User login

Ultrasound renal denervation drops BP in patients on triple therapy

Renal denervation’s comeback as a potential treatment for patients with drug-resistant hypertension rolls on.

Renal denervation with ultrasound energy produced a significant, median 4.5–mm Hg incremental drop in daytime, ambulatory, systolic blood pressure, compared with sham-treatment after 2 months follow-up in a randomized study of 136 patients with drug-resistant hypertension maintained on a standardized, single-pill, triple-drug regimen during the study.

The results “confirm that ultrasound renal denervation can lower blood pressure across a spectrum of hypertension,” concluded Ajay J. Kirtane, MD, at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology. Renal denervation procedures involve percutaneously placing an endovascular catheter bilaterally inside a patient’s renal arteries and using brief pulses of energy to ablate neurons involved in blood pressure regulation.

A former ‘hot concept’

“Renal denervation was a hot concept a number of years ago, but had been tested only in studies without a sham control,” and initial testing using sham controls failed to show a significant benefit from the intervention, noted Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, an interventional cardiologist and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston who was not involved with the study. The significant reductions in systolic blood pressure reported with renal denervation, compared with control patients in this study, “are believable” because of inclusion of a true control cohort, he added. “This really exciting finding puts renal denervation squarely back on the map,” commented Dr. Bhatt during a press briefing.

Dr. Bhatt added that, while the median 4.5–mm Hg incremental reduction in daytime, ambulatory, systolic blood pressure, compared with control patients – the study’s primary endpoint – may seem modest, “in the world of hypertension it’s a meaningful reduction” that, if sustained over the long term, would be expected to produce meaningful cuts in adverse cardiovascular events such as heart failure, stroke, and MI.

“The question is whether the effects are durable,” highlighted Dr. Bhatt, who helped lead the first sham-controlled trial of renal denervation, SYMPLICITY HTN-3, which failed to show a significant blood pressure reduction, compared with controls using radiofrequency energy to ablate renal nerves. A more recent study that used a different radiofrequency catheter and sham controls showed a significant effect on reducing systolic blood pressure in the SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED Pivotal trial, which by design did not maintain patients on any antihypertensive medications following their renal denervation procedure.

Dr. Kirtane noted that, although the median systolic blood pressure reduction, compared with controls treated by a sham procedure, was 4.5 mm Hg, the total median systolic pressure reduction after 2 months in the actively treated patients was 8.0 mm Hg when compared with their baseline blood pressure.

Concurrently with his report the results also appeared in an article posted online (Lancet. 2021 May 16;doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00788-1).

Denervation coupled with a single, daily three-drug pill

The RADIANCE-HTN TRIO study ran at 53 centers in the United States and Europe, and randomized 136 adults with an office-measured blood pressure of at least 140/90 mm Hg despite being on a stable regimen of at least three antihypertensive drugs including a diuretic. The enrolled cohort averaged 52 years of age and had an average office-measured pressure of about 162/104 mm Hg despite being on an average of four agents, although only about a third of enrolled patients were on treatment with a mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonist (MRA) such as spironolactone.

At the time of enrollment and 4 weeks before their denervation procedure, all patients switched to a uniform drug regimen of a single, daily, oral pill containing the calcium channel blocker amlodipine, the angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan or olmesartan, and the diuretic hydrochlorothiazide with no other drug treatment allowed except for unusual, prespecified clinical circumstances. All patients remained on this drug regimen for the initial 2-month follow-up period unless their blood pressure exceeded 180/110 mm Hg during in-office measurement.

The denervation treatment was well tolerated, although patients reported brief, transient, and “minor” pain associated with the procedure that did not affect treatment blinding or have any lingering consequences, said Dr. Kirtane, professor of medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York.

A reason to use energy delivery by ultrasound rather than by radiofrequency to ablate nerves in the renal arteries is that the ultrasound approach exerts a more uniform effect, allowing effective treatment delivery without need for catheter repositioning into more distal branches of the renal arteries, said Dr. Kirtane, who is also an interventional cardiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

But each method has its advantages, he added.

He also conceded that additional questions need to be addressed regarding which patients are most appropriate for renal denervation. “We need to figure out in which patients we can apply a device-based treatment,” Dr. Kirtane said during the press briefing. Patients with what appears to be drug-resistant hypertension often do not receive treatment with a MRA because of adverse effects, and many of these patients are not usually assessed for primary aldosteronism.

In SYMPLICITY HTN-3, “about half the patients who were seemingly eligible became ineligible” when they started treatment with a MRA, noted Dr. Bhatt. “A little spironolactone can go a long way” toward resolving treatment-resistant hypertension in many patients, he said.

RADIANCE-HTN TRIO was sponsored by ReCor Medical, the company developing the tested ultrasound catheter. Dr. Kirtane has received travel expenses and meals from ReCor Medical and several other companies, and Columbia has received research funding from ReCor Medical and several other companies related to research he has conducted. Dr. Bhatt has no relationship with ReCor Medical. He has been a consultant to and received honoraria from K2P, Level Ex, and MJH Life Sciences; he has been an advisor to Cardax, Cereno Scientific, Myokardia, Novo Nordisk, Phase Bio, and PLx Pharma; and he has received research funding from numerous companies.

Renal denervation’s comeback as a potential treatment for patients with drug-resistant hypertension rolls on.

Renal denervation with ultrasound energy produced a significant, median 4.5–mm Hg incremental drop in daytime, ambulatory, systolic blood pressure, compared with sham-treatment after 2 months follow-up in a randomized study of 136 patients with drug-resistant hypertension maintained on a standardized, single-pill, triple-drug regimen during the study.

The results “confirm that ultrasound renal denervation can lower blood pressure across a spectrum of hypertension,” concluded Ajay J. Kirtane, MD, at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology. Renal denervation procedures involve percutaneously placing an endovascular catheter bilaterally inside a patient’s renal arteries and using brief pulses of energy to ablate neurons involved in blood pressure regulation.

A former ‘hot concept’

“Renal denervation was a hot concept a number of years ago, but had been tested only in studies without a sham control,” and initial testing using sham controls failed to show a significant benefit from the intervention, noted Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, an interventional cardiologist and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston who was not involved with the study. The significant reductions in systolic blood pressure reported with renal denervation, compared with control patients in this study, “are believable” because of inclusion of a true control cohort, he added. “This really exciting finding puts renal denervation squarely back on the map,” commented Dr. Bhatt during a press briefing.

Dr. Bhatt added that, while the median 4.5–mm Hg incremental reduction in daytime, ambulatory, systolic blood pressure, compared with control patients – the study’s primary endpoint – may seem modest, “in the world of hypertension it’s a meaningful reduction” that, if sustained over the long term, would be expected to produce meaningful cuts in adverse cardiovascular events such as heart failure, stroke, and MI.

“The question is whether the effects are durable,” highlighted Dr. Bhatt, who helped lead the first sham-controlled trial of renal denervation, SYMPLICITY HTN-3, which failed to show a significant blood pressure reduction, compared with controls using radiofrequency energy to ablate renal nerves. A more recent study that used a different radiofrequency catheter and sham controls showed a significant effect on reducing systolic blood pressure in the SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED Pivotal trial, which by design did not maintain patients on any antihypertensive medications following their renal denervation procedure.

Dr. Kirtane noted that, although the median systolic blood pressure reduction, compared with controls treated by a sham procedure, was 4.5 mm Hg, the total median systolic pressure reduction after 2 months in the actively treated patients was 8.0 mm Hg when compared with their baseline blood pressure.

Concurrently with his report the results also appeared in an article posted online (Lancet. 2021 May 16;doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00788-1).

Denervation coupled with a single, daily three-drug pill

The RADIANCE-HTN TRIO study ran at 53 centers in the United States and Europe, and randomized 136 adults with an office-measured blood pressure of at least 140/90 mm Hg despite being on a stable regimen of at least three antihypertensive drugs including a diuretic. The enrolled cohort averaged 52 years of age and had an average office-measured pressure of about 162/104 mm Hg despite being on an average of four agents, although only about a third of enrolled patients were on treatment with a mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonist (MRA) such as spironolactone.

