User login

Socioeconomic status affects scleroderma severity in African Americans

according to findings from an analysis of single-center cohort data over a 10-year period.

Indeed, among patients in the cohort of 402 scleroderma patients at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, lower household income was predictive of higher mortality during follow-up, independent of race, according to first author Duncan F. Moore, MD, and his colleagues at the hospital.

Previous studies have demonstrated increased risk for scleroderma in African American patients, who also are more likely than non–African Americans to be diagnosed at a younger age and to have conditions including more diffuse cutaneous disease, more severe restrictive lung disease, more cardiac and renal involvement, and increased mortality, the authors wrote in Arthritis Care & Research.

“We did clearly show that African Americans have worse outcomes and severe pulmonary involvement, but I was surprised that there still was a major contribution of socioeconomic status affecting outcomes for all patients, even though only 10% of our patients were indigent and on medical assistance,” Virginia Steen, MD, senior author of the study and professor of rheumatology at Georgetown University, said in an interview. “I still feel strongly that there are likely genetic issues as to why African Americans have such severe disease. We are eager to learn more from the GRASP [Genome Research in African American Scleroderma Patients] study, which is specifically looking at the genetic issues in African American scleroderma patients,” she said.

Of the 402 scleroderma patients at MedStar Georgetown who were seen during 2006-2016, 202 were African American. A total of 186 African American and 184 non–African American patients in the study met the 2013 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria for systemic sclerosis (SSc). Demographics including gender (87% female) and age (mean of 48 years) were similar between the groups.

Overall, the African American patients showed more severe lung disease, more pulmonary hypertension, and more severe cardiac involvement than did non–African American patients, and autoantibodies were significantly different between the groups.

During follow-up, mortality proved much higher among African Americans at 21%, compared with 11% in non–African Americans (P = .005). However, the unadjusted hazard ratio for death declined from 2.061 (P = .006) to a nonsignificant 1.256 after adjustment for socioeconomic variables.

All socioeconomic measures showed significant differences between the groups. African Americans were more likely to be single and disabled at the initial study visit and to have Medicaid, but they were less likely to be a homemaker, have private insurance, or have a college degree. African Americans’ $74,000 median household income (based on ZIP code) was also a statistically significant $23,000 less than non–African American patients. But the researchers noted that “for every additional $10,000 of household income, independent of race, the hazard of death during follow-up declined by 15.5%.”

Notable differences in antibodies appeared between the groups, with more African American patients having isolated nucleolar ANA, anti-U1RNP antibody, or other positive antinuclear antibodies without SSc-specific antibodies. African American patients also were less likely to have anticentromere or anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including possible bias in the matching process and the use of only index values for socioeconomic variables, the researchers noted.

Regardless of relative socioeconomic and genetic influences, “it is clear that African Americans with scleroderma merit more intensive efforts to facilitate timely diagnosis and access to continued evaluation and suppressive treatment, particularly with respect to cardiopulmonary involvement,” they wrote.

Next steps for research, according to Dr. Steen, include studying clinical subsets of African American patients to try to identify factors to predict outcomes, including the nucleolar pattern ANA, overlap with lupus, history of hypertension, and the relationship with renal crisis.

“We are also looking at whether the African American patients are less responsive to mycophenolate than the non–African American patients. We definitely need to find ways to be more aggressive at identifying and treating African American patients early in their disease,” she added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Steen serves on the MDedge Rheumatology Editorial Advisory Board.

SOURCE: Moore DF et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 March 1. doi: 10.1002/acr.23861.

“Not only do patients who manifest the diffuse cutaneous subset of disease experience a more severe course, but so do affected persons of African American race,” Nadia D. Morgan, MBBS, and Allan C. Gelber, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial. The effects of socioeconomic status should not be overlooked based on the current study, in which the inclusion of socioeconomic factors eliminated the significance of association between race and mortality among scleroderma patients, they wrote.

“Overall, and in the context of these published reports which underscore the disproportionate and adverse impact of scleroderma among African Americans, and in light of the ongoing efforts of the GRASP study, the current paper by Moore et al. emphasizes the importance of socioeconomic status, and of socioeconomic determinants of health, to account for differences in clinically relevant outcomes,” they wrote.

Dr. Gelber is affiliated with the division of rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Morgan, who was also with Johns Hopkins, died before publication of the editorial. They made no conflict of interest disclosures.

“Not only do patients who manifest the diffuse cutaneous subset of disease experience a more severe course, but so do affected persons of African American race,” Nadia D. Morgan, MBBS, and Allan C. Gelber, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial. The effects of socioeconomic status should not be overlooked based on the current study, in which the inclusion of socioeconomic factors eliminated the significance of association between race and mortality among scleroderma patients, they wrote.

“Overall, and in the context of these published reports which underscore the disproportionate and adverse impact of scleroderma among African Americans, and in light of the ongoing efforts of the GRASP study, the current paper by Moore et al. emphasizes the importance of socioeconomic status, and of socioeconomic determinants of health, to account for differences in clinically relevant outcomes,” they wrote.

Dr. Gelber is affiliated with the division of rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Morgan, who was also with Johns Hopkins, died before publication of the editorial. They made no conflict of interest disclosures.

“Not only do patients who manifest the diffuse cutaneous subset of disease experience a more severe course, but so do affected persons of African American race,” Nadia D. Morgan, MBBS, and Allan C. Gelber, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial. The effects of socioeconomic status should not be overlooked based on the current study, in which the inclusion of socioeconomic factors eliminated the significance of association between race and mortality among scleroderma patients, they wrote.

“Overall, and in the context of these published reports which underscore the disproportionate and adverse impact of scleroderma among African Americans, and in light of the ongoing efforts of the GRASP study, the current paper by Moore et al. emphasizes the importance of socioeconomic status, and of socioeconomic determinants of health, to account for differences in clinically relevant outcomes,” they wrote.

Dr. Gelber is affiliated with the division of rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Morgan, who was also with Johns Hopkins, died before publication of the editorial. They made no conflict of interest disclosures.

according to findings from an analysis of single-center cohort data over a 10-year period.

Indeed, among patients in the cohort of 402 scleroderma patients at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, lower household income was predictive of higher mortality during follow-up, independent of race, according to first author Duncan F. Moore, MD, and his colleagues at the hospital.

Previous studies have demonstrated increased risk for scleroderma in African American patients, who also are more likely than non–African Americans to be diagnosed at a younger age and to have conditions including more diffuse cutaneous disease, more severe restrictive lung disease, more cardiac and renal involvement, and increased mortality, the authors wrote in Arthritis Care & Research.

“We did clearly show that African Americans have worse outcomes and severe pulmonary involvement, but I was surprised that there still was a major contribution of socioeconomic status affecting outcomes for all patients, even though only 10% of our patients were indigent and on medical assistance,” Virginia Steen, MD, senior author of the study and professor of rheumatology at Georgetown University, said in an interview. “I still feel strongly that there are likely genetic issues as to why African Americans have such severe disease. We are eager to learn more from the GRASP [Genome Research in African American Scleroderma Patients] study, which is specifically looking at the genetic issues in African American scleroderma patients,” she said.

Of the 402 scleroderma patients at MedStar Georgetown who were seen during 2006-2016, 202 were African American. A total of 186 African American and 184 non–African American patients in the study met the 2013 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria for systemic sclerosis (SSc). Demographics including gender (87% female) and age (mean of 48 years) were similar between the groups.

Overall, the African American patients showed more severe lung disease, more pulmonary hypertension, and more severe cardiac involvement than did non–African American patients, and autoantibodies were significantly different between the groups.

During follow-up, mortality proved much higher among African Americans at 21%, compared with 11% in non–African Americans (P = .005). However, the unadjusted hazard ratio for death declined from 2.061 (P = .006) to a nonsignificant 1.256 after adjustment for socioeconomic variables.

All socioeconomic measures showed significant differences between the groups. African Americans were more likely to be single and disabled at the initial study visit and to have Medicaid, but they were less likely to be a homemaker, have private insurance, or have a college degree. African Americans’ $74,000 median household income (based on ZIP code) was also a statistically significant $23,000 less than non–African American patients. But the researchers noted that “for every additional $10,000 of household income, independent of race, the hazard of death during follow-up declined by 15.5%.”

