User login

Remote cardio visits expand access for underserved during COVID

Remote cardiology clinic visits during COVID-19 were used more often by certain traditionally underserved patient groups, but were also associated with less frequent testing and prescribing, new research shows.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an unprecedented shift in ambulatory cardiovascular care from in-person to remote visits,” lead author Neal Yuan, MD, a cardiology fellow at the Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

Their findings were published online April 5 in JAMA Network Open.

“We wanted to explore whether the transition to remote visits was associated with disparities in how patients accessed care, and also how this transition affected diagnostic test ordering and medication prescribing,” Dr. Yuan said.

The researchers used electronic health records data for all ambulatory cardiology visits at an urban, multisite health system in Los Angeles County during two periods: April 1 to Dec. 31, 2019, the pre-COVID era; and April 1 to Dec. 31, 2020, the COVID era.

The investigators compared patient characteristics and frequencies of medication ordering and cardiology-specific testing across four visit types: pre-COVID in person, used as reference; COVID-era in person; COVID-era video; and COVID-era telephone.

The study looked at 176,781 ambulatory cardiology visits. Of these visits, 87,182 were conducted in person in the pre-COVID period; 74,498 were conducted in person in the COVID era; 4,720 were COVID-era video visits; and 10,381 were COVID-era telephone visits.

In the study cohort, 79,572 patients (45.0%) were female, 127,080 patients (71.9%) were non-Hispanic White, and the mean age was 68.1 years (standard deviation, 17.0).

Patients accessing COVID-era remote visits were more likely to be Asian, Black, or Hispanic, to have private insurance, and to have cardiovascular comorbidities, such as hypertension and heart failure.

Also, patients whose visits were conducted by video were significantly younger than patients whose visits were conducted in person or by telephone (P < .001).

In addition, the study found that clinicians ordered fewer diagnostic tests, such as electrocardiograms and echocardiograms, and were less likely to order any medication, in the pre-COVID era than during the COVID era.

“If you don’t have a patient in front of you, it’s much more difficult to get a physical exam or obtain reliable vital signs,” said Dr. Yuan. Communication can sometimes be difficult, often because of technical issues, like a bad connection. “You might be more reticent to get testing or to prescribe medications if you don’t feel confident knowing what the patient’s vital signs are.”

In addition, he added, “a lot of medications used in the cardiology setting require monitoring patients’ kidney function and electrolytes, and if you can’t do that reliably, you might be more cautious about prescribing those types of medications.”

An eye-opening study

Cardiologist Nieca Goldberg, MD, medical director of the New York University Langone womens’ heart program and spokesperson for the American Heart Association, recounted her experience with telemedicine at the height of the pandemic in New York, when everything, including medical outpatient offices, had to close.

“We were experienced with telemedicine because we had started a virtual urgent care program well ahead of the pandemic,” she said. “We started using that to screen people with potential COVID symptoms so that they wouldn’t have to come into the hospital, the medical center, or to the offices and expose people. We learned that it was great to have the telemedicine option from the infectious disease standpoint, and I did visits like that for my own patient population.”

An equally if not more important finding from the study is the fact that telemedicine increased access to care among traditionally underserved demographics, she said.

“This is eye-opening, that you can actually improve access to care by doing telemedicine visits. It was really important to see that telemedicine has added benefit to the way we can see people in the health care system.”

Telemedicine visits had a positive impact at a time when people were isolated at home, Dr. Goldberg said.

“It was a way for them to connect with their doctor and in some ways it was more personal,” she added. “I actually got to meet some of my patients’ family members. It was like making a remote house call.”

Stable cardiology patients can take their blood pressure at home, weigh themselves, and take their own pulse to give an excellent set of vital signs that will indicate how they are doing, said Dr. Goldberg.

“During a remote visit, we can talk to the patient and notice whether or not they are short of breath or coughing, but we can’t listen to their heart or do an EKG or any of the traditional cardiac testing. Still, for someone who is not having symptoms and is able to reliably monitor their blood pressure and weight, a remote visit is sufficient to give you a good sense of how that patient is doing,” she said. “We can talk to them about their medications, any potential side effects, and we can use their blood pressure information to adjust their medications.”

Many patients are becoming more savvy about using tech gadgets and devices to monitor their health.

“Some of my patients were using Apple watches and the Kardia app to address their heart rate. Many had purchased inexpensive pulse oximeters to check their oxygen during the pandemic, and that also reads the pulse,” Dr. Goldberg said.

In-person visits were reserved for symptomatic cardiac patients, she explained.

“Initially during the pandemic, we did mostly telemedicine visits and we organized the office so that each cardiologist would come in 1 day a week to take care of symptomatic cardiac patients. In that way, we were able to socially distance – they provided us with [personal protective equipment]; at NYU there was no problem with that – and nobody waited in the waiting room. To this day, office issues are more efficient and people are not waiting in the waiting room,” she added. “Telemedicine improves access to health care in populations where such access is limited.”

Dr. Yuan’s research is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Goldberg reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Remote cardiology clinic visits during COVID-19 were used more often by certain traditionally underserved patient groups, but were also associated with less frequent testing and prescribing, new research shows.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an unprecedented shift in ambulatory cardiovascular care from in-person to remote visits,” lead author Neal Yuan, MD, a cardiology fellow at the Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

Their findings were published online April 5 in JAMA Network Open.

“We wanted to explore whether the transition to remote visits was associated with disparities in how patients accessed care, and also how this transition affected diagnostic test ordering and medication prescribing,” Dr. Yuan said.

The researchers used electronic health records data for all ambulatory cardiology visits at an urban, multisite health system in Los Angeles County during two periods: April 1 to Dec. 31, 2019, the pre-COVID era; and April 1 to Dec. 31, 2020, the COVID era.

The investigators compared patient characteristics and frequencies of medication ordering and cardiology-specific testing across four visit types: pre-COVID in person, used as reference; COVID-era in person; COVID-era video; and COVID-era telephone.

The study looked at 176,781 ambulatory cardiology visits. Of these visits, 87,182 were conducted in person in the pre-COVID period; 74,498 were conducted in person in the COVID era; 4,720 were COVID-era video visits; and 10,381 were COVID-era telephone visits.

In the study cohort, 79,572 patients (45.0%) were female, 127,080 patients (71.9%) were non-Hispanic White, and the mean age was 68.1 years (standard deviation, 17.0).

Patients accessing COVID-era remote visits were more likely to be Asian, Black, or Hispanic, to have private insurance, and to have cardiovascular comorbidities, such as hypertension and heart failure.

Also, patients whose visits were conducted by video were significantly younger than patients whose visits were conducted in person or by telephone (P < .001).

In addition, the study found that clinicians ordered fewer diagnostic tests, such as electrocardiograms and echocardiograms, and were less likely to order any medication, in the pre-COVID era than during the COVID era.

“If you don’t have a patient in front of you, it’s much more difficult to get a physical exam or obtain reliable vital signs,” said Dr. Yuan. Communication can sometimes be difficult, often because of technical issues, like a bad connection. “You might be more reticent to get testing or to prescribe medications if you don’t feel confident knowing what the patient’s vital signs are.”

In addition, he added, “a lot of medications used in the cardiology setting require monitoring patients’ kidney function and electrolytes, and if you can’t do that reliably, you might be more cautious about prescribing those types of medications.”

An eye-opening study

Cardiologist Nieca Goldberg, MD, medical director of the New York University Langone womens’ heart program and spokesperson for the American Heart Association, recounted her experience with telemedicine at the height of the pandemic in New York, when everything, including medical outpatient offices, had to close.

“We were experienced with telemedicine because we had started a virtual urgent care program well ahead of the pandemic,” she said. “We started using that to screen people with potential COVID symptoms so that they wouldn’t have to come into the hospital, the medical center, or to the offices and expose people. We learned that it was great to have the telemedicine option from the infectious disease standpoint, and I did visits like that for my own patient population.”

An equally if not more important finding from the study is the fact that telemedicine increased access to care among traditionally underserved demographics, she said.

“This is eye-opening, that you can actually improve access to care by doing telemedicine visits. It was really important to see that telemedicine has added benefit to the way we can see people in the health care system.”

Telemedicine visits had a positive impact at a time when people were isolated at home, Dr. Goldberg said.

“It was a way for them to connect with their doctor and in some ways it was more personal,” she added. “I actually got to meet some of my patients’ family members. It was like making a remote house call.”

Stable cardiology patients can take their blood pressure at home, weigh themselves, and take their own pulse to give an excellent set of vital signs that will indicate how they are doing, said Dr. Goldberg.

“During a remote visit, we can talk to the patient and notice whether or not they are short of breath or coughing, but we can’t listen to their heart or do an EKG or any of the traditional cardiac testing. Still, for someone who is not having symptoms and is able to reliably monitor their blood pressure and weight, a remote visit is sufficient to give you a good sense of how that patient is doing,” she said. “We can talk to them about their medications, any potential side effects, and we can use their blood pressure information to adjust their medications.”

