User login

Noncancer diagnoses on the rise in palliative care

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

Referrals by specialty were led by hospital medicine, which accounted for 48% of all patients referred to palliative care in 2015, with internal medicine/family medicine next at 14%, followed by pulmonary/critical care at 13% and oncology at 7%, the report said.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

"But doc, isn't hospice just for cancer patients?"

"But doc, isn't hospice just for cancer patients?"

"But doc, isn't hospice just for cancer patients?"

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

Referrals by specialty were led by hospital medicine, which accounted for 48% of all patients referred to palliative care in 2015, with internal medicine/family medicine next at 14%, followed by pulmonary/critical care at 13% and oncology at 7%, the report said.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Patients referred to palliative care are most likely to have cancer, but the proportion has gone down since 2009 as other diagnoses have increased, according to a report from the National Palliative Care Registry.

In 2015, cancer patients made up 26% of the patients referred to palliative care, compared with 35% in 2009. The situation was reversed for the next three most common diagnoses in 2015: Cardiac diagnoses rose from 5% in 2009 to 13%, pulmonary diagnoses increased from 6% to 12%, and neurologic diagnoses went from 3% to 8%, the report showed.

Referrals by specialty were led by hospital medicine, which accounted for 48% of all patients referred to palliative care in 2015, with internal medicine/family medicine next at 14%, followed by pulmonary/critical care at 13% and oncology at 7%, the report said.

An increase in overall palliative care penetration was seen from 2009 to 2015, as the percentage of annual hospital admissions seen by a palliative care team increased from 2.7% to 4.8%. Over that same time period, the percentage of palliative care patients who died in the hospital decreased from 29% to 22%, according to the report.

In 2015, there were 420 palliative care programs participating in the registry, which is a joint project of the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Antipsychotics ineffective for symptoms of delirium in palliative care

CLINICAL QUESTION: Do antipsychotics provide symptomatic benefit for delirium in palliative care?

BACKGROUND: Antipsychotics are frequently used for the treatment of delirium and guideline recommended for delirium-associated distress. However, a 2016 meta-analysis found antipsychotics are not associated with change in delirium duration or severity. Antipsychotics for palliative management of delirium at end of life is not well studied.

STUDY DESIGN: Double-blind randomized controlled trial with placebo, haloperidol, and risperidone arms.

SETTING: Eleven Australian inpatient hospice or palliative care services.

SYNOPSIS: 247 patients (mean age, 74.9 years; 88.3% with cancer) with advanced incurable disease and active delirium were studied. Most had mild-moderate severity delirium. All received nonpharmacological measures and plan to address reversible precipitants. Patients were randomized to placebo (84), haloperidol (81), or risperidone (82) for 72 hours. Dose titration was allowed based on delirium symptoms. In intention to treat analysis the delirium severity scores were statistically higher in haloperidol and risperidone arms, compared with placebo. This reached statistical significance although less than the minimum clinically significant difference. Mortality, use of rescue medicines, and extrapyramidal symptoms were higher in antipsychotic groups.

BOTTOM LINE: Antipsychotics cause side effects without efficacy in palliation of symptoms of delirium.

CITATIONS: Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan;177:34-42.

Dr. Cumbler is the associate chief of hospital medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

CLINICAL QUESTION: Do antipsychotics provide symptomatic benefit for delirium in palliative care?

BACKGROUND: Antipsychotics are frequently used for the treatment of delirium and guideline recommended for delirium-associated distress. However, a 2016 meta-analysis found antipsychotics are not associated with change in delirium duration or severity. Antipsychotics for palliative management of delirium at end of life is not well studied.

STUDY DESIGN: Double-blind randomized controlled trial with placebo, haloperidol, and risperidone arms.

SETTING: Eleven Australian inpatient hospice or palliative care services.

SYNOPSIS: 247 patients (mean age, 74.9 years; 88.3% with cancer) with advanced incurable disease and active delirium were studied. Most had mild-moderate severity delirium. All received nonpharmacological measures and plan to address reversible precipitants. Patients were randomized to placebo (84), haloperidol (81), or risperidone (82) for 72 hours. Dose titration was allowed based on delirium symptoms. In intention to treat analysis the delirium severity scores were statistically higher in haloperidol and risperidone arms, compared with placebo. This reached statistical significance although less than the minimum clinically significant difference. Mortality, use of rescue medicines, and extrapyramidal symptoms were higher in antipsychotic groups.

BOTTOM LINE: Antipsychotics cause side effects without efficacy in palliation of symptoms of delirium.

CITATIONS: Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan;177:34-42.

Dr. Cumbler is the associate chief of hospital medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

CLINICAL QUESTION: Do antipsychotics provide symptomatic benefit for delirium in palliative care?

BACKGROUND: Antipsychotics are frequently used for the treatment of delirium and guideline recommended for delirium-associated distress. However, a 2016 meta-analysis found antipsychotics are not associated with change in delirium duration or severity. Antipsychotics for palliative management of delirium at end of life is not well studied.

STUDY DESIGN: Double-blind randomized controlled trial with placebo, haloperidol, and risperidone arms.

SETTING: Eleven Australian inpatient hospice or palliative care services.

SYNOPSIS: 247 patients (mean age, 74.9 years; 88.3% with cancer) with advanced incurable disease and active delirium were studied. Most had mild-moderate severity delirium. All received nonpharmacological measures and plan to address reversible precipitants. Patients were randomized to placebo (84), haloperidol (81), or risperidone (82) for 72 hours. Dose titration was allowed based on delirium symptoms. In intention to treat analysis the delirium severity scores were statistically higher in haloperidol and risperidone arms, compared with placebo. This reached statistical significance although less than the minimum clinically significant difference. Mortality, use of rescue medicines, and extrapyramidal symptoms were higher in antipsychotic groups.

BOTTOM LINE: Antipsychotics cause side effects without efficacy in palliation of symptoms of delirium.

CITATIONS: Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan;177:34-42.

Dr. Cumbler is the associate chief of hospital medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

Hospitalists can do better at end-of-life care, expert says

As a 99-year-old friend neared the end of her life, she offered a lesson for the health care world, said Deborah Korenstein, MD, chief of general internal medicine and director of clinical effectiveness at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, N.Y., in the Tuesday session “Finding High Value Inpatient Care at the End of Life.”

The woman, nicknamed “Mitch,” had bluntly made her preference clear, Dr. Korenstein said: “She wanted to live independently as long as she could, and then, she wanted to be dead.”

But when a pathology report showed urothelial cancer, that preference didn’t stop an oncology urologist from suggesting that Mitch enter a clinical trial on an unproven therapy. Worse, Mitch initially said “yes” to this idea, seemingly because she thought that’s what she was expected to say.

It was only when Dr. Korenstein spoke with her that she changed her mind, entered inpatient hospice care, and died peacefully.

“I think it’s a cautionary tale about when a patient is crystal clear about their wishes,” she said. “The wave of the medical system kind of pushes them along in a particular direction that may go against their wishes.”

Dr. Korenstein said U.S. health care system does fairly well in some areas – for instance, research shows that about 60% of people die in their preferred location, whether at home or somewhere else. But it does not do so well in others – a 2013 Journal of General Internal Medicine study found that, during 2002-2008, Medicare beneficiaries typically spent $39,000 out of pocket on their medical care, and in 25% of cases, what they spent exceeded the total value of their assets.

As far as individual preferences, these tend to correlate poorly with the care that people actually get, Dr. Korenstein said. Patients often don’t express their wishes, doctors are poor judges of what matters to individual people, and care is largely driven by physician preferences and by the care setting involved, she said.

Given those problems, she said, “we cannot possibly be providing high-value individualized care.”

Hospitalists are well positioned to help patients’ preferences align with care, she added. Sometimes, a sustained relationship with a patient, while generally a positive thing, might lead a provider to become invested in their care in “ways that are not always rational.” So a hospitalist can have a helpful vantage point.

As a 99-year-old friend neared the end of her life, she offered a lesson for the health care world, said Deborah Korenstein, MD, chief of general internal medicine and director of clinical effectiveness at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, N.Y., in the Tuesday session “Finding High Value Inpatient Care at the End of Life.”

