-point questionnaire to 385 members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology that included questions assessing clinicians’ knowledge about the reproductive potential of transgender men and women. The recipients were asked to distribute it to faculty members and residents. The survey also described three clinical scenarios in which the physician needed to decide how to register a patient in iPLEDGE. The clinicians largely opted to class transgender men as women with childbearing potential, even if the category conflicted with the patient’s self-identified and legally recognized male gender.

Of the 136 clinicians who responded, 60% were women, almost half were aged 25-34 years. About 12% of respondents said the complexities of prescribing isotretinoin to a transgender patient led them to choose alternative therapies. And the survey revealed some gaps on providers’ general literacy on transgender patients and their reproductive potential. For example, fewer than a third of respondents answered correctly as to whether testosterone treatment decreases the quality and development of an immature ovum.

The researchers wrote that the survey results, while limited by a small sample of respondents that skewed toward younger women providers, suggest that “continued education on fertility in transgender patients is needed because prescribers must fully understand each patient’s reproductive potential to safely prescribe teratogenic medications.” Additionally, they pointed out, the results support ongoing efforts to reform iPLEDGE, as the current categories “do not offer an inclusive approach to care for transgender patients.”

Earlier this year the American Academy of Dermatology issued a position statement that described a number of ongoing initiatives aimed at improving treatment for patients who are members of gender and sexual minorities. These included the “revision of the AAD position statement on isotretinoin to support a gender-neutral categorization model for [iPLEDGE] … based on child-bearing potential rather than on gender identity,” the statement said.

Dr. Ensslin and colleagues reported conflicts of interest related to their research. The study was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Ensslin C et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Dec;81(6):1426-9.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Fast, aggressive eczema treatment linked to fewer food allergies by age 2

Researchers in Japan report that

For their research published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, Yumiko Miyaji, MD, PhD, of Japan’s National Center for Child Health and Development in Tokyo and colleagues looked at 3 years’ worth of records for 177 infants younger than 1 year of age seen at a hospital allergy center for eczema. Of these infants, 89 were treated with betamethasone valerate within 4 months of disease onset, and 88 were treated after 4 months of onset. Most (142) were followed-up at 22-24 months, when all were in complete remission or near remission from eczema.

At follow-up, clinicians collected information about anaphylactic reactions to food, administered specific food challenges, and tested serum immunoglobin E levels for food allergens. Dr. Miyaji and colleagues found a significant difference in the prevalence of allergies between the early-treated and late-treated groups to chicken egg, cow’s milk, wheat, peanuts, soy, or fish (25% vs. 46%, respectively; P equal to .013). For individual food allergies, only chicken egg was associated with a statistically significant difference in prevalence (15% vs 36%, P equal to .006).

“Our present study may be the first to demonstrate that early aggressive topical corticosteroid treatment to shorten the duration of eczema in infants was significantly associated with a decrease in later development of [food allergies],” Dr. Miyaji and colleagues wrote in their analysis.

The investigators acknowledged as limitations of their study some between-group differences at baseline, with characteristics such as Staphylococcus aureus infections and some inflammatory biomarkers higher in the early treatment group.

The Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development supported the study, and the investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest related to their findings.

SOURCE: Miyaji Y et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.11.036

Researchers in Japan report that

For their research published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, Yumiko Miyaji, MD, PhD, of Japan’s National Center for Child Health and Development in Tokyo and colleagues looked at 3 years’ worth of records for 177 infants younger than 1 year of age seen at a hospital allergy center for eczema. Of these infants, 89 were treated with betamethasone valerate within 4 months of disease onset, and 88 were treated after 4 months of onset. Most (142) were followed-up at 22-24 months, when all were in complete remission or near remission from eczema.

At follow-up, clinicians collected information about anaphylactic reactions to food, administered specific food challenges, and tested serum immunoglobin E levels for food allergens. Dr. Miyaji and colleagues found a significant difference in the prevalence of allergies between the early-treated and late-treated groups to chicken egg, cow’s milk, wheat, peanuts, soy, or fish (25% vs. 46%, respectively; P equal to .013). For individual food allergies, only chicken egg was associated with a statistically significant difference in prevalence (15% vs 36%, P equal to .006).

“Our present study may be the first to demonstrate that early aggressive topical corticosteroid treatment to shorten the duration of eczema in infants was significantly associated with a decrease in later development of [food allergies],” Dr. Miyaji and colleagues wrote in their analysis.

The investigators acknowledged as limitations of their study some between-group differences at baseline, with characteristics such as Staphylococcus aureus infections and some inflammatory biomarkers higher in the early treatment group.

The Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development supported the study, and the investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest related to their findings.

SOURCE: Miyaji Y et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.11.036

Researchers in Japan report that

For their research published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, Yumiko Miyaji, MD, PhD, of Japan’s National Center for Child Health and Development in Tokyo and colleagues looked at 3 years’ worth of records for 177 infants younger than 1 year of age seen at a hospital allergy center for eczema. Of these infants, 89 were treated with betamethasone valerate within 4 months of disease onset, and 88 were treated after 4 months of onset. Most (142) were followed-up at 22-24 months, when all were in complete remission or near remission from eczema.