Many patients are becoming more savvy about using tech gadgets and devices to monitor their health.

“Some of my patients were using Apple watches and the Kardia app to address their heart rate. Many had purchased inexpensive pulse oximeters to check their oxygen during the pandemic, and that also reads the pulse,” Dr. Goldberg said.

In-person visits were reserved for symptomatic cardiac patients, she explained.

“Initially during the pandemic, we did mostly telemedicine visits and we organized the office so that each cardiologist would come in 1 day a week to take care of symptomatic cardiac patients. In that way, we were able to socially distance – they provided us with [personal protective equipment]; at NYU there was no problem with that – and nobody waited in the waiting room. To this day, office issues are more efficient and people are not waiting in the waiting room,” she added. “Telemedicine improves access to health care in populations where such access is limited.”

Dr. Yuan’s research is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Goldberg reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Remote cardiology clinic visits during COVID-19 were used more often by certain traditionally underserved patient groups, but were also associated with less frequent testing and prescribing, new research shows.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an unprecedented shift in ambulatory cardiovascular care from in-person to remote visits,” lead author Neal Yuan, MD, a cardiology fellow at the Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

Their findings were published online April 5 in JAMA Network Open.

“We wanted to explore whether the transition to remote visits was associated with disparities in how patients accessed care, and also how this transition affected diagnostic test ordering and medication prescribing,” Dr. Yuan said.

The researchers used electronic health records data for all ambulatory cardiology visits at an urban, multisite health system in Los Angeles County during two periods: April 1 to Dec. 31, 2019, the pre-COVID era; and April 1 to Dec. 31, 2020, the COVID era.

The investigators compared patient characteristics and frequencies of medication ordering and cardiology-specific testing across four visit types: pre-COVID in person, used as reference; COVID-era in person; COVID-era video; and COVID-era telephone.

The study looked at 176,781 ambulatory cardiology visits. Of these visits, 87,182 were conducted in person in the pre-COVID period; 74,498 were conducted in person in the COVID era; 4,720 were COVID-era video visits; and 10,381 were COVID-era telephone visits.

In the study cohort, 79,572 patients (45.0%) were female, 127,080 patients (71.9%) were non-Hispanic White, and the mean age was 68.1 years (standard deviation, 17.0).

Patients accessing COVID-era remote visits were more likely to be Asian, Black, or Hispanic, to have private insurance, and to have cardiovascular comorbidities, such as hypertension and heart failure.

Also, patients whose visits were conducted by video were significantly younger than patients whose visits were conducted in person or by telephone (P < .001).

In addition, the study found that clinicians ordered fewer diagnostic tests, such as electrocardiograms and echocardiograms, and were less likely to order any medication, in the pre-COVID era than during the COVID era.

“If you don’t have a patient in front of you, it’s much more difficult to get a physical exam or obtain reliable vital signs,” said Dr. Yuan. Communication can sometimes be difficult, often because of technical issues, like a bad connection. “You might be more reticent to get testing or to prescribe medications if you don’t feel confident knowing what the patient’s vital signs are.”

In addition, he added, “a lot of medications used in the cardiology setting require monitoring patients’ kidney function and electrolytes, and if you can’t do that reliably, you might be more cautious about prescribing those types of medications.”

An eye-opening study

Cardiologist Nieca Goldberg, MD, medical director of the New York University Langone womens’ heart program and spokesperson for the American Heart Association, recounted her experience with telemedicine at the height of the pandemic in New York, when everything, including medical outpatient offices, had to close.

“We were experienced with telemedicine because we had started a virtual urgent care program well ahead of the pandemic,” she said. “We started using that to screen people with potential COVID symptoms so that they wouldn’t have to come into the hospital, the medical center, or to the offices and expose people. We learned that it was great to have the telemedicine option from the infectious disease standpoint, and I did visits like that for my own patient population.”

An equally if not more important finding from the study is the fact that telemedicine increased access to care among traditionally underserved demographics, she said.

“This is eye-opening, that you can actually improve access to care by doing telemedicine visits. It was really important to see that telemedicine has added benefit to the way we can see people in the health care system.”

Telemedicine visits had a positive impact at a time when people were isolated at home, Dr. Goldberg said.

“It was a way for them to connect with their doctor and in some ways it was more personal,” she added. “I actually got to meet some of my patients’ family members. It was like making a remote house call.”

Stable cardiology patients can take their blood pressure at home, weigh themselves, and take their own pulse to give an excellent set of vital signs that will indicate how they are doing, said Dr. Goldberg.

“During a remote visit, we can talk to the patient and notice whether or not they are short of breath or coughing, but we can’t listen to their heart or do an EKG or any of the traditional cardiac testing. Still, for someone who is not having symptoms and is able to reliably monitor their blood pressure and weight, a remote visit is sufficient to give you a good sense of how that patient is doing,” she said. “We can talk to them about their medications, any potential side effects, and we can use their blood pressure information to adjust their medications.”

Many patients are becoming more savvy about using tech gadgets and devices to monitor their health.

“Some of my patients were using Apple watches and the Kardia app to address their heart rate. Many had purchased inexpensive pulse oximeters to check their oxygen during the pandemic, and that also reads the pulse,” Dr. Goldberg said.

In-person visits were reserved for symptomatic cardiac patients, she explained.

“Initially during the pandemic, we did mostly telemedicine visits and we organized the office so that each cardiologist would come in 1 day a week to take care of symptomatic cardiac patients. In that way, we were able to socially distance – they provided us with [personal protective equipment]; at NYU there was no problem with that – and nobody waited in the waiting room. To this day, office issues are more efficient and people are not waiting in the waiting room,” she added. “Telemedicine improves access to health care in populations where such access is limited.”

Dr. Yuan’s research is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Goldberg reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Six pregnancy complications flag later heart disease risk

Six pregnancy-related complications increase a woman’s risk of developing risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and subsequently developing CVD, the American Heart Association says in a new scientific statement.

They are hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, preterm delivery, gestational diabetes, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) delivery, placental abruption (abruptio placentae), and pregnancy loss.

A history of any of these adverse pregnancy outcomes should prompt “more vigorous primordial prevention of CVD risk factors and primary prevention of CVD,” the writing group says.

“Adverse pregnancy outcomes are linked to women having hypertension, diabetes, abnormal cholesterol, and cardiovascular disease events, including heart attack and stroke, long after their pregnancies,” Nisha I. Parikh, MD, MPH, chair of the writing group, said in a news release.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes can be a “powerful window” into CVD prevention “if women and their health care professionals harness the knowledge and use it for health improvement,” said Dr. Parikh, associate professor of medicine in the cardiovascular division at the University of California, San Francisco.

The statement was published online March 29 in Circulation.

For the scientific statement, the writing group reviewed the latest scientific literature on adverse pregnancy outcomes and CVD risk.

The evidence in the literature linking adverse pregnancy outcomes to later CVD is “consistent over many years and confirmed in nearly every study we examined,” Dr. Parikh said. Among their key findings:

- Gestational hypertension is associated with an increased risk of CVD later in life by 67% and the odds of stroke by 83%. Moderate and severe is associated with a more than twofold increase in the risk for CVD.

- Gestational diabetes is associated with an increase in the risk for CVD by 68% and the risk of developing after pregnancy by 10-fold.

- Preterm delivery (before 37 weeks) is associated with double the risk of developing CVD and is strongly associated with later heart disease, stroke, and CVD.

- Placental abruption is associated with an 82% increased risk for CVD.

- Stillbirth is associated with about double the risk for CVD.

“This statement should inform future prevention guidelines in terms of the important factors to consider for determining women’s risk for heart diseases and stroke,” Dr. Parikh added.

The statement emphasizes the importance of recognizing these adverse pregnancy outcomes when evaluating CVD risk in women but notes that their value in reclassifying CVD risk may not be established.

It highlights the importance of adopting a heart-healthy diet and increasing physical activity among women with any of these pregnancy-related complications, starting right after childbirth and continuing across the life span to decrease CVD risk.

Lactation and breastfeeding may lower a woman’s later cardiometabolic risk, the writing group notes.

‘Golden year of opportunity’

The statement highlights several opportunities to improve transition of care for women with adverse pregnancy outcomes and to implement strategies to reduce their long-term CVD risk.

One strategy is longer postpartum follow-up care, sometimes referred to as the “fourth trimester,” to screen for CVD risk factors and provide CVD prevention counseling.

Another strategy involves improving the transfer of health information between ob/gyns and primary care physicians to eliminate inconsistencies in electronic health record documentation, which should improve patient care.

A third strategy is obtaining a short and targeted health history for each woman to confirm if she has any of the six pregnancy-related complications.

“If a woman has had any of these adverse pregnancy outcomes, consider close blood pressure monitoring, type 2 diabetes and lipid screening, and more aggressive risk factor modification and CVD prevention recommendations,” Dr. Parikh advised.

