User login

CarePostRoe.com: Study seeks to document poor quality medical care due to new abortion bans

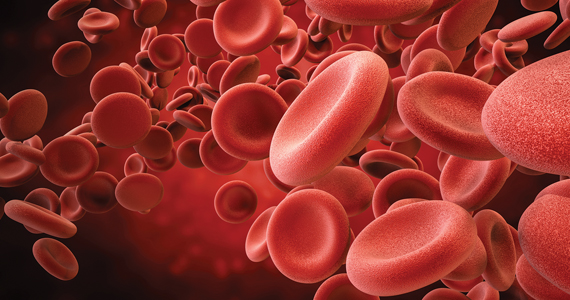

In June 2022, the US Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization removed federal protections for abortion that previously had been codified in Roe v Wade. Since this removal, most abortions have been banned in at least 13 states, and about half of states are expected to attempt to ban or heavily restrict abortion.1,2 These laws banning abortion are having effects on patient care far beyond abortion, leading to uncertainty and fear among providers and denied or delayed care for patients.3,4 It is critical that research documents the harmful effects of this policy change.

Patients that are pregnant with fetuses with severe malformations have had to travel long distances to other states to obtain care.5 Others have faced delays in obtaining treatment for ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and even for other conditions that use medications that could potentially cause an abortion.6,7 These cases have the potential to result in serious harm or death of the patient with altered care. There is a published report from Texas showing how the change in practice due to the 6-week abortion ban imposed in 2021 was associated with a doubling of severe morbidity for patients presenting with preterm premature rupture of membranes and other complications before 22 weeks’ gestation.8

While these cases have been highlighted in the media, there has not been a resource that comprehensively documents the changes in care that clinicians have been forced to make because of abortion bans as well as the consequences for their patients’ health. The media also may not be the most desirable platform for sharing cases of substandard care if providers feel their confidentiality may be breached as they are told by their employers to avoid speaking with reporters.9 Bearing this in mind, our team of researchers at Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health at the University of California San Francisco and the Texas Policy Evaluation Project at the University of Texas at Austin has launched a project aiming to collect stories of poor quality care post-Roe from health care professionals across the United States. The aim of the study is to document examples of the challenges in patient care that have arisen since the Dobbs decision.

The study website CarePostRoe.com was launched in October 2022 to collect narratives from health care providers who participated in the care of a patient whose management was different from the usual standard due to a need to comply with new restrictions on abortion since the Dobbs decision. These providers can include physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, midwives, physician assistants, social workers, pharmacists, psychologists, or other allied health professionals. Clinicians can share information about a case through a brief survey linked on the website that will allow them to either submit a written narrative or a voice memo. The submissions are anonymous, and providers are not asked to submit any protected health information. If the submitter would like to share more information about the case via telephone interview, they will be taken to a separate survey which is not linked to the narrative submission to give contact information to participate in an interview.

Since October, more than 40 cases have been submitted that document patient cases from over half of the states with abortion bans. Clinicians describe pregnant patients with severe fetal malformations who have had to overcome financial and logistical barriers to travel to access abortion care. Several cases of patients with cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies have been submitted, including cases that are being followed expectantly, which is inconsistent with the standard of care.10 We also have received several submissions about cases of preterm premature rupture of membranes in the second trimester where the patient was sent home and presented several days later with a severe infection requiring management in the intensive care unit. Cases of early pregnancy loss that could have been treated safely and routinely also were delayed, increasing the risk to patients who, in addition to receiving substandard medical care, had the trauma of fearing they could be prosecuted for receiving treatment.

We hope these data will be useful to document the impact of the Court’s decision and to improve patient care as health care institutions work to update their policies and protocols to reduce delays in care in the face of legal ambiguities. If you have been involved in such a case since June 2022, including caring for a patient who traveled from another state, please consider submitting it at CarePostRoe.com, and please spread the word through your networks.

- McCann A, Schoenfeld Walker A, Sasani A, et al. Tracking the states where abortion is now banned. New York Times. May 24, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com /interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade .html

- Nash E, Ephross P. State policy trends 2022: in a devastating year, US Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe leads to bans, confusion and chaos. Guttmacher Institute website. Published December 19, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.guttmacher.org/2022/12/state -policy-trends-2022-devastating-year-us -supreme-courts-decision-overturn-roe-leads

- Cha AE. Physicians face confusion and fear in post-Roe world. Washington Post. June 28, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www .washingtonpost.com/health/2022/06/28 /abortion-ban-roe-doctors-confusion/

- Zernike K. Medical impact of Roe reversal goes well beyond abortion clinics, doctors say. New York Times. September 10, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes .com/2022/09/10/us/abortion-bans-medical -care-women.html

- Abrams A. ‘Never-ending nightmare.’ an Ohio woman was forced to travel out of state for an abortion. Time. August 29, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://time.com/6208860/ohio -woman-forced-travel-abortion/

- Belluck P. They had miscarriages, and new abortion laws obstructed treatment. New York Times. July 17, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/17/health /abortion-miscarriage-treatment.html

- Sellers FS, Nirappil F. Confusion post-Roe spurs delays, denials for some lifesaving pregnancy care. Washington Post. July 16, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost .com/health/2022/07/16/abortion-miscarriage -ectopic-pregnancy-care/.

- Nambiar A, Patel S, Santiago-Munoz P, et al. Maternal morbidity and fetal outcomes among pregnant women at 22 weeks’ gestation or less with complications in 2 Texas hospitals after legislation on abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:648-650.e1.

- Cohen E, Lape J, Herman D. “Heartbreaking” stories go untold, doctors say, as employers “muzzle” them in wake of abortion ruling. CNN website. Published October 12, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/12 /health/abortion-doctors-talking/index.html.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), Miller R, Gyamfi-Bannerman C; Publications Committee. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #63: Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy [published online July 16, 2022]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Sep;227:B9-B20. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2022.06.024.

In June 2022, the US Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization removed federal protections for abortion that previously had been codified in Roe v Wade. Since this removal, most abortions have been banned in at least 13 states, and about half of states are expected to attempt to ban or heavily restrict abortion.1,2 These laws banning abortion are having effects on patient care far beyond abortion, leading to uncertainty and fear among providers and denied or delayed care for patients.3,4 It is critical that research documents the harmful effects of this policy change.

Patients that are pregnant with fetuses with severe malformations have had to travel long distances to other states to obtain care.5 Others have faced delays in obtaining treatment for ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and even for other conditions that use medications that could potentially cause an abortion.6,7 These cases have the potential to result in serious harm or death of the patient with altered care. There is a published report from Texas showing how the change in practice due to the 6-week abortion ban imposed in 2021 was associated with a doubling of severe morbidity for patients presenting with preterm premature rupture of membranes and other complications before 22 weeks’ gestation.8

While these cases have been highlighted in the media, there has not been a resource that comprehensively documents the changes in care that clinicians have been forced to make because of abortion bans as well as the consequences for their patients’ health. The media also may not be the most desirable platform for sharing cases of substandard care if providers feel their confidentiality may be breached as they are told by their employers to avoid speaking with reporters.9 Bearing this in mind, our team of researchers at Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health at the University of California San Francisco and the Texas Policy Evaluation Project at the University of Texas at Austin has launched a project aiming to collect stories of poor quality care post-Roe from health care professionals across the United States. The aim of the study is to document examples of the challenges in patient care that have arisen since the Dobbs decision.

The study website CarePostRoe.com was launched in October 2022 to collect narratives from health care providers who participated in the care of a patient whose management was different from the usual standard due to a need to comply with new restrictions on abortion since the Dobbs decision. These providers can include physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, midwives, physician assistants, social workers, pharmacists, psychologists, or other allied health professionals. Clinicians can share information about a case through a brief survey linked on the website that will allow them to either submit a written narrative or a voice memo. The submissions are anonymous, and providers are not asked to submit any protected health information. If the submitter would like to share more information about the case via telephone interview, they will be taken to a separate survey which is not linked to the narrative submission to give contact information to participate in an interview.

