User login

Topical treatment with retinoid/benzoyl peroxide combination reduced acne scars

PARIS – Treatment with the fixed combination in a multicenter, randomized trial, Brigitte Dreno, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“To my knowledge, this is the first time that we have seen a topical therapy showing a reduction in atrophic acne scars,” said Dr. Dreno, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at Nantes (France) University Hospital.

She reported on 67 adolescents and adults with mainly moderate facial acne randomized to treat half their face with adapalene 0.3%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel (Epiduo Forte) and the other half with the product’s vehicle daily for 6 months. Investigators were blinded as to which side was which. At baseline, patients averaged 40 acne lesions and 12 scars per half face.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the atrophic acne scar count per half face at week 24. At that point, the mean total was 9.5 scars on the active treatment side, compared with 13.3 on the control side. This translated to a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 15.5% decrease in scars with active treatment versus a 14.4% increase with vehicle. The between-side difference achieved statistical significance at week 1 and remained so at all follow-up visits through week 24.

By Scar Global Assessment at week 24, 32.9% of half faces treated with the combination product were rated clear or almost clear, compared with 16.4% with vehicle.

At 24 weeks, 24.1% of participants reported having moderately or very visible holes or indents on the active treatment side of their face, compared with 51.8% on the control side. The number of inflammatory acne lesions fell by 86.7% with the active treatment and 57.9% with vehicle over the course of 24 weeks. Again, the difference became statistically significant starting at week 1. By the Investigator’s Global Assessment at week 24, 64.2% of adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel–treated faces were rated clear or almost clear, as were 19.4% with vehicle. In addition, 32% of patients reported a marked improvement in skin texture on their active treatment side at 24 weeks, as did 14% on the control side.

The salutary effect on acne scars documented with a topical therapy in this study represents a real advance in clinical care.

“Facial acne scars are a very important and difficult problem for our patients and also for dermatologists,” Dr. Dreno observed, adding that the evidence base for procedural interventions for acne scars, such as dermabrasion and laser resurfacing, is not top quality.

Not surprisingly with a topical retinoid, skin irritation was the most common treatment-emergent adverse event, reported by 14.9% of patients on their active treatment side and 6% with vehicle. This side effect was typically mild and resolved within the first 2-3 weeks.

The improvement in preexisting acne scars documented in this trial was probably caused by drug-induced remodeling of the dermal matrix, according to Dr. Dreno.

The study was funded by Galderma. Dr. Dreno reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to Galderma, Bioderma, Pierre Fabre, and La Roche–Posay.

PARIS – Treatment with the fixed combination in a multicenter, randomized trial, Brigitte Dreno, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“To my knowledge, this is the first time that we have seen a topical therapy showing a reduction in atrophic acne scars,” said Dr. Dreno, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at Nantes (France) University Hospital.

She reported on 67 adolescents and adults with mainly moderate facial acne randomized to treat half their face with adapalene 0.3%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel (Epiduo Forte) and the other half with the product’s vehicle daily for 6 months. Investigators were blinded as to which side was which. At baseline, patients averaged 40 acne lesions and 12 scars per half face.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the atrophic acne scar count per half face at week 24. At that point, the mean total was 9.5 scars on the active treatment side, compared with 13.3 on the control side. This translated to a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 15.5% decrease in scars with active treatment versus a 14.4% increase with vehicle. The between-side difference achieved statistical significance at week 1 and remained so at all follow-up visits through week 24.

By Scar Global Assessment at week 24, 32.9% of half faces treated with the combination product were rated clear or almost clear, compared with 16.4% with vehicle.

At 24 weeks, 24.1% of participants reported having moderately or very visible holes or indents on the active treatment side of their face, compared with 51.8% on the control side. The number of inflammatory acne lesions fell by 86.7% with the active treatment and 57.9% with vehicle over the course of 24 weeks. Again, the difference became statistically significant starting at week 1. By the Investigator’s Global Assessment at week 24, 64.2% of adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel–treated faces were rated clear or almost clear, as were 19.4% with vehicle. In addition, 32% of patients reported a marked improvement in skin texture on their active treatment side at 24 weeks, as did 14% on the control side.

The salutary effect on acne scars documented with a topical therapy in this study represents a real advance in clinical care.

“Facial acne scars are a very important and difficult problem for our patients and also for dermatologists,” Dr. Dreno observed, adding that the evidence base for procedural interventions for acne scars, such as dermabrasion and laser resurfacing, is not top quality.

Not surprisingly with a topical retinoid, skin irritation was the most common treatment-emergent adverse event, reported by 14.9% of patients on their active treatment side and 6% with vehicle. This side effect was typically mild and resolved within the first 2-3 weeks.

The improvement in preexisting acne scars documented in this trial was probably caused by drug-induced remodeling of the dermal matrix, according to Dr. Dreno.

The study was funded by Galderma. Dr. Dreno reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to Galderma, Bioderma, Pierre Fabre, and La Roche–Posay.

PARIS – Treatment with the fixed combination in a multicenter, randomized trial, Brigitte Dreno, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“To my knowledge, this is the first time that we have seen a topical therapy showing a reduction in atrophic acne scars,” said Dr. Dreno, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at Nantes (France) University Hospital.

She reported on 67 adolescents and adults with mainly moderate facial acne randomized to treat half their face with adapalene 0.3%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel (Epiduo Forte) and the other half with the product’s vehicle daily for 6 months. Investigators were blinded as to which side was which. At baseline, patients averaged 40 acne lesions and 12 scars per half face.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the atrophic acne scar count per half face at week 24. At that point, the mean total was 9.5 scars on the active treatment side, compared with 13.3 on the control side. This translated to a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 15.5% decrease in scars with active treatment versus a 14.4% increase with vehicle. The between-side difference achieved statistical significance at week 1 and remained so at all follow-up visits through week 24.

By Scar Global Assessment at week 24, 32.9% of half faces treated with the combination product were rated clear or almost clear, compared with 16.4% with vehicle.

At 24 weeks, 24.1% of participants reported having moderately or very visible holes or indents on the active treatment side of their face, compared with 51.8% on the control side. The number of inflammatory acne lesions fell by 86.7% with the active treatment and 57.9% with vehicle over the course of 24 weeks. Again, the difference became statistically significant starting at week 1. By the Investigator’s Global Assessment at week 24, 64.2% of adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel–treated faces were rated clear or almost clear, as were 19.4% with vehicle. In addition, 32% of patients reported a marked improvement in skin texture on their active treatment side at 24 weeks, as did 14% on the control side.

The salutary effect on acne scars documented with a topical therapy in this study represents a real advance in clinical care.

“Facial acne scars are a very important and difficult problem for our patients and also for dermatologists,” Dr. Dreno observed, adding that the evidence base for procedural interventions for acne scars, such as dermabrasion and laser resurfacing, is not top quality.

Not surprisingly with a topical retinoid, skin irritation was the most common treatment-emergent adverse event, reported by 14.9% of patients on their active treatment side and 6% with vehicle. This side effect was typically mild and resolved within the first 2-3 weeks.

The improvement in preexisting acne scars documented in this trial was probably caused by drug-induced remodeling of the dermal matrix, according to Dr. Dreno.

The study was funded by Galderma. Dr. Dreno reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to Galderma, Bioderma, Pierre Fabre, and La Roche–Posay.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: A fixed combination adapalene 0.3%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel reduced the number of preexisting facial atrophic acne scars and prevented new scar formation.

