User login

Former Smokers Motivate Quitters

In 2012, the CDC launched the “Tips from Former Smokers” campaign. It was memorable and emotionally forceful—one woman who had oral and throat cancer delivered her ad through an artificial voicebox—but did it have an impact on actual quitting rates?

No study had been done to assess the campaign’s combined, multiyear impact until CDC researchers looked at sustained (6 month) cigarette abstinence during the first 4 years of the campaign (2012-2015).

They found that the Tips campaign led to about 9.15 million total quit attempts. Based on an assumed 5.7% abstinence rate for people attempting to quit, this amounts to approximately 522,000 sustained quits.

The researchers say their findings indicate that the comprehensive approach combining evidence-based messages with the promotion of cessation resources was highly successful. Their finding of more than half-million sustained quits underscores the critical role of national tobacco education campaigns as a “counterpoint” to the substantial pro-tobacco advertising and promotion.

In 2012, the CDC launched the “Tips from Former Smokers” campaign. It was memorable and emotionally forceful—one woman who had oral and throat cancer delivered her ad through an artificial voicebox—but did it have an impact on actual quitting rates?

No study had been done to assess the campaign’s combined, multiyear impact until CDC researchers looked at sustained (6 month) cigarette abstinence during the first 4 years of the campaign (2012-2015).

They found that the Tips campaign led to about 9.15 million total quit attempts. Based on an assumed 5.7% abstinence rate for people attempting to quit, this amounts to approximately 522,000 sustained quits.

The researchers say their findings indicate that the comprehensive approach combining evidence-based messages with the promotion of cessation resources was highly successful. Their finding of more than half-million sustained quits underscores the critical role of national tobacco education campaigns as a “counterpoint” to the substantial pro-tobacco advertising and promotion.

In 2012, the CDC launched the “Tips from Former Smokers” campaign. It was memorable and emotionally forceful—one woman who had oral and throat cancer delivered her ad through an artificial voicebox—but did it have an impact on actual quitting rates?

No study had been done to assess the campaign’s combined, multiyear impact until CDC researchers looked at sustained (6 month) cigarette abstinence during the first 4 years of the campaign (2012-2015).

They found that the Tips campaign led to about 9.15 million total quit attempts. Based on an assumed 5.7% abstinence rate for people attempting to quit, this amounts to approximately 522,000 sustained quits.

The researchers say their findings indicate that the comprehensive approach combining evidence-based messages with the promotion of cessation resources was highly successful. Their finding of more than half-million sustained quits underscores the critical role of national tobacco education campaigns as a “counterpoint” to the substantial pro-tobacco advertising and promotion.

Effective management of severe radiation dermatitis after head and neck radiotherapy

Head and neck cancer is among the most prevalent cancers in developing countries.1 Most of the patients in developing countries present in locally advanced stages, and radical radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy is the standard treatment.1 Radiation therapy is associated with radiation dermatitis, which causes severe symptoms in the patient and can lead to disruption of treatment, diminished rates of disease control rates, and impaired patient quality of life.2 The management of advanced radiation dermatitis is difficult and can cause consequential late morbidity to patients.2 We report here the rare case of a patient with locally advanced tonsil carcinoma who developed grade 3 radiation dermatitis while receiving radical chemoradiation. The patient’s radiation dermatitis was effectively managed with the use of a silver-containing antimicrobial dressing that yielded remarkable results, so the patient was able to resume and complete radiation therapy.

Case presentation and summary

A 48-year-old man was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the right tonsil, with bilateral neck nodes (Stage T4a N2c M0; The American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual, 7th edition). In view of the locally advanced status of his disease, the patient was scheduled for radical radiation therapy at 70 Gy in 35 fractions over 7 weeks along with weekly chemotherapy (cisplatin 40 mg/m2). During the course of radiation therapy, the patient was monitored twice a week, and symptomatic care was done for radiation-therapy–induced toxicities.

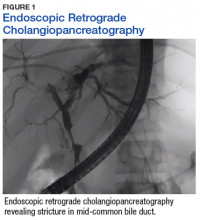

The patient presented with grade 3 radiation dermatitis after receiving 58 Gy in 29 fractions over 5 weeks (grade 0, no change; grades 3 and 4, severe change). The radiation dermatitis involved the anterior and bilateral neck with moist desquamation of the skin (Figure 1).

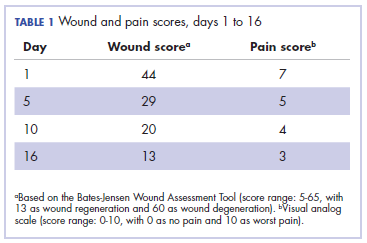

It was associated with severe pain, difficulty in swallowing, and oral mucositis. The patient was subsequently admitted to the hospital; radiation therapy was stopped, and treatment was initiated to ease the effects of the radiation dermatitis. Analgesics were administered for the pain, and adequate hydration and nutritional support was administered through a nasogastric tube. The patient’s score on the Bates-Jensen Wound Assessment Tool (BWAT) for monitoring wound status was 44, which falls in extreme severity status.

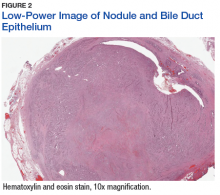

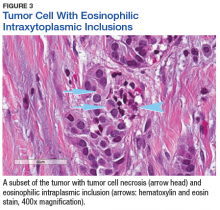

In view of the extreme severity status of the radiation dermatitis, after cleaning the wound with sterile water, we covered it with an antimicrobial dressing that contained silver salt (Mepilex AG; Mölnlycke Health Care, Norcross, GA). The dressing was changed regularly every 4 days. There was a gradual improvement in the radiation dermatitis (Figure 2).

Discussion

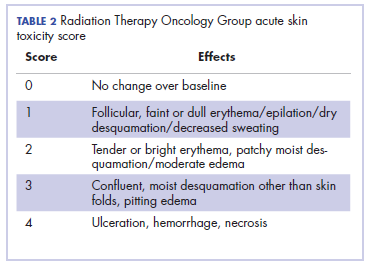

Head and neck cancer is one of the most common cancers in developing countries.1 Most patients present with locally advanced disease, so chemoradiation is the standard treatment in these patents. Radiation therapy is associated with acute and chronic toxicities. The common radiation therapy toxicities are directed at skin and mucosa, which leads to radiation dermatitis and radiation mucositis, respectively.2 These toxicities are graded as per the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) criteria (Table 2).3

Acute radiation dermatitis is radiation therapy dose-dependent and manifests within a few days to weeks after starting external beam radiation therapy. Its presentation varies in severity and gradually manifests as erythema, dry or moist desquamation, and ulceration when severe. These can cause severe symptoms in the patient, leading to frequent breaks in treatment, decreased rates of disease control, and impaired patient quality of life.2 Apart from RTOG grading, radiation dermatitis can also be scored using the BWAT. This tool has been validated across many studies to score initial wound status and monitor the subsequent status numerically.4 The radiation dermatitis of the index case was scored and monitored with both RTOG and BWAT scores.The management of advanced radiation dermatitis is difficult, and it causes consequential late morbidity in patients. A range of topical agents and dressings are used to treat radiation dermatitis, but there is minimal evidence to support their use.5 The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer treatment guidelines for prevention and treatment of radiation dermatitis have also concluded that there is a lack of sufficient evidence in the literature to support the superiority for any specific intervention.6 Management of radiation dermatitis varies among practitioners because of the inconclusive evidence for available treatment options.

The use of silver-based antimicrobial dressings has been reported in the literature in the prevention and treatment of radiation dermatitis, but with mixed results.7 Such dressings absorb exudate, maintain a moist environment that promotes wound healing, fight infection, and minimize the risk for maceration, according to the product information sheet.8 Clinical study findings have shown silver to be effective in fighting many different types of pathogens, including Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other drug-resistant bacteria.

Aquino-Parsons and colleagues studied 196 patients with breast cancer who were undergoing whole-breast radiation therapy.9 They showed that there was no benefit of silver-containing foam dressings for the prevention of acute grade 3 radiation dermatitis compared with patients who received standard skin care (with moisturizing cream, topical steroids, saline compress, and silver sulfadiazine cream). However, the incidence of itching in the last week of radiation and 1 week after treatment completion was lower among the patients who used the dressings.

