User login

A 2-month-old infant with a scalp rash that appeared after birth

With the perinatal history of prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes, the diagnosis of halo scalp ring was made. This occurs secondary to prolonged pressure of the baby’s scalp with the mother’s pelvic bones, uterus, or cervical area, which causes decreased blood flow to the area, secondary ischemic damage, and in some cases scarring and hair loss.1

The degree of involvement is variable as some babies have mild alopecia and others have severe full-thickness necrosis and scarring. These lesions also can present with associated caput succedaneum and scalp molding, but these were not seen in our patient. Predisposing factors for halo scalp ring include caput succedaneum, prolonged or difficult labor, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, vaginal delivery, vertex presentation, first delivery, as well as prematurity.2 On physical examination, a semicircular patch of alopecia with associated scarring, crusting, or erythema can be seen in some more severe cases.

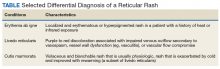

The differential diagnosis includes aplasia cutis. In aplasia cutis, there is congenital loss of skin on the affected areas. The scalp usually is affected, but these lesions can occur in any other part of the body. Most patients with aplasia cutis have no other findings, but there are cases that can be associated with other cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or central nervous system abnormalities. Neonatal lupus also can present with scarring lesions on the scalp, but they usually present a little after birth, mainly affecting the face. The mothers of this children usually have a diagnosis of connective tissue disease and may have positive antibodies to Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A, Sjögren’s syndrome antibody B, or antiribonucleoprotein antibody. Seborrheic dermatitis does not cause scarring alopecia. The lesions present as waxy scaly plaques on the scalp, erythematous waxy plaques behind the ears, face, and folds. Some patients can have hair loss secondary to the inflammation, but the hair grows back once the inflammation is controlled. Dissecting cellulitis is a type of scarring alopecia seen in pubescent and adult individuals. No cases of neonatal dissecting cellulitis have been described.

Halo scalp ring is not associated with any other systemic symptoms or syndromes. Extensive imaging and systemic work-up are not required unless the baby presents with other neurologic symptoms. The areas can be treated with petrolatum and observation as most lesions resolve.

In cases of extensive areas of scarring alopecia, referral to a plastic surgeon can be made to consider tissue expanders or scar revision prior to the child starting school if the lesions are causing psychological stressors.

The true prevalence of this condition is unknown. We believe halo ring alopecia is sometimes not diagnosed, and as lesions tend to resolve, most cases go unreported.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):673.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;26(6):706-8.

3. Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15;22(11).pii:13030/qt7rt592tz.

With the perinatal history of prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes, the diagnosis of halo scalp ring was made. This occurs secondary to prolonged pressure of the baby’s scalp with the mother’s pelvic bones, uterus, or cervical area, which causes decreased blood flow to the area, secondary ischemic damage, and in some cases scarring and hair loss.1

The degree of involvement is variable as some babies have mild alopecia and others have severe full-thickness necrosis and scarring. These lesions also can present with associated caput succedaneum and scalp molding, but these were not seen in our patient. Predisposing factors for halo scalp ring include caput succedaneum, prolonged or difficult labor, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, vaginal delivery, vertex presentation, first delivery, as well as prematurity.2 On physical examination, a semicircular patch of alopecia with associated scarring, crusting, or erythema can be seen in some more severe cases.

The differential diagnosis includes aplasia cutis. In aplasia cutis, there is congenital loss of skin on the affected areas. The scalp usually is affected, but these lesions can occur in any other part of the body. Most patients with aplasia cutis have no other findings, but there are cases that can be associated with other cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or central nervous system abnormalities. Neonatal lupus also can present with scarring lesions on the scalp, but they usually present a little after birth, mainly affecting the face. The mothers of this children usually have a diagnosis of connective tissue disease and may have positive antibodies to Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A, Sjögren’s syndrome antibody B, or antiribonucleoprotein antibody. Seborrheic dermatitis does not cause scarring alopecia. The lesions present as waxy scaly plaques on the scalp, erythematous waxy plaques behind the ears, face, and folds. Some patients can have hair loss secondary to the inflammation, but the hair grows back once the inflammation is controlled. Dissecting cellulitis is a type of scarring alopecia seen in pubescent and adult individuals. No cases of neonatal dissecting cellulitis have been described.

Halo scalp ring is not associated with any other systemic symptoms or syndromes. Extensive imaging and systemic work-up are not required unless the baby presents with other neurologic symptoms. The areas can be treated with petrolatum and observation as most lesions resolve.

In cases of extensive areas of scarring alopecia, referral to a plastic surgeon can be made to consider tissue expanders or scar revision prior to the child starting school if the lesions are causing psychological stressors.

The true prevalence of this condition is unknown. We believe halo ring alopecia is sometimes not diagnosed, and as lesions tend to resolve, most cases go unreported.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):673.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;26(6):706-8.

3. Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15;22(11).pii:13030/qt7rt592tz.

With the perinatal history of prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes, the diagnosis of halo scalp ring was made. This occurs secondary to prolonged pressure of the baby’s scalp with the mother’s pelvic bones, uterus, or cervical area, which causes decreased blood flow to the area, secondary ischemic damage, and in some cases scarring and hair loss.1

The degree of involvement is variable as some babies have mild alopecia and others have severe full-thickness necrosis and scarring. These lesions also can present with associated caput succedaneum and scalp molding, but these were not seen in our patient. Predisposing factors for halo scalp ring include caput succedaneum, prolonged or difficult labor, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, vaginal delivery, vertex presentation, first delivery, as well as prematurity.2 On physical examination, a semicircular patch of alopecia with associated scarring, crusting, or erythema can be seen in some more severe cases.

The differential diagnosis includes aplasia cutis. In aplasia cutis, there is congenital loss of skin on the affected areas. The scalp usually is affected, but these lesions can occur in any other part of the body. Most patients with aplasia cutis have no other findings, but there are cases that can be associated with other cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or central nervous system abnormalities. Neonatal lupus also can present with scarring lesions on the scalp, but they usually present a little after birth, mainly affecting the face. The mothers of this children usually have a diagnosis of connective tissue disease and may have positive antibodies to Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A, Sjögren’s syndrome antibody B, or antiribonucleoprotein antibody. Seborrheic dermatitis does not cause scarring alopecia. The lesions present as waxy scaly plaques on the scalp, erythematous waxy plaques behind the ears, face, and folds. Some patients can have hair loss secondary to the inflammation, but the hair grows back once the inflammation is controlled. Dissecting cellulitis is a type of scarring alopecia seen in pubescent and adult individuals. No cases of neonatal dissecting cellulitis have been described.

Halo scalp ring is not associated with any other systemic symptoms or syndromes. Extensive imaging and systemic work-up are not required unless the baby presents with other neurologic symptoms. The areas can be treated with petrolatum and observation as most lesions resolve.

In cases of extensive areas of scarring alopecia, referral to a plastic surgeon can be made to consider tissue expanders or scar revision prior to the child starting school if the lesions are causing psychological stressors.

The true prevalence of this condition is unknown. We believe halo ring alopecia is sometimes not diagnosed, and as lesions tend to resolve, most cases go unreported.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):673.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;26(6):706-8.

3. Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15;22(11).pii:13030/qt7rt592tz.

A 2-month-old male is referred to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of persistent seborrheic dermatitis. The mother reports that he presented with a rash on his scalp a few days after birth. She has been treating the crusted areas with clotrimazole and hydrocortisone and has noted improvement on the crusting, but now is worried that there is some scarring. The affected areas are not bleeding or tender. There are no other rashes elsewhere in the body.

He was born at 36 weeks from a 35-year-old gravida 1 para 0 woman with adequate prenatal care. The mother was diagnosed with preeclampsia and was induced. She had a prolonged labor and had premature rupture of membranes. The baby was delivered via cesarean section because of failure to progress and fetal distress; forceps, vacuum, and a scalp probe were not used during delivery. He was admitted to the neonatal unit for 5 days for sepsis work-up and respiratory distress. No intubation was needed.

Besides the preeclampsia, the mother denied any other medical conditions and was not taking any medications. He has met all developmental milestones for his age. He has no history of seizures.

On physical exam, there are semicircular patches of alopecia on the scalp. Some areas have pink, rubbery plaques with loss of hair follicles. On the frontal scalp, there are waxy plaques.

There is a blanchable violaceous patch on the occiput and there are some erythematous papules on the cheeks.

Boiling Points

This 37-year-old woman began developing “boils” under both arms at age 12. Over the years, the lesions have become more numerous and bothersome. They are often painful and large and are capable of bursting on their own, releasing purulent material. Occasionally, similar lesions appear under her breasts and in the groin. The problem seems to wax and wane with her menstrual cycle. Family history reveals that both her mother and one of her sisters have had the same problem, again starting around the time of menarche.

