User login

FDA clears 5-minute test for early dementia

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has given marketing clearance to CognICA, an artificial intelligence–powered integrated cognitive assessment for the early detection of dementia.

Developed by Cognetivity Neurosciences, CognICA is a 5-minute, computerized cognitive assessment that is completed using an iPad. The test offers several advantages over traditional pen-and-paper–based cognitive tests, the company said in a news release.

“These include its high sensitivity to early-stage cognitive impairment, avoidance of cultural or educational bias, and absence of learning effect upon repeat testing,” the company notes.

Because the test runs on a computer, it can support remote, self-administered testing at scale and is geared toward seamless integration with existing electronic health record systems, they add.

According to the latest Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures, published by the Alzheimer’s Association, more than 6 million Americans are now living with Alzheimer’s disease. That number is projected to increase to 12.7 million by 2050.

“We’re excited about the opportunity to revolutionize the way cognitive impairment is assessed and managed in the U.S. and make a positive impact on the health and wellbeing of millions of Americans,” Sina Habibi, PhD, cofounder and CEO of Cognetivity, said in the news release.

The test has already received European regulatory approval as a CE-marked medical device and has been deployed in both primary and specialist clinical care in the U.K.’s National Health Service.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has given marketing clearance to CognICA, an artificial intelligence–powered integrated cognitive assessment for the early detection of dementia.

Developed by Cognetivity Neurosciences, CognICA is a 5-minute, computerized cognitive assessment that is completed using an iPad. The test offers several advantages over traditional pen-and-paper–based cognitive tests, the company said in a news release.

“These include its high sensitivity to early-stage cognitive impairment, avoidance of cultural or educational bias, and absence of learning effect upon repeat testing,” the company notes.

Because the test runs on a computer, it can support remote, self-administered testing at scale and is geared toward seamless integration with existing electronic health record systems, they add.

According to the latest Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures, published by the Alzheimer’s Association, more than 6 million Americans are now living with Alzheimer’s disease. That number is projected to increase to 12.7 million by 2050.

“We’re excited about the opportunity to revolutionize the way cognitive impairment is assessed and managed in the U.S. and make a positive impact on the health and wellbeing of millions of Americans,” Sina Habibi, PhD, cofounder and CEO of Cognetivity, said in the news release.

The test has already received European regulatory approval as a CE-marked medical device and has been deployed in both primary and specialist clinical care in the U.K.’s National Health Service.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has given marketing clearance to CognICA, an artificial intelligence–powered integrated cognitive assessment for the early detection of dementia.

Developed by Cognetivity Neurosciences, CognICA is a 5-minute, computerized cognitive assessment that is completed using an iPad. The test offers several advantages over traditional pen-and-paper–based cognitive tests, the company said in a news release.

“These include its high sensitivity to early-stage cognitive impairment, avoidance of cultural or educational bias, and absence of learning effect upon repeat testing,” the company notes.

Because the test runs on a computer, it can support remote, self-administered testing at scale and is geared toward seamless integration with existing electronic health record systems, they add.

According to the latest Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures, published by the Alzheimer’s Association, more than 6 million Americans are now living with Alzheimer’s disease. That number is projected to increase to 12.7 million by 2050.

“We’re excited about the opportunity to revolutionize the way cognitive impairment is assessed and managed in the U.S. and make a positive impact on the health and wellbeing of millions of Americans,” Sina Habibi, PhD, cofounder and CEO of Cognetivity, said in the news release.

The test has already received European regulatory approval as a CE-marked medical device and has been deployed in both primary and specialist clinical care in the U.K.’s National Health Service.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Guidelines for dementia and age-related cognitive changes

It is estimated that by the year 2060, 13.9 million Americans over the age of 65 will be diagnosed with dementia. Few good treatments are currently available.

Earlier this year, the American Psychological Association (APA) Task Force issued clinical guidelines “for the Evaluation of Dementia and Age-Related Cognitive Change.” While these 16 guidelines are aimed at psychologists, primary care doctors are often the first ones to evaluate a patient who may have dementia. As a family physician, I find having these guidelines especially helpful.

Neuropsychiatric testing and defining severity and type

This new guidance places emphasis on neuropsychiatric testing and defining the severity and type of dementia present.

Over the past 2 decades, diagnoses of mild neurocognitive disorders have increased, and this, in part, is due to diagnosing these problems earlier and with greater precision. It is also important to know that biomarkers are being increasingly researched, and it is imperative that we stay current with this research.

Cognitive decline may also occur with the coexistence of other mental health disorders, such as depression, so it is important that we screen for these as well. This is often difficult given the behavioral changes that can arise in dementia, but, as primary care doctors, we must differentiate these to treat our patients appropriately.

Informed consent

Informed consent can become an issue with patients with dementia. It must be assessed whether the patient has the capacity to make an informed decision and can competently communicate that decision.

The diagnosis of dementia alone does not preclude a patient from giving informed consent. A patient’s mental capacity must be determined, and if they are not capable of making an informed decision, the person legally responsible for giving informed consent on behalf of the patient must be identified.

Patients with dementia often have other medical comorbidities and take several medications. It is imperative to keep accurate medical records and medication lists. Sometimes, patients with dementia cannot provide this information. If that is the case, every attempt should be made to obtain records from every possible source.

Cultural competence

The guidelines also stress that there may be cultural differences when applying neuropsychiatric tests. It is our duty to maintain cultural competence and understand these differences. We all need to work to ensure we control our biases, and it is suggested that we review relevant evidence-based literature.

While ageism is common in our society, it shouldn’t be in our practices. For these reasons, outreach in at-risk populations is very important.

Pertinent data

The guidelines also suggest obtaining all possible information in our evaluation, especially when the patient is unable to give it to us.

Often, as primary care physicians, we refer these patients to other providers, and we should be providing all pertinent data to those we are referring these patients to. If all information is not available at the time of evaluation, follow-up visits should be scheduled.

If possible, family members should be present at the time of visit. They often provide valuable information regarding the extent and progression of the decline. Also, they know how the patient is functioning in the home setting and how much assistance they need with activities of daily living.

Caretaker support

Another important factor to consider is caretaker burnout. Caretakers are often under a lot of stress and have high rates of depression. It is important to provide them with education and support, as well as resources that may be available to them. For some, accepting the diagnosis that their loved one has dementia may be a struggle.

As doctors treating dementia patients, we need to know the resources that are available to assist dementia patients and their families. There are many local organizations that can help.

Also, research into dementia is ongoing and we need to stay current. The diagnosis of dementia should be made as early as possible using appropriate screening tools. The sooner the diagnosis is made, the quicker interventions can be started and the family members, as well as the patient, can come to accept the diagnosis.

As the population ages, we can expect the demands of dementia to rise as well. Primary care doctors are in a unique position to diagnose dementia once it starts to appear.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

It is estimated that by the year 2060, 13.9 million Americans over the age of 65 will be diagnosed with dementia. Few good treatments are currently available.

Earlier this year, the American Psychological Association (APA) Task Force issued clinical guidelines “for the Evaluation of Dementia and Age-Related Cognitive Change.” While these 16 guidelines are aimed at psychologists, primary care doctors are often the first ones to evaluate a patient who may have dementia. As a family physician, I find having these guidelines especially helpful.

Neuropsychiatric testing and defining severity and type

This new guidance places emphasis on neuropsychiatric testing and defining the severity and type of dementia present.

Over the past 2 decades, diagnoses of mild neurocognitive disorders have increased, and this, in part, is due to diagnosing these problems earlier and with greater precision. It is also important to know that biomarkers are being increasingly researched, and it is imperative that we stay current with this research.

Cognitive decline may also occur with the coexistence of other mental health disorders, such as depression, so it is important that we screen for these as well. This is often difficult given the behavioral changes that can arise in dementia, but, as primary care doctors, we must differentiate these to treat our patients appropriately.

Informed consent

Informed consent can become an issue with patients with dementia. It must be assessed whether the patient has the capacity to make an informed decision and can competently communicate that decision.

The diagnosis of dementia alone does not preclude a patient from giving informed consent. A patient’s mental capacity must be determined, and if they are not capable of making an informed decision, the person legally responsible for giving informed consent on behalf of the patient must be identified.

Patients with dementia often have other medical comorbidities and take several medications. It is imperative to keep accurate medical records and medication lists. Sometimes, patients with dementia cannot provide this information. If that is the case, every attempt should be made to obtain records from every possible source.

Cultural competence

The guidelines also stress that there may be cultural differences when applying neuropsychiatric tests. It is our duty to maintain cultural competence and understand these differences. We all need to work to ensure we control our biases, and it is suggested that we review relevant evidence-based literature.

While ageism is common in our society, it shouldn’t be in our practices. For these reasons, outreach in at-risk populations is very important.

Pertinent data

The guidelines also suggest obtaining all possible information in our evaluation, especially when the patient is unable to give it to us.

Often, as primary care physicians, we refer these patients to other providers, and we should be providing all pertinent data to those we are referring these patients to. If all information is not available at the time of evaluation, follow-up visits should be scheduled.

If possible, family members should be present at the time of visit. They often provide valuable information regarding the extent and progression of the decline. Also, they know how the patient is functioning in the home setting and how much assistance they need with activities of daily living.

Caretaker support

Another important factor to consider is caretaker burnout. Caretakers are often under a lot of stress and have high rates of depression. It is important to provide them with education and support, as well as resources that may be available to them. For some, accepting the diagnosis that their loved one has dementia may be a struggle.

