User login

Goodbye CHADSVASc: Sex Complicates Stroke Risk Scoring in AF

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) caused a stir when they recommended in their latest atrial fibrillation (AF) management guideline that gender no longer be included in the decision to initiate oral anticoagulation therapy.

The move aims to level the playing field between men and women and follows a more nuanced understanding of stroke risk in patients with AF, said experts. It also acknowledges the lack of evidence in people receiving cross-sex hormone therapy.

In any case, the guidelines, developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery and published by the European Heart Journal on August 30, simply follow 2023’s US recommendations, they added.

One Size Does Not Fit All

So, what to the ESC guidelines actually say?

They underline that, if left untreated, the risk for ischemic stroke is increased fivefold in patients with AF, and the “default approach should therefore be to provide oral anticoagulation to all eligible AF patients, except those at low risk for incident stroke or thromboembolism.”

However, the authors note that there is a lack of strong evidence on how to apply the current risk scores to help inform that decision in real-world patients.

Dipak Kotecha, MBChB, PhD, Professor of Cardiology at the University of Birmingham and University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, England, and senior author of the ESC guidelines, said in an interview that “the available scores have a relatively poor ability to accurately predict which patients will have a stroke or thromboembolic event.”

Instead, he said “a much better approach is for healthcare professionals to look at each patient’s individual risk factors, using the risk scores to identify those patients that might not benefit from oral anticoagulant therapy.”

For these guidelines, the authors therefore wanted to “move away from a one-size-fits-all” approach, Kotecha said, and instead ensure that more patients can benefit from the new range of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) that are easier to take and with much lower chance of side effects or major bleeding.

To achieve this, they separated their clinical recommendations from any particular risk score, and instead focused on the practicalities of implementation.

Risk Modifier Vs Risk Factor

To explain their decision the authors highlight that “the most popular risk score” is the CHA2DS2–VASc, which gives a point for female sex, alongside factors such as congestive heart failure, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, and a sliding scale of points for increasing age.

Kotecha pointed out the score was developed before the DOACs were available and may not account for how risk factors have changed in recent decades.

The result is that CHA2DS2–VASc gives the same number of points to an individual with heart failure or prior transient ischemic attack as to a woman aged less than 65 years, “but the magnitude of increased risk is not the same,” Usha Beth Tedrow, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, said in an interview.

As far back as 2018, it was known that “female sex is a risk modifier, rather than a risk factor for stroke in atrial fibrillation,” noted Jose Joglar, MD, lead author of the 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation said in an interview.

A Danish national registry study involving 239,671 AF patients treated between 1997 and 2015, nearly half of whom were women, showed that, at a CHA2DS2–VASc score of 0, the “risk of stroke between men and women is absolutely the same,” he said.

“It is not until after a CHA2DS2–VASc score of 2 that the curves start to separate,” Joglar, Program Director, Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology Fellowship Program, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, continued, “but by then you have already made the decision to anticoagulate.”

More recently, Kotecha and colleagues conducted a population cohort study of the electronic healthcare records of UK primary care patients treated between 2005 and 2020, and identified 78,852 with AF; more than a third were women.

Their analysis, published on September 1, showed that women had a lower adjusted rate of the primary composite outcome of all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, or arterial thromboembolism, driven by a reduced mortality rate.

“Removal of gender from clinical risk scoring could simplify the approach to which patients with AF should be offered oral anticoagulation,” Kotecha and colleagues concluded.

Joglar clarified that “women are at increased risk for stroke than men” overall, but by the time that risk “becomes manifest, other risk factors have come into play, and they have already met the criteria for anticoagulation.”

The authors of the latest ESC guideline therefore concluded that the “inclusion of gender complicates clinical practice both for healthcare professionals and patients.” Their solution was to remove the question of gender for decisions over initiating oral anticoagulant therapy in clinical practice altogether.

This includes individuals who identify as transgender or are undergoing sex hormone therapy, as all the experts interviewed by Medscape Medical News agreed that there is currently insufficient evidence to know if that affects stroke risk.

Instead, guidelines state that the drugs are “recommended in those with a CHA2DS2-VA score of 2 or more and should be considered in those with a CHA2DS2-VA score of 1, following a patient-centered and shared care approach.”

“Dropping the gender part of the risk score is not really a substantial change” from previous ESC or other guidelines, as different points were required in the past to recommend anticoagulants for women and men, Kotecha said, adding that “making the approach easier for clinicians may avoid penalizing women as well as nonbinary and transgender patients.”

Anne B. Curtis, MD, SUNY Distinguished Professor, Department of Medicine, Jacobs School of Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo in New York, agreed.

Putting aside the question of female sex, she said that there are not a lot of people under the age of 65 years with “absolutely no risk factors,” and so, “if the only reason you would anticoagulate” someone of that age is because they are a woman that “doesn’t make a lot of sense to me.”

The ESC guidelines are “trying to say, ‘look at the other risk factors, and if anything is there, go ahead and anticoagulate,” Curtis said in an interview.

“It’s actually a very thoughtful decision,” Tedrow said, and not “intended to discount risk in women.” Rather, it’s a statement that acknowledges the problem of recommending anticoagulation therapy in women “for whom it is not appropriate.”

Joglar pointed out that that recommendation, although not characterized in the same way, was in fact included in the 2023 US guidelines.

“We wanted to use a more nuanced approach,” he said, and move away from using CHA2DS2–VASc as the prime determinant of whether to start oral anticoagulation and towards a magnitude risk assessment, in which female sex is seen as a risk modifier.

“The Europeans and the Americans are looking at the same data, so we often reach the same conclusions,” Joglar said, although “we sometimes use different wordings.”

Overall, Kotecha expressed the hope that the move “will lead to better implementation of guidelines, at the end of the day.”

“That’s all we can hope for: Patients will be offered a more individualized approach, leading to more appropriate use of treatment in the right patients.”

The newer direct oral anticoagulation is “a much simpler therapy,” he added. “There is very little monitoring, a similar risk of bleeding as aspirin, and yet the ability to largely prevent the high rate of stroke and thromboembolism associated with atrial fibrillation.”

“So, it’s a big ticket item for our communities and public health, particularly as atrial fibrillation is expected to double in prevalence in the next few decades and evidence is building that it can lead to vascular dementia in the long-term.”

No funding was declared. Kotecha declares relationships with Bayer, Protherics Medicines Development, Boston Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS-Pfizer Alliance, Amomed, MyoKardia. Curtis declared relationships with Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Abbott. Joglar declared no relevant relationships. Tedrow declared no relevant relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) caused a stir when they recommended in their latest atrial fibrillation (AF) management guideline that gender no longer be included in the decision to initiate oral anticoagulation therapy.

The move aims to level the playing field between men and women and follows a more nuanced understanding of stroke risk in patients with AF, said experts. It also acknowledges the lack of evidence in people receiving cross-sex hormone therapy.

In any case, the guidelines, developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery and published by the European Heart Journal on August 30, simply follow 2023’s US recommendations, they added.

One Size Does Not Fit All

So, what to the ESC guidelines actually say?

They underline that, if left untreated, the risk for ischemic stroke is increased fivefold in patients with AF, and the “default approach should therefore be to provide oral anticoagulation to all eligible AF patients, except those at low risk for incident stroke or thromboembolism.”

However, the authors note that there is a lack of strong evidence on how to apply the current risk scores to help inform that decision in real-world patients.

Dipak Kotecha, MBChB, PhD, Professor of Cardiology at the University of Birmingham and University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, England, and senior author of the ESC guidelines, said in an interview that “the available scores have a relatively poor ability to accurately predict which patients will have a stroke or thromboembolic event.”

Instead, he said “a much better approach is for healthcare professionals to look at each patient’s individual risk factors, using the risk scores to identify those patients that might not benefit from oral anticoagulant therapy.”

For these guidelines, the authors therefore wanted to “move away from a one-size-fits-all” approach, Kotecha said, and instead ensure that more patients can benefit from the new range of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) that are easier to take and with much lower chance of side effects or major bleeding.

To achieve this, they separated their clinical recommendations from any particular risk score, and instead focused on the practicalities of implementation.

Risk Modifier Vs Risk Factor

To explain their decision the authors highlight that “the most popular risk score” is the CHA2DS2–VASc, which gives a point for female sex, alongside factors such as congestive heart failure, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, and a sliding scale of points for increasing age.

Kotecha pointed out the score was developed before the DOACs were available and may not account for how risk factors have changed in recent decades.