“Our data [lend] support to the prior AHA recommendation that these important adverse pregnancy outcomes should be ‘risk enhancers’ to guide consideration for statin therapy aimed at CVD prevention in women,” Dr. Parikh added.

In a commentary in Circulation, Eliza C. Miller, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Columbia University, New York, notes that pregnancy and the postpartum period are a critical time window in a woman’s life to identify CVD risk and improve a woman’s health trajectory.

“The so-called ‘Golden Hour’ for conditions such as sepsis and acute stroke refers to a critical time window for early recognition and treatment, when we can change a patient’s clinical trajectory and prevent severe morbidity and mortality,” writes Dr. Miller.

“Pregnancy and the postpartum period can be considered a ‘Golden Year’ in a woman’s life, offering a rare opportunity for clinicians to identify young women at risk and work with them to improve their cardiovascular health trajectories,” she notes.

This scientific statement was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the AHA Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; the Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and the Stroke Council.

The authors of the scientific statement have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Miller received personal compensation from Finch McCranie and Argionis & Associates for expert testimony regarding maternal stroke; and personal compensation from Elsevier for editorial work on Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 171 and 172 (Neurology of Pregnancy).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Six pregnancy-related complications increase a woman’s risk of developing risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and subsequently developing CVD, the American Heart Association says in a new scientific statement.

They are hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, preterm delivery, gestational diabetes, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) delivery, placental abruption (abruptio placentae), and pregnancy loss.

A history of any of these adverse pregnancy outcomes should prompt “more vigorous primordial prevention of CVD risk factors and primary prevention of CVD,” the writing group says.

“Adverse pregnancy outcomes are linked to women having hypertension, diabetes, abnormal cholesterol, and cardiovascular disease events, including heart attack and stroke, long after their pregnancies,” Nisha I. Parikh, MD, MPH, chair of the writing group, said in a news release.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes can be a “powerful window” into CVD prevention “if women and their health care professionals harness the knowledge and use it for health improvement,” said Dr. Parikh, associate professor of medicine in the cardiovascular division at the University of California, San Francisco.

The statement was published online March 29 in Circulation.

For the scientific statement, the writing group reviewed the latest scientific literature on adverse pregnancy outcomes and CVD risk.

The evidence in the literature linking adverse pregnancy outcomes to later CVD is “consistent over many years and confirmed in nearly every study we examined,” Dr. Parikh said. Among their key findings:

- Gestational hypertension is associated with an increased risk of CVD later in life by 67% and the odds of stroke by 83%. Moderate and severe is associated with a more than twofold increase in the risk for CVD.

- Gestational diabetes is associated with an increase in the risk for CVD by 68% and the risk of developing after pregnancy by 10-fold.

- Preterm delivery (before 37 weeks) is associated with double the risk of developing CVD and is strongly associated with later heart disease, stroke, and CVD.

- Placental abruption is associated with an 82% increased risk for CVD.

- Stillbirth is associated with about double the risk for CVD.

“This statement should inform future prevention guidelines in terms of the important factors to consider for determining women’s risk for heart diseases and stroke,” Dr. Parikh added.

The statement emphasizes the importance of recognizing these adverse pregnancy outcomes when evaluating CVD risk in women but notes that their value in reclassifying CVD risk may not be established.

It highlights the importance of adopting a heart-healthy diet and increasing physical activity among women with any of these pregnancy-related complications, starting right after childbirth and continuing across the life span to decrease CVD risk.

Lactation and breastfeeding may lower a woman’s later cardiometabolic risk, the writing group notes.

‘Golden year of opportunity’

The statement highlights several opportunities to improve transition of care for women with adverse pregnancy outcomes and to implement strategies to reduce their long-term CVD risk.

One strategy is longer postpartum follow-up care, sometimes referred to as the “fourth trimester,” to screen for CVD risk factors and provide CVD prevention counseling.

Another strategy involves improving the transfer of health information between ob/gyns and primary care physicians to eliminate inconsistencies in electronic health record documentation, which should improve patient care.

A third strategy is obtaining a short and targeted health history for each woman to confirm if she has any of the six pregnancy-related complications.

“If a woman has had any of these adverse pregnancy outcomes, consider close blood pressure monitoring, type 2 diabetes and lipid screening, and more aggressive risk factor modification and CVD prevention recommendations,” Dr. Parikh advised.

“Our data [lend] support to the prior AHA recommendation that these important adverse pregnancy outcomes should be ‘risk enhancers’ to guide consideration for statin therapy aimed at CVD prevention in women,” Dr. Parikh added.

In a commentary in Circulation, Eliza C. Miller, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Columbia University, New York, notes that pregnancy and the postpartum period are a critical time window in a woman’s life to identify CVD risk and improve a woman’s health trajectory.

“The so-called ‘Golden Hour’ for conditions such as sepsis and acute stroke refers to a critical time window for early recognition and treatment, when we can change a patient’s clinical trajectory and prevent severe morbidity and mortality,” writes Dr. Miller.

“Pregnancy and the postpartum period can be considered a ‘Golden Year’ in a woman’s life, offering a rare opportunity for clinicians to identify young women at risk and work with them to improve their cardiovascular health trajectories,” she notes.

This scientific statement was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the AHA Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; the Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and the Stroke Council.

The authors of the scientific statement have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Miller received personal compensation from Finch McCranie and Argionis & Associates for expert testimony regarding maternal stroke; and personal compensation from Elsevier for editorial work on Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 171 and 172 (Neurology of Pregnancy).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Six pregnancy-related complications increase a woman’s risk of developing risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and subsequently developing CVD, the American Heart Association says in a new scientific statement.

They are hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, preterm delivery, gestational diabetes, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) delivery, placental abruption (abruptio placentae), and pregnancy loss.

A history of any of these adverse pregnancy outcomes should prompt “more vigorous primordial prevention of CVD risk factors and primary prevention of CVD,” the writing group says.

“Adverse pregnancy outcomes are linked to women having hypertension, diabetes, abnormal cholesterol, and cardiovascular disease events, including heart attack and stroke, long after their pregnancies,” Nisha I. Parikh, MD, MPH, chair of the writing group, said in a news release.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes can be a “powerful window” into CVD prevention “if women and their health care professionals harness the knowledge and use it for health improvement,” said Dr. Parikh, associate professor of medicine in the cardiovascular division at the University of California, San Francisco.

The statement was published online March 29 in Circulation.

For the scientific statement, the writing group reviewed the latest scientific literature on adverse pregnancy outcomes and CVD risk.

The evidence in the literature linking adverse pregnancy outcomes to later CVD is “consistent over many years and confirmed in nearly every study we examined,” Dr. Parikh said. Among their key findings:

- Gestational hypertension is associated with an increased risk of CVD later in life by 67% and the odds of stroke by 83%. Moderate and severe is associated with a more than twofold increase in the risk for CVD.

- Gestational diabetes is associated with an increase in the risk for CVD by 68% and the risk of developing after pregnancy by 10-fold.

- Preterm delivery (before 37 weeks) is associated with double the risk of developing CVD and is strongly associated with later heart disease, stroke, and CVD.

- Placental abruption is associated with an 82% increased risk for CVD.

- Stillbirth is associated with about double the risk for CVD.

“This statement should inform future prevention guidelines in terms of the important factors to consider for determining women’s risk for heart diseases and stroke,” Dr. Parikh added.

The statement emphasizes the importance of recognizing these adverse pregnancy outcomes when evaluating CVD risk in women but notes that their value in reclassifying CVD risk may not be established.

It highlights the importance of adopting a heart-healthy diet and increasing physical activity among women with any of these pregnancy-related complications, starting right after childbirth and continuing across the life span to decrease CVD risk.

Lactation and breastfeeding may lower a woman’s later cardiometabolic risk, the writing group notes.

‘Golden year of opportunity’

The statement highlights several opportunities to improve transition of care for women with adverse pregnancy outcomes and to implement strategies to reduce their long-term CVD risk.

One strategy is longer postpartum follow-up care, sometimes referred to as the “fourth trimester,” to screen for CVD risk factors and provide CVD prevention counseling.

Another strategy involves improving the transfer of health information between ob/gyns and primary care physicians to eliminate inconsistencies in electronic health record documentation, which should improve patient care.

A third strategy is obtaining a short and targeted health history for each woman to confirm if she has any of the six pregnancy-related complications.

“If a woman has had any of these adverse pregnancy outcomes, consider close blood pressure monitoring, type 2 diabetes and lipid screening, and more aggressive risk factor modification and CVD prevention recommendations,” Dr. Parikh advised.

“Our data [lend] support to the prior AHA recommendation that these important adverse pregnancy outcomes should be ‘risk enhancers’ to guide consideration for statin therapy aimed at CVD prevention in women,” Dr. Parikh added.

In a commentary in Circulation, Eliza C. Miller, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Columbia University, New York, notes that pregnancy and the postpartum period are a critical time window in a woman’s life to identify CVD risk and improve a woman’s health trajectory.

“The so-called ‘Golden Hour’ for conditions such as sepsis and acute stroke refers to a critical time window for early recognition and treatment, when we can change a patient’s clinical trajectory and prevent severe morbidity and mortality,” writes Dr. Miller.

