User login

Skin testing and decision support can clarify penicillin allergy

Penicillin allergy skin testing or a computerized guideline app with decision support can increase the use of penicillin or cephalosporin among inpatients reporting penicillin allergy.

“Despite a reported penicillin allergy, more than 95% of patients evaluated for such allergy are found penicillin and cephalosporin tolerant,” wrote Kimberly G. Blumenthal, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and her coauthors.

In this study, they recruited 625 patients reporting penicillin allergy and explored three approaches over three periods of time. These were standard of care, in which penicillin skin testing and test dose challenge is performed only after allergy/immunology consultation; penicillin skin testing performed in all patients not otherwise ineligible for skin testing; and a computerized guideline available on any computer or mobile device within the hospital.

Researchers saw a significant 80% increase in the odds of penicillin or cephalosporin use overall during the period in which the computerized guidelines were available (P = .02).

“The guideline empowered inpatient providers to group allergic reactions into hypersensitivity type, then recommended if and how specific beta-lactam antibiotics [should] be used (i.e. very low risk: full doses; low risk: test doses; medium to high risk: Allergy/Immunology consultation; serious type II-IV hypersensitivity reactions: avoidance),” the authors wrote.

While patients during the skin testing period did not have a significantly increased odds of receiving the antibiotics overall, the adjusted per-protocol analysis showed a nearly sixfold higher odds of receiving penicillin or cephalosporin (odds ratio, 5.7; P less than .001).

Among the 278 patients present during the skin-testing period, 179 (64%) were eligible for skin testing, in that they did not have penicillin intolerances such as gastrointestinal upset, were not taking medications that interfered with skin testing, didn’t have multiple beta-lactam allergies, had not experienced penicillin anaphylaxis in the last 5 years, or had a type II-IV hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin. Of these, 43 (24%) were tested, none of whom were allergic.

The per-protocol analysis of skin testing also showed a 2.5-fold increase in the odds of discharge use of penicillin or cephalosporin (P = .04).

“Since the impact of overreporting penicillin allergy is felt beyond antibiotic utilization to resultant readmissions, treatment failures, and adverse events, safely increasing the use of penicillin and cephalosporin antibiotics in this patient population is a crucial first step towards improved quality of care and reduced cost,” the authors wrote.

The study was supported by the Brigham Care Redesign Incubator and Start-Up Program. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Penicillin allergy skin testing or a computerized guideline app with decision support can increase the use of penicillin or cephalosporin among inpatients reporting penicillin allergy.

“Despite a reported penicillin allergy, more than 95% of patients evaluated for such allergy are found penicillin and cephalosporin tolerant,” wrote Kimberly G. Blumenthal, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and her coauthors.

In this study, they recruited 625 patients reporting penicillin allergy and explored three approaches over three periods of time. These were standard of care, in which penicillin skin testing and test dose challenge is performed only after allergy/immunology consultation; penicillin skin testing performed in all patients not otherwise ineligible for skin testing; and a computerized guideline available on any computer or mobile device within the hospital.

Researchers saw a significant 80% increase in the odds of penicillin or cephalosporin use overall during the period in which the computerized guidelines were available (P = .02).

“The guideline empowered inpatient providers to group allergic reactions into hypersensitivity type, then recommended if and how specific beta-lactam antibiotics [should] be used (i.e. very low risk: full doses; low risk: test doses; medium to high risk: Allergy/Immunology consultation; serious type II-IV hypersensitivity reactions: avoidance),” the authors wrote.

While patients during the skin testing period did not have a significantly increased odds of receiving the antibiotics overall, the adjusted per-protocol analysis showed a nearly sixfold higher odds of receiving penicillin or cephalosporin (odds ratio, 5.7; P less than .001).

Among the 278 patients present during the skin-testing period, 179 (64%) were eligible for skin testing, in that they did not have penicillin intolerances such as gastrointestinal upset, were not taking medications that interfered with skin testing, didn’t have multiple beta-lactam allergies, had not experienced penicillin anaphylaxis in the last 5 years, or had a type II-IV hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin. Of these, 43 (24%) were tested, none of whom were allergic.

The per-protocol analysis of skin testing also showed a 2.5-fold increase in the odds of discharge use of penicillin or cephalosporin (P = .04).

“Since the impact of overreporting penicillin allergy is felt beyond antibiotic utilization to resultant readmissions, treatment failures, and adverse events, safely increasing the use of penicillin and cephalosporin antibiotics in this patient population is a crucial first step towards improved quality of care and reduced cost,” the authors wrote.

The study was supported by the Brigham Care Redesign Incubator and Start-Up Program. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Penicillin allergy skin testing or a computerized guideline app with decision support can increase the use of penicillin or cephalosporin among inpatients reporting penicillin allergy.

“Despite a reported penicillin allergy, more than 95% of patients evaluated for such allergy are found penicillin and cephalosporin tolerant,” wrote Kimberly G. Blumenthal, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and her coauthors.

In this study, they recruited 625 patients reporting penicillin allergy and explored three approaches over three periods of time. These were standard of care, in which penicillin skin testing and test dose challenge is performed only after allergy/immunology consultation; penicillin skin testing performed in all patients not otherwise ineligible for skin testing; and a computerized guideline available on any computer or mobile device within the hospital.

Researchers saw a significant 80% increase in the odds of penicillin or cephalosporin use overall during the period in which the computerized guidelines were available (P = .02).

“The guideline empowered inpatient providers to group allergic reactions into hypersensitivity type, then recommended if and how specific beta-lactam antibiotics [should] be used (i.e. very low risk: full doses; low risk: test doses; medium to high risk: Allergy/Immunology consultation; serious type II-IV hypersensitivity reactions: avoidance),” the authors wrote.

While patients during the skin testing period did not have a significantly increased odds of receiving the antibiotics overall, the adjusted per-protocol analysis showed a nearly sixfold higher odds of receiving penicillin or cephalosporin (odds ratio, 5.7; P less than .001).

Among the 278 patients present during the skin-testing period, 179 (64%) were eligible for skin testing, in that they did not have penicillin intolerances such as gastrointestinal upset, were not taking medications that interfered with skin testing, didn’t have multiple beta-lactam allergies, had not experienced penicillin anaphylaxis in the last 5 years, or had a type II-IV hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin. Of these, 43 (24%) were tested, none of whom were allergic.

The per-protocol analysis of skin testing also showed a 2.5-fold increase in the odds of discharge use of penicillin or cephalosporin (P = .04).

“Since the impact of overreporting penicillin allergy is felt beyond antibiotic utilization to resultant readmissions, treatment failures, and adverse events, safely increasing the use of penicillin and cephalosporin antibiotics in this patient population is a crucial first step towards improved quality of care and reduced cost,” the authors wrote.

The study was supported by the Brigham Care Redesign Incubator and Start-Up Program. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY

Key clinical point: Penicillin skin testing or a computerized guideline app with decision support can increase the use of penicillin or cephalosporin among inpatients reporting penicillin allergy.

Major finding: Skin testing and computerized decision support increased the odds of patients’ receiving penicillin or cephalosporin 1.8-5.7 fold.

Data source: A prospective study of 625 inpatients patients reporting penicillin allergy.

Disclosures: The Brigham Care Redesign Incubator and Startup Program supported the study. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FDA: Recall of select EpiPen products

Meridian Medical Technologies has issued a voluntary recall for 13 lots of EpiPen products, according to a press release from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The voluntary recall includes EpiPen and EpiPen Jr. Auto-Injector distributed between Dec. 17, 2015, and July 1, 2016 by Mylan Specialty. Products included in the recall may contain a defective part which would prevent the device from activating.

Consumers who need their EpiPens should keep them until a they obtain a replacement, the FDA recommended.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

Meridian Medical Technologies has issued a voluntary recall for 13 lots of EpiPen products, according to a press release from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The voluntary recall includes EpiPen and EpiPen Jr. Auto-Injector distributed between Dec. 17, 2015, and July 1, 2016 by Mylan Specialty. Products included in the recall may contain a defective part which would prevent the device from activating.

