User login

What’s the best way to sort out red nail discoloration?

NEW YORK – Nail discoloration, in all its variety, has a wide differential. And while that differential narrows when a patient presents with concerns about nails with red discoloration, there’s still a long list of diagnoses to consider.

During a nail-focused session at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting, Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, took attendees through a presentation-based approach that gets to the root etiology of erythronychia and guides diagnosis and treatment options.

“However, regardless of the etiology, erythronychia shares a common pathogenesis,” said Dr. Lipner, a dermatologist at New York–Presbyterian Hospital and Weil Cornell Medicine. The process begins in the distal nail matrix, resulting in a thin long strip of ventral nail becoming discolored, with the nail bed filling in the concavity. The engorged nail bed also makes the affected nail unit prone to splinter hemorrhages, and the thinned, transparent nail makes the erythema more visible, she explained.

Polydactylous longitudinal erythronychia

For erythronychia affecting several nails, onychotillomania is among the possible causes. This condition “often goes hand in hand with onychophagia,” and trichotillomania, skin-picking, or other self-mutilating disorders may also be present, she said. In both the adult and pediatric population, onychotillomania can accompany psychiatric disorders, including depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder, and may be associated with suicidal ideation, she added.

When onychotillomania is the cause, erythronychia may be accompanied by paronychia, and patients will often have a shortened nail bed and an atrophic nail plate. Dorsal pterygium may also be present.

Dermoscopy can provide some clues that onychotillomania is the culprit, said Dr. Lipner, citing a study that looked at dermoscopic images of 36 cases, which found scales in 94%, absence of the nail plate in 83%, and characteristic wavy lines in 69% (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Oct;79[4]:702-5). Other frequent dermoscopy findings included hemorrhages (64%), crusts (61%), nail bed pigmentation (47%), and speckled dots (39%).

Lichen planus can also affect the nails, with erythronychia among its manifestations, she noted. Though lichen planus is thought of as a disease of middle or older age, usually affecting those aged 50-70 years, “15% of those affected are less than 20 years old,” she said.

The erythronychia of lichen planus is often accompanied by longitudinal riding, splitting, and atrophy of the nail plate, she said. Pterygium can also be present, representing a scar in the nail matrix. Dermatopathology will reveal a patchy, bandlike lichenoid infiltrate, with variable sawtooth hypergranulosis and hyperplasia.

“There’s not much evidence about how to treat lichen planus of the nails,” noted Dr. Lipner. Options can include intralesional corticosteroid injections at the nail matrix, topical corticosteroids, oral methotrexate, and retinoids.

Darier disease, an inherited condition caused by mutations in ATP2A2, has both skin and nail manifestations. Characteristic skin signs include hyperkeratotic papules, cobblestone papules, and palmar pits, she said. When nails are affected – as they are in up to 95% of Darier disease patients – they can have a characteristic “candy cane” appearance, with bands of longitudinal erythronychia alternating with normal-colored nail. The nails can also have V-shaped notching, she added.

Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus can also have longitudinal erythronychia; here, dermoscopy will show the characteristic prominent capillary loops in the proximal nail folds, she said.

Foreign substances such as nail polish and dyes, when they’re the source of erythronychia in one or several nails, can usually be wiped off with alcohol or acetone; also, “the proximal margin of discoloration will follow the same pattern as the nail fold,” said Dr. Lipner.

Localized longitudinal erythronychia

When the red discoloration is limited to a single nail, the differential shifts, said Dr. Lipner. With a hematoma, there’s often a history of trauma, and dermoscopy will show characteristic globules and streaks.

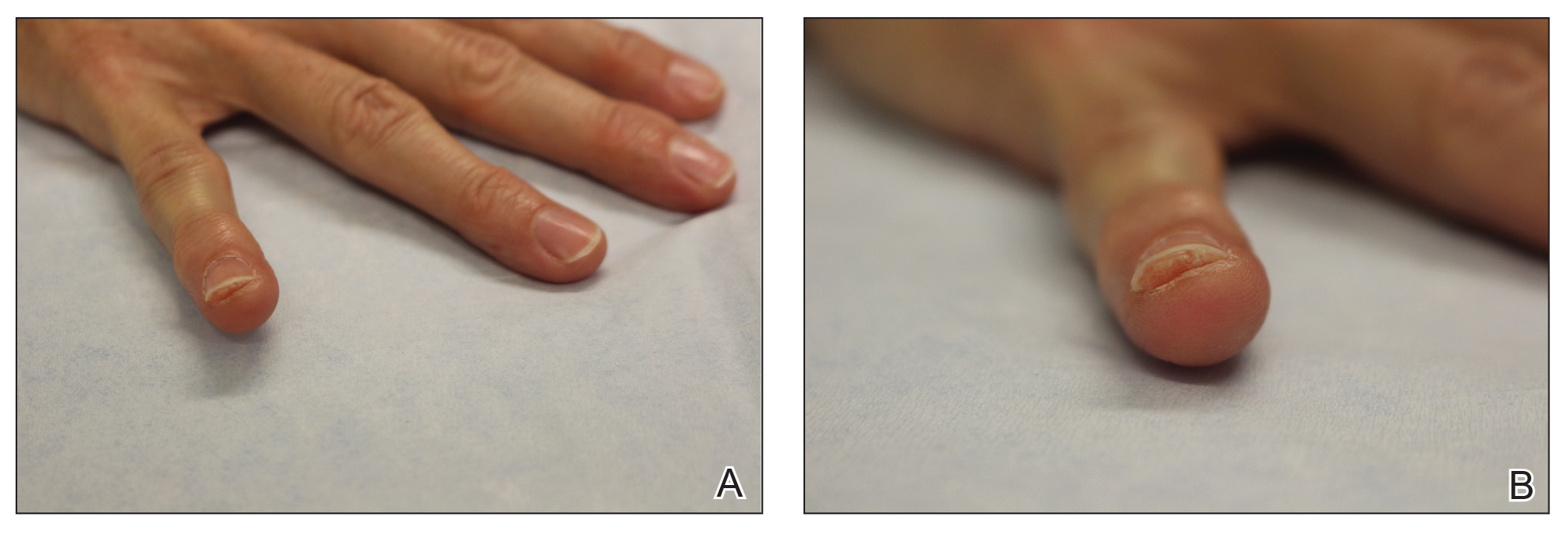

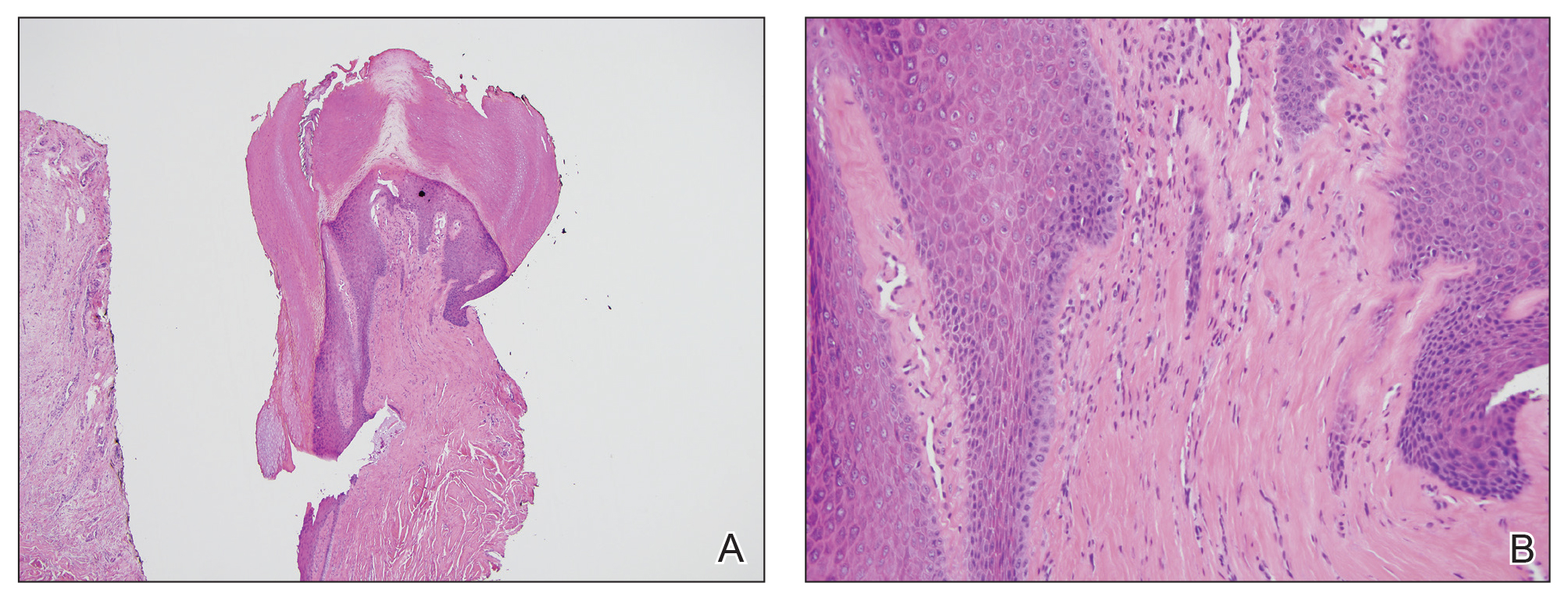

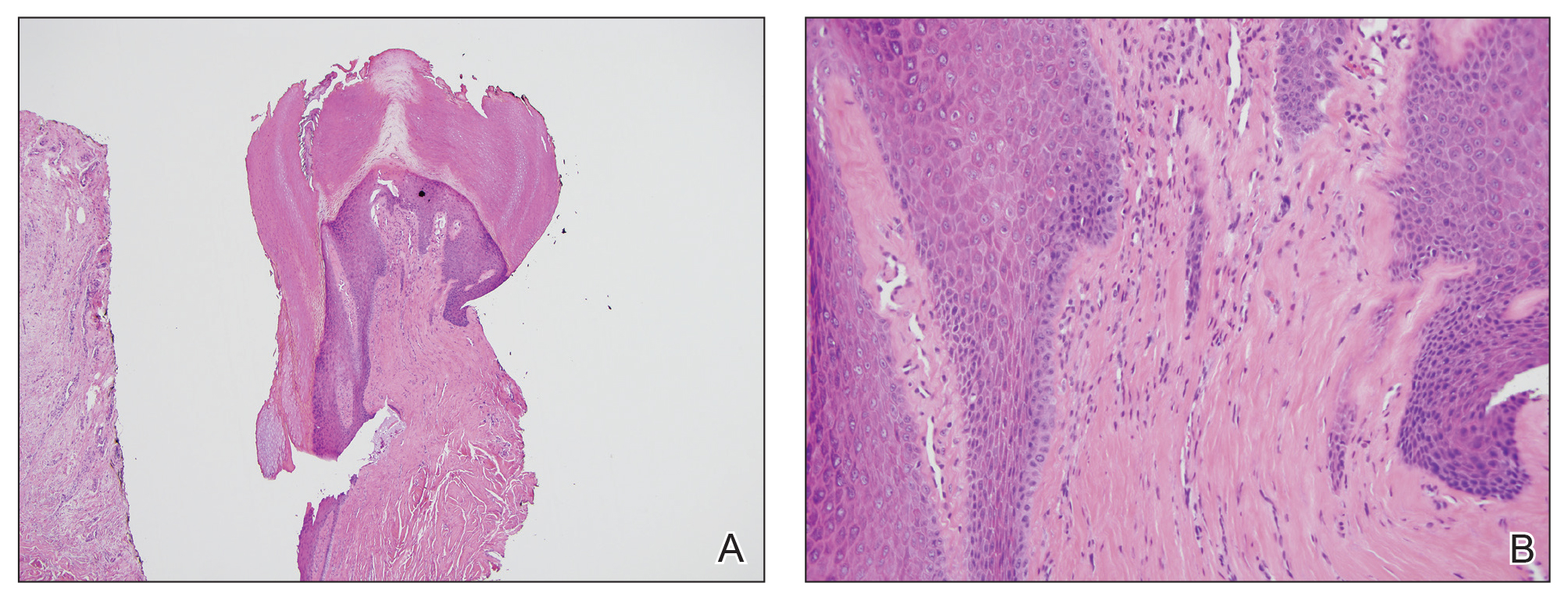

The first clue that erythronychia caused by onychopapilloma can be seen at the lunula: There will often be a comet- or pencil-shaped point to the discoloration in that region. But, she said, “the key is to do dermoscopy at the free edge of the nail plate. In 100 percent of cases, there will be a subungual hyperkeratotic papule” that will solidify the diagnosis.

Histopathology of onychopapillomas – a relatively recently recognized entity – will show nail bed and distal matrix acanthosis, with the distal nail bed showing matrix metaplasia, Dr. Lipner said.

Glomus tumors arise from cells of the glomus body, a specialized vascular apparatus that is involved in temperature regulation. “These structures are abundant in the digits and the subungual region,” said Dr. Lipner, which means that glomus tumors – a benign lesion – may develop subungually. Glomus tumors can be idiopathic, but she added, “think neurofibromatosis type 1 if you see multiple glomus tumors.”

Glomus tumors will present with longitudinal erythronychia, with a distal split of the nail sometimes accompanying the discoloration. A round bluish to gray nodule can also be seen. A thorough history and exam can help solidify the diagnosis, said Dr. Lipner; there’s a characteristic triad of point tenderness with the application of pressure to the nail, pain, and cold hypersensitivity.

Classically, the point tenderness is assessed by Love’s test, which elicits severe pain when the subungual tumor is pressed with a small object like the end of paper clip or a ballpoint pen. Application of a tourniquet to the arm after elevation, termed Hildreth’s test, should alleviate subungual glomus tumor pain, and release of the tourniquet causes an abrupt and marked recurrence of pain. Immersing the patient’s affected hand in cold water also increases glomus tumor pain.

“Imaging can be quite helpful” to confirm a glomus tumor diagnosis, said Dr. Lipner. “X-ray is cheap, and you can see erosions in 50% of patients.” However, she added, doppler ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging are more sensitive, detecting tumors as small as 2 mm.

