User login

Rash on both palms

The FP diagnosed erythema multiforme (EM) in this patient based on the target lesions with central epithelial disruption on his palms. In this case, the EM was due to the herpes simplex outbreak on the patient’s lips (herpes labialis) that had occurred about a week earlier.

EM is a hypersensitivity reaction that is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in ≥ 60% of cases.

The patient did not know that cold sores were due to herpes simplex and most oral HSV is due to HSV1 infection. He acknowledged that he experienced cold sores about every 2 months that were usually related to stress or exposure to intense sunlight. The FP recommended that the patient avoid intense sunlight (midday sun avoidance; wearing sunscreen and hats) and use lip protection with at least an SPF of 15. As the lip lesions were > 90% healed, there was no reason for the FP to prescribe an antiviral agent. The FP did, however, offer a prescription for valacyclovir to be used at the first signs of an oral herpes outbreak to avoid another case of EM (2000 mg by mouth every 12 hours x 2 doses). For symptomatic relief of the EM, the physician prescribed a 15 g tube of 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied to the lesions twice daily.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed erythema multiforme (EM) in this patient based on the target lesions with central epithelial disruption on his palms. In this case, the EM was due to the herpes simplex outbreak on the patient’s lips (herpes labialis) that had occurred about a week earlier.

EM is a hypersensitivity reaction that is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in ≥ 60% of cases.

The patient did not know that cold sores were due to herpes simplex and most oral HSV is due to HSV1 infection. He acknowledged that he experienced cold sores about every 2 months that were usually related to stress or exposure to intense sunlight. The FP recommended that the patient avoid intense sunlight (midday sun avoidance; wearing sunscreen and hats) and use lip protection with at least an SPF of 15. As the lip lesions were > 90% healed, there was no reason for the FP to prescribe an antiviral agent. The FP did, however, offer a prescription for valacyclovir to be used at the first signs of an oral herpes outbreak to avoid another case of EM (2000 mg by mouth every 12 hours x 2 doses). For symptomatic relief of the EM, the physician prescribed a 15 g tube of 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied to the lesions twice daily.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed erythema multiforme (EM) in this patient based on the target lesions with central epithelial disruption on his palms. In this case, the EM was due to the herpes simplex outbreak on the patient’s lips (herpes labialis) that had occurred about a week earlier.

EM is a hypersensitivity reaction that is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in ≥ 60% of cases.

The patient did not know that cold sores were due to herpes simplex and most oral HSV is due to HSV1 infection. He acknowledged that he experienced cold sores about every 2 months that were usually related to stress or exposure to intense sunlight. The FP recommended that the patient avoid intense sunlight (midday sun avoidance; wearing sunscreen and hats) and use lip protection with at least an SPF of 15. As the lip lesions were > 90% healed, there was no reason for the FP to prescribe an antiviral agent. The FP did, however, offer a prescription for valacyclovir to be used at the first signs of an oral herpes outbreak to avoid another case of EM (2000 mg by mouth every 12 hours x 2 doses). For symptomatic relief of the EM, the physician prescribed a 15 g tube of 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied to the lesions twice daily.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1161-1168.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

“Cupping” With Pain

A 30-year-old woman with a history of chronic overexposure to UV light presents to dermatology for a routine skin exam. The patient has a history of poor toleration to UV light, especially as a child, but participated in regular tanning as a teen. However, she stopped tanning when her sister developed a melanoma.

Additionally, the patient has been experiencing upper back pain, for which she has seen a variety of providers. Most recently, she consulted a naturopath, who recommended cupping therapy. Although the patient believes the therapy is alleviating her pain, she is distressed by the subsequent formation of large blemishes on her back and asks about possible treatment.

EXAMINATION

There are 10 large round patches, each measuring 7 cm in diameter, on the patient’s back. These patches consist of multiple petechiae and brown hyperpigmentation. On palpation, there is no surface disturbance or tenderness. The discoloration is nonblanchable. The size, shape, and configuration of the lesions is consistent with the patient's description of the cupping procedures she has undergone on several occasions.

Notably, the patient's skin is categorized as type II on the Fitzpatrick scale, with advanced dermatoheliosis.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

"Cupping," as medical therapy, was first described in ancient texts 3000 to 4000 years ago. The application of cups to the patient’s skin was intended to draw out substances (eg, toxins and fluids) inside the body that were believed to cause a variety of ailments. Though its use has long since been discarded in mainstream medicine, it is still used routinely in both Chinese and alternative medicine.

Cupping has been evaluated by numerous medical individuals and organizations, who uniformly dismiss any benefit it might offer, even as a placebo. From a pathophysiologic standpoint, cupping causes localized dilation of blood and lymph vessels, thus creating telangiectasia that, as they resolve, leave behind postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and edema. (Excessive production of telangiectasia might indicate pathologic capillary fragility, possibly secondary to Rumpel-Leede phenomenon.)

The patient's skin type can affect the rate of resolution (longer for those with darker skin, shorter for those with fair skin); there is little we can do to speed up this process. Although the case patient was disappointed with the lack of available treatment for her blemishes, she was insistent about continuing the cupping therapy.

Interestingly, there is a differential diagnosis for such lesions; it includes injury from tennis balls, racquetballs, paintballs, or even baseballs—though the associated lesions are usually solitary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Cupping, as medical therapy, has been around for thousands of years and is still routinely used in both Chinese and alternative medicine.

- The intention of its use is to draw out noxious substances that purportedly cause the patient's complaint—however, according to numerous medical authorities, the practice is totally ineffective.

- The suction effect of cupping induces edema and telangiectasia, which in turn results in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that clears slowly.

- Similar lesions can result from being struck by paintballs, racquetballs, tennis balls, and baseballs.

A 30-year-old woman with a history of chronic overexposure to UV light presents to dermatology for a routine skin exam. The patient has a history of poor toleration to UV light, especially as a child, but participated in regular tanning as a teen. However, she stopped tanning when her sister developed a melanoma.

Additionally, the patient has been experiencing upper back pain, for which she has seen a variety of providers. Most recently, she consulted a naturopath, who recommended cupping therapy. Although the patient believes the therapy is alleviating her pain, she is distressed by the subsequent formation of large blemishes on her back and asks about possible treatment.

EXAMINATION

There are 10 large round patches, each measuring 7 cm in diameter, on the patient’s back. These patches consist of multiple petechiae and brown hyperpigmentation. On palpation, there is no surface disturbance or tenderness. The discoloration is nonblanchable. The size, shape, and configuration of the lesions is consistent with the patient's description of the cupping procedures she has undergone on several occasions.

Notably, the patient's skin is categorized as type II on the Fitzpatrick scale, with advanced dermatoheliosis.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

"Cupping," as medical therapy, was first described in ancient texts 3000 to 4000 years ago. The application of cups to the patient’s skin was intended to draw out substances (eg, toxins and fluids) inside the body that were believed to cause a variety of ailments. Though its use has long since been discarded in mainstream medicine, it is still used routinely in both Chinese and alternative medicine.

Cupping has been evaluated by numerous medical individuals and organizations, who uniformly dismiss any benefit it might offer, even as a placebo. From a pathophysiologic standpoint, cupping causes localized dilation of blood and lymph vessels, thus creating telangiectasia that, as they resolve, leave behind postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and edema. (Excessive production of telangiectasia might indicate pathologic capillary fragility, possibly secondary to Rumpel-Leede phenomenon.)

The patient's skin type can affect the rate of resolution (longer for those with darker skin, shorter for those with fair skin); there is little we can do to speed up this process. Although the case patient was disappointed with the lack of available treatment for her blemishes, she was insistent about continuing the cupping therapy.

Interestingly, there is a differential diagnosis for such lesions; it includes injury from tennis balls, racquetballs, paintballs, or even baseballs—though the associated lesions are usually solitary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Cupping, as medical therapy, has been around for thousands of years and is still routinely used in both Chinese and alternative medicine.

- The intention of its use is to draw out noxious substances that purportedly cause the patient's complaint—however, according to numerous medical authorities, the practice is totally ineffective.

- The suction effect of cupping induces edema and telangiectasia, which in turn results in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that clears slowly.

- Similar lesions can result from being struck by paintballs, racquetballs, tennis balls, and baseballs.

A 30-year-old woman with a history of chronic overexposure to UV light presents to dermatology for a routine skin exam. The patient has a history of poor toleration to UV light, especially as a child, but participated in regular tanning as a teen. However, she stopped tanning when her sister developed a melanoma.

Additionally, the patient has been experiencing upper back pain, for which she has seen a variety of providers. Most recently, she consulted a naturopath, who recommended cupping therapy. Although the patient believes the therapy is alleviating her pain, she is distressed by the subsequent formation of large blemishes on her back and asks about possible treatment.

EXAMINATION

There are 10 large round patches, each measuring 7 cm in diameter, on the patient’s back. These patches consist of multiple petechiae and brown hyperpigmentation. On palpation, there is no surface disturbance or tenderness. The discoloration is nonblanchable. The size, shape, and configuration of the lesions is consistent with the patient's description of the cupping procedures she has undergone on several occasions.

Notably, the patient's skin is categorized as type II on the Fitzpatrick scale, with advanced dermatoheliosis.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

"Cupping," as medical therapy, was first described in ancient texts 3000 to 4000 years ago. The application of cups to the patient’s skin was intended to draw out substances (eg, toxins and fluids) inside the body that were believed to cause a variety of ailments. Though its use has long since been discarded in mainstream medicine, it is still used routinely in both Chinese and alternative medicine.

Cupping has been evaluated by numerous medical individuals and organizations, who uniformly dismiss any benefit it might offer, even as a placebo. From a pathophysiologic standpoint, cupping causes localized dilation of blood and lymph vessels, thus creating telangiectasia that, as they resolve, leave behind postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and edema. (Excessive production of telangiectasia might indicate pathologic capillary fragility, possibly secondary to Rumpel-Leede phenomenon.)

The patient's skin type can affect the rate of resolution (longer for those with darker skin, shorter for those with fair skin); there is little we can do to speed up this process. Although the case patient was disappointed with the lack of available treatment for her blemishes, she was insistent about continuing the cupping therapy.

Interestingly, there is a differential diagnosis for such lesions; it includes injury from tennis balls, racquetballs, paintballs, or even baseballs—though the associated lesions are usually solitary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Cupping, as medical therapy, has been around for thousands of years and is still routinely used in both Chinese and alternative medicine.

- The intention of its use is to draw out noxious substances that purportedly cause the patient's complaint—however, according to numerous medical authorities, the practice is totally ineffective.

- The suction effect of cupping induces edema and telangiectasia, which in turn results in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that clears slowly.

- Similar lesions can result from being struck by paintballs, racquetballs, tennis balls, and baseballs.

Facial swelling in an adolescent

A 16-year-old boy sought care at a rural hospital in Panama for facial swelling that began 3 months earlier. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a volunteer effort. The patient had difficulty opening his left eye. He denied fever and chills, and said he felt well—other than his inability to see out of his left eye. He denied any changes to his vision when he held the swollen eyelids open. The patient lived on a ranch far outside of town, and he walked down a mountain road alone for 6 hours with one eye swollen shut to present for treatment. The patient was not taking any medications and had not received any health care since his last vaccine several years ago. On physical exam, his vital signs were normal, and the swelling under his left eye was somewhat tender and slightly warm to the touch. There were no lesions on his trunk and the remainder of the exam was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nodulocystic acne

The family physician (FP) diagnosed severe inflammatory nodulocystic acne in this patient. He initially was concerned about possible cellulitis or an abscess, but his clinical experience suggested the swelling was secondary to severe inflammation and not a bacterial infection. The FP noted that the patient was afebrile and lacked systemic symptoms. In addition, the presence of open and closed comedones on the face, as well as the patient’s age and sex, supported the diagnosis of acne. No tests were performed; the diagnosis was made clinically.

