User login

Small fibers, large impact

The details about an individual’s search for information tell us a lot about healthcare concerns and uncertainty across the medical universe. For nearly a decade, one of the most “clicked on” papers we have published in the Journal has been a review of small fiber neuropathy—a clinical entity with a prevalence of perhaps 1 in 1,000 to 2,000 people and, to my knowledge, no associated walkathons or arm bracelets. Yet it certainly piques the interest of clinicians from many specialties far broader than neurology. In this issue of the Journal, Dr. Jinny Tavee updates her 2009 review and provides us with a clinical overview of the disorder and the opportunity to assess how much further we need to more fully understand its management and associated comorbid conditions.

The wide interest in this disorder plugs into our current seeming epidemic of patients with chronic pain. It seems that almost half of my new patients have issues related to chronic pain that are not directly explained by active inflammation or anatomic damage. Many of these patients have diffuse body pains with associated fatigue and sleep disorders and are diagnosed with fibromyalgia. But others describe pain with a burning and tingling quality that seems of neurologic origin, yet their neurologic examination is normal. A few describe a predominantly distal symmetric stocking-and-glove distribution, but most do not. In some patients these pains are spatially random and evanescent, which to me are usually the hardest to fathom. Nerve conduction studies, when performed, are unrevealing.

A number of systemic autoimmune disorders, as discussed by Dr. Tavee in her article, are suggested to have an association with these symptoms. Given the chronicity and the frustrating nature of the symptoms, it is no surprise that a panoply of immune serologies are frequently ordered. Invariably, since serologies (eg, ANA, SSA, SSB, rheumatoid factor) are not specific for any single entity, some will return as positive. The strength of many of these associations is weak; even when the clinical diagnosis of lupus, for example, is definite, treatment of the underlying disease does not necessarily improve the dysesthetic pain. In an alternative scenario, the small fiber neuropathy is ascribed to a systemic autoimmune disorder that has been diagnosed because an autoantibody has been detected, but this rarely helps the patient and may in fact worsen symptoms by increasing anxiety and concern over having a systemic disease such as Sjögren syndrome or lupus (both of which sound terrible when reviewed on the Internet).

Some patients describe autonomic symptoms. Given the biologic basis that has been defined for this entity, it is no surprise that some patients have marked symptoms of decreased exocrine gland function, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and orthostasis. These symptoms may not be recognized unless specifically sought out when interviewing the patient.

Given the chronicity and sometimes the vagaries of symptoms, it is often comforting for patients to get an actual diagnosis. Dr. Tavee notes the relative simplicity of diagnostic procedures. But determining the clinical implications of the results may not be straightforward, and devising a fully and uniformly effective therapeutic approach eludes us still. As she points out, a multidisciplinary approach to therapy and diagnosis can be quite helpful.

The details about an individual’s search for information tell us a lot about healthcare concerns and uncertainty across the medical universe. For nearly a decade, one of the most “clicked on” papers we have published in the Journal has been a review of small fiber neuropathy—a clinical entity with a prevalence of perhaps 1 in 1,000 to 2,000 people and, to my knowledge, no associated walkathons or arm bracelets. Yet it certainly piques the interest of clinicians from many specialties far broader than neurology. In this issue of the Journal, Dr. Jinny Tavee updates her 2009 review and provides us with a clinical overview of the disorder and the opportunity to assess how much further we need to more fully understand its management and associated comorbid conditions.

The wide interest in this disorder plugs into our current seeming epidemic of patients with chronic pain. It seems that almost half of my new patients have issues related to chronic pain that are not directly explained by active inflammation or anatomic damage. Many of these patients have diffuse body pains with associated fatigue and sleep disorders and are diagnosed with fibromyalgia. But others describe pain with a burning and tingling quality that seems of neurologic origin, yet their neurologic examination is normal. A few describe a predominantly distal symmetric stocking-and-glove distribution, but most do not. In some patients these pains are spatially random and evanescent, which to me are usually the hardest to fathom. Nerve conduction studies, when performed, are unrevealing.

A number of systemic autoimmune disorders, as discussed by Dr. Tavee in her article, are suggested to have an association with these symptoms. Given the chronicity and the frustrating nature of the symptoms, it is no surprise that a panoply of immune serologies are frequently ordered. Invariably, since serologies (eg, ANA, SSA, SSB, rheumatoid factor) are not specific for any single entity, some will return as positive. The strength of many of these associations is weak; even when the clinical diagnosis of lupus, for example, is definite, treatment of the underlying disease does not necessarily improve the dysesthetic pain. In an alternative scenario, the small fiber neuropathy is ascribed to a systemic autoimmune disorder that has been diagnosed because an autoantibody has been detected, but this rarely helps the patient and may in fact worsen symptoms by increasing anxiety and concern over having a systemic disease such as Sjögren syndrome or lupus (both of which sound terrible when reviewed on the Internet).

Some patients describe autonomic symptoms. Given the biologic basis that has been defined for this entity, it is no surprise that some patients have marked symptoms of decreased exocrine gland function, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and orthostasis. These symptoms may not be recognized unless specifically sought out when interviewing the patient.

Given the chronicity and sometimes the vagaries of symptoms, it is often comforting for patients to get an actual diagnosis. Dr. Tavee notes the relative simplicity of diagnostic procedures. But determining the clinical implications of the results may not be straightforward, and devising a fully and uniformly effective therapeutic approach eludes us still. As she points out, a multidisciplinary approach to therapy and diagnosis can be quite helpful.

The details about an individual’s search for information tell us a lot about healthcare concerns and uncertainty across the medical universe. For nearly a decade, one of the most “clicked on” papers we have published in the Journal has been a review of small fiber neuropathy—a clinical entity with a prevalence of perhaps 1 in 1,000 to 2,000 people and, to my knowledge, no associated walkathons or arm bracelets. Yet it certainly piques the interest of clinicians from many specialties far broader than neurology. In this issue of the Journal, Dr. Jinny Tavee updates her 2009 review and provides us with a clinical overview of the disorder and the opportunity to assess how much further we need to more fully understand its management and associated comorbid conditions.

The wide interest in this disorder plugs into our current seeming epidemic of patients with chronic pain. It seems that almost half of my new patients have issues related to chronic pain that are not directly explained by active inflammation or anatomic damage. Many of these patients have diffuse body pains with associated fatigue and sleep disorders and are diagnosed with fibromyalgia. But others describe pain with a burning and tingling quality that seems of neurologic origin, yet their neurologic examination is normal. A few describe a predominantly distal symmetric stocking-and-glove distribution, but most do not. In some patients these pains are spatially random and evanescent, which to me are usually the hardest to fathom. Nerve conduction studies, when performed, are unrevealing.

A number of systemic autoimmune disorders, as discussed by Dr. Tavee in her article, are suggested to have an association with these symptoms. Given the chronicity and the frustrating nature of the symptoms, it is no surprise that a panoply of immune serologies are frequently ordered. Invariably, since serologies (eg, ANA, SSA, SSB, rheumatoid factor) are not specific for any single entity, some will return as positive. The strength of many of these associations is weak; even when the clinical diagnosis of lupus, for example, is definite, treatment of the underlying disease does not necessarily improve the dysesthetic pain. In an alternative scenario, the small fiber neuropathy is ascribed to a systemic autoimmune disorder that has been diagnosed because an autoantibody has been detected, but this rarely helps the patient and may in fact worsen symptoms by increasing anxiety and concern over having a systemic disease such as Sjögren syndrome or lupus (both of which sound terrible when reviewed on the Internet).

Some patients describe autonomic symptoms. Given the biologic basis that has been defined for this entity, it is no surprise that some patients have marked symptoms of decreased exocrine gland function, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and orthostasis. These symptoms may not be recognized unless specifically sought out when interviewing the patient.