Consumers who need their EpiPens should keep them until a they obtain a replacement, the FDA recommended.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

Meridian Medical Technologies has issued a voluntary recall for 13 lots of EpiPen products, according to a press release from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The voluntary recall includes EpiPen and EpiPen Jr. Auto-Injector distributed between Dec. 17, 2015, and July 1, 2016 by Mylan Specialty. Products included in the recall may contain a defective part which would prevent the device from activating.

Consumers who need their EpiPens should keep them until a they obtain a replacement, the FDA recommended.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

What happens when a baked egg oral challenge is negative?

ATLANTA – The majority of patients who had cooked egg exposure following a negative physician-supervised baked egg oral challenge are tolerating cooked egg, according to a retrospective study.

However, no correlation between results and development of tolerance was identified with skin prick testing or serum IgE testing.

To find out, Dr. Peng, a second-year fellow in the department of pediatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles, and her associates identified 22 patients who underwent negative physician-supervised baked egg oral challenges from July 2011 until June 2016. They reviewed medical charts to obtain data on age, clinical history, skin prick test results, and results of serum IgE testing to egg and its components. Next, the researchers contacted patients and their families and invited them to participate in a telephone survey about patterns of baked, cooked, and raw egg exposure and associated reactions, following their negative baked challenge. The patients ranged in age from 10 months to 44 years and their mean age was 7 years.

Dr. Peng presented results from 18 of the 22 patients who were successfully contacted. A mean of 26 months had passed since their baked egg oral challenge. Of these patients, 17 (94%) have had continued exposure to egg while 15 (83%) have shown tolerance to cooked egg. The researchers observed variable patterns of baked egg intake following the negative physician-supervised baked egg challenge. “Some patients are able to tolerate cooked egg rapidly but are not interested in continuing frequent consumption,” Dr. Peng said. “They may say, ‘My 3-year-old doesn’t like scrambled eggs, so I’m not going to keep pushing them.’ They’re not considering themselves egg allergic so their quality of life is much better. I understand that tolerating baked egg is a big deal, as an allergist I want to see them do more, such as tolerating cooked egg.”

When patients were asked about adverse reactions to egg consumption, three (17%) described gastrointestinal symptoms, five (28%) described cutaneous symptoms, and three (17%) described respiratory reactions. Dr. Peng noted that of the three patients who have not achieved tolerance to cooked egg, one patient reported mild reaction to baked egg 2 weeks after the baked egg challenge, while the other two continue to have baked egg exposure but have not yet introduced cooked egg into their diets. “I hope that most pediatricians and family practice physicians consider referral to an allergist if they’re not comfortable introducing a baked egg oral challenge.”

The researchers could not identify any correlation between skin prick or serum IgE test results and development of tolerance to cooked egg. “Data in the literature suggests that serum testing is predictive [of tolerance], but it’s not 100%,” Dr. Peng said.

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – The majority of patients who had cooked egg exposure following a negative physician-supervised baked egg oral challenge are tolerating cooked egg, according to a retrospective study.

However, no correlation between results and development of tolerance was identified with skin prick testing or serum IgE testing.

To find out, Dr. Peng, a second-year fellow in the department of pediatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles, and her associates identified 22 patients who underwent negative physician-supervised baked egg oral challenges from July 2011 until June 2016. They reviewed medical charts to obtain data on age, clinical history, skin prick test results, and results of serum IgE testing to egg and its components. Next, the researchers contacted patients and their families and invited them to participate in a telephone survey about patterns of baked, cooked, and raw egg exposure and associated reactions, following their negative baked challenge. The patients ranged in age from 10 months to 44 years and their mean age was 7 years.

Dr. Peng presented results from 18 of the 22 patients who were successfully contacted. A mean of 26 months had passed since their baked egg oral challenge. Of these patients, 17 (94%) have had continued exposure to egg while 15 (83%) have shown tolerance to cooked egg. The researchers observed variable patterns of baked egg intake following the negative physician-supervised baked egg challenge. “Some patients are able to tolerate cooked egg rapidly but are not interested in continuing frequent consumption,” Dr. Peng said. “They may say, ‘My 3-year-old doesn’t like scrambled eggs, so I’m not going to keep pushing them.’ They’re not considering themselves egg allergic so their quality of life is much better. I understand that tolerating baked egg is a big deal, as an allergist I want to see them do more, such as tolerating cooked egg.”

When patients were asked about adverse reactions to egg consumption, three (17%) described gastrointestinal symptoms, five (28%) described cutaneous symptoms, and three (17%) described respiratory reactions. Dr. Peng noted that of the three patients who have not achieved tolerance to cooked egg, one patient reported mild reaction to baked egg 2 weeks after the baked egg challenge, while the other two continue to have baked egg exposure but have not yet introduced cooked egg into their diets. “I hope that most pediatricians and family practice physicians consider referral to an allergist if they’re not comfortable introducing a baked egg oral challenge.”

The researchers could not identify any correlation between skin prick or serum IgE test results and development of tolerance to cooked egg. “Data in the literature suggests that serum testing is predictive [of tolerance], but it’s not 100%,” Dr. Peng said.

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – The majority of patients who had cooked egg exposure following a negative physician-supervised baked egg oral challenge are tolerating cooked egg, according to a retrospective study.

However, no correlation between results and development of tolerance was identified with skin prick testing or serum IgE testing.

To find out, Dr. Peng, a second-year fellow in the department of pediatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles, and her associates identified 22 patients who underwent negative physician-supervised baked egg oral challenges from July 2011 until June 2016. They reviewed medical charts to obtain data on age, clinical history, skin prick test results, and results of serum IgE testing to egg and its components. Next, the researchers contacted patients and their families and invited them to participate in a telephone survey about patterns of baked, cooked, and raw egg exposure and associated reactions, following their negative baked challenge. The patients ranged in age from 10 months to 44 years and their mean age was 7 years.

Dr. Peng presented results from 18 of the 22 patients who were successfully contacted. A mean of 26 months had passed since their baked egg oral challenge. Of these patients, 17 (94%) have had continued exposure to egg while 15 (83%) have shown tolerance to cooked egg. The researchers observed variable patterns of baked egg intake following the negative physician-supervised baked egg challenge. “Some patients are able to tolerate cooked egg rapidly but are not interested in continuing frequent consumption,” Dr. Peng said. “They may say, ‘My 3-year-old doesn’t like scrambled eggs, so I’m not going to keep pushing them.’ They’re not considering themselves egg allergic so their quality of life is much better. I understand that tolerating baked egg is a big deal, as an allergist I want to see them do more, such as tolerating cooked egg.”

When patients were asked about adverse reactions to egg consumption, three (17%) described gastrointestinal symptoms, five (28%) described cutaneous symptoms, and three (17%) described respiratory reactions. Dr. Peng noted that of the three patients who have not achieved tolerance to cooked egg, one patient reported mild reaction to baked egg 2 weeks after the baked egg challenge, while the other two continue to have baked egg exposure but have not yet introduced cooked egg into their diets. “I hope that most pediatricians and family practice physicians consider referral to an allergist if they’re not comfortable introducing a baked egg oral challenge.”

The researchers could not identify any correlation between skin prick or serum IgE test results and development of tolerance to cooked egg. “Data in the literature suggests that serum testing is predictive [of tolerance], but it’s not 100%,” Dr. Peng said.

She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE 2017 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Following a negative physician-supervised baked egg oral challenge 94% of patients have had continued exposure to egg while 83% have shown tolerance to cooked egg.

Data source: A retrospective review of 22 patients who underwent a physician-supervised negative oral baked egg challenge.

