User login

Reintubation avoided by majority of patients on noninvasive ventilation therapy, high-flow oxygen

Extubated patients who either received noninvasive ventilation (NIV) therapy or high-flow nasal cannula oxygen had a lower risk of reintubation, compared with extubated patients who received some form of standard oxygen therapy, according to the results of two multicenter, randomized clinical trials published online in JAMA.

Participants in one of the studies, which included abdominal surgery patients diagnosed with respiratory failure within 7 days following surgery, either received NIV or standard oxygen therapy for 30 days or until ICU discharge, whichever came first. While NIV has been effectively used to treat nonsurgical patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiogenic pulmonary edema, there is no evidence to support the use of NIV in surgical patients with hypoxemic acute respiratory failure after abdominal surgery, according to Dr. Samir Jaber of the Saint Eloi University Hospital and Montpellier School of Medicine, both in Montpellier, France, and his colleagues (JAMA. 2016 Apr 5;315[13]:1345-53).

The second study included adult patients who had received mechanical ventilation for more than 12 hours and who met criteria for being considered at low risk for reintubation. Patients were administered either high-flow oxygen therapy through nasal cannula immediately after extubation or continuous conventional oxygen therapy through nasal cannula or nonrebreather facemask; the patients were observed for 72 hours. High-flow therapy has been shown to improve oxygenation and survival in clinical studies of critically ill patients in the acute phase of respiratory failure. “[A study by S.M. Maggiore and his colleagues (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(3):282-8)] suggested that high-flow therapy after planned extubation decreased the reintubation rate in a general population of critical patients, but the benefits might be mainly attributable to improvements in high-risk patients,” said Dr. Gonzalo Hernandez, of the Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo, Spain, and his colleagues (JAMA. 2016 Apr 5;315[13]:1354-61).

In the first study, 148 patients received NIV and 145 patients received standard oxygen therapy only. NIV was administered through a facemask connected to an ICU- or a NIV-dedicated ventilator, using either a heated humidifier or heat and moisture exchanger to warm and humidify inspired gases. Patients were encouraged to use NIV for 6 hours during the first 24 hours of the study and received standard oxygen therapy at a rate of up to 15 L/minute to maintain an arterial oxygen saturation estimate (SpO2) of at least 94% in between NIV sessions. NIV was started at an inspiratory positive airway pressure of 5 cm H2O, increasing to a maximum inspiratory pressure of 15 cm H2O, aiming to achieve an expiratory tidal volume between 6 and 8 mL/kg of predicted body weight and a respiratory rate lower than 25/min. The patients in this study’s control group only received the standard oxygen therapy.

In the other study, 263 patients received conventional therapy, with the oxygen flow having been adjusted to maintain an arterial oxygen saturation estimate of greater than 92%. This study’s other 264 patients received high-flow oxygen therapy, with the flow having been initially set at 10 L/min and titrated upward in 5-L/min steps until patients experienced discomfort. The high-flow therapy was stopped after 24 hours and was followed by conventional oxygen therapy, when needed.

The primary outcome measure in the study involving NIV was cause for reintubation within 7 days of randomization.

Secondary outcome measures included gas exchange, healthcare-associated infection rate within 30 days, number of ventilator-free days between days 1 and 30, antibiotic use duration, ICU and in-hospital length of stay, and 30- and 90-day mortality.

Reintubation occurred in 49 patients in the NIV group and 66 patients in the standard oxygen therapy group, a significant difference (P = .03). Among the reintubated patients, those who had received NIV spent less time under invasive mechanical ventilation as did the patients given standard oxygen therapy. The interquartile ranges of days of invasive mechanical ventilation were 0-3 for patients in the NIV group and 0-5 for patients in the standard oxygen therapy group (P = .05). At 30 days, NIV was associated with significantly more ventilator-free days than standard oxygen therapy (25.4 vs. 23.2; P = .04). At 90 days, 22 patients in the NIV group and 31 patients in the standard oxygen therapy group had died (P = .15).

“Recent high-impact trials have demonstrated the benefits in nonsurgical hypoxemic respiratory failure or equivalence of high-flow nasal cannula compared with NIV in patients after cardiothoracic surgery with moderate to severe hypoxemia. Future studies comparing use of high-flow oxygen cannula vs standard oxygen therapy and NIV for patients after abdominal surgery as preventive (prophylactic) or curative applications are needed,” according to Dr. Jaber and his colleagues.

The primary outcome measure for the study of patients receiving high-flow oxygen therapy was reintubation within 72 hours after extubation; this occurred in fewer patients in the high-flow oxygen group than in the conventional therapy group (13 or 4.9% vs. 32 or 12.2%.) This statistically significant difference was mainly attributable to a lower incidence of respiratory-related reintubation in the high-flow group, compared with the conventional therapy group (1.5% vs. 8.7%), said Dr. Hernandez and his colleagues.

Secondary outcome measures included postextubation respiratory failure, respiratory infection, sepsis, multiorgan failure, ICU and hospital length of stay and mortality, time to reintubation, and adverse effects. Postintubation respiratory failure was less common in the high-flow therapy group than in the conventional therapy group (22 patients or 8.3% vs. 38 or 14.4%). Differences between the two groups in other secondary outcomes were not statistically significant.

“The main finding of this study was that high-flow oxygen significantly reduced the reintubation rate in critically ill patients at low risk for extubation failure ... High-flow therapy improves oxygenation, and the lower rate of reintubation secondary to hypoxia in the high-flow group corroborates this finding. High-flow oxygen also seems to reduce other causes of respiratory failure such as increased work of breathing and respiratory muscle fatigue, which are frequently associated with reintubation secondary to hypoxia. Another way in which high-flow therapy improves extubation outcome is by conditioning the inspired gas,” said Dr. Hernandez and his colleagues.

No adverse events were reported in either study.

Dr. Hernandez and his colleagues reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Jaber and his colleagues disclosed no potential conflicts of interest with their study’s sponsors, Montpellier (France) University Hospital and the APARD Foundation.

Dr. Eric Gartman, FCCP, comments: These two studies augment a growing body of literature supporting the use of adjunctive therapies immediately following extubation to prevent reintubation for respiratory failure.

It has been known for several years that the use of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) immediately after extubation in COPD patients prevents reintubation rates, and these new data demonstrate efficacy in an expanded population. Further, the use of high-flow humidified oxygen therapy in acute respiratory failure has been shown to prevent progression to initial intubation, and now these data expand potential use to prevent reintubation, as well.

While not studied, if high-flow oxygen therapy is found to be equivalent to NIV to prevent reintubation (similar to the previously-published prevention of intubation studies), that would be clinically important since there is a significant difference in tolerance to these two therapies. Across these trials, the very important point to remember is that these therapies were found to be effective if put on directly after extubation, and one cannot wait to apply them at the point where the patient shows signs of respiratory decline.

Dr. Eric Gartman, FCCP, comments: These two studies augment a growing body of literature supporting the use of adjunctive therapies immediately following extubation to prevent reintubation for respiratory failure.

It has been known for several years that the use of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) immediately after extubation in COPD patients prevents reintubation rates, and these new data demonstrate efficacy in an expanded population. Further, the use of high-flow humidified oxygen therapy in acute respiratory failure has been shown to prevent progression to initial intubation, and now these data expand potential use to prevent reintubation, as well.

While not studied, if high-flow oxygen therapy is found to be equivalent to NIV to prevent reintubation (similar to the previously-published prevention of intubation studies), that would be clinically important since there is a significant difference in tolerance to these two therapies. Across these trials, the very important point to remember is that these therapies were found to be effective if put on directly after extubation, and one cannot wait to apply them at the point where the patient shows signs of respiratory decline.

Dr. Eric Gartman, FCCP, comments: These two studies augment a growing body of literature supporting the use of adjunctive therapies immediately following extubation to prevent reintubation for respiratory failure.