The woman, nicknamed “Mitch,” had bluntly made her preference clear, Dr. Korenstein said: “She wanted to live independently as long as she could, and then, she wanted to be dead.”

But when a pathology report showed urothelial cancer, that preference didn’t stop an oncology urologist from suggesting that Mitch enter a clinical trial on an unproven therapy. Worse, Mitch initially said “yes” to this idea, seemingly because she thought that’s what she was expected to say.

It was only when Dr. Korenstein spoke with her that she changed her mind, entered inpatient hospice care, and died peacefully.

“I think it’s a cautionary tale about when a patient is crystal clear about their wishes,” she said. “The wave of the medical system kind of pushes them along in a particular direction that may go against their wishes.”

Dr. Korenstein said U.S. health care system does fairly well in some areas – for instance, research shows that about 60% of people die in their preferred location, whether at home or somewhere else. But it does not do so well in others – a 2013 Journal of General Internal Medicine study found that, during 2002-2008, Medicare beneficiaries typically spent $39,000 out of pocket on their medical care, and in 25% of cases, what they spent exceeded the total value of their assets.

As far as individual preferences, these tend to correlate poorly with the care that people actually get, Dr. Korenstein said. Patients often don’t express their wishes, doctors are poor judges of what matters to individual people, and care is largely driven by physician preferences and by the care setting involved, she said.

Given those problems, she said, “we cannot possibly be providing high-value individualized care.”

Hospitalists are well positioned to help patients’ preferences align with care, she added. Sometimes, a sustained relationship with a patient, while generally a positive thing, might lead a provider to become invested in their care in “ways that are not always rational.” So a hospitalist can have a helpful vantage point.

As a 99-year-old friend neared the end of her life, she offered a lesson for the health care world, said Deborah Korenstein, MD, chief of general internal medicine and director of clinical effectiveness at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, N.Y., in the Tuesday session “Finding High Value Inpatient Care at the End of Life.”

The woman, nicknamed “Mitch,” had bluntly made her preference clear, Dr. Korenstein said: “She wanted to live independently as long as she could, and then, she wanted to be dead.”

But when a pathology report showed urothelial cancer, that preference didn’t stop an oncology urologist from suggesting that Mitch enter a clinical trial on an unproven therapy. Worse, Mitch initially said “yes” to this idea, seemingly because she thought that’s what she was expected to say.

It was only when Dr. Korenstein spoke with her that she changed her mind, entered inpatient hospice care, and died peacefully.

“I think it’s a cautionary tale about when a patient is crystal clear about their wishes,” she said. “The wave of the medical system kind of pushes them along in a particular direction that may go against their wishes.”

Dr. Korenstein said U.S. health care system does fairly well in some areas – for instance, research shows that about 60% of people die in their preferred location, whether at home or somewhere else. But it does not do so well in others – a 2013 Journal of General Internal Medicine study found that, during 2002-2008, Medicare beneficiaries typically spent $39,000 out of pocket on their medical care, and in 25% of cases, what they spent exceeded the total value of their assets.

As far as individual preferences, these tend to correlate poorly with the care that people actually get, Dr. Korenstein said. Patients often don’t express their wishes, doctors are poor judges of what matters to individual people, and care is largely driven by physician preferences and by the care setting involved, she said.

Given those problems, she said, “we cannot possibly be providing high-value individualized care.”

Hospitalists are well positioned to help patients’ preferences align with care, she added. Sometimes, a sustained relationship with a patient, while generally a positive thing, might lead a provider to become invested in their care in “ways that are not always rational.” So a hospitalist can have a helpful vantage point.

Filling the gap: Hospitalists & palliative care

Most Americans diagnosed with serious illness will be hospitalized in their last months. During these hospitalizations, hospitalists direct their care.

For seriously ill patients, consultation with palliative care specialists has been shown to promote patient- and family-centered care, ensuring that care is consistent with patients’ goals, values, and preferences. Yet, many hospitalized patients lack access to palliative care consultation, and specialists have identified key domains of primary palliative care that can be delivered by nonspecialists.

To fill this gap, SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement partnered with The Hastings Center, a world-renowned bioethics research institution, to develop a resource room focused on hospitalists’ role in providing high-quality communication about prognosis and goals of care. The resource room presents a Prognosis and Goals of Care Communication Pathway, which highlights key processes and maps them onto the daily workflows of hospitalist physicians.

The care pathway is grounded in palliative care communication research and the consensus guidance of The Hastings Center Guidelines for Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment and Care Near the End of Life. It was informed by a national stakeholder meeting of hospitalists, other hospital clinicians, patient and family advocates, bioethicists, social scientists, and other experts, who identified professional values of hospital medicine aligned with communication as part of good care for seriously ill patients.

A collaborative interdisciplinary work group convened by SHM and including hospitalists, palliative medicine physicians, a bioethicist, and a palliative nursing specialist constructed the care pathway in terms of key processes occurring at admission, during hospitalization, and in discharge planning to support primary palliative care integration into normal workflow. The resource room also includes skills-building tools and resources for individual hospitals, teams, and institutions.

The work group will present a workshop on the care pathway at Hospital Medicine 2017: “Demystifying Difficult Decisions: Strategies and Skills to Equip Hospitalists for High-Quality Goals of Care Conversations with Seriously Ill Patients and Their Families.” For more information on the resource room, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/EOL.

Dr. Anderson is associate professor in residence in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. She also serves as attending physician in the Palliative Care Program and codirector of the School of Nursing Interprofessional Palliative Care Training Program at UCSF.

Most Americans diagnosed with serious illness will be hospitalized in their last months. During these hospitalizations, hospitalists direct their care.

For seriously ill patients, consultation with palliative care specialists has been shown to promote patient- and family-centered care, ensuring that care is consistent with patients’ goals, values, and preferences. Yet, many hospitalized patients lack access to palliative care consultation, and specialists have identified key domains of primary palliative care that can be delivered by nonspecialists.

To fill this gap, SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement partnered with The Hastings Center, a world-renowned bioethics research institution, to develop a resource room focused on hospitalists’ role in providing high-quality communication about prognosis and goals of care. The resource room presents a Prognosis and Goals of Care Communication Pathway, which highlights key processes and maps them onto the daily workflows of hospitalist physicians.

The care pathway is grounded in palliative care communication research and the consensus guidance of The Hastings Center Guidelines for Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment and Care Near the End of Life. It was informed by a national stakeholder meeting of hospitalists, other hospital clinicians, patient and family advocates, bioethicists, social scientists, and other experts, who identified professional values of hospital medicine aligned with communication as part of good care for seriously ill patients.

A collaborative interdisciplinary work group convened by SHM and including hospitalists, palliative medicine physicians, a bioethicist, and a palliative nursing specialist constructed the care pathway in terms of key processes occurring at admission, during hospitalization, and in discharge planning to support primary palliative care integration into normal workflow. The resource room also includes skills-building tools and resources for individual hospitals, teams, and institutions.

The work group will present a workshop on the care pathway at Hospital Medicine 2017: “Demystifying Difficult Decisions: Strategies and Skills to Equip Hospitalists for High-Quality Goals of Care Conversations with Seriously Ill Patients and Their Families.” For more information on the resource room, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/EOL.

Dr. Anderson is associate professor in residence in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. She also serves as attending physician in the Palliative Care Program and codirector of the School of Nursing Interprofessional Palliative Care Training Program at UCSF.

Most Americans diagnosed with serious illness will be hospitalized in their last months. During these hospitalizations, hospitalists direct their care.

For seriously ill patients, consultation with palliative care specialists has been shown to promote patient- and family-centered care, ensuring that care is consistent with patients’ goals, values, and preferences. Yet, many hospitalized patients lack access to palliative care consultation, and specialists have identified key domains of primary palliative care that can be delivered by nonspecialists.

To fill this gap, SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement partnered with The Hastings Center, a world-renowned bioethics research institution, to develop a resource room focused on hospitalists’ role in providing high-quality communication about prognosis and goals of care. The resource room presents a Prognosis and Goals of Care Communication Pathway, which highlights key processes and maps them onto the daily workflows of hospitalist physicians.