The result is that CHA2DS2–VASc gives the same number of points to an individual with heart failure or prior transient ischemic attack as to a woman aged less than 65 years, “but the magnitude of increased risk is not the same,” Usha Beth Tedrow, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, said in an interview.

As far back as 2018, it was known that “female sex is a risk modifier, rather than a risk factor for stroke in atrial fibrillation,” noted Jose Joglar, MD, lead author of the 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation said in an interview.

A Danish national registry study involving 239,671 AF patients treated between 1997 and 2015, nearly half of whom were women, showed that, at a CHA2DS2–VASc score of 0, the “risk of stroke between men and women is absolutely the same,” he said.

“It is not until after a CHA2DS2–VASc score of 2 that the curves start to separate,” Joglar, Program Director, Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology Fellowship Program, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, continued, “but by then you have already made the decision to anticoagulate.”

More recently, Kotecha and colleagues conducted a population cohort study of the electronic healthcare records of UK primary care patients treated between 2005 and 2020, and identified 78,852 with AF; more than a third were women.

Their analysis, published on September 1, showed that women had a lower adjusted rate of the primary composite outcome of all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, or arterial thromboembolism, driven by a reduced mortality rate.

“Removal of gender from clinical risk scoring could simplify the approach to which patients with AF should be offered oral anticoagulation,” Kotecha and colleagues concluded.

Joglar clarified that “women are at increased risk for stroke than men” overall, but by the time that risk “becomes manifest, other risk factors have come into play, and they have already met the criteria for anticoagulation.”

The authors of the latest ESC guideline therefore concluded that the “inclusion of gender complicates clinical practice both for healthcare professionals and patients.” Their solution was to remove the question of gender for decisions over initiating oral anticoagulant therapy in clinical practice altogether.

This includes individuals who identify as transgender or are undergoing sex hormone therapy, as all the experts interviewed by Medscape Medical News agreed that there is currently insufficient evidence to know if that affects stroke risk.

Instead, guidelines state that the drugs are “recommended in those with a CHA2DS2-VA score of 2 or more and should be considered in those with a CHA2DS2-VA score of 1, following a patient-centered and shared care approach.”

“Dropping the gender part of the risk score is not really a substantial change” from previous ESC or other guidelines, as different points were required in the past to recommend anticoagulants for women and men, Kotecha said, adding that “making the approach easier for clinicians may avoid penalizing women as well as nonbinary and transgender patients.”

Anne B. Curtis, MD, SUNY Distinguished Professor, Department of Medicine, Jacobs School of Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo in New York, agreed.

Putting aside the question of female sex, she said that there are not a lot of people under the age of 65 years with “absolutely no risk factors,” and so, “if the only reason you would anticoagulate” someone of that age is because they are a woman that “doesn’t make a lot of sense to me.”

The ESC guidelines are “trying to say, ‘look at the other risk factors, and if anything is there, go ahead and anticoagulate,” Curtis said in an interview.

“It’s actually a very thoughtful decision,” Tedrow said, and not “intended to discount risk in women.” Rather, it’s a statement that acknowledges the problem of recommending anticoagulation therapy in women “for whom it is not appropriate.”

Joglar pointed out that that recommendation, although not characterized in the same way, was in fact included in the 2023 US guidelines.

“We wanted to use a more nuanced approach,” he said, and move away from using CHA2DS2–VASc as the prime determinant of whether to start oral anticoagulation and towards a magnitude risk assessment, in which female sex is seen as a risk modifier.

“The Europeans and the Americans are looking at the same data, so we often reach the same conclusions,” Joglar said, although “we sometimes use different wordings.”

Overall, Kotecha expressed the hope that the move “will lead to better implementation of guidelines, at the end of the day.”

“That’s all we can hope for: Patients will be offered a more individualized approach, leading to more appropriate use of treatment in the right patients.”

The newer direct oral anticoagulation is “a much simpler therapy,” he added. “There is very little monitoring, a similar risk of bleeding as aspirin, and yet the ability to largely prevent the high rate of stroke and thromboembolism associated with atrial fibrillation.”

“So, it’s a big ticket item for our communities and public health, particularly as atrial fibrillation is expected to double in prevalence in the next few decades and evidence is building that it can lead to vascular dementia in the long-term.”

No funding was declared. Kotecha declares relationships with Bayer, Protherics Medicines Development, Boston Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS-Pfizer Alliance, Amomed, MyoKardia. Curtis declared relationships with Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Abbott. Joglar declared no relevant relationships. Tedrow declared no relevant relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) caused a stir when they recommended in their latest atrial fibrillation (AF) management guideline that gender no longer be included in the decision to initiate oral anticoagulation therapy.

The move aims to level the playing field between men and women and follows a more nuanced understanding of stroke risk in patients with AF, said experts. It also acknowledges the lack of evidence in people receiving cross-sex hormone therapy.

In any case, the guidelines, developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery and published by the European Heart Journal on August 30, simply follow 2023’s US recommendations, they added.

One Size Does Not Fit All

So, what to the ESC guidelines actually say?

They underline that, if left untreated, the risk for ischemic stroke is increased fivefold in patients with AF, and the “default approach should therefore be to provide oral anticoagulation to all eligible AF patients, except those at low risk for incident stroke or thromboembolism.”

However, the authors note that there is a lack of strong evidence on how to apply the current risk scores to help inform that decision in real-world patients.

Dipak Kotecha, MBChB, PhD, Professor of Cardiology at the University of Birmingham and University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, England, and senior author of the ESC guidelines, said in an interview that “the available scores have a relatively poor ability to accurately predict which patients will have a stroke or thromboembolic event.”

Instead, he said “a much better approach is for healthcare professionals to look at each patient’s individual risk factors, using the risk scores to identify those patients that might not benefit from oral anticoagulant therapy.”

For these guidelines, the authors therefore wanted to “move away from a one-size-fits-all” approach, Kotecha said, and instead ensure that more patients can benefit from the new range of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) that are easier to take and with much lower chance of side effects or major bleeding.

To achieve this, they separated their clinical recommendations from any particular risk score, and instead focused on the practicalities of implementation.

Risk Modifier Vs Risk Factor

To explain their decision the authors highlight that “the most popular risk score” is the CHA2DS2–VASc, which gives a point for female sex, alongside factors such as congestive heart failure, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, and a sliding scale of points for increasing age.

Kotecha pointed out the score was developed before the DOACs were available and may not account for how risk factors have changed in recent decades.

The result is that CHA2DS2–VASc gives the same number of points to an individual with heart failure or prior transient ischemic attack as to a woman aged less than 65 years, “but the magnitude of increased risk is not the same,” Usha Beth Tedrow, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, said in an interview.

As far back as 2018, it was known that “female sex is a risk modifier, rather than a risk factor for stroke in atrial fibrillation,” noted Jose Joglar, MD, lead author of the 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation said in an interview.

A Danish national registry study involving 239,671 AF patients treated between 1997 and 2015, nearly half of whom were women, showed that, at a CHA2DS2–VASc score of 0, the “risk of stroke between men and women is absolutely the same,” he said.

“It is not until after a CHA2DS2–VASc score of 2 that the curves start to separate,” Joglar, Program Director, Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology Fellowship Program, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, continued, “but by then you have already made the decision to anticoagulate.”

More recently, Kotecha and colleagues conducted a population cohort study of the electronic healthcare records of UK primary care patients treated between 2005 and 2020, and identified 78,852 with AF; more than a third were women.

Their analysis, published on September 1, showed that women had a lower adjusted rate of the primary composite outcome of all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, or arterial thromboembolism, driven by a reduced mortality rate.

“Removal of gender from clinical risk scoring could simplify the approach to which patients with AF should be offered oral anticoagulation,” Kotecha and colleagues concluded.

Joglar clarified that “women are at increased risk for stroke than men” overall, but by the time that risk “becomes manifest, other risk factors have come into play, and they have already met the criteria for anticoagulation.”

The authors of the latest ESC guideline therefore concluded that the “inclusion of gender complicates clinical practice both for healthcare professionals and patients.” Their solution was to remove the question of gender for decisions over initiating oral anticoagulant therapy in clinical practice altogether.

This includes individuals who identify as transgender or are undergoing sex hormone therapy, as all the experts interviewed by Medscape Medical News agreed that there is currently insufficient evidence to know if that affects stroke risk.

Instead, guidelines state that the drugs are “recommended in those with a CHA2DS2-VA score of 2 or more and should be considered in those with a CHA2DS2-VA score of 1, following a patient-centered and shared care approach.”

