User login

Bacterial vaginosis linked with persistent HPV infections

Montrouge, France – Four in five women will be infected by one or more human papillomavirus (HPV) strains during their lifetimes. For most of these women, the HPV will be cleared from the body, but 5% of them will develop precancerous lesions in the cervix.

At a press conference ahead of the 46th meeting of the French Colposcopy and Cervical and Vaginal Diseases Society, Julia Maruani, MD, a medical gynecologist in Marseille, France, took the opportunity to discuss the importance of vaginal flora and the need to treat cases of bacterial vaginosis.

Striking a balance

Essential for reducing the risk of sexually transmitted infections, a healthy vaginal flora is made up of millions of microorganisms, mainly lactobacilli, as well as other bacteria (Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae, Prevotella, streptococcus, gonococcus), HPV, and fungi.

Lactobacilli produce lactic acid, which reduces the vagina’s pH, as well as hydrogen peroxide, which is toxic to the other bacteria.

Different factors, such as alcohol, a diet rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids and sugar, and especially smoking, can lead to an imbalance of the bacteria in the vaginal flora and thus result in vaginosis. What occurs is an abnormal multiplication of different types of anaerobic bacteria that are normally present in much lower numbers. There is a relative reduction in lactobacilli, which results in an increased vaginal pH, a greater risk of contracting an STI, and reduced clearance of the HPV infection. “Women who smoke probably experience persistent HPV infections due to an imbalance in vaginal flora,” said Dr. Maruani.

Vaginosis and HPV

When there are fewer lactobacilli than there should be, these bacteria can no longer protect the vaginal mucosa, which is disrupted by other bacteria. “HPV then has access to the basal cells,” said Dr. Maruani, acknowledging that the relationship between bacterial vaginosis and persistent HPV infections has been the subject of numerous research studies over the past decade or so. “For years, I would see this same link in my patients. Those with persistent vaginosis were also the ones with persistent HPV. And I’m not the only one to notice this. Studies have also been carried out investigating this exact correlation,” she added.

These studies have shown that HPV infections persist in cases of vaginosis, resulting in the appearance of epithelial lesions. Additionally, the lesions are more severe when dysbiosis is more severe.

What about probiotics? Can they treat dysbiosis and an HPV infection at the same time? “Probiotics work very well for vaginosis, provided they are used for a long time. We know that they lessen HPV infections and low-grade lesions,” said Dr. Maruani, although no randomized studies support this conclusion. “It’s not a one size fits all. We aren’t about to treat patients with precancerous lesions with probiotics.” There are currently no data concerning the efficacy of probiotics on high-grade lesions. These days, Dr. Maruani has been thinking about a new issue: the benefit of diagnosing cases of asymptomatic vaginosis – because treating them would reduce the risk of persistent HPV infection.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Montrouge, France – Four in five women will be infected by one or more human papillomavirus (HPV) strains during their lifetimes. For most of these women, the HPV will be cleared from the body, but 5% of them will develop precancerous lesions in the cervix.

At a press conference ahead of the 46th meeting of the French Colposcopy and Cervical and Vaginal Diseases Society, Julia Maruani, MD, a medical gynecologist in Marseille, France, took the opportunity to discuss the importance of vaginal flora and the need to treat cases of bacterial vaginosis.

Striking a balance

Essential for reducing the risk of sexually transmitted infections, a healthy vaginal flora is made up of millions of microorganisms, mainly lactobacilli, as well as other bacteria (Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae, Prevotella, streptococcus, gonococcus), HPV, and fungi.

Lactobacilli produce lactic acid, which reduces the vagina’s pH, as well as hydrogen peroxide, which is toxic to the other bacteria.

Different factors, such as alcohol, a diet rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids and sugar, and especially smoking, can lead to an imbalance of the bacteria in the vaginal flora and thus result in vaginosis. What occurs is an abnormal multiplication of different types of anaerobic bacteria that are normally present in much lower numbers. There is a relative reduction in lactobacilli, which results in an increased vaginal pH, a greater risk of contracting an STI, and reduced clearance of the HPV infection. “Women who smoke probably experience persistent HPV infections due to an imbalance in vaginal flora,” said Dr. Maruani.

Vaginosis and HPV

When there are fewer lactobacilli than there should be, these bacteria can no longer protect the vaginal mucosa, which is disrupted by other bacteria. “HPV then has access to the basal cells,” said Dr. Maruani, acknowledging that the relationship between bacterial vaginosis and persistent HPV infections has been the subject of numerous research studies over the past decade or so. “For years, I would see this same link in my patients. Those with persistent vaginosis were also the ones with persistent HPV. And I’m not the only one to notice this. Studies have also been carried out investigating this exact correlation,” she added.

These studies have shown that HPV infections persist in cases of vaginosis, resulting in the appearance of epithelial lesions. Additionally, the lesions are more severe when dysbiosis is more severe.

What about probiotics? Can they treat dysbiosis and an HPV infection at the same time? “Probiotics work very well for vaginosis, provided they are used for a long time. We know that they lessen HPV infections and low-grade lesions,” said Dr. Maruani, although no randomized studies support this conclusion. “It’s not a one size fits all. We aren’t about to treat patients with precancerous lesions with probiotics.” There are currently no data concerning the efficacy of probiotics on high-grade lesions. These days, Dr. Maruani has been thinking about a new issue: the benefit of diagnosing cases of asymptomatic vaginosis – because treating them would reduce the risk of persistent HPV infection.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Montrouge, France – Four in five women will be infected by one or more human papillomavirus (HPV) strains during their lifetimes. For most of these women, the HPV will be cleared from the body, but 5% of them will develop precancerous lesions in the cervix.

At a press conference ahead of the 46th meeting of the French Colposcopy and Cervical and Vaginal Diseases Society, Julia Maruani, MD, a medical gynecologist in Marseille, France, took the opportunity to discuss the importance of vaginal flora and the need to treat cases of bacterial vaginosis.

Striking a balance

Essential for reducing the risk of sexually transmitted infections, a healthy vaginal flora is made up of millions of microorganisms, mainly lactobacilli, as well as other bacteria (Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae, Prevotella, streptococcus, gonococcus), HPV, and fungi.

Lactobacilli produce lactic acid, which reduces the vagina’s pH, as well as hydrogen peroxide, which is toxic to the other bacteria.

Different factors, such as alcohol, a diet rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids and sugar, and especially smoking, can lead to an imbalance of the bacteria in the vaginal flora and thus result in vaginosis. What occurs is an abnormal multiplication of different types of anaerobic bacteria that are normally present in much lower numbers. There is a relative reduction in lactobacilli, which results in an increased vaginal pH, a greater risk of contracting an STI, and reduced clearance of the HPV infection. “Women who smoke probably experience persistent HPV infections due to an imbalance in vaginal flora,” said Dr. Maruani.

Vaginosis and HPV

When there are fewer lactobacilli than there should be, these bacteria can no longer protect the vaginal mucosa, which is disrupted by other bacteria. “HPV then has access to the basal cells,” said Dr. Maruani, acknowledging that the relationship between bacterial vaginosis and persistent HPV infections has been the subject of numerous research studies over the past decade or so. “For years, I would see this same link in my patients. Those with persistent vaginosis were also the ones with persistent HPV. And I’m not the only one to notice this. Studies have also been carried out investigating this exact correlation,” she added.

These studies have shown that HPV infections persist in cases of vaginosis, resulting in the appearance of epithelial lesions. Additionally, the lesions are more severe when dysbiosis is more severe.

What about probiotics? Can they treat dysbiosis and an HPV infection at the same time? “Probiotics work very well for vaginosis, provided they are used for a long time. We know that they lessen HPV infections and low-grade lesions,” said Dr. Maruani, although no randomized studies support this conclusion. “It’s not a one size fits all. We aren’t about to treat patients with precancerous lesions with probiotics.” There are currently no data concerning the efficacy of probiotics on high-grade lesions. These days, Dr. Maruani has been thinking about a new issue: the benefit of diagnosing cases of asymptomatic vaginosis – because treating them would reduce the risk of persistent HPV infection.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Advances in fertility preservation: Q & A

From the first obscure reference until the 19th century, the maternal mortality rate from an ectopic pregnancy was nearly 100%. In the past 140 years, because of early detection and prompt surgical management, the mortality rate from an ectopic pregnancy declined from 72%-90% in 1880 to 0.48% from 2004 to 2008.1 Given this remarkable reduction in mortality, the 20th-century approach to ectopic pregnancy evolved from preserving the life of the mother to preserving fertility by utilizing conservative treatment with methotrexate and/or tubal surgery.