Whenever the patient seeks medical care, usually at the emergency department, the diagnosis is always the same: boils. Normally, the prescribed treatment includes incision, drainage, and packing of the largest lesions, followed by 2 weeks of oral antibiotics. While the problem generally improves after treatment, it invariably returns.

Her health is decent overall. However, she has been overweight for years and has been smoking since she was 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s left axilla shows ropy, hypertrophic scars, many comedones, and several fluctuant cystic subcutaneous masses. There is no frank erythema, although the patient indicates there often is.

No such changes are seen on examination of her right axilla. Instead, there is a slender 12-cm linear scar running across the axillary fold. Upon questioning, the patient reports that several years ago, a surgeon removed three-fourths of the skin and subcutaneous tissue from this area. This procedure cured the “boils” on her right arm, but it also left her with chronic lymphedema in that extremity.

Other intertriginous areas are free of significant changes.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

In the US, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) affects 1% to 4% of the population and about 4 times as many females as males. But as this case demonstrates, it is consistently misidentified as “boils” or “staph infection” by providers unfamiliar with the correct diagnosis.

HS involves hair follicles in intertriginous areas of the body that are rich with apocrine glands (eg, armpit, groin). The condition, initially known as acne inversa, was first described in 1833 by Dr. Alfred Velpeau, a French surgeon. Despite some minor similarities, HS is not actually a form of acne, nor is it an infection. About one-third of HS patients inherit the condition, and generally, onset occurs post puberty, suggesting a hormonal component.

With HS, the hair follicle and associated apocrine gland fail to function normally. As sweat accumulates in subcutaneous tissue, it creates a chronic inflammatory reaction manifesting with large comedones, cysts, and abscesses. Eventually, it can result in ropy, hypertrophic scars on the surface and deep tracts connecting multiple lesions. HS is classified as mild (stage 1), moderate (stage 2), or severe (stage 3) using the Hurley staging system.

HS is notoriously difficult to cure, but the anti-inflammatory effects of some antibiotics (eg, minocycline, doxycycline) can offer some relief, as can anti-androgens (eg, spironolactone). The use of isotretinoin has yielded disappointing results. For small lesions, intralesional injection of glucocorticoids can be useful for short-term relief of pain and swelling.

The most encouraging recent development in HS treatment is the approval for the use of adalimumab (Humira) in severe cases that have failed to respond to other modalities. Even with use of this biologic, decent control is probably the best outcome—and that’s at an annual cost of $50,000, plus the patient’s exposure to potentially serious adverse effects due to immunosuppression.

Another approach is surgical, with all its attendant risks, as this patient experienced in her right axilla. Simple incision and drainage offer little beyond temporary relief of pain.

Environmental factors should not be overlooked; obesity and smoking have both been linked to HS in multiple studies.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Hidradenitis suppurativa, also known as acne inversa, results from malfunction of the hair follicle and associated apocrine glands in intertriginous areas.

- HS can range from mild (with minor pustules and sparse comedones) to and severe (diffuse disease, affecting multiple areas with heavy ropy scarring, large painful abscesses, and connecting tracts).

- HS affects approximately 4 times as many females as males, almost all with post-pubertal onset—strongly suggestive of a hormonal component.

- Treatment is problematic, although the recent approval of adalimumab for use in HS is proving to be helpful, if not curative. Some oral antibiotics and anti-androgens have shown mixed results.

This 37-year-old woman began developing “boils” under both arms at age 12. Over the years, the lesions have become more numerous and bothersome. They are often painful and large and are capable of bursting on their own, releasing purulent material. Occasionally, similar lesions appear under her breasts and in the groin. The problem seems to wax and wane with her menstrual cycle. Family history reveals that both her mother and one of her sisters have had the same problem, again starting around the time of menarche.

Whenever the patient seeks medical care, usually at the emergency department, the diagnosis is always the same: boils. Normally, the prescribed treatment includes incision, drainage, and packing of the largest lesions, followed by 2 weeks of oral antibiotics. While the problem generally improves after treatment, it invariably returns.

Her health is decent overall. However, she has been overweight for years and has been smoking since she was 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s left axilla shows ropy, hypertrophic scars, many comedones, and several fluctuant cystic subcutaneous masses. There is no frank erythema, although the patient indicates there often is.

No such changes are seen on examination of her right axilla. Instead, there is a slender 12-cm linear scar running across the axillary fold. Upon questioning, the patient reports that several years ago, a surgeon removed three-fourths of the skin and subcutaneous tissue from this area. This procedure cured the “boils” on her right arm, but it also left her with chronic lymphedema in that extremity.

Other intertriginous areas are free of significant changes.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

In the US, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) affects 1% to 4% of the population and about 4 times as many females as males. But as this case demonstrates, it is consistently misidentified as “boils” or “staph infection” by providers unfamiliar with the correct diagnosis.

HS involves hair follicles in intertriginous areas of the body that are rich with apocrine glands (eg, armpit, groin). The condition, initially known as acne inversa, was first described in 1833 by Dr. Alfred Velpeau, a French surgeon. Despite some minor similarities, HS is not actually a form of acne, nor is it an infection. About one-third of HS patients inherit the condition, and generally, onset occurs post puberty, suggesting a hormonal component.

With HS, the hair follicle and associated apocrine gland fail to function normally. As sweat accumulates in subcutaneous tissue, it creates a chronic inflammatory reaction manifesting with large comedones, cysts, and abscesses. Eventually, it can result in ropy, hypertrophic scars on the surface and deep tracts connecting multiple lesions. HS is classified as mild (stage 1), moderate (stage 2), or severe (stage 3) using the Hurley staging system.

HS is notoriously difficult to cure, but the anti-inflammatory effects of some antibiotics (eg, minocycline, doxycycline) can offer some relief, as can anti-androgens (eg, spironolactone). The use of isotretinoin has yielded disappointing results. For small lesions, intralesional injection of glucocorticoids can be useful for short-term relief of pain and swelling.

The most encouraging recent development in HS treatment is the approval for the use of adalimumab (Humira) in severe cases that have failed to respond to other modalities. Even with use of this biologic, decent control is probably the best outcome—and that’s at an annual cost of $50,000, plus the patient’s exposure to potentially serious adverse effects due to immunosuppression.

Another approach is surgical, with all its attendant risks, as this patient experienced in her right axilla. Simple incision and drainage offer little beyond temporary relief of pain.

Environmental factors should not be overlooked; obesity and smoking have both been linked to HS in multiple studies.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Hidradenitis suppurativa, also known as acne inversa, results from malfunction of the hair follicle and associated apocrine glands in intertriginous areas.

- HS can range from mild (with minor pustules and sparse comedones) to and severe (diffuse disease, affecting multiple areas with heavy ropy scarring, large painful abscesses, and connecting tracts).

- HS affects approximately 4 times as many females as males, almost all with post-pubertal onset—strongly suggestive of a hormonal component.

- Treatment is problematic, although the recent approval of adalimumab for use in HS is proving to be helpful, if not curative. Some oral antibiotics and anti-androgens have shown mixed results.

This 37-year-old woman began developing “boils” under both arms at age 12. Over the years, the lesions have become more numerous and bothersome. They are often painful and large and are capable of bursting on their own, releasing purulent material. Occasionally, similar lesions appear under her breasts and in the groin. The problem seems to wax and wane with her menstrual cycle. Family history reveals that both her mother and one of her sisters have had the same problem, again starting around the time of menarche.

Whenever the patient seeks medical care, usually at the emergency department, the diagnosis is always the same: boils. Normally, the prescribed treatment includes incision, drainage, and packing of the largest lesions, followed by 2 weeks of oral antibiotics. While the problem generally improves after treatment, it invariably returns.

Her health is decent overall. However, she has been overweight for years and has been smoking since she was 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s left axilla shows ropy, hypertrophic scars, many comedones, and several fluctuant cystic subcutaneous masses. There is no frank erythema, although the patient indicates there often is.

No such changes are seen on examination of her right axilla. Instead, there is a slender 12-cm linear scar running across the axillary fold. Upon questioning, the patient reports that several years ago, a surgeon removed three-fourths of the skin and subcutaneous tissue from this area. This procedure cured the “boils” on her right arm, but it also left her with chronic lymphedema in that extremity.

Other intertriginous areas are free of significant changes.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

In the US, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) affects 1% to 4% of the population and about 4 times as many females as males. But as this case demonstrates, it is consistently misidentified as “boils” or “staph infection” by providers unfamiliar with the correct diagnosis.

HS involves hair follicles in intertriginous areas of the body that are rich with apocrine glands (eg, armpit, groin). The condition, initially known as acne inversa, was first described in 1833 by Dr. Alfred Velpeau, a French surgeon. Despite some minor similarities, HS is not actually a form of acne, nor is it an infection. About one-third of HS patients inherit the condition, and generally, onset occurs post puberty, suggesting a hormonal component.