A case of acne, or a bacterial infection?

The FP considered acne conglobata, acne fulminans, and a bacterial infection as other possible causes of the patient’s facial swelling.

Acne conglobata is a form of severe inflammatory cystic acne that affects the face, chest, and back. It is characterized by nodules, cysts, large open comedones, and interconnecting sinuses.1,2 Although this case of acne was severe, the young man did not have large open comedones or interconnecting sinus tracts. In addition, his trunk was unaffected.

Acne fulminans is a type of severe cystic acne with systemic symptoms, which is mainly seen in adolescent males. It may have a sudden onset and is characterized by ulcerated, nodular, and painful acne that bleeds, crusts, and results in severe scarring. Patients may present with fever, joint pain, and weight loss.1,2 Our patient did not have systemic symptoms despite the severe facial swelling.

Bacterial infections of the skin usually are caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) or Streptococcus pyogenes and can lead to cellulitis and/or abscess formation.3 This process was considered as a complication of the severe acne, but the clinical picture was consistent with severe inflammation rather than a bacterial superinfection.

Continue to: Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

The FP knew that the severe inflammation and swelling needed to be treated with a systemic steroid, so he started the patient on prednisone 60 mg orally once daily at the time of presentation. Additionally, the FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg bid to treat the inflammation and to cover a possible superinfection.

Doxycycline is the oral antibiotic of choice for inflammatory acne.2 It also is a good antibiotic for cutaneous methicillin-resistant S aureus infection.3 Although it is not the treatment of choice for a nonpurulent cellulitis, it is a good option for cellulitis with purulence.3

With the working diagnosis of severe inflammatory acne, it was expected that the prednisone and doxycycline would be effective. Treating with antibiotics alone (for fear of causing immunosuppression with steroids) would have likely been less effective. Since the patient lived 6 hours from the hospital by foot and was alone, he was admitted overnight for observation (with parental permission obtained over the phone).

The patient’s condition improved overnight. Marked improvement in the swelling and inflammation was noted the following morning (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The patient was pleased with the results and was discharged to return home (transportation provided by the hospital) with directions on how to continue the oral prednisone and doxycycline. He was given 1 month of doxycycline to continue (100 mg bid) and enough oral prednisone to take 40 mg/d for 1 week and 20 mg/d for another week. He was given a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks to assess his acne and his ability to tolerate the medications.

He was warned to avoid the sun as much as possible, as doxycycline is photosensitizing, and to use a large hat and sunscreen when the sun could not be avoided. (Another option would have been to prescribe minocycline 100 mg bid because it is equally effective for acne with a lower risk for photosensitization.2)

Continue to: Access to medical care was limited

Access to medical care was limited. Although this patient was a good candidate for oral isotretinoin treatment, he did not have access to this medication in rural Panama. Managing his acne was challenging because of the severity of the case and the patient’s sun exposure in this tropical country. Access to the full range of topical anti-acne treatments also is limited in rural Panama, but fortunately his response to the initial oral medications was good.

The future plan at the follow-up visit consisted of continuing the doxycycline, stopping the prednisone, and adding topical benzoyl peroxide. The purpose of the benzoyl peroxide was to prevent bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.2

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard Usatine, MD, Skin Clinic, 903 W Martin Ave, Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected]

1. Usatine R, Bambekova P, Shiu V. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:717-724.

2. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:E10-E52.

A 16-year-old boy sought care at a rural hospital in Panama for facial swelling that began 3 months earlier. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a volunteer effort. The patient had difficulty opening his left eye. He denied fever and chills, and said he felt well—other than his inability to see out of his left eye. He denied any changes to his vision when he held the swollen eyelids open. The patient lived on a ranch far outside of town, and he walked down a mountain road alone for 6 hours with one eye swollen shut to present for treatment. The patient was not taking any medications and had not received any health care since his last vaccine several years ago. On physical exam, his vital signs were normal, and the swelling under his left eye was somewhat tender and slightly warm to the touch. There were no lesions on his trunk and the remainder of the exam was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nodulocystic acne

The family physician (FP) diagnosed severe inflammatory nodulocystic acne in this patient. He initially was concerned about possible cellulitis or an abscess, but his clinical experience suggested the swelling was secondary to severe inflammation and not a bacterial infection. The FP noted that the patient was afebrile and lacked systemic symptoms. In addition, the presence of open and closed comedones on the face, as well as the patient’s age and sex, supported the diagnosis of acne. No tests were performed; the diagnosis was made clinically.

A case of acne, or a bacterial infection?

The FP considered acne conglobata, acne fulminans, and a bacterial infection as other possible causes of the patient’s facial swelling.

Acne conglobata is a form of severe inflammatory cystic acne that affects the face, chest, and back. It is characterized by nodules, cysts, large open comedones, and interconnecting sinuses.1,2 Although this case of acne was severe, the young man did not have large open comedones or interconnecting sinus tracts. In addition, his trunk was unaffected.

Acne fulminans is a type of severe cystic acne with systemic symptoms, which is mainly seen in adolescent males. It may have a sudden onset and is characterized by ulcerated, nodular, and painful acne that bleeds, crusts, and results in severe scarring. Patients may present with fever, joint pain, and weight loss.1,2 Our patient did not have systemic symptoms despite the severe facial swelling.

Bacterial infections of the skin usually are caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) or Streptococcus pyogenes and can lead to cellulitis and/or abscess formation.3 This process was considered as a complication of the severe acne, but the clinical picture was consistent with severe inflammation rather than a bacterial superinfection.

Continue to: Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

The FP knew that the severe inflammation and swelling needed to be treated with a systemic steroid, so he started the patient on prednisone 60 mg orally once daily at the time of presentation. Additionally, the FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg bid to treat the inflammation and to cover a possible superinfection.

Doxycycline is the oral antibiotic of choice for inflammatory acne.2 It also is a good antibiotic for cutaneous methicillin-resistant S aureus infection.3 Although it is not the treatment of choice for a nonpurulent cellulitis, it is a good option for cellulitis with purulence.3

With the working diagnosis of severe inflammatory acne, it was expected that the prednisone and doxycycline would be effective. Treating with antibiotics alone (for fear of causing immunosuppression with steroids) would have likely been less effective. Since the patient lived 6 hours from the hospital by foot and was alone, he was admitted overnight for observation (with parental permission obtained over the phone).

The patient’s condition improved overnight. Marked improvement in the swelling and inflammation was noted the following morning (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The patient was pleased with the results and was discharged to return home (transportation provided by the hospital) with directions on how to continue the oral prednisone and doxycycline. He was given 1 month of doxycycline to continue (100 mg bid) and enough oral prednisone to take 40 mg/d for 1 week and 20 mg/d for another week. He was given a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks to assess his acne and his ability to tolerate the medications.

He was warned to avoid the sun as much as possible, as doxycycline is photosensitizing, and to use a large hat and sunscreen when the sun could not be avoided. (Another option would have been to prescribe minocycline 100 mg bid because it is equally effective for acne with a lower risk for photosensitization.2)

Continue to: Access to medical care was limited

Access to medical care was limited. Although this patient was a good candidate for oral isotretinoin treatment, he did not have access to this medication in rural Panama. Managing his acne was challenging because of the severity of the case and the patient’s sun exposure in this tropical country. Access to the full range of topical anti-acne treatments also is limited in rural Panama, but fortunately his response to the initial oral medications was good.

The future plan at the follow-up visit consisted of continuing the doxycycline, stopping the prednisone, and adding topical benzoyl peroxide. The purpose of the benzoyl peroxide was to prevent bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.2

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard Usatine, MD, Skin Clinic, 903 W Martin Ave, Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected]

A 16-year-old boy sought care at a rural hospital in Panama for facial swelling that began 3 months earlier. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a volunteer effort. The patient had difficulty opening his left eye. He denied fever and chills, and said he felt well—other than his inability to see out of his left eye. He denied any changes to his vision when he held the swollen eyelids open. The patient lived on a ranch far outside of town, and he walked down a mountain road alone for 6 hours with one eye swollen shut to present for treatment. The patient was not taking any medications and had not received any health care since his last vaccine several years ago. On physical exam, his vital signs were normal, and the swelling under his left eye was somewhat tender and slightly warm to the touch. There were no lesions on his trunk and the remainder of the exam was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nodulocystic acne

The family physician (FP) diagnosed severe inflammatory nodulocystic acne in this patient. He initially was concerned about possible cellulitis or an abscess, but his clinical experience suggested the swelling was secondary to severe inflammation and not a bacterial infection. The FP noted that the patient was afebrile and lacked systemic symptoms. In addition, the presence of open and closed comedones on the face, as well as the patient’s age and sex, supported the diagnosis of acne. No tests were performed; the diagnosis was made clinically.

A case of acne, or a bacterial infection?

The FP considered acne conglobata, acne fulminans, and a bacterial infection as other possible causes of the patient’s facial swelling.

Acne conglobata is a form of severe inflammatory cystic acne that affects the face, chest, and back. It is characterized by nodules, cysts, large open comedones, and interconnecting sinuses.1,2 Although this case of acne was severe, the young man did not have large open comedones or interconnecting sinus tracts. In addition, his trunk was unaffected.

Acne fulminans is a type of severe cystic acne with systemic symptoms, which is mainly seen in adolescent males. It may have a sudden onset and is characterized by ulcerated, nodular, and painful acne that bleeds, crusts, and results in severe scarring. Patients may present with fever, joint pain, and weight loss.1,2 Our patient did not have systemic symptoms despite the severe facial swelling.

Bacterial infections of the skin usually are caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) or Streptococcus pyogenes and can lead to cellulitis and/or abscess formation.3 This process was considered as a complication of the severe acne, but the clinical picture was consistent with severe inflammation rather than a bacterial superinfection.

Continue to: Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

The FP knew that the severe inflammation and swelling needed to be treated with a systemic steroid, so he started the patient on prednisone 60 mg orally once daily at the time of presentation. Additionally, the FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg bid to treat the inflammation and to cover a possible superinfection.

Doxycycline is the oral antibiotic of choice for inflammatory acne.2 It also is a good antibiotic for cutaneous methicillin-resistant S aureus infection.3 Although it is not the treatment of choice for a nonpurulent cellulitis, it is a good option for cellulitis with purulence.3

With the working diagnosis of severe inflammatory acne, it was expected that the prednisone and doxycycline would be effective. Treating with antibiotics alone (for fear of causing immunosuppression with steroids) would have likely been less effective. Since the patient lived 6 hours from the hospital by foot and was alone, he was admitted overnight for observation (with parental permission obtained over the phone).

The patient’s condition improved overnight. Marked improvement in the swelling and inflammation was noted the following morning (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The patient was pleased with the results and was discharged to return home (transportation provided by the hospital) with directions on how to continue the oral prednisone and doxycycline. He was given 1 month of doxycycline to continue (100 mg bid) and enough oral prednisone to take 40 mg/d for 1 week and 20 mg/d for another week. He was given a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks to assess his acne and his ability to tolerate the medications.

He was warned to avoid the sun as much as possible, as doxycycline is photosensitizing, and to use a large hat and sunscreen when the sun could not be avoided. (Another option would have been to prescribe minocycline 100 mg bid because it is equally effective for acne with a lower risk for photosensitization.2)

Continue to: Access to medical care was limited

Access to medical care was limited. Although this patient was a good candidate for oral isotretinoin treatment, he did not have access to this medication in rural Panama. Managing his acne was challenging because of the severity of the case and the patient’s sun exposure in this tropical country. Access to the full range of topical anti-acne treatments also is limited in rural Panama, but fortunately his response to the initial oral medications was good.

