User login

Docs used permanent, not temporary stitches; lawsuits result

The first in what have come to be known as the “wrong stitches” cases has been settled, a story in The Ledger reports.

The former plaintiff in the now-settled suit is Carrie Monk, a Lakeland, Fla., resident who underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy at Lakeland Regional Health Medical Center several years ago. (The medical center is managed by Lakeland Regional Health Systems.) D As a result, over the next 19 months, she experienced abdominal pain and constant bleeding, which in turn affected her personal life as well as her work as a nurse in the intensive care unit. She underwent follow-up surgery to have the permanent sutures removed, but two could not be identified and excised.

In July 2020, Ms. Monk filed a medical malpractice claim against Lakeland Regional Health, its medical center, and the ob-gyns who had performed her surgery. She was among the first of the women who had received the permanent sutures to do so.

On February 28, 2021, The Ledger ran a story on Ms. Monk’s suit. Less than 2 weeks later, Lakeland Regional Health sent letters to patients who had undergone “wrong stitch” surgeries, cautioning of possible postsurgical complications. The company reportedly kept secret how many letters it had sent out.

Since then, at least nine similar suits have been filed against Lakeland Regional Health, bringing the total number of such suits to 12. Four of these suits have been settled, including Ms. Monk’s. Of the remaining eight cases, several are in various pretrial stages.

Under the terms of her settlement, neither Ms. Monk nor her attorney may disclose what financial compensation or other awards she’s received. The attorney, however, referred to the settlement as “amicable.”

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The first in what have come to be known as the “wrong stitches” cases has been settled, a story in The Ledger reports.

The former plaintiff in the now-settled suit is Carrie Monk, a Lakeland, Fla., resident who underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy at Lakeland Regional Health Medical Center several years ago. (The medical center is managed by Lakeland Regional Health Systems.) D As a result, over the next 19 months, she experienced abdominal pain and constant bleeding, which in turn affected her personal life as well as her work as a nurse in the intensive care unit. She underwent follow-up surgery to have the permanent sutures removed, but two could not be identified and excised.

In July 2020, Ms. Monk filed a medical malpractice claim against Lakeland Regional Health, its medical center, and the ob-gyns who had performed her surgery. She was among the first of the women who had received the permanent sutures to do so.

On February 28, 2021, The Ledger ran a story on Ms. Monk’s suit. Less than 2 weeks later, Lakeland Regional Health sent letters to patients who had undergone “wrong stitch” surgeries, cautioning of possible postsurgical complications. The company reportedly kept secret how many letters it had sent out.

Since then, at least nine similar suits have been filed against Lakeland Regional Health, bringing the total number of such suits to 12. Four of these suits have been settled, including Ms. Monk’s. Of the remaining eight cases, several are in various pretrial stages.

Under the terms of her settlement, neither Ms. Monk nor her attorney may disclose what financial compensation or other awards she’s received. The attorney, however, referred to the settlement as “amicable.”

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The first in what have come to be known as the “wrong stitches” cases has been settled, a story in The Ledger reports.

The former plaintiff in the now-settled suit is Carrie Monk, a Lakeland, Fla., resident who underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy at Lakeland Regional Health Medical Center several years ago. (The medical center is managed by Lakeland Regional Health Systems.) D As a result, over the next 19 months, she experienced abdominal pain and constant bleeding, which in turn affected her personal life as well as her work as a nurse in the intensive care unit. She underwent follow-up surgery to have the permanent sutures removed, but two could not be identified and excised.

In July 2020, Ms. Monk filed a medical malpractice claim against Lakeland Regional Health, its medical center, and the ob-gyns who had performed her surgery. She was among the first of the women who had received the permanent sutures to do so.

On February 28, 2021, The Ledger ran a story on Ms. Monk’s suit. Less than 2 weeks later, Lakeland Regional Health sent letters to patients who had undergone “wrong stitch” surgeries, cautioning of possible postsurgical complications. The company reportedly kept secret how many letters it had sent out.

Since then, at least nine similar suits have been filed against Lakeland Regional Health, bringing the total number of such suits to 12. Four of these suits have been settled, including Ms. Monk’s. Of the remaining eight cases, several are in various pretrial stages.

Under the terms of her settlement, neither Ms. Monk nor her attorney may disclose what financial compensation or other awards she’s received. The attorney, however, referred to the settlement as “amicable.”

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hair straighteners’ risk too small for docs to advise against their use

Clarissa Ghazi gets lye relaxers, which contain the chemical sodium hydroxide, applied to her hair two to three times a year.

A recent study that made headlines over a potential link between hair straighteners and uterine cancer is not going to make her stop.

“This study is not enough to cause me to say I’ll stay away from this because [the researchers] don’t prove that using relaxers causes cancer,” Ms. Ghazi said.

Indeed, primary care doctors are unlikely to address the increased risk of uterine cancer in women who frequently use hair straighteners that the study reported.

In the recently published paper on this research, the authors said that they found an 80% higher adjusted risk of uterine cancer among women who had ever “straightened,” “relaxed,” or used “hair pressing products” in the 12 months before enrolling in their study.

This finding is “real, but small,” says internist Douglas S. Paauw, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Dr. Paauw is among several primary care doctors interviewed for this story who expressed little concern about the implications of this research for their patients.

“Since we have hundreds of things we are supposed to discuss at our 20-minute clinic visits, this would not make the cut,” Dr. Paauw said.

While it’s good to be able to answer questions a patient might ask about this new research, the study does not prove anything, he said.

Alan Nelson, MD, an internist-endocrinologist and former special adviser to the CEO of the American College of Physicians, said while the study is well done, the number of actual cases of uterine cancer found was small.

One of the reasons he would not recommend discussing the study with patients is that the brands of hair products used to straighten hair in the study were not identified.

Alexandra White, PhD, lead author of the study, said participants were simply asked, “In the past 12 months, how frequently have you or someone else straightened or relaxed your hair, or used hair pressing products?”

The terms “straightened,” “relaxed,” and “hair pressing products” were not defined, and “some women may have interpreted the term ‘pressing products’ to mean nonchemical products” such as flat irons, Dr. White, head of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’ Environment and Cancer Epidemiology group, said in an email.

Dermatologist Crystal Aguh, MD, associate professor of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, tweeted the following advice in light of the new findings: “The overall risk of uterine cancer is quite low so it’s important to remember that. For now, if you want to change your routine, there’s no downside to decreasing your frequency of hair straightening to every 12 weeks or more, as that may lessen your risk.”

She also noted that “styles like relaxer, silk pressing, and keratin treatments should only be done by a professional, as this will decrease the likelihood of hair damage and scalp irritation.

“I also encourage women to look for hair products free of parabens and phthalates (which are generically listed as “fragrance”) on products to minimize exposure to hormone disrupting chemicals.”

Not ready to go curly

Ms. Ghazi said she decided to stop using keratin straighteners years ago after she learned they are made with several added ingredients. That includes the chemical formaldehyde, a known carcinogen, according to the American Cancer Society.

“People have been relaxing their hair for a very long time, and I feel more comfortable using [a relaxer] to straighten my hair than any of the others out there,” Ms. Ghazi said.

Janaki Ram, who has had her hair chemically straightened several times, said the findings have not made her worried that straightening will cause her to get uterine cancer specifically, but that they are a reminder that the chemicals in these products could harm her in some other way.

She said the new study findings, her knowledge of the damage straightening causes to hair, and the lengthy amount of time receiving a keratin treatment takes will lead her to reduce the frequency with which she gets her hair straightened.

“Going forward, I will have this done once a year instead of twice a year,” she said.

Dr. White, the author of the paper, said in an interview that the takeaway for consumers is that women who reported frequent use of hair straighteners/relaxers and pressing products were more than twice as likely to go on to develop uterine cancer compared to women who reported no use of these products in the previous year.

“However, uterine cancer is relatively rare, so these increases in risks are small,” she said. “Less frequent use of these products was not as strongly associated with risk, suggesting that decreasing use may be an option to reduce harmful exposure. Black women were the most frequent users of these products and therefore these findings are more relevant for Black women.”

In a statement, Dr. White noted, “We estimated that 1.64% of women who never used hair straighteners would go on to develop uterine cancer by the age of 70; but for frequent users, that risk goes up to 4.05%.”

The findings were based on the Sister Study, which enrolled women living in the United States, including Puerto Rico, between 2003 and 2009. Participants needed to have at least one sister who had been diagnosed with breast cancer, been breast cancer-free themselves, and aged 35-74 years. Women who reported a diagnosis of uterine cancer before enrollment, had an uncertain uterine cancer history, or had a hysterectomy were excluded from the study.

