User login

Children having an anaphylactic attack at school may not get proper treatment

Children experiencing an anaphylactic event at school may frequently encounter staff members who are not permitted to administer potentially life-saving epinephrine, according to recent survey study.

Of 6,574 surveys submitted by schools, there were 1,140 anaphylactic events reported in 736 schools.

A total of 6,088 schools provided data on staff training for recognizing anaphylaxis recognition: 30% provided training for all staff, 28% for most staff, 37% for the school nurse and select staff, and 2% for just the school nurse. Of 6,053 schools providing data on who is permitted to administer epinephrine to treat anaphylaxis, 22% permitted all staff, 16% permitted most staff, 55% permitted the school nurse and select trained staff, and 3% permitted the school nurse only, reported Martha V. White, MD, Institute for Asthma and Allergy, Wheaton, Md., and her associates (Pediatr Allerg Immunol Pulmonol. 2016. doi: 10.1089/ped.2016.0675).

These findings “suggest that there may be an opportunity to improve school staff training programs. Only 58.6% of schools surveyed trained all or most staff members to recognize the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis. Similarly,only 37% of responding schools permitted all or most staff to administer epinephrine. ... School policies should be designed to allow for prompt administration of epinephrine during the early stages of an anaphylactic attack,” Dr. White and her associates concluded.

Among students having events for whom grade information was available, 33% occurred in elementary school students, 19% occurred in middle school students, and 45% occurred in high school students. In 1,049 anaphylactic events, the allergy history was known: 68% of events occurred in students with known allergies and 25% were in students with no known allergies.

When triggers were identified (in 78% of cases), food was the most common trigger, occurring in 60%, followed by insect bites or stings in 8%; environmental, medication, or health related triggers in 9%; and latex in 1%.

Data on use of epinephrine autoinjectors (EAIs) was available in 1,059 cases. EAIs were administered in 76% of anaphylactic events, were not administered in 23% cases, and it was unknown whether EAIs were given in the remaining 1%.

This study was supported by Mylan Specialty. Dr. White has served as a consultant for Mylan and Merck, and has received grants, fees, or support from numerous pharmaceutical companies. Christopher Herrem, PhD, is a paid employee of Mylan and may hold stock within the company. The remaining authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Children experiencing an anaphylactic event at school may frequently encounter staff members who are not permitted to administer potentially life-saving epinephrine, according to recent survey study.

Of 6,574 surveys submitted by schools, there were 1,140 anaphylactic events reported in 736 schools.

A total of 6,088 schools provided data on staff training for recognizing anaphylaxis recognition: 30% provided training for all staff, 28% for most staff, 37% for the school nurse and select staff, and 2% for just the school nurse. Of 6,053 schools providing data on who is permitted to administer epinephrine to treat anaphylaxis, 22% permitted all staff, 16% permitted most staff, 55% permitted the school nurse and select trained staff, and 3% permitted the school nurse only, reported Martha V. White, MD, Institute for Asthma and Allergy, Wheaton, Md., and her associates (Pediatr Allerg Immunol Pulmonol. 2016. doi: 10.1089/ped.2016.0675).

These findings “suggest that there may be an opportunity to improve school staff training programs. Only 58.6% of schools surveyed trained all or most staff members to recognize the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis. Similarly,only 37% of responding schools permitted all or most staff to administer epinephrine. ... School policies should be designed to allow for prompt administration of epinephrine during the early stages of an anaphylactic attack,” Dr. White and her associates concluded.

Among students having events for whom grade information was available, 33% occurred in elementary school students, 19% occurred in middle school students, and 45% occurred in high school students. In 1,049 anaphylactic events, the allergy history was known: 68% of events occurred in students with known allergies and 25% were in students with no known allergies.

When triggers were identified (in 78% of cases), food was the most common trigger, occurring in 60%, followed by insect bites or stings in 8%; environmental, medication, or health related triggers in 9%; and latex in 1%.

Data on use of epinephrine autoinjectors (EAIs) was available in 1,059 cases. EAIs were administered in 76% of anaphylactic events, were not administered in 23% cases, and it was unknown whether EAIs were given in the remaining 1%.

This study was supported by Mylan Specialty. Dr. White has served as a consultant for Mylan and Merck, and has received grants, fees, or support from numerous pharmaceutical companies. Christopher Herrem, PhD, is a paid employee of Mylan and may hold stock within the company. The remaining authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Children experiencing an anaphylactic event at school may frequently encounter staff members who are not permitted to administer potentially life-saving epinephrine, according to recent survey study.

Of 6,574 surveys submitted by schools, there were 1,140 anaphylactic events reported in 736 schools.

A total of 6,088 schools provided data on staff training for recognizing anaphylaxis recognition: 30% provided training for all staff, 28% for most staff, 37% for the school nurse and select staff, and 2% for just the school nurse. Of 6,053 schools providing data on who is permitted to administer epinephrine to treat anaphylaxis, 22% permitted all staff, 16% permitted most staff, 55% permitted the school nurse and select trained staff, and 3% permitted the school nurse only, reported Martha V. White, MD, Institute for Asthma and Allergy, Wheaton, Md., and her associates (Pediatr Allerg Immunol Pulmonol. 2016. doi: 10.1089/ped.2016.0675).

These findings “suggest that there may be an opportunity to improve school staff training programs. Only 58.6% of schools surveyed trained all or most staff members to recognize the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis. Similarly,only 37% of responding schools permitted all or most staff to administer epinephrine. ... School policies should be designed to allow for prompt administration of epinephrine during the early stages of an anaphylactic attack,” Dr. White and her associates concluded.

Among students having events for whom grade information was available, 33% occurred in elementary school students, 19% occurred in middle school students, and 45% occurred in high school students. In 1,049 anaphylactic events, the allergy history was known: 68% of events occurred in students with known allergies and 25% were in students with no known allergies.

When triggers were identified (in 78% of cases), food was the most common trigger, occurring in 60%, followed by insect bites or stings in 8%; environmental, medication, or health related triggers in 9%; and latex in 1%.

Data on use of epinephrine autoinjectors (EAIs) was available in 1,059 cases. EAIs were administered in 76% of anaphylactic events, were not administered in 23% cases, and it was unknown whether EAIs were given in the remaining 1%.

This study was supported by Mylan Specialty. Dr. White has served as a consultant for Mylan and Merck, and has received grants, fees, or support from numerous pharmaceutical companies. Christopher Herrem, PhD, is a paid employee of Mylan and may hold stock within the company. The remaining authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM PEDIATRIC ALLERGY, IMMUNOLOGY, AND PULMONOLOGY

Key clinical point: School staff members are often not allowed to administer potentially life-saving epinephrine to children having an anaphylactic event.

Major finding: Of 6,053 schools providing data on who is permitted to administer epinephrine to treat anaphylaxis, 22% permitted all staff, 16% permitted most staff, 55% permitted the school nurse and select trained staff, and 3% permitted the school nurse only.

Data source: A survey of 6,574 schools.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Mylan Specialty. Dr. White has served as a consultant for Mylan and Merck and has received grants, fees, or support from numerous pharmaceutical companies. Christopher Herrem, PhD, is a paid employee of Mylan and may hold stock within the company. The remaining authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

New-onset pediatric AD phenotype differs from adult AD

The skin phenotype of new-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis differs substantially from that in adult AD, according to an assessment of biopsy findings in infants and children.

The study findings have important therapeutic implications, especially in light of the fact that much of the work in this area has been based on adult biomarkers, reflecting “decades of disease activity and chronic use of immunosuppressants in adults,” the investigators reported. Little is known about alterations in early lesions in children, which limits the advancement of targeted therapies, Hitokazu Esaki, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, and colleagues reported online in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (2016 Sep 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.013).