The future plan at the follow-up visit consisted of continuing the doxycycline, stopping the prednisone, and adding topical benzoyl peroxide. The purpose of the benzoyl peroxide was to prevent bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.2

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard Usatine, MD, Skin Clinic, 903 W Martin Ave, Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected]

1. Usatine R, Bambekova P, Shiu V. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:717-724.

2. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:E10-E52.

1. Usatine R, Bambekova P, Shiu V. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:717-724.

2. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:E10-E52.

Multiple hyperpigmented papules and plaques

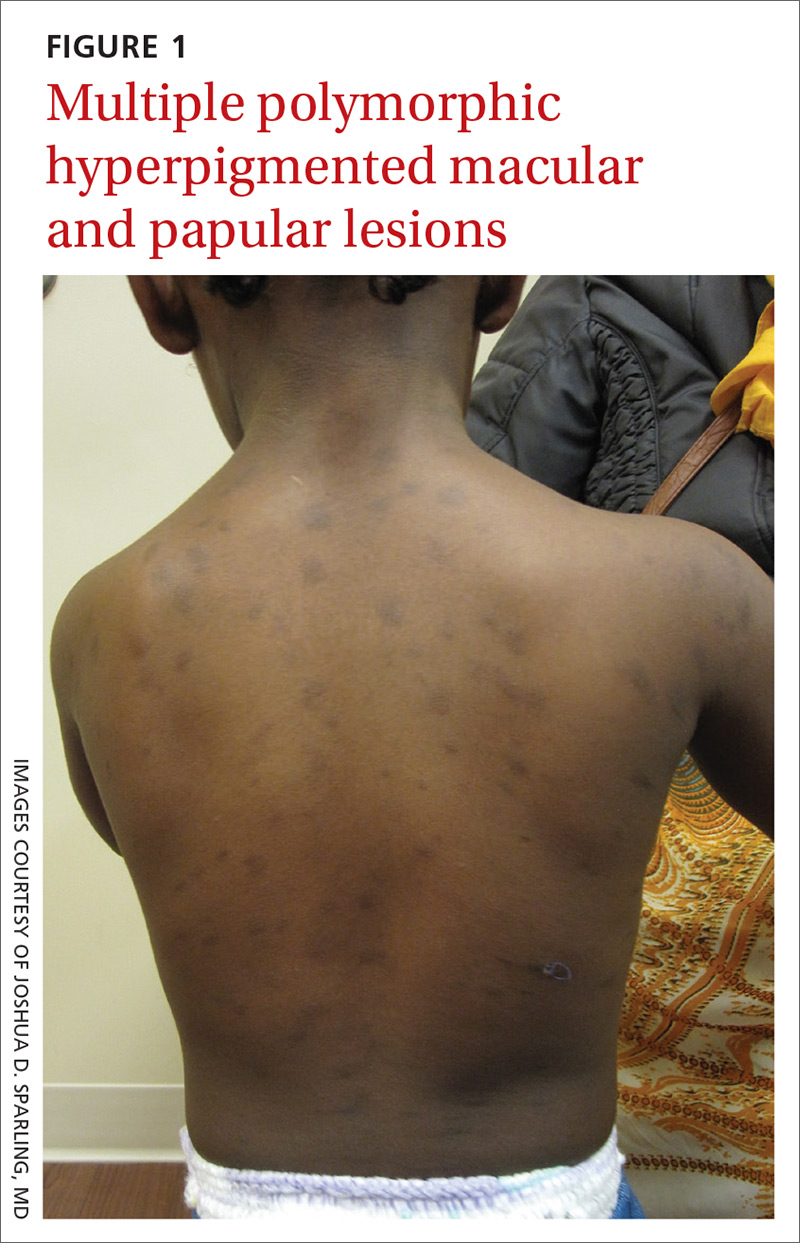

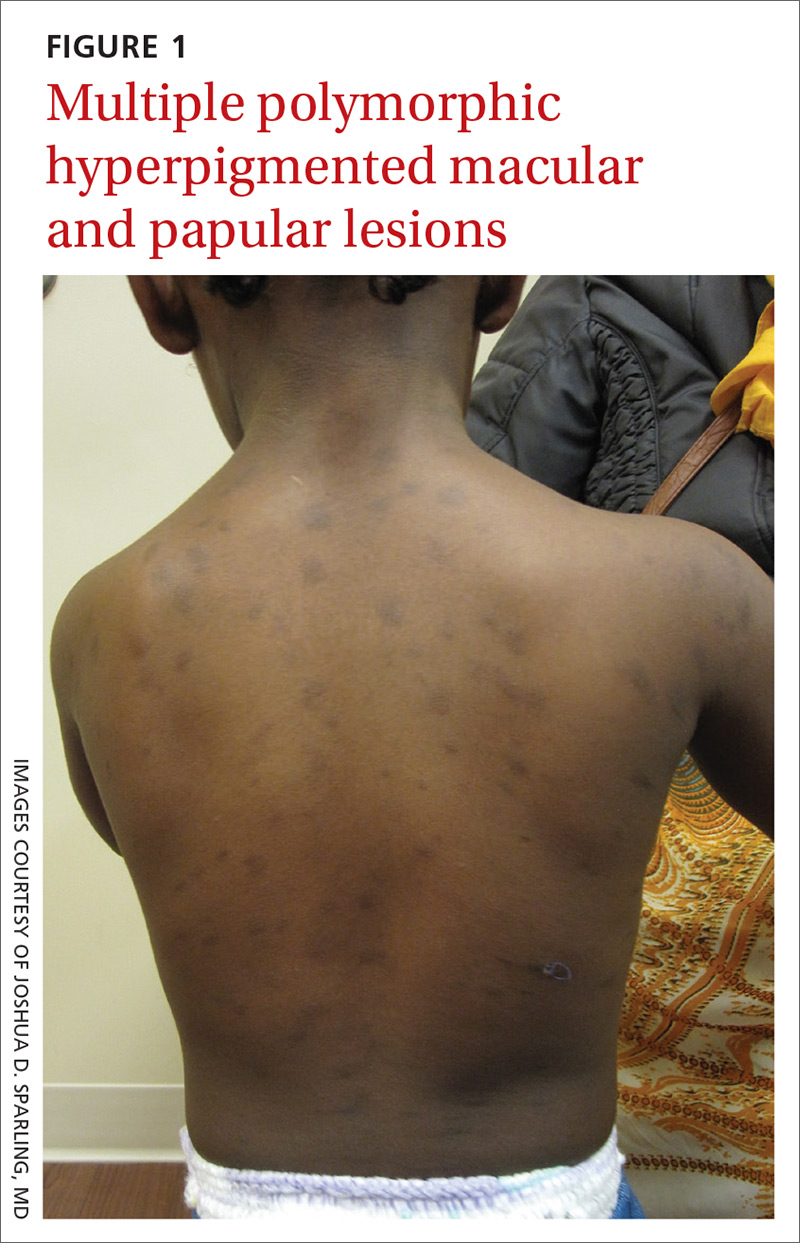

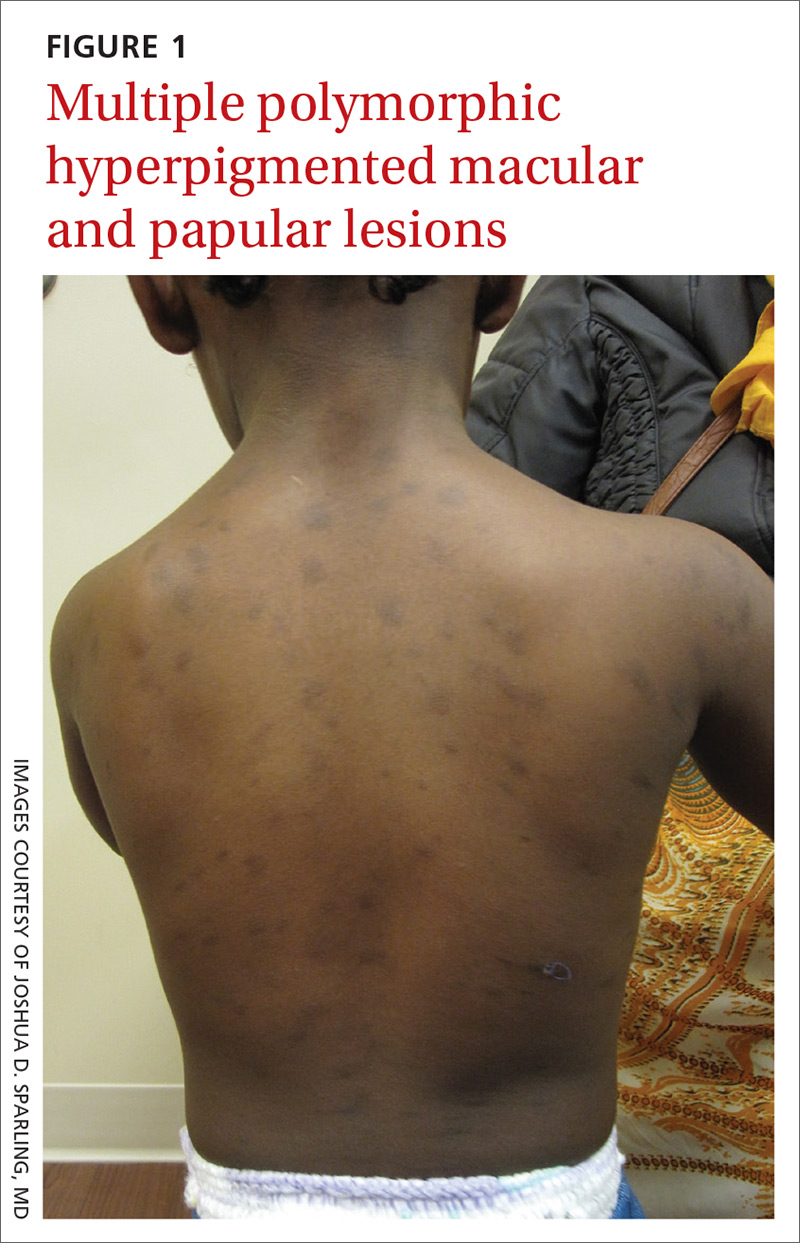

A 2-year-old girl with Fitzpatrick skin type VI who had recently emigrated from Djibouti presented to our dermatology clinic for a rash that appeared when she was 2 months old. The lesions occasionally were pruritic after sun exposure or after crawling outside. There was no associated abdominal pain, diarrhea, flushing, or hypotension. Topical moisturizers were not helpful.

