User login

AD update: New insight into pathogenesis, prevention, and treatments

LAS VEGAS – Recent research has provided a rare triple whammy in the world of atopic dermatitis (AD). Over the last few years, Linda F. Stein Gold, MD, said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

AD affects an estimated 7% of adults in the United States and 13% of children under aged 18 years, according to the National Eczema Association. An estimated one-third of the affected children (3.2 million) have moderate to severe disease.

New information about AD includes more information pinpointing the genetic link. Dr. Stein Gold, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, pointed out that about 70% of patients with AD have a family history of atopic conditions.

Mutations in filaggrin appear to play a role in the development of AD, but a significant proportion of people with AD do not have evidence of filaggrin mutations and about 40% of people with defects never develop AD, she noted.

Emollients may be key to preventing AD. To explore the theory that defects on the skin barrier “might be key initiators of atopic dermatitis and possibly allergic sensitization,” investigators conducted a randomized controlled study of 124 babies at risk of AD in the United States and United Kingdom; parents of 55 babies applied emollients to their whole bodies from shortly after birth until 6 months while a control group used nothing (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Oct; 134[4]:818-23).

At 6 months, those in the emollient group were half as likely to have developed AD (relative risk, 0.50; P = .017).

Bleach baths have received attention on the AD prevention front. Dr. Stein Gold pointed to a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of five studies that found both bleach and water baths reduced AD severity. Bleach baths were effective but not more so than water baths (Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017 Nov;119[5]:435-40). Also, there was no difference in skin infections or colonization with Staphylococcus aureus between the two.

So are water baths just as good as bleach baths? “I’m not 100% sure I buy into this,” Dr. Stein Gold said. “I’m still a bleach bath believer.”

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) can be used as a “proactive,” steroid-sparing treatment to prevent relapses in AD, research suggests. For this purpose, the recommended maintenance dosage is two to three applications per week on areas that tend to flare; the TCI drugs can be used in conjunction with topical corticosteroids (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Jul;71[1]:116-32).

TCIs come with boxed warning because of concerns about such cancers as lymphoma. But recent research has not found a higher risk of lymphoma in patients with AD who are treated with the medication. “We’ve had these drugs for a long time, and they do appear to be safe,” Dr. Stein Gold said.

She referred to a 2015 review of 21 studies of almost 6,000 pediatric patients with AD who were treated with a TCI, which concluded that the drugs are safe and efficacious over the long term (Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2015 Jun;26[4]:306-15).

“Everyone wants to know which ones are better,” Dr. Stein Gold said in regard to TCIs. But there aren’t head-to-head studies, she said, and it’s difficult to compare the available data on response rates between certain topical treatments because the studies are designed differently.

For example, with crisaborole (Eucrisa), the topical phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor approved in 2016 for mild to moderate AD in patients aged 2 years and up, clear/almost clear rates are 49%-52%, compared with 30%-40% with placebo, a 10%-20% difference. Rates with OPA-15406, an investigational topical selective PDE4 inhibitor, and with the TCI pimecrolimus (Elidel cream 1%) have been about 20% higher than with controls, but studies are designed differently, and the results cannot be compared, according to Dr. Stein Gold.

Dupilumab (Dupixent), a monoclonal antibody that inhibits signaling of both interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, approved in 2017 for adults with moderate to severe AD, has been a “game changer” for this population, Dr. Stein Gold said. “It looks like this drug has a good, durable effect,” she added (Lancet. 2017 Jun 10;389[10086]:2287-303).

However, she cautioned that up to 10% of patients treated with dupilumab – or more – may develop conjunctivitis. Researchers studying dupilumab in asthma have not seen this side effect, she said, so it may be unique to AD. “It’s something that’s real,” she said, noting that it’s not clear if it’s viral, allergic, or bacterial. Researchers are exploring the use of the drug in children, she added.

Dr. Stein Gold said there are other drugs in development for AD, but she cautioned that “the field is crowded ... and not all of them are going to make it.”

Drugs in development for AD include nemolizumab (a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin-31 signaling), upadacitinib (a JAK1 selective inhibitor), baricitinib (an oral JAK1/2 inhibitor), and topical tapinarof (an agonist of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor).

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Stein Gold disclosed relationships with Galderma, Valeant, Ranbaxy, Promius, Actavis, Roche, Dermira, Medimetriks, Pfizer, Sanofi/Regeneron, Otsuka, and Taro.

LAS VEGAS – Recent research has provided a rare triple whammy in the world of atopic dermatitis (AD). Over the last few years, Linda F. Stein Gold, MD, said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

AD affects an estimated 7% of adults in the United States and 13% of children under aged 18 years, according to the National Eczema Association. An estimated one-third of the affected children (3.2 million) have moderate to severe disease.

New information about AD includes more information pinpointing the genetic link. Dr. Stein Gold, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, pointed out that about 70% of patients with AD have a family history of atopic conditions.

Mutations in filaggrin appear to play a role in the development of AD, but a significant proportion of people with AD do not have evidence of filaggrin mutations and about 40% of people with defects never develop AD, she noted.

Emollients may be key to preventing AD. To explore the theory that defects on the skin barrier “might be key initiators of atopic dermatitis and possibly allergic sensitization,” investigators conducted a randomized controlled study of 124 babies at risk of AD in the United States and United Kingdom; parents of 55 babies applied emollients to their whole bodies from shortly after birth until 6 months while a control group used nothing (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Oct; 134[4]:818-23).

At 6 months, those in the emollient group were half as likely to have developed AD (relative risk, 0.50; P = .017).

Bleach baths have received attention on the AD prevention front. Dr. Stein Gold pointed to a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of five studies that found both bleach and water baths reduced AD severity. Bleach baths were effective but not more so than water baths (Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017 Nov;119[5]:435-40). Also, there was no difference in skin infections or colonization with Staphylococcus aureus between the two.

So are water baths just as good as bleach baths? “I’m not 100% sure I buy into this,” Dr. Stein Gold said. “I’m still a bleach bath believer.”

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) can be used as a “proactive,” steroid-sparing treatment to prevent relapses in AD, research suggests. For this purpose, the recommended maintenance dosage is two to three applications per week on areas that tend to flare; the TCI drugs can be used in conjunction with topical corticosteroids (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Jul;71[1]:116-32).

TCIs come with boxed warning because of concerns about such cancers as lymphoma. But recent research has not found a higher risk of lymphoma in patients with AD who are treated with the medication. “We’ve had these drugs for a long time, and they do appear to be safe,” Dr. Stein Gold said.

She referred to a 2015 review of 21 studies of almost 6,000 pediatric patients with AD who were treated with a TCI, which concluded that the drugs are safe and efficacious over the long term (Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2015 Jun;26[4]:306-15).

“Everyone wants to know which ones are better,” Dr. Stein Gold said in regard to TCIs. But there aren’t head-to-head studies, she said, and it’s difficult to compare the available data on response rates between certain topical treatments because the studies are designed differently.

For example, with crisaborole (Eucrisa), the topical phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor approved in 2016 for mild to moderate AD in patients aged 2 years and up, clear/almost clear rates are 49%-52%, compared with 30%-40% with placebo, a 10%-20% difference. Rates with OPA-15406, an investigational topical selective PDE4 inhibitor, and with the TCI pimecrolimus (Elidel cream 1%) have been about 20% higher than with controls, but studies are designed differently, and the results cannot be compared, according to Dr. Stein Gold.

Dupilumab (Dupixent), a monoclonal antibody that inhibits signaling of both interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, approved in 2017 for adults with moderate to severe AD, has been a “game changer” for this population, Dr. Stein Gold said. “It looks like this drug has a good, durable effect,” she added (Lancet. 2017 Jun 10;389[10086]:2287-303).

However, she cautioned that up to 10% of patients treated with dupilumab – or more – may develop conjunctivitis. Researchers studying dupilumab in asthma have not seen this side effect, she said, so it may be unique to AD. “It’s something that’s real,” she said, noting that it’s not clear if it’s viral, allergic, or bacterial. Researchers are exploring the use of the drug in children, she added.

Dr. Stein Gold said there are other drugs in development for AD, but she cautioned that “the field is crowded ... and not all of them are going to make it.”

Drugs in development for AD include nemolizumab (a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin-31 signaling), upadacitinib (a JAK1 selective inhibitor), baricitinib (an oral JAK1/2 inhibitor), and topical tapinarof (an agonist of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor).

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Stein Gold disclosed relationships with Galderma, Valeant, Ranbaxy, Promius, Actavis, Roche, Dermira, Medimetriks, Pfizer, Sanofi/Regeneron, Otsuka, and Taro.

LAS VEGAS – Recent research has provided a rare triple whammy in the world of atopic dermatitis (AD). Over the last few years, Linda F. Stein Gold, MD, said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

AD affects an estimated 7% of adults in the United States and 13% of children under aged 18 years, according to the National Eczema Association. An estimated one-third of the affected children (3.2 million) have moderate to severe disease.

New information about AD includes more information pinpointing the genetic link. Dr. Stein Gold, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, pointed out that about 70% of patients with AD have a family history of atopic conditions.

Mutations in filaggrin appear to play a role in the development of AD, but a significant proportion of people with AD do not have evidence of filaggrin mutations and about 40% of people with defects never develop AD, she noted.

Emollients may be key to preventing AD. To explore the theory that defects on the skin barrier “might be key initiators of atopic dermatitis and possibly allergic sensitization,” investigators conducted a randomized controlled study of 124 babies at risk of AD in the United States and United Kingdom; parents of 55 babies applied emollients to their whole bodies from shortly after birth until 6 months while a control group used nothing (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Oct; 134[4]:818-23).

At 6 months, those in the emollient group were half as likely to have developed AD (relative risk, 0.50; P = .017).

Bleach baths have received attention on the AD prevention front. Dr. Stein Gold pointed to a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of five studies that found both bleach and water baths reduced AD severity. Bleach baths were effective but not more so than water baths (Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017 Nov;119[5]:435-40). Also, there was no difference in skin infections or colonization with Staphylococcus aureus between the two.

So are water baths just as good as bleach baths? “I’m not 100% sure I buy into this,” Dr. Stein Gold said. “I’m still a bleach bath believer.”

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) can be used as a “proactive,” steroid-sparing treatment to prevent relapses in AD, research suggests. For this purpose, the recommended maintenance dosage is two to three applications per week on areas that tend to flare; the TCI drugs can be used in conjunction with topical corticosteroids (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Jul;71[1]:116-32).

TCIs come with boxed warning because of concerns about such cancers as lymphoma. But recent research has not found a higher risk of lymphoma in patients with AD who are treated with the medication. “We’ve had these drugs for a long time, and they do appear to be safe,” Dr. Stein Gold said.

She referred to a 2015 review of 21 studies of almost 6,000 pediatric patients with AD who were treated with a TCI, which concluded that the drugs are safe and efficacious over the long term (Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2015 Jun;26[4]:306-15).

“Everyone wants to know which ones are better,” Dr. Stein Gold said in regard to TCIs. But there aren’t head-to-head studies, she said, and it’s difficult to compare the available data on response rates between certain topical treatments because the studies are designed differently.

For example, with crisaborole (Eucrisa), the topical phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor approved in 2016 for mild to moderate AD in patients aged 2 years and up, clear/almost clear rates are 49%-52%, compared with 30%-40% with placebo, a 10%-20% difference. Rates with OPA-15406, an investigational topical selective PDE4 inhibitor, and with the TCI pimecrolimus (Elidel cream 1%) have been about 20% higher than with controls, but studies are designed differently, and the results cannot be compared, according to Dr. Stein Gold.

Dupilumab (Dupixent), a monoclonal antibody that inhibits signaling of both interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, approved in 2017 for adults with moderate to severe AD, has been a “game changer” for this population, Dr. Stein Gold said. “It looks like this drug has a good, durable effect,” she added (Lancet. 2017 Jun 10;389[10086]:2287-303).

However, she cautioned that up to 10% of patients treated with dupilumab – or more – may develop conjunctivitis. Researchers studying dupilumab in asthma have not seen this side effect, she said, so it may be unique to AD. “It’s something that’s real,” she said, noting that it’s not clear if it’s viral, allergic, or bacterial. Researchers are exploring the use of the drug in children, she added.