At follow-up, clinicians collected information about anaphylactic reactions to food, administered specific food challenges, and tested serum immunoglobin E levels for food allergens. Dr. Miyaji and colleagues found a significant difference in the prevalence of allergies between the early-treated and late-treated groups to chicken egg, cow’s milk, wheat, peanuts, soy, or fish (25% vs. 46%, respectively; P equal to .013). For individual food allergies, only chicken egg was associated with a statistically significant difference in prevalence (15% vs 36%, P equal to .006).

“Our present study may be the first to demonstrate that early aggressive topical corticosteroid treatment to shorten the duration of eczema in infants was significantly associated with a decrease in later development of [food allergies],” Dr. Miyaji and colleagues wrote in their analysis.

The investigators acknowledged as limitations of their study some between-group differences at baseline, with characteristics such as Staphylococcus aureus infections and some inflammatory biomarkers higher in the early treatment group.

The Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development supported the study, and the investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest related to their findings.

SOURCE: Miyaji Y et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.11.036

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY: IN PRACTICE

Atopic dermatitis in egg-, milk-allergic kids may up anaphylaxis risk

compared with allergic patients without atopic dermatitis, based on retrospective data from 347 individuals.

Atopic dermatitis has been associated with increased risk of food allergies, but the association and predictive factors of skin reactions to certain foods remain unclear, wrote Bryce C. Hoffman, MD, of National Jewish Health, Denver, and colleagues.

In a letter published in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, the researchers identified children aged 0-18 years with peanut, cow’s milk, and/or egg allergies with or without atopic dermatitis (AD) using an institutional research database and conducted a retrospective study of medical records.

Overall, children with egg and milk allergies plus AD had significantly higher rates of anaphylaxis than allergic children without AD (47% vs. 11% for egg, 50% vs. 19% for milk). Anaphylaxis rates were similar in children with peanut allergies with or without AD (27% vs. 23%).

“This finding may suggest that skin barrier dysfunction plays a role in the severity of [food allergy]. However, this is not universal to all food antigens, and other mechanisms are likely important in the association of anaphylaxis with a particular food,” the researchers noted.

Rates of tolerance for both baked egg and baked milk were similar between AD and non-AD patients (83% vs. 61% for milk; 82% vs. 67% for egg). In addition, levels of total IgE were increased in children with egg and milk allergies plus AD, compared with children without AD. However, children with peanut allergies plus AD had decreased total IgE, compared with children with peanut allergies but no AD. This “may support a link between Th2 polarization and [food allergy] severity, ” Dr. Hoffman and associates wrote.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective study design, exclusion of many patients, and lack of data on the amount of food that triggered anaphylactic reactions, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, the results suggest that children with atopic dermatitis and allergies to eggs and milk are at increased risk and that clinicians should counsel these patients and families about the potential for more-severe reactions to oral food challenges, Dr. Hoffman and associates concluded.

The study was supported by National Jewish Health and the Edelstein Family Chair of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Hoffman BC et al. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.09.008.

compared with allergic patients without atopic dermatitis, based on retrospective data from 347 individuals.

Atopic dermatitis has been associated with increased risk of food allergies, but the association and predictive factors of skin reactions to certain foods remain unclear, wrote Bryce C. Hoffman, MD, of National Jewish Health, Denver, and colleagues.

In a letter published in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, the researchers identified children aged 0-18 years with peanut, cow’s milk, and/or egg allergies with or without atopic dermatitis (AD) using an institutional research database and conducted a retrospective study of medical records.

Overall, children with egg and milk allergies plus AD had significantly higher rates of anaphylaxis than allergic children without AD (47% vs. 11% for egg, 50% vs. 19% for milk). Anaphylaxis rates were similar in children with peanut allergies with or without AD (27% vs. 23%).

“This finding may suggest that skin barrier dysfunction plays a role in the severity of [food allergy]. However, this is not universal to all food antigens, and other mechanisms are likely important in the association of anaphylaxis with a particular food,” the researchers noted.

Rates of tolerance for both baked egg and baked milk were similar between AD and non-AD patients (83% vs. 61% for milk; 82% vs. 67% for egg). In addition, levels of total IgE were increased in children with egg and milk allergies plus AD, compared with children without AD. However, children with peanut allergies plus AD had decreased total IgE, compared with children with peanut allergies but no AD. This “may support a link between Th2 polarization and [food allergy] severity, ” Dr. Hoffman and associates wrote.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective study design, exclusion of many patients, and lack of data on the amount of food that triggered anaphylactic reactions, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, the results suggest that children with atopic dermatitis and allergies to eggs and milk are at increased risk and that clinicians should counsel these patients and families about the potential for more-severe reactions to oral food challenges, Dr. Hoffman and associates concluded.

The study was supported by National Jewish Health and the Edelstein Family Chair of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Hoffman BC et al. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.09.008.

compared with allergic patients without atopic dermatitis, based on retrospective data from 347 individuals.

