User login

Granulomatous Cheilitis: A Stiff Upper Lip

To the Editor:

A 51-year-old woman presented to her dermatologist with recurrent and progressive upper lip swelling of 2 years’ duration. Her condition was previously evaluated by several other physicians without a diagnosis or resolution of the symptoms. The swelling began on the right side of the upper lip and right cheek; however, over the course of 2 years, the swelling had progressed to involve the entire upper lip with complete sparing of the lower lip. She denied pain but reported numbness of the upper lip. The patient visited her dentist who ruled out periodontal infection as the cause of the swelling. Diphenhydramine provided no relief; however, the cheek swelling resolved after a course of antibiotics prescribed by an ear, nose, and throat physician.

She consulted her primary care physician and was subsequently referred to a neurologist and allergist who were unable to provide a definitive diagnosis or complete relief of the symptoms. She denied any history of hypersensitivity reactions, odontogenic infections, gastrointestinal concerns, or any other signs or symptoms of systemic granulomatous disease.

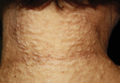

On physical examination, the upper lip was swollen symmetrically without evidence of ulceration, fissuring, or scaling (Figure 1). Palpation of the upper lip was notable for firm, nontender, nonpitting edema without nodularity. The oral mucosa did not appear swollen or erythematous. Examination did not reveal ulceration or a cobblestone appearance.

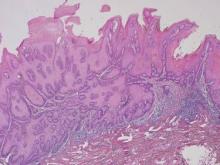

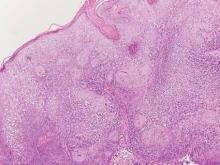

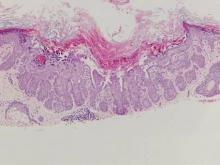

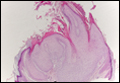

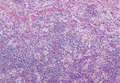

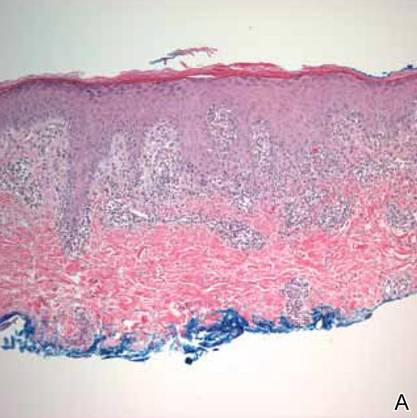

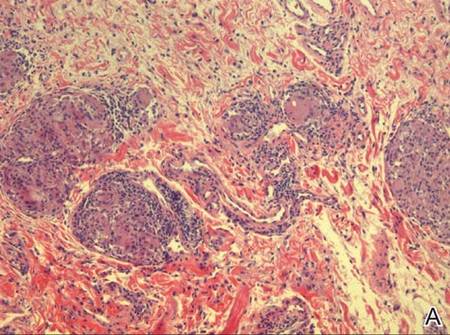

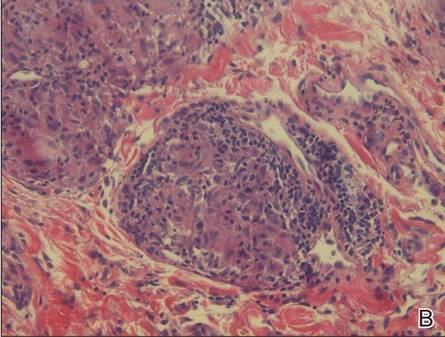

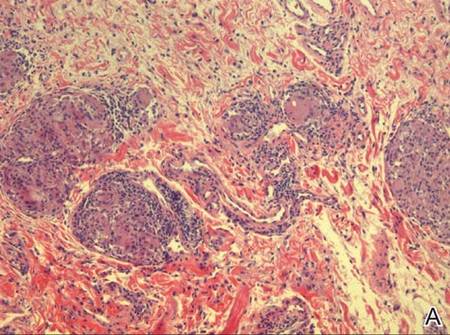

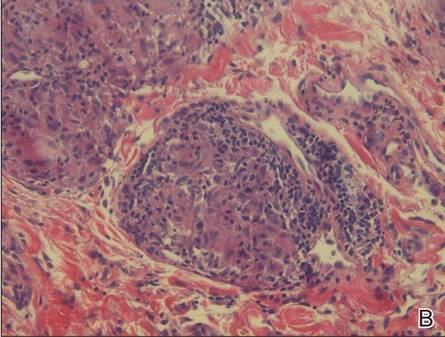

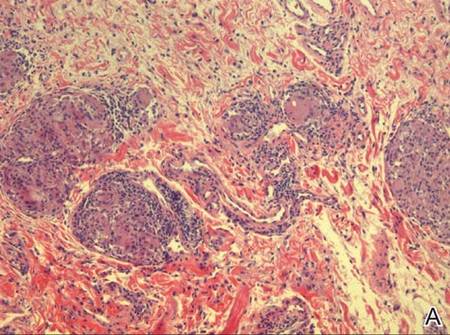

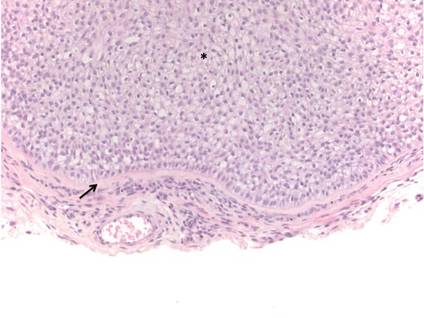

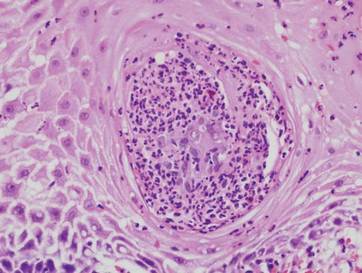

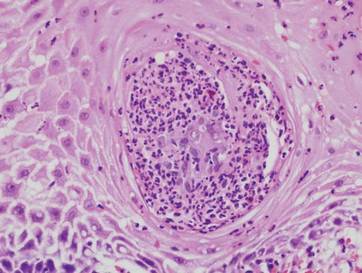

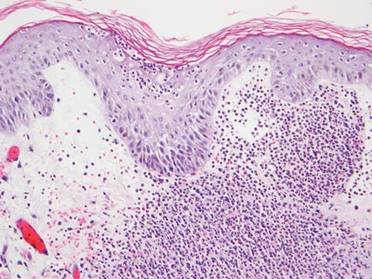

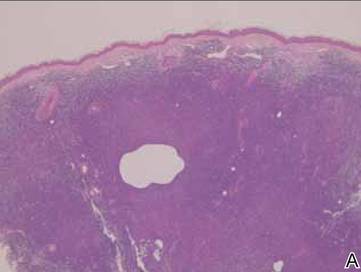

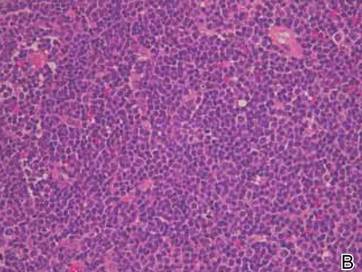

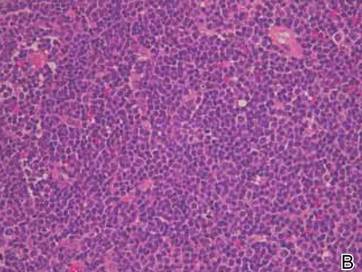

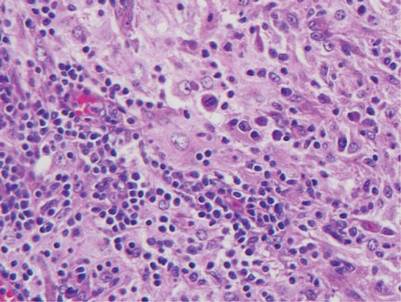

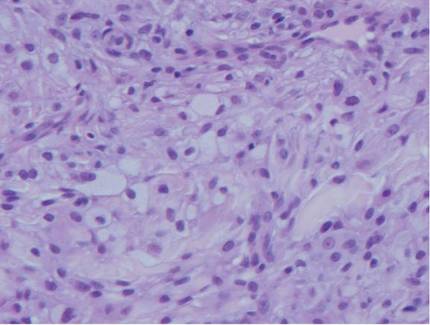

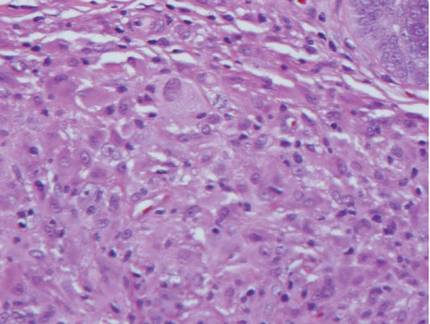

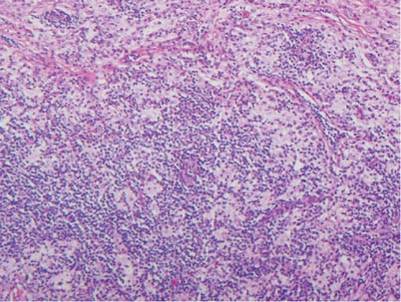

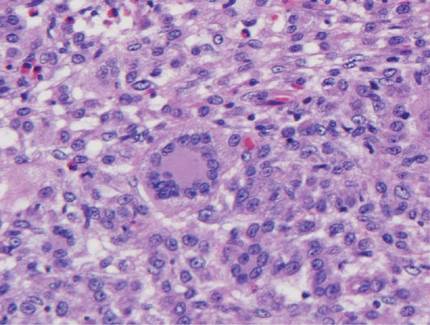

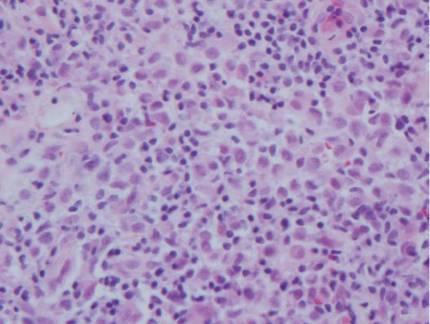

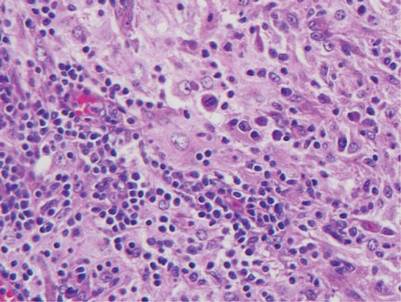

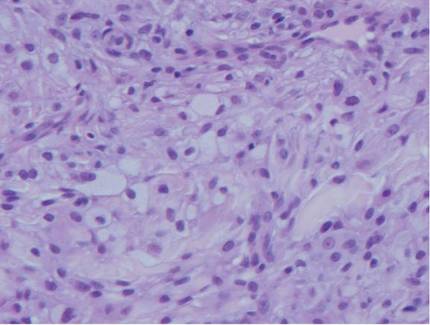

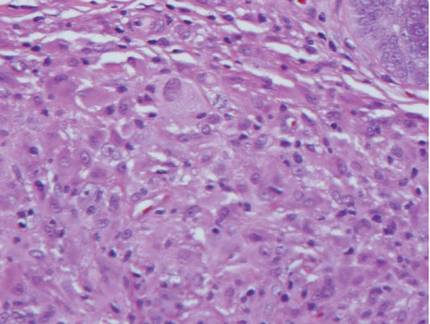

A full-thickness skin biopsy of the upper lip was performed. Histopathology revealed perivascular nonnecrotizing granulomas adjacent to ectatic vascular channels with associated lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal hyphae, tissue Gram stain was negative for bacteria, Fite and acid-fast bacillus stains were both negative for acid-fast organisms, and polariscopy was negative for polarizable foreign material. In this clinical context, the morphologic findings were consistent with the diagnosis of granulomatous cheilitis (GC).

