User login

Enlarging Nodule on the Nipple

The Diagnosis: Nipple Adenoma (Florid Papillomatosis of the Nipple)

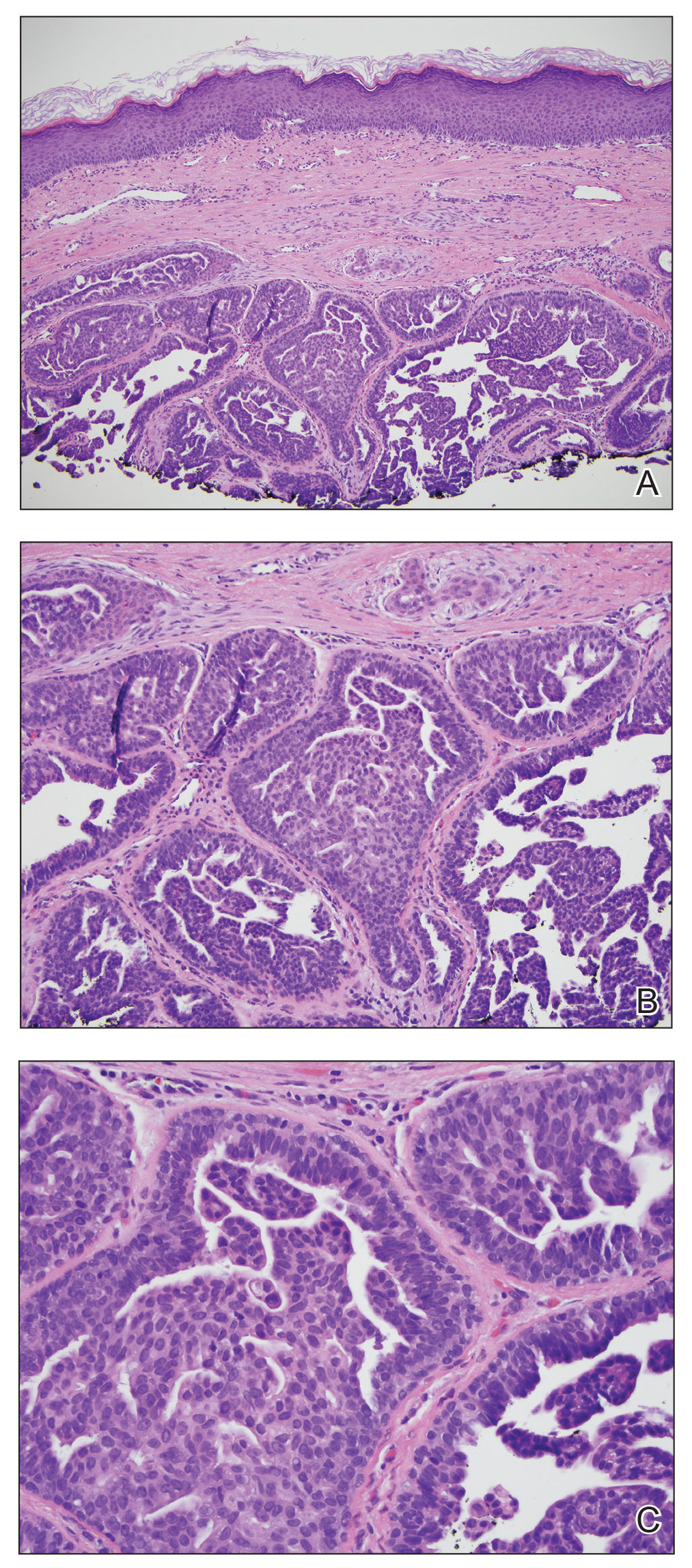

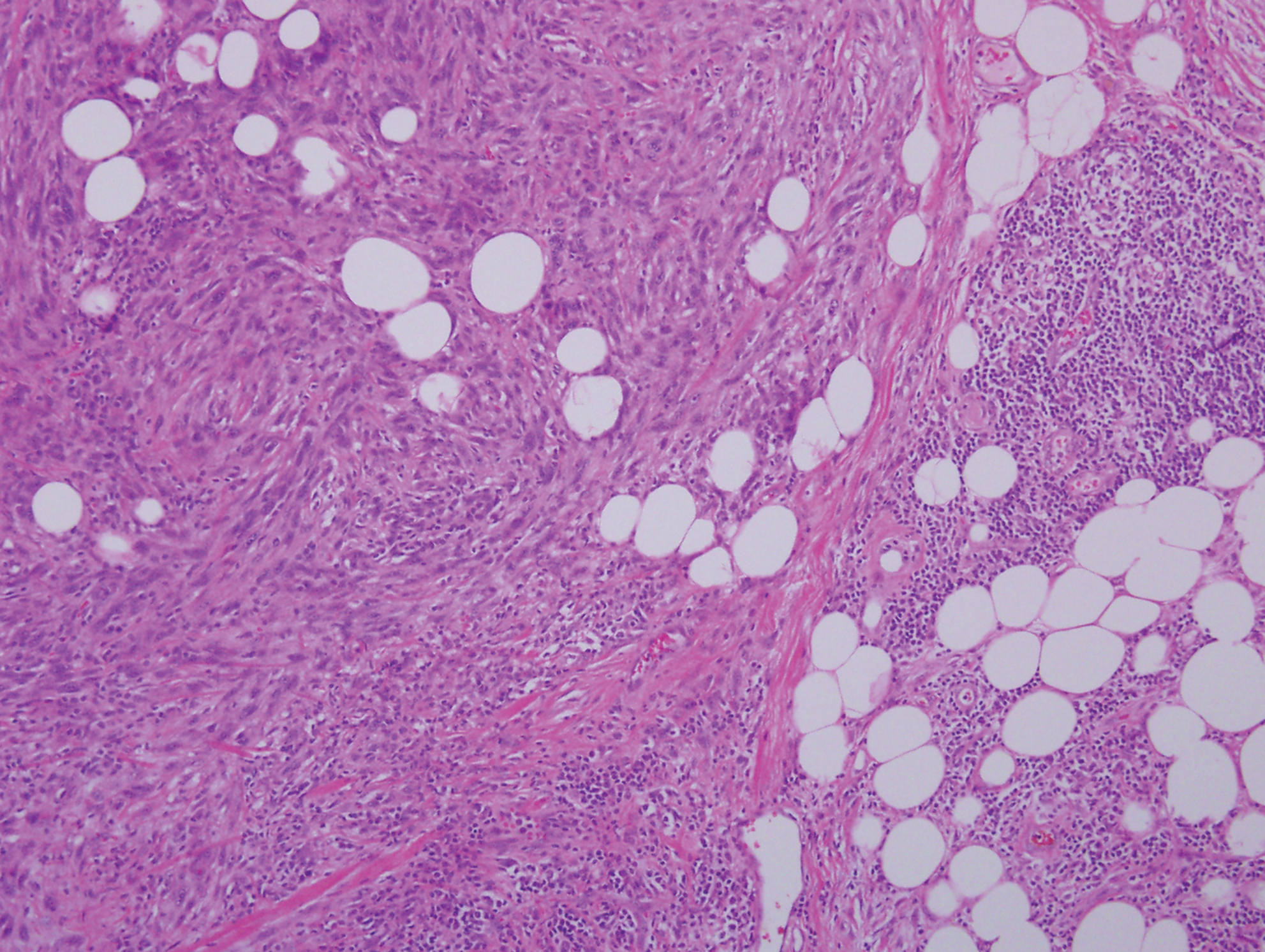

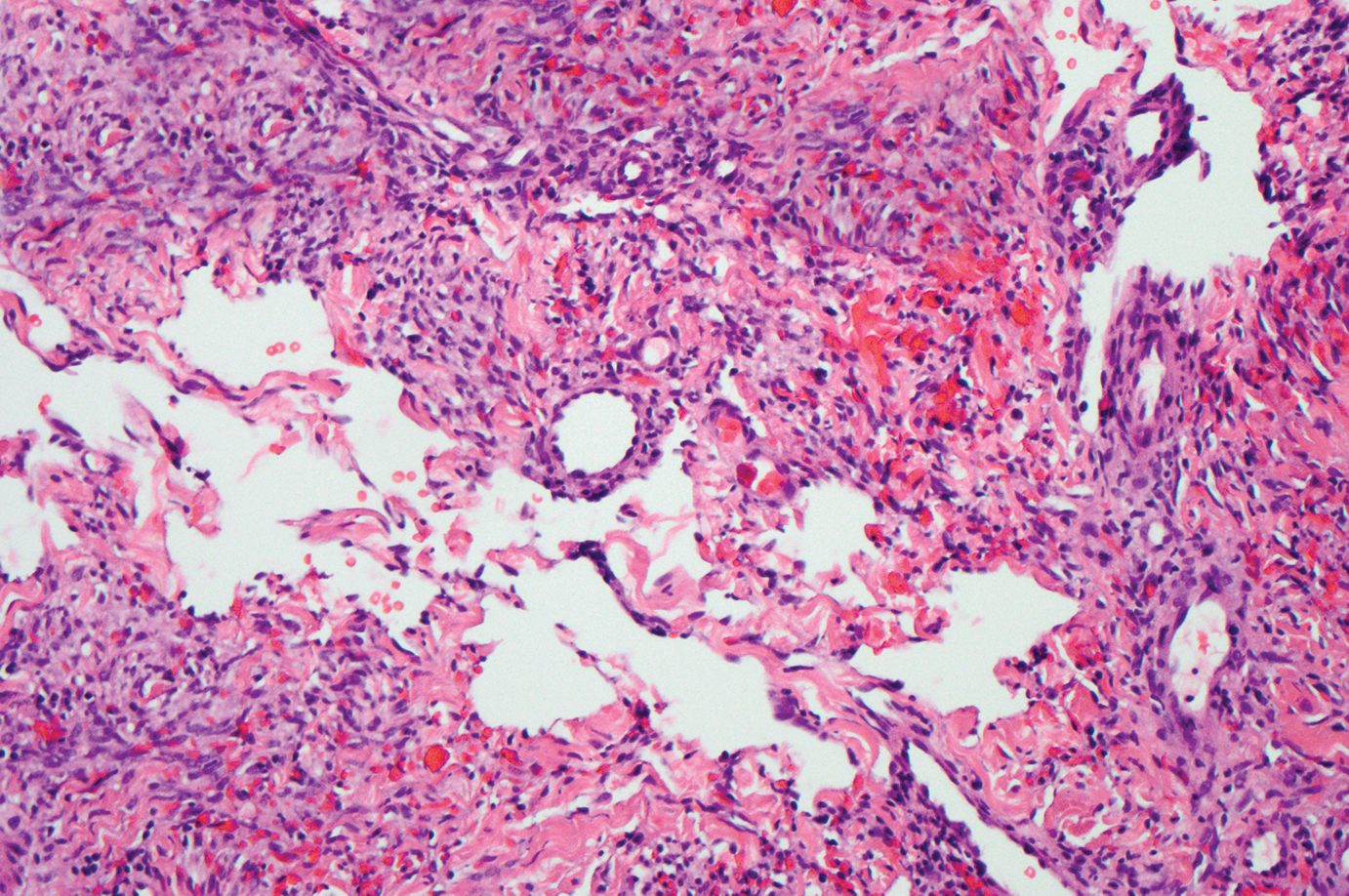

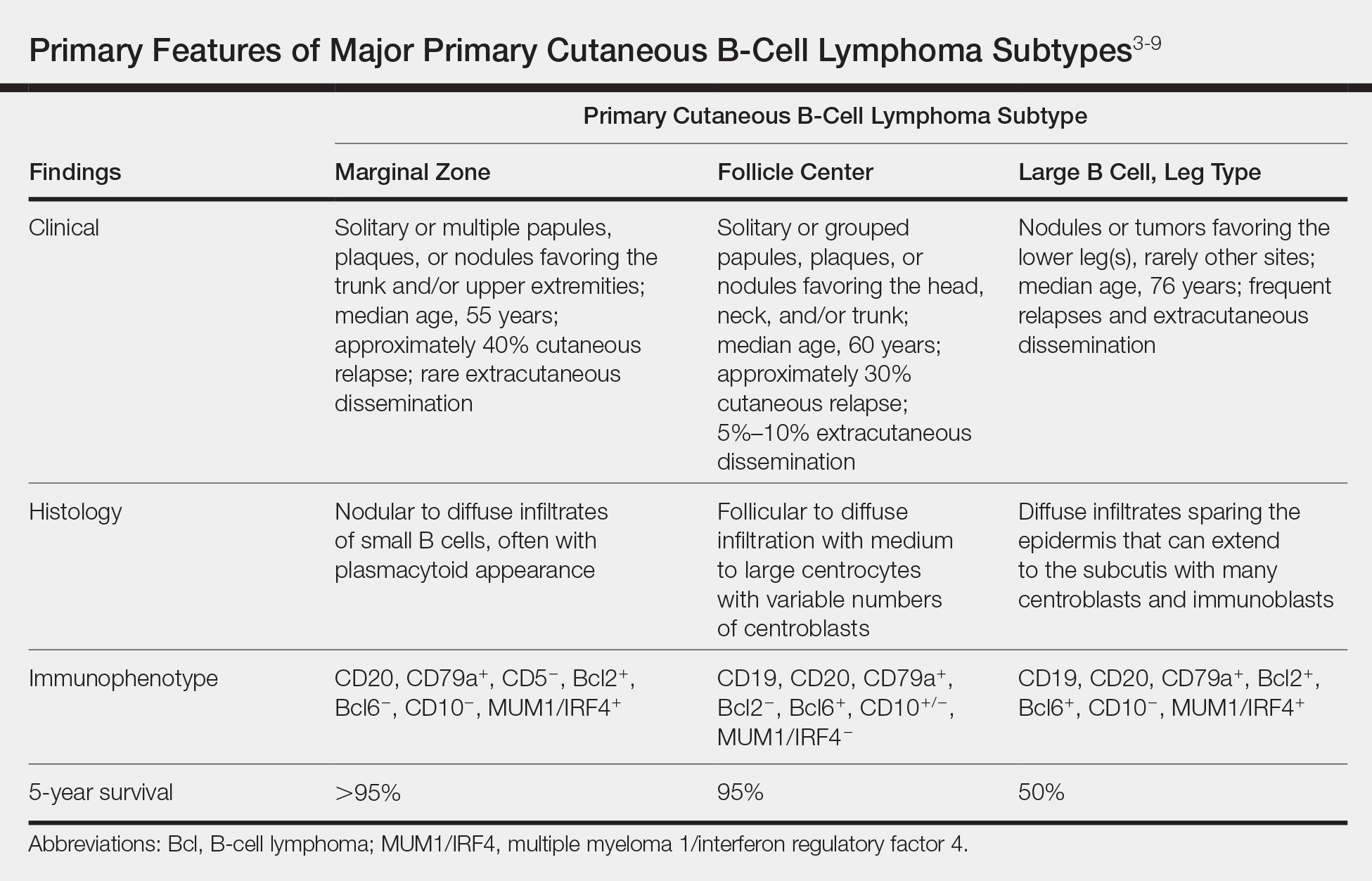

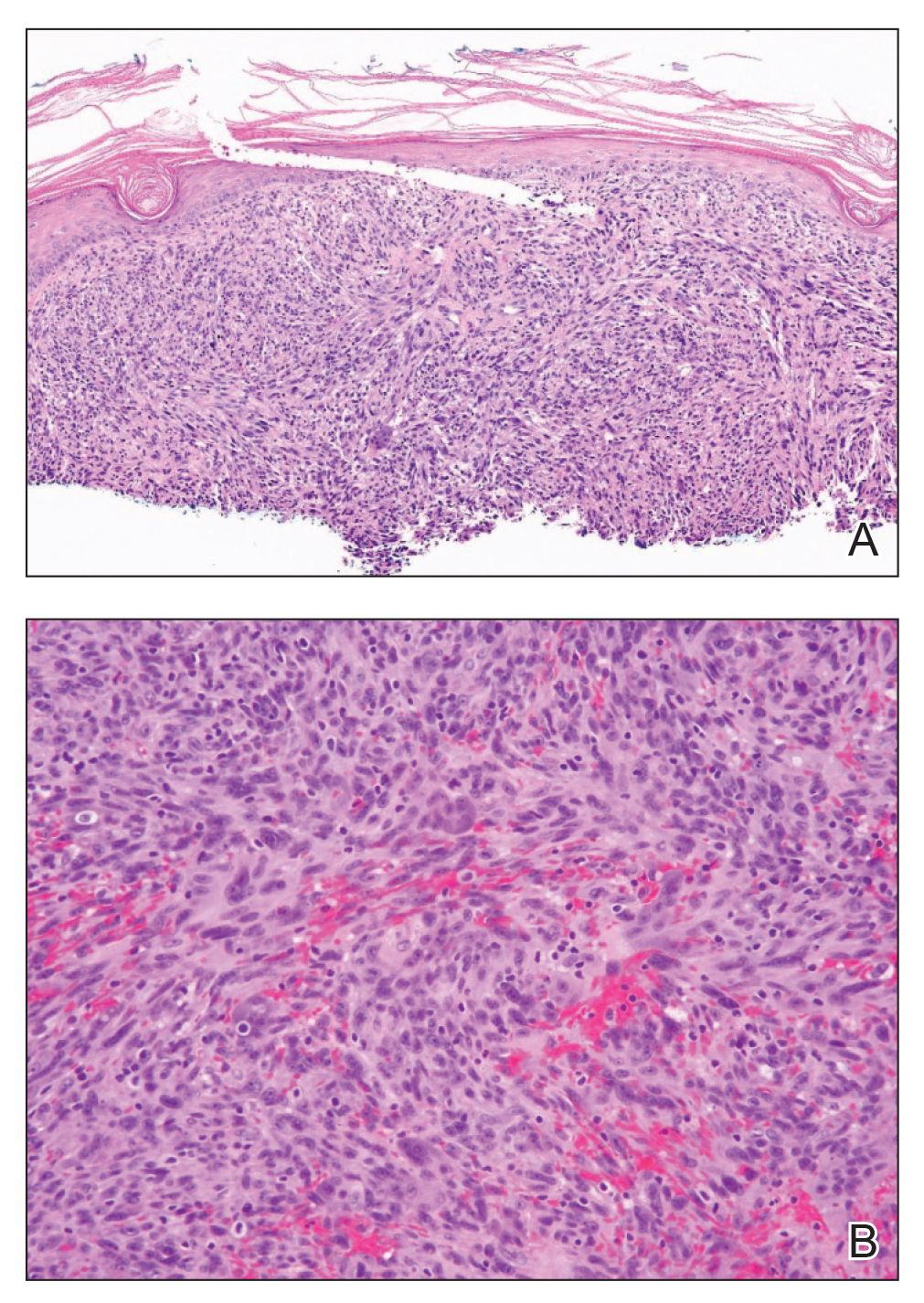

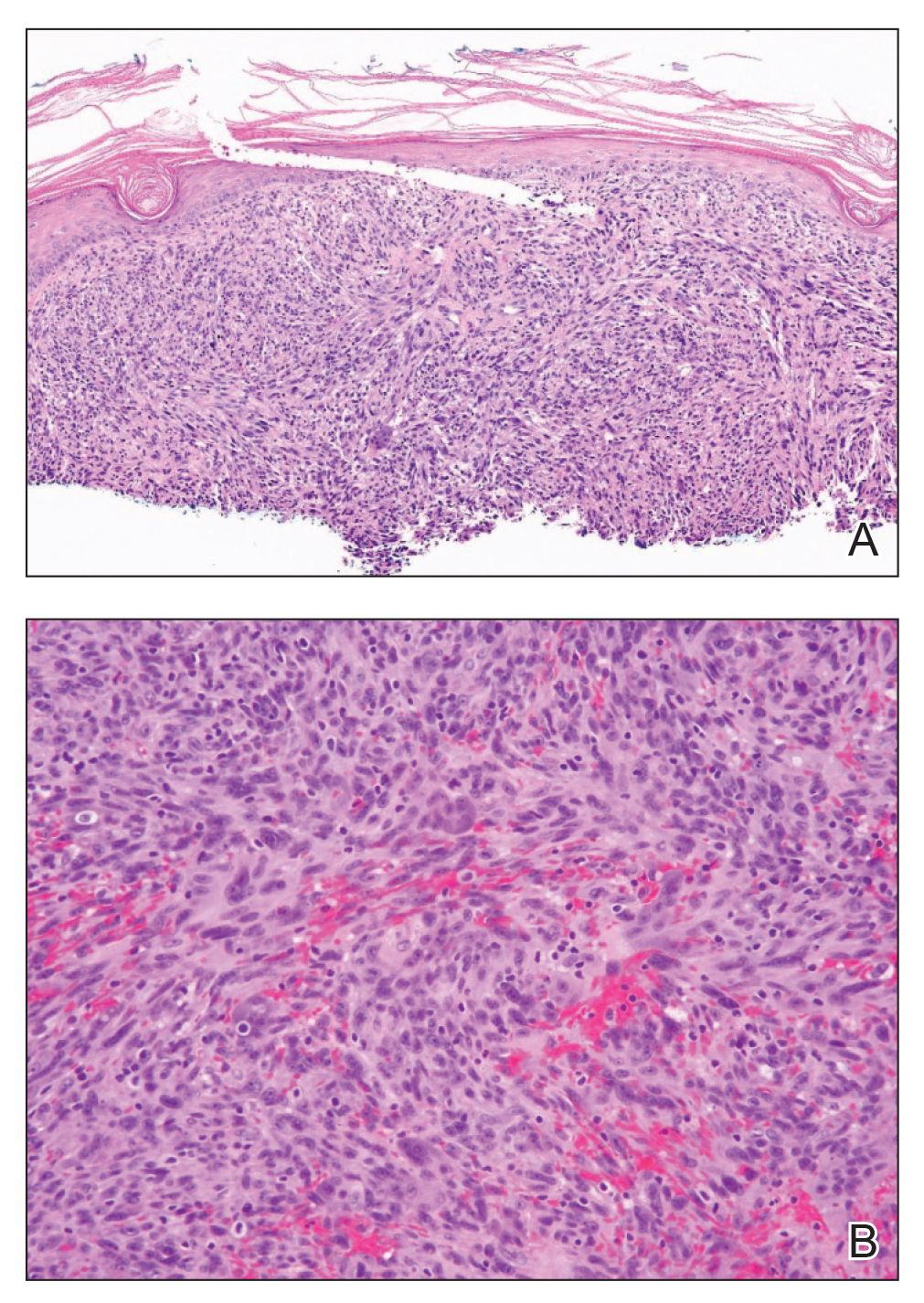

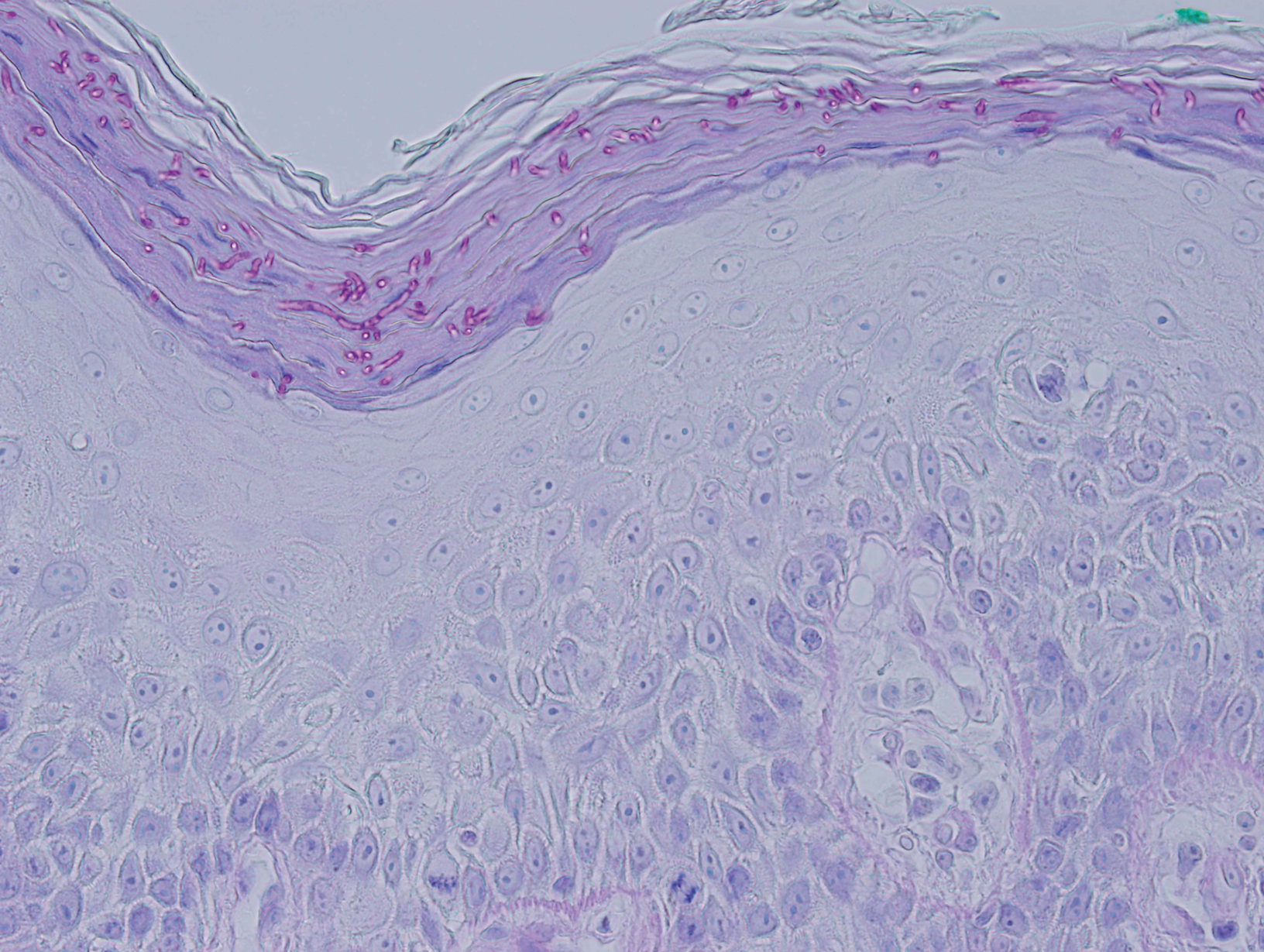

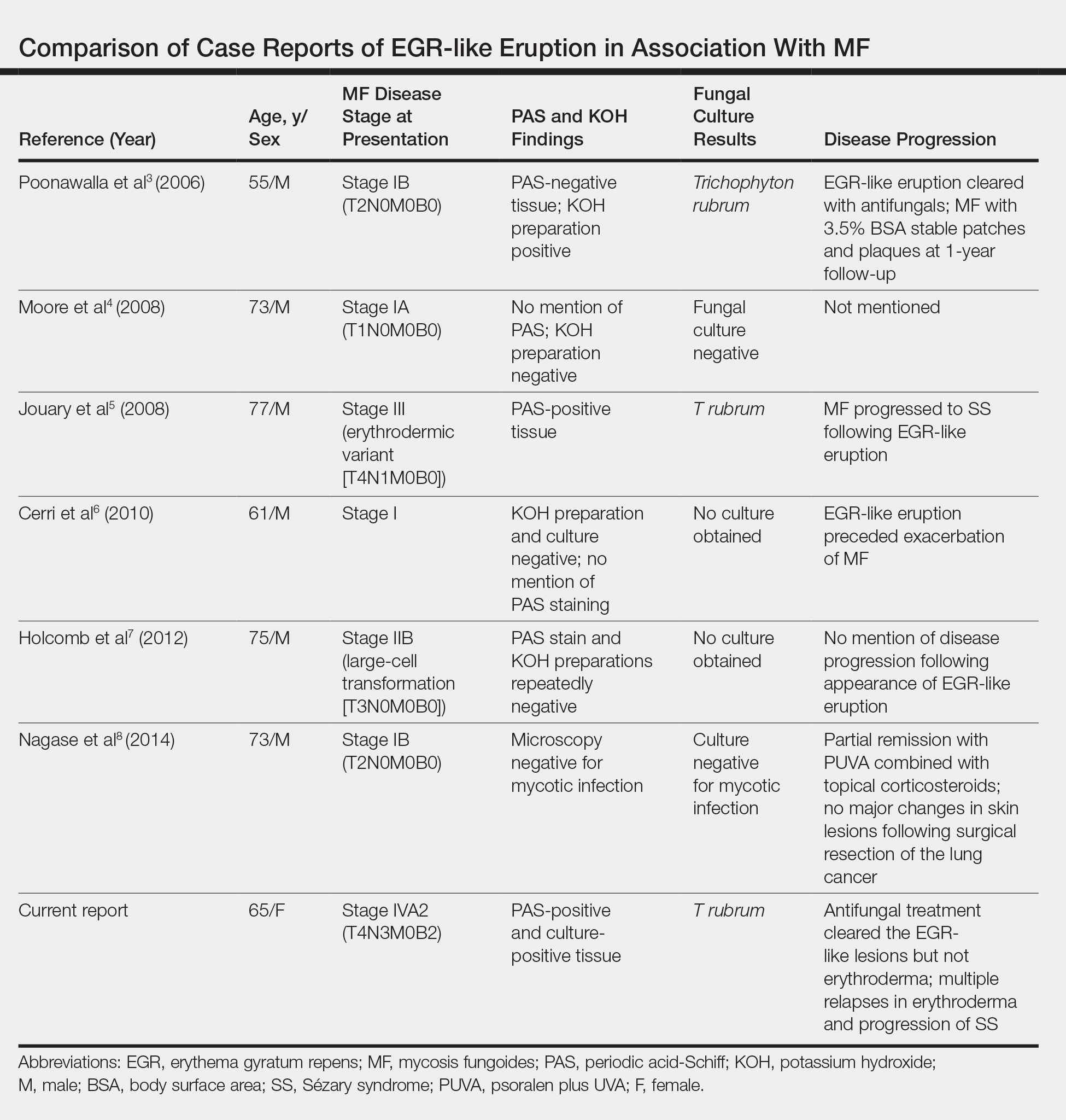

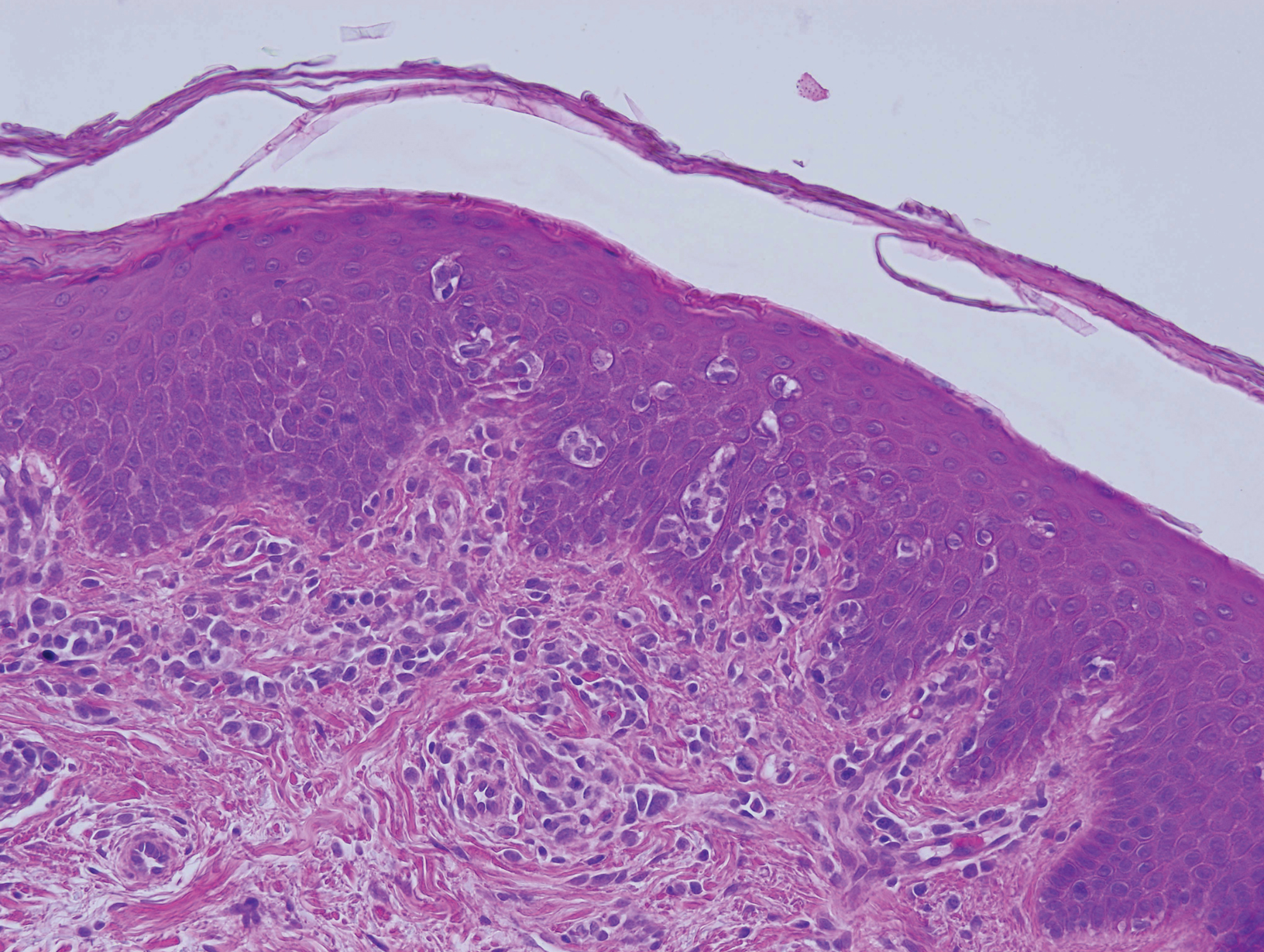

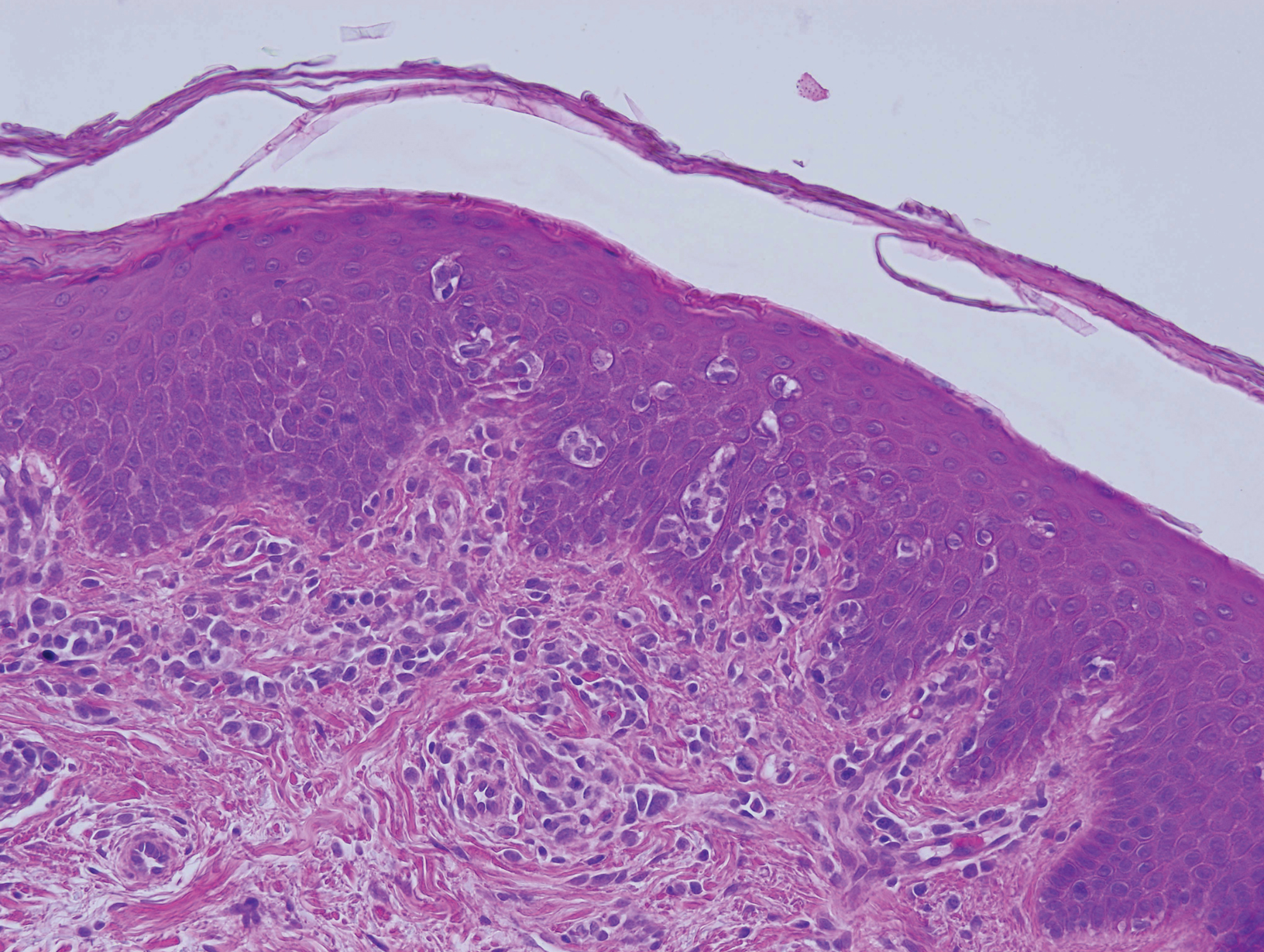

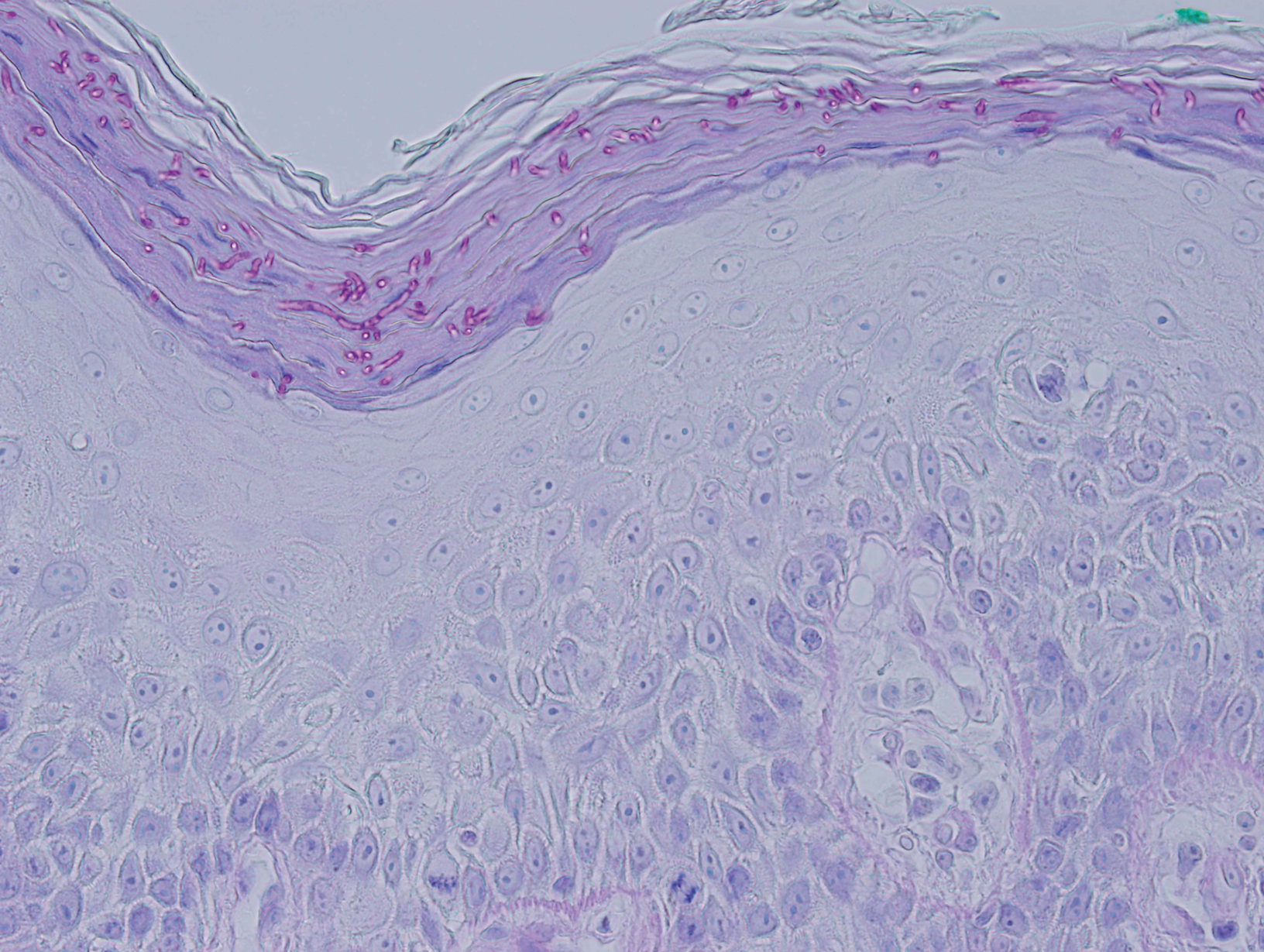

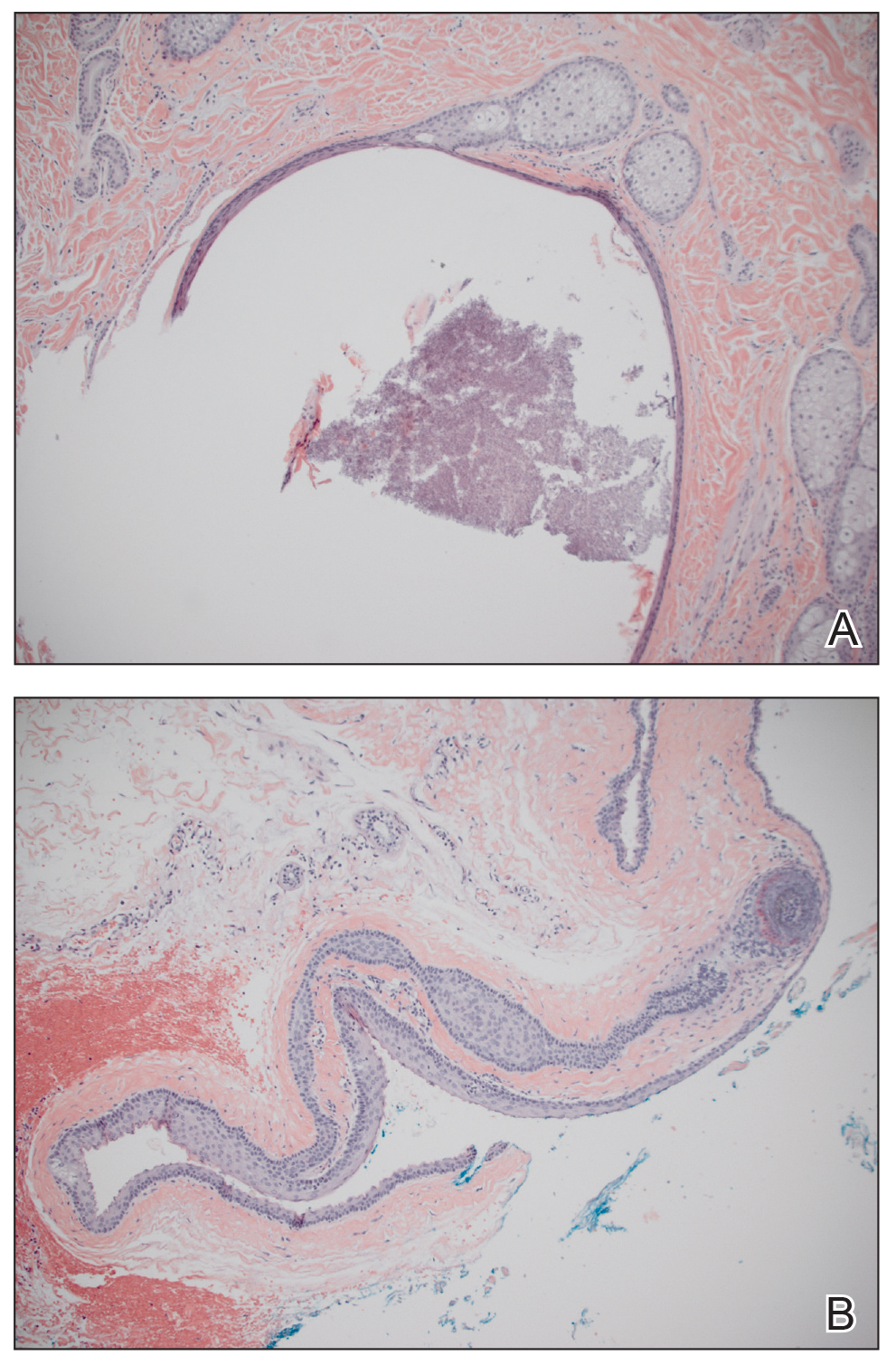

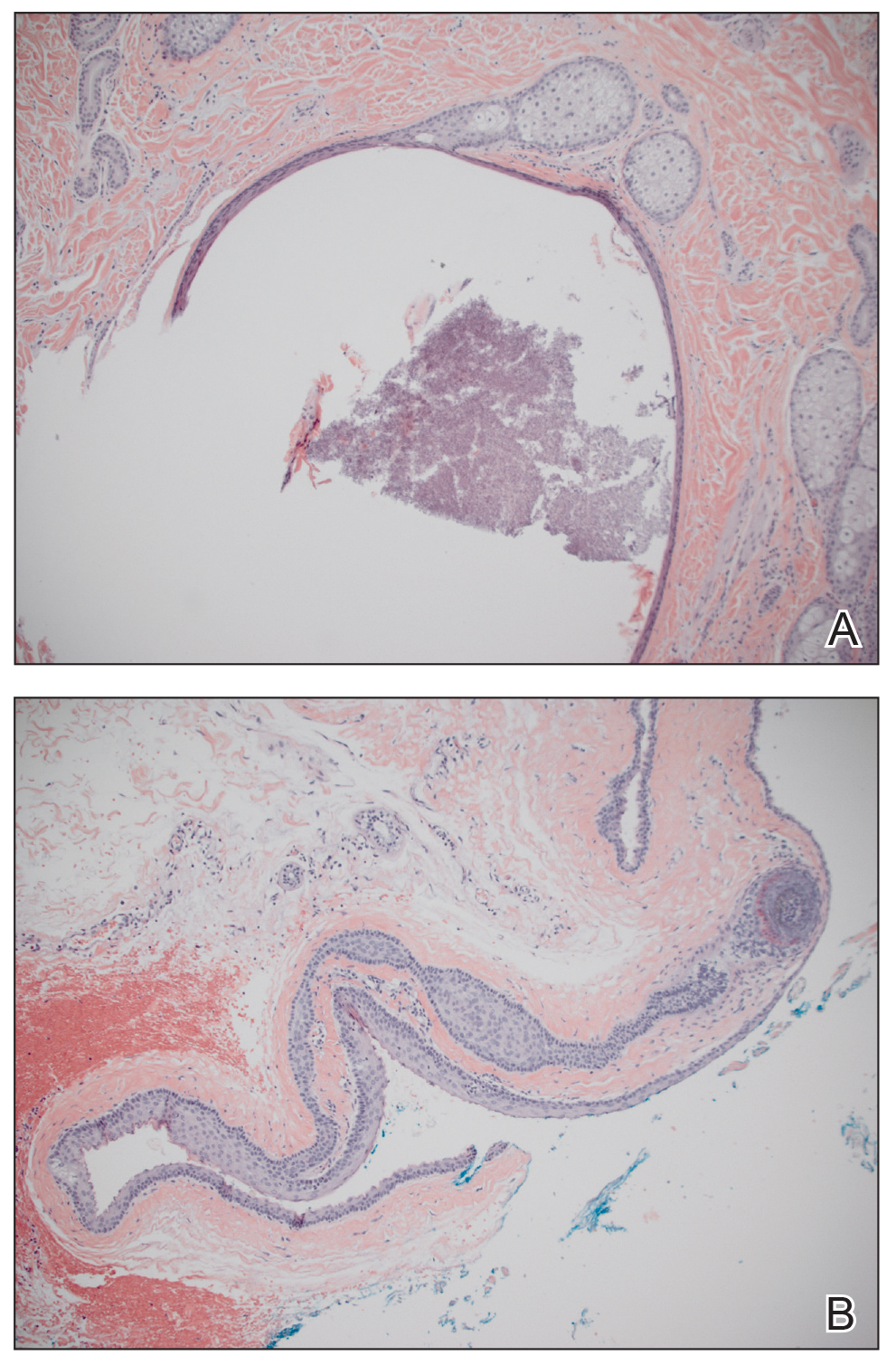

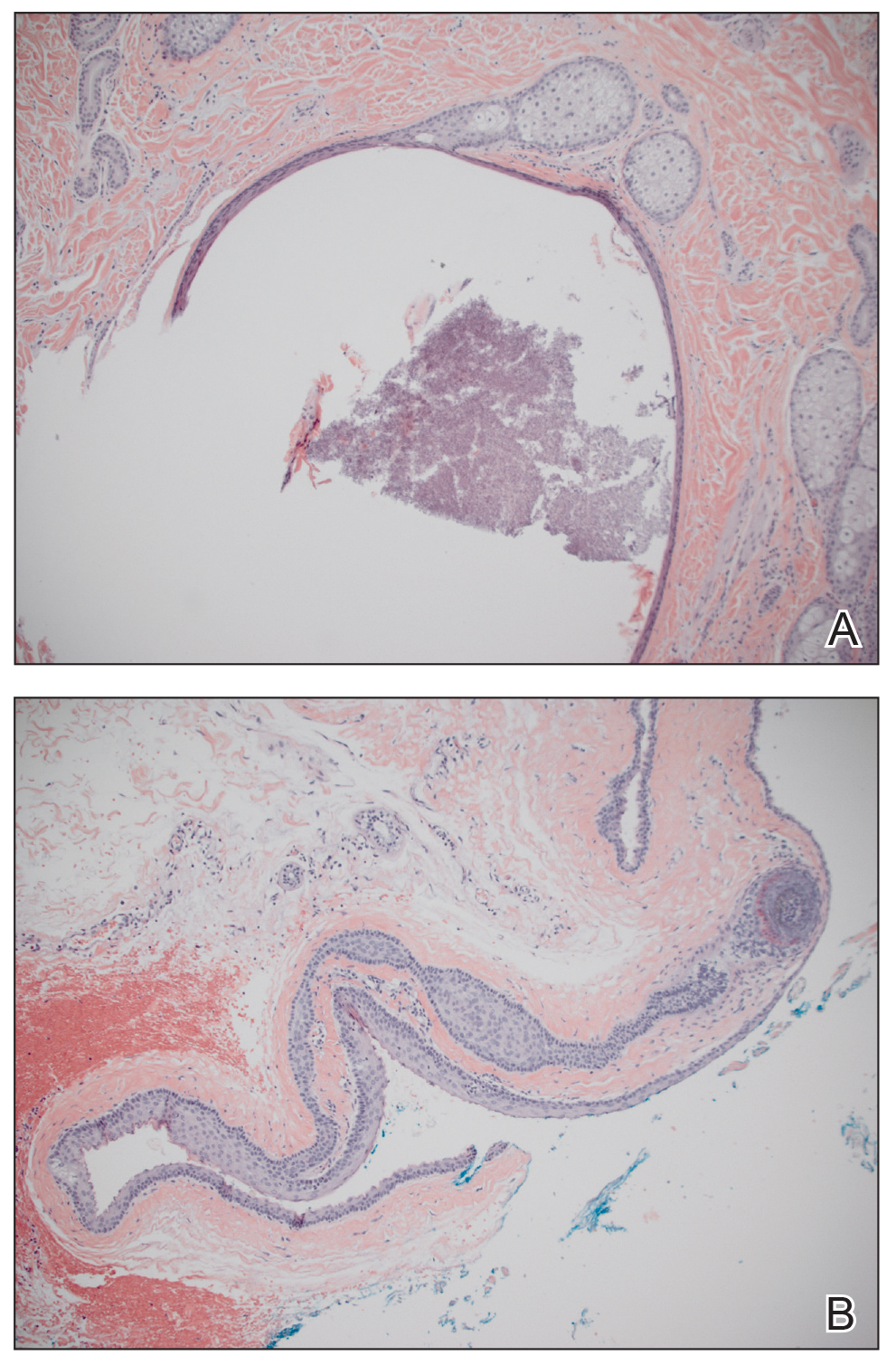

Biopsy of the nodule showed florid papillary hyperplasia of the ductal epithelium within the dermis that was sharply demarcated from the background stroma (Figure, A and B). Neither cytological nor architectural atypia were evident. There was no notable necrosis (Figure C). There was a background of fibrosis whereby the glandular ductal structures assumed a somewhat irregular growth pattern within the dermis with attendant hemorrhage. The patient underwent complete excision of the lesion. No evidence of carcinoma was seen on the final pathology, and the final margins were negative.

First described in 1923 and fully characterized in 1955, nipple adenoma (also known as florid papillomatosis of the nipple) is a benign proliferative neoplasm that originates in the lactiferous ducts of the nipple.1,2 It most commonly affects women aged 40 to 50 years (range, 0-89 years); less than 5% of cases are reported in men.3,4 It predominantly is unilateral, with only rare cases of bilateral papillomatosis reported. Patients often present with serous or serosanguineous discharge and an itching or burning sensation. Symptoms may worsen with the menstrual cycle.4 On physical examination, it presents as an ill-defined red nodule on the nipple with crusting, erosion, or erythema of the nipple surface. Although imaging generally is not used to confirm the diagnosis, mammography should be performed prior to biopsy to rule out underlying breast pathology. Dermoscopy may show linear cherry red structures or red serpiginous and annular structures.5,6 The differential diagnosis of nipple adenoma includes Paget disease of the breast, adenomyoepithelioma, subareolar subsclerosing duct hyperplasia, syringomatous adenoma, adenosis tumor, low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ, tubular carcinoma, and sweat gland tumors.3