Since October, more than 40 cases have been submitted that document patient cases from over half of the states with abortion bans. Clinicians describe pregnant patients with severe fetal malformations who have had to overcome financial and logistical barriers to travel to access abortion care. Several cases of patients with cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies have been submitted, including cases that are being followed expectantly, which is inconsistent with the standard of care.10 We also have received several submissions about cases of preterm premature rupture of membranes in the second trimester where the patient was sent home and presented several days later with a severe infection requiring management in the intensive care unit. Cases of early pregnancy loss that could have been treated safely and routinely also were delayed, increasing the risk to patients who, in addition to receiving substandard medical care, had the trauma of fearing they could be prosecuted for receiving treatment.

We hope these data will be useful to document the impact of the Court’s decision and to improve patient care as health care institutions work to update their policies and protocols to reduce delays in care in the face of legal ambiguities. If you have been involved in such a case since June 2022, including caring for a patient who traveled from another state, please consider submitting it at CarePostRoe.com, and please spread the word through your networks.

In June 2022, the US Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization removed federal protections for abortion that previously had been codified in Roe v Wade. Since this removal, most abortions have been banned in at least 13 states, and about half of states are expected to attempt to ban or heavily restrict abortion.1,2 These laws banning abortion are having effects on patient care far beyond abortion, leading to uncertainty and fear among providers and denied or delayed care for patients.3,4 It is critical that research documents the harmful effects of this policy change.

Patients that are pregnant with fetuses with severe malformations have had to travel long distances to other states to obtain care.5 Others have faced delays in obtaining treatment for ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and even for other conditions that use medications that could potentially cause an abortion.6,7 These cases have the potential to result in serious harm or death of the patient with altered care. There is a published report from Texas showing how the change in practice due to the 6-week abortion ban imposed in 2021 was associated with a doubling of severe morbidity for patients presenting with preterm premature rupture of membranes and other complications before 22 weeks’ gestation.8

While these cases have been highlighted in the media, there has not been a resource that comprehensively documents the changes in care that clinicians have been forced to make because of abortion bans as well as the consequences for their patients’ health. The media also may not be the most desirable platform for sharing cases of substandard care if providers feel their confidentiality may be breached as they are told by their employers to avoid speaking with reporters.9 Bearing this in mind, our team of researchers at Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health at the University of California San Francisco and the Texas Policy Evaluation Project at the University of Texas at Austin has launched a project aiming to collect stories of poor quality care post-Roe from health care professionals across the United States. The aim of the study is to document examples of the challenges in patient care that have arisen since the Dobbs decision.

The study website CarePostRoe.com was launched in October 2022 to collect narratives from health care providers who participated in the care of a patient whose management was different from the usual standard due to a need to comply with new restrictions on abortion since the Dobbs decision. These providers can include physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, midwives, physician assistants, social workers, pharmacists, psychologists, or other allied health professionals. Clinicians can share information about a case through a brief survey linked on the website that will allow them to either submit a written narrative or a voice memo. The submissions are anonymous, and providers are not asked to submit any protected health information. If the submitter would like to share more information about the case via telephone interview, they will be taken to a separate survey which is not linked to the narrative submission to give contact information to participate in an interview.

Since October, more than 40 cases have been submitted that document patient cases from over half of the states with abortion bans. Clinicians describe pregnant patients with severe fetal malformations who have had to overcome financial and logistical barriers to travel to access abortion care. Several cases of patients with cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies have been submitted, including cases that are being followed expectantly, which is inconsistent with the standard of care.10 We also have received several submissions about cases of preterm premature rupture of membranes in the second trimester where the patient was sent home and presented several days later with a severe infection requiring management in the intensive care unit. Cases of early pregnancy loss that could have been treated safely and routinely also were delayed, increasing the risk to patients who, in addition to receiving substandard medical care, had the trauma of fearing they could be prosecuted for receiving treatment.

We hope these data will be useful to document the impact of the Court’s decision and to improve patient care as health care institutions work to update their policies and protocols to reduce delays in care in the face of legal ambiguities. If you have been involved in such a case since June 2022, including caring for a patient who traveled from another state, please consider submitting it at CarePostRoe.com, and please spread the word through your networks.

- McCann A, Schoenfeld Walker A, Sasani A, et al. Tracking the states where abortion is now banned. New York Times. May 24, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com /interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade .html

- Nash E, Ephross P. State policy trends 2022: in a devastating year, US Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe leads to bans, confusion and chaos. Guttmacher Institute website. Published December 19, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.guttmacher.org/2022/12/state -policy-trends-2022-devastating-year-us -supreme-courts-decision-overturn-roe-leads

- Cha AE. Physicians face confusion and fear in post-Roe world. Washington Post. June 28, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www .washingtonpost.com/health/2022/06/28 /abortion-ban-roe-doctors-confusion/

- Zernike K. Medical impact of Roe reversal goes well beyond abortion clinics, doctors say. New York Times. September 10, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes .com/2022/09/10/us/abortion-bans-medical -care-women.html

- Abrams A. ‘Never-ending nightmare.’ an Ohio woman was forced to travel out of state for an abortion. Time. August 29, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://time.com/6208860/ohio -woman-forced-travel-abortion/

- Belluck P. They had miscarriages, and new abortion laws obstructed treatment. New York Times. July 17, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/17/health /abortion-miscarriage-treatment.html

- Sellers FS, Nirappil F. Confusion post-Roe spurs delays, denials for some lifesaving pregnancy care. Washington Post. July 16, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost .com/health/2022/07/16/abortion-miscarriage -ectopic-pregnancy-care/.

- Nambiar A, Patel S, Santiago-Munoz P, et al. Maternal morbidity and fetal outcomes among pregnant women at 22 weeks’ gestation or less with complications in 2 Texas hospitals after legislation on abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:648-650.e1.

- Cohen E, Lape J, Herman D. “Heartbreaking” stories go untold, doctors say, as employers “muzzle” them in wake of abortion ruling. CNN website. Published October 12, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/12 /health/abortion-doctors-talking/index.html.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), Miller R, Gyamfi-Bannerman C; Publications Committee. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #63: Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy [published online July 16, 2022]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Sep;227:B9-B20. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2022.06.024.

- McCann A, Schoenfeld Walker A, Sasani A, et al. Tracking the states where abortion is now banned. New York Times. May 24, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com /interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade .html

- Nash E, Ephross P. State policy trends 2022: in a devastating year, US Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe leads to bans, confusion and chaos. Guttmacher Institute website. Published December 19, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.guttmacher.org/2022/12/state -policy-trends-2022-devastating-year-us -supreme-courts-decision-overturn-roe-leads

- Cha AE. Physicians face confusion and fear in post-Roe world. Washington Post. June 28, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www .washingtonpost.com/health/2022/06/28 /abortion-ban-roe-doctors-confusion/

- Zernike K. Medical impact of Roe reversal goes well beyond abortion clinics, doctors say. New York Times. September 10, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes .com/2022/09/10/us/abortion-bans-medical -care-women.html

- Abrams A. ‘Never-ending nightmare.’ an Ohio woman was forced to travel out of state for an abortion. Time. August 29, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://time.com/6208860/ohio -woman-forced-travel-abortion/

- Belluck P. They had miscarriages, and new abortion laws obstructed treatment. New York Times. July 17, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/17/health /abortion-miscarriage-treatment.html

- Sellers FS, Nirappil F. Confusion post-Roe spurs delays, denials for some lifesaving pregnancy care. Washington Post. July 16, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost .com/health/2022/07/16/abortion-miscarriage -ectopic-pregnancy-care/.

- Nambiar A, Patel S, Santiago-Munoz P, et al. Maternal morbidity and fetal outcomes among pregnant women at 22 weeks’ gestation or less with complications in 2 Texas hospitals after legislation on abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:648-650.e1.

- Cohen E, Lape J, Herman D. “Heartbreaking” stories go untold, doctors say, as employers “muzzle” them in wake of abortion ruling. CNN website. Published October 12, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/12 /health/abortion-doctors-talking/index.html.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), Miller R, Gyamfi-Bannerman C; Publications Committee. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #63: Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy [published online July 16, 2022]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Sep;227:B9-B20. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2022.06.024.