Given the chronicity and sometimes the vagaries of symptoms, it is often comforting for patients to get an actual diagnosis. Dr. Tavee notes the relative simplicity of diagnostic procedures. But determining the clinical implications of the results may not be straightforward, and devising a fully and uniformly effective therapeutic approach eludes us still. As she points out, a multidisciplinary approach to therapy and diagnosis can be quite helpful.

Pancreatitis: The great masquerader?

A 55-year-old man presented to the emergency department with 1 week of bilateral lower-extremity joint pain associated with painful skin nodules. He had a history of chronic recurrent alcoholic pancreatitis. He denied abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Results of initial laboratory testing:

- Alkaline phosphatase 300 IU/L (reference range 36–108)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 81 mm/h (0–15)

- Lipase 20,000 U/L (16–61).

AN ATYPICAL PRESENTATION OF A COMMON DISEASE

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is a rare systemic complication of pancreatic disease occurring most often in middle-aged men with an acute exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis and a history of alcohol use disorder.1,2 It is also associated with pancreatic pseudocyst, pancreas divisum, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.3–6 It is characterized by systemic fat necrosis secondary to severe and persistent elevation of pancreatic enzymes. The mortality rate is high; in a case series of 25 patients, 24% died within days to weeks after admission.1

Clinical presentation and treatment

The diagnosis of pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is often missed. Abdominal pain is mild or absent in over 60% of patients.1 Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required for early diagnosis.

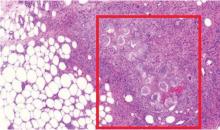

The differential diagnosis includes sarcoidosis (including Löfgren syndrome), subcutaneous infection, and vasculitis. “Ghost adipocytes” on skin biopsy are pathognomonic for pancreatic panniculitis and are the result of saponification; they appear to be anuclear, with basophilic material throughout the cytoplasm.7 Arthrocentesis of affected joints may reveal thick, creamy material, rich in triglycerides, which is diagnostic of pancreatic arthritis.1,8

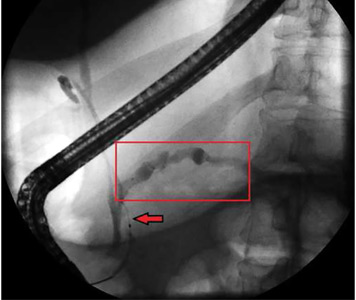

Treatment relies on correction of the underlying pancreatic pathology. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome has been successfully treated by cyst gastrostomy, pancreatic duct stenting, and pancreaticoduodenectomy.7,9–11

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome mimics rheumatologic disease and often presents without abdominal pain.

- The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of elevated serum lipase or amylase, pancreatic imaging showing pancreatitis, and ghost adipocytes on skin biopsy.

- Treatment is aimed at correcting the underlying pancreatic abnormality.

- Narváez J, Bianchi MM, Santo P, et al. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010; 39(5):417–423. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.10.001

- Mourad FH, Hannoush HM, Bahlawan M, Uthman I, Uthman S. Panniculitis and arthritis as the presenting manifestation of chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 32(3):259–261. pmid:11246359

- Borowicz J, Morrison M, Hogan D, Miller R. Subcutaneous fat necrosis/panniculitis and polyarthritis associated with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a rare presentation of pancreatitis, panniculitis and polyarthritis syndrome. J Drugs Dermatol 2010; 9(9):1145–1150. pmid:20865849

- Hudson-Peacock MJ, Regnard CF, Farr PM. Liquefying panniculitis associated with acinous carcinoma of the pancreas responding to octreotide. J R Soc Med 1994; 87(6):361–362. pmid:8046712

- Vasdev V, Bhakuni D, Narayanan K, Jain R. Intramedullary fat necrosis, polyarthritis and panniculitis with pancreatic tumor: a case report. Int J Rheum Dis 2010; 13(4):e74–e78. doi:10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01548.x

- Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 14(2 pt 2):331–334. pmid:3950133

- Francombe J, Kingsnorth AN, Tunn E. Panniculitis, arthritis and pancreatitis. Br J Rheumatol 1995; 34(7):680–683. pmid:7670790

- Price-Forbes AN, Filer A, Udeshi UL, Rai A. Progression of imaging in pancreatitis panniculitis polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol 2006; 35(1):72–74. doi:10.1080/03009740500228073

- Harris MD, Bucobo JC, Buscaglia JM. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis syndrome successfully treated with EUS-guided cyst-gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72(2):456–458. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.11.040

- Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, Thompson JN, Hughes JM, Walters JR. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(9):1835–1837. pmid:8792709

- Potts JR. Pancreatic-portal vein fistula with disseminated fat necrosis treated by pancreaticoduodenectomy. South Med J 1991; 84(5):632–635. pmid:2035087

A 55-year-old man presented to the emergency department with 1 week of bilateral lower-extremity joint pain associated with painful skin nodules. He had a history of chronic recurrent alcoholic pancreatitis. He denied abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Results of initial laboratory testing:

- Alkaline phosphatase 300 IU/L (reference range 36–108)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 81 mm/h (0–15)

- Lipase 20,000 U/L (16–61).

AN ATYPICAL PRESENTATION OF A COMMON DISEASE

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is a rare systemic complication of pancreatic disease occurring most often in middle-aged men with an acute exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis and a history of alcohol use disorder.1,2 It is also associated with pancreatic pseudocyst, pancreas divisum, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.3–6 It is characterized by systemic fat necrosis secondary to severe and persistent elevation of pancreatic enzymes. The mortality rate is high; in a case series of 25 patients, 24% died within days to weeks after admission.1

Clinical presentation and treatment

The diagnosis of pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is often missed. Abdominal pain is mild or absent in over 60% of patients.1 Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required for early diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis includes sarcoidosis (including Löfgren syndrome), subcutaneous infection, and vasculitis. “Ghost adipocytes” on skin biopsy are pathognomonic for pancreatic panniculitis and are the result of saponification; they appear to be anuclear, with basophilic material throughout the cytoplasm.7 Arthrocentesis of affected joints may reveal thick, creamy material, rich in triglycerides, which is diagnostic of pancreatic arthritis.1,8

Treatment relies on correction of the underlying pancreatic pathology. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome has been successfully treated by cyst gastrostomy, pancreatic duct stenting, and pancreaticoduodenectomy.7,9–11

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome mimics rheumatologic disease and often presents without abdominal pain.

- The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of elevated serum lipase or amylase, pancreatic imaging showing pancreatitis, and ghost adipocytes on skin biopsy.

- Treatment is aimed at correcting the underlying pancreatic abnormality.

A 55-year-old man presented to the emergency department with 1 week of bilateral lower-extremity joint pain associated with painful skin nodules. He had a history of chronic recurrent alcoholic pancreatitis. He denied abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Results of initial laboratory testing:

- Alkaline phosphatase 300 IU/L (reference range 36–108)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate 81 mm/h (0–15)

- Lipase 20,000 U/L (16–61).

AN ATYPICAL PRESENTATION OF A COMMON DISEASE

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is a rare systemic complication of pancreatic disease occurring most often in middle-aged men with an acute exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis and a history of alcohol use disorder.1,2 It is also associated with pancreatic pseudocyst, pancreas divisum, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.3–6 It is characterized by systemic fat necrosis secondary to severe and persistent elevation of pancreatic enzymes. The mortality rate is high; in a case series of 25 patients, 24% died within days to weeks after admission.1

Clinical presentation and treatment

The diagnosis of pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome is often missed. Abdominal pain is mild or absent in over 60% of patients.1 Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required for early diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis includes sarcoidosis (including Löfgren syndrome), subcutaneous infection, and vasculitis. “Ghost adipocytes” on skin biopsy are pathognomonic for pancreatic panniculitis and are the result of saponification; they appear to be anuclear, with basophilic material throughout the cytoplasm.7 Arthrocentesis of affected joints may reveal thick, creamy material, rich in triglycerides, which is diagnostic of pancreatic arthritis.1,8

Treatment relies on correction of the underlying pancreatic pathology. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome has been successfully treated by cyst gastrostomy, pancreatic duct stenting, and pancreaticoduodenectomy.7,9–11

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis syndrome mimics rheumatologic disease and often presents without abdominal pain.