Notable differences in antibodies appeared between the groups, with more African American patients having isolated nucleolar ANA, anti-U1RNP antibody, or other positive antinuclear antibodies without SSc-specific antibodies. African American patients also were less likely to have anticentromere or anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including possible bias in the matching process and the use of only index values for socioeconomic variables, the researchers noted.

Regardless of relative socioeconomic and genetic influences, “it is clear that African Americans with scleroderma merit more intensive efforts to facilitate timely diagnosis and access to continued evaluation and suppressive treatment, particularly with respect to cardiopulmonary involvement,” they wrote.

Next steps for research, according to Dr. Steen, include studying clinical subsets of African American patients to try to identify factors to predict outcomes, including the nucleolar pattern ANA, overlap with lupus, history of hypertension, and the relationship with renal crisis.

“We are also looking at whether the African American patients are less responsive to mycophenolate than the non–African American patients. We definitely need to find ways to be more aggressive at identifying and treating African American patients early in their disease,” she added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Steen serves on the MDedge Rheumatology Editorial Advisory Board.

SOURCE: Moore DF et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 March 1. doi: 10.1002/acr.23861.

according to findings from an analysis of single-center cohort data over a 10-year period.

Indeed, among patients in the cohort of 402 scleroderma patients at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, lower household income was predictive of higher mortality during follow-up, independent of race, according to first author Duncan F. Moore, MD, and his colleagues at the hospital.

Previous studies have demonstrated increased risk for scleroderma in African American patients, who also are more likely than non–African Americans to be diagnosed at a younger age and to have conditions including more diffuse cutaneous disease, more severe restrictive lung disease, more cardiac and renal involvement, and increased mortality, the authors wrote in Arthritis Care & Research.

“We did clearly show that African Americans have worse outcomes and severe pulmonary involvement, but I was surprised that there still was a major contribution of socioeconomic status affecting outcomes for all patients, even though only 10% of our patients were indigent and on medical assistance,” Virginia Steen, MD, senior author of the study and professor of rheumatology at Georgetown University, said in an interview. “I still feel strongly that there are likely genetic issues as to why African Americans have such severe disease. We are eager to learn more from the GRASP [Genome Research in African American Scleroderma Patients] study, which is specifically looking at the genetic issues in African American scleroderma patients,” she said.

Of the 402 scleroderma patients at MedStar Georgetown who were seen during 2006-2016, 202 were African American. A total of 186 African American and 184 non–African American patients in the study met the 2013 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria for systemic sclerosis (SSc). Demographics including gender (87% female) and age (mean of 48 years) were similar between the groups.

Overall, the African American patients showed more severe lung disease, more pulmonary hypertension, and more severe cardiac involvement than did non–African American patients, and autoantibodies were significantly different between the groups.

During follow-up, mortality proved much higher among African Americans at 21%, compared with 11% in non–African Americans (P = .005). However, the unadjusted hazard ratio for death declined from 2.061 (P = .006) to a nonsignificant 1.256 after adjustment for socioeconomic variables.

All socioeconomic measures showed significant differences between the groups. African Americans were more likely to be single and disabled at the initial study visit and to have Medicaid, but they were less likely to be a homemaker, have private insurance, or have a college degree. African Americans’ $74,000 median household income (based on ZIP code) was also a statistically significant $23,000 less than non–African American patients. But the researchers noted that “for every additional $10,000 of household income, independent of race, the hazard of death during follow-up declined by 15.5%.”

Notable differences in antibodies appeared between the groups, with more African American patients having isolated nucleolar ANA, anti-U1RNP antibody, or other positive antinuclear antibodies without SSc-specific antibodies. African American patients also were less likely to have anticentromere or anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including possible bias in the matching process and the use of only index values for socioeconomic variables, the researchers noted.

Regardless of relative socioeconomic and genetic influences, “it is clear that African Americans with scleroderma merit more intensive efforts to facilitate timely diagnosis and access to continued evaluation and suppressive treatment, particularly with respect to cardiopulmonary involvement,” they wrote.

Next steps for research, according to Dr. Steen, include studying clinical subsets of African American patients to try to identify factors to predict outcomes, including the nucleolar pattern ANA, overlap with lupus, history of hypertension, and the relationship with renal crisis.

“We are also looking at whether the African American patients are less responsive to mycophenolate than the non–African American patients. We definitely need to find ways to be more aggressive at identifying and treating African American patients early in their disease,” she added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Steen serves on the MDedge Rheumatology Editorial Advisory Board.

SOURCE: Moore DF et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 March 1. doi: 10.1002/acr.23861.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Whether diet, vitamins, or supplements can benefit patients with vitiligo remains unclear

WASHINGTON – Many patients with vitiligo are interested in treating their condition with vitamins, supplements, or a modified diet, but research on whether these measures have an impact remains limited, Nada Elbuluk, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

, “we need more well designed, controlled studies in the future to know where this belongs in our treatment armamentarium,” said Dr. Elbuluk of the department of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

During a session at the AAD meeting, Dr. Elbuluk, who is also director of the pigmentary disorders clinic at USC, reviewed the evidence for the use of these adjunctive therapies in patients with vitiligo.

Vitamins

The pathogenesis of vitiligo includes the overproduction of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress, factors that contribute to melanocyte damage and death. In addition, many patients with vitiligo are deficient in certain vitamins and minerals, the basis of the hypothesis that supplementation could be beneficial, according to Dr. Elbuluk.

Vitamin B12 and folic acid contribute to DNA repair, synthesis, and methylation, and researchers have hypothesized that these vitamins also play a role in melanin synthesis. In a review of the literature, Dr. Elbuluk and her colleagues found four studies that evaluated vitamin B12 and folic acid in vitiligo. In one study, a controlled trial in which patients took B12 and folic acid with and without phototherapy, the investigators observed no significant difference in repigmentation between groups. The other three studies were uncontrolled and thus provide an insufficient understanding of the effect of B12 and folic acid, said Dr. Elbuluk.

Vitamin D is involved in melanocyte and keratinocyte growth and differentiation, and inhibits T cell activation. Data indicate that low vitamin D levels are common in patients with vitiligo and comorbid autoimmune diseases. In one study, patients who received narrow-band UVB had an increase in vitamin D levels that could contribute to photo-induced melanogenesis, and an open-label study indicated that patients who took vitamin D daily (without phototherapy) for 6 months had an increase of repigmentation over time. “Topical vitamin D analogs have also been used in vitiligo treatment with varying success,” Dr. Elbuluk noted.

“I check vitamin D levels on my patients and make sure that they are within normal range. But I think the degree of supplementation and its role in vitiligo needs to be further elucidated,” she said. And because vitamin D is fat soluble, there is a risk of toxicity if a patient takes too much.

Vitamin C, vitamin E, and alpha-lipoic acid have antioxidant properties. In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial, one group of patients took vitamins C and E and alpha-lipoic acid for 2 months before and during treatment with narrow-band UVB twice per week (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007 Nov;32[6]:631-6). Another group underwent phototherapy without supplementation. A significantly greater proportion of patients who received the antioxidants obtained more than 75% repigmentation compared with those who did not. In another study, 73% of patients who received oral vitamin E and narrow band UVB phototherapy had marked to excellent repigmentation, compared with 55.6% of those who had phototherapy only (J Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Jul;49[7]:852-5).

The results of these studies support the idea that antioxidants can stabilize disease, reduce oxidative stress, and improve the effect of phototherapy, Dr. Elbuluk said.

Herbal supplements

Several research teams have examined Ginkgo biloba as a possible treatment for vitiligo. This plant is native to China and has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties; its most common side effect is gastrointestinal distress. Because it entails a risk of coagulopathy, it may not be appropriate for patients receiving anticoagulant treatment, Dr. Elbuluk pointed out. In a double-blinded, randomized, controlled trial comparing ginkgo biloba alone with placebo in patients with vitiligo, treatment was associated with cessation of active disease in most patients, and more than 40% of patients receiving ginkgo biloba had 75% repigmentation or more.

Polypodium leucotomos, a fern native to Central and South America, protects against UV radiation damage, modulates the immune system, and has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. It has a good safety profile and is well tolerated at a dose of 240 mg/day, she said. It sometimes causes gastrointestinal discomfort or pruritus. Several randomized, controlled trials in patients with vitiligo showed that supplementation with polypodium leucotomos improves repigmentation, particularly in photo-exposed areas, she noted.