“Pregnancy and the postpartum period can be considered a ‘Golden Year’ in a woman’s life, offering a rare opportunity for clinicians to identify young women at risk and work with them to improve their cardiovascular health trajectories,” she notes.

This scientific statement was prepared by the volunteer writing group on behalf of the AHA Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; the Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and the Stroke Council.

The authors of the scientific statement have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Miller received personal compensation from Finch McCranie and Argionis & Associates for expert testimony regarding maternal stroke; and personal compensation from Elsevier for editorial work on Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 171 and 172 (Neurology of Pregnancy).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The best exercises for BP control? European statement sorts it out

Recommendations for prescribing exercise to control high blood pressure have been put forward by various medical organizations and expert panels, but finding the bandwidth to craft personalized exercise training for their patients poses a challenge for clinicians.

Now, European cardiology societies have issued a consensus statement that offers an algorithm of sorts for developing personalized exercise programs as part of overall management approach for patients with or at risk of high BP.

The statement, published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology and issued by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology Council on Hypertension, claims to be the first document to focus on personalized exercise for BP.

The statement draws on a systematic review, including meta-analyses, to produce guidance on how to lower BP in three specific types of patients: Those with hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg), high-normal blood pressure (130-139/85-89 mm Hg), and normal blood pressure (<130/84 mm Hg).

By making recommendations for these three specific groups, along with providing guidance for combined exercise – that is, blending aerobic exercise with resistance training (RT) – the consensus statement goes one step further than recommendations other organizations have issued, Matthew W. Martinez, MD, said in an interview.

“What it adds is an algorithmic approach, if you will,” said Dr. Martinez, a sports medicine cardiologist at Morristown (N.J.) Medical Center. “There are some recommendations to help the clinicians to decide what they’re going to offer individuals, but what’s a challenge for us when seeing patients is finding the time to deliver the message and explain how valuable nutrition and exercise are.”

Guidelines, updates, and statements that include the role of exercise in BP control have been issued by the European Society of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and American College of Sports Medicine (Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2019;51:1314-23).

The European consensus statement includes the expected range of BP lowering for each activity. For example, aerobic exercise for patients with hypertension should lead to a reduction from –4.9 to –12 mm Hg systolic and –3.4 to –5.8 mm Hg diastolic.

The consensus statement recommends the following exercise priorities based on a patient’s blood pressure:

- Hypertension: Aerobic training (AT) as a first-line exercise therapy; and low- to moderate-intensity RT – equally using dynamic and isometric RT – as second-line therapy. In non-White patients, dynamic RT should be considered as a first-line therapy. RT can be combined with aerobic exercise on an individual basis if the clinician determines either form of RT would provide a metabolic benefit.

- High-to-normal BP: Dynamic RT as a first-line exercise, which the systematic review determined led to greater BP reduction than that of aerobic training. “Isometric RT is likely to elicit similar if not superior BP-lowering effects as [dynamic RT], but the level of evidence is low and the available data are scarce,” wrote first author Henner Hanssen, MD, of the University of Basel, Switzerland, and coauthors. Combining dynamic resistance training with aerobic training “may be preferable” to dynamic RT alone in patients with a combination of cardiovascular risk factors.

- Normal BP: Isometric RT may be indicated as a first-line intervention in individuals with a family or gestational history or obese or overweight people currently with normal BP. This advice includes a caveat: “The number of studies is limited and the 95% confidence intervals are large,” Dr. Hanssen and coauthors noted. AT is also an option in these patients, with more high-quality meta-analyses than the recommendation for isometric RT. “Hence, the BP-lowering effects of [isometric RT] as compared to AT may be overestimated and both exercise modalities may have similar BP-lowering effects in individuals with normotension,” wrote the consensus statement authors.

They note that more research is needed to validate the BP-lowering effects of combined exercise.

The statement acknowledges the difficulty clinicians face in managing patients with high blood pressure. “From a socioeconomic health perspective, it is a major challenge to develop, promote, and implement individually tailored exercise programs for patients with hypertension under consideration of sustainable costs,” wrote Dr. Hanssen and coauthors.

Dr. Martinez noted that one strength of the consensus statement is that it addresses the impact exercise can have on vascular health and metabolic function. And, it points out existing knowledge gaps.

“Are we going to see greater applicability of this as we use IT health technology?” he asked. “Are wearables and telehealth going to help deliver this message more easily, more frequently? Is there work to be done in terms of differences in gender? Do men and women respond differently, and is there a different exercise prescription based on that as well as ethnicity? We well know there’s a different treatment for African Americans compared to other ethnic groups.”

The statement also raises the stakes for using exercise as part of a multifaceted, integrated approach to hypertension management, he said.

“It’s not enough to talk just about exercise or nutrition, or to just give an antihypertension medicine,” Dr. Martinez said. “Perhaps the sweet spot is in integrating an approach that includes all three.”

Consensus statement coauthor Antonio Coca, MD, reported financial relationships with Abbott, Berlin-Chemie, Biolab, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ferrer, Menarini, Merck, Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. Coauthor Maria Simonenko, MD, reported financial relationships with Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. Linda Pescatello, PhD, is lead author of the American College of Sports Medicine 2019 statement. Dr. Hanssen and all other authors have no disclosures. Dr. Martinez has no relevant relationships to disclose.

Recommendations for prescribing exercise to control high blood pressure have been put forward by various medical organizations and expert panels, but finding the bandwidth to craft personalized exercise training for their patients poses a challenge for clinicians.

Now, European cardiology societies have issued a consensus statement that offers an algorithm of sorts for developing personalized exercise programs as part of overall management approach for patients with or at risk of high BP.

The statement, published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology and issued by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology Council on Hypertension, claims to be the first document to focus on personalized exercise for BP.

The statement draws on a systematic review, including meta-analyses, to produce guidance on how to lower BP in three specific types of patients: Those with hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg), high-normal blood pressure (130-139/85-89 mm Hg), and normal blood pressure (<130/84 mm Hg).

By making recommendations for these three specific groups, along with providing guidance for combined exercise – that is, blending aerobic exercise with resistance training (RT) – the consensus statement goes one step further than recommendations other organizations have issued, Matthew W. Martinez, MD, said in an interview.

“What it adds is an algorithmic approach, if you will,” said Dr. Martinez, a sports medicine cardiologist at Morristown (N.J.) Medical Center. “There are some recommendations to help the clinicians to decide what they’re going to offer individuals, but what’s a challenge for us when seeing patients is finding the time to deliver the message and explain how valuable nutrition and exercise are.”

Guidelines, updates, and statements that include the role of exercise in BP control have been issued by the European Society of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and American College of Sports Medicine (Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2019;51:1314-23).

The European consensus statement includes the expected range of BP lowering for each activity. For example, aerobic exercise for patients with hypertension should lead to a reduction from –4.9 to –12 mm Hg systolic and –3.4 to –5.8 mm Hg diastolic.

The consensus statement recommends the following exercise priorities based on a patient’s blood pressure:

- Hypertension: Aerobic training (AT) as a first-line exercise therapy; and low- to moderate-intensity RT – equally using dynamic and isometric RT – as second-line therapy. In non-White patients, dynamic RT should be considered as a first-line therapy. RT can be combined with aerobic exercise on an individual basis if the clinician determines either form of RT would provide a metabolic benefit.

- High-to-normal BP: Dynamic RT as a first-line exercise, which the systematic review determined led to greater BP reduction than that of aerobic training. “Isometric RT is likely to elicit similar if not superior BP-lowering effects as [dynamic RT], but the level of evidence is low and the available data are scarce,” wrote first author Henner Hanssen, MD, of the University of Basel, Switzerland, and coauthors. Combining dynamic resistance training with aerobic training “may be preferable” to dynamic RT alone in patients with a combination of cardiovascular risk factors.

- Normal BP: Isometric RT may be indicated as a first-line intervention in individuals with a family or gestational history or obese or overweight people currently with normal BP. This advice includes a caveat: “The number of studies is limited and the 95% confidence intervals are large,” Dr. Hanssen and coauthors noted. AT is also an option in these patients, with more high-quality meta-analyses than the recommendation for isometric RT. “Hence, the BP-lowering effects of [isometric RT] as compared to AT may be overestimated and both exercise modalities may have similar BP-lowering effects in individuals with normotension,” wrote the consensus statement authors.

They note that more research is needed to validate the BP-lowering effects of combined exercise.

The statement acknowledges the difficulty clinicians face in managing patients with high blood pressure. “From a socioeconomic health perspective, it is a major challenge to develop, promote, and implement individually tailored exercise programs for patients with hypertension under consideration of sustainable costs,” wrote Dr. Hanssen and coauthors.

Dr. Martinez noted that one strength of the consensus statement is that it addresses the impact exercise can have on vascular health and metabolic function. And, it points out existing knowledge gaps.