With HS, the hair follicle and associated apocrine gland fail to function normally. As sweat accumulates in subcutaneous tissue, it creates a chronic inflammatory reaction manifesting with large comedones, cysts, and abscesses. Eventually, it can result in ropy, hypertrophic scars on the surface and deep tracts connecting multiple lesions. HS is classified as mild (stage 1), moderate (stage 2), or severe (stage 3) using the Hurley staging system.

HS is notoriously difficult to cure, but the anti-inflammatory effects of some antibiotics (eg, minocycline, doxycycline) can offer some relief, as can anti-androgens (eg, spironolactone). The use of isotretinoin has yielded disappointing results. For small lesions, intralesional injection of glucocorticoids can be useful for short-term relief of pain and swelling.

The most encouraging recent development in HS treatment is the approval for the use of adalimumab (Humira) in severe cases that have failed to respond to other modalities. Even with use of this biologic, decent control is probably the best outcome—and that’s at an annual cost of $50,000, plus the patient’s exposure to potentially serious adverse effects due to immunosuppression.

Another approach is surgical, with all its attendant risks, as this patient experienced in her right axilla. Simple incision and drainage offer little beyond temporary relief of pain.

Environmental factors should not be overlooked; obesity and smoking have both been linked to HS in multiple studies.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Hidradenitis suppurativa, also known as acne inversa, results from malfunction of the hair follicle and associated apocrine glands in intertriginous areas.

- HS can range from mild (with minor pustules and sparse comedones) to and severe (diffuse disease, affecting multiple areas with heavy ropy scarring, large painful abscesses, and connecting tracts).

- HS affects approximately 4 times as many females as males, almost all with post-pubertal onset—strongly suggestive of a hormonal component.

- Treatment is problematic, although the recent approval of adalimumab for use in HS is proving to be helpful, if not curative. Some oral antibiotics and anti-androgens have shown mixed results.

Tender swellings on legs

Based on the physical exam findings, the FP diagnosed erythema nodosum (EN) in this patient. He considered doing a punch biopsy down to the fat to prove that this was a panniculus, but realized that this was a classic presentation of EN. The lesions of EN are deep-seated nodules that may be more easily palpated than visualized. These lesions are initially firm, round or oval, and poorly demarcated. As seen in this case, the lesions may be bright red, warm, and painful.

The FP sought to consider the cause, and questioned the patient further about medications and other symptoms; however, he was unable to uncover any likely “suspects.” He then drew labs for a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and uric acid and QuantiFERON TB gold tests. He started the patient on ibuprofen 400 mg tid with meals for the pain and inflammation.

On a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, all of the lab results were normal and the patient was about 50% improved. At this time, the FP obtained a chest x-ray to look for any evidence of sarcoidosis. The x-ray was also normal. (About half of all cases of EN are idiopathic, so the normal results were not surprising.) By the third visit the patient was 90% better and was happy to keep taking the ibuprofen to see if this would resolve completely.

After 6 weeks of treatment, there were no more tender erythematous nodules. All that remained was some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The patient was happy with these results and understood that she should return if the EN came back.

Photo courtesy of Hanuš Rozsypal, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Diaz L, Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the physical exam findings, the FP diagnosed erythema nodosum (EN) in this patient. He considered doing a punch biopsy down to the fat to prove that this was a panniculus, but realized that this was a classic presentation of EN. The lesions of EN are deep-seated nodules that may be more easily palpated than visualized. These lesions are initially firm, round or oval, and poorly demarcated. As seen in this case, the lesions may be bright red, warm, and painful.

The FP sought to consider the cause, and questioned the patient further about medications and other symptoms; however, he was unable to uncover any likely “suspects.” He then drew labs for a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and uric acid and QuantiFERON TB gold tests. He started the patient on ibuprofen 400 mg tid with meals for the pain and inflammation.

On a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, all of the lab results were normal and the patient was about 50% improved. At this time, the FP obtained a chest x-ray to look for any evidence of sarcoidosis. The x-ray was also normal. (About half of all cases of EN are idiopathic, so the normal results were not surprising.) By the third visit the patient was 90% better and was happy to keep taking the ibuprofen to see if this would resolve completely.

After 6 weeks of treatment, there were no more tender erythematous nodules. All that remained was some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The patient was happy with these results and understood that she should return if the EN came back.

Photo courtesy of Hanuš Rozsypal, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Diaz L, Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the physical exam findings, the FP diagnosed erythema nodosum (EN) in this patient. He considered doing a punch biopsy down to the fat to prove that this was a panniculus, but realized that this was a classic presentation of EN. The lesions of EN are deep-seated nodules that may be more easily palpated than visualized. These lesions are initially firm, round or oval, and poorly demarcated. As seen in this case, the lesions may be bright red, warm, and painful.

The FP sought to consider the cause, and questioned the patient further about medications and other symptoms; however, he was unable to uncover any likely “suspects.” He then drew labs for a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and uric acid and QuantiFERON TB gold tests. He started the patient on ibuprofen 400 mg tid with meals for the pain and inflammation.

On a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, all of the lab results were normal and the patient was about 50% improved. At this time, the FP obtained a chest x-ray to look for any evidence of sarcoidosis. The x-ray was also normal. (About half of all cases of EN are idiopathic, so the normal results were not surprising.) By the third visit the patient was 90% better and was happy to keep taking the ibuprofen to see if this would resolve completely.

After 6 weeks of treatment, there were no more tender erythematous nodules. All that remained was some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The patient was happy with these results and understood that she should return if the EN came back.

Photo courtesy of Hanuš Rozsypal, MD, and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Diaz L, Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Maternal factors impact childhood skin microbiota

Bacteria on children’s skin was similar to their mothers’ and affected by factors that included method of delivery and breastfeeding in a study of 154 children aged 10 years and younger.

Understanding the wrote Ting Zhu of Fudan University, Shanghai, China, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, the researchers compared the skin microbiota of the 158 children aged 1-10 years and 50 mothers using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing after collecting study samples from three skin areas: face, calf, and ventral forearm. The samples were pooled into 36 groups based on age, gender, and skin site.

“We observed significant differences in alpha diversity and the most prevalent taxa and identified factors that contributed to variation at each site,” the authors reported.

Overall, the “alpha diversity” – a measure of microbial diversity used in microbiome studies – of the skin microbiome increased with age, with the highest alpha diversity seen in the 10-year-olds (n = 28), notably on the face, but differences in alpha diversity between skin sites were seen only in the 1-year-olds (n = 26). Overall, the most commonly identified bacterial phyla at all skin sites in children were Proteobacteria (42%), Firmicutes (25%), Actinobacteria (13%), and Bacteroidetes (11%). In the three sites, the genera with high relative abundance (over 3%) included Streptococcus (13%), Enhydrobacter (6%), and Propionibacterium (5%). Of these, Streptococcus and Granulicatella showed negative linear correlations with age.

The researchers found significant differences between the bacterial communities of 10-year-olds delivered by Cesarean section and those delivered vaginally, particularly in the facial samples; however the difference wasn’t observed among face samples taken from 1-year-olds, according to the authors. They found significant variation in bacteria in calf samples based on whether the children were fed breast milk, formula, or a combination.

When the researchers examined the correlations between mother/child pairs, they found that the relative abundance of most bacteria in the children were more similar to their mothers than to unrelated adults, and they found the strongest correlations for the genera Deinococcus, Microbacterium, Chryseobacterium, Klebsiella, and Enhydrobacter. The relationships between the bacterial communities of mothers and children may be influenced by the shared living environment, topical products, and daily diet, they noted.

The study findings were limited by not controlling for certain variables, including daily diet, choice of topical products, bathing habits, and daily variation in environmental factors, the researchers wrote. However, the results show “that the skin microbiome is strongly affected by the surrounding microenvironment and that the alpha diversity of the skin microbiome increases during childhood,” they concluded.

The study was fully funded by Johnson & Johnson International, and several coauthors are employees of that company. Lead author Ms. Zhu had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Zhu T et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 August 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.018.

Bacteria on children’s skin was similar to their mothers’ and affected by factors that included method of delivery and breastfeeding in a study of 154 children aged 10 years and younger.

Understanding the wrote Ting Zhu of Fudan University, Shanghai, China, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, the researchers compared the skin microbiota of the 158 children aged 1-10 years and 50 mothers using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing after collecting study samples from three skin areas: face, calf, and ventral forearm. The samples were pooled into 36 groups based on age, gender, and skin site.

“We observed significant differences in alpha diversity and the most prevalent taxa and identified factors that contributed to variation at each site,” the authors reported.

