User login

How Old Are You? Stand on One Leg and I’ll Tell You

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

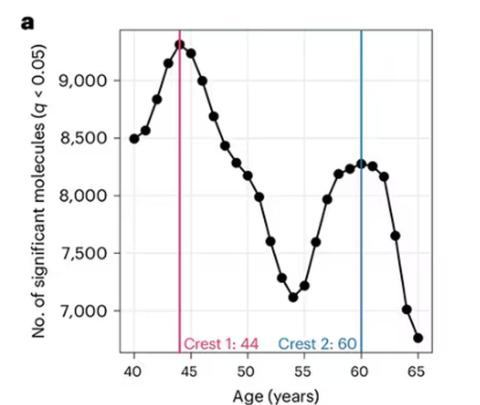

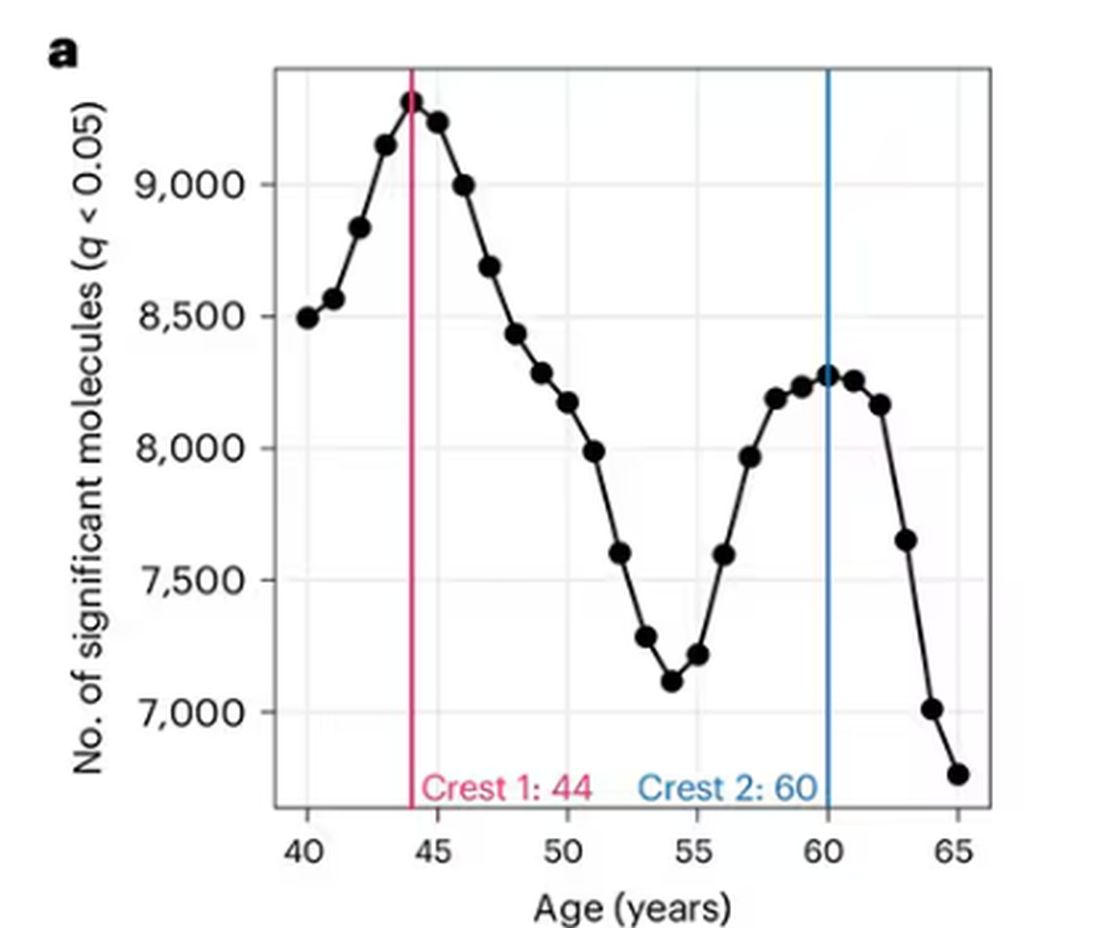

So I was lying in bed the other night, trying to read my phone, and started complaining to my wife about how my vision keeps getting worse, and then how stiff I feel when I wake up in the morning, and how a recent injury is taking too long to heal, and she said, “Well, yeah. You’re 44. That’s when things start to head downhill.”

And I was like, “Forty-four? That seems very specific. I thought 50 was what people complain about.” And she said, “No, it’s a thing — 44 years old and 60 years old. There’s a drop-off there.”

And you know what? She was right.

A study, “Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging,” published in Nature Aging in August 2024, analyzed a ton of proteins and metabolites in people of various ages and found, when you put it all together, that I should know better than to doubt my brilliant spouse.

But deep down, I believe the cliché that age is just a number. I don’t particularly care about being 44, or turning 50 or 60. I care about how my body and brain are aging. If I can be a happy, healthy, 80-year-old in full command of my faculties, I would consider that a major win no matter what the calendar says.

So I’m always interested in ways to quantify how my body is aging, independent of how many birthdays I have passed. And, according to a new study, there’s actually a really easy way to do this: Just stand on one leg.

The surprising results come from “Age-related changes in gait, balance, and strength parameters: A cross-sectional study,” appearing in PLOS One, which analyzed 40 individuals — half under age 65 and half over age 65 — across a variety of domains of strength, balance, and gait. The conceit of the study? We all know that things like strength and balance worsen over time, but what worsens fastest? What might be the best metric to tell us how our bodies are aging?

To that end, you have a variety of correlations between various metrics and calendar age.

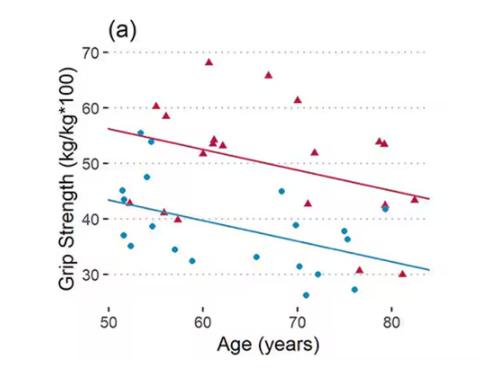

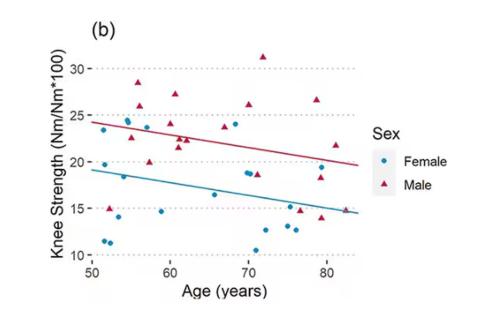

As age increases, grip strength goes down. Men (inexplicably in pink) have higher grip strength overall, and women (confusingly in blue) lower. Somewhat less strong correlations were seen for knee strength.

What about balance?