Disclosures: Dr. Peng reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Oral agent found promising for subset of chronic rhinosinusitis patients

ATLANTA – The use of dexpramipexole by patients with chronic rhinosinusitis was well tolerated and showed robust and tissue eosinophil–lowering activity, according to results from a small study.

Dexpramipexole is an investigational oral agent that has been studied in previous clinical trials for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Calman Prussin, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. The drug did not meet the clinical endpoint for ALS patients, but its investigators noted that it lowered eosinophil counts by about 50%. “It was a serendipitous finding,” said Dr. Prussin, senior director of clinical and translational medicine for Pittsburgh-based Knopp Biosciences. “We do not have a mechanism of action, but we think it’s working on progenitor cells in the bone marrow.”

In all, 16 of the 20 patients completed the trial. Dr. Prussin and his associates found that the baseline eosinophil count fell from 0.525 x 109/L to 0.031 x 109/L at 6 months, a reduction of 94% (P less than.001). “I don’t think any of us expected to see this,” he said, noting that the drug’s maximal eosinophil-lowering effect was maximal after 2 months. No reduction in total polyp score was observed.

Biopsies conducted in 12 of the patients revealed that polyp tissue eosinophilia was reduced from a mean of 233 to 5 eosinophils/high-powered field, a drop of 97% (P = .001). No serious drug-related adverse effects occurred. The most common adverse event was infection (50%), followed by respiratory symptoms (35%) and gastrointestinal disorders (20%).

Knopp Biosciences funded the study. Dr. Prussin is an employee of the company.

ATLANTA – The use of dexpramipexole by patients with chronic rhinosinusitis was well tolerated and showed robust and tissue eosinophil–lowering activity, according to results from a small study.

Dexpramipexole is an investigational oral agent that has been studied in previous clinical trials for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Calman Prussin, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. The drug did not meet the clinical endpoint for ALS patients, but its investigators noted that it lowered eosinophil counts by about 50%. “It was a serendipitous finding,” said Dr. Prussin, senior director of clinical and translational medicine for Pittsburgh-based Knopp Biosciences. “We do not have a mechanism of action, but we think it’s working on progenitor cells in the bone marrow.”

In all, 16 of the 20 patients completed the trial. Dr. Prussin and his associates found that the baseline eosinophil count fell from 0.525 x 109/L to 0.031 x 109/L at 6 months, a reduction of 94% (P less than.001). “I don’t think any of us expected to see this,” he said, noting that the drug’s maximal eosinophil-lowering effect was maximal after 2 months. No reduction in total polyp score was observed.

Biopsies conducted in 12 of the patients revealed that polyp tissue eosinophilia was reduced from a mean of 233 to 5 eosinophils/high-powered field, a drop of 97% (P = .001). No serious drug-related adverse effects occurred. The most common adverse event was infection (50%), followed by respiratory symptoms (35%) and gastrointestinal disorders (20%).

Knopp Biosciences funded the study. Dr. Prussin is an employee of the company.

ATLANTA – The use of dexpramipexole by patients with chronic rhinosinusitis was well tolerated and showed robust and tissue eosinophil–lowering activity, according to results from a small study.

Dexpramipexole is an investigational oral agent that has been studied in previous clinical trials for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Calman Prussin, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. The drug did not meet the clinical endpoint for ALS patients, but its investigators noted that it lowered eosinophil counts by about 50%. “It was a serendipitous finding,” said Dr. Prussin, senior director of clinical and translational medicine for Pittsburgh-based Knopp Biosciences. “We do not have a mechanism of action, but we think it’s working on progenitor cells in the bone marrow.”

In all, 16 of the 20 patients completed the trial. Dr. Prussin and his associates found that the baseline eosinophil count fell from 0.525 x 109/L to 0.031 x 109/L at 6 months, a reduction of 94% (P less than.001). “I don’t think any of us expected to see this,” he said, noting that the drug’s maximal eosinophil-lowering effect was maximal after 2 months. No reduction in total polyp score was observed.

Biopsies conducted in 12 of the patients revealed that polyp tissue eosinophilia was reduced from a mean of 233 to 5 eosinophils/high-powered field, a drop of 97% (P = .001). No serious drug-related adverse effects occurred. The most common adverse event was infection (50%), followed by respiratory symptoms (35%) and gastrointestinal disorders (20%).

Knopp Biosciences funded the study. Dr. Prussin is an employee of the company.

AT THE 2017 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The baseline eosinophil count fell from 0.525 x 109/L to 0.031 x 109/L at 6 months, a reduction of 94% (P less than .001).

Data source: Results from a open-label trial in 16 chronic rhinosinusitis patients who received dexpramipexole 150 mg b.i.d. for 6 months.

Disclosures: Knopp Biosciences funded the study. Dr. Prussin is an employee of the company.

Survey finds chronic rhinosinusitis common, burdensome

ATLANTA – Results from a large cross-sectional survey of adults who meet diagnostic symptom criteria for chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) reveal that most report suffering significant symptoms, high rates of physician visits, and dissatisfaction with current intranasal steroid sprays.

“Chronic rhinosinusitis is common, it’s severe, and people are seeking a lot of medical care,” study author Ramy A. Mahmoud, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. “It’s causing a lot of disruption in their lives, and they’re not satisfied with currently available intranasal steroids.”

In an effort to better characterize the prevalence and burden of illness in adults with symptoms of CRS, Dr. Mahmoud and his associates conducted a population-based survey of 10,336 U.S. adults drawn from a representative general panel of 4.3 million. They recruited participants via websites, email, phone, online communities, and social networks and collected information about nasal symptoms, frequency, duration, and severity/bother of nasal symptoms and health care use and treatments.

The researchers found that almost 12% of survey respondents self-reported symptoms that met diagnostic criteria for CRS. Of these, 63.5% were classified as having severe CRS without known nasal polyps (CRSsNP), 27% had moderate CRSsNP, and 9.6% had CRS with known nasal polyps (CRSwNP). In addition, 87%-99% of patients reported seeing a physician for their symptoms and/or taking a prescription medicine for their CRS symptoms in the past year. In fact, 60% of CRSwNP patients, 58% of severe CRSsNP patients, and 33% of moderate CRSsNP patients said they made more than five physician visits in the past year for nose and sinus symptoms.

The frequency of key CRS symptoms was similar in patients with and without nasal polyps, except that those with severe CRSsNP reported higher rates of facial pain/pressure (in the range of 60%-65%) and loss of smell/taste (46%-56%). The most frequently reported core symptoms were nasal congestion (94%-97%) and drainage (89%-92%). Despite currently available treatment options, up to 46% of CRS patients reported that they remain “extremely” affected by symptoms, and 79% of all CRS patients expressed concern about flare-ups. In addition, a large proportion of respondents expressed frustration with the inadequate symptom relief produced by their current intranasal corticosteroid (87% of CRSwNP patients, 86% of severe CRSsNP patients, and 63% of moderate CRSsNP patients).

Dr. Mahmoud said that the findings indicate a role for more and/or improved treatment options to meet the needs of this patient population. “People who have CRS have it pretty bad,” he said. “Very few people are not seeking a lot of medical care for their symptoms.”

The study was funded by OptiNose.

ATLANTA – Results from a large cross-sectional survey of adults who meet diagnostic symptom criteria for chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) reveal that most report suffering significant symptoms, high rates of physician visits, and dissatisfaction with current intranasal steroid sprays.

“Chronic rhinosinusitis is common, it’s severe, and people are seeking a lot of medical care,” study author Ramy A. Mahmoud, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. “It’s causing a lot of disruption in their lives, and they’re not satisfied with currently available intranasal steroids.”

In an effort to better characterize the prevalence and burden of illness in adults with symptoms of CRS, Dr. Mahmoud and his associates conducted a population-based survey of 10,336 U.S. adults drawn from a representative general panel of 4.3 million. They recruited participants via websites, email, phone, online communities, and social networks and collected information about nasal symptoms, frequency, duration, and severity/bother of nasal symptoms and health care use and treatments.