Risk of expulsion low after early postpartum IUD placement

Intrauterine device (IUD) placement at 2-4 weeks postpartum was noninferior to placement at 6-8 weeks postpartum for complete expulsion, and carried only a slightly higher risk of partial expulsion. A randomized study of expulsion rates reports the risk of expulsion at these points may help patients and clinicians make informed choices about the timing of IUD insertion, wrote the study authors, led by Sarah H. Averbach, MD, MAS, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of California, San Diego. “We found that the risk of complete IUD expulsion was low at 2% after early IUD placement 2-4 weeks after delivery, and was noninferior to interval placement 6-8 weeks after delivery at 0%,” Dr. Averbach said in an interview.

Although the risks of partial expulsion and malposition were modestly greater after early placement, “the possibility of a small increase in the risk of IUD expulsion or malposition with early IUD placement should be weighed against the risk of undesired pregnancy and short-interval pregnancy by delaying placement.”

The timing of IUD placement in the postpartum period should be guided by patients’ goals and preferences, she added. The early postpartum period 2-4 weeks after birth has the advantage of convenience since it coincides with early-postpartum or well-baby visits. The absolute risk differences observed between early and interval placement were small for both complete or partial expulsion at 3.8%, and the rate for complete expulsion after early placement was much lower than historical expulsion rates for immediate postpartum placement within in few days of delivery.

Last year, a large study showed an increase in expulsion risk with IUD insertion within 3 days of delivery. Current guidelines, however, support immediate insertion as a safe practice.

The study

Enrolling 404 participants from diverse settings during the period of 2018 to July 2021, researchers for the noninferiority trial randomly assigned 203 to early IUD placement 14-28 days postpartum and 201 to standard-interval placement at 42-56 days. Patients had a mean age of 29.9 years, 11.4% were Black, 56.4% were White, and 43.3% were Hispanic (some Hispanic participants self-identified as White and some as Black). By 6 months postpartum, 73% of the cohort had received an IUD and completed 6-months of follow-up, while 13% had never received an IUD and 14% were lost to follow-up. Complete expulsion rates were 3 of 149, or 2.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.4-5.8) in the early group and 0 of 145, or 0% (95% CI, 0.0-2.5) in the standard group, for a between-group difference of 2.0 percentage points (95% CI, −0.5 to 5.7, P = .04). Two women chose to replace their IUDs.

Partial expulsion occurred in 14, or 9.4% (95% CI, 5.2-15.3) of patients in the early group and 11, or 7.6% (95% CI, 3.9-13.2) in the standard-interval group, for a between-group difference of 1.8 (95% CI, −4.8 to 8.6) percentage points (P = .22).

The small absolute increase in risk of partial expulsion in the early arm did not meet the prespecified criterion for noninferiority of 6%. Three pelvic infections occurred in the early placement arm.

There were 42 IUD removals: 25 in the early placement group and 17 in the standard interval group. Thirteen participants had their IUDs removed for symptoms such as cramping and bothersome vaginal bleeding.

No perforations were identified in either group at 6 months, suggesting that the rate of uterine perforations is low when IUDs are placed in the early and standard-interval postpartum periods. IUD use at 6 months remained comparable between arms: 69.5% in the early group vs. 67.2% in the standard-interval group.

Commenting on the trial but not involved in it, Maureen K. Baldwin, MD, MPH, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, said it provides further data on the prevalence of expulsion and malposition after placements using ultrasonography as needed. While two failures occurred with asymptomatic malposition, she added, “It should be noted that IUD position can change as a result of pregnancy, so it was not determined that malposition occurred prior to contraceptive failure.”

According to Dr. Baldwin, one strategy to reduce concerns is to use transvaginal ultrasonography at a later time or in the presence of unusual symptoms.

Overall, the study establishes that postpartum placement is an option equivalent to standard timing and it should be incorporated into patient preferences, she said. “Pain may be lowest at early placement compared to other timings, particularly for those who had vaginal birth.”

The study was supported by the Society of Family Planning research fund and the National Institutes of Health - National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Averbach reported personal fees from Bayer Pharmaceuticals for advice on postpartum IUD placement as well as grants from the NIH outside of the submitted work. Dr. Baldwin disclosed no potential conflicts of interest with regard to her comments.

Intrauterine device (IUD) placement at 2-4 weeks postpartum was noninferior to placement at 6-8 weeks postpartum for complete expulsion, and carried only a slightly higher risk of partial expulsion. A randomized study of expulsion rates reports the risk of expulsion at these points may help patients and clinicians make informed choices about the timing of IUD insertion, wrote the study authors, led by Sarah H. Averbach, MD, MAS, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of California, San Diego. “We found that the risk of complete IUD expulsion was low at 2% after early IUD placement 2-4 weeks after delivery, and was noninferior to interval placement 6-8 weeks after delivery at 0%,” Dr. Averbach said in an interview.

Although the risks of partial expulsion and malposition were modestly greater after early placement, “the possibility of a small increase in the risk of IUD expulsion or malposition with early IUD placement should be weighed against the risk of undesired pregnancy and short-interval pregnancy by delaying placement.”

The timing of IUD placement in the postpartum period should be guided by patients’ goals and preferences, she added. The early postpartum period 2-4 weeks after birth has the advantage of convenience since it coincides with early-postpartum or well-baby visits. The absolute risk differences observed between early and interval placement were small for both complete or partial expulsion at 3.8%, and the rate for complete expulsion after early placement was much lower than historical expulsion rates for immediate postpartum placement within in few days of delivery.

Last year, a large study showed an increase in expulsion risk with IUD insertion within 3 days of delivery. Current guidelines, however, support immediate insertion as a safe practice.

The study

Enrolling 404 participants from diverse settings during the period of 2018 to July 2021, researchers for the noninferiority trial randomly assigned 203 to early IUD placement 14-28 days postpartum and 201 to standard-interval placement at 42-56 days. Patients had a mean age of 29.9 years, 11.4% were Black, 56.4% were White, and 43.3% were Hispanic (some Hispanic participants self-identified as White and some as Black). By 6 months postpartum, 73% of the cohort had received an IUD and completed 6-months of follow-up, while 13% had never received an IUD and 14% were lost to follow-up. Complete expulsion rates were 3 of 149, or 2.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.4-5.8) in the early group and 0 of 145, or 0% (95% CI, 0.0-2.5) in the standard group, for a between-group difference of 2.0 percentage points (95% CI, −0.5 to 5.7, P = .04). Two women chose to replace their IUDs.

Partial expulsion occurred in 14, or 9.4% (95% CI, 5.2-15.3) of patients in the early group and 11, or 7.6% (95% CI, 3.9-13.2) in the standard-interval group, for a between-group difference of 1.8 (95% CI, −4.8 to 8.6) percentage points (P = .22).

The small absolute increase in risk of partial expulsion in the early arm did not meet the prespecified criterion for noninferiority of 6%. Three pelvic infections occurred in the early placement arm.

There were 42 IUD removals: 25 in the early placement group and 17 in the standard interval group. Thirteen participants had their IUDs removed for symptoms such as cramping and bothersome vaginal bleeding.

No perforations were identified in either group at 6 months, suggesting that the rate of uterine perforations is low when IUDs are placed in the early and standard-interval postpartum periods. IUD use at 6 months remained comparable between arms: 69.5% in the early group vs. 67.2% in the standard-interval group.

Commenting on the trial but not involved in it, Maureen K. Baldwin, MD, MPH, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, said it provides further data on the prevalence of expulsion and malposition after placements using ultrasonography as needed. While two failures occurred with asymptomatic malposition, she added, “It should be noted that IUD position can change as a result of pregnancy, so it was not determined that malposition occurred prior to contraceptive failure.”

According to Dr. Baldwin, one strategy to reduce concerns is to use transvaginal ultrasonography at a later time or in the presence of unusual symptoms.

Overall, the study establishes that postpartum placement is an option equivalent to standard timing and it should be incorporated into patient preferences, she said. “Pain may be lowest at early placement compared to other timings, particularly for those who had vaginal birth.”

The study was supported by the Society of Family Planning research fund and the National Institutes of Health - National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Averbach reported personal fees from Bayer Pharmaceuticals for advice on postpartum IUD placement as well as grants from the NIH outside of the submitted work. Dr. Baldwin disclosed no potential conflicts of interest with regard to her comments.

