User login

Staff education cuts psychotropic drug use in long-term care

The effect of the intervention was transient, possibly because of high staff turnover, according to the investigators in the new randomized, controlled trial.

The findings were presented by Ulla Aalto, MD, PhD, during a session at the European Geriatric Medicine Society annual congress, a hybrid live and online meeting.

There was a significant reduction in the use of psychotropic agents at 6 months in long-term care wards where the nursing staff had undergone a short training session on drug therapy for older patients, but there was no improvement in wards that were randomly assigned to serve as controls, Dr. Aalto, from Helsinki Hospital, reported during the session.

“Future research would be investigating how we could maintain the positive effects that were gained at 6 months but not seen any more at 1 year, and how to implement the good practice in nursing homes by this kind of staff training,” she said.

Heavy drug use

Psychotropic medications are widely used in long-term care settings, but their indiscriminate use or use of the wrong drug for the wrong patient can be harmful. Inappropriate drug use in long-term care settings is also associated with higher costs, Dr. Aalto said.

To see whether a staff-training intervention could reduce drugs use and lower costs, the investigators conducted a randomized clinical trial in assisted living facilities in Helsinki in 2011, with a total of 227 patients 65 years and older.

Long-term care wards were randomly assigned to either an intervention for nursing staff consisting of two 4-hour sessions on good drug-therapy practice for older adults, or to serve as controls (10 wards in each group).

Drug use and costs were monitored at both 6 and 12 months after randomization. Psychotropic drugs included antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics as classified by the World Health Organization. For the purposes of comparison, actual doses were counted and converted into relative proportions of defined daily doses.

The baseline characteristics of patients in each group were generally similar, with a mean age of around 83 years. In each study arm, nearly two-thirds of patients were on at least one psychotropic drug, and of this group, a third had been prescribed 2 or more psychotropic agents.

Nearly half of the patients were on at least one antipsychotic agent and/or antidepressant.

Short-term benefit

As noted before, in the wards randomized to staff training, there was a significant reduction in use of all psychotropics from baseline at 6 months after randomization (P = .045), but there was no change among the control wards.

By 12 months, however, the differences between the intervention and control arms narrowed, and drug use in the intervention arm was no longer significantly lower over baseline.

Drugs costs significantly decreased in the intervention group at 6 months (P = .027) and were numerically but not statistically lower over baseline at 12 months.

In contrast, drug costs in the control arm were numerically (but not statistically) higher at both 6 and 12 months of follow-up.

Annual drug costs in the intervention group decreased by mean of 12.3 euros ($14.22) whereas costs in the control group increased by a mean of 20.6 euros ($23.81).

“This quite light and feasible intervention succeeded in reducing overall defined daily doses of psychotropics in the short term,” Dr. Aalto said.

The waning of the intervention’s effect on drug use and costs may be caused partly by the high employee turnover rate in long-term care facilities and to the dilution effect, she said, referring to a form of judgment bias in which people tend to devalue diagnostic information when other, nondiagnostic information is also available.

Randomized design

In the question-and-answer session following her presentation, audience member Jesper Ryg, MD, PhD from Odense (Denmark) University Hospital and the University of Southern Denmark, also in Odense, commented: “It’s a great study, doing a [randomized, controlled trial] on deprescribing, we need more of those.”

“But what we know now is that a lot of studies show it is possible to deprescribe and get less drugs, but do we have any clinical data? Does this deprescribing lead to less falls, did it lead to lower mortality?” he asked.

Dr. Aalto replied that, in an earlier report from this study, investigators showed that harmful medication use was reduced and negative outcomes were reduced.

Another audience member asked why nursing staff were the target of the intervention, given that physicians do the actual drug prescribing.

Dr. Aalto responded: “It is the physician of course who prescribes, but in nursing homes and long-term care, nursing staff is there all the time, and the physicians are kind of consultants who just come there once in a while, so it’s important that the nurses also know about these harmful medications and can bring them to the doctor when he or she arrives there.”

Dr. Aalto and Dr. Ryg had no disclosures.

The effect of the intervention was transient, possibly because of high staff turnover, according to the investigators in the new randomized, controlled trial.

The findings were presented by Ulla Aalto, MD, PhD, during a session at the European Geriatric Medicine Society annual congress, a hybrid live and online meeting.

There was a significant reduction in the use of psychotropic agents at 6 months in long-term care wards where the nursing staff had undergone a short training session on drug therapy for older patients, but there was no improvement in wards that were randomly assigned to serve as controls, Dr. Aalto, from Helsinki Hospital, reported during the session.

“Future research would be investigating how we could maintain the positive effects that were gained at 6 months but not seen any more at 1 year, and how to implement the good practice in nursing homes by this kind of staff training,” she said.

Heavy drug use

Psychotropic medications are widely used in long-term care settings, but their indiscriminate use or use of the wrong drug for the wrong patient can be harmful. Inappropriate drug use in long-term care settings is also associated with higher costs, Dr. Aalto said.

To see whether a staff-training intervention could reduce drugs use and lower costs, the investigators conducted a randomized clinical trial in assisted living facilities in Helsinki in 2011, with a total of 227 patients 65 years and older.

Long-term care wards were randomly assigned to either an intervention for nursing staff consisting of two 4-hour sessions on good drug-therapy practice for older adults, or to serve as controls (10 wards in each group).

Drug use and costs were monitored at both 6 and 12 months after randomization. Psychotropic drugs included antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics as classified by the World Health Organization. For the purposes of comparison, actual doses were counted and converted into relative proportions of defined daily doses.

The baseline characteristics of patients in each group were generally similar, with a mean age of around 83 years. In each study arm, nearly two-thirds of patients were on at least one psychotropic drug, and of this group, a third had been prescribed 2 or more psychotropic agents.

Nearly half of the patients were on at least one antipsychotic agent and/or antidepressant.

Short-term benefit

As noted before, in the wards randomized to staff training, there was a significant reduction in use of all psychotropics from baseline at 6 months after randomization (P = .045), but there was no change among the control wards.

By 12 months, however, the differences between the intervention and control arms narrowed, and drug use in the intervention arm was no longer significantly lower over baseline.

Drugs costs significantly decreased in the intervention group at 6 months (P = .027) and were numerically but not statistically lower over baseline at 12 months.

In contrast, drug costs in the control arm were numerically (but not statistically) higher at both 6 and 12 months of follow-up.

Annual drug costs in the intervention group decreased by mean of 12.3 euros ($14.22) whereas costs in the control group increased by a mean of 20.6 euros ($23.81).

“This quite light and feasible intervention succeeded in reducing overall defined daily doses of psychotropics in the short term,” Dr. Aalto said.

The waning of the intervention’s effect on drug use and costs may be caused partly by the high employee turnover rate in long-term care facilities and to the dilution effect, she said, referring to a form of judgment bias in which people tend to devalue diagnostic information when other, nondiagnostic information is also available.

Randomized design

In the question-and-answer session following her presentation, audience member Jesper Ryg, MD, PhD from Odense (Denmark) University Hospital and the University of Southern Denmark, also in Odense, commented: “It’s a great study, doing a [randomized, controlled trial] on deprescribing, we need more of those.”

“But what we know now is that a lot of studies show it is possible to deprescribe and get less drugs, but do we have any clinical data? Does this deprescribing lead to less falls, did it lead to lower mortality?” he asked.

Dr. Aalto replied that, in an earlier report from this study, investigators showed that harmful medication use was reduced and negative outcomes were reduced.

Another audience member asked why nursing staff were the target of the intervention, given that physicians do the actual drug prescribing.

Dr. Aalto responded: “It is the physician of course who prescribes, but in nursing homes and long-term care, nursing staff is there all the time, and the physicians are kind of consultants who just come there once in a while, so it’s important that the nurses also know about these harmful medications and can bring them to the doctor when he or she arrives there.”

Dr. Aalto and Dr. Ryg had no disclosures.

The effect of the intervention was transient, possibly because of high staff turnover, according to the investigators in the new randomized, controlled trial.

The findings were presented by Ulla Aalto, MD, PhD, during a session at the European Geriatric Medicine Society annual congress, a hybrid live and online meeting.

There was a significant reduction in the use of psychotropic agents at 6 months in long-term care wards where the nursing staff had undergone a short training session on drug therapy for older patients, but there was no improvement in wards that were randomly assigned to serve as controls, Dr. Aalto, from Helsinki Hospital, reported during the session.

“Future research would be investigating how we could maintain the positive effects that were gained at 6 months but not seen any more at 1 year, and how to implement the good practice in nursing homes by this kind of staff training,” she said.

Heavy drug use

Psychotropic medications are widely used in long-term care settings, but their indiscriminate use or use of the wrong drug for the wrong patient can be harmful. Inappropriate drug use in long-term care settings is also associated with higher costs, Dr. Aalto said.

To see whether a staff-training intervention could reduce drugs use and lower costs, the investigators conducted a randomized clinical trial in assisted living facilities in Helsinki in 2011, with a total of 227 patients 65 years and older.

Long-term care wards were randomly assigned to either an intervention for nursing staff consisting of two 4-hour sessions on good drug-therapy practice for older adults, or to serve as controls (10 wards in each group).

Drug use and costs were monitored at both 6 and 12 months after randomization. Psychotropic drugs included antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics as classified by the World Health Organization. For the purposes of comparison, actual doses were counted and converted into relative proportions of defined daily doses.