The patient had no known allergies or other notable medical history. Physical examination revealed multiple hyperpigmented, oval-shaped, slightly raised papules and plaques on her torso (FIGURE 1), neck, and arms, and fewer lesions on her face and legs. Darier sign was not appreciated on the initial consult. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the patient’s right middle back was performed at this visit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

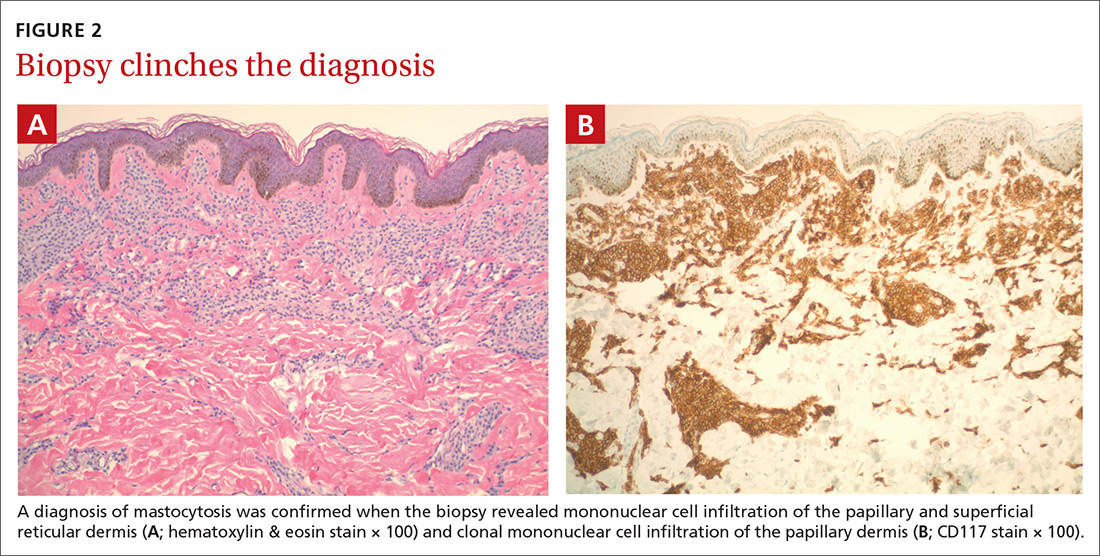

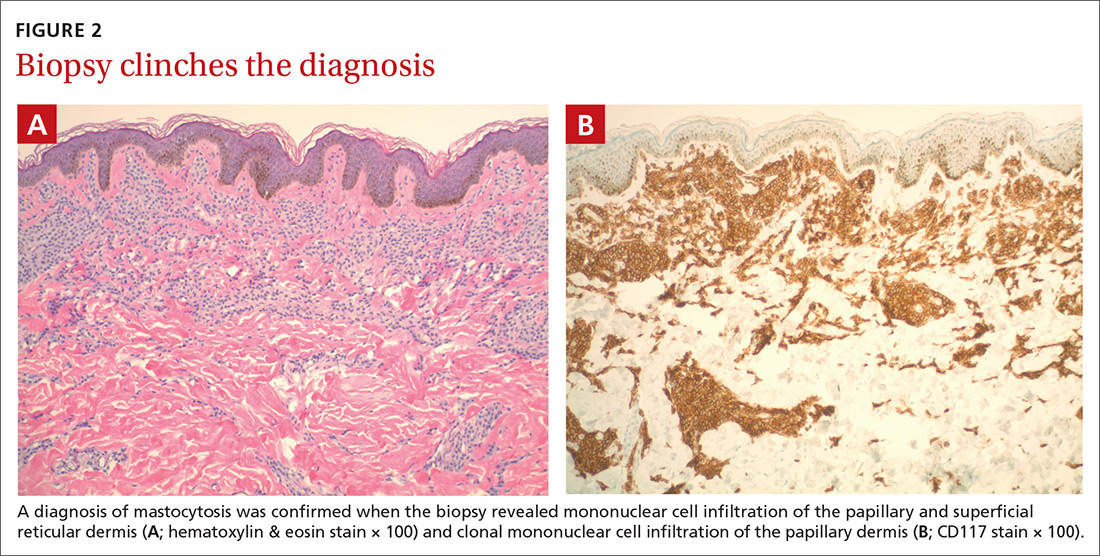

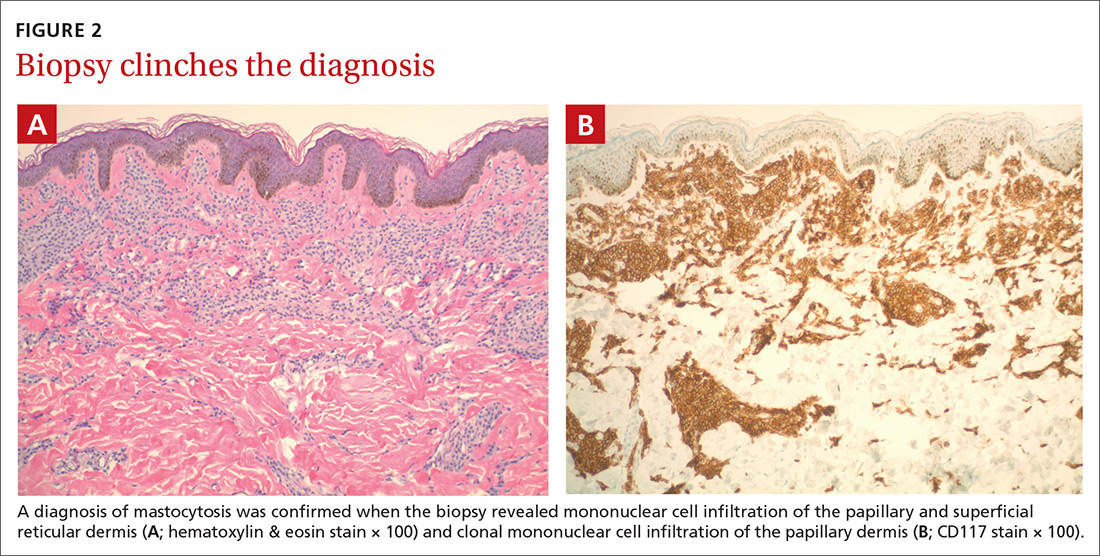

Diagnosis: Mastocytosis

The presence of a hyperpigmented skin lesion that becomes pruritic, raised, and erythematous when rubbed (Darier sign) is the major criterion for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis.1 Minor criteria include a skin biopsy demonstrating a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of mast cells within the papillary dermis and the presence of cKIT mutations.1 In this case, the patient’s punch biopsy results came back positive for clonal mast cell infiltration of the papillary dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B), and her physician elicited a slightly positive Darier sign during a follow-up visit.

Mastocytosis is characterized by pathognomonic proliferation of clonal mast cells with either cutaneous or systemic involvement.1 Mast cell expansion most commonly is found in the skin and bone marrow; however, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes also has been documented.1 Nonhereditary somatic mutations of the cKIT gene have been observed in many studies and may be associated with increased proliferation of clonal mast cells.2

A review of the English-language literature on cutaneous mastocytosis reveals a paucity of reports in darker skin types. However, it is important for clinicians to be able to recognize this disease in all skin types.

Three subcategories. Cutaneous mastocytosis is divided into 3 subcategories: mastocytoma of the skin (1–3 solitary skin lesions), maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, also known as urticaria pigmentosa (as seen in our patient; usually ≥ 4 lesions); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (confluent lesions; leathery appearance of skin).1,3,4 Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, which our patient had, classically develops within the first 6 months of life and presents as hyperpigmented macules and papules.

Keep in mind that systemic involvement in cutaneous mastocytosis occasionally occurs and can be associated with anaphylaxis, flushing, headache, dyspnea, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.2

Continue to: Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Our cas a ase was made somewhat challenging by the patient’s darkly pigmented skin color, which made any erythema and other cutaneous signs less visible. The differential was broad and included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from eczema, multiple congenital nevi, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and cutaneous tuberculosis, all of which can be eliminated by performing a biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnostic criteria include biopsy and laboratory findings

In addition to a skin biopsy, initial assessment in cases of suspected cutaneous mastocytosis should include a complete blood cell count with differential, liver function tests (+/- liver ultrasound), a serum tryptase level, and a peripheral smear. Serum tryptase levels > 20 ng/mL have been shown to correlate with a higher probability of systemic mastocytosis. Higher tryptase levels also correlate with severity of disease in children.5

Treatment focuses on minimizing mast cell degranulation

Due to the relatively benign course of cutaneous mastocytosis, the mainstay of treatment is focused on minimizing mast cell degranulation to control subsequent symptoms. Avoiding precipitating factors such as temperature extremes, external stimulation of lesions, dry skin, infection, and certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, morphine, polymyxin B sulphate, anticholinergics, some systemic anesthetics) that can stimulate mast cell degranulation is encouraged.2 H1 and H2 antihistamines are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms. In refractory cases, leukotriene receptor antagonists or oral cromolyn sodium may be considered.2

Regular follow-up every 6 to 12 months should be established after diagnosis.1 If symptoms persist into adulthood or concern for disease progression is high, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended.1

Our patient

Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a normal serum tryptase level (3.4 ng/mL; reference range < 11.5 ng/mL) and complete blood cell count. A complete metabolic panel demonstrated elevated and high-normal liver function tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 111 u/L (reference range, 10–40 u/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 55 u/L (reference range, 7–56 u/L).

Continue to: As a precaution...

As a precaution and for consideration of further work-up, such as the need for a liver ultrasound, the patient was referred to Pediatric Gastroenterology. The specialist repeated the liver function tests, the results of which were lower (ALT, 42 u/L; AST, 24 u/L); a liver ultrasound was thought to be unnecessary.

Our patient’s otherwise negative review of systems led the specialist to feel confident that no systemic disease was present at the time. These results were discussed with the patient’s parents and counseling about trigger avoidance was provided. The patient was given pediatric-dosed oral and topical H1 antihistamines for symptom relief.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, 6 E Chestnut Street, Ste 340, Augusta, ME 04330; [email protected]

1. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al . Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

2. Abid A, Malone MA, Curci K. Mastocytosis. Prim Care. 2016;43:505-518.

3. Forster A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favourable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1581-1590.

4. Tharp MD, Sofen BD. Mastocytosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2103-2104.

5. Carter MC, Clayton ST, Komarow MD, et al. Assessment of clinical findings, tryptase levels and bone marrow histopathology in the management of pediatric mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin

A 2-year-old girl with Fitzpatrick skin type VI who had recently emigrated from Djibouti presented to our dermatology clinic for a rash that appeared when she was 2 months old. The lesions occasionally were pruritic after sun exposure or after crawling outside. There was no associated abdominal pain, diarrhea, flushing, or hypotension. Topical moisturizers were not helpful.

The patient had no known allergies or other notable medical history. Physical examination revealed multiple hyperpigmented, oval-shaped, slightly raised papules and plaques on her torso (FIGURE 1), neck, and arms, and fewer lesions on her face and legs. Darier sign was not appreciated on the initial consult. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the patient’s right middle back was performed at this visit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mastocytosis

The presence of a hyperpigmented skin lesion that becomes pruritic, raised, and erythematous when rubbed (Darier sign) is the major criterion for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis.1 Minor criteria include a skin biopsy demonstrating a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of mast cells within the papillary dermis and the presence of cKIT mutations.1 In this case, the patient’s punch biopsy results came back positive for clonal mast cell infiltration of the papillary dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B), and her physician elicited a slightly positive Darier sign during a follow-up visit.

Mastocytosis is characterized by pathognomonic proliferation of clonal mast cells with either cutaneous or systemic involvement.1 Mast cell expansion most commonly is found in the skin and bone marrow; however, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes also has been documented.1 Nonhereditary somatic mutations of the cKIT gene have been observed in many studies and may be associated with increased proliferation of clonal mast cells.2

A review of the English-language literature on cutaneous mastocytosis reveals a paucity of reports in darker skin types. However, it is important for clinicians to be able to recognize this disease in all skin types.

Three subcategories. Cutaneous mastocytosis is divided into 3 subcategories: mastocytoma of the skin (1–3 solitary skin lesions), maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, also known as urticaria pigmentosa (as seen in our patient; usually ≥ 4 lesions); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (confluent lesions; leathery appearance of skin).1,3,4 Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, which our patient had, classically develops within the first 6 months of life and presents as hyperpigmented macules and papules.