Why the reference to ectopic pregnancy? Advances in oncology have comparably affected our approach to cancer patients. The increase in survival rates following a cancer diagnosis has fostered revolutionary developments in fertility preservation to obviate the effect of gonadotoxic therapy. We have evolved from shielding and transposing ovaries to ovarian tissue cryopreservation2,3 with rapid implementation.

One of the leaders in the field of female fertility preservation is Kutluk Oktay, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn. I posed the following salient questions to him on the state of fertility preservation as well as expectations for the future.

Q1. What medication/treatment is gonadotoxic that warrants a consultation for fertility preservation?

A: While new drugs for cancer treatment continue to be approved and require testing for gonadotoxicity, evidence is clear on the damaging effects of alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, chlorambucil, and melphalan on primordial follicle reserve.4 A useful tool to determine the risk of alkylating agents affecting fertility is the Cyclophosphamide Equivalent Dose (CED) Calculator. Likewise, topoisomerase inhibitors, such as doxorubicin4 induce ovarian reserve damage by causing double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) in oocytes.5-7 Contrary to common belief, chemotherapy exposure suppresses the mechanisms that can initiate follicle growth.6 When DSBs occur, some oocytes may be able to repair such damage, otherwise apoptosis is triggered, which results in irreversible ovarian reserve loss.7 Younger individuals have much higher repair capacity, the magnitude of damage can be hard to predict, and it is variable.8,9 So, prior exposure to gonadotoxic drugs does not preclude consideration of fertility preservation.10

In addition, pelvic radiation, in a dose-dependent manner, causes severe DSBs and triggers the same cell suicide mechanisms while also potentially damaging uterine function. Additional information can be found in the American Society of Clinical Oncology Fertility Preservation Guidelines.4

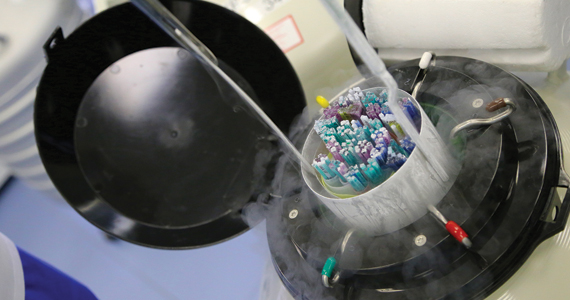

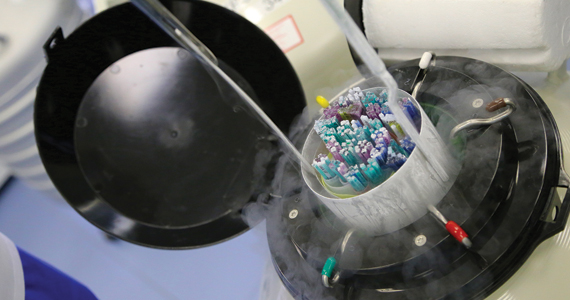

Q2. What are the current options for fertility preservation in patients who will be exposed to gonadotoxic medication/treatment?

A: The current fertility preservation options for female patients faced with gonadotoxic treatments are embryo, oocyte, and ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC). Selection of fertility preservation is typically contingent upon the timetable of treatment. Oocyte and embryo cryopreservation have been the standard of care. Recently, OTC had its experimental designation removed by American Society for Reproductive Medicine11 with the advantage of not requiring ovarian stimulation or sexual maturity; and it may to be performed while patients are receiving chemotherapy. If successful, OTC followed by orthotopic transplantation has the potential to restore natural ovarian function, thereby allowing spontaneous conception.10 Especially in young adults, ovarian reserve loss is fractional and can remain at reasonable levels after a few courses of chemotherapy. Ovarian stimulation is risky after the initiation of chemotherapy because of the severe DNA damage to oocytes of developing follicles and the associated poor response.7 Hence, ovarian stimulation should be initiated and completed before the initiation of chemotherapy.

Q3. How successful are the approved fertility preservation options in obtaining oocytes for future utilization by ART?

A: We have decades of experience with embryo cryopreservation and proven success rates that patients can check on the SART.org website for individual clinics. For oocyte cryopreservation, models are used to provide calculation estimates because the technique is less established.12 Although success rates are approaching those with fresh oocytes, they are still not equal.13 OTC followed by orthotopic tissue transplantation has the least outcomes data (approximately 200 reported livebirths to date with a 25% live birth rate per recipient worldwide10 since the first success was reported in 2000.2,14

With our robotic surgical approach to orthotopic and heterotopic ovarian tissue transplantation and the utility of neovascularizing agents, we have found that ovarian graft longevity is extended. Oocytes/embryos can be obtained and has resulted in one to two livebirths in all our recipients to date.10 Unfortunately, if any of the critical steps are not up to standards (freezing, thawing, or transplantation), success rates can dramatically decline. Therefore, providers and patients should seek centers with experience in all three stages of this procedure to maximize outcomes.

Q4. Are there concerns of increasing recurrence/mortality with fertility preservation given hormonal exposure?

A: Yes, this concern exists, at least in theory for estrogen-sensitive cancers, most commonly breast cancer. We developed ovarian stimulation protocols supplemented with anti-estrogen treatments (tamoxifen, an estrogen-receptor antagonist, and letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor) that appear equally effective and reduce estrogen exposure in any susceptible cancer.15,16 Even in estrogen receptor–negative tumors, high estrogen exposure may activate non–estrogen receptor–dependent pathways. In addition, even those tumors that are practically deemed estrogen receptor negative may still contain a small percentage of estrogen receptors, which may become active at high estrogen levels.

Therefore, when we approach women with estrogen-sensitive cancers, e.g., breast and endometrial, we do not alter our approach based on receptor status. One exception occurs in women with BRCA mutations, especially the BRCA1, as they have 25% lower serum anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) levels,8,17 yield fewer oocytes in response to ovarian stimulation,18,19 and have lower fertilization rates and embryo numbers20 compared with those without the mutations.

Q5. Are all reproductive centers capable of offering fertility preservation? If not, how does a patient find a center?

A: All IVF clinics offer embryo and, presumably, oocyte cryopreservation. Pregnancy outcomes vary based on the center’s experience. Globally, major differences exist in the availability and competency of OTC along with the subsequent transplantation approach. A limited number of centers have competency in all aspects of OTC, i.e., cryopreservation, thawing, and transplantation. In general, fertility preservation patients have a multitude of medical issues that necessitate management expertise and the bandwidth to coordinate with cancer health professionals. The reproductive centers offering fertility preservation should be prepared to respond immediately and accommodate patients about to undergo gonadotoxic treatment.

Q6. How should a patient be counseled before proceeding with fertility preservation?

A: The candidate should be counseled on the likelihood of damage from gonadotoxic therapy and all fertility preservation options, on the basis of the urgency of treatment and the woman’s long-term goals. For example, the desire for a large family may compel a patient to undergo multiple cycles of ovarian stimulation or a combination of oocyte/embryo cryopreservation with OTC. In patients who are undergoing embryo cryopreservation, I recommend preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies, although there are limitations to its application. Other novel pieces of information we are using in counseling are baseline AMH levels and BRCA mutation status for women with breast cancer. In an 8-year-long NIH-funded prospective longitudinal study we found that women with both baseline AMH < 2 ng/mL and BRCA mutations are at significantly higher risk of losing their ovarian reserve and developing amenorrhea.21 Because the oocytes of women with BRCA mutations are deficient in DNA repair as we have previously shown,19 they are more liable to death upon exposure to DNA-damaging cancer drugs such as cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin.22

Q7. What is the time limit for use of cryopreserved oocytes/tissue?

A: Under optimal storage conditions, cryopreserved oocytes/tissue can be utilized indefinitely without a negative effect on pregnancy outcomes.

Q8. What does the future hold for fertility preservation?