“Dropping the gender part of the risk score is not really a substantial change” from previous ESC or other guidelines, as different points were required in the past to recommend anticoagulants for women and men, Kotecha said, adding that “making the approach easier for clinicians may avoid penalizing women as well as nonbinary and transgender patients.”

Anne B. Curtis, MD, SUNY Distinguished Professor, Department of Medicine, Jacobs School of Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo in New York, agreed.

Putting aside the question of female sex, she said that there are not a lot of people under the age of 65 years with “absolutely no risk factors,” and so, “if the only reason you would anticoagulate” someone of that age is because they are a woman that “doesn’t make a lot of sense to me.”

The ESC guidelines are “trying to say, ‘look at the other risk factors, and if anything is there, go ahead and anticoagulate,” Curtis said in an interview.

“It’s actually a very thoughtful decision,” Tedrow said, and not “intended to discount risk in women.” Rather, it’s a statement that acknowledges the problem of recommending anticoagulation therapy in women “for whom it is not appropriate.”

Joglar pointed out that that recommendation, although not characterized in the same way, was in fact included in the 2023 US guidelines.

“We wanted to use a more nuanced approach,” he said, and move away from using CHA2DS2–VASc as the prime determinant of whether to start oral anticoagulation and towards a magnitude risk assessment, in which female sex is seen as a risk modifier.

“The Europeans and the Americans are looking at the same data, so we often reach the same conclusions,” Joglar said, although “we sometimes use different wordings.”

Overall, Kotecha expressed the hope that the move “will lead to better implementation of guidelines, at the end of the day.”

“That’s all we can hope for: Patients will be offered a more individualized approach, leading to more appropriate use of treatment in the right patients.”

The newer direct oral anticoagulation is “a much simpler therapy,” he added. “There is very little monitoring, a similar risk of bleeding as aspirin, and yet the ability to largely prevent the high rate of stroke and thromboembolism associated with atrial fibrillation.”

“So, it’s a big ticket item for our communities and public health, particularly as atrial fibrillation is expected to double in prevalence in the next few decades and evidence is building that it can lead to vascular dementia in the long-term.”

No funding was declared. Kotecha declares relationships with Bayer, Protherics Medicines Development, Boston Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS-Pfizer Alliance, Amomed, MyoKardia. Curtis declared relationships with Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Abbott. Joglar declared no relevant relationships. Tedrow declared no relevant relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Vitamin K Supplementation Reduces Nocturnal Leg Cramps in Older Adults

TOPLINE:

Vitamin K supplementation significantly reduced the frequency, intensity, and duration of nocturnal leg cramps in older adults. No adverse events related to vitamin K were identified.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial in China from September 2022 to December 2023.

- A total of 199 participants aged ≥ 65 years with at least two documented episodes of nocturnal leg cramps during a 2-week screening period were included.

- Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either 180 μg of vitamin K (menaquinone 7) or a placebo daily for 8 weeks.

- The primary outcome was the mean number of nocturnal leg cramps per week, while secondary outcomes were the duration and severity of muscle cramps.

- The ethics committees of Third People’s Hospital of Chengdu and Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent.

TAKEAWAY:

- Vitamin K group experienced a significant reduction in the mean weekly frequency of cramps (mean difference, 2.60 [SD, 0.81] to 0.96 [SD, 1.41]) compared with the placebo group, which maintained a mean weekly frequency of 3.63 (SD, 2.20) (P < .001).

- The severity of nocturnal leg cramps decreased more in the vitamin K group (mean difference, −2.55 [SD, 2.12] points) than in the placebo group (mean difference, −1.24 [SD, 1.16] points).

- The duration of nocturnal leg cramps also decreased more in the vitamin K group (mean difference, −0.90 [SD, 0.88] minutes) than in the placebo group (mean difference, −0.32 [SD, 0.78] minutes).

- No adverse events related to vitamin K use were identified, indicating a good safety profile for the supplementation.

IN PRACTICE:

“Given the generally benign characteristics of NLCs, treatment modality must be both effective and safe, thus minimizing the risk of iatrogenic harm,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Jing Tan, MD, the Third People’s Hospital of Chengdu in Chengdu, China. It was published online on October 28 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

This study did not investigate the quality of life or sleep, which could have provided additional insights into the impact of vitamin K on nocturnal leg cramps. The relatively mild nature of nocturnal leg cramps experienced by the participants may limit the generalizability of the findings to populations with more severe symptoms.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from China Health Promotion Foundation and the Third People’s Hospital of Chengdu Scientific Research Project. Tan disclosed receiving personal fees from BeiGene, AbbVie, Pfizer, Xian Janssen Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Vitamin K supplementation significantly reduced the frequency, intensity, and duration of nocturnal leg cramps in older adults. No adverse events related to vitamin K were identified.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial in China from September 2022 to December 2023.

- A total of 199 participants aged ≥ 65 years with at least two documented episodes of nocturnal leg cramps during a 2-week screening period were included.

- Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either 180 μg of vitamin K (menaquinone 7) or a placebo daily for 8 weeks.

- The primary outcome was the mean number of nocturnal leg cramps per week, while secondary outcomes were the duration and severity of muscle cramps.

- The ethics committees of Third People’s Hospital of Chengdu and Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent.

TAKEAWAY:

- Vitamin K group experienced a significant reduction in the mean weekly frequency of cramps (mean difference, 2.60 [SD, 0.81] to 0.96 [SD, 1.41]) compared with the placebo group, which maintained a mean weekly frequency of 3.63 (SD, 2.20) (P < .001).

- The severity of nocturnal leg cramps decreased more in the vitamin K group (mean difference, −2.55 [SD, 2.12] points) than in the placebo group (mean difference, −1.24 [SD, 1.16] points).

- The duration of nocturnal leg cramps also decreased more in the vitamin K group (mean difference, −0.90 [SD, 0.88] minutes) than in the placebo group (mean difference, −0.32 [SD, 0.78] minutes).

- No adverse events related to vitamin K use were identified, indicating a good safety profile for the supplementation.

IN PRACTICE:

“Given the generally benign characteristics of NLCs, treatment modality must be both effective and safe, thus minimizing the risk of iatrogenic harm,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Jing Tan, MD, the Third People’s Hospital of Chengdu in Chengdu, China. It was published online on October 28 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

This study did not investigate the quality of life or sleep, which could have provided additional insights into the impact of vitamin K on nocturnal leg cramps. The relatively mild nature of nocturnal leg cramps experienced by the participants may limit the generalizability of the findings to populations with more severe symptoms.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from China Health Promotion Foundation and the Third People’s Hospital of Chengdu Scientific Research Project. Tan disclosed receiving personal fees from BeiGene, AbbVie, Pfizer, Xian Janssen Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Vitamin K supplementation significantly reduced the frequency, intensity, and duration of nocturnal leg cramps in older adults. No adverse events related to vitamin K were identified.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial in China from September 2022 to December 2023.

- A total of 199 participants aged ≥ 65 years with at least two documented episodes of nocturnal leg cramps during a 2-week screening period were included.

- Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either 180 μg of vitamin K (menaquinone 7) or a placebo daily for 8 weeks.

- The primary outcome was the mean number of nocturnal leg cramps per week, while secondary outcomes were the duration and severity of muscle cramps.

- The ethics committees of Third People’s Hospital of Chengdu and Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent.

TAKEAWAY:

- Vitamin K group experienced a significant reduction in the mean weekly frequency of cramps (mean difference, 2.60 [SD, 0.81] to 0.96 [SD, 1.41]) compared with the placebo group, which maintained a mean weekly frequency of 3.63 (SD, 2.20) (P < .001).

- The severity of nocturnal leg cramps decreased more in the vitamin K group (mean difference, −2.55 [SD, 2.12] points) than in the placebo group (mean difference, −1.24 [SD, 1.16] points).

- The duration of nocturnal leg cramps also decreased more in the vitamin K group (mean difference, −0.90 [SD, 0.88] minutes) than in the placebo group (mean difference, −0.32 [SD, 0.78] minutes).

- No adverse events related to vitamin K use were identified, indicating a good safety profile for the supplementation.