Major finding: Facial atrophic acne scar count dropped by 15.5% with 6 months of treatment with adapalene 0.3%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel while increasing by 14.4% with vehicle.

Study details: This was a 6-month, prospective, multicenter, randomized, vehicle-controlled, split-face study involving 67 acne patients.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Galderma. The presenter reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to Galderma, Bioderma, Pierre Fabre, and La Roche–Posay.

“It Gets Better With Age”

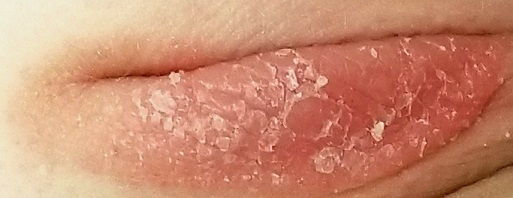

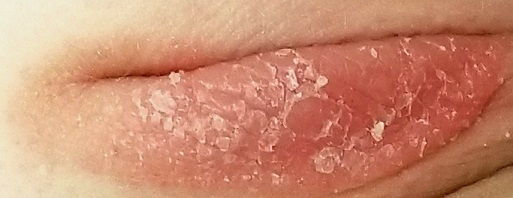

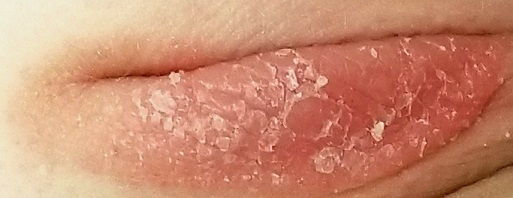

Since birth, this now–13-year-old boy has had redness on his face— the intensity of which has slowly increased with time. Various providers have offered a plethora of diagnoses, but no treatment attempts thus far have helped. The condition is asymptomatic but nonetheless distressing to the patient.

More history-taking reveals that, when he was about 6, crops of tiny papules developed on both triceps, his buttocks, and his upper back. These, too, have resisted treatment with OTC creams.

Neither of the boy’s two siblings have had any similar lesions, and no one in the family has any related health problems (eg, atopic diatheses).

EXAMINATION

The posterior 2/3 of both sides of the patient’s face are strikingly red. His nasolabial folds are spared, but the redness extends posteriorly to the immediate preauricular areas and vertically from the zygoma to the jawline. The erythema is highly blanchable with digital pressure and has a uniformly rough, papular feel. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

The papules on the triceps, anterior thighs, and upper back are uniform in size (pinpoint, measuring ≤ 1 mm) and distribution, obviously originating from follicles. Unlike the face, these areas are not erythematous.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

There are several types of keratosis pilaris (KP), including rubra faceii, the form affecting this patient (distinguished in part by involvement of the facial skin). KP is utterly common, affecting 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide, with no gender preference. This autosomal dominant disorder involves follicular keratinization—normal keratin (produced in the hair follicle) builds up and creates a “plug” that manifests as a firm, dry papule. Obstruction of the follicular orifice may be significant enough to prevent hair from exiting, in which case, the hair continues to grow but simply curls in on itself and accentuates the appearance of the papule.

Although KP is a condition and not a disease, it is often considered part of the atopic diatheses, which include the major diagnostic criteria of eczema, urticaria, and seasonal allergies. KP is often mistaken for acne, especially when it affects the face, but its lack of comedones and pustules is a distinguishing characteristic.

Keratosis follicularis (Darier disease) also features follicular papules, but the distribution and morphology differ significantly. Darier is a more serious problem in terms of extent and symptomatology.

Treatment of KP is unsatisfactory at best, but emollients can make it less bumpy. Salicylic acid and lactic acid–containing preparations can also help, but only temporarily. Gentle exfoliation followed by the application of heavy oils is considered the most effective treatment method. The most encouraging thing we can tell our patients: The problem tends to lessen with age.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is a common inherited defect of follicular keratinization that affects 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide.

- KP results in a distribution of follicular rough papules across the face, triceps, thighs, buttocks, and upper back, beginning in early childhood.

- A significant percentage of affected patients exhibit the variant termed rubra faceii, which involves the posterior 2/3 of the bilateral face.

- Treatment is problematic, but the application of emollients after gentle exfoliation can help; most cases improve as the patient ages.

Since birth, this now–13-year-old boy has had redness on his face— the intensity of which has slowly increased with time. Various providers have offered a plethora of diagnoses, but no treatment attempts thus far have helped. The condition is asymptomatic but nonetheless distressing to the patient.

More history-taking reveals that, when he was about 6, crops of tiny papules developed on both triceps, his buttocks, and his upper back. These, too, have resisted treatment with OTC creams.

Neither of the boy’s two siblings have had any similar lesions, and no one in the family has any related health problems (eg, atopic diatheses).

EXAMINATION

The posterior 2/3 of both sides of the patient’s face are strikingly red. His nasolabial folds are spared, but the redness extends posteriorly to the immediate preauricular areas and vertically from the zygoma to the jawline. The erythema is highly blanchable with digital pressure and has a uniformly rough, papular feel. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

The papules on the triceps, anterior thighs, and upper back are uniform in size (pinpoint, measuring ≤ 1 mm) and distribution, obviously originating from follicles. Unlike the face, these areas are not erythematous.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

There are several types of keratosis pilaris (KP), including rubra faceii, the form affecting this patient (distinguished in part by involvement of the facial skin). KP is utterly common, affecting 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide, with no gender preference. This autosomal dominant disorder involves follicular keratinization—normal keratin (produced in the hair follicle) builds up and creates a “plug” that manifests as a firm, dry papule. Obstruction of the follicular orifice may be significant enough to prevent hair from exiting, in which case, the hair continues to grow but simply curls in on itself and accentuates the appearance of the papule.

Although KP is a condition and not a disease, it is often considered part of the atopic diatheses, which include the major diagnostic criteria of eczema, urticaria, and seasonal allergies. KP is often mistaken for acne, especially when it affects the face, but its lack of comedones and pustules is a distinguishing characteristic.

Keratosis follicularis (Darier disease) also features follicular papules, but the distribution and morphology differ significantly. Darier is a more serious problem in terms of extent and symptomatology.

Treatment of KP is unsatisfactory at best, but emollients can make it less bumpy. Salicylic acid and lactic acid–containing preparations can also help, but only temporarily. Gentle exfoliation followed by the application of heavy oils is considered the most effective treatment method. The most encouraging thing we can tell our patients: The problem tends to lessen with age.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is a common inherited defect of follicular keratinization that affects 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide.

- KP results in a distribution of follicular rough papules across the face, triceps, thighs, buttocks, and upper back, beginning in early childhood.

- A significant percentage of affected patients exhibit the variant termed rubra faceii, which involves the posterior 2/3 of the bilateral face.

- Treatment is problematic, but the application of emollients after gentle exfoliation can help; most cases improve as the patient ages.

Since birth, this now–13-year-old boy has had redness on his face— the intensity of which has slowly increased with time. Various providers have offered a plethora of diagnoses, but no treatment attempts thus far have helped. The condition is asymptomatic but nonetheless distressing to the patient.

More history-taking reveals that, when he was about 6, crops of tiny papules developed on both triceps, his buttocks, and his upper back. These, too, have resisted treatment with OTC creams.