To characterize early pediatric AD skin phenotype, the investigators assessed lesional and nonlesional biopsies from 19 children under age 5 years (mean, 1.3 years) within 6 months of moderate to severe disease onset, as well as those from age-matched controls and adults, and found that, compared with adult AD, early AD involves comparable or greater epidermal hyperplasia and cellular infiltration, similar strong activation of Th2 and Th22 axes, and some Th1 skewing.

In addition, early AD involves significantly higher induction of Th17-related cytokines, compared with adult AD. Expression of filaggrin – an abundant barrier differentiation protein – was similar in AD and healthy children, whereas down-regulation is characteristic in adult AD, the investigators noted.

Nonlesional skin biopsies from the children showed both higher levels of inflammation and epidermal proliferation markers, they said.

The “surprising findings” of an early multicytokine response in new-onset pediatric AD, characterized by marked Th17, Th9, Th2, and Th22 activation, suggest that targeting of multiple cytokine axes may be needed in children with early-onset AD, one of the lead authors on the study, Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, also of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said in an interview.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky, who noted that the study was conducted in close collaboration with Amy S. Paller, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, explained that early AD, compared with adult AD, involves differential immune skewing and barrier responses with features that are in some ways comparable to those of psoriasis – particularly with respect to the consistently higher levels of Th17-related mediators in childhood AD, as psoriasis is considered a Th17-centered disease.

Further, the findings with respect to filaggrin represent another important aspect of the study, she said, noting that they represent a possible challenge to the notion that filaggrin is integral to disease elicitation and instigation of the “atopic march.”

The study findings may suggest novel targets for pediatric AD, and they also suggest a need for early immune intervention, not only to treat the AD, but also to prevent the atopic march, she said.

“These findings are likely to result in both different understanding of AD onset and distinct treatment approaches for infants and children,” she and her colleagues concluded.

This work was funded by a research grant from the LEO Foundation. Individual authors were supported by grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award program. Dr. Esaki reported having no disclosures. Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common chronic inflammatory skin disease. Severe AD places a huge burden on patients, their families, and society in terms of health care dollars spent and lost work days. Considering the prevalence of AD, both families and dermatologists find it understandably frustrating that we have limited and often ineffective tools to treat severe AD in children. Change may be around the corner.

This study by Esaki et al. sheds critical light on the pathogenesis of early onset AD in children and we hope it will set the stage to revolutionize the treatment of AD using the paradigm of psoriasis as a model. Using lesional and nonlesional biopsies from 19 children under age 5 obtained during the first 6 months of onset of AD, Esaki et al. have demonstrated that children with AD have a multicytokine inflammatory infiltrate with Th17 predominance. This sets the stage for biologics focused on the Th17 pathway in these children, although multimodal therapy to address different cytokines may ultimately be required.

The investigators also found that children with AD had similar filaggrin expression compared to control children, implying that atopic dermatitis is at its heart an immunologic disorder rather than a barrier defect although we will likely continue to learn more about this fine balance.

As pediatric dermatologists on the front line caring for patients with severe AD, we welcome further studies and especially look forward to effective treatments for our patients who might finally experience relief of itch, clear skin, and a good night’s sleep.

A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, and Kalyani Marathe, MD, are pediatric dermatologists at Children’s National Health System, in the departments of dermatology and pediatrics at George Washington University, Washington, DC. They are on the editorial advisory board of Dermatology News. They had no disclosures.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common chronic inflammatory skin disease. Severe AD places a huge burden on patients, their families, and society in terms of health care dollars spent and lost work days. Considering the prevalence of AD, both families and dermatologists find it understandably frustrating that we have limited and often ineffective tools to treat severe AD in children. Change may be around the corner.

This study by Esaki et al. sheds critical light on the pathogenesis of early onset AD in children and we hope it will set the stage to revolutionize the treatment of AD using the paradigm of psoriasis as a model. Using lesional and nonlesional biopsies from 19 children under age 5 obtained during the first 6 months of onset of AD, Esaki et al. have demonstrated that children with AD have a multicytokine inflammatory infiltrate with Th17 predominance. This sets the stage for biologics focused on the Th17 pathway in these children, although multimodal therapy to address different cytokines may ultimately be required.

The investigators also found that children with AD had similar filaggrin expression compared to control children, implying that atopic dermatitis is at its heart an immunologic disorder rather than a barrier defect although we will likely continue to learn more about this fine balance.

As pediatric dermatologists on the front line caring for patients with severe AD, we welcome further studies and especially look forward to effective treatments for our patients who might finally experience relief of itch, clear skin, and a good night’s sleep.

A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, and Kalyani Marathe, MD, are pediatric dermatologists at Children’s National Health System, in the departments of dermatology and pediatrics at George Washington University, Washington, DC. They are on the editorial advisory board of Dermatology News. They had no disclosures.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common chronic inflammatory skin disease. Severe AD places a huge burden on patients, their families, and society in terms of health care dollars spent and lost work days. Considering the prevalence of AD, both families and dermatologists find it understandably frustrating that we have limited and often ineffective tools to treat severe AD in children. Change may be around the corner.

This study by Esaki et al. sheds critical light on the pathogenesis of early onset AD in children and we hope it will set the stage to revolutionize the treatment of AD using the paradigm of psoriasis as a model. Using lesional and nonlesional biopsies from 19 children under age 5 obtained during the first 6 months of onset of AD, Esaki et al. have demonstrated that children with AD have a multicytokine inflammatory infiltrate with Th17 predominance. This sets the stage for biologics focused on the Th17 pathway in these children, although multimodal therapy to address different cytokines may ultimately be required.

The investigators also found that children with AD had similar filaggrin expression compared to control children, implying that atopic dermatitis is at its heart an immunologic disorder rather than a barrier defect although we will likely continue to learn more about this fine balance.

As pediatric dermatologists on the front line caring for patients with severe AD, we welcome further studies and especially look forward to effective treatments for our patients who might finally experience relief of itch, clear skin, and a good night’s sleep.

A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, and Kalyani Marathe, MD, are pediatric dermatologists at Children’s National Health System, in the departments of dermatology and pediatrics at George Washington University, Washington, DC. They are on the editorial advisory board of Dermatology News. They had no disclosures.

The skin phenotype of new-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis differs substantially from that in adult AD, according to an assessment of biopsy findings in infants and children.

The study findings have important therapeutic implications, especially in light of the fact that much of the work in this area has been based on adult biomarkers, reflecting “decades of disease activity and chronic use of immunosuppressants in adults,” the investigators reported. Little is known about alterations in early lesions in children, which limits the advancement of targeted therapies, Hitokazu Esaki, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, and colleagues reported online in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (2016 Sep 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.013).

To characterize early pediatric AD skin phenotype, the investigators assessed lesional and nonlesional biopsies from 19 children under age 5 years (mean, 1.3 years) within 6 months of moderate to severe disease onset, as well as those from age-matched controls and adults, and found that, compared with adult AD, early AD involves comparable or greater epidermal hyperplasia and cellular infiltration, similar strong activation of Th2 and Th22 axes, and some Th1 skewing.

In addition, early AD involves significantly higher induction of Th17-related cytokines, compared with adult AD. Expression of filaggrin – an abundant barrier differentiation protein – was similar in AD and healthy children, whereas down-regulation is characteristic in adult AD, the investigators noted.

Nonlesional skin biopsies from the children showed both higher levels of inflammation and epidermal proliferation markers, they said.

The “surprising findings” of an early multicytokine response in new-onset pediatric AD, characterized by marked Th17, Th9, Th2, and Th22 activation, suggest that targeting of multiple cytokine axes may be needed in children with early-onset AD, one of the lead authors on the study, Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, also of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said in an interview.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky, who noted that the study was conducted in close collaboration with Amy S. Paller, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, explained that early AD, compared with adult AD, involves differential immune skewing and barrier responses with features that are in some ways comparable to those of psoriasis – particularly with respect to the consistently higher levels of Th17-related mediators in childhood AD, as psoriasis is considered a Th17-centered disease.