“Biopsy with histopathology is the gold standard in making the diagnosis” of glomus tumor, though, she noted. Pathologic examination will show monomorphic cells with small caliber vascular channels.

Malignancy is actually uncommon with erythronychia, though it’s always in the differential diagnosis, she said.

In one case series examining subungual squamous cell carcinomas, common findings included onycholysis and localized hyperkeratosis, along with longitudinal erythronychia. “This may be subtle; splinter hemorrhages can also be present,” noted Dr. Lipner, adding, “If there are any symptoms, or an evolving band, a biopsy is indicated.”

“Even with erythronychia, the presentation can be quite variable,” she said. Nail unit melanoma can count erythronychia among the presenting signs. Clues that should raise suspicion for melanoma can include a wide band and prominent onycholysis, especially distal onycholysis and splintering. Again, she said, “biopsy with histopathology is the gold standard in making the diagnosis”; any symptoms or evidence of an evolving band should trigger a biopsy.

Dr. Lipner had no conflicts of interest relevant to her presentation.

SOURCE: Lipner S. Summer AAD 2019, Presentation F035.

NEW YORK – Nail discoloration, in all its variety, has a wide differential. And while that differential narrows when a patient presents with concerns about nails with red discoloration, there’s still a long list of diagnoses to consider.

During a nail-focused session at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting, Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, took attendees through a presentation-based approach that gets to the root etiology of erythronychia and guides diagnosis and treatment options.

“However, regardless of the etiology, erythronychia shares a common pathogenesis,” said Dr. Lipner, a dermatologist at New York–Presbyterian Hospital and Weil Cornell Medicine. The process begins in the distal nail matrix, resulting in a thin long strip of ventral nail becoming discolored, with the nail bed filling in the concavity. The engorged nail bed also makes the affected nail unit prone to splinter hemorrhages, and the thinned, transparent nail makes the erythema more visible, she explained.

Polydactylous longitudinal erythronychia

For erythronychia affecting several nails, onychotillomania is among the possible causes. This condition “often goes hand in hand with onychophagia,” and trichotillomania, skin-picking, or other self-mutilating disorders may also be present, she said. In both the adult and pediatric population, onychotillomania can accompany psychiatric disorders, including depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder, and may be associated with suicidal ideation, she added.

When onychotillomania is the cause, erythronychia may be accompanied by paronychia, and patients will often have a shortened nail bed and an atrophic nail plate. Dorsal pterygium may also be present.

Dermoscopy can provide some clues that onychotillomania is the culprit, said Dr. Lipner, citing a study that looked at dermoscopic images of 36 cases, which found scales in 94%, absence of the nail plate in 83%, and characteristic wavy lines in 69% (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Oct;79[4]:702-5). Other frequent dermoscopy findings included hemorrhages (64%), crusts (61%), nail bed pigmentation (47%), and speckled dots (39%).

Lichen planus can also affect the nails, with erythronychia among its manifestations, she noted. Though lichen planus is thought of as a disease of middle or older age, usually affecting those aged 50-70 years, “15% of those affected are less than 20 years old,” she said.

The erythronychia of lichen planus is often accompanied by longitudinal riding, splitting, and atrophy of the nail plate, she said. Pterygium can also be present, representing a scar in the nail matrix. Dermatopathology will reveal a patchy, bandlike lichenoid infiltrate, with variable sawtooth hypergranulosis and hyperplasia.

“There’s not much evidence about how to treat lichen planus of the nails,” noted Dr. Lipner. Options can include intralesional corticosteroid injections at the nail matrix, topical corticosteroids, oral methotrexate, and retinoids.

Darier disease, an inherited condition caused by mutations in ATP2A2, has both skin and nail manifestations. Characteristic skin signs include hyperkeratotic papules, cobblestone papules, and palmar pits, she said. When nails are affected – as they are in up to 95% of Darier disease patients – they can have a characteristic “candy cane” appearance, with bands of longitudinal erythronychia alternating with normal-colored nail. The nails can also have V-shaped notching, she added.

Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus can also have longitudinal erythronychia; here, dermoscopy will show the characteristic prominent capillary loops in the proximal nail folds, she said.

Foreign substances such as nail polish and dyes, when they’re the source of erythronychia in one or several nails, can usually be wiped off with alcohol or acetone; also, “the proximal margin of discoloration will follow the same pattern as the nail fold,” said Dr. Lipner.

Localized longitudinal erythronychia

When the red discoloration is limited to a single nail, the differential shifts, said Dr. Lipner. With a hematoma, there’s often a history of trauma, and dermoscopy will show characteristic globules and streaks.

The first clue that erythronychia caused by onychopapilloma can be seen at the lunula: There will often be a comet- or pencil-shaped point to the discoloration in that region. But, she said, “the key is to do dermoscopy at the free edge of the nail plate. In 100 percent of cases, there will be a subungual hyperkeratotic papule” that will solidify the diagnosis.

Histopathology of onychopapillomas – a relatively recently recognized entity – will show nail bed and distal matrix acanthosis, with the distal nail bed showing matrix metaplasia, Dr. Lipner said.

Glomus tumors arise from cells of the glomus body, a specialized vascular apparatus that is involved in temperature regulation. “These structures are abundant in the digits and the subungual region,” said Dr. Lipner, which means that glomus tumors – a benign lesion – may develop subungually. Glomus tumors can be idiopathic, but she added, “think neurofibromatosis type 1 if you see multiple glomus tumors.”

Glomus tumors will present with longitudinal erythronychia, with a distal split of the nail sometimes accompanying the discoloration. A round bluish to gray nodule can also be seen. A thorough history and exam can help solidify the diagnosis, said Dr. Lipner; there’s a characteristic triad of point tenderness with the application of pressure to the nail, pain, and cold hypersensitivity.

Classically, the point tenderness is assessed by Love’s test, which elicits severe pain when the subungual tumor is pressed with a small object like the end of paper clip or a ballpoint pen. Application of a tourniquet to the arm after elevation, termed Hildreth’s test, should alleviate subungual glomus tumor pain, and release of the tourniquet causes an abrupt and marked recurrence of pain. Immersing the patient’s affected hand in cold water also increases glomus tumor pain.

“Imaging can be quite helpful” to confirm a glomus tumor diagnosis, said Dr. Lipner. “X-ray is cheap, and you can see erosions in 50% of patients.” However, she added, doppler ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging are more sensitive, detecting tumors as small as 2 mm.

“Biopsy with histopathology is the gold standard in making the diagnosis” of glomus tumor, though, she noted. Pathologic examination will show monomorphic cells with small caliber vascular channels.

Malignancy is actually uncommon with erythronychia, though it’s always in the differential diagnosis, she said.

In one case series examining subungual squamous cell carcinomas, common findings included onycholysis and localized hyperkeratosis, along with longitudinal erythronychia. “This may be subtle; splinter hemorrhages can also be present,” noted Dr. Lipner, adding, “If there are any symptoms, or an evolving band, a biopsy is indicated.”

“Even with erythronychia, the presentation can be quite variable,” she said. Nail unit melanoma can count erythronychia among the presenting signs. Clues that should raise suspicion for melanoma can include a wide band and prominent onycholysis, especially distal onycholysis and splintering. Again, she said, “biopsy with histopathology is the gold standard in making the diagnosis”; any symptoms or evidence of an evolving band should trigger a biopsy.

Dr. Lipner had no conflicts of interest relevant to her presentation.

SOURCE: Lipner S. Summer AAD 2019, Presentation F035.

NEW YORK – Nail discoloration, in all its variety, has a wide differential. And while that differential narrows when a patient presents with concerns about nails with red discoloration, there’s still a long list of diagnoses to consider.

During a nail-focused session at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting, Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, took attendees through a presentation-based approach that gets to the root etiology of erythronychia and guides diagnosis and treatment options.

“However, regardless of the etiology, erythronychia shares a common pathogenesis,” said Dr. Lipner, a dermatologist at New York–Presbyterian Hospital and Weil Cornell Medicine. The process begins in the distal nail matrix, resulting in a thin long strip of ventral nail becoming discolored, with the nail bed filling in the concavity. The engorged nail bed also makes the affected nail unit prone to splinter hemorrhages, and the thinned, transparent nail makes the erythema more visible, she explained.

Polydactylous longitudinal erythronychia

For erythronychia affecting several nails, onychotillomania is among the possible causes. This condition “often goes hand in hand with onychophagia,” and trichotillomania, skin-picking, or other self-mutilating disorders may also be present, she said. In both the adult and pediatric population, onychotillomania can accompany psychiatric disorders, including depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder, and may be associated with suicidal ideation, she added.

When onychotillomania is the cause, erythronychia may be accompanied by paronychia, and patients will often have a shortened nail bed and an atrophic nail plate. Dorsal pterygium may also be present.

Dermoscopy can provide some clues that onychotillomania is the culprit, said Dr. Lipner, citing a study that looked at dermoscopic images of 36 cases, which found scales in 94%, absence of the nail plate in 83%, and characteristic wavy lines in 69% (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Oct;79[4]:702-5). Other frequent dermoscopy findings included hemorrhages (64%), crusts (61%), nail bed pigmentation (47%), and speckled dots (39%).

Lichen planus can also affect the nails, with erythronychia among its manifestations, she noted. Though lichen planus is thought of as a disease of middle or older age, usually affecting those aged 50-70 years, “15% of those affected are less than 20 years old,” she said.

The erythronychia of lichen planus is often accompanied by longitudinal riding, splitting, and atrophy of the nail plate, she said. Pterygium can also be present, representing a scar in the nail matrix. Dermatopathology will reveal a patchy, bandlike lichenoid infiltrate, with variable sawtooth hypergranulosis and hyperplasia.

“There’s not much evidence about how to treat lichen planus of the nails,” noted Dr. Lipner. Options can include intralesional corticosteroid injections at the nail matrix, topical corticosteroids, oral methotrexate, and retinoids.

Darier disease, an inherited condition caused by mutations in ATP2A2, has both skin and nail manifestations. Characteristic skin signs include hyperkeratotic papules, cobblestone papules, and palmar pits, she said. When nails are affected – as they are in up to 95% of Darier disease patients – they can have a characteristic “candy cane” appearance, with bands of longitudinal erythronychia alternating with normal-colored nail. The nails can also have V-shaped notching, she added.

Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus can also have longitudinal erythronychia; here, dermoscopy will show the characteristic prominent capillary loops in the proximal nail folds, she said.

Foreign substances such as nail polish and dyes, when they’re the source of erythronychia in one or several nails, can usually be wiped off with alcohol or acetone; also, “the proximal margin of discoloration will follow the same pattern as the nail fold,” said Dr. Lipner.

Localized longitudinal erythronychia

When the red discoloration is limited to a single nail, the differential shifts, said Dr. Lipner. With a hematoma, there’s often a history of trauma, and dermoscopy will show characteristic globules and streaks.

The first clue that erythronychia caused by onychopapilloma can be seen at the lunula: There will often be a comet- or pencil-shaped point to the discoloration in that region. But, she said, “the key is to do dermoscopy at the free edge of the nail plate. In 100 percent of cases, there will be a subungual hyperkeratotic papule” that will solidify the diagnosis.

Histopathology of onychopapillomas – a relatively recently recognized entity – will show nail bed and distal matrix acanthosis, with the distal nail bed showing matrix metaplasia, Dr. Lipner said.

Glomus tumors arise from cells of the glomus body, a specialized vascular apparatus that is involved in temperature regulation. “These structures are abundant in the digits and the subungual region,” said Dr. Lipner, which means that glomus tumors – a benign lesion – may develop subungually. Glomus tumors can be idiopathic, but she added, “think neurofibromatosis type 1 if you see multiple glomus tumors.”

Glomus tumors will present with longitudinal erythronychia, with a distal split of the nail sometimes accompanying the discoloration. A round bluish to gray nodule can also be seen. A thorough history and exam can help solidify the diagnosis, said Dr. Lipner; there’s a characteristic triad of point tenderness with the application of pressure to the nail, pain, and cold hypersensitivity.

Classically, the point tenderness is assessed by Love’s test, which elicits severe pain when the subungual tumor is pressed with a small object like the end of paper clip or a ballpoint pen. Application of a tourniquet to the arm after elevation, termed Hildreth’s test, should alleviate subungual glomus tumor pain, and release of the tourniquet causes an abrupt and marked recurrence of pain. Immersing the patient’s affected hand in cold water also increases glomus tumor pain.

“Imaging can be quite helpful” to confirm a glomus tumor diagnosis, said Dr. Lipner. “X-ray is cheap, and you can see erosions in 50% of patients.” However, she added, doppler ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging are more sensitive, detecting tumors as small as 2 mm.

“Biopsy with histopathology is the gold standard in making the diagnosis” of glomus tumor, though, she noted. Pathologic examination will show monomorphic cells with small caliber vascular channels.

Malignancy is actually uncommon with erythronychia, though it’s always in the differential diagnosis, she said.

In one case series examining subungual squamous cell carcinomas, common findings included onycholysis and localized hyperkeratosis, along with longitudinal erythronychia. “This may be subtle; splinter hemorrhages can also be present,” noted Dr. Lipner, adding, “If there are any symptoms, or an evolving band, a biopsy is indicated.”

“Even with erythronychia, the presentation can be quite variable,” she said. Nail unit melanoma can count erythronychia among the presenting signs. Clues that should raise suspicion for melanoma can include a wide band and prominent onycholysis, especially distal onycholysis and splintering. Again, she said, “biopsy with histopathology is the gold standard in making the diagnosis”; any symptoms or evidence of an evolving band should trigger a biopsy.

Dr. Lipner had no conflicts of interest relevant to her presentation.

SOURCE: Lipner S. Summer AAD 2019, Presentation F035.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SUMMER AAD 2019

Can sunscreens cause frontal fibrosing alopecia? The jury’s out

NEW YORK – Is there an association between sunscreen use and frontal fibrosing alopecia? Perhaps, but causation is far from well established, according to Henry Lim, MD.

“Frontal fibrosing alopecia is becoming more common – definitely,” said Dr. Lim, speaking in an exclusive interview at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. “Those of us who see patients would see, on average, probably a few patients a week with new-onset frontal fibrosing alopecia.”