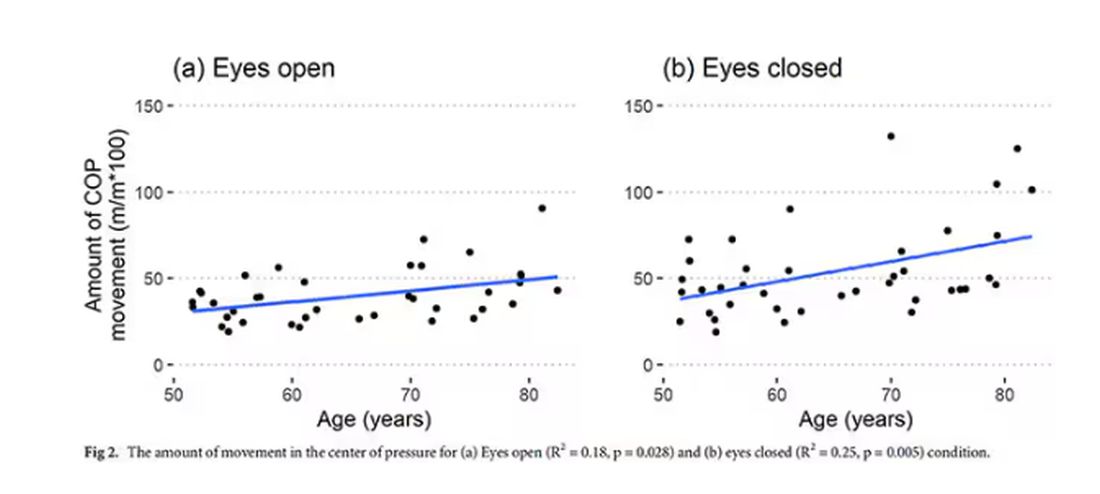

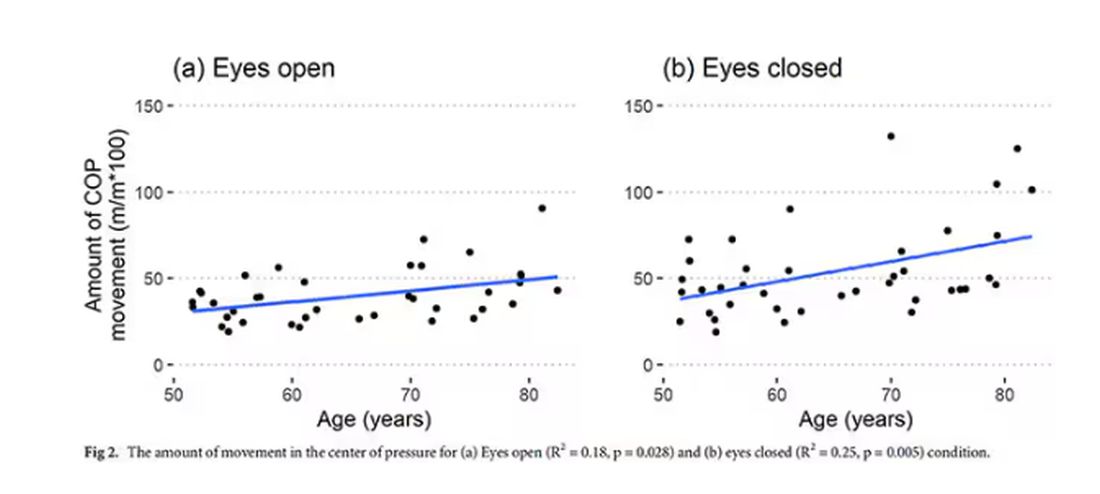

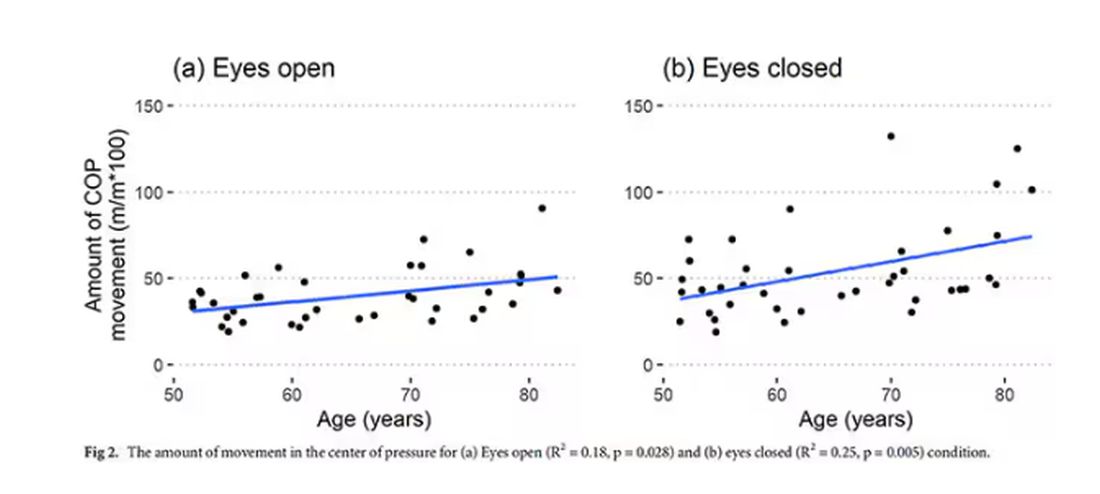

To assess this, the researchers had the participants stand on a pressure plate. In one scenario, they did this with eyes open, and the next with eyes closed. They then measured how much the pressure varied around the center of the individual on the plate — basically, how much the person swayed while they were standing there.

Sway increased as age increased. Sway increased a bit more with eyes closed than with eyes open.

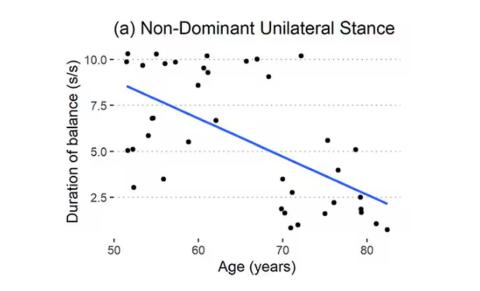

But the strongest correlation between any of these metrics and age was a simple one: How long can you stand on one leg?

Particularly for the nondominant leg, what you see here is a pretty dramatic drop-off in balance time around age 65, with younger people able to do 10 seconds with ease and some older people barely being able to make it to 2.

Of course, I had to try this for myself. And as I was standing around on one leg, it became clear to me exactly why this might be a good metric. It really integrates balance and strength in a way that the other tests don’t: balance, clearly, since you have to stay vertical over a relatively small base; but strength as well, because, well, one leg is holding up all the rest of you. You do feel it after a while.

So this metric passes the smell test to me, at least as a potential proxy for age-related physical decline.

But I should be careful to note that this was a cross-sectional study; the researchers looked at various people who were all different ages, not the same people over time to watch how these things change as they aged.

Also, the use of the correlation coefficient in graphs like this implies a certain linear relationship between age and standing-on-one-foot time. The raw data — the points on this graph — don’t appear that linear to me. As I mentioned above, it seems like there might be a bit of a sharp drop-off somewhere in the mid-60s. That means that we may not be able to use this as a sensitive test for aging that slowly changes as your body gets older. It might be that you’re able to essentially stand on one leg as long as you want until, one day, you can’t. That gives us less warning and less to act on.

And finally, we don’t know that changing this metric will change your health for the better. I’m sure a good physiatrist or physical therapist could design some exercises to increase any of our standing-on-one leg times. And no doubt, with practice, you could get your numbers way up. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re healthier. It’s like “teaching to the test”; you might score better on the standardized exam but you didn’t really learn the material.

So I am not adding one-leg standing to my daily exercise routine. But I won’t lie and tell you that, from time to time, and certainly on my 60th birthday, you may find me standing like a flamingo with a stopwatch in my hand.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

So I was lying in bed the other night, trying to read my phone, and started complaining to my wife about how my vision keeps getting worse, and then how stiff I feel when I wake up in the morning, and how a recent injury is taking too long to heal, and she said, “Well, yeah. You’re 44. That’s when things start to head downhill.”

And I was like, “Forty-four? That seems very specific. I thought 50 was what people complain about.” And she said, “No, it’s a thing — 44 years old and 60 years old. There’s a drop-off there.”

And you know what? She was right.

A study, “Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging,” published in Nature Aging in August 2024, analyzed a ton of proteins and metabolites in people of various ages and found, when you put it all together, that I should know better than to doubt my brilliant spouse.

But deep down, I believe the cliché that age is just a number. I don’t particularly care about being 44, or turning 50 or 60. I care about how my body and brain are aging. If I can be a happy, healthy, 80-year-old in full command of my faculties, I would consider that a major win no matter what the calendar says.

So I’m always interested in ways to quantify how my body is aging, independent of how many birthdays I have passed. And, according to a new study, there’s actually a really easy way to do this: Just stand on one leg.

The surprising results come from “Age-related changes in gait, balance, and strength parameters: A cross-sectional study,” appearing in PLOS One, which analyzed 40 individuals — half under age 65 and half over age 65 — across a variety of domains of strength, balance, and gait. The conceit of the study? We all know that things like strength and balance worsen over time, but what worsens fastest? What might be the best metric to tell us how our bodies are aging?

To that end, you have a variety of correlations between various metrics and calendar age.

As age increases, grip strength goes down. Men (inexplicably in pink) have higher grip strength overall, and women (confusingly in blue) lower. Somewhat less strong correlations were seen for knee strength.

What about balance?

To assess this, the researchers had the participants stand on a pressure plate. In one scenario, they did this with eyes open, and the next with eyes closed. They then measured how much the pressure varied around the center of the individual on the plate — basically, how much the person swayed while they were standing there.

Sway increased as age increased. Sway increased a bit more with eyes closed than with eyes open.

But the strongest correlation between any of these metrics and age was a simple one: How long can you stand on one leg?

Particularly for the nondominant leg, what you see here is a pretty dramatic drop-off in balance time around age 65, with younger people able to do 10 seconds with ease and some older people barely being able to make it to 2.

Of course, I had to try this for myself. And as I was standing around on one leg, it became clear to me exactly why this might be a good metric. It really integrates balance and strength in a way that the other tests don’t: balance, clearly, since you have to stay vertical over a relatively small base; but strength as well, because, well, one leg is holding up all the rest of you. You do feel it after a while.

So this metric passes the smell test to me, at least as a potential proxy for age-related physical decline.

