User login

Pruritic rash on chest and back

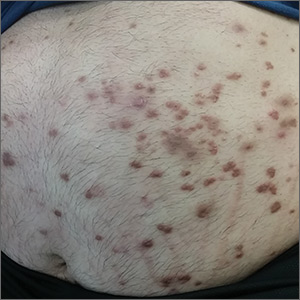

A 26-year-old woman presented to our clinic with pruritic, hyperpigmented, symmetric edematous plaques on her upper flank, chest, and lower back (FIGURE) 3 weeks after starting a strict ketogenic (high fat/low carbohydrate) diet for postpartum weight loss. The patient was an otherwise healthy stay-at-home mother with an unremarkable medical history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Prurigo pigmentosa

We recognized that this was a case of prurigo pigmentosa based on the characteristic pruritic rash that had developed after the patient started a strict ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a benign, pruritic rash that most commonly presents with erythematous or hyperpigmented, symmetrically distributed urticarial papules and plaques on the chest and back. Females represent approximately 70% of cases with a predominant age range of 11 to 30.1

While the pathophysiology remains unknown, the rash most often is reported in association with ketogenic diets.1 Despite occurring in only a fraction of patients on the ketogenic diet, the characteristic presentation has led to the alternative name of the “keto rash” in online nutritional forums and blogs.

Although prurigo pigmentosa is relatively uncommon (with an unknown incidence), primary care physicians may begin to encounter the characteristic rash more frequently, given the number of articles over the past 5 years in the primary care and nutritional literature highlighting the diet’s health benefits.2 The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet with preliminary evidence of improved weight loss, cardiovascular health, and glycemic control suggested by a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials.3 Additionally, the popular press and general public’s rising interest are likely to increase the number of patients on this diet.

A clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis is made clinically, so the appearance of a symmetric pruritic, hyperpigmented rash on the chest and back should prompt the physician to ask about any recent changes in diet. Laboratory analysis is unnecessary, as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and liver function panel are almost always normal. Urinary ketones are present in only 30% to 50% of patients; there is, however, an absence of blood ketones.

Continue to: Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Urticaria presents as individual lesions that often have a pale center. The lesions may occur anywhere on the body and generally last less than 24 hours. History may reveal a trigger including drugs, infection, food, or emotional stress in up to 50% of cases.

Irritant contact dermatitis often is associated with a stinging or burning sensation. Irritant and allergic contact dermatitis may have a geometric, or “outside job,” distribution suggestive of external contact, potentially with plants, alkalis, acids, or solvents.5

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare asymptomatic dermatosis of unknown etiology that presents as hyperpigmented papules on the upper trunk, neck, and axillae. Most patients lack associated pruritis which is in contrast to prurigo pigmentosa.6

Pityriasis rosea is a viral exanthem that may be associated with constitutional symptoms and often presents initially with a herald patch progressing to a classic “Christmas tree” distribution with a fine collarette of scale. It often is asymptomatic, although some cases may be pruritic.5

Treatment focuses on dietary modification

Primary treatment includes resumption of a normal diet. This often leads to rapid resolution of pruritis. Residual hyperpigmentation may take months to fade.

Continue to: Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

If additional treatment is required, minocycline 100 to 200 mg/d has been reported most effective, likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties.1,4 Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines provide symptomatic relief in some patients.1,4

Our patient had resolution of the pruritis and urticarial lesions within 2 days of resuming a normal diet; however, residual asymptomatic hyperpigmentation persisted. A retrial of the ketogenic diet initiated a flare of the rash in the same distribution. It rapidly resolved with carbohydrate intake.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel Croom, MD, 34520 Bob Wilson Dr, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, CA 92134; [email protected]

1. Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897.

2. Abbasi J. Interest in the ketogenic diet grows for weight loss and type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;319:215-217.

3. Bueno NB, de Melo IS, de Oliveira SL, et al. Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1178-1187.

4. Oh YJ, Lee MH. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1149-1153.

5. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Diseases of the skin appendages. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2015:747-788.

6. Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Hsu S, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: case series and differentiation from confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:77-80.

A 26-year-old woman presented to our clinic with pruritic, hyperpigmented, symmetric edematous plaques on her upper flank, chest, and lower back (FIGURE) 3 weeks after starting a strict ketogenic (high fat/low carbohydrate) diet for postpartum weight loss. The patient was an otherwise healthy stay-at-home mother with an unremarkable medical history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Prurigo pigmentosa

We recognized that this was a case of prurigo pigmentosa based on the characteristic pruritic rash that had developed after the patient started a strict ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a benign, pruritic rash that most commonly presents with erythematous or hyperpigmented, symmetrically distributed urticarial papules and plaques on the chest and back. Females represent approximately 70% of cases with a predominant age range of 11 to 30.1

While the pathophysiology remains unknown, the rash most often is reported in association with ketogenic diets.1 Despite occurring in only a fraction of patients on the ketogenic diet, the characteristic presentation has led to the alternative name of the “keto rash” in online nutritional forums and blogs.

Although prurigo pigmentosa is relatively uncommon (with an unknown incidence), primary care physicians may begin to encounter the characteristic rash more frequently, given the number of articles over the past 5 years in the primary care and nutritional literature highlighting the diet’s health benefits.2 The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet with preliminary evidence of improved weight loss, cardiovascular health, and glycemic control suggested by a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials.3 Additionally, the popular press and general public’s rising interest are likely to increase the number of patients on this diet.

A clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis is made clinically, so the appearance of a symmetric pruritic, hyperpigmented rash on the chest and back should prompt the physician to ask about any recent changes in diet. Laboratory analysis is unnecessary, as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and liver function panel are almost always normal. Urinary ketones are present in only 30% to 50% of patients; there is, however, an absence of blood ketones.

Continue to: Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Urticaria presents as individual lesions that often have a pale center. The lesions may occur anywhere on the body and generally last less than 24 hours. History may reveal a trigger including drugs, infection, food, or emotional stress in up to 50% of cases.

Irritant contact dermatitis often is associated with a stinging or burning sensation. Irritant and allergic contact dermatitis may have a geometric, or “outside job,” distribution suggestive of external contact, potentially with plants, alkalis, acids, or solvents.5

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare asymptomatic dermatosis of unknown etiology that presents as hyperpigmented papules on the upper trunk, neck, and axillae. Most patients lack associated pruritis which is in contrast to prurigo pigmentosa.6

Pityriasis rosea is a viral exanthem that may be associated with constitutional symptoms and often presents initially with a herald patch progressing to a classic “Christmas tree” distribution with a fine collarette of scale. It often is asymptomatic, although some cases may be pruritic.5

Treatment focuses on dietary modification

Primary treatment includes resumption of a normal diet. This often leads to rapid resolution of pruritis. Residual hyperpigmentation may take months to fade.

Continue to: Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

If additional treatment is required, minocycline 100 to 200 mg/d has been reported most effective, likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties.1,4 Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines provide symptomatic relief in some patients.1,4

Our patient had resolution of the pruritis and urticarial lesions within 2 days of resuming a normal diet; however, residual asymptomatic hyperpigmentation persisted. A retrial of the ketogenic diet initiated a flare of the rash in the same distribution. It rapidly resolved with carbohydrate intake.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel Croom, MD, 34520 Bob Wilson Dr, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, CA 92134; [email protected]

A 26-year-old woman presented to our clinic with pruritic, hyperpigmented, symmetric edematous plaques on her upper flank, chest, and lower back (FIGURE) 3 weeks after starting a strict ketogenic (high fat/low carbohydrate) diet for postpartum weight loss. The patient was an otherwise healthy stay-at-home mother with an unremarkable medical history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Prurigo pigmentosa

We recognized that this was a case of prurigo pigmentosa based on the characteristic pruritic rash that had developed after the patient started a strict ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a benign, pruritic rash that most commonly presents with erythematous or hyperpigmented, symmetrically distributed urticarial papules and plaques on the chest and back. Females represent approximately 70% of cases with a predominant age range of 11 to 30.1

While the pathophysiology remains unknown, the rash most often is reported in association with ketogenic diets.1 Despite occurring in only a fraction of patients on the ketogenic diet, the characteristic presentation has led to the alternative name of the “keto rash” in online nutritional forums and blogs.

Although prurigo pigmentosa is relatively uncommon (with an unknown incidence), primary care physicians may begin to encounter the characteristic rash more frequently, given the number of articles over the past 5 years in the primary care and nutritional literature highlighting the diet’s health benefits.2 The ketogenic diet is a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet with preliminary evidence of improved weight loss, cardiovascular health, and glycemic control suggested by a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials.3 Additionally, the popular press and general public’s rising interest are likely to increase the number of patients on this diet.

A clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis is made clinically, so the appearance of a symmetric pruritic, hyperpigmented rash on the chest and back should prompt the physician to ask about any recent changes in diet. Laboratory analysis is unnecessary, as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and liver function panel are almost always normal. Urinary ketones are present in only 30% to 50% of patients; there is, however, an absence of blood ketones.

Continue to: Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa

Urticaria presents as individual lesions that often have a pale center. The lesions may occur anywhere on the body and generally last less than 24 hours. History may reveal a trigger including drugs, infection, food, or emotional stress in up to 50% of cases.

Irritant contact dermatitis often is associated with a stinging or burning sensation. Irritant and allergic contact dermatitis may have a geometric, or “outside job,” distribution suggestive of external contact, potentially with plants, alkalis, acids, or solvents.5

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare asymptomatic dermatosis of unknown etiology that presents as hyperpigmented papules on the upper trunk, neck, and axillae. Most patients lack associated pruritis which is in contrast to prurigo pigmentosa.6

Pityriasis rosea is a viral exanthem that may be associated with constitutional symptoms and often presents initially with a herald patch progressing to a classic “Christmas tree” distribution with a fine collarette of scale. It often is asymptomatic, although some cases may be pruritic.5

Treatment focuses on dietary modification

Primary treatment includes resumption of a normal diet. This often leads to rapid resolution of pruritis. Residual hyperpigmentation may take months to fade.

