User login

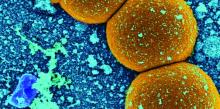

In ICU, pair MRSA testing method with isolation protocol

An ICU’s method of testing for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) should be paired with its patient isolation policy, according to researchers at the University of Colorado at Denver.

In an ICU with all patients preemptively isolated, it is worth the added expense to opt for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test – which generates results in a few hours – so that patients negative for the infection can be moved out of isolation more quickly, wrote Melanie D. Whittington, PhD, and her coauthors. But if the ICU is only isolating MRSA-positive patients, the authors instead recommend the less expensive but slower chromogenic agar 24-hour testing.

The other two MRSA tests the researchers assessed – conventional culture and chromogenic agar 48-hour testing – are less expensive. But when paired with either ICU isolation policy, those tests lead to excessive inappropriate isolation costs while waiting for the results, the study investigators cautioned (Am J Infect Control. 2017 Jan 23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.12.014).

Adding together the cost per patient of the test, the “appropriate isolation costs,” and “inappropriate isolation costs,” the universal isolation policy is least expensive per patient with PCR, at $82.51 per patient. With conventional culture, which can take several days, this cost ballooned to $290.11 per patient, with high inappropriate isolation costs.

Doing the same math with the more targeted isolation policy, the least expensive screening method was the 24-hour chromogenic agar, at $8.54 per patient, while the expense of the PCR test made it the most expensive method when paired with this isolation policy, at $30.95 per patient.

“With knowledge of the screening test that minimizes inappropriate and total costs, hospitals can maximize the efficiency of their resource use and improve the health of their patients,” Dr. Whittington and her coauthors wrote.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

An ICU’s method of testing for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) should be paired with its patient isolation policy, according to researchers at the University of Colorado at Denver.

In an ICU with all patients preemptively isolated, it is worth the added expense to opt for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test – which generates results in a few hours – so that patients negative for the infection can be moved out of isolation more quickly, wrote Melanie D. Whittington, PhD, and her coauthors. But if the ICU is only isolating MRSA-positive patients, the authors instead recommend the less expensive but slower chromogenic agar 24-hour testing.

The other two MRSA tests the researchers assessed – conventional culture and chromogenic agar 48-hour testing – are less expensive. But when paired with either ICU isolation policy, those tests lead to excessive inappropriate isolation costs while waiting for the results, the study investigators cautioned (Am J Infect Control. 2017 Jan 23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.12.014).

Adding together the cost per patient of the test, the “appropriate isolation costs,” and “inappropriate isolation costs,” the universal isolation policy is least expensive per patient with PCR, at $82.51 per patient. With conventional culture, which can take several days, this cost ballooned to $290.11 per patient, with high inappropriate isolation costs.

Doing the same math with the more targeted isolation policy, the least expensive screening method was the 24-hour chromogenic agar, at $8.54 per patient, while the expense of the PCR test made it the most expensive method when paired with this isolation policy, at $30.95 per patient.

“With knowledge of the screening test that minimizes inappropriate and total costs, hospitals can maximize the efficiency of their resource use and improve the health of their patients,” Dr. Whittington and her coauthors wrote.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

An ICU’s method of testing for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) should be paired with its patient isolation policy, according to researchers at the University of Colorado at Denver.

In an ICU with all patients preemptively isolated, it is worth the added expense to opt for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test – which generates results in a few hours – so that patients negative for the infection can be moved out of isolation more quickly, wrote Melanie D. Whittington, PhD, and her coauthors. But if the ICU is only isolating MRSA-positive patients, the authors instead recommend the less expensive but slower chromogenic agar 24-hour testing.

The other two MRSA tests the researchers assessed – conventional culture and chromogenic agar 48-hour testing – are less expensive. But when paired with either ICU isolation policy, those tests lead to excessive inappropriate isolation costs while waiting for the results, the study investigators cautioned (Am J Infect Control. 2017 Jan 23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.12.014).

Adding together the cost per patient of the test, the “appropriate isolation costs,” and “inappropriate isolation costs,” the universal isolation policy is least expensive per patient with PCR, at $82.51 per patient. With conventional culture, which can take several days, this cost ballooned to $290.11 per patient, with high inappropriate isolation costs.

Doing the same math with the more targeted isolation policy, the least expensive screening method was the 24-hour chromogenic agar, at $8.54 per patient, while the expense of the PCR test made it the most expensive method when paired with this isolation policy, at $30.95 per patient.

“With knowledge of the screening test that minimizes inappropriate and total costs, hospitals can maximize the efficiency of their resource use and improve the health of their patients,” Dr. Whittington and her coauthors wrote.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Bezlotoxumab prevents recurrent C. difficile infection

Adding bezlotoxumab to standard antibiotic treatment of primary or recurrent Clostridium difficile infection reduces recurrences by 38% (10 percentage points), according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

As many as 35% of patients who complete initial antibiotic treatment have at least one recurrence of C. difficile infection, and the rate of repeat recurrence rate jumps to 60% after the initial recurrence. Researchers performed two parallel international phase III trials to assess the efficacy and safety of bezlotoxumab, alone or in combination with actoxumab, for preventing such recurrences. Both monoclonal antibodies work by binding to and neutralizing C. difficile toxins; bezlotoxumab targets toxin B and actoxumab targets toxin A, said Mark H. Wilcox, MD, of the division of microbiology, Leeds (England) General Infirmary, and his associates.

The primary efficacy endpoint – the proportion of patients with recurrent C. difficile infection during 12 weeks of follow-up – was substantially lower with bezlotoxumab (17%) than with placebo (28%) in the first trial and in the second trial (16% vs. 26%). This treatment benefit was evident as early as 2 weeks after infusion and persisted throughout follow-up, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602615).

The agent’s persistent effect through 12 weeks is important to note because approximately 30% of the recurrences in this study “occurred beyond the conventional 4-week assessment period for treatment efficacy. The number needed to treat to prevent one episode of recurrent C. difficile infection was 10; it was 6 among participants 65 years of age or older and those with previous C. difficile infection,” Dr. Wilcox and his associates noted.

Bezlotoxumab was consistently effective in several sensitivity analyses. It also was effective in both trials individually as well as in pooled results. And the choice of oral antibiotic appeared to have no effect on bezlotoxumab’s efficacy.

In a post hoc analysis, bezlotoxumab was also effective in the subgroup of 1,964 patients at highest risk for C. difficile recurrence because they were elderly, had compromised immunity, had the most severe infections, had a history of C. difficile infection, or carried a strain of the organism associated with particularly poor outcomes. In this subgroup, 17% of patients given bezlotoxumab and 16% of those given bezlotoxumab plus actoxumab developed recurrences, compared with 30% of those given placebo.

Regarding adverse events, the agent had “a generally favorable safety profile,” and the rates of adverse events “were generally as expected, given the underlying disease severity, baseline coexisting conditions, and ages of the participants.” Two participants discontinued the infusion because of an adverse event. Drug-related adverse events occurred in 7% of the entire study population, serious drug-related adverse events occurred in 1%, and both occurred at similar rates across the study groups.

Both trials were funded by Merck, which also was involved in study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing the reports. Dr. Wilcox and his associates reported ties to Merck and numerous other industry sources.

Bezlotoxumab must be placed in perspective, seen within the context of alternative options currently being evaluated in clinical trials.

These include recently developed drugs such as ridinilazole, surotomycin, cadazolid, RBX2660, and SER-109. Also under assessment is the oral administration of nontoxigenic C. difficile strains to compete with toxigenic strains, as well as three vaccines against the organism. Stool transplantation also is known to be highly successful in preventing recurrent C. difficile infection.

In addition, the cost-effectiveness of bezlotoxumab, especially in relation to these alternative treatments, hasn’t yet been determined.

John G. Bartlett, MD, is in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Bartlett made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Wilcox’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1614726).