It has been known for several years that the use of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) immediately after extubation in COPD patients prevents reintubation rates, and these new data demonstrate efficacy in an expanded population. Further, the use of high-flow humidified oxygen therapy in acute respiratory failure has been shown to prevent progression to initial intubation, and now these data expand potential use to prevent reintubation, as well.

While not studied, if high-flow oxygen therapy is found to be equivalent to NIV to prevent reintubation (similar to the previously-published prevention of intubation studies), that would be clinically important since there is a significant difference in tolerance to these two therapies. Across these trials, the very important point to remember is that these therapies were found to be effective if put on directly after extubation, and one cannot wait to apply them at the point where the patient shows signs of respiratory decline.

Extubated patients who either received noninvasive ventilation (NIV) therapy or high-flow nasal cannula oxygen had a lower risk of reintubation, compared with extubated patients who received some form of standard oxygen therapy, according to the results of two multicenter, randomized clinical trials published online in JAMA.

Participants in one of the studies, which included abdominal surgery patients diagnosed with respiratory failure within 7 days following surgery, either received NIV or standard oxygen therapy for 30 days or until ICU discharge, whichever came first. While NIV has been effectively used to treat nonsurgical patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiogenic pulmonary edema, there is no evidence to support the use of NIV in surgical patients with hypoxemic acute respiratory failure after abdominal surgery, according to Dr. Samir Jaber of the Saint Eloi University Hospital and Montpellier School of Medicine, both in Montpellier, France, and his colleagues (JAMA. 2016 Apr 5;315[13]:1345-53).

The second study included adult patients who had received mechanical ventilation for more than 12 hours and who met criteria for being considered at low risk for reintubation. Patients were administered either high-flow oxygen therapy through nasal cannula immediately after extubation or continuous conventional oxygen therapy through nasal cannula or nonrebreather facemask; the patients were observed for 72 hours. High-flow therapy has been shown to improve oxygenation and survival in clinical studies of critically ill patients in the acute phase of respiratory failure. “[A study by S.M. Maggiore and his colleagues (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(3):282-8)] suggested that high-flow therapy after planned extubation decreased the reintubation rate in a general population of critical patients, but the benefits might be mainly attributable to improvements in high-risk patients,” said Dr. Gonzalo Hernandez, of the Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo, Spain, and his colleagues (JAMA. 2016 Apr 5;315[13]:1354-61).

In the first study, 148 patients received NIV and 145 patients received standard oxygen therapy only. NIV was administered through a facemask connected to an ICU- or a NIV-dedicated ventilator, using either a heated humidifier or heat and moisture exchanger to warm and humidify inspired gases. Patients were encouraged to use NIV for 6 hours during the first 24 hours of the study and received standard oxygen therapy at a rate of up to 15 L/minute to maintain an arterial oxygen saturation estimate (SpO2) of at least 94% in between NIV sessions. NIV was started at an inspiratory positive airway pressure of 5 cm H2O, increasing to a maximum inspiratory pressure of 15 cm H2O, aiming to achieve an expiratory tidal volume between 6 and 8 mL/kg of predicted body weight and a respiratory rate lower than 25/min. The patients in this study’s control group only received the standard oxygen therapy.

In the other study, 263 patients received conventional therapy, with the oxygen flow having been adjusted to maintain an arterial oxygen saturation estimate of greater than 92%. This study’s other 264 patients received high-flow oxygen therapy, with the flow having been initially set at 10 L/min and titrated upward in 5-L/min steps until patients experienced discomfort. The high-flow therapy was stopped after 24 hours and was followed by conventional oxygen therapy, when needed.

The primary outcome measure in the study involving NIV was cause for reintubation within 7 days of randomization.

Secondary outcome measures included gas exchange, healthcare-associated infection rate within 30 days, number of ventilator-free days between days 1 and 30, antibiotic use duration, ICU and in-hospital length of stay, and 30- and 90-day mortality.

Reintubation occurred in 49 patients in the NIV group and 66 patients in the standard oxygen therapy group, a significant difference (P = .03). Among the reintubated patients, those who had received NIV spent less time under invasive mechanical ventilation as did the patients given standard oxygen therapy. The interquartile ranges of days of invasive mechanical ventilation were 0-3 for patients in the NIV group and 0-5 for patients in the standard oxygen therapy group (P = .05). At 30 days, NIV was associated with significantly more ventilator-free days than standard oxygen therapy (25.4 vs. 23.2; P = .04). At 90 days, 22 patients in the NIV group and 31 patients in the standard oxygen therapy group had died (P = .15).

“Recent high-impact trials have demonstrated the benefits in nonsurgical hypoxemic respiratory failure or equivalence of high-flow nasal cannula compared with NIV in patients after cardiothoracic surgery with moderate to severe hypoxemia. Future studies comparing use of high-flow oxygen cannula vs standard oxygen therapy and NIV for patients after abdominal surgery as preventive (prophylactic) or curative applications are needed,” according to Dr. Jaber and his colleagues.

The primary outcome measure for the study of patients receiving high-flow oxygen therapy was reintubation within 72 hours after extubation; this occurred in fewer patients in the high-flow oxygen group than in the conventional therapy group (13 or 4.9% vs. 32 or 12.2%.) This statistically significant difference was mainly attributable to a lower incidence of respiratory-related reintubation in the high-flow group, compared with the conventional therapy group (1.5% vs. 8.7%), said Dr. Hernandez and his colleagues.

Secondary outcome measures included postextubation respiratory failure, respiratory infection, sepsis, multiorgan failure, ICU and hospital length of stay and mortality, time to reintubation, and adverse effects. Postintubation respiratory failure was less common in the high-flow therapy group than in the conventional therapy group (22 patients or 8.3% vs. 38 or 14.4%). Differences between the two groups in other secondary outcomes were not statistically significant.

“The main finding of this study was that high-flow oxygen significantly reduced the reintubation rate in critically ill patients at low risk for extubation failure ... High-flow therapy improves oxygenation, and the lower rate of reintubation secondary to hypoxia in the high-flow group corroborates this finding. High-flow oxygen also seems to reduce other causes of respiratory failure such as increased work of breathing and respiratory muscle fatigue, which are frequently associated with reintubation secondary to hypoxia. Another way in which high-flow therapy improves extubation outcome is by conditioning the inspired gas,” said Dr. Hernandez and his colleagues.

No adverse events were reported in either study.

Dr. Hernandez and his colleagues reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Jaber and his colleagues disclosed no potential conflicts of interest with their study’s sponsors, Montpellier (France) University Hospital and the APARD Foundation.

Extubated patients who either received noninvasive ventilation (NIV) therapy or high-flow nasal cannula oxygen had a lower risk of reintubation, compared with extubated patients who received some form of standard oxygen therapy, according to the results of two multicenter, randomized clinical trials published online in JAMA.

Participants in one of the studies, which included abdominal surgery patients diagnosed with respiratory failure within 7 days following surgery, either received NIV or standard oxygen therapy for 30 days or until ICU discharge, whichever came first. While NIV has been effectively used to treat nonsurgical patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiogenic pulmonary edema, there is no evidence to support the use of NIV in surgical patients with hypoxemic acute respiratory failure after abdominal surgery, according to Dr. Samir Jaber of the Saint Eloi University Hospital and Montpellier School of Medicine, both in Montpellier, France, and his colleagues (JAMA. 2016 Apr 5;315[13]:1345-53).

The second study included adult patients who had received mechanical ventilation for more than 12 hours and who met criteria for being considered at low risk for reintubation. Patients were administered either high-flow oxygen therapy through nasal cannula immediately after extubation or continuous conventional oxygen therapy through nasal cannula or nonrebreather facemask; the patients were observed for 72 hours. High-flow therapy has been shown to improve oxygenation and survival in clinical studies of critically ill patients in the acute phase of respiratory failure. “[A study by S.M. Maggiore and his colleagues (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(3):282-8)] suggested that high-flow therapy after planned extubation decreased the reintubation rate in a general population of critical patients, but the benefits might be mainly attributable to improvements in high-risk patients,” said Dr. Gonzalo Hernandez, of the Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo, Spain, and his colleagues (JAMA. 2016 Apr 5;315[13]:1354-61).