Microscopic features of nipple adenoma have been categorized into 4 subtypes: sclerosing papillomatosis, papillomatosis, adenosis, and a mixed pattern.3,7 The tumors may have keratin cysts and focal necrosis but no atypia, and the myoepithelial cell layer is retained. Nipple adenomas show a glandular proliferation in the dermis that is relatively well circumscribed with glands that vary in appearance between a simple adenosislike pattern of growth to a papillary hyperplasia and/or usual ductal hyperplasia growth pattern. A pseudoinfiltrative pattern can occur when the glandular epithelium is entrapped within stromal fibrosis; however, the myoepithelial layer is retained. Occasionally, the glandular epithelium can grow in continuity with the surface squamous epithelium of the nipple, clinically simulating Paget disease of the breast.8 Immunohistochemical stains, specifically p63, p40, calponin 1, h-caldesmon, cytokeratin 5/6, CD10, and α; smooth muscle actin, highlight the myoepithelial cells, while cytokeratin 7 identifies the ductal epithelium, supporting the diagnosis.6 In addition to biopsy and microscopic tissue examination, touch preparation cytology, curettage cytology, and fine needle aspiration techniques have been used to perform cytologic examination of the lesions, aiding in identification of the benign or malignant nature of the neoplasm.6 Nipple adenoma also is referred to as florid papillomatosis of the nipple, papillary adenoma, erosive adenomatosis, and subareolar duct papillomatosis.7

Although nipple adenoma is a benign tumor, up to 16.5% of affected patients had an ipsilateral or contralateral mammary carcinoma.9 The majority arose coincidentally but separately in the same breast, and carcinoma arose directly from the nipple adenoma in 8 cases; 3 cases were carcinomas that arose in men.10 A definitive association or causal relationship between nipple adenoma and subsequent development of breast cancer has not been identified, and the incidence of nipple adenoma in patients with a positive