Further, the findings with respect to filaggrin represent another important aspect of the study, she said, noting that they represent a possible challenge to the notion that filaggrin is integral to disease elicitation and instigation of the “atopic march.”

The study findings may suggest novel targets for pediatric AD, and they also suggest a need for early immune intervention, not only to treat the AD, but also to prevent the atopic march, she said.

“These findings are likely to result in both different understanding of AD onset and distinct treatment approaches for infants and children,” she and her colleagues concluded.

This work was funded by a research grant from the LEO Foundation. Individual authors were supported by grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award program. Dr. Esaki reported having no disclosures. Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

The skin phenotype of new-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis differs substantially from that in adult AD, according to an assessment of biopsy findings in infants and children.

The study findings have important therapeutic implications, especially in light of the fact that much of the work in this area has been based on adult biomarkers, reflecting “decades of disease activity and chronic use of immunosuppressants in adults,” the investigators reported. Little is known about alterations in early lesions in children, which limits the advancement of targeted therapies, Hitokazu Esaki, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, and colleagues reported online in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (2016 Sep 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.013).

To characterize early pediatric AD skin phenotype, the investigators assessed lesional and nonlesional biopsies from 19 children under age 5 years (mean, 1.3 years) within 6 months of moderate to severe disease onset, as well as those from age-matched controls and adults, and found that, compared with adult AD, early AD involves comparable or greater epidermal hyperplasia and cellular infiltration, similar strong activation of Th2 and Th22 axes, and some Th1 skewing.

In addition, early AD involves significantly higher induction of Th17-related cytokines, compared with adult AD. Expression of filaggrin – an abundant barrier differentiation protein – was similar in AD and healthy children, whereas down-regulation is characteristic in adult AD, the investigators noted.

Nonlesional skin biopsies from the children showed both higher levels of inflammation and epidermal proliferation markers, they said.

The “surprising findings” of an early multicytokine response in new-onset pediatric AD, characterized by marked Th17, Th9, Th2, and Th22 activation, suggest that targeting of multiple cytokine axes may be needed in children with early-onset AD, one of the lead authors on the study, Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, also of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said in an interview.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky, who noted that the study was conducted in close collaboration with Amy S. Paller, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, explained that early AD, compared with adult AD, involves differential immune skewing and barrier responses with features that are in some ways comparable to those of psoriasis – particularly with respect to the consistently higher levels of Th17-related mediators in childhood AD, as psoriasis is considered a Th17-centered disease.

Further, the findings with respect to filaggrin represent another important aspect of the study, she said, noting that they represent a possible challenge to the notion that filaggrin is integral to disease elicitation and instigation of the “atopic march.”

The study findings may suggest novel targets for pediatric AD, and they also suggest a need for early immune intervention, not only to treat the AD, but also to prevent the atopic march, she said.

“These findings are likely to result in both different understanding of AD onset and distinct treatment approaches for infants and children,” she and her colleagues concluded.

This work was funded by a research grant from the LEO Foundation. Individual authors were supported by grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award program. Dr. Esaki reported having no disclosures. Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY

Key clinical point: The skin phenotype of new-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis differs substantially from that in adult AD, which has important therapeutic implications, according to a study of biopsy findings in infants and children.

Major finding: Early AD involves significantly higher induction of Th17-related cytokines, compared with adult AD.

Data source: An analysis of biopsies from 19 children with AD.

Disclosures: This work was funded by a research grant from the LEO Foundation. Individual authors were supported by grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award program. Dr. Esaki reported having no disclosures. Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

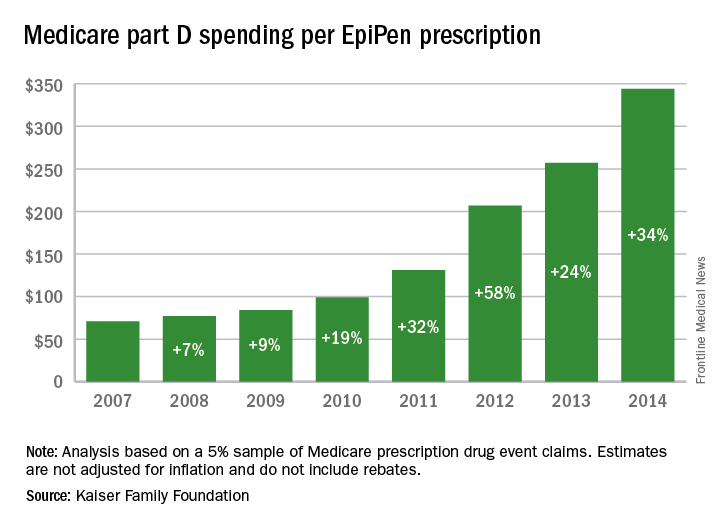

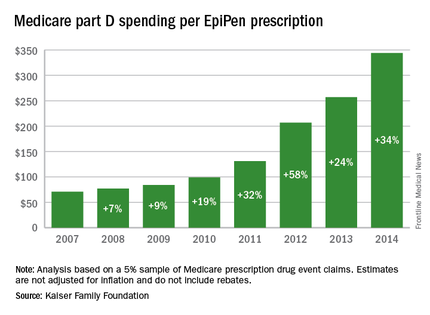

EpiPen cost increases far exceed overall medical inflation

Total Medicare part D spending on EpiPen auto-injectors rose from $7.0 million in 2007 to $87.9 million in 2014 – an increase of 1,151%, according to an analysis released Sept. 20 by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The number of EpiPen users also increased over that time, however, bringing with it a commensurate 159% rise in the number of prescriptions. Those two trends took the average cost of a single EpiPen prescription from $71 in 2007 to $344 in 2014, the Kaiser analysis showed.

That increase in cost per prescription did not fail to at least double overall medical care price inflation for each year from 2008 to 2014. In 2008, when the two trends were closest together, the EpiPen cost per prescription rose 7.4% from the year before, compared with 3.7% for overall medical spending. In 2014, Medicare part D’s cost for an EpiPen prescription rose 34% from the year before, which was 14 times higher than the 2.4% increase in total medical spending, Kaiser noted.

The analysis was based on a 5% sample of Medicare prescription drug event claims and included beneficiaries who had a least 1 month of part D coverage and one EpiPen prescription during the year. Estimates are not adjusted for inflation and do not include any possible manufacturer discounts, Kaiser said.

Total Medicare part D spending on EpiPen auto-injectors rose from $7.0 million in 2007 to $87.9 million in 2014 – an increase of 1,151%, according to an analysis released Sept. 20 by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The number of EpiPen users also increased over that time, however, bringing with it a commensurate 159% rise in the number of prescriptions. Those two trends took the average cost of a single EpiPen prescription from $71 in 2007 to $344 in 2014, the Kaiser analysis showed.

That increase in cost per prescription did not fail to at least double overall medical care price inflation for each year from 2008 to 2014. In 2008, when the two trends were closest together, the EpiPen cost per prescription rose 7.4% from the year before, compared with 3.7% for overall medical spending. In 2014, Medicare part D’s cost for an EpiPen prescription rose 34% from the year before, which was 14 times higher than the 2.4% increase in total medical spending, Kaiser noted.

The analysis was based on a 5% sample of Medicare prescription drug event claims and included beneficiaries who had a least 1 month of part D coverage and one EpiPen prescription during the year. Estimates are not adjusted for inflation and do not include any possible manufacturer discounts, Kaiser said.

Total Medicare part D spending on EpiPen auto-injectors rose from $7.0 million in 2007 to $87.9 million in 2014 – an increase of 1,151%, according to an analysis released Sept. 20 by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The number of EpiPen users also increased over that time, however, bringing with it a commensurate 159% rise in the number of prescriptions. Those two trends took the average cost of a single EpiPen prescription from $71 in 2007 to $344 in 2014, the Kaiser analysis showed.