The researchers found that almost 12% of survey respondents self-reported symptoms that met diagnostic criteria for CRS. Of these, 63.5% were classified as having severe CRS without known nasal polyps (CRSsNP), 27% had moderate CRSsNP, and 9.6% had CRS with known nasal polyps (CRSwNP). In addition, 87%-99% of patients reported seeing a physician for their symptoms and/or taking a prescription medicine for their CRS symptoms in the past year. In fact, 60% of CRSwNP patients, 58% of severe CRSsNP patients, and 33% of moderate CRSsNP patients said they made more than five physician visits in the past year for nose and sinus symptoms.

The frequency of key CRS symptoms was similar in patients with and without nasal polyps, except that those with severe CRSsNP reported higher rates of facial pain/pressure (in the range of 60%-65%) and loss of smell/taste (46%-56%). The most frequently reported core symptoms were nasal congestion (94%-97%) and drainage (89%-92%). Despite currently available treatment options, up to 46% of CRS patients reported that they remain “extremely” affected by symptoms, and 79% of all CRS patients expressed concern about flare-ups. In addition, a large proportion of respondents expressed frustration with the inadequate symptom relief produced by their current intranasal corticosteroid (87% of CRSwNP patients, 86% of severe CRSsNP patients, and 63% of moderate CRSsNP patients).

Dr. Mahmoud said that the findings indicate a role for more and/or improved treatment options to meet the needs of this patient population. “People who have CRS have it pretty bad,” he said. “Very few people are not seeking a lot of medical care for their symptoms.”

The study was funded by OptiNose.

ATLANTA – Results from a large cross-sectional survey of adults who meet diagnostic symptom criteria for chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) reveal that most report suffering significant symptoms, high rates of physician visits, and dissatisfaction with current intranasal steroid sprays.

“Chronic rhinosinusitis is common, it’s severe, and people are seeking a lot of medical care,” study author Ramy A. Mahmoud, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. “It’s causing a lot of disruption in their lives, and they’re not satisfied with currently available intranasal steroids.”

In an effort to better characterize the prevalence and burden of illness in adults with symptoms of CRS, Dr. Mahmoud and his associates conducted a population-based survey of 10,336 U.S. adults drawn from a representative general panel of 4.3 million. They recruited participants via websites, email, phone, online communities, and social networks and collected information about nasal symptoms, frequency, duration, and severity/bother of nasal symptoms and health care use and treatments.

The researchers found that almost 12% of survey respondents self-reported symptoms that met diagnostic criteria for CRS. Of these, 63.5% were classified as having severe CRS without known nasal polyps (CRSsNP), 27% had moderate CRSsNP, and 9.6% had CRS with known nasal polyps (CRSwNP). In addition, 87%-99% of patients reported seeing a physician for their symptoms and/or taking a prescription medicine for their CRS symptoms in the past year. In fact, 60% of CRSwNP patients, 58% of severe CRSsNP patients, and 33% of moderate CRSsNP patients said they made more than five physician visits in the past year for nose and sinus symptoms.

The frequency of key CRS symptoms was similar in patients with and without nasal polyps, except that those with severe CRSsNP reported higher rates of facial pain/pressure (in the range of 60%-65%) and loss of smell/taste (46%-56%). The most frequently reported core symptoms were nasal congestion (94%-97%) and drainage (89%-92%). Despite currently available treatment options, up to 46% of CRS patients reported that they remain “extremely” affected by symptoms, and 79% of all CRS patients expressed concern about flare-ups. In addition, a large proportion of respondents expressed frustration with the inadequate symptom relief produced by their current intranasal corticosteroid (87% of CRSwNP patients, 86% of severe CRSsNP patients, and 63% of moderate CRSsNP patients).

Dr. Mahmoud said that the findings indicate a role for more and/or improved treatment options to meet the needs of this patient population. “People who have CRS have it pretty bad,” he said. “Very few people are not seeking a lot of medical care for their symptoms.”

The study was funded by OptiNose.

AT 2017 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Nearly 12% of survey respondents self-reported symptoms that met diagnostic criteria for CRS.

Data source: A population-based survey of 10,336 US adults drawn from a representative general panel of 4.3 million.

Disclosures: The study was funded by OptiNose.

Uptick found in severe allergy shot reactions

ATLANTA – Systemic reactions against subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy have trended down overall in recent years, but there has been an uptick in reports of severe grade 4 reactions for reasons that are not yet clear, according to a review of 46.6 million injection office visits from 2008-2015.

The data come from annual surveys of members of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, of whom 27%-51% responded each year.

However, on surveys from 2013 to 2015, one grade 4 reaction – hypotension or respiratory failure – was reported for every 160,000 injection visits, up from one per million office visits in previous years. Two-thirds (152/252) of grade 3/4 systemic reactions (SRs) for 2014-2015 occurred in asthmatics. Among the three fatalities directly linked to allergy shots since 2008, all of them occurred in adults; two patients had asthma. The findings highlight the need for good asthma control before shots begin, with a forced expiratory volume of at least 70% in 1 second (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 Feb;139[2]:AB377).

“Asthma remains a major risk factor for severe SRs... [It’s something] allergists need to be vigilant about,” said lead investigator Tolly Epstein, MD, an assistant professor of immunology at the University of Cincinnati.

It’s unclear if there has been a true increase in severe reactions, or simply better reporting of them since the reaction grading system started being used a few years ago. “I was surprised a little bit to see the uptick in severe systemic reactions, but I am not sure if it’s real yet,” Dr. Epstein said. She and her colleagues are collecting more data on the reports of severe reactions.

Dr. Epstein and her colleagues found in previous work that higher maintenance doses may increase the risk of SRs. The right balance between efficacy and safety is still being worked out, she said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The surveys started collecting data on infections from allergy shots in 2014, amid concerns about contaminants in compounded medications. The fact that none were reported probably isn’t a surprise to allergists, but it might be news to others who have raised concerns about the possibility, Dr. Epstein said.

Overall safety was good for sublingual allergen immunotherapy, first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2014. One of the grade 3 reactions was pharyngeal edema; the other involved throat tightening and lower respiratory symptoms.

One of the asthma patients who died was morbidly obese and under treatment for weed allergies during pollen season, and died from overwhelming laryngeal edema. The patient’s weight made IV access difficult. The other asthma patient had severe disease, and was on the maximum dose of fluticasone/salmeterol. He was on an accelerated buildup for dust mites, pollen, mold, and other allergies, and apparently died of asthma complications triggered by the shots. There were no known risk factors in the third death.

Mortalities are lower than they used to be in the past with allergy shots, Dr. Epstein said.

She said she had no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

ATLANTA – Systemic reactions against subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy have trended down overall in recent years, but there has been an uptick in reports of severe grade 4 reactions for reasons that are not yet clear, according to a review of 46.6 million injection office visits from 2008-2015.

The data come from annual surveys of members of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, of whom 27%-51% responded each year.

However, on surveys from 2013 to 2015, one grade 4 reaction – hypotension or respiratory failure – was reported for every 160,000 injection visits, up from one per million office visits in previous years. Two-thirds (152/252) of grade 3/4 systemic reactions (SRs) for 2014-2015 occurred in asthmatics. Among the three fatalities directly linked to allergy shots since 2008, all of them occurred in adults; two patients had asthma. The findings highlight the need for good asthma control before shots begin, with a forced expiratory volume of at least 70% in 1 second (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 Feb;139[2]:AB377).

“Asthma remains a major risk factor for severe SRs... [It’s something] allergists need to be vigilant about,” said lead investigator Tolly Epstein, MD, an assistant professor of immunology at the University of Cincinnati.