Dr. Stein Gold said there are other drugs in development for AD, but she cautioned that “the field is crowded ... and not all of them are going to make it.”

Drugs in development for AD include nemolizumab (a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin-31 signaling), upadacitinib (a JAK1 selective inhibitor), baricitinib (an oral JAK1/2 inhibitor), and topical tapinarof (an agonist of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor).

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Stein Gold disclosed relationships with Galderma, Valeant, Ranbaxy, Promius, Actavis, Roche, Dermira, Medimetriks, Pfizer, Sanofi/Regeneron, Otsuka, and Taro.

REPORTING FROM SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Investigational agent VT-1161 looks promising for onychomycosis

LAS VEGAS – An investigational oral therapy for onychomycosis could be on the horizon as a new treatment option.

VT-1161 is a cytochrome P51 (CYP51) inhibitor with potent in vitro activity against several species of tinea and yeast, David M. Pariser, MD, said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar. It is highly selective for fungal CYP51 over human cytochrome P enzymes.

Dr. Pariser served as an . Patients enrolled were aged 18-70 years, with a mean age of 49. Most were men (80%) and white (85%), as is typical in trials for onychomycosis drugs, noted Dr. Pariser, professor of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk.

Distal subungual onychomycosis was evident in 25%-75% of the nail, and patients needed 2 mm of clear nail to be included in the trial. Disease was confirmed by positive KOH staining and culture.

Patients were randomized into four active treatment groups; a fifth received placebo. All active treatment groups were started on 14 days of a daily loading dose of VT-1161, with one arm getting 300 mg per day and one getting 600 mg per day.

After the loading dose, two groups were treated for 12 weeks with VT-1161 (weekly doses of 300 mg and 600 mg); two other groups had treatment extended out to 24 weeks.

Few patients, roughly 20% in each treatment arm, had achieved the primary endpoint, a complete cure (0% nail involvement and negative KOH stain and culture) at the end of active treatment, Dr. Pariser said.

“I personally think that all of these onychomycosis studies should be carried out for longer than a year, up to 2 years, even if you were able to get rid of all the fungus, because that’s how long it’s going to take for the nail to grow out, especially in older patients with slower nail growth,” Dr. Pariser said.

At 48 weeks, approximately 40% of patients in each active treatment arm achieved complete cure, Dr. Pariser noted. “The results indicated that there was not a lot of difference in outcomes based on the dose the patient received.”

About 60%-70% of treated patients sustained mycologic cure of onychomycosis at 60 weeks.

No serious drug-related adverse events were seen in the study, and no patients dropped out because of lab abnormalities, including liver function tests. Other adverse events were rare and occurred equally in the treatment and placebo arms and consisted of dermatitis, headache, and cough. Nausea, cough, and dysgeusia each occurred in 2% of patients and could have been related to the study drug, Dr. Pariser said.

Looking at both mycologic and complete cure rates of available onychomycosis treatments, the results from the RENOVATE trial are comparable to approved systemic therapies, and superior to topicals, he said.

Dr. Pariser disclosed serving as an investigator for pharmaceutical manufactures Viamet (maker of VT-1161), Valeant, and Ancor/Pharmaderm.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

[email protected]

LAS VEGAS – An investigational oral therapy for onychomycosis could be on the horizon as a new treatment option.

VT-1161 is a cytochrome P51 (CYP51) inhibitor with potent in vitro activity against several species of tinea and yeast, David M. Pariser, MD, said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar. It is highly selective for fungal CYP51 over human cytochrome P enzymes.

Dr. Pariser served as an . Patients enrolled were aged 18-70 years, with a mean age of 49. Most were men (80%) and white (85%), as is typical in trials for onychomycosis drugs, noted Dr. Pariser, professor of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk.

Distal subungual onychomycosis was evident in 25%-75% of the nail, and patients needed 2 mm of clear nail to be included in the trial. Disease was confirmed by positive KOH staining and culture.

Patients were randomized into four active treatment groups; a fifth received placebo. All active treatment groups were started on 14 days of a daily loading dose of VT-1161, with one arm getting 300 mg per day and one getting 600 mg per day.

After the loading dose, two groups were treated for 12 weeks with VT-1161 (weekly doses of 300 mg and 600 mg); two other groups had treatment extended out to 24 weeks.

Few patients, roughly 20% in each treatment arm, had achieved the primary endpoint, a complete cure (0% nail involvement and negative KOH stain and culture) at the end of active treatment, Dr. Pariser said.

“I personally think that all of these onychomycosis studies should be carried out for longer than a year, up to 2 years, even if you were able to get rid of all the fungus, because that’s how long it’s going to take for the nail to grow out, especially in older patients with slower nail growth,” Dr. Pariser said.

At 48 weeks, approximately 40% of patients in each active treatment arm achieved complete cure, Dr. Pariser noted. “The results indicated that there was not a lot of difference in outcomes based on the dose the patient received.”

About 60%-70% of treated patients sustained mycologic cure of onychomycosis at 60 weeks.

No serious drug-related adverse events were seen in the study, and no patients dropped out because of lab abnormalities, including liver function tests. Other adverse events were rare and occurred equally in the treatment and placebo arms and consisted of dermatitis, headache, and cough. Nausea, cough, and dysgeusia each occurred in 2% of patients and could have been related to the study drug, Dr. Pariser said.

Looking at both mycologic and complete cure rates of available onychomycosis treatments, the results from the RENOVATE trial are comparable to approved systemic therapies, and superior to topicals, he said.

Dr. Pariser disclosed serving as an investigator for pharmaceutical manufactures Viamet (maker of VT-1161), Valeant, and Ancor/Pharmaderm.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

[email protected]

LAS VEGAS – An investigational oral therapy for onychomycosis could be on the horizon as a new treatment option.

VT-1161 is a cytochrome P51 (CYP51) inhibitor with potent in vitro activity against several species of tinea and yeast, David M. Pariser, MD, said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar. It is highly selective for fungal CYP51 over human cytochrome P enzymes.

Dr. Pariser served as an . Patients enrolled were aged 18-70 years, with a mean age of 49. Most were men (80%) and white (85%), as is typical in trials for onychomycosis drugs, noted Dr. Pariser, professor of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk.

Distal subungual onychomycosis was evident in 25%-75% of the nail, and patients needed 2 mm of clear nail to be included in the trial. Disease was confirmed by positive KOH staining and culture.

Patients were randomized into four active treatment groups; a fifth received placebo. All active treatment groups were started on 14 days of a daily loading dose of VT-1161, with one arm getting 300 mg per day and one getting 600 mg per day.

After the loading dose, two groups were treated for 12 weeks with VT-1161 (weekly doses of 300 mg and 600 mg); two other groups had treatment extended out to 24 weeks.

Few patients, roughly 20% in each treatment arm, had achieved the primary endpoint, a complete cure (0% nail involvement and negative KOH stain and culture) at the end of active treatment, Dr. Pariser said.

“I personally think that all of these onychomycosis studies should be carried out for longer than a year, up to 2 years, even if you were able to get rid of all the fungus, because that’s how long it’s going to take for the nail to grow out, especially in older patients with slower nail growth,” Dr. Pariser said.

At 48 weeks, approximately 40% of patients in each active treatment arm achieved complete cure, Dr. Pariser noted. “The results indicated that there was not a lot of difference in outcomes based on the dose the patient received.”

About 60%-70% of treated patients sustained mycologic cure of onychomycosis at 60 weeks.

No serious drug-related adverse events were seen in the study, and no patients dropped out because of lab abnormalities, including liver function tests. Other adverse events were rare and occurred equally in the treatment and placebo arms and consisted of dermatitis, headache, and cough. Nausea, cough, and dysgeusia each occurred in 2% of patients and could have been related to the study drug, Dr. Pariser said.

Looking at both mycologic and complete cure rates of available onychomycosis treatments, the results from the RENOVATE trial are comparable to approved systemic therapies, and superior to topicals, he said.

Dr. Pariser disclosed serving as an investigator for pharmaceutical manufactures Viamet (maker of VT-1161), Valeant, and Ancor/Pharmaderm.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

[email protected]

REPORTING FROM SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Delusional infestation: not so rare

PARIS – Ever wonder, when encountering an occasional patient afflicted with delusional infestation, just how common this mental disorder is?

John J. Kohorst, MD, and his coinvestigators at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., have the evidence-based answer.

The age- and sex-adjusted point prevalence of delusional infestation among Olmsted County, Minn., residents on the final day of 2010 was 27.3 cases per 100,000 person-years, he reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“This is the than previously suspected,” according to the dermatologist.

He and his coinvestigators retrospectively analyzed data from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. They identified 22 female and 13 male county residents with a firm diagnosis of delusional infestation, also known as delusional parasitosis. This disorder is marked by a patient’s fixed false belief that they are infested with insects, worms, or other pathogens.

The prevalence was similar in men and women. The most striking study finding was how heavily age-dependent delusional infestation was. Before age 40, the prevalence was a mere 1.2 cases per 100,000 person-years. Among 40- to 59-year-old Olmsted County residents, it was 35/100,000, jumping to 64.5/100,000 in the 60- to 79-year-old age bracket, then doubling to 130.1 cases per 100,000 person-years in individuals aged 80 or older.

Dr. Kohorst reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

PARIS – Ever wonder, when encountering an occasional patient afflicted with delusional infestation, just how common this mental disorder is?

John J. Kohorst, MD, and his coinvestigators at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., have the evidence-based answer.

The age- and sex-adjusted point prevalence of delusional infestation among Olmsted County, Minn., residents on the final day of 2010 was 27.3 cases per 100,000 person-years, he reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“This is the than previously suspected,” according to the dermatologist.

He and his coinvestigators retrospectively analyzed data from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. They identified 22 female and 13 male county residents with a firm diagnosis of delusional infestation, also known as delusional parasitosis. This disorder is marked by a patient’s fixed false belief that they are infested with insects, worms, or other pathogens.

The prevalence was similar in men and women. The most striking study finding was how heavily age-dependent delusional infestation was. Before age 40, the prevalence was a mere 1.2 cases per 100,000 person-years. Among 40- to 59-year-old Olmsted County residents, it was 35/100,000, jumping to 64.5/100,000 in the 60- to 79-year-old age bracket, then doubling to 130.1 cases per 100,000 person-years in individuals aged 80 or older.

Dr. Kohorst reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

PARIS – Ever wonder, when encountering an occasional patient afflicted with delusional infestation, just how common this mental disorder is?

John J. Kohorst, MD, and his coinvestigators at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., have the evidence-based answer.

The age- and sex-adjusted point prevalence of delusional infestation among Olmsted County, Minn., residents on the final day of 2010 was 27.3 cases per 100,000 person-years, he reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“This is the than previously suspected,” according to the dermatologist.

He and his coinvestigators retrospectively analyzed data from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. They identified 22 female and 13 male county residents with a firm diagnosis of delusional infestation, also known as delusional parasitosis. This disorder is marked by a patient’s fixed false belief that they are infested with insects, worms, or other pathogens.

The prevalence was similar in men and women. The most striking study finding was how heavily age-dependent delusional infestation was. Before age 40, the prevalence was a mere 1.2 cases per 100,000 person-years. Among 40- to 59-year-old Olmsted County residents, it was 35/100,000, jumping to 64.5/100,000 in the 60- to 79-year-old age bracket, then doubling to 130.1 cases per 100,000 person-years in individuals aged 80 or older.

Dr. Kohorst reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Delusional infestation may be more common than previously suspected, particularly among older age groups.

Major finding: The age- and sex-adjusted point prevalence of delusional infestation among residents of one county in southeastern Minnesota is 27.3 cases per 100,000 person-years.