Overall, the “alpha diversity” – a measure of microbial diversity used in microbiome studies – of the skin microbiome increased with age, with the highest alpha diversity seen in the 10-year-olds (n = 28), notably on the face, but differences in alpha diversity between skin sites were seen only in the 1-year-olds (n = 26). Overall, the most commonly identified bacterial phyla at all skin sites in children were Proteobacteria (42%), Firmicutes (25%), Actinobacteria (13%), and Bacteroidetes (11%). In the three sites, the genera with high relative abundance (over 3%) included Streptococcus (13%), Enhydrobacter (6%), and Propionibacterium (5%). Of these, Streptococcus and Granulicatella showed negative linear correlations with age.

The researchers found significant differences between the bacterial communities of 10-year-olds delivered by Cesarean section and those delivered vaginally, particularly in the facial samples; however the difference wasn’t observed among face samples taken from 1-year-olds, according to the authors. They found significant variation in bacteria in calf samples based on whether the children were fed breast milk, formula, or a combination.

When the researchers examined the correlations between mother/child pairs, they found that the relative abundance of most bacteria in the children were more similar to their mothers than to unrelated adults, and they found the strongest correlations for the genera Deinococcus, Microbacterium, Chryseobacterium, Klebsiella, and Enhydrobacter. The relationships between the bacterial communities of mothers and children may be influenced by the shared living environment, topical products, and daily diet, they noted.

The study findings were limited by not controlling for certain variables, including daily diet, choice of topical products, bathing habits, and daily variation in environmental factors, the researchers wrote. However, the results show “that the skin microbiome is strongly affected by the surrounding microenvironment and that the alpha diversity of the skin microbiome increases during childhood,” they concluded.

The study was fully funded by Johnson & Johnson International, and several coauthors are employees of that company. Lead author Ms. Zhu had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Zhu T et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 August 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.018.

Bacteria on children’s skin was similar to their mothers’ and affected by factors that included method of delivery and breastfeeding in a study of 154 children aged 10 years and younger.

Understanding the wrote Ting Zhu of Fudan University, Shanghai, China, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, the researchers compared the skin microbiota of the 158 children aged 1-10 years and 50 mothers using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing after collecting study samples from three skin areas: face, calf, and ventral forearm. The samples were pooled into 36 groups based on age, gender, and skin site.

“We observed significant differences in alpha diversity and the most prevalent taxa and identified factors that contributed to variation at each site,” the authors reported.

Overall, the “alpha diversity” – a measure of microbial diversity used in microbiome studies – of the skin microbiome increased with age, with the highest alpha diversity seen in the 10-year-olds (n = 28), notably on the face, but differences in alpha diversity between skin sites were seen only in the 1-year-olds (n = 26). Overall, the most commonly identified bacterial phyla at all skin sites in children were Proteobacteria (42%), Firmicutes (25%), Actinobacteria (13%), and Bacteroidetes (11%). In the three sites, the genera with high relative abundance (over 3%) included Streptococcus (13%), Enhydrobacter (6%), and Propionibacterium (5%). Of these, Streptococcus and Granulicatella showed negative linear correlations with age.

The researchers found significant differences between the bacterial communities of 10-year-olds delivered by Cesarean section and those delivered vaginally, particularly in the facial samples; however the difference wasn’t observed among face samples taken from 1-year-olds, according to the authors. They found significant variation in bacteria in calf samples based on whether the children were fed breast milk, formula, or a combination.

When the researchers examined the correlations between mother/child pairs, they found that the relative abundance of most bacteria in the children were more similar to their mothers than to unrelated adults, and they found the strongest correlations for the genera Deinococcus, Microbacterium, Chryseobacterium, Klebsiella, and Enhydrobacter. The relationships between the bacterial communities of mothers and children may be influenced by the shared living environment, topical products, and daily diet, they noted.

The study findings were limited by not controlling for certain variables, including daily diet, choice of topical products, bathing habits, and daily variation in environmental factors, the researchers wrote. However, the results show “that the skin microbiome is strongly affected by the surrounding microenvironment and that the alpha diversity of the skin microbiome increases during childhood,” they concluded.

The study was fully funded by Johnson & Johnson International, and several coauthors are employees of that company. Lead author Ms. Zhu had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Zhu T et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 August 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.018.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Age, skin site, and maternal factors including delivery method and breastfeeding impact the bacterial makeup of children’s skin.

Major finding: The most common bacteria at all skin sites in children were Proteobacteria (42%), Firmicutes (25%), Actinobacteria (13%), and Bacteroidetes (11%).

Study details: The data come from 158 children aged 10 years and younger and included 474 skin samples.

Disclosures: The study was fully funded by Johnson & Johnson International, and several coauthors are employees of that company. Lead author Ms. Zhu had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Zhu T et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 August 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.018.