But I should be careful to note that this was a cross-sectional study; the researchers looked at various people who were all different ages, not the same people over time to watch how these things change as they aged.

Also, the use of the correlation coefficient in graphs like this implies a certain linear relationship between age and standing-on-one-foot time. The raw data — the points on this graph — don’t appear that linear to me. As I mentioned above, it seems like there might be a bit of a sharp drop-off somewhere in the mid-60s. That means that we may not be able to use this as a sensitive test for aging that slowly changes as your body gets older. It might be that you’re able to essentially stand on one leg as long as you want until, one day, you can’t. That gives us less warning and less to act on.

And finally, we don’t know that changing this metric will change your health for the better. I’m sure a good physiatrist or physical therapist could design some exercises to increase any of our standing-on-one leg times. And no doubt, with practice, you could get your numbers way up. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re healthier. It’s like “teaching to the test”; you might score better on the standardized exam but you didn’t really learn the material.

So I am not adding one-leg standing to my daily exercise routine. But I won’t lie and tell you that, from time to time, and certainly on my 60th birthday, you may find me standing like a flamingo with a stopwatch in my hand.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

So I was lying in bed the other night, trying to read my phone, and started complaining to my wife about how my vision keeps getting worse, and then how stiff I feel when I wake up in the morning, and how a recent injury is taking too long to heal, and she said, “Well, yeah. You’re 44. That’s when things start to head downhill.”

And I was like, “Forty-four? That seems very specific. I thought 50 was what people complain about.” And she said, “No, it’s a thing — 44 years old and 60 years old. There’s a drop-off there.”

And you know what? She was right.

A study, “Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging,” published in Nature Aging in August 2024, analyzed a ton of proteins and metabolites in people of various ages and found, when you put it all together, that I should know better than to doubt my brilliant spouse.

But deep down, I believe the cliché that age is just a number. I don’t particularly care about being 44, or turning 50 or 60. I care about how my body and brain are aging. If I can be a happy, healthy, 80-year-old in full command of my faculties, I would consider that a major win no matter what the calendar says.

So I’m always interested in ways to quantify how my body is aging, independent of how many birthdays I have passed. And, according to a new study, there’s actually a really easy way to do this: Just stand on one leg.

The surprising results come from “Age-related changes in gait, balance, and strength parameters: A cross-sectional study,” appearing in PLOS One, which analyzed 40 individuals — half under age 65 and half over age 65 — across a variety of domains of strength, balance, and gait. The conceit of the study? We all know that things like strength and balance worsen over time, but what worsens fastest? What might be the best metric to tell us how our bodies are aging?

To that end, you have a variety of correlations between various metrics and calendar age.

As age increases, grip strength goes down. Men (inexplicably in pink) have higher grip strength overall, and women (confusingly in blue) lower. Somewhat less strong correlations were seen for knee strength.

What about balance?

To assess this, the researchers had the participants stand on a pressure plate. In one scenario, they did this with eyes open, and the next with eyes closed. They then measured how much the pressure varied around the center of the individual on the plate — basically, how much the person swayed while they were standing there.

Sway increased as age increased. Sway increased a bit more with eyes closed than with eyes open.

But the strongest correlation between any of these metrics and age was a simple one: How long can you stand on one leg?

Particularly for the nondominant leg, what you see here is a pretty dramatic drop-off in balance time around age 65, with younger people able to do 10 seconds with ease and some older people barely being able to make it to 2.

Of course, I had to try this for myself. And as I was standing around on one leg, it became clear to me exactly why this might be a good metric. It really integrates balance and strength in a way that the other tests don’t: balance, clearly, since you have to stay vertical over a relatively small base; but strength as well, because, well, one leg is holding up all the rest of you. You do feel it after a while.

So this metric passes the smell test to me, at least as a potential proxy for age-related physical decline.

But I should be careful to note that this was a cross-sectional study; the researchers looked at various people who were all different ages, not the same people over time to watch how these things change as they aged.

Also, the use of the correlation coefficient in graphs like this implies a certain linear relationship between age and standing-on-one-foot time. The raw data — the points on this graph — don’t appear that linear to me. As I mentioned above, it seems like there might be a bit of a sharp drop-off somewhere in the mid-60s. That means that we may not be able to use this as a sensitive test for aging that slowly changes as your body gets older. It might be that you’re able to essentially stand on one leg as long as you want until, one day, you can’t. That gives us less warning and less to act on.

And finally, we don’t know that changing this metric will change your health for the better. I’m sure a good physiatrist or physical therapist could design some exercises to increase any of our standing-on-one leg times. And no doubt, with practice, you could get your numbers way up. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re healthier. It’s like “teaching to the test”; you might score better on the standardized exam but you didn’t really learn the material.

So I am not adding one-leg standing to my daily exercise routine. But I won’t lie and tell you that, from time to time, and certainly on my 60th birthday, you may find me standing like a flamingo with a stopwatch in my hand.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Blood Tests for Alzheimer’s Are Here... Are Clinicians Ready?

With the approval of anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies to treat early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, the need for accurate and early diagnosis is crucial.

Recently, an expert workgroup convened by the Global CEO Initiative on Alzheimer’s Disease published recommendations for the clinical implementation of Alzheimer’s disease blood-based biomarkers.

“Our hope was to provide some recommendations that clinicians could use to develop the best pathways for their clinical practice,” said workgroup co-chair Michelle M. Mielke, PhD, with Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Triage and Confirmatory Pathways

The group recommends two implementation pathways for Alzheimer’s disease blood biomarkers — one for current use for triaging and another for future use to confirm amyloid pathology once blood biomarker tests have reached sufficient performance for this purpose.

In the triage pathway, a negative blood biomarker test would flag individuals unlikely to have detectable brain amyloid pathology. This outcome would prompt clinicians to focus on evaluating non–Alzheimer’s disease-related causes of cognitive impairment, which may streamline the diagnosis of other causes of cognitive impairment, the authors said.

A positive triage blood test would suggest a higher likelihood of amyloid pathology and prompt referral to secondary care for further assessment and consideration for a second, more accurate test, such as amyloid PET or CSF for amyloid confirmation.

In the confirmatory pathway, a positive blood biomarker test result would identify amyloid pathology without the need for a second test, providing a faster route to diagnosis, the authors noted.

Mielke emphasized that these recommendations represent a “first step” and will need to be updated as experiences with the Alzheimer’s disease blood biomarkers in clinical care increase and additional barriers and facilitators are identified.

“These updates will likely include community-informed approaches that incorporate feedback from patients as well as healthcare providers, alongside results from validation in diverse real-world settings,” said workgroup co-chair Chi Udeh-Momoh, PhD, MSc, with Wake Forest University School of Medicine and the Brain and Mind Institute, Aga Khan University, Nairobi, Kenya.

The Alzheimer’s Association published “appropriate use” recommendations for blood biomarkers in 2022.

“Currently, the Alzheimer’s Association is building an updated library of clinical guidance that distills the scientific evidence using de novo systematic reviews and translates them into clear and actionable recommendations for clinical practice,” said Rebecca M. Edelmayer, PhD, vice president of scientific engagement, Alzheimer’s Association.

“The first major effort with our new process will be the upcoming Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline on the Use of Blood-based Biomarkers (BBMs) in Specialty Care Settings. This guideline’s recommendations will be published in early 2025,” Edelmayer said.

Availability and Accuracy

Research has shown that amyloid beta and tau protein blood biomarkers — especially a high plasma phosphorylated (p)–tau217 levels — are highly accurate in identifying Alzheimer’s disease in patients with cognitive symptoms attending primary and secondary care clinics.

Several tests targeting plasma p-tau217 are now available for use. They include the PrecivityAD2 blood test from C2N Diagnostics and the Simoa p-Tau 217 Planar Kit and LucentAD p-Tau 217 — both from Quanterix.

In a recent head-to-head comparison of seven leading blood tests for AD pathology, measures of plasma p-tau217, either individually or in combination with other plasma biomarkers, had the strongest relationships with Alzheimer’s disease outcomes.

A recent Swedish study showed that the PrecivityAD2 test had an accuracy of 91% for correctly classifying clinical, biomarker-verified Alzheimer’s disease.

“We’ve been using these blood biomarkers in research for a long time and we’re now taking the jump to start using them in clinic to risk stratify patients,” said Fanny Elahi, MD, PhD, director of fluid biomarker research for the Barbara and Maurice Deane Center for Wellness and Cognitive Health at Icahn Mount Sinai in New York City.

New York’s Mount Sinai Health System is among the first in the northeast to offer blood tests across primary and specialty care settings for early diagnosis of AD and related dementias.

Edelmayer cautioned, “There is no single, stand-alone test to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease today. Blood testing is one piece of the diagnostic process.”

“Currently, physicians use well-established diagnostic tools combined with medical history and other information, including neurological exams, cognitive and functional assessments as well as brain imaging and spinal fluid analysis and blood to make an accurate diagnosis and to understand which patients are eligible for approved treatments,” she said.