Study details: This was a retrospective analysis of data from the Rochester (Minn.) Epidemiology Project.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

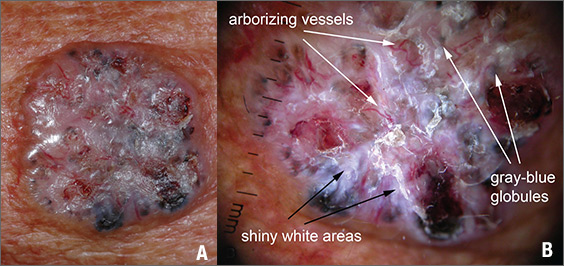

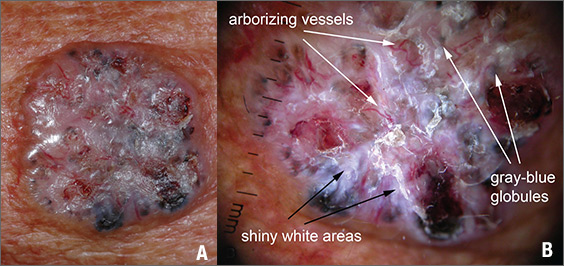

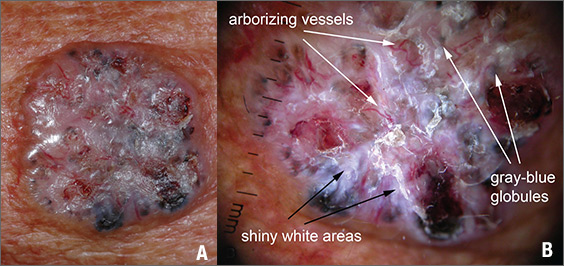

Growth on right cheek

Figure 1

The FP suspected that this was a nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with pigmentation. The physical exam was suspicious because of the pearly appearance, superficial ulcerations, and presence of telangiectasias with a loss of the normal pore pattern. Dermoscopy gave further evidence for a nodular BCC by revealing arborizing “tree-like” telangiectasias, ulcerations, shiny white areas, and gray-blue globules. Skin cancers often produce their own vascular supply and also ulcerate. The shiny white areas (which are the result of collagen deposition and occur in many skin cancers) are best seen with polarized dermoscopy.

The FP recommended a shave biopsy and performed one immediately after obtaining patient consent. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) Knowing that the BCC would be vascular, the FP injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited 15 minutes for the epinephrine to work.

After seeing another patient, he performed the shave biopsy with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to vigorously apply the aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to stop most of the bleeding and then used his electrosurgical instrument—with a sharp tipped electrode—to stop recalcitrant bleeders.

The patient was given a diagnosis of BCC on the follow-up visit. The FP referred the patient for Mohs surgery because of the large size and location of the tumor.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Figure 1

The FP suspected that this was a nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with pigmentation. The physical exam was suspicious because of the pearly appearance, superficial ulcerations, and presence of telangiectasias with a loss of the normal pore pattern. Dermoscopy gave further evidence for a nodular BCC by revealing arborizing “tree-like” telangiectasias, ulcerations, shiny white areas, and gray-blue globules. Skin cancers often produce their own vascular supply and also ulcerate. The shiny white areas (which are the result of collagen deposition and occur in many skin cancers) are best seen with polarized dermoscopy.

The FP recommended a shave biopsy and performed one immediately after obtaining patient consent. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) Knowing that the BCC would be vascular, the FP injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited 15 minutes for the epinephrine to work.

After seeing another patient, he performed the shave biopsy with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to vigorously apply the aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to stop most of the bleeding and then used his electrosurgical instrument—with a sharp tipped electrode—to stop recalcitrant bleeders.

The patient was given a diagnosis of BCC on the follow-up visit. The FP referred the patient for Mohs surgery because of the large size and location of the tumor.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Figure 1

The FP suspected that this was a nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with pigmentation. The physical exam was suspicious because of the pearly appearance, superficial ulcerations, and presence of telangiectasias with a loss of the normal pore pattern. Dermoscopy gave further evidence for a nodular BCC by revealing arborizing “tree-like” telangiectasias, ulcerations, shiny white areas, and gray-blue globules. Skin cancers often produce their own vascular supply and also ulcerate. The shiny white areas (which are the result of collagen deposition and occur in many skin cancers) are best seen with polarized dermoscopy.

The FP recommended a shave biopsy and performed one immediately after obtaining patient consent. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) Knowing that the BCC would be vascular, the FP injected 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and waited 15 minutes for the epinephrine to work.

After seeing another patient, he performed the shave biopsy with a Dermablade, and used a cotton-tipped applicator to vigorously apply the aluminum chloride to the site. He used a twisting motion and pressure to stop most of the bleeding and then used his electrosurgical instrument—with a sharp tipped electrode—to stop recalcitrant bleeders.

The patient was given a diagnosis of BCC on the follow-up visit. The FP referred the patient for Mohs surgery because of the large size and location of the tumor.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:989-998.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Persistent erythematous papulonodular rash

An 80-year-old white woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a rash across her abdomen that had been there for more than a year. While not itchy or painful, the rash was slowly expanding. The patient had tried treatments including topical antifungals and topical corticosteroids, but none had helped.

Her medical history was significant for dementia and stage III triple-negative breast cancer in the left breast (diagnosed 8 years prior), which was treated with a simple left mastectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation. She reported no history of skin cancer. She was not taking any medications and had no known drug allergies. A physical examination revealed an erythematous, papulonodular rash with diffuse induration in a band-like pattern across her entire upper abdomen and left flank (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cutaneous metastasis of primary breast cancer

Based on our patient’s history, we gave a presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous breast cancer metastasis. A punch biopsy was performed. The pathology report showed nests of neoplastic cells within the dermis, which was consistent with this diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains and fluorescence in-situ hybridization confirmed triple-negative breast markers for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2.

An uncommon phenomenonseen mostly with breast cancer

Cutaneous metastatic carcinoma is relatively uncommon; one meta-analysis reported the overall incidence to be 5.3%.1 While it is unusual, any internal malignancy can metastasize to the skin. In women, the most common malignancy to do so is breast cancer. One study found breast cancer to be associated with 26.5% of cutaneous metastatic cases.2 These metastases often occur well after the patient has been treated for the primary malignancy.

Identifying features. Most cutaneous metastases occur near the site of the primary tumor, initially in the form of a firm, mobile, nonpainful nodule.3 This nodule is typically skin-colored or red, but in the case of cutaneous metastases of melanomas, it can appear blue or black. In the case of breast cancer, the lesions most often arise on the chest and abdomen.4 Occasionally, metastases can ulcerate through the skin.

Some forms of cutaneous metastasis, such as carcinoma erysipeloides, can appear in specific patterns. Carcinoma erysipeloides has a similar appearance to cellulitis; it manifests as a sharply demarcated, red, inflammatory patch in the skin adjacent to the primary tumor.

Consider the clinical picture

Cutaneous metastatic lesions have a wide range of differential diagnoses due to their varied appearances. It is important to view the overall clinical picture when distinguishing such lesions. Although cutaneous metastasis is uncommon, it should always be considered when asymptomatic skin lesions resist treatment—even in someone without a known history of malignancy.

Perform a biopsy. The diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy. A punch biopsy is preferable, as visualization of the dermis is crucial, and histology often reveals nests of pleomorphic cells. Further cellular cytology can elicit the primary malignancy of origin.

Making our diagnosis

We ruled out several possibilities before arriving at our diagnosis. An infectious etiology (eg, cutaneous candidiasis) was considered, as was a cutaneous change due to radiation therapy. We also considered shingles, the early stages of which would have been similar in appearance to our patient’s lesions, and urticaria, which can manifest as erythematous papules and wheals across various parts of the body. A lack of specific symptoms (eg, pruritis, pain, fever) made these alternative diagnoses less likely. The fact that our patient’s lesions persisted for more than a year without any response to treatment—and that they continued to grow—alerted us of a more sinister etiology.

Continue to: Treating the tumor is often not possible

Treating the tumor is often not possible

Treatment first involves treating the underlying tumor. For cases in which cutaneous lesions are the first manifestation of an internal malignancy, investigation as to the source should be performed. The lesions can then be treated with a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery.5,6

Unfortunately, in most cases of cutaneous metastases, the primary malignancy is already widespread and possibly untreatable. In such instances, palliative care is offered. Lesions are managed symptomatically, and prevention of skin irritation becomes the primary focus. Keeping the skin clean and dry helps to prevent ulceration and secondary infection.

In cases where the lesions ulcerate or crust, debridement can help. Excision of lesions, as well as pairing laser therapy with electrochemotherapy, may be helpful to improve the patient’s quality of life when lesions cause discomfort.

The prognosis for cutaneous metastasis due to breast cancer is often hard to predict because it is determined by other factors, such as the presence of internal metastases, which indicates a worse prognosis (on the scale of months). Some case reports have demonstrated that patients with metastases limited to the skin may have prolonged survival (on the scale of years).7

Our patient was offered an initial trial of radiation therapy, but she refused all treatment because the lesions did not cause discomfort, and she preferred to not go through further aggressive cancer treatment that could potentially cause complications and pain. We respected the patient’s wishes and counseled her on follow-up if the lesions became symptomatic or she decided she wanted to try treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Araya Zaesim, 1550 College St, Macon, GA, 31207; [email protected]

1. Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

2. Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Patterns of cutaneous metastasis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:862-868.

3. De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Alfaioli B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of breast carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:581-589.

4. Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

5. Moore S. Cutaneous metastatic breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2002;6:255-260.

6. Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011: bcr0620114398.

7. Cho J, Park Y, Lee JC, et al. Case series of different onset of skin metastasis according to the breast cancer subtypes. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46:194-199.

An 80-year-old white woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a rash across her abdomen that had been there for more than a year. While not itchy or painful, the rash was slowly expanding. The patient had tried treatments including topical antifungals and topical corticosteroids, but none had helped.

Her medical history was significant for dementia and stage III triple-negative breast cancer in the left breast (diagnosed 8 years prior), which was treated with a simple left mastectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation. She reported no history of skin cancer. She was not taking any medications and had no known drug allergies. A physical examination revealed an erythematous, papulonodular rash with diffuse induration in a band-like pattern across her entire upper abdomen and left flank (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cutaneous metastasis of primary breast cancer

Based on our patient’s history, we gave a presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous breast cancer metastasis. A punch biopsy was performed. The pathology report showed nests of neoplastic cells within the dermis, which was consistent with this diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains and fluorescence in-situ hybridization confirmed triple-negative breast markers for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2.

An uncommon phenomenonseen mostly with breast cancer

Cutaneous metastatic carcinoma is relatively uncommon; one meta-analysis reported the overall incidence to be 5.3%.1 While it is unusual, any internal malignancy can metastasize to the skin. In women, the most common malignancy to do so is breast cancer. One study found breast cancer to be associated with 26.5% of cutaneous metastatic cases.2 These metastases often occur well after the patient has been treated for the primary malignancy.

Identifying features. Most cutaneous metastases occur near the site of the primary tumor, initially in the form of a firm, mobile, nonpainful nodule.3 This nodule is typically skin-colored or red, but in the case of cutaneous metastases of melanomas, it can appear blue or black. In the case of breast cancer, the lesions most often arise on the chest and abdomen.4 Occasionally, metastases can ulcerate through the skin.

Some forms of cutaneous metastasis, such as carcinoma erysipeloides, can appear in specific patterns. Carcinoma erysipeloides has a similar appearance to cellulitis; it manifests as a sharply demarcated, red, inflammatory patch in the skin adjacent to the primary tumor.

Consider the clinical picture

Cutaneous metastatic lesions have a wide range of differential diagnoses due to their varied appearances. It is important to view the overall clinical picture when distinguishing such lesions. Although cutaneous metastasis is uncommon, it should always be considered when asymptomatic skin lesions resist treatment—even in someone without a known history of malignancy.

Perform a biopsy. The diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy. A punch biopsy is preferable, as visualization of the dermis is crucial, and histology often reveals nests of pleomorphic cells. Further cellular cytology can elicit the primary malignancy of origin.

Making our diagnosis

We ruled out several possibilities before arriving at our diagnosis. An infectious etiology (eg, cutaneous candidiasis) was considered, as was a cutaneous change due to radiation therapy. We also considered shingles, the early stages of which would have been similar in appearance to our patient’s lesions, and urticaria, which can manifest as erythematous papules and wheals across various parts of the body. A lack of specific symptoms (eg, pruritis, pain, fever) made these alternative diagnoses less likely. The fact that our patient’s lesions persisted for more than a year without any response to treatment—and that they continued to grow—alerted us of a more sinister etiology.