“Are we going to see greater applicability of this as we use IT health technology?” he asked. “Are wearables and telehealth going to help deliver this message more easily, more frequently? Is there work to be done in terms of differences in gender? Do men and women respond differently, and is there a different exercise prescription based on that as well as ethnicity? We well know there’s a different treatment for African Americans compared to other ethnic groups.”

The statement also raises the stakes for using exercise as part of a multifaceted, integrated approach to hypertension management, he said.

“It’s not enough to talk just about exercise or nutrition, or to just give an antihypertension medicine,” Dr. Martinez said. “Perhaps the sweet spot is in integrating an approach that includes all three.”

Consensus statement coauthor Antonio Coca, MD, reported financial relationships with Abbott, Berlin-Chemie, Biolab, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ferrer, Menarini, Merck, Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. Coauthor Maria Simonenko, MD, reported financial relationships with Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. Linda Pescatello, PhD, is lead author of the American College of Sports Medicine 2019 statement. Dr. Hanssen and all other authors have no disclosures. Dr. Martinez has no relevant relationships to disclose.

Recommendations for prescribing exercise to control high blood pressure have been put forward by various medical organizations and expert panels, but finding the bandwidth to craft personalized exercise training for their patients poses a challenge for clinicians.

Now, European cardiology societies have issued a consensus statement that offers an algorithm of sorts for developing personalized exercise programs as part of overall management approach for patients with or at risk of high BP.

The statement, published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology and issued by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology Council on Hypertension, claims to be the first document to focus on personalized exercise for BP.

The statement draws on a systematic review, including meta-analyses, to produce guidance on how to lower BP in three specific types of patients: Those with hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg), high-normal blood pressure (130-139/85-89 mm Hg), and normal blood pressure (<130/84 mm Hg).

By making recommendations for these three specific groups, along with providing guidance for combined exercise – that is, blending aerobic exercise with resistance training (RT) – the consensus statement goes one step further than recommendations other organizations have issued, Matthew W. Martinez, MD, said in an interview.

“What it adds is an algorithmic approach, if you will,” said Dr. Martinez, a sports medicine cardiologist at Morristown (N.J.) Medical Center. “There are some recommendations to help the clinicians to decide what they’re going to offer individuals, but what’s a challenge for us when seeing patients is finding the time to deliver the message and explain how valuable nutrition and exercise are.”

Guidelines, updates, and statements that include the role of exercise in BP control have been issued by the European Society of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and American College of Sports Medicine (Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2019;51:1314-23).

The European consensus statement includes the expected range of BP lowering for each activity. For example, aerobic exercise for patients with hypertension should lead to a reduction from –4.9 to –12 mm Hg systolic and –3.4 to –5.8 mm Hg diastolic.

The consensus statement recommends the following exercise priorities based on a patient’s blood pressure:

- Hypertension: Aerobic training (AT) as a first-line exercise therapy; and low- to moderate-intensity RT – equally using dynamic and isometric RT – as second-line therapy. In non-White patients, dynamic RT should be considered as a first-line therapy. RT can be combined with aerobic exercise on an individual basis if the clinician determines either form of RT would provide a metabolic benefit.

- High-to-normal BP: Dynamic RT as a first-line exercise, which the systematic review determined led to greater BP reduction than that of aerobic training. “Isometric RT is likely to elicit similar if not superior BP-lowering effects as [dynamic RT], but the level of evidence is low and the available data are scarce,” wrote first author Henner Hanssen, MD, of the University of Basel, Switzerland, and coauthors. Combining dynamic resistance training with aerobic training “may be preferable” to dynamic RT alone in patients with a combination of cardiovascular risk factors.

- Normal BP: Isometric RT may be indicated as a first-line intervention in individuals with a family or gestational history or obese or overweight people currently with normal BP. This advice includes a caveat: “The number of studies is limited and the 95% confidence intervals are large,” Dr. Hanssen and coauthors noted. AT is also an option in these patients, with more high-quality meta-analyses than the recommendation for isometric RT. “Hence, the BP-lowering effects of [isometric RT] as compared to AT may be overestimated and both exercise modalities may have similar BP-lowering effects in individuals with normotension,” wrote the consensus statement authors.

They note that more research is needed to validate the BP-lowering effects of combined exercise.

The statement acknowledges the difficulty clinicians face in managing patients with high blood pressure. “From a socioeconomic health perspective, it is a major challenge to develop, promote, and implement individually tailored exercise programs for patients with hypertension under consideration of sustainable costs,” wrote Dr. Hanssen and coauthors.

Dr. Martinez noted that one strength of the consensus statement is that it addresses the impact exercise can have on vascular health and metabolic function. And, it points out existing knowledge gaps.

“Are we going to see greater applicability of this as we use IT health technology?” he asked. “Are wearables and telehealth going to help deliver this message more easily, more frequently? Is there work to be done in terms of differences in gender? Do men and women respond differently, and is there a different exercise prescription based on that as well as ethnicity? We well know there’s a different treatment for African Americans compared to other ethnic groups.”

The statement also raises the stakes for using exercise as part of a multifaceted, integrated approach to hypertension management, he said.

“It’s not enough to talk just about exercise or nutrition, or to just give an antihypertension medicine,” Dr. Martinez said. “Perhaps the sweet spot is in integrating an approach that includes all three.”

Consensus statement coauthor Antonio Coca, MD, reported financial relationships with Abbott, Berlin-Chemie, Biolab, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ferrer, Menarini, Merck, Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. Coauthor Maria Simonenko, MD, reported financial relationships with Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. Linda Pescatello, PhD, is lead author of the American College of Sports Medicine 2019 statement. Dr. Hanssen and all other authors have no disclosures. Dr. Martinez has no relevant relationships to disclose.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PREVENTIVE CARDIOLOGY