|

Figure 2. Upper lip biopsy showed dermal edema, vascular ectasia, perivascular nonnecrotizing granulomas, and perivascular lymphocyte predominant inflammatory infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100). Higher magnification of granulomas with perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). |

Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare disorder of the lips and orofacial mucosa that was first described by Meischer1 in 1945 as persistent or recurrent orofacial swelling secondary to lymphatic obstruction by granulomatous proliferation. It often has been described as a monosymptomatic form of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (MRS). In its entirety, MRS constitutes a triad of GC, facial nerve palsy, and lingua plicata (also known as fissured tongue).2,3 Although many authors agree that GC is associated with MRS, some believe that GC is a distinct entity because the majority of patients who present with GC subsequently do not develop MRS.4 Despite its relationship to MRS, the true incidence of GC largely is unknown. The onset of disease usually occurs in early adulthood but can present in middle-aged or older individuals.

The typical course of GC is relapsing and remitting, nontender and nonpitting swelling of the lips that eventually becomes permanent, leading to possible facial distortion and disability. Involvement of the upper lip is the most common, followed by (in order of decreasing frequency) the lower lip and cheeks.5 The swelling may be unilateral or bilateral and generally is not associated with ulceration, fissuring, or scaling; however, these complications have been reported in the terminal stages of the disease in which the macrocheilia has become permanent.

Despite the controversy over the etiology, pathophysiology, and classification of GC, it largely is accepted that when a patient presents clinically with a history of recurrent or persistent lip swelling, a full-thickness skin biopsy of the involved oral mucosa should be taken. Conditions that are considered in the differential diagnosis of orofacial granulomatosis are systemic granulomatous diseases that are known to have oral manifestations including Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, and mycobacterial infections. Given the many causes of orofacial and labial swelling, GC is a diagnosis of exclusion based on a thorough history and physical examination as well as appropriate diagnostic studies, with the cornerstone of the diagnosis resting on the histologic appearance of the lesion. Histologically, the diagnosis lies in the demonstration of granuloma formation, consisting of collections of epithelioid histiocytes and Langerhans giant cells. Once granuloma formation is documented, special stains are used to rule out other granulomatous diseases.

Intralesional steroids have been reported to provide the greatest improvement; however, in the majority of patients, multiple treatments are required.6,7 Allen et al8 suggested that the efficacy of intralesional therapy increases when preceded by local anesthesia of the lip, thus allowing larger doses of triamcinolone to be tolerated by the patient. Systemic corticosteroids also have been used with moderate success, but the side effects of long-term systemic corticosteroid therapy make this treatment option less appealing.9 Other agents with known anti-inflammatory properties also have been used that may offer better side-effect profiles when used for long-term suppressive therapy, including clofazimine, dapsone, sulfapyridine, danazol, hydroxychloroquine, and antibiotics such as doxycycline and metronidazole.10

In severe or recalcitrant cases, surgical intervention by way of a reduction cheiloplasty is considered by some to be an appropriate next step in therapy but is rarely needed. Postoperative intralesional steroid injections are necessary due to reported cases of worsening disease when injections are discontinued after cheiloplasty.11,12

Our patient was treated with 5 mg of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide with 10 separate injections of 0.5 cc each along the affected portions of the upper lip. She also was given doxycycline 100 mg once daily for 30 days. The patient reported complete resolution of the upper lip swelling 7 days after the initiation of therapy. At 1-month follow-up, she reported that the swelling had completely resolved. However, 1 day prior to the scheduled visit, shortly after finishing the course of doxycycline, she noted recurrent swelling. Due to the concomitant initial administration of both the steroid injections and doxycycline, it was unclear which treatment had provided relief. To avoid, or at least delay, the need for chronic intralesional steroid injections, another course of 40 mg doxycycline daily was prescribed. After 2 weeks, the patient reported that the swelling had markedly improved. The patient has maintained remission of the symptoms for approximately 6 months on daily suppressive therapy with 40 mg of doxycycline.

The recurrence of lip swelling after therapy, as in our patient, is typical of GC, and most cases require multiple follow-up visits and frequent alterations in therapy, which is often frustrating for both the patient and physician. However, awareness of this disease entity, its natural course, and the therapeutic options will allow physicians to more appropriately counsel and educate patients of this uncommon disease process.

1. Meischer G. Über essentielle granulomatöse makrocheilie (cheilitis granulomatosa). Dermatologica. 1945;91:57-85.

2. Melkersson E. Ett Fall av recidiverande facialispares i samband med angioneurotiskt ödem. Hygiea (Stockh). 1928;90:737-741.

3. Rosenthal C. Klinish-erbbiologischer beitrag zur konstitutionspathologie: gemeinsames auftreten von (rezidiverender familiärer) facialislähmung, angioneurotischem gesichtsödem und lingua plicata in arthritismus-familien. Z Ges Neurol Psychiat. 1931;131:475-501.

4. van der Waal RI, Schulten EA, van der Meij EH, et al. Cheilitis granulomatosa: overview of 13 patients with long-term follow up–results of management. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:225-229.

5. Worsaae N, Christensen KC, Schiødt M, et al. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and cheilitis granulomatosa. a clinical pathological study of thirty-three patients with special reference to their oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;54:404-413.

6. El-Hakim M, Chauvin P. Orofacial granulomatosis presenting as persistent lip swelling: review of 6 new cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:1114-1117.

7. Williams PM, Greenberg MS. Management of cheilitis granulomatosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:436-439.

8. Allen CM, Camisa C, Hamzeh S, et al. Cheilitis granulomatosa: report of six cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(3, pt 1):444-450.

9. Banks T, Gada S. A comprehensive review of current treatments for granulomatous cheilitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:934-937.

10. Sciubba JJ, Said-Al-Naief N. Orofacial granulomatosis: presentation, pathology and management of 13 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:576-585.

11. Glickman LT, Gruss JS, Birt BD, et al. The surgical management of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:815-821.

12. Krutchkoff D, James R. Cheilitis granulomatosa. successful treatment with combined local triamcinolone injections and surgery. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1203-1206.

To the Editor:

A 51-year-old woman presented to her dermatologist with recurrent and progressive upper lip swelling of 2 years’ duration. Her condition was previously evaluated by several other physicians without a diagnosis or resolution of the symptoms. The swelling began on the right side of the upper lip and right cheek; however, over the course of 2 years, the swelling had progressed to involve the entire upper lip with complete sparing of the lower lip. She denied pain but reported numbness of the upper lip. The patient visited her dentist who ruled out periodontal infection as the cause of the swelling. Diphenhydramine provided no relief; however, the cheek swelling resolved after a course of antibiotics prescribed by an ear, nose, and throat physician.

She consulted her primary care physician and was subsequently referred to a neurologist and allergist who were unable to provide a definitive diagnosis or complete relief of the symptoms. She denied any history of hypersensitivity reactions, odontogenic infections, gastrointestinal concerns, or any other signs or symptoms of systemic granulomatous disease.

On physical examination, the upper lip was swollen symmetrically without evidence of ulceration, fissuring, or scaling (Figure 1). Palpation of the upper lip was notable for firm, nontender, nonpitting edema without nodularity. The oral mucosa did not appear swollen or erythematous. Examination did not reveal ulceration or a cobblestone appearance.

A full-thickness skin biopsy of the upper lip was performed. Histopathology revealed perivascular nonnecrotizing granulomas adjacent to ectatic vascular channels with associated lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal hyphae, tissue Gram stain was negative for bacteria, Fite and acid-fast bacillus stains were both negative for acid-fast organisms, and polariscopy was negative for polarizable foreign material. In this clinical context, the morphologic findings were consistent with the diagnosis of granulomatous cheilitis (GC).

|

Figure 2. Upper lip biopsy showed dermal edema, vascular ectasia, perivascular nonnecrotizing granulomas, and perivascular lymphocyte predominant inflammatory infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100). Higher magnification of granulomas with perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). |

Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare disorder of the lips and orofacial mucosa that was first described by Meischer1 in 1945 as persistent or recurrent orofacial swelling secondary to lymphatic obstruction by granulomatous proliferation. It often has been described as a monosymptomatic form of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (MRS). In its entirety, MRS constitutes a triad of GC, facial nerve palsy, and lingua plicata (also known as fissured tongue).2,3 Although many authors agree that GC is associated with MRS, some believe that GC is a distinct entity because the majority of patients who present with GC subsequently do not develop MRS.4 Despite its relationship to MRS, the true incidence of GC largely is unknown. The onset of disease usually occurs in early adulthood but can present in middle-aged or older individuals.

The typical course of GC is relapsing and remitting, nontender and nonpitting swelling of the lips that eventually becomes permanent, leading to possible facial distortion and disability. Involvement of the upper lip is the most common, followed by (in order of decreasing frequency) the lower lip and cheeks.5 The swelling may be unilateral or bilateral and generally is not associated with ulceration, fissuring, or scaling; however, these complications have been reported in the terminal stages of the disease in which the macrocheilia has become permanent.