In the first study, 148 patients received NIV and 145 patients received standard oxygen therapy only. NIV was administered through a facemask connected to an ICU- or a NIV-dedicated ventilator, using either a heated humidifier or heat and moisture exchanger to warm and humidify inspired gases. Patients were encouraged to use NIV for 6 hours during the first 24 hours of the study and received standard oxygen therapy at a rate of up to 15 L/minute to maintain an arterial oxygen saturation estimate (SpO2) of at least 94% in between NIV sessions. NIV was started at an inspiratory positive airway pressure of 5 cm H2O, increasing to a maximum inspiratory pressure of 15 cm H2O, aiming to achieve an expiratory tidal volume between 6 and 8 mL/kg of predicted body weight and a respiratory rate lower than 25/min. The patients in this study’s control group only received the standard oxygen therapy.

In the other study, 263 patients received conventional therapy, with the oxygen flow having been adjusted to maintain an arterial oxygen saturation estimate of greater than 92%. This study’s other 264 patients received high-flow oxygen therapy, with the flow having been initially set at 10 L/min and titrated upward in 5-L/min steps until patients experienced discomfort. The high-flow therapy was stopped after 24 hours and was followed by conventional oxygen therapy, when needed.

The primary outcome measure in the study involving NIV was cause for reintubation within 7 days of randomization.

Secondary outcome measures included gas exchange, healthcare-associated infection rate within 30 days, number of ventilator-free days between days 1 and 30, antibiotic use duration, ICU and in-hospital length of stay, and 30- and 90-day mortality.

Reintubation occurred in 49 patients in the NIV group and 66 patients in the standard oxygen therapy group, a significant difference (P = .03). Among the reintubated patients, those who had received NIV spent less time under invasive mechanical ventilation as did the patients given standard oxygen therapy. The interquartile ranges of days of invasive mechanical ventilation were 0-3 for patients in the NIV group and 0-5 for patients in the standard oxygen therapy group (P = .05). At 30 days, NIV was associated with significantly more ventilator-free days than standard oxygen therapy (25.4 vs. 23.2; P = .04). At 90 days, 22 patients in the NIV group and 31 patients in the standard oxygen therapy group had died (P = .15).

“Recent high-impact trials have demonstrated the benefits in nonsurgical hypoxemic respiratory failure or equivalence of high-flow nasal cannula compared with NIV in patients after cardiothoracic surgery with moderate to severe hypoxemia. Future studies comparing use of high-flow oxygen cannula vs standard oxygen therapy and NIV for patients after abdominal surgery as preventive (prophylactic) or curative applications are needed,” according to Dr. Jaber and his colleagues.

The primary outcome measure for the study of patients receiving high-flow oxygen therapy was reintubation within 72 hours after extubation; this occurred in fewer patients in the high-flow oxygen group than in the conventional therapy group (13 or 4.9% vs. 32 or 12.2%.) This statistically significant difference was mainly attributable to a lower incidence of respiratory-related reintubation in the high-flow group, compared with the conventional therapy group (1.5% vs. 8.7%), said Dr. Hernandez and his colleagues.

Secondary outcome measures included postextubation respiratory failure, respiratory infection, sepsis, multiorgan failure, ICU and hospital length of stay and mortality, time to reintubation, and adverse effects. Postintubation respiratory failure was less common in the high-flow therapy group than in the conventional therapy group (22 patients or 8.3% vs. 38 or 14.4%). Differences between the two groups in other secondary outcomes were not statistically significant.

“The main finding of this study was that high-flow oxygen significantly reduced the reintubation rate in critically ill patients at low risk for extubation failure ... High-flow therapy improves oxygenation, and the lower rate of reintubation secondary to hypoxia in the high-flow group corroborates this finding. High-flow oxygen also seems to reduce other causes of respiratory failure such as increased work of breathing and respiratory muscle fatigue, which are frequently associated with reintubation secondary to hypoxia. Another way in which high-flow therapy improves extubation outcome is by conditioning the inspired gas,” said Dr. Hernandez and his colleagues.

No adverse events were reported in either study.

Dr. Hernandez and his colleagues reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Jaber and his colleagues disclosed no potential conflicts of interest with their study’s sponsors, Montpellier (France) University Hospital and the APARD Foundation.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Extubated patients who either received noninvasive ventilation (NIV) therapy or high-flow nasal cannula oxygen reduced their risk of reintubation, compared with patients who received some form of standard oxygen therapy.

Major finding: In one study, significantly fewer of the patients who received NIV needed to be reintubated than the patients who received standard oxygen therapy.

Data source: Two multicenter, randomized clinical trials published online in JAMA.

Disclosures: Dr. Hernandez and his colleagues reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Jaber and his colleagues disclosed no potential conflicts of interest with Montpellier (France) University Hospital and the APARD Foundation, who funded their study.

Negative sestamibi scan for primary hyperparathyroidism can mean no referral or surgery

BALTIMORE – In the treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism, clinical guidelines recommend using sestamibi scan for localizing adenoma, but increasingly endocrinologists are using sestamibi results to determine whether or not to refer a patient for parathyroidectomy surgery, while surgeons are using the scans as a factor in deciding whether to perform the operation.

That was the conclusion of a paper Dr. Susana Wu presented at the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons annual meeting. Dr. Wu reported on behalf of her colleagues at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center and at Scripps Clinic in San Diego.

“This study suggests that negative sestamibi scan (SS) results influence management of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism,” Dr. Wu said. “Endocrinologists were less likely to refer to surgeons and surgeons were less likely to offer parathyroidectomy to a patient with a negative sestamibi scan.”

The study involved a retrospective chart review of all 539 patients with primary hyperparathyroidism in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California database from December 2011 to December 2013, 452 of whom were seen by 63 endocrinologists at 14 centers. Among these patients, 260 had SS – 120 negative and 140 positive. The study identified statistically significant variations in how both endocrinologists and surgeons managed patients depending on SS results. The researchers used Kaiser Permanente’s electronic referral system to track referrals.

“The most significant negative predictor for endocrinologists referring to surgeons was a negative sestamibi scan, with an odds ratio of 0.36,” Dr. Wu said.

Endocrinologists referred 86% of patients with positive SS to surgeons, but only 68% of those with negative SS. Surgeons exhibited a similar practice pattern. “Surgeons were less likely to recommend parathyroidectomy for patients with a negative sestamibi scan, with an odds ratio of 0.20,” Dr. Wu said. Surgeons operated on 87% of patients with a negative SS scan but 96% with a positive SS.

In an interview, study coauthor Dr. Philip Haigh explained that parathyroidectomy when the SS is negative is a more difficult operation for the surgeon, and that might make some physicians hesitate before going forward with surgery. “It has been previously shown by other studies that it is a more difficult operation when the sestamibi scan is negative because you have to look at four glands instead of removing just one, but if the surgeon is experienced, it should achieve a high success rate,” Dr. Haigh said. He said that parathyroidectomy in sestamibi-negative hyperparathyroidism had a cure rate as high as 98% in the study presented.

He offered two thoughts on how clinicians should use the study results. “To the endocrinologist, if you’re going to order a sestamibi scan, don’t change your referral practice depending on the result,” Dr. Haigh said. “To the surgeon, if you’re not comfortable operating on a patient with a negative sestamibi scan, then find someone who is.”

The study had a few limitations, Dr. Wu said. Along with its retrospective nature, the study also did not account for potential disparity in radiological vs. surgeon interpretation of the scans.