Diggelmann and colleagues studied 24 patients with breast cancer who were undergoing radiation therapy.10 Each of the erythematous areas (n = 34) was randomly divided into 2 groups; 1 group was treated with Mepilex Lite dressing and the other with standard aqueous cream. There was a significant reduction in the severity of acute radiation dermatitis in the areas on which Mepilex Lite dressings were used compared with the areas on which standard aqueous cream was used.

The patient in the present case had severe grade 3 acute radiation dermatitis with a BWAT score indicative of extreme severity. After cleaning the wound with sterile water, instead of using the standard aqueous cream on the wounds, we used Mepilex AG, an antimicrobial dressing that contains silver salt. The results were remarkable (Figure 2 and Table 2). The patient was able to restart radiation therapy, and he completed his scheduled doses.

This case highlights the effectiveness of a silver-based antimicrobial dressing in the management of advanced and severe radiation dermatitis. Further large and randomized studies are needed to test the routine use of the dressing in the management of radiation dermatitis.

1. Simard EP, Torre LA, Jemal A. International trends in head and neck cancer incidence rates: differences by country, sex and anatomic site. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(5):387-403.

2. Hymes SR, Strom EA, Fife C. Radiation dermatitis: clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and treatment 2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(1):28-46.

3. Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(5):1341-1346.

4. Harris C, Bates-Jensen B, Parslow N, Raizman R, Singh M, Ketchen R. Bates‐Jensen wound assessment tool: pictorial guide validation project. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010;37(3):253-259.

5. Lucey P, Zouzias C, Franco L, Chennupati SK, Kalnicki S, McLellan BN. Practice patterns for the prophylaxis and treatment of acute radiation dermatitis in the United States. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(9):2857-2862.

6. Wong RK, Bensadoun RJ, Boers-Doets CB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of acute and late radiation reactions from the MASCC Skin Toxicity Study Group. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(10):2933-2948.

7. Vavassis P, Gelinas M, Chabot Tr J, Nguyen-Tân PF. Phase 2 study of silver leaf dressing for treatment of radiation-induced dermatitis in patients receiving radiotherapy to the head and neck. J Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 2008;37(1):124-129.

8. Mepilex Ag product information. Mölnlycke Health Care website. http://www.molnlycke.us/advanced-wound-care-products/antimicrobial-products/mepilex-ag/#confirm. Accessed May 3, 2018.

9. Aquino-Parsons C, Lomas S, Smith K, et al. Phase III study of silver leaf nylon dressing vs standard care for reduction of inframammary moist desquamation in patients undergoing adjuvant whole breast radiation therapy. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2010;41(4):215-221.

10. Diggelmann KV, Zytkovicz AE, Tuaine JM, Bennett NC, Kelly LE, Herst PM. Mepilex Lite dressings for the management of radiation-induced erythema: a systematic inpatient controlled clinical trial. Br J Radiol. 2010;83(995):971-978.

Head and neck cancer is among the most prevalent cancers in developing countries.1 Most of the patients in developing countries present in locally advanced stages, and radical radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy is the standard treatment.1 Radiation therapy is associated with radiation dermatitis, which causes severe symptoms in the patient and can lead to disruption of treatment, diminished rates of disease control rates, and impaired patient quality of life.2 The management of advanced radiation dermatitis is difficult and can cause consequential late morbidity to patients.2 We report here the rare case of a patient with locally advanced tonsil carcinoma who developed grade 3 radiation dermatitis while receiving radical chemoradiation. The patient’s radiation dermatitis was effectively managed with the use of a silver-containing antimicrobial dressing that yielded remarkable results, so the patient was able to resume and complete radiation therapy.

Case presentation and summary

A 48-year-old man was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the right tonsil, with bilateral neck nodes (Stage T4a N2c M0; The American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual, 7th edition). In view of the locally advanced status of his disease, the patient was scheduled for radical radiation therapy at 70 Gy in 35 fractions over 7 weeks along with weekly chemotherapy (cisplatin 40 mg/m2). During the course of radiation therapy, the patient was monitored twice a week, and symptomatic care was done for radiation-therapy–induced toxicities.

The patient presented with grade 3 radiation dermatitis after receiving 58 Gy in 29 fractions over 5 weeks (grade 0, no change; grades 3 and 4, severe change). The radiation dermatitis involved the anterior and bilateral neck with moist desquamation of the skin (Figure 1).

It was associated with severe pain, difficulty in swallowing, and oral mucositis. The patient was subsequently admitted to the hospital; radiation therapy was stopped, and treatment was initiated to ease the effects of the radiation dermatitis. Analgesics were administered for the pain, and adequate hydration and nutritional support was administered through a nasogastric tube. The patient’s score on the Bates-Jensen Wound Assessment Tool (BWAT) for monitoring wound status was 44, which falls in extreme severity status.

In view of the extreme severity status of the radiation dermatitis, after cleaning the wound with sterile water, we covered it with an antimicrobial dressing that contained silver salt (Mepilex AG; Mölnlycke Health Care, Norcross, GA). The dressing was changed regularly every 4 days. There was a gradual improvement in the radiation dermatitis (Figure 2).

Discussion

Head and neck cancer is one of the most common cancers in developing countries.1 Most patients present with locally advanced disease, so chemoradiation is the standard treatment in these patents. Radiation therapy is associated with acute and chronic toxicities. The common radiation therapy toxicities are directed at skin and mucosa, which leads to radiation dermatitis and radiation mucositis, respectively.2 These toxicities are graded as per the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) criteria (Table 2).3

Acute radiation dermatitis is radiation therapy dose-dependent and manifests within a few days to weeks after starting external beam radiation therapy. Its presentation varies in severity and gradually manifests as erythema, dry or moist desquamation, and ulceration when severe. These can cause severe symptoms in the patient, leading to frequent breaks in treatment, decreased rates of disease control, and impaired patient quality of life.2 Apart from RTOG grading, radiation dermatitis can also be scored using the BWAT. This tool has been validated across many studies to score initial wound status and monitor the subsequent status numerically.4 The radiation dermatitis of the index case was scored and monitored with both RTOG and BWAT scores.The management of advanced radiation dermatitis is difficult, and it causes consequential late morbidity in patients. A range of topical agents and dressings are used to treat radiation dermatitis, but there is minimal evidence to support their use.5 The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer treatment guidelines for prevention and treatment of radiation dermatitis have also concluded that there is a lack of sufficient evidence in the literature to support the superiority for any specific intervention.6 Management of radiation dermatitis varies among practitioners because of the inconclusive evidence for available treatment options.

The use of silver-based antimicrobial dressings has been reported in the literature in the prevention and treatment of radiation dermatitis, but with mixed results.7 Such dressings absorb exudate, maintain a moist environment that promotes wound healing, fight infection, and minimize the risk for maceration, according to the product information sheet.8 Clinical study findings have shown silver to be effective in fighting many different types of pathogens, including Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other drug-resistant bacteria.

Aquino-Parsons and colleagues studied 196 patients with breast cancer who were undergoing whole-breast radiation therapy.9 They showed that there was no benefit of silver-containing foam dressings for the prevention of acute grade 3 radiation dermatitis compared with patients who received standard skin care (with moisturizing cream, topical steroids, saline compress, and silver sulfadiazine cream). However, the incidence of itching in the last week of radiation and 1 week after treatment completion was lower among the patients who used the dressings.

Diggelmann and colleagues studied 24 patients with breast cancer who were undergoing radiation therapy.10 Each of the erythematous areas (n = 34) was randomly divided into 2 groups; 1 group was treated with Mepilex Lite dressing and the other with standard aqueous cream. There was a significant reduction in the severity of acute radiation dermatitis in the areas on which Mepilex Lite dressings were used compared with the areas on which standard aqueous cream was used.

The patient in the present case had severe grade 3 acute radiation dermatitis with a BWAT score indicative of extreme severity. After cleaning the wound with sterile water, instead of using the standard aqueous cream on the wounds, we used Mepilex AG, an antimicrobial dressing that contains silver salt. The results were remarkable (Figure 2 and Table 2). The patient was able to restart radiation therapy, and he completed his scheduled doses.

This case highlights the effectiveness of a silver-based antimicrobial dressing in the management of advanced and severe radiation dermatitis. Further large and randomized studies are needed to test the routine use of the dressing in the management of radiation dermatitis.