Khellin is an extract from the Mediterranean khella plant that is thought to stimulate melanocyte proliferation and melanogenesis. Several studies have examined khellin supplementation in combination with phototherapy. Khellin can be administered orally or topically and appears to be more beneficial than sunlight or phototherapy alone in stabilizing disease or inducing repigmentation. Oral khellin can cause many side effects, including nausea, transaminitis, and hypotension, so researchers have been more interested in using topical khellin as a liposomal vehicle to improve drug delivery, Dr. Elbuluk said.

Minerals

Some patients with vitiligo have deficiencies in zinc and copper. Zinc is an antioxidant that aids wound healing, protects against free radicals, supports melanogenesis, and possibly prevents melanocyte death, but can cause gastrointestinal irritation. Copper, too, is an antioxidant and coenzyme involved in melanogenesis. One study compared topical steroid treatment with and without oral zinc supplementation. Dual treatment was associated with greater repigmentation, but the difference was not statistically significant. No studies have examined copper supplementation, she said.

L-phenylalanine, diet, and green tea

Investigators have proposed that the amino acid L-phenylalanine, a precursor to tyrosine in the pathway of melanin synthesis, might interfere with antibody production against melanocytes. This supplement is administered orally by weight, typically in conjunction with phototherapy or sunlight. Various studies have observed positive outcomes of L-phenylalanine combined with phototherapy or sunlight. L-phenylalanine tends to be safe and has been administered to children with vitiligo.

Many patients with vitiligo “have already tried diets by the time they come to me,” said Dr. Elbuluk. No controlled studies have analyzed the role of diet in the prevention or treatment of vitiligo, but case reports describe gluten-free diets in this population, including one report of a patient with celiac disease whose vitiligo improved after adoption of such a diet. Another case report described a patient without celiac disease who had refractory acrofacial vitiligo, which improved after the adoption of a gluten-free diet. Evidence supports a gluten-free diet for patients with celiac disease, but does not support this challenging diet for people without celiac disease, she pointed out.

Green tea includes catechins, which have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Its main component is epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), which is thought to modulate T cell mediated responses. In one animal study, administration of EGCG delayed the onset of vitiligo and decreased the area of depigmentation in a mouse model. Although these findings are promising, clinical trials are needed to determine whether EGCG is beneficial in humans with vitiligo, said Dr. Elbuluk.

The literature on diets and supplementation as treatments for vitiligo has several shortcomings, with studies that used heterogeneous methodologies, and many that used nonstandard outcome measures that have not been validated. Sample sizes often are small, and many trials are uncontrolled. “These limitations make it harder to make sense of the data and have take-home conclusions,” Dr. Elbuluk said.

She had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Elbuluk N. AAD 19, Session S002.

WASHINGTON – Many patients with vitiligo are interested in treating their condition with vitamins, supplements, or a modified diet, but research on whether these measures have an impact remains limited, Nada Elbuluk, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

, “we need more well designed, controlled studies in the future to know where this belongs in our treatment armamentarium,” said Dr. Elbuluk of the department of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

During a session at the AAD meeting, Dr. Elbuluk, who is also director of the pigmentary disorders clinic at USC, reviewed the evidence for the use of these adjunctive therapies in patients with vitiligo.

Vitamins

The pathogenesis of vitiligo includes the overproduction of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress, factors that contribute to melanocyte damage and death. In addition, many patients with vitiligo are deficient in certain vitamins and minerals, the basis of the hypothesis that supplementation could be beneficial, according to Dr. Elbuluk.

Vitamin B12 and folic acid contribute to DNA repair, synthesis, and methylation, and researchers have hypothesized that these vitamins also play a role in melanin synthesis. In a review of the literature, Dr. Elbuluk and her colleagues found four studies that evaluated vitamin B12 and folic acid in vitiligo. In one study, a controlled trial in which patients took B12 and folic acid with and without phototherapy, the investigators observed no significant difference in repigmentation between groups. The other three studies were uncontrolled and thus provide an insufficient understanding of the effect of B12 and folic acid, said Dr. Elbuluk.

Vitamin D is involved in melanocyte and keratinocyte growth and differentiation, and inhibits T cell activation. Data indicate that low vitamin D levels are common in patients with vitiligo and comorbid autoimmune diseases. In one study, patients who received narrow-band UVB had an increase in vitamin D levels that could contribute to photo-induced melanogenesis, and an open-label study indicated that patients who took vitamin D daily (without phototherapy) for 6 months had an increase of repigmentation over time. “Topical vitamin D analogs have also been used in vitiligo treatment with varying success,” Dr. Elbuluk noted.

“I check vitamin D levels on my patients and make sure that they are within normal range. But I think the degree of supplementation and its role in vitiligo needs to be further elucidated,” she said. And because vitamin D is fat soluble, there is a risk of toxicity if a patient takes too much.

Vitamin C, vitamin E, and alpha-lipoic acid have antioxidant properties. In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial, one group of patients took vitamins C and E and alpha-lipoic acid for 2 months before and during treatment with narrow-band UVB twice per week (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007 Nov;32[6]:631-6). Another group underwent phototherapy without supplementation. A significantly greater proportion of patients who received the antioxidants obtained more than 75% repigmentation compared with those who did not. In another study, 73% of patients who received oral vitamin E and narrow band UVB phototherapy had marked to excellent repigmentation, compared with 55.6% of those who had phototherapy only (J Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Jul;49[7]:852-5).

The results of these studies support the idea that antioxidants can stabilize disease, reduce oxidative stress, and improve the effect of phototherapy, Dr. Elbuluk said.

Herbal supplements

Several research teams have examined Ginkgo biloba as a possible treatment for vitiligo. This plant is native to China and has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties; its most common side effect is gastrointestinal distress. Because it entails a risk of coagulopathy, it may not be appropriate for patients receiving anticoagulant treatment, Dr. Elbuluk pointed out. In a double-blinded, randomized, controlled trial comparing ginkgo biloba alone with placebo in patients with vitiligo, treatment was associated with cessation of active disease in most patients, and more than 40% of patients receiving ginkgo biloba had 75% repigmentation or more.

Polypodium leucotomos, a fern native to Central and South America, protects against UV radiation damage, modulates the immune system, and has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. It has a good safety profile and is well tolerated at a dose of 240 mg/day, she said. It sometimes causes gastrointestinal discomfort or pruritus. Several randomized, controlled trials in patients with vitiligo showed that supplementation with polypodium leucotomos improves repigmentation, particularly in photo-exposed areas, she noted.

Khellin is an extract from the Mediterranean khella plant that is thought to stimulate melanocyte proliferation and melanogenesis. Several studies have examined khellin supplementation in combination with phototherapy. Khellin can be administered orally or topically and appears to be more beneficial than sunlight or phototherapy alone in stabilizing disease or inducing repigmentation. Oral khellin can cause many side effects, including nausea, transaminitis, and hypotension, so researchers have been more interested in using topical khellin as a liposomal vehicle to improve drug delivery, Dr. Elbuluk said.

Minerals

Some patients with vitiligo have deficiencies in zinc and copper. Zinc is an antioxidant that aids wound healing, protects against free radicals, supports melanogenesis, and possibly prevents melanocyte death, but can cause gastrointestinal irritation. Copper, too, is an antioxidant and coenzyme involved in melanogenesis. One study compared topical steroid treatment with and without oral zinc supplementation. Dual treatment was associated with greater repigmentation, but the difference was not statistically significant. No studies have examined copper supplementation, she said.

L-phenylalanine, diet, and green tea

Investigators have proposed that the amino acid L-phenylalanine, a precursor to tyrosine in the pathway of melanin synthesis, might interfere with antibody production against melanocytes. This supplement is administered orally by weight, typically in conjunction with phototherapy or sunlight. Various studies have observed positive outcomes of L-phenylalanine combined with phototherapy or sunlight. L-phenylalanine tends to be safe and has been administered to children with vitiligo.

Many patients with vitiligo “have already tried diets by the time they come to me,” said Dr. Elbuluk. No controlled studies have analyzed the role of diet in the prevention or treatment of vitiligo, but case reports describe gluten-free diets in this population, including one report of a patient with celiac disease whose vitiligo improved after adoption of such a diet. Another case report described a patient without celiac disease who had refractory acrofacial vitiligo, which improved after the adoption of a gluten-free diet. Evidence supports a gluten-free diet for patients with celiac disease, but does not support this challenging diet for people without celiac disease, she pointed out.