- The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of elevated serum lipase or amylase, pancreatic imaging showing pancreatitis, and ghost adipocytes on skin biopsy.

- Treatment is aimed at correcting the underlying pancreatic abnormality.

- Narváez J, Bianchi MM, Santo P, et al. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010; 39(5):417–423. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.10.001

- Mourad FH, Hannoush HM, Bahlawan M, Uthman I, Uthman S. Panniculitis and arthritis as the presenting manifestation of chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 32(3):259–261. pmid:11246359

- Borowicz J, Morrison M, Hogan D, Miller R. Subcutaneous fat necrosis/panniculitis and polyarthritis associated with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a rare presentation of pancreatitis, panniculitis and polyarthritis syndrome. J Drugs Dermatol 2010; 9(9):1145–1150. pmid:20865849

- Hudson-Peacock MJ, Regnard CF, Farr PM. Liquefying panniculitis associated with acinous carcinoma of the pancreas responding to octreotide. J R Soc Med 1994; 87(6):361–362. pmid:8046712

- Vasdev V, Bhakuni D, Narayanan K, Jain R. Intramedullary fat necrosis, polyarthritis and panniculitis with pancreatic tumor: a case report. Int J Rheum Dis 2010; 13(4):e74–e78. doi:10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01548.x

- Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 14(2 pt 2):331–334. pmid:3950133

- Francombe J, Kingsnorth AN, Tunn E. Panniculitis, arthritis and pancreatitis. Br J Rheumatol 1995; 34(7):680–683. pmid:7670790

- Price-Forbes AN, Filer A, Udeshi UL, Rai A. Progression of imaging in pancreatitis panniculitis polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol 2006; 35(1):72–74. doi:10.1080/03009740500228073

- Harris MD, Bucobo JC, Buscaglia JM. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis syndrome successfully treated with EUS-guided cyst-gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72(2):456–458. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.11.040

- Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, Thompson JN, Hughes JM, Walters JR. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(9):1835–1837. pmid:8792709

- Potts JR. Pancreatic-portal vein fistula with disseminated fat necrosis treated by pancreaticoduodenectomy. South Med J 1991; 84(5):632–635. pmid:2035087

- Narváez J, Bianchi MM, Santo P, et al. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010; 39(5):417–423. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.10.001

- Mourad FH, Hannoush HM, Bahlawan M, Uthman I, Uthman S. Panniculitis and arthritis as the presenting manifestation of chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 32(3):259–261. pmid:11246359

- Borowicz J, Morrison M, Hogan D, Miller R. Subcutaneous fat necrosis/panniculitis and polyarthritis associated with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a rare presentation of pancreatitis, panniculitis and polyarthritis syndrome. J Drugs Dermatol 2010; 9(9):1145–1150. pmid:20865849

- Hudson-Peacock MJ, Regnard CF, Farr PM. Liquefying panniculitis associated with acinous carcinoma of the pancreas responding to octreotide. J R Soc Med 1994; 87(6):361–362. pmid:8046712

- Vasdev V, Bhakuni D, Narayanan K, Jain R. Intramedullary fat necrosis, polyarthritis and panniculitis with pancreatic tumor: a case report. Int J Rheum Dis 2010; 13(4):e74–e78. doi:10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01548.x

- Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 14(2 pt 2):331–334. pmid:3950133

- Francombe J, Kingsnorth AN, Tunn E. Panniculitis, arthritis and pancreatitis. Br J Rheumatol 1995; 34(7):680–683. pmid:7670790

- Price-Forbes AN, Filer A, Udeshi UL, Rai A. Progression of imaging in pancreatitis panniculitis polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol 2006; 35(1):72–74. doi:10.1080/03009740500228073

- Harris MD, Bucobo JC, Buscaglia JM. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis syndrome successfully treated with EUS-guided cyst-gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72(2):456–458. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2009.11.040

- Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, Thompson JN, Hughes JM, Walters JR. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(9):1835–1837. pmid:8792709

- Potts JR. Pancreatic-portal vein fistula with disseminated fat necrosis treated by pancreaticoduodenectomy. South Med J 1991; 84(5):632–635. pmid:2035087

FDA approves cemiplimab for advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo) for the treatment of metastatic or locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, the agency announced in a press release.

The approval was granted based on data from two open-label clinical trials involving a total of 108 patients: the phase 2 EMPOWER-CSCC-1 trial (NCT02760498) and two expansion cohorts from an open-label, nonrandomized phase 1 trial.

These trials, which included 75 patients with metastatic disease and 33 with locally advanced disease, found an overall response rate of 47.2%, and most of those patients still showed ongoing responses at the time of data analysis. Among patients with metastatic disease, 5% had a complete response, according to a press release from the manufacturer, Sanofi.

This is the sixth FDA approval for a checkpoint inhibitor targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. The drug was evaluated under the FDA’s Priority Review program for drugs that represent significant improvements in the safety or effectiveness of treatments for serious conditions. Manufacturer Sanofi was granted Breakthrough Therapy designation for cemiplimab in 2017 for advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and the drug is also being reviewed by the European Medicines Agency.

Cemiplimab is administered as a 350-mg intravenous therapy every 3 weeks – costing $9,100 per treatment – until the disease progresses or patients experience unacceptable toxicity, according to the manufacturer. The most common side effects include fatigue, rash and diarrhea, but more serious adverse events can include immune-mediated reactions such as pneumonitis, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, and skin and kidney problems.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo) for the treatment of metastatic or locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, the agency announced in a press release.

The approval was granted based on data from two open-label clinical trials involving a total of 108 patients: the phase 2 EMPOWER-CSCC-1 trial (NCT02760498) and two expansion cohorts from an open-label, nonrandomized phase 1 trial.

These trials, which included 75 patients with metastatic disease and 33 with locally advanced disease, found an overall response rate of 47.2%, and most of those patients still showed ongoing responses at the time of data analysis. Among patients with metastatic disease, 5% had a complete response, according to a press release from the manufacturer, Sanofi.

This is the sixth FDA approval for a checkpoint inhibitor targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. The drug was evaluated under the FDA’s Priority Review program for drugs that represent significant improvements in the safety or effectiveness of treatments for serious conditions. Manufacturer Sanofi was granted Breakthrough Therapy designation for cemiplimab in 2017 for advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and the drug is also being reviewed by the European Medicines Agency.

Cemiplimab is administered as a 350-mg intravenous therapy every 3 weeks – costing $9,100 per treatment – until the disease progresses or patients experience unacceptable toxicity, according to the manufacturer. The most common side effects include fatigue, rash and diarrhea, but more serious adverse events can include immune-mediated reactions such as pneumonitis, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, and skin and kidney problems.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo) for the treatment of metastatic or locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, the agency announced in a press release.

The approval was granted based on data from two open-label clinical trials involving a total of 108 patients: the phase 2 EMPOWER-CSCC-1 trial (NCT02760498) and two expansion cohorts from an open-label, nonrandomized phase 1 trial.

These trials, which included 75 patients with metastatic disease and 33 with locally advanced disease, found an overall response rate of 47.2%, and most of those patients still showed ongoing responses at the time of data analysis. Among patients with metastatic disease, 5% had a complete response, according to a press release from the manufacturer, Sanofi.