The baseline characteristics of patients in each group were generally similar, with a mean age of around 83 years. In each study arm, nearly two-thirds of patients were on at least one psychotropic drug, and of this group, a third had been prescribed 2 or more psychotropic agents.

Nearly half of the patients were on at least one antipsychotic agent and/or antidepressant.

Short-term benefit

As noted before, in the wards randomized to staff training, there was a significant reduction in use of all psychotropics from baseline at 6 months after randomization (P = .045), but there was no change among the control wards.

By 12 months, however, the differences between the intervention and control arms narrowed, and drug use in the intervention arm was no longer significantly lower over baseline.

Drugs costs significantly decreased in the intervention group at 6 months (P = .027) and were numerically but not statistically lower over baseline at 12 months.

In contrast, drug costs in the control arm were numerically (but not statistically) higher at both 6 and 12 months of follow-up.

Annual drug costs in the intervention group decreased by mean of 12.3 euros ($14.22) whereas costs in the control group increased by a mean of 20.6 euros ($23.81).

“This quite light and feasible intervention succeeded in reducing overall defined daily doses of psychotropics in the short term,” Dr. Aalto said.

The waning of the intervention’s effect on drug use and costs may be caused partly by the high employee turnover rate in long-term care facilities and to the dilution effect, she said, referring to a form of judgment bias in which people tend to devalue diagnostic information when other, nondiagnostic information is also available.

Randomized design

In the question-and-answer session following her presentation, audience member Jesper Ryg, MD, PhD from Odense (Denmark) University Hospital and the University of Southern Denmark, also in Odense, commented: “It’s a great study, doing a [randomized, controlled trial] on deprescribing, we need more of those.”

“But what we know now is that a lot of studies show it is possible to deprescribe and get less drugs, but do we have any clinical data? Does this deprescribing lead to less falls, did it lead to lower mortality?” he asked.

Dr. Aalto replied that, in an earlier report from this study, investigators showed that harmful medication use was reduced and negative outcomes were reduced.

Another audience member asked why nursing staff were the target of the intervention, given that physicians do the actual drug prescribing.

Dr. Aalto responded: “It is the physician of course who prescribes, but in nursing homes and long-term care, nursing staff is there all the time, and the physicians are kind of consultants who just come there once in a while, so it’s important that the nurses also know about these harmful medications and can bring them to the doctor when he or she arrives there.”

Dr. Aalto and Dr. Ryg had no disclosures.

FROM EUGMS 2021

MIND diet preserves cognition, new data show

Adherence to the MIND diet can improve memory and thinking skills of older adults, even in the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology, new data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) show.

“The MIND diet was associated with better cognitive functions independently of brain pathologies related to Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that diet may contribute to cognitive resilience, which ultimately indicates that it is never too late for dementia prevention,” lead author Klodian Dhana, MD, PhD, with the Rush Institute of Healthy Aging at Rush University, Chicago, said in an interview.

The study was published online Sept. 14, 2021, in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Impact on brain pathology

“While previous investigations determined that the MIND diet is associated with a slower cognitive decline, the current study furthered the diet and brain health evidence by assessing the impact of brain pathology in the diet-cognition relationship,” Dr. Dhana said.

The MIND diet was pioneered by the late Martha Clare Morris, ScD, a Rush nutritional epidemiologist, who died in 2020 of cancer at age 64. A hybrid of the Mediterranean and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets, the MIND diet includes green leafy vegetables, fish, nuts, berries, beans, and whole grains and limits consumption of fried and fast foods, sweets, and pastries.

The current study focused on 569 older adults who died while participating in the MAP study, which began in 1997. Participants in the study were mostly White and were without known dementia. All of the participants agreed to undergo annual clinical evaluations. They also agreed to undergo brain autopsy after death.

Beginning in 2004, participants completed annual food frequency questionnaires, which were used to calculate a MIND diet score based on how often the participants ate specific foods.

The researchers used a series of regression analyses to examine associations of the MIND diet, dementia-related brain pathologies, and global cognition near the time of death. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education, apo E4, late-life cognitive activities, and total energy intake.

(beta, 0.119; P = .003).

Notably, the researchers said, neither the strength nor the significance of association changed markedly when AD pathology and other brain pathologies were included in the model (beta, 0.111; P = .003).

The relationship between better adherence to the MIND diet and better cognition remained significant when the analysis was restricted to individuals without mild cognitive impairment at baseline (beta, 0.121; P = .005) as well as to persons in whom a postmortem diagnosis of AD was made on the basis of NIA-Reagan consensus recommendations (beta, 0.114; P = .023).

The limitations of the study include the reliance on self-reported diet information and a sample made up of mostly White volunteers who agreed to annual evaluations and postmortem organ donation, thus limiting generalizability.

Strengths of the study include the prospective design with annual assessment of cognitive function using standardized tests and collection of the dietary information using validated questionnaires. Also, the neuropathologic evaluations were performed by examiners blinded to clinical data.

“Diet changes can impact cognitive functioning and risk of dementia, for better or worse. There are fairly simple diet and lifestyle changes a person could make that may help to slow cognitive decline with aging and contribute to brain health,” Dr. Dhana said in a news release.

Builds resilience

Weighing in on the study, Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said this “interesting study sheds light on the impact of nutrition on cognitive function.

“The findings add to the growing literature that lifestyle factors – like access to a heart-healthy diet – may help the brain be more resilient to disease-specific changes,” Snyder said in an interview.

“The Alzheimer’s Association’s US POINTER study is investigating how lifestyle interventions, including nutrition guidance, like the MIND diet, may impact a person’s risk of cognitive decline. An ancillary study of the US POINTER will include brain imaging to investigate how these lifestyle interventions impact the biology of the brain,” Dr. Snyder noted.

The research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dhana and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adherence to the MIND diet can improve memory and thinking skills of older adults, even in the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology, new data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) show.

“The MIND diet was associated with better cognitive functions independently of brain pathologies related to Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that diet may contribute to cognitive resilience, which ultimately indicates that it is never too late for dementia prevention,” lead author Klodian Dhana, MD, PhD, with the Rush Institute of Healthy Aging at Rush University, Chicago, said in an interview.

The study was published online Sept. 14, 2021, in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Impact on brain pathology

“While previous investigations determined that the MIND diet is associated with a slower cognitive decline, the current study furthered the diet and brain health evidence by assessing the impact of brain pathology in the diet-cognition relationship,” Dr. Dhana said.

The MIND diet was pioneered by the late Martha Clare Morris, ScD, a Rush nutritional epidemiologist, who died in 2020 of cancer at age 64. A hybrid of the Mediterranean and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets, the MIND diet includes green leafy vegetables, fish, nuts, berries, beans, and whole grains and limits consumption of fried and fast foods, sweets, and pastries.

The current study focused on 569 older adults who died while participating in the MAP study, which began in 1997. Participants in the study were mostly White and were without known dementia. All of the participants agreed to undergo annual clinical evaluations. They also agreed to undergo brain autopsy after death.

Beginning in 2004, participants completed annual food frequency questionnaires, which were used to calculate a MIND diet score based on how often the participants ate specific foods.

The researchers used a series of regression analyses to examine associations of the MIND diet, dementia-related brain pathologies, and global cognition near the time of death. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education, apo E4, late-life cognitive activities, and total energy intake.

(beta, 0.119; P = .003).

Notably, the researchers said, neither the strength nor the significance of association changed markedly when AD pathology and other brain pathologies were included in the model (beta, 0.111; P = .003).

The relationship between better adherence to the MIND diet and better cognition remained significant when the analysis was restricted to individuals without mild cognitive impairment at baseline (beta, 0.121; P = .005) as well as to persons in whom a postmortem diagnosis of AD was made on the basis of NIA-Reagan consensus recommendations (beta, 0.114; P = .023).

The limitations of the study include the reliance on self-reported diet information and a sample made up of mostly White volunteers who agreed to annual evaluations and postmortem organ donation, thus limiting generalizability.

Strengths of the study include the prospective design with annual assessment of cognitive function using standardized tests and collection of the dietary information using validated questionnaires. Also, the neuropathologic evaluations were performed by examiners blinded to clinical data.

“Diet changes can impact cognitive functioning and risk of dementia, for better or worse. There are fairly simple diet and lifestyle changes a person could make that may help to slow cognitive decline with aging and contribute to brain health,” Dr. Dhana said in a news release.

Builds resilience

Weighing in on the study, Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said this “interesting study sheds light on the impact of nutrition on cognitive function.

“The findings add to the growing literature that lifestyle factors – like access to a heart-healthy diet – may help the brain be more resilient to disease-specific changes,” Snyder said in an interview.

“The Alzheimer’s Association’s US POINTER study is investigating how lifestyle interventions, including nutrition guidance, like the MIND diet, may impact a person’s risk of cognitive decline. An ancillary study of the US POINTER will include brain imaging to investigate how these lifestyle interventions impact the biology of the brain,” Dr. Snyder noted.

The research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dhana and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adherence to the MIND diet can improve memory and thinking skills of older adults, even in the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology, new data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) show.

“The MIND diet was associated with better cognitive functions independently of brain pathologies related to Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that diet may contribute to cognitive resilience, which ultimately indicates that it is never too late for dementia prevention,” lead author Klodian Dhana, MD, PhD, with the Rush Institute of Healthy Aging at Rush University, Chicago, said in an interview.

The study was published online Sept. 14, 2021, in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Impact on brain pathology

“While previous investigations determined that the MIND diet is associated with a slower cognitive decline, the current study furthered the diet and brain health evidence by assessing the impact of brain pathology in the diet-cognition relationship,” Dr. Dhana said.