Head and neck cancer is among the most prevalent cancers in developing countries.1 Most of the patients in developing countries present in locally advanced stages, and radical radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy is the standard treatment.1 Radiation therapy is associated with radiation dermatitis, which causes severe symptoms in the patient and can lead to disruption of treatment, diminished rates of disease control rates, and impaired patient quality of life.2 The management of advanced radiation dermatitis is difficult and can cause consequential late morbidity to patients.2 We report here the rare case of a patient with locally advanced tonsil carcinoma who developed grade 3 radiation dermatitis while receiving radical chemoradiation. The patient’s radiation dermatitis was effectively managed with the use of a silver-containing antimicrobial dressing that yielded remarkable results, so the patient was able to resume and complete radiation therapy.

Case presentation and summary

A 48-year-old man was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the right tonsil, with bilateral neck nodes (Stage T4a N2c M0; The American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual, 7th edition). In view of the locally advanced status of his disease, the patient was scheduled for radical radiation therapy at 70 Gy in 35 fractions over 7 weeks along with weekly chemotherapy (cisplatin 40 mg/m2). During the course of radiation therapy, the patient was monitored twice a week, and symptomatic care was done for radiation-therapy–induced toxicities.

The patient presented with grade 3 radiation dermatitis after receiving 58 Gy in 29 fractions over 5 weeks (grade 0, no change; grades 3 and 4, severe change). The radiation dermatitis involved the anterior and bilateral neck with moist desquamation of the skin (Figure 1).

It was associated with severe pain, difficulty in swallowing, and oral mucositis. The patient was subsequently admitted to the hospital; radiation therapy was stopped, and treatment was initiated to ease the effects of the radiation dermatitis. Analgesics were administered for the pain, and adequate hydration and nutritional support was administered through a nasogastric tube. The patient’s score on the Bates-Jensen Wound Assessment Tool (BWAT) for monitoring wound status was 44, which falls in extreme severity status.

In view of the extreme severity status of the radiation dermatitis, after cleaning the wound with sterile water, we covered it with an antimicrobial dressing that contained silver salt (Mepilex AG; Mölnlycke Health Care, Norcross, GA). The dressing was changed regularly every 4 days. There was a gradual improvement in the radiation dermatitis (Figure 2).

Discussion

Head and neck cancer is one of the most common cancers in developing countries.1 Most patients present with locally advanced disease, so chemoradiation is the standard treatment in these patents. Radiation therapy is associated with acute and chronic toxicities. The common radiation therapy toxicities are directed at skin and mucosa, which leads to radiation dermatitis and radiation mucositis, respectively.2 These toxicities are graded as per the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) criteria (Table 2).3

Acute radiation dermatitis is radiation therapy dose-dependent and manifests within a few days to weeks after starting external beam radiation therapy. Its presentation varies in severity and gradually manifests as erythema, dry or moist desquamation, and ulceration when severe. These can cause severe symptoms in the patient, leading to frequent breaks in treatment, decreased rates of disease control, and impaired patient quality of life.2 Apart from RTOG grading, radiation dermatitis can also be scored using the BWAT. This tool has been validated across many studies to score initial wound status and monitor the subsequent status numerically.4 The radiation dermatitis of the index case was scored and monitored with both RTOG and BWAT scores.The management of advanced radiation dermatitis is difficult, and it causes consequential late morbidity in patients. A range of topical agents and dressings are used to treat radiation dermatitis, but there is minimal evidence to support their use.5 The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer treatment guidelines for prevention and treatment of radiation dermatitis have also concluded that there is a lack of sufficient evidence in the literature to support the superiority for any specific intervention.6 Management of radiation dermatitis varies among practitioners because of the inconclusive evidence for available treatment options.

The use of silver-based antimicrobial dressings has been reported in the literature in the prevention and treatment of radiation dermatitis, but with mixed results.7 Such dressings absorb exudate, maintain a moist environment that promotes wound healing, fight infection, and minimize the risk for maceration, according to the product information sheet.8 Clinical study findings have shown silver to be effective in fighting many different types of pathogens, including Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other drug-resistant bacteria.

Aquino-Parsons and colleagues studied 196 patients with breast cancer who were undergoing whole-breast radiation therapy.9 They showed that there was no benefit of silver-containing foam dressings for the prevention of acute grade 3 radiation dermatitis compared with patients who received standard skin care (with moisturizing cream, topical steroids, saline compress, and silver sulfadiazine cream). However, the incidence of itching in the last week of radiation and 1 week after treatment completion was lower among the patients who used the dressings.

Diggelmann and colleagues studied 24 patients with breast cancer who were undergoing radiation therapy.10 Each of the erythematous areas (n = 34) was randomly divided into 2 groups; 1 group was treated with Mepilex Lite dressing and the other with standard aqueous cream. There was a significant reduction in the severity of acute radiation dermatitis in the areas on which Mepilex Lite dressings were used compared with the areas on which standard aqueous cream was used.

The patient in the present case had severe grade 3 acute radiation dermatitis with a BWAT score indicative of extreme severity. After cleaning the wound with sterile water, instead of using the standard aqueous cream on the wounds, we used Mepilex AG, an antimicrobial dressing that contains silver salt. The results were remarkable (Figure 2 and Table 2). The patient was able to restart radiation therapy, and he completed his scheduled doses.

This case highlights the effectiveness of a silver-based antimicrobial dressing in the management of advanced and severe radiation dermatitis. Further large and randomized studies are needed to test the routine use of the dressing in the management of radiation dermatitis.

1. Simard EP, Torre LA, Jemal A. International trends in head and neck cancer incidence rates: differences by country, sex and anatomic site. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(5):387-403.

2. Hymes SR, Strom EA, Fife C. Radiation dermatitis: clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and treatment 2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(1):28-46.

3. Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(5):1341-1346.

4. Harris C, Bates-Jensen B, Parslow N, Raizman R, Singh M, Ketchen R. Bates‐Jensen wound assessment tool: pictorial guide validation project. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010;37(3):253-259.

5. Lucey P, Zouzias C, Franco L, Chennupati SK, Kalnicki S, McLellan BN. Practice patterns for the prophylaxis and treatment of acute radiation dermatitis in the United States. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(9):2857-2862.

6. Wong RK, Bensadoun RJ, Boers-Doets CB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of acute and late radiation reactions from the MASCC Skin Toxicity Study Group. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(10):2933-2948.

7. Vavassis P, Gelinas M, Chabot Tr J, Nguyen-Tân PF. Phase 2 study of silver leaf dressing for treatment of radiation-induced dermatitis in patients receiving radiotherapy to the head and neck. J Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 2008;37(1):124-129.

8. Mepilex Ag product information. Mölnlycke Health Care website. http://www.molnlycke.us/advanced-wound-care-products/antimicrobial-products/mepilex-ag/#confirm. Accessed May 3, 2018.

9. Aquino-Parsons C, Lomas S, Smith K, et al. Phase III study of silver leaf nylon dressing vs standard care for reduction of inframammary moist desquamation in patients undergoing adjuvant whole breast radiation therapy. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2010;41(4):215-221.

10. Diggelmann KV, Zytkovicz AE, Tuaine JM, Bennett NC, Kelly LE, Herst PM. Mepilex Lite dressings for the management of radiation-induced erythema: a systematic inpatient controlled clinical trial. Br J Radiol. 2010;83(995):971-978.

1. Simard EP, Torre LA, Jemal A. International trends in head and neck cancer incidence rates: differences by country, sex and anatomic site. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(5):387-403.

2. Hymes SR, Strom EA, Fife C. Radiation dermatitis: clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and treatment 2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(1):28-46.

3. Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(5):1341-1346.

4. Harris C, Bates-Jensen B, Parslow N, Raizman R, Singh M, Ketchen R. Bates‐Jensen wound assessment tool: pictorial guide validation project. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010;37(3):253-259.

5. Lucey P, Zouzias C, Franco L, Chennupati SK, Kalnicki S, McLellan BN. Practice patterns for the prophylaxis and treatment of acute radiation dermatitis in the United States. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(9):2857-2862.

6. Wong RK, Bensadoun RJ, Boers-Doets CB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of acute and late radiation reactions from the MASCC Skin Toxicity Study Group. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(10):2933-2948.

7. Vavassis P, Gelinas M, Chabot Tr J, Nguyen-Tân PF. Phase 2 study of silver leaf dressing for treatment of radiation-induced dermatitis in patients receiving radiotherapy to the head and neck. J Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 2008;37(1):124-129.

8. Mepilex Ag product information. Mölnlycke Health Care website. http://www.molnlycke.us/advanced-wound-care-products/antimicrobial-products/mepilex-ag/#confirm. Accessed May 3, 2018.