There are also emerging biomarkers in the research pipeline, Edelmayer said.

“For example, some researchers think retinal imaging has the potential to detect biological signs of Alzheimer’s disease within certain areas of the eye,” she explained.

“Other emerging biomarkers include examining components in saliva and the skin for signals that may indicate early biological changes in the brain. These biomarkers are still very exploratory, and more research is needed before these tests or biomarkers can be used more routinely to study risk or aid in diagnosis,” Edelmayer said.

Ideal Candidates for Alzheimer’s Disease Blood Testing?

Experts agree that blood tests represent a convenient and scalable option to address the anticipated surge in demand for biomarker testing with the availability of disease-modifying treatments. For now, however, they are not for all older adults worried about their memory.

“Current practice should focus on using these blood biomarkers in individuals with cognitive impairment rather than in those with normal cognition or subjective cognitive decline until further research demonstrates effective interventions for individuals considered cognitively normal with elevated levels of amyloid,” the authors of a recent JAMA editorial noted.

At Mount Sinai, “we’re not starting with stone-cold asymptomatic individuals. But ultimately, this is what the blood tests are intended for — screening,” Elahi noted.

She also noted that Mount Sinai has a “very diverse population” — some with young onset cognitive symptoms, so the entry criteria for testing are “very wide.”

“Anyone above age 40 with symptoms can qualify to get a blood test. We do ask at this stage that either the individual report symptoms or someone in their life or their clinician be worried about their cognition or their brain function,” Elahi said.

Ethical Considerations, Counseling

Elahi emphasized the importance of counseling patients who come to the clinic seeking an Alzheimer’s disease blood test. This should include how the diagnostic process will unfold and what the next steps are with a given result.

Elahi said patients need to be informed that Alzheimer’s disease blood biomarkers are still “relatively new,” and a test can help a patient “know the likelihood of having the disease, but it won’t be 100% definitive.”

To ensure the ethical principle of “do no harm,” counseling should ensure that patients are fully prepared for the implications of the test results and ensure that the decision to test aligns with the patient’s readiness and well-being, Elahi said.

Edelmayer said the forthcoming clinical practice guidelines will provide “evidence-based recommendations for physicians to help guide them through the decision-making process around who should be tested and when. In the meantime, the Alzheimer’s Association urges providers to refer to the 2022 appropriate use recommendations for blood tests in clinical practice and trial settings.”

Mielke has served on scientific advisory boards and/or having consulted for Acadia, Biogen, Eisai, LabCorp, Lilly, Merck, PeerView Institute, Roche, Siemens Healthineers, and Sunbird Bio. Edelmayer and Elahi had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

With the approval of anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies to treat early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, the need for accurate and early diagnosis is crucial.

Recently, an expert workgroup convened by the Global CEO Initiative on Alzheimer’s Disease published recommendations for the clinical implementation of Alzheimer’s disease blood-based biomarkers.

“Our hope was to provide some recommendations that clinicians could use to develop the best pathways for their clinical practice,” said workgroup co-chair Michelle M. Mielke, PhD, with Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Triage and Confirmatory Pathways

The group recommends two implementation pathways for Alzheimer’s disease blood biomarkers — one for current use for triaging and another for future use to confirm amyloid pathology once blood biomarker tests have reached sufficient performance for this purpose.

In the triage pathway, a negative blood biomarker test would flag individuals unlikely to have detectable brain amyloid pathology. This outcome would prompt clinicians to focus on evaluating non–Alzheimer’s disease-related causes of cognitive impairment, which may streamline the diagnosis of other causes of cognitive impairment, the authors said.

A positive triage blood test would suggest a higher likelihood of amyloid pathology and prompt referral to secondary care for further assessment and consideration for a second, more accurate test, such as amyloid PET or CSF for amyloid confirmation.

In the confirmatory pathway, a positive blood biomarker test result would identify amyloid pathology without the need for a second test, providing a faster route to diagnosis, the authors noted.

Mielke emphasized that these recommendations represent a “first step” and will need to be updated as experiences with the Alzheimer’s disease blood biomarkers in clinical care increase and additional barriers and facilitators are identified.

“These updates will likely include community-informed approaches that incorporate feedback from patients as well as healthcare providers, alongside results from validation in diverse real-world settings,” said workgroup co-chair Chi Udeh-Momoh, PhD, MSc, with Wake Forest University School of Medicine and the Brain and Mind Institute, Aga Khan University, Nairobi, Kenya.

The Alzheimer’s Association published “appropriate use” recommendations for blood biomarkers in 2022.

“Currently, the Alzheimer’s Association is building an updated library of clinical guidance that distills the scientific evidence using de novo systematic reviews and translates them into clear and actionable recommendations for clinical practice,” said Rebecca M. Edelmayer, PhD, vice president of scientific engagement, Alzheimer’s Association.

“The first major effort with our new process will be the upcoming Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline on the Use of Blood-based Biomarkers (BBMs) in Specialty Care Settings. This guideline’s recommendations will be published in early 2025,” Edelmayer said.

Availability and Accuracy

Research has shown that amyloid beta and tau protein blood biomarkers — especially a high plasma phosphorylated (p)–tau217 levels — are highly accurate in identifying Alzheimer’s disease in patients with cognitive symptoms attending primary and secondary care clinics.

Several tests targeting plasma p-tau217 are now available for use. They include the PrecivityAD2 blood test from C2N Diagnostics and the Simoa p-Tau 217 Planar Kit and LucentAD p-Tau 217 — both from Quanterix.

In a recent head-to-head comparison of seven leading blood tests for AD pathology, measures of plasma p-tau217, either individually or in combination with other plasma biomarkers, had the strongest relationships with Alzheimer’s disease outcomes.

A recent Swedish study showed that the PrecivityAD2 test had an accuracy of 91% for correctly classifying clinical, biomarker-verified Alzheimer’s disease.

“We’ve been using these blood biomarkers in research for a long time and we’re now taking the jump to start using them in clinic to risk stratify patients,” said Fanny Elahi, MD, PhD, director of fluid biomarker research for the Barbara and Maurice Deane Center for Wellness and Cognitive Health at Icahn Mount Sinai in New York City.

New York’s Mount Sinai Health System is among the first in the northeast to offer blood tests across primary and specialty care settings for early diagnosis of AD and related dementias.

Edelmayer cautioned, “There is no single, stand-alone test to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease today. Blood testing is one piece of the diagnostic process.”

“Currently, physicians use well-established diagnostic tools combined with medical history and other information, including neurological exams, cognitive and functional assessments as well as brain imaging and spinal fluid analysis and blood to make an accurate diagnosis and to understand which patients are eligible for approved treatments,” she said.

There are also emerging biomarkers in the research pipeline, Edelmayer said.

“For example, some researchers think retinal imaging has the potential to detect biological signs of Alzheimer’s disease within certain areas of the eye,” she explained.

“Other emerging biomarkers include examining components in saliva and the skin for signals that may indicate early biological changes in the brain. These biomarkers are still very exploratory, and more research is needed before these tests or biomarkers can be used more routinely to study risk or aid in diagnosis,” Edelmayer said.

Ideal Candidates for Alzheimer’s Disease Blood Testing?

Experts agree that blood tests represent a convenient and scalable option to address the anticipated surge in demand for biomarker testing with the availability of disease-modifying treatments. For now, however, they are not for all older adults worried about their memory.

“Current practice should focus on using these blood biomarkers in individuals with cognitive impairment rather than in those with normal cognition or subjective cognitive decline until further research demonstrates effective interventions for individuals considered cognitively normal with elevated levels of amyloid,” the authors of a recent JAMA editorial noted.

At Mount Sinai, “we’re not starting with stone-cold asymptomatic individuals. But ultimately, this is what the blood tests are intended for — screening,” Elahi noted.

She also noted that Mount Sinai has a “very diverse population” — some with young onset cognitive symptoms, so the entry criteria for testing are “very wide.”

“Anyone above age 40 with symptoms can qualify to get a blood test. We do ask at this stage that either the individual report symptoms or someone in their life or their clinician be worried about their cognition or their brain function,” Elahi said.

Ethical Considerations, Counseling

Elahi emphasized the importance of counseling patients who come to the clinic seeking an Alzheimer’s disease blood test. This should include how the diagnostic process will unfold and what the next steps are with a given result.

Elahi said patients need to be informed that Alzheimer’s disease blood biomarkers are still “relatively new,” and a test can help a patient “know the likelihood of having the disease, but it won’t be 100% definitive.”

To ensure the ethical principle of “do no harm,” counseling should ensure that patients are fully prepared for the implications of the test results and ensure that the decision to test aligns with the patient’s readiness and well-being, Elahi said.