The MIND diet was pioneered by the late Martha Clare Morris, ScD, a Rush nutritional epidemiologist, who died in 2020 of cancer at age 64. A hybrid of the Mediterranean and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets, the MIND diet includes green leafy vegetables, fish, nuts, berries, beans, and whole grains and limits consumption of fried and fast foods, sweets, and pastries.

The current study focused on 569 older adults who died while participating in the MAP study, which began in 1997. Participants in the study were mostly White and were without known dementia. All of the participants agreed to undergo annual clinical evaluations. They also agreed to undergo brain autopsy after death.

Beginning in 2004, participants completed annual food frequency questionnaires, which were used to calculate a MIND diet score based on how often the participants ate specific foods.

The researchers used a series of regression analyses to examine associations of the MIND diet, dementia-related brain pathologies, and global cognition near the time of death. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education, apo E4, late-life cognitive activities, and total energy intake.

(beta, 0.119; P = .003).

Notably, the researchers said, neither the strength nor the significance of association changed markedly when AD pathology and other brain pathologies were included in the model (beta, 0.111; P = .003).

The relationship between better adherence to the MIND diet and better cognition remained significant when the analysis was restricted to individuals without mild cognitive impairment at baseline (beta, 0.121; P = .005) as well as to persons in whom a postmortem diagnosis of AD was made on the basis of NIA-Reagan consensus recommendations (beta, 0.114; P = .023).

The limitations of the study include the reliance on self-reported diet information and a sample made up of mostly White volunteers who agreed to annual evaluations and postmortem organ donation, thus limiting generalizability.

Strengths of the study include the prospective design with annual assessment of cognitive function using standardized tests and collection of the dietary information using validated questionnaires. Also, the neuropathologic evaluations were performed by examiners blinded to clinical data.

“Diet changes can impact cognitive functioning and risk of dementia, for better or worse. There are fairly simple diet and lifestyle changes a person could make that may help to slow cognitive decline with aging and contribute to brain health,” Dr. Dhana said in a news release.

Builds resilience

Weighing in on the study, Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said this “interesting study sheds light on the impact of nutrition on cognitive function.

“The findings add to the growing literature that lifestyle factors – like access to a heart-healthy diet – may help the brain be more resilient to disease-specific changes,” Snyder said in an interview.

“The Alzheimer’s Association’s US POINTER study is investigating how lifestyle interventions, including nutrition guidance, like the MIND diet, may impact a person’s risk of cognitive decline. An ancillary study of the US POINTER will include brain imaging to investigate how these lifestyle interventions impact the biology of the brain,” Dr. Snyder noted.

The research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dhana and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pelvic floor dysfunction imaging: New guidelines provide recommendations

New consensus guidelines from a multispecialty working group of the Pelvic Floor Disorders Consortium (PFDC) clear up inconsistencies in the use of magnetic resonance defecography (MRD) and provide universal recommendations on MRD technique, interpretation, reporting, and other factors.

“The consensus language used to describe pelvic floor disorders is critical, so as to allow the various experts who treat these patients [to] communicate and collaborate effectively with each other,” coauthor Liliana Bordeianou, MD, MPH, an associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and chair of the Massachusetts General Hospital Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Centers, told this news organization.

“These diseases do not choose an arbitrary side in the pelvis,” she noted. “Instead, these diseases affect the entire pelvis and require a multidisciplinary and collaborative solution.”

MRD is a key component in that solution, providing dynamic evaluation of pelvic floor function and visualization of the complex interaction in pelvic compartments among patients with defecatory pelvic floor disorders, such as vaginal or uterine prolapse, constipation, incontinence, or other pelvic floor dysfunctions.

However, a key shortcoming has been a lack of consistency in nomenclature and the reporting of MRD findings among institutions and subspecialties.

Clinicians may wind up using different definitions for the same condition and different thresholds for grading severity, resulting in inconsistent communication not only between clinicians across institutions but even within the same institution, the report notes.

To address the situation, radiologists with the Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Disease Focused Panel of the Society of Abdominal Radiology (SAR) published recommendations on MRD protocol and technique in April.

However, even with that guidance, there has been significant variability in the interpretation and utilization of MRD findings among specialties outside of radiology.

The new report was therefore developed to include input from the broad variety of specialists involved in the treatment of patients with pelvic floor disorders, including colorectal surgeons, urogynecologists, urologists, gynecologists, gastroenterologists, radiologists, physiotherapists, and other advanced care practitioners.

“The goal of this effort was to create a universal set of recommendations and language for MRD technique, interpretation, and reporting that can be utilized and carry the same significance across disciplines,” write the authors of the report, published in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

One key area addressed in the report is a recommendation that MRD can be performed in either the upright or supine position, which has been a topic of inconsistency, said Brooke Gurland, MD, medical director of the Pelvic Health Center at Stanford University, California, a co-author on the consensus statement.

“Supine versus upright position was a source of debate, but ultimately there was a consensus that supine position was acceptable,” she told said in an interview.

Regarding positioning, the recommendations conclude that “given the variable results from different studies, consortium members agreed that it is acceptable to perform MRD in the supine position when upright MRD is not available.”

“Importantly, consortium experts stressed that it is very important that this imaging be performed after proper patient education on the purpose of the examination,” they note.

Other recommendations delve into contrast medium considerations, such as the recommendation that MRD does not require the routine use of vaginal contrast medium for adequate imaging of pathology.

And guidance on the technique and grading of relevant pathology include a recommendation to use the pubococcygeal line (PCL) as a point of reference to quantify the prolapse of organs in all compartments of the pelvic floor.

“There is an increasing appreciation that most patients with pelvic organ prolapse experience dual or even triple compartment pathology, making it important to describe the observations in all three compartments to ensure the mobilization of the appropriate team of experts to treat the patient,” the authors note.

The consensus report features an interpretative template providing synopses of the recommendations, which can be adjusted and modified according to additional radiologic information, as well as individualized patient information or clinician preferences.

However, “the suggested verbiage and steps should be advocated as the minimum requirements when performing and interpreting MRD in patients with evacuation disorders of the pelvic floor,” the authors note.

Dr. Gurland added that, in addition to providing benefits in the present utilization of MRD, the clearer guidelines should help advance its use to improve patient care in the future.

“Standardizing imaging techniques, reporting, and language is critical to improving our understanding and then developing therapies for pelvic floor disorders,” she said.

“In the future, correlating MRD with surgical outcomes and identifying modifiable risk factors will improve patient care.”

In addition to being published in the AJR, the report was published concurrently in the journals Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, International Urogynecology Journal, and Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery.

The authors of the guidelines have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New consensus guidelines from a multispecialty working group of the Pelvic Floor Disorders Consortium (PFDC) clear up inconsistencies in the use of magnetic resonance defecography (MRD) and provide universal recommendations on MRD technique, interpretation, reporting, and other factors.

“The consensus language used to describe pelvic floor disorders is critical, so as to allow the various experts who treat these patients [to] communicate and collaborate effectively with each other,” coauthor Liliana Bordeianou, MD, MPH, an associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and chair of the Massachusetts General Hospital Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Centers, told this news organization.

“These diseases do not choose an arbitrary side in the pelvis,” she noted. “Instead, these diseases affect the entire pelvis and require a multidisciplinary and collaborative solution.”

MRD is a key component in that solution, providing dynamic evaluation of pelvic floor function and visualization of the complex interaction in pelvic compartments among patients with defecatory pelvic floor disorders, such as vaginal or uterine prolapse, constipation, incontinence, or other pelvic floor dysfunctions.

However, a key shortcoming has been a lack of consistency in nomenclature and the reporting of MRD findings among institutions and subspecialties.

Clinicians may wind up using different definitions for the same condition and different thresholds for grading severity, resulting in inconsistent communication not only between clinicians across institutions but even within the same institution, the report notes.

To address the situation, radiologists with the Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Disease Focused Panel of the Society of Abdominal Radiology (SAR) published recommendations on MRD protocol and technique in April.

However, even with that guidance, there has been significant variability in the interpretation and utilization of MRD findings among specialties outside of radiology.

The new report was therefore developed to include input from the broad variety of specialists involved in the treatment of patients with pelvic floor disorders, including colorectal surgeons, urogynecologists, urologists, gynecologists, gastroenterologists, radiologists, physiotherapists, and other advanced care practitioners.

“The goal of this effort was to create a universal set of recommendations and language for MRD technique, interpretation, and reporting that can be utilized and carry the same significance across disciplines,” write the authors of the report, published in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

One key area addressed in the report is a recommendation that MRD can be performed in either the upright or supine position, which has been a topic of inconsistency, said Brooke Gurland, MD, medical director of the Pelvic Health Center at Stanford University, California, a co-author on the consensus statement.

“Supine versus upright position was a source of debate, but ultimately there was a consensus that supine position was acceptable,” she told said in an interview.

Regarding positioning, the recommendations conclude that “given the variable results from different studies, consortium members agreed that it is acceptable to perform MRD in the supine position when upright MRD is not available.”

“Importantly, consortium experts stressed that it is very important that this imaging be performed after proper patient education on the purpose of the examination,” they note.

Other recommendations delve into contrast medium considerations, such as the recommendation that MRD does not require the routine use of vaginal contrast medium for adequate imaging of pathology.

And guidance on the technique and grading of relevant pathology include a recommendation to use the pubococcygeal line (PCL) as a point of reference to quantify the prolapse of organs in all compartments of the pelvic floor.