Despite the controversy over the etiology, pathophysiology, and classification of GC, it largely is accepted that when a patient presents clinically with a history of recurrent or persistent lip swelling, a full-thickness skin biopsy of the involved oral mucosa should be taken. Conditions that are considered in the differential diagnosis of orofacial granulomatosis are systemic granulomatous diseases that are known to have oral manifestations including Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, and mycobacterial infections. Given the many causes of orofacial and labial swelling, GC is a diagnosis of exclusion based on a thorough history and physical examination as well as appropriate diagnostic studies, with the cornerstone of the diagnosis resting on the histologic appearance of the lesion. Histologically, the diagnosis lies in the demonstration of granuloma formation, consisting of collections of epithelioid histiocytes and Langerhans giant cells. Once granuloma formation is documented, special stains are used to rule out other granulomatous diseases.

Intralesional steroids have been reported to provide the greatest improvement; however, in the majority of patients, multiple treatments are required.6,7 Allen et al8 suggested that the efficacy of intralesional therapy increases when preceded by local anesthesia of the lip, thus allowing larger doses of triamcinolone to be tolerated by the patient. Systemic corticosteroids also have been used with moderate success, but the side effects of long-term systemic corticosteroid therapy make this treatment option less appealing.9 Other agents with known anti-inflammatory properties also have been used that may offer better side-effect profiles when used for long-term suppressive therapy, including clofazimine, dapsone, sulfapyridine, danazol, hydroxychloroquine, and antibiotics such as doxycycline and metronidazole.10

In severe or recalcitrant cases, surgical intervention by way of a reduction cheiloplasty is considered by some to be an appropriate next step in therapy but is rarely needed. Postoperative intralesional steroid injections are necessary due to reported cases of worsening disease when injections are discontinued after cheiloplasty.11,12

Our patient was treated with 5 mg of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide with 10 separate injections of 0.5 cc each along the affected portions of the upper lip. She also was given doxycycline 100 mg once daily for 30 days. The patient reported complete resolution of the upper lip swelling 7 days after the initiation of therapy. At 1-month follow-up, she reported that the swelling had completely resolved. However, 1 day prior to the scheduled visit, shortly after finishing the course of doxycycline, she noted recurrent swelling. Due to the concomitant initial administration of both the steroid injections and doxycycline, it was unclear which treatment had provided relief. To avoid, or at least delay, the need for chronic intralesional steroid injections, another course of 40 mg doxycycline daily was prescribed. After 2 weeks, the patient reported that the swelling had markedly improved. The patient has maintained remission of the symptoms for approximately 6 months on daily suppressive therapy with 40 mg of doxycycline.

The recurrence of lip swelling after therapy, as in our patient, is typical of GC, and most cases require multiple follow-up visits and frequent alterations in therapy, which is often frustrating for both the patient and physician. However, awareness of this disease entity, its natural course, and the therapeutic options will allow physicians to more appropriately counsel and educate patients of this uncommon disease process.

To the Editor:

A 51-year-old woman presented to her dermatologist with recurrent and progressive upper lip swelling of 2 years’ duration. Her condition was previously evaluated by several other physicians without a diagnosis or resolution of the symptoms. The swelling began on the right side of the upper lip and right cheek; however, over the course of 2 years, the swelling had progressed to involve the entire upper lip with complete sparing of the lower lip. She denied pain but reported numbness of the upper lip. The patient visited her dentist who ruled out periodontal infection as the cause of the swelling. Diphenhydramine provided no relief; however, the cheek swelling resolved after a course of antibiotics prescribed by an ear, nose, and throat physician.

She consulted her primary care physician and was subsequently referred to a neurologist and allergist who were unable to provide a definitive diagnosis or complete relief of the symptoms. She denied any history of hypersensitivity reactions, odontogenic infections, gastrointestinal concerns, or any other signs or symptoms of systemic granulomatous disease.

On physical examination, the upper lip was swollen symmetrically without evidence of ulceration, fissuring, or scaling (Figure 1). Palpation of the upper lip was notable for firm, nontender, nonpitting edema without nodularity. The oral mucosa did not appear swollen or erythematous. Examination did not reveal ulceration or a cobblestone appearance.

A full-thickness skin biopsy of the upper lip was performed. Histopathology revealed perivascular nonnecrotizing granulomas adjacent to ectatic vascular channels with associated lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal hyphae, tissue Gram stain was negative for bacteria, Fite and acid-fast bacillus stains were both negative for acid-fast organisms, and polariscopy was negative for polarizable foreign material. In this clinical context, the morphologic findings were consistent with the diagnosis of granulomatous cheilitis (GC).

|

Figure 2. Upper lip biopsy showed dermal edema, vascular ectasia, perivascular nonnecrotizing granulomas, and perivascular lymphocyte predominant inflammatory infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100). Higher magnification of granulomas with perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). |

Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare disorder of the lips and orofacial mucosa that was first described by Meischer1 in 1945 as persistent or recurrent orofacial swelling secondary to lymphatic obstruction by granulomatous proliferation. It often has been described as a monosymptomatic form of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (MRS). In its entirety, MRS constitutes a triad of GC, facial nerve palsy, and lingua plicata (also known as fissured tongue).2,3 Although many authors agree that GC is associated with MRS, some believe that GC is a distinct entity because the majority of patients who present with GC subsequently do not develop MRS.4 Despite its relationship to MRS, the true incidence of GC largely is unknown. The onset of disease usually occurs in early adulthood but can present in middle-aged or older individuals.

The typical course of GC is relapsing and remitting, nontender and nonpitting swelling of the lips that eventually becomes permanent, leading to possible facial distortion and disability. Involvement of the upper lip is the most common, followed by (in order of decreasing frequency) the lower lip and cheeks.5 The swelling may be unilateral or bilateral and generally is not associated with ulceration, fissuring, or scaling; however, these complications have been reported in the terminal stages of the disease in which the macrocheilia has become permanent.

Despite the controversy over the etiology, pathophysiology, and classification of GC, it largely is accepted that when a patient presents clinically with a history of recurrent or persistent lip swelling, a full-thickness skin biopsy of the involved oral mucosa should be taken. Conditions that are considered in the differential diagnosis of orofacial granulomatosis are systemic granulomatous diseases that are known to have oral manifestations including Crohn disease, sarcoidosis, and mycobacterial infections. Given the many causes of orofacial and labial swelling, GC is a diagnosis of exclusion based on a thorough history and physical examination as well as appropriate diagnostic studies, with the cornerstone of the diagnosis resting on the histologic appearance of the lesion. Histologically, the diagnosis lies in the demonstration of granuloma formation, consisting of collections of epithelioid histiocytes and Langerhans giant cells. Once granuloma formation is documented, special stains are used to rule out other granulomatous diseases.

Intralesional steroids have been reported to provide the greatest improvement; however, in the majority of patients, multiple treatments are required.6,7 Allen et al8 suggested that the efficacy of intralesional therapy increases when preceded by local anesthesia of the lip, thus allowing larger doses of triamcinolone to be tolerated by the patient. Systemic corticosteroids also have been used with moderate success, but the side effects of long-term systemic corticosteroid therapy make this treatment option less appealing.9 Other agents with known anti-inflammatory properties also have been used that may offer better side-effect profiles when used for long-term suppressive therapy, including clofazimine, dapsone, sulfapyridine, danazol, hydroxychloroquine, and antibiotics such as doxycycline and metronidazole.10

In severe or recalcitrant cases, surgical intervention by way of a reduction cheiloplasty is considered by some to be an appropriate next step in therapy but is rarely needed. Postoperative intralesional steroid injections are necessary due to reported cases of worsening disease when injections are discontinued after cheiloplasty.11,12

Our patient was treated with 5 mg of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide with 10 separate injections of 0.5 cc each along the affected portions of the upper lip. She also was given doxycycline 100 mg once daily for 30 days. The patient reported complete resolution of the upper lip swelling 7 days after the initiation of therapy. At 1-month follow-up, she reported that the swelling had completely resolved. However, 1 day prior to the scheduled visit, shortly after finishing the course of doxycycline, she noted recurrent swelling. Due to the concomitant initial administration of both the steroid injections and doxycycline, it was unclear which treatment had provided relief. To avoid, or at least delay, the need for chronic intralesional steroid injections, another course of 40 mg doxycycline daily was prescribed. After 2 weeks, the patient reported that the swelling had markedly improved. The patient has maintained remission of the symptoms for approximately 6 months on daily suppressive therapy with 40 mg of doxycycline.

The recurrence of lip swelling after therapy, as in our patient, is typical of GC, and most cases require multiple follow-up visits and frequent alterations in therapy, which is often frustrating for both the patient and physician. However, awareness of this disease entity, its natural course, and the therapeutic options will allow physicians to more appropriately counsel and educate patients of this uncommon disease process.

1. Meischer G. Über essentielle granulomatöse makrocheilie (cheilitis granulomatosa). Dermatologica. 1945;91:57-85.

2. Melkersson E. Ett Fall av recidiverande facialispares i samband med angioneurotiskt ödem. Hygiea (Stockh). 1928;90:737-741.

3. Rosenthal C. Klinish-erbbiologischer beitrag zur konstitutionspathologie: gemeinsames auftreten von (rezidiverender familiärer) facialislähmung, angioneurotischem gesichtsödem und lingua plicata in arthritismus-familien. Z Ges Neurol Psychiat. 1931;131:475-501.

4. van der Waal RI, Schulten EA, van der Meij EH, et al. Cheilitis granulomatosa: overview of 13 patients with long-term follow up–results of management. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:225-229.

5. Worsaae N, Christensen KC, Schiødt M, et al. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and cheilitis granulomatosa. a clinical pathological study of thirty-three patients with special reference to their oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;54:404-413.

6. El-Hakim M, Chauvin P. Orofacial granulomatosis presenting as persistent lip swelling: review of 6 new cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:1114-1117.

7. Williams PM, Greenberg MS. Management of cheilitis granulomatosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:436-439.

8. Allen CM, Camisa C, Hamzeh S, et al. Cheilitis granulomatosa: report of six cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(3, pt 1):444-450.

9. Banks T, Gada S. A comprehensive review of current treatments for granulomatous cheilitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:934-937.

10. Sciubba JJ, Said-Al-Naief N. Orofacial granulomatosis: presentation, pathology and management of 13 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:576-585.

11. Glickman LT, Gruss JS, Birt BD, et al. The surgical management of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:815-821.

12. Krutchkoff D, James R. Cheilitis granulomatosa. successful treatment with combined local triamcinolone injections and surgery. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1203-1206.