Keep in mind that systemic involvement in cutaneous mastocytosis occasionally occurs and can be associated with anaphylaxis, flushing, headache, dyspnea, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.2

Continue to: Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Our cas a ase was made somewhat challenging by the patient’s darkly pigmented skin color, which made any erythema and other cutaneous signs less visible. The differential was broad and included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from eczema, multiple congenital nevi, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and cutaneous tuberculosis, all of which can be eliminated by performing a biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnostic criteria include biopsy and laboratory findings

In addition to a skin biopsy, initial assessment in cases of suspected cutaneous mastocytosis should include a complete blood cell count with differential, liver function tests (+/- liver ultrasound), a serum tryptase level, and a peripheral smear. Serum tryptase levels > 20 ng/mL have been shown to correlate with a higher probability of systemic mastocytosis. Higher tryptase levels also correlate with severity of disease in children.5

Treatment focuses on minimizing mast cell degranulation

Due to the relatively benign course of cutaneous mastocytosis, the mainstay of treatment is focused on minimizing mast cell degranulation to control subsequent symptoms. Avoiding precipitating factors such as temperature extremes, external stimulation of lesions, dry skin, infection, and certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, morphine, polymyxin B sulphate, anticholinergics, some systemic anesthetics) that can stimulate mast cell degranulation is encouraged.2 H1 and H2 antihistamines are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms. In refractory cases, leukotriene receptor antagonists or oral cromolyn sodium may be considered.2

Regular follow-up every 6 to 12 months should be established after diagnosis.1 If symptoms persist into adulthood or concern for disease progression is high, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended.1

Our patient

Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a normal serum tryptase level (3.4 ng/mL; reference range < 11.5 ng/mL) and complete blood cell count. A complete metabolic panel demonstrated elevated and high-normal liver function tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 111 u/L (reference range, 10–40 u/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 55 u/L (reference range, 7–56 u/L).

Continue to: As a precaution...

As a precaution and for consideration of further work-up, such as the need for a liver ultrasound, the patient was referred to Pediatric Gastroenterology. The specialist repeated the liver function tests, the results of which were lower (ALT, 42 u/L; AST, 24 u/L); a liver ultrasound was thought to be unnecessary.

Our patient’s otherwise negative review of systems led the specialist to feel confident that no systemic disease was present at the time. These results were discussed with the patient’s parents and counseling about trigger avoidance was provided. The patient was given pediatric-dosed oral and topical H1 antihistamines for symptom relief.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, 6 E Chestnut Street, Ste 340, Augusta, ME 04330; [email protected]

A 2-year-old girl with Fitzpatrick skin type VI who had recently emigrated from Djibouti presented to our dermatology clinic for a rash that appeared when she was 2 months old. The lesions occasionally were pruritic after sun exposure or after crawling outside. There was no associated abdominal pain, diarrhea, flushing, or hypotension. Topical moisturizers were not helpful.

The patient had no known allergies or other notable medical history. Physical examination revealed multiple hyperpigmented, oval-shaped, slightly raised papules and plaques on her torso (FIGURE 1), neck, and arms, and fewer lesions on her face and legs. Darier sign was not appreciated on the initial consult. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the patient’s right middle back was performed at this visit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mastocytosis

The presence of a hyperpigmented skin lesion that becomes pruritic, raised, and erythematous when rubbed (Darier sign) is the major criterion for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis.1 Minor criteria include a skin biopsy demonstrating a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of mast cells within the papillary dermis and the presence of cKIT mutations.1 In this case, the patient’s punch biopsy results came back positive for clonal mast cell infiltration of the papillary dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B), and her physician elicited a slightly positive Darier sign during a follow-up visit.

Mastocytosis is characterized by pathognomonic proliferation of clonal mast cells with either cutaneous or systemic involvement.1 Mast cell expansion most commonly is found in the skin and bone marrow; however, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes also has been documented.1 Nonhereditary somatic mutations of the cKIT gene have been observed in many studies and may be associated with increased proliferation of clonal mast cells.2

A review of the English-language literature on cutaneous mastocytosis reveals a paucity of reports in darker skin types. However, it is important for clinicians to be able to recognize this disease in all skin types.

Three subcategories. Cutaneous mastocytosis is divided into 3 subcategories: mastocytoma of the skin (1–3 solitary skin lesions), maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, also known as urticaria pigmentosa (as seen in our patient; usually ≥ 4 lesions); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (confluent lesions; leathery appearance of skin).1,3,4 Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, which our patient had, classically develops within the first 6 months of life and presents as hyperpigmented macules and papules.

Keep in mind that systemic involvement in cutaneous mastocytosis occasionally occurs and can be associated with anaphylaxis, flushing, headache, dyspnea, nausea, emesis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.2

Continue to: Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Narrowing down a broad differential diagnosis

Our cas a ase was made somewhat challenging by the patient’s darkly pigmented skin color, which made any erythema and other cutaneous signs less visible. The differential was broad and included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from eczema, multiple congenital nevi, sarcoidosis, leprosy, and cutaneous tuberculosis, all of which can be eliminated by performing a biopsy of the lesion.

Diagnostic criteria include biopsy and laboratory findings

In addition to a skin biopsy, initial assessment in cases of suspected cutaneous mastocytosis should include a complete blood cell count with differential, liver function tests (+/- liver ultrasound), a serum tryptase level, and a peripheral smear. Serum tryptase levels > 20 ng/mL have been shown to correlate with a higher probability of systemic mastocytosis. Higher tryptase levels also correlate with severity of disease in children.5

Treatment focuses on minimizing mast cell degranulation

Due to the relatively benign course of cutaneous mastocytosis, the mainstay of treatment is focused on minimizing mast cell degranulation to control subsequent symptoms. Avoiding precipitating factors such as temperature extremes, external stimulation of lesions, dry skin, infection, and certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, morphine, polymyxin B sulphate, anticholinergics, some systemic anesthetics) that can stimulate mast cell degranulation is encouraged.2 H1 and H2 antihistamines are the first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms. In refractory cases, leukotriene receptor antagonists or oral cromolyn sodium may be considered.2

Regular follow-up every 6 to 12 months should be established after diagnosis.1 If symptoms persist into adulthood or concern for disease progression is high, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended.1

Our patient

Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a normal serum tryptase level (3.4 ng/mL; reference range < 11.5 ng/mL) and complete blood cell count. A complete metabolic panel demonstrated elevated and high-normal liver function tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 111 u/L (reference range, 10–40 u/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 55 u/L (reference range, 7–56 u/L).

Continue to: As a precaution...

As a precaution and for consideration of further work-up, such as the need for a liver ultrasound, the patient was referred to Pediatric Gastroenterology. The specialist repeated the liver function tests, the results of which were lower (ALT, 42 u/L; AST, 24 u/L); a liver ultrasound was thought to be unnecessary.

Our patient’s otherwise negative review of systems led the specialist to feel confident that no systemic disease was present at the time. These results were discussed with the patient’s parents and counseling about trigger avoidance was provided. The patient was given pediatric-dosed oral and topical H1 antihistamines for symptom relief.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joshua D. Sparling, MD, 6 E Chestnut Street, Ste 340, Augusta, ME 04330; [email protected]

1. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al . Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

2. Abid A, Malone MA, Curci K. Mastocytosis. Prim Care. 2016;43:505-518.

3. Forster A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favourable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1581-1590.

4. Tharp MD, Sofen BD. Mastocytosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2103-2104.

5. Carter MC, Clayton ST, Komarow MD, et al. Assessment of clinical findings, tryptase levels and bone marrow histopathology in the management of pediatric mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin

1. Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al . Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

2. Abid A, Malone MA, Curci K. Mastocytosis. Prim Care. 2016;43:505-518.

3. Forster A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favourable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1581-1590.

4. Tharp MD, Sofen BD. Mastocytosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2103-2104.

5. Carter MC, Clayton ST, Komarow MD, et al. Assessment of clinical findings, tryptase levels and bone marrow histopathology in the management of pediatric mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin

Managing dermatologic changes of targeted cancer therapy

Advances in cancer therapy have improved survival, such that many cancers have been transformed from a terminal illness to a chronic disease, and the population of patients living with cancer or who are disease-free has grown. However, these patients face complex medical problems because of the systemic effects of their treatment and many endure a constellation of treatment-emergent adverse effects that require ongoing care and support.1

Primary care physicians have been called on to take a larger role in the care of these adverse effects as the growing number of treatments has meant more affected patients. In addition, an urgent, unmet need has developed for better coordination between specialists and family physicians for providing this supportive care.2

In this article, we (1) describe the most commonly encountered cancer treatment–related skin toxicities, paying particular attention to the effects of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–targeting therapies, and (2) review up-to-date management recommendations in an area of practice where established clinical guidance from the scientific literature is limited.

Biggest culprit: Targeted cancer therapies

Skin rash and dermatologic adverse effects are commonplace in patients undergoing cancer treatment; timely management can often prevent long-term skin damage.3 Dermatologic effects have been associated with various therapeutic agents, but are most commonly associated with targeted therapies—specifically, agents targeting EGFR.

Why the attention to EGFR inhibition? EGFR is overexpressed or mutated in a multitude of solid tumors; as such, agents have been developed that target this aberrant signaling pathway. EGFR is highly expressed in the skin and dermal tissue, where it plays a number of roles, including protection against ultraviolet radiation damage.4