IN PRACTICE:

“Given the generally benign characteristics of NLCs, treatment modality must be both effective and safe, thus minimizing the risk of iatrogenic harm,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Jing Tan, MD, the Third People’s Hospital of Chengdu in Chengdu, China. It was published online on October 28 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

This study did not investigate the quality of life or sleep, which could have provided additional insights into the impact of vitamin K on nocturnal leg cramps. The relatively mild nature of nocturnal leg cramps experienced by the participants may limit the generalizability of the findings to populations with more severe symptoms.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from China Health Promotion Foundation and the Third People’s Hospital of Chengdu Scientific Research Project. Tan disclosed receiving personal fees from BeiGene, AbbVie, Pfizer, Xian Janssen Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Heat Waves Pose Significant Health Risks for Dually Eligible Older Individuals

TOPLINE:

Heat waves are associated with an increase in heat-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths among dually eligible individuals older than 65 years.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted a retrospective time-series study using national Medicare and Medicaid data from 2016 to 2019 to assess the link between heat waves during warm months and adverse health events.

- A total of 5,448,499 dually eligible individuals (66% women; 20% aged ≥ 85 years) were included from 28,404 zip code areas across 50 states and Washington, DC.

- Heat waves were defined as three or more consecutive days of extreme heat with a maximum temperature of at least 90 °F and within the 97th percentile of daily maximum temperatures for each zip code.

- Primary outcomes were daily counts of heat-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations.

- Secondary outcomes were all-cause and heat-specific emergency department visits, all-cause and heat-specific hospitalizations, deaths, and long-term nursing facility placements within 3 months after a heat wave.

TAKEAWAY:

- Heat waves were associated with a 10% increase in heat-related emergency department visits (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.10; 95% CI, 1.08-1.12) and a 7% increase in heat-related hospitalizations (IRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09).

- Mortality rates were 4% higher during heat wave days than during non–heat wave days (IRR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01-1.07).

- No significant difference was found in rates of long-term nursing facility placements or heat-related emergency department visits for nursing facility residents.

- All racial and ethnic groups showed higher incidence rates of heat-related emergency department visits during heat waves, especially among beneficiaries identified as Asian (IRR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.12-1.29). Rates were higher among individuals residing in the Northwest, Ohio Valley, and the West.

IN PRACTICE:

“In healthcare settings, clinicians should incorporate routine heat wave risk assessments into clinical practice, especially in regions more susceptible to extreme heat, for all dual-eligible beneficiaries and other at-risk patients,” wrote Jose F. Figueroa, MD, MPH, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, in an invited commentary. “Beyond offering preventive advice, clinicians can adjust medications that may increase their patients’ susceptibility during heat waves, or they can refer patients to social workers and social service organizations to ensure that they are protected at home.”

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hyunjee Kim, PhD, of the Center for Health Systems Effectiveness at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. It was published online in JAMA Health Forum.

LIMITATIONS:

This study relied on a claims database to identify adverse events, which may have led to omissions in coding, particularly for heat-related conditions if the diagnostic codes for heat-related symptoms had not been adopted. This study did not adjust for variations in air quality or green space, which could have confounded the association of interest. Indoor heat exposures or adaptive behaviors, such as air conditioning use, were not considered. The analysis could not compare the association of heat waves with adverse events between those with dual eligibility and those without dual eligibility.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging. One author reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Heat waves are associated with an increase in heat-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths among dually eligible individuals older than 65 years.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted a retrospective time-series study using national Medicare and Medicaid data from 2016 to 2019 to assess the link between heat waves during warm months and adverse health events.

- A total of 5,448,499 dually eligible individuals (66% women; 20% aged ≥ 85 years) were included from 28,404 zip code areas across 50 states and Washington, DC.

- Heat waves were defined as three or more consecutive days of extreme heat with a maximum temperature of at least 90 °F and within the 97th percentile of daily maximum temperatures for each zip code.

- Primary outcomes were daily counts of heat-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations.

- Secondary outcomes were all-cause and heat-specific emergency department visits, all-cause and heat-specific hospitalizations, deaths, and long-term nursing facility placements within 3 months after a heat wave.

TAKEAWAY:

- Heat waves were associated with a 10% increase in heat-related emergency department visits (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.10; 95% CI, 1.08-1.12) and a 7% increase in heat-related hospitalizations (IRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09).

- Mortality rates were 4% higher during heat wave days than during non–heat wave days (IRR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01-1.07).

- No significant difference was found in rates of long-term nursing facility placements or heat-related emergency department visits for nursing facility residents.

- All racial and ethnic groups showed higher incidence rates of heat-related emergency department visits during heat waves, especially among beneficiaries identified as Asian (IRR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.12-1.29). Rates were higher among individuals residing in the Northwest, Ohio Valley, and the West.

IN PRACTICE:

“In healthcare settings, clinicians should incorporate routine heat wave risk assessments into clinical practice, especially in regions more susceptible to extreme heat, for all dual-eligible beneficiaries and other at-risk patients,” wrote Jose F. Figueroa, MD, MPH, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, in an invited commentary. “Beyond offering preventive advice, clinicians can adjust medications that may increase their patients’ susceptibility during heat waves, or they can refer patients to social workers and social service organizations to ensure that they are protected at home.”

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hyunjee Kim, PhD, of the Center for Health Systems Effectiveness at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. It was published online in JAMA Health Forum.

LIMITATIONS:

This study relied on a claims database to identify adverse events, which may have led to omissions in coding, particularly for heat-related conditions if the diagnostic codes for heat-related symptoms had not been adopted. This study did not adjust for variations in air quality or green space, which could have confounded the association of interest. Indoor heat exposures or adaptive behaviors, such as air conditioning use, were not considered. The analysis could not compare the association of heat waves with adverse events between those with dual eligibility and those without dual eligibility.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging. One author reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Heat waves are associated with an increase in heat-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths among dually eligible individuals older than 65 years.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted a retrospective time-series study using national Medicare and Medicaid data from 2016 to 2019 to assess the link between heat waves during warm months and adverse health events.

- A total of 5,448,499 dually eligible individuals (66% women; 20% aged ≥ 85 years) were included from 28,404 zip code areas across 50 states and Washington, DC.

- Heat waves were defined as three or more consecutive days of extreme heat with a maximum temperature of at least 90 °F and within the 97th percentile of daily maximum temperatures for each zip code.

- Primary outcomes were daily counts of heat-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations.

- Secondary outcomes were all-cause and heat-specific emergency department visits, all-cause and heat-specific hospitalizations, deaths, and long-term nursing facility placements within 3 months after a heat wave.

TAKEAWAY:

- Heat waves were associated with a 10% increase in heat-related emergency department visits (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.10; 95% CI, 1.08-1.12) and a 7% increase in heat-related hospitalizations (IRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09).

- Mortality rates were 4% higher during heat wave days than during non–heat wave days (IRR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01-1.07).

- No significant difference was found in rates of long-term nursing facility placements or heat-related emergency department visits for nursing facility residents.

- All racial and ethnic groups showed higher incidence rates of heat-related emergency department visits during heat waves, especially among beneficiaries identified as Asian (IRR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.12-1.29). Rates were higher among individuals residing in the Northwest, Ohio Valley, and the West.

IN PRACTICE:

“In healthcare settings, clinicians should incorporate routine heat wave risk assessments into clinical practice, especially in regions more susceptible to extreme heat, for all dual-eligible beneficiaries and other at-risk patients,” wrote Jose F. Figueroa, MD, MPH, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, in an invited commentary. “Beyond offering preventive advice, clinicians can adjust medications that may increase their patients’ susceptibility during heat waves, or they can refer patients to social workers and social service organizations to ensure that they are protected at home.”

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hyunjee Kim, PhD, of the Center for Health Systems Effectiveness at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. It was published online in JAMA Health Forum.

LIMITATIONS:

This study relied on a claims database to identify adverse events, which may have led to omissions in coding, particularly for heat-related conditions if the diagnostic codes for heat-related symptoms had not been adopted. This study did not adjust for variations in air quality or green space, which could have confounded the association of interest. Indoor heat exposures or adaptive behaviors, such as air conditioning use, were not considered. The analysis could not compare the association of heat waves with adverse events between those with dual eligibility and those without dual eligibility.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging. One author reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On Second Thought: Aspirin for Primary Prevention — What We Really Know

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Our recommendations vis-à-vis aspirin have evolved at a dizzying pace. The young’uns watching us right now don’t know what things were like in the 1980s. The Reagan era was a wild, heady time where nuclear war was imminent and we didn’t prescribe aspirin to patients.