Long-haul COVID-19 brings welcome attention to POTS

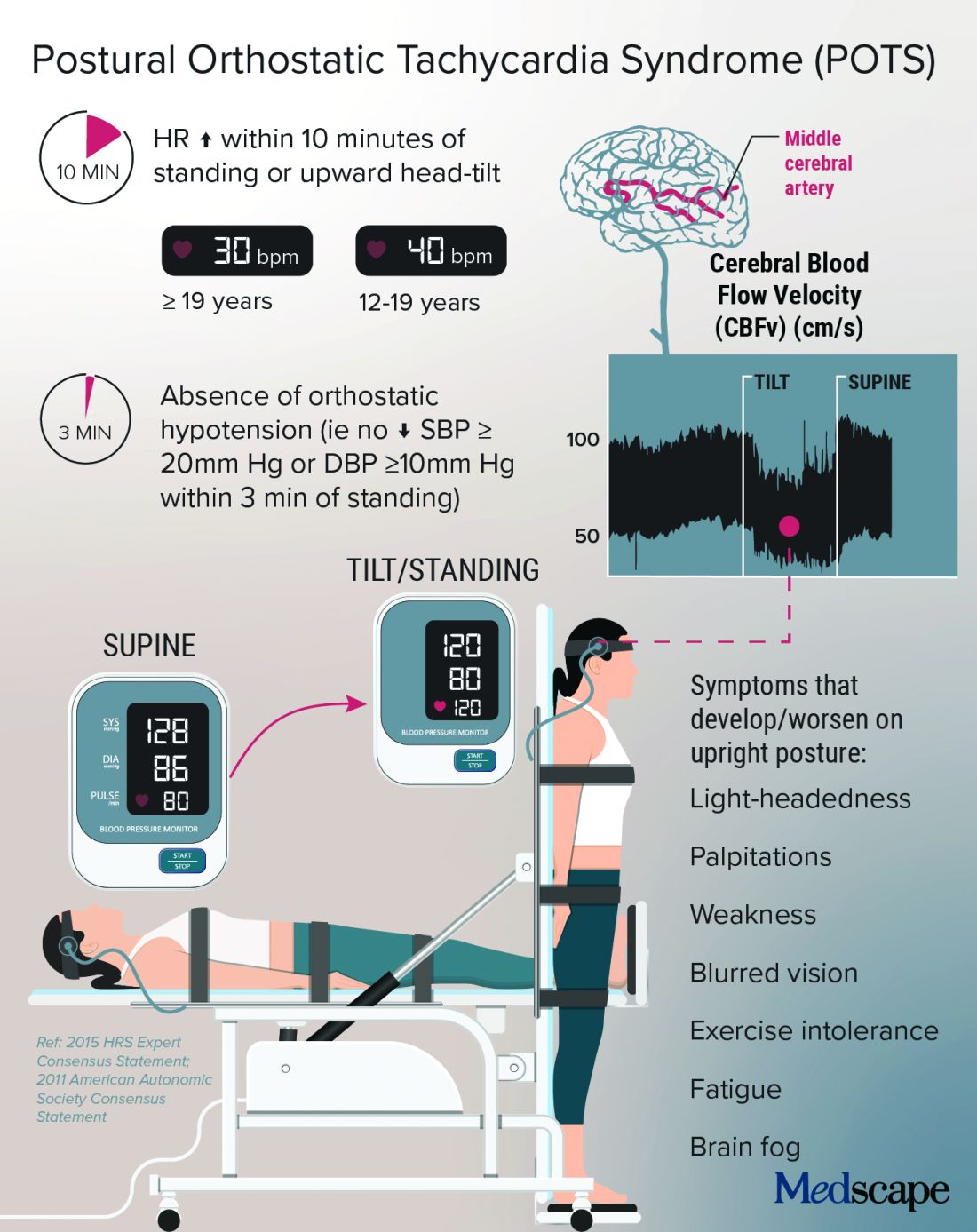

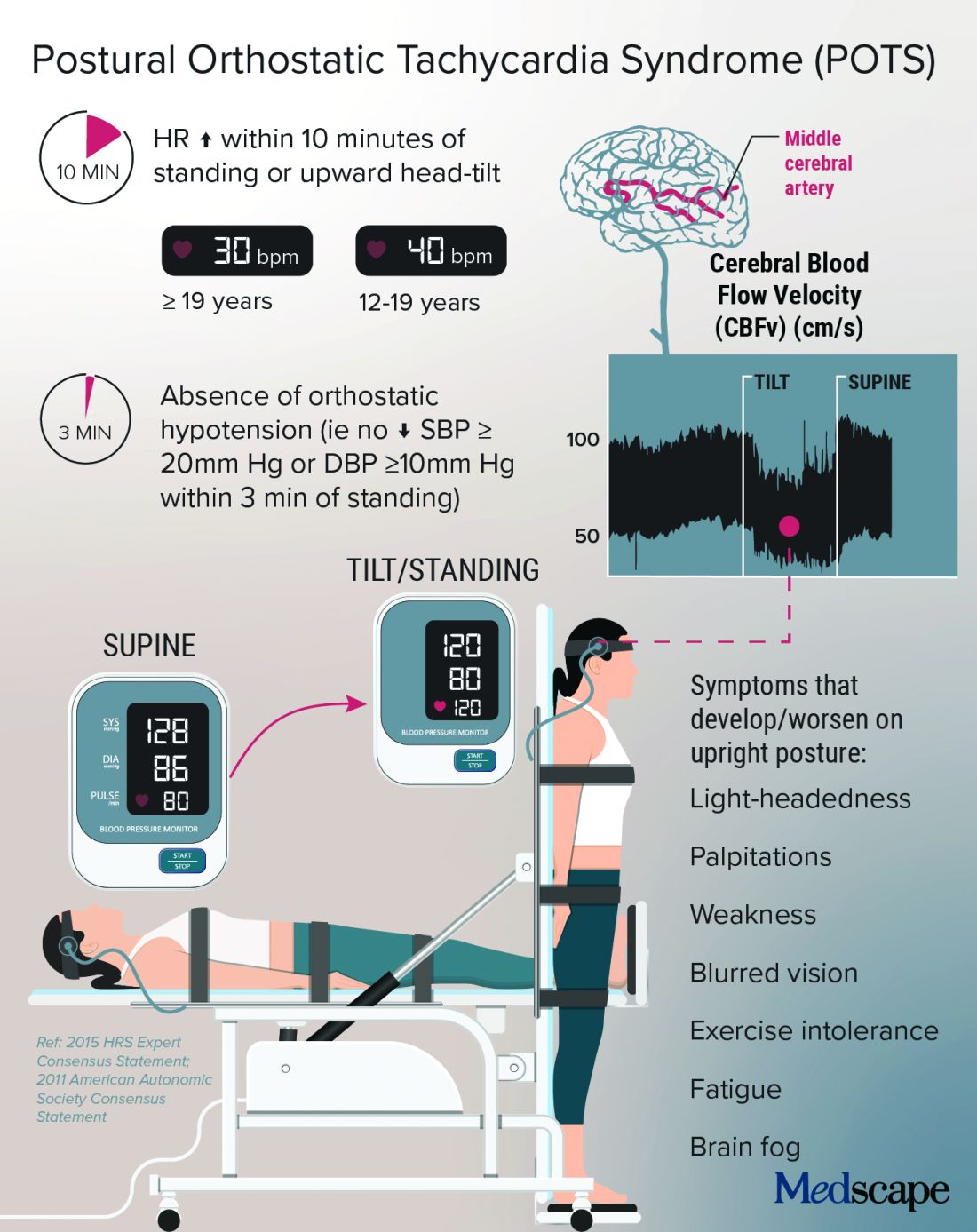

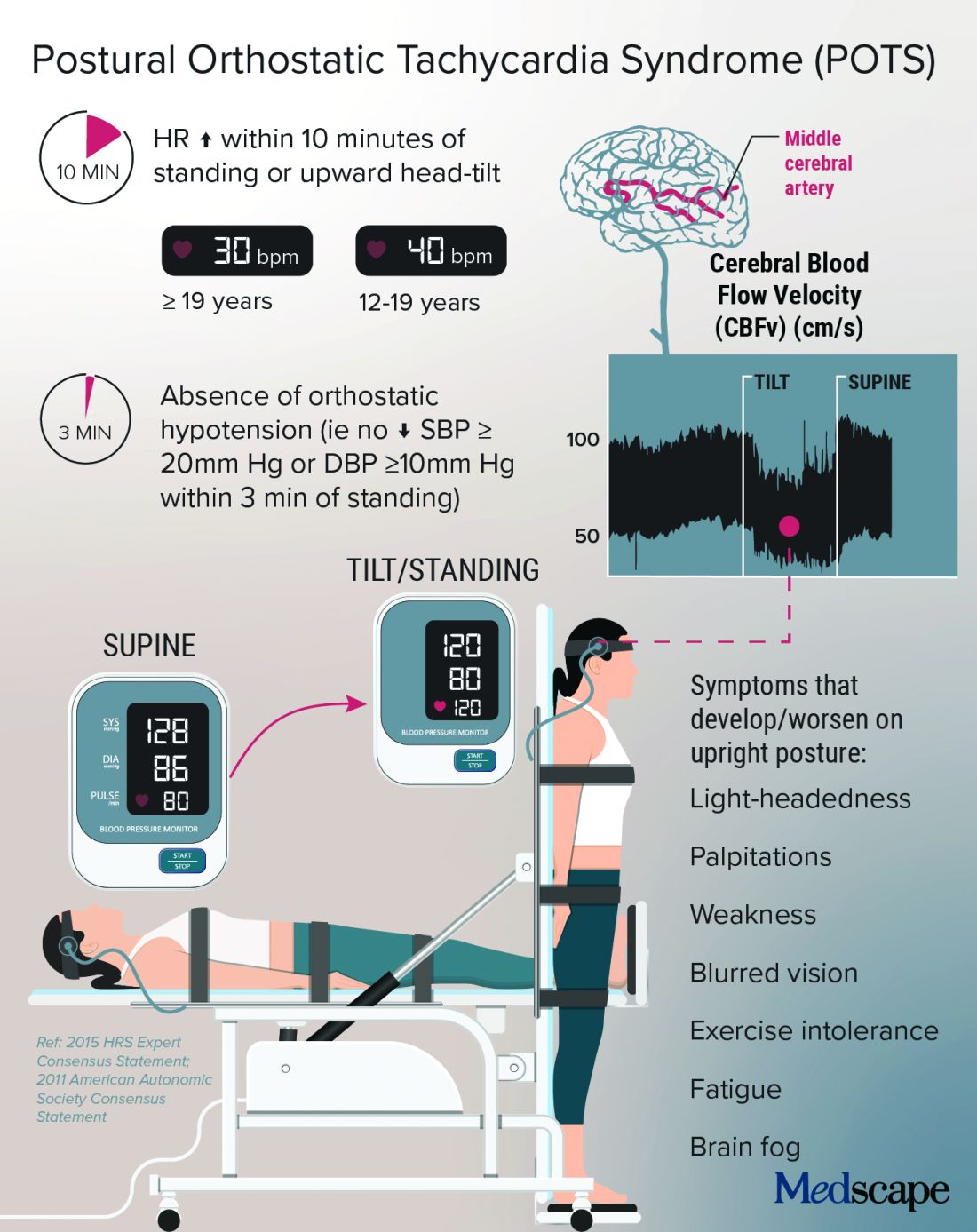

Before COVID-19, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) was one of those diseases that many people, including physicians, dismissed.

“They thought it was just anxious, crazy young women,” said Pam R. Taub, MD, who runs the cardiac rehabilitation program at the University of California, San Diego.

The cryptic autonomic condition was estimated to affect 1-3 million Americans before the pandemic hit. Now case reports confirm that it is a manifestation of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), or so-called long-haul COVID-19.

“I’m excited that this condition that has been so often the ugly stepchild of both cardiology and neurology is getting some attention,” said Dr. Taub. She said she is hopeful that the National Institutes of Health’s commitment to PASC research will benefit patients affected by the cardiovascular dysautonomia characterized by orthostatic intolerance in the absence of orthostatic hypotension.