Dr. Lim, program director of dermatology research and the photomedicine fellowship at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, said in a presentation at the meeting that, in the medical literature, just four surveys have been identified that examined the potential association of UV filters in sunscreen preparations with the risk for frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA).

The first survey-based study questioned 205 women – 105 of whom had FFA – about sunscreen use, finding increased risk for FFA when sunscreen use was reported at least twice a week (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Oct;175:762-7). The second study, by contrast, looked at men only, examining 17 patients with FFA and 73 control participants. This study found increased frequency of FFA in patients who reported use of sunscreen or sunscreen-containing moisturizers (Br J Dermatol. 2011 Jul;177:260-1).

The final two survey-based studies each also found increased FFA frequency in patients using sunscreens, said Dr. Lim. The first of these was the largest among the FFA studies, surveying 308 patients, 19 of whom were men, with FFA and 347 control participants (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019 Jun;44:404-10). The other study, involving women only, compared 130 patients with FFA and 130 control participants (Br J Dermatol. 2019 Apr;180:943-4).

Several factors need to be taken into consideration when evaluating the available data, said Dr. Lim. “With any type of retrospective study, there are some limitations, recall bias being one. No. 2, the studies were not designed to look at which sunscreens’ ingredient is causing the frontal fibrosing alopecia, so all we can say is that there is an association of sunscreen with frontal fibrosing alopecia without knowing which active ingredient is involved.”

Also, “there is no conclusion that we can draw in terms of causation,” he said. Data are insufficient for this kind of inference.

Titanium dioxide, a mineral filter used in some sunscreen preparations, has also been implicated in FFA. Elemental titanium has been detected in the hair shafts of some patients with alopecia, said Dr. Lim, noting a case report and another small study. In the smaller study, 20 patients were included. Of them, 16 were FFA-affected women, 4 were unaffected women, and 1 was an unaffected man. Here, however, titanium was found in the hair shaft of all participants save the one unaffected man (Br J Dermatol. 2019 Jul;181:216-7).

However, he warned, “the studies are still early. The numbers are still relatively small that have been examined.” Furthermore, the controls, meaning individuals who did not have FFA in the study, also had titanium element in their hair shaft. All of this means that it’s too early to draw firm conclusions about whether there’s a causal relationship between titanium-containing preparations and FFA.

In questioning after the session, an audience member pointed out that sunscreens are not the sole source of titanium among topical preparations; many cosmetics and hair products also use titanium.

Dr. Lim reported financial relationships with Eli Lilly, Estee Lauder, Ferndale Laboratories, Incyte Corporation, ISDIN, Pierre Fabre Dermatologie, and Unigen.

NEW YORK – Is there an association between sunscreen use and frontal fibrosing alopecia? Perhaps, but causation is far from well established, according to Henry Lim, MD.

“Frontal fibrosing alopecia is becoming more common – definitely,” said Dr. Lim, speaking in an exclusive interview at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. “Those of us who see patients would see, on average, probably a few patients a week with new-onset frontal fibrosing alopecia.”

Dr. Lim, program director of dermatology research and the photomedicine fellowship at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, said in a presentation at the meeting that, in the medical literature, just four surveys have been identified that examined the potential association of UV filters in sunscreen preparations with the risk for frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA).

The first survey-based study questioned 205 women – 105 of whom had FFA – about sunscreen use, finding increased risk for FFA when sunscreen use was reported at least twice a week (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Oct;175:762-7). The second study, by contrast, looked at men only, examining 17 patients with FFA and 73 control participants. This study found increased frequency of FFA in patients who reported use of sunscreen or sunscreen-containing moisturizers (Br J Dermatol. 2011 Jul;177:260-1).

The final two survey-based studies each also found increased FFA frequency in patients using sunscreens, said Dr. Lim. The first of these was the largest among the FFA studies, surveying 308 patients, 19 of whom were men, with FFA and 347 control participants (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019 Jun;44:404-10). The other study, involving women only, compared 130 patients with FFA and 130 control participants (Br J Dermatol. 2019 Apr;180:943-4).

Several factors need to be taken into consideration when evaluating the available data, said Dr. Lim. “With any type of retrospective study, there are some limitations, recall bias being one. No. 2, the studies were not designed to look at which sunscreens’ ingredient is causing the frontal fibrosing alopecia, so all we can say is that there is an association of sunscreen with frontal fibrosing alopecia without knowing which active ingredient is involved.”

Also, “there is no conclusion that we can draw in terms of causation,” he said. Data are insufficient for this kind of inference.

Titanium dioxide, a mineral filter used in some sunscreen preparations, has also been implicated in FFA. Elemental titanium has been detected in the hair shafts of some patients with alopecia, said Dr. Lim, noting a case report and another small study. In the smaller study, 20 patients were included. Of them, 16 were FFA-affected women, 4 were unaffected women, and 1 was an unaffected man. Here, however, titanium was found in the hair shaft of all participants save the one unaffected man (Br J Dermatol. 2019 Jul;181:216-7).

However, he warned, “the studies are still early. The numbers are still relatively small that have been examined.” Furthermore, the controls, meaning individuals who did not have FFA in the study, also had titanium element in their hair shaft. All of this means that it’s too early to draw firm conclusions about whether there’s a causal relationship between titanium-containing preparations and FFA.

In questioning after the session, an audience member pointed out that sunscreens are not the sole source of titanium among topical preparations; many cosmetics and hair products also use titanium.

Dr. Lim reported financial relationships with Eli Lilly, Estee Lauder, Ferndale Laboratories, Incyte Corporation, ISDIN, Pierre Fabre Dermatologie, and Unigen.

NEW YORK – Is there an association between sunscreen use and frontal fibrosing alopecia? Perhaps, but causation is far from well established, according to Henry Lim, MD.

“Frontal fibrosing alopecia is becoming more common – definitely,” said Dr. Lim, speaking in an exclusive interview at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. “Those of us who see patients would see, on average, probably a few patients a week with new-onset frontal fibrosing alopecia.”

Dr. Lim, program director of dermatology research and the photomedicine fellowship at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, said in a presentation at the meeting that, in the medical literature, just four surveys have been identified that examined the potential association of UV filters in sunscreen preparations with the risk for frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA).

The first survey-based study questioned 205 women – 105 of whom had FFA – about sunscreen use, finding increased risk for FFA when sunscreen use was reported at least twice a week (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Oct;175:762-7). The second study, by contrast, looked at men only, examining 17 patients with FFA and 73 control participants. This study found increased frequency of FFA in patients who reported use of sunscreen or sunscreen-containing moisturizers (Br J Dermatol. 2011 Jul;177:260-1).

The final two survey-based studies each also found increased FFA frequency in patients using sunscreens, said Dr. Lim. The first of these was the largest among the FFA studies, surveying 308 patients, 19 of whom were men, with FFA and 347 control participants (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019 Jun;44:404-10). The other study, involving women only, compared 130 patients with FFA and 130 control participants (Br J Dermatol. 2019 Apr;180:943-4).

Several factors need to be taken into consideration when evaluating the available data, said Dr. Lim. “With any type of retrospective study, there are some limitations, recall bias being one. No. 2, the studies were not designed to look at which sunscreens’ ingredient is causing the frontal fibrosing alopecia, so all we can say is that there is an association of sunscreen with frontal fibrosing alopecia without knowing which active ingredient is involved.”

Also, “there is no conclusion that we can draw in terms of causation,” he said. Data are insufficient for this kind of inference.

Titanium dioxide, a mineral filter used in some sunscreen preparations, has also been implicated in FFA. Elemental titanium has been detected in the hair shafts of some patients with alopecia, said Dr. Lim, noting a case report and another small study. In the smaller study, 20 patients were included. Of them, 16 were FFA-affected women, 4 were unaffected women, and 1 was an unaffected man. Here, however, titanium was found in the hair shaft of all participants save the one unaffected man (Br J Dermatol. 2019 Jul;181:216-7).

However, he warned, “the studies are still early. The numbers are still relatively small that have been examined.” Furthermore, the controls, meaning individuals who did not have FFA in the study, also had titanium element in their hair shaft. All of this means that it’s too early to draw firm conclusions about whether there’s a causal relationship between titanium-containing preparations and FFA.

In questioning after the session, an audience member pointed out that sunscreens are not the sole source of titanium among topical preparations; many cosmetics and hair products also use titanium.

Dr. Lim reported financial relationships with Eli Lilly, Estee Lauder, Ferndale Laboratories, Incyte Corporation, ISDIN, Pierre Fabre Dermatologie, and Unigen.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SUMMER AAD 2019

Alopecia areata: Study finds racial disparities

, according to a new study involving registry data for more than 11,000 individuals.

These new findings “raise a different perspective from the conventional view that AA does not differ by race/ethnicity,” said Hemin Lee, MD, MPH, of the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and associates.

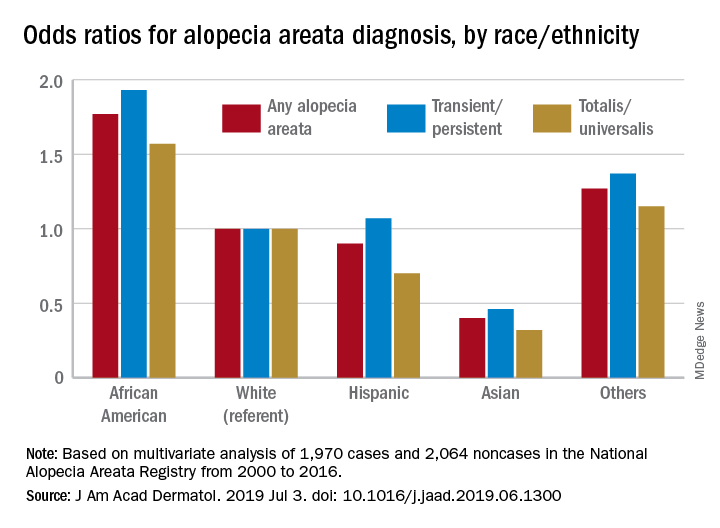

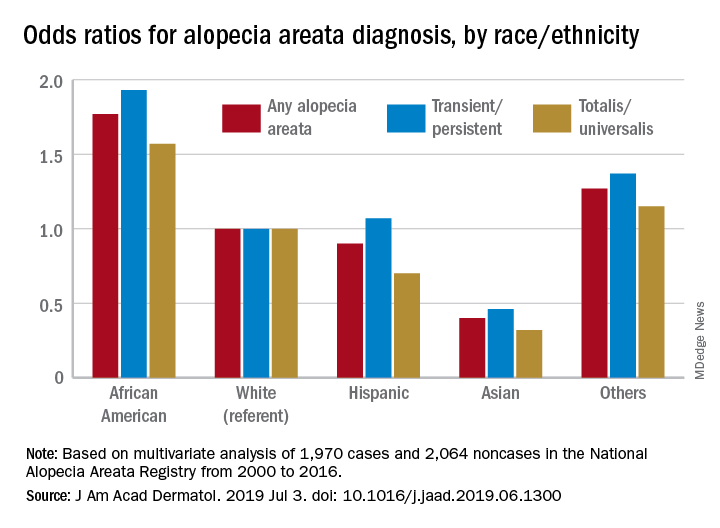

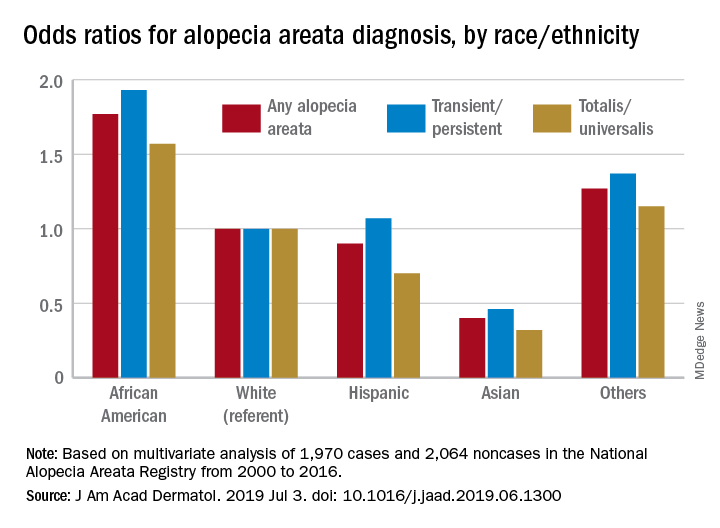

Multivariate-adjusted odds ratios for ever-diagnosis of AA were 1.77 for African Americans and 0.4 for Asians when whites were the referent group. Hispanics/Latinos were similar to whites, with an odds ratio of 0.9, and the group of other races/ethnicities (including American Indians and Pacific Islanders) was higher at 1.27, the investigators noted. The report is in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The odds played out in a similar fashion when broken down by AA subtype. With whites as the referent at 1.0, blacks were most likely to have been diagnosed with AA transient/persistent at 1.93 and Asians were lowest at 0.46. For AA totalis/universalis, odds ratios were 1.57 for blacks and 0.32 for Asians, they said, based on 2000-2016 data from the National Alopecia Areata Registry.

“An intricate interplay between genetic and environmental factors may account for the racial differences. Pathogenesis of AA is at times linked with autoimmunity by its strong association with HLA class II alleles,” Dr. Lee and associates wrote.

The study involved 11,404 participants from the registry: 9,340 had reported at least one episode of AA and 2,064 had no history of lifetime alopecia. The multivariate analysis was based on the same group of noncases but a subgroup of 1,970 AA patients who had been enrolled in the registry “through academic institutions after dermatologist-confirmed diagnosis,” they said.

There was no funding source to report. One of Dr. Lee’s associates has received honoraria from Abbvie, Amgen, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Amgen, which have been donated to charity, and is an investigator for Sanofi/Regeneron with no financial compensation. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lee H et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.1300.

, according to a new study involving registry data for more than 11,000 individuals.

These new findings “raise a different perspective from the conventional view that AA does not differ by race/ethnicity,” said Hemin Lee, MD, MPH, of the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and associates.