Intrauterine device (IUD) placement at 2-4 weeks postpartum was noninferior to placement at 6-8 weeks postpartum for complete expulsion, and carried only a slightly higher risk of partial expulsion. A randomized study of expulsion rates reports the risk of expulsion at these points may help patients and clinicians make informed choices about the timing of IUD insertion, wrote the study authors, led by Sarah H. Averbach, MD, MAS, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of California, San Diego. “We found that the risk of complete IUD expulsion was low at 2% after early IUD placement 2-4 weeks after delivery, and was noninferior to interval placement 6-8 weeks after delivery at 0%,” Dr. Averbach said in an interview.

Although the risks of partial expulsion and malposition were modestly greater after early placement, “the possibility of a small increase in the risk of IUD expulsion or malposition with early IUD placement should be weighed against the risk of undesired pregnancy and short-interval pregnancy by delaying placement.”

The timing of IUD placement in the postpartum period should be guided by patients’ goals and preferences, she added. The early postpartum period 2-4 weeks after birth has the advantage of convenience since it coincides with early-postpartum or well-baby visits. The absolute risk differences observed between early and interval placement were small for both complete or partial expulsion at 3.8%, and the rate for complete expulsion after early placement was much lower than historical expulsion rates for immediate postpartum placement within in few days of delivery.

Last year, a large study showed an increase in expulsion risk with IUD insertion within 3 days of delivery. Current guidelines, however, support immediate insertion as a safe practice.

The study

Enrolling 404 participants from diverse settings during the period of 2018 to July 2021, researchers for the noninferiority trial randomly assigned 203 to early IUD placement 14-28 days postpartum and 201 to standard-interval placement at 42-56 days. Patients had a mean age of 29.9 years, 11.4% were Black, 56.4% were White, and 43.3% were Hispanic (some Hispanic participants self-identified as White and some as Black). By 6 months postpartum, 73% of the cohort had received an IUD and completed 6-months of follow-up, while 13% had never received an IUD and 14% were lost to follow-up. Complete expulsion rates were 3 of 149, or 2.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.4-5.8) in the early group and 0 of 145, or 0% (95% CI, 0.0-2.5) in the standard group, for a between-group difference of 2.0 percentage points (95% CI, −0.5 to 5.7, P = .04). Two women chose to replace their IUDs.

Partial expulsion occurred in 14, or 9.4% (95% CI, 5.2-15.3) of patients in the early group and 11, or 7.6% (95% CI, 3.9-13.2) in the standard-interval group, for a between-group difference of 1.8 (95% CI, −4.8 to 8.6) percentage points (P = .22).

The small absolute increase in risk of partial expulsion in the early arm did not meet the prespecified criterion for noninferiority of 6%. Three pelvic infections occurred in the early placement arm.

There were 42 IUD removals: 25 in the early placement group and 17 in the standard interval group. Thirteen participants had their IUDs removed for symptoms such as cramping and bothersome vaginal bleeding.

No perforations were identified in either group at 6 months, suggesting that the rate of uterine perforations is low when IUDs are placed in the early and standard-interval postpartum periods. IUD use at 6 months remained comparable between arms: 69.5% in the early group vs. 67.2% in the standard-interval group.

Commenting on the trial but not involved in it, Maureen K. Baldwin, MD, MPH, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, said it provides further data on the prevalence of expulsion and malposition after placements using ultrasonography as needed. While two failures occurred with asymptomatic malposition, she added, “It should be noted that IUD position can change as a result of pregnancy, so it was not determined that malposition occurred prior to contraceptive failure.”

According to Dr. Baldwin, one strategy to reduce concerns is to use transvaginal ultrasonography at a later time or in the presence of unusual symptoms.

Overall, the study establishes that postpartum placement is an option equivalent to standard timing and it should be incorporated into patient preferences, she said. “Pain may be lowest at early placement compared to other timings, particularly for those who had vaginal birth.”

The study was supported by the Society of Family Planning research fund and the National Institutes of Health - National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Averbach reported personal fees from Bayer Pharmaceuticals for advice on postpartum IUD placement as well as grants from the NIH outside of the submitted work. Dr. Baldwin disclosed no potential conflicts of interest with regard to her comments.

FROM JAMA

Ectopic pregnancy risk and levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs

Researchers report that use of any levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system was associated with a significantly increased risk of ectopic pregnancy, compared with other hormonal contraceptives, in a study published in JAMA.

A national health database analysis headed by Amani Meaidi, MD, PhD, of the Danish Cancer Society Research Center, Cancer Surveillance and Pharmacoepidemiology, in Copenhagen, compared the 13.5-mg with the 19.5-mg and 52-mg dosages of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems (IUSs).

The hormone content in levonorgestrel-releasing IUSs must be high enough to maintain optimal contraceptive effect but sufficiently low to minimize progestin-related adverse events, Dr. Meaidi and colleagues noted; they advised using the middle dosage of 19.5 mg. All dosages are recommended for contraception, with the highest dosage also recommended for heavy menstrual bleeding.

“If 10,000 women using the hormonal IUD for 1 year were given the 19.5-mg hormonal IUD instead of the 13.5-mg hormonal IUD, around nine ectopic pregnancies would be avoided,” Dr. Meaidi said in an interview.

“Ectopic pregnancy is an acknowledged adverse event of hormonal IUD use. Although a rare event, it is a serious one, and a difference in ectopic pregnancy safety between the two low-dose hormonal IUDs would impact my recommendations to women.”

The study

Dr. Meaidi’s group followed 963,964 women for 7.8 million person-years. For users of levonorgestrel IUS dosages 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg, and other hormonal contraceptives, the median ages were 24, 22, 22, and 21 years, respectively.

Eligible women were nulliparous with no previous ectopic pregnancy, abdominal or pelvic surgery, infertility treatment, endometriosis, or use of a levonorgestrel IUS. They were followed from Jan. 1, 2001, or their 15th birthday, until July 1, 2021, age 35, pregnancy, death, emigration, or the occurrence of any exclusion criterion.

During the study period, the cohort registered 2,925 ectopic pregnancies, including 35 at 52 mg, 32 at 19.5 mg, and 80 at 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel. For all other types of hormonal contraception, there were 763 ectopic pregnancies.

In terms of adjusted absolute rates of ectopic pregnancy per 10,000 person-years, compared with other hormonal contraceptives (rate = 2.4), these were 7.7 with 52 mg levonorgestrel IUS, 7.1 with 19.5 mg, and 15.7 with 13.5 mg. They translated to comparative differences of 5.3 (95% confidence interval, 1.9-8.7), 4.8 (95% CI, 1.5-8.0), and 13.4 (95% CI, 8.8-18.1), respectively.

Corresponding adjusted relative rate ratios were 3.4, 4.1, and 7.9. For each levonorgestrel IUS dosage; the ectopic pregnancy rate increased with duration of use.

The adjusted ectopic pregnancy rate difference per 10,000 person-years between the 19.5-mg and 52-mg levonorgestrel dosages was −0.6 , and between the 13.5-mg and 52-mg doses, 8.0, with a rate ratio of 2.3. The rate difference between the 13.5-mg and 19.5-mg levonorgestrel IUS was 8.6, with a rate ratio of 1.9.

An outsider’s perspective

Offering an outsider’s perspective on the study, Eran Bornstein, MD, vice-chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, said these data should spark further evaluation of risk of ectopic pregnancy with levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs. “The best advice for clinicians is to individualize the choice of which contraceptive to use, and when levonorgestrel IUD is selected, to individualize the appropriate dose and timing of placement,” he said in an interview.

Several additional factors may determine the best choice, Dr. Bornstein added, including medical conditions that contraindicate other contraceptives and those conditions that justify avoidance of pregnancy, as well as uterine myomas or malformation, the ability of the patient to comply with other options, and informed patient choice. “It is important to remember the potential risk for expulsion and ectopic pregnancy, maintain alertness, and use ultrasound to exclude these potential complications if suspected,” he said.

Dr. Meaidi said the mechanism of ectopic pregnancy with hormonal IUDs is unclear, but in vitro and animal studies have observed that levonorgestrel reduces the ciliary beat frequency in the fallopian tubes. “Thus, it could be hypothesized that if a woman was unfortunate enough to become pregnant using a hormonal IUD, the hormone could inhibit or slow down the movement of the zygote into the uterus for rightful intrauterine implantation and thereby increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy.”