This is the sixth FDA approval for a checkpoint inhibitor targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. The drug was evaluated under the FDA’s Priority Review program for drugs that represent significant improvements in the safety or effectiveness of treatments for serious conditions. Manufacturer Sanofi was granted Breakthrough Therapy designation for cemiplimab in 2017 for advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and the drug is also being reviewed by the European Medicines Agency.

Cemiplimab is administered as a 350-mg intravenous therapy every 3 weeks – costing $9,100 per treatment – until the disease progresses or patients experience unacceptable toxicity, according to the manufacturer. The most common side effects include fatigue, rash and diarrhea, but more serious adverse events can include immune-mediated reactions such as pneumonitis, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, and skin and kidney problems.

No evidence of subclinical axial involvement seen in skin psoriasis

A study of individuals with longstanding skin psoriasis but no clinical arthritis or spondylitis has found no evidence of subclinical involvement of the sacroiliac joint or spine.

The prevalence of sacroiliac lesions on blinded MRI assessment was similar in 20 patients who had skin psoriasis for a median of 23 years and in 22 healthy controls, and no sacroiliac ankylosis was seen in either group. Similarly, there was no significant difference between the two groups in spinal lesions on MRI, nor in any of the five levels of lesion frequency, Vlad A. Bratu, MD, of the department of radiology at University Hospital Basel (Switzerland) and his coauthors reported in Arthritis Care & Research.

On blinded MRI assessment, five (25%) patients with skin psoriasis and two (9.1%) controls were classified as having inflammation of the sacroiliac joint. Three of these patients in the psoriasis group and one in the control group were older than 50, and the three with psoriasis had had the condition for 26-35 years.

Dr. Bratu and his colleagues said that subclinical peripheral joint inflammation on MRI had previously been a common finding in patients who had skin psoriasis but no clinical signs of psoriatic arthritis. But given the limited evidence of concomitant subclinical axial or spinal inflammation in their study, the authors argued there was no support for routine screening for potential subclinical axial inflammation in patients with longstanding skin psoriasis.

They noted that bone marrow edema lesions in at least two sacroiliac joint quadrants were seen in 35% of patients with psoriasis and 23% of healthy controls, a finding that reflected those seen in other studies in healthy individuals.

“If a specificity threshold for a given MRI lesion of at least 0.9 is applied for axial MRI to discriminate between axial SpA [spondyloarthritis] and background variation in healthy controls or in differential diagnostic conditions, no more than 10% of healthy controls in our study should meet this criterion by an individual level data analysis,” they wrote.

The authors also pointed out the impact of age on lesion frequency, which was more evident in spinal lesions.

“This observation supports the hypothesis that some spinal alterations in higher age may reflect degenerative rather than inflammatory changes,” they wrote. “However, there is a gap in knowledge with virtually no evidence about presence and pattern of degenerative versus inflammatory spinal lesions in subjects beyond 50 years of age.”

The study was supported by the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Bratu V et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Sep 22. doi: 10.1002/acr.23767.

A study of individuals with longstanding skin psoriasis but no clinical arthritis or spondylitis has found no evidence of subclinical involvement of the sacroiliac joint or spine.

The prevalence of sacroiliac lesions on blinded MRI assessment was similar in 20 patients who had skin psoriasis for a median of 23 years and in 22 healthy controls, and no sacroiliac ankylosis was seen in either group. Similarly, there was no significant difference between the two groups in spinal lesions on MRI, nor in any of the five levels of lesion frequency, Vlad A. Bratu, MD, of the department of radiology at University Hospital Basel (Switzerland) and his coauthors reported in Arthritis Care & Research.

On blinded MRI assessment, five (25%) patients with skin psoriasis and two (9.1%) controls were classified as having inflammation of the sacroiliac joint. Three of these patients in the psoriasis group and one in the control group were older than 50, and the three with psoriasis had had the condition for 26-35 years.

Dr. Bratu and his colleagues said that subclinical peripheral joint inflammation on MRI had previously been a common finding in patients who had skin psoriasis but no clinical signs of psoriatic arthritis. But given the limited evidence of concomitant subclinical axial or spinal inflammation in their study, the authors argued there was no support for routine screening for potential subclinical axial inflammation in patients with longstanding skin psoriasis.

They noted that bone marrow edema lesions in at least two sacroiliac joint quadrants were seen in 35% of patients with psoriasis and 23% of healthy controls, a finding that reflected those seen in other studies in healthy individuals.

“If a specificity threshold for a given MRI lesion of at least 0.9 is applied for axial MRI to discriminate between axial SpA [spondyloarthritis] and background variation in healthy controls or in differential diagnostic conditions, no more than 10% of healthy controls in our study should meet this criterion by an individual level data analysis,” they wrote.

The authors also pointed out the impact of age on lesion frequency, which was more evident in spinal lesions.

“This observation supports the hypothesis that some spinal alterations in higher age may reflect degenerative rather than inflammatory changes,” they wrote. “However, there is a gap in knowledge with virtually no evidence about presence and pattern of degenerative versus inflammatory spinal lesions in subjects beyond 50 years of age.”

The study was supported by the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Bratu V et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Sep 22. doi: 10.1002/acr.23767.

A study of individuals with longstanding skin psoriasis but no clinical arthritis or spondylitis has found no evidence of subclinical involvement of the sacroiliac joint or spine.

The prevalence of sacroiliac lesions on blinded MRI assessment was similar in 20 patients who had skin psoriasis for a median of 23 years and in 22 healthy controls, and no sacroiliac ankylosis was seen in either group. Similarly, there was no significant difference between the two groups in spinal lesions on MRI, nor in any of the five levels of lesion frequency, Vlad A. Bratu, MD, of the department of radiology at University Hospital Basel (Switzerland) and his coauthors reported in Arthritis Care & Research.

On blinded MRI assessment, five (25%) patients with skin psoriasis and two (9.1%) controls were classified as having inflammation of the sacroiliac joint. Three of these patients in the psoriasis group and one in the control group were older than 50, and the three with psoriasis had had the condition for 26-35 years.

Dr. Bratu and his colleagues said that subclinical peripheral joint inflammation on MRI had previously been a common finding in patients who had skin psoriasis but no clinical signs of psoriatic arthritis. But given the limited evidence of concomitant subclinical axial or spinal inflammation in their study, the authors argued there was no support for routine screening for potential subclinical axial inflammation in patients with longstanding skin psoriasis.

They noted that bone marrow edema lesions in at least two sacroiliac joint quadrants were seen in 35% of patients with psoriasis and 23% of healthy controls, a finding that reflected those seen in other studies in healthy individuals.

“If a specificity threshold for a given MRI lesion of at least 0.9 is applied for axial MRI to discriminate between axial SpA [spondyloarthritis] and background variation in healthy controls or in differential diagnostic conditions, no more than 10% of healthy controls in our study should meet this criterion by an individual level data analysis,” they wrote.

The authors also pointed out the impact of age on lesion frequency, which was more evident in spinal lesions.

“This observation supports the hypothesis that some spinal alterations in higher age may reflect degenerative rather than inflammatory changes,” they wrote. “However, there is a gap in knowledge with virtually no evidence about presence and pattern of degenerative versus inflammatory spinal lesions in subjects beyond 50 years of age.”

The study was supported by the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Bratu V et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Sep 22. doi: 10.1002/acr.23767.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The prevalence of sacroiliac bone marrow lesions was similar between patients with skin psoriasis and healthy controls.

Study details: Case-control study in 20 patients with skin psoriasis and 22 healthy controls.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Bratu V et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2018 Sep 22. doi: 10.1002/acr.23767.

Sporting an Old Lesion

The lesion on this 12-year-old girl’s trunk has been present since birth, growing slowly as she has. Recently, an abrasion sustained during a basketball game caused the lesion to become swollen and tender. It has since returned to its original size and nontender state, but the change in appearance raised enough concern to prompt dermatologic consultation.

The child is otherwise healthy and reports having had very few sunburns, tanning easily (though seldom).