Neither of the boy’s two siblings have had any similar lesions, and no one in the family has any related health problems (eg, atopic diatheses).

EXAMINATION

The posterior 2/3 of both sides of the patient’s face are strikingly red. His nasolabial folds are spared, but the redness extends posteriorly to the immediate preauricular areas and vertically from the zygoma to the jawline. The erythema is highly blanchable with digital pressure and has a uniformly rough, papular feel. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

The papules on the triceps, anterior thighs, and upper back are uniform in size (pinpoint, measuring ≤ 1 mm) and distribution, obviously originating from follicles. Unlike the face, these areas are not erythematous.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

There are several types of keratosis pilaris (KP), including rubra faceii, the form affecting this patient (distinguished in part by involvement of the facial skin). KP is utterly common, affecting 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide, with no gender preference. This autosomal dominant disorder involves follicular keratinization—normal keratin (produced in the hair follicle) builds up and creates a “plug” that manifests as a firm, dry papule. Obstruction of the follicular orifice may be significant enough to prevent hair from exiting, in which case, the hair continues to grow but simply curls in on itself and accentuates the appearance of the papule.

Although KP is a condition and not a disease, it is often considered part of the atopic diatheses, which include the major diagnostic criteria of eczema, urticaria, and seasonal allergies. KP is often mistaken for acne, especially when it affects the face, but its lack of comedones and pustules is a distinguishing characteristic.

Keratosis follicularis (Darier disease) also features follicular papules, but the distribution and morphology differ significantly. Darier is a more serious problem in terms of extent and symptomatology.

Treatment of KP is unsatisfactory at best, but emollients can make it less bumpy. Salicylic acid and lactic acid–containing preparations can also help, but only temporarily. Gentle exfoliation followed by the application of heavy oils is considered the most effective treatment method. The most encouraging thing we can tell our patients: The problem tends to lessen with age.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Keratosis pilaris (KP) is a common inherited defect of follicular keratinization that affects 30% to 50% of the white population worldwide.

- KP results in a distribution of follicular rough papules across the face, triceps, thighs, buttocks, and upper back, beginning in early childhood.

- A significant percentage of affected patients exhibit the variant termed rubra faceii, which involves the posterior 2/3 of the bilateral face.

- Treatment is problematic, but the application of emollients after gentle exfoliation can help; most cases improve as the patient ages.

Sore on nose

The FP suspected a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma.

Informed consent was obtained, and the FP numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine using a 30 gauge needle. The area was exquisitely tender, so a small needle was used and the anesthesia was injected slowly. (It is safe and recommended to use epinephrine for biopsy on or around the nose.) The physician performed a shave biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The biopsy results confirmed an infiltrative BCC. The physician recognized this as a more aggressive BCC and its location at the nasolabial fold suggested that the patient was at an increased risk for recurrence. He communicated these risk factors to the patient, and she accepted a referral for Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma.

Informed consent was obtained, and the FP numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine using a 30 gauge needle. The area was exquisitely tender, so a small needle was used and the anesthesia was injected slowly. (It is safe and recommended to use epinephrine for biopsy on or around the nose.) The physician performed a shave biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The biopsy results confirmed an infiltrative BCC. The physician recognized this as a more aggressive BCC and its location at the nasolabial fold suggested that the patient was at an increased risk for recurrence. He communicated these risk factors to the patient, and she accepted a referral for Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma.

Informed consent was obtained, and the FP numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine using a 30 gauge needle. The area was exquisitely tender, so a small needle was used and the anesthesia was injected slowly. (It is safe and recommended to use epinephrine for biopsy on or around the nose.) The physician performed a shave biopsy. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The biopsy results confirmed an infiltrative BCC. The physician recognized this as a more aggressive BCC and its location at the nasolabial fold suggested that the patient was at an increased risk for recurrence. He communicated these risk factors to the patient, and she accepted a referral for Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Growth on forehead

The FP was concerned about a possible melanoma due to the dark pigmentation and the positive “ABDCE criteria” of melanoma. The FP used his dermatoscope to determine whether this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

The multiple leaf-like structures and blue-gray ovoid nests seen with dermoscopy suggested that this was a pigmented BCC. (The ulceration could be seen in either melanoma or BCC.) The FP told the patient that this was most certainly a skin cancer and she needed a biopsy that day. The patient consented and anesthesia was obtained with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine. The physician used a DermaBlade to perform a deep shave (saucerization) under the pigmentation. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The pathology confirmed pigmented BCC. The physician recommended an elliptical excision and scheduled it for the following week.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP was concerned about a possible melanoma due to the dark pigmentation and the positive “ABDCE criteria” of melanoma. The FP used his dermatoscope to determine whether this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

The multiple leaf-like structures and blue-gray ovoid nests seen with dermoscopy suggested that this was a pigmented BCC. (The ulceration could be seen in either melanoma or BCC.) The FP told the patient that this was most certainly a skin cancer and she needed a biopsy that day. The patient consented and anesthesia was obtained with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine. The physician used a DermaBlade to perform a deep shave (saucerization) under the pigmentation. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The pathology confirmed pigmented BCC. The physician recommended an elliptical excision and scheduled it for the following week.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP was concerned about a possible melanoma due to the dark pigmentation and the positive “ABDCE criteria” of melanoma. The FP used his dermatoscope to determine whether this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

The multiple leaf-like structures and blue-gray ovoid nests seen with dermoscopy suggested that this was a pigmented BCC. (The ulceration could be seen in either melanoma or BCC.) The FP told the patient that this was most certainly a skin cancer and she needed a biopsy that day. The patient consented and anesthesia was obtained with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine. The physician used a DermaBlade to perform a deep shave (saucerization) under the pigmentation. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

The pathology confirmed pigmented BCC. The physician recommended an elliptical excision and scheduled it for the following week.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

What is your diagnosis?

Lichen nitidus, which literally means “shiny moss,” is a relatively rare, chronic skin eruption that is characterized clinically by asymptomatic, flat-topped, sharply-demarcated, skin-colored papules, which are sometimes described as being “pinpoint.”

Lichen nitidus mainly affects children and young adults. The most common sites of involvement are the trunk, flexor aspects of upper extremities, dorsal aspects of hands, and genitalia, but lesions can occur anywhere on the skin. The lesions also can develop in sites of trauma (Koebner phenomenon), and this can be a significant clinical clue to aid in the diagnosis of lichen nitidus in favor of other conditions which may present as many small papules.1 Nail changes can occur but are rare, presenting as dystrophy, pitting, riding, or loss of nail(s).2

Lichen nitidus can be a challenging diagnosis to make, especially if a practitioner is not used to seeing it. Many dermatologic conditions present with many fine papules, including the other answer choices in the given quiz question (molluscum contagiosum, keratosis pilaris, verruca vulgaris, papular eczema). What allows for a clearer diagnosis of lichen nitidus is the history provided by the patient as well as the exam. Lichen nitidus lesions typically arise without a known trigger and often persist for months while remaining asymptomatic.

Molluscum contagiosum tends to include papules that are larger and more substantial than lichen nitidus papules and may be accompanied by background hyperpigmentation or erythema, known as the “beginning of the end” sign. Keratosis pilaris is commonly thought of as a skin type more so than a skin condition, and is more commonly seen in fair-skinned individuals along the lateral arms and cheeks. It is commonly paired with a background of erythema and skin than tends to be more xerotic. Verruca are typically larger lesions, sometimes with a rough surface, and are not typically shiny. Verruca are more likely to present as a single lesion or a few lesions at a given location, as opposed to lichen nitidus which has many individual papules at a single location. Papular eczema typically is intensely pruritic and is associated with xerosis and atopy.