The researchers examined hair product usage and uterine cancer incidence during an 11-year period among 33 ,947 women. The analysis controlled for variables such as age, race, and risk factors. At baseline, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire on hair products use in the previous 12 months.

“One of the original aims of the study was to better understand the environmental and genetic causes of breast cancer, but we are also interested in studying ovarian cancer, uterine cancer, and many other cancers and chronic diseases,” Dr. White said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Clarissa Ghazi gets lye relaxers, which contain the chemical sodium hydroxide, applied to her hair two to three times a year.

A recent study that made headlines over a potential link between hair straighteners and uterine cancer is not going to make her stop.

“This study is not enough to cause me to say I’ll stay away from this because [the researchers] don’t prove that using relaxers causes cancer,” Ms. Ghazi said.

Indeed, primary care doctors are unlikely to address the increased risk of uterine cancer in women who frequently use hair straighteners that the study reported.

In the recently published paper on this research, the authors said that they found an 80% higher adjusted risk of uterine cancer among women who had ever “straightened,” “relaxed,” or used “hair pressing products” in the 12 months before enrolling in their study.

This finding is “real, but small,” says internist Douglas S. Paauw, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Dr. Paauw is among several primary care doctors interviewed for this story who expressed little concern about the implications of this research for their patients.

“Since we have hundreds of things we are supposed to discuss at our 20-minute clinic visits, this would not make the cut,” Dr. Paauw said.

While it’s good to be able to answer questions a patient might ask about this new research, the study does not prove anything, he said.

Alan Nelson, MD, an internist-endocrinologist and former special adviser to the CEO of the American College of Physicians, said while the study is well done, the number of actual cases of uterine cancer found was small.

One of the reasons he would not recommend discussing the study with patients is that the brands of hair products used to straighten hair in the study were not identified.

Alexandra White, PhD, lead author of the study, said participants were simply asked, “In the past 12 months, how frequently have you or someone else straightened or relaxed your hair, or used hair pressing products?”

The terms “straightened,” “relaxed,” and “hair pressing products” were not defined, and “some women may have interpreted the term ‘pressing products’ to mean nonchemical products” such as flat irons, Dr. White, head of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’ Environment and Cancer Epidemiology group, said in an email.

Dermatologist Crystal Aguh, MD, associate professor of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, tweeted the following advice in light of the new findings: “The overall risk of uterine cancer is quite low so it’s important to remember that. For now, if you want to change your routine, there’s no downside to decreasing your frequency of hair straightening to every 12 weeks or more, as that may lessen your risk.”

She also noted that “styles like relaxer, silk pressing, and keratin treatments should only be done by a professional, as this will decrease the likelihood of hair damage and scalp irritation.

“I also encourage women to look for hair products free of parabens and phthalates (which are generically listed as “fragrance”) on products to minimize exposure to hormone disrupting chemicals.”

Not ready to go curly

Ms. Ghazi said she decided to stop using keratin straighteners years ago after she learned they are made with several added ingredients. That includes the chemical formaldehyde, a known carcinogen, according to the American Cancer Society.

“People have been relaxing their hair for a very long time, and I feel more comfortable using [a relaxer] to straighten my hair than any of the others out there,” Ms. Ghazi said.

Janaki Ram, who has had her hair chemically straightened several times, said the findings have not made her worried that straightening will cause her to get uterine cancer specifically, but that they are a reminder that the chemicals in these products could harm her in some other way.

She said the new study findings, her knowledge of the damage straightening causes to hair, and the lengthy amount of time receiving a keratin treatment takes will lead her to reduce the frequency with which she gets her hair straightened.

“Going forward, I will have this done once a year instead of twice a year,” she said.

Dr. White, the author of the paper, said in an interview that the takeaway for consumers is that women who reported frequent use of hair straighteners/relaxers and pressing products were more than twice as likely to go on to develop uterine cancer compared to women who reported no use of these products in the previous year.

“However, uterine cancer is relatively rare, so these increases in risks are small,” she said. “Less frequent use of these products was not as strongly associated with risk, suggesting that decreasing use may be an option to reduce harmful exposure. Black women were the most frequent users of these products and therefore these findings are more relevant for Black women.”

In a statement, Dr. White noted, “We estimated that 1.64% of women who never used hair straighteners would go on to develop uterine cancer by the age of 70; but for frequent users, that risk goes up to 4.05%.”

The findings were based on the Sister Study, which enrolled women living in the United States, including Puerto Rico, between 2003 and 2009. Participants needed to have at least one sister who had been diagnosed with breast cancer, been breast cancer-free themselves, and aged 35-74 years. Women who reported a diagnosis of uterine cancer before enrollment, had an uncertain uterine cancer history, or had a hysterectomy were excluded from the study.

The researchers examined hair product usage and uterine cancer incidence during an 11-year period among 33 ,947 women. The analysis controlled for variables such as age, race, and risk factors. At baseline, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire on hair products use in the previous 12 months.

“One of the original aims of the study was to better understand the environmental and genetic causes of breast cancer, but we are also interested in studying ovarian cancer, uterine cancer, and many other cancers and chronic diseases,” Dr. White said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Clarissa Ghazi gets lye relaxers, which contain the chemical sodium hydroxide, applied to her hair two to three times a year.

A recent study that made headlines over a potential link between hair straighteners and uterine cancer is not going to make her stop.

“This study is not enough to cause me to say I’ll stay away from this because [the researchers] don’t prove that using relaxers causes cancer,” Ms. Ghazi said.

Indeed, primary care doctors are unlikely to address the increased risk of uterine cancer in women who frequently use hair straighteners that the study reported.

In the recently published paper on this research, the authors said that they found an 80% higher adjusted risk of uterine cancer among women who had ever “straightened,” “relaxed,” or used “hair pressing products” in the 12 months before enrolling in their study.

This finding is “real, but small,” says internist Douglas S. Paauw, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Dr. Paauw is among several primary care doctors interviewed for this story who expressed little concern about the implications of this research for their patients.

“Since we have hundreds of things we are supposed to discuss at our 20-minute clinic visits, this would not make the cut,” Dr. Paauw said.

While it’s good to be able to answer questions a patient might ask about this new research, the study does not prove anything, he said.

Alan Nelson, MD, an internist-endocrinologist and former special adviser to the CEO of the American College of Physicians, said while the study is well done, the number of actual cases of uterine cancer found was small.

One of the reasons he would not recommend discussing the study with patients is that the brands of hair products used to straighten hair in the study were not identified.

Alexandra White, PhD, lead author of the study, said participants were simply asked, “In the past 12 months, how frequently have you or someone else straightened or relaxed your hair, or used hair pressing products?”

The terms “straightened,” “relaxed,” and “hair pressing products” were not defined, and “some women may have interpreted the term ‘pressing products’ to mean nonchemical products” such as flat irons, Dr. White, head of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’ Environment and Cancer Epidemiology group, said in an email.

Dermatologist Crystal Aguh, MD, associate professor of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, tweeted the following advice in light of the new findings: “The overall risk of uterine cancer is quite low so it’s important to remember that. For now, if you want to change your routine, there’s no downside to decreasing your frequency of hair straightening to every 12 weeks or more, as that may lessen your risk.”

She also noted that “styles like relaxer, silk pressing, and keratin treatments should only be done by a professional, as this will decrease the likelihood of hair damage and scalp irritation.

“I also encourage women to look for hair products free of parabens and phthalates (which are generically listed as “fragrance”) on products to minimize exposure to hormone disrupting chemicals.”

Not ready to go curly

Ms. Ghazi said she decided to stop using keratin straighteners years ago after she learned they are made with several added ingredients. That includes the chemical formaldehyde, a known carcinogen, according to the American Cancer Society.

“People have been relaxing their hair for a very long time, and I feel more comfortable using [a relaxer] to straighten my hair than any of the others out there,” Ms. Ghazi said.

Janaki Ram, who has had her hair chemically straightened several times, said the findings have not made her worried that straightening will cause her to get uterine cancer specifically, but that they are a reminder that the chemicals in these products could harm her in some other way.

She said the new study findings, her knowledge of the damage straightening causes to hair, and the lengthy amount of time receiving a keratin treatment takes will lead her to reduce the frequency with which she gets her hair straightened.

“Going forward, I will have this done once a year instead of twice a year,” she said.