EXAMINATION

The lesion—an oval, nevoid, hair-bearing, uniformly brown plaque with a mammilated surface—is located on the right lower anterior abdominal wall and measures just short of 3 cm x 2 cm. It bears no sign of the recent trauma. The margins are clearly defined, and the lesion is nontender on palpation. No increased warmth is detected.

Overall, the patient’s type III skin has little, if any, evidence of excessive sun exposure.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) affect about 1% of newborns, appearing within months after birth. There is no unanimity in opinion regarding their origin, although they appear to be hereditary in some cases.

About 50% of CMNs occur on the trunk and 15% on the head or neck; the rest are scattered about on the extremities. The distinctive morphologic appearance of the lesion helps to distinguish it from other items in the differential, such as warts or cancer.

Only rarely do CMNs raise concern for malignant potential. (Trauma cannot cause a benign lesion to undergo malignant transformation.) So-called “giant” CMNs (> 20 cm) appear to be associated with the greatest risk, though the incidence of melanoma in children younger than 9 is only about 0.7 cases per million. Of particular concern are “bathing trunk” CMNs, which occasionally cover more than half of the body; affected patients need special attention from pediatric dermatologists who have the appropriate experience.

Neither “small” (< 2 cm) nor “medium” CMNs (> 2 cm, < 20 cm) are particularly worrisome in terms of malignancy. But depending on the location and original size, CMNs can become the object of unwanted attention or ridicule from peers—a little 1-cm lesion on an infant’s neck can grow four to six times its original size by puberty. And at that point, excision becomes much more problematic due to the likelihood of scarring.

Therefore, many experts advise excising some lesions early on, while the lesion and resulting scar are small—and before the child has a chance to develop any anxiety over it. If not excised, CMNs simply need to be watched for change (size, uniformity of color, and border).

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) < 20 cm in diameter are generally quite safe but can grow much larger—often becoming a source of ridicule.

- Depending on the size, location, and appearance of the lesion, excision is justifiable before it has a chance to grow and become problematic.

- Children younger than 10 almost never develop melanoma (the rate is 0.7 cases per million)—and even when they do, it is almost never related to malignant transformation of a CMN.

- Trauma cannot cause a benign lesion to undergo malignant transformation.

The lesion on this 12-year-old girl’s trunk has been present since birth, growing slowly as she has. Recently, an abrasion sustained during a basketball game caused the lesion to become swollen and tender. It has since returned to its original size and nontender state, but the change in appearance raised enough concern to prompt dermatologic consultation.

The child is otherwise healthy and reports having had very few sunburns, tanning easily (though seldom).

EXAMINATION

The lesion—an oval, nevoid, hair-bearing, uniformly brown plaque with a mammilated surface—is located on the right lower anterior abdominal wall and measures just short of 3 cm x 2 cm. It bears no sign of the recent trauma. The margins are clearly defined, and the lesion is nontender on palpation. No increased warmth is detected.

Overall, the patient’s type III skin has little, if any, evidence of excessive sun exposure.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) affect about 1% of newborns, appearing within months after birth. There is no unanimity in opinion regarding their origin, although they appear to be hereditary in some cases.

About 50% of CMNs occur on the trunk and 15% on the head or neck; the rest are scattered about on the extremities. The distinctive morphologic appearance of the lesion helps to distinguish it from other items in the differential, such as warts or cancer.

Only rarely do CMNs raise concern for malignant potential. (Trauma cannot cause a benign lesion to undergo malignant transformation.) So-called “giant” CMNs (> 20 cm) appear to be associated with the greatest risk, though the incidence of melanoma in children younger than 9 is only about 0.7 cases per million. Of particular concern are “bathing trunk” CMNs, which occasionally cover more than half of the body; affected patients need special attention from pediatric dermatologists who have the appropriate experience.

Neither “small” (< 2 cm) nor “medium” CMNs (> 2 cm, < 20 cm) are particularly worrisome in terms of malignancy. But depending on the location and original size, CMNs can become the object of unwanted attention or ridicule from peers—a little 1-cm lesion on an infant’s neck can grow four to six times its original size by puberty. And at that point, excision becomes much more problematic due to the likelihood of scarring.

Therefore, many experts advise excising some lesions early on, while the lesion and resulting scar are small—and before the child has a chance to develop any anxiety over it. If not excised, CMNs simply need to be watched for change (size, uniformity of color, and border).

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) < 20 cm in diameter are generally quite safe but can grow much larger—often becoming a source of ridicule.

- Depending on the size, location, and appearance of the lesion, excision is justifiable before it has a chance to grow and become problematic.

- Children younger than 10 almost never develop melanoma (the rate is 0.7 cases per million)—and even when they do, it is almost never related to malignant transformation of a CMN.

- Trauma cannot cause a benign lesion to undergo malignant transformation.

The lesion on this 12-year-old girl’s trunk has been present since birth, growing slowly as she has. Recently, an abrasion sustained during a basketball game caused the lesion to become swollen and tender. It has since returned to its original size and nontender state, but the change in appearance raised enough concern to prompt dermatologic consultation.

The child is otherwise healthy and reports having had very few sunburns, tanning easily (though seldom).

EXAMINATION

The lesion—an oval, nevoid, hair-bearing, uniformly brown plaque with a mammilated surface—is located on the right lower anterior abdominal wall and measures just short of 3 cm x 2 cm. It bears no sign of the recent trauma. The margins are clearly defined, and the lesion is nontender on palpation. No increased warmth is detected.

Overall, the patient’s type III skin has little, if any, evidence of excessive sun exposure.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) affect about 1% of newborns, appearing within months after birth. There is no unanimity in opinion regarding their origin, although they appear to be hereditary in some cases.

About 50% of CMNs occur on the trunk and 15% on the head or neck; the rest are scattered about on the extremities. The distinctive morphologic appearance of the lesion helps to distinguish it from other items in the differential, such as warts or cancer.

Only rarely do CMNs raise concern for malignant potential. (Trauma cannot cause a benign lesion to undergo malignant transformation.) So-called “giant” CMNs (> 20 cm) appear to be associated with the greatest risk, though the incidence of melanoma in children younger than 9 is only about 0.7 cases per million. Of particular concern are “bathing trunk” CMNs, which occasionally cover more than half of the body; affected patients need special attention from pediatric dermatologists who have the appropriate experience.

Neither “small” (< 2 cm) nor “medium” CMNs (> 2 cm, < 20 cm) are particularly worrisome in terms of malignancy. But depending on the location and original size, CMNs can become the object of unwanted attention or ridicule from peers—a little 1-cm lesion on an infant’s neck can grow four to six times its original size by puberty. And at that point, excision becomes much more problematic due to the likelihood of scarring.

Therefore, many experts advise excising some lesions early on, while the lesion and resulting scar are small—and before the child has a chance to develop any anxiety over it. If not excised, CMNs simply need to be watched for change (size, uniformity of color, and border).

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) < 20 cm in diameter are generally quite safe but can grow much larger—often becoming a source of ridicule.

- Depending on the size, location, and appearance of the lesion, excision is justifiable before it has a chance to grow and become problematic.

- Children younger than 10 almost never develop melanoma (the rate is 0.7 cases per million)—and even when they do, it is almost never related to malignant transformation of a CMN.

- Trauma cannot cause a benign lesion to undergo malignant transformation.

Growth lateral to right eye

The FP noted a horn-like growth on the patient's face with some scaling around it. He recommended a shave biopsy. His differential diagnosis included actinic keratosis and Bowen’s disease (also known as squamous cell carcinoma in situ).

A biopsy was performed with a DermaBlade using a shave technique deep enough to get the base of the horn and a good sampling of the abnormal-looking tissue. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed a cutaneous horn in a squamous cell carcinoma in situ.