A: The future holds promise for both the medical and nonmedical (planned) utility of fertility preservation. With the former, we will see that the utility of OTC and orthotopic and heterotopic tissue transplantation increase as success rates improve. Improved neovascularizing agents will make the transplants last longer and enhance pregnancy outcomes.23,24 I see planned fertility preservation increasing, based on the experience gained from cancer patients and some preliminary experience with planned OTC, especially for healthy women who wish to consider delaying menopause.25,26

Because of attrition from apoptosis, approximately 2,000 oocytes are wasted per ovulation. Through calculation models, we predict that if an equivalent of one-third of a woman’s ovarian cortex can be cryopreserved (which may not significantly affect the age at natural menopause) before age 40 years, transplantation at perimenopause may provide sufficient primordial follicles to delay menopause for 5 years or longer.26 Because ovarian tissue can also be transplanted subcutaneously under local anesthesia, as we have shown,27,28 repeated heterotopic transplants can be performed in an office setting at reduced cost, invasiveness, and with enhanced effectiveness. We can expect increasing reports and progress on this planned use of OTC and transplantation in the future.

Dr. Oktay is professor of obstetrics & gynecology and reproductive sciences and director of the Laboratory of Molecular Reproduction and Fertility Preservation at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Lurie S. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1992 Jan 9;43(1):1-7.

2. Oktay K and Karlikaya G. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jun 22;342(25):1919.

3. Sonmezer and Oktay K. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10(3):251-66.

4. Oktay K et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jul 1;36(19):1994-2001.

5. Goldfarb SB et al. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;185:165-73.

6. Titus S et al. Sci Rep. 2021 Jan 11;11(1):407.

7. Soleimani R et al. Aging (Albany NY). 2011 Aug;3(8):782-93.

8. Titus S et al. Sci Transl Med. 2013 Feb 13;5(172):172ra21.

9. Oktay KH et al. Fertil Steril. 2022 Jan 5:S0015-0282(21)02293-7.

10. Oktay K et al. Fertil Steril. 2022;117(1):181-92.

11. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(6):1022–33.

12. Cil A et al. Fertil Steril. 2013 Aug;100(2):492-9.e3.

13. Goldman KN et al. Fertil Steril. 2013 Sep;100(3):712-7.

14. Marin L and Oktay K. Scientific history of ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation. In: Oktay K (ed.), Principles and Practice of Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation and Transplantation. Elsevier;2022:1-10.

15. Oktay K et al. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jul 1;23(19):4347-53.

16. Kim JY et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Apr;101(4):1364-71.

17. Turan V et al. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:18.

18. Oktay K et al. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Jan 10;28(2):240-4.

19. Lin W et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(10):3839-47.

20. Turan V et al. Reprod Sci. 2018;(25):26-32.

21. Oktay K et al. Presence of BRCA mutations and a pre-chemotherapy AMH level of < 2ng/mL strongly predict risk of amenorrhea in women with breast cancer P-291. Presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine 78th annual meeting, Anaheim, Calif. Oct. 22-26, 2022.

22. Oktay KH et al. Fertil Steril. 2020;113(6):1251‐60.e1.

23. Soleimani R et al. PLoS One. 2011 Apr 29;6(4):e19475.

24. Marin L et al. Future aspects of ovarian cryopreservation and transplantation. In: Oktay K (ed.). Principles and Practice of Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation and Transplantation. Elsevier; 2022;223-30.

25. Oktay KH et al. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(8):753-61.

26. Oktay K and Marin L. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation for delaying childbearing and menopause. In: Oktay, K. (Ed.), Principles and Practice of Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation and Transplantation. Elsevier;2022:195-204.

27. Oktay K et al. JAMA. 2001 Sep 26;286(12):1490-3.

28. Oktay K et al. Lancet. 2004 Mar 13;363(9412):837-40.

From the first obscure reference until the 19th century, the maternal mortality rate from an ectopic pregnancy was nearly 100%. In the past 140 years, because of early detection and prompt surgical management, the mortality rate from an ectopic pregnancy declined from 72%-90% in 1880 to 0.48% from 2004 to 2008.1 Given this remarkable reduction in mortality, the 20th-century approach to ectopic pregnancy evolved from preserving the life of the mother to preserving fertility by utilizing conservative treatment with methotrexate and/or tubal surgery.

Why the reference to ectopic pregnancy? Advances in oncology have comparably affected our approach to cancer patients. The increase in survival rates following a cancer diagnosis has fostered revolutionary developments in fertility preservation to obviate the effect of gonadotoxic therapy. We have evolved from shielding and transposing ovaries to ovarian tissue cryopreservation2,3 with rapid implementation.

One of the leaders in the field of female fertility preservation is Kutluk Oktay, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn. I posed the following salient questions to him on the state of fertility preservation as well as expectations for the future.

Q1. What medication/treatment is gonadotoxic that warrants a consultation for fertility preservation?

A: While new drugs for cancer treatment continue to be approved and require testing for gonadotoxicity, evidence is clear on the damaging effects of alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, chlorambucil, and melphalan on primordial follicle reserve.4 A useful tool to determine the risk of alkylating agents affecting fertility is the Cyclophosphamide Equivalent Dose (CED) Calculator. Likewise, topoisomerase inhibitors, such as doxorubicin4 induce ovarian reserve damage by causing double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) in oocytes.5-7 Contrary to common belief, chemotherapy exposure suppresses the mechanisms that can initiate follicle growth.6 When DSBs occur, some oocytes may be able to repair such damage, otherwise apoptosis is triggered, which results in irreversible ovarian reserve loss.7 Younger individuals have much higher repair capacity, the magnitude of damage can be hard to predict, and it is variable.8,9 So, prior exposure to gonadotoxic drugs does not preclude consideration of fertility preservation.10

In addition, pelvic radiation, in a dose-dependent manner, causes severe DSBs and triggers the same cell suicide mechanisms while also potentially damaging uterine function. Additional information can be found in the American Society of Clinical Oncology Fertility Preservation Guidelines.4

Q2. What are the current options for fertility preservation in patients who will be exposed to gonadotoxic medication/treatment?

A: The current fertility preservation options for female patients faced with gonadotoxic treatments are embryo, oocyte, and ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC). Selection of fertility preservation is typically contingent upon the timetable of treatment. Oocyte and embryo cryopreservation have been the standard of care. Recently, OTC had its experimental designation removed by American Society for Reproductive Medicine11 with the advantage of not requiring ovarian stimulation or sexual maturity; and it may to be performed while patients are receiving chemotherapy. If successful, OTC followed by orthotopic transplantation has the potential to restore natural ovarian function, thereby allowing spontaneous conception.10 Especially in young adults, ovarian reserve loss is fractional and can remain at reasonable levels after a few courses of chemotherapy. Ovarian stimulation is risky after the initiation of chemotherapy because of the severe DNA damage to oocytes of developing follicles and the associated poor response.7 Hence, ovarian stimulation should be initiated and completed before the initiation of chemotherapy.

Q3. How successful are the approved fertility preservation options in obtaining oocytes for future utilization by ART?

A: We have decades of experience with embryo cryopreservation and proven success rates that patients can check on the SART.org website for individual clinics. For oocyte cryopreservation, models are used to provide calculation estimates because the technique is less established.12 Although success rates are approaching those with fresh oocytes, they are still not equal.13 OTC followed by orthotopic tissue transplantation has the least outcomes data (approximately 200 reported livebirths to date with a 25% live birth rate per recipient worldwide10 since the first success was reported in 2000.2,14

With our robotic surgical approach to orthotopic and heterotopic ovarian tissue transplantation and the utility of neovascularizing agents, we have found that ovarian graft longevity is extended. Oocytes/embryos can be obtained and has resulted in one to two livebirths in all our recipients to date.10 Unfortunately, if any of the critical steps are not up to standards (freezing, thawing, or transplantation), success rates can dramatically decline. Therefore, providers and patients should seek centers with experience in all three stages of this procedure to maximize outcomes.

Q4. Are there concerns of increasing recurrence/mortality with fertility preservation given hormonal exposure?