It’s unclear if there has been a true increase in severe reactions, or simply better reporting of them since the reaction grading system started being used a few years ago. “I was surprised a little bit to see the uptick in severe systemic reactions, but I am not sure if it’s real yet,” Dr. Epstein said. She and her colleagues are collecting more data on the reports of severe reactions.

Dr. Epstein and her colleagues found in previous work that higher maintenance doses may increase the risk of SRs. The right balance between efficacy and safety is still being worked out, she said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The surveys started collecting data on infections from allergy shots in 2014, amid concerns about contaminants in compounded medications. The fact that none were reported probably isn’t a surprise to allergists, but it might be news to others who have raised concerns about the possibility, Dr. Epstein said.

Overall safety was good for sublingual allergen immunotherapy, first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2014. One of the grade 3 reactions was pharyngeal edema; the other involved throat tightening and lower respiratory symptoms.

One of the asthma patients who died was morbidly obese and under treatment for weed allergies during pollen season, and died from overwhelming laryngeal edema. The patient’s weight made IV access difficult. The other asthma patient had severe disease, and was on the maximum dose of fluticasone/salmeterol. He was on an accelerated buildup for dust mites, pollen, mold, and other allergies, and apparently died of asthma complications triggered by the shots. There were no known risk factors in the third death.

Mortalities are lower than they used to be in the past with allergy shots, Dr. Epstein said.

She said she had no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

ATLANTA – Systemic reactions against subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy have trended down overall in recent years, but there has been an uptick in reports of severe grade 4 reactions for reasons that are not yet clear, according to a review of 46.6 million injection office visits from 2008-2015.

The data come from annual surveys of members of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, of whom 27%-51% responded each year.

However, on surveys from 2013 to 2015, one grade 4 reaction – hypotension or respiratory failure – was reported for every 160,000 injection visits, up from one per million office visits in previous years. Two-thirds (152/252) of grade 3/4 systemic reactions (SRs) for 2014-2015 occurred in asthmatics. Among the three fatalities directly linked to allergy shots since 2008, all of them occurred in adults; two patients had asthma. The findings highlight the need for good asthma control before shots begin, with a forced expiratory volume of at least 70% in 1 second (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 Feb;139[2]:AB377).

“Asthma remains a major risk factor for severe SRs... [It’s something] allergists need to be vigilant about,” said lead investigator Tolly Epstein, MD, an assistant professor of immunology at the University of Cincinnati.

It’s unclear if there has been a true increase in severe reactions, or simply better reporting of them since the reaction grading system started being used a few years ago. “I was surprised a little bit to see the uptick in severe systemic reactions, but I am not sure if it’s real yet,” Dr. Epstein said. She and her colleagues are collecting more data on the reports of severe reactions.

Dr. Epstein and her colleagues found in previous work that higher maintenance doses may increase the risk of SRs. The right balance between efficacy and safety is still being worked out, she said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The surveys started collecting data on infections from allergy shots in 2014, amid concerns about contaminants in compounded medications. The fact that none were reported probably isn’t a surprise to allergists, but it might be news to others who have raised concerns about the possibility, Dr. Epstein said.

Overall safety was good for sublingual allergen immunotherapy, first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2014. One of the grade 3 reactions was pharyngeal edema; the other involved throat tightening and lower respiratory symptoms.

One of the asthma patients who died was morbidly obese and under treatment for weed allergies during pollen season, and died from overwhelming laryngeal edema. The patient’s weight made IV access difficult. The other asthma patient had severe disease, and was on the maximum dose of fluticasone/salmeterol. He was on an accelerated buildup for dust mites, pollen, mold, and other allergies, and apparently died of asthma complications triggered by the shots. There were no known risk factors in the third death.

Mortalities are lower than they used to be in the past with allergy shots, Dr. Epstein said.

She said she had no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

AT THE 2017 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: for reasons that are not yet clear, according to a review of 46.6 million injection office visits from 2008-2015.

Major finding: On surveys from 2013 to 2015, one grade 4 reaction – hypotension or respiratory failure – was reported for every 160,000 injection visits, up from one per million office visits in previous years. Two-thirds (152/252) of grade 3/4 systemic reactions for 2014-2015 occurred in patients with asthma.

Data source: Allergist surveys from 2008 to 2015.

Disclosures: The lead investigator said she had no relevant disclosures.

Lanadelumab reduced hereditary angioedema attacks by 88%-100%

Lanadelumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits kallikrein, reduced attacks of hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency by 88%-100% in a small, phase I trial.

Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency is a rare disorder characterized by unpredictable, recurrent, and potentially life-threatening episodes of subcutaneous or submucosal swelling, typically affecting the hands and feet, abdomen, face, larynx, or genitourinary tract. It is caused by a deficiency or dysfunction of the C1 inhibitor, which regulates the complement, coagulation, and kallikrein-kinin cascades.

They performed a multicenter, double-blind, randomized study to assess the safety and adverse-effect profile of four doses of this new agent or placebo in 37 adults (aged 18-71 years, mean age, 39.9 years) who received two injections, 2 weeks apart, and were followed for 6 weeks. Given their histories, all the study participants had “a reasonable probability of having one or more attacks” during the study period, the researchers noted.

Four participants received a 30-mg dose, 4 received a 100-mg dose, 5 received a 300-mg dose, 11 received a 400-mg dose, and 13 received placebo.

There were no serious adverse events, no deaths, and no discontinuations of the study medication because of an adverse effect. One patient each developed severe adverse events: pain at the injection site that lasted for 1 minute and headache plus night sweats.

Pharmacodynamic assessments showed that lanadelumab inhibited kallikrein in a linear, dose-dependent manner, and the two higher doses reduced levels of cleaved high-molecular-weight kininogen to those reported in healthy control subjects. At the same time, the two higher doses decreased the number of attacks by 88% and 100%, respectively, compared with placebo.

All the patients in the 300-mg group and 9 of the 11 in the 400-mg group had no attacks during the study period, the investigators said.

These findings “provide proof of concept that lanadelumab has the potential to correct the pathophysiological abnormality underlying attacks of angioedema and may be a new therapeutic option for hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency,” Dr. Banerji and her associates said.

The HELP Study, a phase III trial assessing the safety and efficacy of 6 months of lanadelumab treatment, is now underway, they added.

The trial was sponsored by Dyax, which also participated in the study design, data collection and interpretation, and writing of the results. Dr. Banerji reported ties to Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, CSL Behring, Dyax, and Shire; her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

This preliminary study suggests that a new agent, in injections that would be convenient and widely accessible, could provide an unprecedented level of protection against angioedema.

If these findings are confirmed, and if lanadelumab is affordable, it could transform the way hereditary angioedema is managed and the life prospects for affected families.

Moreover, kallikrein is implicated in other forms of bradykinin-mediated angioedema, such as that associated with ACE inhibitors, and plays a key role in the generation of inflammation and pain. So, the sustained inhibition of kallikrein potentially could be beneficial for a much wider range of disorders.

Hilary J. Longhurst, MD, is at Barts Health National Health Service Trust, London. She reported having ties to BioCryst, CSL Behring, and Shire. Dr. Longhurst made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Banerji’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 23;376[8]:788-9).

This preliminary study suggests that a new agent, in injections that would be convenient and widely accessible, could provide an unprecedented level of protection against angioedema.

If these findings are confirmed, and if lanadelumab is affordable, it could transform the way hereditary angioedema is managed and the life prospects for affected families.

Moreover, kallikrein is implicated in other forms of bradykinin-mediated angioedema, such as that associated with ACE inhibitors, and plays a key role in the generation of inflammation and pain. So, the sustained inhibition of kallikrein potentially could be beneficial for a much wider range of disorders.

Hilary J. Longhurst, MD, is at Barts Health National Health Service Trust, London. She reported having ties to BioCryst, CSL Behring, and Shire. Dr. Longhurst made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Banerji’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 23;376[8]:788-9).