During the discussion, Dr. Samuel Snyder, of Baylor Scott & White Health, Temple, Tex., said he concurred with the results Dr. Wu reported. “It really worries me about what is happening to patients who have negative scans,” he said. “What I’ve seen in patients referred for surgery is a lot of variation in how the sestamibi scan is done.” He asked if the study accounted for the different types of sestamibi scans and how they were performed, but Dr. Wu said it did not.

Dr. Christopher McHenry of MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, also concurred. “I think this is a phenomenon that occurs more often than we think or we’re aware of,” he said. “I continue to be amazed with how clinicians equate a negative sestamibi scan with not having primary hyperparathyroidism. I think it needs to reemphasized that the sestamibi scan is not diagnostic; it’s for localization.”

He asked Dr. Wu, “How do we change behavior to deal with this problem?”

Dr. Wu said her institution is developing a safety-net program that would aim to increase the identification and chart coding of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism, automate essential labs to be ordered in patients with high calcium, and automate referral to endocrinologists. The study and its findings will be disseminated to endocrinologists in the region.

The study authors had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – In the treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism, clinical guidelines recommend using sestamibi scan for localizing adenoma, but increasingly endocrinologists are using sestamibi results to determine whether or not to refer a patient for parathyroidectomy surgery, while surgeons are using the scans as a factor in deciding whether to perform the operation.

That was the conclusion of a paper Dr. Susana Wu presented at the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons annual meeting. Dr. Wu reported on behalf of her colleagues at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center and at Scripps Clinic in San Diego.

“This study suggests that negative sestamibi scan (SS) results influence management of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism,” Dr. Wu said. “Endocrinologists were less likely to refer to surgeons and surgeons were less likely to offer parathyroidectomy to a patient with a negative sestamibi scan.”

The study involved a retrospective chart review of all 539 patients with primary hyperparathyroidism in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California database from December 2011 to December 2013, 452 of whom were seen by 63 endocrinologists at 14 centers. Among these patients, 260 had SS – 120 negative and 140 positive. The study identified statistically significant variations in how both endocrinologists and surgeons managed patients depending on SS results. The researchers used Kaiser Permanente’s electronic referral system to track referrals.

“The most significant negative predictor for endocrinologists referring to surgeons was a negative sestamibi scan, with an odds ratio of 0.36,” Dr. Wu said.

Endocrinologists referred 86% of patients with positive SS to surgeons, but only 68% of those with negative SS. Surgeons exhibited a similar practice pattern. “Surgeons were less likely to recommend parathyroidectomy for patients with a negative sestamibi scan, with an odds ratio of 0.20,” Dr. Wu said. Surgeons operated on 87% of patients with a negative SS scan but 96% with a positive SS.

In an interview, study coauthor Dr. Philip Haigh explained that parathyroidectomy when the SS is negative is a more difficult operation for the surgeon, and that might make some physicians hesitate before going forward with surgery. “It has been previously shown by other studies that it is a more difficult operation when the sestamibi scan is negative because you have to look at four glands instead of removing just one, but if the surgeon is experienced, it should achieve a high success rate,” Dr. Haigh said. He said that parathyroidectomy in sestamibi-negative hyperparathyroidism had a cure rate as high as 98% in the study presented.

He offered two thoughts on how clinicians should use the study results. “To the endocrinologist, if you’re going to order a sestamibi scan, don’t change your referral practice depending on the result,” Dr. Haigh said. “To the surgeon, if you’re not comfortable operating on a patient with a negative sestamibi scan, then find someone who is.”

The study had a few limitations, Dr. Wu said. Along with its retrospective nature, the study also did not account for potential disparity in radiological vs. surgeon interpretation of the scans.

During the discussion, Dr. Samuel Snyder, of Baylor Scott & White Health, Temple, Tex., said he concurred with the results Dr. Wu reported. “It really worries me about what is happening to patients who have negative scans,” he said. “What I’ve seen in patients referred for surgery is a lot of variation in how the sestamibi scan is done.” He asked if the study accounted for the different types of sestamibi scans and how they were performed, but Dr. Wu said it did not.

Dr. Christopher McHenry of MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, also concurred. “I think this is a phenomenon that occurs more often than we think or we’re aware of,” he said. “I continue to be amazed with how clinicians equate a negative sestamibi scan with not having primary hyperparathyroidism. I think it needs to reemphasized that the sestamibi scan is not diagnostic; it’s for localization.”

He asked Dr. Wu, “How do we change behavior to deal with this problem?”

Dr. Wu said her institution is developing a safety-net program that would aim to increase the identification and chart coding of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism, automate essential labs to be ordered in patients with high calcium, and automate referral to endocrinologists. The study and its findings will be disseminated to endocrinologists in the region.

The study authors had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – In the treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism, clinical guidelines recommend using sestamibi scan for localizing adenoma, but increasingly endocrinologists are using sestamibi results to determine whether or not to refer a patient for parathyroidectomy surgery, while surgeons are using the scans as a factor in deciding whether to perform the operation.

That was the conclusion of a paper Dr. Susana Wu presented at the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons annual meeting. Dr. Wu reported on behalf of her colleagues at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center and at Scripps Clinic in San Diego.

“This study suggests that negative sestamibi scan (SS) results influence management of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism,” Dr. Wu said. “Endocrinologists were less likely to refer to surgeons and surgeons were less likely to offer parathyroidectomy to a patient with a negative sestamibi scan.”

The study involved a retrospective chart review of all 539 patients with primary hyperparathyroidism in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California database from December 2011 to December 2013, 452 of whom were seen by 63 endocrinologists at 14 centers. Among these patients, 260 had SS – 120 negative and 140 positive. The study identified statistically significant variations in how both endocrinologists and surgeons managed patients depending on SS results. The researchers used Kaiser Permanente’s electronic referral system to track referrals.

“The most significant negative predictor for endocrinologists referring to surgeons was a negative sestamibi scan, with an odds ratio of 0.36,” Dr. Wu said.

Endocrinologists referred 86% of patients with positive SS to surgeons, but only 68% of those with negative SS. Surgeons exhibited a similar practice pattern. “Surgeons were less likely to recommend parathyroidectomy for patients with a negative sestamibi scan, with an odds ratio of 0.20,” Dr. Wu said. Surgeons operated on 87% of patients with a negative SS scan but 96% with a positive SS.

In an interview, study coauthor Dr. Philip Haigh explained that parathyroidectomy when the SS is negative is a more difficult operation for the surgeon, and that might make some physicians hesitate before going forward with surgery. “It has been previously shown by other studies that it is a more difficult operation when the sestamibi scan is negative because you have to look at four glands instead of removing just one, but if the surgeon is experienced, it should achieve a high success rate,” Dr. Haigh said. He said that parathyroidectomy in sestamibi-negative hyperparathyroidism had a cure rate as high as 98% in the study presented.

He offered two thoughts on how clinicians should use the study results. “To the endocrinologist, if you’re going to order a sestamibi scan, don’t change your referral practice depending on the result,” Dr. Haigh said. “To the surgeon, if you’re not comfortable operating on a patient with a negative sestamibi scan, then find someone who is.”

The study had a few limitations, Dr. Wu said. Along with its retrospective nature, the study also did not account for potential disparity in radiological vs. surgeon interpretation of the scans.

During the discussion, Dr. Samuel Snyder, of Baylor Scott & White Health, Temple, Tex., said he concurred with the results Dr. Wu reported. “It really worries me about what is happening to patients who have negative scans,” he said. “What I’ve seen in patients referred for surgery is a lot of variation in how the sestamibi scan is done.” He asked if the study accounted for the different types of sestamibi scans and how they were performed, but Dr. Wu said it did not.

Dr. Christopher McHenry of MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, also concurred. “I think this is a phenomenon that occurs more often than we think or we’re aware of,” he said. “I continue to be amazed with how clinicians equate a negative sestamibi scan with not having primary hyperparathyroidism. I think it needs to reemphasized that the sestamibi scan is not diagnostic; it’s for localization.”