Green tea includes catechins, which have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Its main component is epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), which is thought to modulate T cell mediated responses. In one animal study, administration of EGCG delayed the onset of vitiligo and decreased the area of depigmentation in a mouse model. Although these findings are promising, clinical trials are needed to determine whether EGCG is beneficial in humans with vitiligo, said Dr. Elbuluk.

The literature on diets and supplementation as treatments for vitiligo has several shortcomings, with studies that used heterogeneous methodologies, and many that used nonstandard outcome measures that have not been validated. Sample sizes often are small, and many trials are uncontrolled. “These limitations make it harder to make sense of the data and have take-home conclusions,” Dr. Elbuluk said.

She had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Elbuluk N. AAD 19, Session S002.

WASHINGTON – Many patients with vitiligo are interested in treating their condition with vitamins, supplements, or a modified diet, but research on whether these measures have an impact remains limited, Nada Elbuluk, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

, “we need more well designed, controlled studies in the future to know where this belongs in our treatment armamentarium,” said Dr. Elbuluk of the department of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

During a session at the AAD meeting, Dr. Elbuluk, who is also director of the pigmentary disorders clinic at USC, reviewed the evidence for the use of these adjunctive therapies in patients with vitiligo.

Vitamins

The pathogenesis of vitiligo includes the overproduction of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress, factors that contribute to melanocyte damage and death. In addition, many patients with vitiligo are deficient in certain vitamins and minerals, the basis of the hypothesis that supplementation could be beneficial, according to Dr. Elbuluk.

Vitamin B12 and folic acid contribute to DNA repair, synthesis, and methylation, and researchers have hypothesized that these vitamins also play a role in melanin synthesis. In a review of the literature, Dr. Elbuluk and her colleagues found four studies that evaluated vitamin B12 and folic acid in vitiligo. In one study, a controlled trial in which patients took B12 and folic acid with and without phototherapy, the investigators observed no significant difference in repigmentation between groups. The other three studies were uncontrolled and thus provide an insufficient understanding of the effect of B12 and folic acid, said Dr. Elbuluk.

Vitamin D is involved in melanocyte and keratinocyte growth and differentiation, and inhibits T cell activation. Data indicate that low vitamin D levels are common in patients with vitiligo and comorbid autoimmune diseases. In one study, patients who received narrow-band UVB had an increase in vitamin D levels that could contribute to photo-induced melanogenesis, and an open-label study indicated that patients who took vitamin D daily (without phototherapy) for 6 months had an increase of repigmentation over time. “Topical vitamin D analogs have also been used in vitiligo treatment with varying success,” Dr. Elbuluk noted.

“I check vitamin D levels on my patients and make sure that they are within normal range. But I think the degree of supplementation and its role in vitiligo needs to be further elucidated,” she said. And because vitamin D is fat soluble, there is a risk of toxicity if a patient takes too much.

Vitamin C, vitamin E, and alpha-lipoic acid have antioxidant properties. In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial, one group of patients took vitamins C and E and alpha-lipoic acid for 2 months before and during treatment with narrow-band UVB twice per week (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007 Nov;32[6]:631-6). Another group underwent phototherapy without supplementation. A significantly greater proportion of patients who received the antioxidants obtained more than 75% repigmentation compared with those who did not. In another study, 73% of patients who received oral vitamin E and narrow band UVB phototherapy had marked to excellent repigmentation, compared with 55.6% of those who had phototherapy only (J Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Jul;49[7]:852-5).

The results of these studies support the idea that antioxidants can stabilize disease, reduce oxidative stress, and improve the effect of phototherapy, Dr. Elbuluk said.

Herbal supplements

Several research teams have examined Ginkgo biloba as a possible treatment for vitiligo. This plant is native to China and has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties; its most common side effect is gastrointestinal distress. Because it entails a risk of coagulopathy, it may not be appropriate for patients receiving anticoagulant treatment, Dr. Elbuluk pointed out. In a double-blinded, randomized, controlled trial comparing ginkgo biloba alone with placebo in patients with vitiligo, treatment was associated with cessation of active disease in most patients, and more than 40% of patients receiving ginkgo biloba had 75% repigmentation or more.

Polypodium leucotomos, a fern native to Central and South America, protects against UV radiation damage, modulates the immune system, and has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. It has a good safety profile and is well tolerated at a dose of 240 mg/day, she said. It sometimes causes gastrointestinal discomfort or pruritus. Several randomized, controlled trials in patients with vitiligo showed that supplementation with polypodium leucotomos improves repigmentation, particularly in photo-exposed areas, she noted.

Khellin is an extract from the Mediterranean khella plant that is thought to stimulate melanocyte proliferation and melanogenesis. Several studies have examined khellin supplementation in combination with phototherapy. Khellin can be administered orally or topically and appears to be more beneficial than sunlight or phototherapy alone in stabilizing disease or inducing repigmentation. Oral khellin can cause many side effects, including nausea, transaminitis, and hypotension, so researchers have been more interested in using topical khellin as a liposomal vehicle to improve drug delivery, Dr. Elbuluk said.

Minerals

Some patients with vitiligo have deficiencies in zinc and copper. Zinc is an antioxidant that aids wound healing, protects against free radicals, supports melanogenesis, and possibly prevents melanocyte death, but can cause gastrointestinal irritation. Copper, too, is an antioxidant and coenzyme involved in melanogenesis. One study compared topical steroid treatment with and without oral zinc supplementation. Dual treatment was associated with greater repigmentation, but the difference was not statistically significant. No studies have examined copper supplementation, she said.

L-phenylalanine, diet, and green tea

Investigators have proposed that the amino acid L-phenylalanine, a precursor to tyrosine in the pathway of melanin synthesis, might interfere with antibody production against melanocytes. This supplement is administered orally by weight, typically in conjunction with phototherapy or sunlight. Various studies have observed positive outcomes of L-phenylalanine combined with phototherapy or sunlight. L-phenylalanine tends to be safe and has been administered to children with vitiligo.

Many patients with vitiligo “have already tried diets by the time they come to me,” said Dr. Elbuluk. No controlled studies have analyzed the role of diet in the prevention or treatment of vitiligo, but case reports describe gluten-free diets in this population, including one report of a patient with celiac disease whose vitiligo improved after adoption of such a diet. Another case report described a patient without celiac disease who had refractory acrofacial vitiligo, which improved after the adoption of a gluten-free diet. Evidence supports a gluten-free diet for patients with celiac disease, but does not support this challenging diet for people without celiac disease, she pointed out.

Green tea includes catechins, which have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Its main component is epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), which is thought to modulate T cell mediated responses. In one animal study, administration of EGCG delayed the onset of vitiligo and decreased the area of depigmentation in a mouse model. Although these findings are promising, clinical trials are needed to determine whether EGCG is beneficial in humans with vitiligo, said Dr. Elbuluk.

The literature on diets and supplementation as treatments for vitiligo has several shortcomings, with studies that used heterogeneous methodologies, and many that used nonstandard outcome measures that have not been validated. Sample sizes often are small, and many trials are uncontrolled. “These limitations make it harder to make sense of the data and have take-home conclusions,” Dr. Elbuluk said.

She had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Elbuluk N. AAD 19, Session S002.

REPORTING FROM AAD 19

VIDEO: Immunomodulators for inflammatory skin diseases

WASHINGTON – During a session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Adam Friedman, MD, presented on off-label use of immunomodulators for inflammatory skin diseases, the highlights of which he shared with fellow George Washington University dermatologist, A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, in an interview following the session.

Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington,

For example, as reflected in PubMed searches, low-dose naltrexone, which has to be compounded, is being used for such diseases as Hailey-Hailey and lichen planopilaris, said Dr. Friedman, who is using it for his mast cell activation syndrome patients. During the interview, he also describes his treatment approach for urticaria.

In his final remarks, Dr. Friedman encourages colleagues to “get creative,” publish, and talk about their experiences with off-label treatments in dermatology, citing the example of an article that mentioned using pioglitazone for lichen planopilaris. This article stimulated interest in using the type 2 diabetes agent pioglitazone to treat this skin disease, he notes.

Dr. Friedman and Dr. Kirkorian, a pediatric dermatologist at George Washington University and interim chief of pediatric dermatology at Children’s National in Washington had no relevant disclosures.