Continue to: Treating the tumor is often not possible

Treating the tumor is often not possible

Treatment first involves treating the underlying tumor. For cases in which cutaneous lesions are the first manifestation of an internal malignancy, investigation as to the source should be performed. The lesions can then be treated with a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery.5,6

Unfortunately, in most cases of cutaneous metastases, the primary malignancy is already widespread and possibly untreatable. In such instances, palliative care is offered. Lesions are managed symptomatically, and prevention of skin irritation becomes the primary focus. Keeping the skin clean and dry helps to prevent ulceration and secondary infection.

In cases where the lesions ulcerate or crust, debridement can help. Excision of lesions, as well as pairing laser therapy with electrochemotherapy, may be helpful to improve the patient’s quality of life when lesions cause discomfort.

The prognosis for cutaneous metastasis due to breast cancer is often hard to predict because it is determined by other factors, such as the presence of internal metastases, which indicates a worse prognosis (on the scale of months). Some case reports have demonstrated that patients with metastases limited to the skin may have prolonged survival (on the scale of years).7

Our patient was offered an initial trial of radiation therapy, but she refused all treatment because the lesions did not cause discomfort, and she preferred to not go through further aggressive cancer treatment that could potentially cause complications and pain. We respected the patient’s wishes and counseled her on follow-up if the lesions became symptomatic or she decided she wanted to try treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Araya Zaesim, 1550 College St, Macon, GA, 31207; [email protected]

An 80-year-old white woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a rash across her abdomen that had been there for more than a year. While not itchy or painful, the rash was slowly expanding. The patient had tried treatments including topical antifungals and topical corticosteroids, but none had helped.

Her medical history was significant for dementia and stage III triple-negative breast cancer in the left breast (diagnosed 8 years prior), which was treated with a simple left mastectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation. She reported no history of skin cancer. She was not taking any medications and had no known drug allergies. A physical examination revealed an erythematous, papulonodular rash with diffuse induration in a band-like pattern across her entire upper abdomen and left flank (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cutaneous metastasis of primary breast cancer

Based on our patient’s history, we gave a presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous breast cancer metastasis. A punch biopsy was performed. The pathology report showed nests of neoplastic cells within the dermis, which was consistent with this diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains and fluorescence in-situ hybridization confirmed triple-negative breast markers for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2.

An uncommon phenomenonseen mostly with breast cancer

Cutaneous metastatic carcinoma is relatively uncommon; one meta-analysis reported the overall incidence to be 5.3%.1 While it is unusual, any internal malignancy can metastasize to the skin. In women, the most common malignancy to do so is breast cancer. One study found breast cancer to be associated with 26.5% of cutaneous metastatic cases.2 These metastases often occur well after the patient has been treated for the primary malignancy.

Identifying features. Most cutaneous metastases occur near the site of the primary tumor, initially in the form of a firm, mobile, nonpainful nodule.3 This nodule is typically skin-colored or red, but in the case of cutaneous metastases of melanomas, it can appear blue or black. In the case of breast cancer, the lesions most often arise on the chest and abdomen.4 Occasionally, metastases can ulcerate through the skin.

Some forms of cutaneous metastasis, such as carcinoma erysipeloides, can appear in specific patterns. Carcinoma erysipeloides has a similar appearance to cellulitis; it manifests as a sharply demarcated, red, inflammatory patch in the skin adjacent to the primary tumor.

Consider the clinical picture

Cutaneous metastatic lesions have a wide range of differential diagnoses due to their varied appearances. It is important to view the overall clinical picture when distinguishing such lesions. Although cutaneous metastasis is uncommon, it should always be considered when asymptomatic skin lesions resist treatment—even in someone without a known history of malignancy.

Perform a biopsy. The diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy. A punch biopsy is preferable, as visualization of the dermis is crucial, and histology often reveals nests of pleomorphic cells. Further cellular cytology can elicit the primary malignancy of origin.

Making our diagnosis

We ruled out several possibilities before arriving at our diagnosis. An infectious etiology (eg, cutaneous candidiasis) was considered, as was a cutaneous change due to radiation therapy. We also considered shingles, the early stages of which would have been similar in appearance to our patient’s lesions, and urticaria, which can manifest as erythematous papules and wheals across various parts of the body. A lack of specific symptoms (eg, pruritis, pain, fever) made these alternative diagnoses less likely. The fact that our patient’s lesions persisted for more than a year without any response to treatment—and that they continued to grow—alerted us of a more sinister etiology.

Continue to: Treating the tumor is often not possible

Treating the tumor is often not possible

Treatment first involves treating the underlying tumor. For cases in which cutaneous lesions are the first manifestation of an internal malignancy, investigation as to the source should be performed. The lesions can then be treated with a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery.5,6

Unfortunately, in most cases of cutaneous metastases, the primary malignancy is already widespread and possibly untreatable. In such instances, palliative care is offered. Lesions are managed symptomatically, and prevention of skin irritation becomes the primary focus. Keeping the skin clean and dry helps to prevent ulceration and secondary infection.

In cases where the lesions ulcerate or crust, debridement can help. Excision of lesions, as well as pairing laser therapy with electrochemotherapy, may be helpful to improve the patient’s quality of life when lesions cause discomfort.

The prognosis for cutaneous metastasis due to breast cancer is often hard to predict because it is determined by other factors, such as the presence of internal metastases, which indicates a worse prognosis (on the scale of months). Some case reports have demonstrated that patients with metastases limited to the skin may have prolonged survival (on the scale of years).7

Our patient was offered an initial trial of radiation therapy, but she refused all treatment because the lesions did not cause discomfort, and she preferred to not go through further aggressive cancer treatment that could potentially cause complications and pain. We respected the patient’s wishes and counseled her on follow-up if the lesions became symptomatic or she decided she wanted to try treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Araya Zaesim, 1550 College St, Macon, GA, 31207; [email protected]

1. Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

2. Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Patterns of cutaneous metastasis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:862-868.

3. De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Alfaioli B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of breast carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:581-589.

4. Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

5. Moore S. Cutaneous metastatic breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2002;6:255-260.

6. Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011: bcr0620114398.

7. Cho J, Park Y, Lee JC, et al. Case series of different onset of skin metastasis according to the breast cancer subtypes. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46:194-199.

1. Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

2. Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Patterns of cutaneous metastasis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:862-868.

3. De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Alfaioli B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of breast carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:581-589.

4. Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, et al. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

5. Moore S. Cutaneous metastatic breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2002;6:255-260.

6. Ahmed M. Cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011: bcr0620114398.

7. Cho J, Park Y, Lee JC, et al. Case series of different onset of skin metastasis according to the breast cancer subtypes. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46:194-199.

Progressive discoloration over the right shoulder

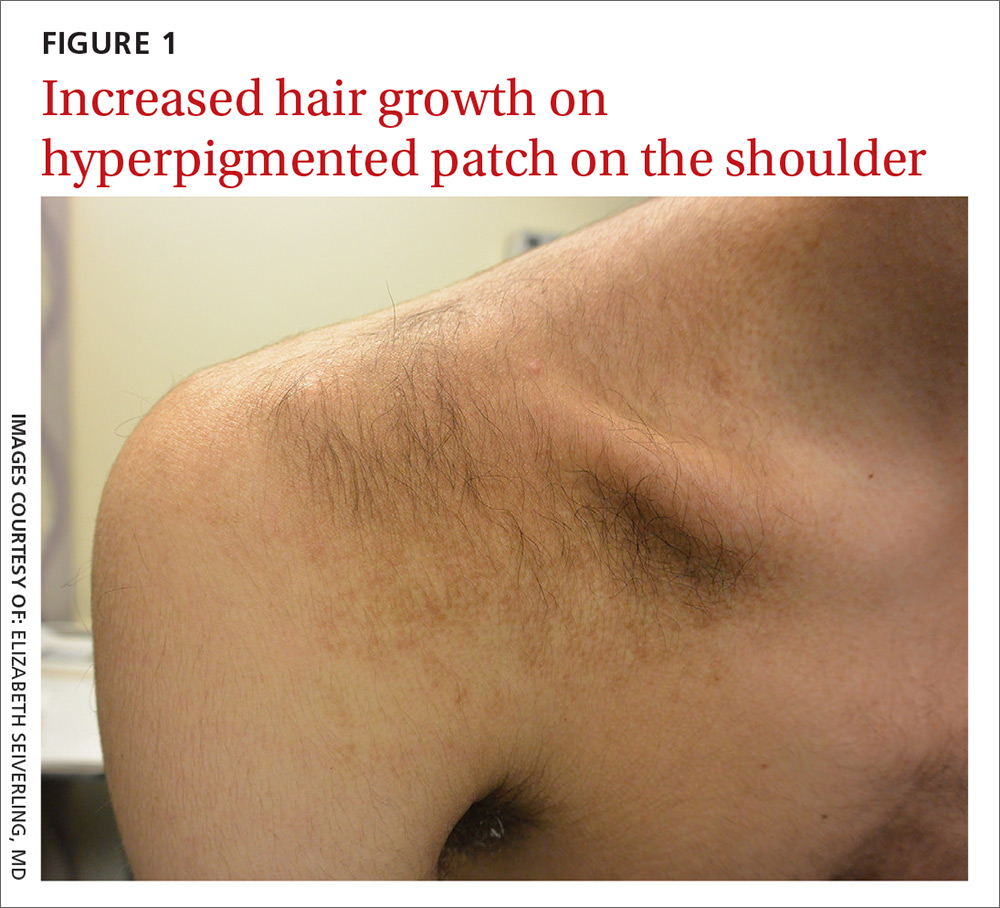

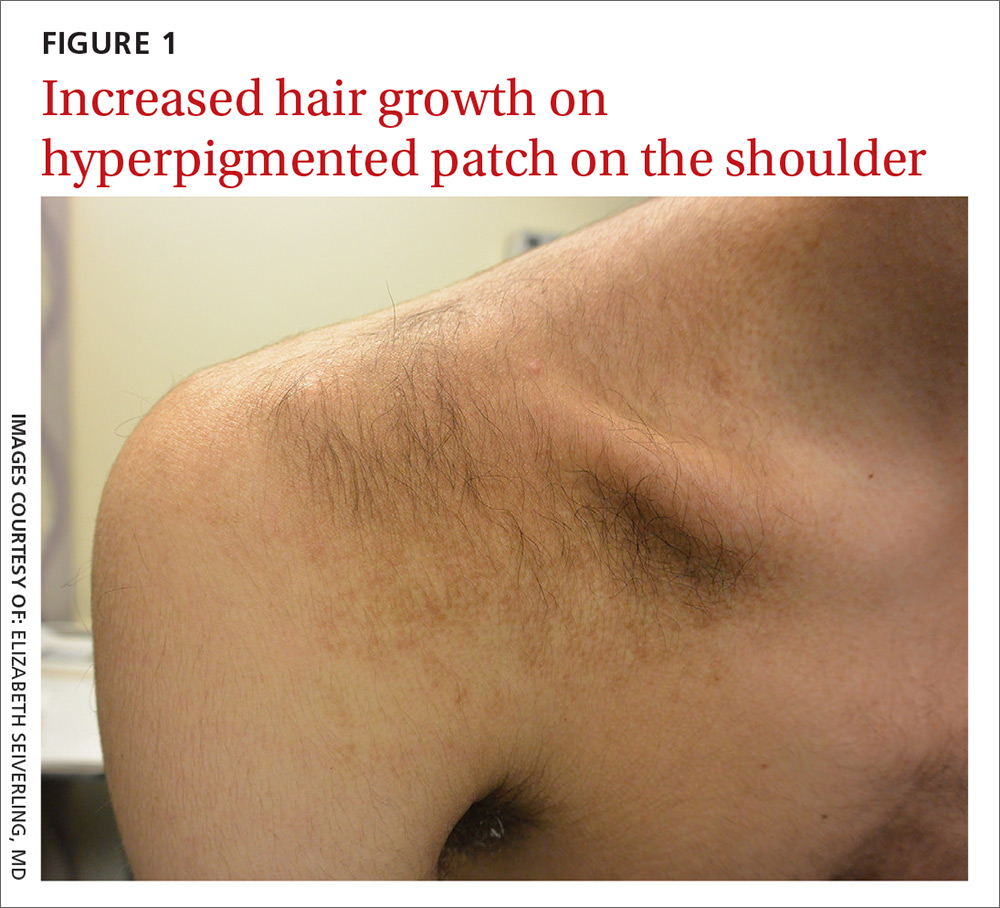

A 15-year-old Caucasian boy presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic brown patch on his right shoulder. While the patient’s mother first noticed the patch when he was 5 years old, the discolored area had recently been expanding in size and had developed hypertrichosis. The patient was otherwise healthy; he took no medications and denied any symptoms or history of trauma to the area. None of his siblings were similarly affected.