As doctors treating dementia patients, we need to know the resources that are available to assist dementia patients and their families. There are many local organizations that can help.

Also, research into dementia is ongoing and we need to stay current. The diagnosis of dementia should be made as early as possible using appropriate screening tools. The sooner the diagnosis is made, the quicker interventions can be started and the family members, as well as the patient, can come to accept the diagnosis.

As the population ages, we can expect the demands of dementia to rise as well. Primary care doctors are in a unique position to diagnose dementia once it starts to appear.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

It is estimated that by the year 2060, 13.9 million Americans over the age of 65 will be diagnosed with dementia. Few good treatments are currently available.

Earlier this year, the American Psychological Association (APA) Task Force issued clinical guidelines “for the Evaluation of Dementia and Age-Related Cognitive Change.” While these 16 guidelines are aimed at psychologists, primary care doctors are often the first ones to evaluate a patient who may have dementia. As a family physician, I find having these guidelines especially helpful.

Neuropsychiatric testing and defining severity and type

This new guidance places emphasis on neuropsychiatric testing and defining the severity and type of dementia present.

Over the past 2 decades, diagnoses of mild neurocognitive disorders have increased, and this, in part, is due to diagnosing these problems earlier and with greater precision. It is also important to know that biomarkers are being increasingly researched, and it is imperative that we stay current with this research.

Cognitive decline may also occur with the coexistence of other mental health disorders, such as depression, so it is important that we screen for these as well. This is often difficult given the behavioral changes that can arise in dementia, but, as primary care doctors, we must differentiate these to treat our patients appropriately.

Informed consent

Informed consent can become an issue with patients with dementia. It must be assessed whether the patient has the capacity to make an informed decision and can competently communicate that decision.

The diagnosis of dementia alone does not preclude a patient from giving informed consent. A patient’s mental capacity must be determined, and if they are not capable of making an informed decision, the person legally responsible for giving informed consent on behalf of the patient must be identified.

Patients with dementia often have other medical comorbidities and take several medications. It is imperative to keep accurate medical records and medication lists. Sometimes, patients with dementia cannot provide this information. If that is the case, every attempt should be made to obtain records from every possible source.

Cultural competence

The guidelines also stress that there may be cultural differences when applying neuropsychiatric tests. It is our duty to maintain cultural competence and understand these differences. We all need to work to ensure we control our biases, and it is suggested that we review relevant evidence-based literature.

While ageism is common in our society, it shouldn’t be in our practices. For these reasons, outreach in at-risk populations is very important.

Pertinent data

The guidelines also suggest obtaining all possible information in our evaluation, especially when the patient is unable to give it to us.

Often, as primary care physicians, we refer these patients to other providers, and we should be providing all pertinent data to those we are referring these patients to. If all information is not available at the time of evaluation, follow-up visits should be scheduled.

If possible, family members should be present at the time of visit. They often provide valuable information regarding the extent and progression of the decline. Also, they know how the patient is functioning in the home setting and how much assistance they need with activities of daily living.

Caretaker support

Another important factor to consider is caretaker burnout. Caretakers are often under a lot of stress and have high rates of depression. It is important to provide them with education and support, as well as resources that may be available to them. For some, accepting the diagnosis that their loved one has dementia may be a struggle.

As doctors treating dementia patients, we need to know the resources that are available to assist dementia patients and their families. There are many local organizations that can help.

Also, research into dementia is ongoing and we need to stay current. The diagnosis of dementia should be made as early as possible using appropriate screening tools. The sooner the diagnosis is made, the quicker interventions can be started and the family members, as well as the patient, can come to accept the diagnosis.

As the population ages, we can expect the demands of dementia to rise as well. Primary care doctors are in a unique position to diagnose dementia once it starts to appear.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

Let’s talk about healthy aging (but where to begin?)

This month’s cover story, “A 4-pronged approach to foster healthy aging in older adults,” by Wilson and colleagues (page 376) provides a wealth of information about aspects of healthy aging that we should consider when we see our older patients. After reading this manuscript, I was a bit overwhelmed by the amount of information presented and, more so, by the thought of attempting to incorporate into my practice all of the possible screenings and interventions available to help older adults improve and maintain their health.

There is no debate about the importance of issues such as diet, exercise and mobility, mental health and cognition, vision and hearing, and strong social connections for maintaining health as we age. The difficulty comes in deciding how to spend our limited time with older patients during office encounters. Most older adults have several chronic diseases that need our attention, and they often have various medications that need to be monitored for effectiveness and safety, which can be time consuming. And, of course, we need to take time to screen for cardiovascular risk and cancer, too. Where to start?

Dr. Wilson’s solution makes sense to me: Take advantage of the annual wellness visit to discuss diet, exercise, mental health, vision and hearing, and social relationships. I am not so sure, however, if using formal screening instruments is the best way to do this, especially since there is no strong research that demonstrates improved patient-relevant outcomes using screening instruments, except, perhaps, for periodically screening for anxiety and depression.

It may be as effective to use what I will call the “chat technique.” Start with open-ended questions and statements, such as: “How are things going for you?” “Tell me about your family.” “What do you do for physical activity?” and “How has your mood been lately?”

An excellent complement to the chat technique is the goal-setting approach championed by geriatrician and family physician Jim Mold.1 His premise is that health itself is not the most important goal for most people, but rather a means to an end. That end is very specific to every person. An elderly, frail woman’s main life goal, for example, might be to remain in her own home for as long as possible or to live long enough to attend her great-grandson’s wedding.

Goal setting provides an excellent context for true shared decision-making. I agree with Dr. Wilson’s closing statement:

“As family physicians, it is important to capitalize on longitudinal relationships with patients and begin educating younger patients using this multidimensional framework to promote living ‘a productive and meaningful life’at any age.”

1. Mold, JW. Goal-Oriented Medical Care: Helping Patients Achieve Their Personal Health Goals. Full Court Press; 2017.

This month’s cover story, “A 4-pronged approach to foster healthy aging in older adults,” by Wilson and colleagues (page 376) provides a wealth of information about aspects of healthy aging that we should consider when we see our older patients. After reading this manuscript, I was a bit overwhelmed by the amount of information presented and, more so, by the thought of attempting to incorporate into my practice all of the possible screenings and interventions available to help older adults improve and maintain their health.

There is no debate about the importance of issues such as diet, exercise and mobility, mental health and cognition, vision and hearing, and strong social connections for maintaining health as we age. The difficulty comes in deciding how to spend our limited time with older patients during office encounters. Most older adults have several chronic diseases that need our attention, and they often have various medications that need to be monitored for effectiveness and safety, which can be time consuming. And, of course, we need to take time to screen for cardiovascular risk and cancer, too. Where to start?

Dr. Wilson’s solution makes sense to me: Take advantage of the annual wellness visit to discuss diet, exercise, mental health, vision and hearing, and social relationships. I am not so sure, however, if using formal screening instruments is the best way to do this, especially since there is no strong research that demonstrates improved patient-relevant outcomes using screening instruments, except, perhaps, for periodically screening for anxiety and depression.

It may be as effective to use what I will call the “chat technique.” Start with open-ended questions and statements, such as: “How are things going for you?” “Tell me about your family.” “What do you do for physical activity?” and “How has your mood been lately?”

An excellent complement to the chat technique is the goal-setting approach championed by geriatrician and family physician Jim Mold.1 His premise is that health itself is not the most important goal for most people, but rather a means to an end. That end is very specific to every person. An elderly, frail woman’s main life goal, for example, might be to remain in her own home for as long as possible or to live long enough to attend her great-grandson’s wedding.

Goal setting provides an excellent context for true shared decision-making. I agree with Dr. Wilson’s closing statement:

“As family physicians, it is important to capitalize on longitudinal relationships with patients and begin educating younger patients using this multidimensional framework to promote living ‘a productive and meaningful life’at any age.”

This month’s cover story, “A 4-pronged approach to foster healthy aging in older adults,” by Wilson and colleagues (page 376) provides a wealth of information about aspects of healthy aging that we should consider when we see our older patients. After reading this manuscript, I was a bit overwhelmed by the amount of information presented and, more so, by the thought of attempting to incorporate into my practice all of the possible screenings and interventions available to help older adults improve and maintain their health.

There is no debate about the importance of issues such as diet, exercise and mobility, mental health and cognition, vision and hearing, and strong social connections for maintaining health as we age. The difficulty comes in deciding how to spend our limited time with older patients during office encounters. Most older adults have several chronic diseases that need our attention, and they often have various medications that need to be monitored for effectiveness and safety, which can be time consuming. And, of course, we need to take time to screen for cardiovascular risk and cancer, too. Where to start?

Dr. Wilson’s solution makes sense to me: Take advantage of the annual wellness visit to discuss diet, exercise, mental health, vision and hearing, and social relationships. I am not so sure, however, if using formal screening instruments is the best way to do this, especially since there is no strong research that demonstrates improved patient-relevant outcomes using screening instruments, except, perhaps, for periodically screening for anxiety and depression.

It may be as effective to use what I will call the “chat technique.” Start with open-ended questions and statements, such as: “How are things going for you?” “Tell me about your family.” “What do you do for physical activity?” and “How has your mood been lately?”