Multivariate-adjusted odds ratios for ever-diagnosis of AA were 1.77 for African Americans and 0.4 for Asians when whites were the referent group. Hispanics/Latinos were similar to whites, with an odds ratio of 0.9, and the group of other races/ethnicities (including American Indians and Pacific Islanders) was higher at 1.27, the investigators noted. The report is in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The odds played out in a similar fashion when broken down by AA subtype. With whites as the referent at 1.0, blacks were most likely to have been diagnosed with AA transient/persistent at 1.93 and Asians were lowest at 0.46. For AA totalis/universalis, odds ratios were 1.57 for blacks and 0.32 for Asians, they said, based on 2000-2016 data from the National Alopecia Areata Registry.

“An intricate interplay between genetic and environmental factors may account for the racial differences. Pathogenesis of AA is at times linked with autoimmunity by its strong association with HLA class II alleles,” Dr. Lee and associates wrote.

The study involved 11,404 participants from the registry: 9,340 had reported at least one episode of AA and 2,064 had no history of lifetime alopecia. The multivariate analysis was based on the same group of noncases but a subgroup of 1,970 AA patients who had been enrolled in the registry “through academic institutions after dermatologist-confirmed diagnosis,” they said.

There was no funding source to report. One of Dr. Lee’s associates has received honoraria from Abbvie, Amgen, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Amgen, which have been donated to charity, and is an investigator for Sanofi/Regeneron with no financial compensation. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lee H et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.1300.

, according to a new study involving registry data for more than 11,000 individuals.

These new findings “raise a different perspective from the conventional view that AA does not differ by race/ethnicity,” said Hemin Lee, MD, MPH, of the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and associates.

Multivariate-adjusted odds ratios for ever-diagnosis of AA were 1.77 for African Americans and 0.4 for Asians when whites were the referent group. Hispanics/Latinos were similar to whites, with an odds ratio of 0.9, and the group of other races/ethnicities (including American Indians and Pacific Islanders) was higher at 1.27, the investigators noted. The report is in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The odds played out in a similar fashion when broken down by AA subtype. With whites as the referent at 1.0, blacks were most likely to have been diagnosed with AA transient/persistent at 1.93 and Asians were lowest at 0.46. For AA totalis/universalis, odds ratios were 1.57 for blacks and 0.32 for Asians, they said, based on 2000-2016 data from the National Alopecia Areata Registry.

“An intricate interplay between genetic and environmental factors may account for the racial differences. Pathogenesis of AA is at times linked with autoimmunity by its strong association with HLA class II alleles,” Dr. Lee and associates wrote.

The study involved 11,404 participants from the registry: 9,340 had reported at least one episode of AA and 2,064 had no history of lifetime alopecia. The multivariate analysis was based on the same group of noncases but a subgroup of 1,970 AA patients who had been enrolled in the registry “through academic institutions after dermatologist-confirmed diagnosis,” they said.

There was no funding source to report. One of Dr. Lee’s associates has received honoraria from Abbvie, Amgen, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Amgen, which have been donated to charity, and is an investigator for Sanofi/Regeneron with no financial compensation. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lee H et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.1300.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Clinical Pearl: Benzethonium Chloride for Habit-Tic Nail Deformity

Practice Gap

Habit-tic nail deformity results from repetitive manipulation of the cuticle and/or proximal nail fold. It most commonly affects one or both thumbnails and presents with a characteristic longitudinal midline furrow with parallel transverse ridges in the nail plate. Complications may include permanent onychodystrophy, frictional melanonychia, and infections. Treatment is challenging, as diagnosis first requires patient insight to the cause of symptoms. Therapeutic options include nonpharmacologic techniques (eg, occlusion of the nails to prevent trauma, cyanoacrylate adhesives, cognitive behavioral therapy) and pharmacologic techniques (eg, N-acetyl cysteine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, antipsychotics), with limited supporting data and potential adverse effects.1