family history of breast cancer has not been examined. Therefore, although various treatments including cryosurgery, nipple splitting enucleation, and Mohs micrographic surgery have been proposed, complete excision remains the gold standard of therapy. Regular breast examinations and digital mammography are necessary to screen for local recurrences.

- Miller E, Lewis D. The significance of serohemorrhagic or hemorrhagic discharge from the nipple. JAMA. 1923;81:1651-1657.

- Jones DB. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. Cancer. 1955;8:315-319.

- Rosen PP. Rosen's Breast Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:120-128.

- Brownstein MH, Phelps RG, Maqnin PH. Papillary adenoma of the nipple: analysis of fifteen new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:707-715.

- Takashima S, Fujita Y, Miyauchi T, et al. Dermoscopic observation in adenoma of the nipple. J Dermatol. 2015;42:341-342.

- Spohn G, Trotter S, Tozbikian G, et al. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4.

- Shin SJ. Nipple adenoma (florid papillomatosis of the nipple). In: Dabbs DJ, ed. Breast Pathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:286-292.

- Schnitt SJ, Collins LC. Biopsy Interpretation of the Breast. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- Salemis NS. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple: a rare presentation and review of the literature. Breast Dis. 2015;35:153-156.

- Di Bonito M, Cantile M, Collina F, et al. Adenoma of the nipple: a clinicopathological report of 13 cases. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1839-1842.

The Diagnosis: Nipple Adenoma (Florid Papillomatosis of the Nipple)

Biopsy of the nodule showed florid papillary hyperplasia of the ductal epithelium within the dermis that was sharply demarcated from the background stroma (Figure, A and B). Neither cytological nor architectural atypia were evident. There was no notable necrosis (Figure C). There was a background of fibrosis whereby the glandular ductal structures assumed a somewhat irregular growth pattern within the dermis with attendant hemorrhage. The patient underwent complete excision of the lesion. No evidence of carcinoma was seen on the final pathology, and the final margins were negative.