9. Aquino-Parsons C, Lomas S, Smith K, et al. Phase III study of silver leaf nylon dressing vs standard care for reduction of inframammary moist desquamation in patients undergoing adjuvant whole breast radiation therapy. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2010;41(4):215-221.

10. Diggelmann KV, Zytkovicz AE, Tuaine JM, Bennett NC, Kelly LE, Herst PM. Mepilex Lite dressings for the management of radiation-induced erythema: a systematic inpatient controlled clinical trial. Br J Radiol. 2010;83(995):971-978.

The impact of inpatient rehabilitation on outcomes for patients with cancer

The American Cancer Society reports that 1.6 million people are diagnosed with cancer each year, of whom 78% are aged 55 years or older. The 5-year survival rate for cancer is 68%.1 Almost 15.5 million living Americans have been diagnosed with cancer.2 Many patients with cancer have difficulty walking and with activities of daily living. Patients with primary brain tumors or tumors metastatic to the brain may present with focal weakness or cognitive deficits similar to patients with stroke. Patients with tumors metastatic to the spine may have the same deficits as a patient with a traumatic spinal cord injury. Patients with metastasis to bone may have pathologic fractures of the hip or long bones. Patients may develop peripheral neuropathy associated with a paraneoplastic syndrome, chemotherapy, or critical illness neuropathy. Lehmann and colleagues evaluated 805 patients admitted to hospitals affiliated with the University of Washington Medical School with a diagnosis of cancer and found that 15% had difficulty walking and 20% had difficulty with activities of daily living.3

Many patients with cancer can benefit from inpatient rehabilitation.4,5 Study findings have shown that patients with impairments in function related to cancer are often not referred for rehabilitation. Among the reasons mentioned for that are that oncologists are more focused on treating the patients’ cancer than on their functional deficits and that specialists in rehabilitation medicine do not want to be involved with patients with complex medical problems. Rehabilitation facilities may not want to incur the costs associated with caring for patients with cancer.6

The present paper looks at the outcomes of 61 consecutive patients with cancer who were admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF) and received radiation therapy concurrent with rehabilitation. It compares the outcomes of the cancer patients with the outcomes of patients without cancer who were admitted with stroke or spinal cord injury, conditions more commonly treated at an IRF.

Methods

We reviewed electronic medical records of all patients with cancer admitted to the IRF from 2008 through 2013 who received radiation therapy while at the facility. We also reviewed the data of all patients without cancer admitted with a diagnosis of stroke in 2013 and all patients admitted with a diagnosis of traumatic spinal cord injury in 2012 and 2013. No patients were excluded from stroke and traumatic spinal cord injury groups.

We recorded the sex, age, diagnostic group, Functional Independence Measure (FIM) admission score, FIM discharge score, length of stay (LoS) in the IRF, place of discharge of each patient (eg, home, acute care, or subacute care), and calculated the FIM efficiency score (change in FIM/LoS) for each patient. The FIM is an instrument that has 18 items measuring mobility, participation in activities of daily living, ability to communicate, and cognitive function.7 Each item is scored from 1 to 7, with 1 denoting that the patient cannot perform the task and 7 that the activity can be performed independently. The minimum score is 18 (complete dependence), and the maximum score is 126 (independent function). Thirteen items compose the motor FIM score: eating, grooming, bathing, dressing upper body, dressing lower body, toileting, bladder management, management of bowel, transfer to bed or wheelchair, transfer to toilet, tub transfer, walking (or wheelchair use), and climbing stairs. Five items – comprehension, expression, social interaction, problem solving, and memory – compose the cognitive FIM score.

We used a 1-way analysis of variance to evaluate differences between age and cancer type, age and diagnostic group, admission FIM score and cancer type, discharge FIM score and cancer type, change in FIM and cancer type, LoS and cancer type, and LoS and diagnostic group. The Pearson chi-square test was used to test the goodness of fit between the place of disposition and diagnostic group. The paired t test was used to evaluate the improvement in FIM of the patients who were in the cancer groups. The Tukey Simultaneous Tests for Differences of Means was used to compare the FIM efficiency scores of the groups. A 2-sample t test was used to evaluate the factors associated with the need for transfer from the IRF to the acute medical service.

Results

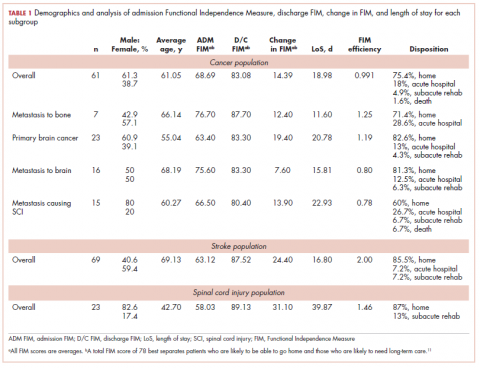

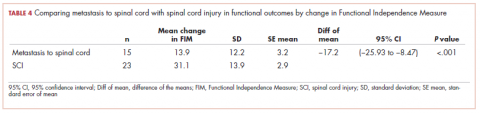

The demographic characteristics of the patients in the study and the admission and discharge FIM scores are reported in Table 1. There were initially 62 cancer patients in the radiation group, which was further divided into 4 subgroups based on the site of the primary tumor or metastasis. In all, 23 had a primary malignant brain tumor and received radiation and temozolomide. Sixteen patients had malignancies metastatic to the brain, 15 patients had tumors metastatic to the spine, and 7 had tumors metastatic to the long bones. One patient had laryngeal cancer and was excluded from the study because we did not think that we could do an analysis of a group with only 1 patient. The final number of patients in the cancer group was therefore 61. There were 69 patients in the stroke group and 23 in the spinal cord injury group.

We report improvement in total FIM, motor FIM, and cognitive FIM scores and were able to identify all 18 of the items of the FIM score on 60 of the 61 patients in the cancer group. Improvement in total FIM of the 61 patients in the cancer groups was significant at P P P = .05. Just over 75% of the patients in the cancer group had sufficient enough improvement in their level of function that they were able to return to their homes (Table 1). The average FIM score at the time of discharge was 83.08. This was not significantly different than the level of function of patients discharged after stroke (87.52) or traumatic spinal cord injury (89.13).

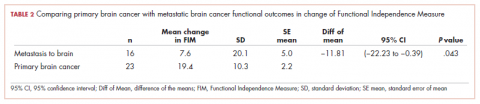

The patients with primary brain tumors were younger than the patients with cancer metastatic to the brain (P = .013). The patients with a primary brain tumor had lower admission FIM scores than patients with tumors metastatic to the brain (P = .027). The patients with a primary brain tumor had a greater increase in FIM score than patients with metastasis to the brain (P = .043; Table 2). There was not a significant difference between these 2 groups in FIM score at discharge or in the likelihood of discharge to home (Table 1). The FIM efficiency score was 1.12 for the patients in the primary brain tumor group and .80 in those with metastasis to the brain. This difference was not significant P = .96.

There were 69 patients in the stroke group. We compared the 39 patients with primary or metastatic brain lesion to the stroke group. The patients with primary or metastatic cancer of the brain were younger than the patients with stroke, 60.4 years old versus 69.1 years old (P = .004). The patients in the combined cancer group had a higher admission FIM score compared with the stroke patients (68.4 vs 63.12; P = .05). The discharge FIM scores were 83.3 in the combined cancer group and 87.5 in the stroke group (Table 1). This difference was not significant, but the improvement in the combined cancer group (14.6) was less than the improvement in the stroke group (24.40; P = .002) (Table 3).

The average LoS in the IRF was 18.7 days in the combined cancer group and 16.8 days in the stroke group. This difference was not significant. An average of 82% of the patients in the primary tumor or brain metastasis group and 85.5% of the patients in the stroke group were discharged to home. This difference was not significant. The FIM efficiency score of the patients in the stroke group was 2.0. This was significantly greater than the score for the patients in the metastasis to the brain group (0.80; P = .044) but not significantly greater than the primary brain cancer group (1.19; P = .22).