Dr. White, the author of the paper, said in an interview that the takeaway for consumers is that women who reported frequent use of hair straighteners/relaxers and pressing products were more than twice as likely to go on to develop uterine cancer compared to women who reported no use of these products in the previous year.

“However, uterine cancer is relatively rare, so these increases in risks are small,” she said. “Less frequent use of these products was not as strongly associated with risk, suggesting that decreasing use may be an option to reduce harmful exposure. Black women were the most frequent users of these products and therefore these findings are more relevant for Black women.”

In a statement, Dr. White noted, “We estimated that 1.64% of women who never used hair straighteners would go on to develop uterine cancer by the age of 70; but for frequent users, that risk goes up to 4.05%.”

The findings were based on the Sister Study, which enrolled women living in the United States, including Puerto Rico, between 2003 and 2009. Participants needed to have at least one sister who had been diagnosed with breast cancer, been breast cancer-free themselves, and aged 35-74 years. Women who reported a diagnosis of uterine cancer before enrollment, had an uncertain uterine cancer history, or had a hysterectomy were excluded from the study.

The researchers examined hair product usage and uterine cancer incidence during an 11-year period among 33 ,947 women. The analysis controlled for variables such as age, race, and risk factors. At baseline, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire on hair products use in the previous 12 months.

“One of the original aims of the study was to better understand the environmental and genetic causes of breast cancer, but we are also interested in studying ovarian cancer, uterine cancer, and many other cancers and chronic diseases,” Dr. White said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Models stratify hysterectomy risk with benign conditions

New models can help predict whether women having a hysterectomy for benign conditions are likely to have major complications, according to researchers.

The models, which use routinely collected data, are meant to aid surgeons in counseling women before surgery and help guide shared decision-making. The tools may lead to referrals for centers with greater surgical experience or may result in seeking nonsurgical treatment options, the researchers indicate.

The tools are not applicable to patients having hysterectomy for malignant disease.

Findings of the study, led by Krupa Madhvani, MD, of Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry in London, are published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Calculators complement surgeons’ intuition

“Our aim was to generate prediction models that can be used in conjunction with a surgeon’s intuition to enhance preoperative patient counseling and match the advances made in the technical aspects of surgery,” the authors write.

“Internal–external cross-validation and external validation showed moderate discrimination,” they note.

The study included 68,599 patients who had laparoscopic hysterectomies and 125,971 patients who had an abdominal hysterectomy, all English National Health System patients between 2011 and 2018.

Among their findings were that major complications occurred in 4.4% of laparoscopic and 4.9% of abdominal hysterectomies. Major complications in this study included ureteric, gastrointestinal, and vascular injury and wound complications.

Adhesions biggest predictors of complications

Adhesions were most predictive of complications – with double the odds – in both models (laparoscopic: odds ratio, 1.92; 95% confidence interval, 1.73-2.13; abdominal: OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 2.27-2.66). That finding was consistent with previous literature.

“Adhesions should be suspected if there is a previous history of laparotomy, cesarean section, pelvic infection, or endometriosis, and can be reliably diagnosed preoperatively using ultrasonography,” the authors write. “As the global rate of cesarean sections continues to rise, this will undoubtedly remain a key determinant of major complications.”

Other factors that best predicted complications included adenomyosis in the laparoscopic model, and Asian ethnicity and diabetes in the abdominal model. Diabetes was not a predictive factor for complications in laparoscopic hysterectomy as it was in a previous study.

Obesity was not a significant predictor of major complications for either form of hysterectomy.

Factors protective against major complications included younger age and diagnosed menstrual disorders or benign adnexal mass (both models) and diagnosis of fibroids in the abdominal model.

Models miss surgeon experience

Jon Ivar Einarsson MD, PhD, MPH, founder of the division of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said it’s good to have these models to estimate risk as “there’s possibly a tendency to underestimate the risk by the surgeon.”

However, he told this publication that, though these models are based on a very large data set, the models are missing some key variables – often a problem with database studies – that are more indicative of complications. The most important factor missing, he said, is surgeon experience.

“We’ve shown in our publications that there’s a correlation between that and the risk of complications,“ Dr. Einarsson said.

Among other variables missing, he noted, are some that the authors list when acknowledging the limitations: severity of endometriosis and severity of adhesions.

He said his team wouldn’t use such models because they rely on their own data for gauging risk. He encourages other surgeons to track their own data and outcomes as well.

“I think the external validity here is nonexistent because we’re dealing with a different patient population in a different country with different surgeons [who] have various degrees of expertise,” Dr. Einarsson said.

“But if surgeons have not collected their own data, then this could be useful,” he said.

Links to online calculators

The online calculator can be found at www.evidencio.com (laparoscopic, www.evidencio.com/models/show/2551; abdominal, www.evidencio.com/models/show/2552).

The large, national multi-institutional database helps with generalizability of findings, the authors write. Additionally, patients had a unique identifier number so if patients were admitted to a different hospital after surgery, they were not lost to follow-up.

Limitations, in addition to those mentioned, include gaps in detailed clinical information, such as exact body mass index, and location, type, and size of leiomyoma, the authors write.

“Further research should focus on improving the discriminatory ability of these tools by including factors other than patient characteristics, including surgeon volume, as this has been shown to reduce complications,” they write.

Dr. Madhvani has received article-processing fees from Elly Charity (East London International Women’s Health Charity). No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Einarsson reports no relevant financial relationships. The acquisition of the data was funded by the British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy. They were not involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication. Coauthor Khalid Khan, MD is a distinguished investigator funded by the Beatriz Galindo Program grant given to the University of Granada by the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities of the Government of Spain.

New models can help predict whether women having a hysterectomy for benign conditions are likely to have major complications, according to researchers.

The models, which use routinely collected data, are meant to aid surgeons in counseling women before surgery and help guide shared decision-making. The tools may lead to referrals for centers with greater surgical experience or may result in seeking nonsurgical treatment options, the researchers indicate.

The tools are not applicable to patients having hysterectomy for malignant disease.

Findings of the study, led by Krupa Madhvani, MD, of Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry in London, are published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Calculators complement surgeons’ intuition

“Our aim was to generate prediction models that can be used in conjunction with a surgeon’s intuition to enhance preoperative patient counseling and match the advances made in the technical aspects of surgery,” the authors write.

“Internal–external cross-validation and external validation showed moderate discrimination,” they note.

The study included 68,599 patients who had laparoscopic hysterectomies and 125,971 patients who had an abdominal hysterectomy, all English National Health System patients between 2011 and 2018.

Among their findings were that major complications occurred in 4.4% of laparoscopic and 4.9% of abdominal hysterectomies. Major complications in this study included ureteric, gastrointestinal, and vascular injury and wound complications.

Adhesions biggest predictors of complications

Adhesions were most predictive of complications – with double the odds – in both models (laparoscopic: odds ratio, 1.92; 95% confidence interval, 1.73-2.13; abdominal: OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 2.27-2.66). That finding was consistent with previous literature.

“Adhesions should be suspected if there is a previous history of laparotomy, cesarean section, pelvic infection, or endometriosis, and can be reliably diagnosed preoperatively using ultrasonography,” the authors write. “As the global rate of cesarean sections continues to rise, this will undoubtedly remain a key determinant of major complications.”

Other factors that best predicted complications included adenomyosis in the laparoscopic model, and Asian ethnicity and diabetes in the abdominal model. Diabetes was not a predictive factor for complications in laparoscopic hysterectomy as it was in a previous study.

Obesity was not a significant predictor of major complications for either form of hysterectomy.

Factors protective against major complications included younger age and diagnosed menstrual disorders or benign adnexal mass (both models) and diagnosis of fibroids in the abdominal model.

Models miss surgeon experience

Jon Ivar Einarsson MD, PhD, MPH, founder of the division of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said it’s good to have these models to estimate risk as “there’s possibly a tendency to underestimate the risk by the surgeon.”

However, he told this publication that, though these models are based on a very large data set, the models are missing some key variables – often a problem with database studies – that are more indicative of complications. The most important factor missing, he said, is surgeon experience.

“We’ve shown in our publications that there’s a correlation between that and the risk of complications,“ Dr. Einarsson said.

Among other variables missing, he noted, are some that the authors list when acknowledging the limitations: severity of endometriosis and severity of adhesions.

He said his team wouldn’t use such models because they rely on their own data for gauging risk. He encourages other surgeons to track their own data and outcomes as well.