This preliminary study suggests that a new agent, in injections that would be convenient and widely accessible, could provide an unprecedented level of protection against angioedema.

If these findings are confirmed, and if lanadelumab is affordable, it could transform the way hereditary angioedema is managed and the life prospects for affected families.

Moreover, kallikrein is implicated in other forms of bradykinin-mediated angioedema, such as that associated with ACE inhibitors, and plays a key role in the generation of inflammation and pain. So, the sustained inhibition of kallikrein potentially could be beneficial for a much wider range of disorders.

Hilary J. Longhurst, MD, is at Barts Health National Health Service Trust, London. She reported having ties to BioCryst, CSL Behring, and Shire. Dr. Longhurst made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Banerji’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 23;376[8]:788-9).

Lanadelumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits kallikrein, reduced attacks of hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency by 88%-100% in a small, phase I trial.

Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency is a rare disorder characterized by unpredictable, recurrent, and potentially life-threatening episodes of subcutaneous or submucosal swelling, typically affecting the hands and feet, abdomen, face, larynx, or genitourinary tract. It is caused by a deficiency or dysfunction of the C1 inhibitor, which regulates the complement, coagulation, and kallikrein-kinin cascades.

They performed a multicenter, double-blind, randomized study to assess the safety and adverse-effect profile of four doses of this new agent or placebo in 37 adults (aged 18-71 years, mean age, 39.9 years) who received two injections, 2 weeks apart, and were followed for 6 weeks. Given their histories, all the study participants had “a reasonable probability of having one or more attacks” during the study period, the researchers noted.

Four participants received a 30-mg dose, 4 received a 100-mg dose, 5 received a 300-mg dose, 11 received a 400-mg dose, and 13 received placebo.

There were no serious adverse events, no deaths, and no discontinuations of the study medication because of an adverse effect. One patient each developed severe adverse events: pain at the injection site that lasted for 1 minute and headache plus night sweats.

Pharmacodynamic assessments showed that lanadelumab inhibited kallikrein in a linear, dose-dependent manner, and the two higher doses reduced levels of cleaved high-molecular-weight kininogen to those reported in healthy control subjects. At the same time, the two higher doses decreased the number of attacks by 88% and 100%, respectively, compared with placebo.

All the patients in the 300-mg group and 9 of the 11 in the 400-mg group had no attacks during the study period, the investigators said.

These findings “provide proof of concept that lanadelumab has the potential to correct the pathophysiological abnormality underlying attacks of angioedema and may be a new therapeutic option for hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency,” Dr. Banerji and her associates said.

The HELP Study, a phase III trial assessing the safety and efficacy of 6 months of lanadelumab treatment, is now underway, they added.

The trial was sponsored by Dyax, which also participated in the study design, data collection and interpretation, and writing of the results. Dr. Banerji reported ties to Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, CSL Behring, Dyax, and Shire; her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Lanadelumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits kallikrein, reduced attacks of hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency by 88%-100% in a small, phase I trial.

Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency is a rare disorder characterized by unpredictable, recurrent, and potentially life-threatening episodes of subcutaneous or submucosal swelling, typically affecting the hands and feet, abdomen, face, larynx, or genitourinary tract. It is caused by a deficiency or dysfunction of the C1 inhibitor, which regulates the complement, coagulation, and kallikrein-kinin cascades.

They performed a multicenter, double-blind, randomized study to assess the safety and adverse-effect profile of four doses of this new agent or placebo in 37 adults (aged 18-71 years, mean age, 39.9 years) who received two injections, 2 weeks apart, and were followed for 6 weeks. Given their histories, all the study participants had “a reasonable probability of having one or more attacks” during the study period, the researchers noted.

Four participants received a 30-mg dose, 4 received a 100-mg dose, 5 received a 300-mg dose, 11 received a 400-mg dose, and 13 received placebo.

There were no serious adverse events, no deaths, and no discontinuations of the study medication because of an adverse effect. One patient each developed severe adverse events: pain at the injection site that lasted for 1 minute and headache plus night sweats.

Pharmacodynamic assessments showed that lanadelumab inhibited kallikrein in a linear, dose-dependent manner, and the two higher doses reduced levels of cleaved high-molecular-weight kininogen to those reported in healthy control subjects. At the same time, the two higher doses decreased the number of attacks by 88% and 100%, respectively, compared with placebo.

All the patients in the 300-mg group and 9 of the 11 in the 400-mg group had no attacks during the study period, the investigators said.

These findings “provide proof of concept that lanadelumab has the potential to correct the pathophysiological abnormality underlying attacks of angioedema and may be a new therapeutic option for hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency,” Dr. Banerji and her associates said.

The HELP Study, a phase III trial assessing the safety and efficacy of 6 months of lanadelumab treatment, is now underway, they added.

The trial was sponsored by Dyax, which also participated in the study design, data collection and interpretation, and writing of the results. Dr. Banerji reported ties to Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, CSL Behring, Dyax, and Shire; her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Lanadelumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits kallikrein, reduced attacks of hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency by 88%-100%.

Major finding: All the patients in the 300-mg group and 9 of the 11 in the 400-mg group had no angioedema attacks during the study period.

Data source: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase Ib trial involving 37 adults who had hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency.

Disclosures: The trial was sponsored by Dyax, which also participated in the study design, data collection and interpretation, and writing the results. Dr. Banerji reported ties to Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, CSL Behring, Dyax, and Shire; her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Adverse event reporting in second-dose varicella vaccination shows no surprises

No new or unexpected adverse events were reported in association with second-dose varicella vaccination in children age 4-18 years during 2006-2014.

During the study period of 2006-2014, 14,641 reports regarding second-dose varicella vaccinations were made to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, according to John Su, MD, PhD, and his associates. Of these reports, only 3% were serious adverse events (AE), with the most common nonserious AE being injection-site reaction, which occurred in 48% of patients age 4-6 years reporting AEs, and in 38% of patients age 7-18 years reporting AEs.

Of the 494 serious AEs reported, pyrexia was the most common in children age 4-6 years, and headache and vomiting were the most common in children age 7-18 years. A total of seven deaths from various causes were reported, though no causal relation to vaccination was seen, and significant chronic medical problems were common in these children.

“The safety data on second-dose varicella vaccination are reassuring,” the investigators noted. “Reported AEs after second-dose varicella vaccination were mild, self limiting, and similar in reported frequency to AEs after first-dose vaccination, with no new or unexpected safety concerns.”

Find the full study in Pediatrics (2017 Feb 7. doi: 1542/peds.2016-2536).

No new or unexpected adverse events were reported in association with second-dose varicella vaccination in children age 4-18 years during 2006-2014.

During the study period of 2006-2014, 14,641 reports regarding second-dose varicella vaccinations were made to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, according to John Su, MD, PhD, and his associates. Of these reports, only 3% were serious adverse events (AE), with the most common nonserious AE being injection-site reaction, which occurred in 48% of patients age 4-6 years reporting AEs, and in 38% of patients age 7-18 years reporting AEs.

Of the 494 serious AEs reported, pyrexia was the most common in children age 4-6 years, and headache and vomiting were the most common in children age 7-18 years. A total of seven deaths from various causes were reported, though no causal relation to vaccination was seen, and significant chronic medical problems were common in these children.

“The safety data on second-dose varicella vaccination are reassuring,” the investigators noted. “Reported AEs after second-dose varicella vaccination were mild, self limiting, and similar in reported frequency to AEs after first-dose vaccination, with no new or unexpected safety concerns.”

Find the full study in Pediatrics (2017 Feb 7. doi: 1542/peds.2016-2536).

No new or unexpected adverse events were reported in association with second-dose varicella vaccination in children age 4-18 years during 2006-2014.