That increase in cost per prescription did not fail to at least double overall medical care price inflation for each year from 2008 to 2014. In 2008, when the two trends were closest together, the EpiPen cost per prescription rose 7.4% from the year before, compared with 3.7% for overall medical spending. In 2014, Medicare part D’s cost for an EpiPen prescription rose 34% from the year before, which was 14 times higher than the 2.4% increase in total medical spending, Kaiser noted.

The analysis was based on a 5% sample of Medicare prescription drug event claims and included beneficiaries who had a least 1 month of part D coverage and one EpiPen prescription during the year. Estimates are not adjusted for inflation and do not include any possible manufacturer discounts, Kaiser said.

ACOS definitions under fire

LONDON – A study comparing patient data with six definitions of the Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS) found only one of the patients analyzed met all definitions. This provoked an animated discussion at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society about the utility of ACOS as a clinical entity.

Of 864 patients diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma drawn from the Netherlands Epidemiology of Obesity cohort (a population-based study with 5,784 patients), 39.1% (338 patients) met at least one of the definitions of ACOS, while 0.1% (one patient) met the criteria for all six definitions.

When this finding was presented, the ERS audience first laughed and then applauded. At the end of the presentation, long lines formed at the microphones. Every comment made was hostile to the concept of ACOS.

“Let us bring ACOS to an honorable death,” said one audience member. His point, reiterated by all who commented subsequently, was that ACOS confuses efforts to treat the underlying respiratory symptoms. Even in those who have both asthma and COPD, the speaker, like other members of the audience, said he considered the diagnosis of ACOS unhelpful.

The six definitions in the study included the latest and just published consensus definition from the ERS (Eur Respir J. 2016;48[3]:664-73). According to the ERS definition, the key features of ACOS are age greater than 40 years, long-term history of asthma (since childhood or early adulthood), and significant exposure to cigarette or biomass smoke.

The other definitions analyzed included a medical history of both asthma and COPD, a self-reported history of both asthma and COPD, and a record of the proportion of a person’s vital capacity that he/she is able to expire in 1 second of forced expiration of less than 0.7 plus a record of fractionated nitric oxide concentration in exhaled breath of greater than or equal to 45 parts per billion.

Although attempted, a Venn diagram that would show overlapping subsets of patients that fell into these definitions “was not possible,” according to Tobias Bonten, MD, University of Leiden, the Netherlands.

Asthma duration was just over 10 years in those identified as having ACOS by medical history alone (registry-based definitions), just over 20 years in those with a medical history and objective evidence of impaired lung function, but about 40 years in those with a self-report of both asthma and COPD.

One area that all groups created by the ACOS definitions did have in common was demographic variables, such as median age, proportion of patients defined as overweight or obese by body mass index, and proportion who were current smokers.

Members of the audience acknowledged the importance of considering the coexistence of asthma and COPD, but expressed skepticism about the value of ACOS as a separate entity in the clinic.

“ACOS is something like the emperor’s new clothes,” one audience member said during the discussion. “It is important to identify asthma patients with obstruction because they have reduced lung function that should be treated more actively, but I find the definition [of ACOS] unnecessary,” he said.

A similar conclusion was drawn in a review article devoted to ACOS published last year (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[13]:1241-9). “It is premature to recommend the designation of ACOS as a disease entity,” the authors wrote.

This is a position widely shared by clinicians, judging from audience comments provoked by this demonstration.

For the sake of time, the moderators were forced to end the discussion with significant lines of clinicians at the microphone.

“It is quite clear that ACOS should die,” said one of the last speakers given a chance to voice an opinion. He suggested that the coexistence of asthma and COPD is something that “quite clearly can happen,” but he objected to definitions he said are unhelpful for clinical care.

Dr. Bonten reported no relevant financial relationships.

LONDON – A study comparing patient data with six definitions of the Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS) found only one of the patients analyzed met all definitions. This provoked an animated discussion at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society about the utility of ACOS as a clinical entity.

Of 864 patients diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma drawn from the Netherlands Epidemiology of Obesity cohort (a population-based study with 5,784 patients), 39.1% (338 patients) met at least one of the definitions of ACOS, while 0.1% (one patient) met the criteria for all six definitions.

When this finding was presented, the ERS audience first laughed and then applauded. At the end of the presentation, long lines formed at the microphones. Every comment made was hostile to the concept of ACOS.

“Let us bring ACOS to an honorable death,” said one audience member. His point, reiterated by all who commented subsequently, was that ACOS confuses efforts to treat the underlying respiratory symptoms. Even in those who have both asthma and COPD, the speaker, like other members of the audience, said he considered the diagnosis of ACOS unhelpful.

The six definitions in the study included the latest and just published consensus definition from the ERS (Eur Respir J. 2016;48[3]:664-73). According to the ERS definition, the key features of ACOS are age greater than 40 years, long-term history of asthma (since childhood or early adulthood), and significant exposure to cigarette or biomass smoke.

The other definitions analyzed included a medical history of both asthma and COPD, a self-reported history of both asthma and COPD, and a record of the proportion of a person’s vital capacity that he/she is able to expire in 1 second of forced expiration of less than 0.7 plus a record of fractionated nitric oxide concentration in exhaled breath of greater than or equal to 45 parts per billion.

Although attempted, a Venn diagram that would show overlapping subsets of patients that fell into these definitions “was not possible,” according to Tobias Bonten, MD, University of Leiden, the Netherlands.

Asthma duration was just over 10 years in those identified as having ACOS by medical history alone (registry-based definitions), just over 20 years in those with a medical history and objective evidence of impaired lung function, but about 40 years in those with a self-report of both asthma and COPD.

One area that all groups created by the ACOS definitions did have in common was demographic variables, such as median age, proportion of patients defined as overweight or obese by body mass index, and proportion who were current smokers.

Members of the audience acknowledged the importance of considering the coexistence of asthma and COPD, but expressed skepticism about the value of ACOS as a separate entity in the clinic.

“ACOS is something like the emperor’s new clothes,” one audience member said during the discussion. “It is important to identify asthma patients with obstruction because they have reduced lung function that should be treated more actively, but I find the definition [of ACOS] unnecessary,” he said.

A similar conclusion was drawn in a review article devoted to ACOS published last year (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[13]:1241-9). “It is premature to recommend the designation of ACOS as a disease entity,” the authors wrote.

This is a position widely shared by clinicians, judging from audience comments provoked by this demonstration.

For the sake of time, the moderators were forced to end the discussion with significant lines of clinicians at the microphone.

“It is quite clear that ACOS should die,” said one of the last speakers given a chance to voice an opinion. He suggested that the coexistence of asthma and COPD is something that “quite clearly can happen,” but he objected to definitions he said are unhelpful for clinical care.

Dr. Bonten reported no relevant financial relationships.

LONDON – A study comparing patient data with six definitions of the Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS) found only one of the patients analyzed met all definitions. This provoked an animated discussion at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society about the utility of ACOS as a clinical entity.

Of 864 patients diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma drawn from the Netherlands Epidemiology of Obesity cohort (a population-based study with 5,784 patients), 39.1% (338 patients) met at least one of the definitions of ACOS, while 0.1% (one patient) met the criteria for all six definitions.

When this finding was presented, the ERS audience first laughed and then applauded. At the end of the presentation, long lines formed at the microphones. Every comment made was hostile to the concept of ACOS.

“Let us bring ACOS to an honorable death,” said one audience member. His point, reiterated by all who commented subsequently, was that ACOS confuses efforts to treat the underlying respiratory symptoms. Even in those who have both asthma and COPD, the speaker, like other members of the audience, said he considered the diagnosis of ACOS unhelpful.