Continue to: Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

Pharmaceutical intervention may be necessary

If additional treatment is required, minocycline 100 to 200 mg/d has been reported most effective, likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties.1,4 Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines provide symptomatic relief in some patients.1,4

Our patient had resolution of the pruritis and urticarial lesions within 2 days of resuming a normal diet; however, residual asymptomatic hyperpigmentation persisted. A retrial of the ketogenic diet initiated a flare of the rash in the same distribution. It rapidly resolved with carbohydrate intake.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel Croom, MD, 34520 Bob Wilson Dr, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, CA 92134; [email protected]

1. Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897.

2. Abbasi J. Interest in the ketogenic diet grows for weight loss and type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;319:215-217.

3. Bueno NB, de Melo IS, de Oliveira SL, et al. Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1178-1187.

4. Oh YJ, Lee MH. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1149-1153.

5. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Diseases of the skin appendages. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2015:747-788.

6. Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Hsu S, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: case series and differentiation from confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:77-80.

1. Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897.

2. Abbasi J. Interest in the ketogenic diet grows for weight loss and type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;319:215-217.

3. Bueno NB, de Melo IS, de Oliveira SL, et al. Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1178-1187.

4. Oh YJ, Lee MH. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1149-1153.

5. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Diseases of the skin appendages. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2015:747-788.

6. Shevchenko A, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Hsu S, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: case series and differentiation from confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:77-80.

FDA extends Dupixent indication for 12- to 17-year-olds

The Food and Drug Administration has approved dupilumab for adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) that has been inadequately controlled with topical prescription treatments “or when those therapies are not advisable.”

Dupilumab (Dupixent), which inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, was initially approved in March 2017, for the same indication, becoming the first targeted biologic treatment for AD. The adolescent approval was announced by the manufacturer.

While there are several systemic medications used as second-line therapy for treatment of pediatric AD, dupilumab is the first FDA-approved biologic for treatment of the disease in adolescents aged 12-17 years, Dawn Marie R. Davis, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester (MN), and current president of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, said in an interview.

FDA approval should decrease insurance barriers and the need for prior authorization, thus increasing access to the drug, she noted, adding, “I hope it will offer a successful alternative to other advanced therapies, as the medicine works through a different mechanism of action, compared to the current systemic medications available.”

With the expanded indication to include adolescents, “patients with more moderate to severe disease who aren’t well controlled with a topical therapy are going to get treatment that will change their lives for many years to come,” dupilumab investigator Eric L. Simpson, MD, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview. “On the whole, patients are likely being undertreated and suffering from the disease more than they need to be,” said Dr. Simpson, “With the advent of this new therapy and the new data, it’s going to change the risk benefit calculation for providers and for patients.”

Results from a phase 3 clinical trial of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate to severe AD were presented last fall at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress in Paris. In that study, the proportion of patients who achieved a 75% or greater improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index at 16 weeks was 38.1% with monthly dupilumab, 41.5% with dupilumab every 2 weeks, and 8.2% with placebo. Dr. Simpson, the first author of this study, presented the results at that meeting.

Dr. Simpson said that he hopes dupilumab approval for adolescents and the clinical trial results will help providers recognize when patients are not in good control of their AD, and which patients qualify for a step-up in therapy when treatments such as topical therapy or prednisone are not effective. “There are so many patients out there who qualify for a step-up in therapy,” he commented. “I hope that provides comfort to both patients and providers, that it’s OK to take the next step, because the results show us that, not only it can improve your skin rash, but it can have dramatic effects on all the downstream effects of the condition.”

These downstream effects include not only quality of life and comorbidities of mental health but also the patient’s emotional state. Hopefully, dupilumab can reduce stigmatization of AD and feelings of embarrassment for adolescents at a time in life when “socialization, education, and activity is so important in creating your kind of identity in yourself and your sense of self-worth,” Dr. Simpson said.

“It is important to remember atopic dermatitis is a disease that impacts not only the skin, but the patient as a whole,” said Dr. Davis. “It is an exciting time to be caring for atopic dermatitis patients with the various new medications coming to market.”

The FDA had granted a priority review for the adolescent indication; previously the FDA had granted Breakthrough Therapy designation for dupilumab in 2016 for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in adolescents and severe AD in children aged 6 months to 11 years who are insufficiently controlled with topical medications

The dosing for adolescents is weight based; two doses are available, 200 mg and 300 mg, administered subcutaneously, every other week after a loading dose. The updated prescribing information is available at https://www.regeneron.com/sites/default/files/Dupixent_FPI.pdf.Dr. Simpson reports relationships with Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Davis reports no relevant financial disclosures.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved dupilumab for adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) that has been inadequately controlled with topical prescription treatments “or when those therapies are not advisable.”

Dupilumab (Dupixent), which inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, was initially approved in March 2017, for the same indication, becoming the first targeted biologic treatment for AD. The adolescent approval was announced by the manufacturer.

While there are several systemic medications used as second-line therapy for treatment of pediatric AD, dupilumab is the first FDA-approved biologic for treatment of the disease in adolescents aged 12-17 years, Dawn Marie R. Davis, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester (MN), and current president of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, said in an interview.

FDA approval should decrease insurance barriers and the need for prior authorization, thus increasing access to the drug, she noted, adding, “I hope it will offer a successful alternative to other advanced therapies, as the medicine works through a different mechanism of action, compared to the current systemic medications available.”

With the expanded indication to include adolescents, “patients with more moderate to severe disease who aren’t well controlled with a topical therapy are going to get treatment that will change their lives for many years to come,” dupilumab investigator Eric L. Simpson, MD, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview. “On the whole, patients are likely being undertreated and suffering from the disease more than they need to be,” said Dr. Simpson, “With the advent of this new therapy and the new data, it’s going to change the risk benefit calculation for providers and for patients.”

Results from a phase 3 clinical trial of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate to severe AD were presented last fall at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress in Paris. In that study, the proportion of patients who achieved a 75% or greater improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index at 16 weeks was 38.1% with monthly dupilumab, 41.5% with dupilumab every 2 weeks, and 8.2% with placebo. Dr. Simpson, the first author of this study, presented the results at that meeting.

Dr. Simpson said that he hopes dupilumab approval for adolescents and the clinical trial results will help providers recognize when patients are not in good control of their AD, and which patients qualify for a step-up in therapy when treatments such as topical therapy or prednisone are not effective. “There are so many patients out there who qualify for a step-up in therapy,” he commented. “I hope that provides comfort to both patients and providers, that it’s OK to take the next step, because the results show us that, not only it can improve your skin rash, but it can have dramatic effects on all the downstream effects of the condition.”

These downstream effects include not only quality of life and comorbidities of mental health but also the patient’s emotional state. Hopefully, dupilumab can reduce stigmatization of AD and feelings of embarrassment for adolescents at a time in life when “socialization, education, and activity is so important in creating your kind of identity in yourself and your sense of self-worth,” Dr. Simpson said.

“It is important to remember atopic dermatitis is a disease that impacts not only the skin, but the patient as a whole,” said Dr. Davis. “It is an exciting time to be caring for atopic dermatitis patients with the various new medications coming to market.”

The FDA had granted a priority review for the adolescent indication; previously the FDA had granted Breakthrough Therapy designation for dupilumab in 2016 for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in adolescents and severe AD in children aged 6 months to 11 years who are insufficiently controlled with topical medications

The dosing for adolescents is weight based; two doses are available, 200 mg and 300 mg, administered subcutaneously, every other week after a loading dose. The updated prescribing information is available at https://www.regeneron.com/sites/default/files/Dupixent_FPI.pdf.Dr. Simpson reports relationships with Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Davis reports no relevant financial disclosures.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved dupilumab for adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) that has been inadequately controlled with topical prescription treatments “or when those therapies are not advisable.”

Dupilumab (Dupixent), which inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, was initially approved in March 2017, for the same indication, becoming the first targeted biologic treatment for AD. The adolescent approval was announced by the manufacturer.

While there are several systemic medications used as second-line therapy for treatment of pediatric AD, dupilumab is the first FDA-approved biologic for treatment of the disease in adolescents aged 12-17 years, Dawn Marie R. Davis, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester (MN), and current president of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, said in an interview.

FDA approval should decrease insurance barriers and the need for prior authorization, thus increasing access to the drug, she noted, adding, “I hope it will offer a successful alternative to other advanced therapies, as the medicine works through a different mechanism of action, compared to the current systemic medications available.”

With the expanded indication to include adolescents, “patients with more moderate to severe disease who aren’t well controlled with a topical therapy are going to get treatment that will change their lives for many years to come,” dupilumab investigator Eric L. Simpson, MD, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview. “On the whole, patients are likely being undertreated and suffering from the disease more than they need to be,” said Dr. Simpson, “With the advent of this new therapy and the new data, it’s going to change the risk benefit calculation for providers and for patients.”

Results from a phase 3 clinical trial of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate to severe AD were presented last fall at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress in Paris. In that study, the proportion of patients who achieved a 75% or greater improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index at 16 weeks was 38.1% with monthly dupilumab, 41.5% with dupilumab every 2 weeks, and 8.2% with placebo. Dr. Simpson, the first author of this study, presented the results at that meeting.

Dr. Simpson said that he hopes dupilumab approval for adolescents and the clinical trial results will help providers recognize when patients are not in good control of their AD, and which patients qualify for a step-up in therapy when treatments such as topical therapy or prednisone are not effective. “There are so many patients out there who qualify for a step-up in therapy,” he commented. “I hope that provides comfort to both patients and providers, that it’s OK to take the next step, because the results show us that, not only it can improve your skin rash, but it can have dramatic effects on all the downstream effects of the condition.”

These downstream effects include not only quality of life and comorbidities of mental health but also the patient’s emotional state. Hopefully, dupilumab can reduce stigmatization of AD and feelings of embarrassment for adolescents at a time in life when “socialization, education, and activity is so important in creating your kind of identity in yourself and your sense of self-worth,” Dr. Simpson said.

“It is important to remember atopic dermatitis is a disease that impacts not only the skin, but the patient as a whole,” said Dr. Davis. “It is an exciting time to be caring for atopic dermatitis patients with the various new medications coming to market.”