1. Meischer G. Über essentielle granulomatöse makrocheilie (cheilitis granulomatosa). Dermatologica. 1945;91:57-85.

2. Melkersson E. Ett Fall av recidiverande facialispares i samband med angioneurotiskt ödem. Hygiea (Stockh). 1928;90:737-741.

3. Rosenthal C. Klinish-erbbiologischer beitrag zur konstitutionspathologie: gemeinsames auftreten von (rezidiverender familiärer) facialislähmung, angioneurotischem gesichtsödem und lingua plicata in arthritismus-familien. Z Ges Neurol Psychiat. 1931;131:475-501.

4. van der Waal RI, Schulten EA, van der Meij EH, et al. Cheilitis granulomatosa: overview of 13 patients with long-term follow up–results of management. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:225-229.

5. Worsaae N, Christensen KC, Schiødt M, et al. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and cheilitis granulomatosa. a clinical pathological study of thirty-three patients with special reference to their oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;54:404-413.

6. El-Hakim M, Chauvin P. Orofacial granulomatosis presenting as persistent lip swelling: review of 6 new cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:1114-1117.

7. Williams PM, Greenberg MS. Management of cheilitis granulomatosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:436-439.

8. Allen CM, Camisa C, Hamzeh S, et al. Cheilitis granulomatosa: report of six cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(3, pt 1):444-450.

9. Banks T, Gada S. A comprehensive review of current treatments for granulomatous cheilitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:934-937.

10. Sciubba JJ, Said-Al-Naief N. Orofacial granulomatosis: presentation, pathology and management of 13 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:576-585.

11. Glickman LT, Gruss JS, Birt BD, et al. The surgical management of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:815-821.

12. Krutchkoff D, James R. Cheilitis granulomatosa. successful treatment with combined local triamcinolone injections and surgery. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1203-1206.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Verrucous Carcinoma

An 81-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a nodule on the right labia majora that had been present for 1 year. She had a history of intertriginous psoriasis, and several biopsies were performed at an outside facility over the last 5 years that revealed psoriasis but were otherwise noncontributory. Physical examination revealed erythema and scaling on the buttocks with maceration in the intertriginous area (top) and the perineum associated with a verrucous nodule (bottom).

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Carcinoma

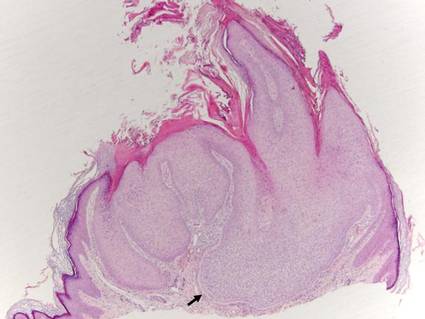

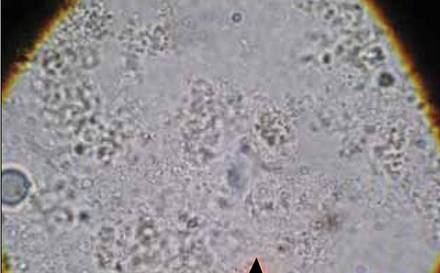

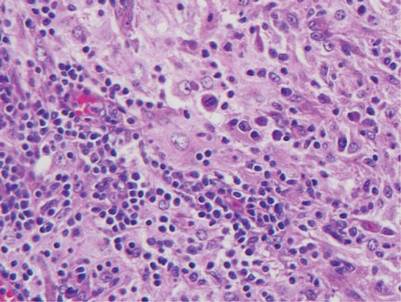

Biopsies of early lesions often may be difficult to interpret without clinicopathological correlation. Our patient’s tumor was associated with intertriginous psoriasis, which was the only abnormality previously noted on superficial biopsies performed at an outside facility. The patient was scheduled for an excisional biopsy due to the large tumor size and clinical suspicion that the prior biopsies were inadequate and failed to demonstrate the primary underlying pathology. Excisional biopsy of the verrucous tumor revealed epithelium composed of keratinocytes with glassy cytoplasm. Papillomatosis was noted along with an endophytic component of well-differentiated epithelial cells extending into the dermis in a bulbous pattern consistent with the verrucous carcinoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)(Figure). Verrucous carcinoma often requires correlation with both the clinical and histopathologic findings for definitive diagnosis, as keratinocytes often appear to be well differentiated.1

Verrucous carcinoma may begin as an innocuous papule that slowly grows into a large fungating tumor. Verrucous carcinomas typically are slow growing, exophytic, and low grade. The etiology of verrucous carcinoma is not clear, and the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is controversial.2 Best classified as a well-differentiated SCC, verrucous carcinoma rarely metastasizes but may invade adjacent tissues.

Differential diagnoses include a giant inflamed seborrheic keratosis, condyloma acuminatum, rupioid psoriasis, and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN). Although large and inflamed seborrheic keratoses may have squamous eddies that mimic SCC, seborrheic keratoses do not invade the dermis and typically have a well-circumscribed stuck-on appearance. Abnormal mitotic figures are not identified. Condylomas are genital warts caused by HPV infection that often are clustered, well circumscribed, and exophytic. Large lesions can be difficult to distinguish from verrucous carcinomas, and biopsy generally reveals koilocytes identified by perinuclear clearing and raisinlike nuclei. Immunohistochemical staining and in situ hybridization studies can be of value in diagnosis and in identifying those lesions that are at high risk for malignant transformation. High-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-35, and HPV-39, as well as other types, whereas low-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-42, and others.2 Differentiating squamous cell hyperplasia from squamous cell carcinoma in situ also can be aided by immunohistochemistry. Squamous cell hyperplasia is usually negative for INK4 p16Ink4A and p53 and exhibits variable Ki-67 staining. Differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in situ exhibits a profile that is p16Ink4A negative, Ki-67 positive, and exhibits variable p53 staining.3 Basaloid and warty intraepithelial neoplasia is consistently p16Ink4A positive, Ki-67 positive, and variably positive for p53.3 Therefore, p16 staining of high-grade areas is a useful biomarker that can help establish diagnosis of associated squamous cell carcinoma.4 The role of papillomaviruses in the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer is an area of active study, and research suggests that papillomaviruses may have a much greater role than previously suspected.5

At times, psoriasis may be markedly hyperkeratotic, clinically mimicking a verrucous neoplasm. This hyperkeratotic type of psoriasis is known as rupioid psoriasis. However, these psoriatic lesions are exophytic, are associated with spongiform pustules, and lack the atypia and endophytic pattern typically seen with verrucous carcinoma. An ILVEN also lacks atypia and an endophytic pattern and usually presents in childhood as a persistent linear plaque, rather than the verrucous plaque noted in our patient. Squamous cell carcinoma has been reported to arise in the setting of verrucoid ILVEN but is exceptionally uncommon.6

Successful treatment of verrucous carcinoma is best achieved by complete excision. Oral retinoids and immunomodulators such as imiquimod also may be of value.7 Our patient’s tumor qualifies as T2N0M0 because it was greater than 2 cm in size.8 A Breslow thickness of 2 mm or greater and Clark level IV are high-risk features associated with a worse prognosis, but clinical evaluation of our patient’s lymph nodes was unremarkable and no distant metastases were identified. Our patient continues to do well with no evidence of recurrence.

1. Bambao C, Nofech-Mozes S, Shier M. Giant condyloma versus verrucous carcinoma: a case report. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010;14:230-233.

2. Asiaf A, Ahmad ST, Mohannad SO, et al. Review of the current knowledge on the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prevention of human papillomavirus infection. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014;23:206-224.

3. Chaux A, Pfannl R, Rodríguez IM, et al. Distinctive immunohistochemical profile of penile intraepithelial lesions: a study of 74 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:553-562.

4. Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1266-1297.

5. Aldabagh B, Angeles J, Cardones AR, et al. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and human papillomavirus: is there an association? Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1-23.

6. Turk BG, Ertam I, Urkmez A, et al. Development of squamous cell carcinoma on an inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus in the genital area. Cutis. 2012;89:273-275.

7. Erkek E, Basar H, Bozdogan O, et al. Giant condyloma acuminata of Buschke-Löwenstein: successful treatment with a combination of surgical excision, oral acitretin and topical imiquimod. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:366-368.

8. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:301-314.

An 81-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a nodule on the right labia majora that had been present for 1 year. She had a history of intertriginous psoriasis, and several biopsies were performed at an outside facility over the last 5 years that revealed psoriasis but were otherwise noncontributory. Physical examination revealed erythema and scaling on the buttocks with maceration in the intertriginous area (top) and the perineum associated with a verrucous nodule (bottom).

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Carcinoma

Biopsies of early lesions often may be difficult to interpret without clinicopathological correlation. Our patient’s tumor was associated with intertriginous psoriasis, which was the only abnormality previously noted on superficial biopsies performed at an outside facility. The patient was scheduled for an excisional biopsy due to the large tumor size and clinical suspicion that the prior biopsies were inadequate and failed to demonstrate the primary underlying pathology. Excisional biopsy of the verrucous tumor revealed epithelium composed of keratinocytes with glassy cytoplasm. Papillomatosis was noted along with an endophytic component of well-differentiated epithelial cells extending into the dermis in a bulbous pattern consistent with the verrucous carcinoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)(Figure). Verrucous carcinoma often requires correlation with both the clinical and histopathologic findings for definitive diagnosis, as keratinocytes often appear to be well differentiated.1

Verrucous carcinoma may begin as an innocuous papule that slowly grows into a large fungating tumor. Verrucous carcinomas typically are slow growing, exophytic, and low grade. The etiology of verrucous carcinoma is not clear, and the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is controversial.2 Best classified as a well-differentiated SCC, verrucous carcinoma rarely metastasizes but may invade adjacent tissues.