That only started in 1988, which was a banner year in human history. Not because a number of doves were incinerated by the lighting of the Olympic torch at the Seoul Olympics — look it up if you don’t know what I’m talking about — but because 1988 saw the publication of the ISIS-2 trial, which first showed a mortality benefit to prescribing aspirin post–myocardial infarction (MI).

Giving patients aspirin during or after a heart attack is not controversial. It’s one of the few things in this business that isn’t, but that’s secondary prevention — treating somebody after they develop a disease. Primary prevention, treating them before they have their incident event, is a very different ballgame. Here, things are messy.

For one thing, the doses used have been very inconsistent. We should point out that the reason for 81 mg of aspirin is very arbitrary and is rooted in the old apothecary system of weights and measurements. A standard dose of aspirin was 5 grains, where 20 grains made 1 scruple, 3 scruples made 1 dram, 8 drams made 1 oz, and 12 oz made 1 lb - because screw you, metric system. Therefore, 5 grains was 325 mg of aspirin, and 1 quarter of the standard dose became 81 mg if you rounded out the decimal.

People have tried all kinds of dosing structures with aspirin prophylaxis. The Physicians’ Health Study used a full-dose aspirin, 325 mg every 2 days, while the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) trial tested 75 mg daily and the Women’s Health Study tested 100 mg, but every other day.

Ironically, almost no one has studied 81 mg every day, which is weird if you think about it. The bigger problem here is not the variability of doses used, but the discrepancy when you look at older vs newer studies.

Older studies, like the Physicians’ Health Study, did show a benefit, at least in the subgroup of patients over age 50 years, which is probably where the “everybody over 50 should be taking an aspirin” idea comes from, at least as near as I can tell.

More recent studies, like the Women’s Health Study, ASPREE, or ASPIRE, didn’t show a benefit. I know what you’re thinking: Newer stuff is always better. That’s why you should never trust anybody over age 40 years. The context of primary prevention studies has changed. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, people smoked more and we didn’t have the same medications that we have today. We talked about all this in the beta-blocker video to explain why beta-blockers don’t seem to have a benefit post MI.

We have a similar issue here. The magnitude of the benefit with aspirin primary prevention has decreased because we’re all just healthier overall. So, yay! Progress! Here’s where the numbers matter. No one is saying that aspirin doesn’t help. It does.

If we look at the 2019 meta-analysis published in JAMA, there is a cardiovascular benefit. The numbers bear that out. I know you’re all here for the math, so here we go. Aspirin reduced the composite cardiovascular endpoint from 65.2 to 60.2 events per 10,000 patient-years; or to put it more meaningfully in absolute risk reduction terms, because that’s my jam, an absolute risk reduction of 0.41%, which means a number needed to treat of 241, which is okay-ish. It’s not super-great, but it may be justifiable for something that costs next to nothing.

The tradeoff is bleeding. Major bleeding increased from 16.4 to 23.1 bleeds per 10,000 patient-years, or an absolute risk increase of 0.47%, which is a number needed to harm of 210. That’s the problem. Aspirin does prevent heart disease. The benefit is small, for sure, but the real problem is that it’s outweighed by the risk of bleeding, so you’re not really coming out ahead.

The real tragedy here is that the public is locked into this idea of everyone over age 50 years should be taking an aspirin. Even today, even though guidelines have recommended against aspirin for primary prevention for some time, data from the National Health Interview Survey sample found that nearly one in three older adults take aspirin for primary prevention when they shouldn’t be. That’s a large number of people. That’s millions of Americans — and Canadians, but nobody cares about us. It’s fine.

That’s the point. We’re not debunking aspirin. It does work. The benefits are just really small in a primary prevention population and offset by the admittedly also really small risks of bleeding. It’s a tradeoff that doesn’t really work in your favor.

But that’s aspirin for cardiovascular disease. When it comes to cancer or DVT prophylaxis, that’s another really interesting story. We might have to save that for another time. Do I know how to tease a sequel or what?

Labos, a cardiologist at Kirkland Medical Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Our recommendations vis-à-vis aspirin have evolved at a dizzying pace. The young’uns watching us right now don’t know what things were like in the 1980s. The Reagan era was a wild, heady time where nuclear war was imminent and we didn’t prescribe aspirin to patients.

That only started in 1988, which was a banner year in human history. Not because a number of doves were incinerated by the lighting of the Olympic torch at the Seoul Olympics — look it up if you don’t know what I’m talking about — but because 1988 saw the publication of the ISIS-2 trial, which first showed a mortality benefit to prescribing aspirin post–myocardial infarction (MI).

Giving patients aspirin during or after a heart attack is not controversial. It’s one of the few things in this business that isn’t, but that’s secondary prevention — treating somebody after they develop a disease. Primary prevention, treating them before they have their incident event, is a very different ballgame. Here, things are messy.

For one thing, the doses used have been very inconsistent. We should point out that the reason for 81 mg of aspirin is very arbitrary and is rooted in the old apothecary system of weights and measurements. A standard dose of aspirin was 5 grains, where 20 grains made 1 scruple, 3 scruples made 1 dram, 8 drams made 1 oz, and 12 oz made 1 lb - because screw you, metric system. Therefore, 5 grains was 325 mg of aspirin, and 1 quarter of the standard dose became 81 mg if you rounded out the decimal.

People have tried all kinds of dosing structures with aspirin prophylaxis. The Physicians’ Health Study used a full-dose aspirin, 325 mg every 2 days, while the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) trial tested 75 mg daily and the Women’s Health Study tested 100 mg, but every other day.

Ironically, almost no one has studied 81 mg every day, which is weird if you think about it. The bigger problem here is not the variability of doses used, but the discrepancy when you look at older vs newer studies.

Older studies, like the Physicians’ Health Study, did show a benefit, at least in the subgroup of patients over age 50 years, which is probably where the “everybody over 50 should be taking an aspirin” idea comes from, at least as near as I can tell.

More recent studies, like the Women’s Health Study, ASPREE, or ASPIRE, didn’t show a benefit. I know what you’re thinking: Newer stuff is always better. That’s why you should never trust anybody over age 40 years. The context of primary prevention studies has changed. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, people smoked more and we didn’t have the same medications that we have today. We talked about all this in the beta-blocker video to explain why beta-blockers don’t seem to have a benefit post MI.

We have a similar issue here. The magnitude of the benefit with aspirin primary prevention has decreased because we’re all just healthier overall. So, yay! Progress! Here’s where the numbers matter. No one is saying that aspirin doesn’t help. It does.

If we look at the 2019 meta-analysis published in JAMA, there is a cardiovascular benefit. The numbers bear that out. I know you’re all here for the math, so here we go. Aspirin reduced the composite cardiovascular endpoint from 65.2 to 60.2 events per 10,000 patient-years; or to put it more meaningfully in absolute risk reduction terms, because that’s my jam, an absolute risk reduction of 0.41%, which means a number needed to treat of 241, which is okay-ish. It’s not super-great, but it may be justifiable for something that costs next to nothing.

The tradeoff is bleeding. Major bleeding increased from 16.4 to 23.1 bleeds per 10,000 patient-years, or an absolute risk increase of 0.47%, which is a number needed to harm of 210. That’s the problem. Aspirin does prevent heart disease. The benefit is small, for sure, but the real problem is that it’s outweighed by the risk of bleeding, so you’re not really coming out ahead.

The real tragedy here is that the public is locked into this idea of everyone over age 50 years should be taking an aspirin. Even today, even though guidelines have recommended against aspirin for primary prevention for some time, data from the National Health Interview Survey sample found that nearly one in three older adults take aspirin for primary prevention when they shouldn’t be. That’s a large number of people. That’s millions of Americans — and Canadians, but nobody cares about us. It’s fine.

That’s the point. We’re not debunking aspirin. It does work. The benefits are just really small in a primary prevention population and offset by the admittedly also really small risks of bleeding. It’s a tradeoff that doesn’t really work in your favor.

But that’s aspirin for cardiovascular disease. When it comes to cancer or DVT prophylaxis, that’s another really interesting story. We might have to save that for another time. Do I know how to tease a sequel or what?

Labos, a cardiologist at Kirkland Medical Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Our recommendations vis-à-vis aspirin have evolved at a dizzying pace. The young’uns watching us right now don’t know what things were like in the 1980s. The Reagan era was a wild, heady time where nuclear war was imminent and we didn’t prescribe aspirin to patients.

That only started in 1988, which was a banner year in human history. Not because a number of doves were incinerated by the lighting of the Olympic torch at the Seoul Olympics — look it up if you don’t know what I’m talking about — but because 1988 saw the publication of the ISIS-2 trial, which first showed a mortality benefit to prescribing aspirin post–myocardial infarction (MI).