A: Yes, this concern exists, at least in theory for estrogen-sensitive cancers, most commonly breast cancer. We developed ovarian stimulation protocols supplemented with anti-estrogen treatments (tamoxifen, an estrogen-receptor antagonist, and letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor) that appear equally effective and reduce estrogen exposure in any susceptible cancer.15,16 Even in estrogen receptor–negative tumors, high estrogen exposure may activate non–estrogen receptor–dependent pathways. In addition, even those tumors that are practically deemed estrogen receptor negative may still contain a small percentage of estrogen receptors, which may become active at high estrogen levels.

Therefore, when we approach women with estrogen-sensitive cancers, e.g., breast and endometrial, we do not alter our approach based on receptor status. One exception occurs in women with BRCA mutations, especially the BRCA1, as they have 25% lower serum anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) levels,8,17 yield fewer oocytes in response to ovarian stimulation,18,19 and have lower fertilization rates and embryo numbers20 compared with those without the mutations.

Q5. Are all reproductive centers capable of offering fertility preservation? If not, how does a patient find a center?

A: All IVF clinics offer embryo and, presumably, oocyte cryopreservation. Pregnancy outcomes vary based on the center’s experience. Globally, major differences exist in the availability and competency of OTC along with the subsequent transplantation approach. A limited number of centers have competency in all aspects of OTC, i.e., cryopreservation, thawing, and transplantation. In general, fertility preservation patients have a multitude of medical issues that necessitate management expertise and the bandwidth to coordinate with cancer health professionals. The reproductive centers offering fertility preservation should be prepared to respond immediately and accommodate patients about to undergo gonadotoxic treatment.

Q6. How should a patient be counseled before proceeding with fertility preservation?

A: The candidate should be counseled on the likelihood of damage from gonadotoxic therapy and all fertility preservation options, on the basis of the urgency of treatment and the woman’s long-term goals. For example, the desire for a large family may compel a patient to undergo multiple cycles of ovarian stimulation or a combination of oocyte/embryo cryopreservation with OTC. In patients who are undergoing embryo cryopreservation, I recommend preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies, although there are limitations to its application. Other novel pieces of information we are using in counseling are baseline AMH levels and BRCA mutation status for women with breast cancer. In an 8-year-long NIH-funded prospective longitudinal study we found that women with both baseline AMH < 2 ng/mL and BRCA mutations are at significantly higher risk of losing their ovarian reserve and developing amenorrhea.21 Because the oocytes of women with BRCA mutations are deficient in DNA repair as we have previously shown,19 they are more liable to death upon exposure to DNA-damaging cancer drugs such as cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin.22

Q7. What is the time limit for use of cryopreserved oocytes/tissue?

A: Under optimal storage conditions, cryopreserved oocytes/tissue can be utilized indefinitely without a negative effect on pregnancy outcomes.

Q8. What does the future hold for fertility preservation?

A: The future holds promise for both the medical and nonmedical (planned) utility of fertility preservation. With the former, we will see that the utility of OTC and orthotopic and heterotopic tissue transplantation increase as success rates improve. Improved neovascularizing agents will make the transplants last longer and enhance pregnancy outcomes.23,24 I see planned fertility preservation increasing, based on the experience gained from cancer patients and some preliminary experience with planned OTC, especially for healthy women who wish to consider delaying menopause.25,26

Because of attrition from apoptosis, approximately 2,000 oocytes are wasted per ovulation. Through calculation models, we predict that if an equivalent of one-third of a woman’s ovarian cortex can be cryopreserved (which may not significantly affect the age at natural menopause) before age 40 years, transplantation at perimenopause may provide sufficient primordial follicles to delay menopause for 5 years or longer.26 Because ovarian tissue can also be transplanted subcutaneously under local anesthesia, as we have shown,27,28 repeated heterotopic transplants can be performed in an office setting at reduced cost, invasiveness, and with enhanced effectiveness. We can expect increasing reports and progress on this planned use of OTC and transplantation in the future.

Dr. Oktay is professor of obstetrics & gynecology and reproductive sciences and director of the Laboratory of Molecular Reproduction and Fertility Preservation at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Lurie S. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1992 Jan 9;43(1):1-7.

2. Oktay K and Karlikaya G. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jun 22;342(25):1919.

3. Sonmezer and Oktay K. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10(3):251-66.

4. Oktay K et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jul 1;36(19):1994-2001.

5. Goldfarb SB et al. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;185:165-73.

6. Titus S et al. Sci Rep. 2021 Jan 11;11(1):407.

7. Soleimani R et al. Aging (Albany NY). 2011 Aug;3(8):782-93.

8. Titus S et al. Sci Transl Med. 2013 Feb 13;5(172):172ra21.

9. Oktay KH et al. Fertil Steril. 2022 Jan 5:S0015-0282(21)02293-7.

10. Oktay K et al. Fertil Steril. 2022;117(1):181-92.

11. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(6):1022–33.

12. Cil A et al. Fertil Steril. 2013 Aug;100(2):492-9.e3.

13. Goldman KN et al. Fertil Steril. 2013 Sep;100(3):712-7.

14. Marin L and Oktay K. Scientific history of ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation. In: Oktay K (ed.), Principles and Practice of Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation and Transplantation. Elsevier;2022:1-10.

15. Oktay K et al. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jul 1;23(19):4347-53.

16. Kim JY et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Apr;101(4):1364-71.

17. Turan V et al. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:18.

18. Oktay K et al. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Jan 10;28(2):240-4.

19. Lin W et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(10):3839-47.

20. Turan V et al. Reprod Sci. 2018;(25):26-32.

21. Oktay K et al. Presence of BRCA mutations and a pre-chemotherapy AMH level of < 2ng/mL strongly predict risk of amenorrhea in women with breast cancer P-291. Presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine 78th annual meeting, Anaheim, Calif. Oct. 22-26, 2022.

22. Oktay KH et al. Fertil Steril. 2020;113(6):1251‐60.e1.

23. Soleimani R et al. PLoS One. 2011 Apr 29;6(4):e19475.

24. Marin L et al. Future aspects of ovarian cryopreservation and transplantation. In: Oktay K (ed.). Principles and Practice of Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation and Transplantation. Elsevier; 2022;223-30.

25. Oktay KH et al. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(8):753-61.

26. Oktay K and Marin L. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation for delaying childbearing and menopause. In: Oktay, K. (Ed.), Principles and Practice of Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation and Transplantation. Elsevier;2022:195-204.

27. Oktay K et al. JAMA. 2001 Sep 26;286(12):1490-3.

28. Oktay K et al. Lancet. 2004 Mar 13;363(9412):837-40.

From the first obscure reference until the 19th century, the maternal mortality rate from an ectopic pregnancy was nearly 100%. In the past 140 years, because of early detection and prompt surgical management, the mortality rate from an ectopic pregnancy declined from 72%-90% in 1880 to 0.48% from 2004 to 2008.1 Given this remarkable reduction in mortality, the 20th-century approach to ectopic pregnancy evolved from preserving the life of the mother to preserving fertility by utilizing conservative treatment with methotrexate and/or tubal surgery.

Why the reference to ectopic pregnancy? Advances in oncology have comparably affected our approach to cancer patients. The increase in survival rates following a cancer diagnosis has fostered revolutionary developments in fertility preservation to obviate the effect of gonadotoxic therapy. We have evolved from shielding and transposing ovaries to ovarian tissue cryopreservation2,3 with rapid implementation.

One of the leaders in the field of female fertility preservation is Kutluk Oktay, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn. I posed the following salient questions to him on the state of fertility preservation as well as expectations for the future.

Q1. What medication/treatment is gonadotoxic that warrants a consultation for fertility preservation?

A: While new drugs for cancer treatment continue to be approved and require testing for gonadotoxicity, evidence is clear on the damaging effects of alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, chlorambucil, and melphalan on primordial follicle reserve.4 A useful tool to determine the risk of alkylating agents affecting fertility is the Cyclophosphamide Equivalent Dose (CED) Calculator. Likewise, topoisomerase inhibitors, such as doxorubicin4 induce ovarian reserve damage by causing double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) in oocytes.5-7 Contrary to common belief, chemotherapy exposure suppresses the mechanisms that can initiate follicle growth.6 When DSBs occur, some oocytes may be able to repair such damage, otherwise apoptosis is triggered, which results in irreversible ovarian reserve loss.7 Younger individuals have much higher repair capacity, the magnitude of damage can be hard to predict, and it is variable.8,9 So, prior exposure to gonadotoxic drugs does not preclude consideration of fertility preservation.10

In addition, pelvic radiation, in a dose-dependent manner, causes severe DSBs and triggers the same cell suicide mechanisms while also potentially damaging uterine function. Additional information can be found in the American Society of Clinical Oncology Fertility Preservation Guidelines.4

Q2. What are the current options for fertility preservation in patients who will be exposed to gonadotoxic medication/treatment?