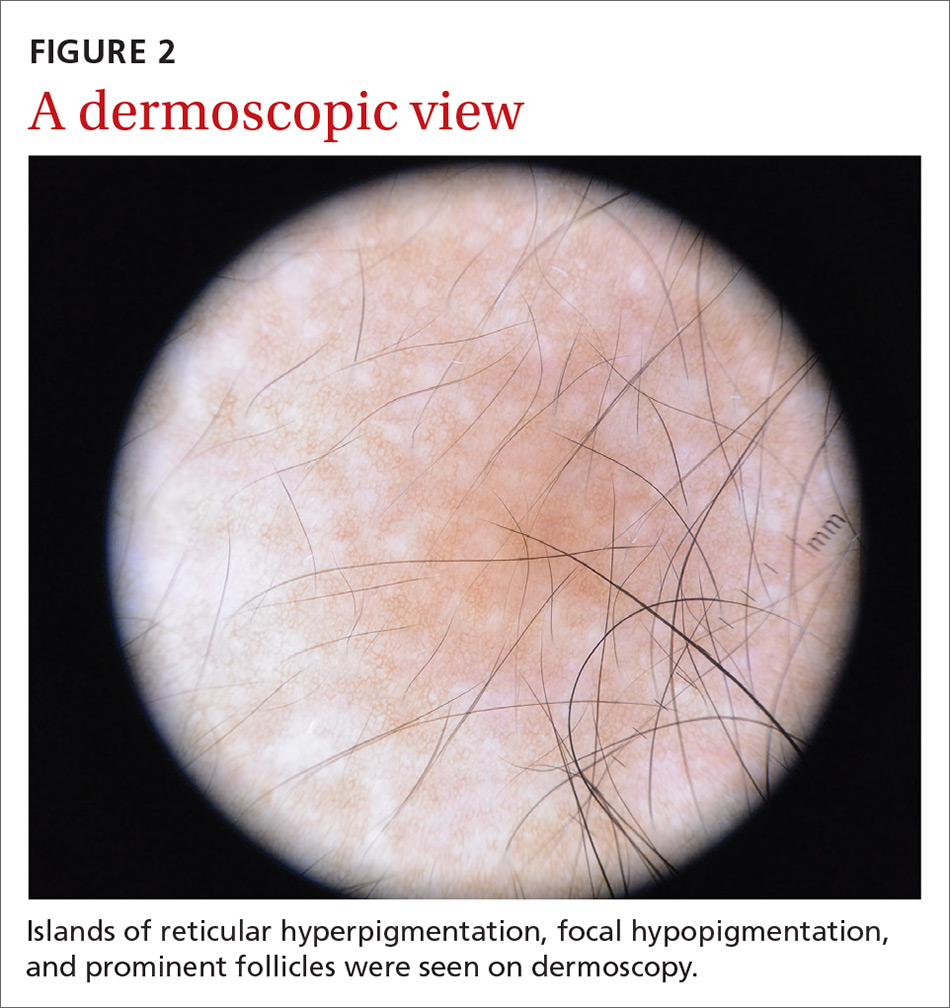

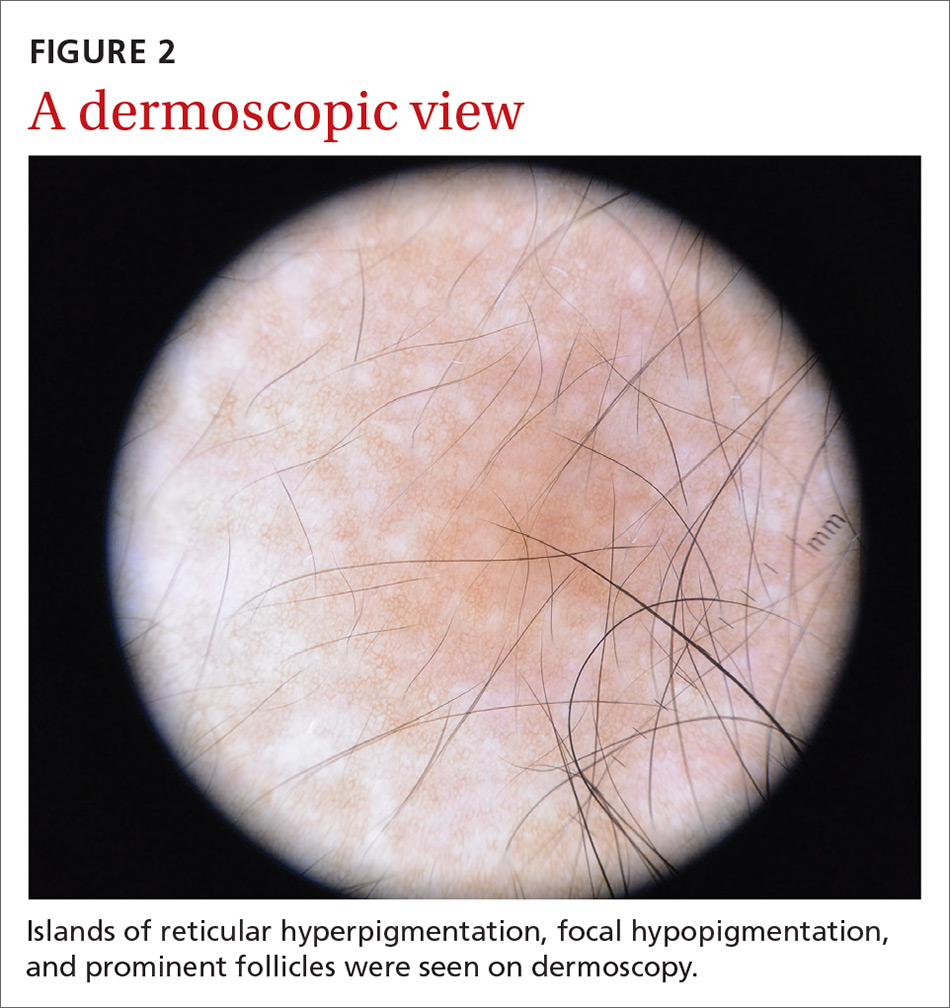

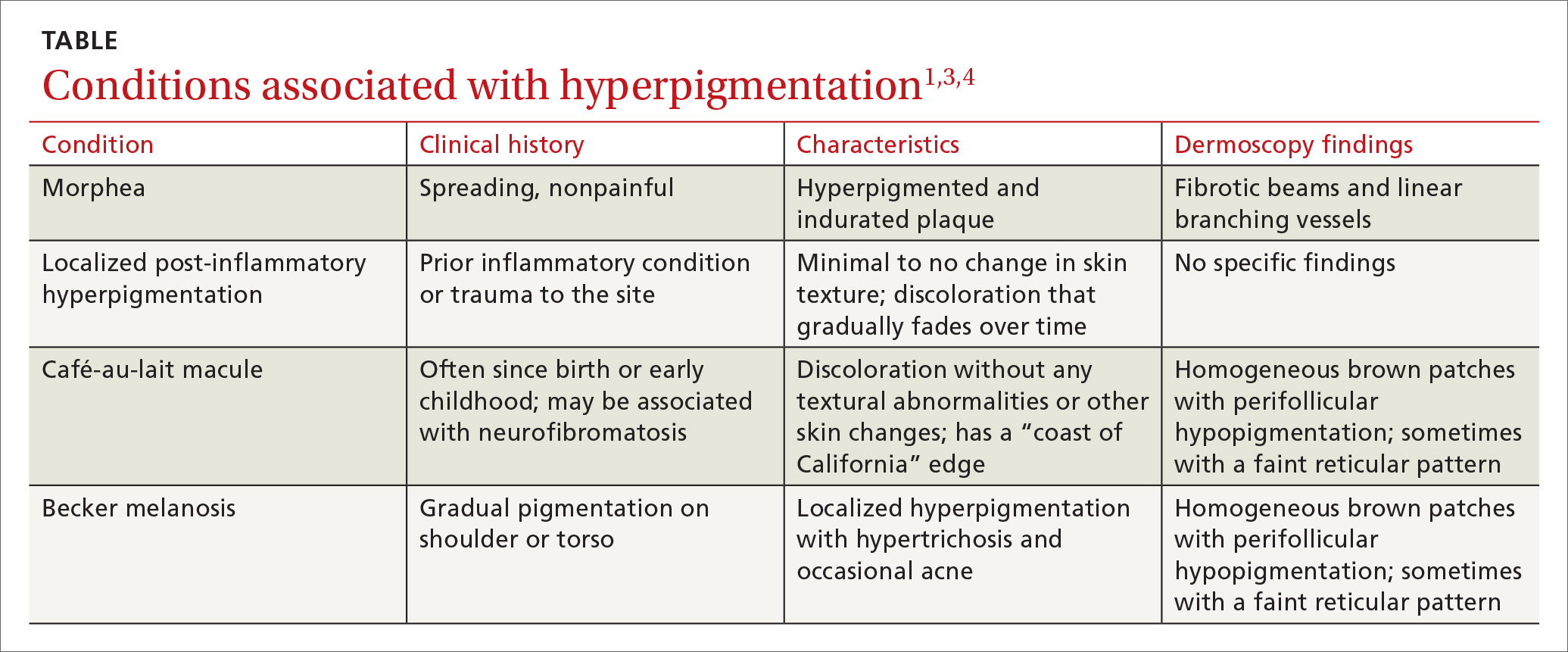

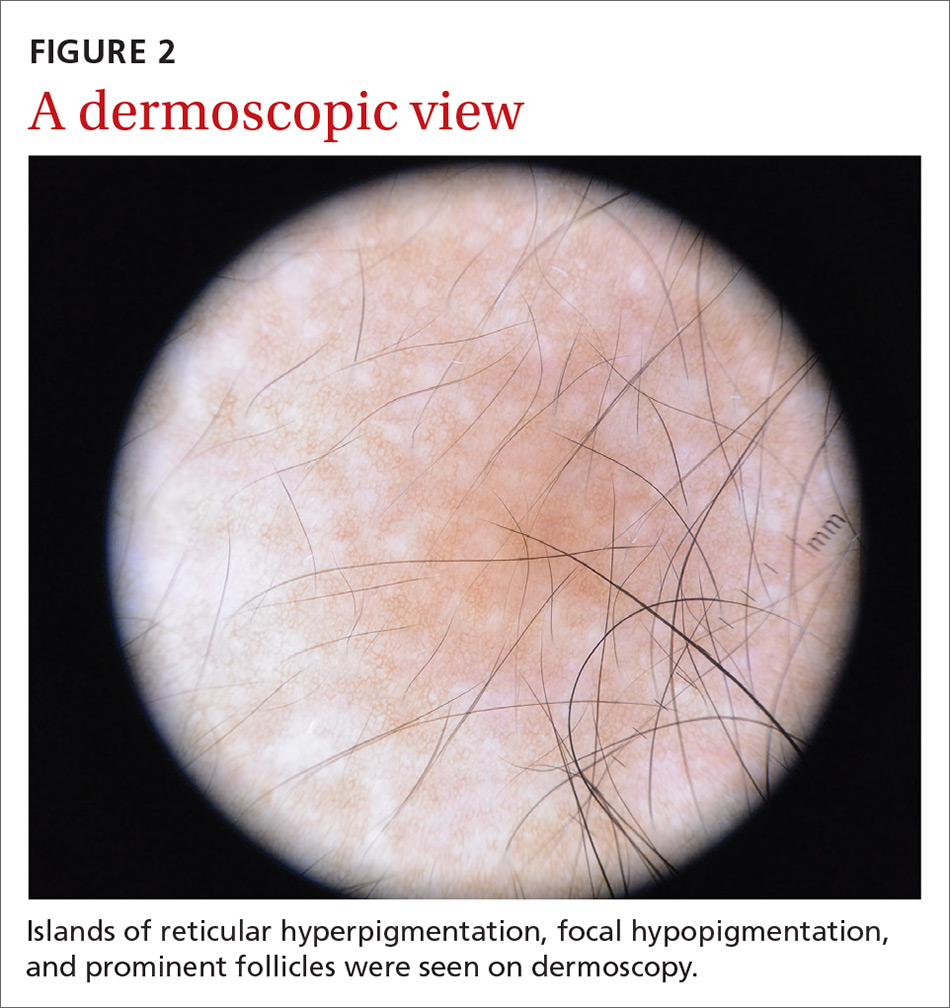

A physical examination revealed a well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch with an irregularly shaped border and an increased number of terminal hairs (FIGURE 1). The affected area was not indurated, and there were no muscular or skeletal abnormalities on inspection. Examination of the patch under a dermatoscope revealed islands of reticular (lattice-like) hyperpigmentation, focal hypopigmentation, and prominent follicles (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

DIAGNOSIS: Becker melanosis

Becker melanosis (also called Becker’s nevus or Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma) is an organoid hamartoma that is most common among males.1 This benign area of hyperpigmentation typically manifests as a circumscribed patch with an irregular border on the upper trunk, shoulders, or upper arms of young men. Becker melanosis is usually acquired and typically comes to medical attention around the time of puberty, although there may be a history of discoloration (as was true in this case).