He asked Dr. Wu, “How do we change behavior to deal with this problem?”

Dr. Wu said her institution is developing a safety-net program that would aim to increase the identification and chart coding of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism, automate essential labs to be ordered in patients with high calcium, and automate referral to endocrinologists. The study and its findings will be disseminated to endocrinologists in the region.

The study authors had no disclosures.

AT AAES 2016

Key clinical point: Endocrinologists and surgeons are less likely to order surgery when patients with primary hyperparathyroidism have negative sestamibi scan (SS) results.

Major finding: Endocrinologists referred 86% of patients with positive SS to surgeons, but only 68% of those with negative SS.

Data source: A retrospective chart review of all 539 patients with primary hyperparathyroidism in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California database over a 2-year period.

Disclosures: Dr. Wu and her coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

Fresh Press: ACS Surgery News April digital issue is available

The April issue of ACS Surgery News is available online. Use the mobile app to download or view as a pdf.

This month’s issue features a story on an underrecognized problem among surgeons: chronic pain in the hands, neck, and back due to long hours of operating. In a related story, the AAOS has issued guidelines on, and rated the strength of, evidence for treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Don’t miss the commentary from Dr. Layton F. Rikkers, Editor-in-Chief of ACS Surgery News, on the value of input from the quiet or introverted members of a team, and how to elicit their participation.

The April issue of ACS Surgery News is available online. Use the mobile app to download or view as a pdf.

This month’s issue features a story on an underrecognized problem among surgeons: chronic pain in the hands, neck, and back due to long hours of operating. In a related story, the AAOS has issued guidelines on, and rated the strength of, evidence for treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Don’t miss the commentary from Dr. Layton F. Rikkers, Editor-in-Chief of ACS Surgery News, on the value of input from the quiet or introverted members of a team, and how to elicit their participation.

The April issue of ACS Surgery News is available online. Use the mobile app to download or view as a pdf.

This month’s issue features a story on an underrecognized problem among surgeons: chronic pain in the hands, neck, and back due to long hours of operating. In a related story, the AAOS has issued guidelines on, and rated the strength of, evidence for treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Don’t miss the commentary from Dr. Layton F. Rikkers, Editor-in-Chief of ACS Surgery News, on the value of input from the quiet or introverted members of a team, and how to elicit their participation.

STAMPEDE: Metabolic surgery bests medical therapy long term

CHICAGO – The superiority of metabolic surgery over intensive medical therapy for achieving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes was largely maintained at the final 5-year follow-up evaluation in the randomized, controlled STAMPEDE trial.

The 150 subjects, who had “fairly severe diabetes” with an average disease duration of 8 years, were randomized to receive intensive medical therapy alone, or intensive medical therapy with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery or sleeve gastrectomy surgery. The primary endpoint of hemoglobin A1c less than 6% was achieved in 5%, 29%, and 23% of patients in the groups, respectively. The difference was statistically significant in favor of both types of surgery, Dr. Philip Raymond Schauer reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Furthermore, patients in the surgery groups fared better than those in the intensive medical therapy group on several other measures, including disease remission (defied as HbA1c less than 6% without diabetes medication), HbA1c less than 7% (the American Diabetes Association target for therapy), change in fasting plasma glucose from baseline, and changes in high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, said Dr. Schauer, director of the Cleveland Clinic Bariatric and Metabolic Institute.

Patients in the surgery groups also experienced a significantly greater reduction in the use of antihypertensive medications and lipid-lowering agents, he added.

The “very dramatic drop” in HbA1c seen early on in the surgical patients was, for the most part, sustained out to 5 years, he said.

The results for both surgeries were significantly better than those for intensive medical therapy, but the results with gastric bypass were more effective at 5 years than were those for sleeve gastrectomy, he added, noting that the surgery patients had better quality of life, compared with the intensive medical therapy patients.

As for adverse events in the surgery groups, no perioperative deaths occurred, and while there were some surgical complications, none resulted in long-term disability, Dr. Schauer said.

Anemia was more common in the surgery patients, but was fairly mild. The most common complication was weight gain in 20% of patients, and the overall reoperation rate was 7%.

Of note, patients in the study had body mass index ranging from 27 to 43 kg/m2, and those with BMI less than 35 had similar benefits as those with more severe obesity. This is important, as many insurance companies won’t cover metabolic surgery for patients with BMI less than 35, he explained.

These findings represent the longest follow-up to date comparing the efficacy of the two most common metabolic surgery procedures with medical treatment of type 2 diabetes for maintaining glycemic control or reducing end-organ complications. Three-year outcomes of STAMPEDE (Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) were reported in 2014 (N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2002-13).

The participants ranged in age from 20 to 60 years. The average HbA1c was about 9%, the average BMI was 36, and most were on at least three antidiabetic medications at baseline. Half were on insulin.

The findings are important, because of the roughly 25 million Americans with type 2 diabetes, only about half have good glycemic control on their current medical treatment strategies, Dr. Schauer said.

Though limited by the single-center study design, the STAMPEDE findings show that metabolic surgery is more effective long term than intensive medical therapy in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and should be considered a treatment option in this population, he concluded, adding that multicenter studies would be helpful for determining the generalizability of the findings.

Dr. Schauer reported receiving consulting fees/honoraria from Ethicon Endosurgery and The Medicines Company, and having ownership interest in Surgical Excellence.

CHICAGO – The superiority of metabolic surgery over intensive medical therapy for achieving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes was largely maintained at the final 5-year follow-up evaluation in the randomized, controlled STAMPEDE trial.

The 150 subjects, who had “fairly severe diabetes” with an average disease duration of 8 years, were randomized to receive intensive medical therapy alone, or intensive medical therapy with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery or sleeve gastrectomy surgery. The primary endpoint of hemoglobin A1c less than 6% was achieved in 5%, 29%, and 23% of patients in the groups, respectively. The difference was statistically significant in favor of both types of surgery, Dr. Philip Raymond Schauer reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Furthermore, patients in the surgery groups fared better than those in the intensive medical therapy group on several other measures, including disease remission (defied as HbA1c less than 6% without diabetes medication), HbA1c less than 7% (the American Diabetes Association target for therapy), change in fasting plasma glucose from baseline, and changes in high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, said Dr. Schauer, director of the Cleveland Clinic Bariatric and Metabolic Institute.

Patients in the surgery groups also experienced a significantly greater reduction in the use of antihypertensive medications and lipid-lowering agents, he added.

The “very dramatic drop” in HbA1c seen early on in the surgical patients was, for the most part, sustained out to 5 years, he said.

The results for both surgeries were significantly better than those for intensive medical therapy, but the results with gastric bypass were more effective at 5 years than were those for sleeve gastrectomy, he added, noting that the surgery patients had better quality of life, compared with the intensive medical therapy patients.

As for adverse events in the surgery groups, no perioperative deaths occurred, and while there were some surgical complications, none resulted in long-term disability, Dr. Schauer said.

Anemia was more common in the surgery patients, but was fairly mild. The most common complication was weight gain in 20% of patients, and the overall reoperation rate was 7%.

Of note, patients in the study had body mass index ranging from 27 to 43 kg/m2, and those with BMI less than 35 had similar benefits as those with more severe obesity. This is important, as many insurance companies won’t cover metabolic surgery for patients with BMI less than 35, he explained.

These findings represent the longest follow-up to date comparing the efficacy of the two most common metabolic surgery procedures with medical treatment of type 2 diabetes for maintaining glycemic control or reducing end-organ complications. Three-year outcomes of STAMPEDE (Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) were reported in 2014 (N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2002-13).

The participants ranged in age from 20 to 60 years. The average HbA1c was about 9%, the average BMI was 36, and most were on at least three antidiabetic medications at baseline. Half were on insulin.

The findings are important, because of the roughly 25 million Americans with type 2 diabetes, only about half have good glycemic control on their current medical treatment strategies, Dr. Schauer said.