“I think the external validity here is nonexistent because we’re dealing with a different patient population in a different country with different surgeons [who] have various degrees of expertise,” Dr. Einarsson said.

“But if surgeons have not collected their own data, then this could be useful,” he said.

Links to online calculators

The online calculator can be found at www.evidencio.com (laparoscopic, www.evidencio.com/models/show/2551; abdominal, www.evidencio.com/models/show/2552).

The large, national multi-institutional database helps with generalizability of findings, the authors write. Additionally, patients had a unique identifier number so if patients were admitted to a different hospital after surgery, they were not lost to follow-up.

Limitations, in addition to those mentioned, include gaps in detailed clinical information, such as exact body mass index, and location, type, and size of leiomyoma, the authors write.

“Further research should focus on improving the discriminatory ability of these tools by including factors other than patient characteristics, including surgeon volume, as this has been shown to reduce complications,” they write.

Dr. Madhvani has received article-processing fees from Elly Charity (East London International Women’s Health Charity). No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Einarsson reports no relevant financial relationships. The acquisition of the data was funded by the British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy. They were not involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication. Coauthor Khalid Khan, MD is a distinguished investigator funded by the Beatriz Galindo Program grant given to the University of Granada by the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities of the Government of Spain.

New models can help predict whether women having a hysterectomy for benign conditions are likely to have major complications, according to researchers.

The models, which use routinely collected data, are meant to aid surgeons in counseling women before surgery and help guide shared decision-making. The tools may lead to referrals for centers with greater surgical experience or may result in seeking nonsurgical treatment options, the researchers indicate.

The tools are not applicable to patients having hysterectomy for malignant disease.

Findings of the study, led by Krupa Madhvani, MD, of Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry in London, are published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Calculators complement surgeons’ intuition

“Our aim was to generate prediction models that can be used in conjunction with a surgeon’s intuition to enhance preoperative patient counseling and match the advances made in the technical aspects of surgery,” the authors write.

“Internal–external cross-validation and external validation showed moderate discrimination,” they note.

The study included 68,599 patients who had laparoscopic hysterectomies and 125,971 patients who had an abdominal hysterectomy, all English National Health System patients between 2011 and 2018.

Among their findings were that major complications occurred in 4.4% of laparoscopic and 4.9% of abdominal hysterectomies. Major complications in this study included ureteric, gastrointestinal, and vascular injury and wound complications.

Adhesions biggest predictors of complications

Adhesions were most predictive of complications – with double the odds – in both models (laparoscopic: odds ratio, 1.92; 95% confidence interval, 1.73-2.13; abdominal: OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 2.27-2.66). That finding was consistent with previous literature.

“Adhesions should be suspected if there is a previous history of laparotomy, cesarean section, pelvic infection, or endometriosis, and can be reliably diagnosed preoperatively using ultrasonography,” the authors write. “As the global rate of cesarean sections continues to rise, this will undoubtedly remain a key determinant of major complications.”

Other factors that best predicted complications included adenomyosis in the laparoscopic model, and Asian ethnicity and diabetes in the abdominal model. Diabetes was not a predictive factor for complications in laparoscopic hysterectomy as it was in a previous study.

Obesity was not a significant predictor of major complications for either form of hysterectomy.

Factors protective against major complications included younger age and diagnosed menstrual disorders or benign adnexal mass (both models) and diagnosis of fibroids in the abdominal model.

Models miss surgeon experience

Jon Ivar Einarsson MD, PhD, MPH, founder of the division of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said it’s good to have these models to estimate risk as “there’s possibly a tendency to underestimate the risk by the surgeon.”

However, he told this publication that, though these models are based on a very large data set, the models are missing some key variables – often a problem with database studies – that are more indicative of complications. The most important factor missing, he said, is surgeon experience.

“We’ve shown in our publications that there’s a correlation between that and the risk of complications,“ Dr. Einarsson said.

Among other variables missing, he noted, are some that the authors list when acknowledging the limitations: severity of endometriosis and severity of adhesions.

He said his team wouldn’t use such models because they rely on their own data for gauging risk. He encourages other surgeons to track their own data and outcomes as well.

“I think the external validity here is nonexistent because we’re dealing with a different patient population in a different country with different surgeons [who] have various degrees of expertise,” Dr. Einarsson said.

“But if surgeons have not collected their own data, then this could be useful,” he said.

Links to online calculators

The online calculator can be found at www.evidencio.com (laparoscopic, www.evidencio.com/models/show/2551; abdominal, www.evidencio.com/models/show/2552).

The large, national multi-institutional database helps with generalizability of findings, the authors write. Additionally, patients had a unique identifier number so if patients were admitted to a different hospital after surgery, they were not lost to follow-up.

Limitations, in addition to those mentioned, include gaps in detailed clinical information, such as exact body mass index, and location, type, and size of leiomyoma, the authors write.

“Further research should focus on improving the discriminatory ability of these tools by including factors other than patient characteristics, including surgeon volume, as this has been shown to reduce complications,” they write.

Dr. Madhvani has received article-processing fees from Elly Charity (East London International Women’s Health Charity). No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Einarsson reports no relevant financial relationships. The acquisition of the data was funded by the British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy. They were not involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication. Coauthor Khalid Khan, MD is a distinguished investigator funded by the Beatriz Galindo Program grant given to the University of Granada by the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities of the Government of Spain.

FROM CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL

Steps to minimize morbidity from unanticipated placenta accreta spectrum

CASE Placenta accreta spectrum following uncomplicated vaginal delivery

Imagine you are an obstetric hospitalist taking call at a level II maternal level of care hospital. Your patient is a 35-year-old woman, gravida 2, para 1, with a past history of retained placenta requiring dilation and curettage and intravenous antibiotics for endomyometritis. This is an in vitro fertilization pregnancy that has progressed normally, and the patient labored spontaneously at 38 weeks’ gestation. Following an uncomplicated vaginal delivery, the placenta has not delivered, and you attempt a manual placental extraction after a 40-minute third stage. While there is epidural analgesia and you can reach the uterine fundus, you are unable to create a separation plane between the placenta and uterus.

What do you do next?

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) includes a broad range of clinical scenarios with abnormal placental attachment as their common denominator. The condition has classically been defined pathologically, with chorionic villi attaching directly to the myometrium (“accreta”) or extending more deeply into the myometrium (“increta”) or attaching to surrounding tissues and structures (“percreta”).1 It is most commonly encountered in patients with low placental implantation on a prior cesarean section scar; indeed, placenta previa, particularly with a history of cesarean delivery, is the strongest risk factor for the development of PAS.2 In addition to abnormal placental attachment, these placental attachments are often hypervascular and can lead to catastrophic hemorrhage if not managed appropriately. For this reason, patients with sonographic or radiologic signs of PAS should be referred to specialized centers for further workup, counseling, and delivery planning.3

Although delivery at a specialized PAS center has been associated with improved patient outcomes,4 not all patients with PAS will be identified in the antepartum period. Ultrasonography may miss up to 40% to 50% of PAS cases, particularly when the sonologist has not been advised to look for the condition,5 and not all patients with PAS will have a previa implanted in a prior cesarean scar. A recent study found that these patients with nonprevia PAS were identified by imaging less than 40% of the time and were significantly less likely to be managed by a specialized team of clinicians.6 Thus, it falls upon every obstetric care provider to be aware of this diagnosis, promptly recognize its unanticipated presentations, and have a plan to optimize patient safety.