A diagnosis that’s usually made clinically

Androgenic origin. Because of the male predominance and association with hypertrichosis (and for that matter, acne), androgens have been thought to play a role in the development of Becker melanosis.2 The condition affects about 1 in 200 young men.1 To date, no specific gene defect has been identified.

Underlying hypoplasia of the breast or musculoskeletal abnormalities are uncommonly associated with Becker melanosis. When these abnormalities are present, the condition is known as Becker’s nevus syndrome.3

Look for the pattern. Becker melanosis is associated with homogenous brown patches with perifollicular hypopigmentation, sometimes with a faint reticular pattern.4,5 The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, but a skin biopsy can be helpful to confirm questionable cases. Dermoscopy can also assist in diagnosis. In this case, our patient’s presentation was typical, and additional studies were not needed.

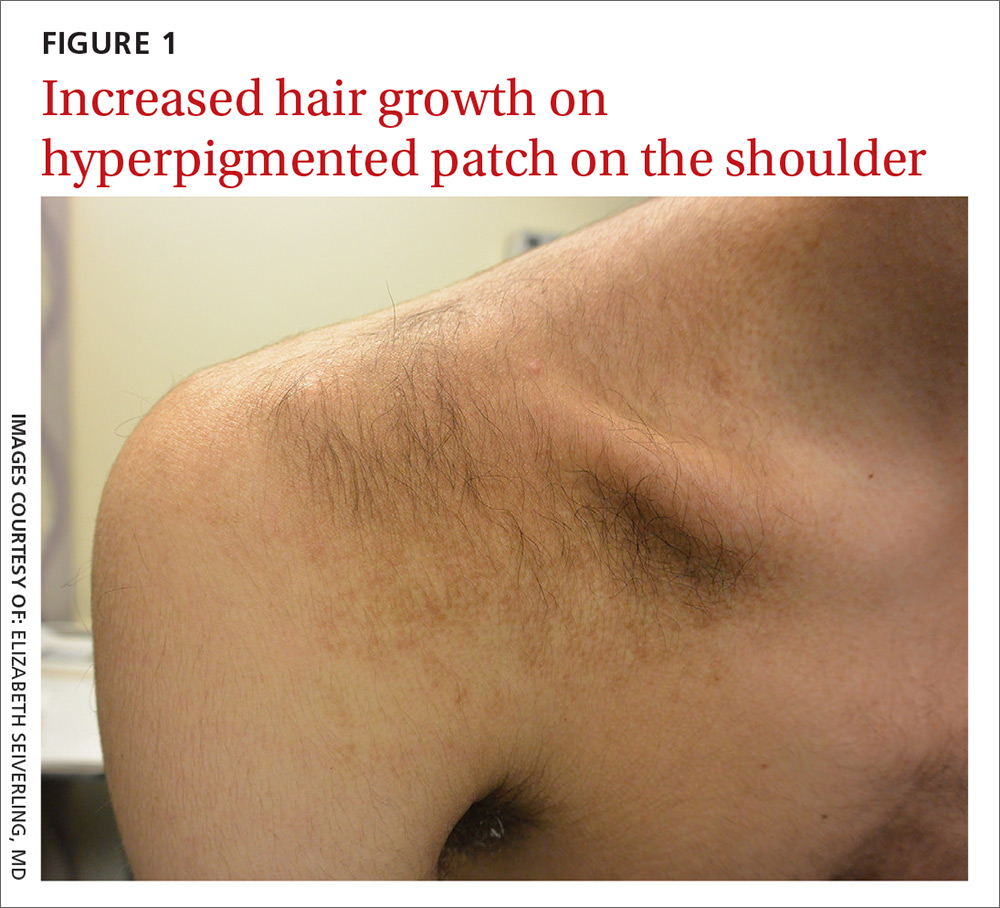

Other causes of hyperpigmentation

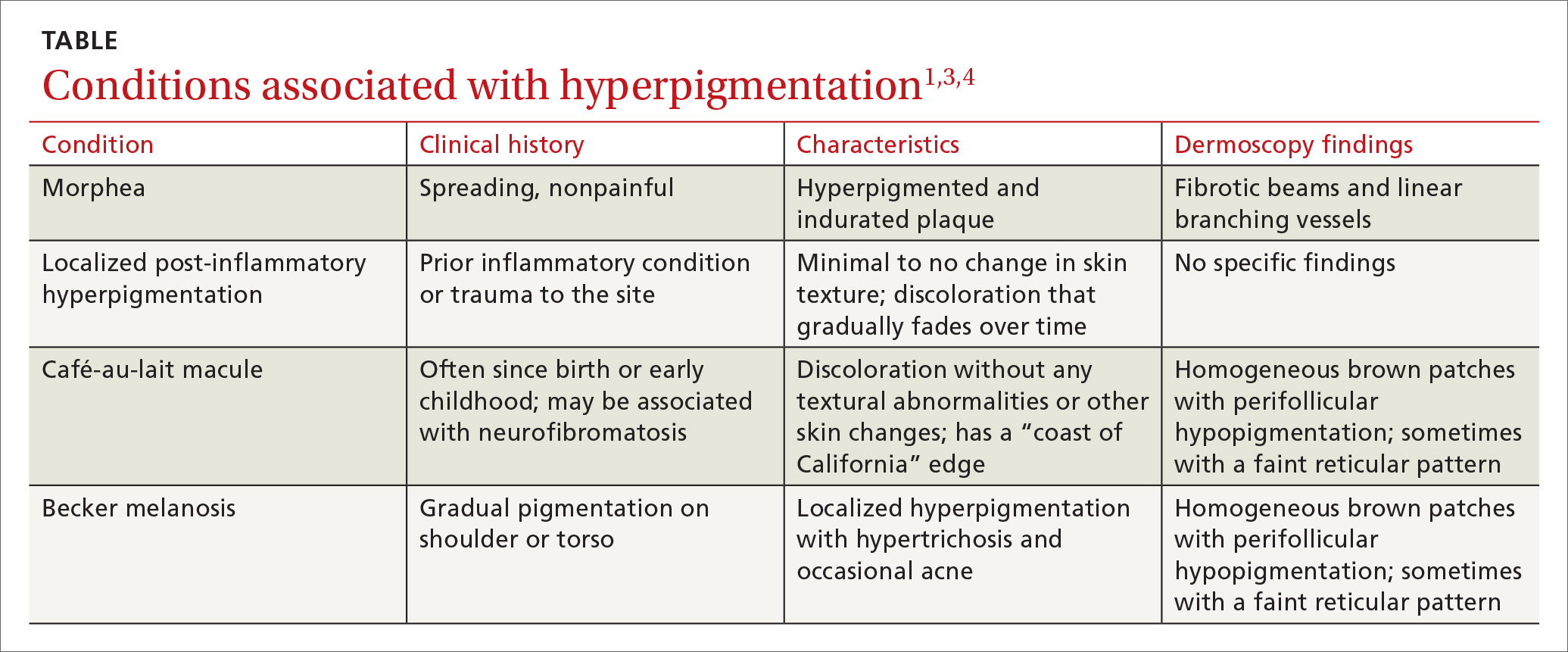

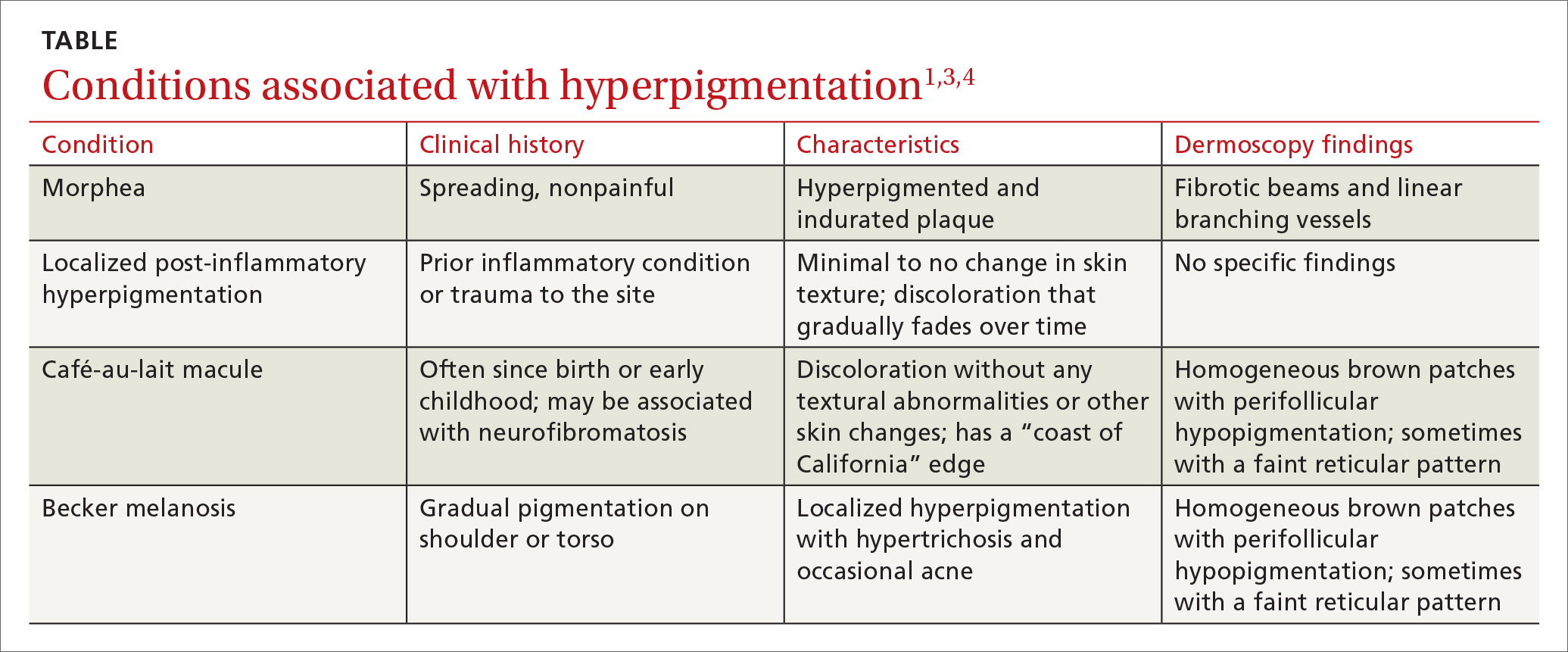

The differential diagnosis includes other localized disorders associated with hyperpigmentation (TABLE1,3,4).