Bezlotoxumab must be placed in perspective, seen within the context of alternative options currently being evaluated in clinical trials.

These include recently developed drugs such as ridinilazole, surotomycin, cadazolid, RBX2660, and SER-109. Also under assessment is the oral administration of nontoxigenic C. difficile strains to compete with toxigenic strains, as well as three vaccines against the organism. Stool transplantation also is known to be highly successful in preventing recurrent C. difficile infection.

In addition, the cost-effectiveness of bezlotoxumab, especially in relation to these alternative treatments, hasn’t yet been determined.

John G. Bartlett, MD, is in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Bartlett made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Wilcox’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1614726).

Bezlotoxumab must be placed in perspective, seen within the context of alternative options currently being evaluated in clinical trials.

These include recently developed drugs such as ridinilazole, surotomycin, cadazolid, RBX2660, and SER-109. Also under assessment is the oral administration of nontoxigenic C. difficile strains to compete with toxigenic strains, as well as three vaccines against the organism. Stool transplantation also is known to be highly successful in preventing recurrent C. difficile infection.

In addition, the cost-effectiveness of bezlotoxumab, especially in relation to these alternative treatments, hasn’t yet been determined.

John G. Bartlett, MD, is in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Bartlett made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Wilcox’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1614726).

Adding bezlotoxumab to standard antibiotic treatment of primary or recurrent Clostridium difficile infection reduces recurrences by 38% (10 percentage points), according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

As many as 35% of patients who complete initial antibiotic treatment have at least one recurrence of C. difficile infection, and the rate of repeat recurrence rate jumps to 60% after the initial recurrence. Researchers performed two parallel international phase III trials to assess the efficacy and safety of bezlotoxumab, alone or in combination with actoxumab, for preventing such recurrences. Both monoclonal antibodies work by binding to and neutralizing C. difficile toxins; bezlotoxumab targets toxin B and actoxumab targets toxin A, said Mark H. Wilcox, MD, of the division of microbiology, Leeds (England) General Infirmary, and his associates.

The primary efficacy endpoint – the proportion of patients with recurrent C. difficile infection during 12 weeks of follow-up – was substantially lower with bezlotoxumab (17%) than with placebo (28%) in the first trial and in the second trial (16% vs. 26%). This treatment benefit was evident as early as 2 weeks after infusion and persisted throughout follow-up, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602615).

The agent’s persistent effect through 12 weeks is important to note because approximately 30% of the recurrences in this study “occurred beyond the conventional 4-week assessment period for treatment efficacy. The number needed to treat to prevent one episode of recurrent C. difficile infection was 10; it was 6 among participants 65 years of age or older and those with previous C. difficile infection,” Dr. Wilcox and his associates noted.

Bezlotoxumab was consistently effective in several sensitivity analyses. It also was effective in both trials individually as well as in pooled results. And the choice of oral antibiotic appeared to have no effect on bezlotoxumab’s efficacy.

In a post hoc analysis, bezlotoxumab was also effective in the subgroup of 1,964 patients at highest risk for C. difficile recurrence because they were elderly, had compromised immunity, had the most severe infections, had a history of C. difficile infection, or carried a strain of the organism associated with particularly poor outcomes. In this subgroup, 17% of patients given bezlotoxumab and 16% of those given bezlotoxumab plus actoxumab developed recurrences, compared with 30% of those given placebo.

Regarding adverse events, the agent had “a generally favorable safety profile,” and the rates of adverse events “were generally as expected, given the underlying disease severity, baseline coexisting conditions, and ages of the participants.” Two participants discontinued the infusion because of an adverse event. Drug-related adverse events occurred in 7% of the entire study population, serious drug-related adverse events occurred in 1%, and both occurred at similar rates across the study groups.

Both trials were funded by Merck, which also was involved in study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing the reports. Dr. Wilcox and his associates reported ties to Merck and numerous other industry sources.

Adding bezlotoxumab to standard antibiotic treatment of primary or recurrent Clostridium difficile infection reduces recurrences by 38% (10 percentage points), according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

As many as 35% of patients who complete initial antibiotic treatment have at least one recurrence of C. difficile infection, and the rate of repeat recurrence rate jumps to 60% after the initial recurrence. Researchers performed two parallel international phase III trials to assess the efficacy and safety of bezlotoxumab, alone or in combination with actoxumab, for preventing such recurrences. Both monoclonal antibodies work by binding to and neutralizing C. difficile toxins; bezlotoxumab targets toxin B and actoxumab targets toxin A, said Mark H. Wilcox, MD, of the division of microbiology, Leeds (England) General Infirmary, and his associates.

The primary efficacy endpoint – the proportion of patients with recurrent C. difficile infection during 12 weeks of follow-up – was substantially lower with bezlotoxumab (17%) than with placebo (28%) in the first trial and in the second trial (16% vs. 26%). This treatment benefit was evident as early as 2 weeks after infusion and persisted throughout follow-up, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602615).

The agent’s persistent effect through 12 weeks is important to note because approximately 30% of the recurrences in this study “occurred beyond the conventional 4-week assessment period for treatment efficacy. The number needed to treat to prevent one episode of recurrent C. difficile infection was 10; it was 6 among participants 65 years of age or older and those with previous C. difficile infection,” Dr. Wilcox and his associates noted.

Bezlotoxumab was consistently effective in several sensitivity analyses. It also was effective in both trials individually as well as in pooled results. And the choice of oral antibiotic appeared to have no effect on bezlotoxumab’s efficacy.

In a post hoc analysis, bezlotoxumab was also effective in the subgroup of 1,964 patients at highest risk for C. difficile recurrence because they were elderly, had compromised immunity, had the most severe infections, had a history of C. difficile infection, or carried a strain of the organism associated with particularly poor outcomes. In this subgroup, 17% of patients given bezlotoxumab and 16% of those given bezlotoxumab plus actoxumab developed recurrences, compared with 30% of those given placebo.

Regarding adverse events, the agent had “a generally favorable safety profile,” and the rates of adverse events “were generally as expected, given the underlying disease severity, baseline coexisting conditions, and ages of the participants.” Two participants discontinued the infusion because of an adverse event. Drug-related adverse events occurred in 7% of the entire study population, serious drug-related adverse events occurred in 1%, and both occurred at similar rates across the study groups.

Both trials were funded by Merck, which also was involved in study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing the reports. Dr. Wilcox and his associates reported ties to Merck and numerous other industry sources.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Adding bezlotoxumab to standard antibiotic treatment of primary or recurrent Clostridium difficile infection reduced recurrences by 38% (10 percentage points).

Major finding: The number needed to treat to prevent one episode of recurrent C. difficile infection was 10; it was 6 among high-risk participants who were 65 years of age or older or who had previous C. difficile infection.

Data source: Two parallel randomized double-blind placebo-controlled international trials involving 2,655 adults followed for 12 weeks.

Disclosures: Both trials were funded by Merck, which also was involved in study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing the reports. Dr. Wilcox and his associates reported ties to Merck and numerous other industry sources.

57% drop in central venous catheter–related infections after QI interventions

Quality improvement (QI) interventions related to the use of central venous catheters (CVCs) were, on average, associated with 57% fewer infections and $1.85 million in net savings to hospitals within 1-3 years of implementation, based on the results of a meta-analysis of data from 113 hospitals.

“Hospitals that have already attained very low infection rates (through the use of quality improvement checklists) would likely see smaller clinical benefits and savings than in the studies we have reviewed,” said Dr. Teryl Nuckols of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. “Nonetheless, we found that QI interventions can be associated with declines in CLABSI (central line-associated bloodstream infection) and/or CRBSI (catheter-related bloodstream infection) and net savings when checklists are already in use, and when hospitals have CLABSI rates as low as 1.7-3.7 per 1,000 CVC-days.”