The Technique

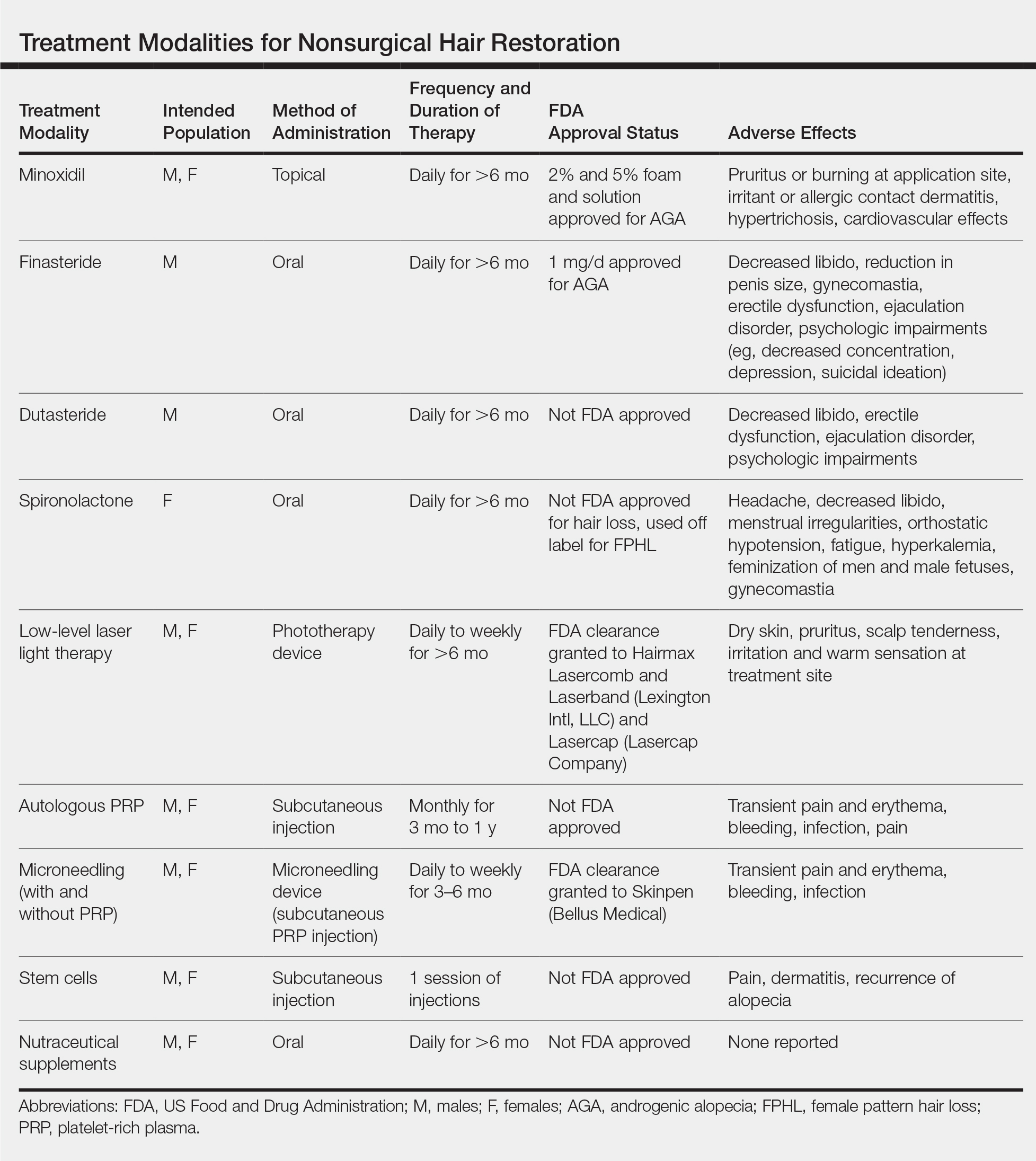

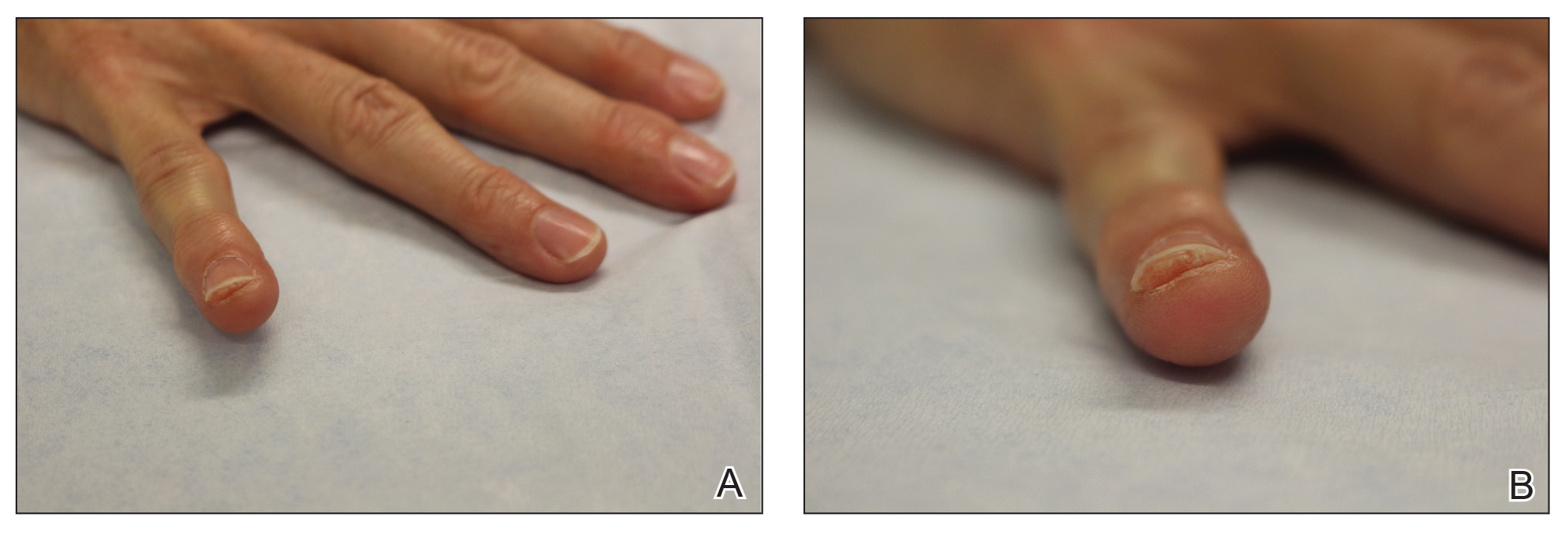

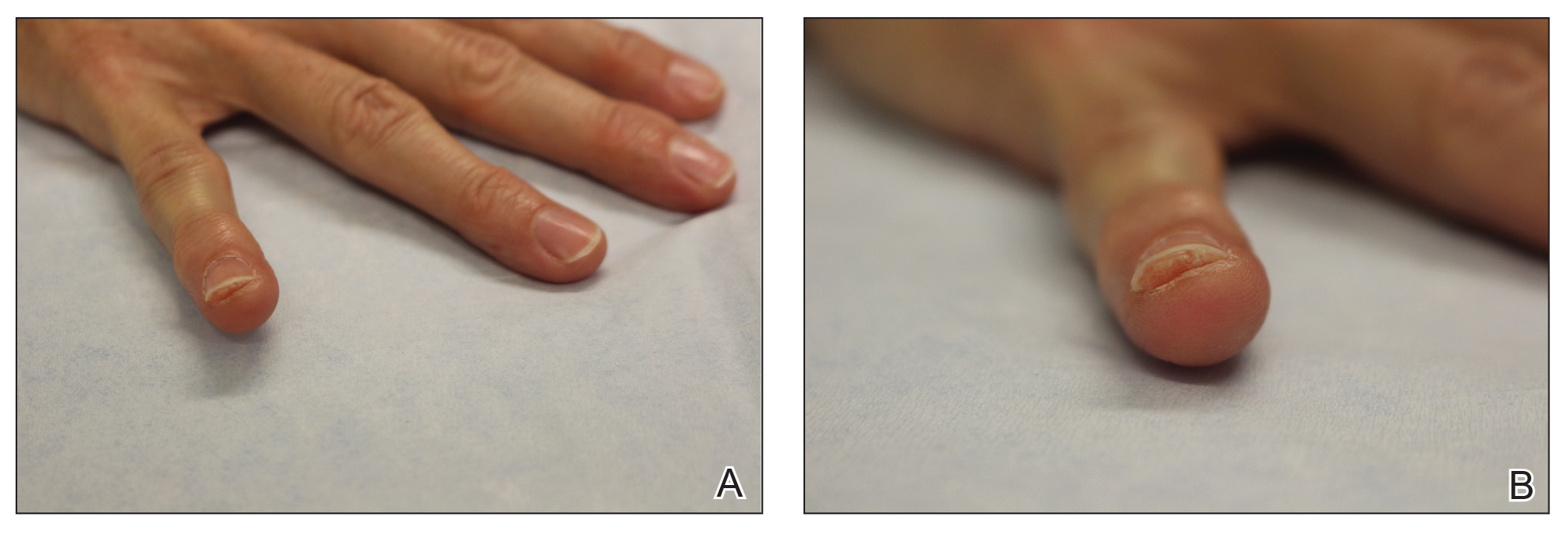

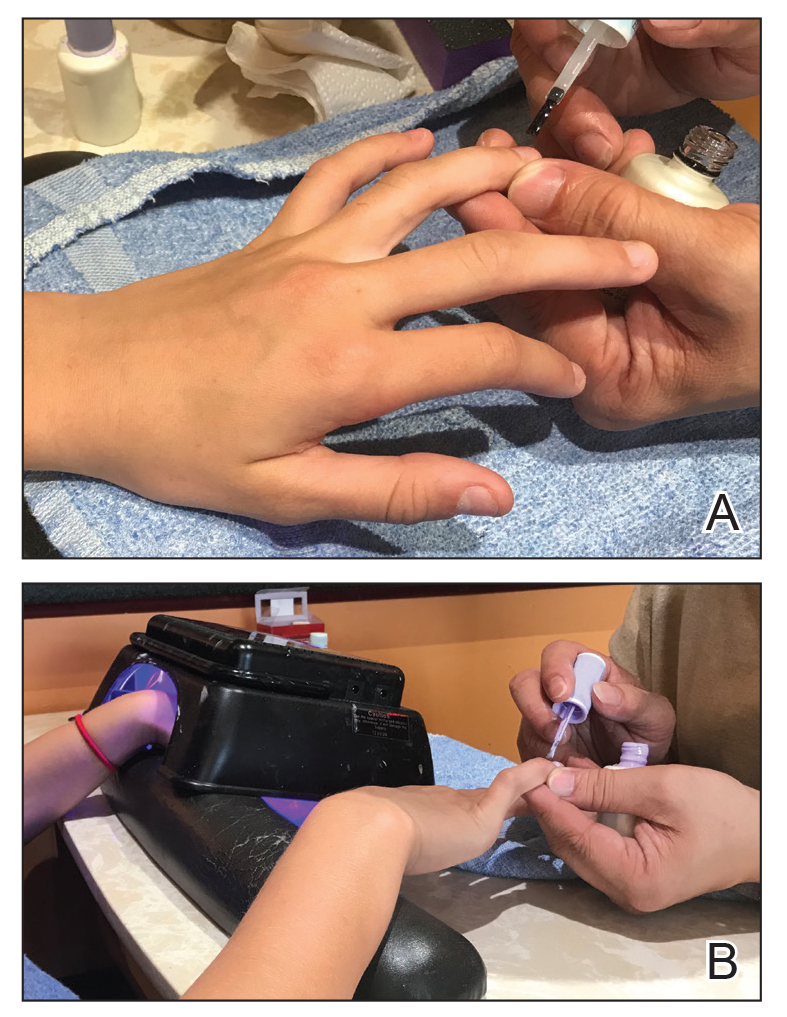

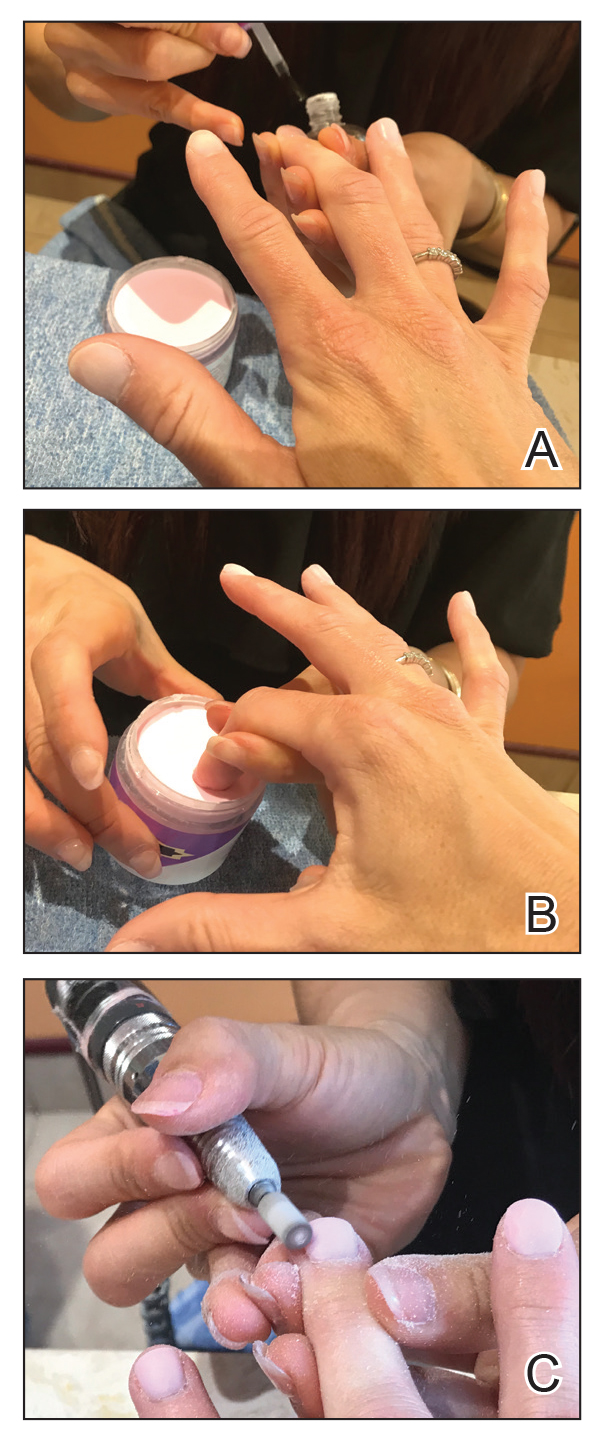

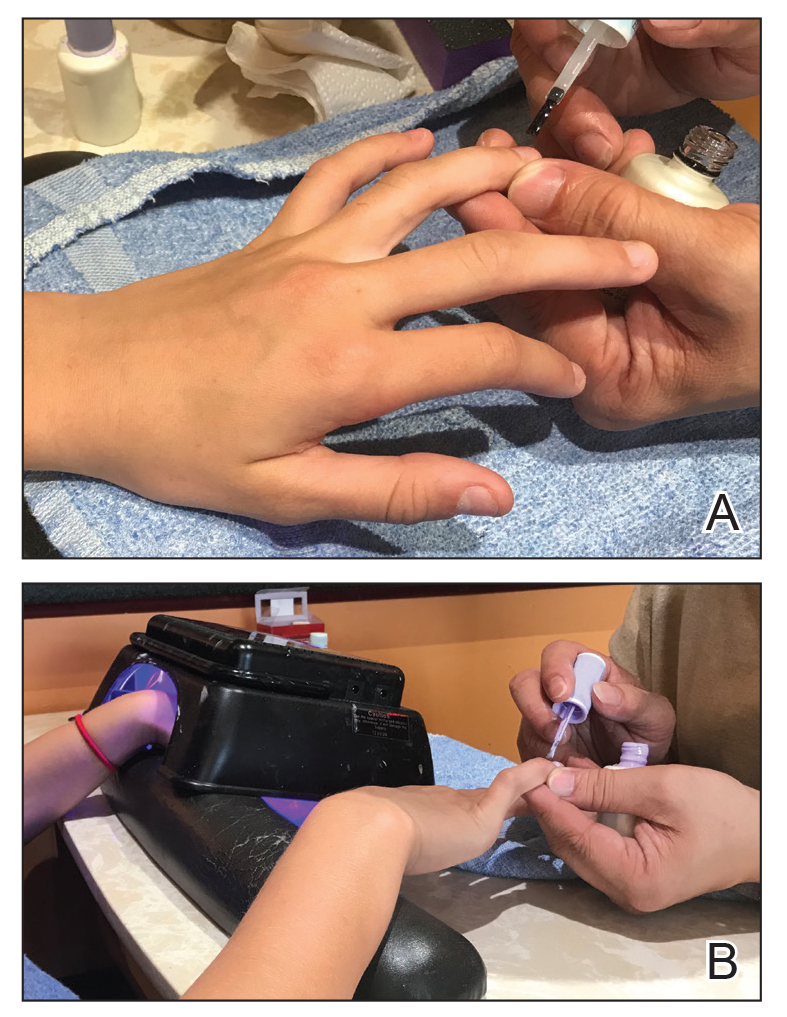

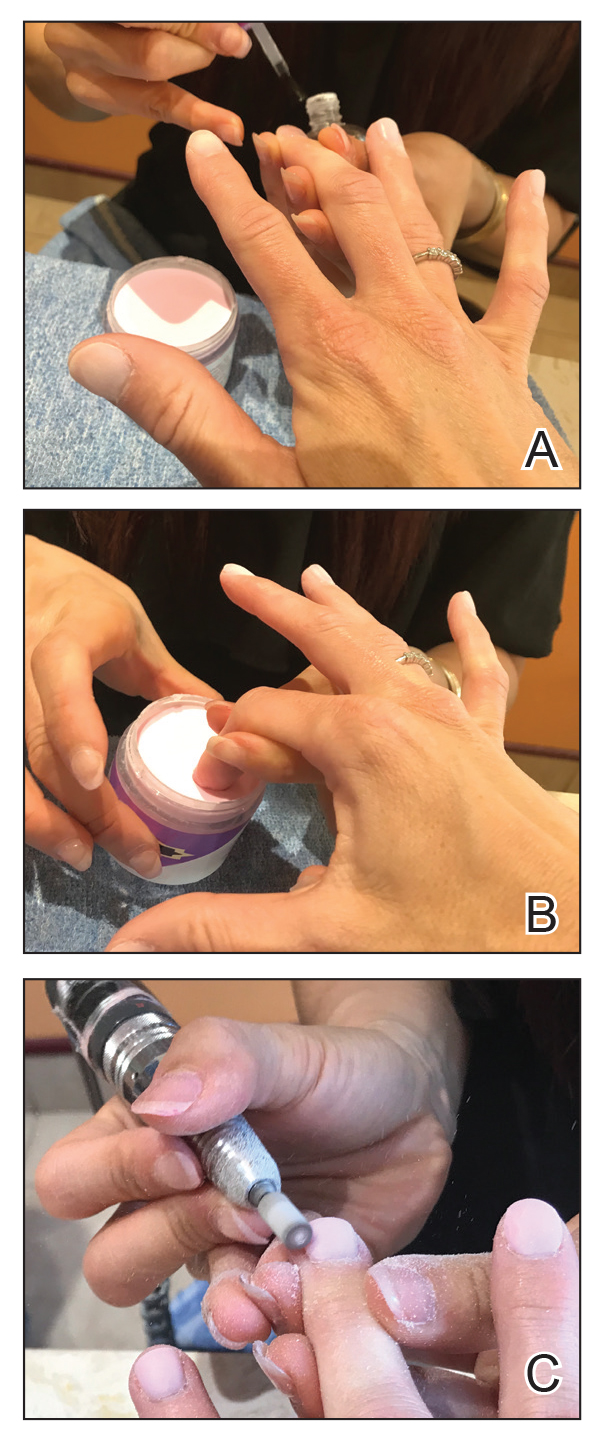

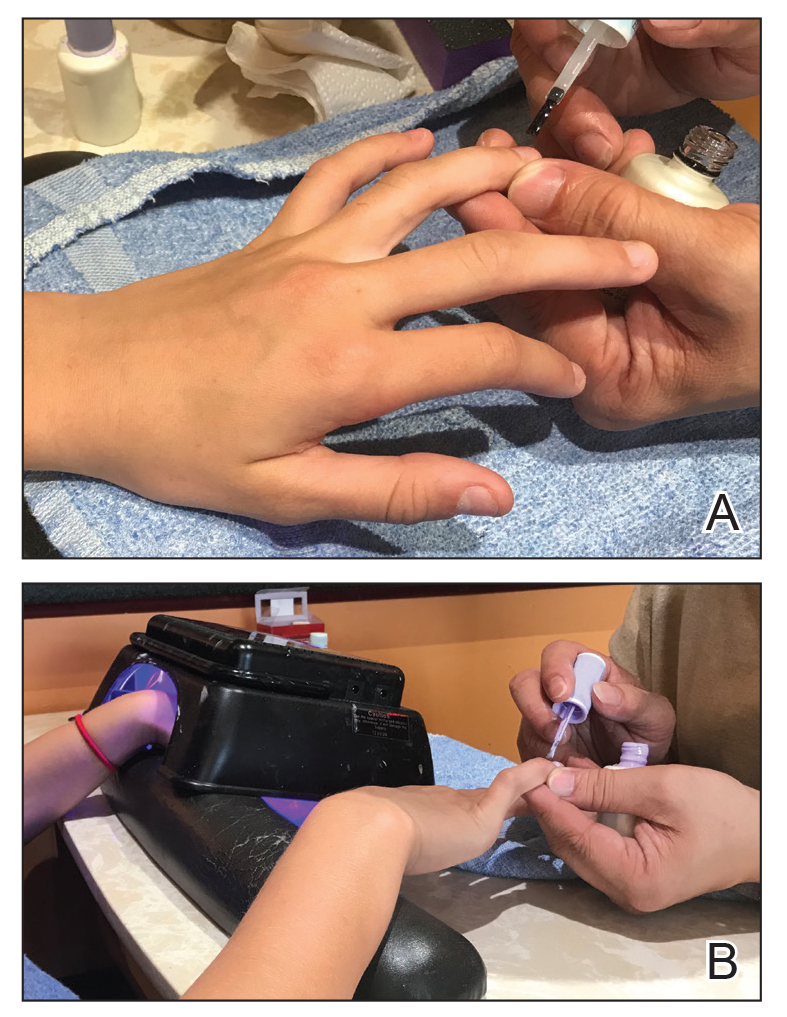

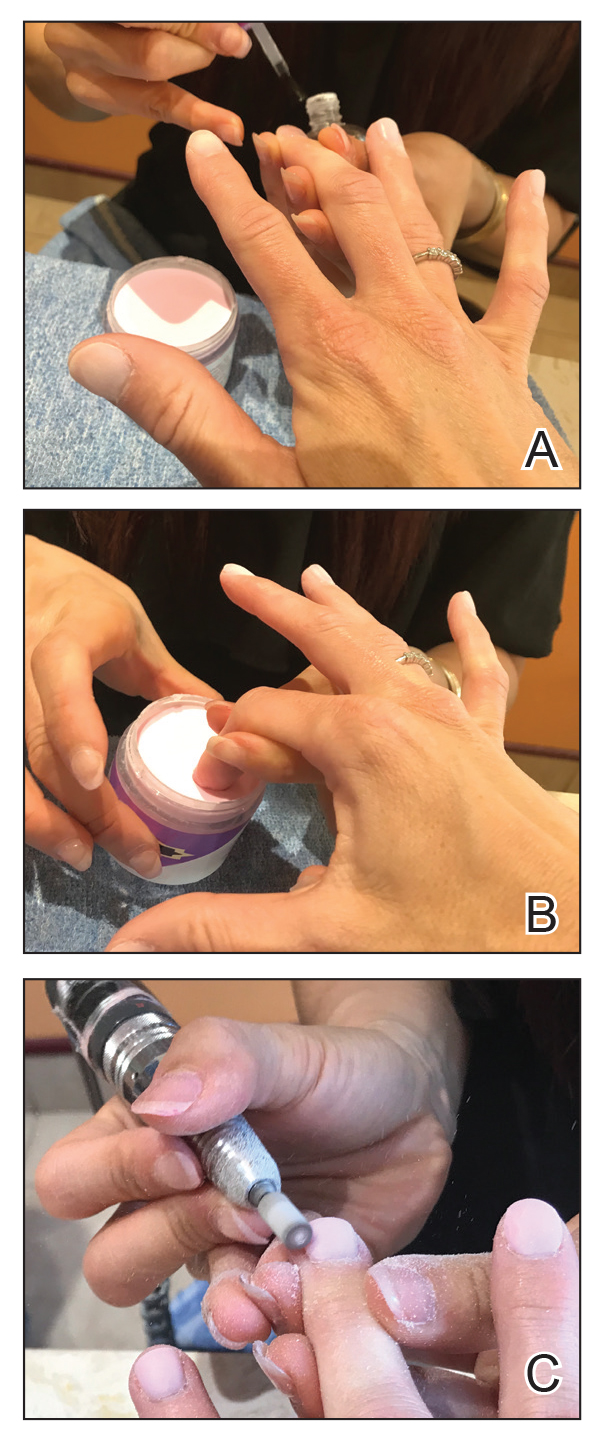

Benzethonium chloride solution 0.2% is an antiseptic that creates a polymeric layer that binds to the skin. It normally is used to treat small skin erosions and prevent blisters. In patients with habit-tic nail deformity, we recommend once-daily application of benzethonium chloride to the proximal nail fold, thereby artificially recreating the cuticle and forming a sustainable barrier from trauma (Figure, A). Patients should be reminded not to manipulate the cuticle and/or nail fold during treatment. In one 36-year-old man with habit tic nail deformity, we saw clear nail growth after 4 months of treatment (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Successful treatment of habit-tic nail deformity requires patients to have some insight into their behavior. The benzethonium chloride serves as a reminder for patients to stop picking as an unfamiliar artificial barrier and reminds them to substitute the picking behavior for another more positive behavior. Therefore, benzethonium chloride may be offered to patients as a novel therapy to both protect the cuticle and alter behavior in patients with habit-tic nail deformity, as it can be difficult to treat with few available therapies.