Two coauthors of the study reported financial support from private-sector companies. Dr. Meaidi had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Bornstein disclosed no competing interests.

Researchers report that use of any levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system was associated with a significantly increased risk of ectopic pregnancy, compared with other hormonal contraceptives, in a study published in JAMA.

A national health database analysis headed by Amani Meaidi, MD, PhD, of the Danish Cancer Society Research Center, Cancer Surveillance and Pharmacoepidemiology, in Copenhagen, compared the 13.5-mg with the 19.5-mg and 52-mg dosages of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems (IUSs).

The hormone content in levonorgestrel-releasing IUSs must be high enough to maintain optimal contraceptive effect but sufficiently low to minimize progestin-related adverse events, Dr. Meaidi and colleagues noted; they advised using the middle dosage of 19.5 mg. All dosages are recommended for contraception, with the highest dosage also recommended for heavy menstrual bleeding.

“If 10,000 women using the hormonal IUD for 1 year were given the 19.5-mg hormonal IUD instead of the 13.5-mg hormonal IUD, around nine ectopic pregnancies would be avoided,” Dr. Meaidi said in an interview.

“Ectopic pregnancy is an acknowledged adverse event of hormonal IUD use. Although a rare event, it is a serious one, and a difference in ectopic pregnancy safety between the two low-dose hormonal IUDs would impact my recommendations to women.”

The study

Dr. Meaidi’s group followed 963,964 women for 7.8 million person-years. For users of levonorgestrel IUS dosages 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg, and other hormonal contraceptives, the median ages were 24, 22, 22, and 21 years, respectively.

Eligible women were nulliparous with no previous ectopic pregnancy, abdominal or pelvic surgery, infertility treatment, endometriosis, or use of a levonorgestrel IUS. They were followed from Jan. 1, 2001, or their 15th birthday, until July 1, 2021, age 35, pregnancy, death, emigration, or the occurrence of any exclusion criterion.

During the study period, the cohort registered 2,925 ectopic pregnancies, including 35 at 52 mg, 32 at 19.5 mg, and 80 at 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel. For all other types of hormonal contraception, there were 763 ectopic pregnancies.

In terms of adjusted absolute rates of ectopic pregnancy per 10,000 person-years, compared with other hormonal contraceptives (rate = 2.4), these were 7.7 with 52 mg levonorgestrel IUS, 7.1 with 19.5 mg, and 15.7 with 13.5 mg. They translated to comparative differences of 5.3 (95% confidence interval, 1.9-8.7), 4.8 (95% CI, 1.5-8.0), and 13.4 (95% CI, 8.8-18.1), respectively.

Corresponding adjusted relative rate ratios were 3.4, 4.1, and 7.9. For each levonorgestrel IUS dosage; the ectopic pregnancy rate increased with duration of use.

The adjusted ectopic pregnancy rate difference per 10,000 person-years between the 19.5-mg and 52-mg levonorgestrel dosages was −0.6 , and between the 13.5-mg and 52-mg doses, 8.0, with a rate ratio of 2.3. The rate difference between the 13.5-mg and 19.5-mg levonorgestrel IUS was 8.6, with a rate ratio of 1.9.

An outsider’s perspective

Offering an outsider’s perspective on the study, Eran Bornstein, MD, vice-chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, said these data should spark further evaluation of risk of ectopic pregnancy with levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs. “The best advice for clinicians is to individualize the choice of which contraceptive to use, and when levonorgestrel IUD is selected, to individualize the appropriate dose and timing of placement,” he said in an interview.

Several additional factors may determine the best choice, Dr. Bornstein added, including medical conditions that contraindicate other contraceptives and those conditions that justify avoidance of pregnancy, as well as uterine myomas or malformation, the ability of the patient to comply with other options, and informed patient choice. “It is important to remember the potential risk for expulsion and ectopic pregnancy, maintain alertness, and use ultrasound to exclude these potential complications if suspected,” he said.

Dr. Meaidi said the mechanism of ectopic pregnancy with hormonal IUDs is unclear, but in vitro and animal studies have observed that levonorgestrel reduces the ciliary beat frequency in the fallopian tubes. “Thus, it could be hypothesized that if a woman was unfortunate enough to become pregnant using a hormonal IUD, the hormone could inhibit or slow down the movement of the zygote into the uterus for rightful intrauterine implantation and thereby increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy.”

Two coauthors of the study reported financial support from private-sector companies. Dr. Meaidi had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Bornstein disclosed no competing interests.

Researchers report that use of any levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system was associated with a significantly increased risk of ectopic pregnancy, compared with other hormonal contraceptives, in a study published in JAMA.

A national health database analysis headed by Amani Meaidi, MD, PhD, of the Danish Cancer Society Research Center, Cancer Surveillance and Pharmacoepidemiology, in Copenhagen, compared the 13.5-mg with the 19.5-mg and 52-mg dosages of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems (IUSs).

The hormone content in levonorgestrel-releasing IUSs must be high enough to maintain optimal contraceptive effect but sufficiently low to minimize progestin-related adverse events, Dr. Meaidi and colleagues noted; they advised using the middle dosage of 19.5 mg. All dosages are recommended for contraception, with the highest dosage also recommended for heavy menstrual bleeding.

“If 10,000 women using the hormonal IUD for 1 year were given the 19.5-mg hormonal IUD instead of the 13.5-mg hormonal IUD, around nine ectopic pregnancies would be avoided,” Dr. Meaidi said in an interview.

“Ectopic pregnancy is an acknowledged adverse event of hormonal IUD use. Although a rare event, it is a serious one, and a difference in ectopic pregnancy safety between the two low-dose hormonal IUDs would impact my recommendations to women.”

The study

Dr. Meaidi’s group followed 963,964 women for 7.8 million person-years. For users of levonorgestrel IUS dosages 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg, and other hormonal contraceptives, the median ages were 24, 22, 22, and 21 years, respectively.

Eligible women were nulliparous with no previous ectopic pregnancy, abdominal or pelvic surgery, infertility treatment, endometriosis, or use of a levonorgestrel IUS. They were followed from Jan. 1, 2001, or their 15th birthday, until July 1, 2021, age 35, pregnancy, death, emigration, or the occurrence of any exclusion criterion.

During the study period, the cohort registered 2,925 ectopic pregnancies, including 35 at 52 mg, 32 at 19.5 mg, and 80 at 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel. For all other types of hormonal contraception, there were 763 ectopic pregnancies.

In terms of adjusted absolute rates of ectopic pregnancy per 10,000 person-years, compared with other hormonal contraceptives (rate = 2.4), these were 7.7 with 52 mg levonorgestrel IUS, 7.1 with 19.5 mg, and 15.7 with 13.5 mg. They translated to comparative differences of 5.3 (95% confidence interval, 1.9-8.7), 4.8 (95% CI, 1.5-8.0), and 13.4 (95% CI, 8.8-18.1), respectively.

Corresponding adjusted relative rate ratios were 3.4, 4.1, and 7.9. For each levonorgestrel IUS dosage; the ectopic pregnancy rate increased with duration of use.

The adjusted ectopic pregnancy rate difference per 10,000 person-years between the 19.5-mg and 52-mg levonorgestrel dosages was −0.6 , and between the 13.5-mg and 52-mg doses, 8.0, with a rate ratio of 2.3. The rate difference between the 13.5-mg and 19.5-mg levonorgestrel IUS was 8.6, with a rate ratio of 1.9.

An outsider’s perspective

Offering an outsider’s perspective on the study, Eran Bornstein, MD, vice-chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, said these data should spark further evaluation of risk of ectopic pregnancy with levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs. “The best advice for clinicians is to individualize the choice of which contraceptive to use, and when levonorgestrel IUD is selected, to individualize the appropriate dose and timing of placement,” he said in an interview.

Several additional factors may determine the best choice, Dr. Bornstein added, including medical conditions that contraindicate other contraceptives and those conditions that justify avoidance of pregnancy, as well as uterine myomas or malformation, the ability of the patient to comply with other options, and informed patient choice. “It is important to remember the potential risk for expulsion and ectopic pregnancy, maintain alertness, and use ultrasound to exclude these potential complications if suspected,” he said.