Atopic dermatitis has been associated with increased risk of food allergies, but the association and predictive factors of skin reactions to certain foods remain unclear, wrote Bryce C. Hoffman, MD, of National Jewish Health, Denver, and colleagues.

In a letter published in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, the researchers identified children aged 0-18 years with peanut, cow’s milk, and/or egg allergies with or without atopic dermatitis (AD) using an institutional research database and conducted a retrospective study of medical records.

Overall, children with egg and milk allergies plus AD had significantly higher rates of anaphylaxis than allergic children without AD (47% vs. 11% for egg, 50% vs. 19% for milk). Anaphylaxis rates were similar in children with peanut allergies with or without AD (27% vs. 23%).

“This finding may suggest that skin barrier dysfunction plays a role in the severity of [food allergy]. However, this is not universal to all food antigens, and other mechanisms are likely important in the association of anaphylaxis with a particular food,” the researchers noted.

Rates of tolerance for both baked egg and baked milk were similar between AD and non-AD patients (83% vs. 61% for milk; 82% vs. 67% for egg). In addition, levels of total IgE were increased in children with egg and milk allergies plus AD, compared with children without AD. However, children with peanut allergies plus AD had decreased total IgE, compared with children with peanut allergies but no AD. This “may support a link between Th2 polarization and [food allergy] severity, ” Dr. Hoffman and associates wrote.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective study design, exclusion of many patients, and lack of data on the amount of food that triggered anaphylactic reactions, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, the results suggest that children with atopic dermatitis and allergies to eggs and milk are at increased risk and that clinicians should counsel these patients and families about the potential for more-severe reactions to oral food challenges, Dr. Hoffman and associates concluded.

The study was supported by National Jewish Health and the Edelstein Family Chair of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Hoffman BC et al. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.09.008.

FROM THE ANNALS OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA & IMMUNOLOGY

Frequent soaks ease pediatric atopic dermatitis

A regimen of twice-daily baths followed by occlusive moisturizer improved atopic dermatitis in children with moderate to severe disease more effectively than did a twice-weekly protocol, based on data from 42 children.

Guidelines for bathing frequency for children with atopic dermatitis are inconsistent and often confusing for parents, according to Ivan D. Cardona, MD, of Maine Medical Research Institute, Portland, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, the researchers randomized 42 children aged 6 months to 11 years with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis to a routine of twice-weekly “soak and seal” (SS) procedures consisting of soaking baths for 10 minutes or less, followed by an occlusive emollient, or to twice-daily SS with baths of 15-20 minutes followed by emollient. The groups were treated for 2 weeks, then switched protocols. The study included a total of four clinic visits over 5 weeks. All patients also received standard of care low-potency topical corticosteroids and moisturizer.

Overall, the frequent bathing (“wet method”) led to a decrease of 21.2 on the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis Index (SCORAD) compared with the less frequent bathing (“dry method”). Improvements in SCORAD (the primary outcome) correlated with a secondary outcome of improved scores on the parent-rated Atopic Dermatitis Quickscore.

The findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size, large rate of attrition prior to randomization among initially screened children, lack of data on environmental factors such as water temperature and quality, and the lack of a washout period between the treatment protocols, the researchers noted. They acknowledged that “twice-daily SS bathing in the real world can be time consuming, making adherence difficult for families.”

However, the results suggest that the frequent bathing protocol was safe and effective at improving symptoms of atopic dermatitis, and may reduce steroid use, they concluded.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Cardona ID et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.10.042.

A regimen of twice-daily baths followed by occlusive moisturizer improved atopic dermatitis in children with moderate to severe disease more effectively than did a twice-weekly protocol, based on data from 42 children.

Guidelines for bathing frequency for children with atopic dermatitis are inconsistent and often confusing for parents, according to Ivan D. Cardona, MD, of Maine Medical Research Institute, Portland, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, the researchers randomized 42 children aged 6 months to 11 years with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis to a routine of twice-weekly “soak and seal” (SS) procedures consisting of soaking baths for 10 minutes or less, followed by an occlusive emollient, or to twice-daily SS with baths of 15-20 minutes followed by emollient. The groups were treated for 2 weeks, then switched protocols. The study included a total of four clinic visits over 5 weeks. All patients also received standard of care low-potency topical corticosteroids and moisturizer.

Overall, the frequent bathing (“wet method”) led to a decrease of 21.2 on the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis Index (SCORAD) compared with the less frequent bathing (“dry method”). Improvements in SCORAD (the primary outcome) correlated with a secondary outcome of improved scores on the parent-rated Atopic Dermatitis Quickscore.

The findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size, large rate of attrition prior to randomization among initially screened children, lack of data on environmental factors such as water temperature and quality, and the lack of a washout period between the treatment protocols, the researchers noted. They acknowledged that “twice-daily SS bathing in the real world can be time consuming, making adherence difficult for families.”

However, the results suggest that the frequent bathing protocol was safe and effective at improving symptoms of atopic dermatitis, and may reduce steroid use, they concluded.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Cardona ID et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.10.042.