An excellent complement to the chat technique is the goal-setting approach championed by geriatrician and family physician Jim Mold.1 His premise is that health itself is not the most important goal for most people, but rather a means to an end. That end is very specific to every person. An elderly, frail woman’s main life goal, for example, might be to remain in her own home for as long as possible or to live long enough to attend her great-grandson’s wedding.

Goal setting provides an excellent context for true shared decision-making. I agree with Dr. Wilson’s closing statement:

“As family physicians, it is important to capitalize on longitudinal relationships with patients and begin educating younger patients using this multidimensional framework to promote living ‘a productive and meaningful life’at any age.”

1. Mold, JW. Goal-Oriented Medical Care: Helping Patients Achieve Their Personal Health Goals. Full Court Press; 2017.

1. Mold, JW. Goal-Oriented Medical Care: Helping Patients Achieve Their Personal Health Goals. Full Court Press; 2017.

Bone risk: Is time since menopause a better predictor than age?

Although early menopause is linked to increased risks in bone loss and fracture, new research indicates that, even among the majority of women who have menopause after age 45, the time since the final menstrual period can be a stronger predictor than chronological age for key risks in bone health and fracture.

In a large longitudinal cohort, the number of years since a woman’s final menstrual period specifically showed a stronger association with femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) than chronological age, while an earlier age at menopause – even among those over 45 years, was linked to an increased risk of fracture.

“Most of our clinical tools to predict osteoporosis-related outcomes use chronological age,” first author Albert Shieh, MD, told this news organization.

“Our findings suggest that more research should be done to examine whether ovarian age (time since final menstrual period) should be used in these tools as well.”

An increased focus on the significance of age at the time of the final menstrual period, compared with chronological age, has gained interest in risk assessment because of the known acceleration in the decline of BMD that occurs 1 year prior to the final menstrual period and continues at a rapid pace for 3 years afterwards before slowing.

To further investigate the association with BMD, Dr. Shieh, an endocrinologist specializing in osteoporosis at the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues turned to data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a longitudinal cohort study of ambulatory women with pre- or early perimenopausal baseline data and 15 annual follow-up assessments.

Outcomes regarding postmenopausal lumbar spine (LS) or femoral neck (FN) BMD were evaluated in 1,038 women, while the time to fracture in relation to the final menstrual period was separately evaluated in 1,554 women.

In both cohorts, the women had a known final menstrual period at age 45 or older, and on average, their final menstrual period occurred at age 52.

After a multivariate adjustment for age, body mass index, and various other factors, they found that each additional year after a woman’s final menstrual period was associated with a significant (0.006 g/cm2) reduction in postmenopausal lumbar spine BMD and a 0.004 g/cm2 reduction femoral neck BMD (both P < .0001).

Conversely, chronological age was not associated with a change in femoral neck BMD when evaluated independently of years since the final menstrual period, the researchers reported in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Regarding lumbar spine BMD, chronological age was unexpectedly associated not just with change, but in fact with increases in lumbar spine BMD (P < .0001 per year). However, the authors speculate the change “is likely a reflection of age-associated degenerative changes causing false elevations in BMD measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.”

Fracture risk with earlier menopause

In terms of the fracture risk analysis, despite the women all being aged 45 or older, earlier age at menopause was still tied to an increased risk of incident fracture, with a 5% increase in risk for each earlier year in age at the time of the final menstrual period (P = .02).

Compared with women who had their final menstrual period at age 55, for instance, those who finished menstruating at age 47 had a 6.3% greater 20-year cumulative fracture risk, the authors note.

While previous findings from the Malmo Perimenopausal Study showed menopause prior to the age of 47 to be associated with an 83% and 59% greater risk of densitometric osteoporosis and fracture, respectively, by age 77, the authors note that the new study is unique in including only women who had a final menstrual period over the age of 45, therefore reducing the potential confounding of data on women under 45.

The new results “add to a growing body of literature suggesting that the endocrine changes that occur during the menopause transition trigger a pathophysiologic cascade that leads to organ dysfunction,” the authors note.

In terms of implications in risk assessment, “future studies should examine whether years since the final menstrual period predicts major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures, specifically, and, if so, whether replacing chronological age with years since the final menstrual period improves the performance of clinical prediction tools, such as FRAX [Fracture Risk Assessment Tool],” they add.

Addition to guidelines?

Commenting on the findings, Peter Ebeling, MD, the current president of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, noted that the study importantly “confirms what we had previously anticipated, that in women with menopause who are 45 years of age or older a lower age of final menstrual period is associated with lower spine and hip BMD and more fractures.”

“We had already known this for women with premature ovarian insufficiency or an early menopause, and this extends the observation to the vast majority of women – more than 90% – with a normal menopause age,” said Dr. Ebeling, professor of medicine at Monash Health, Monash University, in Melbourne.

Despite the known importance of the time since final menstrual period, guidelines still focus on age in terms of chronology, rather than biology, emphasizing the risk among women over 50, in general, rather than the time since the last menstrual period, he noted.

“There is an important difference [between those two], as shown by this study,” he said. “Guidelines could be easily adapted to reflect this.”

Specifically, the association between lower age of final menstrual period and lower spine and hip BMD and more fractures requires “more formal assessment to determine whether adding age of final menstrual period to existing fracture risk calculator tools, like FRAX, can improve absolute fracture risk prediction,” Dr. Ebeling noted.

The authors and Dr. Ebeling had no disclosures to report.

Although early menopause is linked to increased risks in bone loss and fracture, new research indicates that, even among the majority of women who have menopause after age 45, the time since the final menstrual period can be a stronger predictor than chronological age for key risks in bone health and fracture.

In a large longitudinal cohort, the number of years since a woman’s final menstrual period specifically showed a stronger association with femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) than chronological age, while an earlier age at menopause – even among those over 45 years, was linked to an increased risk of fracture.

“Most of our clinical tools to predict osteoporosis-related outcomes use chronological age,” first author Albert Shieh, MD, told this news organization.

“Our findings suggest that more research should be done to examine whether ovarian age (time since final menstrual period) should be used in these tools as well.”

An increased focus on the significance of age at the time of the final menstrual period, compared with chronological age, has gained interest in risk assessment because of the known acceleration in the decline of BMD that occurs 1 year prior to the final menstrual period and continues at a rapid pace for 3 years afterwards before slowing.

To further investigate the association with BMD, Dr. Shieh, an endocrinologist specializing in osteoporosis at the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues turned to data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a longitudinal cohort study of ambulatory women with pre- or early perimenopausal baseline data and 15 annual follow-up assessments.

Outcomes regarding postmenopausal lumbar spine (LS) or femoral neck (FN) BMD were evaluated in 1,038 women, while the time to fracture in relation to the final menstrual period was separately evaluated in 1,554 women.

In both cohorts, the women had a known final menstrual period at age 45 or older, and on average, their final menstrual period occurred at age 52.

After a multivariate adjustment for age, body mass index, and various other factors, they found that each additional year after a woman’s final menstrual period was associated with a significant (0.006 g/cm2) reduction in postmenopausal lumbar spine BMD and a 0.004 g/cm2 reduction femoral neck BMD (both P < .0001).

Conversely, chronological age was not associated with a change in femoral neck BMD when evaluated independently of years since the final menstrual period, the researchers reported in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Regarding lumbar spine BMD, chronological age was unexpectedly associated not just with change, but in fact with increases in lumbar spine BMD (P < .0001 per year). However, the authors speculate the change “is likely a reflection of age-associated degenerative changes causing false elevations in BMD measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.”

Fracture risk with earlier menopause

In terms of the fracture risk analysis, despite the women all being aged 45 or older, earlier age at menopause was still tied to an increased risk of incident fracture, with a 5% increase in risk for each earlier year in age at the time of the final menstrual period (P = .02).

Compared with women who had their final menstrual period at age 55, for instance, those who finished menstruating at age 47 had a 6.3% greater 20-year cumulative fracture risk, the authors note.

While previous findings from the Malmo Perimenopausal Study showed menopause prior to the age of 47 to be associated with an 83% and 59% greater risk of densitometric osteoporosis and fracture, respectively, by age 77, the authors note that the new study is unique in including only women who had a final menstrual period over the age of 45, therefore reducing the potential confounding of data on women under 45.

The new results “add to a growing body of literature suggesting that the endocrine changes that occur during the menopause transition trigger a pathophysiologic cascade that leads to organ dysfunction,” the authors note.

In terms of implications in risk assessment, “future studies should examine whether years since the final menstrual period predicts major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures, specifically, and, if so, whether replacing chronological age with years since the final menstrual period improves the performance of clinical prediction tools, such as FRAX [Fracture Risk Assessment Tool],” they add.

Addition to guidelines?

Commenting on the findings, Peter Ebeling, MD, the current president of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, noted that the study importantly “confirms what we had previously anticipated, that in women with menopause who are 45 years of age or older a lower age of final menstrual period is associated with lower spine and hip BMD and more fractures.”

“We had already known this for women with premature ovarian insufficiency or an early menopause, and this extends the observation to the vast majority of women – more than 90% – with a normal menopause age,” said Dr. Ebeling, professor of medicine at Monash Health, Monash University, in Melbourne.

Despite the known importance of the time since final menstrual period, guidelines still focus on age in terms of chronology, rather than biology, emphasizing the risk among women over 50, in general, rather than the time since the last menstrual period, he noted.

“There is an important difference [between those two], as shown by this study,” he said. “Guidelines could be easily adapted to reflect this.”