The cause of lichen nitidus is unknown, and there are no reported genetic factors that contribute to its presentation.3 It is thought to be a subtype of lichen planus, although this is still debated. There is more work that needs to be done to find answers to these questions and to assess what triggers these fine papules to present and in whom.

The dermatoscopic features of lichen nitidus were reported in a series of eight cases and include absent dermatoglyphics, radial ridges, ill-defined hypopigmentation, diffuse erythema, linear vessels within the lesion, and peripheral scaling.4 These features are distinctive in combination and can in some cases be used to clinically diagnose lichen nitidus without the need for a skin biopsy, which is an invasive procedure that should be avoided when possible, especially given the benign nature of lichen nitidus.

If a biopsy is performed, the histologic features that commonly are seen include well-circumscribed granuloma-like lymphohistiocytic infiltrates in the papillary dermis adjacent to ridges, mimicking a “ball-and-claw” formation.1,5

Lichen nitidus generally is self-limiting, with minimal cosmetic disruption; therefore, treatment usually is not necessary. The lesions typically resolve within 1 year of presentation – and often sooner. Topical steroids can be used for symptomatic relief of pruritus, but generally do not hasten resolution of the papules themselves. Additionally, there have been reports in the literature of the successful resolution of lesions using topical calcineurin inhibitors and UVB therapy.

In a case report of an 8-year-old child with histologically confirmed lichen nitidus that had been present for 2 years, pimecrolimus 1% cream was used twice daily for 2 months with improvement and flattening of the papules.6 This report is compelling because the lesions persisted for twice the expected time of resolution without improvement and then showed relatively quick response to pimecrolimus. In a case of a 32-year-old male with lichen nitidus on his penis, tacrolimus 0.1% was used for 4 weeks with resolution of the papules.7 Although given that lichen nitidus can self-resolve in this same time period, it is unclear in this case whether the tacrolimus was the independent cause of the resolution.

With regard to UVB therapy, there have been reports of lichen nitidus resolution after 17-30 irradiation sessions in patients with lesions present for 3-6 months, although again, it is possible that the resolution observed was simply the natural course of the lichen nitidus for these patients rather than a therapeutic benefit of UVB therapy.8,9

Given that lichen nitidus is benign and typically asymptomatic or with mild pruritus, it is reasonable to monitor the lesions without treating them. If the lesions persist beyond 1 year, it also is reasonable to trial therapies, such as topical calcineurin inhibitors and UVB therapy, although using these treatments earlier in the disease course has only limited supporting data and any improvement seen within 1 year of onset may be attributed to the natural disease course as opposed to an effect of the intervention. Considerations of the cost of therapy, as well as the degree to which the patient is bothered by the lesions and how long the lesions have persisted, should be undertaken when considering whether an intervention should be made.

Ms. Natsis is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures for Ms. Natsis or Dr. Eichenfield. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Cutis. 1999 Aug 1;64(2):135-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Oct;51(4):606-24.

3. Papulosquamous diseases, in “Pediatric Dermatology,” 4th ed. (St Louis: Mosby; 2011, Vol. 2.

4. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018. doi: 10.1111/pde.13576.

5. Cutis. 2013 Dec;92(6):288, 297-8.

6. Dermatol Online J. 2011 Jul 15;17(7):11.

7. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004 Nov-Dec;3(6):683-4.

8. Int J Dermatol. 2004 Dec 23;45:615-7.

9. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2013 Aug;29(4):215-7.

Lichen nitidus, which literally means “shiny moss,” is a relatively rare, chronic skin eruption that is characterized clinically by asymptomatic, flat-topped, sharply-demarcated, skin-colored papules, which are sometimes described as being “pinpoint.”

Lichen nitidus mainly affects children and young adults. The most common sites of involvement are the trunk, flexor aspects of upper extremities, dorsal aspects of hands, and genitalia, but lesions can occur anywhere on the skin. The lesions also can develop in sites of trauma (Koebner phenomenon), and this can be a significant clinical clue to aid in the diagnosis of lichen nitidus in favor of other conditions which may present as many small papules.1 Nail changes can occur but are rare, presenting as dystrophy, pitting, riding, or loss of nail(s).2

Lichen nitidus can be a challenging diagnosis to make, especially if a practitioner is not used to seeing it. Many dermatologic conditions present with many fine papules, including the other answer choices in the given quiz question (molluscum contagiosum, keratosis pilaris, verruca vulgaris, papular eczema). What allows for a clearer diagnosis of lichen nitidus is the history provided by the patient as well as the exam. Lichen nitidus lesions typically arise without a known trigger and often persist for months while remaining asymptomatic.

Molluscum contagiosum tends to include papules that are larger and more substantial than lichen nitidus papules and may be accompanied by background hyperpigmentation or erythema, known as the “beginning of the end” sign. Keratosis pilaris is commonly thought of as a skin type more so than a skin condition, and is more commonly seen in fair-skinned individuals along the lateral arms and cheeks. It is commonly paired with a background of erythema and skin than tends to be more xerotic. Verruca are typically larger lesions, sometimes with a rough surface, and are not typically shiny. Verruca are more likely to present as a single lesion or a few lesions at a given location, as opposed to lichen nitidus which has many individual papules at a single location. Papular eczema typically is intensely pruritic and is associated with xerosis and atopy.

The cause of lichen nitidus is unknown, and there are no reported genetic factors that contribute to its presentation.3 It is thought to be a subtype of lichen planus, although this is still debated. There is more work that needs to be done to find answers to these questions and to assess what triggers these fine papules to present and in whom.

The dermatoscopic features of lichen nitidus were reported in a series of eight cases and include absent dermatoglyphics, radial ridges, ill-defined hypopigmentation, diffuse erythema, linear vessels within the lesion, and peripheral scaling.4 These features are distinctive in combination and can in some cases be used to clinically diagnose lichen nitidus without the need for a skin biopsy, which is an invasive procedure that should be avoided when possible, especially given the benign nature of lichen nitidus.

If a biopsy is performed, the histologic features that commonly are seen include well-circumscribed granuloma-like lymphohistiocytic infiltrates in the papillary dermis adjacent to ridges, mimicking a “ball-and-claw” formation.1,5

Lichen nitidus generally is self-limiting, with minimal cosmetic disruption; therefore, treatment usually is not necessary. The lesions typically resolve within 1 year of presentation – and often sooner. Topical steroids can be used for symptomatic relief of pruritus, but generally do not hasten resolution of the papules themselves. Additionally, there have been reports in the literature of the successful resolution of lesions using topical calcineurin inhibitors and UVB therapy.

In a case report of an 8-year-old child with histologically confirmed lichen nitidus that had been present for 2 years, pimecrolimus 1% cream was used twice daily for 2 months with improvement and flattening of the papules.6 This report is compelling because the lesions persisted for twice the expected time of resolution without improvement and then showed relatively quick response to pimecrolimus. In a case of a 32-year-old male with lichen nitidus on his penis, tacrolimus 0.1% was used for 4 weeks with resolution of the papules.7 Although given that lichen nitidus can self-resolve in this same time period, it is unclear in this case whether the tacrolimus was the independent cause of the resolution.