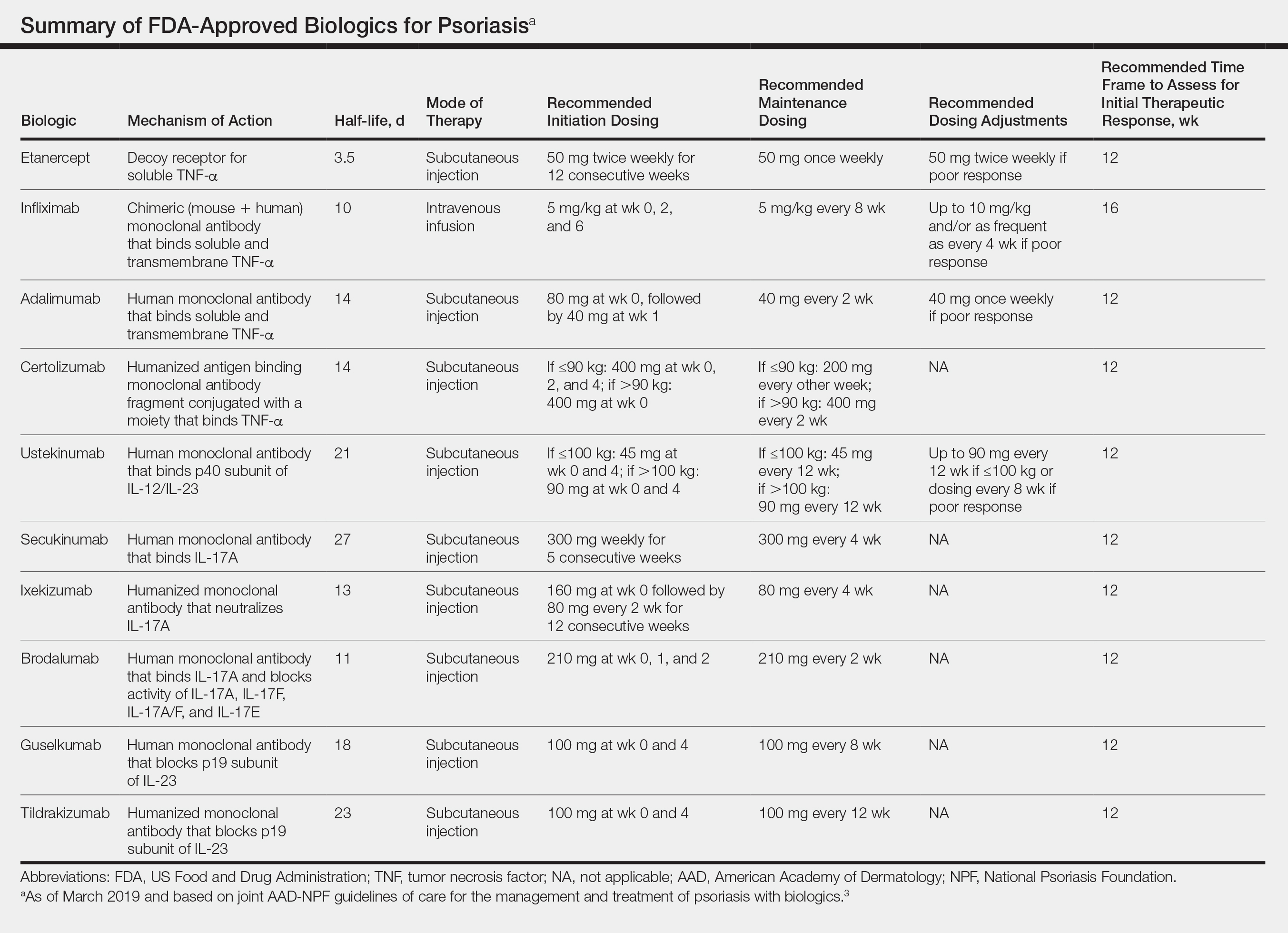

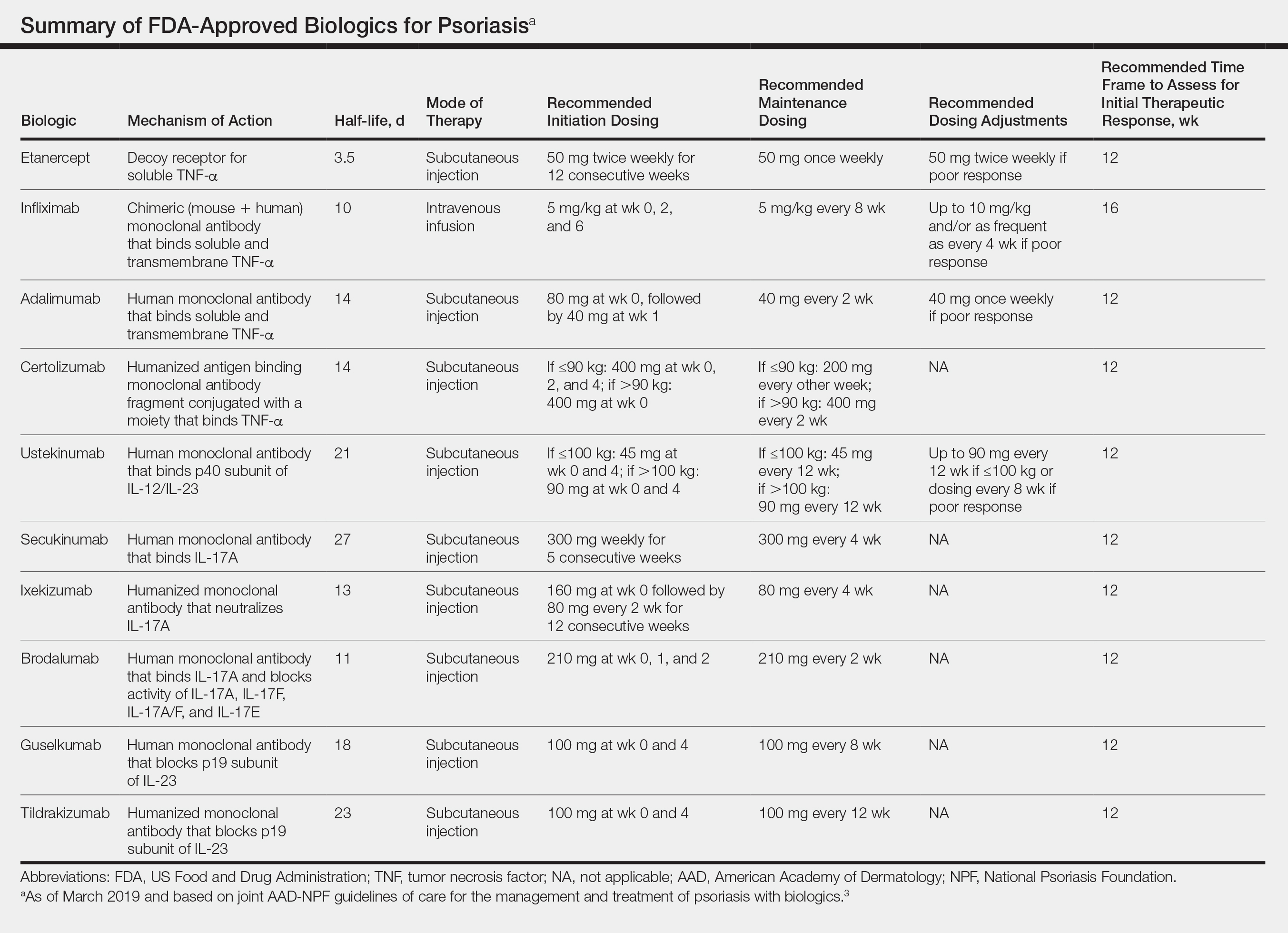

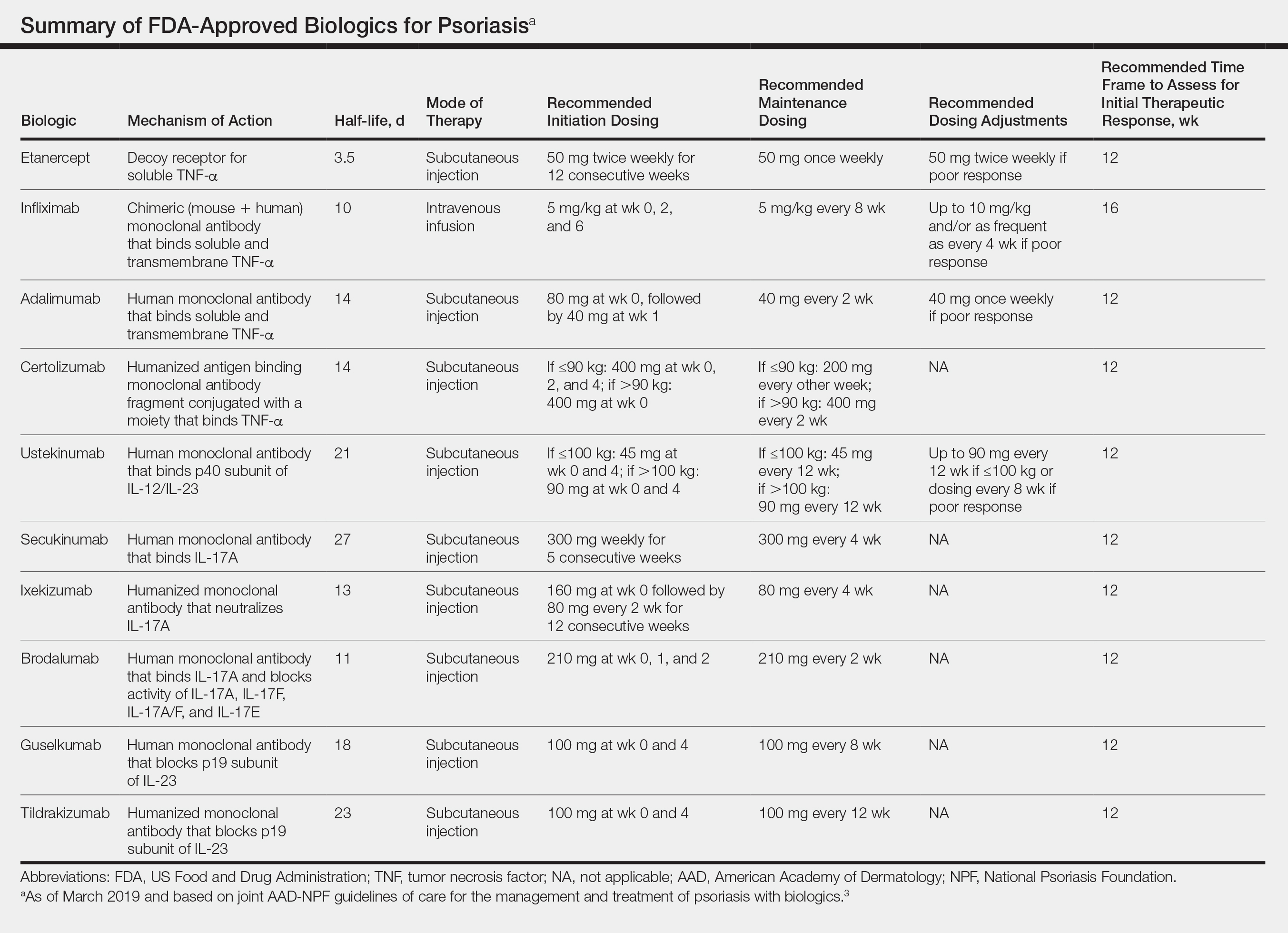

Translating the 2019 AAD-NPF Guidelines of Care for the Management of Psoriasis With Biologics to Clinical Practice

Psoriasis is a systemic immune-mediated disorder characterized by erythematous, scaly, well-demarcated plaques on the skin that affects approximately 3% of the world’s population.1 The disease is moderate to severe for approximately 1 in 6 individuals with psoriasis.2 These patients, particularly those with symptoms that are refractory to topical therapy and/or phototherapy, can benefit from the use of biologic agents, which are monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins engineered to inhibit the action of cytokines that drive psoriatic inflammation.

In February 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released an updated set of guidelines for the use of biologics in treating adult patients with psoriasis.3 The prior guidelines were released in 2008 when just 3 biologics—etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab—were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of psoriasis. These older recommendations were mostly based on studies of the efficacy and safety of biologics for patients with psoriatic arthritis.4 Over the last 11 years, 8 novel biologics have gained FDA approval, and numerous large phase 2 and phase 3 trials evaluating the risks and benefits of biologics have been conducted. The new guidelines contain considerably more detail and are based on evidence more specific to psoriasis rather than to psoriatic arthritis. Given the large repertoire of biologics available today and the increased amount of published research regarding each one, these guidelines may aid dermatologists in choosing the optimal biologic and managing therapy.