First described in 1923 and fully characterized in 1955, nipple adenoma (also known as florid papillomatosis of the nipple) is a benign proliferative neoplasm that originates in the lactiferous ducts of the nipple.1,2 It most commonly affects women aged 40 to 50 years (range, 0-89 years); less than 5% of cases are reported in men.3,4 It predominantly is unilateral, with only rare cases of bilateral papillomatosis reported. Patients often present with serous or serosanguineous discharge and an itching or burning sensation. Symptoms may worsen with the menstrual cycle.4 On physical examination, it presents as an ill-defined red nodule on the nipple with crusting, erosion, or erythema of the nipple surface. Although imaging generally is not used to confirm the diagnosis, mammography should be performed prior to biopsy to rule out underlying breast pathology. Dermoscopy may show linear cherry red structures or red serpiginous and annular structures.5,6 The differential diagnosis of nipple adenoma includes Paget disease of the breast, adenomyoepithelioma, subareolar subsclerosing duct hyperplasia, syringomatous adenoma, adenosis tumor, low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ, tubular carcinoma, and sweat gland tumors.3

Microscopic features of nipple adenoma have been categorized into 4 subtypes: sclerosing papillomatosis, papillomatosis, adenosis, and a mixed pattern.3,7 The tumors may have keratin cysts and focal necrosis but no atypia, and the myoepithelial cell layer is retained. Nipple adenomas show a glandular proliferation in the dermis that is relatively well circumscribed with glands that vary in appearance between a simple adenosislike pattern of growth to a papillary hyperplasia and/or usual ductal hyperplasia growth pattern. A pseudoinfiltrative pattern can occur when the glandular epithelium is entrapped within stromal fibrosis; however, the myoepithelial layer is retained. Occasionally, the glandular epithelium can grow in continuity with the surface squamous epithelium of the nipple, clinically simulating Paget disease of the breast.8 Immunohistochemical stains, specifically p63, p40, calponin 1, h-caldesmon, cytokeratin 5/6, CD10, and α; smooth muscle actin, highlight the myoepithelial cells, while cytokeratin 7 identifies the ductal epithelium, supporting the diagnosis.6 In addition to biopsy and microscopic tissue examination, touch preparation cytology, curettage cytology, and fine needle aspiration techniques have been used to perform cytologic examination of the lesions, aiding in identification of the benign or malignant nature of the neoplasm.6 Nipple adenoma also is referred to as florid papillomatosis of the nipple, papillary adenoma, erosive adenomatosis, and subareolar duct papillomatosis.7

Although nipple adenoma is a benign tumor, up to 16.5% of affected patients had an ipsilateral or contralateral mammary carcinoma.9 The majority arose coincidentally but separately in the same breast, and carcinoma arose directly from the nipple adenoma in 8 cases; 3 cases were carcinomas that arose in men.10 A definitive association or causal relationship between nipple adenoma and subsequent development of breast cancer has not been identified, and the incidence of nipple adenoma in patients with a positive family history of breast cancer has not been examined. Therefore, although various treatments including cryosurgery, nipple splitting enucleation, and Mohs micrographic surgery have been proposed, complete excision remains the gold standard of therapy. Regular breast examinations and digital mammography are necessary to screen for local recurrences.

The Diagnosis: Nipple Adenoma (Florid Papillomatosis of the Nipple)

Biopsy of the nodule showed florid papillary hyperplasia of the ductal epithelium within the dermis that was sharply demarcated from the background stroma (Figure, A and B). Neither cytological nor architectural atypia were evident. There was no notable necrosis (Figure C). There was a background of fibrosis whereby the glandular ductal structures assumed a somewhat irregular growth pattern within the dermis with attendant hemorrhage. The patient underwent complete excision of the lesion. No evidence of carcinoma was seen on the final pathology, and the final margins were negative.

First described in 1923 and fully characterized in 1955, nipple adenoma (also known as florid papillomatosis of the nipple) is a benign proliferative neoplasm that originates in the lactiferous ducts of the nipple.1,2 It most commonly affects women aged 40 to 50 years (range, 0-89 years); less than 5% of cases are reported in men.3,4 It predominantly is unilateral, with only rare cases of bilateral papillomatosis reported. Patients often present with serous or serosanguineous discharge and an itching or burning sensation. Symptoms may worsen with the menstrual cycle.4 On physical examination, it presents as an ill-defined red nodule on the nipple with crusting, erosion, or erythema of the nipple surface. Although imaging generally is not used to confirm the diagnosis, mammography should be performed prior to biopsy to rule out underlying breast pathology. Dermoscopy may show linear cherry red structures or red serpiginous and annular structures.5,6 The differential diagnosis of nipple adenoma includes Paget disease of the breast, adenomyoepithelioma, subareolar subsclerosing duct hyperplasia, syringomatous adenoma, adenosis tumor, low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ, tubular carcinoma, and sweat gland tumors.3

Microscopic features of nipple adenoma have been categorized into 4 subtypes: sclerosing papillomatosis, papillomatosis, adenosis, and a mixed pattern.3,7 The tumors may have keratin cysts and focal necrosis but no atypia, and the myoepithelial cell layer is retained. Nipple adenomas show a glandular proliferation in the dermis that is relatively well circumscribed with glands that vary in appearance between a simple adenosislike pattern of growth to a papillary hyperplasia and/or usual ductal hyperplasia growth pattern. A pseudoinfiltrative pattern can occur when the glandular epithelium is entrapped within stromal fibrosis; however, the myoepithelial layer is retained. Occasionally, the glandular epithelium can grow in continuity with the surface squamous epithelium of the nipple, clinically simulating Paget disease of the breast.8 Immunohistochemical stains, specifically p63, p40, calponin 1, h-caldesmon, cytokeratin 5/6, CD10, and α; smooth muscle actin, highlight the myoepithelial cells, while cytokeratin 7 identifies the ductal epithelium, supporting the diagnosis.6 In addition to biopsy and microscopic tissue examination, touch preparation cytology, curettage cytology, and fine needle aspiration techniques have been used to perform cytologic examination of the lesions, aiding in identification of the benign or malignant nature of the neoplasm.6 Nipple adenoma also is referred to as florid papillomatosis of the nipple, papillary adenoma, erosive adenomatosis, and subareolar duct papillomatosis.7

Although nipple adenoma is a benign tumor, up to 16.5% of affected patients had an ipsilateral or contralateral mammary carcinoma.9 The majority arose coincidentally but separately in the same breast, and carcinoma arose directly from the nipple adenoma in 8 cases; 3 cases were carcinomas that arose in men.10 A definitive association or causal relationship between nipple adenoma and subsequent development of breast cancer has not been identified, and the incidence of nipple adenoma in patients with a positive family history of breast cancer has not been examined. Therefore, although various treatments including cryosurgery, nipple splitting enucleation, and Mohs micrographic surgery have been proposed, complete excision remains the gold standard of therapy. Regular breast examinations and digital mammography are necessary to screen for local recurrences.

- Miller E, Lewis D. The significance of serohemorrhagic or hemorrhagic discharge from the nipple. JAMA. 1923;81:1651-1657.

- Jones DB. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. Cancer. 1955;8:315-319.

- Rosen PP. Rosen's Breast Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:120-128.

- Brownstein MH, Phelps RG, Maqnin PH. Papillary adenoma of the nipple: analysis of fifteen new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:707-715.

- Takashima S, Fujita Y, Miyauchi T, et al. Dermoscopic observation in adenoma of the nipple. J Dermatol. 2015;42:341-342.

- Spohn G, Trotter S, Tozbikian G, et al. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4.

- Shin SJ. Nipple adenoma (florid papillomatosis of the nipple). In: Dabbs DJ, ed. Breast Pathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:286-292.

- Schnitt SJ, Collins LC. Biopsy Interpretation of the Breast. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- Salemis NS. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple: a rare presentation and review of the literature. Breast Dis. 2015;35:153-156.

- Di Bonito M, Cantile M, Collina F, et al. Adenoma of the nipple: a clinicopathological report of 13 cases. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1839-1842.

- Miller E, Lewis D. The significance of serohemorrhagic or hemorrhagic discharge from the nipple. JAMA. 1923;81:1651-1657.

- Jones DB. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. Cancer. 1955;8:315-319.

- Rosen PP. Rosen's Breast Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:120-128.

- Brownstein MH, Phelps RG, Maqnin PH. Papillary adenoma of the nipple: analysis of fifteen new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:707-715.

- Takashima S, Fujita Y, Miyauchi T, et al. Dermoscopic observation in adenoma of the nipple. J Dermatol. 2015;42:341-342.

- Spohn G, Trotter S, Tozbikian G, et al. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4.

- Shin SJ. Nipple adenoma (florid papillomatosis of the nipple). In: Dabbs DJ, ed. Breast Pathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:286-292.

- Schnitt SJ, Collins LC. Biopsy Interpretation of the Breast. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- Salemis NS. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple: a rare presentation and review of the literature. Breast Dis. 2015;35:153-156.

- Di Bonito M, Cantile M, Collina F, et al. Adenoma of the nipple: a clinicopathological report of 13 cases. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1839-1842.

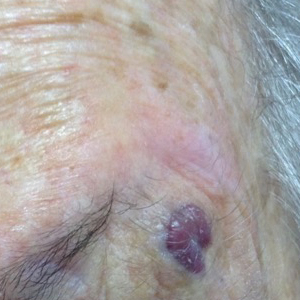

A healthy 48-year-old woman presented with a growth on the right nipple that had been slowly enlarging over the last few months. She initially noticed mild swelling in the area that persisted and formed a soft lump. She described mild pain with intermittent drainage but no bleeding. Her medical history was unremarkable, including a negative personal and family history of breast and skin cancer. She was taking no medications prior to development of the mass. She had no recent history of pregnancy or breastfeeding. A mammogram and breast ultrasound were not concerning for carcinoma. Physical examination showed a soft, exophytic, mildly tender, pink nodule on the right nipple that measured 12.2×7 mm; no drainage, bleeding, or ulceration was present. The surrounding skin of the areola and breast demonstrated no clinical changes. The contralateral breast, areola, and nipple were unaffected. The patient had no appreciable axillary or cervical lymphadenopathy. A deep shave biopsy of the nodule was performed and sent for histopathologic examination.

Pigmented Mass on the Shoulder

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (PDFSP), also known as Bednar tumor, is an uncommon variant of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans constitutes 1% to 5% of all DFSP cases and most commonly is seen in nonwhite adults in the fourth decade of life, with occasional cases seen in pediatric patients, including some congenital cases. Typical sites of involvement include the shoulders, trunk, arms, legs, head, and neck.1,2 It also has been reported at sites of prior immunization, trauma, and insect bites.3