The FDA had granted a priority review for the adolescent indication; previously the FDA had granted Breakthrough Therapy designation for dupilumab in 2016 for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in adolescents and severe AD in children aged 6 months to 11 years who are insufficiently controlled with topical medications

The dosing for adolescents is weight based; two doses are available, 200 mg and 300 mg, administered subcutaneously, every other week after a loading dose. The updated prescribing information is available at https://www.regeneron.com/sites/default/files/Dupixent_FPI.pdf.Dr. Simpson reports relationships with Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Davis reports no relevant financial disclosures.

Abdominal Wall Schwannoma

Schwannomas are benign tumors exclusively composed of Schwann cells that arise from the peripheral nerve sheath; these tumors theoretically can present anywhere in the body where nerves reside. They tend to occur in the head and neck region (classically an acoustic neuroma) but also occur in other locations, including the retroperitoneal space and the extremities, particularly flexural surfaces. Patients with cutaneous schwannomas are most likely to present to their primary care provider’s office reporting skin findings or localized pain, and providers should be aware of schwannomas on the differential for painful nodular growths.

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to the primary care clinic for intermittent, sharp, localized left lower quadrant abdominal wall pain that was gradually progressive over the previous few months. The patient noticed the development of a small nodule 7 to 8 months prior to the visit, at which time the pain was less frequent and less severe. He reported no postprandial association of the pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, or other gastrointestinal symptoms.

Ten months prior to the presentation, he was involved in a low-impact motor vehicle collision as a pedestrian in which he fell face-first onto the hood of an oncoming car. At that time, he did not note any abdominal trauma or pain. Evaluation at a local emergency department did not reveal any major injuries. In the interim, he had self-administered insulin in his abdominal region, as he had without incident for the previous 2 years. He reported that he was not injecting near the site of the nodule since it had formed. He could not recall whether the location was a previous insulin administration site.

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were normal as were the cardiac and respiratory examinations. An abdominal exam revealed normal bowel sounds and no overlying skin changes or discoloration. Palpation revealed a 1.5 x 1 cm rubbery-to-firm, well-circumscribed subcutaneous nodule along his mid-left abdomen, about 7 cm lateral to the umbilicus. The nodule was sensitive to both light touch and deep pressure. It was firmer than expected for an abdominal wall lipoma. There was no central puncta or pore to suggest an epidermal inclusion cyst. There was no surrounding erythema or induration to suggest an abscess.

The patient was referred for surgery and underwent excisional biopsy of the mass. Pathology revealed a well-circumscribed vascular/spindle-cell lesion consistent with a schwannoma. His postoperative course was uncomplicated. At 4-week follow-up the incision had healed completely and the patient was pain free.

Discussion

Soft-tissue nodules are common—about two-thirds of soft-tissue tumors are classified into 7 diagnostic categories: lipoma and lipoma variants (16%), fibrous histiocytoma (13%), nodular fasciitis (11%), hemangioma (8%), fibromatosis (7%), neurofibroma (5%), and schwannoma (5%).1 Peripheral nerve tumors (schwannomas, neurofibromas) can be associated with pain or paresthesias, and less commonly, neurologic deficits, such as motor weakness. Peripheral nerve tumors have several classifications, such as nonneoplastic vs neoplastic, benign vs malignant, and sheath vs nonsheath origins. Schwannomas are considered part of the neoplastic subset due to their growth; otherwise, they are benign with a sheath origin. In contrast to neurofibromas, benign schwannomas have a slower rate of progression, lower association with pain, and fewer neurologic symptoms.2

The neural sheath is made up of 3 types of cells: the fibroblast, the Schwann cell, and the perineural cell, which lacks a basement membrane. It is the Schwann cell that can give rise to the 3 main types of cutaneous nerve tumors: neuromas, neurofibromas, and schwannomas.3 A nerve that is both entering and exiting a mass is a classic presentation for a peripheral nerve sheath tumor. If the nerve is eccentric to the lesion, then it is consistent with a schwannoma (not a neurofibroma).4 Schwannomas are made exclusively of Schwann cells that arise from the nerve sheath, whereas neurofibromas are made up of all the different cell types that constitute a nerve. Bilateral vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas) are virtually pathognomonic of neurofibromatosis 2 (NF-2), which can manifest as hearing loss, tinnitus, and equilibrium problems. In contrast, neurofibromatosis 1 (NF-1) is more common, characterized by multiple café au lait spots, freckling in the axillary and groin regions, increased risk of cancers overall, and development of pedunculated skin growths, brain, or organ-based neurofibromas.

Diagnosis

A workup generally includes a thorough history and examination as well as imaging. In cases of superficial subcutaneous lesions, an ultrasound is often the imaging modality of choice. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans are frequently used for more deep-seated lesions. There can be significant differences between malignant and benign neural lesions on MRI and CT in terms of contrast-uptake and heterogeneity of tissue, but the visual features are not consistent. Best estimates for MRI suggest 61% sensitivity and 90% specificity for the diagnosis of high-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors based on imaging alone.5

Definitive diagnosis requires surgical excision. Fine-needle aspiration can be used to diagnose subcutaneous nodules, but there is a possibility that degenerative changes and nuclear atypia seen on a smaller sample may be confused with a more aggressive sarcoma. For example, long-standing schwannomas are often called ancient, meaning that they break down over time, and the atypia they display is a regressive phenomenon.6 Therefore, a small or limited tissue sampling may not be representative of the entire lesion.7 As such, patients will likely need referral for surgical removal to determine the exact nature of the growth.

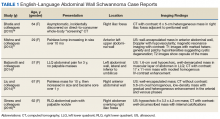

Although schwannomas are uncommon overall, the highest incidence is in the fourth decade of life with a slight predominance in females. They are often incidentally found as a palpable mass but can be symptomatic with paresthesias, pain, or neurologic changes—particularly when identified in the retroperitoneum or along joints. Schwannomas are most commonly found in the retroperitoneum (32%), mediastinum (23%), head and neck (18%), and extremities (16%).8 The majority of cases (about 90%) are sporadic; whereas 2% are related to NF-2.9 The abdominal wall schwannoma is rare. Our review of English-language literature in PubMed and EMBASE found only 5 other case reports (Table 1).

On physical examination, superficial lesions are freely movable except for a single point of attachment, which is generally along the long axis of the nerve.

Pathology

On gross pathology examination, schwannomas have a well-circumscribed smooth external surface. On microscopy, schwannomas are truly encapsulated, uninodular, spindle-cell proliferations arranged in a streaming pattern within a background of thick, hyalinized blood vessels. Classic schwannomas typically exhibit a biphasic pattern of alternating areas of high and low cellularity and are named for Swedish neurologist Nils Antoni. The more cellular regions are referred to as Antoni A areas and consist of streaming fascicles of compact spindle cells that often palisade around acellular eosinophilic areas of fibrillary processes known as Verocay bodies.

In contrast, the lower cellularity regions (Antoni B areas) consist of multipolar, loosely textured cells with abundant cytoplasm, haphazardly arranged processes, and an overall myxoid appearance.11 Schwannomas are known to have widely variable proportions of Antoni A and Antoni B areas; in this case, the excised specimen was noted to have predominately Antoni A areas without well-defined Verocay bodies and only scattered foci showing some suggestion of the hypocellular Antoni B architecture (Figure 2).9,12

Immunohistochemical stains for S100 and SOX10 (used to identify cells derived from a neural crest lineage) were strongly positive, which is characteristic of schwannomas.13 Although there have only been rare reports of extracranial schwannomas undergoing malignant transformation, it is critical to rule out the possibility of a de novo malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST).13 In general, MPNSTs tend to be more cellular, have brisk mitotic activity, areas of necrosis, hyperchromatic nuclei, and conspicuous pleomorphism. Mitotic figures, which can be concerning for malignant potential if present in high number, were noted occasionally in our patient; however, occasional mitosis may be seen in classic schwannomas. Clinically, MPNSTs have a poor prognosis. Based on case reports, disease-specific survival at 10 years is 31.6% for localized disease and only 7.5% for metastatic disease.14 In this case, there was no evidence of any of the high-grade features of a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, thus supporting the diagnosis of schwannoma (neurilemmoma).

Treatment

Schwannomas are exclusively treated by excision. Prognosis is good with low recurrence rates. It is unknown what the recurrence rates are for completely resected abdominal wall schwannomas since there are so few reports in the literature. For other well-known entities, such as vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuromas), the recurrence rates are generally 2% to 3%.15 Transformation of schwannomas into MPNSTs are so unusual that they are only described in single case reports.

Conclusion

Soft-tissue masses are a common complaint. Most are benign and do not require excision unless it interferes with the quality of life of the patient or if the diagnosis is uncertain. It is important to be aware of schwannomas in the differential diagnosis of soft-tissue masses. Diagnosis may be achieved through the combination of imaging and biopsy, but the definitive diagnosis is made on complete excision of the mass.

Acknowledgments

Contributors: Michael Lewis, MD, Department of Pathology, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Written permission also was obtained from the patient.

1. Kransdorf MJ. Benign soft-tissue tumors in a large referral population: distribution of specific diagnoses by age, sex, and location. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164(2):395-402.

2. Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ismaili N, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Symptoms associated with malignancy of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a retrospective study of 69 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(1):79-82.

3. Patterson JW. Neural and neuroendocrine tumors. In: Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1042-1049.

4. Balzarotti R, Rondelli F, Barizzi J, Cartolari R. Symptomatic schwannoma of the abdominal wall: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(3):1095-1098.

5. Wasa J, Nishida Y, Tsukushi S, et al. MRI features in the differentiation of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and neurofibromas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(6):1568-1574.

6. Dodd LG, Marom EM, Dash RC, Matthews MR, McLendon RE. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of “ancient” schwannoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;20(5):307-311.

7. Powers CN, Berardo MD, Frable WJ. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy: pitfalls in the diagnosis of spindle-cell lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;10(3):232-240; discussion 241.

8. White W, Shiu MH, Rosenblum MK, Erlandson RA, Woodruff JM. Cellular schwannoma: a clinicopathologic study of 57 patients and 58 tumors. Cancer. 1990;66(6):1266-1275.