The AAD-NPF recommendations discuss the mechanism of action, efficacy, safety, and adverse events of the 10 biologics that have been FDA approved for the treatment of psoriasis as of March 2019, plus risankizumab, which was pending FDA approval at the time of publication and was later approved in April 2019. They also address dosing regimens, potential to combine biologics with other therapies, and different forms of psoriasis for which each may be effective.3 The purpose of this discussion is to present these guidelines in a condensed form to prescribers of biologic therapies and review the most clinically significant considerations during each step of treatment. Of note, we highlight only treatment of adult patients and do not discuss information relevant to risankizumab, as it was not FDA approved when the AAD-NPF guidelines were released.

Choosing a Biologic

Biologic therapy may be considered for patients with psoriasis that affects more than 3% of the body’s surface and is recalcitrant to localized therapies. There is no particular first-line biologic recommended for all patients with psoriasis; rather, choice of therapy should be individualized to the patient, considering factors such as body parts affected, comorbidities, lifestyle, and drug cost.

All 10 FDA-approved biologics (Table) have been ranked by the AAD and NPF as having grade A evidence for efficacy as monotherapy in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis. Involvement of difficult-to-treat areas may be considered when choosing a specific therapy. The tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors etanercept and adalimumab, the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab, and the IL-23 inhibitor guselkumab have the greatest evidence for efficacy in treatment of nail disease. For scalp involvement, etanercept and guselkumab have the highest-quality evidence, and for palmoplantar disease, adalimumab, secukinumab, and guselkumab are considered the most effective. The TNF-α inhibitors are considered the optimal treatment option for concurrent psoriatic arthritis, though the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab and the IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab also have shown grade A evidence of efficacy. Of note, because TNF-α inhibitors received the earliest FDA approval, there is most evidence available for this class. Therapies with lower evidence quality for certain forms of psoriasis may show real-world effectiveness in individual patients, though more trials will be necessary to generate a body of evidence to change these clinical recommendations.

In pregnant women or those are anticipating pregnancy, certolizumab may be considered, as it is the only biologic shown to have minimal to no placental transfer. Other TNF-α inhibitors may undergo active placental transfer, particularly during the latter half of pregnancy,5 and the greatest theoretical risk of transfer occurs in the third trimester. Although these drugs may not directly harm the fetus, they do cause fetal immunosuppression for up to the first 3 months of life. All TNF-α inhibitors are considered safe during lactation. There are inadequate data regarding the safety of other classes of biologics during pregnancy and lactation.

Overweight and obese patients also require unique considerations when choosing a biologic. Infliximab is the only approved psoriasis biologic that utilizes proportional-to-weight dosing and hence may be particularly efficacious in patients with higher body mass. Ustekinumab dosing also takes patient weight into consideration; patients heavier than 100 kg should receive 90-mg doses at initiation and during maintenance compared to 45 mg for patients who weigh 100 kg or less. Other approved biologics also may be utilized in these patients but may require closer monitoring of treatment efficacy.

There are few serious contraindications for specific biologic therapies. Any history of allergic reaction to a particular therapy is an absolute contraindication to its use. In patients for whom IL-17 inhibitor treatment is being considered, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be ruled out given the likelihood that IL-17 could reactivate or worsen IBD. Of note, TNF-α inhibitors and ustekinumab are approved therapies for patients with IBD and may be recommended in patients with comorbid psoriasis. Phase 2 and phase 3 trials have found no reactivation or worsening of IBD in patients with psoriasis who were treated with the IL-23 inhibitor tildrakizumab,6 and phase 2 trials of treatment of IBD with guselkumab are currently underway (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03466411). In patients with New York Heart Association class III and class IV congestive heart failure or multiple sclerosis, initiation of TNF-α inhibitors should be avoided. Among 3 phase 3 trials encompassing nearly 3000 patients treated with the IL-17 inhibitor brodalumab, a total of 3 patients died by suicide7,8; hence, the FDA has issued a black box warning cautioning against use of this drug in patients with history of suicidal ideation or recent suicidal behavior. Although a causal relationship between brodalumab and suicide has not been well established,9 a thorough psychiatric history should be obtained in those initiating treatment with brodalumab.

Initiation of Therapy

Prior to initiating biologic therapy, it is important to obtain a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, tuberculosis testing, and hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus serologies. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus may be pursued at the clinician’s discretion. It is important to address any positive or concerning results prior to starting biologics. In patients with active infections, therapy may be initiated alongside guidance from an infectious disease specialist. Those with a positive purified protein derivative test, T-SPOT test, or QuantiFERON-TB Gold test must be referred for chest radiographs to rule out active tuberculosis. Patients with active HBV infection should receive appropriate referral to initiate antiviral therapy as well as core antibody testing, and those with active hepatitis C virus infection may only receive biologics under the combined discretion of a dermatologist and an appropriate specialist. Patients with human immunodeficiency virus must concurrently receive highly active antiretroviral therapy, show normal CD4+ T-cell count and undetectable viral load, and have no recent history of opportunistic infection.

Therapy should be commenced using specific dosing regimens, which are unique for each biologic (Table). Patients also must be educated on routine follow-up to assess treatment response and tolerability.

Assessment and Optimization of Treatment Response

Patients taking biologics may experience primary treatment failure, defined as lack of response to therapy from initiation. One predisposing factor may be increased body mass; patients who are overweight and obese are less likely to respond to standard regimens of TNF-α inhibitors and 45-mg dosing of ustekinumab. In most cases, however, the cause of primary nonresponse is unpredictable. For patients in whom therapy has failed within the recommended initial time frame (Table), dose escalation or shortening of dosing intervals may be pursued. Recommended dosing adjustments are outlined in the Table. Alternatively, patients may be switched to a different biologic.

If desired effectiveness is not reached with biologic monotherapy, topical corticosteroids, topical vitamin D analogues, or narrowband UVB light therapy may be concurrently used for difficult-to-treat areas. Evidence for safety and effectiveness of systemic adjuncts to biologics is moderate to low, warranting caution with their use. Methotrexate, cyclosporine, and apremilast have synergistic effects with biologics, though they may increase the risk for immunosuppression-related complications. Acitretin, an oral retinoid, likely is the most reasonable systemic adjunct to biologics because of its lack of immunosuppressive properties.

In patients with a suboptimal response to biologics, particularly those taking therapies that require frequent dosing, poor compliance should be considered.10 These patients may be switched to a biologic with less-frequent maintenance dosing (Table). Ustekinumab and tildrakizumab may be the best options for optimizing compliance, as they require dosing only once every 12 weeks after administration of loading doses.

Secondary treatment failure is diminished efficacy of treatment following successful initial response despite no changes in regimen. The best-known factor contributing to secondary nonresponse to biologics is the development of antidrug antibodies (ADAs), a phenomenon known as immunogenicity. The development of efficacy-limiting ADAs has been observed in response to most biologics, though ADAs against etanercept and guselkumab do not limit therapeutic response. Patients taking adalimumab and infliximab have particularly well-documented efficacy-limiting immunogenicity, and those who develop ADAs to infliximab are considered more prone to developing infusion reactions. Methotrexate, which limits antibody formation, may concomitantly be prescribed in patients who experience secondary treatment failure. It should be considered in all patients taking infliximab to increase efficacy and tolerability of therapy.

Considerations During Active Therapy

In addition to monitoring adherence and response to regimens, dermatologists must be heavily involved in counseling patients regarding the risks and adverse effects associated with these therapies. During maintenance therapy with biologics, patients must follow up with the prescriber at minimum every 3 to 6 months to evaluate for continued efficacy of treatment, extent of side effects, and effects of treatment on overall health and quality of life. Given the immunosuppressive effects of biologics, annual testing for tuberculosis should be considered in high-risk individuals. In those who are considered at low risk, tuberculosis testing may be done at the discretion of the dermatologist. In those with a history of HBV infection, HBV serologies should be pursued routinely given the risk for reactivation.

Annual screening for nonmelanoma skin cancer should be performed in all patients taking biologics. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy in particular confers an elevated risk for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, especially in patients who are immunosuppressed at baseline and those with history of UV phototherapy. Use of acitretin alongside TNF-α inhibitors or ustekinumab may prevent squamous cell carcinoma formation in high-risk patients.