At the time of enrollment and 4 weeks before their denervation procedure, all patients switched to a uniform drug regimen of a single, daily, oral pill containing the calcium channel blocker amlodipine, the angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan or olmesartan, and the diuretic hydrochlorothiazide with no other drug treatment allowed except for unusual, prespecified clinical circumstances. All patients remained on this drug regimen for the initial 2-month follow-up period unless their blood pressure exceeded 180/110 mm Hg during in-office measurement.

The denervation treatment was well tolerated, although patients reported brief, transient, and “minor” pain associated with the procedure that did not affect treatment blinding or have any lingering consequences, said Dr. Kirtane, professor of medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York.

A reason to use energy delivery by ultrasound rather than by radiofrequency to ablate nerves in the renal arteries is that the ultrasound approach exerts a more uniform effect, allowing effective treatment delivery without need for catheter repositioning into more distal branches of the renal arteries, said Dr. Kirtane, who is also an interventional cardiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

But each method has its advantages, he added.

He also conceded that additional questions need to be addressed regarding which patients are most appropriate for renal denervation. “We need to figure out in which patients we can apply a device-based treatment,” Dr. Kirtane said during the press briefing. Patients with what appears to be drug-resistant hypertension often do not receive treatment with a MRA because of adverse effects, and many of these patients are not usually assessed for primary aldosteronism.

In SYMPLICITY HTN-3, “about half the patients who were seemingly eligible became ineligible” when they started treatment with a MRA, noted Dr. Bhatt. “A little spironolactone can go a long way” toward resolving treatment-resistant hypertension in many patients, he said.

RADIANCE-HTN TRIO was sponsored by ReCor Medical, the company developing the tested ultrasound catheter. Dr. Kirtane has received travel expenses and meals from ReCor Medical and several other companies, and Columbia has received research funding from ReCor Medical and several other companies related to research he has conducted. Dr. Bhatt has no relationship with ReCor Medical. He has been a consultant to and received honoraria from K2P, Level Ex, and MJH Life Sciences; he has been an advisor to Cardax, Cereno Scientific, Myokardia, Novo Nordisk, Phase Bio, and PLx Pharma; and he has received research funding from numerous companies.

Renal denervation’s comeback as a potential treatment for patients with drug-resistant hypertension rolls on.

Renal denervation with ultrasound energy produced a significant, median 4.5–mm Hg incremental drop in daytime, ambulatory, systolic blood pressure, compared with sham-treatment after 2 months follow-up in a randomized study of 136 patients with drug-resistant hypertension maintained on a standardized, single-pill, triple-drug regimen during the study.

The results “confirm that ultrasound renal denervation can lower blood pressure across a spectrum of hypertension,” concluded Ajay J. Kirtane, MD, at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology. Renal denervation procedures involve percutaneously placing an endovascular catheter bilaterally inside a patient’s renal arteries and using brief pulses of energy to ablate neurons involved in blood pressure regulation.

A former ‘hot concept’

“Renal denervation was a hot concept a number of years ago, but had been tested only in studies without a sham control,” and initial testing using sham controls failed to show a significant benefit from the intervention, noted Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, an interventional cardiologist and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston who was not involved with the study. The significant reductions in systolic blood pressure reported with renal denervation, compared with control patients in this study, “are believable” because of inclusion of a true control cohort, he added. “This really exciting finding puts renal denervation squarely back on the map,” commented Dr. Bhatt during a press briefing.

Dr. Bhatt added that, while the median 4.5–mm Hg incremental reduction in daytime, ambulatory, systolic blood pressure, compared with control patients – the study’s primary endpoint – may seem modest, “in the world of hypertension it’s a meaningful reduction” that, if sustained over the long term, would be expected to produce meaningful cuts in adverse cardiovascular events such as heart failure, stroke, and MI.

“The question is whether the effects are durable,” highlighted Dr. Bhatt, who helped lead the first sham-controlled trial of renal denervation, SYMPLICITY HTN-3, which failed to show a significant blood pressure reduction, compared with controls using radiofrequency energy to ablate renal nerves. A more recent study that used a different radiofrequency catheter and sham controls showed a significant effect on reducing systolic blood pressure in the SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED Pivotal trial, which by design did not maintain patients on any antihypertensive medications following their renal denervation procedure.

Dr. Kirtane noted that, although the median systolic blood pressure reduction, compared with controls treated by a sham procedure, was 4.5 mm Hg, the total median systolic pressure reduction after 2 months in the actively treated patients was 8.0 mm Hg when compared with their baseline blood pressure.

Concurrently with his report the results also appeared in an article posted online (Lancet. 2021 May 16;doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00788-1).

Denervation coupled with a single, daily three-drug pill

The RADIANCE-HTN TRIO study ran at 53 centers in the United States and Europe, and randomized 136 adults with an office-measured blood pressure of at least 140/90 mm Hg despite being on a stable regimen of at least three antihypertensive drugs including a diuretic. The enrolled cohort averaged 52 years of age and had an average office-measured pressure of about 162/104 mm Hg despite being on an average of four agents, although only about a third of enrolled patients were on treatment with a mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonist (MRA) such as spironolactone.

At the time of enrollment and 4 weeks before their denervation procedure, all patients switched to a uniform drug regimen of a single, daily, oral pill containing the calcium channel blocker amlodipine, the angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan or olmesartan, and the diuretic hydrochlorothiazide with no other drug treatment allowed except for unusual, prespecified clinical circumstances. All patients remained on this drug regimen for the initial 2-month follow-up period unless their blood pressure exceeded 180/110 mm Hg during in-office measurement.

The denervation treatment was well tolerated, although patients reported brief, transient, and “minor” pain associated with the procedure that did not affect treatment blinding or have any lingering consequences, said Dr. Kirtane, professor of medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York.

A reason to use energy delivery by ultrasound rather than by radiofrequency to ablate nerves in the renal arteries is that the ultrasound approach exerts a more uniform effect, allowing effective treatment delivery without need for catheter repositioning into more distal branches of the renal arteries, said Dr. Kirtane, who is also an interventional cardiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

But each method has its advantages, he added.

He also conceded that additional questions need to be addressed regarding which patients are most appropriate for renal denervation. “We need to figure out in which patients we can apply a device-based treatment,” Dr. Kirtane said during the press briefing. Patients with what appears to be drug-resistant hypertension often do not receive treatment with a MRA because of adverse effects, and many of these patients are not usually assessed for primary aldosteronism.

In SYMPLICITY HTN-3, “about half the patients who were seemingly eligible became ineligible” when they started treatment with a MRA, noted Dr. Bhatt. “A little spironolactone can go a long way” toward resolving treatment-resistant hypertension in many patients, he said.

RADIANCE-HTN TRIO was sponsored by ReCor Medical, the company developing the tested ultrasound catheter. Dr. Kirtane has received travel expenses and meals from ReCor Medical and several other companies, and Columbia has received research funding from ReCor Medical and several other companies related to research he has conducted. Dr. Bhatt has no relationship with ReCor Medical. He has been a consultant to and received honoraria from K2P, Level Ex, and MJH Life Sciences; he has been an advisor to Cardax, Cereno Scientific, Myokardia, Novo Nordisk, Phase Bio, and PLx Pharma; and he has received research funding from numerous companies.

FROM ACC 2021

ACC 21 looks to repeat success despite pandemic headwinds

The American College of Cardiology pulled off an impressive all-virtual meeting in March 2020, less than 3 weeks after canceling its in-person event and just 2 weeks after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency.

Optimistic plans for the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology (ACC 2021) to be a March hybrid affair in Atlanta pivoted not once, but twice, as the pandemic evolved, with the date pushed back 2 full months, to May 15-17, and the format revised to fully virtual.

“While this meeting is being delivered virtually, I think you’ll see there have been benefits in the time to plan and also the lessons that ACC has learned in virtual education over the past year. This has come together to really create a robust educational and scientific agenda,” ACC 2021 chair Pamela B. Morris, MD, said in a press conference focused on the upcoming meeting.