The patient was referred to Dermatology for further treatment. Options included treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (over weeks to months), standard excision, or Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Cutaneous horn. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:985-988.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP noted a horn-like growth on the patient's face with some scaling around it. He recommended a shave biopsy. His differential diagnosis included actinic keratosis and Bowen’s disease (also known as squamous cell carcinoma in situ).

A biopsy was performed with a DermaBlade using a shave technique deep enough to get the base of the horn and a good sampling of the abnormal-looking tissue. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed a cutaneous horn in a squamous cell carcinoma in situ.

The patient was referred to Dermatology for further treatment. Options included treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (over weeks to months), standard excision, or Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Cutaneous horn. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:985-988.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP noted a horn-like growth on the patient's face with some scaling around it. He recommended a shave biopsy. His differential diagnosis included actinic keratosis and Bowen’s disease (also known as squamous cell carcinoma in situ).

A biopsy was performed with a DermaBlade using a shave technique deep enough to get the base of the horn and a good sampling of the abnormal-looking tissue. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathology report revealed a cutaneous horn in a squamous cell carcinoma in situ.

The patient was referred to Dermatology for further treatment. Options included treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (over weeks to months), standard excision, or Mohs surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Cutaneous horn. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:985-988.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Dupilumab positive in phase 3 study for treating adolescent atopic dermatitis

PARIS – Dupilumab scorched its way through a landmark pivotal phase 3 clinical trial in adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD), achieving unprecedented clinically meaningful improvements in signs and symptoms of the disease along with important quality of life benefits, Eric L. Simpson, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Indeed, akin to that previously shown in adults with moderate to severe AD in phase 3 trials that earned the biologic U.S. and European regulatory approval in the adult population, noted Dr. Simpson, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

This positive phase 3 study represents a major development in pediatric dermatology because of the pressing unmet need for better treatments for teens with moderate to severe AD whose disease can’t be controlled with topical therapies. The adolescent years are, after all, a critical period in growth and development, and a debilitating, uncontrolled disease can reshape that experience in unwelcome ways.

“Atopic dermatitis profoundly affects quality of life in adolescents and their family: The itching affects mood and sleep, these patients commonly have anxiety and depression, and the chronic and relapsing nature of the disease adversely affects the family,” the dermatologist observed.

Currently, no systemic agent is approved for pediatric patients with AD because evidence demonstrating a favorable benefit-to-risk profile has been lacking. The dupilumab study was the first-ever phase 3 trial of a biologic in such a population.

The phase 3 adolescent trial was a 16-week, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study of 251 patients aged 12-17 years with moderate to severe AD, which could not be adequately controlled with topical therapies. Participants averaged 14 years of age, with a 12-year history of AD. “These patients had the disease basically their whole life,” Dr. Simpson noted.

They were more severely affected than participants in the adult clinical trials, with mean Eczema Area And Severity Index (EASI) scores in the mid-30s and an average 56% involved body surface area. The adolescent AD patients had a heavy burden of comorbid allergic type 2 immune comorbidity: Fully 92% of them had documented asthma, food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and/or some other form of allergic comorbidity. The majority of the teens were categorized as having severe AD, whereas most participants in the adult phase 3 trials of dupilumab had moderate disease. That distinction becomes relevant in comparing the trial results.

Participants were randomized to once-monthly subcutaneous injections of dupilumab at 300 mg, following a 600-mg loading dose, or to an injection of 200 mg or 300 mg every 2 weeks with an initial dose of 400 mg or 600 mg based upon a body weight cutoff of 60 kg, or to biweekly placebo injections.

The coprimary endpoints were the proportion of patients who achieved an EASI 75 response at week 16 and achievement of an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1, meaning clear or almost clear, on a 5-point scale at week 16.

This trial introduced an important new design feature that physicians can expect to see more of in the future: regulatory agencies now want to see the effects of monotherapy in pivotal studies in AD. Previously, participants in AD studies of systemic agents could also utilize topical steroids as needed. No longer. In the adolescent dupilumab study, resort to rescue topical steroids led to exclusion from inclusion in the primary outcome results. Not surprisingly, this lack of access to rescue medication resulted in a 60% dropout rate by 16 weeks in placebo-treated controls, a 30% dropout rate in teens on dupilumab every 4 weeks, and a 20% dropout rate with biweekly dupilumab.

The EASI 75 rate at week 16 was 8.2% with placebo, 38.1% with monthly dupilumab, and 41.5% with biweekly dosing. The other coprimary endpoint – an IGA of 0 or 1 at 16 weeks – was achieved in 2.4% of controls, 17.9% with dupilumab at 300 mg every 4 weeks, and 41.5% with biweekly dosing.

Turning to secondary endpoints, Dr. Simpson reported that baseline peak pruritus Numeric Rating Scale scores dropped by 19% with placebo at 16 weeks, compared with reductions of 45.5% and 47.9% with monthly and biweekly dupilumab, respectively.

An EASI 50 response,while not as impressive as an EASI 75, is nonetheless considered clinically meaningful improvement. It was attained in 12.9% on placebo and 54.8% and 61% on monthly and biweekly dupilumab.

From a mean baseline score of 13.6 on the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, scores improved over the course of 16 weeks by a mean of 5.1 points with placebo, 8.5 points with monthly dupilumab, and 8.8 points with biweekly biologic therapy. The same pattern was noted with regard to the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure or POEM.

Adverse events mirrored those documented in the pivotal trials in adults: increased rates of mild to moderate conjunctivitis: 4.7% with placebo, 10.8% with monthly dupilumab, and 9.8% with biweekly dupilumab, along with single-digit rates of injection-site reactions. As in adult AD patients, however, these side effects were counterbalanced by significantly reduced rates of skin infections in the adolescent group: 20% during 16 weeks with placebo, and 13.3% and 11% with monthly and biweekly biologic therapy, respectively.

Study participants had a mean baseline score of 12.5 on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, which is categorized as clinically significant psychiatric disease. The impact of dupilumab therapy on those scores will be the topic of a future presentation, Dr. Simpson said.

Across the board, specific outcomes were consistently numerically better in patients who received dupilumab biweekly than monthly, albeit not statistically significantly so. Dr. Simpson thinks he knows why: Lab studies showed that the mean serum concentration of functional dupilumab in patients who got the biologic biweekly was nearly twice that for the group with monthly dosing.

At first glance, the IGA “clear” or “almost clear” response rates seen with dupilumab in the adolescent study appeared to be less robust than in the adult pivotal phase 3 trials, such as the SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 trials (N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 15;375[24]:2335-48), also led by Dr. Simpson.

“I think that’s because of the greater severity of that baseline adolescent population,” he commented. “It made for a much lower placebo response rate. But when you correct for the placebo-subtracted difference, the rates are actually pretty similar, and a lot of the other endpoints are the same or even better than in SOLO.”

After his presentation, Dr. Simpson commented, “This is huge. This is the study we’ve been waiting for.”

Elsewhere at the EADV congress, Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, deemed the pivotal phase 3 trial in adolescent AD patients one of the meeting’s highlights. And it’s a harbinger of more good things to come, because the investigational drug pipeline for AD is full of promising candidates addressing the disease from a variety of novel directions. The long therapeutic drought in AD appears to have finally ended, observed Dr. Guttman-Yassky, professor and vice-chair of the department of dermatology at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

That’s welcome news because AD is the most common inflammatory skin disease, both in adults, where the latest data puts the prevalence at 7%-10%, and in children, where the global rate is 15%-25%.

And while at the EADV congress only the 16-week data were reported in the new adolescent study, there is reason to be optimistic that the benefits will remain durable over time. Dr. Guttman-Yassky cited the published 52-week data from the large phase 3 CHRONOS trial in adults with moderate to severe AD. In that trial, in which patients could use concomitant topical steroids, the EASI 75 rates at week 16 were 69% in patients on dupilumab at 300 mg every 2 weeks, 64% with 300 mg weekly, and 23% with placebo. Reassuringly, at 52 weeks the EASI 75 response rates were essentially unchanged: 65%, 64%, and 22% (Lancet. 2017 Jun 10;389[10086]:2287-303).