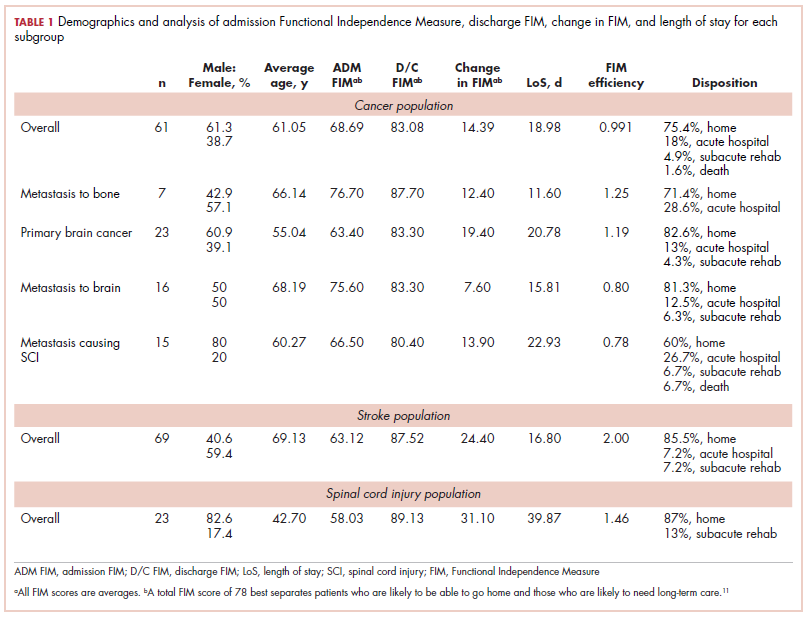

There were 23 patients in the traumatic spinal cord injury group. A comparison of the patients with tumors metastatic to the spine and patients with traumatic spinal cord injury showed that the patients in the cancer group were older (60.27 and 42.70 years, respectively; P = .001). In all, 80% of patients with tumors metastatic to the spine were men. This was not significantly different from the percentage of men in the traumatic spinal cord injury group (82.6%; Table 1). The admission FIM score of the patients with cancer was 66.5 (standard deviation [SD], 13.3) and 58.03 (SD, 15.1) in the patients with a traumatic spinal cord injury (Table 1). The FIM score at discharge was 80.4 (SD, 19.1) in the patients with cancer and 89.1 (SD, 20.3) in the patients with a traumatic spinal cord injury (Table 1). Neither of these were statistically significant. The improvement in patients with cancer was 13.9 (SD, 12.2) and 31.1 (SD, 13.9) in the traumatic spinal cord injured patients. This difference was significant (P

The median LoS was 18.98 days in the cancer metastasis to spine group (interquartile range [IQR] is the 25th-75th percentile, 12-30 days). In the traumatic group the median LoS was 23 days (IQR, 16-50 days). This difference was not significant (P = .14 Mann-Whitney test). The mean FIM efficiency score was 1.46 in the traumatic spinal cord injury group and .78 in the group with cancer metastatic to the spine. This difference was not significant (P = .72). Sixty percent of the patients in the cancer group were discharged to home, and 87% of patients in the traumatic spinal cord group were discharged to home. This difference was not significant (P = .12; Fisher exact test).

As far as we can ascertain, this is the first paper that has looked at the outcomes of patients receiving rehabilitation concurrent with radiation of the long bones. The average improvement in FIM was 12.4 (Table 1). The LoS was 11.6 days, and the FIM efficiency was 1.25. In all, 71.4% made enough progress to go home.

Of the total number of cancer patients, 18% were transferred to the acute medical service of the hospital (Table 1). Neither age, sex, type of cancer, nor admission FIM score were associated with the need for transfer to acute hospital care. Change in FIM score was inversely associated with transfer to acute hospital care (P = .027). Patients whose function did not improve with rehabilitation were most likely to be transferred back to acute hospital care.

Discussion

Radiation therapy is considered a service that is provided to people who come for treatment as an outpatient. Caregivers may have difficulty transporting patients to radiation if the patient has deficits in mobility. This may be particularly true if the patient is heavy, the caregivers are frail, or perhaps if they live in rural settings where there is no wheelchair-accessible public transportation. There are many factors that help determine whether a patient with functional deficits can be discharged to his or her home. These include sex, age, marital status, family and/or community support, income, and insurance.8 The FIM is an instrument that indicates how much help a patient needs with mobility and self-care skills. It also correlates with the amount of time that caregivers must spend helping a patient.9 Study findings have shown that the FIM score is an important determinant of whether a patient can be discharged to home. The total FIM score is as useful as an analysis of the components of the FIM score in predicting whether a patient can return to the community.10,11 Reistetter and colleagues found a total FIM score of 78 to be the score that best separates patients who are likely to be able to go home and patients who are likely to need long-term care.11 Bottemiller and colleagues10 reported that 37% of patients with total discharge FIM scores of less than 40 were discharged to home. They reported that 62% of patients with FIM scores between 40 and 79 were discharged to home, and 88% of patients with scores of 80 or above were discharged to home.10 The goal in bringing patients to the IRF was to accept and treat patients with reasonable community support and potential to achieve a functional level compatible with discharge to the community. Most patients in each of the cancer groups were able to reach an FIM score of 78 to 80 and to be discharged to home.

Most of the patients in the cancer groups had underlying problems that are not considered curable. The primary goal was to enable the patients to have some time at home with their families before requiring readmission to a hospital or hospice care. Reasonable LoS and rate of progress are now expected or required by third-party payors and hospital administrators. Physicians at the Mayo Clinic have indicated that a rehabilitation service should aim for an FIM efficiency score of at least .6 points per day.10 The FIM efficiency of patients in each of the 4 cancer subgroups in this study was higher than this level.

J. Herbert Dietz, Jr was an early advocate of the need to provide comprehensive rehabilitation services for patients with cancer. He first described his work in 1969.12 Since that time, there have been many papers that have documented the benefits of IRF for patients with cancer. O’Toole and Golden have shown outcomes of a large series of patients from an IRF. They reported that at the time of admission, 14% of patients could ambulate, but at discharge, 80% could ambulate without hands-on assistance. They reported significant improvements in continence, FIM score, and score on the Karnofsky Performance Scale.13 Marciniak,14 Hunter,15 Shin,16 and Cole,17 and their respective colleagues have all shown that patients with many different types of cancer benefit from rehabilitation at the IRF level. Gallegos-Kearin and colleagues4 reported on the care of 115,570 patients admitted to IRF with cancer from 2002 to 2014. Patients had significant improvement in function, with more than 70% of patients discharged to home.4 Ng and colleagues studied a group of 200 patients who received IRF care and found there was significant improvement in function. Ninety-four percent of patients rated their stay as either extremely good or very good.5

Metastasis to the spine is a common problem. It is found in 30% of cancer patients at autopsy. The most common sources of metastasis to the spine are breast, lung, prostate, kidney, and thyroid.18 Multiple myeloma and lymphoma may also involve the spine. Several authors have shown that these patients benefit from inpatient rehabilitation. Mckinley and colleagues19 have noted that patients with metastasis to the spine make significant improvement with care at an IRF. Compared with patients with a traumatic spinal cord injury, the cancer patients had shorter LoS, smaller improvement in FIM, equal FIM efficiency (FIM gain/LoS), and equal success in making enough progress to be discharged to home.19 Eriks and colleagues showed that patients at an IRF in Amsterdam made significant improvement in function as measured by the Barthel’s Index.20 Tang .,21 and Parsch22 and their respective colleagues, Murray,23 and New24 and colleagues have published findings confirming that patients with spinal cord injury caused by metastasis to the spine make significant progress with inpatient rehabilitation programs. The present study adds to the literature by showing that patients with metastasis to the spine who are receiving radiation can make progress and be discharged to the community.

There are 24,000 new cases of primary malignant brain tumors in the United States each year.25 The incidence of metastatic cancer to the brain has been estimated to be 100,000 cases per year in the United States. The most common cancer sources are lung, breast, melanoma, kidney, and colon.26,27 The first study of patients admitted to an IRF for treatment of brain tumors was published in 1998 by Huang and colleagues28 who compared the outcomes of 63 patients with brain tumors with the outcomes of 63 patients with stroke. They reported that the patients with the brain tumors made significant improvement in function. There was not a significant difference between the 2 groups of patients in improvement in function, FIM efficiency, or success in discharging the patients to home.28 Greenberg29 and Bartolo30 and their respective colleagues compared the outcomes of patients admitted with brain tumors and patients with stroke and found that improvement in function and discharge to home was similar in the 2 groups. In 2000, Huang and his same colleagues31 compared a group of patients with brain tumors to a group of patients with traumatic brain injury. They found significant improvement in the function of the patients with brain tumors. Patients in the traumatic brain injury group made more progress but had longer LoS. FIM efficiency was not significantly different between the groups.31

Three papers have reported outcomes of patients who received radiation concurrent with inpatient rehabilitation. Tang and colleagues32 reported 63 patients, of whom 48% percent received radiation concurrent with rehabilitation. The patients who received radiation made significant gains in function, and more than 70% were discharged to home. There was no difference in the outcomes of the patients in the radiation and nonradiation groups.32 Marciniak33 and O’Dell34 and their colleagues also reported that patients with brain tumors that required radiation therapy can benefit from inpatient rehabilitation. The present paper is the fourth (with the largest patient group) to show that patients with primary and metastatic tumors to the brain can benefit from a program that provides radiation concurrent with inpatient rehabilitation. We have shown that patients can achieve functional levels and rates of discharge to home that are not significantly different from those of the most commonly admitted group of patients to IRF – patients with stroke.