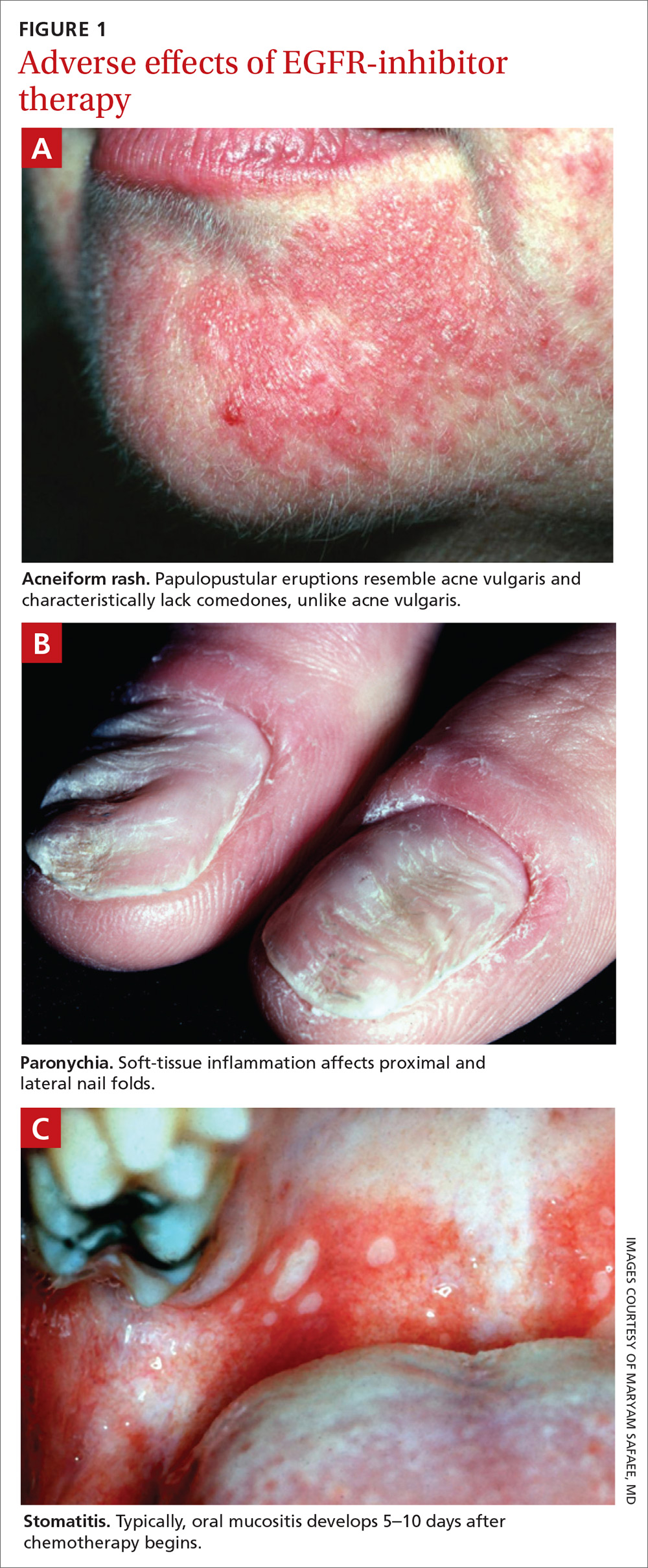

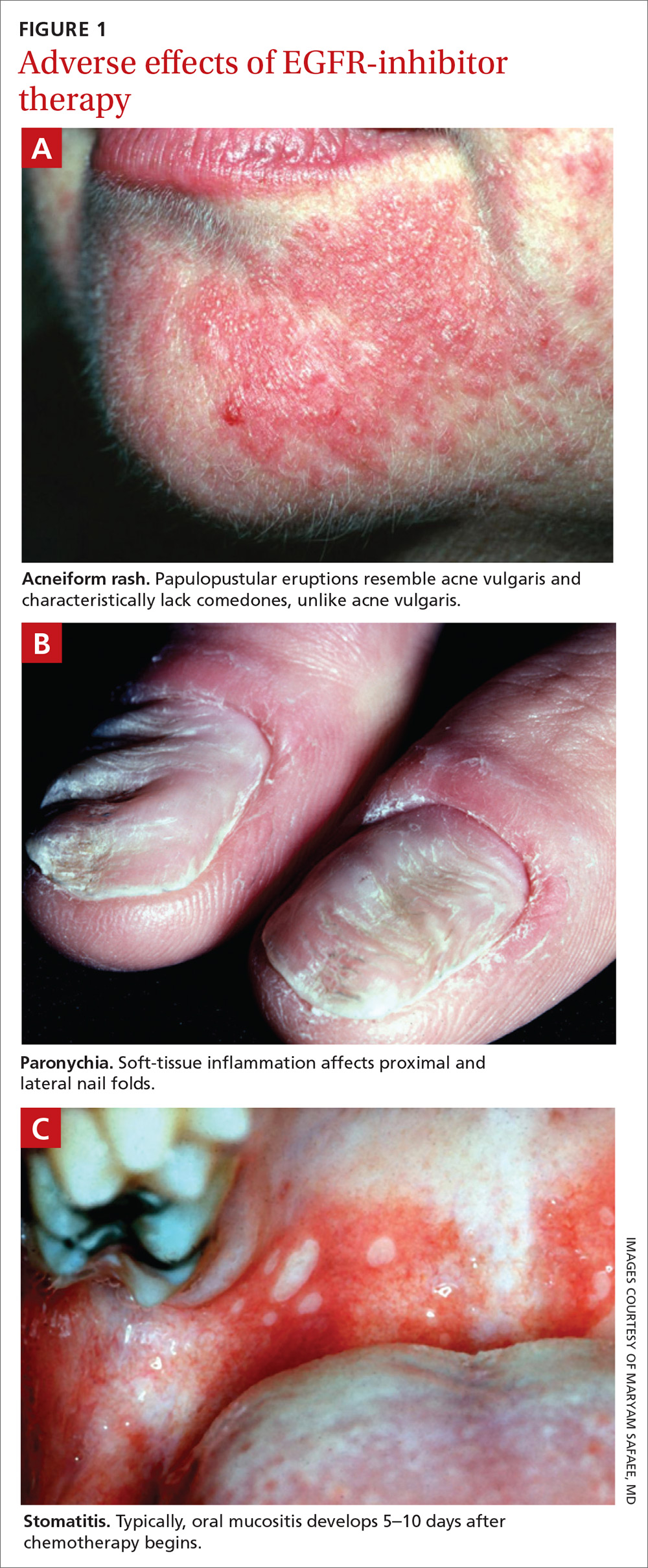

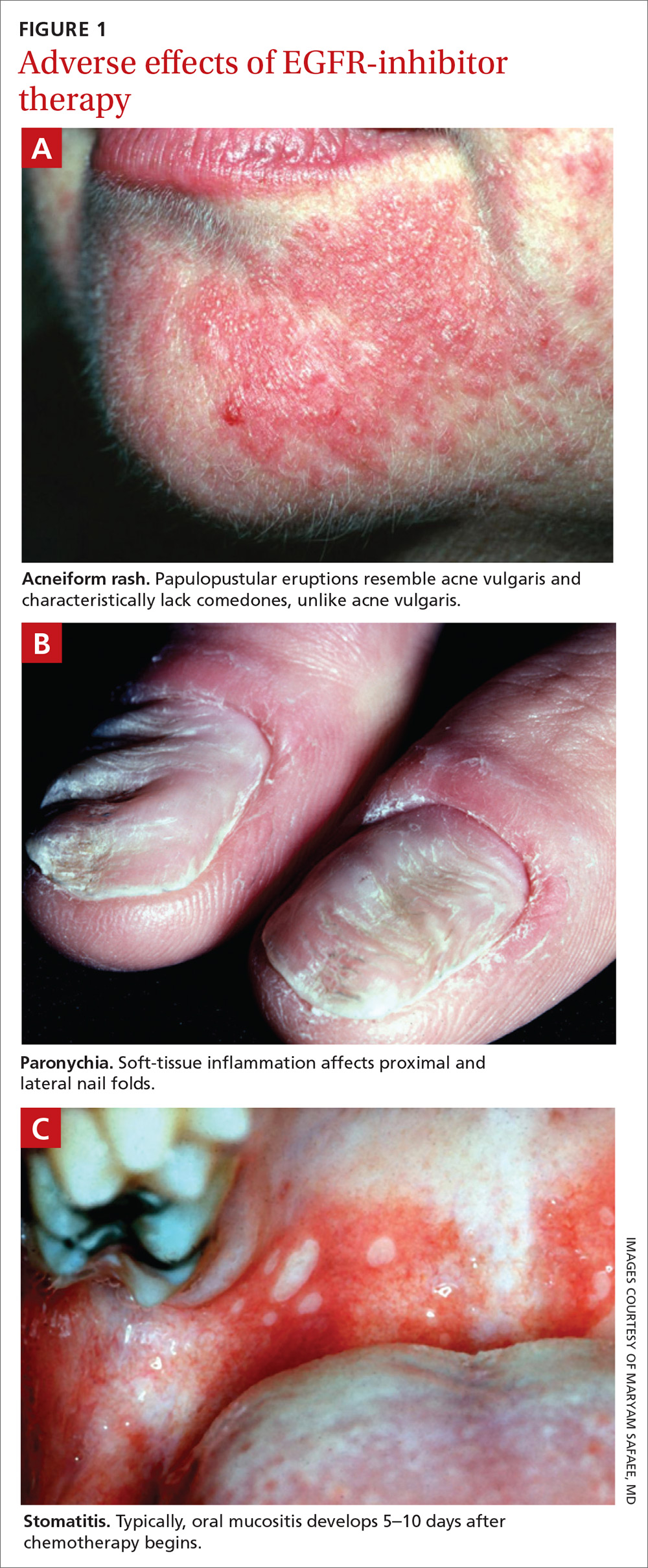

Blockade of the EGFR molecule leads to dermal changes, however, presenting as acneiform rash, skin fissure and xerosis, and pruritus.5 In extreme instances, toxic effects can manifest as paronychia, facial hypertrichosis, and trichomegaly. These skin changes can be deforming as well as painful, and can have physiological and psychological consequences.6

In turn, a decrease in quality of life (as reported by patients suffering from skin toxicity) can affect cancer treatment adherence and efficacy,7 and severe skin changes can result in the need to reduce the dosage of anti-cancer therapies.8 Skillful evaluation and appropriate management of skin eruptions in patients undergoing cancer therapy is therefore vital to an overall satisfactory outcome.

Continue to: How common a problem?