Studies were eligible for the analysis if they reported or estimated the quality improvement intervention’s clinical effectiveness, measured or modeled its costs, compared alternatives to the intervention, and reported both program and infection-related costs.

Insertion checklists were examined in 12 studies, physician education in 11 studies, ultrasound-guided placement of catheters in 3 studies, all-inclusive catheter kits in 5 studies, sterile dressings in 5 studies, chlorhexidine gluconate sponge or antimicrobial dressing in 2 studies, and antimicrobial catheters in 2 studies.

Overall, the weighted mean incidence rate ratio was 0.43 (95% confidence interval, 0.35-0.51) and incremental net savings were $1.85 million (95% CI, $1.30 million to $2.40 million) per hospital over 3 years (2015 U.S. dollars). Each $100,000 increase in program cost was associated with $315,000 greater savings (95% CI, $166 000-$464 000; P less than .001). Infections and net costs declined when hospitals already used checklists or had baseline infection rates of 1.7-3.7 per 1,000 catheter-days. (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6610)

Dr. Nuckols acknowledged that the price tag for achieving these savings “may be burdensome for hospitals with limited financial resources … wages and benefits account for two-thirds of all spending by hospitals, and a quarter of hospitals have had negative operating margins in recent years. We found that, for CLABSI- and CRBSI-prevention interventions, median program costs were about $270,000 per hospital over 3 years – but reached $500,000 to $750,000 in some studies.”

The researchers recommended that “future research should more thoroughly examine the relationships among hospital financial performance, economic investments in QI, and effects on quality of care.”

Quality improvement (QI) interventions related to the use of central venous catheters (CVCs) were, on average, associated with 57% fewer infections and $1.85 million in net savings to hospitals within 1-3 years of implementation, based on the results of a meta-analysis of data from 113 hospitals.

“Hospitals that have already attained very low infection rates (through the use of quality improvement checklists) would likely see smaller clinical benefits and savings than in the studies we have reviewed,” said Dr. Teryl Nuckols of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. “Nonetheless, we found that QI interventions can be associated with declines in CLABSI (central line-associated bloodstream infection) and/or CRBSI (catheter-related bloodstream infection) and net savings when checklists are already in use, and when hospitals have CLABSI rates as low as 1.7-3.7 per 1,000 CVC-days.”

Studies were eligible for the analysis if they reported or estimated the quality improvement intervention’s clinical effectiveness, measured or modeled its costs, compared alternatives to the intervention, and reported both program and infection-related costs.

Insertion checklists were examined in 12 studies, physician education in 11 studies, ultrasound-guided placement of catheters in 3 studies, all-inclusive catheter kits in 5 studies, sterile dressings in 5 studies, chlorhexidine gluconate sponge or antimicrobial dressing in 2 studies, and antimicrobial catheters in 2 studies.

Overall, the weighted mean incidence rate ratio was 0.43 (95% confidence interval, 0.35-0.51) and incremental net savings were $1.85 million (95% CI, $1.30 million to $2.40 million) per hospital over 3 years (2015 U.S. dollars). Each $100,000 increase in program cost was associated with $315,000 greater savings (95% CI, $166 000-$464 000; P less than .001). Infections and net costs declined when hospitals already used checklists or had baseline infection rates of 1.7-3.7 per 1,000 catheter-days. (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6610)

Dr. Nuckols acknowledged that the price tag for achieving these savings “may be burdensome for hospitals with limited financial resources … wages and benefits account for two-thirds of all spending by hospitals, and a quarter of hospitals have had negative operating margins in recent years. We found that, for CLABSI- and CRBSI-prevention interventions, median program costs were about $270,000 per hospital over 3 years – but reached $500,000 to $750,000 in some studies.”

The researchers recommended that “future research should more thoroughly examine the relationships among hospital financial performance, economic investments in QI, and effects on quality of care.”

Quality improvement (QI) interventions related to the use of central venous catheters (CVCs) were, on average, associated with 57% fewer infections and $1.85 million in net savings to hospitals within 1-3 years of implementation, based on the results of a meta-analysis of data from 113 hospitals.

“Hospitals that have already attained very low infection rates (through the use of quality improvement checklists) would likely see smaller clinical benefits and savings than in the studies we have reviewed,” said Dr. Teryl Nuckols of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. “Nonetheless, we found that QI interventions can be associated with declines in CLABSI (central line-associated bloodstream infection) and/or CRBSI (catheter-related bloodstream infection) and net savings when checklists are already in use, and when hospitals have CLABSI rates as low as 1.7-3.7 per 1,000 CVC-days.”

Studies were eligible for the analysis if they reported or estimated the quality improvement intervention’s clinical effectiveness, measured or modeled its costs, compared alternatives to the intervention, and reported both program and infection-related costs.

Insertion checklists were examined in 12 studies, physician education in 11 studies, ultrasound-guided placement of catheters in 3 studies, all-inclusive catheter kits in 5 studies, sterile dressings in 5 studies, chlorhexidine gluconate sponge or antimicrobial dressing in 2 studies, and antimicrobial catheters in 2 studies.

Overall, the weighted mean incidence rate ratio was 0.43 (95% confidence interval, 0.35-0.51) and incremental net savings were $1.85 million (95% CI, $1.30 million to $2.40 million) per hospital over 3 years (2015 U.S. dollars). Each $100,000 increase in program cost was associated with $315,000 greater savings (95% CI, $166 000-$464 000; P less than .001). Infections and net costs declined when hospitals already used checklists or had baseline infection rates of 1.7-3.7 per 1,000 catheter-days. (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6610)

Dr. Nuckols acknowledged that the price tag for achieving these savings “may be burdensome for hospitals with limited financial resources … wages and benefits account for two-thirds of all spending by hospitals, and a quarter of hospitals have had negative operating margins in recent years. We found that, for CLABSI- and CRBSI-prevention interventions, median program costs were about $270,000 per hospital over 3 years – but reached $500,000 to $750,000 in some studies.”

The researchers recommended that “future research should more thoroughly examine the relationships among hospital financial performance, economic investments in QI, and effects on quality of care.”

Ultrashort course antibiotics may be enough in stable VAP

Ultrashort courses of antibiotics led to similar outcomes as longer durations of therapy among adults with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia but minimal and stable ventilator settings, according to a large retrospective observational study.

The duration of antibiotic therapy did not significantly affect the time to extubation alive (hazard ratio, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.0-1.4), time to hospital discharge (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.3), rates of ventilator death (HR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6-1.2), or rates of hospital death (HR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.8-1.31).), said Michael Klompas, MD, and his associates at Harvard Medical School in Boston. If confirmed, the findings would support surveillance of serial ventilator settings to “identify candidates for early antibiotic discontinuation,” the investigators reported (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Dec 29. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw870).

Suspected respiratory infections account for up to 70% of ICU antibiotic prescriptions, a “substantial fraction” of which may be unnecessary, the researchers said. “The predilection to overprescribe antibiotics for patients with possible ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is not due to poor clinical skills per se, but rather the tension between practice guidelines that encourage early and aggressive prescribing [and] the difficulty [of] accurately diagnosing VAP,” they wrote. While withholding antibiotics in suspected VAP is “unrealistic” and can contribute to mortality, observing clinical trajectories and stopping antibiotics early when appropriate “may be more promising,” they added.

To test that idea, the researchers studied 1,290 cases of suspected VAP treated at Brigham and Women’s Hospital between 2006 and 2014. On the day antibiotics were started and during each of the next 2 days, all patients had a daily minimum positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of no more than 5 cm H2O and a daily minimum fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of no more than 40%.

A total of 259 patients received 1-3 days of antibiotics, while 1,031 patients received more than 3 days of therapy. These two groups were similar demographically, clinically, and in terms of comorbidities. Point estimates tended to favor ultrashort course antibiotics, but no association reached statistical significance in the overall analysis or in subgroups based on confirmed VAP diagnosis, confirmed pathogenic infection, or propensity-matched pairs.