In the present study, 18% of all of the cancer patients were transferred to medical services and/or acute hospital care (Table 1). This is consistent with a paper by Asher and colleagues35 who reported that 17.4% of patients at an IRF with a diagnosis of cancer required transfer back to medical service, and that low admission motor FIM score correlated with the likelihood of transfer back to medical service. In the present paper, the total admission FIM score was not related to the likelihood of return to medical service, although a lack of improvement in the FIM score did correlate with transfer to medical service.

All of the papers we reviewed found that appropriately selected patients with cancer make significant improvement in function with treatment at an IRF. Tang and colleagues have also shown that for patients with malignant brain tumors and metastasis to the spine, improvement in function correlates with increased survival.32 Our paper confirms that patients with primary malignant brain tumors, malignant tumors metastatic to the brain or spine, and tumors metastatic to long bones may benefit from rehabilitation concurrent with radiation. Rehabilitation units are traditionally associated with treating patients with stroke and spinal cord injury. The patients in our study had cancer and were receiving radiation therapy. They had significant improvement in function and FIM efficiency scores that are not below the threshold set as expected for care at an IRF. Most patients in our study achieved a functional level consistent with what is needed to go home.

There is a prospective payment or reimbursement system for rehabilitation units.36 The payments are based on the admitting diagnosis, the admission FIM score, the age of the patient, and comorbidities. There are 4 tiers for comorbidities with no additional payments for patients in tier 0 but with additional payments for patients with conditions that qualify for tiers 1 through 3. The highest payments are for patients in tier 1. Examples of conditions that can increase payment include morbid obesity, congestive heart failure, vocal cord paralysis, and the need for hemodialysis. There is no increased payment for provision of radiation therapy. There are no reports on the feasibility, in terms of finances, of providing radiation on an IRF. We asked the finance office of the Albany Medical Center to comment on the cost to the hospital of providing radiation therapy to patients on the rehabilitation unit. The hospital’s finance department reviewed available data and reported that the variable cost of providing radiation therapy is about 6.5% of the revenue collected from third-party payors for caring for patients who receive that service (personal communication from the finance office of Albany Medical Center to George Forrest, 2015). Our findings suggest that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should make an adjustment to the payment system to support the cost of providing radiation to patients at an IRF. Even under the current payment system, for a hospital that has the equipment and personnel to provide radiation treatments, the variable cost of 6.5% of revenue should not be an absolute barrier to providing this service.

Limitations

This study reports on the experience of only 1 facility. The number of patients in the radiation group is greater than the number of patients in any previous report of people receiving radiation at an IRF, but the statistician does not think it is large enough to allow statistical analysis of covariates such as age, sex, and comorbid conditions. In addition, we did not investigate all of the factors that influence the type of care patients are offered and their LoS, such as hospital policy, insurance coverage, income, and family structure.

Conclusions

Acute care medical units are now challenged to both reduce LoS and reduce the number of patients who are readmitted to the hospital. Rehabilitation units are challenged to maintain census, as government and private payors are shifting patients from acute rehabilitation units to subacute rehabilitation units. We found that patients with cancer who need radiation are a population of patients who are seen by payors as needing to be in a facility with excellent nursing, therapy, and comprehensive physician services. A comprehensive cancer care program within a rehabilitation unit can be a great benefit to the acute care services, the IRF, and, most importantly, patients and their families.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2016. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2016.

2. National Cancer Institute: Office of cancer survivorship: statistics. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/statistics/statistics.html. Updated October 17, 2016. Accessed April 21, 2018.

3. Lehmann JF, DeLisa JA, Warren CG, deLateur BJ, Bryant PL, Nicholson CG. Cancer rehabilitation: assessment of need, development and evaluation of a model of care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1978;59(9):410-419.

4. Gallegos-Kearin V, Knowlton SE, Goldstein R, et al. Outcome trends of adult cancer patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation: a 13-year review [published online Feb 21, 2018]. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. doi:10.1097/PHM.0000000000000911

5. Ng AH, Gupta E, Fontillas RC, et al. Patient-reported usefulness of acute cancer rehabilitation. PM R. 2017;9(11):1135-1143.

6. Cheville AL, Kornblith AB, Basford JR. An examination of the causes for the underutilization of rehabilitation services among people with advanced cancer. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90(5 suppl 1):S27-S37.

7. Cohen ME, Marino RJ. The tools of disability outcomes research functional status measures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(12 suppl 2):S21-S29.

8. Nguyen VQ, PrvuBettger J, Guerrier T, et al. Factors associated with discharge to home versus discharge to institutional care after inpatient stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(7):1297-1303.

9. Forrest G, Schwam A, Cohen E. Time of care required by patients discharged from a rehabilitation unit. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81(1):57-62.

10. Bottemiller KL, Bieber PL, Basford JR, Harris M. FIM scores, FIM efficiency and discharge following inpatient stroke rehabilitation. Rehabil Nurs. 2006;31(1):22-25.

11. Reistetter TA, Graham JE, Deutsch A, Granger CV, Markello S, Ottenbacher KJ. Utility of functional status for classifying community versus institutional discharges after inpatient rehabilitation for stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(3):345-350.

12. Dietz JH Jr. Rehabilitation of the cancer patient. Med Clin North Am. 1969;53(3):607-624.

13. O'Toole DM, Golden AM. Evaluating cancer patients for rehabilitation potential. West J Med. 1991;155(4):384-387.

14. Marciniak CM, Sliwa JA, Spill G, Heinemann AW, Semik PE. Functional outcome following rehabilitation of the cancer patient. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77(1):54-57.

15. Hunter EG, Baltisberger J. Functional outcomes by age for inpatient cancer rehabilitation: a retrospective chart review. J Appl Gerontol. 2013;32(4):443-456.

16. Shin KY, Guo Y, Konzen B, Fu J, Yadav R, Bruera E. Inpatient cancer rehabilitation: the experience of a national comprehensive cancer center. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90(5 suppl 1):S63-S68.

17. Cole RP, Scialla S, Bednarz L. Functional recovery in cancer rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(5):623-627.

18. White AP, Kwon BK, Lindskog DM, Friedlaender GE, Grauer JN. Metastatic disease of the spine. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(11):587-598.

19. McKinley WO, Huang ME, Tewksbury MA. Neoplastic vs traumatic spinal cord injury: an inpatient rehabilitation comparison. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;79(2):138-144.

20. Eriks IE, Angenot EL, Lankhorst GJ. Epidural metastatic spinal cord compression: functional outcome and survival after inpatient rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2004;42(4):235-239.

21. Tang V, Harvey D, Park Dorsay J, Jiang S, Rathbone MP. Prognostic indicators in metastatic spinal cord compression: using functional independence measure and Tokuhashi scale to optimize rehabilitation planning. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(10):671-677.

22. Parsch D, Mikut R, Abel R. Postacute management of patients with spinal cord injury due to metastatic tumor disease: survival and efficacy of rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2003;41:205-210.

23. Murray PK. Functional outcome and survival in spinal cord injury secondary to neoplasia. Cancer. 1985;55:197-201.

24. New PW. Functional outcomes and disability after nontraumatic spinal cord injury rehabilitation: results from a retrospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(2):250-261

25. Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States: 2016 CBTRUS fact sheet. www.cbtrus.org/factsheet/factsheet.html. Updated 2017. Accessed May 28, 2016.

26. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center: Metastatic brain tumors & secondary brain cancer. https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/types/brain-tumors-metastatic. Updated 2018. Accessed April 21, 2018.

27. Bruckner JC, Brown PD, O'Neill BP, Meyer FB, Wetmore CJ, Uhm JH. Central nervous system tumors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(10):1271-1286.

28. Huang ME, Cifu DX, Keyser-Marcus L. Functional outcome after brain tumor and acute stroke: a comparative analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(11):1386-1390.