With regard to UVB therapy, there have been reports of lichen nitidus resolution after 17-30 irradiation sessions in patients with lesions present for 3-6 months, although again, it is possible that the resolution observed was simply the natural course of the lichen nitidus for these patients rather than a therapeutic benefit of UVB therapy.8,9

Given that lichen nitidus is benign and typically asymptomatic or with mild pruritus, it is reasonable to monitor the lesions without treating them. If the lesions persist beyond 1 year, it also is reasonable to trial therapies, such as topical calcineurin inhibitors and UVB therapy, although using these treatments earlier in the disease course has only limited supporting data and any improvement seen within 1 year of onset may be attributed to the natural disease course as opposed to an effect of the intervention. Considerations of the cost of therapy, as well as the degree to which the patient is bothered by the lesions and how long the lesions have persisted, should be undertaken when considering whether an intervention should be made.

Ms. Natsis is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures for Ms. Natsis or Dr. Eichenfield. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Cutis. 1999 Aug 1;64(2):135-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Oct;51(4):606-24.

3. Papulosquamous diseases, in “Pediatric Dermatology,” 4th ed. (St Louis: Mosby; 2011, Vol. 2.

4. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018. doi: 10.1111/pde.13576.

5. Cutis. 2013 Dec;92(6):288, 297-8.

6. Dermatol Online J. 2011 Jul 15;17(7):11.

7. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004 Nov-Dec;3(6):683-4.

8. Int J Dermatol. 2004 Dec 23;45:615-7.

9. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2013 Aug;29(4):215-7.

Lichen nitidus, which literally means “shiny moss,” is a relatively rare, chronic skin eruption that is characterized clinically by asymptomatic, flat-topped, sharply-demarcated, skin-colored papules, which are sometimes described as being “pinpoint.”

Lichen nitidus mainly affects children and young adults. The most common sites of involvement are the trunk, flexor aspects of upper extremities, dorsal aspects of hands, and genitalia, but lesions can occur anywhere on the skin. The lesions also can develop in sites of trauma (Koebner phenomenon), and this can be a significant clinical clue to aid in the diagnosis of lichen nitidus in favor of other conditions which may present as many small papules.1 Nail changes can occur but are rare, presenting as dystrophy, pitting, riding, or loss of nail(s).2

Lichen nitidus can be a challenging diagnosis to make, especially if a practitioner is not used to seeing it. Many dermatologic conditions present with many fine papules, including the other answer choices in the given quiz question (molluscum contagiosum, keratosis pilaris, verruca vulgaris, papular eczema). What allows for a clearer diagnosis of lichen nitidus is the history provided by the patient as well as the exam. Lichen nitidus lesions typically arise without a known trigger and often persist for months while remaining asymptomatic.

Molluscum contagiosum tends to include papules that are larger and more substantial than lichen nitidus papules and may be accompanied by background hyperpigmentation or erythema, known as the “beginning of the end” sign. Keratosis pilaris is commonly thought of as a skin type more so than a skin condition, and is more commonly seen in fair-skinned individuals along the lateral arms and cheeks. It is commonly paired with a background of erythema and skin than tends to be more xerotic. Verruca are typically larger lesions, sometimes with a rough surface, and are not typically shiny. Verruca are more likely to present as a single lesion or a few lesions at a given location, as opposed to lichen nitidus which has many individual papules at a single location. Papular eczema typically is intensely pruritic and is associated with xerosis and atopy.

The cause of lichen nitidus is unknown, and there are no reported genetic factors that contribute to its presentation.3 It is thought to be a subtype of lichen planus, although this is still debated. There is more work that needs to be done to find answers to these questions and to assess what triggers these fine papules to present and in whom.

The dermatoscopic features of lichen nitidus were reported in a series of eight cases and include absent dermatoglyphics, radial ridges, ill-defined hypopigmentation, diffuse erythema, linear vessels within the lesion, and peripheral scaling.4 These features are distinctive in combination and can in some cases be used to clinically diagnose lichen nitidus without the need for a skin biopsy, which is an invasive procedure that should be avoided when possible, especially given the benign nature of lichen nitidus.

If a biopsy is performed, the histologic features that commonly are seen include well-circumscribed granuloma-like lymphohistiocytic infiltrates in the papillary dermis adjacent to ridges, mimicking a “ball-and-claw” formation.1,5

Lichen nitidus generally is self-limiting, with minimal cosmetic disruption; therefore, treatment usually is not necessary. The lesions typically resolve within 1 year of presentation – and often sooner. Topical steroids can be used for symptomatic relief of pruritus, but generally do not hasten resolution of the papules themselves. Additionally, there have been reports in the literature of the successful resolution of lesions using topical calcineurin inhibitors and UVB therapy.

In a case report of an 8-year-old child with histologically confirmed lichen nitidus that had been present for 2 years, pimecrolimus 1% cream was used twice daily for 2 months with improvement and flattening of the papules.6 This report is compelling because the lesions persisted for twice the expected time of resolution without improvement and then showed relatively quick response to pimecrolimus. In a case of a 32-year-old male with lichen nitidus on his penis, tacrolimus 0.1% was used for 4 weeks with resolution of the papules.7 Although given that lichen nitidus can self-resolve in this same time period, it is unclear in this case whether the tacrolimus was the independent cause of the resolution.

With regard to UVB therapy, there have been reports of lichen nitidus resolution after 17-30 irradiation sessions in patients with lesions present for 3-6 months, although again, it is possible that the resolution observed was simply the natural course of the lichen nitidus for these patients rather than a therapeutic benefit of UVB therapy.8,9

Given that lichen nitidus is benign and typically asymptomatic or with mild pruritus, it is reasonable to monitor the lesions without treating them. If the lesions persist beyond 1 year, it also is reasonable to trial therapies, such as topical calcineurin inhibitors and UVB therapy, although using these treatments earlier in the disease course has only limited supporting data and any improvement seen within 1 year of onset may be attributed to the natural disease course as opposed to an effect of the intervention. Considerations of the cost of therapy, as well as the degree to which the patient is bothered by the lesions and how long the lesions have persisted, should be undertaken when considering whether an intervention should be made.

Ms. Natsis is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures for Ms. Natsis or Dr. Eichenfield. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Cutis. 1999 Aug 1;64(2):135-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Oct;51(4):606-24.

3. Papulosquamous diseases, in “Pediatric Dermatology,” 4th ed. (St Louis: Mosby; 2011, Vol. 2.

4. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018. doi: 10.1111/pde.13576.

5. Cutis. 2013 Dec;92(6):288, 297-8.

6. Dermatol Online J. 2011 Jul 15;17(7):11.

7. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004 Nov-Dec;3(6):683-4.

8. Int J Dermatol. 2004 Dec 23;45:615-7.

9. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2013 Aug;29(4):215-7.

Location Does Not Matter

Several months ago, this 7-year-old girl noticed a lesion on her outer vagina. In addition to growing larger, the lesion has begun to itch.

The patient’s mother has attempted treatment with anti-yeast cream and 1% hydrocortisone cream; neither has helped.

Both mother and daughter deny any recent trauma to the area, presence of similar lesions, or family history of skin disease or arthritis.