Step 1: Recognition

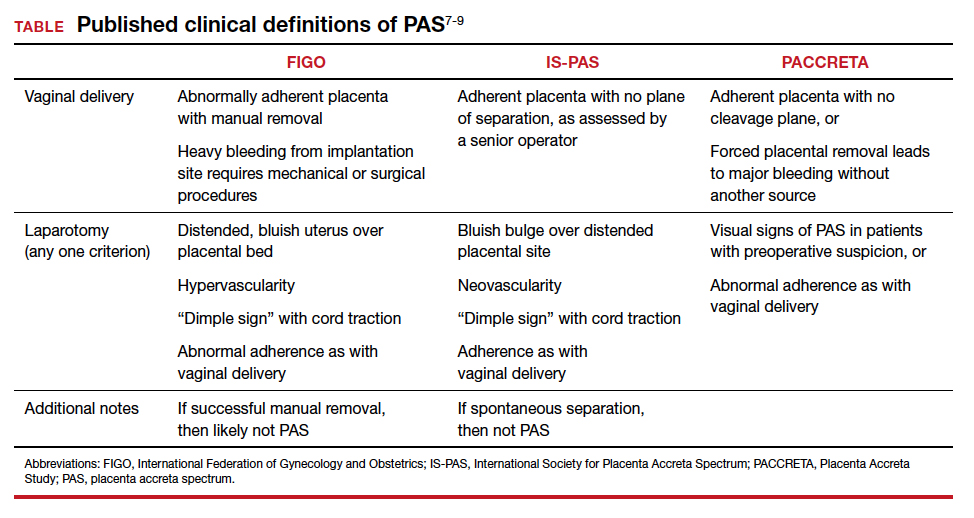

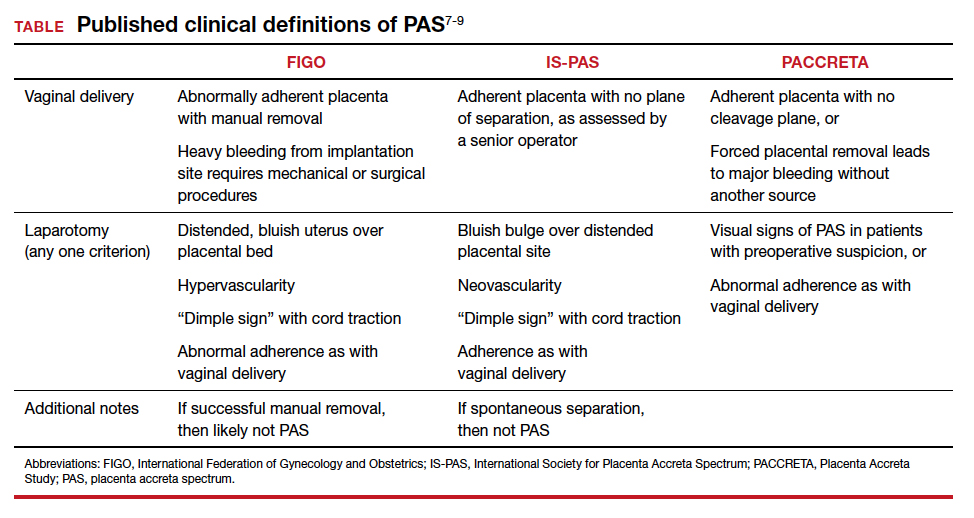

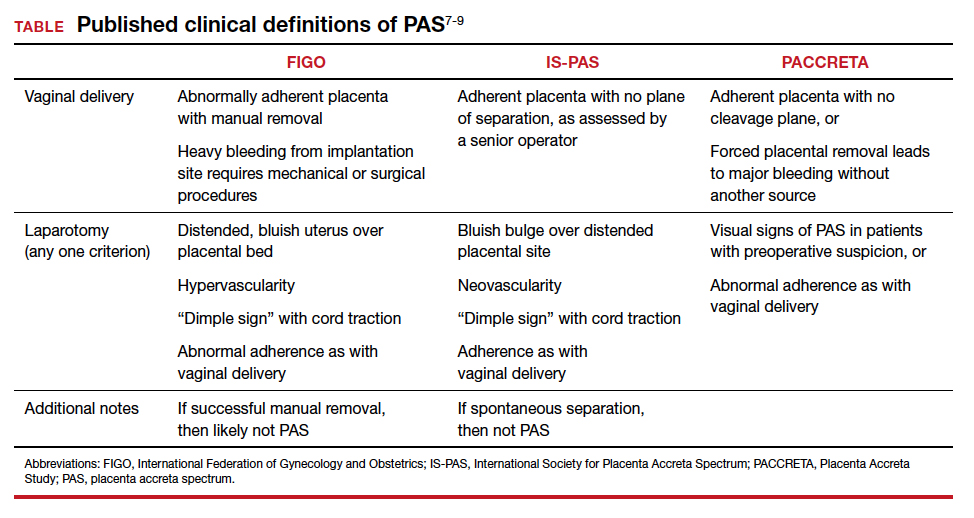

While PAS is classically defined as a pathologic condition, no clinician has the luxury of histology in the delivery room. Researchers have variously defined PAS clinically, with the common trait of abnormal placental adherence.7-9 The TABLE compares published definitions that have been used in the literature. While some definitions include hemorrhage, no clinician wants to induce significant hemorrhage to confirm their patient’s diagnosis. Thus, practically, the clinical PAS diagnosis comes down to abnormal placental attachment: If it is apparent that some or all of the placenta will not separate from the uterine wall with digital manipulation or careful curettage, then PAS should be suspected, and appropriate steps should be taken before further removal attempts.

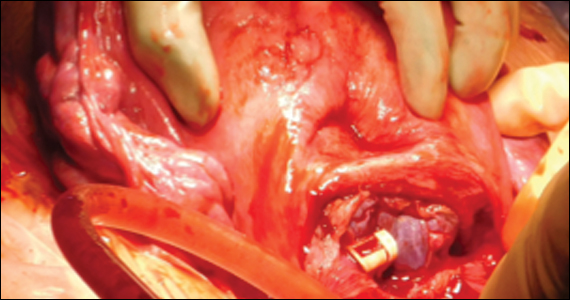

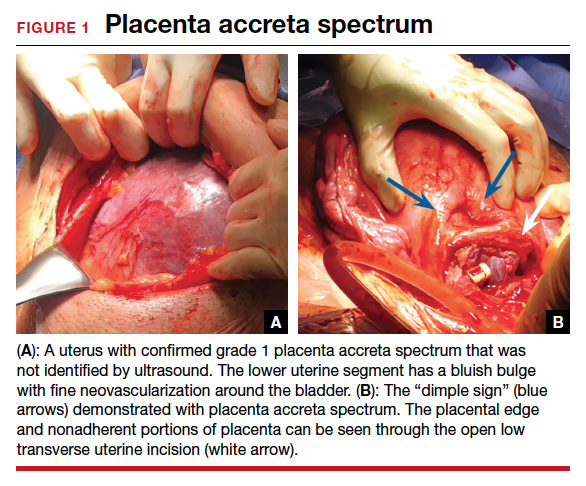

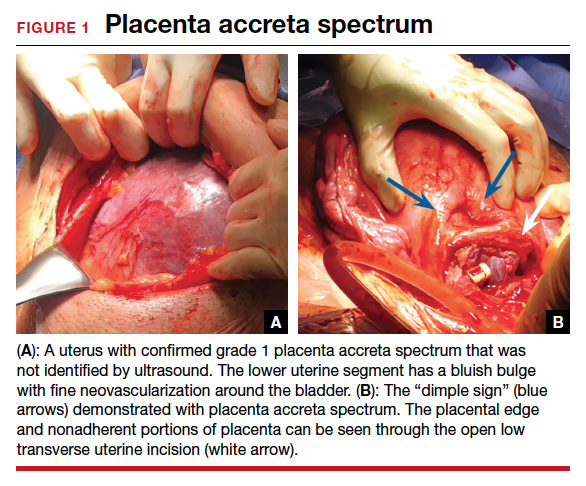

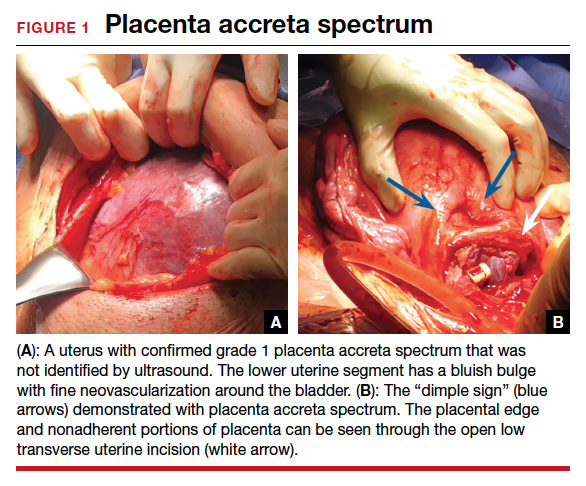

At cesarean delivery, the PAS diagnosis may be aided by visual cues. With placenta previa, the lower uterine segment may bulge and take on a bluish hue, distinctly different from the upper healthy myometrium. PAS may also manifest with neovascularization, particularly behind the bladder. As with vaginal births, the placenta will fail to separate after the delivery, and controlled traction on the umbilical cord can produce a “dimple sign,” or visible myometrial retraction at the site of implantation (FIGURE 1). Finally, if the diagnosis is still in doubt, attempts to gently form a cleavage plane between the placenta and myometrium will be unsuccessful if PAS is present.8

Step 2: Initial management—pause, plan

Most importantly, do not attempt to forcibly remove the placenta. It can be left attached to the uterus until appropriate resources are secured. Efforts to forcibly remove an adherent placenta may well lead to major hemorrhage, and thus it falls on the patient’s care team to pause and plan for PAS care at this point. FIGURE 2 displays an algorithm for patient management. Further steps depend primarily on whether or not the patient is already hemorrhaging. In a stable situation, the patient should be counseled regarding the abnormal findings and the suspected PAS diagnosis. This includes the possibility of further procedures, blood transfusion, and hysterectomy. Local resources, including nursing, anesthesia, and the blood bank, should be notified about the situation and for the potential to call in specialized services. If on-site experienced specialists are not available, then patient transfer to a PAS specialty center should be strongly considered. While awaiting additional help or transport, the patient requires close monitoring for gross and physiologic signs of hemorrhage. If pursued, transport to a PAS specialty center should be expedited.