“This is what we are seeking: not just treatment that is able to quickly modify disease, but we want the treatment to be sustained, and of course we want it to be safe for our patients because we know we cannot use cyclosporine for a long time,” Dr. Guttman-Yassky said.

Dr. Simpson reported serving as a consultant to and recipient of research grants from Sanofi and Regeneron, which sponsored the adolescent study, as well as more than a dozen other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported serving as an advisor and consultant, and has received grants/research funding from Regeneron, and multiple other companies.

PARIS – Dupilumab scorched its way through a landmark pivotal phase 3 clinical trial in adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD), achieving unprecedented clinically meaningful improvements in signs and symptoms of the disease along with important quality of life benefits, Eric L. Simpson, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Indeed, akin to that previously shown in adults with moderate to severe AD in phase 3 trials that earned the biologic U.S. and European regulatory approval in the adult population, noted Dr. Simpson, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

This positive phase 3 study represents a major development in pediatric dermatology because of the pressing unmet need for better treatments for teens with moderate to severe AD whose disease can’t be controlled with topical therapies. The adolescent years are, after all, a critical period in growth and development, and a debilitating, uncontrolled disease can reshape that experience in unwelcome ways.

“Atopic dermatitis profoundly affects quality of life in adolescents and their family: The itching affects mood and sleep, these patients commonly have anxiety and depression, and the chronic and relapsing nature of the disease adversely affects the family,” the dermatologist observed.

Currently, no systemic agent is approved for pediatric patients with AD because evidence demonstrating a favorable benefit-to-risk profile has been lacking. The dupilumab study was the first-ever phase 3 trial of a biologic in such a population.

The phase 3 adolescent trial was a 16-week, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study of 251 patients aged 12-17 years with moderate to severe AD, which could not be adequately controlled with topical therapies. Participants averaged 14 years of age, with a 12-year history of AD. “These patients had the disease basically their whole life,” Dr. Simpson noted.

They were more severely affected than participants in the adult clinical trials, with mean Eczema Area And Severity Index (EASI) scores in the mid-30s and an average 56% involved body surface area. The adolescent AD patients had a heavy burden of comorbid allergic type 2 immune comorbidity: Fully 92% of them had documented asthma, food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and/or some other form of allergic comorbidity. The majority of the teens were categorized as having severe AD, whereas most participants in the adult phase 3 trials of dupilumab had moderate disease. That distinction becomes relevant in comparing the trial results.

Participants were randomized to once-monthly subcutaneous injections of dupilumab at 300 mg, following a 600-mg loading dose, or to an injection of 200 mg or 300 mg every 2 weeks with an initial dose of 400 mg or 600 mg based upon a body weight cutoff of 60 kg, or to biweekly placebo injections.

The coprimary endpoints were the proportion of patients who achieved an EASI 75 response at week 16 and achievement of an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1, meaning clear or almost clear, on a 5-point scale at week 16.

This trial introduced an important new design feature that physicians can expect to see more of in the future: regulatory agencies now want to see the effects of monotherapy in pivotal studies in AD. Previously, participants in AD studies of systemic agents could also utilize topical steroids as needed. No longer. In the adolescent dupilumab study, resort to rescue topical steroids led to exclusion from inclusion in the primary outcome results. Not surprisingly, this lack of access to rescue medication resulted in a 60% dropout rate by 16 weeks in placebo-treated controls, a 30% dropout rate in teens on dupilumab every 4 weeks, and a 20% dropout rate with biweekly dupilumab.

The EASI 75 rate at week 16 was 8.2% with placebo, 38.1% with monthly dupilumab, and 41.5% with biweekly dosing. The other coprimary endpoint – an IGA of 0 or 1 at 16 weeks – was achieved in 2.4% of controls, 17.9% with dupilumab at 300 mg every 4 weeks, and 41.5% with biweekly dosing.

Turning to secondary endpoints, Dr. Simpson reported that baseline peak pruritus Numeric Rating Scale scores dropped by 19% with placebo at 16 weeks, compared with reductions of 45.5% and 47.9% with monthly and biweekly dupilumab, respectively.

An EASI 50 response,while not as impressive as an EASI 75, is nonetheless considered clinically meaningful improvement. It was attained in 12.9% on placebo and 54.8% and 61% on monthly and biweekly dupilumab.

From a mean baseline score of 13.6 on the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, scores improved over the course of 16 weeks by a mean of 5.1 points with placebo, 8.5 points with monthly dupilumab, and 8.8 points with biweekly biologic therapy. The same pattern was noted with regard to the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure or POEM.

Adverse events mirrored those documented in the pivotal trials in adults: increased rates of mild to moderate conjunctivitis: 4.7% with placebo, 10.8% with monthly dupilumab, and 9.8% with biweekly dupilumab, along with single-digit rates of injection-site reactions. As in adult AD patients, however, these side effects were counterbalanced by significantly reduced rates of skin infections in the adolescent group: 20% during 16 weeks with placebo, and 13.3% and 11% with monthly and biweekly biologic therapy, respectively.

Study participants had a mean baseline score of 12.5 on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, which is categorized as clinically significant psychiatric disease. The impact of dupilumab therapy on those scores will be the topic of a future presentation, Dr. Simpson said.

Across the board, specific outcomes were consistently numerically better in patients who received dupilumab biweekly than monthly, albeit not statistically significantly so. Dr. Simpson thinks he knows why: Lab studies showed that the mean serum concentration of functional dupilumab in patients who got the biologic biweekly was nearly twice that for the group with monthly dosing.

At first glance, the IGA “clear” or “almost clear” response rates seen with dupilumab in the adolescent study appeared to be less robust than in the adult pivotal phase 3 trials, such as the SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 trials (N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 15;375[24]:2335-48), also led by Dr. Simpson.

“I think that’s because of the greater severity of that baseline adolescent population,” he commented. “It made for a much lower placebo response rate. But when you correct for the placebo-subtracted difference, the rates are actually pretty similar, and a lot of the other endpoints are the same or even better than in SOLO.”

After his presentation, Dr. Simpson commented, “This is huge. This is the study we’ve been waiting for.”

Elsewhere at the EADV congress, Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, deemed the pivotal phase 3 trial in adolescent AD patients one of the meeting’s highlights. And it’s a harbinger of more good things to come, because the investigational drug pipeline for AD is full of promising candidates addressing the disease from a variety of novel directions. The long therapeutic drought in AD appears to have finally ended, observed Dr. Guttman-Yassky, professor and vice-chair of the department of dermatology at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

That’s welcome news because AD is the most common inflammatory skin disease, both in adults, where the latest data puts the prevalence at 7%-10%, and in children, where the global rate is 15%-25%.

And while at the EADV congress only the 16-week data were reported in the new adolescent study, there is reason to be optimistic that the benefits will remain durable over time. Dr. Guttman-Yassky cited the published 52-week data from the large phase 3 CHRONOS trial in adults with moderate to severe AD. In that trial, in which patients could use concomitant topical steroids, the EASI 75 rates at week 16 were 69% in patients on dupilumab at 300 mg every 2 weeks, 64% with 300 mg weekly, and 23% with placebo. Reassuringly, at 52 weeks the EASI 75 response rates were essentially unchanged: 65%, 64%, and 22% (Lancet. 2017 Jun 10;389[10086]:2287-303).

“This is what we are seeking: not just treatment that is able to quickly modify disease, but we want the treatment to be sustained, and of course we want it to be safe for our patients because we know we cannot use cyclosporine for a long time,” Dr. Guttman-Yassky said.