Over the 3 days, there will be more than 200 education sessions, 10 guideline-specific sessions, and 11 learning pathways that include core areas, but also special topics, such as COVID-19 and the emerging cardio-obstetrics subspecialty.

The meeting will be delivered through a new virtual education program built to optimize real-time interaction between faculty members and attendees, she said. A dedicated portal on the platform will allow attendees to interact virtually, for example, with presenters of the nearly 3,000 ePosters and 420 moderated posters.

For those suffering from Zoom fatigue, the increasingly popular Heart2Heart stage talks have also been converted to podcasts, which cover topics like gender equity in cardiology, the evolving role of advanced practice professionals, and “one of my favorites: art as a tool for healing,” said Dr. Morris, from the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. “Those sessions are really not to be missed.”

Reconnecting is an underlying theme of the meeting but the great divider will not be ignored. COVID-19 will be the focus of two 90-minute Intensive Sessions on Saturday, May 15, the first kicking off at 10:30 a.m. ET, with the Bishop Keynote lecture on bringing health equity to the frontline of cardiovascular care, followed by lessons learned during the pandemic, how to conduct clinical trials, and vaccine development.

The second session, set for 12:15 p.m., continues the “silver linings” theme, with case presentations on advances in telehealth, myocardial involvement, and thrombosis in COVID. For those wanting more, 18 abstracts are on tap in a 2-hour Spotlight on Special Topics session beginning at 2:30 p.m.

Asked about the pandemic’s effect on bringing science to fruition this past year, Dr. Morris said there’s no question it’s slowed some of the progress the cardiology community had made but, like clinical practice, “we’ve also surmounted many of those obstacles.”

“I think research has rebounded,” she said. “Just in terms of the number of abstracts and the quality of abstracts that were submitted this year, I don’t think there’s any question that we are right on par with previous years.”

Indeed, 5,258 abstracts from 76 countries were submitted, with more than 3,400 chosen for oral and poster presentation, including 25 late-breaking clinical trials to be presented in five sessions.

The late-breaking presentations and discussions will be prerecorded but speakers and panelists have been invited to be present during the streaming to answer live any questions that may arise in the chat box, ACC 2021 vice chair Douglas Drachman, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

Late-breaking clinical trials

The Joint ACC/JACC Late-Breaking Clinical Trials I (Saturday, May 15, 9:00 a.m.–-10:00 a.m.) kicks off with PARADISE-MI, the first head-to-head comparison of an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) and an ACE inhibitor in patients with reduced ejection fractions (EFs) after MI but no history of heart failure (HF), studying 200 mg sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) versus 5 mg of ramipril, both twice daily, in 5,669 patients.

Sacubitril/valsartan was initially approved for HF with reduced EF and added a new indication to treat some HF patients with preserved EF. Novartis, however, recently told investors that although numerical trends consistently favored the ARNI over the ACE inhibitor ramipril, the phase 3 study failed to meet the primary endpoint for efficacy superiority of reducing the risk for cardiovascular (CV) death and HF events after an acute MI.

Second up is ADAPTABLE, which looks to close a surprising evidence gap over whether 81 mg or 325 mg daily is the optimal dose of the ubiquitously prescribed aspirin for secondary prevention in high-risk patients with established atherosclerotic CV disease.

The open-label, randomized study will look at efficacy and major bleeding over roughly 4 years in 15,000 patients within PCORnet, the National Patient-centered Clinical Research Network, a partnership of clinical research, health plan research, and patient-powered networks created to streamline patient-reported outcomes research.

“This study will not only give important clinical information for us, practically speaking, whether we should prescribe lower- or higher-dose aspirin, but it may also serve as a template for future pragmatic clinical trial design in the real world,” Dr. Drachman said during the press conference.

Up next is the 4,812-patient Canadian LAAOS III, the largest trial to examine the efficacy of left atrial appendage occlusion for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) already undergoing cardiac surgery. The primary outcome is the first occurrence of stroke or systemic arterial embolism over an average follow-up of 4 years.

Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage (LAA) has been shown to reduce stroke in AFib patients at high-risk of bleeding on systemic anticoagulation. But these devices can be expensive and studies haven’t included patients who also have valvular heart disease, a group that actually comprises more than half of patients undergoing cardiac surgery who also have AFib, he noted.

At the same time, surgical LAA closure studies have been small and have had very mixed results. “There isn’t a large-scale rigorous assessment out there for these patients undergoing surgery, so I think this is going to be fascinating to see,” Dr. Drachman said.

The session closes with ATLANTIS, which looks to shed some light on the role of anticoagulation therapy in patients after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR or TAVI). POPular TAVI, presented at ACC 2020, showed aspirin alone was the preferred antithrombotic therapy over aspirin plus clopidogrel (Plavix) in patients not on oral anticoagulants, but the optimal anticoagulation regimen remains unsettled.

The French open-label, 1,510-patient ATLANTIS trial examined whether the novel oral anticoagulant apixaban (Eliquis) is superior in preventing CV events after TAVR, compared with antiplatelet therapy in patients without an indication for anticoagulation and compared with vitamin K antagonists in those receiving anticoagulants.

An ATLANTIS 4D CT substudy of valve thrombosis is also slated for Saturday’s Featured Clinical Research 1 session at 12:15 p.m. to 1:45 p.m..

Sunday LBCTs

Dr. Drachman highlighted a series of other late-breaking studies, including the global DARE-19 trial testing the diabetes and HF drug dapagliflozin (Farxiga) given with local standard-of-care therapy for 30 days in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with CV, metabolic, or renal risk factors.

Although sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors have been white-hot of late, top-line results reported last month show dapagliflozin failed to achieve statistical significance for the primary endpoints of reducing organ dysfunction and all-cause mortality and for improving recovery. Details will be presented in the Joint ACC/JAMA Late-Breaking Clinical Trials II (Sunday, May 16, 8:00 a.m.-9:30 a.m.).

Two trials, FLOWER-MI and RADIANCE-HTN TRIO, were singled out in the Joint ACC/New England Journal of Medicine Late-Breaking Clinical Trials III (Sunday, May 16, 10:45 a.m.-12:00 p.m.). FLOWER-MI examines whether fractional flow reserve (FFR) is better than angiography to guide complete multivessel revascularization in ST-elevation MI patients with at least 50% stenosis in at least one nonculprit lesion requiring percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Recent studies have shown the superiority of FFR-guided PCI for nonculprit lesions, compared with culprit lesion treatment-only, but this is the first time FFR- and angiography-guided PCI have been compared in STEMI patients.

RADIANCE-HTN TRIO already tipped its hand, with top-line results reported in late 2020 showing that the trial met its primary efficacy endpoint of greater reduction in daytime blood pressure over 2 months with the Paradise endovascular ultrasound renal denervation system, compared with a sham procedure, in 136 patients with resistant hypertension, importantly, after being given a single pill containing a calcium channel blocker, angiotensin II receptor blocker, and diuretic.

Renal denervation for hypertension has been making something of a comeback, with the 2018 RADIANCE-HTN SOLO reporting better ambulatory blood pressure control with the Paradise system than with a sham procedure in the absence of antihypertensive agents. The device has been granted breakthrough device designation from the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of hypertensive patients who are unable to sufficiently respond to or are intolerant of antihypertensive therapy.

Monday LBCTs

In the Late-Breaking Clinical Trials IV session (Monday, May 17, 8 a.m.–9:30 a.m.), Drachman called out a secondary analysis from GALATIC-HF looking at the impact of EF on the therapeutic effect of omecamtiv mecarbil. In last year’s primary analysis, the selective cardiac myosin activator produced a modest but significant reduction in HF events or CV death in 8,232 patients with HF and an EF of 35% or less.

Rounding out the list is the Canadian CAPITAL CHILL study of moderate versus mild therapeutic hypothermia in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, to be presented in the final Late-Breaking Clinical Trials V session (Monday, May 17, 10:45 a.m.–12:00 p.m.).