“There is an increasing appreciation that most patients with pelvic organ prolapse experience dual or even triple compartment pathology, making it important to describe the observations in all three compartments to ensure the mobilization of the appropriate team of experts to treat the patient,” the authors note.

The consensus report features an interpretative template providing synopses of the recommendations, which can be adjusted and modified according to additional radiologic information, as well as individualized patient information or clinician preferences.

However, “the suggested verbiage and steps should be advocated as the minimum requirements when performing and interpreting MRD in patients with evacuation disorders of the pelvic floor,” the authors note.

Dr. Gurland added that, in addition to providing benefits in the present utilization of MRD, the clearer guidelines should help advance its use to improve patient care in the future.

“Standardizing imaging techniques, reporting, and language is critical to improving our understanding and then developing therapies for pelvic floor disorders,” she said.

“In the future, correlating MRD with surgical outcomes and identifying modifiable risk factors will improve patient care.”

In addition to being published in the AJR, the report was published concurrently in the journals Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, International Urogynecology Journal, and Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery.

The authors of the guidelines have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New consensus guidelines from a multispecialty working group of the Pelvic Floor Disorders Consortium (PFDC) clear up inconsistencies in the use of magnetic resonance defecography (MRD) and provide universal recommendations on MRD technique, interpretation, reporting, and other factors.

“The consensus language used to describe pelvic floor disorders is critical, so as to allow the various experts who treat these patients [to] communicate and collaborate effectively with each other,” coauthor Liliana Bordeianou, MD, MPH, an associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and chair of the Massachusetts General Hospital Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Centers, told this news organization.

“These diseases do not choose an arbitrary side in the pelvis,” she noted. “Instead, these diseases affect the entire pelvis and require a multidisciplinary and collaborative solution.”

MRD is a key component in that solution, providing dynamic evaluation of pelvic floor function and visualization of the complex interaction in pelvic compartments among patients with defecatory pelvic floor disorders, such as vaginal or uterine prolapse, constipation, incontinence, or other pelvic floor dysfunctions.

However, a key shortcoming has been a lack of consistency in nomenclature and the reporting of MRD findings among institutions and subspecialties.

Clinicians may wind up using different definitions for the same condition and different thresholds for grading severity, resulting in inconsistent communication not only between clinicians across institutions but even within the same institution, the report notes.

To address the situation, radiologists with the Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Disease Focused Panel of the Society of Abdominal Radiology (SAR) published recommendations on MRD protocol and technique in April.

However, even with that guidance, there has been significant variability in the interpretation and utilization of MRD findings among specialties outside of radiology.

The new report was therefore developed to include input from the broad variety of specialists involved in the treatment of patients with pelvic floor disorders, including colorectal surgeons, urogynecologists, urologists, gynecologists, gastroenterologists, radiologists, physiotherapists, and other advanced care practitioners.

“The goal of this effort was to create a universal set of recommendations and language for MRD technique, interpretation, and reporting that can be utilized and carry the same significance across disciplines,” write the authors of the report, published in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

One key area addressed in the report is a recommendation that MRD can be performed in either the upright or supine position, which has been a topic of inconsistency, said Brooke Gurland, MD, medical director of the Pelvic Health Center at Stanford University, California, a co-author on the consensus statement.

“Supine versus upright position was a source of debate, but ultimately there was a consensus that supine position was acceptable,” she told said in an interview.

Regarding positioning, the recommendations conclude that “given the variable results from different studies, consortium members agreed that it is acceptable to perform MRD in the supine position when upright MRD is not available.”

“Importantly, consortium experts stressed that it is very important that this imaging be performed after proper patient education on the purpose of the examination,” they note.

Other recommendations delve into contrast medium considerations, such as the recommendation that MRD does not require the routine use of vaginal contrast medium for adequate imaging of pathology.

And guidance on the technique and grading of relevant pathology include a recommendation to use the pubococcygeal line (PCL) as a point of reference to quantify the prolapse of organs in all compartments of the pelvic floor.

“There is an increasing appreciation that most patients with pelvic organ prolapse experience dual or even triple compartment pathology, making it important to describe the observations in all three compartments to ensure the mobilization of the appropriate team of experts to treat the patient,” the authors note.

The consensus report features an interpretative template providing synopses of the recommendations, which can be adjusted and modified according to additional radiologic information, as well as individualized patient information or clinician preferences.

However, “the suggested verbiage and steps should be advocated as the minimum requirements when performing and interpreting MRD in patients with evacuation disorders of the pelvic floor,” the authors note.

Dr. Gurland added that, in addition to providing benefits in the present utilization of MRD, the clearer guidelines should help advance its use to improve patient care in the future.

“Standardizing imaging techniques, reporting, and language is critical to improving our understanding and then developing therapies for pelvic floor disorders,” she said.

“In the future, correlating MRD with surgical outcomes and identifying modifiable risk factors will improve patient care.”

In addition to being published in the AJR, the report was published concurrently in the journals Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, International Urogynecology Journal, and Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery.

The authors of the guidelines have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Improving Physicians’ Bowel Documentation on Geriatric Wards

From Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Sheffield, UK, S5 7AU.

Objective: Constipation is widely prevalent in older adults and may result in complications such as urinary retention, delirium, and bowel obstruction. Previous studies have indicated that while the nursing staff do well in completing stool charts, doctors monitor them infrequently. This project aimed to improve the documentation of bowel movement by doctors on ward rounds to 85%, by the end of a 3-month period.

Methods: Baseline, postintervention, and sustainability data were collected from inpatient notes on weekdays on a geriatric ward in Northern General Hospital, Sheffield, UK. Posters and stickers of the poo emoji were placed on walls and in inpatient notes, respectively, as a reminder.

Results: Data on bowel activity documentation were collected from 28 patients. The baseline data showed that bowel activity was monitored daily on the ward 60.49% of the time. However, following the interventions, there was a significant increase in documentation, to 86.78%. The sustainability study showed that bowel activity was documented on the ward 56.56% of the time.

Conclusion: This study shows how a strong initial effect on behavioral change can be accomplished through simple interventions such as stickers and posters. As most wards currently still use paper notes, this is a generalizable model that other wards can trial. However, this study also shows the difficulty in maintaining behavioral change over extended periods of time.

Keywords: bowel movement; documentation; obstruction; constipation; geriatrics; incontinence; junior doctor; quality improvement.

Constipation is widely prevalent in the elderly, encountered frequently in both community and hospital medicine.1 Its estimated prevalence in adults over 84 years old is 34% for women and 25% for men, rising to up to 80% for long-term care residents.2

Chronic constipation is generally characterized by unsatisfactory defecation due to infrequent bowel emptying or difficulty with stool passage, which may lead to incomplete evacuation.2-4 Constipation in the elderly, in addition to causing abdominal pain, nausea, and reduced appetite, may result in complications such as fecal incontinence (and overflow diarrhea), urinary retention, delirium, and bowel obstruction, which may in result in life-threatening perforation.5,6 For inpatients on geriatric wards, these consequences may increase morbidity and mortality, while prolonging hospital stays, thereby also increasing exposure to hospital-acquired infections.7 Furthermore, constipation is also associated with impaired health-related quality of life.8

Management includes treating the cause, stopping contributing medications, early mobilization, diet modification, and, if all else fails, prescription laxatives. Therefore, early identification and appropriate treatment of constipation is beneficial in inpatient care, as well as when planning safe and patient-centered discharges.

Given the risks and complications of constipation in the elderly, we, a group of Foundation Year 2 (FY2) doctors in the UK Foundation Programme, decided to explore how doctors can help to recognize this condition early. Regular bowel movement documentation in patient notes on ward rounds is crucial, as it has been shown to reduce constipation-associated complications.5 However, complications from constipation can take significant amounts of time to develop and, therefore, documenting bowel movements on a daily basis is not necessary.

Based on these observations along with targets set out in previous studies,7 our aim was to improve documentation of bowel movement on ward rounds to 85% by March 2020.

Methods

Before the data collection process, a fishbone diagram was designed to identify the potential causes of poor documentation of bowel movement on geriatric wards. There were several aspects that were reviewed, including, for example, patients, health care professionals, organizational policies, procedures, and equipment. It was then decided to focus on raising awareness of the documentation of bowel movement by doctors specifically.