If the patient is already hemorrhaging or unstable, then appropriate local resources must be activated. At a minimum, this requires an obstetrician and anesthesiologist at the bedside and activation of hemorrhage protocols (eg, a massive transfusion protocol). If blood products are unavailable, consider whether they can be transported from other nearby blood banks, and start that process promptly. Next, contact backup services. Based on local resources and clinical severity, this may include maternal-fetal medicine specialists, pelvic surgeons, general and trauma surgeons, intensivists, interventional radiologists, and transfusion specialists. Even if the patient cannot be safely transferred to another hospital, the obstetrician can call an outside PAS specialist to discuss next steps in care and begin transfer plans, assuming the patient can be stabilized. Based on the Maternal Levels of Care definitions published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine,10 patients with PAS should be managed at level III or level IV centers. However, delivery units at every level of maternal care should have a protocol for securing local help and reaching an appropriate consultant if a PAS case is encountered. Know which center in your area specializes in PAS so that when an unanticipated case arises, you know who to call.

Continue to: Step 3: Ultimate management—mobilize and prepare for bleeding...

Step 3: Ultimate management—mobilize and prepare for bleeding

If diagnosis occurs intraoperatively at a PAS specialty center, or if safe transport is not possible, then the team should mobilize for the possibility of hysterectomy and prepare for massive bleeding, which can occur regardless of the treatment chosen. Many patients require or will opt for hysterectomy. For example, a patient who has finished childbearing may consent to a hysterectomy upon hearing she likely has PAS. In patients with suspected PAS who are actively hemorrhaging or are unstable, hysterectomy is required.

Uterine conservation may be considered in stable patients who strongly desire future childbearing or uterine retention. This often requires leaving densely adherent placental tissue in situ and thus requires thorough counseling regarding the risks of delayed hemorrhage, infection, and emergent hysterectomy.11 This may not be desirable or safe for some patients, so informed consent is crucial. In such cases, we strongly recommend consultation with a PAS specialist, even if that requires immediate control of the placental blood supply (such as with arterial embolization), and transfer to a PAS specialty center.

Clinical scenarios

Vaginal delivery

The patient in the opening case was never expected to have PAS given her normal placental location and absence of a uterine scar. Even though she had some possible PAS risk factors (past retained placenta with instrumentation and in vitro fertilization), her absolute risk for the condition was low. Nevertheless, inability to create a separation plane should be considered PAS until proven otherwise. Although at this point many obstetricians would move to an operating room for uterine curettage, we recommend that the care team pause and put measures in place for possible PAS and hemorrhage. This involves notification of the blood bank, crossmatching of blood products, alerting the anesthesia team, and having a clear plan in place should a major hemorrhage ensue. This may involve use of balloon tamponade, activation of an interventional radiology team, or possible laparotomy with arterial ligations or hysterectomy. Avoidance of a prolonged third stage should be balanced against the need for preparation with these cases.

It is important for clinicians to bear in mind, and communicate to the patient, that hysterectomy is the standard of care for PAS. Significant delays in performing an indicated hysterectomy can lead to coagulopathy and patient instability. Timeliness is key; we find that delays in the decision to perform an indicated hysterectomy are often at the root of the cause for worsened morbidity in patients with unanticipated PAS. With an unscarred uterus and no placenta previa, a postpartum hysterectomy can be performed by many obstetrician-gynecologists experienced in this abdominal procedure.

Cesarean delivery

Undiagnosed PAS may present at cesarean delivery with or without placenta previa and a prior uterine scar. With this combination, PAS is often visually apparent upon opening the abdominal cavity (TABLE and FIGURE 1). Such surgical findings call for a clinical pause, as further actions at this point can lead to catastrophic hemorrhage. The obstetrician should consider a series of questions:

1. Are appropriate surgical and transfusion resources immediately available? If yes, they should be notified in case they are needed urgently. If not, then the obstetrician should ask whether the delivery must occur now.

2. Is this a scheduled delivery with a stable patient and fetus? If so, then closing the abdominal incision, monitoring the patient and fetus, and either transferring the patient to a PAS center or awaiting appropriate local specialists may be a lifesaving step.

3. Is immediate delivery required? If the fetus must be delivered, then it is imperative to create a hysterotomy out of the way of the placenta. Disrupting the adherent placenta with either an incision or manual manipulation may trigger a massive hemorrhage and should be avoided. This may require rectus muscle transection or creating a “T” incision on the skin to reach the uterine fundus and creating a hysterotomy over the top or even the back of the uterus. Once the fetus is delivered and lack of uterine hemorrhage confirmed (both abdominally and vaginally), the hysterotomy and abdomen can be closed with anticipation of urgent patient transfer to a PAS team or center.

4. Is the patient hemorrhaging? If the patient is hemorrhaging and closure is not an option, then recruitment of local emergent surgical teams is warranted, even if that requires packing the abdomen until an appropriate surgeon can arrive.

Diagnosis at cesarean delivery requires expedited and complex patient counseling. A patient who is unstable or hemorrhaging needs to be told that hysterectomy is lifesaving in this situation. For patients who are stable, it may be appropriate to close the abdomen and leave the placenta in situ, perform comprehensive counseling, and assess the possibility of transfer to a specialty center.

Summary

All obstetric care providers should be familiar with the clinical presentation of undiagnosed accreta spectrum. While hemorrhage is often part of the diagnosis, recognition of abnormal placental adherence and PAS-focused management should ideally be undertaken before this occurs. Once PAS is suspected, avoidance of further placental disruption may save significant morbidity, even if that means leaving the placenta attached until appropriate resources can be obtained. A local protocol for consultation, emergency transfer, and deployment of local resources should be part of every delivery unit’s emergency preparedness plan.

CASE Outcome

This patient is stabilized, with an adherent, retained placenta and no signs of hemorrhage. You administer uterotonics and notify your anesthesiologist and backup obstetrician that you have a likely case of accreta spectrum. A second intravenous line is placed, and blood products are crossmatched. The closest level III hospital is called, and they accept your patient for transfer. There, she is counseled about PAS, and she expresses no desire for future childbearing. After again confirming no placental separation in the operating room, the patient is moved immediately to perform laparotomy and total abdominal hysterectomy through a Pfannenstiel incision. She does not require a blood transfusion, and the pathology returns with grade I placenta accreta spectrum. ●

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 7: placenta accreta spectrum. Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 132:e259-e275. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002983.

- Carusi DA. The placenta accreta spectrum: epidemiology and risk factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61:733-742. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000391.

- Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:561-568. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.018.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Salmanian B, et al. Maternal morbidity in patients with morbidly adherent placenta treated with and without a standardized multidisciplinary approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:218.e1-9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.08.019.

- Bowman ZS, Eller AG, Kennedy AM, et al. Accuracy of ultrasound for the prediction of placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:177.e1-7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.029.

- Carusi DA, Fox KA, Lyell DJ, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum without placenta previa. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:458-465. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003970.

- Kayem G, Seco A, Beucher G, et al. Clinical profiles of placenta accreta spectrum: the PACCRETA population-based study. BJOG. 2021;128:1646-1655. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.16647.

- Jauniaux E, Ayres-de-Campos D, Langhoff-Roos J, et al. FIGO classification for the clinical diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;146:20-24. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12761.

- Collins SL, Alemdar B, van Beekhuizen HJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of abnormally invasive placenta: recommendations from the International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(6):511-526. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.054.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric care consensus. No. 7: placenta accreta spectrum. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e259-e275. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002983.