Edelmayer said the forthcoming clinical practice guidelines will provide “evidence-based recommendations for physicians to help guide them through the decision-making process around who should be tested and when. In the meantime, the Alzheimer’s Association urges providers to refer to the 2022 appropriate use recommendations for blood tests in clinical practice and trial settings.”

Mielke has served on scientific advisory boards and/or having consulted for Acadia, Biogen, Eisai, LabCorp, Lilly, Merck, PeerView Institute, Roche, Siemens Healthineers, and Sunbird Bio. Edelmayer and Elahi had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

With the approval of anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies to treat early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, the need for accurate and early diagnosis is crucial.

Recently, an expert workgroup convened by the Global CEO Initiative on Alzheimer’s Disease published recommendations for the clinical implementation of Alzheimer’s disease blood-based biomarkers.

“Our hope was to provide some recommendations that clinicians could use to develop the best pathways for their clinical practice,” said workgroup co-chair Michelle M. Mielke, PhD, with Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Triage and Confirmatory Pathways

The group recommends two implementation pathways for Alzheimer’s disease blood biomarkers — one for current use for triaging and another for future use to confirm amyloid pathology once blood biomarker tests have reached sufficient performance for this purpose.

In the triage pathway, a negative blood biomarker test would flag individuals unlikely to have detectable brain amyloid pathology. This outcome would prompt clinicians to focus on evaluating non–Alzheimer’s disease-related causes of cognitive impairment, which may streamline the diagnosis of other causes of cognitive impairment, the authors said.

A positive triage blood test would suggest a higher likelihood of amyloid pathology and prompt referral to secondary care for further assessment and consideration for a second, more accurate test, such as amyloid PET or CSF for amyloid confirmation.

In the confirmatory pathway, a positive blood biomarker test result would identify amyloid pathology without the need for a second test, providing a faster route to diagnosis, the authors noted.

Mielke emphasized that these recommendations represent a “first step” and will need to be updated as experiences with the Alzheimer’s disease blood biomarkers in clinical care increase and additional barriers and facilitators are identified.

“These updates will likely include community-informed approaches that incorporate feedback from patients as well as healthcare providers, alongside results from validation in diverse real-world settings,” said workgroup co-chair Chi Udeh-Momoh, PhD, MSc, with Wake Forest University School of Medicine and the Brain and Mind Institute, Aga Khan University, Nairobi, Kenya.

The Alzheimer’s Association published “appropriate use” recommendations for blood biomarkers in 2022.

“Currently, the Alzheimer’s Association is building an updated library of clinical guidance that distills the scientific evidence using de novo systematic reviews and translates them into clear and actionable recommendations for clinical practice,” said Rebecca M. Edelmayer, PhD, vice president of scientific engagement, Alzheimer’s Association.

“The first major effort with our new process will be the upcoming Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline on the Use of Blood-based Biomarkers (BBMs) in Specialty Care Settings. This guideline’s recommendations will be published in early 2025,” Edelmayer said.

Availability and Accuracy

Research has shown that amyloid beta and tau protein blood biomarkers — especially a high plasma phosphorylated (p)–tau217 levels — are highly accurate in identifying Alzheimer’s disease in patients with cognitive symptoms attending primary and secondary care clinics.

Several tests targeting plasma p-tau217 are now available for use. They include the PrecivityAD2 blood test from C2N Diagnostics and the Simoa p-Tau 217 Planar Kit and LucentAD p-Tau 217 — both from Quanterix.

In a recent head-to-head comparison of seven leading blood tests for AD pathology, measures of plasma p-tau217, either individually or in combination with other plasma biomarkers, had the strongest relationships with Alzheimer’s disease outcomes.

A recent Swedish study showed that the PrecivityAD2 test had an accuracy of 91% for correctly classifying clinical, biomarker-verified Alzheimer’s disease.

“We’ve been using these blood biomarkers in research for a long time and we’re now taking the jump to start using them in clinic to risk stratify patients,” said Fanny Elahi, MD, PhD, director of fluid biomarker research for the Barbara and Maurice Deane Center for Wellness and Cognitive Health at Icahn Mount Sinai in New York City.

New York’s Mount Sinai Health System is among the first in the northeast to offer blood tests across primary and specialty care settings for early diagnosis of AD and related dementias.

Edelmayer cautioned, “There is no single, stand-alone test to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease today. Blood testing is one piece of the diagnostic process.”

“Currently, physicians use well-established diagnostic tools combined with medical history and other information, including neurological exams, cognitive and functional assessments as well as brain imaging and spinal fluid analysis and blood to make an accurate diagnosis and to understand which patients are eligible for approved treatments,” she said.

There are also emerging biomarkers in the research pipeline, Edelmayer said.

“For example, some researchers think retinal imaging has the potential to detect biological signs of Alzheimer’s disease within certain areas of the eye,” she explained.

“Other emerging biomarkers include examining components in saliva and the skin for signals that may indicate early biological changes in the brain. These biomarkers are still very exploratory, and more research is needed before these tests or biomarkers can be used more routinely to study risk or aid in diagnosis,” Edelmayer said.

Ideal Candidates for Alzheimer’s Disease Blood Testing?

Experts agree that blood tests represent a convenient and scalable option to address the anticipated surge in demand for biomarker testing with the availability of disease-modifying treatments. For now, however, they are not for all older adults worried about their memory.

“Current practice should focus on using these blood biomarkers in individuals with cognitive impairment rather than in those with normal cognition or subjective cognitive decline until further research demonstrates effective interventions for individuals considered cognitively normal with elevated levels of amyloid,” the authors of a recent JAMA editorial noted.

At Mount Sinai, “we’re not starting with stone-cold asymptomatic individuals. But ultimately, this is what the blood tests are intended for — screening,” Elahi noted.

She also noted that Mount Sinai has a “very diverse population” — some with young onset cognitive symptoms, so the entry criteria for testing are “very wide.”

“Anyone above age 40 with symptoms can qualify to get a blood test. We do ask at this stage that either the individual report symptoms or someone in their life or their clinician be worried about their cognition or their brain function,” Elahi said.

Ethical Considerations, Counseling

Elahi emphasized the importance of counseling patients who come to the clinic seeking an Alzheimer’s disease blood test. This should include how the diagnostic process will unfold and what the next steps are with a given result.

Elahi said patients need to be informed that Alzheimer’s disease blood biomarkers are still “relatively new,” and a test can help a patient “know the likelihood of having the disease, but it won’t be 100% definitive.”

To ensure the ethical principle of “do no harm,” counseling should ensure that patients are fully prepared for the implications of the test results and ensure that the decision to test aligns with the patient’s readiness and well-being, Elahi said.

Edelmayer said the forthcoming clinical practice guidelines will provide “evidence-based recommendations for physicians to help guide them through the decision-making process around who should be tested and when. In the meantime, the Alzheimer’s Association urges providers to refer to the 2022 appropriate use recommendations for blood tests in clinical practice and trial settings.”

Mielke has served on scientific advisory boards and/or having consulted for Acadia, Biogen, Eisai, LabCorp, Lilly, Merck, PeerView Institute, Roche, Siemens Healthineers, and Sunbird Bio. Edelmayer and Elahi had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

How Effective Is the High-Dose Flu Vaccine in Older Adults?

How can the immunogenicity and effectiveness of flu vaccines be improved in older adults? Several strategies are available, one being the addition of an adjuvant. For example, the MF59-adjuvanted vaccine has shown superior immunogenicity. However, “we do not have data from controlled and randomized clinical trials showing superior clinical effectiveness versus the standard dose,” Professor Odile Launay, an infectious disease specialist at Cochin Hospital in Paris, France, noted during a press conference. Another option is to increase the antigen dose in the vaccine, creating a high-dose (HD) flu vaccine.

Why is there a need for an HD vaccine? “The elderly population bears the greatest burden from the flu,” explained Launay. “This is due to three factors: An aging immune system, a higher number of comorbidities, and increased frailty.” Standard-dose flu vaccines are seen as offering suboptimal protection for those older than 65 years, which led to the development of a quadrivalent vaccine with four times the antigen dose of standard flu vaccines. This HD vaccine was introduced in France during the 2021/2022 flu season. A real-world cohort study has since been conducted to evaluate its effectiveness in the target population — those aged 65 years or older. The results were recently published in Clinical Microbiology and Infection.

Cohort Study

The study included 405,385 noninstitutionalized people aged 65 years or older matched with 1,621,540 individuals in a 1:4 ratio. The first group received the HD vaccine, while the second group received the standard-dose vaccine. Both the groups had an average age of 77 years, with 56% women, and 51% vaccinated in pharmacies. The majority had been previously vaccinated against flu (91%), and 97% had completed a full COVID-19 vaccination schedule. More than half had at least one chronic illness.

Hospitalization rates for flu — the study’s primary outcome — were 69.5 vs 90.5 per 100,000 person-years in the HD vs standard-dose group. This represented a 23.3% reduction (95% CI, 8.4-35.8; P = .003).