Differential diagnoses include a giant inflamed seborrheic keratosis, condyloma acuminatum, rupioid psoriasis, and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN). Although large and inflamed seborrheic keratoses may have squamous eddies that mimic SCC, seborrheic keratoses do not invade the dermis and typically have a well-circumscribed stuck-on appearance. Abnormal mitotic figures are not identified. Condylomas are genital warts caused by HPV infection that often are clustered, well circumscribed, and exophytic. Large lesions can be difficult to distinguish from verrucous carcinomas, and biopsy generally reveals koilocytes identified by perinuclear clearing and raisinlike nuclei. Immunohistochemical staining and in situ hybridization studies can be of value in diagnosis and in identifying those lesions that are at high risk for malignant transformation. High-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-35, and HPV-39, as well as other types, whereas low-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-42, and others.2 Differentiating squamous cell hyperplasia from squamous cell carcinoma in situ also can be aided by immunohistochemistry. Squamous cell hyperplasia is usually negative for INK4 p16Ink4A and p53 and exhibits variable Ki-67 staining. Differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in situ exhibits a profile that is p16Ink4A negative, Ki-67 positive, and exhibits variable p53 staining.3 Basaloid and warty intraepithelial neoplasia is consistently p16Ink4A positive, Ki-67 positive, and variably positive for p53.3 Therefore, p16 staining of high-grade areas is a useful biomarker that can help establish diagnosis of associated squamous cell carcinoma.4 The role of papillomaviruses in the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer is an area of active study, and research suggests that papillomaviruses may have a much greater role than previously suspected.5

At times, psoriasis may be markedly hyperkeratotic, clinically mimicking a verrucous neoplasm. This hyperkeratotic type of psoriasis is known as rupioid psoriasis. However, these psoriatic lesions are exophytic, are associated with spongiform pustules, and lack the atypia and endophytic pattern typically seen with verrucous carcinoma. An ILVEN also lacks atypia and an endophytic pattern and usually presents in childhood as a persistent linear plaque, rather than the verrucous plaque noted in our patient. Squamous cell carcinoma has been reported to arise in the setting of verrucoid ILVEN but is exceptionally uncommon.6

Successful treatment of verrucous carcinoma is best achieved by complete excision. Oral retinoids and immunomodulators such as imiquimod also may be of value.7 Our patient’s tumor qualifies as T2N0M0 because it was greater than 2 cm in size.8 A Breslow thickness of 2 mm or greater and Clark level IV are high-risk features associated with a worse prognosis, but clinical evaluation of our patient’s lymph nodes was unremarkable and no distant metastases were identified. Our patient continues to do well with no evidence of recurrence.

An 81-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a nodule on the right labia majora that had been present for 1 year. She had a history of intertriginous psoriasis, and several biopsies were performed at an outside facility over the last 5 years that revealed psoriasis but were otherwise noncontributory. Physical examination revealed erythema and scaling on the buttocks with maceration in the intertriginous area (top) and the perineum associated with a verrucous nodule (bottom).

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Carcinoma

Biopsies of early lesions often may be difficult to interpret without clinicopathological correlation. Our patient’s tumor was associated with intertriginous psoriasis, which was the only abnormality previously noted on superficial biopsies performed at an outside facility. The patient was scheduled for an excisional biopsy due to the large tumor size and clinical suspicion that the prior biopsies were inadequate and failed to demonstrate the primary underlying pathology. Excisional biopsy of the verrucous tumor revealed epithelium composed of keratinocytes with glassy cytoplasm. Papillomatosis was noted along with an endophytic component of well-differentiated epithelial cells extending into the dermis in a bulbous pattern consistent with the verrucous carcinoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)(Figure). Verrucous carcinoma often requires correlation with both the clinical and histopathologic findings for definitive diagnosis, as keratinocytes often appear to be well differentiated.1

Verrucous carcinoma may begin as an innocuous papule that slowly grows into a large fungating tumor. Verrucous carcinomas typically are slow growing, exophytic, and low grade. The etiology of verrucous carcinoma is not clear, and the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is controversial.2 Best classified as a well-differentiated SCC, verrucous carcinoma rarely metastasizes but may invade adjacent tissues.

Differential diagnoses include a giant inflamed seborrheic keratosis, condyloma acuminatum, rupioid psoriasis, and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN). Although large and inflamed seborrheic keratoses may have squamous eddies that mimic SCC, seborrheic keratoses do not invade the dermis and typically have a well-circumscribed stuck-on appearance. Abnormal mitotic figures are not identified. Condylomas are genital warts caused by HPV infection that often are clustered, well circumscribed, and exophytic. Large lesions can be difficult to distinguish from verrucous carcinomas, and biopsy generally reveals koilocytes identified by perinuclear clearing and raisinlike nuclei. Immunohistochemical staining and in situ hybridization studies can be of value in diagnosis and in identifying those lesions that are at high risk for malignant transformation. High-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-35, and HPV-39, as well as other types, whereas low-risk condylomas are associated with HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-42, and others.2 Differentiating squamous cell hyperplasia from squamous cell carcinoma in situ also can be aided by immunohistochemistry. Squamous cell hyperplasia is usually negative for INK4 p16Ink4A and p53 and exhibits variable Ki-67 staining. Differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in situ exhibits a profile that is p16Ink4A negative, Ki-67 positive, and exhibits variable p53 staining.3 Basaloid and warty intraepithelial neoplasia is consistently p16Ink4A positive, Ki-67 positive, and variably positive for p53.3 Therefore, p16 staining of high-grade areas is a useful biomarker that can help establish diagnosis of associated squamous cell carcinoma.4 The role of papillomaviruses in the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer is an area of active study, and research suggests that papillomaviruses may have a much greater role than previously suspected.5

At times, psoriasis may be markedly hyperkeratotic, clinically mimicking a verrucous neoplasm. This hyperkeratotic type of psoriasis is known as rupioid psoriasis. However, these psoriatic lesions are exophytic, are associated with spongiform pustules, and lack the atypia and endophytic pattern typically seen with verrucous carcinoma. An ILVEN also lacks atypia and an endophytic pattern and usually presents in childhood as a persistent linear plaque, rather than the verrucous plaque noted in our patient. Squamous cell carcinoma has been reported to arise in the setting of verrucoid ILVEN but is exceptionally uncommon.6

Successful treatment of verrucous carcinoma is best achieved by complete excision. Oral retinoids and immunomodulators such as imiquimod also may be of value.7 Our patient’s tumor qualifies as T2N0M0 because it was greater than 2 cm in size.8 A Breslow thickness of 2 mm or greater and Clark level IV are high-risk features associated with a worse prognosis, but clinical evaluation of our patient’s lymph nodes was unremarkable and no distant metastases were identified. Our patient continues to do well with no evidence of recurrence.

1. Bambao C, Nofech-Mozes S, Shier M. Giant condyloma versus verrucous carcinoma: a case report. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010;14:230-233.

2. Asiaf A, Ahmad ST, Mohannad SO, et al. Review of the current knowledge on the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prevention of human papillomavirus infection. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014;23:206-224.

3. Chaux A, Pfannl R, Rodríguez IM, et al. Distinctive immunohistochemical profile of penile intraepithelial lesions: a study of 74 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:553-562.

4. Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1266-1297.

5. Aldabagh B, Angeles J, Cardones AR, et al. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and human papillomavirus: is there an association? Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1-23.

6. Turk BG, Ertam I, Urkmez A, et al. Development of squamous cell carcinoma on an inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus in the genital area. Cutis. 2012;89:273-275.

7. Erkek E, Basar H, Bozdogan O, et al. Giant condyloma acuminata of Buschke-Löwenstein: successful treatment with a combination of surgical excision, oral acitretin and topical imiquimod. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:366-368.

8. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:301-314.

1. Bambao C, Nofech-Mozes S, Shier M. Giant condyloma versus verrucous carcinoma: a case report. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010;14:230-233.

2. Asiaf A, Ahmad ST, Mohannad SO, et al. Review of the current knowledge on the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prevention of human papillomavirus infection. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014;23:206-224.

3. Chaux A, Pfannl R, Rodríguez IM, et al. Distinctive immunohistochemical profile of penile intraepithelial lesions: a study of 74 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:553-562.

4. Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1266-1297.

5. Aldabagh B, Angeles J, Cardones AR, et al. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and human papillomavirus: is there an association? Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1-23.

6. Turk BG, Ertam I, Urkmez A, et al. Development of squamous cell carcinoma on an inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus in the genital area. Cutis. 2012;89:273-275.

7. Erkek E, Basar H, Bozdogan O, et al. Giant condyloma acuminata of Buschke-Löwenstein: successful treatment with a combination of surgical excision, oral acitretin and topical imiquimod. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:366-368.

8. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:301-314.

Trichilemmoma

Trichilemmomas are benign follicular neoplasms that exhibit differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the pilosebaceous follicular epithelium.1 Trichilemmomas clinically present as individual or multiple, slowly growing, verrucous papules appearing most commonly on the face or neck. The lesions may coalesce to form small plaques. Although trichilemmomas typically are isolated, patients with multiple trichilemmomas require a cancer screening workup due to their association with Cowden disease, which results from a mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog tumor suppressor gene, PTEN.2 An easy way to remember the association between trichilemmomas and Cowden disease is to alter the spelling to “trichile-moo-moo,” using the “moo moo” sound of an animal cow as a clue linking the tumor to Cowden disease.