Specifically, the association between lower age of final menstrual period and lower spine and hip BMD and more fractures requires “more formal assessment to determine whether adding age of final menstrual period to existing fracture risk calculator tools, like FRAX, can improve absolute fracture risk prediction,” Dr. Ebeling noted.

The authors and Dr. Ebeling had no disclosures to report.

Although early menopause is linked to increased risks in bone loss and fracture, new research indicates that, even among the majority of women who have menopause after age 45, the time since the final menstrual period can be a stronger predictor than chronological age for key risks in bone health and fracture.

In a large longitudinal cohort, the number of years since a woman’s final menstrual period specifically showed a stronger association with femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) than chronological age, while an earlier age at menopause – even among those over 45 years, was linked to an increased risk of fracture.

“Most of our clinical tools to predict osteoporosis-related outcomes use chronological age,” first author Albert Shieh, MD, told this news organization.

“Our findings suggest that more research should be done to examine whether ovarian age (time since final menstrual period) should be used in these tools as well.”

An increased focus on the significance of age at the time of the final menstrual period, compared with chronological age, has gained interest in risk assessment because of the known acceleration in the decline of BMD that occurs 1 year prior to the final menstrual period and continues at a rapid pace for 3 years afterwards before slowing.

To further investigate the association with BMD, Dr. Shieh, an endocrinologist specializing in osteoporosis at the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues turned to data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a longitudinal cohort study of ambulatory women with pre- or early perimenopausal baseline data and 15 annual follow-up assessments.

Outcomes regarding postmenopausal lumbar spine (LS) or femoral neck (FN) BMD were evaluated in 1,038 women, while the time to fracture in relation to the final menstrual period was separately evaluated in 1,554 women.

In both cohorts, the women had a known final menstrual period at age 45 or older, and on average, their final menstrual period occurred at age 52.

After a multivariate adjustment for age, body mass index, and various other factors, they found that each additional year after a woman’s final menstrual period was associated with a significant (0.006 g/cm2) reduction in postmenopausal lumbar spine BMD and a 0.004 g/cm2 reduction femoral neck BMD (both P < .0001).

Conversely, chronological age was not associated with a change in femoral neck BMD when evaluated independently of years since the final menstrual period, the researchers reported in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Regarding lumbar spine BMD, chronological age was unexpectedly associated not just with change, but in fact with increases in lumbar spine BMD (P < .0001 per year). However, the authors speculate the change “is likely a reflection of age-associated degenerative changes causing false elevations in BMD measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.”

Fracture risk with earlier menopause

In terms of the fracture risk analysis, despite the women all being aged 45 or older, earlier age at menopause was still tied to an increased risk of incident fracture, with a 5% increase in risk for each earlier year in age at the time of the final menstrual period (P = .02).

Compared with women who had their final menstrual period at age 55, for instance, those who finished menstruating at age 47 had a 6.3% greater 20-year cumulative fracture risk, the authors note.

While previous findings from the Malmo Perimenopausal Study showed menopause prior to the age of 47 to be associated with an 83% and 59% greater risk of densitometric osteoporosis and fracture, respectively, by age 77, the authors note that the new study is unique in including only women who had a final menstrual period over the age of 45, therefore reducing the potential confounding of data on women under 45.

The new results “add to a growing body of literature suggesting that the endocrine changes that occur during the menopause transition trigger a pathophysiologic cascade that leads to organ dysfunction,” the authors note.

In terms of implications in risk assessment, “future studies should examine whether years since the final menstrual period predicts major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures, specifically, and, if so, whether replacing chronological age with years since the final menstrual period improves the performance of clinical prediction tools, such as FRAX [Fracture Risk Assessment Tool],” they add.

Addition to guidelines?

Commenting on the findings, Peter Ebeling, MD, the current president of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, noted that the study importantly “confirms what we had previously anticipated, that in women with menopause who are 45 years of age or older a lower age of final menstrual period is associated with lower spine and hip BMD and more fractures.”

“We had already known this for women with premature ovarian insufficiency or an early menopause, and this extends the observation to the vast majority of women – more than 90% – with a normal menopause age,” said Dr. Ebeling, professor of medicine at Monash Health, Monash University, in Melbourne.

Despite the known importance of the time since final menstrual period, guidelines still focus on age in terms of chronology, rather than biology, emphasizing the risk among women over 50, in general, rather than the time since the last menstrual period, he noted.

“There is an important difference [between those two], as shown by this study,” he said. “Guidelines could be easily adapted to reflect this.”

Specifically, the association between lower age of final menstrual period and lower spine and hip BMD and more fractures requires “more formal assessment to determine whether adding age of final menstrual period to existing fracture risk calculator tools, like FRAX, can improve absolute fracture risk prediction,” Dr. Ebeling noted.

The authors and Dr. Ebeling had no disclosures to report.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY AND METABOLISM

FDA proposes new rule for over-the-counter hearing aids

The action comes nearly 5 years after Congress passed a law to allow over-the-counter sales for people with mild to moderate hearing loss.

Those with severe hearing loss or people under 18 years old would still need to see a doctor or specialist for a hearing device.

In the United States, access to hearing aids can be difficult and expensive. Usually, patients have to go see their health care providers for a prescription. Then, they go to an audiologist, or a hearing aid specialist, to get the devices fitted.

With the proposed rule, patients could skip both of those steps and buy hearing aids in retail stores or online. This would make the process easier and more cost-friendly, as well increase access to specialists for many Americans who don’t have it.

“This allows us to put hearing devices more in reach of communities that have often been left out. Communities of color and the underserved typically and traditionally lacked access to hearing aids,” Xavier Becerra, secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, said at a news briefing.

The FDA says it’s unclear exactly when the new products will be in stores, but finalizing the ruling is a top priority.

For new products, the ruling is expected to go into effect 60 days after it is finalized. Current products would have 180 days to make changes, according to the FDA.

The American Academy of Audiology said in a statement that it is reviewing the proposed rules and will provide comments to the FDA. But in July, Angela Shoup, PhD, a professor at the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences at the University of Texas at Dallas, wrote to Mr. Becerra with concerns about over-the-counter sales of hearing aids.

“While we certainly support efforts to lower costs and improve access to hearing aids, we have grave concerns about the oversimplification of hearing loss and treatment in the advancement of OTC devices,” she wrote.

“It is through involvement of an audiologist that consumers will achieve the best possible outcomes with OTC hearing aids and avoid the risks of under- or untreated hearing loss,” Dr. Shoup said.

This new category would apply to certain air conduction hearing aids, which are worn inside of the ear and improve hearing by boosting sound into the ear canal.

The FDA is proposing labeling requirements for the hearing devices, including warnings, age restrictions, and information on severe hearing loss and other medical conditions that would prompt patients to seek treatment from their doctors.

The FDA said that it would closely monitor the marketplace to make sure companies advertising hearing loss products follow federal regulations.

There are a number of reasons for hearing loss, including exposure to extremely loud noises, aging, and various medical conditions. Approximately 38 million Americans 18 years old and older report having hearing trouble, said Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the FDA.

About 20% of people who could benefit from hearing aids are using them, with barriers to access being a major factor, she added.

“Hearing loss can have a profound impact on daily communication, social interaction, and overall health and quality of life for millions of Americans,” Dr. Woodcock said.

The FDA has updated its guidance on hearing devices and personal sound amplification products.

Personal sound amplification products (PSAPs) are nonmedical devices designed to amplify sounds for people with normal hearing and are usually used for activities such as bird-watching and hunting.

Amplification devices are not regulated by the FDA.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The action comes nearly 5 years after Congress passed a law to allow over-the-counter sales for people with mild to moderate hearing loss.

Those with severe hearing loss or people under 18 years old would still need to see a doctor or specialist for a hearing device.

In the United States, access to hearing aids can be difficult and expensive. Usually, patients have to go see their health care providers for a prescription. Then, they go to an audiologist, or a hearing aid specialist, to get the devices fitted.

With the proposed rule, patients could skip both of those steps and buy hearing aids in retail stores or online. This would make the process easier and more cost-friendly, as well increase access to specialists for many Americans who don’t have it.

“This allows us to put hearing devices more in reach of communities that have often been left out. Communities of color and the underserved typically and traditionally lacked access to hearing aids,” Xavier Becerra, secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, said at a news briefing.

The FDA says it’s unclear exactly when the new products will be in stores, but finalizing the ruling is a top priority.

For new products, the ruling is expected to go into effect 60 days after it is finalized. Current products would have 180 days to make changes, according to the FDA.

The American Academy of Audiology said in a statement that it is reviewing the proposed rules and will provide comments to the FDA. But in July, Angela Shoup, PhD, a professor at the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences at the University of Texas at Dallas, wrote to Mr. Becerra with concerns about over-the-counter sales of hearing aids.

“While we certainly support efforts to lower costs and improve access to hearing aids, we have grave concerns about the oversimplification of hearing loss and treatment in the advancement of OTC devices,” she wrote.

“It is through involvement of an audiologist that consumers will achieve the best possible outcomes with OTC hearing aids and avoid the risks of under- or untreated hearing loss,” Dr. Shoup said.

This new category would apply to certain air conduction hearing aids, which are worn inside of the ear and improve hearing by boosting sound into the ear canal.

The FDA is proposing labeling requirements for the hearing devices, including warnings, age restrictions, and information on severe hearing loss and other medical conditions that would prompt patients to seek treatment from their doctors.