Strengths and Limitations

Among the strengths of the study, Launay highlighted the large number of vaccinated participants older than 65 years — more than 7 million — and the widespread use of polymerase chain reaction flu tests in cases of hospitalization for respiratory infections, which improved flu coding in the database used. Additionally, the results were consistent with those of previous studies.

However, limitations included the retrospective design, which did not randomize participants and introduced potential bias. For example, the HD vaccine may have been prioritized for the oldest people or those with multiple comorbidities. Additionally, the 2021/2022 flu season was atypical, with the simultaneous circulation of the flu virus and SARS-CoV-2, as noted by Launay.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this first evaluation of the HD flu vaccine’s effectiveness in France showed a 25% reduction in hospitalizations, consistent with existing data covering 12 flu seasons. The vaccine has been available for a longer period in the United States and Northern Europe.

“The latest unpublished data from the 2022/23 season show a 27% reduction in hospitalizations with the HD vaccine in people over 65,” added Launay.

Note: Due to a pricing disagreement with the French government, Sanofi’s HD flu vaccine Efluelda, intended for people older than 65 years, will not be available this year. (See: Withdrawal of the Efluelda Influenza Vaccine: The Academy of Medicine Reacts). However, the company has submitted a dossier for a trivalent form for a return in the 2025/2026 season and is working on developing mRNA vaccines. Additionally, a combined flu/COVID-19 vaccine is currently in development.

The study was funded by Sanofi. Several authors are Sanofi employees. Odile Launay reported conflicts of interest with Sanofi, MSD, Pfizer, GSK, and Moderna.

This story was translated from Medscape’s French edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

How can the immunogenicity and effectiveness of flu vaccines be improved in older adults? Several strategies are available, one being the addition of an adjuvant. For example, the MF59-adjuvanted vaccine has shown superior immunogenicity. However, “we do not have data from controlled and randomized clinical trials showing superior clinical effectiveness versus the standard dose,” Professor Odile Launay, an infectious disease specialist at Cochin Hospital in Paris, France, noted during a press conference. Another option is to increase the antigen dose in the vaccine, creating a high-dose (HD) flu vaccine.

Why is there a need for an HD vaccine? “The elderly population bears the greatest burden from the flu,” explained Launay. “This is due to three factors: An aging immune system, a higher number of comorbidities, and increased frailty.” Standard-dose flu vaccines are seen as offering suboptimal protection for those older than 65 years, which led to the development of a quadrivalent vaccine with four times the antigen dose of standard flu vaccines. This HD vaccine was introduced in France during the 2021/2022 flu season. A real-world cohort study has since been conducted to evaluate its effectiveness in the target population — those aged 65 years or older. The results were recently published in Clinical Microbiology and Infection.

Cohort Study

The study included 405,385 noninstitutionalized people aged 65 years or older matched with 1,621,540 individuals in a 1:4 ratio. The first group received the HD vaccine, while the second group received the standard-dose vaccine. Both the groups had an average age of 77 years, with 56% women, and 51% vaccinated in pharmacies. The majority had been previously vaccinated against flu (91%), and 97% had completed a full COVID-19 vaccination schedule. More than half had at least one chronic illness.

Hospitalization rates for flu — the study’s primary outcome — were 69.5 vs 90.5 per 100,000 person-years in the HD vs standard-dose group. This represented a 23.3% reduction (95% CI, 8.4-35.8; P = .003).

Strengths and Limitations

Among the strengths of the study, Launay highlighted the large number of vaccinated participants older than 65 years — more than 7 million — and the widespread use of polymerase chain reaction flu tests in cases of hospitalization for respiratory infections, which improved flu coding in the database used. Additionally, the results were consistent with those of previous studies.

However, limitations included the retrospective design, which did not randomize participants and introduced potential bias. For example, the HD vaccine may have been prioritized for the oldest people or those with multiple comorbidities. Additionally, the 2021/2022 flu season was atypical, with the simultaneous circulation of the flu virus and SARS-CoV-2, as noted by Launay.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this first evaluation of the HD flu vaccine’s effectiveness in France showed a 25% reduction in hospitalizations, consistent with existing data covering 12 flu seasons. The vaccine has been available for a longer period in the United States and Northern Europe.

“The latest unpublished data from the 2022/23 season show a 27% reduction in hospitalizations with the HD vaccine in people over 65,” added Launay.

Note: Due to a pricing disagreement with the French government, Sanofi’s HD flu vaccine Efluelda, intended for people older than 65 years, will not be available this year. (See: Withdrawal of the Efluelda Influenza Vaccine: The Academy of Medicine Reacts). However, the company has submitted a dossier for a trivalent form for a return in the 2025/2026 season and is working on developing mRNA vaccines. Additionally, a combined flu/COVID-19 vaccine is currently in development.

The study was funded by Sanofi. Several authors are Sanofi employees. Odile Launay reported conflicts of interest with Sanofi, MSD, Pfizer, GSK, and Moderna.

This story was translated from Medscape’s French edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

How can the immunogenicity and effectiveness of flu vaccines be improved in older adults? Several strategies are available, one being the addition of an adjuvant. For example, the MF59-adjuvanted vaccine has shown superior immunogenicity. However, “we do not have data from controlled and randomized clinical trials showing superior clinical effectiveness versus the standard dose,” Professor Odile Launay, an infectious disease specialist at Cochin Hospital in Paris, France, noted during a press conference. Another option is to increase the antigen dose in the vaccine, creating a high-dose (HD) flu vaccine.

Why is there a need for an HD vaccine? “The elderly population bears the greatest burden from the flu,” explained Launay. “This is due to three factors: An aging immune system, a higher number of comorbidities, and increased frailty.” Standard-dose flu vaccines are seen as offering suboptimal protection for those older than 65 years, which led to the development of a quadrivalent vaccine with four times the antigen dose of standard flu vaccines. This HD vaccine was introduced in France during the 2021/2022 flu season. A real-world cohort study has since been conducted to evaluate its effectiveness in the target population — those aged 65 years or older. The results were recently published in Clinical Microbiology and Infection.

Cohort Study

The study included 405,385 noninstitutionalized people aged 65 years or older matched with 1,621,540 individuals in a 1:4 ratio. The first group received the HD vaccine, while the second group received the standard-dose vaccine. Both the groups had an average age of 77 years, with 56% women, and 51% vaccinated in pharmacies. The majority had been previously vaccinated against flu (91%), and 97% had completed a full COVID-19 vaccination schedule. More than half had at least one chronic illness.

Hospitalization rates for flu — the study’s primary outcome — were 69.5 vs 90.5 per 100,000 person-years in the HD vs standard-dose group. This represented a 23.3% reduction (95% CI, 8.4-35.8; P = .003).

Strengths and Limitations

Among the strengths of the study, Launay highlighted the large number of vaccinated participants older than 65 years — more than 7 million — and the widespread use of polymerase chain reaction flu tests in cases of hospitalization for respiratory infections, which improved flu coding in the database used. Additionally, the results were consistent with those of previous studies.

However, limitations included the retrospective design, which did not randomize participants and introduced potential bias. For example, the HD vaccine may have been prioritized for the oldest people or those with multiple comorbidities. Additionally, the 2021/2022 flu season was atypical, with the simultaneous circulation of the flu virus and SARS-CoV-2, as noted by Launay.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this first evaluation of the HD flu vaccine’s effectiveness in France showed a 25% reduction in hospitalizations, consistent with existing data covering 12 flu seasons. The vaccine has been available for a longer period in the United States and Northern Europe.

“The latest unpublished data from the 2022/23 season show a 27% reduction in hospitalizations with the HD vaccine in people over 65,” added Launay.

Note: Due to a pricing disagreement with the French government, Sanofi’s HD flu vaccine Efluelda, intended for people older than 65 years, will not be available this year. (See: Withdrawal of the Efluelda Influenza Vaccine: The Academy of Medicine Reacts). However, the company has submitted a dossier for a trivalent form for a return in the 2025/2026 season and is working on developing mRNA vaccines. Additionally, a combined flu/COVID-19 vaccine is currently in development.

The study was funded by Sanofi. Several authors are Sanofi employees. Odile Launay reported conflicts of interest with Sanofi, MSD, Pfizer, GSK, and Moderna.

This story was translated from Medscape’s French edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Risk Assessment Tool Can Help Predict Fractures in Cancer

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Cancer-specific guidelines recommend using FRAX to assess fracture risk, but its applicability in patients with cancer remains unclear.

- This retrospective cohort study included 9877 patients with cancer (mean age, 67.1 years) and 45,875 matched control individuals without cancer (mean age, 66.2 years). All participants had dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans.

- Researchers collected data on bone mineral density and fractures. The 10-year probabilities of major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures were calculated using FRAX, and the observed 10-year probabilities of these fractures were compared with FRAX-derived probabilities.