The double-blind trial sought to determine whether neurologic outcomes at 6 months are improved by targeting a core temperature of 31 ˚C versus 34 ˚C after the return of spontaneous circulation in comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

“For me, I think this could really change practice and has personal relevance from experience with cardiac arrest survivors that I’ve known and care for very deeply,” Dr. Drachman said in an interview. “I think that there’s a lot of opportunity here as well.”

Asked what other trials have the potential to change practice, Dr. Drachman said FLOWER-MI holds particular interest because it looks at how to manage patients with STEMI with multiple lesions at the point of care.

“We’ve gained a lot of clarity from several other prior clinical trials, but this will help to answer the question in a slightly different way of saying: can you eyeball it, can you look at the angiogram and say whether or not that other, nonculprit lesion ought to be treated in the same hospitalization or should you really be using a pressure wire,” he said. “For me as an interventionalist, this is really important because when you finish up doing an intervention on a patient it might be the middle of the night and the patient may be more or less stable, but you’ve already exposed them to the risk of a procedure, should you then move on and do another aspect of the procedure to interrogate with a pressure wire a remaining narrowing? I think that’s very important; that’ll help me make decisions on a day-to-day basis.”

Dr. Drachman also cited RADIANCE-HTN TRIO because it employs an endovascular technique to control blood pressure in patients with hypertension, specifically those resistant to multiple drugs.

During the press conference, Dr. Morris, a preventive cardiologist, put her money on the ADAPTABLE study of aspirin dosing, reiterating that the unique trial design could inform future research, and on Sunday’s 8:45 a.m. late-breaking post hoc analysis from the STRENGTH trial that looks to pick up where the controversy over omega-3 fatty acid preparations left off at last year’s American Heart Association meeting.

A lack of benefit on CV event rates reported with Epanova, a high-dose combination of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid, led to a contentious debate over how to reconcile STRENGTH with the findings from REDUCE-IT, which showed a 25% relative risk reduction in major CV events with the EPA product icosapent ethyl (Vascepa).

STRENGTH investigator Steven Nissen, MD, Cleveland Clinic, and REDUCE-IT investigator and session panelist Deepak Bhatt, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, will share the virtual stage at ACC 2021, but Dr. Morris said the “good news” is both researchers know one another very well and “will really be focusing on no political issues, just the omega-3 fatty levels in the bloodstream and what does that mean in either trial.

“This is not designed to be a debate, point counterpoint,” she added.

For that, as all cardiologists and journalists know, there will be the wild and woolly #CardioTwitter sphere.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American College of Cardiology pulled off an impressive all-virtual meeting in March 2020, less than 3 weeks after canceling its in-person event and just 2 weeks after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency.

Optimistic plans for the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology (ACC 2021) to be a March hybrid affair in Atlanta pivoted not once, but twice, as the pandemic evolved, with the date pushed back 2 full months, to May 15-17, and the format revised to fully virtual.

“While this meeting is being delivered virtually, I think you’ll see there have been benefits in the time to plan and also the lessons that ACC has learned in virtual education over the past year. This has come together to really create a robust educational and scientific agenda,” ACC 2021 chair Pamela B. Morris, MD, said in a press conference focused on the upcoming meeting.

Over the 3 days, there will be more than 200 education sessions, 10 guideline-specific sessions, and 11 learning pathways that include core areas, but also special topics, such as COVID-19 and the emerging cardio-obstetrics subspecialty.

The meeting will be delivered through a new virtual education program built to optimize real-time interaction between faculty members and attendees, she said. A dedicated portal on the platform will allow attendees to interact virtually, for example, with presenters of the nearly 3,000 ePosters and 420 moderated posters.

For those suffering from Zoom fatigue, the increasingly popular Heart2Heart stage talks have also been converted to podcasts, which cover topics like gender equity in cardiology, the evolving role of advanced practice professionals, and “one of my favorites: art as a tool for healing,” said Dr. Morris, from the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. “Those sessions are really not to be missed.”

Reconnecting is an underlying theme of the meeting but the great divider will not be ignored. COVID-19 will be the focus of two 90-minute Intensive Sessions on Saturday, May 15, the first kicking off at 10:30 a.m. ET, with the Bishop Keynote lecture on bringing health equity to the frontline of cardiovascular care, followed by lessons learned during the pandemic, how to conduct clinical trials, and vaccine development.

The second session, set for 12:15 p.m., continues the “silver linings” theme, with case presentations on advances in telehealth, myocardial involvement, and thrombosis in COVID. For those wanting more, 18 abstracts are on tap in a 2-hour Spotlight on Special Topics session beginning at 2:30 p.m.

Asked about the pandemic’s effect on bringing science to fruition this past year, Dr. Morris said there’s no question it’s slowed some of the progress the cardiology community had made but, like clinical practice, “we’ve also surmounted many of those obstacles.”

“I think research has rebounded,” she said. “Just in terms of the number of abstracts and the quality of abstracts that were submitted this year, I don’t think there’s any question that we are right on par with previous years.”

Indeed, 5,258 abstracts from 76 countries were submitted, with more than 3,400 chosen for oral and poster presentation, including 25 late-breaking clinical trials to be presented in five sessions.

The late-breaking presentations and discussions will be prerecorded but speakers and panelists have been invited to be present during the streaming to answer live any questions that may arise in the chat box, ACC 2021 vice chair Douglas Drachman, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

Late-breaking clinical trials

The Joint ACC/JACC Late-Breaking Clinical Trials I (Saturday, May 15, 9:00 a.m.–-10:00 a.m.) kicks off with PARADISE-MI, the first head-to-head comparison of an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) and an ACE inhibitor in patients with reduced ejection fractions (EFs) after MI but no history of heart failure (HF), studying 200 mg sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) versus 5 mg of ramipril, both twice daily, in 5,669 patients.

Sacubitril/valsartan was initially approved for HF with reduced EF and added a new indication to treat some HF patients with preserved EF. Novartis, however, recently told investors that although numerical trends consistently favored the ARNI over the ACE inhibitor ramipril, the phase 3 study failed to meet the primary endpoint for efficacy superiority of reducing the risk for cardiovascular (CV) death and HF events after an acute MI.

Second up is ADAPTABLE, which looks to close a surprising evidence gap over whether 81 mg or 325 mg daily is the optimal dose of the ubiquitously prescribed aspirin for secondary prevention in high-risk patients with established atherosclerotic CV disease.

The open-label, randomized study will look at efficacy and major bleeding over roughly 4 years in 15,000 patients within PCORnet, the National Patient-centered Clinical Research Network, a partnership of clinical research, health plan research, and patient-powered networks created to streamline patient-reported outcomes research.

“This study will not only give important clinical information for us, practically speaking, whether we should prescribe lower- or higher-dose aspirin, but it may also serve as a template for future pragmatic clinical trial design in the real world,” Dr. Drachman said during the press conference.

Up next is the 4,812-patient Canadian LAAOS III, the largest trial to examine the efficacy of left atrial appendage occlusion for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) already undergoing cardiac surgery. The primary outcome is the first occurrence of stroke or systemic arterial embolism over an average follow-up of 4 years.

Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage (LAA) has been shown to reduce stroke in AFib patients at high-risk of bleeding on systemic anticoagulation. But these devices can be expensive and studies haven’t included patients who also have valvular heart disease, a group that actually comprises more than half of patients undergoing cardiac surgery who also have AFib, he noted.

At the same time, surgical LAA closure studies have been small and have had very mixed results. “There isn’t a large-scale rigorous assessment out there for these patients undergoing surgery, so I think this is going to be fascinating to see,” Dr. Drachman said.

The session closes with ATLANTIS, which looks to shed some light on the role of anticoagulation therapy in patients after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR or TAVI). POPular TAVI, presented at ACC 2020, showed aspirin alone was the preferred antithrombotic therapy over aspirin plus clopidogrel (Plavix) in patients not on oral anticoagulants, but the optimal anticoagulation regimen remains unsettled.