9. Goldblum JR, Weiss SW, Folpe AL. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:813-828.

10. Naversen DN, Trask DM, Watson FH, Burket JM. Painful tumors of the skin: “LEND AN EGG.” J Am Acad Deramatol. 1993;28(2, pt 2):298-300.

11. Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. Diagnostic Pathology: Neuropathology. 1st ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2012.

12. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, eds. World Health Organization Histological Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Vol. 1. Paris, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016.

13. Woodruff JM, Selig AM, Crowley K, Allen PW. Schwannoma (neurilemoma) with malignant transformation. A rare, distinctive peripheral nerve tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(9)82-895.

14. Zou C, Smith KD, Liu J, et al. Clinical, pathological, and molecular variables predictive of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor outcome. Ann Surg. 2009;249(6):1014-1022.

15. Ahmad RA, Sivalingam S, Topsakal V, Russo A, Taibah A, Sanna M. Rate of recurrent vestibular schwannoma after total removal via different surgical approaches. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2012;121(3):156-161.

16. Bhatia RK, Banerjea A, Ram M, Lovett BE. Benign ancient schwannoma of the abdominal wall: an unwanted birthday present. BMC Surg. 2010;10:1-5.

17. Mishra A, Hamadto M, Azzabi M, Elfagieh M. Abdominal wall schwannoma: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Radiol. 2013;2013:456863.

18. Liu Y, Chen X, Wang T, Wang Z. Imaging observations of a schwannoma of low malignant potential in the anterior abdominal wall: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(3):1159-1162.

19. Ginesu GC, Puledda M, Feo CF et al. Abdominal wall schwannoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(10):1781-1783.

Schwannomas are benign tumors exclusively composed of Schwann cells that arise from the peripheral nerve sheath; these tumors theoretically can present anywhere in the body where nerves reside. They tend to occur in the head and neck region (classically an acoustic neuroma) but also occur in other locations, including the retroperitoneal space and the extremities, particularly flexural surfaces. Patients with cutaneous schwannomas are most likely to present to their primary care provider’s office reporting skin findings or localized pain, and providers should be aware of schwannomas on the differential for painful nodular growths.

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to the primary care clinic for intermittent, sharp, localized left lower quadrant abdominal wall pain that was gradually progressive over the previous few months. The patient noticed the development of a small nodule 7 to 8 months prior to the visit, at which time the pain was less frequent and less severe. He reported no postprandial association of the pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, or other gastrointestinal symptoms.

Ten months prior to the presentation, he was involved in a low-impact motor vehicle collision as a pedestrian in which he fell face-first onto the hood of an oncoming car. At that time, he did not note any abdominal trauma or pain. Evaluation at a local emergency department did not reveal any major injuries. In the interim, he had self-administered insulin in his abdominal region, as he had without incident for the previous 2 years. He reported that he was not injecting near the site of the nodule since it had formed. He could not recall whether the location was a previous insulin administration site.

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were normal as were the cardiac and respiratory examinations. An abdominal exam revealed normal bowel sounds and no overlying skin changes or discoloration. Palpation revealed a 1.5 x 1 cm rubbery-to-firm, well-circumscribed subcutaneous nodule along his mid-left abdomen, about 7 cm lateral to the umbilicus. The nodule was sensitive to both light touch and deep pressure. It was firmer than expected for an abdominal wall lipoma. There was no central puncta or pore to suggest an epidermal inclusion cyst. There was no surrounding erythema or induration to suggest an abscess.

The patient was referred for surgery and underwent excisional biopsy of the mass. Pathology revealed a well-circumscribed vascular/spindle-cell lesion consistent with a schwannoma. His postoperative course was uncomplicated. At 4-week follow-up the incision had healed completely and the patient was pain free.

Discussion

Soft-tissue nodules are common—about two-thirds of soft-tissue tumors are classified into 7 diagnostic categories: lipoma and lipoma variants (16%), fibrous histiocytoma (13%), nodular fasciitis (11%), hemangioma (8%), fibromatosis (7%), neurofibroma (5%), and schwannoma (5%).1 Peripheral nerve tumors (schwannomas, neurofibromas) can be associated with pain or paresthesias, and less commonly, neurologic deficits, such as motor weakness. Peripheral nerve tumors have several classifications, such as nonneoplastic vs neoplastic, benign vs malignant, and sheath vs nonsheath origins. Schwannomas are considered part of the neoplastic subset due to their growth; otherwise, they are benign with a sheath origin. In contrast to neurofibromas, benign schwannomas have a slower rate of progression, lower association with pain, and fewer neurologic symptoms.2

The neural sheath is made up of 3 types of cells: the fibroblast, the Schwann cell, and the perineural cell, which lacks a basement membrane. It is the Schwann cell that can give rise to the 3 main types of cutaneous nerve tumors: neuromas, neurofibromas, and schwannomas.3 A nerve that is both entering and exiting a mass is a classic presentation for a peripheral nerve sheath tumor. If the nerve is eccentric to the lesion, then it is consistent with a schwannoma (not a neurofibroma).4 Schwannomas are made exclusively of Schwann cells that arise from the nerve sheath, whereas neurofibromas are made up of all the different cell types that constitute a nerve. Bilateral vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas) are virtually pathognomonic of neurofibromatosis 2 (NF-2), which can manifest as hearing loss, tinnitus, and equilibrium problems. In contrast, neurofibromatosis 1 (NF-1) is more common, characterized by multiple café au lait spots, freckling in the axillary and groin regions, increased risk of cancers overall, and development of pedunculated skin growths, brain, or organ-based neurofibromas.

Diagnosis

A workup generally includes a thorough history and examination as well as imaging. In cases of superficial subcutaneous lesions, an ultrasound is often the imaging modality of choice. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans are frequently used for more deep-seated lesions. There can be significant differences between malignant and benign neural lesions on MRI and CT in terms of contrast-uptake and heterogeneity of tissue, but the visual features are not consistent. Best estimates for MRI suggest 61% sensitivity and 90% specificity for the diagnosis of high-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors based on imaging alone.5

Definitive diagnosis requires surgical excision. Fine-needle aspiration can be used to diagnose subcutaneous nodules, but there is a possibility that degenerative changes and nuclear atypia seen on a smaller sample may be confused with a more aggressive sarcoma. For example, long-standing schwannomas are often called ancient, meaning that they break down over time, and the atypia they display is a regressive phenomenon.6 Therefore, a small or limited tissue sampling may not be representative of the entire lesion.7 As such, patients will likely need referral for surgical removal to determine the exact nature of the growth.

Although schwannomas are uncommon overall, the highest incidence is in the fourth decade of life with a slight predominance in females. They are often incidentally found as a palpable mass but can be symptomatic with paresthesias, pain, or neurologic changes—particularly when identified in the retroperitoneum or along joints. Schwannomas are most commonly found in the retroperitoneum (32%), mediastinum (23%), head and neck (18%), and extremities (16%).8 The majority of cases (about 90%) are sporadic; whereas 2% are related to NF-2.9 The abdominal wall schwannoma is rare. Our review of English-language literature in PubMed and EMBASE found only 5 other case reports (Table 1).

On physical examination, superficial lesions are freely movable except for a single point of attachment, which is generally along the long axis of the nerve.

Pathology

On gross pathology examination, schwannomas have a well-circumscribed smooth external surface. On microscopy, schwannomas are truly encapsulated, uninodular, spindle-cell proliferations arranged in a streaming pattern within a background of thick, hyalinized blood vessels. Classic schwannomas typically exhibit a biphasic pattern of alternating areas of high and low cellularity and are named for Swedish neurologist Nils Antoni. The more cellular regions are referred to as Antoni A areas and consist of streaming fascicles of compact spindle cells that often palisade around acellular eosinophilic areas of fibrillary processes known as Verocay bodies.

In contrast, the lower cellularity regions (Antoni B areas) consist of multipolar, loosely textured cells with abundant cytoplasm, haphazardly arranged processes, and an overall myxoid appearance.11 Schwannomas are known to have widely variable proportions of Antoni A and Antoni B areas; in this case, the excised specimen was noted to have predominately Antoni A areas without well-defined Verocay bodies and only scattered foci showing some suggestion of the hypocellular Antoni B architecture (Figure 2).9,12

Immunohistochemical stains for S100 and SOX10 (used to identify cells derived from a neural crest lineage) were strongly positive, which is characteristic of schwannomas.13 Although there have only been rare reports of extracranial schwannomas undergoing malignant transformation, it is critical to rule out the possibility of a de novo malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST).13 In general, MPNSTs tend to be more cellular, have brisk mitotic activity, areas of necrosis, hyperchromatic nuclei, and conspicuous pleomorphism. Mitotic figures, which can be concerning for malignant potential if present in high number, were noted occasionally in our patient; however, occasional mitosis may be seen in classic schwannomas. Clinically, MPNSTs have a poor prognosis. Based on case reports, disease-specific survival at 10 years is 31.6% for localized disease and only 7.5% for metastatic disease.14 In this case, there was no evidence of any of the high-grade features of a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, thus supporting the diagnosis of schwannoma (neurilemmoma).

Treatment

Schwannomas are exclusively treated by excision. Prognosis is good with low recurrence rates. It is unknown what the recurrence rates are for completely resected abdominal wall schwannomas since there are so few reports in the literature. For other well-known entities, such as vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuromas), the recurrence rates are generally 2% to 3%.15 Transformation of schwannomas into MPNSTs are so unusual that they are only described in single case reports.

Conclusion

Soft-tissue masses are a common complaint. Most are benign and do not require excision unless it interferes with the quality of life of the patient or if the diagnosis is uncertain. It is important to be aware of schwannomas in the differential diagnosis of soft-tissue masses. Diagnosis may be achieved through the combination of imaging and biopsy, but the definitive diagnosis is made on complete excision of the mass.

Acknowledgments

Contributors: Michael Lewis, MD, Department of Pathology, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Written permission also was obtained from the patient.