Postinfection POTS is not exclusive to SARS-CoV-2. It has been reported after Lyme disease and Epstein-Barr virus infections, for example. One theory is that some of the antibodies generated against the virus cross react and damage the autonomic nervous system, which regulates heart rate and blood pressure, Dr. Taub explained.

It is not known whether COVID-19 is more likely to trigger POTS than are other infections or whether the rise in cases merely reflects the fact that more than 115 million people worldwide have been infected with the novel coronavirus.

Low blood volume, dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, and autoimmunity may all play a role in POTS, perhaps leading to distinct subtypes, according to a State of the Science document from the NIH; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

In Dr. Taub’s experience, “The truth is that patients actually have a mix of the subtypes.”

Kamal Shouman, MD, an autonomic neurologist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said in an interview that he has seen patients present with post–COVID-19 POTS in “all flavors,” including “neuropathic POTS, which is thought of as the classic postinfectious phenomenon.”

Why does it mostly affect athletic women?

The condition, which can be the result of dehydration or prolonged bed rest, leading to deconditioning, affects women disproportionately.

According to Manesh Patel, MD, if a patient with POTS who is not a young woman is presented on medical rounds, the response is, “Tell me again why you think this patient has POTS.”

Dr. Patel, chief of the division of cardiology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., has a theory for why many of the women who have POTS are athletes or are highly active: They likely have an underlying predisposition, compounded by a smaller body volume, leaving less margin for error. “If they decondition and lose 500 cc’s, it makes a bigger difference to them than, say, a 300-pound offensive lineman,” Dr. Patel explained.

That hypothesis makes sense to Dr. Taub, who added, “There are just some people metabolically that are more hyperadrenergic,” and it may be that “all their activity really helps tone down that sympathetic output,” but the infection affects these regulatory processes, and deconditioning disrupts things further.

Women also have more autoimmune disorders than do men. The driving force of the dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system is thought to be “immune mediated; we think it’s triggered by a response to a virus,” she said.

Dr. Shouman said the underlying susceptibility may predispose toward orthostatic intolerance. For example, patients will tell him, “Well, many years ago, I was prone to fainting.” He emphasized that POTS is not exclusive to women – he sees men with POTS, and one of the three recent case reports of post–COVID-19 POTS involved a 37-year-old man. So far, the male POTS patients that Dr. Patel has encountered have been deconditioned athletes.

Poor (wo)man’s tilt test and treatment options

POTS is typically diagnosed with a tilt test and transcranial Doppler. Dr. Taub described her “poor man’s tilt test” of asking the patient to lie down for 5-10 minutes and then having the patient stand up.

She likes the fact that transcranial Doppler helps validate the brain fog that patients report, which can be dismissed as “just your excuse for not wanting to work.” If blood perfusion to the brain is cut by 40%-50%, “how are you going to think clearly?” she said.

Dr. Shouman noted that overall volume expansion with salt water, compression garments, and a graduated exercise program play a major role in the rehabilitation of all POTS patients.

He likes to tailor treatments to the most likely underlying cause. But patients should first undergo a medical assessment by their internists to make sure there isn’t a primary lung or heart problem.

“Once the decision is made for them to be evaluated in the autonomic practice and [a] POTS diagnosis is made, I think it is very useful to determine what type of POTS,” he said.

With hyperadrenergic POTS, “you are looking at a standing norepinephrine level of over 600 pg/mL or so.” For these patients, drugs such as ivabradine or beta-blockers can help, he noted.

Dr. Taub recently conducted a small study that showed a benefit with the selective If channel blocker ivabradine for patients with hyperadrenergic POTS unrelated to COVID-19. She tends to favor ivabradine over beta-blockers because it lowers heart rate but not blood pressure. In addition, beta-blockers can exacerbate fatigue and brain fog.

A small crossover study will compare propranolol and ivabradine in POTS. For someone who is very hypovolemic, “you might try a salt tablet or a prescription drug like fludrocortisone,” Dr. Taub explained.

Another problem that patients with POTS experience is an inability to exercise because of orthostatic intolerance. Recumbent exercise targets deconditioning and can tamp down the hyperadrenergic effect. Dr. Shouman’s approach is to start gradually with swimming or the use of a recumbent bike or a rowing machine.

Dr. Taub recommends wearables to patients because POTS is “a very dynamic condition” that is easy to overmedicate or undermedicate. If it’s a good day, the patients are well hydrated, and the standing heart rate is only 80 bpm, she tells them they could titrate down their second dose of ivabradine, for example. The feedback from wearables also helps patients manage their exercise response.

For Dr. Shouman, wearables are not always as accurate as he would like. He tells his patients that it’s okay to use one as long as it doesn’t become a source of anxiety such that they’re constantly checking it.

POTS hope: A COVID-19 silver lining?

With increasing attention being paid to long-haul COVID-19, are there any concerns that POTS will get lost among the myriad symptoms connected to PASC?

Dr. Shouman cautioned, “Not all long COVID is POTS,” and said that clinicians at long-haul clinics should be able to recognize the different conditions “when POTS is suspected. I think it is useful for those providers to make the appropriate referral for POTS clinic autonomic assessment.”

He and his colleagues at Mayo have seen quite a few patients who have post–COVID-19 autonomic dysfunction, such as vasodepressor syncope, not just POTS. They plan to write about this soon.

“Of all the things I treat in cardiology, this is the most complex, because there’s so many different systems involved,” said Dr. Taub, who has seen patients recover fully from POTS. “There’s a spectrum, and there’s people that are definitely on one end of the spectrum where they have very severe diseases.”

For her, the important message is, “No matter where you are on the spectrum, there are things we can do to make your symptoms better.” And with grant funding for PASC research, “hopefully we will address the mechanisms of disease, and we’ll be able to cure this,” she said.

Dr. Patel has served as a consultant for Bayer, Janssen, AstraZeneca, and Heartflow and has received research grants from Bayer, Janssen, AstraZeneca, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Shouman reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Taub has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer, Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; is a shareholder in Epirium Bio; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the Department of Homeland Security/FEMA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Before COVID-19, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) was one of those diseases that many people, including physicians, dismissed.

“They thought it was just anxious, crazy young women,” said Pam R. Taub, MD, who runs the cardiac rehabilitation program at the University of California, San Diego.

The cryptic autonomic condition was estimated to affect 1-3 million Americans before the pandemic hit. Now case reports confirm that it is a manifestation of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), or so-called long-haul COVID-19.

“I’m excited that this condition that has been so often the ugly stepchild of both cardiology and neurology is getting some attention,” said Dr. Taub. She said she is hopeful that the National Institutes of Health’s commitment to PASC research will benefit patients affected by the cardiovascular dysautonomia characterized by orthostatic intolerance in the absence of orthostatic hypotension.

Postinfection POTS is not exclusive to SARS-CoV-2. It has been reported after Lyme disease and Epstein-Barr virus infections, for example. One theory is that some of the antibodies generated against the virus cross react and damage the autonomic nervous system, which regulates heart rate and blood pressure, Dr. Taub explained.

It is not known whether COVID-19 is more likely to trigger POTS than are other infections or whether the rise in cases merely reflects the fact that more than 115 million people worldwide have been infected with the novel coronavirus.

Low blood volume, dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, and autoimmunity may all play a role in POTS, perhaps leading to distinct subtypes, according to a State of the Science document from the NIH; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

In Dr. Taub’s experience, “The truth is that patients actually have a mix of the subtypes.”

Kamal Shouman, MD, an autonomic neurologist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said in an interview that he has seen patients present with post–COVID-19 POTS in “all flavors,” including “neuropathic POTS, which is thought of as the classic postinfectious phenomenon.”

Why does it mostly affect athletic women?

The condition, which can be the result of dehydration or prolonged bed rest, leading to deconditioning, affects women disproportionately.

According to Manesh Patel, MD, if a patient with POTS who is not a young woman is presented on medical rounds, the response is, “Tell me again why you think this patient has POTS.”

Dr. Patel, chief of the division of cardiology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., has a theory for why many of the women who have POTS are athletes or are highly active: They likely have an underlying predisposition, compounded by a smaller body volume, leaving less margin for error. “If they decondition and lose 500 cc’s, it makes a bigger difference to them than, say, a 300-pound offensive lineman,” Dr. Patel explained.

That hypothesis makes sense to Dr. Taub, who added, “There are just some people metabolically that are more hyperadrenergic,” and it may be that “all their activity really helps tone down that sympathetic output,” but the infection affects these regulatory processes, and deconditioning disrupts things further.

Women also have more autoimmune disorders than do men. The driving force of the dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system is thought to be “immune mediated; we think it’s triggered by a response to a virus,” she said.

Dr. Shouman said the underlying susceptibility may predispose toward orthostatic intolerance. For example, patients will tell him, “Well, many years ago, I was prone to fainting.” He emphasized that POTS is not exclusive to women – he sees men with POTS, and one of the three recent case reports of post–COVID-19 POTS involved a 37-year-old man. So far, the male POTS patients that Dr. Patel has encountered have been deconditioned athletes.