The FDA said that it would closely monitor the marketplace to make sure companies advertising hearing loss products follow federal regulations.

There are a number of reasons for hearing loss, including exposure to extremely loud noises, aging, and various medical conditions. Approximately 38 million Americans 18 years old and older report having hearing trouble, said Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the FDA.

About 20% of people who could benefit from hearing aids are using them, with barriers to access being a major factor, she added.

“Hearing loss can have a profound impact on daily communication, social interaction, and overall health and quality of life for millions of Americans,” Dr. Woodcock said.

The FDA has updated its guidance on hearing devices and personal sound amplification products.

Personal sound amplification products (PSAPs) are nonmedical devices designed to amplify sounds for people with normal hearing and are usually used for activities such as bird-watching and hunting.

Amplification devices are not regulated by the FDA.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The action comes nearly 5 years after Congress passed a law to allow over-the-counter sales for people with mild to moderate hearing loss.

Those with severe hearing loss or people under 18 years old would still need to see a doctor or specialist for a hearing device.

In the United States, access to hearing aids can be difficult and expensive. Usually, patients have to go see their health care providers for a prescription. Then, they go to an audiologist, or a hearing aid specialist, to get the devices fitted.

With the proposed rule, patients could skip both of those steps and buy hearing aids in retail stores or online. This would make the process easier and more cost-friendly, as well increase access to specialists for many Americans who don’t have it.

“This allows us to put hearing devices more in reach of communities that have often been left out. Communities of color and the underserved typically and traditionally lacked access to hearing aids,” Xavier Becerra, secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, said at a news briefing.

The FDA says it’s unclear exactly when the new products will be in stores, but finalizing the ruling is a top priority.

For new products, the ruling is expected to go into effect 60 days after it is finalized. Current products would have 180 days to make changes, according to the FDA.

The American Academy of Audiology said in a statement that it is reviewing the proposed rules and will provide comments to the FDA. But in July, Angela Shoup, PhD, a professor at the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences at the University of Texas at Dallas, wrote to Mr. Becerra with concerns about over-the-counter sales of hearing aids.

“While we certainly support efforts to lower costs and improve access to hearing aids, we have grave concerns about the oversimplification of hearing loss and treatment in the advancement of OTC devices,” she wrote.

“It is through involvement of an audiologist that consumers will achieve the best possible outcomes with OTC hearing aids and avoid the risks of under- or untreated hearing loss,” Dr. Shoup said.

This new category would apply to certain air conduction hearing aids, which are worn inside of the ear and improve hearing by boosting sound into the ear canal.

The FDA is proposing labeling requirements for the hearing devices, including warnings, age restrictions, and information on severe hearing loss and other medical conditions that would prompt patients to seek treatment from their doctors.

The FDA said that it would closely monitor the marketplace to make sure companies advertising hearing loss products follow federal regulations.

There are a number of reasons for hearing loss, including exposure to extremely loud noises, aging, and various medical conditions. Approximately 38 million Americans 18 years old and older report having hearing trouble, said Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the FDA.

About 20% of people who could benefit from hearing aids are using them, with barriers to access being a major factor, she added.

“Hearing loss can have a profound impact on daily communication, social interaction, and overall health and quality of life for millions of Americans,” Dr. Woodcock said.

The FDA has updated its guidance on hearing devices and personal sound amplification products.

Personal sound amplification products (PSAPs) are nonmedical devices designed to amplify sounds for people with normal hearing and are usually used for activities such as bird-watching and hunting.

Amplification devices are not regulated by the FDA.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A 4-pronged approach to foster healthy aging in older adults

Our approach to caring for the growing number of community-dwelling US adults ages ≥ 65 years has shifted. Although we continue to manage disease and disability, there is an increasing emphasis on the promotion of healthy aging by optimizing health care needs and quality of life (QOL).

The American Geriatric Society (AGS) uses the term “healthy aging” to reflect a dedication to improving the health, independence, and QOL of older people.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines healthy aging as “the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age.”2 Functional ability encompasses capabilities that align with a person’s values, including meeting basic needs; learning, growing, and making independent decisions; being mobile; building and maintaining healthy relationships; and contributing to society.2 Similarly, the US Department of Health and Human Services has adopted a multidimensional approach to support people in creating “a productive and meaningful life” as they grow older.3

Numerous theoretical models have emerged from research on aging as a multidimensional construct, as evidenced by a 2016 citation analysis that identified 1755 articles written between 1902 and 2015 relating to “successful aging.”4 The analysis revealed 609 definitions operationalized by researchers’ measurement tools (mostly focused on physical function and other health metrics) and 1146 descriptions created by older adults, many emphasizing psychosocial strategies and cultural factors as key to successful aging.4

One approach that is likely to be useful for family physicians is the Age-Friendly Health System. This is an initiative of The John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement that uses a multidisciplinary approach to create environments that foster inclusivity and address the needs of older people.5 Following this guidance, primary care providers use evidence-informed strategies that promote safety and address what matters most to older adults and their family caregivers.

The Age-Friendly Health System, as well as AGS and WHO, recognize that there are multiple aspects to well-being as one grows older. By using focused, evidence-based screening, assessments, and interventions, family physicians can best support aging patients in living their most fulfilling lives.

Here we present a review of evidence-based strategies that promote safety and address what matters most to older adults and their family caregivers using a 4-pronged framework, in the style of the Age-Friendly Health System model. However, the literature on healthy aging includes important messages about patient context and lifelong health behaviors, which we capture in an expanded set of thematic guidance. As such, we encourage family physicians to approach healthy aging as follows: (1) monitor health (screening and prevention), (2) promote mobility (physical function), (3) manage mentation (emotional health and cognitive function), and (4) encourage maintenance of social connections (social networks and QOL).

Monitoring health

Leverage Medicare annual wellness visits. A systematic approach is needed to prevent frailty and functional decline, and thus increase the QOL of older adults. To do this, it is important to focus on health promotion and disease prevention, while addressing existing ailments. One method is to leverage the Medicare annual wellness visit (AWV), which provides an opportunity to assess current health status as well as discuss behavior-change and risk-reduction strategies with patients.

Continue to: Although AWVs...

Although AWVs are an opportunity to improve patient outcomes, we are not taking full advantage of them.6 While AWVs have gained traction since their introduction in 2011, usage rates among ethnoracial minority groups has lagged behind.6 A 2018 cohort study examined reasons for disparate utilization rates among individuals ages ≥ 66 years (N = 14,687).7 Researchers found that differences in utilization between ethnoracial groups were explained by socioeconomic factors. Lower education and lower income, as well as rural living, were associated with lower rates of AWV completion.7 In addition, having a usual, nonemergent place to obtain medical care served as a powerful predictor of AWV utilization for all groups.7

Strategies to increase AWV completion rates among all eligible adults include increasing staff awareness of health literacy challenges and ensuring communication strategies are inclusive by providing printed materials in multiple languages, Braille, or larger typefaces; using accessible vocabulary that does not include medical jargon; and making medical interpreters accessible. In addition, training clinicians about unconscious bias and cultural humility can help foster empathy and awareness of differences in health beliefs and behaviors within diverse patient populations.

A 2019 scoping review of 11 studies (N > 60 million) focused on outcomes from Medicare AWVs for patients ages ≥ 65 years.8 This included uptake of preventive services, such as vaccinations or cancer screenings; advice, education, or referrals offered during the AWV; medication use; and hospitalization rates. Overall findings showed that older adults who received a Medicare AWV were more likely to receive referrals for preventive screenings and follow-through on these recommendations compared with those who did not undergo an AWV.8

Completion rates for vaccines, while remaining low overall, were higher among those who completed an AWV. Additionally, these studies showed improved completion of screenings for breast cancer, bone density, and colon cancer. Several studies in the scoping review supported the use of AWVs as an effective means by which to offer health education and advice related to health promotion and risk reduction, such as diet and lifestyle modifications.8 Little evidence exists on long-term outcomes related to AWV completion.8

Utilize shared decision-making to determine whether preventive screening makes sense for your patient. Although cancer remains the second leading cause of death among Americans ages ≥ 65 years,9 clear screening guidelines for this age group remain elusive.10 Physicians and patients often are reluctant to stop cancer screening despite lower life expectancy and fewer potential benefits of diagnosis in this population.9 Some recent studies reinforce the heterogeneity of the older adult population and further underscore the importance of individual-level decision-making.11-14 It is important to let older adult patients and their caregivers know about the potential risks of screening tests, especially the possibility that incidental findings may lead to unwarranted additional care or monitoring.9

Continue to: Avoid these screening conversation missteps

Avoid these screening conversation missteps. A 2017 qualitative study asked 40 community-dwelling older adults (mean age = 76 years) about their preferences for discussing screening cessation with their physicians.13 Three themes emerged.First, they were open to stopping their screenings, especially when suggested by a trusted physician. Second, health status and physical function made sense as decision points, but life expectancy did not. Finally, lengthy discussions with expanded details about risks and benefits were not appreciated, especially if coupled with comments on the limited benefits for those nearing the end of life. When discussing life expectancy, patients preferred phrasing that focused on how the screening was unnecessary because it would not help them live longer.13

Ensure that your message is understood—and culturally relevant. Recent studies on lower health literacy among older adults15,16 and ethnic and racial minorities17-21—as revealed in the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy22—might offer clues to patient receptivity to discussions about preventive screening and other health decisions.