The care pathway is grounded in palliative care communication research and the consensus guidance of The Hastings Center Guidelines for Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment and Care Near the End of Life. It was informed by a national stakeholder meeting of hospitalists, other hospital clinicians, patient and family advocates, bioethicists, social scientists, and other experts, who identified professional values of hospital medicine aligned with communication as part of good care for seriously ill patients.

A collaborative interdisciplinary work group convened by SHM and including hospitalists, palliative medicine physicians, a bioethicist, and a palliative nursing specialist constructed the care pathway in terms of key processes occurring at admission, during hospitalization, and in discharge planning to support primary palliative care integration into normal workflow. The resource room also includes skills-building tools and resources for individual hospitals, teams, and institutions.

The work group will present a workshop on the care pathway at Hospital Medicine 2017: “Demystifying Difficult Decisions: Strategies and Skills to Equip Hospitalists for High-Quality Goals of Care Conversations with Seriously Ill Patients and Their Families.” For more information on the resource room, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/EOL.

Dr. Anderson is associate professor in residence in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. She also serves as attending physician in the Palliative Care Program and codirector of the School of Nursing Interprofessional Palliative Care Training Program at UCSF.

VIDEO: About 1 in 20 ALS patients in Washington state chose assisted suicide

BOSTON – A new study estimates that 3.4%-6.7% of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients in Washington state sought to commit physician-assisted suicide over a 5-year period.

The rate is many times higher than that among cancer patients in the state, researchers found. They also discovered that ALS patients were significantly more likely than were other terminally ill people to use the deadly medication after getting prescriptions for it.

The findings appear to reflect the unique hopelessness facing ALS patients. “They’re not afforded as much denial of decline and death as are patients with other terminal illnesses,” said Linda Ganzini, MD, MPH, a professor of psychiatry and medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, who has studied end of life in ALS patients.

“Many cancer patients, even in the final days of life, receive treatments that they hope will extend their lives,” she said in an interview after reviewing the study findings. “In contrast, treatments for ALS are minimally effective.”

Physician-assisted suicide is legal in California, Colorado, the District of Columbia, Montana, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington.

A team led by Leo H. Wang, MD, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, examined the medical records of 39 ALS patients who sought medication to end their lives at three hospitals in Seattle from March 2009 to Dec. 31, 2014.

Washington’s Death with Dignity (DWD) law, which went into effect in 2009, allows physicians to prescribe lethal medication if the patient has a terminal illness and a prognosis of less than 6 months to live as judged by two physicians.

The researchers reported their findings, a follow-up to a previous study (Neurology. 2016 Nov 15;87[20]:2117-22), at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The median age of the ALS patients at symptom onset was 64 (range, 42-83), and a median of 712 days passed (range, 207-2,407) from the date of diagnosis to date of prescription for lethal medication.

The median time from prescription to death was 22 days, with at least one patient dying immediately (range, 0-386 days). All 39 patients had limb involvement, and 82%-92% had bulbar involvement, dysarthria, dysphagia, and/or dyspnea.

The researchers estimate that 3.4%-6.7% of 1,146 ALS patients in Washington who died over the time period of the study sought a physician-assisted death. The 3.4% figure assumes that the 39 patients at the three hospitals make up all the ALS patients who received medication prescriptions. The 6.7% figure assumes that all patients with neurodegenerative disease who sought DWD in the state over that period had ALS.

“Similarly, 5% (92 of 1,795) of Oregon ALS patient who died sought medication under DWD between 1998 and 2014,” Dr. Wang said. “This is slightly increased compared to the percentage during the first decade, following enactment of the Oregon law (1998-2007), when 2.7% (26 of 962) of ALS patients died using DWD medication.”

Using Washington state data, researchers also estimated that 0.6% of 73,319 cancer patients and 0.2% of 298,178 people in the state who died of all causes sought DWD over the study period.

A total of 30 (77%) ALS patients who received the deadly prescriptions chose to take them, compared with 67% of all-cause patients who took advantage of the DWD law and 60% of cancer patients.

All 30 patients died. The nine who chose to not take the prescribed medication died after a median of 76 days. The patients who did not take the medication were more likely to be married (88% vs. 69%), to be college educated (100% vs. 74%), and to use a motorized wheelchair (78% vs. 31%).

Those who chose to not take the prescribed medication were also less motivated by loss of dignity (63% vs. 93% among those who took the medication) and by being a burden on others (25% vs. 66%). They were more likely to identify themselves as religious (80% vs. 35%).

Multiple factors may explain why ALS patients made different choices regarding the deadly drugs, lead study author Dr. Wang said in an interview. “We thought that the loss of communication may have played a role based on our finding, as most patients who followed through had more substantial trouble speaking,” he said. “For the patients who ultimately did not choose to take the medication, we found more of them had stronger religious beliefs than those who did not.”

As for pain, he reported that it was not a major issue. “Only about 10% of ALS patients were worried about pain, as opposed to 30% of the general Death with Dignity patients,” he said.

Dr. Ganzini noted that some patients who seek the prescribed drugs “want reassurance that, if their quality of life becomes unbearable, they have the option of physician-assisted death. But, they continue to cope and find reasons to live. As such, they ultimately die of their disease without taking the medications. Others lose the ability to ingest the medications, often because of sudden worsening of their disease.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

No specific funding was reported. Dr. Ganzini and Dr. Wang had no disclosures.

BOSTON – A new study estimates that 3.4%-6.7% of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients in Washington state sought to commit physician-assisted suicide over a 5-year period.

The rate is many times higher than that among cancer patients in the state, researchers found. They also discovered that ALS patients were significantly more likely than were other terminally ill people to use the deadly medication after getting prescriptions for it.

The findings appear to reflect the unique hopelessness facing ALS patients. “They’re not afforded as much denial of decline and death as are patients with other terminal illnesses,” said Linda Ganzini, MD, MPH, a professor of psychiatry and medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, who has studied end of life in ALS patients.

“Many cancer patients, even in the final days of life, receive treatments that they hope will extend their lives,” she said in an interview after reviewing the study findings. “In contrast, treatments for ALS are minimally effective.”

Physician-assisted suicide is legal in California, Colorado, the District of Columbia, Montana, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington.

A team led by Leo H. Wang, MD, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, examined the medical records of 39 ALS patients who sought medication to end their lives at three hospitals in Seattle from March 2009 to Dec. 31, 2014.

Washington’s Death with Dignity (DWD) law, which went into effect in 2009, allows physicians to prescribe lethal medication if the patient has a terminal illness and a prognosis of less than 6 months to live as judged by two physicians.

The researchers reported their findings, a follow-up to a previous study (Neurology. 2016 Nov 15;87[20]:2117-22), at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The median age of the ALS patients at symptom onset was 64 (range, 42-83), and a median of 712 days passed (range, 207-2,407) from the date of diagnosis to date of prescription for lethal medication.

The median time from prescription to death was 22 days, with at least one patient dying immediately (range, 0-386 days). All 39 patients had limb involvement, and 82%-92% had bulbar involvement, dysarthria, dysphagia, and/or dyspnea.

The researchers estimate that 3.4%-6.7% of 1,146 ALS patients in Washington who died over the time period of the study sought a physician-assisted death. The 3.4% figure assumes that the 39 patients at the three hospitals make up all the ALS patients who received medication prescriptions. The 6.7% figure assumes that all patients with neurodegenerative disease who sought DWD in the state over that period had ALS.

“Similarly, 5% (92 of 1,795) of Oregon ALS patient who died sought medication under DWD between 1998 and 2014,” Dr. Wang said. “This is slightly increased compared to the percentage during the first decade, following enactment of the Oregon law (1998-2007), when 2.7% (26 of 962) of ALS patients died using DWD medication.”

Using Washington state data, researchers also estimated that 0.6% of 73,319 cancer patients and 0.2% of 298,178 people in the state who died of all causes sought DWD over the study period.

A total of 30 (77%) ALS patients who received the deadly prescriptions chose to take them, compared with 67% of all-cause patients who took advantage of the DWD law and 60% of cancer patients.