A: The current fertility preservation options for female patients faced with gonadotoxic treatments are embryo, oocyte, and ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC). Selection of fertility preservation is typically contingent upon the timetable of treatment. Oocyte and embryo cryopreservation have been the standard of care. Recently, OTC had its experimental designation removed by American Society for Reproductive Medicine11 with the advantage of not requiring ovarian stimulation or sexual maturity; and it may to be performed while patients are receiving chemotherapy. If successful, OTC followed by orthotopic transplantation has the potential to restore natural ovarian function, thereby allowing spontaneous conception.10 Especially in young adults, ovarian reserve loss is fractional and can remain at reasonable levels after a few courses of chemotherapy. Ovarian stimulation is risky after the initiation of chemotherapy because of the severe DNA damage to oocytes of developing follicles and the associated poor response.7 Hence, ovarian stimulation should be initiated and completed before the initiation of chemotherapy.

Q3. How successful are the approved fertility preservation options in obtaining oocytes for future utilization by ART?

A: We have decades of experience with embryo cryopreservation and proven success rates that patients can check on the SART.org website for individual clinics. For oocyte cryopreservation, models are used to provide calculation estimates because the technique is less established.12 Although success rates are approaching those with fresh oocytes, they are still not equal.13 OTC followed by orthotopic tissue transplantation has the least outcomes data (approximately 200 reported livebirths to date with a 25% live birth rate per recipient worldwide10 since the first success was reported in 2000.2,14

With our robotic surgical approach to orthotopic and heterotopic ovarian tissue transplantation and the utility of neovascularizing agents, we have found that ovarian graft longevity is extended. Oocytes/embryos can be obtained and has resulted in one to two livebirths in all our recipients to date.10 Unfortunately, if any of the critical steps are not up to standards (freezing, thawing, or transplantation), success rates can dramatically decline. Therefore, providers and patients should seek centers with experience in all three stages of this procedure to maximize outcomes.

Q4. Are there concerns of increasing recurrence/mortality with fertility preservation given hormonal exposure?

A: Yes, this concern exists, at least in theory for estrogen-sensitive cancers, most commonly breast cancer. We developed ovarian stimulation protocols supplemented with anti-estrogen treatments (tamoxifen, an estrogen-receptor antagonist, and letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor) that appear equally effective and reduce estrogen exposure in any susceptible cancer.15,16 Even in estrogen receptor–negative tumors, high estrogen exposure may activate non–estrogen receptor–dependent pathways. In addition, even those tumors that are practically deemed estrogen receptor negative may still contain a small percentage of estrogen receptors, which may become active at high estrogen levels.

Therefore, when we approach women with estrogen-sensitive cancers, e.g., breast and endometrial, we do not alter our approach based on receptor status. One exception occurs in women with BRCA mutations, especially the BRCA1, as they have 25% lower serum anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) levels,8,17 yield fewer oocytes in response to ovarian stimulation,18,19 and have lower fertilization rates and embryo numbers20 compared with those without the mutations.

Q5. Are all reproductive centers capable of offering fertility preservation? If not, how does a patient find a center?

A: All IVF clinics offer embryo and, presumably, oocyte cryopreservation. Pregnancy outcomes vary based on the center’s experience. Globally, major differences exist in the availability and competency of OTC along with the subsequent transplantation approach. A limited number of centers have competency in all aspects of OTC, i.e., cryopreservation, thawing, and transplantation. In general, fertility preservation patients have a multitude of medical issues that necessitate management expertise and the bandwidth to coordinate with cancer health professionals. The reproductive centers offering fertility preservation should be prepared to respond immediately and accommodate patients about to undergo gonadotoxic treatment.

Q6. How should a patient be counseled before proceeding with fertility preservation?

A: The candidate should be counseled on the likelihood of damage from gonadotoxic therapy and all fertility preservation options, on the basis of the urgency of treatment and the woman’s long-term goals. For example, the desire for a large family may compel a patient to undergo multiple cycles of ovarian stimulation or a combination of oocyte/embryo cryopreservation with OTC. In patients who are undergoing embryo cryopreservation, I recommend preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies, although there are limitations to its application. Other novel pieces of information we are using in counseling are baseline AMH levels and BRCA mutation status for women with breast cancer. In an 8-year-long NIH-funded prospective longitudinal study we found that women with both baseline AMH < 2 ng/mL and BRCA mutations are at significantly higher risk of losing their ovarian reserve and developing amenorrhea.21 Because the oocytes of women with BRCA mutations are deficient in DNA repair as we have previously shown,19 they are more liable to death upon exposure to DNA-damaging cancer drugs such as cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin.22

Q7. What is the time limit for use of cryopreserved oocytes/tissue?

A: Under optimal storage conditions, cryopreserved oocytes/tissue can be utilized indefinitely without a negative effect on pregnancy outcomes.

Q8. What does the future hold for fertility preservation?

A: The future holds promise for both the medical and nonmedical (planned) utility of fertility preservation. With the former, we will see that the utility of OTC and orthotopic and heterotopic tissue transplantation increase as success rates improve. Improved neovascularizing agents will make the transplants last longer and enhance pregnancy outcomes.23,24 I see planned fertility preservation increasing, based on the experience gained from cancer patients and some preliminary experience with planned OTC, especially for healthy women who wish to consider delaying menopause.25,26

Because of attrition from apoptosis, approximately 2,000 oocytes are wasted per ovulation. Through calculation models, we predict that if an equivalent of one-third of a woman’s ovarian cortex can be cryopreserved (which may not significantly affect the age at natural menopause) before age 40 years, transplantation at perimenopause may provide sufficient primordial follicles to delay menopause for 5 years or longer.26 Because ovarian tissue can also be transplanted subcutaneously under local anesthesia, as we have shown,27,28 repeated heterotopic transplants can be performed in an office setting at reduced cost, invasiveness, and with enhanced effectiveness. We can expect increasing reports and progress on this planned use of OTC and transplantation in the future.

Dr. Oktay is professor of obstetrics & gynecology and reproductive sciences and director of the Laboratory of Molecular Reproduction and Fertility Preservation at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Lurie S. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1992 Jan 9;43(1):1-7.

2. Oktay K and Karlikaya G. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jun 22;342(25):1919.

3. Sonmezer and Oktay K. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10(3):251-66.

4. Oktay K et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jul 1;36(19):1994-2001.

5. Goldfarb SB et al. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;185:165-73.

6. Titus S et al. Sci Rep. 2021 Jan 11;11(1):407.

7. Soleimani R et al. Aging (Albany NY). 2011 Aug;3(8):782-93.

8. Titus S et al. Sci Transl Med. 2013 Feb 13;5(172):172ra21.

9. Oktay KH et al. Fertil Steril. 2022 Jan 5:S0015-0282(21)02293-7.

10. Oktay K et al. Fertil Steril. 2022;117(1):181-92.

11. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(6):1022–33.

12. Cil A et al. Fertil Steril. 2013 Aug;100(2):492-9.e3.

13. Goldman KN et al. Fertil Steril. 2013 Sep;100(3):712-7.

14. Marin L and Oktay K. Scientific history of ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation. In: Oktay K (ed.), Principles and Practice of Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation and Transplantation. Elsevier;2022:1-10.

15. Oktay K et al. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jul 1;23(19):4347-53.

16. Kim JY et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Apr;101(4):1364-71.

17. Turan V et al. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:18.

18. Oktay K et al. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Jan 10;28(2):240-4.

19. Lin W et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(10):3839-47.

20. Turan V et al. Reprod Sci. 2018;(25):26-32.

21. Oktay K et al. Presence of BRCA mutations and a pre-chemotherapy AMH level of < 2ng/mL strongly predict risk of amenorrhea in women with breast cancer P-291. Presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine 78th annual meeting, Anaheim, Calif. Oct. 22-26, 2022.