One study found a significant correlation between higher self-rated health literacy and higher engagement in health behaviors such as mammography screening, moderate physical activity, and tobacco avoidance.16 Perceptions of personal control over health status, as well as perceived social standing, also correlated with health literacy score levels.16 Another study concluded that lower health literacy combined with lower self-efficacy, cultural beliefs about health topics (eg, diet and exercise), and distrust in the health care system contributed to lower rates of preventive care utilization among ethnocultural minority older adults in Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia.18

Ensuring that easy-to-understand information is equitably shared with older adults of all races and ethnicities is critical. A 2018 study showed that distrust of the health system and cultural issues contributed to the lower incidence of colorectal cancer screenings in Hispanic and Asian American patients ages 50 to 75 years.21 Patients whose physicians engaged in “health literate practices” (eg, offering clear explanations of diagnostic plans and asking patients to describe what they understood) were more likely to obtain recommended breast and colorectal cancer screenings.20 In particular, researchers found that non-Hispanic Blacks were nearly twice as likely to follow through on colorectal cancer screening if their physicians engaged in health literate practices.20 In addition, receiving clear instructions from physicians increased the odds of completing breast cancer screening among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women.20

Overall, screening information and recommendations should be standardized for all patients. This is particularly important in light of research that found that older non-Hispanic Black patients were less likely than their non-Hispanic White counterparts to receive information from their physicians about colorectal cancer screening.20

Continue to: Mobility

Mobility

Encourage physical activity. Frequent exercise and other forms of physical activity are associated with healthy aging, as shown in a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 23 studies (N = 174,114).23 Despite considerable heterogeneity between studies in how researchers defined healthy aging and physical activity, they found that adults who incorporate regular movement and exercise into daily life are likely to continue to benefit from it into older age.23 In addition, a 2016 secondary analysis of data from the InCHIANTI longitudinal aging study concluded that adults ages ≥ 65 years (N = 1149) who had maintained higher physical activity levels throughout adulthood had less physical function decline and reduced rates of mobility disability and premature death compared with those who reported being less active.24

Preserve gait speed (and bolster health) with these activities. Walking speed, or gait, measured on a level surface has been used as a predictor for various aspects of well-being in older age, such as daily function, mobility, independence, falls, mortality, and hospitalization risk.25 Reduced gait speed is also one of the key indicators of functional impairment in older adults.

A 2015 systematic review sought to determine which type of exercise intervention (resistance, coordination, or multimodal training) would be most effective in preserving gait speed in healthy older adults (N = 2495; mean age = 74.2 years).25 While the 42 included studies were deemed to be fairly low quality, the review revealed (with large effect size [0.84]) that a number of exercise modalities might stave off loss of gait speed in older adults. Patients in the resistance training group had the greatest improvement in gait speed (0.11 m/s), followed by those in the coordination training group (0.09 m/s) and the multimodal training group (0.05 m/s).25

Finally, muscle mass and strength offer a measure of physical performance and functionality. A 2020 systematic review of 83 studies (N = 108,428) showed that low muscle mass and strength, reduced handgrip strength, and lower physical performance were predictive of reduced capacities in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.26 It is important to counsel adults to remain active throughout their lives and to include resistance training to maintain muscle mass and strength to preserve their motor function, mobility, independence, and QOL.