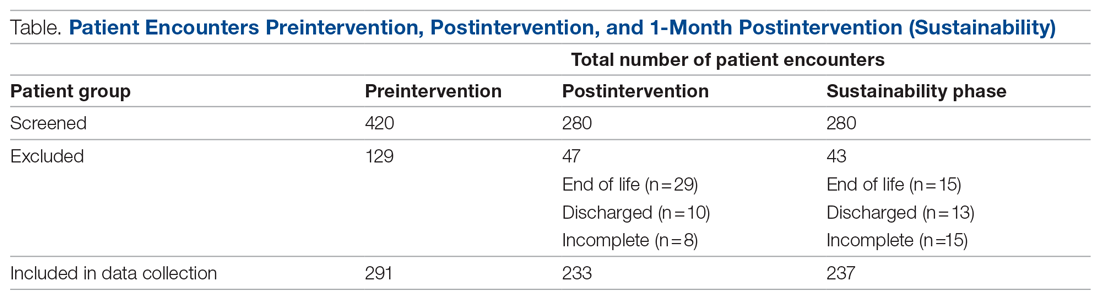

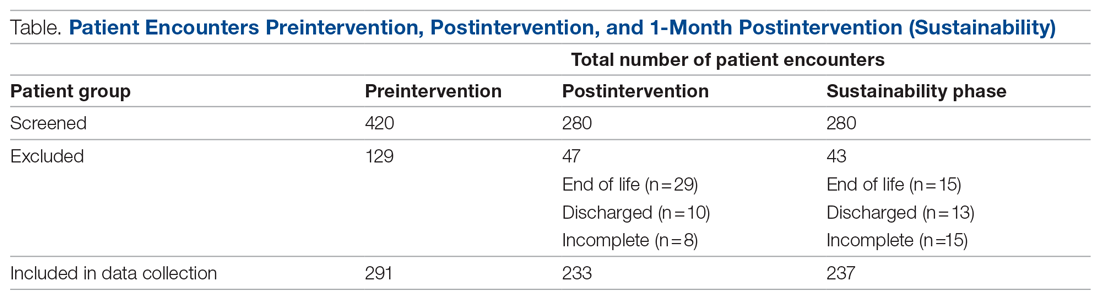

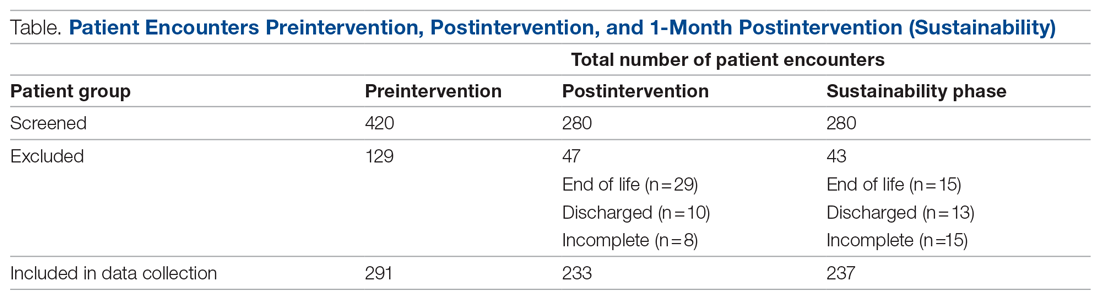

Retrospective data were collected from the inpatient paper notes of 28 patients on Brearley 6, a geriatric ward at the Northern General Hospital within Sheffield Teaching Hospitals (STH), on weekdays over a 3-week period. The baseline data collected included the bed number of the patient, whether or not bowel movement on initial ward round was documented, and whether it was the junior, registrar, or consultant leading the ward round. End-of-life and discharged patients were excluded (Table).

The interventions consisted of posters and stickers. Posters were displayed on Brearley 6, including the doctors’ office, nurses’ station, and around the bays where notes were kept, in order to emphasize their importance. The stickers of the poo emoji were also printed and placed at the front of each set of inpatient paper notes as a reminder for the doctor documenting on the ward round. The interventions were also introduced in the morning board meeting to ensure all staff on Brearley 6 were aware of them.

Data were collected on weekdays over a 3-week period starting 2 weeks after the interventions were put in place (Table). In order to assess that the intervention had been sustained, data were again collected 1 month later over a 2-week period (Table). Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) was used to analyze all data, and control charts were used to assess variability in the data.

Results

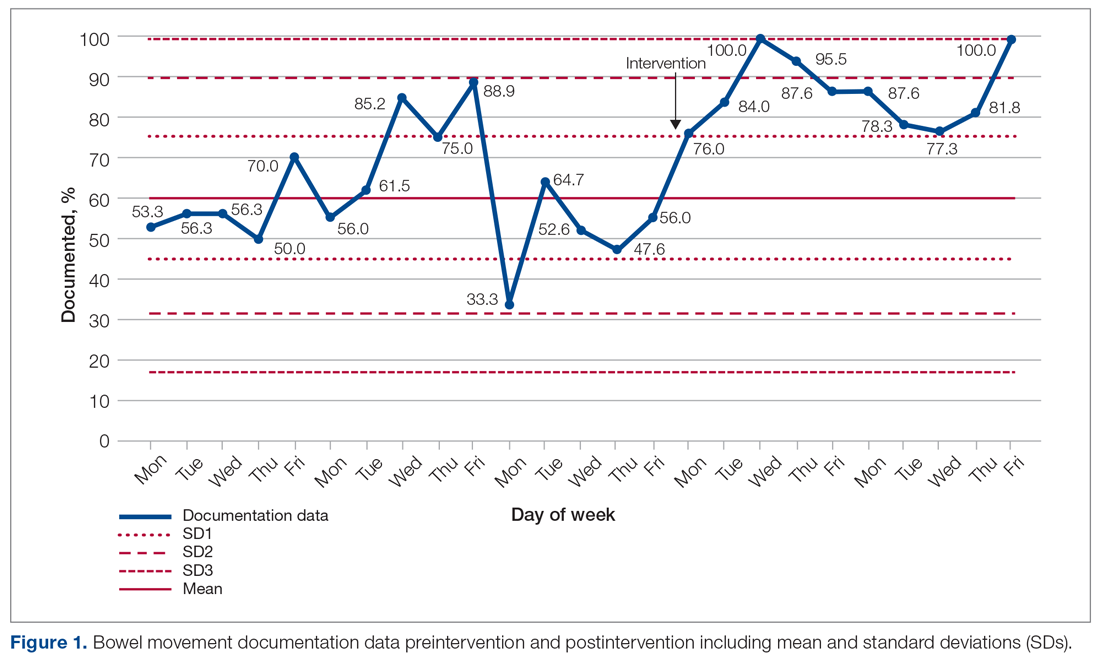

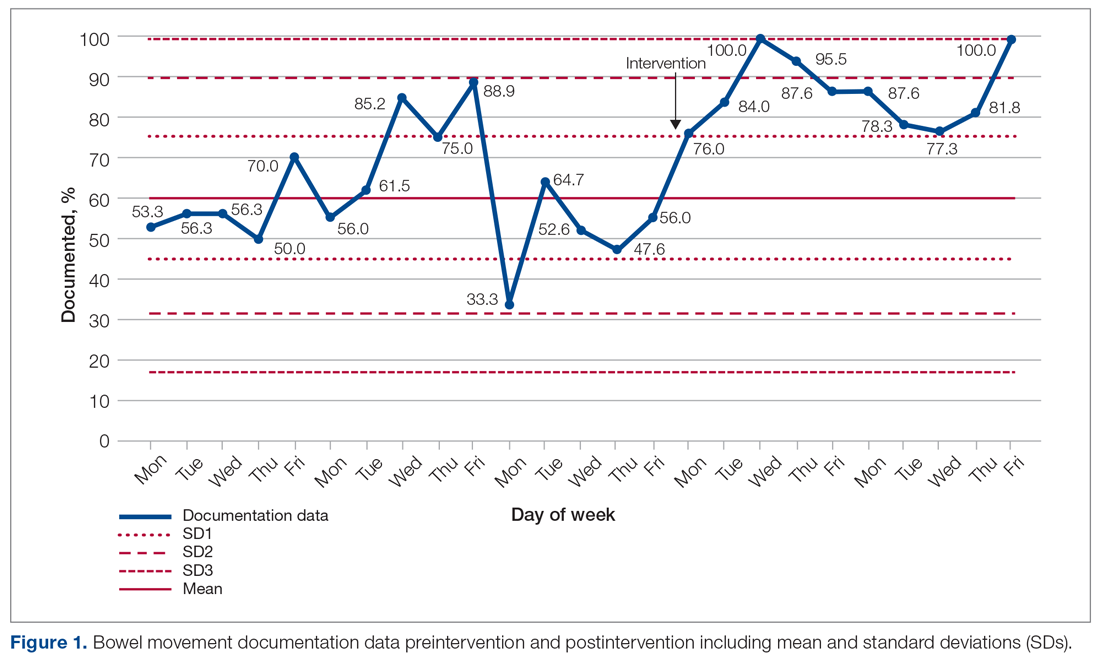

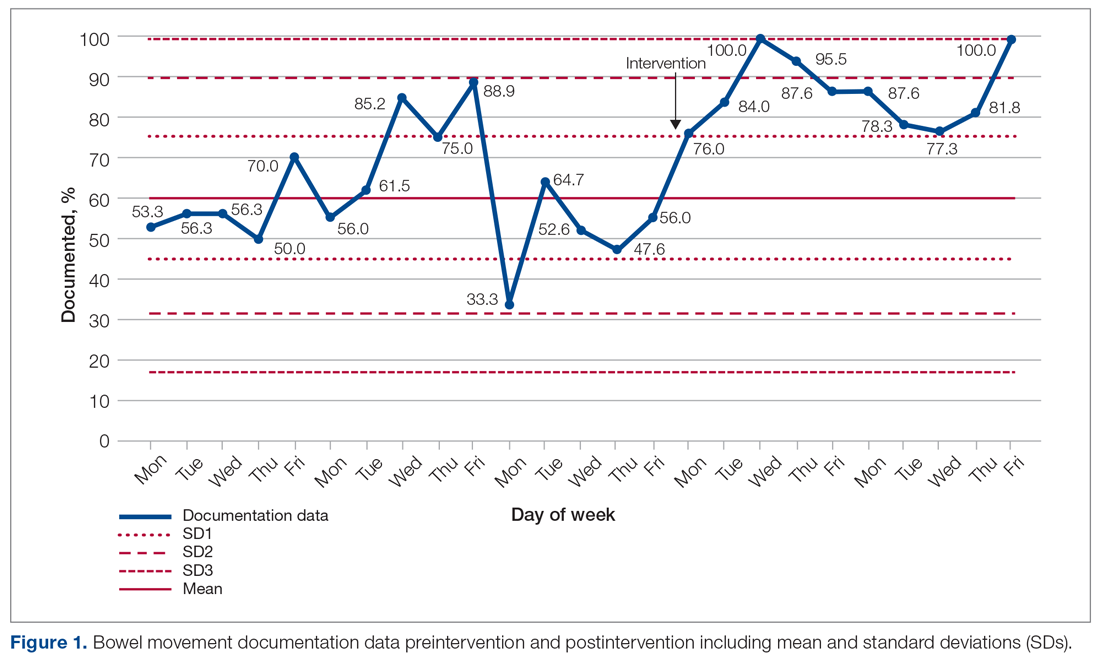

The baseline data showed that bowel movement was documented 60.49% of the time by doctors on the initial ward round before intervention, as illustrated in Figure 1. There was no evidence of an out-of-control process in this baseline data set.