Schwannomas are benign tumors exclusively composed of Schwann cells that arise from the peripheral nerve sheath; these tumors theoretically can present anywhere in the body where nerves reside. They tend to occur in the head and neck region (classically an acoustic neuroma) but also occur in other locations, including the retroperitoneal space and the extremities, particularly flexural surfaces. Patients with cutaneous schwannomas are most likely to present to their primary care provider’s office reporting skin findings or localized pain, and providers should be aware of schwannomas on the differential for painful nodular growths.

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to the primary care clinic for intermittent, sharp, localized left lower quadrant abdominal wall pain that was gradually progressive over the previous few months. The patient noticed the development of a small nodule 7 to 8 months prior to the visit, at which time the pain was less frequent and less severe. He reported no postprandial association of the pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, or other gastrointestinal symptoms.

Ten months prior to the presentation, he was involved in a low-impact motor vehicle collision as a pedestrian in which he fell face-first onto the hood of an oncoming car. At that time, he did not note any abdominal trauma or pain. Evaluation at a local emergency department did not reveal any major injuries. In the interim, he had self-administered insulin in his abdominal region, as he had without incident for the previous 2 years. He reported that he was not injecting near the site of the nodule since it had formed. He could not recall whether the location was a previous insulin administration site.

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were normal as were the cardiac and respiratory examinations. An abdominal exam revealed normal bowel sounds and no overlying skin changes or discoloration. Palpation revealed a 1.5 x 1 cm rubbery-to-firm, well-circumscribed subcutaneous nodule along his mid-left abdomen, about 7 cm lateral to the umbilicus. The nodule was sensitive to both light touch and deep pressure. It was firmer than expected for an abdominal wall lipoma. There was no central puncta or pore to suggest an epidermal inclusion cyst. There was no surrounding erythema or induration to suggest an abscess.

The patient was referred for surgery and underwent excisional biopsy of the mass. Pathology revealed a well-circumscribed vascular/spindle-cell lesion consistent with a schwannoma. His postoperative course was uncomplicated. At 4-week follow-up the incision had healed completely and the patient was pain free.

Discussion

Soft-tissue nodules are common—about two-thirds of soft-tissue tumors are classified into 7 diagnostic categories: lipoma and lipoma variants (16%), fibrous histiocytoma (13%), nodular fasciitis (11%), hemangioma (8%), fibromatosis (7%), neurofibroma (5%), and schwannoma (5%).1 Peripheral nerve tumors (schwannomas, neurofibromas) can be associated with pain or paresthesias, and less commonly, neurologic deficits, such as motor weakness. Peripheral nerve tumors have several classifications, such as nonneoplastic vs neoplastic, benign vs malignant, and sheath vs nonsheath origins. Schwannomas are considered part of the neoplastic subset due to their growth; otherwise, they are benign with a sheath origin. In contrast to neurofibromas, benign schwannomas have a slower rate of progression, lower association with pain, and fewer neurologic symptoms.2

The neural sheath is made up of 3 types of cells: the fibroblast, the Schwann cell, and the perineural cell, which lacks a basement membrane. It is the Schwann cell that can give rise to the 3 main types of cutaneous nerve tumors: neuromas, neurofibromas, and schwannomas.3 A nerve that is both entering and exiting a mass is a classic presentation for a peripheral nerve sheath tumor. If the nerve is eccentric to the lesion, then it is consistent with a schwannoma (not a neurofibroma).4 Schwannomas are made exclusively of Schwann cells that arise from the nerve sheath, whereas neurofibromas are made up of all the different cell types that constitute a nerve. Bilateral vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas) are virtually pathognomonic of neurofibromatosis 2 (NF-2), which can manifest as hearing loss, tinnitus, and equilibrium problems. In contrast, neurofibromatosis 1 (NF-1) is more common, characterized by multiple café au lait spots, freckling in the axillary and groin regions, increased risk of cancers overall, and development of pedunculated skin growths, brain, or organ-based neurofibromas.

Diagnosis

A workup generally includes a thorough history and examination as well as imaging. In cases of superficial subcutaneous lesions, an ultrasound is often the imaging modality of choice. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans are frequently used for more deep-seated lesions. There can be significant differences between malignant and benign neural lesions on MRI and CT in terms of contrast-uptake and heterogeneity of tissue, but the visual features are not consistent. Best estimates for MRI suggest 61% sensitivity and 90% specificity for the diagnosis of high-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors based on imaging alone.5

Definitive diagnosis requires surgical excision. Fine-needle aspiration can be used to diagnose subcutaneous nodules, but there is a possibility that degenerative changes and nuclear atypia seen on a smaller sample may be confused with a more aggressive sarcoma. For example, long-standing schwannomas are often called ancient, meaning that they break down over time, and the atypia they display is a regressive phenomenon.6 Therefore, a small or limited tissue sampling may not be representative of the entire lesion.7 As such, patients will likely need referral for surgical removal to determine the exact nature of the growth.

Although schwannomas are uncommon overall, the highest incidence is in the fourth decade of life with a slight predominance in females. They are often incidentally found as a palpable mass but can be symptomatic with paresthesias, pain, or neurologic changes—particularly when identified in the retroperitoneum or along joints. Schwannomas are most commonly found in the retroperitoneum (32%), mediastinum (23%), head and neck (18%), and extremities (16%).8 The majority of cases (about 90%) are sporadic; whereas 2% are related to NF-2.9 The abdominal wall schwannoma is rare. Our review of English-language literature in PubMed and EMBASE found only 5 other case reports (Table 1).

On physical examination, superficial lesions are freely movable except for a single point of attachment, which is generally along the long axis of the nerve.

Pathology

On gross pathology examination, schwannomas have a well-circumscribed smooth external surface. On microscopy, schwannomas are truly encapsulated, uninodular, spindle-cell proliferations arranged in a streaming pattern within a background of thick, hyalinized blood vessels. Classic schwannomas typically exhibit a biphasic pattern of alternating areas of high and low cellularity and are named for Swedish neurologist Nils Antoni. The more cellular regions are referred to as Antoni A areas and consist of streaming fascicles of compact spindle cells that often palisade around acellular eosinophilic areas of fibrillary processes known as Verocay bodies.

In contrast, the lower cellularity regions (Antoni B areas) consist of multipolar, loosely textured cells with abundant cytoplasm, haphazardly arranged processes, and an overall myxoid appearance.11 Schwannomas are known to have widely variable proportions of Antoni A and Antoni B areas; in this case, the excised specimen was noted to have predominately Antoni A areas without well-defined Verocay bodies and only scattered foci showing some suggestion of the hypocellular Antoni B architecture (Figure 2).9,12

Immunohistochemical stains for S100 and SOX10 (used to identify cells derived from a neural crest lineage) were strongly positive, which is characteristic of schwannomas.13 Although there have only been rare reports of extracranial schwannomas undergoing malignant transformation, it is critical to rule out the possibility of a de novo malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST).13 In general, MPNSTs tend to be more cellular, have brisk mitotic activity, areas of necrosis, hyperchromatic nuclei, and conspicuous pleomorphism. Mitotic figures, which can be concerning for malignant potential if present in high number, were noted occasionally in our patient; however, occasional mitosis may be seen in classic schwannomas. Clinically, MPNSTs have a poor prognosis. Based on case reports, disease-specific survival at 10 years is 31.6% for localized disease and only 7.5% for metastatic disease.14 In this case, there was no evidence of any of the high-grade features of a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, thus supporting the diagnosis of schwannoma (neurilemmoma).

Treatment

Schwannomas are exclusively treated by excision. Prognosis is good with low recurrence rates. It is unknown what the recurrence rates are for completely resected abdominal wall schwannomas since there are so few reports in the literature. For other well-known entities, such as vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuromas), the recurrence rates are generally 2% to 3%.15 Transformation of schwannomas into MPNSTs are so unusual that they are only described in single case reports.

Conclusion

Soft-tissue masses are a common complaint. Most are benign and do not require excision unless it interferes with the quality of life of the patient or if the diagnosis is uncertain. It is important to be aware of schwannomas in the differential diagnosis of soft-tissue masses. Diagnosis may be achieved through the combination of imaging and biopsy, but the definitive diagnosis is made on complete excision of the mass.

Acknowledgments

Contributors: Michael Lewis, MD, Department of Pathology, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Written permission also was obtained from the patient.

1. Kransdorf MJ. Benign soft-tissue tumors in a large referral population: distribution of specific diagnoses by age, sex, and location. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164(2):395-402.

2. Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ismaili N, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Symptoms associated with malignancy of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a retrospective study of 69 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(1):79-82.

3. Patterson JW. Neural and neuroendocrine tumors. In: Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1042-1049.

4. Balzarotti R, Rondelli F, Barizzi J, Cartolari R. Symptomatic schwannoma of the abdominal wall: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(3):1095-1098.

5. Wasa J, Nishida Y, Tsukushi S, et al. MRI features in the differentiation of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and neurofibromas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(6):1568-1574.

6. Dodd LG, Marom EM, Dash RC, Matthews MR, McLendon RE. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of “ancient” schwannoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;20(5):307-311.

7. Powers CN, Berardo MD, Frable WJ. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy: pitfalls in the diagnosis of spindle-cell lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;10(3):232-240; discussion 241.

8. White W, Shiu MH, Rosenblum MK, Erlandson RA, Woodruff JM. Cellular schwannoma: a clinicopathologic study of 57 patients and 58 tumors. Cancer. 1990;66(6):1266-1275.

9. Goldblum JR, Weiss SW, Folpe AL. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:813-828.

10. Naversen DN, Trask DM, Watson FH, Burket JM. Painful tumors of the skin: “LEND AN EGG.” J Am Acad Deramatol. 1993;28(2, pt 2):298-300.

11. Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. Diagnostic Pathology: Neuropathology. 1st ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2012.

12. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, eds. World Health Organization Histological Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Vol. 1. Paris, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016.

13. Woodruff JM, Selig AM, Crowley K, Allen PW. Schwannoma (neurilemoma) with malignant transformation. A rare, distinctive peripheral nerve tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(9)82-895.

14. Zou C, Smith KD, Liu J, et al. Clinical, pathological, and molecular variables predictive of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor outcome. Ann Surg. 2009;249(6):1014-1022.