Giving patients aspirin during or after a heart attack is not controversial. It’s one of the few things in this business that isn’t, but that’s secondary prevention — treating somebody after they develop a disease. Primary prevention, treating them before they have their incident event, is a very different ballgame. Here, things are messy.

For one thing, the doses used have been very inconsistent. We should point out that the reason for 81 mg of aspirin is very arbitrary and is rooted in the old apothecary system of weights and measurements. A standard dose of aspirin was 5 grains, where 20 grains made 1 scruple, 3 scruples made 1 dram, 8 drams made 1 oz, and 12 oz made 1 lb - because screw you, metric system. Therefore, 5 grains was 325 mg of aspirin, and 1 quarter of the standard dose became 81 mg if you rounded out the decimal.

People have tried all kinds of dosing structures with aspirin prophylaxis. The Physicians’ Health Study used a full-dose aspirin, 325 mg every 2 days, while the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) trial tested 75 mg daily and the Women’s Health Study tested 100 mg, but every other day.

Ironically, almost no one has studied 81 mg every day, which is weird if you think about it. The bigger problem here is not the variability of doses used, but the discrepancy when you look at older vs newer studies.

Older studies, like the Physicians’ Health Study, did show a benefit, at least in the subgroup of patients over age 50 years, which is probably where the “everybody over 50 should be taking an aspirin” idea comes from, at least as near as I can tell.

More recent studies, like the Women’s Health Study, ASPREE, or ASPIRE, didn’t show a benefit. I know what you’re thinking: Newer stuff is always better. That’s why you should never trust anybody over age 40 years. The context of primary prevention studies has changed. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, people smoked more and we didn’t have the same medications that we have today. We talked about all this in the beta-blocker video to explain why beta-blockers don’t seem to have a benefit post MI.

We have a similar issue here. The magnitude of the benefit with aspirin primary prevention has decreased because we’re all just healthier overall. So, yay! Progress! Here’s where the numbers matter. No one is saying that aspirin doesn’t help. It does.

If we look at the 2019 meta-analysis published in JAMA, there is a cardiovascular benefit. The numbers bear that out. I know you’re all here for the math, so here we go. Aspirin reduced the composite cardiovascular endpoint from 65.2 to 60.2 events per 10,000 patient-years; or to put it more meaningfully in absolute risk reduction terms, because that’s my jam, an absolute risk reduction of 0.41%, which means a number needed to treat of 241, which is okay-ish. It’s not super-great, but it may be justifiable for something that costs next to nothing.

The tradeoff is bleeding. Major bleeding increased from 16.4 to 23.1 bleeds per 10,000 patient-years, or an absolute risk increase of 0.47%, which is a number needed to harm of 210. That’s the problem. Aspirin does prevent heart disease. The benefit is small, for sure, but the real problem is that it’s outweighed by the risk of bleeding, so you’re not really coming out ahead.

The real tragedy here is that the public is locked into this idea of everyone over age 50 years should be taking an aspirin. Even today, even though guidelines have recommended against aspirin for primary prevention for some time, data from the National Health Interview Survey sample found that nearly one in three older adults take aspirin for primary prevention when they shouldn’t be. That’s a large number of people. That’s millions of Americans — and Canadians, but nobody cares about us. It’s fine.

That’s the point. We’re not debunking aspirin. It does work. The benefits are just really small in a primary prevention population and offset by the admittedly also really small risks of bleeding. It’s a tradeoff that doesn’t really work in your favor.

But that’s aspirin for cardiovascular disease. When it comes to cancer or DVT prophylaxis, that’s another really interesting story. We might have to save that for another time. Do I know how to tease a sequel or what?

Labos, a cardiologist at Kirkland Medical Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Primary Care Physicians Underutilize Nonantibiotic Prophylaxis for Recurrent UTIs

While primary care physicians are generally comfortable prescribing vaginal estrogen therapy for recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), other nonantibiotic prophylactic options remain significantly underutilized, according to new research that highlights a crucial gap in antibiotic stewardship practices among primary care physicians.

UTIs are the most common bacterial infection in women of all ages, and an estimated 30%-40% of women will experience reinfection within 6 months. Recurrent UTI is typically defined as two or more infections within 6 months or a greater number of infections within a year, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Antibiotics are the first line of defense in preventing and treating recurrent UTIs, but repeated and prolonged use could lead to antibiotic resistance.

Researchers at the University of North Carolina surveyed 40 primary care physicians at one academic medical center and found that 96% of primary care physicians prescribe vaginal estrogen therapy for recurrent UTI prevention, with 58% doing so “often.” Estrogen deficiency and urinary retention are strong contributors to infection.

However, 78% of physicians surveyed said they had never prescribed methenamine hippurate, and 85% said they had never prescribed D-mannose.

Physicians with specialized training in menopausal care felt more at ease prescribing vaginal estrogen therapy to patients with complex medical histories, such as those with a family history of breast cancer or endometrial cancer. This suggests that enhanced education could play a vital role in increasing comfort levels among general practitioners, said Lauren Tholemeier, MD, a urogynecology fellow at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“Primary care physicians are the front line of managing patients with recurrent UTI,” said Tholemeier.

“There’s an opportunity for further education on, and even awareness of, methenamine hippurate and D-mannose as an option that has data behind it and can be included as a tool” for patient care, she said.

Indeed, physicians who saw six or more recurrent patients with UTI each month were more likely to prescribe methenamine hippurate, the study found, suggesting that familiarity with recurrent UTI cases can lead to greater confidence in employing alternative prophylactic strategies.

Tholemeier presented her research at the American Urogynecologic Society’s PFD Week in Washington, DC.

Expanding physician knowledge and utilization of all available nonantibiotic therapies can help them better care for patients who don’t necessarily have access to a subspecialist, Tholemeier said.

According to the American Urogynecologic Society’s best practice guidelines, there is limited evidence supporting routine use of D-mannose to prevent recurrent UTI. Methenamine hippurate, however, may be effective for short-term UTI prevention, according to the group.

By broadening the use of vaginal estrogen therapy, methenamine hippurate, and D-mannose, primary care physicians can help reduce reliance on antibiotics for recurrent UTI prevention — a practice that may contribute to growing antibiotic resistance, said Tholemeier.

“The end goal isn’t going to be to say that we should never prescribe antibiotics for UTI infection,” said Tholemeier, adding that, in some cases, physicians can consider using these other medications in conjunction with antibiotics.

“But it’s knowing they [clinicians] have some other options in their toolbox,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While primary care physicians are generally comfortable prescribing vaginal estrogen therapy for recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), other nonantibiotic prophylactic options remain significantly underutilized, according to new research that highlights a crucial gap in antibiotic stewardship practices among primary care physicians.

UTIs are the most common bacterial infection in women of all ages, and an estimated 30%-40% of women will experience reinfection within 6 months. Recurrent UTI is typically defined as two or more infections within 6 months or a greater number of infections within a year, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Antibiotics are the first line of defense in preventing and treating recurrent UTIs, but repeated and prolonged use could lead to antibiotic resistance.

Researchers at the University of North Carolina surveyed 40 primary care physicians at one academic medical center and found that 96% of primary care physicians prescribe vaginal estrogen therapy for recurrent UTI prevention, with 58% doing so “often.” Estrogen deficiency and urinary retention are strong contributors to infection.

However, 78% of physicians surveyed said they had never prescribed methenamine hippurate, and 85% said they had never prescribed D-mannose.

Physicians with specialized training in menopausal care felt more at ease prescribing vaginal estrogen therapy to patients with complex medical histories, such as those with a family history of breast cancer or endometrial cancer. This suggests that enhanced education could play a vital role in increasing comfort levels among general practitioners, said Lauren Tholemeier, MD, a urogynecology fellow at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“Primary care physicians are the front line of managing patients with recurrent UTI,” said Tholemeier.

“There’s an opportunity for further education on, and even awareness of, methenamine hippurate and D-mannose as an option that has data behind it and can be included as a tool” for patient care, she said.

Indeed, physicians who saw six or more recurrent patients with UTI each month were more likely to prescribe methenamine hippurate, the study found, suggesting that familiarity with recurrent UTI cases can lead to greater confidence in employing alternative prophylactic strategies.

Tholemeier presented her research at the American Urogynecologic Society’s PFD Week in Washington, DC.