Though limited by the single-center study design, the STAMPEDE findings show that metabolic surgery is more effective long term than intensive medical therapy in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and should be considered a treatment option in this population, he concluded, adding that multicenter studies would be helpful for determining the generalizability of the findings.

Dr. Schauer reported receiving consulting fees/honoraria from Ethicon Endosurgery and The Medicines Company, and having ownership interest in Surgical Excellence.

CHICAGO – The superiority of metabolic surgery over intensive medical therapy for achieving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes was largely maintained at the final 5-year follow-up evaluation in the randomized, controlled STAMPEDE trial.

The 150 subjects, who had “fairly severe diabetes” with an average disease duration of 8 years, were randomized to receive intensive medical therapy alone, or intensive medical therapy with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery or sleeve gastrectomy surgery. The primary endpoint of hemoglobin A1c less than 6% was achieved in 5%, 29%, and 23% of patients in the groups, respectively. The difference was statistically significant in favor of both types of surgery, Dr. Philip Raymond Schauer reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Furthermore, patients in the surgery groups fared better than those in the intensive medical therapy group on several other measures, including disease remission (defied as HbA1c less than 6% without diabetes medication), HbA1c less than 7% (the American Diabetes Association target for therapy), change in fasting plasma glucose from baseline, and changes in high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, said Dr. Schauer, director of the Cleveland Clinic Bariatric and Metabolic Institute.

Patients in the surgery groups also experienced a significantly greater reduction in the use of antihypertensive medications and lipid-lowering agents, he added.

The “very dramatic drop” in HbA1c seen early on in the surgical patients was, for the most part, sustained out to 5 years, he said.

The results for both surgeries were significantly better than those for intensive medical therapy, but the results with gastric bypass were more effective at 5 years than were those for sleeve gastrectomy, he added, noting that the surgery patients had better quality of life, compared with the intensive medical therapy patients.

As for adverse events in the surgery groups, no perioperative deaths occurred, and while there were some surgical complications, none resulted in long-term disability, Dr. Schauer said.

Anemia was more common in the surgery patients, but was fairly mild. The most common complication was weight gain in 20% of patients, and the overall reoperation rate was 7%.

Of note, patients in the study had body mass index ranging from 27 to 43 kg/m2, and those with BMI less than 35 had similar benefits as those with more severe obesity. This is important, as many insurance companies won’t cover metabolic surgery for patients with BMI less than 35, he explained.

These findings represent the longest follow-up to date comparing the efficacy of the two most common metabolic surgery procedures with medical treatment of type 2 diabetes for maintaining glycemic control or reducing end-organ complications. Three-year outcomes of STAMPEDE (Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) were reported in 2014 (N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2002-13).

The participants ranged in age from 20 to 60 years. The average HbA1c was about 9%, the average BMI was 36, and most were on at least three antidiabetic medications at baseline. Half were on insulin.

The findings are important, because of the roughly 25 million Americans with type 2 diabetes, only about half have good glycemic control on their current medical treatment strategies, Dr. Schauer said.

Though limited by the single-center study design, the STAMPEDE findings show that metabolic surgery is more effective long term than intensive medical therapy in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and should be considered a treatment option in this population, he concluded, adding that multicenter studies would be helpful for determining the generalizability of the findings.

Dr. Schauer reported receiving consulting fees/honoraria from Ethicon Endosurgery and The Medicines Company, and having ownership interest in Surgical Excellence.

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: The superiority of metabolic surgery over intensive medical therapy for achieving glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes in the randomized, controlled STAMPEDE persisted at the final 5-year follow-up evaluation.

Major finding: The primary endpoint of HbA1c less than 6% was achieved in 5%, 29%, and 23% of patients in the medication and medication plus Roux-en-Y or sleeve gastrectomy groups, respectively.

Data source: The randomized, controlled STAMPEDE trial in 150 subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Schauer reported receiving consulting fees/honoraria from Ethicon Endosurgery and The Medicines Company, and having ownership interest in Surgical Excellence.

Earlier bariatric surgery may improve cardiovascular outcomes

CHICAGO – Sooner may be better than later when it comes to the timing of bariatric surgery in patients with morbid obesity.

Of 828 patients with body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2 who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding performed by a single surgeon and were followed for up to 11 years (mean of 10 years), 423 were aged 45 years or younger, and 405 were over age 45 years at the time of surgery. A comparison of outcomes between the two age groups showed that older age at the time of surgery was an independent predictor of cardiovascular events (hazard ratio, 1.8), Maharaj Singh, Ph.D., a biostatistician at the Aurora Research Institute, Milwaukee, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Despite a similar reduction in body weight after gastric banding surgery, the older patients experienced more cardiovascular events: myocardial infarction occurred in 0.2% and 1.7% of patients in the younger and older age groups, respectively, pulmonary embolism occurred in 0.7% and 4.3%, congestive heart failure occurred in 2.8% and 7.8%, and stroke occurred in 3.7% and 7.6%, Dr. Singh said.

“Although the older group had more comorbidities, these were accounted for by multivariate analysis and age over 45 years remained an independent predictor of poor cardiovascular outcomes,” senior coauthor Dr. Arshad Jahangir, professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in an interview.

Other independent predictors of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in the study were sleep apnea (hazard ratio, 4), history of hypertension (HR, 1.9), and depression, (HR, 1.8), Dr. Jahangir said.

“Gender, race, and diabetes mellitus did not independently predict cardiovascular events,” he said.

Weight loss after bariatric surgery has been shown to reduce the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, but it has remained unclear whether the reduction in risk varies based on age at the time of surgery, he said.

The current findings suggest that the effects of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding–induced weight loss on cardiovascular outcomes are greater in patients who undergo the surgery at a younger age, he said, adding that the findings also “raise important questions about whether better control of sleep apnea, hypertension, and depression could help further reduce cardiovascular events in morbidly obese individuals undergoing bariatric surgery and should be addressed in a prospective study of these patients.”

The authors reported having no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Sooner may be better than later when it comes to the timing of bariatric surgery in patients with morbid obesity.

Of 828 patients with body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2 who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding performed by a single surgeon and were followed for up to 11 years (mean of 10 years), 423 were aged 45 years or younger, and 405 were over age 45 years at the time of surgery. A comparison of outcomes between the two age groups showed that older age at the time of surgery was an independent predictor of cardiovascular events (hazard ratio, 1.8), Maharaj Singh, Ph.D., a biostatistician at the Aurora Research Institute, Milwaukee, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Despite a similar reduction in body weight after gastric banding surgery, the older patients experienced more cardiovascular events: myocardial infarction occurred in 0.2% and 1.7% of patients in the younger and older age groups, respectively, pulmonary embolism occurred in 0.7% and 4.3%, congestive heart failure occurred in 2.8% and 7.8%, and stroke occurred in 3.7% and 7.6%, Dr. Singh said.

“Although the older group had more comorbidities, these were accounted for by multivariate analysis and age over 45 years remained an independent predictor of poor cardiovascular outcomes,” senior coauthor Dr. Arshad Jahangir, professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in an interview.

Other independent predictors of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in the study were sleep apnea (hazard ratio, 4), history of hypertension (HR, 1.9), and depression, (HR, 1.8), Dr. Jahangir said.

“Gender, race, and diabetes mellitus did not independently predict cardiovascular events,” he said.

Weight loss after bariatric surgery has been shown to reduce the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, but it has remained unclear whether the reduction in risk varies based on age at the time of surgery, he said.

The current findings suggest that the effects of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding–induced weight loss on cardiovascular outcomes are greater in patients who undergo the surgery at a younger age, he said, adding that the findings also “raise important questions about whether better control of sleep apnea, hypertension, and depression could help further reduce cardiovascular events in morbidly obese individuals undergoing bariatric surgery and should be addressed in a prospective study of these patients.”

The authors reported having no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Sooner may be better than later when it comes to the timing of bariatric surgery in patients with morbid obesity.