15. Ahmad RA, Sivalingam S, Topsakal V, Russo A, Taibah A, Sanna M. Rate of recurrent vestibular schwannoma after total removal via different surgical approaches. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2012;121(3):156-161.

16. Bhatia RK, Banerjea A, Ram M, Lovett BE. Benign ancient schwannoma of the abdominal wall: an unwanted birthday present. BMC Surg. 2010;10:1-5.

17. Mishra A, Hamadto M, Azzabi M, Elfagieh M. Abdominal wall schwannoma: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Radiol. 2013;2013:456863.

18. Liu Y, Chen X, Wang T, Wang Z. Imaging observations of a schwannoma of low malignant potential in the anterior abdominal wall: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(3):1159-1162.

19. Ginesu GC, Puledda M, Feo CF et al. Abdominal wall schwannoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(10):1781-1783.

1. Kransdorf MJ. Benign soft-tissue tumors in a large referral population: distribution of specific diagnoses by age, sex, and location. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164(2):395-402.

2. Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ismaili N, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Symptoms associated with malignancy of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a retrospective study of 69 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(1):79-82.

3. Patterson JW. Neural and neuroendocrine tumors. In: Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1042-1049.

4. Balzarotti R, Rondelli F, Barizzi J, Cartolari R. Symptomatic schwannoma of the abdominal wall: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(3):1095-1098.

5. Wasa J, Nishida Y, Tsukushi S, et al. MRI features in the differentiation of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and neurofibromas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(6):1568-1574.

6. Dodd LG, Marom EM, Dash RC, Matthews MR, McLendon RE. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of “ancient” schwannoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;20(5):307-311.

7. Powers CN, Berardo MD, Frable WJ. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy: pitfalls in the diagnosis of spindle-cell lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;10(3):232-240; discussion 241.

8. White W, Shiu MH, Rosenblum MK, Erlandson RA, Woodruff JM. Cellular schwannoma: a clinicopathologic study of 57 patients and 58 tumors. Cancer. 1990;66(6):1266-1275.

9. Goldblum JR, Weiss SW, Folpe AL. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:813-828.

10. Naversen DN, Trask DM, Watson FH, Burket JM. Painful tumors of the skin: “LEND AN EGG.” J Am Acad Deramatol. 1993;28(2, pt 2):298-300.

11. Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. Diagnostic Pathology: Neuropathology. 1st ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2012.

12. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, eds. World Health Organization Histological Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Vol. 1. Paris, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016.

13. Woodruff JM, Selig AM, Crowley K, Allen PW. Schwannoma (neurilemoma) with malignant transformation. A rare, distinctive peripheral nerve tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(9)82-895.

14. Zou C, Smith KD, Liu J, et al. Clinical, pathological, and molecular variables predictive of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor outcome. Ann Surg. 2009;249(6):1014-1022.

15. Ahmad RA, Sivalingam S, Topsakal V, Russo A, Taibah A, Sanna M. Rate of recurrent vestibular schwannoma after total removal via different surgical approaches. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2012;121(3):156-161.

16. Bhatia RK, Banerjea A, Ram M, Lovett BE. Benign ancient schwannoma of the abdominal wall: an unwanted birthday present. BMC Surg. 2010;10:1-5.

17. Mishra A, Hamadto M, Azzabi M, Elfagieh M. Abdominal wall schwannoma: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Radiol. 2013;2013:456863.

18. Liu Y, Chen X, Wang T, Wang Z. Imaging observations of a schwannoma of low malignant potential in the anterior abdominal wall: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(3):1159-1162.

19. Ginesu GC, Puledda M, Feo CF et al. Abdominal wall schwannoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(10):1781-1783.