22. Oktay KH et al. Fertil Steril. 2020;113(6):1251‐60.e1.

23. Soleimani R et al. PLoS One. 2011 Apr 29;6(4):e19475.

24. Marin L et al. Future aspects of ovarian cryopreservation and transplantation. In: Oktay K (ed.). Principles and Practice of Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation and Transplantation. Elsevier; 2022;223-30.

25. Oktay KH et al. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(8):753-61.

26. Oktay K and Marin L. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation for delaying childbearing and menopause. In: Oktay, K. (Ed.), Principles and Practice of Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation and Transplantation. Elsevier;2022:195-204.

27. Oktay K et al. JAMA. 2001 Sep 26;286(12):1490-3.

28. Oktay K et al. Lancet. 2004 Mar 13;363(9412):837-40.

35 years in service to you, our community of reproductive health care clinicians

The mission of OBG

OBG

We wish all our readers a wonderful New Year and the best health possible for our patients.

Arnold P. Advincula, MD

I serve on the executive board that oversees the Fellowships in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery (FMIGS), and in January 2023 will transition into the role of President. I bring to this leadership role nearly 25 years of surgical experience, both as a clinician educator and inventor. My goal during the next 2 years will be to move toward subspecialty recognition of Complex Gynecology.

Linda D. Bradley, MD

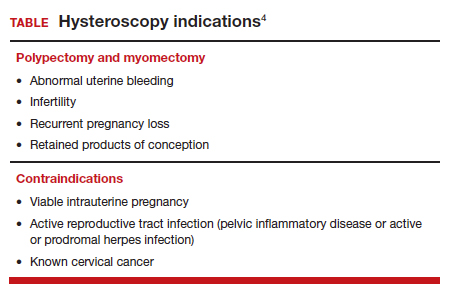

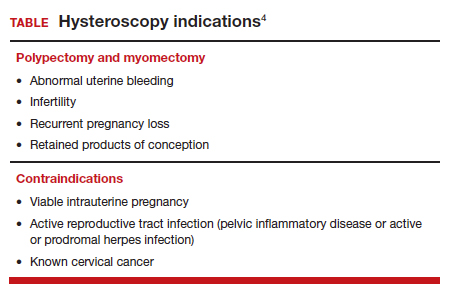

My passion is diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy, simple procedures that can both evaluate and treat intrauterine pathology. Recently, I was thrilled to coauthor an article on office hysteroscopy for Obstetrics & Gynecology (September 2022). I will have a chapter on operative hysteroscopy in the 2023 edition of TeLinde’s Textbook of Gynecology, and I am an author for the topic Office and Operative Hysteroscopy in UpToDate. Locally, I am known as the “foodie gynecologist”—I travel, take cooking classes, and I have more cookbooks than gynecology textbooks. Since Covid, I have embraced biking and just completed a riverboat biking cruise from Salamanca, Spain, to Lisbon, Portugal.

Amy L. Garcia, MD

I am fellowship trained as a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon (MIGS) and have had a private surgical practice since 2005. I am involved with The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), AAGL, and international surgical education for office hysteroscopy and related practice management. I am passionate about working with start-up companies in the gynecologic medical device arena and innovation in gynecologic surgery.

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, NCMP, CCD

I just completed my term as President of the International Menopause Society. This culminated in the society’s 18th World Congress in Lisbon, attended by over 1,700 health care providers from 76 countries. I delivered the Pieter van Keep Memorial Lecture, named for one of the society’s founders who died prematurely of pancreatic cancer. I was further honored by receiving the society’s Distinguished Service Award. I am very proud to have previously received the NAMS Thomas B. Clarkson award for Outstanding Clinical and Basic Science Research in Menopause. I also have one foot in the gynecologic ultrasound world and was given the Joseph H. Holmes Pioneer Award and was the 2023 recipient of the William J. Fry Memorial Lecture Award, both from the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, having written the second book ever on vaginal ultrasonography.

On a personal level, I love to play golf (in spite of my foot drop and 14 orthopedic surgeries). My season tickets show some diversity—the New York City Ballet and St. John’s basketball.

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD

I am the 49th president of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, the 5th woman to hold this position, and the first of Filipino-American descent. I recognize that it is only through extraordinary mentorship and support from other giants in gynecology, like Drs. Andrew Kaunitz (fellow OBG

PS—In the spirit of continually learning, I want to add the Argentine tango to my dancing repertoire and go on an African safari; both are on my bucket list as the pandemic eases.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, NCMP

Since starting with the University of Florida College of Medicine-Jacksonville in 1984, I have enjoyed caring for patients, training residents and medical students, and being involved with publications and research. My areas of focus are menopause, contraception, gyn ultrasound and evaluation/management of women with abnormal uterine bleeding. In 2020, I received the North American Menopause Society/Leon Speroff Outstanding Educator Award. In 2021, I received the ACOG Distinguished Service Award. I enjoy spending time with my family, neighborhood bicycling, and searching for sharks’ teeth at the beach.

Barbara Levy, MD

I have been privileged to serve on the OBG

Continue to: David G. Mutch, MD...

David G. Mutch, MD

I am ending my 6-year term as Chair of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) gynecologic cancer steering committee. That is the committee that vets all NCI-sponsored clinical trials in gynecologic oncology. I am on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Cancer committee, Co-Chair of the American Joint Committee on Cancer gyn staging committee and on the Reproductive Scientist Development Program selection committee. I also am completing my term as Chair of the Foundation for Women’s Cancer; this is the C3, charitable arm, of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. We have distributed more than $3.5 million to young investigators to help start their research careers in gynecologic oncology.

Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, MBA

I am a physician-scientist with subspecialty training in high-risk obstetrics (maternal-fetal medicine). I was born and raised in Cape Town, South Africa, and I have trained/practiced in 5 countries on 3 continents. My research interests include the pathophysiology, prediction, prevention, and management of pregnancy complications, primarily preterm birth and preeclampsia. I am a member of the Board of Scientific Counselors of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. I am currently President & CEO of Newton-Wellesley Hospital, a comprehensive community-based academic medical center and a member of the Mass General Brigham health care system in Boston, Massachusetts.

Jaimey Pauli, MD

I am the Division Chief and Professor of Maternal-Fetal Medicine (MFM) at the Penn State College of Medicine and Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. I had exceptional mentoring throughout my medical career, particularly by a former member of the Editorial Board, Dr. John T. Repke. One of the biggest perks of my job is that our division provides full-scope MFM care. While I often serve as the more traditional MFM consultant and academic educator, I also provide longitudinal prenatal care and deliver many of my own patients, often through subsequent pregnancies. Serving as a member of the Editorial Board combines my passion for clinical obstetrical care with my talents (as a former English major) of reading, writing, and editing. I believe that the work we do provides accessible, evidence-based, and practical guidance for our colleagues so they can provide excellence in obstetrical care.

JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, NCMP

I am a Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Division Chief of Midlife Health at the University of Virginia (UVA) Health. Passionate about menopause, I am an executive director emeritus of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and past-President of NAMS (2008-2009). Within the past few years, I have served as an expert advisor for the recent ACOG Clinical Practice Guidelines on Osteoporosis, the NAMS Position Statements on Hormone Therapy and Osteoporosis, and the Global Consensus on Menopause and Androgen Therapy. I received the 2022 South Atlantic Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Lifetime Achievement Award for my expertise and work in menopause and the NAMS 2020 Ann Voda Community Service Award for my biannual community educational symposiums. I remain active in research, currently the lead and UVA principal investigator for the Oasis 2 multicenter clinical trial, which is testing a neurokinin receptor antagonist as a nonhormone therapy for the relief of hot flashes. Serving on the OBG

Joseph S. Sanfilippo, MD, MBA

I feel honored and privileged to have received the Golden Apple Teaching Award from the Universityof Pittsburgh School of Medicine. I am also fortunate to be the recipient of the Faculty Educator of the Month Award for resident teaching. I have been named Top Doctor 20 years in a row. My current academic activities include, since 2007, Program Director for Reproductive Endocrinology & Infertility Fellowship at the University of Pittsburgh and Chair of the Mentor-Mentee Program at University of Pittsburgh Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences. I am Guest Editor for the medical malpractice section of the journal Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. Recently, I completed a patient-focused book, “Experts Guide to Fertility,” which will be published in May 2023 by J Hopkins University Publisher and is designed for patients going through infertility treatment. Regarding outside events, I enjoy climbing steep hills and riding far and wide on my “electric bike.” Highly recommend it!