The six definitions in the study included the latest and just published consensus definition from the ERS (Eur Respir J. 2016;48[3]:664-73). According to the ERS definition, the key features of ACOS are age greater than 40 years, long-term history of asthma (since childhood or early adulthood), and significant exposure to cigarette or biomass smoke.

The other definitions analyzed included a medical history of both asthma and COPD, a self-reported history of both asthma and COPD, and a record of the proportion of a person’s vital capacity that he/she is able to expire in 1 second of forced expiration of less than 0.7 plus a record of fractionated nitric oxide concentration in exhaled breath of greater than or equal to 45 parts per billion.

Although attempted, a Venn diagram that would show overlapping subsets of patients that fell into these definitions “was not possible,” according to Tobias Bonten, MD, University of Leiden, the Netherlands.

Asthma duration was just over 10 years in those identified as having ACOS by medical history alone (registry-based definitions), just over 20 years in those with a medical history and objective evidence of impaired lung function, but about 40 years in those with a self-report of both asthma and COPD.

One area that all groups created by the ACOS definitions did have in common was demographic variables, such as median age, proportion of patients defined as overweight or obese by body mass index, and proportion who were current smokers.

Members of the audience acknowledged the importance of considering the coexistence of asthma and COPD, but expressed skepticism about the value of ACOS as a separate entity in the clinic.

“ACOS is something like the emperor’s new clothes,” one audience member said during the discussion. “It is important to identify asthma patients with obstruction because they have reduced lung function that should be treated more actively, but I find the definition [of ACOS] unnecessary,” he said.

A similar conclusion was drawn in a review article devoted to ACOS published last year (N Engl J Med. 2015;373[13]:1241-9). “It is premature to recommend the designation of ACOS as a disease entity,” the authors wrote.

This is a position widely shared by clinicians, judging from audience comments provoked by this demonstration.

For the sake of time, the moderators were forced to end the discussion with significant lines of clinicians at the microphone.

“It is quite clear that ACOS should die,” said one of the last speakers given a chance to voice an opinion. He suggested that the coexistence of asthma and COPD is something that “quite clearly can happen,” but he objected to definitions he said are unhelpful for clinical care.

Dr. Bonten reported no relevant financial relationships.

AT THE ERS CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point: A study comparing current definitions of Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS) provoked criticism of the very concept.

Major finding: When six definitions of ACOS were compared in a population-based study, only 1 (0.1%) of 864 possible candidates met all criteria of all definitions.

Data source: Population-based cohort study.

Disclosures: Dr. Bonten reported no relevant financial relationships.

Benralizumab reduces exacerbations in pivotal severe asthma trials

LONDON – The investigational treatment benralizumab significantly reduced the number of exacerbations that patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma experienced during the course of a year in two phase III studies.

In the SIROCCO and CALIMA trials, which altogether involved more than 2,000 adult patients, the annual exacerbation rate (AER) was cut by 28%-51%, compared with placebo when benralizumab was added to standard combination therapy of an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA).

Benralizumab treatment was also associated with significant improvements in lung function (up to 159 mL increase in FEV1), and reduced daily asthma symptoms of wheeze, cough, and dyspnea versus placebo. There were also improvements seen in patient-reported measures of asthma control and quality of life.

The results of these two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group studies were published in full online in The Lancet to coincide with their presentation at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Benralizumab is a humanized, monoclonal antibody that has been shown to rapidly and almost completely deplete the number of eosinophils in the blood, airways, and bone marrow, Eugene R Bleecker, MD, who presented the results of the SIROCCO study, explained at the meeting.

Dr. Bleecker, who is the director of the Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine Research at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., observed that benralizumab “works a little bit differently” to other interleukin (IL)-5–targeting monoclonal antibodies, such as mepolizumab and reslizumab. Rather than target the IL-5 ligand itself, benralizumab binds to IL-5 receptors present on the surface of eosinophils. This action activates natural killer cells, which then destroy the eosinophils via antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

Phase IIb data have already shown a benefit for benralizumab versus placebo in patients with uncontrolled asthma with high (300 cells/mcL or greater) eosinophil counts in the blood. The aim of the SIROCCO and CALIMA phase III trials was thus to examine the efficacy and safety of the novel agent further in this patient population.

In SIROCCO, 1,205 patients were randomized, and 1,306 were randomized in CALIMA. Key inclusion criteria were physician-diagnosed asthma requiring ICS/LABA therapy and at least two exacerbations in the past 12 months. Patients also needed to be symptomatic during a 4-week run-in period before being randomized to one of three study groups. The groups included one that received benralizumab at a subcutaneous dose of 30 mg every 4 weeks; another that received benralizumab at a subcutaneous dose of 30 mg every 4 weeks for the first three doses then a 30 mg dose or placebo injection alternating every 4 weeks; and a third group that received placebo injections every 4 weeks.

The mean age of patients in both studies and across treatment arms was broadly similar, ranging from 47 to 50 years. Around two thirds of the study population was female, with similar baseline characteristics.

The primary endpoint was the AER in patients with a blood eosinophil count of 300 cells/mcL or higher. In SIROCCO this was measured at 48 weeks and in CALIMA at 56 weeks. The respective AERs for placebo and for the 4- and 8-week dosing regimens of benralizumab were 1.33, 0.73, and 0.65 in SIROCCO and 0.93, 0.6, and 0.66 in CALIMA. This represented a 45% reduction in the AER for the 4-week and a 51% reduction for the 8-week regimens of benralizumab versus placebo in SIROCCO, and a 36% and 28% reduction, respectively, in CALIMA.

There was a large placebo effect and the overall population recruited into CALIMA may have had less severe asthma than the patients who participated in SIROCCO, the principal investigator for CALIMA, Mark FitzGerald, MD, pointed out during a press briefing organized by AstraZeneca. “But when you look at the composite of both studies together, you can see that the results are quite robust,” said Dr. FitzGerald, the director of the Centre for Lung and Heart Health at Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute.

There was also some evidence that patients who had three or more prior exacerbations fared better, he said, highlighting the importance of defining the patient population who may benefit the most from this treatment.

Something that needs to be investigated further is why patients given the 8-week benralizumab regimen seemed to do better, at least numerically, than those given the 4-week regimen. Dr. FitzGerald suggested that “because eosinophil cells are such a powerful driver of disease, perhaps you may not actually need to be treated as frequently as historically we might have done.”

Other similar biologic agents need dosing every 2 to 4 weeks, but perhaps every 8 weeks is a possibility in the future for benralizumab. A lot can be learned from how biologics are used in rheumatology, he suggested, where treatments have started being given less frequently, because the biology of the various rheumatic diseases is now better understood.

Any adverse event was reported by a similar percentage of actively-treated (71%-75%) and placebo-treated (73%-78%) patients. The frequency and nature of other adverse events were similar to placebo.

The SIROCCO and CALIMA trial data will form part of AstraZeneca’s U.S. and EU regulatory submissions later this year for benralizumab as a treatment for severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma.

“Potentially, when it becomes available, benralizumab will provide a new therapeutic option for this class of patient.” Dr. FitzGerald said.

Benralizumab is also being investigated as a possible treatment for patients with less severe eosinophilic asthma in the BISE phase III study and as an option for those with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who have high levels of eosinophils in the phase III VOYAGER program.

AstraZeneca and Kyowa Hakko Kirin funded the studies. Dr. Bleecker is the principal investigator for the SIROCCO trial and disclosed receiving research funding or consulting for AstraZeneca-MedImmune, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Cephalon/Teva, and Regeneron-Sanofi. Dr. FitzGerald disclosed acting as an advisory board participant, receiving funding or fees, or both from AstraZeneca, ALK Abello, Boehringer Ingelheim, Hoffman-La Roche, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, and Teva.