The results suggest “that patients with suspected VAP but minimal and stable ventilator settings can be adequately managed with very short courses of antibiotics,” Dr. Klompas and his associates concluded. “If these findings are confirmed, assessing ventilator settings may prove to be a simple and objective strategy to identify potential candidates for early antibiotic discontinuation.”

The work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Prevention Epicenters Program. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

Ultrashort courses of antibiotics led to similar outcomes as longer durations of therapy among adults with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia but minimal and stable ventilator settings, according to a large retrospective observational study.

The duration of antibiotic therapy did not significantly affect the time to extubation alive (hazard ratio, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.0-1.4), time to hospital discharge (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.3), rates of ventilator death (HR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6-1.2), or rates of hospital death (HR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.8-1.31).), said Michael Klompas, MD, and his associates at Harvard Medical School in Boston. If confirmed, the findings would support surveillance of serial ventilator settings to “identify candidates for early antibiotic discontinuation,” the investigators reported (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Dec 29. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw870).

Suspected respiratory infections account for up to 70% of ICU antibiotic prescriptions, a “substantial fraction” of which may be unnecessary, the researchers said. “The predilection to overprescribe antibiotics for patients with possible ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is not due to poor clinical skills per se, but rather the tension between practice guidelines that encourage early and aggressive prescribing [and] the difficulty [of] accurately diagnosing VAP,” they wrote. While withholding antibiotics in suspected VAP is “unrealistic” and can contribute to mortality, observing clinical trajectories and stopping antibiotics early when appropriate “may be more promising,” they added.

To test that idea, the researchers studied 1,290 cases of suspected VAP treated at Brigham and Women’s Hospital between 2006 and 2014. On the day antibiotics were started and during each of the next 2 days, all patients had a daily minimum positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of no more than 5 cm H2O and a daily minimum fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of no more than 40%.

A total of 259 patients received 1-3 days of antibiotics, while 1,031 patients received more than 3 days of therapy. These two groups were similar demographically, clinically, and in terms of comorbidities. Point estimates tended to favor ultrashort course antibiotics, but no association reached statistical significance in the overall analysis or in subgroups based on confirmed VAP diagnosis, confirmed pathogenic infection, or propensity-matched pairs.

The results suggest “that patients with suspected VAP but minimal and stable ventilator settings can be adequately managed with very short courses of antibiotics,” Dr. Klompas and his associates concluded. “If these findings are confirmed, assessing ventilator settings may prove to be a simple and objective strategy to identify potential candidates for early antibiotic discontinuation.”

The work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Prevention Epicenters Program. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

Ultrashort courses of antibiotics led to similar outcomes as longer durations of therapy among adults with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia but minimal and stable ventilator settings, according to a large retrospective observational study.

The duration of antibiotic therapy did not significantly affect the time to extubation alive (hazard ratio, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.0-1.4), time to hospital discharge (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.3), rates of ventilator death (HR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6-1.2), or rates of hospital death (HR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.8-1.31).), said Michael Klompas, MD, and his associates at Harvard Medical School in Boston. If confirmed, the findings would support surveillance of serial ventilator settings to “identify candidates for early antibiotic discontinuation,” the investigators reported (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Dec 29. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw870).

Suspected respiratory infections account for up to 70% of ICU antibiotic prescriptions, a “substantial fraction” of which may be unnecessary, the researchers said. “The predilection to overprescribe antibiotics for patients with possible ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is not due to poor clinical skills per se, but rather the tension between practice guidelines that encourage early and aggressive prescribing [and] the difficulty [of] accurately diagnosing VAP,” they wrote. While withholding antibiotics in suspected VAP is “unrealistic” and can contribute to mortality, observing clinical trajectories and stopping antibiotics early when appropriate “may be more promising,” they added.

To test that idea, the researchers studied 1,290 cases of suspected VAP treated at Brigham and Women’s Hospital between 2006 and 2014. On the day antibiotics were started and during each of the next 2 days, all patients had a daily minimum positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of no more than 5 cm H2O and a daily minimum fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of no more than 40%.

A total of 259 patients received 1-3 days of antibiotics, while 1,031 patients received more than 3 days of therapy. These two groups were similar demographically, clinically, and in terms of comorbidities. Point estimates tended to favor ultrashort course antibiotics, but no association reached statistical significance in the overall analysis or in subgroups based on confirmed VAP diagnosis, confirmed pathogenic infection, or propensity-matched pairs.

The results suggest “that patients with suspected VAP but minimal and stable ventilator settings can be adequately managed with very short courses of antibiotics,” Dr. Klompas and his associates concluded. “If these findings are confirmed, assessing ventilator settings may prove to be a simple and objective strategy to identify potential candidates for early antibiotic discontinuation.”

The work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Prevention Epicenters Program. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

Key clinical point: Ultrashort antibiotic courses yielded outcomes that were similar to those with longer courses in patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia but minimal and stable ventilator settings.

Major finding: The groups did not significantly differ based on time to extubation alive (hazard ratio, 1.2), time to hospital discharge (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.3), rates of ventilator death (HR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6-1.2), or rates of hospital death (HR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.8-1.31).

Data source: A single-center retrospective observational study of 1,290 patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Disclosures: The work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Prevention Epicenters Program. The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

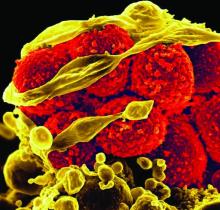

VA MRSA Prevention Initiative reports continued health care–associated infection declines

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs MRSA Prevention Initiative, implemented in October 2007, has shown progress at limiting health care–associated infections of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus through 2011 and 2012.

A new report published in the January 2017 issue of the American Journal of Infection Control tracks continued declines in infection through September 2015.

Monthly rates of health care–associated infections fell significantly in all settings from October 2007 to September 2015: an 87% decrease in ICUs, 80.1% in non-ICUs, 80.9% in spinal cord injury units, and 49.4% in long-term care facilities (P for all less than .0001).

“The VA data suggest that active surveillance followed by contact precautions (with or without decolonization) may be most useful when MRSA [health care–associated infection] rates are unacceptably high (as they were in VA facilities during 2007) or to decrease infections in high-risk units such as ICUs,” Dr. Evans and his colleagues concluded.

Details about the implementation of the initiative were previously published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011, including the initiative’s goal to promote “a change in the institutional culture whereby infection control would become the responsibility of everyone who had contact with patients” (N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1419-30).

Dr. Evans and his colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs MRSA Prevention Initiative, implemented in October 2007, has shown progress at limiting health care–associated infections of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus through 2011 and 2012.

A new report published in the January 2017 issue of the American Journal of Infection Control tracks continued declines in infection through September 2015.

Monthly rates of health care–associated infections fell significantly in all settings from October 2007 to September 2015: an 87% decrease in ICUs, 80.1% in non-ICUs, 80.9% in spinal cord injury units, and 49.4% in long-term care facilities (P for all less than .0001).

“The VA data suggest that active surveillance followed by contact precautions (with or without decolonization) may be most useful when MRSA [health care–associated infection] rates are unacceptably high (as they were in VA facilities during 2007) or to decrease infections in high-risk units such as ICUs,” Dr. Evans and his colleagues concluded.

Details about the implementation of the initiative were previously published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011, including the initiative’s goal to promote “a change in the institutional culture whereby infection control would become the responsibility of everyone who had contact with patients” (N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1419-30).

Dr. Evans and his colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs MRSA Prevention Initiative, implemented in October 2007, has shown progress at limiting health care–associated infections of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus through 2011 and 2012.

A new report published in the January 2017 issue of the American Journal of Infection Control tracks continued declines in infection through September 2015.