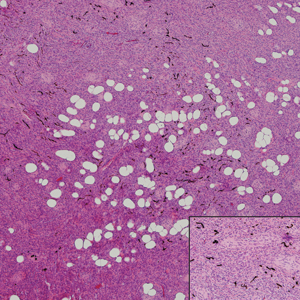

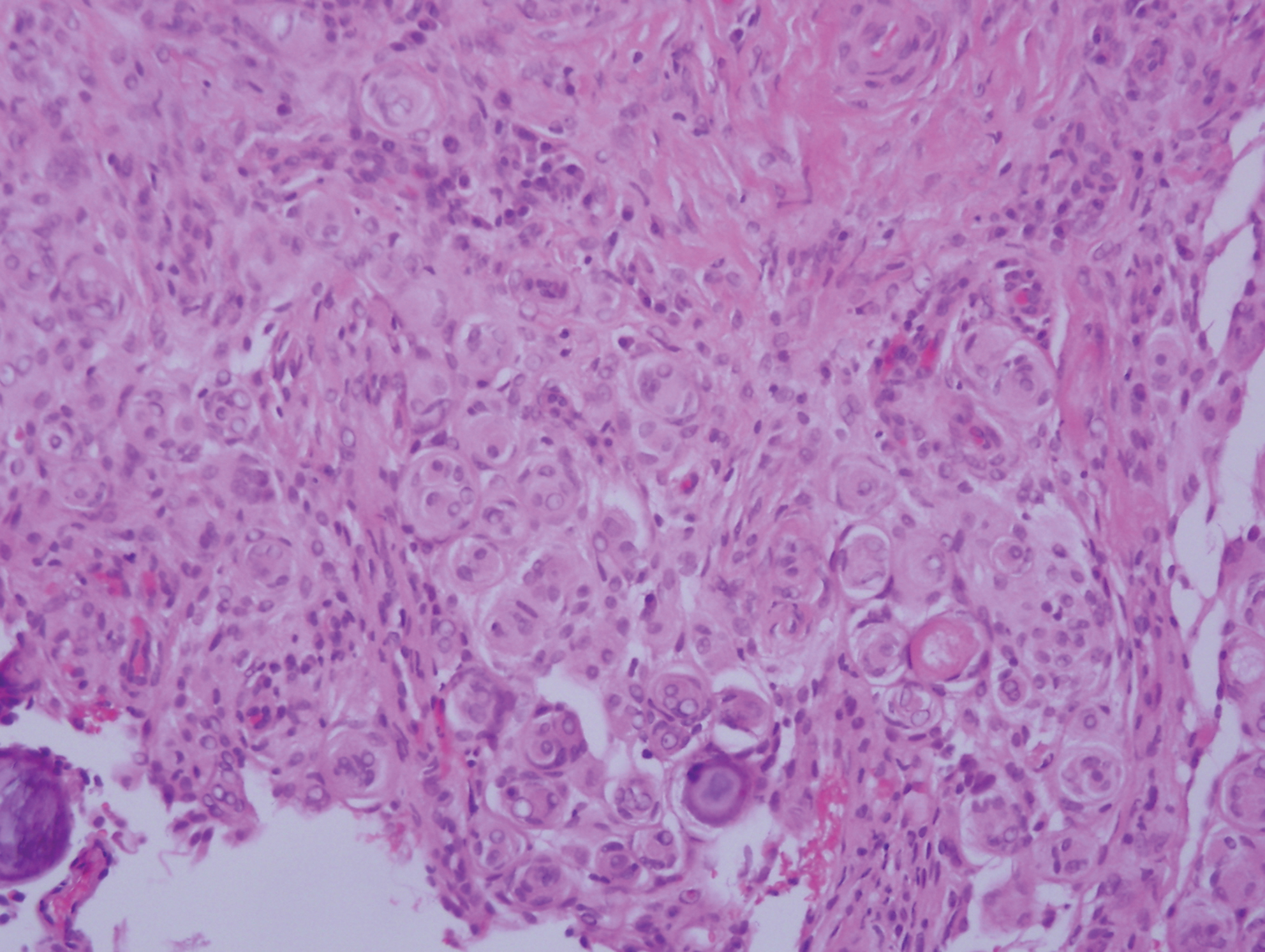

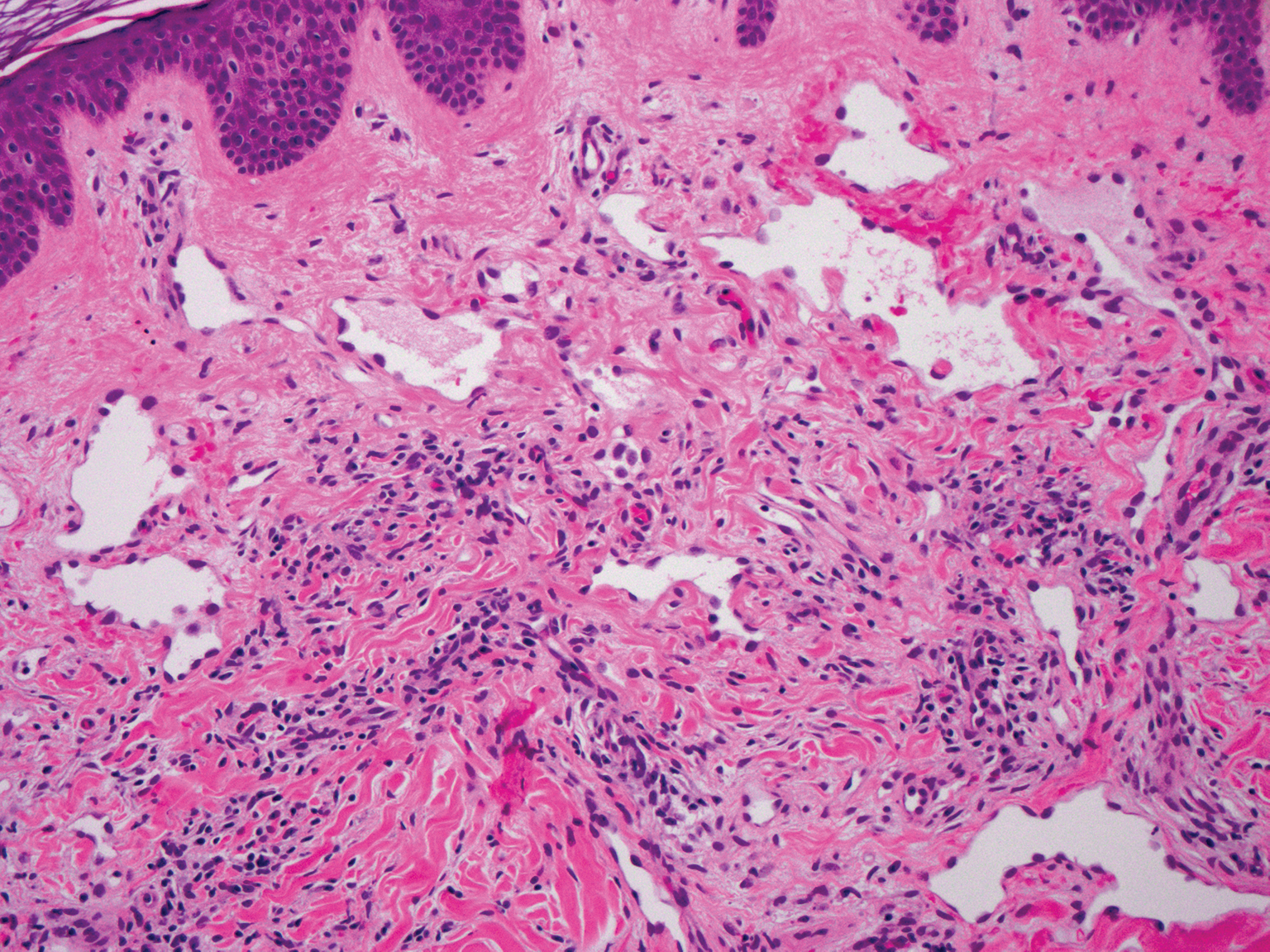

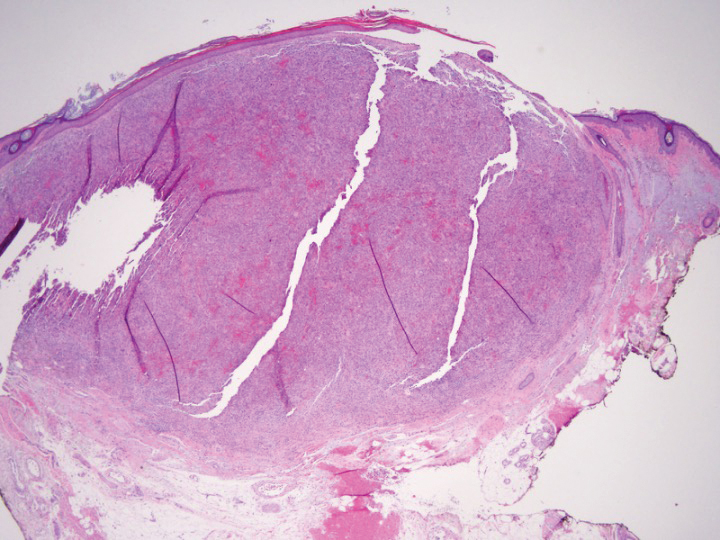

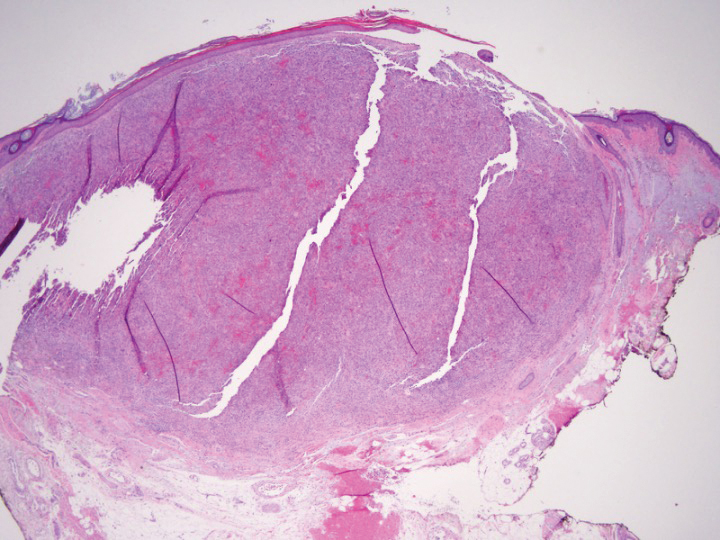

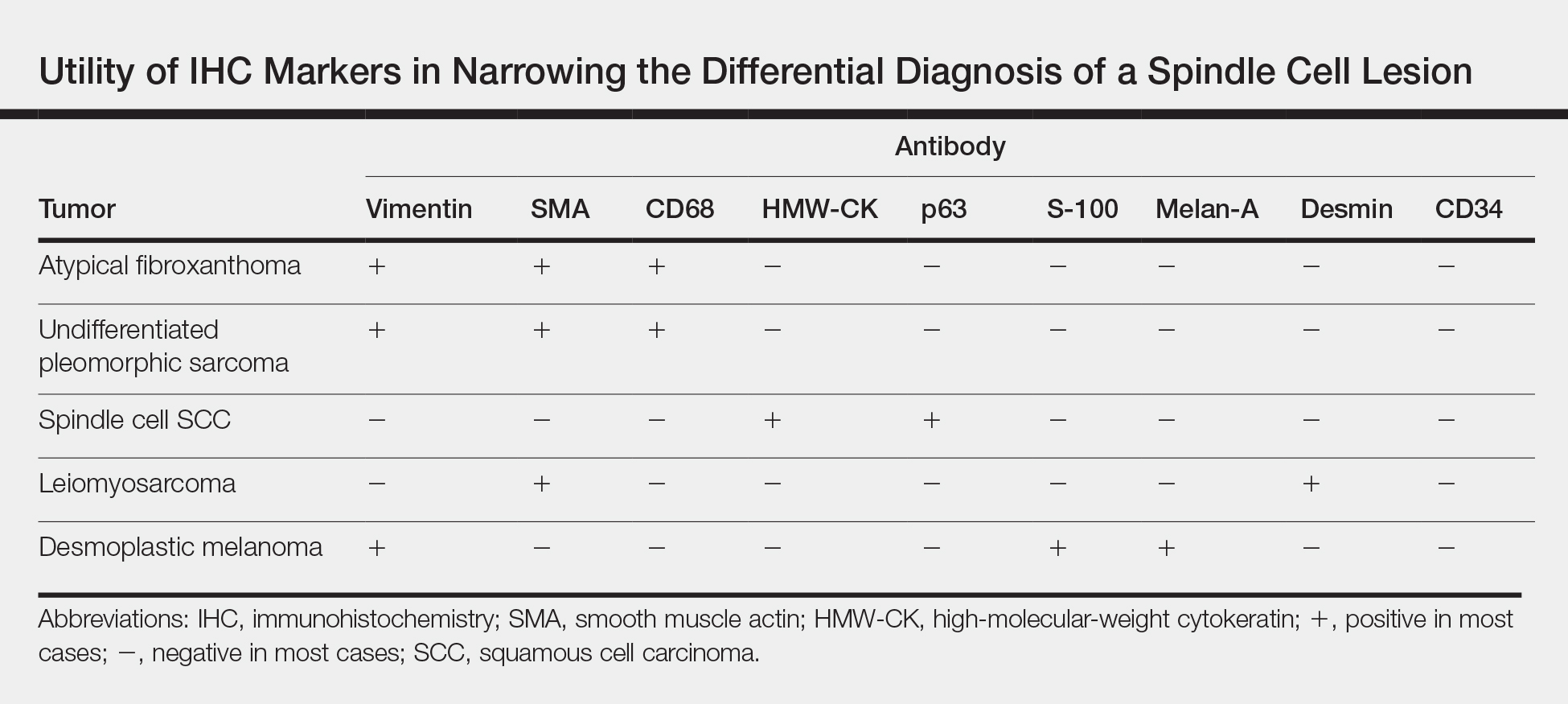

Histopathologic examination of our patient's shoulder nodule revealed an infiltrative neoplasm in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue composed of spindled cells with a storiform pattern and foci of scattered elongated dendritic pigmented cells. A narrow grenz zone separated the tumor from the epidermis, and characteristic honeycomb infiltration by tumor cells was noted in the subcutaneous fat. The nuclei were bland and monomorphous with areas of neuroid differentiation containing whorls and nerve cord-like structures (quiz image). The tumor cells were diffusely CD34 and vimentin positive, while S-100, SOX-10, neurofilament, smooth muscle actin, desmin, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratins were negative. The immunophenotype excluded the possibility of neurogenic, pericytic, myofibroblastic, and myoid differentiation.

Wang and Yang4 previously reported a case of PDFSP with prominent meningothelial-like whorls focally resembling extracranial meningioma; however, the tumor cells were CD34 positive and epithelial membrane antigen negative, weighing against a diagnosis of meningioma. Most cases of PDFSP demonstrate the COL1A1-PDGFB (collagen type I α; 1/platelet-derived growth factor B-chain) fusion protein caused by the translocation t(17;22)(q22;q13), as in classic DFSP.5

Cellular blue nevus (CBN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm that can present at any age and often occurs on the buttocks and in the sacrococcygeal region. Clinically, CBN presents as a firm, bluish black to bluish gray, dome-shaped nodule. The size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters.6,7 Histologically, CBN is located completely in the dermis, extending along the adnexae into the subcutaneous tissue with a dumbbell-shaped outline (Figure 1).6-8 The tumor demonstrates oval epithelioid melanocytes with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for melanocytic markers such as S-100, SOX-10, MART-1, and human melanoma black 45. CD34 expression rarely is reported in a subset of CBN.9

Pigmented neurofibroma is a rare variant of neurofibroma that produces melanin pigment and has a strong association with neurofibromatosis.10 It occurs most frequently in dark-skinned populations (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The most common location is the head and neck region.11,12 Histologically, pigmented neurofibroma resembles a diffuse neurofibroma admixed with melanin-producing cells (Figure 2).12 Immunostaining shows positivity for S-100 in both pigmented and Schwann cells; however, the pigmented cells stain positively for human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, and tyrosinase.10 CD34 can be fingerprint positive in neurofibroma, but a distinction from DFSP can be made by S-100 and SOX-10 immunostaining.13

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is an uncommon variant of malignant melanoma and has a higher tendency for persistent local growth and less frequent metastases than other variants of melanoma. It has a predilection for chronically sun-exposed areas such as the head and neck and occurs later in life. Clinically, DM appears as nonspecific, often amelanotic nodules or plaques or as scarlike lesions.14 Histologically, DM can be classified as mixed or pure based on the degree of desmoplasia and cellularity. A paucicellular proliferation of malignant spindled melanocytes within a densely fibrotic stroma with lymphoid nodules in the dermis is characteristic (Figure 3); perineural involvement is common.14,15 The most reliable confirmative stains are S-100 and SOX-10.16

Cutaneous meningioma is a rare tumor and could be subtyped into 3 groups. Type I is primary cutaneous meningioma and usually is present at birth on the scalp and paravertebral regions with a relatively good prognosis. Type II is ectopic soft-tissue meningioma that extends into the skin from around the sensory organs on the face. Type III is local invasion or true metastasis from a central nervous system meningioma. Types II and III develop later in life and the prognosis is poor.17,18 Clinically, lesions present as firm subcutaneous nodules or swellings. Cutaneous meningioma has several histopathologic variants. The classic presentation reveals concentric wrapping of tumor cells with round-oval nuclei containing delicate chromatin. Psammoma bodies are a common finding (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, tumor cells are diffusely positive for epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin.18,19

- Amonkar GP, Rupani A, Shah A, et al. Bednar tumor: an uncommon entity. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2016;3:36-38.

- El Hachem M, Diociaiuti A, Latella E, et al. Congenital myxoid and pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E74-E77.

- Anon-Requena MJ, Pico-Valimana M, Munoz-Arias G. Bednar tumor (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:618-620.

- Wang J, Yang W. Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with prominent meningothelial-like whorls. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):65-69.

- Zardawi IM, Kattampallil J, Rode J. An unusual pigmented skin tumour. Bednar tumour, dorsum of left foot (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans). Pathology. 2004;36:358-361.

- Sugianto JZ, Ralston JS, Metcalf JS, et al. Blue nevus and "malignant blue nevus": a concise review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:219-224.

- Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:401-415.

- Zembowicz A, Granter SR, McKee PH, et al. Amelanotic cellular blue nevus: a hypopigmented variant of the cellular blue nevus: clinicopathologic analysis of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1493-1500.

- Smith K, Germain M, Williams J, et al. CD34-positive cellular blue nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:145-150.

- Inaba M, Yamamoto T, Minami R, et al. Pigmented neurofibroma: report of two cases and literature review. Pathol Int. 2001;51:565-569.

- Fetsch JF, Michal M, Miettinen M. Pigmented (melanotic) neurofibroma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 19 lesions from 17 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:331-343.

- Motoi T, Ishida T, Kawato A, et al. Pigmented neurofibroma: review of Japanese patients with an analysis of melanogenesis demonstrating coexpression of c-met protooncogene and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:871-877.

- Yeh I, McCalmont TH. Distinguishing neurofibroma from desmoplastic melanoma: the value of the CD34 fingerprint. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:625-630.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanoma. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:321-330.

- Schleich C, Ferringer T. Desmoplastic melanoma. Cutis. 2015;96:306, 313-314, 335.

- Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningiomas--a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974;34:728-744.

- Miedema JR, Zedek D. Cutaneous meningioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:208-211.

- Bhanusali DG, Heath C, Gur D, et al. Metastatic meningioma of the scalp. Cutis. 2018;101:386-389.

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (PDFSP), also known as Bednar tumor, is an uncommon variant of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans constitutes 1% to 5% of all DFSP cases and most commonly is seen in nonwhite adults in the fourth decade of life, with occasional cases seen in pediatric patients, including some congenital cases. Typical sites of involvement include the shoulders, trunk, arms, legs, head, and neck.1,2 It also has been reported at sites of prior immunization, trauma, and insect bites.3

Histopathologic examination of our patient's shoulder nodule revealed an infiltrative neoplasm in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue composed of spindled cells with a storiform pattern and foci of scattered elongated dendritic pigmented cells. A narrow grenz zone separated the tumor from the epidermis, and characteristic honeycomb infiltration by tumor cells was noted in the subcutaneous fat. The nuclei were bland and monomorphous with areas of neuroid differentiation containing whorls and nerve cord-like structures (quiz image). The tumor cells were diffusely CD34 and vimentin positive, while S-100, SOX-10, neurofilament, smooth muscle actin, desmin, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratins were negative. The immunophenotype excluded the possibility of neurogenic, pericytic, myofibroblastic, and myoid differentiation.

Wang and Yang4 previously reported a case of PDFSP with prominent meningothelial-like whorls focally resembling extracranial meningioma; however, the tumor cells were CD34 positive and epithelial membrane antigen negative, weighing against a diagnosis of meningioma. Most cases of PDFSP demonstrate the COL1A1-PDGFB (collagen type I α; 1/platelet-derived growth factor B-chain) fusion protein caused by the translocation t(17;22)(q22;q13), as in classic DFSP.5

Cellular blue nevus (CBN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm that can present at any age and often occurs on the buttocks and in the sacrococcygeal region. Clinically, CBN presents as a firm, bluish black to bluish gray, dome-shaped nodule. The size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters.6,7 Histologically, CBN is located completely in the dermis, extending along the adnexae into the subcutaneous tissue with a dumbbell-shaped outline (Figure 1).6-8 The tumor demonstrates oval epithelioid melanocytes with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for melanocytic markers such as S-100, SOX-10, MART-1, and human melanoma black 45. CD34 expression rarely is reported in a subset of CBN.9

Pigmented neurofibroma is a rare variant of neurofibroma that produces melanin pigment and has a strong association with neurofibromatosis.10 It occurs most frequently in dark-skinned populations (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The most common location is the head and neck region.11,12 Histologically, pigmented neurofibroma resembles a diffuse neurofibroma admixed with melanin-producing cells (Figure 2).12 Immunostaining shows positivity for S-100 in both pigmented and Schwann cells; however, the pigmented cells stain positively for human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, and tyrosinase.10 CD34 can be fingerprint positive in neurofibroma, but a distinction from DFSP can be made by S-100 and SOX-10 immunostaining.13

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is an uncommon variant of malignant melanoma and has a higher tendency for persistent local growth and less frequent metastases than other variants of melanoma. It has a predilection for chronically sun-exposed areas such as the head and neck and occurs later in life. Clinically, DM appears as nonspecific, often amelanotic nodules or plaques or as scarlike lesions.14 Histologically, DM can be classified as mixed or pure based on the degree of desmoplasia and cellularity. A paucicellular proliferation of malignant spindled melanocytes within a densely fibrotic stroma with lymphoid nodules in the dermis is characteristic (Figure 3); perineural involvement is common.14,15 The most reliable confirmative stains are S-100 and SOX-10.16

Cutaneous meningioma is a rare tumor and could be subtyped into 3 groups. Type I is primary cutaneous meningioma and usually is present at birth on the scalp and paravertebral regions with a relatively good prognosis. Type II is ectopic soft-tissue meningioma that extends into the skin from around the sensory organs on the face. Type III is local invasion or true metastasis from a central nervous system meningioma. Types II and III develop later in life and the prognosis is poor.17,18 Clinically, lesions present as firm subcutaneous nodules or swellings. Cutaneous meningioma has several histopathologic variants. The classic presentation reveals concentric wrapping of tumor cells with round-oval nuclei containing delicate chromatin. Psammoma bodies are a common finding (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, tumor cells are diffusely positive for epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin.18,19

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (PDFSP), also known as Bednar tumor, is an uncommon variant of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans constitutes 1% to 5% of all DFSP cases and most commonly is seen in nonwhite adults in the fourth decade of life, with occasional cases seen in pediatric patients, including some congenital cases. Typical sites of involvement include the shoulders, trunk, arms, legs, head, and neck.1,2 It also has been reported at sites of prior immunization, trauma, and insect bites.3

Histopathologic examination of our patient's shoulder nodule revealed an infiltrative neoplasm in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue composed of spindled cells with a storiform pattern and foci of scattered elongated dendritic pigmented cells. A narrow grenz zone separated the tumor from the epidermis, and characteristic honeycomb infiltration by tumor cells was noted in the subcutaneous fat. The nuclei were bland and monomorphous with areas of neuroid differentiation containing whorls and nerve cord-like structures (quiz image). The tumor cells were diffusely CD34 and vimentin positive, while S-100, SOX-10, neurofilament, smooth muscle actin, desmin, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratins were negative. The immunophenotype excluded the possibility of neurogenic, pericytic, myofibroblastic, and myoid differentiation.

Wang and Yang4 previously reported a case of PDFSP with prominent meningothelial-like whorls focally resembling extracranial meningioma; however, the tumor cells were CD34 positive and epithelial membrane antigen negative, weighing against a diagnosis of meningioma. Most cases of PDFSP demonstrate the COL1A1-PDGFB (collagen type I α; 1/platelet-derived growth factor B-chain) fusion protein caused by the translocation t(17;22)(q22;q13), as in classic DFSP.5

Cellular blue nevus (CBN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm that can present at any age and often occurs on the buttocks and in the sacrococcygeal region. Clinically, CBN presents as a firm, bluish black to bluish gray, dome-shaped nodule. The size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters.6,7 Histologically, CBN is located completely in the dermis, extending along the adnexae into the subcutaneous tissue with a dumbbell-shaped outline (Figure 1).6-8 The tumor demonstrates oval epithelioid melanocytes with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for melanocytic markers such as S-100, SOX-10, MART-1, and human melanoma black 45. CD34 expression rarely is reported in a subset of CBN.9

Pigmented neurofibroma is a rare variant of neurofibroma that produces melanin pigment and has a strong association with neurofibromatosis.10 It occurs most frequently in dark-skinned populations (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The most common location is the head and neck region.11,12 Histologically, pigmented neurofibroma resembles a diffuse neurofibroma admixed with melanin-producing cells (Figure 2).12 Immunostaining shows positivity for S-100 in both pigmented and Schwann cells; however, the pigmented cells stain positively for human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, and tyrosinase.10 CD34 can be fingerprint positive in neurofibroma, but a distinction from DFSP can be made by S-100 and SOX-10 immunostaining.13

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) is an uncommon variant of malignant melanoma and has a higher tendency for persistent local growth and less frequent metastases than other variants of melanoma. It has a predilection for chronically sun-exposed areas such as the head and neck and occurs later in life. Clinically, DM appears as nonspecific, often amelanotic nodules or plaques or as scarlike lesions.14 Histologically, DM can be classified as mixed or pure based on the degree of desmoplasia and cellularity. A paucicellular proliferation of malignant spindled melanocytes within a densely fibrotic stroma with lymphoid nodules in the dermis is characteristic (Figure 3); perineural involvement is common.14,15 The most reliable confirmative stains are S-100 and SOX-10.16

Cutaneous meningioma is a rare tumor and could be subtyped into 3 groups. Type I is primary cutaneous meningioma and usually is present at birth on the scalp and paravertebral regions with a relatively good prognosis. Type II is ectopic soft-tissue meningioma that extends into the skin from around the sensory organs on the face. Type III is local invasion or true metastasis from a central nervous system meningioma. Types II and III develop later in life and the prognosis is poor.17,18 Clinically, lesions present as firm subcutaneous nodules or swellings. Cutaneous meningioma has several histopathologic variants. The classic presentation reveals concentric wrapping of tumor cells with round-oval nuclei containing delicate chromatin. Psammoma bodies are a common finding (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, tumor cells are diffusely positive for epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin.18,19

- Amonkar GP, Rupani A, Shah A, et al. Bednar tumor: an uncommon entity. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2016;3:36-38.

- El Hachem M, Diociaiuti A, Latella E, et al. Congenital myxoid and pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E74-E77.

- Anon-Requena MJ, Pico-Valimana M, Munoz-Arias G. Bednar tumor (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:618-620.

- Wang J, Yang W. Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with prominent meningothelial-like whorls. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):65-69.

- Zardawi IM, Kattampallil J, Rode J. An unusual pigmented skin tumour. Bednar tumour, dorsum of left foot (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans). Pathology. 2004;36:358-361.

- Sugianto JZ, Ralston JS, Metcalf JS, et al. Blue nevus and "malignant blue nevus": a concise review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:219-224.

- Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:401-415.

- Zembowicz A, Granter SR, McKee PH, et al. Amelanotic cellular blue nevus: a hypopigmented variant of the cellular blue nevus: clinicopathologic analysis of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1493-1500.

- Smith K, Germain M, Williams J, et al. CD34-positive cellular blue nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:145-150.

- Inaba M, Yamamoto T, Minami R, et al. Pigmented neurofibroma: report of two cases and literature review. Pathol Int. 2001;51:565-569.

- Fetsch JF, Michal M, Miettinen M. Pigmented (melanotic) neurofibroma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 19 lesions from 17 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:331-343.

- Motoi T, Ishida T, Kawato A, et al. Pigmented neurofibroma: review of Japanese patients with an analysis of melanogenesis demonstrating coexpression of c-met protooncogene and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:871-877.

- Yeh I, McCalmont TH. Distinguishing neurofibroma from desmoplastic melanoma: the value of the CD34 fingerprint. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:625-630.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanoma. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:321-330.

- Schleich C, Ferringer T. Desmoplastic melanoma. Cutis. 2015;96:306, 313-314, 335.

- Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningiomas--a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974;34:728-744.

- Miedema JR, Zedek D. Cutaneous meningioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:208-211.

- Bhanusali DG, Heath C, Gur D, et al. Metastatic meningioma of the scalp. Cutis. 2018;101:386-389.

- Amonkar GP, Rupani A, Shah A, et al. Bednar tumor: an uncommon entity. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2016;3:36-38.

- El Hachem M, Diociaiuti A, Latella E, et al. Congenital myxoid and pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E74-E77.

- Anon-Requena MJ, Pico-Valimana M, Munoz-Arias G. Bednar tumor (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:618-620.

- Wang J, Yang W. Pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with prominent meningothelial-like whorls. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):65-69.

- Zardawi IM, Kattampallil J, Rode J. An unusual pigmented skin tumour. Bednar tumour, dorsum of left foot (pigmented dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans). Pathology. 2004;36:358-361.

- Sugianto JZ, Ralston JS, Metcalf JS, et al. Blue nevus and "malignant blue nevus": a concise review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:219-224.

- Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:401-415.

- Zembowicz A, Granter SR, McKee PH, et al. Amelanotic cellular blue nevus: a hypopigmented variant of the cellular blue nevus: clinicopathologic analysis of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1493-1500.

- Smith K, Germain M, Williams J, et al. CD34-positive cellular blue nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:145-150.

- Inaba M, Yamamoto T, Minami R, et al. Pigmented neurofibroma: report of two cases and literature review. Pathol Int. 2001;51:565-569.

- Fetsch JF, Michal M, Miettinen M. Pigmented (melanotic) neurofibroma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 19 lesions from 17 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:331-343.

- Motoi T, Ishida T, Kawato A, et al. Pigmented neurofibroma: review of Japanese patients with an analysis of melanogenesis demonstrating coexpression of c-met protooncogene and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:871-877.

- Yeh I, McCalmont TH. Distinguishing neurofibroma from desmoplastic melanoma: the value of the CD34 fingerprint. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:625-630.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanoma. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:321-330.

- Schleich C, Ferringer T. Desmoplastic melanoma. Cutis. 2015;96:306, 313-314, 335.

- Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningiomas--a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974;34:728-744.

- Miedema JR, Zedek D. Cutaneous meningioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:208-211.

- Bhanusali DG, Heath C, Gur D, et al. Metastatic meningioma of the scalp. Cutis. 2018;101:386-389.

A 37-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic, indurated, pigmented, subcutaneous nodule on the right shoulder of more than 3 years' duration. The lesion had gradually increased in size with no associated symptoms. The patient had a history of endometrial adenocarcinoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma, which had been treated by hysterectomy-oophorectomy and right thyroidectomy, respectively. She had no other notable systemic abnormalities, and there was no family history of genetic disease or cancer. Physical examination demonstrated a 1.2×1.8-cm nontender, pigmented, subcutaneous nodule with a rough surface and indistinct borders. An excisional biopsy was performed.

Well-Circumscribed Tumor on the Hand

The Diagnosis: Nodular Kaposi Sarcoma

Epidemic Kaposi sarcoma (KS) primarily affects patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Kaposi sarcoma can appear as brown, red, or blue-black macules, plaques, patches, nodules, or tumors, and it often is observed as multifocal cutaneous lesions located on the head, neck, and upper aspects of the trunk in a fulminant manner. Kaposi sarcoma portends a poor prognosis and is an AIDS-defining malignancy.1-3 Importantly, antiretroviral therapy does not preclude its consideration in those without AIDS-defining CD4 cell counts and undetectable HIV viremia presenting with cutaneous manifestations.2,3 A retrospective review by Daly et al4 reported KS lesions in patients with CD4 lymphocyte counts greater than 300 cells/µL, most of whom were antiretroviral therapy-naïve patients. Also, those with higher CD4 counts tended to have a solitary KS lesion at presentation, while those with CD4 counts less than 300 cells/µL tended to present with multiple foci.4 Epidemic KS lesions are clinically indistinguishable from other common cutaneous conditions in the differential diagnosis of KS, necessitating biopsy for histopathologic examination. Light microscopy findings help to delineate the diagnosis of KS. Immunohistochemical staining to the latent nuclear antigen 1 of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) confirms the KS diagnosis.5,6 Our patient's presentation as a solitary acral lesion was atypical for KS.

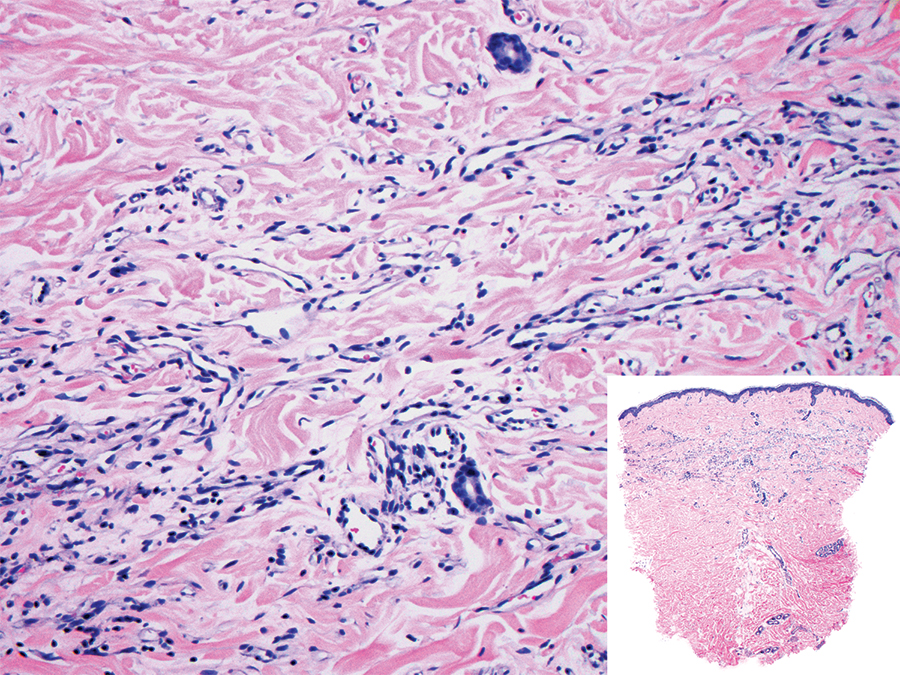

Light microscopy of our patient's biopsy demonstrated a large tumor on the acral surface of the right hand. Dermal collections of basophilic spindled cells clustered with small slitlike vascular spaces with abundant erythrocyte extravasation and numerous large ectatic vessels at the periphery were seen (Figure, A). At higher magnification, interlaced bundles of spindle cells with slitlike vessels with scattered lymphocytes and plasma cells were seen (Figure, B). An immunohistochemical stain for HHV-8 was positive and largely confined to spindle cells (Figure, C). These findings confirmed KS and met AIDS-defining criteria. Awareness of these histopathologic features is key in differentiating KS from other conditions in the differential diagnosis.

The patient's history of late latent syphilis coinfected with HIV and persistently elevated rapid plasma reagin that was recalcitrant to therapy placed an atypical nodular presentation within reason for the differential diagnosis. Deviations from the typical papulosquamous presentation with acral involvement in an immunocompromised patient mandates a consideration for syphilis with an atypical presentation. Atypical presentations include nodular, annular, pustular, lues maligna, frambesiform, corymbose, and photosensitive distributions.7,8 Notably, coinfection with HIV modifies the clinical presentation, serology, and efficacy of treatment.7-10 Atypical presentations are more common in coinfected HIV-positive patients, mandating a high degree of suspicion. Nodular secondary syphilis and the noduloulcerative form (lues maligna) often spare the palmar and plantar surfaces, and patients often have constitutional symptoms accompanying the cutaneous eruptions. In questionable cases, a biopsy lends clarification. Light microscopy on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining may display acanthosis, superficial and deep perivascular swelling, plasma, histiocyte infiltrates, dermoepidermal junction changes, mixed patterns, epidermal hyperplasia, and dermal vascular thickening.7-9,11 Spirochetes may be observed on Warthin-Starry stain; however, artifact obscuration from melanin granules and reticular fibers or paucity of organisms can make identification difficult. Immunohistochemical staining may prove useful when H&E stains are atypical or have a paucity of organisms or plasma cells or when silver stains have artifactual obscuration.9 Our patient's solitary palmar lesion without constitutional symptoms made an atypical nodular secondary syphilis presentation less likely. Ultimately, the histopathologic findings were consistent with KS.

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) is caused by Bartonella species and results in vascular proliferation with cutaneous manifestation. It frequently is observed in patients with HIV or other immunosuppressive conditions as well as patients with exposure to mammals or their vectors. Protean cutaneous manifestations and distributions of BA exist. The number of lesions can be singular to thousands. Solitary superficial pyogenic granuloma-like lesions can be clinically indistinguishable from both KS and pyogenic granuloma (PG). Superficial lesions often begin as red, violaceous, or flesh-colored papules that hemorrhage easily with trauma. The morphology of the papule can progress to be exophytic with dome-shaped or ulcerative surface features and is rubbery on palpation.12 Biopsy is required to differentiate BA from KS. Bacillary angiomatosis on light microscopy with H&E shows protuberant, lobulated, round vessels with plump endothelial cells with or without necrosis. A neutrophil infiltrate in close proximity to bacilli may be noted. Warthin-Starry stain demonstrates numerous bacilli juxtaposed to these endothelial cells. The lack of immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8 also differentiates BA from KS.12,13

Pyogenic granuloma is resultant from proliferation of endothelial cells with a lobular architecture. Pyogenic granulomas are benign, rapidly progressive, acquired lesions presenting in the skin and mucous membranes. Pyogenic granuloma often presents as a single painless papule or nodule with a glistening red-violaceous color that occasionally appears with a perilesional collarette. The lesions are friable and easily hemorrhage. Pyogenic granuloma has been associated with local skin trauma and estrogen hormones. Histopathologic examination of PG assists with differentiation from other nodular lesions. Light microscopy with standard H&E staining demonstrates a network of capillaries arranged into a lobule surrounded by a fibrous matrix. Endothelial cells appear round and protrude into the vascular lamina. Mitotic activity is increased. Lack of findings on Warthin-Starry stain assists with differentiating PG from BA, while the microscopy architecture and immunohistochemical staining differentiates PG from KS.6,13,14

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the primary malignant cancer of the hand. The dorsal aspect of the hand is the most common location; SCC less commonly is located on the palmar surface, fingers, nail bed, or intertriginous areas.15-17 Chakrabarti et al16 found that these lesions were invasive SCC when located on the palmar surface. Morphologically, SCC takes an exophytic papular, nodular, or scaly appearance with a red to flesh-colored appearance and poor demarcation of the borders. Progression to large ulcerated or secondarily infected lesions also can occur. The inflammatory reaction may cause tenderness to palpation and hemorrhage with trauma. Histopathologic examination of invasive SCC reveals atypical keratinocytes violating the basement membrane and abundant cytoplasm. Our patient's clinical presentation placed invasive SCC low on the differential diagnosis, and the histopathologic and immunohistochemical results eliminated SCC as the diagnosis.

- Antman K, Chang Y. Kaposi's sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1027-1038.

- Pipette WW. The incidence of second malignancies in subsets of Kaposi's sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:855-861.

- Shiels MS, Engels EA. Evolving epidemiology of HIV-associated malignancies. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12:6-11.

- Daly ML, Fogo A, McDonald C, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: no longer an AIDS-defining illness? a retrospective study of Kaposi sarcoma cases with CD4 counts above 300/mm³ at presentation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:7-12.

- Broccolo F, Tassan Din C, Viganò MG, et al. HHV-8 DNA replication correlates with the clinical status in AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. J Clin Virol. 2016;78:47-52.

- Pereira PF, Cuzzi T, Galhardo MC. Immunohistochemical detection of the latent nuclear antigen-1 of the human herpesvirus type 8 to differentiate cutaneous epidemic Kaposi sarcoma and its histological simulators. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:243-246.

- Gevorgyan O, Owen BD, Balavenkataraman A, et al. A nodular-ulcerative form of secondary syphilis in AIDS. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2017;30:80-82.

- Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:595-599.

- Yayli S, della Torre R, Hegyi I, et al. Late secondary syphilis with nodular lesions mimicking Kaposi sarcoma in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E71-E73.

- Jeerapaet P, Ackerman AB. Histologic patterns of secondary syphilis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:373-377.

- Cockerell CJ, LeBoit PE. Bacillary angiomatosis: a newly characterized, pseudoneoplastic, infectious, cutaneous vascular disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:501-512.

- Forrestel AK, Naujokas A, Martin JN, et al. Bacillary angiomatosis masquerading as Kaposi's sarcoma in East Africa. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14:21-25.

- Fortna RR, Junkins-Hopkins JM. A case of lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma), localized to the subcutaneous tissue, and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:408-411.

- Marks R. Squamous cell carcinoma. Lancet. 1996;347:735-738.

- Chakrabarti I, Watson JD, Dorrance H. Skin tumours of the hand. a 10-year review. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18:484-486.

- Sobanko JF, Dagum AB, Davis IC, et al. Soft tissue tumors of the hand. 2. malignant. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:771-785.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Kaposi Sarcoma

Epidemic Kaposi sarcoma (KS) primarily affects patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Kaposi sarcoma can appear as brown, red, or blue-black macules, plaques, patches, nodules, or tumors, and it often is observed as multifocal cutaneous lesions located on the head, neck, and upper aspects of the trunk in a fulminant manner. Kaposi sarcoma portends a poor prognosis and is an AIDS-defining malignancy.1-3 Importantly, antiretroviral therapy does not preclude its consideration in those without AIDS-defining CD4 cell counts and undetectable HIV viremia presenting with cutaneous manifestations.2,3 A retrospective review by Daly et al4 reported KS lesions in patients with CD4 lymphocyte counts greater than 300 cells/µL, most of whom were antiretroviral therapy-naïve patients. Also, those with higher CD4 counts tended to have a solitary KS lesion at presentation, while those with CD4 counts less than 300 cells/µL tended to present with multiple foci.4 Epidemic KS lesions are clinically indistinguishable from other common cutaneous conditions in the differential diagnosis of KS, necessitating biopsy for histopathologic examination. Light microscopy findings help to delineate the diagnosis of KS. Immunohistochemical staining to the latent nuclear antigen 1 of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) confirms the KS diagnosis.5,6 Our patient's presentation as a solitary acral lesion was atypical for KS.

Light microscopy of our patient's biopsy demonstrated a large tumor on the acral surface of the right hand. Dermal collections of basophilic spindled cells clustered with small slitlike vascular spaces with abundant erythrocyte extravasation and numerous large ectatic vessels at the periphery were seen (Figure, A). At higher magnification, interlaced bundles of spindle cells with slitlike vessels with scattered lymphocytes and plasma cells were seen (Figure, B). An immunohistochemical stain for HHV-8 was positive and largely confined to spindle cells (Figure, C). These findings confirmed KS and met AIDS-defining criteria. Awareness of these histopathologic features is key in differentiating KS from other conditions in the differential diagnosis.

The patient's history of late latent syphilis coinfected with HIV and persistently elevated rapid plasma reagin that was recalcitrant to therapy placed an atypical nodular presentation within reason for the differential diagnosis. Deviations from the typical papulosquamous presentation with acral involvement in an immunocompromised patient mandates a consideration for syphilis with an atypical presentation. Atypical presentations include nodular, annular, pustular, lues maligna, frambesiform, corymbose, and photosensitive distributions.7,8 Notably, coinfection with HIV modifies the clinical presentation, serology, and efficacy of treatment.7-10 Atypical presentations are more common in coinfected HIV-positive patients, mandating a high degree of suspicion. Nodular secondary syphilis and the noduloulcerative form (lues maligna) often spare the palmar and plantar surfaces, and patients often have constitutional symptoms accompanying the cutaneous eruptions. In questionable cases, a biopsy lends clarification. Light microscopy on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining may display acanthosis, superficial and deep perivascular swelling, plasma, histiocyte infiltrates, dermoepidermal junction changes, mixed patterns, epidermal hyperplasia, and dermal vascular thickening.7-9,11 Spirochetes may be observed on Warthin-Starry stain; however, artifact obscuration from melanin granules and reticular fibers or paucity of organisms can make identification difficult. Immunohistochemical staining may prove useful when H&E stains are atypical or have a paucity of organisms or plasma cells or when silver stains have artifactual obscuration.9 Our patient's solitary palmar lesion without constitutional symptoms made an atypical nodular secondary syphilis presentation less likely. Ultimately, the histopathologic findings were consistent with KS.

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) is caused by Bartonella species and results in vascular proliferation with cutaneous manifestation. It frequently is observed in patients with HIV or other immunosuppressive conditions as well as patients with exposure to mammals or their vectors. Protean cutaneous manifestations and distributions of BA exist. The number of lesions can be singular to thousands. Solitary superficial pyogenic granuloma-like lesions can be clinically indistinguishable from both KS and pyogenic granuloma (PG). Superficial lesions often begin as red, violaceous, or flesh-colored papules that hemorrhage easily with trauma. The morphology of the papule can progress to be exophytic with dome-shaped or ulcerative surface features and is rubbery on palpation.12 Biopsy is required to differentiate BA from KS. Bacillary angiomatosis on light microscopy with H&E shows protuberant, lobulated, round vessels with plump endothelial cells with or without necrosis. A neutrophil infiltrate in close proximity to bacilli may be noted. Warthin-Starry stain demonstrates numerous bacilli juxtaposed to these endothelial cells. The lack of immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8 also differentiates BA from KS.12,13

Pyogenic granuloma is resultant from proliferation of endothelial cells with a lobular architecture. Pyogenic granulomas are benign, rapidly progressive, acquired lesions presenting in the skin and mucous membranes. Pyogenic granuloma often presents as a single painless papule or nodule with a glistening red-violaceous color that occasionally appears with a perilesional collarette. The lesions are friable and easily hemorrhage. Pyogenic granuloma has been associated with local skin trauma and estrogen hormones. Histopathologic examination of PG assists with differentiation from other nodular lesions. Light microscopy with standard H&E staining demonstrates a network of capillaries arranged into a lobule surrounded by a fibrous matrix. Endothelial cells appear round and protrude into the vascular lamina. Mitotic activity is increased. Lack of findings on Warthin-Starry stain assists with differentiating PG from BA, while the microscopy architecture and immunohistochemical staining differentiates PG from KS.6,13,14

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the primary malignant cancer of the hand. The dorsal aspect of the hand is the most common location; SCC less commonly is located on the palmar surface, fingers, nail bed, or intertriginous areas.15-17 Chakrabarti et al16 found that these lesions were invasive SCC when located on the palmar surface. Morphologically, SCC takes an exophytic papular, nodular, or scaly appearance with a red to flesh-colored appearance and poor demarcation of the borders. Progression to large ulcerated or secondarily infected lesions also can occur. The inflammatory reaction may cause tenderness to palpation and hemorrhage with trauma. Histopathologic examination of invasive SCC reveals atypical keratinocytes violating the basement membrane and abundant cytoplasm. Our patient's clinical presentation placed invasive SCC low on the differential diagnosis, and the histopathologic and immunohistochemical results eliminated SCC as the diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Kaposi Sarcoma

Epidemic Kaposi sarcoma (KS) primarily affects patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Kaposi sarcoma can appear as brown, red, or blue-black macules, plaques, patches, nodules, or tumors, and it often is observed as multifocal cutaneous lesions located on the head, neck, and upper aspects of the trunk in a fulminant manner. Kaposi sarcoma portends a poor prognosis and is an AIDS-defining malignancy.1-3 Importantly, antiretroviral therapy does not preclude its consideration in those without AIDS-defining CD4 cell counts and undetectable HIV viremia presenting with cutaneous manifestations.2,3 A retrospective review by Daly et al4 reported KS lesions in patients with CD4 lymphocyte counts greater than 300 cells/µL, most of whom were antiretroviral therapy-naïve patients. Also, those with higher CD4 counts tended to have a solitary KS lesion at presentation, while those with CD4 counts less than 300 cells/µL tended to present with multiple foci.4 Epidemic KS lesions are clinically indistinguishable from other common cutaneous conditions in the differential diagnosis of KS, necessitating biopsy for histopathologic examination. Light microscopy findings help to delineate the diagnosis of KS. Immunohistochemical staining to the latent nuclear antigen 1 of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) confirms the KS diagnosis.5,6 Our patient's presentation as a solitary acral lesion was atypical for KS.

Light microscopy of our patient's biopsy demonstrated a large tumor on the acral surface of the right hand. Dermal collections of basophilic spindled cells clustered with small slitlike vascular spaces with abundant erythrocyte extravasation and numerous large ectatic vessels at the periphery were seen (Figure, A). At higher magnification, interlaced bundles of spindle cells with slitlike vessels with scattered lymphocytes and plasma cells were seen (Figure, B). An immunohistochemical stain for HHV-8 was positive and largely confined to spindle cells (Figure, C). These findings confirmed KS and met AIDS-defining criteria. Awareness of these histopathologic features is key in differentiating KS from other conditions in the differential diagnosis.