Expanding physician knowledge and utilization of all available nonantibiotic therapies can help them better care for patients who don’t necessarily have access to a subspecialist, Tholemeier said.

According to the American Urogynecologic Society’s best practice guidelines, there is limited evidence supporting routine use of D-mannose to prevent recurrent UTI. Methenamine hippurate, however, may be effective for short-term UTI prevention, according to the group.

By broadening the use of vaginal estrogen therapy, methenamine hippurate, and D-mannose, primary care physicians can help reduce reliance on antibiotics for recurrent UTI prevention — a practice that may contribute to growing antibiotic resistance, said Tholemeier.

“The end goal isn’t going to be to say that we should never prescribe antibiotics for UTI infection,” said Tholemeier, adding that, in some cases, physicians can consider using these other medications in conjunction with antibiotics.

“But it’s knowing they [clinicians] have some other options in their toolbox,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While primary care physicians are generally comfortable prescribing vaginal estrogen therapy for recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), other nonantibiotic prophylactic options remain significantly underutilized, according to new research that highlights a crucial gap in antibiotic stewardship practices among primary care physicians.

UTIs are the most common bacterial infection in women of all ages, and an estimated 30%-40% of women will experience reinfection within 6 months. Recurrent UTI is typically defined as two or more infections within 6 months or a greater number of infections within a year, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Antibiotics are the first line of defense in preventing and treating recurrent UTIs, but repeated and prolonged use could lead to antibiotic resistance.

Researchers at the University of North Carolina surveyed 40 primary care physicians at one academic medical center and found that 96% of primary care physicians prescribe vaginal estrogen therapy for recurrent UTI prevention, with 58% doing so “often.” Estrogen deficiency and urinary retention are strong contributors to infection.

However, 78% of physicians surveyed said they had never prescribed methenamine hippurate, and 85% said they had never prescribed D-mannose.

Physicians with specialized training in menopausal care felt more at ease prescribing vaginal estrogen therapy to patients with complex medical histories, such as those with a family history of breast cancer or endometrial cancer. This suggests that enhanced education could play a vital role in increasing comfort levels among general practitioners, said Lauren Tholemeier, MD, a urogynecology fellow at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“Primary care physicians are the front line of managing patients with recurrent UTI,” said Tholemeier.

“There’s an opportunity for further education on, and even awareness of, methenamine hippurate and D-mannose as an option that has data behind it and can be included as a tool” for patient care, she said.

Indeed, physicians who saw six or more recurrent patients with UTI each month were more likely to prescribe methenamine hippurate, the study found, suggesting that familiarity with recurrent UTI cases can lead to greater confidence in employing alternative prophylactic strategies.

Tholemeier presented her research at the American Urogynecologic Society’s PFD Week in Washington, DC.

Expanding physician knowledge and utilization of all available nonantibiotic therapies can help them better care for patients who don’t necessarily have access to a subspecialist, Tholemeier said.

According to the American Urogynecologic Society’s best practice guidelines, there is limited evidence supporting routine use of D-mannose to prevent recurrent UTI. Methenamine hippurate, however, may be effective for short-term UTI prevention, according to the group.

By broadening the use of vaginal estrogen therapy, methenamine hippurate, and D-mannose, primary care physicians can help reduce reliance on antibiotics for recurrent UTI prevention — a practice that may contribute to growing antibiotic resistance, said Tholemeier.

“The end goal isn’t going to be to say that we should never prescribe antibiotics for UTI infection,” said Tholemeier, adding that, in some cases, physicians can consider using these other medications in conjunction with antibiotics.

“But it’s knowing they [clinicians] have some other options in their toolbox,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PFD WEEK 2024

VHA Support for Home Health Agency Staff and Patients During Natural Disasters

As large-scale natural disasters become more common, health care coalitions and the engagement of health systems with local, state, and federal public health departments have effectively bolstered communities’ resilience via collective sharing and distribution of resources.1 These resources may include supplies and the dissemination of emergency information, education, and training.2 The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that larger health care systems including hospital networks and nursing homes are better connected to health care coalition resources than smaller, independent systems, such as community home health agencies.3 This leaves some organizations on their own to meet requirements that maintain continuity of care and support their patients and staff throughout a natural disaster.

Home health care workers play important roles in the care of older adults.4 Older adults experience high levels of disability and comorbidities that put them at risk during emergencies; they often require support from paid, family, and neighborhood caregivers to live independently.5 More than 9.3 million US adults receive paid care from 2.6 million home health care workers (eg, home health aides and personal care assistants).6 Many of these individuals are hired through small independent home health agencies (HHAs), while others may work directly for an individual. When neighborhood resources and family caregiving are disrupted during emergencies, the critical services these workers administer become even more essential to ensuring continued access to medical care and social services.

The importance of these services was underscored by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2017 inclusion of HHAs in federal emergency preparedness guidelines.7,8 The fractured and decentralized nature of the home health care industry means many HHAs struggle to maintain continuous care during emergencies and protect their staff. HHAs, and health care workers in the home, are often isolated, under-resourced, and disconnected from broader emergency planning efforts. Additionally, home care jobs are largely part-time, unstable, and low paying, making the workers themselves vulnerable during emergencies.3,9-13