LONDON – The investigational treatment benralizumab significantly reduced the number of exacerbations that patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma experienced during the course of a year in two phase III studies.

In the SIROCCO and CALIMA trials, which altogether involved more than 2,000 adult patients, the annual exacerbation rate (AER) was cut by 28%-51%, compared with placebo when benralizumab was added to standard combination therapy of an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA).

Benralizumab treatment was also associated with significant improvements in lung function (up to 159 mL increase in FEV1), and reduced daily asthma symptoms of wheeze, cough, and dyspnea versus placebo. There were also improvements seen in patient-reported measures of asthma control and quality of life.

The results of these two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group studies were published in full online in The Lancet to coincide with their presentation at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Benralizumab is a humanized, monoclonal antibody that has been shown to rapidly and almost completely deplete the number of eosinophils in the blood, airways, and bone marrow, Eugene R Bleecker, MD, who presented the results of the SIROCCO study, explained at the meeting.

Dr. Bleecker, who is the director of the Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine Research at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., observed that benralizumab “works a little bit differently” to other interleukin (IL)-5–targeting monoclonal antibodies, such as mepolizumab and reslizumab. Rather than target the IL-5 ligand itself, benralizumab binds to IL-5 receptors present on the surface of eosinophils. This action activates natural killer cells, which then destroy the eosinophils via antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

Phase IIb data have already shown a benefit for benralizumab versus placebo in patients with uncontrolled asthma with high (300 cells/mcL or greater) eosinophil counts in the blood. The aim of the SIROCCO and CALIMA phase III trials was thus to examine the efficacy and safety of the novel agent further in this patient population.

In SIROCCO, 1,205 patients were randomized, and 1,306 were randomized in CALIMA. Key inclusion criteria were physician-diagnosed asthma requiring ICS/LABA therapy and at least two exacerbations in the past 12 months. Patients also needed to be symptomatic during a 4-week run-in period before being randomized to one of three study groups. The groups included one that received benralizumab at a subcutaneous dose of 30 mg every 4 weeks; another that received benralizumab at a subcutaneous dose of 30 mg every 4 weeks for the first three doses then a 30 mg dose or placebo injection alternating every 4 weeks; and a third group that received placebo injections every 4 weeks.

The mean age of patients in both studies and across treatment arms was broadly similar, ranging from 47 to 50 years. Around two thirds of the study population was female, with similar baseline characteristics.

The primary endpoint was the AER in patients with a blood eosinophil count of 300 cells/mcL or higher. In SIROCCO this was measured at 48 weeks and in CALIMA at 56 weeks. The respective AERs for placebo and for the 4- and 8-week dosing regimens of benralizumab were 1.33, 0.73, and 0.65 in SIROCCO and 0.93, 0.6, and 0.66 in CALIMA. This represented a 45% reduction in the AER for the 4-week and a 51% reduction for the 8-week regimens of benralizumab versus placebo in SIROCCO, and a 36% and 28% reduction, respectively, in CALIMA.

There was a large placebo effect and the overall population recruited into CALIMA may have had less severe asthma than the patients who participated in SIROCCO, the principal investigator for CALIMA, Mark FitzGerald, MD, pointed out during a press briefing organized by AstraZeneca. “But when you look at the composite of both studies together, you can see that the results are quite robust,” said Dr. FitzGerald, the director of the Centre for Lung and Heart Health at Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute.

There was also some evidence that patients who had three or more prior exacerbations fared better, he said, highlighting the importance of defining the patient population who may benefit the most from this treatment.

Something that needs to be investigated further is why patients given the 8-week benralizumab regimen seemed to do better, at least numerically, than those given the 4-week regimen. Dr. FitzGerald suggested that “because eosinophil cells are such a powerful driver of disease, perhaps you may not actually need to be treated as frequently as historically we might have done.”

Other similar biologic agents need dosing every 2 to 4 weeks, but perhaps every 8 weeks is a possibility in the future for benralizumab. A lot can be learned from how biologics are used in rheumatology, he suggested, where treatments have started being given less frequently, because the biology of the various rheumatic diseases is now better understood.

Any adverse event was reported by a similar percentage of actively-treated (71%-75%) and placebo-treated (73%-78%) patients. The frequency and nature of other adverse events were similar to placebo.

The SIROCCO and CALIMA trial data will form part of AstraZeneca’s U.S. and EU regulatory submissions later this year for benralizumab as a treatment for severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma.

“Potentially, when it becomes available, benralizumab will provide a new therapeutic option for this class of patient.” Dr. FitzGerald said.

Benralizumab is also being investigated as a possible treatment for patients with less severe eosinophilic asthma in the BISE phase III study and as an option for those with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who have high levels of eosinophils in the phase III VOYAGER program.

AstraZeneca and Kyowa Hakko Kirin funded the studies. Dr. Bleecker is the principal investigator for the SIROCCO trial and disclosed receiving research funding or consulting for AstraZeneca-MedImmune, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Cephalon/Teva, and Regeneron-Sanofi. Dr. FitzGerald disclosed acting as an advisory board participant, receiving funding or fees, or both from AstraZeneca, ALK Abello, Boehringer Ingelheim, Hoffman-La Roche, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, and Teva.

LONDON – The investigational treatment benralizumab significantly reduced the number of exacerbations that patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma experienced during the course of a year in two phase III studies.

In the SIROCCO and CALIMA trials, which altogether involved more than 2,000 adult patients, the annual exacerbation rate (AER) was cut by 28%-51%, compared with placebo when benralizumab was added to standard combination therapy of an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA).

Benralizumab treatment was also associated with significant improvements in lung function (up to 159 mL increase in FEV1), and reduced daily asthma symptoms of wheeze, cough, and dyspnea versus placebo. There were also improvements seen in patient-reported measures of asthma control and quality of life.

The results of these two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group studies were published in full online in The Lancet to coincide with their presentation at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Benralizumab is a humanized, monoclonal antibody that has been shown to rapidly and almost completely deplete the number of eosinophils in the blood, airways, and bone marrow, Eugene R Bleecker, MD, who presented the results of the SIROCCO study, explained at the meeting.

Dr. Bleecker, who is the director of the Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine Research at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., observed that benralizumab “works a little bit differently” to other interleukin (IL)-5–targeting monoclonal antibodies, such as mepolizumab and reslizumab. Rather than target the IL-5 ligand itself, benralizumab binds to IL-5 receptors present on the surface of eosinophils. This action activates natural killer cells, which then destroy the eosinophils via antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

Phase IIb data have already shown a benefit for benralizumab versus placebo in patients with uncontrolled asthma with high (300 cells/mcL or greater) eosinophil counts in the blood. The aim of the SIROCCO and CALIMA phase III trials was thus to examine the efficacy and safety of the novel agent further in this patient population.

In SIROCCO, 1,205 patients were randomized, and 1,306 were randomized in CALIMA. Key inclusion criteria were physician-diagnosed asthma requiring ICS/LABA therapy and at least two exacerbations in the past 12 months. Patients also needed to be symptomatic during a 4-week run-in period before being randomized to one of three study groups. The groups included one that received benralizumab at a subcutaneous dose of 30 mg every 4 weeks; another that received benralizumab at a subcutaneous dose of 30 mg every 4 weeks for the first three doses then a 30 mg dose or placebo injection alternating every 4 weeks; and a third group that received placebo injections every 4 weeks.

The mean age of patients in both studies and across treatment arms was broadly similar, ranging from 47 to 50 years. Around two thirds of the study population was female, with similar baseline characteristics.