Dr. Meaidi said the mechanism of ectopic pregnancy with hormonal IUDs is unclear, but in vitro and animal studies have observed that levonorgestrel reduces the ciliary beat frequency in the fallopian tubes. “Thus, it could be hypothesized that if a woman was unfortunate enough to become pregnant using a hormonal IUD, the hormone could inhibit or slow down the movement of the zygote into the uterus for rightful intrauterine implantation and thereby increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy.”

Two coauthors of the study reported financial support from private-sector companies. Dr. Meaidi had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Bornstein disclosed no competing interests.

FROM JAMA

Iron deficiency and anemia in patients with heavy menstrual bleeding: Mechanisms and management

Recurrent episodic blood loss from normal menstruation is not expected to result in anemia. But without treatment, chronic heavy periods will progress through the stages of low iron stores to iron deficiency and then to anemia. When iron storage levels are low, the bone marrow’s blood cell factory cannot keep up with continued losses. Every patient with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) or prolonged menstrual episodes should be tested and treated for iron deficiency and anemia.1,2

Particular attention should be paid to assessment of iron storage levels with serum ferritin, recognizing that low iron levels progress to anemia once the storage is depleted. Recovery from anemia is much slower in individuals with iron deficiency, so assessment for iron storage also should be included in preoperative assessments and following a diagnosis of acute blood loss anemia.

The mechanics of erythropoiesis, hemoglobin, and oxygen transport

Red blood cells (erythrocytes) have a short life cycle and require constant replacement. Erythrocytes are generated on demand in erythropoiesis by a hormonal signaling process, regardless of whether sufficient components are available.3 Hemoglobin, the main intracellular component of erythrocytes, is comprised of 4 globin chains, which each contain 1 iron atom bound to a heme molecule. After erythrocytes are assembled, they are sent out into circulation for approximately 120 days. A hemoglobin level measures the oxygen-carrying capacity of erythrocytes, and anemia is defined as hemoglobin less than 12 g/dL.

Unless erythrocytes are lost from bleeding, they are decommissioned—that is, the heme molecule is metabolized into bilirubin and excreted, and the iron atoms are recycled back to the bone marrow or to storage.4 Ferritin is the storage molecule that binds to iron, a glycoprotein with numerous subunits around a core that can contain about 4,000 iron atoms. Most ferritin is intracellular, but a small proportion is present in serum, where it can be measured.

Serum ferritin is a good marker for the iron supply in healthy individuals because it has high correlation to iron in the bone marrow and correlates to total intracellular storage unless there is inflammation, when mobilization to serum increases. The ferritin level at which the iron supply is deficient to meet demand, defined as iron deficiency, is hotly debated and ranges from less than 15 to 50 ng/mL in menstruating individuals, with higher thresholds based on onset of erythropoiesis signaling and the lower threshold being the World Health Organization recommendation.5-7 When iron atoms are in short supply, erythrocytes still are generated but they have lower amounts of intracellular hemoglobin, which makes them thinner, smaller, and paler—and less effective at oxygen transport.

CASE Patient seeks treatment for HMB-associated symptoms

A 17-year-old patient presents with HMB, fatigue, and difficulty with concentration. She reports that her periods have been regular and lasting 7 days since menarche at age 13. While they are manageable, they seem to be getting heavier, soaking pads in 2 to 3 hours. The patient reports that she would like to start treatment for her progressively heavy bleeding and prefers lighter scheduled bleeding; she currently does not desire contraception. The patient has no family history of bleeding problems and self-reports no personal history of epistaxis or bleeding with tooth extraction or tonsillectomy. Laboratory tests confirm iron deficiency with a hemoglobin level of 12.5 g/dL (reference range, 12.0–17.5 g/dL) and a serum ferritin level of 8 ng/mL (reference range, 50–420 ng/mL). Results from a coagulopathy panel are normal, as are von Willebrand factor levels.

Untreated iron deficiency will progress to anemia

This patient has iron deficiency without anemia, which warrants significant attention in HMB because without treatment it eventually will progress to anemia. The prevalence of iron deficiency, which makes up half of all causes of anemia, is at least double that of iron deficiency anemia.3

Adult bodies usually contain about 3 to 4 g of iron, with two-thirds in erythrocytes as hemoglobin.8 Approximately 40 to 60 mg of iron is recycled daily, 1 to 2 mg/day is lost from sloughed cells and sweat, and at least 1 mg/day is lost during normal menstruation. These losses are balanced with gastrointestinal uptake of 1 to 2 mg/day until bleeding exceeds about 10 mL/day. In this 17-year-old patient, iron stores have likely been on a progressive decline since menarche.

For normally menstruating individuals to maintain iron homeostasis, the daily dietary iron requirement is 18 mg/day. Iron requirements also increase during periods of illness or inflammation due to hormonal signaling in the iron absorption and transport pathway, in athletes due to sweating, foot strike hemolysis and bruising, and during growth spurts.9

Continue to: Managing iron deficiency and anemia...

Managing iron deficiency and anemia

Management of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in the setting of HMB includes:

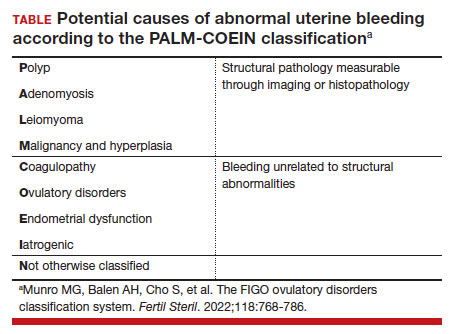

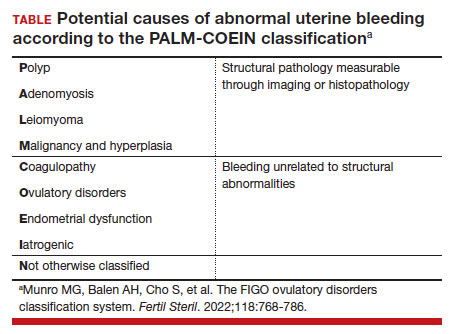

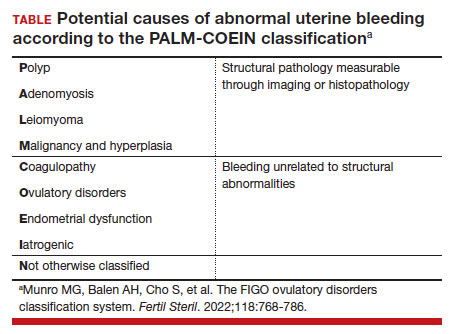

- workup for the etiology of the abnormal uterine bleeding (TABLE)

- reducing the source of blood loss, and

- iron supplementation to correct the iron deficiency state.

In most cases, workup, reduction, and repletion can occur simultaneously. The goal is not always complete cessation of menstrual bleeding; even short-term therapy can allow time to replenish iron storage. Use a shared decision-making process to assess what is important to the patient, and provide information about relative amounts of bleeding cessation that can be expected with various therapies.10

Treatment options

Medical treatments to decrease menstrual iron losses are recommended prior to proceeding with surgical interventions.11 Hormonal treatments are the most consistently recommended, with many guidelines citing the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG IUD) as first-line treatment due to its substantial reduction in the amount of bleeding, HMB treatment indication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and evidence of success in those with HMB.12

Any progestin or combined hormonal medication with estrogen and a progestin will result in an approximately 60% to 90% bleeding reduction, thus providing many effective options for blood loss while considering patient preferences for bleeding pattern, route of administration, and concomitant benefits. While only 1 oral product (estradiol valerate/dienogest) is FDA approved for managementof HMB, use of any of the commercially available contraceptive products will provide substantial benefit.11,13