Of 828 patients with body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2 who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding performed by a single surgeon and were followed for up to 11 years (mean of 10 years), 423 were aged 45 years or younger, and 405 were over age 45 years at the time of surgery. A comparison of outcomes between the two age groups showed that older age at the time of surgery was an independent predictor of cardiovascular events (hazard ratio, 1.8), Maharaj Singh, Ph.D., a biostatistician at the Aurora Research Institute, Milwaukee, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Despite a similar reduction in body weight after gastric banding surgery, the older patients experienced more cardiovascular events: myocardial infarction occurred in 0.2% and 1.7% of patients in the younger and older age groups, respectively, pulmonary embolism occurred in 0.7% and 4.3%, congestive heart failure occurred in 2.8% and 7.8%, and stroke occurred in 3.7% and 7.6%, Dr. Singh said.

“Although the older group had more comorbidities, these were accounted for by multivariate analysis and age over 45 years remained an independent predictor of poor cardiovascular outcomes,” senior coauthor Dr. Arshad Jahangir, professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in an interview.

Other independent predictors of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in the study were sleep apnea (hazard ratio, 4), history of hypertension (HR, 1.9), and depression, (HR, 1.8), Dr. Jahangir said.

“Gender, race, and diabetes mellitus did not independently predict cardiovascular events,” he said.

Weight loss after bariatric surgery has been shown to reduce the risk of adverse cardiovascular events, but it has remained unclear whether the reduction in risk varies based on age at the time of surgery, he said.

The current findings suggest that the effects of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding–induced weight loss on cardiovascular outcomes are greater in patients who undergo the surgery at a younger age, he said, adding that the findings also “raise important questions about whether better control of sleep apnea, hypertension, and depression could help further reduce cardiovascular events in morbidly obese individuals undergoing bariatric surgery and should be addressed in a prospective study of these patients.”

The authors reported having no disclosures.

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: Morbidly obese patients who underwent bariatric surgery before age 45 years had a reduced risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes vs. those aged 45 or older at the time of surgery, despite similar weight loss.

Major finding: Older vs. younger age at the time of surgery was an independent predictor of cardiovascular events (hazard ratio, 1.8).

Data source: A review of outcomes in 828 laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding patients.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no disclosures.

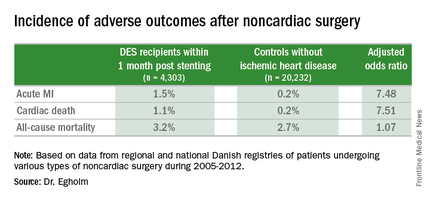

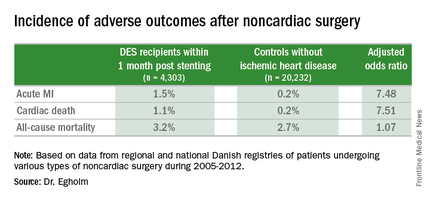

Drug-eluting stent recipients can safely have surgery sooner

CHICAGO – Current U.S. and European guidelines recommending postponement of noncardiac surgery for 6-12 months after drug-eluting stent implantation appear to be excessive, Dr. Gro Egholm reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

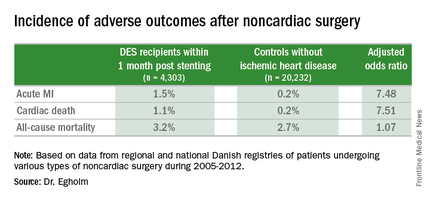

She presented a large retrospective observational study of outcomes in patients undergoing various types of noncardiac surgery in western Denmark during 2005-2012. Among 4,303 patients who had noncardiac surgery within 12 months after receiving a drug-eluting stent (DES), only those whose operations took place during the first month post stenting had increased risks of acute MI and cardiac death within 30 days post surgery.

Risks of major adverse cardiac events among the DES recipients who had noncardiac surgery within that first month post–percutaneous coronary intervention were increased roughly 7.5-fold compared with controls, but for surgery performed after that the risks of MI and cardiac death dropped off abruptly and were no different from rates in 20,232 controls without ischemic heart disease or stents who were matched for age, gender, surgical procedure, and Charlson Comorbidity Index, according to Dr. Egholm of Aarhus (Denmark) University.

Moreover, even in DES recipients undergoing noncardiac surgery during the first month post stenting, all-cause mortality was no greater than in controls.

“Surgery could be performed much earlier than recommended,” she concluded.

Her study was carried out by linking data from comprehensive regional and national Danish health care registries. Most patients with DES remained on dual antiplatelet therapy periprocedurally. The exceptions were neurosurgical operations and others where it’s standard that dual antiplatelet therapy must be stopped.

“If you can continue only one antiplatelet agent, aspirin would be the most appealing,” she said.

Of the DES participants, 56% received their device as treatment for an acute coronary syndrome. The average time from stent placement to noncardiac surgery in this large series was 147 days.

Session co-chair Dr. Sunil V. Rao of Duke University in Durham, N.C., called this work “a very important study that’s relevant to daily practice.” However, he found the 23% incidence of noncardiac surgery within 12 months following DES implantation reported in Dr. Egholm’s study to be “shockingly high.” She agreed, noting that rates in some non-Danish registries she’s looked at are more in the 8%-15% range. But Denmark’s health care registries are known for rigorous accuracy and completeness.

Dr. Egholm reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

CHICAGO – Current U.S. and European guidelines recommending postponement of noncardiac surgery for 6-12 months after drug-eluting stent implantation appear to be excessive, Dr. Gro Egholm reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

She presented a large retrospective observational study of outcomes in patients undergoing various types of noncardiac surgery in western Denmark during 2005-2012. Among 4,303 patients who had noncardiac surgery within 12 months after receiving a drug-eluting stent (DES), only those whose operations took place during the first month post stenting had increased risks of acute MI and cardiac death within 30 days post surgery.

Risks of major adverse cardiac events among the DES recipients who had noncardiac surgery within that first month post–percutaneous coronary intervention were increased roughly 7.5-fold compared with controls, but for surgery performed after that the risks of MI and cardiac death dropped off abruptly and were no different from rates in 20,232 controls without ischemic heart disease or stents who were matched for age, gender, surgical procedure, and Charlson Comorbidity Index, according to Dr. Egholm of Aarhus (Denmark) University.

Moreover, even in DES recipients undergoing noncardiac surgery during the first month post stenting, all-cause mortality was no greater than in controls.

“Surgery could be performed much earlier than recommended,” she concluded.

Her study was carried out by linking data from comprehensive regional and national Danish health care registries. Most patients with DES remained on dual antiplatelet therapy periprocedurally. The exceptions were neurosurgical operations and others where it’s standard that dual antiplatelet therapy must be stopped.

“If you can continue only one antiplatelet agent, aspirin would be the most appealing,” she said.

Of the DES participants, 56% received their device as treatment for an acute coronary syndrome. The average time from stent placement to noncardiac surgery in this large series was 147 days.

Session co-chair Dr. Sunil V. Rao of Duke University in Durham, N.C., called this work “a very important study that’s relevant to daily practice.” However, he found the 23% incidence of noncardiac surgery within 12 months following DES implantation reported in Dr. Egholm’s study to be “shockingly high.” She agreed, noting that rates in some non-Danish registries she’s looked at are more in the 8%-15% range. But Denmark’s health care registries are known for rigorous accuracy and completeness.

Dr. Egholm reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

CHICAGO – Current U.S. and European guidelines recommending postponement of noncardiac surgery for 6-12 months after drug-eluting stent implantation appear to be excessive, Dr. Gro Egholm reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

She presented a large retrospective observational study of outcomes in patients undergoing various types of noncardiac surgery in western Denmark during 2005-2012. Among 4,303 patients who had noncardiac surgery within 12 months after receiving a drug-eluting stent (DES), only those whose operations took place during the first month post stenting had increased risks of acute MI and cardiac death within 30 days post surgery.