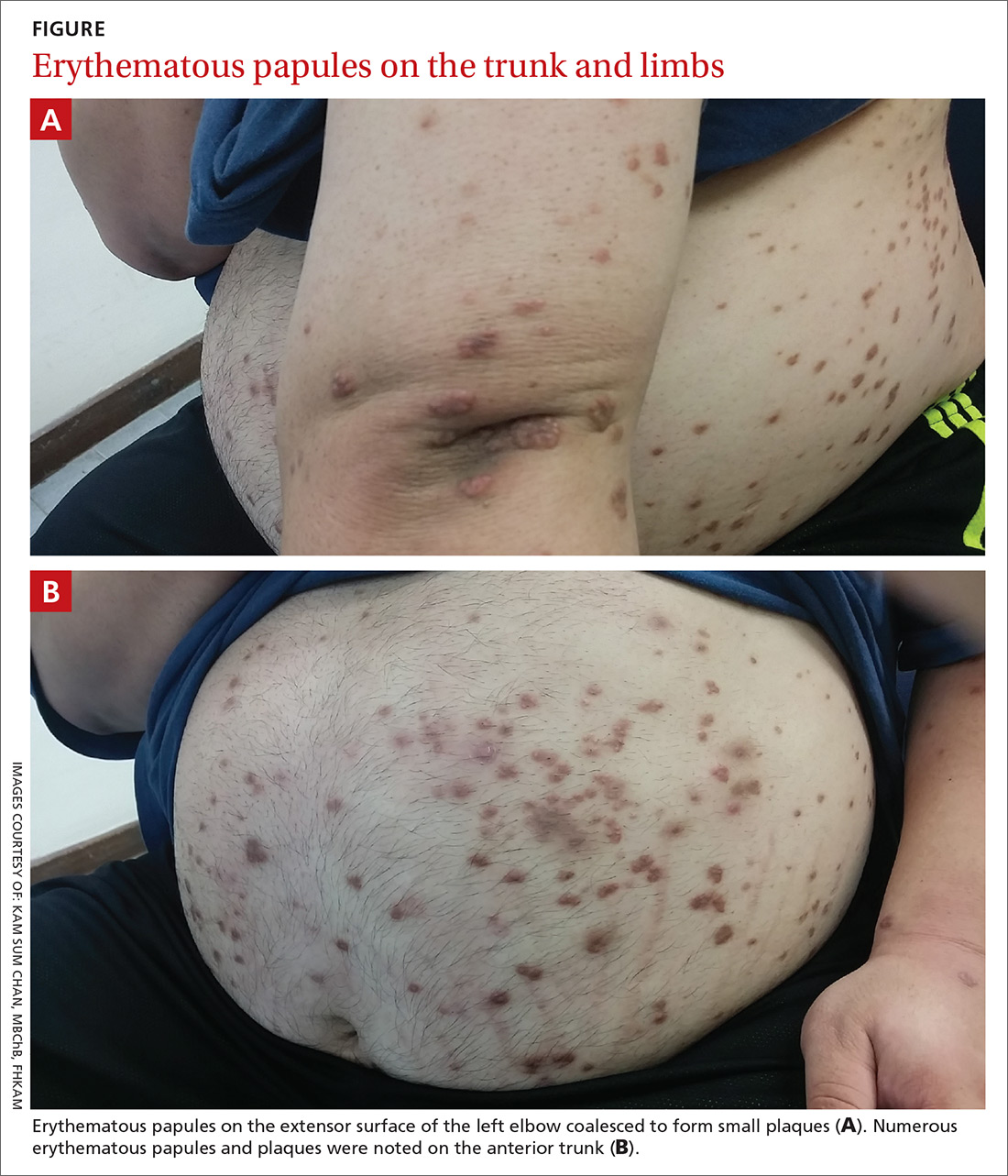

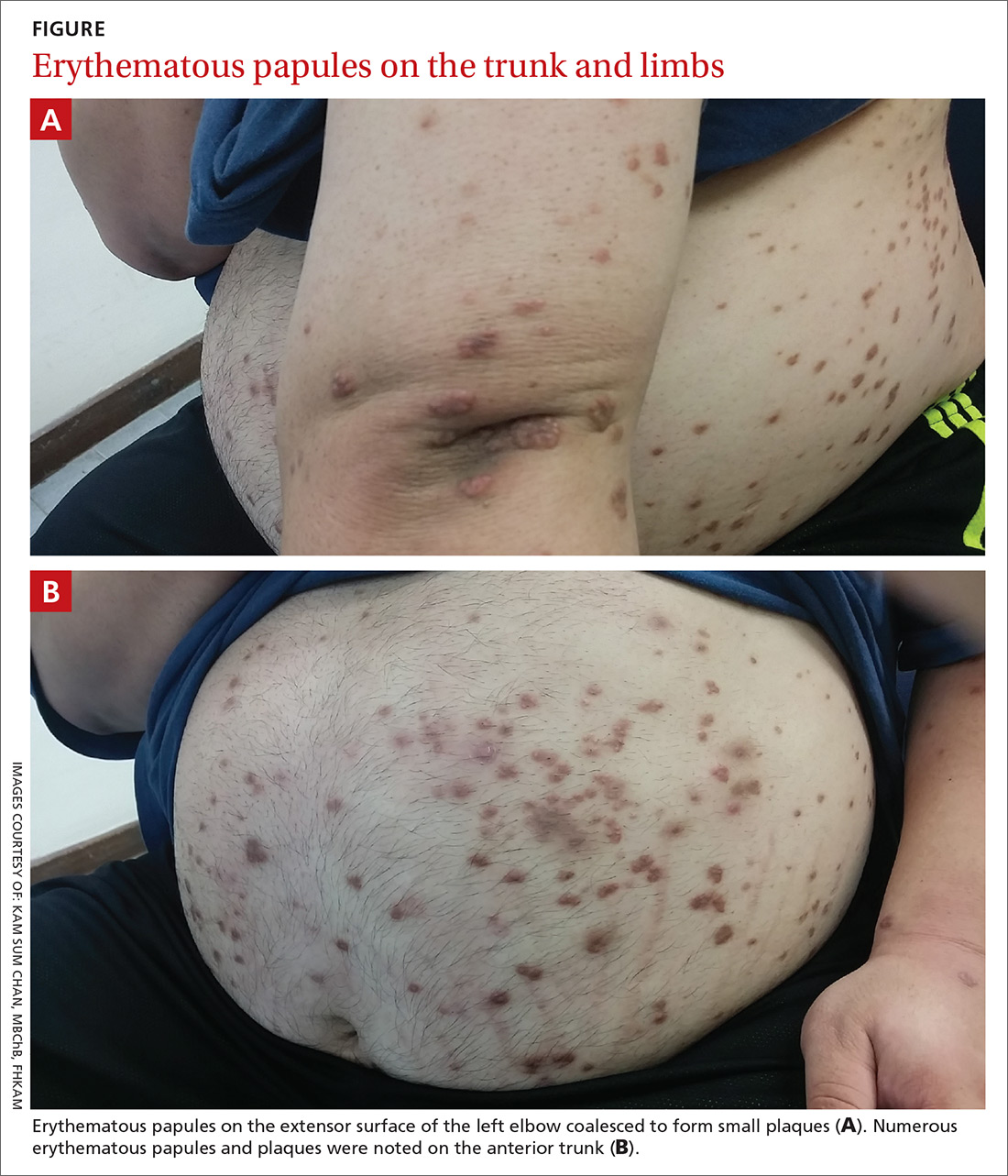

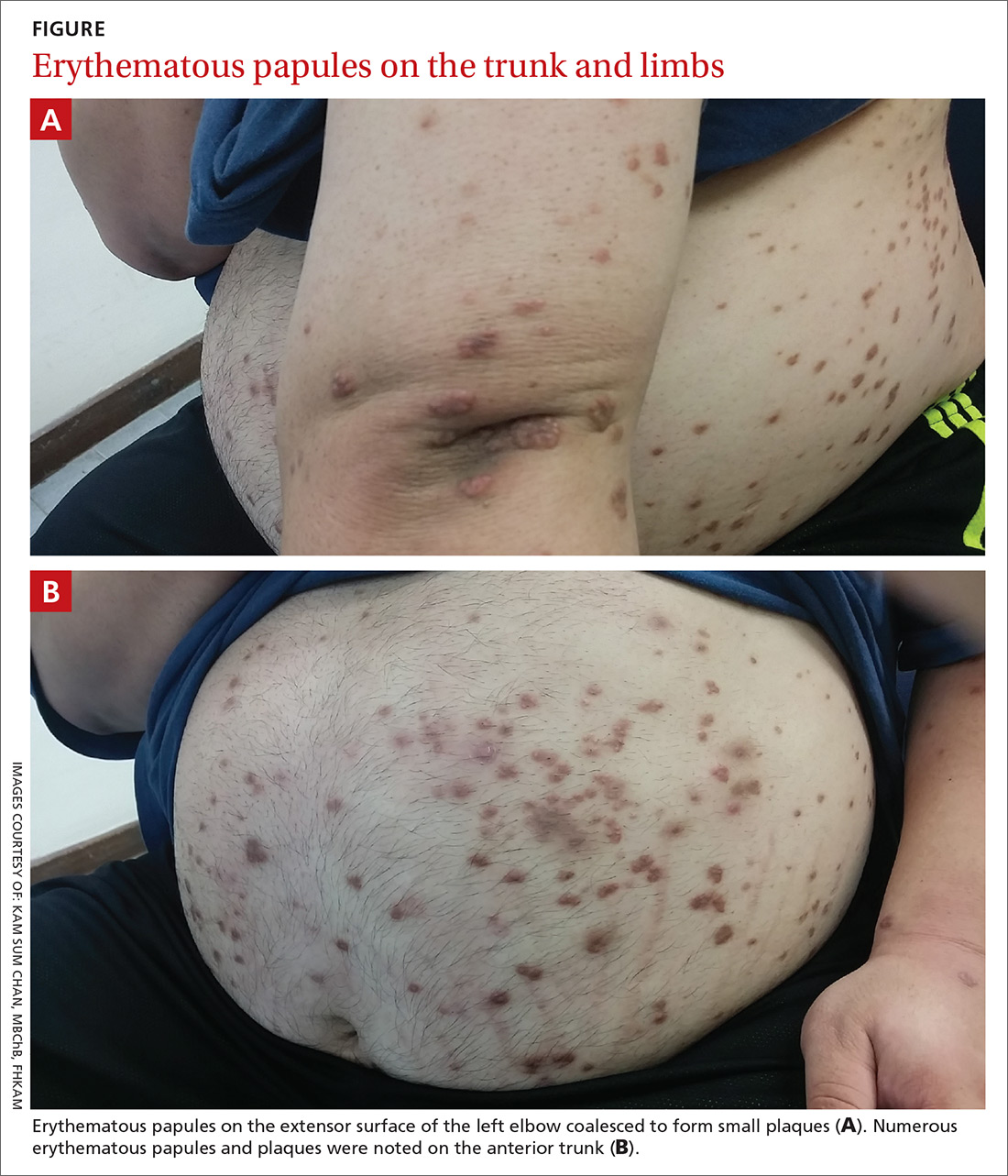

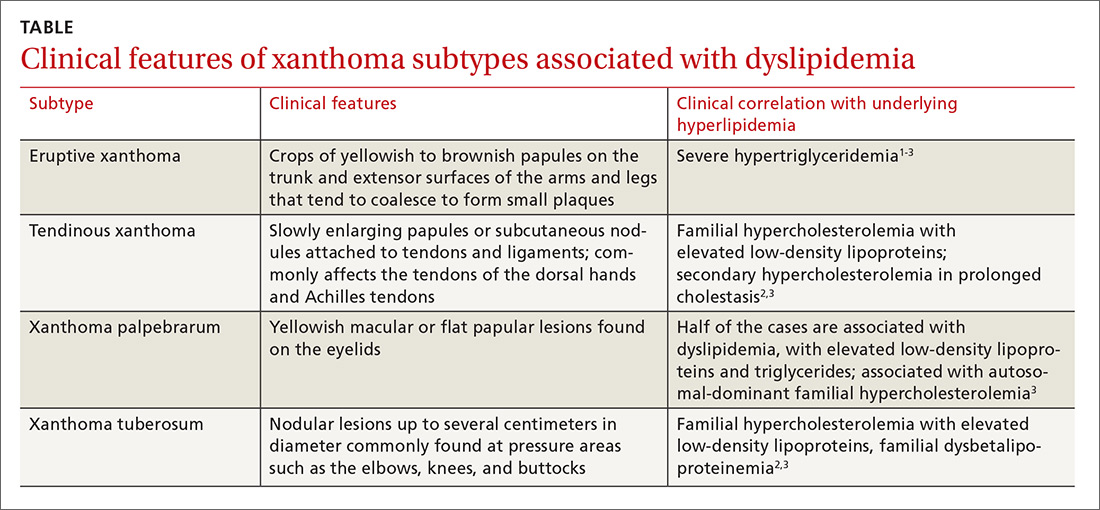

Sudden-onset rash on the trunk and limbs • morbid obesity • family history of diabetes mellitus • Dx?

THE CASE

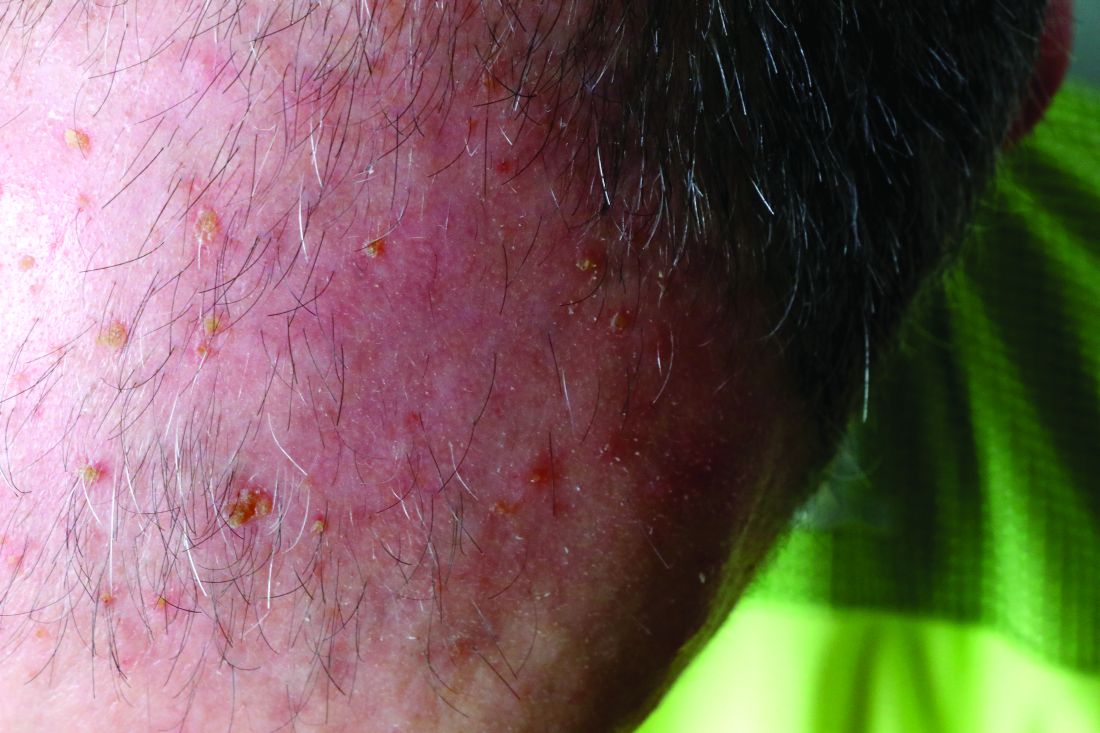

A 37-year-old man presented with a sudden-onset, nonpruritic, nonpainful, papular rash of 1 month’s duration on his trunk and both arms and legs. Two weeks prior to the current presentation, he consulted a general practitioner, who treated the rash with a course of unknown oral antibiotics; the patient showed no improvement. He recalled that on a few occasions, he used his fingers to express a creamy discharge from some of the lesions. This temporarily reduced the size of those papules.

His medical history was unremarkable except for morbid obesity. He did not drink alcohol regularly and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the rash. He had no family history of hyperlipidemia, but his mother had a history of diabetes mellitus.