The comparison between the preintervention and postintervention data is illustrated in Figure 1. The postintervention data, which were taken 2 weeks after intervention, showed a significant increase in the documentation of bowel movements, to 86.78%. The figure displays a number of features consistent with an out-of-control process: beyond limits (≥ 1 points beyond control limits), Zone A rule (2 out of 3 consecutive points beyond 2 standard deviations from the mean), Zone B rule (4 out of 5 consecutive points beyond 1 standard deviation from the mean), and Zone C rule (≥ 8 consecutive points on 1 side of the mean). These findings demonstrate a special cause variation in the documentation of bowel movements.

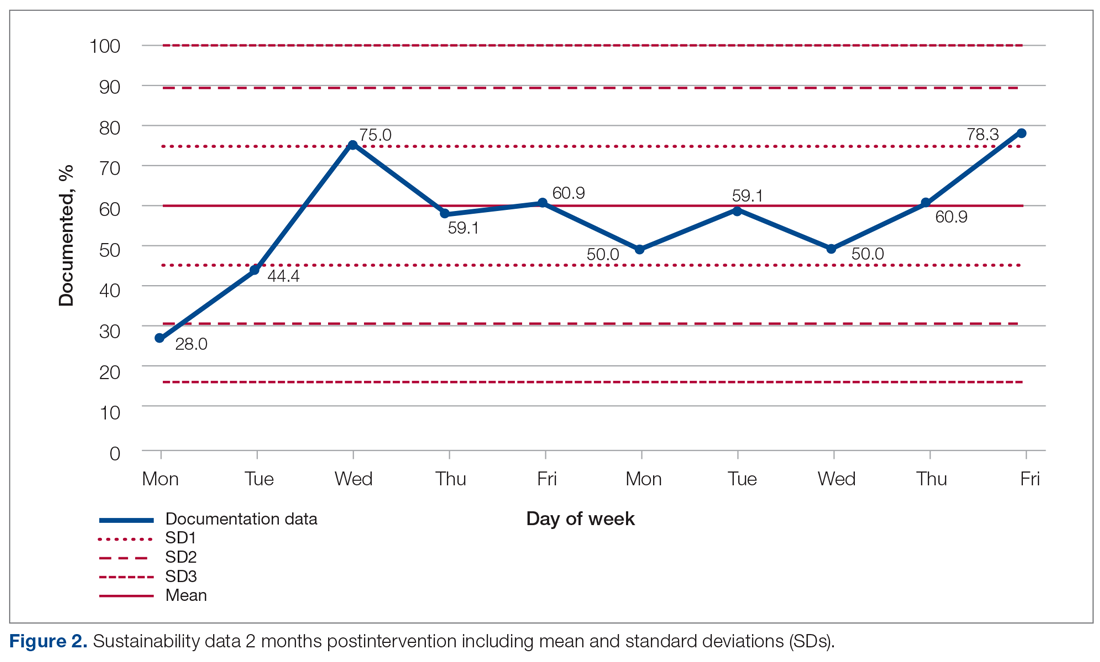

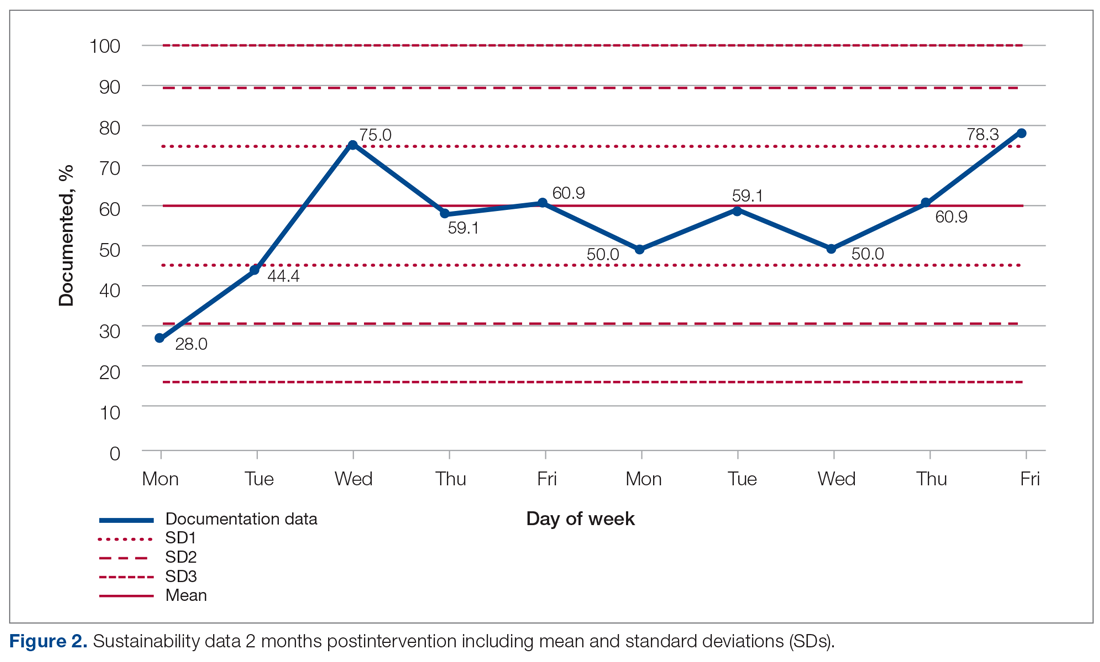

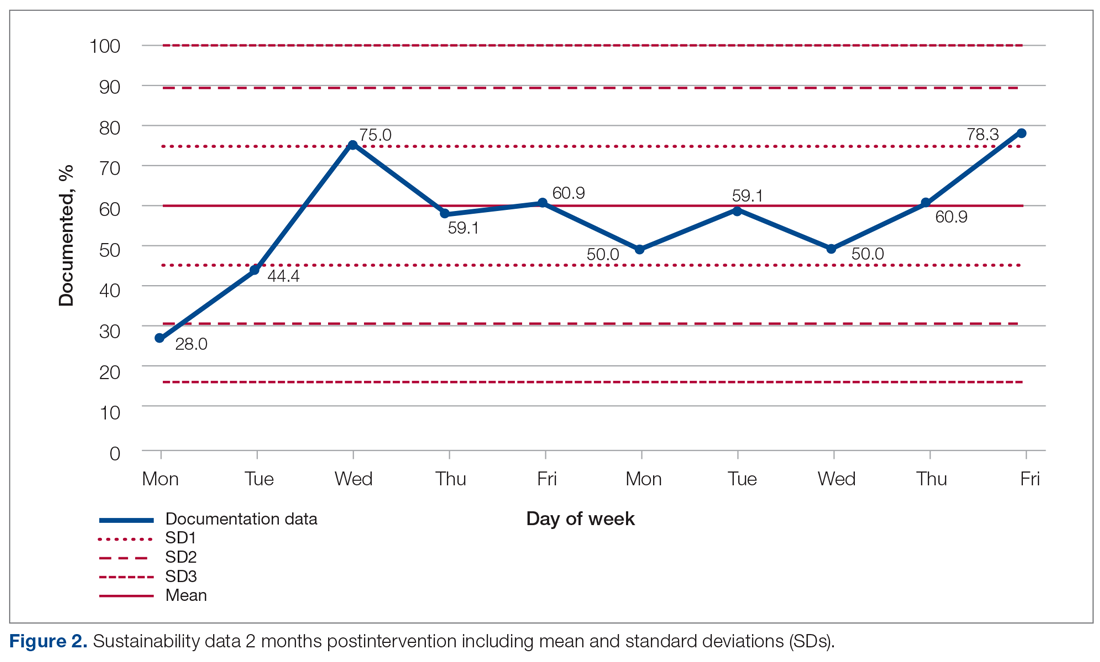

Figure 2 shows the sustainability of the intervention, which averaged 56.56% postintervention nearly 2 months later. The data returned to preintervention variability levels.

Discussion

Our project explored an important issue that was frequently encountered by department clinicians. Our team of FY2 doctors, in general, had little experience with quality improvement. We have developed our understanding and experience through planning, making, and measuring improvement.

It was challenging deciding on how to deal with the problem. A number of ways were considered to improve the paper rounding chart, but the nursing team had already planned to make changes to it. Bowel activity is mainly documented by nursing staff, but there was no specific protocol for recognizing constipation and when to inform the medical team. We decided to focus on doctors’ documentation in patient notes during the ward round, as this is where the decision regarding management of bowels is made, including interventions that could only be done by doctors, such as prescribing laxatives.