All 30 patients died. The nine who chose to not take the prescribed medication died after a median of 76 days. The patients who did not take the medication were more likely to be married (88% vs. 69%), to be college educated (100% vs. 74%), and to use a motorized wheelchair (78% vs. 31%).

Those who chose to not take the prescribed medication were also less motivated by loss of dignity (63% vs. 93% among those who took the medication) and by being a burden on others (25% vs. 66%). They were more likely to identify themselves as religious (80% vs. 35%).

Multiple factors may explain why ALS patients made different choices regarding the deadly drugs, lead study author Dr. Wang said in an interview. “We thought that the loss of communication may have played a role based on our finding, as most patients who followed through had more substantial trouble speaking,” he said. “For the patients who ultimately did not choose to take the medication, we found more of them had stronger religious beliefs than those who did not.”

As for pain, he reported that it was not a major issue. “Only about 10% of ALS patients were worried about pain, as opposed to 30% of the general Death with Dignity patients,” he said.

Dr. Ganzini noted that some patients who seek the prescribed drugs “want reassurance that, if their quality of life becomes unbearable, they have the option of physician-assisted death. But, they continue to cope and find reasons to live. As such, they ultimately die of their disease without taking the medications. Others lose the ability to ingest the medications, often because of sudden worsening of their disease.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

No specific funding was reported. Dr. Ganzini and Dr. Wang had no disclosures.

BOSTON – A new study estimates that 3.4%-6.7% of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients in Washington state sought to commit physician-assisted suicide over a 5-year period.

The rate is many times higher than that among cancer patients in the state, researchers found. They also discovered that ALS patients were significantly more likely than were other terminally ill people to use the deadly medication after getting prescriptions for it.

The findings appear to reflect the unique hopelessness facing ALS patients. “They’re not afforded as much denial of decline and death as are patients with other terminal illnesses,” said Linda Ganzini, MD, MPH, a professor of psychiatry and medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, who has studied end of life in ALS patients.

“Many cancer patients, even in the final days of life, receive treatments that they hope will extend their lives,” she said in an interview after reviewing the study findings. “In contrast, treatments for ALS are minimally effective.”

Physician-assisted suicide is legal in California, Colorado, the District of Columbia, Montana, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington.

A team led by Leo H. Wang, MD, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, examined the medical records of 39 ALS patients who sought medication to end their lives at three hospitals in Seattle from March 2009 to Dec. 31, 2014.

Washington’s Death with Dignity (DWD) law, which went into effect in 2009, allows physicians to prescribe lethal medication if the patient has a terminal illness and a prognosis of less than 6 months to live as judged by two physicians.

The researchers reported their findings, a follow-up to a previous study (Neurology. 2016 Nov 15;87[20]:2117-22), at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The median age of the ALS patients at symptom onset was 64 (range, 42-83), and a median of 712 days passed (range, 207-2,407) from the date of diagnosis to date of prescription for lethal medication.

The median time from prescription to death was 22 days, with at least one patient dying immediately (range, 0-386 days). All 39 patients had limb involvement, and 82%-92% had bulbar involvement, dysarthria, dysphagia, and/or dyspnea.

The researchers estimate that 3.4%-6.7% of 1,146 ALS patients in Washington who died over the time period of the study sought a physician-assisted death. The 3.4% figure assumes that the 39 patients at the three hospitals make up all the ALS patients who received medication prescriptions. The 6.7% figure assumes that all patients with neurodegenerative disease who sought DWD in the state over that period had ALS.

“Similarly, 5% (92 of 1,795) of Oregon ALS patient who died sought medication under DWD between 1998 and 2014,” Dr. Wang said. “This is slightly increased compared to the percentage during the first decade, following enactment of the Oregon law (1998-2007), when 2.7% (26 of 962) of ALS patients died using DWD medication.”

Using Washington state data, researchers also estimated that 0.6% of 73,319 cancer patients and 0.2% of 298,178 people in the state who died of all causes sought DWD over the study period.

A total of 30 (77%) ALS patients who received the deadly prescriptions chose to take them, compared with 67% of all-cause patients who took advantage of the DWD law and 60% of cancer patients.

All 30 patients died. The nine who chose to not take the prescribed medication died after a median of 76 days. The patients who did not take the medication were more likely to be married (88% vs. 69%), to be college educated (100% vs. 74%), and to use a motorized wheelchair (78% vs. 31%).

Those who chose to not take the prescribed medication were also less motivated by loss of dignity (63% vs. 93% among those who took the medication) and by being a burden on others (25% vs. 66%). They were more likely to identify themselves as religious (80% vs. 35%).

Multiple factors may explain why ALS patients made different choices regarding the deadly drugs, lead study author Dr. Wang said in an interview. “We thought that the loss of communication may have played a role based on our finding, as most patients who followed through had more substantial trouble speaking,” he said. “For the patients who ultimately did not choose to take the medication, we found more of them had stronger religious beliefs than those who did not.”

As for pain, he reported that it was not a major issue. “Only about 10% of ALS patients were worried about pain, as opposed to 30% of the general Death with Dignity patients,” he said.

Dr. Ganzini noted that some patients who seek the prescribed drugs “want reassurance that, if their quality of life becomes unbearable, they have the option of physician-assisted death. But, they continue to cope and find reasons to live. As such, they ultimately die of their disease without taking the medications. Others lose the ability to ingest the medications, often because of sudden worsening of their disease.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

No specific funding was reported. Dr. Ganzini and Dr. Wang had no disclosures.

At AAN 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: An estimated 3.4%-6.7% of ALS patients in Washington state sought physician-assisted death, and 77% took the prescribed deadly medication, a higher rate than all-cause (67%) and cancer patients (60%).

Data source: Analysis of 39 ALS patients who sought deadly medication from three Seattle hospitals from March 2009 to Dec. 31, 2014.

Disclosures: No specific funding was reported, and Dr. Wang had no disclosures.