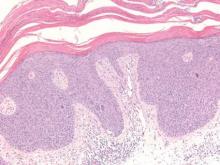

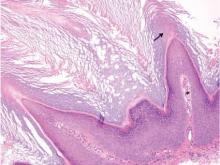

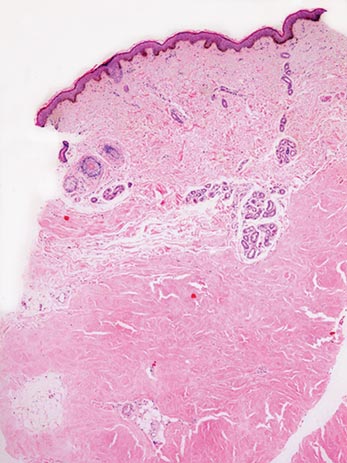

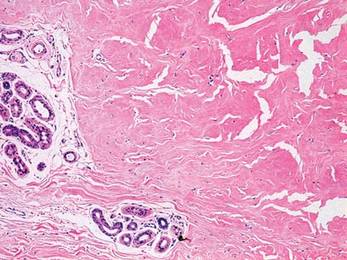

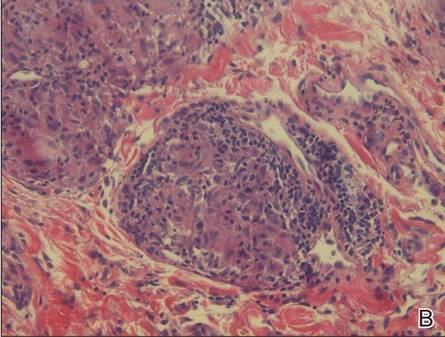

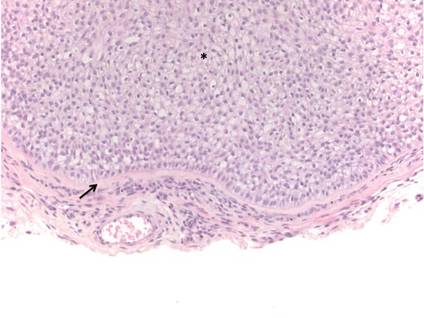

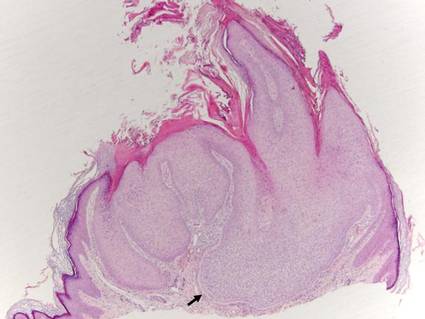

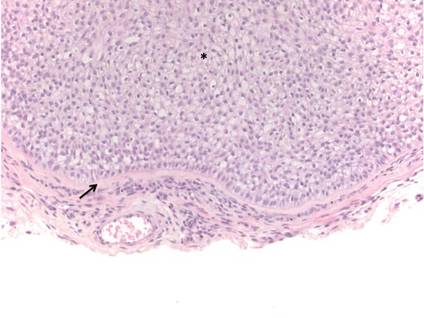

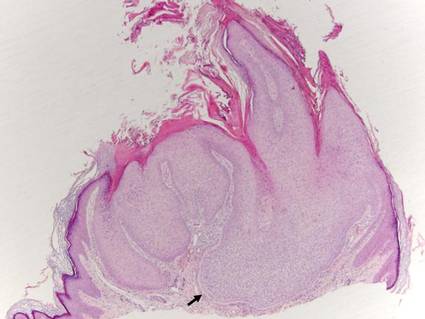

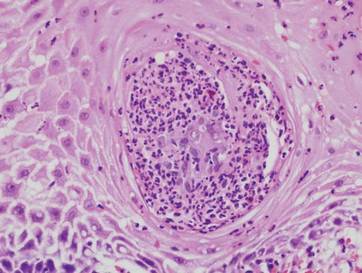

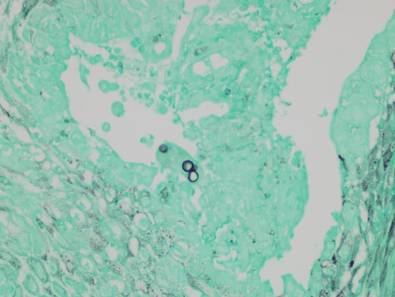

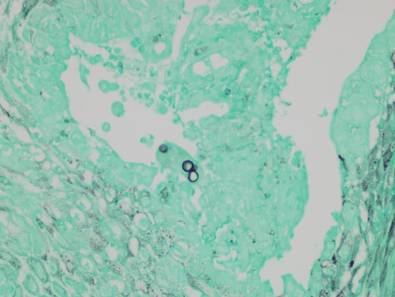

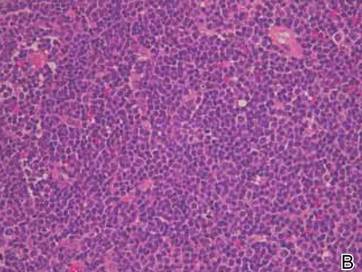

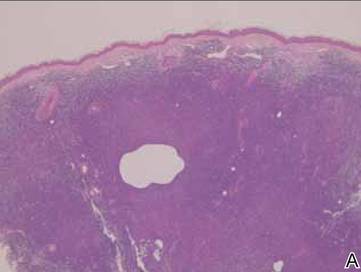

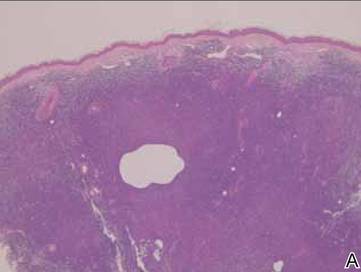

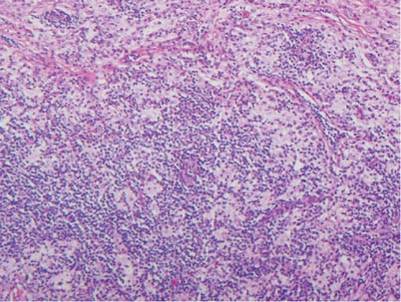

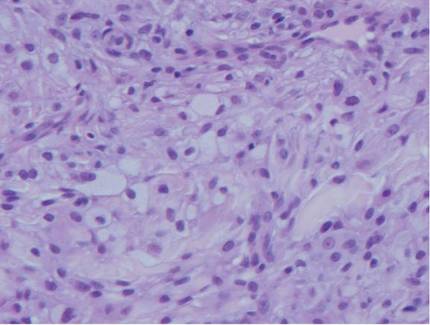

Histologically, trichilemmomas exhibit a lobular epidermal downgrowth into the dermis (Figure 1). The surface of the lesion may be hyperkeratotic and somewhat papillomatous. Cells toward the center of the lobule are pale staining, periodic acid–Schiff positive, and diastase labile due to high levels of intracellular glycogen (Figure 2). Cells toward the periphery of the lobule usually appear basophilic with a palisading arrangement of the peripheral cells. The entire lobule is enclosed within an eosinophilic basement membrane that stains positively with periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 2).1 Consistent with the tumor’s differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, trichilemmomas have been reported to express CD34 focally or diffusely.3

|

|

Similar to trichilemmoma, inverted follicular keratosis (IFK) commonly presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule on the face. Inverted follicular keratosis is a somewhat controversial entity, with some authorities arguing IFK is a variant of verruca vulgaris or seborrheic keratosis. Histologically, IFKs can be differentiated by the presence of squamous eddies (concentric layers of squamous cells in a whorled pattern), which are diagnostic, and central longitudinal crypts that contain keratin and are lined by squamous epithelium.4 Basaloid cells can be seen at the periphery of the tumors; however, IFKs lack an eosinophilic basement membrane surrounding the tumor (Figure 3).

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ classically appears as an erythematous hyperkeratotic papule or plaque on sun-exposed sites that can become crusted or ulcerated. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinoma in situ displays full-thickness disorderly maturation of keratinocytes. The keratinocytes exhibit nuclear pleomorphism. Atypical mitotic figures and dyskeratotic keratinocytes also can be seen throughout the full thickness of the epidermis (Figure 4).5

Verruca vulgaris (Figure 5) histologically demonstrates hyperkeratosis with tiers of parakeratosis, digitated epidermal hyperplasia, and dilated tortuous capillaries within the dermal papillae. At the edges of the lesion there often is inward turning of elongated rete ridges,6,7 which can be thought of as the rete reaching out for a hug of sorts to spread the human papillomavirus infection. Although the surface of a trichilemmoma can bear resemblance to a verruca vulgaris, the remainder of the histologic features can be used to help differentiate these tumors. Additionally, there has been no evidence suggestive of a viral etiology for trichilemmomas.8

Warty dyskeratoma features an umbilicated papule, usually on the face, head, or neck, that is associated with a follicular unit. The papule shows a cup-shaped, keratin-filled invagination; suprabasilar clefting; and acantholytic dyskeratotic cells, which are features that are not seen in trichilemmomas (Figure 6).9

Acknowledgment—The authors would like to thank Brandon Litzner, MD, St Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

1. Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Trichilemmoma: analysis of 40 new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:866-869.

2. Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg J, Prieto V, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:493-499.

3. Tardío JC. CD34-reactive tumors of the skin. an updated review of an ever-growing list of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:89-102.

4. Mehregan A. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

5. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 2):11-17.

6. Jabłonska S, Majewski S, Obalek S, et al. Cutaneous warts. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:309-319.

7. Hardin J, Gardner J, Colome M, et al. Verrucous cyst with melanocytic and sebaceous differentiation. Arch Path Lab Med. 2013;137:576-579.

8. Johnson BL, Kramer EM, Lavker RM. The keratotic tumors of Cowden’s disease: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:291-298.

9. Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

Trichilemmomas are benign follicular neoplasms that exhibit differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the pilosebaceous follicular epithelium.1 Trichilemmomas clinically present as individual or multiple, slowly growing, verrucous papules appearing most commonly on the face or neck. The lesions may coalesce to form small plaques. Although trichilemmomas typically are isolated, patients with multiple trichilemmomas require a cancer screening workup due to their association with Cowden disease, which results from a mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog tumor suppressor gene, PTEN.2 An easy way to remember the association between trichilemmomas and Cowden disease is to alter the spelling to “trichile-moo-moo,” using the “moo moo” sound of an animal cow as a clue linking the tumor to Cowden disease.

Histologically, trichilemmomas exhibit a lobular epidermal downgrowth into the dermis (Figure 1). The surface of the lesion may be hyperkeratotic and somewhat papillomatous. Cells toward the center of the lobule are pale staining, periodic acid–Schiff positive, and diastase labile due to high levels of intracellular glycogen (Figure 2). Cells toward the periphery of the lobule usually appear basophilic with a palisading arrangement of the peripheral cells. The entire lobule is enclosed within an eosinophilic basement membrane that stains positively with periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 2).1 Consistent with the tumor’s differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, trichilemmomas have been reported to express CD34 focally or diffusely.3

|

|

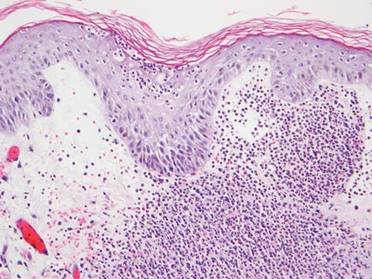

Similar to trichilemmoma, inverted follicular keratosis (IFK) commonly presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule on the face. Inverted follicular keratosis is a somewhat controversial entity, with some authorities arguing IFK is a variant of verruca vulgaris or seborrheic keratosis. Histologically, IFKs can be differentiated by the presence of squamous eddies (concentric layers of squamous cells in a whorled pattern), which are diagnostic, and central longitudinal crypts that contain keratin and are lined by squamous epithelium.4 Basaloid cells can be seen at the periphery of the tumors; however, IFKs lack an eosinophilic basement membrane surrounding the tumor (Figure 3).