Allergic contact dermatitis to benzethonium chloride is a potential side effect and patients should be cautioned prior to treatment; however, it is extremely rare with 6 cases reported to date based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms allergic contact dermatitis and benzethonium chloride,2 and much rarer than contact allergy to cyanoacrylates.

- Halteh P, Scher RK, Lipner SR. Onychotillomania: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:763-770.

- Hirata Y, Yanagi T, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Ulcerative contact dermatitis caused by benzethonium chloride. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:188-190.

Practice Gap

Habit-tic nail deformity results from repetitive manipulation of the cuticle and/or proximal nail fold. It most commonly affects one or both thumbnails and presents with a characteristic longitudinal midline furrow with parallel transverse ridges in the nail plate. Complications may include permanent onychodystrophy, frictional melanonychia, and infections. Treatment is challenging, as diagnosis first requires patient insight to the cause of symptoms. Therapeutic options include nonpharmacologic techniques (eg, occlusion of the nails to prevent trauma, cyanoacrylate adhesives, cognitive behavioral therapy) and pharmacologic techniques (eg, N-acetyl cysteine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, antipsychotics), with limited supporting data and potential adverse effects.1

The Technique

Benzethonium chloride solution 0.2% is an antiseptic that creates a polymeric layer that binds to the skin. It normally is used to treat small skin erosions and prevent blisters. In patients with habit-tic nail deformity, we recommend once-daily application of benzethonium chloride to the proximal nail fold, thereby artificially recreating the cuticle and forming a sustainable barrier from trauma (Figure, A). Patients should be reminded not to manipulate the cuticle and/or nail fold during treatment. In one 36-year-old man with habit tic nail deformity, we saw clear nail growth after 4 months of treatment (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Successful treatment of habit-tic nail deformity requires patients to have some insight into their behavior. The benzethonium chloride serves as a reminder for patients to stop picking as an unfamiliar artificial barrier and reminds them to substitute the picking behavior for another more positive behavior. Therefore, benzethonium chloride may be offered to patients as a novel therapy to both protect the cuticle and alter behavior in patients with habit-tic nail deformity, as it can be difficult to treat with few available therapies.

Allergic contact dermatitis to benzethonium chloride is a potential side effect and patients should be cautioned prior to treatment; however, it is extremely rare with 6 cases reported to date based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms allergic contact dermatitis and benzethonium chloride,2 and much rarer than contact allergy to cyanoacrylates.

Practice Gap

Habit-tic nail deformity results from repetitive manipulation of the cuticle and/or proximal nail fold. It most commonly affects one or both thumbnails and presents with a characteristic longitudinal midline furrow with parallel transverse ridges in the nail plate. Complications may include permanent onychodystrophy, frictional melanonychia, and infections. Treatment is challenging, as diagnosis first requires patient insight to the cause of symptoms. Therapeutic options include nonpharmacologic techniques (eg, occlusion of the nails to prevent trauma, cyanoacrylate adhesives, cognitive behavioral therapy) and pharmacologic techniques (eg, N-acetyl cysteine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, antipsychotics), with limited supporting data and potential adverse effects.1

The Technique

Benzethonium chloride solution 0.2% is an antiseptic that creates a polymeric layer that binds to the skin. It normally is used to treat small skin erosions and prevent blisters. In patients with habit-tic nail deformity, we recommend once-daily application of benzethonium chloride to the proximal nail fold, thereby artificially recreating the cuticle and forming a sustainable barrier from trauma (Figure, A). Patients should be reminded not to manipulate the cuticle and/or nail fold during treatment. In one 36-year-old man with habit tic nail deformity, we saw clear nail growth after 4 months of treatment (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Successful treatment of habit-tic nail deformity requires patients to have some insight into their behavior. The benzethonium chloride serves as a reminder for patients to stop picking as an unfamiliar artificial barrier and reminds them to substitute the picking behavior for another more positive behavior. Therefore, benzethonium chloride may be offered to patients as a novel therapy to both protect the cuticle and alter behavior in patients with habit-tic nail deformity, as it can be difficult to treat with few available therapies.

Allergic contact dermatitis to benzethonium chloride is a potential side effect and patients should be cautioned prior to treatment; however, it is extremely rare with 6 cases reported to date based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms allergic contact dermatitis and benzethonium chloride,2 and much rarer than contact allergy to cyanoacrylates.

- Halteh P, Scher RK, Lipner SR. Onychotillomania: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:763-770.

- Hirata Y, Yanagi T, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Ulcerative contact dermatitis caused by benzethonium chloride. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:188-190.

- Halteh P, Scher RK, Lipner SR. Onychotillomania: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:763-770.

- Hirata Y, Yanagi T, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Ulcerative contact dermatitis caused by benzethonium chloride. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:188-190.

Nonsurgical Hair Restoration Treatment

Hair plays an important role in identity, self-perception, and psychosocial functioning. Hair loss can be a devastating experience that decreases self-esteem and feelings of personal attractiveness while also leading to depression and anxiety.1,2 Although increasingly popular, surgical hair restoration, including hair transplantation, is costly and carries considerable risk.