The child is well in all other respects; she takes no medications and has no history of serious illnesses or surgeries.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, 8- x 2-cm, salmon-pink plaque covered with uniform tenacious white scale is located on the left labia majora in a vertical orientation. The margins are sharply defined. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

No similar changes are seen on the elbows, knees, scalp, trunk, or nails.

A biopsy of the lesion is performed. The pathology report shows parakeratosis and elongation of rete ridges.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The morphology of this lesion is a perfect fit for psoriasis, a very common disease affecting about 3% of the white population in this country. Mentally repositioning this lesion to the elbow, trunk, or knee would have made the diagnosis obvious; these are the most commonly affected areas, while the genitals are among the least common. But a white-feathered bird with an orange bill and feet who greets you with a quack is probably a duck, even if it’s sitting on your dining room table.

Even for an experienced dermatology provider (35 years in the field), seeing this lesion in this location was a momentary shock. After all, there’s an 18-item differential for genital rashes—but very few look like this.

Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus is commonly seen on young girls in this area, but it is atrophic with almost no scale. Lichen simplex chronicus can be scaly and plaquish, but it rarely appears this organized.

In most primary care settings, this would be (and was) called a “yeast infection.” Not only do yeast infections not look a thing like this, there also needs to be an underlying reason for that diagnosis (eg, use of antibiotics, history of diabetes).

Biopsy is the only way to confirm this diagnosis, to give the family some peace of mind and guide appropriate therapy.

We discussed the diagnosis thoroughly with the parents, including the etiology, potential treatments, and prognosis. Treatment was initiated with topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid. If it proves necessary, we could increase the potency of the steroid, inject the lesion with steroid, or even start her on methotrexate.

She’ll also be closely followed for signs of worsening disease and for psoriatic arthropathy, which affects almost 25% of patients with psoriasis. She’ll be fortunate if this is the extent of her disease.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Salmon-pink, scaly plaques are psoriatic until proven otherwise.

- Psoriasis is common, affecting almost 3% of the white population.

- Though most often seen on extensor surfaces of arms, legs, and trunk, psoriasis can appear virtually anywhere.

- Mentally transpositioning a lesion to another location can be helpful in sorting through this differential.

Several months ago, this 7-year-old girl noticed a lesion on her outer vagina. In addition to growing larger, the lesion has begun to itch.

The patient’s mother has attempted treatment with anti-yeast cream and 1% hydrocortisone cream; neither has helped.

Both mother and daughter deny any recent trauma to the area, presence of similar lesions, or family history of skin disease or arthritis.

The child is well in all other respects; she takes no medications and has no history of serious illnesses or surgeries.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, 8- x 2-cm, salmon-pink plaque covered with uniform tenacious white scale is located on the left labia majora in a vertical orientation. The margins are sharply defined. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

No similar changes are seen on the elbows, knees, scalp, trunk, or nails.

A biopsy of the lesion is performed. The pathology report shows parakeratosis and elongation of rete ridges.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The morphology of this lesion is a perfect fit for psoriasis, a very common disease affecting about 3% of the white population in this country. Mentally repositioning this lesion to the elbow, trunk, or knee would have made the diagnosis obvious; these are the most commonly affected areas, while the genitals are among the least common. But a white-feathered bird with an orange bill and feet who greets you with a quack is probably a duck, even if it’s sitting on your dining room table.

Even for an experienced dermatology provider (35 years in the field), seeing this lesion in this location was a momentary shock. After all, there’s an 18-item differential for genital rashes—but very few look like this.

Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus is commonly seen on young girls in this area, but it is atrophic with almost no scale. Lichen simplex chronicus can be scaly and plaquish, but it rarely appears this organized.

In most primary care settings, this would be (and was) called a “yeast infection.” Not only do yeast infections not look a thing like this, there also needs to be an underlying reason for that diagnosis (eg, use of antibiotics, history of diabetes).

Biopsy is the only way to confirm this diagnosis, to give the family some peace of mind and guide appropriate therapy.

We discussed the diagnosis thoroughly with the parents, including the etiology, potential treatments, and prognosis. Treatment was initiated with topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid. If it proves necessary, we could increase the potency of the steroid, inject the lesion with steroid, or even start her on methotrexate.

She’ll also be closely followed for signs of worsening disease and for psoriatic arthropathy, which affects almost 25% of patients with psoriasis. She’ll be fortunate if this is the extent of her disease.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Salmon-pink, scaly plaques are psoriatic until proven otherwise.

- Psoriasis is common, affecting almost 3% of the white population.

- Though most often seen on extensor surfaces of arms, legs, and trunk, psoriasis can appear virtually anywhere.

- Mentally transpositioning a lesion to another location can be helpful in sorting through this differential.

Several months ago, this 7-year-old girl noticed a lesion on her outer vagina. In addition to growing larger, the lesion has begun to itch.

The patient’s mother has attempted treatment with anti-yeast cream and 1% hydrocortisone cream; neither has helped.

Both mother and daughter deny any recent trauma to the area, presence of similar lesions, or family history of skin disease or arthritis.

The child is well in all other respects; she takes no medications and has no history of serious illnesses or surgeries.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, 8- x 2-cm, salmon-pink plaque covered with uniform tenacious white scale is located on the left labia majora in a vertical orientation. The margins are sharply defined. There is no tenderness or increased warmth on palpation.

No similar changes are seen on the elbows, knees, scalp, trunk, or nails.

A biopsy of the lesion is performed. The pathology report shows parakeratosis and elongation of rete ridges.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The morphology of this lesion is a perfect fit for psoriasis, a very common disease affecting about 3% of the white population in this country. Mentally repositioning this lesion to the elbow, trunk, or knee would have made the diagnosis obvious; these are the most commonly affected areas, while the genitals are among the least common. But a white-feathered bird with an orange bill and feet who greets you with a quack is probably a duck, even if it’s sitting on your dining room table.

Even for an experienced dermatology provider (35 years in the field), seeing this lesion in this location was a momentary shock. After all, there’s an 18-item differential for genital rashes—but very few look like this.

Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus is commonly seen on young girls in this area, but it is atrophic with almost no scale. Lichen simplex chronicus can be scaly and plaquish, but it rarely appears this organized.

In most primary care settings, this would be (and was) called a “yeast infection.” Not only do yeast infections not look a thing like this, there also needs to be an underlying reason for that diagnosis (eg, use of antibiotics, history of diabetes).

Biopsy is the only way to confirm this diagnosis, to give the family some peace of mind and guide appropriate therapy.

We discussed the diagnosis thoroughly with the parents, including the etiology, potential treatments, and prognosis. Treatment was initiated with topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid. If it proves necessary, we could increase the potency of the steroid, inject the lesion with steroid, or even start her on methotrexate.

She’ll also be closely followed for signs of worsening disease and for psoriatic arthropathy, which affects almost 25% of patients with psoriasis. She’ll be fortunate if this is the extent of her disease.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Salmon-pink, scaly plaques are psoriatic until proven otherwise.

- Psoriasis is common, affecting almost 3% of the white population.

- Though most often seen on extensor surfaces of arms, legs, and trunk, psoriasis can appear virtually anywhere.

- Mentally transpositioning a lesion to another location can be helpful in sorting through this differential.

Rash on arm

The FP looked closely at the so-called rash and realized that while it could be nummular eczema it could also be a superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

He explained the differential diagnosis to the patient and suggested that he perform a shave biopsy that day. The patient consented to the biopsy, and the physician numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine. He used a DermaBlade and obtained hemostasis with aluminum chloride in water. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The biopsy result confirmed the FP’s suspicion: The lesion was a superficial BCC.