29. Greenberg E, Treger I, Ring H. Rehabilitation outcomes in patients with brain tumors and acute stroke: comparative study of inpatient rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(7):568-573.

30. Bartolo M, Zucchella C, Pace A, et al. Early rehabilitation after surgery improves functional outcomes in inpatients with brain tumours. J Neurooncol. 2012;107(3);537-544.

31. Huang ME, Cifu DX, Keyser-Marcus L. Functional outcomes in patients with brain tumor after inpatient rehabilitation: comparison with traumatic brain injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;79(4):327-335.

32. Tang V, Rathbone M, Park Dorsay J, Jiang S, Harvey D. Rehabilitation in primary and metastatic brain tumours: impact of functional outcomes on survival. J Neurol. 2008;255(6):820-827.

33. Marciniak CM, Sliwa JA, Heinemann AW, Semik PE. Functional outcomes of persons with brain tumors after inpatient rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(4):457-463.

34. O'Dell MW, Barr K, Spanier D, Warnick RE. Functional outcome of inpatient rehabilitation in persons with brain tumors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(12):1530-1534.

35. Asher A, Roberts PS, Bresee C, Zabel G, Riggs RV, Rogatko A. Transferring inpatient rehabilitation facility cancer patients back to acute care (TRIPBAC). PM R. 2014;6(9):808-813.

36. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Inpatient rehabilitation facilities. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/InpatientRehab.html. Published March 5, 2012. Accessed May 21, 2018.

The American Cancer Society reports that 1.6 million people are diagnosed with cancer each year, of whom 78% are aged 55 years or older. The 5-year survival rate for cancer is 68%.1 Almost 15.5 million living Americans have been diagnosed with cancer.2 Many patients with cancer have difficulty walking and with activities of daily living. Patients with primary brain tumors or tumors metastatic to the brain may present with focal weakness or cognitive deficits similar to patients with stroke. Patients with tumors metastatic to the spine may have the same deficits as a patient with a traumatic spinal cord injury. Patients with metastasis to bone may have pathologic fractures of the hip or long bones. Patients may develop peripheral neuropathy associated with a paraneoplastic syndrome, chemotherapy, or critical illness neuropathy. Lehmann and colleagues evaluated 805 patients admitted to hospitals affiliated with the University of Washington Medical School with a diagnosis of cancer and found that 15% had difficulty walking and 20% had difficulty with activities of daily living.3

Many patients with cancer can benefit from inpatient rehabilitation.4,5 Study findings have shown that patients with impairments in function related to cancer are often not referred for rehabilitation. Among the reasons mentioned for that are that oncologists are more focused on treating the patients’ cancer than on their functional deficits and that specialists in rehabilitation medicine do not want to be involved with patients with complex medical problems. Rehabilitation facilities may not want to incur the costs associated with caring for patients with cancer.6

The present paper looks at the outcomes of 61 consecutive patients with cancer who were admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF) and received radiation therapy concurrent with rehabilitation. It compares the outcomes of the cancer patients with the outcomes of patients without cancer who were admitted with stroke or spinal cord injury, conditions more commonly treated at an IRF.

Methods

We reviewed electronic medical records of all patients with cancer admitted to the IRF from 2008 through 2013 who received radiation therapy while at the facility. We also reviewed the data of all patients without cancer admitted with a diagnosis of stroke in 2013 and all patients admitted with a diagnosis of traumatic spinal cord injury in 2012 and 2013. No patients were excluded from stroke and traumatic spinal cord injury groups.

We recorded the sex, age, diagnostic group, Functional Independence Measure (FIM) admission score, FIM discharge score, length of stay (LoS) in the IRF, place of discharge of each patient (eg, home, acute care, or subacute care), and calculated the FIM efficiency score (change in FIM/LoS) for each patient. The FIM is an instrument that has 18 items measuring mobility, participation in activities of daily living, ability to communicate, and cognitive function.7 Each item is scored from 1 to 7, with 1 denoting that the patient cannot perform the task and 7 that the activity can be performed independently. The minimum score is 18 (complete dependence), and the maximum score is 126 (independent function). Thirteen items compose the motor FIM score: eating, grooming, bathing, dressing upper body, dressing lower body, toileting, bladder management, management of bowel, transfer to bed or wheelchair, transfer to toilet, tub transfer, walking (or wheelchair use), and climbing stairs. Five items – comprehension, expression, social interaction, problem solving, and memory – compose the cognitive FIM score.

We used a 1-way analysis of variance to evaluate differences between age and cancer type, age and diagnostic group, admission FIM score and cancer type, discharge FIM score and cancer type, change in FIM and cancer type, LoS and cancer type, and LoS and diagnostic group. The Pearson chi-square test was used to test the goodness of fit between the place of disposition and diagnostic group. The paired t test was used to evaluate the improvement in FIM of the patients who were in the cancer groups. The Tukey Simultaneous Tests for Differences of Means was used to compare the FIM efficiency scores of the groups. A 2-sample t test was used to evaluate the factors associated with the need for transfer from the IRF to the acute medical service.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the patients in the study and the admission and discharge FIM scores are reported in Table 1. There were initially 62 cancer patients in the radiation group, which was further divided into 4 subgroups based on the site of the primary tumor or metastasis. In all, 23 had a primary malignant brain tumor and received radiation and temozolomide. Sixteen patients had malignancies metastatic to the brain, 15 patients had tumors metastatic to the spine, and 7 had tumors metastatic to the long bones. One patient had laryngeal cancer and was excluded from the study because we did not think that we could do an analysis of a group with only 1 patient. The final number of patients in the cancer group was therefore 61. There were 69 patients in the stroke group and 23 in the spinal cord injury group.

We report improvement in total FIM, motor FIM, and cognitive FIM scores and were able to identify all 18 of the items of the FIM score on 60 of the 61 patients in the cancer group. Improvement in total FIM of the 61 patients in the cancer groups was significant at P P P = .05. Just over 75% of the patients in the cancer group had sufficient enough improvement in their level of function that they were able to return to their homes (Table 1). The average FIM score at the time of discharge was 83.08. This was not significantly different than the level of function of patients discharged after stroke (87.52) or traumatic spinal cord injury (89.13).

The patients with primary brain tumors were younger than the patients with cancer metastatic to the brain (P = .013). The patients with a primary brain tumor had lower admission FIM scores than patients with tumors metastatic to the brain (P = .027). The patients with a primary brain tumor had a greater increase in FIM score than patients with metastasis to the brain (P = .043; Table 2). There was not a significant difference between these 2 groups in FIM score at discharge or in the likelihood of discharge to home (Table 1). The FIM efficiency score was 1.12 for the patients in the primary brain tumor group and .80 in those with metastasis to the brain. This difference was not significant P = .96.

There were 69 patients in the stroke group. We compared the 39 patients with primary or metastatic brain lesion to the stroke group. The patients with primary or metastatic cancer of the brain were younger than the patients with stroke, 60.4 years old versus 69.1 years old (P = .004). The patients in the combined cancer group had a higher admission FIM score compared with the stroke patients (68.4 vs 63.12; P = .05). The discharge FIM scores were 83.3 in the combined cancer group and 87.5 in the stroke group (Table 1). This difference was not significant, but the improvement in the combined cancer group (14.6) was less than the improvement in the stroke group (24.40; P = .002) (Table 3).

The average LoS in the IRF was 18.7 days in the combined cancer group and 16.8 days in the stroke group. This difference was not significant. An average of 82% of the patients in the primary tumor or brain metastasis group and 85.5% of the patients in the stroke group were discharged to home. This difference was not significant. The FIM efficiency score of the patients in the stroke group was 2.0. This was significantly greater than the score for the patients in the metastasis to the brain group (0.80; P = .044) but not significantly greater than the primary brain cancer group (1.19; P = .22).

There were 23 patients in the traumatic spinal cord injury group. A comparison of the patients with tumors metastatic to the spine and patients with traumatic spinal cord injury showed that the patients in the cancer group were older (60.27 and 42.70 years, respectively; P = .001). In all, 80% of patients with tumors metastatic to the spine were men. This was not significantly different from the percentage of men in the traumatic spinal cord injury group (82.6%; Table 1). The admission FIM score of the patients with cancer was 66.5 (standard deviation [SD], 13.3) and 58.03 (SD, 15.1) in the patients with a traumatic spinal cord injury (Table 1). The FIM score at discharge was 80.4 (SD, 19.1) in the patients with cancer and 89.1 (SD, 20.3) in the patients with a traumatic spinal cord injury (Table 1). Neither of these were statistically significant. The improvement in patients with cancer was 13.9 (SD, 12.2) and 31.1 (SD, 13.9) in the traumatic spinal cord injured patients. This difference was significant (P

The median LoS was 18.98 days in the cancer metastasis to spine group (interquartile range [IQR] is the 25th-75th percentile, 12-30 days). In the traumatic group the median LoS was 23 days (IQR, 16-50 days). This difference was not significant (P = .14 Mann-Whitney test). The mean FIM efficiency score was 1.46 in the traumatic spinal cord injury group and .78 in the group with cancer metastatic to the spine. This difference was not significant (P = .72). Sixty percent of the patients in the cancer group were discharged to home, and 87% of patients in the traumatic spinal cord group were discharged to home. This difference was not significant (P = .12; Fisher exact test).

As far as we can ascertain, this is the first paper that has looked at the outcomes of patients receiving rehabilitation concurrent with radiation of the long bones. The average improvement in FIM was 12.4 (Table 1). The LoS was 11.6 days, and the FIM efficiency was 1.25. In all, 71.4% made enough progress to go home.

Of the total number of cancer patients, 18% were transferred to the acute medical service of the hospital (Table 1). Neither age, sex, type of cancer, nor admission FIM score were associated with the need for transfer to acute hospital care. Change in FIM score was inversely associated with transfer to acute hospital care (P = .027). Patients whose function did not improve with rehabilitation were most likely to be transferred back to acute hospital care.

Discussion

Radiation therapy is considered a service that is provided to people who come for treatment as an outpatient. Caregivers may have difficulty transporting patients to radiation if the patient has deficits in mobility. This may be particularly true if the patient is heavy, the caregivers are frail, or perhaps if they live in rural settings where there is no wheelchair-accessible public transportation. There are many factors that help determine whether a patient with functional deficits can be discharged to his or her home. These include sex, age, marital status, family and/or community support, income, and insurance.8 The FIM is an instrument that indicates how much help a patient needs with mobility and self-care skills. It also correlates with the amount of time that caregivers must spend helping a patient.9 Study findings have shown that the FIM score is an important determinant of whether a patient can be discharged to home. The total FIM score is as useful as an analysis of the components of the FIM score in predicting whether a patient can return to the community.10,11 Reistetter and colleagues found a total FIM score of 78 to be the score that best separates patients who are likely to be able to go home and patients who are likely to need long-term care.11 Bottemiller and colleagues10 reported that 37% of patients with total discharge FIM scores of less than 40 were discharged to home. They reported that 62% of patients with FIM scores between 40 and 79 were discharged to home, and 88% of patients with scores of 80 or above were discharged to home.10 The goal in bringing patients to the IRF was to accept and treat patients with reasonable community support and potential to achieve a functional level compatible with discharge to the community. Most patients in each of the cancer groups were able to reach an FIM score of 78 to 80 and to be discharged to home.

Most of the patients in the cancer groups had underlying problems that are not considered curable. The primary goal was to enable the patients to have some time at home with their families before requiring readmission to a hospital or hospice care. Reasonable LoS and rate of progress are now expected or required by third-party payors and hospital administrators. Physicians at the Mayo Clinic have indicated that a rehabilitation service should aim for an FIM efficiency score of at least .6 points per day.10 The FIM efficiency of patients in each of the 4 cancer subgroups in this study was higher than this level.

J. Herbert Dietz, Jr was an early advocate of the need to provide comprehensive rehabilitation services for patients with cancer. He first described his work in 1969.12 Since that time, there have been many papers that have documented the benefits of IRF for patients with cancer. O’Toole and Golden have shown outcomes of a large series of patients from an IRF. They reported that at the time of admission, 14% of patients could ambulate, but at discharge, 80% could ambulate without hands-on assistance. They reported significant improvements in continence, FIM score, and score on the Karnofsky Performance Scale.13 Marciniak,14 Hunter,15 Shin,16 and Cole,17 and their respective colleagues have all shown that patients with many different types of cancer benefit from rehabilitation at the IRF level. Gallegos-Kearin and colleagues4 reported on the care of 115,570 patients admitted to IRF with cancer from 2002 to 2014. Patients had significant improvement in function, with more than 70% of patients discharged to home.4 Ng and colleagues studied a group of 200 patients who received IRF care and found there was significant improvement in function. Ninety-four percent of patients rated their stay as either extremely good or very good.5

Metastasis to the spine is a common problem. It is found in 30% of cancer patients at autopsy. The most common sources of metastasis to the spine are breast, lung, prostate, kidney, and thyroid.18 Multiple myeloma and lymphoma may also involve the spine. Several authors have shown that these patients benefit from inpatient rehabilitation. Mckinley and colleagues19 have noted that patients with metastasis to the spine make significant improvement with care at an IRF. Compared with patients with a traumatic spinal cord injury, the cancer patients had shorter LoS, smaller improvement in FIM, equal FIM efficiency (FIM gain/LoS), and equal success in making enough progress to be discharged to home.19 Eriks and colleagues showed that patients at an IRF in Amsterdam made significant improvement in function as measured by the Barthel’s Index.20 Tang .,21 and Parsch22 and their respective colleagues, Murray,23 and New24 and colleagues have published findings confirming that patients with spinal cord injury caused by metastasis to the spine make significant progress with inpatient rehabilitation programs. The present study adds to the literature by showing that patients with metastasis to the spine who are receiving radiation can make progress and be discharged to the community.

There are 24,000 new cases of primary malignant brain tumors in the United States each year.25 The incidence of metastatic cancer to the brain has been estimated to be 100,000 cases per year in the United States. The most common cancer sources are lung, breast, melanoma, kidney, and colon.26,27 The first study of patients admitted to an IRF for treatment of brain tumors was published in 1998 by Huang and colleagues28 who compared the outcomes of 63 patients with brain tumors with the outcomes of 63 patients with stroke. They reported that the patients with the brain tumors made significant improvement in function. There was not a significant difference between the 2 groups of patients in improvement in function, FIM efficiency, or success in discharging the patients to home.28 Greenberg29 and Bartolo30 and their respective colleagues compared the outcomes of patients admitted with brain tumors and patients with stroke and found that improvement in function and discharge to home was similar in the 2 groups. In 2000, Huang and his same colleagues31 compared a group of patients with brain tumors to a group of patients with traumatic brain injury. They found significant improvement in the function of the patients with brain tumors. Patients in the traumatic brain injury group made more progress but had longer LoS. FIM efficiency was not significantly different between the groups.31

Three papers have reported outcomes of patients who received radiation concurrent with inpatient rehabilitation. Tang and colleagues32 reported 63 patients, of whom 48% percent received radiation concurrent with rehabilitation. The patients who received radiation made significant gains in function, and more than 70% were discharged to home. There was no difference in the outcomes of the patients in the radiation and nonradiation groups.32 Marciniak33 and O’Dell34 and their colleagues also reported that patients with brain tumors that required radiation therapy can benefit from inpatient rehabilitation. The present paper is the fourth (with the largest patient group) to show that patients with primary and metastatic tumors to the brain can benefit from a program that provides radiation concurrent with inpatient rehabilitation. We have shown that patients can achieve functional levels and rates of discharge to home that are not significantly different from those of the most commonly admitted group of patients to IRF – patients with stroke.

In the present study, 18% of all of the cancer patients were transferred to medical services and/or acute hospital care (Table 1). This is consistent with a paper by Asher and colleagues35 who reported that 17.4% of patients at an IRF with a diagnosis of cancer required transfer back to medical service, and that low admission motor FIM score correlated with the likelihood of transfer back to medical service. In the present paper, the total admission FIM score was not related to the likelihood of return to medical service, although a lack of improvement in the FIM score did correlate with transfer to medical service.

All of the papers we reviewed found that appropriately selected patients with cancer make significant improvement in function with treatment at an IRF. Tang and colleagues have also shown that for patients with malignant brain tumors and metastasis to the spine, improvement in function correlates with increased survival.32 Our paper confirms that patients with primary malignant brain tumors, malignant tumors metastatic to the brain or spine, and tumors metastatic to long bones may benefit from rehabilitation concurrent with radiation. Rehabilitation units are traditionally associated with treating patients with stroke and spinal cord injury. The patients in our study had cancer and were receiving radiation therapy. They had significant improvement in function and FIM efficiency scores that are not below the threshold set as expected for care at an IRF. Most patients in our study achieved a functional level consistent with what is needed to go home.