WASHINGTON – During a session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Adam Friedman, MD, presented on off-label use of immunomodulators for inflammatory skin diseases, the highlights of which he shared with fellow George Washington University dermatologist, A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, in an interview following the session.

Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington,

For example, as reflected in PubMed searches, low-dose naltrexone, which has to be compounded, is being used for such diseases as Hailey-Hailey and lichen planopilaris, said Dr. Friedman, who is using it for his mast cell activation syndrome patients. During the interview, he also describes his treatment approach for urticaria.

In his final remarks, Dr. Friedman encourages colleagues to “get creative,” publish, and talk about their experiences with off-label treatments in dermatology, citing the example of an article that mentioned using pioglitazone for lichen planopilaris. This article stimulated interest in using the type 2 diabetes agent pioglitazone to treat this skin disease, he notes.

Dr. Friedman and Dr. Kirkorian, a pediatric dermatologist at George Washington University and interim chief of pediatric dermatology at Children’s National in Washington had no relevant disclosures.

WASHINGTON – During a session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Adam Friedman, MD, presented on off-label use of immunomodulators for inflammatory skin diseases, the highlights of which he shared with fellow George Washington University dermatologist, A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, in an interview following the session.

Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington,

For example, as reflected in PubMed searches, low-dose naltrexone, which has to be compounded, is being used for such diseases as Hailey-Hailey and lichen planopilaris, said Dr. Friedman, who is using it for his mast cell activation syndrome patients. During the interview, he also describes his treatment approach for urticaria.

In his final remarks, Dr. Friedman encourages colleagues to “get creative,” publish, and talk about their experiences with off-label treatments in dermatology, citing the example of an article that mentioned using pioglitazone for lichen planopilaris. This article stimulated interest in using the type 2 diabetes agent pioglitazone to treat this skin disease, he notes.

Dr. Friedman and Dr. Kirkorian, a pediatric dermatologist at George Washington University and interim chief of pediatric dermatology at Children’s National in Washington had no relevant disclosures.

What is your diagnosis?

A skin biopsy of one of the lesions on the right toe showed dermal edema with an associated lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. There are scattered areas of perieccrine involvement and areas of vasculitis. Laboratory work up showed a normal complete blood count, a negative antinuclear antibodies (ANA) titer, a negative double-stranded DNA, normal levels of inflammatory markers, and negative cryoglobulins and cold agglutinins. The patient was diagnosed with pernio. The lesions improved within several weeks. She now wears thicker socks when she is ice skating.

Children, women, and the elderly are at a higher risk.1 This condition is frequently described in Northwestern Europe and the United Kingdom, especially in those living in houses without central heating.2

Clinically, the lesions appear a few hours or days after cold exposure on the toes, fingers, and in some unusual cases on the nose and the ears. The lesions present as erythematous to violaceous macules, papules, or nodules that in severe cases may blister and ulcerate. The lesions may be asymptomatic, pruritic, or tender. In children, pernio can be associated with the presence of cryoglobulins, cold agglutinins, anorexia nervosa, and genetic interferonopathy; it may precede the diagnosis of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and may occur as a presenting sign of a blast crisis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia.3,4 The skin lesions usually resolve within days to a few weeks. Histopathologic analysis shows dermal edema with associated superficial and deep lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and perieccrine involvement.

The differential diagnosis of pernio includes other cold-induced syndromes such as Raynaud’s syndrome, cold panniculitis, cold urticaria, livedo reticularis, acrocyanosis, and chilblain lupus. In chilblain lupus (a form of chronic cutaneous lupus), the lesions may be very similar to pernio but the histopathology is consistent with changes of discoid lupus. Lesions of idiopathic palmoplantar hidradenitis present as erythematous tender nodules on the palms and the soles.5 The lesions can be triggered by vigorous physical activity, exposure to moisture, and excessive sweating. White, blue, and red discoloration of the fingers is seen in Raynaud’s phenomenon rather than the fixed erythematous to violaceous macules, papules, or nodules seen in pernio. Patients with erythromelalgia present with red painful palms and soles triggered by heat and, in contrast to pernio, relieved by cooling. Sweet syndrome, a febrile neutrophilic dermatoses, is characterized by tender erythematous papules and plaques with associated systemic symptoms. These patients may have an associated internal malignancy or infection, or the disorder may be triggered by medications or pregnancy.

Our patient had no systemic symptoms, and the pathology didn’t show any neutrophils. When the diagnosis is in doubt, a skin biopsy may help elucidate the diagnosis.

Once the diagnosis of pernio is made, it is recommended to order a complete blood count to rule out blood malignancies and cryoproteins.

Treatment of this condition consists of rewarming the extremity. If rewarming does not improve the patient’s symptoms, systemic treatment with nifedipine may be warranted.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Dr. Matiz said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2005 Sep;116(3):e472-5.

2. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Feb;89(2):207-15.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan;35(1):e74-5.

4. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000 Mar-Apr;17(2):97-9.

5. Eur J Pediatr. 2001 Mar;160(3):189-91.

A skin biopsy of one of the lesions on the right toe showed dermal edema with an associated lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. There are scattered areas of perieccrine involvement and areas of vasculitis. Laboratory work up showed a normal complete blood count, a negative antinuclear antibodies (ANA) titer, a negative double-stranded DNA, normal levels of inflammatory markers, and negative cryoglobulins and cold agglutinins. The patient was diagnosed with pernio. The lesions improved within several weeks. She now wears thicker socks when she is ice skating.

Children, women, and the elderly are at a higher risk.1 This condition is frequently described in Northwestern Europe and the United Kingdom, especially in those living in houses without central heating.2

Clinically, the lesions appear a few hours or days after cold exposure on the toes, fingers, and in some unusual cases on the nose and the ears. The lesions present as erythematous to violaceous macules, papules, or nodules that in severe cases may blister and ulcerate. The lesions may be asymptomatic, pruritic, or tender. In children, pernio can be associated with the presence of cryoglobulins, cold agglutinins, anorexia nervosa, and genetic interferonopathy; it may precede the diagnosis of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and may occur as a presenting sign of a blast crisis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia.3,4 The skin lesions usually resolve within days to a few weeks. Histopathologic analysis shows dermal edema with associated superficial and deep lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and perieccrine involvement.

The differential diagnosis of pernio includes other cold-induced syndromes such as Raynaud’s syndrome, cold panniculitis, cold urticaria, livedo reticularis, acrocyanosis, and chilblain lupus. In chilblain lupus (a form of chronic cutaneous lupus), the lesions may be very similar to pernio but the histopathology is consistent with changes of discoid lupus. Lesions of idiopathic palmoplantar hidradenitis present as erythematous tender nodules on the palms and the soles.5 The lesions can be triggered by vigorous physical activity, exposure to moisture, and excessive sweating. White, blue, and red discoloration of the fingers is seen in Raynaud’s phenomenon rather than the fixed erythematous to violaceous macules, papules, or nodules seen in pernio. Patients with erythromelalgia present with red painful palms and soles triggered by heat and, in contrast to pernio, relieved by cooling. Sweet syndrome, a febrile neutrophilic dermatoses, is characterized by tender erythematous papules and plaques with associated systemic symptoms. These patients may have an associated internal malignancy or infection, or the disorder may be triggered by medications or pregnancy.

Our patient had no systemic symptoms, and the pathology didn’t show any neutrophils. When the diagnosis is in doubt, a skin biopsy may help elucidate the diagnosis.

Once the diagnosis of pernio is made, it is recommended to order a complete blood count to rule out blood malignancies and cryoproteins.

Treatment of this condition consists of rewarming the extremity. If rewarming does not improve the patient’s symptoms, systemic treatment with nifedipine may be warranted.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Dr. Matiz said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2005 Sep;116(3):e472-5.

2. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Feb;89(2):207-15.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan;35(1):e74-5.

4. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000 Mar-Apr;17(2):97-9.

5. Eur J Pediatr. 2001 Mar;160(3):189-91.

A skin biopsy of one of the lesions on the right toe showed dermal edema with an associated lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. There are scattered areas of perieccrine involvement and areas of vasculitis. Laboratory work up showed a normal complete blood count, a negative antinuclear antibodies (ANA) titer, a negative double-stranded DNA, normal levels of inflammatory markers, and negative cryoglobulins and cold agglutinins. The patient was diagnosed with pernio. The lesions improved within several weeks. She now wears thicker socks when she is ice skating.