The patient's history of late latent syphilis coinfected with HIV and persistently elevated rapid plasma reagin that was recalcitrant to therapy placed an atypical nodular presentation within reason for the differential diagnosis. Deviations from the typical papulosquamous presentation with acral involvement in an immunocompromised patient mandates a consideration for syphilis with an atypical presentation. Atypical presentations include nodular, annular, pustular, lues maligna, frambesiform, corymbose, and photosensitive distributions.7,8 Notably, coinfection with HIV modifies the clinical presentation, serology, and efficacy of treatment.7-10 Atypical presentations are more common in coinfected HIV-positive patients, mandating a high degree of suspicion. Nodular secondary syphilis and the noduloulcerative form (lues maligna) often spare the palmar and plantar surfaces, and patients often have constitutional symptoms accompanying the cutaneous eruptions. In questionable cases, a biopsy lends clarification. Light microscopy on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining may display acanthosis, superficial and deep perivascular swelling, plasma, histiocyte infiltrates, dermoepidermal junction changes, mixed patterns, epidermal hyperplasia, and dermal vascular thickening.7-9,11 Spirochetes may be observed on Warthin-Starry stain; however, artifact obscuration from melanin granules and reticular fibers or paucity of organisms can make identification difficult. Immunohistochemical staining may prove useful when H&E stains are atypical or have a paucity of organisms or plasma cells or when silver stains have artifactual obscuration.9 Our patient's solitary palmar lesion without constitutional symptoms made an atypical nodular secondary syphilis presentation less likely. Ultimately, the histopathologic findings were consistent with KS.

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) is caused by Bartonella species and results in vascular proliferation with cutaneous manifestation. It frequently is observed in patients with HIV or other immunosuppressive conditions as well as patients with exposure to mammals or their vectors. Protean cutaneous manifestations and distributions of BA exist. The number of lesions can be singular to thousands. Solitary superficial pyogenic granuloma-like lesions can be clinically indistinguishable from both KS and pyogenic granuloma (PG). Superficial lesions often begin as red, violaceous, or flesh-colored papules that hemorrhage easily with trauma. The morphology of the papule can progress to be exophytic with dome-shaped or ulcerative surface features and is rubbery on palpation.12 Biopsy is required to differentiate BA from KS. Bacillary angiomatosis on light microscopy with H&E shows protuberant, lobulated, round vessels with plump endothelial cells with or without necrosis. A neutrophil infiltrate in close proximity to bacilli may be noted. Warthin-Starry stain demonstrates numerous bacilli juxtaposed to these endothelial cells. The lack of immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8 also differentiates BA from KS.12,13

Pyogenic granuloma is resultant from proliferation of endothelial cells with a lobular architecture. Pyogenic granulomas are benign, rapidly progressive, acquired lesions presenting in the skin and mucous membranes. Pyogenic granuloma often presents as a single painless papule or nodule with a glistening red-violaceous color that occasionally appears with a perilesional collarette. The lesions are friable and easily hemorrhage. Pyogenic granuloma has been associated with local skin trauma and estrogen hormones. Histopathologic examination of PG assists with differentiation from other nodular lesions. Light microscopy with standard H&E staining demonstrates a network of capillaries arranged into a lobule surrounded by a fibrous matrix. Endothelial cells appear round and protrude into the vascular lamina. Mitotic activity is increased. Lack of findings on Warthin-Starry stain assists with differentiating PG from BA, while the microscopy architecture and immunohistochemical staining differentiates PG from KS.6,13,14

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the primary malignant cancer of the hand. The dorsal aspect of the hand is the most common location; SCC less commonly is located on the palmar surface, fingers, nail bed, or intertriginous areas.15-17 Chakrabarti et al16 found that these lesions were invasive SCC when located on the palmar surface. Morphologically, SCC takes an exophytic papular, nodular, or scaly appearance with a red to flesh-colored appearance and poor demarcation of the borders. Progression to large ulcerated or secondarily infected lesions also can occur. The inflammatory reaction may cause tenderness to palpation and hemorrhage with trauma. Histopathologic examination of invasive SCC reveals atypical keratinocytes violating the basement membrane and abundant cytoplasm. Our patient's clinical presentation placed invasive SCC low on the differential diagnosis, and the histopathologic and immunohistochemical results eliminated SCC as the diagnosis.

- Antman K, Chang Y. Kaposi's sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1027-1038.

- Pipette WW. The incidence of second malignancies in subsets of Kaposi's sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:855-861.

- Shiels MS, Engels EA. Evolving epidemiology of HIV-associated malignancies. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12:6-11.

- Daly ML, Fogo A, McDonald C, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: no longer an AIDS-defining illness? a retrospective study of Kaposi sarcoma cases with CD4 counts above 300/mm³ at presentation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:7-12.

- Broccolo F, Tassan Din C, Viganò MG, et al. HHV-8 DNA replication correlates with the clinical status in AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. J Clin Virol. 2016;78:47-52.

- Pereira PF, Cuzzi T, Galhardo MC. Immunohistochemical detection of the latent nuclear antigen-1 of the human herpesvirus type 8 to differentiate cutaneous epidemic Kaposi sarcoma and its histological simulators. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:243-246.

- Gevorgyan O, Owen BD, Balavenkataraman A, et al. A nodular-ulcerative form of secondary syphilis in AIDS. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2017;30:80-82.

- Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:595-599.

- Yayli S, della Torre R, Hegyi I, et al. Late secondary syphilis with nodular lesions mimicking Kaposi sarcoma in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E71-E73.

- Jeerapaet P, Ackerman AB. Histologic patterns of secondary syphilis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:373-377.

- Cockerell CJ, LeBoit PE. Bacillary angiomatosis: a newly characterized, pseudoneoplastic, infectious, cutaneous vascular disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:501-512.

- Forrestel AK, Naujokas A, Martin JN, et al. Bacillary angiomatosis masquerading as Kaposi's sarcoma in East Africa. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14:21-25.

- Fortna RR, Junkins-Hopkins JM. A case of lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma), localized to the subcutaneous tissue, and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:408-411.

- Marks R. Squamous cell carcinoma. Lancet. 1996;347:735-738.

- Chakrabarti I, Watson JD, Dorrance H. Skin tumours of the hand. a 10-year review. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18:484-486.

- Sobanko JF, Dagum AB, Davis IC, et al. Soft tissue tumors of the hand. 2. malignant. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:771-785.

- Antman K, Chang Y. Kaposi's sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1027-1038.

- Pipette WW. The incidence of second malignancies in subsets of Kaposi's sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:855-861.

- Shiels MS, Engels EA. Evolving epidemiology of HIV-associated malignancies. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12:6-11.

- Daly ML, Fogo A, McDonald C, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: no longer an AIDS-defining illness? a retrospective study of Kaposi sarcoma cases with CD4 counts above 300/mm³ at presentation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:7-12.

- Broccolo F, Tassan Din C, Viganò MG, et al. HHV-8 DNA replication correlates with the clinical status in AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. J Clin Virol. 2016;78:47-52.

- Pereira PF, Cuzzi T, Galhardo MC. Immunohistochemical detection of the latent nuclear antigen-1 of the human herpesvirus type 8 to differentiate cutaneous epidemic Kaposi sarcoma and its histological simulators. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:243-246.

- Gevorgyan O, Owen BD, Balavenkataraman A, et al. A nodular-ulcerative form of secondary syphilis in AIDS. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2017;30:80-82.

- Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:595-599.

- Yayli S, della Torre R, Hegyi I, et al. Late secondary syphilis with nodular lesions mimicking Kaposi sarcoma in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E71-E73.

- Jeerapaet P, Ackerman AB. Histologic patterns of secondary syphilis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:373-377.

- Cockerell CJ, LeBoit PE. Bacillary angiomatosis: a newly characterized, pseudoneoplastic, infectious, cutaneous vascular disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:501-512.

- Forrestel AK, Naujokas A, Martin JN, et al. Bacillary angiomatosis masquerading as Kaposi's sarcoma in East Africa. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14:21-25.

- Fortna RR, Junkins-Hopkins JM. A case of lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma), localized to the subcutaneous tissue, and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:408-411.

- Marks R. Squamous cell carcinoma. Lancet. 1996;347:735-738.

- Chakrabarti I, Watson JD, Dorrance H. Skin tumours of the hand. a 10-year review. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18:484-486.

- Sobanko JF, Dagum AB, Davis IC, et al. Soft tissue tumors of the hand. 2. malignant. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:771-785.

A 52-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 2×3-cm, fungating, dome-shaped, ulcerative, moist, well-circumscribed tumor with peripheral maceration on the volar aspect of the right hand of 3 months’ duration. The tumor was malodorous, painful, and hemorrhaged easily with minimal trauma. The patient’s medical history was notable for human immunodeficiency virus and latent syphilis, with elevated rapid plasma reagin titers and a positive Treponema palladium antibody on chemiluminescent immunoassay, that was refractory to 3 treatments with penicillin. The patient was not on antiretroviral therapy. He had a CD4+ lymphocyte count of 980 cells/µL (reference range, 359–1519 cells/µL) and a viral load of 8560 copies/mL (reference range, <200 copies/mL). No other skin or systemic concerns were noted, and the patient denied any recent travel, exposure to animals, or constitutional symptoms. A deep shave biopsy of the lesion was performed.