The French open-label, 1,510-patient ATLANTIS trial examined whether the novel oral anticoagulant apixaban (Eliquis) is superior in preventing CV events after TAVR, compared with antiplatelet therapy in patients without an indication for anticoagulation and compared with vitamin K antagonists in those receiving anticoagulants.

An ATLANTIS 4D CT substudy of valve thrombosis is also slated for Saturday’s Featured Clinical Research 1 session at 12:15 p.m. to 1:45 p.m..

Sunday LBCTs

Dr. Drachman highlighted a series of other late-breaking studies, including the global DARE-19 trial testing the diabetes and HF drug dapagliflozin (Farxiga) given with local standard-of-care therapy for 30 days in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with CV, metabolic, or renal risk factors.

Although sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors have been white-hot of late, top-line results reported last month show dapagliflozin failed to achieve statistical significance for the primary endpoints of reducing organ dysfunction and all-cause mortality and for improving recovery. Details will be presented in the Joint ACC/JAMA Late-Breaking Clinical Trials II (Sunday, May 16, 8:00 a.m.-9:30 a.m.).

Two trials, FLOWER-MI and RADIANCE-HTN TRIO, were singled out in the Joint ACC/New England Journal of Medicine Late-Breaking Clinical Trials III (Sunday, May 16, 10:45 a.m.-12:00 p.m.). FLOWER-MI examines whether fractional flow reserve (FFR) is better than angiography to guide complete multivessel revascularization in ST-elevation MI patients with at least 50% stenosis in at least one nonculprit lesion requiring percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Recent studies have shown the superiority of FFR-guided PCI for nonculprit lesions, compared with culprit lesion treatment-only, but this is the first time FFR- and angiography-guided PCI have been compared in STEMI patients.

RADIANCE-HTN TRIO already tipped its hand, with top-line results reported in late 2020 showing that the trial met its primary efficacy endpoint of greater reduction in daytime blood pressure over 2 months with the Paradise endovascular ultrasound renal denervation system, compared with a sham procedure, in 136 patients with resistant hypertension, importantly, after being given a single pill containing a calcium channel blocker, angiotensin II receptor blocker, and diuretic.

Renal denervation for hypertension has been making something of a comeback, with the 2018 RADIANCE-HTN SOLO reporting better ambulatory blood pressure control with the Paradise system than with a sham procedure in the absence of antihypertensive agents. The device has been granted breakthrough device designation from the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of hypertensive patients who are unable to sufficiently respond to or are intolerant of antihypertensive therapy.

Monday LBCTs

In the Late-Breaking Clinical Trials IV session (Monday, May 17, 8 a.m.–9:30 a.m.), Drachman called out a secondary analysis from GALATIC-HF looking at the impact of EF on the therapeutic effect of omecamtiv mecarbil. In last year’s primary analysis, the selective cardiac myosin activator produced a modest but significant reduction in HF events or CV death in 8,232 patients with HF and an EF of 35% or less.

Rounding out the list is the Canadian CAPITAL CHILL study of moderate versus mild therapeutic hypothermia in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, to be presented in the final Late-Breaking Clinical Trials V session (Monday, May 17, 10:45 a.m.–12:00 p.m.).

The double-blind trial sought to determine whether neurologic outcomes at 6 months are improved by targeting a core temperature of 31 ˚C versus 34 ˚C after the return of spontaneous circulation in comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

“For me, I think this could really change practice and has personal relevance from experience with cardiac arrest survivors that I’ve known and care for very deeply,” Dr. Drachman said in an interview. “I think that there’s a lot of opportunity here as well.”

Asked what other trials have the potential to change practice, Dr. Drachman said FLOWER-MI holds particular interest because it looks at how to manage patients with STEMI with multiple lesions at the point of care.

“We’ve gained a lot of clarity from several other prior clinical trials, but this will help to answer the question in a slightly different way of saying: can you eyeball it, can you look at the angiogram and say whether or not that other, nonculprit lesion ought to be treated in the same hospitalization or should you really be using a pressure wire,” he said. “For me as an interventionalist, this is really important because when you finish up doing an intervention on a patient it might be the middle of the night and the patient may be more or less stable, but you’ve already exposed them to the risk of a procedure, should you then move on and do another aspect of the procedure to interrogate with a pressure wire a remaining narrowing? I think that’s very important; that’ll help me make decisions on a day-to-day basis.”

Dr. Drachman also cited RADIANCE-HTN TRIO because it employs an endovascular technique to control blood pressure in patients with hypertension, specifically those resistant to multiple drugs.

During the press conference, Dr. Morris, a preventive cardiologist, put her money on the ADAPTABLE study of aspirin dosing, reiterating that the unique trial design could inform future research, and on Sunday’s 8:45 a.m. late-breaking post hoc analysis from the STRENGTH trial that looks to pick up where the controversy over omega-3 fatty acid preparations left off at last year’s American Heart Association meeting.

A lack of benefit on CV event rates reported with Epanova, a high-dose combination of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid, led to a contentious debate over how to reconcile STRENGTH with the findings from REDUCE-IT, which showed a 25% relative risk reduction in major CV events with the EPA product icosapent ethyl (Vascepa).

STRENGTH investigator Steven Nissen, MD, Cleveland Clinic, and REDUCE-IT investigator and session panelist Deepak Bhatt, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, will share the virtual stage at ACC 2021, but Dr. Morris said the “good news” is both researchers know one another very well and “will really be focusing on no political issues, just the omega-3 fatty levels in the bloodstream and what does that mean in either trial.

“This is not designed to be a debate, point counterpoint,” she added.

For that, as all cardiologists and journalists know, there will be the wild and woolly #CardioTwitter sphere.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American College of Cardiology pulled off an impressive all-virtual meeting in March 2020, less than 3 weeks after canceling its in-person event and just 2 weeks after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency.

Optimistic plans for the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology (ACC 2021) to be a March hybrid affair in Atlanta pivoted not once, but twice, as the pandemic evolved, with the date pushed back 2 full months, to May 15-17, and the format revised to fully virtual.

“While this meeting is being delivered virtually, I think you’ll see there have been benefits in the time to plan and also the lessons that ACC has learned in virtual education over the past year. This has come together to really create a robust educational and scientific agenda,” ACC 2021 chair Pamela B. Morris, MD, said in a press conference focused on the upcoming meeting.

Over the 3 days, there will be more than 200 education sessions, 10 guideline-specific sessions, and 11 learning pathways that include core areas, but also special topics, such as COVID-19 and the emerging cardio-obstetrics subspecialty.

The meeting will be delivered through a new virtual education program built to optimize real-time interaction between faculty members and attendees, she said. A dedicated portal on the platform will allow attendees to interact virtually, for example, with presenters of the nearly 3,000 ePosters and 420 moderated posters.

For those suffering from Zoom fatigue, the increasingly popular Heart2Heart stage talks have also been converted to podcasts, which cover topics like gender equity in cardiology, the evolving role of advanced practice professionals, and “one of my favorites: art as a tool for healing,” said Dr. Morris, from the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. “Those sessions are really not to be missed.”

Reconnecting is an underlying theme of the meeting but the great divider will not be ignored. COVID-19 will be the focus of two 90-minute Intensive Sessions on Saturday, May 15, the first kicking off at 10:30 a.m. ET, with the Bishop Keynote lecture on bringing health equity to the frontline of cardiovascular care, followed by lessons learned during the pandemic, how to conduct clinical trials, and vaccine development.

The second session, set for 12:15 p.m., continues the “silver linings” theme, with case presentations on advances in telehealth, myocardial involvement, and thrombosis in COVID. For those wanting more, 18 abstracts are on tap in a 2-hour Spotlight on Special Topics session beginning at 2:30 p.m.

Asked about the pandemic’s effect on bringing science to fruition this past year, Dr. Morris said there’s no question it’s slowed some of the progress the cardiology community had made but, like clinical practice, “we’ve also surmounted many of those obstacles.”

“I think research has rebounded,” she said. “Just in terms of the number of abstracts and the quality of abstracts that were submitted this year, I don’t think there’s any question that we are right on par with previous years.”