Because infliximab treatment poses an elevated risk of liver injury,11 liver function tests should be repeated 3 months following initiation of treatment and then every 6 to 12 months subsequently if results are normal. Periodic assessment of suicidal ideation is recommended in patients on brodalumab therapy, which may necessitate more frequent follow-up visits and potentially psychiatry referrals in certain patients. Patients taking IL-17 inhibitors, particularly those who are concurrently taking methotrexate, are at increased risk for developing mucocutaneous Candida infections; these patients should be monitored for such infections and treated appropriately.12

It is additionally important for prescribing dermatologists to ensure that patients on biologics are following up with their general providers to receive timely age-appropriate preventative screenings and vaccines. Inactivated vaccinations may be administered during therapy with any biologic; however, live vaccinations may induce systemic infection in those who are immunocompromised, which theoretically includes individuals taking biologic agents, though incidence data in this patient population are scarce.13 Some experts believe that administration of live vaccines warrants temporary discontinuation of biologic therapy for 2 to 3 half-lives before and after vaccination (Table). Others recommend stopping treatment at least 4 weeks before and until 2 weeks after vaccination. For patients taking biologics with half-lives greater than 20 days, which would theoretically require stopping the drug 2 months prior to vaccination, the benefit of vaccination should be weighed against the risk of prolonged discontinuation of therapy. Until recently, this recommendation was particularly important, as a live herpes zoster vaccination was recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for adults older than 60 years. In 2017, a new inactivated herpes zoster vaccine was introduced and is now the preferred vaccine for all patients older than 50 years.14 It is especially important that patients on biologics receive this vaccine to avoid temporary drug discontinuation.

Evidence that any particular class of biologics increases risk for solid tumors or lymphoreticular malignancy is limited. One case-control analysis reported that more than 12 months of treatment with TNF-α inhibitors may increase risk for malignancy; however, the confidence interval reported hardly allows for statistical significance.15 Another retrospective cohort study found no elevated incidence of cancer in patients on TNF-α inhibitors compared to nonbiologic comparators.16 Ustekinumab was shown to confer no increased risk for malignancy in 1 large study,15 but no large studies have been conducted for other classes of drugs. Given the limited and inconclusive evidence available, the guidelines recommend that age-appropriate cancer screenings recommended for the general population should be pursued in patients taking biologics.

Surgery while taking biologics may lead to stress-induced augmentation of immunosuppression, resulting in elevated risk of infection.17 Low-risk surgeries that do not warrant discontinuation of treatment include endoscopic, ophthalmologic, dermatologic, orthopedic, and breast procedures. In patients preparing for elective surgery in which respiratory, gastrointestinal, or genitourinary tracts will be entered, biologics may be discontinued at least 3 half-lives (Table) prior to surgery if the dermatologist and surgeon collaboratively deem that risk of infection outweighs benefit of continued therapy.18 Therapy may be resumed within 1 to 2 weeks postoperatively if there are no surgical complications.

Switching Biologics

Changing therapy to another biologic should be considered if there is no response to treatment or the patient experiences adverse effects while taking a particular biologic. Because evidence is limited regarding the ideal time frame between discontinuation of a prior medication and initiation of a new biologic, this interval should be determined at the discretion of the provider based on the patient’s disease severity and response to prior treatment. For individuals who experience primary or secondary treatment failure while maintaining appropriate dosing and treatment compliance, switching to a different biologic is recommended to maximize treatment response.19 Changing therapy to a biologic within the same class is generally effective,20 and switching to a biologic with another mechanism of action should be considered if a class-specific adverse effect is the major reason for altering the regimen. Nonetheless, some patients may be unresponsive to biologic changes. Further research is necessary to determine which biologics may be most effective when previously used biologics have failed and particular factors that may predispose patients to biologic unresponsiveness.

Resuming Biologic Treatment Following Cessation

In cases where therapy is discontinued for any reason, it may be necessary to repeat initiation dosing when resuming treatment. In patients with severe or flaring disease or if more than 3 to 4 half-lives have passed since the most recent dose, it may be necessary to restart therapy with the loading dose (Table). Unfortunately, restarting therapy may preclude some patients from experiencing the maximal response that they attained prior to cessation. In such cases, switching biologic therapy to a different class may prove beneficial.

Final Thoughts

These recommendations contain valuable information that will assist dermatologists when initiating biologics and managing outcomes of their psoriasis patients. It is, however, crucial to bear in mind that these guidelines serve as merely a tool. Given the paucity of comprehensive research, particularly regarding some of the more recently approved therapies, there are many questions that are unanswered within the guidelines. Their utility for each individual patient situation is therefore limited, and clinical judgement may outweigh the information presented. The recommendations nevertheless provide a pivotal and unprecedented framework that promotes discourse among patients, dermatologists, and other providers to optimize the efficacy of biologic therapy for psoriasis.

- Michalek IM, Loring B, John SM. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:205-212.

- Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003-2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:218-224.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics [published online February 13, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-850.

- Förger F, Villiger PM. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy: present and future. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12:937-944.

- Gooderham M, Elewski B, Pariser D, et al. Incidence of serious gastrointestinal events and inflammatory bowel disease among tildrakizumab-treated patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: data from 3 large randomized clinical trials [abstract]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(suppl 1):AB166.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-328.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273-286

- Beck KM, Koo J. Brodalumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: up-to-date. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:287-292.

- Fouéré S, Adjadj L, Pawin H. How patients experience psoriasis: results from a European survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(suppl 3):2-6.

- Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, et al. Incidence, presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1419-1425, 1425.e1-3; quiz e19-20.

- Saunte DM, Mrowietz U, Puig L, et al. Candida infections in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treated with interleukin-17 inhibitors and their practical management. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:47-62.

- Huber F, Ehrensperger B, Hatz C, et al. Safety of live vaccines on immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory therapy—a retrospective study in three Swiss Travel Clinics [published online January 1, 2018]. J Travel Med. doi:10.1093/jtm/tax082.

- Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:103-108.

- Fiorentino D, Ho V, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of malignancy with systemic psoriasis treatment in the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment Registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:845-854.e5.

- Haynes K, Beukelman T, Curtis JR, et al. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy and cancer risk in chronic immune-mediated diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:48-58.

- Fabiano A, De Simone C, Gisondi P, et al. Management of patients with psoriasis treated with biologic drugs needing a surgical treatment. Drug Dev Res. 2014;75(suppl 1):S24-S26.

- Choi YM, Debbaneh M, Weinberg JM, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: perioperative management of systemic immunomodulatory agents in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:798-805.e7.

- Honda H, Umezawa Y, Kikuchi S, et al. Switching of biologics in psoriasis: reasons and results. J Dermatol. 2017;44:1015-1019.

- Bracke S, Lambert J. Viewpoint on handling anti-TNF failure in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2013;305:945-950.

Psoriasis is a systemic immune-mediated disorder characterized by erythematous, scaly, well-demarcated plaques on the skin that affects approximately 3% of the world’s population.1 The disease is moderate to severe for approximately 1 in 6 individuals with psoriasis.2 These patients, particularly those with symptoms that are refractory to topical therapy and/or phototherapy, can benefit from the use of biologic agents, which are monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins engineered to inhibit the action of cytokines that drive psoriatic inflammation.

In February 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released an updated set of guidelines for the use of biologics in treating adult patients with psoriasis.3 The prior guidelines were released in 2008 when just 3 biologics—etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab—were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of psoriasis. These older recommendations were mostly based on studies of the efficacy and safety of biologics for patients with psoriatic arthritis.4 Over the last 11 years, 8 novel biologics have gained FDA approval, and numerous large phase 2 and phase 3 trials evaluating the risks and benefits of biologics have been conducted. The new guidelines contain considerably more detail and are based on evidence more specific to psoriasis rather than to psoriatic arthritis. Given the large repertoire of biologics available today and the increased amount of published research regarding each one, these guidelines may aid dermatologists in choosing the optimal biologic and managing therapy.

The AAD-NPF recommendations discuss the mechanism of action, efficacy, safety, and adverse events of the 10 biologics that have been FDA approved for the treatment of psoriasis as of March 2019, plus risankizumab, which was pending FDA approval at the time of publication and was later approved in April 2019. They also address dosing regimens, potential to combine biologics with other therapies, and different forms of psoriasis for which each may be effective.3 The purpose of this discussion is to present these guidelines in a condensed form to prescribers of biologic therapies and review the most clinically significant considerations during each step of treatment. Of note, we highlight only treatment of adult patients and do not discuss information relevant to risankizumab, as it was not FDA approved when the AAD-NPF guidelines were released.

Choosing a Biologic

Biologic therapy may be considered for patients with psoriasis that affects more than 3% of the body’s surface and is recalcitrant to localized therapies. There is no particular first-line biologic recommended for all patients with psoriasis; rather, choice of therapy should be individualized to the patient, considering factors such as body parts affected, comorbidities, lifestyle, and drug cost.