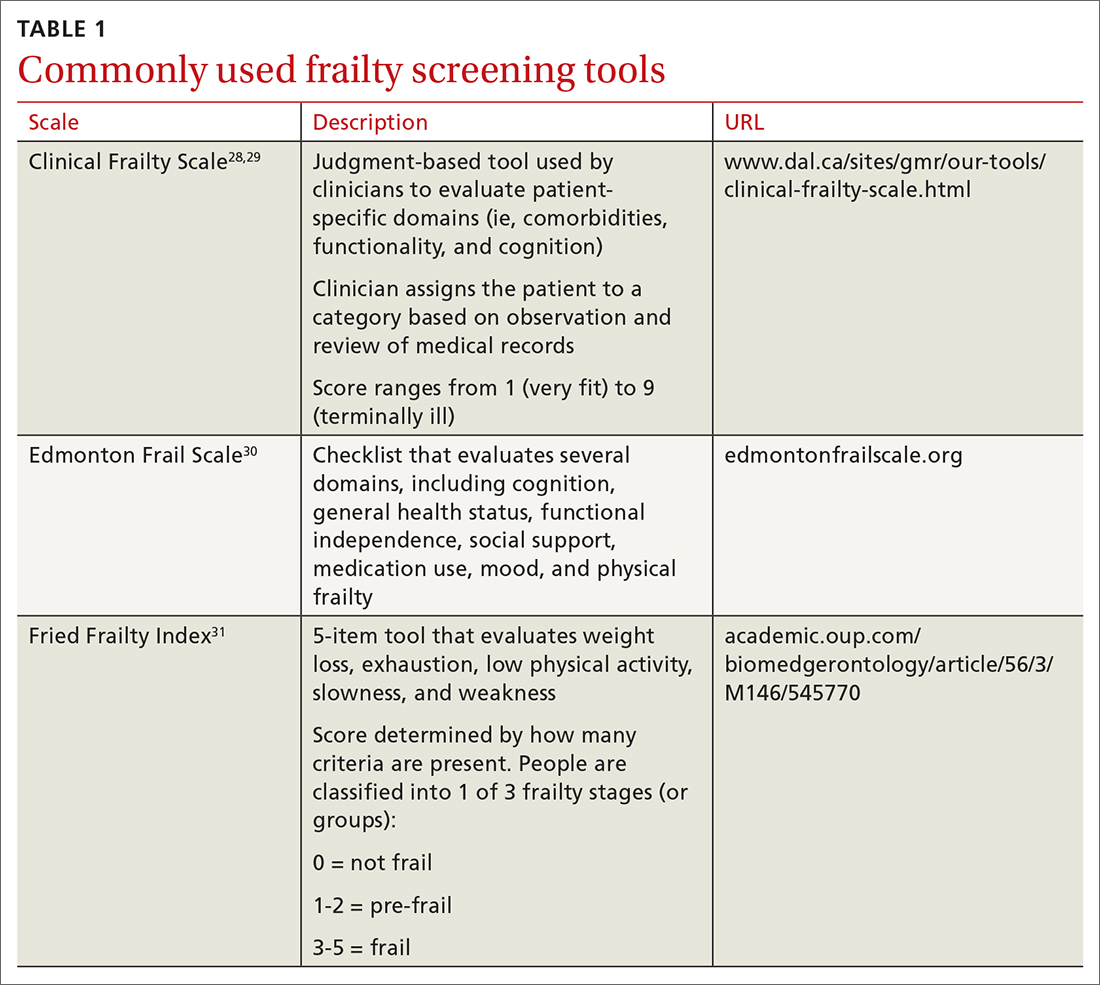

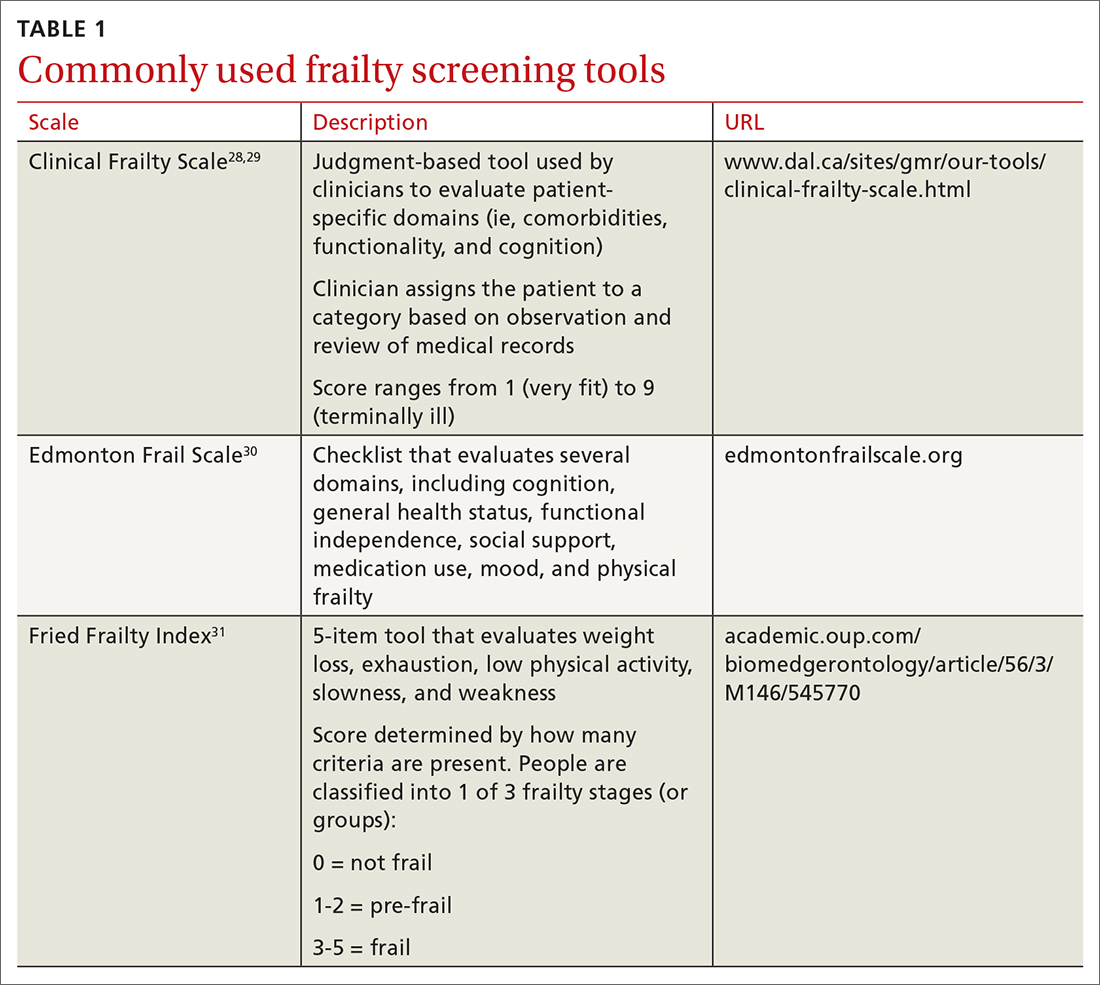

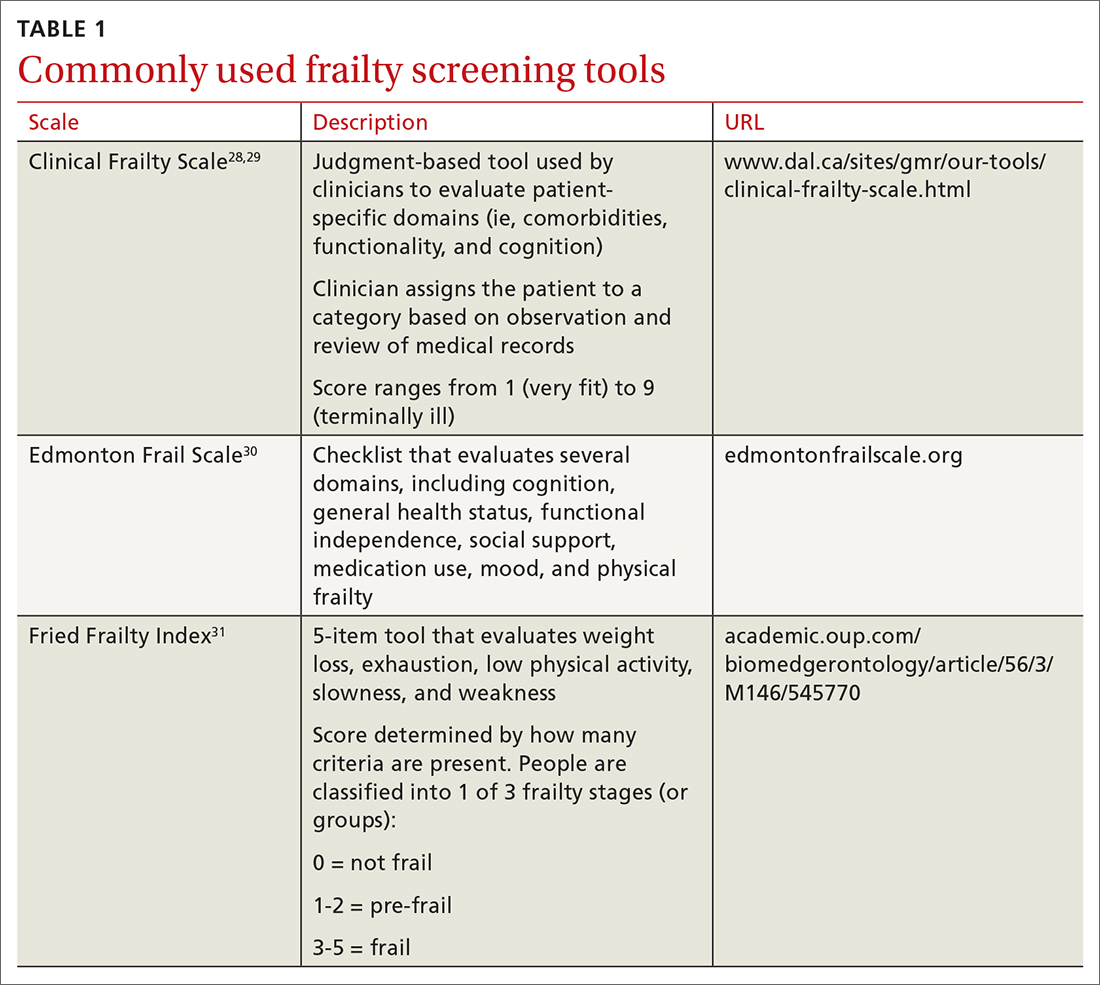

Use 1 of these scales to identify frailty. Frailty is a distinct clinical syndrome, in which an individual has low reserves and is highly vulnerable to internal and external stressors. It affects many community-dwelling older adults. Within the literature, there has been ongoing discussion regarding the definition of frailty27 (TABLE 128-31).

Continue to: The Fried Frailty Index...

The Fried Frailty Index defines frailty as a purely physical condition; patients need to exhibit 3 of 5 components (ie, weight loss, exhaustion, weakness, slowness, and low physical activity) to be deemed frail.31 The Edmonton Frail Scale is commonly used in geriatric assessments and counts impairments across several domains including physical activity, mood, cognition, and incontinence.30,32,33 Physicians need to complete a training course prior to its use. Finally, the definition of frailty used by Rockwood et al28, 29 was used to develop the Clinical Frailty Scale, which relies on broader criteria that include social and psychological elements in addition to physical elements.The Clinical Frailty Scale uses clinician judgment to evaluate patient-specific domains (eg, comorbidities, functionality, and cognition) and to generate a score ranging from 1 (very fit) to 9 (terminally ill).29 This scale is accessible and easy to implement. As a result, use of this scale has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. All definitions include a pre-frail state, indicating the dynamic nature of frailty over time.

It is important to identify pre-frail and frail older adults using 1 of these screening tools. Interventions to reverse frailty that can be initiated in the primary care setting include identifying treatable medical conditions, assessing medication appropriateness, providing nutritional advice, and developing an exercise plan.34

Conduct a nutritional assessment; consider this diet. Studies show that nutritional status can predict physical function and frailty risk in older adults. A 2017 systematic review of 19 studies (N = 22,270) of frail adults ages ≥ 65 years found associations related to specific dietary constructs (ie, micronutrients, macronutrients, antioxidants, overall diet quality, and timing of consumption).35 Plant-based diets with higher levels of micronutrients, such as vitamins C and E and beta-carotene, or diets with more protein or macronutrients, regardless of source foods, all resulted in inverse associations with frailty syndrome.35

A 2017 study showed that physical exercise and maintaining good nutritional status may be effective for preventing frailty in community-dwelling pre-frail older individuals.36 A 2019 study showed that a combination of muscle strength training and protein supplementation was the most effective intervention to delay or reverse frailty and was easiest to implement in primary care.37 A 2020 meta-analysis of 31 studies (N = 4794) addressing frailty among primary care patients > 60 years showed that interventions using predominantly resistance-based exercise and nutrition supplementation improved frailty status over the control.38 Researchers also found that a comprehensive geriatric assessment or exercise—alone or in combination with nutrition education—reduced physical frailty.

Mentation

Screen and treat cognitive impairments. Cognitive function and autonomy in decision-making are important factors in healthy aging. Aspects of mental health (eg, depression and anxiety), sensory impairment (eg, visual and auditory impairment), and mentation issues (eg, delirium, dementia, and related conditions), as well as diet, physical exercise, and mobility, can all impede cognitive functionality. The long-term effects of depression, anxiety,39 sensory deficits,40 mobility,41 diet,42 and, ultimately, aging may impact Alzheimer disease (AD). The risk of an AD diagnosis increases with age.39

Continue to: A 2018 prospective cohort study...

A 2018 prospective cohort study using data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center followed individuals (N = 12,053) who were cognitively asymptomatic at their initial visits to determine who developed clinical signs of AD.39 Survival analysis showed several psychosocial factors—anxiety, sleep disturbances, and depressive episodes of any type (occurring within the past 2 years, clinician verified, lifetime report)—were significantly associated with an eventual AD diagnosis and increased the risk of AD.39 More research is needed to verify the impact of early intervention for these conditions on neurodegenerative disease; however, screening and treating psychosocial factors such as anxiety and depression should be maintained.

Researchers evaluated the impact of a dual sensory impairment (DSI) on dementia risk using data from 2051 participants in the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study.40 Hearing and visual impairments (defined as DSI when these conditions coexist) or visual impairment alone were significantly associated with increased risk of dementia in older adults. The researchers reported that DSI was significantly associated with a higher risk of all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.86; 95% CI, 1.25-2.76) and AD (HR = 2.12; 95% CI, 1.34-3.36).40 Visual impairment alone was associated with an increased risk of all-cause dementia (HR = 1.32; 95% CI, 1.02-1.71).40 These results suggest that screening of DSI or visual impairment earlier in the patient’s lifespan may identify those at high risk of dementia in older adulthood.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends patients with healthy eyes be screened once during their 20s and twice in their 30s; a full examination is recommended by age 40. For patients ages ≥ 65 years, it is recommended that eye examinations occur every 1 to 2 years.43

Diet and mobility play a big role in cognition. Diet43 and exercise41,42,44 are believed to have an impact on mentation, and recent studies show memory and global cognition could be malleable later in life. A 2015 meta-analysis of 490 treatment arms of 24 randomized controlled studies showed improvement in global cognition with consumption of a Mediterranean diet plus olive oil (effect size [ES] standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.16-0.27) and tai chi exercises (ES SMD = 0.18; 95% CI, 0.06-0.29).42 The analysis also found improved memory among participants who consumed the Mediterranean diet/olive oil combination (ES SMD = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.12-0.32) and soy isoflavone supplements (ES SMD = 0.11; 95% CI, 0.04-0.17). Although the ESs are small, they are significant and offer promising evidence that individual choices related to nutrition or exercise may influence cognition and memory.