The primary endpoint was the AER in patients with a blood eosinophil count of 300 cells/mcL or higher. In SIROCCO this was measured at 48 weeks and in CALIMA at 56 weeks. The respective AERs for placebo and for the 4- and 8-week dosing regimens of benralizumab were 1.33, 0.73, and 0.65 in SIROCCO and 0.93, 0.6, and 0.66 in CALIMA. This represented a 45% reduction in the AER for the 4-week and a 51% reduction for the 8-week regimens of benralizumab versus placebo in SIROCCO, and a 36% and 28% reduction, respectively, in CALIMA.

There was a large placebo effect and the overall population recruited into CALIMA may have had less severe asthma than the patients who participated in SIROCCO, the principal investigator for CALIMA, Mark FitzGerald, MD, pointed out during a press briefing organized by AstraZeneca. “But when you look at the composite of both studies together, you can see that the results are quite robust,” said Dr. FitzGerald, the director of the Centre for Lung and Heart Health at Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute.

There was also some evidence that patients who had three or more prior exacerbations fared better, he said, highlighting the importance of defining the patient population who may benefit the most from this treatment.

Something that needs to be investigated further is why patients given the 8-week benralizumab regimen seemed to do better, at least numerically, than those given the 4-week regimen. Dr. FitzGerald suggested that “because eosinophil cells are such a powerful driver of disease, perhaps you may not actually need to be treated as frequently as historically we might have done.”

Other similar biologic agents need dosing every 2 to 4 weeks, but perhaps every 8 weeks is a possibility in the future for benralizumab. A lot can be learned from how biologics are used in rheumatology, he suggested, where treatments have started being given less frequently, because the biology of the various rheumatic diseases is now better understood.

Any adverse event was reported by a similar percentage of actively-treated (71%-75%) and placebo-treated (73%-78%) patients. The frequency and nature of other adverse events were similar to placebo.

The SIROCCO and CALIMA trial data will form part of AstraZeneca’s U.S. and EU regulatory submissions later this year for benralizumab as a treatment for severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma.

“Potentially, when it becomes available, benralizumab will provide a new therapeutic option for this class of patient.” Dr. FitzGerald said.

Benralizumab is also being investigated as a possible treatment for patients with less severe eosinophilic asthma in the BISE phase III study and as an option for those with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who have high levels of eosinophils in the phase III VOYAGER program.

AstraZeneca and Kyowa Hakko Kirin funded the studies. Dr. Bleecker is the principal investigator for the SIROCCO trial and disclosed receiving research funding or consulting for AstraZeneca-MedImmune, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Cephalon/Teva, and Regeneron-Sanofi. Dr. FitzGerald disclosed acting as an advisory board participant, receiving funding or fees, or both from AstraZeneca, ALK Abello, Boehringer Ingelheim, Hoffman-La Roche, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, and Teva.

AT THE ERS CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point: Benralizumab significantly reduced the annual exacerbation rate (AER), improved lung function, and reduced asthma symptoms.

Major finding: There was a 28%-51% decrease in the AER comparing (primary endpoint) two benralizumab regimens with placebo added to standard combination therapy.

Data source: Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group, phase III studies involving more than 2,000 adult patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma.

Disclosures: AstraZeneca and Kyowa Hakko Kirin funded the studies. Dr. Bleecker is the principal investigator for the SIROCCO trial and disclosed receiving research funding or consulting for AstraZeneca-MedImmune, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson (Jansen), Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Cephalon/Teva, and Regeneron-Sanofi. Dr. FitzGerald is the principal investigator for the CALIMA trial. He disclosed acting as an advisory board participant, receiving funding or fees, or both from AstraZeneca, ALK Abello, Boehringer Ingelheim, Hoffman-La Roche, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, and Teva.

LABA withdrawal does not worsen asthma control

LONDON – Real-life experience shows that stopping treatment with a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) does not worsen asthma control, nor does it lead to any immediate decline in lung function.

Spirometric parameters were similar before and 3 weeks after stopping LABA therapy in an observational study of 58 patients who had stable asthma and were being treated with an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a LABA.

The forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was 88.8% at baseline and 89.5% at the 3-week visit after stepping down their LABA therapy (P = .55). Patients’ average peak expiratory flow rate was 462 L/min both before and after LABA withdrawal.

In addition, no changes were seen in lung function based on impulse oscillometry, a noninvasive method for measuring airway resistance and reactance (Chest. 2014;146[3]:841-7). Similar levels of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO, 38 and 36 ppb) were recorded.

The findings were presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and have been published in an early online edition of the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.07.022).

“About 45% of the UK adult asthma population are taking step 3 GINA [Global Initiative for Asthma] therapy, which is ICS/LABA,” explained Sunny Jabbal, MD, of the Scottish Centre for Respiratory Research at Ninewells Hospital in Dundee, Scotland, where the study was conducted. Patients should be on the lowest of the five steps in the 2016 GINA guidelines that achieve asthma control and should be regularly reviewed.

To test whether the LABA could be safely withdrawn, that is stepped down to ICS only [GINA step 2], Dr. Jabbal and colleagues studied 58 patients with a mean age of 39 years. All had well-controlled asthma, and had been receiving ICS/LABA for at least 3 months with no asthma exacerbations requiring treatment. None of the patients were current smokers.

At study entry, patients underwent spirometry, impulse oscillometry, and had FeNO measured. Their LABA was then stopped, and patients were reassessed 3 weeks later. “In accordance with GINA, their ICS dose was also reduced by approximately 25%,” Dr. Jabbal said.

Patients recorded their symptoms and short-term reliever (albuterol) use on simple diary cards. They were also given a 24-hour emergency mobile number, but no calls were received and no adverse events reported. The mean daily symptom score recorded during the step down process was 0.4 (out of a possible score of 3), and the mean albuterol usage was one puff per day.

One of the chairs of the session, Omar Usmani, MD, of Imperial College London noted that some clinicians are “very apprehensive” about stopping LABA and stepping down ICS therapy in their patients.

This was a short-term study, Dr. Jabbal acknowledged. Although a follow-up of 3 weeks may be enough to determine the effects of stopping a LABA, that time may not be sufficient to assess the effects of stepping down the ICS. Further real-life studies are needed to evaluate outcomes such as exacerbations and overall quality of life.

Improved adherence with ICS therapy after LABA withdrawal might explain the lack of deleterious effects, or perhaps some patients may not have initially needed an ICS/LABA combination, he speculated. Maybe even the steroid dose could be reduced further in this particular patient population.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Jabbal had no conflicts of interest related to his presentation.

LONDON – Real-life experience shows that stopping treatment with a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) does not worsen asthma control, nor does it lead to any immediate decline in lung function.

Spirometric parameters were similar before and 3 weeks after stopping LABA therapy in an observational study of 58 patients who had stable asthma and were being treated with an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a LABA.

The forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was 88.8% at baseline and 89.5% at the 3-week visit after stepping down their LABA therapy (P = .55). Patients’ average peak expiratory flow rate was 462 L/min both before and after LABA withdrawal.

In addition, no changes were seen in lung function based on impulse oscillometry, a noninvasive method for measuring airway resistance and reactance (Chest. 2014;146[3]:841-7). Similar levels of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO, 38 and 36 ppb) were recorded.

The findings were presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and have been published in an early online edition of the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.07.022).

“About 45% of the UK adult asthma population are taking step 3 GINA [Global Initiative for Asthma] therapy, which is ICS/LABA,” explained Sunny Jabbal, MD, of the Scottish Centre for Respiratory Research at Ninewells Hospital in Dundee, Scotland, where the study was conducted. Patients should be on the lowest of the five steps in the 2016 GINA guidelines that achieve asthma control and should be regularly reviewed.

To test whether the LABA could be safely withdrawn, that is stepped down to ICS only [GINA step 2], Dr. Jabbal and colleagues studied 58 patients with a mean age of 39 years. All had well-controlled asthma, and had been receiving ICS/LABA for at least 3 months with no asthma exacerbations requiring treatment. None of the patients were current smokers.