All 10 FDA-approved biologics (Table) have been ranked by the AAD and NPF as having grade A evidence for efficacy as monotherapy in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis. Involvement of difficult-to-treat areas may be considered when choosing a specific therapy. The tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors etanercept and adalimumab, the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab, and the IL-23 inhibitor guselkumab have the greatest evidence for efficacy in treatment of nail disease. For scalp involvement, etanercept and guselkumab have the highest-quality evidence, and for palmoplantar disease, adalimumab, secukinumab, and guselkumab are considered the most effective. The TNF-α inhibitors are considered the optimal treatment option for concurrent psoriatic arthritis, though the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab and the IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab also have shown grade A evidence of efficacy. Of note, because TNF-α inhibitors received the earliest FDA approval, there is most evidence available for this class. Therapies with lower evidence quality for certain forms of psoriasis may show real-world effectiveness in individual patients, though more trials will be necessary to generate a body of evidence to change these clinical recommendations.

In pregnant women or those are anticipating pregnancy, certolizumab may be considered, as it is the only biologic shown to have minimal to no placental transfer. Other TNF-α inhibitors may undergo active placental transfer, particularly during the latter half of pregnancy,5 and the greatest theoretical risk of transfer occurs in the third trimester. Although these drugs may not directly harm the fetus, they do cause fetal immunosuppression for up to the first 3 months of life. All TNF-α inhibitors are considered safe during lactation. There are inadequate data regarding the safety of other classes of biologics during pregnancy and lactation.

Overweight and obese patients also require unique considerations when choosing a biologic. Infliximab is the only approved psoriasis biologic that utilizes proportional-to-weight dosing and hence may be particularly efficacious in patients with higher body mass. Ustekinumab dosing also takes patient weight into consideration; patients heavier than 100 kg should receive 90-mg doses at initiation and during maintenance compared to 45 mg for patients who weigh 100 kg or less. Other approved biologics also may be utilized in these patients but may require closer monitoring of treatment efficacy.

There are few serious contraindications for specific biologic therapies. Any history of allergic reaction to a particular therapy is an absolute contraindication to its use. In patients for whom IL-17 inhibitor treatment is being considered, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be ruled out given the likelihood that IL-17 could reactivate or worsen IBD. Of note, TNF-α inhibitors and ustekinumab are approved therapies for patients with IBD and may be recommended in patients with comorbid psoriasis. Phase 2 and phase 3 trials have found no reactivation or worsening of IBD in patients with psoriasis who were treated with the IL-23 inhibitor tildrakizumab,6 and phase 2 trials of treatment of IBD with guselkumab are currently underway (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03466411). In patients with New York Heart Association class III and class IV congestive heart failure or multiple sclerosis, initiation of TNF-α inhibitors should be avoided. Among 3 phase 3 trials encompassing nearly 3000 patients treated with the IL-17 inhibitor brodalumab, a total of 3 patients died by suicide7,8; hence, the FDA has issued a black box warning cautioning against use of this drug in patients with history of suicidal ideation or recent suicidal behavior. Although a causal relationship between brodalumab and suicide has not been well established,9 a thorough psychiatric history should be obtained in those initiating treatment with brodalumab.

Initiation of Therapy

Prior to initiating biologic therapy, it is important to obtain a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, tuberculosis testing, and hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus serologies. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus may be pursued at the clinician’s discretion. It is important to address any positive or concerning results prior to starting biologics. In patients with active infections, therapy may be initiated alongside guidance from an infectious disease specialist. Those with a positive purified protein derivative test, T-SPOT test, or QuantiFERON-TB Gold test must be referred for chest radiographs to rule out active tuberculosis. Patients with active HBV infection should receive appropriate referral to initiate antiviral therapy as well as core antibody testing, and those with active hepatitis C virus infection may only receive biologics under the combined discretion of a dermatologist and an appropriate specialist. Patients with human immunodeficiency virus must concurrently receive highly active antiretroviral therapy, show normal CD4+ T-cell count and undetectable viral load, and have no recent history of opportunistic infection.

Therapy should be commenced using specific dosing regimens, which are unique for each biologic (Table). Patients also must be educated on routine follow-up to assess treatment response and tolerability.

Assessment and Optimization of Treatment Response

Patients taking biologics may experience primary treatment failure, defined as lack of response to therapy from initiation. One predisposing factor may be increased body mass; patients who are overweight and obese are less likely to respond to standard regimens of TNF-α inhibitors and 45-mg dosing of ustekinumab. In most cases, however, the cause of primary nonresponse is unpredictable. For patients in whom therapy has failed within the recommended initial time frame (Table), dose escalation or shortening of dosing intervals may be pursued. Recommended dosing adjustments are outlined in the Table. Alternatively, patients may be switched to a different biologic.

If desired effectiveness is not reached with biologic monotherapy, topical corticosteroids, topical vitamin D analogues, or narrowband UVB light therapy may be concurrently used for difficult-to-treat areas. Evidence for safety and effectiveness of systemic adjuncts to biologics is moderate to low, warranting caution with their use. Methotrexate, cyclosporine, and apremilast have synergistic effects with biologics, though they may increase the risk for immunosuppression-related complications. Acitretin, an oral retinoid, likely is the most reasonable systemic adjunct to biologics because of its lack of immunosuppressive properties.

In patients with a suboptimal response to biologics, particularly those taking therapies that require frequent dosing, poor compliance should be considered.10 These patients may be switched to a biologic with less-frequent maintenance dosing (Table). Ustekinumab and tildrakizumab may be the best options for optimizing compliance, as they require dosing only once every 12 weeks after administration of loading doses.

Secondary treatment failure is diminished efficacy of treatment following successful initial response despite no changes in regimen. The best-known factor contributing to secondary nonresponse to biologics is the development of antidrug antibodies (ADAs), a phenomenon known as immunogenicity. The development of efficacy-limiting ADAs has been observed in response to most biologics, though ADAs against etanercept and guselkumab do not limit therapeutic response. Patients taking adalimumab and infliximab have particularly well-documented efficacy-limiting immunogenicity, and those who develop ADAs to infliximab are considered more prone to developing infusion reactions. Methotrexate, which limits antibody formation, may concomitantly be prescribed in patients who experience secondary treatment failure. It should be considered in all patients taking infliximab to increase efficacy and tolerability of therapy.

Considerations During Active Therapy

In addition to monitoring adherence and response to regimens, dermatologists must be heavily involved in counseling patients regarding the risks and adverse effects associated with these therapies. During maintenance therapy with biologics, patients must follow up with the prescriber at minimum every 3 to 6 months to evaluate for continued efficacy of treatment, extent of side effects, and effects of treatment on overall health and quality of life. Given the immunosuppressive effects of biologics, annual testing for tuberculosis should be considered in high-risk individuals. In those who are considered at low risk, tuberculosis testing may be done at the discretion of the dermatologist. In those with a history of HBV infection, HBV serologies should be pursued routinely given the risk for reactivation.

Annual screening for nonmelanoma skin cancer should be performed in all patients taking biologics. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy in particular confers an elevated risk for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, especially in patients who are immunosuppressed at baseline and those with history of UV phototherapy. Use of acitretin alongside TNF-α inhibitors or ustekinumab may prevent squamous cell carcinoma formation in high-risk patients.

Because infliximab treatment poses an elevated risk of liver injury,11 liver function tests should be repeated 3 months following initiation of treatment and then every 6 to 12 months subsequently if results are normal. Periodic assessment of suicidal ideation is recommended in patients on brodalumab therapy, which may necessitate more frequent follow-up visits and potentially psychiatry referrals in certain patients. Patients taking IL-17 inhibitors, particularly those who are concurrently taking methotrexate, are at increased risk for developing mucocutaneous Candida infections; these patients should be monitored for such infections and treated appropriately.12

It is additionally important for prescribing dermatologists to ensure that patients on biologics are following up with their general providers to receive timely age-appropriate preventative screenings and vaccines. Inactivated vaccinations may be administered during therapy with any biologic; however, live vaccinations may induce systemic infection in those who are immunocompromised, which theoretically includes individuals taking biologic agents, though incidence data in this patient population are scarce.13 Some experts believe that administration of live vaccines warrants temporary discontinuation of biologic therapy for 2 to 3 half-lives before and after vaccination (Table). Others recommend stopping treatment at least 4 weeks before and until 2 weeks after vaccination. For patients taking biologics with half-lives greater than 20 days, which would theoretically require stopping the drug 2 months prior to vaccination, the benefit of vaccination should be weighed against the risk of prolonged discontinuation of therapy. Until recently, this recommendation was particularly important, as a live herpes zoster vaccination was recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for adults older than 60 years. In 2017, a new inactivated herpes zoster vaccine was introduced and is now the preferred vaccine for all patients older than 50 years.14 It is especially important that patients on biologics receive this vaccine to avoid temporary drug discontinuation.