A 2018 systematic review found that all domains of cognition showed improvement with 45 to 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical exercise.44 Attention, executive function, memory, and working memory showed significant increases, whereas global cognition improvements were not statistically significant.44 A 2016 meta-analysis of 26 studies (N = 26,355) found a positive association between an objective mobility measure (gait, lower-extremity function, and balance) and cognitive function (global, executive function, memory, and processing speed) in older adults.41 These results highlight that diet, mobility, and physical exercise impact cognitive functioning.

Continue to: Maintaining social connections

Maintaining social connections

Social isolation and loneliness—compounded by a pandemic. The US Department of Health and Human Services notes that “community connections” are among the key factors required for healthy aging.3 Similarly, the WHO definition of healthy aging considers whether individuals can build and sustain relationships with other people and find ways to engender their personal values through these connections.2

As people age, their social connections often decrease due to the death of friends and family, shifts in living arrangements, loss of mobility or eyesight (and thus self-transport), and the onset or increased acuity of illness or chronic conditions.45 This has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has spurred shelter-in-place and stay-at-home orders along with recommendations for physical distancing (also known as social distancing), especially for older adults who are at higher risk.46 Smith et al47 calls this the COVID-19 Social Connectivity Paradox, in which older adults limit their interactions with others to protect their physical health and reduce their risk of contracting the virus, but as a result they may undermine their psychosocial health by placing themselves at risk of social isolation and loneliness.47

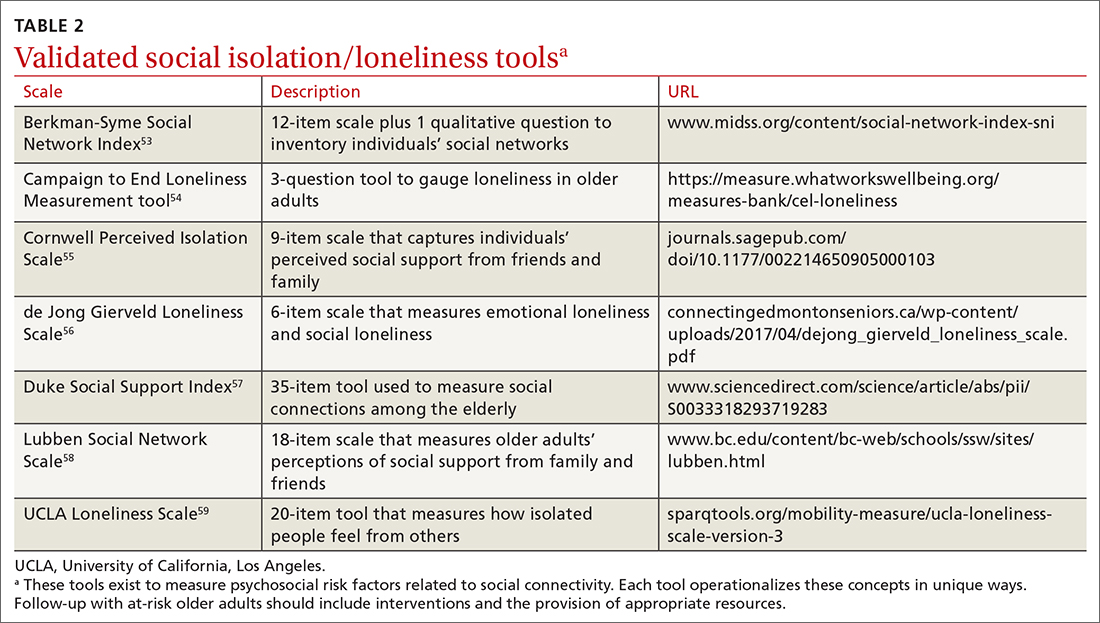

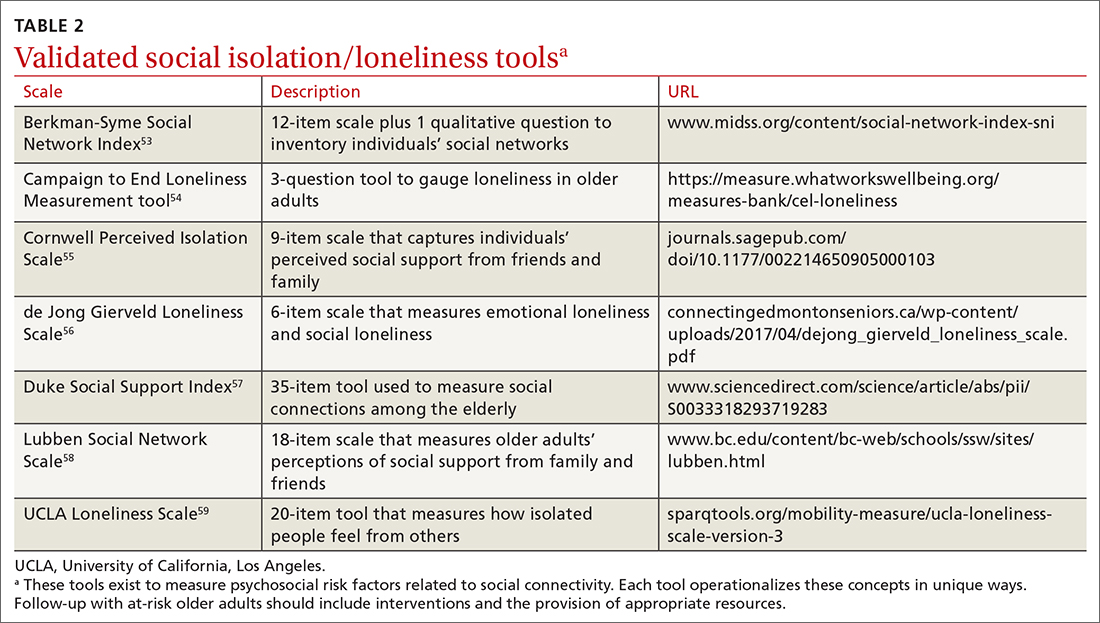

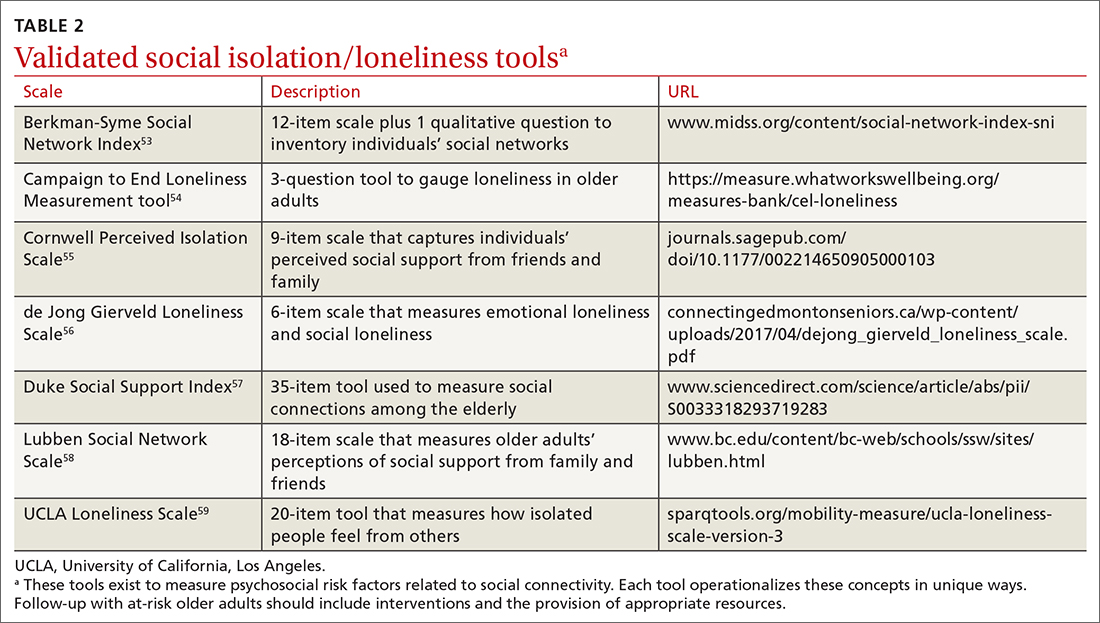

The double threat. Social isolation and loneliness have been shown to negatively impact physical health and well-being, resulting in an increased risk of early death48-50; higher likelihood of specific diagnoses, including dementia and cardiovascular conditions48,50; and more frequent use of health care services.50 These concepts, while related, represent different mechanisms for negative health outcomes. Social isolation is an objective condition when one has a lack of opportunities for interaction with other people; loneliness refers to the emotional disconnect one feels when separated from others. Few studies have compared outcomes between these concepts, but in those that have, social isolation appears to be more strongly associated with early death.48-50