Indeed, 5,258 abstracts from 76 countries were submitted, with more than 3,400 chosen for oral and poster presentation, including 25 late-breaking clinical trials to be presented in five sessions.

The late-breaking presentations and discussions will be prerecorded but speakers and panelists have been invited to be present during the streaming to answer live any questions that may arise in the chat box, ACC 2021 vice chair Douglas Drachman, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

Late-breaking clinical trials

The Joint ACC/JACC Late-Breaking Clinical Trials I (Saturday, May 15, 9:00 a.m.–-10:00 a.m.) kicks off with PARADISE-MI, the first head-to-head comparison of an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) and an ACE inhibitor in patients with reduced ejection fractions (EFs) after MI but no history of heart failure (HF), studying 200 mg sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) versus 5 mg of ramipril, both twice daily, in 5,669 patients.

Sacubitril/valsartan was initially approved for HF with reduced EF and added a new indication to treat some HF patients with preserved EF. Novartis, however, recently told investors that although numerical trends consistently favored the ARNI over the ACE inhibitor ramipril, the phase 3 study failed to meet the primary endpoint for efficacy superiority of reducing the risk for cardiovascular (CV) death and HF events after an acute MI.

Second up is ADAPTABLE, which looks to close a surprising evidence gap over whether 81 mg or 325 mg daily is the optimal dose of the ubiquitously prescribed aspirin for secondary prevention in high-risk patients with established atherosclerotic CV disease.

The open-label, randomized study will look at efficacy and major bleeding over roughly 4 years in 15,000 patients within PCORnet, the National Patient-centered Clinical Research Network, a partnership of clinical research, health plan research, and patient-powered networks created to streamline patient-reported outcomes research.

“This study will not only give important clinical information for us, practically speaking, whether we should prescribe lower- or higher-dose aspirin, but it may also serve as a template for future pragmatic clinical trial design in the real world,” Dr. Drachman said during the press conference.

Up next is the 4,812-patient Canadian LAAOS III, the largest trial to examine the efficacy of left atrial appendage occlusion for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) already undergoing cardiac surgery. The primary outcome is the first occurrence of stroke or systemic arterial embolism over an average follow-up of 4 years.

Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage (LAA) has been shown to reduce stroke in AFib patients at high-risk of bleeding on systemic anticoagulation. But these devices can be expensive and studies haven’t included patients who also have valvular heart disease, a group that actually comprises more than half of patients undergoing cardiac surgery who also have AFib, he noted.

At the same time, surgical LAA closure studies have been small and have had very mixed results. “There isn’t a large-scale rigorous assessment out there for these patients undergoing surgery, so I think this is going to be fascinating to see,” Dr. Drachman said.

The session closes with ATLANTIS, which looks to shed some light on the role of anticoagulation therapy in patients after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR or TAVI). POPular TAVI, presented at ACC 2020, showed aspirin alone was the preferred antithrombotic therapy over aspirin plus clopidogrel (Plavix) in patients not on oral anticoagulants, but the optimal anticoagulation regimen remains unsettled.

The French open-label, 1,510-patient ATLANTIS trial examined whether the novel oral anticoagulant apixaban (Eliquis) is superior in preventing CV events after TAVR, compared with antiplatelet therapy in patients without an indication for anticoagulation and compared with vitamin K antagonists in those receiving anticoagulants.

An ATLANTIS 4D CT substudy of valve thrombosis is also slated for Saturday’s Featured Clinical Research 1 session at 12:15 p.m. to 1:45 p.m..

Sunday LBCTs

Dr. Drachman highlighted a series of other late-breaking studies, including the global DARE-19 trial testing the diabetes and HF drug dapagliflozin (Farxiga) given with local standard-of-care therapy for 30 days in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with CV, metabolic, or renal risk factors.

Although sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors have been white-hot of late, top-line results reported last month show dapagliflozin failed to achieve statistical significance for the primary endpoints of reducing organ dysfunction and all-cause mortality and for improving recovery. Details will be presented in the Joint ACC/JAMA Late-Breaking Clinical Trials II (Sunday, May 16, 8:00 a.m.-9:30 a.m.).

Two trials, FLOWER-MI and RADIANCE-HTN TRIO, were singled out in the Joint ACC/New England Journal of Medicine Late-Breaking Clinical Trials III (Sunday, May 16, 10:45 a.m.-12:00 p.m.). FLOWER-MI examines whether fractional flow reserve (FFR) is better than angiography to guide complete multivessel revascularization in ST-elevation MI patients with at least 50% stenosis in at least one nonculprit lesion requiring percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Recent studies have shown the superiority of FFR-guided PCI for nonculprit lesions, compared with culprit lesion treatment-only, but this is the first time FFR- and angiography-guided PCI have been compared in STEMI patients.

RADIANCE-HTN TRIO already tipped its hand, with top-line results reported in late 2020 showing that the trial met its primary efficacy endpoint of greater reduction in daytime blood pressure over 2 months with the Paradise endovascular ultrasound renal denervation system, compared with a sham procedure, in 136 patients with resistant hypertension, importantly, after being given a single pill containing a calcium channel blocker, angiotensin II receptor blocker, and diuretic.

Renal denervation for hypertension has been making something of a comeback, with the 2018 RADIANCE-HTN SOLO reporting better ambulatory blood pressure control with the Paradise system than with a sham procedure in the absence of antihypertensive agents. The device has been granted breakthrough device designation from the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of hypertensive patients who are unable to sufficiently respond to or are intolerant of antihypertensive therapy.

Monday LBCTs

In the Late-Breaking Clinical Trials IV session (Monday, May 17, 8 a.m.–9:30 a.m.), Drachman called out a secondary analysis from GALATIC-HF looking at the impact of EF on the therapeutic effect of omecamtiv mecarbil. In last year’s primary analysis, the selective cardiac myosin activator produced a modest but significant reduction in HF events or CV death in 8,232 patients with HF and an EF of 35% or less.

Rounding out the list is the Canadian CAPITAL CHILL study of moderate versus mild therapeutic hypothermia in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, to be presented in the final Late-Breaking Clinical Trials V session (Monday, May 17, 10:45 a.m.–12:00 p.m.).

The double-blind trial sought to determine whether neurologic outcomes at 6 months are improved by targeting a core temperature of 31 ˚C versus 34 ˚C after the return of spontaneous circulation in comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

“For me, I think this could really change practice and has personal relevance from experience with cardiac arrest survivors that I’ve known and care for very deeply,” Dr. Drachman said in an interview. “I think that there’s a lot of opportunity here as well.”

Asked what other trials have the potential to change practice, Dr. Drachman said FLOWER-MI holds particular interest because it looks at how to manage patients with STEMI with multiple lesions at the point of care.

“We’ve gained a lot of clarity from several other prior clinical trials, but this will help to answer the question in a slightly different way of saying: can you eyeball it, can you look at the angiogram and say whether or not that other, nonculprit lesion ought to be treated in the same hospitalization or should you really be using a pressure wire,” he said. “For me as an interventionalist, this is really important because when you finish up doing an intervention on a patient it might be the middle of the night and the patient may be more or less stable, but you’ve already exposed them to the risk of a procedure, should you then move on and do another aspect of the procedure to interrogate with a pressure wire a remaining narrowing? I think that’s very important; that’ll help me make decisions on a day-to-day basis.”

Dr. Drachman also cited RADIANCE-HTN TRIO because it employs an endovascular technique to control blood pressure in patients with hypertension, specifically those resistant to multiple drugs.

During the press conference, Dr. Morris, a preventive cardiologist, put her money on the ADAPTABLE study of aspirin dosing, reiterating that the unique trial design could inform future research, and on Sunday’s 8:45 a.m. late-breaking post hoc analysis from the STRENGTH trial that looks to pick up where the controversy over omega-3 fatty acid preparations left off at last year’s American Heart Association meeting.