Poor (wo)man’s tilt test and treatment options

POTS is typically diagnosed with a tilt test and transcranial Doppler. Dr. Taub described her “poor man’s tilt test” of asking the patient to lie down for 5-10 minutes and then having the patient stand up.

She likes the fact that transcranial Doppler helps validate the brain fog that patients report, which can be dismissed as “just your excuse for not wanting to work.” If blood perfusion to the brain is cut by 40%-50%, “how are you going to think clearly?” she said.

Dr. Shouman noted that overall volume expansion with salt water, compression garments, and a graduated exercise program play a major role in the rehabilitation of all POTS patients.

He likes to tailor treatments to the most likely underlying cause. But patients should first undergo a medical assessment by their internists to make sure there isn’t a primary lung or heart problem.

“Once the decision is made for them to be evaluated in the autonomic practice and [a] POTS diagnosis is made, I think it is very useful to determine what type of POTS,” he said.

With hyperadrenergic POTS, “you are looking at a standing norepinephrine level of over 600 pg/mL or so.” For these patients, drugs such as ivabradine or beta-blockers can help, he noted.

Dr. Taub recently conducted a small study that showed a benefit with the selective If channel blocker ivabradine for patients with hyperadrenergic POTS unrelated to COVID-19. She tends to favor ivabradine over beta-blockers because it lowers heart rate but not blood pressure. In addition, beta-blockers can exacerbate fatigue and brain fog.

A small crossover study will compare propranolol and ivabradine in POTS. For someone who is very hypovolemic, “you might try a salt tablet or a prescription drug like fludrocortisone,” Dr. Taub explained.

Another problem that patients with POTS experience is an inability to exercise because of orthostatic intolerance. Recumbent exercise targets deconditioning and can tamp down the hyperadrenergic effect. Dr. Shouman’s approach is to start gradually with swimming or the use of a recumbent bike or a rowing machine.

Dr. Taub recommends wearables to patients because POTS is “a very dynamic condition” that is easy to overmedicate or undermedicate. If it’s a good day, the patients are well hydrated, and the standing heart rate is only 80 bpm, she tells them they could titrate down their second dose of ivabradine, for example. The feedback from wearables also helps patients manage their exercise response.

For Dr. Shouman, wearables are not always as accurate as he would like. He tells his patients that it’s okay to use one as long as it doesn’t become a source of anxiety such that they’re constantly checking it.

POTS hope: A COVID-19 silver lining?

With increasing attention being paid to long-haul COVID-19, are there any concerns that POTS will get lost among the myriad symptoms connected to PASC?

Dr. Shouman cautioned, “Not all long COVID is POTS,” and said that clinicians at long-haul clinics should be able to recognize the different conditions “when POTS is suspected. I think it is useful for those providers to make the appropriate referral for POTS clinic autonomic assessment.”

He and his colleagues at Mayo have seen quite a few patients who have post–COVID-19 autonomic dysfunction, such as vasodepressor syncope, not just POTS. They plan to write about this soon.

“Of all the things I treat in cardiology, this is the most complex, because there’s so many different systems involved,” said Dr. Taub, who has seen patients recover fully from POTS. “There’s a spectrum, and there’s people that are definitely on one end of the spectrum where they have very severe diseases.”

For her, the important message is, “No matter where you are on the spectrum, there are things we can do to make your symptoms better.” And with grant funding for PASC research, “hopefully we will address the mechanisms of disease, and we’ll be able to cure this,” she said.

Dr. Patel has served as a consultant for Bayer, Janssen, AstraZeneca, and Heartflow and has received research grants from Bayer, Janssen, AstraZeneca, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Shouman reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Taub has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer, Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; is a shareholder in Epirium Bio; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the Department of Homeland Security/FEMA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Before COVID-19, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) was one of those diseases that many people, including physicians, dismissed.

“They thought it was just anxious, crazy young women,” said Pam R. Taub, MD, who runs the cardiac rehabilitation program at the University of California, San Diego.

The cryptic autonomic condition was estimated to affect 1-3 million Americans before the pandemic hit. Now case reports confirm that it is a manifestation of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), or so-called long-haul COVID-19.

“I’m excited that this condition that has been so often the ugly stepchild of both cardiology and neurology is getting some attention,” said Dr. Taub. She said she is hopeful that the National Institutes of Health’s commitment to PASC research will benefit patients affected by the cardiovascular dysautonomia characterized by orthostatic intolerance in the absence of orthostatic hypotension.

Postinfection POTS is not exclusive to SARS-CoV-2. It has been reported after Lyme disease and Epstein-Barr virus infections, for example. One theory is that some of the antibodies generated against the virus cross react and damage the autonomic nervous system, which regulates heart rate and blood pressure, Dr. Taub explained.

It is not known whether COVID-19 is more likely to trigger POTS than are other infections or whether the rise in cases merely reflects the fact that more than 115 million people worldwide have been infected with the novel coronavirus.

Low blood volume, dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, and autoimmunity may all play a role in POTS, perhaps leading to distinct subtypes, according to a State of the Science document from the NIH; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

In Dr. Taub’s experience, “The truth is that patients actually have a mix of the subtypes.”

Kamal Shouman, MD, an autonomic neurologist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said in an interview that he has seen patients present with post–COVID-19 POTS in “all flavors,” including “neuropathic POTS, which is thought of as the classic postinfectious phenomenon.”

Why does it mostly affect athletic women?

The condition, which can be the result of dehydration or prolonged bed rest, leading to deconditioning, affects women disproportionately.

According to Manesh Patel, MD, if a patient with POTS who is not a young woman is presented on medical rounds, the response is, “Tell me again why you think this patient has POTS.”

Dr. Patel, chief of the division of cardiology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., has a theory for why many of the women who have POTS are athletes or are highly active: They likely have an underlying predisposition, compounded by a smaller body volume, leaving less margin for error. “If they decondition and lose 500 cc’s, it makes a bigger difference to them than, say, a 300-pound offensive lineman,” Dr. Patel explained.

That hypothesis makes sense to Dr. Taub, who added, “There are just some people metabolically that are more hyperadrenergic,” and it may be that “all their activity really helps tone down that sympathetic output,” but the infection affects these regulatory processes, and deconditioning disrupts things further.

Women also have more autoimmune disorders than do men. The driving force of the dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system is thought to be “immune mediated; we think it’s triggered by a response to a virus,” she said.

Dr. Shouman said the underlying susceptibility may predispose toward orthostatic intolerance. For example, patients will tell him, “Well, many years ago, I was prone to fainting.” He emphasized that POTS is not exclusive to women – he sees men with POTS, and one of the three recent case reports of post–COVID-19 POTS involved a 37-year-old man. So far, the male POTS patients that Dr. Patel has encountered have been deconditioned athletes.

Poor (wo)man’s tilt test and treatment options

POTS is typically diagnosed with a tilt test and transcranial Doppler. Dr. Taub described her “poor man’s tilt test” of asking the patient to lie down for 5-10 minutes and then having the patient stand up.

She likes the fact that transcranial Doppler helps validate the brain fog that patients report, which can be dismissed as “just your excuse for not wanting to work.” If blood perfusion to the brain is cut by 40%-50%, “how are you going to think clearly?” she said.

Dr. Shouman noted that overall volume expansion with salt water, compression garments, and a graduated exercise program play a major role in the rehabilitation of all POTS patients.

He likes to tailor treatments to the most likely underlying cause. But patients should first undergo a medical assessment by their internists to make sure there isn’t a primary lung or heart problem.

“Once the decision is made for them to be evaluated in the autonomic practice and [a] POTS diagnosis is made, I think it is very useful to determine what type of POTS,” he said.

With hyperadrenergic POTS, “you are looking at a standing norepinephrine level of over 600 pg/mL or so.” For these patients, drugs such as ivabradine or beta-blockers can help, he noted.

Dr. Taub recently conducted a small study that showed a benefit with the selective If channel blocker ivabradine for patients with hyperadrenergic POTS unrelated to COVID-19. She tends to favor ivabradine over beta-blockers because it lowers heart rate but not blood pressure. In addition, beta-blockers can exacerbate fatigue and brain fog.

A small crossover study will compare propranolol and ivabradine in POTS. For someone who is very hypovolemic, “you might try a salt tablet or a prescription drug like fludrocortisone,” Dr. Taub explained.

Another problem that patients with POTS experience is an inability to exercise because of orthostatic intolerance. Recumbent exercise targets deconditioning and can tamp down the hyperadrenergic effect. Dr. Shouman’s approach is to start gradually with swimming or the use of a recumbent bike or a rowing machine.

Dr. Taub recommends wearables to patients because POTS is “a very dynamic condition” that is easy to overmedicate or undermedicate. If it’s a good day, the patients are well hydrated, and the standing heart rate is only 80 bpm, she tells them they could titrate down their second dose of ivabradine, for example. The feedback from wearables also helps patients manage their exercise response.