Children, women, and the elderly are at a higher risk.1 This condition is frequently described in Northwestern Europe and the United Kingdom, especially in those living in houses without central heating.2

Clinically, the lesions appear a few hours or days after cold exposure on the toes, fingers, and in some unusual cases on the nose and the ears. The lesions present as erythematous to violaceous macules, papules, or nodules that in severe cases may blister and ulcerate. The lesions may be asymptomatic, pruritic, or tender. In children, pernio can be associated with the presence of cryoglobulins, cold agglutinins, anorexia nervosa, and genetic interferonopathy; it may precede the diagnosis of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and may occur as a presenting sign of a blast crisis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia.3,4 The skin lesions usually resolve within days to a few weeks. Histopathologic analysis shows dermal edema with associated superficial and deep lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and perieccrine involvement.

The differential diagnosis of pernio includes other cold-induced syndromes such as Raynaud’s syndrome, cold panniculitis, cold urticaria, livedo reticularis, acrocyanosis, and chilblain lupus. In chilblain lupus (a form of chronic cutaneous lupus), the lesions may be very similar to pernio but the histopathology is consistent with changes of discoid lupus. Lesions of idiopathic palmoplantar hidradenitis present as erythematous tender nodules on the palms and the soles.5 The lesions can be triggered by vigorous physical activity, exposure to moisture, and excessive sweating. White, blue, and red discoloration of the fingers is seen in Raynaud’s phenomenon rather than the fixed erythematous to violaceous macules, papules, or nodules seen in pernio. Patients with erythromelalgia present with red painful palms and soles triggered by heat and, in contrast to pernio, relieved by cooling. Sweet syndrome, a febrile neutrophilic dermatoses, is characterized by tender erythematous papules and plaques with associated systemic symptoms. These patients may have an associated internal malignancy or infection, or the disorder may be triggered by medications or pregnancy.

Our patient had no systemic symptoms, and the pathology didn’t show any neutrophils. When the diagnosis is in doubt, a skin biopsy may help elucidate the diagnosis.

Once the diagnosis of pernio is made, it is recommended to order a complete blood count to rule out blood malignancies and cryoproteins.

Treatment of this condition consists of rewarming the extremity. If rewarming does not improve the patient’s symptoms, systemic treatment with nifedipine may be warranted.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Dr. Matiz said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2005 Sep;116(3):e472-5.

2. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Feb;89(2):207-15.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan;35(1):e74-5.

4. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000 Mar-Apr;17(2):97-9.

5. Eur J Pediatr. 2001 Mar;160(3):189-91.

An 8-year-old girl comes to our pediatric dermatology clinic in the company of her mother for evaluation of painless purple spots on her toes. The lesions have been present for about 2 weeks. She has not been treated with any medications or creams. She denies any fevers, weight loss, mouth ulcers, sun sensitivity, joint pain, or any other symptoms. The patient has been a very healthy girl with occasional colds and no recent illnesses. The girl has never been admitted to the hospital. All her vaccinations are up to date. She takes no chronic medications. She lives in San Diego with her parents and two siblings. The girl recently started practicing ice-skating several times a week. There is no family history of any chronic medical conditions. She has no pets.

New cantharidin formulation alleviates molluscum contagiosum in pivotal trials

WASHINGTON – compared with placebo, according to the results of two trials presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

VP-102, a drug-device combination, was well tolerated and was not associated with serious adverse events.

No Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment is available for treating molluscum contagiosum, which is routinely treated with cantharidin, a naturally occurring vesicant.

VP-102 is a novel formulation of 0.7% cantharidin solution, provided in a single-use applicator, to provide consistent delivery and long-term drug stability.

To test the efficacy and safety of VP-102, Lawrence Eichenfield, MD, chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, and his associates conducted the CAMP-1 (Cantharidin Application in Molluscum Patients) and CAMP-2 phase 3 studies, which had similar designs. The studies enrolled patients with molluscum contagiosum aged 2 years and older who had not received any treatment in the 2 weeks before enrollment. Patients were randomized to VP-102 or vehicle for 12 weeks. Treatment was administered topically to each lesion every 3 weeks for a maximum of four applications, and washed off with soap and warm water 24 hours after application.

The trials’ primary endpoint was the percentage of patients with complete clearance of their lesions. Secondary endpoints were the percentage of patients with complete clearance at 3, 6, and 9 weeks, and decrease in lesions over time. The researchers also assessed safety and tolerability.

In the two studies, 528 patients aged 2-60 years (mean age, approximately 7 years) were randomized to treatment or vehicle. About 30% of participants had prior treatment. The baseline lesion count ranged from 1 to 184.

At day 84, the proportion of patients in the VP-102 arm who achieved complete clearance of lesions was 46% in CAMP-1 and 54% in CAMP-2, compared with 18% and 13%, respectively, among controls (P less than .0001). By day 84, among treated patients, the lesion count had decreased by a mean of 69% in CAMP-1 and 83% in CAMP-2, compared with 20% and 19%, respectively, among controls. Results among controls were “probably consistent with natural history,” Dr. Eichenfield observed.

The researchers observed a high incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events among patients receiving VP-102. “Any crust or vesiculation was considered to be a treatment-emergent adverse event,” Dr. Eichenfield said. Most adverse events were mild, although five patients discontinued the studies because of treatment-emergent adverse events. Vesiculation was a common adverse event in the VP-102 group; pruritus and application-site pain were reported as well.

Verrica Pharmaceuticals developed VP-102 and funded the study. Dr. Eichenfield reported receiving no funding from the company; several other investigators are employees of Verrica, which plans to submit for FDA approval in the second half of 2019.

SOURCE: Eichenfield L et al. AAD 19, Abstract 11251.

WASHINGTON – compared with placebo, according to the results of two trials presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

VP-102, a drug-device combination, was well tolerated and was not associated with serious adverse events.

No Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment is available for treating molluscum contagiosum, which is routinely treated with cantharidin, a naturally occurring vesicant.

VP-102 is a novel formulation of 0.7% cantharidin solution, provided in a single-use applicator, to provide consistent delivery and long-term drug stability.

To test the efficacy and safety of VP-102, Lawrence Eichenfield, MD, chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, and his associates conducted the CAMP-1 (Cantharidin Application in Molluscum Patients) and CAMP-2 phase 3 studies, which had similar designs. The studies enrolled patients with molluscum contagiosum aged 2 years and older who had not received any treatment in the 2 weeks before enrollment. Patients were randomized to VP-102 or vehicle for 12 weeks. Treatment was administered topically to each lesion every 3 weeks for a maximum of four applications, and washed off with soap and warm water 24 hours after application.

The trials’ primary endpoint was the percentage of patients with complete clearance of their lesions. Secondary endpoints were the percentage of patients with complete clearance at 3, 6, and 9 weeks, and decrease in lesions over time. The researchers also assessed safety and tolerability.

In the two studies, 528 patients aged 2-60 years (mean age, approximately 7 years) were randomized to treatment or vehicle. About 30% of participants had prior treatment. The baseline lesion count ranged from 1 to 184.

At day 84, the proportion of patients in the VP-102 arm who achieved complete clearance of lesions was 46% in CAMP-1 and 54% in CAMP-2, compared with 18% and 13%, respectively, among controls (P less than .0001). By day 84, among treated patients, the lesion count had decreased by a mean of 69% in CAMP-1 and 83% in CAMP-2, compared with 20% and 19%, respectively, among controls. Results among controls were “probably consistent with natural history,” Dr. Eichenfield observed.

The researchers observed a high incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events among patients receiving VP-102. “Any crust or vesiculation was considered to be a treatment-emergent adverse event,” Dr. Eichenfield said. Most adverse events were mild, although five patients discontinued the studies because of treatment-emergent adverse events. Vesiculation was a common adverse event in the VP-102 group; pruritus and application-site pain were reported as well.

Verrica Pharmaceuticals developed VP-102 and funded the study. Dr. Eichenfield reported receiving no funding from the company; several other investigators are employees of Verrica, which plans to submit for FDA approval in the second half of 2019.

SOURCE: Eichenfield L et al. AAD 19, Abstract 11251.

WASHINGTON – compared with placebo, according to the results of two trials presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

VP-102, a drug-device combination, was well tolerated and was not associated with serious adverse events.

No Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment is available for treating molluscum contagiosum, which is routinely treated with cantharidin, a naturally occurring vesicant.