Continue to: Morphea

Morphea represents a thickening of collagen bundles in the skin. Although morphea can affect the shoulder and trunk, as Becker melanosis does, lesions of morphea feel firm to the touch and are not associated with hypertrichosis.

Localized post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs following a traumatic event, such as a burn, or a prior dermatosis, such as zoster. Careful history-taking can uncover an antecedent inflammatory condition. Post-inflammatory pigment changes do not typically result in hypertrichosis.

Café-au-lait macules can manifest as isolated areas of discoloration. These macules can be an important indicator of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder in which tumors grow in the nervous system. Melanocytic hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules), axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign), or multiple cutaneous neurofibromas serve as additional clues to neurofibromatosis. In ambiguous cases, a skin biopsy can help differentiate a café au lait macule from Becker melanosis.

To treat or not to treat?

No treatment other than reassurance is needed in most cases of Becker melanosis, as it is a benign condition. Protecting the area from sunlight can minimize darkening and contrast with the surrounding skin. Electrolysis and laser therapy can be used to treat the associated hypertrichosis; laser therapy can also reduce the hyperpigmentation. Nonablative fractional resurfacing accompanied by laser hair removal is also reported to be of value.6

Our patient was satisfied with reassurance of the benign nature of the condition and did not elect treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, 500 University Drive, Suite 4300, Department of Dermatology, HU14, UPC II, Hershey, PA 17033-2360; [email protected]

1. Rabinovitz HS, Barnhill RL. Benign melanocytic neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012;112:1853-1854.

2. Person JR, Longcope C. Becker’s nevus: an androgen-mediated hyperplasia with increased androgen receptors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:235-238.

3. Cosendey FE, Martinez NS, Bernhard GA, et al. Becker nevus syndrome. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:379-384.

4. Ingordo V, Iannazzone SS, Cusano F, et al. Dermoscopic features of congenital melanocytic nevus and Becker nevus in an adult male population: an analysis with 10-fold magnification. Dermatology. 2006;212:354-360.

5. Luk DC, Lam SY, Cheung PC, et al. Dermoscopy for common skin problems in Chinese children using a novel Hong Kong-made dermoscope. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:495-503.

6. Balaraman B, Friedman PM. Hypertrichotic Becker’s nevi treated with combination 1,550nm non-ablative fractional photothermolysis and laser hair removal. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:350-353.

A 15-year-old Caucasian boy presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic brown patch on his right shoulder. While the patient’s mother first noticed the patch when he was 5 years old, the discolored area had recently been expanding in size and had developed hypertrichosis. The patient was otherwise healthy; he took no medications and denied any symptoms or history of trauma to the area. None of his siblings were similarly affected.

A physical examination revealed a well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch with an irregularly shaped border and an increased number of terminal hairs (FIGURE 1). The affected area was not indurated, and there were no muscular or skeletal abnormalities on inspection. Examination of the patch under a dermatoscope revealed islands of reticular (lattice-like) hyperpigmentation, focal hypopigmentation, and prominent follicles (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

DIAGNOSIS: Becker melanosis

Becker melanosis (also called Becker’s nevus or Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma) is an organoid hamartoma that is most common among males.1 This benign area of hyperpigmentation typically manifests as a circumscribed patch with an irregular border on the upper trunk, shoulders, or upper arms of young men. Becker melanosis is usually acquired and typically comes to medical attention around the time of puberty, although there may be a history of discoloration (as was true in this case).

A diagnosis that’s usually made clinically

Androgenic origin. Because of the male predominance and association with hypertrichosis (and for that matter, acne), androgens have been thought to play a role in the development of Becker melanosis.2 The condition affects about 1 in 200 young men.1 To date, no specific gene defect has been identified.

Underlying hypoplasia of the breast or musculoskeletal abnormalities are uncommonly associated with Becker melanosis. When these abnormalities are present, the condition is known as Becker’s nevus syndrome.3

Look for the pattern. Becker melanosis is associated with homogenous brown patches with perifollicular hypopigmentation, sometimes with a faint reticular pattern.4,5 The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, but a skin biopsy can be helpful to confirm questionable cases. Dermoscopy can also assist in diagnosis. In this case, our patient’s presentation was typical, and additional studies were not needed.

Other causes of hyperpigmentation

The differential diagnosis includes other localized disorders associated with hyperpigmentation (TABLE1,3,4).

Continue to: Morphea

Morphea represents a thickening of collagen bundles in the skin. Although morphea can affect the shoulder and trunk, as Becker melanosis does, lesions of morphea feel firm to the touch and are not associated with hypertrichosis.

Localized post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs following a traumatic event, such as a burn, or a prior dermatosis, such as zoster. Careful history-taking can uncover an antecedent inflammatory condition. Post-inflammatory pigment changes do not typically result in hypertrichosis.

Café-au-lait macules can manifest as isolated areas of discoloration. These macules can be an important indicator of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder in which tumors grow in the nervous system. Melanocytic hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules), axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign), or multiple cutaneous neurofibromas serve as additional clues to neurofibromatosis. In ambiguous cases, a skin biopsy can help differentiate a café au lait macule from Becker melanosis.

To treat or not to treat?

No treatment other than reassurance is needed in most cases of Becker melanosis, as it is a benign condition. Protecting the area from sunlight can minimize darkening and contrast with the surrounding skin. Electrolysis and laser therapy can be used to treat the associated hypertrichosis; laser therapy can also reduce the hyperpigmentation. Nonablative fractional resurfacing accompanied by laser hair removal is also reported to be of value.6

Our patient was satisfied with reassurance of the benign nature of the condition and did not elect treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, 500 University Drive, Suite 4300, Department of Dermatology, HU14, UPC II, Hershey, PA 17033-2360; [email protected]

A 15-year-old Caucasian boy presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic brown patch on his right shoulder. While the patient’s mother first noticed the patch when he was 5 years old, the discolored area had recently been expanding in size and had developed hypertrichosis. The patient was otherwise healthy; he took no medications and denied any symptoms or history of trauma to the area. None of his siblings were similarly affected.

A physical examination revealed a well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch with an irregularly shaped border and an increased number of terminal hairs (FIGURE 1). The affected area was not indurated, and there were no muscular or skeletal abnormalities on inspection. Examination of the patch under a dermatoscope revealed islands of reticular (lattice-like) hyperpigmentation, focal hypopigmentation, and prominent follicles (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

DIAGNOSIS: Becker melanosis

Becker melanosis (also called Becker’s nevus or Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma) is an organoid hamartoma that is most common among males.1 This benign area of hyperpigmentation typically manifests as a circumscribed patch with an irregular border on the upper trunk, shoulders, or upper arms of young men. Becker melanosis is usually acquired and typically comes to medical attention around the time of puberty, although there may be a history of discoloration (as was true in this case).

A diagnosis that’s usually made clinically

Androgenic origin. Because of the male predominance and association with hypertrichosis (and for that matter, acne), androgens have been thought to play a role in the development of Becker melanosis.2 The condition affects about 1 in 200 young men.1 To date, no specific gene defect has been identified.

Underlying hypoplasia of the breast or musculoskeletal abnormalities are uncommonly associated with Becker melanosis. When these abnormalities are present, the condition is known as Becker’s nevus syndrome.3

Look for the pattern. Becker melanosis is associated with homogenous brown patches with perifollicular hypopigmentation, sometimes with a faint reticular pattern.4,5 The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, but a skin biopsy can be helpful to confirm questionable cases. Dermoscopy can also assist in diagnosis. In this case, our patient’s presentation was typical, and additional studies were not needed.

Other causes of hyperpigmentation

The differential diagnosis includes other localized disorders associated with hyperpigmentation (TABLE1,3,4).

Continue to: Morphea

Morphea represents a thickening of collagen bundles in the skin. Although morphea can affect the shoulder and trunk, as Becker melanosis does, lesions of morphea feel firm to the touch and are not associated with hypertrichosis.

Localized post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs following a traumatic event, such as a burn, or a prior dermatosis, such as zoster. Careful history-taking can uncover an antecedent inflammatory condition. Post-inflammatory pigment changes do not typically result in hypertrichosis.

Café-au-lait macules can manifest as isolated areas of discoloration. These macules can be an important indicator of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder in which tumors grow in the nervous system. Melanocytic hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules), axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign), or multiple cutaneous neurofibromas serve as additional clues to neurofibromatosis. In ambiguous cases, a skin biopsy can help differentiate a café au lait macule from Becker melanosis.

To treat or not to treat?

No treatment other than reassurance is needed in most cases of Becker melanosis, as it is a benign condition. Protecting the area from sunlight can minimize darkening and contrast with the surrounding skin. Electrolysis and laser therapy can be used to treat the associated hypertrichosis; laser therapy can also reduce the hyperpigmentation. Nonablative fractional resurfacing accompanied by laser hair removal is also reported to be of value.6

Our patient was satisfied with reassurance of the benign nature of the condition and did not elect treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, 500 University Drive, Suite 4300, Department of Dermatology, HU14, UPC II, Hershey, PA 17033-2360; [email protected]

1. Rabinovitz HS, Barnhill RL. Benign melanocytic neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012;112:1853-1854.

2. Person JR, Longcope C. Becker’s nevus: an androgen-mediated hyperplasia with increased androgen receptors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:235-238.

3. Cosendey FE, Martinez NS, Bernhard GA, et al. Becker nevus syndrome. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:379-384.

4. Ingordo V, Iannazzone SS, Cusano F, et al. Dermoscopic features of congenital melanocytic nevus and Becker nevus in an adult male population: an analysis with 10-fold magnification. Dermatology. 2006;212:354-360.

5. Luk DC, Lam SY, Cheung PC, et al. Dermoscopy for common skin problems in Chinese children using a novel Hong Kong-made dermoscope. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:495-503.

6. Balaraman B, Friedman PM. Hypertrichotic Becker’s nevi treated with combination 1,550nm non-ablative fractional photothermolysis and laser hair removal. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:350-353.

1. Rabinovitz HS, Barnhill RL. Benign melanocytic neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012;112:1853-1854.

2. Person JR, Longcope C. Becker’s nevus: an androgen-mediated hyperplasia with increased androgen receptors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:235-238.

3. Cosendey FE, Martinez NS, Bernhard GA, et al. Becker nevus syndrome. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:379-384.

4. Ingordo V, Iannazzone SS, Cusano F, et al. Dermoscopic features of congenital melanocytic nevus and Becker nevus in an adult male population: an analysis with 10-fold magnification. Dermatology. 2006;212:354-360.

5. Luk DC, Lam SY, Cheung PC, et al. Dermoscopy for common skin problems in Chinese children using a novel Hong Kong-made dermoscope. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:495-503.

6. Balaraman B, Friedman PM. Hypertrichotic Becker’s nevi treated with combination 1,550nm non-ablative fractional photothermolysis and laser hair removal. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:350-353.

How could improved provider communication have improved the care this patient received?

THE CASE

A 40-year-old white woman presented to clinic with multiple pruritic skin lesions on her abdomen, arms, and legs that had developed over a 2-month period. The patient reported that she’d been feeling tired and had been experiencing psychological stressors in her personal life. Her medical history was significant for psoriasis (which was controlled), and her family history was significant for breast and bone cancer (mother) and asbestos-related lung cancer (maternal grandfather).