A lack of benefit on CV event rates reported with Epanova, a high-dose combination of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid, led to a contentious debate over how to reconcile STRENGTH with the findings from REDUCE-IT, which showed a 25% relative risk reduction in major CV events with the EPA product icosapent ethyl (Vascepa).

STRENGTH investigator Steven Nissen, MD, Cleveland Clinic, and REDUCE-IT investigator and session panelist Deepak Bhatt, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, will share the virtual stage at ACC 2021, but Dr. Morris said the “good news” is both researchers know one another very well and “will really be focusing on no political issues, just the omega-3 fatty levels in the bloodstream and what does that mean in either trial.

“This is not designed to be a debate, point counterpoint,” she added.

For that, as all cardiologists and journalists know, there will be the wild and woolly #CardioTwitter sphere.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

High teen BMI linked to stroke risk in young adulthood

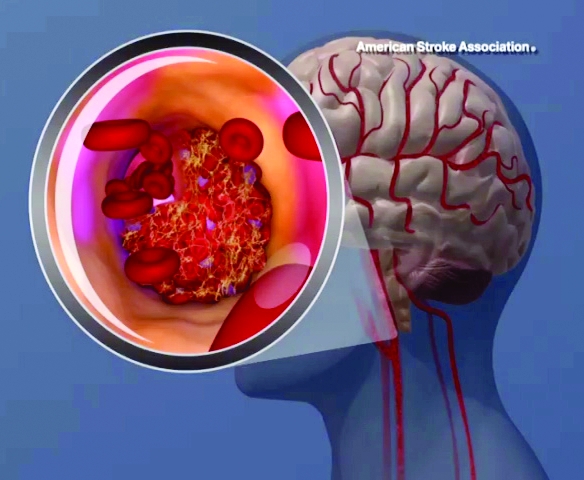

High and even high-normal body mass index (BMI) were linked to increased ischemic stroke risk, regardless of whether or not individuals had diabetes.

Overweight and obese adolescent groups in the study had a roughly two- to threefold increased risk of ischemic stroke, which was apparent even before age 30 years in the study that was based on records of Israeli adolescents evaluated prior to mandatory military service.

These findings highlight the importance of treating and preventing high BMI among adolescence, study coauthor Gilad Twig, MD, MPH, PhD, said in a press release.

“Adults who survive stroke earlier in life face poor functional outcomes, which can lead to unemployment, depression and anxiety,” said Dr. Twig, associate professor in the department of military medicine in The Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

The costs of stroke prevention and care, already high, are expected to become even higher as the adolescent obesity prevalence goes up, fueling further increases in stroke rate, Dr. Twig added.

This is believed to be the first study showing that stroke risk is associated with higher BMI values in both men and women, not just men, Dr. Twig and coauthors said in their article, published May 13, 2021 in the journal Stroke. Previous studies assessing the stroke-BMI relationship in adolescents were based on records of Swedish men evaluated during military conscription at age 18.

In the present study, Dr. Twig and coauthors assessed the linkage between adolescent BMI and first stroke event in 1.9 million male and female adolescents in Israel who were evaluated 1 year prior to mandatory military service, between the years of 1985 and 2013.

They cross-referenced that information with stroke events in a national registry to which all hospitals in Israel are required to report.

The adolescents were about 17 years of age on average at the time of evaluation, 58% were male, and 84% were born in Israel. The mean age at the beginning of follow-up for stroke was about 31 years.

Over the follow-up period, investigators identified 1,088 first stroke events, including 921 ischemic and 167 hemorrhagic strokes.

A gradual increase in stroke rate was seen across BMI categories for ischemic strokes, but not so much for hemorrhagic strokes, investigators found.

Hazard ratios for first ischemic stroke event were 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.6) for the high-normal BMI group, 2.0 (95% CI, 1.6-2.4) for the overweight group, and 3.5 (95% CI, 2.8-4.5) for the obese group after adjusting for age and sex at beginning of follow-up, investigators reported.

When the adjusted results were stratified by presence or absence of diabetes, estimates were similar to what was seen in the overall risk model, they added.

Among those young adults who developed ischemic stroke, 43% smoked, 29% had high blood pressure, 17% had diabetes, and 32% had abnormal lipids at the time of diagnosis, the reported data showed.

The clinical and public health implications of these findings could be substantial, since strokes are associated with worse medical and socioeconomic outcomes in younger as compared with older individuals, according to Dr. Twig and coauthors.

Younger individuals with stroke have a higher risk of recurrent stroke, heart attack, long-term care, or death, they said. Moreover, about half of young-adult stroke survivors have poor functional outcomes, and their risk of unemployment and depression/anxiety is higher than in young individuals without stroke.

One limitation of the study is that follow-up BMI data were not available for all participants. As a result, the contribution of obesity to stroke risk over time could not be assessed, and the independent risk of BMI during adolescence could not be determined. In addition, the authors said the study underrepresents orthodox and ultraorthodox Jewish women, as they are not obligated to serve in the Israeli military.

The study authors had no disclosures related to the study, which was supported by a medical corps Israel Defense Forces research grant.

High and even high-normal body mass index (BMI) were linked to increased ischemic stroke risk, regardless of whether or not individuals had diabetes.

Overweight and obese adolescent groups in the study had a roughly two- to threefold increased risk of ischemic stroke, which was apparent even before age 30 years in the study that was based on records of Israeli adolescents evaluated prior to mandatory military service.

These findings highlight the importance of treating and preventing high BMI among adolescence, study coauthor Gilad Twig, MD, MPH, PhD, said in a press release.

“Adults who survive stroke earlier in life face poor functional outcomes, which can lead to unemployment, depression and anxiety,” said Dr. Twig, associate professor in the department of military medicine in The Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

The costs of stroke prevention and care, already high, are expected to become even higher as the adolescent obesity prevalence goes up, fueling further increases in stroke rate, Dr. Twig added.

This is believed to be the first study showing that stroke risk is associated with higher BMI values in both men and women, not just men, Dr. Twig and coauthors said in their article, published May 13, 2021 in the journal Stroke. Previous studies assessing the stroke-BMI relationship in adolescents were based on records of Swedish men evaluated during military conscription at age 18.

In the present study, Dr. Twig and coauthors assessed the linkage between adolescent BMI and first stroke event in 1.9 million male and female adolescents in Israel who were evaluated 1 year prior to mandatory military service, between the years of 1985 and 2013.

They cross-referenced that information with stroke events in a national registry to which all hospitals in Israel are required to report.

The adolescents were about 17 years of age on average at the time of evaluation, 58% were male, and 84% were born in Israel. The mean age at the beginning of follow-up for stroke was about 31 years.

Over the follow-up period, investigators identified 1,088 first stroke events, including 921 ischemic and 167 hemorrhagic strokes.

A gradual increase in stroke rate was seen across BMI categories for ischemic strokes, but not so much for hemorrhagic strokes, investigators found.

Hazard ratios for first ischemic stroke event were 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.6) for the high-normal BMI group, 2.0 (95% CI, 1.6-2.4) for the overweight group, and 3.5 (95% CI, 2.8-4.5) for the obese group after adjusting for age and sex at beginning of follow-up, investigators reported.

When the adjusted results were stratified by presence or absence of diabetes, estimates were similar to what was seen in the overall risk model, they added.

Among those young adults who developed ischemic stroke, 43% smoked, 29% had high blood pressure, 17% had diabetes, and 32% had abnormal lipids at the time of diagnosis, the reported data showed.

The clinical and public health implications of these findings could be substantial, since strokes are associated with worse medical and socioeconomic outcomes in younger as compared with older individuals, according to Dr. Twig and coauthors.

Younger individuals with stroke have a higher risk of recurrent stroke, heart attack, long-term care, or death, they said. Moreover, about half of young-adult stroke survivors have poor functional outcomes, and their risk of unemployment and depression/anxiety is higher than in young individuals without stroke.

One limitation of the study is that follow-up BMI data were not available for all participants. As a result, the contribution of obesity to stroke risk over time could not be assessed, and the independent risk of BMI during adolescence could not be determined. In addition, the authors said the study underrepresents orthodox and ultraorthodox Jewish women, as they are not obligated to serve in the Israeli military.