VP-102 is a novel formulation of 0.7% cantharidin solution, provided in a single-use applicator, to provide consistent delivery and long-term drug stability.

To test the efficacy and safety of VP-102, Lawrence Eichenfield, MD, chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, and his associates conducted the CAMP-1 (Cantharidin Application in Molluscum Patients) and CAMP-2 phase 3 studies, which had similar designs. The studies enrolled patients with molluscum contagiosum aged 2 years and older who had not received any treatment in the 2 weeks before enrollment. Patients were randomized to VP-102 or vehicle for 12 weeks. Treatment was administered topically to each lesion every 3 weeks for a maximum of four applications, and washed off with soap and warm water 24 hours after application.

The trials’ primary endpoint was the percentage of patients with complete clearance of their lesions. Secondary endpoints were the percentage of patients with complete clearance at 3, 6, and 9 weeks, and decrease in lesions over time. The researchers also assessed safety and tolerability.

In the two studies, 528 patients aged 2-60 years (mean age, approximately 7 years) were randomized to treatment or vehicle. About 30% of participants had prior treatment. The baseline lesion count ranged from 1 to 184.

At day 84, the proportion of patients in the VP-102 arm who achieved complete clearance of lesions was 46% in CAMP-1 and 54% in CAMP-2, compared with 18% and 13%, respectively, among controls (P less than .0001). By day 84, among treated patients, the lesion count had decreased by a mean of 69% in CAMP-1 and 83% in CAMP-2, compared with 20% and 19%, respectively, among controls. Results among controls were “probably consistent with natural history,” Dr. Eichenfield observed.

The researchers observed a high incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events among patients receiving VP-102. “Any crust or vesiculation was considered to be a treatment-emergent adverse event,” Dr. Eichenfield said. Most adverse events were mild, although five patients discontinued the studies because of treatment-emergent adverse events. Vesiculation was a common adverse event in the VP-102 group; pruritus and application-site pain were reported as well.

Verrica Pharmaceuticals developed VP-102 and funded the study. Dr. Eichenfield reported receiving no funding from the company; several other investigators are employees of Verrica, which plans to submit for FDA approval in the second half of 2019.

SOURCE: Eichenfield L et al. AAD 19, Abstract 11251.

REPORTING FROM AAD 2019

Key clinical point: VP-102 is an effective treatment for molluscum contagiosum.

Major finding: In two studies, 46% and 54% of actively treated patients had complete resolution, compared with 13% and 18% of controls, respectively.

Study details: Two phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of 528 patients with molluscum contagiosum.

Disclosures: Verrica Pharmaceuticals sponsored the study. Dr. Eichenfield reported receiving no funding from the company; several other investigators are employees of Verrica Pharmaceuticals.Source: Eichenfield L et al. AAD 19, Abstract 11251.

There’s No Doubt: Blame the Drug

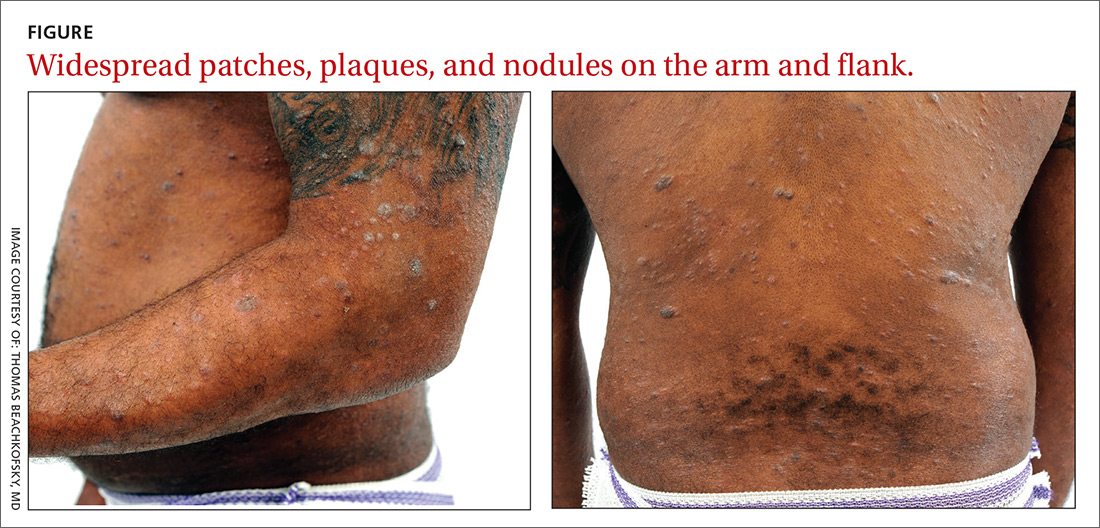

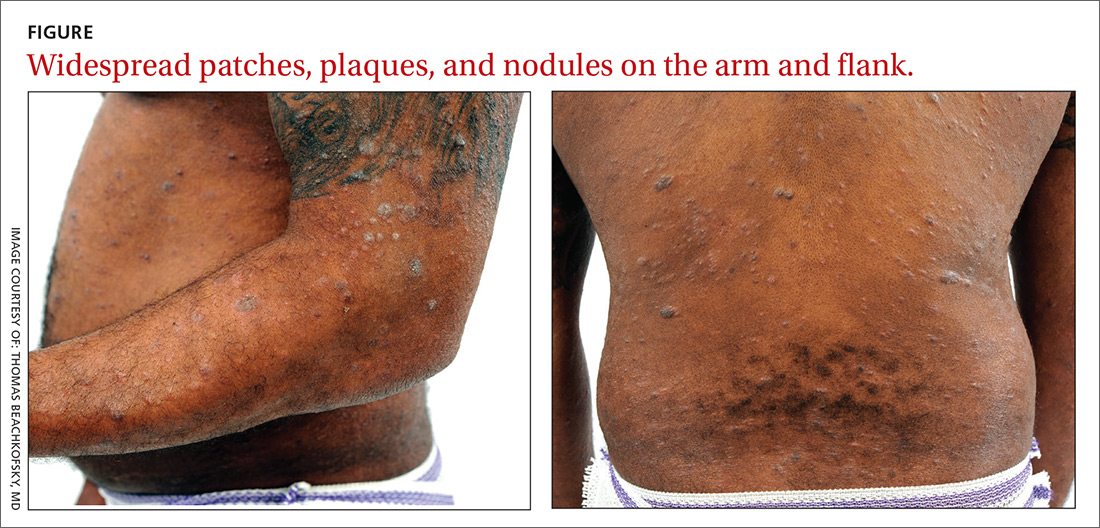

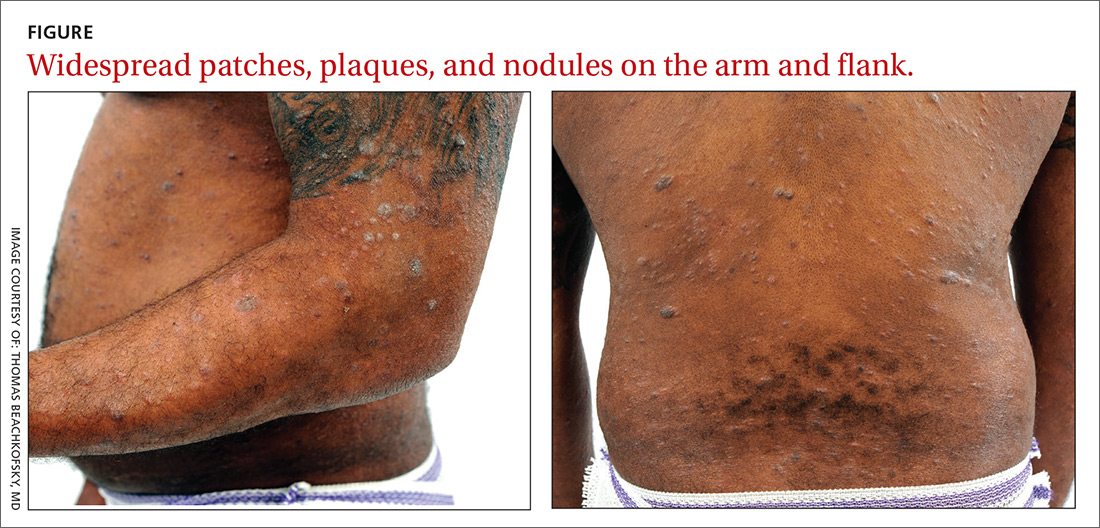

It’s taken 2 years for family members to convince this 50-year-old black woman to consult dermatology about dark circles on her arms and trunk. The asymptomatic lesions were only faintly discolored at manifestation but have darkened with each recurrence. The 6 lesions she currently has are in the exact locations they originally manifested in.