James Simon, MD, CCD, IF, NCMP

It’s been an honor serving on the OBG

I asked our distinguished Board of Editors to identify the most important changes that they believe will occur over the next 5 years, influencing the practice of obstetrics and gynecology. Their expert predictions are summarized below.

Arnold Advincula, MD

As one of the world’s most experienced gynecologic robotic surgeons, the role of this technology will become even more refined over the next 2-5 years with the introduction of sophisticated image guidance, “smart molecules,” and artificial intelligence. All of this will transform both the patient and surgeon experience as well as impact how we train future surgeons.

Linda Bradley, MD

My hope is that a partnership with industry and hysteroscopy thought leaders will enable new developments/technology in performing hysteroscopic sterilization. Conquering the tubal ostia for sterilization in an office setting would profoundly improve contraceptive options for women. Conquering the tubal ostia is the last frontier in gynecology.

Amy Garcia, MD

I predict that new technologies will allow for a significant increase in the number of gynecologists who perform in-office hysteroscopy and that a paradigm shift will occur to replace blind biopsy with hysteroscopy-directed biopsy and evaluation of the uterine cavity.

Steven Goldstein, MD, NCMP, CCD

Among the most important changes in the next 5 years, in my opinion, will be in the arenas of precision medicine, genetic advancement, and artificial intelligence. In addition, unfortunately, there will be an even greater movement toward guidelines utilizing algorithms and clinical pathways. I leave you with the following quote:

“Neither evidence nor clinical judgement alone is sufficient. Evidence without judgement can be applied by a technician. Judgement without evidence can be applied by a friend. But the integration of evidence and judgement is what the healthcare provider does in order to dispense the best clinical care.” —Hertzel Gerstein, MD

Cheryl Iglesia, MD

Technology related to minimally invasive surgery will continue to change our practice, and I predict that surgery will be more centralized to high volume practices. Reimbursements for these procedures may remain a hot button issue, however. The materials used for pelvic reconstruction will be derived from autologous stem cells and advancements made in regenerative medicine.

Andrew Kaunitz, MD, NCMP

As use of contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices continues to grow, I anticipate the incidence of unintended pregnancies will continue to decline. As the novel gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists combined with estrogen-progestin add-back grow in use, I anticipate this will provide our patients with more nonsurgical options for managing abnormal uterine bleeding, including that associated with uterine fibroids.

Barbara Levy, MD

Quality will be redefined by patient-defined outcome measures that assess what matters to the people we serve. Real-world evidence will be incorporated to support those measures and provide data on patient outcomes in populations not studied in the randomized controlled trials on which we have created guidelines. This will help to refine guidelines and support more equitable and accessible care.

David Mutch, MD

Over the next 5 years, our expanding insights into the molecular biology of cancer will lead to targeted therapies that will yield better responses with less toxicity.

Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, MBA

In the near future we will use predictive AI algorithms to: 1) identify patients at risk of adverse pregnancy events; 2) stratify patients into high-, average-, and low-risk; and 3) design a personalized obstetric care journey for each patient based on their individualized risk stratification with a view to improving safety and quality outcome metrics, addressing health care disparity, and lowering the cost of care.

Jaimey Pauli, MD

I predict (and fervently hope) that breakthroughs will occur in the prevention of two of the most devastating diseases to affect obstetric patients and their families—preterm birth and preeclampsia.

JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, NCMP

New nonhormone management therapies will be available to treat hot flashes and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. These treatments will be especially welcomed by patients who cannot or choose not to take hormone therapy. We should not allow new technology to overshadow the patient. We must remember to treat the patient with the condition, not just the disease. Consider what is important to the individual woman, her quality of life, and her ability to function, and keep that in mind when deciding what therapy to suggest.

Joseph S. Sanfilippo, MD, MBA

Artificial intelligence will change the way we educate and provide patient care. Three-dimensional perspectives will cross a number of horizons, some of which include:

- advances in assisted reproductive technology (IVF), offering the next level of “in vitro maturation” of oocytes for patients heretofore unable to conceive. They can progress to having a baby with decreased ovarian reserve or in association with “life after cancer.”

- biogenic engineering and bioinformatics will allow correction of genetic defects in embryos prior to implantation

- the surgical arena will incorporate direct robotic initiated procedures and bring robotic surgery to the next level

- with regard to medical education, at all levels, virtual reality, computer-generated 3-dimensional imaging will provide innovative tools.

James Simon, MD, CCD, IF, NCMP

Medicine’s near-term future portends the realization of truly personalized medicine based upon one’s genetic predisposition to disease, and intentional genetic manipulation to mitigate it. Such advances are here already, simply pending regulatory and ethical approval. My concern going forward is that such individualization, and an algorithm-driven decision-making process will result in taking the personal out of personalized medicine. We humans are more than the collected downstream impact of our genes. In our quest for advances, let’s not forget the balance between nature (our genes) and nurture (environment). The risk of forgetting this aphorism, like the electronic health record, gives me heartburn, or worse, burnout!

The mission of OBG

OBG

We wish all our readers a wonderful New Year and the best health possible for our patients.

Arnold P. Advincula, MD

I serve on the executive board that oversees the Fellowships in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery (FMIGS), and in January 2023 will transition into the role of President. I bring to this leadership role nearly 25 years of surgical experience, both as a clinician educator and inventor. My goal during the next 2 years will be to move toward subspecialty recognition of Complex Gynecology.

Linda D. Bradley, MD

My passion is diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy, simple procedures that can both evaluate and treat intrauterine pathology. Recently, I was thrilled to coauthor an article on office hysteroscopy for Obstetrics & Gynecology (September 2022). I will have a chapter on operative hysteroscopy in the 2023 edition of TeLinde’s Textbook of Gynecology, and I am an author for the topic Office and Operative Hysteroscopy in UpToDate. Locally, I am known as the “foodie gynecologist”—I travel, take cooking classes, and I have more cookbooks than gynecology textbooks. Since Covid, I have embraced biking and just completed a riverboat biking cruise from Salamanca, Spain, to Lisbon, Portugal.

Amy L. Garcia, MD

I am fellowship trained as a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon (MIGS) and have had a private surgical practice since 2005. I am involved with The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), AAGL, and international surgical education for office hysteroscopy and related practice management. I am passionate about working with start-up companies in the gynecologic medical device arena and innovation in gynecologic surgery.

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, NCMP, CCD

I just completed my term as President of the International Menopause Society. This culminated in the society’s 18th World Congress in Lisbon, attended by over 1,700 health care providers from 76 countries. I delivered the Pieter van Keep Memorial Lecture, named for one of the society’s founders who died prematurely of pancreatic cancer. I was further honored by receiving the society’s Distinguished Service Award. I am very proud to have previously received the NAMS Thomas B. Clarkson award for Outstanding Clinical and Basic Science Research in Menopause. I also have one foot in the gynecologic ultrasound world and was given the Joseph H. Holmes Pioneer Award and was the 2023 recipient of the William J. Fry Memorial Lecture Award, both from the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, having written the second book ever on vaginal ultrasonography.

On a personal level, I love to play golf (in spite of my foot drop and 14 orthopedic surgeries). My season tickets show some diversity—the New York City Ballet and St. John’s basketball.

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD

I am the 49th president of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, the 5th woman to hold this position, and the first of Filipino-American descent. I recognize that it is only through extraordinary mentorship and support from other giants in gynecology, like Drs. Andrew Kaunitz (fellow OBG

PS—In the spirit of continually learning, I want to add the Argentine tango to my dancing repertoire and go on an African safari; both are on my bucket list as the pandemic eases.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, NCMP

Since starting with the University of Florida College of Medicine-Jacksonville in 1984, I have enjoyed caring for patients, training residents and medical students, and being involved with publications and research. My areas of focus are menopause, contraception, gyn ultrasound and evaluation/management of women with abnormal uterine bleeding. In 2020, I received the North American Menopause Society/Leon Speroff Outstanding Educator Award. In 2021, I received the ACOG Distinguished Service Award. I enjoy spending time with my family, neighborhood bicycling, and searching for sharks’ teeth at the beach.