On the follow-up visit the FP explained the options for treatment, including electrodesiccation and curettage, cryosurgery, or an elliptical excision. He told the patient that the cure rates are about the same, regardless of which of these treatments were chosen. He also explained that either of the 2 destructive methods could be performed immediately, whereas the elliptical excision would require scheduling a longer appointment.

The patient chose the cryosurgery. (See the Watch & Learn video on cryosurgery.) After numbing the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, the physician froze the lesion with a 3 mm halo for 30 seconds using liquid nitrogen spray. At follow-up 3 months later, there was some hypopigmentation, but no evidence of the BCC.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP looked closely at the so-called rash and realized that while it could be nummular eczema it could also be a superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

He explained the differential diagnosis to the patient and suggested that he perform a shave biopsy that day. The patient consented to the biopsy, and the physician numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine. He used a DermaBlade and obtained hemostasis with aluminum chloride in water. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The biopsy result confirmed the FP’s suspicion: The lesion was a superficial BCC.

On the follow-up visit the FP explained the options for treatment, including electrodesiccation and curettage, cryosurgery, or an elliptical excision. He told the patient that the cure rates are about the same, regardless of which of these treatments were chosen. He also explained that either of the 2 destructive methods could be performed immediately, whereas the elliptical excision would require scheduling a longer appointment.

The patient chose the cryosurgery. (See the Watch & Learn video on cryosurgery.) After numbing the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, the physician froze the lesion with a 3 mm halo for 30 seconds using liquid nitrogen spray. At follow-up 3 months later, there was some hypopigmentation, but no evidence of the BCC.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP looked closely at the so-called rash and realized that while it could be nummular eczema it could also be a superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

He explained the differential diagnosis to the patient and suggested that he perform a shave biopsy that day. The patient consented to the biopsy, and the physician numbed the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine. He used a DermaBlade and obtained hemostasis with aluminum chloride in water. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The biopsy result confirmed the FP’s suspicion: The lesion was a superficial BCC.

On the follow-up visit the FP explained the options for treatment, including electrodesiccation and curettage, cryosurgery, or an elliptical excision. He told the patient that the cure rates are about the same, regardless of which of these treatments were chosen. He also explained that either of the 2 destructive methods could be performed immediately, whereas the elliptical excision would require scheduling a longer appointment.

The patient chose the cryosurgery. (See the Watch & Learn video on cryosurgery.) After numbing the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, the physician froze the lesion with a 3 mm halo for 30 seconds using liquid nitrogen spray. At follow-up 3 months later, there was some hypopigmentation, but no evidence of the BCC.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Consider different etiologies in patients with vaginal pruritus

CHICAGO – Diagnosing the cause of vaginal itching, which can have a significant negative impact on a woman’s quality of life, can be particularly difficult for multiple reasons, according to Rachel Kornik, MD, of the departments of dermatology and obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

“The anatomy is really challenging in this area, and there’s a broad differential. Often there’s more than one thing happening,” Dr. Kornik said during a session on diagnosing and managing genital pruritus in women at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. Like hair loss, vaginal pruritus is also very emotionally distressing.

“Patients are very anxious when they have all this itching,” she said. “It has an impact on personal relationships. Some patients find it difficult to talk about because it’s a taboo subject, so we have to make them comfortable.”

Dr. Kornik showed a chart of the inflammatory, neoplastic, infections, infestations, environmental, neuropathic, and hormonal. But she focused her presentation primarily on the most common causes: contact dermatitis, lichen sclerosus, and lichen simplex chronicus.

Contact dermatitis

The most common factors that contribute to contact dermatitis are friction, hygiene practices, unique body exposures (such as body fluids and menstrual and personal care products), and occlusion/maceration, which facilitates penetration of external agents. Estrogen deficiency may also play a role.

Taking a thorough history from the patient is key to finding out possible causes. Dr. Kornik provided a list of common irritants to consider.

- Hygiene-related irritants, such as frequent washing and the use of soaps, wash cloths, loofahs, wipes, bath oil, bubbles, and water.

- Laundry products, such as fabric softeners or dryer sheets.

- Menstrual products, such as panty liners, pads, and scents or additives for retaining moisture.

- Over-the-counter itch products, such as those containing benzocaine.

- Medications, such as alcohol-based creams and gels, trichloroacetic acid, fluorouracil (Efudex), imiquimod, and topical antifungals.

- Heat-related irritants, such as use of hair dryers and heating pads.

- Body fluids, including urine, feces, menstrual blood, sweat, semen, and excessive discharge.

It’s also important to consider whether there is an allergic cause. “Contact dermatitis and allergic dermatitis can look very similar both clinically and histologically, and patients can even have them both at the same time,” Dr. Kornik said. “So really, patch testing is essential sometimes to identify a true allergic contact dermatitis.”

She cited a study that identified the top five most common allergens as fragrance mixes, balsam of Peru, benzocaine, terconazole, and quaternium-15 (a formaldehyde-releasing preservative) (Dermatitis. 2013 Mar-Apr;24(2):64-72).

“If somebody’s coming into your office and they have vulvar itching for any reason, the No. 1 thing is making sure that they eliminate and not use any products with fragrances,” Dr. Kornik said. “It’s also important to note that over time, industries’ use of preservatives does change, the concentrations change, and so we may see more emerging allergens or different ones over time.”

The causative allergens are rarely consumed orally, but they may be ectopic, such as shampoo or nail polish.

“What I’ve learned over the years in treating patients with vulvar itching is that they don’t always think to tell you about everything they are applying,” Dr. Kornik said. “You have to ask specific questions. Are you using any wipes or using any lubricants? What is the type and brand of menstrual pad you’re using?”

Patients might also think they can eliminate the cause of irritation by changing products, but “there are cross reactants in many preservatives and fragrances in many products, so they might not eliminate exposure, and intermittent exposures can lead to chronic dermatitis,” she pointed out.

One example is wipes: Some women may use them only periodically, such as after a yoga class, and not think of this as a possibility or realize that wipes could perpetuate chronic dermatitis.

Research has also found that it’s very common for patients with allergic contact dermatitis to have a concomitant vulvar diagnosis. In one study, more than half of patients had another condition, the most common of which was lichen sclerosus. Others included simplex chronicus, atopic dermatitis, condyloma acuminatum, psoriasis, and Paget disease.

Therefore, if patients are not responding as expected, it’s important to consider that the condition is multifactorial “and consider allergic contact dermatitis in addition to whatever other underlying dermatosis they have,” Dr. Kornik said.

Lichen sclerosus

Prevalence of the scarring disorder lichen sclerosus ranges from 1.7% to 3% in the research literature and pathogenesis is likely multifactorial.

“It’s a very frustrating condition for patients and for physicians because we don’t know exactly what causes it, but it definitely has a predilection for the vulva area, and it affects women of all ages,” she said. “I also think it’s more common than we think.”

Loss of normal anatomical structures are a key feature, so physicians need to know their anatomy well to look for what’s not there. Lichen sclerosus involves modified mucous membranes and the perianal area, and it may spread to the crural folds and upper thighs. Symptoms can include periclitoral edema, white patches, pale skin, textural changes (such as wrinkling, waxiness, or hyperkeratosis), fissures, melanosis, and sometimes ulcerations or erosions from scratching.