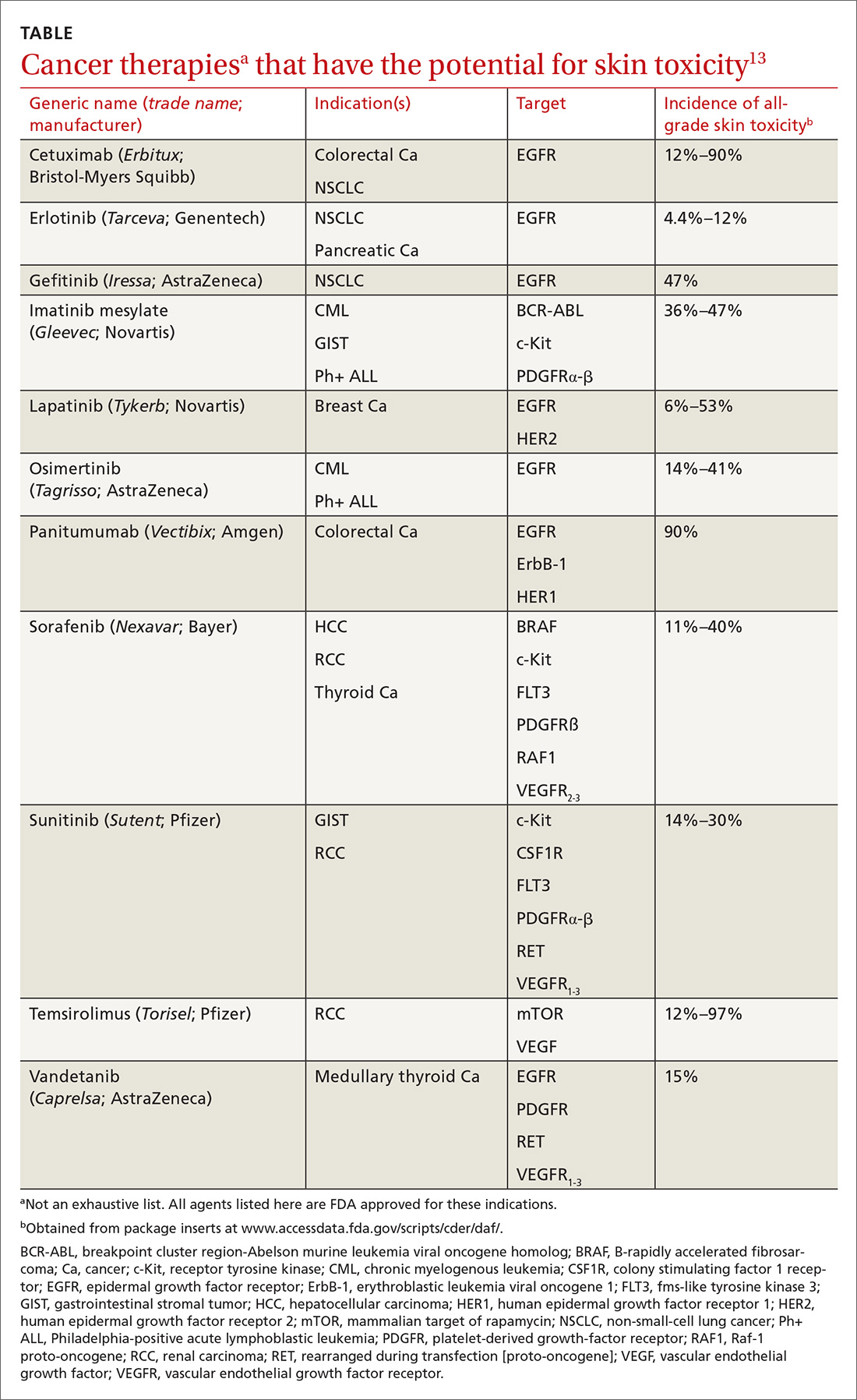

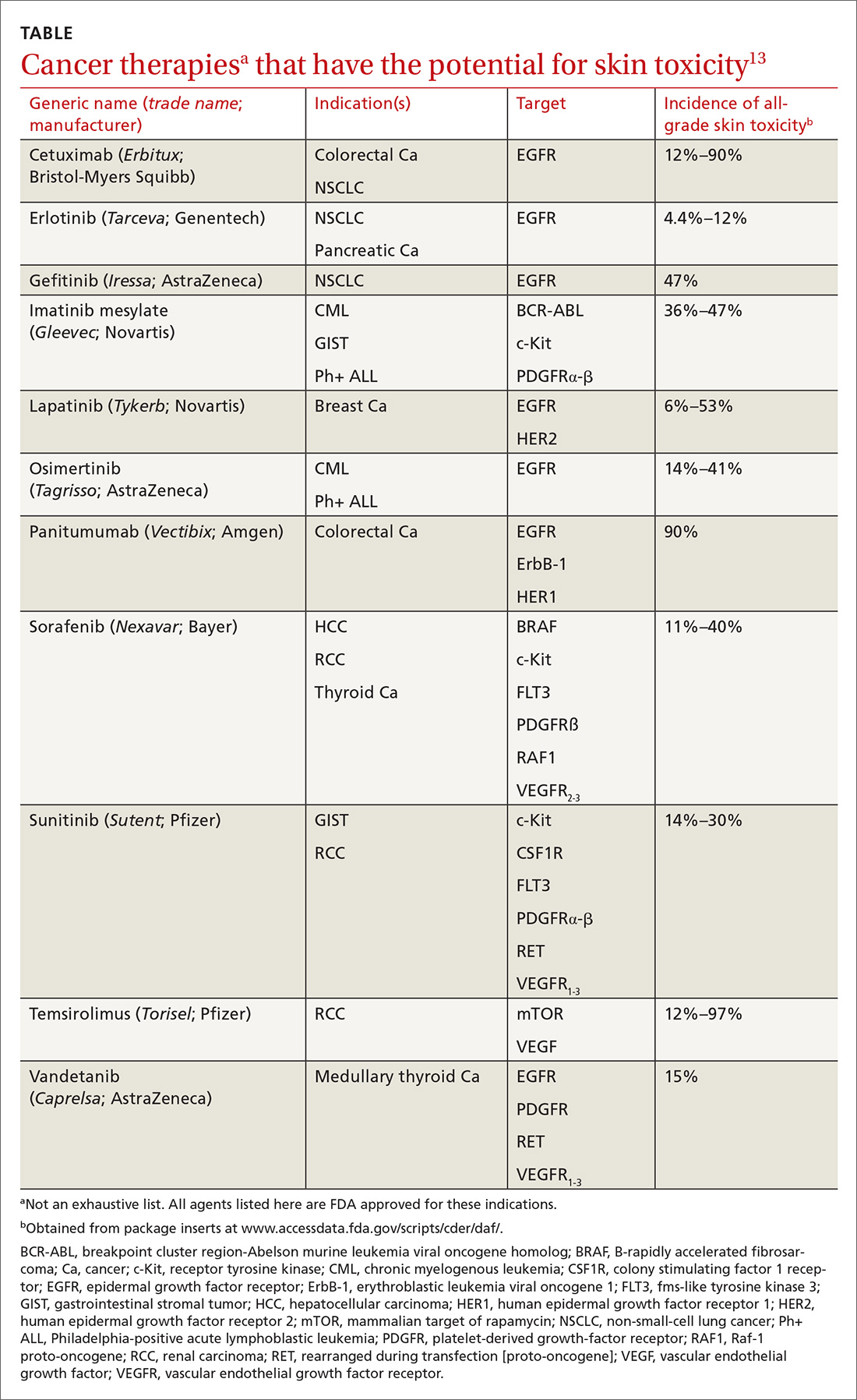

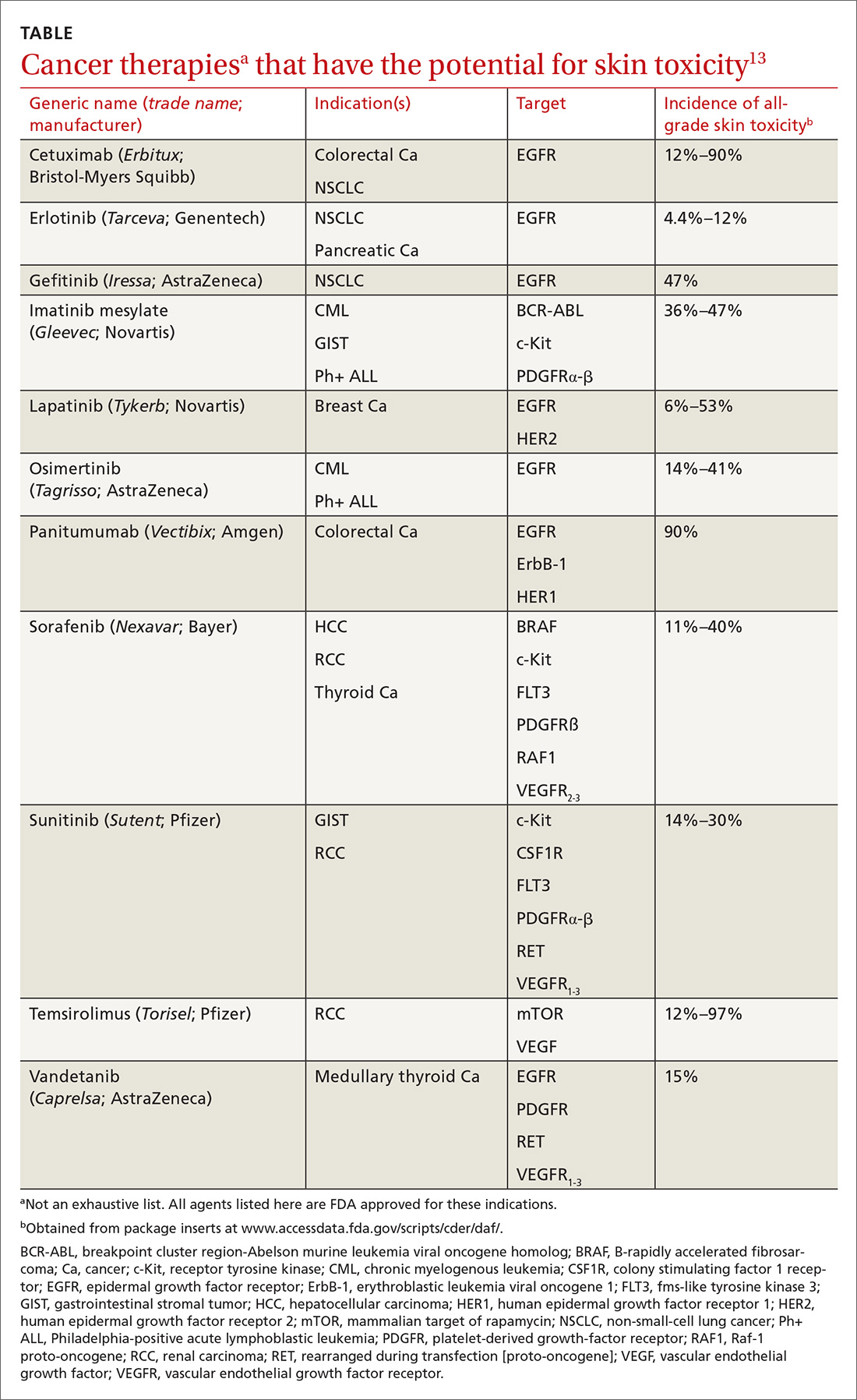

How common a problem? The incidence of EGFR inhibitor (EGFRI)–related rash is noteworthy: Overall incidence ranges from 45% to 100% of treated patients, with 10% experiencing Grade 3 to 4 changes (covering > 30% of body surface, restricting activities of daily living, severe itching).9 Monoclonal antibody therapies that target EGFR, such as cetuximab, have a reported 90% risk of skin rash, with 10% also being of Grade 3 to 4.10 Risk factors for rash include skin phototype, male gender, and younger age.11,12 Common cancer therapies with known skin effects are listed in the TABLE.13

What should you look for? The most common clinical manifestation of dermatologic toxicity is an acneiform, or papulopustular, rash marked by eruptions characterized as “acne-like” pustules with monotonous lesion morphology (Figure 1a). A hallmark of these lesions that can be used to help distinguish them from acne vulgaris is the absence of comedones on eruptions.

The timeline of the rash has been well characterized and is another tool that you can use to guide management:

- During Week 1 of cancer treatment, the patient often experiences sensory disturbances, with erythema and edema.14

- Throughout Weeks 2 and 3, erythematous skin evolves into papulopustular eruptions.

- By Week 4, eruptions typically crust over and leave persistently dry skin for weeks.15,16

Of note, the rash is dosage related; we recommend scrupulous vigilance when a patient is receiving a high dosage of a targeted therapy agent.

Controlling a rash

Treatment of EGFRI-associated skin changes stems from recommendations from a number of individual investigators and studies; however, few consensus guidelines exist to guide practice. Understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanism of skin changes has evolved, but preventive and treatment modalities remain unchanged—and limited.

Continue to: Always counsel patients...

Always counsel patients before a rash develops (and, ideally, before chemotherapy begins) that they should report a rash early in its development, to you or their oncologist, so that timely treatment can occur. Early recognition and intervention have proven benefits and can prevent the rash and its symptoms from becoming worse17; if the rash remains uncontrolled, dosage reduction of the chemotherapeutic agent is an inevitable reality, and the clinical outcome of the primary disease might therefore not be ideal.18

Prophylaxis. Daily application of an alcohol-free emollient cream is highly recommended as a preventive measure. Patients should be counseled to avoid activities and skin products that lead to dry skin, including long and hot showers; perfumes or other alcohol-based products; and soaps marketed for treating acne, which have a profound skin-drying effect.

Cornerstones of treatment include topical moisturizers, steroids, and antihistamines for symptom control. Once an identifiable skin rash has developed, a topical steroid cream is first-line treatment. Successful control has been reported with 1% hydrocortisone lotion applied daily to the affected area.15

Second- and third-line Tx. If the rash progresses in size or severity, we recommend switching to 2% hydrocortisone valerate cream, applied twice daily. For a moderate-to-severe rash, an oral tetracycline is a valid option for its anti-inflammatory effects and, possibly, to prevent secondary infection. In the event of progression, refer the patient to an oncologist, who can consider suspending the anti-EGRF drug temporarily until the rash improves. If disease persists, consultation with a dermatologist is appropriate for consideration of systemic prednisolone.

Alleviating discomfort. Patients commonly report pruritus and mild-to-moderate pain with the rash; standard analgesic therapy is appropriate.19 Severe pain might indicate secondary infection; in that case, consider antibiotic therapy for presumed cellulitis. Moreover, because of the risk of thrombosis in the cancer population, underlying deep-vein thrombosis must always remain in the differential diagnosis of an erythematous rash.

Continue to: A short course...

A short course of systemic steroids might be beneficial for pain control; however, no data from clinical trials suggest that this is beneficial. Dermatology consultation is recommended before prescribing a systemic steroid.

Regrettably, treatment options for pruritus are limited. Antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine and hydroxyzine, can be considered, but their effectiveness is marginal.20 If a patient reports a painful rash, we recommend that you collaborate with the dermatologist and oncologist to make adjustments to the cancer treatment plan.

Retinoids: Caution is advised. Several case reports and a small investigational study describe a potential role for retinoids such as isotretinoin, a 13-cis retinoic acid, in the treatment of chemotherapy-related skin changes.21,22 Isotretinoin is available under several trade names in pill and cream formulations.