Strom et al9 have described a number of successful quality improvement interventions, and we decided to follow the authors’ guidance to implement a reminder system strategy using both posters and stickers to prompt doctors to document bowel activity. Both of these were simple, and the text on the poster was concise. The only cost incurred on the project was from printing the stickers; this totalled £2.99 (US $4.13). Individual stickers for each ward round entry were considered but not used, as it would create an additional task for doctors.

The data initially indicated that the interventions had their desired effect. However, this positive change was unsustainable, most likely suggesting that the novelty of the stickers and posters wore off at some point, leading to junior doctors no longer noticing them. Further Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles should examine the reasons why the change is difficult to sustain and implement new policies that aim to overcome them.

There were a number of limitations to this study. A patient could be discharged before data collection, which was done twice weekly. This could have resulted in missed data during the collection period. In addition, the accuracy of the documentation is dependent on nursing staff correctly recording—as well as the doctors correctly viewing—all sources of information on bowel activity. Observer bias is possible, too, as a steering group member was involved in data collection. Their awareness of the project could cause a positive skew in the data. And, unfortunately, the project came to an abrupt end because of COVID-19 cases on the ward.

We examined the daily documentation of bowel activity, which may not be necessary considering that internationally recognized constipation classifications, such as the Rome III criteria, define constipation as fewer than 3 bowel movements per week.10 However, the data collection sheet did not include patient identifiers, so it was impossible to determine whether bowel activity had been documented 3 or more times per week for each patient. This is important because a clinician may only decide to act if there is no bowel movement activity for 3 or more days.

Because our data were collected on a single geriatric ward, which had an emphasis on Parkinson’s disease, it is unclear whether our findings are generalizable to other clinical areas in STH. However, constipation is common in the elderly, so it is likely to be relevant to other wards, as more than a third of STH hospital beds are occupied by patients aged 75 years and older.11

Conclusion

Overall, our study highlights the fact that monitoring bowel activity is important on a geriatric ward. Recognizing constipation early prevents complications and delays to discharge. As mentioned earlier, our aim was achieved initially but not sustained. Therefore, future development should focus on sustainability. For example, laxative-focused ward rounds have shown to be effective at recognizing and preventing constipation by intervening early.12 Future cycles that we considered included using an electronic reminder on the hospital IT system, as the trust is aiming to introduce electronic documentation. Focus could also be placed on improving documentation in bowel charts by ward staff. This could be achieved by organizing regular educational sessions on the complications of constipation and when to inform the medical team regarding concerns.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Dr. Jamie Kapur, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, for his guidance and supervision, as well as our collaborators: Rachel Hallam, Claire Walker, Monisha Chakravorty, and Hamza Khan.

Corresponding author: Alexander P. Noar, BMBCh, BA, 10 Stanhope Gardens, London, N6 5TS; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Forootan M, Bagheri N, Darvishi M. Chronic constipation: A review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e10631. doi:10.1097/MD.00000000000.10631

2. Schuster BG, Kosar L, Kamrul R. Constipation in older adults: stepwise approach to keep things moving. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:152-158.

3. Gray JR. What is chronic constipation? Definition and diagnosis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25 (Suppl B):7B-10B.

4. American Gastroenterological Association, Bharucha AE, Dorn SD, Lembo A, Pressman A. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:211-217. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.029

5. Maung TZ, Singh K. Regular monitoring with stool chart prevents constipation, urinary retention and delirium in elderly patients: an audit leading to clinical effectiveness, efficiency and patient centredness. Future Healthc J. 2019;6(Suppl 2):3. doi:10.7861/futurehosp.6-2s-s3

6. Mostafa SM, Bhandari S, Ritchie G, et al. Constipation and its implications in the critically ill patient. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:815-819. doi:10.1093/bja/aeg275

7. Jackson R, Cheng P, Moreman S, et al. “The constipation conundrum”: Improving recognition of constipation on a gastroenterology ward. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1):u212167.w3007. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u212167.w3007

8. Rao S, Go JT. Update on the management of constipation in the elderly: new treatment options. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:163-171. doi:10.2147/cia.s8100

9. Strom KL. Quality improvement interventions: what works? J Healthc Qual. 2001;23(5):4-24. doi:10.1111/j.1945-1474.2001.tb00368.x

10. De Giorgio R, Ruggeri E, Stanghellini V, et al. Chronic constipation in the elderly: a primer for the gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:130. doi:10.1186/s12876-015-366-3

11. The Health Foundation. Improving the flow of older people. April 2013. Accessed August 11, 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/sheff-study.pdf

12. Linton A. Improving management of constipation in an inpatient setting using a care bundle. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3(1):u201903.w1002. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u201903.w1002

From Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Sheffield, UK, S5 7AU.

Objective: Constipation is widely prevalent in older adults and may result in complications such as urinary retention, delirium, and bowel obstruction. Previous studies have indicated that while the nursing staff do well in completing stool charts, doctors monitor them infrequently. This project aimed to improve the documentation of bowel movement by doctors on ward rounds to 85%, by the end of a 3-month period.

Methods: Baseline, postintervention, and sustainability data were collected from inpatient notes on weekdays on a geriatric ward in Northern General Hospital, Sheffield, UK. Posters and stickers of the poo emoji were placed on walls and in inpatient notes, respectively, as a reminder.

Results: Data on bowel activity documentation were collected from 28 patients. The baseline data showed that bowel activity was monitored daily on the ward 60.49% of the time. However, following the interventions, there was a significant increase in documentation, to 86.78%. The sustainability study showed that bowel activity was documented on the ward 56.56% of the time.

Conclusion: This study shows how a strong initial effect on behavioral change can be accomplished through simple interventions such as stickers and posters. As most wards currently still use paper notes, this is a generalizable model that other wards can trial. However, this study also shows the difficulty in maintaining behavioral change over extended periods of time.

Keywords: bowel movement; documentation; obstruction; constipation; geriatrics; incontinence; junior doctor; quality improvement.

Constipation is widely prevalent in the elderly, encountered frequently in both community and hospital medicine.1 Its estimated prevalence in adults over 84 years old is 34% for women and 25% for men, rising to up to 80% for long-term care residents.2

Chronic constipation is generally characterized by unsatisfactory defecation due to infrequent bowel emptying or difficulty with stool passage, which may lead to incomplete evacuation.2-4 Constipation in the elderly, in addition to causing abdominal pain, nausea, and reduced appetite, may result in complications such as fecal incontinence (and overflow diarrhea), urinary retention, delirium, and bowel obstruction, which may in result in life-threatening perforation.5,6 For inpatients on geriatric wards, these consequences may increase morbidity and mortality, while prolonging hospital stays, thereby also increasing exposure to hospital-acquired infections.7 Furthermore, constipation is also associated with impaired health-related quality of life.8

Management includes treating the cause, stopping contributing medications, early mobilization, diet modification, and, if all else fails, prescription laxatives. Therefore, early identification and appropriate treatment of constipation is beneficial in inpatient care, as well as when planning safe and patient-centered discharges.

Given the risks and complications of constipation in the elderly, we, a group of Foundation Year 2 (FY2) doctors in the UK Foundation Programme, decided to explore how doctors can help to recognize this condition early. Regular bowel movement documentation in patient notes on ward rounds is crucial, as it has been shown to reduce constipation-associated complications.5 However, complications from constipation can take significant amounts of time to develop and, therefore, documenting bowel movements on a daily basis is not necessary.

Based on these observations along with targets set out in previous studies,7 our aim was to improve documentation of bowel movement on ward rounds to 85% by March 2020.

Methods

Before the data collection process, a fishbone diagram was designed to identify the potential causes of poor documentation of bowel movement on geriatric wards. There were several aspects that were reviewed, including, for example, patients, health care professionals, organizational policies, procedures, and equipment. It was then decided to focus on raising awareness of the documentation of bowel movement by doctors specifically.

Retrospective data were collected from the inpatient paper notes of 28 patients on Brearley 6, a geriatric ward at the Northern General Hospital within Sheffield Teaching Hospitals (STH), on weekdays over a 3-week period. The baseline data collected included the bed number of the patient, whether or not bowel movement on initial ward round was documented, and whether it was the junior, registrar, or consultant leading the ward round. End-of-life and discharged patients were excluded (Table).

The interventions consisted of posters and stickers. Posters were displayed on Brearley 6, including the doctors’ office, nurses’ station, and around the bays where notes were kept, in order to emphasize their importance. The stickers of the poo emoji were also printed and placed at the front of each set of inpatient paper notes as a reminder for the doctor documenting on the ward round. The interventions were also introduced in the morning board meeting to ensure all staff on Brearley 6 were aware of them.

Data were collected on weekdays over a 3-week period starting 2 weeks after the interventions were put in place (Table). In order to assess that the intervention had been sustained, data were again collected 1 month later over a 2-week period (Table). Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) was used to analyze all data, and control charts were used to assess variability in the data.

Results

The baseline data showed that bowel movement was documented 60.49% of the time by doctors on the initial ward round before intervention, as illustrated in Figure 1. There was no evidence of an out-of-control process in this baseline data set.

The comparison between the preintervention and postintervention data is illustrated in Figure 1. The postintervention data, which were taken 2 weeks after intervention, showed a significant increase in the documentation of bowel movements, to 86.78%. The figure displays a number of features consistent with an out-of-control process: beyond limits (≥ 1 points beyond control limits), Zone A rule (2 out of 3 consecutive points beyond 2 standard deviations from the mean), Zone B rule (4 out of 5 consecutive points beyond 1 standard deviation from the mean), and Zone C rule (≥ 8 consecutive points on 1 side of the mean). These findings demonstrate a special cause variation in the documentation of bowel movements.