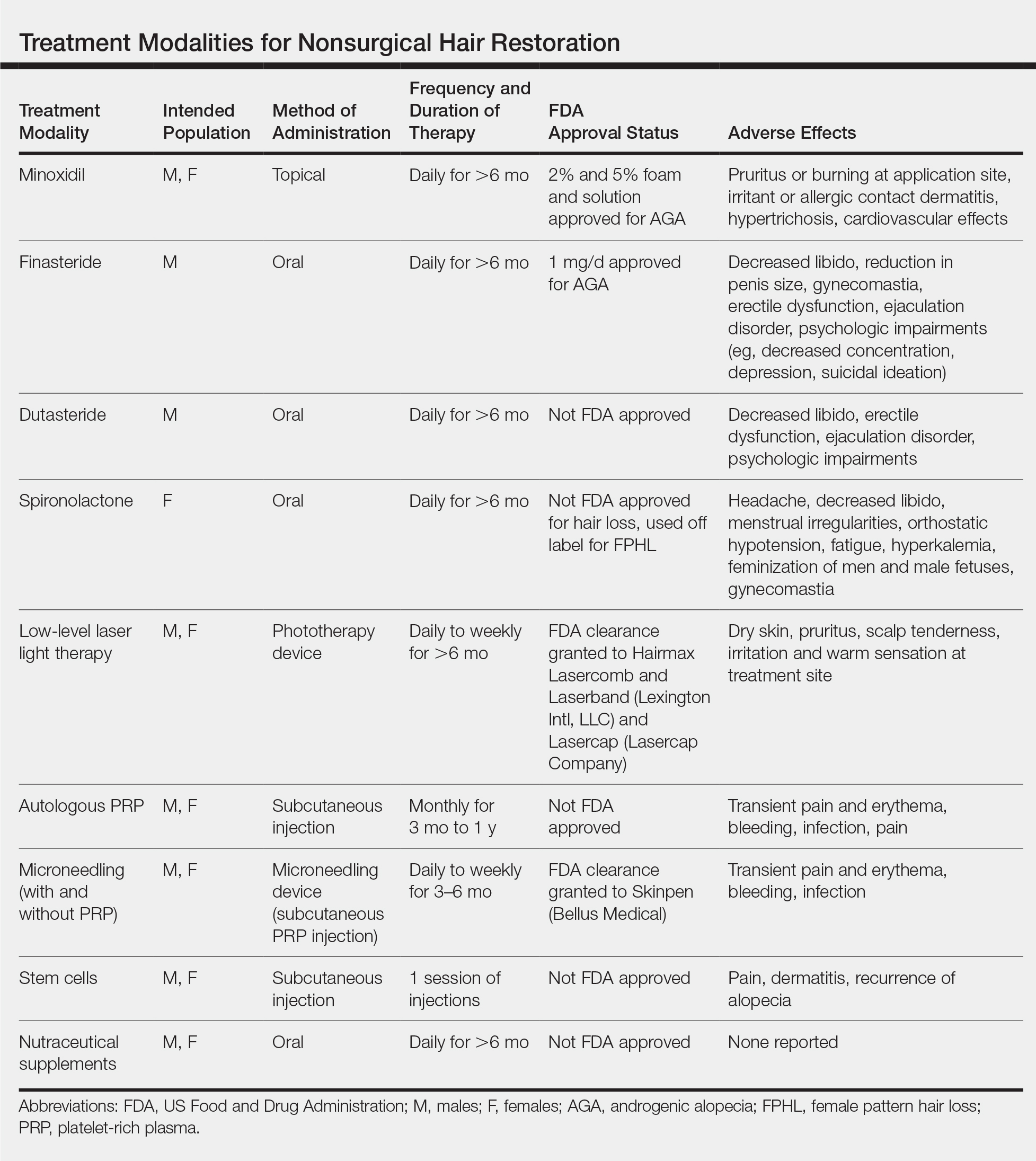

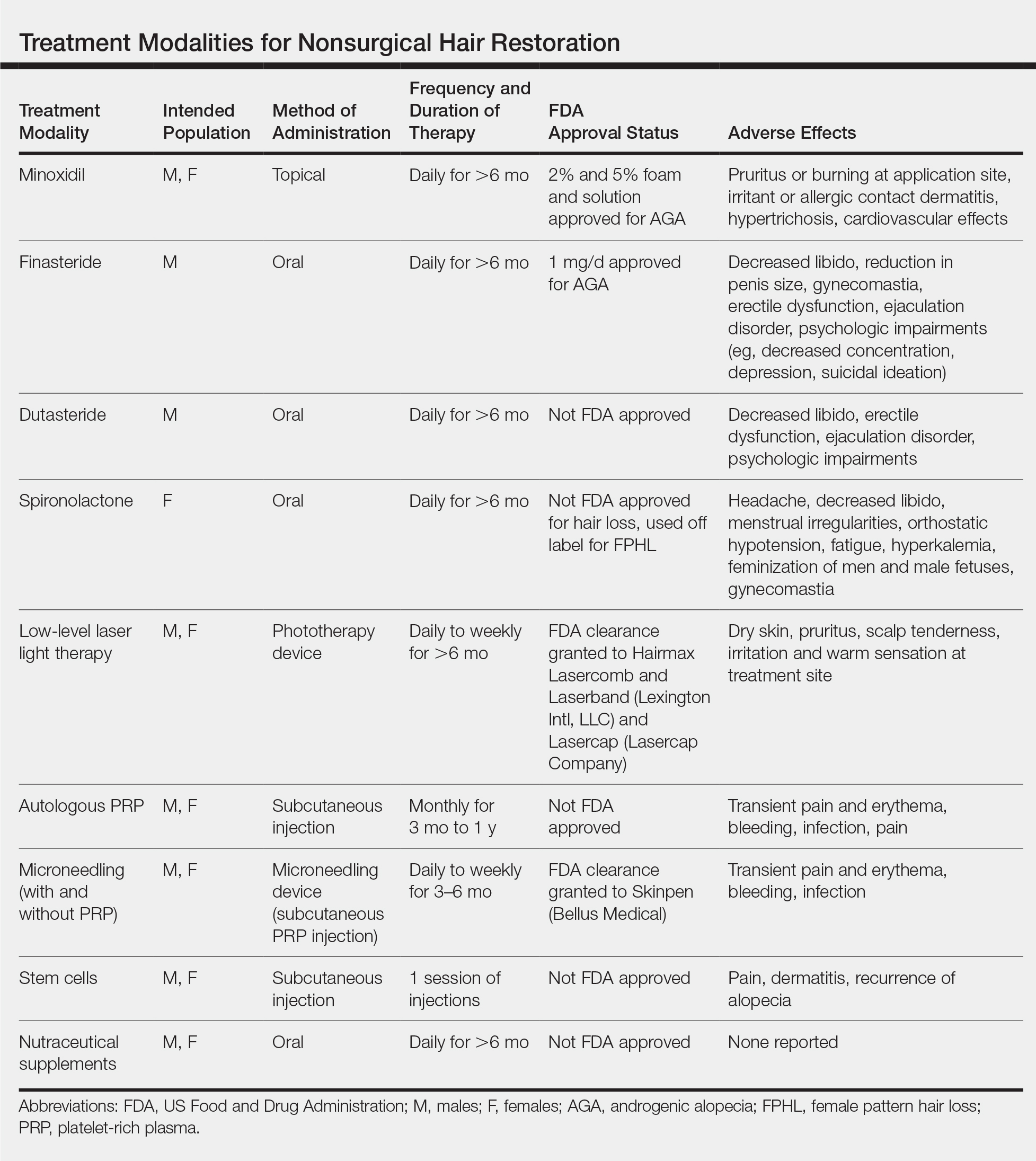

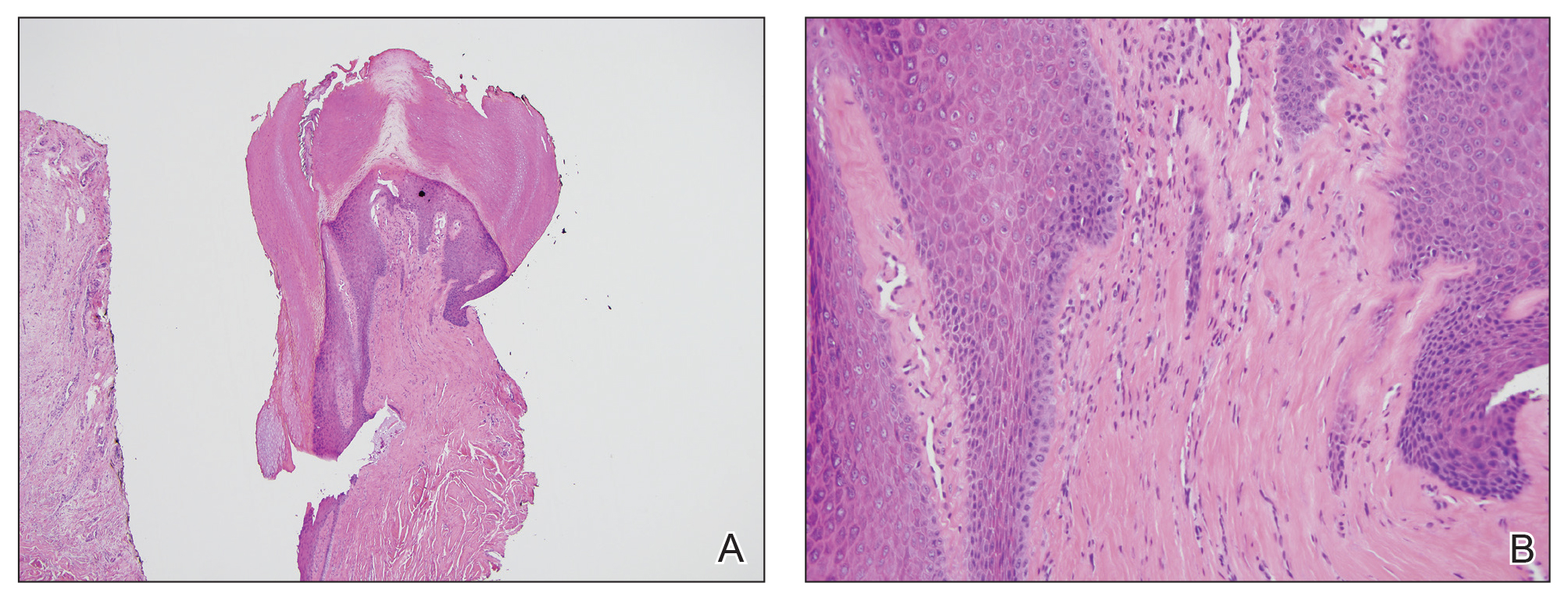

Results of nonsurgical hair restoration are not immediate and may not be as dramatic; however, they do not carry the risks or recovery associated with surgical options. Treatments such as sex steroid hormone and biologic response modifiers have been used to inhibit hair miniaturization and stabilize hair loss in cases of androgenic alopecia (AGA).3 Currently, minoxidil and finasteride are the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved medications for the treatment of hair loss; however, other nonsurgical treatment options have gained popularity, including dutasteride, spironolactone, low-level laser therapy (LLLT), platelet-rich plasma (PRP), microneedling, stem cells, and nutraceutical supplements. We provide an overview of these treatment options to help dermatologists select appropriate therapies for the treatment of alopecia (Table).

Minoxidil

Minoxidil has been known to improve hair growth for more than 40 years. Oral minoxidil was first introduced for hypertension in the 1970s with a common adverse effect of hypertrichosis; the 2% solution was marketed for AGA shortly thereafter in 1986.4 Minoxidil is a biologic response modifier that is thought to promote hair growth through vasodilation and stimulation of hair follicles into the growth phase.5 In animal studies, topical minoxidil has been shown to shorten telogen, prolong anagen, and increase hair follicle size.6,7 More recently, topical minoxidil was shown to have anti-inflammatory effects by downregulating IL-1, which may confer an additional role in combatting alopecia.8

Minoxidil is FDA approved for treatment of AGA in men and women and often is used as first-line therapy.9 In 3 separate meta-analyses of topical minoxidil, it was shown to be more effective than placebo for treating AGA in men and women, with a notable increase in target area hair growth.10 A study of 777 male patients treated with topical minoxidil 2% found that 45% subjectively experienced new hair growth.11 However, results may vary, and research indicates that higher concentrations are more effective. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 381 women with female pattern hair loss (FPHL), minoxidil solution 2% was found to be superior to placebo after 48 weeks, with average changes in nonvellus hair counts of 20.7/cm2 in the minoxidil group vs 9.4/cm2 in the placebo group.12 In a separate meta-analysis, minoxidil solution 5% demonstrated superiority to both the 2% formulation and placebo with a mean change in nonvellus hair counts of 26.0/cm2.13

Minoxidil also has demonstrated promising benefits in preventing chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Although oncologists most often use the scalp cooling method to prevent hair loss by decreasing perfusion and uptake of cytotoxic agents, cost may be prohibitive, as it is often not reimbursable by insurance companies.14,15 On the other hand, minoxidil is easily procured over-the-counter and has been successfully used to decrease the duration of alopecia caused by chemotherapeutic agents such as fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide, as well as endocrine therapies used to treat breast cancer in women.16-18 Minoxidil also has been used off label to treat other forms of alopecia, including alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, eyebrow hypotrichosis, and monilethrix; however, there is inconclusive evidence for its efficacy.5,13,19

Compared to other nonsurgical treatments for hair loss, a meta-analysis found that minoxidil was associated with the highest rate of adverse effects (AEs).16,17 Potential side effects include pruritus or burning at the application site; irritant or allergic contact dermatitis; hypertrichosis; and cardiovascular effects, which may be due to the vasodilatory mechanism of action of minoxidil.20 One randomized double-blind study found that while topical minoxidil did not affect blood pressure, it increased heart rate by 3 to 5 beats per minute, caused considerable increases in left ventricular end-diastolic volume, an increase in cardiac output (by 0.751 min-1), and an increase in left ventricular mass (by 5 g m-2). The authors concluded that short-term use is safe in healthy individuals, but providers should ask about history of coronary artery disease to avoid potential cardiac side effects.21

Patients also should be advised that at least 6 months of minoxidil therapy may be necessary.11 Furthermore, measurable hair changes may disappear within 3 months if the patient chooses to discontinue treatment.22 Finally, providers must consider patient perception of improvement and hair growth while on this medication. In one study, although investigator assessments of hair growth and hair count were increased with the use of minoxidil solution 5% compared to placebo, differences in patient assessment of hair growth were not significant at 48 weeks.22 Therefore, dermatologists should address patient expectations and consider additional treatments if necessary.

Finasteride

Finasteride is an oral medication that is FDA approved at a dose of 1 mg daily for the treatment of AGA in men. It competitively inhibits the type I and type II 5α-reductase enzymes, with a strong affinity for the type II enzyme, thereby inhibiting the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the potent androgen responsible for terminal hair follicle miniaturization and transformation of terminal hair into vellus hair.21,23

Finasteride has demonstrated efficacy and high tolerability in large-scale, placebo-controlled, randomized trials with only rare complications of sexual dysfunction, supporting its status as a first-line agent.24,25 One study found that in a population of 3177 Japanese men, an overall increase in hair growth was seen in 87.1% of men receiving oral finasteride 1 mg daily, with AEs such as decreased libido occurring in only 0.7% of patients.26 However, postmarketing studies described more severe complications in men taking finasteride to treat AGA or benign prostatic hyperplasia, even after the discontinuation of medication, described as postfinasteride syndrome.27,28 These side effects include decreased libido, reduction in penis size, gynecomastia, erectile dysfunction, and ejaculation disorder, in addition to psychologic impairments, including decreased concentration, depression, and suicidal ideation, presumably due to the role of 5α-reductase interacting with the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAA) receptor within the central nervous system.29 The incidence of persistent erectile dysfunction was reported to be as low as 1.4% in a study assessing 11,909 men prescribed up to 5 mg once daily of finasteride to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia and AGA. The incidence was higher in patients using higher doses of finasteride and longer treatment courses as well as in patients with prostate disease.29 These potential side effects should be discussed with male patients prior to prescribing finasteride.

Finasteride is not FDA approved for use in women and is considered category X in pregnancy due to animal studies that demonstrated external genital abnormalities in male fetuses exposed to type II 5α-reductase inhibitors.30 Despite this potential teratogenicity, finasteride is prescribed off label to treat FPHL and hirsutism. A meta-analysis of 2683 women participating in 65 studies found that finasteride, when used at dosages of 0.5 to 5 mg daily, may improve FPHL and frontal fibrosing alopecia after 6 to 12 months.30 However, available studies have used varying treatment methods, yielding differing results. For example, one randomized trial of 137 postmenopausal women with FPHL and normal androgen levels found no benefit with 1 mg daily31; however, another trial of 87 women with normal levels of androgens found that 5 mg daily of finasteride showed significant improvements in hair quantity and thickness after 12 months (P<.01).32 Further studies are needed to assess the appropriate female population that may benefit from use of finasteride. Premenopausal women interested in this therapy should be counseled about the risk of teratogenicity, as well as potential breast tenderness, loss of libido, and menstrual irregularities.33 Furthermore, finasteride use in women may pose a theoretical risk of breast cancer, as DHT inhibition results in conversion of excess testosterone to estrogen, thereby altering the estrogen to androgen ratio.34

Dutasteride

Dutasteride is 100-times more potent than finasteride as an inhibitor of type I 5α-reductase enzyme and 3-times more potent as an inhibitor of type I 5α-reductase enzyme.35 Therefore, it has been hypothesized that dutasteride may be more effective than finasteride for restoring hair loss, though it is not yet FDA approved for this indication.

Research evaluating the efficacy of dutasteride is emerging. Randomized controlled trials in men with AGA are promising and suggest reversed hair miniaturization.36 One randomized trial of 153 men found that dutasteride 0.5 mg daily was superior to placebo for the treatment of hair loss, as evidenced by an increase in hair counts in dutasteride patients (12.2/cm2) compared to controls (4.7/cm2). Furthermore, 0.5-mg dutasteride resulted in significantly increased new hair growth after 24 weeks compared to a placebo control (23/cm2 vs 4/cm2; P<.05).37

Dutasteride also is now being used off label to treat FPHL. Little evidence-based research exists regarding the use of dutasteride in women, though 1 case report described successful treatment of FPHL after 6 months of treatment with 0.5 mg daily of dutasteride in a 46-year-old woman who showed only minimal improvement on oral finasteride.38

The side-effect profile is similar to finasteride, and research in the urologic literature demonstrated that the rate of AEs is comparable between the 2 drugs, with reports of sexual side effects occurring in 11% of patients taking dutasteride 0.5 mg daily vs 14% of patients taking finasteride 5 mg daily.39 In the dermatologic literature, there was no statistically significant difference between the rate of AEs, specifically sexual AEs, in patients taking dutasteride 0.5 mg daily vs finasteride 1 mg daily.36 Safety of dutasteride in women is not well established. The side-effect profile described for finasteride, including the risk of potential fetal anomalies, should be discussed with women receiving dutasteride therapy.