At study entry, patients underwent spirometry, impulse oscillometry, and had FeNO measured. Their LABA was then stopped, and patients were reassessed 3 weeks later. “In accordance with GINA, their ICS dose was also reduced by approximately 25%,” Dr. Jabbal said.

Patients recorded their symptoms and short-term reliever (albuterol) use on simple diary cards. They were also given a 24-hour emergency mobile number, but no calls were received and no adverse events reported. The mean daily symptom score recorded during the step down process was 0.4 (out of a possible score of 3), and the mean albuterol usage was one puff per day.

One of the chairs of the session, Omar Usmani, MD, of Imperial College London noted that some clinicians are “very apprehensive” about stopping LABA and stepping down ICS therapy in their patients.

This was a short-term study, Dr. Jabbal acknowledged. Although a follow-up of 3 weeks may be enough to determine the effects of stopping a LABA, that time may not be sufficient to assess the effects of stepping down the ICS. Further real-life studies are needed to evaluate outcomes such as exacerbations and overall quality of life.

Improved adherence with ICS therapy after LABA withdrawal might explain the lack of deleterious effects, or perhaps some patients may not have initially needed an ICS/LABA combination, he speculated. Maybe even the steroid dose could be reduced further in this particular patient population.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Jabbal had no conflicts of interest related to his presentation.

LONDON – Real-life experience shows that stopping treatment with a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) does not worsen asthma control, nor does it lead to any immediate decline in lung function.

Spirometric parameters were similar before and 3 weeks after stopping LABA therapy in an observational study of 58 patients who had stable asthma and were being treated with an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a LABA.

The forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was 88.8% at baseline and 89.5% at the 3-week visit after stepping down their LABA therapy (P = .55). Patients’ average peak expiratory flow rate was 462 L/min both before and after LABA withdrawal.

In addition, no changes were seen in lung function based on impulse oscillometry, a noninvasive method for measuring airway resistance and reactance (Chest. 2014;146[3]:841-7). Similar levels of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO, 38 and 36 ppb) were recorded.

The findings were presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and have been published in an early online edition of the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.07.022).

“About 45% of the UK adult asthma population are taking step 3 GINA [Global Initiative for Asthma] therapy, which is ICS/LABA,” explained Sunny Jabbal, MD, of the Scottish Centre for Respiratory Research at Ninewells Hospital in Dundee, Scotland, where the study was conducted. Patients should be on the lowest of the five steps in the 2016 GINA guidelines that achieve asthma control and should be regularly reviewed.

To test whether the LABA could be safely withdrawn, that is stepped down to ICS only [GINA step 2], Dr. Jabbal and colleagues studied 58 patients with a mean age of 39 years. All had well-controlled asthma, and had been receiving ICS/LABA for at least 3 months with no asthma exacerbations requiring treatment. None of the patients were current smokers.

At study entry, patients underwent spirometry, impulse oscillometry, and had FeNO measured. Their LABA was then stopped, and patients were reassessed 3 weeks later. “In accordance with GINA, their ICS dose was also reduced by approximately 25%,” Dr. Jabbal said.

Patients recorded their symptoms and short-term reliever (albuterol) use on simple diary cards. They were also given a 24-hour emergency mobile number, but no calls were received and no adverse events reported. The mean daily symptom score recorded during the step down process was 0.4 (out of a possible score of 3), and the mean albuterol usage was one puff per day.

One of the chairs of the session, Omar Usmani, MD, of Imperial College London noted that some clinicians are “very apprehensive” about stopping LABA and stepping down ICS therapy in their patients.

This was a short-term study, Dr. Jabbal acknowledged. Although a follow-up of 3 weeks may be enough to determine the effects of stopping a LABA, that time may not be sufficient to assess the effects of stepping down the ICS. Further real-life studies are needed to evaluate outcomes such as exacerbations and overall quality of life.

Improved adherence with ICS therapy after LABA withdrawal might explain the lack of deleterious effects, or perhaps some patients may not have initially needed an ICS/LABA combination, he speculated. Maybe even the steroid dose could be reduced further in this particular patient population.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Jabbal had no conflicts of interest related to his presentation.

AT THE ERS CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point: Step-down treatment works well in routine asthma care, with no loss of control or lung function decline.

Major finding: No significant changes in FEV1 (88.8% vs. 89.5%), PEF (462 L/min vs. 462 L/min), or other lung function variables were seen before or 3 weeks after LABA withdrawal.

Data source: Observational study of 58 stable asthmatic patients being treated with ICS/LABA (GINA step 3).

Disclosures: The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Jabbal had no conflicts of interest related to his presentation.

When should primary care physicians prescribe antibiotics to children with respiratory infection symptoms?

Duration of illness, age, and the presence of specific symptoms are key predictors of hospitalization risk due to respiratory infection, according to a study published in The Lancet. These demographic and clinical factors should guide a primary care physician’s decision to prescribe antibiotics.

“More than 80% of all health-service antibiotics [are] prescribed by primary care clinicians,” reported Alastair Hay, MD, of the University of Bristol, England, and his associates.

“Antibiotic prescribing in primary care is increasing and directly affects antimicrobial resistance,” the researchers noted, adding that many primary care clinicians prescribe antibiotics to pediatric patients with respiratory tract infections and/or cough to “mitigate perceived risk of future hospital admission and complications.”

A total of 8,394 pediatric patients who presented with acute cough and one or more other symptoms of respiratory tract infection (such as fever and coryza) were enrolled in the study by primary care physicians at 247 clinical sites in England. All eligible patients were between the ages of 3 months and 16 years; children were excluded if they presented with noninfective exacerbation of asthma, were at high risk of serious infection, or required a throat swab. The study’s primary outcome was hospital admission for any respiratory tract infection within 30 days of enrollment; the data were collected from a review of electronic medical records (Lancet. 2016. Sept 1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600[16]30223-5).

The median age of the pediatric cohort was 3 years, 52% were male, and 78% were white. A total of 3,121 patients (37%) were prescribed an antibiotic by their primary care physicians, but only 78 patients (0.9%) were admitted to the hospital, and 27% of discharge diagnoses suggested a possible bacterial cause (lower respiratory tract infection, tonsillitis, and pneumonia).

Multivariate modeling with bootstrap validation demonstrated that duration of illness, age, and the presence or absence of specific respiratory symptoms were the key factors that should be used to identify children at low, normal, and high risk for hospitalization due to respiratory infection. Younger patients with shorter illness durations who presented with wheeze, fever, vomiting, intercostal or subcostal recession, and/or asthma were at higher risk for hospitalization.

“Our data show that 1,846 (33%) of the very-low-risk stratum children received antibiotics. Because these children represent the majority (67%) of all the participants, a 10% overall reduction in antibiotic prescription would be achieved if prescription in this group halved, remained static in the normal risk stratum, and increased to 90% in the high risk stratum, resulting in a similar effect size to other contemporary antimicrobial stewardship interventions,” Dr. Hay and his associates concluded.

This study received funding and sponsorship from the National Institute for Health Research and the University of Bristol. Two investigators reported receiving financial compensation or honoraria from multiple companies including companies with an interest in diagnostic microbiology in respiratory tract infections.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

Duration of illness, age, and the presence of specific symptoms are key predictors of hospitalization risk due to respiratory infection, according to a study published in The Lancet. These demographic and clinical factors should guide a primary care physician’s decision to prescribe antibiotics.

“More than 80% of all health-service antibiotics [are] prescribed by primary care clinicians,” reported Alastair Hay, MD, of the University of Bristol, England, and his associates.

“Antibiotic prescribing in primary care is increasing and directly affects antimicrobial resistance,” the researchers noted, adding that many primary care clinicians prescribe antibiotics to pediatric patients with respiratory tract infections and/or cough to “mitigate perceived risk of future hospital admission and complications.”