Monthly rates of health care–associated infections fell significantly in all settings from October 2007 to September 2015: an 87% decrease in ICUs, 80.1% in non-ICUs, 80.9% in spinal cord injury units, and 49.4% in long-term care facilities (P for all less than .0001).

“The VA data suggest that active surveillance followed by contact precautions (with or without decolonization) may be most useful when MRSA [health care–associated infection] rates are unacceptably high (as they were in VA facilities during 2007) or to decrease infections in high-risk units such as ICUs,” Dr. Evans and his colleagues concluded.

Details about the implementation of the initiative were previously published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011, including the initiative’s goal to promote “a change in the institutional culture whereby infection control would become the responsibility of everyone who had contact with patients” (N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1419-30).

Dr. Evans and his colleagues had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF INFECTION CONTROL

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Endoscope reprocessing guidelines are an improvement

While the 2016 Multi-Society Task Force Endoscope Reprocessing Guidelines are an improvement over the 2011 guidelines, some of its minor changes are unlikely to guarantee against prevention of future outbreaks, according to Susan Hutfless, PhD, and Anthony N. Kalloo, MD.*

“The prevention of future outbreaks is left to the manufacturers to modify their protocols and the endoscopy units to adopt the protocols rapidly,” the authors, both from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in a commentary about the 2016 guidelines, which contain 41 recommendations and were endorsed by the AGA. “If followed, the guidelines will make it possible to better track the source of future outbreaks if the tracking and monitoring suggested is performed.” They added that the current cleaning paradigm for duodenoscopes “is ineffective and these guidelines reflect changes to contain, rather than prevent, future outbreaks.”

Some of the specific changes to the 2016 guidelines include recommendation no. 5, which has been revised to recommend “strict adherence” to manufacturer guidance. “The expectation is that all personnel will remain up to date with the manufacturer guidelines and that there will be documentation of the training,” Dr. Hutfless and Dr. Kalloo wrote. The 2016 guidelines specifically state that a “single standard work process within one institution may be insufficient, given differences among manufacturers’ instructions and varied instrument designs.” However, Dr. Hutfless and Dr. Kalloo point out that “an individual or group of individuals may need to be identified to keep up with the FDA, CDC, manufacturer and professional societies in order to modify and implement the changes to the cleaning and training protocols and update the training of all individuals in the unit. It is unclear from the guidelines what the minimum time should be between change in recommendations and updated training.”

Recommendation no. 24 is new and includes a suggestion consistent with the 2015 FDA endoscope reprocessing communications. “Beyond the reprocessing steps discussed in these recommendations, no validated methods for additional duodenoscope reprocessing currently exist,” the guidelines state. “However, units should review and consider the feasibility and appropriateness for their practice of employing one or more of the additional modalities suggested by the FDA for duodenoscopes: intermittent or per procedure culture surveillance of reprocessing outcomes, sterilization with ethylene oxide gas, repeat application of standard high level disinfection, or use of a liquid chemical germicide.” For their part, Dr. Hutfless and Dr. Kalloo pointed out the limitations of these additional modalities. For example, they wrote, “the per procedure culture surveillance modality suggested by the FDA is not cost-effective unless the unit’s transmission probability of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae is 24% or greater. Sterilization with ethylene oxide is problematic because a unit that used this approach still encountered an endoscope with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae detected by culture. This unit also incurred extra costs to purchase additional scopes due to the longer reprocessing time for sterilization and had a greater number of endoscopes with damage, although the damage was not directly attributable to sterilization” (Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Aug;84:259-62).

In 2016, the FDA approved the first disposable colonoscope, a product that is expected to be available in the United States in early 2017. Dr. Hutfless and Dr. Kalloo ended their commentary by suggesting that a disposable endoscope with an elevator mechanism, though not currently available, could be a solution to several of the unresolved issues that were present in the 2003, 2011, and 2016 guidelines. “These unresolved issues include interval of storage after reprocessing, microbiologic surveillance, and endoscope durability and longevity,” they wrote. “If the outbreaks persist after the use of disposable endoscopes it is possible that it is some other product or procedure within the endoscopic procedure that is the source of the infectious transmission.”

*This story was update on Jan. 26, 2017.

While the 2016 Multi-Society Task Force Endoscope Reprocessing Guidelines are an improvement over the 2011 guidelines, some of its minor changes are unlikely to guarantee against prevention of future outbreaks, according to Susan Hutfless, PhD, and Anthony N. Kalloo, MD.*

“The prevention of future outbreaks is left to the manufacturers to modify their protocols and the endoscopy units to adopt the protocols rapidly,” the authors, both from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in a commentary about the 2016 guidelines, which contain 41 recommendations and were endorsed by the AGA. “If followed, the guidelines will make it possible to better track the source of future outbreaks if the tracking and monitoring suggested is performed.” They added that the current cleaning paradigm for duodenoscopes “is ineffective and these guidelines reflect changes to contain, rather than prevent, future outbreaks.”

Some of the specific changes to the 2016 guidelines include recommendation no. 5, which has been revised to recommend “strict adherence” to manufacturer guidance. “The expectation is that all personnel will remain up to date with the manufacturer guidelines and that there will be documentation of the training,” Dr. Hutfless and Dr. Kalloo wrote. The 2016 guidelines specifically state that a “single standard work process within one institution may be insufficient, given differences among manufacturers’ instructions and varied instrument designs.” However, Dr. Hutfless and Dr. Kalloo point out that “an individual or group of individuals may need to be identified to keep up with the FDA, CDC, manufacturer and professional societies in order to modify and implement the changes to the cleaning and training protocols and update the training of all individuals in the unit. It is unclear from the guidelines what the minimum time should be between change in recommendations and updated training.”

Recommendation no. 24 is new and includes a suggestion consistent with the 2015 FDA endoscope reprocessing communications. “Beyond the reprocessing steps discussed in these recommendations, no validated methods for additional duodenoscope reprocessing currently exist,” the guidelines state. “However, units should review and consider the feasibility and appropriateness for their practice of employing one or more of the additional modalities suggested by the FDA for duodenoscopes: intermittent or per procedure culture surveillance of reprocessing outcomes, sterilization with ethylene oxide gas, repeat application of standard high level disinfection, or use of a liquid chemical germicide.” For their part, Dr. Hutfless and Dr. Kalloo pointed out the limitations of these additional modalities. For example, they wrote, “the per procedure culture surveillance modality suggested by the FDA is not cost-effective unless the unit’s transmission probability of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae is 24% or greater. Sterilization with ethylene oxide is problematic because a unit that used this approach still encountered an endoscope with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae detected by culture. This unit also incurred extra costs to purchase additional scopes due to the longer reprocessing time for sterilization and had a greater number of endoscopes with damage, although the damage was not directly attributable to sterilization” (Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Aug;84:259-62).

In 2016, the FDA approved the first disposable colonoscope, a product that is expected to be available in the United States in early 2017. Dr. Hutfless and Dr. Kalloo ended their commentary by suggesting that a disposable endoscope with an elevator mechanism, though not currently available, could be a solution to several of the unresolved issues that were present in the 2003, 2011, and 2016 guidelines. “These unresolved issues include interval of storage after reprocessing, microbiologic surveillance, and endoscope durability and longevity,” they wrote. “If the outbreaks persist after the use of disposable endoscopes it is possible that it is some other product or procedure within the endoscopic procedure that is the source of the infectious transmission.”

*This story was update on Jan. 26, 2017.