Spironolactone

Although topical minoxidil is still considered first-line therapy for women experiencing hair loss, spironolactone is growing in popularity as an off-label treatment of FPHL, though it is not FDA approved for this indication. Spironolactone is a synthetic steroid that has been used as a potassium-sparing diuretic for more than 60 years. Its primary metabolite, canrenone, competitively inhibits aldosterone.37 It is FDA approved for the treatment of essential hypertension (25–100 mg), congestive heart failure (25 mg), diuretic-induced hypokalemia (25–100 mg), and primary hyperaldosteronism (100–400 mg).37,40 Spironolactone was serendipitously discovered to treat hirsutism, acne, and seborrhea associated with polycystic ovary syndrome.41

Androgens are well studied in male pattern hair loss, and their role in FPHL is now becoming evident, with new research supporting the role of spironolactone as a useful antiandrogen.42,43 An Australian open-label trial randomized 80 women with biopsy-proven FPHL to receive either spironolactone 200 mg daily or cyproterone acetate, an antiandrogen used abroad, including in European countries, in conjunction with an oral contraceptive pill for premenopausal women.42 Spironolactone was found to be as effective as the alternate regimen, with 44% of patients experiencing hair regrowth, 44% experiencing no progression of hair loss, and only 12% experiencing continued hair loss.44 Spironolactone used in combination with minoxidil has been shown to demonstrate greater efficacy when compared to spironolactone alone.45 One observational study of 100 women with FPHL found that once-daily capsules of minoxidil 0.25 mg combined with once daily spironolactone 25 mg was a safe and effective treatment of FPHL.44 Spironolactone also is considered safe and effective to treat FPHL in postmenopausal women by inhibiting the relative androgen excess.46

The starting dose for spironolactone usually is 25 mg twice daily and increased by 50 mg daily up to 200 mg daily as tolerated. Furthermore, results should be monitored for at least 6 months to assess efficacy accurately.47 Side effects include headache, decreased libido, menstrual irregularities, orthostatic hypotension, fatigue, and hyperkalemia. Although hyperkalemia is a known side effect of spironolactone, one study of 974 male and female participants receiving spironolactone found that only 0.72% of participants experienced mild hyperkalemia (5.1–6.0 mEq/L) with no patients experiencing moderate or severe hyperkalemia. Regardless, providers may consider checking potassium levels within 4 to 8 weeks of initiating treatment with spironolactone.48 Other potential AEs include gynecomastia and feminization; therefore, it is not recommended for use in men.42 Oral contraception is recommended to prevent pregnancy in premenopausal women, as spironolactone may cause feminization of the male fetus. Because of the antiandrogenic and progestogenic effects of spironolactone, there has been a theoretical concern for risk of inducing breast cancer, especially in postmenopausal women. However, a study conducted in the United Kingdom of more than 1 million female patients older than 55 years found that there was no increased risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.49

Low-Level Laser Light Therapy

Low-level laser light therapy has been used to reduce pain, treat edema, and promote would healing for almost 50 years and is now one of the few FDA-cleared devices to treat alopecia. Low-level laser light therapy uses red beam or near-infrared nonthermal lasers at a wavelength of 600 to 1000 nm and from 5 to 500 mW. The exact mechanism of hair growth stimulation is not known; however, it is believed that LLLT accelerates mitosis, stimulates hair follicle stem cells to activate follicular keratinocytes, and alters cellular metabolism by inhibiting nitric oxide from cytochrome c oxidase.50

Trials evaluating the efficacy of LLLT laser combs for the treatment of AGA have demonstrated notable improvements in hair density. For example, one sham device–controlled, double-blind clinical trial randomized 334 men and women to treatment with either an FDA-cleared laser comb vs sham devices.51 The treatment devices were used 3 times weekly for 26 weeks. Hair counts for those treated with the 7-, 9-, and 12-beam LLLT laser combs were significantly higher than the sham after 26 weeks (P<.05), without any serious AEs being reported.51 Another study in men with AGA proved similarly efficacious results using at-home LLLT therapy of 655 nm to the scalp every other day for 16 weeks (60 treatments).52 However, a 24-week randomized, double-blind, sham device–controlled, multicenter trial evaluating the LLLT helmet (combining 650-nm laser with 630- and 660-nm light-emitting diodes) among male and female patients with AGA failed to show promising results. Although mean (SD) hair thickness (12.6 [9.4] in LLLT group vs 3.9 [7.3] in control group [P=.01]) and hair density (17.2 [12.1] in LLLT group vs –2.1 [18.3] in control group [P=.003]) increased significantly, there was no significant difference in subject assessment of global appearance between the 2 groups.53

Low-level laser light therapy devices are available both for use at home and in office, with 650- to 900-nm wavelengths at 5 mW being the recommended dose for men and women.51 With regard to AEs, the safety profile for LLLT is relatively favorable. Adverse events can include dry skin, pruritus, scalp tenderness, irritation, and a warm sensation at the treatment site.52

Platelet-Rich Plasma

Originally used in the orthopedic literature to stimulate collagen growth, PRP has since been used in dermatology to promote hair regrowth by releasing platelet-derived growth factors, vascular endothelial growth factor, epidermal growth factor, insulinlike growth factor, and fibroblast growth factors to stimulate vascularization to the dermal papillary cells.54,55 Platelet-rich plasma is derived from the supernatant of centrifuged whole blood and then injected in the dermis of the scalp to stimulate hair growth.

Although use of PRP is not approved or cleared by the FDA for treatment of hair loss, several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of autologous PRP use for treating AGA.56 One pilot study of 19 male and female participants given a total of 5 PRP injections monthly for 3 months and subsequently at months 4 and 7 found a statistically significant improvement in mean hair density, hair diameter, and terminal-vellus hair ratio at 1-year follow-up (P<.05). Furthermore, histomorphometric evaluation demonstrated a decrease in perivascular inflammatory infiltrate.57 On the other hand, 2 separate studies failed to show statistically significant improvements in hair growth after use of PRP.58,59 Varying levels of success may be due in part to lack of a standard protocol for performing PRP injections. Studies comparing efficacy of different PRP administration regimens are emerging. A trial of 40 men and women found that subdermal PRP injections administered 3 times per month with booster injections administered 3 months later was more effective than other injection regimens, including once monthly injections.58,59 Activators such as collagen, thrombin, 10% calcium chloride, and calcium gluconate may be added to the PRP serum to promote further growth factor secretion upon platelet activation.60 However, different means of activation are used in different trials, potentially leading to varying results in clinical trials, with no one proven superior method.61-63 The main drawback of PRP use is that there is no consensus regarding exact concentration, utility of activators, dosing parameters, depth of injection, or frequency of sessions.60 Transient pain and erythema are the most common side effects of PRP injections, with no major AEs reported in the literature.64

Microneedling

Microneedling is a minimally invasive procedure that uses needles to puncture the stratum corneum of the skin.65 It was first used cosmetically more than 20 years ago due to its ability to increase collagen and elastin formation.51 Since its discovery, microneedling has been used to reduce the appearance of scars; augment transdermal drug delivery; and treat active acne vulgaris, melasma, hyperhidrosis, and alopecia.65 Although there are numerous at-home and professional microneedling devices on the market, only one device has been FDA cleared thus far.

Microneedling is proposed to increase hair regrowth by triggering the wound healing response, which ultimately augments the release of platelet-derived and epidermal growth factors while also activating the hair bulge.66 Treatment often is performed with a roller instrument that uses needles 0.5- to 2.5-mm long. Topical anesthetic cream may be applied prior to treatment.67 The treated area is then washed and an antibiotic ointment is applied.55 Management regimens typically require daily to weekly treatments with a total of 12 to 28 weeks to demonstrate an effect.

Microneedling has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of hair loss, especially when combined with minoxidil. One study randomized 68 patients to undergo microneedling with minoxidil solution 5% twice daily compared to a control group of minoxidil solution 5% twice daily alone. After 12 weeks, patients treated with microneedling and minoxidil had significantly higher hair counts than the control group (P<.05).68 It is speculated that microneedling increases penetration of topical medications, including minoxidil across the skin barrier, thereby enhancing absorption of large molecules.66

Topical PRP has been used synergistically to augment the effects of microneedling. A trial randomized 93 patients with alopecia to receive minoxidil solution 5% alone, minoxidil solution 5% plus PRP, or microneedling with PRP.69 Hair growth was appreciated in 26 of 31 patients treated with microneedling and PRP compared to 10 of 31 and 17 of 31 in the other 2 groups, respectively. However, when hair growth occurred in the minoxidil-treated group, it occurred faster, with changes in hair growth at 12 weeks compared to 26 weeks in the microneedling group.69 When evaluating the efficacy of microneedling and PRP, it must be noted that there is no established leading protocol for treating hair loss, which may affect the success of the treatment.

The reported side-effect profile for microneedling and PRP injections has been favorable without any major AEs noted in clinical trials.56,64,70 The possibility of bleeding, pain, erythema, and infection should be discussed with the patient nonetheless. More severe side effects such as allergic granulomatous reactions have been reported in the literature with the use of microneedling for facial rejuvenation.71

Stem Cells

Stem cell hair therapy is a new and promising area of research with the potential to treat alopecia. Although not yet FDA approved for this indication, human umbilical cord blood–derived mesenchymal stem cells (HUCB-MSCs) have received particular attention due to their proposed ability to promote tissue differentiation and repair, to replace aged and damaged hair cells, and to promote secretion of multiple growth factors.72 More recently, HUCB-MSCs have been shown to successfully differentiate into human hair follicles in vitro after 3 weeks of cell culture, establishing a method for high-speed and high-purity hair follicle cell differentiation with the hope of future injections to affected areas with hair loss.73 Another study found that HUCB-MSCs enhanced growth of human follicular stem cells in vitro; the authors proposed an altered Wnt/β‐catenin and JAK/STAT pathway was responsible for improved growth of hair follicular cells.74

Although umbilical cord blood is replete with the most rapidly dividing stem cells, autologous stem cells derived from the hair follicle or mononuclear cells also may be used to treat alopecia. One recent study randomized 40 patients with AGA and alopecia areata to receive 1 session of either autologous hair follicle or mononuclear cell–derived stem cell injections to the scalp.75 Mononuclear cells were acquired from the upper iliac crest bone marrow of patients who were treated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor 3 days prior to the procedure. Follicular stem cells were taken from 4-mm punch biopsies of the unaffected scalp. After 6 months, there was a notable improvement in hair growth confirmed by immunostaining and dermoscopy, without a significant difference between the forms of autologous stem cell source. Of note, 45% of study patients with alopecia areata showed recurrence of disease at 1-year follow-up. The most common AEs were scalp dermatitis in 20% of participants. Participants who underwent bone marrow biopsy experienced bone pain, hematoma, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor–induced fatigue and chills.75

Furthermore, the cost of stem cell therapy may be prohibitive. Therefore, although stem cell therapy is a novel and promising treatment for hair loss, future research is necessary to establish safety, efficacy, best practices, and accessibility.

Supplements

Patients failing routine treatments for alopecia may turn to holistic therapies. Nutrafol (Nutraceutical Wellness Inc), a novel nutraceutical product, is one such option that has been described for its anti-inflammatory, adaptogenic, antioxidant, and DHT-inhibiting properties. This supplement is not FDA approved or cleared, and large-scale clinical trials are lacking; however, one randomized controlled trial of 40 women with self-reported hair loss found a statistically significant increase in the number of terminal and vellus hair based on phototrichograms performed after 90 and 180 days (P=.009), with no AEs reported. This study, however, was limited by a small sample size.76

Lamdapil (ISDIN) is another oral supplement being investigated for hair loss. It contains L-cystine amino acids; zinc; vitamins B3, B5, B6; biotin; and the plant extract Serenoa repens.71Serenoa repens has reported activity inhibiting the enzyme 5α-reductase with the other vitamins, and amino acids are thought to maintain keratin and collagen growth in normal hair.77 One randomized trial investigated use of Lamdapil capsules in a total of 70 patients, which included men with AGA and women experiencing telogen effluvium. For men, the anagen-telogen ratio increased in the Lamdapil-treated group by 23.4%, indicating that more hair was in the growing phase compared to placebo (P<.05). Women with telogen effluvium experienced a significantly greater improvement in the hair-pull test compared to placebo (P<.05).77

Marine-derived nutraceutical substances also have been investigated for their role in treating hair loss. Viviscal, originally marketed under the name Hairgain, is one such supplement, which was shown to significantly reduce hair shedding at 3 and 6 months in a group of 96 premenopausal women diagnosed with subclinical hair thinning (P<.05). Additionally, phototrichogram images demonstrated a statistically significant increase in the mean velluslike hair diameter at 6 months compared to baseline.78

Although nutraceutical products are not first-line therapy for hair loss, dermatologists may recommend these treatments in patients refusing prescription medications, specifically requesting a natural treatment, or in addition to a first-line agent such as minoxidil. It must be noted, however, that both supplements are new, and there is need for further investigation on their efficacy, safety, and dosing, as neither is FDA regulated.

Conclusion

Hair loss affects millions of Americans each year and has detrimental effects on self-esteem and psychosocial functioning. Nonsurgical treatment options will undoubtedly continue to intrigue patients, as they are often less costly and do not carry risks associated with surgery. Minoxidil, finasteride, and LLLT remain staples of therapy, with the strongest evidence supporting their safety and efficacy. Numerous other treatment options are emerging, including PRP, microneedling, mesenchymal and autologous stem cell therapy, and oral supplements, though further research must be conducted to establish dosing, safety, and best practices. Physicians must discuss patient preference and anticipated length of treatment when discussing alopecia treatment to maximize patient satisfaction.

- Saed S, Ibrahim O, Bergfeld WF. Hair camouflage: a comprehensive review. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2016;2:122-127.

- Alfonso M, Richter-Appelt H, Tosti A, et al. The psychosocial impact of hair loss among men: a multinational European study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1829-1836.

- Konior RJ. Complications in hair-restoration surgery. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013;21:505-520.

- Manabe M, Tsuboi R, Itami S, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of male-pattern and female-pattern hair loss, 2017 version [published online June 4, 2018]. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1031-1043.

- Gupta AK, Mays RR, Dotzert MS, et al. Efficacy of non-surgical treatments for androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:2112-2125.

- Mehta PK, Mamdani B, Shansky RM, et al. Severe hypertension. treatment with minoxidil. JAMA. 1975;233:249-252.

- Zappacosta AR. Reversal of baldness in patient receiving minoxidil for hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1480-1481.

- Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:186-194.

- Mori O, Uno H. The effect of topical minoxidil on hair follicular cycles of rats. J Dermatol. 1990;17:276-281.

- Pekmezci E, Turkoglu M, Gokalp H, et al. Minoxidil downregulates interleukin-1 alpha gene expression in HaCaT cells. Int J Trichol. 2018;10:108-112.

- Roenigk HH Jr, Pepper E, Kuruvilla S. Topical minoxidil therapy for hereditary male pattern alopecia. Cutis. 1987;39:337-342.

- Lucky AW, Piacquadio DJ, Ditre CM, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 5% and 2% topical minoxidil solutions in the treatment of female pattern hair loss. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:541-553.

- Adil A, Godwin M. The effectiveness of treatments for androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:136-141.e135.

- Nangia J, Wang T, Osborne C, et al. Effect of a scalp cooling device on alopecia in women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer: the SCALP randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:596-605.

- Rugo HS, Melin SA, Voigt J. Scalp cooling with adjuvant/neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer and the risk of scalp metastases: systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;163:199-205.

- Duvic M, Lemak NA, Valero V, et al. A randomized trial of minoxidil in chemotherapy-induced alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:74-78.

- Yeager CE, Olsen EA. Treatment of chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:432-442.

- Freites-Martinez A, Shapiro J, Chan D, et al. Endocrine therapy-induced alopecia in patients with breast cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:670-675.

- Gupta AK, Foley KA. 5% minoxidil: treatment for female pattern hair loss. Skin Ther Lett. 2014;19:5-7.

- Stoehr JR, Choi JN, Colavincenzo M, et al. Off-label use of topical minoxidil in alopecia: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:237-250.