- Sentilhes L, Kayem G, Silver RM. Conservative management of placenta accreta spectrum. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 61(4):783-794. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000395.

CASE Placenta accreta spectrum following uncomplicated vaginal delivery

Imagine you are an obstetric hospitalist taking call at a level II maternal level of care hospital. Your patient is a 35-year-old woman, gravida 2, para 1, with a past history of retained placenta requiring dilation and curettage and intravenous antibiotics for endomyometritis. This is an in vitro fertilization pregnancy that has progressed normally, and the patient labored spontaneously at 38 weeks’ gestation. Following an uncomplicated vaginal delivery, the placenta has not delivered, and you attempt a manual placental extraction after a 40-minute third stage. While there is epidural analgesia and you can reach the uterine fundus, you are unable to create a separation plane between the placenta and uterus.

What do you do next?

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) includes a broad range of clinical scenarios with abnormal placental attachment as their common denominator. The condition has classically been defined pathologically, with chorionic villi attaching directly to the myometrium (“accreta”) or extending more deeply into the myometrium (“increta”) or attaching to surrounding tissues and structures (“percreta”).1 It is most commonly encountered in patients with low placental implantation on a prior cesarean section scar; indeed, placenta previa, particularly with a history of cesarean delivery, is the strongest risk factor for the development of PAS.2 In addition to abnormal placental attachment, these placental attachments are often hypervascular and can lead to catastrophic hemorrhage if not managed appropriately. For this reason, patients with sonographic or radiologic signs of PAS should be referred to specialized centers for further workup, counseling, and delivery planning.3

Although delivery at a specialized PAS center has been associated with improved patient outcomes,4 not all patients with PAS will be identified in the antepartum period. Ultrasonography may miss up to 40% to 50% of PAS cases, particularly when the sonologist has not been advised to look for the condition,5 and not all patients with PAS will have a previa implanted in a prior cesarean scar. A recent study found that these patients with nonprevia PAS were identified by imaging less than 40% of the time and were significantly less likely to be managed by a specialized team of clinicians.6 Thus, it falls upon every obstetric care provider to be aware of this diagnosis, promptly recognize its unanticipated presentations, and have a plan to optimize patient safety.

Step 1: Recognition

While PAS is classically defined as a pathologic condition, no clinician has the luxury of histology in the delivery room. Researchers have variously defined PAS clinically, with the common trait of abnormal placental adherence.7-9 The TABLE compares published definitions that have been used in the literature. While some definitions include hemorrhage, no clinician wants to induce significant hemorrhage to confirm their patient’s diagnosis. Thus, practically, the clinical PAS diagnosis comes down to abnormal placental attachment: If it is apparent that some or all of the placenta will not separate from the uterine wall with digital manipulation or careful curettage, then PAS should be suspected, and appropriate steps should be taken before further removal attempts.

At cesarean delivery, the PAS diagnosis may be aided by visual cues. With placenta previa, the lower uterine segment may bulge and take on a bluish hue, distinctly different from the upper healthy myometrium. PAS may also manifest with neovascularization, particularly behind the bladder. As with vaginal births, the placenta will fail to separate after the delivery, and controlled traction on the umbilical cord can produce a “dimple sign,” or visible myometrial retraction at the site of implantation (FIGURE 1). Finally, if the diagnosis is still in doubt, attempts to gently form a cleavage plane between the placenta and myometrium will be unsuccessful if PAS is present.8

Step 2: Initial management—pause, plan

Most importantly, do not attempt to forcibly remove the placenta. It can be left attached to the uterus until appropriate resources are secured. Efforts to forcibly remove an adherent placenta may well lead to major hemorrhage, and thus it falls on the patient’s care team to pause and plan for PAS care at this point. FIGURE 2 displays an algorithm for patient management. Further steps depend primarily on whether or not the patient is already hemorrhaging. In a stable situation, the patient should be counseled regarding the abnormal findings and the suspected PAS diagnosis. This includes the possibility of further procedures, blood transfusion, and hysterectomy. Local resources, including nursing, anesthesia, and the blood bank, should be notified about the situation and for the potential to call in specialized services. If on-site experienced specialists are not available, then patient transfer to a PAS specialty center should be strongly considered. While awaiting additional help or transport, the patient requires close monitoring for gross and physiologic signs of hemorrhage. If pursued, transport to a PAS specialty center should be expedited.

If the patient is already hemorrhaging or unstable, then appropriate local resources must be activated. At a minimum, this requires an obstetrician and anesthesiologist at the bedside and activation of hemorrhage protocols (eg, a massive transfusion protocol). If blood products are unavailable, consider whether they can be transported from other nearby blood banks, and start that process promptly. Next, contact backup services. Based on local resources and clinical severity, this may include maternal-fetal medicine specialists, pelvic surgeons, general and trauma surgeons, intensivists, interventional radiologists, and transfusion specialists. Even if the patient cannot be safely transferred to another hospital, the obstetrician can call an outside PAS specialist to discuss next steps in care and begin transfer plans, assuming the patient can be stabilized. Based on the Maternal Levels of Care definitions published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine,10 patients with PAS should be managed at level III or level IV centers. However, delivery units at every level of maternal care should have a protocol for securing local help and reaching an appropriate consultant if a PAS case is encountered. Know which center in your area specializes in PAS so that when an unanticipated case arises, you know who to call.

Continue to: Step 3: Ultimate management—mobilize and prepare for bleeding...

Step 3: Ultimate management—mobilize and prepare for bleeding

If diagnosis occurs intraoperatively at a PAS specialty center, or if safe transport is not possible, then the team should mobilize for the possibility of hysterectomy and prepare for massive bleeding, which can occur regardless of the treatment chosen. Many patients require or will opt for hysterectomy. For example, a patient who has finished childbearing may consent to a hysterectomy upon hearing she likely has PAS. In patients with suspected PAS who are actively hemorrhaging or are unstable, hysterectomy is required.

Uterine conservation may be considered in stable patients who strongly desire future childbearing or uterine retention. This often requires leaving densely adherent placental tissue in situ and thus requires thorough counseling regarding the risks of delayed hemorrhage, infection, and emergent hysterectomy.11 This may not be desirable or safe for some patients, so informed consent is crucial. In such cases, we strongly recommend consultation with a PAS specialist, even if that requires immediate control of the placental blood supply (such as with arterial embolization), and transfer to a PAS specialty center.

Clinical scenarios

Vaginal delivery

The patient in the opening case was never expected to have PAS given her normal placental location and absence of a uterine scar. Even though she had some possible PAS risk factors (past retained placenta with instrumentation and in vitro fertilization), her absolute risk for the condition was low. Nevertheless, inability to create a separation plane should be considered PAS until proven otherwise. Although at this point many obstetricians would move to an operating room for uterine curettage, we recommend that the care team pause and put measures in place for possible PAS and hemorrhage. This involves notification of the blood bank, crossmatching of blood products, alerting the anesthesia team, and having a clear plan in place should a major hemorrhage ensue. This may involve use of balloon tamponade, activation of an interventional radiology team, or possible laparotomy with arterial ligations or hysterectomy. Avoidance of a prolonged third stage should be balanced against the need for preparation with these cases.

It is important for clinicians to bear in mind, and communicate to the patient, that hysterectomy is the standard of care for PAS. Significant delays in performing an indicated hysterectomy can lead to coagulopathy and patient instability. Timeliness is key; we find that delays in the decision to perform an indicated hysterectomy are often at the root of the cause for worsened morbidity in patients with unanticipated PAS. With an unscarred uterus and no placenta previa, a postpartum hysterectomy can be performed by many obstetrician-gynecologists experienced in this abdominal procedure.

Cesarean delivery

Undiagnosed PAS may present at cesarean delivery with or without placenta previa and a prior uterine scar. With this combination, PAS is often visually apparent upon opening the abdominal cavity (TABLE and FIGURE 1). Such surgical findings call for a clinical pause, as further actions at this point can lead to catastrophic hemorrhage. The obstetrician should consider a series of questions:

1. Are appropriate surgical and transfusion resources immediately available? If yes, they should be notified in case they are needed urgently. If not, then the obstetrician should ask whether the delivery must occur now.

2. Is this a scheduled delivery with a stable patient and fetus? If so, then closing the abdominal incision, monitoring the patient and fetus, and either transferring the patient to a PAS center or awaiting appropriate local specialists may be a lifesaving step.