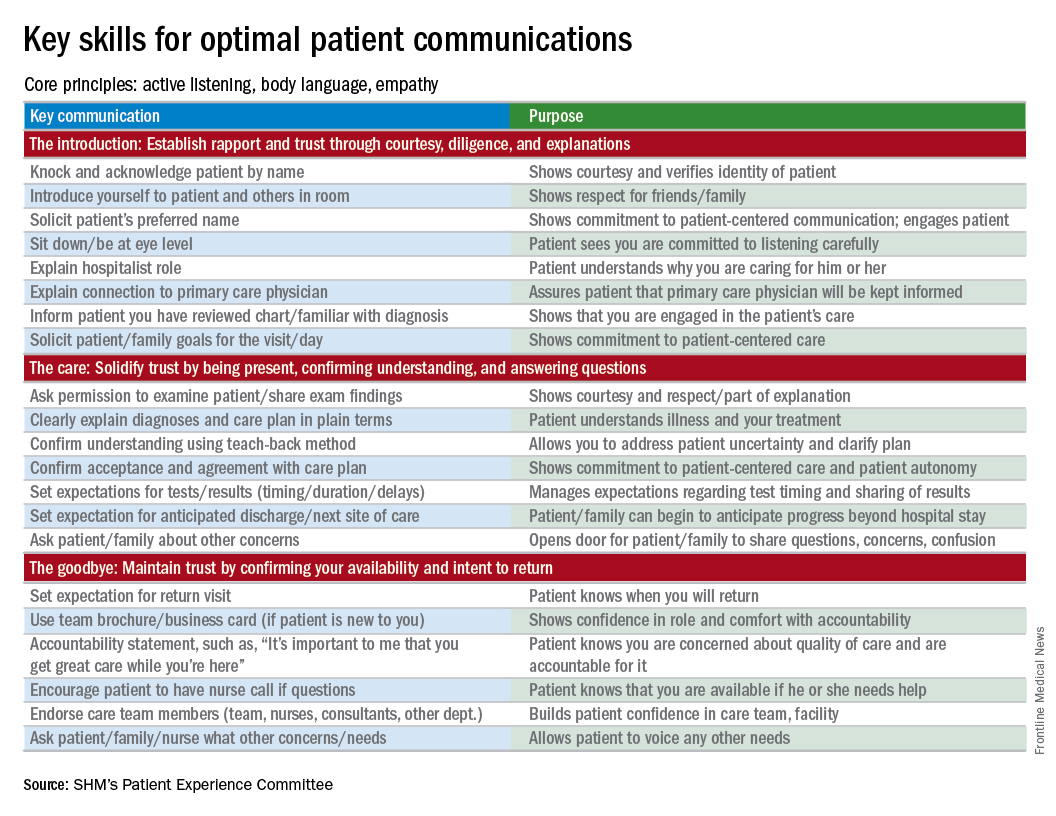

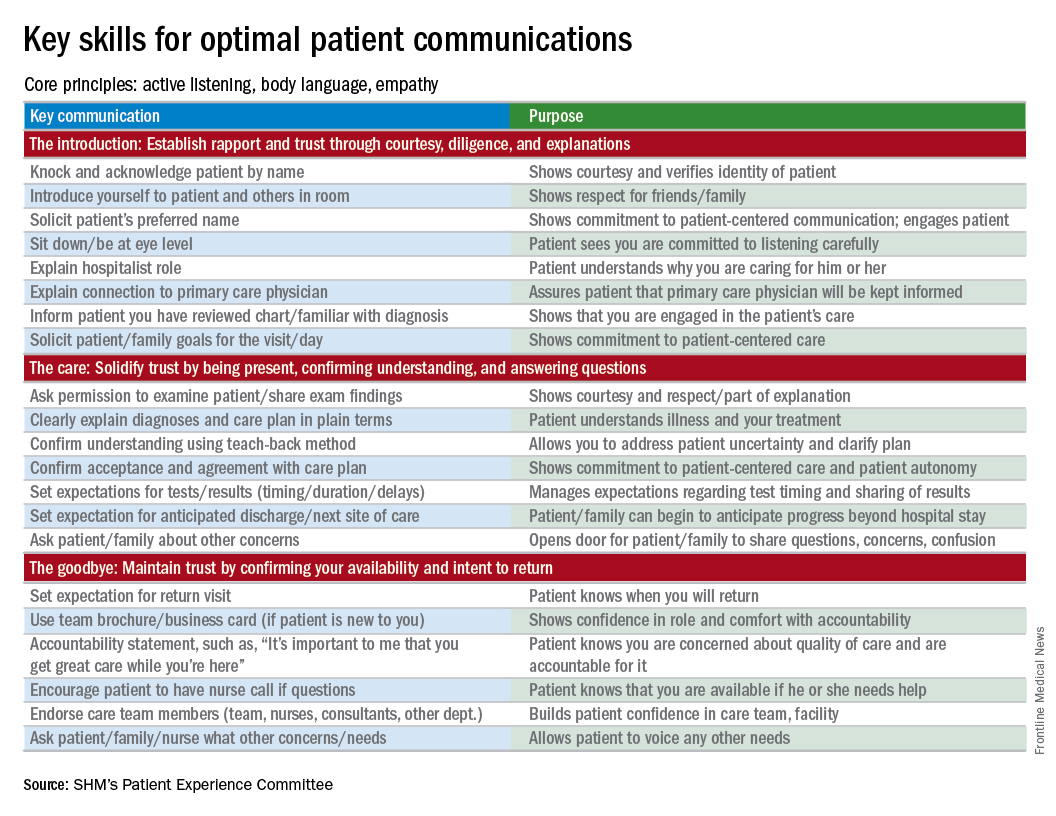

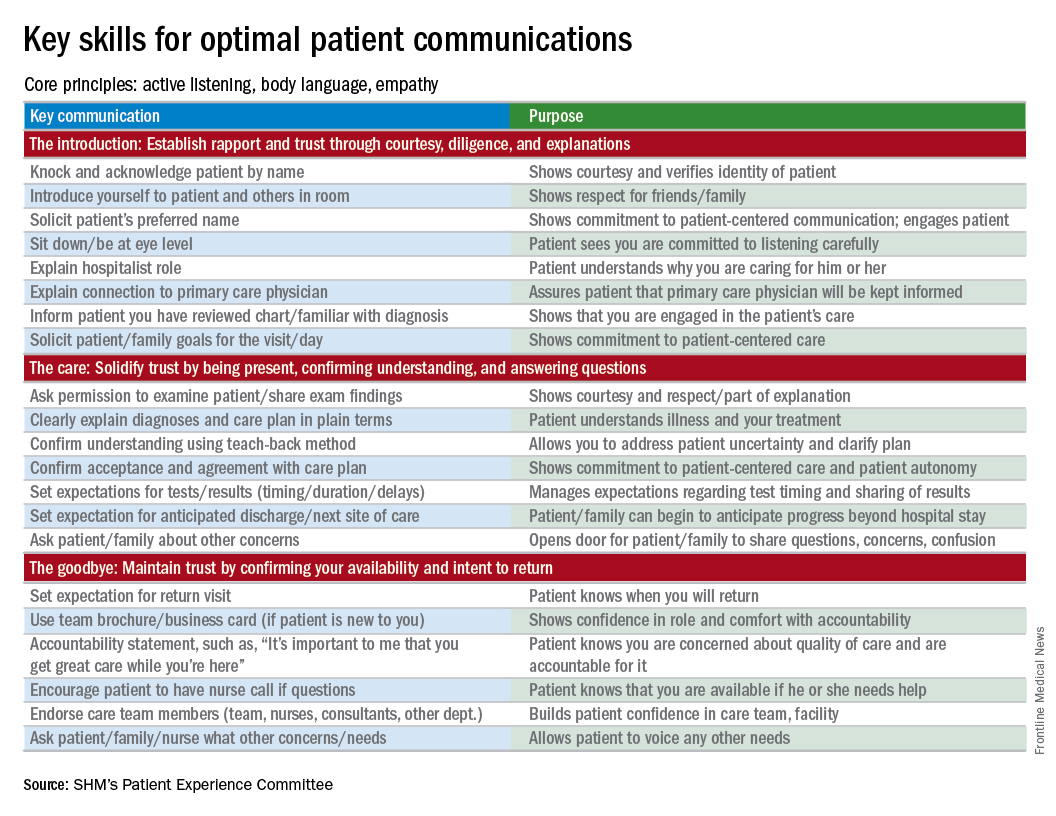

Everything We Say and Do: Discussing advance care planning

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experiences of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I empower all of my patients by giving them the opportunity to consider advance care planning.

Why I do it

Everyone deserves advance care planning, and every health care encounter, including a hospitalization, is an opportunity to better identify and document patients’ wishes for care should they become unable to express them. If we wait for patients to develop serious advanced illness before having advance care planning conversations, we risk depriving them of the care they would want in these situations. Additionally, we place a huge burden on family members who may struggle with excruciatingly difficult decisions in the absence of guidance about their loved one’s wishes.

How I do it

I start by identifying which components of advance care planning each patient needs, using a simple algorithm (see figure). All of my patients are queried about code status, and I give them the opportunity to better understand the value of having a healthcare proxy and advance directives, if they are not already in place.

For the remainder of this column, I’m going to focus on patients who have an acute and/or chronic treatable illness – those who require simpler advance-care-planning conversations.

To comfortably initiate the conversation about advance care planning, I always start by asking permission. I commonly say, “There are a couple of important items I discuss with all of my patients to make sure they get the care they want. Would it be okay for us to talk about those now?” This respectfully puts the patient in control. I then initiate a discussion of code status by saying, “It’s important that all of us on your care team know what you would like us to do if you got so sick that we couldn’t communicate with you. I’m not expecting this to happen, but I ask all my patients this question so that we have your instructions.” From there, the conversation evolves depending on whether the patient has any familiarity with this question and its implications.

To introduce the concept of a health care proxy and advance directives, I ask, “Have you ever thought about who you might choose to make medical decisions on your behalf if you became too sick to make those decisions yourself?” Then, finally, I share the following information, usually referring to the blank advance directives document they received in their admission packet: “There is a valuable way to put your wishes about specific care options in writing so others will know your wishes if you’re unable to communicate with them. Would you like to talk about that right now?” Again, this gives the patient control of the situation and an opportunity to decline the conversation if they are not interested or comfortable at that time.