- Compared with individuals without cancer, patients with cancer had a shorter mean follow-up duration (8.5 vs 7.6 years), a slightly higher mean body mass index, and a higher percentage of parental hip fractures (7.0% vs 8.2%); additionally, patients with cancer were more likely to have secondary causes of osteoporosis (10% vs 38.4%) and less likely to receive osteoporosis medication (9.9% vs 4.2%).

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with individuals without cancer, patients with cancer had a significantly higher incidence rate of major fractures (12.9 vs 14.5 per 1000 person-years) and hip fractures (3.5 vs 4.2 per 1000 person-years).

- FRAX with bone mineral density exhibited excellent calibration for predicting major osteoporotic fractures (slope, 1.03) and hip fractures (0.97) in patients with cancer, regardless of the site of cancer diagnosis. FRAX without bone mineral density, however, underestimated the risk for both major (0.87) and hip fractures (0.72).

- In patients with cancer, FRAX with bone mineral density findings were associated with incident major osteoporotic fractures (hazard ratio [HR] per SD, 1.84) and hip fractures (HR per SD, 3.61).

- When models were adjusted for FRAX with bone mineral density, patients with cancer had an increased risk for both major osteoporotic fractures (HR, 1.17) and hip fractures (HR, 1.30). No difference was found in the risk for fracture between patients with and individuals without cancer when the models were adjusted for FRAX without bone mineral density, even when considering osteoporosis medication use.

IN PRACTICE:

“This retrospective cohort study demonstrates that individuals with cancer are at higher risk of fracture than individuals without cancer and that FRAX, particularly with BMD [bone mineral density], may accurately predict fracture risk in this population. These results, along with the known mortality risk of osteoporotic fractures among cancer survivors, further emphasize the clinical importance of closing the current osteoporosis care gap among cancer survivors,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study, led by Carrie Ye, MD, MPH, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, was published online in JAMA Oncology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study cohort included a selected group of cancer survivors who were referred for DXA scans and may not represent the general cancer population. The cohort consisted predominantly of women, limiting the generalizability to men with cancer. Given the heterogeneity of the population, the findings may not be applicable to all cancer subgroups. Information on cancer stage or the presence of bone metastases at the time of fracture risk assessment was lacking, which could have affected the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by the CancerCare Manitoba Foundation. Three authors reported having ties with various sources, including two who received grants from various organizations.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Cancer-specific guidelines recommend using FRAX to assess fracture risk, but its applicability in patients with cancer remains unclear.

- This retrospective cohort study included 9877 patients with cancer (mean age, 67.1 years) and 45,875 matched control individuals without cancer (mean age, 66.2 years). All participants had dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans.

- Researchers collected data on bone mineral density and fractures. The 10-year probabilities of major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures were calculated using FRAX, and the observed 10-year probabilities of these fractures were compared with FRAX-derived probabilities.

- Compared with individuals without cancer, patients with cancer had a shorter mean follow-up duration (8.5 vs 7.6 years), a slightly higher mean body mass index, and a higher percentage of parental hip fractures (7.0% vs 8.2%); additionally, patients with cancer were more likely to have secondary causes of osteoporosis (10% vs 38.4%) and less likely to receive osteoporosis medication (9.9% vs 4.2%).

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with individuals without cancer, patients with cancer had a significantly higher incidence rate of major fractures (12.9 vs 14.5 per 1000 person-years) and hip fractures (3.5 vs 4.2 per 1000 person-years).

- FRAX with bone mineral density exhibited excellent calibration for predicting major osteoporotic fractures (slope, 1.03) and hip fractures (0.97) in patients with cancer, regardless of the site of cancer diagnosis. FRAX without bone mineral density, however, underestimated the risk for both major (0.87) and hip fractures (0.72).

- In patients with cancer, FRAX with bone mineral density findings were associated with incident major osteoporotic fractures (hazard ratio [HR] per SD, 1.84) and hip fractures (HR per SD, 3.61).

- When models were adjusted for FRAX with bone mineral density, patients with cancer had an increased risk for both major osteoporotic fractures (HR, 1.17) and hip fractures (HR, 1.30). No difference was found in the risk for fracture between patients with and individuals without cancer when the models were adjusted for FRAX without bone mineral density, even when considering osteoporosis medication use.

IN PRACTICE:

“This retrospective cohort study demonstrates that individuals with cancer are at higher risk of fracture than individuals without cancer and that FRAX, particularly with BMD [bone mineral density], may accurately predict fracture risk in this population. These results, along with the known mortality risk of osteoporotic fractures among cancer survivors, further emphasize the clinical importance of closing the current osteoporosis care gap among cancer survivors,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study, led by Carrie Ye, MD, MPH, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, was published online in JAMA Oncology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study cohort included a selected group of cancer survivors who were referred for DXA scans and may not represent the general cancer population. The cohort consisted predominantly of women, limiting the generalizability to men with cancer. Given the heterogeneity of the population, the findings may not be applicable to all cancer subgroups. Information on cancer stage or the presence of bone metastases at the time of fracture risk assessment was lacking, which could have affected the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by the CancerCare Manitoba Foundation. Three authors reported having ties with various sources, including two who received grants from various organizations.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Cancer-specific guidelines recommend using FRAX to assess fracture risk, but its applicability in patients with cancer remains unclear.

- This retrospective cohort study included 9877 patients with cancer (mean age, 67.1 years) and 45,875 matched control individuals without cancer (mean age, 66.2 years). All participants had dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans.

- Researchers collected data on bone mineral density and fractures. The 10-year probabilities of major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures were calculated using FRAX, and the observed 10-year probabilities of these fractures were compared with FRAX-derived probabilities.

- Compared with individuals without cancer, patients with cancer had a shorter mean follow-up duration (8.5 vs 7.6 years), a slightly higher mean body mass index, and a higher percentage of parental hip fractures (7.0% vs 8.2%); additionally, patients with cancer were more likely to have secondary causes of osteoporosis (10% vs 38.4%) and less likely to receive osteoporosis medication (9.9% vs 4.2%).

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with individuals without cancer, patients with cancer had a significantly higher incidence rate of major fractures (12.9 vs 14.5 per 1000 person-years) and hip fractures (3.5 vs 4.2 per 1000 person-years).

- FRAX with bone mineral density exhibited excellent calibration for predicting major osteoporotic fractures (slope, 1.03) and hip fractures (0.97) in patients with cancer, regardless of the site of cancer diagnosis. FRAX without bone mineral density, however, underestimated the risk for both major (0.87) and hip fractures (0.72).

- In patients with cancer, FRAX with bone mineral density findings were associated with incident major osteoporotic fractures (hazard ratio [HR] per SD, 1.84) and hip fractures (HR per SD, 3.61).

- When models were adjusted for FRAX with bone mineral density, patients with cancer had an increased risk for both major osteoporotic fractures (HR, 1.17) and hip fractures (HR, 1.30). No difference was found in the risk for fracture between patients with and individuals without cancer when the models were adjusted for FRAX without bone mineral density, even when considering osteoporosis medication use.

IN PRACTICE:

“This retrospective cohort study demonstrates that individuals with cancer are at higher risk of fracture than individuals without cancer and that FRAX, particularly with BMD [bone mineral density], may accurately predict fracture risk in this population. These results, along with the known mortality risk of osteoporotic fractures among cancer survivors, further emphasize the clinical importance of closing the current osteoporosis care gap among cancer survivors,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study, led by Carrie Ye, MD, MPH, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, was published online in JAMA Oncology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study cohort included a selected group of cancer survivors who were referred for DXA scans and may not represent the general cancer population. The cohort consisted predominantly of women, limiting the generalizability to men with cancer. Given the heterogeneity of the population, the findings may not be applicable to all cancer subgroups. Information on cancer stage or the presence of bone metastases at the time of fracture risk assessment was lacking, which could have affected the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by the CancerCare Manitoba Foundation. Three authors reported having ties with various sources, including two who received grants from various organizations.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

These Patients May Be Less Adherent to nAMD Treatment

TOPLINE:

BARCELONA, SPAIN — Patients who receive a diagnosis of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) from their primary care clinician may be less likely to adhere to treatment than those who receive the diagnosis from a specialist who provides anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy, according to global survey results presented at the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA) 2024. Likewise, patients who self-pay for the medication or who have bilateral nAMD may be less adherent to therapy, researchers found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed data from 4558 patients with nAMD who participated in the Barometer Global Survey, which involved 77 clinics in 24 countries, including Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Germany, and France.

- The survey included multiple-choice questions on personal characteristics, disease awareness, experiences with treatment, and logistical challenges with getting to appointments.

- An exploratory statistical analysis identified 19 variables that influenced patient adherence to anti-VEGF therapy.