While the 2016 Multi-Society Task Force Endoscope Reprocessing Guidelines are an improvement over the 2011 guidelines, some of its minor changes are unlikely to guarantee against prevention of future outbreaks, according to Susan Hutfless, PhD, and Anthony N. Kalloo, MD.*

“The prevention of future outbreaks is left to the manufacturers to modify their protocols and the endoscopy units to adopt the protocols rapidly,” the authors, both from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in a commentary about the 2016 guidelines, which contain 41 recommendations and were endorsed by the AGA. “If followed, the guidelines will make it possible to better track the source of future outbreaks if the tracking and monitoring suggested is performed.” They added that the current cleaning paradigm for duodenoscopes “is ineffective and these guidelines reflect changes to contain, rather than prevent, future outbreaks.”

Some of the specific changes to the 2016 guidelines include recommendation no. 5, which has been revised to recommend “strict adherence” to manufacturer guidance. “The expectation is that all personnel will remain up to date with the manufacturer guidelines and that there will be documentation of the training,” Dr. Hutfless and Dr. Kalloo wrote. The 2016 guidelines specifically state that a “single standard work process within one institution may be insufficient, given differences among manufacturers’ instructions and varied instrument designs.” However, Dr. Hutfless and Dr. Kalloo point out that “an individual or group of individuals may need to be identified to keep up with the FDA, CDC, manufacturer and professional societies in order to modify and implement the changes to the cleaning and training protocols and update the training of all individuals in the unit. It is unclear from the guidelines what the minimum time should be between change in recommendations and updated training.”

Recommendation no. 24 is new and includes a suggestion consistent with the 2015 FDA endoscope reprocessing communications. “Beyond the reprocessing steps discussed in these recommendations, no validated methods for additional duodenoscope reprocessing currently exist,” the guidelines state. “However, units should review and consider the feasibility and appropriateness for their practice of employing one or more of the additional modalities suggested by the FDA for duodenoscopes: intermittent or per procedure culture surveillance of reprocessing outcomes, sterilization with ethylene oxide gas, repeat application of standard high level disinfection, or use of a liquid chemical germicide.” For their part, Dr. Hutfless and Dr. Kalloo pointed out the limitations of these additional modalities. For example, they wrote, “the per procedure culture surveillance modality suggested by the FDA is not cost-effective unless the unit’s transmission probability of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae is 24% or greater. Sterilization with ethylene oxide is problematic because a unit that used this approach still encountered an endoscope with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae detected by culture. This unit also incurred extra costs to purchase additional scopes due to the longer reprocessing time for sterilization and had a greater number of endoscopes with damage, although the damage was not directly attributable to sterilization” (Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Aug;84:259-62).

In 2016, the FDA approved the first disposable colonoscope, a product that is expected to be available in the United States in early 2017. Dr. Hutfless and Dr. Kalloo ended their commentary by suggesting that a disposable endoscope with an elevator mechanism, though not currently available, could be a solution to several of the unresolved issues that were present in the 2003, 2011, and 2016 guidelines. “These unresolved issues include interval of storage after reprocessing, microbiologic surveillance, and endoscope durability and longevity,” they wrote. “If the outbreaks persist after the use of disposable endoscopes it is possible that it is some other product or procedure within the endoscopic procedure that is the source of the infectious transmission.”

*This story was update on Jan. 26, 2017.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Rhinovirus most often caused HA-VRIs in two hospitals

Health care–associated viral respiratory infections (HA-VRIs) were common in two pediatric hospitals, with rhinovirus the most frequent cause of the infections in a 3-year analysis.

The incidence rate of laboratory-confirmed HA-VRIs was 1.29/1,000 patient-days in an examination of the hospitals’ patient data. Forty-eight percent of all 323 HA-VRI cases were caused by rhinovirus, with an overall incidence rate of 0.72/1,000 patient-days. Additionally, rhinovirus was the most frequently identified virus in cases of HA-VRI in all units of both hospitals, followed by parainfluenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus. An exception was the medical/surgical ward of Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center (CCMC) of New York; in this unit of the CCMC, the incidence rate of parainfluenza virus was higher than that of rhinovirus (0.21/1,000 patient-days vs. 0.15/1,000 patient-days) (J Ped Inf Dis. 2016. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw072).

The researchers used infection prevention and control surveillance databases from Montreal Children’s Hospital (MCH) in Quebec and the CCMC to identify HA-VRIs that occurred between April 1, 2010, and March 31, 2013, In both hospitals, HAIs were attributed to the unit to which the patient was admitted at the time of transmission. Both hospitals used a multiplex nucleic acid amplification test for respiratory virus detection on nasopharyngeal swabs or aspirates.

“An HA-VRI with an onset of symptoms after hospital discharge would be detected and included only for patients who presented to the emergency department or were readmitted for VRI and tested,” according to Caroline Quach, MD, of the Montreal Children’s Hospital, McGill University Health Centre, Quebec, and her colleagues.

The HA-VRI rate was 1.91/1,000 patient-days at Montreal Children’s Hospital, compared with 0.80/1,000 patient-days at the CCMC (P less than .0001). At the CCMC, the HA-VRI incidence rate was lowest in the neonatal ICU, but at Montgomery Children’s Hospital, the hematology/oncology ward had the lowest rate of HA-VRI.

Having less than 50% single rooms in a given unit was associated with a statistically significantly higher rate of HA-VRI, after the investigators adjusted for unit type and took the correlation of HA-VRI rates within a hospital into consideration. The study authors’ model predicted that units with less than 50% single rooms have 1.33 times higher HA-VRI rates than units with at least 50% single rooms, regardless of unit type.

Dr. Quach has received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Sage, and AbbVie for an unrelated research project, while the other authors disclosed no financial relationships.

Health care–associated viral respiratory infections (HA-VRIs) were common in two pediatric hospitals, with rhinovirus the most frequent cause of the infections in a 3-year analysis.

The incidence rate of laboratory-confirmed HA-VRIs was 1.29/1,000 patient-days in an examination of the hospitals’ patient data. Forty-eight percent of all 323 HA-VRI cases were caused by rhinovirus, with an overall incidence rate of 0.72/1,000 patient-days. Additionally, rhinovirus was the most frequently identified virus in cases of HA-VRI in all units of both hospitals, followed by parainfluenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus. An exception was the medical/surgical ward of Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center (CCMC) of New York; in this unit of the CCMC, the incidence rate of parainfluenza virus was higher than that of rhinovirus (0.21/1,000 patient-days vs. 0.15/1,000 patient-days) (J Ped Inf Dis. 2016. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw072).

The researchers used infection prevention and control surveillance databases from Montreal Children’s Hospital (MCH) in Quebec and the CCMC to identify HA-VRIs that occurred between April 1, 2010, and March 31, 2013, In both hospitals, HAIs were attributed to the unit to which the patient was admitted at the time of transmission. Both hospitals used a multiplex nucleic acid amplification test for respiratory virus detection on nasopharyngeal swabs or aspirates.

“An HA-VRI with an onset of symptoms after hospital discharge would be detected and included only for patients who presented to the emergency department or were readmitted for VRI and tested,” according to Caroline Quach, MD, of the Montreal Children’s Hospital, McGill University Health Centre, Quebec, and her colleagues.

The HA-VRI rate was 1.91/1,000 patient-days at Montreal Children’s Hospital, compared with 0.80/1,000 patient-days at the CCMC (P less than .0001). At the CCMC, the HA-VRI incidence rate was lowest in the neonatal ICU, but at Montgomery Children’s Hospital, the hematology/oncology ward had the lowest rate of HA-VRI.

Having less than 50% single rooms in a given unit was associated with a statistically significantly higher rate of HA-VRI, after the investigators adjusted for unit type and took the correlation of HA-VRI rates within a hospital into consideration. The study authors’ model predicted that units with less than 50% single rooms have 1.33 times higher HA-VRI rates than units with at least 50% single rooms, regardless of unit type.

Dr. Quach has received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Sage, and AbbVie for an unrelated research project, while the other authors disclosed no financial relationships.

Health care–associated viral respiratory infections (HA-VRIs) were common in two pediatric hospitals, with rhinovirus the most frequent cause of the infections in a 3-year analysis.