It’s important to document the nature and outcome of these conversations. Keep in mind, advance care planning discussions need not occur at the time of admission. In fact, admission may be the worst time for some patients, further underscoring the importance of documentation so that subsequent providers can see whether advance care planning has been addressed during the hospital stay.

Note: For useful educational resources that address goals-of-care conversations in patients toward the end of life, the Center to Advance Palliative Care (www.capc.org) has a number of educational courses that address these important communication skills.

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash. and chair of the SHM Patient Experience Committee .

Reference

1. Moss, A.H., Ganjoo, J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High Mortality. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2008;3(5):1379-84. doi:10.2215/CJN.00940208.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experiences of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I empower all of my patients by giving them the opportunity to consider advance care planning.

Why I do it

Everyone deserves advance care planning, and every health care encounter, including a hospitalization, is an opportunity to better identify and document patients’ wishes for care should they become unable to express them. If we wait for patients to develop serious advanced illness before having advance care planning conversations, we risk depriving them of the care they would want in these situations. Additionally, we place a huge burden on family members who may struggle with excruciatingly difficult decisions in the absence of guidance about their loved one’s wishes.

How I do it

I start by identifying which components of advance care planning each patient needs, using a simple algorithm (see figure). All of my patients are queried about code status, and I give them the opportunity to better understand the value of having a healthcare proxy and advance directives, if they are not already in place.

For the remainder of this column, I’m going to focus on patients who have an acute and/or chronic treatable illness – those who require simpler advance-care-planning conversations.

To comfortably initiate the conversation about advance care planning, I always start by asking permission. I commonly say, “There are a couple of important items I discuss with all of my patients to make sure they get the care they want. Would it be okay for us to talk about those now?” This respectfully puts the patient in control. I then initiate a discussion of code status by saying, “It’s important that all of us on your care team know what you would like us to do if you got so sick that we couldn’t communicate with you. I’m not expecting this to happen, but I ask all my patients this question so that we have your instructions.” From there, the conversation evolves depending on whether the patient has any familiarity with this question and its implications.

To introduce the concept of a health care proxy and advance directives, I ask, “Have you ever thought about who you might choose to make medical decisions on your behalf if you became too sick to make those decisions yourself?” Then, finally, I share the following information, usually referring to the blank advance directives document they received in their admission packet: “There is a valuable way to put your wishes about specific care options in writing so others will know your wishes if you’re unable to communicate with them. Would you like to talk about that right now?” Again, this gives the patient control of the situation and an opportunity to decline the conversation if they are not interested or comfortable at that time.

It’s important to document the nature and outcome of these conversations. Keep in mind, advance care planning discussions need not occur at the time of admission. In fact, admission may be the worst time for some patients, further underscoring the importance of documentation so that subsequent providers can see whether advance care planning has been addressed during the hospital stay.

Note: For useful educational resources that address goals-of-care conversations in patients toward the end of life, the Center to Advance Palliative Care (www.capc.org) has a number of educational courses that address these important communication skills.

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash. and chair of the SHM Patient Experience Committee .

Reference

1. Moss, A.H., Ganjoo, J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High Mortality. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2008;3(5):1379-84. doi:10.2215/CJN.00940208.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experiences of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I empower all of my patients by giving them the opportunity to consider advance care planning.

Why I do it

Everyone deserves advance care planning, and every health care encounter, including a hospitalization, is an opportunity to better identify and document patients’ wishes for care should they become unable to express them. If we wait for patients to develop serious advanced illness before having advance care planning conversations, we risk depriving them of the care they would want in these situations. Additionally, we place a huge burden on family members who may struggle with excruciatingly difficult decisions in the absence of guidance about their loved one’s wishes.

How I do it

I start by identifying which components of advance care planning each patient needs, using a simple algorithm (see figure). All of my patients are queried about code status, and I give them the opportunity to better understand the value of having a healthcare proxy and advance directives, if they are not already in place.

For the remainder of this column, I’m going to focus on patients who have an acute and/or chronic treatable illness – those who require simpler advance-care-planning conversations.

To comfortably initiate the conversation about advance care planning, I always start by asking permission. I commonly say, “There are a couple of important items I discuss with all of my patients to make sure they get the care they want. Would it be okay for us to talk about those now?” This respectfully puts the patient in control. I then initiate a discussion of code status by saying, “It’s important that all of us on your care team know what you would like us to do if you got so sick that we couldn’t communicate with you. I’m not expecting this to happen, but I ask all my patients this question so that we have your instructions.” From there, the conversation evolves depending on whether the patient has any familiarity with this question and its implications.

To introduce the concept of a health care proxy and advance directives, I ask, “Have you ever thought about who you might choose to make medical decisions on your behalf if you became too sick to make those decisions yourself?” Then, finally, I share the following information, usually referring to the blank advance directives document they received in their admission packet: “There is a valuable way to put your wishes about specific care options in writing so others will know your wishes if you’re unable to communicate with them. Would you like to talk about that right now?” Again, this gives the patient control of the situation and an opportunity to decline the conversation if they are not interested or comfortable at that time.

It’s important to document the nature and outcome of these conversations. Keep in mind, advance care planning discussions need not occur at the time of admission. In fact, admission may be the worst time for some patients, further underscoring the importance of documentation so that subsequent providers can see whether advance care planning has been addressed during the hospital stay.

Note: For useful educational resources that address goals-of-care conversations in patients toward the end of life, the Center to Advance Palliative Care (www.capc.org) has a number of educational courses that address these important communication skills.

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash. and chair of the SHM Patient Experience Committee .

Reference

1. Moss, A.H., Ganjoo, J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High Mortality. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2008;3(5):1379-84. doi:10.2215/CJN.00940208.

Antipsychotics ineffective for symptoms of delirium in palliative care

CLINICAL QUESTION: Do antipsychotics provide symptomatic benefit for delirium in palliative care?

BACKGROUND: Antipsychotics are frequently used for the treatment of delirium and guideline recommended for delirium-associated distress. However, a 2016 meta-analysis found antipsychotics are not associated with change in delirium duration or severity. Antipsychotics for palliative management of delirium at end of life is not well studied.

STUDY DESIGN: Double-blind randomized controlled trial with placebo, haloperidol, and risperidone arms.

SETTING: Eleven Australian inpatient hospice or palliative care services.

SYNOPSIS: 247 patients (mean age, 74.9 years; 88.3% with cancer) with advanced incurable disease and active delirium were studied. Most had mild-moderate severity delirium. All received nonpharmacological measures and plan to address reversible precipitants. Patients were randomized to placebo (84), haloperidol (81), or risperidone (82) for 72 hours. Dose titration was allowed based on delirium symptoms. In intention to treat analysis the delirium severity scores were statistically higher in haloperidol and risperidone arms, compared with placebo. This reached statistical significance although less than the minimum clinically significant difference. Mortality, use of rescue medicines, and extrapyramidal symptoms were higher in antipsychotic groups.

BOTTOM LINE: Antipsychotics cause side effects without efficacy in palliation of symptoms of delirium.

CITATIONS: Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan;177:34-42.

Dr. Cumbler is the associate chief of hospital medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

CLINICAL QUESTION: Do antipsychotics provide symptomatic benefit for delirium in palliative care?

BACKGROUND: Antipsychotics are frequently used for the treatment of delirium and guideline recommended for delirium-associated distress. However, a 2016 meta-analysis found antipsychotics are not associated with change in delirium duration or severity. Antipsychotics for palliative management of delirium at end of life is not well studied.

STUDY DESIGN: Double-blind randomized controlled trial with placebo, haloperidol, and risperidone arms.

SETTING: Eleven Australian inpatient hospice or palliative care services.