Retinoids exert their effect at the level of DNA transcription, and act as a transcription factor in keratinocytes. Their downstream signaling pathway includes EGFR signaling ligands; introduction of exogenous retinoids has been shown to deter development of EGFRI-associated skin toxicity.23 Given the lack of clinical data, retinoid-based medications should be used at the discretion of a dermatologist; thorough discussion is encouraged among the dermatologist, oncologist, and primary care physician before employing a retinoid.

Recommend a sunscreen? Given the endogenous role of EGFR in protecting skin from ultraviolet B damage, some clinicians have recommended that patients use a sunscreen. However, randomized, controlled trials have failed to demonstrate any benefit to their use with regard to incidence or severity of rash or patient-reported discomfort.24 We do not recommend routine use of sunscreen to prevent chemotherapy-induced skin changes, although sensible use during periods of prolonged sun exposure is encouraged.

Continue to: Risk of infection and the role of antibiotics

Risk of infection and the role of antibiotics

Skin damage can lead to further complications—namely, leaving the skin vulnerable to bacterial overgrowth and serious infection.14 The primary acneiform eruption is believed to be inflammatory in nature, with most cases being sterile and lacking bacterial growth.25 However, rash-associated infections are a common complication and leave the immunocompromised patient at risk of systemic infection: Harandi et al26 reported a 35% rate of secondary infection. Viral or bacterial growth (the primary pathogen is Staphylococcus aureus) within the wound can aggravate the severity of the rash, prohibit effective healing, and exacerbate the disfiguring appearance of the rash.

The use of a prophylactic antibiotic for treating a rash in this setting has been an active area of discussion and research, although no guidelines or recommendations exist that can be routinely employed. A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that, in patients undergoing EGFR-based therapy, those who received a prophylactic antibiotic had a lower risk of developing folliculitis than those who did not (odds ratio = 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.39-0.72; P < .01). 27

A consensus agreement on the use of prophylactic antibiotics has yet to be reached. An emerging clinical practice entails the use of oral minocycline (100 mg/d) during the first 4 weeks of EGFRI-based therapy because studies have shown a benefit from this regimen in reducing eruptions.28

Other adverse dermatologic effects to watch for

Paronychia is common in patients undergoing EGFRI therapy but, unlike the acneiform rash that typically occurs within 1 week of treatment, paronychia can occur weeks or months after initiation of therapy. Careful examination of the nail beds is important in patients undergoing EGFRI therapy (FIGURE 1B). Paronychia can affect the nail beds of the fingers and toes—most often, the first digits.29

No evidence-based trials have been conducted to evaluate treatment options; recommendations provided are drawn from the literature and expert opinion. Patients are encouraged to apply petroleum jelly or an emollient daily both as a preventive measure and for mild cases. Patient counseling on the importance of nail hygiene and avoidance of aggressive manicures and pedicures is encouraged.30

Continue to: In the general population...

In the general population, acute and chronic paronychia entail infection with S aureus and Candida spp, respectively. To this end, there is a role for antibacterial and antifungal intervention. As is the case of the EGFRI-associated acneiform rash, inflammation in paronychia is sterile, with only rare pathogen involvement.

There is no role for topical or systemic antibiotics in the cancer population suffering from paronychia. A viable treatment option for moderate lesions is betamethasone valerate, applied 2 or 3 times daily; if there is no resolution, clobetasol cream, applied 2 or 3 times daily, can be prescribed.30 The role of tetracyclines as anti-inflammatory agents in paronychia has not been studied to the extent it has been for acneiform rash; however, studies have shown a protective effect in small patient samples.31 In severe disease, the patient can be instructed to temporarily discontinue the drug and you can provide a referral to a dermatologist.

Stomatitis is also an area of concern in this patient population (FIGURE 1c). Prior to initiating treatment, a thorough examination of the patient’s oral cavity and oropharynx should be conducted. Loose or improperly fitting dentures should be adjusted because they can prohibit effective healing after ulceration develops.

Stomatitis initially presents as erythematous or aphthous-like lesions, and can develop into acutely painful, large, continuous lesions.29 Timely management of stomatitis is beneficial to patient outcomes because it can lead to severe pain and interference in oral intake; uncontrolled disease requires interruption and dosage-reduction of cancer therapy.14,32

Patients should be encouraged to use soft-bristle toothbrushes and rinse with normal saline, not with commercial mouthwashes that typically contain alcohol. Grade 1 stomatitis (ie, pain and erythema) can be treated with triamcinolone dental paste, which can reduce inflammation caused by the ulcers. If disease progresses to Grade 2 to 3 stomatitis (erythema; ulceration; difficulty swallowing, or inability to swallow food), oral erythromycin (250-350 mg/d) or minocycline (50 mg/d) should be prescribed and the patient referred to a dermatologist.30

Continue to: Does rash correlate with cancer treatment efficacy?

Does rash correlate with cancer treatment efficacy?

Despite troubling dermatologic effects of cancer therapies, a retrospective analysis of several clinical trials has revealed another side to this coin: namely, the appearance, and the severity, of a rash correlates positively with objective tumor response.14 That correlation allows the oncologist to use a rash as a surrogate marker of treatment efficacy20 (although, notably, there remains a lack of prospective trials that would validate a rash as such a marker). Epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors are mainly prescribed in patients who harbor an activating EGFR mutation; no studies have stratified patients by EGFR mutation and incidence of rash.33

The upshot? Although there are gaps in our understanding of the relationship between a rash and overall survival, we are nevertheless presented with this paradigm: A patient who is taking an EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor and who develops a rash should be continued on that treatment for as long as can be tolerated, because the rash is presumed to be a sign that the patient is deriving the greatest clinical benefit from therapy.14,20,33

CORRESPONDENCE

Kevin Zarrabi, MD, MSc, Department of Medicine, Health Science Center T16, Room 020, Stony Brook, NY 11790-8160; [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Ali John Zarrabi, MD, provided skillful editing of the manuscript of this article.

1. Phillips JL, Currow DC. Cancer as a chronic disease. Collegian. 2010;17:47-50.

2. Klabunde CN, Ambs A, Keating NL, et al. The role of primary care physicians in cancer care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1029-1036.

3. Agha R, Kinahan K, Bennett CL, et al. Dermatologic challenges in cancer patients and survivors. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21:1462-1472; discussion 1473,1476,1481 passim.

4. Mitchell EP, Pérez-Soler R, Van Cutsem, et al. Clinical presentation and pathophysiology of EGFRI dermatologic toxicities. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21(11 suppl 5):4-9.

5. Liu S, Kurzrock R. Understanding toxicities of targeted agents: implications for anti-tumor activity and management. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:863-875.

6. Romito F, Giuliani F, Cormio C, et al. Psychological effects of cetuximab-induced cutaneous rash in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:329-334.

7. Wacker B, Nagrani T, Weinberg J, et al. Correlation between development of rash and efficacy in patients treated with the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in two large phase III studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3913-3921.

8. Chou LS, Garey J, Oishi K, et al. Managing dermatologic toxicities of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;8(suppl 1):S15-S22.

9. Li T, Pérez-Soler R. Skin toxicities associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Target Oncol. 2009;4:107-119.

10. Su X, Lacouture ME, Jia Y, et al. Risk of high-grade skin rash in cancer patients treated with cetuximab—an antibody against epidermal growth factor receptor: systemic review and meta- analysis. Oncology. 2009;77:124-133.

11. Luu M, Boone SL, Patel J, et al. Higher severity grade of erlotinib-induced rash is associated with lower skin phototype. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:733-738.

12. Jatoi A, Green EM, Rowland KM Jr, et al. Clinical predictors of severe cetuximab-induced rash: observations from 933 patients enrolled in North Central Cancer Treatment Group study N0147. Oncology. 2009;77:120-123.

13. Drugs@FDA: FDA approved drug products. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/. Accessed June 4, 2019.

14. Melosky B, Burkes R, Rayson D, et al. Management of skin rash during EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibody treatment for gastrointestinal malignancies: Canadian recommendations. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:16-26.

15. Lacouture ME, Melosky BL. Cutaneous reactions to anticancer agents targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor: a dermatology-oncology perspective. Skin Therapy Lett. 2007; 12:1-5.

16. Eaby B, Culkin A, Lacouture ME. An interdisciplinary consensus on managing skin reactions associated with human epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008; 12:283-290.

17. Hirsh V. Managing treatment-related adverse events associated with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Oncol. 2011;18:126-138.

18. Reguiai Z, Bachet JB, Bachmeyer C, et al. Management of cuta- neous adverse events induced by anti-EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor): a French interdisciplinary therapeutic algo- rithm. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1395-1404.

19. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

20. Pérez-Soler R, Delord JP, Halpern A, et al. HER1/EGFR inhibitor-associated rash: future directions for management and investigation outcomes from the HER1/EGFR Inhibitor Rash Management Forum. Oncologist. 2005;10:345-356.

21. Bidoli P, Cortinovis DL, Colombo I, et al. Isotretinoin plus clindamycin seem highly effective against severe erlotinib-induced skin rash in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1662-1663.

22. Vezzoli P, Marzano AV, Onida F, et al. Cetuximab-induced ac - neiform eruption and the response to isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:84-86.

23. Rittié L, Varani J, Kang S, et al. Retinoid-induced epidermal hyperplasia is mediated by epidermal growth factor receptor activation via specific induction of its ligands heparin-binding EGF and amphiregulin in human skin in vivo. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:732-739.

24. Jatoi A, Thrower A, Sloan JA, et al. Does sunscreen prevent epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor-induced rash? Results of a placebo-controlled trial from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (N05C4). Oncologist. 2010; 15:1016-1022.

25. Lynch TJ Jr, Kim ES, Eaby B, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-associated cutaneous toxicities: an evolving paradigm in clinical management. Oncologist. 2007;12:610-621.

26. Harandi A, Zaidi AS, Stocker AM, et al. Clinical efficacy and toxicity of anti-EGFR therapy in common cancers. J Oncol. 2009;2009:567486.

27. Petrelli F, Borgonovo K, Cabiddu M, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for skin toxicity induced by antiepidermal growth factor receptor agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1166-1174.

28. Scope A, Agero AL, Dusza SW, et al. Randomized double-blind trial of prophylactic oral minocycline and topical tazarotene for cetuximab-associated acne-like eruption. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5390-5396.

29. Lacouture ME, Anadkat MJ, Bensadoun RJ, et al; MASCC Skin Toxicity Study Group. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of EGFR inhibitor-associated dermatologic toxicities. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1079-1095.

30. Melosky B, Leighl NB, Rothenstein J, et al. Management of egfr tki-induced dermatologic adverse events. Curr Oncol. 2015; 22:123-132.

31. Arrieta O, Vega-González MT, López-Macías D, et al. Randomized, open-label trial evaluating the preventive effect of tetracycline on afatinib induced-skin toxicities in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2015;88:282-288.

32. Saito H, Watanabe Y, Sato K, et al. Effects of professional oral health care on reducing the risk of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2935-2940.

33. Kozuki T. Skin problems and EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46:291-298.

Advances in cancer therapy have improved survival, such that many cancers have been transformed from a terminal illness to a chronic disease, and the population of patients living with cancer or who are disease-free has grown. However, these patients face complex medical problems because of the systemic effects of their treatment and many endure a constellation of treatment-emergent adverse effects that require ongoing care and support.1

Primary care physicians have been called on to take a larger role in the care of these adverse effects as the growing number of treatments has meant more affected patients. In addition, an urgent, unmet need has developed for better coordination between specialists and family physicians for providing this supportive care.2

In this article, we (1) describe the most commonly encountered cancer treatment–related skin toxicities, paying particular attention to the effects of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–targeting therapies, and (2) review up-to-date management recommendations in an area of practice where established clinical guidance from the scientific literature is limited.

Biggest culprit: Targeted cancer therapies