The incidence rate of laboratory-confirmed HA-VRIs was 1.29/1,000 patient-days in an examination of the hospitals’ patient data. Forty-eight percent of all 323 HA-VRI cases were caused by rhinovirus, with an overall incidence rate of 0.72/1,000 patient-days. Additionally, rhinovirus was the most frequently identified virus in cases of HA-VRI in all units of both hospitals, followed by parainfluenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus. An exception was the medical/surgical ward of Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center (CCMC) of New York; in this unit of the CCMC, the incidence rate of parainfluenza virus was higher than that of rhinovirus (0.21/1,000 patient-days vs. 0.15/1,000 patient-days) (J Ped Inf Dis. 2016. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw072).

The researchers used infection prevention and control surveillance databases from Montreal Children’s Hospital (MCH) in Quebec and the CCMC to identify HA-VRIs that occurred between April 1, 2010, and March 31, 2013, In both hospitals, HAIs were attributed to the unit to which the patient was admitted at the time of transmission. Both hospitals used a multiplex nucleic acid amplification test for respiratory virus detection on nasopharyngeal swabs or aspirates.

“An HA-VRI with an onset of symptoms after hospital discharge would be detected and included only for patients who presented to the emergency department or were readmitted for VRI and tested,” according to Caroline Quach, MD, of the Montreal Children’s Hospital, McGill University Health Centre, Quebec, and her colleagues.

The HA-VRI rate was 1.91/1,000 patient-days at Montreal Children’s Hospital, compared with 0.80/1,000 patient-days at the CCMC (P less than .0001). At the CCMC, the HA-VRI incidence rate was lowest in the neonatal ICU, but at Montgomery Children’s Hospital, the hematology/oncology ward had the lowest rate of HA-VRI.

Having less than 50% single rooms in a given unit was associated with a statistically significantly higher rate of HA-VRI, after the investigators adjusted for unit type and took the correlation of HA-VRI rates within a hospital into consideration. The study authors’ model predicted that units with less than 50% single rooms have 1.33 times higher HA-VRI rates than units with at least 50% single rooms, regardless of unit type.

Dr. Quach has received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Sage, and AbbVie for an unrelated research project, while the other authors disclosed no financial relationships.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES SOCIETY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The incidence rate of HA-VRIs was 1.29/1,000 patient-days in an examination of two pediatric hospitals’ patient data between April 1, 2010, and March 31, 2013.

Data source: A retrospective comparison of two hospitals’ 3 years of infection prevention and control surveillance data.

Disclosures: Dr. Quach has received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Sage, and AbbVie for an unrelated research project, while the other authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Understanding SSTI admission, treatment crucial to reducing disease burden

Decreasing the burden of treating skin and soft tissue infections is critical to improving care and reducing the costs that SSTIs place on health care facilities, according to a study published in Hospital Practice.

“Despite expert panel recommendations and treatment guidelines, there is no widely accepted classification system for grading SSTIs to outcomes,” wrote the study’s lead author, Kristin E. Linder, PharmD, of Hartford (Conn.) Hospital. “This leads to a considerable variation in treatment approach on initial presentation when deciding which patients should be admitted to receive intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy or treated as outpatients.”

Dr. Linder and her coinvestigators conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study with the primary objective of determining rates of admission and re-presentation, along with average length-of-stay (LOS) and cost of care for both inpatients and outpatients with SSTIs. Patients aged 18 years and older who received a primary diagnosis of an SSTI during May and June of 2015 at Hartford Hospital were screened; 446 were deemed eligible, with 357 ultimately selected for inclusion (Hosp Pract. 2017 Jan 5. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2017.1279519).

Of the 357 patients included for analysis, 106 (29.7%) were admitted as inpatients while the remaining 251 (70.3%) were treated as outpatients. However, there were no significant differences found in re-presentation rates, either overall – 22.6% for inpatients and 28.3% for outpatients (P greater than .05) – or for SSTI-related re-presentation: 10.4% for inpatients and 15.1% for outpatients (P greater than .05). For those patients who did get admitted, mean LOS was 7.3 days.

Patients who presented with a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score of zero were admitted at a rate of 14.1%, compared to 30.1% of those with a CCI score of one, and 60.9% of those with a CCI score of two or higher. The biggest disparity, however, was in terms of cost of care; while outpatient care cost an average of $413 per patient, inpatient care cost an average of $13,313 per patient.

Wound and abscess cultures that were tested found methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) to be the most prevalent gram-positive organism (37.1%) found in inpatients, while for outpatients, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was the most common (66.7%). According to the investigators, Gram-negative bacteria were not isolated in every case, so “prevalent use of combination therapy in this setting may not be warranted.

“Understanding how and where patients with SSTI are treated and their re-presentation rate is important to understand to direct resources for this high frequency disease,” the authors concluded. “This study demonstrated that approximately 70% of patients presenting to the ED with SSTI were treated as outpatients [and] while 30-day re-presentation was similar for inpatient and outpatients, readmission was more likely in those previously admitted.”

This study was not funded, according to the authors. Dr. Linder did not report any relevant financial disclosures, but her coauthors disclosed receiving speakers’ and consultants’ fees from Astellas, Theravance. Bayer, Merck and Pfizer.

Decreasing the burden of treating skin and soft tissue infections is critical to improving care and reducing the costs that SSTIs place on health care facilities, according to a study published in Hospital Practice.

“Despite expert panel recommendations and treatment guidelines, there is no widely accepted classification system for grading SSTIs to outcomes,” wrote the study’s lead author, Kristin E. Linder, PharmD, of Hartford (Conn.) Hospital. “This leads to a considerable variation in treatment approach on initial presentation when deciding which patients should be admitted to receive intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy or treated as outpatients.”

Dr. Linder and her coinvestigators conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study with the primary objective of determining rates of admission and re-presentation, along with average length-of-stay (LOS) and cost of care for both inpatients and outpatients with SSTIs. Patients aged 18 years and older who received a primary diagnosis of an SSTI during May and June of 2015 at Hartford Hospital were screened; 446 were deemed eligible, with 357 ultimately selected for inclusion (Hosp Pract. 2017 Jan 5. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2017.1279519).

Of the 357 patients included for analysis, 106 (29.7%) were admitted as inpatients while the remaining 251 (70.3%) were treated as outpatients. However, there were no significant differences found in re-presentation rates, either overall – 22.6% for inpatients and 28.3% for outpatients (P greater than .05) – or for SSTI-related re-presentation: 10.4% for inpatients and 15.1% for outpatients (P greater than .05). For those patients who did get admitted, mean LOS was 7.3 days.

Patients who presented with a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score of zero were admitted at a rate of 14.1%, compared to 30.1% of those with a CCI score of one, and 60.9% of those with a CCI score of two or higher. The biggest disparity, however, was in terms of cost of care; while outpatient care cost an average of $413 per patient, inpatient care cost an average of $13,313 per patient.

Wound and abscess cultures that were tested found methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) to be the most prevalent gram-positive organism (37.1%) found in inpatients, while for outpatients, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was the most common (66.7%). According to the investigators, Gram-negative bacteria were not isolated in every case, so “prevalent use of combination therapy in this setting may not be warranted.

“Understanding how and where patients with SSTI are treated and their re-presentation rate is important to understand to direct resources for this high frequency disease,” the authors concluded. “This study demonstrated that approximately 70% of patients presenting to the ED with SSTI were treated as outpatients [and] while 30-day re-presentation was similar for inpatient and outpatients, readmission was more likely in those previously admitted.”

This study was not funded, according to the authors. Dr. Linder did not report any relevant financial disclosures, but her coauthors disclosed receiving speakers’ and consultants’ fees from Astellas, Theravance. Bayer, Merck and Pfizer.