SYNOPSIS: 247 patients (mean age, 74.9 years; 88.3% with cancer) with advanced incurable disease and active delirium were studied. Most had mild-moderate severity delirium. All received nonpharmacological measures and plan to address reversible precipitants. Patients were randomized to placebo (84), haloperidol (81), or risperidone (82) for 72 hours. Dose titration was allowed based on delirium symptoms. In intention to treat analysis the delirium severity scores were statistically higher in haloperidol and risperidone arms, compared with placebo. This reached statistical significance although less than the minimum clinically significant difference. Mortality, use of rescue medicines, and extrapyramidal symptoms were higher in antipsychotic groups.

BOTTOM LINE: Antipsychotics cause side effects without efficacy in palliation of symptoms of delirium.

CITATIONS: Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan;177:34-42.

Dr. Cumbler is the associate chief of hospital medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

CLINICAL QUESTION: Do antipsychotics provide symptomatic benefit for delirium in palliative care?

BACKGROUND: Antipsychotics are frequently used for the treatment of delirium and guideline recommended for delirium-associated distress. However, a 2016 meta-analysis found antipsychotics are not associated with change in delirium duration or severity. Antipsychotics for palliative management of delirium at end of life is not well studied.

STUDY DESIGN: Double-blind randomized controlled trial with placebo, haloperidol, and risperidone arms.

SETTING: Eleven Australian inpatient hospice or palliative care services.

SYNOPSIS: 247 patients (mean age, 74.9 years; 88.3% with cancer) with advanced incurable disease and active delirium were studied. Most had mild-moderate severity delirium. All received nonpharmacological measures and plan to address reversible precipitants. Patients were randomized to placebo (84), haloperidol (81), or risperidone (82) for 72 hours. Dose titration was allowed based on delirium symptoms. In intention to treat analysis the delirium severity scores were statistically higher in haloperidol and risperidone arms, compared with placebo. This reached statistical significance although less than the minimum clinically significant difference. Mortality, use of rescue medicines, and extrapyramidal symptoms were higher in antipsychotic groups.

BOTTOM LINE: Antipsychotics cause side effects without efficacy in palliation of symptoms of delirium.

CITATIONS: Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan;177:34-42.

Dr. Cumbler is the associate chief of hospital medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

Development and Implementation of a Veterans’ Cancer Survivorship Program

The aging of the U.S. population has led to an increase in the number of patients diagnosed with cancer each year. Fortunately, advances in screening, detection, and treatments have contributed to an improvement in cancer survival rates during the past few decades. More than 1.6 million new cases of cancer are expected to be diagnosed in 2014. It is estimated that there are currently 14 million cancer survivors, and the number of survivors by 2022 is expected to be 18 million.1,2

The growing number of cancer survivors is exceeding the ability of the cancer care system to meet the demand.3 Many primary care providers (PCPs) lack the confidence to provide cancer surveillance for survivors, but at the same time, patients and physicians continue to expect that PCPs will play a substantial role in general preventive health and in treating other medical problems.4 These conditions make it critical that at a minimum, survivorship care is integrated between oncology and primary care teams through a systematic, coordinated plan.5 This integration is especially important for the vulnerable population of veterans who are cancer survivors, as they have additional survivorship needs.

The purpose of this article is to assist other VA health care providers in establishing a cancer survivorship program to address the unique needs of veterans not only during active treatment, but after their initial treatment is completed. Described are the unique needs of veterans who are cancer survivors and the development and implementation of a cancer survivorship program at a large metropolitan VAMC, which is grounded in VA and national guidelines and evidence-based cancer care. Lessons learned and recommendations for other VA programs seeking to improve coordination of care for veteran cancer survivors are presented.

Cancer Survivorship

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, identified the importance of providing quality survivorship care to those “living with, through, and beyond a diagnosis of cancer.”6,7 The period of survivorship extends from the time of diagnosis, through treatment, long-term survival, and end-of-life.8,9 Although there are several definitions of cancer survivor, the most widely accepted definition is one who has been diagnosed with cancer, regardless of their position on the disease trajectory.8

The complex needs of cancer survivors encompass physical, psychological, social, and spiritual concerns across the disease trajectory.3 Cancer survivors who are also veterans have additional needs and risk factors related to their service that can make survivorship care more challenging.10 Veterans tend to be older compared with the age of the general population, have more comorbid conditions, and many have combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), all of which can complicate the survivorship experience.11

The first challenge for veteran cancer survivors is in the term cancer survivor, which may take on a different meaning for a veteran when compared with a civilian. For some civilians and veterans, survivor is a constant reminder of having had cancer. There are some veterans who prefer not to be called survivors, because they do not feel worthy of this terminology. They believe they have not struggled enough to self-identify as a survivor and that survivorship is “something to be earned, following a physically grueling experience.”12

The meaning of the word survivor may even be culturally linked to the population of veterans who have survived a life-threatening combat experience. More research is needed to understand the veteran cancer survivorship experience. The meaning of survivorship must be explored with each veteran, as it may influence his or her adherence to a survivorship plan of care.

Veterans make up a unique subset of cancer survivors, in part because of risk factors associated with their service. Many veterans developed cancer as a result of their military exposure to toxic chemicals and radiation. To date, VA recognizes that chronic B-cell leukemias, Hodgkin disease, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, prostate cancer, respiratory cancers, and soft tissue sarcomas are all presumptive diseases related to Agent Orange exposure.13 There are other substances also presumed to increase the risk of certain cancers in veterans who have had ionizing radiation exposure.14 There is still much to learn regarding veterans who served during the Gulf War, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation Iraqi Freedom.15,16

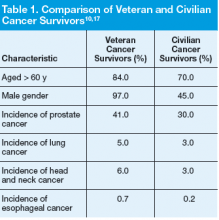

In a comparison of VA data files with U.S. SEER data files from 2007, researchers identified differences in characteristics between veteran cancer survivors and civilian cancer survivors.17 In addition to increased exposure risks, the veteran cancer survivor population is older than the general cancer survivorship population and is mostly male.17 Veterans’ comorbid conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease, Parkinson disease, and peripheral neuropathy, which may be service related, complicate survivorship.17 These characteristics (age, gender, exposure risks, and comorbid conditions) influence the type of cancer diagnosed and treatment options, and they may ultimately impact survivorship needs

(Table 1).

The prevalence of mental health issues in the veteran population is significant.18 Posttraumatic stress disorder affects 7% to 8% of the general population at some point during their lifetime and as many as 16% of those returning from military deployment.19 In a predominantly

male veteran study correlating combat PTSD with cancerrelated PTSD, about half the participants (n = 170) met PTSD Criterion A, viewing their cancer as a traumatic experience.20 Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, and addictive disease all must be addressed in the survivorship plan of care.

Poor mental health has been linked to increased morbidity and mortality and can limit the veteran’s ability to participate in health promotion and medical care.21 Distress related to cancer is well recognized in the civilian population.22,23 Veterans are at risk for moderate-tosevere disabling distress, especially when the cancer is associated with their military service. Vietnam veterans who have a diagnosis of cancer report that they have already served their time and are now serving it again, having to wage a battle on cancer and undergo difficult treatments and associated adverse effects (AEs).24 It is important to note, however, that some veterans have developed strong coping skills, which gives them strength and resilience for the survivorship experience.25

Other factors also contribute to veterans’ unique survivorship needs. Many veterans have limited social and/or economic resources, making it difficult to receive cancer treatment and follow recommendations for a healthful lifestyle as a cancer survivor. Demographics from the VA have illustrated that many veterans have a limited support system (65% do not have a spouse), and many have low incomes.26 Although veterans comprise about 11% of the general population, they make up 26% of the homeless population.26 It is estimated that 260,000 veterans are homeless at some time during the course of a year, and of these, 45% have mental health issues and 70% have substance abuse problems.27 Basic needs such as housing, running water, heat and electricity, and nutrition must be met in order to prevent infection during treatment, maximize the benefit, and reduce the risks associated with treatment. Transportation issues can make it challenging to travel to medical centers for cancer surveillance following treatment.

Models of Care

As defined in the aforementioned IOM report, multiple models of survivorship care have surfaced over the years.6 Much that was originally seen and implemented in adult cancer survivorship was known from pediatric cancer care. Early models that surfaced included shared care models, nurse-led models, and tertiary survivorship clinics. Each model has its strengths and disadvantages.