The study authors had no disclosures related to the study, which was supported by a medical corps Israel Defense Forces research grant.

High and even high-normal body mass index (BMI) were linked to increased ischemic stroke risk, regardless of whether or not individuals had diabetes.

Overweight and obese adolescent groups in the study had a roughly two- to threefold increased risk of ischemic stroke, which was apparent even before age 30 years in the study that was based on records of Israeli adolescents evaluated prior to mandatory military service.

These findings highlight the importance of treating and preventing high BMI among adolescence, study coauthor Gilad Twig, MD, MPH, PhD, said in a press release.

“Adults who survive stroke earlier in life face poor functional outcomes, which can lead to unemployment, depression and anxiety,” said Dr. Twig, associate professor in the department of military medicine in The Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

The costs of stroke prevention and care, already high, are expected to become even higher as the adolescent obesity prevalence goes up, fueling further increases in stroke rate, Dr. Twig added.

This is believed to be the first study showing that stroke risk is associated with higher BMI values in both men and women, not just men, Dr. Twig and coauthors said in their article, published May 13, 2021 in the journal Stroke. Previous studies assessing the stroke-BMI relationship in adolescents were based on records of Swedish men evaluated during military conscription at age 18.

In the present study, Dr. Twig and coauthors assessed the linkage between adolescent BMI and first stroke event in 1.9 million male and female adolescents in Israel who were evaluated 1 year prior to mandatory military service, between the years of 1985 and 2013.

They cross-referenced that information with stroke events in a national registry to which all hospitals in Israel are required to report.

The adolescents were about 17 years of age on average at the time of evaluation, 58% were male, and 84% were born in Israel. The mean age at the beginning of follow-up for stroke was about 31 years.

Over the follow-up period, investigators identified 1,088 first stroke events, including 921 ischemic and 167 hemorrhagic strokes.

A gradual increase in stroke rate was seen across BMI categories for ischemic strokes, but not so much for hemorrhagic strokes, investigators found.

Hazard ratios for first ischemic stroke event were 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.6) for the high-normal BMI group, 2.0 (95% CI, 1.6-2.4) for the overweight group, and 3.5 (95% CI, 2.8-4.5) for the obese group after adjusting for age and sex at beginning of follow-up, investigators reported.

When the adjusted results were stratified by presence or absence of diabetes, estimates were similar to what was seen in the overall risk model, they added.

Among those young adults who developed ischemic stroke, 43% smoked, 29% had high blood pressure, 17% had diabetes, and 32% had abnormal lipids at the time of diagnosis, the reported data showed.

The clinical and public health implications of these findings could be substantial, since strokes are associated with worse medical and socioeconomic outcomes in younger as compared with older individuals, according to Dr. Twig and coauthors.

Younger individuals with stroke have a higher risk of recurrent stroke, heart attack, long-term care, or death, they said. Moreover, about half of young-adult stroke survivors have poor functional outcomes, and their risk of unemployment and depression/anxiety is higher than in young individuals without stroke.

One limitation of the study is that follow-up BMI data were not available for all participants. As a result, the contribution of obesity to stroke risk over time could not be assessed, and the independent risk of BMI during adolescence could not be determined. In addition, the authors said the study underrepresents orthodox and ultraorthodox Jewish women, as they are not obligated to serve in the Israeli military.

The study authors had no disclosures related to the study, which was supported by a medical corps Israel Defense Forces research grant.

FROM STROKE

Coffee intake may be driven by cardiovascular symptoms

An examination of coffee consumption habits of almost 400,000 people suggests that those habits are largely driven by a person’s cardiovascular health.

Data from a large population database showed that people with essential hypertension, angina, or cardiac arrhythmias drank less coffee than people who had none of these conditions. When they did drink coffee, it tended to be decaffeinated.

The investigators, led by Elina Hyppönen, PhD, director of the Australian Centre for Precision Health at the University of South Australia, Adelaide, say that this predilection for avoiding coffee, which is known to produce jitteriness and heart palpitations, is based on genetics.

“If your body is telling you not to drink that extra cup of coffee, there’s likely a reason why,” Dr. Hyppönen said in an interview.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

“People drink coffee as a pick-me-up when they’re feeling tired, or because it tastes good, or simply because it’s part of their daily routine, but what we don’t recognize is that people subconsciously self-regulate safe levels of caffeine based on how high their blood pressure is, and this is likely a result of a protective genetic mechanism, [meaning] that someone who drinks a lot of coffee is likely more genetically tolerant of caffeine, as compared to someone who drinks very little,” Dr. Hyppönen said.

“In addition, we’ve known from past research that when people feel unwell, they tend to drink less coffee. This type of phenomenon, where disease drives behavior, is called reverse causality,” Dr. Hyppönen said.

For this analysis, she and her team used information on 390,435 individuals of European ancestry from the UK Biobank, a large epidemiologic database. Habitual coffee consumption was self-reported, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate were measured at baseline. Cardiovascular symptoms at baseline were gleaned from hospital diagnoses, primary care records, and/or self report, the authors note.

To look at the relationship of systolic BP, diastolic BP, and heart rate with coffee consumption, they used a strategy called Mendelian randomization, which allows genetic information such as variants reflecting higher blood pressures and heart rate to be used to provide evidence for a causal association.

Results showed that participants with essential hypertension, angina, or arrhythmia were “all more likely to drink less caffeinated coffee and to be nonhabitual or decaffeinated coffee drinkers compared with those who did not report related symptoms,” the authors write.

Those with higher systolic and diastolic BP based on their genetics tended to drink less caffeinated coffee at baseline, “with consistent genetic evidence to support a causal explanation across all methods,” they noted.

They also found that those people who have a higher resting heart rate due to their genes were more likely to choose decaffeinated coffee.

“These results have two major implications,” Dr. Hyppönen said. “Firstly, they show that our bodies can regulate behavior in ways that we may not realize, and that if something does not feel good to us, there is a likely to be a reason why.”

“Second, our results show that our health status in part regulates the amount of coffee we drink. This is important, because when disease drives behavior, it can lead to misleading health associations in observational studies, and indeed, create a false impression for health benefits if the group of people who do not drink coffee also includes more people who are unwell,” she said.

For now, doctors can tell their patients that this study provides an explanation as to why research on the health effects of habitual coffee consumption has been conflicting, Dr. Hyppönen said.

“Our study also highlights the uncertainty that underlies the claimed health benefits of coffee, but at the same time, it gives a positive message about the ability of our body to regulate our level of coffee consumption in a way that helps us avoid adverse effects.”

“The most common symptoms of excessive coffee consumption are palpitations and rapid heartbeat, also known as tachycardia,” Nieca Goldberg, MD, medical director of the NYU Women’s Heart Program at NYU Langone Health, said in an interview.

“This study was designed to see if cardiac symptoms affect coffee consumption, and it showed that people with hypertension, angina, history of arrhythmias, and poor health tend to be decaffeinated coffee drinkers or no coffee drinkers,” Dr. Goldberg said.

“People naturally alter their coffee intake base on their blood pressure and symptoms of palpitations and/or rapid heart rate,” she said.

The results also suggest that, “we cannot infer health benefit or harm based on the available coffee studies,” Dr. Goldberg added.

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia. Dr. Hyppönen and Dr. Goldberg have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An examination of coffee consumption habits of almost 400,000 people suggests that those habits are largely driven by a person’s cardiovascular health.

Data from a large population database showed that people with essential hypertension, angina, or cardiac arrhythmias drank less coffee than people who had none of these conditions. When they did drink coffee, it tended to be decaffeinated.

The investigators, led by Elina Hyppönen, PhD, director of the Australian Centre for Precision Health at the University of South Australia, Adelaide, say that this predilection for avoiding coffee, which is known to produce jitteriness and heart palpitations, is based on genetics.

“If your body is telling you not to drink that extra cup of coffee, there’s likely a reason why,” Dr. Hyppönen said in an interview.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.