Nonhormonal options, such as antifibrinolytics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), tend to be listed as second-line therapies or for those who want to avoid hormonal medications. Antifibrinolytics, such as tranexamic acid, require frequent dosing of large pills and result in approximately 40% blood loss reduction, but they are a very successful and well-tolerated method for those seeking on-demand therapy.14 NSAIDs may result in a slight bleeding reduction, but they are far less effective than other therapies.15 Antifibrinolytics have a theoretical risk of thrombosis and a contraindication to use with hormonal contraceptives; therefore, concomitant use with estrogen-containing medications is reserved for patients with refractory heavy bleeding or for heavy bleeding days during the hormone-free interval, when benefits likely outweigh potential risk.16,17

Guidelines for medical management of acute HMB typically cite 3 small comparative studies with high-dose regimens of parenteral conjugated estrogen, combined ethinyl estradiol and progestin, or oral medroxyprogesterone acetate.18,19 Dosing recommendations for the oral medications include a loading dose followed by a taper regimen that is poorly tolerated and for which there is no evidence of superior effectiveness over the standard dose.20,21 In most cases, initiation of the preferred long-term hormonal medication plan will reduce bleeding significantly within 2 to 3 days. Many clinicians who commonly treat acute HMB prescribe norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily (up to 3 times daily, if needed) for effective and safe menstrual suppression.22

Iron replenishment: Dosing frequency, dietary iron, and multivitamins

Iron repletion is usually via the oral route unless surgery is imminent, anemia is severe, or the oral route is not tolerated or effective.23 Oral iron has substantial adverse effects that limit tolerance, including nausea, epigastric pain, diarrhea, and constipation. Fortunately, evidence supports lower oral iron doses than previously used.4

Iron homeostasis is controlled by the peptide hormone hepcidin, produced by the liver, which controls mobilization of iron from the gut and spleen and aids iron absorption from the diet and supplements.24 Hepcidin levels decrease in response to high circulating levels of iron, so the ideal iron repletion dose in iron-deficient nonanemic women was determined by assessing the dose response of hepcidin. Researchers compared iron 60 mg daily for 14 days versus every other day for 28 days and found that iron absorption was greater in the every-other-day group (21.8% vs 16.3%).25 They concluded that changing iron administration to 60 mg or more in a single dose every other day is most efficient in those with iron deficiency without anemia. Since study participants did not have anemia, research is pending on whether different strategies (such as daily dosing) are more effective for more severe cases. The bottom line is that conventional high-dose divided daily oral iron administration results in reduced iron bioavailability compared with alternate-day dosing.

Increasing dietary iron is insufficient to treat low iron storage, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia. Likewise, multivitamins, which contain very little elemental iron, are not recommended for repletion. Any iron salt with 60 to 120 mg of elemental iron can be used (for examples, ferrous sulfate, ferrous gluconate).25 Once ingested, stomach and pancreatic acids release elemental iron from its bound form. For that reason, absorption may be improved by administering iron at least 1 hour before a meal and avoiding antacids, including milk. Meat proteins and ascorbic acid help maintain the soluble ferrous form and also aid absorption. Tea, coffee, and tannins prevent absorption when polyphenol compounds form an insoluble complex with iron (see box at end of article). Gastrointestinal adverse effects can be minimized by decreasing the dose and taking after meals, although with reduced efficacy.

Intravenous iron treatment raises hemoglobin levels significantly faster than oral administration but is limited by cost and availability, so it is reserved for individuals with a hemoglobin level less than 9 g/dL, prior gastrointestinal or bariatric surgery, imminent surgery, and intolerance, poor adherence, or nonresponse to oral iron therapy. Several approved formulations are available, all with equivalent effectiveness and similar safety profiles. Lower-dose formulations (such as iron sucrose) may require several infusions, but higher-dose intravenous iron products (ferric carboxymaltose, low-molecular weight iron dextran, etc) have a stable carbohydrate shell that inhibits free iron release and improves safety, allowing a single administration.26

Common adverse effects of intravenous iron treatment include a metallic taste and headache during administration. More serious adverse effects, such as hypotension, arthralgia, malaise, and nausea, are usually self-limited. With mild infusion reactions (1 in 200), the infusion can be stopped until symptoms improve and can be resumed at a slower rate.27

Continue to: The role of blood transfusion...

The role of blood transfusion

Blood transfusion is expensive and potentially hazardous, so its use is limited to treatment of acute blood loss or severe anemia.

A one-time red blood cell transfusion does not impact diagnostic criteria to assess for iron deficiency with ferritin, and it does not improve underlying iron deficiency.28 Patients with acute blood loss anemia superimposed on chronic blood loss should be screened and treated for iron deficiency even after receiving a transfusion.

Since ferritin levels can rise significantly as an acute phase reactant, even following a hemorrhage, iron deficiency during inflammation is defined as ferritin less than 70 ng/mL.

The potential for iron overload

Since iron is never metabolized or excreted, it is possible to have iron overload following accidental overdose, transfusion dependency, and disorders of iron transport, such as hemochromatosis and thalassemia.

While a low ferritin level always indicates iron deficiency, high ferritin levels can be an acute phase reactant. Ferritin levels greater than 150 ng/mL in healthy menstruating individuals and greater than 500 ng/mL in unhealthy individuals should raise concern for excess iron and should prompt discontinuation of iron intake or workup for conditions at risk for overload.5

Oral iron supplements should be stored away from small children, who are at particular risk of toxicity.

How long to treat?

Treatment duration depends on the individual’s degree of iron deficiency, whether anemia is present, and the amount of ongoing blood loss. The main treatment goal is normalization and maintenance of serum ferritin.

Successful treatment should be confirmed with a complete blood count and ferritin level. Hemoglobin levels improve 2 g/dL after 3 weeks of oral iron therapy, but repletion may take 4 to 6 months.23,29 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends 3 to 6 months of continued iron therapy after resolution of HMB.19

In a comparative study of treatment for HMB with the 52-mg LNG IUD versus hysterectomy, hemoglobin levels increased in both treatment groups but stayed lower in those with initial anemia.8 Ferritin levels normalized only after 5 years and were still lower in individuals with initial anemia.

Increase in hemoglobin is faster after intravenous iron administration but is equivalent to oral therapy by 12 weeks. If management to reduce menstrual losses is discontinued, periodic or maintenance iron repletion will be necessary.

CASE Management plan initiated

This 17-year-old patient with iron deficiency resulting from HMB requests management to reduce menstrual iron losses with a preference for predictable menses. We have already completed a basic workup, which could also include assessment for hypermobility with a Beighton score, as connective tissue disorders also are associated with HMB.30 We discuss the options of cyclic hormonal therapy, antifibrinolytic treatment, and an LNG IUD. The patient is concerned about adherence and wants to avoid unscheduled bleeding, so she opts for a trial of tranexamic acid 1,300 mg 3 times daily for 5 days during menses. This regimen results in a 50% reduction in bleeding amount, which the patient finds satisfactory. Iron repletion with oral ferrous sulfate 325 mg (containing 65 mg of elemental iron) is administered on alternating days with vitamin C taken 1 hour prior to dinner. Repeat laboratory test results at 3 weeks show improvement to a hemoglobin level of 14.2 g/dL and a ferritin level of 12 ng/mL. By 3 months, her ferritin levels are greater than 30 ng/mL and oral iron is administered only during menses.

Summing up

Chronic HMB results in a progressive net loss of iron and eventual anemia. Screening with complete blood count and ferritin and early treatment of low iron storage when ferritin is less than 30 ng/mL will help avoid symptoms. Any amount of reduction of menstrual blood loss can be beneficial, allowing a variety of effective hormonal and nonhormonal treatment options. ●

- Take 60 to 120 mg elemental iron every other day.

- To help with absorption:

—Take 1 hour before a meal, but not with coffee, tea, tannins, antacids, or milk

—Take with vitamin C or other acidic fruit juice

- Recheck complete blood count and ferritin in 2 to 3 weeks to confirm initial response.

- Continue treatment for up to 3 to 6 months until ferritin levels are greater than 30 to 50 ng/mL.

- Munro MG, Mast AE, Powers JM, et al. The relationship between heavy menstrual bleeding, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;S00029378(23)00024-8.

- Tsakiridis I, Giouleka S, Koutsouki G, et al. Investigation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive aged women: a descriptive review of national and international recommendations. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2022;27:504-517.

- Camaschella C. Iron deficiency. Blood. 2019;133:30-39.

- Camaschella C, Nai A, Silvestri L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica. 2020;105:260-272.