The shared care model of survivorship involves a sharing of the responsibility for the survivor among different specialties, potentially at different facilities, and the primary care team. Typically, the PCP refers the patient to the oncologist when cancer is suspected or diagnosed. The primary care team continues to provide routine health maintenance and manages other health problems while the oncology team provides cancer care. The patient is transitioned back to the primary care team with a survivorship care plan (SCP) at 1 to 2 years after completion of cancer therapy or at the discretion of the oncology team.28 For

this model to work, the PCP must be willing to take on this responsibility, and there must be a coordinated effort for seamless communication between teams, which can be potentially challenging.

Nurse-led programs emerged in the pediatric populations. Pediatric nurse-led clinics assume care of the patient after active treatment to manage long-term AEs of cancer treatments, symptom management, care planning, and education. A comprehensive review of the literature identified that “nurse-led follow-up services are acceptable, appropriate, and effective.”6 Barriers to this model of care include a shortage of trained oncology nurses and a preference for physician follow-up by some cancer survivors who want the security of their oncologist for ongoing, long-term care.6

Survivorship follow-up clinics, a tertiary model of care, have been implemented at some larger academic centers. These clinics focus on cancer survivorship and are often separate from other routine health care visits. Typically, these clinics include multiple specialties and are often disease-specific. These types of clinics pose a different set of challenges regarding duplication of services and reimbursement issues.

As of yet, no model has been proven more effective than the others. Each institution and patient population may not lend themselves to a one-size-fits-all model. There may be different models of care needed, based on patient population. Regardless of the model selected, individualized survivorship care plans are an essential component of quality cancer survivorship care.

Addessing Survivorship Care

In 2009, 5 interdisciplinary leaders in VA cancer care (Ellen Ballard, RN; David Haggstrom, MD, MAS; Veronica Reis, PhD; Mark Detzer, PhD; and Tina Gill, MA) attended a breakout session on psychosocial oncology at the Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) meeting in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and most members of this team participated in the 2009-2012 VHA Cancer Care Collaboratives to improve the timeliness and quality of care for veterans who were cancer patients. Dr. Haggstrom and Ms. Ballard developed a SharePoint site for the Survivorship Special Interest Group (SIG) members through the Loma Linda VAMC in California. The SIG workgroup then built the Cancer Survivorship Toolkit, composed of

5 critical tools (Figure).

In July 2012, the VA Cancer Survivorship Toolkit content was disseminated at AVAHO and launched behind the VA firewall. It subsequently received accolades from the national program director for VHA Oncology and was listed on the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) Best Practices website. The toolkit is accessible to all VA programs, and suggestions for new content can be submitted directly on the site (Figure).

The development of a SCP began in late 2011 when SIG members collected examples of SCPs from leading organizations. The members compared this content with the IOM recommendations for SCPs and developed a template. The template was programmed for the VHA computerized patient record system (CPRS) and placed on the internal VA toolkit website. The template included the treatment summary and care plan. The treatment summary portion included the diagnosis and tumor characteristics, diagnostic tests used, dates and types of treatment, chemoprevention or maintenance treatments, supportive services required, the surveillance plan, and signs of recurrence. The care plan portion provided information on the likely course of recovery and a checklist for common long-term AEs in the areas of psychological distress, financial and practical effects, and physical effects. Also included was information about referral, health behaviors, late effects that may develop, contact information, and general resource information.

The computer applications coordinator at any VA can download the template from the toolkit onto their CPRS, and the template can then be brought into any progress note. Individual sites may also edit the template to suit specific needs. The SCP can be completed by any clinician with the appropriate clinical competencies. To date, > 50 sites have downloaded the SCP template for use.

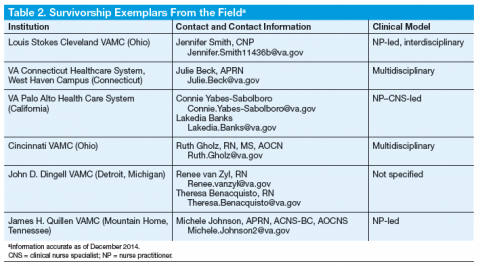

Cancer Survivorship Clinic

At the Louis Stokes Cleveland (LSC) VAMC, a nurse-led model of a cancer survivorship clinic was established with an expert nurse practitioner (NP). A major catalyst for the development of this clinic was the receipt of a Specialty Care Education Center of Excellence, funded by the Offices of Specialty Care and Academic Affiliations. A priority of this project was the implementation of survivorship care for every veteran with a cancer diagnosis. A system redesign was implemented to deliver quality, cost-effective, patient-centered cancer care within an interprofessional, team-based practice. This clinic is imbedded within an interdisciplinary clinic setting where the NP works in close collaboration with the medical and surgical oncologists as well as providers from mental health, social work, nutrition, physical therapy, and others.

The first patients to receive survivorship care in this new model from the time of their diagnosis were veterans with breast cancer, sarcoma, melanoma, and lymphomas. Veterans are followed jointly by the NP and the medical and surgical oncologists during active treatment. The NP provides physical symptom assessment and management for patients both during and after treatment.

At the end of active treatment, patient visits are alternated between oncology physicians and the survivorship NP for 5 years. The timeline for follow-up visits is based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for each cancer type but then individualized based on patient need.29 During this 5-year time period, patients under active surveillance whose conditions have been stable are seen by the NP. Any concerning symptoms are immediately relayed to the primary oncologist or surgical oncologist, often the same day, and patients can be seen the same day if necessary, to improve coordination and access to services.

A unique focus of the clinic is the integration of health promotion and risk reduction that coincides with the active surveillance plan. This transition of active surveillance patients to the NP-led survivorship clinic not only opens access to newly diagnosed cancer patients to be seen by the oncologist, but also allows for seamless transition and coordination to active surveillance. Within the clinic structure, patients receive patient navigation beginning with a cancer concern; patients also receive screening for psychosocial distress at the time of diagnosis and at every visit. Patient navigation and distress screening are both considered essential elements to survivorship care in the most recent CoC guidelines.30 The survivorship NP keeps the primary care team up-to-date regarding patient care across the disease trajectory by alerting them to updates electronically in the CPRS in real time.

Survivorship Care Plan

A focus of the clinic has also been on the implementation of a formal SCP to be completed 3 months after the conclusion of active treatment. The formal SCP was downloaded from the Cancer Survivorship Toolkit and is composed of a 3-part summary. The 3 parts consist of the treatment summary, the plan for rehabilitation, and the plan for the future. The first section of the SCP is completed by the medical oncologist as a summary of treatment received by the veteran. The summary of treatment section is reviewed and discussed with the veteran survivor at the visit, and the second and third sections are completed during the 3-month follow-up visit with the veteran.

Success and Areas for Improvement

The survivorship clinic has been well received by veterans. Patient satisfaction scores have been overwhelmingly positive. Veterans appreciate and feel comfortable knowing their providers from the beginning of diagnosis along the entire disease trajectory. They know that if problems arise, the survivorship NP has direct access to the medical or surgical oncologist for immediate review.

The difficult challenge for the cancer care providers is to know when is the right time to transition care back to the PCP. Transitions of care often come with high anxiety and a sense of loss for the veteran. The 5-year survival mark is not always the appropriate transition time for some veterans. Those with extensive physical and mental health issues may need continuity of care and continued support from the oncology team.

The SCP has presented challenges in terms of when to complete and who should complete the form. There has also been concern over the length of the summary, how long it will take to complete the document, and which summary template to use. Areas for improvement with the template could potentially be to automate population of the chemotherapy and radiation summaries. Some software packages are available, but they are costly. Another issue with external software is getting it accepted by VHA and incorporated into the CPRS.

Recommendations

Many cancer programs are struggling to provide highquality survivorship care. The CoC, recognizing the challenges programs are having implementing survivorship care, has extended the accreditation requirement for full implementation from 2015 to 2019.31

The following recommendations should be considered for the successful implementation of a new survivorship program:

- Collect information from multiple resources to guide the establishment of the survivorship clinic;

- Become familiar with the IOM From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition;6

- Understand local issues and barriers specific to your care delivery system;