Risks of major adverse cardiac events among the DES recipients who had noncardiac surgery within that first month post–percutaneous coronary intervention were increased roughly 7.5-fold compared with controls, but for surgery performed after that the risks of MI and cardiac death dropped off abruptly and were no different from rates in 20,232 controls without ischemic heart disease or stents who were matched for age, gender, surgical procedure, and Charlson Comorbidity Index, according to Dr. Egholm of Aarhus (Denmark) University.

Moreover, even in DES recipients undergoing noncardiac surgery during the first month post stenting, all-cause mortality was no greater than in controls.

“Surgery could be performed much earlier than recommended,” she concluded.

Her study was carried out by linking data from comprehensive regional and national Danish health care registries. Most patients with DES remained on dual antiplatelet therapy periprocedurally. The exceptions were neurosurgical operations and others where it’s standard that dual antiplatelet therapy must be stopped.

“If you can continue only one antiplatelet agent, aspirin would be the most appealing,” she said.

Of the DES participants, 56% received their device as treatment for an acute coronary syndrome. The average time from stent placement to noncardiac surgery in this large series was 147 days.

Session co-chair Dr. Sunil V. Rao of Duke University in Durham, N.C., called this work “a very important study that’s relevant to daily practice.” However, he found the 23% incidence of noncardiac surgery within 12 months following DES implantation reported in Dr. Egholm’s study to be “shockingly high.” She agreed, noting that rates in some non-Danish registries she’s looked at are more in the 8%-15% range. But Denmark’s health care registries are known for rigorous accuracy and completeness.

Dr. Egholm reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: The risk of noncardiac surgery is elevated only when the operation occurs during the first month after stenting.

Major finding: Danish drug-eluting stent recipients who underwent noncardiac surgery within 1 month after stent placement were at 7.5-fold increased risks of acute MI and cardiac death, but surgery performed 2-12 months post stenting carried no increased risks.

Data source: This retrospective observational study based upon large Danish patient registries compared outcomes of noncardiac surgery performed within 12 months after drug-eluting stent placement in 4,303 patients with 20,232 matched controls without ischemic heart disease who underwent the same operations.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Danish research funds. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Surgeons commonly off the mark in estimating blood loss

MONTREAL – Surgeons, nurses, and anesthesia providers were all pretty bad at estimating surgical blood loss in a small study. And more experience doesn’t improve accuracy, though experienced providers were more confident in their estimates.

These were the findings from a study that simulated operating room scenarios and asked providers to estimate blood loss. “Estimation of blood loss is inaccurate and unreliable,” Dr. Luke Rothermel said at the Central Surgical Association’s annual meeting.

Dr. Rothermel, a resident at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, noted that although the Joint Commission requires operative notes to contain estimated blood loss, “no study in the United States has compared the characteristics of operating room personnel or conditions associated with improved accuracy or reliability of blood loss estimation.”

Beyond the required reporting, estimating blood loss (EBL) also provides important guidance in perioperative care. Still, said Dr. Rothermel, previous studies have shown that EBL is typically inaccurate.

To assess providers’ ability to be accurate and reliable in estimating blood loss, Dr. Rothermel and his collaborator, Dr. Jeremy Lipman, assistant residency director at MetroHealth, Cleveland, designed a study to simulate three different operating room scenarios, involving high, medium, and low blood loss volumes. The materials used, such as blood-soaked sponges and suction canisters, were identical to what’s actually used in the operating room (porcine blood was used in the simulations).

Before the study, Dr. Rothermel said that he and Dr. Lipman hypothesized that those providers who had more experience and those who were working at the operating field would be more accurate in estimating blood loss. They also hypothesized that estimations in procedures with lower volumes of blood loss would be more accurate.

The study recruited providers from the surgery, anesthesia, and nursing services at an urban level 1 trauma center. Each scenario included a written description of the procedure performed and the course of surgery, and participants could handle study materials for each scenario under the supervision of study staff.

A total of 60 participants (22 from surgery, 17 from anesthesia, and 21 from nursing) participated; they had an average of 12.8 years of experience. The surgical participants included surgical scrub techs, trainees, and attending physicians. Anesthesia participants included anesthesia assistants, CRNAs, trainees, and attending physicians. Nursing participants were all RNs.

The findings? All over the board: “There was no association between specialty, years of experience, or confidence in ability with the consistency or accuracy of estimated blood loss,” said Dr. Rothermel.

Most participants were far shy of the mark, with just 5% of study participants overall able to come within 25% accuracy in judging EBL in all scenarios. Just over a quarter were consistent in over- or underestimating blood loss.

These findings held true across scenarios, across disciplines, and regardless of the number of years of experience. “Increased years of experience trended toward increased error,” said Dr. Rothermel, though the difference was not statistically significant. However, those with more years of experience tended to be more confident of their judgments.

Dr. Rothermel noted the small study size and single institution studied as limitations. Also, “this model was not a high fidelity representation of the OR experience, “ he said, explaining that during surgery, caregivers continually assess intraoperative blood loss and may form an estimate in a different – and potentially more accurate – manner than occurs when presented with the contrived presentation of a scenario.

The study calls into question the validity of using EBL as a quality indicator in assessing physician performance and patient outcomes, said Dr. Rothermel, who had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

MONTREAL – Surgeons, nurses, and anesthesia providers were all pretty bad at estimating surgical blood loss in a small study. And more experience doesn’t improve accuracy, though experienced providers were more confident in their estimates.

These were the findings from a study that simulated operating room scenarios and asked providers to estimate blood loss. “Estimation of blood loss is inaccurate and unreliable,” Dr. Luke Rothermel said at the Central Surgical Association’s annual meeting.

Dr. Rothermel, a resident at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, noted that although the Joint Commission requires operative notes to contain estimated blood loss, “no study in the United States has compared the characteristics of operating room personnel or conditions associated with improved accuracy or reliability of blood loss estimation.”

Beyond the required reporting, estimating blood loss (EBL) also provides important guidance in perioperative care. Still, said Dr. Rothermel, previous studies have shown that EBL is typically inaccurate.

To assess providers’ ability to be accurate and reliable in estimating blood loss, Dr. Rothermel and his collaborator, Dr. Jeremy Lipman, assistant residency director at MetroHealth, Cleveland, designed a study to simulate three different operating room scenarios, involving high, medium, and low blood loss volumes. The materials used, such as blood-soaked sponges and suction canisters, were identical to what’s actually used in the operating room (porcine blood was used in the simulations).

Before the study, Dr. Rothermel said that he and Dr. Lipman hypothesized that those providers who had more experience and those who were working at the operating field would be more accurate in estimating blood loss. They also hypothesized that estimations in procedures with lower volumes of blood loss would be more accurate.

The study recruited providers from the surgery, anesthesia, and nursing services at an urban level 1 trauma center. Each scenario included a written description of the procedure performed and the course of surgery, and participants could handle study materials for each scenario under the supervision of study staff.

A total of 60 participants (22 from surgery, 17 from anesthesia, and 21 from nursing) participated; they had an average of 12.8 years of experience. The surgical participants included surgical scrub techs, trainees, and attending physicians. Anesthesia participants included anesthesia assistants, CRNAs, trainees, and attending physicians. Nursing participants were all RNs.

The findings? All over the board: “There was no association between specialty, years of experience, or confidence in ability with the consistency or accuracy of estimated blood loss,” said Dr. Rothermel.

Most participants were far shy of the mark, with just 5% of study participants overall able to come within 25% accuracy in judging EBL in all scenarios. Just over a quarter were consistent in over- or underestimating blood loss.

These findings held true across scenarios, across disciplines, and regardless of the number of years of experience. “Increased years of experience trended toward increased error,” said Dr. Rothermel, though the difference was not statistically significant. However, those with more years of experience tended to be more confident of their judgments.