During the study period of 2006-2014, 14,641 reports regarding second-dose varicella vaccinations were made to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, according to John Su, MD, PhD, and his associates. Of these reports, only 3% were serious adverse events (AE), with the most common nonserious AE being injection-site reaction, which occurred in 48% of patients age 4-6 years reporting AEs, and in 38% of patients age 7-18 years reporting AEs.

Of the 494 serious AEs reported, pyrexia was the most common in children age 4-6 years, and headache and vomiting were the most common in children age 7-18 years. A total of seven deaths from various causes were reported, though no causal relation to vaccination was seen, and significant chronic medical problems were common in these children.

“The safety data on second-dose varicella vaccination are reassuring,” the investigators noted. “Reported AEs after second-dose varicella vaccination were mild, self limiting, and similar in reported frequency to AEs after first-dose vaccination, with no new or unexpected safety concerns.”

Find the full study in Pediatrics (2017 Feb 7. doi: 1542/peds.2016-2536).

Erythematous patches with keratotic annular borders on the glans penis

A 31-year-old man presented to the emergency department with meatal inflammation, dysuria, and mucopurulent penile discharge, diagnosed as urethritis and treated empirically with levofloxacin. He was referred to the genitourinary medicine clinic for a full screening for sexually transmitted disease. The results were negative.

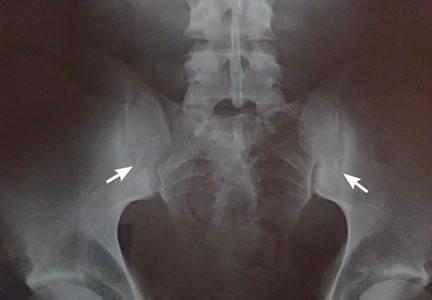

Two months later, he returned with pain and redness in his left eye and inflammatory lumbar pain. The glans penis had small pustules that ruptured, leaving painless superficial erosions that coalesced to form a serpiginous pattern (Figure 1). Radiography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed features of grade 3 bilateral sacroiliitis (Figure 2): subchondral sclerosis of both sacral and iliac articular margins (predominantly on the iliac side), erosions, reduced articular space, widening of the joint space, and incipient ankylosis. A diagnosis of reactive arthritis was made based on the presence of urethritis, ocular symptoms, circinate balanitis, and radiologic evidence of sacroiliitis. In addition, the chronic inflammatory back pain and bilateral sacroiliitis indicated developing ankylosing spondylitis according to the modified New York criteria.

Our patient’s circinate balanitis resolved with hydrocortisone cream, and treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug brought improvement of the joint symptoms.

THE MANY FEATURES OF REACTIVE ARTHRITIS

The American Rheumatology Association diagnostic criteria for reactive arthritis include asymmetric arthritis that lasts at least 1 month and at least one of the following symptoms: urethritis, inflammatory eye disease, mouth ulcers, circinate balanitis, and radiographic evidence of sarcoiliitis, periostitis, or heel spurs.1,2

Keratoderma blennorrhagicum is another extra-articular manifestation. These symptoms typically start within 1 to 6 weeks after urogenital infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or gastrointestinal infection with Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, or Campylobacter species.1–3

There is great variation in the severity, number, and timing of clinical features in reactive arthritis. The diagnosis can be difficult because only about one-third of patients show the complete classic triad (conjunctivitis, urethritis, arthritis). HLA-B27 positivity is associated with more frequent skin lesions and axial involvement.4,5

- Wu IB, Schwartz RA. Reiter’s syndrome: the classic triad and more. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59:113–121.

- Koga T, Miyashita T, Watanabe T, et al. Reactive arthritis which occurred one year after acute chlamydial urethritis. Intern Med 2008; 47:663–666.

- Carter JD. Treating reactive arthritis: insights for the clinician. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2010; 2:45–54.

- Willkens RF, Arnett FC, Bitter T, et al. Reiter’s syndrome: evaluation of preliminary criteria for definite disease. Arthritis Rheum 1981; 24:844–849.

- Bakkour W, Chularojanamontri L, Motta L, Chalmers RJ. Successful use of dapsone for the management of circinate balanitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2014; 39:333–335.

A 31-year-old man presented to the emergency department with meatal inflammation, dysuria, and mucopurulent penile discharge, diagnosed as urethritis and treated empirically with levofloxacin. He was referred to the genitourinary medicine clinic for a full screening for sexually transmitted disease. The results were negative.

Two months later, he returned with pain and redness in his left eye and inflammatory lumbar pain. The glans penis had small pustules that ruptured, leaving painless superficial erosions that coalesced to form a serpiginous pattern (Figure 1). Radiography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed features of grade 3 bilateral sacroiliitis (Figure 2): subchondral sclerosis of both sacral and iliac articular margins (predominantly on the iliac side), erosions, reduced articular space, widening of the joint space, and incipient ankylosis. A diagnosis of reactive arthritis was made based on the presence of urethritis, ocular symptoms, circinate balanitis, and radiologic evidence of sacroiliitis. In addition, the chronic inflammatory back pain and bilateral sacroiliitis indicated developing ankylosing spondylitis according to the modified New York criteria.

Our patient’s circinate balanitis resolved with hydrocortisone cream, and treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug brought improvement of the joint symptoms.

THE MANY FEATURES OF REACTIVE ARTHRITIS

The American Rheumatology Association diagnostic criteria for reactive arthritis include asymmetric arthritis that lasts at least 1 month and at least one of the following symptoms: urethritis, inflammatory eye disease, mouth ulcers, circinate balanitis, and radiographic evidence of sarcoiliitis, periostitis, or heel spurs.1,2

Keratoderma blennorrhagicum is another extra-articular manifestation. These symptoms typically start within 1 to 6 weeks after urogenital infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or gastrointestinal infection with Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, or Campylobacter species.1–3

There is great variation in the severity, number, and timing of clinical features in reactive arthritis. The diagnosis can be difficult because only about one-third of patients show the complete classic triad (conjunctivitis, urethritis, arthritis). HLA-B27 positivity is associated with more frequent skin lesions and axial involvement.4,5

A 31-year-old man presented to the emergency department with meatal inflammation, dysuria, and mucopurulent penile discharge, diagnosed as urethritis and treated empirically with levofloxacin. He was referred to the genitourinary medicine clinic for a full screening for sexually transmitted disease. The results were negative.

Two months later, he returned with pain and redness in his left eye and inflammatory lumbar pain. The glans penis had small pustules that ruptured, leaving painless superficial erosions that coalesced to form a serpiginous pattern (Figure 1). Radiography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed features of grade 3 bilateral sacroiliitis (Figure 2): subchondral sclerosis of both sacral and iliac articular margins (predominantly on the iliac side), erosions, reduced articular space, widening of the joint space, and incipient ankylosis. A diagnosis of reactive arthritis was made based on the presence of urethritis, ocular symptoms, circinate balanitis, and radiologic evidence of sacroiliitis. In addition, the chronic inflammatory back pain and bilateral sacroiliitis indicated developing ankylosing spondylitis according to the modified New York criteria.

Our patient’s circinate balanitis resolved with hydrocortisone cream, and treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug brought improvement of the joint symptoms.

THE MANY FEATURES OF REACTIVE ARTHRITIS

The American Rheumatology Association diagnostic criteria for reactive arthritis include asymmetric arthritis that lasts at least 1 month and at least one of the following symptoms: urethritis, inflammatory eye disease, mouth ulcers, circinate balanitis, and radiographic evidence of sarcoiliitis, periostitis, or heel spurs.1,2

Keratoderma blennorrhagicum is another extra-articular manifestation. These symptoms typically start within 1 to 6 weeks after urogenital infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or gastrointestinal infection with Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, or Campylobacter species.1–3

There is great variation in the severity, number, and timing of clinical features in reactive arthritis. The diagnosis can be difficult because only about one-third of patients show the complete classic triad (conjunctivitis, urethritis, arthritis). HLA-B27 positivity is associated with more frequent skin lesions and axial involvement.4,5

- Wu IB, Schwartz RA. Reiter’s syndrome: the classic triad and more. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59:113–121.