Convinced she had “ringworm,” the patient tried several different antifungal creams, to no avail. Then her primary care provider prescribed a 2-month course of oral antifungal medication (terbinafine)—again, with no change to the lesions.

The patient is otherwise healthy except for osteoarthritis, for which she takes ibuprofen (800 mg 2 or 3 times a day). She denies any history of seizure, chronic urinary tract infection, or other chronic infection.

EXAMINATION

The 6 perfectly round, uniformly pigmented, dark brown macular lesions on the patient’s arms and trunk range from 2 to 5 cm in diameter. A faint, rusty brown halo can be seen around the periphery of the lesions, giving them a targetoid look. The surfaces of the lesions are completely smooth.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The list of dark brown, round macules that come and go in the exact same locations is a short one—in fact, it only includes fixed drug eruption (FDE). This is a unique adverse reaction to one of several medications; common culprits are ibuprofen or other NSAIDs, aspirin, members of the sulfa family, penicillin, and several antiseizure medications.

The exact mechanism for this reaction is unknown, but it does appear to involve the localized production of cytokines. There is a range of morphologic presentations for FDE: some lesions are more targetoid than others; some are darker (especially in patients with darker skin) while others are more pink.

Furthermore, many patients develop additional lesions over time. A few, on the other hand, will reach a point at which they stop reacting to the offending product.

Of all the drugs causing FDE, sulfa-based products are among the more consistent offenders. Thus, we always ask about chronic urinary tract infections.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Fixed drug eruptions (FDE) usually manifest with round, targetoid macules that are occasionally blistery.

- The lesions recur or darken with each “challenge” from the drug, which can be one of several potential offenders.

- The fact that the lesions keep recurring in the same location (ie, fixed) is pathognomic for FDE.

- FDE lesions can occur almost anywhere on the body—even on palms or soles.

It’s taken 2 years for family members to convince this 50-year-old black woman to consult dermatology about dark circles on her arms and trunk. The asymptomatic lesions were only faintly discolored at manifestation but have darkened with each recurrence. The 6 lesions she currently has are in the exact locations they originally manifested in.

Convinced she had “ringworm,” the patient tried several different antifungal creams, to no avail. Then her primary care provider prescribed a 2-month course of oral antifungal medication (terbinafine)—again, with no change to the lesions.

The patient is otherwise healthy except for osteoarthritis, for which she takes ibuprofen (800 mg 2 or 3 times a day). She denies any history of seizure, chronic urinary tract infection, or other chronic infection.

EXAMINATION

The 6 perfectly round, uniformly pigmented, dark brown macular lesions on the patient’s arms and trunk range from 2 to 5 cm in diameter. A faint, rusty brown halo can be seen around the periphery of the lesions, giving them a targetoid look. The surfaces of the lesions are completely smooth.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The list of dark brown, round macules that come and go in the exact same locations is a short one—in fact, it only includes fixed drug eruption (FDE). This is a unique adverse reaction to one of several medications; common culprits are ibuprofen or other NSAIDs, aspirin, members of the sulfa family, penicillin, and several antiseizure medications.

The exact mechanism for this reaction is unknown, but it does appear to involve the localized production of cytokines. There is a range of morphologic presentations for FDE: some lesions are more targetoid than others; some are darker (especially in patients with darker skin) while others are more pink.

Furthermore, many patients develop additional lesions over time. A few, on the other hand, will reach a point at which they stop reacting to the offending product.

Of all the drugs causing FDE, sulfa-based products are among the more consistent offenders. Thus, we always ask about chronic urinary tract infections.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Fixed drug eruptions (FDE) usually manifest with round, targetoid macules that are occasionally blistery.

- The lesions recur or darken with each “challenge” from the drug, which can be one of several potential offenders.

- The fact that the lesions keep recurring in the same location (ie, fixed) is pathognomic for FDE.

- FDE lesions can occur almost anywhere on the body—even on palms or soles.

It’s taken 2 years for family members to convince this 50-year-old black woman to consult dermatology about dark circles on her arms and trunk. The asymptomatic lesions were only faintly discolored at manifestation but have darkened with each recurrence. The 6 lesions she currently has are in the exact locations they originally manifested in.

Convinced she had “ringworm,” the patient tried several different antifungal creams, to no avail. Then her primary care provider prescribed a 2-month course of oral antifungal medication (terbinafine)—again, with no change to the lesions.

The patient is otherwise healthy except for osteoarthritis, for which she takes ibuprofen (800 mg 2 or 3 times a day). She denies any history of seizure, chronic urinary tract infection, or other chronic infection.

EXAMINATION

The 6 perfectly round, uniformly pigmented, dark brown macular lesions on the patient’s arms and trunk range from 2 to 5 cm in diameter. A faint, rusty brown halo can be seen around the periphery of the lesions, giving them a targetoid look. The surfaces of the lesions are completely smooth.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The list of dark brown, round macules that come and go in the exact same locations is a short one—in fact, it only includes fixed drug eruption (FDE). This is a unique adverse reaction to one of several medications; common culprits are ibuprofen or other NSAIDs, aspirin, members of the sulfa family, penicillin, and several antiseizure medications.

The exact mechanism for this reaction is unknown, but it does appear to involve the localized production of cytokines. There is a range of morphologic presentations for FDE: some lesions are more targetoid than others; some are darker (especially in patients with darker skin) while others are more pink.

Furthermore, many patients develop additional lesions over time. A few, on the other hand, will reach a point at which they stop reacting to the offending product.

Of all the drugs causing FDE, sulfa-based products are among the more consistent offenders. Thus, we always ask about chronic urinary tract infections.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Fixed drug eruptions (FDE) usually manifest with round, targetoid macules that are occasionally blistery.

- The lesions recur or darken with each “challenge” from the drug, which can be one of several potential offenders.

- The fact that the lesions keep recurring in the same location (ie, fixed) is pathognomic for FDE.

- FDE lesions can occur almost anywhere on the body—even on palms or soles.

Pigmentation on foot

The FP suspected that this was an acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM).

The FP considered the various ways to biopsy this lesion. Doing a biopsy of the whole lesion was neither practical, nor desirable, given that the lesion was >2 cm and located on the bottom of the patient’s foot. And while incomplete sampling could result in a false negative result, this lesion was so suspicious for melanoma that any well-performed biopsy would likely produce a diagnosis of melanoma. (Of course if melanoma was not diagnosable with partial sampling, a full excisional biopsy would be needed.)

The FP also debated doing a 6-mm punch biopsy vs a shave biopsy; his intent was to get below some of the deeper pigment. Incisional biopsy done as a small ellipse with suturing was also an option. It would also be the most time consuming.

The FP presented the biopsy options to the patient and explained that the shave biopsy would require a dressing and the punch biopsy would require sutures, which would need to be removed at the next visit. Both biopsy methods would likely cause the foot to be uncomfortable to walk on for several days.

The FP and patient decided to do a deep shave biopsy (saucerization). After administering local anesthesia with lidocaine and epinephrine, the FP performed a deep shave biopsy that included about 1 cm of the darkest and thickest portion of the suspected melanoma.

The biopsy results indicated that the patient had an acral lentiginous melanoma, which measured 0.7 mm at its deepest point in the biopsied portion. The patient was referred to Orthopedics for a wide excision and repair. A sentinel node biopsy was not needed because the lesion was less than 1 mm in depth and there was no ulceration. The surgery and healing time were challenging for the patient, but she did not lose her foot and has remained cancer free.

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1103-1111.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was an acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM).

The FP considered the various ways to biopsy this lesion. Doing a biopsy of the whole lesion was neither practical, nor desirable, given that the lesion was >2 cm and located on the bottom of the patient’s foot. And while incomplete sampling could result in a false negative result, this lesion was so suspicious for melanoma that any well-performed biopsy would likely produce a diagnosis of melanoma. (Of course if melanoma was not diagnosable with partial sampling, a full excisional biopsy would be needed.)