Figure 2 shows the sustainability of the intervention, which averaged 56.56% postintervention nearly 2 months later. The data returned to preintervention variability levels.

Discussion

Our project explored an important issue that was frequently encountered by department clinicians. Our team of FY2 doctors, in general, had little experience with quality improvement. We have developed our understanding and experience through planning, making, and measuring improvement.

It was challenging deciding on how to deal with the problem. A number of ways were considered to improve the paper rounding chart, but the nursing team had already planned to make changes to it. Bowel activity is mainly documented by nursing staff, but there was no specific protocol for recognizing constipation and when to inform the medical team. We decided to focus on doctors’ documentation in patient notes during the ward round, as this is where the decision regarding management of bowels is made, including interventions that could only be done by doctors, such as prescribing laxatives.

Strom et al9 have described a number of successful quality improvement interventions, and we decided to follow the authors’ guidance to implement a reminder system strategy using both posters and stickers to prompt doctors to document bowel activity. Both of these were simple, and the text on the poster was concise. The only cost incurred on the project was from printing the stickers; this totalled £2.99 (US $4.13). Individual stickers for each ward round entry were considered but not used, as it would create an additional task for doctors.

The data initially indicated that the interventions had their desired effect. However, this positive change was unsustainable, most likely suggesting that the novelty of the stickers and posters wore off at some point, leading to junior doctors no longer noticing them. Further Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles should examine the reasons why the change is difficult to sustain and implement new policies that aim to overcome them.

There were a number of limitations to this study. A patient could be discharged before data collection, which was done twice weekly. This could have resulted in missed data during the collection period. In addition, the accuracy of the documentation is dependent on nursing staff correctly recording—as well as the doctors correctly viewing—all sources of information on bowel activity. Observer bias is possible, too, as a steering group member was involved in data collection. Their awareness of the project could cause a positive skew in the data. And, unfortunately, the project came to an abrupt end because of COVID-19 cases on the ward.

We examined the daily documentation of bowel activity, which may not be necessary considering that internationally recognized constipation classifications, such as the Rome III criteria, define constipation as fewer than 3 bowel movements per week.10 However, the data collection sheet did not include patient identifiers, so it was impossible to determine whether bowel activity had been documented 3 or more times per week for each patient. This is important because a clinician may only decide to act if there is no bowel movement activity for 3 or more days.

Because our data were collected on a single geriatric ward, which had an emphasis on Parkinson’s disease, it is unclear whether our findings are generalizable to other clinical areas in STH. However, constipation is common in the elderly, so it is likely to be relevant to other wards, as more than a third of STH hospital beds are occupied by patients aged 75 years and older.11

Conclusion

Overall, our study highlights the fact that monitoring bowel activity is important on a geriatric ward. Recognizing constipation early prevents complications and delays to discharge. As mentioned earlier, our aim was achieved initially but not sustained. Therefore, future development should focus on sustainability. For example, laxative-focused ward rounds have shown to be effective at recognizing and preventing constipation by intervening early.12 Future cycles that we considered included using an electronic reminder on the hospital IT system, as the trust is aiming to introduce electronic documentation. Focus could also be placed on improving documentation in bowel charts by ward staff. This could be achieved by organizing regular educational sessions on the complications of constipation and when to inform the medical team regarding concerns.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Dr. Jamie Kapur, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, for his guidance and supervision, as well as our collaborators: Rachel Hallam, Claire Walker, Monisha Chakravorty, and Hamza Khan.

Corresponding author: Alexander P. Noar, BMBCh, BA, 10 Stanhope Gardens, London, N6 5TS; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Sheffield, UK, S5 7AU.

Objective: Constipation is widely prevalent in older adults and may result in complications such as urinary retention, delirium, and bowel obstruction. Previous studies have indicated that while the nursing staff do well in completing stool charts, doctors monitor them infrequently. This project aimed to improve the documentation of bowel movement by doctors on ward rounds to 85%, by the end of a 3-month period.

Methods: Baseline, postintervention, and sustainability data were collected from inpatient notes on weekdays on a geriatric ward in Northern General Hospital, Sheffield, UK. Posters and stickers of the poo emoji were placed on walls and in inpatient notes, respectively, as a reminder.

Results: Data on bowel activity documentation were collected from 28 patients. The baseline data showed that bowel activity was monitored daily on the ward 60.49% of the time. However, following the interventions, there was a significant increase in documentation, to 86.78%. The sustainability study showed that bowel activity was documented on the ward 56.56% of the time.

Conclusion: This study shows how a strong initial effect on behavioral change can be accomplished through simple interventions such as stickers and posters. As most wards currently still use paper notes, this is a generalizable model that other wards can trial. However, this study also shows the difficulty in maintaining behavioral change over extended periods of time.

Keywords: bowel movement; documentation; obstruction; constipation; geriatrics; incontinence; junior doctor; quality improvement.

Constipation is widely prevalent in the elderly, encountered frequently in both community and hospital medicine.1 Its estimated prevalence in adults over 84 years old is 34% for women and 25% for men, rising to up to 80% for long-term care residents.2

Chronic constipation is generally characterized by unsatisfactory defecation due to infrequent bowel emptying or difficulty with stool passage, which may lead to incomplete evacuation.2-4 Constipation in the elderly, in addition to causing abdominal pain, nausea, and reduced appetite, may result in complications such as fecal incontinence (and overflow diarrhea), urinary retention, delirium, and bowel obstruction, which may in result in life-threatening perforation.5,6 For inpatients on geriatric wards, these consequences may increase morbidity and mortality, while prolonging hospital stays, thereby also increasing exposure to hospital-acquired infections.7 Furthermore, constipation is also associated with impaired health-related quality of life.8

Management includes treating the cause, stopping contributing medications, early mobilization, diet modification, and, if all else fails, prescription laxatives. Therefore, early identification and appropriate treatment of constipation is beneficial in inpatient care, as well as when planning safe and patient-centered discharges.

Given the risks and complications of constipation in the elderly, we, a group of Foundation Year 2 (FY2) doctors in the UK Foundation Programme, decided to explore how doctors can help to recognize this condition early. Regular bowel movement documentation in patient notes on ward rounds is crucial, as it has been shown to reduce constipation-associated complications.5 However, complications from constipation can take significant amounts of time to develop and, therefore, documenting bowel movements on a daily basis is not necessary.

Based on these observations along with targets set out in previous studies,7 our aim was to improve documentation of bowel movement on ward rounds to 85% by March 2020.

Methods

Before the data collection process, a fishbone diagram was designed to identify the potential causes of poor documentation of bowel movement on geriatric wards. There were several aspects that were reviewed, including, for example, patients, health care professionals, organizational policies, procedures, and equipment. It was then decided to focus on raising awareness of the documentation of bowel movement by doctors specifically.

Retrospective data were collected from the inpatient paper notes of 28 patients on Brearley 6, a geriatric ward at the Northern General Hospital within Sheffield Teaching Hospitals (STH), on weekdays over a 3-week period. The baseline data collected included the bed number of the patient, whether or not bowel movement on initial ward round was documented, and whether it was the junior, registrar, or consultant leading the ward round. End-of-life and discharged patients were excluded (Table).

The interventions consisted of posters and stickers. Posters were displayed on Brearley 6, including the doctors’ office, nurses’ station, and around the bays where notes were kept, in order to emphasize their importance. The stickers of the poo emoji were also printed and placed at the front of each set of inpatient paper notes as a reminder for the doctor documenting on the ward round. The interventions were also introduced in the morning board meeting to ensure all staff on Brearley 6 were aware of them.

Data were collected on weekdays over a 3-week period starting 2 weeks after the interventions were put in place (Table). In order to assess that the intervention had been sustained, data were again collected 1 month later over a 2-week period (Table). Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) was used to analyze all data, and control charts were used to assess variability in the data.

Results

The baseline data showed that bowel movement was documented 60.49% of the time by doctors on the initial ward round before intervention, as illustrated in Figure 1. There was no evidence of an out-of-control process in this baseline data set.

The comparison between the preintervention and postintervention data is illustrated in Figure 1. The postintervention data, which were taken 2 weeks after intervention, showed a significant increase in the documentation of bowel movements, to 86.78%. The figure displays a number of features consistent with an out-of-control process: beyond limits (≥ 1 points beyond control limits), Zone A rule (2 out of 3 consecutive points beyond 2 standard deviations from the mean), Zone B rule (4 out of 5 consecutive points beyond 1 standard deviation from the mean), and Zone C rule (≥ 8 consecutive points on 1 side of the mean). These findings demonstrate a special cause variation in the documentation of bowel movements.

Figure 2 shows the sustainability of the intervention, which averaged 56.56% postintervention nearly 2 months later. The data returned to preintervention variability levels.

Discussion

Our project explored an important issue that was frequently encountered by department clinicians. Our team of FY2 doctors, in general, had little experience with quality improvement. We have developed our understanding and experience through planning, making, and measuring improvement.

It was challenging deciding on how to deal with the problem. A number of ways were considered to improve the paper rounding chart, but the nursing team had already planned to make changes to it. Bowel activity is mainly documented by nursing staff, but there was no specific protocol for recognizing constipation and when to inform the medical team. We decided to focus on doctors’ documentation in patient notes during the ward round, as this is where the decision regarding management of bowels is made, including interventions that could only be done by doctors, such as prescribing laxatives.