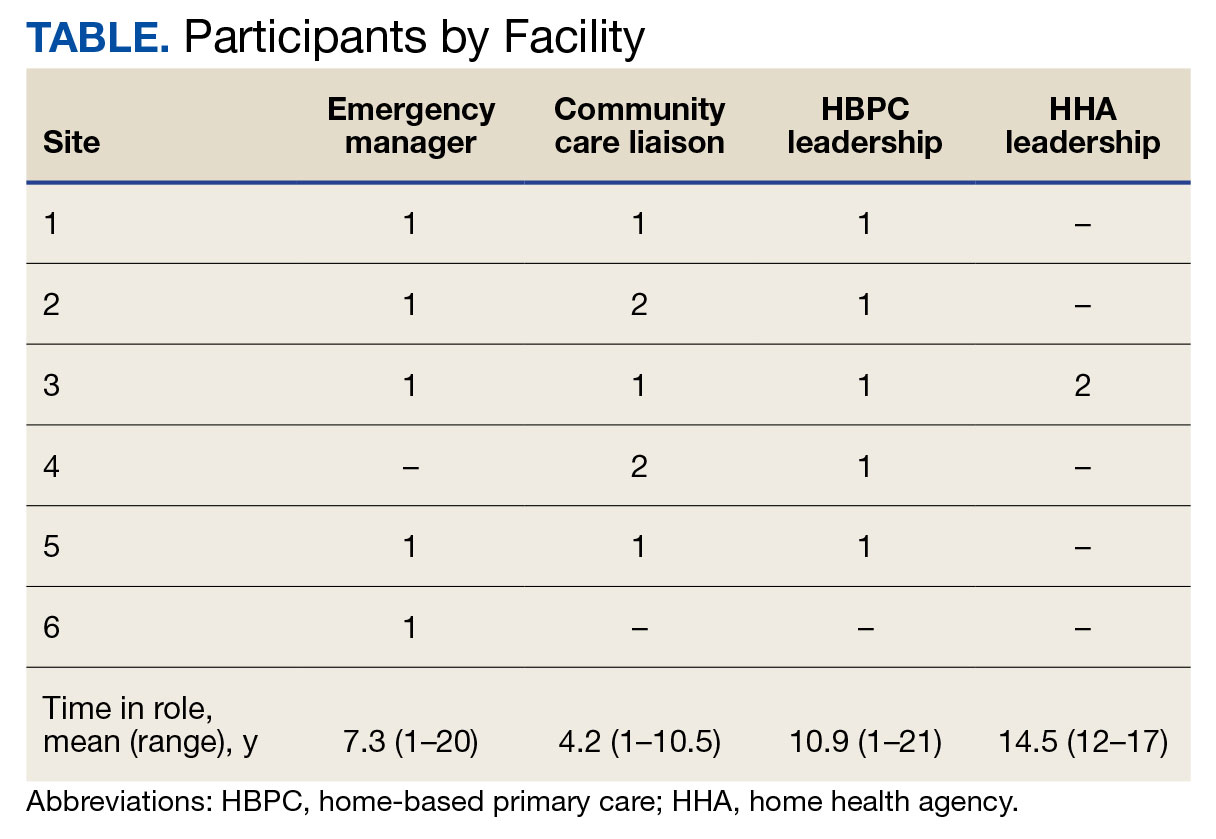

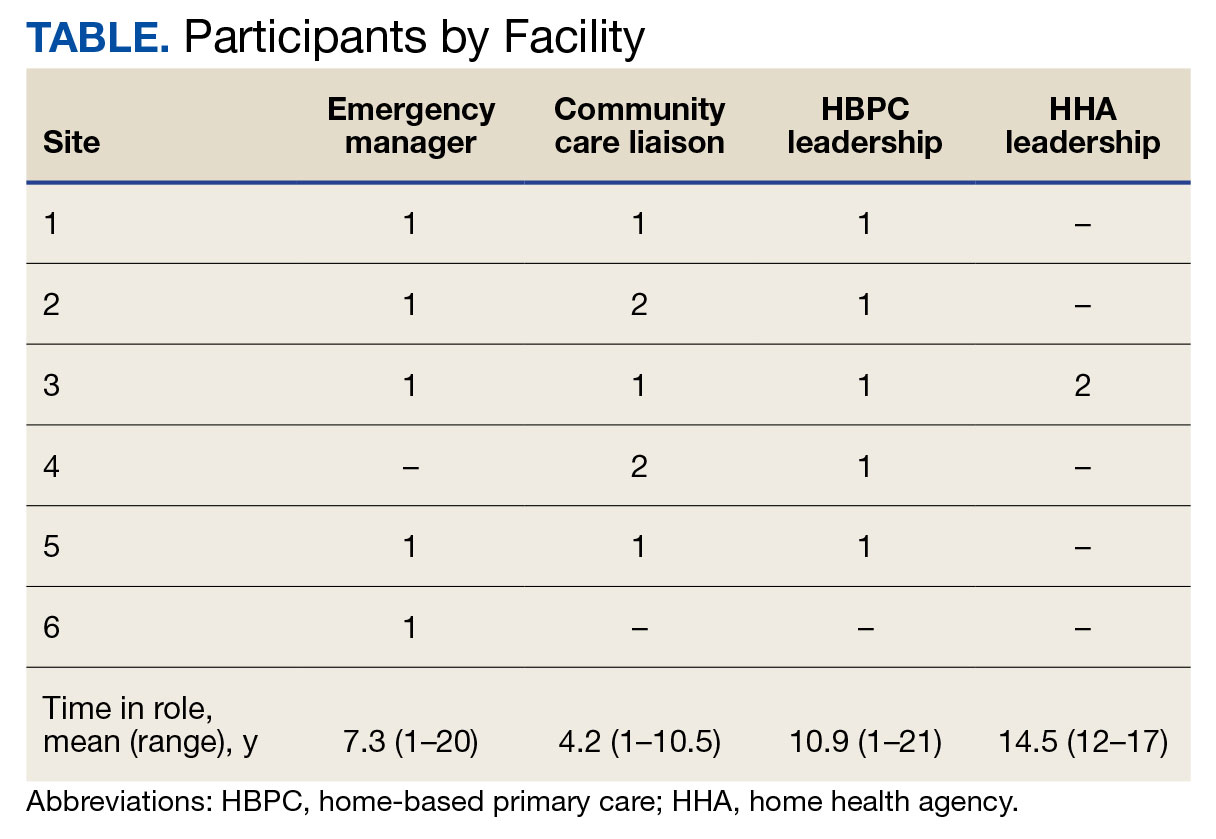

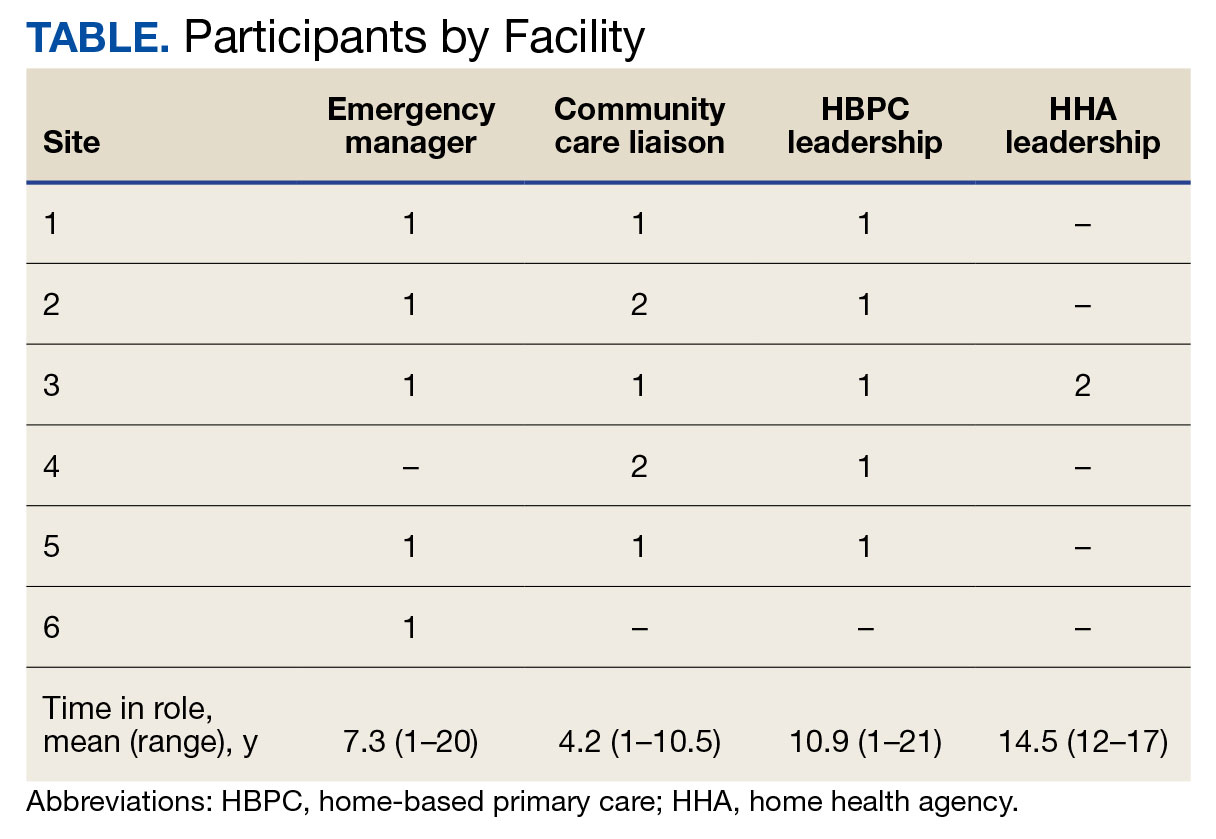

This is a significant issue for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which annually purchases 10.5 million home health care worker visits for 150,000 veterans from community-based HHAs to enable those individuals to live independently. Figure 1 illustrates the existing structure of directly provided and contracted VHA services for community-dwelling veterans, highlighting the circle of care around the veteran.8,9 Home health care workers anchored health care teams during the COVID-19 pandemic, observing and reporting on patients’ well-being to family caregivers, primary care practitioners, and HHAs. They also provided critical emotional support and companionship to patients isolated from family and friends.9 These workers also exposed themselves and their families to considerable risk and often lacked the protection afforded by personal protective equipment (PPE) in accordance with infection prevention guidance.3,12

Abbreviations: HBPC, home based primary care; HHA, home health agency; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

aAdapted with permission from Wyte-Lake and Franzosa.8,9

Through a combination of its national and local health care networks, the VHA has a robust and well-positioned emergency infrastructure to supportcommunity-dwelling older adults during disasters.14 This network is supported by the VHA Office of Emergency Management, which shares resources and guidance with local emergency managers at each facility as well as individual programs such as the VHA Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) program, which provides 38,000 seriously ill veterans with home medical visits.15 Working closely with their local and national hospital networks and emergency managers, individual VHA HBPC programs were able to maintain the safety of staff and continuity of care for patients enrolled in HBPC by rapidly administering COVID-19 vaccines to patients, caregivers, and staff, and providing emergency assistance during the 2017 hurricane season.16,17 These efforts were successful because HBPC practitioners and their patients, had access to a level of emergency-related information, resources, and technology that are often out of reach for individual community-based health care practitioners (HCPs). The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) also supports local communities through its Fourth Mission, which provides emergency resources to non-VHA health care facilities (ie, hospitals and nursing homes) during national emergencies and natural disasters.17 Although there has been an expansion in the definition of shared resources, such as extending behavioral health support to local communities, the VHA has not historically provided these resources to HHAs.14