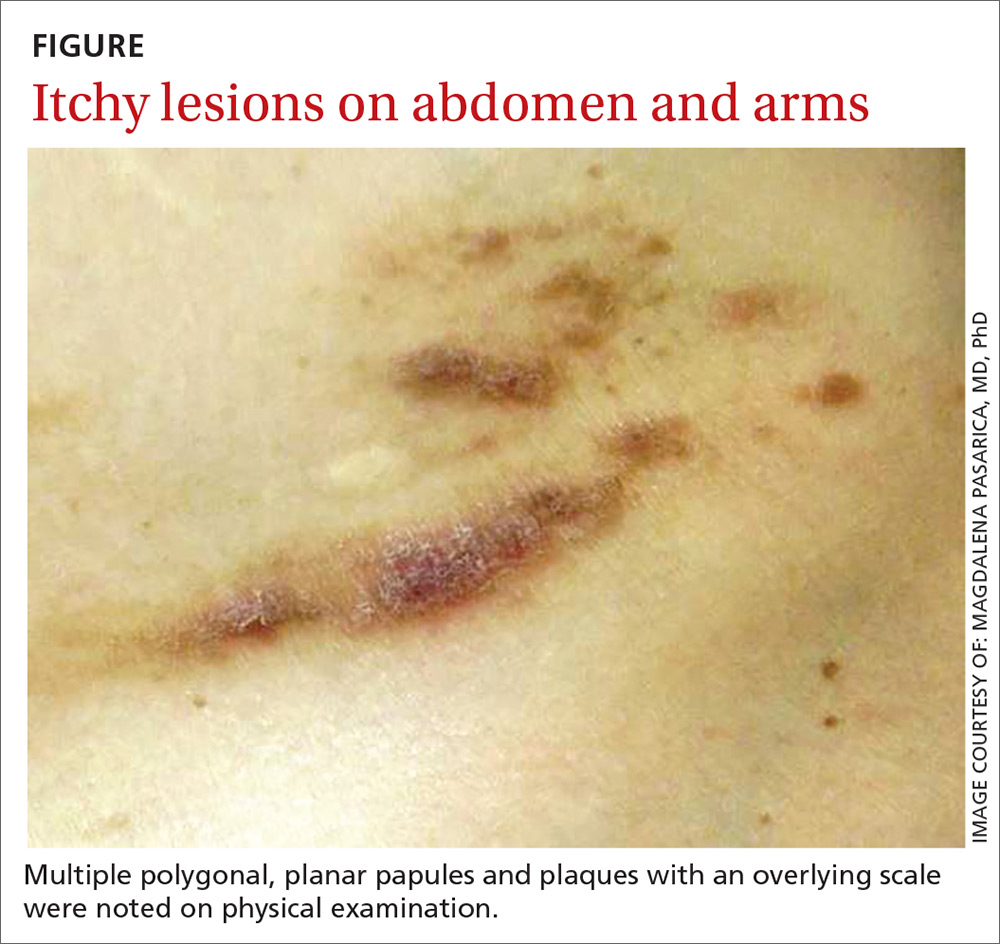

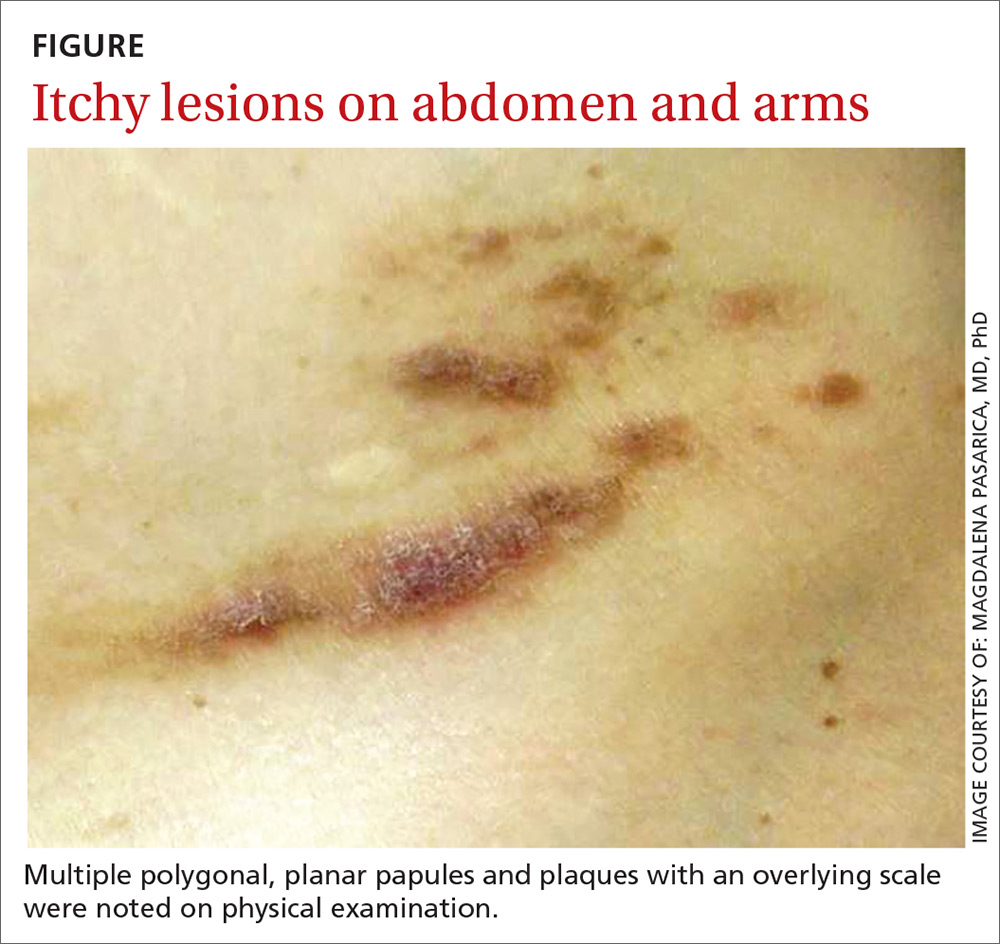

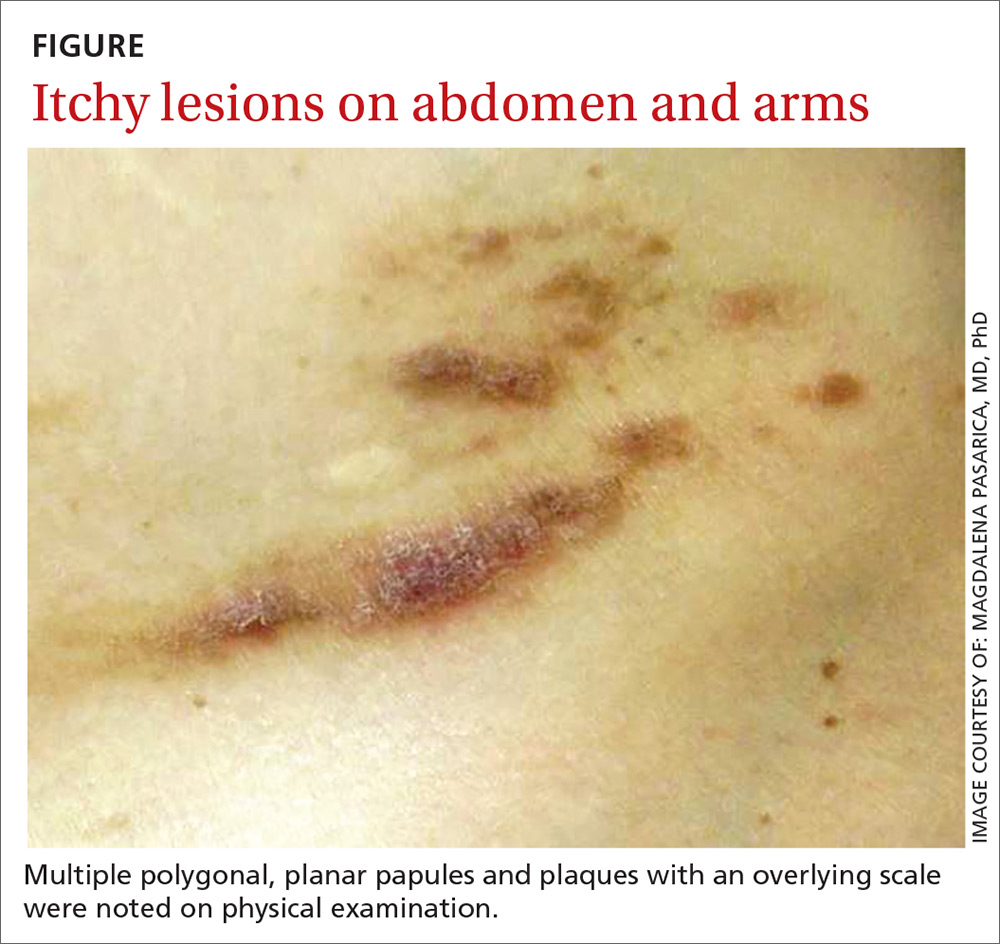

A physical examination, which included breast and pelvic exams, was unremarkable apart from the lesions located on her abdomen, arms, and legs. On skin examination, we noted multiple polygonal, planar papules and plaques of varying size with an overlying scale (FIGURE).

THE DIAGNOSIS

The physician obtained a biopsy of one of the skin lesions, and it was sent to a dermatopathologist to evaluate. Unfortunately, though, the patient’s history and a description of the lesion were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form. Based on the biopsy sample alone, the dermatopathologist’s report indicated a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis.

A search for malignancy. Any case of sudden, extensive seborrheic keratosis is suspected to be a Leser-Trélat sign, which is known to be associated with human immunodeficiency virus or underlying malignancy—especially in the gastrointestinal system. The physician talked to the patient about the possibility of malignancy, and an extensive work-up was performed, including multiple laboratory tests, computed tomography (CT) imaging, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, a colonoscopy, and mammography. None of the test results showed signs of an underlying malignancy.

In light of the negative findings, the physician reached out to the dermatopathologist to further discuss the case. It was determined that the dermatopathologist did not receive any clinical information (prior to this discussion) from the primary care office. This was surprising to the primary care physician, who was under the assumption that the clinical chart would be sent along with the biopsy sample. With this new information, the dermatopathologist reexamined the slides and diagnosed the lesion as lichen planus, a rather common skin disease not associated with cancer.

[polldaddy:10153197]

DISCUSSION

A root-cause analysis of this case identified multiple system failures, focused mainly on a lack of communication between providers:

- The description of the lesion and of the patient’s history were not included with the initial biopsy requisition form due to a lack of communication between the nurse and the physician performing the procedure.

- The dermatopathologist did not seek additional clinical information from the referring physician after receiving the sample.

- When the various providers did communicate, an accurate diagnosis was reached—but only after extensive investigation (and worry).

Communication is key to an accurate diagnosis

In 2000, it was estimated that health care costs due to preventable adverse events represent more than half of the $37.6 billion spent on health care.1 Since then, considerable effort has been made to address patient safety, misdiagnosis, and cost-effectiveness. Root cause analysis is one of the most popular methods used to evaluate and prevent future serious adverse events.2

Continue to: Diagnostic errors are often unreported...

Diagnostic errors are often unreported or unrecognized, especially in the outpatient setting.3 Studies focused on reducing diagnostic error show that a second review of pathology slides reduces error, controls costs, and improves quality of health care.4

Don’t rely (exclusively) on the health record. Gaps in effective communication between providers are a leading cause of preventable adverse events.5,6 The incorporation of electronic health records has allowed for more streamlined communication between providers. However, the mere presence of patient records in a common system does not guarantee the receipt or communication of information. The next step after entering the information into the record is to communicate it.

Our patient underwent a battery of costly and unnecessary tests and procedures, many of which were unwarranted at her age. In addition to being exposed to harmful radiation, she also experienced significant stress secondary to the tests and anticipation of the results. However, a root cause analysis of the case led to an improved protocol for communication between providers at the outpatient clinic. We now emphasize the necessity of including a clinical history and corresponding physical findings with all biopsies. We also encourage more direct communication between nursing staff, primary care physicians, and specialists.

THE TAKEAWAY

As medical professionals become increasingly reliant on the many emerging studies available to them, we sometimes forget that communication is key to optimal medical care, an accurate diagnosis, and patient safety.

Continue to: In addition, a second review...

In addition, a second review of dermatopathologic slides may be warranted if the pathologic diagnosis is inconsistent with the clinical picture or if the diagnosed condition is resistant to the usual therapies of choice. Incorrect diagnoses are more likely to occur when tests are interpreted in a vacuum without the corresponding clinical correlation. The weight of these mistakes is felt not only by the health care system, but by the patients themselves.

CORRESPONDENCE

Magdalena Pasarica, MD, PhD, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, 6850 Lake Nona Boulevard, Orlando, FL 32827; [email protected]

1. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.