Dr. Simpson reported serving as a consultant to and recipient of research grants from Sanofi and Regeneron, which sponsored the adolescent study, as well as more than a dozen other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported serving as an advisor and consultant, and has received grants/research funding from Regeneron, and multiple other companies.

PARIS – Dupilumab scorched its way through a landmark pivotal phase 3 clinical trial in adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD), achieving unprecedented clinically meaningful improvements in signs and symptoms of the disease along with important quality of life benefits, Eric L. Simpson, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Indeed, akin to that previously shown in adults with moderate to severe AD in phase 3 trials that earned the biologic U.S. and European regulatory approval in the adult population, noted Dr. Simpson, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

This positive phase 3 study represents a major development in pediatric dermatology because of the pressing unmet need for better treatments for teens with moderate to severe AD whose disease can’t be controlled with topical therapies. The adolescent years are, after all, a critical period in growth and development, and a debilitating, uncontrolled disease can reshape that experience in unwelcome ways.

“Atopic dermatitis profoundly affects quality of life in adolescents and their family: The itching affects mood and sleep, these patients commonly have anxiety and depression, and the chronic and relapsing nature of the disease adversely affects the family,” the dermatologist observed.

Currently, no systemic agent is approved for pediatric patients with AD because evidence demonstrating a favorable benefit-to-risk profile has been lacking. The dupilumab study was the first-ever phase 3 trial of a biologic in such a population.

The phase 3 adolescent trial was a 16-week, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study of 251 patients aged 12-17 years with moderate to severe AD, which could not be adequately controlled with topical therapies. Participants averaged 14 years of age, with a 12-year history of AD. “These patients had the disease basically their whole life,” Dr. Simpson noted.

They were more severely affected than participants in the adult clinical trials, with mean Eczema Area And Severity Index (EASI) scores in the mid-30s and an average 56% involved body surface area. The adolescent AD patients had a heavy burden of comorbid allergic type 2 immune comorbidity: Fully 92% of them had documented asthma, food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and/or some other form of allergic comorbidity. The majority of the teens were categorized as having severe AD, whereas most participants in the adult phase 3 trials of dupilumab had moderate disease. That distinction becomes relevant in comparing the trial results.

Participants were randomized to once-monthly subcutaneous injections of dupilumab at 300 mg, following a 600-mg loading dose, or to an injection of 200 mg or 300 mg every 2 weeks with an initial dose of 400 mg or 600 mg based upon a body weight cutoff of 60 kg, or to biweekly placebo injections.

The coprimary endpoints were the proportion of patients who achieved an EASI 75 response at week 16 and achievement of an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1, meaning clear or almost clear, on a 5-point scale at week 16.

This trial introduced an important new design feature that physicians can expect to see more of in the future: regulatory agencies now want to see the effects of monotherapy in pivotal studies in AD. Previously, participants in AD studies of systemic agents could also utilize topical steroids as needed. No longer. In the adolescent dupilumab study, resort to rescue topical steroids led to exclusion from inclusion in the primary outcome results. Not surprisingly, this lack of access to rescue medication resulted in a 60% dropout rate by 16 weeks in placebo-treated controls, a 30% dropout rate in teens on dupilumab every 4 weeks, and a 20% dropout rate with biweekly dupilumab.

The EASI 75 rate at week 16 was 8.2% with placebo, 38.1% with monthly dupilumab, and 41.5% with biweekly dosing. The other coprimary endpoint – an IGA of 0 or 1 at 16 weeks – was achieved in 2.4% of controls, 17.9% with dupilumab at 300 mg every 4 weeks, and 41.5% with biweekly dosing.

Turning to secondary endpoints, Dr. Simpson reported that baseline peak pruritus Numeric Rating Scale scores dropped by 19% with placebo at 16 weeks, compared with reductions of 45.5% and 47.9% with monthly and biweekly dupilumab, respectively.

An EASI 50 response,while not as impressive as an EASI 75, is nonetheless considered clinically meaningful improvement. It was attained in 12.9% on placebo and 54.8% and 61% on monthly and biweekly dupilumab.

From a mean baseline score of 13.6 on the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, scores improved over the course of 16 weeks by a mean of 5.1 points with placebo, 8.5 points with monthly dupilumab, and 8.8 points with biweekly biologic therapy. The same pattern was noted with regard to the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure or POEM.

Adverse events mirrored those documented in the pivotal trials in adults: increased rates of mild to moderate conjunctivitis: 4.7% with placebo, 10.8% with monthly dupilumab, and 9.8% with biweekly dupilumab, along with single-digit rates of injection-site reactions. As in adult AD patients, however, these side effects were counterbalanced by significantly reduced rates of skin infections in the adolescent group: 20% during 16 weeks with placebo, and 13.3% and 11% with monthly and biweekly biologic therapy, respectively.

Study participants had a mean baseline score of 12.5 on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, which is categorized as clinically significant psychiatric disease. The impact of dupilumab therapy on those scores will be the topic of a future presentation, Dr. Simpson said.

Across the board, specific outcomes were consistently numerically better in patients who received dupilumab biweekly than monthly, albeit not statistically significantly so. Dr. Simpson thinks he knows why: Lab studies showed that the mean serum concentration of functional dupilumab in patients who got the biologic biweekly was nearly twice that for the group with monthly dosing.

At first glance, the IGA “clear” or “almost clear” response rates seen with dupilumab in the adolescent study appeared to be less robust than in the adult pivotal phase 3 trials, such as the SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 trials (N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 15;375[24]:2335-48), also led by Dr. Simpson.

“I think that’s because of the greater severity of that baseline adolescent population,” he commented. “It made for a much lower placebo response rate. But when you correct for the placebo-subtracted difference, the rates are actually pretty similar, and a lot of the other endpoints are the same or even better than in SOLO.”

After his presentation, Dr. Simpson commented, “This is huge. This is the study we’ve been waiting for.”

Elsewhere at the EADV congress, Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, deemed the pivotal phase 3 trial in adolescent AD patients one of the meeting’s highlights. And it’s a harbinger of more good things to come, because the investigational drug pipeline for AD is full of promising candidates addressing the disease from a variety of novel directions. The long therapeutic drought in AD appears to have finally ended, observed Dr. Guttman-Yassky, professor and vice-chair of the department of dermatology at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

That’s welcome news because AD is the most common inflammatory skin disease, both in adults, where the latest data puts the prevalence at 7%-10%, and in children, where the global rate is 15%-25%.

And while at the EADV congress only the 16-week data were reported in the new adolescent study, there is reason to be optimistic that the benefits will remain durable over time. Dr. Guttman-Yassky cited the published 52-week data from the large phase 3 CHRONOS trial in adults with moderate to severe AD. In that trial, in which patients could use concomitant topical steroids, the EASI 75 rates at week 16 were 69% in patients on dupilumab at 300 mg every 2 weeks, 64% with 300 mg weekly, and 23% with placebo. Reassuringly, at 52 weeks the EASI 75 response rates were essentially unchanged: 65%, 64%, and 22% (Lancet. 2017 Jun 10;389[10086]:2287-303).

“This is what we are seeking: not just treatment that is able to quickly modify disease, but we want the treatment to be sustained, and of course we want it to be safe for our patients because we know we cannot use cyclosporine for a long time,” Dr. Guttman-Yassky said.

Dr. Simpson reported serving as a consultant to and recipient of research grants from Sanofi and Regeneron, which sponsored the adolescent study, as well as more than a dozen other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported serving as an advisor and consultant, and has received grants/research funding from Regeneron, and multiple other companies.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Dupilumab gets solid green-light evidence for use in teens with atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Dupilumab was as safe and effective in adolescents with moderate to severe AD as previously established in adult patients.

Study details: This prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 16-week pivotal phase 3 trial included 251 adolescents with moderate to severe AD.