Barbara Levy, MD

I have been privileged to serve on the OBG

Continue to: David G. Mutch, MD...

David G. Mutch, MD

I am ending my 6-year term as Chair of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) gynecologic cancer steering committee. That is the committee that vets all NCI-sponsored clinical trials in gynecologic oncology. I am on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Cancer committee, Co-Chair of the American Joint Committee on Cancer gyn staging committee and on the Reproductive Scientist Development Program selection committee. I also am completing my term as Chair of the Foundation for Women’s Cancer; this is the C3, charitable arm, of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. We have distributed more than $3.5 million to young investigators to help start their research careers in gynecologic oncology.

Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, MBA

I am a physician-scientist with subspecialty training in high-risk obstetrics (maternal-fetal medicine). I was born and raised in Cape Town, South Africa, and I have trained/practiced in 5 countries on 3 continents. My research interests include the pathophysiology, prediction, prevention, and management of pregnancy complications, primarily preterm birth and preeclampsia. I am a member of the Board of Scientific Counselors of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. I am currently President & CEO of Newton-Wellesley Hospital, a comprehensive community-based academic medical center and a member of the Mass General Brigham health care system in Boston, Massachusetts.

Jaimey Pauli, MD

I am the Division Chief and Professor of Maternal-Fetal Medicine (MFM) at the Penn State College of Medicine and Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. I had exceptional mentoring throughout my medical career, particularly by a former member of the Editorial Board, Dr. John T. Repke. One of the biggest perks of my job is that our division provides full-scope MFM care. While I often serve as the more traditional MFM consultant and academic educator, I also provide longitudinal prenatal care and deliver many of my own patients, often through subsequent pregnancies. Serving as a member of the Editorial Board combines my passion for clinical obstetrical care with my talents (as a former English major) of reading, writing, and editing. I believe that the work we do provides accessible, evidence-based, and practical guidance for our colleagues so they can provide excellence in obstetrical care.

JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, NCMP

I am a Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Division Chief of Midlife Health at the University of Virginia (UVA) Health. Passionate about menopause, I am an executive director emeritus of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and past-President of NAMS (2008-2009). Within the past few years, I have served as an expert advisor for the recent ACOG Clinical Practice Guidelines on Osteoporosis, the NAMS Position Statements on Hormone Therapy and Osteoporosis, and the Global Consensus on Menopause and Androgen Therapy. I received the 2022 South Atlantic Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Lifetime Achievement Award for my expertise and work in menopause and the NAMS 2020 Ann Voda Community Service Award for my biannual community educational symposiums. I remain active in research, currently the lead and UVA principal investigator for the Oasis 2 multicenter clinical trial, which is testing a neurokinin receptor antagonist as a nonhormone therapy for the relief of hot flashes. Serving on the OBG

Joseph S. Sanfilippo, MD, MBA

I feel honored and privileged to have received the Golden Apple Teaching Award from the Universityof Pittsburgh School of Medicine. I am also fortunate to be the recipient of the Faculty Educator of the Month Award for resident teaching. I have been named Top Doctor 20 years in a row. My current academic activities include, since 2007, Program Director for Reproductive Endocrinology & Infertility Fellowship at the University of Pittsburgh and Chair of the Mentor-Mentee Program at University of Pittsburgh Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences. I am Guest Editor for the medical malpractice section of the journal Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. Recently, I completed a patient-focused book, “Experts Guide to Fertility,” which will be published in May 2023 by J Hopkins University Publisher and is designed for patients going through infertility treatment. Regarding outside events, I enjoy climbing steep hills and riding far and wide on my “electric bike.” Highly recommend it!

James Simon, MD, CCD, IF, NCMP

It’s been an honor serving on the OBG

I asked our distinguished Board of Editors to identify the most important changes that they believe will occur over the next 5 years, influencing the practice of obstetrics and gynecology. Their expert predictions are summarized below.

Arnold Advincula, MD

As one of the world’s most experienced gynecologic robotic surgeons, the role of this technology will become even more refined over the next 2-5 years with the introduction of sophisticated image guidance, “smart molecules,” and artificial intelligence. All of this will transform both the patient and surgeon experience as well as impact how we train future surgeons.

Linda Bradley, MD

My hope is that a partnership with industry and hysteroscopy thought leaders will enable new developments/technology in performing hysteroscopic sterilization. Conquering the tubal ostia for sterilization in an office setting would profoundly improve contraceptive options for women. Conquering the tubal ostia is the last frontier in gynecology.

Amy Garcia, MD

I predict that new technologies will allow for a significant increase in the number of gynecologists who perform in-office hysteroscopy and that a paradigm shift will occur to replace blind biopsy with hysteroscopy-directed biopsy and evaluation of the uterine cavity.

Steven Goldstein, MD, NCMP, CCD

Among the most important changes in the next 5 years, in my opinion, will be in the arenas of precision medicine, genetic advancement, and artificial intelligence. In addition, unfortunately, there will be an even greater movement toward guidelines utilizing algorithms and clinical pathways. I leave you with the following quote:

“Neither evidence nor clinical judgement alone is sufficient. Evidence without judgement can be applied by a technician. Judgement without evidence can be applied by a friend. But the integration of evidence and judgement is what the healthcare provider does in order to dispense the best clinical care.” —Hertzel Gerstein, MD

Cheryl Iglesia, MD

Technology related to minimally invasive surgery will continue to change our practice, and I predict that surgery will be more centralized to high volume practices. Reimbursements for these procedures may remain a hot button issue, however. The materials used for pelvic reconstruction will be derived from autologous stem cells and advancements made in regenerative medicine.

Andrew Kaunitz, MD, NCMP

As use of contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices continues to grow, I anticipate the incidence of unintended pregnancies will continue to decline. As the novel gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists combined with estrogen-progestin add-back grow in use, I anticipate this will provide our patients with more nonsurgical options for managing abnormal uterine bleeding, including that associated with uterine fibroids.

Barbara Levy, MD

Quality will be redefined by patient-defined outcome measures that assess what matters to the people we serve. Real-world evidence will be incorporated to support those measures and provide data on patient outcomes in populations not studied in the randomized controlled trials on which we have created guidelines. This will help to refine guidelines and support more equitable and accessible care.

David Mutch, MD

Over the next 5 years, our expanding insights into the molecular biology of cancer will lead to targeted therapies that will yield better responses with less toxicity.

Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, MBA

In the near future we will use predictive AI algorithms to: 1) identify patients at risk of adverse pregnancy events; 2) stratify patients into high-, average-, and low-risk; and 3) design a personalized obstetric care journey for each patient based on their individualized risk stratification with a view to improving safety and quality outcome metrics, addressing health care disparity, and lowering the cost of care.

Jaimey Pauli, MD

I predict (and fervently hope) that breakthroughs will occur in the prevention of two of the most devastating diseases to affect obstetric patients and their families—preterm birth and preeclampsia.

JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, NCMP

New nonhormone management therapies will be available to treat hot flashes and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. These treatments will be especially welcomed by patients who cannot or choose not to take hormone therapy. We should not allow new technology to overshadow the patient. We must remember to treat the patient with the condition, not just the disease. Consider what is important to the individual woman, her quality of life, and her ability to function, and keep that in mind when deciding what therapy to suggest.

Joseph S. Sanfilippo, MD, MBA

Artificial intelligence will change the way we educate and provide patient care. Three-dimensional perspectives will cross a number of horizons, some of which include:

- advances in assisted reproductive technology (IVF), offering the next level of “in vitro maturation” of oocytes for patients heretofore unable to conceive. They can progress to having a baby with decreased ovarian reserve or in association with “life after cancer.”

- biogenic engineering and bioinformatics will allow correction of genetic defects in embryos prior to implantation

- the surgical arena will incorporate direct robotic initiated procedures and bring robotic surgery to the next level

- with regard to medical education, at all levels, virtual reality, computer-generated 3-dimensional imaging will provide innovative tools.

James Simon, MD, CCD, IF, NCMP