Physical examination showed numerous discrete erythematous papules with a creamy center on his trunk and his arms and legs. The lesions were more numerous on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs. Some of the papules coalesced to form small plaques (FIGURE). There was no scaling, and the lesions were firm in texture. The patient’s face was spared, and there was no mucosal involvement. The patient was otherwise systemically well.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the morphology, distribution, and abrupt onset of the diffuse nonpruritic papules in this morbidly obese (but otherwise systemically well) middle-aged man, a clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma was suspected. Subsequent blood testing revealed an elevated serum triglyceride level of 47.8 mmol/L (reference range, <1.7 mmol/L), elevated serum total cholesterol of 7.1 mmol/L (reference range, <6.2 mmol/L), and low serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol of 0.7 mmol/L (reference range, >1 mmol/L in men). He also had an elevated fasting serum glucose level of 12.9 mmol/L (reference range, 3.9–5.6 mmol/L) and an elevated hemoglobin A1c (glycated hemoglobin) level of 10.9%.

Subsequent thyroid, liver, and renal function tests were normal, but the patient had heavy proteinuria, with an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 355.6 mg/mmol (reference range, ≤2.5 mg/mmol). The patient was referred to a dermatologist, who confirmed the clinical diagnosis without the need for a skin biopsy.

DISCUSSION

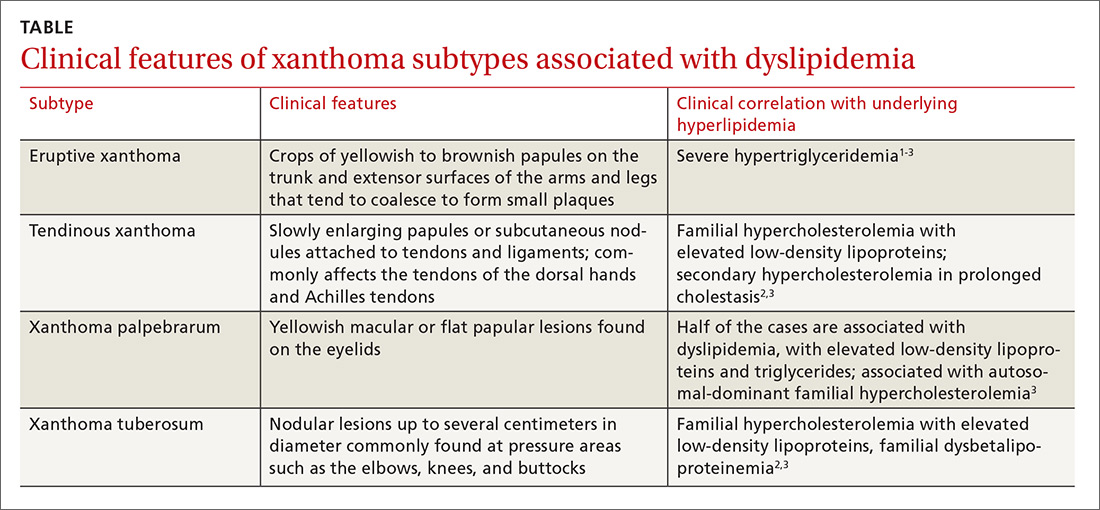

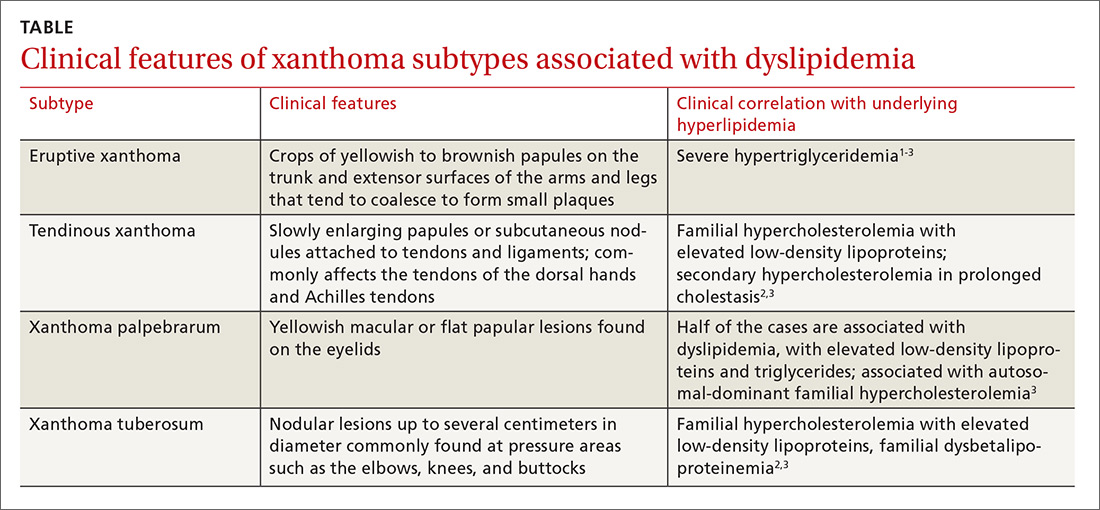

Eruptive xanthoma is characterized by an abrupt onset of crops of multiple yellowish to brownish papules that can coalesce into small plaques. The lesions can be generalized, but tend to be more densely distributed on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, buttocks, and thighs.5 Eruptive xanthoma often is associated with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be primary—as a result of a genetic defect caused by familial hypertriglyceridemia—or secondary, associated with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, excessive alcohol consumption, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism, primary biliary cholangitis, and drugs like estrogen replacement therapies, corticosteroids, and isotretinoin.6 Pruritus and tenderness may or may not be present, and the Köbner phenomenon may occur.7

Continue to: The differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for eruptive xanthoma includes xanthoma disseminatum, non–Langerhans cell histiocytoses (eg, generalized eruptive histiocytosis), and cutaneous mastocytosis.1

Xanthoma disseminatum is an extremely rare, but benign, disorder of non–Langerhans cell origin. The average age of onset is older than 40 years. The rash consists of multiple red-yellow papules and nodules that most commonly present in flexural areas. Forty percent to 60% of patients have mucosal involvement, and rarely the central nervous system is involved.8

Generalized eruptive histiocytosis is another rare non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis that occurs mainly in adults and is characterized by widespread, symmetric, red-brown papules on the trunk, arms, and legs, and rarely the mucous membranes.9

Cutaneous mastocytosis, especially xanthelasmoid mastocytosis, consists of multiple pruritic, yellowish, papular or nodular lesions that may mimic eruptive xanthoma. It occurs mainly in children and rarely in adults.10

Confirming the diagnosis, initiating treatment

The diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma can be confirmed by skin biopsy if other differential diagnoses cannot be ruled out or the lesions do not resolve with treatment. Skin biopsy will reveal lipid-laden macrophages (known as foam cells) deposited in the dermis.7

Continue to: Treatment of eruptive xanthoma

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma involves management of the underlying causes of the condition. In most cases, dietary control, intensive triglyceride-lowering therapies, and treatment of other secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia result in complete resolution of the lesions within several weeks.5

Our patient’s outcome

Our patient’s sudden-onset rash alerted us to the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia, and heavy proteinuria, which he was not aware of previously. We counselled him about stringent low-sugar, low-lipid diet control and exercise, and we started him on metformin and gemfibrozil. He was referred to an internal medicine specialist for further assessment and management of his severe hypertriglyceridemia and heavy proteinuria.

The rash started to wane 1 month after the patient started the metformin and gemfibrozil, and his drug regimen was changed to combination therapy with metformin/glimepiride and fenofibrate/simvastatin 6 weeks later when he was seen in the medical specialty clinic. Fundus photography performed 1 month after starting oral antidiabetic therapy showed no diabetic retinopathy or lipemia retinalis.

After 3 months of treatment, his serum triglycerides and hemoglobin A1c levels dropped to 3.8 mmol/L and 8.7%, respectively. The rash also resolved considerably, with only residual papules on the abdomen. This rapid clinical response to treatment of the underlying hypertriglyceridemia and diabetes further supported the clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma.

THE TAKEAWAY

Eruptive xanthoma is relatively rare, but it is important for family physicians to recognize this clinical presentation as a potential indicator of severe hypertriglyceridemia. Recognizing hypertriglyceridemia early is important, as it can be associated with an increased risk for acute pancreatitis. Moreover, eruptive xanthoma might be the sole presenting symptom of underlying diabetes mellitus or familial hyperlipidemia, both of which can lead to a significant increase in cardiovascular risk if uncontrolled.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chan Kam Sum, MBChB, FRACGP, Tseung Kwan O Jockey Club General Out-patient Clinic, 99 Po Lam Road North, G/F, Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon, Hong Kong; [email protected]

1. Tang WK. Eruptive xanthoma. [case reports]. Hong Kong Dermatol Venereol Bull. 2001;9:172-175.

2. Frew J, Murrell D, Haber R. Fifty shades of yellow: a review of the xanthodermatoses. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1109-1123.

3. Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

4. Sandhu S, Al-Sarraf A, Taraboanta C, et al. Incidence of pancreatitis, secondary causes, and treatment of patients referred to specialty lipid clinic with severe hypertriglyceridemia: a retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:157.

5. Holsinger JM, Campbell SM, Witman P. Multiple erythematous-yellow, dome-shaped papules. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:517.

6. Loeckermann S, Braun-Falco M. Eruptive xanthomas in association with metabolic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:565-566.

7. Merola JF, Mengden SJ, Soldano A, et al. Eruptive xanthomas. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

8. Park M, Boone B, Devas S. Xanthoma disseminatum: case report and mini-review of the literature. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2014;22:150-154.

9. Attia A, Seleit I, El Badawy N, et al. Photoletter to the editor: generalized eruptive histiocytoma. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:53-55.

10. Nabavi NS, Nejad MH, Feli S, et al. Adult onset of xanthelasmoid mastocytosis: report of a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:468.

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man presented with a sudden-onset, nonpruritic, nonpainful, papular rash of 1 month’s duration on his trunk and both arms and legs. Two weeks prior to the current presentation, he consulted a general practitioner, who treated the rash with a course of unknown oral antibiotics; the patient showed no improvement. He recalled that on a few occasions, he used his fingers to express a creamy discharge from some of the lesions. This temporarily reduced the size of those papules.