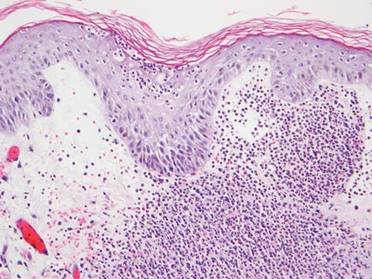

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ classically appears as an erythematous hyperkeratotic papule or plaque on sun-exposed sites that can become crusted or ulcerated. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinoma in situ displays full-thickness disorderly maturation of keratinocytes. The keratinocytes exhibit nuclear pleomorphism. Atypical mitotic figures and dyskeratotic keratinocytes also can be seen throughout the full thickness of the epidermis (Figure 4).5

Verruca vulgaris (Figure 5) histologically demonstrates hyperkeratosis with tiers of parakeratosis, digitated epidermal hyperplasia, and dilated tortuous capillaries within the dermal papillae. At the edges of the lesion there often is inward turning of elongated rete ridges,6,7 which can be thought of as the rete reaching out for a hug of sorts to spread the human papillomavirus infection. Although the surface of a trichilemmoma can bear resemblance to a verruca vulgaris, the remainder of the histologic features can be used to help differentiate these tumors. Additionally, there has been no evidence suggestive of a viral etiology for trichilemmomas.8

Warty dyskeratoma features an umbilicated papule, usually on the face, head, or neck, that is associated with a follicular unit. The papule shows a cup-shaped, keratin-filled invagination; suprabasilar clefting; and acantholytic dyskeratotic cells, which are features that are not seen in trichilemmomas (Figure 6).9

Acknowledgment—The authors would like to thank Brandon Litzner, MD, St Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

Trichilemmomas are benign follicular neoplasms that exhibit differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the pilosebaceous follicular epithelium.1 Trichilemmomas clinically present as individual or multiple, slowly growing, verrucous papules appearing most commonly on the face or neck. The lesions may coalesce to form small plaques. Although trichilemmomas typically are isolated, patients with multiple trichilemmomas require a cancer screening workup due to their association with Cowden disease, which results from a mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog tumor suppressor gene, PTEN.2 An easy way to remember the association between trichilemmomas and Cowden disease is to alter the spelling to “trichile-moo-moo,” using the “moo moo” sound of an animal cow as a clue linking the tumor to Cowden disease.

Histologically, trichilemmomas exhibit a lobular epidermal downgrowth into the dermis (Figure 1). The surface of the lesion may be hyperkeratotic and somewhat papillomatous. Cells toward the center of the lobule are pale staining, periodic acid–Schiff positive, and diastase labile due to high levels of intracellular glycogen (Figure 2). Cells toward the periphery of the lobule usually appear basophilic with a palisading arrangement of the peripheral cells. The entire lobule is enclosed within an eosinophilic basement membrane that stains positively with periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 2).1 Consistent with the tumor’s differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, trichilemmomas have been reported to express CD34 focally or diffusely.3

|

|

Similar to trichilemmoma, inverted follicular keratosis (IFK) commonly presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule on the face. Inverted follicular keratosis is a somewhat controversial entity, with some authorities arguing IFK is a variant of verruca vulgaris or seborrheic keratosis. Histologically, IFKs can be differentiated by the presence of squamous eddies (concentric layers of squamous cells in a whorled pattern), which are diagnostic, and central longitudinal crypts that contain keratin and are lined by squamous epithelium.4 Basaloid cells can be seen at the periphery of the tumors; however, IFKs lack an eosinophilic basement membrane surrounding the tumor (Figure 3).

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ classically appears as an erythematous hyperkeratotic papule or plaque on sun-exposed sites that can become crusted or ulcerated. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinoma in situ displays full-thickness disorderly maturation of keratinocytes. The keratinocytes exhibit nuclear pleomorphism. Atypical mitotic figures and dyskeratotic keratinocytes also can be seen throughout the full thickness of the epidermis (Figure 4).5

Verruca vulgaris (Figure 5) histologically demonstrates hyperkeratosis with tiers of parakeratosis, digitated epidermal hyperplasia, and dilated tortuous capillaries within the dermal papillae. At the edges of the lesion there often is inward turning of elongated rete ridges,6,7 which can be thought of as the rete reaching out for a hug of sorts to spread the human papillomavirus infection. Although the surface of a trichilemmoma can bear resemblance to a verruca vulgaris, the remainder of the histologic features can be used to help differentiate these tumors. Additionally, there has been no evidence suggestive of a viral etiology for trichilemmomas.8

Warty dyskeratoma features an umbilicated papule, usually on the face, head, or neck, that is associated with a follicular unit. The papule shows a cup-shaped, keratin-filled invagination; suprabasilar clefting; and acantholytic dyskeratotic cells, which are features that are not seen in trichilemmomas (Figure 6).9

Acknowledgment—The authors would like to thank Brandon Litzner, MD, St Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

1. Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Trichilemmoma: analysis of 40 new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:866-869.

2. Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg J, Prieto V, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:493-499.

3. Tardío JC. CD34-reactive tumors of the skin. an updated review of an ever-growing list of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:89-102.

4. Mehregan A. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

5. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 2):11-17.

6. Jabłonska S, Majewski S, Obalek S, et al. Cutaneous warts. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:309-319.

7. Hardin J, Gardner J, Colome M, et al. Verrucous cyst with melanocytic and sebaceous differentiation. Arch Path Lab Med. 2013;137:576-579.

8. Johnson BL, Kramer EM, Lavker RM. The keratotic tumors of Cowden’s disease: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:291-298.

9. Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

1. Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Trichilemmoma: analysis of 40 new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:866-869.

2. Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg J, Prieto V, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:493-499.

3. Tardío JC. CD34-reactive tumors of the skin. an updated review of an ever-growing list of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:89-102.

4. Mehregan A. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

5. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 2):11-17.

6. Jabłonska S, Majewski S, Obalek S, et al. Cutaneous warts. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:309-319.

7. Hardin J, Gardner J, Colome M, et al. Verrucous cyst with melanocytic and sebaceous differentiation. Arch Path Lab Med. 2013;137:576-579.

8. Johnson BL, Kramer EM, Lavker RM. The keratotic tumors of Cowden’s disease: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:291-298.

9. Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

Perianal North American Blastomycosis

Cutaneous North American blastomycosis is a deep fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus that is endemic to the Great Lakes region as well as the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys where it thrives in moist acidic soil enriched with organic material.1,2 In humans, the annual incidence rate is estimated to be 0.6 cases per million,3 though it may be as high as 42 cases per 100,000 in endemic areas.4 Infection typically results from the inhalation of conidia and manifests as either acute or chronic pneumonia.5 Most patients with acute disease present with nonspecific flulike symptoms and a nonproductive cough.

Dissemination occurs in approximately 25% of cases,6 most commonly affecting the skin. Other potential sites of dissemination include bone, the genitourinary tract, and the central nervous system. Cutaneous lesions, which may be either verrucous or ulcerative plaques, often occur on or around orifices contiguous to the respiratory tract.7 Verrucous lesions tend to have an irregular shape with well-defined borders and surface crusting. Ulcerative lesions have heaped-up borders and often have an exudative base.8 The differential diagnosis of cutaneous North American blastomycosis lesions includes squamous cell carcinoma, giant keratoacanthoma, verrucae, basal cell carcinoma, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, nocardiosis, syphilis, bromoderma, iododerma, granuloma inguinale, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, mycetoma, and actinomycosis.7,8

Although periorificial cutaneous manifestations of disseminated blastomycosis are common, perianal lesions are rare. The differential diagnosis of perianal verrucous plaques includes condyloma acuminatum, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, Buschke-Löwenstein tumor, actinomycosis, and localized fungal infections such as blastomycosis.9

Case Report

A 57-year-old man presented with a palpable perianal mass that produced small amounts of blood in his underwear and on toilet paper. The patient reported no history of hemorrhoids, anoreceptive intercourse, or sexually transmitted disease. Four months prior to presentation, he had a prolonged upper respiratory tract illness with a subjective fever and productive cough of 2 months’ duration. The patient described himself as an avid outdoorsman who worked at a summer resort and spent a great deal of time in the forests of central Wisconsin last autumn. Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, firm, moist plaque with a verrucous surface that measured 3.5×2.7 cm and extended from the anal verge to the perianal skin (Figure 1).

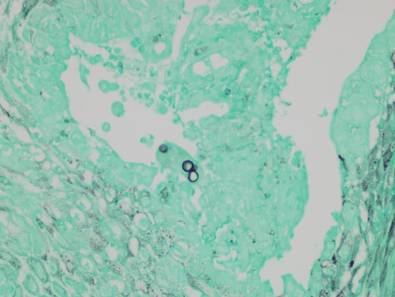

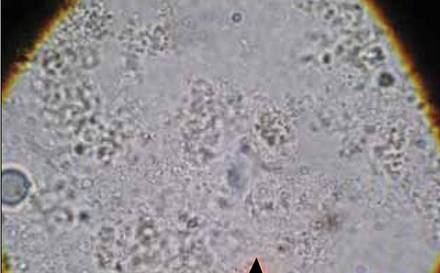

Potassium hydroxide preparation of a biopsy specimen (Figure 2), a punch biopsy of the lesion (Figure 3), and Gomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 4) revealed scattered yeast spores, some demonstrating broad-based budding, with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal neutrophils, and intraepithelial microabscesses. The patient’s urine was positive for Blastomyces antigen (1.04 ng/mL). Chest radiography demonstrated a localized infiltrate in the right hilum with possible mass effect. Computed tomography showed a consolidative opacity measuring 4.0×3.4 cm in the upper lobe of the right lung (Figure 5).

|

|

The patient was diagnosed with cutaneous North American blastomycosis and prescribed a 6-month course of oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily. At his 3-month follow-up visit, the perianal plaque hadalmost completely resolved (Figure 6). However, because the patient had increasing lower extremity edema, subjective hearing loss, and abnormal liver function tests, itraconazole treatment was discontinued and replaced with oral fluconazole 400 mg daily for the next 3 months. The right hilar mass had visibly improved on follow-up chest radiography 2 months after the patient started antifungal therapy with itraconazole and had resolved within another 3 months of treatment.

|

|

Comment

Cutaneous blastomycosis results most often from the hematogenous spread of B dermatitidis from the lungs and rarely from direct inoculation.5,10 Skin lesions tend to occur on exposed areas, such as the face, scalp, hands, wrists, feet, and ankles.7,11-13 Dissemination to the perianal skin is rare, though it has been reported in 2 other patients; both patients, similar to our patient, had evidence of pulmonary involvement at some point in their clinical course.9,14

Diagnosis is based on identification of B dermatitidis by microscopy or culture. Potassium hydroxide preparation of biopsy specimens typically shows broad-based budding yeast.13 Characteristic findings of histopathologic studies include pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal abscesses, and a dermal infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes.15 On fungal culture, B dermatitidis is slow growing and may require a 2- to 4-week incubation period. Serologic tests are available, but sensitivity is low, at 9%, 28%, and 77% for complement fixation, immunodiffusion, and enzyme immunoassay, respectively.16

Conclusion

North American blastomycosis should be considered in patients who have verrucous or ulcerative perianal lesions and have lived in or traveled to endemic regions, especially if they have recent or ongoing pulmonary symptoms. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal staining of biopsy specimens can aid in diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation’s Office of Scientific Writing and Publication (Marshfield, Wisconsin) for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

1. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Davis JP. Epidemiologic aspects of blastomycosis, the enigmatic systemic mycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1986;1:29-39.

2. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Weeks RJ, et al. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:529-534.

3. Reingold AL, Lu XD, Plikaytis BD, et al. Systemic mycoses in the United States, 1980-1982. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:433-436.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Blastomycosis—Wisconsin, 1986-1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:601-603.

5. Smith JA, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:173-180.

6. Goldman M, Johnson PC, Sarosi GA. Fungal pneumonias. the endemic mycoses. Clin Chest Med. 1999;20:507-519.

7. Mercurio MG, Elewski BE. Cutaneous blastomycosis. Cutis. 1992;50:422-424.

8. Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

9. Ricciardi R, Alavi K, Filice GA, et al. Blastomyces dermatitidis of the perianal skin: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:118-121.

10. Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis [published online ahead of print April 17, 2002]. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:e44-e49.

11. Kisso B, Mahmoud F, Thakkar JR. Blastomycosis presenting as recurrent tender cutaneous nodules. S D Med. 2006;59:255-259.

12. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

13. Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

14. Linn JE. Pseudo-epitheliomatous lesions of the perirectal tissue: report of a case of squamous epithelioma due to blastomycosis. South Med J. 1958;51:1101-1104.

15. Woofter MJ, Cripps DJ, Warner TF. Verrucous plaques on the face. North American blastomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547, 550.

16. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Kaufman L, et al. Serological tests for blastomycosis: assessments during a large point-source outbreak in Wisconsin. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:262-268.

Cutaneous North American blastomycosis is a deep fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus that is endemic to the Great Lakes region as well as the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys where it thrives in moist acidic soil enriched with organic material.1,2 In humans, the annual incidence rate is estimated to be 0.6 cases per million,3 though it may be as high as 42 cases per 100,000 in endemic areas.4 Infection typically results from the inhalation of conidia and manifests as either acute or chronic pneumonia.5 Most patients with acute disease present with nonspecific flulike symptoms and a nonproductive cough.

Dissemination occurs in approximately 25% of cases,6 most commonly affecting the skin. Other potential sites of dissemination include bone, the genitourinary tract, and the central nervous system. Cutaneous lesions, which may be either verrucous or ulcerative plaques, often occur on or around orifices contiguous to the respiratory tract.7 Verrucous lesions tend to have an irregular shape with well-defined borders and surface crusting. Ulcerative lesions have heaped-up borders and often have an exudative base.8 The differential diagnosis of cutaneous North American blastomycosis lesions includes squamous cell carcinoma, giant keratoacanthoma, verrucae, basal cell carcinoma, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, nocardiosis, syphilis, bromoderma, iododerma, granuloma inguinale, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, mycetoma, and actinomycosis.7,8

Although periorificial cutaneous manifestations of disseminated blastomycosis are common, perianal lesions are rare. The differential diagnosis of perianal verrucous plaques includes condyloma acuminatum, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, Buschke-Löwenstein tumor, actinomycosis, and localized fungal infections such as blastomycosis.9

Case Report

A 57-year-old man presented with a palpable perianal mass that produced small amounts of blood in his underwear and on toilet paper. The patient reported no history of hemorrhoids, anoreceptive intercourse, or sexually transmitted disease. Four months prior to presentation, he had a prolonged upper respiratory tract illness with a subjective fever and productive cough of 2 months’ duration. The patient described himself as an avid outdoorsman who worked at a summer resort and spent a great deal of time in the forests of central Wisconsin last autumn. Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, firm, moist plaque with a verrucous surface that measured 3.5×2.7 cm and extended from the anal verge to the perianal skin (Figure 1).

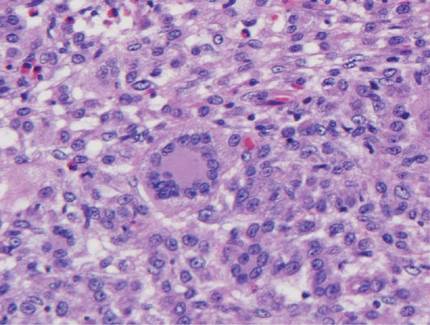

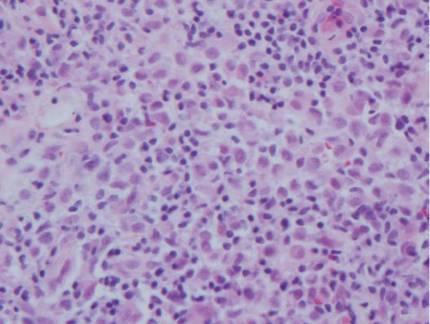

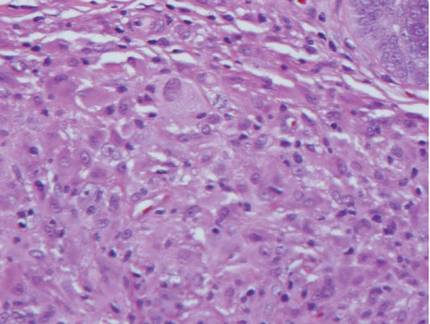

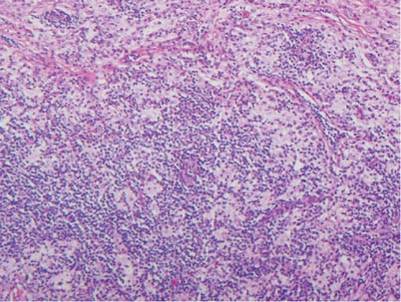

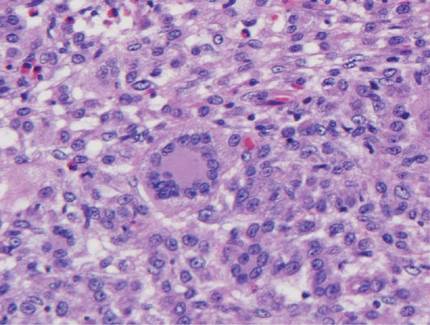

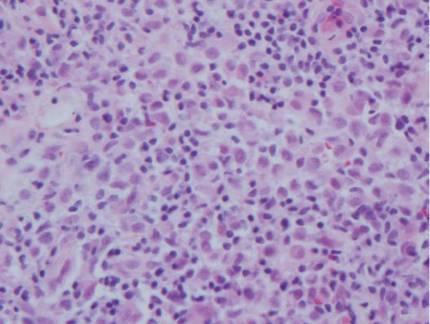

Potassium hydroxide preparation of a biopsy specimen (Figure 2), a punch biopsy of the lesion (Figure 3), and Gomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 4) revealed scattered yeast spores, some demonstrating broad-based budding, with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal neutrophils, and intraepithelial microabscesses. The patient’s urine was positive for Blastomyces antigen (1.04 ng/mL). Chest radiography demonstrated a localized infiltrate in the right hilum with possible mass effect. Computed tomography showed a consolidative opacity measuring 4.0×3.4 cm in the upper lobe of the right lung (Figure 5).

|

|

The patient was diagnosed with cutaneous North American blastomycosis and prescribed a 6-month course of oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily. At his 3-month follow-up visit, the perianal plaque hadalmost completely resolved (Figure 6). However, because the patient had increasing lower extremity edema, subjective hearing loss, and abnormal liver function tests, itraconazole treatment was discontinued and replaced with oral fluconazole 400 mg daily for the next 3 months. The right hilar mass had visibly improved on follow-up chest radiography 2 months after the patient started antifungal therapy with itraconazole and had resolved within another 3 months of treatment.

|

|

Comment

Cutaneous blastomycosis results most often from the hematogenous spread of B dermatitidis from the lungs and rarely from direct inoculation.5,10 Skin lesions tend to occur on exposed areas, such as the face, scalp, hands, wrists, feet, and ankles.7,11-13 Dissemination to the perianal skin is rare, though it has been reported in 2 other patients; both patients, similar to our patient, had evidence of pulmonary involvement at some point in their clinical course.9,14

Diagnosis is based on identification of B dermatitidis by microscopy or culture. Potassium hydroxide preparation of biopsy specimens typically shows broad-based budding yeast.13 Characteristic findings of histopathologic studies include pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal abscesses, and a dermal infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes.15 On fungal culture, B dermatitidis is slow growing and may require a 2- to 4-week incubation period. Serologic tests are available, but sensitivity is low, at 9%, 28%, and 77% for complement fixation, immunodiffusion, and enzyme immunoassay, respectively.16

Conclusion

North American blastomycosis should be considered in patients who have verrucous or ulcerative perianal lesions and have lived in or traveled to endemic regions, especially if they have recent or ongoing pulmonary symptoms. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal staining of biopsy specimens can aid in diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation’s Office of Scientific Writing and Publication (Marshfield, Wisconsin) for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Cutaneous North American blastomycosis is a deep fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus that is endemic to the Great Lakes region as well as the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys where it thrives in moist acidic soil enriched with organic material.1,2 In humans, the annual incidence rate is estimated to be 0.6 cases per million,3 though it may be as high as 42 cases per 100,000 in endemic areas.4 Infection typically results from the inhalation of conidia and manifests as either acute or chronic pneumonia.5 Most patients with acute disease present with nonspecific flulike symptoms and a nonproductive cough.

Dissemination occurs in approximately 25% of cases,6 most commonly affecting the skin. Other potential sites of dissemination include bone, the genitourinary tract, and the central nervous system. Cutaneous lesions, which may be either verrucous or ulcerative plaques, often occur on or around orifices contiguous to the respiratory tract.7 Verrucous lesions tend to have an irregular shape with well-defined borders and surface crusting. Ulcerative lesions have heaped-up borders and often have an exudative base.8 The differential diagnosis of cutaneous North American blastomycosis lesions includes squamous cell carcinoma, giant keratoacanthoma, verrucae, basal cell carcinoma, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, nocardiosis, syphilis, bromoderma, iododerma, granuloma inguinale, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, mycetoma, and actinomycosis.7,8

Although periorificial cutaneous manifestations of disseminated blastomycosis are common, perianal lesions are rare. The differential diagnosis of perianal verrucous plaques includes condyloma acuminatum, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, Buschke-Löwenstein tumor, actinomycosis, and localized fungal infections such as blastomycosis.9

Case Report