Decreasing the burden of treating skin and soft tissue infections is critical to improving care and reducing the costs that SSTIs place on health care facilities, according to a study published in Hospital Practice.

“Despite expert panel recommendations and treatment guidelines, there is no widely accepted classification system for grading SSTIs to outcomes,” wrote the study’s lead author, Kristin E. Linder, PharmD, of Hartford (Conn.) Hospital. “This leads to a considerable variation in treatment approach on initial presentation when deciding which patients should be admitted to receive intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy or treated as outpatients.”

Dr. Linder and her coinvestigators conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study with the primary objective of determining rates of admission and re-presentation, along with average length-of-stay (LOS) and cost of care for both inpatients and outpatients with SSTIs. Patients aged 18 years and older who received a primary diagnosis of an SSTI during May and June of 2015 at Hartford Hospital were screened; 446 were deemed eligible, with 357 ultimately selected for inclusion (Hosp Pract. 2017 Jan 5. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2017.1279519).

Of the 357 patients included for analysis, 106 (29.7%) were admitted as inpatients while the remaining 251 (70.3%) were treated as outpatients. However, there were no significant differences found in re-presentation rates, either overall – 22.6% for inpatients and 28.3% for outpatients (P greater than .05) – or for SSTI-related re-presentation: 10.4% for inpatients and 15.1% for outpatients (P greater than .05). For those patients who did get admitted, mean LOS was 7.3 days.

Patients who presented with a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score of zero were admitted at a rate of 14.1%, compared to 30.1% of those with a CCI score of one, and 60.9% of those with a CCI score of two or higher. The biggest disparity, however, was in terms of cost of care; while outpatient care cost an average of $413 per patient, inpatient care cost an average of $13,313 per patient.

Wound and abscess cultures that were tested found methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) to be the most prevalent gram-positive organism (37.1%) found in inpatients, while for outpatients, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was the most common (66.7%). According to the investigators, Gram-negative bacteria were not isolated in every case, so “prevalent use of combination therapy in this setting may not be warranted.

“Understanding how and where patients with SSTI are treated and their re-presentation rate is important to understand to direct resources for this high frequency disease,” the authors concluded. “This study demonstrated that approximately 70% of patients presenting to the ED with SSTI were treated as outpatients [and] while 30-day re-presentation was similar for inpatient and outpatients, readmission was more likely in those previously admitted.”

This study was not funded, according to the authors. Dr. Linder did not report any relevant financial disclosures, but her coauthors disclosed receiving speakers’ and consultants’ fees from Astellas, Theravance. Bayer, Merck and Pfizer.

FROM HOSPITAL PRACTICE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Re-presentation rates between inpatients and outpatients with SSTIs were not significantly different – 10.4% versus 15.1%, respectively (P greater than .05) – but cost of care was much higher for inpatients than outpatients: $13,313 versus $413, respectively.

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of 357 SSTI patients during May and June of 2015.

Disclosures: The study was not funded. Two authors reported potential financial conflicts.

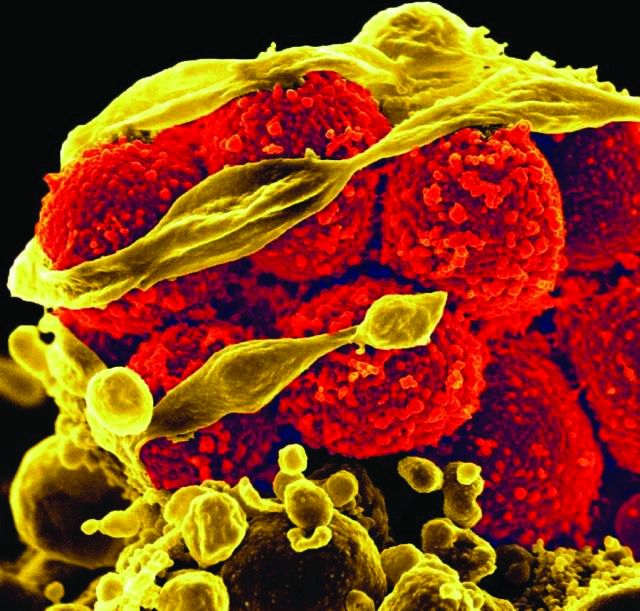

When to discontinue contact precautions for patients with MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a common hospital-acquired infection with significant morbidity and mortality. The CDC currently recommends contact precautions as a mainstay to prevent transmission of MRSA in health care settings. Most hospitals routinely screen patients for MRSA and use contact precautions for those who screen positive. The duration of these precautions vary across hospitals and no standard recommendation exists.

A recent study of members of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) research network indicated that the majority of physicians (94%) and nurses (76%) dislike contact precautions (CP) and most (63%) were in favor of implementing CP in a different way than current practice.1 Patients also report less satisfaction and increased isolation.1

My colleagues and I recently published a study2 in the American Journal of Infection Control to explore the necessary duration of contact precautions for hospitalized patients with MRSA. Our goal was to maintain contact precautions as long as necessary to prevent undesired MRSA infections and colonization but minimize unnecessary days in contact isolation. We also sought to figure out whether patients with positive MRSA surveillance cultures should always remain in isolation and, if not, at what point they could be considered for rescreening and removal of precautions if culture negative.

Our hospital has been performing active surveillance cultures weekly to screen for MRSA among our hospitalized patients for many years; however from 2010 to 2014, we began screening patients who were previously known to be positive for MRSA colonization or infection for at least 1 year. We then assessed medical and demographic factors associated with persistent carriage of MRSA.

In our study, more than 400 patients with known MRSA were rescreened with an active surveillance culture at a subsequent hospital admission. Ultimately 20% of the patients remained MRSA positive on the active surveillance culture. Most patients who were culture positive for MRSA were found on the first active surveillance culture (16.4%) but the remaining positive cultures were found on a second active surveillance culture or a clinical culture.

The amount of time that passed since the patient was culture positive was significantly associated with a lower risk of a positive culture at screening. This continued to drop over time with only 12.5% of patients remaining active surveillance culture positive for MRSA at 5 years after the original positive culture.

Two factors were found to significantly impact the MRSA culture on the multivariate analysis: (1) Female sex reduced the risk of positivity, and (2) Presence of a foreign body increased the risk of positivity.

Most patients who remained positive for an MRSA culture were found with the first active surveillance culture, less than 4% were detected subsequently with a repeat surveillance or clinical culture and this percentage also decreased over time. This indicates that in the absence of a positive active surveillance culture it may be reasonable to discontinue contact precautions, which could result in a substantial cost savings for the hospital and improved patient and provider satisfaction without increasing the risk of MRSA transmission.

We concluded that in the absence of a foreign body and with at least a year from the last known positive culture, patients with known MRSA should be rescreened and, if negative on an active surveillance culture, should be removed from contact precautions.

Lauren Richey, MD, MPH, is assistant professor in the infectious diseases division at the Medical University of South Carolina.

References

1. Morgan DJ, Diekema DJ, Sepkowitz K, Perencevich EN. Adverse outcomes associated with contact precautions: A review of the literature. Am J Infect Control. 2009 Mar;37(2):85-93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.04.257.

2. Richey LE, Oh Y, Tchamba DM, Engle M, Formby L, Salgado CD. When should contact precautions be discontinued for patients with Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus? Am J Infect Control. 2016 Aug 30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.05.030.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a common hospital-acquired infection with significant morbidity and mortality. The CDC currently recommends contact precautions as a mainstay to prevent transmission of MRSA in health care settings. Most hospitals routinely screen patients for MRSA and use contact precautions for those who screen positive. The duration of these precautions vary across hospitals and no standard recommendation exists.

A recent study of members of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) research network indicated that the majority of physicians (94%) and nurses (76%) dislike contact precautions (CP) and most (63%) were in favor of implementing CP in a different way than current practice.1 Patients also report less satisfaction and increased isolation.1