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline on use of ferritin concentrations to assess iron status in individuals and populations. April 21, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240000124

- Mei Z, Addo OY, Jefferds ME, et al. Physiologically based serum ferritin thresholds for iron deficiency in children and non-pregnant women: a US National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) serial cross-sectional study. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8: e572-e582.

- Galetti V, Stoffel NU, Sieber C, et al. Threshold ferritin and hepcidin concentrations indicating early iron deficiency in young women based on upregulation of iron absorption. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101052.

- Percy L, Mansour D, Fraser I. Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;40:55-67.

- Brittenham GM. Short-term periods of strenuous physical activity lower iron absorption. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113:261-262.

- Chen M, Lindley A, Kimport K, et al. An in-depth analysis of the use of shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2019;99:187-191.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Dias S, Jordan V, et al. Interventions for heavy menstrual bleeding; overview of Cochrane reviews and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD013180.

- Mansour D, Hofmann A, Gemzell-Danielsson K. A review of clinical guidelines on the management of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in women with heavy menstrual bleeding. Adv Ther. 2021;38:201-225.

- Micks EA, Jensen JT. Treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding with the estradiol valerate and dienogest oral contraceptive pill. Adv Ther. 2013;30:1-13.

- Bryant-Smith AC, Lethaby A, Farquhar C, et al. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:CD000249.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9:CD000400.

- Relke N, Chornenki NLJ, Sholzberg M. Tranexamic acid evidence and controversies: an illustrated review. Res Pract T hromb Haemost. 2021;5:e12546.

- Reid RL, Westhoff C, Mansour D, et al. Oral contraceptives and venous thromboembolism consensus opinion from an international workshop held in Berlin, Germany in December 2009. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2010;36:117-122.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 557: management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:891-896.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 785: screening and management of bleeding disorders in adolescents with heavy menstrual bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e71-e83.

- Haamid F, Sass AE, Dietrich JE. Heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30:335-340.

- Roth LP, Haley KM, Baldwin MK. A retrospective comparison of time to cessation of acute heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents following two dose regimens of combined oral hormonal therapy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2022;35:294-298.

- Huguelet PS, Buyers EM, Lange-Liss JH, et al. Treatment of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescents: what are providers doing in various specialties? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:286-291.

- Elstrott B, Khan L, Olson S, et al. The role of iron repletion in adult iron deficiency anemia and other diseases. Eur J Haematol. 2020;104:153-161.

- Pagani A, Nai A, Silvestri L, et al. Hepcidin and anemia: a tight relationship. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1294.

- Stoffel NU, von Siebenthal HK, Moretti D, et al. Oral iron supplementation in iron-deficient women: how much and how often? Mol Aspects Med. 2020;75:100865.

- Auerbach M, Adamson JW. How we diagnose and treat iron deficiency anemia. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:31-38.

- Dave CV, Brittenham GM, Carson JL, et al. Risks for anaphylaxis with intravenous iron formulations: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:656-664.

- Froissart A, Rossi B, Ranque B, et al; SiMFI Group. Effect of a red blood cell transfusion on biological markers used to determine the cause of anemia: a prospective study. Am J Med. 2018;131:319-322.

- Carson JL, Brittenham GM. How I treat anemia with red blood cell transfusion and iron. Blood. 2022;blood.2022018521.

- Borzutzky C, Jaffray J. Diagnosis and management of heavy menstrual bleeding and bleeding disorders in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:186-194.

Recurrent episodic blood loss from normal menstruation is not expected to result in anemia. But without treatment, chronic heavy periods will progress through the stages of low iron stores to iron deficiency and then to anemia. When iron storage levels are low, the bone marrow’s blood cell factory cannot keep up with continued losses. Every patient with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) or prolonged menstrual episodes should be tested and treated for iron deficiency and anemia.1,2

Particular attention should be paid to assessment of iron storage levels with serum ferritin, recognizing that low iron levels progress to anemia once the storage is depleted. Recovery from anemia is much slower in individuals with iron deficiency, so assessment for iron storage also should be included in preoperative assessments and following a diagnosis of acute blood loss anemia.

The mechanics of erythropoiesis, hemoglobin, and oxygen transport

Red blood cells (erythrocytes) have a short life cycle and require constant replacement. Erythrocytes are generated on demand in erythropoiesis by a hormonal signaling process, regardless of whether sufficient components are available.3 Hemoglobin, the main intracellular component of erythrocytes, is comprised of 4 globin chains, which each contain 1 iron atom bound to a heme molecule. After erythrocytes are assembled, they are sent out into circulation for approximately 120 days. A hemoglobin level measures the oxygen-carrying capacity of erythrocytes, and anemia is defined as hemoglobin less than 12 g/dL.

Unless erythrocytes are lost from bleeding, they are decommissioned—that is, the heme molecule is metabolized into bilirubin and excreted, and the iron atoms are recycled back to the bone marrow or to storage.4 Ferritin is the storage molecule that binds to iron, a glycoprotein with numerous subunits around a core that can contain about 4,000 iron atoms. Most ferritin is intracellular, but a small proportion is present in serum, where it can be measured.

Serum ferritin is a good marker for the iron supply in healthy individuals because it has high correlation to iron in the bone marrow and correlates to total intracellular storage unless there is inflammation, when mobilization to serum increases. The ferritin level at which the iron supply is deficient to meet demand, defined as iron deficiency, is hotly debated and ranges from less than 15 to 50 ng/mL in menstruating individuals, with higher thresholds based on onset of erythropoiesis signaling and the lower threshold being the World Health Organization recommendation.5-7 When iron atoms are in short supply, erythrocytes still are generated but they have lower amounts of intracellular hemoglobin, which makes them thinner, smaller, and paler—and less effective at oxygen transport.

CASE Patient seeks treatment for HMB-associated symptoms

A 17-year-old patient presents with HMB, fatigue, and difficulty with concentration. She reports that her periods have been regular and lasting 7 days since menarche at age 13. While they are manageable, they seem to be getting heavier, soaking pads in 2 to 3 hours. The patient reports that she would like to start treatment for her progressively heavy bleeding and prefers lighter scheduled bleeding; she currently does not desire contraception. The patient has no family history of bleeding problems and self-reports no personal history of epistaxis or bleeding with tooth extraction or tonsillectomy. Laboratory tests confirm iron deficiency with a hemoglobin level of 12.5 g/dL (reference range, 12.0–17.5 g/dL) and a serum ferritin level of 8 ng/mL (reference range, 50–420 ng/mL). Results from a coagulopathy panel are normal, as are von Willebrand factor levels.

Untreated iron deficiency will progress to anemia

This patient has iron deficiency without anemia, which warrants significant attention in HMB because without treatment it eventually will progress to anemia. The prevalence of iron deficiency, which makes up half of all causes of anemia, is at least double that of iron deficiency anemia.3

Adult bodies usually contain about 3 to 4 g of iron, with two-thirds in erythrocytes as hemoglobin.8 Approximately 40 to 60 mg of iron is recycled daily, 1 to 2 mg/day is lost from sloughed cells and sweat, and at least 1 mg/day is lost during normal menstruation. These losses are balanced with gastrointestinal uptake of 1 to 2 mg/day until bleeding exceeds about 10 mL/day. In this 17-year-old patient, iron stores have likely been on a progressive decline since menarche.

For normally menstruating individuals to maintain iron homeostasis, the daily dietary iron requirement is 18 mg/day. Iron requirements also increase during periods of illness or inflammation due to hormonal signaling in the iron absorption and transport pathway, in athletes due to sweating, foot strike hemolysis and bruising, and during growth spurts.9

Continue to: Managing iron deficiency and anemia...

Managing iron deficiency and anemia

Management of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in the setting of HMB includes:

- workup for the etiology of the abnormal uterine bleeding (TABLE)

- reducing the source of blood loss, and

- iron supplementation to correct the iron deficiency state.

In most cases, workup, reduction, and repletion can occur simultaneously. The goal is not always complete cessation of menstrual bleeding; even short-term therapy can allow time to replenish iron storage. Use a shared decision-making process to assess what is important to the patient, and provide information about relative amounts of bleeding cessation that can be expected with various therapies.10

Treatment options