There is no standardized treatment for lichen sclerosus. Research suggests using a high potency topical steroid treatment daily until skin texture normalizes, which can take anywhere from 6 weeks to 5 months, depending on severity, Dr. Kornik said. Few data are available for management if topical steroids do not work, she added.*

If dealing with recalcitrant disease, she recommends first checking the patients’ compliance and then considering alternative diagnoses or secondary conditions. Do patch testing, rule out contact dermatitis, and rebiopsy if needed. Other options are to add tacrolimus ointment, offer intralesional triamcinolone, consider a systemic agent (acitretin, methotrexate, or possibly hydroxychloroquine), or try laser or photodynamic therapy. She emphasizes the importance of demonstrating to the patient where to apply ointment, since they may not be applying to the right areas.*

Lichen simplex chronicus

Lichen simplex chronicus is a clinical description of the result of chronic rubbing and scratching. It might be triggered by something that has now resolved or be linked to other itching conditions, but clinicians need to consider the possibility of neuropathic itch as well.

Features of lichen simplex chronicus can include bilateral or unilateral involvement of the labia majora, erythematous plaques with lichenification, hyper- or hypopigmentation, or angulated excoriations and hypertrophy of labia caused by thickened skin, though the signs may be subtle, she said.

Treatment requires management of the skin problem itself – the underlying cause of the itch – as well as the behavioral component. Topical steroids are first line, plus an antihistamine at night as needed to stop the scratching. If those are insufficient, the next treatments to consider are intralesional triamcinolone (Kenalog), tacrolimus ointment, topical or oral doxepin, mirtazapine, or even selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Women using topical steroids should also be aware of the possible side effects, including atrophy, infections, and allergic contact dermatitis if the steroid itself or the cream it’s in is an allergen. If stinging or burning occurs, switch to a steroid without propylene glycol, she added.

If no changes occur in the skin, clinicians may have to consider the existence of neuropathic pruritus diagnosis, an injury or dysfunction along the afferent itch pathway. Burning is more common with this neuropathy, but itching can occur too.

Other issues include symptoms that worsen with sitting and pain that worsens throughout the day. Causes can include childbirth, surgery, pelvic trauma, infection, and chemoradiation, and diagnosis requires imaging to rule out other possible causes. Treatment involves pelvic floor physical therapy, pudendal nerve block, or gabapentin.

Dr. Kornik wrapped up with a reminder that vulvar itch is often multifactorial, so clinicians need to chip away at the potential causes – sometimes with cultures, scrapes, and biopsies as needed.

She reported no financial disclosures.

Correction, 10/26/18: Dr. Kornik's treatment recommendations for lichen sclerosus were misstated.

CHICAGO – Diagnosing the cause of vaginal itching, which can have a significant negative impact on a woman’s quality of life, can be particularly difficult for multiple reasons, according to Rachel Kornik, MD, of the departments of dermatology and obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

“The anatomy is really challenging in this area, and there’s a broad differential. Often there’s more than one thing happening,” Dr. Kornik said during a session on diagnosing and managing genital pruritus in women at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. Like hair loss, vaginal pruritus is also very emotionally distressing.

“Patients are very anxious when they have all this itching,” she said. “It has an impact on personal relationships. Some patients find it difficult to talk about because it’s a taboo subject, so we have to make them comfortable.”

Dr. Kornik showed a chart of the inflammatory, neoplastic, infections, infestations, environmental, neuropathic, and hormonal. But she focused her presentation primarily on the most common causes: contact dermatitis, lichen sclerosus, and lichen simplex chronicus.

Contact dermatitis

The most common factors that contribute to contact dermatitis are friction, hygiene practices, unique body exposures (such as body fluids and menstrual and personal care products), and occlusion/maceration, which facilitates penetration of external agents. Estrogen deficiency may also play a role.

Taking a thorough history from the patient is key to finding out possible causes. Dr. Kornik provided a list of common irritants to consider.

- Hygiene-related irritants, such as frequent washing and the use of soaps, wash cloths, loofahs, wipes, bath oil, bubbles, and water.

- Laundry products, such as fabric softeners or dryer sheets.

- Menstrual products, such as panty liners, pads, and scents or additives for retaining moisture.

- Over-the-counter itch products, such as those containing benzocaine.

- Medications, such as alcohol-based creams and gels, trichloroacetic acid, fluorouracil (Efudex), imiquimod, and topical antifungals.

- Heat-related irritants, such as use of hair dryers and heating pads.

- Body fluids, including urine, feces, menstrual blood, sweat, semen, and excessive discharge.

It’s also important to consider whether there is an allergic cause. “Contact dermatitis and allergic dermatitis can look very similar both clinically and histologically, and patients can even have them both at the same time,” Dr. Kornik said. “So really, patch testing is essential sometimes to identify a true allergic contact dermatitis.”

She cited a study that identified the top five most common allergens as fragrance mixes, balsam of Peru, benzocaine, terconazole, and quaternium-15 (a formaldehyde-releasing preservative) (Dermatitis. 2013 Mar-Apr;24(2):64-72).

“If somebody’s coming into your office and they have vulvar itching for any reason, the No. 1 thing is making sure that they eliminate and not use any products with fragrances,” Dr. Kornik said. “It’s also important to note that over time, industries’ use of preservatives does change, the concentrations change, and so we may see more emerging allergens or different ones over time.”

The causative allergens are rarely consumed orally, but they may be ectopic, such as shampoo or nail polish.

“What I’ve learned over the years in treating patients with vulvar itching is that they don’t always think to tell you about everything they are applying,” Dr. Kornik said. “You have to ask specific questions. Are you using any wipes or using any lubricants? What is the type and brand of menstrual pad you’re using?”

Patients might also think they can eliminate the cause of irritation by changing products, but “there are cross reactants in many preservatives and fragrances in many products, so they might not eliminate exposure, and intermittent exposures can lead to chronic dermatitis,” she pointed out.

One example is wipes: Some women may use them only periodically, such as after a yoga class, and not think of this as a possibility or realize that wipes could perpetuate chronic dermatitis.

Research has also found that it’s very common for patients with allergic contact dermatitis to have a concomitant vulvar diagnosis. In one study, more than half of patients had another condition, the most common of which was lichen sclerosus. Others included simplex chronicus, atopic dermatitis, condyloma acuminatum, psoriasis, and Paget disease.

Therefore, if patients are not responding as expected, it’s important to consider that the condition is multifactorial “and consider allergic contact dermatitis in addition to whatever other underlying dermatosis they have,” Dr. Kornik said.

Lichen sclerosus

Prevalence of the scarring disorder lichen sclerosus ranges from 1.7% to 3% in the research literature and pathogenesis is likely multifactorial.

“It’s a very frustrating condition for patients and for physicians because we don’t know exactly what causes it, but it definitely has a predilection for the vulva area, and it affects women of all ages,” she said. “I also think it’s more common than we think.”

Loss of normal anatomical structures are a key feature, so physicians need to know their anatomy well to look for what’s not there. Lichen sclerosus involves modified mucous membranes and the perianal area, and it may spread to the crural folds and upper thighs. Symptoms can include periclitoral edema, white patches, pale skin, textural changes (such as wrinkling, waxiness, or hyperkeratosis), fissures, melanosis, and sometimes ulcerations or erosions from scratching.