3. Is immediate delivery required? If the fetus must be delivered, then it is imperative to create a hysterotomy out of the way of the placenta. Disrupting the adherent placenta with either an incision or manual manipulation may trigger a massive hemorrhage and should be avoided. This may require rectus muscle transection or creating a “T” incision on the skin to reach the uterine fundus and creating a hysterotomy over the top or even the back of the uterus. Once the fetus is delivered and lack of uterine hemorrhage confirmed (both abdominally and vaginally), the hysterotomy and abdomen can be closed with anticipation of urgent patient transfer to a PAS team or center.

4. Is the patient hemorrhaging? If the patient is hemorrhaging and closure is not an option, then recruitment of local emergent surgical teams is warranted, even if that requires packing the abdomen until an appropriate surgeon can arrive.

Diagnosis at cesarean delivery requires expedited and complex patient counseling. A patient who is unstable or hemorrhaging needs to be told that hysterectomy is lifesaving in this situation. For patients who are stable, it may be appropriate to close the abdomen and leave the placenta in situ, perform comprehensive counseling, and assess the possibility of transfer to a specialty center.

Summary

All obstetric care providers should be familiar with the clinical presentation of undiagnosed accreta spectrum. While hemorrhage is often part of the diagnosis, recognition of abnormal placental adherence and PAS-focused management should ideally be undertaken before this occurs. Once PAS is suspected, avoidance of further placental disruption may save significant morbidity, even if that means leaving the placenta attached until appropriate resources can be obtained. A local protocol for consultation, emergency transfer, and deployment of local resources should be part of every delivery unit’s emergency preparedness plan.

CASE Outcome

This patient is stabilized, with an adherent, retained placenta and no signs of hemorrhage. You administer uterotonics and notify your anesthesiologist and backup obstetrician that you have a likely case of accreta spectrum. A second intravenous line is placed, and blood products are crossmatched. The closest level III hospital is called, and they accept your patient for transfer. There, she is counseled about PAS, and she expresses no desire for future childbearing. After again confirming no placental separation in the operating room, the patient is moved immediately to perform laparotomy and total abdominal hysterectomy through a Pfannenstiel incision. She does not require a blood transfusion, and the pathology returns with grade I placenta accreta spectrum. ●

CASE Placenta accreta spectrum following uncomplicated vaginal delivery

Imagine you are an obstetric hospitalist taking call at a level II maternal level of care hospital. Your patient is a 35-year-old woman, gravida 2, para 1, with a past history of retained placenta requiring dilation and curettage and intravenous antibiotics for endomyometritis. This is an in vitro fertilization pregnancy that has progressed normally, and the patient labored spontaneously at 38 weeks’ gestation. Following an uncomplicated vaginal delivery, the placenta has not delivered, and you attempt a manual placental extraction after a 40-minute third stage. While there is epidural analgesia and you can reach the uterine fundus, you are unable to create a separation plane between the placenta and uterus.

What do you do next?

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) includes a broad range of clinical scenarios with abnormal placental attachment as their common denominator. The condition has classically been defined pathologically, with chorionic villi attaching directly to the myometrium (“accreta”) or extending more deeply into the myometrium (“increta”) or attaching to surrounding tissues and structures (“percreta”).1 It is most commonly encountered in patients with low placental implantation on a prior cesarean section scar; indeed, placenta previa, particularly with a history of cesarean delivery, is the strongest risk factor for the development of PAS.2 In addition to abnormal placental attachment, these placental attachments are often hypervascular and can lead to catastrophic hemorrhage if not managed appropriately. For this reason, patients with sonographic or radiologic signs of PAS should be referred to specialized centers for further workup, counseling, and delivery planning.3

Although delivery at a specialized PAS center has been associated with improved patient outcomes,4 not all patients with PAS will be identified in the antepartum period. Ultrasonography may miss up to 40% to 50% of PAS cases, particularly when the sonologist has not been advised to look for the condition,5 and not all patients with PAS will have a previa implanted in a prior cesarean scar. A recent study found that these patients with nonprevia PAS were identified by imaging less than 40% of the time and were significantly less likely to be managed by a specialized team of clinicians.6 Thus, it falls upon every obstetric care provider to be aware of this diagnosis, promptly recognize its unanticipated presentations, and have a plan to optimize patient safety.

Step 1: Recognition

While PAS is classically defined as a pathologic condition, no clinician has the luxury of histology in the delivery room. Researchers have variously defined PAS clinically, with the common trait of abnormal placental adherence.7-9 The TABLE compares published definitions that have been used in the literature. While some definitions include hemorrhage, no clinician wants to induce significant hemorrhage to confirm their patient’s diagnosis. Thus, practically, the clinical PAS diagnosis comes down to abnormal placental attachment: If it is apparent that some or all of the placenta will not separate from the uterine wall with digital manipulation or careful curettage, then PAS should be suspected, and appropriate steps should be taken before further removal attempts.

At cesarean delivery, the PAS diagnosis may be aided by visual cues. With placenta previa, the lower uterine segment may bulge and take on a bluish hue, distinctly different from the upper healthy myometrium. PAS may also manifest with neovascularization, particularly behind the bladder. As with vaginal births, the placenta will fail to separate after the delivery, and controlled traction on the umbilical cord can produce a “dimple sign,” or visible myometrial retraction at the site of implantation (FIGURE 1). Finally, if the diagnosis is still in doubt, attempts to gently form a cleavage plane between the placenta and myometrium will be unsuccessful if PAS is present.8

Step 2: Initial management—pause, plan

Most importantly, do not attempt to forcibly remove the placenta. It can be left attached to the uterus until appropriate resources are secured. Efforts to forcibly remove an adherent placenta may well lead to major hemorrhage, and thus it falls on the patient’s care team to pause and plan for PAS care at this point. FIGURE 2 displays an algorithm for patient management. Further steps depend primarily on whether or not the patient is already hemorrhaging. In a stable situation, the patient should be counseled regarding the abnormal findings and the suspected PAS diagnosis. This includes the possibility of further procedures, blood transfusion, and hysterectomy. Local resources, including nursing, anesthesia, and the blood bank, should be notified about the situation and for the potential to call in specialized services. If on-site experienced specialists are not available, then patient transfer to a PAS specialty center should be strongly considered. While awaiting additional help or transport, the patient requires close monitoring for gross and physiologic signs of hemorrhage. If pursued, transport to a PAS specialty center should be expedited.

If the patient is already hemorrhaging or unstable, then appropriate local resources must be activated. At a minimum, this requires an obstetrician and anesthesiologist at the bedside and activation of hemorrhage protocols (eg, a massive transfusion protocol). If blood products are unavailable, consider whether they can be transported from other nearby blood banks, and start that process promptly. Next, contact backup services. Based on local resources and clinical severity, this may include maternal-fetal medicine specialists, pelvic surgeons, general and trauma surgeons, intensivists, interventional radiologists, and transfusion specialists. Even if the patient cannot be safely transferred to another hospital, the obstetrician can call an outside PAS specialist to discuss next steps in care and begin transfer plans, assuming the patient can be stabilized. Based on the Maternal Levels of Care definitions published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine,10 patients with PAS should be managed at level III or level IV centers. However, delivery units at every level of maternal care should have a protocol for securing local help and reaching an appropriate consultant if a PAS case is encountered. Know which center in your area specializes in PAS so that when an unanticipated case arises, you know who to call.

Continue to: Step 3: Ultimate management—mobilize and prepare for bleeding...

Step 3: Ultimate management—mobilize and prepare for bleeding

If diagnosis occurs intraoperatively at a PAS specialty center, or if safe transport is not possible, then the team should mobilize for the possibility of hysterectomy and prepare for massive bleeding, which can occur regardless of the treatment chosen. Many patients require or will opt for hysterectomy. For example, a patient who has finished childbearing may consent to a hysterectomy upon hearing she likely has PAS. In patients with suspected PAS who are actively hemorrhaging or are unstable, hysterectomy is required.

Uterine conservation may be considered in stable patients who strongly desire future childbearing or uterine retention. This often requires leaving densely adherent placental tissue in situ and thus requires thorough counseling regarding the risks of delayed hemorrhage, infection, and emergent hysterectomy.11 This may not be desirable or safe for some patients, so informed consent is crucial. In such cases, we strongly recommend consultation with a PAS specialist, even if that requires immediate control of the placental blood supply (such as with arterial embolization), and transfer to a PAS specialty center.

Clinical scenarios

Vaginal delivery