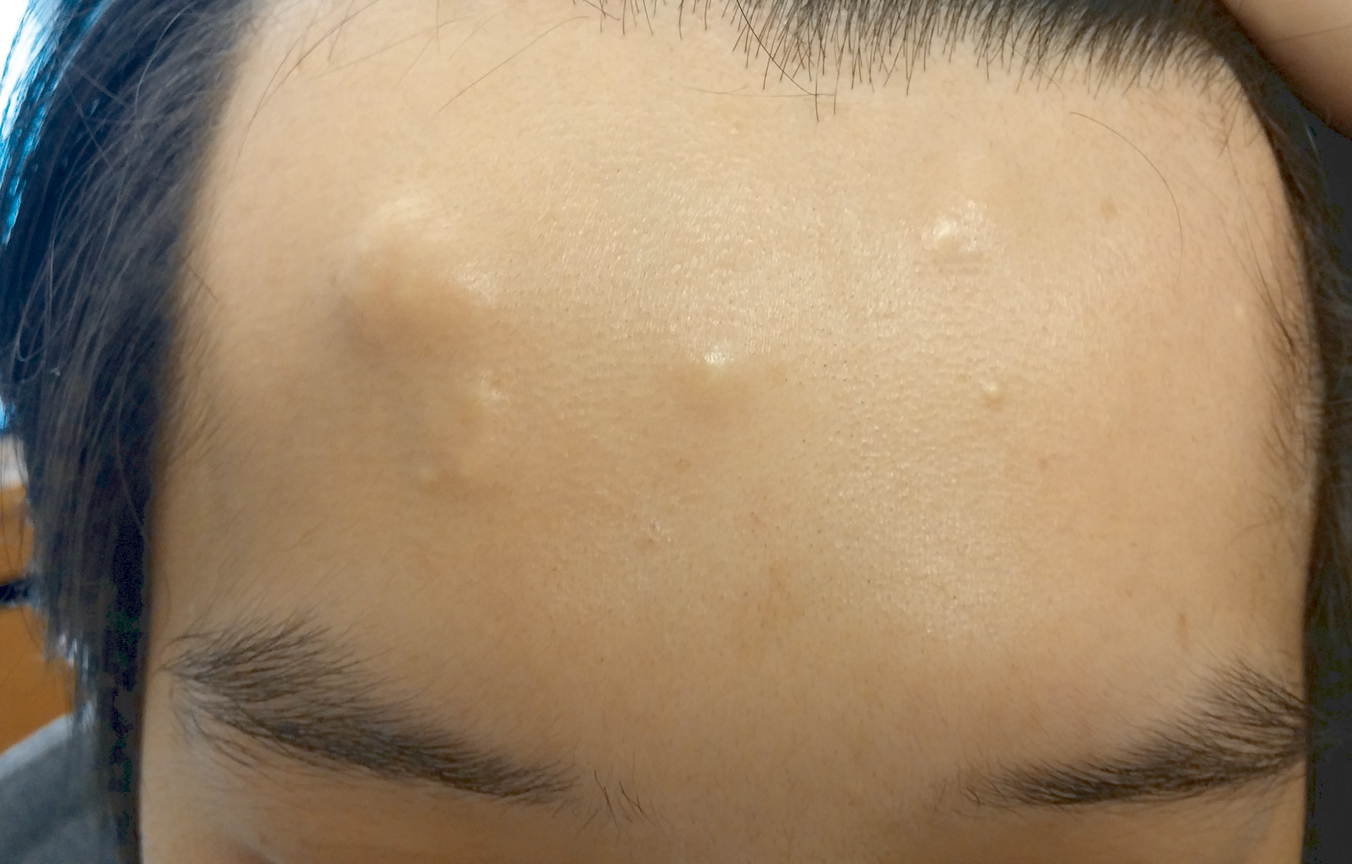

Rapidly Growing Retroauricular Tumor

The Diagnosis: Milia En Plaque

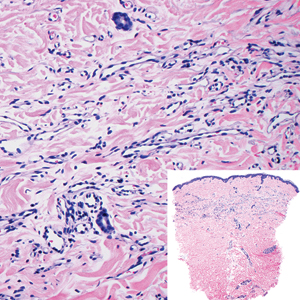

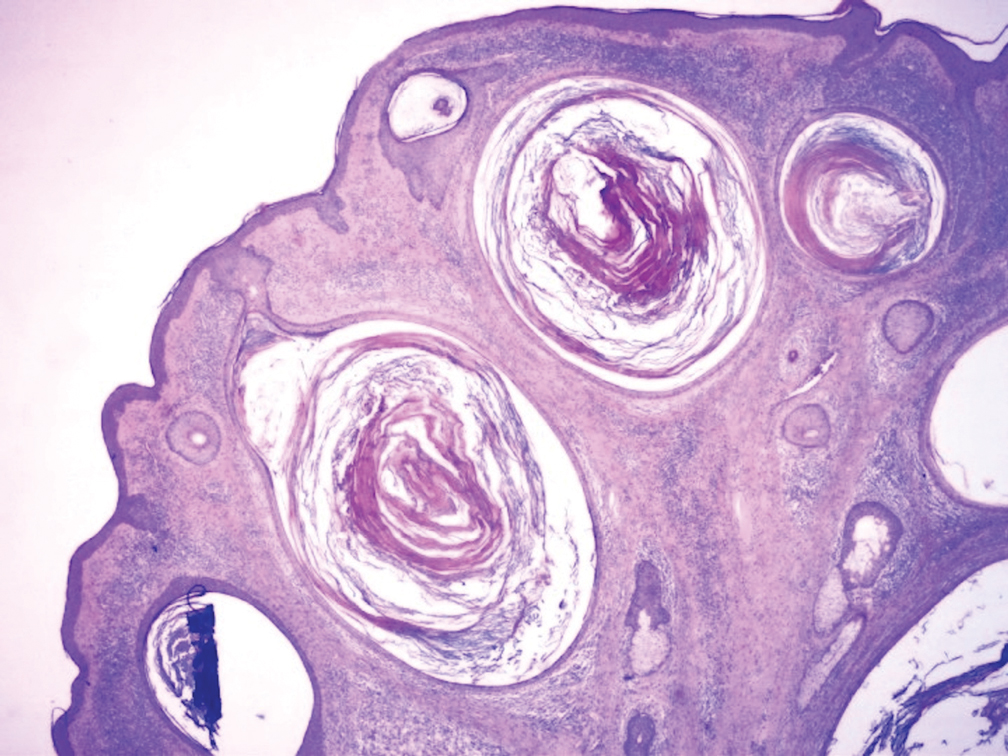

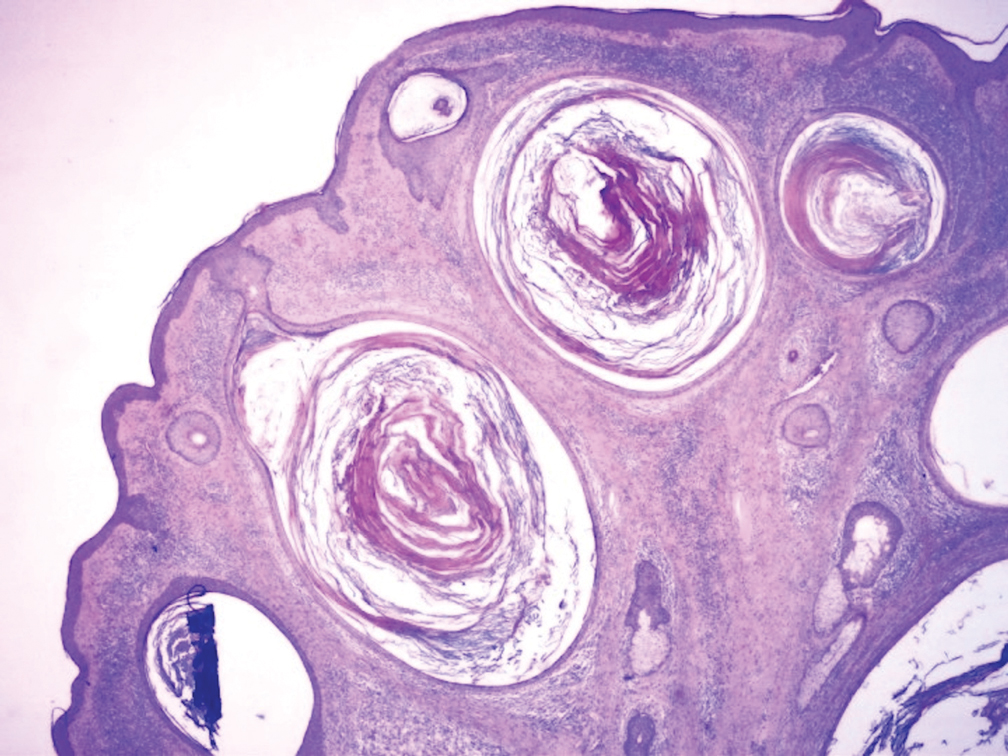

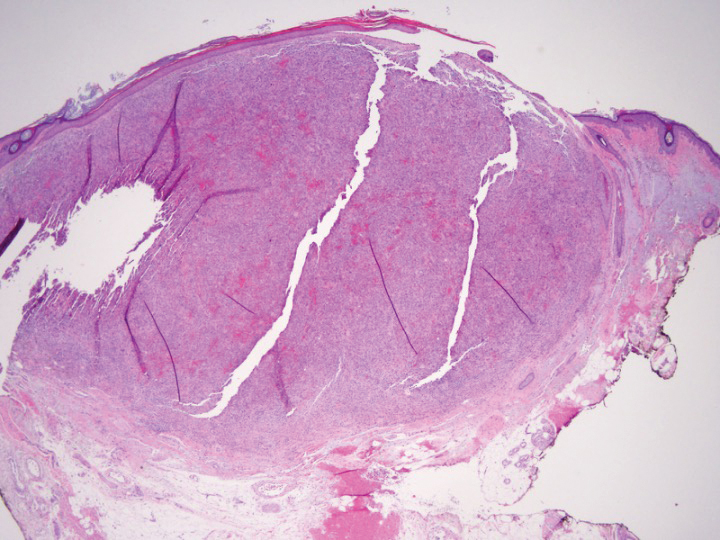

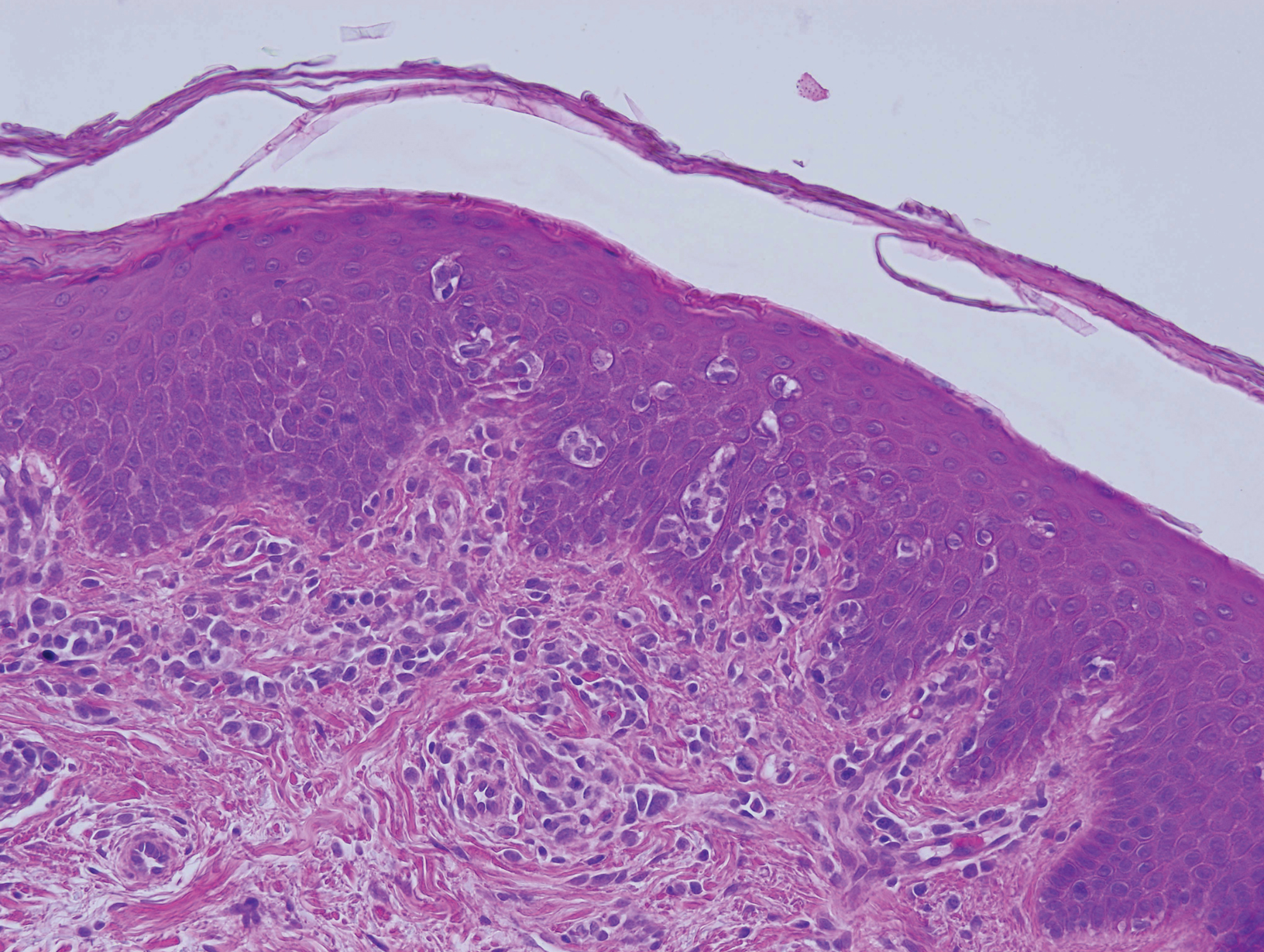

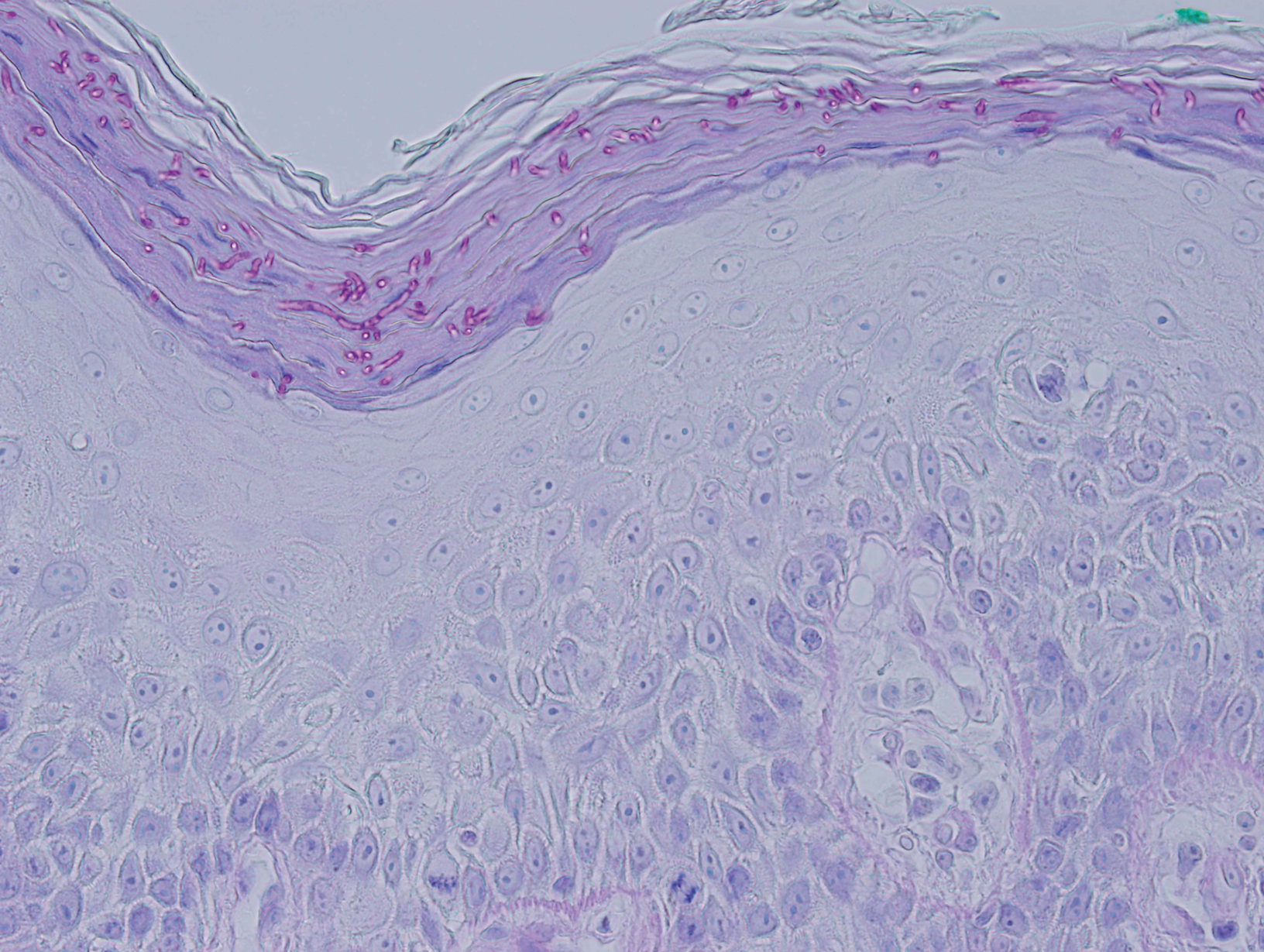

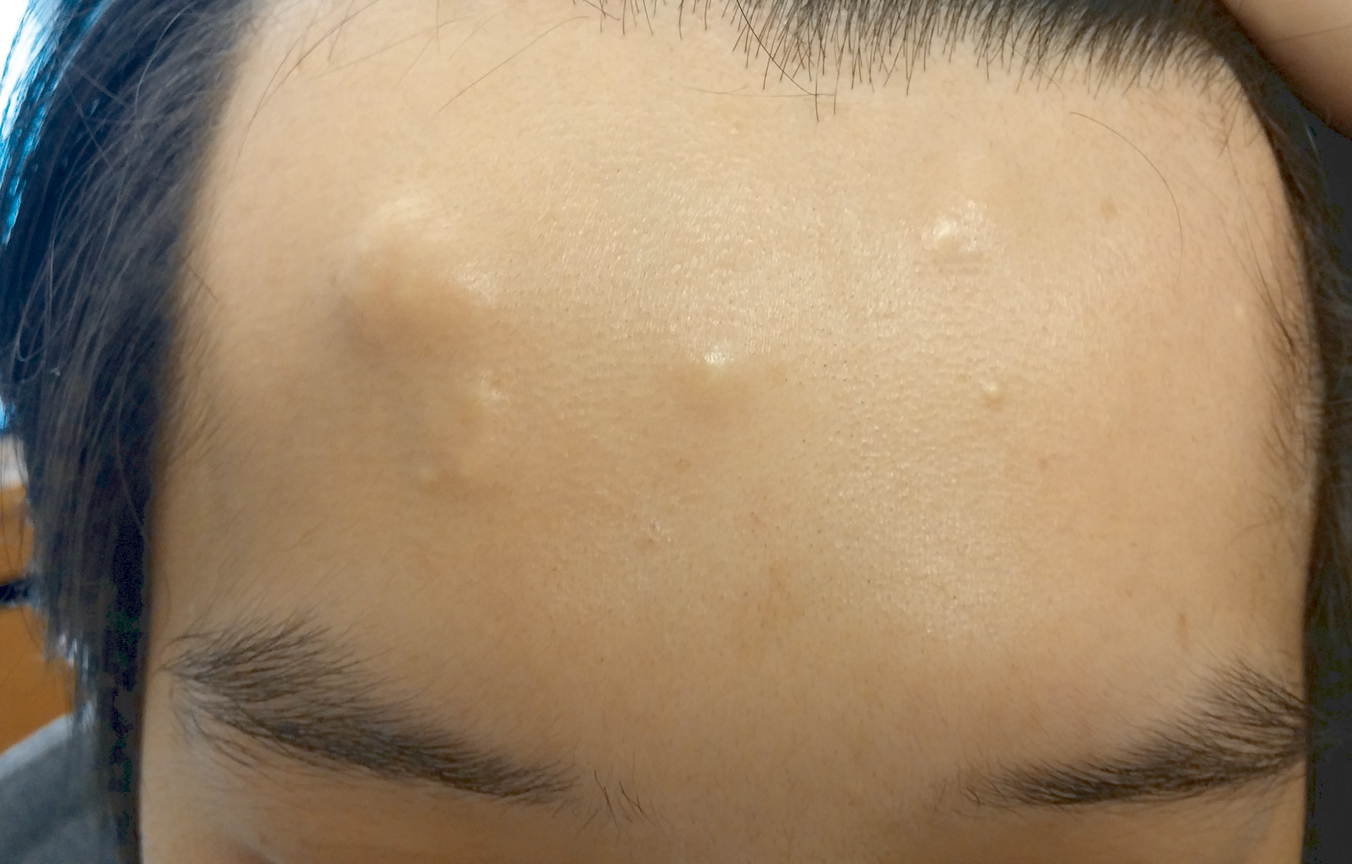

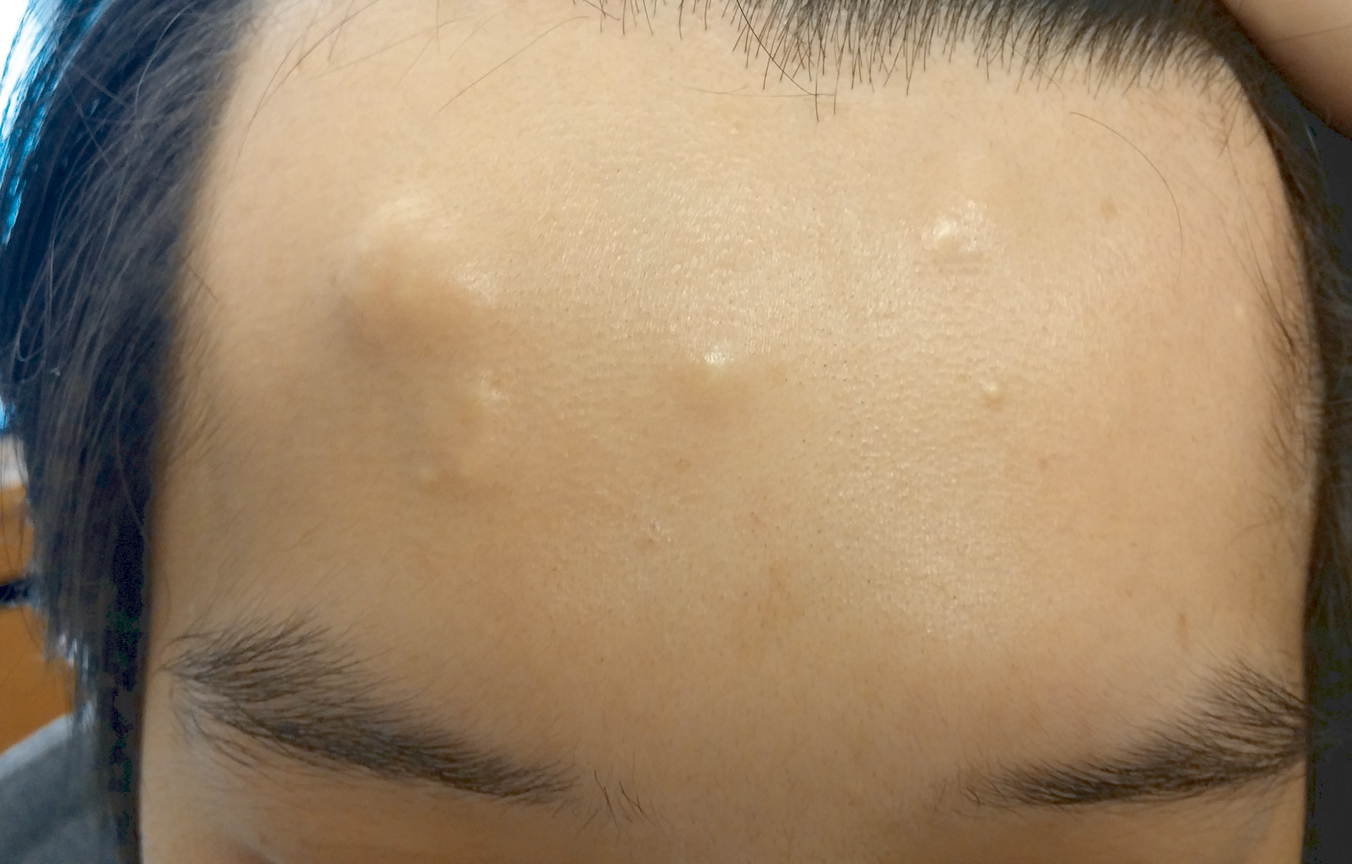

Biopsy results revealed a normal epidermis; the dermis showed multiple small cystic structures lined by a stratified squamous epithelium containing eosinophilic keratin surrounded by a mononuclear cell infiltrate and some melanophages (Figure).

Milia en plaque was first described in 1903 by Balzer and Fouquet.1 In 1978, Hubler et al2 presented 2 cases with an asymptomatic, erythematous, and edematous plaque and white milialike lesions. On histopathology, they showed multiple cystic structures characterized by central laminated keratin and an intense polymorphic inflammatory reaction surrounding the cyst and epidermal appendages. Both patients were treated with topical tretinoin with complete response at 3 months. The authors suggested the term milia en plaque to describe this clinical entity.2

Milia en plaque is described as an infrequent condition that more often presents on the head, neck, and trunk, as well as the periocular, periauricular, and perinasal areas. It has been reported to occur at any age3 but appears more frequently in middle-aged adults and females. A congenital case also has been reported.4 It has been associated with pseudoxanthoma elasticum, lichen planus, trauma, kidney transplant, and cyclosporine use, but it also can present in healthy individuals,3 as in our patient. No clear cause has been identified.

Pathology is characteristic, with multiple cysts filled with keratin and surrounded by 2 or 3 layers of epithelial cells, associated with a mononuclear, nonlichenoid, mononuclear infiltrate.5 Structures similar to follicular infundibular tumors have been described, suggesting a common origin of follicular lesions as milia en plaque.6

Treatment includes surgical excision, cryosurgery, dermabrasion, electrodesiccation, trichloroacetic acid, photodynamic therapy, CO2 and erbium lasers, topical retinoids, minocycline, and etretinate.7 We performed a complete surgical excision in our patient.

In acneform reactions, erythematous papules and pustules can be found on the cheeks and forehead. Nevus comedonicus appears during childhood and presents with multiple open comedones. Postinflammatory milia is present in chronic inflammatory pathologies such as porphyria cutanea tarda. Histopathologic findings in adnexal tumors show a benign proliferation of any cellular type of a cutaneous annex.

Milia en plaque is an unusual but benign condition that is distinguished clinically by its characteristic presentation.

- Balzer F, Fouquet C. Milium confluent retroauricularies bilateral. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1903;14:361.

- Hubler WR, Rudolph AH, Kelleher RM. Milia en plaque. Cutis. 1978;22:67-70.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1050-1063.

- Wang AR, Bercovitch L. Congenital milia en plaque. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:258-259.

- Muñoz-Martínez R, Santamarina-Albertos A, Sanz-Muñoz C, et al. Milia en plaque. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:638-640.

- Terui H, Hashimoto A, Yamasaki K, et al. Milia en plaque as a distinct follicular hamartoma with cystic trichoepitheliomatous features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:212-217.

- Tenna S, Filoni A, Pagliarello C, et al. Eyelid milia en plaque: a treatment challenge with a new CO2 fractional laser. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:65-67.

The Diagnosis: Milia En Plaque

Biopsy results revealed a normal epidermis; the dermis showed multiple small cystic structures lined by a stratified squamous epithelium containing eosinophilic keratin surrounded by a mononuclear cell infiltrate and some melanophages (Figure).

Milia en plaque was first described in 1903 by Balzer and Fouquet.1 In 1978, Hubler et al2 presented 2 cases with an asymptomatic, erythematous, and edematous plaque and white milialike lesions. On histopathology, they showed multiple cystic structures characterized by central laminated keratin and an intense polymorphic inflammatory reaction surrounding the cyst and epidermal appendages. Both patients were treated with topical tretinoin with complete response at 3 months. The authors suggested the term milia en plaque to describe this clinical entity.2

Milia en plaque is described as an infrequent condition that more often presents on the head, neck, and trunk, as well as the periocular, periauricular, and perinasal areas. It has been reported to occur at any age3 but appears more frequently in middle-aged adults and females. A congenital case also has been reported.4 It has been associated with pseudoxanthoma elasticum, lichen planus, trauma, kidney transplant, and cyclosporine use, but it also can present in healthy individuals,3 as in our patient. No clear cause has been identified.

Pathology is characteristic, with multiple cysts filled with keratin and surrounded by 2 or 3 layers of epithelial cells, associated with a mononuclear, nonlichenoid, mononuclear infiltrate.5 Structures similar to follicular infundibular tumors have been described, suggesting a common origin of follicular lesions as milia en plaque.6

Treatment includes surgical excision, cryosurgery, dermabrasion, electrodesiccation, trichloroacetic acid, photodynamic therapy, CO2 and erbium lasers, topical retinoids, minocycline, and etretinate.7 We performed a complete surgical excision in our patient.

In acneform reactions, erythematous papules and pustules can be found on the cheeks and forehead. Nevus comedonicus appears during childhood and presents with multiple open comedones. Postinflammatory milia is present in chronic inflammatory pathologies such as porphyria cutanea tarda. Histopathologic findings in adnexal tumors show a benign proliferation of any cellular type of a cutaneous annex.

Milia en plaque is an unusual but benign condition that is distinguished clinically by its characteristic presentation.

The Diagnosis: Milia En Plaque

Biopsy results revealed a normal epidermis; the dermis showed multiple small cystic structures lined by a stratified squamous epithelium containing eosinophilic keratin surrounded by a mononuclear cell infiltrate and some melanophages (Figure).