- Koga T, Miyashita T, Watanabe T, et al. Reactive arthritis which occurred one year after acute chlamydial urethritis. Intern Med 2008; 47:663–666.

- Carter JD. Treating reactive arthritis: insights for the clinician. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2010; 2:45–54.

- Willkens RF, Arnett FC, Bitter T, et al. Reiter’s syndrome: evaluation of preliminary criteria for definite disease. Arthritis Rheum 1981; 24:844–849.

- Bakkour W, Chularojanamontri L, Motta L, Chalmers RJ. Successful use of dapsone for the management of circinate balanitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2014; 39:333–335.

- Wu IB, Schwartz RA. Reiter’s syndrome: the classic triad and more. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59:113–121.

- Koga T, Miyashita T, Watanabe T, et al. Reactive arthritis which occurred one year after acute chlamydial urethritis. Intern Med 2008; 47:663–666.

- Carter JD. Treating reactive arthritis: insights for the clinician. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2010; 2:45–54.

- Willkens RF, Arnett FC, Bitter T, et al. Reiter’s syndrome: evaluation of preliminary criteria for definite disease. Arthritis Rheum 1981; 24:844–849.

- Bakkour W, Chularojanamontri L, Motta L, Chalmers RJ. Successful use of dapsone for the management of circinate balanitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2014; 39:333–335.

A rose by any other name is still a rose—but why a rose?

Christopher Columbus, age 41, returned to Europe from his first voyage to the New World suffering from what would turn out to be a chronic illness that included recurrent febrile bouts of severe lower-extremity arthritis. For many years he was thought to have had gout, but careful reanalysis led Allison1 and then Arnett et al2 to propose an alternative diagnosis. Based on the pattern of Columbus’s arthritis and the accompanying symptoms, which these clinicians linked to the arthritis, they proposed the diagnosis of reactive arthritis—actually a subset of reactive arthritis, which at the time of their publications was called Reiter’s syndrome. Arnett discussed this extensively at a historic clinicopathologic conference, noting that the bouts of arthritis were prolonged (too long for typical gout) and that the historically described recurrent episodes of red (“bleeding”) eyes with intermittent “blindness” and ultimate immobility due to spine pain (arthritis) would not be typical of gout. Arnett et al recognized the pattern of this arthritis—lower-extremity-predominant with prolonged episodes, associated inflammatory eye disease, spine involvement, and the protracted course of nearly a decade—as far more typical of a reactive arthritis than gout (or ongoing bacterial infection), occurring in a likely HLA-B27-positive individual. They proposed that the probable trigger for the arthritis was an episode of food-borne bacterial infection acquired during the extensive transatlantic journey.

Fast forward about 470 years to an epidemic aboard a US Navy ship of Shigella-associated dysentery that was accompanied by readily diagnosed reactive arthritis.3 Several diarrheal epidemics with associated reactive arthritis aboard cruise ships have been described, and the association is well documented following Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, and nondiarrheal chlamydial infections.

In this issue of the Journal, Gómez-Moyano et al present images of a patient with dermatologic features of reactive arthritis. I have two points to make in introducing this historical background. First, I want to highlight some features of this syndrome that are distinctive enough as a clinical pattern to enable a diagnosis by appearance alone or, as in the case of Columbus, by historical description alone. But second and more important, I wonder, as perhaps you do, why similar inflammatory features occur in patients of seemingly diverse backgrounds, triggered by different organisms that may have infected different mucosal areas. Why does this rose look like a rose and not a gardenia?

Reactive arthritis is classically thought of as self-limited, lasting less than 6 months. But a significant minority of patients may have chronic disease, particularly with spondylitis, which may be more common in patients who have the HLA-B27 haplotype. The peripheral arthritis generally affects relatively few joints, with the larger lower-extremity joints a common target. Enthesitis, especially at the Achilles tendon heel insertion, is common, and dactylitis or “sausage digits” can occur. These features may also be seen in patients with psoriatic or enteropathic arthritis. Inflammation of the skin (as shown by Gómez-Moyano et al), the eye (conjunctivitis, uveitis, episcleritis), oral mucosa, and the genitourinary tract (urethritis, prostatitis) can also occur. Urethritis can occur in patients with enteric diarrhea as the trigger; thus, it is not just associated with genitourinary infections like chlamydia. What all these sites have in common to be targeted following an infection is not known with certainty; relevant bacterial antigens cannot always be detected in the involved tissues. It is intriguing that transgenic rats engineered to contain many copies of the human HLA-B27 gene develop arthritis along with mucosal, eye, and skin inflammation, which can be avoided if the animals are raised in a germ-free environment. But probably fewer than 50% of patients with reactive arthritis have the B27 gene, so other factors must contribute to this uncommon syndrome. B27 is thus not a generally useful diagnostic test.

When a patient presents with acute inflammatory asymmetric oligoarthritis (affecting < 4 joints), infectious arthritis and crystal-induced arthritis need to be excluded. But looking for and finding other features more typical of reactive arthritis may spare the patient a more extensive and expensive inpatient evaluation.

Recognizing a rose can provide an aesthetic moment, even if we can’t define exactly what makes it a rose. Pattern recognition matters in clinical practice, even without full understanding of the molecular backdrop.

- Allison DJ. Christopher Columbus: first case of Reiter’s disease in the Old World? Lancet 1980; 2:1309.

- Arnett FC, Merrill C, Albardaner F, Mackowiak PA. A mariner with crippling arthritis and bleeding eyes. Am J Med Sci 2006; 332:123–130.

- Noer HR. An “experimental” epidemic of Reiter’s syndrome. JAMA 1966; 198:693–698.

Christopher Columbus, age 41, returned to Europe from his first voyage to the New World suffering from what would turn out to be a chronic illness that included recurrent febrile bouts of severe lower-extremity arthritis. For many years he was thought to have had gout, but careful reanalysis led Allison1 and then Arnett et al2 to propose an alternative diagnosis. Based on the pattern of Columbus’s arthritis and the accompanying symptoms, which these clinicians linked to the arthritis, they proposed the diagnosis of reactive arthritis—actually a subset of reactive arthritis, which at the time of their publications was called Reiter’s syndrome. Arnett discussed this extensively at a historic clinicopathologic conference, noting that the bouts of arthritis were prolonged (too long for typical gout) and that the historically described recurrent episodes of red (“bleeding”) eyes with intermittent “blindness” and ultimate immobility due to spine pain (arthritis) would not be typical of gout. Arnett et al recognized the pattern of this arthritis—lower-extremity-predominant with prolonged episodes, associated inflammatory eye disease, spine involvement, and the protracted course of nearly a decade—as far more typical of a reactive arthritis than gout (or ongoing bacterial infection), occurring in a likely HLA-B27-positive individual. They proposed that the probable trigger for the arthritis was an episode of food-borne bacterial infection acquired during the extensive transatlantic journey.

Fast forward about 470 years to an epidemic aboard a US Navy ship of Shigella-associated dysentery that was accompanied by readily diagnosed reactive arthritis.3 Several diarrheal epidemics with associated reactive arthritis aboard cruise ships have been described, and the association is well documented following Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, and nondiarrheal chlamydial infections.

In this issue of the Journal, Gómez-Moyano et al present images of a patient with dermatologic features of reactive arthritis. I have two points to make in introducing this historical background. First, I want to highlight some features of this syndrome that are distinctive enough as a clinical pattern to enable a diagnosis by appearance alone or, as in the case of Columbus, by historical description alone. But second and more important, I wonder, as perhaps you do, why similar inflammatory features occur in patients of seemingly diverse backgrounds, triggered by different organisms that may have infected different mucosal areas. Why does this rose look like a rose and not a gardenia?