- The researchers classified 670 patients who missed two or more appointments during a 12-month period as nonadherent.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients with nAMD diagnosed by their family doctor or general practitioner had a threefold higher risk for nonadherence than those diagnosed by the physician treating their nAMD.

- Self-pay was associated with more than twice the odds of nonadherence compared with having insurance coverage (odds ratio [OR], 2.5).

- Compared with unilateral nAMD, bilateral nAMD was associated with higher odds of multiple missed appointments (OR, 1.7).

- Nonadherence increased with the number of anti-VEGF injections, which may show that “longer treatment durations could permit more opportunities for absenteeism,” the investigators noted.

IN PRACTICE:

“Identifying patient characteristics and challenges that may be associated with nonadherence allows clinicians to recognize patients at risk for nonadherence and provide further support before these patients begin to miss appointments,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Laurent Kodjikian, MD, PhD, with Croix-Rousse University Hospital and the University of Lyon in France. The findings were presented in a poster at EURETINA 2024 (September 19-22).

LIMITATIONS:

The survey relied on participant responses using Likert scales and single-choice questions. Patients from the United States were not included in the study.

DISCLOSURES:

The survey and medical writing support for the study were funded by Bayer Consumer Care. Kodjikian and co-authors disclosed consulting work for Bayer and other pharmaceutical companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

BARCELONA, SPAIN — Patients who receive a diagnosis of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) from their primary care clinician may be less likely to adhere to treatment than those who receive the diagnosis from a specialist who provides anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy, according to global survey results presented at the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA) 2024. Likewise, patients who self-pay for the medication or who have bilateral nAMD may be less adherent to therapy, researchers found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed data from 4558 patients with nAMD who participated in the Barometer Global Survey, which involved 77 clinics in 24 countries, including Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Germany, and France.

- The survey included multiple-choice questions on personal characteristics, disease awareness, experiences with treatment, and logistical challenges with getting to appointments.

- An exploratory statistical analysis identified 19 variables that influenced patient adherence to anti-VEGF therapy.

- The researchers classified 670 patients who missed two or more appointments during a 12-month period as nonadherent.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients with nAMD diagnosed by their family doctor or general practitioner had a threefold higher risk for nonadherence than those diagnosed by the physician treating their nAMD.

- Self-pay was associated with more than twice the odds of nonadherence compared with having insurance coverage (odds ratio [OR], 2.5).

- Compared with unilateral nAMD, bilateral nAMD was associated with higher odds of multiple missed appointments (OR, 1.7).

- Nonadherence increased with the number of anti-VEGF injections, which may show that “longer treatment durations could permit more opportunities for absenteeism,” the investigators noted.

IN PRACTICE:

“Identifying patient characteristics and challenges that may be associated with nonadherence allows clinicians to recognize patients at risk for nonadherence and provide further support before these patients begin to miss appointments,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Laurent Kodjikian, MD, PhD, with Croix-Rousse University Hospital and the University of Lyon in France. The findings were presented in a poster at EURETINA 2024 (September 19-22).

LIMITATIONS:

The survey relied on participant responses using Likert scales and single-choice questions. Patients from the United States were not included in the study.

DISCLOSURES:

The survey and medical writing support for the study were funded by Bayer Consumer Care. Kodjikian and co-authors disclosed consulting work for Bayer and other pharmaceutical companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

BARCELONA, SPAIN — Patients who receive a diagnosis of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) from their primary care clinician may be less likely to adhere to treatment than those who receive the diagnosis from a specialist who provides anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy, according to global survey results presented at the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA) 2024. Likewise, patients who self-pay for the medication or who have bilateral nAMD may be less adherent to therapy, researchers found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed data from 4558 patients with nAMD who participated in the Barometer Global Survey, which involved 77 clinics in 24 countries, including Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Germany, and France.

- The survey included multiple-choice questions on personal characteristics, disease awareness, experiences with treatment, and logistical challenges with getting to appointments.

- An exploratory statistical analysis identified 19 variables that influenced patient adherence to anti-VEGF therapy.

- The researchers classified 670 patients who missed two or more appointments during a 12-month period as nonadherent.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients with nAMD diagnosed by their family doctor or general practitioner had a threefold higher risk for nonadherence than those diagnosed by the physician treating their nAMD.

- Self-pay was associated with more than twice the odds of nonadherence compared with having insurance coverage (odds ratio [OR], 2.5).

- Compared with unilateral nAMD, bilateral nAMD was associated with higher odds of multiple missed appointments (OR, 1.7).

- Nonadherence increased with the number of anti-VEGF injections, which may show that “longer treatment durations could permit more opportunities for absenteeism,” the investigators noted.

IN PRACTICE:

“Identifying patient characteristics and challenges that may be associated with nonadherence allows clinicians to recognize patients at risk for nonadherence and provide further support before these patients begin to miss appointments,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Laurent Kodjikian, MD, PhD, with Croix-Rousse University Hospital and the University of Lyon in France. The findings were presented in a poster at EURETINA 2024 (September 19-22).

LIMITATIONS:

The survey relied on participant responses using Likert scales and single-choice questions. Patients from the United States were not included in the study.

DISCLOSURES:

The survey and medical writing support for the study were funded by Bayer Consumer Care. Kodjikian and co-authors disclosed consulting work for Bayer and other pharmaceutical companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is BMI Underestimating Breast Cancer Risk in Postmenopausal Women?

TOPLINE:

Accurate body fat measures are crucial for effective cancer prevention.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a case-control study including 1033 breast cancer cases and 1143 postmenopausal population controls from the MCC-Spain study.

- Participants were aged 20-85 years. BMI was calculated as the ratio of weight to height squared and categorized using World Health Organization standards: < 25, 25-29.9, 30-34.9, and ≥ 35.

- CUN-BAE was calculated using a specific equation and categorized according to the estimated percentage of body fat: < 35%, 35%-39.9%, 40%-44.9%, and ≥ 45%.

- Odds ratios (ORs) were estimated with 95% CIs for both measures (BMI and CUN-BAE) for breast cancer cases using unconditional logistic regression.

TAKEAWAY:

- Excess body weight attributable to the risk for breast cancer was 23% when assessed using a BMI value > 30 and 38% when assessed using a CUN-BAE value > 40% body fat.

- Hormone receptor stratification showed that these differences in population-attributable fractions were only observed in hormone receptor–positive cases, with an estimated burden of 19.9% for BMI and 41.9% for CUN-BAE.

- The highest categories of CUN-BAE showed an increase in the risk for postmenopausal breast cancer (OR, 2.13 for body fat ≥ 45% compared with the reference category < 35%).

- No similar trend was observed for BMI, as the gradient declined after a BMI ≥ 35.

IN PRACTICE:

“The results of our study indicate that excess body fat is a significant risk factor for hormone receptor–positive breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Our findings suggest that the population impact could be underestimated when using traditional BMI estimates, and that more accurate measures of body fat, such as CUN-BAE, should be considered,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Verónica Dávila-Batista, University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain. It was published online in Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.

LIMITATIONS:

The case-control design of the study may have limited the ability to establish causal relationships. BMI was self-reported at the time of the interview for controls and 1 year before diagnosis for cancer cases, which may have introduced recall bias. The formula for CUN-BAE was calculated from a sedentary convenience sample, which may not have been representative of the general population. The small sample size of cases that did not express hormone receptors was another limitation. The study’s findings may not be generalizable to non-White populations as non-White participants were excluded.

DISCLOSURES:

Dávila-Batista disclosed receiving grants from the Carlos III Health Institute. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Accurate body fat measures are crucial for effective cancer prevention.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a case-control study including 1033 breast cancer cases and 1143 postmenopausal population controls from the MCC-Spain study.

- Participants were aged 20-85 years. BMI was calculated as the ratio of weight to height squared and categorized using World Health Organization standards: < 25, 25-29.9, 30-34.9, and ≥ 35.

- CUN-BAE was calculated using a specific equation and categorized according to the estimated percentage of body fat: < 35%, 35%-39.9%, 40%-44.9%, and ≥ 45%.

- Odds ratios (ORs) were estimated with 95% CIs for both measures (BMI and CUN-BAE) for breast cancer cases using unconditional logistic regression.

TAKEAWAY:

- Excess body weight attributable to the risk for breast cancer was 23% when assessed using a BMI value > 30 and 38% when assessed using a CUN-BAE value > 40% body fat.

- Hormone receptor stratification showed that these differences in population-attributable fractions were only observed in hormone receptor–positive cases, with an estimated burden of 19.9% for BMI and 41.9% for CUN-BAE.

- The highest categories of CUN-BAE showed an increase in the risk for postmenopausal breast cancer (OR, 2.13 for body fat ≥ 45% compared with the reference category < 35%).

- No similar trend was observed for BMI, as the gradient declined after a BMI ≥ 35.

IN PRACTICE: